«Sheger» redirects here. For Irish-bred Thoroughbred racehorse, see Shergar.

|

Addis Ababa

|

|

|---|---|

|

Capital and chartered city |

|

|

From top, left to right: Skyline of Meskel Square; Monument to the Lion of Judah; St. George’s Cathedral; Addis Ababa University; Sheraton Addis; Sheger Park; Addis Ababa Light Rail Vehicle and Holy Trinity Cathedral |

|

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nicknames:

City of Humans, Sheger, Adu Genet |

|

|

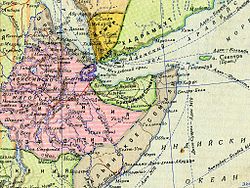

Addis Ababa Location within Ethiopia Addis Ababa Location within the Horn of Africa Addis Ababa Location within Africa |

|

| Coordinates: 9°1′48″N 38°44′24″E / 9.03000°N 38.74000°ECoordinates: 9°1′48″N 38°44′24″E / 9.03000°N 38.74000°E | |

| Country | |

| Founded | 1886 |

| Incorporated as capital city | 1889 |

| Founded by |

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Adanech Abebe |

| Area | |

| • Total | 527 km2 (203 sq mi) |

| • Land | 527 km2 (203 sq mi) |

| [1] | |

| Elevation | 2,355 m (7,726 ft) |

| Population

(2007)[2] |

|

| • Total | 2,739,551 |

| • Estimate

(2021)[3] |

3,774,000 |

| • Density | 5,165.1/km2 (13,378/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Addis Ababan |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (East Africa Time) |

| Area code | (+251) 11 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.722[4] High · 1st of 11 |

| Website | cityaddisababa.gov.et |

Addis Ababa (;[5] Amharic: አዲስ አበባ, lit. ‘new flower’ [adˈdis ˈabəba] (listen)) is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia.[6][7][8] In the 2007 census, the city’s population was estimated to be 2,739,551 inhabitants.[2] Addis Ababa is a highly developed and important cultural, artistic, financial and administrative centre of Ethiopia.[9]

Addis Ababa was portrayed in the 15th century as a fortified location called «Barara» that housed the emperors of Ethiopia at the time. Prior to Emperor Dawit II, Barara was completely destroyed during the Ethiopian–Adal War and Oromo expansions. The founding history of Addis Ababa dates back in late 19th-century by Menelik II, Negus of Shewa, in 1886 after finding Mount Entoto unpleasant two years prior.[10] At the time, the city was a resort town; its large mineral spring abundance attracted nobilities of the empire and led them to establish permanent settlement. It also attracted many members of the working classes — including artisans and merchants — and foreign visitors. Menelik II then formed his imperial palace in 1887.[11][12] Addis Ababa became the empire’s capital in 1889, and subsequently international embassies were opened.[13][14] Addis Ababa urban development began at the beginning of the 20th century, and without any preplanning.[10]

Addis Ababa saw a wide-scale economic boom in 1926 and 1927, and an increase in the number of buildings owned by the middle class, including stone houses filled with imported European furniture. The middle class also imported newly manufactured automobiles and expanded banking institutions.[13] During the Italian occupation, urbanization and modernization steadily increased by a master plan which they hoped Addis Ababa would be more colonial city and continued after their occupation. Consequent master plans were designed by French and British consultants from the 1940s onwards focusing on monumental structures, satellite cities and inner-city. Similarly, the Italo-Ethiopian master plan also projected in 1986 concerning only urban structure and accommodating service, which was later adapted by the 2003 master plan.

Addis Ababa remains federal chartered city in accordance with the Addis Ababa City Government Charter Proclamation No. 87/1997 in the FDRE Constitution.[15] Called «the political capital of Africa» due to its historical, diplomatic, and political significance for the continent, Addis Ababa serves as the headquarters of major international organizations such as the African Union and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.[16]

The city lies a few kilometres west of the East African Rift, which splits Ethiopia into two, between the Nubian Plate and the Somali Plate.[17] The city is surrounded by the Special Zone of Oromia and is populated by people from the different regions of Ethiopia. It is home to Addis Ababa University. The city has a high human development index and is known for its vibrant culture, strong fashion scene, high involvement of young people, thriving arts scene, and for having the fastest economic growth of any country in the world.[18]

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

A study based on DNA evidence from almost 1,000 people around the world suggests that all humans spread out from a place close to current Addis Ababa 100,000 years ago.[19] The research indicated that genetic diversity decreases steadily the further one’s ancestors travelled from Addis Ababa.[20]

Middle Ages[edit]

Mount Entoto, a high tableland to the north of current Addis Ababa, is one of a handful of sites put forward as a possible location for a medieval imperial capital known as Barara. This permanent fortified city was established during the early-to-mid 15th century, and it served as the main residence of several successive emperors up to the early 16th-century reign of Libne Dengel.[21] The city was depicted standing between Mount Zuqualla and Menegasha on a map drawn by the Italian cartographer Fra Mauro in around 1450, and it was razed and plundered by Ahmed Gragn while the imperial army was trapped on the south of the Awash River in 1529, an event witnessed and documented two years later by the Yemeni writer Arab-Faqih. The suggestion that Barara was located on Mount Entoto is supported by the very recent discovery of a large medieval town overlooking Addis Ababa located between rock-hewn Washa Mikael and the more modern church of Entoto Maryam, founded in the late 19th century. Dubbed the Pentagon, the 30-hectare site incorporates a castle with 12 towers, along with 520 meters of stone walls measuring up to 5-meter high.[22]

Foundation[edit]

Initial settlements[edit]

The city’s immediate predecessor as the capital of Ethiopia, Entoto, was established by Menelik II in 1884. In addition, he had used it for garrison base.[10] Menelik, initially the King of the Shewa province, had found Mount Entoto a useful base for military operations in the south of his realm, and in 1879 he visited the reputed ruins of the medieval town and the unfinished rock church. His interest in the area grew when his wife Taytu began work on a church on Mount Entoto, and Menelik endowed a second church in the area.[21][22] It was given that Menelik had strong interest to settle in the area due to partly influenced by establishing his old empire and serving as metropolis.[10] After some time, Entoto was found to be unsatisfactory as capital because of its cold climate, lack of water, and an acute shortage of firewood.[23]

Founding[edit]

In 1886, settlement began in the valley south of the mountain in a place called Finfinne in Oromo, a name which refers to the presence of hot springs. The site was chosen by Empress Taytu Betul. Initially, she built a house for herself near the «Filwuha» hot mineral springs, where she and members of the Shewan Royal Court liked to take mineral baths. Other nobility and their staff and households settled in the vicinity, and Menelik expanded his wife’s house to become the Imperial Palace in 1887 which remains the seat of government in Addis Ababa today.[24] In 1886, the city was renamed to Addis Ababa as the capital of Menelik’s kingdom of Shewa. It become the capital of Ethiopia in 1889, when Menelik became Emperor.[25] The town grew by leaps and bounds. Not only for noble, but also the site attracted to numerous working class in sort: the artisans, merchant, and foreign visitors.

The earliest urban dwelling typically made up of hut cluster. Here is an example of British legation pictured in 1910.

Early residential dwelling typically made of circular huts; walls were constructed with mud (Amharic: ጭቃ, cheka) and straw plastered on wooden frame, and thatched roofs. Addis Ababa growth rate began in early marked by rapid urbanization without preplanned intention. This was the time where nobilities embarked concentrated permanent settlement, and altered by social pattern; i.e. each neighborhoods (sefer) was located in higher grounds, sorted by noncontiguous from adjacent settlements. The early social milieu contributed the contemporary admixture of classic neighborhood. One of Emperor Menelik’s contributions that are still visible today is the planting of numerous eucalyptus trees along the city streets.[26][10]

Moreover, the city held strong social organizations pattern prior Italian invasion. According to Richard Pankhurst (1968), the city accelerated population growth due to factors of provisional governors and their troops, the 1892 famine, eventually the Battle of Adwa. Another include the 1907 land act, municipal administration in 1909, and railway and modernized transportation system boom beginning in the 20th century, culminating in continual growth. Additional supplements, for example the laid of Ethio-Djibouti Railways and topographical factors more led the city’s boundary to expand southward.[10]

20th-century[edit]

Pre-Italian occupation (1916–1935)[edit]

Addis Ababa in aerial view (1934)

Marketplace in Addis Ababa (c. February 1934)

Gebrehiwot Baykedagn took major administrative division post, and Addis Ababa–Djibouti railways in 1916,[27] which also connects Addis Ababa with French Somaliland port of Djibouti.[28] Ras Tafari Mekonnen, later became Emperor Haile Selassie I was the most powerful figure in the city following his appointment in 1917. He transformed the city by recognizing an importance of modernization and urbanization, he distributed wealth to support emerging class. From this point, Ras Tafari gained a legitimate power as regency council in 1918.

By 1926 and 1927, a large-scale economic revolution occurred, a surplus of coffee production began growing as a result to capital accumulation. Profited from this wealth, the bourgeoisie benefited the city by constructing new, stone-fitted houses with imported European furniture and an importation of the latest automobiles, and expansion of banks across the locales. The total register of automobiles were 76 in 1926 and went to 578 in 1930. The first popular road transportation opened between Addis Ababa and Djibouti, about 97 miles northward in the direction of Dessie. Initially intended to connect Italian occupied Assab with Addis Ababa in the Italo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1928, the road was considered for motor vehicle route. The highway seemingly important to French railway of Djibouti with freight rate was very high wherein lack of competition, and increase of cargo between Ethiopia and Assab.[29]

In 1930, the Emperor was crowned and proceeded with new technologies and building infrastructure. Among them, he installed power lines and telephones, and erected several monuments (such as Meyazia 27 Square).

During Italian occupation (1936–1941)[edit]

Military parade of Italian troops in Addis Ababa (1936)

Following all the major engagements of their invasion, the Italian troops from the colony of Eritrea entered Addis Ababa on 5 May 1936. Along with Dire Dawa, the city had been spared the aerial bombardment (including the use of chemical weapons such as mustard gas) practiced elsewhere in Ethiopia. This also allowed its railway to Djibouti to remain intact. After the occupation, the city served as the Duke of Aosta’s capital for unified Italian East Africa until 1941, when it was abandoned in favor of Amba Alagi and other redoubts during the Second World War’s East African Campaign. According to Soviet estimates, 15,000 Ethiopians casualties were victim of chemical weapons, especially by sulfur mustard.[30]

The Italian ambition regarding Addis Ababa was to create a beautified colonial capital city along with a new master plan launched by seven architects such as Marcello Piacentini, Alessandro Bianchi, Enrico Del Debbio, Giuseppe Vaccaro, Le Corbusier, Ignazio Guidi and Cesare Valle. Despite contradictory and different ideas for each other, the plan was intended to focus the general architectural plan of the city. Two preparations were approved from the master plan: the Le Corbusier and Guidi and Valle. During an invitation to Mussolini, the French Swiss architect Le Corbusier illustrated the master plan in a guideline sketch involving traversing route monumental structure by a grand boulevard across the city from north to south, as he extracted from his 1930–1933 Radiant City concept. His two counterparts, Guildi and Valle prepared the master plan in summer 1936 likely emphasizing fascist ideology with monumental structure and no native Ethiopian participation in designing sector. Two parallel axis were drawn in European character connecting Arada/Giyorgis with the railway station to the south end five kilometers long and varied width spanning from 40 to 90 meters.[31]

On 5 May 1941, the city was liberated by Major Orde Wingate and Emperor Haile Selassie for Ethiopian Gideon Force and Ethiopian resistance in time to permit Emperor Haile Selassie’s return on 5 May 1941, five years to the day after he had left.

Post-Italian occupation (1941–1974)[edit]

In aftermath, Addis Ababa suffered from economic stagnation and rapid population growth, the inner-city affected by urban morphology initiated by Italian occupation and the peripheral area were in urban sprawl. In 1946, Haile Selassie invited famous British master planner Sir Patrick Abercrombie with goals of modelling beautifying the city to become the capital for Africa. By organizing module, Abercrombie launched the master plan with neighborhood units surrounded by green parkways, and he was encouraged to draw ring roads characterized by radial shapes to channel traffic pathway from central area.[31]

His careful master plan of major traffic route was completed by segregating neighborhood units, as he extracted from his 1943 London traffic problem. In 1959, the British consultant team named Bolton Hennessy and Partners commissioned an improvement of Abercrombie’s 1954–1956 satellite towns. From the place, they did not incorporated outer area like Mekenissa and West of the old Air Port in the proposal, while Rapi, Gefersa, Kaliti and Kotebe proposed as outlet of Jimma, Ambo and Dessie respectively (the four regional highways). The Hennessy and Partners illustration would be physically larger to current size of Addis Ababa with surrounded satellite towns. In 1965, the French Mission for Urban Studies and Habitat led by Luis De Marien launched another master plan responsible to create monumental axis through Addis Ababa City Hall with an extension across Gofa Mazoria in the southern part of the city. Marien’s difference to the previous Italian master plan was the use of single monumental axis while they used the double one.[31]

Haile Selassie also helped to form the Organisation of African Unity in 1963, which was later dissolved in 2002 and replaced by the African Union (AU), which is also headquartered in the city, airports and industrial parks. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa founded in 1958, also has its headquarters in Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa was also the site of the Council of the Oriental Orthodox Churches in 1965. Pankhurst (1962) noted in a survey of total land of 212 square kilometers, 58% owned by 1,768, owing to 10,000 square meters, and 12% were given to church whereas other small areas were still acquired in the name of posthumous nobilities such as Dejazemach Wube Haile Mariam, Fitawrari Aba Koran, and a bridge named «Fitawrari Habtegiorgis» after Habte Giyorgis Dinagde.[32] According to 1965 master plan, the city covered the area of 21,000 hectares and would increased to 51,000 hectares by 1984 master plan.[31]

In 1965, the first student march took place in response to the feudal imperial government of Haile Selassie, in which they chanted «Land for the Tiller», culminating in a Marxist–Leninist movement in Ethiopia. In addition, the 1973 oil crisis heavily impacted the city. 1,500 peasants in Addis Ababa marched to plead for food to be returned by police, and intellectual from Addis Ababa University forced the government to take a measure against the spreading famine, a report which Haile Selassie government denounced as «fabrication». Haile Selassie responded later «rich and poor have always existed and will, Why? Because there are those that work…and those that prefer to do nothing…Each individual is responsible for his misfortunes, his fate.» Students around the city gathered to protest in February 1974, eventually Haile Selassie was successfully deposed from office in 1974 by group of police officers. Later, the group named themselves Derg, officially «Provisional Military Administrative Council» (PMAC).[33] The city had only 10 woredas.[31]

Marketplace on 3 October 1973

The Derg administration (1974–1991)[edit]

After the Derg came to power, roughly two-third of housing stock transferred to rental housing. The population growth declined from 6.5% to 3.7%. In 1975, the Derg nationalized «extra» rental structures built by private stockholders. As a result, the Proclamationon No. 47/1975 issued weakened buildings with small amount of living was administered by kebele units, while rental houses with large quality fell under Agency for Rental Housing Administration (ARHA). If those rental properties value less than 100 birr (US$48.31), they would be put under kebele administration.[10] The administrative divisions showed an increase of woredas to 25 and 284 kebeles.[31]

Hungarian architect C.K. Polonyi was the first person to embark the city’s master plan during the Derg period with assistance of the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing. He used two formula concentrating an integration Addis Ababa with suburbs of rural areas and developing inner-city. Polonyi also worked to redesign Meskel Square, which was renamed Abiyot Square by the time, implemented immediately after the name change.[31]

In 1986, the Italo-Ethiopian master plan was set up by 45 Ethiopian professional along with 75 Italian experts with 207 sectorial reports documented as references. The plan dealt with a balanced urban system and services in urban area such as water supply. Akaki incorporated to Addis Ababa to supply industrial and freight terminal services. The bureaucratic rule of the Derg postponed the master plane for eight years until 1994, which caused failure of basic issues in public service and unplanned development.[31]

Federal Democratic Republic (1991–present)[edit]

On 28 May 1991, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition party in course of overthrowing the Derg, seized Addis Ababa. They entered Menelik II Avenue and ordering a curfew for 24 hours. According to witness, residents of Addis Ababa were totally ignorant and not terrible by the event. One of the militants told them «We think it’s safe now». The military went to central place of the city such as Hilton Hotel. They displayed a slogan banner «Peace, Solidarity, Friendship». At 5:30 am, they took control of presidential place and large-scale tanks were seen overrun the area.[34]

A new constitution was adapted in 1994 and enacted year later; while all cities in Ethiopia accountable rule by regional authority, Addis Ababa (Proclamation No 87/1997) and Dire Dawa (Proclamation No 416/2004) remain chartered city, mandates for self-governing and developmental center.[35] The Proclamation No. 112/1995 legitimized privatization of government houses except few, and the kebele houses was remained in tenture. The kebele dwelling and their largely unplanned settings continued to incorporated core areas of Addis Ababa.[10]

21st-century[edit]

Addis Ababa landscape taken on 27 August 2009

From the end of 1998, new project was launched by Addis Ababa City Administration naming Office for Revision of Addis Ababa Master Plan (ORAAMP), covering from 1999 to 2003. The plan goal was to meet the standard of market economy with favorable political system resembles the revised 1986 master plan in terms of urban area.[31]

2014 Addis Ababa Master Plan[edit]

A controversial plan to expand the boundaries of Addis Ababa, by 1.1 million hectares into the Oromia special zone in April 2014,[36][37] sparked the Oromo protests on 25 April 2014 against expansion of the boundaries of Addis Ababa. The government responded by shooting at and beating peaceful protesters.[38] This escalated to full blown strikes and street protests on 12 November 2015 by university students in Ginchi town, located 80 km southwest of Addis Ababa city, encircled by Oromia Region.[39][40][41] The controversial master plan was cancelled on 12 January 2016. By that time, 140 protesters were killed.[42][43][44]

Recent history[edit]

United Nations Population Projections estimated the population of metro area of Addis Ababa to be 5,228,000 in 2022, a 4.43% increase from 2021.[45] During Abiy Ahmed’s premiership, Addis Ababa and its vicinities underwent Beautifying Sheger. This project is aimed to enhance the green coverage and beauty of the city. In 2018, Abiy initiated a project called «Riverside» planned to expand riverbanks for 56 kilometres (35 mi), from the Entoto Mountains to the Akaki river.[46][47][48][49][50]

Relation with Oromia Regional State[edit]

Thanksgiving Irreecha Festival in Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa is located in the heart of the Oromia state[51][52] and the major ecosystem services to the city provided by Oromia state.[53] The city was abandoned by the Oromo since the late 19th century due to its conquest by Menelik. Oromos were physically removed from the vicinity of the city during the Haile Selassie and Derg eras.[54] Article 49(5) of the Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia states:[55][56]

«The special interest of the State of Oromia in Addis Ababa, regarding the provision of social services or the utilization of natural resources and other similar matters, as well as joint administrative matters arising from the location of Addis Ababa within the State of Oromia, shall be respected. Particulars shall be determined by law.»

In 2000, Oromia’s capital was moved from Addis Ababa to Adama.[57] Because this move sparked considerable controversy and protests among Oromo students, the Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organization (OPDO), part of the ruling EPRDF coalition, on 10 June 2005, officially announced plans to move the regional capital back to Addis Ababa.[58] Due to the historical and natural connection between the city and the Oromo people, the Oromia Government has asserted its ownership of Addis Ababa.[59][60] Both the current mayor of Addis Ababa, Adanech Abebe, and the former mayor, Takele Uma Banti are from the former ruling party of Oromia.[61]

Geography[edit]

Addis Ababa seen from SPOT satellite

District map of Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa lies at an elevation of 2,355 metres (7,726 ft) and is a grassland biome, located at 9°1′48″N 38°44′24″E / 9.03000°N 38.74000°E.[62] The city lies at the foot of Mount Entoto and forms part of the watershed for the Awash. From its lowest point, around Bole International Airport, at 2,326 metres (7,631 ft) above sea level in the southern periphery, Addis Ababa rises to over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) in the Entoto Mountains to the north.

Subdivision[edit]

The city is divided into 10 boroughs, called subcities (Amharic: ክፍለ ከተማ, kifle ketema), and 99 wards (Amharic: ቀበሌ, kebele).[63][64] The 10 subcities are:

| Nr | Subcity | Area (km2) | Population | Density | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Addis Ketema[65] | 7.41 | 271,644 | 36,659.1 |

|

| 2 | Akaky Kaliti[66] | 118.08 | 195,273 | 1,653.7 |

|

| 3 | Arada[67] | 9.91 | 225,999 | 23,000 |

|

| 4 | Bole[68] | 122.08 | 328,900 | 2,694.1 |

|

| 5 | Gullele[69] | 30.18 | 284,865 | 9,438.9 |

|

| 6 | Kirkos[70] | 14.62 | 235,441 | 16,104 |

|

| 7 | Kolfe Keranio[71] | 61.25 | 546,219 | 7,448.5 |

|

| 8 | Lideta[72] | 9.18 | 214,769 | 23,000 |

|

| 9 | Nifas Silk-Lafto[73] | 68.30 | 335,740 | 4,915.7 |

|

| 10 | Yeka[74] | 85.46 | 337,575 | 3950.1 |

|

*Lemi-Kura sub-city was added as the eleventh sub-city of Addis Ababa in 2020

| Addis Ababa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Climate[edit]

Addis Ababa has a subtropical highland climate (Köppen: Cwb) with precipitation varying considerably by the month.[76] The city has a complex mix of alpine climate zones, with temperature differences of up to 10 °C (18 °F), depending on elevation and prevailing wind patterns. The high elevation moderates temperatures year-round, and the city’s position near the equator means that temperatures are very constant from month to month. As such the climate would be maritime if its elevation was not taken into account, as no month is above 22 °C (72 °F) in mean temperatures.

Mid-November to January is a season for occasional rain. The highland climate regions are characterised by dry winters, and this is the dry season in Addis Ababa. During this season the daily maximum temperatures are usually not more than 23 °C (73 °F), and the night-time minimum temperatures can drop to freezing. The short rainy season is from February to May. During this period, the difference between the daytime maximum temperatures and the night-time minimum temperatures is not as great as during other times of the year, with minimum temperatures in the range of 10–15 °C (50–59 °F). At this time of the year, the city experiences warm temperatures and pleasant rainfall. The long wet season is from June to mid-September; it is the major winter season of the country. This period coincides with summer, but the temperatures are much lower than at other times of year because of the frequent rain and hail and the abundance of cloud cover and fewer hours of sunshine. This time of the year is characterised by dark, chilly and wet days and nights.[citation needed] The autumn which follows is a transitional period between the wet and dry seasons.

The highest temperature on record was 30.6 °C (87.1 °F) 26 February 2019, while the lowest temperature on record was 0 °C (32 °F) recorded on multiple occasions.[77]

| Climate data for Addis Ababa (1981–2010, extremes 1898–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.8 (83.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24 (75) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

23 (73) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (74) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.0 (60.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.4 (61.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

9 (48) |

10 (50) |

11 (52) |

11 (52) |

10 (50) |

10 (50) |

10 (50) |

10 (50) |

9 (48) |

7 (45) |

7 (45) |

9 (49) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.4 (41.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 13 (0.5) |

30 (1.2) |

58 (2.3) |

82 (3.2) |

84 (3.3) |

138 (5.4) |

280 (11.0) |

290 (11.4) |

149 (5.9) |

27 (1.1) |

7 (0.3) |

7 (0.3) |

1,165 (45.9) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 27 | 26 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 132 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 52 | 51 | 53 | 59 | 55 | 68 | 78 | 80 | 75 | 57 | 53 | 53 | 62 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 266.6 | 206.2 | 241.8 | 210.0 | 238.7 | 174.0 | 111.6 | 133.3 | 162.0 | 248.0 | 267.0 | 288.3 | 2,547.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.6 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 7.0 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation (average high and low, and rainfall)[78] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (mean temperatures 1961–1990, humidity 1951–1990, and sun 1985–1998)[79] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[77] |

Demographics[edit]

As of the 2007 population census conducted by the Ethiopian national statistics authorities, Addis Ababa has a total population of 2,739,551 urban and rural inhabitants. For the capital city 662,728 households were counted living in 628,984 housing units, which results in an average of 5.3 persons to a household. Although all Ethiopian ethnic groups are represented in Addis Ababa because it is the capital of the country, the largest groups include the Amhara (47.05%), Oromo (19.51%), Gurage (16.34%), Tigrayan (6.18%), Silt’e (2.94%), and Gamo (1.68%). Languages spoken as mother tongues include Amharic (70.99%), Afaan Oromo (10.72%), Gurage (8.37%), Tigrinya (3.60%), Silt’e (1.82%) and Gamo (1.03%). The religion with the most believers in Addis Ababa is Ethiopian Orthodox with 74.66% of the population, while 16.21% are Muslim, 7.77% Protestant, and 0.48% Catholic.[2]

Languages of Addis Ababa as of 2007 Census[80]

Other (3.48%)

Religion in Addis Ababa (2007)[80]

Other (0.8%)

In the previous census, conducted in 1994, the city’s population was reported to be 2,112,737, of whom 1,023,452 were men and 1,089,285 were women. At that time not all of the population were urban inhabitants; only 2,084,588 or 98.7% were. For the entire administrative council there were 404,783 households in 376,568 housing units, with an average of 5.2 persons per household. The major ethnic groups included the Amhara (48.27%), Oromo (19.24%), Gurage (13.54%; 9.40% Sebat Bet, and 4.14% Sodo), Tigrayan 7.65%, Silt’e 3.98%, and foreigners from Eritrea 1.34%. Languages spoken included Amharic (72.64%), Afaan Oromo (10.01%), Gurage (6.45%), Tigrinya (5.41%), and Silt’e 2.29%. In 1994 the predominant religion was also Ethiopian Orthodox with 82.0% of the population, while 12.67% were Muslim, 3.87% Protestant, and 0.78% Catholic.[81]

Historical population| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1,412,575 | — |

| 1994 | 2,112,737 | +49.6% |

| 2007 | 2,739,551 | +29.7% |

| 2015 | 3,273,000 | +19.5% |

| source:[82] |

Languages[edit]

Standard of living[edit]

According to the 2007 national census, 98.64% of the housing units of Addis Ababa had access to safe drinking water, while 14.9% had flush toilets, 70.7% pit toilets (both ventilated and unventilated), and 14.3% had no toilet facilities.[83] In 2014, there were 63 public toilets in the city, with plans to build more.[84] Values for other reported common indicators of the standard of living for Addis Ababa as of 2005 include the following: 0.1% of the inhabitants fall into the lowest wealth quintile; adult literacy for men is 93.6% and for women 79.95%, the highest in the nation for both sexes; and the civic infant mortality rate is 45 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, which is less than the nationwide average of 77; at least half of these deaths occurred in the infants’ first month of life.[85]

The city is partially powered by water at the Koka Reservoir.

Economy[edit]

Addis Ababa night skyline in 2021

The economic activities in Addis Ababa are diverse. According to official statistics from the federal government, some 119,197 people in the city are engaged in trade and commerce; 113,977 in manufacturing and industry; 80,391 homemakers of a different variety; 71,186 in civil administration; 50,538 in transport and communication; 42,514 in education, health and social services; 32,685 in hotel and catering services; and 16,602 in agriculture. In addition to the residents of rural parts of Addis Ababa, the city dwellers also participate in animal husbandry and the cultivation of gardens. 677 hectares (1,670 acres) of land is irrigated annually, on which 129,880 quintals of vegetables are cultivated.[citation needed] It is a relatively clean and safe city, with the most common crimes being pickpocketing, scams and minor burglary.[86] The city has recently been in a construction boom with tall buildings rising in many places. Various luxury services have also become available and the construction of shopping malls has recently increased. According to Tia Goldenberg of IOL, area spa professionals said that some people have labelled the city, «the spa capital of Africa.»[87]

The Ethiopian Airlines has its headquarters on the grounds of Addis Ababa Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa.[88]

Development[edit]

The city hosts the We Are the Future centre, a child care centre that provides children with a higher standard of living. The centre is managed under the direction of the mayor’s office, and the international NGO Glocal Forum serves as the fundraiser and program planner and coordinator for the WAF child centre in each city. Each WAF city is linked to several peer cities and public and private partners to create a unique international coalition.

Launched in 2004, the program is the result of a strategic partnership between the Glocal Forum, the Quincy Jones Listen Up Foundation, and Mr Hani Masri, with the support of the World Bank, UN agencies and major companies.

Tourism[edit]

Tourism is a growing industry within Addis Ababa and Ethiopia as a whole. In July 2015, the European Council on Tourism and Trade named Ethiopia the best nation for inbound tourism.[89] The COVID-19 pandemic and Tigray War caused a decrease in tourism.

Zoo[edit]

Addis Ababa Zoo kept 15 lions in 2011. Their hair samples were used in a genetic analysis, which revealed that they were genetically diverse. It was therefore proposed to include them in a captive breeding programme.[90]

Law and government[edit]

Government[edit]

Under the Ethiopian Constitution of 1995, the city of Addis Ababa is one of the two federal cities that are accountable to the Federal Government of Ethiopia. The other city with the same status is Dire Dawa in the east of the country and both are federal cities. Earlier, following the establishment of the federal structure in 1991 under the Transitional Charter of Ethiopia, the City Government of Addis Ababa was one of the then-new 14 regional governments. However, that structure was changed by the federal constitution in 1995 and as a result, Addis Ababa does not have statehood status.

The administration of Addis Ababa city consists of the Mayor, who leads the executive branch, and the City Council, which enacts city regulations. However, as part of the Federal Government, the federal legislature enacts laws that are binding in Addis Ababa. Members of the City Council are directly elected by the residents of the city and the council, in turn, elects the Mayor among its members. The term of office for elected officials is five years. However, the Federal Government, when it deems necessary, can dissolve the City Council and the entire administration and replace it with a temporary administration until elections take place next. Residents of Addis Ababa are represented in the federal legislature, the House of Peoples’ Representatives. However, the city is not represented in the House of Federation, which is the federal upper house constituted by the representatives of the member states. The executive branch under the Mayor comprises the City Manager and various branches of civil service offices.

Adanech Abebe is serving as the Mayor of Addis Ababa since 2020, preceded by Takele Uma Banti. She is the first woman to hold mayorship since its creation in 1910. Before Takele, the Federal Government appointed Berhane Deressa to lead the temporary caretaker administration that served from 9 May 2006 to 30 October 2008 following the 2005 election crisis. In the 2005 national election, the ruling EPRDF party suffered a major defeat in Addis Ababa. However, the opposition who won in Addis Ababa did not take part in the government both on the regional and federal levels. This situation forced the EPRDF-led Federal Government to assign a temporary administration until a new election was carried out. As a result, Berhane Deressa, an independent citizen, was appointed.

Some of the notable past mayors of Addis Ababa are Arkebe Oqubay (2003–06), Zewde Teklu (1985–89), Alemu Abebe (1977–85) and Zewde Gebrehiwot (1960–69).

Crime[edit]

Addis Ababa is considered to be extremely safe in comparison to the other cities in the region.[91] However, there are a number of crimes within the city including theft, scams, mugging, robbery and others. Rural-urban migration and unemployment has been preliminary factors affecting the city by elevating crime rate.[92]

The Addis Ababa Federal Police is the main department of the Federal Police established in 2003.[93]

Places of worship[edit]

Among the places of worship, there are predominantly Christian churches and temples: Seventh-day Adventist Church, Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus (Lutheran World Federation), Ethiopian Kale Heywet Church, Ethiopian Catholic Archeparchy of Addis Ababa (Catholic Church), Ethiopian Full Gospel Believers’ Church[94] and also Muslim mosques.

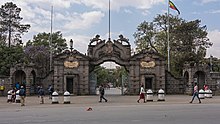

In most churches, Emperor Haile Selassie employed political propagandic panel that demonstrate his imperial power, cult of personality and ultranationalist views. Saint George’s Cathedral has central of subjects involving incident of Second Italo-Ethiopian War that he struggled for independence. This church named after an Ark (tabot) carried during Battle of Adwa.[95] It was once ruined by Fascist Italian government in 1937 but was immediately reconstructed after liberation of Ethiopia in 1941. The church, located at the northern end of Churchill Road—is unique octagonal architecture—has a museum of imperial weaponry including swords and tridents and giant helmets made from the manes of lions which was used during the Italian invasion. Holy Trinity Cathedral also sits in the city serving as the headquarter of Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. As a largest and highest cathedral in the country, Holy Trinity Cathedral was founded in commemoration of victory against the Italian invasion, and second most important place after the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum. Before reign of Emperor Menelik II, the church was monastery. The church served burial of major prominent people in Ethiopia, also tombs of imperial family such as Haile Selassie and his wife Menen Asfaw, the third patriarch Abuna Tekle Haymanot and Abune Paulos. Former Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi also interred to this church. Other include British Ethiopianist and suffragate Sylvia Pankhurst also entombed here. The Ba’etta Mariam Orthodox Church embodies Menelik Palace and Mausoleum and the biggest church around the place with smaller churches stand in front of it. It is frequently visited church. The other nearby church is Gebbi Gabriel which has unique decorated cross at the dome of the church and at its entrance.[96]

From mosque, the most notable is the Grand Anwar Mosque, which was located in Merkato, at the heart of the city. It was built in 1922 by the order of Italian government.[97] Nur Mosque counted as an oldest Islamic temple recently rebuilt with Islamic architecture characterized by the use of domes, towers and piers.[96]

Architecture[edit]

A financial district is under construction in Addis Ababa.[98]

Former mayor Kuma Demeksa embarked on a quest to improve investment for the buildings in the city. Addis Ababa is the headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Union.[99]

Notable taller architecture in Addis Ababa includes the CBE headquarters, NIB international bank, Zemen bank, Hibret bank, Huda Tower, Nani Tower, Bank Misr Building, as well as the approved Angola World Trade Center Tower, Abyssinia Bank Tower, Mexico Square Tower, and the $200m AU Conference Center and Office Complex.[100]

Notable buildings include St George’s Cathedral (founded in 1896 and also home to a museum), Holy Trinity Cathedral (once the largest Ethiopian Orthodox Cathedral and the location of Sylvia Pankhurst’s tomb) as well as the burial place of Emperor Haile Selassie and the Imperial family, and those who fought the Italian invasion during World War II.

In the Merkato district, which is the largest open market in Africa, is the Grand Anwar Mosque, the biggest mosque in Ethiopia built during the Italian occupation. A few meters to the southwest of the Anwar Mosque is the Raguel Church built after the liberation by Empress Menen. The proximity of the mosque and the church has symbolized the long peaceful relations between Christianity and Islam in Ethiopia. The Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Holy Family is also in the Merkato district. Near Bole International Airport is the new Medhane Alem (Savior of the World) Orthodox Cathedral, which is the second-largest in Africa.

The Entoto Mountains start among the northern suburbs. Suburbs of the city include Shiro Meda and Entoto in the north, Urael and Bole (home to Bole International Airport) in the east, Nifas Silk in the south-east, Mekanisa in the south, and Keraniyo and Kolfe in the west. Kolfe was mentioned in Nelson Mandela’s Autobiography «A Long Walk to Freedom», as the place he got military training.

Addis Ababa has a distinct architectural style. Unlike many African cities, Addis Ababa was not built as a colonial settlement. This means that the city has not a European style of architecture. This changed with the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1936. The Piazza district in the city centre is the most evident indicator of Italian influence. The buildings are very much Italian in style and there are many Italian restaurants, as well as small cafes, and European-style shopping centres.[101]

Parks include the Africa Park, which is situated along Menelik II Avenue and Unity Park at the Palace.[102]

Other features of the city include the large Mercato market, the Jan Meda racecourse, Bihere Tsige Recreation Centre and a railway line to Djibouti.

The city is home to the Ethiopian National Library, the Ethiopian Ethnological Museum (and former Guenete Leul Palace), the Addis Ababa Museum, the Ethiopian Natural History Museum, the Ethiopian Railway Museum and National Postal Museum.

There is also Menelik’s old Imperial palace which remains the official seat of government, and the National Palace formerly known as the Jubilee Palace (built to mark Emperor Haile Selassie’s Silver Jubilee in 1955) which is the residence of the President of Ethiopia. Jubilee Palace was also modeled after Buckingham Palace in the United Kingdom. Africa Hall is located across Menelik II avenue from this Palace and is where the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa is headquartered as well as most UN offices in Ethiopia. It is also the site of the founding of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which eventually became the African Union (AU). The African Union is now housed in a new headquarters built on the site of the demolished Akaki Prison, on land donated by Ethiopia for this purpose in the southwestern part of the city. The Hager Fikir Theatre, the oldest theatre in Ethiopia, is located in the Piazza district. Near Holy Trinity Cathedral is the art deco Parliament building, built during the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie, with its clock tower. It continues to serve as the seat of Parliament today. Across from the Parliament is the Shengo Hall, built by the Derg regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam as its new parliament hall. The Shengo Hall was the world’s largest pre-fabricated building, which was constructed in Finland before being assembled in Addis Ababa. It is used for large meetings and conventions. Itegue Taitu Hotel, built-in 1898 (Ethiopian Calendar) in the middle of the city (Piazza), was the first hotel in Ethiopia.

Meskel Square is one of the noted squares in the city, serving as the site for the annual Meskel at the end of September annually when thousands gather in celebration.

The fossilized skeleton and a plaster replica of the early hominid Lucy (known in Ethiopia as Dinkinesh) is preserved at the National Museum of Ethiopia.

Culture[edit]

Addis Ababa is a melting pot of different communities throughout the country’s regions, along with Dire Dawa.[103] In Addis Ababa, cultural assimilation is ubiquitous and widely known.[104]

Arts and museums[edit]

The National Museum of Ethiopia hosts many artifacts and artistic treasures in Ethiopia. It is also home of archaeological exhibition. The partial specimen of Australopithecus afarensis, and its successor Selam are noteworthy among viewed galleries in the museum. The museum also has wide-range ceremonial costumes of Solomonic dynasty, which was initiated in 1936. Arts include mostly works of Afewerk Tekle, one of the most renowned gallery, and the depiction of meeting between Solomon and Queen of Sheba.[105]

Theatres and cinemas[edit]

Addis Ababa is home of many theatres, including the long run Hager Fikir Theatre, which served many prominent figures performance. In addition, the Ethiopian National Theatre is also located in the city’s hub. It was founded by Emperor Haile Selassie in 1955, who eponymously renamed it. Historically, the Amhara culture dominated the country’s art scene; rituals connected to priesthood based on Coptic church, most often using improvised art such as shinsheba and qene.

Tekle Hawariat introduced modern European dramas based on La Fontaine‘s fable around 1916.[106] Mattewos Bekele and Iyoel Yohannes became famous playwright, and Makonnen Endalkachew’s David and Orion and King David III was renowned by that time. In the Derg era, propagandic communist pieces often conceded and several new theatres were opened until the successive government under EPRDF altered new form of cultural life with continuation of development.[107]

Notable modern cinemas including:[108]

- Children Youth Theatre

- Agona Cinema

- Haile & Alem Inter

- Cinema Yoftahe

- Sebastopol

- Matin Multiplex

Science and technology[edit]

There are variety of scientific and research institutes in Addis Ababa. The Addis Ababa Science and Technology University has a goal of to bring «Ethiopia economically and industrialized state». The university was founded in 2011 under Directive of the Council of Ministers No. 216/2011. The city is home of various scientific organizations notably the Science and Technology Information Center. Addis Ababa has a science museum built by MadaTech’s exhibition crew. The national museum is 250 square foot with 30 interactive images of scientific objects. The museum was launched by Jewish-American businessman Mark Gelfand, who spent his money more than in MadaTech and sought resurrection of science museum in all over of the world.[109] Some prominent facilities of scientific and technology include the Ethiopian Biotechnology Institute, while the National Intelligence and Security Service also headquartered in Addis Ababa responsible for upholding national security of the country.

Media[edit]

Addis Ababa has the largest mass media concentration in the country. Radio stations generally state-owned with 50 community licensed by the Ethiopian Broadcasting Authority, with four licensing opts for 29 local languages. The Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation is a public broadcaster which has its headquarters in Addis Ababa. Private television commenced with the launch of EBS TV in 2008, and many private channels grew in the beginning of 2016. For example, Kana TV, Fana TV, LTV and JTV Ethiopia. As of October 2016, the Ethiopian Broadcasting Agency licensed with Fana Broadcasting Corporate, Walta Information Center and Arki Broadcasting Service and Ed Stelar Training as commercial FM stations. There were reached eight analogue and nine television stations in Ethiopia. Nine stations were available in Addis Ababa and were public owned.[110]

Sport[edit]

Addis Ababa serves major sporting events, notably the Jan Meda International Cross Country. It hosts four races, with senior and junior (under-20) for both sexes. The city is known for annual 10 km road event called the Great Ethiopian Run, created by athlete Haile Gebrselassie, Peter Middlebrook and Abi Masefield in late October 2000. Yet, course records were broken by Deriba Merga (28:18.61 in 2006) and Yalemzerf Yehualaw (31:55 in 2019) of both men and women respectively.

Addis Ababa is home to Addis Ababa Stadium, Abebe Bikila Stadium, named after Shambel Abebe Bikila, and Nyala Stadium. The 2008 African Championships in Athletics were held in Addis Ababa.

Education[edit]

Emperor Menelik II started modernizing Addis Ababa by introducing new educational scheme in the early 20th century. He replaced this by centuries old traditional Christian schools with secular one. The first school was opened in 1906. However Menelik faced disapprobation by general populace who adapted traditional element, though he encouraged to expand educational institution, forced parents to send their children to school.[111]

Addis Ababa University was founded in 1950 and was originally named «University College of Addis Ababa», then renamed in 1962 for the former Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I who had donated his Genete Leul Palace to be the university’s main campus in the previous year. It is the home of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies and the Ethnological Museum. The city also has numerous public universities and private colleges including Addis Ababa Science and Technology University, Ethiopian Civil Service University, Admas University College, St. Mary’s University, Unity University, Kotebe Metropolitan University and Rift Valley University.

In 2022 the new Abrehot Library was completed on former parkland opposite the Parliament Building. It is the largest library in Ethiopia.

Researches indicate that an increase of private education sector in Addis Ababa is as a result of demand of quality education. In 2002/2003, the number of privately owned school accounted for 98, 78, 53, 41, and 67 percent of preschool, primary, secondary, technical and vocational and colleges institutions compared to survey of 1994. Adequate enrollment to school however frequently met with problematic, parents often prefer their children to enroll private school than governmental. Those primary schools always successful at resourcing, business and financial management, and educational protocol that do not offer more bureaucratic administrations.[112]

Private school often raise school fee that thought to be an exploitative practice without reasonable price. For example, it was observed in Unity University that led to protest. There is an improvement of school expansion in all sorts.

Transport[edit]

Blue and white taxi is the main public transport in Addis Ababa

Public transport is through public buses from three different companies (Anbessa City Bus Service Enterprise, Sheger, Alliance), Light Rail or blue and white taxis. The taxis are usually minibuses that can seat at most twelve people, which follow somewhat pre-defined routes. The minibus taxis are typically operated by two people, the driver and a weyala who collects fares and calls out the taxi’s destination. Sedan taxis work like normal taxis and are driven to the desired destination on demand. In recent years, new taxi companies have appeared, which use other designs, including one large company using yellow sedan taxis and a few ride-hailing companies (Ride taxi, Feres, etc.) have become widely accessible in the city.

Road[edit]

The construction of the Addis Ababa Ring Road was initiated in 1998 to implement the city master plan and enhance peripheral development. The Ring Road was divided into three major phases that connect all the five main gates in and out of Addis Ababa with all other regions (Jimma, Bishoftu, Dessie, Gojjam and Ambo). For this project, China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) was the partner of Addis Ababa City Roads Authority (AACRA).[113] The Ring Road has greatly helped to decongest and alleviate city traffic.

Intercity bus service is provided by the Lion City Bus Services.

Air[edit]

The city is served by Addis Ababa Bole International Airport, where a new terminal opened in 2003.

Railway[edit]

Addis Ababa originally had a railway connection with Djibouti City, with a picturesque French-style railway station, but this route has been abandoned. The new Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway started operation in September 2016, running parallel to the route of the original railway line.

Light rail[edit]

Addis Ababa opened its light rail system to the public on 20 September 2015. The system is the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Ethiopian Railway Corporation reached a funding agreement worth millions of dollars with the Export and Import Bank of China in September 2010 and the light rail project was completed in January 2015. The route is a 34.25-kilometre (21.28 mi) network with two lines; the operational line running from the centre to the south of the city. Upon completion, the east–west line will run from Ayat to the Torhailoch ring-road, and from Menelik Square to Merkato Bus Station, Meskel Square and Akaki.[114]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Addis Ababa is twinned with:[115][116]

- Ankara, Turkey

- Beersheba, Israel

- Beijing, China

- Chuncheon, South Korea

- Harare, Zimbabwe

- Johannesburg, South Africa

- Khartoum, Sudan

- Leipzig, Germany

- Lusaka, Zambia

- Lyon, France

- Nairobi, Kenya

- Washington, D.C., United States

Gallery[edit]

-

Arat Kilo monument

-

Addis Ababa Sheger Park

-

Unity Park Addis Ababa

-

-

-

-

-

Ethiopian Radio and Television station

-

Headquarters of the Ethiopian Federal Police

-

Light rail overpass at Mexico Square

Notable people[edit]

- Ephraim Isaac: Scholar of Ancient Semitic Studies[117]

- Mohammed Hussein Al Amoudi: richest person in Ethiopia (worth $8.1 billion)[118]

- Haile Gebrselassie: Ethiopian long-distance runner

- Kenenisa Bekele: Ethiopian long-distance runner

- Tedros Adhanom: Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO)

- Saladin Said: Ethiopian soccer player

- Mahder Assefa: Actress

- Mulatu Astatke: Ethiopian Jazz musician

- Mahmoud Ahmed: Ethiopian singer

- Teddy Afro: Ethiopian singer

- Bethlehem Tilahun Alemu: Founder of Sole Rebels[119]

- Eténèsh Wassié: Ethiopian azmari

- Ruth Negga: Actress[120]

See also[edit]

- Oromia Region

- Large Cities Climate Leadership Group

- Zewditu Hospital

- ALERT (medical facility)

- Oromia Special Zone Surrounding Finfinne

References[edit]

- ^ «2011 National Statistics». Csa.gov.et. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ a b c «Census 2007 Tables: Addis Abeba» Archived 14 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.5, 3.1, 3.2 and 3.4. For Silt’e, the statistics of reported Shitagne speakers were used, on the assumption that this was a typographical error.

- ^ «Population Projection Towns as of July 2021» (PDF). Ethiopian Statistics Agency. 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ «Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab». globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ «Addis Ababa – English Definition and Meaning». Lexico.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Ethiopia in Brief, n.d., archived from the original on 28 December 2021, retrieved 20 April 2021

- ^ «Oromia Regional State». Ethiopia. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ «| Human Development Reports». hdr.undp.org. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ «Addis Ababa | national capital, Ethiopia». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «City Profile Addis Ababa» (PDF). 17 February 2022.

- ^ «Ethiopia’s Imperial Palace opened to the public after more than a century». This is africa. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ «Ethiopia opens doors to its Imperial Palace for the first time». Embassy of Ethiopia, London. 16 October 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b Anacker, Caelen (16 March 2010). «Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (1886– ) •». Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Benti, Getahun (2000). «A History of Addis Ababa from Its Foundation in 1886 to 1910 (review)». Northeast African Studies. 7 (2): 143–145. doi:10.1353/nas.2004.0013. ISSN 1535-6574. S2CID 144623037.

- ^ Federal Negarit Gazeta. 2003. p. 1.

- ^ «United Nations Economic Commission for Africa». UNECA. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ Gizaw, Berhanu. «The origin of high bicarbonate and fluoride concentrations in waters of the Main Ethiopian Rift Valley, East African Rift system.» Journal of African Earth Sciences 22.4 (1996): 391–402.

- ^ James Jeffrey. «Addis Ababa: 10 best things to do in Ethiopia’s capital». CNN. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ «DNA Studies Trace Migration from Ethiopia». bnd.com. St. Louis: Los Angeles Times. bnd. 22 February 2008. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Brown, David (22 February 2008). «Genetic Mutations Offer Insights on Human Diversity». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ a b Philip Briggs. Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides (2015) pp. 49–50

- ^ a b Philip Briggs. Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides (2015) pp. 131–132

- ^ «Addis Ababa | History, Population, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com.

- ^ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 6

- ^ «Finfinne» – via The Free Dictionary.

- ^ Pankhurst, p. 195

- ^ Zewde, Bahru (2002). Pioneers of Change in Ethiopia: The Reformist Intellectuals of the Early Twentieth Century. J. Currey. ISBN 978-0-85255-452-4.

- ^ Daily Consular and Trade Reports. Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of Manufactures. 1927.

- ^ Freidson, Irving (1930). Motor Roads in Africa: (except Union of South Africa). U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Weapons of War: Environmental Impact: Environmental Impact. KW Publishers Pvt Ltd. 15 August 2013. ISBN 978-93-85714-71-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tufa, Dandena (2008). «Historical Development of Addis Ababa: plans and realities». Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 41 (1/2): 27–59. ISSN 0304-2243. JSTOR 41967609.

- ^ Alemayehu, Elias Yitbarek; Stark, Laura (30 November 2018). The Transformation of Addis Ababa: A Multiform African City. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-2272-5.

- ^ Kumar, B. G. (1991), Drèze, Jean; Sen, Amartya (eds.), «3 Ethiopian Famines 1973–1985: A Case‐Study», The Political Economy of Hunger: Volume 2: Famine Prevention, Oxford: Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198286363.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-828636-3, retrieved 20 March 2022

- ^ «Addis Ababa falls to dawn onslaught | | The Guardian». amp.theguardian.com. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ «Addis Ababa City Government Revised Charter Proclamation» (PDF). Federal Negarit Gazeta. 22 April 2022.

- ^ Ethiopia’s ‘Master Plan’ – good for development, damaging for minorities, 12 August 2014, retrieved 12 August 2014

- ^ The Roots of Popular Mobilization in Ethiopia, 16 June 2017, retrieved 16 June 2017

- ^ Ethiopia: Brutal Crackdown on Protests, 5 May 2014, retrieved 5 May 2014

- ^ Oromo Protests: Defiance Amidst Pain and Suffering, 16 December 2015, retrieved 16 December 2015

- ^ Ethiopia: Lethal Force Against Protesters, 18 December 2015, retrieved 18 December 2015

- ^ Country Policy and Guidance Note Ethiopia Oromos including the Oromo Protests (PDF), November 2017

- ^ Ethiopia Scraps Plan for Capital Area that Sparked Protests, retrieved 13 January 2016

- ^ Chala, Endalk (14 January 2016), «Ethiopia scraps Addis Ababa ‘master plan’ after protests kill 140», The Guardian, retrieved 14 January 2016

- ^ «Ethiopia cancels Addis Ababa master plan after Oromo protests», BBC News, 13 January 2016, retrieved 13 January 2016

- ^ «Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Metro Area Population 1950-2022». www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ «The Danger of Ambition and Neglect: The Case of Beautifying Sheger Project» (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ «Arada». www.ethiopians.com. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ «Riverside: green redevelopment for Addis Ababa |». en. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ «Ethiopia: ‘Sheger Project Signals Premier’s Promise-Fulfilling’ — Residents». allAfrica.com. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ «addis ababa city administration latest news». casabrasilis.com.br. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ Ethiopia PM moves to resolve Oromia – Addis Ababa boundary rift, 9 March 2019

- ^ Urban Centers in Oromia:Consequences of Spatial Concentration of Power in Multinational Ethiopia, January 2010

- ^ State of Oromia’s Interest in Addis Ababa (Finfinnee): Undelivered Constitutional Promises, November 2014

- ^ Benti, Getahun (3 November 2002), «A Nation without a City [a Blind Person without a Cane]: The Oromo Struggle for Addis Ababa», Northeast African Studies, 9 (3): 115–131, doi:10.1353/nas.2007.0009, JSTOR 41931283, S2CID 144274717

- ^ A Draft Proclamation to Determine the Special Interest of the State of Oromia in Addis Ababa City, 15 January 2018

- ^ Commentary on the draft proclamation of special interest of state of Oromia in Addis Ababa city, 23 November 2017, archived from the original on 7 September 2021, retrieved 22 July 2021

- ^ Yohannes Mekonnen (2013). Ethiopia: the Land, its People, History and Culture. Washington, DC: New Africa Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-9987160242. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ «Chief Administrator of Oromia says decision to move capital city based on study». Walta Information Center. 11 June 2005. Archived from the original on 13 June 2005. Retrieved 25 February 2006.

- ^ Ethiopians are having a tense debate over who really owns Addis Ababa, 7 July 2017

- ^ Abate, Abebe Gizachew (30 August 2019), «The Addis Ababa Integrated Master Plan and the Oromo Claims to Finfinnee in Ethiopia», International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 26 (4): 620–638, doi:10.1163/15718115-02604121, S2CID 150796037

- ^ NEWS: ODP CONCLUDES CONFERENCE, ELECTS NINE CRUCIAL MEMBERS OF ITS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE. SEE WHO IS WHO, 21 September 2018

- ^ «NGA: Country Files». Earth-info.nga.mil. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ «Addis Ababa city website (site map, see the list in «Sub Cities» section)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Article at unhabitat.org (map of Addis Ababa, page 9)» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Addis Ketema page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Akaky Kaliti page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Arada page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Bole page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Gullele page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Kirkos page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Kolfe Keranio page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Lideta page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Nifas Silk-Lafto page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «Yeka page (Addis Ababa website)». Addisababacity.gov.et. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ «NMA of Ethiopia». National Meteorological Agency of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ «Climate: Addis Abeba (altitude: 2350m) – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table». Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ a b

«Station Addis Abeba» (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 31 March 2019. - ^ «World Weather Information Service – Addis Ababa». World Meteorological Organisation. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^

«Klimatafel von Addis Abeba (Adis Ababa) / Äthiopien» (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 31 March 2019. - ^ a b «Population and Housing Census 2007 Report, National». Central Statistical Agency. 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ «The 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Results for Addis Ababa», Tables 2.1, 2.2, 2.8, 2.13A Archived 15 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Ethiopia: Regions, Major Cities & Towns — Population Statistics in Maps and Charts». www.citypopulation.de.

- ^ «Census 2007 Tables: Addis Abeba», Tables, 8.7, 8.8

- ^ Smith, David (28 August 2014). «Ethiopians’ plight: ‘The toilets are unhealthy, but we don’t have a choice’«. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ Macro International Inc. «2008. Ethiopia Atlas of Key Demographic and Health Indicators, 2005.» (Calverton: Macro International, 2008) Archived 5 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 2, 3, 10 (Retrieved 30 September 2010)

- ^ Overseas Security Advisory Council – Ethiopia 2007 Crime and Safety Report[dead link].

- ^ Massages and manicures hit Addis Ababa Archived 15 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine by Tia Goldenberg. Retrieved 15 January 2010. IOL. 6 November 2007.

- ^ «Company Profile Archived 5 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine.» Ethiopian Airlines. Retrieved on 3 October 2009.

- ^ Sophie Eastaugh, for. «What makes Ethiopia the world’s best spot for tourism?». CNN. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Bruche, S.; Gusset, M.; Lippold, S.; Barnett, R.; Eulenberger, K.; Junhold, J.; Driscoll, C. A.; Hofreiter, M. (2012). «A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia». European Journal of Wildlife Research. 59 (2): 215–225. doi:10.1007/s10344-012-0668-5. S2CID 508478.

- ^ «5 Reasons to Visit Addis Ababa Now». www.fodors.com. 12 December 2014. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ «Crime Victimization and its Impact» (PDF). 1 August 2022.

- ^ «Federal Negarit Gazeta» (PDF). 8 August 2022.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 1004-1007

- ^ Rubinkowska-Anioł, Hanna. «The Paintings in St George Church in Addis Ababa as a Method of Conveying Information about History and Power». Studies in African Languages and Cultures (49): 115–141.

- ^ a b «City Walk: Religious Buildings, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia». GPSmyCity. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ «The Grand Anwar Mosque». www.addisababa.travel. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Solomon, Abiy. «Ethiopia building a Financial District in Addis Ababa». Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Lagasse, Paul (2018). The Columbia Encyclopedia (8th ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press – via Credo Reference.

- ^ Addis Today by Molalign GIRMA, 2014

- ^ «Ethiopia Capital City, About Addis Ababa Tourism and Travel». Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ «Unity Park (Addis Ababa) – 2021 All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (with Photos)». Tripadvisor. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Sew, Mistir (2 August 2021). «Dire Dawa’s dilemma: Sharing power in Ethiopia’s eastern melting pot». Ethiopia Insight. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ «Addis Ababa: Culture – Tripadvisor». en.tripadvisor.com.hk. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ «Photographs of the National Museum of Ethiopia». Independent Travellers. independent-travellers.com. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ Organization, World Intellectual Property (31 March 2016). National Studies on Assessing the Economic Contribution of the Copyright-Based Industries — Series no. 9. WIPO. ISBN 978-92-805-2745-2.

- ^ «Theater in Ethiopia – All Country List». Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ «Best Cinemas in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia – List of Cinemas Ethiopia». www.ethyp.com. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ «The science museum in Addis Ababa — Ethiopia». www.madatech.org.il. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Communities, Africa Business. «Ethiopian Broadcasting Agency grants satellite TV licenses to three stations as it eyes digital migration». Africa Business Communities. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Mulgeta, Eteffa (19 March 2022). «Education In Ethiopia In Its Historical And Cultural Content». Foreign Curriculum Consultant Wayne County Intermediate School District Detroit, Michigan: 5–6.

- ^ «School Choice And Policy Response: A Comparative Context Between Private And Public Schools In Urban Ethiopia». 19 March 2022.

- ^ «International Conference on Multi-National Construction Projects: Addis Ababa Ring Road Project – A Case Study of a Chinese …» Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ «Railway Gazette: Chinese funding for Addis Abeba light rail». Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ «Ethiopia: Addis’ sister cities, historical ties». tuckmagazine.com. Tuck Magazine. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ «Harare, S. Korean city strengthen ties». The Herald (Zimbabwe). 27 February 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via PressReader.

- ^ «Institute of Semitic Studies». instituteofsemiticstudies.org. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ «Mohammed Al Amoudi». Forbes. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ «Our Founder». soleRebels. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ «Ruth Negga: tipped for Oscars glory». The Telegraph. 19 January 2017 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

Further reading[edit]

- Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A History (Peoples of Africa). Wiley-Blackwell; New Ed edition. ISBN 0-631-22493-9.

External links[edit]

- Addis Ababa City Administration

«Sheger» redirects here. For Irish-bred Thoroughbred racehorse, see Shergar.

|

Addis Ababa

|

|

|---|---|

|

Capital and chartered city |

|

|

From top, left to right: Skyline of Meskel Square; Monument to the Lion of Judah; St. George’s Cathedral; Addis Ababa University; Sheraton Addis; Sheger Park; Addis Ababa Light Rail Vehicle and Holy Trinity Cathedral |

|

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nicknames:

City of Humans, Sheger, Adu Genet |

|

|

Addis Ababa Location within Ethiopia Addis Ababa Location within the Horn of Africa Addis Ababa Location within Africa |

|

| Coordinates: 9°1′48″N 38°44′24″E / 9.03000°N 38.74000°ECoordinates: 9°1′48″N 38°44′24″E / 9.03000°N 38.74000°E | |

| Country | |

| Founded | 1886 |

| Incorporated as capital city | 1889 |

| Founded by |

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Adanech Abebe |

| Area | |

| • Total | 527 km2 (203 sq mi) |

| • Land | 527 km2 (203 sq mi) |

| [1] | |

| Elevation | 2,355 m (7,726 ft) |

| Population

(2007)[2] |

|

| • Total | 2,739,551 |

| • Estimate

(2021)[3] |

3,774,000 |

| • Density | 5,165.1/km2 (13,378/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Addis Ababan |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (East Africa Time) |

| Area code | (+251) 11 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.722[4] High · 1st of 11 |

| Website | cityaddisababa.gov.et |

Addis Ababa (;[5] Amharic: አዲስ አበባ, lit. ‘new flower’ [adˈdis ˈabəba] (listen)) is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia.[6][7][8] In the 2007 census, the city’s population was estimated to be 2,739,551 inhabitants.[2] Addis Ababa is a highly developed and important cultural, artistic, financial and administrative centre of Ethiopia.[9]

Addis Ababa was portrayed in the 15th century as a fortified location called «Barara» that housed the emperors of Ethiopia at the time. Prior to Emperor Dawit II, Barara was completely destroyed during the Ethiopian–Adal War and Oromo expansions. The founding history of Addis Ababa dates back in late 19th-century by Menelik II, Negus of Shewa, in 1886 after finding Mount Entoto unpleasant two years prior.[10] At the time, the city was a resort town; its large mineral spring abundance attracted nobilities of the empire and led them to establish permanent settlement. It also attracted many members of the working classes — including artisans and merchants — and foreign visitors. Menelik II then formed his imperial palace in 1887.[11][12] Addis Ababa became the empire’s capital in 1889, and subsequently international embassies were opened.[13][14] Addis Ababa urban development began at the beginning of the 20th century, and without any preplanning.[10]

Addis Ababa saw a wide-scale economic boom in 1926 and 1927, and an increase in the number of buildings owned by the middle class, including stone houses filled with imported European furniture. The middle class also imported newly manufactured automobiles and expanded banking institutions.[13] During the Italian occupation, urbanization and modernization steadily increased by a master plan which they hoped Addis Ababa would be more colonial city and continued after their occupation. Consequent master plans were designed by French and British consultants from the 1940s onwards focusing on monumental structures, satellite cities and inner-city. Similarly, the Italo-Ethiopian master plan also projected in 1986 concerning only urban structure and accommodating service, which was later adapted by the 2003 master plan.

Addis Ababa remains federal chartered city in accordance with the Addis Ababa City Government Charter Proclamation No. 87/1997 in the FDRE Constitution.[15] Called «the political capital of Africa» due to its historical, diplomatic, and political significance for the continent, Addis Ababa serves as the headquarters of major international organizations such as the African Union and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.[16]

The city lies a few kilometres west of the East African Rift, which splits Ethiopia into two, between the Nubian Plate and the Somali Plate.[17] The city is surrounded by the Special Zone of Oromia and is populated by people from the different regions of Ethiopia. It is home to Addis Ababa University. The city has a high human development index and is known for its vibrant culture, strong fashion scene, high involvement of young people, thriving arts scene, and for having the fastest economic growth of any country in the world.[18]

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

A study based on DNA evidence from almost 1,000 people around the world suggests that all humans spread out from a place close to current Addis Ababa 100,000 years ago.[19] The research indicated that genetic diversity decreases steadily the further one’s ancestors travelled from Addis Ababa.[20]

Middle Ages[edit]

Mount Entoto, a high tableland to the north of current Addis Ababa, is one of a handful of sites put forward as a possible location for a medieval imperial capital known as Barara. This permanent fortified city was established during the early-to-mid 15th century, and it served as the main residence of several successive emperors up to the early 16th-century reign of Libne Dengel.[21] The city was depicted standing between Mount Zuqualla and Menegasha on a map drawn by the Italian cartographer Fra Mauro in around 1450, and it was razed and plundered by Ahmed Gragn while the imperial army was trapped on the south of the Awash River in 1529, an event witnessed and documented two years later by the Yemeni writer Arab-Faqih. The suggestion that Barara was located on Mount Entoto is supported by the very recent discovery of a large medieval town overlooking Addis Ababa located between rock-hewn Washa Mikael and the more modern church of Entoto Maryam, founded in the late 19th century. Dubbed the Pentagon, the 30-hectare site incorporates a castle with 12 towers, along with 520 meters of stone walls measuring up to 5-meter high.[22]

Foundation[edit]

Initial settlements[edit]