А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

а́льфа Цента́вра, (звезда)

Рядом по алфавиту:

а́льфа Цента́вра , (звезда)

а́льфа-радиоакти́вный

а́льфа-радио́метр , -а

а́льфа-распа́д , -а

а́льфа-ри́тм , -а

а́льфа-спе́ктр , -а

а́льфа-спектро́метр , -а

а́льфа-спектрометри́ческий

а́льфа-спектрометри́я , -и

а́льфа-спектроскопи́ческий

а́льфа-спектроскопи́я , -и

а́льфа-стабилиза́тор , -а

а́льфа-терапи́я , -и

а́льфа-тести́рование , -я

а́льфа-части́цы , -и́ц, ед. -и́ца, -ы, тв. -ей

альфати́п , -а

альфатро́н , -а

а́льфёльд , -а (геогр.) и А́льфёльд, -а (территория в Венгрии)

а́льфовец , -вца, тв. -вцем, р. мн. -вцев

а́льфовский , (от «А́льфа»)

альфо́ль , -и

альфо́нс , -а (любовник, находящийся на содержании женщины)

альфре́йный , (альфре́йная жи́вопись, альфре́йная ро́спись)

альфре́йщик , -а

альфре́ско , и афре́ско, неизм. и нескл., с.

альфу́ры , -ов, ед. -фу́р, -а (в этнографии)

Альцге́ймер , -а: боле́знь Альцге́ймера

Альцио́на , -ы (мифол.; звезда)

алья́нс , -а

алья́с , -а (псевдоним пользователя компьютером)

алюме́ль , -я

Обновлено: 02.05.2022

Альфой Центавра, а не Альфа Центаврой По идее гравитационное поле границ не имеет вообще. Т. е. сила притяжения между звёздами присутствует. НО Во-первых кроме неё присутствуют и другие силы (в том числе притяжения к другим звёздам) потому воздействие сил притяжения между двух упомянутых звёзд ничтожно и будет гаситься иными силами. Во-вторых (как сейчас принято считать) есть некая сила, которая вызывает отдаление галактик друг от друга с ускорением. И кто сказал, что эта же сила не воздействует на звёзды в пределах одной галактики?

В общем, формулой не помогу, но Солнце не упадёт на Альфу Центавра.

К слову, когда-то видел расчёт, когда Земля упадёт на Солнце. И она таки упадёт, но через такой промежуток времени, который Солнце просто не протянет, раньше бабахнет и погаснет.

Кстати, нет, Земля отдаляется от Солнца, по расчетам примерно на 12 см в год, но это довольно сложно проверить измерением.

Сергей Мыслитель (5034) Ну может и отдаляется. Я, как бы, не проверял За достоверность тех расчётов тоже не ручаюсь.

Есть, но мизерное. Вас какой именно компонент Толимана интересует? А или Б? А может расчет провести между всей тройной системой Альфа Центавра А и Б + Проксима и Солнце? Сам-то расчет тривиальный, сила равна произведению масс и обратна квадрату расстояния.

Конечно есть. какие проблемы посчитать-то, световой год грубо говоря 10^16 метров, массы грубо говоря считаем равными 2*10^30

получаем 6.7*10^-11 * 2*10^30 * 2*10^30 / (10^16)^2 = 3*10^18

вообще-то неслабо.

интереснее посмотреть ускорение, поделить на массу Солнца, получится 10^-12. а это уже маловато.

а еще интереснее посчитать время свободного падения (если бы обе звезды были неподвижны). Но мне сейчас лень, я как-то считал время падения на Солнце с расстояния светового года, получилось порядка миллионов лет. Немало, но по астрономическим меркам — ерунда. Кстати, за сопоставимое время холодное газовое облако в 1 св. год может сжаться в звезду.

если не лень — можете посчитать просто по Кеплеру как половину периода орбиты с полуосью, равной расстоянию между звездами.

Как склоняется «Альфа Центавра»?

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как склоняется «Альфа Центавра»?

Так обозначается двойная звезда в созвездии Центавра, поэтому склоняется только первое слово, а для второго сохраняется родительный падеж со значением «принадлежности Центавру».

Альфа Центавра

Альфы Центавра

Альфе Центавра

Альфу Центавра

Альфой Центавра

об Альфе Центавра

42.8k 2 2 золотых знака 11 11 серебряных знаков 27 27 бронзовых знаков

Поиск ответа

Название не склоняется: салон как у » Альфа -Ромео» .

Здравствуйте!

Подскажите пожалуйста, как будет правильно писаться выражение:

ООО «Концерн » АЛЬФА » в лице директора Иванова И. И. передало оборудование.

или передал?

Заранее благодарю за ответ.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

как правильно:(ПРОВОДИМОМ или ПРОВОДИМЫМ)

представлять интересы ООО « Альфа » на конкурсе «Страхование ответственности организаций» по Лоту № 3, проводимом ООО «Саратоворгсинтез»

или

представлять интересы ОАО « Альфа » на конкурсе «Страхование ответственности организаций » по Лоту № 3, проводимым ООО «Саратоворгсинтез»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: на конкурсе (каком) проводимом .

Задала вам вопрос, используя символ альфа . В ответе увидела, что вместо символа — набор знаков. Я правильно поняла, что корректно писать «интерферон- альфа «? На основании какого правила? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Неизменяемые приложения присоединяются дефисом. См.: Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник. М., 2006. – С. 163.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В этих случаях руководствуются регистрационными документами. Считаем возможными варианты, представленные на сайтах компаний: УРАЛСИБ, Альфа -Банк и т. д.

Здравствуйте, уважаемая редакция! Подсказите, пожалуйста, как правильно: ГУ НИИ » Альфа » создало (учреждение) или создал (институт)? И если та же » Альфа «- в тексте дальше: бухгалтер «Альфы», » Альфа » начислила (женского рода)? Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

1. Правильно: учреждение создало. 2. Вы написали правильно.

Альфа Центавра — с прописной или строчной буквы?

Подскажите, пожалуйста, с прописной или строчной пишется название Альфа Центавра, если имеется в виду звездная система, состоящая из трех звезд: α Центавра А, α Центавра B и Проксима — α Центавра С.

Орфографический словарь дает вариант со строчной: альфа Центавра, с пометкой «звезда». Может, при значении «звездной системы» нужна все-таки прописная заглавная буква? И будет ли тогда склоняться первая часть «альфа-» или нет?

Как отдельная звезда, так и вся звездная система пишется с заглавной буквы: Альфа Центавра. Склоняется как обычно, по женскому образцу: Альфа, Альфы, Альфе, Альфу, Альфой, об Альфе.

Читайте также:

- Как быстро строится в майнкрафт в бед варс

- Как вернуть диабло 3

- Через сколько дней после дождя появляются грибы белые

- Как разводить рыбу в stardew valley

- Ты и я как огонь светит нам одна звезда

| Альфа Центавра ABC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Кратная звезда | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Расположение α Центавра показано стрелкой |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Прямое восхождение | 14ч 39м | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Склонение | −60° 50′ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Расстояние | 4,36 св. лет | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Видимая звёздная величина (V) | −0,01 / +1,34 / +11,05 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Созвездие | Центавр | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Лучевая скорость (Rv) | −21,6 км/c | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Собственное движение | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • прямое восхождение | −3678,19 mas в год | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • склонение | 481,84 mas в год | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Параллакс (π) | 747,23 ± 1,17 mas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Абсолютная звёздная величина (V) | 4,38 / 5,71 / 15,49 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Спектральный класс | G2V / K1V / M5,5Ve | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Показатель цвета | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • B−V | 0,71 / 0,88 / 1,97 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • U−B | 0,24 / 0,64 / 1,54 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Масса | 1,10 / 0,90 / 0,123[1] M⊙ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Радиус | 1,227 / 0,865 / 0,14 R⊙ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Возраст | (6±1)⋅109[2] лет | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Температура | 5750 / 5250[2] / 2700 K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Светимость | 1,519 / 0,500 / 0,00006 L⊙ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Металличность | 130–230 %☉ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Часть от | G-Cloud[d][12] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Свойства | gravity=4,30 / 4,37[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Период (P) | 79,91 лет. 500 000 лет |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Большая полуось (a) | 17,59″ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Эксцентриситет (e) | 0,516 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Наклонение (i) | 79,24°v | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Узел (Ω) | 204,87° | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Эпоха периастра (T) | 1955,56 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Коды в каталогах Rigil Kentaurus, Rigil Kent, Toliman, Bungula α Cen BHD 128621, HIP 71681, HR 5460, LHS 51, Gl 559 Proxima Cen HIP 70890, LHS 49 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SIMBAD | данные | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ARICNS | данные | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| У звезды существует 3 компонента Их параметры представлены ниже: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Источники: [11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

А́льфа Цента́вра, α Центавра, α Центавра AB — тройная звёздная система в созвездии Центавра. Два компонента, солнцеподобные α Центавра А и α Центавра B, невооружённому глазу видны как одна звезда −0,27m, благодаря чему α Центавра является третьей по яркости звездой ночного неба. Третий компонент — невидимый невооружённым глазом красный карлик Проксима Центавра, или α Центавра C, который находится от яркой двойной звезды на угловом расстоянии 2,2°. Все три являются ближайшими к Солнцу звёздами (4,36 световых года), причём на данный момент Проксима Центавра несколько ближе остальных[13][14].

Несмотря на свою яркость и близость, альфа Центавра отсутствует на флаге Бразилии, где изображено 27 звёзд, видимых в Южном полушарии[14].

Все компоненты α Центавра согласно официально принятому МАС в 2016 году списку собственных названий звезд[15] получили имена: компонент А — Ри́гил Кента́урус[16] (или Ри́гель Кента́урус, (латинизированная форма от араб. رجل القنطور [riʤl al-qanatûr] — «нога Кентавра»), а компонент B — Толима́н (возможно, от араб. الظلمان [ал-Зулман] «Страусы»)[17]. Для третьего компонента сохранено традиционное название Проксима Центавра[14]. До получения официальных имен в 2016 году, также можно было встретить название Бунгула[14] (возможно, от лат. ungula — «копыто»).

Обозначения в основных звёздных каталогах:

- α Центавра А: HD 128620, HR 5459, CP−60°5483, GCTP 3309.00A, LHS 50.

- α Центавра B: HD 128621, HR 5460, GCTP 3309.00B, LHS 51.

Характеристики системы[править | править код]

Сравнительные размеры компонентов системы α Центавра и Солнца

Две главные звезды α Центавра А и α Центавра B принадлежат главной последовательности и близки по характеристикам к Солнцу. α Центавра А оказалась первой звездой, для которой удалось провести прямое наблюдение атмосферы, показавшее её схожесть со светилом нашей системы (в атмосфере обнаружен тонкий холодный слой)[18]. Возраст системы оценивается в 6 миллиардов лет, что больше возраста Солнца, который составляет 4,5 миллиарда лет. Обе звезды α Центавра вращаются вокруг общего центра масс по эллиптической орбите с эксцентриситетом 0,52 и большой полуосью 23,4 а.е. Период обращения 79,91 года[19]. Их тригонометрический параллакс равен 742,1 ± 1,4 угловой миллисекунды. Собственное движение звёзд A и B равно −3,643 ± 0,012 угловой секунды в год по прямому восхождению и +0,697 ± 0,009 угловой секунды в год по склонению[источник не указан 1178 дней], радиальная скорость составляет −22,445 ± 0,0024 км/с. Максимальное угловое расстояние на небесной сфере между ними примерно равно 22″.

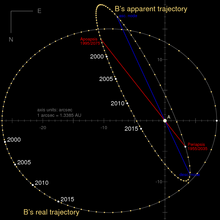

Кажущееся и истинное движение звёзд в системе Альфы Центавра. Компонент А для наглядности полагается неподвижным, и показано относительное орбитальное движение компонента В. Тонкий эллипс обозначает траекторию, видимую с Земли; истинной же является форма орбиты, если рассматривать её перпендикулярно плоскости орбитального движения. Исходя из скорости обращения, радиальное разделение A и B вдоль линии визирования достигло максимума в 2007 году, когда B находился за A. На орбите здесь указаны 80 точек, расстояние во времени между которыми приближённо равно 0,99888 лет, или 364,84 дня.

Наклонение орбиты звёздной пары альфы Центавра A и B к картинной плоскости наблюдателя с Земли составляет 79,205 ± 0,041 градуса, то есть орбита системы наблюдается почти с ребра, что повышает вероятность обнаружения планет в системе методом транзита. Плоскость двойной системы Альфа Центавра AB не компланарна плоскости орбиты Проксимы Центавра вокруг Альфы Центавра AB.

Кинематические характеристики Проксимы Центавра отличаются от характеристик главных звёзд системы. Проксиму от α Центавра АB на небесной сфере отделяет угловое расстояние около 2°, что в 4 раза больше углового диаметра Луны. Проксима Центавра (лат. proxima — «ближайшая») находится примерно в 15 000 ± 700 а.е. (около 0,21 св. года) от двух центральных звёзд системы. Период обращения Проксимы вокруг α Центавра АB составляет ок. 500 тыс. лет.

Координаты α Центавра А:

- прямое восхождение α2000 = 14ч39м36с,5,

- склонение δ2000 = −60°50′02″.

Координаты α Центавра B:

- прямое восхождение α2000 = 14ч39м35с,1,

- склонение δ2000 = −60°50′13″.

| α Центавра А | α Центавра B | Проксима Центавра | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Абсолютная звёздная величина | 4,38 | 5,71 | 15,53 |

| Спектральный класс | G2V | K1V | M5,5Ve |

| Светимость (в солнечных) | 1,519 | 0,5 | 6⋅10−5 |

| Диаметр (в солнечных) | 1,227 | 0,865 | 0,14 |

| Расстояние до Солнца, св. лет (1) | 4,36 | 4,22 |

(1) (учитывается время, которое прошёл свет до Солнца, а не наоборот, и с учётом искривления света под воздействием центра нашей галактики и иных объектов)

Взаимное расположение Солнца, Альфы Центавра и Проксимы Центавра (серая точка под «Alpha Centauri AB» — это проекция положения Проксимы Центавра на то же расстояние от Солнца, что и до Альфы Центавра)

Наблюдения[править | править код]

Главные звёзды системы A и B слишком близки друг к другу, чтобы их можно было различить невооружённым глазом, поскольку угловое расстояние между ними варьируется между 1,7 и 22 угловыми секундами[20] но, благодаря вытянутости орбит, обе звезды легко различимы с помощью небольших (диаметром объектива порядка 5 см) телескопов[21].

В 2010 году угловое расстояние между компонентами составляло 6,74 угловой секунды, в 2011 году — 6,04 угловой секунды. Угловое расстояние между компонентами стало минимальным (4 угловых секунды) в феврале 2016 года. Наибольшее угловое расстояние между компонентами системы последний раз наблюдалось в феврале 1976 года, следующее наступит в январе 2056 года.

В южном полушарии альфа Центавра образует внешнюю звезду Указателей, или Южных указателей (навигационный астеризм)[21], названных так потому, что линия через бету Центавра (Хадар, Агену)[22],

в 4,5° западнее[21], указывает прямо на созвездие Южный крест[21]. «Указатели» легко отличают настоящий Южный крест от Ложного креста[23].

Южнее 29°10′ ю. ш. звезда альфа Центавра является незаходящей звездой[24]. Среди городов, где она никогда не заходит за горизонт, — Сантьяго, Монтевидео, Буэнос-Айрес, Порту-Алегри, Кейптаун, Канберра, Сидней, Мельбурн. Так же как и Южный крест, эта звезда слишком удалена на юг, чтобы могла быть видима наблюдателем из средних северных широт. На территории бывшего СССР она не видна совсем: даже в Кушке не восходит. Южнее приблизительно +29°10′ северной широты (то есть южнее Дели, Кувейта и Хьюстона) и до экватора на протяжении северного лета альфа Центавра видна близко у горизонта на юге[22]. Кульминация звезды ежегодно происходит в полночь 24 апреля или в 21:00 8 июня[22][25].

Планетная система[править | править код]

На март 2022 года в системе известны одна подтверждённая и три неподтверждённые экзопланеты. Большое количество детальной информации об этой системе ожидается в ближайшие годы, от её обследования новыми телескопами: уже вступившим в строй JWST, планируемым Толиман и другими.

Альфа Центавра A b[править | править код]

У Альфы Центавра A в феврале 2021 года был обнаружен кандидат в экзопланеты Альфа Центавра A b в зоне обитаемости с орбитальным радиусом и периодом, примерно равными земным, подтверждение (или опровержение) существования которого ещё предстоит.

Альфа Центавра B b[править | править код]

Проводимые наблюдения долгое время не могли обнаружить планеты в системе альфы Центавра[26][27]. Только 16 октября 2012 года астрономы Европейской южной обсерватории объявили об открытии планеты Альфа Центавра B b с массой, близкой к земной, на орбите вокруг α Центавра B[28][29]. Планета была обнаружена методом измерения колебаний лучевых скоростей с помощью спектрографа HARPS. Для этого астрономам понадобилось более четырёх лет наблюдений[30].

Женевская группа наблюдала спектр звезды альфа Центавра B с февраля 2008 по июль 2011 года. Всего было сделано 459 измерений лучевой скорости, точность единичного измерения составила 0,8 м/с. Такое большое количество накопленных данных позволило выявить и учесть различные источники шума: звёздные колебания (поверхность звезды альфа Центавра B слегка колеблется с периодами менее 5 минут), грануляцию поверхности, влияние пятен на среднюю лучевую скорость звезды, долговременную активность, связанную с магнитным полем, и пр. Дело отчасти облегчилось тем, что блеск альфы Центавра B, как и многих других оранжевых карликов спектральных классов K0 V и K1 V, исключительно стабилен. Считалось, что планета b находится очень близко к светилу, в 0,04 а.е. (6 миллионов км), не попадая в обитаемую зону. Период обращения вокруг звезды оценён в 3,236 дня, а минимальная масса планеты — около 1,13 земной.

В октябре 2015 года планета была «закрыта», так как было доказано, что 3,26-дневный RV-сигнал в измерениях женевской группы появился из-за особенностей математической обработки данных[31][32].

Проксима Центавра b или Альфа Центавра C b[править | править код]

12 августа 2016 года в журнале Der Spiegel появилось сообщение об открытии планеты Проксима Центавра b у красного карлика Проксима Центавра[33]. 24 августа 2016 года эта информация была подтверждена сотрудниками Европейской южной обсерватории[34].

Проксима Центавра c или Альфа Центавра C c[править | править код]

Проксима Центавра c — неподтверждённая планета, находящаяся гораздо дальше зоны обитаемости. Открыта в январе 2020 года.

Проксима Центавра d или Альфа Центавра C d[править | править код]

Проксима Центавра d — неподтверждённая планета (миниземля) массой ≥0,26±0,05 массы Земли (четверть массы Земли, в два раза больше массы Марса), находящаяся ближе зоны обитаемости. Открыта в 2020 году[35].

Другие возможные планеты[править | править код]

Вид с гипотетической планеты, вращающейся вокруг α Центавра A, в представлении художника. α Центавра B — яркая звезда слева

Предполагаемые планеты могут обращаться отдельно вокруг α Центавра А или α Центавра B или Проксимы Центавра, или могут иметь большие орбиты вокруг двойной системы α Центавра АB[36][37]. Поскольку обе звезды приблизительно подобны Солнцу (например в возрасте и металличности), астрономы проявляют особенный интерес к поиску планет в этой системе. Несколько команд, заявивших о своих исследованиях в этом направлении, используют различные методы лучевой скорости или прохождения звёзд для исследования этой системы[26].

Компьютерное моделирование показало возможность формирования планеты в пределах 1,1 а.е. (160 млн км) от α Центавра B, и что орбита этой планеты может оставаться стабильной не менее 250 миллионов лет[38]. Тела вокруг звезды A могут обращаться на немного больших расстояниях, вследствие более сильной гравитации звезды А. Кроме того, отсутствие коричневых карликов и газовых гигантов вокруг А и В, наоборот, увеличивают шансы обнаружения планет земного типа[39]. По состоянию на 2002 год технологии не позволяли обнаружить планеты земной группы вокруг Альфы Центавра[39]. Но теоретические расчёты возможностей обнаружения методом лучевой скорости показали, что целенаправленные и регулярные исследования телескопом класса 1m[прояснить] могут с большой вероятностью обнаружить гипотетическую планету с массой в 1,8 массы Земли в зоне обитаемости α Центавра B в течение трёх лет[40].

По данным наблюдений космического телескопа Hubble в 2013 и 2014 годах за звездой альфа Центавра B, учёные предположили возможность существования у этой звезды планеты размером примерно с Землю, обращающейся вокруг альфы Центавра B менее чем за 20,4 дня[41][42].

Одно из исследований 2012 года, проведённое астрономами из Эдинбургского университета, показывает, что у звезды α Центавра B обитаемая зона находится на расстоянии не менее 0,5 и не более 0,9 а.е. от звезды[источник не указан 895 дней]. При этом средняя температура поверхности гипотетической планеты в пределах этой зоны будет отличаться всего на 4—5 кельвинов в зависимости от расстояния до второй звезды α Центавра А. Моделирование показывает, что планета, обращающаяся вокруг α Центавра B, будет лишь раз в 70 лет приближаться к звезде α Центавра А на расстояние, при котором эта звезда будет влиять на климат планеты. В остальное время она влияния на климат планеты оказывать не будет. Также исследователи отмечают, что подобные сценарии возможны только при наличии на планете океанов, подобных земным. Если же планета будет представлять собой сухую пустыню, как Марс, то колебания температуры будут гораздо сильнее[43].

В 2019 году с помощью теплового инфракрасного коронографа NEAR (англ. Near Earths in the AlphaCen Region), установленного на одном из четырёх 8,2-метровых телескопов комплекса Очень большого телескопа Европейской южной обсерватории в Чили, в системе Альфа Центавра начался поиск планет в «обитаемой зоне» у звёзд A и B[44]. После почти 100 часов наблюдений спектрометром VISIR в инфракрасном диапазоне на длине волн менее 10 микрон и удаления ложных сигналов, на окончательном изображении выявили источник света «C1», который может быть экзопланетой Альфа Центавра A b размером с Нептун внутри обитаемой зоны или пылевым диском[45].

Межзвёздные полёты[править | править код]

Предполагается, что альфа Центавра станет одной из первых целей межзвёздных полётов. Преодоление расстояния между Солнцем и α Центавра при использовании современных технологий в разумные сроки невозможно. Однако возможности технологий солнечного паруса или ядерного ракетного двигателя могут позволить совершить такой перелёт за несколько десятилетий[46][47]. В 2016 году было заявлено о начале подготовки полёта «наноспутника на лазерных парусах» (Breakthrough Starshot) на Альфу Центавра, который может преодолеть расстояние до ближайшей звезды за 15 лет[48].

Ближайшее окружение звезды[править | править код]

Ближайшее окружение Солнца

Следующие звёздные системы находятся на расстоянии в пределах 10 световых лет от системы Альфы Центавра:

| Звезда | Спектральный класс | Расстояние, св. лет |

|---|---|---|

| Луман 16 AB | L7,5 / T0,5 | 3,68 |

| Солнце | G2 V | 4,37 |

| Звезда Барнарда | M4,0 V | 6,5 |

| Росс 154 | M3,5 Ve | 8,1 |

| Вольф 359 | M5,8 Ve | 8,3 |

| Сириус AB | A1 V / DA2 VII | 9,5 |

| Эпсилон Эридана | K2 Ve | 9,7 |

В массовой культуре[править | править код]

Поскольку данная звёздная система является ближайшей к нам, фантасты издавна связывали с ней начало эры межзвёздных перелётов.

- «Дальний Центавр» (англ. Far Centaurus; 1944) — научно-фантастический рассказ канадско-американского писателя А. Э. ван Фогта.

- «Задача трёх тел» (кит. трад. 三體, упр. 三体, пиньинь Sān tǐ) — научно-фантастический роман китайского писателя фантаста Лю Цисиня.

- «Аватар» (англ. Avatar, МФА: [ˈæv.ə.tɑɹ]) — американский научно-фантастический фильм 2009 года сценариста и режиссёра Джеймса Кэмерона с Сэмом Уортингтоном и Зои Салдана в главных ролях.

- James Cameron’s Avatar: The Game (рус. «Аватар Джеймса Кэмерона: Игра») — компьютерная игра, шутер от третьего лица.

См. также[править | править код]

- Альфа Центавра B b

- Список ближайших звёзд

- Список самых ярких звёзд

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ Anosova, J.; Orlov, V. V.; Pavlova, N. A. Dynamics of nearby multiple stars. The alpha Centauri system (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics : journal. — EDP Sciences, 1994. — Vol. 292, no. 1. — P. 115—118.

- ↑ 1 2 England, M. N. A spectroscopic analysis of the Alpha Centauri system (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society : journal. — Oxford University Press, 1980. — Vol. 191. — P. 23—35.

- ↑ Gilli, G.; Israelian, G.; Ecuvillon, A.; Santos, N. C.; Mayor, M. Abundances of Refractory Elements in the Atmospheres of Stars with Extrasolar Planets (англ.) // Astronomy and Astrophysics : journal. — EDP Sciences, 2006. — Vol. 449, no. 2. — P. 723—736. — doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053850.

- ↑ 1 2 Ducati J. R. Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson’s 11-color system (англ.) — 2002. — Vol. 2237.

- ↑ 1 2 Torres C. A. O., Quast G. R., Silva L. d., Reza R. d. l., Melo C. H. F., Sterzik M. Search for associations containing young stars (SACY) (англ.) // Astron. Astrophys. / T. Forveille — EDP Sciences, 2006. — Vol. 460, Iss. 3. — P. 695—708. — ISSN 0004-6361; 0365-0138; 1432-0746; 1286-4846 — doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065602 — arXiv:astro-ph/0609258

- ↑ 1 2 3 Luck R. E. Abundances in the local region. III. Southern F, G, and K dwarfs (англ.) // Astron. J. / J. G. III, E. Vishniac — IOP Publishing, American Astronomical Society, University of Chicago Press, AIP, 2018. — Vol. 155. — P. 111–111. — ISSN 0004-6256; 1538-3881 — doi:10.3847/1538-3881/AAA9B5

- ↑ Abia C., Rebolo R., Beckman J. E., Crivellari L. Abundances of light metals and Ni in a sample of disc stars (англ.) // Astron. Astrophys. / T. Forveille — EDP Sciences, 1988. — Vol. 206. — P. 100–107. — ISSN 0004-6361; 0365-0138; 1432-0746; 1286-4846

- ↑ Smith G., Edvardsson B., Frisk U. Non-resonance lines of neutral calcium in the spectra of the alpha Centauri binary system (англ.) // Astron. Astrophys. / T. Forveille — EDP Sciences, 1986. — Vol. 165. — P. 126–134. — ISSN 0004-6361; 0365-0138; 1432-0746; 1286-4846

- ↑ Edvardsson B. Spectroscopic surface gravities and chemical compositions for 8 nearby single sub-giants (англ.) // Astron. Astrophys. / T. Forveille — EDP Sciences, 1988. — Vol. 190. — P. 148–166. — ISSN 0004-6361; 0365-0138; 1432-0746; 1286-4846

- ↑ 1 2 Martínez-Arnáiz R., Maldonado J., Montes D., Eiroa C., Montesinos B. Chromospheric activity and rotation of FGK stars in the solar vicinity (англ.) // Astron. Astrophys. / T. Forveille — EDP Sciences, 2010. — Vol. 520. — P. 79–79. — ISSN 0004-6361; 0365-0138; 1432-0746; 1286-4846 — doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200913725 — arXiv:1002.4391

- ↑ [1] (недоступная ссылка)

- ↑ Our Local Galactic Neighborhood

- ↑ Сурдин В. Г. Звёзды. — М.: Физматлит, 2009. — С. 95—99.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Алексей Понятов. Ближайшая // Наука и жизнь. — 2017. — № 1. — С. 6—13.

- ↑ Naming Stars. IAU.org. Дата обращения: 19 января 2021.

- ↑ Ближайшей к нам звездной системе Альфа Центавра присвоено новое официальное название.

- ↑ Kunitzsch P., Smart, T., A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations, Cambridge, Sky Pub. Corp., 2006, p. 27.

- ↑ Атмосфера ближайшей звезды // Космос-журнал.

- ↑ Hartkopf, W.; Mason, D. M. Sixth Catalog of Orbits of Visual Binaries (недоступная ссылка). U.S. Naval Observatory. Дата обращения: 19 октября 2012. Архивировано 12 апреля 2009 года.

- ↑

Van Zyl, Johannes Ebenhaezer. Unveiling the Universe: An Introduction to Astronomy (англ.). — Springer, 1996. — ISBN 3540760237. - ↑ 1 2 3 4

Hartung, E. J., Frew, David Malin, David. Astronomical Objects for Southern Telescopes, Cambridge University Press. - ↑ 1 2 3

Norton, A. P. Norton’s 2000.0 :Star Atlas and Reference Handbook (англ.) / I. Ridpath. — Longman Scientific and Technical, 1986. — P. 39—40. - ↑

Mitton, Jacquelin. The Penguin Dictionary of Astronomy. — Penguin Books, 1993. — С. 148. - ↑ Рассчитано из известного склонения звезды (δ) по формуле (90° + δ): склонение альфы Центавра −60° 50′, так что широты, где звезда является незаходящей, будут располагаться южнее −29°10′, то есть 29° ю. ш. Аналогично, в северном полушарии альфа Центавра будет являться невосходящей севернее широты (90° + δ), то есть +29° с. ш.

- ↑

The Constellations. Part 2: Culmination Times (недоступная ссылка). Southern Astronomical Delights. Дата обращения: 6 августа 2008. Архивировано 4 февраля 2012 года. - ↑ 1 2

Why Haven’t Planets Been Detected around Alpha Centauri. Universe Today. Дата обращения: 19 апреля 2008. Архивировано 4 февраля 2012 года. - ↑

Tim Stephens. Nearby star should harbor detectable, Earth-like planets (недоступная ссылка). News & Events. UC Santa Cruz (7 марта 2008). Дата обращения: 19 апреля 2008. Архивировано 4 февраля 2012 года. - ↑ SETH BORENSTEIN. Earth-Sized Planet Found Just Outside Solar System (англ.) (недоступная ссылка). abc News (17 октября 2012). Дата обращения: 17 октября 2012. Архивировано 20 октября 2012 года.

- ↑ НИКОЛАЙ ПОДОРВАНЮК, АННА САБУРОВА. Земля в альфа Центавра. Gazeta.ru (17 октября 2012). Дата обращения: 17 октября 2012.

- ↑ Mike Wall. Discovery! Earth-Size Alien Planet at Alpha Centauri Is Closest Ever Seen (англ.). space.com (16 октября 2012). Дата обращения: 17 октября 2012. Архивировано 20 октября 2012 года.

- ↑ Ghost in the time series: no planet for Alpha Cen B.

- ↑ Планетологи опровергли открытие планеты у Альфы Центавра.

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg Germany. Wissenschaftliche Sensation: Mögliche zweite Erde in unserer Nachbarschaft entdeckt (нем.). SPIEGEL ONLINE. Дата обращения: 29 августа 2016.

- ↑ information@eso.org. Planet Found in Habitable Zone Around Nearest Star — Pale Red Dot campaign reveals Earth-mass world in orbit around Proxima Centauri (англ.) (недоступная ссылка). www.eso.org. Дата обращения: 29 августа 2016. Архивировано 28 августа 2016 года.

- ↑ Faria, J. P.; Suárez Mascareño, A.; Figueira, P.; et al. (2022). “A candidate short-period sub-Earth orbiting Proxima Centauri” (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. EDP Sciences. 658: A115. DOI:10.1051/0004-6361/202142337.

- ↑ Новости научного мира: в Альфа Центавре могут быть планеты земного типа (недоступная ссылка). Дата обращения: 29 января 2012. Архивировано 8 ноября 2011 года.

- ↑ Теоретики «нашли» каменные планеты у Альфа Центавра.

- ↑

Thebault, P., Marzazi, F., Scholl, H. Planet formation in the habitable zone of alpha centauri B (англ.) // Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society : journal. — Oxford University Press, 2009. — Vol. 393. — P. L21—L25. — doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2008.00590.x. — Bibcode: 2009MNRAS.393L..21T. — arXiv:0811.0673. - ↑ 1 2

Quintana, E. V.; Lissauer, J. J.; Chambers, J. E.; Duncan, M. J.;. Terrestrial Planet Formation in the Alpha Centauri System (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal : journal. — IOP Publishing, 2002. — Vol. 2, no. 2. — P. 982. — doi:10.1086/341808. — Bibcode: 2002ApJ…576..982Q. - ↑

Javiera M. Guedes, Eugenio J. Rivera, Erica Davis, Gregory Laughlin, Elisa V. Quintana, Debra A. Fischer. Formation and Detectability of Terrestrial Planets Around Alpha Centauri B (англ.) // The Astrophysical Journal : journal. — IOP Publishing, 2008. — Vol. 679, no. 2. — P. 1582—1587. — doi:10.1086/587799. — Bibcode: 2008ApJ…679.1582G. — arXiv:0802.3482. - ↑ [1503.07528] Hubble Space Telescope search for the transit of the Earth-mass exoplanet Alpha Centauri Bb.

- ↑ Астрономы заподозрили наличие в Альфе Центавра ещё одной суперземли.

- ↑ Смоделирована планета в обитаемой зоне вокруг α Центавра B (недоступная ссылка). compulenta.ru (26 марта 2012). Дата обращения: 28 марта 2012. Архивировано 28 марта 2012 года.

- ↑ Началась охота за обитаемыми планетами в системе Альфа Центавра, 10 июня 2019.

- ↑ Wagner K. et al. Imaging low-mass planets within the habitable zone of α Centauri, 10 February 2021

- ↑

Ian O’Neill, Ian. How Long Would it Take to Travel to the Nearest Star?. Universe Today (8 июля 2008). Архивировано 4 февраля 2012 года. - ↑ Колесников Ю. «Вам строить звездолёты». Москва, 1990. ISBN 5-08-000617-X

- ↑ Хокинг и Мильнер полетят на альфу Центавра.

Ссылки[править | править код]

- Alpha Centauri (англ.)

- Alpha Centauri 3 (Solstation) (англ.)

- Данные обсерватории SIMBAD (англ.)

Всего найдено: 33

Почему алфавит назвали алфавитом

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Приведем словарную статью для слова алфавит из школьного этимологического словаря «Почему не иначе?» Л. В. Успенского.

Алфави́т. Помните, что мы говорили о нашем слове «азбука»? Оно — точная копия греческого «alfabetos»: оба слова построены совершенно одинаково.

Две первые буквы греческого письма звались «альфа» и «бета». Их история не простая; они были получены греками от финикийцев вместе со всей финикийской, семитической, письменностью. Письменность эта была некогда иероглифической. Каждый иероглиф назывался словом, начинавшимся со звука, который обозначался этим значком.

Первый в их ряду имел очертания головы быка; «бык» — по-финикийски «алеф». Вторым стоял рисунок дома; слово «дом» звучало как «бет». Постепенно эти значки стали означать звуки «а» и «б».

Значения финикийских слов греки не знали, но названия значков-букв они сохранили, чуть переделав их на свой лад: «альфа» и «бета». Их сочетание «альфабе́тос» превратилось в слово, означавшее: «обычный порядок букв», «азбука». Из него получилось и наше «алфавит». Впрочем, в Греции было такое время, когда слово «альфабетос» могло звучать и как «альфавитос»: в разные времена жизни греков они один и тот же звук произносили то как «б» то как «в».

Здравствуйте! допустимо ли переносить наименования организаций? Например: ОАО — на одной строке, «Альфа-Банк» — на другой; или ПАО «НК — на одной строке, «Транснефть» — на следующей?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Не рекомендуем отрывать аббревиатуру в роли родового слова от названия.

Здравствуйте! Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильно написать «кофе-культ» или «кофекульт»? (Варианты принять не смогу, поскольку это название заведения. Увы.) Какая тут логика? Кофемашина, кофеварка — но кофе-брейк

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Название заведения нужно писать в соответствии с учредительными документами. А так как слово кофе?культ словарями не зафиксировано и подпадает под разные орфографические правила, то возможны и разные варианты написания. Связано это с тем, что часть кофе допускает несколько трактовок: 1) как часть с соединительной гласной е, 2) как первый компонент в сочетании существительного с приложением, 3) как сокращение слова кофейный. Возможность неоднозначной трактовки приводит к возможности применения разных правил.

Сложные существительные, содержащие соединительную гласную на стыке частей, пишутся слитно, например: паровоз, бактерионоситель, птицеферма, вишнеслива, волколис, религиоведение, музееведение. Этому правилу подчиняются слова кофеварка, кофемашина, кофемолка, кофезаменитель.

Сложные существительные и сочетания с однословным приложением, если в их состав входят самостоятельно употребляющиеся существительные и обе части или только вторая часть склоняются, пишутся через дефис, например: альфа-частица, баба-яга, бас-гитара, бизнес-тур, гольф-клуб, шоу-бизнес, а также кофе-пресс, кофе-автомат, кофе-брейк, кофе-пауза, кофе-порошок, кофе-суррогат.

Сложносокращенные слова пишутся слитно, напр.: главбух, госзаказ, детсад, домработница, жилплощадь, завскладом, канцтовары, спорткафе. Ср.: кофейная машина – кофемашина.

Новым словам приходится встраиваться в эту систему орфографических закономерностей. По первому и третьему правилу можно написать кофекульт, по второму – кофе-культ. А ведь еще культ может стать собственным названием кофе (кофе «Культ») или видом кофе (кофе культ).

Как правильно писать название организации в брошюрах, на сайте и т.п.? По правосустанавливающим документам название организации пишется прописными буквами ОАО «АЛЬФА-БАНК», допустимо ли написание данного названия строчными буквами? Например, ОАО «Альфа-Банк»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вне документов возможно (и уместно) написание с использованием строчных букв.

Если вы дает ссылку на какой-то старый ответ в виде числа, такая ссылка НИКОГДА НЕ ДАЕТ НИКАКИХ ОТВЕТОВ. Бесполезная трата места и разочарование для людей, которые хотели получить ответ на вопрос.

ПРИМЕР.

Вопрос № 238520

Повторяю вопрос: Надо ли закавычивать названия банков типа МДМ-банк, Газпромбанк, Альфа-Банк и каким правилом это регламентируется? Очень надеюсь на ответ!

NAL

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

См. ответ № 194965.

КАК ВСЕГДА, ПОСЛЕ КЛИКА НА ЛЮБУЮ ТАКУЮ ССЫЛКУ И НА ЭТУ ТОЖЕ НИКАКОГО ОТВЕТА НЕТ, открывается только окно справки и реклама под ним:СПРАВОЧНОЕ БЮРО

Яндекс.Директ

Индукционная плита Siemens Интеллектуальная зона нагрева FlexInduction: любая посуда любой формы!

***

Сэкономить на iPhone 5? Легко! На eBay низкие цены на iPhone и доставка в твой город. Попробуй!

***Яндекс.Директ

Квартиры от 2 млн в Новой Москве! Узнайте, как решить квартирный вопрос недорого!

***

Ученые в шоке: покойники не хотят Ученые в шоке: покойники не хотят разлагаться! … Горячая новость на

***

18+

Ищете бытовую технику? Воспользуйтесь Яндекс.Маркетом. Поиск по параметрам. Отзывы. Выбирайте!

***

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Здравствуйте. Дело в том, что старый архив ответов «Справки» сейчас закрыт, поэтому ссылки на него не работают. Сейчас мы не ссылаемся на закрытый архив, но в более ранних ответах такие ссылки, к сожалению, не редкость.

Объяснить значения фразеологических оборотов и крылатых фраз:

Альфа и омега, Аника-воин, Содом и Гоморра, Вавилонское столпотворение, Буриданов осел.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

А сюда заглядывали?

http://www.gramota.ru/spravka/phrases/

Посдскажите, пожалуйста, как корректно писать в СМИ такие названия компаний, как «МедиаЛайн», «АльфаСтрахование»? Грамотно писать заглавную букву в посередине слова названия?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Прописная буква внутри слова не пишется. Однако для собственных наименований организаций, торговых марок и т. п. может быть сделано исключение, если таково официальное (задокументированное) название фирмы.

Добрый день!

Подскажите пожалуйста, как правильно писать «альфа-ритм мозга» или «альфа ритм мозга». С дефисом или без?

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Альфа-… — первая часть сложных слов, пишется через дефис, но: альфаметр, альфатип, альфатрон. Должно быть: альфа-ритм.

как изменяется по падежам альфа центавра

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: альфа Центавра, без альфы Центавра, к альфе Центавра…

Доброго дня. Сейчас весьма часто в наименованиях фирмы употребляется слово «группа», но не в иностранном значении. Например, «Азия групп», «Альфа групп» и т.п. Насколько верно в слове «групп» писать две буквы «п», а не одну? Замечу, слово «групп» не от русскогоо «груППа», а — английского «group». Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вряд ли Вы найдете однозначное подтверждение тому, что это заимствование — именно из английского языка. Может быть, из немецкого или французского?

Что касается собственных наименований, то теоретически в них может быть хоть четыре П подряд — ограничений нет.

Скажите, пожалуйста, правильно ли писать

«О Интернет Банке», как написано на сайте альфа банка (https://click.alfabank.ru/ALFAIBSR/)?

Ведь по правилам русского языка надо вместо «О» перед гласной использовать «Об»!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: об интернет-банке.

Скажите, как правильно:

Он сотрудничал с такими известными компаниями, как «Альфа«, «Бета» и прочими.

Он сотрудничал с такими известными компаниями, как «Альфа«, «Бета», и прочими.

Он сотрудничал с такими известными компаниями, как «Альфа«, «Бета» и прочие.

Очень надеюсь, что вы все-таки ответите!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: Он сотрудничал с такими известными компаниями, как «Альфа«, «Бета» и прочие.

Как правильно — «Беловежская пуща» или «Беловежская Пуща»? Речь идет о географическом понятии. Проверка слова на gramota.ru дает ответ — «Беловежская Пуща». В то же время в разделе «Действующие правила правописания» написано следующее: «§ 100. Пишутся с прописной буквы индивидуальные названия aстрономических и географических объектов (в том числе и названия государств и их административно-политических частей), улиц, зданий. Если эти названия составлены из двух или нескольких слов, то с прописной буквы пишутся все слова, кроме служебных слов и родовых названий, как-то: остров, мыс, море, звезда, залив, созвездие, комета, улица, площадь и т. п., или порядковых обозначений светил (альфа, бета и т. п.)»

Похоже, что «пуща» как раз и есть родовое название.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: Беловежская Пуща. Противоречия с правилами нет, т. к. мы не можем сказать, что слово пуща употребляется только как родовое наименование, не передавая дополнительных смыслов: все же Беловежская Пуща – это не просто название некоего леса (основное значение слова пуща – обширный густой лес), а наименование природного заповедника, территории, обладающей особым историческим и культурным статусом.

Отметим, что орфографические словари предназначены именно для того, чтобы фиксировать частные орфографические случаи (в отличие от свода правил правописания, описывающего общие закономерности письма), регламентировать написание конкретных слов и словосочетаний. Фиксация в орфографическом словаре означает, что данное написание является нормативным и в дальнейшем обращении к правилам правописания уже нет необходимости.

Нужно ли склонять наименования греческих букв, обозначающие некоторые математические величины? Например: «В результате преобразований мы получили меньшую альфа«. Или «альфу»? Или «меньшее альфа«?

Примечание. Специфика текста такова, что замена названия (например, «альфа«) на соотвествующую греческую букву не подходит.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: меньшее (число) альфа, меньшую альфу.

Правильно ли употреблять слово АНАЛФАБЕТИЗМ (АНАЛЬФАБЕТИЗМ) в значении БЕЗГРАМОТНОСТЬ/НЕГРАМОТНОСТЬ? И существует ли в русском языке такое слово и его производные вообще?

С уважением, Нинель

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Такое слово можно встретить в Интернете, задав соответствующий поисковый запрос, но словари русского языка его (это слово) не фиксируют.

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как склоняется «Альфа Центавра»?

задан 1 авг 2016 в 12:51

adpadp

1612 серебряных знака7 бронзовых знаков

1 ответ

Так обозначается двойная звезда в созвездии Центавра, поэтому склоняется только первое слово, а для второго сохраняется родительный падеж со значением «принадлежности Центавру».

Альфа Центавра

Альфы Центавра

Альфе Центавра

Альфу Центавра

Альфой Центавра

об Альфе Центавра

ответ дан 1 авг 2016 в 13:50

Alex_anderAlex_ander

43.4k2 золотых знака13 серебряных знаков27 бронзовых знаков

альфа Центавра

- альфа Центавра

-

‘альфа Цент’авра (звезда)

Русский орфографический словарь. / Российская академия наук. Ин-т рус. яз. им. В. В. Виноградова. — М.: «Азбуковник».

.

1999.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «альфа Центавра» в других словарях:

-

Альфа Центавра B b — Экзопланета Списки экзопланет … Википедия

-

АЛЬФА ЦЕНТАВРА — АЛЬФА ЦЕНТАВРА, самая яркая звезда в созвездии Центавра и третья по яркости звезда небосвода. Это визуальная двойная звезда, т.е. и она, и парная с нею звезда, более слабая Проксима Центавра, обе видны в телескоп. Расстояние до них 4,3 световых… … Научно-технический энциклопедический словарь

-

альфа центавра — сущ., кол во синонимов: 1 • звезда (503) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

Альфа Центавра — Запрос «Alpha Centauri» перенаправляется сюда; о компьютерной игре см. Sid Meier s Alpha Centauri … Википедия

-

Альфа Центавра (значения) — Альфа Центавра (значения): Альфа Центавра звёздная система в созвездии Центавра, ближайшая к Солнцу Альфа Центавра B b экзопланета, которая обращается вокруг меньшего компонента двойной системы Альфа Центавра, звезды Альфа Центавра B … Википедия

-

Альфа-Центавра — … Википедия

-

Планетарная система Альфа Центавра — – вымышленная планетарная система, в которой разворачивается действие фильма «Аватар» и игры «Аватар Джеймса Камерона» по мотивам фильма. Содержание 1 Описание 2 Планетарная система АСА … Википедия

-

Планетная система Альфа Центавра (Аватар) — Планетная система Альфа Центавра (Аватар) вымышленная планетная система, в которой разворачивается действие фильма «Аватар» и игры «Аватар Джеймса Камерона» по мотивам фильма. Содержание 1 Описание 2 Планетная система АСА … Википедия

-

Альфа (значения) — В Викисловаре есть статья «альфа» Альфа первая буква греческого алфавита (греч … Википедия

-

Альфа (буква) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Альфа (значения). Греческий алфавит Αα Альфа … Википедия

|

Alpha Centauri AB (left) forms a triple star system with Proxima Centauri, circled in red. The bright star system to the right is Beta Centauri. |

|

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 |

|

|---|---|

| Constellation | Centaurus |

| Alpha Centauri A | |

| Right ascension | 14h 39m 36.49400s[1] |

| Declination | −60° 50′ 02.3737″ |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +0.01[2] |

| Alpha Centauri B | |

| Right ascension | 14h 39m 35.06311s[1] |

| Declination | −60° 50′ 15.0992″ |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +1.33[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| A | |

| Spectral type | G2V[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.24 |

| B−V color index | +0.71[2] |

| B | |

| Spectral type | K1V[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.68 |

| B−V color index | +0.88[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| A | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −21.4±0.76 [4] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −3679.25 mas/yr Dec.: 473.67 mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 750.81 ± 0.38 mas[5] |

| Distance | 4.344 ± 0.002 ly (1.3319 ± 0.0007 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 4.38[6] |

| B | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −18.6±1.64[4] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −3614.39[1] mas/yr Dec.: 802.98 mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 750.81 ± 0.38 mas[5] |

| Distance | 4.344 ± 0.002 ly (1.3319 ± 0.0007 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 5.71[6] |

| Orbit[5] | |

| Primary | A |

| Companion | B |

| Period (P) | 79.762±0.019 yr |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 17.493±0.0096″ |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.51947±0.00015 |

| Inclination (i) | 79.243±0.0089° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 205.073±0.025° |

| Periastron epoch (T) | 1875.66±0.012 |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) |

231.519±0.027° |

| Details | |

| Alpha Centauri A | |

| Mass | 1.0788±0.0029[5] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.2175±0.0055[5] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 1.5059±0.0019[5] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.30[7] cgs |

| Temperature | 5,790 K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | <0.20 dex |

| Rotation | 22±5.9 d |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 2.7±0.7[8] km/s |

| Alpha Centauri B | |

| Mass | 0.9092±0.0025[5] M☉ |

| Radius | 0.8591±0.0036[5] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 0.4981±0.0007[5] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.37[7] cgs |

| Temperature | 5,260 K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | 0.23 dex |

| Rotation | 36 days[9] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 1.1±0.8[10] km/s |

| Age | 5.3±0.3[11] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

|

Gliese 559, FK5 538, CD−60°5483, CCDM J14396-6050, GC 19728 |

|

| α Cen A: Rigil Kentaurus, Rigil Kent, α1 Centauri, HR 5459, HD 128620, GCTP 3309.00, LHS 50, SAO 252838, HIP 71683 | |

| α Cen B: Toliman, α2 Centauri, HR 5460, HD 128621, LHS 51, HIP 71681 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | AB |

| A | |

| B | |

| Exoplanet Archive | data |

| ARICNS | data |

| Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia |

data |

Alpha Centauri (α Centauri, Alpha Cen, or α Cen) is a triple star system in the southern constellation of Centaurus. It consists of 3 stars: Rigil Kentaurus (Alpha Centauri A), Toliman (B) and Proxima Centauri (C).[12] Proxima Centauri is also the closest star to the Sun at 4.2465 light-years (1.3020 pc).

Alpha Centauri A and B are Sun-like stars (Class G and K, respectively), and together they form the binary star system Alpha Centauri AB. To the naked eye, the two main components appear to be a single star with an apparent magnitude of −0.27. It is the brightest star in the constellation and the third-brightest in the night sky, outshone only by Sirius and Canopus.

Alpha Centauri A has 1.1 times the mass and 1.5 times the luminosity of the Sun, while Alpha Centauri B is smaller and cooler, at 0.9 times the Sun’s mass and less than 0.5 times its luminosity.[13] The pair orbit around a common centre with an orbital period of 79 years.[14] Their elliptical orbit is eccentric, so that the distance between A and B varies from 35.6 astronomical units (AU), or about the distance between Pluto and the Sun, to 11.2 AU, or about the distance between Saturn and the Sun.

Alpha Centauri C, or Proxima Centauri, is a small faint red dwarf (Class M). Though not visible to the naked eye, Proxima Centauri is the closest star to the Sun at a distance of 4.24 ly (1.30 pc), slightly closer than Alpha Centauri AB. Currently, the distance between Proxima Centauri and Alpha Centauri AB is about 13,000 AU (0.21 ly),[15] equivalent to about 430 times the radius of Neptune’s orbit.

Proxima Centauri has two confirmed planets: Proxima b, an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone discovered in 2016, and Proxima d, a candidate sub-Earth which orbits very closely to the star, announced in 2022.[16] The existence of Proxima c, a mini-Neptune 1.5 AU away discovered in 2019, is controversial.[17] Alpha Centauri A may have a candidate Neptune-sized planet in the habitable zone, though it is not yet known to be planetary in nature and could be an artifact of the discovery mechanism.[18] Alpha Centauri B has no known planets: planet Bb, purportedly discovered in 2012, was later disproven,[19] and no other planet has yet been confirmed.

Etymology and nomenclature[edit]

α Centauri (Latinised to Alpha Centauri) is the system’s designation given by Johann Bayer in 1603. It bears the traditional name Rigil Kentaurus, which is a Latinisation of the Arabic name رجل القنطورس Rijl al-Qinṭūrus, meaning ‘the Foot of the Centaur’.[20][21] The name is frequently abbreviated to Rigil Kent or even Rigil, though the latter name is better known for Rigel (Beta Orionis).[22]

An alternative name found in European sources, Toliman, is an approximation of the Arabic الظليمان aẓ-Ẓalīmān (in older transcription, aṭ-Ṭhalīmān), meaning ‘the (two male) Ostriches’, an appellation Zakariya al-Qazwini had applied to Lambda and Mu Sagittarii, also in the southern hemisphere.[23]

A third name that has been used is Bungula (). Its origin is not known, but it may have been coined from the Greek letter beta (β) and Latin ungula ‘hoof’.[22]

Alpha Centauri C was discovered in 1915 by Robert T. A. Innes,[24] who suggested that it be named Proxima Centaurus,[25] from Latin ‘the nearest [star] of Centaurus’.[26] The name Proxima Centauri later became more widely used and is now listed by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as the approved proper name.[27][28]

In 2016, the Working Group on Star Names of the IAU,[12] having decided to attribute proper names to individual component stars rather than to multiple systems,[29] approved the name Rigil Kentaurus () as being restricted to Alpha Centauri A and the name Proxima Centauri () for Alpha Centauri C.[30] On 10 August 2018, the IAU approved the name Toliman () for Alpha Centauri B.[31]

Observation[edit]

Location of Alpha Centauri in Centaurus

To the naked eye, Alpha Centauri AB appears to be a single star, the brightest in the southern constellation of Centaurus.[32] Their apparent angular separation varies over about 80 years between 2 and 22 arcsec (the naked eye has a resolution of 60 arcsec),[33] but through much of the orbit, both are easily resolved in binoculars or small telescopes.[34] At −0.27 apparent magnitude (combined for A and B magnitudes), Alpha Centauri is a first-magnitude star and is fainter only than Sirius and Canopus.[32] It is the outer star of The Pointers or The Southern Pointers,[34] so called because the line through Beta Centauri (Hadar/Agena),[35] some 4.5° west,[34] points to the constellation Crux — the Southern Cross.[34] The Pointers easily distinguish the true Southern Cross from the fainter asterism known as the False Cross.[36]

South of about 29° South latitude, Alpha Centauri is circumpolar and never sets below the horizon.[note 2] North of about 29° N latitude, Alpha Centauri never rises. Alpha Centauri lies close to the southern horizon when viewed from the 29° North latitude to the equator (close to Hermosillo and Chihuahua City in Mexico; Galveston, Texas; Ocala, Florida; and Lanzarote, the Canary Islands of Spain), but only for a short time around its culmination.[35] The star culminates each year at local midnight on 24 April and at local 9 p.m. on 8 June.[35][37]

As seen from Earth, Proxima Centauri is 2.2° southwest from Alpha Centauri AB, about four times the angular diameter of the Moon.[38] Proxima Centauri appears as a deep-red star of a typical apparent magnitude of 11.1 in a sparsely populated star field, requiring moderately sized telescopes to be seen. Listed as V645 Cen in the General Catalogue of Variable Stars Version 4.2, this UV Ceti-type flare star can unexpectedly brighten rapidly by as much as 0.6 magnitude at visual wavelengths, then fade after only a few minutes.[39] Some amateur and professional astronomers regularly monitor for outbursts using either optical or radio telescopes.[40] In August 2015, the largest recorded flares of the star occurred, with the star becoming 8.3 times brighter than normal on 13 August, in the B band (blue light region).[41]

Alpha Centauri may be inside the G-cloud of the Local Bubble,[42] and its nearest known system is the binary brown dwarf system Luhman 16 at 3.6 ly (1.1 pc).[43]

Observational history[edit]

Alpha Centauri is listed in the 2nd-century star catalog of Ptolemy. He gave its ecliptic coordinates, but texts differ as to whether the ecliptic latitude reads 44° 10′ South or 41° 10′ South.[44] (Presently the ecliptic latitude is 43.5° South, but it has decreased by a fraction of a degree since Ptolemy’s time due to proper motion.) In Ptolemy’s time, Alpha Centauri was visible from Alexandria, Egypt, at 31° N, but, due to precession, its declination is now –60° 51′ South, and it can no longer be seen at that latitude. English explorer Robert Hues brought Alpha Centauri to the attention of European observers in his 1592 work Tractatus de Globis, along with Canopus and Achernar, noting:

Now, therefore, there are but three Stars of the first magnitude that I could perceive in all those parts which are never seene here in England. The first of these is that bright Star in the sterne of Argo which they call Canobus [Canopus]. The second [Achernar] is in the end of Eridanus. The third [Alpha Centauri] is in the right foote of the Centaure.[45]

The binary nature of Alpha Centauri AB was recognized in December 1689 by Jean Richaud, while observing a passing comet from his station in Puducherry. Alpha Centauri was only the second binary star to be discovered, preceded by Acrux.[46]

The large proper motion of Alpha Centauri AB was discovered by Manuel John Johnson, observing from Saint Helena, who informed Thomas Henderson at the Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope of it. The parallax of Alpha Centauri was subsequently determined by Henderson from many exacting positional observations of the AB system between April 1832 and May 1833. He withheld his results, however, because he suspected they were too large to be true, but eventually published them in 1839 after Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel released his own accurately determined parallax for 61 Cygni in 1838.[47] For this reason, Alpha Centauri is sometimes considered as the second star to have its distance measured because Henderson’s work was not fully acknowledged at first.[47] (The distance of Alpha Centauri from the Earth is now reckoned at 4.396 ly (41.59×1012 km).)

Alpha Centauri A is of the same stellar type G2 as the Sun, while Alpha Centauri B is a K1-type star.[48]

Later, John Herschel made the first micrometrical observations in 1834.[49] Since the early 20th century, measures have been made with photographic plates.[50]

By 1926, William Stephen Finsen calculated the approximate orbit elements close to those now accepted for this system.[51] All future positions are now sufficiently accurate for visual observers to determine the relative places of the stars from a binary star ephemeris.[52] Others, like D. Pourbaix (2002), have regularly refined the precision of new published orbital elements.[14]

Robert T. A. Innes discovered Proxima Centauri in 1915 by blinking photographic plates taken at different times during a proper motion survey. These showed large proper motion and parallax similar in both size and direction to those of Alpha Centauri AB, which suggested that Proxima Centauri is part of the Alpha Centauri system and slightly closer to Earth than Alpha Centauri AB. As such, Innes concluded that Proxima Centauri was the closest star to Earth yet discovered.

Kinematics[edit]

All components of Alpha Centauri display significant proper motion against the background sky. Over centuries, this causes their apparent positions to slowly change.[53] Proper motion was unknown to ancient astronomers. Most assumed that the stars were permanently fixed on the celestial sphere, as stated in the works of the philosopher Aristotle.[54] In 1718, Edmond Halley found that some stars had significantly moved from their ancient astrometric positions.[55]

In the 1830s, Thomas Henderson discovered the true distance to Alpha Centauri by analysing his many astrometric mural circle observations.[56][57] He then realised this system also likely had a high proper motion.[58][59][51] In this case, the apparent stellar motion was found using Nicolas Louis de Lacaille’s astrometric observations of 1751–1752,[60] by the observed differences between the two measured positions in different epochs.

Calculated proper motion of the centre of mass for Alpha Centauri AB is about 3620 mas/y (milliarcseconds per year) toward the west and 694 mas/y toward the north, giving an overall motion of 3686 mas/y in a direction 11° north of west.[61][note 3] The motion of the centre of mass is about 6.1 arcmin each century, or 1.02° each millennium. The speed in the western direction is 23.0 km/s (14.3 mi/s) and in the northerly direction 4.4 km/s (2.7 mi/s). Using spectroscopy the mean radial velocity has been determined to be around 22.4 km/s (13.9 mi/s) towards the Solar System.[61] This gives a speed with respect to the Sun of 32.4 km/s (20.1 mi/s), very close to the peak in the distribution of speeds of nearby stars.[62]

Since Alpha Centauri AB is almost exactly in the plane of the Milky Way as viewed from Earth, many stars appear behind it. In early May 2028, Alpha Centauri A will pass between the Earth and a distant red star, when there is a 45% probability that an Einstein ring will be observed. Other conjunctions will also occur in the coming decades, allowing accurate measurement of proper motions and possibly giving information on planets.[61]

Predicted future changes[edit]

Distances of the nearest stars from 20,000 years ago until 80,000 years in the future

Animation showing motion of Alpha Centauri through the sky. (The other stars are held fixed for didactic reasons) «Oggi» means today; «anni» means years.

Based on the system’s common proper motion and radial velocities, Alpha Centauri will continue to change its position in the sky significantly and will gradually brighten. For example, in about 6,200 AD, α Centauri’s true motion will cause an extremely rare first-magnitude stellar conjunction with Beta Centauri, forming a brilliant optical double star in the southern sky.[63] It will then pass just north of the Southern Cross or Crux, before moving northwest and up towards the present celestial equator and away from the galactic plane. By about 26,700 AD, in the present-day constellation of Hydra, Alpha Centauri will reach perihelion at 0.90 pc or 2.9 ly away,[64] though later calculations suggest that this will occur in 27,000 AD.[65] At nearest approach, Alpha Centauri will attain a maximum apparent magnitude of −0.86, comparable to present-day magnitude of Canopus, but it will still not surpass that of Sirius, which will brighten incrementally over the next 60,000 years, and will continue to be the brightest star as seen from Earth (other than the Sun) for the next 210,000 years.[66]

Stellar system[edit]

Alpha Centauri is a triple star system, with its two main stars, Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B, together comprising a binary component. The AB designation, or older A×B, denotes the mass centre of a main binary system relative to companion star(s) in a multiple star system.[67] AB-C refers to the component of Proxima Centauri in relation to the central binary, being the distance between the centre of mass and the outlying companion. Because the distance between Proxima (C) and either of Alpha Centauri A or B is similar, the AB binary system is sometimes treated as a single gravitational object.[68]

Orbital properties[edit]

Apparent and true orbits of Alpha Centauri. The A component is held stationary, and the relative orbital motion of the B component is shown. The apparent orbit (thin ellipse) is the shape of the orbit as seen by an observer on Earth. The true orbit is the shape of the orbit viewed perpendicular to the plane of the orbital motion. According to the radial velocity versus time,[69] the radial separation of A and B along the line of sight had reached a maximum in 2007, with B being further from Earth than A. The orbit is divided here into 80 points: each step refers to a timestep of approx. 0.99888 years or 364.84 days.

The A and B components of Alpha Centauri have an orbital period of 79.762 years.[5] Their orbit is moderately eccentric, as it has an eccentricity of almost 0.52;[5] their closest approach or periastron is 11.2 AU (1.68×109 km), or about the distance between the Sun and Saturn; and their furthest separation or apastron is 35.6 AU (5.33×109 km), about the distance between the Sun and Pluto.[14] The most recent periastron was in August 1955 and the next will occur in May 2035; the most recent apastron was in May 1995 and will next occur in 2075.

Viewed from Earth, the apparent orbit of A and B means that their separation and position angle (PA) are in continuous change throughout their projected orbit. Observed stellar positions in 2019 are separated by 4.92 arcsec through the PA of 337.1°, increasing to 5.49 arcsec through 345.3° in 2020.[14] The closest recent approach was in February 2016, at 4.0 arcsec through the PA of 300°.[14][70] The observed maximum separation of these stars is about 22 arcsec, while the minimum distance is 1.7 arcsec.[51] The widest separation occurred during February 1976, and the next will be in January 2056.[14]

Alpha Centauri C is about 13,000 AU (0.21 ly; 1.9×1012 km) from Alpha Centauri AB, equivalent to about 5% of the distance between Alpha Centauri AB and the Sun.[15][38][50] Until 2017, measurements of its small speed and its trajectory were of too little accuracy and duration in years to determine whether it is bound to Alpha Centauri AB or unrelated.

Radial velocity measurements made in 2017 were precise enough to show that Proxima Centauri and Alpha Centauri AB are gravitationally bound.[15] The orbital period of Proxima Centauri is approximately 511000+41000

−30000 years, with an eccentricity of 0.5, much more eccentric than Mercury’s. Proxima Centauri comes within 4100+700

−600 AU of AB at periastron, and its apastron occurs at 12300+200

−100 AU.[5]

Physical properties[edit]

The relative sizes and colours of stars in the Alpha Centauri system, compared to the Sun

Asteroseismic studies, chromospheric activity, and stellar rotation (gyrochronology) are all consistent with the Alpha Centauri system being similar in age to, or slightly older than, the Sun.[71] Asteroseismic analyses that incorporate tight observational constraints on the stellar parameters for the Alpha Centauri stars have yielded age estimates of 4.85±0.5 Gyr,[72] 5.0±0.5 Gyr,[73] 5.2 ± 1.9 Gyr,[74] 6.4 Gyr,[75] and 6.52±0.3 Gyr.[76] Age estimates for the stars based on chromospheric activity (Calcium H & K emission) yield 4.4 ± 2.1 Gyr, whereas gyrochronology yields 5.0±0.3 Gyr.[71] Stellar evolution theory implies both stars are slightly older than the Sun at 5 to 6 billion years, as derived by their mass and spectral characteristics.[38][77]

From the orbital elements, the total mass of Alpha Centauri AB is about 2.0 M☉[note 4] – or twice that of the Sun.[51] The average individual stellar masses are about 1.08 M☉ and 0.91 M☉, respectively,[5] though slightly different masses have also been quoted in recent years, such as 1.14 M☉ and 0.92 M☉,[78] totalling 2.06 M☉. Alpha Centauri A and B have absolute magnitudes of +4.38 and +5.71, respectively.

Alpha Centauri AB System[edit]

Alpha Centauri A[edit]

Alpha Centauri A, also known as Rigil Kentaurus, is the principal member, or primary, of the binary system. It is a solar-like main-sequence star with a similar yellowish colour,[79] whose stellar classification is spectral type G2-V;[3] it is about 10% more massive than the Sun,[72] with a radius about 22% larger.[80] When considered among the individual brightest stars in the night sky, it is the fourth-brightest at an apparent magnitude of +0.01,[2] being slightly fainter than Arcturus at an apparent magnitude of −0.05.

The type of magnetic activity on Alpha Centauri A is comparable to that of the Sun, showing coronal variability due to star spots, as modulated by the rotation of the star. However, since 2005 the activity level has fallen into a deep minimum that might be similar to the Sun’s historical Maunder Minimum. Alternatively, it may have a very long stellar activity cycle and is slowly recovering from a minimum phase.[81]

Alpha Centauri B[edit]

Alpha Centauri B, also known as Toliman, is the secondary star of the binary system. It is a main-sequence star of spectral type K1-V, making it more an orange colour than Alpha Centauri A;[79] it has around 90% of the mass of the Sun and a 14% smaller diameter. Although it has a lower luminosity than A, Alpha Centauri B emits more energy in the X-ray band.[82] Its light curve varies on a short time scale, and there has been at least one observed flare.[82] It is more magnetically active than Alpha Centauri A, showing a cycle of 8.2±0.2 yr compared to 11 years for the Sun, and has about half the minimum-to-peak variation in coronal luminosity of the Sun.[81] Alpha Centauri B has an apparent magnitude of +1.35, slightly dimmer than Mimosa.[30]

Alpha Centauri C (Proxima Centauri)[edit]

Alpha Centauri C, better known as Proxima Centauri, is a small main-sequence red dwarf of spectral class M6-Ve. It has an absolute magnitude of +15.60, over 20,000 times fainter than the Sun. Its mass is calculated to be 0.1221 M☉.[83] It is the closest star to the Sun but is too faint to be visible to the naked eye.[84]

Relative positions of Sun, Alpha Centauri AB and Proxima Centauri. Grey dot is projection of Proxima Centauri, located at the same distance as Alpha Centauri AB.

Planetary system[edit]

The Alpha Centauri system as a whole has two confirmed planets, both of them around Proxima Centauri. While other planets have been claimed to exist around all of the stars, none of the discoveries have been confirmed.

Planets of Proxima Centauri[edit]

Proxima Centauri b is a terrestrial planet discovered in 2016 by astronomers at the European Southern Observatory (ESO). It has an estimated minimum mass of 1.17 MEarth (Earth masses) and orbits approximately 0.049 AU from Proxima Centauri, placing it in the star’s habitable zone.[85][86]

Proxima Centauri c is a planet that was formally published in 2020 and could be a super-Earth or mini-Neptune.[87][88] It has a mass of roughly 7 MEarth and orbits about 1.49 AU from Proxima Centauri with a period of 1,928 days (5.28 yr).[89] In June 2020, a possible direct imaging detection of the planet hinted at the potential presence of a large ring system.[90] However, a 2022 study disputed the existence of this planet.[17]

A 2020 paper refining Proxima b’s mass excludes the presence of extra companions with masses above 0.6 MEarth at periods shorter than 50 days, but the authors detected a radial-velocity curve with a periodicity of 5.15 days, suggesting the presence of a planet with a mass of about 0.29 MEarth.[86] This planet, Proxima Centauri d, was confirmed in 2022.[16][17]

Planets of Alpha Centauri A[edit]

The discovery image of Alpha Centauri’s candidate Neptunian planet, marked here as «C1»

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (unconfirmed) | ~9–35[note 5] M🜨 | 1.1 | ~360 | — | ~65 ± 25° | ~3.3–7 R⊕ |

In 2021, a candidate planet named Candidate 1 (abbreviated as C1) was detected around Alpha Centauri A, thought to orbit at approximately 1.1 AU with a period of about one year, and to have a mass between that of Neptune and one-half that of Saturn, though it may be a dust disk or an artifact. The possibility of C1 being a background star has been ruled out.[91][18] If this candidate is confirmed, the temporary name C1 will most likely be replaced with the scientific designation Alpha Centauri Ab in accordance with current naming conventions.[92]

GO Cycle 1 observations are planned for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to search for planets around Alpha Centauri A.[93] The observations are planned to occur at a date between July and August 2023.[94] Pre-launch estimates predicted that JWST will be able to find planets with a radius of 5 REarth at 1–3 au. Multiple observations every 3–6 months could push the limit down to 3 REarth.[95] Post-processing techniques could push the limit down to 0.5 to 0.7 REarth.[93] Post-launch estimates based on observations of HIP 65426 b find that JWST will be able to find planets even closer to Alpha Centauri A and could find a 5 REarth planet at 0.5 to 2.5 au.[96] Candidate 1 has an estimated radius between 3.3 and 11 REarth[18] and orbits at 1.1 au. It is therefore likely within the reach of JWST observations.

Planets of Alpha Centauri B[edit]

In 2012, a planet around Alpha Centauri B was reported, Alpha Centauri Bb, but in 2015 a new analysis concluded that that report was an artifact of the datum analysis.[97][98][19]

A possible transit-like event was observed in 2013, which could be associated with a separate planet. The transit event could correspond to a planetary body with a radius around 0.92 REarth. This planet would most likely orbit Alpha Centauri B with an orbital period of 20.4 days or less, with only a 5% chance of it having a longer orbit. The median of the likely orbits is 12.4 days. Its orbit would likely have an eccentricity of 0.24 or less.[99] It could have lakes of molten lava and would be far too close to Alpha Centauri B to harbour life.[100] If confirmed, this planet might be called Alpha Centauri Bc. However, the name has not been used in the literature, as it is not a claimed discovery. As of 2023, it appears that no further transit-like events have been observed.

Hypothetical planets[edit]

Additional planets may exist in the Alpha Centauri system, either orbiting Alpha Centauri A or Alpha Centauri B individually, or in large orbits around Alpha Centauri AB. Because both stars are fairly similar to the Sun (for example, in age and metallicity), astronomers have been especially interested in making detailed searches for planets in the Alpha Centauri system. Several established planet-hunting teams have used various radial velocity or star transit methods in their searches around these two bright stars.[101] All the observational studies have so far failed to find evidence for brown dwarfs or gas giants.[101][102]

In 2009, computer simulations showed that a planet might have been able to form near the inner edge of Alpha Centauri B’s habitable zone, which extends from 0.5 to 0.9 AU from the star. Certain special assumptions, such as considering that the Alpha Centauri pair may have initially formed with a wider separation and later moved closer to each other (as might be possible if they formed in a dense star cluster), would permit an accretion-friendly environment farther from the star.[103] Bodies around Alpha Centauri A would be able to orbit at slightly farther distances due to its stronger gravity. In addition, the lack of any brown dwarfs or gas giants in close orbits around Alpha Centauri make the likelihood of terrestrial planets greater than otherwise.[104] A theoretical study indicates that a radial velocity analysis might detect a hypothetical planet of 1.8 MEarth in Alpha Centauri B’s habitable zone.[105]

Radial velocity measurements of Alpha Centauri B made with the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher spectrograph were sufficiently sensitive to detect a 4 MEarth planet within the habitable zone of the star (i.e. with an orbital period P = 200 days), but no planets were detected.[106]

Current estimates place the probability of finding an Earth-like planet around Alpha Centauri at roughly 75%.[107] The observational thresholds for planet detection in the habitable zones by the radial velocity method are currently (2017) estimated to be about 50 MEarth for Alpha Centauri A, 8 MEarth for Alpha Centauri B, and 0.5 MEarth for Proxima Centauri.[108]

Early computer-generated models of planetary formation predicted the existence of terrestrial planets around both Alpha Centauri A and B,[105][note 6] but most recent numerical investigations have shown that the gravitational pull of the companion star renders the accretion of planets difficult.[103][109] Despite these difficulties, given the similarities to the Sun in spectral types, star type, age and probable stability of the orbits, it has been suggested that this stellar system could hold one of the best possibilities for harbouring extraterrestrial life on a potential planet.[6][104][110][111]

In the Solar System, it was once thought that Jupiter and Saturn were probably crucial in perturbing comets into the inner Solar System, providing the inner planets with a source of water and various other ices.[112] However, since isotope measurements of the deuterium to hydrogen (D/H) ratio in comets Halley, Hyakutake, Hale–Bopp, 2002T7, and Tuttle yield values approximately twice that of Earth’s oceanic water, more recent models and research predict that less than 10% of Earth’s water was supplied from comets. In the Alpha Centauri system, Proxima Centauri may have influenced the planetary disk as the Alpha Centauri system was forming, enriching the area around Alpha Centauri with volatile materials.[113] This would be discounted if, for example, Alpha Centauri B happened to have gas giants orbiting Alpha Centauri A (or vice versa), or if Alpha Centauri A and B themselves were able to perturb comets into each other’s inner systems as Jupiter and Saturn presumably have done in the Solar System.[112] Such icy bodies probably also reside in Oort clouds of other planetary systems. When they are influenced gravitationally by either the gas giants or disruptions by passing nearby stars, many of these icy bodies then travel star-wards.[112] Such ideas also apply to the close approach of Alpha Centauri or other stars to the Solar System, when, in the distant future, the Oort Cloud might be disrupted enough to increase the number of active comets.[64]

To be in the habitable zone, a planet around Alpha Centauri A would have an orbital radius of between about 1.2 and 2.1 AU so as to have similar planetary temperatures and conditions for liquid water to exist.[114] For the slightly less luminous and cooler Alpha Centauri B, the habitable zone is between about 0.7 and 1.2 AU.[114]

With the goal of finding evidence of such planets, both Proxima Centauri and Alpha Centauri-AB were among the listed «Tier-1» target stars for NASA’s Space Interferometry Mission (S.I.M.). Detecting planets as small as three Earth-masses or smaller within two AU of a «Tier-1» target would have been possible with this new instrument.[115] The S.I.M. mission, however, was cancelled due to financial issues in 2010.[116]

Circumstellar discs[edit]