Самое первое с чего стоит начинать изучение языка это английский алфавит (English Alphabet). Вам не обязательно учить его в порядке следования букв, как на уроках в школе. Но знать, как правильно читаются и пишутся буквы английского языка просто необходимо.

Современные реалии таковы, что с буквами английского алфавита мы сталкиваемся каждый день. Читать английские слова сегодня, может даже ребенок, но делают это многие люди, как правило, с ошибками в произношении.

С вами наверное случалась такая ситуация, когда вы по телефону, пытались продиктовать какое то иностранное слово или ваш личный E-mail. И в ход шли «буква S — как знак доллара» или «буква i которая пишется как палочка с точкой наверху».

Специально создание нами интерактивные упражнения и таблицы помогут узнать, как правильно произносятся буквы английского алфавита и ускорить ваше обучение в несколько раз, если вы будете уделять им всего лишь по несколько минут в день, и все это совершенно бесплатно.

Алфавит с транскрипцией и произношением

Упражнение № 1

Ниже представлена интерактивная таблица английского алфавита транскрипцией и переводом на русский язык. В таблице вы можете скрывать необходимые колонки, а после клика на строки они вновь появятся.

Вы также можете посмотреть печатный и письменный вариант английского алфавита и увидеть, как правильно пишутся английская буквы.

Для того чтобы услышать правильное произношение нужной вам буквы алфавита, просто нажмите на неё и прослушайте аудио произношение

Этот способ изучения поможет вам быстрее запомнить буквы английского алфавита, но стоит заметить, что перевод произношения на русский язык, является лишь условным.

Написание английских букв

Скрыть колонки для изучения

| № | буквы алфавита | английская транскипция | русское произношение |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

A a |

[ei] |

эй |

|

2 |

B b |

[bi:] |

би |

|

3 |

C c |

[si:] |

си |

|

4 |

D d |

[di:] |

ди |

|

5 |

E e |

[i:] |

и |

|

6 |

F f |

[ef] |

эф |

|

7 |

G g |

[dʒi:] |

джи |

|

8 |

H h |

[eitʃ] |

эйч |

|

9 |

I i |

[ai] |

ай |

|

10 |

J j |

[dʒei] |

джей |

|

11 |

K k |

[kei] |

кей |

|

12 |

L l |

[el] |

эл |

|

13 |

M m |

[em] |

эм |

|

14 |

N n |

[en] |

эн |

|

15 |

O o |

[ou] |

оу |

|

16 |

P p |

[pi:] |

пи |

|

17 |

Q q |

[kju:] |

кью |

|

18 |

R r |

[a:r] |

а: или ар |

|

19 |

S s |

[es] |

эс |

|

20 |

T t |

[ti:] |

ти |

|

21 |

U u |

[ju:] |

ю |

|

22 |

V v |

[vi:] |

ви |

|

23 |

W w |

[`dʌblju:] |

дабл-ю |

|

24 |

X x |

[eks] |

экс |

|

25 |

Y y |

[wai] |

вай |

|

26 |

Z z |

[zed] |

зи или зед |

| English alphabet | |

|---|---|

An English pangram displaying all the characters in context, in FF Dax Regular typeface |

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

c.1500 to present |

| Languages | English |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(Proto-writing)

|

|

Child systems |

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Latin |

|

Unicode range |

U+0000 to U+007E Basic Latin and punctuation |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The alphabet for Modern English is a Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters, each having an upper- and lower-case form. The word alphabet is a compound of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha and beta. The alphabet originated around the 7th century CE to write Old English from Latin script. Since then, letters have been added or removed to give the current letters:

- A a

- B b

- C c

- D d

- E e

- F f

- G g

- H h

- I i

- J j

- K k

- L l

- M m

- N n

- O o

- P p

- Q q

- R r

- S s

- T t

- U u

- V v

- W w

- X x

- Y y

- Z z

The exact shape of printed letters varies depending on the typeface (and font), and the standard printed form may differ significantly from the shape of handwritten letters (which varies between individuals), especially cursive.

The English alphabet has 5 vowels, 19 consonants, and 2 letters (Y and W) that can function as constants or vowels.

Written English has a large number of digraphs (e.g., would, beak, moat); it stands out (almost uniquely) as a European language without diacritics in native words. The only exceptions are:

- a diaeresis (e.g., «coöperation») may be used to distinguish two vowels with separate pronunciation from a double vowel[nb 1][1]

- a grave accent, very occasionally, (as in learnèd, an adjective) may be used to indicate that a normally silent vowel is pronounced

Letter names

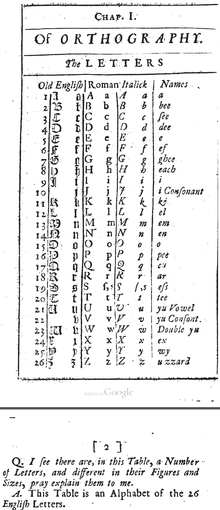

English alphabet from 1740, with some unusual letter names.

The names of the letters are commonly spelled out in compound words and initialisms (e.g., tee-shirt, deejay, emcee, okay, etc.), derived forms (e.g., exed out, effing, to eff and blind, aitchless, etc.), and objects named after letters (e.g., en and em in printing, and wye in railroading). The spellings listed below are from the Oxford English Dictionary. Plurals of consonant names are formed by adding -s (e.g., bees, efs or effs, ems) or -es in the cases of aitches, esses, exes. Plurals of vowel names also take -es (i.e., aes, ees, ies, oes, ues), but these are rare. For a letter as a letter, the letter itself is most commonly used, generally in capitalized form, in which case the plural just takes -s or -‘s (e.g. Cs or c’s for cees).

| Letter | Name | Name pronunciation | Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern English | Latin | Modern English | Latin | Old French | Middle English | ||

| A | a | ā | , [nb 2] | /aː/ | /aː/ | /aː/ | 8.17% |

| B | bee | bē | /beː/ | /beː/ | /beː/ | 1.49% | |

| C | cee | cē | /keː/ | /tʃeː/ > /tseː/ > /seː/ | /seː/ | 2.78% | |

| D | dee | dē | /deː/ | /deː/ | /deː/ | 4.25% | |

| E | e | ē | /eː/ | /eː/ | /eː/ | 12.70% | |

| F | ef, eff | ef | /ɛf/ | /ɛf/ | /ɛf/ | 2.23% | |

| eff as a verb | |||||||

| G | gee | gē | /ɡeː/ | /dʒeː/ | /dʒeː/ | 2.02% | |

| H | aitch | hā | /haː/ > /ˈaha/ > /ˈakːa/ | /ˈaːtʃə/ | /aːtʃ/ | 6.09% | |

| haitch[nb 3] | |||||||

| I | i | ī | /iː/ | /iː/ | /iː/ | 6.97% | |

| J | jay | – | – | – | [nb 4] | 0.15% | |

| jy[nb 5] | |||||||

| K | kay | kā | /kaː/ | /kaː/ | /kaː/ | 0.77% | |

| L | el, ell[nb 6] | el | /ɛl/ | /ɛl/ | /ɛl/ | 4.03% | |

| M | em | em | /ɛm/ | /ɛm/ | /ɛm/ | 2.41% | |

| N | en | en | /ɛn/ | /ɛn/ | /ɛn/ | 6.75% | |

| O | o | ō | /oː/ | /oː/ | /oː/ | 7.51% | |

| P | pee | pē | /peː/ | /peː/ | /peː/ | 1.93% | |

| Q | cue, kew, kue, que[nb 7] | qū | /kuː/ | /kyː/ | /kiw/ | 0.10% | |

| R | ar | er | /ɛr/ | /ɛr/ | /ɛr/ > /ar/ | 5.99% | |

| or[nb 8] | |||||||

| S | ess | es | /ɛs/ | /ɛs/ | /ɛs/ | 6.33% | |

| es- in compounds[nb 9] | |||||||

| T | tee | tē | /teː/ | /teː/ | /teː/ | 9.06% | |

| U | u | ū | /uː/ | /yː/ | /iw/ | 2.76% | |

| V | vee | – | – | – | – | 0.98% | |

| W | double-u | – | [nb 10] | – | – | – | 2.36% |

| X | ex | ex | /ɛks/ | /iks/ | /ɛks/ | 0.15% | |

| ix | /ɪks/ | ||||||

| Y | wy, wye, why[nb 11] | hȳ | /hyː/ | ui, gui ? | /wiː/ | 1.97% | |

| /iː/ | |||||||

| ī graeca | /iː ˈɡraɪka/ | /iː ɡrɛːk/ | |||||

| Z | zed[nb 12] | zēta | /ˈzeːta/ | /ˈzɛːdə/ | /zɛd/ | 0.07% | |

| zee[nb 13] |

Etymology

The names of the letters are for the most part direct descendants, via French, of the Latin (and Etruscan) names. (See Latin alphabet: Origins.)

The regular phonological developments (in rough chronological order) are:

- palatalization before front vowels of Latin /k/ successively to /tʃ/, /ts/, and finally to Middle French /s/. Affects C.

- palatalization before front vowels of Latin /ɡ/ to Proto-Romance and Middle French /dʒ/. Affects G.

- fronting of Latin /uː/ to Middle French /yː/, becoming Middle English /iw/ and then Modern English /juː/. Affects Q, U.

- the inconsistent lowering of Middle English /ɛr/ to /ar/. Affects R.

- the Great Vowel Shift, shifting all Middle English long vowels. Affects A, B, C, D, E, G, H, I, K, O, P, T, and presumably Y.

The novel forms are aitch, a regular development of Medieval Latin acca; jay, a new letter presumably vocalized like neighboring kay to avoid confusion with established gee (the other name, jy, was taken from French); vee, a new letter named by analogy with the majority; double-u, a new letter, self-explanatory (the name of Latin V was ū); wye, of obscure origin but with an antecedent in Old French wi; izzard, from the Romance phrase i zed or i zeto «and Z» said when reciting the alphabet; and zee, an American levelling of zed by analogy with other consonants.

Some groups of letters, such as pee and bee, or em and en, are easily confused in speech, especially when heard over the telephone or a radio communications link. Spelling alphabets such as the ICAO spelling alphabet, used by aircraft pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other.

Ampersand

The ampersand (&) has sometimes appeared at the end of the English alphabet, as in Byrhtferð’s list of letters in 1011.[2] & was regarded as the 27th letter of the English alphabet, as taught to children in the US and elsewhere. An example may be seen in M. B. Moore’s 1863 book The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks.[3] Historically, the figure is a ligature for the letters Et. In English and many other languages, it is used to represent the word and, plus occasionally the Latin word et, as in the abbreviation &c (et cetera).

Archaic letters

Old and Middle English had a number of non-Latin letters that have since dropped out of use. These either took the names of the equivalent runes, since there were no Latin names to adopt, or (thorn, wyn) were runes themselves.

- Æ æ ash or æsc , used for the vowel , which disappeared from the language and then reformed. Replaced by ae[nb 14] and e now.

- Ð ð edh, eð or eth , and Þ þ thorn or þorn , both used for the consonants and (which did not become phonemically distinct until after these letters had fallen out of use). Replaced by th now.

- Ŋ ŋ eng or engma,[citation needed] used for voiced velar nasal sound produced by «ng» in English. Replaced by ng now.

- Œ œ ethel, ēðel, œ̄þel, etc. , used for the vowel /œ/, which disappeared from the language quite early. Replaced by oe[nb 15] and e now.

- Ƿ ƿ wyn, ƿen or wynn , used for the consonant . (The letter ‘w’ had not yet been invented.) Replaced by w now.

- Ȝ ȝ yogh, ȝogh or yoch or , used for various sounds derived from , such as and . Replaced by y, j[nb 16] and ch[nb 17] now.

- ſ long s, an earlier form of the lowercase «s» that continued to be used alongside the modern lowercase s into the 1800s. Replaced by lowercase s now.

Diacritics

The most common diacritic marks seen in English publications are the acute (é), grave (è), circumflex (â, î, or ô), tilde (ñ), umlaut and diaeresis (ü or ï—the same symbol is used for two different purposes), and cedilla (ç).[4] Diacritics used for tonal languages may be replaced with tonal numbers or omitted.

Loanwords

Diacritic marks mainly appear in loanwords such as naïve and façade. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them.

As such words become naturalised in English, there is a tendency to drop the diacritics, as has happened with many older borrowings from French, such as hôtel. Words that are still perceived as foreign tend to retain them; for example, the only spelling of soupçon found in English dictionaries (the OED and others) uses the diacritic. However, diacritics are likely to be retained even in naturalised words where they would otherwise be confused with a common native English word (for example, résumé rather than resume).[5] Rarely, they may even be added to a loanword for this reason (as in maté, from Spanish yerba mate but following the pattern of café, from French, to distinguish from mate).

Native English words

Occasionally, especially in older writing, diacritics are used to indicate the syllables of a word: cursed (verb) is pronounced with one syllable, while cursèd (adjective) is pronounced with two. For this, è is used widely in poetry, e.g., in Shakespeare’s sonnets. J.R.R. Tolkien used ë, as in O wingëd crown.

Similarly, while in chicken coop the letters -oo- represent a single vowel sound (a digraph), they less often represent two which may be marked with a diaresis as in zoölogist[6] and coöperation. This use of the diaeresis is rare but found in some well-known publications, such as MIT Technology Review and The New Yorker. Some publications, particularly in UK usage, have replaced the diaeresis with a hyphen such as in co-operative.[citation needed]

In general, these devices are not used even where they would serve to alleviate some degree of confusion.

Punctuation marks within words

Apostrophe

The apostrophe (ʼ) is not considered part of the English alphabet nor used as a diacritic, even in loanwords. But it is used for two important purposes in written English: to mark the «possessive»[nb 18] and to mark contracted words. Current standards require its use for both purposes. Therefore, apostrophes are necessary to spell many words even in isolation, unlike most punctuation marks, which are concerned with indicating sentence structure and other relationships among multiple words.

- It distinguishes (from the otherwise identical regular plural inflection -s) the English possessive morpheme ‘s (apostrophe alone after a regular plural affix, giving -s’ as the standard mark for plural + possessive). Practice settled in the 18th century; before then, practices varied but typically all three endings were written -s (but without cumulation). This meant that only regular nouns bearing neither could be confidently identified, and plural and possessive could be potentially confused (e.g., «the Apostles words»; «those things over there are my husbands»[7])—which undermines the logic of «marked» forms.

- Most common contractions have near-homographs from which they are distinguished in writing only by an apostrophe, for example it’s (it is or it has), or she’d (she would or she had).

Hyphen

Hyphens are often used in English compound words. Written compound words may be hyphenated, open or closed, so specifics are guided by stylistic policy. Some writers may use a slash in certain instances.

Frequencies

The letter most commonly used in English is E. The least used letter is Z. The frequencies shown in the table may differ in practice according to the type of text.[8]

Phonology

The letters A, E, I, O, and U are considered vowel letters, since (except when silent) they represent vowels, although I and U represent consonants in words such as «onion» and «quail» respectively.

The letter Y sometimes represents a consonant (as in «young») and sometimes a vowel (as in «myth»). Very rarely, W may represent a vowel (as in «cwm», a Welsh loanword).

The consonant sounds represented by the letters W and Y in English (/w/ and /j/ as in yes /jɛs/ and went /wɛnt/) are referred to as semi-vowels (or glides) by linguists, however this is a description that applies to the sounds represented by the letters and not to the letters themselves.

The remaining letters are considered consonant letters, since when not silent they generally represent consonants.

History

Old English

The English language itself was first written in the Anglo-Saxon futhorc runic alphabet, in use from the 5th century. This alphabet was brought to what is now England, along with the proto-form of the language itself, by Anglo-Saxon settlers. Very few examples of this form of written Old English have survived, mostly as short inscriptions or fragments.

The Latin script, introduced by Christian missionaries, began to replace the Anglo-Saxon futhorc from about the 7th century, although the two continued in parallel for some time. As such, the Old English alphabet began to employ parts of the Roman alphabet in its construction.[9] Futhorc influenced the emerging English alphabet by providing it with the letters thorn (Þ þ) and wynn (Ƿ ƿ). The letter eth (Ð ð) was later devised as a modification of dee (D d), and finally yogh (Ȝ ȝ) was created by Norman scribes from the insular g in Old English and Irish, and used alongside their Carolingian g.

The a-e ligature ash (Æ æ) was adopted as a letter in its own right, named after a futhorc rune æsc. In very early Old English the o-e ligature ethel (Œ œ) also appeared as a distinct letter, likewise named after a rune, œðel[citation needed]. Additionally, the v-v or u-u ligature double-u (W w) was in use.

In the year 1011, a monk named Byrhtferð recorded the traditional order of the Old English alphabet.[2] He listed the 24 letters of the Latin alphabet first, including the ampersand, then 5 additional English letters, starting with the Tironian note ond (⁊), an insular symbol for and:

A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z & ⁊ Ƿ Þ Ð Æ

Modern English

In the orthography of Modern English, the letters thorn (þ), eth (ð), eng (ŋ),[dubious – discuss] wynn (ƿ), yogh (ȝ), ash (æ), and ethel (œ) are obsolete. Latin borrowings reintroduced homographs of æ and œ into Middle English and Early Modern English, though they are largely obsolete (see «Ligatures in recent usage» below), and where they are used they are not considered to be separate letters (e.g., for collation purposes), but rather ligatures. Thorn and eth were both replaced by th, though thorn continued in existence for some time, its lowercase form gradually becoming graphically indistinguishable from the minuscule y in most handwriting. Y for th can still be seen in pseudo-archaisms such as «Ye Olde Booke Shoppe». The letters þ and ð are still used in present-day Icelandic (where they now represent two separate sounds, /θ/ and /ð/ having become phonemically-distinct — as indeed also happened in Modern English), while ð is still used in present-day Faroese (although only as a silent letter). Wynn disappeared from English around the 14th century when it was supplanted by uu, which ultimately developed into the modern w. Yogh disappeared around the 15th century and was typically replaced by gh.

The letters u and j, as distinct from v and i, were introduced in the 16th century, and w assumed the status of an independent letter. The variant lowercase form long s (ſ) lasted into early modern English, and was used in non-final position up to the early 19th century. Today, the English alphabet is considered to consist of the following 26 letters:

- A a

- B b

- C c

- D d

- E e

- F f

- G g

- H h

- I i

- J j

- K k

- L l

- M m

- N n

- O o

- P p

- Q q

- R r

- S s

- T t

- U u

- V v

- W w

- X x

- Y y

- Z z

Written English has a number[10] of digraphs, but they are not considered separate letters of the alphabet:

- ch (usually makes tsh sound)

- ci (makes s sound)

- ck (makes k sound)

- gh (makes f or g sound (also silent))

- ng (makes Voiced velar nasal)

- ph (makes f sound)

- qu (makes kw sound)

- rh (makes r sound)

- sc (makes s sound (also a blend))

- sh (makes ch sound without t)

- th (makes theta or eth sound)

- ti (makes sh sound)

- wh (makes w sound)

- wr (makes r sound)

- zh (makes j sound without d)

Ligatures in recent usage

Outside of professional papers on specific subjects that traditionally use ligatures in loanwords, ligatures are seldom used in modern English. The ligatures æ and œ were until the 19th century (slightly later in American English)[citation needed] used in formal writing for certain words of Greek or Latin origin, such as encyclopædia and cœlom, although such ligatures were not used in either classical Latin or ancient Greek. These are now usually rendered as «ae» and «oe» in all types of writing,[citation needed] although in American English, a lone e has mostly supplanted both (for example, encyclopedia for encyclopaedia, and maneuver for manoeuvre).

Some fonts for typesetting English contain commonly used ligatures, such as for ⟨tt⟩, ⟨fi⟩, ⟨fl⟩, ⟨ffi⟩, and ⟨ffl⟩. These are not independent letters, but rather allographs.

Proposed reforms

Alternative scripts have been proposed for written English—mostly extending or replacing the basic English alphabet—such as the Deseret alphabet and the Shavian alphabet.

See also

- Alphabet song

- NATO phonetic alphabet

- English orthography

- English-language spelling reform

- American manual alphabet

- Two-handed manual alphabets

- English Braille

- American Braille

- New York Point

- Chinese respelling of the English alphabet

- Burmese respelling of the English alphabet

- Base36

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ As an example, this article contains a diaeresis in «coöperate», a cedilla in «façades» and a circumflex in the word «crêpe»: Grafton, Anthony (2006-10-23), «The Nutty Professors: The History of Academic Dharisma», The New Yorker (Books section), retrieved 2019-06-17.

- ^ often in Hiberno-English, due to the letter’s pronunciation in the Irish language

- ^ The usual form in Hiberno-English and Australian English

- ^ The letter J did not occur in Old French or Middle English. The Modern French name is ji /ʒi/, corresponding to Modern English jy (rhyming with i), which in most areas was later replaced with jay (rhyming with kay).

- ^ in Scottish English

- ^ In the US, an L-shaped object may be spelled ell.

- ^ One of the few letter names commonly spelled without the letter in question.

- ^ in Hiberno-English

- ^ in compounds such as es-hook

- ^ Especially in American English, the /l/ is often not pronounced in informal speech. (Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed). Common colloquial pronunciations are , , and (as in the nickname «Dubya») or just , especially in terms like www.

- ^ why is a homophone of y

- ^ in British English, Hiberno-English and Commonwealth English

- ^ in American English, Newfoundland English and Philippine English

- ^ in British English

- ^ in British English

- ^ in words like hallelujah

- ^ in words like loch in Scottish English

- ^ Linguistic analyses vary on how best to characterise the English possessive morpheme -‘s: a noun case inflectional suffix distinct to possession, a genitive case inflectional suffix equivalent to prepositional periphrastic of X (or rarely for X), an edge inflection that uniquely attaches to a noun phrase’s final (rather than head) word, or an enclitic postposition.

References

- ‘^ «The New Yorkers Odd Mark—The Diaeresis»

- ^ a b Michael Everson, Evertype, Baldur Sigurðsson, Íslensk Málstöð, On the Status of the Latin Letter Þorn and of its Sorting Order

- ^ «The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks». Branson, Farrar & Co., Raleigh NC.

- ^ Strizver, Ilene, «Accents & Accented Characters», Fontology, Monotype Imaging, retrieved 2019-06-17

- ^ Modern Humanities Research Association (2013), MHRA Style Guide: A Handbook for Authors and Editors (pdf) (3rd ed.), London, Section 2.2, ISBN 978-1-78188-009-8, retrieved 2019-06-17.

- ^ Zoölogist, Minnesota Office of the State (1892). Report of the State Zoölogist.

- ^ Kingsley Amis quoted in Jane Fyne, «Little Things that Matter,» Courier Mail (2007-04-26) Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- ^ Beker, Henry; Piper, Fred (1982). Cipher Systems: The Protection of Communications. Wiley-Interscience. p. 397. Table also available from

Lewand, Robert (2000). Cryptological Mathematics. Mathematical Association of America. p. 36. ISBN 978-0883857199. and «English letter frequencies». Archived from the original on 2008-07-08. Retrieved 2008-06-25. - ^ Shaw, Phillip (May 2013). «Adapting the Roman alphabet for Writing Old English: Evidence from Coin Epigraphy and Single-Sheet Characters». 21: 115–139 – via Ebscohost.

- ^ «Digraphs (Phonics on the Web)». phonicsontheweb.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-13. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

Further reading

- Michael Rosen (2015). Alphabetical: How Every Letter Tells a Story. Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1619027022.

- Upward, Christopher; Davidson, George (2011), The History of English Spelling, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9024-4, LCCN 2011008794.

| English alphabet | |

|---|---|

An English pangram displaying all the characters in context, in FF Dax Regular typeface |

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

c.1500 to present |

| Languages | English |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(Proto-writing)

|

|

Child systems |

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latn (215), Latin |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Latin |

|

Unicode range |

U+0000 to U+007E Basic Latin and punctuation |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The alphabet for Modern English is a Latin-script alphabet consisting of 26 letters, each having an upper- and lower-case form. The word alphabet is a compound of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha and beta. The alphabet originated around the 7th century CE to write Old English from Latin script. Since then, letters have been added or removed to give the current letters:

- A a

- B b

- C c

- D d

- E e

- F f

- G g

- H h

- I i

- J j

- K k

- L l

- M m

- N n

- O o

- P p

- Q q

- R r

- S s

- T t

- U u

- V v

- W w

- X x

- Y y

- Z z

The exact shape of printed letters varies depending on the typeface (and font), and the standard printed form may differ significantly from the shape of handwritten letters (which varies between individuals), especially cursive.

The English alphabet has 5 vowels, 19 consonants, and 2 letters (Y and W) that can function as constants or vowels.

Written English has a large number of digraphs (e.g., would, beak, moat); it stands out (almost uniquely) as a European language without diacritics in native words. The only exceptions are:

- a diaeresis (e.g., «coöperation») may be used to distinguish two vowels with separate pronunciation from a double vowel[nb 1][1]

- a grave accent, very occasionally, (as in learnèd, an adjective) may be used to indicate that a normally silent vowel is pronounced

Letter names

English alphabet from 1740, with some unusual letter names.

The names of the letters are commonly spelled out in compound words and initialisms (e.g., tee-shirt, deejay, emcee, okay, etc.), derived forms (e.g., exed out, effing, to eff and blind, aitchless, etc.), and objects named after letters (e.g., en and em in printing, and wye in railroading). The spellings listed below are from the Oxford English Dictionary. Plurals of consonant names are formed by adding -s (e.g., bees, efs or effs, ems) or -es in the cases of aitches, esses, exes. Plurals of vowel names also take -es (i.e., aes, ees, ies, oes, ues), but these are rare. For a letter as a letter, the letter itself is most commonly used, generally in capitalized form, in which case the plural just takes -s or -‘s (e.g. Cs or c’s for cees).

| Letter | Name | Name pronunciation | Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern English | Latin | Modern English | Latin | Old French | Middle English | ||

| A | a | ā | , [nb 2] | /aː/ | /aː/ | /aː/ | 8.17% |

| B | bee | bē | /beː/ | /beː/ | /beː/ | 1.49% | |

| C | cee | cē | /keː/ | /tʃeː/ > /tseː/ > /seː/ | /seː/ | 2.78% | |

| D | dee | dē | /deː/ | /deː/ | /deː/ | 4.25% | |

| E | e | ē | /eː/ | /eː/ | /eː/ | 12.70% | |

| F | ef, eff | ef | /ɛf/ | /ɛf/ | /ɛf/ | 2.23% | |

| eff as a verb | |||||||

| G | gee | gē | /ɡeː/ | /dʒeː/ | /dʒeː/ | 2.02% | |

| H | aitch | hā | /haː/ > /ˈaha/ > /ˈakːa/ | /ˈaːtʃə/ | /aːtʃ/ | 6.09% | |

| haitch[nb 3] | |||||||

| I | i | ī | /iː/ | /iː/ | /iː/ | 6.97% | |

| J | jay | – | – | – | [nb 4] | 0.15% | |

| jy[nb 5] | |||||||

| K | kay | kā | /kaː/ | /kaː/ | /kaː/ | 0.77% | |

| L | el, ell[nb 6] | el | /ɛl/ | /ɛl/ | /ɛl/ | 4.03% | |

| M | em | em | /ɛm/ | /ɛm/ | /ɛm/ | 2.41% | |

| N | en | en | /ɛn/ | /ɛn/ | /ɛn/ | 6.75% | |

| O | o | ō | /oː/ | /oː/ | /oː/ | 7.51% | |

| P | pee | pē | /peː/ | /peː/ | /peː/ | 1.93% | |

| Q | cue, kew, kue, que[nb 7] | qū | /kuː/ | /kyː/ | /kiw/ | 0.10% | |

| R | ar | er | /ɛr/ | /ɛr/ | /ɛr/ > /ar/ | 5.99% | |

| or[nb 8] | |||||||

| S | ess | es | /ɛs/ | /ɛs/ | /ɛs/ | 6.33% | |

| es- in compounds[nb 9] | |||||||

| T | tee | tē | /teː/ | /teː/ | /teː/ | 9.06% | |

| U | u | ū | /uː/ | /yː/ | /iw/ | 2.76% | |

| V | vee | – | – | – | – | 0.98% | |

| W | double-u | – | [nb 10] | – | – | – | 2.36% |

| X | ex | ex | /ɛks/ | /iks/ | /ɛks/ | 0.15% | |

| ix | /ɪks/ | ||||||

| Y | wy, wye, why[nb 11] | hȳ | /hyː/ | ui, gui ? | /wiː/ | 1.97% | |

| /iː/ | |||||||

| ī graeca | /iː ˈɡraɪka/ | /iː ɡrɛːk/ | |||||

| Z | zed[nb 12] | zēta | /ˈzeːta/ | /ˈzɛːdə/ | /zɛd/ | 0.07% | |

| zee[nb 13] |

Etymology

The names of the letters are for the most part direct descendants, via French, of the Latin (and Etruscan) names. (See Latin alphabet: Origins.)

The regular phonological developments (in rough chronological order) are:

- palatalization before front vowels of Latin /k/ successively to /tʃ/, /ts/, and finally to Middle French /s/. Affects C.

- palatalization before front vowels of Latin /ɡ/ to Proto-Romance and Middle French /dʒ/. Affects G.

- fronting of Latin /uː/ to Middle French /yː/, becoming Middle English /iw/ and then Modern English /juː/. Affects Q, U.

- the inconsistent lowering of Middle English /ɛr/ to /ar/. Affects R.

- the Great Vowel Shift, shifting all Middle English long vowels. Affects A, B, C, D, E, G, H, I, K, O, P, T, and presumably Y.

The novel forms are aitch, a regular development of Medieval Latin acca; jay, a new letter presumably vocalized like neighboring kay to avoid confusion with established gee (the other name, jy, was taken from French); vee, a new letter named by analogy with the majority; double-u, a new letter, self-explanatory (the name of Latin V was ū); wye, of obscure origin but with an antecedent in Old French wi; izzard, from the Romance phrase i zed or i zeto «and Z» said when reciting the alphabet; and zee, an American levelling of zed by analogy with other consonants.

Some groups of letters, such as pee and bee, or em and en, are easily confused in speech, especially when heard over the telephone or a radio communications link. Spelling alphabets such as the ICAO spelling alphabet, used by aircraft pilots, police and others, are designed to eliminate this potential confusion by giving each letter a name that sounds quite different from any other.

Ampersand

The ampersand (&) has sometimes appeared at the end of the English alphabet, as in Byrhtferð’s list of letters in 1011.[2] & was regarded as the 27th letter of the English alphabet, as taught to children in the US and elsewhere. An example may be seen in M. B. Moore’s 1863 book The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks.[3] Historically, the figure is a ligature for the letters Et. In English and many other languages, it is used to represent the word and, plus occasionally the Latin word et, as in the abbreviation &c (et cetera).

Archaic letters

Old and Middle English had a number of non-Latin letters that have since dropped out of use. These either took the names of the equivalent runes, since there were no Latin names to adopt, or (thorn, wyn) were runes themselves.

- Æ æ ash or æsc , used for the vowel , which disappeared from the language and then reformed. Replaced by ae[nb 14] and e now.

- Ð ð edh, eð or eth , and Þ þ thorn or þorn , both used for the consonants and (which did not become phonemically distinct until after these letters had fallen out of use). Replaced by th now.

- Ŋ ŋ eng or engma,[citation needed] used for voiced velar nasal sound produced by «ng» in English. Replaced by ng now.

- Œ œ ethel, ēðel, œ̄þel, etc. , used for the vowel /œ/, which disappeared from the language quite early. Replaced by oe[nb 15] and e now.

- Ƿ ƿ wyn, ƿen or wynn , used for the consonant . (The letter ‘w’ had not yet been invented.) Replaced by w now.

- Ȝ ȝ yogh, ȝogh or yoch or , used for various sounds derived from , such as and . Replaced by y, j[nb 16] and ch[nb 17] now.

- ſ long s, an earlier form of the lowercase «s» that continued to be used alongside the modern lowercase s into the 1800s. Replaced by lowercase s now.

Diacritics

The most common diacritic marks seen in English publications are the acute (é), grave (è), circumflex (â, î, or ô), tilde (ñ), umlaut and diaeresis (ü or ï—the same symbol is used for two different purposes), and cedilla (ç).[4] Diacritics used for tonal languages may be replaced with tonal numbers or omitted.

Loanwords

Diacritic marks mainly appear in loanwords such as naïve and façade. Informal English writing tends to omit diacritics because of their absence from the keyboard, while professional copywriters and typesetters tend to include them.

As such words become naturalised in English, there is a tendency to drop the diacritics, as has happened with many older borrowings from French, such as hôtel. Words that are still perceived as foreign tend to retain them; for example, the only spelling of soupçon found in English dictionaries (the OED and others) uses the diacritic. However, diacritics are likely to be retained even in naturalised words where they would otherwise be confused with a common native English word (for example, résumé rather than resume).[5] Rarely, they may even be added to a loanword for this reason (as in maté, from Spanish yerba mate but following the pattern of café, from French, to distinguish from mate).

Native English words

Occasionally, especially in older writing, diacritics are used to indicate the syllables of a word: cursed (verb) is pronounced with one syllable, while cursèd (adjective) is pronounced with two. For this, è is used widely in poetry, e.g., in Shakespeare’s sonnets. J.R.R. Tolkien used ë, as in O wingëd crown.

Similarly, while in chicken coop the letters -oo- represent a single vowel sound (a digraph), they less often represent two which may be marked with a diaresis as in zoölogist[6] and coöperation. This use of the diaeresis is rare but found in some well-known publications, such as MIT Technology Review and The New Yorker. Some publications, particularly in UK usage, have replaced the diaeresis with a hyphen such as in co-operative.[citation needed]

In general, these devices are not used even where they would serve to alleviate some degree of confusion.

Punctuation marks within words

Apostrophe

The apostrophe (ʼ) is not considered part of the English alphabet nor used as a diacritic, even in loanwords. But it is used for two important purposes in written English: to mark the «possessive»[nb 18] and to mark contracted words. Current standards require its use for both purposes. Therefore, apostrophes are necessary to spell many words even in isolation, unlike most punctuation marks, which are concerned with indicating sentence structure and other relationships among multiple words.

- It distinguishes (from the otherwise identical regular plural inflection -s) the English possessive morpheme ‘s (apostrophe alone after a regular plural affix, giving -s’ as the standard mark for plural + possessive). Practice settled in the 18th century; before then, practices varied but typically all three endings were written -s (but without cumulation). This meant that only regular nouns bearing neither could be confidently identified, and plural and possessive could be potentially confused (e.g., «the Apostles words»; «those things over there are my husbands»[7])—which undermines the logic of «marked» forms.

- Most common contractions have near-homographs from which they are distinguished in writing only by an apostrophe, for example it’s (it is or it has), or she’d (she would or she had).

Hyphen

Hyphens are often used in English compound words. Written compound words may be hyphenated, open or closed, so specifics are guided by stylistic policy. Some writers may use a slash in certain instances.

Frequencies

The letter most commonly used in English is E. The least used letter is Z. The frequencies shown in the table may differ in practice according to the type of text.[8]

Phonology

The letters A, E, I, O, and U are considered vowel letters, since (except when silent) they represent vowels, although I and U represent consonants in words such as «onion» and «quail» respectively.

The letter Y sometimes represents a consonant (as in «young») and sometimes a vowel (as in «myth»). Very rarely, W may represent a vowel (as in «cwm», a Welsh loanword).

The consonant sounds represented by the letters W and Y in English (/w/ and /j/ as in yes /jɛs/ and went /wɛnt/) are referred to as semi-vowels (or glides) by linguists, however this is a description that applies to the sounds represented by the letters and not to the letters themselves.

The remaining letters are considered consonant letters, since when not silent they generally represent consonants.

History

Old English

The English language itself was first written in the Anglo-Saxon futhorc runic alphabet, in use from the 5th century. This alphabet was brought to what is now England, along with the proto-form of the language itself, by Anglo-Saxon settlers. Very few examples of this form of written Old English have survived, mostly as short inscriptions or fragments.

The Latin script, introduced by Christian missionaries, began to replace the Anglo-Saxon futhorc from about the 7th century, although the two continued in parallel for some time. As such, the Old English alphabet began to employ parts of the Roman alphabet in its construction.[9] Futhorc influenced the emerging English alphabet by providing it with the letters thorn (Þ þ) and wynn (Ƿ ƿ). The letter eth (Ð ð) was later devised as a modification of dee (D d), and finally yogh (Ȝ ȝ) was created by Norman scribes from the insular g in Old English and Irish, and used alongside their Carolingian g.

The a-e ligature ash (Æ æ) was adopted as a letter in its own right, named after a futhorc rune æsc. In very early Old English the o-e ligature ethel (Œ œ) also appeared as a distinct letter, likewise named after a rune, œðel[citation needed]. Additionally, the v-v or u-u ligature double-u (W w) was in use.

In the year 1011, a monk named Byrhtferð recorded the traditional order of the Old English alphabet.[2] He listed the 24 letters of the Latin alphabet first, including the ampersand, then 5 additional English letters, starting with the Tironian note ond (⁊), an insular symbol for and:

A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z & ⁊ Ƿ Þ Ð Æ

Modern English

In the orthography of Modern English, the letters thorn (þ), eth (ð), eng (ŋ),[dubious – discuss] wynn (ƿ), yogh (ȝ), ash (æ), and ethel (œ) are obsolete. Latin borrowings reintroduced homographs of æ and œ into Middle English and Early Modern English, though they are largely obsolete (see «Ligatures in recent usage» below), and where they are used they are not considered to be separate letters (e.g., for collation purposes), but rather ligatures. Thorn and eth were both replaced by th, though thorn continued in existence for some time, its lowercase form gradually becoming graphically indistinguishable from the minuscule y in most handwriting. Y for th can still be seen in pseudo-archaisms such as «Ye Olde Booke Shoppe». The letters þ and ð are still used in present-day Icelandic (where they now represent two separate sounds, /θ/ and /ð/ having become phonemically-distinct — as indeed also happened in Modern English), while ð is still used in present-day Faroese (although only as a silent letter). Wynn disappeared from English around the 14th century when it was supplanted by uu, which ultimately developed into the modern w. Yogh disappeared around the 15th century and was typically replaced by gh.

The letters u and j, as distinct from v and i, were introduced in the 16th century, and w assumed the status of an independent letter. The variant lowercase form long s (ſ) lasted into early modern English, and was used in non-final position up to the early 19th century. Today, the English alphabet is considered to consist of the following 26 letters:

- A a

- B b

- C c

- D d

- E e

- F f

- G g

- H h

- I i

- J j

- K k

- L l

- M m

- N n

- O o

- P p

- Q q

- R r

- S s

- T t

- U u

- V v

- W w

- X x

- Y y

- Z z

Written English has a number[10] of digraphs, but they are not considered separate letters of the alphabet:

- ch (usually makes tsh sound)

- ci (makes s sound)

- ck (makes k sound)

- gh (makes f or g sound (also silent))

- ng (makes Voiced velar nasal)

- ph (makes f sound)

- qu (makes kw sound)

- rh (makes r sound)

- sc (makes s sound (also a blend))

- sh (makes ch sound without t)

- th (makes theta or eth sound)

- ti (makes sh sound)

- wh (makes w sound)

- wr (makes r sound)

- zh (makes j sound without d)

Ligatures in recent usage

Outside of professional papers on specific subjects that traditionally use ligatures in loanwords, ligatures are seldom used in modern English. The ligatures æ and œ were until the 19th century (slightly later in American English)[citation needed] used in formal writing for certain words of Greek or Latin origin, such as encyclopædia and cœlom, although such ligatures were not used in either classical Latin or ancient Greek. These are now usually rendered as «ae» and «oe» in all types of writing,[citation needed] although in American English, a lone e has mostly supplanted both (for example, encyclopedia for encyclopaedia, and maneuver for manoeuvre).

Some fonts for typesetting English contain commonly used ligatures, such as for ⟨tt⟩, ⟨fi⟩, ⟨fl⟩, ⟨ffi⟩, and ⟨ffl⟩. These are not independent letters, but rather allographs.

Proposed reforms

Alternative scripts have been proposed for written English—mostly extending or replacing the basic English alphabet—such as the Deseret alphabet and the Shavian alphabet.

See also

- Alphabet song

- NATO phonetic alphabet

- English orthography

- English-language spelling reform

- American manual alphabet

- Two-handed manual alphabets

- English Braille

- American Braille

- New York Point

- Chinese respelling of the English alphabet

- Burmese respelling of the English alphabet

- Base36

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ As an example, this article contains a diaeresis in «coöperate», a cedilla in «façades» and a circumflex in the word «crêpe»: Grafton, Anthony (2006-10-23), «The Nutty Professors: The History of Academic Dharisma», The New Yorker (Books section), retrieved 2019-06-17.

- ^ often in Hiberno-English, due to the letter’s pronunciation in the Irish language

- ^ The usual form in Hiberno-English and Australian English

- ^ The letter J did not occur in Old French or Middle English. The Modern French name is ji /ʒi/, corresponding to Modern English jy (rhyming with i), which in most areas was later replaced with jay (rhyming with kay).

- ^ in Scottish English

- ^ In the US, an L-shaped object may be spelled ell.

- ^ One of the few letter names commonly spelled without the letter in question.

- ^ in Hiberno-English

- ^ in compounds such as es-hook

- ^ Especially in American English, the /l/ is often not pronounced in informal speech. (Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed). Common colloquial pronunciations are , , and (as in the nickname «Dubya») or just , especially in terms like www.

- ^ why is a homophone of y

- ^ in British English, Hiberno-English and Commonwealth English

- ^ in American English, Newfoundland English and Philippine English

- ^ in British English

- ^ in British English

- ^ in words like hallelujah

- ^ in words like loch in Scottish English

- ^ Linguistic analyses vary on how best to characterise the English possessive morpheme -‘s: a noun case inflectional suffix distinct to possession, a genitive case inflectional suffix equivalent to prepositional periphrastic of X (or rarely for X), an edge inflection that uniquely attaches to a noun phrase’s final (rather than head) word, or an enclitic postposition.

References

- ‘^ «The New Yorkers Odd Mark—The Diaeresis»

- ^ a b Michael Everson, Evertype, Baldur Sigurðsson, Íslensk Málstöð, On the Status of the Latin Letter Þorn and of its Sorting Order

- ^ «The Dixie Primer, for the Little Folks». Branson, Farrar & Co., Raleigh NC.

- ^ Strizver, Ilene, «Accents & Accented Characters», Fontology, Monotype Imaging, retrieved 2019-06-17

- ^ Modern Humanities Research Association (2013), MHRA Style Guide: A Handbook for Authors and Editors (pdf) (3rd ed.), London, Section 2.2, ISBN 978-1-78188-009-8, retrieved 2019-06-17.

- ^ Zoölogist, Minnesota Office of the State (1892). Report of the State Zoölogist.

- ^ Kingsley Amis quoted in Jane Fyne, «Little Things that Matter,» Courier Mail (2007-04-26) Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- ^ Beker, Henry; Piper, Fred (1982). Cipher Systems: The Protection of Communications. Wiley-Interscience. p. 397. Table also available from

Lewand, Robert (2000). Cryptological Mathematics. Mathematical Association of America. p. 36. ISBN 978-0883857199. and «English letter frequencies». Archived from the original on 2008-07-08. Retrieved 2008-06-25. - ^ Shaw, Phillip (May 2013). «Adapting the Roman alphabet for Writing Old English: Evidence from Coin Epigraphy and Single-Sheet Characters». 21: 115–139 – via Ebscohost.

- ^ «Digraphs (Phonics on the Web)». phonicsontheweb.com. Archived from the original on 2016-04-13. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

Further reading

- Michael Rosen (2015). Alphabetical: How Every Letter Tells a Story. Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1619027022.

- Upward, Christopher; Davidson, George (2011), The History of English Spelling, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9024-4, LCCN 2011008794.

- Русский алфавит

- Алфавиты и азбуки

- Английский алфавит

Английский алфавит

В современном английском алфавите 26 букв. По количеству букв и их написанию он полностью совпадает с латинским алфавитом.

100%

Английский алфавит с названием букв на русском языке.

A aэй B bби C cси D dди E eи F fэф G gджи H hэйч I iай J jджей K kкей L lэл M mэм N nэн O oоу P pпи Q qкью R rа, ар S sэс T tти U uю V vви W wдабл-ю X xэкс Y yуай Z zзед, зи

Английский алфавит с нумерацией: буквы в прямом и обратном порядке с указанием позиции.

- Aa

1

26 - Bb

2

25 - Cc

3

24 - Dd

4

23 - Ee

5

22 - Ff

6

21 - Gg

7

20 - Hh

8

19 - Ii

9

18 - Jj

10

17 - Kk

11

16 - Ll

12

15 - Mm

13

14 - Nn

14

13 - Oo

15

12 - Pp

16

11 - Qq

17

10 - Rr

18

9 - Ss

19

8 - Tt

20

7 - Uu

21

6 - Vv

22

5 - Ww

23

4 - Xx

24

3 - Yy

25

2 - Zz

26

1

Английский алфавит с названием букв, транскрипцией, русским произношением и частотностью в процентах (подробно про частотность написано на главной странице сайта).

| Буква | Транскрипция (произношение) |

Название | Название на русском | Частотность |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A a | [eɪ] | a | эй | 8.17% |

| B b | [biː] | bee | би | 1.49% |

| C c | [siː] | cee | си | 2.78% |

| D d | [diː] | dee | ди | 4.25% |

| E e | [iː] | e | и | 12.7% |

| F f | [ef] | ef | эф | 2.23% |

| G g | [dʒiː] | gee | джи | 2.02% |

| H h | [eɪtʃ] | aitch | эйч | 6.09% |

| I i | [aɪ] | i | ай | 6.97% |

| J j | [dʒeɪ] | jay | джей | 0.15% |

| K k | [keɪ] | kay | кей | 0.77% |

| L l | [el] | el | эл | 4.03% |

| M m | [em] | em | эм | 2.41% |

| N n | [ɛn] | en | эн | 6.75% |

| O o | [əʊ] | o | оу | 7.51% |

| P p | [piː] | pee | пи | 1.93% |

| Q q | [kjuː] | cue | кью | 0.1% |

| R r | [ɑː, ar] | ar | а, ар | 5.99% |

| S s | [es] | ess | эс | 6.33% |

| T t | [tiː] | tee | ти | 9.06% |

| U u | [juː] | u | ю | 2.76% |

| V v | [viː] | vee | ви | 0.98% |

| W w | [‘dʌbljuː] | double-u | дабл-ю | 2.36% |

| X x | [eks] | ex | экс | 0.15% |

| Y y | [waɪ] | wy | уай | 1.97% |

| Z z | [zɛd, ziː] | zed, zee | зед, зи | 0.05% |

Самая известная английская панграмма, содержащая все 26 букв английского алфавита: The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

Изучать любой иностранный язык лучше с детства. Известно, что дети, выросшие в мультиязычной среде, гораздо легче адаптируются и намного быстрее впитывают в себя новую информацию.

Чтобы ребенок начал изучать английский как можно раньше и не заскучал от этого процесса — достаточно превратить нудное обучение в игру. Так запоминать новые слова и фразы малышу станет гораздо проще, а вы будете проводить время со своим чадом не только весело, но и продуктивно.

В этой статье расскажем о том, как просто и легко выучить английский алфавит как детям, так и всем начинающим и дадим несколько стихов и песенок для изучения.

Английский алфавит

Алфавит в английском называется alphabet или просто ABC. В нем 26 букв, из них 20 согласных (consonants) и всего 6 гласных (vowels).

Гласные: A, E, I, O, U, Y

Согласные: B, C, D, F, G, H, J, K, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, W, X, Z

Алфавит с транскрипцией и произношением:

Aa [ ei ] [эй]

Bb [ bi: ] [би]

Cc [ si: ] [си]

Dd [ di: ] [ди]

Ee [ i: ] [и]

Ff [ ef ] [эф]

Gg [ dʒi: ] [джи]

Hh [ eitʃ ] [эйч]

Ii [ ai ] [ай]

Jj [ dʒei ] [джей]

Kk [ kei ] [кей]

Ll [ el ] [эл]

Mm [ em ] [эм]

Nn [ en ] [эн]

Oo [ ou ] [оу]

Pp [ pi: ] [пи]

Qq [ kju: ] [кью]

Rr [ a: ] [аа, ар]

Ss [ es ] [эс]

Tt [ ti: ] [ти]

Uu [ ju: ] [ю]

Vv [ vi: ] [ви]

Ww [ `dʌbl `ju: ] [дабл-ю]

Xx [ eks ] [экс]

Yy [ wai ] [уай]

Zz [ zed ] [зед]

Практически все буквы алфавита американцы и британцы произносят одинаково, кроме последней. В американском английском Z будет звучать как «зи» [ziː].

Изучение алфавита обычно начинается с alphabet song (алфавитной песенки): так ребенку проще запомнить произношение. Напевается она по строчкам:

Do you know your ABC?

You can learn along with me!

A, B, C, D, E, F, G

H, I, J, K

L, M, N, O, P

Q, R, S,

T, U, V

W, X, Y and Z

Now you know your alphabet!

Кстати, из-за разницы в произношении буквы «Z» конец этой песни в британском и американском варианте будет звучать по-разному:

Британский

X, Y, Z — Now I know my alphabet (Теперь я знаю свой алфавит) или Now you know your alphabet (Теперь ты знаешь свой алфавит).

Американский

Now I know my ABC, twenty-six letters from A to Z (Теперь я знаю свой алфавит, двадцать шесть букв от A до Z) или Now I know my ABC, next time won’t you sing with me (Теперь я знаю свой алфавит, не хотел бы ты спеть в следующий раз со мной).

Именно с изучения алфавита начинается увлекательное путешествие в любой иностранный язык. ABC нужно знать на зубок каждому, чтобы знать, как правильно пишутся и произносятся отдельные буквы. Особенно, если потребуется to spell a word. Spelling — это то, как произносится слово по буквам. Прямого аналога spelling в русском языке нет, а вот у американцев есть даже целая игра Spelling Bee, в которой нужно назвать по буквам слово без ошибок. В США часто проводятся соревнования и конкурсы по Spelling Bee.

Но начинать нужно с простого, тем более детям. Рассказываем несколько приемов как сделать так, чтобы ребенку выучить алфавит было as easy as ABC (легче легкого).

Карточки со словами

Один из эффективных способов выучить новые слова и запомнить алфавит — сделать ребенку яркие карточки с буквами и словами, которые на них начинаются и повесить их на видном месте.

Этот же прием можно использовать для обогащения лексики: просто развесьте карточки с переводом над предметами, которые есть у вас в квартире — пусть ребенок запоминает, как пишутся и произносятся слова.

Один из самых легких вариантов — использовать хорошо знакомые ребенку слова. Это могут быть названия животных или повседневные предметы.

Вот буквы с соответствующими словами, которые позволят запомнить не только написание, но и потренировать произношение:

A — Apple (Яблоко)

B — Banana (Банан)

C — Cat (Кошка)

D — Dog (Собака)

E — Elephant (Слон)

F — Fox (Лиса)

G — Giraffe (Жираф)

H — House (Дом)

I — Ice-cream (Мороженое)

J — Jam (Джем)

K — Key (Ключ)

L — Lemon (Лимон)

M — Mouse (Мышь)

N — Nose (Нос)

O — Owl (Сова)

P — Panda (Панда)

Q — Queen (Королева)

R — Rabbit (Кролик)

S — Squirrel (Белка)

T — Turtle (Черепаха)

U — Umbrella (Зонт)

V — Violin (Скрипка)

W — Wolf (Волк)

X — Ox (Бык)

Y — Yacht (Яхта)

Z — Zebra (Зебра)

Найти комплект таких карточек можно в любом книжном магазине, а можно сделать и самим.

Стих для изучения английского алфавита

В стихотворной форме намного легче запомнить порядок букв и слова, начинающиеся с этой буквы. Многие преподаватели читают самым маленьким ученикам вот такой стишок для знакомства с алфавитом:

В нашу дверь стучатся.

— Кто там?

— Буква A и осень — autumn.

Каждому, чтоб грустным не был,

Дарят яблоко — an apple.

Буква B, как мячик — ball

Скачет, прячется под стол.

Жаль, играть мне недосуг:

Я читаю книжку — book

На охоту вышла С.

— Мыши! Лапы уноси!

Чтоб сегодня на обед

Не достаться кошке — cat.

К букве D не подходи,

А не то укусит D.

Кот бежит, не чуя ног,

Во дворе собака — dog.

Буква Е белей, чем снег.

С Е берет начало egg,

Egg высиживает квочка.

Тут конец — the end. И точка!

На листок зеленый сев,

Громко квакнет буква F,

Потому что frog — лягушка,

Знаменитая квакушка.

С этой буквой не дружи,

Зазнается буква G.

Важно голову задрав,

Смотрит свысока — giraffe.

H утрет любому нос.

Мчится вихрем конь мой — horse.

Для него преграды нет,

Если всадник в шляпе — hat.

С буквой I мы так похожи:

I и я — одно и то же.

Мы не плачем, не хандрим,

Если есть пломбир — ice-cream.

Сладкоежка буква J

Слаще булок и коржей.

Буква J знакома всем,

Кто отведал сладкий jam.

K откроет всем замки,

У нее есть ключик — key,

В царство — kingdom отведет,

Мир волшебный распахнет.

Буква L пришла затем,

Чтоб помочь ягненку — lamb,

Он в кровать боится лечь,

Просит лампу — lamp зажечь.

Буква М для обезьянки,

Для веселой шустрой monkey.

Угощенья ждет она,

Melon — дыня ей нужна.

N висеть не надоест.

На ветвях гнездо — a nest.

В нем птенцы. Хотелось нам бы

Посчитать число их — number.

От зари и до зари

Машет веткой дуб — oak-tree.

Всех зовет под свод ветвей,

Бормоча под нос: «O.K.»

Pirate — молодой пират

С parrot — попугаем рад:

— Посмотрите, это нам

Машет веткой пальма — palm!

Тут я песенку спою

В честь прекрасной буквы Q,

Потому что queen — царица

Очень любит веселиться.

Почему идет молва

«Берегитесь буквы R»?

Я открою вам секрет

Нет противней крысы — rat!

Не случайно буква S

Вызывает интерес:

В небе — sky сверкает star —

Очень яркая звезда.

В «Детский мир» зовет нас T.

В гости рады мы зайти:

Там подружится с тобой

Каждая игрушка — toy.

Если встретишь букву U,

Значит скоро быть дождю.

U сегодня подобрела —

Подарила зонт — umbrella.

Эй! Беги, держи, лови!

На подаче буква V.

Прямо в небо мяч ушел,

Обожаю volleyball.

W, известно всем,

Перевернутая М.

В темноте, клыком сверкнув,

Ходит серый волк — a wolf.

Врач сказал из-за дверей:

— Я беру вас на X-ray.

— Что такое? Может, в плен?

— Нет, всего лишь на рентген.

Эй, на весла налегай!

Мчится в море буква Y.

В дальний путь ребят зовет

Белый парусник — a yacht.

Что такое буква Z?

Ты увидишь, взяв билет,

Волка, тигра, и козу

В зоопарке — in the Zoo.

Игры для изучения английского алфавита для детей

Интересные игры с использованием тех же карточек позволят ребенку быстрее освоится и не заскучать во время изучения английского алфавита. Во что можно поиграть с ребенком:

«Изобрази букву»

Назовите ребенку букву английского алфавита и попросите изобразить ее пальцами или своим телом. Можно играть по-очереди и показывать какие-то буквы самому.

«Нарисуй букву»

Положите перед ребенком карточки с алфавитом и предложите ему нарисовать на листе бумаги букву самому. Так он быстрее научится не только визуально распознавать буквы, но и писать их в дальнейшем. Аналогично, можно взять пластилин и попросить малыша слепить из него буквы английского алфавита.

«Слово-мяч»

Более подвижная игра, в которой можно передавать друг другу мяч и называть буквы в алфавитном порядке или, для более продвинутых, слова, начинающиеся на эту букву.

«Стоп-песня»

Разложите перед ребенком карточки с буквами и включите алфавитную песенку на английском. Остановите ее в произвольный момент — ребенок должен повторить последнюю услышанную букву и показать соответствующую карточку.

«Да-нет»

Для этой игры можно использовать карточки как с буквами, так и со словами. Покажите ребенку изображение на картинке и назовите слово. Так, можно показать картинку с хрюшкой (pig) а вслух сказать «тигр» (tiger). Если ребенок говорит «нет», то должен назвать то, что на самом деле изображено на картинке.

Придумывайте свои игры и задания, спросите у малыша, во что бы он хотел поиграть. Смотрите вместе мультики на английском языке и иногда обращайтесь к нему с обычными просьбами на английском и пусть он тоже иногда использует английские слова в повседневной речи.

Можно заниматься с ребенком и онлайн. Puzzle English разработал специальный курс английского языка для детей, который включает в себя изучение алфавита, бытовых предметов, простых вопросов и многое другое. И все это с яркими картинками и нескучными заданиями, чтобы малыш не заскучал. Мы рекомендуем начать обучение детей английскому языку именно с него.

Главное — чтобы ребенку не было скучно и изучение языка не превратилось для него в рутину.

Английский алфавит, в основе которого лежат латинские буквы, имеет интересную и долгую историю. C течением времени алфавит претерпел значительные изменения. Теперь английский представляет чётко оформленную систему. Различают печатный и прописной английский алфавит, каждый из которых отличается преимуществами и недостатками.

Буквы английского алфавита

В составе английского алфавита 26 букв, из которых:

- 6 передают гласные звуки;

- 21 передаёт согласные звуки.

Это обусловлено тем, что “Y” передаёт как гласный звук, так и согласный, что зависит от типа слога. Звуков намного больше: 26 букв используются для создания 24 согласных и 20 гласных звуков.

Название последней буквы – “Z” – пишется и произносится двумя способами:

- в британском варианте как “zed” (читается [zɛd]);

- в американском как “zee” (читается [ziː]).

Таблица английского алфавита

Таблица заглавных и строчных букв, а также транскрипция:

| Заглавная буква | Строчная буква | Как произносится название |

| A | a | [ei] |

| B | b | [biː] |

| C | c | [siː] |

| D | d | [diː] |

| E | e | [iː] |

| F | f | [ef] |

| G | g | [dʒiː] |

| H | h | [eɪtʃ] |

| I | i | [ai] |

| J | j | [dʒeɪ] |

| K | k | [kei] |

| L | l | [el] |

| M | m | [em] |

| N | n | [ɛn] |

| O | o | [əʊ] |

| P | p | [piː] |

| Q | q | [kjuː] |

| R | r | [ɑː, ar] |

| S | s | [es] |

| T | t | [tiː] |

| U | u | [juː] |

| V | v | [viː] |

| W | w | [‘dʌbljuː] |

| X | x | [eks] |

| Y | y | [waɪ] |

| Z | z | [zɛd, ziː] |

Плюсы и минусы прописных букв английского алфавита

| Плюсы | Минусы |

| Отлично развивают моторику, поэтому используются при обучении детей. | Нужно время, чтобы научиться писать красиво. |

| Повышают скорость письма, так как буквы в слове соединяются между собой. | Иногда трудно разобрать то, что написано. |

| При аккуратном почерке текст с прописными буквами выглядит опрятнее. | Используются все реже и реже. |

| Нет строгих правил написания, поэтому можно добавлять что-то своё. | |

| Владея этим типом письма, проще разобраться рукописные источники. | |

| Развивают аккуратность. |

Прописные буквы английского алфавита

Представить алфавит этого языка без прописных букв невозможно. Прописной алфавит — комфортный и быстрый способ письма. Кроме того, прописные буквы не подразумевают полное копирование образцов. Вы сами можете создавать собственный стиль письма, главное, чтобы буквы были разборчивы.

Заметьте, раньше прописная буква “A”в английском писалась так же, как и в русском. Сейчас буква встречается как строчная “a”, только в увеличенном размере.

Каллиграфический английский алфавит

Каллиграфию считают декоративным стилем, поэтому требует немало времени, креативности и точности. Нельзя утверждать, что научиться этому нельзя, когда у человека плохой почерк. Освоить каллиграфию могут все. Это займёт время, но принесёт пользу.

Так как каллиграфия становится популярной проводят удобные мастер-классы и уроки по ее освоению. Научиться можно не выходя из дома.

Вам потребуется только:

- бумага;

- необходимые принадлежности (ручка, перо, тушь);

- терпение и желание.

Прописи английского алфавита

Несколько прописей, которые можно скачать и распечатать:

Песни для запоминания английского алфавита

Чтобы запомнить порядок алфавита и произношение букв самым маленьким, начинать изучение стоит с раскрасок и песен. Здесь представлены популярные песни, которые будут помогать изучать алфавит малышам.

ARVE Error: Mode: lazyload not available (ARVE Pro not active?), switching to normal mode

ARVE Error: Mode: lazyload not available (ARVE Pro not active?), switching to normal mode

ARVE Error: Mode: lazyload not available (ARVE Pro not active?), switching to normal mode

Заключение

Английский алфавит существует в прописном и печатном варианте написания, как и в некоторых других языках, например, русском. Овладеть письменным алфавитом не так трудно, если научиться каллиграфии. Пропись имеет преимущества, почему и стоит уделить ей внимание.

Для вашего удобства приводим различные варианты написания The ABC: английский алфавит в строку, в прямом и обратном порядке, прописные и строчные буквы английского алфавита без пробелов, подряд с пробелами, с нумерацией и другие варианты (см. в статье «Английский алфавит без пробелов и др.варианты».

Про то, как читается алфавит, как пишутся печатные и письменные буквы, история создания, интересные факты об английском алфавите — читайте в статье «Английский алфавит … в удобных таблицах«.

Прописные английские буквы без пробела в одну строку

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

Здесь вы можете скопировать английский алфавит в том написании, как вам это требуется.

Строчные английские буквы без пробела в одну строку

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

Английский алфавит в обратную сторону

Прописные английские буквы без пробела в одну строку, в обратную сторону

ZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Строчные буквы английского алфавита без пробела в одну строку, в обратную сторону

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcba

ПРОПИСНЫЕ И СТРОЧНЫЕ АНГЛИЙСКИЕ БУКВЫ С ПРОБЕЛОМ

Прописные английские буквы с пробелом в одну строку

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Строчные английские буквы с пробелом в одну строку

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

Прописные и строчные английские буквы с пробелом в обратную сторону

Z Y X W V U T S R Q P O N M L K J I H G F E D C B A

z y x w v u t s r q p o n m l k j i h g f e d c b a

Прописные и строчные английские буквы через запятую

Прописные английские буквы через запятую в одну строку скопировать.

A , B , C , D , E , F , G , H , I , J , K , L , M , N , O , P , Q , R , S , T , U , V , W , X , Y , Z

A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z

Английские строчные буквы через запятую в одну строчку

a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z,

И прописные, и строчные английские буквы через запятую в одну строку

A a, B b, C c, D d, E e, F f, G g, H h, I i, J j, K k, L l, M m, N n, O o, P p, Q q, R r, S s, T t, U u, V v, W w, X x, Y y, Z z

И без пробела между строчной и прописной буквами:

Aa, Bb, Cc, Dd, Ee, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Oo, Pp, Qq, Rr, Ss, Tt, Uu, Vv, Ww, Xx, Yy, Zz

Прописные и строчные буквы английского алфавита в столбик

Прописные английские буквы в столбик

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

Строчные английские буквы в столбик

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

l

m

n

o

p

q

r

s

t

u

v

w

x

y

z

Прописные и строчные английские буквы в столбик

A a

B b

C c

D d

E e

F f

G g

H h

I i

J j

K k

L l

M m

N n

O o

P p

Q q

R r

S s

T t

U u

V v

W w

X x

Y y

Z z

Строчные и прописные буквы английского алфавита в столбик, с запятой

A a,

B b,

C c,

D d,

E e,

F f,

G g,

H h,

I i,

J j,

K k,

L l,

M m,

N n,

O o,

P p,

Q q,

R r,

S s,

T t,

U u,

V v,

W w,

X x,

Y y,

Z z

Гласные буквы английского языка

Отдельно Гласные и согласные буквы английского алфавита и интересные факты о них можно посмотреть в этой статье.

A E I O U Y

B C D F G H J K L M N P Q R S T V W X Z

Перечень гласных и согласных через запятую — см. в статье, указанной выше.

Если вас интересует еще какая-то комбинация букв, просьба писать в комментариях. Сделаем. ))

маленькие английские буквы, английский алфавит маленькие буквы, английский алфавит большие и маленькие буквы, английские буквы большие и маленькие,