|

David Ben-Gurion |

|

|---|---|

| דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן | |

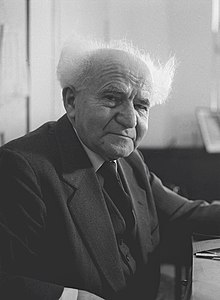

Ben-Gurion in 1960 |

|

| 1st Prime Minister of Israel | |

| In office 3 November 1955 – 26 June 1963 |

|

| President |

|

| Preceded by | Moshe Sharett |

| Succeeded by | Levi Eshkol |

| In office 17 May 1948 – 26 January 1954 |

|

| President |

|

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Moshe Sharett |

| Chairman of the Provisional State Council of Israel | |

| In office 14 May 1948 – 16 May 1948 |

|

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Chaim Weizmann |

| Minister of Defense | |

| In office 21 February 1955 – 26 June 1963 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Pinhas Lavon |

| Succeeded by | Levi Eshkol |

| In office 14 May 1948 – 26 January 1954 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Pinhas Lavon |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

David Grün 16 October 1886 |

| Died | 1 December 1973 (aged 87) Ramat Gan, Israel |

| Citizenship |

|

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Paula Munweis (m. 1917; died 1968) |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Istanbul University |

| Signature | |

David Ben-Gurion ( ben GOOR-ee-ən; Hebrew: דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן [daˈvid ben ɡuʁˈjon ] (listen); born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel.

Born in the town of Płońsk, then in Russian-ruled Poland, he moved to Palestine in 1906. Adopting the name of Ben-Gurion in 1909, he rose to become the preeminent leader of the Jewish community in British-ruled Mandatory Palestine from 1935 until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, which he led until 1963 with a short break in 1954–55.

Ben-Gurion’s passion for Zionism, which began early in life, led him to become a major Zionist leader and executive head of the World Zionist Organization in 1946.[1] As head of the Jewish Agency from 1935, and later president of the Jewish Agency Executive, he was the de facto leader of the Jewish community in Palestine, and largely led its struggle for an independent Jewish state in Mandatory Palestine. On 14 May 1948, he formally proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel, and was the first to sign the Israeli Declaration of Independence, which he had helped to write. Ben-Gurion led Israel during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and united the various Jewish militias into the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Subsequently, he became known as «Israel’s founding father».[2]

Following the war, Ben-Gurion served as Israel’s first prime minister and minister of defence. As prime minister, he helped build state institutions, presiding over national projects aimed at the development of the country. He also oversaw the absorption of vast numbers of Jews from all over the world. A centerpiece of his foreign policy was improving relationships with the West Germans. He worked with Konrad Adenauer’s government in Bonn, and West Germany provided large sums (in the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany) in compensation for Nazi Germany’s confiscation of Jewish property during the Holocaust.[3]

In 1954 he resigned as prime minister and minister of defence but remained a member of the Knesset. He returned as minister of defence in 1955 after the Lavon Affair and the resignation of Pinhas Lavon. Later that year he became prime minister again, following the 1955 elections. Under his leadership, Israel responded aggressively to Arab guerrilla attacks, and in 1956, invaded Egypt along with British and French forces after Egypt nationalised the Suez Canal during the Suez Crisis.

He stepped down from office in 1963, and retired from political life in 1970. He then moved to his modest «hut» in Sde Boker, a kibbutz in the Negev desert, where he lived until his death. Posthumously, Ben-Gurion was named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Important People of the 20th century.

Early life

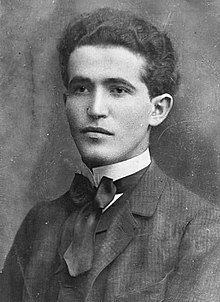

Poalei Zion’s «Ezra» group in Plonsk, 1905. David Grün (David Ben-Gurion) in the first row, third on the right.

Ben Gurion with Rachel Nelkin and members of Ezra on eve of their departure to Palestine, August 1906; His father and step-mother sitting in the windows

Ben Gurion working at Rishon Lezion winery (front row, 6th from right), 1908.

Childhood and education

David Ben-Gurion was born in Płońsk in Congress Poland—then part of the Russian Empire. His father, Avigdor Grün, was a «pokątnym doradcą» (secret adviser), navigating his clients through the often corrupt Imperial legal system.[4] Following the publication of Theodore Herzl’s Der Judenstaat in 1896 Avigdor co-founded a Zionist group called Beni Zion—Children of Zion. In 1900 it had a membership of 200.[5] David was the youngest of three boys with an older and younger sister. His mother, Scheindel (Broitman),[6] died of sepsis following a stillbirth in 1897. It was her eleventh pregnancy.[7] Two years later his father remarried.[8] Ben-Gurion’s birth certificate, found in Poland in 2003, indicated that he had a twin brother who died shortly after birth.[9] Between the ages of 5 and 13 Ben Gurion attended 5 different heders as well as compulsory Russian classes. Two of the heders were ‘modern’ and taught in Hebrew rather than Yiddish. His father could not afford to enroll Ben-Gurion in Płońsk’s Beth midrash so Ben Gurion’s formal education ended after his Bar Mitzvah.[10] At the age of 14 he and two friends formed a youth club, Ezra, promoting Hebrew studies and emigration to the Holy Land. The group ran Hebrew classes for local youth and in 1903 collected funds for the victims of the Kishinev pogrom. One biographer writes that Ezra had 150 members within a year.[11] A different source estimates the group never had more than ‘several dozen’ members.[12]

In 1904 Ben Gurion moved to Warsaw where he hoped to enroll in the Warsaw Mechanical-Technical School founded by Hipolit Wawelberg. He did not have sufficient qualifications to matriculate and took work teaching Hebrew in a Warsaw heder. Inspired by Tolstoy he had become a vegetarian.[11] He became involved in Zionist politics and in October 1905 he joined the clandestine Social-Democratic Jewish Workers’ Party—Poalei Zion. Two months later he was the delegate from Płońsk at a local conference.[13] While in Warsaw the Russian Revolution of 1905 broke out and he was in the city during the clamp down that followed; he was arrested twice, the second time he was held for two weeks and only released with the help of his father. In December 1905 he returned to Płońsk as a full-time Poalei Zion operative. There he worked to oppose the anti-Zionist Bund who were trying to establish a base. He also organised a strike over working conditions amongst garment workers. He was known to use intimidatory tactics, such as extorting money from wealthy Jews at gunpoint to raise funds for Jewish workers.[14][15][16]

Ben-Gurion discussed his hometown in his memoirs, saying:

«For many of us, anti-Semitic feeling had little to do with our dedication [to Zionism]. I personally never suffered anti-Semitic persecution. Płońsk was remarkably free of it … Nevertheless, and I think this very significant, it was Płońsk that sent the highest proportion of Jews to Eretz Israel from any town in Poland of comparable size. We emigrated not for negative reasons of escape but for the positive purpose of rebuilding a homeland … Life in Płońsk was peaceful enough. There were three main communities: Russians, Jews and Poles. … The number of Jews and Poles in the city were roughly equal, about five thousand each. The Jews, however, formed a compact, centralized group occupying the innermost districts whilst the Poles were more scattered, living in outlying areas and shading off into the peasantry. Consequently, when a gang of Jewish boys met a Polish gang the latter would almost inevitably represent a single suburb and thus be poorer in fighting potential than the Jews who even if their numbers were initially fewer could quickly call on reinforcements from the entire quarter. Far from being afraid of them, they were rather afraid of us. In general, however, relations were amicable, though distant.»[17]

In autumn of 1906 he left Poland to go to Palestine. He travelled with his sweetheart Rachel Nelkin and her mother, as well as Shlomo Zemach his comrade from Ezra. His voyage was funded by his father.[18]

Ottoman Empire and Constantinople

Immediately on landing in Jaffa, 7 September 1906, Ben Gurion set off, on foot, in a group of fourteen, to Petah Tikva.[19][20] It was the largest of the 13 Jewish agricultural settlements and consisted of 80 households with a population of nearly 1500; of these around 200 were Second Aliyah pioneers like Ben Gurion. He found work as a day labourer, waiting each morning hoping to be chosen by an overseer. Jewish workers found it difficult competing with local villagers who were more skilled and prepared to work for less. Ben Gurion was shocked at the number of Arabs employed. In November he caught malaria and the doctor advised he return to Europe. By the time he left Petah Tikva in summer of 1907 he had worked an average 10 days a month which frequently left him with no money for food.[21][22] He wrote long letters in Hebrew to his father and friends. They rarely revealed how difficult life was. Others who had come from Płońsk were writing about tuberculosis, cholera and people dying of hunger.[23]

On his disembarkation at Jaffa Ben Gurion had been spotted by Israel Shochat who had arrived two years previously and had established a group of around 25 Poale Zion followers. Shochat made a point of inspecting new arrivals looking for recruits. A month after his arrival at Petah Tikva Shochat invited Ben Gurion to attend the founding conference of the Jewish Social Democratic Workers’ Party in the Land of Israel in Jaffa. The conference, 4–6 October 1906, was attended by 60 or so people. Shochat engineered the elections so that Ben Gurion was elected onto the 5-man Central Committee and the 10-man Manifesto Committee. He also arranged that Ben Gurion was chosen as chairman of the sessions. These Ben Gurion conducted in Hebrew, forbidding the translation of his address into Russian or Yiddish. The conference was divided: a large faction—Rostovians—wanted to create a single Arab-Jewish proletariat. This Shochat and Ben Gurion opposed. The conference delegated the Manifesto Committee the task of deciding the new party’s objectives. They produced The Ramleh Program which was approved by a second smaller 15-man conference held in Jaffa the following January 1907. The program stated «the party aspires to political independence[24] of the Jewish People in this country.» All activities were to be conducted in Hebrew; there should be segregation of the Jewish and the Arab economies; and a Jewish trade union was to be established. Three members of the Central Committee resigned and Ben Gurion and Shochat continued meeting weekly in Jaffa or Ben Shemen where Shochat was working. Ben Gurion walked to the meetings from Petah Tikva until he moved to Jaffa where he gave occasional Hebrew lessons. His political activity resulted in the establishment of three small trade unions amongst some tailors, carpenters and shoemakers. He set up the Jaffa Professional Trade Union Alliance with 75 members. He and Shochat also brokered a settlement to a strike at the Rishon Le Zion winery where six workers had been sacked. After three months the two-man Central Committee was dissolved, partly because, at that time, Ben Gurion was less militant than Shochat and the Rostovians. Ben Gurion returned to Petah Tikva.[25][26][27][28]

During this time Ben Gurion sent a letter to Yiddish Kemfer (The Jewish Fighter), a Yiddish newspaper in New York City. It was an appeal for funds and was the first time something written by Ben Gurion was published.[29]

The arrival of Yitzhak Ben Zvi in April 1907 revitalised the local Poale Zion. Eighty followers attended a conference in May at which Ben Zvi was elected onto a two-man Central Committee and all Ben Gurion’s policies were reversed: Yiddish, not Hebrew, was the language to be used; the future lay with a united Jewish and Arab proletariat. Further disappointment came when Ben Zvi and Shochat were elected as representatives to go to the World Zionist Congress. Ben Gurion came last of five candidates. He was not aware that at the next gathering, on Ben Zvi’s return, a secret para-military group was set up—Bar-Giora—under Shochat’s leadership. Distancing himself from Poale Zion activism Ben Gurion, who had been a day-labourer at Kfar Saba, moved to Rishon Lezion where he remained for two months. He made detailed plans with which he tried to entice his father to come and be a farmer.[30]

In October 1907, on Shlomo Zemach’s suggestion, Ben-Gurion moved to Sejera. An agricultural training farm had been established at Sejera in the 1880s and since then a number of family-owned farms, moshavah, had been established forming a community of around 200 Jews. It was one of the most remote colonies in the foothills of north-eastern Galilee. It took the two young men three days to walk there.[31] Coincidently at the same time Bar Giora, now with about 20 members and calling themselves ‘the collective’ but still led by Shochat, took on the operating of the training farm. Ben Gurion found work in the farm but, excluded from ‘the collective’, he later became a labourer for one of the moshav families. One of the first acts of ‘the collective’ was organising sacking of the farm’s circassian nightwatchman. As a result, shots were fired at the farms every night for several months. Guns were brought and the workforce armed. Ben Gurion took turns patrolling the farm at night.[32]

In the autumn of 1908 Ben Gurion returned to Plonsk to be conscripted into the army and avoid his father facing a heavy fine. He immediately deserted and returned to Sejera, travelling, via Germany, with forged papers.[33]

On 12 April 1909 two Jews from Sejera were killed in clashes with local Arabs following the death of a villager from Kfar Kanna, shot in an attempted robbery. There is little conformation of Ben Gurion’s accounts of his part in this event.[34]

Later that summer Ben Gurion moved to Zichron Yaakov. From where the following spring he was invited, by Ben Zvi, to join the staff of Paole Zion’s new Hebrew periodical, Ha’ahdut (The Unity), which was being established in Jerusalem.[35] They needed his fluency in Hebrew for translating and proof reading.[36] It was the end of his career as a farm labourer. The first three editions came out monthly with an initial run of 1000 copies. It then became a weekly with a print run of 450 copies.[37][36] He contributed 15 articles over the first year, using various pen names, eventually settling for Ben Gurion.[38] The adopting of Hebrew names was common amongst those who remained during the Second Aliyah. He chose Ben Gurion after the historic Joseph ben Gurion.[39]

In the spring of 1911, faced with the collapse of the Second Aliyah, Poale Zion’s leadership decided the future lay in «Ottomanisation». Ben Zvi, Manya and Israel Shochat announced their intention to move to Istanbul. Ben Zvi and Shochat planned to study law; Ben Gurion was to join them but first needed to learn Turkish, spending eight months in Salonika, at that time the most advanced Jewish community in the area. Whilst studying he had to conceal that he was Ashkanazi due to local Sephardic prejudices. Ben Zvi obtained a forged secondary school certificate so Ben Gurion could join him in Istanbul University. Ben Gurion was entirely dependent on funding from his father, while Ben Zvi found work teaching. Struggling with ill health Ben Gurion spent some time in hospital.[40][41]

Ben-Gurion in America 1915–1918

Ben-Gurion was at sea, returning from Istanbul, when the First World War broke out. He was not amongst the thousands of foreign nationals deported in December 1914.[42] Based in Jerusalem he and Ben Zvi recruited forty Jews into a Jewish militia to assist the Ottoman Army. Despite his pro-Ottoman declarations he was deported to Egypt in March 1915.[43] From there he made his way to the United States, arriving in May. For the next 4 months Ben-Gurion and Ben Zvi embarked on a speaking tour planned to visit Poale Zion groups in 35 cities in an attempt to raise a pioneer army, Hechalutz, of 10,000 men to fight on the Ottoman side.[44] The tour was a disappointment. Audiences were small; Poale Zion had fewer than 3,000 members, mostly in the New York area. Ben-Gurion was hospitalised with diphtheria for two weeks and only spoke on 5 occasions and was poorly received. Ben Zvi spoke to 14 groups as well as an event in New York City and succeeded in recruiting 44 volunteers for Hechalutz; Ben-Gurion recruited 19.[45] Ben-Gurion embarked on a second tour in December, speaking at 19 meetings, mostly in small towns with larger events in Minneapolis and Galveston.[46] Due to the lack of awareness of Poale Zion’s activities in Palestine it was decided to republish Yizkor in Yiddish. The Hebrew original was published in Jaffa in 1911; it consisted of eulogies to Zionist martyrs and included an account by Ben-Gurion of his Petah Tikva and Sejera experiences. The first edition appeared in February 1916 and was an immediate success; all 3,500 copies were sold. A second edition of 16,000 was published in August. Martin Buber wrote the introduction to the 1918 German edition. The follow-up was conceived as an anthology of work from Poale Zion leaders; in fact Ben-Gurion took over as editor, writing the introduction and two-thirds of the text. He suspended all his Paole Zion activities and spent most of the next 18 months in New York Public Library. Ben Zvi, originally designated as co-editor, contributed a section on Jewish history in which he expounded the theory that the fellahin currently living in the area were descendants of pre-Roman conquest Jews. Eretz Israel – Past and Present was published in April 1918. It cost $2 and was 500 pages long, over twice the length of Yizkor. It was an immediate success, selling 7,000 copies in 4 months; second and third editions were printed. Total sales of 25,000 copies made a profit of $20,000 for Poale Zion. It made David Ben-Gurion the most prominent Poale Zion leader in America.[47][48]

In May 1918 Ben-Gurion joined the newly formed Jewish Legion of the British Army and trained at Fort Edward in Windsor, Nova Scotia. He volunteered for the 38th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, one of the four which constituted the Jewish Legion. His unit fought against the Ottomans as part of Chaytor’s Force during the Palestine Campaign, though he remained in a Cairo hospital with dysentery. In 1918, after a period of guarding prisoners of war in the Egyptian desert, his battalion was transferred to Sarafand. On 13 December 1918 he was demoted from corporal to private, fined 3 days’ pay and transferred to the lowest company in the battalion. He had been 5 days absent without leave visiting friends in Jaffa. He was demobilised in early 1919.[49]

David and Paula Ben-Gurion, 1 June 1918.

Marriage and family

One of Ben Gurion’s companions when he made the Aliyah was Rachel Nelkin. Her step-father, Reb Simcha Isaac, was the leading Zionist in Płońsk, and they met three years previously at one of his meetings. It was expected that their relationship would continue when they landed in Jaffa but he shut her out after she was fired on her first day labouring—manuring the citrus groves of Petah Tikva.[50][51][52]

Whilst in New York City in 1915, he met Russian-born Paula Munweis and they married in 1917. In November 1919, after an 18-month separation, Paula and their daughter Geula joined Ben Gurion in Jaffa. It was the first time he met his one-year-old daughter.[53] The couple had three children: a son, Amos, and two daughters, Geula Ben-Eliezer and Renana Leshem. Already pregnant with their first child, Amos married Mary Callow, an Irish gentile, and although Reform rabbi Joachim Prinz converted her to Judaism soon after, neither the Palestine rabbinate nor her mother-in-law Paula Ben-Gurion considered her a real Jew until she underwent an Orthodox conversion many years later.[54][55][56] Amos became Deputy Inspector-General of the Israel Police, and also the director-general of a textile factory. He and Mary had six granddaughters from their two daughters and a son, Alon, who married a Greek gentile.[57] Geula had two sons and a daughter, and Renana, who worked as a microbiologist at the Israel Institute for Biological Research, had a son.[58]

Zionist leadership between 1919 and 1948

After the death of theorist Ber Borochov, the left-wing and centrist of Poalei Zion split in February 1919 with Ben-Gurion and his friend Berl Katznelson leading the centrist faction of the Labor Zionist movement. The moderate Poalei Zion formed Ahdut HaAvoda with Ben-Gurion as leader in March 1919.

The Histadrut committee in 1920. Ben Gurion is in the 2nd row, 4th from the right.

In 1920 he assisted in the formation of the Histadrut, the Zionist Labor Federation in Palestine, and served as its general secretary from 1921 until 1935. At Ahdut HaAvoda’s 3rd Congress, held in 1924 at Ein Harod, Shlomo Kaplansky, a veteran leader from Poalei Zion, proposed that the party should support the British Mandatory authorities’ plans for setting up an elected legislative council in Palestine. He argued that a Parliament, even with an Arab majority, was the way forward. Ben-Gurion, already emerging as the leader of the Yishuv, succeeded in getting Kaplansky’s ideas rejected.[59]

From left: David Ben-Gurion and Paula with youngest daughter Renana on BG’s lap, daughter Geula, father Avigdor Grün and son Amos, 1929

In 1930, Hapoel Hatzair (founded by A. D. Gordon in 1905) and Ahdut HaAvoda joined forces to create Mapai, the more moderate Zionist labour party (it was still a left-wing organisation, but not as far-left as other factions) under Ben-Gurion’s leadership. In the 1940s the left-wing of Mapai broke away to form Mapam. Labor Zionism became the dominant tendency in the World Zionist Organization and in 1935 Ben-Gurion became chairman of the executive committee of the Jewish Agency, a role he kept until the creation of the state of Israel in 1948.

During the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, Ben-Gurion instigated a policy of restraint («Havlagah») in which the Haganah and other Jewish groups did not retaliate for Arab attacks against Jewish civilians, concentrating only on self-defense. In 1937, the Peel Commission recommended partitioning Palestine into Jewish and Arab areas and Ben-Gurion supported this policy.[60] This led to conflict with Ze’ev Jabotinsky who opposed partition and as a result Jabotinsky’s supporters split with the Haganah and abandoned Havlagah.

The house where he lived from 1931 on, and for part of each year after 1953, is now a historic house museum in Tel Aviv, the «Ben-Gurion House». He also lived in London for some months in 1941.[61]

In 1946, Ben-Gurion and North Vietnam’s Politburo chairman Ho Chi Minh became very friendly when they stayed at the same hotel in Paris. Ho Chi Minh offered Ben-Gurion a Jewish home-in-exile in Vietnam. Ben-Gurion declined, telling Ho Chi Minh: «I am certain we shall be able to establish a Jewish Government in Palestine.»[62][63]

Views and opinions

Decisiveness and pragmatism

According to his biographer Tom Segev, Ben-Gurion deeply admired Lenin and intended to be a ‘Zionist Lenin’.[64][65] In Ben-Gurion: A Political Life by Shimon Peres and David Landau, Peres recalls his first meeting with Ben-Gurion as a young activist in the No’ar Ha’Oved youth movement. Ben-Gurion gave him a lift, and out of the blue told him why he preferred Lenin to Trotsky: «Lenin was Trotsky’s inferior in terms of intellect», but Lenin, unlike Trotsky, «was decisive». When confronted with a dilemma, Trotsky would do what Ben-Gurion despised about the old-style diaspora Jews: he manoeuvred; as opposed to Lenin, who would cut the Gordian knot, accepting losses while focusing on the essentials. In Peres’ opinion, the essence of Ben-Gurion’s life work were «the decisions he made at critical junctures in Israel’s history», and none was as important as the acceptance of the 1947 partition plan, a painful compromise which gave the emerging Jewish state little more than a fighting chance, but which, according to Peres, enabled the establishment of the State of Israel.[66]

Role in 1948 exodus of Palestinians

Israeli historian Benny Morris wrote that the idea of expulsion of Palestinian Arabs was endorsed in practice by mainstream Zionist leaders, particularly Ben-Gurion. He did not give clear or written orders in that regard, but Morris claims that Ben-Gurion’s subordinates understood his policy well.[67]

«From April 1948, Ben-Gurion is projecting a message of transfer. There is no explicit order of his in writing, there is no orderly comprehensive policy, but there is an atmosphere of [population] transfer. The transfer idea is in the air. The entire leadership understands that this is the idea. The officer corps understands what is required of them. Under Ben-Gurion, a consensus of transfer is created.»[68]

Attitude towards Arabs

Ben-Gurion published two volumes setting out his views on relations between Zionists and the Arab world: We and Our Neighbors, published in 1931, and My Talks with Arab Leaders published in 1967. Ben-Gurion believed in the equal rights of Arabs who remained in and would become citizens of Israel. He was quoted as saying, «We must start working in Jaffa. Jaffa must employ Arab workers. And there is a question of their wages. I believe that they should receive the same wage as a Jewish worker. An Arab has also the right to be elected president of the state, should he be elected by all.»[69]

Ben-Gurion recognised the strong attachment of Palestinian Arabs to the land. In an address to the United Nations on 2 October 1947, he doubted the likelihood of peace:

This is our native land; it is not as birds of passage that we return to it. But it is situated in an area engulfed by Arabic-speaking people, mainly followers of Islam. Now, if ever, we must do more than make peace with them; we must achieve collaboration and alliance on equal terms. Remember what Arab delegations from Palestine and its neighbors say in the General Assembly and in other places: talk of Arab-Jewish amity sound fantastic, for the Arabs do not wish it, they will not sit at the same table with us, they want to treat us as they do the Jews of Bagdad, Cairo, and Damascus.[70]

Nahum Goldmann criticised Ben-Gurion for what he viewed as a confrontational approach to the Arab world. Goldmann wrote, «Ben-Gurion is the man principally responsible for the anti-Arab policy, because it was he who molded the thinking of generations of Israelis.»[71] Simha Flapan quoted Ben-Gurion as stating in 1938: «I believe in our power, in our power which will grow, and if it will grow agreement will come…»[72]

In 1909, Ben-Gurion attempted to learn Arabic but gave up. He later became fluent in Turkish. The only other languages he was able to use when in discussions with Arab leaders were English, and to a lesser extent, French.[73]

Attitude towards the British

The British 1939 White paper stipulated that Jewish immigration to Palestine was to be limited to 15,000 a year for the first five years, and would subsequently be contingent on Arab consent. Restrictions were also placed on the rights of Jews to buy land from Arabs. After this Ben-Gurion changed his policy towards the British, stating: «Peace in Palestine is not the best situation for thwarting the policy of the White Paper».[74] Ben-Gurion believed a peaceful solution with the Arabs had no chance and soon began preparing the Yishuv for war. According to Teveth «through his campaign to mobilize the Yishuv in support of the British war effort, he strove to build the nucleus of a ‘Hebrew Army’, and his success in this endeavor later brought victory to Zionism in the struggle to establish a Jewish state.»[75]

During the Second World War, Ben-Gurion encouraged the Jewish population to volunteer for the British Army. He famously told Jews to «support the British as if there is no White Paper and oppose the White Paper as if there is no war».[76] About 10% of the Jewish population of Palestine volunteered for the British Armed Forces, including many women. At the same time Ben-Gurion assisted the illegal immigration of thousands of European Jewish refugees to Palestine during a period when the British placed heavy restrictions on Jewish immigration.

In 1944, the Irgun and Lehi, two Jewish right-wing armed groups, declared a rebellion against British rule and began attacking British administrative and police targets. Ben-Gurion and other mainstream Zionist leaders opposed armed action against the British, and after Lehi assassinated Lord Moyne, the British Minister of State in the Middle East, decided to stop it by force. While Lehi was convinced to suspend operations, the Irgun refused and as a result, the Haganah began supplying intelligence to the British enabling them to arrest Irgun members, and abducting and often torturing Irgun members, handing some over to the British while keeping others detained in secret Haganah prisons. This campaign, which was called the Saison or «Hunting Season», left the Irgun unable to continue operations as they struggled to survive. Irgun leader Menachem Begin ordered his fighters not to retaliate so as to prevent a civil war. The Saison became increasingly controversial in the Yishuv, including within the ranks of the Haganah, and it was aborted at the end of March 1945.[77][78]

At the end of World War II, the Zionist leadership in Palestine had expected a British decision to establish a Jewish state. However, it became clear that the British had no intention of immediately establishing a Jewish state and that limits on Jewish immigration would remain for the time being. As a result, with Ben-Gurion’s approval the Haganah entered into a secret alliance with the Irgun and Lehi called the Jewish Resistance Movement in October 1945 and participated in attacks against the British. In June 1946, the British launched Operation Agatha, a large police and military operation throughout Palestine, searching for arms and arresting Jewish leaders and Haganah members in order to stop the attacks and find documentary evidence of the alliance the British suspected existed between the Haganah, Irgun, and Lehi. The British had intended to detain Ben-Gurion during the operation but he was visiting Paris at the time. The British stored the documents they had captured from the Jewish Agency headquarters in the King David Hotel, which was being used as a military and administrative headquarters. Ben-Gurion agreed to the Irgun’s plan to bomb the King David Hotel in order to destroy incriminating documents that Ben-Gurion feared would prove that the Haganah had been participating in the violent insurrection against the British in cooperation with the Irgun and Lehi with the approval of himself and other Jewish Agency officials. However, Ben-Gurion asked that the operation be delayed, but the Irgun refused. The Irgun carried out the King David Hotel bombing in July 1946, killing 91 people. Ben-Gurion publicly condemned the bombing. In the aftermath of the bombing, Ben-Gurion ordered that the Jewish Resistance Movement be dissolved. From then on, the Irgun and Lehi continued to regularly attack the British, but the Haganah rarely did so, and while Ben-Gurion along with other mainstream Zionist leaders publicly condemned the Irgun and Lehi attacks, in practice the Haganah under their direction rarely cooperated with the British in attempting to suppress the insurgency.[77][78][79]

Due to the Jewish insurgency, bad publicity over the restriction of Jewish immigrants to Palestine, non-acceptance of a partitioned state (as suggested by the United Nations) amongst Arab leaders, and the cost of keeping 100,000 troops in Palestine the British Government referred the matter to the United Nations. In September 1947, the British decided to terminate the Mandate. In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution approving the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. While the Jewish Agency under Ben-Gurion accepted, the Arabs rejected the plan and the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine broke out. Ben-Gurion’s strategy was for the Haganah to hold on to every position with no retreat or surrender and then launch an offensive when British forces had evacuated to such an extent that there would be no more danger of British intervention. This strategy was successful, and by May 1948 Jewish forces were winning the civil war. On 14 May 1948, a few hours before the British Mandate officially terminated, Ben-Gurion declared Israeli independence in a ceremony in Tel Aviv. A few hours later, the State of Israel officially came into being when the British Mandate terminated on 15 May. The 1948 Arab–Israeli War began immediately afterwards as numerous Arab nations then invaded Israel.[78]

Attitude towards conquering the West Bank

After the ten-day campaign during the 1948 war, the Israelis were militarily superior to their enemies and the Cabinet subsequently considered where and when to attack next.[80] On 24 September, an incursion made by the Palestinian irregulars in the Latrun sector (killing 23 Israeli soldiers) precipitated the debate. On 26 September, Ben-Gurion put his argument to the Cabinet to attack Latrun again and conquer the whole or a large part of West Bank.[81][82][83][84] The motion was rejected by a vote of seven to five after discussions.[84] Ben-Gurion qualified the cabinet’s decision as bechiya ledorot («a source of lament for generations») considering Israel may have lost forever the Old City of Jerusalem.[85][86][87]

There is a controversy around these events. According to Uri Bar-Joseph, Ben-Gurion placed a plan that called for a limited action aimed at the conquest of Latrun, and not for an all-out offensive. According to David Tal, in the cabinet meeting, Ben-Gurion reacted to what he had been just told by a delegation from Jerusalem. He points out that this view that Ben-Gurion had planned to conquer the West Bank is unsubstantiated in both Ben-Gurion’s diary and in the Cabinet protocol.[88][89][90][91]

The topic came back at the end of the 1948 war, when General Yigal Allon also proposed the conquest of the West Bank up to the Jordan River as the natural, defensible border of the state. This time, Ben-Gurion refused although he was aware that the IDF was militarily strong enough to carry out the conquest. He feared the reaction of Western powers and wanted to maintain good relations with the United States and not to provoke the British. Moreover, in his opinion the results of the war were already satisfactory and Israeli leaders had to focus on the building of a nation.[92][93][94]

According to Benny Morris, «Ben-Gurion got cold feet during the war. (…). If [he] had carried out a large expulsion and cleansed the whole country -the whole Land of Israel, as far as the Jordan River. It may yet turn out that this was his fatal mistake. If he had carried out a full expulsion rather than a partial one- he would have stabilized the State of Israel for generations.»[95]

Religious parties and status quo

In order to prevent the coalescence of the religious right, the Histadrut agreed to a vague «status quo» agreement with Mizrahi in 1935.

Ben-Gurion was aware that world Jewry could and would only feel comfortable to throw their support behind the nascent state, if it was shrouded with religious mystique. That would include an orthodox tacit acquiescence to the entity. Therefore, in September 1947 Ben-Gurion decided to reach a formal status quo agreement with the Orthodox Agudat Yisrael party. He sent a letter to Agudat Yisrael stating that while being committed to establishing a non-theocratic state with freedom of religion, he promised that the Shabbat would be Israel’s official day of rest, that in state-provided kitchens there would be access to kosher food, that every effort would be made to provide a single jurisdiction for Jewish family affairs, and that each sector would be granted autonomy in the sphere of education, provided minimum standards regarding the curriculum be observed.[96] To a large extent this agreement provided the framework for religious affairs in Israel till the present day, and is often used as a benchmark regarding the arrangement of religious affairs in Israel.

Religious belief

Ben-Gurion described himself as an irreligious person who developed atheism in his youth and who demonstrated no great sympathy for the elements of traditional Judaism, though he quoted the Bible extensively in his speeches and writings.[97] Modern Orthodox philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz considered Ben-Gurion «to have hated Judaism more than any other man he had met».[98] He was proud of the fact that he had only set foot in a synagogue once in Israel,[99] worked on Yom Kippur and ate pork.[54] In later time, Ben-Gurion refused to define himself as «secular», and he regarded himself a believer in God. In a 1970 interview, he described himself as a pantheist, and stated that «I don’t know if there’s an afterlife. I think there is.»[100] During an interview with the leftist weekly Hotam two years before his death, he revealed, «I too have a deep faith in the Almighty. I believe in one God, the omnipotent Creator. My consciousness is aware of the existence of material and spirit … [But] I cannot understand how order reigns in nature, in the world and universe—unless there exists a superior force. This supreme Creator is beyond my comprehension . . . but it directs everything.»[101]

In a letter to the writer Eliezer Steinman, he wrote «Today, more than ever, the ‘religious’ tend to relegate Judaism to observing dietary laws and preserving the Sabbath. This is considered religious reform. I prefer the Fifteenth Psalm, lovely are the psalms of Israel. The Shulchan Aruch is a product of our nation’s life in the Exile. It was produced in the Exile, in conditions of Exile. A nation in the process of fulfilling its every task, physically and spiritually … must compose a ‘New Shulchan’—and our nation’s intellectuals are required, in my opinion, to fulfill their responsibility in this.»[101]

Military leadership

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War Ben-Gurion oversaw the nascent state’s military operations. During the first weeks of Israel’s independence, he ordered all militias to be replaced by one national army, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). To that end, Ben-Gurion used a firm hand during the Altalena Affair, a ship carrying arms purchased by the Irgun led by Menachem Begin. He insisted that all weapons be handed over to the IDF. When fighting broke out on the Tel Aviv beach he ordered it be taken by force and to shell the ship. Sixteen Irgun fighters and three IDF soldiers were killed in this battle. Following the policy of a unified military force, he also ordered that the Palmach headquarters be disbanded and its units be integrated with the rest of the IDF, to the chagrin of many of its members. By absorbing the Irgun force into Israel’s IDF, the Israelis eliminated competition and the central government controlled all military forces within the country. His attempts to reduce the number of Mapam members in the senior ranks led to the «Generals’ Revolt» in June 1948.

As head of the Jewish Agency from 1935, Ben-Gurion was de facto leader of the Jewish population even before the state was declared. In this position, Ben-Gurion played a major role in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. When the IDF archives and others were opened in the late 1980s, scholars started to reconsider the events and the role of Ben-Gurion.[102][clarification needed]

Founding of Israel

David Ben-Gurion proclaiming independence beneath a large portrait of Theodor Herzl, founder of modern Zionism.

On 14 May 1948, on the last day of the British Mandate, Ben-Gurion declared the independence of the State of Israel.[103] In the Israeli declaration of independence, he stated that the new nation would «uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race».

In his War Diaries in February 1948, Ben-Gurion wrote: «The war shall give us the land. The concepts of ‘ours’ and ‘not ours’ are peace concepts only, and they lose their meaning during war.»[104] Also later he confirmed this by stating that, «In the Negev we shall not buy the land. We shall conquer it. You forget that we are at war.»[104] The Arabs, meanwhile, also vied with Israel over the control of territory by means of war, while the Jordanian Arab Legion had decided to concentrate its forces in Bethlehem and in Hebron in order to save that district for its Arab inhabitants, and to prevent territorial gains for Israel.[105] Israeli historian Benny Morris has written of the massacres of Palestinian Arabs in 1948, and has stated that Ben-Gurion «covered up for the officers who did the massacres.»[106]

U.S. President Harry S. Truman in the Oval Office, receiving a Menorah as a gift from the Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion (center). To the right is Abba Eban, the Ambassador of Israel to the United States.

After leading Israel during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Ben-Gurion was elected Prime Minister of Israel when his Mapai (Labour) party won the largest number of Knesset seats in the first national election, held on 14 February 1949. He remained in that post until 1963, except for a period of nearly two years between 1954 and 1955. As prime minister, he oversaw the establishment of the state’s institutions. He presided over various national projects aimed at the rapid development of the country and its population: Operation Magic Carpet, the airlift of Jews from Arab countries, the construction of the National Water Carrier, rural development projects and the establishment of new towns and cities. In particular, he called for pioneering settlement in outlying areas, especially in the Negev. Ben-Gurion saw the struggle to make the Negev desert bloom as an area where the Jewish people could make a major contribution to humanity as a whole.[107] He believed that the sparsely populated and barren Negev desert offered a great opportunity for the Jews to settle in Palestine with minimal obstruction of the Arab population,[dubious – discuss] and set a personal example by settling in kibbutz Sde Boker at the center of the Negev.[107]

During this period, Palestinian fedayeen repeatedly infiltrated into Israel from Arab territory. In 1953, after a handful of unsuccessful retaliatory actions, Ben-Gurion charged Ariel Sharon, then security chief of the northern region, with setting up a new commando unit designed to respond to fedayeen infiltrations. Ben-Gurion told Sharon, «The Palestinians must learn that they will pay a high price for Israeli lives.» Sharon formed Unit 101, a small commando unit answerable directly to the IDF General Staff tasked with retaliating for fedayeen raids. During its five months of existence, the unit launched repeated raids against military targets and villages used as bases by the fedayeen.[108] These attacks became known as the reprisal operations.

In 1953, Ben-Gurion announced his intention to withdraw from government and was replaced by Moshe Sharett, who was elected the second Prime Minister of Israel in January 1954. However, Ben-Gurion temporarily served as acting prime minister when Sharett visited the United States in 1955. During Ben-Gurion’s tenure as acting prime minister, the IDF carried out Operation Olive Leaves, a successful attack on fortified Syrian emplacements near the northeastern shores of the Sea of Galilee. The operation was a response to Syrian attacks on Israeli fishermen. Ben-Gurion had ordered the operation without consulting the Israeli cabinet and seeking a vote on the matter, and Sharett would later bitterly complain that Ben-Gurion had exceeded his authority.[109]

David Ben-Gurion speaking at the Knesset, 1957

Ben-Gurion returned to government in 1955. He assumed the post of defence minister and was soon re-elected prime minister. When he returned to government, Israeli forces began responding more aggressively to Egyptian-sponsored Palestinian guerrilla attacks from Gaza, which was under Egyptian rule. Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser signed the Egyptian-Czech arms deal and purchased a large amount of modern arms. The Israelis responded by arming themselves with help from France. Nasser blocked the passage of Israeli ships through the Straits of Tiran and the Suez Canal. In July 1956, the United States and Britain withdrew their offer to fund the Aswan High Dam project on the Nile and a week later, Nasser ordered the nationalisation of the French and British-controlled Suez Canal. In late 1956, the bellicosity of Arab statements prompted Israel to remove the threat of the concentrated Egyptian forces in the Sinai, and Israel invaded the Egyptian Sinai peninsula. Other Israeli aims were elimination of the fedayeen incursions into Israel that made life unbearable for its southern population, and opening the blockaded Straits of Tiran for Israeli ships.[110][111][112][113][114] Israel occupied much of the peninsula within a few days. As agreed beforehand, within a couple of days, Britain and France invaded too, aiming at regaining Western control of the Suez Canal and removing the Egyptian president Nasser. The United States pressure forced the British and French to back down and Israel to withdraw from Sinai in return for free Israeli navigation through the Red Sea. The United Nations responded by establishing its first peacekeeping force, (UNEF). It was stationed between Egypt and Israel and for the next decade it maintained peace and stopped the fedayeen incursions into Israel.

In 1959, Ben-Gurion learned from West German officials of reports that the notorious Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, was likely living in hiding in Argentina. In response, Ben-Gurion ordered the Israel foreign intelligence service, the Mossad, to capture the international fugitive alive for trial in Israel. In 1960, the mission was accomplished and Eichmann was tried and convicted in an internationally publicised trial for various offences including crimes against humanity, and was subsequently executed in 1962.

Ben-Gurion is said to have been «nearly obsessed» with Israel’s obtaining nuclear weapons, feeling that a nuclear arsenal was the only way to counter the Arabs’ superiority in numbers, space, and financial resources, and that it was the only sure guarantee of Israel’s survival and the prevention of another Holocaust.[115] During his final months as premier Ben-Gurion was engaged in a, now declassified, diplomatic standoff with the United States.[116][117]

Ben-Gurion stepped down as prime minister on 16 June 1963, According to historian Yechiam Weitz, when he unexpectedly resigned:

He was asked to reconsider his decision by the cabinet. The country, however, seemed to have anticipated his move and, unlike the response to his resignation in 1953, no serious efforts were made to dissuade him from resigning…. [His reasons include] his political isolation, suspicion of colleagues and rivals, apparent inability to interact with the full spectrum of reality, and belief that his life’s work was disintegrating. His resignation was not an act of farewell but another act of his personal struggle and possibly an indication of his mental state.[118]

Ben-Gurion chose Levi Eshkol as his successor. A year later a bitter rivalry developed between the two on the issue of the Lavon Affair, a failed 1954 Israeli covert operation in Egypt. Ben-Gurion had insisted that the operation be properly investigated, while Eshkol refused. After failing to unseat Eshkol as Mapai party leader in the 1965 Mapai leadership election, Ben-Gurion subsequently broke with Mapai in June 1965 and formed a new party, Rafi, while Mapai merged with Ahdut HaAvoda to form Alignment, with Eshkol as its head. Alignment defeated Rafi in the November 1965 election, establishing Eshkol as the country’s leader.

Later political career

Ben-Gurion on the cover of Time (16 August 1948)

In May 1967, Egypt began massing forces in the Sinai Peninsula after expelling UN peacekeepers and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. This, together with the actions of other Arab states, caused Israel to begin preparing for war. The situation lasted until the outbreak of the Six-Day War on 5 June. In Jerusalem, there were calls for a national unity government or an emergency government. During this period, Ben-Gurion met with his old rival Menachem Begin in Sde Boker. Begin asked Ben-Gurion to join Eshkol’s national unity government. Although Eshkol’s Mapai party initially opposed the widening of its government, it eventually changed its mind.[119] On 23 May, IDF Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin met with Ben-Gurion to ask for reassurance. Ben-Gurion, however, accused Rabin of putting Israel in mortal danger by mobilising the reserves and openly preparing for war with an Arab coalition. Ben-Gurion told Rabin that at the very least, he should have obtained the support of a foreign power, as he had done during the Suez Crisis. Rabin was shaken by the meeting and took to bed for 36 hours.[citation needed]

After the Israeli government decided to go to war, planning a preemptive strike to destroy the Egyptian Air Force followed by a ground offensive, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan told Ben-Gurion of the impending attack on the night of 4–5 June. Ben-Gurion subsequently wrote in his diary that he was troubled by Israel’s impending offensive. On 5 June, the Six-Day War began with Operation Focus, an Israeli air attack that decimated the Egyptian air force. Israel then captured the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the West Bank, including East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria in a series of campaigns. Following the war, Ben-Gurion was in favour of returning all the captured territories apart from East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights and Mount Hebron as part of a peace agreement.[120]

On 11 June, Ben-Gurion met with a small group of supporters in his home. During the meeting, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan proposed autonomy for the West Bank, the transfer of Gazan refugees to Jordan, and a united Jerusalem serving as Israel’s capital. Ben-Gurion agreed with him, but foresaw problems in transferring Palestinian refugees from Gaza to Jordan, and recommended that Israel insist on direct talks with Egypt, favouring withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula in exchange for peace and free navigation through the Straits of Tiran. The following day, he met with Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek in his Knesset office. Despite occupying a lower executive position, Ben-Gurion treated Kollek like a subordinate.[121]

Following the Six-Day War, Ben-Gurion criticised what he saw as the government’s apathy towards the construction and development of the city. To ensure that a united Jerusalem remained in Israeli hands, he advocated a massive Jewish settlement program for the Old City and the hills surrounding the city, as well as the establishment of large industries in the Jerusalem area to attract Jewish migrants. He argued that no Arabs would have to be evicted in the process.[121] Ben-Gurion also urged extensive Jewish settlement in Hebron.

In 1968, when Rafi merged with Mapai to form the Alignment, Ben-Gurion refused to reconcile with his old party. He favoured electoral reforms in which a constituency-based system would replace what he saw as a chaotic proportional representation method. He formed another new party, the National List, which won four seats in the 1969 election.

Final years and death

Ben-Gurion retired from politics in 1970 and spent his last years living in a modest home on the kibbutz, working on an 11-volume history of Israel’s early years. In 1971, he visited Israeli positions along the Suez Canal during the War of Attrition.

On 18 November 1973, shortly after the Yom Kippur War, Ben-Gurion suffered a cerebral haemorrhage, and was taken to Sheba Medical Center in Tel HaShomer, Ramat Gan. His condition began deteriorating on 23 November and he died a few weeks later.[122] His body lay in state in the Knesset compound before being flown by helicopter to Sde Boker. Sirens sounded across the country to mark his death. He was buried alongside his wife Paula at Midreshet Ben-Gurion.

Awards

- In 1949, Ben-Gurion was awarded the Solomon Bublick Award of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in recognition of his contributions to the State of Israel.[123]

- In both 1951 and 1971, he was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.[124]

Commemoration

- Israel’s largest airport, Ben Gurion International Airport, is named in his honour.

- One of Israel’s major universities, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, located in Beersheva, is named after him.

- Numerous streets, as well as schools, throughout Israel have been named after him.

- An Israeli modification of the British Centurion Tank was named after Ben-Gurion

- Ben-Gurion’s Hut in Kibbutz Sde Boker which is now a visitors’ center.

- A desert research center, Midreshet Ben-Gurion, near his «hut» in Kibbutz Sde Boker has been named in his honour. Ben-Gurion’s grave is in the research center.

- An English Heritage blue plaque, unveiled in 1986, marks where Ben-Gurion lived in London at 75 Warrington Crescent, Maida Vale, W9.[125]

- In the 7th arrondissement of Paris, part of a riverside promenade of the Seine is named after him.[126]

- His portrait appears on both the 500 lirot[127] and the 50 (old) sheqalim notes issued by the Bank of Israel.[128]

-

«Feet on the ground» statue of Ben-Gurion by Rafael Maimon at his «hut» in Sde Boker. Ben-Gurion was a yoga enthusiast who would do the same posture as the statue.

-

Esplanade Ben Gourion, Paris, near the Seine, in front of the Musée du Quai Branly

-

David Ben-Gurion Square—site of the house where Ben-Gurion was born, Płońsk, Wspólna Street.

-

House at town square in Płońsk, Poland, where David Ben-Gurion grew up

See also

- List of Bialik Prize recipients

- Jewish Agency for Israel

- Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany

References

- ^ Brenner, Michael; Frisch, Shelley (April 2003). Zionism: A Brief History. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 184.

- ^ «1973: Israel’s founding father dies». BBC. 1 December 1973. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ George Lavy, Germany and Israel: moral debt and national interest (1996) p. 45

- ^ Teveth, Shabtai (1987) Ben-Gurion. The Burning Ground. 1886–1948. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-35409-9. p.7

- ^ Segev, Tom (2018–2019 translation Haim Watzman) A State at Any Cost. The Life of David Ben-Gurion. Apollo. ISBN 9-781789-544633. pp. 24,25

- ^ «Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy». G. Mokotoff. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Segev (2019). pp. 20,21

- ^ Teveth (1987). p.3

- ^ «Ben-Gurion may have been a twin». Haaretz.

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. 12–13

- ^ a b Teveth (1987) p.14

- ^ Segev (2019). p.23

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. 28,30

- ^ Segev (2019) pp. Warsaw 32,35, college rejection 41, 1905 revolution 43, Poalie Zion 46, prison 47, labor boss 49

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. revolution 25, Poale Zion 28,31, gunman 30

- ^ Adam Shatz, ‘We Are Conquerors,’ London Review of Books Vol. 41 No. 20, 24 October 2019

- ^ Memoirs: David Ben-Gurion (1970), p. 36.

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. 35,36 Shlomo Zemach, Rachel Nelkin + her mother

- ^ Bar-Zohar, Michael (1978) Ben-Gurion. Translated by Peretz Kidron. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London. ISBN 0-297-77401-8. Originally published in Israel 1977. p. 14

- ^ Teveth (1987). p.40

- ^ Teveth (1987). p. population 40, malaria 43

- ^ Segev (2019). p. hunger 64

- ^ Teveth p. 42

- ^ Bar-Zohar. has «independence», Lockman, Zachary (1996) Comrades and Enemies. Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906–1948. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20419-0 has «autonomy»

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. 39, 47–51, 72–73

- ^ Lockman (1996). pp. 46–47

- ^ Ben-Zohar (1978). p.17

- ^ Negev (2019). p.73

- ^ Teveth (1987). p. 48

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. 51–55

- ^ Segev p.87

- ^ Segev p.90

- ^ Bar Zohar p.22

- ^ Segev p.94

- ^ Bar Zohar p. 26

- ^ a b Teveth 1987 p.72

- ^ Segev pp.101,103

- ^ Teveth (1989) p.73

- ^ Segev p.105

- ^ Segev, Tom (2018–2019 translation Haim Watzman) A State at Any Cost. The Life of David Ben-Gurion. Apollo. ISBN 9-781789-544633 pp.109–115

- ^ Oswego.edu Archived 30 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Gila Hadar, «Space and Time in Salonika on the Eve of World War II and the Expulsion and Extermination of Salonika Jewry», Yalkut Moseshet 4, Winter 2006

- ^ Teveth (1987). mass deportations p. 117

- ^ Segev (2019). pp. 116,117

- ^ Teveth (1985). pp. 25, 26.

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. membership 100, tour & illness 103, recruits 104

- ^ Teveth (1987). p. 107

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. 108,115–117

- ^ Segev (2019) pp. 132–134

- ^ Teveth (1987) pp. court martial 135,136, demob 144

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. 20,37,43,44

- ^ Bar-Zohar. p. 20. «probably the most profound love he was ever to experience.»

- ^ Segev p.50

- ^ Teveth (1987). pp. 125, 146

- ^ a b Tom Segev (24 September 2019). A State at Any Cost: The Life of David Ben-Gurion. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 466. ISBN 978-1-4299-5184-5.

- ^ «Mary Ben-Gurion (biographical details)». cosmos.ucc.ie. Retrieved 31 August 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Amos Ben-Gurion (biographical details)». cosmos.ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Pradeep Thakur. The Most Important People of the 20th Century (Part-I): Leaders & Revolutionaries. Lulu.com. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-557-77886-7.

- ^ Beckerman, Gal (29 May 2006). «The apples sometimes fall far from the tree». The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ Teveth, Shabtai (1985) Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs. From Peace to War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503562-3. pp. 66–70

- ^ Morris, Benny (3 October 2002). «Two years of the intifada – A new exodus for the Middle East?». The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ Shindler, Colin (3 October 2019). «How David Ben-Gurion stood with Britain in its darkest hour». The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ «Ben-gurion Reveals Suggestion of North Vietnam’s Communist Leader». Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 8 November 1966. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ «Israel Was Everything». The New York Times. 21 June 1987. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ On his return from Moscow in 1922 he outlined what he admired in Lenin: ‘A man who disdains all obstacles, faithful to his goal, who knows no concessions or discounts, the extreme of extremes; who knows how to crawl on his belly in the utter depths in order to reach his goal; a man of iron will who does not spare human life and the blood of innocent children for the sake of the revolution. . .he is not afraid of rejecting today what he required yesterday, and requiring tomorrow what he rejected today; he will not be caught in the net of platitude, or in the trap of dogma; for the naked reality, the cruel truth and the reality of power relations will be before his sharp and clear eyes . .the single goal, burning with red flame- the goal of the great revolution.’Tom Segev, A State at Any Cost: The Life of David Ben-Gurion, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-1-429-95184-5p.182.

- ^ Assaf Sharon, ‘This Obstinate Little Man, ’ in New York Review of Books 4 November 2021 pp.45–47 p.45

- ^ «Secrets of Ben-Gurion’s Leadership». Forward.com. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ Research Fellow Truman Institute Benny Morris; Benny Morris; Morris Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. pp. 597–. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

But no expulsion policy was ever enunciated and Ben-Gurion always refrained from issuing clear or written expulsion orders; he preferred that his generals ‘understand’ what he wanted. He probably wished to avoid going down in history as the ‘great expeller’ and he did not want his government to be blamed for a morally questionable policy.

- ^ «Morris in an interview with Haaretz, 8 January 2004″. Archived from the original on 4 April 2004. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ Efraim Karsh, «Fabricating Israeli history: the ‘new historians'», Edition 2, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0-7146-5011-1, p. 213.

- ^ David Ben-Gurion, statement to the Assembly of Palestine Jewry, 2 October 1947

- ^ Nahum Goldmann, The Jewish Paradox A Personal Memoir, translated by Steve Cox, 1978, ISBN 0-448-15166-9, pp. 98, 99, 100

- ^ Simha Flapan, Zionism and the Palestinians, 1979, ISBN 0-85664-499-4, pp. 142–144

- ^ Teveth, Shabtai (1985) Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs. From Peace to War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503562-3. p. 118.

- ^ Shabtai Teveth, 1985, Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs, p. 199

- ^ S. Teveth, 1985, Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs, p. 200

- ^ «Ben-Gurion’s road to the State» (in Hebrew). Ben-Gurion Archives. Archived from the original on 15 February 2006.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Bruce: Anonymous Soldiers (2015)

- ^ a b c Bell, Bowyer J.: Terror out of Zion (1976)

- ^ Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews, p. 523.

- ^ Benny Morris (2008), pp. 315–316.

- ^ Benny Morris (2008), pp. 317.

- ^ Uri Ben-Eliezer, The Making of Israeli Militarism, Indiana University Press, 1998, p. 185 writes: «Ben-Gurion describes to the Minister his plans to conquer the entire West Bank, involving warfare against entire Jordan’s Arab Legion, but to his surprise the ministers rejected his proposal.»

- ^ «Ben Gurion proposal to conquer Latrun, the cabinet meeting, 26 sept 1948 (hebrew)». Israel state archive blog. israelidocuments.blogspot.co.il/2015/02/1948.html (Hebrew).

- ^ a b Benny Morris (2008), p. 318.

- ^ Mordechai Bar-On, Never-Ending Conflict: Israeli Military History, Stackpole Books, 2006, p. 60 writes : «Originally, this was an idiom that Ben-Gurion used after the government rejected his demand to attack the Legion and occupy Samaria in the wake of a Mujuhidin’s attack near Latrun in September 1948.

- ^ Yoav Gelber, Israeli-Jordanian Dialogue, 1948–1953, Sussex Academic Press, 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Benny Morris (2008), pp. 315.

- ^ Zaki Shalom (2002). David Ben-Gurion, the State of Israel and the Arab World, 1949–1956. Sussex Academic Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-902210-21-6.

A great satisfaction with the armistice borders…(Concerning the) area intended to pass into Israeli…(Ben Gurions’) statements reveal the ambiguity over this subject

- ^ Zaki Shalom (2002). David Ben-Gurion, the State of Israel and the Arab World, 1949–1956. Sussex Academic Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-902210-21-6.

If BG had been fully convinced that the IDF should have fought more aggressively for Jerusalem and the surrounding area, then Sharet’s opposition would not have stood in the way of government consent

- ^ David Tal (24 June 2004). War in Palestine, 1948: Israeli and Arab Strategy and Diplomacy. Routledge. pp. 406–407. ISBN 978-1-135-77513-1.

Nothing of this sort appears in the diary he kept at the time or in the minutes of the Cabinet meeting from which he is ostensibly quoting… Ben Gurion once more raised the idea of conquering Latrun in the cabinet. Ben Gurion was in fact reacting to what he had been told by a delegation from Jerusalem… The «everlasting shame» view is unsubstantiated in both Ben Gurion’s diary and in the Cabinet protocol.

- ^ Uri Bar-Joseph (19 December 2013). The Best of Enemies: Israel and Transjordan in the War of 1948. Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-135-17010-3.

the plan place by BG before the government call not for an all-out offensive, but rather for a limited action aimed at the conquest of Latrun…more than 13 years later ..(he) claim that his proposal had been far more comprehensive

- ^ Anita Shapira (25 November 2014). Ben-Gurion: Father of Modern Israel. Yale University Press. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-0-300-18273-6.

«(Ben Gurion) He also did not flinch from provoking the United Nations by breaking the truce agreement. But the limit of his fearlessness was a clash with a Western power. Vainly, the right and Mapam accused him of defeatism. He did not flinch from confronting them but chose to maintain good relations with the United States, which he perceived as a potential ally of the new state, and also not to provoke the British lion, even though its fangs had been drawn. At the end of the war, when Yigal Allon, who represented the younger generation of commanders that had grown up in the war, demanded the conquest of the West Bank up to the Jordan River as the natural, defensible border of the state, Ben-Gurion refused. He recognized that the IDF was militarily strong enough to carry out the conquest, but he believed that the young state should not bite off more than it had already chewed. There was a limit to what the world was prepared to accept. Furthermore, the armistice borders—which later became known as the Green Line—were better than those he had dreamed of at the beginning of the war. In Ben-Gurion’s opinion, in terms of territory Israel was satisfied. It was time to send the troops home and start work on building the new nation.

- ^ Benny Morris (2009). One state, two states: resolving the Israel/Palestine conflict. Yale University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780300122817.

in March 1949, just before the signing of the Israel-Jordan armistice agreement, when IDF general Yigal Allon proposed conquering the West Bank, Ben-Gurion turned him down flat. Like most Israelis, Ben-Gurion had given up the dream

- ^ Zaki Shalom (2002). David Ben-Gurion, the State of Israel and the Arab World, 1949–1956. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-1-902210-21-6.

The clearest expression of this ‘activist’ approach is found in a «personal, top secret» letter sent by Yigal Allon to BG shortly after … We cannot imagine a border more stable than the Jordan River, which runs the entire length of the country

- ^ Ari Shavit, Survival of the fittest : An Interview with Benny Morris, Ha’aretz Friday Magazine, 9 January 2004.

- ^ The Status Quo Letter Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, in Hebrew

- ^ «Biography: David Ben-Gurion: For the Love of Zion». vision.org. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Michael Prior (12 November 2012). Zionism and the State of Israel: A Moral Inquiry. Routledge. pp. 293–. ISBN 978-1-134-62877-3. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Zvi Zameret; Moshe Tlamim (1999). «Judaism in Israel: Ben-Gurion’s Private Beliefs and Public Policy». Israel Studies. Indiana University Press. 4. Fall, 1999 (2): 64–89. JSTOR 30245511.

He prided himself on not having set foot inside a synagogue in Eretz Israel, except on one occasion: «Only once did I go inside, when independence was declared, at the request of Rabbi Bar-Ilan of the Mizrachi Party. However, he added, when abroad he enjoyed attending synagogue on Sabbath. Away from Israel his tastes changed: he viewed the synagogue as a natural meeting place for Jewish brethren, a kind of community center.

- ^ Kinsolving, Lester (21 January 1970). «An Interview with David Ben Gurion». The Free Lance-Star. Retrieved 31 August 2018 – via Google News.

- ^ a b Tsameret, Tsevi; Tlamim, Moshe (1 July 1999). «Judaism in Israel: Ben-Gurion’s Private Beliefs and Public Policy». Israel Studies. 4 (2): 64–89. doi:10.1353/is.1999.0016. S2CID 144777972.

- ^ See e.g. Benny Morris, the Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem and The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited

- ^ Sherzer, Adi (January 2021). Kedourie, Helen; Kelly, Saul (eds.). «The Jewish past and the ‘birth’ of the Israeli nation state: The case of Ben-Gurion’s Independence Day speeches». Middle Eastern Studies. Taylor & Francis. 57 (2): 310–326. doi:10.1080/00263206.2020.1862801. eISSN 1743-7881. ISSN 0026-3206. LCCN 65009869. OCLC 875122033. S2CID 231741621.

- ^ a b Mêrôn Benveniśtî, Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948, p. 120

- ^ Sir John Bagot Glubb, A Soldier with the Arabs, London 1957, p. 200

- ^ Ari Shavit’Survival of the fittest,’ Haaretz 8 January 2004:»The worst cases were Saliha (70–80 killed), Deir Yassin (100–110), Lod (250), Dawayima (hundreds) and perhaps Abu Shusha (70). There is no unequivocal proof of a large-scale massacre at Tantura, but war crimes were perpetrated there. At Jaffa there was a massacre about which nothing had been known until now. The same at Arab al Muwassi, in the north. About half of the acts of massacre were part of Operation Hiram [in the north, in October 1948]: at Safsaf, Saliha, Jish, Eilaboun, Arab al Muwasi, Deir al Asad, Majdal Krum, Sasa. In Operation Hiram there was a unusually high concentration of executions of people against a wall or next to a well in an orderly fashion.That can’t be chance. It’s a pattern. Apparently, various officers who took part in the operation understood that the expulsion order they received permitted them to do these deeds in order to encourage the population to take to the roads. The fact is that no one was punished for these acts of murder. Ben-Gurion silenced the matter. He covered up for the officers who did the massacres.»

- ^ a b David Ben-Gurion (17 January 1955). «Importance of the Negev» (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 23 February 2007.

- ^ «Unit 101 (Israel) | Specwar.info ||». En.specwar.info. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ Vital (2001), p. 182

- ^ Moshe Shemesh; Selwyn Illan Troen (5 October 2005). The Suez-Sinai Crisis: A Retrospective and Reappraisal. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-135-77863-7.

The aims were to be threefold: to remove the threat, wholly or partially, of the Egyptian rmy in the Sinai, to destroy the framework of the fedaiyyun, and to secure the freedom of navigation through the straits of Tiran.

- ^ Isaac Alteras (1993). Eisenhower and Israel: U.S.-Israeli Relations, 1953–1960. University Press of Florida. pp. 192–. ISBN 978-0-8130-1205-6.

the removal of the Egyptian blockade of the Straits of Tiran at the entrance of the Gulf of Aqaba. The blockade closed Israel’s sea lane to East Africa and the Far East, hindering the development of Israel’s southern port of Eilat and its hinterland, the Nege. Another important objective of the Israeli war plan was the elimination of the terrorist bases in the Gaza Strip, from which daily fedayeen incursions into Israel made life unbearable for its southern population. And last but not least, the concentration of the Egyptian forces in the Sinai Peninsula, armed with the newly acquired weapons from the Soviet bloc, prepared for an attack on Israel. Here, Ben-Gurion believed, was a time bomb that had to be defused before it was too late. Reaching the Suez Canal did not figure at all in Israel’s war objectives.

- ^ Dominic Joseph Caraccilo (January 2011). Beyond Guns and Steel: A War Termination Strategy. ABC-CLIO. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-313-39149-1.

The escalation continued with the Egyptian blockade of the Straits of Tiran, and Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal in July 1956. On October 14, Nasser made clear his intent:»I am not solely fighting against Israel itself. My task is to deliver the Arab world from destruction through Israel’s intrigue, which has its roots abroad. Our hatred is very strong. There is no sense in talking about peace with Israel. There is not even the smallest place for negotiations.» Less than two weeks later, on October 25, Egypt signed a tripartite agreement with Syria and Jordan placing Nasser in command of all three armies. The continued blockade of the Suez Canal and Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping, combined with the increased fedayeen attacks and the bellicosity of recent Arab statements, prompted Israel, with the backing of Britain and France, to attack Egypt on October 29, 1956.

- ^ Alan Dowty (20 June 2005). Israel/Palestine. Polity. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-7456-3202-5.

Gamal Abdel Nasser, who declared in one speech that «Egypt has decided to dispatch her heroes, the disciples of Pharaoh and the sons of Islam and they will cleanse the land of Palestine….There will be no peace on Israel’s border because we demand vengeance, and vengeance is Israel’s death.»…The level of violence against Israelis, soldiers and civilians alike, seemed to be rising inexorably.

- ^ Ian J. Bickerton (15 September 2009). The Arab-Israeli Conflict: A History. Reaktion Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-86189-527-1.

(p. 101) To them the murderous fedayeen raids and constant harassment were just another form of Arab warfare against Israel…(p. 102) Israel’s aims were to capture the Sinai peninsula in order to open the straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, and to seize the Gaza strip to end fedayeen attacks.

- ^ Zaki Shalom, Israel’s Nuclear Option: Behind the Scenes Diplomacy Between Dimona and Washington, (Portland, Ore.: Sussex Academic Press, 2005), p. 44

- ^ Cohen, Avner (3 May 2019). «How a Standoff with the U.S. Almost Blew up Israel’s Nuclear Program». Haaretz.

- ^ «The Battle of the Letters, 1963: John F. Kennedy, David Ben-Gurion, Levi Eshkol, and the U.S. Inspections of Dimona | National Security Archive». 29 April 2019.

- ^ Yechiam Weitz, «Taking Leave of the’Founding Father’: Ben-Gurion’s Resignation as Prime Minister in 1963.» Middle Eastern Studies 37.2 (2001): 131–152, from Abstract at doi:10.1080/714004392

- ^ Druckman, Yaron (20 June 1995). «The Six Day War – May 1967, one moment before». Ynetnews. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill, The Six Day War, 1967 p. 199 citing The World at One, BBC radio, 12 July 1967

- ^ a b Shalom, Zaki: Ben-Gurion’s political struggles, 1963–1967

- ^ The Evening Independent (1 December 1973 issue)

- ^ «Ben Gurion Receives Bublick Award; Gives It to University As Prize for Essay on Plato» (10 August 1949). Jewish Telegraphic Agency. www.jta.org. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ «List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004» (PDF) (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv Municipality website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2007.

- ^ «Ben-Gurioin, David (1886–1973)». English Heritage. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ Byron, Joseph (15 May 2010). «Paris Mayor inaugurates David Ben-Gurion esplanade along Seine river, rejects protests». European Jewish Press. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ «BANKNOTE COLLECTION». Banknote.ws. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ «BANKNOTE COLLECTION». Banknote.ws. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

Further reading

- Aronson, Shlomo. «Leadership, preventive war and territorial expansion: David Ben-Gurion and Levi Eshkol.» Israel Affairs 18.4 (2012): 526–545.

- Aronson, Shlomo. «David Ben-Gurion and the British Constitutional Model.» Israel Studies 3.2 (1998): 193–214. online

- Aronson, Shlomo. «David Ben-Gurion, Levi Eshkol and the Struggle over Dimona: A Prologue to the Six-Day War and its (Un) Anticipated Results.» Israel Affairs 15.2 (2009): 114–134.

- Aronson, Shlomo (2011). David Ben-Gurion and the Jewish Renaissance. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19748-9..

- Cohen, Mitchell. «Zion and State: Nation, Class and the Shaping of Modern Israel» (Columbia University Press, 1987)

- Eldar, Eran. «David Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir: from partnership to enmity.» Israel Affairs 26.2 (2020): 174–182. online[dead link]

- Friling, Tuvia, and Ora Cummings. Arrows in the Dark: David Ben-Gurion, the Yishuv Leadership, and Rescue Attempts during the Holocaust (2 vol. University of Wisconsin Press, 2005).

- Gal, Allon. David Ben-Gurion and the American Alignment for a Jewish State (Indiana UP, 1991).

- Getzoff, Joseph F. «Zionist frontiers: David Ben-Gurion, labor Zionism, and transnational circulations of settler development.» Settler Colonial Studies 10.1 (2020): 74–93.

- Kedar, Nir. David Ben-Gurion and the Foundation of Israeli Democracy (Indiana UP, 2021).

- Oren, Michael B. «Ambivalent Adversaries: David Ben-Gurion and Israel vs. the United Nations and Dag Hammarskjold, 1956–57.» Journal of Contemporary History 27.1 (1992): 89–127.

- Pappe, Ilan. «Moshe Sharett, David Ben‐Gurion and the ‘Palestinian option,’ 1948–1956.» Studies in Zionism 7.1 (1986): 77–96.

- Peres, Shimon. Ben-Gurion (Schocken Pub., 2011) ISBN 978-0-8052-4282-9.

- Reynold, Nick. The War of the Zionist Giants: David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018).

- Rosenberg-Friedman, Lilach. «David Ben-Gurion and the ‘Demographic Threat’: His Dualistic Approach to Natalism, 1936–63.» Middle Eastern Studies 51.5 (2015): 742–766.

- Sachar, Howard Morley. A history of Israel: From the rise of Zionism to our time (Knopf, 2007).

- St. John, Robert William. Builder of Israel; the story of Ben-Gurion, (Doubleday, 1961) online

- Segev, Tom. A State at Any Cost: The Life of David Ben-Gurion (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019) Finalist for 2019 National Jewish Book Award.

- Shatz, Adam, «We Are Conquerors» (review of Tom Segev, A State at Any Cost: The Life of David Ben-Gurion, Head of Zeus, 2019, 804 pp., ISBN 978 1 78954 462 6), London Review of Books, vol. 41, no. 20 (24 October 2019), pp. 37–38, 40–42. «Segev’s biography… shows how central exclusionary nationalism, war and racism were to Ben-Gurion’s vision of the Jewish homeland in Palestine, and how contemptuous he was not only of the Arabs but of Jewish life outside Zion. Liberal Jews may look at the state that Ben-Gurion built, and ask if the cost has been worth it.» (p. 42 of Shatz’s review.)

- Teveth, Shabtai (1985). Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs: from peace to war. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503562-9.

- Teveth, Shabtai (1996). Ben-Gurion and the Holocaust. Harcourt Brace & Co. ISBN 9780151002375.