ЗАКОН БОЙЛЯ-МАРИОТТА

- ЗАКОН БОЙЛЯ-МАРИОТТА

-

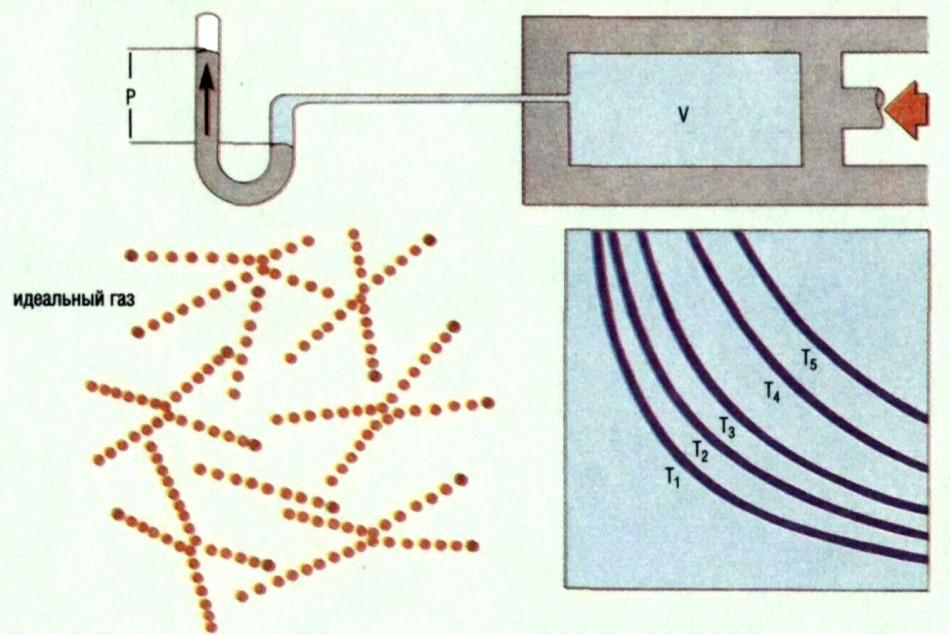

ЗАКОН БОЙЛЯ-МАРИОТТА, закон, согласно которому объем газа при постоянной температуре обратно пропорционален давлению. Это означает, что по мере возрастания давления объем газа уменьшается. Впервые этот закон был сформулирован в 1662 г. Робертом БОЙЛЕМ. Поскольку к его созданию причастен также французский ученый МАРИОТТ, в других странах, кроме Англии, этот закон называют двойным именем. Он представляет собой частный случай ЗАКОНА ИДЕАЛЬНОГО ГАЗА (описывающего гипотетический газ, идеально подчиняющийся всем законам поведения газов).

Когда некоторое количество газа подвергается сжатию, его давление повышается по мере уменьшения объема. Закон Бойля-Мариотта утверждает, что при любой заданной температуре произведение давления на объем остается неизменным как при сжатии, так и при расширении. На гра-фиш показаны эти соотно-шения. Газ, который бы в точности подчинялся этому закону, называемый идеальным газом, можно представить в виде скопления бесконечно малых, совершенно эластичных, сталкивающихся друг с другом частиц (наподобие стальных шарикоподшипников). Обозначения: Р — давление, V—объем, Т), Tj, Тз и т.д. — различные температуры (большие номера соответствуют более высоким температурам).

Научно-технический энциклопедический словарь.

Смотреть что такое «ЗАКОН БОЙЛЯ-МАРИОТТА» в других словарях:

-

Закон Бойля — Мариотта — Воздух (или инертный газ), находящийся в запечатанном пакете с печеньем расширяется, когда продукт поднят на значительную высоту над уровнем моря (ок 2000 м) Закон Бойля Мариотта один из основных газовых з … Википедия

-

Закон Бойля-Мариотта — Закон Бойля Мариотта один из основных газовых законов. Закон назван в честь ирландского физика, химика и философа Роберта Бойля (1627 1691), открывшего его в 1662, а также в честь французского физика Эдма Мариотта (1620 1684), который открыл… … Википедия

-

ЗАКОН БОЙЛЯ МАРИОТТА — один из основных газовых законов, согласно которому при постоянной температуре Т для данной массы m идеального (см.) произведение давления р на занимаемый им объём V есть величина постоянная: pV = const … Большая политехническая энциклопедия

-

закон Бойля-Мариотта — Boilio ir Marioto dėsnis statusas T sritis Standartizacija ir metrologija apibrėžtis Idealiųjų dujų dėsnis: suslėgtų dujų slėgio ir tūrio sandauga, kai temperatūra pastovi, nekinta, t. y. pV = const. Realiosioms dujoms galioja tik apytiksliai… … Penkiakalbis aiškinamasis metrologijos terminų žodynas

-

закон Бойля-Мариотта — Boilio ir Marioto dėsnis statusas T sritis fizika atitikmenys: angl. Boyle and Mariotte law; Boyle Mariotte law vok. Boyle Mariottesches Gesetz, n rus. закон Бойля Мариотта, m pranc. loi de Boyle Mariotte, f … Fizikos terminų žodynas

-

закон Бойля-Мариотта и Гей-Люссака — Boilio, Marioto ir Gei Liusako dėsnis statusas T sritis fizika atitikmenys: angl. Boyle Charles law; Boyle Gay Lussac law vok. Boyle Charlessches Gesetz, n; Boyle Mariotte Gay Lussacsches Gesetz, n rus. закон Бойля Мариотта и Гей Люссака, m pranc … Fizikos terminų žodynas

-

Бойля-Мариотта закон — закон, связывающий изменения объема газа при постоянной температуре с изменениями его упругости. Этот закон, открытый в 1660 г. англ. физиком Бойлем и позже, но, независимо от него, Мариоттом во Франции, по своей простоте и определенности… … Энциклопедический словарь Ф.А. Брокгауза и И.А. Ефрона

-

закон бойля-маріотта — закон Бойля Мариотта Boyle’s and Mariotte’s law *Boyle Mariottesches Gesetz – закон iдеальних газiв, згiдно з яким добуток тиску на об єм незмiнної маси такого газу при сталiй температурi є величина стала: (pV) т = const. У певних межах… … Гірничий енциклопедичний словник

-

Бойля-Мариотта закон — Уравнение состояния Статья является частью серии «Термодинамика». Уравнение состояния идеального газа Уравнение Ван дер Ваальса Уравнение Дитеричи Разделы термодинамики Начала термодинамики Уравнен … Википедия

-

Бойля-Мариотта закон — Бойля Мариотта закон: произведение объёма данной массы идеального газа на его давление постоянно при постоянной температуре; установлен независимо Р. Бойлем (1662) и Э. Мариоттом (1676). * * * БОЙЛЯ МАРИОТТА ЗАКОН БОЙЛЯ МАРИОТТА ЗАКОН, один из… … Энциклопедический словарь

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An animation showing the relationship between pressure and volume when mass and temperature are held constant

Boyle’s law, also referred to as the Boyle–Mariotte law, or Mariotte’s law (especially in France), is an experimental gas law that describes the relationship between pressure and volume of a confined gas. Boyle’s law has been stated as:

The absolute pressure exerted by a given mass of an ideal gas is inversely proportional to the volume it occupies if the temperature and amount of gas remain unchanged within a closed system.[1][2]

Mathematically, Boyle’s law can be stated as:

|

Pressure is inversely proportional to the volume |

or

| PV = k | Pressure multiplied by volume equals some constant k |

where P is the pressure of the gas, V is the volume of the gas, and k is a constant.

Boyle’s Law states that when the temperature of a given mass of confined gas is constant, the product of its pressure and volume is also constant. When comparing the same substance under two different sets of conditions, the law can be expressed as:

showing that as volume increases, the pressure of a gas decreases proportionally, and vice versa. Boyle’s Law is named after Robert Boyle, who published the original law in 1662.[3]

History[edit]

The relationship between pressure and volume was first noted by Richard Towneley and Henry Power in the 17th century.[4][5] Robert Boyle confirmed their discovery through experiments and published the results.[6] According to Robert Gunther and other authorities, it was Boyle’s assistant, Robert Hooke, who built the experimental apparatus. Boyle’s law is based on experiments with air, which he considered to be a fluid of particles at rest in between small invisible springs. Boyle may have begun experimenting with gases due to an interest in air as an essential element of life;[7] for example, he published works on the growth of plants without air.[8] Boyle used a closed J-shaped tube and after pouring mercury from one side he forced the air on the other side to contract under the pressure of mercury. After repeating the experiment several times and using different amounts of mercury he found that under controlled conditions, the pressure of a gas is inversely proportional to the volume occupied by it.[9]

The French physicist Edme Mariotte (1620–1684) discovered the same law independently of Boyle in 1679,[10] after Boyle had published it in 1662.[9] Mariotte did, however, discover that air volume changes with temperature.[11] Thus this law is sometimes referred to as Mariotte’s law or the Boyle–Mariotte law. Later, in 1687 in the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Newton showed mathematically that in an elastic fluid consisting of particles at rest, between which are repulsive forces inversely proportional to their distance, the density would be directly proportional to the pressure,[12] but this mathematical treatise is not the physical explanation for the observed relationship. Instead of a static theory, a kinetic theory is needed, which was provided two centuries later by Maxwell and Boltzmann.

This law was the first physical law to be expressed in the form of an equation describing the dependence of two variable quantities.[9]

Definition[edit]

Boyle’s law demonstrations

The law itself can be stated as follows:

For a fixed mass of an ideal gas kept at a fixed temperature, pressure and volume are inversely proportional.[2]

Or Boyle’s law is a gas law, stating that the pressure and volume of a gas have an inverse relationship. If volume increases, then pressure decreases and vice versa, when the temperature is held constant.

Therefore, when the volume is halved, the pressure is doubled; and if the volume is doubled, the pressure is halved.

Relation with kinetic theory and ideal gases[edit]

Boyle’s law states that at constant temperature the volume of a given mass of a dry gas is inversely proportional to its pressure.

Most gases behave like ideal gases at moderate pressures and temperatures. The technology of the 17th century could not produce very high pressures or very low temperatures. Hence, the law was not likely to have deviations at the time of publication. As improvements in technology permitted higher pressures and lower temperatures, deviations from the ideal gas behavior became noticeable, and the relationship between pressure and volume can only be accurately described employing real gas theory.[13] The deviation is expressed as the compressibility factor.

Boyle (and Mariotte) derived the law solely by experiment. The law can also be derived theoretically based on the presumed existence of atoms and molecules and assumptions about motion and perfectly elastic collisions (see kinetic theory of gases). These assumptions were met with enormous resistance in the positivist scientific community at the time, however, as they were seen as purely theoretical constructs for which there was not the slightest observational evidence.

Daniel Bernoulli (in 1737–1738) derived Boyle’s law by applying Newton’s laws of motion at the molecular level. It remained ignored until around 1845, when John Waterston published a paper building the main precepts of kinetic theory; this was rejected by the Royal Society of England. Later works of James Prescott Joule, Rudolf Clausius and in particular Ludwig Boltzmann firmly established the kinetic theory of gases and brought attention to both the theories of Bernoulli and Waterston.[14]

The debate between proponents of energetics and atomism led Boltzmann to write a book in 1898, which endured criticism until his suicide in 1906.[14] Albert Einstein in 1905 showed how kinetic theory applies to the Brownian motion of a fluid-suspended particle, which was confirmed in 1908 by Jean Perrin.[14]

Equation[edit]

The mathematical equation for Boyle’s law is:

where P denotes the pressure of the system, V denotes the volume of the gas, k is a constant value representative of the temperature and volume of the system.

So long as temperature remains constant the same amount of energy given to the system persists throughout its operation and therefore, theoretically, the value of k will remain constant. However, due to the derivation of pressure as perpendicular applied force and the probabilistic likelihood of collisions with other particles through collision theory, the application of force to a surface may not be infinitely constant for such values of V, but will have a limit when differentiating such values over a given time. Forcing the volume V of the fixed quantity of gas to increase, keeping the gas at the initially measured temperature, the pressure P must decrease proportionally. Conversely, reducing the volume of the gas increases the pressure. Boyle’s law is used to predict the result of introducing a change, in volume and pressure only, to the initial state of a fixed quantity of gas.

The initial and final volumes and pressures of the fixed amount of gas, where the initial and final temperatures are the same (heating or cooling will be required to meet this condition), are related by the equation:

Here P1 and V1 represent the original pressure and volume, respectively, and P2 and V2 represent the second pressure and volume.

Boyle’s law, Charles’s law, and Gay-Lussac’s law form the combined gas law. The three gas laws in combination with Avogadro’s law can be generalized by the ideal gas law.

Human breathing system[edit]

Boyle’s law is often used as part of an explanation on how the breathing system works in the human body. This commonly involves explaining how the lung volume may be increased or decreased and thereby cause a relatively lower or higher air pressure within them (in keeping with Boyle’s law). This forms a pressure difference between the air inside the lungs and the environmental air pressure, which in turn precipitates either inhalation or exhalation as air moves from high to low pressure.[15]

See also[edit]

Related phenomena:

- Water thief

- Industrial Revolution

- Steam engine

Other gas laws:

- Dalton’s law – Gas law describing pressure contributions of component gases in a mixture

- Charles’s law – Relationship between volume and temperature of a gas at constant pressure

Citations[edit]

- ^ Levine, Ira. N (1978). «Physical Chemistry» University of Brooklyn: McGraw-Hill

- ^ a b Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p. 12 gives the original definition.

- ^ In 1662, he published a second edition of the 1660 book New Experiments Physico-Mechanical, Touching the Spring of the Air, and its Effects with an addendum Whereunto is Added a Defence of the Authors Explication of the Experiments, Against the Obiections of Franciscus Linus and Thomas Hobbes; see J Appl Physiol 98: 31–39, 2005. (Jap.physiology.org Online.)

- ^ See:

- Henry Power, Experimental Philosophy, in Three Books (London: Printed by T. Roycroft for John Martin and James Allestry, 1663), pp. 126–130. Available online at Early English Books Online. On page 130, Power presents (not very clearly) the relation between the pressure and the volume of a given quantity of air: «That the measure of the Mercurial Standard, and Mercurial Complement, are measured onely by their perpendicular heights, over the Surface of the restagnant Quicksilver in the Vessel: But Ayr, the Ayr’s Dilatation, and Ayr Dilated, by the Spaces they fill. So that here is now four Proportionals, and by any three given, you may strike out the fourth, by Conversion, Transposition, and Division of them. So that by these Analogies you may prognosticate the effects, which follow in all Mercurial Experiments, and predemonstrate them, by calculation, before the senses give an Experimental [eviction] thereof.» In other words, if one knows the volume V1 («Ayr») of a given quantity of air at the pressure p1 («Mercurial standard», i.e., atmospheric pressure at a low altitude), then one can predict the volume V2 («Ayr dilated») of the same quantity of air at the pressure p2 («Mercurial complement», i.e., atmospheric pressure at a higher altitude) by means of a proportion (because p1 V1 = p2 V2).

- Charles Webster (1965). «The discovery of Boyle’s law, and the concept of the elasticity of air in seventeenth century», Archive for the History of Exact Sciences, 2 (6): 441–502; see especially pp. 473–477.

- Charles Webster (1963). «Richard Towneley and Boyle’s Law», Nature, 197 (4864): 226–228.

- Robert Boyle acknowledged his debts to Towneley and Power in: R. Boyle, A Defence of the Doctrine Touching the Spring and Weight of the Air (London, England: Thomas Robinson, 1662). Available online at La Biblioteca Virtual de Patrimonio Bibliográfico. On pages 50, 55–56, and 64, Boyle cites experiments by Towneley and Power showing that air expands as the ambient pressure decreases. On p. 63, Boyle acknowledges Towneley’s help in interpreting Boyle’s data from experiments relating the pressure to the volume of a quantity of air. (Also, on p. 64, Boyle acknowledges that Lord Brouncker had also investigated the same subject.)

- ^ Gerald James Holton (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure: From Copernicus to Einstein and Beyond. Rutgers University Press. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-0-8135-2908-0.

- ^ R. Boyle, A Defence of the Doctrine Touching the Spring and Weight of the Air (London: Thomas Robinson, 1662). Available online at Spain’s La Biblioteca Virtual de Patrimonio Bibliográfico. Boyle presents his law in «Chap. V. Two new experiments touching the measure of the force of the spring of air compress’d and dilated», pp. 57–68. On p. 59, Boyle concludes that «the same air being brought to a degree of density about twice as that it had before, obtains a spring twice as strong as formerly». That is, doubling the density of a quantity of air doubles its pressure. Since air’s density is proportional to its pressure, then for a fixed quantity of air, the product of its pressure and its volume is constant. On page 60, he presents his data on the compression of air: «A Table of the Condensation of the Air.» The legend (p. 60) accompanying the table states: «E. What the pressure should be according to the Hypothesis, that supposes the pressures and expansions to be in reciprocal relation.» On p. 64, Boyle presents his data on the expansion of air: «A Table of the Rarefaction of the Air.»

- ^ The Boyle Papers BP 9, fol. 75v–76r. Archived 2009-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Boyle Papers, BP 10, fol. 138v–139r. Archived 2009-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Scientists and Inventors of the Renaissance. Britannica Educational Publishing. 2012. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-1615308842.

- ^ See:

- Mariotte, Essais de Physique, ou mémoires pour servir à la science des choses naturelles (Paris, France: E. Michallet, 1679); «Second essai. De la nature de l’air».

- Mariotte, Edmé, Oeuvres de Mr. Mariotte, de l’Académie royale des sciences, vol. 1 (Leiden, Netherlands: P. Vander Aa, 1717); see especially pp. 151–153.

- Mariotte’s essay «De la nature de l’air» was reviewed by the French Royal Academy of Sciences in 1679. See: Anon. (1733), «Sur la nature de l’air», Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, 1: 270–278.

- Mariotte’s essay «De la nature de l’air» was also reviewed in the Journal des Sçavans (later: Journal des Savants) on 20 November 1679. See: Anon. (20 November 1679), «Essais de physique», Journal des Sçavans, pp. 265–269.

- ^ Ley, Willy (June 1966). «The Re-Designed Solar System». For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–106.

- ^ Principia, Sec. V, prop. XXI, Theorem XVI

- ^ Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p. 11 notes that deviations occur with high pressures and temperatures.

- ^ a b c Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p. 400 – Historical background of Boyle’s law relation to Kinetic Theory

- ^ Gerald J. Tortora, Bryan Dickinson, ‘Pulmonary Ventilation’ in Principles of Anatomy and Physiology 11th edition, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006, pp. 863–867

External links[edit]

Media related to Boyle’s Law at Wikimedia Commons

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An animation showing the relationship between pressure and volume when mass and temperature are held constant

Boyle’s law, also referred to as the Boyle–Mariotte law, or Mariotte’s law (especially in France), is an experimental gas law that describes the relationship between pressure and volume of a confined gas. Boyle’s law has been stated as:

The absolute pressure exerted by a given mass of an ideal gas is inversely proportional to the volume it occupies if the temperature and amount of gas remain unchanged within a closed system.[1][2]

Mathematically, Boyle’s law can be stated as:

|

Pressure is inversely proportional to the volume |

or

| PV = k | Pressure multiplied by volume equals some constant k |

where P is the pressure of the gas, V is the volume of the gas, and k is a constant.

Boyle’s Law states that when the temperature of a given mass of confined gas is constant, the product of its pressure and volume is also constant. When comparing the same substance under two different sets of conditions, the law can be expressed as:

showing that as volume increases, the pressure of a gas decreases proportionally, and vice versa. Boyle’s Law is named after Robert Boyle, who published the original law in 1662.[3]

History[edit]

The relationship between pressure and volume was first noted by Richard Towneley and Henry Power in the 17th century.[4][5] Robert Boyle confirmed their discovery through experiments and published the results.[6] According to Robert Gunther and other authorities, it was Boyle’s assistant, Robert Hooke, who built the experimental apparatus. Boyle’s law is based on experiments with air, which he considered to be a fluid of particles at rest in between small invisible springs. Boyle may have begun experimenting with gases due to an interest in air as an essential element of life;[7] for example, he published works on the growth of plants without air.[8] Boyle used a closed J-shaped tube and after pouring mercury from one side he forced the air on the other side to contract under the pressure of mercury. After repeating the experiment several times and using different amounts of mercury he found that under controlled conditions, the pressure of a gas is inversely proportional to the volume occupied by it.[9]

The French physicist Edme Mariotte (1620–1684) discovered the same law independently of Boyle in 1679,[10] after Boyle had published it in 1662.[9] Mariotte did, however, discover that air volume changes with temperature.[11] Thus this law is sometimes referred to as Mariotte’s law or the Boyle–Mariotte law. Later, in 1687 in the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Newton showed mathematically that in an elastic fluid consisting of particles at rest, between which are repulsive forces inversely proportional to their distance, the density would be directly proportional to the pressure,[12] but this mathematical treatise is not the physical explanation for the observed relationship. Instead of a static theory, a kinetic theory is needed, which was provided two centuries later by Maxwell and Boltzmann.

This law was the first physical law to be expressed in the form of an equation describing the dependence of two variable quantities.[9]

Definition[edit]

Boyle’s law demonstrations

The law itself can be stated as follows:

For a fixed mass of an ideal gas kept at a fixed temperature, pressure and volume are inversely proportional.[2]

Or Boyle’s law is a gas law, stating that the pressure and volume of a gas have an inverse relationship. If volume increases, then pressure decreases and vice versa, when the temperature is held constant.

Therefore, when the volume is halved, the pressure is doubled; and if the volume is doubled, the pressure is halved.

Relation with kinetic theory and ideal gases[edit]

Boyle’s law states that at constant temperature the volume of a given mass of a dry gas is inversely proportional to its pressure.

Most gases behave like ideal gases at moderate pressures and temperatures. The technology of the 17th century could not produce very high pressures or very low temperatures. Hence, the law was not likely to have deviations at the time of publication. As improvements in technology permitted higher pressures and lower temperatures, deviations from the ideal gas behavior became noticeable, and the relationship between pressure and volume can only be accurately described employing real gas theory.[13] The deviation is expressed as the compressibility factor.

Boyle (and Mariotte) derived the law solely by experiment. The law can also be derived theoretically based on the presumed existence of atoms and molecules and assumptions about motion and perfectly elastic collisions (see kinetic theory of gases). These assumptions were met with enormous resistance in the positivist scientific community at the time, however, as they were seen as purely theoretical constructs for which there was not the slightest observational evidence.

Daniel Bernoulli (in 1737–1738) derived Boyle’s law by applying Newton’s laws of motion at the molecular level. It remained ignored until around 1845, when John Waterston published a paper building the main precepts of kinetic theory; this was rejected by the Royal Society of England. Later works of James Prescott Joule, Rudolf Clausius and in particular Ludwig Boltzmann firmly established the kinetic theory of gases and brought attention to both the theories of Bernoulli and Waterston.[14]

The debate between proponents of energetics and atomism led Boltzmann to write a book in 1898, which endured criticism until his suicide in 1906.[14] Albert Einstein in 1905 showed how kinetic theory applies to the Brownian motion of a fluid-suspended particle, which was confirmed in 1908 by Jean Perrin.[14]

Equation[edit]

The mathematical equation for Boyle’s law is:

where P denotes the pressure of the system, V denotes the volume of the gas, k is a constant value representative of the temperature and volume of the system.

So long as temperature remains constant the same amount of energy given to the system persists throughout its operation and therefore, theoretically, the value of k will remain constant. However, due to the derivation of pressure as perpendicular applied force and the probabilistic likelihood of collisions with other particles through collision theory, the application of force to a surface may not be infinitely constant for such values of V, but will have a limit when differentiating such values over a given time. Forcing the volume V of the fixed quantity of gas to increase, keeping the gas at the initially measured temperature, the pressure P must decrease proportionally. Conversely, reducing the volume of the gas increases the pressure. Boyle’s law is used to predict the result of introducing a change, in volume and pressure only, to the initial state of a fixed quantity of gas.

The initial and final volumes and pressures of the fixed amount of gas, where the initial and final temperatures are the same (heating or cooling will be required to meet this condition), are related by the equation:

Here P1 and V1 represent the original pressure and volume, respectively, and P2 and V2 represent the second pressure and volume.

Boyle’s law, Charles’s law, and Gay-Lussac’s law form the combined gas law. The three gas laws in combination with Avogadro’s law can be generalized by the ideal gas law.

Human breathing system[edit]

Boyle’s law is often used as part of an explanation on how the breathing system works in the human body. This commonly involves explaining how the lung volume may be increased or decreased and thereby cause a relatively lower or higher air pressure within them (in keeping with Boyle’s law). This forms a pressure difference between the air inside the lungs and the environmental air pressure, which in turn precipitates either inhalation or exhalation as air moves from high to low pressure.[15]

See also[edit]

Related phenomena:

- Water thief

- Industrial Revolution

- Steam engine

Other gas laws:

- Dalton’s law – Gas law describing pressure contributions of component gases in a mixture

- Charles’s law – Relationship between volume and temperature of a gas at constant pressure

Citations[edit]

- ^ Levine, Ira. N (1978). «Physical Chemistry» University of Brooklyn: McGraw-Hill

- ^ a b Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p. 12 gives the original definition.

- ^ In 1662, he published a second edition of the 1660 book New Experiments Physico-Mechanical, Touching the Spring of the Air, and its Effects with an addendum Whereunto is Added a Defence of the Authors Explication of the Experiments, Against the Obiections of Franciscus Linus and Thomas Hobbes; see J Appl Physiol 98: 31–39, 2005. (Jap.physiology.org Online.)

- ^ See:

- Henry Power, Experimental Philosophy, in Three Books (London: Printed by T. Roycroft for John Martin and James Allestry, 1663), pp. 126–130. Available online at Early English Books Online. On page 130, Power presents (not very clearly) the relation between the pressure and the volume of a given quantity of air: «That the measure of the Mercurial Standard, and Mercurial Complement, are measured onely by their perpendicular heights, over the Surface of the restagnant Quicksilver in the Vessel: But Ayr, the Ayr’s Dilatation, and Ayr Dilated, by the Spaces they fill. So that here is now four Proportionals, and by any three given, you may strike out the fourth, by Conversion, Transposition, and Division of them. So that by these Analogies you may prognosticate the effects, which follow in all Mercurial Experiments, and predemonstrate them, by calculation, before the senses give an Experimental [eviction] thereof.» In other words, if one knows the volume V1 («Ayr») of a given quantity of air at the pressure p1 («Mercurial standard», i.e., atmospheric pressure at a low altitude), then one can predict the volume V2 («Ayr dilated») of the same quantity of air at the pressure p2 («Mercurial complement», i.e., atmospheric pressure at a higher altitude) by means of a proportion (because p1 V1 = p2 V2).

- Charles Webster (1965). «The discovery of Boyle’s law, and the concept of the elasticity of air in seventeenth century», Archive for the History of Exact Sciences, 2 (6): 441–502; see especially pp. 473–477.

- Charles Webster (1963). «Richard Towneley and Boyle’s Law», Nature, 197 (4864): 226–228.

- Robert Boyle acknowledged his debts to Towneley and Power in: R. Boyle, A Defence of the Doctrine Touching the Spring and Weight of the Air (London, England: Thomas Robinson, 1662). Available online at La Biblioteca Virtual de Patrimonio Bibliográfico. On pages 50, 55–56, and 64, Boyle cites experiments by Towneley and Power showing that air expands as the ambient pressure decreases. On p. 63, Boyle acknowledges Towneley’s help in interpreting Boyle’s data from experiments relating the pressure to the volume of a quantity of air. (Also, on p. 64, Boyle acknowledges that Lord Brouncker had also investigated the same subject.)

- ^ Gerald James Holton (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure: From Copernicus to Einstein and Beyond. Rutgers University Press. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-0-8135-2908-0.

- ^ R. Boyle, A Defence of the Doctrine Touching the Spring and Weight of the Air (London: Thomas Robinson, 1662). Available online at Spain’s La Biblioteca Virtual de Patrimonio Bibliográfico. Boyle presents his law in «Chap. V. Two new experiments touching the measure of the force of the spring of air compress’d and dilated», pp. 57–68. On p. 59, Boyle concludes that «the same air being brought to a degree of density about twice as that it had before, obtains a spring twice as strong as formerly». That is, doubling the density of a quantity of air doubles its pressure. Since air’s density is proportional to its pressure, then for a fixed quantity of air, the product of its pressure and its volume is constant. On page 60, he presents his data on the compression of air: «A Table of the Condensation of the Air.» The legend (p. 60) accompanying the table states: «E. What the pressure should be according to the Hypothesis, that supposes the pressures and expansions to be in reciprocal relation.» On p. 64, Boyle presents his data on the expansion of air: «A Table of the Rarefaction of the Air.»

- ^ The Boyle Papers BP 9, fol. 75v–76r. Archived 2009-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Boyle Papers, BP 10, fol. 138v–139r. Archived 2009-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Scientists and Inventors of the Renaissance. Britannica Educational Publishing. 2012. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-1615308842.

- ^ See:

- Mariotte, Essais de Physique, ou mémoires pour servir à la science des choses naturelles (Paris, France: E. Michallet, 1679); «Second essai. De la nature de l’air».

- Mariotte, Edmé, Oeuvres de Mr. Mariotte, de l’Académie royale des sciences, vol. 1 (Leiden, Netherlands: P. Vander Aa, 1717); see especially pp. 151–153.

- Mariotte’s essay «De la nature de l’air» was reviewed by the French Royal Academy of Sciences in 1679. See: Anon. (1733), «Sur la nature de l’air», Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, 1: 270–278.

- Mariotte’s essay «De la nature de l’air» was also reviewed in the Journal des Sçavans (later: Journal des Savants) on 20 November 1679. See: Anon. (20 November 1679), «Essais de physique», Journal des Sçavans, pp. 265–269.

- ^ Ley, Willy (June 1966). «The Re-Designed Solar System». For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 94–106.

- ^ Principia, Sec. V, prop. XXI, Theorem XVI

- ^ Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p. 11 notes that deviations occur with high pressures and temperatures.

- ^ a b c Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p. 400 – Historical background of Boyle’s law relation to Kinetic Theory

- ^ Gerald J. Tortora, Bryan Dickinson, ‘Pulmonary Ventilation’ in Principles of Anatomy and Physiology 11th edition, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006, pp. 863–867

External links[edit]

Media related to Boyle’s Law at Wikimedia Commons

Орфографический словарь русского языка (онлайн)

Как пишется слово «Бойль-Мариоттовский закон» ?

Правописание слова «Бойль-Мариоттовский закон»

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

Бо́йль-Марио́ттовский зако́н

Рядом по алфавиту:

бой-ба́ба , -ы

бой-де́вка , -и, р. мн. -вок

бо́йга , -и

бо́йи , бо́йев (племенная группа, ист.)

бо́йкий , кр. ф. бо́ек, бойка́, бо́йко

бо́йкость , -и

бойко́т , -а

бойкоти́рование , -я

бойкоти́рованный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана

бойкоти́ровать(ся) , -рую(сь), -рует(ся)

бойкоти́ст , -а

бо́йлер , -а

бо́йлерная , -ой

бо́йлерный

Бойль , -я: зако́н Бо́йля – Марио́тта, то́чки Бо́йля, крива́я Бо́йля

Бо́йль-Марио́ттовский зако́н

бойни́ца , -ы, тв. -ей

бойни́чный

бо́йня , -и, р. мн. бо́ен

бойска́ут , -а

бойскаути́зм , -а

бойска́утский

бойфре́нд , -а

бойфре́ндовский

бойцо́вский

бойцо́вый

бо́йче , и бойче́е, сравн. ст.

бок , -а, предл. в (на) боку́, мн. бока́, -о́в

бока́ж , -а, тв. -ем

бока́л , -а

бокалови́дный , кр. ф. -ден, -дна

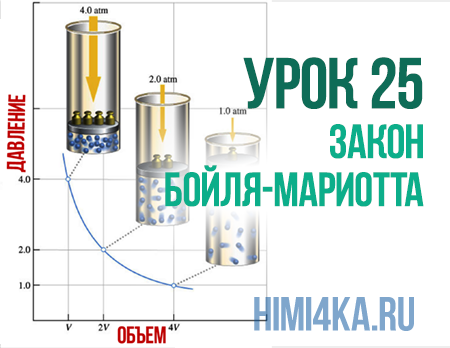

В уроке 25 «Закон Бойля-Мариотта» из курса «Химия для чайников» рассмотрим закон, связывающий давление и объем газа, а также графики зависимости давления от объема и объема от давления. Напомню, что в прошлом уроке «Давление газа» мы рассмотрели устройство и принцип действия ртутного барометра, а также дали определение давлению и рассмотрели его единицы измерения.

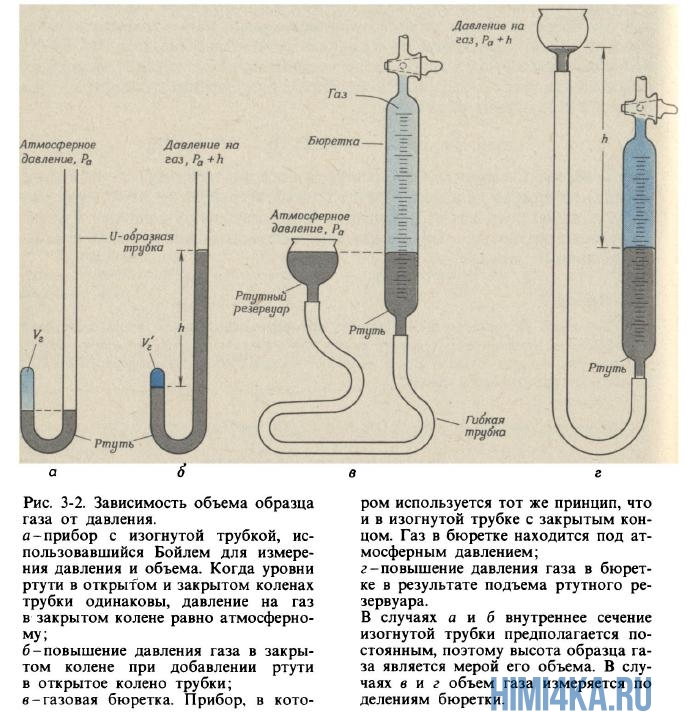

Роберт Бойль (1627-1691), которому мы обязаны первым практически правильным определением химического элемента (узнаем в гл. 6), интересовался также явлениями, происходящими в сосудах с разреженным воздухом. Изобретая вакуумные насосы для выкачивания воздуха из закрытых сосудов, он обратил внимание на свойство, знакомое каждому, кому случалось накачивать камеру футбольного мяча или осторожно сжимать воздушный шарик: чем сильнее сжимают воздух в закрытом сосуде, тем сильнее он сопротивляется сжатию. Бойль называл это свойство «пружинистостью» воздуха и измерял его при помощи простого устройства, показанного на рис. 3.2, а и б.

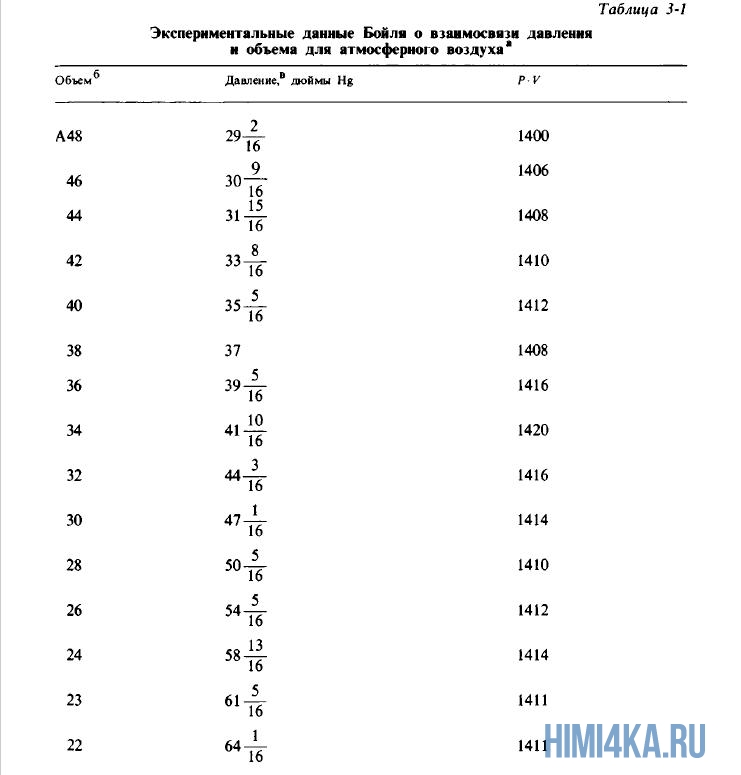

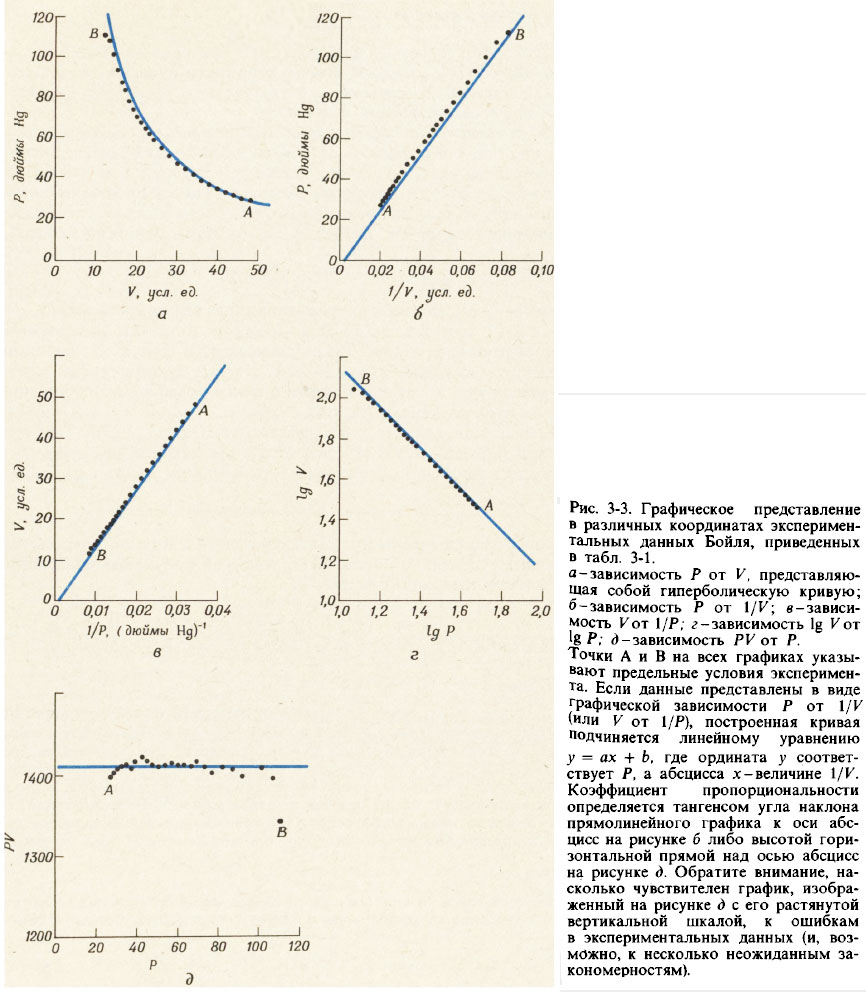

Бойль запирал ртутью немного воздуха в закрытом конце изогнутой трубки (рис. 3-2, а) а затем сжимал этот воздух, понемногу добавляя ртуть в открытый конец трубки (рис. 3-2, б). Давление, испытываемое воздухом в закрытой части трубки, равно сумме атмосферного давления и давления столбика ртути высотой h (h — высота, на которую уровень ртути в открытом конце трубки превышает уровень ртути в закрытом конце). Полученные Бойлем данные измерения давления и объема приведены в табл. 3-1. Хотя Бойль не предпринимал специальных мер для поддержания постоянной температуры газа, по-видимому, в его опытах она менялась лишь незначительно. Тем не менее Бойль заметил, что тепло от пламени свечи вызывало значительные изменения свойств воздуха.

Анализ данных о давлении и объеме воздуха при его сжатии

Таблица 3-1, которая содержит экспериментальные данные Бойля о взаимосвязи давления и объема для атмосферного воздуха, расположена под спойлером.

После того как исследователь получает данные, подобные приведенным в табл. 3-1, он пытается найти математическое уравнение, связывающее между собой две зависящие друг от друга величины, которые он измерял. Один из способов получения такого уравнения заключается в графическом построении зависимости различных степеней одной величины от другой в надежде получить прямолинейный график. Общее уравнение прямой линии имеет вид:

- y = ах + b (3-2)

где х и у — связанные между собой переменные, а a и b — постоянные числа. Если b равно нулю, прямая линия проходит через начало координат.

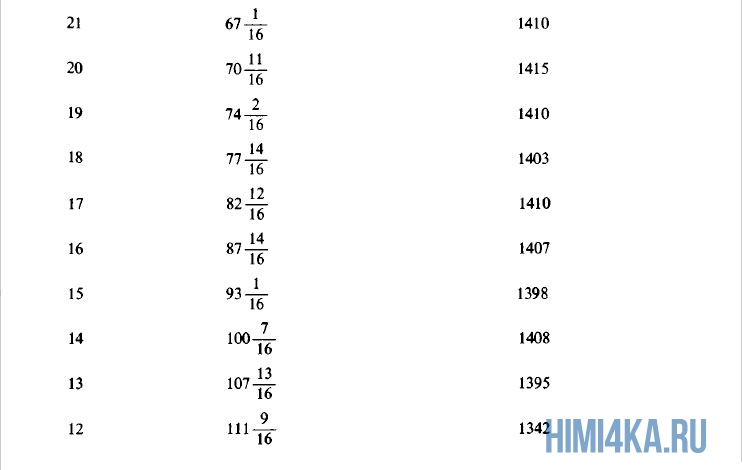

На рис. 3-3 показаны различные способы графического представления данных для давления Р и объема V, приведенных в табл. 3-1. Графики зависимости Р от 1/К и зависимости V от 1/Р представляют собой прямые линии, проходящие через начало координат. График зависимости логарифма Р от логарифма V также является прямой линией с отрицательным наклоном, тангенс угла которого равен — 1. Все эти три графика приводят к эквивалентным уравнениям:

- P = a / V (3-3а)

- V = a / P (3-3б)

и

- lg V = lg а — lg Р (3-3в)

Каждое из этих уравнений представляет собой один из вариантов закона Бойля-Мариотта, который обычно формулируется так: для заданного числа молей газа его давление пропорционально объему, при условии что температура газа остается постоянной.

Кстати, наверняка вам стало интересно, почему закон Бойля-Мариотта назван двойным именем. Это произошло так, потому что этот закон независимо от Роберта Бойля, который открыл его в 1662 году, был переоткрыт Эдмом Мариоттом в 1676 году. Вот так вот.

Когда взаимосвязь между двумя измеряемыми величинами проста до такой степени, как в данном случае, ее можно установить и численным способом. Если каждое значение давления Р умножить на соответствующее значение объема V, нетрудно убедиться, что все произведения для заданного образца газа при постоянной температуре оказываются приблизительно одинаковыми (см. табл. 3-1). Таким образом, можно записать, что

- P·V = а ≈ 1410 (3-3г)

Уравнение (З-Зг) описывает гиперболическую зависимость между величинами Р и V (см. рис. 3-3,а). Для проверки того, что построенный по экспериментальным данным график зависимости Р от V действительно соответствует гиперболе, построим еще дополнительный график зависимости произведения P·V от Р и убедимся, что он представляет собой горизонтальную прямую линию (см. рис. 3-3,д).

Бойль установил, что для заданного количества любого газа при постоянной температуре взаимосвязь между давлением Р и объемом V вполне удовлетворительно описывается соотношением

- P·V = const (при постоянных Т и n) (3-4)

Формула из закона Бойля-Мариотта

Для сопоставления объемов и давлений одного и того же образца газа при различных условиях (но постоянной температуре) удобно представить закон Бойля-Мариотта в следующей формуле:

- P1·V1 = Р2·V2 (3-5)

где индексы 1 и 2 соответствуют двум различным условиям.

Пример 4. Доставляемые на плато Колорадо пластмассовые мешочки с пищевыми продуктами (см. пример 3) часто лопаются, потому что воздух, находящийся в них, при подъеме от уровня моря на высоту 2500 м, в условиях пониженного атмосферного давления, расширяется. Если предположить, что внутри мешочка при атмосферном давлении, соответствующем уровню моря, заключено 100 см3 воздуха, какой объем должен занимать этот воздух при той же температуре на плато Колорадо? (Допустим, что для доставки продуктов используются сморщенные мешочки, не ограничивающие расширение воздуха; недостающие данные следует взять из примера 3.)

Решение

Воспользуемся законом Бойля в форме уравнения (3-5), где индекс 1 будем относить к условиям на уровне моря, а индекс 2 — к условиям на высоте 2500 м над уровнем моря. Тогда Р1 = 1,000 атм, V1 = 100 см3, Р2 = 0,750 атм, а V2 следует вычислить. Итак,

- P1·V1 = Р2·V2

- 1,000 атм · 100 см3 = 0,750 атм · V2

откуда

- V2 = 133 см3

Надеюсь, что после изучения урока 25 «Закон Бойля-Мариотта» вы запомните зависимость объема и давления газа друг от друга.. Если у вас возникли вопросы, пишите их в комментарии. Если вопросов нет, то переходите к следующему уроку.