|

Czech Republic Česká republika (Czech) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Motto: Pravda vítězí (Czech) «Truth prevails» |

|

| Anthem: Kde domov můj (Czech) «Where my home is» |

|

![Location of the Czech Republic (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark gray) – in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/EU-Czech_Republic.svg/250px-EU-Czech_Republic.svg.png)

Location of the Czech Republic (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark gray) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Prague 50°05′N 14°28′E / 50.083°N 14.467°E |

| Official language | Czech[1] |

| Ethnic groups

(2021)[2] |

|

| Religion

(2021)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Czech |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

|

• President |

Miloš Zeman |

|

• Prime Minister |

Petr Fiala |

| Legislature | Parliament |

|

• Upper house |

Senate |

|

• Lower house |

Chamber of Deputies |

| Establishment history | |

|

• Duchy of Bohemia |

c. 870 |

|

• Kingdom of Bohemia |

1198 |

|

• Czechoslovakia |

28 October 1918 |

|

• Czech Republic |

1 January 1993 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

78,871 km2 (30,452 sq mi) (115th) |

|

• Water (%) |

2.14 (as of 2021)[4] |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

|

|

• 2021 census |

|

|

• Density |

133/km2 (344.5/sq mi) (91st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 32nd |

| Currency | Czech koruna (CZK) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | d. m. yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +420[a] |

| ISO 3166 code | CZ |

| Internet TLD | .cz[b] |

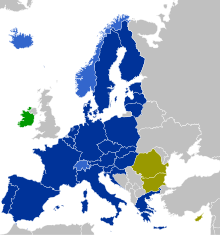

The Czech Republic,[c][12] also known as Czechia,[d][13] is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia,[14] it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast.[15] The Czech Republic has a hilly landscape that covers an area of 78,871 square kilometers (30,452 sq mi) with a mostly temperate continental and oceanic climate. The capital and largest city is Prague; other major cities and urban areas include Brno, Ostrava, Plzeň and Liberec.

The Duchy of Bohemia was founded in the late 9th century under Great Moravia. It was formally recognized as an Imperial State of the Holy Roman Empire in 1002 and became a kingdom in 1198.[16][17] Following the Battle of Mohács in 1526, the whole Crown of Bohemia was gradually integrated into the Habsburg monarchy. The Protestant Bohemian Revolt led to the Thirty Years’ War. After the Battle of White Mountain, the Habsburgs consolidated their rule. With the dissolution of the Holy Empire in 1806, the Crown lands became part of the Austrian Empire.

In the 19th century, the Czech lands became more industrialized, and in 1918 most of it became part of the First Czechoslovak Republic following the collapse of Austria-Hungary after World War I.[18] Czechoslovakia was the only country in Central and Eastern Europe to remain a parliamentary democracy during the entirety of the interwar period.[19] After the Munich Agreement in 1938, Nazi Germany systematically took control over the Czech lands. Czechoslovakia was restored in 1945 and three years later became an Eastern Bloc communist state following a coup d’état in 1948. Attempts to liberalize the government and economy were suppressed by a Soviet-led invasion of the country during the Prague Spring in 1968. In November 1989, the Velvet Revolution ended communist rule in the country and restored Democracy. On 31 December 1992, Czechoslovakia was peacefully dissolved, with its constituent states becoming the independent states of the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

The Czech Republic is a unitary parliamentary republic and developed country with an advanced, high-income social market economy. It is a welfare state with a European social model, universal health care and free-tuition university education. It ranks 16th in the UN inequality-adjusted human development, 32nd in the Human Development Index and 24th in the World Bank Human Capital Index. As of 2022, it ranks as the 8th safest and most peaceful country and 25th in democratic governance. The Czech Republic is a member of the United Nations, NATO, the European Union, the OECD, the OSCE, and the Council of Europe.

Name

The traditional English name «Bohemia» derives from Latin: Boiohaemum, which means «home of the Boii» (a Gallic tribe). The current English name comes from the Polish ethnonym associated with the area, which ultimately comes from the Czech word Čech.[20][21][22] The name comes from the Slavic tribe (Czech: Češi, Čechové) and, according to legend, their leader Čech, who brought them to Bohemia, to settle on Říp Mountain. The etymology of the word Čech can be traced back to the Proto-Slavic root *čel-, meaning «member of the people; kinsman», thus making it cognate to the Czech word člověk (a person).[23]

The country has been traditionally divided into three lands, namely Bohemia (Čechy) in the west, Moravia (Morava) in the east, and Czech Silesia (Slezsko; the smaller, south-eastern part of historical Silesia, most of which is located within modern Poland) in the northeast.[24] Known as the lands of the Bohemian Crown since the 14th century, a number of other names for the country have been used, including Czech/Bohemian lands, Bohemian Crown, Czechia[25] and the lands of the Crown of Saint Wenceslaus. When the country regained its independence after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1918, the new name of Czechoslovakia was coined to reflect the union of the Czech and Slovak nations within one country.[26]

After Czechoslovakia dissolved on the last day of 1992, Česko was adopted as the Czech short name for the new state and the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs recommended Czechia for the English-language equivalent.[27] This form was not widely adopted at the time, leading to the long name Czech Republic being used in English in nearly all circumstances. The Czech government directed use of Czechia as the official English short name in 2016.[28] The short name has been listed by the United Nations[29] and is used by other organizations such as the European Union,[30] NATO,[31] the CIA,[32] and Google Maps.[33]

History

Prehistory

Archaeologists have found evidence of prehistoric human settlements in the area, dating back to the Paleolithic era.

In the classical era, as a result of the 3rd century BC Celtic migrations, Bohemia became associated with the Boii.[35] The Boii founded an oppidum near the site of modern Prague.[36] Later in the 1st century, the Germanic tribes of the Marcomanni and Quadi settled there.[37]

Slavs from the Black Sea–Carpathian region settled in the area (their migration was pushed by an invasion of peoples from Siberia and Eastern Europe into their area:[38] Huns, Avars, Bulgars and Magyars).[39] In the sixth century, the Huns had moved westwards into Bohemia, Moravia, and some of present-day Austria and Germany.[39]

During the 7th century, the Frankish merchant Samo, supporting the Slavs fighting against nearby settled Avars,[40] became the ruler of the first documented Slavic state in Central Europe, Samo’s Empire. The principality of Great Moravia, controlled by Moymir dynasty, arose in the 8th century.[41] It reached its zenith in the 9th (during the reign of Svatopluk I of Moravia), holding off the influence of the Franks. Great Moravia was Christianized, with a role being played by the Byzantine mission of Cyril and Methodius. They codified the Old Church Slavonic language, the first literary and liturgical language of the Slavs, and the Glagolitic alphabet.[42]

Bohemia

The Crown of Bohemia within the Holy Roman Empire (1600). The Czech lands were part of the Empire in 1002–1806, and Prague was the imperial seat in 1346–1437 and 1583–1611.

The Duchy of Bohemia emerged in the late 9th century when it was unified by the Přemyslid dynasty. Bohemia was from 1002 until 1806 an Imperial State of the Holy Roman Empire.[43]

In 1212, Přemysl Ottokar I extracted the Golden Bull of Sicily from the emperor, confirming Ottokar and his descendants’ royal status; the Duchy of Bohemia was raised to a Kingdom.[44] German immigrants settled in the Bohemian periphery in the 13th century.[45] The Mongols in the invasion of Europe carried their raids into Moravia but were defensively defeated at Olomouc.[46]

After a series of dynastic wars, the House of Luxembourg gained the Bohemian throne.[47]

Efforts for a reform of the church in Bohemia started already in the late 14th century. Jan Hus’s followers seceded from some practices of the Roman Church and in the Hussite Wars (1419–1434) defeated five crusades organized against them by Sigismund. During the next two centuries, 90% of the population in Bohemia and Moravia were considered Hussites. The pacifist thinker Petr Chelčický inspired the movement of the Moravian Brethren (by the middle of the 15th century) that completely separated from the Roman Catholic Church.[48]

On 21 December 1421, Jan Žižka, a successful military commander and mercenary, led his group of forces in the Battle of Kutná Hora, resulting in a victory for the Hussites. He is honoured to this day as a national hero.

After 1526 Bohemia came increasingly under Habsburg control as the Habsburgs became first the elected and then in 1627 the hereditary rulers of Bohemia. Between 1583 and 1611 Prague was the official seat of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II and his court.

The Defenestration of Prague and subsequent revolt against the Habsburgs in 1618 marked the start of the Thirty Years’ War. In 1620, the rebellion in Bohemia was crushed at the Battle of White Mountain and the ties between Bohemia and the Habsburgs’ hereditary lands in Austria were strengthened. The leaders of the Bohemian Revolt were executed in 1621. The nobility and the middle class Protestants had to either convert to Catholicism or leave the country.[49]

The following era of 1620 to the late 18th century became known as the «Dark Age». During the Thirty Years’ War, the population of the Czech lands declined by a third through the expulsion of Czech Protestants as well as due to the war, disease and famine.[50] The Habsburgs prohibited all Christian confessions other than Catholicism.[51] The flowering of Baroque culture shows the ambiguity of this historical period.

Ottoman Turks and Tatars invaded Moravia in 1663.[52] In 1679–1680 the Czech lands faced the Great Plague of Vienna and an uprising of serfs.[53]

There were peasant uprisings influenced by famine.[54] Serfdom was abolished between 1781 and 1848. Several battles of the Napoleonic Wars took place on the current territory of the Czech Republic.

The end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 led to degradation of the political status of Bohemia which lost its position of an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire as well as its own political representation in the Imperial Diet.[55] Bohemian lands became part of the Austrian Empire. During the 18th and 19th century the Czech National Revival began its rise, with the purpose to revive Czech language, culture, and national identity. The Revolution of 1848 in Prague, striving for liberal reforms and autonomy of the Bohemian Crown within the Austrian Empire, was suppressed.[56]

It seemed that some concessions would be made also to Bohemia, but in the end, the Emperor Franz Joseph I affected a compromise with Hungary only. The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 and the never realized coronation of Franz Joseph as King of Bohemia led to a disappointment of some Czech politicians.[56] The Bohemian Crown lands became part of the so-called Cisleithania.

The Czech Social Democratic and progressive politicians started the fight for universal suffrage. The first elections under universal male suffrage were held in 1907.[57]

Czechoslovakia

In 1918, during the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy at the end of World War I, the independent republic of Czechoslovakia, which joined the winning Allied powers, was created, with Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in the lead.[59] This new country incorporated the Bohemian Crown.[60]

The First Czechoslovak Republic comprised only 27% of the population of the former Austria-Hungary, but nearly 80% of the industry, which enabled it to compete with Western industrial states.[58] In 1929 compared to 1913, the gross domestic product increased by 52% and industrial production by 41%. In 1938 Czechoslovakia held 10th place in the world industrial production.[61] Czechoslovakia was the only country in Central and Eastern Europe to remain a liberal democracy throughout the entire

interwar period.[62] Although the First Czechoslovak Republic was a unitary state, it provided certain rights to its minorities, the largest being Germans (23.6% in 1921), Hungarians (5.6%) and Ukrainians (3.5%).[63]

Western Czechoslovakia was occupied by Nazi Germany, which placed most of the region into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The Protectorate was proclaimed part of the Third Reich, and the president and prime minister were subordinated to Nazi Germany’s Reichsprotektor. One Nazi concentration camp was located within the Czech territory at Terezín, north of Prague. The vast majority of the Protectorate’s Jews were murdered in Nazi-run concentration camps. The Nazi Generalplan Ost called for the extermination, expulsion, Germanization or enslavement of most or all Czechs for the purpose of providing more living space for the German people.[64] There was Czechoslovak resistance to Nazi occupation as well as reprisals against the Czechoslovaks for their anti-Nazi resistance. The German occupation ended on 9 May 1945, with the arrival of the Soviet and American armies and the Prague uprising.[65] Most of Czechoslovakia’s German-speakers were forcibly expelled from the country, first as a result of local acts of violence and then under the aegis of an «organized transfer» confirmed by the Soviet Union, the United States, and Great Britain at the Potsdam Conference.[66]

In the 1946 elections, the Communist Party gained 38%[67] of the votes and became the largest party in the Czechoslovak parliament, formed a coalition with other parties, and consolidated power. A coup d’état came in 1948 and a single-party government was formed. For the next 41 years, the Czechoslovak Communist state conformed to Eastern Bloc economic and political features.[68] The Prague Spring political liberalization was stopped by the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. Analysts believe that the invasion caused the communist movement to fracture, ultimately leading to the Revolutions of 1989.

Czech Republic

In November 1989, Czechoslovakia again became a liberal democracy through the Velvet Revolution. However, Slovak national aspirations strengthened (Hyphen War) and on 31 December 1992, the country peacefully split into the independent countries of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Both countries went through economic reforms and privatizations, with the intention of creating a market economy. This process was largely successful; in 2006 the Czech Republic was recognized by the World Bank as a «developed country»,[69] and in 2009 the Human Development Index ranked it as a nation of «Very High Human Development».[70]

From 1991, the Czech Republic, originally as part of Czechoslovakia and since 1993 in its own right, has been a member of the Visegrád Group and from 1995, the OECD. The Czech Republic joined NATO on 12 March 1999 and the European Union on 1 May 2004. On 21 December 2007 the Czech Republic joined the Schengen Area.[71]

Until 2017, either the centre-left Czech Social Democratic Party or the centre-right Civic Democratic Party led the governments of the Czech Republic. In October 2017, the populist movement ANO 2011, led by the country’s second-richest man, Andrej Babiš, won the elections with three times more votes than its closest rival, the Civic Democrats.[72] In December 2017, Czech president Miloš Zeman appointed Andrej Babiš as the new prime minister.[73]

In the 2021 elections, ANO 2011 was narrowly defeated and Petr Fiala became the new prime minister.[74] He formed a government coalition of the alliance SPOLU (Civic Democratic Party, KDU-ČSL and TOP 09) and the alliance of Pirates and Mayors. In January 2023, retired general Petr Pavel won the presidential election, becoming new Czech president to succeed Miloš Zeman.[75] Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the country took in half a million Ukrainian refugees, the largest number per capita in the world.[76][77]

Geography

The Czech Republic lies mostly between latitudes 48° and 51° N and longitudes 12° and 19° E.

Bohemia, to the west, consists of a basin drained by the Elbe (Czech: Labe) and the Vltava rivers, surrounded by mostly low mountains, such as the Krkonoše range of the Sudetes. The highest point in the country, Sněžka at 1,603 m (5,259 ft), is located here. Moravia, the eastern part of the country, is also hilly. It is drained mainly by the Morava River, but it also contains the source of the Oder River (Czech: Odra).

Water from the Czech Republic flows to three different seas: the North Sea, Baltic Sea, and Black Sea. The Czech Republic also leases the Moldauhafen, a 30,000-square-meter (7.4-acre) lot in the middle of the Hamburg Docks, which was awarded to Czechoslovakia by Article 363 of the Treaty of Versailles, to allow the landlocked country a place where goods transported down river could be transferred to seagoing ships. The territory reverts to Germany in 2028.

Phytogeographically, the Czech Republic belongs to the Central European province of the Circumboreal Region, within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the territory of the Czech Republic can be subdivided into four ecoregions: the Western European broadleaf forests, Central European mixed forests, Pannonian mixed forests, and Carpathian montane conifer forests.[78]

There are four national parks in the Czech Republic. The oldest is Krkonoše National Park (Biosphere Reserve), and the others are Šumava National Park (Biosphere Reserve), Podyjí National Park, and Bohemian Switzerland.

The three historical lands of the Czech Republic (formerly some countries of the Bohemian Crown) correspond with the river basins of the Elbe and the Vltava basin for Bohemia, the Morava one for Moravia, and the Oder river basin for Czech Silesia (in terms of the Czech territory).

Climate

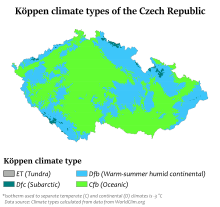

The Czech Republic has a temperate climate, situated in the transition zone between the oceanic and continental climate types, with warm summers and cold, cloudy and snowy winters. The temperature difference between summer and winter is due to the landlocked geographical position.[79]

Temperatures vary depending on the elevation. In general, at higher altitudes, the temperatures decrease and precipitation increases. The wettest area in the Czech Republic is found around Bílý Potok in Jizera Mountains and the driest region is the Louny District to the northwest of Prague. Another factor is the distribution of the mountains.

At the highest peak of Sněžka (1,603 m or 5,259 ft), the average temperature is −0.4 °C (31 °F), whereas in the lowlands of the South Moravian Region, the average temperature is as high as 10 °C (50 °F). The country’s capital, Prague, has a similar average temperature, although this is influenced by urban factors.

The coldest month is usually January, followed by February and December. During these months, there is snow in the mountains and sometimes in the cities and lowlands. During March, April, and May, the temperature usually increases, especially during April, when the temperature and weather tends to vary during the day. Spring is also characterized by higher water levels in the rivers, due to melting snow with occasional flooding.

The warmest month of the year is July, followed by August and June. On average, summer temperatures are about 20–30 °C (36–54 °F) higher than during winter. Summer is also characterized by rain and storms.

Autumn generally begins in September, which is still warm and dry. During October, temperatures usually fall below 15 °C (59 °F) or 10 °C (50 °F) and deciduous trees begin to shed their leaves. By the end of November, temperatures usually range around the freezing point.

The coldest temperature ever measured was in Litvínovice near České Budějovice in 1929, at −42.2 °C (−44.0 °F) and the hottest measured, was at 40.4 °C (104.7 °F) in Dobřichovice in 2012.[80]

Most rain falls during the summer. Sporadic rainfall is throughout the year (in Prague, the average number of days per month experiencing at least 0.1 mm (0.0039 in) of rain varies from 12 in September and October to 16 in November) but concentrated rainfall (days with more than 10 mm (0.39 in) per day) are more frequent in the months of May to August (average around two such days per month).[81] Severe thunderstorms, producing damaging straight-line winds, hail, and occasional tornadoes occur, especially during the summer period.[82][83]

Environment

As of 2020, the Czech Republic ranks as the 21st most environmentally conscious country in the world in Environmental Performance Index.[84] It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 1.71/10, ranking it 160th globally out of 172 countries.[85] The Czech Republic has four National Parks (Šumava National Park, Krkonoše National Park, České Švýcarsko National Park, Podyjí National Park) and 25 Protected Landscape Areas.

Government

The Czech Republic is a pluralist multi-party parliamentary representative democracy. The Parliament (Parlament České republiky) is bicameral, with the Chamber of Deputies (Czech: Poslanecká sněmovna, 200 members) and the Senate (Czech: Senát, 81 members).[86] The members of the Chamber of Deputies are elected for a four-year term by proportional representation, with a 5% election threshold. There are 14 voting districts, identical to the country’s administrative regions. The Chamber of Deputies, the successor to the Czech National Council, has the powers and responsibilities of the now defunct federal parliament of the former Czechoslovakia. The members of the Senate are elected in single-seat constituencies by two-round runoff voting for a six-year term, with one-third elected every even year in the autumn. This arrangement is modeled on the U.S. Senate, but each constituency is roughly the same size and the voting system used is a two-round runoff.

The president is a formal head of state with limited and specific powers, who appoints the prime minister, as well the other members of the cabinet on a proposal by the prime minister. From 1993 until 2012, the President of the Czech Republic was selected by a joint session of the parliament for a five-year term, with no more than two consecutive terms (2x Václav Havel, 2x Václav Klaus). Since 2013 the presidential election is direct.[87] Some commentators have argued that, with the introduction of direct election of the President, the Czech Republic has moved away from the parliamentary system and towards a semi-presidential one.[88] The Government’s exercise of executive power derives from the Constitution. The members of the government are the Prime Minister, Deputy prime ministers and other ministers. The Government is responsible to the Chamber of Deputies.[89] The Prime Minister is the head of government and wields powers such as the right to set the agenda for most foreign and domestic policy and choose government ministers.[90]

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Miloš Zeman | SPOZ | 8 March 2013 |

| President of the Senate | Miloš Vystrčil | ODS | 19 February 2020 |

| President of the Chamber of Deputies | Markéta Pekarová Adamová | TOP 09 | 10 November 2021 |

| Prime Minister | Petr Fiala | ODS | 28 November 2021 |

Law

The Czech Republic is a unitary state,[91] with a civil law system based on the continental type, rooted in Germanic legal culture. The basis of the legal system is the Constitution of the Czech Republic adopted in 1993.[92] The Penal Code is effective from 2010. A new Civil code became effective in 2014. The court system includes district, county, and supreme courts and is divided into civil, criminal, and administrative branches. The Czech judiciary has a triumvirate of supreme courts. The Constitutional Court consists of 15 constitutional judges and oversees violations of the Constitution by either the legislature or by the government.[92] The Supreme Court is formed of 67 judges and is the court of highest appeal for most legal cases heard in the Czech Republic. The Supreme Administrative Court decides on issues of procedural and administrative propriety. It also has jurisdiction over certain political matters, such as the formation and closure of political parties, jurisdictional boundaries between government entities, and the eligibility of persons to stand for public office.[92] The Supreme Court and the Supreme Administrative Court are both based in Brno, as is the Supreme Public Prosecutor’s Office.[92]

Foreign relations

The Czech Republic has ranked as one of the safest or most peaceful countries for the past few decades.[93] It is a member of the United Nations, the European Union, NATO, OECD, Council of Europe and is an observer to the Organization of American States.[94] The embassies of most countries with diplomatic relations with the Czech Republic are located in Prague, while consulates are located across the country.

The Czech passport is restricted by visas. According to the 2018 Henley & Partners Visa Restrictions Index, Czech citizens have visa-free access to 173 countries, which ranks them 7th along with Malta and New Zealand.[95] The World Tourism Organization ranks the Czech passport 24th.[96] The US Visa Waiver Program applies to Czech nationals.

The Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs have primary roles in setting foreign policy, although the President also has influence and represents the country abroad. Membership in the European Union and NATO is central to the Czech Republic’s foreign policy. The Office for Foreign Relations and Information (ÚZSI) serves as the foreign intelligence agency responsible for espionage and foreign policy briefings, as well as protection of Czech Republic’s embassies abroad.

The Czech Republic has ties with Slovakia, Poland and Hungary as a member of the Visegrád Group,[97] as well as with Germany,[98] Israel,[99] the United States[100] and the European Union and its members.

Czech officials have supported dissenters in Belarus, Moldova, Myanmar and Cuba.[101]

Famous Czech diplomats of the past included Count Philip Kinsky of Wchinitz and Tettau, Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg, Edvard Beneš, Jan Masaryk, Jiří Dienstbier and Prince Karel Schwarzenberg.

Military

The Czech armed forces consist of the Czech Land Forces, the Czech Air Force and of specialized support units. The armed forces are managed by the Ministry of Defence. The President of the Czech Republic is Commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In 2004 the army transformed itself into a fully professional organization and compulsory military service was abolished. The country has been a member of NATO since 12 March 1999. Defence spending is approximately 1.28% of the GDP (2021).[102] The armed forces are charged with protecting the Czech Republic and its allies, promoting global security interests, and contributing to NATO.

Currently, as a member of NATO, the Czech military are participating in the Resolute Support and KFOR operations and have soldiers in Afghanistan, Mali, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Egypt, Israel and Somalia. The Czech Air Force also served in the Baltic states and Iceland.[103] The main equipment of the Czech military includes JAS 39 Gripen multi-role fighters, Aero L-159 Alca combat aircraft, Mi-35 attack helicopters, armored vehicles (Pandur II, OT-64, OT-90, BVP-2) and tanks (T-72 and T-72M4CZ).

The most famous Czech, and therefore Czechoslovak, soldiers and military leaders of the past were Jan Žižka, Albrecht von Wallenstein, Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg, Joseph Radetzky von Radetz, Josef Šnejdárek, Heliodor Píka, Ludvík Svoboda, Jan Kubiš, Jozef Gabčík, František Fajtl and Petr Pavel.

Human rights

Human rights in the Czech Republic are guaranteed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms and international treaties on human rights. Nevertheless, there were cases of human rights violations such as discrimination against Roma children,[104] for which the European Commission asked the Czech Republic to provide an explanation,[105] or the illegal sterilization of Roma women,[106] for which the government apologized.[107]

Administrative divisions

Since 2000, the Czech Republic has been divided into thirteen regions (Czech: kraje, singular kraj) and the capital city of Prague. Every region has its own elected regional assembly and a regional governor. In Prague, the assembly and presidential powers are executed by the city council and the mayor.

The older seventy-six districts (okresy, singular okres) including three «statutory cities» (without Prague, which had special status) lost most of their importance in 1999 in an administrative reform; they remain as territorial divisions and seats of various branches of state administration.[108]

The smallest administrative units are obce (municipalities). As of 2021, the Czech Republic is divided into 6,254 municipalities. Cities and towns are also municipalities. The capital city of Prague is a region and municipality at the same time.

Map of the Czech Republic with traditional regions and current administrative regions

Map with court districts

Economy

Real GPD per capita development the Czech Republic 1973 to 2018

The Czech Republic has a developed,[109] high-income[110] export-oriented social market economy based in services, manufacturing and innovation, that maintains a welfare state and the European social model.[111] The Czech Republic participates in the European Single Market as a member of the European Union and is therefore a part of the economy of the European Union, but uses its own currency, the Czech koruna, instead of the euro. It has a per capita GDP rate that is 91% of the EU average[112] and is a member of the OECD. Monetary policy is conducted by the Czech National Bank, whose independence is guaranteed by the Constitution. The Czech Republic ranks 12th in the UN inequality-adjusted human development and 24th in World Bank Human Capital Index. It was described by The Guardian as «one of Europe’s most flourishing economies».[113]

As of 2023, the country’s GDP per capita at purchasing power parity is $51,329[114] and $29,856 at nominal value.[115] According to Allianz A.G., in 2018 the country was an MWC (mean wealth country), ranking 26th in net financial assets.[116] The country experienced a 4.5% GDP growth in 2017.[117] The 2016 unemployment rate was the lowest in the EU at 2.4%,[118] and the 2016 poverty rate was the second lowest of OECD members.[119] Czech Republic ranks 27th in the 2021 Index of Economic Freedom,[120] 30th in the 2022 Global Innovation Index, down from 24th in the 2016,[121]

[122] 29th in the Global Competitiveness Report,[123] and 25th in the Global Enabling Trade Report.[124]

The Czech Republic has a diverse economy that ranks 7th in the 2016 Economic Complexity Index.[125] The industrial sector accounts for 37.5% of the economy, while services account for 60% and agriculture for 2.5%.[126] The largest trading partner for both export and import is Germany and the EU in general. Dividends worth CZK 270 billion were paid to the foreign owners of Czech companies in 2017, which has become a political issue.[127] The country has been a member of the Schengen Area since 1 May 2004, having abolished border controls, completely opening its borders with all of its neighbors on 21 December 2007.[128]

Industry

In 2018 the largest companies by revenue in the Czech Republic were: automobile manufacturer Škoda Auto, utility company ČEZ Group, conglomerate Agrofert, energy trading company EPH, oil processing company Unipetrol, electronics manufacturer Foxconn CZ and steel producer Moravia Steel.[129] Other Czech transportation companies include: Škoda Transportation (tramways, trolleybuses, metro), Tatra (heavy trucks, the second oldest car maker in the world), Avia (medium trucks), Karosa and SOR Libchavy (buses), Aero Vodochody (military aircraft), Let Kunovice (civil aircraft), Zetor (tractors), Jawa Moto (motorcycles) and Čezeta (electric scooters).

Škoda Transportation is the fourth largest tram producer in the world; nearly one third of all trams in the world come from Czech factories.[130] The Czech Republic is also the world’s largest vinyl records manufacturer, with GZ Media producing about 6 million pieces annually in Loděnice.[131] Česká zbrojovka is among the ten largest firearms producers in the world and five who produce automatic weapons.[132]

In the food industry, Czech companies include Agrofert, Kofola and Hamé.

Energy

Production of Czech electricity exceeds consumption by about 10 TWh per year, the excess being exported. Nuclear power presently provides about 30 percent of the total power needs, its share is projected to increase to 40 percent. In 2005, 65.4 percent of electricity was produced by steam and combustion power plants (mostly coal); 30 percent by nuclear plants; and 4.6 percent came from renewable sources, including hydropower. The largest Czech power resource is Temelín Nuclear Power Station, with another nuclear power plant in Dukovany.

The Czech Republic is reducing its dependence on highly polluting low-grade brown coal as a source of energy. Natural gas is procured from Russian Gazprom, roughly three quarters of domestic consumption, and from Norwegian companies, which make up most of the remaining quarter. Russian gas is imported via Ukraine, Norwegian gas is transported through Germany.[133] Gas consumption (approx. 100 TWh in 2003–2005) is almost double electricity consumption. South Moravia has small oil and gas deposits.

Transportation infrastructure

As of 2020, the road network in the Czech Republic is 55,768.3 kilometers (34,652.82 mi) long, out of which 1,276.4 kilometers (793.1 mi) are motorways.[134] The speed limit is 50 km/h within towns, 90 km/h outside of towns and 130 km/h on motorways.[135]

The Czech Republic has one of the densest rail networks in the world. As of 2020, the country has 9,542 kilometers (5,929 mi) of lines. Of that number, 3,236 kilometers (2,011 mi) is electrified, 7,503 kilometers (4,662 mi) are single-line tracks and 2,040 kilometers (1,270 mi) are double and multiple-line tracks.[136] The length of tracks is 15,360 kilometers (9,540 mi), out of which 6,917 kilometers (4,298 mi) is electrified.[137]

České dráhy (the Czech Railways) is the main railway operator in the country, with about 180 million passengers carried yearly. Maximum speed is limited to 160 km/h.

Václav Havel Airport in Prague is the main international airport in the country. In 2019, it handled 17.8 million passengers.[138] In total, the Czech Republic has 91 airports, six of which provide international air services. The public international airports are in Brno, Karlovy Vary, Mnichovo Hradiště, Mošnov (near Ostrava), Pardubice and Prague.[139] The non-public international airports capable of handling airliners are in Kunovice and Vodochody.[140]

Russia, via pipelines through Ukraine and to a lesser extent, Norway, via pipelines through Germany, supply the Czech Republic with liquid and natural gas.[133]

Communications and IT

Founders and owners of the antivirus group Avast

The Czech Republic ranks in the top 10 countries worldwide with the fastest average internet speed.[141] By the beginning of 2008, there were over 800 mostly local WISPs,[142][143] with about 350,000 subscribers in 2007. Plans based on either GPRS, EDGE, UMTS or CDMA2000 are being offered by all three mobile phone operators (T-Mobile, O2, Vodafone) and internet provider U:fon. Government-owned Český Telecom slowed down broadband penetration. At the beginning of 2004, local-loop unbundling began and alternative operators started to offer ADSL and also SDSL. This and later privatization of Český Telecom helped drive down prices.

On 1 July 2006, Český Telecom was acquired by globalized company (Spain-owned) Telefónica group and adopted the new name Telefónica O2 Czech Republic. As of 2017, VDSL and ADSL2+ are offered in variants, with download speeds of up to 50 Mbit/s and upload speeds of up to 5 Mbit/s. Cable internet is gaining more popularity with its higher download speeds ranging from 50 Mbit/s to 1 Gbit/s.

Two computer security companies, Avast and AVG, were founded in the Czech Republic. In 2016, Avast led by Pavel Baudiš bought rival AVG for US$1.3 billion, together at the time, these companies had a user base of about 400 million people and 40% of the consumer market outside of China.[144][145] Avast is the leading provider of antivirus software, with a 20.5% market share.[146]

Tourism

Prague is the fifth most visited city in Europe after London, Paris, Istanbul and Rome.[147] In 2001, the total earnings from tourism reached 118 billion CZK, making up 5.5% of GNP and 9% of overall export earnings. The industry employs more than 110,000 people – over 1% of the population.[148]

Guidebooks and tourists reporting overcharging by taxi drivers and pickpocketing problems are mainly in Prague, though the situation has improved recently.[149][150] Since 2005, Prague’s mayor, Pavel Bém, has worked to improve this reputation by cracking down on petty crime[150] and, aside from these problems, Prague is a «safe» city.[151] The Czech Republic’s crime rate is described by the United States State department as «low».[152]

One of the tourist attractions in the Czech Republic[153] is the Nether district Vítkovice in Ostrava.

The Czech Republic boasts 16 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, 3 of them are transnational. As of 2021, further 14 sites are on the tentative list.[154]

Architectural heritage is an object of interest to visitors – it includes castles and châteaux from different historical epoques, namely Karlštejn Castle, Český Krumlov and the Lednice–Valtice Cultural Landscape. There are 12 cathedrals and 15 churches elevated to the rank of basilica by the Pope, calm monasteries.

Away from the towns, areas such as Bohemian Paradise, Bohemian Forest and the Giant Mountains attract visitors seeking outdoor pursuits. There is a number of beer festivals.

The country is also known for its various museums. Puppetry and marionette exhibitions are with a number of puppet festivals throughout the country.[155] Aquapalace Prague in Čestlice is the largest water park in the country.

Science

The Czech lands have a long and well-documented history of scientific innovation.[156][157] Today, the Czech Republic has a highly sophisticated, developed, high-performing, innovation-oriented scientific community supported by the government,[158] industry,[159] and leading Czech Universities.[160] Czech scientists are embedded members of the global scientific community.[161] They contribute annually to multiple international academic journals and collaborate with their colleagues across boundaries and fields.[162][163][164][165] The Czech Republic was ranked 24th in the Global Innovation Index in 2020 and 2021, up from 26th in 2019.[166][167][168]

Historically, the Czech lands, especially Prague, have been the seat of scientific discovery going back to early modern times, including Tycho Brahe, Nicolaus Copernicus, and Johannes Kepler. In 1784 the scientific community was first formally organized under the charter of the Royal Czech Society of Sciences. Currently, this organization is known as the Czech Academy of Sciences.[169] Similarly, the Czech lands have a well-established history of scientists,[170][171] including Nobel laureates biochemists Gerty and Carl Ferdinand Cori, chemist Jaroslav Heyrovský, chemist Otto Wichterle, physicist Peter Grünberg and chemist Antonín Holý.[172] Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, was born in Příbor,[173] Gregor Mendel, the founder of genetics, was born in Hynčice and spent most of his life in Brno.[174]

Eli Beamlines Science Center with the most powerful laser in the world in Dolní Břežany

Most of the scientific research was recorded in Latin or in German and archived in libraries supported and managed by religious groups and other denominations as evidenced by historical locations of international renown and heritage such as the Strahov Monastery and the Clementinum in Prague. Increasingly, Czech scientists publish their work and that of their history in English.[175][176]

The current important scientific institution is the already mentioned Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, the CEITEC Institute in Brno or the HiLASE and Eli Beamlines centers with the most powerful laser in the world in Dolní Břežany. Prague is the seat of the administrative center of the GSA Agency operating the European navigation system Galileo and the European Union Agency for the Space Programme.

Demographics

The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2020 was estimated at 1.71 children per woman, which is below the replacement rate of 2.1.[177] The Czech Republic’s population has an average age of 43.3 years.[178] The life expectancy in 2021 was estimated to be 79.5 years (76.55 years male, 82.61 years female).[179] About 77,000 people immigrate to the Czech Republic annually.[180] Vietnamese immigrants began settling in the country during the Communist period, when they were invited as guest workers by the Czechoslovak government.[181] In 2009, there were about 70,000 Vietnamese in the Czech Republic.[182] Most decide to stay in the country permanently.[183]

According to results of the 2021 census, the majority of the inhabitants of the Czech Republic are Czechs (57.3%), followed by Moravians (3.4%), Slovaks (0.9%), Ukrainians (0.7%), Viets (0.3%), Poles (0.3%), Russians (0.2%), Silesians (0.1%) and Germans (0.1%). Another 4.0% declared combination of two nationalities (3.6% combination of Czech and other nationality). As the ‘nationality’ was an optional item, a number of people left this field blank (31.6%).[2] According to some estimates, there are about 250,000 Romani people in the Czech Republic.[184][185] The Polish minority resides mainly in the Zaolzie region.[186]

There were 496,413 foreigners (4.5% of the population) residing in the country in 2016, according to the Czech Statistical Office, with the largest groups being Ukrainian (22%), Slovak (22%), Vietnamese (12%), Russian (7%) and German (4%). Most of the foreign population lives in Prague (37.3%) and Central Bohemia Region (13.2%).[187]

The Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia, 118,000 according to the 1930 census, was nearly annihilated by the Nazi Germans during the Holocaust.[188] There were approximately 3,900 Jews in the Czech Republic in 2021.[189] The former Czech prime minister, Jan Fischer, is of Jewish faith.[190]

Nationality of residents, who answered the question in the Census 2021:[191][192]

| Nationality | Share |

|---|---|

| Czech | 83.76% |

| Moravian | 4.99% |

| Czech and Moravian | 2.50% |

| Slovak | 1.33% |

| Ukrainian | 1.08% |

| Czech and Slovak | 0.82% |

| Vietnamese | 0.44% |

| Polish | 0.37% |

| Russian | 0.35% |

| Other | 4.36% |

Largest cities

Largest municipalities in the Czech Republic Czech Statistical Office[193] |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Prague  Brno |

1 | Prague | Prague | 1,313,508 | 11 | Zlín | Zlín | 75,112 |  Ostrava  Plzeň |

| 2 | Brno | South Moravian | 377,440 | 12 | Havířov | Moravian-Silesian | 75,049 | ||

| 3 | Ostrava | Moravian-Silesian | 294,200 | 13 | Kladno | Central Bohemian | 68,552 | ||

| 4 | Plzeň | Plzeň | 169,033 | 14 | Most | Ústí nad Labem | 67,089 | ||

| 5 | Liberec | Liberec | 102,562 | 15 | Opava | Moravian-Silesian | 57,772 | ||

| 6 | Olomouc | Olomouc | 100,378 | 16 | Frýdek-Místek | Moravian-Silesian | 56,945 | ||

| 7 | Ústí nad Labem | Ústí nad Labem | 93,409 | 17 | Karviná | Moravian-Silesian | 55,985 | ||

| 8 | České Budějovice | South Bohemian | 93,285 | 18 | Jihlava | Vysočina | 50,521 | ||

| 9 | Hradec Králové | Hradec Králové | 92,808 | 19 | Teplice | Ústí nad Labem | 50,079 | ||

| 10 | Pardubice | Pardubice | 89,693 | 20 | Děčín | Ústí nad Labem | 49,833 |

Religion

| Religion in the Czech Republic (2011)[194] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Undeclared | 44.7% | |

| Irreligion | 34.5% | |

| Catholicism | 10.5% | |

| Believers, not members of other religions | 6.8% | |

| Other Christian churches | 1.1% | |

| Protestantism | 1% | |

| Believers, members of other religions | 0.7% | |

| Other religions / Unknown | 0.7% |

About 75%[195] to 79%[196] of residents of the Czech Republic do not declare having any religion or faith in surveys, and the proportion of convinced atheists (30%) is the third highest in the world behind those of China (47%) and Japan (31%).[197] The Czech people have been historically characterized as «tolerant and even indifferent towards religion».[198]

Christianization in the 9th and 10th centuries introduced Catholicism. After the Bohemian Reformation, most Czechs became followers of Jan Hus, Petr Chelčický and other regional Protestant Reformers. Taborites and Utraquists were Hussite groups. Towards the end of the Hussite Wars, the Utraquists changed sides and allied with the Catholic Church. Following the joint Utraquist—Catholic victory, Utraquism was accepted as a distinct form of Christianity to be practiced in Bohemia by the Catholic Church while all remaining Hussite groups were prohibited. After the Reformation, some Bohemians went with the teachings of Martin Luther, especially Sudeten Germans. In the wake of the Reformation, Utraquist Hussites took a renewed increasingly anti-Catholic stance, while some of the defeated Hussite factions were revived. After the Habsburgs regained control of Bohemia, the whole population was forcibly converted to Catholicism—even the Utraquist Hussites. Going forward, Czechs have become more wary and pessimistic of religion as such. A history of resistance to the Catholic Church followed. It suffered a schism with the neo-Hussite Czechoslovak Hussite Church in 1920, lost the bulk of its adherents during the Communist era and continues to lose in the modern, ongoing secularization. Protestantism never recovered after the Counter-Reformation was introduced by the Austrian Habsburgs in 1620. Prior to the Holocaust, the Czech Republic had a sizable Jewish community of around 100,000. There are many historically important and culturally relevant Synagogues in the Czech Republic such as Europe’s oldest active Synagogue, The Old New Synagogue and the second largest Synagogue in Europe, the Great Synagogue (Plzeň). The Holocaust decimated Czech Jewry and the Jewish population as of 2021 is 3,900.[199]

According to the 2011 census, 34% of the population stated they had no religion, 10.3% was Catholic, 0.8% was Protestant (0.5% Czech Brethren and 0.4% Hussite),[200] and 9% followed other forms of religion both denominational or not (of which 863 people answered they are Pagan). 45% of the population did not answer the question about religion.[194] From 1991 to 2001 and further to 2011 the adherence to Catholicism decreased from 39% to 27% and then to 10%; Protestantism similarly declined from 3.7% to 2% and then to 0.8%.[201] The Muslim population is estimated to be 20,000 representing 0.2% of the population.[202]

The proportion of religious believers varies significantly across the country, from 55% in Zlín Region to 16% in Ústí nad Labem Region.[203]

Education and health care

Education in the Czech Republic is compulsory for nine years and citizens have access to a free-tuition university education, while the average number of years of education is 13.1.[204] Additionally, the Czech Republic has a «relatively equal» educational system in comparison with other countries in Europe.[204] Founded in 1348, Charles University was the first university in Central Europe. Other major universities in the country are Masaryk University, Czech Technical University, Palacký University, Academy of Performing Arts and University of Economics.

The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks the Czech education system as the 15th most successful in the world, higher than the OECD average.[205] The UN Education Index ranks the Czech Republic 10th as of 2013 (positioned behind Denmark and ahead of South Korea).[206]

Health care in the Czech Republic is similar in quality to that of other developed nations. The Czech universal health care system is based on a compulsory insurance model, with fee-for-service care funded by mandatory employment-related insurance plans.[207] According to the 2016 Euro health consumer index, a comparison of healthcare in Europe, the Czech healthcare is 13th, ranked behind Sweden and two positions ahead of the United Kingdom.[208]

Culture

Art

Venus of Dolní Věstonice is the treasure of prehistoric art. Theodoric of Prague was a painter in the Gothic era who decorated the castle Karlstejn. In the Baroque era, there were Wenceslaus Hollar, Jan Kupecký, Karel Škréta, Anton Raphael Mengs or Petr Brandl, sculptors Matthias Braun and Ferdinand Brokoff. In the first half of the 19th century, Josef Mánes joined the romantic movement. In the second half of the 19th century had the main say the so-called «National Theatre generation»: sculptor Josef Václav Myslbek and painters Mikoláš Aleš, Václav Brožík, Vojtěch Hynais or Julius Mařák. At the end of the century came a wave of Art Nouveau. Alfons Mucha became the main representative. He is known for Art Nouveau posters and his cycle of 20 large canvases named the Slav Epic, which depicts the history of Czechs and other Slavs.

As of 2012, the Slav Epic can be seen in the Veletržní Palace of the National Gallery in Prague, which manages the largest collection of art in the Czech Republic. Max Švabinský was another Art nouveau painter. The 20th century brought an avant-garde revolution. In the Czech lands mainly expressionist and cubist: Josef Čapek, Emil Filla, Bohumil Kubišta, Jan Zrzavý. Surrealism emerged particularly in the work of Toyen, Josef Šíma and Karel Teige. In the world, however, he pushed mainly František Kupka, a pioneer of abstract painting. As illustrators and cartoonists in the first half of the 20th century gained fame Josef Lada, Zdeněk Burian or Emil Orlík. Art photography has become a new field (František Drtikol, Josef Sudek, later Jan Saudek or Josef Koudelka).

The Czech Republic is known for its individually made, mouth-blown, and decorated Bohemian glass.

Architecture

The earliest preserved stone buildings in Bohemia and Moravia date back to the time of the Christianization in the 9th and 10th centuries. Since the Middle Ages, the Czech lands have been using the same architectural styles as most of Western and Central Europe. The oldest still standing churches were built in the Romanesque style. During the 13th century, it was replaced by the Gothic style. In the 14th century, Emperor Charles IV invited architects from France and Germany, Matthias of Arras and Peter Parler, to his court in Prague. During the Middle Ages, some fortified castles were built by the king and aristocracy, as well as some monasteries.

The Renaissance style penetrated the Bohemian Crown in the late 15th century when the older Gothic style started to be mixed with Renaissance elements. An example of pure Renaissance architecture in Bohemia is the Queen Anne’s Summer Palace, which was situated in the garden of Prague Castle. Evidence of the general reception of the Renaissance in Bohemia, involving an influx of Italian architects, can be found in spacious chateaus with arcade courtyards and geometrically arranged gardens.[209] Emphasis was placed on comfort, and buildings that were built for entertainment purposes also appeared.[210]

In the 17th century, the Baroque style spread throughout the Crown of Bohemia.[211]

In the 18th century, Bohemia produced an architectural peculiarity – the Baroque Gothic style, a synthesis of the Gothic and Baroque styles.[209]

During the 19th century stands the revival architectural styles. Some churches were restored to their presumed medieval appearance and there were constructed buildings in the Neo-Romanesque, Neo-Gothic and Neo-Renaissance styles. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the new art style appeared in the Czech lands – Art Nouveau.

Bohemia contributed an unusual style to the world’s architectural heritage when Czech architects attempted to transpose the Cubism of painting and sculpture into architecture.

Between World Wars I and II, Functionalism, with its sober, progressive forms, took over as the main architectural style.[209]

After World War II and the Communist coup in 1948, art in Czechoslovakia became Soviet-influenced. The Czechoslovak avant-garde artistic movement is known as the Brussels style came up in the time of political liberalization of Czechoslovakia in the 1960s. Brutalism dominated in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Czech Republic is not shying away from the more modern trends of international architecture, an example is the Dancing House (Tančící dům) in Prague, Golden Angel in Prague or Congress Centre in Zlín.[209]

Influential Czech architects include Peter Parler, Benedikt Rejt, Jan Santini Aichel, Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer, Josef Fanta, Josef Hlávka, Josef Gočár, Pavel Janák, Jan Kotěra, Věra Machoninová, Karel Prager, Karel Hubáček, Jan Kaplický, Eva Jiřičná or Josef Pleskot.

Literature

The literature from the area of today’s Czech Republic was mostly written in Czech, but also in Latin and German or even Old Church Slavonic. Franz Kafka, while bilingual in Czech and German,[212][213] wrote his works (The Trial, The Castle) in German.

In the second half of the 13th century, the royal court in Prague became one of the centers of German Minnesang and courtly literature. The Czech German-language literature can be seen in the first half of the 20th century.

Bible translations played a role in the development of Czech literature. The oldest Czech translation of the Psalms originated in the late 13th century and the first complete Czech translation of the Bible was finished around 1360. The first complete printed Czech Bible was published in 1488. The first complete Czech Bible translation from the original languages was published between 1579 and 1593. The Codex Gigas from the 12th century is the largest extant medieval manuscript in the world.[214]

Czech-language literature can be divided into several periods: the Middle Ages; the Hussite period; the Renaissance humanism; the Baroque period; the Enlightenment and Czech reawakening in the first half of the 19th century, modern literature in the second half of the 19th century; the avant-garde of the interwar period; the years under Communism; and the Czech Republic.

The antiwar comedy novel The Good Soldier Švejk is the most translated Czech book in history.

The international literary award the Franz Kafka Prize is awarded in the Czech Republic.[215]

The Czech Republic has the densest network of libraries in Europe.[216]

Czech literature and culture played a role on at least two occasions when Czechs lived under oppression and political activity was suppressed. On both of these occasions, in the early 19th century and then again in the 1960s, the Czechs used their cultural and literary effort to strive for political freedom, establishing a confident, politically aware nation.[217]

Music

The musical tradition of the Czech lands arose from the first church hymns, whose first evidence is suggested at the break of the 10th and 11th centuries. Some pieces of Czech music include two chorales, which in their time performed the function of anthems: «Lord, Have Mercy on Us» and the hymn «Saint Wenceslaus» or «Saint Wenceslaus Chorale».[218] The authorship of the anthem «Lord, Have Mercy on Us» is ascribed by some historians to Saint Adalbert of Prague (sv.Vojtěch), bishop of Prague, living between 956 and 997.[219]

The wealth of musical culture lies in the classical music tradition during all historical periods, especially in the Baroque, Classicism, Romantic, modern classical music and in the traditional folk music of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. Since the early era of artificial music, Czech musicians and composers have been influenced the folk music of the region and dance.

Czech music can be considered to have been «beneficial» in both the European and worldwide context, several times co-determined or even determined a newly arriving era in musical art,[220] above all of Classical era, as well as by original attitudes in Baroque, Romantic and modern classical music. Some Czech musical works are The Bartered Bride, New World Symphony, Sinfonietta and Jenůfa.

A music festival in the country is Prague Spring International Music Festival of classical music, a permanent showcase for performing artists, symphony orchestras and chamber music ensembles of the world.

Theatre

The roots of Czech theatre can be found in the Middle Ages, especially in the cultural life of the Gothic period. In the 19th century, the theatre played a role in the national awakening movement and later, in the 20th century, it became a part of modern European theatre art. The original Czech cultural phenomenon came into being at the end of the 1950s. This project called Laterna magika, resulting in productions that combined theater, dance, and film in a poetic manner, considered the first multimedia art project in an international context.

A drama is Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R., which introduced the word «robot».[221]

The country has a tradition of puppet theater. In 2016, Czech and Slovak Puppetry was included on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[222]

Film

The tradition of Czech cinematography started in the second half of the 1890s. Peaks of the production in the era of silent movies include the historical drama The Builder of the Temple and the social and erotic drama Erotikon directed by Gustav Machatý.[223] The early Czech sound film era was productive, above all in mainstream genres, with the comedies of Martin Frič or Karel Lamač. There were dramatic movies sought internationally.

Hermína Týrlová (11 December 1900 in Březové Hory – 3 May 1993 in Zlín) was a prominent Czech animator, screenwriter, and film director. She was often called the mother of Czech animation. Over the course of her career, she produced over 60 animated children’s short films using puppets and the technique of stop motion animation.

Before the German occupation, in 1933, filmmaker and animator Irena Dodalová established the first Czech animation studio «IRE Film» with her husband Karel Dodal.

After the period of Nazi occupation and early communist official dramaturgy of socialist realism in movies at the turn of the 1940s and 1950s with fewer exceptions such as Krakatit or Men without wings (awarded by Palme d’Or in 1946), an era of the Czech film began with animated films, performed in anglophone countries under the name «The Fabulous World of Jules Verne» from 1958, which combined acted drama with animation, and Jiří Trnka, the founder of the modern puppet film.[224] This began a tradition of animated films (Mole etc.).

In the 1960s, the hallmark of Czechoslovak New Wave’s films were improvised dialogues, black and absurd humor and the occupation of non-actors. Directors are trying to preserve natural atmosphere without refinement and artificial arrangement of scenes. A personality of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s with original manuscript and psychological impact is František Vláčil. Another international author is Jan Švankmajer, a filmmaker and artist whose work spans several media. He is a self-labeled surrealist known for animations and features.[225]

The Barrandov Studios in Prague are the largest film studios with film locations in the country.[226] Filmmakers have come to Prague to shoot scenery no longer found in Berlin, Paris and Vienna. The city of Karlovy Vary was used as a location for the 2006 James Bond film Casino Royale.[227]

The Czech Lion is the highest Czech award for film achievement. Karlovy Vary International Film Festival is one of the film festivals that have been given competitive status by the FIAPF. Other film festivals held in the country include Febiofest, Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival, One World Film Festival, Zlín Film Festival and Fresh Film Festival.

Media

Czech journalists and media enjoy a degree of freedom. There are restrictions against writing in support of Nazism, racism or violating Czech law. The Czech press was ranked as the 40th most free press in the World Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders in 2021.[228] Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty has its headquarters in Prague.

The national public television service is Czech Television that operates the 24-hour news channel ČT24 and the news website ct24.cz. As of 2020, Czech Television is the most watched television, followed by private televisions TV Nova and Prima TV. However, TV Nova has the most watched main news program and prime time program.[229] Other public services include the Czech Radio and the Czech News Agency.

The best-selling daily national newspapers in 2020/21 are Blesk (average 703,000 daily readers), Mladá fronta DNES (average 461,000 daily readers), Právo (average 182,000 daily readers), Lidové noviny (average 163,000 daily readers) and Hospodářské noviny (average 162,000 daily readers).[230]

Most Czechs (87%[231]) read their news online,[232] with Seznam.cz, iDNES.cz, Novinky.cz, iPrima.cz and Seznam Zprávy.cz being the most visited as of 2021.[233]

Cuisine

Czech cuisine is marked by an emphasis on meat dishes with pork, beef, and chicken. Goose, duck, rabbit, and venison are served. Fish is less common, with the occasional exception of fresh trout and carp, which is served at Christmas.[234][235]

There is a variety of local sausages, wurst, pâtés, and smoked and cured meats. Czech desserts include a variety of whipped cream, chocolate, and fruit pastries and tarts, crêpes, creme desserts and cheese, poppy-seed-filled and other types of traditional cakes such as buchty, koláče and štrúdl.[236]

Czech beer has a history extending more than a millennium; the earliest known brewery existed in 993. Today the Czech Republic has the highest beer consumption per capita in the world. The pilsner style beer (pils) originated in Plzeň, where the world’s first blond lager Pilsner Urquell is still produced. It has served as the inspiration for more than two-thirds of the beer produced in the world today. The city of České Budějovice has similarly lent its name to its beer, known as Budweiser Budvar.

The South Moravian region has been producing wine since the Middle Ages; about 94% of vineyards in the Czech Republic are Moravian. Aside from beer, slivovitz and wine, the Czech Republic also produces two liquors, Fernet Stock and Becherovka. Kofola is a non-alcoholic domestic cola soft drink which competes with Coca-Cola and Pepsi.

Sport

The two leading sports in the Czech Republic are football and ice hockey. The most watched sporting events are the Olympic tournament and World Championships of ice hockey.[237][238] Other most popular sports include tennis, volleyball, floorball, golf, ball hockey, athletics, basketball and skiing.[239]

The country has won 15 gold medals in the Summer Olympics and nine in the Winter Games. (See Olympic history.) The Czech ice hockey team won the gold medal at the 1998 Winter Olympics and has won twelve gold medals at the World Championships, including three straight from 1999 to 2001.

The Škoda Motorsport is engaged in competition racing since 1901 and has gained a number of titles with various vehicles around the world. MTX automobile company was formerly engaged in the manufacture of racing and formula cars since 1969.

Hiking is a popular sport. The word for ‘tourist’ in Czech, turista, also means ‘trekker’ or ‘hiker’. For hikers, thanks to the more than 120-year-old tradition, there is a Czech Hiking Markers System of trail blazing, that has been adopted by countries worldwide. There is a network of around 40,000 km of marked short- and long-distance trails crossing the whole country and all the Czech mountains.[240][241]

See also

- List of Czech Republic-related topics

- Outline of the Czech Republic

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ «Czech language». Czech Republic – Official website. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ a b c «Národnost». Census 2021 (in Czech). Czech Statistical Office. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ «Náboženská víra». Census 2021 (in Czech). Czech Statistical Office. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ «Public database: Land use (as at 31 December)». Czech Statistical Office. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ «Population of Municipalities – 1 January 2022». Czech Statistical Office. 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d «World Economic Outlook Database April 2022». IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ «Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income». Eurostat. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ «Human Development Report 2021/2022» (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Citizens belonging to minorities, which traditionally and on a long-term basis live within the territory of the Czech Republic, enjoy the right to use their language in communication with authorities and in courts of law (for the list of recognized minorities see National Minorities Policy of the Government of the Czech Republic Archived 7 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Belarusian and Vietnamese since 4 July 2013, see Česko má nové oficiální národnostní menšiny. Vietnamce a Bělorusy Archived 8 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine). Article 25 of the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms ensures the right of the national and ethnic minorities to education and communication with the authorities in their own language. Act No. 500/2004 Coll. (The Administrative Rule) in its paragraph 16 (4) (Procedural Language) ensures that a citizen of the Czech Republic who belongs to a national or an ethnic minority, which traditionally and on a long-term basis lives within the territory of the Czech Republic, has the right to address an administrative agency and proceed before it in the language of the minority. If the administrative agency has no employee with knowledge of the language, the agency is bound to obtain a translator at the agency’s own expense. According to Act No. 273/2001 (Concerning the Rights of Members of Minorities) paragraph 9 (The right to use language of a national minority in dealing with authorities and in front of the courts of law) the same also applies to members of national minorities in the courts of law.

- ^ The Slovak language may be considered an official language in the Czech Republic under certain circumstances, as defined by several laws – e.g. law 500/2004, 337/1992. Source: http://portal.gov.cz Archived 10 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Cited: «Například Správní řád (zákon č. 500/2004 Sb.) stanovuje: «V řízení se jedná a písemnosti se vyhotovují v českém jazyce. Účastníci řízení mohou jednat a písemnosti mohou být předkládány i v jazyce slovenském …» (§ 16, odstavec 1). Zákon o správě daní a poplatků (337/1992 Sb.) «Úřední jazyk: Před správcem daně se jedná v jazyce českém nebo slovenském. Veškerá písemná podání se předkládají v češtině nebo slovenštině …» (§ 3, odstavec 1). http://portal.gov.cz

- ^ «Oxford English Dictionary». Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ «Publications Office — Interinstitutional style guide — 7.1. Countries — 7.1.1. Designations and abbreviations to use». Publications Office. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ «the Czech Republic». The United Nations Terminology Database. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ Šitler, Jiří (12 July 2016). «From Bohemia to Czechia». Czech Radio. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ «Information about the Czech Republic». Czech Foreign Ministry. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Mlsna, Petr; Šlehofer, F.; Urban, D. (2010). «The Path of Czech Constitutionality» (PDF). 1st edition (in Czech and English). Praha: Úřad Vlády České Republiky (The Office of the Government of the Czech Republic). pp. 10–11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Čumlivski, Denko (2012). «800 let Zlaté buly sicilské» (in Czech). National Archives of the Czech Republic (Národní Archiv České Republiky). Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ Dijk, Ruud van; Gray, William Glenn; Savranskaya, Svetlana; Suri, Jeremi; Zhai, Qiang (2013). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-1135923112. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Timothy Garton Ash The Uses of Adversity Granta Books, 1991 ISBN 0-14-014038-7 p. 60

- ^ «Czech definition and meaning». Collins English Dictionary. Collins. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

C19: from Polish, from Czech Čech

- ^ «Czech». American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

[Polish, from Czech Čech.]

- ^ «Czech — Definition in English». Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

Origin Polish spelling of Czech Čech.

- ^ Spal, Jaromír. «Původ jména Čech». Naše řeč. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ Sviták, Zbyněk (2014). «Úvod do historické topografie českých zemí: Územní vývoj českých zemí» (PDF). 1st edition (in Czech). Brno. pp. 75–80, 82, 92–96. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ «From Bohemia to Czechia — Radio Prague». 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Wayne C. (2012). Nordic, Central and Southeastern Europe 2012. Stryker Post. pp. 345–. ISBN 978-1-61048-892-1.

- ^ «Czechia — the civic initiative». www.czechia-initiative.com. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ «Vláda schválila doplnení jednoslovného názvu Cesko v cizích jazycích do databází OSN» [The government has approved the addition of one-word Czech name in foreign languages to UN databases]. Ministerstvo zahraničních věcí České republiky (in Czech). 5 May 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ UNGEGN. «UNGEGN List of Country Names» (PDF). p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ European Union (5 July 2016). «Czechia». European Union. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ NATO. «Member countries». NATO. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ «Czechia». The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 31 May 2021. (Archived 2021 edition)

- ^ «Czechia: mapping progress one year on». Radio Prague International. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ «Top items – Head of a Celt». Muzeum 3000.

- ^ Rankin, David (2002). Celts and the Classical World. Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-134-74722-1.

- ^ Kartografie Praha (Firm) (1997). Praha, plán města. Kartografie Praha. p. 17. ISBN 978-80-7011-468-1.

- ^ Vasco La Salvia (2007). Iron Making During the Migration Period: The Case of the Lombards. Archaeopress. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4073-0159-4.

- ^ Hugh LeCaine Agnew (2004). The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. Hoover Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8179-4492-6.

- ^ a b Hahn, Sylvia; Nadel, Stanley (2014). Asian Migrants in Europe: Transcultural Connections. V&R unipress GmbH. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-3-8471-0254-0.

- ^ Bartl, Július; Škvarna, Dušan (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-86516-444-4.

- ^ Champion, Tim (2005). Centre and Periphery: Comparative Studies in Archaeology. Routledge. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-134-80679-9.

- ^ Benedetto, Robert; Duke, James O. (2008). The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The early, medieval, and Reformation eras. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 474. ISBN 978-0-664-22416-5.

- ^ Pánek, Jaroslav; Tůma, Oldřich (2019). A History of the Czech Lands. Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-80-246-2227-9.

- ^ Pánek, Jaroslav; Tůma, Oldřich (2019). A History of the Czech Lands. Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-80-246-2227-9.

- ^ Pánek, Jaroslav; Tůma, Oldřich (2019). A History of the Czech Lands. Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-80-246-2227-9.

- ^ Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ «Václav II. český král». panovnici.cz. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ «Mentor and precursor of the Reformation». Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ «Protestantism in Bohemia and Moravia (Czech Republic)». Virtual Museum of Protestantism. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Oskar Krejčí, Martin C. Styan, Ústav politických vied SAV. (2005). Geopolitics of the Central European region: the view from Prague and Bratislava. p.293. ISBN 80-224-0852-2

- ^ «RP’s History Online – Habsburgs». Archiv.radio.cz. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ «History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century. Part 2. The So-Called Tartars of Russia and Central Asia. Division 1«. Henry Hoyle Howorth. p.557. ISBN 1-4021-7772-0

- ^ «The new Cambridge modern history: The ascendancy of France, 1648–88«. Francis Ludwig Carsten (1979). p.494. ISBN 0-521-04544-4

- ^ «The Cambridge economic history of Europe: The economic organization of early modern Europe«. E. E. Rich, C. H. Wilson, M. M. Postan (1977). p.614. ISBN 0-521-08710-4

- ^ Hlavačka, Milan (2009). «Formování moderního českého národa 1815–1914». Historický Obzor (in Czech). 20 (9/10): 195.

- ^ a b Cole, Laurence; Unowsky, David (eds.). The Limits of Loyalty: Imperial Symbolism, Popular Allegiances, and State Patriotism in the Late Habsburg Monarchy (PDF). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ «Františka Plamínková: the feminist suffragette who ensured Czechoslovakia’s Constitution of 1920 lived up to the principle of equality». Radio Prague International. 29 February 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ a b Stephen J. Lee. Aspects of European History 1789–1980. Page 107. Chapter «Austria-Hungary and the successor states». Routledge. 28 January 2008.

- ^ Preclík, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 pages, first issue — vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná, Czech Republic) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, pages 22 — 81, 85-86, 111-112, 124–125, 128, 129, 132, 140–148, 184–209.

- ^ «Tab. 3 Národnost československých státních příslušníků podle žup a zemí k 15 February 1921» (PDF) (in Czech). Czech Statistical Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- ^ «Ekonomika ČSSR v letech padesátých a šedesátých». Blisty.cz. 21 August 1968. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Dijk, Ruud van; Gray, William Glenn; Savranskaya, Svetlana; Suri, Jeremi; Zhai, Qiang (2013). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-1135923112. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Rothenbacher, Franz (2002). The European Population 1850–1945. Palgrave Macmillan, London. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-349-65611-0.

- ^ Chad Bryant (2009) Prague in Black: Nazi Rule and Czech Nationalism (Harvard University Press, 2009), pp 104-178. Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. p. 160. ISBN 0465002390

- ^ «A Companion to Russian History Archived 6 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine«. Abbott Gleason (2009). Wiley-Blackwell. p.409. ISBN 1-4051-3560-3

- ^ Chad Bryant (2009) Prague in Black: Nazi Rule and Czech Nationalism (Harvard University Press, 2009), 208-252.

- ^ F. Čapka: Dějiny zemí Koruny české v datech Archived 20 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. XII. Od lidově demokratického po socialistické Československo – pokračování. Libri.cz (in Czech)

- ^ «Czech schools revisit communism». Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.