Что такое кириллица и в чем ее отличие от глаголицы

Здравствуйте, уважаемые читатели блога KtoNaNovenkogo.ru. Национальная культура – производная от особенностей мышления целого народа. Но сформулировать мысль возможно только при наличии языка, а его развитию способствует в том числе наличие письменной формы.

При этом для любого носителя языка особое значение обретают такие вопросы, как, например: что было в истоках, как появился мой язык, как он развивался и принял те формы, которые мы используем сейчас.

Когда человек ищет ответы на эти вопросы, он познает не только свою историю и культуру, но и духовные основы своего народа. А без знания подобных вещей нельзя существовать. Поэтому вклад кириллицы в формирование славяноязычного культурного пространства так важен и ценен.

Сегодня мы попытаемся разобраться, когда и как появились буквы кириллицы – алфавит, послуживший прототипом для современного русского языка, а заодно узнаем, почему кириллица и глаголица – это совсем не одно и то же.

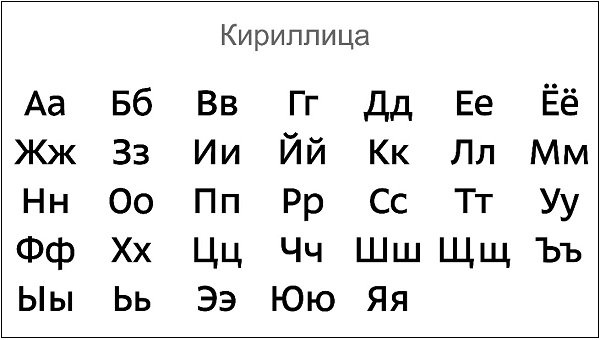

Кириллица – это какие буквы?

Прежде чем мы перейдем к непосредственной связи между кириллицей и глаголицей, уточним:

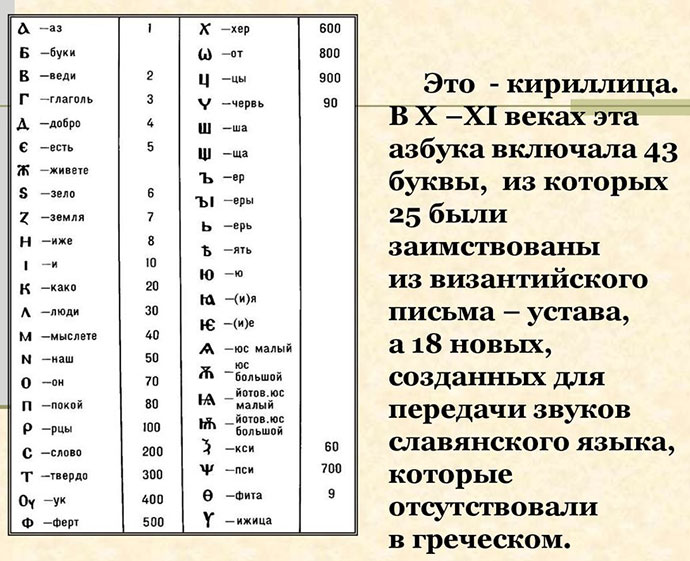

Кириллица – это одна из древнейших форм записи древнеславянского языка, распространение которой началось примерно в середине IX века.

Название, кстати, происходит от имени христианского святого Кирилла (Константина), который, по легенде, вместе со своим братом Мефодием переработал греческий алфавит в древнерусское руническое письмо и создал на этой основе славянскую азбуку.

И только спустя много времени ученики и последователи братьев-византийцев изменили графику первых букв и преобразовали созданную Кириллом азбуку в церковнославянский язык, ставший самой первой систематической буквенной письменностью, которой у славян до тех пор не существовало.

| Буква Кириллицы | Название | Произношение |

|---|---|---|

| А | аз | [а] |

| Б | бу́ки | [б] |

| В | ве́ди | [в] |

| Г | глаго́ль | [г] |

| Д | добро́ | [д] |

| Е, Є | есть | [е] |

| Ж | живе́те | [ж] |

| Ѕ | зело́ | [дз’] |

| Z, З | земля́ | [з] |

| И | и́же (8-ричное) | [и] |

| І, Ї | и (10‑ричное) | [и] |

| К | ка́ко | [к] |

| Л | лю́ди | [л] |

| М | мысле́те | [м] |

| Н | наш | [н] |

| О | он | [о] |

| П | поко́й | [п] |

| Р | рцы | [р] |

| С | сло́во | [с] |

| Т | тве́рдо | [т] |

| Ѹ, ȣ |

ук | [у] |

| Ф | ферт | [ф] |

| Х | хер | [х] |

| Ѡ | оме́га | [о] |

| Ц | цы | [ц] |

| Ч | червь | [ч’] |

| Ш | ша | [ш] |

| Щ | ща | [ш’т’] ([ш’ч’]) |

| Ъ | ер | [ъ] |

| Ы | еры́ | [ы] |

| Ь | ерь | [ь] |

| Ѣ | ять | [æ], [ие] |

| Ю | ю | [йу] |

| Ꙗ | А йотированное | [йа] |

| Ѥ | Е йотированное | [йэ] |

| Ѧ | Малый юс | [эн] |

| Ѫ | Большой юс | [он] |

| Ѩ | юс малый йотированный | [йэн] |

| Ѭ | юс большой йотированный | [йон] |

| Ѯ | кси | [кс] |

| Ѱ | пси | [пс] |

| Ѳ | фита́ | [θ], [ф] |

| Ѵ | и́жица | [и], [в] |

Однако термин вошел в научную сферу лишь к середине XIX века, а первое его упоминание относят к 1805 году – за авторством немецкого историка Шлецера, использовавшего слово «kyrillitza». Исследователи ссылаются на этот факт, используя источники из Далмации, нынешнего региона Хорватии.

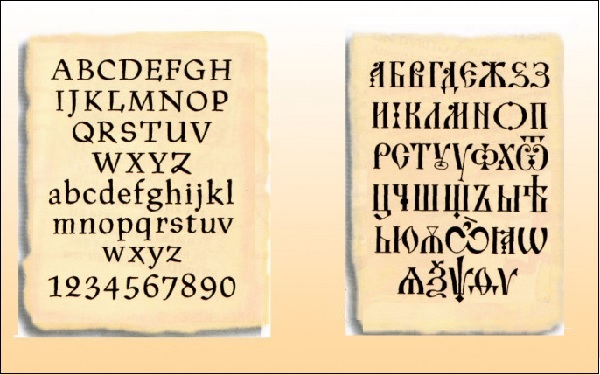

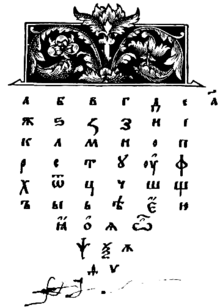

Изначально символы кириллицы выглядели не так, как в церковнославянском алфавите, – их начертание напоминало сильно упрощенную графику широкоупотребительных греческих букв, тем не менее это была не новообразованная азбука, а несколько модифицированная и видоизмененная глаголица, существовавшая у славян наряду с рунической тайнописью.

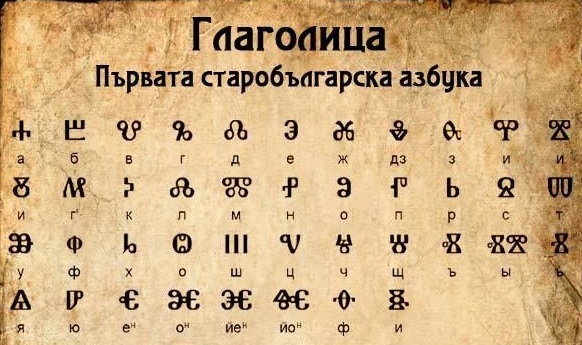

Глаголица – это вторая форма древнеславянской письменности.

Ее появление считается более ранним, но популяризация происходила параллельно с термином «кириллица», хотя слово восходит к южно-хорватскому «glagoljica» в значении «азбука», которое само произошло от церковнославянского «глаголати»:

- проповедовать;

- говорить.

И хотя современный русский алфавит – кириллический, у лингвистов с историками до сих пор нет единодушия в вопросах о времени происхождения и популярности обеих форм письменности.

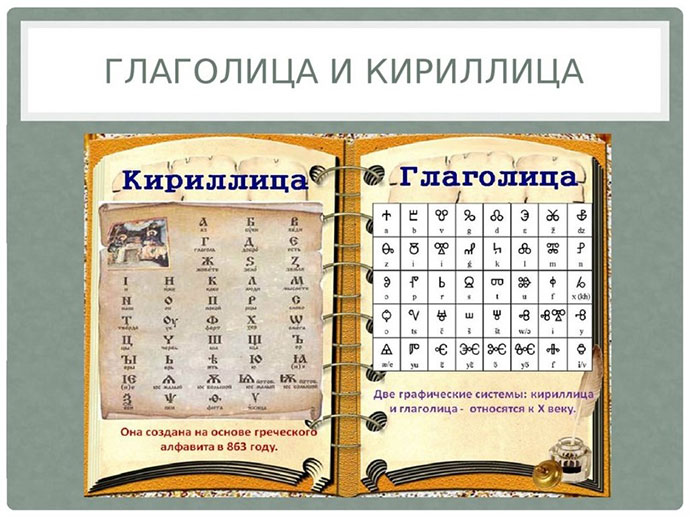

Кириллица и глаголица – в чем отличие

Главное: эти алфавиты появились благодаря христианским миссионерам. Но распространение обоих связывают с приказом византийского императора Михаила III от 863 года, изданном в силу жизненной необходимости.

Дело в том, что тогда было довольно сложно распространять религиозные тексты на греческом языке, непонятном местному населению. А попытки записать славянские звуки с помощью латинских или греческих символов не увенчались успехом из-за языковых особенностей. Так возникла необходимость в создании уникального алфавита, учитывавшего нюансы речевой культуры славянских народов.

Новая форма письменности получила широкий охват после принятия Болгарией православной веры. Симеон I Великий основал Преславскую книжную школу, откуда вместе с богослужебными текстами среди южных и восточных славян начала распространяться кириллица.

Но глаголица – это аутентичный алфавит, не основанный на других письменных школах.

Какое-то время считалось, что его придумали и использовали на территориях, где кириллица была официально запрещена, однако впоследствии ученые выдвинули несколько доказательств более раннего происхождения глаголицы:

- древнейшие тексты с территорий, где непосредственно работали Кирилл с Мефодием;

- структура речи в глаголических текстах более архаична;

- лингвисты доказали, что тексты переписывались с глаголицы на кириллицу, но не наоборот;

- существуют пергаменты, где глаголическое письмо было стерто ради написания нового, кириллического.

На этом основании делают вывод, что именно глаголицу изначально придумал Кирилл, взяв за основу три символических христианских символа:

- крест;

- круг;

- треугольник.

В качестве дополнительного аргумента приводятся такие факты, как, например, большее количество символов, передающих на письме звуки, свойственные речи славян того времени, по сравнению с кириллицей. Впрочем, в слегка измененной форме глаголица просуществовала в Хорватии до середины XIX века, что подчеркивает ее актуальность для культур, не подвергавшихся серьезным языковым реформам.

Эволюция кириллического письма

Кириллица – это алфавит, не только ставший более востребованным, но и подвергавшийся множеству преобразований.

Самым первым был факт его появления: считается, что на основе глаголического письма Климент и Наум Орхидские, а также Константин Преславский создали кириллическое (примерно в 886 – 889 годах), переделав оригинальное написание на греческий манер и добавив буквы, свойственные пришедшим из греческого языка терминам.

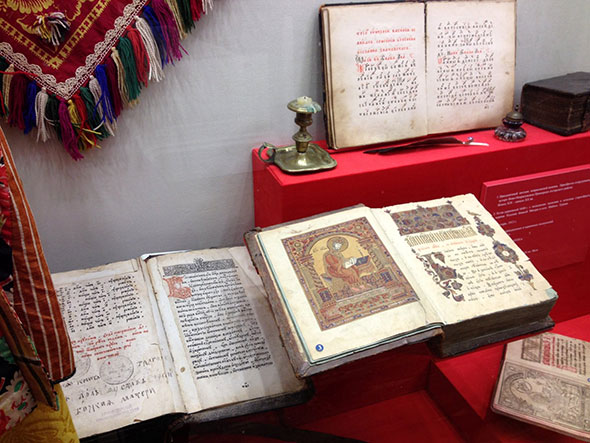

Уже в X веке Русская Православная Церковь взяла новый алфавит на вооружение, связав с древнерусским языком, а в равной мере – противопоставив собственные богословские книги католическим, написанным латиницей. После этого в развитии кириллицы на Руси можно выделить пять эпох:

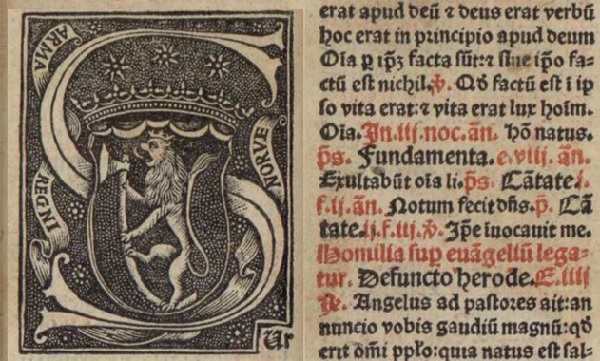

- с X по XIV века – «Устав»;

- с XIV по XVIII век – «полуустав»;

- петровские реформы;

- большевистские реформы;

- советский период.

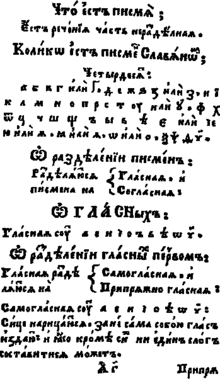

Хотя развитие письменной культуры в разных странах отличалось, на первом этапе была схожесть. «Устав» отличался прямолинейностью и угловатостью, крупным размером и отсутствием пробелов, а цифры записывались буквами.

Развитию «полуустава» способствовало появление в XV веке скорописи. Буквы стали округлыми, компактными, появились знаки препинания, а вытянутые элементы были как снизу, так и сверху. Появилась возможность писать заглавия витиеватой вязью, что придавало текстам особую эстетичность.

Вместо заключения – интересные факты

Петр I в рамках реформы впервые ввел заглавные буквы и переделал написание строчных так, чтобы они больше походили на европейские – для упрощения последующего развития печати в Российской империи. Появились арабские цифры, исчезли надстрочные знаки, и ведение дел с Европой сильно упростилось.

А в 1918-м большевики протолкнули реформу, разработанную еще в начале века, и это обусловило последующую борьбу с неграмотностью. Из кириллицы убрали несколько символов, практически не влиявших на понимание написанного.

И, наконец, в 1956 году провели последнюю реформу, устранившую неоднозначность в ряде орфографических правил и упростившую изучение языка до сегодняшнего уровня.

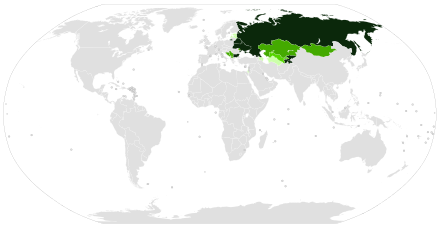

This article is about the variants of the Cyrillic alphabet. For the writing system as a whole, see Cyrillic script.

Countries with widespread use of the Cyrillic script:

Sole official script

Co-official with another script (either because the official language is biscriptal, or the state is bilingual)

Being replaced with Latin, but is still in official use

Legacy script for the official language, or large minority use

Cyrillic is not widely used

Numerous Cyrillic alphabets are based on the Cyrillic script. The early Cyrillic alphabet was developed in the 9th century AD and replaced the earlier Glagolitic script developed by the Byzantine theologians Cyril and Methodius. It is the basis of alphabets used in various languages, past and present, Slavic origin, and non-Slavic languages influenced by Russian. As of 2011, around 252 million people in Eurasia use it as the official alphabet for their national languages. About half of them are in Russia. Cyrillic is one of the most-used writing systems in the world. The birth place of the Cyrillic alphabet is Bulgaria. The creator is Saint Clement of Ohrid from the Preslav literary school in the First Bulgarian Empire.

Some of these are illustrated below; for others, and for more detail, see the links. Sounds are transcribed in the IPA. While these languages largely have phonemic orthographies, there are occasional exceptions—for example, Russian ⟨г⟩ is pronounced /v/ in a number of words, an orthographic relic from when they were pronounced /ɡ/ (e.g. его yego ‘him/his’, is pronounced [jɪˈvo] rather than [jɪˈɡo]).

Spellings of names transliterated into the Roman alphabet may vary, especially й (y/j/i), but also г (gh/g/h) and ж (zh/j).

Unlike the Latin script, which is usually adapted to different languages by adding diacritical marks/supplementary glyphs (such as accents, umlauts, fadas, tildes and cedillas) to standard Roman letters, by assigning new phonetic values to existing letters (e.g. ⟨c⟩, whose original value in Latin was /k/, represents /ts/ in West Slavic languages, /ʕ/ in Somali, /t͡ʃ/ in many African languages and /d͡ʒ/ in Turkish), or by the use of digraphs (such as ⟨sh⟩, ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ng⟩ and ⟨ny⟩), the Cyrillic script is usually adapted by the creation of entirely new letter shapes. However, in some alphabets invented in the 19th century, such as Mari, Udmurt and Chuvash, umlauts and breves also were used.

Bulgarian and Bosnian Sephardim without Hebrew typefaces occasionally printed Judeo-Spanish in Cyrillic.[1]

Spread[edit]

Non-Slavic alphabets are generally modelled after Russian, but often bear striking differences, particularly when adapted for Caucasian languages. The first few of these alphabets were developed by Orthodox missionaries for the Finnic and Turkic peoples of Idel-Ural (Mari, Udmurt, Mordva, Chuvash, and Kerashen Tatars) in the 1870s. Later, such alphabets were created for some of the Siberian and Caucasus peoples who had recently converted to Christianity. In the 1930s, some of those languages were switched to the Uniform Turkic Alphabet. All of the peoples of the former Soviet Union who had been using an Arabic or other Asian script (Mongolian script etc.) also adopted Cyrillic alphabets, and during the Great Purge in the late 1930s, all of the Latin alphabets of the peoples of the Soviet Union were switched to Cyrillic as well (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were occupied and annexed by Soviet Union in 1940, and were not affected by this change). The Abkhazian and Ossetian languages were switched to Georgian script, but after the death of Joseph Stalin, both also adopted Cyrillic. The last language to adopt Cyrillic was the Gagauz language, which had used Greek script before.

In Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, the use of Cyrillic to write local languages has often been a politically controversial issue since the collapse of the Soviet Union, as it evokes the era of Soviet rule and Russification. Some of Russia’s peoples such as the Tatars have also tried to drop Cyrillic, but the move was halted under Russian law. A number of languages have switched from Cyrillic to either a Roman-based orthography or a return to a former script.

Cyrillic alphabets continue to be used in several Slavic (Russian, Ukrainian, Serbian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Belarusian) and non-Slavic (Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tajik, Azeri, Gagauz, Turkmen, Mongolian) languages.

Common letters[edit]

The following table lists the Cyrillic letters which are used in the alphabets of most of the national languages which use a Cyrillic alphabet. Exceptions and additions for particular languages are noted below.

| Upright | Italic | Name(s) | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| А а | А а | A | /a/ |

| Б б | Б б | Be | /b/ |

| В в | В в | Ve | /v/ |

| Г г | Г г | Ge | /ɡ/ |

| Д д | Д д | De | /d/ |

| Е е | Е е |

|

|

| Ж ж | Ж ж |

|

/ʒ/ |

| З з | З з | Ze | /z/ |

| И и | И и | I |

|

| Й й | Й й | Short I[a] | /j/ |

| К к | К к | Ka | /k/ |

| Л л | Л л | El | /l/ |

| М м | М м | Em | /m/ |

| Н н | Н н |

|

/n/ |

| О о | О о | O | /o/ |

| П п | П п | Pe | /p/ |

| Р р | Р р |

|

/r/ |

| С с | С с | Es | /s/ |

| Т т | Т т | Te | /t/ |

| У у | У у | U | /u/ |

| Ф ф | Ф ф |

|

/f/ |

| Х х | Х х |

|

/x/ |

| Ц ц | Ц ц |

|

|

| Ч ч | Ч ч |

|

|

| Ш ш | Ш ш |

|

/ʃ/ |

| Щ щ | Щ щ |

|

[b] |

| Ь ь | Ь ь |

|

/ʲ/[e] |

| Э э | Э э | E | /e/ |

| Ю ю | Ю ю |

|

|

| Я я | Я я |

|

|

- ^ Russian: и краткое, i kratkoye; Bulgarian: и кратко, i kratko. Both mean «short i».

- ^ See the notes for each language for details

- ^ Russian: мягкий знак, myagkiy znak

- ^ Bulgarian: ер малък, er malâk

- ^ The soft sign ⟨ь⟩ usually does not represent a sound, but modifies the sound of the preceding letter, indicating palatalization («softening»), also separates the consonant and the following vowel. Sometimes it does not have phonetic meaning, just orthographic; e.g. Russian туш, tush [tuʂ] ‘flourish after a toast’; тушь, tushʹ [tuʂ] ‘India ink’. In some languages, a hard sign ⟨ъ⟩ or apostrophe ⟨’⟩ just separates the consonant and the following vowel (бя [bʲa], бья [bʲja], бъя = б’я [bja]).

Slavic languages[edit]

Cyrillic alphabets used by Slavic languages can be divided into two categories:

- East South Slavic languages and East Slavic languages, such as Bulgarian and Russian, share common features such as Й, ь, and я.

- West South Slavic languages, such as all varieties of Serbo-Croatian, share common features such as Ј and љ.

East Slavic[edit]

Russian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф |

| Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Yo (Ё ё) /jo/

- The Hard Sign¹ (Ъ ъ) indicates no palatalization²

- Yery (Ы ы) indicates [ɨ] (an allophone of /i/)

- E (Э э) /e/

- Ж and Ш indicate sounds that are retroflex

Notes:

- In the pre-reform Russian orthography, in Old East Slavic and in Old Church Slavonic the letter is called yer. Historically, the «hard sign» takes the place of a now-absent vowel, which is still preserved as a distinct vowel in Bulgarian (which represents it with ъ) and Slovene (which is written in the Latin alphabet and writes it as e), but only in some places in the word.

- When an iotated vowel (vowel whose sound begins with [j]) follows a consonant, the consonant is palatalized. The Hard Sign indicates that this does not happen, and the [j] sound will appear only in front of the vowel. The Soft Sign indicates that the consonant should be palatalized in addition to a [j] preceding the vowel. The Soft Sign also indicates that a consonant before another consonant or at the end of a word is palatalized. Examples: та ([ta]); тя ([tʲa]); тья ([tʲja]); тъя ([tja]); т (/t/); ть ([tʲ]).

Before 1918, there were four extra letters in use: Іі (replaced by Ии), Ѳѳ (Фита «Fita», replaced by Фф), Ѣѣ (Ять «Yat», replaced by Ее), and Ѵѵ (ижица «Izhitsa», replaced by Ии); these were eliminated by reforms of Russian orthography.

Belarusian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | (Ґ ґ) | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | І і | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ў ў | Ф ф |

| Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | ‘ |

The Belarusian alphabet displays the following features:

- He (Г г) represents a voiced velar fricative /ɣ/.

- Yo (Ё ё) /jo/

- I (І і), also known as the dotted I or decimal I, resembles the Latin letter I. Unlike Russian and Ukrainian, «И» is not used.

- Short I (Й й), however, uses the base И glyph.

- Short U (Ў ў) is the letter У with a breve and represents /w/, or like the u part of the diphthong in loud. The use of the breve to indicate a semivowel is analogous to the Short I (Й).

- A combination of Sh and Ch (ШЧ шч) is used where those familiar only with Russian and or Ukrainian would expect Shcha (Щ щ).

- Yery (Ы ы) /ɨ/

- E (Э э) /ɛ/

- An apostrophe (’) is used to indicate depalatalization[clarification needed] of the preceding consonant. This orthographical symbol used instead of the traditional Cyrillic letter Yer (Ъ), also known as the hard sign.

- The letter combinations Dzh (Дж дж) and Dz (Дз дз) appear after D (Д д) in the Belarusian alphabet in some publications. These digraphs represent consonant clusters Дж /dʒ/ and Дз /dz/ correspondingly.

- Before 1933, the letter Ґ ґ (Ge) was used.

Ukrainian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ґ ґ | Д д | Е е | Є є | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| І і | Ї ї | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ь ь | Ю ю | Я я |

The Ukrainian alphabet displays the following features:

- Ve (В) represents /ʋ/ (which may be pronounced [w] in a word final position and before consonants).

- He (Г, г) represents a voiced glottal fricative, (/ɦ/).

- Ge (Ґ, ґ) appears after He, represents /ɡ/. It looks like He with an «upturn» pointing up from the right side of the top bar. (This letter was removed in Soviet Ukraine in 1933–1990, so it may be missing from older Cyrillic fonts.)

- E (Е, е) represents /ɛ/.

- Ye (Є, є) appears after E, represents /jɛ/.

- E, И (И, и) represent /ɪ/ if unstressed.

- I (І, і) appears after Y, represents /i/.

- Yi (Ї, ї) appears after I, represents /ji/.

- Yy (Й, й) represents /j/.

- Shcha (Щ, щ) represents /ʃtʃ/.

- An apostrophe (’) is used to mark nonpalatalization of the preceding consonant before Ya (Я, я), Yu (Ю, ю), Ye (Є, є), Yi (Ї, ї).

- As in Belarusian Cyrillic, the sounds /dʒ/, /dz/ are represented by digraphs Дж and Дз respectively.

Rusyn[edit]

The Rusyn language is spoken by the Carpatho-Rusyns in Carpathian Ruthenia, Slovakia, and Poland, and the Pannonian Rusyns in Croatia and Serbia.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ґ ґ | Д д | Е е | Є є | Ё ё* | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | І і* | Ы ы* | Ї ї | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п |

| Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ѣ ѣ* |

| Э э* | Ю ю | Я я | Ь ь | Ъ ъ* |

The Rusyn Alphabet makes the Following Rules:

Є (Ё)

І (Ы)

Щ (Ѣ)

Ь (Э)

Ъ is the last letter.

Ї = /ɪ̈/

Є = /ɪ̈ɛ/

Ѣ = /jɨ/

*Letters absent from Pannonian Rusyn.

South Slavic[edit]

Bosnian[edit]

Bulgarian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ь ь | Ю ю | Я я |

The Bulgarian alphabet features:

- The Bulgarian names for the consonants are [bɤ], [kɤ], [ɫɤ] etc. instead of [bɛ], [ka], [ɛl] etc.

- Е represents /ɛ/ and is called «е» [ɛ].

- The sounds /dʒ/ (/d͡ʒ/) and /dz/ (/d͡z/) are represented by дж and дз respectively.

- Yot (Й, й) represents /j/.

- Щ represents /ʃt/ (/ʃ͡t/) and is called «щъ» [ʃtɤ] ([ʃ͡tɤ]).

- Ъ represents the vowel /ɤ/, and is called «ер голям» [ˈɛr ɡoˈljam] (‘big er’). In spelling however, Ъ is referred to as /ɤ/ where its official label «ер голям» (used only to refer to Ъ in the alphabet) may cause some confusion. The vowel Ъ /ɤ/ is sometimes approximated to the /ə/ (schwa) sound found in many languages for easier comprehension of its Bulgarian pronunciation for foreigners, but it is actually a back vowel, not a central vowel.[citation needed]

- Ь is used on rare occasions (only after a consonant [and] before the vowel «о»), such as in the words ‘каньон’ (canyon), ‘шофьор’ (driver), etc. It is called «ер малък» (‘small er’).

The Cyrillic alphabet was originally developed in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 9th – 10th century AD at the Preslav Literary School.[2][3]

It has been used in Bulgaria (with modifications and exclusion of certain archaic letters via spelling reforms) continuously since then, superseding the previously used Glagolitic alphabet, which was also invented and used there before the Cyrillic script overtook its use as a written script for the Bulgarian language. The Cyrillic alphabet was used in the then much bigger territory of Bulgaria (including most of today’s Serbia), North Macedonia, Kosovo, Albania, Northern Greece (Macedonia region), Romania and Moldova, officially from 893. It was also transferred from Bulgaria and adopted by the East Slavic languages in Kievan Rus’ and evolved into the Russian alphabet and the alphabets of many other Slavic (and later non-Slavic) languages. Later, some Slavs modified it and added/excluded letters from it to better suit the needs of their own language varieties.

Croatian[edit]

Historically, the Croatian language briefly used the Cyrillic script in areas with large Croatian language or Bosnian language populations.[4]

Serbian[edit]

Alternate variants of lowercase Cyrillic letters: Б/б, Д/д, Г/г, И/и, П/п, Т/т, Ш/ш.

Default Russian (Eastern) forms on the left.

Alternate Bulgarian (Western) upright forms in the middle.

Alternate Serbian/Macedonian (Southern) italic forms on the right.

See also:

South Slavic Cyrillic alphabets (with the exception of Bulgarian) are generally derived from Serbian Cyrillic. It, and by extension its descendants, differs from the East Slavic ones in that the alphabet has generally been simplified: Letters such as Я, Ю, and Ё, representing /ja/, /ju/, and /jo/ in Russian, respectively, have been removed. Instead, these are represented by the digraphs ⟨ја⟩, ⟨јu⟩, and ⟨јо⟩, respectively. Additionally, the letter Е, representing /je/ in Russian, is instead pronounced /e/ or /ɛ/, with /je/ being represented by ⟨јe⟩. Alphabets based on the Serbian that add new letters often do so by adding an acute accent ⟨´⟩ over an existing letter.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ђ ђ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | Ћ ћ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Serbian alphabet shows the following features:

- E represents /ɛ/.

- Between Д and E is the letter Dje (Ђ, ђ), which represents /dʑ/, and looks like Tshe, except that the loop of the h curls farther and dips downwards.

- Between И and К is the letter Je (Ј, ј), represents /j/, which looks like the Latin letter J.

- Between Л and М is the letter Lje (Љ, љ), representing /ʎ/, which looks like a ligature of Л and the Soft Sign.

- Between Н and О is the letter Nje (Њ, њ), representing /ɲ/, which looks like a ligature of Н and the Soft Sign.

- Between Т and У is the letter Tshe (Ћ, ћ), representing /tɕ/ and looks like a lowercase Latin letter h with a bar. On the uppercase letter, the bar appears at the top; on the lowercase letter, the bar crosses the top at half of the vertical line.

- Between Ч and Ш is the letter Dzhe (Џ, џ), representing /dʒ/, which looks like Tse but with the descender moved from the right side of the bottom bar to the middle of the bottom bar.

- Ш is the last letter.

- Certain letters are handwritten differently,[5] as seen in the adjacent image.

Macedonian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ѓ ѓ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | Ѕ ѕ | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | Ќ ќ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Macedonian alphabet differs from Serbian in the following ways:

- Between Ze (З з) and I (И и) is the letter Dze (Ѕ ѕ), which looks like the Latin letter S and represents /d͡z/.

- Dje (Ђ ђ) is replaced by Gje (Ѓ ѓ), which represents /ɟ/ (voiced palatal stop). In some dialects, it represents /d͡ʑ/ instead, like Dje. It is written ⟨Ǵ ǵ⟩ in the corresponding Macedonian Latin alphabet.

- Tshe (Ћ ћ) is replaced by Kje (Ќ ќ), which represents /c/ (voiceless palatal stop). In some dialects, it represents /t͡ɕ/ instead, like Tshe. It is written ⟨Ḱ ḱ⟩ in the corresponding Macedonian Latin alphabet.

- Lje (Љ љ) often represents the consonant cluster /lj/ instead of /ʎ/.

- Certain letters are handwritten differently, as seen in the adjacent image.[6]

Montenegrin[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ђ ђ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | З́ з́ | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| С́ с́ | Т т | Ћ ћ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Montenegrin alphabet differs from Serbian in the following ways:

- Between Ze (З з) and I (И и) is the letter З́, which represents /ʑ/ (voiced alveolo-palatal fricative). It is written ⟨Ź ź⟩ in the corresponding Montenegrin Latin alphabet, previously written ⟨Zj zj⟩ or ⟨Žj žj⟩.

- Between Es (С с) and Te (Т т) is the letter С́, which represents /ɕ/ (voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative). It is written ⟨Ś ś⟩ in the corresponding Montenegrin Latin alphabet, previously written ⟨Sj sj⟩ or ⟨Šj šj⟩.

- The letter Dze (Ѕ ѕ), from Macedonian, is used in scientific literature when representing the /d͡z/ phoneme, although it is not officially part of the alphabet. A Latin equivalent was proposed that looks identical to Ze (З з).

Uralic languages[edit]

Uralic languages using the Cyrillic script (currently or in the past) include:

- Finnic: Karelian until 1921 and 1937–1940 (Ludic, Olonets Karelian); Veps; Votic

- Kildin Sami in Russia (since the 1980s)

- Komi (Zyrian (since the 17th century, modern alphabet since the 1930s); Permyak; Yodzyak)

- Udmurt

- Khanty

- Mansi (writing has not received distribution since 1937)

- Samoyedic: Enets; Yurats; Nenets since 1937 (Forest Nenets; Tundra Nenets); Nganasan; Kamassian; Koibal; Mator; Selkup (since the 1950s; not used recently)

- Mari, since the 19th century (Hill; Meadow)

- Mordvin, since the 18th century (Erzya; Moksha)

- Other: Merya; Muromian; Meshcherian

Karelian[edit]

The first lines of the Book of Matthew in Karelian using the Cyrillic script, 1820

The Karelian language was written in the Cyrillic script in various forms until 1940 when publication in Karelian ceased in favor of Finnish, except for Tver Karelian, written in a Latin alphabet. In 1989 publication began again in the other Karelian dialects and Latin alphabets were used, in some cases with the addition of Cyrillic letters such as ь.

Kildin Sámi[edit]

Over the last century, the alphabet used to write Kildin Sámi has changed three times: from Cyrillic to Latin and back again to Cyrillic. Work on the latest version of the official orthography commenced in 1979. It was officially approved in 1982 and started to be widely used by 1987.[7]

Komi-Permyak[edit]

The Komi-Permyak Cyrillic alphabet:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё |

| Ж ж | З з | И и | I i | Й й | К к | Л л |

| М м | Н н | О о | Ӧ ӧ | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш |

| Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Mari alphabets[edit]

Meadow Mari Cyrillic alphabet:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ҥ ҥ | О о | Ӧ ӧ | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӱ ӱ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ |

| Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Hill Mari Cyrillic alphabet

| А а | Ӓ ӓ | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ӧ ӧ | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӱ ӱ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ |

| Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ӹ ӹ | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Non-Slavic Indo-European languages[edit]

Iranian languages[edit]

Kurdish[edit]

Kurds in the former Soviet Union use a Cyrillic alphabet:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Г’ г’ | Д д | Е е |

| Ә ә | Ә’ ә’ | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| К’ к’ | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ö ö | П п |

| П’ п’ | Р р | Р’ р’ | С с | Т т | Т’ т’ | У у |

| Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Һ’ һ’ | Ч ч | Ч’ ч’ | Ш ш |

| Щ щ | Ь ь | Э э | Ԛ ԛ | Ԝ ԝ |

Ossetian[edit]

The Ossetic language has officially used the Cyrillic script since 1937.

| А а | Ӕ ӕ | Б б | В в | Г г | Гъ гъ | Д д | Дж дж |

| Дз дз | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Къ къ | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Пъ пъ | Р р |

| С с | Т т | Тъ тъ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Хъ хъ | Ц ц |

| Цъ цъ | Ч ч | Чъ чъ | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь |

| Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Tajik[edit]

The Tajik alphabet is written using a Cyrillic-based alphabet.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ғ ғ | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| Ӣ ӣ | Й й | К к | Қ қ | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | У у | Ӯ ӯ | Ф ф | Х х | Ҳ ҳ | Ч ч | Ҷ ҷ | Ш ш | Ъ ъ | Э э |

| Ю ю | Я я |

Other[edit]

- Shughni

- Tat

- Judeo-Tat

- Yaghnobi

- Yazghulami

Romance languages[edit]

Romanian Cyrillic alphabet

- Romanian (up to the 19th century; see Romanian Cyrillic alphabet).

- The Moldovan language (an alternative name of the Romanian language in Bessarabia, Moldavian ASSR, Moldavian SSR and Moldova) used varieties of the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet in 1812–1918, and the Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet (derived from the Russian alphabet and standardised in the Soviet Union) in 1924–1932 and 1938–1989. Nowadays, this alphabet is still official in the unrecognized republic of Transnistria (see Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet).

- Ladino in occasional Bulgarian Sephardic publications.

Indo-Aryan[edit]

Romani[edit]

Romani is written in Cyrillic in Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and the former USSR.

Mongolian[edit]

The Mongolic languages include Khalkha (in Mongolia; Cyrillic is official since 1941, in practice from 1946), Buryat (around Lake Baikal; Cyrillic is used since the 1930s) and Kalmyk (northwest of the Caspian Sea; Cyrillic is used in various forms since the 1920-30s). Khalkha Mongolian is also written with the Mongol vertical alphabet, which was the official script before 1941.[8] Since the beginning of the 1990s Mongolia has been making attempts to extend the rather limited use of Mongol script and the most recent National Plan for Mongol Script aims to bring its use to the same level as Cyrillic by 2025 and maintain a dual-script system (digraphia).[9]

Overview[edit]

This table contains all the characters used.

Һһ is shown twice as it appears at two different locations in Buryat and Kalmyk

| Mongolian | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buryat | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | ||||

| Kalmyk | Аа | Әә | Бб | Вв | Гг | Һһ | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Җҗ | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Ңң | Оо |

| Khalk-Mongolia | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Фф | Хх | Цц | Чч | Шш | Щщ | Ъъ | Ыы | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя | |

| Buryat | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Фф | Хх | Һһ | Цц | Чч | Шш | Щщ | Ъъ | Ыы | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя |

| Kalmyk | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Фф | Хх | Цц | Чч | Шш | Щщ | Ъъ | ЫЫ | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя |

Khalkha[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э |

| Ю ю | Я я |

- В в = /w/

- Е е = /jɛ/, /jœ/

- Ё ё = /jo/

- Ж ж = /dʒ/

- З з = /dz/

- Ий ий = /iː/

- Й й = the second element of closing diphthongs (ай, ой, etc.) and long /iː/ (ий), it never indicates /j/ in native words

- Н н = /n-/, /-ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- У у = /ʊ/

- Ү ү = /u/

- Ы ы = /iː/ (in suffixes after a hard consonant)

- Ь ь = palatalization of the preceding consonant

- Ю ю = /ju/, /jy/

Long vowels are indicated with double letters. The Cyrillic letters Кк, Пп, Фф and Щщ are not used in native Mongolian words, but only for Russian or other loans (Пп may occur in native onomatopoeic words).

Buryat[edit]

The Buryat (буряад) Cyrillic script is similar to the Khalkha above, but Ьь indicates palatalization as in Russian. Buryat does not use Вв, Кк, Пп, Фф, Цц, Чч, Щщ or Ъъ in its native words (Пп may occur in native onomatopoeic words).

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү |

| Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Е е = /jɛ/, /jœ/

- Ё ё = /jo/

- Ж ж = /dʒ/

- Й й = the second element of closing diphthongs (ай, ой, etc.), it never indicates /j/ in native words

- Н н = /n-/, /-ŋ/

- Өө өө = /œː/, ө does not occur in short form in literary Buryat based on the Khori dialect

- У у = /ʊ/

- Ү ү = /u/

- Һ һ = /h/

- Ы ы = /ei/, /iː/

- Ю ю = /ju/

Kalmyk[edit]

The Kalmyk (хальмг) Cyrillic script differs from Khalkha in some respects: there are additional letters (Әә, Җҗ, Ңң), letters Ээ, Юю and Яя appear only word-initially, long vowels are written double in the first syllable (нөөрин), but single in syllables after the first. Short vowels are omitted altogether in syllables after the first syllable (хальмг = /xaʎmaɡ/). Жж and Пп are used in loanwords only (Russian, Tibetan, etc.), but Пп may occur in native onomatopoeic words.

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Һ һ | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | Җ җ | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю |

| Я я |

- Ә ә = /æ/

- В в = /w/

- Һ һ = /ɣ/

- Е е = /ɛ/, /jɛ-/

- Җ җ = /dʒ/

- Ң ң = /ŋ/

- Ө ө = /ø/

- У у = /ʊ/

- Ү ү = /u/

Caucasian languages[edit]

Northwest Caucasian languages[edit]

Living Northwest Caucasian languages are generally written using Cyrillic alphabets.

Abkhaz[edit]

Abkhaz is a Caucasian language, spoken in the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, Georgia.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Гь гь | Ӷ ӷ | Ӷь ӷь | Д д | Дә дә | Е е | |

| Ж ж | Жь жь | Жә жә | З з | Ӡ ӡ | Ӡә ӡә | И и | Й й | К к | Кь кь | |

| Қ қ | Қь қь | Ҟ ҟ | Ҟь ҟь | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Ԥ ԥ | Ҧ ҧ |

| Р р | С с | Т т | Тә тә | Ҭ ҭ | Ҭә ҭә | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Хь хь | |

| Ҳ ҳ | Ҳә ҳә | Ц ц | Цә цә | Ҵ ҵ | Ҵә ҵә | Ч ч | Ҷ ҷ | Ҽ ҽ | Ҿ ҿ | |

| Ш ш | Шь шь | Шә шә | Ы ы | Ҩ ҩ | Џ џ | Џь џь | Ь ь | Ә ә |

Other[edit]

- Abaza

- Adyghe

- Kabardian

Northeast Caucasian languages[edit]

Northeast Caucasian languages are generally written using Cyrillic alphabets.

Avar[edit]

Avar is a Caucasian language, spoken in the Republic of Dagestan, of the Russian Federation, where it is co-official together with other Caucasian languages like Dargwa, Lak, Lezgian and Tabassaran. All these alphabets, and other ones (Abaza, Adyghe, Chechen, Ingush, Kabardian) have an extra sign: palochka (Ӏ), which gives voiceless occlusive consonants its particular ejective sound.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Гъ гъ | Гь гь | Гӏ гӏ | Д д |

| Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к | Къ къ |

| Кь кь | Кӏ кӏ | Кӏкӏ кӏкӏ | Кк кк | Л л | М м | Н н | О о |

| П п | Р р | С с | Т т | Тӏ тӏ | У у | Ф ф | Х х |

| Хх хх | Хъ хъ | Хь хь | Хӏ хӏ | Ц ц | Цц цц | Цӏ цӏ | Цӏцӏ цӏцӏ |

| Ч ч | Чӏ чӏ | Чӏчӏ чӏчӏ | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь |

| Э э | Ю ю | Я я | Ӏ |

- В = /w/

- гъ = /ʁ/

- гь = /h/

- гӀ = /ʕ/

- къ = /qːʼ/

- кӀ = /kʼ/

- кь = /t͡ɬːʼ/

- кӀкӀ = /t͡ɬː/, is also written ЛӀ лӀ.

- кк = /ɬ/, is also written Лъ лъ.

- тӀ = /tʼ/

- х = /χ/

- хъ = /qː/

- хь = /x/

- хӀ = /ħ/

- цӀ = /t͡sʼ/

- чӀ = /t͡ʃʼ/

- Double consonants, called «fortis», are pronounced longer than single consonants (called «lenis»).

Lezgian[edit]

Lezgian is spoken by the Lezgins, who live in southern Dagestan and northern Azerbaijan. Lezgian is a literary language and an official language of Dagestan.

Other[edit]

- Chechen (since 1938, also with Roman 1991–2000, but switch back to Cyrillic alphabets since 2001.)

- Dargwa

- Lak

- Tabassaran

- Ingush

- Archi

Turkic languages[edit]

Azerbaijani[edit]

| First version (1939–1958): | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Ғғ | Дд | Ее | Әә | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Ҝҝ | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Фф | Хх | Һһ | Цц | Чч | Ҹҹ | Шш | Ыы | Ээ | Юю | Яя | ʼ | |

| Second version (1958–1991): still used today by Dagestan |

Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Ғғ | Дд | Ее | Әә | Жж | Зз | Ии | Ыы | Јј | Кк | Ҝҝ | Лл | Мм | Нн | |

| Оо | Өө | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Үү | Фф | Хх | Һһ | Чч | Ҹҹ | Шш | ʼ |

- Latin Alphabet (as of 1992)

- Aa, Bb, Cc, Çç, Dd, Ee, Əə, Ff, Gg, Ğğ, Hh, Iı, İi, Jj, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Oo, Öö, Pp, Qq, Rr, Ss, Şş, Tt, Uu, Üü, Vv, (Ww), Xx, Yy, Zz

Bashkir[edit]

The Cyrillic script was used for the Bashkir language after the winter of 1938.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ғ ғ | Д д | Ҙ ҙ | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Ҡ ҡ | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п |

| Р р | С с | Ҫ ҫ | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч |

| Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ә ә | Ю ю | Я я |

Chuvash[edit]

The Cyrillic alphabet is used for the Chuvash language since the late 19th century, with some changes in 1938.

| А а | Ӑ ӑ | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ӗ ӗ | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Ҫ ҫ |

| Т т | У у | Ӳ ӳ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Kazakh[edit]

Kazakh can be alternatively written in the Latin alphabet. Latin is going to be the only used alphabet in 2022, alongside the modified Arabic alphabet (in the People’s Republic of China, Iran and Afghanistan).

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Ғ ғ | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | Й й | К к | Қ қ | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п |

| Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ұ ұ | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч |

| Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | І і | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Ә ә = /æ/

- Ғ ғ = /ʁ/ (voiced uvular fricative)

- Е е = /jɪ/

- И и = /ɪj/, /ɘj/

- Қ қ = /q/ (voiceless uvular plosive)

- Ң ң = /ŋ/, /ɴ/

- О о = /o/, /ʷo/, /ʷʊ/

- Ө ө = /œ/, /ʷœ/, /ʷʏ/

- У у = /ʊw/, /ʉw/, /w/

- Ұ ұ = /ʊ/

- Ү ү = /ʉ/, /ʏ/

- Һ һ = /h/

- Ы ы = /ɯ/, /ә/

- І і = /ɪ/, /ɘ/

The Cyrillic letters Вв, Ёё, Цц, Чч, Щщ, Ъъ, Ьь and Ээ are not used in native Kazakh words, but only for Russian loans.

Kyrgyz[edit]

Kyrgyz has also been written in Latin and in Arabic.

| А а | Б б | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ү ү | Х х | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Ң ң = /ŋ/ (velar nasal)

- Ү ү = /y/ (close front rounded vowel)

- Ө ө = /œ/ (open-mid front rounded vowel)

Tatar[edit]

Tatar has used Cyrillic since 1939, but the Russian Orthodox Tatar community has used Cyrillic since the 19th century. In 2000 a new Latin alphabet was adopted for Tatar, but it is used generally on the Internet.

| А а | Ә ә | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | Җ җ |

| З з | И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө |

| П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц |

| Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Ә ә = /æ/

- Ң ң = /ŋ/

- Ө ө = /œ/

- У у = /uw/, /yw/, /w/

- Ү ү = /y/

- Һ һ = /h/

- Җ җ = /ʑ/

The Cyrillic letters Ёё, Цц, Щщ are not used in native Tatar words, but only for Russian loans.

Turkmen[edit]

Turkmen, written 1940–1994 exclusively in Cyrillic, since 1994 officially in Roman, but in everyday communication Cyrillic is still used along with Roman script.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | Җ җ | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | (Ц ц) | Ч ч | Ш ш | (Щ щ) | (Ъ ъ) | Ы ы | (Ь ь) | Э э | Ә ә |

| Ю ю | Я я |

- Latin alphabet version 2

- Aa, Ää, Bb, (Cc), Çç, Dd, Ee, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Ňň, Oo, Öö, Pp, (Qq), Rr, Ss, Şş, Tt, Uu, Üü, (Vv), Ww, (Xx), Yy, Ýý, Zz, Žž

- Latin alphabet version 1

- Aa, Bb, Çç, Dd, Ee, Êê, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Žž, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Ññ, Oo, Ôô, Pp, Rr, Ss, Şş, Tt, Uu, Ûû, Ww, Yy, Ýý, Zz

Uzbek[edit]

From 1941 the Cyrillic script was used exclusively. In 1998 the government has adopted a Latin alphabet to replace it. The deadline for making this transition has however been repeatedly changed, and Cyrillic is still more common. It is not clear that the transition will be made at all.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й | К к |

| Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ч ч |

| Ш ш | Ъ ъ | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | Ў ў | Қ қ | Ғ ғ | Ҳ ҳ |

- В в = /w/

- Ж ж = /dʒ/

- Ф ф = /ɸ/

- Х х = /χ/

- Ъ ъ = /ʔ/

- Ў ў = /ө/

- Қ қ = /q/

- Ғ ғ = /ʁ/

- Ҳ ҳ = /h/

Other[edit]

- Altai

- Crimean Tatar (1938–1991, now mostly replaced by Roman)

- Gagauz (1957–1990s, exclusively in Cyrillic, since 1990s officially in Roman, but in reality in everyday communication Cyrillic is used along with Roman script)

- Karachay-Balkar

- Karakalpak (1940s–1990s)

- Karaim (20th century)

- Khakas

- Kumyk

- Nogai

- Tuvan

- Uyghur – Uyghur Cyrillic alphabet (Uyghur Siril Yëziqi). Used along with Uyghur Arabic alphabet (Uyghur Ereb Yëziqi), New Script (Uyghur Yëngi Yëziqi, Pinyin-based), and modern Uyghur Latin alphabet (Uyghur Latin Yëziqi).

- Yakut

- Dolgan

- Balkan Gagauz Turkish

- Urum

- Siberian Tatar

- Siberian Turkic

Sinitic[edit]

Dungan language[edit]

Since 1953.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ә ә | Ж ж | Җ җ | З з | И и |

| Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ў ў | Ү ү | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э |

| Ю ю | Я я |

- Letters in bold are used only in Russian loanwords.

Tungusic languages[edit]

- Even

- Evenk (since 1937)

- Nanai

- Udihe (Udekhe) (not used recently)

- Orok (since 2007)

- Ulch (since late 1980s)

Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages[edit]

- Chukchi (since 1936)

- Koryak (since 1936)

- Itelmen (since late 1980s)

- Alyutor

Languages of North America[edit]

- Aleut (Bering dialect)

- Naukan Yupik

- Central Siberian Yupik

- Chaplino dialect

| А а | А̄ а̄ | Б б | В в | Г г | Ӷ ӷ | Гў гў | Д д | Д̆ д̆ | Е е | Е̄ е̄ | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Ӣ ӣ |

| Й й | ʼЙ ʼй | К к | Ӄ ӄ | Л л | ʼЛ ʼл | М м | ʼМ ʼм | Н н | ʼН ʼн | Ӈ ӈ | ʼӇ ʼӈ | О о | О̄ о̄ | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӯ ӯ | Ф ф | Х х | Ӽ ӽ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ы̄ ы̄ | Ь ь | Э э |

| Э̄ э̄ | Ю ю | Ю̄ ю̄ | Я я | Я̄ я̄ | ʼ | ʼЎ ʼў |

Other languages[edit]

- Ainu (in Russia)

- Assyrian Neo-Aramaic (Aisor)

- Ket (since 1980s)

- Nivkh

- Tlingit (in Russian Alaska)

- Yukaghirs (Tundra Yukaghir, Forest Yukaghir)

Constructed languages[edit]

- International auxiliary languages

- Interslavic

- Lingua Franca Nova

- Fictional languages

- Brutopian (Donald Duck stories)

- Syldavian (The Adventures of Tintin)

Summary table[edit]

Here are the Letters.

| The Cyrillic script | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slavic letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-Slavic letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Archaic or unused letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Early scripts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Church Slavonic | А | Б | В | Г | Д | (Ѕ) | Е | Ж | Ѕ/З | И | І | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | Оу | (Ѡ) | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ѣ | Ь | Ю | Ꙗ | Ѥ | Ѧ | Ѩ | Ѫ | Ѭ | Ѯ | Ѱ | Ѳ | Ѵ | Ҁ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most common shared letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ь | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| South Slavic languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulgarian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Дж | Дз | Е | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ь | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Macedonian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Ѓ | Ѕ | Е | Ж | З | И | Ј | К | Л | Љ | М | Н | Њ | О | П | Р | С | Т | Ќ | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Џ | Ш | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serbian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Ђ | Е | Ж | З | И | Ј | К | Л | Љ | М | Н | Њ | О | П | Р | С | Т | Ћ | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Џ | Ш | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Montenegrin | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Ђ | Е | Ж | З | З́ | И | Ј | К | Л | Љ | М | Н | Њ | О | П | Р | С | С́ | Т | Ћ | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Џ | Ш | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| East Slavic languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Belarusian | А | Б | В | Г | Ґ | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | І | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ў | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | ’ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ukrainian | А | Б | В | Г | Ґ | Д | Е | Є | Ж | З | И | І | Ї | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | ’ | Ь | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rusyn | А | Б | В | Г | Ґ | Д | Е | Є | Ё | Ж | З | И | І | Ы | Ї | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ѣ | Ь | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iranian languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kurdish | А | Б | В | Г | Г’ | Д | Е | Ә | Ә’ | Ж | З | И | Й | К | К’ | Л | М | Н | О | Ö | П | П’ | Р | Р’ | С | Т | Т’ | У | Ф | Х | Һ | Һ’ | Ч | Ч’ | Ш | Щ | Ь | Э | Ԛ | Ԝ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ossetian | А | Ӕ | Б | В | Г | Гъ | Д | Дж | Дз | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Къ | Л | М | Н | О | П | Пъ | Р | С | Т | Тъ | У | Ф | Х | Хъ | Ц | Цъ | Ч | Чъ | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tajik | А | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Ӣ | Й | К | Қ | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ӯ | Ф | Х | Ҳ | Ч | Ҷ | Ш | Ъ | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romance languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Moldovan | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ж | Ӂ | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uralic languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Komi-Permyak | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | І | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | Ӧ | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Meadow Mari | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ҥ | О | Ӧ | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ӱ | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hill Mari | А | Ӓ | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | Ӧ | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ӱ | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ӹ | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kildin Sami | А | Ӓ | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | Ҋ | Ј | К | Л | Ӆ | М | Ӎ | Н | Ӊ | Ӈ | О | П | Р | Ҏ | С | Т | У | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Ҍ | Э | Ӭ | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turkic languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Azerbaijani | А | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Е | Ә | Ё | Ж | З | Ы | И | Ј | Й | К | Ҝ | Л | М | Н | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ҹ | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bashkir | А | Ә | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Ҙ | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Ҡ | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Ҫ | Т | У | Ү | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ә | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chuvash | А | Ӑ | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ӗ | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Ҫ | Т | У | Ӳ | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakh | А | Ә | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | І | Й | К | Қ | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ұ | Ү | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyrgyz | А | Б | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Х | Ч | Ш | Ы | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tatar | А | Ә | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | Җ | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Ф | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uzbek | А | Б | В | Г | Ғ | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Қ | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ў | Ф | Х | Ҳ | Ч | Ш | Ъ | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Buryat | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | Л | М | Н | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Х | Һ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khalkha | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kalmyk | А | Ә | Б | В | Г | Һ | Д | Е | Ж | Җ | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ң | О | Ө | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ү | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Ь | Э | Ю | Я | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abkhaz | А | Б | В | Г | Ҕ | Д | Дә | Џ | Е | Ҽ | Ҿ | Ж | Жә | З | Ӡ Ӡә | И | Й | К | Қ | Ҟ | Л | М | Н | О | Ҩ | П | Ҧ | Р | С | Т Тә | Ҭ Ҭә | У | Ф | Х | Ҳ Ҳә | Ц Цә | Ҵ Ҵә | Ч | Ҷ | Ш Шә | Щ | Ы | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sino-Tibetan languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dungan | А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ё | Ж | Җ | З | И | Й | К | Л | М | Н | Ң | Ә | О | П | Р | С | Т | У | Ў | Ү | Ф | Х | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | Ы | Ь | Э | Ю | Я |

See also[edit]

- List of Cyrillic letters

- Cyrillic script

- Cyrillic script in Unicode

- Old Church Slavonic

References[edit]

- ^ Šmid (2002), pp. 113–24: «Es interesante el hecho que en Bulgaria se imprimieron unas pocas publicaciones en alfabeto cirílico búlgaro y en Grecia en alfabeto griego… Nezirović (1992: 128) anota que también en Bosnia se ha encontrado un documento en que la lengua sefardí está escrita en alfabeto cirilico.» Translation: «It is an interesting fact that in Bulgaria a few [Sephardic] publications are printed in the Bulgarian Cyrillic alphabet and in Greece in the Greek alphabet… Nezirović (1992:128) writes that in Bosnia a document has also been found in which the Sephardic language is written in the Cyrillic alphabet.»

- ^ Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250, Cambridge Medieval Textbooks, Florin Curta, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521815398, pp. 221–222.

- ^ The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire, Oxford History of the Christian Church, J. M. Hussey, Andrew Louth, Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 0191614882, p. 100.

- ^ «Croats Revive Forgotten Cyrillic Through Stone». January 8, 2013.

- ^ Peshikan, Mitar; Jerković, Jovan; Pižurica, Mato (1994). Pravopis srpskoga jezika. Beograd: Matica Srpska. p. 42. ISBN 86-363-0296-X.

- ^ Pravopis na makedonskiot jazik (PDF). Skopje: Institut za makedonski jazik Krste Misirkov. 2017. p. 3. ISBN 978-608-220-042-2.

- ^ Rießler, Michael. Towards a digital infrastructure for Kildin Saami. In: Sustaining Indigenous Knowledge, ed. by Erich Kasten, Erich and Tjeerd de Graaf. Fürstenberg, 2013, 195–218.

- ^ Veronika, Kapišovská (2005). «Language Planning in Mongolia I». Mongolica Pragensia. 2005: 55–83 – via academia.edu.

- ^ «Монгол бичгийн үндэсний хөтөлбөр III (National Plan for Mongol Script III)». Эрх Зүйн Мэдээллийн Нэгдсэн Систем. 2020. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Ivan G. Iliev. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet. Plovdiv. 2012. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet

- Philipp Ammon: Tractatus slavonicus. in: Sjani (Thoughts) Georgian Scientific Journal of Literary Theory and Comparative Literature, N 17, 2016, pp. 248–56

- Appendix:Cyrillic script, Wiktionary

External links[edit]

- Cyrillic Alphabets of Slavic Languages review of Cyrillic charsets in Slavic Languages.

This article is about the variants of the Cyrillic alphabet. For the writing system as a whole, see Cyrillic script.

Countries with widespread use of the Cyrillic script:

Sole official script

Co-official with another script (either because the official language is biscriptal, or the state is bilingual)

Being replaced with Latin, but is still in official use

Legacy script for the official language, or large minority use

Cyrillic is not widely used

Numerous Cyrillic alphabets are based on the Cyrillic script. The early Cyrillic alphabet was developed in the 9th century AD and replaced the earlier Glagolitic script developed by the Byzantine theologians Cyril and Methodius. It is the basis of alphabets used in various languages, past and present, Slavic origin, and non-Slavic languages influenced by Russian. As of 2011, around 252 million people in Eurasia use it as the official alphabet for their national languages. About half of them are in Russia. Cyrillic is one of the most-used writing systems in the world. The birth place of the Cyrillic alphabet is Bulgaria. The creator is Saint Clement of Ohrid from the Preslav literary school in the First Bulgarian Empire.

Some of these are illustrated below; for others, and for more detail, see the links. Sounds are transcribed in the IPA. While these languages largely have phonemic orthographies, there are occasional exceptions—for example, Russian ⟨г⟩ is pronounced /v/ in a number of words, an orthographic relic from when they were pronounced /ɡ/ (e.g. его yego ‘him/his’, is pronounced [jɪˈvo] rather than [jɪˈɡo]).

Spellings of names transliterated into the Roman alphabet may vary, especially й (y/j/i), but also г (gh/g/h) and ж (zh/j).

Unlike the Latin script, which is usually adapted to different languages by adding diacritical marks/supplementary glyphs (such as accents, umlauts, fadas, tildes and cedillas) to standard Roman letters, by assigning new phonetic values to existing letters (e.g. ⟨c⟩, whose original value in Latin was /k/, represents /ts/ in West Slavic languages, /ʕ/ in Somali, /t͡ʃ/ in many African languages and /d͡ʒ/ in Turkish), or by the use of digraphs (such as ⟨sh⟩, ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ng⟩ and ⟨ny⟩), the Cyrillic script is usually adapted by the creation of entirely new letter shapes. However, in some alphabets invented in the 19th century, such as Mari, Udmurt and Chuvash, umlauts and breves also were used.

Bulgarian and Bosnian Sephardim without Hebrew typefaces occasionally printed Judeo-Spanish in Cyrillic.[1]

Spread[edit]

Non-Slavic alphabets are generally modelled after Russian, but often bear striking differences, particularly when adapted for Caucasian languages. The first few of these alphabets were developed by Orthodox missionaries for the Finnic and Turkic peoples of Idel-Ural (Mari, Udmurt, Mordva, Chuvash, and Kerashen Tatars) in the 1870s. Later, such alphabets were created for some of the Siberian and Caucasus peoples who had recently converted to Christianity. In the 1930s, some of those languages were switched to the Uniform Turkic Alphabet. All of the peoples of the former Soviet Union who had been using an Arabic or other Asian script (Mongolian script etc.) also adopted Cyrillic alphabets, and during the Great Purge in the late 1930s, all of the Latin alphabets of the peoples of the Soviet Union were switched to Cyrillic as well (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were occupied and annexed by Soviet Union in 1940, and were not affected by this change). The Abkhazian and Ossetian languages were switched to Georgian script, but after the death of Joseph Stalin, both also adopted Cyrillic. The last language to adopt Cyrillic was the Gagauz language, which had used Greek script before.

In Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, the use of Cyrillic to write local languages has often been a politically controversial issue since the collapse of the Soviet Union, as it evokes the era of Soviet rule and Russification. Some of Russia’s peoples such as the Tatars have also tried to drop Cyrillic, but the move was halted under Russian law. A number of languages have switched from Cyrillic to either a Roman-based orthography or a return to a former script.

Cyrillic alphabets continue to be used in several Slavic (Russian, Ukrainian, Serbian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Belarusian) and non-Slavic (Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tajik, Azeri, Gagauz, Turkmen, Mongolian) languages.

Common letters[edit]

The following table lists the Cyrillic letters which are used in the alphabets of most of the national languages which use a Cyrillic alphabet. Exceptions and additions for particular languages are noted below.

| Upright | Italic | Name(s) | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| А а | А а | A | /a/ |

| Б б | Б б | Be | /b/ |

| В в | В в | Ve | /v/ |

| Г г | Г г | Ge | /ɡ/ |

| Д д | Д д | De | /d/ |

| Е е | Е е |

|

|

| Ж ж | Ж ж |

|

/ʒ/ |

| З з | З з | Ze | /z/ |

| И и | И и | I |

|

| Й й | Й й | Short I[a] | /j/ |

| К к | К к | Ka | /k/ |

| Л л | Л л | El | /l/ |

| М м | М м | Em | /m/ |

| Н н | Н н |

|

/n/ |

| О о | О о | O | /o/ |

| П п | П п | Pe | /p/ |

| Р р | Р р |

|

/r/ |

| С с | С с | Es | /s/ |

| Т т | Т т | Te | /t/ |

| У у | У у | U | /u/ |

| Ф ф | Ф ф |

|

/f/ |

| Х х | Х х |

|

/x/ |

| Ц ц | Ц ц |

|

|

| Ч ч | Ч ч |

|

|

| Ш ш | Ш ш |

|

/ʃ/ |

| Щ щ | Щ щ |

|

[b] |

| Ь ь | Ь ь |

|

/ʲ/[e] |

| Э э | Э э | E | /e/ |

| Ю ю | Ю ю |

|

|

| Я я | Я я |

|

|

- ^ Russian: и краткое, i kratkoye; Bulgarian: и кратко, i kratko. Both mean «short i».

- ^ See the notes for each language for details

- ^ Russian: мягкий знак, myagkiy znak

- ^ Bulgarian: ер малък, er malâk

- ^ The soft sign ⟨ь⟩ usually does not represent a sound, but modifies the sound of the preceding letter, indicating palatalization («softening»), also separates the consonant and the following vowel. Sometimes it does not have phonetic meaning, just orthographic; e.g. Russian туш, tush [tuʂ] ‘flourish after a toast’; тушь, tushʹ [tuʂ] ‘India ink’. In some languages, a hard sign ⟨ъ⟩ or apostrophe ⟨’⟩ just separates the consonant and the following vowel (бя [bʲa], бья [bʲja], бъя = б’я [bja]).

Slavic languages[edit]

Cyrillic alphabets used by Slavic languages can be divided into two categories:

- East South Slavic languages and East Slavic languages, such as Bulgarian and Russian, share common features such as Й, ь, and я.

- West South Slavic languages, such as all varieties of Serbo-Croatian, share common features such as Ј and љ.

East Slavic[edit]

Russian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф |

| Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

- Yo (Ё ё) /jo/

- The Hard Sign¹ (Ъ ъ) indicates no palatalization²

- Yery (Ы ы) indicates [ɨ] (an allophone of /i/)

- E (Э э) /e/

- Ж and Ш indicate sounds that are retroflex

Notes:

- In the pre-reform Russian orthography, in Old East Slavic and in Old Church Slavonic the letter is called yer. Historically, the «hard sign» takes the place of a now-absent vowel, which is still preserved as a distinct vowel in Bulgarian (which represents it with ъ) and Slovene (which is written in the Latin alphabet and writes it as e), but only in some places in the word.

- When an iotated vowel (vowel whose sound begins with [j]) follows a consonant, the consonant is palatalized. The Hard Sign indicates that this does not happen, and the [j] sound will appear only in front of the vowel. The Soft Sign indicates that the consonant should be palatalized in addition to a [j] preceding the vowel. The Soft Sign also indicates that a consonant before another consonant or at the end of a word is palatalized. Examples: та ([ta]); тя ([tʲa]); тья ([tʲja]); тъя ([tja]); т (/t/); ть ([tʲ]).

Before 1918, there were four extra letters in use: Іі (replaced by Ии), Ѳѳ (Фита «Fita», replaced by Фф), Ѣѣ (Ять «Yat», replaced by Ее), and Ѵѵ (ижица «Izhitsa», replaced by Ии); these were eliminated by reforms of Russian orthography.

Belarusian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | (Ґ ґ) | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | І і | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ў ў | Ф ф |

| Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | ‘ |

The Belarusian alphabet displays the following features:

- He (Г г) represents a voiced velar fricative /ɣ/.

- Yo (Ё ё) /jo/

- I (І і), also known as the dotted I or decimal I, resembles the Latin letter I. Unlike Russian and Ukrainian, «И» is not used.

- Short I (Й й), however, uses the base И glyph.

- Short U (Ў ў) is the letter У with a breve and represents /w/, or like the u part of the diphthong in loud. The use of the breve to indicate a semivowel is analogous to the Short I (Й).

- A combination of Sh and Ch (ШЧ шч) is used where those familiar only with Russian and or Ukrainian would expect Shcha (Щ щ).

- Yery (Ы ы) /ɨ/

- E (Э э) /ɛ/

- An apostrophe (’) is used to indicate depalatalization[clarification needed] of the preceding consonant. This orthographical symbol used instead of the traditional Cyrillic letter Yer (Ъ), also known as the hard sign.

- The letter combinations Dzh (Дж дж) and Dz (Дз дз) appear after D (Д д) in the Belarusian alphabet in some publications. These digraphs represent consonant clusters Дж /dʒ/ and Дз /dz/ correspondingly.

- Before 1933, the letter Ґ ґ (Ge) was used.

Ukrainian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ґ ґ | Д д | Е е | Є є | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| І і | Ї ї | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ь ь | Ю ю | Я я |

The Ukrainian alphabet displays the following features:

- Ve (В) represents /ʋ/ (which may be pronounced [w] in a word final position and before consonants).

- He (Г, г) represents a voiced glottal fricative, (/ɦ/).

- Ge (Ґ, ґ) appears after He, represents /ɡ/. It looks like He with an «upturn» pointing up from the right side of the top bar. (This letter was removed in Soviet Ukraine in 1933–1990, so it may be missing from older Cyrillic fonts.)

- E (Е, е) represents /ɛ/.

- Ye (Є, є) appears after E, represents /jɛ/.

- E, И (И, и) represent /ɪ/ if unstressed.

- I (І, і) appears after Y, represents /i/.

- Yi (Ї, ї) appears after I, represents /ji/.

- Yy (Й, й) represents /j/.

- Shcha (Щ, щ) represents /ʃtʃ/.

- An apostrophe (’) is used to mark nonpalatalization of the preceding consonant before Ya (Я, я), Yu (Ю, ю), Ye (Є, є), Yi (Ї, ї).

- As in Belarusian Cyrillic, the sounds /dʒ/, /dz/ are represented by digraphs Дж and Дз respectively.

Rusyn[edit]

The Rusyn language is spoken by the Carpatho-Rusyns in Carpathian Ruthenia, Slovakia, and Poland, and the Pannonian Rusyns in Croatia and Serbia.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Ґ ґ | Д д | Е е | Є є | Ё ё* | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | І і* | Ы ы* | Ї ї | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п |

| Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ѣ ѣ* |

| Э э* | Ю ю | Я я | Ь ь | Ъ ъ* |

The Rusyn Alphabet makes the Following Rules:

Є (Ё)

І (Ы)

Щ (Ѣ)

Ь (Э)

Ъ is the last letter.

Ї = /ɪ̈/

Є = /ɪ̈ɛ/

Ѣ = /jɨ/

*Letters absent from Pannonian Rusyn.

South Slavic[edit]

Bosnian[edit]

Bulgarian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ь ь | Ю ю | Я я |

The Bulgarian alphabet features:

- The Bulgarian names for the consonants are [bɤ], [kɤ], [ɫɤ] etc. instead of [bɛ], [ka], [ɛl] etc.

- Е represents /ɛ/ and is called «е» [ɛ].

- The sounds /dʒ/ (/d͡ʒ/) and /dz/ (/d͡z/) are represented by дж and дз respectively.

- Yot (Й, й) represents /j/.

- Щ represents /ʃt/ (/ʃ͡t/) and is called «щъ» [ʃtɤ] ([ʃ͡tɤ]).

- Ъ represents the vowel /ɤ/, and is called «ер голям» [ˈɛr ɡoˈljam] (‘big er’). In spelling however, Ъ is referred to as /ɤ/ where its official label «ер голям» (used only to refer to Ъ in the alphabet) may cause some confusion. The vowel Ъ /ɤ/ is sometimes approximated to the /ə/ (schwa) sound found in many languages for easier comprehension of its Bulgarian pronunciation for foreigners, but it is actually a back vowel, not a central vowel.[citation needed]

- Ь is used on rare occasions (only after a consonant [and] before the vowel «о»), such as in the words ‘каньон’ (canyon), ‘шофьор’ (driver), etc. It is called «ер малък» (‘small er’).

The Cyrillic alphabet was originally developed in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 9th – 10th century AD at the Preslav Literary School.[2][3]

It has been used in Bulgaria (with modifications and exclusion of certain archaic letters via spelling reforms) continuously since then, superseding the previously used Glagolitic alphabet, which was also invented and used there before the Cyrillic script overtook its use as a written script for the Bulgarian language. The Cyrillic alphabet was used in the then much bigger territory of Bulgaria (including most of today’s Serbia), North Macedonia, Kosovo, Albania, Northern Greece (Macedonia region), Romania and Moldova, officially from 893. It was also transferred from Bulgaria and adopted by the East Slavic languages in Kievan Rus’ and evolved into the Russian alphabet and the alphabets of many other Slavic (and later non-Slavic) languages. Later, some Slavs modified it and added/excluded letters from it to better suit the needs of their own language varieties.

Croatian[edit]

Historically, the Croatian language briefly used the Cyrillic script in areas with large Croatian language or Bosnian language populations.[4]

Serbian[edit]

Alternate variants of lowercase Cyrillic letters: Б/б, Д/д, Г/г, И/и, П/п, Т/т, Ш/ш.

Default Russian (Eastern) forms on the left.

Alternate Bulgarian (Western) upright forms in the middle.

Alternate Serbian/Macedonian (Southern) italic forms on the right.

See also:

South Slavic Cyrillic alphabets (with the exception of Bulgarian) are generally derived from Serbian Cyrillic. It, and by extension its descendants, differs from the East Slavic ones in that the alphabet has generally been simplified: Letters such as Я, Ю, and Ё, representing /ja/, /ju/, and /jo/ in Russian, respectively, have been removed. Instead, these are represented by the digraphs ⟨ја⟩, ⟨јu⟩, and ⟨јо⟩, respectively. Additionally, the letter Е, representing /je/ in Russian, is instead pronounced /e/ or /ɛ/, with /je/ being represented by ⟨јe⟩. Alphabets based on the Serbian that add new letters often do so by adding an acute accent ⟨´⟩ over an existing letter.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ђ ђ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | Ћ ћ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Serbian alphabet shows the following features:

- E represents /ɛ/.

- Between Д and E is the letter Dje (Ђ, ђ), which represents /dʑ/, and looks like Tshe, except that the loop of the h curls farther and dips downwards.

- Between И and К is the letter Je (Ј, ј), represents /j/, which looks like the Latin letter J.

- Between Л and М is the letter Lje (Љ, љ), representing /ʎ/, which looks like a ligature of Л and the Soft Sign.

- Between Н and О is the letter Nje (Њ, њ), representing /ɲ/, which looks like a ligature of Н and the Soft Sign.

- Between Т and У is the letter Tshe (Ћ, ћ), representing /tɕ/ and looks like a lowercase Latin letter h with a bar. On the uppercase letter, the bar appears at the top; on the lowercase letter, the bar crosses the top at half of the vertical line.

- Between Ч and Ш is the letter Dzhe (Џ, џ), representing /dʒ/, which looks like Tse but with the descender moved from the right side of the bottom bar to the middle of the bottom bar.

- Ш is the last letter.

- Certain letters are handwritten differently,[5] as seen in the adjacent image.

Macedonian[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ѓ ѓ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | Ѕ ѕ | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | Ќ ќ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Macedonian alphabet differs from Serbian in the following ways:

- Between Ze (З з) and I (И и) is the letter Dze (Ѕ ѕ), which looks like the Latin letter S and represents /d͡z/.

- Dje (Ђ ђ) is replaced by Gje (Ѓ ѓ), which represents /ɟ/ (voiced palatal stop). In some dialects, it represents /d͡ʑ/ instead, like Dje. It is written ⟨Ǵ ǵ⟩ in the corresponding Macedonian Latin alphabet.

- Tshe (Ћ ћ) is replaced by Kje (Ќ ќ), which represents /c/ (voiceless palatal stop). In some dialects, it represents /t͡ɕ/ instead, like Tshe. It is written ⟨Ḱ ḱ⟩ in the corresponding Macedonian Latin alphabet.

- Lje (Љ љ) often represents the consonant cluster /lj/ instead of /ʎ/.

- Certain letters are handwritten differently, as seen in the adjacent image.[6]

Montenegrin[edit]

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Ђ ђ | Е е | Ж ж | З з | З́ з́ | И и |

| Ј ј | К к | Л л | Љ љ | М м | Н н | Њ њ | О о | П п | Р р | С с |

| С́ с́ | Т т | Ћ ћ | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Џ џ | Ш ш |

The Montenegrin alphabet differs from Serbian in the following ways:

- Between Ze (З з) and I (И и) is the letter З́, which represents /ʑ/ (voiced alveolo-palatal fricative). It is written ⟨Ź ź⟩ in the corresponding Montenegrin Latin alphabet, previously written ⟨Zj zj⟩ or ⟨Žj žj⟩.

- Between Es (С с) and Te (Т т) is the letter С́, which represents /ɕ/ (voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative). It is written ⟨Ś ś⟩ in the corresponding Montenegrin Latin alphabet, previously written ⟨Sj sj⟩ or ⟨Šj šj⟩.

- The letter Dze (Ѕ ѕ), from Macedonian, is used in scientific literature when representing the /d͡z/ phoneme, although it is not officially part of the alphabet. A Latin equivalent was proposed that looks identical to Ze (З з).

Uralic languages[edit]

Uralic languages using the Cyrillic script (currently or in the past) include:

- Finnic: Karelian until 1921 and 1937–1940 (Ludic, Olonets Karelian); Veps; Votic

- Kildin Sami in Russia (since the 1980s)

- Komi (Zyrian (since the 17th century, modern alphabet since the 1930s); Permyak; Yodzyak)

- Udmurt

- Khanty

- Mansi (writing has not received distribution since 1937)

- Samoyedic: Enets; Yurats; Nenets since 1937 (Forest Nenets; Tundra Nenets); Nganasan; Kamassian; Koibal; Mator; Selkup (since the 1950s; not used recently)

- Mari, since the 19th century (Hill; Meadow)

- Mordvin, since the 18th century (Erzya; Moksha)

- Other: Merya; Muromian; Meshcherian

Karelian[edit]

The first lines of the Book of Matthew in Karelian using the Cyrillic script, 1820

The Karelian language was written in the Cyrillic script in various forms until 1940 when publication in Karelian ceased in favor of Finnish, except for Tver Karelian, written in a Latin alphabet. In 1989 publication began again in the other Karelian dialects and Latin alphabets were used, in some cases with the addition of Cyrillic letters such as ь.

Kildin Sámi[edit]

Over the last century, the alphabet used to write Kildin Sámi has changed three times: from Cyrillic to Latin and back again to Cyrillic. Work on the latest version of the official orthography commenced in 1979. It was officially approved in 1982 and started to be widely used by 1987.[7]

Komi-Permyak[edit]

The Komi-Permyak Cyrillic alphabet:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё |

| Ж ж | З з | И и | I i | Й й | К к | Л л |

| М м | Н н | О о | Ӧ ӧ | П п | Р р | С с |

| Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш |

| Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Mari alphabets[edit]

Meadow Mari Cyrillic alphabet:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж | З з | И и |

| Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | Ҥ ҥ | О о | Ӧ ӧ | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӱ ӱ | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ |

| Ъ ъ | Ы ы | Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |