|

Central African Republic

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

Motto:

|

|

Anthem:

|

|

|

|

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Bangui 4°22′N 18°35′E / 4.367°N 18.583°E |

| Official languages | French • Sango |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion

(2020)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Central African |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

|

• President |

Faustin-Archange Touadéra |

|

• Prime Minister |

Félix Moloua |

|

• President of the National Assembly |

Simplice Sarandji |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

|

• Republic established |

1 December 1958 |

|

• from France |

13 August 1960 |

|

• Central African Empire established |

4 December 1976 |

|

• Coronation of Bokassa I |

4 December 1977 |

|

• Bokassa I’s overthrow and republic restored |

21 September 1979 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

622,984 km2 (240,535 sq mi) (44th) |

|

• Water (%) |

0 |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

5,454,533[2] (119th) |

|

• Density |

7.1/km2 (18.4/sq mi) (221st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

|

• Total |

$4.262 billion[3] (162nd) |

|

• Per capita |

$823[3] (184th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

|

• Total |

$2.321 billion[3] (163th) |

|

• Per capita |

$448[3] (181st) |

| Gini (2008) | 56.3[4] high · 28th |

| HDI (2021) | low · 188th |

| Currency |

|

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right[7] |

| Calling code | +236 |

| ISO 3166 code | CF |

| Internet TLD | .cf |

The Central African Republic (CAR; Sango: Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka IPA: [kōdōrōsésè tí bé.àfríkà]; French: République centrafricaine, RCA;[8] French: [ʁepyblik sɑ̃tʁafʁikɛn], or Centrafrique, [sɑ̃tʁafʁik]) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south, the Republic of the Congo to the southwest, and Cameroon to the west.

The Central African Republic covers a land area of about 620,000 square kilometres (240,000 sq mi). As of 2021, it had an estimated population of around 5.5 million. As of 2023, the Central African Republic was the scene of a civil war, ongoing since 2012.[9]

Most of the Central African Republic consists of Sudano-Guinean savannas, but the country also includes a Sahelo-Sudanian zone in the north and an equatorial forest zone in the south. Two-thirds of the country is within the Ubangi River basin (which flows into the Congo), while the remaining third lies in the basin of the Chari, which flows into Lake Chad.

What is today the Central African Republic has been inhabited for millennia;[when?] however, the country’s current borders were established by France, which ruled the country as a colony starting in the late 19th century. After gaining independence from France in 1960, the Central African Republic was ruled by a series of autocratic leaders, including an abortive attempt at a monarchy.[10]

By the 1990s, calls for democracy led to the first multi-party democratic elections in 1993. Ange-Félix Patassé became president, but was later removed by General François Bozizé in the 2003 coup. The Central African Republic Bush War began in 2004 and, despite a peace treaty in 2007 and another in 2011, civil war resumed in 2012. The civil war perpetuated the country’s poor human rights record: it was characterized by widespread and increasing abuses by various participating armed groups, such as arbitrary imprisonment, torture, and restrictions on freedom of the press and freedom of movement.

Despite (or arguably because of) its significant mineral deposits and other resources, such as uranium reserves, crude oil, gold, diamonds, cobalt, lumber, and hydropower,[11] as well as significant quantities of arable land, the Central African Republic is among the ten poorest countries in the world, with the lowest GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in the world as of 2017.[12] As of 2019, according to the Human Development Index (HDI), the country had the second-lowest level of human development (only ahead of Niger), ranking 188 out of 189 countries. The country had the lowest inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI), ranking 150th out of 150 countries.[13] The Central African Republic is also estimated to be the unhealthiest country[14] as well as the worst country in which to be young.[15]

The Central African Republic is a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the Economic Community of Central African States, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie and the Non-Aligned Movement.

Etymology[edit]

The name of the Central African Republic is derived from the country’s geographical location in the central region of Africa and its republican form of government. From 1976 to 1979, the country was known as the Central African Empire.

During the colonial era, the country’s name was Ubangi-Shari (French: Oubangui-Chari), a name derived from the Ubangi River and the Chari River. Barthélemy Boganda, the country’s first prime minister, favored the name «Central African Republic» over Ubangi-Shari, reportedly because he envisioned a larger union of countries in Central Africa.[16]

History[edit]

The Bouar Megaliths, pictured here on a 1967 Central African stamp, date back to the very late Neolithic Era (c. 3500–2700 BCE).

Early history[edit]

Approximately 10,000 years ago, desertification forced hunter-gatherer societies south into the Sahel regions of northern Central Africa, where some groups settled.[17] Farming began as part of the Neolithic Revolution.[18] Initial farming of white yam progressed into millet and sorghum, and before 3000 BCE[19] the domestication of African oil palm improved the groups’ nutrition and allowed for expansion of the local populations.[20] This Agricultural Revolution, combined with a «Fish-stew Revolution», in which fishing began to take place, and the use of boats, allowed for the transportation of goods. Products were often moved in ceramic pots, which are the first known examples of artistic expression from the region’s inhabitants.[citation needed]

The Bouar Megaliths in the western region of the country indicate an advanced level of habitation dating back to the very late Neolithic Era (c. 3500–2700 BCE).[21][22] Ironworking developed in the region around 1000 BCE.[23]

The Ubangian people settled along the Ubangi River in what is today Central and East Central African Republic while some Bantu peoples migrated from the southwest from Cameroon.[24]

Bananas arrived in the region during the first millennium BCE[25] and added an important source of carbohydrates to the diet; they were also used in the production of alcoholic beverages. Production of copper, salt, dried fish, and textiles dominated the economic trade in the Central African region.[26]

16th–19th century[edit]

In the 16th and 17th centuries slave traders began to raid the region as part of the expansion of the Saharan and Nile River slave routes. Their captives were enslaved and shipped to the Mediterranean coast, Europe, Arabia, the Western Hemisphere, or to the slave ports and factories along the West and North Africa or South along the Ubanqui and Congo rivers.[27][28] In the mid 19th century, the Bobangi people became major slave traders and sold their captives to the Americas using the Ubangi river to reach the coast.[29] During the 18th century Bandia-Nzakara Azande peoples established the Bangassou Kingdom along the Ubangi River.[28] In 1875, the Sudanese sultan Rabih az-Zubayr governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day Central African Republic.[30]

French colonial period[edit]

The European invasion of Central African territory began in the late 19th century during the Scramble for Africa.[31] Europeans, primarily the French, Germans, and Belgians, arrived in the area in 1885. France seized and colonized Ubangi-Shari territory in 1894. In 1911 at the Treaty of Fez, France ceded a nearly 300,000 km2 portion of the Sangha and Lobaye basins to the German Empire which ceded a smaller area (in present-day Chad) to France. After World War I France again annexed the territory. Modeled on King Leopold’s Congo Free State, concessions were doled out to private companies that endeavored to strip the region’s assets as quickly and cheaply as possible before depositing a percentage of their profits into the French treasury. The concessionary companies forced local people to harvest rubber, coffee, and other commodities without pay and held their families hostage until they met their quotas.[32]

In 1920 French Equatorial Africa was established and Ubangi-Shari was administered from Brazzaville.[33] During the 1920s and 1930s the French introduced a policy of mandatory cotton cultivation,[33] a network of roads was built, attempts were made to combat sleeping sickness, and Protestant missions were established to spread Christianity.[34] New forms of forced labor were also introduced and a large number of Ubangians were sent to work on the Congo-Ocean Railway. Through the period of construction until 1934 there was a continual heavy cost in human lives, with total deaths among all workers along the railway estimated in excess of 17,000 of the construction workers, from a combination of both industrial accidents and diseases including malaria.[35] In 1928, a major insurrection, the Kongo-Wara rebellion or ‘war of the hoe handle’, broke out in Western Ubangi-Shari and continued for several years. The extent of this insurrection, which was perhaps the largest anti-colonial rebellion in Africa during the interwar years, was carefully hidden from the French public because it provided evidence of strong opposition to French colonial rule and forced labor.[36]

In September 1940, during the Second World War, pro-Gaullist French officers took control of Ubangi-Shari and General Leclerc established his headquarters for the Free French Forces in Bangui.[37] In 1946 Barthélemy Boganda was elected with 9,000 votes to the French National Assembly, becoming the first representative of the Central African Republic in the French government. Boganda maintained a political stance against racism and the colonial regime but gradually became disheartened with the French political system and returned to the Central African Republic to establish the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (Mouvement pour l’évolution sociale de l’Afrique noire, MESAN) in 1950.[38]

Since independence (1960–present)[edit]

In the Ubangi-Shari Territorial Assembly election in 1957, MESAN captured 347,000 out of the total 356,000 votes[39] and won every legislative seat,[40] which led to Boganda being elected president of the Grand Council of French Equatorial Africa and vice-president of the Ubangi-Shari Government Council.[41] Within a year, he declared the establishment of the Central African Republic and served as the country’s first prime minister. MESAN continued to exist, but its role was limited.[42] The Central Africa Republic was granted autonomy within the French Community on 1 December 1958, a status which meant it was still counted as part of the French Empire in Africa.[43]

After Boganda’s death in a plane crash on 29 March 1959, his cousin, David Dacko, took control of MESAN. Dacko became the country’s first president when the Central African Republic formally received independence from France at midnight on 13 August 1960, a date celebrated by the country’s Independence Day holiday.[44] Dacko threw out his political rivals, including Abel Goumba, former Prime Minister and leader of Mouvement d’évolution démocratique de l’Afrique centrale (MEDAC), whom he forced into exile in France. With all opposition parties suppressed by November 1962, Dacko declared MESAN as the official party of the state.[45]

Bokassa and the Central African Empire (1965–1979)[edit]

On 31 December 1965, Dacko was overthrown in the Saint-Sylvestre coup d’état by Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa, who suspended the constitution and dissolved the National Assembly. President Bokassa declared himself President for Life in 1972 and named himself Emperor Bokassa I of the Central African Empire (as the country was renamed) on 4 December 1976. A year later, Emperor Bokassa crowned himself in a lavish and expensive ceremony that was ridiculed by much of the world.[10]

In April 1979, young students protested against Bokassa’s decree that all school pupils were required to buy uniforms from a company owned by one of his wives. The government violently suppressed the protests, killing 100 children and teenagers. Bokassa might have been personally involved in some of the killings.[46] In September 1979, France overthrew Bokassa and restored Dacko to power (subsequently restoring the official name of the country and the original government to the Central African Republic). Dacko, in turn, was again overthrown in a coup by General André Kolingba on 1 September 1981.[47]

Central African Republic under Kolingba[edit]

Kolingba suspended the constitution and ruled with a military junta until 1985. He introduced a new constitution in 1986 which was adopted by a nationwide referendum. Membership in his new party, the Rassemblement Démocratique Centrafricain (RDC), was voluntary. In 1987 and 1988, semi-free elections to parliament were held, but Kolingba’s two major political opponents, Abel Goumba and Ange-Félix Patassé, were not allowed to participate.[48]

By 1990, inspired by the fall of the Berlin Wall, a pro-democracy movement arose. Pressure from the United States, France, and from a group of locally represented countries and agencies called GIBAFOR (France, the US, Germany, Japan, the EU, the World Bank, and the UN) finally led Kolingba to agree, in principle, to hold free elections in October 1992 with help from the UN Office of Electoral Affairs. After using the excuse of alleged irregularities to suspend the results of the elections as a pretext for holding on to power, President Kolingba came under intense pressure from GIBAFOR to establish a «Conseil National Politique Provisoire de la République» (Provisional National Political Council, CNPPR) and to set up a «Mixed Electoral Commission», which included representatives from all political parties.[48]

When a second round of elections were finally held in 1993, again with the help of the international community coordinated by GIBAFOR, Ange-Félix Patassé won in the second round of voting with 53% of the vote while Goumba won 45.6%. Patassé’s party, the Mouvement pour la Libération du Peuple Centrafricain (MLPC) or Movement for the Liberation of the Central African People, gained a plurality (relative majority) but not an absolute majority of seats in parliament, which meant Patassé’s party required coalition partners.[48]

Patassé government (1993–2003)[edit]

Patassé purged many of the Kolingba elements from the government and Kolingba supporters accused Patassé’s government of conducting a «witch hunt» against the Yakoma. A new constitution was approved on 28 December 1994 but had little impact on the country’s politics. In 1996–1997, reflecting steadily decreasing public confidence in the government’s erratic behavior, three mutinies against Patassé’s administration were accompanied by widespread destruction of property and heightened ethnic tension. During this time (1996), the Peace Corps evacuated all its volunteers to neighboring Cameroon. To date, the Peace Corps has not returned to the Central African Republic. The Bangui Agreements, signed in January 1997, provided for the deployment of an inter-African military mission, to the Central African Republic and re-entry of ex-mutineers into the government on 7 April 1997. The inter-African military mission was later replaced by a U.N. peacekeeping force (MINURCA). Since 1997, the country has hosted almost a dozen peacekeeping interventions, earning it the title of «world champion of peacekeeping».[32]

In 1998, parliamentary elections resulted in Kolingba’s RDC winning 20 out of 109 seats. The next year, however, in spite of widespread public anger in urban centers over his corrupt rule, Patassé won a second term in the presidential election.[49]

On 28 May 2001, rebels stormed strategic buildings in Bangui in an unsuccessful coup attempt. The army chief of staff, Abel Abrou, and General François N’Djadder Bedaya were killed, but Patassé regained the upper hand by bringing in at least 300 troops of the Congolese rebel leader Jean-Pierre Bemba and Libyan soldiers.[50]

In the aftermath of the failed coup, militias loyal to Patassé sought revenge against rebels in many neighborhoods of Bangui and incited unrest including the murder of many political opponents. Eventually, Patassé came to suspect that General François Bozizé was involved in another coup attempt against him, which led Bozizé to flee with loyal troops to Chad. In March 2003, Bozizé launched a surprise attack against Patassé, who was out of the country. Libyan troops and some 1,000 soldiers of Bemba’s Congolese rebel organization failed to stop the rebels and Bozizé’s forces succeeded in overthrowing Patassé.[51]

Civil wars[edit]

Rebel militia in the northern countryside, 2007.

François Bozizé suspended the constitution and named a new cabinet, which included most opposition parties. Abel Goumba was named vice-president, which gave Bozizé’s new government a positive image.[why?] Bozizé established a broad-based National Transition Council to draft a new constitution, and announced that he would step down and run for office once the new constitution was approved.[52]

In 2004, the Central African Republic Bush War began, as forces opposed to Bozizé took up arms against his government. In May 2005, Bozizé won the presidential election, which excluded Patassé, and in 2006 fighting continued between the government and the rebels.[53] In November 2006, Bozizé’s government requested French military support to help them repel rebels who had taken control of towns in the country’s northern regions.[54]

Though the initial public details of the agreement pertained to logistics and intelligence, by December the French assistance included airstrikes by Dassault Mirage 2000 fighters against rebel positions.[55][56]

The Syrte Agreement in February and the Birao Peace Agreement in April 2007 called for a cessation of hostilities, the billeting of FDPC fighters and their integration with FACA, the liberation of political prisoners, integration of FDPC into government, an amnesty for the UFDR, its recognition as a political party, and the integration of its fighters into the national army. Several groups continued to fight but other groups signed on to the agreement, or similar agreements with the government (e.g. UFR on 15 December 2008). The only major group not to sign an agreement at the time was the CPJP, which continued its activities and signed a peace agreement with the government on 25 August 2012.[57]

In 2011, Bozizé was reelected in an election which was widely considered fraudulent.[11]

In November 2012, Séléka, a coalition of rebel groups, took over towns in the northern and central regions of the country. These groups eventually reached a peace deal with the Bozizé’s government in January 2013 involving a power sharing government[11] but this deal broke down and the rebels seized the capital in March 2013 and Bozizé fled the country.[58][59]

Refugees of the fighting in the Central African Republic, January 2014

Michel Djotodia took over as president. Prime Minister Nicolas Tiangaye requested a UN peacekeeping force from the UN Security Council and on 31 May former President Bozizé was indicted for crimes against humanity and incitement of genocide.[60]

By the end of the year there were international warnings of a «genocide»[61][62] and fighting was largely from reprisal attacks on civilians from Seleka’s predominantly Muslim fighters and Christian militias called «anti-balaka.»[63] By August 2013, there were reports of over 200,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs)[64][65]

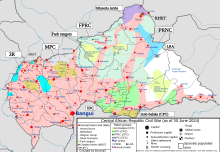

Current military situation in Central African Republic

French President François Hollande called on the UN Security Council and African Union to increase their efforts to stabilize the country. On 18 February 2014, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called on the UN Security Council to immediately deploy 3,000 troops to the country, bolstering the 6,000 African Union soldiers and 2,000 French troops already in the country, to combat civilians being murdered in large numbers. The Séléka government was said to be divided,[66] and in September 2013, Djotodia officially disbanded Seleka, but many rebels refused to disarm, becoming known as ex-Seleka, and veered further out of government control.[63] It is argued that the focus of the initial disarmament efforts exclusively on the Seleka inadvertently handed the anti-Balaka the upper hand, leading to the forced displacement of Muslim civilians by anti-Balaka in Bangui and western Central African Republic.[32]

On 11 January 2014, Michael Djotodia and Nicolas Tiengaye resigned as part of a deal negotiated at a regional summit in neighboring Chad.[67] Catherine Samba-Panza was elected as interim president by the National Transitional Council,[68] becoming the first ever female Central African president. On 23 July 2014, following Congolese mediation efforts, Séléka and anti-balaka representatives signed a ceasefire agreement in Brazzaville.[69] By the end of 2014, the country was de facto partitioned with the anti-Balaka in the southwest and ex-Seleka in the northeast.[32] In March 2015, Samantha Power, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, said 417 of the country’s 436 mosques had been destroyed, and Muslim women were so scared of going out in public they were giving birth in their homes instead of going to the hospital.[70] On 14 December 2015, Séléka rebel leaders declared an independent Republic of Logone.[71]

Touadéra government (2016–)[edit]

Presidential elections were held in December 2015. As no candidate received more than 50% of the vote, a second round of elections was held on 14 February 2016 with run-offs on 31 March 2016.[72][73] In the second round of voting, former Prime Minister Faustin-Archange Touadéra was declared the winner with 63% of the vote, defeating Union for Central African Renewal candidate Anicet-Georges Dologuélé, another former Prime Minister.[74] While the elections suffered from many potential voters being absent as they had taken refuge in other countries, the fears of widespread violence were ultimately unfounded and the African Union regarded the elections as successful.[75]

Touadéra was sworn in on 30 March 2016. No representatives of the Seleka rebel group or the «anti-balaka» militias were included in the subsequently formed government.[76]

After the end of Touadéra’s first term, presidential elections were held on 27 December 2020 with a possible second round planned for 14 February 2021.[77] Former president François Bozizé announced his candidacy on 25 July 2020 but was rejected by the Constitutional Court of the country, which held that Bozizé did not satisfy the “good morality” requirement for candidates because of an international warrant and United Nations sanctions against him for alleged assassinations, torture and other crimes.[78]

As large parts of the country were at the time controlled by armed groups, the election could not be conducted in many areas of the country.[79][80] Some 800 of the country’s polling stations, 14% of the total, were closed due to violence.[81] Three Burundian peacekeepers were killed and an additional two were wounded during the run-up to the election.[82][83] President Faustin-Archange Touadéra was reelected in the first round of the election in December 2020.[84] Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group have supported President Faustin-Archange Touadéra in the fight against rebels. Russia’s Wagner group has been accused of harassing and intimidating civilians.[85][86] In December 2022 Roger Cohen wrote in the New York Times that «Wagner shock troops form a Praetorian Guard for Mr. Touadéra, who is also protected by Rwandan forces, in return for an untaxed license to exploit and export the Central African Republic’s resources» and that «one Western ambassador called the Central African Republic’s status as a “vassal state” of the Kremlin.»[87]

Geography[edit]

Falls of Boali on the Mbali River

A village in the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic is a landlocked nation within the interior of the African continent. It is bordered by Cameroon, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the Congo. The country lies between latitudes 2° and 11°N, and longitudes 14° and 28°E.[88]

Much of the country consists of flat or rolling plateau savanna approximately 500 metres (1,640 ft) above sea level. In addition to the Fertit Hills in the northeast of the Central African Republic, there are scattered hills in the southwest regions. In the northwest is the Yade Massif, a granite plateau with an altitude of 348 metres (1,143 ft). The Central African Republic contains six terrestrial ecoregions: Northeastern Congolian lowland forests, Northwestern Congolian lowland forests, Western Congolian swamp forests, East Sudanian savanna, Northern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic, and Sahelian Acacia savanna.[89]

At 622,984 square kilometres (240,535 sq mi), the Central African Republic is the world’s 44th-largest country. It is comparable in size to Ukraine, as Ukraine is 603,500 square kilometres (233,000 sq mi) in area, according to List of countries and dependencies by area.[90]

Much of the southern border is formed by tributaries of the Congo River; the Mbomou River in the east merges with the Uele River to form the Ubangi River, which also comprises portions of the southern border. The Sangha River flows through some of the western regions of the country, while the eastern border lies along the edge of the Nile River watershed.[88]

It has been estimated that up to 8% of the country is covered by forest, with the densest parts generally located in the southern regions. The forests are highly diverse and include commercially important species of Ayous, Sapelli and Sipo.[91] The deforestation rate is about 0.4% per annum, and lumber poaching is commonplace.[92] The Central African Republic had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.28/10, ranking it seventh globally out of 172 countries.[93]

In 2008, Central African Republic was the world’s least light pollution affected country.[94]

The Central African Republic is the focal point of the Bangui Magnetic Anomaly, one of the largest magnetic anomalies on Earth.[95]

Wildlife[edit]

In the southwest, the Dzanga-Sangha National Park is located in a rain forest area. The country is noted for its population of forest elephants and western lowland gorillas. In the north, the Manovo-Gounda St Floris National Park is well-populated with wildlife, including leopards, lions, cheetahs and rhinos, and the Bamingui-Bangoran National Park is located in the northeast of the Central African Republic. The parks have been seriously affected by the activities of poachers, particularly those from Sudan, over the past two decades.[96]

Climate[edit]

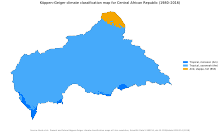

Central African Republic map of Köppen climate classification.

The climate of the Central African Republic is generally tropical, with a wet season that lasts from June to September in the northern regions of the country, and from May to October in the south. During the wet season, rainstorms are an almost daily occurrence, and early morning fog is commonplace. Maximum annual precipitation is approximately 1,800 millimetres (71 in) in the upper Ubangi region.[97]

The northern areas are hot and humid from February to May,[98] but can be subject to the hot, dry, and dusty trade wind known as the Harmattan. The southern regions have a more equatorial climate, but they are subject to desertification, while the extreme northeast regions of the country are a steppe.[99]

Prefectures and sub-prefectures[edit]

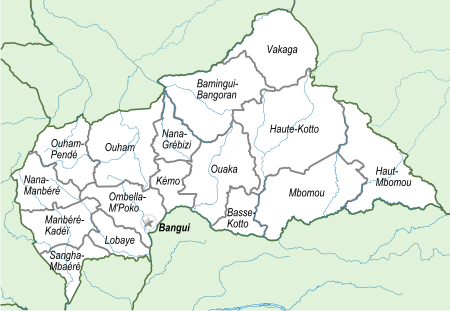

A clickable map of the fourteen prefectures of the Central African Republic.

The Central African Republic is divided into 16 administrative prefectures (préfectures), two of which are economic prefectures (préfectures economiques), and one an autonomous commune; the prefectures are further divided into 71 sub-prefectures (sous-préfectures).[100][101]

The prefectures are Bamingui-Bangoran, Basse-Kotto, Haute-Kotto, Haut-Mbomou, Kémo, Lobaye, Mambéré-Kadéï, Mbomou, Nana-Mambéré, Ombella-M’Poko, Ouaka, Ouham, Ouham-Pendé and Vakaga. The economic prefectures are Nana-Grébizi and Sangha-Mbaéré, while the commune is the capital city of Bangui.[100]

Politics and government[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Recent developments and Russian influence. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (December 2022) |

Politics in the Central African Republic formally take place in a framework of a presidential republic. In this system, the President is the head of state, with a Prime Minister as head of government. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and parliament.[11]

Changes in government have occurred in recent years by three methods: violence, negotiations, and elections. A new constitution was approved by voters in a referendum held on 5 December 2004. The government was rated ‘Partly Free’ from 1991 to 2001 and from 2004 to 2013.[102]

Executive branch[edit]

The president is elected by popular vote for a six-year term, and the prime minister is appointed by the president. The president also appoints and presides over the Council of Ministers, which initiates laws and oversees government operations. However, as of 2018 the official government is not in control of large parts of the country, which are governed by rebel groups.[103]

Acting president since April 2016 is Faustin-Archange Touadéra who followed the interim government under Catherine Samba-Panza, interim prime minister André Nzapayeké.[104]

Legislative branch[edit]

The National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale) has 140 members, elected for a five-year term using the two-round (or Run-off) system.[11]

Judicial branch[edit]

As in many other former French colonies, the Central African Republic’s legal system is based on French law.[105] The Supreme Court, or Cour Supreme, is made up of judges appointed by the president. There is also a Constitutional Court, and its judges are also appointed by the president.[11]

Foreign relations[edit]

The Central African Republic relies heavily on Russian mercenaries for the protection of its diamond mines.[106]

Foreign aid and UN Involvement[edit]

The Central African Republic is heavily dependent upon foreign aid and numerous NGOs provide services that the government does not provide.[107] In 2019, over US$100 million in foreign aid was spent in the country, mostly on humanitarian assistance.[108]

In 2006, due to ongoing violence, over 50,000 people in the country’s northwest were at risk of starvation,[109] but this was averted due to assistance from the United Nations.[110] On 8 January 2008, the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon declared that the Central African Republic was eligible to receive assistance from the Peacebuilding Fund.[111] Three priority areas were identified: first, the reform of the security sector; second, the promotion of good governance and the rule of law; and third, the revitalization of communities affected by conflicts. On 12 June 2008, the Central African Republic requested assistance from the UN Peacebuilding Commission,[112] which was set up in 2005 to help countries emerging from conflict avoid devolving back into war or chaos.[113]

In response to concerns of a potential genocide, a peacekeeping force – the International Support Mission to the Central African Republic (MISCA) – was authorized in December 2013. This African Union force of 6,000 personnel was accompanied by the French Operation Sangaris.[114]

In 2017, Central African Republic signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[115]

Human rights[edit]

The 2009 Human Rights Report by the United States Department of State noted that human rights in the Central African Republic were poor and expressed concerns over numerous government abuses.[116] The U.S. State Department alleged that major human rights abuses such as extrajudicial executions by security forces, torture, beatings and rape of suspects and prisoners occurred with impunity. It also alleged harsh and life-threatening conditions in prisons and detention centers, arbitrary arrest, prolonged pretrial detention and denial of a fair trial, restrictions on freedom of movement, official corruption, and restrictions on workers’ rights.[116]

The State Department report also cites widespread mob violence, the prevalence of female genital mutilation, discrimination against women and Pygmies, human trafficking, forced labor, and child labor.[117] Freedom of movement is limited in the northern part of the country «because of actions by state security forces, armed bandits, and other nonstate armed entities», and due to fighting between government and anti-government forces, many persons have been internally displaced.[118]

Violence against children and women in relation to accusations of witchcraft has also been cited as a serious problem in the country.[119][120][121] Witchcraft is a criminal offense under the penal code.[119]

Freedom of speech is addressed in the country’s constitution, but there have been incidents of government intimidation of the media.[116] A report by the International Research & Exchanges Board’s media sustainability index noted that «the country minimally met objectives, with segments of the legal system and government opposed to a free media system».[116]

Approximately 68% of girls are married before they turn 18,[122] and the United Nations’ Human Development Index ranked the country 188 out of 188 countries surveyed.[123] The Bureau of International Labor Affairs has also mentioned it in its last edition of the List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor.

Demographics[edit]

The population of the Central African Republic has almost quadrupled since independence. In 1960, the population was 1,232,000; as of a 2021 UN estimate, it is approximately 5,457,154.[124][125]

The United Nations estimates that approximately 4% of the population aged between 15 and 49 is HIV positive.[126] Only 3% of the country has antiretroviral therapy available, compared to a 17% coverage in the neighboring countries of Chad and the Republic of the Congo.[127]

The nation is divided into over 80 ethnic groups, each having its own language. The largest ethnic groups are the Baggara Arabs, Baka, Banda, Bayaka, Fula, Gbaya, Kara, Kresh, Mbaka, Mandja, Ngbandi, Sara, Vidiri, Wodaabe, Yakoma, Yulu, Zande, with others including Europeans of mostly French descent.[11]

|

Largest cities or towns in Central African Republic According to the 2003 Census[128] |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Prefecture | Pop. | Rank | Name | Prefecture | Pop. | |

Bangui |

1 | Bangui | Bangui | 622,771 | 11 | Kaga-Bandoro | Nana-Grébizi | 24,661 |

| 2 | Bimbo | Ombella-M’Poko | 124,176 | 12 | Sibut | Kémo | 22,419 | |

| 3 | Berbérati | Mambéré-Kadéï | 76,918 | 13 | Mbaïki | Lobaye | 22,166 | |

| 4 | Carnot | Mambéré-Kadéï | 45,421 | 14 | Bozoum | Ouham-Pendé | 20,665 | |

| 5 | Bambari | Ouaka | 41,356 | 15 | Paoua | Ouham-Pendé | 17,370 | |

| 6 | Bouar | Nana-Mambéré | 40,353 | 16 | Batangafo | Ouham | 16,420 | |

| 7 | Bossangoa | Ouham | 36,478 | 17 | Kabo | Ouham | 16,279 | |

| 8 | Bria | Haute-Kotto | 35,204 | 18 | Bocaranga | Ouham-Pendé | 15,744 | |

| 9 | Bangassou | Mbomou | 31,553 | 19 | Ippy | Ouaka | 15,196 | |

| 10 | Nola | Sangha-Mbaéré | 29,181 | 20 | Alindao | Basse-Kotto | 14,401 |

Religion[edit]

According to the 2003 national census, 80.3% of the population was Christian (51.4% Protestant and 28.9% Roman Catholic), 10% was Muslim and 4.5 percent other religious groups, with 5.5 percent having no religious beliefs.[129] More recent work from the Pew Research Center estimated that, as of 2010, Christians constituted 89.8% of the population (60.7% Protestant and 28.5% Catholic) while Muslims made up 8.9%.[130][131] The Catholic Church claims over 1.5 million adherents, approximately one-third of the population.[132] Indigenous belief (animism) is also practiced, and many indigenous beliefs are incorporated into Christian and Islamic practice.[133] A UN director described religious tensions between Muslims and Christians as being high.[134]

There are many missionary groups operating in the country, including Lutherans, Baptists, Catholics, Grace Brethren, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. While these missionaries are predominantly from the United States, France, Italy, and Spain, many are also from Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and other African countries. Large numbers of missionaries left the country when fighting broke out between rebel and government forces in 2002–3, but many of them have now returned to continue their work.[135]

According to Overseas Development Institute research, during the crisis ongoing since 2012, religious leaders have mediated between communities and armed groups; they also provided refuge for people seeking shelter.[114]

Languages[edit]

The Central African Republic’s two official languages are French and Sango (also spelled Sangho),[136] a creole developed as an inter-ethnic lingua franca based on the local Ngbandi language. The Central African Republic is one of the few African countries to have granted official status to an African language.

Healthcare[edit]

Mothers and babies aged between 0 and 5 years are lining up in a Health Post at Begoua, a district of Bangui, waiting for the two drops of the oral polio vaccine.

The largest hospitals in the country are located in the Bangui district. As a member of the World Health Organization, the Central African Republic receives vaccination assistance, such as a 2014 intervention for the prevention of a measles epidemic.[137] In 2007, female life expectancy at birth was 48.2 years and male life expectancy at birth was 45.1 years.[138]

Women’s health is poor in the Central African Republic. As of 2010, the country had the fourth highest maternal mortality rate in the world.[139]

The total fertility rate in 2014 was estimated at 4.46 children born/woman.[11] Approximately 25% of women had undergone female genital mutilation.[140] Many births in the country are guided by traditional birth attendants, who often have little or no formal training.[141]

Malaria is endemic in the Central African Republic, and one of the leading causes of death.[142]

According to 2009 estimates, the HIV/AIDS prevalence rate is about 4.7% of the adult population (ages 15–49).[143] This is in general agreement with the 2016 United Nations estimate of approximately 4%.[144] Government expenditure on health was US$20 (PPP) per person in 2006[138] and 10.9% of total government expenditure in 2006.[138] There was only around 1 physician for every 20,000 persons in 2009.[145]

Education[edit]

Public education in the Central African Republic is free and is compulsory from ages 6 to 14.[146] However, approximately half of the adult population of the country is illiterate.[147] The two institutions of higher education in the Central African Republic are the University of Bangui, a public university located in Bangui, which includes a medical school; and Euclid University, an international university.[148][149]

Economy[edit]

A proportional representation of Central African Republic exports, 2019

GDP per capita development in the Central African Republic

The per capita income of the Republic is often listed as being approximately $400 a year, one of the lowest in the world, but this figure is based mostly on reported sales of exports and largely ignores the unregistered sale of foods, locally produced alcoholic beverages, diamonds, ivory, bushmeat, and traditional medicine.[150]

The currency of the Central African Republic is the CFA franc, which is accepted across the former countries of French West Africa and trades at a fixed rate to the euro. Diamonds constitute the country’s most important export, accounting for 40–55% of export revenues, but it is estimated that between 30% and 50% of those produced each year leave the country clandestinely.[150]

On 27 April 2022,[151] Bitcoin (BTC) was adopted as an additional legal tender. Lawmakers unanimously adopted a bill that made bitcoin legal tender alongside the CFA franc and legalized the use of cryptocurrencies. President Faustin-Archange Touadéra signed the measure into law, said his chief of staff Obed Namsio.

Agriculture is dominated by the cultivation and sale of food crops such as cassava, peanuts, maize, sorghum, millet, sesame, and plantain. The annual real GDP growth rate is just above 3%. The importance of food crops over exported cash crops is indicated by the fact that the total production of cassava, the staple food of most Central Africans, ranges between 200,000 and 300,000 tonnes a year, while the production of cotton, the principal exported cash crop, ranges from 25,000 to 45,000 tonnes a year. Food crops are not exported in large quantities, but still constitute the principal cash crops of the country, because Central Africans derive far more income from the periodic sale of surplus food crops than from exported cash crops such as cotton or coffee.[150] Much of the country is self-sufficient in food crops; however, livestock development is hindered by the presence of the tsetse fly.[152]

The Republic’s primary import partner is France (17.1%). Other imports come from the United States (12.3%), India (11.5%), and China (8.2%). Its largest export partner is France (31.2%), followed by Burundi (16.2%), China (12.5%), Cameroon (9.6%), and Austria (7.8%).[11]

The Central African Republic is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA). In the 2009 World Bank Group’s report Doing Business, it was ranked 183rd of 183 as regards ‘ease of doing business’, a composite index which takes into account regulations that enhance business activity and those that restrict it.[153]

Infrastructure[edit]

Transportation[edit]

Bangui is the transport hub of the Central African Republic. As of 1999, eight roads connected the city to other main towns in the country, Cameroon, Chad and South Sudan; of these, only the toll roads are paved. During the rainy season from July to October, some roads are impassable.[154][155]

River ferries sail from the river port at Bangui to Brazzaville and Zongo. The river can be navigated most of the year between Bangui and Brazzaville. From Brazzaville, goods are transported by rail to Pointe-Noire, Congo’s Atlantic port.[156] The river port handles the overwhelming majority of the country’s international trade and has a cargo handling capacity of 350,000 tons; it has 350 metres (1,150 ft) length of wharfs and 24,000 square metres (260,000 sq ft) of warehousing space.[154]

Bangui M’Poko International Airport is Central African Republic’s only international airport. As of June 2014 it had regularly scheduled direct flights to Brazzaville, Casablanca, Cotonou, Douala, Kinshasa, Lomé, Luanda, Malabo, N’Djamena, Paris, Pointe-Noire, and Yaoundé.[citation needed]

Since at least 2002 there have been plans to connect Bangui by rail to the Transcameroon Railway.[157]

Energy[edit]

The Central African Republic primarily uses hydroelectricity as there are few other low cost resources for generating electricity.[158]

Communications[edit]

Presently, the Central African Republic has active television services, radio stations, internet service providers, and mobile phone carriers; Socatel is the leading provider for both internet and mobile phone access throughout the country. The primary governmental regulating bodies of telecommunications are the Ministère des Postes and Télécommunications et des Nouvelles Technologies. In addition, the Central African Republic receives international support on telecommunication related operations from ITU Telecommunication Development Sector (ITU-D) within the International Telecommunication Union to improve infrastructure.[159]

Culture[edit]

Sports[edit]

Football is the country’s most popular sport. The national football team is governed by the Central African Football Federation and stages matches at the Barthélemy Boganda Stadium.[160]

Basketball also is popular[161][162] and its national team won the African Championship twice and was the first Sub-Saharan African team to qualify for the Basketball World Cup, in 1974.

See also[edit]

- Outline of the Central African Republic

- Central African Republic–Chad border,

- Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of the Congo to the southwest, and Cameroon to the west.

- List of Central African Republic–related topics

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «National Profiles». www.thearda.com.

- ^ «Central African Republic». The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d «Central African Republic». International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ «Gini Index». World Bank. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ «Central African Republic adopts bitcoin as legal currency». news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Which side of the road do they drive on? Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Brian Lucas. August 2005. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ «Central African Republic – CAR – Country Profile – Nations Online Project». www.nationsonline.org.

- ^ Mudge, Lewis (11 December 2018). «Central African Republic: Events of 2018». World Report 2019: Rights Trends in Central African Republic. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ a b c ‘Cannibal’ dictator Bokassa given posthumous pardon Archived 1 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. 3 December 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Central African Republic. The World Factbook (CIA World Factbook) Central Intelligence Agency

- ^ World Economic Outlook Database, January 2018 Archived 3 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine, International Monetary Fund Archived 14 February 2006 at Archive-It. Database updated on 12 April 2017. Accessed on 21 April 2017.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «These are the world’s unhealthiest countries – The Express Tribune». The Express Tribune. 25 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Foundation, Thomson Reuters. «Central African Republic worst country in the world for young people – study». Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Palmer, Brian (9 March 2012). «Why Does the Central African Republic Have Such a Boring Name?». Slate.

- ^ McKenna, p. 4

- ^ Brierley, Chris; Manning, Katie; Maslin, Mark (1 October 2018). «Pastoralism may have delayed the end of the green Sahara». Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4018. Bibcode:2018NatCo…9.4018B. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06321-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6167352. PMID 30275473.

- ^ Fran Osseo-Asare (2005) Food Culture in Sub Saharan Africa. Greenwood. ISBN 0313324883. p. xxi

- ^ McKenna, p. 5

- ^ Methodology and African Prehistory by, UNESCO. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa, p. 548

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. «Les mégalithes de Bouar» Archived 3 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. UNESCO.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (2002). The civilizations of Africa : a history to 1800. Oxford: James Currey. p. 161. ISBN 0-85255-476-1. OCLC 59451060.

- ^ Mozaffari, Mehdi (2002), «Globalization, civilizations and world order», Globalization and Civilizations, Taylor & Francis, pp. 24–50, doi:10.4324/9780203217979_chapter_2, ISBN 978-0-203-29460-4

- ^ Mbida, Christophe M.; Van Neer, Wim; Doutrelepont, Hugues; Vrydaghs, Luc (15 March 1999). «Evidence for banana cultivation and animal husbandry during the first millennium BCE in the forest of southern Cameroon». Journal of Archaeological Science. 27 (2): 151–162. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0447.

- ^ McKenna, p. 10

- ^ International Business Publications, USA (7 February 2007). Central African Republic Foreign Policy and Government Guide (World Strategic and Business Information Library). Vol. 1. Int’l Business Publications. p. 47. ISBN 978-1433006210. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ a b Alistair Boddy-Evans. Central Africa Republic Timeline – Part 1: From Prehistory to Independence (13 August 1960), A Chronology of Key Events in Central Africa RepublicArchived 23 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. About.com

- ^ «Central African Republic Archived 13 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine». Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ «Rābiḥ az-Zubayr | African military leader». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ French Colonies – Central African Republic Archived 21 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Discoverfrance.net. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d «One day we will start a big war». Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ a b Thomas O’Toole (1997) Political Reform in Francophone Africa. Westview Press. p. 111

- ^ Gardinier, David E. (1985). «Vocational and Technical Education in French Equatorial Africa (1842–1960)». Proceedings of the Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society. Michigan State University Press. 8: 113–123. ISSN 0362-7055. JSTOR 42952135.

- ^ «In pictures: Malaria train, Mayomba forest». news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ Kalck, Pierre. (2005). Historical dictionary of the Central African Republic (3rd ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4913-5. OCLC 55487416.

- ^ Central African Republic: The colonial era – Britannica Online Encyclopedia Archived 12 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ «Rābiḥ az-Zubayr | African military leader». Encyclopedia Britannica. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Cherkaoui, Said El Mansour (1991). «Central African Republic». In Olson, James S. (ed.). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. Greenwood. p. 122. ISBN 0-313-26257-8.

- ^ Kalck, p. xxxi.

- ^ Kalck, p. 90.

- ^ Kalck, p. 136.

- ^ Langer’s Encyclopedia of World History, page 1268.

- ^ «Central African Republic». African Union Development Agency. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Kalck, p. xxxii.

- ^ «‘Good old days’ under Bokassa? Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine». BBC News. 2 January 2009

- ^ Prial, Frank J.; Times, Special To the New York (2 September 1981). «Army Tropples Leader of Central African Republic». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ a b c «Central African Republic – Discover World». www.discoverworld.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ «EISA Central African Republic: 1999 Presidential election results». www.eisa.org.za. African Democracy Encyclopaedia Project. October 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ International Crisis Group. «Central African Republic: Anatomy of a Phantom State» (PDF). CrisisGroup.org. International Crisis Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ «Central African Republic History». DiscoverWorld.com. 2018. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ «Bozize to step down after transitional period». The New Humanitarian. 28 April 2003. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (10 December 2006). «On the Run as War Crosses Another Line in Africa». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ «CAR hails French pledge on rebels». BBC. 14 November 2006. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ «Central African Republic: Hundreds flee Birao as French jets strike – Central African Republic». ReliefWeb. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ «French planes attack CAR rebels». BBC. 30 November 2006. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ «PA-X: Peace Agreements Database». www.peaceagreements.org. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Central African Republic president flees capital amid violence, official says». CNN. 24 March 2013. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Lydia Polgreen (25 March 2013). «Leader of Central African Republic Fled to Cameroon, Official Says». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ «CrisisWatch N°117» Archived 20 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. crisisgroup.org.

- ^ «UN warning over Central African Republic genocide risk». BBC News. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 19 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ «France says Central African Republic on verge of genocide». Reuters. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ a b Smith, David (22 November 2013) Unspeakable horrors in a country on the verge of genocide Archived 2 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian. Retrieved 23 November 2013

- ^ «CrisisWatch N°118» Archived 20 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. crisisgroup.org.

- ^ «CrisisWatch N°119» Archived 20 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. crisisgroup.org.

- ^ Mark Tran (14 August 2013). «Central African Republic crisis to be scrutinised by UN security council». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ «CAR interim President Michel Djotodia resigns». BBC News. 11 January 2014. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ Paul-Marin Ngoupana (11 January 2014). «Central African Republic’s capital tense as ex-leader heads into exile». Reuters. Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ «RCA : signature d’un accord de cessez-le-feu à Brazzaville Archived 29 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine». VOA. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ «Almost all 436 Central African Republic mosques destroyed: U.S. diplomat». 17 March 2015.

- ^ «Rebel declares autonomous state in Central African Republic Archived 18 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine». Reuters. 16 December 2015.

- ^ Centrafrique : Le corps électoral convoqué le 14 février pour le 1er tour des législatives et le second tour de la présidentielle Archived 4 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine (in French), RJDH, 28 January 2016

- ^ New Central African president takes on a country in ruins ENCA, 28 March 2016

- ^ CAR presidential election: Faustin Touadera declared winner BBC News, 20 February 2016

- ^ «Central African Republic: Freedom in the World 2020 Country Report». Freedom House.

- ^ Vincent Duhem, «Centrafrique : ce qu’il faut retenir du nouveau gouvernement dévoilé par Touadéra», Jeune Afrique, 13 April 2016 (in French).

- ^ «Code électoral de la République Centrafricaine (Titre 2, Chapitre 1, Art. 131)» (PDF). Droit-Afrique.com (in French). 20 August 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ «RCA : présidentielle du 27 décembre, la Cour Constitutionnelle publie la liste définitive des candidats». 3 December 2020.

- ^ «Centrafrique : » ces élections, c’est une escroquerie politique «, dixit le candidat à la présidentielle Martin Ziguélé». 29 December 2020.

- ^ «Élections en Centrafrique: la légitimité du scrutin, perturbé en province, divise à Bangui». 29 December 2020.

- ^ «CAR violence forced closure of 800 polling stations: Commission». aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera English. 28 December 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ «Three UN peacekeepers killed in CAR ahead of Sunday’s elections». www.aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera. 26 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ «UN chief condemns attacks against peacekeepers in the Central African Republic». UN News. UN News. United Nations News Service. 26 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ «Central African Republic President Touadéra wins re-election». 4 January 2021.

- ^ «Wagner Group: Why the EU is alarmed by Russian mercenaries in Central Africa». BBC News. 19 December 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Roger; Lima, Mauricio (24 December 2022). «Putin Wants Fealty, and He’s Found It in Africa». The New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Roger Cohen. Africa’s Allegiance to Putin. New York Times, International Edition; 31 Dec 2022 / 1 Jan 2023, page A1+.

- ^ a b Moen, John. «Geography of Central African Republic, Landforms – World Atlas». www.worldatlas.com. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). «An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm». BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ «UNData app». data.un.org. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ «Sold Down the River (English)» Archived 13 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine. forestsmonitor.org.

- ^ «The Forests of the Congo Basin: State of the Forest 2006». Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2010.. CARPE 13 July 2007

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). «Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material». Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ National Geographic Magazine, November 2008

- ^ L. A. G. Antoine; W. U. Reimold; A. Tessema (1999). «The Bangui Magnetic Anomaly Revisited» (PDF). Proceedings 62nd Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting. 34: A9. Bibcode:1999M&PSA..34Q…9A. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ «Wildlife of northern Central African Republic in danger». phys.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Central African Republic: Country Study Guide volume 1, p. 24.

- ^ Ward, Inna, ed. (2007). Whitaker’s Almanack (139th ed.). London: A & C Black. p. 796. ISBN 978-0-7136-7660-0.

- ^ Peek, Philip M.; Yankah, Kwesi (March 2004). African Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135948733.

- ^ a b «Central African Republic». The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 5 June 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- ^ «Central African Republic Prefectures». www.statoids.com. 30 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ «FIW Score». Freedom House. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ Losh, Jack (26 March 2018). «Rebels in the Central African Republic are filling the void of an absent government». The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ «Central African Republic profile». BBC News. 1 August 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ «Legal System». The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ Searcey, Dionne (30 September 2019). «Gems, Warlords and Mercenaries: Russia’s Playbook in Central African Republic». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Jauer, Kersten (July 2009). «Stuck in the ‘recovery gap’: the role of humanitarian aid in the Central African Republic». Humanitarian Practice Network. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ «Central African Republic | ForeignAssistance.gov». www.foreignassistance.gov. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ CAR: Food shortages increase as fighting intensifies in the northwest Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. irinnews.org, 29 March 2006

- ^ «Central African Republic Executive Summary 2006» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Central African Republic Peacebuilding Fund – Overview Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations.

- ^ «Peacebuilding Commission Places Central African Republic on Agenda; Ambassador Tells Body ‘CAR Will Always Walk Side By Side With You, Welcome Your Advice’«. United Nations. 2 July 2008. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ «Mandate | UNITED NATIONS PEACEBUILDING». www.un.org. United Nations. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ a b Veronique Barbelet (2015) Central African Republic: addressing the protection crisis Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ «Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons». United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d 2009 Human Rights Report: Central African Republic . U.S. Department of State, 11 March 2010.

- ^ «Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor – Central African Republic» Archived 3 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. dol.gov.

- ^ «2010 Human Rights Report: Central African Republic». US Department of State. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ a b «UNICEF WCARO – Media Centre – Central African Republic: Children, not witches». Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ «Report: Accusations of child witchcraft on the rise in Africa». Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ UN human rights chief says impunity major challenge in run-up to elections in Central African Republic Archived 27 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. ohchr.org. 19 February 2010

- ^ «Child brides around the world sold off like cattle». USA Today. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ «Central African Republic». International Human Development Indicators. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ «World Population Prospects 2022». population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ «World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100» (XSLX). population.un.org («Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)»). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ «Central African Republic». Unaids.org. 29 July 2008. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ ANNEX 3: Country progress indicators Archived 9 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine. 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. unaids.org

- ^ «Central African Republic». City Population.

- ^ «International Religious Freedom Report 2010». U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ «Table: Christian Population as Percentages of Total Population by Country». Pew Research Center. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ «Table: Muslim Population by Country». Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ «Central African Republic, Statistics by Diocese». Catholic-Hierarchy.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ «Central African Republic». U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ «Central African Republic: Religious tinderbox». BBC News. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ «Central African Republic. International Religious Freedom Report 2006». U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ «Central African Republic 2016 Constitution». Constitute. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ «WHO – Health in Central African Republic». Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ a b c «Human Development Report 2009 – Central African Republic». Hdrstats.undp.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ «Country Comparison :: Maternal mortality rate». The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ «WHO – Female genital mutilation and other harmful practices». Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ «Mother and child health in Central African Republic». Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ «Malaria – one of the leading causes of death in the Central African Republic». Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ CIA World Factbook: HIV/AIDS – adult prevalence rate Archived 21 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Cia.gov. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ «Central African Republic». Unaids.org. 29 July 2016. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «WHO Country Offices in the WHO African Region – WHO | Regional Office for Africa». Afro.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ «Central African Republic». Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor (2001). Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ «Central African Republic – Statistics». UNICEF. Archived from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ «Accueil — Université de Bangui». www.univ-bangui.org. 18 August 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ University, EUCLID. «EUCLID (Euclid University) | Official Site». www.euclid.int.

- ^ a b c «Central African Republic – Systematic Country Diagnostic : Priorities for Ending Poverty and Boosting Shared Prosperity». The World Bank. Washington, D.C.: 1–96 19 June 2019 – via documents.worldbank.org/.

- ^ «Central African Republic adopts bitcoin as legal currency». news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Gouteux, J. P.; Blanc, F.; Pounekrozou, E.; Cuisance, D.; Mainguet, M.; D’Amico, F.; Le Gall, F. (1994). «Tsetse and livestock in Central African Republic: retreat of Glossina morsitans submorsitans (Diptera, Glossinidae)». Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique. 87 (1): 52–56. ISSN 0037-9085. PMID 8003908.

- ^ Doing Business 2010. Central African Republic. Doing Business. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; The World Bank. 2009. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-7961-5. ISBN 978-0-8213-7961-5.

- ^ a b Eur, pp. 200–202

- ^ Graham Booth; G. R McDuell; John Sears (1999). World of Science: 2. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-19-914698-7. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^

«Central African Republic: Finance and trade». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013. - ^ Eur, p. 185

- ^ «Hydropower in Central Africa – Hydro News Africa – ANDRITZ HYDRO». www.andritz.com. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ «Regional Regulatory Associations in Africa». www.itu.int. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ «Central African Republic — TheSportsDB.com». www.thesportsdb.com. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Country Profile – Central African Republic-Sports and Activities Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Indo-African Chamber of Commerce and Industry Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Central African Republic — Things to Do Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, iExplore Retrieved 24 September 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Eur (31 October 2002). Africa South of the Sahara 2003. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-85743-131-5.

- Kalck, Pierre (2004). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic.

- McKenna, Amy (2011). The History of Central and Eastern Africa. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1615303229.

- Balogh, Besenyo, Miletics, Vogel: La République Centrafricaine

Further reading[edit]

- Doeden, Matt, Central African Republic in Pictures (Twentyfirst Century Books, 2009).

- Petringa, Maria, Brazza, A Life for Africa (2006). ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0.

- Titley, Brian, Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa, 2002.

- Woodfrok, Jacqueline, Culture and Customs of the Central African Republic (Greenwood Press, 2006).

External links[edit]

Overviews[edit]

- Country Profile from BBC News

- Central African Republic. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Central African Republic from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Central African Republic at Curlie

Wikimedia Atlas of the Central African Republic

- Key Development Forecasts for the Central African Republic from International Futures

News[edit]

- Central African Republic news headline links from AllAfrica.com

Other[edit]

- Central African Republic at Humanitarian and Development Partnership Team (HDPT)

- Johann Hari in Birao, Central African Republic. «Inside France’s Secret War» from The Independent, 5 October 2007

Coordinates: 7°N 21°E / 7°N 21°E

|

Central African Republic

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

Motto:

|

|

Anthem:

|

|

|

|

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Bangui 4°22′N 18°35′E / 4.367°N 18.583°E |

| Official languages | French • Sango |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion

(2020)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Central African |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

|

• President |

Faustin-Archange Touadéra |

|

• Prime Minister |

Félix Moloua |

|

• President of the National Assembly |

Simplice Sarandji |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

|

• Republic established |

1 December 1958 |

|

• from France |

13 August 1960 |

|

• Central African Empire established |

4 December 1976 |

|

• Coronation of Bokassa I |

4 December 1977 |

|

• Bokassa I’s overthrow and republic restored |

21 September 1979 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

622,984 km2 (240,535 sq mi) (44th) |

|

• Water (%) |

0 |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

5,454,533[2] (119th) |

|

• Density |

7.1/km2 (18.4/sq mi) (221st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

|

• Total |

$4.262 billion[3] (162nd) |

|

• Per capita |

$823[3] (184th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

|

• Total |

$2.321 billion[3] (163th) |

|

• Per capita |

$448[3] (181st) |

| Gini (2008) | 56.3[4] high · 28th |

| HDI (2021) | low · 188th |

| Currency |

|

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right[7] |

| Calling code | +236 |

| ISO 3166 code | CF |

| Internet TLD | .cf |

The Central African Republic (CAR; Sango: Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka IPA: [kōdōrōsésè tí bé.àfríkà]; French: République centrafricaine, RCA;[8] French: [ʁepyblik sɑ̃tʁafʁikɛn], or Centrafrique, [sɑ̃tʁafʁik]) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south, the Republic of the Congo to the southwest, and Cameroon to the west.

The Central African Republic covers a land area of about 620,000 square kilometres (240,000 sq mi). As of 2021, it had an estimated population of around 5.5 million. As of 2023, the Central African Republic was the scene of a civil war, ongoing since 2012.[9]

Most of the Central African Republic consists of Sudano-Guinean savannas, but the country also includes a Sahelo-Sudanian zone in the north and an equatorial forest zone in the south. Two-thirds of the country is within the Ubangi River basin (which flows into the Congo), while the remaining third lies in the basin of the Chari, which flows into Lake Chad.

What is today the Central African Republic has been inhabited for millennia;[when?] however, the country’s current borders were established by France, which ruled the country as a colony starting in the late 19th century. After gaining independence from France in 1960, the Central African Republic was ruled by a series of autocratic leaders, including an abortive attempt at a monarchy.[10]

By the 1990s, calls for democracy led to the first multi-party democratic elections in 1993. Ange-Félix Patassé became president, but was later removed by General François Bozizé in the 2003 coup. The Central African Republic Bush War began in 2004 and, despite a peace treaty in 2007 and another in 2011, civil war resumed in 2012. The civil war perpetuated the country’s poor human rights record: it was characterized by widespread and increasing abuses by various participating armed groups, such as arbitrary imprisonment, torture, and restrictions on freedom of the press and freedom of movement.

Despite (or arguably because of) its significant mineral deposits and other resources, such as uranium reserves, crude oil, gold, diamonds, cobalt, lumber, and hydropower,[11] as well as significant quantities of arable land, the Central African Republic is among the ten poorest countries in the world, with the lowest GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in the world as of 2017.[12] As of 2019, according to the Human Development Index (HDI), the country had the second-lowest level of human development (only ahead of Niger), ranking 188 out of 189 countries. The country had the lowest inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI), ranking 150th out of 150 countries.[13] The Central African Republic is also estimated to be the unhealthiest country[14] as well as the worst country in which to be young.[15]

The Central African Republic is a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the Economic Community of Central African States, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie and the Non-Aligned Movement.

Etymology[edit]

The name of the Central African Republic is derived from the country’s geographical location in the central region of Africa and its republican form of government. From 1976 to 1979, the country was known as the Central African Empire.

During the colonial era, the country’s name was Ubangi-Shari (French: Oubangui-Chari), a name derived from the Ubangi River and the Chari River. Barthélemy Boganda, the country’s first prime minister, favored the name «Central African Republic» over Ubangi-Shari, reportedly because he envisioned a larger union of countries in Central Africa.[16]

History[edit]

The Bouar Megaliths, pictured here on a 1967 Central African stamp, date back to the very late Neolithic Era (c. 3500–2700 BCE).

Early history[edit]