§ 13. После ж, ш, ч, щ, ц пишутся буквы а, у (и не

пишутся я, ю) напр.: жаль, Жанна, межа;

шар, лапша; час, свеча, молчащий; площадка, плаща; цапля, отца; жуткий, скажу;

шум, Шура, большущий; чувство, молчу; щука, прощу; цугом, отцу.

Примечание 1. В нескольких иноязычных

нарицательных существительных после ж, ш пишется буква ю: жюри,

жюльен, брошюра, парашют и некоторые другие, более редкие.

Примечание 2. В некоторых иноязычных

собственных именах, этнических названиях после ж, ш, ц пишутся буквы я, ю, напр.: Жямайтская возвышенность, Жюль, Сен-Жюст, Жю-райтис,

Шяуляй, Цюрих, Коцюбинский, Цюрупа, Цюй Юань, Цявловский, Цяньцзян, цян

(народность). В этих случаях звуки, передаваемые буквами ж, ш, ц, нередко произносятся мягко.

Буквы ю

и я пишутся по традиции

после ч в некоторых

фамилиях (ю — преимущественно

в литовских), напр.: Чюрлёнис,

Степонавичюс, Мкртчян, Чюмина.

как правильно перенести слово Цюрих

- Варианты переноса для хорошей оценки для слова цю-рих

А вот так правильно писать Цюрих

Как написать слово «цюрихский» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «цюрихский»?

цю́рихский

Правильное написание — цюрихский, ударение падает на букву: ю, безударными гласными являются: и, и.

Выделим согласные буквы — цюрихский, к согласным относятся: ц, р, х, с, к, й, звонкие согласные: р, й, глухие согласные: ц, х, с, к.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 9,

- слогов — 3,

- гласных — 3,

- согласных — 6.

Формы слова: цю́рихский (от Цю́рих).

цю́рихский

цю́рихский (от Цю́рих)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я обязательно научусь отличать широко распространённые слова от узкоспециальных.

Насколько понятно значение слова попоститься (глагол), попостится:

Синонимы к слову «цюрихский»

Предложения со словом «цюрихский»

- – Догадываюсь, тебе снилось, что ты цюрихский бургомистр?..

- Просто села на цюрихский поезд, понадеявшись на свой немецкий язык и на то, что в купе первого класса пограничные чиновники заходить не станут.

- Ведь известно, что цюрихский филиал фирмы, например, согласен принять в число своих клиентов только лиц, имеющих капитал не меньше, чем 1 млн швейц. франков.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «цюрихский»

- В 1849 году я поместил моего сына, пяти лет от роду, в цюрихский институт глухонемых.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

×òî òàêîå «Öþðèõ»? Êàê ïðàâèëüíî ïèøåòñÿ äàííîå ñëîâî. Ïîíÿòèå è òðàêòîâêà.

Öþðèõ

(Zurich)

ãîðîä â Øâåéöàðèè, íà Öþðèõñêîì îçåðå, ó èñòîêà ð. Ëèììàò. Àäìèíèñòðàòèâíûé öåíòð êàíòîíà Öþðèõ. Ñàìûé êðóïíûé ïî êîëè÷åñòâó æèòåëåé ãîðîä â ñòðàíå 395,8 òûñ. (1975), ñ ïðèãîðîäàìè è ãîðîäàìè-ñïóòíèêàìè 720,8 òûñ. Òðàíñïîðòíûé óçåë; ïðèñòàíü; àýðîïîðò ìåæäóíàðîäíîãî çíà÷åíèÿ â Êëîòåíå. Ãëàâíûé ïðîìûøëåííûé è òîðãîâî-ôèíàíñîâûé öåíòð ñòðàíû. Ìàøèíîñòðîåíèå è ìåòàëëîîáðàáîòêà (ìåòàëëîðåæóùèå, òåêñòèëüíûå è äð. ñòàíêè, ëîêîìîòèâî- è âàãîíîñòðîåíèå, ïðèáîðîñòðîåíèå, ýëåêòðîòåõíè÷åñêîå è äð. ïðîìûøëåííîå îáîðóäîâàíèå), õèìè÷åñêàÿ, òåêñòèëüíàÿ, øâåéíàÿ, áóìàæíàÿ, ïîëèãðàôè÷åñêàÿ ïðîìûøëåííîñòü.

Öþðèõ — Öþðèõ

(Zürich), ãîðîä â Øâåéöàðèè, íà áåðåãó Öþðèõñêîãî îçåðà, ó èñòîêîâ ðåêè Ëèììàò. Âîçíèê… Õóäîæåñòâåííàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

Öþðèõ —

êàíòîí â Øâåéöàðèè.  1843 âûï. ñîáñòâåííûå ìàðêè ñ èçîáðàæåíèåì öèôð íîìèíàëà (÷åðíàÿ ïå÷à… Áîëüøîé ôèëàòåëèñòè÷åñêèé ñëîâàðü

Разбор слова «цюрих»: для переноса, на слоги, по составу

Объяснение правил деление (разбивки) слова «цюрих» на слоги для переноса.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «цюрих» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «цюрих».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «цюрих» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «цюрих»

- 3 Синонимы слова «цюрих»

- 4 Ударение в слове «цюрих»

- 5 Фонетическая транскрипция слова «цюрих»

- 6 Фонетический разбор слова «цюрих» на буквы и звуки (Звуко-буквенный)

- 7 Значение слова «цюрих»

- 8 Как правильно пишется слово «цюрих»

- 9 Ассоциации к слову «цюрих»

Слоги в слове «цюрих» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 2

По слогам: цю-рих

Как перенести слово «цюрих»

цю—рих

Синонимы слова «цюрих»

Ударение в слове «цюрих»

цю́рих — ударение падает на 1-й слог

Фонетическая транскрипция слова «цюрих»

[ц`ур’их]

Фонетический разбор слова «цюрих» на буквы и звуки (Звуко-буквенный)

| Буква | Звук | Характеристики звука | Цвет |

|---|---|---|---|

| ц | [ц] | согласный, глухой непарный, твёрдый, шумный | ц |

| ю | [`у] | гласный, ударный | ю |

| р | [р’] | согласный, звонкий непарный (сонорный), мягкий | р |

| и | [и] | гласный, безударный | и |

| х | [х] | согласный, глухой непарный, твёрдый, шумный | х |

Число букв и звуков:

На основе сделанного разбора делаем вывод, что в слове 5 букв и 5 звуков.

Буквы: 2 гласных буквы, 3 согласных букв.

Звуки: 2 гласных звука, 3 согласных звука.

Значение слова «цюрих»

Цю́рих (нем. Zürich [ˈtsyːrɪç]; швейц. Züri [tsy:ri], фр. Zurich, итал. Zurigo) — город на северо-востоке Швейцарии. Столица немецкоязычного кантона Цюрих и административный центр одноимённого округа. (Википедия)

Как правильно пишется слово «цюрих»

Правописание слова «цюрих»

Орфография слова «цюрих»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «цюрих» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Ассоциации к слову «цюрих»

-

Швейцария

-

Женева

-

Берн

-

Кантон

-

Мюнхен

-

Брюссель

-

Лейпциг

-

Амстердам

-

Гамбург

-

Атлетика

-

Копенгаген

-

Швейцарец

-

Стокгольм

-

Люксембург

-

Берлин

-

Юнга

-

Будапешт

-

Торонто

-

Лиссабон

-

Прага

-

Милан

-

Дрезден

-

Альп

-

Вена

-

Эйнштейн

-

Берлина

-

Рейс

-

Штаб-квартира

-

Лион

-

Иоганн

-

Гонконг

-

Дублин

-

Ницца

-

Ульрих

-

Турин

-

Токио

-

Барселона

-

Консульство

-

Авиакомпания

-

Сингапур

-

Мадрид

-

Банк

-

Конгресс

-

Борн

-

Стамбул

-

Париж

-

Белград

-

Эмигрант

-

Уефа

-

Пауль

-

Кембридж

-

Банка

-

Аэропорт

-

Вольфганг

-

Шанхай

-

Суворов

-

Филиал

-

Коммуна

-

Рихард

-

Анатомия

-

Лондон

-

Банкир

-

Богословие

-

Пианист

-

Пригород

-

Магда

-

Манчестер

-

Эрнст

-

Вагнер

-

Сейм

-

Дирижёр

-

Австрия

-

Медицина

-

Йозеф

-

Чикаго

-

Конфедерация

-

Фриц

-

Университет

-

Афины

-

Эдит

-

Пекин

-

Марсель

-

Фрейд

-

Учёба

-

Краков

-

Кредит

-

Швейцарский

-

Политехнический

-

Банковый

-

Банковский

-

Трамвайный

-

Оперный

-

Альпийский

-

Протестантский

-

Докторский

-

Хоккейный

-

Технический

-

Венский

-

Эмигрировать

-

Преподавать

|

Zürich |

|

|---|---|

|

Municipality in Switzerland |

|

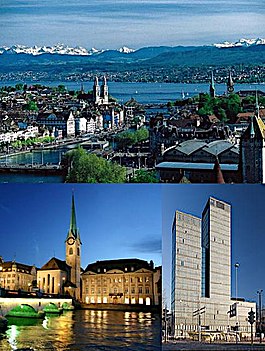

|

From top to bottom: View over Zürich from the Grossmünster, the Opera House, Prime Tower at night, ETH main building and Fraumünster church in the old town. |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

|

Location of Zürich |

|

|

Zürich Zürich |

|

| Coordinates: 47°22′28″N 08°32′28″E / 47.37444°N 8.54111°ECoordinates: 47°22′28″N 08°32′28″E / 47.37444°N 8.54111°E | |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Canton | Zürich |

| District | Zürich |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Stadtrat with 9 members |

| • Mayor | Stadtpräsidentin (list) Corine Mauch SPS/PSS (as of February 2014) |

| • Parliament | Gemeinderat with 125 members |

| Area

[1][2] |

|

| • Total | 87.88 km2 (33.93 sq mi) |

| Elevation

(Zürich Hauptbahnhof) |

408 m (1,339 ft) |

| Highest elevation

(Uetliberg) |

871 m (2,858 ft) |

| Lowest elevation

(Limmat) |

392 m (1,286 ft) |

| Population

(2018-12-31)[3][4] |

|

| • Total | 415,215 |

| • Density | 4,700/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym | German: Zürcher(in) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (Central European Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (Central European Summer Time) |

| Postal code(s) |

8000–8099 |

| SFOS number | 0261 |

| Surrounded by | Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon |

| Twin towns | Kunming, San Francisco |

| Website | www.stadt-zuerich.ch SFSO statistics |

Logo of the city of Zürich

Zürich ( ZURE-ik, ZOOR-ik, German: [ˈtsyːrɪç] (listen); see below) is the largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland,[5] at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2020, the municipality has 434,335 inhabitants, the urban area 1.315 million (2009),[6] and the Zürich metropolitan area 1.83 million (2011).[7] Zürich is a hub for railways, roads, and air traffic. Both Zurich Airport and Zürich’s main railway station are the largest and busiest in the country.

Permanently settled for over 2,000 years, Zürich was founded by the Romans, who called it Turicum. However, early settlements have been found dating back more than 6,400 years (although this only indicates human presence in the area and not the presence of a town that early).[8] During the Middle Ages, Zürich gained the independent and privileged status of imperial immediacy and, in 1519, became a primary centre of the Protestant Reformation in Europe under the leadership of Huldrych Zwingli.[9]

The official language of Zürich is German,[a] but the main spoken language is Zürich German, the local variant of the Alemannic Swiss German dialect.

Many museums and art galleries can be found in the city, including the Swiss National Museum and Kunsthaus. Schauspielhaus Zürich is considered to be one of the most important theatres in the German-speaking world.[10]

Zürich is home to many financial institutions and banking companies.

Name[edit]

In German, the city name is written Zürich, and pronounced [ˈtsyːrɪç] in Swiss Standard German or [ˈtsyːʁɪç] (listen) in German Standard German. In the local dialect, the name is pronounced without the final consonant, as Züri [ˈtsyri], although the adjective remains Zürcher(in). The city is called Zurich [zyʁik] in French, Zurigo [dzuˈriːɡo] in Italian, and Turitg [tuˈritɕ] (

listen) in Romansh.

The name is traditionally written in English as Zurich, without the umlaut. It is pronounced ZURE-ik or ZOOR-ik.[11]

The earliest known form of the city’s name is Turicum, attested on a tombstone of the late 2nd century AD in the form STA(tio) TURICEN(sis) («Turicum tax post»).The name is interpreted as a derivation from a given name, possibly the Gaulish personal name Tūros, for a reconstructed native form of the toponym of *Turīcon.[12] The Latin stress on the long vowel of the Gaulish name, [tʊˈriːkõː], was lost in German [ˈtsyːrɪç] but is preserved in Italian [dzuˈriːɡo] and in Romansh [tuˈritɕ]. The first development towards its later Germanic form is attested as early as the 6th century with the form Ziurichi. From the 9th century onward, the name is established in an Old High German form Zuri(c)h (857 in villa Zurih, 924 in Zurich curtem, 1416 Zürich Stadt).[13] In the early modern period, the name became associated with the name of the Tigurini, and the name Tigurum rather than the historical Turicum is sometimes encountered in Modern Latin contexts.[14]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Settlements of the Neolithic and Bronze Age were found around Lake Zürich. Traces of pre-Roman Celtic, La Tène settlements were discovered near the Lindenhof, a morainic hill dominating the SE — NW waterway constituted by Lake Zurich and the river Limmat.[15] In Roman times, during the conquest of the alpine region in 15 BC, the Romans built a castellum on the Lindenhof.[15] Later here was erected Turicum (a toponym of clear Celtic origin), a tax-collecting point for goods trafficked on the Limmat, which constituted part of the border between Gallia Belgica (from AD 90 Germania Superior) and Raetia: this customs point developed later into a vicus.[15] After Emperor Constantine’s reforms in AD 318, the border between Gaul and Italy (two of the four praetorian prefectures of the Roman Empire) was located east of Turicum, crossing the river Linth between Lake Walen and Lake Zürich, where a castle and garrison looked over Turicum’s safety. The earliest written record of the town dates from the 2nd century, with a tombstone referring to it as to the Statio Turicensis Quadragesima Galliarum («Zürich post for collecting the 2.5% value tax of the Galliae»), discovered at the Lindenhof.[15]

In the 5th century, the Germanic Alemanni tribe settled in the Swiss Plateau. The Roman castle remained standing until the 7th century. A Carolingian castle, built on the site of the Roman castle by the grandson of Charlemagne, Louis the German, is mentioned in 835 (in castro Turicino iuxta fluvium Lindemaci). Louis also founded the Fraumünster abbey in 853 for his daughter Hildegard. He endowed the Benedictine convent with the lands of Zürich, Uri, and the Albis forest, and granted the convent immunity, placing it under his direct authority. In 1045, King Henry III granted the convent the right to hold markets, collect tolls, and mint coins, and thus effectively made the abbess the ruler of the city.[16]

Zürich gained Imperial immediacy (Reichsunmittelbar, becoming an Imperial free city) in 1218 with the extinction of the main line of the Zähringer family and attained a status comparable to statehood. During the 1230s, a city wall was built, enclosing 38 hectares, when the earliest stone houses on the Rennweg were built as well. The Carolingian castle was used as a quarry, as it had started to fall into ruin.[17]

Emperor Frederick II promoted the abbess of the Fraumünster to the rank of a duchess in 1234. The abbess nominated the mayor, and she frequently delegated the minting of coins to citizens of the city. The political power of the convent slowly waned in the 14th century, beginning with the establishment of the Zunftordnung (guild laws) in 1336 by Rudolf Brun, who also became the first independent mayor, i.e. not nominated by the abbess.

An important event in the early 14th century was the completion of the Manesse Codex, a key source of medieval German poetry. The famous illuminated manuscript – described as «the most beautifully illumined German manuscript in centuries;»[18] – was commissioned by the Manesse family of Zürich, copied and illustrated in the city at some time between 1304 and 1340. Producing such a work was a highly expensive prestige project, requiring several years work by highly skilled scribes[19] and miniature painters, and it clearly testifies to the increasing wealth and pride of Zürich citizens in this period. The work contains 6 songs by Süsskind von Trimberg, who may have been a Jew, since the work itself contains reflections on medieval Jewish life, though little is known about him.[20]

The first mention of Jews in Zürich was in 1273. Sources show that there was a synagogue in Zürich in the 13th century, implying the existence of a Jewish community.[21] With the rise of the Black Death in 1349, Zürich, like most other Swiss cities, responded by persecuting and burning the local Jews, marking the end of the first Jewish community there. The second Jewish community of Zürich, formed towards the end of the 14th century, was short-lived, and Jews were expulsed and banned from the city from 1423 until the 19th century.[22]

Archaeological findings[edit]

A woman who died in about 200 BC was found buried in a carved tree trunk during a construction project at the Kern school complex in March 2017 in Aussersihl. Archaeologists revealed that she was approximately 40 years old when she died and likely carried out little physical labor when she was alive. A sheepskin coat, a belt chain, a fancy wool dress, a scarf and a pendant made of glass and amber beads were also discovered with the woman.[23][24][25][26]

Old Swiss Confederacy[edit]

A scene depicting the Old Zürich War in 1443 (1514, illustration in Federal Chronicle by Werner Schodoler)

On 1 May 1351, the citizens of Zürich had to swear allegiance before representatives of the cantons of Lucerne, Schwyz, Uri and Unterwalden, the other members of the Swiss Confederacy. Thus, Zürich became the fifth member of the Confederacy, which was at that time a loose confederation of de facto independent states. Zürich was the presiding canton of the Diet from 1468 to 1519. This authority was the executive council and lawmaking body of the confederacy, from the Middle Ages until the establishment of the Swiss federal state in 1848. Zürich was temporarily expelled from the confederacy in 1440 due to a war with the other member states over the territory of Toggenburg (the Old Zürich War). Neither side had attained significant victory when peace was agreed upon in 1446, and Zürich was readmitted to the confederation in 1450.[27]

Zwingli started the Swiss Reformation at the time when he was the main preacher in the 1520s, at the Grossmünster. He lived there from 1484 until his death in 1531. The Zürich Bible, based on that of Zwingli, was issued in 1531. The Reformation resulted in major changes in state matters and civil life in Zürich, spreading also to a number of other cantons. Several cantons remained Catholic and became the basis of serious conflicts that eventually led to the outbreak of the Wars of Kappel.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Council of Zürich adopted an isolationist attitude, resulting in a second ring of imposing fortifications built in 1624. The Thirty Years’ War which raged across Europe motivated the city to build these walls. The fortifications required a lot of resources, which were taken from subject territories without reaching any agreement. The following revolts were crushed brutally. In 1648, Zürich proclaimed itself a republic, shedding its former status of a free imperial city.[27] In this time the political system of Zürich was an oligarchy (Patriziat): the dominant families of the city were the following ones: Bonstetten, Brun, Bürkli, Escher vom Glas, Escher vom Luchs, Hirzel, Jori (or von Jori), Kilchsperger, Landenberg, Manesse, Meiss, Meyer von Knonau, Mülner, von Orelli.

The Helvetic Revolution of 1798 saw the fall of the Ancien Régime. Zürich lost control of the land and its economic privileges, and the city and the canton separated their possessions between 1803 and 1805. In 1839, the city had to yield to the demands of its urban subjects, following the Züriputsch of 6 September. Most of the ramparts built in the 17th century were torn down, without ever having been besieged, to allay rural concerns over the city’s hegemony. The Treaty of Zürich between Austria, France, and Sardinia was signed in 1859.[28]

Modern history[edit]

Zürich was the Federal capital for 1839–40, and consequently, the victory of the Conservative party there in 1839 caused a great stir throughout Switzerland. But when in 1845 the Radicals regained power at Zürich, which was again the Federal capital for 1845–46, Zürich took the lead in opposing the Sonderbund cantons. Following the Sonderbund war and the formation of the Swiss Federal State, Zürich voted in favour of the Federal constitutions of 1848 and of 1874. The enormous immigration from the country districts into the town from the 1830s onwards created an industrial class which, though «settled» in the town, did not possess the privileges of burghership, and consequently had no share in the municipal government. First of all in 1860 the town schools, hitherto open to «settlers» only on paying high fees, were made accessible to all, next in 1875 ten years’ residence ipso facto conferred the right of burghership, and in 1893 the eleven outlying districts were incorporated within the town proper.

When Jews also began to settle in Zürich following their equality in 1862, the Israelitische Cultusgemeinde Zürich was founded.[29]

Extensive developments took place during the 19th century. From 1847, the Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn, the first railway on Swiss territory, connected Zürich with Baden, putting the Zürich Hauptbahnhof at the origin of the Swiss rail network. The present building of the Hauptbahnhof (the main railway station) dates to 1871. Zürich’s Bahnhofstrasse (Station Street) was laid out in 1867, and the Zürich Stock Exchange was founded in 1877. Industrialisation led to migration into the cities and to rapid population growth, particularly in the suburbs of Zürich.

The Quaianlagen are an important milestone in the development of the modern city of Zürich, as the construction of the new lake front transformed Zürich from a small medieval town on the rivers Limmat and Sihl to an attractive modern city on the Zürichsee shore, under the guidance of the city engineer Arnold Bürkli.[30]

In 1893, the twelve outlying districts were incorporated into Zürich, including Aussersihl, the workman’s quarter on the left bank of the Sihl, and additional land was reclaimed from Lake Zürich.[31]

In 1934, eight additional districts in the north and west of Zürich were incorporated.

Zürich was accidentally bombed during World War II. As persecuted Jews sought refuge in Switzerland, the SIG (Israelite Community of Switzerland) raised financial resources. The central committee for refugee aid, created in 1933, was located in Zürich.

The canton of Zürich did not recognise the Jewish religious communities as legal entities (and therefore as equal to national churches) until 2005.[29]

Coat of arms[edit]

The blue and white coat of arms of Zürich is attested from 1389 and was derived from banners with blue and white stripes in use since 1315. The first certain testimony of banners with the same design is from 1434. The coat of arms is flanked by two lions. The red Schwenkel on top of the banner had varying interpretations: For the people of Zürich, it was a mark of honour, granted by Rudolph I. Zürich’s neighbours mocked it as a sign of shame, commemorating the loss of the banner at Winterthur in 1292. Today, the Canton of Zürich uses the same coat of arms as the city.[32][unreliable source]

Politics[edit]

City districts[edit]

Zürich’s twelve municipal districts

The previous boundaries of the city of Zürich (before 1893) were more or less synonymous with the location of the old town. Two large expansions of the city limits occurred in 1893 and in 1934 when the city of Zürich merged with many surrounding municipalities, that had been growing increasingly together since the 19th century. Today, the city is divided into twelve districts (known as Kreis in German), numbered 1 to 12, each one of which contains between one and four neighborhoods:

- Kreis 1, known as Altstadt, contains the old town, both to the east and west of the start of the Limmat. District 1 contains the neighbourhoods of Hochschulen, Rathaus, Lindenhof, and City.

- Kreis 2 lies along the west side of Lake Zürich, and contains the neighbourhoods of Enge, Wollishofen and Leimbach.

- Kreis 3, known as Wiedikon is between the Sihl and the Uetliberg, and contains the neighbourhoods of Alt-Wiedikon, Sihlfeld and Friesenberg.

- Kreis 4, known as Aussersihl lies between the Sihl and the train tracks leaving Zürich Hauptbahnhof, and contains the neighbourhoods of Werd, Langstrasse, and Hard.

- Kreis 5, known as Industriequartier, is between the Limmat and the train tracks leaving Zürich Hauptbahnhof, it contains the former industrial area of Zürich which has undergone large-scale rezoning to create upscale modern housing, retail, and commercial real estate. It contains the neighborhoods of Gewerbeschule and Escher-Wyss.

- Kreis 6 is on the edge of the Zürichberg, a hill overlooking the eastern part of the city. District 6 contains the neighbourhoods of Oberstrass and Unterstrass.

- Kreis 7 is on the edge of the Adlisberg hill as well as the Zürichberg, on the eastern side of the city. District 7 contains the neighbourhoods of Fluntern, Hottingen, and Hirslanden. These neighbourhoods are home to Zürich’s wealthiest and more prominent residents. The neighbourhood Witikon also belongs to district 7.

- Kreis 8, officially called Riesbach, but colloquially known as Seefeld, lies on the eastern side of Lake Zürich. District 8 consists of the neighbourhoods of Seefeld, Mühlebach, and Weinegg.

- Kreis 9 is between the Limmat to the north and the Uetliberg to the south. It contains the neighbourhoods Altstetten and Albisrieden.

- Kreis 10 is to the east of the Limmat and to the south of the Hönggerberg and Käferberg hills. District 10 contains the neighbourhoods of Höngg and Wipkingen.

- Kreis 11 is in the area north of the Hönggerberg and Käferberg and between the Glatt Valley and the Katzensee (Cats Lake). It contains the neighbourhoods of Affoltern, Oerlikon and Seebach.

- Kreis 12, known as Schwamendingen, is located in the Glattal (Glatt valley) on the northern side of the Zürichberg. District 12 contains the neighbourhoods of Saatlen, Schwamendigen Mitte, and Hirzenbach.

Most of the district boundaries are fairly similar to the original boundaries of the previously existing municipalities before they were incorporated into the city of Zürich.

Government[edit]

The City Council (Stadtrat) constitutes the executive government of the City of Zürich and operates as a collegiate authority. It is composed of nine councilors, each presiding over a department. Departmental tasks, coordination measures and implementation of laws decreed by the Municipal Council are carried out by the City Council. The regular election of the City Council by any inhabitant valid to vote is held every four years. The mayor (German: Stadtpräsident(in)) is elected as such by a public election by a system of Majorz while the heads of the other departments are assigned by the collegiate. Any resident of Zurich allowed to vote can be elected as a member of the City Council. In the mandate period 2018–2022 (Legislatur) the City Council is presided by mayor Corine Mauch. The executive body holds its meetings in the City Hall (German: Stadthaus), on the left bank of the Limmat. The building was built in 1883 in Renaissance style.

As of May 2018, the Zürich City Council was made up of three representatives of the SP (Social Democratic Party, one of whom is the mayor), two members each of the Green Party and the FDP (Free Democratic Party), and one member each of GLP (Green Liberal Party) and AL (Alternative Left Party), giving the left parties a combined six out of nine seats.[33] The last regular election was held on 4 March 2018.[33]

- ^ Mayor (Stadtpräsidentin)

Claudia Cuche-Curti is Town Chronicler (Stadtschreiberin) since 2012, and Peter Saile is Legal Counsel (Rechtskonsulent) since 2000 for the City Council.

Parliament[edit]

The Gemeinderat of Zürich for the mandate period of 2018–2022

AL (8%)

SP (34.4%)

GPS (12.8%)

GLP (11.2%)

EVP (3.2%)

FDP (16.8%)

SVP (13.6%)

The Municipal Council (Gemeinderat) holds the legislative power. It is made up of 125 members (Gemeindrat / Gemeinderätin), with elections held every four years. The Municipal Council decrees regulations and by-laws that are executed by the City Council and the administration. The sessions of the Municipal Council are held in public. Unlike those of the City Council, the members of the Municipal Council are not politicians by profession but are paid a fee based on their attendance. Any resident of Zürich allowed to vote can be elected as a member of the Municipal Council. The legislative body holds its meetings in the town hall (Rathaus), on the right bank of the Limmat opposite to the City Hall (Stadthaus).[34]

The last election of the Municipal Council was held on 4 March 2018 for the mandate period of 2018–2022.[33] As of May 2018, the Municipal Council consist of 43 members of the Social Democratic Party (SP), 21 The Liberals (FDP), 17 members of the Swiss People’s Party (SVP), 16 Green Party (GPS), 14 Green Liberal Party (GLP), 10 Alternative List (AL), and four members of the Evangelical People’s Party (EVP), giving the left parties an absolute majority of 69.[35]

Elections[edit]

National Council[edit]

In the 2019 federal election for the Swiss National Council the most popular party was the SPS which received 25.6% (-6) of the vote. The next four most popular parties were the GPS (20.9%, +9.7), GLP (15.7%, +6.4), SVP (13.7%, -4.3), the FDP (11.8%, -2.2), the AL (4%, new), and the CVP (3.5%, -0.2).[36] In the federal election, a total of 110,760 voters were cast, and the voter turnout was 47.7%.[37]

In the 2015 federal election for the Swiss National Council the most popular party was the SPS which received 31.6% of the vote. The next four most popular parties were the SVP (18%), the FDP (14%), the GPS (10.7%), the GLP (9.2%). In the federal election, a total of 114,377 voters were cast, and the voter turnout was 46.2%.[38]

International relations[edit]

Twin towns and sister cities[edit]

Zürich is partnered with two sister cities: Kunming and San Francisco.[39]

Geography[edit]

The city stretches on both sides of the Limmat, which flows out of Lake Zürich. The Alps can be seen from the city center, background to the lake.

Zürich is situated at 408 m (1,339 ft) above sea level on the lower (northern) end of Lake Zürich (Zürichsee) about 30 km (19 mi) north of the Alps, nestling between the wooded hills on the west and east side. The Old Town stretches on both sides of the Limmat, which flows from the lake, running northwards at first and then gradually turning into a curve to the west. The geographic (and historic) centre of the city is the Lindenhof, a small natural hill on the west bank of the Limmat, about 700 m (2,300 ft) north of where the river issues from Lake Zürich. Today the incorporated city stretches somewhat beyond the natural confines of the hills and includes some districts to the northeast in the Glatt Valley (Glattal) and to the north in the Limmat Valley (Limmattal). The boundaries of the older city are easy to recognize by the Schanzengraben canal. This artificial watercourse has been used for the construction of the third fortress in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Topography[edit]

The municipality of Zürich has an area of 91.88 km2 (35.48 sq mi), of which 4.1 km2 (1.6 sq mi) is made up of Lake Zürich. The area includes a section of the northern Swiss Plateau. The banks of the Limmat constitute the densest part of the city. The river is oriented in the southeast–northwest direction, with the flat valley floor having a width of two to three km (1.2 to 1.9 mi). The partially channeled and straightened Limmat does not flow in the central part of the valley, but always along its right (northeastern) side. The Sihl meets with the Limmat at the end of Platzspitz, which borders the Swiss National Museum. The Limmat reaches the lowest point of the municipality in Oberengstringen at 392 m (1,286 ft) above sea level.[citation needed]

Topographic map of Zürich and surroundings

Felsenegg from Lake Zürich

On its west side, the Limmat valley is flanked by the wooded heights of the Albis chain, which runs along the western border. The Uetliberg is, with 869 m (2,851 ft) above sea level, the highest elevation of the surrounding area. Its summit can be reached easily by the Uetlibergbahn. From the platform of the observation tower on the summit, an impressive panorama of the city, the lake, and the Alps can be seen.[citation needed]

The northeast side of the Limmat valley includes a range of hills, which marks the watershed between the Limmat and the Glatt. From the northwest to the southeast, the height of the mostly wooded knolls generally increases: the Gubrist (615 m or 2,018 ft), the Hönggerberg (541 m or 1,775 ft), the Käferberg (571 m or 1,873 ft), the Zürichberg (676 m or 2,218 ft), the Adlisberg (701 m or 2,300 ft) and the Öschbrig (696 m or 2,283 ft). Between the Käferberg and the Zürichberg is located the saddle of the Milchbuck (about 470 m or 1,540 ft), an important passage from the Limmat valley to the Glatt valley.[citation needed]

The northernmost part of the municipality extends to the plain of the Glatt valley and to the saddle which makes the connection between the Glattal and Furttal. Also, a part of the Katzensee (nature reserve) and the Büsisee, both of which are drained by the Katzenbach to Glatt, belong to the city.[citation needed]

Climate[edit]

Zürich has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb), with warm summers and four distinct seasons.[40] Decisive for the climate of Zürich are both the winds from westerly directions, which often result in precipitation and, on the other hand, the Bise (east or north-east wind), which is usually associated with high-pressure situations, but cooler weather phases with temperatures lower than the average. The Foehn wind, which plays an important role in the northern alpine valleys also has some impact on Zürich.[41]

The annual mean temperature at the measuring station of the Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology in Zürich-Fluntern (556 m[1,824 ft] above sea level on the slope of the Zürichberg, 150 m[490 ft] above the level of the city centre) is 9.3 °C (48.7 °F). The lowest monthly mean of daily minimum temperature are measured in January with −2.0 °C (28.4 °F) and the highest monthly mean of daily maximum temperature are measured in July with 24.0 °C (75.2 °F). On average there are 74.9 days in which the minimum temperature is below 0 °C (32 °F) (so-called frost days), and 23.7 days in which the maximum temperature is below 0 °C (32 °F) (so-called ice days). There are on average 30 so-called summer days (maximum temperature equal to or above 25 °C [77 °F]) throughout the year, while so-called heat days (with maximum temperature equal to or above 30 °C [86 °F]) are 5.8 days.[42]

The average high temperature in July is 24.0 °C (75.2 °F) and average low temperature is 14 °C (57.2 °F). The highest recorded temperature in Zürich was 37.7 °C (100 °F), recorded in July 1947, and typically the warmest day reaches an average of 32.2 °C (90.0 °F).[43][44]

Spring and autumn are generally cool to mild, but sometimes with large differences between warm and cold days even during the same year. The highest temperature of the month March in 2014 was on the 20th at 20.6 °C (69.1 °F) during a sunny afternoon and the lowest temperature was on the 25th at −0.4 °C (31.3 °F) during the night/early morning.[45] Record low of average daily temperatures in March since 1864 is −12 °C (10 °F) and record high of average daily temperatures in March is 16 °C (61 °F). Record low of average daily temperatures in October is −16 °C (3 °F) and record high of average daily temperatures in October is 20 °C (68 °F).[46]

Zürich has an average of 1,544 hours of sunshine per year and shines on 38% of its potential time throughout the year. During the months April until September the sun shines between 150 and 215 hours per month. The 1,134 mm (44.6 in) rainfall spread on 133.9 days with precipitation throughout the year. Roughly about every third day you will encounter at least some precipitation, which is very much a Swiss average. During the warmer half of the year and especially during the three summer months, the strength of rainfall is higher than those measured in winter, but the days with precipitation stays about the same throughout the year (in average 9.9–12.7 days per month). October has the lowest number (9.9) of days with some precipitation. There is an average of 59.5 so-called bright days (number of days with sunshine duration greater than 80%) through the year, the most in July and August (7.4, 7.7 days), and the least in January and December (2.7, 1.8 days). The average number of days with sunshine duration less than 20%, so-called cloudy days, is 158.4 days, while the most cloudy days are in November (17.8 days), December (21.7 days), and January with 19 days.[42]

| Climate data for Zürich (Fluntern), elevation: 556 m (1,824 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1901–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.9 (62.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

32.4 (90.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

36.2 (97.2) |

32.5 (90.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

23.8 (74.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

37.7 (99.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.4 (29.5) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

1.9 (35.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.8 (−5.4) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.9 (33.6) |

5.3 (41.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−18.5 (−1.3) |

−24.2 (−11.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 63 (2.5) |

60 (2.4) |

71 (2.8) |

80 (3.1) |

128 (5.0) |

128 (5.0) |

126 (5.0) |

119 (4.7) |

87 (3.4) |

85 (3.3) |

76 (3.0) |

83 (3.3) |

1,108 (43.6) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 14 (5.5) |

18 (7.1) |

10 (3.9) |

2 (0.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.8) |

7 (2.8) |

19 (7.5) |

72 (28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.1 | 9.0 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 12.4 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 11.5 | 130.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 4.1 | 4.8 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 4.4 | 17.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 77 | 71 | 67 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 74 | 79 | 84 | 85 | 85 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 60 | 89 | 144 | 177 | 192 | 207 | 229 | 216 | 164 | 109 | 61 | 47 | 1,694 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 24 | 34 | 42 | 47 | 45 | 48 | 53 | 53 | 48 | 35 | 24 | 20 | 42 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: MeteoSwiss[47] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[48] |

| Climate data for Zürich (Fluntern), elevation: 556 m (1,824 ft), 1961-1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

30.8 (87.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

26.7 (80.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

35.8 (96.4) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 9.8 (49.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.5 (70.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

29.8 (85.6) |

28.9 (84.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

29.8 (85.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

12.6 (54.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

12.3 (54.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.6 (63.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.7 (38.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −10.1 (13.8) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.7 (42.3) |

7.8 (46.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.8 (−5.4) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−10.3 (13.5) |

−14.7 (5.5) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69.0 (2.72) |

70.0 (2.76) |

70.0 (2.76) |

89.0 (3.50) |

105.0 (4.13) |

125.0 (4.92) |

118.0 (4.65) |

135.0 (5.31) |

94.0 (3.70) |

69.0 (2.72) |

82.0 (3.23) |

75.0 (2.95) |

1,101 (43.35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 134 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.0 | 80.0 | 75.0 | 72.0 | 73.0 | 74.0 | 73.0 | 77.0 | 81.0 | 84.0 | 84.0 | 85.0 | 78.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 42.4 | 76.2 | 118.0 | 139.5 | 166.1 | 178.3 | 210.7 | 191.9 | 158.1 | 104.6 | 58.2 | 38.0 | 1,482 |

| Source: NOAA[49] |

Climate protection[edit]

In November 2008[50] the people of Zürich voted in a public referendum to write into law the quantifiable and fixed deadline of one tonne of CO2 per person per annum by 2050. This forces any decision of the executive to support this goal, even if the costs are higher in all dimensions. Some examples are the new disinfection section of the public city hospital in Triemli (Minergie-P quality – passive house),[clarification needed] the continued optimisation and creation of public transportation, enlargement of the bicycle-only network, research and projects for renewable energy and enclosure of speed-ways.[clarification needed]

Urban area[edit]

The areas surrounding the Limmat are almost completely developed with residential, industrial, and commercial zones. The sunny and desirable residential areas in the hills overlooking Zürich, Waidberg and Zürichberg, and the bottom part of the slope on the western side of the valley on the Uetliberg, are also densely built.

The «green lungs» of the city include the vast forest areas of Adlisberg, Zürichberg, Käferberg, Hönggerberg and Uetliberg. Major parks are also located along the lakeshore (Zürichhorn and Enge), while smaller parks dot the city. Larger contiguous agricultural lands are located near Affoltern and Seebach. Of the total area of the municipality of Zürich (in 1996, without the lake), 45.4% is residential, industrial and commercial, 15.5% is transportation infrastructure, 26.5% is forest, 11%: is agriculture and 1.2% is water.

View over Zürich and Lake Zürich from the Uetliberg

Transport[edit]

Public transport[edit]

A paddle steamer on Lake Zürich

Public transport is extremely popular in Zürich, and its inhabitants use public transport in large numbers. About 70% of the visitors to the city use the tram or bus, and about half of the journeys within the municipality take place on public transport.[51] The ZVV network of public transport contains at least four means of mass-transit: any train that stops within the network’s borders, in particular the S-Bahn (local trains), Zürich trams, and buses (both diesel and electric, also called trolley buses) and boats on the lake and river. In addition, the public transport network includes funicular railways and even the Luftseilbahn Adliswil-Felsenegg (LAF), a cable car between Adliswil and Felsenegg. Tickets purchased for a trip are valid on all means of public transportation (train, tram, bus, boat). The Zürichsee-Schifffahrtsgesellschaft (commonly abbreviated to ZSG) operates passenger vessels on the Limmat and the Lake Zürich, connecting surrounding towns between Zürich and Rapperswil.

The busy Hauptbahnhof main hall

Zürich is a mixed hub for railways, roads, and air traffic. Zürich Hauptbahnhof (Zürich HB) is the largest and busiest station in Switzerland and is an important railway hub in Europe. As of early 2020, Zürich HB served around 470,000 passengers and nearly 3,000 trains every day.[52] Among the 16 railway stations (and 10 additional train stops) within Zürich’s city borders, there are five other major passenger railway stations. Three of them belong to the ten most frequented railway stations in Switzerland: Stadelhofen, Oerlikon, Altstetten, Hardbrücke, and Enge. The railway network is mainly operated by the Swiss Federal Railways (SBB CFF FFS), but Zürich is also served by major EuroCity trains from the neighbouring countries and is a destination for both French/Swiss (TGV Lyria) and German (ICE) high-speed trains, as well as by Austrian RailJet.

Zurich Airport[edit]

Zurich Airport is located less than 10 km (6.2 mi) northeast of the city in Kloten. Zurich Airport has its own railway station, which is located underground. It is directly connected to Zürich and most of the major Swiss cities. Zurich Airport is served by more than 60 passenger airlines from around the world. It is also served by one cargo airline and is a hub for Swiss International Air Lines. There is also an airfield in Dübendorf.

Road traffic[edit]

The A1, A3 and A4 motorways pass close to Zürich. The A1 heads west towards Bern and Geneva and eastwards towards St. Gallen; the A4 leads northwards to Schaffhausen and southwards to Altdorf connecting with the A2 towards Chiasso; and the A3 heads northwest towards Basel and southeast along Lake Zürich and Lake Walen towards Sargans.

Bicycle transport[edit]

In 2012, the city council launched a program to improve the city’s attractiveness for bicycle traffic. The so-called «Masterplan Velo»[53] is part of the superordinate framework Stadtverkehr 2025 which shapes the future of the different means of transport. Research revealed that infrastructure and the social environment are essential factors in improving a city’s appeal to bicycle traffic.[54] Three main goals are specified: First, the modal share of bicycle traffic should be enhanced to twice the value of 2011 by 2015. Second, cyclists’ safety should be improved to lower the overall accident risk. Third, cycling should be established as an everyday means of transport with a special focus on children and young people.

In terms of infrastructure, the city aims to build up a network of distinctive bicycle routes in order to achieve these objectives. At a final stage, the network will consist of main routes (Hauptrouten) for everyday use and comfort routes (Komfortrouten), with the latter focusing on leisure cycling. Additional measures such as special Velostationen providing bike-related services are expected to help to further improve the quality. One of the key projects of the system is a tunnel beneath the tracks of the main railway station planned to combine a main connection with staffed possibilities where commuters can leave their bikes throughout the day.[55] Apart from infrastructural measures, further approaches are planned in the fields of communication, education and administration.

However, these efforts cause critique, mainly due to postponing. The institution of the bike tunnel at the main railway station, originally planned for 2016, is currently (2016) delayed to at least 2019.[56] Pro Velo, a nationwide interest group, has publicly questioned whether the masterplan already failed.[57] The critique aims at badly governed traffic management at construction sites, missing possibilities to park bikes in the city as well as rather diffident ambitions. In response, the responsible city department points to the big investments made every year and mentions ongoing discussions that would finally lead to even better results.[58]

Demographics[edit]

Population[edit]

There are 421,878 people living in Zürich (as of 31 December 2020),[59] making it Switzerland’s largest city. Of registered inhabitants (in 2016), 32% (133,473) do not hold Swiss citizenship.[60] Of these, German citizens make up the largest group with 8% (33,548), followed by Italians 3.5% (14,543).[60] As of 2011, the population of the city, including suburbs, totaled 1.17 million people.[7] The entire metropolitan area (including the cities of Winterthur, Baden, Brugg, Schaffhausen, Frauenfeld, Uster / Wetzikon, Rapperswil-Jona, and Zug) had a population of around 1.82 million people.[7]

| Nationality | Number | % total (foreigners) |

|---|---|---|

| 33,548 | 8.1% (25.1%) | |

| 14,543 | 3.5% (10.9%) | |

| 8,274 | 2.0% (6.2%) | |

| 6,207 | 1.5% (4.7%) | |

| 4,809 | 1.2% (3.6%) | |

| 4,244 | 1.0% (3.2%) | |

| 3,597 | 0.9% (2.7%) | |

| 3,483 | 0.8% (2.6%) | |

| 3,402 | 0.8% (2.5%) | |

| 2,437 | 0.6% (1.8%) | |

| 2,126 | 0.5% (1.8%) |

Languages[edit]

The official formal language used by governmental institutions, print, news, schools and universities, courts, theatres and in any kind of written form is the Swiss variety of Standard German, while the spoken language is Zürich German (Züritüütsch), one of the several more or less distinguishable, but mutually intelligible Swiss German dialects of Switzerland with roots in the medieval Alemannic German dialect groups. However, because of Zürich’s national importance, and therefore its existing high fluctuation,[clarification needed] its inhabitants and commuters speak all kinds of Swiss German dialects. As of the December 2010 census, 69.3% of the population speaks diglossic Swiss German/Swiss Standard German as their mother-tongue at home. Some 22.7% of inhabitants speak Standard German in their family environment («at home»). Dramatically increasing, according to the last census in 2000, 8.8% now speak English. Italian follows behind at 7.1% of the population, then French at 4.5%. Other languages spoken here include: Bosnian (4.1%), Spanish (3.9%), Portuguese (3.1%), and Albanian (2.3%). (Multiple choices were possible.) Thus, 20% of the population speak two or more languages at home.[61]

Religion[edit]

| Religion in Zürich — 2010[62] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religion | Nationality | Total-Pop. | ||

| Roman Catholic | Swiss | 28% | 30% | |

| Other | 35% | |||

| Unaffiliated | Swiss | 25% | 27% | |

| Other | 31% | |||

| Swiss Reformed | Swiss | 33% | 26% | |

| Other | 9% | |||

| Other Christians | Swiss | 6% | 7% | |

| Other | 9% | |||

| Islam | Swiss | 3% | 5% | |

| Other | 9% | |||

| Other Religion | Swiss | 2% | 2% | |

| Other | 4% | |||

| No answer | Swiss | 2% | 2% | |

| Other | 2% | |||

| Jewish | Swiss | 1% | 1% | |

| Other | 1% |

Before the Protestant Reformation reached Zürich, it was de jure and de facto Roman Catholic.

The Protestant Reformation, led by Huldrych Zwingli, made Zürich both a theological centre and a stronghold of Protestantism in Switzerland. Another Swiss city with a comparable status was Geneva, the so-called Protestant Rome, where John Calvin and his Protestant Reformers operated, as well as Basel. Zürich attracted other influential Protestant Reformers like Heinrich Bullinger. Zwingli translated the Bible (Zürich Bible) into the local variety of German, and introduced the Reformation by winning support of the magistrates, the princess abbess Katharina von Zimmern, and the largely peasant population of the Canton of Zürich. The canton unanimously adopted the Reformed tradition, as represented by Zwingli. Religious wars between Catholics and Protestants tormented the Swiss Confederacy. Zwingli died for political and religious reasons by defending the Canton of Zürich in the Battle of Kappel. Bullinger took over his role as the city’s spiritual leader.

In 1970, about 53% of the population were Swiss Reformed, while almost 40% were Roman Catholic. Since then, both large Swiss churches, the Roman Catholic Church and Swiss Reformed Church, have been constantly losing members, though for the Catholic Church, the decrease started 20 years later, in around 1990. Nevertheless, for the last twenty years, both confessions have been reduced by 10%, to the current figures (census 2010): 30% Roman Catholic, and 26% Swiss Reformed (organized in Evangelical Reformed Church of the Canton of Zürich). In 1970, only 2% of Zürich’s inhabitants claimed to be not affiliated with any religious confession. In accordance with the loss by the large Swiss churches, the number of people declaring themselves as non-affiliated rose to 17% in the year 2000. In the last ten years, this figure rose to more than 25%. For the group of people, being between 24 and 44 years old, this is as high as one in every third person.[63]

5% of Zürich’s inhabitants are Muslims, a slight decrease of 1%, compared to the year 2000. The Mahmood Mosque Zürich, situated in Forchstrasse, is the first mosque built in Switzerland.[63][64]

The population of Jewish ethnicity and religion has been more or less constant since 1970, at about 1%. The Synagoge Zürich Löwenstrasse is the oldest and largest synagogue of Zürich.[63][65]

[edit]

The level of unemployment in Zürich was 3.2%[66] in July 2012. In 2008, the average monthly income was about CHF 7000 before any deductions for social insurances and taxes.[67] In 2010, there were 12,994 cases (on average per month) of direct or indirect welfare payments from the state.[68]

Quality of living[edit]

Zürich often performs very well in international rankings, some of which are mentioned below:

- Monocle’s 2012 «Quality of Life Survey» ranked Zürich first on a list of the top 25 cities in the world «to make a base within».[69] In 2019 Zürich was ranked among the ten most liveable cities in the world by Mercer together with Geneva and Basel.[70]

- In fDi Magazine‘s «Global Cities of the Future 2021/22» report, Zürich placed 16th in the overall rankings (all categories).[71][72] In the category «Mid-sized and small cities», Zürich was 2nd overall, behind Wroclaw, having also placed 2nd in the subcategory «Human capital and lifestyle» and 3rd under «Business friendliness». In the category «FDI strategy, overall» (relating to foreign direct investment), Zürich ranked 9th, behind such cities as New York, Montreal (1st and 2nd) and Dubai (at number 8).[72]

Main sites[edit]

Most of Zürich’s sites are located within the area on either side of the Limmat, between the Main railway station and Lake Zürich. The churches and houses of the old town are clustered here, as are the most expensive shops along the famous Bahnhofstrasse. The Lindenhof in the old town is the historical site of the Roman castle, and the later Carolingian Imperial Palace.

Churches[edit]

- Grossmünster (Great Minster) According to legend, Charlemagne discovered the graves of the city’s martyrs Felix and Regula and had built the first church as a monastery; start of current building around 1100; in the first half of the 16th century, the Great Minster was the starting point of the Swiss-German Reformation led by Huldrych Zwingli and Heinrich Bullinger; declared by Charlemagne imperial church; romanesque crypt, romanesque capitals in the church and cloister; choir windows by Augusto Giacometti (1932) and Sigmar Polke (2009), bronze doors by Otto Münch (1935 and 1950).[73]

- Fraumünster (Women’s Minster) Church of a former abbey for aristocratical women from southern Germany which was founded in 853 by Louis the German for his daughter Hildegard; first church built before 874; the romanesque choir dates from 1250 to 1270; the church enjoyed the patronage of kings and had the right of coinage from Zürich to the 13th century; after the Reformation, church and convent passed into the possession of the city; the most important jewelry – in addition to the largest organ in the canton with its 5,793 pipes and 92 stops – are color windows: the window in the north transept of Augusto Giacometti (1945), the five-part cycle in the choir (1970) and the rosette in the southern transept (1978) are by Marc Chagall; also the church of Zürich’s largest choir with 100 and more singers.[74]

- St. Peter romanesque-gothic-baroque church built on remains of former churches from before the 9th century; with the largest church clock face in Europe built 1538; baptismal font of 1598, baroque stucco; individual stalls from the 15th century from city repealed monasteries with rich carvings and armrests; Kanzellettner (increased barrier between the nave and choir with built-pulpit) of 1705 pulpit sounding board about 1790; rich Akanthus embellishment with Bible verse above the pulpit; 1971 new crystal chandelier modeled according 1710 design; organ in 1974 with 53 stops; Bells: five from 1880, the largest, A minor, without clapper weighs about 6,000 kg (13,228 lb); fire guard in the tower to the Middle Ages to 1911.[75]

- Predigerkirche is one of the four main churches of the old town, first built in 1231 AD as a Romanesque church of the then Dominican Predigerkloster nearby the Neumarkt. It was converted in the first half of the 14th century, and the choir rebuilt between 1308 and 1350. Due to its construction and for that time unusual high bell tower, it was regarded as the most high Gothic edifice in Zürich.[citation needed]

Museums[edit]

- Zürich Museum of Art – The Museum of Art, also known as Kunsthaus Zürich, is one of the significant art museums of Europe. It holds one of the largest collections in Classic Modern art in the world (Munch, Picasso, Braque, Giacometti, etc.). The museum also features a large library collection of photographs.[76]

- Swiss National Museum – The National Museum (German: Landesmuseum) displays many objects that illustrate the cultural and historical background of Switzerland. It also contains many ancient artifacts, including stained glass, costumes, painted furniture and weapons. The museum is located in the Platzspitz park opposite to the Hauptbahnhof.[77]

- Centre Le Corbusier – Located on the shore of the Lake Zürich nearby Zürichhorn, the Centre Le Corbusier (also named: Heidi Weber Museum), is an art museum dedicated to the work of the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, inside the last house he designed.

- Rietberg Museum – The Rietberg Museum, situated in Gablerstrasse, is one of the great repositories of art and culture in Zürich. The museum also displays exhibits gathered from various corners of the world: bronze artifacts from Tibet, ceramics and jade, Indian sculpture, Chinese grave decorations, masks by African tribes, etc.

- Museum of Design – The Museum of Design is a museum for industrial design, visual communication, architecture and craft. It is part of the Department of Cultural Analysis of the Zürich University of the Arts.[78]

- Haus Konstruktiv – The Haus Konstruktiv is a museum with Swiss-wide and international recognition. The museum is about constructive, concrete and conceptual art and design. It testimonies to Zürich’s industrial architecture in the immediate vicinity of the Main Station.[79]

- Uhrenmuseum Beyer – The Uhrenmuseum is located in the heart of the city. Documenting the history of timekeeping and timekeepers, the museum is home to a large collection of mechanical timepieces as well as a collection of primitive time keeping devices such as water clocks, sundials and hourglasses

- No Show Museum – the No Show Museum is the first museum dedicated to nothing and its various manifestations throughout the history of art.

- Guild houses – The Guild houses (German: Zunfthaus) are located along the Limmat (downstream from the Grossmünster): Meisen (also a porcelain and faience museum), Rüden, Haue, Saffran, Schneidern, Schmiden, Zimmerleuten, and some more.

- Tram Museum – The Tram Museum is located at Burgwies in Zürich’s eastern suburbs, and chronicles the history of Zürich’s iconic tram system with exhibits varying in date from 1897 to the present day.

- North America Native Museum – The North American Native Museum specializes in the conservation, documentation and presentation of ethnographic objects and art of Native American, First Nation and Inuit cultures.

- FIFA Museum — The museum exhibits memorabilities from the world of Association Football (Soccer), founded by the Féderation Internationale de Football Association

Parks and nature[edit]

- Zoological Garden – The zoological garden holds about 260 species of animals and houses about 2200 animals. One can come across separate enclosures of snow leopards, India lions, clouded leopards, Amur leopards, otters and pandas in the zoo.[80]

- Botanical Garden – The Botanical Garden houses about 15,000 species of plants and trees and contains as many as three million plants. In the garden, many rare plant species from south western part of Africa, as well as from New Caledonia can be found. The University of Zürich holds the ownership of the Botanical Garden.

- Chinese Garden – The Chinese Garden is a gift by Zürich’s Chinese partner town Kunming, as remiscence for Zürich’s technical and scientific assistance in the development of the Kunming city drinking water supply and drainage. The garden is an expression of one of the main themes of Chinese culture, the «Three Friends of Winter» – three plants that together brave the cold season – pine, bamboo, and plum.

- Uetliberg – Located to the west of the city at an altitude of 813 m (2,667 ft) above sea level, the Uetliberg is the highest hill and offers views over the city. The summit is easily accessible by train from Zürich main station.[81]

Kunst und Bau (construction permit office)[edit]

Information pamphlet providing information about why these frescos were made

In 1922 Augusto Giacometti won the competition to paint the entrance hall of Amtshaus I, which the city promised to brighten up this gloomy room, which was once used as a cellar, and at the same time to alleviate the precarious economic situation of the local artists. Giacometti brought in the painters Jakob Gubler, Giuseppe Scartezzini and Franz Riklin for the execution of this fresco, which encompasses the ceiling and walls, thereby creating a unique color space that appears almost sacred in its luminosity.[82]

Architecture[edit]

The 88-metre[83] Sunrise Tower (2005) was the first approved high-rise building in twenty years.

Compared to other cities, there are few tall buildings in Zürich. The municipal building regulations (Article 9)[84] limit the construction of high-rise buildings to areas in the west and north of the city. In the industrial district, Altstetten and Oerlikon, buildings up to 80 m (260 ft) in height are allowed (high-rise area I). In the adjacent high-rise areas II and III the height is limited to 40 m (130 ft). Around the year 2000, regulations became more flexible and high-rise buildings were again planned and built. The people’s initiative «40 m (130 ft) is enough,» which would have reduced both the maximum height and the high-rise buildings area, was clearly rejected on 29 November 2009.[85] At this time in Zürich about a dozen high-rise buildings were under construction or in planning, including the Prime Tower as the tallest skyscraper in Switzerland at the time of its construction. There are numerous examples of brutalist buildings throughout the city, including the Swissmill Tower which, at 118m, is the world’s tallest grain silo.

World heritage sites[edit]

The prehistoric settlements at Enge Alpenquai and Grosser Hafner and Kleiner Hafner are part of the Prehistoric Pile dwellings around the Alps a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[86]

Economy[edit]

In a 2009 survey by CityMayors.com, Zürich was ranked 9th among the «World’s 10 Most Powerful Cities».[87] In the 2017 Global Financial Centres Index, Zürich was ranked as having the 11th most competitive financial center in the world, and second most competitive in Europe after London.[88] The Greater Zürich Area is Switzerland’s economic centre and home to many international companies. By far the most important sector in the economy of Zürich is the service industry, which employs nearly four-fifths of workers. Other important industries include light industry, machine and textile industries and tourism. Located in Zürich, the Swiss Stock Exchange was established in 1877 and is now the fourth most prominent stock exchange in the world. In addition, Zürich is the world’s largest gold trading centre.[citation needed]

Ten of the country’s 50 largest companies have their head offices in Zürich, among them ABB, UBS,[89] Credit Suisse, Swiss Re and Zürich Financial Services.[90] Most Swiss banks have their headquarters in Zürich and there are numerous foreign banks in the Greater Zürich Area. «Gnomes of Zürich» is a colloquial term used for Swiss bankers [91] on account of their alleged secrecy and speculative dealing.[92]

Contributory factors to economic strength[edit]

The high quality of life has been cited as a reason for economic growth in Zürich. The consulting firm Mercer has[when?] for many years ranked Zürich as a city with the highest quality of life in the world.[93][94] In particular, Zürich received high scores for work, housing, leisure, education and safety. Local planning authorities ensure clear separation between urban and recreational areas and there are many protected nature reserves.[95] Zürich is also ranked[when?] the third most expensive city in the world, behind Hong Kong and Tokyo and ahead of Singapore.[96]

Zürich benefits from the high level of investment in education which is typical of Switzerland in general and provides skilled labour at all levels. The city is home to two major universities, thus enabling access to graduates and high technology research. Professional training incorporates a mix of practical work experience and academic study while, in general, emphasis is placed on obtaining a good level of general education and language ability. As a result, the city is home to many multilingual people and employees generally demonstrate a high degree of motivation and a low level of absenteeism. The employment laws are less restrictive as nearby Germany or France. Technology new start, FinTech and others in MedTech secure good seed and starter funding.[95]

The Swiss stock exchange[edit]

The Swiss stock exchange is called SIX Swiss Exchange, formerly known as SWX. The SIX Swiss Exchange is the head group of several different worldwide operative financial systems: Eurex, Eurex US, EXFEED, STOXX, and virt-x. The exchange turnover generated at the SWX was in 2007 of 1,780,499.5 million CHF; the number of transactions arrived in the same period at 35,339,296 and the Swiss Performance Index (SPI) arrived at a total market capitalization of 1,359,976.2 million CHF.[97][98]

Education and research[edit]

Main building of the University of Zürich

About 70,000 people study at the 20 universities, colleges and institutions of higher education in Zürich in 2019.[99] Two of Switzerland’s most distinguished universities are located in the city: the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich), which is controlled by the federal government, and the University of Zurich, under direction of the canton of Zürich. Both universities were listed in the top 50 world universities rated in 2007, while the ETH has consistently remained in the top 10 universities worldwide since 2016.[100][101]

ETH was founded in 1854 by the Swiss Confederation and opened its doors in 1855 as a polytechnic institute. ETH achieved its reputation particularly in the fields of chemistry, mathematics and physics and there are 21 Nobel Laureates who are associated with the institution. ETH is usually ranked the top university in continental Europe.[102] The institution consists of two campuses, the main building in the heart of the city and the new campus on the outskirts of the city.

The University of Zurich was founded in 1833, although its beginnings date back to 1525 when the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli founded a college of theology. Nowadays with its 24,000 students and 1,900 graduations each year, the University of Zürich is the largest in Switzerland and offers the widest range of subjects and courses at any Swiss higher education institution.

The Pedagogical College, the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) and the Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK) are another three top-class technical colleges which contribute to Zürich’s reputation as a knowledge and research pole by providing applied research and development. Zürich is also one of the co-location centres of the Knowledge and Innovation Community (Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation) of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology.[103]

In addition to the university libraries, the city is also served by the Zentralbibliothek Zürich, a research and public library, and the Pestalozzi-Bibliothek Zürich, a public library with 14 locations.

State universities by size in canton of Zürich[edit]

Media[edit]

Many large Swiss media conglomerates are headquartered in Zürich, such as tamedia, Ringier and the NZZ-Verlag.

Television and radio[edit]

Swiss television’s building

The headquarters of Switzerland’s national licence fee-funded German language television network («SF») are located in the Leutschenbach neighborhood, to the north of the Oerlikon railway station. Regional commercial television station «TeleZüri» (Zürich Television) has its headquarters near Escher-Wyss Platz. The production facilities for other commercial stations «Star TV», «u1» TV and «3+» are located in Schlieren.

One section of the Swiss German language licence fee-funded public radio station «Schweizer Radio DRS» is located in Zürich. There are commercial local radio stations broadcasting from Zürich, such as «Radio 24» on the Limmatstrasse, «Energy Zürich» in Seefeld on the Kreuzstrasse, Radio «LoRa» and «Radio 1». There are other radio stations that operate only during certain parts of the year, such as «CSD Radio» (May/June), «Radio Streetparade» (July/August) and «rundfunk.fm» (August/September).

Print media[edit]

There are three large daily newspapers published in Zürich that are known across Switzerland. The Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), the Tages-Anzeiger and Blick, the largest Swiss tabloid. All three of those newspapers publish Sunday editions. These are the NZZ am Sonntag, SonntagsZeitung and SonntagsBlick. Besides the three main daily newspapers, there is a free daily commuter newspaper which is widely distributed: 20 Minuten (20 minutes), published weekdays in the mornings.

A number of magazines from major publishers are based in Zürich. Some examples are Bilanz, Die Weltwoche, Annabelle, Schweizer Familie and Schweizer Illustrierte.

Culture[edit]

In addition to high-quality museums and galleries, Zürich has high-calibre chamber and symphony orchestras and several important theatres.[105]

The Zurich Film Festival is an international film festival, lasting 11 days and featuring popular international productions.[106]

One of the largest and most popular annual events in Zürich is the Street Parade, which is also one of the largest techno and dance music festivals in the world. Proceeding along the side of Lake Zürich, it is normally held on the second Saturday in August. The first edition was held in 1992 with about 1,000 participants. By 2001 the event attracted one million participants.[107][108] The Zürifäscht, on the other hand, is a triennial public festival. It features music, fireworks set to music,[108] and other attractions throughout the old town. It is the largest public festival in Switzerland and attracts up to 2 million visitors.[109]

The Kunst Zürich is an international contemporary art fair with an annual guest city; it combines most recent arts with the works of well-established artists.[110] Another annual public art exhibit is the city campaign, sponsored by the City Vereinigung (the local equivalent of a chamber of commerce) with the cooperation of the city government. It consists of decorated sculptures distributed over the city centre, in public places. Past themes have included lions (1986), cows (1998), benches (2003), teddy bears (2005), and huge flower pots (2009). From this originated the concept of the CowParade that has been featured in other major world cities.

Zürich has been the home to several art movements. The Dada movement was founded in 1916 at the Cabaret Voltaire. Artists like Max Bill, Marcel Breuer, Camille Graeser or Richard Paul Lohse had their ateliers in Zürich, which became even more important after the takeover of power by the Nazi regime in Germany and World War II.

The best known traditional holiday in Zürich is the Sechseläuten (Sächsilüüte), including a parade of the guilds and the burning of «winter» in effigy at the Sechseläutenplatz. During this festival the popular march known as the Sechseläutenmarsch is played. It has no known composer but likely originated in Russia.[111] Another is the Knabenschiessen target shooting competition for teenagers (originally boys, open to female participants since 1991).

Opera, ballet, and theaters[edit]

The Zürich Opera House (German: Zürcher Opernhaus), built in 1834, was the first permanent theatre in the heart of Zürich and was at the time, the main seat of Richard Wagner’s activities. Later in 1890, the theatre was re-built as an ornate building with a neo-classical architecture. The portico is made of white and grey stone ornamented with the busts of Wagner, Weber and Mozart. Later, busts of Schiller, Shakespeare and Goethe were also added. The auditorium is designed in the rococo style. Once a year, it hosts the Zürcher Opernball with the President of the Swiss Confederation and the economic and cultural élite of Switzerland.[112] The Ballet Zürich performs at the opera house. The Zürich Opera Ball, a major social event, is held annually at the Opera House as a fundraiser for the opera and ballet companies.

The Schauspielhaus Zürich is the main theatre complex of the city. It has two dépendances: Pfauen in the Central City District and Schiffbauhalle, an old industrial hall, in Zürich West. The Schauspielhaus was home to emigrants such as Bertolt Brecht or Thomas Mann, and saw premieres of works of Max Frisch, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Botho Strauss or Elfriede Jelinek. The Schauspielhaus is one of the most prominent and important theatres in Switzerland.[113]

The Theater am Neumarkt is one of the oldest theatres of the city. Established by the old guilds in the Old City District, it is located in a baroque palace near Niederdorf Street. It has two stages staging mostly avantgarde works by European directors.

The Zürcher Theater Spektakel is an international theatre festival, featuring contemporary performing arts.[114]

Food[edit]

The traditional cuisine of Zürich reflects the centuries of rule by patrician burghers as well as the lasting imprint of Huldrych Zwingli’s puritanism. Traditional dishes include Zürcher Geschnetzeltes and Tirggel.

Nightlife and clubbing[edit]

Zürich is host city of the Street Parade, which takes place in August every year (see above).

The most famous districts for Nightlife are the Niederdorf in the old town with bars, restaurants, lounges, hotels, clubs, etc. and a lot of fashion shops for a young and stylish public and the Langstrasse in the districts 4 and 5 of the city. There are authentic amusements: bars, punk clubs, hip hop stages, Caribbean restaurants, arthouse cinemas, Turkish kebabs and Italian espresso-bars, but also sex shops or the famous red-light district of Zürich.

In the past ten years[when?] new parts of the city have risen into the spotlight. Notably, the area known as Zürich West in district 5, near the Escher-Wyss square and the S-Bahn Station of Zürich Hardbrücke.[citation needed]

Sports[edit]

Zürich is home to several international sport federations. The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) is headquartered in the city. In 2007 were inaugurated the new FIFA headquarters building, designed by architect Tilla Theus.