далай-лама

- далай-лама

-

далай-лама, далай-ламы

Слитно или раздельно? Орфографический словарь-справочник. — М.: Русский язык.

.

1998.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «далай-лама» в других словарях:

-

ДАЛАЙ-ЛАМА — (тибет.). Буддийский первосвященник, который живет в Тибете и, кроме духовной власти, имеет и светскую. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910. ДАЛАЙ ЛАМА [монг. букв. лама, обладающий безграничной, как… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

Далай-лама IV — Далай лама IV, Ёнтэн Гьямцхо (yon tan rgya mtsho, ཡོན་ཏན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་)(1589 1616) был обнаружен среди монголов. Он был внуком Алтан хана, одного из наиболее могущественных монгольских правителей. Так между монгольскими ханами и школой Гэлуг возникло… … Википедия

-

ДАЛАЙ-ЛАМА — ДАЛАЙ ЛАМА, далай ламы, муж. (монгольско тибетск. dalai blama, букв. море лама, лама с властью, безграничной как море). Верховный глава ламаистской церкви, живущий в Тибете, совмещающий церковную и светскую власть. Толковый словарь Ушакова. Д.Н.… … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

Далай-лама — [монгольское далай море (мудрости) и лама высший] титул (с 16 в.) первосвященника буддийской церкви в Тибете (происхождение института далай ламы относится к началу 15 в.) … Исторический словарь

-

далай-лама — первосвященник Словарь русских синонимов. далай лама сущ., кол во синонимов: 3 • глава (63) • … Словарь синонимов

-

Далай-лама — высшее духовное лицо сев. буддистов, с светскою властью.Лама, слово тибетское, значит верховный (старший); далайпо монгольски: великий . Этот термин появился в буддийской иерархиисравнительно недавно. У реформатора новейшего буддизма, Цзонхавы… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

ДАЛАЙ-ЛАМА — ДАЛАЙ ЛАМА, ы, муж. В Тибете: титул ламаистского первосвященника, а также лицо, имеющее этот титул. Толковый словарь Ожегова. С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова. 1949 1992 … Толковый словарь Ожегова

-

Далай-лама — Стиль этой статьи неэнциклопедичен или нарушает нормы русского языка. Статью следует исправить согласно стилистическим правилам Википедии. Эта статья о линии передачи Далай лам. О&# … Википедия

-

Далай Лама — Эта статья посвящена линии передачи Далай лам. Информацию о нынешнем Далай ламе можно найти в статье Далай лама XIV. Далай лама XIII (1876 1933) Далай лама (тиб. ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ་ taa la’i bla ma, кит. 达赖喇嘛 Dálài Lǎmā). Далай ламы линия передачи… … Википедия

-

Далай-лама V — Нгаванг Лобсанг Гьяцо … Википедия

03.06.2008

В связи с повышенным в последнее время интересом к китайско-тибетским отношениям, выясним, как всё-таки правильно пишется титул духовного лидера буддистов. С маленькой буквы или с большой? С дефисом или раздельно?

Согласно орфографическому словарю, это слово следует писать с маленькой буквы и через дефис: далай-лама. Палестинцы не пустили далай-ламу в Вифлеем. Это правило действует в общем случае; однако при официальном титуловании требуется прописная буква: Несколько лет назад Далай-лама XIV посетил Калмыкию.

Слово лама происходит от тибетского blama — «духовный наставник», а приставка «далай» — от монгольского dalai — «океан» и символизирует величие учителя. Кроме далай-ламы, есть ещё один значительный лама: панчен-лама. Он второй по рангу, однако именно на него возложена миссия распознать реинкарнацию следующего далай-ламы. Его титул происходит от санскритского pandita — «учёный» и тибетского chen-po — «великий».

Что же касается южноамериканских животных, напоминающих длинношеих овец — лам, то к буддизму они никакого отношения не имеют, и их название происходит от кечуанского llama.

Ежи Лисовский

- До 7 класса: Алгоритмика, Кодланд, Реботика.

- 8-11 класс: Умскул, Годограф, Знанио.

- Английский: Инглекс, Puzzle, Novakid.

- Взрослым: Skillbox, Нетология, Geekbrains, Яндекс, Otus, SkillFactory.

Как писать правильно слово: «далай-лама» или «далайлама»?

Правила

Слово «далай-лама» нужно писать с дефисом. Первая часть этого сложного слова встречается только в составе таких слов. Отдельно не употребляется, соответственно в русском языке подобные сложные существительные принято писать через дефис.

Значение

«Далай-лама» — титул священника в ламаистской церкви.

Примеры слова в предложениях

- Путешествуя по Тибету, нам удалось встретиться с далай-ламой и провести немного времени в удивительных по красоте местах.

- Легендарный далай-лама – это тот, ради кого некоторые люди стараются приезжать в Тибет.

- До 7 класса: Алгоритмика, Кодланд, Реботика.

- 8-11 класс: Умскул, Годограф, Знанио.

- Английский: Инглекс, Puzzle, Novakid.

- Взрослым: Skillbox, Нетология, Geekbrains, Яндекс, Otus, SkillFactory.

Правила

Слово «далай-лама» нужно писать с дефисом. Первая часть этого сложного слова встречается только в составе таких слов. Отдельно не употребляется, соответственно в русском языке подобные сложные существительные принято писать через дефис.

Значение

«Далай-лама» — титул священника в ламаистской церкви.

Примеры слова в предложениях

- Путешествуя по Тибету, нам удалось встретиться с далай-ламой и провести немного времени в удивительных по красоте местах.

- Легендарный далай-лама – это тот, ради кого некоторые люди стараются приезжать в Тибет.

Выбери ответ

Предметы

Сервисы

Онлайн-школы

Становимся грамотнее за минуту

Ответ:

Правильное написание слова — далай-лама

Ударение и произношение — дал`ай-л`ама

Значение слова -м. Титул первосвященника ламаистской церкви в Тибете.

Выберите, на какой слог падает ударение в слове — НАДОЛГО?

Слово состоит из букв:

Д,

А,

Л,

А,

Й,

-,

Л,

А,

М,

А,

Похожие слова:

дактилоскопия

дактиль

дала

Даладье

даламбера

далась

дале

далее

далей

Рифма к слову далай-лама

срама, мадиама, мама, шрама, панорама, адама, рама, ваграма, храма, сама, потсдама, дама, герасима, непоколебима, сознаваема, немыслима, патриотизма, программа, эконома, руководима, необходима, механизма, цнайма, зима, неудержима, дома, мистицизма, непостижима, займа, деспотизма, рима, любима, педантизма, организма, отбиваема, рассматриваема, подъема, знакома, дилемма, ведома, эгоизма, иерусалима, система, приема, оказываема, сумма, неопровержима, параллелограмма, ерема, рома

Толкование слова. Правильное произношение слова. Значение слова.

Как правильно пишется слово «далай-лама»

дала́й-ла́ма

дала́й-ла́ма, -ы, м.

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: стоечка — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Предложения со словом «далай-лама»

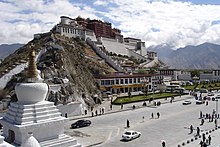

- На фоне окрашенной сумраком равнины дворец далай-ламы предстаёт словно в ореоле излучаемого им самим света.

- Но в XVII веке при пятом далай-ламе дворец восстановили по сохранившимся фрескам, и в своём нынешнем виде он существует 350 лет.

- Забальзамированные мощи покойных далай-лам и панчен-лам хранятся в золотых ступах, украшающих молельные залы ламаистских святилищ.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «далай-лама»

- Теперь поставьте меня лицом к лицу хоть с самим Далай-Ламой, — я и у него табачку попрошу понюхать.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Каким бывает «далай-лама»

Значение слова «далай-лама»

-

ДАЛА́Й-ЛА́МА, -ы, м. Верховный правитель Тибета и глава тибетской церкви. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова ДАЛАЙ-ЛАМА

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

| Dalai Lama | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Incumbent |

|

| Residence | McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala, India |

| Formation | 1391 |

| First holder | Gendün Drubpa, 1st Dalai Lama, posthumously awarded after 1578. |

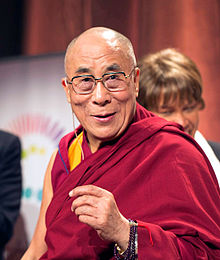

| Website | dalailama.com |

Dalai Lama (, ;[1][2] Tibetan: ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ་, Wylie: Tā la’i bla ma [táːlɛː láma]) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or «Yellow Hat» school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism.[3] The 14th and current Dalai Lama is Tenzin Gyatso, who lives as a refugee in India. The Dalai Lama is also considered to be the successor in a line of tulkus who are believed[2] to be incarnations of Avalokiteśvara,[1] the Bodhisattva of Compassion.[4][5]

Since the time of the 5th Dalai Lama in the 17th century, his personage has always been a symbol of unification of the state of Tibet, where he has represented Buddhist values and traditions.[6] The Dalai Lama was an important figure of the Geluk tradition, which was politically and numerically dominant in Central Tibet, but his religious authority went beyond sectarian boundaries. While he had no formal or institutional role in any of the religious traditions, which were headed by their own high lamas, he was a unifying symbol of the Tibetan state, representing Buddhist values and traditions above any specific school.[7] The traditional function of the Dalai Lama as an ecumenical figure, holding together disparate religious and regional groups, has been taken up by the fourteenth Dalai Lama. He has worked to overcome sectarian and other divisions in the exiled community and has become a symbol of Tibetan nationhood for Tibetans both in Tibet and in exile.[8]

From 1642 until 1705 and from 1750 to the 1950s, the Dalai Lamas or their regents headed the Tibetan government (or Ganden Phodrang) in Lhasa, which governed all or most of the Tibetan Plateau with varying degrees of autonomy.[9] This Tibetan government enjoyed the patronage and protection of firstly Mongol kings of the Khoshut and Dzungar Khanates (1642–1720) and then of the emperors of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1720–1912).[9] In 1913, several Tibetan representatives including Agvan Dorzhiev signed a treaty between Tibet and Mongolia, proclaiming mutual recognition and their independence from China. However, the legitimacy of the treaty and declared independence of Tibet was rejected by both the Republic of China and the current People’s Republic of China.[10][11] Nonetheless, the Dalai Lamas headed the Tibetan government until 1951.

Names[edit]

The name «Dalai Lama» is a combination of the Mongolic word dalai meaning «ocean» or «big» (coming from Mongolian title Dalaiyin qan or Dalaiin khan,[12] translated as Gyatso or rgya-mtsho in Tibetan)[13][14] and the Tibetan word བླ་མ་ (bla-ma) meaning «master, guru».[15]

The Dalai Lama is also known in Tibetan as the Rgyal-ba Rin-po-che («Precious Conqueror»)[14] or simply as the Rgyal-ba.[16]: 23

History[edit]

In Central Asian Buddhist countries, it has been widely believed for the last millennium that Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, has a special relationship with the people of Tibet and intervenes in their fate by incarnating as benevolent rulers and teachers such as the Dalai Lamas. This is according to The Book of Kadam, the main text of the Kadampa school, to which the 1st Dalai Lama, Gendun Drup, first belonged.[17]

In fact, this text is said to have laid the foundation for the Tibetans’ later identification of the Dalai Lamas as incarnations of Avalokiteśvara.[18][better source needed]

It traces the legend of the bodhisattva’s incarnations as early Tibetan kings and emperors such as Songtsen Gampo and later as Dromtönpa (1004–1064).[19]

This lineage has been extrapolated by Tibetans up to and including the Dalai Lamas.[20]

Origins in myth and legend[edit]

Thus, according to such sources, an informal line of succession of the present Dalai Lamas as incarnations of Avalokiteśvara stretches back much further than Gendun Drub. The Book of Kadam,[21] the compilation of Kadampa teachings largely composed around discussions between the Indian sage Atiśa (980–1054) and his Tibetan host and chief disciple Dromtönpa[22][23] and Tales of the Previous Incarnations of Arya Avalokiteśvara,[24] nominate as many as sixty persons prior to Gendun Drub who are enumerated as earlier incarnations of Avalokiteśvara and predecessors in the same lineage leading up to him. In brief, these include a mythology of 36 Indian personalities plus 10 early Tibetan kings and emperors, all said to be previous incarnations of Dromtönpa, and fourteen further Nepalese and Tibetan yogis and sages in between him and the 1st Dalai Lama.[25] In fact, according to the «Birth to Exile» article on the 14th Dalai Lama’s website, he is «the seventy-fourth in a lineage that can be traced back to a Brahmin boy who lived in the time of Buddha Shakyamuni.»[26]

Avalokiteśvara’s «Dalai Lama master plan»[edit]

According to the 14th Dalai Lama, long ago Avalokiteśvara had promised the Buddha to guide and defend the Tibetan people and in the late Middle Ages, his master plan to fulfill this promise was the stage-by-stage establishment of the Dalai Lama theocracy in Tibet.[27]

First, Tsongkhapa established three great monasteries around Lhasa in the province of Ü before he died in 1419.[28] The 1st Dalai Lama soon became Abbot of the greatest one, Drepung, and developed a large popular power base in Ü. He later extended this to cover Tsang,[29] where he constructed a fourth great monastery, Tashi Lhunpo, at Shigatse.[30] The 2nd studied there before returning to Lhasa,[27] where he became Abbot of Drepung.[31] Having reactivated the 1st’s large popular followings in Tsang and Ü,[32] the 2nd then moved on to southern Tibet and gathered more followers there who helped him construct a new monastery, Chokorgyel.[33] He also established the method by which later Dalai Lama incarnations would be discovered through visions at the «oracle lake», Lhamo Lhatso.[34] The 3rd built on his predecessors’ fame by becoming Abbot of the two great monasteries of Drepung and Sera.[34] The stage was set for the great Mongol King Altan Khan, hearing of his reputation, to invite the 3rd to Mongolia where he converted the King and his followers to Buddhism, as well as other Mongol princes and their followers covering a vast tract of central Asia. Thus most of Mongolia was added to the Dalai Lama’s sphere of influence, founding a spiritual empire which largely survives to the modern age.[35] After being given the Mongolian name ‘Dalai’,[36] he returned to Tibet to found the great monasteries of Lithang in Kham, eastern Tibet and Kumbum in Amdo, north-eastern Tibet.[37] The 4th was then born in Mongolia as the great-grandson of Altan Khan, thus cementing strong ties between Central Asia, the Dalai Lamas, the Gelugpa and Tibet.[38] Finally, in fulfilment of Avalokiteśvara’s master plan, the 5th in the succession used the vast popular power base of devoted followers built up by his four predecessors. By 1642, a strategy that was planned and carried out by his resourceful chagdzo or manager Sonam Rapten with the military assistance of his devoted disciple Gushri Khan, Chieftain of the Khoshut Mongols, enabled the ‘Great 5th’ to found the Dalai Lamas’ religious and political reign over more or less the whole of Tibet that survived for over 300 years.[39]

Thus the Dalai Lamas became pre-eminent spiritual leaders in Tibet and 25 Himalayan and Central Asian kingdoms and countries bordering Tibet and their prolific literary works have «for centuries acted as major sources of spiritual and philosophical inspiration to more than fifty million people of these lands».[40] Overall, they have played «a monumental role in Asian literary, philosophical and religious history».[41]

Establishment of the Dalai Lama lineage[edit]

Gendun Drup (1391–1474), a disciple of the founder Je Tsongkapa,[42] was the ordination name of the monk who came to be known as the ‘First Dalai Lama’, but only from 104 years after he died.[43]

There had been resistance, since first he was ordained a monk in the Kadampa tradition[33] and for various reasons, for hundreds of years the Kadampa school had eschewed the adoption of the tulku system to which the older schools adhered.[44] Tsongkhapa largely modelled his new, reformed Gelugpa school on the Kadampa tradition and refrained from starting a tulku system.[45] Therefore, although Gendun Drup grew to be a very important Gelugpa lama, after he died in 1474 there was no question of any search being made to identify his incarnation.[44]

Despite this, when the Tashilhunpo monks started hearing what seemed credible accounts that an incarnation of Gendun Drup had appeared nearby and repeatedly announced himself from the age of two, their curiosity was aroused.[46] It was some 55 years after Tsongkhapa’s death when eventually, the monastic authorities saw compelling evidence that convinced them the child in question was indeed the incarnation of their founder. They felt obliged to break with their own tradition and in 1487, the boy was renamed Gendun Gyatso and installed at Tashilhunpo as Gendun Drup’s tulku, albeit informally.[47]

Gendun Gyatso died in 1542 and the lineage of Dalai Lama tulkus finally became firmly established when the third incarnation, Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588), came forth. He made himself known as the tulku of Gendun Gyatso and was formally recognised and enthroned at Drepung in 1546.[48] When Gendun Gyatso was given the titular name «Dalai Lama» by the Tümed Altan Khan in 1578,[49]: 153 his two predecessors were accorded the title posthumously and he became known as the third in the lineage.[43]

1st Dalai Lama[edit]

The Dalai Lama title was posthumously given to Gedun Drupa after 1578. The Dalai Lama lineage started from humble beginnings.[50] ‘Pema Dorje’ (1391–1474), the boy who was to become the first in the line, was born in a cattle pen[51] in Shabtod, Tsang in 1391.[33] His nomad parents kept sheep and goats and lived in tents. When his father died in 1398 his mother was unable to support the young goatherd so she entrusted him to his uncle, a monk at Narthang, a major Kadampa monastery near Shigatse, for education as a Buddhist monk.[52] Narthang ran the largest printing press in Tibet[53] and its celebrated library attracted scholars and adepts from far and wide, so Pema Dorje received an education beyond the norm at the time as well as exposure to diverse spiritual schools and ideas.[54] He studied Buddhist philosophy extensively and in 1405, ordained by Narthang’s abbot, he took the name of Gendun Drup.[33] Soon recognised as an exceptionally gifted pupil, the abbot tutored him personally and took special interest in his progress.[54] In 12 years he passed the 12 grades of monkhood and took the highest vows.[51] After completing his intensive studies at Narthang he left to continue at specialist monasteries in Central Tibet, his grounding at Narthang was revered among many he encountered.[55]

In 1415 Gendun Drup met Tsongkhapa, founder of the Gelugpa school, and became his student; their meeting was of decisive historical and political significance as he was later to be known as the 1st Dalai Lama.[56] When eventually Tsongkhapa’s successor the Panchen Lama Khedrup Je died, Gendun Drup became the leader of the Gelugpa.[51] He rose to become Abbot of Drepung, the greatest Gelugpa monastery, outside Lhasa.[31]

It was mainly due to Gendun Drup’s energy and ability that Tsongkhapa’s new school grew into an expanding order capable of competing with others on an equal footing.[57] Taking advantage of good relations with the nobility and a lack of determined opposition from rival orders, on the very edge of Karma Kagyu-dominated territory he founded Tashilhunpo Monastery at Shigatse.[57] He was based there, as its Abbot, from its founding in 1447 until his death.[58] Tashilhunpo, ‘Mountain of Blessings’, became the fourth great Gelugpa monastery in Tibet, after Ganden, Drepung and Sera had all been founded in Tsongkhapa’s time.[28] It later became the seat of the Panchen Lamas.[59]

By establishing it at Shigatse in the middle of Tsang, he expanded the Gelugpa sphere of influence, and his own, from the Lhasa region of Ü to this province, which was the stronghold of the Karma Kagyu school and their patrons, the rising Tsangpa dynasty.[28][60] Tashilhunpo was destined to become ‘Southern Tibet’s greatest monastic university’[61] with a complement of 3,000 monks.[33]

Gendun Drup was said to be the greatest scholar-saint ever produced by Narthang Monastery[61] and became ‘the single most important lama in Tibet’.[62] Through hard work he became a leading lama, known as ‘Perfecter of the Monkhood’, ‘with a host of disciples’.[59] Famed for his Buddhist scholarship he was also referred to as Panchen Gendun Drup, ‘Panchen’ being an honorary title designating ‘great scholar’.[33] By the great Jonangpa master Bodong Chokley Namgyal[63] he was accorded the honorary title Tamchey Khyenpa meaning «The Omniscient One», an appellation that was later assigned to all Dalai Lama incarnations.[64]

At the age of 50, he entered meditation retreat at Narthang. As he grew older, Karma Kagyu adherents, finding their sect was losing too many recruits to the monkhood to burgeoning Gelugpa monasteries, tried to contain Gelug expansion by launching military expeditions against them in the region.[65] This led to decades of military and political power struggles between Tsangpa dynasty forces and others across central Tibet.[66] In an attempt to ameliorate these clashes, from his retreat Gendun Drup issued a poem of advice to his followers advising restraint from responding to violence with more violence and to practice compassion and patience instead. The poem, entitled Shar Gang Rima, «The Song of the Eastern Snow Mountains», became one of his most enduring popular literary works.[67]

Although he was born in a cattle pen to be a simple goatherd, Gendun Drup rose to become one of the most celebrated and respected teachers in Tibet and Central Asia. His spiritual accomplishments brought him substantial donations from devotees which he used to build and furnish new monasteries, to print and distribute Buddhist texts and to maintain monks and meditators.[68] At last, at the age of 84, older than any of his 13 successors, in 1474 he went on foot to visit Narthang Monastery on a final teaching tour. Returning to Tashilhunpo[69] he died ‘in a blaze of glory, recognised as having attained Buddhahood’.[59]

His mortal remains were interred in a bejewelled silver stupa at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, which survived the Cultural Revolution and can still be seen.[44]

2nd Dalai Lama[edit]

Like the Kadampa, the Gelugpa eschewed the tulku system.[70] After Gendun Drup died, however, a boy called Sangyey Pel born to Nyngma adepts at Yolkar in Tsang,[33][71] declared himself at 3 to be «Gendun Drup» and asked to be ‘taken home’ to Tashilhunpo. He spoke in mystical verses, quoted classical texts out of the blue[72] and said he was Dromtönpa, an earlier incarnation of the Dalai Lamas.[73] When he saw monks from Tashilhunpo he greeted the disciples of the late Gendun Drup by name.[74] The Gelugpa elders had to break with tradition and recognised him as Gendun Drup’s tulku.[47]

He was then 8, but until his 12th year his father took him on his teachings and retreats, training him in all the family Nyingma lineages.[75] At 12 he was installed at Tashilhunpo as Gendun Drup’s incarnation, ordained, enthroned and renamed Gendun Gyatso Palzangpo (1475–1542).[47]

Tutored personally by the abbot he made rapid progress and from 1492 at 17 he was requested to teach all over Tsang, where thousands gathered to listen and give obeisance, including senior scholars and abbots.[76] In 1494, at 19, he met some opposition from the Tashilhunpo establishment when tensions arose over conflicts between advocates of the two types of succession, the traditional abbatial election through merit, and incarnation. Although he had served for some years as Tashilhunpo’s abbot, he therefore moved to central Tibet, where he was invited to Drepung and where his reputation as a brilliant young teacher quickly grew.[77][78] He was accorded all the loyalty and devotion that Gendun Drup had earned and the Gelug school remained as united as ever.[28] This move had the effect of shifting central Gelug authority back to Lhasa. Under his leadership, the sect went on growing in size and influence[79] and with its appeal of simplicity, devotion and austerity its lamas were asked to mediate in disputes between other rivals.[80]

Gendun Gyatso’s popularity in Ü-Tsang grew as he went on pilgrimage, travelling, teaching and studying from masters such as the adept Khedrup Norzang Gyatso in the Olklha mountains.[81] He also stayed in Kongpo and Dagpo[82] and became known all over Tibet.[34] He spent his winters in Lhasa, writing commentaries and the rest of the year travelling and teaching many thousands of monks and lay people.[83]

In 1509 he moved to southern Tibet to build Chokorgyel Monastery near the ‘Oracle Lake’, Lhamo Latso,[34] completing it by 1511.[84] That year he saw visions in the lake and ’empowered’ it to impart clues to help identify incarnate lamas. All Dalai Lamas from the 3rd on were found with the help of such visions granted to regents.[34][85] By now widely regarded as one of Tibet’s greatest saints and scholars[86] he was invited back to Tashilhunpo. On his return in 1512, he was given the residence built for Gendun Drup, to be occupied later by the Panchen Lamas.[33] He was made abbot of Tashilhunpo[87] and stayed there teaching in Tsang for 9 months.[88]

Gendun Gyatso continued to travel widely and teach while based at Tibet’s largest monastery, Drepung and became known as ‘Drepung Lama’,[79] his fame and influence spreading all over Central Asia as the best students from hundreds of lesser monasteries in Asia were sent to Drepung for education.[84]

Throughout Gendun Gyatso’s life, the Gelugpa were opposed and suppressed by older rivals, particularly the Karma Kagyu and their Ringpung clan patrons from Tsang, who felt threatened by their loss of influence.[89] In 1498 the Ringpung army captured Lhasa and banned the Gelugpa annual New Year Monlam Prayer Festival[89] started by Tsongkhapa for world peace and prosperity.[90] Gendun Gyatso was promoted to abbot of Drepung in 1517[84] and that year Ringpung forces were forced to withdraw from Lhasa.[89][91] Gendun Gyatso then went to the Gongma (King) Drakpa Jungne[92] to obtain permission for the festival to be held again.[90] The next New Year, the Gongma was so impressed by Gendun Gyatso’s performance leading the Festival that he sponsored construction of a large new residence for him at Drepung, ‘a monastery within a monastery’.[90] It was called the Ganden Phodrang, a name later adopted by the Tibetan Government,[33] and it served as home for Dalai Lamas until the Fifth moved to the Potala Palace in 1645.

In 1525, already abbot of Chokhorgyel, Drepung and Tashilhunpo, he was made abbot of Sera monastery as well, and seeing the number of monks was low he worked to increase it.[93]

Based at Drepung in winter and Chokorgyel in summer, he spent his remaining years in composing commentaries, regional teaching tours, visiting Tashilhunpo from time to time and acting as abbot of these four great monasteries.[93] As abbot, he made Drepung the largest monastery in the whole of Tibet.[94] He attracted many students and disciples ‘from Kashmir to China’[93] as well as major patrons and disciples such as Gongma Nangso Donyopa of Droda who built a monastery at Zhekar Dzong in his honour and invited him to name it and be its spiritual guide.[95]

Gongma Gyaltsen Palzangpo of Khyomorlung at Tolung and his Queen Sangyey Paldzomma also became his favourite devoted lay patrons and disciples in the 1530s and he visited their area to carry out rituals as ‘he chose it for his next place of rebirth’.[96] He died in meditation at Drepung in 1542 at 67 and his reliquary stupa was constructed at Khyomorlung.[97] It was said that, by the time he died, through his disciples and their students, his personal influence covered the whole of Buddhist Central Asia where ‘there was nobody of any consequence who did not know of him’.[97] The Dalai Lama title was posthumously granted to Gedun Gyatso after 1578.

3rd Dalai Lama[edit]

The Third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) was born in Tolung, near Lhasa,[98]

as predicted by his predecessor.[96] Claiming he was Gendun Gyatso and readily recalling events from his previous life, he was recognised as the incarnation, named ‘Sonam Gyatso’ and installed at Drepung, where ‘he quickly excelled his teachers in knowledge and wisdom and developed extraordinary powers’.[99] Unlike his predecessors, he came from a noble family, connected with the Sakya and the Phagmo Drupa (Karma Kagyu affiliated) dynasties,[94] and it is to him that the effective conversion of Mongolia to Buddhism is due.[59]

A brilliant scholar and teacher,[100] he had the spiritual maturity to be made Abbot of Drepung,[101] taking responsibility for the material and spiritual well-being of Tibet’s largest monastery at the age of nine. At 10 he led the Monlam Prayer Festival, giving daily discourses to the assembly of all Gelugpa monks.[102] His influence grew so quickly that soon the monks at Sera Monastery also made him their Abbot[34] and his mediation was being sought to prevent fighting between political power factions. At 16, in 1559, he was invited to Nedong by King Ngawang Tashi Drakpa, a Karma Kagyu supporter, and became his personal teacher. At 17, when fighting broke out in Lhasa between Gelug and Kagyu parties and efforts by local lamas to mediate failed, Sonam Gyatso negotiated a peaceful settlement. At 19, when the Kyichu River burst its banks and flooded Lhasa, he led his followers to rescue victims and repair the dykes. He then instituted a custom whereby on the last day of Monlam, all the monks would work on strengthening the flood defences.[98] Gradually, he was shaping himself into a national leader.[103] His popularity and renown became such that in 1564 when the Nedong King died, it was Sonam Gyatso at the age of 21 who was requested to lead his funeral rites, rather than his own Kagyu lamas.[34]

Required to travel and teach without respite after taking full ordination in 1565, he still maintained extensive meditation practices in the hours before dawn and again at the end of the day.[104] In 1569, at age 26, he went to Tashilhunpo to study the layout and administration of the monastery built by his predecessor Gendun Drup. Invited to become the Abbot he declined, already being Abbot of Drepung and Sera, but left his deputy there in his stead.[105] From there he visited Narthang, the first monastery of Gendun Drup and gave numerous discourses and offerings to the monks in gratitude.[104]

Meanwhile, Altan Khan, chief of all the Mongol tribes near China’s borders, had heard of Sonam Gyatso’s spiritual prowess and repeatedly invited him to Mongolia.[94] By 1571, when Altan Khan received a title of Shunyi Wang (King) from the Ming dynasty of China[106] and swore allegiance to Ming,[107] although he remained de facto quite independent,[49]: 106 he had fulfilled his political destiny and a nephew advised him to seek spiritual salvation, saying that «in Tibet dwells Avalokiteshvara», referring to Sonam Gyatso, then 28 years old.[108] China was also happy to help Altan Khan by providing necessary translations of holy scripture, and also lamas.[109] At the second invitation, in 1577–78 Sonam Gyatso travelled 1,500 miles to Mongolia to see him. They met in an atmosphere of intense reverence and devotion[110] and their meeting resulted in the re-establishment of strong Tibet-Mongolia relations after a gap of 200 years.[94]

To Altan Khan, Sonam Gyatso identified himself as the incarnation of Drogön Chögyal Phagpa, and Altan Khan as that of Kubilai Khan, thus placing the Khan as heir to the Chingizid lineage whilst securing his patronage.[111]

Altan Khan and his followers quickly adopted Buddhism as their state religion, replacing the prohibited traditional Shamanism.[100]

Mongol law was reformed to accord with Tibetan Buddhist law. From this time Buddhism spread rapidly across Mongolia[111] and soon the Gelugpa had won the spiritual allegiance of most of the Mongolian tribes.[100]

As proposed by Sonam Gyatso, Altan Khan sponsored the building of Thegchen Chonkhor Monastery at the site of Sonam Gyatso’s open-air teachings given to the whole Mongol population. He also called Sonam Gyatso «Dalai», Mongolian for ‘Gyatso’ (Ocean).[112]

In October 1587, as requested by the family of Altan Khan, Gyalwa Sonam Gyatso was promoted to Duǒ Er Zhǐ Chàng (Chinese:朵儿只唱) by the emperor of China, seal of authority and golden sheets were granted.[113]

The name «Dalai Lama», by which the lineage later became known throughout the non-Tibetan world, was thus established and it was applied to the first two incarnations retrospectively.[43]

In 1579, the Ming allowed the third Dalai Lama to pay regular tribute.[114] Returning eventually to Tibet by a roundabout route and invited to stay and teach all along the way, in 1580 Sonam Gyatso was in Hohhot [or Ningxia], not far from Beijing, when the Chinese Emperor summoned him to his court.[115][116]

By then he had established a religious empire of such proportions that it was unsurprising the Emperor wanted to summon him and grant him a diploma.[110] Through Altan Khan, the 3rd Dalai Lama requested to pay tribute to the Emperor of China in order to raise his State Tutor ranking, the Ming imperial court of China agreed with the request.[117] In 1582, he heard Altan Khan had died and invited by his son Dhüring Khan he decided to return to Mongolia. Passing through Amdo, he founded a second great monastery, Kumbum, at the birthplace of Tsongkhapa near Kokonor.[116] Further on, he was asked to adjudicate on border disputes between Mongolia and China. It was the first time a Dalai Lama had exercised such political authority.[118]

Arriving in Mongolia in 1585, he stayed 2 years with Dhüring Khan, teaching Buddhism to his people[116] and converting more Mongol princes and their tribes. Receiving a second invitation from the Emperor in Beijing he accepted, but died en route in 1588.[119] As he was dying, his Mongolian converts urged him not to leave them, as they needed his continuing religious leadership. He promised them he would be incarnated next in Mongolia, as a Mongolian.[118]

4th Dalai Lama[edit]

The Fourth Dalai Lama, Yonten Gyatso (1589–1617) was a Mongolian, the great-grandson of Altan Khan[120] who was a descendant of Kublai Khan and King of the Tümed Mongols who had already been converted to Buddhism by the Third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588).[31] This strong connection caused the Mongols to zealously support the Gelugpa sect in Tibet, strengthening their status and position but also arousing intensified opposition from the Gelugpa’s rivals, particularly the Tsang Karma Kagyu in Shigatse and their Mongolian patrons and the Bönpo in Kham and their allies.[31] Being the newest school, unlike the older schools the Gelugpa lacked an established network of Tibetan clan patronage and were thus more reliant on foreign patrons.[121] At the age of 10 with a large Mongol escort he travelled to Lhasa where he was enthroned. He studied at Drepung and became its abbot but being a non-Tibetan he met with opposition from some Tibetans, especially the Karma Kagyu who felt their position was threatened by these emerging events; there were several attempts to remove him from power.[122] Seal of authority was granted in 1616 by Wanli Emperor of Ming.[123] Yonten Gyatso died at the age of 27 under suspicious circumstances and his chief attendant Sonam Rapten went on to discover the 5th Dalai Lama, became his chagdzo or manager and after 1642 he went on to be his regent, the Desi.[124]

5th Dalai Lama[edit]

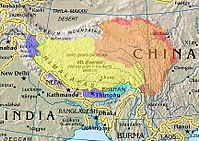

Map showing the extent of the Khoshut Khanate, 1642–1717, after the Unification of Tibet under the 5th Dalai Lama with Sonam Chöphel and Güshi Khan

‘Greater Tibet’ as claimed by exiled groups

The death of the Fourth Dalai Lama in 1617 led to open conflict breaking out between various parties.[121] Firstly, the Tsangpa dynasty, rulers of Central Tibet from Shigatse, supporters of the Karmapa school and rivals to the Gelugpa, forbade the search for his incarnation.[125] However, in 1618 Sonam Rabten, the former attendant of the 4th Dalai Lama who had become the Ganden Phodrang treasurer, secretly identified the child,[126] who had been born to the noble Zahor family at Tagtse castle, south of Lhasa. Then, the Panchen Lama, in Shigatse, negotiated the lifting of the ban, enabling the boy to be recognised as Lobsang Gyatso, the 5th Dalai Lama.[125]

Also in 1618, the Tsangpa King, Karma Puntsok Namgyal, whose Mongol patron was Choghtu Khong Tayiji of the Khalkha Mongols, attacked the Gelugpa in Lhasa to avenge an earlier snub and established two military bases there to control the monasteries and the city. This caused Sonam Rabten who became the 5th Dalai Lama’s changdzo or manager,[127] to seek more active Mongol patronage and military assistance for the Gelugpa while the Fifth was still a boy.[121] So, in 1620, Mongol troops allied to the Gelugpa who had camped outside Lhasa suddenly attacked and destroyed the two Tsangpa camps and drove them out of Lhasa, enabling the Dalai Lama to be brought out of hiding and publicly enthroned there in 1622.[126]

In fact, throughout the 5th’s minority, it was the influential and forceful Sonam Rabten who inspired the Dzungar Mongols to defend the Gelugpa by attacking their enemies. These enemies included other Mongol tribes who supported the Tsangpas, the Tsangpa themselves and their Bönpo allies in Kham who had also opposed and persecuted Gelugpas. Ultimately, this strategy led to the destruction of the Tsangpa dynasty, the defeat of the Karmapas and their other allies and the Bönpos, by armed forces from the Lhasa valley aided by their Mongol allies, paving the way for Gelugpa political and religious hegemony in Central Tibet.[125] Apparently by general consensus, by virtue of his position as the Dalai Lama’s changdzo (chief attendant, minister), after the Dalai Lama became absolute ruler of Tibet in 1642 Sonam Rabten became the «Desi» or «Viceroy», in fact, the de facto regent or day-to-day ruler of Tibet’s governmental affairs. During these years and for the rest of his life (he died in 1658), «there was little doubt that politically Sonam Chophel [Rabten] was more powerful than the Dalai Lama».[128] As a young man, being 22 years his junior, the Dalai Lama addressed him reverentially as «Zhalngo«, meaning «the Presence».[129]

During the 1630s Tibet was deeply entangled in rivalry, evolving power struggles and conflicts, not only between the Tibetan religious sects but also between the rising Manchus and the various rival Mongol and Oirat factions, who were also vying for supremacy amongst themselves and on behalf of the religious sects they patronised.[121] For example, Ligdan Khan of the Chahars, a Mongol subgroup who supported the Tsang Karmapas, after retreating from advancing Manchu armies headed for Kokonor intending destroy the Gelug. He died on the way, in 1634[130] but his vassal Choghtu Khong Tayiji, continued to advance against the Gelugpas, even having his own son Arslan killed after Arslan changed sides, submitted to the Dalai Lama and become a Gelugpa monk.[131] By the mid-1630s, thanks again to the efforts of Sonam Rabten,[125] the 5th Dalai Lama had found a powerful new patron in Güshi Khan of the Khoshut Mongols, a subgroup of the Dzungars, who had recently migrated to the Kokonor area from Dzungaria.[121] He attacked Choghtu Khong Tayiji at Kokonor in 1637 and defeated and killed him, thus eliminating the Tsangpa and the Karmapa’s main Mongol patron and protector.[121]

Next, Donyo Dorje, the Bönpo king of Beri in Kham was found writing to the Tsangpa king in Shigatse to propose a co-ordinated ‘pincer attack’ on the Lhasa Gelugpa monasteries from east and west, seeking to utterly destroy them once and for all.[132] The intercepted letter was sent to Güshi Khan who used it as a pretext to invade central Tibet in 1639 to attack them both, the Bönpo and the Tsangpa. By 1641 he had defeated Donyo Dorje and his allies in Kham and then he marched on Shigatse where after laying siege to their strongholds he defeated Karma Tenkyong, broke the power of the Tsang Karma Kagyu in 1642 and ended the Tsangpa dynasty.[133]

Güshi Khan’s attack on the Tsangpa was made on the orders of Sonam Rapten while being publicly and robustly opposed by the Dalai Lama, who, as a matter of conscience, out of compassion and his vision of tolerance for other religious schools, refused to give permission for more warfare in his name after the defeat of the Beri king.[128][134] Sonam Rabten deviously went behind his master’s back to encourage Güshi Khan, to facilitate his plans and to ensure the attacks took place;[125] for this defiance of his master’s wishes, Rabten was severely rebuked by the 5th Dalai Lama.[134]

After Desi Sonam Rapten died in 1658, the following year the 5th Dalai Lama appointed his younger brother Depa Norbu (aka Nangso Norbu) as his successor.[135] However, after a few months, Norbu betrayed him and led a rebellion against the Ganden Phodrang Government. With his accomplices he seized Samdruptse fort at Shigatse and tried to raise a rebel army from Tsang and Bhutan, but the Dalai Lama skilfully foiled his plans without any fighting taking place and Norbu had to flee.[136] Four other Desis were appointed after Depa Norbu: Trinle Gyatso, Lozang Tutop, Lozang Jinpa and Sangye Gyatso.[137]

Re-unification of Tibet[edit]

Having thus defeated all the Gelugpa’s rivals and resolved all regional and sectarian conflicts Güshi Khan became the undisputed patron of a unified Tibet and acted as a «Protector of the Gelug»,[138] establishing the Khoshut Khanate which covered almost the entire Tibetan plateau, an area corresponding roughly to ‘Greater Tibet’ including Kham and Amdo, as claimed by exiled groups (see maps). At an enthronement ceremony in Shigatse he conferred full sovereignty over Tibet on the Fifth Dalai Lama,[139] unified for the first time since the collapse of the Tibetan Empire exactly eight centuries earlier.[121][140] Güshi Khan then retired to Kokonor with his armies[121] and [according to Smith] ruled Amdo himself directly thus creating a precedent for the later separation of Amdo from the rest of Tibet.[140]

In this way, Güshi Khan established the Fifth Dalai Lama as the highest spiritual and political authority in Tibet. ‘The Great Fifth’ became the temporal ruler of Tibet in 1642 and from then on the rule of the Dalai Lama lineage over some, all or most of Tibet lasted with few breaks for the next 317 years, until 1959, when the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India.[141] In 1645, the Great Fifth began the construction of the Potala Palace in Lhasa.[142]

Güshi Khan died in 1655 and was succeeded by his descendants Dayan, Tenzin Dalai Khan and Tenzin Wangchuk Khan. However, Güshi Khan’s other eight sons had settled in Amdo but fought amongst themselves over territory so the Fifth Dalai Lama sent governors to rule them in 1656 and 1659, thereby bringing Amdo and thus the whole of Greater Tibet under his personal rule and Gelugpa control. The Mongols in Amdo became absorbed and Tibetanised.[143]

Visit to Beijing[edit]

In 1636 the Manchus proclaimed their dynasty as the Qing dynasty and by 1644 they had completed their conquest of China under the prince regent Dorgon.[144] The following year their forces approached Amdo on northern Tibet, causing the Oirat and Khoshut Mongols there to submit in 1647 and send tribute. In 1648, after quelling a rebellion of Tibetans of Kansu-Xining, the Qing invited the Fifth Dalai Lama to visit their court at Beijing since they wished to engender Tibetan influence in their dealings with the Mongols. The Qing were aware the Dalai Lama had extraordinary influence with the Mongols and saw relations with the Dalai Lama as a means to facilitate submission of the Khalka Mongols, traditional patrons of the Karma Kagyu sect. Similarly, since the Tibetan Gelugpa were keen to revive a priest-patron relationship with the dominant power in China and Inner Asia, the Qing invitation was accepted. After five years of complex diplomatic negotiations about whether the emperor or his representatives should meet the Dalai Lama inside or outside the Great Wall, when the meeting would be astrologically favourable, how it would be conducted and so on, it eventually took place in Beijing in 1653. The Shunzhi Emperor was then 16 years old, having in the meantime ascended the throne in 1650 after the death of Dorgon. For the Qing, although the Dalai Lama was not required to kowtow to the emperor, who rose from his throne and advanced 30 feet to meet him, the significance of the visit was that of nominal political submission by the Dalai Lama since Inner Asian heads of state did not travel to meet each other but sent envoys. For Tibetan Buddhist historians however it was interpreted as the start of an era of independent rule of the Dalai Lamas, and of Qing patronage alongside that of the Mongols.[145]

When the 5th Dalai Lama returned, he was granted by the emperor of China a golden seal of authority and golden sheets with texts written in Manchu, Tibetan and Chinese languages.[146][147] The 5th Dalai Lama wanted to use the golden seal of authority right away.[146] However, Lobzang Gyatsho noted that «The Tibetan version of the inscription of the seal was translated by a Mongolian translator but was not a good translation». After correction, it read: «The one who resides in the Western peaceful and virtuous paradise is unalterable Vajradhara, Ocen Lama, unifier of the doctrines of the Buddha for all beings under the sky». The words of the diploma ran: «Proclamation, to let all the people of the western hemisphere know».[147] Tibetan historian Nyima Gyaincain points out that based on the texts written on golden sheets, Dalai Lama was only a subordinate of the Emperor of China.[148]

However, despite such patronising attempts by Chinese officials and historians to symbolically show for the record that they held political influence over Tibet, the Tibetans themselves did not accept any such symbols imposed on them by the Chinese with this kind of motive. For example, concerning the above-mentioned ‘golden seal’, the Fifth Dalai Lama comments in Dukula, his autobiography, on leaving China after this courtesy visit to the emperor in 1653, that «the emperor made his men bring a golden seal for me that had three vertical lines in three parallel scripts: Chinese, Mongolian and Tibetan». He also criticised the words carved on this gift as being faultily translated into Tibetan, writing that «The Tibetan version of the inscription of the seal was translated by a Mongol translator but was not a good translation».[147] Furthermore, when he arrived back in Tibet, he discarded the emperor’s famous golden seal and made a new one for important state usage, writing in his autobiography: «Leaving out the Chinese characters that were on the seal given by the emperor, a new seal was carved for stamping documents that dealt with territorial issues. The first imprint of the seal was offered with prayers to the image of Lokeshvara …».[149]

Relations with the Qing dynasty[edit]

The 17th-century struggles for domination between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the various Mongol groups spilled over to involve Tibet because of the Fifth Dalai Lama’s strong influence over the Mongols as a result of their general adoption of Tibetan Buddhism and their consequent deep loyalty to the Dalai Lama as their guru. Until 1674, the Fifth Dalai Lama had mediated in Dzungar Mongol affairs whenever they required him to do so, and the Kangxi Emperor, who had succeeded the Shunzhi Emperor in 1661, would accept and confirm his decisions automatically. For the Kangxi Emperor however, the alliance between the Dzungar Mongols and the Tibetans was unsettling because he feared it had the potential to unite all the other Mongol tribes together against the Qing Empire, including those tribes who had already submitted. Therefore, in 1674, the Kangxi Emperor, annoyed by the Fifth’s less than full cooperation in quelling a rebellion against the Qing in Yunnan, ceased deferring to him as regards Mongol affairs and started dealing with them directly.[150]

In the same year, 1674, the Dalai Lama, then at the height of his powers and conducting a foreign policy independent of the Qing, caused Mongol troops to occupy the border post of Dartsedo between Kham and Sichuan, further annoying the Kangxi Emperor who (according to Smith) already considered Tibet as part of the Qing Empire. It also increased Qing suspicion about Tibetan relations with the Mongol groups and led him to seek strategic opportunities to oppose and undermine Mongol influence in Tibet and eventually, within 50 years, to defeat the Mongols militarily and to establish the Qing as sole ‘patrons and protectors’ of Tibet in their place.[150]

Cultural development[edit]

The time of the Fifth Dalai Lama, who reigned from 1642 to 1682 and founded the government known as the Ganden Phodrang, was a period of rich cultural development.[151] His reign and that of Desi Sangye Gyatso are noteworthy for the upsurge in literary activity and of cultural and economic life that occurred. The same goes for the great increase in the number of foreign visitors thronging Lhasa during the period as well as for the number of inventions and institutions that are attributed to the ‘Great Fifth’, as the Tibetans refer to him.[152] The most dynamic and prolific of the early Dalai Lamas, he composed more literary works than all the other Dalai Lamas combined. Writing on a wide variety of subjects he is specially noted for his works on history, classical Indian poetry in Sanskrit and his biographies of notable personalities of his epoch, as well as his own two autobiographies, one spiritual in nature and the other political (see Further Reading).[153] He also taught and travelled extensively, reshaped the politics of Central Asia, unified Tibet, conceived and constructed the Potala Palace and is remembered for establishing systems of national medical care and education.[153]

Death of the fifth Dalai Lama[edit]

The Fifth Dalai Lama died in 1682. Tibetan historian Nyima Gyaincain points out that the written wills from the fifth Dalai Lama before he died explicitly said his title and authority were from the Emperor of China, and he was subordinate of the Emperor of China

.[148]

The Fifth Dalai Lama’s death in 1682 was kept secret for fifteen years by his regent Desi Sangye Gyatso. He pretended the Dalai Lama was in retreat and ruled on his behalf, secretly selecting the 6th Dalai Lama and presenting him as someone else. Tibetan historian Nyima Gyaincain points out that Desi Sangye Gyatso wanted to consolidate his personal status and power by not reporting the death of the fifth Dalai Lama to the Emperor of China, and also collude with the rebellion group of the Qing dynasty, Mongol Dzungar tribe in order to counter influence from another Mongol Khoshut tribe in Tibet. Being afraid of prosecution by the Kangxi Emperor of China, Desi Sangye Gyatso explained with fear and trepidation the reason behind his action to the Emperor. In 1705, Desi Sangye Gyatso was killed by Lha-bzang Khan of the Mongol Khoshut tribe because of his actions including his illegal action of selecting the 6th Dalai Lama. Since the Kangxi Emperor was not happy about Desi Sangye Gyatso’s action of not reporting, the Emperor gave Lha-bzang Khan additional title and golden seal. The Kangxi Emperor also ordered Lha-bzang Khan to arrest the 6th Dalai Lama and send him to Beijing, the 6th Dalai Lama died when he was en route to Beijing.[148] Journalist Thomas Laird argues that it was apparently done so that construction of the Potala Palace could be finished, and it was to prevent Tibet’s neighbors, the Mongols and the Qing, from taking advantage of an interregnum in the succession of the Dalai Lamas.[154]

6th Dalai Lama[edit]

The Sixth Dalai Lama (1683–1706) was born near Tawang, now in India, and picked out in 1685 but not enthroned until 1697 when the death of the Fifth was announced. After 16 years of study as a novice monk, in 1702 in his 20th year he rejected full ordination and gave up his monk’s robes and monastic life, preferring the lifestyle of a layman.[155][156]

In 1703 Güshi Khan’s ruling grandson Tenzin Wangchuk Khan was murdered by his brother Lhazang Khan who usurped the Khoshut’s Tibetan throne, but unlike his four predecessors he started interfering directly in Tibetan affairs in Lhasa; he opposed the Fifth Dalai Lama’s regent, Desi Sangye Gyatso for his deceptions and in the same year, with the support of the Kangxi Emperor, he forced him out of office. Then in 1705, he used the Sixth’s escapades as an excuse to seize full control of Tibet. Most Tibetans, though, still supported their Dalai Lama despite his behaviour and deeply resented Lhazang Khan’s interference. When Lhazang was requested by the Tibetans to leave Lhasa politics to them and to retire to Kokonor like his predecessors, he quit the city, but only to gather his armies in order to return, capture Lhasa militarily and assume full political control of Tibet.[157] The regent was then murdered by Lhazang or his wife, and, in 1706 with the compliance of the Kangxi Emperor the Sixth Dalai Lama was deposed and arrested by Lhazang who considered him to be an impostor set up by the regent. Lhazang Khan, now acting as the only outright foreign ruler that Tibet had ever had, then sent him to Beijing under escort to appear before the emperor but he died mysteriously on the way near Lake Qinghai, ostensibly from illness.[158][159]

Having discredited and deposed the Sixth Dalai Lama, whom he considered an impostor, and having removed the regent, Lhazang Khan pressed the Lhasa Gelugpa lamas to endorse a new Dalai Lama in Tsangyang Gyatso’s place as the true incarnation of the Fifth. They eventually nominated one Pekar Dzinpa, a monk but also rumored to be Lhazang’s son,[160] and Lhazang had him installed as the ‘real’ Sixth Dalai Lama, endorsed by the Panchen Lama and named Yeshe Gyatso in 1707.[161] This choice was in no way accepted by the Tibetan people, however, nor by Lhazang’s princely Mongol rivals in Kokonor who resented his usurpation of the Khoshut Tibetan throne as well as his meddling in Tibetan affairs. The Kangxi Emperor concurred with them, after sending investigators, initially declining to recognize Yeshe Gyatso. He did recognize him in 1710, however, after sending a Qing official party to assist Lhazang in ‘restoring order’; these were the first Chinese representatives of any sort to officiate in Tibet.[159] At the same time, while this puppet ‘Dalai Lama’ had no political power, the Kangxi Emperor secured from Lhazang Khan in return for this support the promise of regular payments of tribute; this was the first time tribute had been paid to the Manchu by the Mongols in Tibet and the first overt acknowledgment of Qing supremacy over Mongol rule in Tibet.[162]

7th Dalai Lama[edit]

In 1708, in accordance with an indication given by the 6th Dalai Lama when quitting Lhasa a child called Kelzang Gyatso had been born at Lithang in eastern Tibet who was soon claimed by local Tibetans to be his incarnation. After going into hiding out of fear of Lhazang Khan, he was installed in Lithang monastery. Along with some of the Kokonor Mongol princes, rivals of Lhazang, in defiance of the situation in Lhasa the Tibetans of Kham duly recognised him as the Seventh Dalai Lama in 1712, retaining his birth-name of Kelzang Gyatso. For security reasons he was moved to Derge monastery and eventually, in 1716, now also backed and sponsored by the Kangxi Emperor of China.[163] The Tibetans asked Dzungars to bring a true Dalai Lama to Lhasa, but the Manchu Chinese did not want to release Kelsan Gyatso to the Mongol Dzungars. The Regent Taktse Shabdrung and Tibetan officials then wrote a letter to the Manchu Chinese Emperor that they recognized Kelsang Gyatso as the Dalai Lama. The Emperor then granted Kelsang Gyatso a golden seal of authority.[164] The Sixth Dalai Lama was taken to Amdo at the age of 8 to be installed in Kumbum Monastery with great pomp and ceremony.[163]

According to Smith, the Kangxi Emperor now arranged to protect the child and keep him at Kumbum monastery in Amdo in reserve just in case his ally Lhasang Khan and his ‘real’ Sixth Dalai Lama, were overthrown.[165] According to Mullin, however, the emperor’s support came from genuine spiritual recognition and respect rather than being politically motivated.[166]

Dzungar invasion[edit]

In any case, the Kangxi Emperor took full advantage of having Kelzang Gyatso under Qing control at Kumbum after other Mongols from the Dzungar tribes led by Tsewang Rabtan who was related to his supposed ally Lhazang Khan, deceived and betrayed the latter by invading Tibet and capturing Lhasa in 1717.[167][168]

These Dzungars, who were Buddhist, had supported the Fifth Dalai Lama and his regent. They were secretly petitioned by the Lhasa Gelugpa lamas to invade with their help in order to rid them of their foreign ruler Lhazang Khan and to replace the unpopular Sixth Dalai Lama pretender with the young Kelzang Gyatso. This plot suited the devious Dzungar leaders’ ambitions and they were only too happy to oblige.[169][170] Early in 1717, after conspiring to undermine Lhazang Khan through treachery they entered Tibet from the northwest with a large army, sending a smaller force to Kumbum to collect Kelzang Gyatso and escort him to Lhasa. By the end of the year, with Tibetan connivance they had captured Lhasa, killed Lhazang and all his family and deposed Yeshe Gyatso. Their force sent to fetch Kelzang Gyatso however was intercepted and destroyed by Qing armies alerted by Lhazang. In Lhasa, the unruly Dzungar not only failed to produce the boy but also went on the rampage, looting and destroying the holy places, abusing the populace, killing hundreds of Nyingma monks, causing chaos and bloodshed and turning their Tibetan allies against them. The Tibetans were soon appealing to the Kangxi Emperor to rid them of the Dzungars.[171][172]

When the Dzungars had first attacked, the weakened Lhazang sent word to the Qing for support and they quickly dispatched two armies to assist, the first Chinese armies ever to enter Tibet, but they arrived too late. In 1718 they were halted not far from Lhasa to be defeated and then ruthlessly annihilated by the triumphant Dzungars in the Battle of the Salween River.[173][174]

Enthronement in Lhasa[edit]

This humiliation only determined the Kangxi Emperor to expel the Dzungars from Tibet once and for all and he set about assembling and dispatching a much larger force to march on Lhasa, bringing the emperor’s trump card the young Kelzang Gyatso with it. On the imperial army’s stately passage from Kumbum to Lhasa with the boy being welcomed adoringly at every stage, Khoshut Mongols and Tibetans were happy (and well paid) to join and swell its ranks.[175] By the autumn of 1720 the marauding Dzungar Mongols had been vanquished from Tibet and the Qing imperial forces had entered Lhasa triumphantly with the 12-year-old, acting as patrons of the Dalai Lama, liberators of Tibet, allies of the Tibetan anti-Dzungar forces led by Kangchenas and Polhanas, and allies of the Khoshut Mongol princes. The delighted Tibetans enthroned him as the Seventh Dalai Lama at the Potala Palace.[176][177]

A new Tibetan government was established consisting of a Kashag or cabinet of Tibetan ministers headed by Kangchenas. Kelzang Gyatso, too young to participate in politics, studied Buddhism. He played a symbolic role in government, and, being profoundly revered by the Mongols, he exercised much influence with the Qing who now had now taken over Tibet’s patronage and protection from them.[178]

Exile to Kham[edit]

Having vanquished the Dzungars, the Qing army withdrew leaving the Seventh Dalai Lama as a political figurehead and only a Khalkha Mongol as the Qing amban or representative and a garrison in Lhasa.[179][180] After the Kangxi Emperor died in 1722 and was succeeded by his son, the Yongzheng Emperor, these were also withdrawn, leaving the Tibetans to rule autonomously and showing the Qing were interested in an alliance, not conquest.[179][180] In 1723, however, after brutally quelling a major rebellion by zealous Tibetan patriots and disgruntled Khoshut Mongols from Amdo who attacked Xining, the Qing intervened again, splitting Tibet by putting Amdo and Kham under their own more direct control.[181] Continuing Qing interference in Central Tibetan politics and religion incited an anti-Qing faction to quarrel with the Qing-sympathising Tibetan nobles in power in Lhasa, led by Kanchenas who was supported by Polhanas. This led eventually to the murder of Kanchenas in 1727 and a civil war that was resolved in 1728 with the canny Polhanas, who had sent for Qing assistance, the victor. When the Qing forces did arrive they punished the losers and exiled the Seventh Dalai Lama to Kham, under the pretence of sending him to Beijing, because his father had assisted the defeated, anti-Qing faction. He studied and taught Buddhism there for the next seven years.[182]

Return to Lhasa[edit]

In 1735 he was allowed back to Lhasa to study and teach, but still under strict control, being mistrusted by the Qing, while Polhanas ruled Central Tibet under nominal Qing supervision. Meanwhile, the Qing had promoted the Fifth Panchen Lama to be a rival leader and reinstated the ambans and the Lhasa garrison. Polhanas died in 1747 and was succeeded by his son Gyurme Namgyal, the last dynastic ruler of Tibet, who was far less cooperative with the Qing. On the contrary, he built a Tibetan army and started conspiring with the Dzungars to rid Tibet of Qing influence.[183] In 1750, when the ambans realised this, they invited him and personally assassinated him and then, despite the Dalai Lama’s attempts to calm the angered populace a vengeful Tibetan mob assassinated the ambans in turn, along with most of their escort.[184]

Restoration as Tibet’s political leader[edit]

The Qing sent yet another force ‘to restore order’ but when it arrived the situation had already been stabilised under the leadership of the 7th Dalai Lama who was now seen to have demonstrated loyalty to the Qing. Just as Güshi Khan had done with the Fifth Dalai Lama, they therefore helped reconstitute the government with the Dalai Lama presiding over a Kashag of four Tibetans, reinvesting him with temporal power in addition to his already established spiritual leadership. This arrangement, with a Kashag under the Dalai Lama or his regent, outlasted the Qing dynasty which collapsed in 1912.[185] The ambans and their garrison were also reinstated to observe and to some extent supervise affairs, however, although their influence generally waned with the power of their empire which gradually declined after 1792 along with its influence over Tibet, a decline aided by a succession of corrupt or incompetent ambans.[186] Moreover, there was soon no reason for the Qing to fear the Dzungar; by the time the Seventh Dalai Lama died in 1757 at the age of 49, the entire Dzungar people had been practically exterminated through years of genocidal campaigns by Qing armies, and deadly smallpox epidemics, with the survivors being forcibly transported into China. Their emptied lands were then awarded to other peoples.[187]

According to Mullin, despite living through such violent times Kelzang Gyatso was perhaps ‘the most spiritually learned and accomplished of any Dalai Lama’, his written works comprising several hundred titles including ‘some of Tibet’s finest spiritual literary achievements’.[188] In addition, despite his apparent lack of zeal in politics, Kelzang Gyatso is credited with establishing in 1751 the reformed government of Tibet headed by the Dalai Lama, which continued over 200 years until the 1950s, and then in exile.[189] Construction of the Norbulingka, the ‘Summer Palace’ of the Dalai Lamas in Lhasa was also started during Kelzang Gyatso’s reign.[190][191]

8th Dalai Lama[edit]

The Eighth Dalai Lama, Jamphel Gyatso was born in Tsang in 1758 and died aged 46 having taken little part in Tibetan politics, mostly leaving temporal matters to his regents and the ambans.[192] The 8th Dalai Lama was approved by the Emperor of China to be exempted from the lot-drawing ceremony of using Chinese Golden Urn.[193][194] Qianlong Emperor officially accept Gyiangbai as the 8th Dalai Lama when the 6th Panchen Erdeni came to congratulate the Emperor on his 70th birthday in 1780. The 8th Dalai Lama was granted a jade seal of authority and jade sheets of confirmation of authority by the Emperor of China.[195][196] The jade sheets of confirmation of authority says

You, the Dalai Lama, is the legal incarnation of Zhongkapa. You are granted the jade certificate of confirmation of authority and jade seal of authority, which you enshrine in the Potala monastery to guard the gate of Buddhism forever. All documents sent for the country’s important ceremonies must be stamped with this seal, and all the other reports can be stamped with the original seal. Since you enjoy such honor, you have to make efforts to promote self-cultivation, study and propagate Buddhism, also help me in promoting Buddhism and goodness of the previous generation of the Dalai Lama for the people, and also for the long life of our country»[197][196]

The Dalai Lama, his later generations and the local government cherished both the jade seal of authority, and the jade sheets of authority. They were properly preserved as the root to their ruling power.[196]

Although the 8th Dalai Lama lived almost as long as the Seventh he was overshadowed by many contemporary lamas in terms of both religious and political accomplishment. According to Mullin, the 14th Dalai Lama has pointed to certain indications that Jamphel Gyatso might not have been the incarnation of the 7th Dalai Lama but of Jamyang Chojey, a disciple of Tsongkhapa and founder of Drepung monastery who was also reputed to be an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara. In any case, he mainly lived a quiet and unassuming life as a devoted and studious monk, uninvolved in the kind of dramas that had surrounded his predecessors.[198]

Nevertheless, Jamphel Gyatso was also said to possess all the signs of being the true incarnation of the Seventh. This was also claimed to have been confirmed by many portents clear to the Tibetans and so, in 1762, at the age of 5, he was duly enthroned as the Eighth Dalai Lama at the Potala Palace.[199] At the age of 23 he was persuaded to assume the throne as ruler of Tibet with a Regent to assist him and after three years of this, when the Regent went to Beijing as ambassador in 1784, he continued to rule solo for a further four years. Feeling unsuited to worldly affairs, however, and unhappy in this role, he then retired from public office to concentrate on religious activities for his remaining 16 years until his death in 1804.[200] He is also credited with the construction of the Norbulingka ‘Summer Palace’ started by his predecessor in Lhasa and with ordaining some ten thousand monks in his efforts to foster monasticism.[201]

9th to 12th Dalai Lamas[edit]

Hugh Richardson’s summary of the period covering the four short-lived, 19th-century Dalai Lamas:

After him [the 8th Dalai Lama, Jamphel Gyatso], the 9th and 10th Dalai Lamas died before attaining their majority: one of them is credibly stated to have been murdered and strong suspicion attaches to the other. The 11th and 12th were each enthroned but died soon after being invested with power. For 113 years, therefore, supreme authority in Tibet was in the hands of a Lama Regent, except for about two years when a lay noble held office and for short periods of nominal rule by the 11th and 12th Dalai Lamas.[note 1]

It has sometimes been suggested that this state of affairs was brought about by the Ambans—the Imperial Residents in Tibet—because it would be easier to control the Tibet through a Regent than when a Dalai Lama, with his absolute power, was at the head of the government. That is not true. The regular ebb and flow of events followed its set course. The Imperial Residents in Tibet, after the first flush of zeal in 1750, grew less and less interested and efficient. Tibet was, to them, exile from the urbanity and culture of Peking; and so far from dominating the Regents, the Ambans allowed themselves to be dominated. It was the ambition and greed for power of Tibetans that led to five successive Dalai Lamas being subjected to continuous tutelage.[202]

Thubten Jigme Norbu, the elder brother of the 14th Dalai Lama, described these unfortunate events as follows, although there are few, if any, indications that any of the four were said to be ‘Chinese-appointed imposters’:

It is perhaps more than a coincidence that between the seventh and the thirteenth holders of that office, only one reached his majority. The eighth, Gyampal Gyatso, died when he was in his thirties, Lungtog Gyatso when he was eleven, Tsultrim Gyatso at eighteen, Khadrup Gyatso when he was eighteen also, and Krinla Gyatso at about the same age. The circumstances are such that it is very likely that some, if not all, were poisoned, either by loyal Tibetans for being Chinese-appointed impostors, or by the Chinese for not being properly manageable. Many Tibetans think that this was done at the time when the young [Dalai Lama] made his ritual visit to the Lake Lhamtso. … Each of the four [Dalai Lamas] to die young expired shortly after his visit to the lake. Many said it was because they were not the true reincarnations, but imposters imposed by the Chinese. Others tell stories of how the cooks of the retinue, which in those days included many Chinese, were bribed to put poison in the [Dalai Lama’s] food. The 13th [Dalai Lama] did not visit Lhamtso until he was 25 years old. He was adequately prepared by spiritual exercise and he also had faithful cooks. The Chinese were disappointed when he did not die like his predecessors, and he was to live long enough to give them much more cause for regret.[203][note 2]

According to Mullin, on the other hand, it is improbable that the Manchus would have murdered any of these four for being ‘unmanageable’ since it would have been in their best interests to have strong Dalai Lamas ruling in Lhasa, he argues, agreeing with Richardson that it was rather «the ambition and greed for power of Tibetans» that might have caused the Lamas’ early deaths.[note 3] Further, if Tibetan nobles murdered any of them, it would more likely have been in order to protect or enhance their family interests rather than out of suspicion that the Dalai Lamas were seen as Chinese-appointed imposters as suggested by Norbu. They could also have died from illnesses, possibly contracted from diseases to which they had no immunity, carried to Lhasa by the multitudes of pilgrims visiting from nearby countries for blessings. Finally, from the Buddhist point of view, Mullin says, «Simply stated, these four Dalai Lamas died young because the world did not have enough good karma to deserve their presence».[204]

Tibetan historian K. Dhondup, however, in his history The Water-Bird and Other Years, based on the Tibetan minister Surkhang Sawang Chenmo’s historical manuscripts,[205] disagrees with Mullin’s opinion that having strong Dalai Lamas in power in Tibet would have been in China’s best interests. He notes that many historians are compelled to suspect Manchu foul play in these serial early deaths because the Ambans had such latitude to interfere; the Manchu, he says, «to perpetuate their domination over Tibetan affairs, did not desire a Dalai Lama who will ascend the throne and become a strong and capable ruler over his own country and people«. The life and deeds of the 13th Dalai Lama [in successfully upholding de facto Tibetan independence from China from 1912 to 1950] serve as the living proof of this argument, he points out.[206] This account also corresponds with TJ Norbu’s observations above.

Finally, while acknowledging the possibility, the 14th Dalai Lama himself doubts they were poisoned. He ascribes the probable cause of these early deaths to negligence, foolishness and lack of proper medical knowledge and attention. «Even today» he is quoted as saying, «when people get sick, some [Tibetans] will say: ‘Just do your prayers, you don’t need medical treatment.’«[207]

9th Dalai Lama[edit]

Born in Kham in 1805–6 amidst the usual miraculous signs the Ninth Dalai Lama, Lungtok Gyatso was appointed by the 7th Panchen Lama’s search team at the age of two and enthroned in the Potala in 1808 at an impressive ceremony attended by representatives from China, Mongolia, Nepal and Bhutan. Exemption from using Golden Urn was approved by the Emperor.[208][209] Tibetan historian Nyima Gyaincain and Wang Jiawei point out that the 9th Dalai Lama was allowed to use the seal of authority given to the late 8th Dalai Lama by the Emperor of China[210]

His second Regent Demo Tulku was the biographer of the 8th and 9th Dalai Lamas and though the 9th died at the age of 9, his biography is as lengthy as those of many of the early Dalai Lamas.[211] In 1793 under Manchu pressure, Tibet had closed its borders to foreigners,[212][213] but in 1811, a British Sinologist, Thomas Manning became the first Englishman to visit Lhasa. Considered to be ‘the first Chinese scholar in Europe’[214] he stayed five months and gave enthusiastic accounts in his journal of his regular meetings with the Ninth Dalai Lama whom he found fascinating: «beautiful, elegant, refined, intelligent, and entirely self-possessed, even at the age of six».[215] Three years later in March 1815 the young Lungtok Gyatso caught a severe cold and, leaving the Potala Palace to preside over the Monlam Prayer Festival, he contracted pneumonia from which he soon died.[216][217]

10th Dalai Lama[edit]

Like the Seventh Dalai Lama, the Tenth, Tsultrim Gyatso, was born in Lithang, Kham, where the Third Dalai Lama had built a monastery. It was 1816 and Regent Demo Tulku and the Seventh Panchen Lama followed indications from Nechung, the ‘state oracle’ which led them to appoint him at the age of two. He passed all the tests and was brought to Lhasa but official recognition was delayed until 1822 when he was enthroned and ordained by the Seventh Panchen Lama. There are conflicting reports about whether the Chinese ‘Golden Urn’ was utilised by drawing lots to choose him, but lot-drawing result was reported and approved by emperor. [218] The 10th Dalai Lama mentioned in his biography that he was allowed to use the golden seal of authority based on the convention set up by the late Dalai Lama. At the investiture, decree of the Emperor of China was issued and read out.[219] After 15 years of intensive studies and failing health he died, in 1837, at the age of 20 or 21.[220][221] He identified with ordinary people rather than the court officials and often sat on his verandah in the sunshine with the office clerks. Intending to empower the common people he planned to institute political and economic reforms to share the nation’s wealth more equitably. Over this period his health had deteriorated, the implication being that he may have suffered from slow poisoning by Tibetan aristocrats whose interests these reforms were threatening.[222] He was also dissatisfied with his Regent and the Kashag and scolded them for not alleviating the condition of the common people, who had suffered much in small ongoing regional civil wars waged in Kokonor between Mongols, local Tibetans and the government over territory, and in Kham to extract unpaid taxes from rebellious Tibetan communities.[218][223]

11th Dalai Lama[edit]

Born in Gathar, Kham in 1838 and soon discovered by the official search committee with the help of the Nechung Oracle, the Eleventh Dalai Lama was brought to Lhasa in 1841 and recognised, enthroned and named Khedrup Gyatso by the Panchen Lama in 1842, who also ordained him in 1846. After that he was immersed in religious studies under the Panchen Lama, amongst other great masters. Meanwhile, there were court intrigues and ongoing power struggles taking place between the various Lhasa factions, the Regent, the Kashag, the powerful nobles and the abbots and monks of the three great monasteries. The Tsemonling Regent[224] became mistrusted and was forcibly deposed, there were machinations, plots, beatings and kidnappings of ministers and so forth, resulting at last in the Panchen Lama being appointed as interim Regent to keep the peace. Eventually the Third Reting Rinpoche was made Regent, and in 1855, Khedrup Gyatso, appearing to be an extremely promising prospect, was requested to take the reins of power at the age of 17. He was enthroned as ruler of Tibet in 1855,[225][226] on orders of the Xianfeng Emperor.[227] He died after just 11 months, no reason for his sudden and premature death being given in these accounts, Shakabpa and Mullin’s histories both being based on untranslated Tibetan chronicles. The respected Reting Rinpoche was recalled once again to act as Regent and requested to lead the search for the next incarnation, the twelfth.[225][226]

12th Dalai Lama[edit]

In 1856, a child was born in south central Tibet amidst all the usual extraordinary signs. He came to the notice of the search team, was investigated, passed the traditional tests and was recognised as the 12th Dalai Lama in 1858. The use of the Chinese Golden Urn at the insistence of the Regent, who was later accused of being a Chinese lackey, confirmed this choice to the satisfaction of all. Renamed Trinley Gyatso and enthroned in 1860 the boy underwent 13 years of intensive tutelage and training before stepping up to rule Tibet at the age of 17.[228]