Морфемный разбор слова:

Однокоренные слова к слову:

Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации (1956 г.)

ХIII Неударяемые частицы НЕ и НИ

Орфография

ХIII Неударяемые частицы НЕ и НИ

§ 48. Следует различать правописание неударяемых частиц не и ни. Частицы эти различаются по значению и употреблению.

1. Частица не употребляется для отрицания, например: Не я говорил об этом. Я не говорил об этом. Я говорил не об этом.

Необходимо обратить внимание на отдельные случаи употребления этой частицы:

а) При наличии отрицательной частицы не и в первой, и во второй части составного глагольного сказуемого предложение получает утвердительный смысл, например: не могу не упомянуть. (т. е. «должен упомянуть»), нельзя не сознаться. (т. е. «надо сознаться»).

б) В вопросительных и восклицательных предложениях частица не примыкает к местоимениям, наречиям и частицам, образуя с ними сочетания: как не, кто не, кто только не, где не, где только не, чем не, чего не, чего только не и т. п.; сюда примыкают вопросительные предложения с сочетанием не – ли, например: Ну, как не порадеть родному человечку! (Грибоедов). Кто не проклинал станционных смотрителей, кто с ними не бранивался? (Пушкин). Чем ты не молодец? (Пушкин). Где он только не бывал! Чего он только не видал! Чем не работа! Обрыскал свет; не хочешь ли жениться? (Грибоедов). Да не изволишь ли сенца? (Крылов).

в) В соединении с союзом пока частица не употребляется в придаточных предложениях времени, обозначающих предел, до которого длится действие, выраженное сказуемым главного предложения, например: Сиди тут, пока не приду.

г) Частица не входит в состав устойчивых сочетаний: едва ли не, чуть ли не, вряд ли не, обозначающих предположение, далеко не, отнюдь не, ничуть не, нисколько не, вовсе не, обозначающих усиленное отрицание, например: едва ли не лучший стрелок, чуть ли не в пять часов утра, отнюдь не справедливое решение, вовсе не плохой товар, далеко не надежное средствo.

д) Частица не входит в состав сочинительных союзов: не то; не то – не то; не только – но; не то что не – а; не то чтобы не – а, например: Отдай кольцо и ступай; не то я с тобой сделаю то, чего ты не ожидаешь (Пушкин). Наверху за потолком кто-то не то стонет, не то смеется (Чехов). У партизан были не только винтовки, но и пулеметы (Ставский).

2. Частица ни употребляется для усиления отрицания, например: Ни косточкой нигде не мог я поживиться (Крылов). На небе позади не было ни одного просвета (Фадеев). Метелица даже ни разу не посмотрел на спрашивающих (Фадеев). В деревне теперь ни души: все в noлe(Фадеев).

Повторяющаяся частица ни приобретает значение союза, например: Нигде не было видно ни воды, ни деревьев (Чехов). Ни музы, ни труды, ни радости досуга – ничто не заменит единственного друга (Пушкин). Но толпы бегут, не замечая ни его, ни его тоски (Чехов). Я не знаю ни кто вы, ни кто он (Тургенев).

Необходимо обратить внимание на отдельные случаи употребления частицы ни:

а) Частица ни употребляется перед сказуемым в придаточных предложениях для усиления утвердительного смысла, например: Слушайтесь его во всем, что ни прикажет (Пушкин). Не мог он ямба от хорея, как мы ни бились, отличить (Пушкин). Куда ни оглянусь, повсюду рожь густая (Майков). Кто ни проедет, всякий похвалит (Пушкин).

Частица ни в придаточных предложениях указанного типа примыкает к относительному слову или к союзу, и поэтому придаточные предложения начинаются сочетаниями: кто ни, кто бы ни, что ни, что бы ни, как ни, как бы ни, сколько ни, сколько бы ни, куда ни, куда бы ни, где ни, где бы ни, какой ни, какой бы ни, чей ни, чей бы ни, когда ни, когда бы ни и т. п.

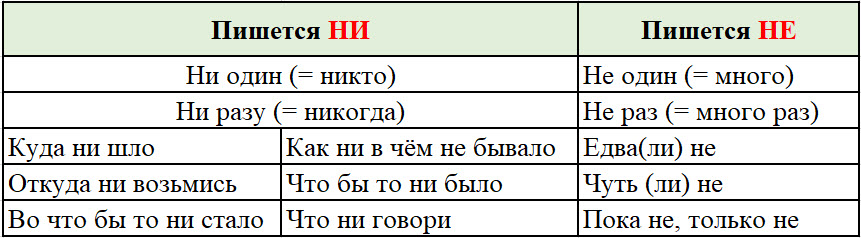

Эти сочетания вошли в некоторые устойчивые обороты: куда ни шло, откуда ни возьмись, во что бы то ни стало и т. п.

б) Частица ни встречается в устойчивых сочетаниях, которые имеют значение категорического приказания, например: ни с места, ни шагу далee, ни слова и т. п.

в) Частица ни входит в состав отрицательных местоимений: никто, никого (ни у кого) и т. д.; ничто, ничего (ни до чего) и т. д.; никакой, никакого (ни у какого) и т. д.; ничей, ничьего (ни у чьего) и т. д. и наречий: никогда, нигде, никуда, ниоткуда, никак, нисколько, нипочем, ничуть, а также в состав частицы -нибудь.

Пишется ни в устойчивых сочетаниях, в которые входят местоимения, например: остался ни при чем, остался ни с чем, пропал ни за что.

г) Двойное ни входит в устойчивые обороты, представляющие собой сочетание двух противопоставляемых понятий, например: ни жив ни мертв; ни то ни се; ни рыба ни мясо; ни дать ни взять; ни пава ни ворона и т. п.

Источник

Двойное отрицание как пишется не или ни

Частицы НЕ и НИ. Частица НЕ может писаться со словами слитно или раздельно, частица НИ пишется раздельно со всеми словами, кроме отрицательных наречий (ниоткуда, нигде) и местоимений без предлога (никого, но ни от кого). Чтобы правильно употреблять частицы НЕ и НИ на письме, необходимо разграничивать их значения.

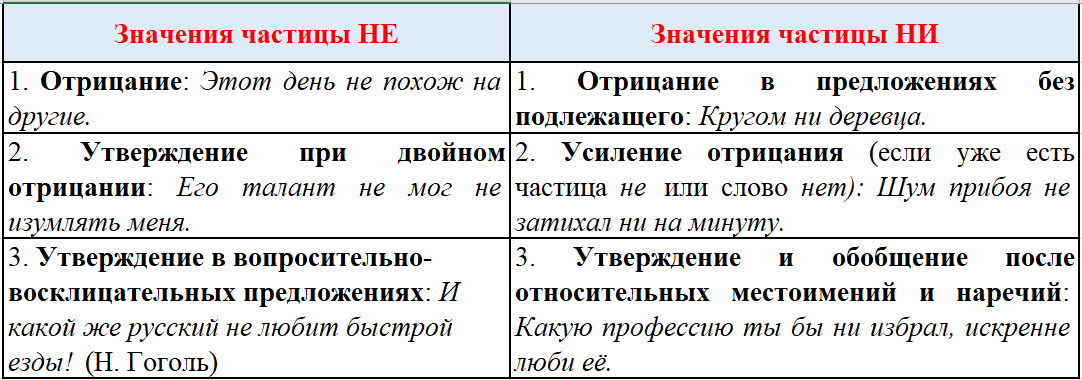

Значения частицы НЕ

1. Отрицание: частица НЕ придаёт предложению или отдельному слову отрицательный смысл: Не ходите туда! — отрицательный смысл всего предложения; Эта вещь принадлежит не мне — отрицательный смысл отдельного слова.

2. Утверждение при двойном отрицании: повторяющаяся частица НЕ (первая не перед глаголом мочь, вторая не — перед неопределённой формой другого глагола) имеет утвердительный смысл: не мог не знать = знал. При этом возникает оттенок необходимости, долженствования: не мог не сказать = должен был сказать.

3. Утверждение в вопросительно-восклицательных предложениях: в подобных предложениях (риторических вопросах) частица НЕ имеет утвердительный смысл: Где я только не побывал! (= везде побывал); Кто у меня только не гостил! (= все гостили).

Значения частицы НИ

1. Отрицание в предложениях без подлежащего: частица НИ обозначает отрицание в предложениях без подлежащего при дополнении в родительном падеже: На небе ни тучки; Вокруг ни звука; Ни с места! Ни слова! Частица НИ в этом случае усиливает отрицание, которое подразумевается. Отрицательное слово НЕТ или сказуемое, при котором есть НЕ, опущены.

2. Усиление отрицания: если в предложении есть отрицание (слово нет, частица не при глаголе-сказуемом, причастии или деепричастии), то НИ усиливает это отрицание: На небе нет ни тучки; не говоря ни слова; не смотревший ни вправо, ни влево. В этом случае частицу НИ можно опустить, смысл предложения не изменится, пропадёт лишь оттенок усиления: У меня не было ни минуты на размышление. — У меня не было минуты на размышление. Подобные случаи нужно отличать от двойного употребления частицы НЕ для обозначения утверждения. Сравним: Он не мог не знать и не сказать — утвердительный смысл (он знал и сказал); Он не мог ни знать, ни догадаться — отрицательный смысл, ни можно отбросить (он не мог знать или догадаться).

3. Утверждение и обобщение после относительных местоимений и наречий в придаточном предложении: частица НИ придаёт обобщающее утвердительное значение словам кто, что, где, когда, сколько и т.д., которые служат средством связи придаточного предложения с главным. Кто ни придёт, всем здесь рады = любой человек придёт; Сколько ни вглядывался, ничего не заметил = долго, пристально вглядывался; Где ни бывал, везде находил друзей = бывал в разных местах. Подобные случаи надо отличать от тех сложноподчинённых предложений, в которых придаточные имеют отрицательное значение и в которых пишется частица НЕ. Сравним: Кто не прочитает эту книгу, тот многого не узнает — придаточное имеет отрицательное значение, действие не совершено (книга не прочитана); Кто ни прочитает эту книгу, всем она нравится — придаточное имеет утвердительный смысл, действие совершено (книга прочитана).

Обратите внимание! Повторяющаяся при однородных членах частица НИ рассматривается как сочинительный союз: Не было слышно ни звука, ни шороха.

Нужно запомнить!

1. Если повторяющаяся частица НИ употребляется в устойчивом выражении, то запятая между частями этого оборота не ставится:

| Ни больше ни меньше | Ни да ни нет | Ни днём ни ночью |

| Ни конца ни края | Ни много ни мало | Ни себе ни людям |

| Ни стать ни сесть | Ни взад ни вперёд | Ни дать ни взять |

| Ни два ни полтора | Ни жив ни мёртв | Ни за что ни про что |

| Ни нашим ни вашим | Ни ответа ни привета | Ни рыба ни мясо |

| Ни свет ни заря | Ни пуха ни пера | Ни слуху ни духу |

| Ни с того ни с сего | Ни там ни сям | Ни то ни сё |

| Ни туда ни сюда | Ни шатко ни валко | Ни так ни сяк |

Таблица «Частицы НЕ и НИ»

Конспект урока «Частицы НЕ и НИ. Значение и правописание».

Раздел: «Орфография» и «Служебные части речи».

Источник

Правописание НЕ и НИ с разными частями речи

Содержание:

Отрицательные частицы с одними частями речи выступают как словообразовательные, т.е. становятся приставками, образуя новые слова, с другими пишутся всегда отдельно. Сначала надо разобраться, какую частицу выбрать – НЕ или НИ.

НЕ или НИ

Обе частицы называются отрицательными, но НЕ обычно обозначает само отрицание, а НИ в большинстве случаев усиливает отрицание. Выбор частицы зависит от того, в каком предложении, простом или сложном, она употреблена, и от того значения, которое привносит в текст или речь.

Отрицательная частица НЕ в предложениях с одной грамматической основой имеет значение:

Отрицательная частица НИ в простых предложениях- усилитель отрицания, а в придаточных сложных обозначает утверждение в сочетании с наречиями и местоимениями:

Всегда слитно

НЕ всегда пишется слитно, если:

НЕДОкрутил сальто – ПЕРЕкрутил сальто;

НЕДОсыпал песок в раствор – ПЕРЕсыпал песок в раствор.

Всегда раздельно

Всегда, кроме случаев, описанных в предыдущем пункте, раздельно пишут частицу НЕ со следующими словами:

Для раздельного употребления НЕ в перечисленных ситуациях не требуется знание правил – надо запомнить, что в этих случаях НЕ всегда частица.

Есть варианты – применяем правило

Одни и те же слова пишутся с НЕ слитно или раздельно. Выбрать правильный вариант помогут правила, разный для частей речи:

Часть речи

Раздельно

Слитно

Примеры

Если есть противопоставление – антоним или сочетание с союзом а. Слово с не не заменяется синонимом.

Нет противопоставления, а слово с не заменяется близким по значению.

Не тихое озерцо, а бурная река. Не мелкий пруд – глубокое озеро. Неглубокое озерцо (мелкое).

Причастия в полн. форме

Если входит в оборот (есть зависимые слова (ЗС)

Одиночное, кроме слов-усилителей – чрезвычайно, абсолютно, совершенно, очень, крайне

Еще не прочитанная повесть (ЗС)

Совершенно непонятая тема (усилитель)

Невыученный урок (без зав.слов)

Не к кому обратиться, не за чем идти

Некому рассказать, нечем поделиться.

Трудные случаи употребления частиц надо запомнить:

Практика ЕГЭ по русскому языку:

Источник

Правильное написание НЕ и НИ: примеры, правила, разъяснения

Содержание статьи:

Краткий видео-обзор статьи:

В русском языке одними из самых труднозапоминаемых остаются правила правописания «не» и «ни».

Частицы НЕ, НИ в словах, правило их употребления всегда вызывают множество трудностей. И как не запутаться, что и когда писать? В этой статье вам будет предложено на конкретных примерах разобраться с основополагающими моментами и запомнить их.

Чтобы писать грамотно, для начала Вам необходимо хорошо выучить группы слов, которые всегда будут писаться слитно или раздельно с частицей НЕ.

Всегда слитно НЕ пишется с теми словами, которые нельзя употребить без «НЕ».

Например: нехватка (сущ.), невзрачный (прил.), нелепый (прил.), невежда (сущ.), невмоготу (нар.), ненароком (нар.) и другие.

Как видите, эти слова относятся к разным частям речи, и систематизировать как-либо их нельзя. Поэтому их нужно просто запоминать.

Всегда раздельно НЕ пишется:

Отдельное внимание стоит здесь обратить еще на один момент.

Например: недоставать (не хватать), недосыпать (слишком мало спать, не высыпаться), недосмотреть (за ребенком), недоедать (слишком мало есть).

Итак, для того чтобы не ошибиться в постановке правильной частицы в русском языке, необходимо следовать определенному алгоритму.

Частица НЕ с разными частями речи

С существительными и прилагательными

НЕ пишется слитно, если слова без НЕ не употребляются (небрежный, невежда, ненастный и т.п.) или к слову можно подобрать близкое по значению слово – синоним без не.

Примеры: Он говорит неправду (т.е. ложь). Нам предстоит неблизкий (далекий) путь.

НЕ пишется раздельно, если есть противопоставление, выраженное союзом А и нельзя подобрать синоним.

Примеры: Нас постигла не удача, а разочарование. Помещение не большое, а маленькое. К сожалению, я не специалист в этой сфере.

С наречиями

Примеры: Разговаривайте, пожалуйста, негромко (тихо). В этой ситуации я выглядела совершенно нелепо.

Примеры: Мы шли не быстро, а медленно. Ты одета совсем не по-зимнему.

Также НЕ с наречиями пишется раздельно в том случае, когда НЕ употребляется в сочетаниях: вовсе не, ничуть не, совсем не, далеко не, никогда не, отнюдь не, нисколько не.

Примеры: Я чувствую себя совсем не плохо. Он далеко не идеально выполнил эту работу.

С местоимениями

НЕ с местоимениями пишется раздельно.

Примеры: не я, не она, не твой, не сами.

С отрицательными и неопределенными местоимениями (некто, нечто, некого, нечего и т.п.) НЕ пишется слитно. Но если между НЕ и местоимением этих групп есть предлог, то в таком случае НЕ будет писаться раздельно.

Примеры: Некто зашел в комнату и спрятался за занавеской. В сложившейся ситуации мне было не у кого просить помощи. Здесь просто не к чему придраться.

С причастиями

НЕ пишется слитно с причастиями, которые не употребляются без НЕ (ненавидящий, негодующий); причастиями, у которых есть приставка НЕДО- (недооценивавший, недоговоривший и т.п.) и причастиями, у которых нет зависимых слов.

Примеры: Недоумевающий человек выбежал из автобуса со скоростью света. Недолюбливавший кашу, он отодвинул тарелку в сторону. Ненаписанное сочинение не давало мне покоя.

НЕ пишется раздельно с причастиями, у которых есть зависимые слова (т.е. в причастном обороте), со всеми краткими причастиями (не сделана, не прочитана и т.п.) и в предложениях, в которых есть противопоставления с союзами А, НО.

Примеры: Сад наполняли цветы не увядшие, а свежие. В ресторане нам подали овощи не отваренные, а запеченные. Это был спортсмен, не победивший, но участвовавший в соревнованиях. Книга была не прочитана (краткая форма причастия). Отчет, не отправленный начальнику вовремя, будет зафиксирован (зависимое слово: не отправленный кому? – начальнику).

С деепричастиями

НЕ с деепричастиями пишется раздельно. Исключительными являются случаи, когда деепричастие образовано от глагола, который без «НЕ» не употребляется (ненавидя, негодуя и др.).

Примеры: Не отдохнув, он поехал на работу. Ненавидя друг друга, они продолжали совместный проект.

Итак, вы ознакомились с основными правилами написания НЕ с различными частями речи.

По аналогии, давайте рассмотрим особенности правописания с частицей НИ.

Частица НИ с разными частями речи

В остальных же случаях, частица «НИ» пишется раздельно.

Как вы видите, с НИ информации для запоминания в разы меньше. И поэтому теперь, когда усвоено правило НЕ, НИ, слитно или раздельно они пишутся, важно научиться различать случаи, когда необходимо писать частицу НЕ, а когда НИ.

Чем отличаются частицы НЕ и НИ?

Правило написания этих неударяемых частиц зависит, в первую очередь, от их значения. Поэтому рассмотрим разные случаи употребления НЕ, НИ, правило и примеры для более точного понимания.

НЕ, НИ: правило, примеры

Частица «НЕ» используется:

В простых предложениях, если она имеет значение отрицания при глаголе, причастии или деепричастии.

Примеры: Я не хочу читать. Не интересующаяся историей молодежь.

В составном глагольном сказуемом при отрицании частице «НЕ» в первой и второй его части, дает утвердительный смысл.

Примеры: Не могу не сообщить. Не смогу не купить.

В вопросительных и восклицательных предложениях в сочетаниях с местоимениями, наречиями и частицами (только не, как не, чего не, чего только не и т.п.)

Примеры: Кого я только не знаю! Как не порадовать любимого человека?

В придаточной части сложного предложения в сочетании с союзом ПОКА.

Примеры: Стой тут, пока не скажу! Сиди, пока не придут за тобой.

В составе устойчивых сочетаний, которые обозначают предположение (далеко не, ничуть не, отнюдь не, вовсе не, нисколько не) и отрицание (чуть ли не, едва ли не, вряд ли не).

Примеры: Едва ли не каждый был виновен в этом. Им было принято отнюдь не справедливое решение.

В составе сочинительных союзов: не то; не то – не то; не только – но; не то что не – а; не то чтобы не – а.

Примеры: Наверху за потолком кто-то не то стонет, не то смеется (А. П. Чехов). Отдай кольцо и ступай; не то я с тобой сделаю то, чего ты не ожидаешь (А. С. Пушкин).

Частица «НИ» используется:

Для усиления отрицания.

Примеры: Ни кусочка нигде я не могла найти. У нас не было ни одного шанса.

При повторении, приобретая значение союза.

Примеры: Он не мог найти ни книгу, ни тетрадь. Ни он, ни его родители не замечали происходящего.

В придаточных предложениях для усиления утвердительного смысла.

Примеры: Делайте, пожалуйста, все, что ни скажу! Куда ни посмотрю, повсюду беспорядок.

В устойчивых сочетаниях со значением категорического приказания: ни с места, ни слова, ни шагу назад и т.п.

В устойчивых оборотах, представленных сочетанием двух противопоставляемых понятий: ни рыба ни мясо; ни жив ни мертв; ни дать ни взять и т.п.

Теперь, когда мы разобрали все примеры НЕ и НИ в предложениях, правило должно стать более понятным. Главное, постарайтесь попрактиковаться и придумать несколько собственных примеров на каждый пункт правил. Тогда материал лучше закрепится в памяти. Успехов!

Источник

Не, ни, не, ни.

Не или ни? Ни или не? Кто только ни задавался этим вопросом, кто (да что уж там, сознаемся!) ни проклинал все на свете, пытаясь вспомнить правило из школьной программы: что же, что именно здесь надо написать, не или ни.

А поскольку ошибки все-таки встречаются, причем и в рекламе, и в журнальных текстах, не говоря уж об Интернете, можно сделать вывод, что вспомнить удается далеко не всегда. Тогда в силу вступает правило, известное всем как «русский авось». Вот исходя из этого правила обычно и выбирают: не или ни.

Итак, ни. Существуют случаи, которые смело можно назвать простыми.

Мы пишем ни, и только ни в устойчивых выражениях (таких, как ни свет ни заря, ни днем ни ночью, ни жив ни мертв, ни рыба ни мясо). Ни с места! Ни шагу назад! Ни один человек не пришел на акцию (то есть никто). Он ни разу мне не позвонил (то есть нисколько). Это запомнить просто.

Но есть и непростые ситуации, куда же без них!

О, это «ни для усиления отрицания». Со школьных времен мы думаем о тебе с содроганием. А напрасно, между прочим. И это можно попробовать запомнить. Итак, в предложениях, где ни используется для усиления отрицания, обычно уже имеется отрицание (нет или не): Нет ни копейки денег. Он не дал мне ни рубля. Иногда отрицание только подразумевается: Ни копеечки (не было) в кармане.

Существует, правда, двойное отрицание с не (ты не мог меня не заметить). Но это двойное отрицание придает предложению смысл утверждения, а вовсе не отрицания! Что такое не мог не заметить? Это значит «заметил». Как сказали бы математики, «минус на минус дает плюс».

Однако вернемся к ни.

Если же речь идет о независимом восклицательном или вопросительном предложении, то пишется не: Кто не восхищался ею! Что он только не передумал!

Ни, и только ни мы напишем в так называемых уступительных придаточных, чтобы усилить утверждение.

Тут будет уместно вспомнить шлягер Аллы Пугачевой: «Я отправлюсь за тобой, что бы путь мне ни пророчил». Да, знаю, сама она поет не пророчил. Но это ошибка, увы. Ни пророчил, и только ни!

Источник

Теперь вы знаете какие однокоренные слова подходят к слову Двойное отрицание как пишется не или ни, а так же какой у него корень, приставка, суффикс и окончание. Вы можете дополнить список однокоренных слов к слову «Двойное отрицание как пишется не или ни», предложив свой вариант в комментариях ниже, а также выразить свое несогласие проведенным с морфемным разбором.

Немного теории. Чаще всего выбор между «не» и «ни» зависит от смысла фразы: «не» — отрицает, «ни» — усиливает. Давайте осмыслим.

Начнём с самых простых примеров отрицаний:

Я пришёл не один (а с товарищем).

Не раз я приходил (а пять раз).

В свою очередь, усиление выглядит следующим образом:

Ни один не пришёл (совсем никто).

На пляже ни души (совсем никого).

Также отрицание можно выразить с помощью союзов «не то чтобы не»; «если не, то»; «не только, но и»; «не то, не то». В данных конструкциях следует употреблять только «не».

Теперь отметим устойчивые формы с «ни»:

- ни дать ни взять;

- откуда ни возьмись;

- во что бы то ни стало;

- ни с того ни с сего;

- как бы там ни было.

Именно с «не» употребляются следующие наречия: пока, едва, только.

«Ни» встречается в похожих друг на друга конструкциях: где бы ни, что бы ни, какой бы ни, сколько бы ни.

И снова вернёмся к отрицанию. Рассмотрим двойное отрицание. Смысл у него получается противоположный:

Не мог не посмотреть — значит посмотрел.

Не смог не взять — значит взял.

Применяем в данных случаях только «не».

Если предполагаемое «не» или «ни» в предложении (например, «не увидел ни луны, ни звёзд») заменяет собой союз «и», соединяющий однородные члены, то мы пишем «ни».

Чтобы убедиться в этом, разберём два похожих друг на друга примера:

«Где я только не был!»

«Где я ни был, везде хорошо».

Почему в первом случае пишется «не», а во втором — «ни»? В простых предложениях с восклицанием или «вопрошанием» надо писать «не», а в придаточном предложении — «ни».

В данной ситуации правильность выбора между «не» и «ни» можно легко проверить: если частицу убрать и смысл предложения не потеряется — надо писать «ни»; если потеряется или изменится — «не». «Где я только был» — предложение не имеет смысла. «Где я был, везде хорошо» — смысл остался прежним.

Рассмотрим случай, в котором выбор между «не» и «ни» зависит непосредственно от ударения. Например, нЕкто, но никтО; нЕ у кого, но ни у когО, т. е. выбор правильности написания частицы вновь зависит от смысла. Но в данной позиции попадаются и исключения: сложно будет определиться, к примеру, с правильностью написания наречия «немало/нимало».

Рассмотрим с ним пару примеров.

«Немало воды утекло» и «Нимало не испугался».

Здесь можно применить уже использованное выше правило правописания «изменения смысла при отсутствии конструкции». Если из предложений убрать именно «не» и «ни», то получится: мало воды утекло (полностью меняется смысл фразы) и мало не испугался (получается неверный набор слов, но в общем смысл текста не меняется — чуть не испугался).

Но есть и более простой вариант: «немало» — значит много, а «нимало» — значит совсем. В первом случае факт отрицаем, во втором — усиливаем. И снова делаем вывод, что выбор правильности написания «не» или «ни» зависит от смысла. Думаю, примеры наглядно это подчеркнули.

Запоминайте примеры, ловите смысл слов и пишите грамотно! Любите русский язык!

«Частицы НЕ и НИ. Значение и правописание»

Частицы НЕ и НИ. Частица НЕ может писаться со словами слитно или раздельно, частица НИ пишется раздельно со всеми словами, кроме отрицательных наречий (ниоткуда, нигде) и местоимений без предлога (никого, но ни от кого). Чтобы правильно употреблять частицы НЕ и НИ на письме, необходимо разграничивать их значения.

Значения частицы НЕ

1. Отрицание: частица НЕ придаёт предложению или отдельному слову отрицательный смысл: Не ходите туда! — отрицательный смысл всего предложения; Эта вещь принадлежит не мне — отрицательный смысл отдельного слова.

2. Утверждение при двойном отрицании: повторяющаяся частица НЕ (первая не перед глаголом мочь, вторая не — перед неопределённой формой другого глагола) имеет утвердительный смысл: не мог не знать = знал. При этом возникает оттенок необходимости, долженствования: не мог не сказать = должен был сказать.

3. Утверждение в вопросительно-восклицательных предложениях: в подобных предложениях (риторических вопросах) частица НЕ имеет утвердительный смысл: Где я только не побывал! (= везде побывал); Кто у меня только не гостил! (= все гостили).

Значения частицы НИ

1. Отрицание в предложениях без подлежащего: частица НИ обозначает отрицание в предложениях без подлежащего при дополнении в родительном падеже: На небе ни тучки; Вокруг ни звука; Ни с места! Ни слова! Частица НИ в этом случае усиливает отрицание, которое подразумевается. Отрицательное слово НЕТ или сказуемое, при котором есть НЕ, опущены.

2. Усиление отрицания: если в предложении есть отрицание (слово нет, частица не при глаголе-сказуемом, причастии или деепричастии), то НИ усиливает это отрицание: На небе нет ни тучки; не говоря ни слова; не смотревший ни вправо, ни влево. В этом случае частицу НИ можно опустить, смысл предложения не изменится, пропадёт лишь оттенок усиления: У меня не было ни минуты на размышление. — У меня не было минуты на размышление. Подобные случаи нужно отличать от двойного употребления частицы НЕ для обозначения утверждения. Сравним: Он не мог не знать и не сказать — утвердительный смысл (он знал и сказал); Он не мог ни знать, ни догадаться — отрицательный смысл, ни можно отбросить (он не мог знать или догадаться).

3. Утверждение и обобщение после относительных местоимений и наречий в придаточном предложении: частица НИ придаёт обобщающее утвердительное значение словам кто, что, где, когда, сколько и т.д., которые служат средством связи придаточного предложения с главным. Кто ни придёт, всем здесь рады = любой человек придёт; Сколько ни вглядывался, ничего не заметил = долго, пристально вглядывался; Где ни бывал, везде находил друзей = бывал в разных местах. Подобные случаи надо отличать от тех сложноподчинённых предложений, в которых придаточные имеют отрицательное значение и в которых пишется частица НЕ. Сравним: Кто не прочитает эту книгу, тот многого не узнает — придаточное имеет отрицательное значение, действие не совершено (книга не прочитана); Кто ни прочитает эту книгу, всем она нравится — придаточное имеет утвердительный смысл, действие совершено (книга прочитана).

Обратите внимание! Повторяющаяся при однородных членах частица НИ рассматривается как сочинительный союз: Не было слышно ни звука, ни шороха.

Нужно запомнить!

1. Если повторяющаяся частица НИ употребляется в устойчивом выражении, то запятая между частями этого оборота не ставится:

| Ни больше ни меньше | Ни да ни нет | Ни днём ни ночью |

| Ни конца ни края | Ни много ни мало | Ни себе ни людям |

| Ни стать ни сесть | Ни взад ни вперёд | Ни дать ни взять |

| Ни два ни полтора | Ни жив ни мёртв | Ни за что ни про что |

| Ни нашим ни вашим | Ни ответа ни привета | Ни рыба ни мясо |

| Ни свет ни заря | Ни пуха ни пера | Ни слуху ни духу |

| Ни с того ни с сего | Ни там ни сям | Ни то ни сё |

| Ни туда ни сюда | Ни шатко ни валко | Ни так ни сяк |

2. Когда пишется НЕ, а когда — НИ ? (при раздельном написании)

Таблица «Частицы НЕ и НИ»

Конспект урока «Частицы НЕ и НИ. Значение и правописание».

Следующая тема: «Морфологический разбор частицы»

Раздел: «Орфография» и «Служебные части речи».

A double negative is a construction occurring when two forms of grammatical negation are used in the same sentence. Multiple negation is the more general term referring to the occurrence of more than one negative in a clause. In some languages, double negatives cancel one another and produce an affirmative; in other languages, doubled negatives intensify the negation. Languages where multiple negatives affirm each other are said to have negative concord or emphatic negation.[1] Portuguese, Persian, French, Russian, Greek, Spanish, Old English, Italian, Afrikaans, Hebrew are examples of negative-concord languages. This is also true of many vernacular dialects of modern English.[2][3] Chinese,[4] Latin, German, Dutch, Japanese, Swedish and modern Standard English[5] are examples of languages that do not have negative concord. Typologically, it occurs in a minority of languages.[6][7]

Languages without negative concord typically have negative polarity items that are used in place of additional negatives when another negating word already occurs. Examples are «ever», «anything» and «anyone» in the sentence «I haven’t ever owed anything to anyone» (cf. «I haven’t never owed nothing to no one» in negative-concord dialects of English, and «Nunca devi nada a ninguém» in Portuguese, lit. «Never have I owed nothing to no one», or «Non ho mai dovuto nulla a nessuno» in Italian). Negative polarity can be triggered not only by direct negatives such as «not» or «never», but also by words such as «doubt» or «hardly» («I doubt he has ever owed anything to anyone» or «He has hardly ever owed anything to anyone»).

Because standard English does not have negative concord but many varieties and registers of English do, and because most English speakers can speak or comprehend across varieties and registers, double negatives as collocations are functionally auto-antonymic (contranymic) in English; for example, a collocation such as «ain’t nothin» or «not nothing» can mean either «something» or «nothing», and its disambiguation is resolved via the contexts of register, variety, locution, and content of ideas.

Stylistically, in English, double negatives can sometimes be used for affirmation (e.g. «I’m not feeling unwell»), an understatement of the positive («I’m feeling well»). The rhetorical term for this is litotes.

English[edit]

Two negatives resolving to a positive[edit]

When two negatives are used in one independent clause, in standard English the negatives are understood to cancel one another and produce a weakened affirmative (see the Robert Lowth citation below): this is known as litotes. However, depending on how such a sentence is constructed, in some dialects if a verb or adverb is in between two negatives then the latter negative is assumed to be intensifying the former thus adding weight or feeling to the negative clause of the sentence. For this reason, it is difficult to portray double negatives in writing as the level of intonation to add weight in one’s speech is lost. A double negative intensifier does not necessarily require the prescribed steps, and can easily be ascertained by the mood or intonation of the speaker. Compare

- There isn’t no other way.

- = There’s some other way. Negative: isn’t (is not), no

versus

- There isn’t no other way!

- = There’s no other way!

These two sentences would be different in how they are communicated by speech. Any assumption would be correct, and the first sentence can be just as right or wrong in intensifying a negative as it is in cancelling it out; thereby rendering the sentence’s meaning ambiguous. Since there is no adverb or verb to support the latter negative, the usage here is ambiguous and lies totally on the context behind the sentence. In light of punctuation, the second sentence can be viewed as the intensifier; and the former being a statement thus an admonishment.

In Standard English, two negatives are understood to resolve to a positive. This rule was observed as early as 1762, when Bishop Robert Lowth wrote A Short Introduction to English Grammar with Critical Notes.[8] For instance, «I don’t disagree» could mean «I certainly agree», «I agree», «I sort of agree», «I don’t understand your point of view (POV)», «I have no opinion», and so on; it is a form of «weasel words». Further statements are necessary to resolve which particular meaning was intended.

This is opposed to the single negative «I don’t agree», which typically means «I disagree». However, the statement «I don’t completely disagree» is a similar double negative to «I don’t disagree» but needs little or no clarification.

With the meaning «I completely agree», Lowth would have been referring to litotes wherein two negatives simply cancel each other out. However, the usage of intensifying negatives and examples are presented in his work, which could also imply he wanted either usage of double negatives abolished. Because of this ambiguity, double negatives are frequently employed when making back-handed compliments. The phrase «Mr. Jones wasn’t incompetent.» will seldom mean «Mr. Jones was very competent» since the speaker would’ve found a more flattering way to say so. Instead, some kind of problem is implied, though Mr. Jones possesses basic competence at his tasks.

Two or more negatives resolving to a negative[edit]

Discussing English grammar, the term «double negative» is often,[9] though not universally,[10][11] applied to the non-standard use of a second negative as an intensifier to a negation.

Double negatives are usually associated with regional and ethnical dialects such as Southern American English, African American Vernacular English, and various British regional dialects. Indeed, they were used in Middle English: for example, Chaucer made extensive use of double, triple, and even quadruple negatives in his Canterbury Tales. About the Friar, he writes «Ther nas no man no wher so vertuous» («There never was no man nowhere so virtuous»). About the Knight, «He nevere yet no vileynye ne sayde / In all his lyf unto no maner wight» («He never yet no vileness didn’t say / In all his life to no manner of man»).

Following the battle of Marston Moor, Oliver Cromwell quoted his nephew’s dying words in a letter to the boy’s father Valentine Walton: «A little after, he said one thing lay upon his spirit. I asked him what it was. He told me it was that God had not suffered him to be no more the executioner of His enemies.»[12][13] Although this particular letter has often been reprinted, it is frequently changed to read «not … to be any more» instead.[citation needed]

Whereas some double negatives may resolve to a positive, in some dialects others resolve to intensify the negative clause within a sentence. For example:

- I didn’t go nowhere today.

- I’m not hungry no more.

- You don’t know nothing.

- There was never no more laziness at work than before.

In contrast, some double negatives become positives:

- I didn’t not go to the park today.

- We can’t not go to sleep!

- This is something you can’t not watch.

The key to understanding the former examples and knowing whether a double negative is intensive or negative is finding a verb between the two negatives. If a verb is present between the two, the latter negative becomes an intensifier which does not negate the former. In the first example, the verb to go separates the two negatives; therefore the latter negative does not negate the already negated verb. Indeed, the word ‘nowhere’ is thus being used as an adverb and does not negate the argument of the sentence. Double negatives such as I don’t want to know no more contrast with Romance languages such as French in Je ne veux pas savoir.[14]

An exception is when the second negative is stressed, as in I’m not doing nothing; I’m thinking. A sentence can otherwise usually only become positive through consecutive uses of negatives, such as those prescribed in the later examples, where a clause is void of a verb and lacks an adverb to intensify it. Two of them also use emphasis to make the meaning clearer. The last example is a popular example of a double negative that resolves to a positive. This is because the verb ‘to doubt’ has no intensifier which effectively resolves a sentence to a positive. Had we added an adverb thus:

- I never had no doubt this sentence is false.

Then what happens is that the verb to doubt becomes intensified, which indeed deduces that the sentence is indeed false since nothing was resolved to a positive. The same applies to the third example, where the adverb ‘more’ merges with the prefix no- to become a negative word, which when combined with the sentence’s former negative only acts as an intensifier to the verb hungry. Where people think that the sentence I’m not hungry no more resolves to a positive is where the latter negative no becomes an adjective which only describes its suffix counterpart more which effectively becomes a noun, instead of an adverb. This is a valid argument since adjectives do indeed describe the nature of a noun; yet some fail to take into account that the phrase no more is only an adverb and simply serves as an intensifier. Another argument used to support the position double negatives aren’t acceptable is a mathematical analogy: negating a negative number results in a positive one; e.g., − −2 = +2; therefore, it is argued, I did not go nowhere resolves to I went somewhere.

Other forms of double negatives, which are popular to this day and do strictly enhance the negative rather than destroying it, are described thus:

- I’m not entirely familiar with Nihilism nor Existentialism.

Philosophies aside, this form of double negative is still in use whereby the use of ‘nor’ enhances the negative clause by emphasizing what isn’t to be. Opponents of double negatives would have preferred I’m not entirely familiar with Nihilism or Existentialism; however this renders the sentence somewhat empty of the negative clause being advanced in the sentence. This form of double negative along with others described are standard ways of intensifying as well as enhancing a negative. The use of ‘nor’ to emphasise the negative clause is still popular today, and has been popular in the past through the works of Shakespeare and Milton:

- Nor did they not perceive the evil plight

- In which they were ~ John Milton — Paradise Lost

- I never was, nor never will be ~ William Shakespeare — Richard III

The negatives herein do not cancel each other out but simply emphasize the negative clause.

Distinction of duplex negatio affirmat (logical double negation) and duplex negatio negat (negative concord and pleonastic a.k.a. explective, paratactic, sympathetic, abusive negation) phenomena[15]

Up to the 18th century, double negatives were used to emphasize negation.[16] «Prescriptive grammarians» recorded and codified a shift away from the double negative in the 1700s. Double negatives continue to be spoken by those of Vernacular English, such as those of Appalachian English and African American Vernacular English.[17] To such speakers, they view double negatives as emphasizing the negative rather than cancelling out the negatives. Researchers have studied African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and trace its origins back to colonial English.[18] This shows that double negatives were present in colonial English, and thus presumably English as a whole, and were acceptable at that time. English after the 18th century was changed to become more logical and double negatives became seen as canceling each other as in mathematics. The use of double negatives became associated with being uneducated and illogical.[19]

In his Essay towards a practical English Grammar of 1711, James Greenwood first recorded the rule: «Two Negatives, or two Adverbs of Denying do in English affirm».[20] Robert Lowth stated in his grammar textbook A Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762) that «two negatives in English destroy one another, or are equivalent to an affirmative».[20] Grammarians have assumed that Latin was the model for Lowth and other early grammarians in prescribing against negative concord, as Latin does not feature it. Data indicates, however, that negative concord had already fallen into disuse in Standard English by the time of Lowth’s grammar, and no evidence exists that the loss was driven by prescriptivism, which was well established by the time it appeared.[21]

In film and TV[edit]

Double negatives have been employed in various films and television shows. In the film Mary Poppins (1964), the chimney sweep Bert employs a double negative when he says, «If you don’t wanna go nowhere…» Another is used by the bandits in the «Stinking Badges» scene of John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948): «Badges? We ain’t got no badges. We don’t need no badges!.»

The Simpsons episode «Hello Gutter, Hello Fadder» (1999) features Bart writing «I won’t not use no double negatives»[22] (pictured) as part of the opening sequence chalkboard gag. More recently, the British television show EastEnders has received some publicity over the Estuary accent of character Dot Branning, who speaks with double and triple negatives («I ain’t never heard of no licence.»).[citation needed]. In the Harry Enfield sketch «Mr Cholmondley-Warner’s Guide to the Working-Class», a stereotypical Cockney employs a septuple-negative: «Inside toilet? I ain’t never not heard of one of them nor I ain’t nor nothing.»

In music, double negatives can be employed to similar effect (as in Pink Floyd’s «Another Brick in the Wall», in which schoolchildren chant «We don’t need no education / We don’t need no thought control») or used to establish a frank and informal tone (as in The Rolling Stones’ «(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction»). Other examples include Ain’t Nobody (Chaka Khan), Ain’t No Sunshine (Bill Withers), and Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (Marvin Gaye)

Other Germanic languages[edit]

Double negation is uncommon in other West Germanic languages. A notable exception is Afrikaans in which it is mandatory (for example, «He cannot speak Afrikaans» becomes Hy kan nie Afrikaans praat nie, «He cannot Afrikaans speak not»). Dialectal Dutch, French and San have been suggested as possible origins for this trait. Its proper use follows a set of fairly complex rules as in these examples provided by Bruce Donaldson:[23]

- Ek het nie geweet dat hy sou kom nie. («I did not know that he would be coming.»)

- Ek het geweet dat hy nie sou kom nie. («I knew that he would not be coming.»)

- Hy sal nie kom nie, want hy is siek. («He will not be coming because he is sick.»)

- Dit is nie so moeilik om Afrikaans te leer nie. («It is not so difficult to learn Afrikaans.»)

Another point of view is that the construction is not really an example of a «double negative» but simply a grammatical template for negation. The second nie cannot be understood as a noun or adverb (unlike pas in French, for example), and it cannot be substituted by any part of speech other than itself with the sentence remaining grammatical. The grammatical particle has no independent meaning and happens to be spelled and pronounced the same as the embedded nie, meaning «not», by a historical accident.

The second nie is used if and only if the sentence or phrase does not already end with either nie or another negating adverb.

- Ek sien jou nie. («I don’t see you»)

- Ek sien jou nooit. («I never see you»)

Afrikaans shares with English the property that two negatives make a positive:[citation needed]

- Ek stem nie met jou saam nie. («I don’t agree with you.» )

- Ek stem nie nié met jou saam nie. («I don’t not agree with you,» i.e., I agree with you.)

Double negation is still found in the Low Franconian dialects of west Flanders (e.g., Ik ne willen da nie doen, «I do not want to do that») and in some villages in the central Netherlands such as Garderen, but it takes a different form than that found in Afrikaans. Belgian Dutch dialects, however, still have some widely-used expressions like nooit niet («never not») for «never».

Like some dialects of English, Bavarian has both single and double negation, with the latter denoting special emphasis. For example, the Bavarian Des hob i no nia ned g’hört («This have I yet never not heard») can be compared to the Standard German «Das habe ich noch nie gehört«. The German emphatic «niemals!» (roughly «never ever») corresponds to Bavarian «(går) nia ned» or even «nie nicht» in the Standard German pronunciation.

Another exception is Yiddish for which Slavic influence causes the double (and sometimes even triple) negative to be quite common.

A few examples would be:

- איך האב קיינמאל נישט געזאגט («I never didn’t say»)

- איך האב נישט קיין מורא פאר קיינעם ניט («I have no fear of no one not«)

- It is common to add נישט («not») after the Yiddish word גארנישט («nothing»), i.e. איך האב גארנישט נישט געזאגט («I haven’t said nothing»)

Latin and Romance languages[edit]

In Latin a second negative word appearing along with non turns the meaning into a positive one: ullus means «any», nullus means «no», non…nullus(nonnullus) means «some». In the same way, umquam means «ever», numquam means «never», non…numquam (nonnumquam) means «sometimes». In many Romance languages a second term indicating a negative is required.

In French, the usual way to express simple negation is to employ two words, e.g. ne [verb] pas, ne [verb] plus, or ne [verb] jamais, as in the sentences Je ne sais pas, Il n’y a plus de batterie, and On ne sait jamais. The second term was originally an emphatic; pas, for example, derives from the Latin passus, meaning «step», so that French Je ne marche pas and Catalan No camino pas originally meant «I will not walk a single step.» This initial usage spread so thoroughly that it became a necessary element of any negation in the modern French language[24] to such a degree that ne is generally dropped entirely, as in Je sais pas. In Northern Catalan, no may be omitted in colloquial language, and Occitan, which uses non only as a short answer to questions. In Venetian, the double negation no … mìa can likewise lose the first particle and rely only on the second: magno mìa («I eat not») and vegno mìa («I come not»). These exemplify Jespersen’s cycle.

Jamais, rien, personne and nulle part (never, nothing, no one, nowhere) can be mixed with each other, and/or with ne…plus (not anymore/not again) in French, e.g. to form sentences like Je n’ai rien dit à personne (I didn’t say anything to anyone)[25] or even Il ne dit jamais plus rien à personne (He never says anything to anyone anymore).

The Spanish, Italian, Portuguese and Romanian languages usually employ doubled negative correlatives. Portuguese Não vejo nada, Spanish No veo nada, Romanian Nu văd nimic and Italian Non vedo niente[26] (literally, «I do not see nothing») are used to express «I do not see anything». In Italian, a second following negative particle non turns the phrase into a positive one, but with a slightly different meaning. For instance, while both Voglio mangiare («I want to eat») and Non voglio non mangiare («I don’t want not to eat») mean «I want to eat», the latter phrase more precisely means «I’d prefer to eat».

Other Romance languages employ double negatives less regularly. In Asturian, an extra negative particle is used with negative adverbs: Yo nunca nun lu viera («I had not never seen him») means «I have never seen him» and A mi tampoco nun me presta («I neither do not like it») means «I do not like it either». Standard Catalan and Galician also used to possess a tendency to double no with other negatives, so Jo tampoc no l’he vista or Eu tampouco non a vira, respectively meant «I have not seen her either». This practice is dying out.

Welsh[edit]

In spoken Welsh, the word ddim (not) often occurs with a prefixed or mutated verb form that is negative in meaning: Dydy hi ddim yma (word-for-word, «Not-is she not here») expresses «She is not here» and Chaiff Aled ddim mynd (word-for-word, «Not-will-get Aled not go») expresses «Aled is not allowed to go».

Negative correlatives can also occur with already negative verb forms. In literary Welsh, the mutated verb form is caused by an initial negative particle, ni or nid. The particle is usually omitted in speech but the mutation remains: [Ni] wyddai neb (word-for-word, «[Not] not-knew nobody») means «Nobody knew» and [Ni] chaiff Aled fawr o bres (word-for-word, «[Not] not-will-get Aled lots of money») means «Aled will not get much money». This is not usually regarded as three negative markers, however, because the negative mutation is really just an effect of the initial particle on the following word.[27]

Greek[edit]

Ancient Greek[edit]

Doubled negatives are perfectly correct in Ancient Greek. With few exceptions, a simple negative (οὐ or μή) following another negative (for example, οὐδείς, no one) results in an affirmation: οὐδείς οὐκ ἔπασχέ τι («No one was not suffering») means more simply «Everyone was suffering». Meanwhile, a compound negative following a negative strengthens the negation: μὴ θορυβήσῃ μηδείς («Do not permit no one to raise an uproar») means «Let not a single one among them raise an uproar».

Those constructions apply only when the negatives all refer to the same word or expression. Otherwise, the negatives simply work independently of one another: οὐ διὰ τὸ μὴ ἀκοντίζειν οὐκ ἔβαλον αὐτόν means «It was not on account of their not throwing that they did not hit him», and one should not blame them for not trying.

Modern Greek[edit]

In Modern Greek, a double negative can express either an affirmation or a negation, depending on the word combination. When expressing negation, it usually carries an emphasis with it. Native speakers can usually understand the sentence meaning from the voice tone and the context.

Examples

A combination of χωρίς/δίχως and δε/δεν has an affirmative meaning: «Χωρίς/δίχως αυτό να σημαίνει ότι δε μπορούμε να το βρούμε.» translates «Without that meaning that we can’t find it.» i.e. We can find it.

A combination of δε/δεν and δε/δεν also has an affirmative meaning: «Δε(ν) σημαίνει ότι δε(ν) μπορούμε να το βρούμε.» translates «Doesn’t mean that we can’t find it.» i.e. We can find it.

A combination of δε/δεν and κανείς/κανένας/καμία/κανένα has a negative meaning: «Δε(ν) θα πάρεις κανένα βιβλίο.» translates «You won’t get any book.»

Slavic languages[edit]

In Slavic languages, multiple negatives affirm each other. Indeed, if a sentence contains a negated verb, any indefinite pronouns or adverbs must be used in their negative forms. For example, in the Serbo-Croatian, ni(t)ko nikad(a) nigd(j)e ništa nije uradio («Nobody never did not do nothing nowhere») means «Nobody has ever done anything, anywhere», and nikad nisam tamo išao/išla («Never I did not go there») means «I have never been there». In Czech, it is nikdy jsem nikde nikoho neviděl («I have not seen never no-one nowhere»). In Bulgarian, it is: никога не съм виждал никого никъде [nikoga ne sam vishdal nikogo nikade], lit. «I have not seen never no-one nowhere», or не знам нищо (‘ne znam nishto‘), lit. «I don’t know nothing». In Russian, «I know nothing» is я ничего не знаю [ya nichevo nye znayu], lit. «I don’t know nothing».

Negating the verb without negating the pronoun (or vice versa), while syntactically correct, may result in a very unusual meaning or make no sense at all. Saying «I saw nobody» in Polish (widziałem nikogo) instead of the more usual «I did not see nobody» (Nikogo nie widziałem) might mean «I saw an instance of nobody» or «I saw Mr Nobody» but it would not have its plain English meaning. Likewise, in Slovenian, saying «I do not know anyone» (ne poznam kogarkoli) in place of «I do not know no one» (ne poznam nikogar) has the connotation «I do not know just anyone: I know someone important or special.»

In Czech, like in many other languages, a standard double negative is used in sentences with a negative pronoun or negative conjunction, where the verb is also negated (nikdo nepřišel «nobody came», literally «nobody didn’t come»). However, this doubleness is also transferred to forms where the verbal copula is released and the negation is joined to the nominal form, and such a phrase can be ambiguous: nikdo nezraněn («nobody unscathed») can mean both «nobody healthy» and «all healthy». Similarly, nepřítomen nikdo («nobody absent») or plánovány byly tři úkoly, nesplněn žádný («three tasks were planned, none uncompleted»).[28] The sentence, všichni tam nebyli («all don’t were there») means not «all absented» but «there were not all» (= «at least one of them absenteed»). If all absented, it should be said nikdo tam nebyl («nobody weren’t there»).[29] However, in many cases, a double, triple quadruple negative can really work in such a way that each negative cancels out the next negative, and such a sentence may be a catch and may be incomprehensible to a less attentive or less intelligent addressee. E.g. the sentence, nemohu se nikdy neoddávat nečinnosti («I can’t never not indulge in inaction») contains 4 negations and it is very confusing which of them create a «double negative» and which of them eliminated from each other. Such confusing sentences can then diplomatically soften or blur rejection or unpleasant information or even agreement, but at the expense of intelligibility: nelze nevidět («it can’t be not seen»), nejsem nespokojen («I’m not dissatisfied»), není nezajímavý («it/he is not uninteresting»), nemohu nesouhlasit («I can’t disagree»).[30]

Baltic languages[edit]

As with most synthetic satem languages double negative is mandatory[citation needed] in Latvian and Lithuanian. Furthermore, all verbs and indefinite pronouns in a given statement must be negated, so it could be said that multiple negative is mandatory in Latvian.

For instance, a statement «I have not ever owed anything to anyone» would be rendered as es nekad nevienam neko neesmu bijis parādā. The only alternative would be using a negating subordinate clause and subjunctive in the main clause, which could be approximated in English as «there has not ever been an instance that I would have owed anything to anyone» (nav bijis tā, ka es kādreiz būtu kādam bijis kaut ko parādā), where negative pronouns (nekad, neviens, nekas) are replaced by indefinite pronouns (kādreiz, kāds, kaut kas) more in line with the English «ever, any» indefinite pronoun structures.

Uralic languages[edit]

Double or multiple negatives are grammatically required in Hungarian with negative pronouns: Nincs semmim (word for word: «[doesn’t-exists] [nothing-of-mine]», and translates literally as «I do not have nothing») means «I do not have anything». Negative pronouns are constructed by means of adding the prefixes se-, sem-, and sen- to interrogative pronouns.

Something superficially resembling double negation is required also in Finnish, which uses the auxiliary verb ei to express negation. Negative pronouns are constructed by adding one of the suffixes -an, -än, -kaan, or -kään to interrogative pronouns: Kukaan ei soittanut minulle means «No one called me». These suffixes are, however, never used alone, but always in connection with ei. This phenomenon is commonplace in Finnish, where many words have alternatives that are required in negative expressions, for example edes for jopa («even»), as in jopa niin paljon meaning «even so much», and ei edes niin paljoa meaning «not even so much».

Turkish[edit]

Negative verb forms are grammatically required in Turkish phrases with negative pronouns or adverbs that impart a negative meaning on the whole phrase. For example, Hiçbir şeyim yok (literally, word for word, «Not-one thing-of-mine exists-not») means «I don’t have anything». Likewise, Asla memnun değilim (literally, «Never satisfied not-I-am») means «I’m never satisfied».

Japanese[edit]

Japanese employs litotes to phrase ideas in a more indirect and polite manner. Thus, one can indicate necessity by emphasizing that not doing something would not be proper. For instance, しなければならない (shinakereba naranai, «must», more literally «if not done, [can] not be») means «not doing [it] wouldn’t be proper». しなければいけない (shinakereba ikenai, also «must», «if not done, can not go’) similarly means «not doing [it] can’t go forward».

Of course, indirectness can also be employed to put an edge on one’s rudeness as well. Whilst «He has studied Japanese, so he should be able to write kanji» can be phrased 彼は日本語を勉強したから漢字で書けないわけがない (kare wa nihongo o benkyō shita kara kanji de kakenai wake ga nai), there is a harsher idea in it: «As he’s studied Japanese, the reasoning that he can’t write Kanji doesn’t exist».

Chinese[edit]

Mandarin Chinese and most Chinese languages also employ litotes in a likewise manner. One common construction is «不得不» (Pinyin: bù dé bù, «mustn’t not» or «shalln’t not«), which is used to express (or feign) a necessity more regretful and convenable than that expressed by «必须» (bìxū, «must»). Compared with «我必须走» (Wǒ bìxū zǒu, «I must go»), «我不得不走» (Wǒ bù dé bù zǒu, «I mustn’t not go») emphasizes that the situation is out of the speaker’s hands and that the speaker has no choice in the matter: «Unfortunately, I have got to go». Similarly, «没有人不知道» (méiyǒu rén bù zhīdào) or idiomatically «无人不知» (wú rén bù zhī , «There is no one who does not know») is a more emphatic way to express «Every single one knows».

A double negative almost always resolves to a positive meaning and even more so in colloquial speech where the speaker particularly stresses the first negative word. Meanwhile, a triple negative resolves to a negative meaning, which bares a stronger negativity than a single negative. For example, «我不覺得没有人不知道» (Wǒ bù juédé méiyǒu rén bù zhīdào, «I do not think there is no one who does not know») ambiguously means either «I don’t think everyone knows» or «I think someone does not know». A quadruple negative further resolves to a positive meaning embedded with stronger affirmation than a double negative; for example, «我不是不知道没人不喜欢他» (Wǒ bú shì bù zhīdào méi rén bù xǐhuan tā, «It is not the case that I do not know that no one doesn’t like him») means «I do know that everyone likes him». However, more than triple negatives are frequently perceived as obscure and rarely encountered.

Historical development[edit]

An illustration of Jespersen’s cycle in French

Many languages, including all living Germanic languages, French, Welsh and some Berber and Arabic dialects, have gone through a process known as Jespersen’s cycle, where an original negative particle is replaced by another, passing through an intermediate stage employing two particles (e.g. Old French jeo ne dis → Modern Standard French je ne dis pas → Modern Colloquial French je dis pas «I don’t say»).

In many cases, the original sense of the new negative particle is not negative per se (thus in French pas «step», originally «not a step» = «not a bit»). However, in Germanic languages such as English and German, the intermediate stage was a case of double negation, as the current negatives not and nicht in these languages originally meant «nothing»: e.g. Old English ic ne seah «I didn’t see» >> Middle English I ne saugh nawiht, lit. «I didn’t see nothing» >> Early Modern English I saw not.[31][32]

A similar development to a circumfix from double negation can be seen in non-Indo-European languages, too: for example, in Maltese, kiel «he ate» is negated as ma kielx «he did not eat», where the verb is preceded by a negative particle ma— «not» and followed by the particle -x, which was originally a shortened form of xejn «nothing» — thus, «he didn’t eat nothing».[33]

See also[edit]

- Affirmative and negative

- Agreement (linguistics)

- Idiom

- Jespersen’s cycle

- List of common English usage misconceptions

- Litotes

- Negation

- Pleonasm

- Redundancy (linguistics)

References[edit]

- ^ Wouden, Ton van der (November 2002). Negative Contexts: Collocation, Polarity and Multiple Negation. Routledge. p. 243. ISBN 9781134773336.

- ^ Examples of Double Negatives: From Sentences to Lyrics

- ^ Grammarly blog (June, 2021), «Double Negatives: 3 Rules You Must Know»

- ^ «The use of double negative in Chinese». Decode Mandarin Chinese. 4 December 2016.

- ^ «Double Negatives». NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY.

- ^ van der Auwera, Johan; Van Alsenoy, Lauren (2016-10-14). «On the typology of negative concord». Studies in Language. 40 (3): 473–512. doi:10.1075/sl.40.3.01van. hdl:10067/1361340151162165141. ISSN 0378-4177.

- ^ «More Ado about Nothing: On the Typology of Negative Indefinites», Pragmatics, Truth and Underspecification, BRILL, pp. 107–146, 2018-06-06, doi:10.1163/9789004365445_005, ISBN 9789004341999, S2CID 201437288, retrieved 2022-06-02

- ^ Fromkin, Victoria; Rodman, Robert; Hyams, Nina (2002). An Introduction to Language, Seventh Edition. Heinle. p. 15. ISBN 0-15-508481-X.

- ^ «double negative». Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ^ «double negative». The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins.

- ^ «double negative». Memidex/WordNet Dictionary. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ^ Fraser, Antonia (1973). Cromwell : the Lord Protector. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-917657-90-0. OCLC 728428.

- ^ Forster, John (1840). The Statesmen of the Commonwealth of England: With a Treatise on the Popular Progress in English History. Longman, Orme, Brown, Green & Longmans. pp. 139–140.

- ^ See the article regarding Romance languages explaining this form of double negation.

- ^ Horn, LR (2010). «Multiple negation in English and other languages». In Horn, LR (ed.). The expression of negation. The expression of cognitive categories. Vol. 4. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter-Mouton. p. 112. ISBN 978-3-110-21929-6. OCLC 884495145.

- ^ Kirby, Philippa (n.d.). Double and Multiple Negatives (PDF). American University. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-03. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ Kirby n.d., p. 4.

- ^ Kirby n.d., p. 5.

- ^ «Grammar myths #3: Don’t know nothing about double negatives? Read on…» Oxford Dictionaries Blog. Archived from the original on 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ^ a b Kallel, Amel (2011). The Loss of Negative Concord in Standard English: A Case of Lexical Reanalysis. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-2815-4.

- ^ Kallel 2011, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Bates, James W.; Gimple, Scott M.; McCann, Jesse L.; Richmond, Ray; Seghers, Christine, eds. (2010). Simpsons World The Ultimate Episode Guide: Seasons 1–20 (1st ed.). Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 532–533. ISBN 978-0-00-738815-8.

- ^ Donaldson, Bruce C. (1993). A Grammar of Afrikaans, Bruce C. Donaldson, Walter de Gruyter, 1993, p. 404. ISBN 9783110134261. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ There are literary cases in which «ne» can be used without «pas«; many of these are traditional phrases stemming from a time before the emphatic became an essential part of negation.

- ^ Drouard, Aurélie. «Using double and multiple negatives (negation)».

- ^ In Italian a simple negative phrase, Non vedo alcunché («I don’t see anything»), is also possible.

- ^

Borsley, Robert; Tallerman, M; Willis, D (2007). «7. Syntax and mutation». The Syntax of Welsh. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83630-2. - ^ «nikdo nezraněn». Institute of the Czech Language (in Czech). 1997-01-01.

- ^ Jiří Haller, V. Š.: O českém záporu. I, Naše řeč, ročník 32 (1948), číslo 2–3, s. 21–36

- ^ Tereza Filinová: Klady záporu, Český rozhlas (Czech Broadcasting), 2011 April 9

- ^ Kastovsky, Dieter. 1991. Historical English syntax. p. 452

- ^ Van Gelderen, Elly. 2006. A history of the English language. p. 130

- ^ «Grazio Falzon. Basic Maltese Grammar». Aboutmalta.com. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

A double negative is a construction occurring when two forms of grammatical negation are used in the same sentence. Multiple negation is the more general term referring to the occurrence of more than one negative in a clause. In some languages, double negatives cancel one another and produce an affirmative; in other languages, doubled negatives intensify the negation. Languages where multiple negatives affirm each other are said to have negative concord or emphatic negation.[1] Portuguese, Persian, French, Russian, Greek, Spanish, Old English, Italian, Afrikaans, Hebrew are examples of negative-concord languages. This is also true of many vernacular dialects of modern English.[2][3] Chinese,[4] Latin, German, Dutch, Japanese, Swedish and modern Standard English[5] are examples of languages that do not have negative concord. Typologically, it occurs in a minority of languages.[6][7]

Languages without negative concord typically have negative polarity items that are used in place of additional negatives when another negating word already occurs. Examples are «ever», «anything» and «anyone» in the sentence «I haven’t ever owed anything to anyone» (cf. «I haven’t never owed nothing to no one» in negative-concord dialects of English, and «Nunca devi nada a ninguém» in Portuguese, lit. «Never have I owed nothing to no one», or «Non ho mai dovuto nulla a nessuno» in Italian). Negative polarity can be triggered not only by direct negatives such as «not» or «never», but also by words such as «doubt» or «hardly» («I doubt he has ever owed anything to anyone» or «He has hardly ever owed anything to anyone»).

Because standard English does not have negative concord but many varieties and registers of English do, and because most English speakers can speak or comprehend across varieties and registers, double negatives as collocations are functionally auto-antonymic (contranymic) in English; for example, a collocation such as «ain’t nothin» or «not nothing» can mean either «something» or «nothing», and its disambiguation is resolved via the contexts of register, variety, locution, and content of ideas.

Stylistically, in English, double negatives can sometimes be used for affirmation (e.g. «I’m not feeling unwell»), an understatement of the positive («I’m feeling well»). The rhetorical term for this is litotes.

English[edit]

Two negatives resolving to a positive[edit]

When two negatives are used in one independent clause, in standard English the negatives are understood to cancel one another and produce a weakened affirmative (see the Robert Lowth citation below): this is known as litotes. However, depending on how such a sentence is constructed, in some dialects if a verb or adverb is in between two negatives then the latter negative is assumed to be intensifying the former thus adding weight or feeling to the negative clause of the sentence. For this reason, it is difficult to portray double negatives in writing as the level of intonation to add weight in one’s speech is lost. A double negative intensifier does not necessarily require the prescribed steps, and can easily be ascertained by the mood or intonation of the speaker. Compare

- There isn’t no other way.

- = There’s some other way. Negative: isn’t (is not), no

versus

- There isn’t no other way!

- = There’s no other way!

These two sentences would be different in how they are communicated by speech. Any assumption would be correct, and the first sentence can be just as right or wrong in intensifying a negative as it is in cancelling it out; thereby rendering the sentence’s meaning ambiguous. Since there is no adverb or verb to support the latter negative, the usage here is ambiguous and lies totally on the context behind the sentence. In light of punctuation, the second sentence can be viewed as the intensifier; and the former being a statement thus an admonishment.

In Standard English, two negatives are understood to resolve to a positive. This rule was observed as early as 1762, when Bishop Robert Lowth wrote A Short Introduction to English Grammar with Critical Notes.[8] For instance, «I don’t disagree» could mean «I certainly agree», «I agree», «I sort of agree», «I don’t understand your point of view (POV)», «I have no opinion», and so on; it is a form of «weasel words». Further statements are necessary to resolve which particular meaning was intended.

This is opposed to the single negative «I don’t agree», which typically means «I disagree». However, the statement «I don’t completely disagree» is a similar double negative to «I don’t disagree» but needs little or no clarification.

With the meaning «I completely agree», Lowth would have been referring to litotes wherein two negatives simply cancel each other out. However, the usage of intensifying negatives and examples are presented in his work, which could also imply he wanted either usage of double negatives abolished. Because of this ambiguity, double negatives are frequently employed when making back-handed compliments. The phrase «Mr. Jones wasn’t incompetent.» will seldom mean «Mr. Jones was very competent» since the speaker would’ve found a more flattering way to say so. Instead, some kind of problem is implied, though Mr. Jones possesses basic competence at his tasks.

Two or more negatives resolving to a negative[edit]

Discussing English grammar, the term «double negative» is often,[9] though not universally,[10][11] applied to the non-standard use of a second negative as an intensifier to a negation.

Double negatives are usually associated with regional and ethnical dialects such as Southern American English, African American Vernacular English, and various British regional dialects. Indeed, they were used in Middle English: for example, Chaucer made extensive use of double, triple, and even quadruple negatives in his Canterbury Tales. About the Friar, he writes «Ther nas no man no wher so vertuous» («There never was no man nowhere so virtuous»). About the Knight, «He nevere yet no vileynye ne sayde / In all his lyf unto no maner wight» («He never yet no vileness didn’t say / In all his life to no manner of man»).

Following the battle of Marston Moor, Oliver Cromwell quoted his nephew’s dying words in a letter to the boy’s father Valentine Walton: «A little after, he said one thing lay upon his spirit. I asked him what it was. He told me it was that God had not suffered him to be no more the executioner of His enemies.»[12][13] Although this particular letter has often been reprinted, it is frequently changed to read «not … to be any more» instead.[citation needed]

Whereas some double negatives may resolve to a positive, in some dialects others resolve to intensify the negative clause within a sentence. For example:

- I didn’t go nowhere today.

- I’m not hungry no more.

- You don’t know nothing.

- There was never no more laziness at work than before.

In contrast, some double negatives become positives:

- I didn’t not go to the park today.

- We can’t not go to sleep!

- This is something you can’t not watch.

The key to understanding the former examples and knowing whether a double negative is intensive or negative is finding a verb between the two negatives. If a verb is present between the two, the latter negative becomes an intensifier which does not negate the former. In the first example, the verb to go separates the two negatives; therefore the latter negative does not negate the already negated verb. Indeed, the word ‘nowhere’ is thus being used as an adverb and does not negate the argument of the sentence. Double negatives such as I don’t want to know no more contrast with Romance languages such as French in Je ne veux pas savoir.[14]

An exception is when the second negative is stressed, as in I’m not doing nothing; I’m thinking. A sentence can otherwise usually only become positive through consecutive uses of negatives, such as those prescribed in the later examples, where a clause is void of a verb and lacks an adverb to intensify it. Two of them also use emphasis to make the meaning clearer. The last example is a popular example of a double negative that resolves to a positive. This is because the verb ‘to doubt’ has no intensifier which effectively resolves a sentence to a positive. Had we added an adverb thus:

- I never had no doubt this sentence is false.

Then what happens is that the verb to doubt becomes intensified, which indeed deduces that the sentence is indeed false since nothing was resolved to a positive. The same applies to the third example, where the adverb ‘more’ merges with the prefix no- to become a negative word, which when combined with the sentence’s former negative only acts as an intensifier to the verb hungry. Where people think that the sentence I’m not hungry no more resolves to a positive is where the latter negative no becomes an adjective which only describes its suffix counterpart more which effectively becomes a noun, instead of an adverb. This is a valid argument since adjectives do indeed describe the nature of a noun; yet some fail to take into account that the phrase no more is only an adverb and simply serves as an intensifier. Another argument used to support the position double negatives aren’t acceptable is a mathematical analogy: negating a negative number results in a positive one; e.g., − −2 = +2; therefore, it is argued, I did not go nowhere resolves to I went somewhere.

Other forms of double negatives, which are popular to this day and do strictly enhance the negative rather than destroying it, are described thus:

- I’m not entirely familiar with Nihilism nor Existentialism.

Philosophies aside, this form of double negative is still in use whereby the use of ‘nor’ enhances the negative clause by emphasizing what isn’t to be. Opponents of double negatives would have preferred I’m not entirely familiar with Nihilism or Existentialism; however this renders the sentence somewhat empty of the negative clause being advanced in the sentence. This form of double negative along with others described are standard ways of intensifying as well as enhancing a negative. The use of ‘nor’ to emphasise the negative clause is still popular today, and has been popular in the past through the works of Shakespeare and Milton:

- Nor did they not perceive the evil plight

- In which they were ~ John Milton — Paradise Lost

- I never was, nor never will be ~ William Shakespeare — Richard III

The negatives herein do not cancel each other out but simply emphasize the negative clause.

Distinction of duplex negatio affirmat (logical double negation) and duplex negatio negat (negative concord and pleonastic a.k.a. explective, paratactic, sympathetic, abusive negation) phenomena[15]

Up to the 18th century, double negatives were used to emphasize negation.[16] «Prescriptive grammarians» recorded and codified a shift away from the double negative in the 1700s. Double negatives continue to be spoken by those of Vernacular English, such as those of Appalachian English and African American Vernacular English.[17] To such speakers, they view double negatives as emphasizing the negative rather than cancelling out the negatives. Researchers have studied African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and trace its origins back to colonial English.[18] This shows that double negatives were present in colonial English, and thus presumably English as a whole, and were acceptable at that time. English after the 18th century was changed to become more logical and double negatives became seen as canceling each other as in mathematics. The use of double negatives became associated with being uneducated and illogical.[19]

In his Essay towards a practical English Grammar of 1711, James Greenwood first recorded the rule: «Two Negatives, or two Adverbs of Denying do in English affirm».[20] Robert Lowth stated in his grammar textbook A Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762) that «two negatives in English destroy one another, or are equivalent to an affirmative».[20] Grammarians have assumed that Latin was the model for Lowth and other early grammarians in prescribing against negative concord, as Latin does not feature it. Data indicates, however, that negative concord had already fallen into disuse in Standard English by the time of Lowth’s grammar, and no evidence exists that the loss was driven by prescriptivism, which was well established by the time it appeared.[21]

In film and TV[edit]

Double negatives have been employed in various films and television shows. In the film Mary Poppins (1964), the chimney sweep Bert employs a double negative when he says, «If you don’t wanna go nowhere…» Another is used by the bandits in the «Stinking Badges» scene of John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948): «Badges? We ain’t got no badges. We don’t need no badges!.»

The Simpsons episode «Hello Gutter, Hello Fadder» (1999) features Bart writing «I won’t not use no double negatives»[22] (pictured) as part of the opening sequence chalkboard gag. More recently, the British television show EastEnders has received some publicity over the Estuary accent of character Dot Branning, who speaks with double and triple negatives («I ain’t never heard of no licence.»).[citation needed]. In the Harry Enfield sketch «Mr Cholmondley-Warner’s Guide to the Working-Class», a stereotypical Cockney employs a septuple-negative: «Inside toilet? I ain’t never not heard of one of them nor I ain’t nor nothing.»

In music, double negatives can be employed to similar effect (as in Pink Floyd’s «Another Brick in the Wall», in which schoolchildren chant «We don’t need no education / We don’t need no thought control») or used to establish a frank and informal tone (as in The Rolling Stones’ «(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction»). Other examples include Ain’t Nobody (Chaka Khan), Ain’t No Sunshine (Bill Withers), and Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (Marvin Gaye)

Other Germanic languages[edit]

Double negation is uncommon in other West Germanic languages. A notable exception is Afrikaans in which it is mandatory (for example, «He cannot speak Afrikaans» becomes Hy kan nie Afrikaans praat nie, «He cannot Afrikaans speak not»). Dialectal Dutch, French and San have been suggested as possible origins for this trait. Its proper use follows a set of fairly complex rules as in these examples provided by Bruce Donaldson:[23]

- Ek het nie geweet dat hy sou kom nie. («I did not know that he would be coming.»)

- Ek het geweet dat hy nie sou kom nie. («I knew that he would not be coming.»)

- Hy sal nie kom nie, want hy is siek. («He will not be coming because he is sick.»)

- Dit is nie so moeilik om Afrikaans te leer nie. («It is not so difficult to learn Afrikaans.»)