| Данное написание не соответствует ныне действующей норме. Нормативное написание: дзен-буддизм. |

Содержание

- 1 Русский

- 1.1 Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

- 1.2 Произношение

- 1.3 Семантические свойства

- 1.3.1 Значение

- 1.3.2 Синонимы

- 1.3.3 Антонимы

- 1.3.4 Гиперонимы

- 1.3.5 Гипонимы

- 1.4 Родственные слова

- 1.5 Этимология

- 1.6 Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

- 1.7 Перевод

- 1.8 Библиография

Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | дзэн-будди́зм | дзэн-будди́змы |

| Р. | дзэн-будди́зма | дзэн-будди́змов |

| Д. | дзэн-будди́зму | дзэн-будди́змам |

| В. | дзэн-будди́зм | дзэн-будди́змы |

| Тв. | дзэн-будди́змом | дзэн-будди́змами |

| Пр. | дзэн-будди́зме | дзэн-будди́змах |

дзэн—буд—ди́зм

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -дзэн-; корень: -будд-; суффикс: -изм [Тихонов, 1996].

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [ˌd͡zzɛn bʊˈdʲːizm]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- то же, что дзен-буддизм ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

дзэн-буддизм

- дзэн-буддизм

Слитно или раздельно? Орфографический словарь-справочник. — М.: Русский язык.

.

1998.

Смотреть что такое «дзэн-буддизм» в других словарях:

-

ДЗЭН-БУДДИЗМ — – самостоятельное направление япон. буддизма, появившееся в 7 в. Основу дзэн буддизма составляют представление о единстве Будды и всех существ, учение о «естественном пути» развития и вера в мгновенное просветление, постижение истины. Философский … Философская энциклопедия

-

ДЗЭН-БУДДИЗМ — ДЗЭН БУДДИЗМ, ДЗЭН [яп. < санскр.] одно из направлений в буддизме (БУДДИЗМ), возникшее в Китае в первой половине VI в., с XII XIII вв. получившее распространение в Японии. Д. возвысил личный духовный опыт человека, независимый от книжного учения … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

Дзэн-буддизм — Буддизм Культура История Люди Страны Школы Храмы Терминология Тексты Хронология Проект | Портал … Википедия

-

Дзэн-буддизм (zen-buddhism) — Дзэн (медитация, школа Махдидны (Mahdydna), Северный буддизм) стал известен на Западе в первое десятилетие после Второй мировой войны. Его парадоксальные учеб. задачи (коаны) поставили в тупик и заинтриговали зап. ученых. Открыто признаваемая… … Психологическая энциклопедия

-

дзэн-буддизм — м.; = дзэн Толковый словарь Ефремовой. Т. Ф. Ефремова. 2000 … Современный толковый словарь русского языка Ефремовой

-

дзэн-буддизм — дзэн/ будд/изм/ … Морфемно-орфографический словарь

-

Дзэн-буддизм — (Zen Buddhism, кит. чань от санскрит, дхьяна медитация), школа буддизма, возникшая в Китае в 5 6 вв.; с 12 13 вв. получила распространение в Японии. Для Д. б. характерны критическое отношение к тексту как ср ву передачи истинного знания, вера в… … Народы и культуры

-

Дзэн (дзэн буддизм) — восточная философия, основной находкой которой является незавершенность мысли, дающая большой простор ассоциативному мышлению … Теоретические аспекты и основы экологической проблемы: толкователь слов и идеоматических выражений

-

ДЗЭН-ПСИХОТЕРАПИЯ — Дзэн не религия и не философия, это образ жизни, обеспечивающий человеку гармонию с самим собой и с окружающим миром, избавляющий от страха и других тягостных переживаний и ведущий к свободе и полной духовной самореализации. В связи с… … Психотерапевтическая энциклопедия

-

Буддизм во Франции — является четвёртой по количеству последователей религией после христианства, ислама и иудаизма. По данным Le Monde[1], во Франции 5 миллионов человек симпатизирует буддизму, практикует эту религию около 600 000 человек. Интересы буддийской… … Википедия

ДЗЕН, дзэн (япон. прочтение кит. «чань», от санскр. dhyāna – «созерцание, медитация»), название сложившегося в Японии направления буддизма, выдвинувшего в центр своей религ. практики медитацию и вобравшего в себя, наряду с идеями кит. школы чань, элементы учения буддийских школ махасангхиков, мадхьямиков, «Чистой земли», хуаянь (япон. – Кэгон), тяньтай (япон. – Тэндай), чжэньянь (япон. – Сингон), а также некоторые положения даосизма и конфуцианства. Имеет также др. наименование – «сердце (сущность) Будды» (япон. – Бусин, кит. – Фо синь).

Учение

Д., как и его кит. прототип чань, основывается на идее мадхьямиков о безатрибутном, но истинно-реальном Абсолюте (Будда в «теле Закона»), являющемся субстратом всех единичных сущностей и присутствующем в каждом индивиде. В основе догматики Д. лежит принцип дайсинко – «Великая вера» в то, что всё сущее имеет ту же «природу», что и Будда («Смотри в свою природу и станешь Буддой»). Соответственно, гл. форма религ. практики Д. – медитация – представляет собой тренировку психики и сознания, призванную привести адепта к постижению «недвойственности» и «единотаковости» всего Сущего, к обнаружению в себе Будды. Гл. акцент делается на интроспекции, познании себя «изнутри», «свёртывании» внешнего мира до собственного внутреннего пространства. Цель практики Д. – не отключение от внешних впечатлений путём сосредоточения на определённом объекте, не гипнотич. транс, а особое состояние бодрствующего сознания (япон. – сатори), связанное с неожиданным переворотом, опрокидывающим прежние представления адепта и закладывающим фундамент нового видения бытия, которое характеризуется «отсутствием всякого разграничения» и соединением с беспредельным и безатрибутным Абсолютом (Д. не признаёт двойственности даже на уровне оппозиции космич. начал инь – ян, которые воспринимаются как целостность). С точки зрения Д. такое «внезапное просветление», или интуитивное озарение, есть «мгновенная мысль» (тонгаку), которая не требует длительного восхождения по многочисл. ступеням совершенства. В Д. настойчиво подчёркивается возможность достичь «просветления» в этой жизни.

Теоретически Д. отказывался от канонич. обрядности и иконографич. зафиксированности объекта поклонения. Требование внутр. работы, а не пассивной веры означало обращение к обыденному, повседневному, которое в любой миг может стать самым важным и сакральным. Учитель Д. не проводит разграничения между мирянином и монахом: каждый может достичь «просветления».

Важнейшая категория Д. – «безмыслие и бездумие» (мунэн-мусо), состояние непривязанности разума к к.-л. определённой идее, когда сознание пребывает в истинном, безусловном покое. Это состояние означает не «угасание» всякой умственной и психич. деятельности, а лишь приведение всех духовных сил в абсолютное равновесие, полностью исключающее любую возможность доминирования одной мысли над другой.

В Д. особое значение придаётся активному духовно-практич. освоению буддийского учения. В отличие от большинства школ кит. и традиц. инд. буддизма, неотъемлемым элементом религ. практики в школах чань и Д. являлся совместный физич. труд монахов.

История

В период Нара (8 в.) и в начале эпохи Хэйан (9 в.) японцы, побывавшие в Китае, и кит. монахи, направлявшиеся в Японию для распространения учения Будды, были знакомы с отд. аспектами теории и практики чань и даже пытались пропагандировать там чань-буддийскую доктрину. Однако миссионерская деятельность таких проповедников, как Досё (ум. 700), Даосюань (ум. 760), Гёхё (ум. 797), Икун (9 в.), значит. результатов не принесла. Хотя школа чань оказала некоторое влияние на формирование япон. школ Сингон и Тэндай, до кон. 12 в. в Японии о нём почти ничего не знали.

Распространение Д. в Японии (кон. 12 – нач. 13 вв.) в значит. степени было обусловлено назревавшими переменами в духовной жизни общества эпохи Камакура (1185–1333). И новое воен. сословие самураев, и старая родовая аристократия получили возможность посредством Д. приобщиться к достижениям культуры Китая, переживавшей в эпоху Сун (960–1279) ренессанс. Учение и практика чань, с которыми японцы имели возможность познакомиться в этот период, уже в значит. степени отличались от идей его ранних проповедников и харизматич. наставников, с их аскетизмом и протестом против любых форм ритуала, авторитетов и догм.

Чтобы достичь компромисса с более влиятельными школами, наставники Д. (особенно в школах Сёицу-ха и Хатто-ха) на раннем этапе охотно заимствовали положения «тайного учения» (миккё) школы Сингон (переосмысленный япон. вариант тантрич. буддизма; см. Ваджраяна). Из него пришла в Д. и получила широкое распространение теория сокусин дзёбуцу – «в этом теле стать Буддой», являющаяся одной из основополагающих в учении Кукая. От последователя Д. требовалось достигнуть «просветления», находясь внутри сансары. В этом отчётливо проявляется позитивное отношение Д. к жизни: человеческие желания должны не подавляться, а направляться по духовному руслу. Из школы Тэндай в Д. перешёл фундам. принцип возможности спасения всех без исключения живых существ.

Распространение Д.-буддизма в Японии связано с деятельностью Мёана Эйсая (1141–1215), патриарха школы Риндзай. Основой учения Риндзай является положение о «внезапном озарении». Для его достижения учителя Д. применяли систему методов психопрактики, среди которых особое место занимал канна Д. – «созерцание коанов» (особых парадоксальных текстов, нарочито нелепых, алогичных сочетаний слов) с целью разрушения мыслительных стереотипов, переструктурирования сознания, подталкивания его к интуитивному восприятию. Пропаганду эклектич. Д. продолжили ученики Эйсая – Гёю (ум. 1241) и Эйтё (ум. 1247). Гёю совмещал практику Д. и «тайное учение» школы Сингон. Непосредственно в цитадели Сингон – на горе Коя – им была возведена часовня Конгосаммай-ин, где устраивались ритуальные эзотерич. службы. Эйтё также соединял Д. с учениями Тэндай и Сингон.

Высокой степенью синкретизма отличается учение Энни Бэнъэна (1202–80). Вначале он учился Д. у Эйтё и Гёю, от которых унаследовал интерес к тантрич. буддизму, но при этом поддерживал тесные контакты с монахами школ Тэндай и Сингон, что наложило отпечаток на его учение. В своих проповедях Энни Бэнъэн активно развивал теорию «единства трёх учений» (буддизма, даосизма и конфуцианства). Мухон (Синти) Какусин (1207–98), основатель школы Хатто-ха, проповедовал совместную практику Д. и миккё, поэтому в его монастыре помимо ежедневных четырёхразовых занятий сидячей медитацией практиковались ритуалы Сингон. Догэн (1200–53), основатель др. направления Д. – школы Сото (кит. – цаодун), предложил для достижения сатори применять только классич. «сидячую медитацию» (дзадзэн). По мнению Догэна, лишь спокойное сидение, не отягощённое какими бы то ни было размышлениями и специально поставленной целью, позволяет практикующему реализовать присутствующую в нём от рождения «сущность» Будды. В процессе дзадзэн отдавалось предпочтение равномерному естеств. дыханию. Никакие дополнительные объекты, в т. ч. коаны, не использовались.

На протяжении 13–14 вв. Д. имел прежде всего религ. окраску, в нём доминировала школа Риндзай. В этот период оформились два основных центра Д. – Киото и Камакура. Гибкость и способность к адаптации во многом обусловили огромное влияние Д. на широкие слои япон. общества. С эпохи Муромати (1333–1568) началась социально-культурная история Д. в качестве системы япон. образа жизни. На эту эпоху приходится наивысший расцвет Д. в Японии. Дзенские монахи выступали в роли советников в сёгунском и имп. окружении, к ним обращались военные, гос. чиновники, художники и поэты. В 15 в. Д. приобрёл особую значимость в культурной жизни Японии. Он дал толчок развитию новых направлений в живописи, поэзии и драматургии, а также боевых искусств (кэмпо). Наиболее выдающимся учителем Д. раннего периода Муромати является Мусо Сосэки (1275–1351), настоятель ряда крупных дзенских храмов. Взгляды Мусо и его последователей нашли отражение в лит. течении годзан бунгаку – «литература пяти гор», по обобщённому наименованию крупнейших буддийских обителей. Эта литература создавалась на письм. кит. языке (вэньянь, япон. – камбун). Наряду с хронологич. жизнеописаниями (япон. – нэмпу, кит. – няньпу) и «записями речей» (япон. – гороку, кит. – юйлу) известных дзенских наставников, филос. трудами и комментариями к общебуддийским и дзенским трактатам, словарями дзенских терминов, сб-ками коанов, дневниками и эссе, в этой традиции значит. место занимала поэзия, где глубокие филос. сентенции излагались в худож. форме. Крупнейшие представители данного лит. течения – Кокан Сирэн (1278–1346), Тюган Энгэцу (1300–1375), Гидо Сюсин (1325–88), Дзэккай Тюсин (1336–1405), Иккю Содзюн (1394–1481).

В нач. 17 в. получило распространение ещё одно направление Д. – Обаку-сю, последователи которого использовали амидаистскую (см. Амидаизм) практику нэмбуцу (кит. няньфо – «думание о Будде») – рецитацию имени будды Амиды (Амитабхи), который воспринимался ими не как трансцендентальное существо, а как собственно «природа Будды», заключённая в сердце верующего. Поэтому и рай Амиды трактовался как всеобъемлющее пространство «Чистой земли» в человеческих сердцах. Элементы амидаизма и религ. даосизма присутствуют также в учении Хакуина Экаку (1686–1769) о «внутреннем взгляде», содержащем элементы даосских техник достижения бессмертия. Своеобразно их развивая, он связывал идею спасения с обнаружением «Чистой земли» внутри себя и с возвращением во время медитации к своей «изначальной чистой природе». Т. о., в отличие от амидаистских школ, Д. делает акцент на достижении «просветления» путём опоры на собств. силы (дзирики). Мастера Д. позднего Средневековья были не только религиозными, но и культурными деятелями. Так, Хакуин Экаку известен не только как религ. реформатор, но и как оригинальный художник, каллиграф и поэт. Написав множество трактатов на япон. языке (до него буддийские сочинения писались на кит. лит. языке), он сделал учение Д. доступным для мирян.

В эпоху Токугава (17–19 вв.) усиление позиций синтоизма привело к утрате Д. былого влияния в религ. сфере. В результате упрощения практики дзен Хакуином школа Риндзай, которая прежде ориентировалась на правящие круги Киото и знать, нашла опору в простом народе. Отклик в широкой среде находили призывы Хакуина к уважительному отношению к народу, к утверждению конфуцианских идеалов «гуманного правления». В эпоху Токугава акцент в учении Д. переносился с идеи пассивного «просветления» на активное духовное, а также психофизич. совершенствование на обыденном уровне. Наставники Д. обучали методам самоконтроля, необходимым как в религ. практике созерцания, так и в жизненно важных для самурайского сословия боевых искусствах – фехтовании, стрельбе из лука. Дзенские проповедники стали доказывать, что умение мгновенно сосредоточиться на самой сути любой проблемы имеет большое значение не только в монашеской, но и в мирской жизни. Применение принципов Д. к жизни за пределами монастыря сыграло большую роль в формировании социальной психологии японцев и их поведенч. норм.

Монастыри Д. становились в Японии очагами конфуцианских идей, там переписывались книги конфуцианского толка, зарождалось и развивалось многое из того, что впоследствии стало неотъемлемой частью традиц. япон. культуры: своеобразная поэзия на кит. лит. языке, живопись, икебана, иск-во чайной церемонии. Д. внёс вклад в развитие япон. архитектуры, определил мн. направления развития япон. лит-ры и иск-ва, проникая в те их области, где были важны импровизация и интуиция. В монастырях Д. художниками-монахами создавались монохромные пейзажные свитки по кит. образцам. В них запечатлены моменты «созерцания» и «просветления», освобождающего от всего преходящего и временного. Техника их исполнения – суйбоку – основывалась на сопоставлении тушевых мазков и пятен разл. интенсивности, их соотношении со свободным пространством свитка. Выполненные такими крупными мастерами, как Мокукан (сер. 14 в.), Као Нинга (ум. 1345), Бомпо (1348–1426), эти свитки сами становились предметом религ. созерцания. До 15 в. монохромная живопись целиком оставалась в пределах дзенских монастырей. Одна из наиболее знаменитых её школ сложилась при дзенском мон. Сёкокудзи в Киото. Позднее, в 17 в., появилась самобытная «живопись дзенских монахов» (дзенга). В 14–16 вв. эстетич. каноны Д.-буддизма оказали огромное влияние на садово-парковое иск-во. Япон. сад уменьшается в размерах и предназначается уже не для прогулок, а для созерцания. Создавая подобные «философские сады», дзенские монахи стремились передать своё переживание бесконечности природы, времени, пространства, идеи Будды.

В 20 в., благодаря прежде всего усилиям Т. Д. Судзуки, Д. стал достоянием зап. культуры. Многие зап. философы, теологи, писатели, художники, психологи и музыканты проявляли интерес к Д., пытались использовать его идеи в собств. творчестве. Отголоски Д. можно обнаружить в произведениях Г. Гессе, Дж. Сэлинджера, в поэзии А. Гинсберга и Г. Снайдера, в живописи В. Ван Гога и А. Матисса, в философии А. Швейцера, в музыке Г. Малера и Дж. Кейджа, в трудах по психологии К. Г. Юнга и Э. Фромма. В 1960-х гг. идеи Д. стали чрезвычайно востребованными в США.

В нач. 21 в. Д. не является массовым направлением япон. буддизма, но продолжает сохранять прочные позиции в духовной и культурной жизни японцев. Общее число его последователей составляет ок. 10 млн. чел. Монастыри и центры по изучению Д. существуют также за пределами Японии, прежде всего в США и Зап. Европе.

1. религ. разновидность буддизма, окончательно сформировавшаяся в Китае в V–VI веках под большим влиянием даосизма

Все значения слова «дзен-буддизм»

-

Наш учитель затем провёл уже более глубокую ознакомительную лекцию, касавшуюся самых общих основ дзен-буддизма, а также правил поведения.

-

Коуч мысленно выходит из разговора и занимает нейтральную позицию наблюдателя, подобно тому, как в философии дзен-буддизма используется созерцание и интуиция как основа прозрения.

-

В какой-то момент после того, как я стал размышлять о множественных вселенных, я заговорил об этом со своим другом, который, как выяснилось, давно увлекался дзен-буддизмом.

- (все предложения)

- дзэн-буддизм

- сикхизм

- ненасилие

- дао

- ушу

- (ещё синонимы…)

дзен-буддизм

Правильно слово пишется: дзен-будди́зм

Сложное слово, состоящее из 2 частей.

- дзен

- Ударение падает на слог с единственной гласной буквой в слове.

Всего в слове 4 буквы, 1 гласная, 3 согласных, 1 слог.

Гласные: е;

Согласные: д, з, н. - буддизм

- Ударение падает на 2-й слог с буквой и.

Всего в слове 7 букв, 2 гласных, 5 согласных, 2 слога.

Гласные: у, и;

Согласные: б, д, д, з, м.

Номера букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «дзен-буддизм» в прямом и обратном порядке:

- 11

д

1 - 10

з

2 - 9

е

3 - 8

н

4 -

—

- 7

б

5 - 6

у

6 - 5

д

7 - 4

д

8 - 3

и

9 - 2

з

10 - 1

м

11

Слово «дзен-буддизм» состоит из 11-ти букв и 1-го дефиса.

Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

World Psychology:

Psychology by Country ·

Psychology of Displaced Persons

This is a background article on Zen. For psychological aspects see:

- Zen and psychotherapy

Zen (Japanese: 禅) from Dhyana (Sanskrit) via Chán (Chinese: 禅|禅) and Sŏn (Korean: 선|선) is a school of Mahāyāna Buddhism notable for its emphasis on mindful acceptance of the present moment, spontaneous action, and letting go of self-conscious, judgmental thinking[1][2]

It emphasizes dharma practice and experiential wisdom—particularly as realized in the form of meditation known as zazen—in the attainment of awakening. As such, it de-emphasizes both theoretical knowledge and the study of religious texts in favor of direct individual experience of one’s own true nature.

A broader term is the Sanskrit word «dhyana», which exists also in other religions in India.

The emergence of Chán (Zen) as a distinct school of Buddhism was first documented in China in the 7th century CE. It is thought to have developed as an amalgam of various currents in Mahāyāna Buddhist thought—among them the Yogācāra and Madhyamaka philosophies and the Prajñāpāramitā literature—and of local traditions in China, particularly Taoism and Huáyán Buddhism. From China, Chán subsequently spread southwards to Vietnam and eastwards to Korea and Japan. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Zen also began to establish a notable presence in North America and Europe.

The Five Houses of Zen

Developing primarily in the Tang dynasty in China, Classic Zen is traditionally divided historically into the Five Houses of Zen or five «schools». These were not originally regarded as «schools,» or «sects,» but historically, they have come to be understood that way. In their early history, the schools were not institutionalized, they were without dogma, and the teachers which founded them were not idolized.

The Five Houses of Zen are[3] :

- Kuei-Yang, named after masters Kuei-shan Ling-yu (771-854) and Yang-Shen Hui-chi (813-890)

- Lin-chi, from which the modern Rinzai, Obaku, and (now defunct) Fuke schools were formed, named after master Lin-chi I-hsuan (d. 866)

- Tsao-tung, from which the modern Soto school was formed, named after masters Tung-shan Liang-chieh (807-869) and Ts’ao-shan Pen-chi (840-901)

- Yun-men, named after master Yun-men Wen-yen (d. 949)

- Fa-yen, named after master Fa-yen Wen-i (885-958)

Most Zen lineages throughout Asia and the rest of the world originally grew from or were heavily influenced by the original five houses of Zen.

Zen teachings and practices

Basis

File:Huineng Tearing Sutras.jpg The Sixth Patriarch Tearing Up a Sutra by Liáng Kǎi

Zen asserts, as do other schools in Mahayana Buddhism, that all sentient beings have Buddha-nature, the universal nature of inherent wisdom (Sanskrit prajna) and virtue, and emphasizes that Buddha-nature is nothing other than the nature of mind itself. The aim of Zen practice is to discover this Buddha-nature within each person, through meditation and mindfulness of daily experiences. Zen practitioners believe that this provides new perspectives and insights on existence, which ultimately lead to enlightenment.

In distinction to many other Buddhist sects, Zen dis-emphasizes reliance on religious texts and verbal discourse on metaphysical questions. Zen holds that these things lead the practitioner to seek external answers, rather than searching within their own minds for the direct intuitive apperception of Buddha-nature. This search within goes under various terms such as “introspection,” “a backward step,” “turning-about,” or “turning the eye inward.”

In this sense, Zen, as a means to deepen the practice and in contrast to many other religions, could be seen as fiercely anti-philosophical, iconoclastic, anti-prescriptive and anti-theoretical. The importance of Zen’s non-reliance on written words is often misunderstood as being against the use of words. However, Zen is deeply rooted in both the scriptural teachings of the Buddha Siddhārtha Gautama and in Mahāyāna Buddhist thought and philosophy. What Zen emphasizes is that the awakening taught by the Buddha came through his meditation practice, not from any words that he read or discovered, and so it is primarily through meditation that others too may awaken to the same insights as the Buddha.

The teachings on the technique and practice of turning the eye inward are found in many suttas and sutras of Buddhist canons, but in its beginnings in China, Zen primarily referred to the Mahayana Sutras and especially to the Lankavatara Sutra. Ironically, since Bodhidharma taught the turning-about techniques of dhyana with reference to the Lankavatara Sutra, the Zen school was initially identified with that sutra. It was in part through reaction to such limiting identification with one text that Chinese Zen cultivated its famous non-reliance on written words and independence of any one scripture. However, a review of the teachings of the early Zen masters clearly reveals that they were all well versed in various scriptures. For example, in The Platform Sutra of the Sixth ancestor and founder Huineng, this famously «illiterate» Zen master cites and explains the Diamond Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, the Vimalakirti Sutra, the Shurangama Sutra, and the Lankavatara Sutra.

When Buddhism came to China the doctrine of the three core practices or trainings, the training in virtue and discipline in the precepts (Sanskrit Śīla), the training in mind through meditation (dhyana or jhana) sometimes called concentration (samadhi), and the training in discernment and wisdom (prajna), was already established in the Pali canon.(http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an03/an03.088.than.html#trainings) In this context, as Buddhism became adapted to Chinese culture, three types of teachers with expertise in each training practice developed. Vinaya masters were versed in all the rules of discipline for monks and nuns. Dhyana masters were versed in the practice of meditation. And Dharma, i.e., teaching or sutra, masters were versed in the Buddhist texts. Monastaries and practice centers were created that tended to focus on either the vinaya and training of monks or the teachings focused on one scripture or a small group of texts. Dhyana or Chan masters tended to practice in solitary hermitages or to be associated with the Vinaya training monasteries or sutra teaching centers.

After Bodhidharma’s arrival in the late fifth century, the subsequent dhyana-chan masters who were associated with his teaching line consolidated around the practice of meditation and the feeling that mere observance of the rules of discipline or the intellectual teachings of the scriptures did not emphasize enough the actual practice and personal experience of the Buddha’s meditation that led to the Buddha’s awakening. Awakening like the Buddha, and not merely following rules or memorizing texts became the watchword of the dhyana-chan practitioners. Within 200 years after Bodhidharma at the beginning of the Tang Dynasty, by the time of the fifth generation Chan ancestor and founder Daman Hongren (601-674), the Zen of Bodhidharma’s successors had become well established as a separate school of Buddhism and the true Zen school.[4]

The core of Zen practice is seated meditation, widely known by its Japanese name Zazen, and recalls both the posture in which the Buddha is said to have achieved enlightenment under the Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya, and the elements of mindfulness and concentration which are part of the Eightfold Path as taught by the Buddha. All of the Buddha’s fundamental teachings—among them the Eightfold Path, the Four Noble Truths, the idea of dependent origination, the five precepts, the five aggregates, and the three marks of existence—also make up important elements of the perspective that Zen takes for its practice. While Buddhists generally revere certain places as a Bodhimandala (circle or place of enlightenment) in Zen wherever one sits in true meditation is said to be a Bodhimandala.

Additionally, as a development of Mahāyāna Buddhism, Zen draws many of its basic driving concepts, particularly the bodhisattva ideal, from that school. Uniquely Mahāyāna figures such as Guānyīn, Mañjuśrī, Samantabhadra, and Amitābha are venerated alongside the historical Buddha. Despite Zen’s emphasis on transmission independent of scriptures, it has drawn heavily on the Mahāyāna sūtras, particularly the Heart of Perfect Wisdom Sūtra, Hredaya Pranyaparamita the Sūtra of the Perfection of Wisdom of the Diamond that Cuts through Illusion, The Vajrachedika Pranyaparamita the Lankavatara Sūtra, and the «Samantamukha Parivarta» section of the Lotus Sūtra.

Zen has also itself paradoxically produced a rich corpus of written literature which has become a part of its practice and teaching. Among the earliest and most widely studied of the specifically Zen texts, dating back to at least the 9th century CE, is the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, sometimes attributed to Huìnéng. Others include the various collections of kōans and the Shōbōgenzō of Dōgen Zenji.

Zen training emphasizes daily practice, along with intensive periods of meditation. Practicing with others is an integral part of Zen practice. D.T. Suzuki wrote that aspects of this life are: a life of humility; a life of labor; a life of service; a life of prayer and gratitude; and a life of meditation.[5] The Chinese Chan master Baizhang (720–814 CE) left behind a famous saying which had been the guiding principle of his life, «A day without work is a day without food.»[6]

Zen meditation

Zazen

- Main article: Zazen

File:Kodo Sawaki.jpg Kodo Sawaki practicing shikantaza

As the name Zen implies, Zen sitting meditation is the core of Zen practice and is called zazen in Japanese (坐禅; Chinese tso-chan [Wade-Giles] or zuòchán [Pinyin]). During zazen, practitioners usually assume a sitting position such as the lotus, half-lotus, Burmese, or seiza postures. To regulate the mind, awareness is directed towards counting or watching the breath or put in the energy center below the navel (Chinese dan tian, Japanese tanden or hara). [6] Often, a square or round cushion (zafu, 座蒲) placed on a padded mat (zabuton, 座布団) is used to sit on; in some cases, a chair may be used. In Japanese Rinzai Zen tradition practitioners typically sit facing the center of the room; while Japanese Soto practitioners traditionally sit facing a wall.

In Soto Zen, shikantaza meditation («just-sitting», 只管打坐) that is, a meditation with no objects, anchors, or content, is the primary form of practice. The meditator strives to be aware of the stream of thoughts, allowing them to arise and pass away without interference. Considerable textual, philosophical, and phenomenological justification of this practice can be found throughout Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō, as for example in the «Principles of Zazen»[7] and the «Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen».[8] Rinzai Zen, instead, emphasizes attention to the breath and koan practice (q.v.).

The amount of time spent daily in zazen by practitioners varies. Dōgen recommends that five minutes or more daily is beneficial for householders. The key is daily regularity, as Zen teaches that the ego will naturally resist, and the discipline of regularity is essential. Practicing Zen monks may perform four to six periods of zazen during a normal day, with each period lasting 30 to 40 minutes. Normally, a monastery will hold a monthly retreat period (sesshin), lasting between one and seven days. During this time, zazen is practiced more intensively: monks may spend four to eight hours in meditation each day, sometimes supplemented by further rounds of zazen late at night.

Meditation as a practice can be applied to any posture. Walking meditation is called kinhin. Successive periods of zazen are usually interwoven with brief periods of walking meditation to relieve the legs.

Sesshin

- Main article: Sesshin

Zazen practice in monasteries is known as sesshin. One distinctive aspect of Zen meditation in groups is the use of the keisaku, a flat wooden stick or slat used to keep meditators focused and awake.

The Zen teacher

- Main article: Zen teacher

This Japanese scroll calligraphy of Bodhidharma reads “Zen points directly to the human heart, see into your nature and become Buddha”. It was created by Hakuin Ekaku (1685—1768)

Because the Zen tradition emphasizes direct communication over scriptural study, the Zen teacher has traditionally played a central role. Generally speaking, a Zen teacher is a person ordained in any tradition of Zen to teach the Dharma, guide students of meditation, and perform rituals.

An important concept for all Zen sects is the notion of dharma transmission: the claim of a line of authority that goes back to Śākyamuni Buddha via the teachings of each successive master to each successive student. This concept relates to the ideas expressed in a description of Zen attributed to Bodhidharma:

- A special transmission outside the scriptures; (教外別傳)

- No dependence upon words and letters; (不立文字)

- Direct pointing to the human mind; (直指人心)

- Seeing into one’s own nature and attaining Buddhahood. (見性成佛)[9]

The idea of a line of descent from Śākyamuni Buddha is a distinctive institution of Zen which Suzuki (1949:168) contends was invented by hagiographers to grant Zen legitimacy and prestige.

John McRae’s study “Seeing Through Zen” explores this assertion of lineage as a distinctive and central aspect of Zen Buddhism. He writes of this “genealogical” approach so central to Zen’s self-understanding, that while not without precedent, has unique features. It is “relational (involving interaction between individuals rather than being based solely on individual effort), generational (in that it is organized according to parent-child, or rather teacher-student, generations) and reiterative (i.e., intended for emulation and repetition in the lives of present and future teachers and students.”

McRae offers a detailed criticism of lineage, but he also notes it is central to Zen. So much so that it is hard to envision any claim to Zen that discards claims of lineage. Therefore, for example, in Japanese Soto, lineage charts become a central part of the Sanmatsu, the documents of Dharma transmission. And it is common for daily chanting in Zen temples and monasteries to include the lineage of the school.

In Japan during the Tokugawa period (1600–1868), some came to question the lineage system and its legitimacy. The Zen master Dokuan Genko (1630–1698), for example, openly questioned the necessity of written acknowledgment from a teacher, which he dismissed as «paper Zen.» Quite a number of teachers in Japan during the Tokugawa period did not adhere to the lineage system; these were termed mushi dokugo (無師獨悟, «independently enlightened without a teacher») or jigo jisho (自悟自証, «self-enlightened and self-certified»). Modern Zen Buddhists also consider questions about the dynamics of the lineage system, inspired in part by academic research into the history of Zen.

Honorific titles associated with teachers typically include, in Chinese, Fashi (法師) or Chanshi (禪師); in Korean, Sunim (an honorofic for a monk or nun) and Seon Sa (선사); in Japanese, Osho (和尚), Roshi (老師), or Sensei (先生); and in Vietnamese, Thầy. Note that many of these titles are not specific to Zen but are used generally for Buddhist priests; some, such as sensei are not even specific to Buddhism.

The English term Zen master is often used to refer to important teachers, especially ancient and medieval ones. However, there is no specific criterion by which one may be called a Zen master. The term is less common in reference to modern teachers. In the Open Mind Zen School, English terms have been substituted for the Japanese ones to avoid confusion of this issue. «Assistant Zen Teacher» is a person authorized to begin to teach, but still under the supervision of his teacher. «Zen Teacher» applies to one authorized to teach without further direction, and «Zen Master» refers to one who is a Zen Teacher and has founded his or her own teaching center.

Koan practice

- Main article: Koan

File:Wu (negative).svg Chinese character for «no thing.» Chinese: wú (Korean/Japanese: mu). It figures in the famous Zhaozhou’s dog koan

Zen Buddhists may practice koan inquiry during sitting meditation (zazen), walking meditation, and throughout all the activities of daily life. A koan (literally «public case») is a story or dialogue, generally related to Zen or other Buddhist history; the most typical form is an anecdote involving early Chinese Zen masters. Koan practice is particularly emphasized by the Japanese Rinzai school, but it also occurs in other schools or branches of Zen depending on the teaching line.[10]

These anecdotes involving famous Zen teachers are a practical demonstration of their wisdom, and can be used to test a student’s progress in Zen practice. Koans often appear to be paradoxical or linguistically meaningless dialogues or questions. But to Zen Buddhists the koan is «the place and the time and the event where truth reveals itself»[11] unobstructed by the oppositions and differientiations of language. Answering a koan requires a student to let go of conceptual thinking and of the logical way we order the world, so that like creativity in art, the appropriate insight and response arises naturally and spontaneously in the mind.

Koans and their study developed in China within the context of the open questions and answers of teaching sessions conducted by the Chinese Zen masters. Today, the Zen student’s mastery of a given koan is presented to the teacher in a private interview (referred to in Japanese as dokusan (独参), daisan (代参), or sanzen (参禅)). Zen teachers advise that the problem posed by a koan is to be taken quite seriously, and to be approached as literally a matter of life and death. While there is no unique answer to a koan, practitioners are expected to demonstrate their understanding of the koan and of Zen through their responses. The teacher may approve or disapprove of the answer and guide the student in the right direction. There are also various commentaries on koans, written by experienced teachers, that can serve as a guide. These commentaries are also of great value to modern scholarship on the subject.

Chanting and liturgy

A practice in many Zen monasteries and centers is a daily liturgy service. Practitioners chant major sutras such as the Heart Sutra, chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra (often called the «Avalokiteshvara Sutra»), the Song of the Jewel Mirror Awareness, the Great Compassionate Heart Dharani (Daihishin Dharani),[12] and other minor mantras.

The Butsudan is the altar in a monastery where offerings are made to the images of the Buddha or Bodhisattvas. The same term is also used in Japanese homes for the altar where one prays to and communicates with deceased family members. As such, reciting liturgy in Zen can be seen as a means to connect with the Bodhisattvas of the past. Liturgy is often used during funerals, memorials, and other special events as means to invoke the aid of supernatural powers.

Chanting usually centers on major Bodhisattvas like Avalokiteshvara (see also Guan Yin) and Manjusri. According to Mahayana Buddhism, Bodhisattvas are celestial beings which have taken extraordinary vows to liberate all beings from Samsara (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth), while remaining in Samsara themselves. Since the Zen practitioner’s aim is to walk the Bodhisattva path, chanting can be used as a means to connect with these beings and realize this ideal within oneself. By repeatedly chanting the Avalokiteshvara sutra (観世音菩薩普門品 Kanzeon Bosatsu Fumonbon?), for example, one instills the Bodhisattva’s ideals into ones mind. The ultimate goal is given in the end of the sutra, which states,

«In the morning, be one with Avalokiteshvara,

In the evening, be one with Avalokiteshvara,»[13],

Through the realization of the Emptiness of oneself, and the Mahayanist ideal of Buddha-nature in all things, one understands that there is no difference between the cosmic bodhisattva and oneself. The wisdom and compassion of the Boddhisattva one is chanting to is seen to equal the inner wisdom and compassion of the practitioner. Thus, the duality between subject and object, practitioner and Bodhisattva, chanter and sutra is ended.

One modern day Roshi justifies the use of chanting sutras by referring to Zen master Dōgen.[14], Dōgen is known to have refuted the statement «Painted rice cakes will not satisfy hunger». This means that sutras, which are just symbols like painted rice cakes, cannot truly satisfy one’s spiritual hunger. Dōgen, however, saw that there is no separation between metaphor and reality. «There is no difference between paintings, rice cakes, or any thing at all».[15] The symbol and the symbolized were inherently the same, and thus only the sutras could truly satisfy one’s spiritual needs.

To understand this non-dual relationship experientially, one is told to practice liturgy intimately. [16] In distinguishing between ceremony and liturgy, Dōgen states, «In ceremony there are forms and there are sounds, there is understanding and there is believing. In liturgy there is only intimacy.» The practitioner is instructed to listen to and speak liturgy not just with one sense, but with one’s «whole body-and-mind». By listening with one’s entire being, one eliminates the space between the self and the liturgy. Thus, Dōgen’s instructions are to «listen with the eye and see with the ear». By focusing all of one’s being on one specific practice, duality is transcended. Dōgen says, «Let go of the eye, and the whole body-and-mind are nothing but the eye; let go of the ear, and the whole universe is nothing but the ear.» Chanting intimately thus allows one to experience a non-dual reality. The liturgy used is a tool to allow the practitioner to transcend the old conceptions of self and other. In this way, intimate liturgy practice allows one to realize Sunyata, or emptiness, which is at the heart of Buddhist teachings.

Other techniques

There are other techniques common in the Zen tradition which seem unconventional and whose purpose is said to be to shock a student in order to help him or her let go of habitual activities of the mind. Some of these are common today, while others are found mostly in anecdotes. These include the loud belly shout known as katsu. It is common in many Zen traditions today for Zen teachers to have a stick with them during formal ceremonies which is a symbol of authority and which can be also used to strike on the table during a talk. The now defunct Fuke Zen sect was also well-known for practicing suizen, meditation with the shakuhachi, which some Zen Buddhists today also practice.

Mythology

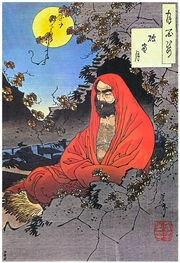

Bodhidharma. Woodcut print by Yoshitoshi, 1887.

Within Zen, and thus from an emic perspective, the origins of Zen Buddhism are ascribed to what is called the Flower Sermon, in which Śākyamuni Buddha is supposed to have passed on special insight to the disciple Mahākāśyapa. The sermon itself was a wordless one in which Śākyamuni merely held up a flower before the assembled disciples, among whom there was no reaction apart from Mahākāśyapa, who smiled. The smile is said to have signified Mahākāśyapa’s understanding, and Śākyamuni acknowledged this by saying:

I possess the true Dharma eye, the marvelous mind of Nirvana, the true form of the formless, the subtle dharma gate that does not rest on words or letters but is a special transmission outside of the scriptures. This I entrust to Mahākāśyapa.[17]

Thus, a way within Buddhism developed which concentrated on direct experience rather than on rational creeds or revealed scriptures. Zen is a method of meditative religion which seeks to enlighten people in the manner that the Mahākāśyapa experienced.[18]

In the Song of Enlightenment (證道歌 Zhèngdào gē) of Yǒngjiā Xuánjué (665-713)[19]—one of the chief disciples of Huìnéng, the 6th patriarch of Chan Buddhism—it is written that Bodhidharma was the 28th patriarch in a line of descent from Mahākāśyapa, a disciple of Śākyamuni Buddha, and the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism:

- Mahākāśyapa was the first, leading the line of transmission;

- Twenty-eight Fathers followed him in the West;

- The Lamp was then brought over the sea to this country;

- And Bodhidharma became the First Father here:

- His mantle, as we all know, passed over six Fathers,

- And by them many minds came to see the Light.[20]

The idea of a line of descent from Śākyamuni Buddha is a distinctive institution of Zen which Suzuki (1949:168) contends was invented by hagiographers to grant Zen legitimacy and prestige. The earliest source for the legend of the «Flower sermon» is from 11th century China.[21].

Early history

- See also: Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

Chán developed as an amalgam of Mahāyāna Buddhism and Taoism.[22] Dumoulin (2005) argues that Chán also has roots in yogic practices, specifically kammaṭṭhāna, the consideration of objects, and kasiṇa, total fixation of the mind.

The entry of Buddhism into China was marked by interaction and syncretism with Taoic faiths, Taoism in particular.[23] Buddhism’s scriptures were translated into Chinese with Taoist vocabulary, because it was originally seen as a kind of foreign Taoism.[24] In the Tang period, Taoism incorporated such Buddhist elements as monasteries, vegetarianism, prohibition of alcohol, the doctrine of emptiness, and collecting scripture into tripartite organisation. During the same time, Chán Buddhism grew to become the largest sect in Chinese Buddhism.[25]

The establishment of Chán is traditionally credited to the Indian prince turned monk Bodhidharma (formerly dated ca 500 CE, but now ca early fifth century[26]), who is recorded as having come to China to teach a «special transmission outside scriptures» which «did not stand upon words». Bodhidharma settled in the kingdom of Wei where he took among his disciples Daoyu and Huike. Early on in China Bodhidharma’s teaching was referred to as the «One Vehicle sect of India.»[27] The One Vehicle (Sanskrit Ekayāna), also known as the Supreme Vehicle or the Buddha Vehicle, was taught in the Lankavatara Sutra which was closely associated with Bodhidharma. However the label «One Vehicle sect» did not become widely used, and Bodhidharma’s teaching became known as the Chan sect for its primary focus on chan training and practice. Shortly before his death, Bodhidharma appointed Huike to succeed him, making Huike the first Chinese born patriarch and the second patriarch of Chán in China. Bodhidharma is said to have passed three items to Huike as a sign of transmission of the Dharma: a robe, a bowl, and a copy of the Lankavatara Sutra. The transmission then passed to the second patriarch (Huike), the third (Sengcan), the fourth patriarch (Dao Xin) and the fifth patriarch (Hongren).

The sixth and last patriarch, Huineng (638–713), was one of the giants of Chán history, and all surviving schools regard him as their ancestor. However, the dramatic story of Huineng’s life tells that there was a controversy over his claim to the title of patriarch. After being chosen by Hongren, the fifth patriarch, Huineng had to flee by night to Nanhua Temple in the south to avoid the wrath of Hongren’s jealous senior disciples. Later, in the middle of the 8th century, monks claiming to be among the successors to Huineng, calling themselves the Southern school, cast themselves in opposition to those claiming to succeed Hongren’s then publicly recognized student Shenxiu (神秀). It is commonly held that at this point—the debates between these rival factions—that Chán enters the realm of fully documented history. The Southern school eventually became predominant and their rivals died out. Modern scholarship, however, has questioned this narrative.

The following are the six Patriarchs of Chán in China as listed in traditional sources:

- Bodhidharma (बोधिधर्म) about 440 — about 528

- Huike (慧可) 487 — 593

- Sengcan (僧燦) ? — 606

- Daoxin (道信) 580 — 651

- Hongren (弘忍) 601 — 674

- Huineng (慧能) 638 — 713

Zen in China (Chán)

- See also: Buddhism in China

In the following centuries, Chán grew to become the largest sect in Chinese Buddhism and, despite its «transmission beyond the scriptures», produced the largest body of literature in Chinese history of any sect or tradition. The teachers claiming Huineng’s posterity began to branch off into numerous different schools, each with their own special emphasis, but all of which kept the same basic focus on meditational practice, personal instruction and personal experience.

During the late Tang and the Song periods, the tradition continued, as a wide number of eminent teachers, such as Mazu (Wade-Giles: Ma-tsu; Japanese: Baso), Shitou (Shih-t’ou; Japanese: Sekito), Baizhang (Pai-chang; Japanese: Hyakujo), Huangbo (Huang-po; Jap.: Obaku), Linji (Lin-chi; Jap.: Rinzai), and Yunmen (Jap.: Ummon) developed specialized teaching methods, which would variously become characteristic of the five houses (五家) of Chán. The traditional five houses were Caodong (曹洞宗), Linji (臨濟宗), Guiyang (潙仰宗), Fayan (法眼宗), and Yunmen (雲門宗). This list does not include earlier schools such as the Hongzhou (洪州宗) of Mazu.

Over the course of Song Dynasty (960–1279), the Guiyang, Fayan, and Yunmen schools were gradually absorbed into the Linji. During the same period, the various developments of Chán teaching methods crystallized into the gong-an (koan) practice which is unique to this school of Buddhism. According to Miura and Sasaki, «it was during the lifetime of Yüan-wu‘s successor, Ta-hui Tsung-kao 大慧宗杲 (Daie Sōkō, 1089-1163) that Koan Zen entered its determinative stage.»[28] Gong-an practice was prevalent in the Linji school, to which Yuanwu and Ta-hui (pinyin: Dahui) belonged, but it was also employed on a more limited basis by the Caodong school. The teaching styles and words of the classical masters were collected in such important texts as the Blue Cliff Record (1125) of Yuanwu, The Gateless Gate (1228) of Wumen, both of the Linji lineage, and the Book of Equanimity (1223) of Wansong, of the Caodong lineage. These texts record classic gong-an cases, together with verse and prose commentaries, which would be studied by later generations of students down to the present.

Chán continued to be influential as a religious force in China, and thrived in the post-Song period; with a vast body of texts being produced up and through the modern period. While traditionally distinct, Chán was taught alongside Pure Land Buddhism in many Chinese Buddhist monasteries. In time much of the distinction between them was lost, and many masters taught both Chán and Pure Land. Chán Buddhism enjoyed something of a revival in the Ming Dynasty with teachers such as Hanshan Deqing (憨山德清), who wrote and taught extensively on both Chán and Pure Land Buddhism; Miyun Yuanwu (密雲圓悟), who came to be seen posthumously as the first patriarch of the Obaku Zen school; as well as Yunqi Zhuhong (雲棲株宏) and Ouyi Zhixu (藕溢智旭).

After further centuries of decline, Chán was revived again in the early 20th century by Hsu Yun, a well-known figure of 20th century Chinese Buddhism. Many Chán teachers today trace their lineage back to Hsu Yun, including Sheng-yen and Hsuan Hua, who have propagated Chán in the West where it has grown steadily through the 20th and 21st century.

It was severely repressed in China during the recent modern era with the appearance of the People’s Republic, but has more recently been re-asserting itself on the mainland, and has a significant following in Taiwan and Hong Kong as well as among Overseas Chinese.

[29]

Zen in Japan

File:Japanese buddhist monk by Arashiyama cut.jpg Sōtō monk in Arashiyama, Kyoto

The schools of Zen that currently exist in Japan are the Sōtō (曹洞), Rinzai (臨済), and Obaku (黃檗). Of these, Sōtō is the largest and Obaku the smallest. Rinzai is itself divided into several subschools based on temple affiliation, including Myoshin-ji, Nanzen-ji, Tenryū-ji, Daitoku-ji, and Tofuku-ji.

Although the Japanese had known Zen-like practices for centuries (Taoism and Shinto), it was not introduced as a separate school until the 12th century, when Myōan Eisai traveled to China and returned to establish a Linji lineage, which is known in Japan as Rinzai. Decades later, Nanpo Jomyo (南浦紹明) also studied Linji teachings in China before founding the Japanese Otokan lineage, the most influential branch of Rinzai. In 1215, Dōgen, a younger contemporary of Eisai’s, journeyed to China himself, where he became a disciple of the Caodong master Tiantong Rujing. After his return, Dōgen established the Sōtō school, the Japanese branch of Caodong. The Obaku lineage was introduced in the 17th century by Ingen, a Chinese monk. Ingen had been a member of the Linji school, the Chinese equivalent of Rinzai, which had developed separately from the Japanese branch for hundreds of years. Thus, when Ingen journeyed to Japan following the fall of the Ming Dynasty to the Manchus, his teachings were seen as a separate school. The Obaku school was named for Mount Obaku (Chinese: Huangboshan), which had been Ingen’s home in China.

Some contemporary Japanese Zen teachers, such as Daiun Harada and Shunryu Suzuki, have criticized Japanese Zen as being a formalized system of empty rituals in which very few Zen practitioners ever actually attain realization. They assert that almost all Japanese temples have become family businesses handed down from father to son, and the Zen priest’s function has largely been reduced to officiating at funerals[How to reference and link to summary or text].

The Japanese Zen establishment—including the Sōtō sect, the major branches of Rinzai, and several renowned teachers— has been criticized for its involvement in Japanese militarism and nationalism during World War II and the preceding period. A notable work on this subject was Zen at War (1998) by Brian Victoria, an American-born Sōtō priest. At the same time, however, one must be aware that this involvement was by no means limited to the Zen school: all orthodox Japanese schools of Buddhism supported the militarist state. What may be most striking, though, as Victoria has argued, is that many Zen masters known for their post-war internationalism and promotion of «world peace» were open nationalists in the inter-war years [7]. And some of them, like Haku’un Yasutani, the founder of the Sanbo Kyodan School, even voiced their anti-semitic and nationalistic opinions after World War II. [8], [9]

This openness has allowed non-Buddhists to practice Zen, especially outside of Asia, and even for the curious phenomenon of an emerging Christian Zen lineage, as well as one or two lines that call themselves «nonsectarian.» With no official governing body, it’s perhaps impossible to declare any authentic lineage «heretical.» Some schools emphasize lineage and trace their line of teachers back to China, Japan, Korea, or Vietnam; other schools do not[How to reference and link to summary or text].

Zen in Vietnam (Thiền)

- See also: Buddhism in Vietnam

Thiền Buddhism (禪宗 Thiền Tông) is the Vietnamese name for the school of Zen Buddhism. Thien is ultimately derived from Chan Zong 禪宗 (simplified, 禅宗), itself a derivative of the Sanskrit «Dhyāna«.

According to traditional accounts of Vietnam, in 580, an Indian monk named Vinitaruci (Vietnamese: Tì-ni-đa-lưu-chi) travelled to Vietnam after completing his studies with Sengcan, the third patriarch of Chinese Zen. This, then, would be the first appearance of Vietnamese Zen, or Thien (thiền) Buddhism. The sect that Vinitaruci and his lone Vietnamese disciple founded would become known as the oldest branch of Thien. After a period of obscurity, the Vinitaruci School became one of the most influential Buddhist groups in Vietnam by the 10th century, particularly so under the patriarch Vạn-Hạnh (died 1018). Other early Vietnamese Zen schools included the Vo Ngon Thong (Vô Ngôn Thông), which was associated with the teaching of Mazu, and the Thao Duong (Thảo Đường), which incorporated nianfo chanting techniques; both were founded by Chinese monks. A new school was founded by one of Vietnam’s religious kings; this was the Truc Lam (Trúc Lâm) school, which evinced a deep influence from Confucian and Taoist philosophy. Nevertheless, Truc Lam’s prestige waned over the following centuries as Confucianism became dominant in the royal court. In the 17th century, a group of Chinese monks led by Nguyen Thieu (Nguyên Thiều) established a vigorous new school, the Lam Te (Lâm Tế), which is the Vietnamese pronunciation of Linji. A more domesticated offshoot of Lam Te, the Lieu Quan (Liễu Quán) school, was founded in the 18th century and has since been the predominant branch of Vietnamese Zen.

The most famous practitioner of synchronized Thiền Buddhism in the West is Thích Nhất Hạnh who has authored dozens of books and founded Dharma center Plum Village in France together with his colleague -Bhikkhuni and Zen Master- Chan Khong.

Zen in Korea (Seon)

- See also: Korean Buddhism

Seon was gradually transmitted into Korea during the late Silla period (7th through 9th centuries) as Korean monks of predominantly Hwaeom (華嚴) and Consciousness-only (唯識) background began to travel to China to learn the newly developing tradition.

During his lifetime, Mazu had begun to attract students from Korea; by tradition, the first Korean to study Seon was named Peomnang (法朗). Mazu’s successors had numerous Korean students, some of whom returned to Korea and established the nine mountain (九山) schools. This was the beginning of Chan in Korea which is called Seon.

Seon received its most significant impetus and consolidation from the Goryeo monk Jinul (知訥) (1158–1210), who established a reform movement and introduced koan practice to Korea. Jinul established the Songgwangsa (松廣寺) as a new center of pure practice.

It was during the time of Jinul the Jogye Order, a primarily Seon sect, became the predominant form of Korean Buddhism, a status it still holds.

which survives down to the present in basically the same status. Toward the end of the Goryeo and during the Joseon period the Jogye Order would first be combined with the scholarly 教 schools, and then be relegated to lesser influence in ruling clas circles by Confucian influenced polity, even as it retained strength outside the cities, among the rural populations and ascetic monks in mountain refuges.

Nevertheless, there would be a series of important Seon teachers during the next several centuries, such as Hyegeun (慧勤), Taego (太古), Gihwa (己和) and Hyujeong (休靜), who continued to develop the basic mold of Korean meditational Buddhism established by Jinul. Seon continues to be practiced in Korea today at a number of major monastic centers, as well as being taught at Dongguk University, which has a major of studies in this religion.

Taego Bou (1301–1382) studied in China with Linji teacher and returned to unite the Nine Mountain Schools. In modern Korea, by far the largest Buddhist denomination is the Jogye Order, which is essentially a Zen sect; the name Jogye is the Korean equivalent of Caoxi (曹溪), another name for Huineng.

Seon is known for its stress on meditation, monasticism, and asceticism. Many Korean monks have few personal possessions and sometimes cut off all relations with the outside world. Several are near mendicants traveling from temple to temple practicing meditation. The hermit-recluse life is prevalent among monks to whom meditation practice is considered of paramount importance.[30]

Currently, Korean Buddhism is in a state of slow transition. While the reigning theory behind Korean Buddhism was based on Jinul‘s «sudden enlightenment, gradual cultivation,» the modern Korean Seon master, Seongcheol‘s revival of Hui Neng‘s «sudden enlightenment, sudden cultivation» has had a strong impact on Korean Buddhism. Although there is resistance to change within the ranks of the Jogye order, with the last three Supreme Patriarchs’ stance that is in accordance with Seongcheol, there has been a gradual change in the atmosphere of Korean Buddhism.

Also, the Kwan Um School of Zen, one of the largest Zen schools in the West, teaches a form of Seon Buddhism. Soeng Hyang Soen Sa Nim (b. 1948), birth name Barbara Trexler (later Barbara Rhodes), is Guiding Dharma Teacher of the international Kwan Um School of Zen and successor of the late Seung Sahn Soen Sa Nim.

Zen in the Western world

Although it is difficult to trace when the West first became aware of Zen as a distinct form of Buddhism, the visit of Soyen Shaku, a Japanese Zen monk, to Chicago during the World Parliament of Religions in 1893 is often pointed to as an event that enhanced its profile in the Western world. It was during the late 1950s and the early 1960s that the number of Westerners, other than the descendants of Asian immigrants, pursuing a serious interest in Zen reached a significant level.

Zen and Western culture

In Europe, the Expressionist and Dada movements in art tend to have much in common thematically with the study of koans and actual Zen. The early French surrealist René Daumal translated D.T. Suzuki as well as Sanskrit Buddhist texts.

Eugen Herrigel‘s book Zen in the Art of Archery (1953),[31] describing his training in the Zen-influenced martial art of Kyūdō, inspired many of the Western world’s early Zen practitioners. However, many scholars are quick to criticize this book. (eg see Yamada Shoji)[32]

The British-American philosopher Alan Watts took a close interest in Zen Buddhism and wrote and lectured extensively on it during the 1950s. He understood it as a vehicle for a mystical transformation of consciousness, and also as a historical example of a non-Western, non-Christian way of life that had fostered both the practical and fine arts.

The Dharma Bums, a novel written by Jack Kerouac and published in 1959, gave its readers a look at how a fascination with Buddhism and Zen was being absorbed into the bohemian lifestyles of a small group of American youths, primarily on the West Coast. Beside the narrator, the main character in this novel was «Japhy Ryder», a thinly-veiled depiction of Gary Snyder. The story was based on actual events taking place while Snyder prepared, in California, for the formal Zen studies that he would pursue in Japanese monasteries between 1956 and 1968.[33]

Thomas Merton (1915–1968) the Trappist monk and priest [10] was internationally recognized as having one of those rare Western minds that was entirely at home in Asian experience. Like his friend, the late D.T. Suzuki, Merton believed that there must be a little of Zen in all authentic creative and spiritual experience. The dialogue between Merton and Suzuki («Wisdom in Emptiness» in: Zen and the Birds of Appetite, 1968) explores the many congruencies of Christian mysticism and Zen. (Main publications: The Way of Chuang Tzu, 1965; Mystics and Zen Masters, 1967; Zen and the Birds of Appetite, 1968).

Reginald Horace Blyth (1898-1964) was an Englishman who went to Japan in 1940 to further his study of Zen. He was interned during the II World War and started writing in prison. He was tutor to the Crown Prince after the war. His greatest work is the 5-volume «Zen and Zen Classics», published in the 1960s. In it, he discusses Zen themes from a philosophical standpoint, often in conjunction with Christian elements in a comparative spirit. His essays include titles such as «God, Buddha, and Buddhahood» or «Zen Sin, and Death». He is an enthusiast of Zen, but not altogether uncritical of it. His writings can be characterized as unorthodox and quirky.

While Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, by

Robert M. Pirsig, was a 1974 bestseller, it in fact has little to do with Zen as a religious practice. Rather it deals with the notion of the metaphysics of «quality» from the point of view of the main character. Pirsig was attending the Minnesota Zen Center at the time of writing the book[11]. He has stated that, despite its title, the book «should in no way be associated with that great body of factual information relating to orthodox Zen Buddhist practice.» Though it may not deal with orthodox Zen Buddhist practice, Pirsig’s book in fact deals with many of the more subtle facets of Zen living and Zen mentality without drawing attention to any religion or religious organization.

A number of contemporary authors have explored the relationship between Zen and a number of other disciplines, including parenting, teaching, and leadership. Leadership expert Timothy H. Warneka uses a number of Zen stories, such as «Understanding Harmony» to explain leadership strategies:

Once upon a time in ancient Japan, a young man was studying martial arts under a famous teacher. Every day the young man would practice in a courtyard along with the other students. One day, as the master watched, he could see that the other students were consistently interfering with the young man’s technique. Sensing the student’s frustration, the master approached the student and tapped him on the shoulder. “What is wrong?” inquired the teacher. “I cannot execute my technique and I do not understand why,” replied the student. “This is because you do not understand harmony. Please follow me,” said the master. Leaving the practice hall, the master and student walked a short distance into the woods until they came upon a stream. After standing silently beside the streambed for a few minutes, the master spoke. “Look at the water,” he instructed. “It does not slam into the rocks and stop out of frustration, but instead flows around them and continues down the stream. Become like the water and you will understand harmony.” Soon, the student learned to move and flow like the stream, and none of the other students could keep him from executing his techniques.[34]

Western Zen lineages

Over the last fifty years mainstream forms of Zen, led by teachers who trained in East Asia and their successors, have begun to take root in the West.

In North America, the Zen lineages derived from the Japanese Soto school are the most numerous. Among these are the lineages of the San Francisco Zen Center, established by Shunryu Suzuki and the White Plum Asanga, founded by Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi. Suzuki’s San Francisco Zen Center established the first Zen Monastery in America in 1967, called Tassajara in the mountains near Big Sur. Maezumi’s successors have created schools including Great Plains Zen Center, founded by Susan Myoyu Andersen, Roshi, the Mountains and Rivers Order, founded by John Daido Loori, the Zen Peacemaker Order, founded by Bernard Tetsugen Glassman and the Ordinary Mind school, founded by Charlotte Joko Beck. The Katagiri lineage, founded by Dainin Katagiri, has a significant presence in the Midwest. Note that both Taizan Maezumi and Dainin Katagiri served as priests at Zenshuji Soto Mission in the 1960s.

Taisen Deshimaru, a student of Kodo Sawaki, was a Soto Zen priest from Japan who taught in France. The International Zen Association, which he founded, remains influential. The American Zen Association, headquartered at the New Orleans Zen Temple, is one of the North American organizations practicing in the Deshimaru tradition.

Soyu Matsuoka, served as superintendent and abbot of the Long Beach Zen Buddhist Temple and Zen Center. The Temple was headquarters to Zen Centers in Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Everett, Washington. He established the Temple at Long Beach in 1971 where he resided until his passing in 1998.

The Sanbo Kyodan is a Japan-based reformist Zen group, founded in 1954 by Yasutani Hakuun, which has had a significant influence on Zen in the West. Sanbo Kyodan Zen is based primarily on the Soto tradition, but also incorporates Rinzai-style koan practice. Yasutani’s approach to Zen first became prominent in the English-speaking world through Philip Kapleau‘s book The Three Pillars of Zen (1965), which was one of the first books to introduce Western audiences to Zen as a practice rather than simply a philosophy. Among the Zen groups in North America, Hawaii, Europe, and New Zealand which derive from Sanbo Kyodan are those associated with Kapleau, Robert Aitken, and John Tarrant.

In the UK, Throssel Hole Abbey was founded as a sister monastery to Shasta Abbey in California by Master Reverend Jiyu Kennett Roshi and has a number of dispersed Priories and centres. Jiyu Kennett, an English woman, was ordained as a priest and Zen master in Shoji-ji, one of the two main Soto Zen temples in Japan (her book The Wild White Goose describes her experiences in Japan). The Order is called the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives. The lineage of Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi Roshi is represented by the White Plum Sangha UK, while Taisen Deshimaru Roshi’s lineage is known in the UK as IZAUK (Intl Zen Assoc. UK). The Zen Centre in London is connected to the Buddhist Society. The Western Chan Fellowship is an association of lay Chan practitioners based in the UK. They are registered as a charity in England and Wales, but also have contacts in Europe, principally in Norway, Poland, Germany, Croatia, Switzerland and the USA.

There are also a number of Rinzai Zen centers in the West. In North America, some of the more prominent include Rinzai-ji founded by Kyozan Joshu Sasaki, Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji established by Eido Shimano and Kyudo Nakagawi Roshi, Chozen-ji founded by Omori Sogen Roshi and Chobo-Ji founded by Genki Takabayshi. In Europe there is Egely Monastery established by a Dharma Heir of Eido Shimano, Denko Mortensen.

Not all the successful Zen teachers in the West have been from Japanese traditions. There have also been teachers of Chan, Seon, and Thien Buddhism. In addition, there are a number of Zen teachers who studied in Asian traditions that because of corruption or political issues decided to strike out on their own. One organization of this type is Open Mind Zen in Melbourne, Florida.

File:CTTBgate.jpg Covering over 480 acres of land and located in Talmage, California, the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas was founded by Hsuan Hua.

The first Chinese master to teach Westerners in North America was Hsuan Hua, who taught Zen, Chinese Pure Land, Tiantai, Vinaya, and Vajrayana Buddhism in San Francisco during the early 1960s. He went on to found the City Of Ten Thousand Buddhas, a monastery and retreat center located on a 237 acre (959,000 m²) property near Ukiah, California. Another Chinese Zen teacher with a Western following is Sheng-yen, a master trained in both the Caodong and Linji schools (equivalent to the Japanese Soto and Rinzai, respectively). He first visited the United States in 1978 under the sponsorship of the Buddhist Association of the United States, and, in 1980, founded the Chan Meditation Center in Queens, New York.[12].

The most prominent Korean Zen teacher in the West was Seung Sahn. Seung Sahn founded the Providence Zen Center in Providence, Rhode Island; this was to become the headquarters of the Kwan Um School of Zen, a large international network of affiliated Zen centers.

Two notable Vietnamese Zen teachers have been influential in Western countries: Thich Thien-An and Thich Nhat Hanh. Thich Thien-An came to America in 1966 as a visiting professor at UCLA and taught traditional Thien meditation. Thich Nhat Hanh was a monk in Vietnam during the Vietnam War, during which he was a peace activist. In response to these activities, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967 by Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1966, he left Vietnam in exile and now resides at Plum Village, a monastery in France. He has written more than one hundred books about Buddhism, which have made him one of the very few most prominent Buddhist authors among the general readership in the West. In his books and talks, Thich Nhat Hanh emphasizes mindfulness (sati) as the most important practice in daily life.

Pan-lineage organizations

Template:Globalise

In the United States, two pan-lineage organizations have formed in the last few years. The oldest is the American Zen Teachers Association which sponsors an annual conference. North American Soto teachers in North America, led by several of the heirs of Taizan Maezumi and Shunryu Suzuki, have also formed the Soto Zen Buddhist Association.

See also

|

|

|

|

Modern

|

|

Traditional

|

Notes

- ↑ The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Zen Living, pg. 174

- ↑ The complete Idiot’s Guide to Zen Living, p. 7

- ↑ Thomas Cleary. Classics of Buddhism and Zen: Volume One, 250, Boston, MA: Shambhala publications.

- ↑ Zen’s Chinese Heritage (http://www.southmountaintours.com/pages/ZCH/zch.htm) by Andy Ferguson, 2000, Wisdom Publications, Boston, page 17.

- ↑ Suzuki, Daisetz T. (2004). The Training of the Zen Budhist Monk, Tokyo: Cosimo, inc.. ISBN 1-5960-5041-1.

- ↑ «Baizhang Huaihai», in Digital Dictionary of Buddhism

- ↑ «Principles of Zazen» (Zazen gi); tr. The Soto Zen Text Project

- ↑ «Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen» (Fukan zazengi); tr. The Soto Zen Text Project

- ↑ Welter, Albert The Disputed Place of «A Special Transmission» Outside the Scriptures in Ch’an. URL accessed on 2006-06-23.

- ↑ For example see the essay «Keizan, Koans, and Succession in the Soto School» by Francis Dojun Cook in «Sitting with Koans -Essential Writings on Zen Koan Introspection», edited by John Daido Loori, 2006, Wisdom Publications, Boston, ISBN 0-86171-369-9

- ↑ «Points of Departure — Zen Buddhism with a Rinzai View» by Eido T. Shimano, 1991, The Zen Studies Society Press, Livingston Manor, NY ISBN 0-962946-0-1, page 152

- ↑ «[1]», in Upaya Zen Center Liturgy

- ↑ «[2]», in Upaya Zen Center Liturgy

- ↑ «[3]», in Loori, John Daido. «Symbol and Symbolized.» Mountain Record: The Zen Practitioner’s Journal, XXV, No. 2 (2007):

- ↑ «[4]», in Translation of Dogen’s Gabyo, by Yasuda Joshu roshi and Anzan Hoshin roshi»

- ↑ «[5]», in Zen Mountain Monastery Dharma Talk by John Daido Loori, Roshi

- ↑ Template:Harvcolnb

- ↑ Great religions of the world. Center for Distance Learning. Tarrant County College DistrictPDF (1.03 MiB)

- ↑ Chang, Chung-Yuan (1967), «Ch’an Buddhism: Logical and Illogical», Philosophy East and West 17: 37-49, http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-PHIL/ew27057.htm.

- ↑ Suzuki, D.T. (1948), Manual of Zen Buddhism, pp. 50, http://consciouslivingfoundation.org/ebooks/new2/ManualOfZenBuddhism-manzen.pdf PDF (211 KiB)

- ↑ Template:Harvcolnb

- ↑ Template:Harvcolnb «the Taoist influence on Buddhism was later to culminate in the teachings of the Zen school.»

- ↑ Maspero, Henri. Translated by Frank A. Kierman, Jr. Taoism and Chinese Religion. pg 46. University of Massachusetts, 1981.

- ↑ Prebish, Charles. Buddhism: A Modern Perspective. Pg 192. Penn State Press, 1975. ISBN 0271011955.

- ↑ Template:Harvcolnb

- ↑ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Volume One), pages 57, 130

- ↑ The Platform Sutra of he Sixth Patriarch, translated with notes by by Philip B. Yampolsky, 1967, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-08361-0, page 29, note 87

- ↑ Template:Harvcolnb

- ↑ WOMEN IN ZEN BUDDHISM: Chinese Bhiksunis in the Ch’an Tradition by Heng-Ching Shih

- ↑ Jogye order of Korean Buddhism

- ↑ Zen in the Art of Archery, (ISBN 0-375-70509-0)

- ↑ Shoji, Yamada The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery. URL accessed on 2007-01-03.

- ↑ Heller, Christine Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder: Chasing Zen Clouds. URL accessed on 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Warneka, T. H. (2005). Leading People the Black Belt Way: Conquering the Five Core Problems Facing Leaders Today.

References

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History, 1: India and China, Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, ISBN 0-941532-89-5.

- Hori, Victor Sogen, Zen Sand

- Miura, Isshū; Sasaki, Ruth Fuller (1993), The Zen Koan, New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, ISBN 0-15-699981-1

- Suzuki, D.T. (1949), Essays in Zen Buddhism, New York: Grove Press, ISBN 0-8021-5118-3.

- An Introduction to Zen Buddhism by D.T. Suzuki

- Nagatomo, Shigenori (2006-06-28), «Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy», Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Blackman, Sushila (1997). Graceful Exits: How Great Beings Die: Death Stories of Tibetan, Hindu & Zen Masters. Weatherhill, Inc.: USA, New York, New York. ISBN 0-8348-0391-7

- Brian Daizen Victoria: Zen at War, (War and Peace Library), Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2nd edition, (August 2006), ISBN 0742539261(10), ISBN 978-0742539266(13)

Further references

Abe, M. (1998). The self in Jung and Zen. New York, NY: North Point Press.

- Aitken, R. (1982). Zen practice and psychotherapy: Journal of Transpersonal Psychology Vol 14(2) 1982, 161-170.

- Akishige, Y. (1977). Psychological studies on Zen: II. Oxford, England: Komazawa U.

- Anbeek, C. W., & de Groot, P. A. (2002). Buddhism and psychotherapy in the West: Nishitani and dialectical behavior therapy. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

- Anzai, J. (1970). Two cases of Zen awakening (Kensho) experiences: I. Master Shibayama’s case: Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient Vol 13(2-3) Sep 1970, 140-144.

- Austin, J. H. (1998). Zen and the brain: Toward an understanding of meditation and consciousness. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Austin, J. H. (2006). Zen-Brain reflections. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ausubel, D. P., Stager, M., & Gaite, A. J. (1968). Retroactive Facilitation in Meaningful Verbal Learning: Journal of Educational Psychology Vol 59(4) Aug 1968, 250-255.

- Ausubel, D. P., Stager, M., & Gaite, A. J. (1969). Proactive effects in meaningful verbal learning and retention: Journal of Educational Psychology Vol 60(1) Feb 1969, 59-64.

- Ausubel, D. P., & Youssef, M. (1963). Role of discriminability in meaningful paralleled learning: Journal of Educational Psychology Vol 54(6) Dec 1963, 331-336.

- Bankart, C. P., Dockett, K. H., & Dudley-Grant, G. R. (2003). On the path of the Buddha: A psychologists’ guide to the history of Buddhism. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Barreira, C. R. A., & Massimi, M. (2003). The Karate-Do Psychopedagogic Ideas and Spirituality According to Gichin Funakoshi’s Work: Psicologia: Reflexao e Critica Vol 16(2) 2003, 379-388.

- Barrett, D. J. (1995). A zen approach to the psychological and pastoral care of dying persons. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Battista, J. R. (1996). Contemporary physics and transpersonal psychiatry. New York, NY: Basic Books.