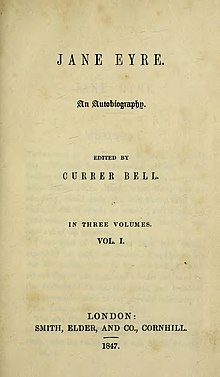

Title page of the first Jane Eyre edition |

|

| Author | Charlotte Brontë |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Gothic Bildungsroman Romance |

| Set in | Northern England, early 19th century[a] |

| Publisher | Smith, Elder & Co. |

|

Publication date |

19 October 1847[1] |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 3163777 |

|

Dewey Decimal |

823.8 |

| Followed by | Shirley |

| Text | Jane Eyre at Wikisource |

Jane Eyre ( AIR; originally published as Jane Eyre: An Autobiography) is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name «Currer Bell» on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The first American edition was published the following year by Harper & Brothers of New York.[2] Jane Eyre is a Bildungsroman which follows the experiences of its eponymous heroine, including her growth to adulthood and her love for Mr Rochester, the brooding master of Thornfield Hall.[3]

The novel revolutionised prose fiction by being the first to focus on its protagonist’s moral and spiritual development through an intimate first-person narrative, where actions and events are coloured by a psychological intensity. Charlotte Brontë has been called the «first historian of the private consciousness», and the literary ancestor of writers like Marcel Proust and James Joyce.[4]

The book contains elements of social criticism with a strong sense of Christian morality at its core, and it is considered by many to be ahead of its time because of Jane’s individualistic character and how the novel approaches the topics of class, sexuality, religion, and feminism.[5][6] It, along with Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, is one of the most famous romance novels.[7]

Plot[edit]

Jane Eyre is divided into 38 chapters. It was originally published in three volumes in the 19th century, comprising chapters 1 to 15, 16 to 27, and 28 to 38.

The second edition was dedicated to William Makepeace Thackeray.

The novel is a first-person narrative from the perspective of the title character. Its setting is somewhere in the north of England, late in the reign of George III (1760–1820).[a] It has five distinct stages: Jane’s childhood at Gateshead Hall, where she is emotionally and physically abused by her aunt and cousins; her education at Lowood School, where she gains friends and role models but suffers privations and oppression; her time as governess at Thornfield Hall, where she falls in love with her mysterious employer, Edward Fairfax Rochester; her time in the Moor House, during which her earnest but cold clergyman cousin, St John Rivers, proposes to her; and ultimately her reunion with, and marriage to, her beloved Rochester. Throughout these sections, it provides perspectives on a number of important social issues and ideas, many of which are critical of the status quo.

The five stages of Jane’s life:

Gateshead Hall[edit]

Young Jane argues with her guardian Mrs Reed of Gateshead, illustration by F. H. Townsend

Jane Eyre, aged 10, lives at Gateshead Hall with her maternal uncle’s family, the Reeds, as a result of her uncle’s dying wish. Jane was orphaned several years earlier when her parents died of typhus. Jane’s uncle, Mr Reed, was the only one in the Reed family who was kind to Jane. Jane’s aunt, Sarah Reed, dislikes her and treats her as a burden. Mrs Reed also discourages her three children from associating with Jane. As a result, Jane becomes defensive against her cruel judgement. The nursemaid, Bessie, proves to be Jane’s only ally in the household, even though Bessie occasionally scolds Jane harshly. Excluded from the family activities, Jane lives an unhappy childhood.

One day, as punishment for defending herself against the bullying of her 14-year-old cousin John, the Reeds’ only son, Jane is locked in the red room in which her late uncle had died; there, she faints from panic after she thinks she has seen his ghost. The red room is significant because it lays the grounds for the «ambiguous relationship between parents and children» which plays out in all of Jane’s future relationships with male figures throughout the novel.[8] She is subsequently attended to by the kindly apothecary Mr Lloyd to whom Jane reveals how unhappy she is living at Gateshead Hall. He recommends to Mrs Reed that Jane should be sent to school, an idea Mrs Reed happily supports.

Mrs Reed then enlists the aid of the harsh Mr Brocklehurst, who is the director of Lowood Institution, a charity school for girls, to enroll Jane. Mrs Reed cautions Mr Brocklehurst that Jane has a «tendency for deceit», which he interprets as Jane being a liar. Before Jane leaves, however, she confronts Mrs Reed and declares that she’ll never call her «aunt» again. Jane also tells Mrs Reed and her daughters, Georgiana and Eliza, that they are the ones who are deceitful, and that she will tell everyone at Lowood how cruelly the Reeds treated her. Mrs Reed is hurt badly by these words, but does not have the courage or tenacity to show this.[9]

Lowood Institution[edit]

At Lowood Institution, a school for poor and orphaned girls, Jane soon finds that life is harsh. She attempts to fit in and befriends an older girl, Helen Burns. During a class session, her new friend is criticised for her poor stance and dirty nails, and receives a lashing as a result. Later, Jane tells Helen that she could not have borne such public humiliation, but Helen philosophically tells her that it would be her duty to do so. Jane then tells Helen how badly she has been treated by Mrs Reed, but Helen tells her that she would be far happier if she did not bear grudges.

In due course, Mr Brocklehurst visits the school. While Jane is trying to make herself look inconspicuous, she accidentally drops her slate, thereby drawing attention to herself. She is then forced to stand on a stool, and is branded a sinner and a liar. Later, Miss Temple, the caring superintendent, facilitates Jane’s self-defence and publicly clears her of any wrongdoing. Helen and Miss Temple are Jane’s two main role models who positively guide her development, despite the harsh treatment she has received from many others.

The 80 pupils at Lowood are subjected to cold rooms, poor meals, and thin clothing. Many students fall ill when a typhus epidemic strikes; Helen dies of consumption in Jane’s arms. When Mr Brocklehurst’s maltreatment of the students is discovered, several benefactors erect a new building and install a sympathetic management committee to moderate Mr Brocklehurst’s harsh rule. Conditions at the school then improve dramatically.

Thornfield Hall[edit]

After six years as a student and two as a teacher at Lowood, Jane decides to leave in pursuit of a new life, growing bored with her life at Lowood. Her friend and confidante, Miss Temple, also leaves after getting married. Jane advertises her services as a governess in a newspaper. The housekeeper at Thornfield Hall, Alice Fairfax, replies to Jane’s advertisement. Jane takes the position, teaching Adèle Varens, a young French girl.

One night, while Jane is carrying a letter to the post from Thornfield, a horseman and dog pass her. The horse slips on ice and throws the rider. Despite the rider’s surliness, Jane helps him get back onto his horse. Later, back at Thornfield, she learns that this man is Edward Rochester, master of the house. Adèle was left in his care when her mother, a famous dancer, abandoned her. It is not immediately apparent whether Adèle is Rochester’s daughter or not.

At Jane’s first meeting with Mr Rochester, he teases her, accusing her of bewitching his horse to make him fall. Jane stands up to his initially arrogant manner. Despite his strange behaviour, Mr Rochester and Jane soon come to enjoy each other’s company, and they spend many evenings together.

Odd things start to happen at the house, such as a strange laugh being heard, a mysterious fire in Mr Rochester’s room (from which Jane saves Rochester by rousing him and throwing water on him), and an attack on a house-guest named Mr Mason.

After Jane saves Mr Rochester from the fire, he thanks her tenderly and emotionally, and that night Jane feels strange emotions of her own towards him. The next day however he leaves unexpectedly for a distant party gathering, and several days later returns with the whole party, including the beautiful and talented Blanche Ingram. Jane sees that Blanche and Mr Rochester favour each other and starts to feel jealous, particularly because she also sees that Blanche is snobbish and heartless.

Jane then receives word that Mrs Reed has suffered a stroke and is calling for her. Jane returns to Gateshead Hall and remains there for a month to tend to her dying aunt. Mrs Reed confesses to Jane that she wronged her, bringing forth a letter from Jane’s paternal uncle, Mr John Eyre, in which he asks for her to live with him and be his heir. Mrs Reed admits to telling Mr Eyre that Jane had died of fever at Lowood. Soon afterward, Mrs Reed dies, and Jane helps her cousins after the funeral before returning to Thornfield.

Back at Thornfield, Jane broods over Mr Rochester’s rumoured impending marriage to Blanche Ingram. However, one midsummer evening, Rochester baits Jane by saying how much he will miss her after getting married and how she will soon forget him. The normally self-controlled Jane reveals her feelings for him. Rochester then is sure that Jane is sincerely in love with him, and he proposes marriage. Jane is at first skeptical of his sincerity, before accepting his proposal. She then writes to her Uncle John, telling him of her happy news.

As she prepares for her wedding, Jane’s forebodings arise when a strange woman sneaks into her room one night and rips Jane’s wedding veil in two. As with the previous mysterious events, Mr Rochester attributes the incident to Grace Poole, one of his servants. During the wedding ceremony, however, Mr Mason and a lawyer declare that Mr Rochester cannot marry because he is already married to Mr Mason’s sister, Bertha. Mr Rochester admits this is true but explains that his father tricked him into the marriage for her money. Once they were united, he discovered that she was rapidly descending into congenital madness, and so he eventually locked her away in Thornfield, hiring Grace Poole as a nurse to look after her. When Grace gets drunk, Rochester’s wife escapes and causes the strange happenings at Thornfield.

It turns out that Jane’s uncle, Mr John Eyre, is a friend of Mr Mason’s and was visited by him soon after Mr Eyre received Jane’s letter about her impending marriage. After the marriage ceremony is broken off, Mr Rochester asks Jane to go with him to the south of France and live with him as husband and wife, even though they cannot be married. Jane is tempted but realises that she will lose herself and her integrity if she allows her passion for a married man to consume her, and she must stay true to her Christian values and beliefs. Refusing to go against her principles, and despite her love for Rochester, Jane leaves Thornfield Hall at dawn before anyone else is up.[10]

Moor House[edit]

St John Rivers admits Jane to Moor House, illustration by F. H. Townsend

Jane travels as far from Thornfield Hall as she can using the little money she had previously saved. She accidentally leaves her bundle of possessions on the coach and is forced to sleep on the moor. She unsuccessfully attempts to trade her handkerchief and gloves for food. Exhausted and starving, she eventually makes her way to the home of Diana and Mary Rivers but is turned away by the housekeeper. She collapses on the doorstep, preparing for her death. Clergyman St John Rivers, Diana and Mary’s brother, rescues her. After Jane regains her health, St John finds her a teaching position at a nearby village school. Jane becomes good friends with the sisters, but St John remains aloof.

The sisters leave for governess jobs, and St John becomes slightly closer to Jane. St John learns Jane’s true identity and astounds her by telling her that her uncle, John Eyre, has died and left her his entire fortune of 20,000 pounds (equivalent to US $2.24 million in 2022[11]). When Jane questions him further, St John reveals that John Eyre is also his and his sisters’ uncle. They had once hoped for a share of the inheritance but were left virtually nothing. Jane, overjoyed by finding that she has living and friendly family members, insists on sharing the money equally with her cousins, and Diana and Mary come back to live at Moor House.

Proposals[edit]

Thinking that the pious and conscientious Jane will make a suitable missionary’s wife, St John asks her to marry him and to go with him to India, not out of love, but out of duty. Jane initially accepts going to India but rejects the marriage proposal, suggesting they travel as brother and sister. As soon as Jane’s resolve against marriage to St John begins to weaken, she mystically hears Mr Rochester’s voice calling her name. Jane then returns to Thornfield Hall to see if Rochester is all right, only to find blackened ruins. She learns that Rochester sent Mrs Fairfax into retirement and Adèle to school a few months following her departure. Shortly afterwards, his wife set the house on fire and died after jumping from the roof. While saving the servants and attempting to rescue his wife, Rochester lost a hand and his eyesight.

Jane reunites with Rochester, and he is overjoyed at her return, but fears that she will be repulsed by his condition. «Am I hideous, Jane?», he asks. «Very, sir; you always were, you know», she replies. Now a humbled man, Rochester vows to live a purer life, and reveals that he has intensely pined for Jane ever since she left; he even called out her name in despair one night (the very call that she heard from Moor House), and heard her reply from miles away, signifying the connection between them. Jane asserts herself as a financially independent woman and assures him of her love, declaring that she will never leave him; Rochester proposes again, and they are married. They live blissfully together in an old house in the woods called Ferndean Manor. The couple stay in touch with Adèle as she grows up, as well as Diana and Mary, who each gain loving husbands of their own. St John moves to India to accomplish his missionary goals, but is implied to have fallen gravely ill there. Rochester regains sight in one eye two years after his and Jane’s marriage, enabling him to see their newborn son.

Major characters[edit]

In order of first line of dialogue:

Chapter 1[edit]

- Jane Eyre: The novel’s narrator and protagonist, she eventually becomes the second wife of Edward Rochester. Orphaned as a baby, Jane struggles through her nearly loveless childhood and becomes a governess at Thornfield Hall. Small and facially plain, Jane is passionate and strongly principled and values freedom and independence. She also has a strong conscience and is a determined Christian. She is ten at the beginning of the novel, and nineteen or twenty at the end of the main narrative. As the final chapter of the novel states that she has been married to Edward Rochester for ten years, she is approximately thirty at its completion.

- Mrs Sarah Reed (née Gibson): Jane’s maternal aunt by marriage, who reluctantly adopted Jane in accordance with her late husband’s wishes. According to Mrs Reed, he pitied Jane and often cared for her more than for his own children. Mrs Reed’s resentment leads her to abuse and neglect the girl. She lies to Mr Brocklehurst about Jane’s tendency to lie, preparing him to be severe with Jane when she arrives at Brocklehurst’s Lowood School.

- John Reed: Jane’s fourteen-year-old first cousin who bullies her incessantly and violently, sometimes in his mother’s presence. Addicted to food and sweets, causing him ill health and bad complexion. John eventually ruins himself as an adult by drinking and gambling and is rumoured to have committed suicide.

- Eliza Reed: Jane’s thirteen-year-old first cousin. Envious of her more attractive younger sister and a slave to a rigid routine, she self-righteously devotes herself to religion. She leaves for a nunnery near Lisle (France) after her mother’s death, determined to estrange herself from her sister.

- Georgiana Reed: Jane’s eleven-year-old first cousin. Although beautiful and indulged, she is insolent and spiteful. Her elder sister Eliza foils Georgiana’s marriage to the wealthy Lord Edwin Vere when the couple is about to elope. Georgiana eventually marries a «wealthy worn-out man of fashion.»

- Bessie Lee: The nursemaid at Gateshead Hall. She often treats Jane kindly, telling her stories and singing her songs, but she has a quick temper. Later, she marries Robert Leaven with whom she has three children.

- Miss Martha Abbot: Mrs Reed’s maid at Gateshead Hall. She is unkind to Jane and tells Jane she has less right to be at Gateshead than a servant does.

Chapter 3[edit]

- Mr Lloyd: A compassionate apothecary who recommends that Jane be sent to school. Later, he writes a letter to Miss Temple confirming Jane’s account of her childhood and thereby clears Jane of Mrs Reed’s charge of lying.

Chapter 4[edit]

- Mr Brocklehurst: The clergyman, director, and treasurer of Lowood School, whose maltreatment of the pupils is eventually exposed. A religious traditionalist, he advocates for his charges the most harsh, plain, and disciplined possible lifestyle, but, hypocritically, not for himself and his own family. His second daughter, Augusta, exclaimed, «Oh, dear papa, how quiet and plain all the girls at Lowood look… they looked at my dress and mama’s, as if they had never seen a silk gown before.»

Chapter 5[edit]

- Miss Maria Temple: The kind superintendent of Lowood School, who treats the pupils with respect and compassion. She helps clear Jane of Mr Brocklehurst’s false accusation of deceit and cares for Helen in her last days. Eventually, she marries Reverend Naysmith.

- Miss Scatcherd: A sour and strict teacher at Lowood. She constantly punishes Helen Burns for her untidiness but fails to see Helen’s substantial good points.

- Helen Burns: Jane’s best friend at Lowood School. She refuses to hate those who abuse her, trusts in God, and prays for peace one day in heaven. She teaches Jane to trust Christianity and dies of consumption in Jane’s arms. Elizabeth Gaskell, in her biography of the Brontë sisters, wrote that Helen Burns was ‘an exact transcript’ of Maria Brontë, who died of consumption at age 11.[12]

Chapter 11[edit]

- Mrs Alice Fairfax: The elderly, kind widow and the housekeeper of Thornfield Hall; distantly related to the Rochesters.

- Adèle Varens: An excitable French child to whom Jane is a governess at Thornfield Hall. Adèle’s mother was a dancer named Céline. She was Mr Rochester’s mistress and claimed that Adèle was Mr Rochester’s daughter, though he refuses to believe it due to Céline’s unfaithfulness and Adèle’s apparent lack of resemblance to him. Adèle seems to believe that her mother is dead (she tells Jane in chapter 11, «I lived long ago with mamma, but she is gone to the Holy Virgin»). Mr Rochester later tells Jane that Céline actually abandoned Adèle and «ran away to Italy with a musician or singer» (ch. 15). Adèle and Jane develop a strong liking for one another, and although Mr Rochester places Adèle in a strict school after Jane flees Thornfield Hall, Jane visits Adèle after her return and finds a better, less severe school for her. When Adèle is old enough to leave school, Jane describes her as «a pleasing and obliging companion—docile, good-tempered and well-principled», and considers her kindness to Adèle well repaid.

- Grace Poole: «…a woman of between thirty and forty; a set, square-made figure, red-haired, and with a hard, plain face…» Mr Rochester pays her a very high salary to keep his mad wife, Bertha, hidden and quiet. Grace is often used as an explanation for odd happenings at the house such as strange laughter that was heard not long after Jane arrived. She has a weakness for drinking that occasionally allows Bertha to escape.

Chapter 12[edit]

- Edward Fairfax Rochester: The master of Thornfield Hall. A Byronic hero, he has a face «dark, strong, and stern.» He married Bertha Mason years before the novel begins.

- Leah: The housemaid at Thornfield Hall.

Chapter 17[edit]

- Blanche Ingram: Young socialite whom Mr Rochester plans to marry. Though possessing great beauty and talent, she treats social inferiors, Jane in particular, with undisguised contempt. Mr Rochester exposes her and her mother’s mercenary motivations when he puts out a rumour that he is far less wealthy than they imagine.

Chapter 18[edit]

- Richard Mason: An Englishman whose arrival at Thornfield Hall from the West Indies unsettles Mr Rochester. He is the brother of Rochester’s first wife, the woman in the attic, and still cares for his sister’s well-being. During the wedding ceremony of Jane and Mr Rochester, he exposes the bigamous nature of the marriage.

Chapter 21[edit]

- Robert Leaven: The coachman at Gateshead Hall, who brings Jane the news of the death of the dissolute John Reed, an event which has brought on Mrs Reed’s stroke. He informs her of Mrs Reed’s wish to see Jane before she dies.

Chapter 26[edit]

- Bertha Antoinetta Mason: The first wife of Edward Rochester. After their wedding, her mental health began to deteriorate, and she is now violent and in a state of intense derangement, apparently unable to speak or go into society. Mr Rochester, who insists that he was tricked into the marriage by a family who knew Bertha was likely to develop this condition, has kept Bertha locked in the attic at Thornfield Hall for years. She is supervised and cared for by Grace Poole, whose drinking sometimes allows Bertha to escape. After Richard Mason stops Jane and Mr Rochester’s wedding, Rochester finally introduces Jane to Bertha: «In the deep shade, at the farther end of the room, a figure ran backwards and forwards. What it was, whether beast or human being, one could not, at first sight, tell… it snatched and growled like some strange wild animal: but it was covered with clothing, and a quantity of dark, grizzled hair, wild as a mane, hid its head and face.» Eventually, Bertha sets fire to Thornfield Hall and throws herself to her death from the roof. Bertha is viewed as Jane’s «double»: Jane is pious and just, while Bertha is savage and animalistic.[13] Though her race is never mentioned, it is sometimes conjectured that she was of mixed race. Rochester suggests that Bertha’s parents wanted her to marry him, because he was of «good race», implying that she was not pure white, while he was. There are also references to her «dark» hair and «discoloured» and «black» face.[14] A number of writers during the Victorian period suggested that madness could result from a racially «impure» lineage, compounded by growing up in a tropical West Indian climate.[15][16]

Chapter 28[edit]

- Diana and Mary Rivers: Sisters in a remote moors house who take Jane in when she is hungry and friendless, having left Thornfield Hall without making any arrangements for herself. Financially poor but intellectually curious, the sisters are deeply engrossed in reading the evening Jane appears at their door. Eventually, they are revealed to be Jane’s cousins. They want Jane to marry their stern clergyman brother so that he will stay in England rather than journey to India as a missionary. Diana marries naval Captain Fitzjames, and Mary marries clergyman Mr Wharton. The sisters remain close to Jane and visit her and Rochester every year.

- Hannah: The kindly housekeeper at the Rivers home; «…comparable with the Brontës’ well-loved servant, Tabitha Aykroyd.»

- St John Eyre Rivers: A handsome, though severe and serious, clergyman who befriends Jane and turns out to be her cousin. St John is thoroughly practical and suppresses all of his human passions and emotions, particularly his love for the beautiful and cheerful heiress Rosamond Oliver, in favour of good works. He wants Jane to marry him and serve as his assistant on his missionary journey to India. After Jane rejects his proposal, St John goes to India unmarried.

Chapter 32[edit]

- Rosamond Oliver: A beautiful, kindly, wealthy, but rather simple young woman, and the patron of the village school where Jane teaches. Rosamond is in love with St John, but he refuses to declare his love for her because she wouldn’t be suitable as a missionary’s wife. She eventually becomes engaged to the respected and wealthy Mr Granby.

- Mr Oliver: Rosamond Oliver’s wealthy father, who owns a foundry and needle factory in the district. «…a tall, massive-featured, middle-aged, and grey-headed man, at whose side his lovely daughter looked like a bright flower near a hoary turret.» He is a kind and charitable man, and he is fond of St John.

Context[edit]

The Salutation pub in Hulme, Manchester, where Brontë began to write Jane Eyre; the pub was a lodge in the 1840s.[17][18]

The early sequences, in which Jane is sent to Lowood, a harsh boarding school, are derived from the author’s own experiences. Helen Burns’s death from tuberculosis (referred to as consumption) recalls the deaths of Charlotte Brontë’s sisters, Elizabeth and Maria, who died of the disease in childhood as a result of the conditions at their school, the Clergy Daughters School at Cowan Bridge, near Tunstall, Lancashire. Mr Brocklehurst is based on Rev. William Carus Wilson (1791–1859), the Evangelical minister who ran the school. Additionally, John Reed’s decline into alcoholism and dissolution recalls the life of Charlotte’s brother Branwell, who became an opium and alcohol addict in the years preceding his death. Finally, like Jane, Charlotte became a governess. These facts were revealed to the public in The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) by Charlotte’s friend and fellow novelist Elizabeth Gaskell.[19]

The Gothic manor of Thornfield Hall was probably inspired by North Lees Hall, near Hathersage in the Peak District in Derbyshire. This was visited by Charlotte Brontë and her friend Ellen Nussey in the summer of 1845, and is described by the latter in a letter dated 22 July 1845. It was the residence of the Eyre family, and its first owner, Agnes Ashurst, was reputedly confined as a lunatic in a padded second floor room.[19] It has been suggested that the Wycoller Hall in Lancashire, close to Haworth, provided the setting for Ferndean Manor to which Mr Rochester retreats after the fire at Thornfield: there are similarities between the owner of Ferndean—Mr Rochester’s father—and Henry Cunliffe, who inherited Wycoller in the 1770s and lived there until his death in 1818; one of Cunliffe’s relatives was named Elizabeth Eyre (née Cunliffe).[20] The sequence in which Mr Rochester’s wife sets fire to the bed curtains was prepared in an August 1830 homemade publication of Brontë’s The Young Men’s Magazine, Number 2.[21] Charlotte Brontë began composing Jane Eyre in Manchester, and she likely envisioned Manchester Cathedral churchyard as the burial place for Jane’s parents and Manchester as the birthplace of Jane herself.[22]

Adaptations and influence[edit]

The novel has been adapted into a number of other forms, including theatre, film, television, and at least two full-length operas, by John Joubert (1987–1997) and Michael Berkeley (2000). The novel has also been the subject of a number of significant rewritings and related interpretations, notably Jean Rhys’s seminal 1966 novel Wide Sargasso Sea.[23]

On 19 May 2016, Cathy Marston’s ballet adaption was premiered by the Northern Ballet at the Cast Theatre in

Doncaster, England with Dreda Blow as Jane and Javier Torres as Rochester.[24]

In November 2016, a manga adaptation by Crystal S. Chan was published by Manga Classics Inc., with artwork by Sunneko Lee.[25][26]

Reception[edit]

Contemporary reviews[edit]

Jane Eyre‘s initial reception contrasts starkly to its reputation today. In 1848, Elizabeth Rigby (later Elizabeth Eastlake), reviewing Jane Eyre in The Quarterly Review, found it «pre-eminently an anti-Christian composition,»[27] declaring: «We do not hesitate to say that the tone of mind and thought which has overthrown authority and violated every code human and divine abroad, and fostered Chartism and rebellion at home, is the same which has also written Jane Eyre.«[27]

An anonymous review in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction writes of «the extraordinary daring of the writer of Jane Eyre«; however, the review is mostly critical, summarizing: «There is not a single natural character throughout the work. Everybody moves on stilts—the opinions are bad—the notions absurd. Religion is stabbed in the dark—our social distinctions attempted to be levelled, and all absurdly moral notions done away with.»[28]

There were some who felt more positive about the novel contemporaneously. George Henry Lewes said, «It reads like a page out of one’s own life; and so do many other pages in the book.»[29] Another critic from the Atlas wrote, «It is full of youthful vigour, of freshness and originality, of nervous diction and concentrated interest …It is a book to make the pulses gallop and the heart beat, and to fill the eyes with tears.»[30]

A review in The Era praised the novel, calling it «an extraordinary book», observing that «there is much to ponder over, rejoice over, and weep over, in its ably-written pages. Much of the heart laid bare, and the mind explored; much of greatness in affliction, and littleness in the ascendant; much of trial and temptation, of fortitude and resignation, of sound sense and Christianity—but no tameness.»[31]

The People’s Journal compliments the novel’s vigour, stating that «the reader never tires, never sleeps: the swell and tide of an affluent existence, an irresistible energy, bears him onward, from first to last. It is impossible to deny that the author possesses native power in an uncommon degree—showing itself now in rapid headlong recital, now in stern, fierce, daring dashes in portraiture—anon in subtle, startling mental anatomy—here in a grand illusion, there in an original metaphor—again in a wild gush of genuine poetry.»[32]

American publication The Nineteenth Century defended the novel against accusations of immorality, describing it as «a work which has produced a decided sensation in this country and in England… Jane Eyre has made its mark upon the age, and even palsied the talons of mercenary criticism. Yes, critics hired to abuse or panegyrize, at so much per line, have felt a throb of human feeling pervade their veins, at the perusal of Jane Eyre. This is extraordinary—almost preternatural—smacking strongly of the miraculous—and yet it is true… We have seen Jane Eyre put down, as a work of gross immorality, and its author described as the very incarnation of sensualism. To any one, who has read the work, this may look ridiculous, and yet it is true.»[33]

The Indicator, concerning speculation regarding the gender of the author, wrote, «We doubt not it will soon cease to be a secret; but on one assertion we are willing to risk our critical reputation—and that is, that no woman wrote it. This was our decided conviction at the first perusal, and a somewhat careful study of the work has strengthened it. No woman in all the annals of feminine celebrity ever wrote such a style, terse yet eloquent, and filled with energy bordering sometimes almost on rudeness: no woman ever conceived such masculine characters as those portrayed here.»[34]

Twentieth century[edit]

Literary critic Jerome Beaty believed the close first-person perspective leaves the reader «too uncritically accepting of her worldview», and often leads reading and conversation about the novel towards supporting Jane, regardless of how irregular her ideas or perspectives are.[35]

In 2003, the novel was ranked number 10 in the BBC’s survey The Big Read.[36]

Romance genre[edit]

Before the Victorian era, Jane Austen wrote literary fiction that influenced later popular fiction, as did the work of the Brontë sisters produced in the 1840s. Brontë’s love romance incorporates elements of both the gothic novel and Elizabethan drama, and «demonstrate[s] the flexibility of the romance novel form.»[37]

Themes[edit]

Race[edit]

Throughout the novel there are frequent themes relating to ideas of ethnicity (specifically that of Bertha), which are a reflection of the society that the novel is set within. Mr Rochester claims to have been forced to take on a «mad» Creole wife, a woman who grew up in the West Indies, and who is thought to be of mixed-race descent.[38] In the analysis of several scholars, Bertha plays the role of the racialized «other» through the shared belief that she chose to follow in the footsteps of her parents. Her alcoholism and apparent mental instability cast her as someone who is incapable of restraining herself, almost forced to submit to the different vices she is a victim of.[38] Many writers of the period believed that one could develop mental instability or mental illnesses simply based on their race.[39]

This means that those who were born of ethnicities associated with a darker complexion, or those who were not fully of European descent, were believed to be more mentally unstable than their white European counterparts were. According to American scholar Susan Meyer, in writing Jane Eyre Brontë was responding to the «seemingly inevitable» analogy in 19th-century European texts which «[compared] white women with blacks in order to degrade both groups and assert the need for white male control».[40] Bertha serves as an example of both the multiracial population and of a ‘clean’ European, as she is seemingly able to pass as a white woman for the most part, but also is hinted towards being of an ‘impure’ race since she does not come from a purely white or European lineage. The title that she is given by others of being a Creole woman leaves her a stranger where she is not black but is also not considered to be white enough to fit into higher society.[41]

Unlike Bertha, Jane Eyre is thought of as being sound of mind before the reader is able to fully understand the character, simply because she is described as having a complexion that is pale and she has grown up in a European society rather than in an «animalistic» setting like Bertha.[16] Jane is favoured heavily from the start of her interactions with Rochester, simply because like Rochester himself, she is deemed to be of a superior ethnic group than that of his first wife. While she still experiences some forms of repression throughout her life (the events of the Lowood Institution) none of them are as heavily taxing on her as that which is experienced by Bertha. Both women go through acts of suppression on behalf of the men in their lives, yet Jane is looked at with favour because of her supposed «beauty» that can be found in the colour of her skin. While both are characterized as falling outside of the normal feminine standards of this time, Jane is thought of as superior to Bertha because she demands respect and is able to use her talents as a governess, whereas Bertha is seen as a creature to be confined in the attic away from «polite» society.[42]

Wide Sargasso Sea[edit]

Jean Rhys intended her critically acclaimed novel Wide Sargasso Sea as an account of the woman whom Rochester married and kept in his attic. The book won the notable WH Smith Literary Award in 1967. Rhys explores themes of dominance and dependence, especially in marriage, depicting the mutually painful relationship between a privileged English man and a Creole woman from Dominica made powerless on being duped and coerced by him and others. Both the man and the woman enter marriage under mistaken assumptions about the other partner. Her female lead marries Mr Rochester and deteriorates in England as «The Madwoman in the Attic». Rhys portrays this woman from a quite different perspective from the one in Jane Eyre.

Feminism[edit]

The idea of the equality of men and women emerged more strongly in the Victorian period in Britain, after works by earlier writers, such as Mary Wollstonecraft. R. B. Martin described Jane Eyre as the first major feminist novel, «although there is not a hint in the book of any desire for political, legal, educational, or even intellectual equality between the sexes.» This is illustrated in chapter 23, when Jane responds to Rochester’s callous and indirect proposal:

-

-

- Do you think I am an automaton? a machine without feelings?…Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong—I have as much soul as you,—and full as much heart…I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh;—it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal,—as we are.[43][44]

-

The novel «acted as a catalyst» to feminist criticism with the publication by S. Gilbert and S. Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), the title of which alludes to Rochester’s wife.[45] The Brontës’ fictions were cited by feminist critic Ellen Moers as prime examples of Female Gothic, exploring woman’s entrapment within domestic space and subjection to patriarchal authority, and the transgressive and dangerous attempts to subvert and escape such restriction.[46] Both Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre explore this theme.[47]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The exact time setting of the novel is impossible to determine, as several references in the text are contradictory. For example, Marmion (pub. 1808) is referred to in Chapter 32 as a «new publication», but Adèle mentions crossing the Channel by steamship, impossible before 1816.

References[edit]

- ^ «On Tuesday next will be published, and may be had at all the libraries, JANE EYRE. An Autobiography. Edited by Currer Bell. 3 vols, post 8vo. London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 65, Cornhill». Daily News (London). 13 October 1847. p. 1.

- ^ «The HarperCollins Timeline». HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Lollar, Cortney. «Jane Eyre: A Bildungsroman». The Victorian Web. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Burt, Daniel S. (2008). The Literature 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Novelists, Playwrights, and Poets of All Time. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438127064.

- ^ Gilbert, Sandra; Gubar, Susan (1979). The Madwoman in the Attic. Yale University Press.

- ^ Martin, Robert B. (1966). Charlotte Brontë’s Novels: The Accents of Persuasion. New York: Norton.

- ^ Roberts, Timothy (2011). Jane Eyre. p. 8.

- ^ Wood, Madeleine. «Jane Eyre in the red-room: Madeleine Wood explores the consequences of Jane’s childhood trauma». Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ Brontë, Charlotte (16 October 1847). Jane Eyre. London, England: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 105.

- ^ Brontë, Charlotte (2008). Jane Eyre. Radford, Virginia: Wilder Publications. ISBN 978-1604594119.

- ^ calculated using the UK Retail Price Index: «Currency Converter, Pounds Sterling to Dollars, 1264 to Present (Java)».

- ^ Gaskell, Elizabeth (1857). The Life of Charlotte Brontë. Vol. 1. Smith, Elder & Co. p. 73.

- ^ Gubar II, Gilbert I (2009). Madwoman in the Attic after Thirty Years. University of Missouri Press.

- ^ Carol Atherton, The figure of Bertha Mason (2014), British Library https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-figure-of-bertha-mason Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Keunjung Cho, Contextualizing Racialized Interpretations of Bertha Mason’s Character (English 151, Brown University, 2003) http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/cho10.html Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ a b Nygren, Alexandra (2016). «Disabled and Colonized: Bertha Mason in Jane Eyre». The Explicator. 74 (2): 117–119. doi:10.1080/00144940.2016.1176001. S2CID 163827804.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Jane Eyre: a Mancunian?». BBC. 10 October 2006. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ «Salutation pub in Hulme thrown a lifeline as historic building is bought by MMU». Manchester Evening News. 2 September 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ a b Stevie Davies, Introduction and Notes to Jane Eyre. Penguin Classics ed., 2006.

- ^ «Wycoller Sheet 3: Ferndean Manor and the Brontë Connection» (PDF). Lancashire Countryside Service Environmental Directorale. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ «Paris museum wins Brontë bidding war». BBC News. 15 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ Alexander, Christine, and Sara L. Pearson. Celebrating Charlotte Brontë: Transforming Life into Literature in Jane Eyre. Brontë Society, 2016, p. 173.

- ^ Kellman, Steve G., ed. (2009). Magill’s Survey of World Literature. Salem Press. p. 2148. ISBN 9781587654312.

- ^ «Jane Eyre». Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Manga Classics: Jane Eyre (2016) Manga Classics Inc. ISBN 978-1927925652

- ^ Iipinski, Andrea (1 June 2017). «The manga in the middle». School Library Journal. 63 (6): 50 – via Gale Academic Onefile.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Arnold (Autumn 1968). «In Defense of Jane Eyre». SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 8 (4): 683. doi:10.2307/449473. JSTOR 449473.

- ^ «Anonymous review of Jane Eyre». The British Library. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ «Review of Jane Eyre by George Henry Lewes». The British Library. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ «Jane Eyre: contemporary critiques». The Sunday Times. 14 March 2003. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Review of Jane Eyre from the Era». The British Library. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ «Jane Eyre: An Autobiography. Edited by Currer Bell. Three Volumes». The People’s Journal. 1848. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Burr, C. Chauncey (1848). «Sensual Critics. Jane Eyre, By Currer Bell». The Nineteenth Century: 3 v. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ «Jane Eyre». The Indicator. 1848. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Beaty, Jerome. «St. John’s Way and the Wayward Reader» in Brontë, Charlotte (2001) [1847]. Dunn, Richard J. (ed.). Jane Eyre (Norton Critical Edition, Third ed.). W W Norton & Company. pp. 491–502. ISBN 0393975428.

- ^ «The Big Read». BBC. April 2003. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ Regis (2003), p. 85.

- ^ a b Atherton, Carol. «The figure of Bertha Mason.» British Library, 15 May 2014,www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-figure-of-bertha-mason. Accessed 3 March 2021.

- ^ Cho, Keunjung. «Contextualizing Racialized Interpretations of Bertha Mason’s Character.» The Victorian Web, 17 April 2003, www.victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/cho10.html. Accessed 3 March 2021.

- ^ Meyer, Susan (1990). «Colonialism and the Figurative Strategy of Jane Eyre». Victorian Studies. 33 (2): 247–268. JSTOR 3828358.

- ^ Thomas, Sue (1999). «The Tropical Extravagance of Bertha Mason». Victorian Literature and Culture. 27 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1017/S106015039927101X. JSTOR 25058436. S2CID 162220216.

- ^ Shuttleworth, Sally (2014). «Jane Eyre and the 19th Century Woman». The British Library.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Martin, Robert B. Charlotte Brontë’s Novels: The Accents of Persuasion. NY: Norton, 1966, p. 252

- ^ «Jane Eyre, Proto-Feminist vs. ‘The Third Person Man'». P. J. Steyer ’98 (English 73, Brown University, 1996). Victorian Web

- ^ The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature, ed. Marion Wynne-Davis. (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1990), p. 633.

- ^ Moers, Ellen (1976). Literary Women. Doubleday. ISBN 9780385074278.

- ^ Rosemary Jackson, Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion, 1981, pp. 123–129.

External links[edit]

- Jane Eyre at Standard Ebooks

- Jane Eyre at Project Gutenberg

Jane Eyre public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Jane Eyre at the Internet Archive

- Jane Eyre at the British Library

Ваш текст переведен частично.

Вы можете переводить не более 999 символов за один раз.

Войдите или зарегистрируйтесь бесплатно на PROMT.One и переводите еще больше!

<>

Jane eyre

существительное

Jane Eyre

имя собственное

Контексты

Well, I was gonna read «Jane Eyre» and eat burritos.

Ну, а я собиралась почитать «Джейн Эйр» и поесть буррито.

Now she provided me with such an exact description of the mysterious Jane Eyre to relieve me of any doubt.

И она снабдила меня таким точным описанием таинственной мисс Джейн Эйр, что у меня не осталось сомнений.

The same incredible imaginations that produced «The Origin of Species,» «Jane Eyre» and «The Remembrance of Things Past,» also generated intense worries that haunted the adult lives of Charles Darwin, Charlotte BrontД Е and Marcel Proust.

Воображение, породившее «Происхождение видов», «Джейн Эйр» и «В поисках потерянного времени», создавало также тревоги и мании, отравлявшие жизнь Чарльза Дарвина, Шарлотты Бронте и Марселя Пруста.

Pip from «Great Expectations» was adopted; Superman was a foster child; Cinderella was a foster child; Lisbeth Salander, the girl with the dragon tattoo, was fostered and institutionalized; Batman was orphaned; Lyra Belacqua from Philip Pullman’s «Northern Lights» was fostered; Jane Eyre, adopted; Roald Dahl’s James from «James and the Giant Peach;» Matilda; Moses — Moses!

Пипа из «Больших надежд» усыновили. Супермен был приёмным ребёнком. Золушка была приёмным ребёнком. Лизбет Саландер, девушка с татуировкой дракона, была усыновлена и взята на попечение. Бэтман был сиротой. Лира Белакуа из «Северного Сияния» Филипа Пулмана была приёмным ребёнком. Джейн Эйр усыновили. Джеймс из «Джеймс и гигантский персик» Роальда Даля. Матильда, Моисей — Моисей!

Miss Eyre, is it your opinion that children are born the way God intended them to be, that bad blood will always be bad blood?

Мисс Эйр, как по-вашему, дети рождаются такими, какими их создал Бог, что дурная кровь всегда будет дурной?

Бесплатный переводчик онлайн с английского на русский

Хотите общаться в чатах с собеседниками со всего мира, понимать, о чем поет Билли Айлиш, читать английские сайты на русском? PROMT.One мгновенно переведет ваш текст с английского на русский и еще на 20+ языков.

Точный перевод с транскрипцией

С помощью PROMT.One наслаждайтесь точным переводом с английского на русский, а для слов и фраз смотрите английскую транскрипцию, произношение и варианты переводов с примерами употребления в разных контекстах. Бесплатный онлайн-переводчик PROMT.One — достойная альтернатива Google Translate и другим сервисам, предоставляющим перевод с английского на русский и с русского на английский.

Нужно больше языков?

PROMT.One бесплатно переводит онлайн с английского на азербайджанский, арабский, греческий, иврит, испанский, итальянский, казахский, китайский, корейский, немецкий, португальский, татарский, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, украинский, финский, французский, эстонский и японский.

Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Bronte

Transcribed from the 1897 Service & Paton edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

JANE EYRE AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

by

CHARLOTTE BRONTË

ILLUSTRATED BY F. H. TOWNSEND

London

SERVICE & PATON

5 henrietta street

1897

The Illustrations

in this Volume are the copyright of

Service & Paton, London

TO

W. M. THACKERAY, Esq.,

This Work

is respectfully inscribed

by

THE AUTHOR

PREFACE

A preface to the first edition of “Jane Eyre” being unnecessary, I gave none: this second edition demands a few words both of acknowledgment and miscellaneous remark.

My thanks are due in three quarters.

To the Public, for the indulgent ear it has inclined to a plain tale with few pretensions.

To the Press, for the fair field its honest suffrage has opened to an obscure aspirant.

To my Publishers, for the aid their tact, their energy, their practical sense and frank liberality have afforded an unknown and unrecommended Author.

The Press and the Public are but vague personifications for me, and I must thank them in vague terms; but my Publishers are definite: so are certain generous critics who have encouraged me as only large-hearted and high-minded men know how to encourage a struggling stranger; to them, i.e., to my Publishers and the select Reviewers, I say cordially, Gentlemen, I thank you from my heart.

Having thus acknowledged what I owe those who have aided and approved me, I turn to another class; a small one, so far as I know, but not, therefore, to be overlooked. I mean the timorous or carping few who doubt the tendency of such books as “Jane Eyre:” in whose eyes whatever is unusual is wrong; whose ears detect in each protest against bigotry—that parent of crime—an insult to piety, that regent of God on earth. I would suggest to such doubters certain obvious distinctions; I would remind them of certain simple truths.

Conventionality is not morality. Self-righteousness is not religion. To attack the first is not to assail the last. To pluck the mask from the face of the Pharisee, is not to lift an impious hand to the Crown of Thorns.

These things and deeds are diametrically opposed: they are as distinct as is vice from virtue. Men too often confound them: they should not be confounded:

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Jane Eyre | |

|---|---|

Mabel Ballin as the title character in the 1921 film Jane Eyre. |

|

| First appearance | Jane Eyre (1847) |

| Created by | Charlotte Brontë |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Jane Elliott |

| Nickname | Janet |

| Title | Miss Eyre Mrs Rochester |

| Occupation | Governess |

| Family | Reverend Eyre (father, deceased) Jane Eyre (née Reed) (mother, deceased) |

| Spouse | Edward Fairfax Rochester |

| Children | Adèle Varens (daughter, adopted) Unnamed son |

| Relatives | John Eyre (uncle) Reed (uncle, deceased) Sarah Reed (née Gibson) (aunt by marriage) John Reed (cousin, deceased) Eliza Reed (cousin) Georgiana Reed (cousin) St. John Eyre Rivers (cousin) Diana Rivers (cousin) Mary Rivers (cousin) |

Jane Eyre is the fictional heroine and the titular protagonist in Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel of the same name. The story follows Jane’s infancy and childhood as an orphan, her employment first as a teacher and then as a governess, and her romantic involvement with her employer, the mysterious and moody Edward Rochester. Jane is noted by critics for her dependability, strong mindedness, and individualism. The author deliberately created Jane as an unglamorous figure, in contrast to conventional heroines of fiction, and possibly part-autobiographical.

Jane is a popular literary figure due to critical acclaim by readers for the impact she held on romantic and feminist writing. The novel has been adapted into a number of other forms, including theatre, film and television.

Development[edit]

Jane Eyre is an orphan living with her maternal uncle and his wealthy wife, Mrs. Reed. After Mr. Reed’s death, his wife is left to care for Jane. Jane is mistreated by her aunt who resents, neglects, and abuses her while claiming that the only reason for her care of Jane is charity, which leads to Jane’s overall anger towards the Reed family.

After a violent argument with her older cousin John, Jane is locked into the Red Room, the room which Mr. Reed died in and which Jane believes is haunted. After Jane believes that she sees her uncle’s ghost in the Red Room, she falls ill and faints. This leads to her being sent away to a school on the recommendation of the apothecary, Mr. Lloyd, who attends her, in lieu of a physician.

Mrs. Reed then sends Jane to Lowood Institution, a school for poor and orphaned girls. At Lowood, Jane is faced with Mr. Brocklehurst, who funds the school which his mother founded but is abusive in his oversight of the girls. At the school Jane befriends Helen Burns, from whom she learns to be more patient. Helen Burns later dies of consumption, while Jane survives a typhoid epidemic at the school.

During her time at Lowood, Jane receives a thorough education and becomes a friend of Miss Maria Temple, the school’s principal. After six years of schooling and two years of teaching at Lowood (without once returning to the Reeds’ house in Gateshead) Jane decides to go out into the world on her own. She seeks work as a governess and is employed at Thornfield Hall to care for a French born orphan, Adele. At Thornfield, Jane learns about the absent master, Mr. Rochester, and starts to teach his ward.

One evening, when Jane is out walking, she helps a mysterious man when his horse slips and he falls. She later learns that this is Mr. Rochester, her master. Jane and Rochester are immediately interested in each other. She is fascinated by his rough and dark appearance, as well as his abrupt, almost rude, manner, which she thinks is easier to handle than polite flattery. As for Mr. Rochester, he is very interested in Jane’s strength of character, comparing her to an elf or sprite and admiring her unusual strength and stubbornness.[1]

Rochester quickly learns that he can rely on Jane in a crisis. One night, after everybody has retired, strange sounds and smoke lead her to Rochester’s room, where she finds Rochester asleep in his bed with all the curtains and bedclothes on fire; she puts out the flames and rescues him.

While Jane is working at Thornfield, Rochester invites his acquaintances over for a week-long stay, including the beautiful Blanche Ingram. Rochester lets Blanche flirt with him constantly in front of Jane to make her jealous and encourages rumours that he is engaged to Blanche, which devastates Jane.

During the house party, a man named Richard Mason arrives, and Rochester appears to be afraid of him. At night, Mason sneaks up to the third floor and somehow gets stabbed and bitten. Rochester asks Jane to tend Richard Mason’s wounds secretly while he fetches the doctor. The next morning before the guests find out what happened, Rochester sneaks Mason out of the house.

Before Jane can discover more about the mysterious situation, she gets a message that her Aunt Reed is very sick and is asking for her. Jane, forgiving Mrs. Reed for mistreating her when she was a child, goes back to see her dying aunt. When Jane returns to Thornfield, Blanche and her friends are gone, and Jane realizes how attached she is to Mr. Rochester. Although he lets her think for a little longer that he is going to marry Blanche, eventually Rochester stops teasing Jane and proposes to her. She accepts.

On the day of Jane’s wedding, two men arrive claiming that Rochester is already married. Rochester admits that he is married to another woman, but tries to justify his attempt to marry Jane by taking them all to see his «wife». Mrs. Rochester is Bertha Mason, the «madwoman in the attic» who tried to burn Rochester to death in his bed, stabbed and bit her own brother (Richard Mason), and who has been carrying out several other unusual acts at night. Rochester was tricked into marrying Bertha fifteen years ago in Jamaica by his father, who wanted him to marry for money. Rochester tried to live with Bertha as husband and wife, but her behaviour was too difficult, so he locked her up at Thornfield with a nursemaid, Grace Poole. Meanwhile, he travelled around Europe for ten years trying to forget Bertha and keeping various mistresses. Adèle Varens (Jane’s student) is the daughter of one of these mistresses, though she may not be Rochester’s daughter. Eventually he got tired of this lifestyle, came home to England and fell in love with Jane.

After explaining all this, Rochester claims that he was not really married because his relationship with Bertha wasn’t a real marriage. He wants Jane to come and live with him in France, where they can pretend to be a married couple and live as husband and wife. Jane refuses to be his next mistress and runs away before she is tempted to agree.

Jane travels in a direction away from Thornfield. Having no money, she is almost starving to death before being taken in by the Rivers family, who live at Moor House near a town called Morton. The Rivers siblings – Diana, Mary, and St. John (pronounced «Sinjun») – are about Jane’s age and well-educated, although somewhat poor. They take whole-heartedly to Jane, who has taken the pseudonym «Jane Elliott» so that Mr. Rochester can’t find her. Jane wants to earn her keep, so St. John arranges for her to become the teacher in a village girls’ school. When Jane’s uncle, Mr. Eyre, dies and leaves his fortune to his niece, it turns out that the Rivers siblings are actually Jane’s cousins, and she shares her inheritance with the other three.

St. John, who is a devoted clergyman, wants to be more than Jane’s cousin. He admires Jane’s work ethic and asks her to marry him, learn Hindustani, and go with him to India on a long-term missionary trip. Jane is tempted because she thinks she would be good at it and that it would be an interesting life. Still, she refuses because she knows she doesn’t love St. John, and he does not love her either. He simply believes Jane would make a good missionary’s wife because of her skills. St. John actually loves a different girl named Rosamond Oliver, but he won’t let himself admit it because he thinks she would make an unsuitable wife for a missionary.

Jane offers to go to India with him, but just as his cousin and co-worker, not as his wife. St. John won’t give up and keeps pressuring Jane to marry him. As she is about to give in, she imagines Mr. Rochester’s voice calling her name.

The next morning, Jane leaves Moor House and goes back to Thornfield to find out what has happened to Mr. Rochester. She finds out that he searched for her everywhere, and, when he couldn’t find her, sent everyone else away from the house and shut himself up alone. After this, Bertha set the house on fire one night and burned it to the ground. Rochester rescued all the servants and tried to save Bertha, too, but she committed suicide and he was injured. Now Rochester has lost an eye and a hand and is blind in the remaining eye.

Jane goes to Mr. Rochester and offers to take care of him as his nurse or housekeeper. He asks her to marry him and they have a quiet wedding, and after two years of marriage Rochester gradually gets his sight back – enough to see their firstborn son.

Characteristics and conception[edit]

Jane Eyre is described as plain, with an elfin look. Jane describes herself as, «poor, obscure, plain and little.» Mr. Rochester once compliments Jane’s «hazel eyes and hazel hair», but she informs the reader that Mr. Rochester was mistaken, as her eyes are not hazel; they are in fact green.

It has been said that «Charlotte Brontë may have created the character of Jane Eyre as a means of coming to terms with elements of her own life.»[2] By all accounts, Brontë’s «homelife was difficult.»[3] It is apparent that much of the poverty and social injustice (particularly towards women) that are prevalent in the novel, were also a part of Charlotte Brontë’s life.[4] Jane’s school, Lowood, is said to be based on the Clergy Daughters School at Cowan Bridge, where two of Brontë’s sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died. Brontë declared, «I will show you a heroine as plain and as small as myself,» in regards to creating Jane Eyre.[3]

When she was twenty, Brontë wrote to Robert Southey for his thoughts on writing. «Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life, and it ought not to be», he said. When Jane Eyre was published about ten years later, it was purportedly written by Jane, and called Jane Eyre: An Autobiography, with Currer Bell (Brontë) merely as editor. And yet, Brontë still published as Currer Bell, a man.[3]

Historical and cultural context[edit]

The Victorian Era in which Charlotte Brontë wrote her novel Jane Eyre provides the cultural framework in which the narrative was developed.[5] Victorian themes are present throughout the novel, including the idea of an angel in the house, the standard of an ideal woman, and the various settings in which the story takes place.[6] The complex role of the woman in Victorian society is highlighted by Bronte’s exploration of the appropriate conventions of gender relations in tandem with economic class, marriage, and social status.[5] This image of Victorian England is challenged by Bronte’s representation of Eyre’s relationship with Rochester, as one that is not motivated by calculated obligation to achieve a desirable social status but rather an autonomous choice made by a woman to marry for love.[5]

Jane Eyre has been described by historian David Hackett Fischer as evocative of a cultural and geographic milieu of the North Midlands of England that in the mid-17th century had produced the Religious Society of Friends, a Protestant religious sect. Many members of this sect immigrated to North America and settled the Delaware Valley in the late 17th and early 18th century.[7] This geographical area had for many centuries contained a significant population of Scandinavian-descended people who were oppressed by and resisted the Norman Conquest based in French Catholicism (the Gothic feature in Jane Eyre, represented by Edward Rochester) and had remained distinct from the Anglo-Saxon culture that produced the Puritan sect (the evangelical Calvinist feature in Jane Eyre, variants of which are represented by Brocklehurst and St. John).[8]

Analysis[edit]

Perhaps the first novel to express the idea of the self was Jane Eyre, who from the very start of the novel «resisted all the way» as she was being carried to the Red Room.[9] As stated by Karen Swallow Prior of The Atlantic: «As unbelievable as many of the events of the novel are, even today, Brontë’s biggest accomplishment wasn’t in plot devices. It was the narrative voice of Jane—who so openly expressed her desire for identity, definition, meaning, and agency—that rang powerfully true to its 19th-century audience.»[9]

However, there are some details that are difficult to analyse as the author’s intentions are unclear. For example, critics have debated if Jane Eyre is supposed to represent the author’s life. Several critics have argued that Brontë wrote Jane Eyre as a reflection of how she sees herself: someone who is unglamorous and misunderstood.[10] Other critics disagree and believe that Brontë disconnects herself entirely from the book by creating a fictional autobiography. They explain that is why Brontë chose to give the book its title, «Jane Eyre: An Autobiography».[10]

Portrayals in adaptations[edit]

Film[edit]

Silent films[edit]

- Irma Taylor as adult Jane and Marie Eline as young Jane in Jane Eyre (1910)[11]

- Lisbeth Blackstone in Jane Eyre (1914)[12]

- Ethel Grandin in Jane Eyre (1914)

- Louise Vale in Jane Eyre (1915)[13]

- Alice Brady in Woman and Wife (1918)[14]

- Mabel Ballin in Jane Eyre (1921)[15]

- Evelyn Holt in Orphan of Lowood (1926)

Feature films[edit]

- Virginia Bruce (adult) and Jean Darling (child) in Jane Eyre (1934)

- Joan Fontaine (adult) and Peggy Ann Garner (child) in Jane Eyre (1943)

- Madhubala as Kamala, Jane’s equivalent in the 1952 Hindi-language adaptation Sangdil (transl. Stone-hearted)

- Magda al-Sabahi as Jane’s equivalent in the 1962 Egyptian adaption The Man I Love

- Chandrakala as Jane’s equivalent in the 1968 Indian Kannada-language film Bedi Bandavalu

- Kanchana as Malathi, Jane’s equivalent in the 1969 Indian Tamil-language film Shanti Nilayam (transl. Peaceful House)

- Anjali Devi as Jane’s equivalent in the 1972 Indian Telagu-language film Shanti Nilayam

- Susannah York (adult) and Sara Gibson (child) in Jane Eyre (1970)

- Charlotte Gainsbourg (adult) and Anna Paquin (child) in Jane Eyre (1996)

- Samantha Morton (adult) and Laura Harling (child) in Jane Eyre (1997)

- Mia Wasikowska (adult) and Amelia Clarkson (child) in Jane Eyre (2011)

Radio[edit]

- Madeleine Carroll in Jane Eyre by The Campbell Playhouse (31 March 1940)[16]

- Bette Davis in Jane Eyre by The Screen Guild Theater (2 March 1941)[17]

- Joan Fontaine in Jane Eyre by The Philco Radio Hall of Fame (13 February 1944)[18]

- Loretta Young in Jane Eyre by The Lux Radio Theatre (5 June 1944)

- Gertrude Warner in Jane Eyre by Matinee Theater (3 December 1944)[19]

- Alice Frost in Jane Eyre by The Mercury Summer Theatre of the Air (28 June 1946)[20]

- Ingrid Bergman in Jane Eyre by The Lux Radio Theatre (14 June 1948)[21]

- Deborah Kerr in Jane Eyre by NBC University Theatre (1949)[22]

- Sophie Thompson in Jane Eyre on BBC Radio 7 (24–27 August 2009)[23]

- Amanda Hale (adult) and Nell Venables (child) in Jane Eyre on BBC Radio 4’s 15 Minute Drama (2016)[24]

Television[edit]

- Mary Sinclair in the Studio One in Hollywood episode Jane Eyre, aired on 12 December 1949[25]

- Katharine Bard in the Studio One in Hollywood episode Jane Eyre, aired on 4 August 1952[26]

- Daphne Slater in the 1956 BBC miniseries Jane Eyre

- Joan Elan in the 1957 NBC Matinee Theatre drama Jane Eyre[27]

- Sally Ann Howes in Jane Eyre, a 1961 television film directed by Marc Daniels[28]

- Ann Bell (adult) and Rachel Clay (child) in the 1963 BBC series Jane Eyre[29]

- Marta Vančurová in Jana Eyrová, a 1972 production by Czechoslovak Television

- Sorcha Cusack (adult) and Juliet Waley (child) in the 1973 BBC serial Jane Eyre[30]

- Daniela Romo (adult) and Erika Carrasco (child) as Mariana, Jane’s equivalent in the 1978 Mexican telenovela Ardiente secreto (transl. The Burning Secret)

- Andrea Martin in BBC Classics Presents: Jane Eyrehead, a parody by SCTV (1982)

- Zelah Clarke (adult) and Sian Pattenden (child) in the 1983 BBC serial Jane Eyre

- Ruth Wilson (adult) and Georgie Henley (child) in the 2006 BBC serial Jane Eyre

- Anarkali Akarsha as Suwimali, Jane’s equivalent in the 2007 Sri Lankan teledrama Kula Kumariya, screened on Swarnavahini

Theatre[edit]

-

Lotten Dorsch in the title role of Jane Eyre at Nya Teatern in 1881.

In other literature[edit]

The character of Jane Eyre features in much literature inspired by the novel, including prequels, sequels, rewritings and reinterpretations from different characters’ perspectives.

References[edit]

- ^ Gilbert, Sandra & Gubar, Susan (1979). The Madwoman in the Attic. Yale University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ «Analysis of Major Characters, «Jane Eyre«». Home : English : Literature Study Guides : Jane Eyre. Sparknotes. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

Charlotte Brontë may have created the character of Jane Eyre as a means of coming to terms with elements of her own life.

- ^ a b c Lilia Melani? (2005-03-29). «Charlotte Brontë, «Jane Eyre«». Core Studies 6: Landmarks of Literature. Brooklyn College. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ Batterson, Courtney (2016-02-19). ««Feminism» and Feminism: A Rhetorical Criticism of Emma Watson’s Address to the U.N.» Quest: A Journal of Undergraduate Research. 5: 1. doi:10.17062/qjur.v5.i1.p1. ISSN 2381-4543.

- ^ a b c Earnshaw, Steven (September 2012). «‘Give me my name’: Naming and Identity In and Around Jane Eyre». Brontë Studies. 37 (3): 174–189. doi:10.1179/1474893212Z.00000000018. ISSN 1474-8932. S2CID 162728294.

- ^ Marchbanks, Paul (2006-12-01). «Jane Air: The Heroine as Caged Bird in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca». Revue LISA / LISA e-journal (Vol. IV – n°4): 118–130. doi:10.4000/lisa.1922. ISSN 1762-6153.

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett (1989). Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford University Press. p. 445. ISBN 978-0-19-506905-1.

- ^ Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America, pp. 445–446.

- ^ a b Prior, Karen Swallow (2016-03-03). «How ‘Jane Eyre’ Helped Popularize the Concept of the Self». The Atlantic. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- ^ a b Berg, Maggie (1987). Jane Eyre : portrait of a life. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-1835-5. OCLC 733952602.

- ^ Q. David Bowers (1995). «Volume 2: Filmography — Jane Eyre». Thanhouser.org. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ «Jane Eyre». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ «Jane Eyre | Movie Synopsis Available, Read the Plot of the Film Online». VH1.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ «Woman and Wife». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ «Jane Eyre». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ «The Campbell Playhouse: Jane Eyre». Orson Welles on the Air, 1938–1946. Indiana University Bloomington. 31 March 1940. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ «Screen Guild Theater Jane Eyre» – via Internet Archive.

- ^ The Philco Radio Hall of Fame – Jane Eyre at the Internet Archive

- ^ The Matinee Theatre – Jane Eyre at the Internet Archive

- ^ «The Mercury Summer Theatre». RadioGOLDINdex. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ The Lux Radio Theatre – Jane Eyre at the Internet Archive

- ^ «NBC University Theater». National Broadcasting Company. 3 April 1949.

- ^ «Jane Eye by Charlotte Bronte, adapted by Michelene Wandor — BBC Radio 7, 24–27 August 009». Radio Drama Reviews Online. 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ «Jane Eyre». 15 Minute Drama, Radio 4. BBC. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ «Studio One in Hollywood – Jane Eyre». Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ «Studio One in Hollywood – Jane Eyre«. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ Hawes, William (2001). Filmed Television Drama, 1952–1958. McFarland. p. 49. ISBN 978-0786411320.

- ^ Dick, Kleiner (13 May 1961). «Differences on Opinion on TV». Morning Herald. Hagerstown, Maryland. p. 5.

- ^ «Drama – Jane Eyre – The History of Jane Eyre On-Screen». BBC. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ Teachman, Debra (2001). Understanding Jane Eyre: A Student Casebook to Issues, Sources, and Historical Documents. Greenwood Press. pp. 202. ISBN 978-0313309397.

Jane Eyre sorcha.

- ^ Stoneman, Patsy (2007). Jane Eyre on Stage, 1848–1898: An Illustrated Edition of Eight Plays With Contextual Notes. Ashgate Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 9780754603481.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Jane Eyre | |

|---|---|

Mabel Ballin as the title character in the 1921 film Jane Eyre. |

|

| First appearance | Jane Eyre (1847) |

| Created by | Charlotte Brontë |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Jane Elliott |

| Nickname | Janet |

| Title | Miss Eyre Mrs Rochester |

| Occupation | Governess |

| Family | Reverend Eyre (father, deceased) Jane Eyre (née Reed) (mother, deceased) |

| Spouse | Edward Fairfax Rochester |

| Children | Adèle Varens (daughter, adopted) Unnamed son |

| Relatives | John Eyre (uncle) Reed (uncle, deceased) Sarah Reed (née Gibson) (aunt by marriage) John Reed (cousin, deceased) Eliza Reed (cousin) Georgiana Reed (cousin) St. John Eyre Rivers (cousin) Diana Rivers (cousin) Mary Rivers (cousin) |

Jane Eyre is the fictional heroine and the titular protagonist in Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel of the same name. The story follows Jane’s infancy and childhood as an orphan, her employment first as a teacher and then as a governess, and her romantic involvement with her employer, the mysterious and moody Edward Rochester. Jane is noted by critics for her dependability, strong mindedness, and individualism. The author deliberately created Jane as an unglamorous figure, in contrast to conventional heroines of fiction, and possibly part-autobiographical.

Jane is a popular literary figure due to critical acclaim by readers for the impact she held on romantic and feminist writing. The novel has been adapted into a number of other forms, including theatre, film and television.

Development[edit]

Jane Eyre is an orphan living with her maternal uncle and his wealthy wife, Mrs. Reed. After Mr. Reed’s death, his wife is left to care for Jane. Jane is mistreated by her aunt who resents, neglects, and abuses her while claiming that the only reason for her care of Jane is charity, which leads to Jane’s overall anger towards the Reed family.

After a violent argument with her older cousin John, Jane is locked into the Red Room, the room which Mr. Reed died in and which Jane believes is haunted. After Jane believes that she sees her uncle’s ghost in the Red Room, she falls ill and faints. This leads to her being sent away to a school on the recommendation of the apothecary, Mr. Lloyd, who attends her, in lieu of a physician.

Mrs. Reed then sends Jane to Lowood Institution, a school for poor and orphaned girls. At Lowood, Jane is faced with Mr. Brocklehurst, who funds the school which his mother founded but is abusive in his oversight of the girls. At the school Jane befriends Helen Burns, from whom she learns to be more patient. Helen Burns later dies of consumption, while Jane survives a typhoid epidemic at the school.

During her time at Lowood, Jane receives a thorough education and becomes a friend of Miss Maria Temple, the school’s principal. After six years of schooling and two years of teaching at Lowood (without once returning to the Reeds’ house in Gateshead) Jane decides to go out into the world on her own. She seeks work as a governess and is employed at Thornfield Hall to care for a French born orphan, Adele. At Thornfield, Jane learns about the absent master, Mr. Rochester, and starts to teach his ward.

One evening, when Jane is out walking, she helps a mysterious man when his horse slips and he falls. She later learns that this is Mr. Rochester, her master. Jane and Rochester are immediately interested in each other. She is fascinated by his rough and dark appearance, as well as his abrupt, almost rude, manner, which she thinks is easier to handle than polite flattery. As for Mr. Rochester, he is very interested in Jane’s strength of character, comparing her to an elf or sprite and admiring her unusual strength and stubbornness.[1]

Rochester quickly learns that he can rely on Jane in a crisis. One night, after everybody has retired, strange sounds and smoke lead her to Rochester’s room, where she finds Rochester asleep in his bed with all the curtains and bedclothes on fire; she puts out the flames and rescues him.

While Jane is working at Thornfield, Rochester invites his acquaintances over for a week-long stay, including the beautiful Blanche Ingram. Rochester lets Blanche flirt with him constantly in front of Jane to make her jealous and encourages rumours that he is engaged to Blanche, which devastates Jane.

During the house party, a man named Richard Mason arrives, and Rochester appears to be afraid of him. At night, Mason sneaks up to the third floor and somehow gets stabbed and bitten. Rochester asks Jane to tend Richard Mason’s wounds secretly while he fetches the doctor. The next morning before the guests find out what happened, Rochester sneaks Mason out of the house.

Before Jane can discover more about the mysterious situation, she gets a message that her Aunt Reed is very sick and is asking for her. Jane, forgiving Mrs. Reed for mistreating her when she was a child, goes back to see her dying aunt. When Jane returns to Thornfield, Blanche and her friends are gone, and Jane realizes how attached she is to Mr. Rochester. Although he lets her think for a little longer that he is going to marry Blanche, eventually Rochester stops teasing Jane and proposes to her. She accepts.

On the day of Jane’s wedding, two men arrive claiming that Rochester is already married. Rochester admits that he is married to another woman, but tries to justify his attempt to marry Jane by taking them all to see his «wife». Mrs. Rochester is Bertha Mason, the «madwoman in the attic» who tried to burn Rochester to death in his bed, stabbed and bit her own brother (Richard Mason), and who has been carrying out several other unusual acts at night. Rochester was tricked into marrying Bertha fifteen years ago in Jamaica by his father, who wanted him to marry for money. Rochester tried to live with Bertha as husband and wife, but her behaviour was too difficult, so he locked her up at Thornfield with a nursemaid, Grace Poole. Meanwhile, he travelled around Europe for ten years trying to forget Bertha and keeping various mistresses. Adèle Varens (Jane’s student) is the daughter of one of these mistresses, though she may not be Rochester’s daughter. Eventually he got tired of this lifestyle, came home to England and fell in love with Jane.

After explaining all this, Rochester claims that he was not really married because his relationship with Bertha wasn’t a real marriage. He wants Jane to come and live with him in France, where they can pretend to be a married couple and live as husband and wife. Jane refuses to be his next mistress and runs away before she is tempted to agree.

Jane travels in a direction away from Thornfield. Having no money, she is almost starving to death before being taken in by the Rivers family, who live at Moor House near a town called Morton. The Rivers siblings – Diana, Mary, and St. John (pronounced «Sinjun») – are about Jane’s age and well-educated, although somewhat poor. They take whole-heartedly to Jane, who has taken the pseudonym «Jane Elliott» so that Mr. Rochester can’t find her. Jane wants to earn her keep, so St. John arranges for her to become the teacher in a village girls’ school. When Jane’s uncle, Mr. Eyre, dies and leaves his fortune to his niece, it turns out that the Rivers siblings are actually Jane’s cousins, and she shares her inheritance with the other three.