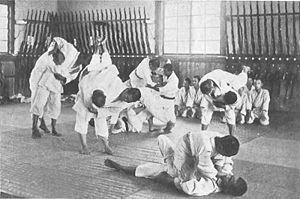

Jujutsu training at an agricultural school in Japan around 1920 |

|

| Also known as | Jujitsu, jiu-jitsu |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking, kicking, grappling, wrestling |

| Country of origin | Japan |

| Famous practitioners | Minamoto no Yoshimitsu, Mataemon Tanabe, Hansuke Nakamura, Kanō Jigorō, Hironori Ōtsuka, Tatsuo Suzuki (martial artist), Seishiro Okazaki, Matsugoro Okuda, Hikosuke Totsuka, Takeda Sōkaku, Morihei Ueshiba, Minoru Mochizuki |

| Parenthood | Various ancient and medieval Japanese martial arts |

| Ancestor arts | Tegoi, sumo |

| Descendant arts | Judo, aikido, kosen judo, wadō-ryū, sambo (via judo), Brazilian jiu-jitsu (via judo), ARB (via judo), bartitsu, yoseikan budō, taiho jutsu, kūdō (via judo), luta livre (via judo), vale tudo, krav maga (via judo and aikido), modern arnis, hapkido, hwa rang do, shoot wrestling, German ju-jutsu, atemi ju-jitsu, JJIF sport jujitsu, danzan-ryū, hakkō-ryū, kajukenbo, kapap, kenpo |

| Olympic sport | Judo |

| Jujutsu | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Jūjutsu in kanji |

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 柔術 | ||

|

Jujutsu ( joo-JIT-soo; Japanese: 柔術 jūjutsu, pronounced [dʑɯꜜːʑɯtsɯ] (listen)), also known as jiu-jitsu and ju-jitsu, is a family of Japanese martial arts and a system of close combat (unarmed or with a minor weapon) that can be used in a defensive or offensive manner to kill or subdue one or more weaponless or armed and armored opponents.[1][2] Jiu-jitsu dates back to the 1530s and was coined by Hisamori Tenenouchi when he officially established the first jiu-jitsu school in Japan. This form of martial arts uses few or no weapons at all and includes strikes, throws, holds, and paralyzing attacks against the enemy. Jujutsu developed from the warrior class around the 17th century in Japan. [3] It was designed to supplement the swordsmanship of a warrior during combat. A subset of techniques from certain styles of jujutsu were used to develop many modern martial arts and combat sports, such as judo, aikido, sambo, ARB, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and mixed martial arts. The official date of foundation of Jiu Jitsu is 1530.

Characteristics[edit]

«Jū» can be translated as «gentle, soft, supple, flexible, pliable, or yielding», and «jutsu» can be translated as «art or technique». «Jujutsu» thus has the meaning of «yielding-art», as its core philosophy is to manipulate the opponent’s force against themself rather than confronting it with one’s own force.[1] Jujutsu developed to combat the samurai of feudal Japan as a method for defeating an armed and armored opponent in which one uses no form of weapon, or only a short weapon.[4] Because striking against an armored opponent proved ineffective, practitioners learned that the most efficient methods for neutralizing an enemy took the form of pins, joint locks, and throws. These techniques were developed around the principle of using an attacker’s energy against them, rather than directly opposing it.[5]

There are many variations of the art, which leads to a diversity of approaches. Jujutsu schools (ryū) may utilize all forms of grappling techniques to some degree (e.g., throwing, takedowns, leg sweeps, trapping, pins, joint locks, holds, chokeholds, strangulation, gouging, biting, hair pulling, disengagements, and striking). In addition to jujutsu, many schools teach the use of weapons. Today, jujutsu is practiced in both traditional self-defense oriented and modern sports forms. Derived sport forms include the Olympic sport and martial art of judo, which was developed by Kanō Jigorō in the late 19th century from several traditional styles of jujutsu, and sambo and Brazilian jiu-jitsu, which were derived from earlier (pre–World War II) versions of Kodokan judo that had more emphasis on ground fighting (which also caused the creation of kosen judo).

Etymology[edit]

Jujutsu, the standard English language spelling, is derived using the Hepburn romanization system. Before the first half of the 20th century, however, jiu-Jitsu and ju-jitsu were preferred, even though the romanization of the second kanji as Jitsu is not faithful to the standard Japanese pronunciation. It was a non-standardized spelling resulting from how English-speakers heard the second short u in the word, which is pronounced /ɯ/ and therefore close to a short English i.[citation needed] This may also be a reflection of the speech of Shitamachi that merges ‘ju’ into ‘ji’. Since Japanese martial arts first became widely known of in the West in that time period, these earlier spellings are still common in many places. Ju-jitsu is still a common spelling in France, Canada, and the United Kingdom while jiu-jitsu is most widely used in Germany and Brazil. Different from the Japanese pronunciation, the word Jujutsu is still usually pronounced as if it is spelled jujitsu in the United States.

Some define jujutsu and similar arts rather narrowly as «unarmed» close combat systems used to defeat or control an enemy who is similarly unarmed. Basic methods of attack include hitting or striking, thrusting or punching, kicking, throwing, pinning or immobilizing, strangling, and joint locking. Great pains were also taken by the bushi (classic warriors) to develop effective methods of defense, including parrying or blocking strikes, thrusts and kicks, receiving throws or joint locking techniques (i.e., falling safely and knowing how to «blend» to neutralize a technique’s effect), releasing oneself from an enemy’s grasp, and changing or shifting one’s position to evade or neutralize an attack. As jujutsu is a collective term, some schools or ryu adopted the principle of ju more than others.

From a broader point of view, based on the curricula of many of the classical Japanese arts themselves, however, these arts may perhaps be more accurately defined as unarmed methods of dealing with an enemy who was armed, together with methods of using minor weapons such as the jutte (truncheon; also called jitter), tantō (knife), or kakushi buki (hidden weapons), such as the ryofundo kusari (weighted chain) or the bankokuchoki (a type of knuckle-duster), to defeat both armed or unarmed opponents.

Furthermore, the term jujutsu was also sometimes used to refer to tactics for infighting used with the warrior’s major weapons: katana or tachi (sword), yari (spear), naginata (glaive), jō (short staff), and bō (quarterstaff). These close combat methods were an important part of the different martial systems that were developed for use on the battlefield. They can be generally characterized as either Sengoku period (1467–1603) katchu bu Jutsu or yoroi kumiuchi (fighting with weapons or grappling while clad in armor), or Edo period (1603–1867) suhada bu Jutsu (fighting while dressed in the normal street clothing of the period, kimono and hakama).

The first Chinese character of jujutsu (Chinese and Japanese: 柔; pinyin: róu; rōmaji: jū; Korean: 유; romaja: yu) is the same as the first one in judo (Chinese and Japanese: 柔道; pinyin: róudào; rōmaji: jūdō; Korean: 유도; romaja: yudo). The second Chinese character of jujutsu (traditional Chinese and Japanese: 術; simplified Chinese: 术; pinyin: shù; rōmaji: jutsu; Korean: 술; romaja: sul) is the same as the second one in bujutsu (traditional Chinese and Japanese: 武術; simplified Chinese: 武术; pinyin: wǔshù; rōmaji: bujutsu; Korean: 무술; romaja: musul).

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The written history of Jujutsu first began during the Nara period (c. 710 – c. 794) combining early forms of Sumo and various Japanese martial arts which were used on the battlefield for close combat. The oldest known styles of Jujutsu are, Shinden Fudo-ryū (c. 1130), Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū (c. 1447), and Takenouchi-ryū, which was founded in 1530s. Many jujutsu forms also extensively taught parrying and counterattacking long weapons such as swords or spears via a dagger or other small weapons. In contrast to the neighbouring nations of China and Okinawa whose martial arts made greater use of striking techniques, Japanese hand-to-hand combat forms focused heavily upon throwing (including joint-locking throws), immobilizing, joint locks, choking, strangulation, and to lesser extent ground fighting.

In the early 17th century during the Edo period, jujutsu would continue to evolve due to the strict laws which were imposed by the Tokugawa shogunate to reduce war as influenced by the Chinese social philosophy of Neo-Confucianism which was obtained during Hideyoshi’s invasions of Korea and spread throughout Japan via scholars such as Fujiwara Seika.[6] During this new ideology, weapons and armor became unused decorative items, so hand-to-hand combat flourished as a form of self-defense and new techniques were created to adapt to the changing situation of unarmored opponents. This included the development of various striking techniques in jujutsu which expanded upon the limited striking previously found in jujutsu which targeted vital areas above the shoulders such as the eyes, throat, and back of the neck. However towards the 18th century the number of striking techniques was severely reduced as they were considered less effective and exert too much energy; instead striking in jujutsu primarily became used as a way to distract the opponent or to unbalance him in the lead up to a joint lock, strangle or throw.

During the same period the numerous jujutsu schools would challenge each other to duels which became a popular pastime for warriors under a peaceful unified government. From these challenges, randori was created to practice without risk of breaking the law and the various styles of each school evolved from combating each other without intention to kill.[7][8]

The term jūjutsu was not coined until the 17th century, after which time it became a blanket term for a wide variety of grappling-related disciplines and techniques. Prior to that time, these skills had names such as «short sword grappling» (小具足腰之廻, kogusoku koshi no mawari), «grappling» (組討 or 組打, kumiuchi), «body art» (体術, taijutsu), «softness» (柔 or 和, yawara), «art of harmony» (和術, wajutsu, yawarajutsu), «catching hand» (捕手, torite), and even the «way of softness» (柔道, jūdō) (as early as 1724, almost two centuries before Kanō Jigorō founded the modern art of Kodokan judo).[2]

Today, the systems of unarmed combat that were developed and practiced during the Muromachi period (1333–1573) are referred to collectively as Japanese old-style jujutsu (日本古流柔術, Nihon koryū jūjutsu). At this period in history, the systems practiced were not systems of unarmed combat, but rather means for an unarmed or lightly armed warrior to fight a heavily armed and armored enemy on the battlefield. In battle, it was often impossible for a samurai to use his long sword or polearm, and would, therefore, be forced to rely on his short sword, dagger, or bare hands. When fully armored, the effective use of such «minor» weapons necessitated the employment of grappling skills.

Methods of combat (as mentioned above) included striking (kicking and punching), various takedowns, trips, throwing (body throws, shoulder and hip throws, joint-locking throws, sacrifice throws, unbalance and leg sweeping throws), restraining (pinning, strangling, grappling, wrestling, and rope tying) and weaponry. Defensive tactics included blocking, evading, off-balancing, blending and escaping. Minor weapons such as the tantō (knife), ryofundo kusari (weighted chain), kabuto wari (helmet breaker), and Kaku shi buki (secret or disguised weapons) were almost always included in Sengoku jujutsu.

Development[edit]

In later times, other ko-ryū developed into systems more familiar to the practitioners of Nihon jujutsu commonly seen today. These are correctly classified as Edo jūjutsu (founded during the Edo period): they are generally designed to deal with opponents neither wearing armor nor in a battlefield environment but instead utilize grips and holds on opponent’s clothing. Most systems of Edo jujutsu include extensive use of atemi waza (vital-striking technique), which would be of little use against an armored opponent on a battlefield.[original research?] They would, however, be quite valuable in confronting an enemy or opponent during peacetime dressed in normal street attire (referred to as «suhada bujutsu»). Occasionally, inconspicuous weapons such as tantō (daggers) or tessen (iron fans) were included in the curriculum of Edo jūjutsu.

1911 French publication on jujutsu

Another seldom-seen historical side is a series of techniques originally included in both Sengoku and Edo jujutsu systems. Referred to as Hojo waza (捕縄術 hojojutsu, Tori Nawa Jutsu, nawa Jutsu, hayanawa and others), it involves the use of a hojo cord, (sometimes the sageo or tasuke) to restrain or strangle an attacker. These techniques have for the most part faded from use in modern times, but Tokyo police units still train in their use and continue to carry a hojo cord in addition to handcuffs. The very old Takenouchi-ryu is one of the better-recognized systems that continue extensive training in hojo waza. Since the establishment of the Meiji period with the abolishment of the Samurai and the wearing of swords, the ancient tradition of Yagyū Shingan-ryū (Sendai and Edo lines) has focused much towards the Jujutsu (Yawara) contained in its syllabus.

Many other legitimate Nihon jujutsu Ryu exist but are not considered koryu (ancient traditions). These are called either Gendai Jujutsu or modern jujutsu. Modern jujutsu traditions were founded after or towards the end of the Tokugawa period (1868) when more than 2000 schools (ryū) of jūjutsu existed. Various supposedly traditional ryu and ryuha that are commonly thought of as koryu jujutsu are actually gendai jūjutsu. Although modern in formation, very few gendai Jujutsu systems have direct historical links to ancient traditions and are incorrectly referred to as traditional martial systems or koryu. Their curriculum reflects an obvious bias towards techniques from judo and Edo jūjutsu systems, and sometimes have little to no emphasis on standing armlocks and joint-locking throws that were common in Koryu styles. They also usually do not teach usage of traditional weapons as opposed to the Sengoku jūjutsu systems that did. The improbability of confronting an armor-clad attacker and using traditional weapons is the reason for this bias.

Over time, Gendai jujutsu has been embraced by law enforcement officials worldwide and continues to be the foundation for many specialized systems used by police. Perhaps the most famous of these specialized police systems is the Keisatsujutsu (police art) Taiho jutsu (arresting art) system formulated and employed by the Tokyo Police Department.

Jujutsu techniques have been the basis for many military unarmed combat techniques (including British/US/Russian special forces and SO1 police units) for many years. Since the early 1900s, every military service in the world has an unarmed combat course that has been founded on the principal teachings of jujutsu.[9]

In the early 1900s[10] Edith Garrud became the first British female teacher of jujutsu,[11] and one of the first female martial arts instructors in the Western world.[12]

There are many forms of sports jujutsu, the original and most popular being judo, now an Olympic sport. One of the most common is mixed-style competitions, where competitors apply a variety of strikes, throws, and holds to score points. There are also kata competitions, where competitors of the same style perform techniques and are judged on their performance. There are also freestyle competitions, where competitors take turns attacking each other, and the defender is judged on performance. Another more recent form of competition growing much more popular in Europe is the Random Attack form of competition, which is similar to Randori but more formalized.

Description[edit]

The word Jujutsu can be broken down into two parts. «Ju» is a concept. The idea behind this meaning of Ju is «to be gentle», «to give way», «to yield», «to blend», «to move out of harm’s way». «Jutsu» is the principle or «the action» part of ju-jutsu. In Japanese this word means art.[13]

Japanese jujutsu systems typically put more emphasis on throwing, pinning, and joint-locking techniques as compared with martial arts such as karate, which rely more on striking techniques. Striking techniques were seen as less important in most older Japanese systems because of the protection of samurai body armor and because they were considered less effective than throws and grappling so were mostly used as set-ups for their grappling techniques and throws, although some styles, such as Yōshin-ryū, Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū and Kyushin-ryū had more emphasis on striking. However, many modern-day jujutsu schools include striking, both as a set-up for further techniques or as a stand-alone action.

In jujutsu, practitioners train in the use of many potentially fatal or crippling moves, such as joint-locking throws. However, because students mostly train in a non-competitive environment, the risk is minimized. Students are taught break falling skills to allow them to safely practice otherwise dangerous throws.

Old schools and derivations[edit]

As jujutsu has so many facets, it has become the foundation for a variety of styles and derivations today. As each instructor incorporated new techniques and tactics into what was taught to them originally, they codified and developed their own ryu (school) or Federation to help other instructors, schools, and clubs. Some of these schools modified the source material enough that they no longer consider themselves a style of jujutsu. Arguments and discussions amongst the martial arts fraternity have evoked to the topic of whether specific methods are in fact not jujitsu at all. Tracing the history of a specific school can be cumbersome and impossible in some circumstances.

Around the year 1600 there were over 2000 jujutsu ko-ryū styles, most with at least some common descent, characteristics, and shared techniques. Specific technical characteristics, list of techniques, and the way techniques were performed varied from school to school. Many of the generalizations noted above do not hold true for some schools of jujutsu. Schools of jujutsu with long lineages include:

- Asayama Ichiden-ryū 浅山一傳流

- Akishima-ryū/Akijima-ryū

- Araki-ryū

- Araki-ryu gunyo-kogusoku

- Maebashi-Han Araki-ryū

- Enka-ryū

- Fuhen-ryū

- Futagami-ryū

- Fuji-ryū Goshindo

- Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu

- Fusen-ryū 不遷流

- Gyokushin-ryū

- Hoshiyama-ryū

- Hongaku Kokki-ryū 本覚克己流

- Hontai Yōshin-ryū 本體楊心流(Takagi Ryu)高木流

- Shingetsu Muso Yanagi-ryū

- Iga-ryū 為我流

- Iga-ryūha-Katsushin-ryu 為我流派勝新流柔術

- Ishiguro-ryū 石黒流

- Kashima Shin-ryū 鹿島神流

- Jigō Tenshin-ryū/Ise Jitoku Tenshin-ryū

- Jishukan-ryū

- Jikishin-ryū

- Koden Koppo Taijutsu Genryu Tenshin-ryū

- Kosogabe-ryū

- Kensō-ryū 兼相流

- Kijin Chosui-ryū/Hontai Kijin Chosui-ryū

- Kiraku-ryū 気楽流

- Kitō-ryū 起倒流

- Takenaka-ha Kitō-ryū

- Kukishin-ryū九鬼神流[14]

- Kasumi Shin-ryū

- Enshin-ryū

- Kyushin-ryū

- Natsuhara-ryū 夏原流(夢想直伝流)

- Nanba Ippo-ryū

- Namba Shoshin-ryū

- Sekiguchi-ryū 関口流

- Senshin-ryū

- Shosho-ryū

- Shinto Tenshin-ryū/Tenshin Ko-ryū

- Shin no Shintō-ryū

- Shindō Yōshin-ryū 神道楊心流

- Shibukawa-ryū 渋川流

- Shibukawa Ichi-ryū

- Shiten-ryū

- Shishin Takuma-ryū

- Shinden Fudo-ryū

- Shinnuki-ryū

- Shin no Shindo-ryū

- Shinkage-ryū

- Sōsuishi-ryū 双水執流 (Sosuishitsu-ryū)

- Takenouchi-ryū 竹内流

- Takenouchi Santo-ryū

- Takenouchi Hogan-ryū

- Bitchū Den Takenouchi-ryū

- Tatsumi-ryū 立身流

- Tatsumi Shin-ryu

- Takagi-ryū

- Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū

- Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū 天神真楊流

- Ito-ha Shin’yō-ryū

- Tsutsumi Hōzan-ryū (Original)

- Inotani-ryū

- Iwaga-ryū

- Tennen Rishin-ryū 天然理心流

- Yagyū Shingan-ryū 柳生心眼流

- Goto-ha Yagyu Shingan-ryū

- Yamada-ryū

- Yōshin-ryū 楊心流

- Akiyama Yoshin-ryū

- Nakamura Yoshin Ko-ryū

- Kurama Yōshin-ryū

- Totsuka-ha Yoshin-ryū

- Sakkatsu Yōshin-ryū

- Shin Shin-ryū

- Shin Yōshin-ryū

- Motoha Yōshin-ryū

- Tagaki Yoshin-ryū

- Miura-ryū

- Mubyoshi-ryū

- Nagaoka Ken-ryū

- Nakazawa-ryū

- Oguri-ryū

- Otsubo-ryū

- Okamoto-ryū

- Ryugo-ryū

- Rikishin-ryū

- Ryōi Shintō-ryū

- Ryōi Shintō Kasahara-ryū

- Ryushin Katchu-ryū

- Yokokoro-ryū

Aikido[edit]

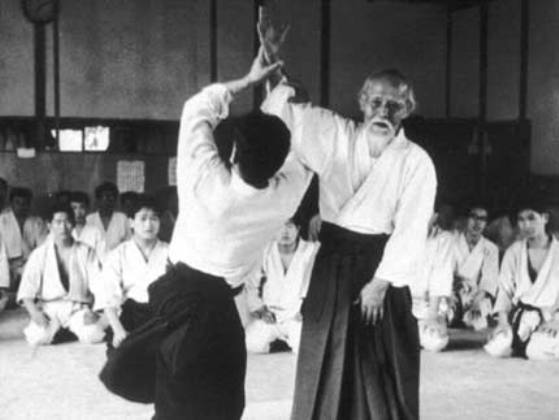

Aikido is a modern martial art developed primarily during the late 1920s through the 1930s by Morihei Ueshiba from the system of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu. Ueshiba was an accomplished student of Takeda Sokaku with aikido being a systemic refinement of defensive techniques from Aiki-Jujutsu in ways that are intended to prevent harm to either the attacker or the defender. Aikido changed much during Ueshiba’s lifetime, so earlier styles (such as Yoshinkan) are more like the original Aiki-Jujutsu than ones (such as Ki-Aikido) that more resemble the techniques and philosophy that Ueshiba stressed towards the end of his life.

Wado Ryu Karate[edit]

Wadō-ryū (和道流) is one of the four major karate styles and was founded by Hironori Otsuka (1892–1982). Wadō-ryū is a hybrid of Japanese Martial Arts such as Shindō Yōshin-ryū Ju-jitsu, Shotokan Karate, and Shito Ryu Karate. The style itself places emphasis on not only striking, but tai sabaki, joint locks and throws. It has its origins within Tomari-te.

From one point of view, Wadō-ryū might be considered a style of jū-jutsu rather than karate. Hironori Ōtsuka embraced ju-jitsu and was its chief instructor for a time. When Ōtsuka first registered his school with the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai in 1938, the style was called «Shinshu Wadō-ryū Karate-Jūjutsu,» a name that reflects its hybrid character. Ōtsuka was a licensed Shindō Yōshin-ryū practitioner and a student of Yōshin-ryū when he first met the Okinawan karate master Gichin Funakoshi. After having learned from Funakoshi, and after their split, with Okinawan masters such as Kenwa Mabuni and Motobu Chōki, Ōtsuka merged Shindō Yōshin-ryū with Okinawan karate. The result of Ōtsuka’s efforts is Wadō-ryū Karate.

Bartitsu[edit]

Jujutsu was first introduced to Europe in 1898 by Edward William Barton-Wright, who had studied Tenjin Shinyō-ryū and Shinden Fudo-ryū in Yokohama and Kobe. He also trained briefly at the Kodokan in Tokyo. Upon returning to England he folded the basics of all of these styles, as well as boxing, savate, and forms of stick fighting, into an eclectic self-defence system called Bartitsu.[15]

Judo[edit]

Main article: Judo

Modern judo is the classic example of a sport that derived from jujutsu. Many who study judo believe as Kanō did, that judo is not a sport but a self-defense system creating a pathway towards peace and universal harmony. Another layer removed, some popular arts had instructors who studied one of these jujutsu derivatives and later made their own derivative succeed in competition. This created an extensive family of martial arts and sports that can trace their lineage to jujutsu in some part.

The way an opponent is dealt with also depends on the teacher’s philosophy with regard to combat. This translates also in different styles or schools of jujutsu.

Not all jujutsu was used in sporting contests, but the practical use in the samurai world ended circa 1890. Techniques like hair-pulling, eye-poking, and groin attacks were and are not considered acceptable in sport, thus, they are excluded from judo competitions or randori. However, judo did preserve some more lethal, dangerous techniques in its kata. The kata were intended to be practised by students of all grades but now are mostly practised formally as complete set-routines for performance, kata competition and grading, rather than as individual self-defense techniques in class. However, judo retained the full set of choking and strangling techniques for its sporting form and all manner of joint locks. Even judo’s pinning techniques have pain-generating, spine-and-rib-squeezing and smothering aspects. A submission induced by a legal pin is considered a legitimate win. Kanō viewed the safe «contest» aspect of judo as an important part of learning how to control an opponent’s body in a real fight. Kanō always considered judo a form of, and development of, jujutsu.

A judo technique starts with gripping the opponent, followed by off-balancing them and using their momentum against them, and then applying the technique. Kuzushi (the art of breaking balance) is also used in jujutsu, whereby an opponent’s attack is deflected using their momentum against them in order to arrest their movements then throw them or pin them with a technique — thus controlling the opponent. It is known in both systems that kuzushi is essential in order to use as little energy as possible. Jujutsu differs from judo in a number of ways. In some circumstances, judoka generate kuzushi by striking one’s opponent along his weak line. Other methods of generating kuzushi include grabbing, twisting, poking or striking areas of the body known as atemi points or pressure points (areas of the body where nerves are close to the skin – see kyusho-jitsu) to unbalance opponent and set up throws.

Brazilian jiu-jitsu[edit]

Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) was developed after Mitsuyo Maeda brought judo to Brazil in 1914. Maeda agreed to teach the art to Luiz França, Jacintho Ferro and Carlos Gracie, son of his friend, businessman and politician Gastão Gracie. Luiz França went on to teach it to Oswaldo Fadda. After Carlos learned the art from Ferro and Maeda, he passed his knowledge to his brothers Oswaldo, Gastão Jr., and George. Meanwhile, Hélio Gracie would peek in and practice the techniques, although he was told he was too young to practise. At the time, Judo was still commonly called Kanō jiu-jitsu (from its founder Kanō Jigorō), which is why this derivative of judo is called Brazilian jiu-jitsu rather than Brazilian judo.

Its emphasis shifted to ground fighting because the Gracie family thought that it was easier to learn than throws and standup grappling, more efficient and much more practical. Carlos and Helio helped the development by promoting fights (mostly against practitioners of other martial arts), competitions and experimenting throughout decades of intense training. BJJ dominated the first large modern mixed martial arts competitions in the United States,[citation needed] causing the emerging field to adopt many of its practices. Less-practised stand-up techniques in Gracie jiujitsu survive in some BJJ clubs from its judo and jujutsu heritage (judo throws, knife defense, gun defense, blocking, striking etc.).

Sambo[edit]

Sambo (an acronym from samozashchita bez oruzhia, Russian for «self defense without a weapon») was an early Soviet martial art, a direct descendant of judo, developed in the 1920s by Viktor Spiridonov, the Dynamo Sports Society jujutsu instructor, and Russo-Japanese War veteran. As it was developed largely for police purposes, a special emphasis in Sambo was placed on the standing armlocks and grappling-counters in order to free oneself from hold, apprehend and escort a suspect without taking him down; Sambo utilized throws mainly as a defensive counter in case of a surprise attack from behind. Instead of takedowns, it used shakedowns to unbalance the opponent without actually dropping him down, while oneself still maintaining a steady balance. It was in essence a standing arm-wrestling, armlock mastery-type of martial art, which utilized a variety of different types of armlocks, knots and compression-holds (and counters to protect oneself from them) applied to the opponent’s fingers, thumbs, wrist, forearm, elbow, biceps, shoulder, and neck, coupled with finger pressure on various trigger points of human body, particularly sensitive to painful pressure, as well as manipulating the opponent’s sleeve and collar to immobilize his upper body, extremities, and subdue him. Sambo combined jujutsu with wrestling, boxing, and savate techniques for extreme street situations.

Later, in the late 1930s it was methodized by Spiridonov’s trainee Vladislav Volkov to be taught at military and police academies, and eventually combined with the judo-based wrestling technique developed by Vasili Oshchepkov, who was the third foreigner to learn judo in Japan and earned a second-degree black belt awarded by Kanō Jigorō himself, encompassing traditional Central Asian styles of folk wrestling researched by Oshchepkov’s disciple Anatoly Kharlampiyev to create sambo. As Spiridonov and Oshchepkov disliked each other very much, and both opposed vehemently to unify their effort, it took their disciples to settle the differences and produce a combined system. Modern sports sambo is similar to sport judo or sport Brazilian jiu-jitsu with differences including use of a sambovka jacket and shorts rather than a full keikogi, and a special emphasis on leglocks and holds, but with much less emphasis on guard and chokes (banned in competition).

Modern schools[edit]

After the introduction of jujutsu to the West, many of these more traditional styles underwent a process of adaptation at the hands of Western practitioners, molding the arts of jujutsu to suit western culture in its myriad varieties. There are today many distinctly westernized styles of jujutsu, that stick to their Japanese roots to varying degrees.[16]

Some of the largest post-reformation (founded post-1905) gendai jujutsu schools include (but are certainly not limited to these in that there are hundreds (possibly thousands), of new branches of «jujutsu»):

- Judo

- Aikido

- Hapkido

- Brazilian jiu-jitsu / Gracie jiu-jitsu

- Wadō-ryū

- Hakkō-ryū

- 10th Planet jiu-jitsu

- Danzan-ryū

- Shorinji Kan Jiu Jitsu

- Hokutoryu Ju-Jutsu

- Guerrilla Jiu-Jitsu

- Small Circle JuJitsu

- Atemi Ju-Jitsu / Pariset Ju-Jitsu

- German ju-jutsu

- Budoshin Ju-Jitsu

- Ryushin Jujitsu

- Budokwai ju-jutsu

- Seibukan jujutsu

- Nihon jujutsu

- Nihon-Ryu Goshin-Jutsu

- Sentou-Ryu Aiki-Jujutsu

- Goshindo

- Jugoshin ryu

- Jiushin ryu

- Kumite-ryu jujutsu

- Quantum jujitsu

- Miletich jiu-jitsu

- Daito-ryu Saigo-ha Aiki-jujutsu

- Nami-ryu Aikijujutsu

- Hakkō Denshin-ryū

- Kokusai jujutsu renmei

- Ishin Ryu ju-jitsu

- Olivecrona jiujitsu

- Kodoryu jujitsu 鴻道流

- Yamabujin Goshin Jutsu

- Matsudaira-Ryu Nikon Juijitsu

- Taigawa-ryu Jujitsu

Sport jujutsu[edit]

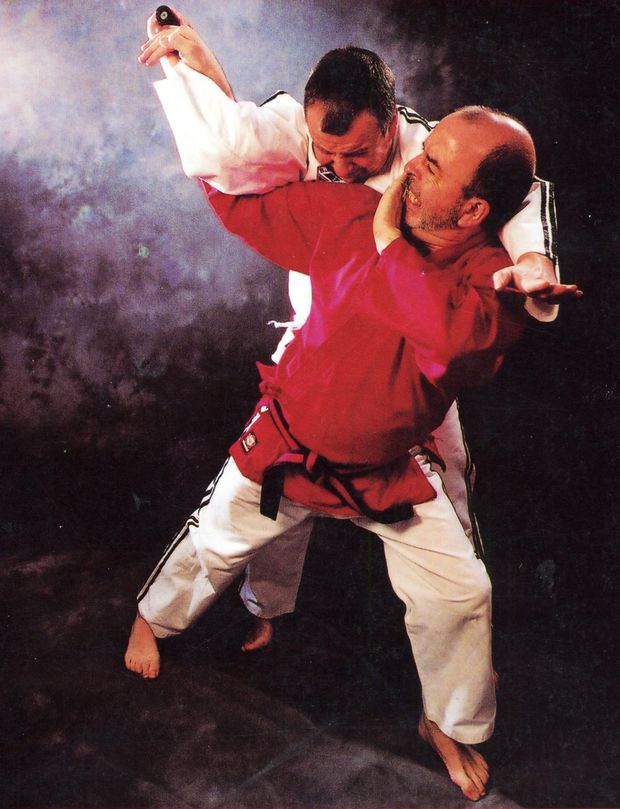

Competition at the 8th Annual West Japan Jujitsu Championship in Hiroshima, 2010 |

|

| Highest governing body | Ju-Jitsu International Federation |

|---|---|

| Derived from | jujutsu/judo, karate, mixed styles |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Yes |

| Mixed-sex | No |

| Type | Martial art |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | No |

| World Games |

|

There are many types of sport jujutsu. One version of sport jujutsu is known as «JJIF Rules Sport Ju-Jitsu», organized by Ju-Jitsu International Federation (JJIF). The JJIF is a member of GAISF and has been recognized as an official sport of the World Games.

Sport jujutsu comes in three main variants. In Duo (self-defense demonstration), both the tori (attacker) and the uke (defender) come from the same team and demonstrate self-defense techniques. In this variant, there is a special system named Random Attacks, focusing on instilling quick reaction times against any given attack by defending and countering. The tori and the uke are also from the same team but here they do not know what the attack will be, which is given to the tori by the judges, without the uke’s knowledge.

The second variant is the Fighting System (Freefighting) where competitors combine striking, grappling and submissions under rules which emphasise safety. Many of the potentially dangerous techniques such as scissor takedowns, necklocks and digital choking and locking are prohibited in sport jujutsu. There are a number of other styles of sport jujutsu with varying rules.[17][18]

The third variant is the Japanese/Ne Waza (grappling) system in which competitors start standing up and work for a submission. Striking is not allowed.

Other variants of competition include Sparring, with various rule sets. Ground fighting similar to BJJ, Kata and Demonstrations.

Sparring and ground fighting can have various rule sets depending on the organisation. Kata can be open hand or with traditional Jujutsu weapons and Demonstrations can be in pairs or teams of up to 7.[19]

Heritage and philosophy[edit]

Japanese culture and religion have become intertwined with the martial arts in the public imagination. Buddhism, Shinto, Taoism and Confucian philosophy co-exist in Japan, and people generally mix and match to suit. This reflects the variety of outlook one finds in the different schools.

Jujutsu expresses the philosophy of yielding to an opponent’s force rather than trying to oppose force with force. Manipulating an opponent’s attack using his force and direction allows jujutsuka to control the balance of their opponent and hence prevent the opponent from resisting the counterattack.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Takahashi, Masao (May 3, 2005). Mastering Judo. Human Kinetics. p. viii. ISBN 0-7360-5099-X.

- ^ a b Mol, Serge (2001). Classical Fighting Arts of Japan: A Complete Guide to Koryū Jūjutsu. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International. pp. 24–54. ISBN 4-7700-2619-6.

- ^ jujitsu. (n.d.). Britannica. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/sports/jujitsu

- ^ Kanō, Jigorō (2006) [2005]. «A Brief History of Jujutsu». In Murata, Naoki (ed.). Mind over muscle: writings from the founder of Judo. trans. Nancy H. Ross (2 ed.). Japan: Kodansha International. p. 13. ISBN 4-7700-3015-0.

- ^ Skoss, Meik (1995). «Jujutsu and Taijutsu». Aikido Journal. 103. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ «儒学者 藤原惺窩 / 三木市». City.miki.lg.jp. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

- ^ 日本武道全集. 第5巻. Shin-Jinbutsuoraisha. 1966. ASIN B000JB7T9U.

- ^ Matsuda, Ryuichi (2004). 秘伝日本柔術. Doujinshi. ISBN 4-915906-49-3.

- ^ «Jiu Jitsu Perth Martial Arts». Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-07-01.

- ^ Bowman, Paul (2020). The Invention of Martial Arts: Popular Culture Between Asia and America. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780197540336.

- ^ Brousse, Michel (2001). Christensen, Karen; Guttman, Allen; Pfister, Gertrud (eds.). International Encyclopedia of Women and Sports. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 614. ISBN 978-0-02-864954-2.

- ^ Gagne, Tammy (2020). Trends in Martial Arts. Dance and Fitness Trends. eBooks2go Incorporated. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-5457-5146-6.

- ^ «Jujutsu». Mysensei.net. 2009-02-09. Archived from the original on 2009-09-18. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ «A history of Kukishin Ryu». Shinjin.co.jp. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ «Bartitsu».

- ^ World of Martial Arts ! — Robert HILL — Google Books. 8 September 2010. ISBN 9780557016631.

- ^ «Jiu-Jitsu Rules». Cmgc.ca. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ «AAU Freestyle Jujitsu Rules» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-12. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ «Competition». British Ryushin Jujitsu Surrey Quays. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jujutsu.

Look up jujitsu in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «Jujutsu» by Jigorō Kanō and T. Lindsay, 1887 (Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Volume 15). On jujutsu and the origins of judo.

- «Ju-Jutsu» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 546–547.

- Spalding Athletic Library, Jiu Jitsu, The Effective Japanese Mode of Self Defense

Jujutsu training at an agricultural school in Japan around 1920 |

|

| Also known as | Jujitsu, jiu-jitsu |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking, kicking, grappling, wrestling |

| Country of origin | Japan |

| Famous practitioners | Minamoto no Yoshimitsu, Mataemon Tanabe, Hansuke Nakamura, Kanō Jigorō, Hironori Ōtsuka, Tatsuo Suzuki (martial artist), Seishiro Okazaki, Matsugoro Okuda, Hikosuke Totsuka, Takeda Sōkaku, Morihei Ueshiba, Minoru Mochizuki |

| Parenthood | Various ancient and medieval Japanese martial arts |

| Ancestor arts | Tegoi, sumo |

| Descendant arts | Judo, aikido, kosen judo, wadō-ryū, sambo (via judo), Brazilian jiu-jitsu (via judo), ARB (via judo), bartitsu, yoseikan budō, taiho jutsu, kūdō (via judo), luta livre (via judo), vale tudo, krav maga (via judo and aikido), modern arnis, hapkido, hwa rang do, shoot wrestling, German ju-jutsu, atemi ju-jitsu, JJIF sport jujitsu, danzan-ryū, hakkō-ryū, kajukenbo, kapap, kenpo |

| Olympic sport | Judo |

| Jujutsu | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Jūjutsu in kanji |

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 柔術 | ||

|

Jujutsu ( joo-JIT-soo; Japanese: 柔術 jūjutsu, pronounced [dʑɯꜜːʑɯtsɯ] (listen)), also known as jiu-jitsu and ju-jitsu, is a family of Japanese martial arts and a system of close combat (unarmed or with a minor weapon) that can be used in a defensive or offensive manner to kill or subdue one or more weaponless or armed and armored opponents.[1][2] Jiu-jitsu dates back to the 1530s and was coined by Hisamori Tenenouchi when he officially established the first jiu-jitsu school in Japan. This form of martial arts uses few or no weapons at all and includes strikes, throws, holds, and paralyzing attacks against the enemy. Jujutsu developed from the warrior class around the 17th century in Japan. [3] It was designed to supplement the swordsmanship of a warrior during combat. A subset of techniques from certain styles of jujutsu were used to develop many modern martial arts and combat sports, such as judo, aikido, sambo, ARB, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and mixed martial arts. The official date of foundation of Jiu Jitsu is 1530.

Characteristics[edit]

«Jū» can be translated as «gentle, soft, supple, flexible, pliable, or yielding», and «jutsu» can be translated as «art or technique». «Jujutsu» thus has the meaning of «yielding-art», as its core philosophy is to manipulate the opponent’s force against themself rather than confronting it with one’s own force.[1] Jujutsu developed to combat the samurai of feudal Japan as a method for defeating an armed and armored opponent in which one uses no form of weapon, or only a short weapon.[4] Because striking against an armored opponent proved ineffective, practitioners learned that the most efficient methods for neutralizing an enemy took the form of pins, joint locks, and throws. These techniques were developed around the principle of using an attacker’s energy against them, rather than directly opposing it.[5]

There are many variations of the art, which leads to a diversity of approaches. Jujutsu schools (ryū) may utilize all forms of grappling techniques to some degree (e.g., throwing, takedowns, leg sweeps, trapping, pins, joint locks, holds, chokeholds, strangulation, gouging, biting, hair pulling, disengagements, and striking). In addition to jujutsu, many schools teach the use of weapons. Today, jujutsu is practiced in both traditional self-defense oriented and modern sports forms. Derived sport forms include the Olympic sport and martial art of judo, which was developed by Kanō Jigorō in the late 19th century from several traditional styles of jujutsu, and sambo and Brazilian jiu-jitsu, which were derived from earlier (pre–World War II) versions of Kodokan judo that had more emphasis on ground fighting (which also caused the creation of kosen judo).

Etymology[edit]

Jujutsu, the standard English language spelling, is derived using the Hepburn romanization system. Before the first half of the 20th century, however, jiu-Jitsu and ju-jitsu were preferred, even though the romanization of the second kanji as Jitsu is not faithful to the standard Japanese pronunciation. It was a non-standardized spelling resulting from how English-speakers heard the second short u in the word, which is pronounced /ɯ/ and therefore close to a short English i.[citation needed] This may also be a reflection of the speech of Shitamachi that merges ‘ju’ into ‘ji’. Since Japanese martial arts first became widely known of in the West in that time period, these earlier spellings are still common in many places. Ju-jitsu is still a common spelling in France, Canada, and the United Kingdom while jiu-jitsu is most widely used in Germany and Brazil. Different from the Japanese pronunciation, the word Jujutsu is still usually pronounced as if it is spelled jujitsu in the United States.

Some define jujutsu and similar arts rather narrowly as «unarmed» close combat systems used to defeat or control an enemy who is similarly unarmed. Basic methods of attack include hitting or striking, thrusting or punching, kicking, throwing, pinning or immobilizing, strangling, and joint locking. Great pains were also taken by the bushi (classic warriors) to develop effective methods of defense, including parrying or blocking strikes, thrusts and kicks, receiving throws or joint locking techniques (i.e., falling safely and knowing how to «blend» to neutralize a technique’s effect), releasing oneself from an enemy’s grasp, and changing or shifting one’s position to evade or neutralize an attack. As jujutsu is a collective term, some schools or ryu adopted the principle of ju more than others.

From a broader point of view, based on the curricula of many of the classical Japanese arts themselves, however, these arts may perhaps be more accurately defined as unarmed methods of dealing with an enemy who was armed, together with methods of using minor weapons such as the jutte (truncheon; also called jitter), tantō (knife), or kakushi buki (hidden weapons), such as the ryofundo kusari (weighted chain) or the bankokuchoki (a type of knuckle-duster), to defeat both armed or unarmed opponents.

Furthermore, the term jujutsu was also sometimes used to refer to tactics for infighting used with the warrior’s major weapons: katana or tachi (sword), yari (spear), naginata (glaive), jō (short staff), and bō (quarterstaff). These close combat methods were an important part of the different martial systems that were developed for use on the battlefield. They can be generally characterized as either Sengoku period (1467–1603) katchu bu Jutsu or yoroi kumiuchi (fighting with weapons or grappling while clad in armor), or Edo period (1603–1867) suhada bu Jutsu (fighting while dressed in the normal street clothing of the period, kimono and hakama).

The first Chinese character of jujutsu (Chinese and Japanese: 柔; pinyin: róu; rōmaji: jū; Korean: 유; romaja: yu) is the same as the first one in judo (Chinese and Japanese: 柔道; pinyin: róudào; rōmaji: jūdō; Korean: 유도; romaja: yudo). The second Chinese character of jujutsu (traditional Chinese and Japanese: 術; simplified Chinese: 术; pinyin: shù; rōmaji: jutsu; Korean: 술; romaja: sul) is the same as the second one in bujutsu (traditional Chinese and Japanese: 武術; simplified Chinese: 武术; pinyin: wǔshù; rōmaji: bujutsu; Korean: 무술; romaja: musul).

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The written history of Jujutsu first began during the Nara period (c. 710 – c. 794) combining early forms of Sumo and various Japanese martial arts which were used on the battlefield for close combat. The oldest known styles of Jujutsu are, Shinden Fudo-ryū (c. 1130), Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū (c. 1447), and Takenouchi-ryū, which was founded in 1530s. Many jujutsu forms also extensively taught parrying and counterattacking long weapons such as swords or spears via a dagger or other small weapons. In contrast to the neighbouring nations of China and Okinawa whose martial arts made greater use of striking techniques, Japanese hand-to-hand combat forms focused heavily upon throwing (including joint-locking throws), immobilizing, joint locks, choking, strangulation, and to lesser extent ground fighting.

In the early 17th century during the Edo period, jujutsu would continue to evolve due to the strict laws which were imposed by the Tokugawa shogunate to reduce war as influenced by the Chinese social philosophy of Neo-Confucianism which was obtained during Hideyoshi’s invasions of Korea and spread throughout Japan via scholars such as Fujiwara Seika.[6] During this new ideology, weapons and armor became unused decorative items, so hand-to-hand combat flourished as a form of self-defense and new techniques were created to adapt to the changing situation of unarmored opponents. This included the development of various striking techniques in jujutsu which expanded upon the limited striking previously found in jujutsu which targeted vital areas above the shoulders such as the eyes, throat, and back of the neck. However towards the 18th century the number of striking techniques was severely reduced as they were considered less effective and exert too much energy; instead striking in jujutsu primarily became used as a way to distract the opponent or to unbalance him in the lead up to a joint lock, strangle or throw.

During the same period the numerous jujutsu schools would challenge each other to duels which became a popular pastime for warriors under a peaceful unified government. From these challenges, randori was created to practice without risk of breaking the law and the various styles of each school evolved from combating each other without intention to kill.[7][8]

The term jūjutsu was not coined until the 17th century, after which time it became a blanket term for a wide variety of grappling-related disciplines and techniques. Prior to that time, these skills had names such as «short sword grappling» (小具足腰之廻, kogusoku koshi no mawari), «grappling» (組討 or 組打, kumiuchi), «body art» (体術, taijutsu), «softness» (柔 or 和, yawara), «art of harmony» (和術, wajutsu, yawarajutsu), «catching hand» (捕手, torite), and even the «way of softness» (柔道, jūdō) (as early as 1724, almost two centuries before Kanō Jigorō founded the modern art of Kodokan judo).[2]

Today, the systems of unarmed combat that were developed and practiced during the Muromachi period (1333–1573) are referred to collectively as Japanese old-style jujutsu (日本古流柔術, Nihon koryū jūjutsu). At this period in history, the systems practiced were not systems of unarmed combat, but rather means for an unarmed or lightly armed warrior to fight a heavily armed and armored enemy on the battlefield. In battle, it was often impossible for a samurai to use his long sword or polearm, and would, therefore, be forced to rely on his short sword, dagger, or bare hands. When fully armored, the effective use of such «minor» weapons necessitated the employment of grappling skills.

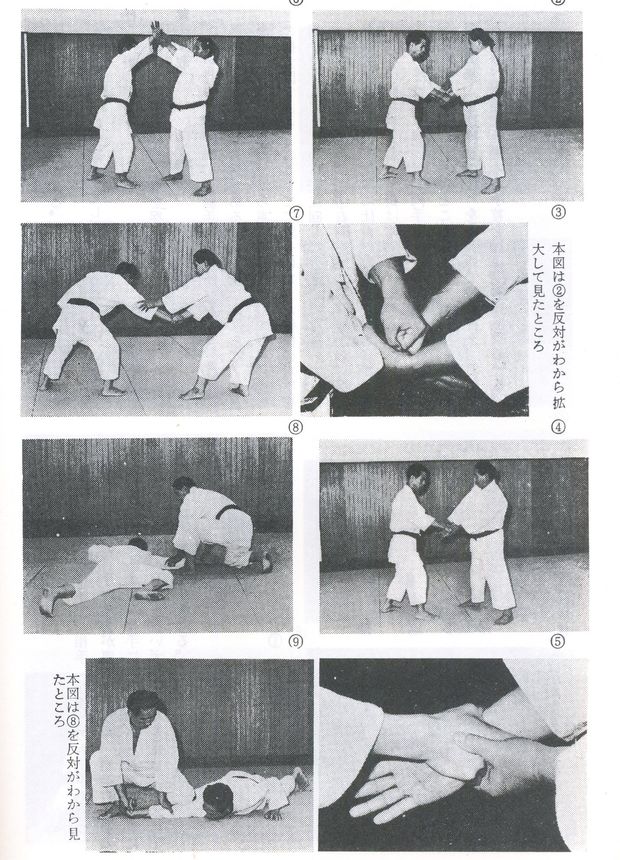

Methods of combat (as mentioned above) included striking (kicking and punching), various takedowns, trips, throwing (body throws, shoulder and hip throws, joint-locking throws, sacrifice throws, unbalance and leg sweeping throws), restraining (pinning, strangling, grappling, wrestling, and rope tying) and weaponry. Defensive tactics included blocking, evading, off-balancing, blending and escaping. Minor weapons such as the tantō (knife), ryofundo kusari (weighted chain), kabuto wari (helmet breaker), and Kaku shi buki (secret or disguised weapons) were almost always included in Sengoku jujutsu.

Development[edit]

In later times, other ko-ryū developed into systems more familiar to the practitioners of Nihon jujutsu commonly seen today. These are correctly classified as Edo jūjutsu (founded during the Edo period): they are generally designed to deal with opponents neither wearing armor nor in a battlefield environment but instead utilize grips and holds on opponent’s clothing. Most systems of Edo jujutsu include extensive use of atemi waza (vital-striking technique), which would be of little use against an armored opponent on a battlefield.[original research?] They would, however, be quite valuable in confronting an enemy or opponent during peacetime dressed in normal street attire (referred to as «suhada bujutsu»). Occasionally, inconspicuous weapons such as tantō (daggers) or tessen (iron fans) were included in the curriculum of Edo jūjutsu.

1911 French publication on jujutsu

Another seldom-seen historical side is a series of techniques originally included in both Sengoku and Edo jujutsu systems. Referred to as Hojo waza (捕縄術 hojojutsu, Tori Nawa Jutsu, nawa Jutsu, hayanawa and others), it involves the use of a hojo cord, (sometimes the sageo or tasuke) to restrain or strangle an attacker. These techniques have for the most part faded from use in modern times, but Tokyo police units still train in their use and continue to carry a hojo cord in addition to handcuffs. The very old Takenouchi-ryu is one of the better-recognized systems that continue extensive training in hojo waza. Since the establishment of the Meiji period with the abolishment of the Samurai and the wearing of swords, the ancient tradition of Yagyū Shingan-ryū (Sendai and Edo lines) has focused much towards the Jujutsu (Yawara) contained in its syllabus.

Many other legitimate Nihon jujutsu Ryu exist but are not considered koryu (ancient traditions). These are called either Gendai Jujutsu or modern jujutsu. Modern jujutsu traditions were founded after or towards the end of the Tokugawa period (1868) when more than 2000 schools (ryū) of jūjutsu existed. Various supposedly traditional ryu and ryuha that are commonly thought of as koryu jujutsu are actually gendai jūjutsu. Although modern in formation, very few gendai Jujutsu systems have direct historical links to ancient traditions and are incorrectly referred to as traditional martial systems or koryu. Their curriculum reflects an obvious bias towards techniques from judo and Edo jūjutsu systems, and sometimes have little to no emphasis on standing armlocks and joint-locking throws that were common in Koryu styles. They also usually do not teach usage of traditional weapons as opposed to the Sengoku jūjutsu systems that did. The improbability of confronting an armor-clad attacker and using traditional weapons is the reason for this bias.

Over time, Gendai jujutsu has been embraced by law enforcement officials worldwide and continues to be the foundation for many specialized systems used by police. Perhaps the most famous of these specialized police systems is the Keisatsujutsu (police art) Taiho jutsu (arresting art) system formulated and employed by the Tokyo Police Department.

Jujutsu techniques have been the basis for many military unarmed combat techniques (including British/US/Russian special forces and SO1 police units) for many years. Since the early 1900s, every military service in the world has an unarmed combat course that has been founded on the principal teachings of jujutsu.[9]

In the early 1900s[10] Edith Garrud became the first British female teacher of jujutsu,[11] and one of the first female martial arts instructors in the Western world.[12]

There are many forms of sports jujutsu, the original and most popular being judo, now an Olympic sport. One of the most common is mixed-style competitions, where competitors apply a variety of strikes, throws, and holds to score points. There are also kata competitions, where competitors of the same style perform techniques and are judged on their performance. There are also freestyle competitions, where competitors take turns attacking each other, and the defender is judged on performance. Another more recent form of competition growing much more popular in Europe is the Random Attack form of competition, which is similar to Randori but more formalized.

Description[edit]

The word Jujutsu can be broken down into two parts. «Ju» is a concept. The idea behind this meaning of Ju is «to be gentle», «to give way», «to yield», «to blend», «to move out of harm’s way». «Jutsu» is the principle or «the action» part of ju-jutsu. In Japanese this word means art.[13]

Japanese jujutsu systems typically put more emphasis on throwing, pinning, and joint-locking techniques as compared with martial arts such as karate, which rely more on striking techniques. Striking techniques were seen as less important in most older Japanese systems because of the protection of samurai body armor and because they were considered less effective than throws and grappling so were mostly used as set-ups for their grappling techniques and throws, although some styles, such as Yōshin-ryū, Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū and Kyushin-ryū had more emphasis on striking. However, many modern-day jujutsu schools include striking, both as a set-up for further techniques or as a stand-alone action.

In jujutsu, practitioners train in the use of many potentially fatal or crippling moves, such as joint-locking throws. However, because students mostly train in a non-competitive environment, the risk is minimized. Students are taught break falling skills to allow them to safely practice otherwise dangerous throws.

Old schools and derivations[edit]

As jujutsu has so many facets, it has become the foundation for a variety of styles and derivations today. As each instructor incorporated new techniques and tactics into what was taught to them originally, they codified and developed their own ryu (school) or Federation to help other instructors, schools, and clubs. Some of these schools modified the source material enough that they no longer consider themselves a style of jujutsu. Arguments and discussions amongst the martial arts fraternity have evoked to the topic of whether specific methods are in fact not jujitsu at all. Tracing the history of a specific school can be cumbersome and impossible in some circumstances.

Around the year 1600 there were over 2000 jujutsu ko-ryū styles, most with at least some common descent, characteristics, and shared techniques. Specific technical characteristics, list of techniques, and the way techniques were performed varied from school to school. Many of the generalizations noted above do not hold true for some schools of jujutsu. Schools of jujutsu with long lineages include:

- Asayama Ichiden-ryū 浅山一傳流

- Akishima-ryū/Akijima-ryū

- Araki-ryū

- Araki-ryu gunyo-kogusoku

- Maebashi-Han Araki-ryū

- Enka-ryū

- Fuhen-ryū

- Futagami-ryū

- Fuji-ryū Goshindo

- Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu

- Fusen-ryū 不遷流

- Gyokushin-ryū

- Hoshiyama-ryū

- Hongaku Kokki-ryū 本覚克己流

- Hontai Yōshin-ryū 本體楊心流(Takagi Ryu)高木流

- Shingetsu Muso Yanagi-ryū

- Iga-ryū 為我流

- Iga-ryūha-Katsushin-ryu 為我流派勝新流柔術

- Ishiguro-ryū 石黒流

- Kashima Shin-ryū 鹿島神流

- Jigō Tenshin-ryū/Ise Jitoku Tenshin-ryū

- Jishukan-ryū

- Jikishin-ryū

- Koden Koppo Taijutsu Genryu Tenshin-ryū

- Kosogabe-ryū

- Kensō-ryū 兼相流

- Kijin Chosui-ryū/Hontai Kijin Chosui-ryū

- Kiraku-ryū 気楽流

- Kitō-ryū 起倒流

- Takenaka-ha Kitō-ryū

- Kukishin-ryū九鬼神流[14]

- Kasumi Shin-ryū

- Enshin-ryū

- Kyushin-ryū

- Natsuhara-ryū 夏原流(夢想直伝流)

- Nanba Ippo-ryū

- Namba Shoshin-ryū

- Sekiguchi-ryū 関口流

- Senshin-ryū

- Shosho-ryū

- Shinto Tenshin-ryū/Tenshin Ko-ryū

- Shin no Shintō-ryū

- Shindō Yōshin-ryū 神道楊心流

- Shibukawa-ryū 渋川流

- Shibukawa Ichi-ryū

- Shiten-ryū

- Shishin Takuma-ryū

- Shinden Fudo-ryū

- Shinnuki-ryū

- Shin no Shindo-ryū

- Shinkage-ryū

- Sōsuishi-ryū 双水執流 (Sosuishitsu-ryū)

- Takenouchi-ryū 竹内流

- Takenouchi Santo-ryū

- Takenouchi Hogan-ryū

- Bitchū Den Takenouchi-ryū

- Tatsumi-ryū 立身流

- Tatsumi Shin-ryu

- Takagi-ryū

- Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū

- Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū 天神真楊流

- Ito-ha Shin’yō-ryū

- Tsutsumi Hōzan-ryū (Original)

- Inotani-ryū

- Iwaga-ryū

- Tennen Rishin-ryū 天然理心流

- Yagyū Shingan-ryū 柳生心眼流

- Goto-ha Yagyu Shingan-ryū

- Yamada-ryū

- Yōshin-ryū 楊心流

- Akiyama Yoshin-ryū

- Nakamura Yoshin Ko-ryū

- Kurama Yōshin-ryū

- Totsuka-ha Yoshin-ryū

- Sakkatsu Yōshin-ryū

- Shin Shin-ryū

- Shin Yōshin-ryū

- Motoha Yōshin-ryū

- Tagaki Yoshin-ryū

- Miura-ryū

- Mubyoshi-ryū

- Nagaoka Ken-ryū

- Nakazawa-ryū

- Oguri-ryū

- Otsubo-ryū

- Okamoto-ryū

- Ryugo-ryū

- Rikishin-ryū

- Ryōi Shintō-ryū

- Ryōi Shintō Kasahara-ryū

- Ryushin Katchu-ryū

- Yokokoro-ryū

Aikido[edit]

Aikido is a modern martial art developed primarily during the late 1920s through the 1930s by Morihei Ueshiba from the system of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu. Ueshiba was an accomplished student of Takeda Sokaku with aikido being a systemic refinement of defensive techniques from Aiki-Jujutsu in ways that are intended to prevent harm to either the attacker or the defender. Aikido changed much during Ueshiba’s lifetime, so earlier styles (such as Yoshinkan) are more like the original Aiki-Jujutsu than ones (such as Ki-Aikido) that more resemble the techniques and philosophy that Ueshiba stressed towards the end of his life.

Wado Ryu Karate[edit]

Wadō-ryū (和道流) is one of the four major karate styles and was founded by Hironori Otsuka (1892–1982). Wadō-ryū is a hybrid of Japanese Martial Arts such as Shindō Yōshin-ryū Ju-jitsu, Shotokan Karate, and Shito Ryu Karate. The style itself places emphasis on not only striking, but tai sabaki, joint locks and throws. It has its origins within Tomari-te.

From one point of view, Wadō-ryū might be considered a style of jū-jutsu rather than karate. Hironori Ōtsuka embraced ju-jitsu and was its chief instructor for a time. When Ōtsuka first registered his school with the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai in 1938, the style was called «Shinshu Wadō-ryū Karate-Jūjutsu,» a name that reflects its hybrid character. Ōtsuka was a licensed Shindō Yōshin-ryū practitioner and a student of Yōshin-ryū when he first met the Okinawan karate master Gichin Funakoshi. After having learned from Funakoshi, and after their split, with Okinawan masters such as Kenwa Mabuni and Motobu Chōki, Ōtsuka merged Shindō Yōshin-ryū with Okinawan karate. The result of Ōtsuka’s efforts is Wadō-ryū Karate.

Bartitsu[edit]

Jujutsu was first introduced to Europe in 1898 by Edward William Barton-Wright, who had studied Tenjin Shinyō-ryū and Shinden Fudo-ryū in Yokohama and Kobe. He also trained briefly at the Kodokan in Tokyo. Upon returning to England he folded the basics of all of these styles, as well as boxing, savate, and forms of stick fighting, into an eclectic self-defence system called Bartitsu.[15]

Judo[edit]

Main article: Judo

Modern judo is the classic example of a sport that derived from jujutsu. Many who study judo believe as Kanō did, that judo is not a sport but a self-defense system creating a pathway towards peace and universal harmony. Another layer removed, some popular arts had instructors who studied one of these jujutsu derivatives and later made their own derivative succeed in competition. This created an extensive family of martial arts and sports that can trace their lineage to jujutsu in some part.

The way an opponent is dealt with also depends on the teacher’s philosophy with regard to combat. This translates also in different styles or schools of jujutsu.

Not all jujutsu was used in sporting contests, but the practical use in the samurai world ended circa 1890. Techniques like hair-pulling, eye-poking, and groin attacks were and are not considered acceptable in sport, thus, they are excluded from judo competitions or randori. However, judo did preserve some more lethal, dangerous techniques in its kata. The kata were intended to be practised by students of all grades but now are mostly practised formally as complete set-routines for performance, kata competition and grading, rather than as individual self-defense techniques in class. However, judo retained the full set of choking and strangling techniques for its sporting form and all manner of joint locks. Even judo’s pinning techniques have pain-generating, spine-and-rib-squeezing and smothering aspects. A submission induced by a legal pin is considered a legitimate win. Kanō viewed the safe «contest» aspect of judo as an important part of learning how to control an opponent’s body in a real fight. Kanō always considered judo a form of, and development of, jujutsu.

A judo technique starts with gripping the opponent, followed by off-balancing them and using their momentum against them, and then applying the technique. Kuzushi (the art of breaking balance) is also used in jujutsu, whereby an opponent’s attack is deflected using their momentum against them in order to arrest their movements then throw them or pin them with a technique — thus controlling the opponent. It is known in both systems that kuzushi is essential in order to use as little energy as possible. Jujutsu differs from judo in a number of ways. In some circumstances, judoka generate kuzushi by striking one’s opponent along his weak line. Other methods of generating kuzushi include grabbing, twisting, poking or striking areas of the body known as atemi points or pressure points (areas of the body where nerves are close to the skin – see kyusho-jitsu) to unbalance opponent and set up throws.

Brazilian jiu-jitsu[edit]

Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) was developed after Mitsuyo Maeda brought judo to Brazil in 1914. Maeda agreed to teach the art to Luiz França, Jacintho Ferro and Carlos Gracie, son of his friend, businessman and politician Gastão Gracie. Luiz França went on to teach it to Oswaldo Fadda. After Carlos learned the art from Ferro and Maeda, he passed his knowledge to his brothers Oswaldo, Gastão Jr., and George. Meanwhile, Hélio Gracie would peek in and practice the techniques, although he was told he was too young to practise. At the time, Judo was still commonly called Kanō jiu-jitsu (from its founder Kanō Jigorō), which is why this derivative of judo is called Brazilian jiu-jitsu rather than Brazilian judo.

Its emphasis shifted to ground fighting because the Gracie family thought that it was easier to learn than throws and standup grappling, more efficient and much more practical. Carlos and Helio helped the development by promoting fights (mostly against practitioners of other martial arts), competitions and experimenting throughout decades of intense training. BJJ dominated the first large modern mixed martial arts competitions in the United States,[citation needed] causing the emerging field to adopt many of its practices. Less-practised stand-up techniques in Gracie jiujitsu survive in some BJJ clubs from its judo and jujutsu heritage (judo throws, knife defense, gun defense, blocking, striking etc.).

Sambo[edit]

Sambo (an acronym from samozashchita bez oruzhia, Russian for «self defense without a weapon») was an early Soviet martial art, a direct descendant of judo, developed in the 1920s by Viktor Spiridonov, the Dynamo Sports Society jujutsu instructor, and Russo-Japanese War veteran. As it was developed largely for police purposes, a special emphasis in Sambo was placed on the standing armlocks and grappling-counters in order to free oneself from hold, apprehend and escort a suspect without taking him down; Sambo utilized throws mainly as a defensive counter in case of a surprise attack from behind. Instead of takedowns, it used shakedowns to unbalance the opponent without actually dropping him down, while oneself still maintaining a steady balance. It was in essence a standing arm-wrestling, armlock mastery-type of martial art, which utilized a variety of different types of armlocks, knots and compression-holds (and counters to protect oneself from them) applied to the opponent’s fingers, thumbs, wrist, forearm, elbow, biceps, shoulder, and neck, coupled with finger pressure on various trigger points of human body, particularly sensitive to painful pressure, as well as manipulating the opponent’s sleeve and collar to immobilize his upper body, extremities, and subdue him. Sambo combined jujutsu with wrestling, boxing, and savate techniques for extreme street situations.

Later, in the late 1930s it was methodized by Spiridonov’s trainee Vladislav Volkov to be taught at military and police academies, and eventually combined with the judo-based wrestling technique developed by Vasili Oshchepkov, who was the third foreigner to learn judo in Japan and earned a second-degree black belt awarded by Kanō Jigorō himself, encompassing traditional Central Asian styles of folk wrestling researched by Oshchepkov’s disciple Anatoly Kharlampiyev to create sambo. As Spiridonov and Oshchepkov disliked each other very much, and both opposed vehemently to unify their effort, it took their disciples to settle the differences and produce a combined system. Modern sports sambo is similar to sport judo or sport Brazilian jiu-jitsu with differences including use of a sambovka jacket and shorts rather than a full keikogi, and a special emphasis on leglocks and holds, but with much less emphasis on guard and chokes (banned in competition).

Modern schools[edit]

After the introduction of jujutsu to the West, many of these more traditional styles underwent a process of adaptation at the hands of Western practitioners, molding the arts of jujutsu to suit western culture in its myriad varieties. There are today many distinctly westernized styles of jujutsu, that stick to their Japanese roots to varying degrees.[16]

Some of the largest post-reformation (founded post-1905) gendai jujutsu schools include (but are certainly not limited to these in that there are hundreds (possibly thousands), of new branches of «jujutsu»):

- Judo

- Aikido

- Hapkido

- Brazilian jiu-jitsu / Gracie jiu-jitsu

- Wadō-ryū

- Hakkō-ryū

- 10th Planet jiu-jitsu

- Danzan-ryū

- Shorinji Kan Jiu Jitsu

- Hokutoryu Ju-Jutsu

- Guerrilla Jiu-Jitsu

- Small Circle JuJitsu

- Atemi Ju-Jitsu / Pariset Ju-Jitsu

- German ju-jutsu

- Budoshin Ju-Jitsu

- Ryushin Jujitsu

- Budokwai ju-jutsu

- Seibukan jujutsu

- Nihon jujutsu

- Nihon-Ryu Goshin-Jutsu

- Sentou-Ryu Aiki-Jujutsu

- Goshindo

- Jugoshin ryu

- Jiushin ryu

- Kumite-ryu jujutsu

- Quantum jujitsu

- Miletich jiu-jitsu

- Daito-ryu Saigo-ha Aiki-jujutsu

- Nami-ryu Aikijujutsu

- Hakkō Denshin-ryū

- Kokusai jujutsu renmei

- Ishin Ryu ju-jitsu

- Olivecrona jiujitsu

- Kodoryu jujitsu 鴻道流

- Yamabujin Goshin Jutsu

- Matsudaira-Ryu Nikon Juijitsu

- Taigawa-ryu Jujitsu

Sport jujutsu[edit]

Competition at the 8th Annual West Japan Jujitsu Championship in Hiroshima, 2010 |

|

| Highest governing body | Ju-Jitsu International Federation |

|---|---|

| Derived from | jujutsu/judo, karate, mixed styles |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Yes |

| Mixed-sex | No |

| Type | Martial art |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | No |

| World Games |

|

There are many types of sport jujutsu. One version of sport jujutsu is known as «JJIF Rules Sport Ju-Jitsu», organized by Ju-Jitsu International Federation (JJIF). The JJIF is a member of GAISF and has been recognized as an official sport of the World Games.

Sport jujutsu comes in three main variants. In Duo (self-defense demonstration), both the tori (attacker) and the uke (defender) come from the same team and demonstrate self-defense techniques. In this variant, there is a special system named Random Attacks, focusing on instilling quick reaction times against any given attack by defending and countering. The tori and the uke are also from the same team but here they do not know what the attack will be, which is given to the tori by the judges, without the uke’s knowledge.

The second variant is the Fighting System (Freefighting) where competitors combine striking, grappling and submissions under rules which emphasise safety. Many of the potentially dangerous techniques such as scissor takedowns, necklocks and digital choking and locking are prohibited in sport jujutsu. There are a number of other styles of sport jujutsu with varying rules.[17][18]

The third variant is the Japanese/Ne Waza (grappling) system in which competitors start standing up and work for a submission. Striking is not allowed.

Other variants of competition include Sparring, with various rule sets. Ground fighting similar to BJJ, Kata and Demonstrations.

Sparring and ground fighting can have various rule sets depending on the organisation. Kata can be open hand or with traditional Jujutsu weapons and Demonstrations can be in pairs or teams of up to 7.[19]

Heritage and philosophy[edit]

Japanese culture and religion have become intertwined with the martial arts in the public imagination. Buddhism, Shinto, Taoism and Confucian philosophy co-exist in Japan, and people generally mix and match to suit. This reflects the variety of outlook one finds in the different schools.

Jujutsu expresses the philosophy of yielding to an opponent’s force rather than trying to oppose force with force. Manipulating an opponent’s attack using his force and direction allows jujutsuka to control the balance of their opponent and hence prevent the opponent from resisting the counterattack.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Takahashi, Masao (May 3, 2005). Mastering Judo. Human Kinetics. p. viii. ISBN 0-7360-5099-X.

- ^ a b Mol, Serge (2001). Classical Fighting Arts of Japan: A Complete Guide to Koryū Jūjutsu. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International. pp. 24–54. ISBN 4-7700-2619-6.

- ^ jujitsu. (n.d.). Britannica. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/sports/jujitsu

- ^ Kanō, Jigorō (2006) [2005]. «A Brief History of Jujutsu». In Murata, Naoki (ed.). Mind over muscle: writings from the founder of Judo. trans. Nancy H. Ross (2 ed.). Japan: Kodansha International. p. 13. ISBN 4-7700-3015-0.

- ^ Skoss, Meik (1995). «Jujutsu and Taijutsu». Aikido Journal. 103. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ «儒学者 藤原惺窩 / 三木市». City.miki.lg.jp. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

- ^ 日本武道全集. 第5巻. Shin-Jinbutsuoraisha. 1966. ASIN B000JB7T9U.

- ^ Matsuda, Ryuichi (2004). 秘伝日本柔術. Doujinshi. ISBN 4-915906-49-3.

- ^ «Jiu Jitsu Perth Martial Arts». Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-07-01.

- ^ Bowman, Paul (2020). The Invention of Martial Arts: Popular Culture Between Asia and America. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780197540336.

- ^ Brousse, Michel (2001). Christensen, Karen; Guttman, Allen; Pfister, Gertrud (eds.). International Encyclopedia of Women and Sports. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 614. ISBN 978-0-02-864954-2.

- ^ Gagne, Tammy (2020). Trends in Martial Arts. Dance and Fitness Trends. eBooks2go Incorporated. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-5457-5146-6.

- ^ «Jujutsu». Mysensei.net. 2009-02-09. Archived from the original on 2009-09-18. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ «A history of Kukishin Ryu». Shinjin.co.jp. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ «Bartitsu».

- ^ World of Martial Arts ! — Robert HILL — Google Books. 8 September 2010. ISBN 9780557016631.

- ^ «Jiu-Jitsu Rules». Cmgc.ca. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ «AAU Freestyle Jujitsu Rules» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-12. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ «Competition». British Ryushin Jujitsu Surrey Quays. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jujutsu.

Look up jujitsu in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «Jujutsu» by Jigorō Kanō and T. Lindsay, 1887 (Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Volume 15). On jujutsu and the origins of judo.

- «Ju-Jutsu» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 546–547.

- Spalding Athletic Library, Jiu Jitsu, The Effective Japanese Mode of Self Defense

Философская основа

Джиу-джитсу по-японски звучит как Jūjutsu (柔術) и переводится как «искусство мягкости» (柔 – прилагательное 柔らかい, а術 — искусство). Это не отдельная техника, а целый комплекс боевых искусств как с оружием, так и без. В основном, под джиу-джитсу понимают ведение рукопашного боя, характерным для которого является мягкая техника движений.

Как и любое восточное боевое искусство, джиу-джитсу не просто драка или защита от нападающего. Оно базируется на философских аспектах. Относится к наиболее древним японским видам борьбы. Основной аспект состоит в том, чтобы не сопротивляться противнику, а укрываться от ударов и умело направлять силу и движения противника в нужную для себя сторону, заманивая тем самым врага в ловушку, где и будет нанесен сокрушающий удар. Человек, владеющий джиу-джитсу, может применить его в условиях ограниченного пространства, отсутствия видимости и т.д. Одной из разновидностей применения техники является выматывание противника захватами до такого состояния, что тот уже ничего не может сделать, даже если он превосходит защищающегося по силе и весу.

Согласно легенде, джиу-джитсу создал врач Сиробэе Акаяме, который наблюдал за деревьями. Он заметил, что ветки могучих деревьев под натиском бури ломаются, а ветки ивы остаются невредимыми, благодаря своей гибкости. Ива как бы поддаётся стихии, не сопротивляется и тем самым обеспечивает себе сохранность.

Занятие джиу-джутсу призвано укреплять в человеке все четыре основы, которые образовывают «крепость» жизни:

— здоровье,

— взаимодействие с окружающими,

— знания и труд/работа;

— духовность.

История джиу-джитсу

Искусство мягкости появилось в Японии в середине XVI века. Хисамори Такэноути собрал различные военные искусства, использовавшиеся в ближнем бою при бесполезности применения оружия. В Китае и Корее боевые искусства сосредотачивались на технике удара, а в Японии — на бросках, блокировке и удушье, так как удары были бесполезны из-за доспехов. Также японцы применяли уворачивание от холодного оружия.

Почти через два столетия настал расцвет джиу-джитсу благодаря прекращению вооруженных конфликтов, когда доспехи и оружие стали лишь напоминанием о былых стычках и воинах. Тогда рукопашные бои стали применяться для самообороны и учитывали отсутствие оружия у противника. Также тогда в японское джиу-джитсу было включено китайское ушу, привезённое китайскими послами. Однако в период Эдо многие

удары, особенно руками и ногами, были исключены за ненадобностью, так как требовали много энергии, а в качестве основных остались удары, направленные на жизненно-важные точки с медицинской точки зрения и ранних техник джиу-джитсу. Тогда же получили своё развитие соревнования между школами (а их было около семисот), где проводили своё время и обучались воины в мирное время. В основном, школы отличались постановкой дыхания, набором приёмов и базовыми стойками. Иногда, как дополнение, в занятия включались и техники по владению оружием.

К традиционным школам относят те, в которых не было существенных изменений в течение нескольких поколений учеников, и те, которые признаны культурным наследием Японии. Однако время требует некоторых поправок, и, ввиду некоторых факторов, были созданы современные школы. К таких факторам можно отнести необходимость специализированных направлений (например, для полицейских, военных), применение техники в современных ситуациях самообороны и создание спортивных направлений. Современные спецслужбы многих стран мира владеют джиу-джитсу.

Базовые приемы можно классифицировать по разделам:

· позиции и стойки;

· передвижения;

· повороты и подвороты;

· броски;

· удары по болевым точкам;

· защита;

· удушения;

· удержания;

· болевые приемы;

· захваты;

· падения.

Мягкость в джиу-джитсу

Мягкость в этом искусстве заключается в том, что вначале человек поддаётся натиску врага, а затем обращает его же силу против его самого. Удары против подготовленного и защищенного противника неэффективны, поэтому в технике множество заломов и бросков, при помощи которых нейтрализация противника производится довольно легко. Отсюда вытекает неважность количества противников для мастера джиу-джитсу – нет препятствий и преград для энергии воли.

Как и в других боевых искусствах, в джиу-джитсу важно сохранение ясности ума и самообладание. Вероятно, из-за этого оно было взято на вооружение спецслужбами – оно позволяет нейтрализовать правонарушителей без причинения им вреда. А в двадцатом веке джиу-джитсу легло в основу самообороны для женщин. В современных школах изучают как древнейшие приёмы, так и придуманные позднее на основе традиционных.

Женское джиу-джитсу

С увеличением прав женщин в обществе встал вопрос о самообороне «слабого пола». Джиу-джитсу является первым единоборством, освоенным женщинами, по нескольким причинам:

— популярные тогда бокс и борьба были слишком жестоки;

— не было подходящей женской спортивной одежды;

— джиу-джитсу – это искусство поддаваться, что вполне подошло для женщин;

— возможность слабой и хрупкой жертве противостоять более сильному сопернику как раз подходила для целей самообороны для женщин.

Джиу-джитсу позволяло женщинам развиваться и физически, и духовно, и занимались им представительницы для своего удовольствия. Оно считалось женственным и элегантным в противовес борьбе, направленной на прямое силовое противостояние.

Движение за права женщин называлось suffrage, и активисток этого движения стали называть джиу-суффражистками, а женское боевое искусство суффраджитсу. В Лондоне в начале двадцатого века стали популярными вечера, на которых женщины учились этому искусству у приглашённых инструкторов.

Терминология, использующаяся в джиу-джитсу:

足 (asi) — нога

足払い (asibarai) — подсечка

技 (waza) — техника

技あり(wazaari) — оценка технических действий в полпобеды

下段 (Gedan) — нижний уровень

段階 (Dankai) — ступень, стадия, этап (Свод правил)

時間です (Jikan desu) — время (период) завершилось

よい (yoi) — изготовиться, принять положение

横 (yoko) — бок

横へ (yoko-e) — в бок (о направлении)

開脚座 (kaikiyakuza) — шпагат (спорт.)