Много лет назад, в начале 1990-х, когда в Москву приехали представители Махариши Махеш Йоги, в Москве услышали о Джотише, или Ведической Астрологии. И именно тогда какой-то очень старательный, но не очень грамотный переводчик решил, что английское слово Jyotish следует писать по-русски как Джйотиш. К сожалению, это непроизносимое сочетание букв закрепилось и распространилось.

Чтобы понять, почему оно неправильно, надо выяснить разницу между языками фонетическими и нефонетическими. Русский язык фонетичен. Это значит, что в нём «как слышится, так и пишется»: буквы в словах довольно точно соответствуют звукам. Мы просто произносим буквы друг за другом, и получается правильно произнесенное слово.

С другой стороны, английский язык — нефонетический. В нём произношение слов определяется не последовательностью букв, а специальными правилами прочтения. Возьмите, к примеру, слово thought, мысль. В нём слышатся только три звука, а букв используется целых семь.

Чтобы понять, как правильно писать по-русски слово Jyotish, надо услышать, как оно произносится, и затем просто записать это звучание русскими буквами. Я слышал много раз, как это слово произносится и англичанами, и индусами, в том числе во время конференций по Ведической Астрологии, и могу засвидетельствовать: самый точный способ изобразить это слово по-русски — именно Джотиш. Первый слог идентичен тому, как по-русски произносится имя Джо. Никто и никогда не произносит ничего напоминающего «джйотиш» или «джьотиш». Это было бы очень трудное сочетание звуков в любом языке.

Остаётся вопрос: а почему же англичане пишут это слово именно так: Jyotish? Почему не, скажем, «Jotish»? Потому что, следуя правилам чтения английского языка, «Jotish» читалось бы как «джоутиш», а это было бы неправильно. Поскольку слово это происходит из Санскрита (фонетического языка) английские своеобычные правила прочтения здесь неприменимы. Приходится изобретать. Когда англичанин читает слово «Jyotish», он понятия не имеет, как его следует произносить, но понимает, что обычные правила на него не распространяются. Потому что сочетание букв «yo» отсутствует в английском языке. Это ж Санскрит! Значит, надо спросить того, кто знает.

К счастью, в нашем фонетическом русском языке все эти ужимки и прыжки не нужны. Просто говорите Джотиш: как пишется, так и слышится. Точно так же, как английское имя Джон (John) читается по-русски как Джон, а не «джохн», и имя James читается как Джеймс (как слышится), а не как пишется («джамес»).

Я далёк от ожиданий, что после стольких лет безграмотности люди начнут писать Джотиш правильно, но если хоть один из вас поймёт, что буквосочетание «джйотиш» непроизносимо и неприемлемо, я буду считать свою задачу выполненной.

Александр Колесников

Источник

Это статья Александра Колесникова, известного Астролога, наконец-то прояснила ситуацию с правильным произношением и написанием такой популярной сейчас в России Ведической Астрологии. Можно смело перестать ломать язык, пытаясь произнести правильно это непонятное слово «Джйотиш». Все оказалось намного проще, что меня очень порадовало.

Share This

Добрый день. Английское слово «джимейл» часто мы слышим, именно им обозначается почта на «гугл», но не все знают, как его правильно писать. Для поиска ответа, можно просто обратиться к этому популярному сервису, чтобы прочитать, как они обозначают свою почту.

Зайдя на «google» и перейдя на их почту, мы быстро находим ответ, слово «джимейл» на английском пишется «gmail». Данное слово обычно указывается в почте после символа собачка (@).

Название Ведической астрологии — ‘Джйотиш‘ — можно встретить в самых различных вариантах написания.

Помимо правильного написания ‘Джйотиш‘ в книгах ина интернетовских сайтах встречаются следующие неправильные (неточные) варианты:

- Джйотиша (почти правильный)

- Джотиш

- Джотишь

- Джйотиш

- Джйотишь

- Джьотиш

- Джьотишь

Вот как пишется слово ‘Джйотиш‘ на его «родном» языке

— на Санскрите:

Это слово сотоит их четырех слогов:

Прочитаем по слогам:

— дж

— йо

— ти

— ш (ша)

Получается ‘Джйотиш‘ или ‘Джйотиша‘.

При чем оба варианта не дают точного соответствия санскритскому оригиналу.

Во-первых, буква

перешаются звуком «ш» не точно, на самом деле она звучит мягче и ее

произношение является промежуточным звуком между «ш» и «с»,

как в словах «Шива», «Вишну», «Кришна», «Шукра, «Шани», «даша», «раши» и так далее.

Во-вторых, буква

обычно (то есть в начале или середине слова) звучит как «ша»,

а, будучи последней буквой слова, она укорачивает продолжительность звучния «а»,

и длина «а» равна 1/4 от обычной продолжительность звука «а».

Поэтому ни «ша», ни «ш» не будет правильно передавать оконечную букву

.

Поскольку во всем мире сложилась традиция писать ‘Jyotish‘, а не ‘Jyotisha‘

(Google находит 14100 слов ‘Jyotish’ и только 1800 слов ‘Jyotisha’),

то более правильным будет писать ‘Джйотиш‘, а не ‘Джйотиша‘,

хотя оба варианта являются наиболее точными из всех встречающихся.

И в завершение немного интернетовской статистики по вариантам написания слова ‘Джйотиш’:

| Вариант | Поиск на Google http://google.com |

Поиск на Яндексе http://ya.ru |

Поиск на Рамблере http://rambler.ru |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| документов | слов | страниц | серверов | «документов» | сайтов | |

| Джйотиш | 792 | 2119 | 875 | 117 | 545 | 67 |

| Джотиш | 120 | 123 | 89 | 35 | 52 | 17 |

| Джотишь | no pages | 8 | 5 | 2 | ненайдено |

Звуковые файлы терминов Джйотиша [Ведической астрологии] на Санскрите.

Джйотиш — Ведическая астрология.

Лучший ответ

Камила Рафикова

Ученик

(171)

12 лет назад

ответ «SH» Dasha

ДашаМастер (2098)

12 лет назад

спасибо)))…я выиграла))))а то думала,что я совсем уже…

Остальные ответы

Наташа Павлова

Мыслитель

(5689)

12 лет назад

Второй вариант

Мс†SV†Girl_OF

Ученик

(152)

12 лет назад

Sh

Natasha

Мудрец

(10827)

12 лет назад

sh вот так и пишется

Simple Eazy

Просветленный

(25400)

12 лет назад

Первый вариант читается как «Ч»,а SH- как «Ш»

ЛАНА***

Профи

(600)

12 лет назад

Попробую Вам помочь. sh (анг. ) — наша русская Ш.

Владимир Александров

Профи

(825)

12 лет назад

sh или LLI

Jina Kyfon

Знаток

(470)

12 лет назад

sh — это «ш», так как сh — это «ч».

V.I.P. Programist Умный ))

Знаток

(417)

12 лет назад

Русская буква Ш пишется по английски sh. а ch это вообще буква переводится как Ч

ДашаМастер (2098)

12 лет назад

да,да,да!!!просто вчера меня яро пытались переубедить в обратном!!а я ведь ещё со школы писала Dasha!!!!Вот умеют же люди в оману вводить!!)Спасибо за ответ!

Гена Шерешев

Ученик

(147)

5 лет назад

точно?

Григорий Игнатьев

Знаток

(281)

5 лет назад

SH

Кирилл Байдак

Знаток

(288)

4 года назад

ch — Буква Ч sh — Буква Ш

АНАСТАСИЯ ЕРМОЛИНА

Знаток

(290)

4 года назад

Sh — ш ;ch-ч

MaSHa CHurch

Джьотиш(а) (санскр. ज्योतिष — IAST: jyotiṣa — «астрономия, астрология»[1] от IAST: jyotis — «свет, небесное светило»[2]) — астрология индуизма. Также называется индийской астрологией или ведической астрологией.

Разделы

По традиции подразделяется на три ветви[3]:

- Сиддханта — традиционная индийская астрономия.

- Самхита, также называемая Медини Джьотиша (мунданная астрология) — предсказание важных событий в стране на основе анализа астрологической динамики её гороскопа, а также всеобщие события, как, например, война, землетрясение, политические перемены, финансовые показатели, элективная астрология.

- Хора — хорарная астрология, основанная на анализе гороскопа, построенного на момент возникновения вопроса.

Последние две являются частью предсказательной астрологии (Пхалита). Поэтому в целом индийская астрология подразделяется на две ветви Ганита (Сиддханта) и Пхалита (Самхита и Хора).

Особенности

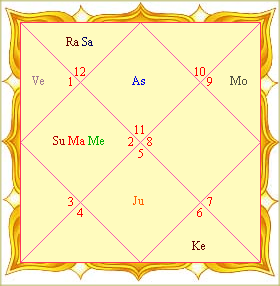

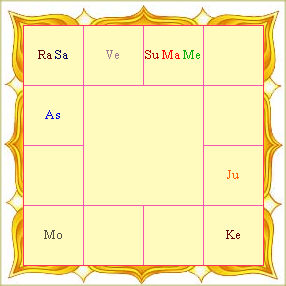

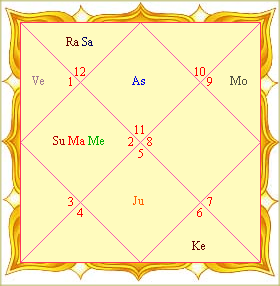

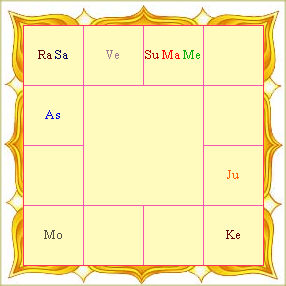

Основание джьотиши — бандху. Это понятие встречается в Ведах и означает связь между микрокосмом и макрокосмом. На практике джьотиша основывается на сидерическом зодиаке, который отличен от тропического, используемого в западной астрологии. В джьотише делается коррекция в связи с прецессией точки весеннего равноденствия. Джьотиша включает несколько подсистем интерпретации и предсказания с некоторыми элементами, которые отсутствуют в западной астрологии, например, система лунных стоянок. В Индии используют два стиля гороскопа: южный и северный.

Североиндийский гороскоп

Южноиндийский гороскоп

Астрология имеет важное значение в жизни индуистов. В индийской культуре новорождённым по традиции дают имя, основанное на их гороскопах, а понятия и идеи джьотиши глубоко проникли в систему календарей и праздников, также как и в другие области жизни. Например, джьотиша используется при принятии решения о бракосочетании, открытии нового бизнеса или переезде в новое жилище. Астрология даже сохраняет свою позицию среди «традиционных наук» в современной Индии[4]. После спорного решения Высшего Суда штата Андхра-Прадеш (2001) некоторые индийские университеты стали предлагать учёную степень по ведической астрологии[5], однако введение курса джьотиши в университетах вызвало резкую реакцию научного сообщества Индии, выразившего протест[6][7] против попыток придания научного статуса псевдонауке[8][9].

История

Термин джьотиша как одна из Веданг (шести вспомогательных дисциплин ведийской религии) используется в «Мундака-упанишаде» и поэтому, вероятно, датируется временами Маурьев. «Веданга-джьотиша» была записана Лагадхой и содержала правила отслеживания движения солнца и луны.

Документированная история джьотиши берёт начало с взаимодействия индийской и эллинской культур во время индо-греческого периода. Самые древние сохранившиеся трактаты, такие как «Явана-джатака» или «Врихат-самхита», датируются первыми веками нашей эры. Самый древний астрологический трактат на санскрите «Явана-джатака» («Высказывания греков») — это стихотворное переложение, выполненное Спхуджидхваджей в 269 — 290 годах, являющееся переводом ныне утерянного греческого трактата греко-индийского астролога Яванешвары (II в.)[10].

Первые известные авторы, которые писали трактаты по астрономии, появились в V веке н. э., когда начался классический период индийской астрономии. Кроме теорий Арьябхаты, изложенных в «Арьябхатии» и утерянной «Арья-сиддханте», существует также «Панча-сиддхантика» Вараха Михиры.

Основные тексты, на которые опирается индийская астрология, это компиляции раннего Средневековья, в особенности «Брихат-парашара-хора-шастра» и «Саравали». «Хора-шастра» состоит из 71 главы. Первая её часть (главы 1-51) датируется VII веком и началом VIII-го, а вторая (главы 52-71) — концом VIII века. «Саравали» также датируется около 800 года[11]. Английские переводы этих книг были опубликованы Н. Н. Кришнарау и В. Б. Чудхари в 1963 и 1961 годах соответственно.

Развитие астрологии в Индии было важным фактором в развитии астрономии раннего Средневековья.

В современной Индии

Дэвид Пингри отмечает, что джьотиша и аюрведа — это две традиционные дисциплины, которые лучше всех выжили в современной Индии, хотя обе были трансформированы под влиянием Запада[12].

В начале 2000-х джьотиша стала предметом политической борьбы между представителями религии и академического сообщества. Комиссия по университетским грантам и Министерство по развитию человеческих ресурсов решили ввести курс «ведической астрологии» (IAST: jyotir vijñāna) в индийских университетах, подкрепляя это решением Высшего суда штата Андхра-Прадеш, несмотря на широкие протесты от научного сообщества Индии и индийских учёных, работающих за рубежом[8][9], и извещение от Высшего Суда Индии, что это скачок назад, подрывающий научное доверие, которое заработала страна к этому времени[6]. Высший суд индийского мегаполиса Мумбаи в 2011 году отклонил требование запретить рекламу астрологии, заключив, что она является «уважаемой наукой», практикуемой 4 тыс. лет, и не подпадает под действие закона 1954 года[13], запрещающего публично выступать с ложными прогнозами[14][15]. В настоящее время несколько индийских университетов предлагают учёные степени в джьотише[16][17][18][19]. Ряд исследований в Индии показал неэффективность предсказаний индийских астрологов[9][20].

См. также

- Веданга

- Наваратна

- Бхавишья-пурана

- Наваграха

- Астрологическая эра

- Древнеиндийский календарь

- Индийская астрономия

- Юга

- Индуистская космология

- Джьотиша-веданга

- Титхи

- Джьотишастра[en]

- Астрология Нади[en]

- Фонетическая астрология[en]— Swar Shaastra

- Панчангам[en]

- Ведическая археоастрономия[en]

- Бхригу Самхита[en]

Примечания

- ↑ jyotiṣa in Sanskrit dictionary (англ.)

- ↑ jyotiṣ in Sanskrit dictionary (англ.)

- ↑ Asoke Chatterjee Piṅgalacchandaḥsūtra: a study. — University of Calcutta, 1987. С.46

- ↑ Пингри Д., Гилберт Р. «Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times» // Encyclopedia Britannica, 2008

«В таких странах, как Индия, где только небольшая интеллектуальная элита обучалась физике на Западе, астрология продолжает удерживать свои позиции среди наук» - ↑ Rao M. Female foeticide: where do we go? // Indian Journal of Medical Ethics Oct-Dec2001-9(4) [1];

- ↑ 1 2 Supreme Court questions ‘Jyotir Vigyan’ // Times of India, 3.09.2001. (англ.)

- ↑ Astrology not a science, reiterates Narlikar // Times of India (TNN, 5.12.2010)

- ↑ 1 2 Jayaraman T. A judicial blow Архивировано 28 июня 2009 года. // Frontline, Volume 18 — Issue 12, Jun. 09 — 22, 2001. (англ.)

- ↑ 1 2 3 Komath M. Testing astrology // Current Science (англ.) (рус., Vol. 96, No. 12, 25 june 2009 (копия)

- ↑ Mc Evilley T. The shape of ancient thought: comparative studies in Greek and Indian philosophies. Allworth Communications, Inc., 2002. 732p. (Aesthetics Today Series) ISBN 1-58115-203-5, ISBN 978-1-58115-203-6. p.385: «Яванаджатака — это самый ранний из сохранившихся текстов на санскрите по астрологии»

- ↑ Pingree, 1981, p. 81.

- ↑ Pingree D. Review of G. Prakash «Science and the Imagination of Modern India» // Journal of the American Oriental Society (2002), P. 154

«…the traditional Indian sciences that have survived best into the modem age are astrology and ayurveda» - ↑ The Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisements) Act, 1954 Архивная копия от 24 июля 2011 на Wayback Machine (недоступная ссылка с 11-05-2013 [3275 дней]) // Indian Legislation

- ↑ HC strikes down PIL against astrology // The Times of India (Hetal Vyas, TNN, 3.02.2011)

- ↑ Астрология — это наука, постановил индийский суд // ru.euronews.net (ИТАР-ТАСС, 7.02.2011). Версия NEWSru.com, 8.02.2011

- ↑ См. напр. Отделение Джьотиши на факультете Санскрита Университета в Бенаресе Архивная копия от 24 сентября 2010 на Wayback Machine (англ.)

- ↑ Department of Jyotish, Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeeta Архивная копия от 20 февраля 2015 на Wayback Machine (англ.)

- ↑ Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha Архивная копия от 7 июля 2012 на Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ch.Charan Singh University Архивная копия от 19 сентября 2010 на Wayback Machine (недоступная ссылка с 11-05-2013 [3275 дней]) (англ.)

«P.G. Diploma in Jyotish (one year) is also offered by the Department» - ↑ Jayant V. Narlikar, Sudhakar Kunte, Narendra Dabholkar and Prakash Ghatpande A statistical test of astrology // Current Science (англ.) (рус., Vol. 96, No. 5, 10 March 2009. (англ.) (Дата обращения: 20 февраля 2015) (копия)

Jayant V. Narlikar. An Indian Test of Indian Astrology (англ.) // Skeptical Inquirer. — March/April 2013. — Vol. 37.2. Архивировано 4 октября 2013 года.

Литература

Академическая литература

- Энциклопедии

- Булич С. К. Джьотиша // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- Kim Plofker, «South Asian mathematics; The role of astronomy and astrology», Encyclopedia Britannica (online edition, 2008)

- Pingree D., Gilbert R. A. «Astrology», Encyclopedia Britannica

- «Hindu Chronology», Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911)

- Статьи

- Chandra S. (англ.) (рус. «Religion and State in India and Search for Rationality», Social Scientist (2002).

- Pingree D.«Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran» , Isis — Journal of The History of Science Society (1963), 229—246.

- Pingree D. Jyotiḥśāstra: Astral and Mathematical Literature. — Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag (нем.) (рус., 1981. — 149 p. — (A history of Indian literature : Vol. 6: Scientific and technical literature: Pt. 3., Fasc. 4; J. Gonda (Ed.)). — ISBN 3-447-02165-9.

- Burgess E. «On the Origin of the Lunar Division of the Zodiac represented in the Nakshatra System of the Hindus», Journal of the American Oriental Society (англ.) (рус. (1866).

- Whitney W. D. «On the Views of Biot and Weber Respecting the Relations of the Hindu and Chinese Systems of Asterisms»», Journal of the American Oriental Society (англ.) (рус. (1866).

Литература по ведической астрологии

- Антон Михайлович Кузнецов. «9 Грах — 9 Сил жизни в Джйотише», Львов 2014 ISBN: 9789665085560.

- Махариши Парашара. «Брихат-Парашара-Хора-Шастра», Донецк 1999, ISBN: 9789965083549.

- Антон Кузнецов, Юлия Король. «Ведическая Нумерология и Тантра-Джйотиш», Хмельницкий 2020 ISBN: 9786175136287.

- Дхундхирадж. «Джатака-Бхаранам», Киев 2008 ISBN: 9789965084623.

- Антон Михайлович Кузнецов. «9 Грах — 9 Сил жизни в Джйотише», Хмельницкий 2016 ISBN: 9786175133408.

Ссылки

- Jyotiṣa (англ.)

- Ссылки

- Глоссарий

- Программное обеспечение

- Джйотиш. Тексты (недоступная ссылка)

Джьотиш(а) (санскр. ज्योतिष — IAST: jyotiṣa — «астрономия, астрология»[1] от IAST: jyotis — «свет, небесное светило»[2]) — астрология индуизма. Также называется индийской астрологией или ведической астрологией.

Разделы[ | ]

По традиции подразделяется на три ветви[3]:

- Сиддханта — традиционная индийская астрономия.

- Самхита, также называемая Медини Джьотиша (мунданная астрология) — предсказание важных событий в стране на основе анализа астрологической динамики её гороскопа, а также всеобщие события, как, например, война, землетрясение, политические перемены, финансовые показатели, элективная астрология.

- Хора — хорарная астрология, основанная на анализе гороскопа, построенного на момент возникновения вопроса.

Последние две являются частью предсказательной астрологии (Пхалита). Поэтому в целом индийская астрология подразделяется на две ветви Ганита (Сиддханта) и Пхалита (Самхита и Хора).

Особенности[ | ]

Основание джьотиши — бандху. Это понятие встречается в Ведах и означает связь между микрокосмом и макрокосмом. На практике джьотиша основывается на сидерическом зодиаке, который отличен от тропического, используемого в западной астрологии. В джьотише делается коррекция в связи с прецессией точки весеннего равноденствия. Джьотиша включает несколько подсистем интерпретации и предсказания с некоторыми элементами, которые отсутствуют в западной астрологии, например, система лунных стоянок. В Индии используют два стиля гороскопа: южный и северный.

Североиндийский гороскоп

Южноиндийский гороскоп

Астрология имеет важное значение в жизни индуистов. В индийской культуре новорождённым по традиции дают имя, основанное на их гороскопах, а понятия и идеи джьотиши глубоко проникли в систему календарей и праздников, также как и в другие области жизни. Например, джьотиша используется при принятии решения о бракосочетании, открытии нового бизнеса или переезде в новое жилище. Астрология даже сохраняет свою позицию среди «традиционных наук» в современной Индии[4]. После спорного решения Высшего Суда штата Андхра-Прадеш (2001) некоторые индийские университеты стали предлагать учёную степень по ведической астрологии[5], однако введение курса джьотиши в университетах вызвало резкую реакцию научного сообщества Индии, выразившего протест[6][7] против попыток придания научного статуса псевдонауке[8][9].

История[ | ]

Термин джьотиша как одна из Веданг (шести вспомогательных дисциплин ведийской религии) используется в «Мундака-упанишаде» и поэтому, вероятно, датируется временами Маурьев. «Веданга-джьотиша» была записана Лагадхой и содержала правила отслеживания движения солнца и луны.

Документированная история джьотиши берёт начало с взаимодействия индийской и эллинской культур во время индо-греческого периода. Самые древние сохранившиеся трактаты, такие как «Явана-джатака» или «Врихат-самхита», датируются первыми веками нашей эры. Самый древний астрологический трактат на санскрите «Явана-джатака» («Высказывания греков») — это стихотворное переложение, выполненное Спхуджидхваджей в 269 — 290 годах, являющееся переводом ныне утерянного греческого трактата греко-индийского астролога Яванешвары (II в.)[10].

Первые известные авторы, которые писали трактаты по астрономии, появились в V веке н. э., когда начался классический период индийской астрономии. Кроме теорий Арьябхаты, изложенных в «Арьябхатии» и утерянной «Арья-сиддханте», существует также «Панча-сиддхантика» Вараха Михиры.

Основные тексты, на которые опирается индийская астрология, это компиляции раннего Средневековья, в особенности «Брихат-парашара-хора-шастра» и «Саравали». «Хора-шастра» состоит из 71 главы. Первая её часть (главы 1-51) датируется VII веком и началом VIII-го, а вторая (главы 52-71) — концом VIII века. «Саравали» также датируется около 800 года[11]. Английские переводы этих книг были опубликованы Н. Н. Кришнарау и В. Б. Чудхари в 1963 и 1961 годах соответственно.

Развитие астрологии в Индии было важным фактором в развитии астрономии раннего Средневековья.

В современной Индии[ | ]

Дэвид Пингри отмечает, что джьотиша и аюрведа — это две традиционные дисциплины, которые лучше всех выжили в современной Индии, хотя обе были трансформированы под влиянием Запада[12].

В начале 2000-х джьотиша стала предметом политической борьбы между представителями религии и академического сообщества. Комиссия по университетским грантам и Министерство по развитию человеческих ресурсов решили ввести курс «ведической астрологии» (IAST: jyotir vijñāna) в индийских университетах, подкрепляя это решением Высшего суда штата Андхра-Прадеш, несмотря на широкие протесты от научного сообщества Индии и индийских учёных, работающих за рубежом[8][9], и извещение от Высшего Суда Индии, что это скачок назад, подрывающий научное доверие, которое заработала страна к этому времени[6]. Высший суд индийского мегаполиса Мумбаи в 2011 году отклонил требование запретить рекламу астрологии, заключив, что она является «уважаемой наукой», практикуемой 4 тыс. лет, и не подпадает под действие закона 1954 года[13], запрещающего публично выступать с ложными прогнозами[14][15]. В настоящее время несколько индийских университетов предлагают учёные степени в джьотише[16][17][18][19]. Ряд исследований в Индии показал неэффективность предсказаний индийских астрологов[9][20].

См. также[ | ]

- Веданга

- Наваратна

- Бхавишья-пурана

- Наваграха

- Астрологическая эра

- Древнеиндийский календарь

- Индийская астрономия

- Юга

- Индуистская космология

- Джьотиша-веданга

- Титхи

- Джьотишастра[en]

- Астрология Нади[en]

- Фонетическая астрология[en]— Swar Shaastra

- Панчангам[en]

- Ведическая археоастрономия[en]

- Бхригу Самхита[en]

Примечания[ | ]

- ↑ jyotiṣa in Sanskrit dictionary (англ.)

- ↑ jyotiṣ in Sanskrit dictionary (англ.)

- ↑ Asoke Chatterjee Piṅgalacchandaḥsūtra: a study. — University of Calcutta, 1987. С.46

- ↑ Пингри Д., Гилберт Р. «Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times» // Encyclopedia Britannica, 2008

«В таких странах, как Индия, где только небольшая интеллектуальная элита обучалась физике на Западе, астрология продолжает удерживать свои позиции среди наук» - ↑ Rao M. Female foeticide: where do we go? // Indian Journal of Medical Ethics Oct-Dec2001-9(4) [1];

- ↑ 1 2 Supreme Court questions ‘Jyotir Vigyan’ // Times of India, 3.09.2001. (англ.)

- ↑ Astrology not a science, reiterates Narlikar // Times of India (TNN, 5.12.2010)

- ↑ 1 2 Jayaraman T. A judicial blow Архивировано 28 июня 2009 года. // Frontline, Volume 18 — Issue 12, Jun. 09 — 22, 2001. (англ.)

- ↑ 1 2 3 Komath M. Testing astrology // Current Science (англ.) (рус., Vol. 96, No. 12, 25 june 2009 (копия)

- ↑ Mc Evilley T. The shape of ancient thought: comparative studies in Greek and Indian philosophies. Allworth Communications, Inc., 2002. 732p. (Aesthetics Today Series) ISBN 1-58115-203-5, ISBN 978-1-58115-203-6. p.385: «Яванаджатака — это самый ранний из сохранившихся текстов на санскрите по астрологии»

- ↑ Pingree, 1981, p. 81.

- ↑ Pingree D. Review of G. Prakash «Science and the Imagination of Modern India» // Journal of the American Oriental Society (2002), P. 154

«…the traditional Indian sciences that have survived best into the modem age are astrology and ayurveda» - ↑ The Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisements) Act, 1954 Архивная копия от 24 июля 2011 на Wayback Machine (недоступная ссылка с 11-05-2013 [3275 дней]) // Indian Legislation

- ↑ HC strikes down PIL against astrology // The Times of India (Hetal Vyas, TNN, 3.02.2011)

- ↑ Астрология — это наука, постановил индийский суд // ru.euronews.net (ИТАР-ТАСС, 7.02.2011). Версия NEWSru.com, 8.02.2011

- ↑ См. напр. Отделение Джьотиши на факультете Санскрита Университета в Бенаресе Архивная копия от 24 сентября 2010 на Wayback Machine (англ.)

- ↑ Department of Jyotish, Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeeta Архивная копия от 20 февраля 2015 на Wayback Machine (англ.)

- ↑ Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha Архивная копия от 7 июля 2012 на Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ch.Charan Singh University Архивная копия от 19 сентября 2010 на Wayback Machine (недоступная ссылка с 11-05-2013 [3275 дней]) (англ.)

«P.G. Diploma in Jyotish (one year) is also offered by the Department» - ↑ Jayant V. Narlikar, Sudhakar Kunte, Narendra Dabholkar and Prakash Ghatpande A statistical test of astrology // Current Science (англ.) (рус., Vol. 96, No. 5, 10 March 2009. (англ.) (Дата обращения: 20 февраля 2015) (копия)

Jayant V. Narlikar. An Indian Test of Indian Astrology (англ.) // Skeptical Inquirer. — March/April 2013. — Vol. 37.2. Архивировано 4 октября 2013 года.

Литература[ | ]

Академическая литература[ | ]

- Энциклопедии

- Булич С. К. Джьотиша // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- Kim Plofker, «South Asian mathematics; The role of astronomy and astrology», Encyclopedia Britannica (online edition, 2008)

- Pingree D., Gilbert R. A. «Astrology», Encyclopedia Britannica

- «Hindu Chronology», Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911)

- Статьи

- Chandra S. (англ.) (рус. «Religion and State in India and Search for Rationality», Social Scientist (2002).

- Pingree D.«Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran» , Isis — Journal of The History of Science Society (1963), 229—246.

- Pingree D. Jyotiḥśāstra: Astral and Mathematical Literature. — Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag (нем.) (рус., 1981. — 149 p. — (A history of Indian literature : Vol. 6: Scientific and technical literature: Pt. 3., Fasc. 4; J. Gonda (Ed.)). — ISBN 3-447-02165-9.

- Burgess E. «On the Origin of the Lunar Division of the Zodiac represented in the Nakshatra System of the Hindus», Journal of the American Oriental Society (англ.) (рус. (1866).

- Whitney W. D. «On the Views of Biot and Weber Respecting the Relations of the Hindu and Chinese Systems of Asterisms»», Journal of the American Oriental Society (англ.) (рус. (1866).

Литература по ведической астрологии[ | ]

- Антон Михайлович Кузнецов. «9 Грах — 9 Сил жизни в Джйотише», Львов 2014 ISBN: 9789665085560.

- Махариши Парашара. «Брихат-Парашара-Хора-Шастра», Донецк 1999, ISBN: 9789965083549.

- Антон Кузнецов, Юлия Король. «Ведическая Нумерология и Тантра-Джйотиш», Хмельницкий 2020 ISBN: 9786175136287.

- Дхундхирадж. «Джатака-Бхаранам», Киев 2008 ISBN: 9789965084623.

- Антон Михайлович Кузнецов. «9 Грах — 9 Сил жизни в Джйотише», Хмельницкий 2016 ISBN: 9786175133408.

Ссылки[ | ]

- Jyotiṣa (англ.)

- Ссылки

- Глоссарий

- Программное обеспечение

- Джйотиш. Тексты (недоступная ссылка)

Jyotisha or Jyotishya (from Sanskrit jyotiṣa, from jyót “light, heavenly body» and ish — from Isvara or God) is the traditional Hindu system of astrology, also known as Hindu astrology, Indian astrology and more recently Vedic astrology. It is one of the six auxiliary disciplines in Hinduism that is connected with the study of the Vedas.

The Vedanga Jyotisha is one of the earliest texts about astronomy within the Vedas.[1][2][3][4] Some scholars believe that the horoscopic astrology practiced in the Indian subcontinent came from Hellenistic influences.[5][6] However, this is a point of intense debate, and other scholars believe that Jyotisha developed independently, although it may have interacted with Greek astrology.[7]

Following a judgment of the Andhra Pradesh High Court in 2001 which favored astrology, some Indian universities now offer advanced degrees in Hindu astrology. The scientific consensus is that astrology is a pseudoscience.[8][9][10][11][12]

Etymology[edit]

Jyotisha, states Monier-Williams, is rooted in the word Jyotish, which means light, such as that of the sun or the moon or heavenly body. The term Jyotisha includes the study of astronomy, astrology and the science of timekeeping using the movements of astronomical bodies.[13][14] It aimed to keep time, maintain calendars, and predict auspicious times for Vedic rituals.[13][14]

History and core principles[edit]

Jyotiṣa is one of the Vedāṅga, the six auxiliary disciplines used to support Vedic rituals.[15]: 376 Early jyotiṣa is concerned with the preparation of a calendar to determine dates for sacrificial rituals,[15]: 377 with nothing written regarding planets.[15]: 377 There are mentions of eclipse-causing «demons» in the Atharvaveda and Chāndogya Upaniṣad, the latter mentioning Rāhu (a shadow entity believed responsible for eclipses and meteors).[15]: 382 The term graha, which is now taken to mean the planet, originally meant demon.[15]: 381 The Ṛigveda also mentions an eclipse-causing demon, Svarbhānu. However, the specific term graha was not applied to Svarbhānu until the later Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa.[15]: 382

The foundation of Hindu astrology is the notion of bandhu of the Vedas (scriptures), which is the connection between the microcosm and the macrocosm. The practice relies primarily on the sidereal zodiac, which differs from the tropical zodiac used in Western (Hellenistic) astrology in that an ayanāṃśa adjustment is made for the gradual precession of the vernal equinox. Hindu astrology includes several nuanced sub-systems of interpretation and prediction with elements not found in Hellenistic astrology, such as its system of lunar mansions (Nakṣatra). It was only after the transmission of Hellenistic astrology that the order of planets in India was fixed in that of the seven-day week.[15]: 383 [16] Hellenistic astrology and astronomy also transmitted the twelve zodiacal signs beginning with Aries and the twelve astrological places beginning with the ascendant.[15]: 384 The first evidence of the introduction of Greek astrology to India is the Yavanajātaka which dates to the early centuries CE.[15]: 383 The Yavanajātaka (lit. «Sayings of the Greeks») was translated from Greek to Sanskrit by Yavaneśvara during the 2nd century CE, and is considered the first Indian astrological treatise in the Sanskrit language.[17] However the only version that survives is the verse version of Sphujidhvaja which dates to AD 270.[15]: 383 The first Indian astronomical text to define the weekday was the Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa (born AD 476).[15]: 383

According to Michio Yano, Indian astronomers must have been occupied with the task of Indianizing and Sanskritizing Greek astronomy during the 300 or so years between the first Yavanajataka and the Āryabhaṭīya.[15]: 388 The astronomical texts of these 300 years are lost.[15]: 388 The later Pañcasiddhāntikā of Varāhamihira summarizes the five known Indian astronomical schools of the sixth century.[15]: 388 Indian astronomy preserved some of the older pre-Ptolemaic elements of Greek astronomy.[15]: 389 [18][19][20][14]

The main texts upon which classical Indian astrology is based are early medieval compilations, notably the Bṛhat Parāśara Horāśāstra, and Sārāvalī by Kalyāṇavarma.

The Horāshastra is a composite work of 71 chapters, of which the first part (chapters 1–51) dates to the 7th to early 8th centuries and the second part (chapters 52–71) to the later 8th century.[citation needed] The Sārāvalī likewise dates to around 800 CE.[21] English translations of these texts were published by N. N. Krishna Rau and V. B. Choudhari in 1963 and 1961, respectively.

Modern Hindu astrology[edit]

Nomenclature of the last two centuries

Astrology remains an important facet of folk belief in the contemporary lives of many Hindus. In Hindu culture, newborns are traditionally named based on their jyotiṣa charts (Kundali), and astrological concepts are pervasive in the organization of the calendar and holidays, and in making major decisions such as those about marriage, opening a new business, or moving into a new home. Many Hindus believe that heavenly bodies, including the planets, have an influence throughout the life of a human being, and these planetary influences are the «fruit of karma». The Navagraha, planetary deities, are considered subordinate to Ishvara (the Hindu concept of a supreme being) in the administration of justice. Thus, it is believed that these planets can influence earthly life.[22]

Astrology as a science[edit]

Astrology has been rejected by the scientific community as having no explanatory power for describing the universe. Scientific testing of astrology has been conducted, and no evidence has been found to support any of the premises or purported effects outlined in astrological traditions.[23]: 424 There is no mechanism proposed by astrologers through which the positions and motions of stars and planets could affect people and events on Earth. In spite of its status as a pseudoscience, in certain religious, political, and legal contexts, astrology retains a position among the sciences in modern India.[24]

India’s University Grants Commission and Ministry of Human Resource Development decided to introduce «Jyotir Vigyan» (i.e. jyotir vijñāna) or «Vedic astrology» as a discipline of study in Indian universities, stating that «vedic astrology is not only one of the main subjects of our traditional and classical knowledge but this is the discipline, which lets us know the events happening in human life and in universe on time scale»[25] in spite of the complete lack of evidence that astrology actually does allow for such accurate predictions.[26] The decision was backed by a 2001 judgement of the Andhra Pradesh High Court, and some Indian universities offer advanced degrees in astrology.[27][28]

This was met with widespread protests from the scientific community in India and Indian scientists working abroad.[29] A petition sent to the Supreme Court of India stated that the introduction of astrology to university curricula is «a giant leap backwards, undermining whatever scientific credibility the country has achieved so far».[25]

In 2004, the Supreme Court dismissed the petition,[30][31] concluding that the teaching of astrology did not qualify as the promotion of religion.[32][33] In February 2011, the Bombay High Court referred to the 2004 Supreme Court ruling when it dismissed a case which had challenged astrology’s status as a science.[34] As of 2014, despite continuing complaints by scientists,[35][36] astrology continues to be taught at various universities in India,[33][37] and there is a movement in progress to establish a national Vedic University to teach astrology together with the study of tantra, mantra, and yoga.[38]

Indian astrologers have consistently made claims that have been thoroughly debunked by skeptics. For example, although the planet Saturn is in the constellation Aries roughly every 30 years (e.g. 1909, 1939, 1968), the astrologer Bangalore Venkata Raman claimed that «when Saturn was in Aries in 1939 England had to declare war against Germany», ignoring all the other dates.[39] Astrologers regularly fail in attempts to predict election results in India, and fail to predict major events such as the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Predictions by the head of the Indian Astrologers Federation about war between India and Pakistan in 1982 also failed.[39]

In 2000, when several planets happened to be close to one another, astrologers predicted that there would be catastrophes, volcanic eruptions and tidal waves. This caused an entire sea-side village in the Indian state of Gujarat to panic and abandon their houses. The predicted events did not occur and the vacant houses were burgled.[12]

Texts[edit]

Time keeping

[The current year] minus one,

multiplied by twelve,

multiplied by two,

added to the elapsed [half months of current year],

increased by two for every sixty [in the sun],

is the quantity of half-months (syzygies).

— Rigveda Jyotisha-vedanga 4

Translator: Kim Plofker[40]

The ancient extant text on Jyotisha is the Vedanga-Jyotisha, which exists in two editions, one linked to Rigveda and other to Yajurveda.[41] The Rigveda version consists of 36 verses, while the Yajurveda recension has 43 verses of which 29 verses are borrowed from the Rigveda.[42][43] The Rigveda version is variously attributed to sage Lagadha, and sometimes to sage Shuci.[43] The Yajurveda version credits no particular sage, has survived into the modern era with a commentary of Somakara, and is the more studied version.[43]

The Jyotisha text Brahma-siddhanta, probably composed in the 5th century CE, discusses how to use the movement of planets, sun and moon to keep time and calendar.[44] This text also lists trigonometry and mathematical formulae to support its theory of orbits, predict planetary positions and calculate relative mean positions of celestial nodes and apsides.[44] The text is notable for presenting very large integers, such as 4.32 billion years as the lifetime of the current universe.[45]

The ancient Hindu texts on Jyotisha only discuss time keeping, and never mention astrology or prophecy.[46] These ancient texts predominantly cover astronomy, but at a rudimentary level.[47] Technical horoscopes and astrology ideas in India came from Greece and developed in the early centuries of the 1st millennium CE.[48][18][19] Later medieval era texts such as the Yavana-jataka and the Siddhanta texts are more astrology-related.[49]

Discussion[edit]

The field of Jyotisha deals with ascertaining time, particularly forecasting auspicious day and time for Vedic rituals.[14] The field of Vedanga structured time into Yuga which was a 5-year interval,[40] divided into multiple lunisolar intervals such as 60 solar months, 61 savana months, 62 synodic months and 67 sidereal months.[41] A Vedic Yuga had 1,860 tithis (तिथि, dates), and it defined a savana-day (civil day) from one sunrise to another.[50]

The Rigvedic version of Jyotisha may be a later insertion into the Veda, states David Pingree, possibly between 513 and 326 BCE, when Indus valley was occupied by the Achaemenid from Mesopotamia.[51] The mathematics and devices for time keeping mentioned in these ancient Sanskrit texts, proposes Pingree, such as the water clock may also have arrived in India from Mesopotamia. However, Yukio Ohashi considers this proposal as incorrect,[18] suggesting instead that the Vedic timekeeping efforts, for forecasting appropriate time for rituals, must have begun much earlier and the influence may have flowed from India to Mesopotamia.[50] Ohashi states that it is incorrect to assume that the number of civil days in a year equal 365 in both Hindu and Egyptian–Persian year.[52] Further, adds Ohashi, the Mesopotamian formula is different from the Indian formula for calculating time, each can only work for their respective latitude, and either would make major errors in predicting time and calendar in the other region.[53] According to Asko Parpola, the Jyotisha and luni-solar calendar discoveries in ancient India, and similar discoveries in China in «great likelihood result from convergent parallel development», and not from diffusion from Mesopotamia.[54]

Kim Plofker states that while a flow of timekeeping ideas from either side is plausible, each may have instead developed independently, because the loan-words typically seen when ideas migrate are missing on both sides as far as words for various time intervals and techniques.[55][56] Further, adds Plofker, and other scholars, that the discussion of time keeping concepts are found in the Sanskrit verses of the Shatapatha Brahmana, a 2nd millennium BCE text.[55][57] Water clock and sun dials are mentioned in many ancient Hindu texts such as the Arthashastra.[58][59] Some integration of Mesopotamian and Indian Jyotisha-based systems may have occurred in a roundabout way, states Plofker, after the arrival of Greek astrology ideas in India.[60]

The Jyotisha texts present mathematical formulae to predict the length of day time, sun rise and moon cycles.[50][61][62] For example,

- The length of daytime =

muhurtas[63]

- where n is the number of days after or before the winter solstice, and one muhurta equals 1⁄30 of a day (48 minutes).[64]

Water clock

A prastha of water [is] the increase in day, [and] decrease in night in the [sun’s] northern motion; vice versa in the southern. [There is] a six-muhurta [difference] in a half year.— Yajurveda Jyotisha-vedanga 8, Translator: Kim Plofker[63]

Elements[edit]

There are sixteen Varga (Sanskrit: varga, ‘part, division’), or divisional, charts used in Hindu astrology:[65][unreliable source?]: 61–64

Zodiac[edit]

The Nirayana, or sidereal zodiac, is an imaginary belt of 360 degrees, which, like the Sāyana, or tropical zodiac, is divided into 12 equal parts. Each part (of 30 degrees) is called a sign or rāśi (Sanskrit: ‘part’). Vedic (Jyotiṣa) and Western zodiacs differ in the method of measurement. While synchronically, the two systems are identical, Jyotiṣa primarily uses the sidereal zodiac (in which stars are considered to be the fixed background against which the motion of the planets is measured), whereas most Western astrology uses the tropical zodiac (the motion of the planets is measured against the position of the Sun on the spring equinox). After two millennia, as a result of the precession of the equinoxes, the origin of the ecliptic longitude has shifted by about 22 degrees. As a result, the placement of planets in the Jyotiṣa system is roughly aligned with the constellations, while tropical astrology is based on the solstices and equinoxes.

| English | Sanskrit[66] | Starting | Representation | Element | Quality | Ruling body |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aries | मेष, meṣa | 0° | ram | fire | movable (chara) | Mars |

| Taurus | वृषभ, vṛṣabha | 30° | bull | earth | fixed (sthira) | Venus |

| Gemini | मिथुन, mithuna | 60° | twins | air | dual (dvisvabhava) | Mercury |

| Cancer | कर्क, karka | 90° | crab | water | movable | Moon |

| Leo | सिंह, siṃha | 120° | lion | fire | fixed | Sun |

| Virgo | कन्या, kanyā | 150° | virgin girl | earth | dual | Mercury |

| Libra | तुला, tulā | 180° | balance | air | movable | Venus |

| Scorpio | वृश्चिक, vṛścika | 210° | scorpion | water | fixed | Mars |

| Sagittarius | धनुष, dhanuṣa | 240° | bow and arrow | fire | dual | Jupiter |

| Capricorn | मकर, makara | 270° | crocodile | earth | movable | Saturn |

| Aquarius | कुम्भ, khumba | 300° | water-bearer | air | fixed | Saturn |

| Pisces | मीन, mīna | 330° | fishes | water | dual | Jupiter |

Nakṣhatras, or lunar mansions[edit]

The nakshatras or lunar mansions are 27 equal divisions of the night sky used in Hindu astrology, each identified by its prominent star(s).[65]: 168

Historical (medieval) Hindu astrology enumerated either 27 or 28 nakṣatras. In modern astrology, a rigid system of 27 nakṣatras is generally used, each covering 13° 20′ of the ecliptic. The missing 28th nakshatra is Abhijeeta. Each nakṣatra is divided into equal quarters or padas of 3° 20′. Of greatest importance is the Abhiśeka Nakṣatra, which is held as king over the other nakṣatras. Worshipping and gaining favour over this nakṣhatra is said to give power to remedy all the other nakṣatras, and is of concern in predictive astrology and mitigating Karma.[citation needed]

The junction of two rashis as well as Nakshatras is known as Gandanta.[67]

Daśās – planetary periods[edit]

The word dasha (Devanāgarī: दशा, Sanskrit,daśā, ‘planetary period’) means ‘state of being’ and it is believed that the daśā largely governs the state of being of a person. The Daśā system shows which planets may be said to have become particularly active during the period of the Daśā. The ruling planet (the Daśānātha or ‘lord of the Daśā’) eclipses the mind of the person, compelling him or her to act per the nature of the planet.

There are several dasha systems, each with its own utility and area of application. There are Daśās of grahas (planets) as well as Daśās of the Rāśis (zodiac signs). The primary system used by astrologers is the Viṁśottarī Daśā system, which has been considered universally applicable in the Kali Yuga to all horoscopes.

The first Mahā-Daśā is determined by the position of the natal Moon in a given Nakṣatra. The lord of the Nakṣatra governs the Daśā. Each Mahā-Dāśā is divided into sub-periods called bhuktis, or antar-daśās, which are proportional divisions of the maha-dasa. Further proportional sub-divisions can be made, but error margins based on accuracy of the birth time grow exponentially. The next sub-division is called pratyantar-daśā, which can in turn be divided into sookshma-antardasa, which can in turn be divided into praana-antardaśā, which can be sub-divided into deha-antardaśā. Such sub-divisions also exist in all other Daśā systems.

Heavenly bodies[edit]

The navagraha (Sanskrit: नवग्रह, romanized: navagraha, lit. ‘nine planets’)[68] are the nine celestial bodies used in Hindu astrology:[65]: 38–51

- Surya (Sun)

- Chandra (Moon)

- Budha (Mercury)

- Shukra (Venus)

- Mangala (Mars)

- Bṛhaspati, or «Guru» (Jupiter)

- Shani (Saturn)

- Rahu (North node of the Moon)

- Ketu (South node of the Moon)

The navagraha are said to be forces that capture or eclipse the mind and the decision making of human beings. When the grahas are active in their daśās, or periodicities they are said to be particularly empowered to direct the affairs of people and events.

Planets are held to signify major details,[69] such as profession, marriage and longevity.[70] Of these indicators, known as Karakas, Parashara considers Atmakaraka most important, signifying broad contours of a person’s life.[70]: 316

Rahu and Ketu correspond to the points where the moon crosses the ecliptic plane (known as the ascending and descending nodes of the moon). Classically known in Indian and Western astrology as the «head and tail of the dragon», these planets are represented as a serpent-bodied demon beheaded by the Sudarshan Chakra of Vishnu after attempting to swallow the sun. They are primarily used to calculate the dates of eclipses. They are described as «shadow planets» because they are not visible in the night sky. Rahu and Ketu have an orbital cycle of 18 years and they are always retrograde in motion and 180 degrees from each other.

Gocharas – transits[edit]

A natal chart shows the position of the grahas at the moment of birth. Since that moment, the grahas have continued to move around the zodiac, interacting with the natal chart grahas. This period of interaction is called gochara (Sanskrit: gochara, ‘transit’).[65]: 227

The study of transits is based on the transit of the Moon (Chandra), which spans roughly two days, and also on the movement of Mercury (Budha) and Venus (Śukra) across the celestial sphere, which is relatively fast as viewed from Earth. The movement of the slower planets – Jupiter (Guru), Saturn (Śani) and Rāhu–Ketu — is always of considerable importance. Astrologers study the transit of the Daśā lord from various reference points in the horoscope.

Yogas – planetary combinations[edit]

In Hindu astronomy, yoga (Sanskrit: yoga, ‘union’) is a combination of planets placed in a specific relationship to each other.[65]: 265

Rāja yogas are perceived as givers of fame, status and authority, and are typically formed by the association of the Lord of Keṅdras (‘quadrants’), when reckoned from the Lagna (‘ascendant’), and the Lords of the Trikona (‘trines’, 120 degrees—first, fifth and ninth houses). The Rāja yogas are culminations of the blessings of Viṣṇu and Lakṣmī. Some planets, such as Mars for Leo Lagna, do not need another graha (or Navagraha, ‘planet’) to create Rājayoga, but are capable of giving Rājayoga by themselves due to their own lordship of the 4th Bhāva (‘astrological house’) and the 9th Bhāva from the Lagna, the two being a Keṅdra (‘angular house’—first, fourth, seventh and tenth houses) and Trikona Bhāva respectively.

Dhana Yogas are formed by the association of wealth-giving planets such as the Dhaneśa or the 2nd Lord and the Lābheśa or the 11th Lord from the Lagna. Dhana Yogas are also formed due to the auspicious placement of the Dārāpada (from dara, ‘spouse’ and pada, ‘foot’—one of the four divisions—3 degrees and 20 minutes—of a Nakshatra in the 7th house), when reckoned from the Ārūḍha Lagna (AL). The combination of the Lagneśa and the Bhāgyeśa also leads to wealth through the Lakṣmī Yoga.

Sanyāsa Yogas are formed due to the placement of four or more grahas, excluding the Sun, in a Keṅdra Bhāva from the Lagna.

There are some overarching yogas in Jyotiṣa such as Amāvasyā Doṣa, Kāla Sarpa Yoga-Kāla Amṛta Yoga and Graha Mālika Yoga that can take precedence over Yamaha yogar planetary placements in the horoscope.

Bhāvas – houses[edit]

The Hindu Jātaka or Janam Kundali or birth chart, is the Bhāva Chakra (Sanskrit: ‘division’ ‘wheel’), the complete 360° circle of life, divided into houses, and represents a way of enacting the influences in the wheel. Each house has associated kāraka (Sanskrit: ‘significator’) planets that can alter the interpretation of a particular house.[65]: 93–167 Each Bhāva spans an arc of 30° with twelve Bhāvas in any chart of the horoscope. These are a crucial part of any horoscopic study since the Bhāvas, understood as ‘state of being’, personalize the Rāśis/ Rashis to the native and each Rāśi/ Rashi apart from indicating its true nature reveals its impact on the person based on the Bhāva occupied. The best way to study the various facets of Jyotiṣa is to see their role in chart evaluation of actual persons and how these are construed.

Dṛiṣṭis[edit]

Drishti (Sanskrit: Dṛṣṭi, ‘sight’) is an aspect to an entire house. Grahas cast only forward aspects, with the furthest aspect being considered the strongest. For example, Jupiter aspects the 5th, 7th and 9th house from its position, Mars aspects the 4th, 7th, and 8th houses from its position, and its 8th house.[65]: 26–27

The principle of Drishti (aspect) was devised on the basis of the aspect of an army of planets as deity and demon in a war field.[71][72] Thus the Sun, a deity king with only one full aspect, is more powerful than the demon king Saturn, which has three full aspects.

Aspects can be cast both by the planets (Graha Dṛṣṭi) and by the signs (Rāśi Dṛṣṭi). Planetary aspects are a function of desire, while sign aspects are a function of awareness and cognizance.

There are some higher aspects of Graha Dṛṣṭi (planetary aspects) that are not limited to the Viśeṣa Dṛṣṭi or the special aspects. Rāśi Dṛṣṭi works based on the following formulaic structure: all movable signs aspect fixed signs except the one adjacent, and all dual and mutable signs aspect each other without exception.

See also[edit]

- Archaeoastronomy and Vedic chronology

- Hindu calendar

- Hindu cosmology

- History of astrology

- Indian astronomy

- Jyotiḥśāstra

- Nadi astrology

- Panchangam

- Horoscopic astrology

- Synoptical astrology

- Indian units of measurement

References[edit]

- ^ Thompson, Richard L. (2004). Vedic Cosmography and Astronomy. pp. 9–240.

- ^ Jha, Parmeshwar (1988). Āryabhaṭa I and his contributions to mathematics. p. 282.

- ^ Puttaswamy, T.K. (2012). Mathematical Achievements of Pre-Modern Indian Mathematicians. p. 1.

- ^ Witzel 2001.

- ^ Pingree 1981, pp. 67ff, 81ff, 101ff.

- ^ Samuel 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Tripathi, Vijaya Narayan (2008), «Astrology in India», in Selin, Helaine (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 264–267, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_9749, ISBN 978-1-4020-4425-0, retrieved 5 November 2020

- ^ Thagard, Paul R. (1978). «Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience» (PDF). Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association. 1: 223–234. doi:10.1086/psaprocbienmeetp.1978.1.192639. S2CID 147050929.

- ^ Sven Ove Hansson; Edward N. Zalta. «Science and Pseudo-Science». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ «Astronomical Pseudo-Science: A Skeptic’s Resource List». Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

- ^ Hartmann, P.; Reuter, M.; Nyborga, H. (May 2006). «The relationship between date of birth and individual differences in personality and general intelligence: A large-scale study». Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (7): 1349–1362. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.017.

To optimise the chances of finding even remote relationships between date of birth and individual differences in personality and intelligence we further applied two different strategies. The first one was based on the common chronological concept of time (e.g. month of birth and season of birth). The second strategy was based on the (pseudo-scientific) concept of astrology (e.g. Sun Signs, The Elements, and astrological gender), as discussed in the book Astrology: Science or superstition? by Eysenck and Nias (1982).

- ^ a b Narlikar, Jayant V. (2009). «Astronomy, pseudoscience and rational thinking». In Pasachoff, Jay; Percy, John (eds.). Teaching and Learning Astronomy: Effective Strategies for Educators Worldwide. Cambridge University Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 9780521115391. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ a b Monier Monier-Williams (1923). A Sanskrit–English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 353.

- ^ a b c d James Lochtefeld (2002), «Jyotisha» in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, pages 326–327

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Flood, Gavin. Yano, Michio. 2003. The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden: Blackwell.

- ^ Flood, p.

382 - ^ Mc Evilley «The shape of ancient thought», p. 385 («The Yavanajātaka is the earliest surviving Sanskrit text in horoscopy, and constitute the basis of all later Indian developments in horoscopy», himself quoting David Pingree «The Yavanajātaka of Sphujidhvaja» p. 5)

- ^ a b c Ohashi 1999, pp. 719–721.

- ^ a b Pingree 1973, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Erik Gregersen (2011). The Britannica Guide to the History of Mathematics. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-61530-127-0.

- ^ David Pingree, Jyotiḥśāstra (J. Gonda (Ed.) A History of Indian Literature, Vol VI Fasc 4), p. 81

- ^ Karma, an anthropological inquiry, pg. 134, at Google Books

- ^ Zarka, Philippe (2011). «Astronomy and astrology». Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 5 (S260): 420–425. Bibcode:2011IAUS..260..420Z. doi:10.1017/S1743921311002602.

- ^ «In countries such as India, where only a small intellectual elite has been trained in Western physics, astrology manages to retain here and there its position among the sciences.» David Pingree and Robert Gilbert, «Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times» Encyclopædia Britannica 2008

- ^ a b Supreme Court questions ‘Jyotir Vigyan’, Times of India, 3 September 2001 timesofindia.indiatimes.com

- ^ «Heavens, it’s not Science». The Times of India. 3 May 2001. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Mohan Rao, Female foeticide: where do we go? Indian Journal of Medical Ethics Oct-Dec2001-9(4), issuesinmedicalethics.org Archived 27 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ T. Jayaraman, A judicial blow, Frontline Volume 18 – Issue 12, Jun. 09 – 22, 2001 hinduonnet.com

- ^ T. Jayaraman, A judicial blow, Frontline Volume 18 – Issue 12, June 09 – 22, 2001 hinduonnet.com[Usurped!]

- ^ Astrology On A Pedestal, Ram Ramachandran, Frontline Volume 21, Issue 12, Jun. 05 — 18, 2004

- ^ Introduction of Vedic astrology courses in varsities upheld, The Hindu, Thursday, May 06, 2004

- ^ «Supreme Court: Bhargava v. University Grants Commission, Case No.: Appeal (civil) 5886 of 2002». Archived from the original on 12 March 2005.

- ^ a b «Introduction of Vedic astrology courses in universities upheld». The Hindu. 5 May 2004. Archived from the original on 23 September 2004.

- ^ «Astrology is a science: Bombay HC». The Times of India. 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2011.

- ^ «Integrate Indian medicine with modern science». The Hindu. 26 October 2003. Archived from the original on 13 November 2003.

- ^ Narlikar, Jayant V. (2013). «An Indian Test of Indian Astrology». Skeptical Inquirer. 37 (2). Archived from the original on 23 July 2013.

- ^ «People seek astrological advise from Banaras Hindu University experts to tackle health issues». The Times of India. 13 February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014.

- ^ «Set-up Vedic university to promote astrology». The Times of India. 9 February 2013. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013.

- ^ a b Narlikar, Jayant V. (March–April 2013). «An Indian Test of Indian Astrology». Skeptical Inquirer. 37 (2).

- ^ a b Plofker 2009, p. 36.

- ^ a b Ohashi 1999, p. 719.

- ^ Plofker 2009, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b c Pingree 1973, p. 1.

- ^ a b Plofker 2009, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Plofker 2009, pp. 68–71.

- ^ C. K. Raju (2007). Cultural Foundations of Mathematics. Pearson. p. 205. ISBN 978-81-317-0871-2.

- ^ Friedrich Max Müller (1860). A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature. Williams and Norgate. pp. 210–215.

- ^ Nicholas Campion (2012). Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions. New York University Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-8147-0842-2.

- ^ Plofker 2009, pp. 116–120, 259–261.

- ^ a b c Ohashi 1993, pp. 185–251.

- ^ Pingree 1973, p. 3.

- ^ Ohashi 1999, pp. 719–720.

- ^ Yukio Ohashi (2013). S.M. Ansari (ed.). History of Oriental Astronomy. Springer Science. pp. 75–82. ISBN 978-94-015-9862-0.

- ^ Asko Parpola (2013), «Beginnings of Indian Astronomy, with Reference to a Parallel Development in China», History of Science in South Asia, Vol. 1, pages 21–25

- ^ a b Plofker 2009, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Sarma, Nataraja (2000). «Diffusion of astronomy in the ancient world». Endeavour. Elsevier. 24 (4): 157–164. doi:10.1016/s0160-9327(00)01327-2. PMID 11196987.

- ^ Helaine Selin (2012). Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy. Springer Science. pp. 320–321. ISBN 978-94-011-4179-6.

- ^ Hinuber, Oskar V. (1978). «Probleme der Technikgeschichte im alten Indien». Saeculum (in German). Bohlau Verlag. 29 (3): 215–230. doi:10.7788/saeculum.1978.29.3.215. S2CID 171007726.

- ^ Kauṭilya (2013). King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India: Kautilya’s Arthasastra. Translated by Olivelle, Patrick. Oxford University Press. pp. 473 with note 1.7.8. ISBN 978-0-19-989182-5.

- ^ Kim Plofker (2008). Micah Ross (ed.). From the Banks of the Euphrates: Studies in Honor of Alice Louise Slotsky. Eisenbrauns. pp. 193–203. ISBN 978-1-57506-144-3.

- ^ Plofker 2009, pp. 35–40.

- ^ Winternitz 1963, p. 269.

- ^ a b Plofker 2009, p. 37.

- ^ Ohashi 1999, p. 720.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sutton, Komilla (1999). The Essentials of Vedic Astrology, The Wessex Astrologer Ltd, England

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ Defouw, Hart; Svoboda, Robert E. (1 October 2000). Light on Relationships: The Synatry of Indian Astrology. Weiser Books. ISBN 978-1-57863-148-3. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ Sanskrit-English Dictionary by Monier-Williams, (c) 1899

- ^ Raman, Bangalore V. (15 October 2003). Studies in Jaimini Astrology. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 978-81-208-1397-7.

Each planet is supposed to be the karaka or indicator of certain events in life

- ^ a b Santhanam, R. (1984). Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra (vol. 1). Ranjan Publications. p. 319.

- ^ Sanat Kumar Jain, ‘Astrology a science or myth’, Atlantic Publishers, New Delhi.

- ^ Sanat Kumar Jain, «Jyotish Kitna Sahi Kitna Galat’ (Hindi).

Bibliography[edit]

- Ohashi, Yukio (1999). Andersen, Johannes (ed.). Highlights of Astronomy, Volume 11B. Springer Science. ISBN 978-0-7923-5556-4.

- Ohashi, Yukio (1993). «Development of Astronomical Observations in Vedic and post-Vedic India». Indian Journal of History of Science. 28 (3).

- Plofker, Kim (2009). Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6.

- Pingree, David (1973). «The Mesopotamian Origin of Early Indian Mathematical Astronomy». Journal for the History of Astronomy. SAGE. 4 (1): 1–12. Bibcode:1973JHA…..4….1P. doi:10.1177/002182867300400102. S2CID 125228353.

- Pingree, David (1981). Jyotihśāstra: Astral and Mathematical Literature. Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447021654.

- Raman, BV (1992). Planetary Influences on Human Affairs. South Asian Books. ISBN 978-8185273907.

- Samuel, Samuel (2010). The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Cambridge University Press.

- Winternitz, Maurice (1963). History of Indian Literature. Vol. 1. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0056-4.

- Witzel, Michael (25 May 2001). «Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts». Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 7 (3).

Further reading[edit]

- Burgess, Ebenezer (1866). «On the Origin of the Lunar Division of the Zodiac represented in the Nakshatra System of the Hindus». Journal of the American Oriental Society.

- Chandra, Satish (2002). «Religion and State in India and Search for Rationality». Social Scientist

- Fleet, John F. (1911). «Hindu Chronology» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 491–501.

- Jain, Sanat K. «Astrology a science or myth», New Delhi, Atlasntic Publishers 2005 — highlighting how every principle like sign lord, aspect, friendship-enmity, exalted-debilitated, Mool trikon, dasha, Rahu-Ketu, etc. were framed on the basis of the ancient concept that Sun is nearer than the Moon from the Earth, etc.

- Pingree, David (1963). «Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran». Isis – Journal of The History of Science Society. pp. 229–246.

- Pingree, David (1981). Jyotiḥśāstra in J. Gonda (ed.) A History of Indian Literature. Vol VI. Fasc 4. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Pingree, David and Gilbert, Robert (2008). «Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times». Encyclopædia Britannica. online ed.

- Plofker, Kim. (2008). «South Asian mathematics; The role of astronomy and astrology». Encyclopædia Britannica, online ed.

- Whitney, William D. (1866). «On the Views of Biot and Weber Respecting the Relations of the Hindu and Chinese Systems of Asterisms», Journal of the American Oriental Society

- Popular treatments

- Frawley, David (2000). Astrology of the Seers: A Guide to Vedic (Hindu) Astrology. Twin Lakes Wisconsin: Lotus Press. ISBN 0-914955-89-6

- Frawley, David (2005). Ayurvedic Astrology: Self-Healing Through the Stars. Twin Lakes Wisconsin: Lotus Press. ISBN 0-940985-88-8

- Sutton, Komilla (1999). The Essentials of Vedic Astrology. The Wessex Astrologer, Ltd.: Great Britain. ISBN 1902405064

External links[edit]

- Hindu astrology at Curlie

Jyotisha or Jyotishya (from Sanskrit jyotiṣa, from jyót “light, heavenly body» and ish — from Isvara or God) is the traditional Hindu system of astrology, also known as Hindu astrology, Indian astrology and more recently Vedic astrology. It is one of the six auxiliary disciplines in Hinduism that is connected with the study of the Vedas.

The Vedanga Jyotisha is one of the earliest texts about astronomy within the Vedas.[1][2][3][4] Some scholars believe that the horoscopic astrology practiced in the Indian subcontinent came from Hellenistic influences.[5][6] However, this is a point of intense debate, and other scholars believe that Jyotisha developed independently, although it may have interacted with Greek astrology.[7]

Following a judgment of the Andhra Pradesh High Court in 2001 which favored astrology, some Indian universities now offer advanced degrees in Hindu astrology. The scientific consensus is that astrology is a pseudoscience.[8][9][10][11][12]

Etymology[edit]

Jyotisha, states Monier-Williams, is rooted in the word Jyotish, which means light, such as that of the sun or the moon or heavenly body. The term Jyotisha includes the study of astronomy, astrology and the science of timekeeping using the movements of astronomical bodies.[13][14] It aimed to keep time, maintain calendars, and predict auspicious times for Vedic rituals.[13][14]

History and core principles[edit]

Jyotiṣa is one of the Vedāṅga, the six auxiliary disciplines used to support Vedic rituals.[15]: 376 Early jyotiṣa is concerned with the preparation of a calendar to determine dates for sacrificial rituals,[15]: 377 with nothing written regarding planets.[15]: 377 There are mentions of eclipse-causing «demons» in the Atharvaveda and Chāndogya Upaniṣad, the latter mentioning Rāhu (a shadow entity believed responsible for eclipses and meteors).[15]: 382 The term graha, which is now taken to mean the planet, originally meant demon.[15]: 381 The Ṛigveda also mentions an eclipse-causing demon, Svarbhānu. However, the specific term graha was not applied to Svarbhānu until the later Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa.[15]: 382

The foundation of Hindu astrology is the notion of bandhu of the Vedas (scriptures), which is the connection between the microcosm and the macrocosm. The practice relies primarily on the sidereal zodiac, which differs from the tropical zodiac used in Western (Hellenistic) astrology in that an ayanāṃśa adjustment is made for the gradual precession of the vernal equinox. Hindu astrology includes several nuanced sub-systems of interpretation and prediction with elements not found in Hellenistic astrology, such as its system of lunar mansions (Nakṣatra). It was only after the transmission of Hellenistic astrology that the order of planets in India was fixed in that of the seven-day week.[15]: 383 [16] Hellenistic astrology and astronomy also transmitted the twelve zodiacal signs beginning with Aries and the twelve astrological places beginning with the ascendant.[15]: 384 The first evidence of the introduction of Greek astrology to India is the Yavanajātaka which dates to the early centuries CE.[15]: 383 The Yavanajātaka (lit. «Sayings of the Greeks») was translated from Greek to Sanskrit by Yavaneśvara during the 2nd century CE, and is considered the first Indian astrological treatise in the Sanskrit language.[17] However the only version that survives is the verse version of Sphujidhvaja which dates to AD 270.[15]: 383 The first Indian astronomical text to define the weekday was the Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa (born AD 476).[15]: 383

According to Michio Yano, Indian astronomers must have been occupied with the task of Indianizing and Sanskritizing Greek astronomy during the 300 or so years between the first Yavanajataka and the Āryabhaṭīya.[15]: 388 The astronomical texts of these 300 years are lost.[15]: 388 The later Pañcasiddhāntikā of Varāhamihira summarizes the five known Indian astronomical schools of the sixth century.[15]: 388 Indian astronomy preserved some of the older pre-Ptolemaic elements of Greek astronomy.[15]: 389 [18][19][20][14]

The main texts upon which classical Indian astrology is based are early medieval compilations, notably the Bṛhat Parāśara Horāśāstra, and Sārāvalī by Kalyāṇavarma.

The Horāshastra is a composite work of 71 chapters, of which the first part (chapters 1–51) dates to the 7th to early 8th centuries and the second part (chapters 52–71) to the later 8th century.[citation needed] The Sārāvalī likewise dates to around 800 CE.[21] English translations of these texts were published by N. N. Krishna Rau and V. B. Choudhari in 1963 and 1961, respectively.

Modern Hindu astrology[edit]

Nomenclature of the last two centuries

Astrology remains an important facet of folk belief in the contemporary lives of many Hindus. In Hindu culture, newborns are traditionally named based on their jyotiṣa charts (Kundali), and astrological concepts are pervasive in the organization of the calendar and holidays, and in making major decisions such as those about marriage, opening a new business, or moving into a new home. Many Hindus believe that heavenly bodies, including the planets, have an influence throughout the life of a human being, and these planetary influences are the «fruit of karma». The Navagraha, planetary deities, are considered subordinate to Ishvara (the Hindu concept of a supreme being) in the administration of justice. Thus, it is believed that these planets can influence earthly life.[22]

Astrology as a science[edit]

Astrology has been rejected by the scientific community as having no explanatory power for describing the universe. Scientific testing of astrology has been conducted, and no evidence has been found to support any of the premises or purported effects outlined in astrological traditions.[23]: 424 There is no mechanism proposed by astrologers through which the positions and motions of stars and planets could affect people and events on Earth. In spite of its status as a pseudoscience, in certain religious, political, and legal contexts, astrology retains a position among the sciences in modern India.[24]

India’s University Grants Commission and Ministry of Human Resource Development decided to introduce «Jyotir Vigyan» (i.e. jyotir vijñāna) or «Vedic astrology» as a discipline of study in Indian universities, stating that «vedic astrology is not only one of the main subjects of our traditional and classical knowledge but this is the discipline, which lets us know the events happening in human life and in universe on time scale»[25] in spite of the complete lack of evidence that astrology actually does allow for such accurate predictions.[26] The decision was backed by a 2001 judgement of the Andhra Pradesh High Court, and some Indian universities offer advanced degrees in astrology.[27][28]

This was met with widespread protests from the scientific community in India and Indian scientists working abroad.[29] A petition sent to the Supreme Court of India stated that the introduction of astrology to university curricula is «a giant leap backwards, undermining whatever scientific credibility the country has achieved so far».[25]

In 2004, the Supreme Court dismissed the petition,[30][31] concluding that the teaching of astrology did not qualify as the promotion of religion.[32][33] In February 2011, the Bombay High Court referred to the 2004 Supreme Court ruling when it dismissed a case which had challenged astrology’s status as a science.[34] As of 2014, despite continuing complaints by scientists,[35][36] astrology continues to be taught at various universities in India,[33][37] and there is a movement in progress to establish a national Vedic University to teach astrology together with the study of tantra, mantra, and yoga.[38]

Indian astrologers have consistently made claims that have been thoroughly debunked by skeptics. For example, although the planet Saturn is in the constellation Aries roughly every 30 years (e.g. 1909, 1939, 1968), the astrologer Bangalore Venkata Raman claimed that «when Saturn was in Aries in 1939 England had to declare war against Germany», ignoring all the other dates.[39] Astrologers regularly fail in attempts to predict election results in India, and fail to predict major events such as the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Predictions by the head of the Indian Astrologers Federation about war between India and Pakistan in 1982 also failed.[39]

In 2000, when several planets happened to be close to one another, astrologers predicted that there would be catastrophes, volcanic eruptions and tidal waves. This caused an entire sea-side village in the Indian state of Gujarat to panic and abandon their houses. The predicted events did not occur and the vacant houses were burgled.[12]

Texts[edit]

Time keeping

[The current year] minus one,

multiplied by twelve,

multiplied by two,

added to the elapsed [half months of current year],

increased by two for every sixty [in the sun],

is the quantity of half-months (syzygies).

— Rigveda Jyotisha-vedanga 4

Translator: Kim Plofker[40]

The ancient extant text on Jyotisha is the Vedanga-Jyotisha, which exists in two editions, one linked to Rigveda and other to Yajurveda.[41] The Rigveda version consists of 36 verses, while the Yajurveda recension has 43 verses of which 29 verses are borrowed from the Rigveda.[42][43] The Rigveda version is variously attributed to sage Lagadha, and sometimes to sage Shuci.[43] The Yajurveda version credits no particular sage, has survived into the modern era with a commentary of Somakara, and is the more studied version.[43]

The Jyotisha text Brahma-siddhanta, probably composed in the 5th century CE, discusses how to use the movement of planets, sun and moon to keep time and calendar.[44] This text also lists trigonometry and mathematical formulae to support its theory of orbits, predict planetary positions and calculate relative mean positions of celestial nodes and apsides.[44] The text is notable for presenting very large integers, such as 4.32 billion years as the lifetime of the current universe.[45]

The ancient Hindu texts on Jyotisha only discuss time keeping, and never mention astrology or prophecy.[46] These ancient texts predominantly cover astronomy, but at a rudimentary level.[47] Technical horoscopes and astrology ideas in India came from Greece and developed in the early centuries of the 1st millennium CE.[48][18][19] Later medieval era texts such as the Yavana-jataka and the Siddhanta texts are more astrology-related.[49]

Discussion[edit]

The field of Jyotisha deals with ascertaining time, particularly forecasting auspicious day and time for Vedic rituals.[14] The field of Vedanga structured time into Yuga which was a 5-year interval,[40] divided into multiple lunisolar intervals such as 60 solar months, 61 savana months, 62 synodic months and 67 sidereal months.[41] A Vedic Yuga had 1,860 tithis (तिथि, dates), and it defined a savana-day (civil day) from one sunrise to another.[50]

The Rigvedic version of Jyotisha may be a later insertion into the Veda, states David Pingree, possibly between 513 and 326 BCE, when Indus valley was occupied by the Achaemenid from Mesopotamia.[51] The mathematics and devices for time keeping mentioned in these ancient Sanskrit texts, proposes Pingree, such as the water clock may also have arrived in India from Mesopotamia. However, Yukio Ohashi considers this proposal as incorrect,[18] suggesting instead that the Vedic timekeeping efforts, for forecasting appropriate time for rituals, must have begun much earlier and the influence may have flowed from India to Mesopotamia.[50] Ohashi states that it is incorrect to assume that the number of civil days in a year equal 365 in both Hindu and Egyptian–Persian year.[52] Further, adds Ohashi, the Mesopotamian formula is different from the Indian formula for calculating time, each can only work for their respective latitude, and either would make major errors in predicting time and calendar in the other region.[53] According to Asko Parpola, the Jyotisha and luni-solar calendar discoveries in ancient India, and similar discoveries in China in «great likelihood result from convergent parallel development», and not from diffusion from Mesopotamia.[54]

Kim Plofker states that while a flow of timekeeping ideas from either side is plausible, each may have instead developed independently, because the loan-words typically seen when ideas migrate are missing on both sides as far as words for various time intervals and techniques.[55][56] Further, adds Plofker, and other scholars, that the discussion of time keeping concepts are found in the Sanskrit verses of the Shatapatha Brahmana, a 2nd millennium BCE text.[55][57] Water clock and sun dials are mentioned in many ancient Hindu texts such as the Arthashastra.[58][59] Some integration of Mesopotamian and Indian Jyotisha-based systems may have occurred in a roundabout way, states Plofker, after the arrival of Greek astrology ideas in India.[60]

The Jyotisha texts present mathematical formulae to predict the length of day time, sun rise and moon cycles.[50][61][62] For example,

- The length of daytime =

muhurtas[63]

- where n is the number of days after or before the winter solstice, and one muhurta equals 1⁄30 of a day (48 minutes).[64]

Water clock