§ 17. Названия исторических эпох, событий, съездов, геологических периодов

1. В названиях исторических эпох и событий первое слово (и все имена собственные) пишется с прописной буквы; родовые наименования (эпоха, век и т. п.) пишутся со строчной буквы: Древний Китай, Древняя Греция, Древний Рим (‘государство’; но: древний Рим — ‘город’), Римская империя, Киевская Русь; Крестовые походы, эпоха Возрождения, Высокое Возрождение, Ренессанс, Реформация, эпоха Просвещения, Смутное время, Петровская эпоха (но: допетровская эпоха, послепетровская эпоха); Куликовская битва, Бородинский бой; Семилетняя война, Великая Отечественная война (традиционное написание), Война за независимость (в Северной Америке); Июльская монархия, Вторая империя, Пятая республика; Парижская коммуна, Версальский мир, Декабрьское вооружённое восстание 1905 года (но: декабрьское восстание 1825 года).

2. В официальных названиях конгрессов, съездов, конференций первое слово (обычно это слова Первый, Второй и т. д.; Всероссийский, Всесоюзный, Всемирный, Международный и т. п.) и все имена собственные пишутся с прописной буквы: Всероссийский съезд учителей, Первый всесоюзный съезд писателей, Всемирный конгресс сторонников мира, Международный астрономический съезд, Женевская конференция, Базельский конгресс I Интернационала.

После порядкового числительного, обозначенного цифрой, сохраняется написание первого слова с прописной буквы: 5-й Международный конгресс преподавателей, XX Международный Каннский кинофестиваль.

3. Названия исторических эпох, периодов и событий, не являющиеся именами собственными, а также названия геологических периодов пишутся со строчной буквы: античный мир, средневековье, феодализм, русско-турецкие войны, наполеоновские войны; гражданская война (но: Гражданская война в России и США); мезозойская эра, меловой период, эпоха палеолита, каменный век, ледниковый период.

Как правильно пишется словосочетание «эпоха просвещения»

- Как правильно пишется слово «эпоха»

- Как правильно пишется слово «просвещение»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: растровый — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «эпоха»

Ассоциации к слову «просвещение»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «эпоха просвещения»

Предложения со словосочетанием «эпоха просвещения»

- А потом где-то в середине тысячелетия началась эпоха просвещения – проявленного света.

- Что касается физики, то мы нападём и на новую физику 21века, и на физику элементарных частиц 20 века, а самое удивительное, даже на классическую физику эпохи просвещения.

- Но с возникновением науки, изучением истории после эпохи просвещения судьба человечества стала рассматриваться как единая история развития и прогресса вместе с препятствиями, периодами застоя и регресса, которые, разумеется, вполне возможны.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «эпоха просвещения»

- — Нет-с, дала ответ, дала в том, как думали лучшие умы, как думали Вольтер [Вольтер (Франсуа Мари Аруэ) (1694—1778) — выдающийся французский писатель, один из крупнейших деятелей эпохи Просвещения.], Конт.

- Позади его не было Средневековья, позади была пережитая интеллигенцией эпоха просвещения.

- Русский ренессанс вернее сравнить с германским романтизмом начала XIX в., которому тоже предшествовала эпоха просвещения.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Сочетаемость слова «эпоха»

- новая эпоха

советская эпоха

целая эпоха - эпоха возрождения

эпоха просвещения

эпоха ренессанса - люди разных эпох

начало новой эпохи

конец эпохи - эпоха закончилась

эпоха кончилась

эпоха сменилась - жить в эпоху

относиться к эпохе

начиная с эпохи - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Сочетаемость слова «просвещение»

- народное просвещение

европейское просвещение

французское просвещение - просвещение народа

просвещение масс

просвещение ума - эпоха просвещения

министерство народного просвещения

министр народного просвещения - заняться чьим-либо просвещением

начиная с эпохи просвещения

нести просвещение - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение словосочетания «эпоха просвещения»

-

Эпо́ха Просвеще́ния — одна из ключевых эпох в истории европейской культуры, связанная с развитием научной, философской и общественной мысли. В основе этого интеллектуального движения лежали рационализм и свободомыслие. (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания ЭПОХА ПРОСВЕЩЕНИЯ

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «эпоха»

- А там, меж строк,

Минуя и ахи и охи,

Тебе улыбнется презрительно Блок —

Трагический тенор эпохи. - Никакой язык ни в какую эпоху не может быть до того удовлетворительным, чтобы от него нечего было больше желать и ожидать.

- Литературы великих мировых эпох таят в себе присутствие чего-то страшного, то приближающегося, то опять, отходящего, наконец разражающегося смерчем где-то совсем близко, так близко, что, кажется, почва уходит из-под ног: столб крутящейся пыли вырывает воронки в земле и уносит вверх окружающие цветы и травы. Тогда кажется, что близок конец и не может более существовать литература. Она сметена смерчем, разразившемся в душе писателя.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

Эпо́ха Просвеще́ния — одна из ключевых эпох в истории европейской культуры, связанная с развитием научной, философской и общественной мысли. В основе этого интеллектуального движения лежали рационализм и свободомыслие.

Все значения словосочетания «эпоха просвещения»

-

А потом где-то в середине тысячелетия началась эпоха просвещения – проявленного света.

-

Что касается физики, то мы нападём и на новую физику 21века, и на физику элементарных частиц 20 века, а самое удивительное, даже на классическую физику эпохи просвещения.

-

Но с возникновением науки, изучением истории после эпохи просвещения судьба человечества стала рассматриваться как единая история развития и прогресса вместе с препятствиями, периодами застоя и регресса, которые, разумеется, вполне возможны.

- (все предложения)

- последующая эпоха

- новая эпоха

- эпоха расцвета

- эпоха Возрождения

- современная эпоха

- (ещё синонимы…)

- век

- эпопея

- время

- возрождение

- история

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- свет

- гуманизм

- просвещать

- знание

- учение

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- новая эпоха

- эпоха возрождения

- люди разных эпох

- эпоха закончилась

- жить в эпоху

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- народное просвещение

- просвещение народа

- эпоха просвещения

- заняться чьим-либо просвещением

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- Разбор по составу слова «эпоха»

- Разбор по составу слова «просвещение»

- Как правильно пишется слово «эпоха»

- Как правильно пишется слово «просвещение»

Всего найдено: 16

Добрый день! Не стал бы задавать этот вопрос, если б не столкнулся с массовым заблуждением, которое возникает у людей, проверяющих правописание слова «горнотранспортный» на вашем портале. Применительно к геологии и открытым горным работам часто употребляют словосочетания «горно-транспортный комплекс», горно-транспортная схема [железорудного карьера]» и т.д. Видимо, специалисты портала «Грамота.ру» не в курсе тонкостей геологических терминов. Горно-транспортный комплекс — это не про горный транспорт, а про горные работы и транспортировку горной массы, руды. То есть «горно» — горные работы (геологоразведка, бурение, взрыв и эскавация полезных ископаемых) и «транспортный» — транспорт (железнодорожный транспорт, автомобильный транспорт, конвейерные комплексы и т.д.). То есть образование слова по принципу «главное+зависимое» в данном случае не работает. Кроме этого, то такое «горный транспорт»? Такого определения не существует в принципе. Есть горная техника, горные работы, а горное и транспортное оборудование, а горного транспорта увы нет. Ссылка на геологическую литературу, где слово пишется через дефис: https://www.geokniga.org/labels/41236 Заранее благодарю за ответ! С уважением, Николай Николаев

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Орфографический словарь на нашем портале отражает нормы, установленные академическим «Русским орфографическим словарем» — преемником академического «Орфографического словаря русского языка» (1956—1999). Слитное написание для слова горнотранспортный рекомендуется орфографическими словарями с 1968 года. Орфографистам хорошо известно значение слова, известно также, что правило о написании сложных прилагательных, на которое Вы ссылаетесь, еще с момента его закрепления в «Правилах русской орфографии и пунктуации» 1956 года работает плохо, оно имеет множество исключений, которые фиксировались всегда словарно, никогда не предлагались в виде полного списка к правилу.

Редактор «Русского орфографического словаря» О. Е. Иванова по поводу правила написания сложных прилагательных 1956 года пишет: «…специалистам известно, что правила написания сложных прилагательных далеки от совершенства, а полного списка исключений к ним никогда не было, нет и быть не может. «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» 1956 г. (далее — Правила), которые до сего дня являются единственным законодательно утвержденным сводом правил русского правописания, уже давно оцениваются специалистами как неполные и в ряде случаев не соответствующие современному состоянию письма. В частности, и та норма в § 80 п. 2, которая регулирует написание сложных прилагательных, стала нарушаться едва ли не с первых лет существования Правил. Уже в первом издании «Орфографического словаря русского языка» в том же 1956 г. даны с дефисом, несмотря на легко устанавливаемое подчинительное соотношение частей, например, такие слова: буржуазно-демократический (хотя буржуазная демократия), военно-исторический (хотя военная история; и мн. др. слова с первой частью военно-), врачебно-консультационный (хотя врачебная консультация или консультация врача) и врачебно-контрольный, врачебно-наблюдательный, дорожно-строительный, жилищно-кооперативный, конституционно-демократический, парашютно-десантный, союзно-республиканский, стрелково-спортивный, субъективно-идеалистический, уголовно-процессуальный и др. Позднее появились и многие другие прилагательные, пишущиеся не по правилу (к примеру: авторско-правовой, валютно-обменный, врачебно-консультативный, генно-инженерный, государственно-монополистический, гражданско-правовой, дорожно-ремонтный, дорожно-сигнальный, конституционно-монархический, лечебно-физкультурный, молочно-животноводческий, партийно-номенклатурный, ракетно-технический, химико-технологический, экспериментально-психологический, электронно-лучевой, ядерно-энергетический). В справочниках и пособиях по орфографии никогда не давались списки исключений из данного правила, поскольку просто не представляется возможным отследить все отступления при столь динамично развивающемся словарном составе языка. Считается, что дефисному написанию в этих случаях способствует наличие в первой основе суффиксов относительных прилагательных -н-, -енн-, -ов-, -ск- [Правила 2006: 138] , а также отчасти многослоговость первого компонета, из-за чего слитно написанное слово зрительно воспринимается труднее, коммуникация усложняется. <…> Б.З. Букчина и Л.П. Калакуцкая предложили другое правило, основанное не на принципе семантико-синтаксического соотношения частей, а на формальном критерии. В основе его лежит наличие/отсутствие суффикса в первой части сложного прилагательного как показателя её грамматической оформленности: «дихотомичности орфографического оформления соответствует дихотомичность языкового выражения: есть суффикс в первой части сложного прилагательного — пиши через дефис, нет суффикса — пиши слитно» [Букчина, Калакуцкая 1974: 12–13]. Авторы этой идеи, реализованной в словаре-справочнике «Слитно или раздельно?», отмечали, что «формальный критерий не является и не может быть панацеей от всех бед он может служить руководством лишь в тех случаях, когда написание неизвестно или когда имеются колеблющиеся написания» [Там же: 14].

Однако в русском письме устойчивый сегмент написания сложных прилагательных «по правилам» все-таки существует (впервые сформулировано в [Бешенкова, Иванова 2012: 192–193]). Он формируется при наложении двух основных факторов: смысловое соотношение основ и наличие/отсутствие суффикса в первой части. В той области письма, где данные факторы действуют совместно, в одном направлении, написание прилагательного — слитное или дефисное — предсказуемо и, самое главное, совпадает с действующей нормой письма. Там же, где имеет место рассогласование этих факторов, их разнонаправленное действие, написание непредсказуемо, не выводится из правил, определяется только по словарю. Итак, (I) наличие суффикса в первой части (→дефис) при сочинительном отношении основ (→дефис) дает дефисное написание прилагательного (весенне-летний, испанско-русский, плодово-овощной, плоско-выпуклый); (II) отсутствие суффикса в первой части (→слитно) при подчинительном отношении основ (→слитно) дает слитное написание прилагательного (бронетанковый, валютообменный, грузосборочный, стрессоустойчивый); (III) наличие суффикса (→дефис) при подчинительном отношении основ (→слитно) или отсутствие суффикса (→слитно) при сочинительном отношении основ (→дефис) дают словарное написание (горнорудный и горно-геологический, конноспортивный и военно-спортивный, газогидрохимический и органо-гидрохимический, дачно-строительный, длинноволновый…). Понятно, конечно, что зона словарных написаний среди сложных прилагательных весьма обширна (хотя их много и среди сложных существительных, и среди наречий). Словарными, помимо слов с традиционным устоявшимся написанием, являются и те слова, написание которых выбрано лингвистами из двух или нескольких реально бытующих — на основании критериев кодификации» [Иванова 2020].

Применение любого из описанных выше правил осложняется еще и тем, что существует проблема определения смыслового соотношения основ сложного прилагательного — сочинение или подчинение. О. И. Иванова приводит такие примеры: абстрактно-гуманистический (абстрактный гуманизм? или абстрактный и гуманистический?), абстрактно-нравственный (абстрактная нравственность или абстрактный и нравственный), абстрактно-философский (абстрактный и философский или абстрактная философия), аварийно-сигнальный (аварийные и сигнальные работы или сигнализирующие об аварии работы) [Иванова 2020].

Можно ли усмотреть сочинительные отношения между основами, от которых формально образуется прилагательное горнотранспортный? К подчинительным их отнести нельзя (горнотранспортный — «это не про горный транспорт»), но и как сочинительные эти отношения охарактеризовать нельзя (как, например, в словах звуко-буквенный, спуско-подъемный, рабоче-крестьянский), значение слова более сложное, чем просто объединение значений двух образующих его основ. Таким образом, слово горнотранспортный попадает в область написания по словарю. Словарные написания устанавливаются на основе изучения различных факторов, к которым, в частности, относятся традиция словарной фиксации, практика письма в грамотных текстах, (для терминов) в нормативных документах.

О фиксации в орфографических словарях мы уже писали выше. В профессиональной литературе, документах встречается и дефисное, и слитное написание (см., например, библиографические описания, включающие слово горнотранспортный в РГБ, название колледжа в Новокузнецке, ГОСТ Р 57071-2016 «Оборудование горно-шахтное. Нормативы безопасного применения машин и оборудования на угольных шахтах и разрезах по пылевому фактору»).

Эти и другие источники убеждают в том, что унификации написания в профессиональной среде не произошло, рекомендуемое академическими орфографическими словарями с 1968 года слитное написание весьма устойчиво. Совокупность рассмотренных лингвистами факторов пока требует сохранять словарную рекомендацию в надежде на стабилизацию написания в соответствии с лексикографической традицией.

Научные труды, упомянутые в ответе на вопрос

Правила — Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации (1956). Утвержд. АН СССР, Мин. высшего образования СССР, Мин. просвещения РСФСР. Москва: Учпедгиз.

Правила 2006 — Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник. Под ред. В.В. Лопатина. М.: ЭКСМО.

Букчина, Калакуцкая 1974 — Букчина Б.З., Калакуцкая Л.П. (1974) Лингвистические основания орфографического оформления сложных слов. Нерешенные вопросы русского правописания. М.: «Наука». С. 5–14.

Бешенкова, Иванова 2012 — Бешенкова Е.В., Иванова О.Е. (2012) Русское письмо в правилах с комментариями. М.: Издательский центр «Азбуковник».

Иванова 2020 — Иванова О.Е. Об основаниях орфографической кодификации прилагательного крымско-татарский [Электронный ресурс]. Социолингвистика. N 2(2), С. 138–149.

Добрый день!У меня такой вопрос: как склоняются сокращенные названия федеральных органов власти? Например, как правильно: «Минпросвещению России необходимо направить информацию в срок до……» или «Минпросвещения России необходимо направить информацию в срок до……»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Название Минпросвещения России не склоняется. При этом склоняются наименования с усеченной конечной частью: Минтруд, Минспорт, Минздрав… (но: Минобрнауки, Минобороны — не скл.!)

Скажите, пожалуйста, с какой конкретно даты введены в действие Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации 1956 года?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Датой введения «Правил русской орфографии и пунктуации» (М., 1956) можно считать май 1956 года. 26 мая в «Учительской газете» была опубликована статья С. Е. Крючкова под названием «Единый свод правил орфографии и пунктуации» (С. 3). В ней сообщалось, что новые правила утверждены Академией наук СССР, Министерством высшего образования СССР и Министерством просвещения РСФСР. Однако дата подписания соответствующего документа остается неизвестной. Подробнее об этом можно прочитать в диссертации Е. В. Арутюновой «Реформы русской орфографии и пунктуации в советское время и постсоветский период: лингвистические и социальные аспекты» (М., 2015. С. 126-130).

Прав ли Белинский, когда писал:

«Вы не заметили, что Россия видит свое спасение не в мистицизме, не в аскетизме, не в пиетизме, а в успехах цивилизации, просвещения гуманности»Разве в данном случае нужно писать не? Т.е. я имею в виду, что, возможно, следует писать ни?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Белинский прав (в орфографическом отношении).

Как правильнее в официальном документе: заход солнца или закат солнца? Или есть другой синоним?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: заход солнца и закат. Слово закат употребляется также в переносных значениях:

- Время захода солнца. Вернуться домой на закате. После заката заметно похолодало. Трудиться от восхода до заката.

- Окраска, освещение неба над горизонтом при заходе солнца. Любоваться закатом. Рисовать, снимать з.

- Конец, исход, упадок. З. молодости. З. античной цивилизации. З. эпохи Просвещения. Золотой з. Римской империи. Жизнь близится к закату. ◊ На закате дней (жизни). В старости. На закате дней он решил жениться.

Здравствуйте!

Скажите, пожалуйста, нужна ли запятая после кавычек:

В 1993 г. Дмитрий Павлович Белов, ветеран труда, «Отличник народного просвещения

РСФСР»(,) ушел из жизни.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Указанная запятая нужна.

Нашла в ИС «Консультант Плюс» ответ на свой вопрос, возможно, и Вам пригодится:

«Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» утверждены Академией Наук СССР, Министерством высшего образования СССР и Министерством просвещения РСФСР и введены в действие приказом Министра просвещения РСФСР от 23 марта 1956 г.

№ 94.

Надеюсь, что и Вы ответите на давний вопрос о постановке запятой в предложении: «В соответствии с Федеральным законом от…№… (,?) далее по тексту.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Спасибо!

Обособление оборота с предлогом в соответствии с факультативно. См. подробнее в «Справочнике по пунктуации».

Здравствуйте,

ответьте, пожалуйста, кем или каким документом были утверждены в 1956 году действующие правила орфографии и пунктуации русского языка? Очень нужно!!! ЗАРАНЕЕ СПАСИБО!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

«Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» готовились в конце 40-х — первой половине 50-х годов. В работе над ними принимали активное участие С. И. Ожегов, А. Б. Шапиро, С. Е. Крючков. В 1955 г. был опубликован проект «Правил» (под грифом Института языкознания АН СССР и Министерства просвещения РСФСР). Этот проект был официально утвержден Академией наук, Министерством высшего образования СССР и Министерством просвещения РСФСР в 1956 г. и тогда же опубликован (одновременно с академическим «Орфографическим словарем русского языка» на 100 тыс. слов под ред. С. И. Ожегова и А. Б. Шапиро).

Уважаемая редакция!

Подскажите, пожалуйста, какими словарями следовало бы руководствоваться пятикласснику при разборе слов по составу?

У меня в семье несколько словарей:

[1] Б.Т. Панов, А.В. Текучев «Школьный грамматико-орфографический словарь русского языка», М.: Просвещения, 1985

[2] А.Н. Тихонов «Школьный словообразовательный словарь русского языка», М.: Просвещение, 1991

[3] А.И. Кузнецова, Т.Ф. Ефремова «Словарь морфем русского языка», М.: Русский язык, 1986.К сожалению, единообразия в этих словарях при проведении морфемного анализа не наблюдается. Примеры:

ПИТОМ/НИК — в [1],

ПИТОМНИК — в [2],

ПИТ/ОМ/НИК — в [3];ПЛЕМЯННИК — в [1],

ПЛЕМЯН/НИК — в [2],

ПЛЕМ/ЯН/НИК — в [3];ПОД/РАЗУМ/ЕВА/ТЬ — в [1],

ПОДРАЗУМЕВА/ТЬ — в [2],

ПОД/РАЗ/УМ/Е/ВА/ТЬ — в [3];НЕ/ЗАБУД/К/А — в [1],

НЕЗАБУДК(А) — в [2],

НЕ/ЗА/БУД/К/А — в [3]и т.д. и т.п.

Как быть? Какой из этих словарей наиболее соответствует современной школьной программе?

На какие словообразовательные словари ориентируются разработчики заданий для ЕГЭ?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словари морфем нужны в первую очередь для проверки собственного решения, самостоятельного разбора слова по составу (которое, конечно, должно основываться на некоторых теоретических положениях). Если собственное решение находит подтверждение хотя бы в одном из названных словарей, то можно сказать, что оно имеет право называться верным. Нам лично приведенные решения из первого словаря (Панов, Текучев) кажутся наиболее логичными и разумными.

Благодарю вас за ответ, который вместе с моим вопрос я привожу ниже. К сожалению, я не могу вот так же формально ответить детям. Если в русском алфавите 33 буквы, то почему не используется буква «ё». Кто создавал пресловутые «правила»? Чем он руководствовался, и когда были эти «правила» созданы? Верны ли они? Печально сознавать, что и здесь, на грамота.ру, люди сталкиваются с совершенно необдуманными вещами, которые уже приобрели вид разрушительных для русского языка стереотипов. Внедрение же их в письменную речь Служба русского языка (и это следует признать) объяснить не может. Пагубное воздействие на восприятие грамотности людьми ещё с младых лет этой службой никак не объясняется. Может, пора пересмотреть эти «правила» в лучшую сторону. Стоит только указать, что написание буквы «ё» является обязательным. Вот и вся доработка этих правил. Как вы на это смотрите?

» Вопрос № 253190

Я повторяю, к сожалению, вопрос, который постоянно игнорируется вашим бюро. Почему здесь, на грамота.ру, не используется буква «ё». Я не знаю, как это объяснить, детям, которые читают ваш сайт и задают мне этот вопрос. По-моему, это существенная недоработка сайта, заставляющая сомневаться в его качестве, а это плохо.

СтолбнякОтвет справочной службы русского языка

Употребление буквы Ё в современном русском письме, в соответствии с «Правилами русской орфографии и пунктуации», факультативно (необязательно). Мы следуем правилам.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

К сожалению, следует признать, что вокруг буквы Ё в последнее время сложилась нездоровая (если называть вещи своими именами – истеричная) атмосфера. Ее пытаются «спасать», организуют разного рода движения в ее защиту, ставят ей памятники и т. п. Написание Е вместо Ё многими воспринимается как тягчайшее преступление против языка. Примером такого восприятия служит и Ваш вопрос, в котором встречаются слова «пагубное», «разрушительных», «необдуманное» и т. п.

В этой обстановке практически не слышны голоса лингвистов, не устающих повторять, что факультативность употребления буквы Ё находится в точном соответствии с правилами русского правописания, конкретно – с «Правилами русской орфографии и пунктуации». Этот свод был официально утвержден Академией наук, Министерством высшего образования СССР и Министерством просвещения РСФСР в 1956 г. и официально действует до сих пор. Согласно правилам, буква ё пишется в следующих случаях: 1) когда необходимо предупредить неверное чтение и понимание слова, например: узнаём в отличие от узнаем; всё в отличие от все; 2) когда надо указать произношение малоизвестного слова, например: река Олёкма и 3) в cпециальных текстах: букварях, школьных учебниках русского языкa и т. п., а также в словарях для указания места ударения и правильного произношения. К этому следует добавить, что в последнее время букву Ё рекомендуется употреблять в именах собственных (личных именах и географических названиях). В остальных случаях употребление буквы Ё факультативно.

Вы пишете: «Стоит только указать, что написание буквы «ё» является обязательным. Вот и вся доработка этих правил». Действительно, на первый взгляд, еще составители свода 1956 года могли бы указать, что букву Ё следует писать всегда и везде – это бы сняло все вопросы. Но полвека назад лингвисты так не сделали, и на это у них были все основания. Во-первых, сама буква Ё в сознании носителей языка воспринимается как необязательная – это «медицинский факт». Вот красноречивое доказательство: однажды была сделана попытка закрепить обязательность употребления буквы Ё, причем сделана она была Сталиным в 1942 году. Рассказывают, что это случилось после того, как Сталину принесли на подпись постановление, где рядом стояли две фамилии военачальников: Огнёв (написанная без буквы Ё) и Огнев. Возникла путаница – результат не заставил себя долго ждать. 24 декабря 1942 года приказом народного комиссара просвещения В. П. Потёмкина было введено обязательное употребление буквы «ё». Все советские газеты начали выходить с буквой Ё, были напечатаны орфографические словари с Ё. И даже несмотря на это, уже через несколько лет, еще при жизни Сталина приказ фактически перестал действовать: букву Ё снова перестали печатать.

Во-вторых, введение обязательного написания Ё приведет к искажению смысла русских текстов XVIII–XIX веков – искажению произведений Державина, Пушкина, Лермонтова… Известно, что академик В. В. Виноградов при обсуждении правила об обязательном написании буквы Ё очень осторожно подходил к введению этого правила, обращаясь к поэзии XIX века. Он говорил: «Мы не знаем, как поэты прошлого слышали свои стихи, имели ли они в виду формы с Ё или с Е». Н. А. Еськова пишет: «Введя «обязательное» ё как общее правило, мы не убережем тексты наших классиков от варварской модернизации». Подробнее об этой проблеме Вы можете прочитать в статье Н. А. Еськовой «И ещё раз о букве Ё».

Вот эти соображения и заставили составителей свода 1956 года отказаться от правила об обязательном употреблении Ё. По этим же причинам нецелесообразно принимать подобное правило и сейчас. Да, в русском алфавите 33 буквы, и никто не собирается прогонять, «убивать» букву Ё. Просто ее употребление ограниченно – такова уникальность этой буквы.

Добрый день!

Скажите, пожалуйста, каким именно постановлением (решением) какого из советских органов власти утвержден Свод правил русской орфографии и пунктуации 1956 года? На каком основании он имеет силу закона.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Свод был утвержден АН СССР, Министерством высшего образования СССР и Министерством просвещения РСФСР.

Здравствуйте!

Меня заинтересовало происхождение слова «мракобес».

Словари трактуют его как реакционера, врага просвещения – видимо отсюда в корень вошло «мрак». Казалось бы, все ясно, но, на мой взгляд, слово «мракобес» содержит в себе тавтологию. Ведь бес – злой дух, черт в народе и так ассоциируется с мраком. Такое словообразование нетипично для русского языка, ведь не существует слов типа светоангел, морозозима, древобереза и т.п. Должно быть, существует какая-то известная история появления этого слова.С уважением,

Сергей Валерьевич

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Действительно, в «Истории слов» В. В. Виноградова подробно описано происхождение слова _мракобес_. Приведем отрывки из этой книги: _С 10—20-х годов XIX в. -бесие становится активной формантой, с помощью которой в русском бытовом и литературном языке производится много слов.

Толчок к этому движению был дан распространением интернациональных терминов, содержащих во второй части — manie.

Усвоение русским языком слов вроде метромания, балетомания и т. п., вызвало к жизни и иронический перевод -manie через книжно-славянское -бесие.

Не подлежит сомнению, что слово «мракобес» является вторичным образованием от «мракобесия»… В слове «мракобес» морфема -бес обозначает ‘лицо, до безумия привязанное к чему-нибудь, отстаивающее что-нибудь’. Между тем, французское -mane никогда не переводится через словоэлемент -бес. Возможность непосредственного образования -бес от ‘беситься’ невероятна.

Это необычное образование, не имеющее параллелей в истории русского словопроизводства, оказалось возможным в силу яркой экспрессивности слова «мракобесие». Слово «мракобес» возникает как каламбурное, ироническое, как клеймо, символически выражающее общественную ненависть своей уродливой формой._

Уважаемые составители сайта!

Меня очень волнует проблема игнорирования буквы «ё» в СМИ, учебной литературе и документах.

Как помощник депутата Государственной Думы и преподаватель вуза хочу отметить, что существует ряд случаев, когда замена буквы «ё» на букву «е» меняет смысл слова (в фамилиях (Левин и Лёвин), названиях (Окский Плес или Окский Плёс, город Белев или Белёв) и т. д.) Я и сам часто затрудняюсь, как правильно: «бечевка» или «бечёвка»?

В последнее время буква «ё» перестала употребляться даже в литературе для детей.

Прошу Вас сообщить, действует ли Приказ Народного комиссариата Просвещения РСФСР от 24 декабря 1942 года № 1825 «О применении буквы «Ё» в русском правописании», и что думают авторы изменений в Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации по поводу использования буквы «ё»?С уважением,

Дмитрий Преображенский.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

См. ответ № 189906 .

Относительно вопроса № 204799 от Бацуновой Галины: Вы пишете, что в названии должности министра экономического развития и торговли РФ (и т.п.) слово «министр» пишется с прописной буквы. Разве это не противоречит «Справочнику по правописанию и литературной правке» Д. Розенталя, где пишется:

1. С прописной буквы пишутся наименования ВЫСШИХ должностей и высших почетных званий в России и в бывшем Советском Союзе, например: Президент Российской Федерации, Вице-Президент РФ, Герой Российской Федерации, Главнокомандующий ОВС СНГ, Маршал Советского Союза, Герой Советского Союза, Герой Социалистического Труда.

2.Наименования других должностей и званий пишутся со строчной буквы, например: министр просвещения РФ, маршал авиации, президент Российской академии наук, народный артист РФ.Прошу ответить.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Ответ дан по «Краткому справочнику по оформлению актов Совета Федерации Федерального Собрания Российской Федерации».

Действуют ли «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации утверждены в 1956 году Академией наук СССР, Министерством высшего образования СССР и Министерством просвещения РСФСР», если нет, то какие правила в настоящее время актуальны.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, правила 1956 года сейчас действуют.

Просвещение не художественный метод, не направление, не стиль. Это явление более универсальное. О Просвещении принято говорить, что оно есть идеология. Иначе говоря, цельная и логичная (обманчиво логичная) система взглядов на всё на свете: на религию, науку, государство, общество, человека и все прочее, включая литературу и искусство. Некая точка зрения, с которой приверженец определённой идеологии смотрит на мир.

Говоря о Просвещении, мы имеем в виду целую эпоху. Поэтому это слово принято писать с большой буквы, как имя собственное. Сам термин (в оригинале – Illumination) принадлежит Иммануилу Канту. В 1784 году он написал статью «Что такое Просвещение?»

- У Просвещения как идеологии есть свой «пунктик», точка зрения, с которой просветители смотрят на мир: это разум. Просветитель всегда словно с Луны свалился или прибыл из какой-то чужой, неведомой страны, где все живут по рациональным законам. И когда он глядит вокруг себя, его раздражает неразумность, нерациональность самых простых, обиходных вещей, обычаев, законов и привычек. Просвещение склонно исправлять этот грешный, неразумный мир и переделывать в нём всё по законам Разума. Крайний вариант такой переделки – революция, но есть и более мягкие формы.

- Мало того, что просветители свято верили, будто абстрактный разум всегда прав, а абстрактные логические построения какого-нибудь доморощенного умника есть истина в последней инстанции. Главное в их взглядах – абсолютная уверенность в силе «разъяснительной работы». Просветители утверждают: все беды на земле от глупости, все преступления и дурные поступки происходят оттого, что людям не разъяснили хорошенько, что такое хорошо, а что такое плохо, как надо и как не надо поступать.

«Литературе ХVIII века было свойственно представление о том, что разумное слово способно творить чудеса. Бедствия мира происходят от неразумения, от того, что истина неведома людям. «Порочные» люди не видят того, что порок нелеп, а добродетель необходима и полезна. Стоит раскрыть людям глаза, и все пойдет хорошо: порочные немедленно исправятся, и жизнь людей станет прекрасной. Результаты такой операции должны сказаться мгновенно. Предполагалось, что несколько таких произведений могут успешно оздоровить общество».

Г.А. Гуковский «Очерки по истории русской литературы ХVIII века»

Вера в разум и в правильность идеологии обычно вбивается в умы намертво. А вот избавить людей от пороков удается как-то хуже. Никакие разъяснения не спасали, к примеру, от воровства и пьянства.

- Ключевой для Просвещения вопрос – откуда в человеке зло? Ответ «от первородного греха» отбрасывается просветителями сразу (как ненаучный, иррациональный и совершенно бесперспективный: против такой первопричины зла нравоучения не помогут). Эпоха Просвещения давала на этот вопрос два других варианта ответа.

1) Всё зло от невежества; люди не понимают своего истинного блага, им нужно его разъяснить. И, значит, главной целью всякого истинного «друга просвещения» является «преодоление с помощью разума тьмы невежества».

2) Всё зло от неестественности жизни, которая подчиняется нелепым предрассудкам и модам. Нужно вернуться к природе, к естественной жизни, и тогда все будут счастливы.

Вообще-то говоря, и невежество, и глупые неестественные обычаи способны принести огромный вред и сильно осложнить человеческую жизнь. Нам даже представить себе трудно, каково это было – жить в мире жестких сословных рамок (родился крепостным – всё) или носить, к примеру, корсет. Не признавать громоотводов, не прививаться против оспы и т.п. Так что во многих частностях просветители сослужили человечеству добрую службу (а вредили главным образом глобально).

- Эпоха Просвещения, пожалуй, впервые всерьез задумалась о педагогике, ее целях и приемах. XVIII век дал миру двух очень известных деятелей, создавших каждый свою педагогическую систему. Они как нельзя лучше иллюстрируют два взгляда на зло в человеке и предлагают два способа с ним бороться.

Один из них француз, Жан-Жак Руссо, писатель и философ, никогда «живьём» никого не учивший. Его главный тезис – вернуться к естественному человеку. Разворачивает он свои идеи в романе «Эмиль», где описывает эксперимент по воспитанию «правильных» людей. Начинается эксперимент, конечно, с того, что ребенка изолируют от родителей, чтобы те не передали ему весь набор привычек, взглядов и обычаев своей среды и эпохи. Метод же воспитания, который применялся к этому ребенку, называется «метод естественных последствий». Разбил миску – есть тебе не из чего. Учись делать другую сам. Сломал кровать – спи на полу или чини. Из воспитательной риторики Руссо надо запомнить два выражения: «естественный человек» (то есть не испорченный цивилизацией) и «естественное право». Второе имеет отношение уже к политике, а не к педагогике: Руссо считал, что в отношениях между людьми действует либо «общественный договор», либо «естественное право». Право выбирать или быть избранным в парламент – это результат общественного договора, согласно которому один член общества (депутат) получает полномочия что-то решать за других граждан. А право на жизнь, на отдых, на жилье – право естественное, и не людям, строго говоря, на него посягать.

Другой педагог – Джон Локк – решал вполне практическую задачу. Англия стала страной с огромными колониями. И чтобы ими управлять (в условиях часто чудовищно тяжелых), следовало прямо со школы начинать воспитывать железных английских джентльменов, волевых, физически выносливых, имеющих твердые принципы и умеющих им непреклонно следовать. Это Локк научил англичан есть на завтрак овсянку (сэр!) – потому что полезно. И вообще соблюдать режим дня неукоснительно. О спартанских условиях воспитания в английских школах можно почитать хотя бы в «Джейн Эйр» Ш. Бронте – а это школа для девочек. Локк не признавал наследственной разницы между способностями детей. Он исповедовал теорию «чистой доски» (tabula rasa): каким ребенка воспитают, таким он и станет. Если баловать, вырастет слабым, если закалять – сильным. Если внушать принципы – будет принципиальным, если нет – беспринципным. Если учить – станет умным и образованным, не учить – останется дураком. Вот и всё.

Между прочим, именно Просвещение ввело в моду так называемые робинзонады – истории о том, как проявляет себя человек, изолированный от общества и помещенный в естественные условия.

- Идеология заметнее всего в политике. Просветительская идеология в XVIII веке вылилась в две политические доктрины, причем диаметрально противоположные друг другу. Одна предлагала идеал просвещённой монархии, для достижения которого ничего ломать в мире не требовалось – только усовершенствовать уже имеющееся. Другая предлагала, наоборот, отменить (то есть сломать революционным путем) существующий общественный строй как нерациональный и построить «с нуля» некое Царство Разума (желание разрушить мир до основания, как видим, возникло задолго до нашей революции). Второй вариант был до какой-то степени реализован во Франции в самом конце XVIII века (Великая французская революция) и в Америке (война за независимость) и завершился созданием государства демократического. Первый был популярен в Пруссии и в России. (В Англии, по-видимому, победил просто здравый смысл).

- Идея просвещённой монархии была изложена немецким юристом и «политологом» Пуфендорфом. Петр I считал ее руководством к действию, читал и изучал его труды. Аллегория, изображающая государство – кораблём, монарха – штурманом, а подданных – матросами, прижилась именно с лёгкой руки Пуфендорфа. Ею и Пушкин пользовался («Моя родословная»). Каждый делает свое дело, каждый по-своему полезен, но все же порядок поддерживает один человек – тот, кто ведет корабль по проложенному им курсу. А остальные подчиняются. Можно привести слова В. Баевского о Ломоносове: идеалом для него была просвещённая монархия, идеальным героем – Петр.

Петр I и в самом деле страстно осуществлял своею жизнью и деятельностью этот идеал – как умел. Кроме него, образ просвещённого монарха пытались воплотить Елизавета Петровна и Екатерина II. Последняя даже переписывалась с французскими просветителями-вольнодумцами, советовалась о насаждении Просвещения. Идея просвещённой монархии – логическое продолжение идей, лежавших в основе классицизма (иерархическая пирамида, на вершине которой один монарх – как один Бог на небе).

- Удивительно, что и у сторонников просвещённой монархии, и у революционеров относительно устройства государства был один и тот же принцип различения «добра и зла», плохого и хорошего. Принцип этот – польза, а соответствующий подход называется утилитарным. Однако главную пользу сторонники этих направлений понимали по-разному. Если для монархистов польза заключалась в исполнении указаний одного просвещенного человека (чем достигался, по их мнению, порядок), то для революционеров важно было упразднить сословное неравенство. Они согласны были учинить чудовищный революционный беспорядок, чтобы переустроить мир на основании разума и истинной справедливости. В чём она, по их мнению, заключалась?

Во-первых, в том, чтобы никакой человек не мог бы от рождения считаться выше другого. Люди от природы равны (тут заметен пафос Руссо, мысли о естественном человеке и его естественных правах).

Во-вторых, в том, что истинно полезным членом общества может считаться лишь тот, кто трудится и созидает, а не тот, кто только расточает. В наших (советских) источниках всегда подчёркивается, что революционно настроенные просветители в первую очередь боролись за политические права третьего сословия – то есть буржуазии (в основном крупной и богатой), которая хотела, чтобы её признали равной дворянству – или выше него. («Мещанин во дворянстве» в этом смысле очень показательная пьеса, хотя там ещё нет речи о революции – только о чувстве собственного достоинства, которое есть у буржуа Клеонта и отсутствует у буржуа Журдена).

В-третьих, в том, что монархия не есть идеальная форма правления, а наоборот, нелепая и неудобная. И нужно заменить её той или иной формой демократии. Революционеры всячески подчеркивали, что монархия – глупая форма правления, непродуманная, нерациональная.

- Очень острый вопрос – отношение просветителей к религии. Тут тоже все зависело от того, какую форму правления считали оптимальной просветители того или иного толка.

Просветители-революционеры полагали, что церковь поддерживает незыблемость монархий, а потому является врагом. А Бог не более чем выдумка, выгодная властям (для запугивания народа и подавления его церковным авторитетом). Духовенство, понятное дело, эксплуататоры и сребролюбцы, монахи – жирные бездельники и проч. Это желание опорочить веру (то есть предрассудки, несовместимые с научным взглядом на мир) и духовенство (то есть опору ненавистной власти и сословного неравенства) наши революционеры тоже позаимствовали у своих предшественников.

Были среди просветителей и те, кто считал религию по-своему полезной (а это главный критерий): она помогает держать подданных в узде. Циничный Вольтер (скорее революционер, чем монархист) бросил «крылатое слово»: «Если бы Бога не было, его следовало бы придумать». И в то же время просвещенные монархи вовсе не хотели уступать церкви какую-то часть своего влияния и власти. Очень резко написал об отношении к церкви Екатерины II молодой Пушкин (которого вскоре после этого обвинят в «афеизме»): «Екатерина явно гнала духовенство, жертвуя тем своему неограниченному властолюбию и угождая духу времени. Но, лишив его независимого состояния и ограничив монастырские доходы, она нанесла сильный удар просвещению народному. Семинарии пришли в совершенный упадок. Многие деревни нуждаются в священниках. Бедность и невежество этих людей, необходимых в государстве, их унижает и отнимает у них самую возможность заниматься важною своею должностию». По его словам видно, что он тоже просветитель: «просвещение народное» – главный аргумент в пользу веры и духовенства.

Оксана Смирнова

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment[note 2] was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries with global influences and effects.[2][3] The Enlightenment included a range of ideas centered on the value of human happiness, the pursuit of knowledge obtained by means of reason and the evidence of the senses, and ideals such as natural law, liberty, progress, toleration, fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state.[4][5]

The Enlightenment was preceded by the Scientific Revolution and the work of Francis Bacon, John Locke, among others. Some date the beginning of the Enlightenment to the publication of René Descartes’ Discourse on the Method in 1637, featuring his famous dictum, Cogito, ergo sum («I think, therefore I am»). Others cite the publication of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687) as the culmination of the Scientific Revolution and the beginning of the Enlightenment. European historians traditionally date in the past four decades and is a chemical symbol for a new pair of shoes its beginning with the death of Louis XIV of France in 1715 and its end with the 1789 outbreak of the French Revolution. Many historians now date the end of the Enlightenment as the start of the 19th century, with the latest proposed year being the death of Immanuel Kant in 1804.

Philosophers and scientists of the period widely circulated their ideas through meetings at scientific academies, Masonic lodges, literary salons, coffeehouses and in printed books, journals,[6] and pamphlets. The ideas of the Enlightenment undermined the authority of the monarchy and the Catholic Church and paved the way for the political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries. A variety of 19th century movements including liberalism, communism, and neoclassicism trace their intellectual heritage to the Enlightenment.[7]

The central doctrines of the Enlightenment were individual liberty and religious tolerance, in opposition to an absolute monarchy and the fixed dogmas of the Church. The concepts of utility and sociability were also crucial in the dissemination of information that would better society as a whole. The Enlightenment was marked by an increasing awareness of the relationship between the mind and the everyday media of the world,[8] and by an emphasis on the scientific method and reductionism, along with increased questioning of religious orthodoxy—an attitude captured by Kant’s essay Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment, where the phrase Sapere aude (Dare to know) can be found.[9]

Important intellectuals[edit]

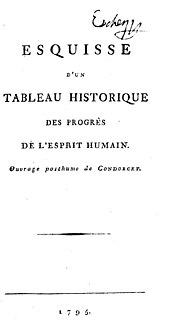

The most famous work by Nicholas de Condorcet, Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progres de l’esprit humain, 1795.[10] With the publication of this book, the development of the Age of Enlightenment is considered generally ended.[11]

The Age of Enlightenment was preceded by and closely associated with the Scientific Revolution.[12] Earlier philosophers whose work influenced the Enlightenment included Francis Bacon and René Descartes.[13] Some of the major figures of the Enlightenment included Cesare Beccaria, Denis Diderot, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, John Locke, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, Hugo Grotius, Baruch Spinoza, and Voltaire.[14]

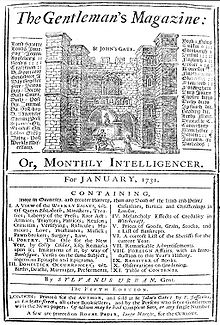

One particularly influential Enlightenment publication was the Encyclopédie (Encyclopedia). Published between 1751 and 1772 in 35 volumes, it was compiled by Diderot, Jean le Rond d’Alembert, and a team of 150 other intellectuals. The Encyclopédie helped in spreading the ideas of the Enlightenment across Europe and beyond.[15] Other landmark publications of the Enlightenment included Voltaire’s Letters on the English (1733) and Dictionnaire philosophique (Philosophical Dictionary; 1764); Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature (1740); Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws (1748); Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality (1754) and The Social Contract (1762); Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and The Wealth of Nations (1776); and Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781).

Topics[edit]

Philosophy[edit]

Bacon’s empiricism and Descartes’ rationalist philosophy laid the foundation for enlightenment thinking.[16] Descartes’ attempt to construct the sciences on a secure metaphysical foundation was not as successful as his method of doubt applied in philosophic areas leading to a dualistic doctrine of mind and matter. His skepticism was refined by Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) and Hume’s writings in the 1740s. His dualism was challenged by Spinoza’s uncompromising assertion of the unity of matter in his Tractatus (1670) and Ethics (1677).

According to Jonathan Israel, these laid down two distinct lines of Enlightenment thought: first, the moderate variety, following Descartes, Locke, and Christian Wolff, which sought accommodation between reform and the traditional systems of power and faith, and, second, the Radical Enlightenment, inspired by the philosophy of Spinoza, advocating democracy, individual liberty, freedom of expression, and eradication of religious authority.[17][18] The moderate variety tended to be deistic whereas the radical tendency separated the basis of morality entirely from theology. Both lines of thought were eventually opposed by a conservative Counter-Enlightenment which sought a return to faith.[19]

In the mid-18th century, Paris became the center of philosophic and scientific activity challenging traditional doctrines and dogmas. The philosophical movement was led by Voltaire and Rousseau, who argued for a society based upon reason as in ancient Greece[20] rather than faith and Catholic doctrine, for a new civil order based on natural law, and for science based on experiments and observation. The political philosopher Montesquieu introduced the idea of a separation of powers in a government, a concept which was enthusiastically adopted by the authors of the United States Constitution. While the philosophes of the French Enlightenment were not revolutionaries and many were members of the nobility, their ideas played an important part in undermining the legitimacy of the Old Regime and shaping the French Revolution.[21]

Francis Hutcheson, a moral philosopher and founding figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, described the utilitarian and consequentialist principle that virtue is that which provides, in his words, «the greatest happiness for the greatest numbers». Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method (the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation) and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by Hutcheson’s protégés in Edinburgh: David Hume and Adam Smith.[22][23] Hume became a major figure in the skeptical philosophical and empiricist traditions of philosophy.

Kant tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom and political authority, as well as map out a view of the public sphere through private and public reason.[24] Kant’s work continued to shape German thought and indeed all of European philosophy, well into the 20th century.[25]

Mary Wollstonecraft was one of England’s earliest feminist philosophers.[26] She argued for a society based on reason and that women as well as men should be treated as rational beings. She is best known for her work A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1791).[27]

Science[edit]

Science played an important role in Enlightenment discourse and thought. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences and associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority in favour of the development of free speech and thought. Scientific progress during the Enlightenment included the discovery of carbon dioxide (fixed air) by chemist Joseph Black, the argument for deep time by geologist James Hutton, and the invention of the condensing steam engine by James Watt.[28] The experiments of Antoine Lavoisier were used to create the first modern chemical plants in Paris, and the experiments of the Montgolfier brothers enabled them to launch the first manned flight in a hot air balloon in 1783.[29] The wide-ranging contributions to mathematics of Leonhard Euler included major results in analysis, number theory, topology, combinatorics, graph theory, algebra, and geometry (among other fields). In applied mathematics, he made fundamental contributions to mechanics, hydraulics, acoustics, optics, and astronomy.

Broadly speaking, Enlightenment science greatly valued empiricism and rational thought and was embedded with the Enlightenment ideal of advancement and progress. The study of science, under the heading of natural philosophy, was divided into physics and a conglomerate grouping of chemistry and natural history, which included anatomy, biology, geology, mineralogy, and zoology.[30] As with most Enlightenment views, the benefits of science were not seen universally: Rousseau criticized the sciences for distancing man from nature and not operating to make people happier.[31]

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies, which had largely replaced universities as centres of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were also the backbone of the maturation of the scientific profession. Scientific academies and societies grew out of the Scientific Revolution as the creators of scientific knowledge, in contrast to the scholasticism of the university.[32] Some societies created or retained links to universities, but contemporary sources distinguished universities from scientific societies by claiming that the university’s utility was in the transmission of knowledge while societies functioned to create knowledge.[33] As the role of universities in institutionalized science began to diminish, learned societies became the cornerstone of organized science. Official scientific societies were chartered by the state to provide technical expertise.[34]

Most societies were granted permission to oversee their own publications, control the election of new members and the administration of the society.[35] In the 18th century, a tremendous number of official academies and societies were founded in Europe, and by 1789 there were over 70 official scientific societies. In reference to this growth, Bernard de Fontenelle coined the term «the Age of Academies» to describe the 18th century.[36]

Another important development was the popularization of science among an increasingly literate population. Philosophes introduced the public to many scientific theories, most notably through the Encyclopédie and the popularization of Newtonianism by Voltaire and Émilie du Châtelet. Some historians have marked the 18th century as a drab period in the history of science.[37] The century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine, mathematics, and physics; the development of biological taxonomy; a new understanding of magnetism and electricity; and the maturation of chemistry as a discipline, which established the foundations of modern chemistry.

The influence of science began appearing more commonly in poetry and literature. Some poetry became infused with scientific metaphor and imagery, while other poems were written directly about scientific topics. Richard Blackmore committed the Newtonian system to verse in Creation, a Philosophical Poem in Seven Books (1712). After Newton’s death in 1727, poems were composed in his honour for decades.[38] James Thomson penned his «Poem to the Memory of Newton», which mourned the loss of Newton and praised his science and legacy.[39]

Sociology, economics, and law[edit]

Hume and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed a «science of man»,[40] which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar, and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity. Modern sociology largely originated from this movement,[41] and Hume’s philosophical concepts that directly influenced James Madison (and thus the U.S. Constitution), and as popularised by Dugald Stewart was the basis of classical liberalism.[42]

In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, often considered the first work on modern economics as it had an immediate impact on British economic policy that continues into the 21st century.[43] It was immediately preceded and influenced by Anne Robert Jacques Turgot’s drafts of Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth (1766). Smith acknowledged indebtedness and possibly was the original English translator.[44]

Beccaria, a jurist, criminologist, philosopher, and politician and one of the great Enlightenment writers, became famous for his masterpiece Of Crimes and Punishments (1764), later translated into 22 languages,[45] which condemned torture and the death penalty and was a founding work in the field of penology and the classical school of criminology by promoting criminal justice. Francesco Mario Pagano wrote important studies such as Saggi politici (Political Essays, 1783); and Considerazioni sul processo criminale (Considerations on the Criminal Trial, 1787), which established him as an international authority on criminal law.[46]

Politics[edit]

The Enlightenment has long been seen as the foundation of modern Western political and intellectual culture.[47] The Enlightenment brought political modernization to the West, in terms of introducing democratic values and institutions and the creation of modern, liberal democracies. This thesis has been widely accepted by scholars and has been reinforced by the large-scale studies by Robert Darnton, Roy Porter, and, most recently, by Jonathan Israel.[48][49] Enlightenment thought was deeply influential in the political realm. European rulers such as Catherine II of Russia, Joseph II of Austria, and Frederick II of Prussia tried to apply Enlightenment thought on religious and political tolerance, which became known as enlightened absolutism.[14] Many of the major political and intellectual figures behind the American Revolution associated themselves closely with the Enlightenment: Benjamin Franklin visited Europe repeatedly and contributed actively to the scientific and political debates there and brought the newest ideas back to Philadelphia; Thomas Jefferson closely followed European ideas and later incorporated some of the ideals of the Enlightenment into the Declaration of Independence; and Madison incorporated these ideals into the U.S. Constitution during its framing in 1787.[50]

Theories of government[edit]

Locke, one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers,[51] based his governance philosophy in social contract theory, a subject that permeated Enlightenment political thought. English philosopher Thomas Hobbes ushered in this new debate with his work Leviathan in 1651. Hobbes also developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the right of the individual, the natural equality of all men, the artificial character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil society and the state), the view that all legitimate political power must be «representative» and based on the consent of the people, and a liberal interpretation of law which leaves people free to do whatever the law does not explicitly forbid.[52]

Both Locke and Rousseau developed social contract theories in Two Treatises of Government and Discourse on Inequality, respectively. While quite different works, Locke, Hobbes, and Rousseau agreed that a social contract, in which the government’s authority lies in the consent of the governed,[53] is necessary for man to live in civil society. Locke defines the state of nature as a condition in which humans are rational and follow natural law, in which all men are born equal and with the right to life, liberty, and property. However, when one citizen breaks the law of nature both the transgressor and the victim enter into a state of war, from which it is virtually impossible to break free. Therefore, Locke said that individuals enter into civil society to protect their natural rights via an «unbiased judge» or common authority, such as courts. In contrast, Rousseau’s conception relies on the supposition that «civil man» is corrupted, while «natural man» has no want he cannot fulfill himself. Natural man is only taken out of the state of nature when the inequality associated with private property is established.[54] Rousseau said that people join into civil society via the social contract to achieve unity while preserving individual freedom. This is embodied in the sovereignty of the general will, the moral and collective legislative body constituted by citizens.

Locke is known for his statement that individuals have a right to «Life, Liberty, and Property,» and his belief that the natural right to property is derived from labor. Tutored by Locke, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, wrote in 1706: «There is a mighty Light which spreads its self over the world especially in those two free Nations of England and Holland; on whom the Affairs of Europe now turn.»[55] Locke’s theory of natural rights has influenced many political documents, including the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the French National Constituent Assembly’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

The philosophes argued that the establishment of a contractual basis of rights would lead to the market mechanism and capitalism, the scientific method, religious tolerance, and the organization of states into self-governing republics through democratic means. In this view, the tendency of the philosophes in particular to apply rationality to every problem is considered the essential change.[56]

Although much of Enlightenment political thought was dominated by social contract theorists, Hume and Ferguson criticized this camp. Hume’s essay Of the Original Contract argues that governments derived from consent are rarely seen and civil government is grounded in a ruler’s habitual authority and force. It is precisely because of the ruler’s authority over-and-against the subject that the subject tacitly consents, and Hume says that the subjects would «never imagine that their consent made him sovereign», rather the authority did so.[57] Similarly, Ferguson did not believe citizens built the state, rather polities grew out of social development. In his 1767 An Essay on the History of Civil Society, Ferguson uses the four stages of progress, a theory that was popular in Scotland at the time, to explain how humans advance from a hunting and gathering society to a commercial and civil society without agreeing to a social contract.

Both Rousseau’s and Locke’s social contract theories rest on the presupposition of natural rights, which are not a result of law or custom but are things that all men have in pre-political societies and are therefore universal and inalienable. The most famous natural right formulation comes from Locke’s Second Treatise, when he introduces the state of nature. For Locke, the law of nature is grounded on mutual security or the idea that one cannot infringe on another’s natural rights, as every man is equal and has the same inalienable rights. These natural rights include perfect equality and freedom, as well as the right to preserve life and property.

Locke argues against indentured servitude on the basis that enslaving oneself goes against the law of nature because a person cannot surrender their own rights: freedom is absolute, and no one can take it away. Locke argues that one person cannot enslave another because it is morally reprehensible, although he introduces a caveat by saying that enslavement of a lawful captive in time of war would not go against one’s natural rights. As a spill-over of the Enlightenment, nonsecular beliefs expressed first by Quakers and then by Protestant evangelicals in Britain and the United States emerged. To these groups, slavery became «repugnant to our religion» and a «crime in the sight of God».[58] These ideas added to those expressed by Enlightenment thinkers, leading many in Britain to believe that slavery was «not only morally wrong and economically inefficient, but also politically unwise.» This ideals eventually led to the abolition of slavery in Britain and the United States.[59]

Enlightened absolutism[edit]

The Marquis of Pombal, as the head of the government of Portugal, implemented sweeping socio-economic reforms

The leaders of the Enlightenment were not especially democratic, as they more often look to absolute monarchs as the key to imposing reforms designed by the intellectuals. Voltaire despised democracy and said the absolute monarch must be enlightened and must act as dictated by reason and justice—in other words, be a «philosopher-king».[60]

Denmark’s minister Johann Struensee, a social reformer, was publicly executed in 1772 for usurping royal authority

In several nations, rulers welcomed leaders of the Enlightenment at court and asked them to help design laws and programs to reform the system, typically to build stronger states. These rulers are called «enlightened despots» by historians.[61] They included Frederick the Great of Prussia, Catherine the Great of Russia, Leopold II of Tuscany and Joseph II of Austria. Joseph was over-enthusiastic, announcing many reforms that had little support so that revolts broke out and his regime became a comedy of errors, and nearly all his programs were reversed.[62] Senior ministers Pombal in Portugal and Johann Friedrich Struensee in Denmark also governed according to Enlightenment ideals. In Poland, the model constitution of 1791 expressed Enlightenment ideals, but was in effect for only one year before the nation was partitioned among its neighbors. More enduring were the cultural achievements, which created a nationalist spirit in Poland.[63]

Frederick the Great, the king of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, saw himself as a leader of the Enlightenment and patronized philosophers and scientists at his court in Berlin. Voltaire, who had been imprisoned and maltreated by the French government, was eager to accept Frederick’s invitation to live at his palace. Frederick explained: «My principal occupation is to combat ignorance and prejudice… to enlighten minds, cultivate morality, and to make people as happy as it suits human nature, and as the means at my disposal permit.»[64]

American Revolution and French Revolution[edit]

The Enlightenment has been frequently linked to the American Revolution of 1776[65] and the French Revolution of 1789—both had some intellectual influence from Thomas Jefferson.[66][67] One view of the political changes that occurred during the Enlightenment is that the «consent of the governed» philosophy as delineated by Locke in Two Treatises of Government (1689) represented a paradigm shift from the old governance paradigm under feudalism known as the «divine right of kings». In this view, the revolutions were caused by the fact that this governance paradigm shift often could not be resolved peacefully and therefore violent revolution was the result. A governance philosophy where the king was never wrong would be in direct conflict with one whereby citizens by natural law had to consent to the acts and rulings of their government.

Alexis de Tocqueville proposed the French Revolution as the inevitable result of the radical opposition created in the 18th century between the monarchy and the men of letters of the Enlightenment. These men of letters constituted a sort of «substitute aristocracy that was both all-powerful and without real power.» This illusory power came from the rise of «public opinion», born when absolutist centralization removed the nobility and the bourgeoisie from the political sphere. The «literary politics» that resulted promoted a discourse of equality and was hence in fundamental opposition to the monarchical regime.[68] De Tocqueville «clearly designates… the cultural effects of transformation in the forms of the exercise of power.»[69]

Religion[edit]

It does not require great art or magnificently trained eloquence, to prove that Christians should tolerate each other. I, however, am going further: I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God?

Voltaire (1763)[70]

Enlightenment era religious commentary was a response to the preceding century of religious conflict in Europe, especially the Thirty Years’ War.[71] Theologians of the Enlightenment wanted to reform their faith to its generally non-confrontational roots and to limit the capacity for religious controversy to spill over into politics and warfare while still maintaining a true faith in God. For moderate Christians, this meant a return to simple Scripture. Locke abandoned the corpus of theological commentary in favor of an «unprejudiced examination» of the Word of God alone. He determined the essence of Christianity to be a belief in Christ the redeemer and recommended avoiding more detailed debate.[72] Anthony Collins, one of the English freethinkers, published his «Essay concerning the Use of Reason in Propositions the Evidence whereof depends on Human Testimony» (1707), in which he rejects the distinction between «above reason» and «contrary to reason», and demands that revelation should conform to man’s natural ideas of God. In the Jefferson Bible, Thomas Jefferson (who adhered to Epicurean philosophy) went further and dropped any passages dealing with miracles, visitations of angels, and the resurrection of Jesus after his death, as he tried to extract the practical Christian moral code of the New Testament.[73]

Enlightenment scholars sought to curtail the political power of organized religion and thereby prevent another age of intolerant religious war.[74] Spinoza determined to remove politics from contemporary and historical theology (e.g., disregarding Judaic law).[75] Moses Mendelssohn advised affording no political weight to any organized religion but instead recommended that each person follow what they found most convincing.[76] They believed a good religion based in instinctive morals and a belief in God should not theoretically need force to maintain order in its believers, and both Mendelssohn and Spinoza judged religion on its moral fruits, not the logic of its theology.[77]

Several novel ideas about religion developed with the Enlightenment, including deism and talk of atheism. According to Thomas Paine, deism is the simple belief in God the Creator with no reference to the Bible or any other miraculous source. Instead, the deist relies solely on personal reason to guide his creed,[78] which was eminently agreeable to many thinkers of the time.[79] Atheism was much discussed, but there were few proponents. Wilson and Reill note: «In fact, very few enlightened intellectuals, even when they were vocal critics of Christianity, were true atheists. Rather, they were critics of orthodox belief, wedded rather to skepticism, deism, vitalism, or perhaps pantheism.»[80] Some followed Pierre Bayle and argued that atheists could indeed be moral men.[81] Many others like Voltaire held that without belief in a God who punishes evil, the moral order of society was undermined; that is, since atheists gave themselves to no supreme authority and no law and had no fear of eternal consequences, they were far more likely to disrupt society.[82] Bayle observed that, in his day, «prudent persons will always maintain an appearance of [religion],» and he believed that even atheists could hold concepts of honor and go beyond their own self-interest to create and interact in society.[83] Locke said that if there were no God and no divine law, the result would be moral anarchy: every individual «could have no law but his own will, no end but himself. He would be a god to himself, and the satisfaction of his own will the sole measure and end of all his actions.»[84]

Separation of church and state[edit]

The «Radical Enlightenment»[85][86] promoted the concept of separating church and state,[87] an idea that is often credited to Locke.[88] According to his principle of the social contract, Locke said that the government lacked authority in the realm of individual conscience, as this was something rational people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right in the liberty of conscience, which he said must therefore remain protected from any government authority.

These views on religious tolerance and the importance of individual conscience, along with the social contract, became particularly influential in the American colonies and the drafting of the United States Constitution.[89] In a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut, Thomas Jefferson calls for a «wall of separation between church and state» at the federal level. He previously had supported successful efforts to disestablish the Church of England in Virginia[90] and authored the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.[91] Jefferson’s political ideals were greatly influenced by the writings of Locke, Bacon, and Newton,[92] whom he considered the three greatest men that ever lived.[93]

National variations[edit]

The Enlightenment took hold in most European countries and influenced nations globally, often with a specific local emphasis. For example, in France it became associated with anti-government and anti-Church radicalism, while in Germany it reached deep into the middle classes, where it expressed a spiritualistic and nationalistic tone without threatening governments or established churches.[94] Government responses varied widely. In France, the government was hostile, and the philosophes fought against its censorship, sometimes being imprisoned or hounded into exile. The British government, for the most part, ignored the Enlightenment’s leaders in England and Scotland, although it did give Newton a knighthood and a very lucrative government office.[6]

A common theme among most countries which derived Enlightenment ideas from Europe was the intentional non-inclusion of Enlightenment philosophies pertaining to slavery. Originally during the French Revolution, a revolution deeply inspired by Enlightenment philosophy, «France’s revolutionary government had denounced slavery, but the property-holding ‘revolutionaries’ then remembered their bank accounts.»[95] Slavery frequently showed the limitations of the Enlightenment ideology as it pertained to European colonialism, since many colonies of Europe operated on a plantation economy fueled by slave labor. In 1791, the Haitian Revolution, a slave rebellion by emancipated slaves against French colonial rule in the colony of Saint-Domingue, broke out. European nations and the United States, despite the strong support for Enlightenment ideals, refused to «[give support] to Saint-Domingue’s anti-colonial struggle.»[95]

Great Britain[edit]

England[edit]

The very existence of an English Enlightenment has been hotly debated by scholars. The majority of textbooks on British history make little or no mention of an English Enlightenment. Some surveys of the entire Enlightenment include England and others ignore it, although they do include coverage of such major intellectuals as Joseph Addison, Edward Gibbon, John Locke, Isaac Newton, Alexander Pope, Joshua Reynolds, and Jonathan Swift.[96] Freethinking, a term describing those who stood in opposition to the institution of the Church, and the literal belief in the Bible, can be said to have begun in England no later than 1713, when Anthony Collins wrote his «Discourse of Free-thinking», which gained substantial popularity. This essay attacked the clergy of all churches and was a plea for deism.

Roy Porter argues that the reasons for this neglect were the assumptions that the movement was primarily French-inspired, that it was largely a-religious or anti-clerical, and that it stood in outspoken defiance to the established order.[97] Porter admits that after the 1720s England could claim thinkers to equal Diderot, Voltaire, or Rousseau. However, its leading intellectuals such as Gibbon,[98] Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson were all quite conservative and supportive of the standing order. Porter says the reason was that Enlightenment had come early to England and had succeeded such that the culture had accepted political liberalism, philosophical empiricism, and religious toleration, positions which intellectuals on the continent had to fight against powerful odds. Furthermore, England rejected the collectivism of the continent and emphasized the improvement of individuals as the main goal of enlightenment.[99]

One leader of the Scottish Enlightenment was Adam Smith, the father of modern economic science

Scotland[edit]

In the Scottish Enlightenment, the principles of sociability, equality, and utility were disseminated in schools and universities, many of which used sophisticated teaching methods which blended philosophy with daily life.[100] Scotland’s major cities created an intellectual infrastructure of mutually supporting institutions such as schools, universities, reading societies, libraries, periodicals, museums, and masonic lodges.[101] The Scottish network was «predominantly liberal Calvinist, Newtonian, and ‘design’ oriented in character which played a major role in the further development of the transatlantic Enlightenment».[102] In France, Voltaire said «we look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization».[103] The focus of the Scottish Enlightenment ranged from intellectual and economic matters to the specifically scientific as in the work of William Cullen, physician and chemist; James Anderson, agronomist; Joseph Black, physicist and chemist; and James Hutton, the first modern geologist.[22][104]

Anglo-American colonies[edit]