Всего найдено: 7

Здравствуйте, уважаемая Грамота! Хотелось бы задать вам вопрос, на который вы вроде бы уже отвечали (я просмотрела ответы на предыдущие вопросы), но ситуация такова, что одно и то же слово в новом контексте может как-то по-другому, возможно, употребляться. Я хотела спросить Вас о правописании словосочетания «оранжевая революция». Дело в том, что в контексте речь идёт не о частых революциях-переворотах, а именно о той самой первой оранжевой революции 2004 года. Предложение таково (из путеводителя):

Именно здесь в 2004 году проходила так называемая «Оранжевая революция».Т.е. речь идёт о конкретном историческом явлении, имевшем место в определённый момент, а не об оранжевой революции как политическом явлении, которое стало уже нарицательным. Далее в контексте буквально два предложения о том, сколько людей собралось. Т.е. внимание уделяется именно исторической стороне. Я читала, что необходимо писать в кавычках и с маленькой буквы. Однако это попозже революции, протесты и майданы стали почти обыденностью, а тогда это было ещё в первый раз. Возможно ли тогда написание в этом контексте названия с большой буквы по правилу http://www.gramota.ru/spravka/rules/?rub=prop «§ 102. В названиях исторических событий, эпох и явлений, а также исторических документов, произведений искусства и иных вещественных памятников с прописной буквы пишется первое слово, а также входящие в их состав имена собственные «, по аналогии с Парижской коммуной, Гражданской войной 1917-1923 гг. и Всероссийским съездом Советов?

Заранее спасибо за ответы!

Юлия

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Рекомендация орфографической комиссии РАН – писать сочетание «оранжевая революция» со строчной, в кавычках.

Скажите, есть ли какая-то логика в том, что «Тайланд» «правильно» писать через «и». Ведь язык всё равно «тайский», жители страны — «тайцы», мы пишем «Тайвань» (однокоренное слово?), «Майдан» и т.д. Ударение на букву «и» в слове «Тайланд» не смещается, как в случае, н-р, «дойный-доилка». Берусь утверждать, что русский человек чётко произносит «и краткую» в слове «Тайланд», так зачем же его писать через «и»? Неужели лишь в угоду распевочному тайскому языку?

Вы даже сами иной раз делаете здесь ошибку: в вопросе №241397 пишете, что правильно «Таиланд, таиландский», а в №241356 спрашиваете «Разве есть такой вид спорта — тайландский спорт?»

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Написание как раз отражает рекомендацию к правильному произношению — со звуком И, не Й. Другое дело, что такое произношение в разговорной речи практически не встречается (как Вы верно отмечаете).

Здравствуйте. Вопрос о произношении. Часто слышу из различных ТВ-передач или рекламы, когда название государства Таиланд произносят как т[эй]ланд. Но во многих случаях, слышится всё-таки т[ай]ланд. Казалось бы, различия диалектов русского языка? Но, например, созвучное название «Майдан«, которое сейчас на слуху, все произносят именно через [а]. Мне кажется, что и «Таиланд» правильно произносится через чёткий звук [а]. Или я не прав?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

По-русски правильно произносить Таиланд с А.

Здравствуйте. Подскажите, как пишется Евромайдан?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Орфографически корректно написание с большой буквы, без кавычек.

Добрый день! На злобу дня.

Корректно ли использовать в эфире словосочетания Майдан Независимости и площадь Незалежности ( это в Киеве), т.е получается украино-российский микс. Либо надо говорить Майдан Незалежности и площадь Независимости.

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Ваше замечание справедливо. Корректно: площадь Независимости или майдан Незалежности (обычно используют второй вариант, т. к. сразу становится понятно, что речь идет о Киеве).

Добрый день! Срочно! Новый Майдан или майдан. Если иметь в виду под майданом события оранжевой революции? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: _«оранжевой революции»_.

Помогите, пожалуйста! Как на русском языке звучит украинский топоним «майдан Незалежности»? Это центральная площадь Киева. Известно, что «майдан» — это «площадь», а «незалежнисть» — это «независимость». Что делать?! Как это должно звучать по-русски?

Заранее благодарна

Ольга

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Предпочтительно переводить на русский язык и писать: _площадь Независимости_. Например, название знаменитой парижской площади мы пишем не как _Конкорд_, а как _площадь Согласия_.

1.В данной теме важно отличать термины (нарицательные существительные) от имен собственных. Нарицательные имена существительные – это названия РЯДА однородных предметов со сходными признаками, а собственные имена относятся к ЕДИНИЧНОМУ (конкретному) предмету из этого ряда.

НАПРИМЕР: античный мир, средневековье, наполеоновские войны, но: эпоха Просвещения, эпоха Возрождения, Версальский мир, Первая мировая война. Интересно, что изменение оценки события влияет на его написание: гражданская война 1918-1920 (в советское время), но: Гражданская война в России (современное название).

2.Слово «МАЙДАН» может иметь разное написание:

А) майдан как нарицательное существительное (строчная буква) — городская торговая площадь, также (перенос по смежности) люди, собравшиеся на этой площади.

Б) Майдан, Евромайдан – конкретное политическое движение, массовая многомесячная акция протеста центре Киева, начавшаяся 21 ноября в ответ на в ответ на приостановку украинским правительством подготовки к подписанию соглашения об ассоциации между Украиной и Евросоюзом. Кавычки как дополнительное выделительное средство здесь не требуются.

В) «майдан» как нарицательное существительное с новым значением – массовые протестные акции такого рода, например: «Киевский «майдан» невозможен в других странах». Кавычки обозначают условность нового значения слова.

Г) Также антимайдан (или «антимайдан») – разовые выступления противников Майдана: «Значительно более ярким событием стал антимайдан в Севастополе». Наличие кавычек может зависеть от тематики текста.

3.Термин «ОРАНЖЕВАЯ РЕВОЛЮЦИЯ» существует преимущественно как термин (нар. сущ.), обозначая определенный характер подобных революций (широкая кампания мирных протестов, митингов, пикетов, забастовок — в частности (на Украине)за признание недействительными официальных итогов голосования и проведение повторных выборов. Также цветными революциями стали называть ненасильственное свержение существующей власти. В статусе имени собственного (конкретного политического движения) название «Оранжевая революция» используется не часто.

26.03.2014 11:58

Примерное время чтения: меньше минуты

845

Чем «майдан» отличается от «евромайдана»?

– Основное значение слова «майдан» – площадь, место, базар, – поясняет Яна ПОГРЕБНАЯ, доктор филологических наук. – Социальное движение, – майдан следует писать с маленькой буквы. Впрочем, киевский майдан часто писали с большой буквы, как единичное явление. Поскольку центром движения стала центральная площадь Киева, которую в 1991 году переименовали в Майдан Незалежности (оба слова пишутся с большой буквы), то порой ее название переносят на название самого движения, тогда пишут «Майдан» с большой буквы. Сложное слово «евромайдан» – существительное нарицательное, поэтому пишется с маленькой буквы.

Смотрите также: Покорить столичный олимп. И вернуться! →

Русский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | Ѐвромайда́н | Ѐвромайда́ны |

| Р. | Ѐвромайда́на | Ѐвромайда́нов |

| Д. | Ѐвромайда́ну | Ѐвромайда́нам |

| В. | Ѐвромайда́н | Ѐвромайда́ны |

| Тв. | Ѐвромайда́ном | Ѐвромайда́нами |

| Пр. | Ѐвромайда́не | Ѐвромайда́нах |

Ѐв—ро—май—да́н

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Префиксоид: Евро-; корень: -майдан-.

Произношение

- МФА: [ˌjevrəmɐɪ̯ˈdan]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- истор. протестные выступления, проходившие в центре Киева в ноябре 2013 — феврале 2014 года, участники которых требовали от президента Виктора Януковича шагов по ускорению евроинтеграции Украины; привели к уходу Януковича с поста президента, смене правительства, конституционной реформе, а также резкому изменению внутренней и внешней политики Украины ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

- еврореволюция, революция достоинства

Антонимы

Гиперонимы

- майдан

Гипонимы

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Связано со словом майдан (девятью годами ранее протест случился из-за обвинения в нечестных выборах) и поводом к протесту — отказом Виктора Януковича подписать соглашение об ассоциации с ЕС.

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

Библиография

- Словарь перемен — 2014 / Сост. М. Вишневецкая. — М. : Три квадрата, 2015. — С. 18. — ISBN 978-5-94607-204-5.

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

| Euromaidan | ||

|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: A large European flag is waved across Maidan on 27 November 2013; opposition activist and popular singer Ruslana addresses the crowds on Maidan on 29 November 2013; Euromaidan on European Square on 1 December; plinth of the toppled Lenin statue; crowds direct hose at militsiya; tree decorated with flags and posters. |

||

| Date | 21 November 2013 – 22 February 2014 (3 months and 1 day) | |

| Location |

Ukraine, primarily Maidan Nezalezhnosti in Kyiv |

|

| Caused by |

Main catalyst:

Other factors:

|

|

| Goals |

|

|

| Methods | Demonstrations, civil disobedience, civil resistance, hacktivism,[11] occupation of administrative buildings[nb 1] | |

| Resulted in |

Full results

|

|

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||

|

||

| Lead figures | ||

|

Arseniy Yatsenyuk Viktor Yanukovych |

||

| Number | ||

|

||

| Casualties and losses | ||

|

Euromaidan (;[82][83] Ukrainian: Євромайдан, romanized: Yevromaidan, lit. ‘Euro Square’, IPA: [jeu̯romɐjˈdɑn][nb 6]), or the Maidan Uprising,[87] was a wave of demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protests in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv. The protests were sparked by President Viktor Yanukovych’s sudden decision not to sign the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement, instead choosing closer ties to Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union. Ukraine’s parliament had overwhelmingly approved of finalizing the Agreement with the EU,[88] but Russia had put pressure on Ukraine to reject it.[89] The scope of the protests widened, with calls for the resignation of Yanukovych and the Azarov government.[90] Protesters opposed what they saw as widespread government corruption, abuse of power, human rights violations,[91] and the influence of oligarchs.[92] Transparency International named Yanukovych as the top example of corruption in the world.[93] The violent dispersal of protesters on 30 November caused further anger.[5] The Euromaidan led to the 2014 Revolution of Dignity.

During the uprising, Independence Square (Maidan) in Kyiv was a huge protest camp occupied by thousands of protesters and protected by makeshift barricades. It had kitchens, first aid posts and broadcasting facilities, as well as stages for speeches, lectures, debates and performances.[94][95] It was guarded by ‘Maidan Self-Defense’ units made up of volunteers in improvised uniform and helmets, carrying shields and armed with sticks, stones and petrol bombs. Protests were also held in many other parts of Ukraine. In Kyiv, there were clashes with police on 1 December; and police assaulted the camp on 11 December. Protests increased from mid-January, in response to the government introducing draconian anti-protest laws. There were deadly clashes on Hrushevsky Street on 19–22 January. Protesters then occupied government buildings in many regions of Ukraine. The uprising climaxed on 18–20 February, when fierce fighting in Kyiv between Maidan activists and police resulted in the deaths of almost 100 protesters and 13 police.[71]

As a result, Yanukovych and the parliamentary opposition signed an agreement on 21 February to bring about an interim unity government, constitutional reforms and early elections. Police abandoned central Kyiv that afternoon, then Yanukovych and other government ministers fled the city that evening.[96] The next day, parliament removed Yanukovych from office[97] and installed an interim government.[98] The Revolution of Dignity was soon followed by the Russian annexation of Crimea and pro-Russian unrest in Eastern Ukraine, eventually escalating into the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Overview[edit]

The demonstrations began on the night of 21 November 2013, when protests erupted in the capital, Kyiv, after the Ukrainian government rejected draft laws that would allow the release of jailed opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko and suspend preparations for signing the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement with the European Union, to seek closer economic relations with Russia.[99] The reversal was preceded by a campaign of threats, insults and preemptive trade restrictions from Russia.[100][101][102][103]

On 24 November 2013, clashes between protesters and police began. Protesters strived to break cordon. Police used tear gas and batons. Protesters also used tear gas and some fire crackers (according to the police, protesters were the first to use them).[104] After a few days of demonstrations an increasing number of university students joined the protests.[105] The Euromaidan has been characterised as an event of major political symbolism for the European Union itself, particularly as «the largest ever pro-European rally in history.»[106]

Pro-EU demonstration in Kyiv, 27 November 2013

The protests continued despite heavy police presence,[107][108] regularly sub-freezing temperatures, and snow. Escalating violence from government forces in the early morning of 30 November caused the level of protests to rise, with 400,000–800,000 protesters, according to Russia’s opposition politician Boris Nemtsov, demonstrating in Kyiv on the weekends of 1 December[60] and 8 December.[109] In the preceding weeks, protest attendance had fluctuated from 50,000 to 200,000 during organised rallies.[110][111] Violent riots took place 1 December and 19 January through 25 January in response to police brutality and government repression.[112] Starting 23 January, several Western Ukrainian Oblast (province) government buildings and regional councils were occupied in a revolt by Euromaidan activists.[16] In the Russophone cities of Zaporizhzhya, Sumy, and Dnipropetrovsk, protesters also tried to take over their local government buildings and were met with considerable force from both police and government supporters.[16]

According to journalist Lecia Bushak writing in the 18 February 2014 issue of Newsweek magazine,

EuroMaidan [had] grown into something far bigger than just an angry response to the fallen-through EU deal. It’s now about ousting Yanukovych and his corrupt government; guiding Ukraine away from its 200-year-long, deeply intertwined and painful relationship with Russia; and standing up for basic human rights to protest, speak and think freely and to act peacefully without the threat of punishment.[113]

A turning point came in late February, when enough members of the president’s party fled or defected for the party to lose its majority in parliament, leaving the opposition large enough to form the necessary quorum. This allowed parliament to pass a series of laws that removed police from Kyiv, canceled anti-protest operations, restored the 2004 constitution, freed political detainees, and removed President Yanukovych from office. Yanukovych then fled to Ukraine’s second-largest city of Kharkiv, refusing to recognise the parliament’s decisions. The parliament assigned early elections for May 2014.[114]

In early 2019, a Ukrainian court found Yanukovych guilty of treason. Yanukovych was also charged with asking Vladimir Putin to send Russian troops to invade Ukraine after he had fled the country. The charges have had little practical effect on Yanukovych, who has lived in exile in the Russian city of Rostov since fleeing Ukraine under armed guard in 2014.[115]

Background[edit]

Name history[edit]

The term «Euromaidan» was initially used as a hashtag of Twitter.[84] A Twitter account named Euromaidan was created on the first day of the protests.[116] It soon became popular in the international media.[117] The name is composed of two parts: «Euro» is short for Europe, reflecting the pro-European aspirations of the protestors, and «maidan» refers to Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), the large square in the downtown of Kyiv, where the protests mostly took place. The word «Maidan» is a Persian word meaning «square» or «open space». It is a loanword in many other languages and was adopted into both the Ukrainian language and the Russian as spoken in Ukraine from the Ottoman Empire. During the protests, the word «Maidan» acquired the meaning of the public practice of politics and protest.[118]

When Euromaidan first began, media outlets in Ukraine dubbed the movement Eurorevolution[119] (Ukrainian: Єврореволюція, Russian: Еврореволюция), though the term soon fell out of use.

The term «Ukrainian Spring» was occasionally used during the protests, echoing the term Arab Spring.[120][121]

Initial causes[edit]

On 30 March 2012 the European Union (EU) and Ukraine initiated an Association Agreement;[122] however, the EU leaders later stated that the agreement would not be ratified unless Ukraine addressed concerns over a «stark deterioration of democracy and the rule of law», including the imprisonment of Yulia Tymoshenko and Yuriy Lutsenko in 2011 and 2012.[123][nb 7] In the months leading up to the protests Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych urged the parliament to adopt laws so that Ukraine would meet the EU’s criteria.[125][126] On 25 September 2013 Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine’s parliament) Volodymyr Rybak stated he was sure that his parliament would pass all the laws needed to fit the EU criteria for the Association Agreement since, except for the Communist Party of Ukraine, «The Verkhovna Rada has united around these bills.»[127] According to Pavlo Klimkin, one of the Ukrainian negotiators of the Association Agreement, initially «the Russians simply did not believe [the association agreement with the EU] could come true. They didn’t believe in our ability to negotiate a good agreement and didn’t believe in our commitment to implement a good agreement.»[128]

In mid-August 2013 Russia changed its customs regulations on imports from Ukraine[129] such that on 14 August 2013, the Russian Custom Service stopped all goods coming from Ukraine[130] and prompted politicians[131] and sources[132][133][134] to view the move as the start of a trade war against Ukraine to prevent Ukraine from signing a trade agreement with the European Union. Ukrainian Industrial Policy Minister Mykhailo Korolenko stated on 18 December 2013 that because of this Ukraine’s exports had dropped by $1.4 billion (or a 10% year-on-year decrease through the first 10 months of the year).[129] The State Statistics Service of Ukraine reported in November 2013 that in comparison with the same months of 2012, industrial production in Ukraine in October 2013 had fallen by 4.9 percent, in September 2013 by 5.6 percent, and in August 2013 by 5.4 percent (and that the industrial production in Ukraine in 2012 total had fallen by 1.8 percent).[135]

On 21 November 2013 a Ukrainian government decree suspended preparations for signing of the Association Agreement.[136][137][138] The reason given was that in the previous months Ukraine had experienced «a drop in industrial production and our relations with CIS [Commonwealth of Independent States] countries».[139][nb 8] The government also assured, «Ukraine will resume preparing the agreement when the drop in industrial production and our relations with Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries are compensated by the European market.»[139] According to Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov, «the extremely harsh conditions» of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan (presented by the IMF on 20 November 2013), which included big budget cuts and a 40% increase in gas bills, had been the last argument in favour of the Ukrainian government’s decision to suspend preparations for signing the Association Agreement.[141][142] On 7 December 2013 the IMF clarified that it was not insisting on a single-stage increase in natural gas tariffs in Ukraine by 40%, but recommended that they be gradually raised to an economically justified level while compensating the poorest segments of the population for the losses from such an increase by strengthening targeted social assistance.[143] The same day, IMF Resident Representative in Ukraine Jerome Vacher stated that this particular IMF loan was worth US$4 billion and that it would be linked with «policy, which would remove disproportions and stimulate growth».[144][nb 9]

President Yanukovych attended the 28–29 November 2013 EU summit in Vilnius (where originally it was planned that the Association Agreement would be signed on 29 November 2013),[125] but the Association Agreement was not signed.[146][147] Both Yanukovych and high level EU officials signalled that they wanted to sign the Association Agreement at a later date.[148][149][150]

In an interview with Lally Weymouth, Ukrainian billionaire businessman and opposition leader Petro Poroshenko said,

From the beginning, I was one of the organizers of the Maidan. My television channel—Channel 5—played a tremendously important role. … On the 11th of December, when we had [U.S. Assistant Secretary of State] Victoria Nuland and [E.U. diplomat] Catherine Ashton in Kyiv, during the night they started to storm the Maidan.[151]

On 11 December 2013 the Prime Minister, Mykola Azarov, said he had asked for €20 billion (US$27 billion) in loans and aid to offset the cost of the EU deal.[152] The EU was willing to offer €610 million (US$838 million) in loans,[153] but Russia was willing to offer US$15 billion in loans.[153] Russia also offered Ukraine cheaper gas prices.[153] As a condition for the loans, the EU required major changes to the regulations and laws in Ukraine. Russia did not.[152]

Public opinion about Euromaidan[edit]

According to December 2013 polls (by three different pollsters), between 45% and 50% of Ukrainians supported Euromaidan, while between 42% and 50% opposed it.[154][155][156] The biggest support for the protest was found in Kyiv (about 75%) and western Ukraine (more than 80%).[154][157] Among Euromaidan protesters, 55% were from the west of the country, with 24% from central Ukraine and 21% from the east.[158]

In a poll taken on 7–8 December, 73% of protesters had committed to continue protesting in Kyiv as long as needed until their demands were fulfilled.[5] This number had increased to 82% as of 3 February 2014.[158] Polls also showed that the nation was divided in age: while a majority of young people were pro-EU, older generations (50 and above) more often preferred the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia.[159] More than 41% of protesters were ready to take part in the seizure of administrative buildings as of February, compared to 13 and 19 percent during polls on 10 and 20 December 2013. At the same time, more than 50 percent were ready to take part in the creation of independent military units, compared to 15 and 21 percent during the past studies, respectively.[158]

According to a January poll, 45% of Ukrainians supported the protests, and 48% of Ukrainians disapproved of Euromaidan.[160]

In a March poll, 57% of Ukrainians said they supported the Euromaidan protests.[161]

A study of public opinion in regular and social media found that 74% of Russian speakers in Ukraine supported the Euromaidan movement, and a quarter opposed.[162]

Public opinion about joining the EU[edit]

According to an August 2013 study by a Donetsk company, Research & Branding Group,[163] 49% of Ukrainians supported signing the Association Agreement, while 31% opposed it and the rest had not decided yet. However, in a December poll by the same company, only 30% claimed that terms of the Association Agreement would be beneficial for the Ukrainian economy, while 39% said they were unfavourable for Ukraine. In the same poll, only 30% said the opposition would be able to stabilise the society and govern the country well, if coming to power, while 37% disagreed.[164]

Authors of the GfK Ukraine poll conducted 2–15 October 2013 claim that 45% of respondents believed Ukraine should sign an Association Agreement with the EU, whereas only 14% favoured joining the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia, and 15% preferred non-alignment. Full text of the EU-related question asked by GfK reads, «Should Ukraine sign the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, and, in the future, become an EU member?»[165][166]

Another poll conducted in November by IFAK Ukraine for DW-Trend showed 58% of Ukrainians supporting the country’s entry into the European Union.[167] On the other hand, a November 2013 poll by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology showed 39% supporting the country’s entry into the European Union and 37% supporting Ukraine’s accession to the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia.[168]

In December 2013, then Prime Minister of Ukraine Mykola Azarov refuted the pro-EU poll numbers claiming that many polls posed questions about Ukraine joining the EU, and that Ukraine had never been invited to join the Union,[169] but only to sign the European Union Association Agreement (a treaty between the EU and a non-EU nation).[170]

Comparison with the Orange Revolution[edit]

| External image |

|---|

The pro-European Union protests are Ukraine’s largest since the Orange Revolution of 2004, which saw Yanukovych forced to resign as prime minister over allegations of voting irregularities. Although comparing the 2013 events in the same East-West vector as 2004, with Ukraine remaining «a key geopolitical prize in eastern Europe» for Russia and the EU, The Moscow Times noted that Yanukovych’s government was in a significantly stronger position following his election in 2010.[171] The Financial Times said the 2013 protests were «largely spontaneous, sparked by social media, and have caught Ukraine’s political opposition unprepared» compared to their well-organised predecessors.[172] The hashtag #euromaidan (Ukrainian: #євромайдан, Russian: #евромайдан), emerged immediately on the first meeting of the protests and was highly useful as a communication instrument for protesters.[173] Vitali Klitschko wrote in a tweet[174] «Friends! All those who came to Maydan [Independence Square], well done! Who has not done it yet – join us now!» The protest hashtag also gained traction on the VKontakte social media network, and Klitschko tweeted a link to a speech[175] he made on the square saying that once the protest was 100,000-strong, «we’ll go for Yanukovych» – referring to President Viktor Yanukovych.[173]

In an interview, opposition leader Yuriy Lutsenko, when asked if the current opposition was weaker than it was in 2004, argued that the opposition was stronger because the stakes were higher, «I asked each [of the opposition leaders]: ‘Do you realise that this is not a protest? It is a revolution […] we have two roads – we go to prison or we win.'»[176]

Paul Robert Magocsi illustrated the effect of the Orange Revolution on Euromaidan, saying,

Was the Orange Revolution a genuine revolution? Yes it was. And we see the effects today. The revolution wasn’t a revolution of the streets or a revolution of (political) elections; it was a revolution of the minds of people, in the sense that for the first time in a long time, Ukrainians and people living in territorial Ukraine saw the opportunity to protest and change their situation. This was a profound change in the character of the population of the former Soviet Union.[177]

Lviv-based historian Yaroslav Hrytsak also remarked on the generational shift,

This is a revolution of the generation that we call the contemporaries of Ukraine’s independence (who were born around the time of 1991); it is more similar to the Occupy Wall Street protests or those in Istanbul demonstrations (of this year). It’s a revolution of young people who are very educated, people who are active in social media, who are mobile and 90 percent of whom have university degrees, but who don’t have futures.[107]

According to Hrytsak: «Young Ukrainians resemble young Italians, Czech, Poles, or Germans more than they resemble Ukrainians who are 50 and older. This generation has a stronger desire for European integration and fewer regional divides than their seniors.»[178] In a Kyiv International Institute of Sociology poll taken in September, joining the European Union was mostly supported by young Ukrainians (69.8% of those aged 18 to 29), higher than the national average of 43.2% support.[179][180] A November 2013 poll by the same institute found the same result with 70.8% aged 18 to 29 wanting to join the European Union while 39.7% was the national average of support.[179] An opinion poll by GfK conducted 2–15 October found that among respondents aged 16–29 with a position on integration, 73% favoured signing an Association Agreement with the EU, while only 45% of those over the age of 45 favoured Association. The lowest support for European integration was among people with incomplete secondary and higher education.[165]

Escalation to violence[edit]

Euromaidan protest in Kyiv, 18 February 2014

The movement started peacefully but violence broke out, especially in January and February 2014.[181] The Associated Press said on 19 February 2014:

The latest bout of street violence began Tuesday when protesters attacked police lines and set fires outside parliament, accusing Yanukovych of ignoring their demands to enact constitutional reforms that would limit the president’s power—a key opposition demand. Parliament, dominated by his supporters, was stalling on taking up a constitutional reform to limit presidential powers.

Police responded by attacking the protest camp. Armed with water cannons, stun grenades and rubber bullets, police dismantled some barricades. But the protesters held their ground through the night, encircling the protest camp with new burning barricades of tires, furniture and debris.[182]

In the early stages of Euromaidan, there was discussion about whether the Euromaidan movement constituted a revolution. At the time many protest leaders (such as Oleh Tyahnybok) had already used this term frequently when addressing the public. Tyahnybok called in an official 2 December press release for police officers and members of the military to defect to ‘the Ukrainian revolution’.[183]

In a Skype interview with media analyst Andrij Holovatyj, Vitaly Portnikov, Council Member of the «Maidan» National Alliance and President and Editor-in-Chief of the Ukrainian television channel TVi, stated «EuroMaidan is a revolution and revolutions can drag on for years» and that «what is happening in Ukraine goes much deeper. It is changing the national fabric of Ukraine.»[184]

On 10 December Yanukovych said, «Calls for a revolution pose a threat to national security.»[185] Former Georgian president Mikhail Saakashvili has described the movement as «the first geopolitical revolution of the 21st century».[186]

Political expert Anders Åslund commented on this aspect,

Revolutionary times have their own logic that is very different from the logic of ordinary politics, as writers from Alexis de Tocqueville to Crane Brinton have taught. The first thing to understand about Ukraine today is that it has entered a revolutionary stage. Like it or not, we had better deal with the new environment rationally.[187]

Demands[edit]

On 29 November, a formal resolution by protest organisers made the following demands:[107]

- The formation of a co-ordinating committee to communicate with the European community.

- A statement indicating that the president, parliament, and the Cabinet of Ministers weren’t capable of carrying out a geopolitically strategic course of development for the state and demanding Yanukovych’s resignation.

- The cessation of political repression against EuroMaidan activists, students, civic activists and opposition leaders.

The resolution stated that on 1 December, on the 22nd anniversary of Ukraine’s independence referendum, the group would gather at noon on Independence Square to announce their further course of action.[107]

After the forced police dispersal of all protesters from Maidan Nezalezhnosti on the night of 30 November, the dismissal of Minister of Internal Affairs Vitaliy Zakharchenko became one of the protesters’ main demands.[188]

A petition to the US White House demanding sanctions against Viktor Yanukovych and Ukrainian government ministers gathered over 100,000 signatures in four days.[189][190][191][192]

Ukrainian students nationwide also demanded the dismissal of Minister of Education Dmytro Tabachnyk.

On 5 December, Batkivshchyna faction leader Arseniy Yatsenyuk stated,

Our three demands to the Verkhovna Rada and the president remained unchanged: the resignation of the government; the release of all political prisoners, first and foremost; [the release of former Ukrainian Prime Minister] Yulia Tymoshenko; and [the release of] nine individuals [who were illegally convicted after being present at a rally on Bankova Street on December 1]; the suspension of all criminal cases; and the arrest of all Berkut officers who were involved in the illegal beating up of children on Maidan Nezalezhnosti.[193]

The opposition also demanded that the government resume negotiations with the IMF for a loan that they saw as key to helping Ukraine «through economic troubles that have made Yanukovych lean toward Russia».[194]

Timeline of the events[edit]

Euromaidan protestors on 27 November 2013, Kyiv, Ukraine

Bulldozer clashes with Internal Troops on Bankova Street, 1 December 2013

The Euromaidan protest movement began late at night on 21 November 2013 as a peaceful protest.[195] The 1,500 protesters were summoned following a Facebook post by a journalist, Mustafa Nayyem, calling for a rally against the government.[196][197]

Riots in Kyiv[edit]

On 30 November 2013, protests were dispersed violently by Berkut riot police units, sparking riots the following day in Kyiv.[198] On 1 December 2013, protesters reoccupied the square, and through December, further clashes with the authorities and political ultimatums by the opposition ensued. This culminated in a series of anti-protest laws by the government on 16 January 2014 and further rioting on Hrushevskoho Street. Early February 2014 saw a bombing of the Trade Unions Building,[199] as well as the formation of «Self Defense» teams by protesters.[200]

1 December 2013 riots[edit]

11 December 2013 assault on Maidan[edit]

Hrushevsky Street riots[edit]

On 19 January a Sunday mass protest, the ninth in a row, took place, gathering up to 200,000 in central Kyiv to protest against the new anti-protest laws, dubbed the Dictatorship Laws. Many protesters ignored the face concealment ban by wearing party masks, hard hats and gas masks. Opposition leader Vitali Klitschko appeared covered with powder after he was sprayed with a fire extinguisher. Riot police and government supporters cornered a group of people who were trying to seize government buildings. The number of riot police on Hrushevskoho Street increased after buses and army trucks showed up. The latter resulted in the buses being burned as a barricade. The next day, a clean-up began in Kyiv. On 22 January, more violence erupted in Kyiv. This resulted in 8–9 people dead.

February 2014: Revolution[edit]

The deadliest clashes were on 18–20 February, which saw the most severe violence in Ukraine since it regained independence.[201] Thousands of protesters advanced towards parliament, led by activists with shields and helmets, and were fired on by police snipers. Almost 100 were killed.[202]

On 21 February, an agreement was signed by Yanukovych and leaders of the parliamentary opposition (Vitaly Klitschko, Arseny Yatsenyuk, Oleh Tyahnybok) under the mediation of EU and Russian representatives. There was to be an interim unity government formed, constitutional reforms to reduce the president’s powers, and early elections.[92] Protesters were to leave occupied buildings and squares, and the government would not apply a state of emergency.[92] The United States supported a stipulation that Yanukovych remain president in the meantime, but Maidan protesters demanded his resignation.[92] The signing was witnessed by Foreign Ministers of Poland, Germany and France.[203] The Russian representative would not sign the agreement.[92]

The next day, 22 February, Yanukovych fled to Donetsk and Crimea and parliament voted to remove him from office.[204][205][206] On 24 February Yanukovych arrived in Russia.[207]

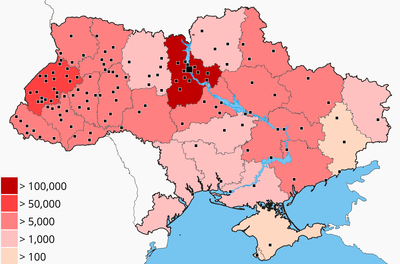

Protests across Ukraine[edit]

|

|

|||

| City | Peak attendees | Date | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kyiv | 400,000–800,000 | 1 Dec | [60] |

| Lviv | 50,000 | 1 Dec | [63] |

| Kharkiv | 30,000 | 22 Feb | [208] |

| Cherkasy | 20,000 | 23 Jan | [64] |

| Ternopil | 20,000+ | 8 Dec | [209] |

| Dnipropetrovsk (now Dnipro) | 15,000 | 2 Mar | [107][210] |

| Ivano-Frankivsk | 10,000+ | 8 Dec | [211] |

| Lutsk | 8,000 | 1 Dec | [212] |

| Sumy | 10,000 | 2 Mar | [213] |

| Poltava | 10,000 | 24 Jan | [214] |

| Donetsk | 10,000 | 5 Mar | [215] |

| Zaporizhia | 10,000 | 26 Jan | [216] |

| Chernivtsi | 4,000–5,000 | 1 Dec | [212] |

| Simferopol | 5,000+ | 23 Feb | [217] |

| Rivne | 4,000–8,000 | 2 Dec | [218] |

| Mykolaiv | 10,000 | 2 Mar | [219] |

| Mukacheve | 3,000 | 24 Nov | [220] |

| Odesa | 10,000 | 2 Mar | [221] |

| Khmelnytskyi | 8,000 | 24 Jan | [211] |

| Bila Tserkva | 2,000+ | 24 Jan | [222] |

| Sambir | 2,000+ | 1 Dec | [223] |

| Vinnytsia | 5,000 | 8 Dec 22 Jan | [224] |

| Zhytomyr | 2,000 | 23 Jan | [225] |

| Kirovohrad | 1,000 | 8 Dec 24 Jan | [214][226] |

| Kryvyi Rih | 1,000 | 1 Dec | [227] |

| Luhansk | 1,000 | 8 Dec | [228] |

| Uzhhorod | 1,000 | 24 Jan | [229] |

| Drohobych | 500–800 | 25 Nov | [230] |

| Kherson | 2,500 | 3 Mar | [231] |

| Mariupol | 400 | 26 Jan | [232] |

| Chernihiv | 150–200 | 22 Nov | [233] |

| Izmail | 150 | 22 Feb | [234] |

| Vasylkiv | 70 | 4 Dec | [235] |

| Yalta | 50 | 20 Feb | [236] |

A 24 November 2013 protest in Ivano-Frankivsk saw several thousand protestors gather at the regional administration building.[237] No classes were held in the universities of western Ukrainian cities such as Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Uzhhorod.[238] Protests also took place in other large Ukrainian cities, such as Kharkiv, Donetsk, Dnipropetrovsk (now Dnipro), and Luhansk. The rally in Lviv in support of the integration of Ukraine into the EU was initiated by the students of local universities. This rally saw 25–30 thousand protesters gather on Prospect Svobody (Freedom Avenue) in Lviv. The organisers planned to continue this rally until the 3rd Eastern Partnership summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, on 28–29 November 2013.[239] A rally in Simferopol, which drew around 300, saw nationalists and Crimean Tatars unite to support European integration; the protesters sang both the Ukrainian national anthem and the anthem of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen.[240]

7 people were injured after a tent encampment in Dnipropetrovsk was ordered cleared by court order on 25 November and it appeared that thugs had undertaken to perform the clearance.[241][242] Officials estimated the number of attackers to be 10–15,[243] and police did not intervene in the attacks.[244] Similarly, police in Odesa ignored calls to stop the demolition of Euromaidan camps in the city by a group of 30, and instead removed all parties from the premises.[245] 50 police officers and men in plain clothes also drove out a Euromaidan protest in Chernihiv the same day.[246]

On 25 November, in Odesa, 120 police raided and destroyed a tent encampment made by protesters at 5:20 in the morning. The police detained three of the protesters, including the leader of the Odesa branch of Democratic Alliance, Alexei Chorny. All three were beaten in the police vehicle and then taken to the Portofrankovsk Police Station without their arrival being recorded. The move came after the District Administrative Court earlier issued a ban restricting citizens’ right to peaceful assembly until New Year. The court ruling places a blanket ban on all demonstrations, the use of tents, sound equipment and vehicles until the end of the year.[247]

On 26 November, a rally of 50 was held in Donetsk.[248]

On 28 November, a rally was held in Yalta; university faculty who attended were pressured to resign by university officials.[249]

On 29 November, Lviv protesters numbered some 20,000.[250] Like in Kyiv, they locked hands in a human chain, symbolically linking Ukraine to the European Union (organisers claimed that some 100 people even crossed the Ukrainian-Polish border to extend the chain to the European Union).[250][251]

The largest pro-European Union protests outside Kyiv took place at the Taras Shevchenko monument in Lviv

Pro-European Union protests in Luhansk

On 1 December, the largest rally outside of Kyiv took place in Lviv by the statue of Taras Shevchenko, where over 50,000 protesters attended. Mayor Andriy Sadovy, council chairman Peter Kolody, and prominent public figures and politicians were in attendance.[63] An estimated 300 rallied in the eastern city of Donetsk demanding that President Viktor Yanukovych and the government of Prime Minister Mykola Azarov resign.[252] Meanwhile, in Kharkiv, thousands rallied with writer Serhiy Zhadan during a speech, calling for revolution. The protest was peaceful.[253][254][255] Protesters claimed at least 4,000 attended,[256] with other sources saying 2,000.[257] In Dnipropetrovsk, 1,000 gathered to protest the EU agreement suspension, show solidarity with those in Kyiv, and demanded the resignation of local and metropolitan officials. They later marched, shouting «Ukraine is Europe» and «Revolution».[258] EuroMaidan protests were also held in Simferopol (where 150–200 attended)[259] and Odesa.[260]

On 2 December, in an act of solidarity, Lviv Oblast declared a general strike to mobilise support for protests in Kyiv,[261] which was followed by the formal order of a general strike by the cities of Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk.[262]

In Dnipropetrovsk on 3 December, a group of 300 protested in favour of European integration and demanded the resignation of local authorities, heads of local police units, and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).[263]

On 7 December it was reported that police were prohibiting those from Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk from driving to Kyiv.[264]

Protests on 8 December saw record turnout in many Ukrainian cities, including several in eastern Ukraine. On the evening, the fall of the monument to Lenin in Kyiv took place.[265] The statue made out of stone was completely hacked to pieces by jubilant demonstrators.

On 9 December, a statue of Vladimir Lenin was destroyed in the town of Kotovsk in Odesa Oblast.[266] In Ternopil, Euromaidan organisers were prosecuted by authorities.[267]

The removal or destruction of Lenin monuments and statues gained particular momentum after the destruction of the Kyiv Lenin statue. The statue removal process was soon termed “Leninopad” (Ukrainian: Ленінопад, Russian: Ленинопад), literally meaning “Leninfall” in English. Soon, activists pulled down a dozen monuments in the Kyiv region, Zhytomyr, Chmelnitcki, and elsewhere, or damaged them during the course of the Euromaidan protests into spring of 2014.[268] In other cities and towns, monuments were removed by organised heavy equipment and transported to scrapyards or dumps.[269]

On 14 December, Euromaidan supporters in Kharkiv voiced their disapproval of authorities fencing off Freedom Square from the public by covering the metal fence in placards.[270] From 5 December, they became victims of theft and arson.[271] A Euromaidan activist in Kharkiv was attacked by two men and stabbed twelve times. The assailants were unknown but activists told the Kharkiv-based civic organisation Maidan that they believe the city’s mayor, Gennady Kernes, to be behind the attack.[272]

On 22 December, 2,000 rallied in Dnipropetrovsk.[273]

New Year celebration on Maidan

In late December, 500 marched in Donetsk. Due to the regime’s hegemony in the city, foreign commentators have suggested that, «For 500 marchers to assemble in Donetsk is the equivalent of 50,000 in Lviv or 500,000 in Kyiv.»[274][better source needed] On 5 January, marches in support of Euromaidan were held in Donetsk, Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa, and Kharkiv, the latter three drawing several hundred and Donetsk only 100.[275]

On 11 January 2014, 150 activists met in Kharkiv for a general forum on uniting the nationwide Euromaidan efforts. A church where some were meeting was stormed by over a dozen thugs, and others attacked meetings in a book store, smashing windows and deploying tear gas to stop the Maidan meetings from taking place.[276]

Police clash with protesters

On 22 January in Donetsk, two simultaneous rallies were held – one pro-Euromaidan and one pro-government. The pro-government rally attracted 600 attendees, compared to about 100 from the Euromaidan side. Police reports claimed 5,000 attended to support the government, compared to only 60 from Euromaidan. In addition, approximately 150 titushky appeared and encircled the Euromaidan protesters with megaphones and began a conflict, burning wreaths and Svoboda Party flags, shouting, «Down with fascists!», but were separated by police.[277] Meanwhile, Donetsk City Council pleaded with the government to take tougher measures against Euromaidan protesters in Kyiv.[278] Reports indicated a media blackout took place in Donetsk.[citation needed]

In Lviv on 22 January, amid the police shootings of protesters in the capital, military barracks were surrounded by protesters. Many of the protesters included mothers whose sons were serving in the military, who pleaded with them not to deploy to Kyiv.[279]

In Vinnytsia on 22 January, thousands of protesters blocked the main street of the city and the traffic. Also, they brought «democracy in coffin» to the city hall, as a present to Yanukovych.[280]

On 23 January. Odesa city council member and Euromaidan activist Oleksandr Ostapenko’s car was bombed.[281] The Mayor of Sumy threw his support behind the Euromaidan movement on 24 January, laying blame for the civil disorder in Kyiv on the Party of Regions and Communists.[282]

The Crimean parliament repeatedly stated that because of the events in Kyiv it was ready to join autonomous Crimea to Russia. On 27 February, armed men seized the Crimean parliament and raised the Russian flag.[283] 27 February was later declared a day of celebration for the Russian Spetsnaz special forces by Vladimir Putin by presidential decree.[284]

In the beginning of March, thousands of Crimean Tatars in support of Euromaidan clashed with pro-Russian protesters in Simferopol.

On 4 March 2014, a mass pro-Euromaidan rally was held in Donetsk for the first time. About 2,000 people were there. Donetsk is a major city in the far east of Ukraine and served as Yanukovych’s stronghold and the base of his supporters. On 5 March 2014, 7,000–10,000 people rallied in support of Euromaidan in the same place.[285] After a leader declared the rally over, a fight broke out between pro-Euromaidan and 2,000 pro-Russian protesters.[285][286]

Occupation of administrative buildings[edit]

Starting on 23 January, several Western Ukrainian oblast (province) government buildings and Regional State Administrations (RSAs) were occupied by Euromaidan activists.[16] Several RSAs of the occupied oblasts then decided to ban the activities and symbols of the Communist Party of Ukraine and Party of Regions in their oblast.[17] In the cities of Zaporizhzhia, Dnipropetrovsk and Odesa, protesters also tried to take over their local RSAs.[16]

Protests outside Ukraine[edit]

Smaller protests or Euromaidans have been held internationally, primarily among the larger Ukrainian diaspora populations in North America and Europe. The largest took place on 8 December 2013 in New York, with over 1,000 attending. Notably, in December 2013, Warsaw’s Palace of Culture and Science,[287] the Buffalo Electric Vehicle Company Tower in Buffalo, New York,[288][better source needed] Cira Centre in Philadelphia,[289] the Tbilisi City Assembly in Georgia,[290] and Niagara Falls on the US-Canada border[291] were illuminated in blue and yellow as a symbol of solidarity with Ukraine.

Antimaidan and pro-government rallies[edit]

Pro-government rallies during Euromaidan were largely credited as funded by the government.[292][293] Several news outlets investigated the claims to confirm that by and large, attendees at pro-government rallies did so for financial compensation and not for political reasons, and were not an organic response to the Euromaidan. «People stand at Euromaidan protesting against the violation of human rights in the state, and they are ready to make sacrifices,» said Oleksiy Haran, a political scientist at Kyiv Mohyla Academy in Kyiv. «People at Antimaidan stand for money only. The government uses these hirelings to provoke resistance. They won’t be sacrificing anything.»[294]

Euromaidan groups[edit]

Automaidan[edit]

Automaidan[295] was a movement within Euromaidan that sought the resignation of Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych. It was made up mainly of drivers who would protect the protest camps and blockade streets. It organised a car procession on 29 December 2013 to the president’s residence in Mezhyhirya to voice their protests at his refusal to sign the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement in December 2013. The motorcade was stopped a couple of hundred metres short of his residence. Automaidan was the repeated target of violent attacks by government forces and supporters.

Self-defence groups[edit]

On 30 November 2013, the day after the dispersion of the first major protests, Euromaidan activists, with the support of pro-Maidan political parties such as Svoboda, and aided by the Ukrainian politician and businessman Arsen Avakov,[296] created a self-defence group entitled “Self-Defence of the Maidan» or “Maidan Self-Defence” – an independent police force that aimed to protect protesters from riot police and provide security within Kyiv.[297][298] At the time, the head of the group was designated as Andriy Parubiy.[299]

“Self-Defence of the Maidan” adhered to a charter that “promoted the European choice and unity of Ukraine”,[300] and were not officially allowed to mask themselves or carry weapons, although most men in the group did not adhere to such rules and groups of volunteers were mainly fractured under a centralised leadership. The group ran its headquarters from a former women’s shoe store in central Kyiv, organising patrols, recruiting new members, and taking queries from the public. The makeshift headquarters was ran by volunteers from across Ukraine.[301] After the ousting of President Yanukovych, the group took on a much larger role, serving as the de facto police force in Kyiv in early 2014, as most police officers abandoned their posts for fears of reprisal.[302] Aiming to prevent looting or arson from tainting the success of Euromaidan, government buildings were among the first buildings to be protected by the group, with institutions such as the Verkhovna Rada (Parliament of Ukraine) and the National Bank of Ukraine under 24-hour supervision during this time.[303]

“Self-defence” groups such as “Self-Defence of the Maidan” were divided up into sotnias (plural: sotni) or ‘hundreds’, which were described as a «force that is providing the tip of the spear in the violent showdown with government security forces». The sotni take their name from a traditional form of Cossacks cavalry formation, and were also used in the Ukrainian People’s Army, Ukrainian Insurgent Army, and Ukrainian National Army.[304]

Along with “Self-Defence of the Maidan”, there were also some «independent» divisions of enforcers (some of them were also referred to as sotnias and even as “Self-Defence” groups), like the security of the Trade Unions Building until 2 January 2014,[305] Narnia and Vikings from Kyiv City State Administration,[306] Volodymr Parasyuk’s sotnia from Conservatory building,[307][308] although Andriy Parubiy officially asked such divisions to not term themselves as “Self-Defence” groups.[309]

Pravy Sektor coordinates its actions with Self-defence and is formally a 23rd sotnia,[310] although already had hundreds of members at the time of registering as a sotnia. Second sotnia (staffed by Svoboda’s members) tends to dissociate itself from «sotnias of self-defence of Maidan».[311]

Some Russian citizens sympathetic to the opposition joined the protest movement as part of the Misanthropic Division, many of them later becoming Ukrainian citizens.[39]

Casualties[edit]

Deaths[edit]

The first of the major casualties occurred on the Day of Unity of Ukraine, 22 January 2014. Four people permanently lost their vision,[312] and one man died by falling from a colonnade. The circumstances of his death are unclear. At least five more people were confirmed dead during the clashes on 22 January,[313] and four people perished from gunshot wounds.[313] Medics confirmed bullet wounds to be from firearms such as a Dragunov sniper rifle (7.62 mm) and possibly a Makarov handgun (9 mm) in the deaths of Nihoyan and Zhyznevskyi, respectively.[314][315] There are photos of Berkut police forces utilising shotguns (such as the RPC Fort), and reporters verified the presence of shotgun casings littering the ground.[316] The Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office confirmed two deaths from gunshot wounds in Kyiv protests.[317] «We are pursuing several lines of inquiry into these murders, including [that they may have been committed] by Berkut [special police unit] officers,» Vitali Sakal, first deputy chief of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry’s Main Investigative Directorate told a press conference in Kyiv on Friday. «It was established that the weapons and cartridges that were used to commit these killings are hunting cartridges. Such is the conclusion of forensic experts. Most likely, it was a smoothbore firearm. I want to stress that the cartridges which were used to commit the murders were not used by, and are not in use of, the police. They have no such cartridges», said first deputy chief of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry’s Main Investigative Directorate. The MVS has not ruled out that Berkut officers committed the killings.[318]

On 31 January it was discovered that 26 unidentified, unclaimed bodies remained in the Kyiv central morgue, 14 of which were from January alone.[319][320] Journalists revealed that a mass burial was planned on 4 February 2014.[319] The Kyiv city administration followed on the announcement with its own statement informing that there were 14 such bodies, 5 from January.[321]

On 18 and 19 February, at least 26 people were killed in clashes with police,[322] and a self-defense soldier from Maidan was found dead. Journalist Vyacheslav Veremiy was murdered by pro-government titushky and shot in the chest when they attacked his taxi. It was announced that an additional 40–50 people died in the fire that engulfed the Trade Union building after police attempted to seize it the night before.[323][unreliable source?]

On 20 February, gunfire killed 60 people, according to an opposition medical service.[324]

At the onset of the conflict, more than 100 people were killed and 2,500 injured in clashes with security forces. The death toll included at least 13 police officers, according to Ukrainian authorities.[325]

Investigation into shooters/snipers[edit]

Those responsible for the murders have never been found. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy stated in 2020 that «evidence and documents have been lost, while the scene of the crime has been tampered with and ‘cleaned up.'» He could not say when those who gave the orders would be found, but gave assurances that the matter is being “dealt with faster than several years ago.”[326]

Hrushevskoho Street riot shootings[edit]

During the 2014 Hrushevskoho Street riots of 22–25 January, 3 protesters were killed by firearms.

Oleh Tatarov, deputy chief of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry’s Main Investigative Directorate under Yanukovych, claimed in January that «[t]he theory we are looking at is the killing was by unidentified persons. This is an official theory, and the unidentified persons could be various people, a whole host of them… It could have been motivated by disruptive behavior, or with the aim of provocation.» He then claimed the cartridges and weapons used in the shootings were not police issue.[318] Forensics experts found that protesters were killed with both buckshot and rifle bullets,[327] while medics confirmed the bullet wounds to be from firearms such as the Dragunov sniper rifle (7.62×54 mmR) and possibly 9×18 mm Makarov cartridges.[328]

A report published on 25 January by Armament Research Services, a speciality arms and munitions consultancy in Perth, Australia, stated that the mysterious cufflink-shaped projectiles presumably fired by riot police on Hrushevskoho Street at protesters during clashes were not meant for riot control, but for stopping vehicles, busting through doors and piercing armour. The bullets were reported to be special armour-piercing 12-gauge shotgun projectiles, likely developed and produced by the Spetstekhnika (Specialized Equipment) design bureau, a facility located in Kyiv and associated with the Ministry of Internal Affairs.[329]

On 31 January 2014, Vitali Sakal, first deputy chief of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry’s Main Investigative Directorate told a press conference that «[w]e are pursuing several lines of inquiry into these murders, including [that they may have been committed] by Berkut (special police unit) officers.»[318]

On 10 October 2014 Reuters published a report about their examination of Ukraine’s probes into the Maidan shootings.[330] They have uncovered «serious flaws» in the case against Berkut (special police force) officers arrested by the new Ukrainian government and charged with murder of 39 unarmed protesters.[331] For example, as Reuters’ own investigation found out, the senior among arrested officers was missing his right hand after an accident 6 years ago. This dismissed main evidence presented by prosecutor, a photograph of a man holding his rifle with both hands. Other «flaws» according to Reuters included the fact that no one was charged with killing policemen and that the prosecutors and the minister in charge of the investigation all took part in the uprising.[citation needed]

Snipers deployed during the climax of the protests[edit]

Following the revolution of 18–23 February that saw over 100 killed in gunfire, the government’s new health minister, Oleh Musiy, a doctor who helped oversee medical treatment for casualties during the protests, suggested to the Associated Press that the similarity of bullet wounds suffered by opposition victims and police indicates the shooters were trying to stoke tensions on both sides and spark even greater violence, with the goal of toppling Yanukovych and justifying a Russian invasion. «I think it wasn’t just a part of the old regime that (plotted the provocation), but it was also the work of Russian special forces who served and maintained the ideology of the (old) regime,» he said, citing forensic evidence.[332] Hennadiy Moskal, a former deputy head of Ukraine’s main security agency, the SBU, and of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, suggested in an interview published in the Ukrainian newspaper Dzerkalo Tyzhnia that snipers from the MIA and SBU were responsible for the shootings, not foreign agents, acting on contingency plans dating back to Soviet times, stating: «Snipers received orders to shoot not only protesters, but also police forces. This was all done to escalate the conflict, to justify the police operation to clear Maidan.»[333][334]

The International Business Times reported that a telephone call between Estonian foreign minister Urmas Paet and High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Catherine Ashton had been intercepted in which Paet stated that a doctor named Olga stated that victims from both sides were shot by the same snipers and that Olga had photos of the shooting victims with the same «handwriting». Paet said he found it «really disturbing that now the new coalition [doesn’t] want to investigate what exactly happened», and that «there is a stronger and stronger understanding that behind snipers it was not Yanukovych, it was somebody from the new coalition».[335] However, Paet later denied that he implicated the opposition in anything as he was merely relaying rumours he had heard without giving any assessment of their veracity, while acknowledging that the phone call was genuine.[336] A spokesperson for the US state department described the leaking of the call as an example of «Russian tradecraft».[337]

Olga Bogomolets, the doctor, who allegedly claimed that protesters and Berkut troops came under fire from the same source, said she had not told Paet that policemen and protesters had been killed in the same manner, that she did not imply that the opposition was implicated in the killings, and that the government informed her that an investigation had been started.[338] German TV ARD investigation met one of the few doctors that treated the wounded of both sides. «The wounded that we treated, all had the same type of bullet wounds. The bullets were all identical. That’s all I can say. In the bodies of the wounded militia, and the opposition.» Lawyers representing relatives of the dead complained: «We haven’t been informed of the type of weapons, we have no access to the official reports, and to the operation schedules. We have no documents to the investigation, state prosecutors won’t show us any papers.»[339]

On 12 March 2014, Interior Minister Avakov has stated that the conflict was provoked by a ‘non-Ukrainian’ third party, and that an investigation was ongoing.[340]

On 31 March 2014, The Daily Beast published photos and videos which appear to show that the snipers were members of the Ukrainian Security Services (SBU) «anti-terrorist» Alfa Team unit, who had been trained in Russia.[341]

On 2 April 2014, law enforcement authorities announced in a press conference they had detained nine suspects in the 18–20 February shootings of Euromaidan activists, acting Prosecutor General of Ukraine Oleh Makhnytsky reported. Among the detainees was the leader of the sniper squad. All of the detained are officers of the Kyiv City Berkut unit, and verified the involvement of the SBU’s Alfa Group in the shootings. Officials also reported that they plan to detain additional suspects in the Maidan shootings in the near future, and stressed that the investigation is ongoing, but hindered by the outgoing regime’s destruction of all documents and evidence. Ukraine’s Ministry of Internal Affairs confirmed that Viktor Yanukovych gave the order to fire on protesters on 20 February.[342][343] During the press conference, Ukraine’s interior minister, chief prosecutor and top security chief implicated more than 30 Russian FSB agents in the crackdown on protesters, who in addition to taking part in the planning, flew large quantities of explosives into an airport near Kyiv. Valentyn Nalyvaichenko, the interim head of Ukraine’s SBU state security agency, said the agents were stationed in Kyiv during the entire Euromaidan protests, were provided with «state telecommunications» while residing at an SBU compound, and in regular contact with Ukrainian security officials. «We have substantiated grounds to consider that these very groups which were located at an SBU training ground took part in the planning and execution of activities of this so-called antiterrorist operation,» said Nalyvaichenko. Investigators, he said, had established that Yanukovych’s SBU chief Oleksandr Yakymenko, who had fled the country, had received reports from FSB agents while they were stationed in Ukraine, and that Yakymenko held several briefings with the agents. Russia’s Federal Security Bureau rejected the comments as «groundless accusations» and otherwise refused to comment.[344]

In 2015 BBC published a story based on an interview with an anonymous sniper who said he was firing at anti-riot police from Conservatory (music academy) building on the morning of 20 January 2014. The sniper said he was recruited by an unknown man «he describes only as a retired military officer». These morning shots are said to have provoked return fire from police snipers that resulted in many deaths. Andriy Shevchenko from Euromaidan leadership said he received calls from anti-riot police command reporting that his people are being shot by sniper bullets from the areas controlled by the protesters. Another Euromaidan leader, Andriy Parubiy, said his team searched the Conservatory and found no snipers. He confirmed that many victims on both sides were shot by snipers, but they were shooting from other, taller buildings surrounding the Conservatory and was convinced they were snipers controlled by Russia.[345]

Press and medics injured by police attacks[edit]

A number of attacks by law enforcement agents on members of the media and medical personnel have been reported. Some 40 journalists were injured during the staged assault at Bankova Street on 1 December 2013. At least 42 more journalists were victims of police attacks at Hrushevskoho Street on 22 January 2014.[346] On 22 January 2014, Television News Service (TSN) reported that journalists started to remove their identifying uniform (vests and helmets), as they were being targeted, sometimes on purpose, sometimes accidentally.[347] Since 21 November 2013, a total of 136 journalists have been injured.[348]

- On 21 January 2014, 26 journalists were injured, with at least two badly injured by police stun grenades;[349] 2 others were arrested by police.[350]

- On 22 January, a correspondent of Reuters, Vasiliy Fedosenko, was intentionally shot in the head by a marksman with rubber ammunition during clashes at Hrushevskoho Street.[351][352][353] Later, a journalist of Espresso TV Dmytro Dvoychenkov was kidnapped, beaten and taken to an unknown location, but later a parliamentarian was informed that he was finally released.[354]

- On 24 January, President Yanukovych ordered the release of all journalists from custody.[355]

- On 31 January, a video from 22 January 2014 was published that showed policemen in Berkut uniforms intentionally firing at a medic who raised his hands.[356]

- On 18 February 2014, American photojournalist Mark Estabrook was injured by Berkut forces, who threw two separate concussion grenades at him just inside the gate at the Hrushevskoho Street barricade, with shrapnel hitting him in the shoulder and lower leg. He continued bleeding all the way to Cologne, Germany for surgery. He was informed upon his arrival in Maidan to stay away from the hospitals in Kyiv to avoid Yanukovych’s Berkut police capture (February 2014)[357][358][359]

Impact[edit]

Support for Euromaidan in Ukraine[edit]

Opposition leaders, 8 December 2013

According to a 4 to 9 December 2013 study[154] by Research & Branding Group, 49% of all Ukrainians supported Euromaidan and 45% had the opposite opinion. It was mostly supported in Western (84%) and Central Ukraine (66%). A third (33%) of residents of South Ukraine and 13% of residents of Eastern Ukraine supported Euromaidan as well. The percentage of people who do not support the protesters was 81% in East Ukraine, 60% in South Ukraine[nb 10], in Central Ukraine 27% and in Western Ukraine 11%. Polls have shown that two-thirds of Kyivans support the ongoing protests.[157]

A poll conducted by the Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Fund and Razumkov Center, between 20 and 24 December, showed that over 50% of Ukrainians supported the Euromaidan protests, while 42% opposed it.[156]

Another Research & Branding Group survey (conducted from 23 to 27 December) showed that 45% of Ukrainians supported Euromaidan, while 50% did not.[155] 43% of those polled thought that Euromaidan’s consequences «sooner could be negative», while 31% of the respondents thought the opposite; 17% believed that Euromaidan would bring no negative consequences.[155]

An Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation survey of protesters conducted 7 and 8 December 2013 found that 92% of those who came to Kyiv from across Ukraine came on their own initiative, 6.3% was organised by a public movement, and 1.8% were organised by a party.[5][361] 70% Said they came to protest the police brutality of 30 November, and 54% to protest in support of the European Union Association Agreement signing. Among their demands, 82% wanted detained protesters freed, 80% wanted the government to resign, and 75% want president Yanukovych to resign and for snap elections.[5][362] The poll showed that 49.8% of the protesters are residents of Kyiv and 50.2% came from elsewhere in Ukraine. 38% Of the protesters are aged between 15 and 29, 49% are aged between 30 and 54, and 13% are 55 or older. A total of 57.2% of the protesters are men.[5][361]

In the eastern regions of Donetsk, Luhansk and Kharkiv, 29% of the population believe «In certain circumstances, an authoritarian regime may be preferable to a democratic one.»[363][364]

According to polls, 11% of the Ukrainian population has participated in the Euromaidan demonstrations, and another 9% has supported the demonstrators with donations.[365]

Public opinion about Association Agreement[edit]

According to a 4 to 9 December 2013 study[154] by Research & Branding Group 46% of Ukrainians supported the integration of the country into EU, and 36% into the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia. Most support for EU integration could be found in West (81%) and in Central (56%) Ukraine; 30% of residents of South Ukraine and 18% of residents of Eastern Ukraine supported the integration with EU as well. Integration with the Customs Union was supported by 61% of East Ukraine and 54% of South Ukraine and also by 22% of Central and 7% of Western Ukraine.

According to a 7 to 17 December 2013 poll by the Sociological group «RATING», 49.1% of respondents would vote for Ukraine’s accession to the European Union in a referendum, and 29.6% would vote against the motion.[366] Meanwhile, 32.5% of respondents would vote for Ukraine’s accession to the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia, and 41.9% would vote against.[366]

Political impact[edit]

US Senator John McCain addresses crowds in Kyiv, 15 December.

During the annual World Economic Forum meeting at the end of January 2014 in Davos (Switzerland) Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov received no invitations to the main events; according to the Financial Times’s Gideon Rachman because the Ukrainian government was blamed for the violence of the 2014 Hrushevskoho Street riots.[367]

A telephone call was leaked of US diplomat Victoria Nuland speaking to the US Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt about the future of the country, in which she said that Klitschko should not be in the future government, and expressed her preference for Arseniy Yatsenyuk, who became interim Prime Minister. She also casually stated «fuck the EU.»[368][369] German chancellor Angela Merkel said she deemed Nuland’s comment «completely unacceptable».[370] Commenting on the situation afterwards, State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki said that Nuland had apologized to her EU counterparts[371] while White House spokesman Jay Carney alleged that because it had been «tweeted out by the Russian government, it says something about Russia’s role».[372]

In February 2014 IBTimes reported, «if Svoboda and other far-right groups gain greater exposure through their involvement in the protests, there are fears they could gain more sympathy and support from a public grown weary of political corruption and Russian influence on Ukraine.»[373] In the following late October 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election Svoboda lost 31 seats of the 37 seats it had won in the 2012 parliamentary election.[374][375] The other main far-right party Right Sector won 1 seat (of the 450 seats in the Ukrainian parliament) in the same 2014 election.[374] From 27 February 2014 till 12 November 2014 three members of Svoboda did hold positions in Ukraine’s government.[376]

On 21 February, after negotiations between President Yanukovych and representatives of opposition with mediation of representatives of the European Union and Russia, the agreement «About settlement of political crisis in Ukraine» was signed. The agreement provided return to the constitution of 2004, that is to a parliamentary presidential government, carrying out early elections of the president until the end of 2014 and formation of «the government of national trust».[377] The Verkhovna Rada adopted the law on release of all detainees during protest actions. Divisions of «Golden eagle» and internal troops left the center of Kyiv. On 21 February, at the public announcement leaders of parliamentary opposition of conditions of the signed Agreement, representatives of «Right Sector» declared that they don’t accept the gradualness of political reforms stipulated in the document, and demanded immediate resignation of the president Yanukovych—otherwise they intended to go for storm of Presidential Administration and Verkhovna Rada.[378]

On the night of 22 February activists of Euromaidan seized the government quarter[379] left by law enforcement authorities and made a number of new demands—in particular, immediate resignation of the president Yanukovych.[380] Earlier that day, they stormed into Yanukovych’s mansion.[381]

On 23 February 2014, following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, the Rada passed a bill that would have altered the law on languages of minorities, including Russian. The bill would have made Ukrainian the sole state language at all levels.[382] However, on the next week 1 March, President Turchynov vetoed the bill.[383]

Following the Protests, Euromaidan activists mobilized toward state transformation. Activists began to, «promote reforms, drafting and advocating for legislative proposals and monitoring reform implementations.»[384] Civic Activists stepped into peculiar roles (such as the armed defense and hard security provision), which was considered unusual at the time. Since the conclusion of the Euromaidan protests Civil Society in Ukraine has become a vibrant and active political actor, however civil society does not appear to have the capacity to truly hold government to account.[citation needed]

Human rights impact[edit]

In the wake of the 2014 Euromaidan, Eduard Dolinsky, executive director of the Kyiv-based Ukrainian Jewish Committee, expressed concern over the rise of antisemitism in Ukraine in an opinion for the New York Times, citing the social acceptance of previously marginal far-right groups and the government’s policy of historical negationism with regard to antisemitic views of, and collaboration in the Holocaust by Ukrainian nationalists. Dolinsky also pointed out that Ukrainian Jews overwhelmingly supported and often participated in the Euromaidan protests.[385]

Economic impact[edit]

The Prime Minister, Mykola Azarov, asked for 20 billion Euros (US$27 billion) in loans and aid from the EU[152] The EU was willing to offer 610 million euros (838 million US) in loans,[153] however Russia was willing to offer 15 billion US in loans.[153] Russia also offered Ukraine cheaper gas prices.[153] As a condition for the loans, the EU required major changes to the regulations and laws in Ukraine. Russia did not.[152]

Moody’s Investors Service reported on 4 December 2013 «As a consequence of the severity of the protests, demand for foreign currency is likely to rise» and noted that this was another blow to Ukraine’s already poor solvency.[386] First deputy Prime Minister Serhiy Arbuzov stated on 7 December Ukraine risked a default if it failed to raise $10 billion «I asked for a loan to support us, and Europe [the EU] agreed, but a mistake was made – we failed to put it on paper.»[387]

On 3 December, Azarov warned that Ukraine might not be able to fulfill its natural gas contracts with Russia.[388] And he blamed the deal on restoring gas supplies of 18 January 2009 for this.[388]

On 5 December, Prime Minister Mykola Azarov stated that «money to finance the payment of pensions, wages, social payments, support of the operation of the housing and utility sector and medical institutions do not appear due to unrest in the streets» and he added that authorities were doing everything possible to ensure the timely financing of them.[389] Minister of Social Policy of Ukraine Natalia Korolevska stated on 2 January 2014 that these January 2014 payments would begin according to schedule.[390]

On 11 December, the second Azarov Government postponed social payments due to «the temporarily blocking of the government».[391] The same day Reuters commented (when talking about Euromaidan) «The crisis has added to the financial hardship of a country on the brink of bankruptcy» and added that (at the time) investors thought it more likely than not that Ukraine would default over the next five years (since it then cost Ukraine over US$1 million a year to insure $10 million in state debt).[392]