|

|

| Headquarters | Ostend district, Frankfurt, Germany |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50°06′32″N 8°42′12″E / 50.1089°N 8.7034°E |

| Established | 1 June 1998 (24 years ago) |

| Governing body |

|

| Key people |

|

| Currency | Euro (€) EUR (ISO 4217) |

| Reserves |

€526 billion

|

| Bank rate | 3.00% (Main refinancing operations)[1] 3.25% (Marginal lending facility)[1] |

| Interest on reserves | 2.50% (Deposit facility)[1] |

| Preceded by |

20 central banks

|

| Website | ecb.europa.eu |

Euro Monetary policy

Euro Zone inflation year/year

M3 money supply increases

Marginal Lending Facility

Main Refinancing Operations

Deposit Facility Rate

Frankfurt am Main, the European Central Bank from Alte Mainbrücke

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the prime component of the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union.[2] It is one of the world’s most important central banks.

The ECB Governing Council makes monetary policy for the Eurozone and the European Union, administers the foreign exchange reserves of EU member states, engages in foreign exchange operations, and defines the intermediate monetary objectives and key interest rate of the EU. The ECB Executive Board enforces the policies and decisions of the Governing Council, and may direct the national central banks when doing so.[3] The ECB has the exclusive right to authorise the issuance of euro banknotes. Member states can issue euro coins, but the volume must be approved by the ECB beforehand. The bank also operates the TARGET2 payments system.

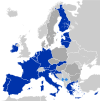

The ECB was established by the Treaty of Amsterdam in May 1999 with the purpose of guaranteeing and maintaining price stability. On 1 December 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon became effective and the bank gained the official status of an EU institution. When the ECB was created, it covered a Eurozone of eleven members. Since then, Greece joined in January 2001, Slovenia in January 2007, Cyprus and Malta in January 2008, Slovakia in January 2009, Estonia in January 2011, Latvia in January 2014, Lithuania in January 2015 and Croatia in January 2023.[4] The current President of the ECB is Christine Lagarde. Seated in Frankfurt, Germany, the bank formerly occupied the Eurotower prior to the construction of its new seat.

The ECB is directly governed by European Union law. Its capital stock, worth €11 billion, is owned by all 27 central banks of the EU member states as shareholders.[5] The initial capital allocation key was determined in 1998 on the basis of the states’ population and GDP, but the capital key has been readjusted since.[5] Shares in the ECB are not transferable and cannot be used as collateral.

History[edit]

Early years of the ECB (1998–2007)[edit]

The European Central Bank is the de facto successor of the European Monetary Institute (EMI).[6] The EMI was established at the start of the second stage of the EU’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) to handle the transitional issues of states adopting the euro and prepare for the creation of the ECB and European System of Central Banks (ESCB).[6] The EMI itself took over from the earlier European Monetary Cooperation Fund (EMCF).[4]

The ECB formally replaced the EMI on 1 June 1998 by virtue of the Treaty on European Union (TEU, Treaty of Maastricht), however it did not exercise its full powers until the introduction of the euro on 1 January 1999, signalling the third stage of EMU.[6] The bank was the final institution needed for EMU, as outlined by the EMU reports of Pierre Werner and President Jacques Delors. It was established on 1 June 1998 The first President of the Bank was Wim Duisenberg, the former president of the Dutch central bank and the European Monetary Institute.[7] While Duisenberg had been the head of the EMI (taking over from Alexandre Lamfalussy of Belgium) just before the ECB came into existence,[7] the French government wanted Jean-Claude Trichet, former head of the French central bank, to be the ECB’s first president.[7] The French argued that since the ECB was to be located in Germany, its president should be French. This was opposed by the German, Dutch and Belgian governments who saw Duisenberg as a guarantor of a strong euro.[8] Tensions were abated by a gentleman’s agreement in which Duisenberg would stand down before the end of his mandate, to be replaced by Trichet.[9]

Trichet replaced Duisenberg as president in November 2003. Until 2007, the ECB had very successfully managed to maintain inflation close but below 2%.

The ECB’s response to the financial crises (2008–2014)[edit]

The European Central Bank underwent through a deep internal transformation as it faced the global financial crisis and the Eurozone debt crisis.

|

This section needs expansion with: here we need some headline facts on the early response to the Lehman shock: interest cuts, repos & swap lines, securitized bond purchases…. You can help by adding to it. (April 2021) |

Early response to the Eurozone debt crisis[edit]

The so-called European debt crisis began after Greece’s new elected government uncovered the real level indebtedness and budget deficit and warned EU institutions of the imminent danger of a Greek sovereign default.

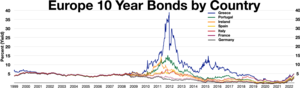

Foreseeing a possible sovereign default in the eurozone, the general public, international and European institutions, and the financial community reassessed the economic situation and creditworthiness of some Eurozone member states, in particular Southern countries. Consequently, sovereign bonds yields of several Eurozone countries started to rise sharply. This provoked a self-fulfilling panic on financial markets: the more Greek bonds yields rose, the more likely a default became possible, the more bond yields increased in turn.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

This panic was also aggravated because of the inability of the ECB to react and intervene on sovereign bonds markets for two reasons. First, because the ECB’s legal framework normally forbids the purchase of sovereign bonds (Article 123. TFEU),[17] This prevented the ECB from implementing quantitative easing like the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England did as soon as 2008, which played an important role in stabilizing markets.

Secondly, a decision by the ECB made in 2005 introduced a minimum credit rating (BBB-) for all Eurozone sovereign bonds to be eligible as collateral to the ECB’s open market operations. This meant that if a private rating agencies were to downgrade a sovereign bond below that threshold, many banks would suddenly become illiquid because they would lose access to ECB refinancing operations. According to former member of the governing council of the ECB Athanasios Orphanides, this change in the ECB’s collateral framework «planted the seed» of the euro crisis.[18]

Faced with those regulatory constraints, the ECB led by Jean-Claude Trichet in 2010 was reluctant to intervene to calm down financial markets. Up until 6 May 2010, Trichet formally denied at several press conferences[19] the possibility of the ECB to embark into sovereign bonds purchases, even though Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy faced waves of credit rating downgrades and increasing interest rate spreads.

ECB’s market interventions (2010–2011)[edit]

ECB Securities Markets Programme (SMP) covering bond purchases since May 2010

In a remarkable u-turn, the ECB announced on 10 May 2010,[20] the launch of a «Securities Market Programme» (SMP) which involved the discretionary purchase of sovereign bonds in secondary markets. Extraordinarily, the decision was taken by the Governing Council during a teleconference call only three days after the ECB’s usual meeting of 6 May (when Trichet still denied the possibility of purchasing sovereign bonds). The ECB justified this decision by the necessity to «address severe tensions in financial markets.» The decision also coincided with the EU leaders decision of 10 May to establish the European Financial Stabilisation mechanism, which would serve as a crisis fighting fund to safeguard the euro area from future sovereign debt crisis.[21]

The ECB’s bond buying focused primarily on Spanish and Italian debt.[22] They were intended to dampen international speculation against those countries, and thus avoid a contagion of the Greek crisis towards other Eurozone countries. The assumption is that speculative activity will decrease over time and the value of the assets increase.

Although SMP did involve an injection of new money into financial markets, all ECB injections were «sterilized» through weekly liquidity absorption. So the operation was neutral for the overall money supply.[23][citation needed][24]

In September 2011, ECB’s Board member Jürgen Stark, resigned in protest against the «Securities Market Programme» which involved the purchase of sovereign bonds from Southern member states, a move that he considered as equivalent to monetary financing, which is prohibited by the EU Treaty. The Financial Times Deutschland referred to this episode as «the end of the ECB as we know it», referring to its hitherto perceived «hawkish» stance on inflation and its historical Deutsche Bundesbank influence.[25]

As of 18 June 2012, the ECB in total had spent €212.1bn (equal to 2.2% of the Eurozone GDP) for bond purchases covering outright debt, as part of the Securities Markets Programme.[26] Controversially, the ECB made substantial profits out of SMP, which were largely redistributed to Eurozone countries.[27][28] In 2013, the Eurogroup decided to refund those profits to Greece, however the payments were suspended over 2014 until 2017 over the conflict between Yanis Varoufakis and ministers of the Eurogroup. In 2018, profits refunds were reinstalled by the Eurogroup. However, several NGOs complained that a substantial part of the ECB profits would never be refunded to Greece.[29]

Role in the Troika (2010–2015)[edit]

The ECB played a controversial role in the «Troika» by rejecting all forms of debt restructuring of public and private debts,[30] forcing governments to adopt bailout programmes and structural reforms through secret letters to Italian, Spanish, Greek and Irish governments. It has further been accused of interfering in the Greek referendum of July 2015 by constraining liquidity to Greek commercial banks.[31]

|

This section needs expansion with: explanations on the role of ECB for Greece, Italy, Spain, Cyprus, Portugal.. You can help by adding to it. (April 2021) |

In November 2010, it became clear that Ireland would not be able to afford to bail out its failing banks, and Anglo Irish Bank in particular which needed around 30 billion euros, a sum the government obviously could not borrow from financial markets when its bond yields were soaring to comparable levels with the Greek bonds. Instead, the government issued a 31bn EUR «promissory note» (an IOU) to Anglo – which it had nationalized. In turn, the bank supplied the promissory note as collateral to the Central Bank of Ireland, so it could access emergency liquidity assistance (ELA). This way, Anglo was able to repay its bondholders. The operation became very controversial, as it basically shifted Anglo’s private debts onto the government’s balance sheet.

It became clear later that the ECB played a key role in making sure the Irish government did not let Anglo default on its debts, in order to avoid a financial instability risks. On 15 October and 6 November 2010, the ECB President Jean-Claude Trichet sent two secret letters[32] to the Irish finance Minister which essentially informed the Irish government of the possible suspension of ELA’s credit lines, unless the government requested a financial assistance programme to the Eurogroup under condition of further reforms and fiscal consolidation.

Over 2012 and 2013, the ECB repeatedly insisted that the promissory note should be repaid in full, and refused the Government’s proposal to swap the notes with a long-term (and less costly) bond until February 2013.[33] In addition, the ECB insisted that no debt restructuring (or bail-in) should be applied to the nationalized banks’ bondholders, a measure which could have saved Ireland 8 billion euros.[34]

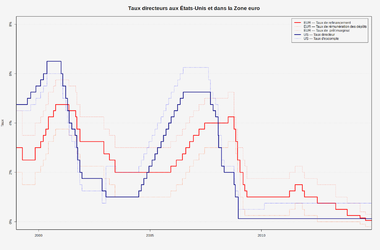

In April 2011, the ECB raised interest rates for the first time since 2008 from 1% to 1.25%,[35] with a further increase to 1.50% in July 2011.[36] However, in 2012–2013 the ECB sharply lowered interest rates to encourage economic growth, reaching the historically low 0.25% in November 2013.[1] Soon after the rates were cut to 0.15%, then on 4 September 2014 the central bank reduced the rates by two thirds from 0.15% to 0.05%.[37] Recently, the interest rates were further reduced reaching 0.00%, the lowest rates on record.[1]

In a report adopted on 13 March 2014, the European Parliament criticized the «potential conflict of interest between the current role of the ECB in the Troika as ‘technical advisor’ and its position as creditor of the four Member States, as well as its mandate under the Treaty». The report was led by Austrian right-wing MEP Othmar Karas and French Socialist MEP Liem Hoang Ngoc.

The ECB’s response under Mario Draghi (2012–2015)[edit]

Current accounts at the ECB

On 1 November 2011, Mario Draghi replaced Jean-Claude Trichet as President of the ECB.[38] This change in leadership also marks the start of a new era under which the ECB will become more and more interventionist and eventually ended the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis.

Draghi’s presidency started with the impressive launch of a new round of 1% interest loans with a term of three years (36 months) – the Long-term Refinancing operations (LTRO). Under this programme, 523 Banks tapped as much as €489.2 bn (US$640 bn). Observers were surprised by the volume of the loans made when it was implemented.[39][40][41] By far biggest amount of €325bn was tapped by banks in Greece, Ireland, Italy and Spain.[42] Although those LTROs loans did not directly benefit EU governments, it effectively allowed banks to do a carry trade, by lending off the LTROs loans to governments with an interest margin. The operation also facilitated the rollover of €200bn of maturing bank debts[43] in the first three months of 2012.

«Whatever it takes» (26 July 2012)[edit]

Facing renewed fears about sovereigns in the eurozone continued Mario Draghi made a decisive speech in London, by declaring that the ECB «…is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the Euro. And believe me, it will be enough.»[44] In light of slow political progress on solving the eurozone crisis, Draghi’s statement has been seen as a key turning point in the eurozone crisis, as it was immediately welcomed by European leaders, and led to a steady decline in bond yields for eurozone countries, in particular Spain, Italy and France.[45][46]

Following up on Draghi’s speech, on 6 September 2012 the ECB announced the Outright Monetary Transactions programme (OMT).[47] Unlike the previous SMP programme, OMT has no ex-ante time or size limit.[48] However, the activation of the purchases remains conditioned to the adherence by the benefitting country to an adjustment programme to the ESM. The program was adopted with near unanimity, the Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann being the sole member of the ECB’s Governing Council to vote against.[49]

Even if OMT was never actually implemented until today, it made the «Whatever it takes» pledge credible and significantly contributed in stabilizing financial markets and ended the sovereign debt crisis. According to various sources, the OMT programme and «whatever it takes» speeches were made possible because EU leaders previously agreed to build the banking union.[50]

Low inflation and quantitative easing (2015–2019)[edit]

In November 2014, the bank moved into its new premises, while the Eurotower building was dedicated to host the newly established supervisory activities of the ECB under the Single Supervisory Mechanism.[51]

Although the sovereign debt crisis was almost solved by 2014, the ECB started to face a repeated decline[52] in the Eurozone inflation rate, indicating that the economy was going towards a deflation. Responding to this threat, the ECB announced on 4 September 2014 the launch of two bond buying purchases programmes: the Covered Bond Purchasing Programme (CBPP3) and Asset-Backed Securities Programme (ABSPP).[53]

On 22 January 2015, the ECB announced an extension of those programmes within a full-fledge «quantitative easing» programme which also included sovereign bonds, to the tune of 60 billion euros per month up until at least September 2016. The programme was started on 9 March 2015.[54]

On 8 June 2016, the ECB added corporate bonds to its asset purchases portfolio with the launch of the corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP).[55] Under this programme, it conducted net purchase of corporate bonds until January 2019 to reach about €177 billion. While the programme was halted for 11 months in January 2019, the ECB restarted net purchases in November 2019.[56]

As of 2021, the size of the ECB’s quantitative easing programme had reached 2947 billion euros.[57]

Christine Lagarde’s era (2019– )[edit]

In July 2019, EU leaders nominated Christine Lagarde to replace Mario Draghi as ECB President. Lagarde resigned from her position as managing director of the International Monetary Fund in July 2019[58] and formally took over the ECB’s presidency on 1 November 2019.[59]

Lagarde immediately signaled a change of style in the ECB’s leadership. She embarked the ECB’s into a strategic review of the ECB’s monetary policy strategy, an exercise the ECB had not done for 17 years. As part of this exercise, Lagarde committed the ECB to look into how monetary policy could contribute to address climate change,[60] and promised that «no stone would be left unturned.» The ECB president also adopted a change of communication style, in particular in her use of social media to promote gender equality,[61] and by opening dialogue with civil society stakeholders.[62][63]

Response to the COVID-19 crisis[edit]

However, Lagarde’s ambitions were quickly slowed down with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis.

In March 2020, the ECB responded quickly and boldly by launching a package of measures including a new asset purchase programme: the €1,350 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) which aimed to lower borrowing costs and increase lending in the euro area.[64] The PEPP was extended to cover an additional €500 billion in December 2020.[64] The ECB also re-launched more TLTRO loans to banks at historically low levels and record-high take-up (€1.3 trillion in June 2020).[65] Lending by banks to SMEs was also facilitated by collateral easing measures, and other supervisory relaxations. The ECB also reactivated currency swap lines and enhanced existing swap lines with central banks across the globe.[66]

Strategy Review[edit]

As a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis, the ECB extended the duration of the strategy review until September 2021. On 13 July 2021, the ECB presented the outcomes of the strategy review, with the main following announcements:

- The ECB announced a new inflation target at 2% instead of its «close but below two percent» inflation target. The ECB also made it clear it could overshoot its target under certain circumstances.[67]

- The ECB announced it would try to incorporate the cost of housing (imputed rents) into its inflation measurement

- The ECB announced an action plan on climate change[68]

The ECB also said it would carry out another strategy review in 2025.

Mandate and inflation target[edit]

Unlike many other central banks, the ECB does not have a dual mandate where it has to pursue two equally important objectives such as price stability and full employment (like the US Federal Reserve System). The ECB has only one primary objective – price stability – subject to which it may pursue secondary objectives.

Primary mandate[edit]

The primary objective of the European Central Bank, set out in Article 127(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, is to maintain price stability within the Eurozone.[69] However the EU Treaties do not specify exactly how the ECB should pursue this objective. The European Central Bank has ample discretion over the way it pursues its price stability objective, as it can self-decide on the inflation target, and may also influence the way inflation is being measured.

The Governing Council in October 1998[70] defined price stability as inflation of under 2%, «a year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area of below 2%» and added that price stability «was to be maintained over the medium term».[71] In May 2003, following a thorough review of the ECB’s monetary policy strategy, the Governing Council clarified that «in the pursuit of price stability, it aims to maintain inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term».[70]

Since 2016, the European Central Bank’s president has further adjusted its communication, by introducing the notion of «symmetry» in its definition of its target,[72] thus making it clear that the ECB should respond both to inflationary pressure to deflationary pressures. As Draghi once said «symmetry meant not only that we would not accept persistently low inflation, but also that there was no cap on inflation at 2%.»[73]

On 8 July 2021, as a result of the strategic review led by the new president Christine Lagarde, the ECB officially abandoned the «below but close to two percent» definition and adopted instead a 2% symmetric target.[67][74]

Secondary mandate[edit]

Without prejudice to the objective of price stability, the Treaty (127 TFEU) also provides room for the ECB to pursue other objectives:

Without prejudice to the objective of price stability, the ESCB shall support the general economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union as laid down in Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union.[75]

This legal provision is often considered to provide a «secondary mandate» to the ECB, and offers ample justifications for the ECB to also prioritize other considerations such as full employment or environmental protection,[76] which are mentioned in the Article 3 of the Treaty on the European Union. At the same time, economists and commentators are often divided on whether and how the ECB should pursue those secondary objectives, in particular the environmental impact.[77] ECB official have also frequently pointed out the possible contradictions between those secondary objectives.[78] To better guide the ECB’s action on its secondary objectives, it has been suggested that closer consultation with the European Parliament would be warranted.[79][80][81]

Tasks[edit]

To carry out its main mission, the ECB’s tasks include:

- Defining and implementing monetary policy[82]

- Managing foreign exchange operations

- Maintaining the payment system to promote smooth operation of the financial market infrastructure under the TARGET2 payments system[83] and being currently developed technical platform for settlement of securities in Europe (TARGET2 Securities).

- Consultative role: by law, the ECB’s opinion is required on any national or EU legislation that falls within the ECB’s competence.

- Collection and establishment of statistics

- International cooperation

- Issuing banknotes: the ECB holds the exclusive right to authorise the issuance of euro banknotes. Member states can issue euro coins, but the amount must be authorised by the ECB beforehand (upon the introduction of the euro, the ECB also had exclusive right to issue coins).[83]

- Financial stability and prudential policy

- Banking supervision: since 2013, the ECB has been put in charge of supervising systemically relevant banks.

Monetary policy tools[edit]

The principal monetary policy tool of the European central bank is collateralised borrowing or repo agreements.[84] These tools are also used by the United States Federal Reserve Bank, but the Fed does more direct purchasing of financial assets than its European counterpart.[85] The collateral used by the ECB is typically high quality public and private sector debt.[84]

All lending to credit institutions must be collateralised as required by Article 18 of the Statute of the ESCB.[86]

The criteria for determining «high quality» for public debt have been preconditions for membership in the European Union: total debt must not be too large in relation to gross domestic product, for example, and deficits in any given year must not become too large.[23] Though these criteria are fairly simple, a number of accounting techniques may hide the underlying reality of fiscal solvency—or the lack of same.[23]

| Type of instrument | Name of instrument | Maintenance period | Rate | Volume (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standing facilities

(rate corridor) |

Marginal lending facility | Overnight | 0.25% | |

| Deposit facility | Overnight | -0.5% | ||

| Refinancing operations

(collateralized repos) |

Main refinancing operations (MROs) | 7 days | 0% | |

| Long-term refinancing operations (LTROs) | 3 months up to 3 years | Average MRO rate | ||

| Targeted-Long Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs) | Up to 4 years | -0.5% or less | ||

| Pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing operations (PELTROs) | 8 to 16 months | -0.25% | ||

| Asset purchases | Covered bonds purchase programme (CBPP) | n/a | n/a | 289,424 |

| Securities markets programme (SMP) | n/a | n/a | 24,023 | |

| Asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP) | n/a | n/a | 28,716 | |

| Public sector purchase programme (PSPP) | n/a | n/a | 2,379,053 | |

| Corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP) | n/a | n/a | 266,060 | |

| Pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) | n/a | n/a | 943,647 | |

| Reserve requirements | Minimum reserves | 0% | 146,471 |

Difference with US Federal Reserve[edit]

In the United States Federal Reserve Bank, the Federal Reserve buys assets: typically, bonds issued by the Federal government.[87] There is no limit on the bonds that it can buy and one of the tools at its disposal in a financial crisis is to take such extraordinary measures as the purchase of large amounts of assets such as commercial paper.[87] The purpose of such operations is to ensure that adequate liquidity is available for functioning of the financial system.[87]

The Eurosystem, on the other hand, uses collateralized lending as a default instrument. There are about 1,500 eligible banks which may bid for short-term repo contracts.[88] The difference is that banks in effect borrow cash from the ECB and must pay it back; the short durations allow interest rates to be adjusted continually. When the repo notes come due the participating banks bid again. An increase in the quantity of notes offered at auction allows an increase in liquidity in the economy. A decrease has the contrary effect. The contracts are carried on the asset side of the European Central Bank’s balance sheet and the resulting deposits in member banks are carried as a liability. In layman terms, the liability of the central bank is money, and an increase in deposits in member banks, carried as a liability by the central bank, means that more money has been put into the economy.[a]

To qualify for participation in the auctions, banks must be able to offer proof of appropriate collateral in the form of loans to other entities. These can be the public debt of member states, but a fairly wide range of private banking securities are also accepted.[89] The fairly stringent membership requirements for the European Union, especially with regard to sovereign debt as a percentage of each member state’s gross domestic product, are designed to ensure that assets offered to the bank as collateral are, at least in theory, all equally good, and all equally protected from the risk of inflation.[89]

Organization[edit]

The ECB has four decision-making bodies, that take all the decisions with the objective of fulfilling the ECB’s mandate:

- the Executive Board,

- the Governing Council,

- the General Council, and

- the Supervisory Board.

Decision-making bodies[edit]

Executive Board[edit]

The Executive Board is responsible for the implementation of monetary policy (defined by the Governing Council) and the day-to-day running of the bank.[90] It can issue decisions to national central banks and may also exercise powers delegated to it by the Governing Council.[90] Executive Board members are assigned a portfolio of responsibilities by the President of the ECB.[91] The executive board normally meets every Tuesday.

It is composed of the President of the Bank (currently Christine Lagarde), the vice-president (currently Luis de Guindos) and four other members.[90] They are all appointed by the European Council for non-renewable terms of eight years.[90] Member of the executive board of the ECB are appointed «from among persons of recognised standing and professional experience in monetary or banking matters by common accord of the governments of the Member States at the level of Heads of State or Government, on a recommendation from the Council, after it has consulted the European Parliament and the Governing Council of the ECB».[92]

José Manuel González-Páramo, a Spanish member of the executive board since June 2004, was due to leave the board in early June 2012, but no replacement had been named as of late May.[93] The Spanish had nominated Barcelona-born Antonio Sáinz de Vicuña – an ECB veteran who heads its legal department – as González-Páramo’s replacement as early as January 2012, but alternatives from Luxembourg, Finland, and Slovenia were put forward and no decision made by May.[94] After a long political battle and delays due to the European Parliament’s protest over the lack of gender balance at the ECB,[95] Luxembourg’s Yves Mersch was appointed as González-Páramo’s replacement.[96]

In December 2020, Frank Elderson succeeded to Yves Mersch at the ECB’s board.[97][98]

Governing Council[edit]

The Governing Council is the main decision-making body of the Eurosystem.[99] It comprises the members of the executive board (six in total) and the governors of the National Central Banks of the euro area countries (20 as of 2023).

According to Article 284 of the TFEU, the President of the European Council and a representative from the European Commission may attend the meetings as observers, but they lack voting rights.

Since January 2015, the ECB has published on its website a summary of the Governing Council deliberations («accounts»).[100] These publications came as a partial response to recurring criticism against the ECB’s opacity.[101] However, in contrast to other central banks, the ECB still does not disclose individual voting records of the governors seating in its council.

| Name | Role | Terms of office | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Board | President | 1 November 2019 | 31 October 2027 | |

| Vice President | 1 June 2018 | 31 May 2026 | ||

| Member of the Executive Board | 1 January 2020 | 31 December 2027 | ||

| Member of the Executive Board Chief Economist |

1 June 2019 | 31 May 2027 | ||

| Member of the Executive Board

Vice-chair of the Supervisory board |

15 December 2020 | 14 December 2028 | ||

| Member of the Executive Board | 1 January 2020 | 31 December 2027 | ||

| National Governors | 11 June 2018 | 10 June 2024 | ||

| 1 January 2022 | ||||

| 2 January 2019 | January 2024 | |||

| June 2020 | June 2026 | |||

| 8 July 2012 | 13 July 2024 | |||

| January 2013 | January 2026 | |||

| 1 November 2015 | November 2027 | |||

| 1 September 2019 | 31 August 2025 | |||

| 1 June 2019 | 1 June 2025 | |||

| 7 April 2021 | 6 April 2026 | |||

| 12 July 2018 | 12 July 2025 | |||

| July 2020 | June 2025 | |||

| 1 January 2021 | 30 December 2025 | |||

| 1 January 2019 | 31 December 2024 | |||

| June 2019 | June 2026 | |||

| 21 December 2019 | 21 December 2025 | |||

| 1 July 2011 | May 2025 | |||

| 11 April 2019 | April 2024 | |||

| 1 September 2019 | 1 September 2026 | |||

| 1 November 2011 | November 2023 |

General Council[edit]

The General Council is a body dealing with transitional issues of euro adoption, for example, fixing the exchange rates of currencies being replaced by the euro (continuing the tasks of the former EMI).[90] It will continue to exist until all EU member states adopt the euro, at which point it will be dissolved.[90] It is composed of the President and vice-president together with the governors of all of the EU’s national central banks.[103][104]

Supervisory Board[edit]

The supervisory board meets twice a month to discuss, plan and carry out the ECB’s supervisory tasks.[105] It proposes draft decisions to the Governing Council under the non-objection procedure. It is composed of Chair (appointed for a non-renewable term of five years), Vice-chair (chosen from among the members of the ECB’s executive board) four ECB representatives and representatives of national supervisors. If the national supervisory authority designated by a Member State is not a national central bank (NCB), the representative of the competent authority can be accompanied by a representative from their NCB. In such cases, the representatives are together considered as one member for the purposes of the voting procedure.[105]

It also includes the Steering Committee, which supports the activities of the supervisory board and prepares the Board’s meetings. It is composed by the chair of the supervisory board, Vice-chair of the supervisory board, one ECB representative and five representatives of national supervisors. The five representatives of national supervisors are appointed by the supervisory board for one year based on a rotation system that ensures a fair representation of countries.[105]

| Composition of the supervisory board of the ECB[106] | |

| Name | Role |

| Chair | |

| Vice-chair | |

| ECB Representative | |

| ECB Representative | |

| ECB Representative | |

| ECB Representative |

Capital subscription[edit]

The ECB is governed by European law directly, but its set-up resembles that of a corporation in the sense that the ECB has shareholders and stock capital. Its initial capital was supposed to be €5 billion[107] and the initial capital allocation key was determined in 1998 on the basis of the member states’ populations and GDP,[5][108] but the key is adjustable.[109] The euro area NCBs were required to pay their respective subscriptions to the ECB’s capital in full. The NCBs of the non-participating countries have had to pay 7% of their respective subscriptions to the ECB’s capital as a contribution to the operational costs of the ECB. As a result, the ECB was endowed with an initial capital of just under €4 billion.[citation needed] The capital is held by the national central banks of the member states as shareholders. Shares in the ECB are not transferable and cannot be used as collateral.[110] The NCBs are the sole subscribers to and holders of the capital of the ECB.

Today, ECB capital is about €11 billion, which is held by the national central banks of the member states as shareholders.[5] The NCBs’ shares in this capital are calculated using a capital key which reflects the respective member’s share in the total population and gross domestic product of the EU. The ECB adjusts the shares every five years and whenever the number of contributing NCBs changes. The adjustment is made on the basis of data provided by the European Commission.

All national central banks (NCBs) that own a share of the ECB capital stock as of 1 February 2020 are listed below. Non-Euro area NCBs are required to pay up only a very small percentage of their subscribed capital, which accounts for the different magnitudes of Euro area and Non-Euro area total paid-up capital.[5]

| NCB | Capital Key (%) | Paid-up Capital (€) |

|---|---|---|

| National Bank of Belgium | 2.9630 | 276,290,916.71 |

| Croatian National Bank | 0.6595 | 2,677,159.56 |

| Deutsche Bundesbank | 21.4394 | 1,999,160,134.91 |

| Bank of Estonia | 0.2291 | 21,362,892.01 |

| Central Bank of Ireland | 1.3772 | 128,419,794.29 |

| Bank of Greece | 2.0117 | 187,585,027.73 |

| Bank of Spain | 9.6981 | 904,318,913.05 |

| Bank of France | 16.6108 | 1,548,907,579.93 |

| Bank of Italy | 13.8165 | 1,288,347,435.28 |

| Central Bank of Cyprus | 0.1750 | 16,318,228.29 |

| Bank of Latvia | 0.3169 | 29,549,980.26 |

| Bank of Lithuania | 0.4707 | 43,891,371.75 |

| Central Bank of Luxembourg | 0.2679 | 24,980,876.34 |

| Central Bank of Malta | 0.0853 | 7,953,970.70 |

| De Nederlandsche Bank | 4.7662 | 444,433,941.0 |

| Oesterreichische Nationalbank | 2.3804 | 221,965,203.55 |

| Banco de Portugal | 1.9035 | 177,495,700.29 |

| Bank of Slovenia | 0.3916 | 36,515,532.56 |

| National Bank of Slovakia | 0.9314 | 86,850,273.32 |

| Bank of Finland | 1.4939 | 136,005,388.82 |

| Total | 81.3286 | 7,583,649,493.38 |

| Non-Euro area: | ||

| Bulgarian National Bank | 0.9832 | 3,991,180.11 |

| Czech National Bank | 1.8794 | 7,629,194.36 |

| Danmarks Nationalbank | 1.7591 | 7,140,851.23 |

| Hungarian National Bank | 1.5488 | 6,287,164.11 |

| National Bank of Poland | 6.0335 | 24,492,255.06 |

| National Bank of Romania | 2.8289 | 11,483,573.44 |

| Sveriges Riksbank | 2.9790 | 12,092,886.02 |

| Total | 18.6714 | 75,794,263.89 |

Reserves[edit]

In addition to capital subscriptions, the NCBs of the member states participating in the euro area provided the ECB with foreign reserve assets equivalent to around €40 billion. The contributions of each NCB is in proportion to its share in the ECB’s subscribed capital, while in return each NCB is credited by the ECB with a claim in euro equivalent to its contribution. 15% of the contributions was made in gold, and the remaining 85% in US dollars and UK pound Sterlings.[citation needed]

Languages[edit]

The internal working language of the ECB is English, and press conferences are held in English. External communications are handled flexibly: English is preferred (though not exclusively) for communication within the ESCB (i.e. with other central banks) and with financial markets; communication with other national bodies and with EU citizens is normally in their respective language, but the ECB website is predominantly English; official documents such as the Annual Report are in the official languages of the EU (generally English, German and French).[111][112]

In 2022, the ECB publishes for the first time details on the nationality of its staff,[113] revealing an over-representation of Germans and Italians along the ECB employees, including in management positions.

Independence[edit]

The European Central Bank (and by extension, the Eurosystem) is often considered as the «most independent central bank in the world».[114][115][116][117] In general terms, this means that the Eurosystem tasks and policies can be discussed, designed, decided and implemented in full autonomy, without pressure or need for instructions from any external body. The main justification for the ECB’s independence is that such an institutional setup assists the maintenance of price stability.[118][119]

In practice, the ECB’s independence is pinned by four key principles:[120]

- Operational and legal independence: the ECB has all required competences to achieve its price stability mandate[citation needed] and thereby can steer monetary policy in full autonomy and by means of high level of discretion. The ECB’s governing council deliberates with a high degree of secrecy, since individual voting records are not disclosed to the public (leading to suspicions that Governing Council members are voting along national lines.[121][122]) In addition to monetary policy decisions, the ECB has the right to issue legally binding regulations, within its competence and if the conditions laid down in Union law are fulfilled, it can sanction non-compliant actors if they violate legal requirements laid down in directly applicable Union regulations. The ECB’s own legal personality also allows the ECB to enter into international legal agreements independently from other EU institutions, and be party of legal proceedings. Finally, the ECB can organise its internal structure as it sees fit.

- Personal independence: the mandate of ECB board members is purposefully very long (8 years) and Governors of national central banks have a minimum renewable term of office of five years.[118] In addition, ECB board members and are vastly immune from judicial proceedings.[123] Indeed, removals from office can only be decided by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), under the request of the ECB’s Governing Council or the executive board (i.e. the ECB itself). Such decision is only possible in the event of incapacity or serious misconduct. National governors of the Eurosystem’ national central banks can be dismissed under national law (with possibility to appeal) in case they can no longer fulfil their functions or are guilty of serious misconduct.

- Financial independence: the ECB is the only body within the EU whose statute guarantees budgetary independence through its own resources and income. The ECB uses its own profits generated by its monetary policy operations and cannot be technically insolvent. The ECB’s financial independence reinforces its political independence. Because the ECB does not require external financing and symmetrically is prohibited from direct monetary financing of public institutions, this shields it from potential pressure from public authorities.

- Political independence: The Community institutions and bodies and the governments of the member states may not seek to influence the members of the decision-making bodies of the ECB or of the NCBs in the performance of their tasks. Symmetrically, EU institutions and national governments are bound by the treaties to respect the ECB’s independence. It is the latter which is the subject of much debate.

Democratic accountability[edit]

In return to its high degree of independence and discretion, the ECB is accountable to the European Parliament (and to a lesser extent to the European Court of Auditors, the European Ombudsman and the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU)). Although no interinstitutional agreement exists between the European Parliament and the ECB to regulate the ECB’s accountability framework, it has been inspired by a resolution of the European Parliament adopted in 1998[124] which was then informally agreed with the ECB and incorporated into the Parliament’s rule of procedure.[125] In 2021, the European Parliament’s ECON Committee requested to start negotiations with the ECB in order to formalize and improve these accountability arrangements.

The accountability framework involves five main mechanisms:[126]

- Annual report: the ECB is bound to publish reports on its activities and has to address its annual report to the European Parliament, the European Commission, the Council of the European Union and the European Council .[127] In return, the European Parliament evaluates the past activities to the ECB via its annual report on the European Central Bank (which is essentially a non legally-binding list of resolutions).

- Quarterly hearings: the Economic and Monetary affairs Committee of the European Parliament organises a hearing (the «Monetary Dialogue») with the ECB every quarter,[128] allowing members of parliament to address oral questions to the ECB president.

- Parliamentary questions: all Members of the European Parliament have the right to address written questions[129] to the ECB president. The ECB president provides a written answer in about six weeks.

- Appointments: The European Parliament is consulted during the appointment process of executive board members of the ECB.[130]

- Legal proceedings: the ECB’s own legal personality allows civil society or public institutions to file complaints against the ECB to the Court of Justice of the EU.

In 2013, an interinstitutional agreement was reached between the ECB and the European Parliament in the context of the establishment of the ECB’s Banking Supervision. This agreement sets broader powers to the European Parliament than the established practice on the monetary policy side of the ECB’s activities. For example, under the agreement, the Parliament can veto the appointment of the chair and vice-chair of the ECB’s supervisory board, and may approve removals if requested by the ECB.[131]

Transparency[edit]

In addition to its independence, the ECB is subject to limited transparency obligations in contrast to EU Institutions standards and other major central banks. Indeed, as pointed out by Transparency International, «The Treaties establish transparency and openness as principles of the EU and its institutions. They do, however, grant the ECB a partial exemption from these principles. According to Art. 15(3) TFEU, the ECB is bound by the EU’s transparency principles «only when exercising [its] administrative tasks» (the exemption – which leaves the term «administrative tasks» undefined – equally applies to the Court of Justice of the European Union and to the European Investment Bank).»[132]

In practice, there are several concrete examples where the ECB is less transparent than other institutions:

- Voting secrecy: while other central banks publish the voting record of its decision makers, the ECB’s Governing Council decisions are made in full discretion. Since 2014, the ECB has published «accounts» of its monetary policy meetings,[133] but those remain rather vague and do not include individual votes.

- Access to documents: The obligation for EU bodies to make documents freely accessible after a 30-year embargo applies to the ECB. However, under the ECB’s Rules of Procedure the Governing Council may decide to keep individual documents classified beyond the 30-year period.

- Disclosure of securities: The ECB is less transparent than the Fed when it comes to disclosing the list of securities being held in its balance sheet under monetary policy operations such as QE.[134]

Location[edit]

The new ECB headquarters, which opened in 2014.

The bank is based in Ostend (East End), Frankfurt am Main. The city is the largest financial centre in the Eurozone and the bank’s location in it is fixed by the Amsterdam Treaty.[135] The bank moved to a new purpose-built headquarters in 2014, designed by a Vienna-based architectural office, Coop Himmelbau.[136] The building is approximately 180 metres (591 ft) tall and is to be accompanied by other secondary buildings on a landscaped site on the site of the former wholesale market in the eastern part of Frankfurt am Main. The main construction on a 120,000 m2 total site area began in October 2008,[136][137] and it was expected that the building would become an architectural symbol for Europe. While it was designed to accommodate double the number of staff who operated in the former Eurotower,[138] that building has been retained by the ECB, owing to more space being required since it took responsibility for banking supervision.[139]

Debates surrounding the ECB[edit]

Debates on ECB independence[edit]

The debate on the independence of the ECB finds its origins in the preparatory stages of the construction of the EMU. The German government agreed to go ahead if certain crucial guarantees were respected, such as a European Central Bank independent of national governments and shielded from political pressure along the lines of the German central bank. The French government, for its part, feared that this independence would mean that politicians would no longer have any room for manoeuvre in the process. A compromise was then reached by establishing a regular dialogue between the ECB and the Council of Finance Ministers of the euro area, the Eurogroupe.

Arguments in favor of independence[edit]

There is strong consensus among economists on the value of central bank independence from politics.[140][141] The rationale behind are both empirical and theoretical. On the theoretical side, it’s believed that time inconsistency suggest the existence of political business cycles where elected officials might take advantage of policy surprises to secure reelection. The politician up to election will therefore be incentivized to introduce expansionary monetary policies, reducing unemployment in the short run. These effects will be most likely temporary. By contrast, in the long run it will increase inflation, with unemployment returning to the natural rate negating the positive effect. Furthermore, the credibility of the central bank will deteriorate, making it more difficult to answer the market.[142][143][144] Additionally, empirical work has been done that defined and measured central bank independence (CBI), looking at the relationship of CBI with inflation.[145]

The arguments against too much independence[edit]

An independence that would be the source of a democratic deficit.[edit]

Demystify the independence of central bankers: According to Christopher Adolph (2009),[146] the alleged neutrality of central bankers is only a legal façade and not an indisputable fact . To achieve this, the author analyses the professional careers of central bankers and mirrors them with their respective monetary decision-making. To explain the results of his analysis, he utilizes he uses the «principal-agent» theory.[147] To explain that in order to create a new entity, one needs a delegator or principal (in this case the heads of state or government of the euro area) and a delegate or agent (in this case the ECB). In his illustration, he describes the financial community as a «shadow principale«[146] which influences the choice of central bankers thus indicating that the central banks indeed act as interfaces between the financial world and the States. It is therefore not surprising, still according to the author, to regain their influence and preferences in the appointment of central bankers, presumed conservative, neutral and impartial according to the model of the Independent Central Bank (ICB),[148] which eliminates this famous «temporal inconsistency«.[146] Central bankers had a professional life before joining the central bank and their careers will most likely continue after their tenure. They are ultimately human beings. Therefore, for the author, central bankers have interests of their own, based on their past careers and their expectations after joining the ECB, and try to send messages to their future potential employers.

The crisis: an opportunity to impose its will and extend its powers:

– Its participation in the troika : Thanks to its three factors which explains its independence, the ECB took advantage of this crisis to implement, through its participation in the troika, the famous structural reforms in the Member States aimed at making, more flexible the various markets, particularly the labour market, which are still considered too rigid under the ordoliberal concept.[149]

— Macro-prudential supervision : At the same time, taking advantage of the reform of the financial supervision system, the Frankfurt Bank has acquired new responsibilities, such as macro-prudential supervision, in other words, supervision of the provision of financial services.[150]

—Take liberties with its mandate to save the Euro : Paradoxically, the crisis undermined the ECB’s ordoliberal discourse «because some of its instruments, which it had to implement, deviated significantly from its principles. It then interpreted the paradigm with enough flexibly to adapt its original reputation to these new economic conditions. It was forced to do so as a last resort to save its one and only raison d’être: the euro. This Independent was thus obliged to be pragmatic by departing from the spirit of its statutes, which is unacceptable to the hardest supporters of ordoliberalism, which will lead to the resignation of the two German leaders present within the ECB: the governor of the Bundesbank, Jens WEIDMANN[151] and the member of the executive board of the ECB, Jürgen STARK.[152]

– Regulation of the financial system : The delegation of this new function to the ECB was carried out with great simplicity and with the consent of European leaders, because neither the Commission nor the Member States really wanted to obtain the monitoring of financial abuses throughout the area. In other words, in the event of a new financial crisis, the ECB would be the perfect scapegoat.[153]

— Capturing exchange rate policy : The event that will most mark the definitive politicization of the ECB is, of course, the operation launched in January 2015: the quantitative easing (QE) operation. Indeed, the Euro is an overvalued currency on the world markets against the dollar and the Euro zone is at risk of deflation. In addition, Member States find themselves heavily indebted, partly due to the rescue of their national banks. The ECB, as the guardian of the stability of the euro zone, is deciding to gradually buy back more than EUR 1 100 billion Member States’ public debt. In this way, money is injected back into the economy, the euro depreciates significantly, prices rise, the risk of deflation is removed, and Member States reduce their debts. However, the ECB has just given itself the right to direct the exchange rate policy of the euro zone without this being granted by the Treaties or with the approval of European leaders, and without public opinion or the public arena being aware of this.[149]

In conclusion, for those in favour of a framework for ECB independence, there is a clear concentration of powers. In the light of these facts, it is clear that the ECB is no longer the simple guardian of monetary stability in the euro area, but has become, over the course of the crisis, a «multi-competent economic player, at ease in this role that no one, especially not the agnostic governments of the euro Member States, seems to have the idea of challenging».[149] This new political super-actor, having captured many spheres of competence and a very strong influence in the economic field in the broad sense (economy, finance, budget…). This new political super-actor can no longer act alone and refuse a counter-power, consubstantial to our liberal democracies.[154] Indeed, the status of independence which the ECB enjoys by essence should not exempt it from a real responsibility regarding the democratic process.

The arguments in favour of a counter power[edit]

In the aftermath of the euro area crisis, several proposals for a countervailing power were put forward, to deal with criticisms of a democratic deficit. For the German economist German Issing (2001) the ECB as a democratic responsibility and should be more transparent. According to him, this transparence could bring several advantages as the improvement of the efficiency and of the credibility by giving to the public adequate information. Others think that the ECB should have a closer relationship with the European Parliament which could play a major role in the evaluation of the democratic responsibility of the ECB.[155] The development of new institutions or the creation of a minister is another solution proposed:

A minister for the Eurozone ?

The idea of a eurozone finance minister is regularly raised and supported by certain political figures, including Emmanuel Macron, as well as former German Chancellor Angela Merkel,[156] former President of the ECB Jean-Claude Trichet and former European Commissioner Pierre Moscovici. For the latter, this position would bring «more democratic legitimacy» and «more efficiency» to European politics. In his view, it is a question of merging the powers of Commissioner for the Economy and Finance with those of the President of the Eurogroup.[157]

The main task of this minister would be to «represent a strong political authority protecting the economic and budgetary interests of the euro area as a whole, and not the interests of individual Member States». According to the Jacques Delors Institute, its competences could be as follows:

- Supervising the coordination of economic and budgetary policies

- Enforcing the rules in case of infringement

- Conducting negotiations in a crisis context

- Contributing to cushioning regional shocks

- Representing the euro area in international institutions and fora[158]

For Jean-Claude Trichet, this minister could also rely on the Eurogroup working group for the preparation and follow-up of meetings in euro zone format, and on the Economic and Financial Committee for meetings concerning all Member States. He would also have under his authority a General Secretariat of the Treasury of the euro area, whose tasks would be determined by the objectives of the budgetary union currently being set up [159][160]

This proposal was nevertheless rejected in 2017 by the Eurogroup, its president, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, spoke of the importance of this institution in relation to the European Commission.[161]

Towards democratic institutions ?

The absence of democratic institutions such as a Parliament or a real government is a regular criticism of the ECB in its management of the euro area, and many proposals have been made in this respect, particularly after the economic crisis, which would have shown the need to improve the governance of the euro area. For Moïse Sidiropoulos, a professor in economy: «The crisis in the euro zone came as no surprise, because the euro remains an unfinished currency, a stateless currency with a fragile political legitimacy».[162]

French economist Thomas Piketty wrote on his blog in 2017 that it was essential to equip the euro zone with democratic institutions. An economic government could for example enable it to have a common budget, common taxes and borrowing and investment capacities. Such a government would then make the euro area more democratic and transparent by avoiding the opacity of a council such as the Eurogroup.

Nevertheless, according to him «there is no point in talking about a government of the euro zone if we do not say to which democratic body this government will be accountable», a real parliament of the euro zone to which a finance minister would be accountable seems to be the real priority for the economist, who also denounces the lack of action in this area.[163]

The creation of a sub-committee within the current European Parliament was also mentioned, on the model of the Eurogroup, which is currently an under-formation of the ECOFIN Committee. This would require a simple amendment to the rules of procedure and would avoid a competitive situation between two separate parliamentary assemblies. The former President of the European Commission had, moreover, stated on this subject that he had «no sympathy for the idea of a specific Eurozone Parliament».[164]

See also[edit]

- European Banking Authority

- European Systemic Risk Board

- Open market operation

- Economic and Monetary Union

- Capital Markets Union

- European banking union

Notes[edit]

- ^ The process is similar, though on a grand scale, to an individual who every month charges $10,000 on his or her credit card, pays it off every month, but also withdraws (and pays off) an additional $10,000 each succeeding month for transaction purposes. Such a person is operating «net borrowed» on a continual basis, and even though the borrowing from the credit card is short term, the effect is a stable increase in the money supply. If the person borrows less, less money circulates in the economy. If he or she borrows more, the money supply increases. An individual’s ability to borrow from his or her credit card company is determined by the credit card company: it reflects the company’s overall judgment of its ability to lend to all borrowers, and also its appraisal of the financial condition of that one particular borrower. The ability of member banks to borrow from the central bank is fundamentally similar.[citation needed]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e «Key ECB interest rates». ecb.europa.eu. 15 December 2022.

- ^ «ECB, ESCB and the Eurosystem». www.ecb.europa.eu. 25 June 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ «STATUTE OF THE EUROPEAN SYSTEM OF CENTRAL BANKS AND OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK». eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ a b «European Central Bank». CVCE. 7 August 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e «Capital Subscription». European Central Bank. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ a b c «ECB: Economic and Monetary Union». ECB. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ a b c «ECB: Economic and Monetary Union». Ecb.int. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ «The third stage of Economic and Monetary Union». CVCE. 7 August 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ «The powerful European Central Bank [E C B] in the heart of Frankfurt/Main – Germany – The Europower in Mainhattan – Enjoy the glances of euro and europe….03/2010….travel round the world….:)». UggBoy♥UggGirl [PHOTO // WORLD // TRAVEL]. Flickr. 6 March 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ Matlock, George (16 February 2010). «Peripheral euro zone government bond spreads widen». Reuters. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ «Acropolis now». The Economist. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ Blackstone, Brian; Lauricella, Tom; Shah, Neil (5 February 2010). «Global Markets Shudder: Doubts About U.S. Economy and a Debt Crunch in Europe Jolt Hopes for a Recovery». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ «Former Iceland Leader Tried Over Financial Crisis of 2008», The New York Times, 5 March 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ Greek/German bond yield spread more than 1,000 bps, Financialmirror.com, 28 April 2010

- ^ «Gilt yields rise amid UK debt concerns». Financial Times. 18 February 2010. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2011.(registration required)

- ^ «The politics of the Maastricht convergence criteria | vox – Research-based policy analysis and commentary from leading economists». Voxeu.org. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ Bagus, The Tragedy of the Euro, 2010, p.75.

- ^ Orphanides, Athanasios (9 March 2018). «Monetary policy and fiscal discipline: How the ECB planted the seeds of the euro area crisis». VoxEU.org. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ «Introductory statement with Q&A». European Central Bank (Press release). Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ «ECB decides on measures to address severe tensions in financial markets». European Central Bank (Press release). Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ «Mixed support for ECB bond purchases». Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ McManus, John; O’Brien, Dan (5 August 2011). «Market rout as Berlin rejects call for more EU action». Irish Times.

- ^ a b c «WOrking paper 2011 / 1 A Comprehensive approach to the EUro-area debt crisis» (PDF). Zsolt Darvas. Corvinus University of Budapest. February 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ «Euro area money growth and the ‘Securities and Markets Programme’» (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2010.

- ^ Proissl, von Wolfgang (9 September 2011). «Das Ende der EZB, wie wir sie kannten» [The end of the ECB, as we knew it]. Kommentar. Financial Times Deutschland (in German). Archived from the original on 15 October 2011.

- ^ «The ECB’s Securities Market Programme (SMP) – about to restart bond purchases?» (PDF). Global Markets Research – International Economics. Commonwealth Bank. 18 June 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ «How Greece lost billions out of an obscure ECB programme». Positive Money Europe. 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ «The ECB as vulture fund: how central banks speculated against Greece and won big – GUE/NGL – Another Europe is possible». guengl.eu. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ «Unfair ECB profits should be returned to Greece, 117,000 citizens demand». Positive Money Europe. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ O’Connell, Hugh. «Everything you need to know about the promissory notes, but were afraid to ask». TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ «Transparency International EU». Transparency International EU. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ «Irish letters». European Central Bank (Press release). Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Reilly, Gavan. «Report: ECB rules out long-term bond to replace promissory note». TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ «Chopra: ECB refusal to burn bondholders burdened taxpayers». The Irish Times. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Blackstone, Brian (2011). «ECB Raises Interest Rates – MarketWatch». marketwatch.com. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ «ECB: Key interest rates». 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ «Draghi slashes interest rates, unveils bond buying plan». europenews.net. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ «Mario Draghi takes centre stage at ECB». BBC. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Draghi, Mario; President of the ECB; Constâncio, Vítor; Vice-President of the ECB (8 December 2011). «Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A)» (Press conference) (Press release). Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Schwartz, Nelson D.; Jolly, David (21 December 2011). «European Bank in Strong Move to Loosen Credit». The New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

the move, by the European Central Bank, could be a turning point in the Continent’s debt crisis

- ^ Norris, Floyd (21 December 2011). «A Central Bank Doing What It Should». The New York Times. Archived from the original (Analysis) on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Wearden, Graeme; Fletcher, Nick (29 February 2012). «Eurozone crisis live: ECB to launch massive cash injection». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ Ewing, Jack; Jolly, David (21 December 2011). «Banks in the euro zone must raise more than 200bn euros in the first three months of 2012». The New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ «Verbatim of the remarks made by Mario Draghi». European Central Bank (Press release). Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ «Itay and Spain respond to ECB treatment». Financial Times. 8 August 2011. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ «ECB ‘will do whatever it takes’ to save the euro». POLITICO. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Ewing, Jack; Erlanger, Steven (6 September 2012). «Europe’s Central Bank Moves Aggressively to Ease Euro Crisis». The New York Times.

- ^ «ECB press conference, 6 September 2012» (Press release). Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ «[…] the decision on Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs) that we took in September 2012 to protect the euro area from speculation that could have forced some countries out of the single currency. That decision was almost unanimous; the single vote against came from the President of the Bundesbank» «Interview with Libération». European Central Bank (Press release). 16 December 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ «Ministers agree deal on EU banking union». EUobserver. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ «Eurotower to house ECB’s banking supervision staff». European Central Bank (Press release). 9 November 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Henderson, Isaiah M. (4 May 2019). «On the Causes of European Political Instability». The California Review. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ «Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A)». European Central Bank (Press release). Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ «Draghi fends off German critics and keeps stimulus untouched». Financial Times. 27 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ «DECISION (EU) 2016/948 OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK of 1 June 2016 on the implementation of the corporate sector purchase programme (ECB/2016/16)» (PDF).

- ^ «Corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP) – Questions & Answers». European Central Bank. 7 December 2021.

- ^ «Asset purchase programmes». European Central Bank. 25 March 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Christine Lagarde resigns as head of IMF». BBC News. 16 July 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Hujer, Marc; Sauga, Michael (30 October 2019). «Elegance and Toughness: Christine Lagarde Brings a New Style to the ECB». Spiegel Online. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ «Lagarde promises to paint the ECB green». POLITICO. 29 August 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ «Christine Lagarde’s uphill battle for ECB gender equality». POLITICO. 5 March 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ «Christine Lagarde meets with Positive Money Europe». Positive Money Europe. 4 December 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Reuters Staff (21 October 2020). «Lagarde turns to civil society in ECB transformation effort». Reuters. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ a b Lynch, Russell (27 November 2020). «France slams ‘dangerous’ Italian pleas to cancel Covid debts». The Telegraph.

- ^ Reuters Staff (18 June 2020). «Banks borrow record 1.31 trillion euros from ECB». Reuters. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ «Our response to the coronavirus pandemic». 19 February 2021.

- ^ a b Amaro, Silvia (8 July 2021). «European Central Bank sets its inflation target at 2% in new policy review». CNBC. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ «ECB presents action plan to include climate change considerations in its monetary policy strategy» (Press release). European Central Bank. 8 July 2021.

- ^ wikisource consolidation

- ^ a b THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK HISTORY, ROLE AND FUNCTIONS BY HANSPETER K. SCHELLER SECOND REVISED EDITION 2006, ISBN 92-899-0022-9 (print) ISBN 92-899-0027-X (online) page 81 at the pdf online version

- ^ «Powers and responsibilities of the European Central Bank». European Central Bank. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ Draghi, Mario (2 June 2016). «Delivering a symmetric mandate with asymmetric tools: monetary policy in a context of low interest rates». European Central Bank (Press release). Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ «Twenty Years of the ECB’s monetary policy». European Central Bank (Press release). 18 June 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ «ECB’s Governing Council approves its new monetary policy strategy». European Central Bank (Press release). 8 July 2021.

- ^ «ECB: Monetary Policy». Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Blot, C., Creel, J., Faure, E. and Hubert, P., Setting New Priorities for the ECB’s Mandate, Study for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament, Luxembourg, 2020.

- ^ «Objectives of the European Central Bank». www.igmchicago.org. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ «Certainly, the protection of the environment is not the only transversal objective assigned to EU institutions and hence to the ECB. Under the Treaty one could equally ask, for example, why the ECB should not promote industries that promise the strongest employment growth, irrespective of their ecological footprint. But equally importantly, the ECB is subject to the Treaty requirement to «act in accordance with the principle of an open market economy with free competition». – «Monetary policy and climate change, Speech from Benoit Cœuré, November 2018

- ^ «How Can the European Parliament Better Oversee the European Central Bank? | Bruegel». Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ «» La BCE devrait avoir un mandat politique clair qui expliciterait quels objectifs secondaires sont les plus pertinents pour l’UE ««. Le Monde.fr (in French). 9 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Van’t Klooster, Jens; De Boer, Nik (25 October 2021). «New report «The ECB’s neglected secondary mandate: An inter-institutional solution»«. Positive Money Europe. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ «Monetary policy» (PDF).

- ^ a b Fairlamb, David; Rossant, John (12 February 2003). «The powers of the European Central Bank». BBC News. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- ^ a b «All about the European debt crisis: In SIMPLE terms». rediff business. rediff.com. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ «Open Market Operation – Fedpoints – Federal Reserve Bank of New York». Federal Reserve Bank of New York. newyorkfed.org. August 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK HISTORY, ROLE AND FUNCTIONS BY HANSPETER K. SCHELLER SECOND REVISED EDITION 2006, ISBN 92-899-0022-9 (print) ISBN 92-899-0027-X (online) page 87 at the pdf online version

- ^ a b c Bernanke, Ben S. (1 December 2008). «Federal Reserve Policies in the Financial Crisis» (Speech). Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce, Austin, Texas: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

To ensure that adequate liquidity is available, consistent with the central bank’s traditional role as the liquidity provider of last resort, the Federal Reserve has taken a number of extraordinary steps.

- ^ In practice, 400–500 banks participate regularly.

Cheun, Samuel; von Köppen-Mertes, Isabel; Weller, Benedict (December 2009), The collateral frameworks of the Eurosystem, the Federal Reserve System and the Bank of England and the financial market turmoil (PDF), ECB, retrieved 24 August 2011 - ^ a b Bertaut, Carol C. (2002). «The European Central Bank and the Eurosystem» (PDF). New England Economic Review (2nd quarter): 25–28.

- ^ a b c d e f «ECB: Governing Council». ECB. ecb.int. 1 January 2002. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ «Distribution of responsibilities among the Members of the Executive Board of the ECB» (PDF).

- ^ Article 11.2 of the ESCB Statute

- ^ Marsh, David, «Cameron irritates as euro’s High Noon approaches», MarketWatch, 28 May 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ «Tag: José Manuel González-Páramo». Financial Times Money Supply blog entries. 23 January 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Davenport, Claire. «EU parliament vetoes Mersch, wants woman for ECB». U.S. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ «Mersch Named to ECB After Longest Euro Appointment Battle». Bloomberg. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ «Frank Elderson officially appointed member of executive boar…» agenceurope.eu. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Benoeming Nederlander Frank Elderson in directie ECB stap dichterbij». nos.nl (in Dutch). 24 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ «ECB: Decision-making bodies». Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ «Monetary policy accounts published in 2016» (Press release). 17 December 2019.

- ^ «The ECB must open itself up». Financial Times. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ «Members of the Governing Council». Archived from the original on 17 July 2004. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ «Composition of the European Central Bank». CVCE. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ «ECB: General Council». European Central Bank. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b c «Supervisory Board». European Central Bank. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ «ECB SSM Supervisory Board Members». Frankfurt: ECB. 1 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ Article 28.1 of the ESCB Statute

- ^ Article 29 of the ESCB Statute

- ^ Article 28.5 of the ESCB Statute

- ^ Article 28.4 of the ESCB Statute

- ^ Buell, Todd (29 October 2014). «Translation Adds Complexity to European Central Bank’s Supervisory Role: ECB Wants Communication in English, But EU Rules Allow Use of Any Official Language». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Athanassiou, Phoebus (February 2006). «The Application of multilingualism in the European Union Context» (PDF). ECB. p. 26. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Bank, European Central (28 April 2022). «Annual Report 2021». European Central Bank.

- ^ «The European Central Bank: independent and accountable». European Central Bank (Press release). 13 May 1997. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ «The role of the Central Bank in the United Europe». European Central Bank (Press release). 4 May 1999. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ Papadia, Francesco; Ruggiero, Gian Paolo (1 February 1999). «Central Bank Independence and Budget Constraints for a Stable Euro». Open Economies Review. 10 (1): 63–90. doi:10.1023/A:1008305128157. ISSN 0923-7992. S2CID 153508547.

- ^ Wood, Geoffrey. «Is the ECB Too Independent?». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ a b «Independence». European Central Bank. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Bank, European Central (12 January 2017). «Why is the ECB independent?». European Central Bank. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ «Transparency International EU – The global coalition against corruption in Brussels». transparency.eu. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ Heinemann, Friedrich; Hüfner, Felix P. (2003). «Is the View from the Eurotower Purely European? — National Divergence and ECB Interest Rate Policy» (PDF). SSRN Electronic Journal. Elsevier BV. doi:10.2139/ssrn.374600. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 12675305.

- ^ Jose Ramon Cancelo, Diego Varela and Jose Manuel Sanchez-Santos (2011) ‘Interest rate setting at the ECB: Individual preferences and collective decision making’, Journal of Policy Modeling 33(6): 804–820. DOI.

- ^ «PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK» (PDF). European Central Bank. 2007.

- ^ «Report on democratic accountability in the third phase of European Monetary Union – Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs and Industrial Policy – A4-0110/1998». europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ «The evolution of the ECB’s accountability practices during the crisis». European Central Bank. 9 August 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.