Всего найдено: 6

Здравствуйте! Напишите, пожалуйста, как надо писать: трасса «Формулы-1» или трасса «Формула-1″? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: трасса «Формулы-1».

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно писать выражение Формула-1 (автоспортивное соревнование) — с кавычками или без? И почему именно так, а не иначе?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Это условное наименование, кавычки нужны: «Формула-1».

Здравствуйте, уважаемые сотрудники «Грамоты»! Нужно ли заключать в кавычки словосоочетания «король болида», «королева бензоколонки»? Если «да», то связана ли постановка кавычек с приданием выражению иронического смысла? В тексте о гонках Формула-1 автогонщик так назван без иронии: «…на седьмом круге трассы «король болида» внезапно вылетел с трассы. Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Ставить кавычки или нет — решать автору текста. Безусловно, «закавыченный» фрагмент текста может восприниматься читателем как иронический.

Гонки Формула 1

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _гонки «Формула-1»_.

Как правильно писать: гонки формула-1 ?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _гонки «Формула-1»_.

1. Он(,) вне всякого сомнения(,) придет.

2. Пилот «Формула-1″ или «Формулы-1»?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Он, вне всякого сомнения, придет. Пилот «Формулы-1»_.

Во время обсуждения текстов о гонках в нашей редакции мы поняли, что не знаем, как правильно называется «Формула-1». То есть Формула 1. Как вообще, черт возьми, она пишется?

Анализ других изданий тоже ничем не помог:

- За Формулу 1: крупнейшие тематические издания F1news.ru и Motorsport.

- За «Формулу-1»: крупные общеспортивные медиа Sports.ru, «СЭ», Sportbox и «Матч ТВ».

«Чемпионат» вообще выбрал промежуточный вариант Формула-1

Что вообще означает «Формула 1»? Что, есть вторая или третья?

Да, есть: полная вертикаль гоночных серий, которые проводит ФИА (аналог ФИФА в футболе), включает Формулу 2, Формулу 3 и даже Формулу 4. Первая реакция – все логично, Формула идет как общее название гонок, а номер отвечает за место в иерархии.

Но все сложнее: спускаемся к истории.

Первые гра-при проводились еще в начале XX века, но после начала Второй мировой войны гонки прекратились. Когда в 1946 году вернулись к их обсуждению, стало понятно, что технологический прогресс сделал машины слишком отличающимися друг от друга, и одно успешное решение отдельной команды способно сделать гонки скучными и неинтересными.

Нет, технические регламенты существовали и раньше, но после войны ФИА все пересмотрела и написала новые правила с нуля. Общий список критериев, которым должны были соответствовать машины, назвали «формулой», а так как гоночных серий уже тогда было несколько, им еще и добавили букву – получились «Формула А» и «Формула Б». Затем они получили современные названия: «Формула 1» и «Формула 2».

Еще раз: изначально «формулами» назвали лишь технические критерии, а не саму серию. Гонки официально назывались просто Гран При, а чемпионат – мировым чемпионатом среди гонщиков. Официально Формула 1 оказалась в названии лишь в 1981 году.

Причины такого сдвига смысла очень просты: именно по «формуле правил» оказалось проще всего отличать гонки младших и старших серий. В разговорной речи это прижилось мгновенно, и фраза «чемпионат по правилам «Формулы 1» быстро сократилась до «чемпионата Формулы 1».

Нужны ли кавычки?

Есть турниры, которые мы пишем всегда без кавычек – как Бундеслига в футболе. А «Ролан Гаррос» всегда идет с ними. Почему – отвечает сайт «Грамота.ру»:

Кавычки выполняют здесь дифференцирующую функцию: помогают отличить название турнира от имени французского летчика, в честь которого назван турнир.

Отчасти это может объяснить, почему многие издания кавычат Формулу 1: таким образом подчеркивают, что слово «формула» тут используется не в прямом смысле. Это же подтверждает тот же сайт «Грамота.ру».

Но тенденция отказа от кавычек понятна: с каждым годом название гоночной серии становится все более самостоятельным и не требующим кавычек для дополнительной дифференциации.

А что с дефисом?

Это самая удивительная часть – иностранные названия в русский язык всегда попадают по-разному. Мы привыкли, что дефис ставится в названиях городов: Нью-Йорк, Сан-Паулу, Сан-Себастьян.

Фамилии чаще идут без него, хотя у арабских, например, встречаются оба варианта: аль-Нахайян и Аль Нахайян. Названия турниров тоже чаще идут без него Серия А, Ла Лига, «Ролан Гаррос».

Поэтому в этом вопросе мы обратились к мнению обычных пользователей: если в начале XXI века оба варианта были равнопопулярны в запросах Google, то сейчас явно доминирует запрос без дефиса.

-

-

October 21 2014, 14:19

- Авто

- Cancel

Всем привет! Подскажите, как правильно писать выражение Формула-1 (вид автоспорта) — с кавычками или без?

Сидоров — чемпион мира Формулы-1 или Сидоров — чемпион мира «Формулы-1»? И самое главное, хотелось бы узнать объяснение, почему именно так а не иначе. Спасибо.

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

фо́рмула, -ы

Рядом по алфавиту:

форм-ро́д , -а (в палеонтологии)

форм-фа́ктор , -а (тех.)

формо́ванный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана

формова́ть(ся) , -му́ю, -му́ет(ся)

формо́вка , -и

формово́й , и фо́рмовый

формо́вочный

формо́вщик , -а

формо́вщица , -ы, тв. -ей

формоизмене́ние , -я

формоизменя́ющий

формообразова́ние , -я

формообразова́тельный

формообразу́ющий

формотво́рчество , -а

фо́рмочка , -и, р. мн. -чек

фо́рмула , -ы

формули́рование , -я

формули́рованный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана

формули́ровать(ся) , -рую, -рует(ся)

формулиро́вка , -и, р. мн. -вок

формулиро́вочка , -и, р. мн. -чек

формулиро́вочный

фо́рмульный

фо́рмульский , (от «Фо́рмула-1»)

формуля́р , -а

формуля́рный

формфа́ктор , -а (физ.) [изменено, ср. РОС 2012: формфа́ктор, -а]

фо́ро , и фо́ра2, неизм. (возглас)

фо́ровый

форозо́ид , -а (зоол.)

| Эта статья в настоящий момент постепенно дописывается. Пожалуйста, если хотите что-либо добавить в статью, сначала обсудите это с другими участниками на странице обсуждения. |

На этой странице приведены указания по написанию статей о Формуле-1, а также о том, что с ней связано. Если вам интересна эта тема, загляните на страницу Проекта Формулы-1. Там вы узнаете, чем и как вы можете помочь автоспортивному разделу Википедии и получить помощь, если потребуется.

В данном разделе перечислены основные положения по именованию и оформлению статей, посвящённых гонках «Формулы-1». Пожалуйста, придерживайтесь этих правил. В случае если какое-либо положение кажется неправильным, то прежде чем вносить исправления сюда, обсудите этот вопрос на странице обсуждения этого подпроекта.

Всегда полезно ознакомиться с уже созданными статьями по данной теме — это позволит лучше понять используемые принципы оформления и наполнения статей.

Общие правила

Правописание

- «Формула-1» пишется через дефис.

- «Гран-при» пишется с заглавной буквы, через дефис.

- «Участвовать в Гран-при», но во всех остальных случаях — «на Гран-при»: «занял 2-е место на Гран-при Великобритании», «новые правила будут использованы на Гран-при Австралии».

- Не используйте слово «трек». Вместо него используйте слова «трасса», «автодром», «кольцо».

Оформление

- В таблицах перед именем гонщика указывайте флаг страны, за которую он выступает. Для флагов используйте шаблоны вида {{Флаг Германии}}.

- В таблицах именуйте гонщиков в формате имя + фамилия (так как их называют при телетрансляциях). Если, однако, это неудобно (таблица становится слишком широкой), можно использовать только фамилию. Тогда для однофамильцев перед фамилией укажите инициал. Инициал отделяется от фамилии неразрывным пробелом. Рекомендуется использовать не , а неразрывный пробел Юникода.

- Отрывы указывайте, по возможности, до тысячных долей секунды. Если отрыв превышает минуту, то вынесите минуты отдельно. Примеры:

+ 1:23.654,+ 24.567. Не забудьте поставить неразрывный пробел между знаком «+» и временем. Минуты отделяются от секунд двоеточием, а секунды от долей — точкой (последнее противоречит правилам выделения долей в русском языке, но так принято в спорте).

Пилот Формулы-1

Пример: —

Название статьи

Статью о пилоте следует называть так же, как и любую статью о персоналии: в формате <фамилия>, <имена>. Например, Баррикелло, Рубенс Гонсалвеш. Если имена (или фамилии) не разделяются в родном языке дефисом, не следует его использовать и в русском написании. Например, вопреки частому «Хуан-Пабло» более правильным является вариант Монтойя, Хуан Пабло Ролдан.

Не забудьте сделать всевозможные редиректы на имя пилота. Чем больше редиректов — тем лучше. В частности, должны быть созданы следующие редиректы:

- Со стандартного написания имени пилота. Если их несколько — значит, с нескольких.

- Просто с фамилии пилота, если в Википедии нет статей про другого человека с той же фамилией. Если же есть, вместо редиректа нужно сделать дизамбиг.

- С неполного википедийного написания имени пилота (например, с Монтойя, Хуан Пабло).

Структура статьи

- Поместите шаблон {{Пилот Формулы-1}} для действующего пилота и {{Бывший пилот Формулы-1}} — для бывшего. Описание шаблонов смотрите на их страницах обсуждения.

- Начните статью с полного имени пилота уже в естественном порядке, затем укажите имя пилота на его родном языке (используя шаблоны вида {{lang-xx}}, где xx — код языка).

- Во введении статьи укажите дату и место рождения пилота (а также дату и место смерти, если пилот уже умер), его основные достижения в Формуле-1 и других местах.

- В разделе «Биография» расскажите о детстве пилота, его родителях и других родственниках, оказавших влияние на его жизнь, о жене и детях. Не стоит заострять изложение на карьере пилота в гоночных сериях — для этого существуют другие разделы. Однако о картинговой карьере можно упомянуть здесь.

- В разделе «Младшие гоночные серии» расскажите о доформульной карьере пилота. Добавьте таблицу статистики выступления в младших гоночных сериях. Пример таблицы см. ниже.

- В разделе «Карьера в Формуле-1» расскажите о карьере пилота в Формуле-1. Сопроводите это полной статистикой выступлений и соответствующей таблицей. Подробнее см. ниже.

Таблица доформульной карьеры

Статистика выступлений в Формуле-1

Требуется указать следующие параметры (которые могут варьироваться в зависимости от значений, то есть от достижений пилота):

- Количество побед, количество побед подряд

- Количество поул-позиций

…

Команда Формулы-1

Пример: —

Название статей

- Название статьи должно иметь вид Рено (команда Формулы-1) для команд, допускающих русское именование, и Scuderia Torro Rosso — для не допускающих. Следует указывать не полное название команды («Mild Seven Renault F1 Team» или, что ещё хуже, «Майлд Север Рено Ф1 Тим»), а его краткое название (Рено, Феррари, МакЛарен, Ред Булл), если это возможно (для Scuderia Torro Rosso это невозможно).

- Уточнение «(команда Формулы-1)» следует ставить только там, где это необходимо. В спорных случаях (например, для команды МакЛарен — существуют дорожно-спортивные автомобили с одноимённым названием) это необходимо.

- В случае, если название команды совпадает с названием какой-либо компании (Рено, Феррари, Ред Булл) следует создать disambig.

- Следует создать редиректы со следующих статей:

- С полного официального английского названия статьи: Mild Seven Renault F1 Team, BMW Williams F1 Team, West McLaren Mercedes и т. д.

- С краткого английского названия статьи с указанием уточнения в скобках: Renault (команда Формулы-1), Williams (команда Формулы-1), McLaren (команда Формулы-1) и т. д.

Содержимое

- Краткая информация о команде.

- Карточка Шаблон:Команда Формулы-1.

- Состав команды.

- История команды.

- Подробно достижения команды (не только те, что в карточке).

- Все пилоты, которые когда-либо выступали за данную команду с указанием срока выступления и достижений пилотов за данную команду.

- Ссылки: Список команд Формулы-1.

- Категоризация: Команды Формулы-1.

Сезон Формулы-1

Статья о сезоне Формулы-1.

Пример: Сезон 2006 Формулы-1

Название статьи

Название статьи о сезоне Формулы-1 должно иметь вид [[Сезон 2005 Формулы-1]]. Редиректов делать не нужно.

Структура статьи

- Навигационный шаблон для перемещения по сезонам: Шаблон:Сезоны Формулы-1.

- Картинка, относящаяся к данному сезону (лучше всего — фотография чемпиона мира этого сезона за рулём болида); Шаблон:Сезон Формулы-1 с общей информацией о сезоне; Шаблон:Статьи о Формуле-1 для навигации по другим статьям проекта. Подробнее об оформлении этого раздела см. ниже «начальные шаблоны».

- В первом абзаце должно быть краткое описание сезона: указание чемпиона и обладателя Кубка конструкторов, количество этапов, дата начала и окончания сезона. Затем в литературной форме должны быть кратко изложены основные события сезона. Не нужно вдаваться в излишние детали, т. к. подробнее события будут рассматриваться в соответствующем разделе.

- Чемпионат мира. Таблица с результатами чемпионата мира. Подробнее — см. ниже.

- Кубок конструкторов. Таблица с результатами Кубка конструкторов. Подробнее — см. ниже.

- Расписание сезона. Таблица с расписанием сезона и основными результатами каждого Гран-при. Подробнее — см. ниже.

- Составы команд. Таблица с составами команд. Подробнее — см. ниже.

- Основные события. Осветите основные события сезона (например, для 2005 года: шинный скандал в Индианаполисе, скандал с двойным топливным баком B.A.R. и дисквалификация команды, вопрос с контрактом Дженсона Баттона).

- Изменения в регламенте. Изменения в спортивном и техническом регламентах до сезона и во время него.

- Рекорды. Перечислите рекорды и достижения, поставленные в этом сезоне.

- Ссылки. Ссылки на материалы по данному сезону. Не нужно давать материалов по каждому Гран-при: их лучше привести в статье, посвящённой этому Гран-при.

- Не нужно добавлять сезон в какую-либо категорию: она автоматически выставляется шаблоном Сезон Формулы-1. А вот интервики проставить следует. Сезоны на английском языке имеют название вида en:2005_Formula_One_season. Не забудьте также проставить обратный интервик в английской статье.

Составы команд

Составы команд

Таблица со списком команд, участвовавших в данном сезоне. Команды упорядочены по местам, которые они заняли в Кубке конструкторов в конце данного сезона.

Отчёт о Гран-при Формулы-1

Статья об одном конкретном Гран-при.

В статье должны быть итоги Гран-при и краткое описание основных событий Гран-при, основных моментов гонки.

Пример: Гран-при Бахрейна 2006 года

Название статьи

Название статьи о Гран-при должно иметь вид Гран-при Малайзии 2006 года.

Следует создать следующий редирект: Гран-при Малайзии Формулы-1, сезон 2006

Структура статьи

- Шаблон:Гран-при Формулы-1 с краткой информацией о Гран-при.

- Дайте краткое описание Гран-при. Укажите победителя; пилотов, занявших 2-е и 3-е места; обладателя поул-позиции; обладателя лучшего круга в гонке. В паре предложений опишите, как они провели гонку.

- Раздел «Гонка». Подробнее — см. ниже.

- Раздел «Квалификация». Подробнее — см. ниже

- Раздел «Свободные заезды». Не нужно указывать полные таблицы на свободных заездах. Кратко опишите стратегию команд, погодные условия, укажите обладателей лучшего времени в каждой из сессий свободных заездов. Дайте ссылки на подробные результаты. В подразделе «тест-пилоты» в таблице укажите тест-пилотов, участвовавших в свободных заездах. Подробнее — см. ниже.

- Если на Гран-при были какие-то события, которые заслуживают отдельного раздела и большого количества текста (например, шинный скандал в Индианаполисе-2005), то разместите такой раздел в этом месте.

- Раздел «События» (или «Рекорды», если в нём будут только рекорды). Здесь следует указывать рекорды, поставленные на этом Гран-при, а также прочие достижения (не обязательно самые рекордные) или интересные события уик-енда.

- Раздел «Пресс-конференции». Дайте ссылки на пресс-конференции, проходившие по ходу Гран-при. Перечислите участников. В двух словах опишите характер вопросов. Целесообразно дать ссылки как на исходную запись пресс-конференции на английском языке (на http://formula1.com), так и на её перевод (например, на http://f1news.ru).

- Раздел «Ссылки». Представьте ссылки на материалы, связанные с Гран-при. Это могут быть обзоры Гран-при, комментарии известных лиц, отзывы пилотов и т. п. Целесообразно в статью о каждом Гран-при ставить ссылки на результаты на официальном сайте (http://www.formula1.com) и ссылки на комментарии после гонки (например, на http://f1news.ru).

- Раздел «Примечания» — для сносок (если нужны).

- Ссылка на предыдущий и следующий Гран-при. Гран-при, проходящий в данный момент, считается следующим.

- Не ставьте категорию: она будет автоматически поставлена с помощью карточки Шаблон:Гран-при Формулы-1.

- Проставьте интервики. В английской Википедии название соответствующей статьи имеет следующий формат: en:2006_Malaysian_Grand_Prix.

Гонка

Опишите ход гонки. Укажите основные события, основные достижения пилотов, участвующих в гонке. Отметьте стратегию пит-стопов, которую предпочли команды. Затем представьте таблицу с результатами гонки.

Таблица должна иметь следующий формат:

Если гонщик сходит с дистанции, вместо номера места пишите «Сход», а в графе «Время/Сход» напишите причину, а в скобках после неё — круг, на котором гонщик сошёл с дистанции.

Для оформления таблицы используйте class="standard" style="font-size:95%". Гонщиков, получивших очки, выделите жирным (выделите всю строку таблицы, а не только имя гонщика) вот так: |- style="font-weight:bold".

После таблицы добавьте следующую информацию:

- Лучший круг. Пример оформления:

- Лидеры в гонке. с указанием кругов, на которых они лидировали;

В скобках указано количество кругов, в течение которых гонщик лидировал. Гонщики располагаются в порядке возрастания первого круга лидерства. Обратите внимание на использование тире в диапазонах.

- Прочую информацию в разделе примечания (заголовок 2-го уровня) — для дополнительной информации о сходах и других происшествиях гонки, если она достойна упоминания.

Квалификация

Кратко опишите квалификации. Представьте таблицу. Оформление таблицы зависит от формата квалификации, использованного на описываемом Гран-при.

3 сессии с выбыванием (2006)

Используйте class="standard" style="font-size:95%". Обладателя поул-позиции, его команду и время поул-позиции выделите жирным. Также жирным выделите лучшее время, показанное в квалификации (оно, очевидно, не обязано совпадать со временем поул-позиции).

В 3-й сессии указывайте отставание от лидера. В других сессиях этого делать не нужно.

Тест-пилоты

В таблице укажите тест-пилотов, участвовавших с пятничных свободных заездах данного Гран-при. Команды следует отсортировать по их «номеру», то есть положению в чемпионате предыдущего года. В третьем столбце таблицы нужно указать лучший круг данного пилота по результатам всех серий заездов.

| Команда | Пилот | Лучший круг |

|---|---|---|

| Williams | Александр Вурц | 1:12.547 |

| Honda | Энтони Дэвидсон | 1:12.653 |

| Red Bull | Михаэль Аммермюллер | 1:14.436 |

Создание простой формулы в Excel

Excel для Microsoft 365 Excel для Microsoft 365 для Mac Excel 2021 Excel 2021 for Mac Excel 2019 Excel 2019 для Mac Excel 2016 Excel 2016 для Mac Excel 2013 Excel 2010 Excel 2007 Excel для Mac 2011 Еще…Меньше

Вы можете создать простую формулу для с суммы, вычитания, умножения и деления значений на вашем компьютере. Простые формулы всегда начинаются со знака равной(=),за которым следуют константы, которые являются числами и операторами вычислений, такими как «плюс»(+),«минус» (— ),«звездочка»*или «косая черта»(/)в начале.

В качестве примера рассмотрим простую формулу.

-

Выделите на листе ячейку, в которую необходимо ввести формулу.

-

Введите = (знак равенства), а затем константы и операторы (не более 8192 знаков), которые нужно использовать при вычислении.

В нашем примере введите =1+1.

Примечания:

-

Вместо ввода констант в формуле можно выбрать ячейки с нужными значениями и ввести операторы между ними.

-

В соответствии со стандартным порядком математических операций, умножение и деление выполняются до сложения и вычитания.

-

-

Нажмите клавишу ВВОД (Windows) или Return (Mac).

Рассмотрим другой вариант простой формулы. Введите =5+2*3 в другой ячейке и нажмите клавишу ВВОД или Return. Excel перемножит два последних числа и добавит первое число к результату умножения.

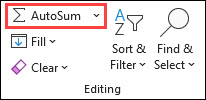

Использование автосуммирования

Для быстрого суммирования чисел в столбце или строке можно использовать кнопку «Автосумма». Выберите ячейку рядом с числами, которые необходимо сложить, нажмите кнопку Автосумма на вкладке Главная, а затем нажмите клавишу ВВОД (Windows) или Return (Mac).

Когда вы нажимаете кнопку Автосумма, Excel автоматически вводит формулу для суммирования чисел (в которой используется функция СУММ).

Примечание: Также в ячейке можно ввести ALT+= (Windows) или ALT+

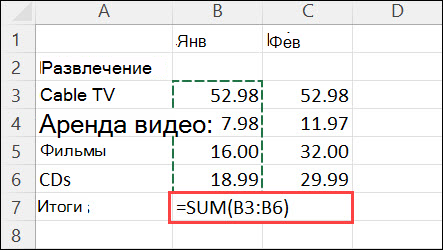

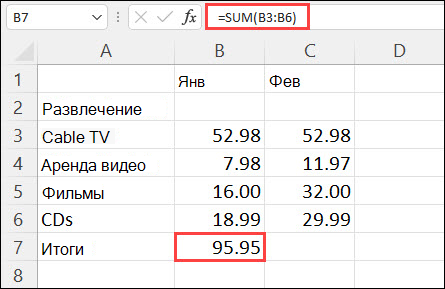

Приведем пример. Чтобы сложить числа за январь в бюджете «Развлечения», выберите ячейку B7, которая непосредственно под столбцом чисел. Затем нажмите кнопку «Автоумма». Формула появится в ячейке B7, а Excel выделит ячейки, которые вы суммируете.

Чтобы отобразить результат (95,94) в ячейке В7, нажмите клавишу ВВОД. Формула также отображается в строке формул вверху окна Excel.

Примечания:

-

Чтобы сложить числа в столбце, выберите ячейку под последним числом в столбце. Чтобы сложить числа в строке, выберите первую ячейку справа.

-

Создав формулу один раз, ее можно копировать в другие ячейки, а не вводить снова и снова. Например, при копировании формулы из ячейки B7 в ячейку C7 формула в ячейке C7 автоматически настроится под новое расположение и подсчитает числа в ячейках C3:C6.

-

Кроме того, вы можете использовать функцию «Автосумма» сразу для нескольких ячеек. Например, можно выделить ячейки B7 и C7, нажать кнопку Автосумма и суммировать два столбца одновременно.

Скопируйте данные из таблицы ниже и вставьте их в ячейку A1 нового листа Excel. При необходимости измените ширину столбцов, чтобы видеть все данные.

Примечание: Чтобы эти формулы выводили результат, выделите их и нажмите клавишу F2, а затем — ВВОД (Windows) или Return (Mac).

|

Данные |

||

|

2 |

||

|

5 |

||

|

Формула |

Описание |

Результат |

|

=A2+A3 |

Сумма значений в ячейках A1 и A2 |

=A2+A3 |

|

=A2-A3 |

Разность значений в ячейках A1 и A2 |

=A2-A3 |

|

=A2/A3 |

Частное от деления значений в ячейках A1 и A2 |

=A2/A3 |

|

=A2*A3 |

Произведение значений в ячейках A1 и A2 |

=A2*A3 |

|

=A2^A3 |

Значение в ячейке A1 в степени, указанной в ячейке A2 |

=A2^A3 |

|

Формула |

Описание |

Результат |

|

=5+2 |

Сумма чисел 5 и 2 |

=5+2 |

|

=5-2 |

Разность чисел 5 и 2 |

=5-2 |

|

=5/2 |

Частное от деления 5 на 2 |

=5/2 |

|

=5*2 |

Произведение чисел 5 и 2 |

=5*2 |

|

=5^2 |

Число 5 во второй степени |

=5^2 |

Дополнительные сведения

Вы всегда можете задать вопрос специалисту Excel Tech Community или попросить помощи в сообществе Answers community.

Нужна дополнительная помощь?

Excel необходим в случаях, когда вам нужно упорядочить, обработать и сохранить много информации. Он поможет автоматизировать вычисления, делает их проще и надежнее. Формулы в Excel позволяют проводить сколь угодно сложные вычисления и получать результаты моментально.

Как написать формулу в Excel

Прежде чем учиться этому, следует понять несколько базовых принципов.

- Каждая начинается со знака «=».

- Участвовать в вычислениях могут значения из ячеек и функции.

- В качестве привычных нам математических знаков операций используются операторы.

- При вставке записи в ячейке по умолчанию отражается результат вычислений.

- Посмотреть конструкцию можно в строке над таблицей.

Каждая ячейка в Excel является неделимой единицей с собственным идентификатором (адрес), который обозначается буквой (номер столбца) и цифрой (номер строки). Отображается адрес в поле над таблицей.

Итак, как создать и вставить формулу в Excel? Действуйте по следующему алгоритму:

Мы узнали, как поставить и посчитать формулу в Excel, а ниже приведен перечень операторов.

Обозначение Значение

+ Сложение

— Вычитание

/ Деление

* Умножение

Если вам необходимо указать число, а не адрес ячейки – вводите его с клавиатуры. Чтобы указать отрицательный знак в формуле Excel, нажмите «-».

Как вводить и скопировать формулы в Excel

Ввод их всегда осуществляется после нажатия на «=». Но что делать, если однотипных расчетов много? В таком случае можно указать одну, а затем ее просто скопировать. Для этого следует ввести формулу, а затем «растянуть» ее в нужном направлении, чтобы размножить.

Установите указатель на копируемую ячейку и наведите указатель мыши на правый нижний угол (на квадратик). Он должен принять вид простого крестика с равными сторонами.

Нажмите левую кнопку и тяните.

Отпустите тогда, когда надо прекратить копирование. В этот момент появятся результаты вычислений.

Также можно растянуть и вправо.

Переведите указатель на соседнюю ячейку. Вы увидите такую же запись, но с другими адресами.

При копировании таким образом номера строки увеличиваются, если сдвиг происходит вниз, или увеличиваются номера столбцов – если вправо. Это называется относительная адресация.

Давайте введем в таблицу значение НДС и посчитаем цену с налогом.

Цена с НДС высчитывается как цена*(1+НДС). Введем последовательность в первую ячейку.

Попробуем скопировать запись.

Результат получился странный.

Проверим содержимое во второй ячейке.

Как видим, при копировании сместилась не только цена, но и НДС. А нам необходимо, чтобы эта ячейка оставалась фиксированной. Закрепим ее с помощью абсолютной ссылки. Для этого переведите указатель на первую ячейку и щелкните в строке формул на адрес B2.

Нажмите F4. Адрес будет разбавлен знаком «$». Это и есть признак абсолютно ячейки.

Теперь после копирования адрес B2 останется неизменным.

Если вы случайно ввели данные не в ту ячейку, просто перенесите их. Для этого наведите указатель мыши на любую границу, дождитесь, когда мышь станет похожа на крестик со стрелочками, нажмите левую кнопку и тяните. В нужном месте просто отпустите манипулятор.

Использование функций для вычислений

Excel предлагает большое количество функций, которые разбиты по категориям. Посмотреть полный перечень можно, нажав на кнопку Fx около строки формул или открыв раздел «Формулы» на панели инструментов.

Расскажем о некоторых функциях.

Как задать формулы «Если» в Excel

Эта функция позволяет задавать условие и проводить расчет в зависимости от его истинности или ложности. Например, если количество проданного товара больше 4 пачек, следует закупить еще.

Чтобы вставить результат в зависимости от условия, добавим еще один столбец в таблицу.

В первой ячейке под заголовком этого столбца установим указатель и нажмем пункт «Логические» на панели инструментов. Выберем функцию «Если».

Как и при вставке любой функции, откроется окно для заполнения аргументов.

Укажем условие. Для этого необходимо щелкнуть в первую строку и выбрать первую ячейку «Продано». Далее поставим знак «>» и укажем число 4.

Во второй строке напишем «Закупить». Эта надпись будет появляться для тех товаров, которые были распроданы. Последнюю строку можно оставить пустой, так как у нас нет действий, если условие ложно.

Нажмите ОК и скопируйте запись для всего столбца.

Чтобы в ячейке не выводилось «ЛОЖЬ» снова откроем функцию и исправим ее. Поставьте указатель на первую ячейку и нажмите Fx около строки формул. Вставьте курсор на третью строку и поставьте пробел в кавычках.

Затем ОК и снова скопируйте.

Теперь мы видим, какой товар следует закупить.

Формула текст в Excel

Эта функция позволяет применить формат к содержимому ячейки. При этом любой тип данных преобразуется в текст, а значит не может быть использован для дальнейших вычислений. Добавим столбец чтобы отформатировать итоговую сумму.

В первую ячейку введем функцию (кнопка «Текстовые» в разделе «Формулы»).

В окне аргументов укажем ссылку на ячейку итоговой суммы и установим формат «#руб.».

Нажмем ОК и скопируем.

Если попробовать использовать эту сумму в вычислениях, то получим сообщение об ошибке.

«ЗНАЧ» обозначает, что вычисления не могут быть произведены.

Примеры форматов вы можете видеть на скриншоте.

Формула даты в Excel

Excel предоставляет много возможностей по работе с датами. Одна из них, ДАТА, позволяет построить дату из трех чисел. Это удобно, если вы имеете три разных столбца – день, месяц, год.

Поставьте указатель на первую ячейку четвертого столбца и выберите функцию из списка «Дата и время».

Расставьте адреса ячеек соответствующим образом и нажмите ОК.

Скопируйте запись.

Автосумма в Excel

На случай, если необходимо сложить большое число данных, в Excel предусмотрена функция СУММ. Для примера посчитаем сумму для проданных товаров.

Поставьте указатель в ячейку F12. В ней будет осуществляться подсчет итога.

Перейдите на панель «Формулы» и нажмите «Автосумма».

Excel автоматически выделит ближайший числовой диапазон.

Вы можете выделить другой диапазон. В данном примере Excel все сделал правильно. Нажмите ОК. Обратите внимание на содержимое ячейки. Функция СУММ подставилась автоматически.

При вставке диапазона указывается адрес первой ячейки, двоеточие и адрес последней ячейки. «:» означает «Взять все ячейки между первой и последней. Если вам надо перечислить несколько ячеек, разделите их адреса точкой с запятой:

СУММ (F5;F8;F11)

Работа в Excel с формулами: пример

Мы рассказали, как сделать формулу в Excel. Это те знания, которые могут пригодиться даже в быту. Вы можете вести свой личный бюджет и контролировать расходы.

На скриншоте показаны формулы, которые вводятся для подсчета сумм доходов и расходов, а также расчет баланса на конец месяца. Добавьте листы в книгу для каждого месяца, если не хотите, чтобы все таблицы располагались на одном. Для этого просто нажмите на «+» внизу окна.

Чтобы переименовать лист, два раза на нем щелкните и введите имя.

Таблицу можно сделать еще подробнее.

Excel – очень полезная программа, а вычисления в нем дают практически неограниченные возможности.

Отличного Вам дня!

|

В данном разделе перечислены основные положения по именованию и оформлению статей, посвящённых гонкам Формула-1, а также всему, что с ней связано. Пожалуйста, придерживайтесь этих правил. В случае если какое-либо положение кажется неправильным, то прежде чем вносить исправления сюда, обсудите этот вопрос на странице обсуждения этих правил. Если вам интересна эта тема, загляните на страницу проекта «Формула-1». Там вы узнаете, чем и как вы можете помочь автоспортивному разделу Википедии и получить помощь, если потребуется.

Правила оформления таблиц в статьях о Формуле-1 описаны в отдельном разделе правил: ВП:Статьи о Формуле-1/Оформление таблиц.

Прежде чем действовать, всегда полезно ознакомиться с уже созданными статьями по данной теме — это позволит лучше понять используемые принципы оформления и наполнения статей.

Общие правила[править код]

Правописание[править код]

- Выражения «Формула-1» и «Гран-при» пишутся без кавычек, с заглавной буквы, через дефис.

- «Участвовать в Гран-при», но во всех остальных случаях — «на Гран-при»: «занял 2-е место на Гран-при Великобритании», «новые правила будут использованы на Гран-при Австралии».

- Не используйте слово «трек» (это слово используется применительно к гонкам по овальным автодромам в стиле IRL IndyCar, а также к велогонкам). Вместо него используйте слова «трасса», «автодром», «кольцо».

- Не используйте фразу «командный зачёт», используйте вместо него «зачёт Кубка конструкторов» (поскольку в зачёт Кубка конструкторов шли результаты, показанные автомобилем вне зависимости от того, какой команде он принадлежал).

Оформление[править код]

- В таблицах перед именем гонщика указывайте флаг страны, за которую он выступает. Для флагов используйте шаблоны вида {{Флаг|ГЕР}} или {{Флаг|Германия}}. Учитывайте, в каком году происходят описываемые события: например, американским гонщикам, участвующим в гонках до 1959 года, соответствует флаг {{Флаг|США|1912}}, принятый в то время.

- В таблицах именуйте гонщиков в формате имя + фамилия (так, как их называют при телетрансляциях). В крайнем случае, если при этом таблица становится слишком широкой, можно использовать только фамилию. Тогда для однофамильцев перед фамилией укажите инициал. Флаг от имени (инициала), а также имя (инициал) от фамилии отделяется неразрывным пробелом (используйте для этого

,{{nbsp}}или{{nobr}}). - Отрывы указывайте с той точностью, с которой проводился хронометраж (в современной Формуле-1 это тысячные доли секунды). Если отрыв превышает минуту, то вынесите минуты отдельно. Примеры:

+1:23,654,+24,567. Между знаком «+» и временем пробела быть не должно. Часы от минут и минуты от секунд отделяются двоеточием, а секунды от долей — запятой (ВП:Ч).

Пилот Формулы-1[править код]

Название статьи[править код]

Статью о пилоте следует называть так же, как и статью о любом человеке: в формате <фамилия>, <имена>. Например, Баррикелло, Рубенс. Если составные имена (или фамилии) не разделяются в родном языке дефисом, не следует его использовать и в русском написании. Например, вопреки частому «Хуан-Пабло Монтойя» более правильным является вариант Монтойя, Хуан Пабло.

Не забудьте сделать все возможные редиректы на имя пилота. Чем больше редиректов — тем лучше. В частности, должны быть созданы следующие редиректы:

- Со стандартного написания имени пилота. Если их несколько — значит, с нескольких.

- Просто с фамилии пилота, если в Википедии нет статей про другого человека с той же фамилией. Если же есть, вместо редиректа нужно сделать дизамбиг.

- С неполного википедийного написания имени пилота (например, с Лехто, Джей-Джей).

Структура статьи[править код]

- Поместите шаблон-карточку {{Пилот Формулы-1}}. Описание шаблона приведено в документации.

- Начните статью с полного имени пилота уже в естественном порядке, затем укажите имя пилота на его родном языке (используя шаблоны вида {{lang-xx}}, где xx — код языка). Укажите дату и место рождения пилота (а также дату и место смерти, если пилот уже умер), кратко укажите его основные достижения в Формуле-1 и других гоночных сериях, а также прочие достижения, например, руководство командой Формулы-1.

- В разделе «Биография» расскажите о детстве пилота, его происхождении, о родственниках, оказавших влияние на его увлечение гонками, о семье. Не следует заострять изложение на карьере пилота в гоночных сериях — для этого существуют другие разделы. Однако о картинговой карьере можно упомянуть здесь.

- В разделе «До Формулы-1» расскажите о доформульной карьере пилота: картинг, младшие гоночные серии, другие соревнования.

- В разделе «Карьера в Формуле-1» расскажите о карьере пилота в Формуле-1. Если необходимо, разделите карьеру на периоды, описав каждый из них в отдельном подразделе.

- В соответствующих разделах опишите также карьеру пилота в других крупных гоночных сериях.

- В отдельном разделе опишите, как складывалась карьера гонщика после окончания выступлений в автоспорте.

- В разделе «Результаты выступлений» приведите две таблицы: с полной статистикой выступлений пилота во всех значимых гоночных сериях, и полную таблицу результатов его выступлений в Формуле-1. Подробнее о таблицах см. соответствующий раздел статьи ВП:Статьи о Формуле-1/Оформление таблиц.

- Если гонщик участвовал также в других значимых гоночных сериях (WEC, IRL, DTM, Формула E), следует добавить также полную таблицу выступлений для каждой из этих серий.

В конце статьи добавьте координационные шаблоны: шаблон {{Чемпионы Формулы-1}}, если пилот входит в их число; соответствующие шаблоны, например, {{Чемпионы Евросерии Формулы-3}}, если пилот становился чемпионом в соответствующих младших сериях. Если пилот выступает в настоящее время, добавьте также шаблоны для его команды, например {{Scuderia Ferrari}} и шаблон {{Команды Формулы-1 текущего сезона}}. Добавьте также соответствующие категории: из верхних категорий Пилоты Формулы-1 по странам, Пилоты Формулы-1 по десятилетиям, Пилоты Формулы-1 по конструкторам и Пилоты Формулы-1 по наилучшему результату. Обратите внимание:

- При категоризации учитывайте только выступления пилота в зачётных Гран-при (например, Патрик Гайяр, занявший 6 место в Гран-при Испании 1980 года, признанном внезачётным, не может относиться к категориям Пилоты Формулы-1 1980-х годов и Пилоты Формулы-1, набиравшие очки, поскольку не участвовал ни в одной зачётной гонке Формулы-1 сезонов 1980—1989 и не набрал очков ни в одной зачётной гонке Формулы-1).

- При добавлении категории из верхней категории Пилоты Формулы-1 по наилучшему результату обратите внимание, что:

- если пилот был «боевым» пилотом (то есть боролся за право стартовать в зачётной гонке), но ни разу не стартовал в гонке (ни разу не прошёл квалификацию либо ни разу не стартовал в гонках, в которых прошёл), нужна только категория Пилоты Формулы-1, которые никогда не участвовали в гонке, а категория Пилоты Формулы-1, не набиравшие очков не нужна;

- если лучший результат пилота — 2 или 3 место, нужна только категория Обладатели подиума в Формуле-1, а категория Пилоты Формулы-1, набиравшие очки не нужна;

- если пилот побеждал в Гран-при, нужна только категория Победители Гран-при Формулы-1, а категории Обладатели подиума в Формуле-1 и Пилоты Формулы-1, набиравшие очки не нужны.

- Категория Чемпионы Формулы-1 не относится к категории Победители Гран-при Формулы-1, так как теоретически можно стать чемпионом Формулы-1, не завоевав в сезоне ни одной победы.

Команда Формулы-1[править код]

Название статей[править код]

- Для именования статей следует использовать краткое название команды на русском языке, например Рено (команда «Формулы-1»), за исключением случаев, когда это название представляет собой аббревиатуру. В таких случаях аббревиатура не переводится и не разворачивается, например BMW (команда «Формулы-1») (но не БМВ (команда «Формулы-1») и тем более не Bayerische Motoren Werke (команда «Формулы-1»)).

- Для частных команд 50-х, 60-х и 70-х годов допускается именование статьи на родном языке, например Ecurie Rosier.

- Уточнение «(команда „Формулы-1“)» следует ставить, если существуют или очевидно могут существовать статьи о других объектах с таким же названием. Например, кроме команды МакЛарен существуют одноимённые дорожно-спортивные автомобили. Часто название команды совпадает с названием какой-либо компании (Рено, Феррари, Ред Булл). В таком случае следует создать дизамбиг.

- Если описываемая команда участвовала не только в Формуле-1, но и в других крупных автоспортивных соревнованиях, следует добавить уточнение «(автогоночная команда)».

- Следует создать редиректы со следующих статей:

- С полного официального английского названия статьи: Mild Seven Renault F1 Team, BMW Williams F1 Team, West McLaren Mercedes и т. д.

- С краткого латинского названия статьи с указанием уточнения в скобках: Renault (команда «Формулы-1»), Williams (команда «Формулы-1»), McLaren (команда «Формулы-1») и т. д.

Содержимое[править код]

- Карточка Шаблон:Команда «Формулы-1».

- Краткая информация о команде: укажите страну происхождения, главные достижения команды (например, количество чемпионских титулов, Кубков конструкторов, и т. п.), напишите, кто сыграл важную роль в истории команды.

- Состав команды. Если команда действующая — укажите нынешних пилотов, если же это нет — укажите наиболее успешных пилотов этой команды, или всех, если пилотов было немного (максимум 5-6 человек).

- История команды.

- Укажите, кто основал команду, и когда. Учтите, что обычно история команды начинается задолго до участия в Формуле-1. Опишите этот «доформульный» период и основные достижения этого времени. Если в тот период за команду выступал кто-либо из известных пилотов Формулы-1 и других гоночных серий — укажите это.

- Опишите «формульный» период развития команды. Если он был достаточно продолжительным (более 3-4 лет), разделите его на логические периоды, опишите каждый более подробно в отдельном разделе. Если же участие команды в Формуле-1 было непродолжительным, можно выделить отдельный раздел под каждый год участия. Однако, в случае единичных гонок на протяжении нескольких лет выделение подразделов нецелесообразно (например, в случае некоторых частных команд в 50-е годы).

- Если команда участвовала также в других крупных спортивных соревнованиях, в отдельных разделах опишите также и это.

- Если команда уже не существует, опишите, как складывалась судьба её пилотов, руководителей, имущества (болидов и оборудования).

- В разделе «Результаты выступлений» приведите две таблицы с полной статистикой выступлений команды. В первой статье должна быть приведена общая статистика выступлений команды во всех гоночных сериях (включая и Формулу-1). В таблице должна содержаться общая информация о выступлениях, такая как число побед, подиумов и других достижений. Вторая таблица должна содержать все результаты команды в Формуле-1: шасси, двигатели, шины, пилоты, результаты на каждом из Гран-при. Подробнее об оформлении таблиц см. страницу ВП:Статьи о Формуле-1/Оформление таблиц.

- В разделе «См. также» укажите Список конструкторов «Формулы-1».

- В разделе «Ссылки» укажите адрес официального сайта команды, если такой существует.

- В конце статьи поместите навигационные шаблоны {{Конструкторы «Формулы-1»}}, а также шаблон подобный {{Osella}}, если таковой существует. Если команда становилась победителем Кубка конструкторов, укажите также шаблон {{Чемпионы-конструкторы «Формулы-1»}}.

- Статью следует включить в категорию Категория:Команды Формулы-1, а также согласно национальной принадлежности в одну из категорий метакатегории Категория:Автогоночные команды по странам.

- Не забудьте указать интервики (через привязку к соответствующему элементу Викиданных).

Сезон Формулы-1[править код]

Статья о сезоне Формулы-1.

Название статьи[править код]

Название статьи о сезоне Формулы-1 должно иметь вид Формула-1 в сезоне 2005. Желательно создать редирект Сезон 2005 Формулы-1.

Структура статьи[править код]

- Начните статью с шаблона {{Сезон Формулы-1}}. В качестве параметров укажите год проведения сезона, и если сезон уже завершён, имя чемпиона, название его команды, команду-победителя Кубка конструкторов, и фотографию чемпиона, сделанную в течение данного сезона.

- В первом абзаце дайте краткое описание сезона: количество этапов, дата начала и окончания сезона, имя чемпиона и обладателя Кубка конструкторов. Затем в литературной форме должны быть очень кратко изложены основные особенности сезона, например, о доминировании какого-либо пилота или команды. Описание должно быть очень кратким, так как подробнее события будут рассматриваться в соответствующем разделе.

- Общие сведения о регламенте чемпионата. В этом разделе должны быть в отдельных подразделах описаны особенности спортивного и технического регламента сезона, расписание сезона, составы команд.

- Технический регламент. Укажите допустимый объём двигателей, разрешён ли турбонаддув, другие особенности правил. Если перед началом этого сезона в технический регламент были внесены изменения, укажите их.

- Спортивный регламент. Укажите систему начисления очков в личном зачёте и зачёте Кубка конструкторов, число зачётных гонок. Также опишите изменения, если таковые были.

- Расписание сезона. В данном подразделе приведите таблицу со списком Гран-при данного сезона. В таблице указывается номер этапа, краткое и полное официальное названия Гран-при, место проведения, автодром, день и время старта гонки (местное и UTC). Пример оформления таблицы см. ниже.

- Составы команд. Таблица со списком команд, участвовавших в данном сезоне. Команды должны быть упорядочены согласно нумерации болидов пилотов, если нумерация (как правило) оставалась неименной в течение сезона. Если номера болидов менялись от гонки к гонке, сначала необходимо в алфавитном порядке указать заводские команды (то есть имеющие поддержку производителя болидов), затем также в алфавитном порядке указать частные команды, и в конце перечислить пилотов-частников. В таблице указывается полное название команды, названия шасси и двигателя, используемая резина, номера болидов (если таковые оставлись неизменными от гонки к гонке), имена основных пилотов команды, этапы, на которых эти пилоты выступали, и при необходимости, имена третьих и тест-пилотов. Подробнее об оформлении таблиц см. страницу ВП:Статьи о Формуле-1/Оформление таблиц.

- Обзор чемпионата. В этом разделе вначале осветите основные события сезона (например, для 2005 года: шинный скандал в Индианаполисе, скандал с двойным топливным баком B.A.R. и дисквалификация команды, вопрос с контрактом Дженсона Баттона). Далее в отдельных подразделах несколькими фразами опишите ход каждого из Гран-при.

- Результаты Гран-при. Таблица с основными результатами Гран-при сезона. В таблице указывается номер, краткое название Гран-при, обладатель поул-позиции, быстрого круга, победитель гонки, конструктор болида победителя гонки, шины победителя гонки, и ссылка на статью о соответствующем Гран-при. Подробнее об оформлении таблиц см. ВП:Статьи о Формуле-1/Оформление таблиц.

- Чемпионат мира. Таблица с полным зачётом чемпионата мира. В таблице указывается место, имя пилота, результаты в каждом Гран-при (используется шаблон {{Ф1Т}}) и количество набранных зачётных очков (в скобках при необходимости указывается полное число очков). Для пилотов, ни разу не классифицированных на финише Гран-при по ходу чемпионата, в столбце «Место» указывается прочерк. При помощи соответствующих параметров шаблона {{Ф1Т}} укажите обладателей поул-позиций и быстрейших кругов. В случае, если пилот управлял по ходу Гран-при двумя и более болидами, соответствующая ячейка данной таблицы должна включать в себя все результаты этого пилота (см. страницу ВП:Статьи о Формуле-1/Оформление таблиц). При этом с каждого результата следует сделать сноску с пояснениями.

- Кубок конструкторов (заполняется только для сезонов, в которых кубок разыгрывался). Таблица с полным зачётом Кубка конструкторов. Заполняется аналогично зачёту чемпионата мира. В сезонах, в которых в зачёт на каждом этапе шёл только лучший результат конструктора — в результатах Гран-при пишется именно этот результат. В сезонах, где в зачёт шли все результаты на каждом этапе — пишется результат всех автомобилей. Указывать обладателей поул-позиций и быстрейших кругов не нужно.

- Статистика. Таблицы со статистическими достижениями пилотов и конструкторов: победы, поул-позиции, быстрые круги, подиумы.

- Ссылки. Ссылки на материалы по данному сезону. Не нужно давать материалы по каждому Гран-при: их лучше привести в статье, посвящённой этому Гран-при.

- Внизу — навигационный шаблон для перемещения по сезонам: Шаблон:Список сезонов Формулы-1.

- Не нужно добавлять сезон в какую-либо категорию: она автоматически выставляется шаблоном Сезон Формулы-1. А вот интервики указать следует (через привязку к соответствующему элементу Викиданных). Статьи о чемпионатах в английской Википедии имеют названия вида 1980 Formula One season (до 1980 года включительно) и вида 1981 Formula One World Championship (начиная с 1981 года).

Отчёт о Гран-при Формулы-1[править код]

Статья об одном конкретном Гран-при.

В статье должны быть итоги Гран-при и краткое описание основных событий Гран-при, основных моментов гонки.

Название статьи[править код]

- Название статьи о Гран-при должно иметь вид <название гонки> <год проведения> года: например, Гран-при Малайзии 2006 года. В отдельных случаях возможны отступления от этой схемы.

- Следует создать редирект следующего вида: Гран-при Малайзии Формулы-1, сезон 2006 (для предыдущего примера).

- Оформление таблиц со статистикой описано в отдельном разделе.

Структура статьи[править код]

- Шаблон-карточка {{Гран-при Формулы-1}} с краткой информацией о Гран-при. Подробнее см. документацию к шаблону.

- Дайте краткое описание Гран-при. Напишите, когда и на каком автодроме состоялась гонка, опишите её основные особенности, например, доминирование какого-либо пилота или команды в ходе Гран-при.

- Раздел «События перед Гран-при». Этот раздел должен в литературной форме содержать описание основных событий, предшествовавших гонке: изменений в правилах, в составе команд, пилотов и спонсоров, смена руководства команд, обновления шасси. Также, если Гран-при было проведено до 1980 года включительно, следует включить также таблицу с составом команд.

- Раздел «Свободные заезды». Не нужно указывать полные таблицы результатов свободных заездов. В литературной форме опишите стратегию команд, погодные условия, дайте таблицу со списком обладателей лучшего времени в каждой из сессий свободных заездов. Дайте внешние ссылки на подробные результаты. В подразделе «тест-пилоты» в таблице укажите тест-пилотов, участвовавших только в свободных заездах.

- Раздел «Предквалификация». Если на данном Гран-при проводилась предквалификация, опишите её. Напишите время и день проведения, причины, по которым она проводилась, прокомментируйте результаты. Дайте таблицу результатов.

- Раздел «Квалификация». Опишите ход квалификации, опишите значимые события. В зависимости от формата квалификации дайте соответствующую таблицу.

- Раздел «Гонка». Опишите ход гонки. Укажите основные события, основные достижения пилотов, участвующих в гонке. Отметьте стратегию пит-стопов, которую предпочли команды. Затем представьте таблицу с результатами гонки.

- Если на Гран-при были какие-то события, которые заслуживают отдельного раздела и большого количества текста (например, шинный скандал в Индианаполисе-2005), то разместите такой раздел в этом месте.

- Раздел «События» (или «Рекорды», если в нём будут только рекорды). Здесь следует указывать рекорды, поставленные на этом Гран-при, а также прочие достижения (не обязательно самые рекордные) или интересные события уик-енда.

- Раздел «Пресс-конференции». Дайте ссылки на пресс-конференции, проходившие по ходу Гран-при. Перечислите участников. В двух словах опишите характер вопросов. Целесообразно дать ссылки как на исходную запись пресс-конференции на английском языке (на https://www.fia.com, https://www.formula1.com), так и на её перевод (например, на https://www.f1news.ru).

- Раздел «Ссылки». Представьте ссылки на материалы, связанные с Гран-при. Это могут быть обзоры Гран-при, комментарии известных лиц, отзывы пилотов и т. п. Целесообразно в статью о каждом Гран-при ставить ссылки на результаты на официальных сайтах (https://www.fia.com, https://www.formula1.com) и ссылки на комментарии после гонки (например, на https://www.f1news.ru).

- Раздел «Примечания» — для сносок (если нужны).

- Ссылка на предыдущий и следующий Гран-при.

- Не ставьте категорию: она будет автоматически поставлена с помощью карточки Шаблон:Гран-при Формулы-1.

- Укажите интервики (через привязку к соответствующему элементу Викиданных). В английской Википедии название соответствующей статьи имеет следующий формат: 2006 Malaysian Grand Prix.

Статья о конкретном шасси Формулы-1[править код]

Название статьи должно быть дано латиницей, с указанием конкретной модели шасси, например Jordan EJ15. Статья должна содержать шаблон-карточку {{Гоночный автомобиль}} с основной информацией о шасси, описание обстоятельств создания шасси, историю её выступлений. Приведите таблицу результатов, в которой укажите только результаты, достигнутые на этом шасси. Однако, указывая место конструктора и число набранных в сезоне очков, указывайте полное число очков и окончательное место в Кубке конструкторов с соответствующей сноской.

Formula One logo since 2018 |

|

| Category | Open-wheel single-seater Formula auto racing |

|---|---|

| Country | International |

| Inaugural season | 1950 |

| Drivers | 20 |

| Teams | 10 |

| Chassis manufacturers | 10 |

| Engine manufacturers |

|

| Tyre suppliers | Pirelli |

| Drivers’ champion | (Red Bull Racing-RBPT) |

| Constructors’ champion | |

| Official website | formula1.com |

Formula One (more commonly known as Formula 1 or F1) is the highest class of international racing for open-wheel single-seater formula racing cars sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). The FIA Formula One World Championship has been one of the premier forms of racing around the world since its inaugural season in 1950. The word formula in the name refers to the set of rules to which all participants’ cars must conform.[1] A Formula One season consists of a series of races, known as Grands Prix. Grands Prix take place in multiple countries and continents around the world on either purpose-built circuits or closed public roads.

A points system is used at Grands Prix to determine two annual World Championships: one for the drivers, and one for the constructors (the teams). Each driver must hold a valid Super Licence, the highest class of racing licence issued by the FIA,[2] and the races must be held on tracks graded «1», the highest grade-rating issued by the FIA for tracks.[2]

Formula One cars are the fastest regulated road-course racing cars in the world, owing to very high cornering speeds achieved through the generation of large amounts of aerodynamic downforce. Much of this downforce is generated by front and rear wings, which have the side effect of causing severe turbulence behind each car. The turbulence reduces the downforce generated by the cars following directly behind, making it hard to overtake. Major changes made to the cars for the 2022 season has seen greater use of ground effect aerodynamics and modified wings to reduce the turbulence behind the cars, with the goal of making overtaking easier.[3] The cars are dependent on electronics, aerodynamics, suspension and tyres. Traction control, launch control, and automatic shifting, plus other electronic driving aids, were first banned in 1994. They were briefly reintroduced in 2001, and have more recently been banned since 2004 and 2008, respectively.[4]

With the average annual cost of running a team – designing, building, and maintaining cars, pay, transport – being approximately £220,000,000 (or $265,000,000),[5] its financial and political battles are widely reported. On 23 January 2017, Liberty Media completed its acquisition of the Formula One Group, from private-equity firm CVC Capital Partners for £6,600,000,000 (or $8,000,000,000).[6][7]

History[edit]

Formula One originated from the European Motor Racing Championships of the 1920s and 1930s. The formula consists of a set of rules that all participants’ cars must follow. Formula One was a new formula agreed upon during 1946 with the first non-championship races taking place during that year. The first Formula One Grand Prix was the 1946 Turin Grand Prix. A number of Grand Prix racing organisations had laid out rules for a motor racing world championship before World War II, but due to the suspension of racing during the conflict, the World Drivers’ Championship did not become formalised until 1947. The first world championship race took place at the Silverstone Circuit in the United Kingdom on 13 May 1950. Giuseppe Farina, competing for Alfa Romeo, won the first Drivers’ World Championship, narrowly defeating his teammate Juan Manuel Fangio. However, Fangio would go on to win the championship in 1951, 1954, 1955, 1956, and 1957 respectively. This set the record for the most World Championships won by a single driver; a record that stood for 46 years until Michael Schumacher won his sixth championship in 2003.

A Constructors’ Championship was added in the 1958 season. Stirling Moss, despite being regarded as one of the greatest Formula One drivers in the 1950s and 1960s, never won the Formula One championship.[8] Between 1955 and 1961, Moss finished second place in the championship four times and in third place the other three times.[9][10] Fangio, however, achieved the record of winning 24 of the 52 races he entered – a record for the highest percentage of Formula One races won by a single driver. This is a record he holds to this day.[11] National championships existed in South Africa and the UK in the 1960s and 1970s. Non-championship Formula One events were held by promoters for many years. However, due to the increasing cost of competition, the last of these was held in 1983.[12]

This time period featured teams managed by road-car manufacturers; such as: Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Mercedes-Benz and Maserati. The first seasons featured pre-war cars like Alfa’s 158. They were front-engined, with narrow tyres and 1.5-litre supercharged or 4.5-litre naturally aspirated engines. The 1952 and 1953 seasons were run to Formula Two regulations, for smaller, less powerful cars, due to concerns over the lack of Formula One cars available.[13][14] When a new Formula One formula for engines limited to 2.5 litres was reinstated to the world championship for 1954, Mercedes-Benz introduced their W196. The W196 featured things never seen on Formula One cars before, such as: desmodromic valves, fuel injection and enclosed streamlined bodywork. Mercedes drivers won the championship for the next two years, before the team withdrew from all motorsport competitions due to the 1955 Le Mans disaster.[15]

Technological developments[edit]

The first major technological development in the sport was Bugatti’s introduction of mid-engined cars. Jack Brabham, the world champion in 1959, 1960, and 1966, soon proved the mid-engine’s superiority over all other engines; and by 1961 all teams had switched to mid-engined cars. The Ferguson P99, a four-wheel drive design, was the last front-engined Formula One car to enter a world championship race. It was entered in the 1961 British Grand Prix, the only front-engined car to compete that year.[16]

During 1962, Lotus introduced a car with an aluminium-sheet monocoque chassis instead of the traditional space-frame design. This proved to be the greatest technological breakthrough since the introduction of mid-engined cars. During 1968, Brabham became the first team to show advertisements on their cars. This introduced sponsorship to the sport.[17] Five months later, Lotus followed Brabham’s example when they painted an Imperial Tobacco livery on their cars at the 1968 Spanish Grand Prix.

Aerodynamic downforce slowly gained importance in car design with the appearance of aerofoils during the late 1960s. During the late 1970s, Lotus introduced ground-effect aerodynamics (previously used on Jim Hall’s Chaparral 2J during 1970) that provided enormous downforce and greatly increased cornering speeds. The aerodynamic forces pressing the cars to the track were up to five times the car’s weight. As a result, extremely stiff springs were needed to maintain a constant ride height, leaving the suspension virtually solid. This meant that the drivers were depending entirely on the tyres for any small amount of cushioning of the car and driver from irregularities of the road surface.[18]

Big business[edit]

Beginning in the 1970s, Bernie Ecclestone rearranged the management of Formula One’s commercial rights; he is widely credited with transforming the sport into the multibillion-dollar business it now is.[19][20] When Ecclestone bought the Brabham team during 1971, he gained a seat on the Formula One Constructors’ Association and during 1978, he became its president.[21] Previously, the circuit owners controlled the income of the teams and negotiated with each individually; however, Ecclestone persuaded the teams to «hunt as a pack» through FOCA.[20] He offered Formula One to circuit owners as a package, which they could take or leave. In return for the package, almost all that was required was to surrender trackside advertising.[19]

The formation of the Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile (FISA) during 1979 set off the FISA–FOCA war, during which FISA and its president Jean-Marie Balestre argued repeatedly with FOCA over television revenues and technical regulations.[22] The Guardian said that Ecclestone and Max Mosley «used [FOCA] to wage a guerrilla war with a very long-term aim in view». FOCA threatened to establish a rival series, boycotted a Grand Prix and FISA withdrew its sanction from races.[19] The result was the 1981 Concorde Agreement, which guaranteed technical stability, as teams were to be given reasonable notice of new regulations.[23] Although FISA asserted its right to the TV revenues, it handed the administration of those rights to FOCA.[24]

FISA imposed a ban on ground-effect aerodynamics during 1983.[25] By then, however, turbocharged engines, which Renault had pioneered in 1977, were producing over 520 kW (700 bhp) and were essential to be competitive. By 1986, a BMW turbocharged engine achieved a flash reading of 5.5 bar (80 psi) pressure, estimated[who?] to be over 970 kW (1,300 bhp) in qualifying for the Italian Grand Prix. The next year, power in race trim reached around 820 kW (1,100 bhp), with boost pressure limited to only 4.0 bar.[26] These cars were the most powerful open-wheel circuit racing cars ever. To reduce engine power output and thus speeds, the FIA limited fuel tank capacity in 1984, and boost pressures in 1988, before banning turbocharged engines completely in 1989.[27]

The development of electronic driver aids began during the 1980s. Lotus began to develop a system of active suspension, which first appeared during 1983 on the Lotus 92.[28] By 1987, this system had been perfected and was driven to victory by Ayrton Senna in the Monaco Grand Prix that year. In the early 1990s, other teams followed suit and semi-automatic gearboxes and traction control were a natural progression. The FIA, due to complaints that technology was determining the outcome of races more than driver skill, banned many such aids for the 1994 season. This resulted in cars that were previously dependent on electronic aids becoming very «twitchy» and difficult to drive. Observers felt the ban on driver aids was in name only, as they «proved difficult to police effectively».[29]

The teams signed a second Concorde Agreement during 1992 and a third in 1997.[30]

On the track, the McLaren and Williams teams dominated the 1980s and 1990s. Brabham were also being competitive during the early part of the 1980s, winning two Drivers’ Championships with Nelson Piquet. Powered by Porsche, Honda, and Mercedes-Benz, McLaren won sixteen championships (seven constructors’ and nine drivers’) in that period, while Williams used engines from Ford, Honda, and Renault to also win sixteen titles (nine constructors’ and seven drivers’). The rivalry between racers Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost became F1’s central focus during 1988 and continued until Prost retired at the end of 1993. Senna died at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix after crashing into a wall on the exit of the notorious curve Tamburello. The FIA worked to improve the sport’s safety standards since that weekend, during which Roland Ratzenberger also died in an accident during Saturday qualifying. No driver died of injuries sustained on the track at the wheel of a Formula One car for 20 years until the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix, where Jules Bianchi collided with a recovery vehicle after aquaplaning off the circuit, dying nine months later from his injuries. Since 1994, three track marshals have died, one at the 2000 Italian Grand Prix,[31] the second at the 2001 Australian Grand Prix[31] and the third at the 2013 Canadian Grand Prix.

Since the deaths of Senna and Ratzenberger, the FIA has used safety as a reason to impose rule changes that otherwise, under the Concorde Agreement, would have had to be agreed upon by all the teams – most notably the changes introduced for 1998. This so-called ‘narrow track’ era resulted in cars with smaller rear tyres, a narrower track overall, and the introduction of grooved tyres to reduce mechanical grip. The objective was to reduce cornering speeds and to produce racing similar to rainy conditions by enforcing a smaller contact patch between tyre and track. This, according to the FIA, was to reduce cornering speeds in the interest of safety.[32]

Results were mixed, as the lack of mechanical grip resulted in the more ingenious designers clawing back the deficit with aerodynamic grip. This resulted in pushing more force onto the tyres through wings and aerodynamic devices, which in turn resulted in less overtaking as these devices tended to make the wake behind the car turbulent or ‘dirty’. This prevented other cars from following closely due to their dependence on ‘clean’ air to make the car stick to the track. The grooved tyres also had the unfortunate side effect of initially being of a harder compound to be able to hold the grooved tread blocks, which resulted in spectacular accidents in times of aerodynamic grip failure, as the harder compound could not grip the track as well.

Drivers from McLaren, Williams, Renault (formerly Benetton), and Ferrari, dubbed the «Big Four», won every World Championship from 1984 to 2008. The teams won every Constructors’ Championship from 1979 to 2008, as well as placing themselves as the top four teams in the Constructors’ Championship in every season between 1989 and 1997, and winning every race but one (the 1996 Monaco Grand Prix) between 1988 and 1997. Due to the technological advances of the 1990s, the cost of competing in Formula One increased dramatically, thus increasing financial burdens. This, combined with the dominance of four teams (largely funded by big car manufacturers such as Mercedes-Benz), caused the poorer independent teams to struggle not only to remain competitive but to stay in business. This effectively forced several teams to withdraw.

Manufacturers’ return[edit]

Michael Schumacher and Ferrari won five consecutive Drivers’ Championships (2000–2004) and six consecutive Constructors’ Championships (1999–2004). Schumacher set many new records, including those for Grand Prix wins (91, since beaten by Lewis Hamilton), wins in a season (thirteen, since beaten by Max Verstappen), and most Drivers’ Championships (seven, tied with Lewis Hamilton as of 2021).[33] Schumacher’s championship streak ended on 25 September 2005, when Renault driver Fernando Alonso became Formula One’s youngest champion at that time (until Lewis Hamilton in 2008 and followed by Sebastian Vettel in 2010). During 2006, Renault and Alonso won both titles again. Schumacher retired at the end of 2006 after sixteen years in Formula One, but came out of retirement for the 2010 season, racing for the newly formed Mercedes works team, following the rebrand of Brawn GP.

During this period, the championship rules were changed frequently by the FIA with the intention of improving the on-track action and cutting costs.[34] Team orders, legal since the championship started during 1950, were banned during 2002, after several incidents, in which teams openly manipulated race results, generating negative publicity, most famously by Ferrari at the 2002 Austrian Grand Prix. Other changes included the qualifying format, the points scoring system, the technical regulations, and rules specifying how long engines and tyres must last. A «tyre war» between suppliers Michelin and Bridgestone saw lap times fall, although, at the 2005 United States Grand Prix at Indianapolis, seven out of ten teams did not race when their Michelin tyres were deemed unsafe for use, leading to Bridgestone becoming the sole tyre supplier to Formula One for the 2007 season by default. Bridgestone then went on to sign a contract on 20 December 2007 that officially made them the exclusive tyre supplier for the next three seasons.[35]

During 2006, Max Mosley outlined a «green» future for Formula One, in which efficient use of energy would become an important factor.[36]

Starting in 2000, with Ford’s purchase of Stewart Grand Prix to form the Jaguar Racing team, new manufacturer-owned teams entered Formula One for the first time since the departure of Alfa Romeo and Renault at the end of 1985. By 2006, the manufacturer teams – Renault, BMW, Toyota, Honda, and Ferrari – dominated the championship, taking five of the first six places in the Constructors’ Championship. The sole exception was McLaren, which at the time was part-owned by Mercedes-Benz. Through the Grand Prix Manufacturers Association (GPMA), the manufacturers negotiated a larger share of Formula One’s commercial profit and a greater say in the running of the sport.[37]

Manufacturers’ decline and return of the privateers[edit]

In 2008 and 2009, Honda, BMW, and Toyota all withdrew from Formula One racing within the space of a year, blaming the economic recession. This resulted in the end of manufacturer dominance within the sport. The Honda F1 team went through a management buyout to become Brawn GP with Ross Brawn and Nick Fry running and owning the majority of the organisation. Brawn GP laid off hundreds of employees, but eventually won the year’s world championships. BMW F1 was bought out by the original founder of the team, Peter Sauber. The Lotus F1 Team[38] were another, formerly manufacturer-owned team that reverted to «privateer» ownership, together with the buy-out of the Renault team by Genii Capital investors. A link with their previous owners still survived, however, with their car continuing to be powered by a Renault engine until 2014.

The three teams that debuted in 2010 (Hispania Racing F1 Team/HRT Formula 1 Team, Lotus Racing/Team Lotus/Caterham F1 Team, and Virgin Racing/Marussia Virgin Racing/Marussia F1 Team/Manor Marussia F1 Team/Manor Racing MRT) all disappeared within seven years of their debuts

McLaren also announced that it was to reacquire the shares in its team from Mercedes-Benz (McLaren’s partnership with Mercedes was reported to have started to sour with the McLaren Mercedes SLR road car project and tough F1 championships which included McLaren being found guilty of spying on Ferrari). Hence, during the 2010 season, Mercedes-Benz re-entered the sport as a manufacturer after its purchase of Brawn GP, and split with McLaren after 15 seasons with the team.

During the 2009 season of Formula One, the sport was gripped by the FIA–FOTA dispute. The FIA President Max Mosley proposed numerous cost-cutting measures for the following season, including an optional budget cap for the teams;[39] teams electing to take the budget cap would be granted greater technical freedom, adjustable front and rear wings and an engine not subject to a rev limiter.[39] The Formula One Teams Association (FOTA) believed that allowing some teams to have such technical freedom would have created a ‘two-tier’ championship, and thus requested urgent talks with the FIA. However, talks broke down and FOTA teams announced, with the exception of Williams and Force India,[40][41] that ‘they had no choice’ but to form a breakaway championship series.[41]

On 24 June, an agreement was reached between Formula One’s governing body and the teams to prevent a breakaway series. It was agreed teams must cut spending to the level of the early 1990s within two years; exact figures were not specified,[42] and Max Mosley agreed he would not stand for re-election to the FIA presidency in October.[43] Following further disagreements, after Max Mosley suggested he would stand for re-election,[44] FOTA made it clear that breakaway plans were still being pursued. On 8 July, FOTA issued a press release stating they had been informed they were not entered for the 2010 season,[45] and an FIA press release said the FOTA representatives had walked out of the meeting.[46] On 1 August, it was announced FIA and FOTA had signed a new Concorde Agreement, bringing an end to the crisis and securing the sport’s future until 2012.[47]

To compensate for the loss of manufacturer teams, four new teams were accepted entry into the 2010 season ahead of a much anticipated ‘cost-cap’. Entrants included a reborn Team Lotus – which was led by a Malaysian consortium including Tony Fernandes, the boss of Air Asia; Hispania Racing – the first Spanish Formula One team; as well as Virgin Racing – Richard Branson’s entry into the series following a successful partnership with Brawn the year before. They were also joined by the US F1 Team, which planned to run out of the United States as the only non-European-based team in the sport. Financial issues befell the squad before they even made the grid. Despite the entry of these new teams, the proposed cost-cap was repealed and these teams – who did not have the budgets of the midfield and top-order teams – ran around at the back of the field until they inevitably collapsed; HRT in 2012, Caterham (formerly Lotus) in 2014 and Manor (formerly Virgin then Marussia), having survived falling into administration in 2014, went under at the end of 2016.

Hybrid era[edit]

A major rule shake-up in 2014 saw the 2.4-litre naturally-aspirated V8 engines replaced by 1.6-litre turbocharged hybrid power units. This prompted Honda to return to the sport in 2015 as the championship’s fourth engine manufacturer. Mercedes emerged as the dominant force after the rule shake-up, with Lewis Hamilton winning the championship closely followed by his main rival and teammate, Nico Rosberg, with the team winning 16 out of the 19 races that season. In 2015, Ferrari was the only challenger to Mercedes, with Vettel taking victory in the three Grands Prix Mercedes did not win.[48]

In the 2016 season, Haas F1 Team joined the grid. The season began in dominant fashion for Nico Rosberg, winning the first 4 Grands Prix. His charge was halted by Max Verstappen, who took his maiden win in Spain in his debut race for Red Bull. After that, the reigning champion Lewis Hamilton decreased the point gap between him and Rosberg to only one point, before taking the championship lead heading into the summer break. Following the break, the 1–2 positioning remained constant until an engine failure for Hamilton in Malaysia left Rosberg in a commanding lead that he would not relinquish in the 5 remaining races. Having won the title by a mere 5 points, Rosberg retired from Formula One at season’s end, becoming the first driver since Alain Prost in 1993 to retire after winning the Drivers’ Championship.

Mercedes won 8 consecutive Constructors’ Championships and driver Lewis Hamilton won 6 Drivers’ Championships during the hybrid era.

2017 and 2018 featured a title battle between Mercedes and Ferrari.[49][50][51][52] However, Mercedes continued to experience dominance for the majority of the era, with some even calling the hybrid era the «Mercedes era».[53] The team won 8 consecutive Constructors’ Championships from 2014 to 2021 and 7 consecutive Drivers’ Championships from 2014 to 2020. The level of dominance was so high that 111 of the 160 races and an average of 78% of the available points from 2014 to 2021 were won by a Mercedes driver, with an average winning margin of 15.5 seconds.[54] Driver Lewis Hamilton won 81 of the races and 6 of the Drivers’ Championships that Mercedes won during this 8-year period.[55][56][57]

This era has seen an increase in car manufacturer presence in the sport. After Honda’s return as an engine manufacturer in 2015, Renault came back as a team in 2016 after buying back the Lotus F1 team. In 2018, Aston Martin and Alfa Romeo became Red Bull and Sauber’s title sponsors, respectively. Sauber was rebranded as Alfa Romeo Racing for the 2019 season, while Racing Point part-owner Lawrence Stroll bought a stake in Aston Martin to rebrand the Racing Point team as Aston Martin for 2021. In August 2020, a new Concorde Agreement was signed by all ten F1 teams committing them to the sport until 2025, including a $145M budget cap for car development to support equal competition and sustainable development in the future.[58][59]

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the sport to adapt to budgetary and logistical limitations. A significant overhaul of the technical regulations intended to be introduced in the 2021 season was pushed back to 2022,[60] with constructors instead using their 2020 chassis for two seasons and a token system limiting which parts could be modified was introduced.[61] The start of the 2020 season was delayed by several months,[62] and both it and 2021 seasons were subject to several postponements, cancellations and rescheduling of races due to the shifting restrictions on international travel. Many races took place behind closed doors and with only essential personnel present to maintain social distancing.[63]

Mercedes dominance began to be challenged by Red Bull in 2021, with the 2021 Drivers’ Championship going to Red Bull driver Max Verstappen after a controversial finish at the 2021 Abu Dhabi Grand Prix.[64][65][66]

In 2022, a major rule and car design change was announced by the F1 governing body, intended to promote closer racing through the use of ground effects, new aerodynamics, larger wheels with low-profile tires, and redesigned nose and wing regulations.[67][68] The 2022 Constructors’ and Drivers’ Championships were won by Red Bull and Verstappen, respectively.[69][70] This marked the end of a dominant era for Mercedes and Hamilton, with Mercedes finishing 3rd and Hamilton finishing 6th with the first winless season in his career.[71]

Racing and strategy[edit]