Бесплатный переводчик онлайн с русского на английский

Вам нужно переводить на английский сообщения в чатах, письма бизнес-партнерам и в службы поддержки онлайн-магазинов или домашнее задание? PROMT.One мгновенно переведет с русского на английский и еще на 20+ языков.

Точный переводчик

С помощью PROMT.One наслаждайтесь точным переводом с русского на английский, а также смотрите английскую транскрипцию, произношение и варианты переводов слов с примерами употребления в предложениях. Бесплатный онлайн-переводчик PROMT.One — достойная альтернатива Google Translate и другим сервисам, предоставляющим перевод с английского на русский и с русского на английский. Переводите в браузере на персональных компьютерах, ноутбуках, на мобильных устройствах или установите мобильное приложение Переводчик PROMT.One для iOS и Android.

Нужно больше языков?

PROMT.One бесплатно переводит онлайн с русского на азербайджанский, арабский, греческий, иврит, испанский, итальянский, казахский, китайский, корейский, немецкий, португальский, татарский, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, украинский, финский, французский, эстонский и японский.

«La France» redirects here. For other uses, see Lafrance.

«French Republic» redirects here. For previous republics, see French Republics.

Coordinates: 47°N 2°E / 47°N 2°E

|

French Republic République française (French) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Emblem[I] |

|

| Motto: «Liberté, égalité, fraternité«

(«Liberty, Equality, Fraternity») |

|

| Anthem: «La Marseillaise» | |

| Great Seal

|

|

|

Location of France (red or dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Paris 48°51′N 2°21′E / 48.850°N 2.350°E |

| Official language and national language |

French[II] |

| Nationality (2021) |

|

| Religion

(2020)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | French |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

|

• President |

Emmanuel Macron |

|

• Prime Minister |

Élisabeth Borne |

| Legislature | Parliament |

|

• Upper house |

Senate |

|

• Lower house |

National Assembly |

| Establishment | |

|

• Kingdom of the West Franks — Treaty of Verdun |

10 August 843 |

|

• Kingdom of France — Capetian rulers of France |

3 July 987 |

|

• French Republic — French First Republic |

22 September 1792 |

|

• Founded the EEC[III] |

1 January 1958 |

|

• Current constitution — French Fifth Republic |

4 October 1958 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

643,801 km2 (248,573 sq mi)[5] (42nd) |

|

• Water (%) |

0.86 (2015)[6] |

|

• Metropolitan France (IGN) |

551,695 km2 (213,011 sq mi)[IV] (50th) |

|

• Metropolitan France (Cadastre) |

543,940.9 km2 (210,016.8 sq mi)[V][7] (50th) |

| Population | |

|

• January 2023 estimate |

|

|

• Density |

105.4627/km2 (106th) |

|

• Metropolitan France, estimate as of January 2023 |

|

|

• Density |

121/km2 (313.4/sq mi) (89th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 28th |

| Currency |

|

| Time zone | UTC+1 (Central European Time) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+2 (Central European Summer Time[IX]) |

| Note: Various other time zones are observed in overseas France.[VIII] Although France is in the UTC (Z) (Western European Time) zone, UTC+01:00 (Central European Time) was enforced as the standard time since 25 February 1940, upon German occupation in WW2, with a +0:50:39 offset (and +1:50:39 during DST) from Paris LMT (UTC+0:09:21).[13] |

|

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +33[X] |

| ISO 3166 code | FR |

| Internet TLD | .fr[XI] |

|

Source gives area of metropolitan France as 551,500 km2 (212,900 sq mi) and lists overseas regions separately, whose areas sum to 89,179 km2 (34,432 sq mi). Adding these give the total shown here for the entire French Republic. The CIA reports the total as 643,801 km2 (248,573 sq mi). |

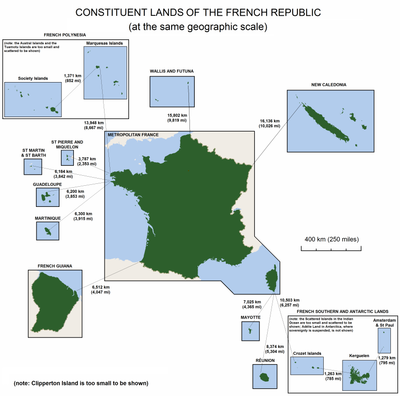

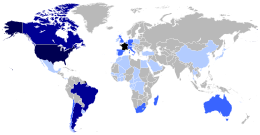

France (French: [fʁɑ̃s] ), officially the French Republic (French: République française [ʁepyblik frɑ̃sɛz]),[14] is a country located primarily in Western Europe. It also includes overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans,[XII] giving it one of the largest discontiguous exclusive economic zones in the world. Its metropolitan area extends from the Rhine to the Atlantic Ocean and from the Mediterranean Sea to the English Channel and the North Sea; overseas territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the North Atlantic, the French West Indies, and many islands in Oceania and the Indian Ocean. Its eighteen integral regions (five of which are overseas) span a combined area of 643,801 km2 (248,573 sq mi) and had a total population of over 68 million as of January 2023.[5][8] France is a unitary semi-presidential republic with its capital in Paris, the country’s largest city and main cultural and commercial centre; other major urban areas include Marseille, Lyon, Toulouse, Lille, Bordeaux, and Nice.

Inhabited since the Palaeolithic era, the territory of Metropolitan France was settled by Celtic tribes known as Gauls during the Iron Age. Rome annexed the area in 51 BC, leading to a distinct Gallo-Roman culture that laid the foundation of the French language. The Germanic Franks formed the Kingdom of Francia, which became the heartland of the Carolingian Empire. The Treaty of Verdun of 843 partitioned the empire, with West Francia becoming the Kingdom of France in 987. In the High Middle Ages, France was a powerful but highly decentralised feudal kingdom. Philip II successfully strengthened royal power and defeated his rivals to double the size of the crown lands; by the end of his reign, France had emerged as the most powerful state in Europe. From the mid-14th to the mid-15th century, France was plunged into a series of dynastic conflicts involving England, collectively known as the Hundred Years’ War, and a distinct French identity emerged as a result. The French Renaissance saw art and culture flourish, conflict with the House of Habsburg, and the establishment of a global colonial empire, which by the 20th century would become the second-largest in the world.[15] The second half of the 16th century was dominated by religious civil wars between Catholics and Huguenots that severely weakened the country. France again emerged as Europe’s dominant power in the 17th century under Louis XIV following the Thirty Years’ War.[16] Inadequate economic policies, inequitable taxes and frequent wars (notably a defeat in the Seven Years’ War and costly involvement in the American War of Independence) left the kingdom in a precarious economic situation by the end of the 18th century. This precipitated the French Revolution of 1789, which overthrew the Ancien Régime and produced the Declaration of the Rights of Man, which expresses the nation’s ideals to this day.

France reached its political and military zenith in the early 19th century under Napoleon Bonaparte, subjugating much of continental Europe and establishing the First French Empire. The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars shaped the course of European and world history. The collapse of the empire initiated a period of relative decline, in which France endured a tumultuous succession of governments until the founding of the French Third Republic during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Subsequent decades saw a period of optimism, cultural and scientific flourishing, as well as economic prosperity, known as the Belle Époque. France was one of the major participants of World War I, from which it emerged victorious at a great human and economic cost. It was among the Allied powers of World War II but was soon occupied by the Axis in 1940. Following liberation in 1944, the short-lived Fourth Republic was established and later dissolved in the course of the Algerian War. The current Fifth Republic was formed in 1958 by Charles de Gaulle. Algeria and most French colonies became independent in the 1960s, with the majority retaining close economic and military ties with France.

France retains its centuries-long status as a global centre of art, science and philosophy. It hosts the fifth-largest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites and is the world’s leading tourist destination, receiving over 89 million foreign visitors in 2018.[17] France is a developed country ranked 28th in the Human Development Index, with the world’s seventh-largest economy by nominal GDP and tenth-largest by PPP; in terms of aggregate household wealth, it ranks fourth in the world.[18] France performs well in international rankings of education, health care, and life expectancy. It remains a great power in global affairs,[19] being one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council and an official nuclear-weapon state. France is a founding and leading member of the European Union and the Eurozone,[20] as well as a key member of the Group of Seven, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Francophonie.

Etymology and pronunciation

Originally applied to the whole Frankish Empire, the name France comes from the Latin Francia, or «realm of the Franks».[21] Modern France is still named today Francia in Italian and Spanish, while Frankreich in German, Frankrijk in Dutch and Frankrike in Swedish all mean «Land/realm of the Franks».

The name of the Franks is related to the English word frank («free»): the latter stems from the Old French franc («free, noble, sincere»), ultimately from Medieval Latin francus («free, exempt from service; freeman, Frank»), a generalisation of the tribal name that emerged as a Late Latin borrowing of the reconstructed Frankish endonym *Frank.[22][23] It has been suggested that the meaning «free» was adopted because, after the conquest of Gaul, only Franks were free of taxation,[24] or more generally because they had the status of freemen in contrast to servants or slaves.[23]

The etymology of *Frank is uncertain. It is traditionally derived from the Proto-Germanic word *frankōn, which translates as «javelin» or «lance» (the throwing axe of the Franks was known as the francisca),[25] although these weapons may have been named because of their use by the Franks, not the other way around.[23]

In English, ‘France’ is pronounced FRANSS in American English and FRAHNSS or FRANSS in British English. The pronunciation with is mostly confined to accents with the trap-bath split such as Received Pronunciation, though it can be also heard in some other dialects such as Cardiff English, in which is in free variation with .[26]

History

Prehistory (before the 6th century BC)

One of the Lascaux paintings: a horse – approximately 17,000 BC.[27]

The oldest traces of human life in what is now France date from approximately 1.8 million years ago.[28] Over the ensuing millennia, humans were confronted by a harsh and variable climate, marked by several glacial periods. Early hominids led a nomadic hunter-gatherer life.[28] France has a large number of decorated caves from the Upper Paleolithic era, including one of the most famous and best-preserved, Lascaux[28] (approximately 18,000 BC). At the end of the last glacial period (10,000 BC), the climate became milder;[28] from approximately 7,000 BC, this part of Western Europe entered the Neolithic era and its inhabitants became sedentary.

After strong demographic and agricultural development between the 4th and 3rd millennia, metallurgy appeared at the end of the 3rd millennium, initially working gold, copper and bronze, as well as later iron.[29] France has numerous megalithic sites from the Neolithic period, including the exceptionally dense Carnac stones site (approximately 3,300 BC).

Antiquity (6th century BC–5th century AD)

In 600 BC, Ionian Greeks from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (present-day Marseille), on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. This makes it France’s oldest city.[30] At the same time, some Gallic Celtic tribes penetrated parts of Eastern and Northern France, gradually spreading through the rest of the country between the 5th and 3rd century BC.[31] The concept of Gaul emerged during this period, corresponding to the territories of Celtic settlement ranging between the Rhine, the Atlantic Ocean, the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean. The borders of modern France roughly correspond to ancient Gaul, which was inhabited by Celtic Gauls. Gaul was then a prosperous country, of which the southernmost part was heavily subject to Greek and Roman cultural and economic influences.

Around 390 BC, the Gallic chieftain Brennus and his troops made their way to Italy through the Alps, defeated the Romans in the Battle of the Allia, and besieged and ransomed Rome.[32] The Gallic invasion left Rome weakened, and the Gauls continued to harass the region until 345 BC when they entered into a formal peace treaty with Rome.[33] But the Romans and the Gauls would remain adversaries for the next centuries, and the Gauls would continue to be a threat in Italy.[34]

Around 125 BC, the south of Gaul was conquered by the Romans, who called this region Provincia Nostra («Our Province»), which over time evolved into the name Provence in French.[35] Julius Caesar conquered the remainder of Gaul and overcame a revolt carried out by the Gallic chieftain Vercingetorix in 52 BC.[36]

Gaul was divided by Augustus into Roman provinces.[37] Many cities were founded during the Gallo-Roman period, including Lugdunum (present-day Lyon), which is considered the capital of the Gauls.[37] These cities were built in traditional Roman style, with a forum, a theatre, a circus, an amphitheatre and thermal baths. The Gauls mixed with Roman settlers and eventually adopted Roman culture and Roman speech (Latin, from which the French language evolved). Roman polytheism merged with Gallic paganism into the same syncretism.

From the 250s to the 280s AD, Roman Gaul suffered a serious crisis with its fortified borders being attacked on several occasions by barbarians.[38] Nevertheless, the situation improved in the first half of the 4th century, which was a period of revival and prosperity for Roman Gaul.[39] In 312, Emperor Constantine I converted to Christianity. Subsequently, Christians, who had been persecuted until then, increased rapidly across the entire Roman Empire.[40] But, from the beginning of the 5th century, the Barbarian Invasions resumed.[41] Teutonic tribes invaded the region from present-day Germany, the Visigoths settling in the southwest, the Burgundians along the Rhine River Valley, and the Franks (from whom the French take their name) in the north.[42]

Early Middle Ages (5th–10th century)

Frankish expansion from 481 to 870

At the end of the Antiquity period, ancient Gaul was divided into several Germanic kingdoms and a remaining Gallo-Roman territory, known as the Kingdom of Syagrius. Simultaneously, Celtic Britons, fleeing the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, settled in the western part of Armorica. As a result, the Armorican peninsula was renamed Brittany, Celtic culture was revived and independent petty kingdoms arose in this region.

The first leader to make himself king of all the Franks was Clovis I, who began his reign in 481, routing the last forces of the Roman governors of the province in 486. Clovis claimed that he would be baptised a Christian in the event of his victory against the Visigoths, which was said to have guaranteed the battle. Clovis regained the southwest from the Visigoths, was baptised in 508 and made himself master of what is now western Germany.

Clovis I was the first Germanic conqueror after the fall of the Roman Empire to convert to Catholic Christianity, rather than Arianism; thus France was given the title «Eldest daughter of the Church» (French: La fille aînée de l’Église) by the papacy,[43] and French kings would be called «the Most Christian Kings of France» (Rex Christianissimus).

The Franks embraced the Christian Gallo-Roman culture and ancient Gaul was eventually renamed Francia («Land of the Franks»). The Germanic Franks adopted Romanic languages, except in northern Gaul where Roman settlements were less dense and where Germanic languages emerged. Clovis made Paris his capital and established the Merovingian dynasty, but his kingdom would not survive his death. The Franks treated land purely as a private possession and divided it among their heirs, so four kingdoms emerged from that of Clovis: Paris, Orléans, Soissons, and Rheims. The last Merovingian kings lost power to their mayors of the palace (head of household). One mayor of the palace, Charles Martel, defeated an Umayyad invasion of Gaul at the Battle of Tours (732) and earned respect and power within the Frankish kingdoms. His son, Pepin the Short, seized the crown of Francia from the weakened Merovingians and founded the Carolingian dynasty. Pepin’s son, Charlemagne, reunited the Frankish kingdoms and built a vast empire across Western and Central Europe.

Proclaimed Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III and thus establishing in earnest the French Government’s longtime historical association with the Catholic Church,[44] Charlemagne tried to revive the Western Roman Empire and its cultural grandeur. Charlemagne’s son, Louis I (Emperor 814–840), kept the empire united; however, this Carolingian Empire would not survive his death. In 843, under the Treaty of Verdun, the empire was divided between Louis’ three sons, with East Francia going to Louis the German, Middle Francia to Lothair I, and West Francia to Charles the Bald. West Francia approximated the area occupied by and was the precursor to, modern France.[45]

During the 9th and 10th centuries, continually threatened by Viking invasions, France became a very decentralised state: the nobility’s titles and lands became hereditary, and the authority of the king became more religious than secular and thus was less effective and constantly challenged by powerful noblemen. Thus was established feudalism in France. Over time, some of the king’s vassals would grow so powerful that they often posed a threat to the king. For example, after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror added «King of England» to his titles, becoming both the vassal to (as Duke of Normandy) and the equal of (as king of England) the king of France, creating recurring tensions.

High and Late Middle Ages (10th–15th century)

The Carolingian dynasty ruled France until 987, when Hugh Capet, Duke of France and Count of Paris, was crowned King of the Franks.[46] His descendants—the Capetians, the House of Valois and the House of Bourbon—progressively unified the country through wars and dynastic inheritance into the Kingdom of France, which was fully declared in 1190 by Philip II of France (Philippe Auguste). Later kings would expand their directly possessed domaine royal to cover over half of modern continental France by the 15th century, including most of the north, centre and west of France. During this process, the royal authority became more and more assertive, centred on a hierarchically conceived society distinguishing nobility, clergy, and commoners.

The French nobility played a prominent role in most Crusades to restore Christian access to the Holy Land. French knights made up the bulk of the steady flow of reinforcements throughout the two-hundred-year span of the Crusades, in such a fashion that the Arabs uniformly referred to the crusaders as Franj caring little whether they came from France.[47] The French Crusaders also imported the French language into the Levant, making French the base of the lingua franca (lit. «Frankish language») of the Crusader states.[47] French knights also made up the majority in both the Hospital and the Temple orders. The latter, in particular, held numerous properties throughout France and by the 13th century were the principal bankers for the French crown, until Philip IV annihilated the order in 1307. The Albigensian Crusade was launched in 1209 to eliminate the heretical Cathars in the southwestern area of modern-day France. In the end, the Cathars were exterminated and the autonomous County of Toulouse was annexed into the crown lands of France.[48]

From the 11th century, the House of Plantagenet, the rulers of the County of Anjou, succeeded in establishing its dominion over the surrounding provinces of Maine and Touraine, then progressively built an «empire» that spanned from England to the Pyrenees and covering half of modern France. Tensions between the kingdom of France and the Plantagenet empire would last a hundred years, until Philip II of France conquered, between 1202 and 1214, most of the continental possessions of the empire, leaving England and Aquitaine to the Plantagenets.

Charles IV the Fair died without an heir in 1328.[49] Under Salic law the crown of France could not pass to a woman nor could the line of kingship pass through the female line.[49] Accordingly, the crown passed to Philip of Valois, rather than through the female line to Edward of Plantagenet, who would soon become Edward III of England. During the reign of Philip of Valois, the French monarchy reached the height of its medieval power.[49] However Philip’s seat on the throne was contested by Edward III of England in 1337, and England and France entered the off-and-on Hundred Years’ War.[50] The exact boundaries changed greatly with time, but landholdings inside France by the English Kings remained extensive for decades. With charismatic leaders, such as Joan of Arc and La Hire, strong French counterattacks won back most English continental territories. Like the rest of Europe, France was struck by the Black Death due to which half of the 17 million population of France died.[51]

Early modern period (15th century–1789)

The French Renaissance saw spectacular cultural development and the first standardisation of the French language, which would become the official language of France and the language of Europe’s aristocracy. It also saw a long set of wars, known as the Italian Wars, between France and the House of Habsburg. French explorers, such as Jacques Cartier or Samuel de Champlain, claimed lands in the Americas for France, paving the way for the expansion of the French colonial empire. The rise of Protestantism in Europe led France to a civil war known as the French Wars of Religion, where, in the most notorious incident, thousands of Huguenots were murdered in the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572.[52] The Wars of Religion were ended by Henry IV’s Edict of Nantes, which granted some freedom of religion to the Huguenots. Spanish troops, the terror of Western Europe,[53] assisted the Catholic side during the Wars of Religion in 1589–1594, and invaded northern France in 1597; after some skirmishing in the 1620s and 1630s, Spain and France returned to all-out war between 1635 and 1659. The war cost France 300,000 casualties.[54]

Under Louis XIII, Cardinal Richelieu promoted the centralisation of the state and reinforced royal power by disarming domestic power holders in the 1620s. He systematically destroyed castles of defiant lords and denounced the use of private violence (dueling, carrying weapons and maintaining private armies). By the end of the 1620s, Richelieu established «the royal monopoly of force» as the doctrine.[55]

From the 16th to the 19th century, France was responsible for 11% of the transatlantic slave trade,[56] second only to Great Britain during the 18th century.[57] While the state began condoning the practice with letters patent in the 1630s, Louis XIII only formalized this authorization more generally in 1642 in the last year of his reign. By the mid-18th century, Nantes had become the primary port involved.[56]

During Louis XIV’s minority and the regency of Queen Anne and Cardinal Mazarin, a period of trouble known as the Fronde occurred in France. This rebellion was driven by the great feudal lords and sovereign courts as a reaction to the rise of royal absolute power in France.

The monarchy reached its peak during the 17th century and the reign of Louis XIV (1643–1715). By turning powerful feudal lords into courtiers at the Palace of Versailles, his command of the military went unchallenged. Remembered for numerous wars, the so-called Sun King made France the leading European power. France became the most populous country in Europe and had tremendous influence over European politics, economy, and culture. French became the most-used language in diplomacy, science, literature and international affairs, and remained so until the 20th century.[58] During his reign, France took colonial control of many overseas territories in the Americas, Africa and Asia. In 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, forcing thousands of Huguenots into exile and published the Code Noir providing the legal framework for slavery and expelling Jewish people from the French colonies.[59]

Under the wars of Louis XV (r. 1715–1774), France lost New France and most of its Indian possessions after its defeat in the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). Its European territory kept growing, however, with notable acquisitions such as Lorraine (1766) and Corsica (1770). An unpopular king, Louis XV’s weak rule, his ill-advised financial, political and military decisions – as well as the debauchery of his court– discredited the monarchy, which arguably paved the way for the French Revolution 15 years after his death.[60]

Louis XVI (r. 1774–1793), actively supported the Americans with money, fleets and armies, helping them win independence from Great Britain. France gained revenge but spent so heavily that the government verged on bankruptcy—a factor that contributed to the French Revolution. Some of the Enlightenment occurred in French intellectual circles, and major scientific breakthroughs and inventions, such as the discovery of oxygen (1778) and the first hot air balloon carrying passengers (1783), were achieved by French scientists. French explorers, such as Bougainville and Lapérouse, took part in the voyages of scientific exploration through maritime expeditions around the globe. The Enlightenment philosophy, in which reason is advocated as the primary source of legitimacy, undermined the power of and support for the monarchy and also was a factor in the French Revolution.

Revolutionary France (1789–1799)

Ouverture des États généraux à Versailles, 5 mai 1789 by Auguste Couder

Facing financial troubles, King Louis XVI summoned the Estates-General (gathering the three Estates of the realm) in May 1789 to propose solutions to his government. As it came to an impasse, the representatives of the Third Estate formed a National Assembly, signaling the outbreak of the French Revolution. Fearing that the king would suppress the newly created National Assembly, insurgents stormed the Bastille on 14 July 1789, a date which would become France’s National Day.

In early August 1789, the National Constituent Assembly abolished the privileges of the nobility such as personal serfdom and exclusive hunting rights. Through the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (27 August 1789), France established fundamental rights for men. The Declaration affirms «the natural and imprescriptible rights of man» to «liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression». Freedom of speech and press were declared, and arbitrary arrests were outlawed. It called for the destruction of aristocratic privileges and proclaimed freedom and equal rights for all men, as well as access to public office based on talent rather than birth. In November 1789, the Assembly decided to nationalise and sell all property of the Catholic Church which had been the largest landowner in the country. In July 1790, a Civil Constitution of the Clergy reorganised the French Catholic Church, cancelling the authority of the Church to levy taxes, et cetera. This fueled much discontent in parts of France, which would contribute to the civil war breaking out some years later. While King Louis XVI still enjoyed popularity among the population, his disastrous flight to Varennes (June 1791) seemed to justify rumours he had tied his hopes of political salvation to the prospects of foreign invasion. His credibility was so deeply undermined that the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic became an increasing possibility.

In the August 1791 Declaration of Pillnitz, the Emperor of Austria and the King of Prussia threatened to restore the French monarch by force. In September 1791, the National Constituent Assembly forced King Louis XVI to accept the French Constitution of 1791, thus turning the French absolute monarchy into a constitutional monarchy. In the newly established Legislative Assembly (October 1791), enmity developed and deepened between a group, later called the ‘Girondins’, who favoured war with Austria and Prussia, and a group later called ‘Montagnards’ or ‘Jacobins’, who opposed such a war. A majority in the Assembly in 1792 however saw a war with Austria and Prussia as a chance to boost the popularity of the revolutionary government and thought that such a war could be won and so declared war on Austria on 20 April 1792.

On 10 August 1792, an angry crowd threatened the palace of King Louis XVI, who took refuge in the Legislative Assembly.[61][62] A Prussian Army invaded France later in August 1792. In early September, Parisians, infuriated by the Prussian Army capturing Verdun and counter-revolutionary uprisings in the west of France, murdered between 1,000 and 1,500 prisoners by raiding the Parisian prisons. The Assembly and the Paris City Council seemed unable to stop that bloodshed.[61][63] The National Convention, chosen in the first elections under male universal suffrage,[61] on 20 September 1792 succeeded the Legislative Assembly and on 21 September abolished the monarchy by proclaiming the French First Republic.

Ex-King Louis XVI was convicted of treason and guillotined in January 1793.

France had declared war on Great Britain and the Dutch Republic in November 1792 and did the same on Spain in March 1793; in the spring of 1793, Austria and Prussia invaded France; in March, France created a «sister republic» in the «Republic of Mainz», and kept it under control.

Also in March 1793, the civil war of the Vendée against Paris started, evoked by both the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 1790 and the nationwide army conscription in early 1793; elsewhere in France rebellion was brewing too. A factionalist feud in the National Convention, smouldering ever since October 1791, came to a climax with the group of the ‘Girondins’ on 2 June 1793 being forced to resign and leave the convention. The counter-revolution, begun in March 1793 in the Vendée, by July had spread to Brittany, Normandy, Bordeaux, Marseilles, Toulon, and Lyon. Paris’ Convention government between October and December 1793 with brutal measures managed to subdue most internal uprisings, at the cost of tens of thousands of lives. Some historians consider the civil war to have lasted until 1796 with a toll of possibly 450,000 lives.[64] By the end of 1793, the allies had been driven from France. France in February 1794 abolished slavery in its American colonies but would reintroduce it later.

Political disagreements and enmity in the National Convention between October 1793 and July 1794 reached unprecedented levels, leading to dozens of Convention members being sentenced to death and guillotined. Meanwhile, France’s external wars in 1794 were prospering, for example in Belgium. In 1795, the government seemed to return to indifference towards the desires and needs of the lower classes concerning freedom of (Catholic) religion and fair distribution of food. Until 1799, politicians, apart from inventing a new parliamentary system (the ‘Directory’), busied themselves with dissuading the people from Catholicism and royalism.

Napoleon and 19th century (1799–1914)

Napoleon Bonaparte seized control of the Republic in 1799 becoming First Consul and later Emperor of the French Empire (1804–1814; 1815). As a continuation of the wars sparked by the European monarchies against the French Republic, changing sets of European Coalitions declared wars on Napoleon’s Empire. His armies conquered most of continental Europe with swift victories such as the battles of Jena-Auerstadt or Austerlitz. Members of the Bonaparte family were appointed as monarchs in some of the newly established kingdoms.[66]

These victories led to the worldwide expansion of French revolutionary ideals and reforms, such as the metric system, the Napoleonic Code and the Declaration of the Rights of Man. In June 1812, Napoleon attacked Russia, reaching Moscow. Thereafter his army disintegrated through supply problems, disease, Russian attacks, and finally winter. After the catastrophic Russian campaign, and the ensuing uprising of European monarchies against his rule, Napoleon was defeated and the Bourbon monarchy restored. About a million Frenchmen died during the Napoleonic Wars.[66] After his brief return from exile, Napoleon was finally defeated in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo, the monarchy was re-established (1815–1830), with new constitutional limitations.

The discredited Bourbon dynasty was overthrown by the July Revolution of 1830, which established the constitutional July Monarchy. In that year, French troops began the conquest of Algeria, establishing the first colonial presence in Africa since Napoleon’s abortive invasion of Egypt in 1798. In 1848, general unrest led to the February Revolution and the end of the July Monarchy. The abolition of slavery and the introduction of male universal suffrage, which were briefly enacted during the French Revolution, was re-enacted in 1848. In 1852, the president of the French Republic, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, Napoleon I’s nephew, was proclaimed emperor of the Second Empire, as Napoleon III. He multiplied French interventions abroad, especially in Crimea, Mexico and Italy which resulted in the annexation of the Duchy of Savoy and the County of Nice, then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia. Napoleon III was unseated following defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and his regime was replaced by the Third Republic. By 1875, the French conquest of Algeria was complete, and approximately 825,000 Algerians had been killed from famine, disease, and violence.[67]

France had colonial possessions, in various forms, since the beginning of the 17th century, but in the 19th and 20th centuries, its global overseas colonial empire extended greatly and became the second-largest in the world behind the British Empire.[15] Including metropolitan France, the total area of land under French sovereignty almost reached 13 million square kilometres in the 1920s and 1930s, 8.6% of the world’s land. Known as the Belle Époque, the turn of the century was a period characterised by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity and technological, scientific and cultural innovations. In 1905, state secularism was officially established.

Early to mid-20th century (1914–1946)

France was invaded by Germany and defended by Great Britain to start World War I in August 1914. A rich industrial area in the northeast was occupied. France and the Allies emerged victorious against the Central Powers at a tremendous human and material cost. World War I left 1.4 million French soldiers dead, 4% of its population.[68]

French Poilus posing with their war-torn flag in 1917, during World War I

Between 27 and 30% of soldiers conscripted from 1912 to 1915 were killed.[69] The interbellum years were marked by intense international tensions and a variety of social reforms introduced by the Popular Front government (annual leave, eight-hour workdays, women in government).

In 1940, France was invaded and quickly defeated by Nazi Germany. France was divided into a German occupation zone in the north, an Italian occupation zone in the southeast and an unoccupied territory, the rest of France, which consisted of the southern French metropolitan territory (two-fifths of pre-war metropolitan France) and the French empire, which included the two protectorates of French Tunisia and French Morocco, and French Algeria; the Vichy government, a newly established authoritarian regime collaborating with Germany, ruled the unoccupied territory. Free France, the government-in-exile led by Charles de Gaulle, was set up in London.[full citation needed]

From 1942 to 1944, about 160,000 French citizens, including around 75,000 Jews,[70] were deported to death camps and concentration camps in Germany and occupied Poland.[71] In September 1943, Corsica was the first French metropolitan territory to liberate itself from the Axis. On 6 June 1944, the Allies invaded Normandy and in August they invaded Provence. Over the following year, the Allies and the French Resistance emerged victorious over the Axis powers and French sovereignty was restored with the establishment of the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF). This interim government, established by de Gaulle, aimed to continue to wage war against Germany and to purge collaborators from office. It also made several important reforms (suffrage extended to women, the creation of a social security system).

Contemporary period (1946–present)

The GPRF laid the groundwork for a new constitutional order that resulted in the Fourth Republic (1946–1958), which saw spectacular economic growth (les Trente Glorieuses). France was one of the founding members of NATO (1949). France attempted to regain control of French Indochina but was defeated by the Viet Minh in 1954 at the climactic Battle of Dien Bien Phu. Only months later, France faced another anti-colonialist conflict in Algeria, then treated as an integral part of France and home to over one million European settlers. During the conflict, the French systematically used torture and repression, including extrajudicial killings to keep control of Algeria.[72]

This conflict wracked the country and nearly led to a coup and civil war in France.[73]

During the May 1958 crisis, the weak and unstable Fourth Republic gave way to the Fifth Republic, which included a strengthened Presidency.[74] In the latter role, Charles de Gaulle managed to keep the country together while taking steps to end the Algerian War. The war was concluded with the Évian Accords in 1962 which led to Algerian independence. Algerian independence came at a high price: it resulted in between half a million and one million deaths and over 2 million internally displaced Algerians.[75] Around one million Pied-Noirs and Harkis fled from Algeria to France upon independence.[76] A vestige of the colonial empire are the French overseas departments and territories.

In the context of the Cold War, De Gaulle pursued a policy of «national independence» towards the Western and Eastern blocs. To this end, he withdrew from NATO’s military-integrated command (while remaining in the NATO alliance itself), launched a nuclear development programme and made France the fourth nuclear power. He restored cordial Franco-German relations to create a European counterweight between the American and Soviet spheres of influence. However, he opposed any development of a supranational Europe, favouring a Europe of sovereign nations. In the wake of the series of worldwide protests of 1968, the revolt of May 1968 had an enormous social impact. In France, it was the watershed moment when a conservative moral ideal (religion, patriotism, respect for authority) shifted towards a more liberal moral ideal (secularism, individualism, sexual revolution). Although the revolt was a political failure (as the Gaullist party emerged even stronger than before) it announced a split between the French people and de Gaulle who resigned shortly after.[77]

In the post-Gaullist era, France remained one of the most developed economies in the world but faced several economic crises that resulted in high unemployment rates and increasing public debt. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, France has been at the forefront of the development of a supranational European Union, notably by signing the Maastricht Treaty (which created the European Union) in 1992, establishing the Eurozone in 1999 and signing the Lisbon Treaty in 2007.[78] France has also gradually but fully reintegrated into NATO and has since participated in most NATO-sponsored wars.[79]

Since the 19th century, France has received many immigrants. These have been mostly male foreign workers from European Catholic countries who generally returned home when not employed.[80] During the 1970s France faced an economic crisis and allowed new immigrants (mostly from the Maghreb)[80] to permanently settle in France with their families and acquire French citizenship. It resulted in hundreds of thousands of Muslims (especially in the larger cities) living in subsidised public housing and suffering from very high unemployment rates.[81] Simultaneously France renounced the assimilation of immigrants, where they were expected to adhere to French traditional values and cultural norms. They were encouraged to retain their distinctive cultures and traditions and required merely to integrate.[82]

Since the 1995 Paris Métro and RER bombings, France has been sporadically targeted by Islamist organisations, notably the Charlie Hebdo attack in January 2015 which provoked the largest public rallies in French history, gathering 4.4 million people,[83] the November 2015 Paris attacks which resulted in 130 deaths, the deadliest attack on French soil since World War II[84] and the deadliest in the European Union since the Madrid train bombings in 2004,[85] as well as the 2016 Nice truck attack, which caused 87 deaths during Bastille Day celebrations. Opération Chammal, France’s military efforts to contain ISIS, killed over 1,000 ISIS troops between 2014 and 2015.[86]

Geography

Location and borders

The vast majority of France’s territory and population is situated in Western Europe and is called Metropolitan France, to distinguish it from the country’s various overseas polities. It is bordered by the North Sea in the north, the English Channel in the northwest, the Atlantic Ocean in the west and the Mediterranean sea in the southeast. Its land borders consist of Belgium and Luxembourg in the northeast, Germany and Switzerland in the east, Italy and Monaco in the southeast, and Andorra and Spain in the south and southwest. Except for the northeast, most of France’s land borders are roughly delineated by natural boundaries and geographic features: to the south and southeast, the Pyrenees and the Alps and the Jura, respectively, and to the east, the Rhine river. Due to its shape, France is often referred to as l’Hexagone («The Hexagon»). Metropolitan France includes various coastal islands, of which the largest is Corsica. Metropolitan France is situated mostly between latitudes 41° and 51° N, and longitudes 6° W and 10° E, on the western edge of Europe, and thus lies within the northern temperate zone. Its continental part covers about 1000 km from north to south and from east to west.

France has several overseas regions across the world, which are organised as follows:

- five have the same status as mainland France’s regions and departments:

- French Guiana in South America;

- Guadeloupe in the Caribbean;

- Martinique in the Caribbean;

- Mayotte in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of East Africa;

- Réunion in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of East Africa.

- nine have special legal status distinct from mainland France’s regions and departments:

- In the Atlantic Ocean: Saint Pierre and Miquelon and, in the Antilles: Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy.

- In the Pacific Ocean: French Polynesia, the special collectivity of New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna and Clipperton Island.

- In the Indian Ocean: the Kerguelen Islands, Crozet Islands, St. Paul and Amsterdam islands, and the Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean

- In the Antarctic: Adélie Land.

France has land borders with Brazil and Suriname via French Guiana and with the Kingdom of the Netherlands through the French portion of Saint Martin.

Metropolitan France covers 551,500 square kilometres (212,935 sq mi),[87] the largest among European Union members.[20] France’s total land area, with its overseas departments and territories (excluding Adélie Land), is 643,801 km2 (248,573 sq mi), 0.45% of the total land area on Earth. France possesses a wide variety of landscapes, from coastal plains in the north and west to mountain ranges of the Alps in the southeast, the Massif Central in the south-central and Pyrenees in the southwest.

Due to its numerous overseas departments and territories scattered across the planet, France possesses the second-largest Exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the world, covering 11,035,000 km2 (4,261,000 sq mi), just behind the EEZ of the United States, which covers 11,351,000 km2 (4,383,000 sq mi), but ahead of the EEZ of Australia, which covers 8,148,250 km2 (3,146,000 sq mi). Its EEZ covers approximately 8% of the total surface of all the EEZs of the world.

Geology, topography and hydrography

Metropolitan France has a wide variety of topographical sets and natural landscapes. Large parts of the current territory of France were raised during several tectonic episodes like the Hercynian uplift in the Paleozoic Era, during which the Armorican Massif, the Massif Central, the Morvan, the Vosges and Ardennes ranges and the island of Corsica were formed. These massifs delineate several sedimentary basins such as the Aquitaine basin in the southwest and the Paris basin in the north, the latter including several areas of particularly fertile ground such as the silt beds of Beauce and Brie. Various routes of natural passage, such as the Rhône Valley, allow easy communication. The Alpine, Pyrenean and Jura mountains are much younger and have less eroded forms. At 4,810.45 metres (15,782 ft)[88] above sea level, Mont Blanc, located in the Alps on the French and Italian border, is the highest point in Western Europe. Although 60% of municipalities are classified as having seismic risks, these risks remain moderate.

The coastlines offer contrasting landscapes: mountain ranges along the French Riviera, coastal cliffs such as the Côte d’Albâtre, and wide sandy plains in the Languedoc. Corsica lies off the Mediterranean coast. France has an extensive river system consisting of the four major rivers Seine, the Loire, the Garonne, the Rhône and their tributaries, whose combined catchment includes over 62% of the metropolitan territory. The Rhône divides the Massif Central from the Alps and flows into the Mediterranean Sea at the Camargue. The Garonne meets the Dordogne just after Bordeaux, forming the Gironde estuary, the largest estuary in Western Europe which after approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) empties into the Atlantic Ocean.[89] Other water courses drain towards the Meuse and Rhine along the northeastern borders. France has 11 million square kilometres (4.2×106 sq mi) of marine waters within three oceans under its jurisdiction, of which 97% are overseas.

Environment

France was one of the first countries to create an environment ministry, in 1971.[90] Although it is one of the most industrialised countries in the world, France is ranked only 19th by carbon dioxide emissions, behind less populous nations such as Canada or Australia. This is due to the country’s heavy investment in nuclear power following the 1973 oil crisis,[91] which now accounts for 75 percent of its electricity production[92] and results in less pollution.[93][94] According to the 2020 Environmental Performance Index conducted by Yale and Columbia, France was the fifth most environmentally conscious country in the world (behind the United Kingdom).[95][96]

Like all European Union state members, France agreed to cut carbon emissions by at least 20% of 1990 levels by 2020,[97] compared to the United States’ plan to reduce emissions by 4% of 1990 levels.[98] As of 2009, French carbon dioxide emissions per capita were lower than that of China.[99] The country was set to impose a carbon tax in 2009 at 17 euros per tonne of carbon emitted,[100] which would have raised 4 billion euros of revenue annually.[101] However, the plan was abandoned due to fears of burdening French businesses.[102]

Forests account for 31 percent of France’s land area—the fourth-highest proportion in Europe—representing an increase of 7 percent since 1990.[103][104][105] French forests are some of the most diverse in Europe, comprising more than 140 species of trees.[106] France had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.52/10, ranking it 123rd globally out of 172 countries.[107] There are nine national parks[108] and 46 natural parks in France,[109] with the government planning to convert 20% of its Exclusive economic zone into a Marine protected area by 2020.[110] A regional nature park[111] (French: parc naturel régional or PNR) is a public establishment in France between local authorities and the national government covering an inhabited rural area of outstanding beauty, to protect the scenery and heritage as well as setting up sustainable economic development in the area.[112] A PNR sets goals and guidelines for managed human habitation, sustainable economic development and protection of the natural environment based on each park’s unique landscape and heritage. The parks foster ecological research programmes and public education in the natural sciences.[113] As of 2019 there are 54 PNRs in France.[114]

Administrative divisions

The French Republic is divided into 18 regions (located in Europe and overseas), five overseas collectivities, one overseas territory, one special collectivity – New Caledonia and one uninhabited island directly under the authority of the Minister of Overseas France – Clipperton.

Regions

Since 2016, France is divided into 18 administrative regions: 13 regions in metropolitan France (including Corsica),[115] and five overseas.[87] The regions are further subdivided into 101 departments,[116] which are numbered mainly alphabetically. The department number is used in postal codes and was formerly used on vehicle registration plates. Among the 101 French departments, five (French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte, and Réunion) are in overseas regions (ROMs) that are simultaneously overseas departments (DOMs), enjoying the same status as metropolitan departments and are thereby included in the European Union.

The 101 departments are subdivided into 335 arrondissements, which are, in turn, subdivided into 2,054 cantons.[117] These cantons are then divided into 36,658 communes, which are municipalities with an elected municipal council.[117] Three communes—Paris, Lyon and Marseille—are subdivided into 45 municipal arrondissements.

The regions, departments and communes are all known as territorial collectivities, meaning they possess local assemblies as well as an executive. Today, arrondissements and cantons are merely administrative divisions. However, this was not always the case. Until 1940, the arrondissements were territorial collectivities with an elected assembly, but these were suspended by the Vichy regime and abolished by the Fourth Republic in 1946.

Overseas territories and collectivities

In addition to the 18 regions and 101 departments, the French Republic has five overseas collectivities (French Polynesia, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Martin, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and Wallis and Futuna), one sui generis collectivity (New Caledonia), one overseas territory (French Southern and Antarctic Lands), and one island possession in the Pacific Ocean (Clipperton Island).

Overseas collectivities and territories form part of the French Republic, but do not form part of the European Union or its fiscal area (except for St. Bartelemy, which seceded from Guadeloupe in 2007). The Pacific Collectivities (COMs) of French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna, and New Caledonia continue to use the CFP franc[118] whose value is strictly linked to that of the euro. In contrast, the five overseas regions used the French franc and now use the euro.[119]

| Name | Constitutional status | Capital |

|---|---|---|

| State private property under the direct authority of the French government | Uninhabited | |

| Designated as an overseas land (pays d’outre-mer or POM), the status is the same as an overseas collectivity. | Papeete | |

| Overseas territory (territoire d’outre-mer or TOM) | Port-aux-Français | |

| Sui generis collectivity | Nouméa | |

| Overseas collectivity (collectivité d’outre-mer or COM) | Gustavia | |

| Overseas collectivity (collectivité d’outre-mer or COM) | Marigot | |

| Overseas collectivity (collectivité d’outre-mer or COM). Still referred to as a collectivité territoriale. | Saint-Pierre | |

| Overseas collectivity (collectivité d’outre-mer or COM). Still referred to as a territoire. | Mata-Utu |

Government and politics

Government

France is a representative democracy organised as a unitary, semi-presidential republic.[120] As one of the earliest republics of the modern world, democratic traditions and values are deeply rooted in French culture, identity and politics.[121] The Constitution of the Fifth Republic was approved by referendum on 28 September 1958, establishing a framework consisting of executive, legislative and judicial branches.[122] It sought to address the instability of the Third and Fourth Republics by combining elements of both parliamentary and presidential systems, while greatly strengthening the authority of the executive relative to the legislature.[121]

The executive branch has two leaders. The President of the Republic, currently Emmanuel Macron, is the head of state, elected directly by universal adult suffrage for a five-year term.[123] The Prime Minister, currently Élisabeth Borne, is the head of government, appointed by the President to lead the government. The President has the power to dissolve Parliament or circumvent it by submitting referendums directly to the people; the President also appoints judges and civil servants, negotiates and ratifies international agreements, as well as serves as commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces. The Prime Minister determines public policy and oversees the civil service, with an emphasis on domestic matters.[124] In the 2022 presidential election president Macron was re-elected.[125]

The legislature consists of the French Parliament, a bicameral body made up of a lower house, the National Assembly (Assemblée nationale) and an upper house, the Senate.[126] Legislators in the National Assembly, known as députés, represent local constituencies and are directly elected for five-year terms.[127] The Assembly has the power to dismiss the government by majority vote. Senators are chosen by an electoral college for six-year terms, with half the seats submitted to election every three years.[128] The Senate’s legislative powers are limited; in the event of disagreement between the two chambers, the National Assembly has the final say.[129] The parliament is responsible for determining the rules and principles concerning most areas of law, political amnesty, and fiscal policy; however, the government may draft specific details concerning most laws.

Until World War II, Radicals were a strong political force in France, embodied by the Republican, Radical and Radical-Socialist Party which was the most important party of the Third Republic. From World War II until 2017, French politics was dominated by two politically opposed groupings: one left-wing, the French Section of the Workers’ International, which was succeeded by the Socialist Party (in 1969); and the other right-wing, the Gaullist Party, whose name changed over time to the Rally of the French People (1947), the Union of Democrats for the Republic (1958), the Rally for the Republic (1976), the Union for a Popular Movement (2007) and The Republicans (since 2015). In the 2017 presidential and legislative elections, the radical centrist party La République En Marche! (LREM) became the dominant force, overtaking both Socialists and Republicans. LREM’s opponent in the second round of the 2017 and 2022 presidential elections was the growing far-right party National Rally. Since 2020, Europe Ecology – The Greens have performed well in mayoral elections in major cities[130] while on a national level, an alliance of Left parties (the NUPES) was the second-largest voting block elected to the lower house in 2022.[131]

The electorate is constitutionally empowered to vote on amendments passed by the Parliament and bills submitted by the president. Referendums have played a key role in shaping French politics and even foreign policy; voters have decided on such matters as Algeria’s independence, the election of the president by popular vote, the formation of the EU, and the reduction of presidential term limits.[132] Waning civic participation has been a matter of vigorous public debate, with a majority of the public reportedly supporting mandatory voting as a solution in 2019.[citation needed]

Law

France uses a civil legal system, wherein law arises primarily from written statutes;[87] judges are not to make law, but merely to interpret it (though the amount of judicial interpretation in certain areas makes it equivalent to case law in a common law system). Basic principles of the rule of law were laid in the Napoleonic Code (which was, in turn, largely based on the royal law codified under Louis XIV). In agreement with the principles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the law should only prohibit actions detrimental to society. As Guy Canivet, first president of the Court of Cassation wrote about the management of prisons: «Freedom is the rule, and its restriction is the exception; any restriction of Freedom must be provided for by Law and must follow the principles of necessity and proportionality.» That is, Law should lay out prohibitions only if they are needed, and if the inconveniences caused by this restriction do not exceed the inconveniences that the prohibition is supposed to remedy.

French law is divided into two principal areas: private law and public law. Private law includes, in particular, civil law and criminal law. Public law includes, in particular, administrative law and constitutional law. However, in practical terms, French law comprises three principal areas of law: civil law, criminal law, and administrative law. Criminal laws can only address the future and not the past (criminal ex post facto laws are prohibited).[133] While administrative law is often a subcategory of civil law in many countries, it is completely separated in France and each body of law is headed by a specific supreme court: ordinary courts (which handle criminal and civil litigation) are headed by the Court of Cassation and administrative courts are headed by the Council of State. To be applicable, every law must be officially published in the Journal officiel de la République française.

France does not recognise religious law as a motivation for the enactment of prohibitions; it has long abolished blasphemy laws and sodomy laws (the latter in 1791). However, «offences against public decency» (contraires aux bonnes mœurs) or disturbing public order (trouble à l’ordre public) have been used to repress public expressions of homosexuality or street prostitution. Since 1999, civil unions for homosexual couples are permitted, and since 2013, same-sex marriage and LGBT adoption are legal.[134] Laws prohibiting discriminatory speech in the press are as old as 1881. Some consider hate speech laws in France to be too broad or severe, undermining freedom of speech.[135]

France has laws against racism and antisemitism,[136] while the 1990 Gayssot Act prohibits Holocaust denial.

Freedom of religion is constitutionally guaranteed by the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State is the basis for laïcité (state secularism): the state does not formally recognise any religion, except in Alsace-Moselle. Nonetheless, it does recognise religious associations. The Parliament has listed many religious movements as dangerous cults since 1995 and has banned wearing conspicuous religious symbols in schools since 2004. In 2010, it banned the wearing of face-covering Islamic veils in public; human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch described the law as discriminatory towards Muslims.[137][138] However, it is supported by most of the population.[139]

Foreign relations

France is a founding member of the United Nations and serves as one of the permanent members of the UN Security Council with veto rights.[140] In 2015, it was described as «the best networked state in the world» due to its membership in more international institutions than any other country;[141] these include the G7, World Trade Organization (WTO),[142] the Pacific Community (SPC)[143] and the Indian Ocean Commission (COI).[144] It is an associate member of the Association of Caribbean States (ACS)[145] and a leading member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) of 84 French-speaking countries.[146]

As a significant hub for international relations, France has the third-largest assembly of diplomatic missions, second only to China and the United States, which are far more populous. It also hosts the headquarters of several international organisations, including the OECD, UNESCO, Interpol, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, and the OIF.[149]

Postwar French foreign policy has been largely shaped by membership in the European Union, of which it was a founding member. Since the 1960s, France has developed close ties with reunified Germany to become the most influential driving force of the EU.[150] In the 1960s, France sought to exclude the British from the European unification process,[151] seeking to build its standing in continental Europe. However, since 1904, France has maintained an «Entente cordiale» with the United Kingdom, and there has been a strengthening of links between the countries, especially militarily.

France is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), but under President de Gaulle excluded itself from the joint military command, in protest of the Special Relationship between the United States and Britain, and to preserve the independence of French foreign and security policies. Under Nicolas Sarkozy, France rejoined the NATO joint military command on 4 April 2009.[152][153][154]

France retains strong political and economic influence in its former African colonies (Françafrique)[155] and has supplied economic aid and troops for peacekeeping missions in Ivory Coast and Chad.[156] From 2012 to 2021, France and other African states intervened in support of the Malian government in the Northern Mali conflict.

In 2017, France was the world’s fourth-largest donor of development aid in absolute terms, behind the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom.[157] This represents 0.43% of its GNP, the 12th highest among the OECD.[158] Aid is provided by the governmental French Development Agency, which finances primarily humanitarian projects in sub-Saharan Africa,[159] with an emphasis on «developing infrastructure, access to health care and education, the implementation of appropriate economic policies and the consolidation of the rule of law and democracy».[159]

Military

The French Armed Forces (Forces armées françaises) are the military and paramilitary forces of France, under the President of the Republic as supreme commander. They consist of the French Army (Armée de Terre), the French Navy (Marine Nationale, formerly called Armée de Mer), the French Air and Space Force (Armée de l’Air et de l’Espace), and the Military Police called National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie nationale), which also fulfils civil police duties in the rural areas of France. Together they are among the largest armed forces in the world and the largest in the EU. According to a 2018 study by Crédit Suisse, the French Armed Forces are ranked as the world’s sixth-most powerful military, and the second most powerful in Europe after Russia.[160] France’s annual military expenditure in 2018 was US$63.8 billion, or 2.3% of its GDP, making it the fifth biggest military spender in the world after the United States, China, Saudi Arabia, and India.[161] There has been no national conscription since 1997.[162]

France has been a recognised nuclear state since 1960. France has signed and ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT)[163] and acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The French nuclear force (formerly known as «Force de Frappe«) consists of four Triomphant class submarines equipped with submarine-launched ballistic missiles. In addition to the submarine fleet, it is estimated that France has about 60 ASMP medium-range air-to-ground missiles with nuclear warheads,[164] of which around 50 are deployed by the Air and Space Force using the Mirage 2000N long-range nuclear strike aircraft, while around 10 are deployed by the French Navy’s Super Étendard Modernisé (SEM) attack aircraft, which operate from the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle. The new Rafale F3 aircraft will gradually replace all Mirage 2000N and SEM in the nuclear strike role with the improved ASMP-A missile with a nuclear warhead.[citation needed]

France has major military industries with one of the largest aerospace industries in the world.[165] Its industries have produced such equipment as the Rafale fighter, the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier, the Exocet missile and the Leclerc tank among others. France is actively investing in European joint projects such as the Eurocopter Tiger, multipurpose frigates, the UCAV demonstrator nEUROn and the Airbus A400M.[citation needed] France is a major arms seller,[166][167] with most of its arsenal’s designs available for the export market, except for the nuclear-powered devices.

One French intelligence unit, the Directorate-General for External Security (Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure), is considered to be a component of the Armed Forces under the authority of the Ministry of Defense. The other, the Central Directorate for Interior Intelligence (Direction centrale du renseignement intérieur) is a division of the National Police Force (Direction générale de la Police Nationale).[citation needed] France’s cybersecurity capabilities are regularly ranked as some of the most robust of any nation in the world.[168][169]

Government finance

The Government of France has run a budget deficit each year since the early 1970s. As of 2016, French government debt levels reached 2.2 trillion euros, the equivalent of 96.4% of French GDP.[170] In late 2012, credit rating agencies warned that growing French Government debt levels risked France’s AAA credit rating, raising the possibility of a future downgrade and subsequent higher borrowing costs for the French authorities.[171]

However, in July 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the French government issued negative-interest rate 10-year bonds for the first time in its history.[172] In 2020, France possessed the fourth-largest gold reserves in the world.[citation needed]

Economy

Overview

Composition of the French economy (GDP) in 2016 by expenditure type

France has a developed, high-income mixed economy, characterised by sizeable government involvement, economic diversity, a skilled labour force, and high innovation. For roughly two centuries, the French economy has consistently ranked among the ten largest globally; it is currently the world’s ninth-largest by purchasing power parity, the seventh-largest by nominal GDP, and the second-largest in the European Union by both metrics.[174] France is considered an economic power, with membership in the Group of Seven leading industrialised countries, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the Group of Twenty largest economies.

France’s economy is highly diversified; services represent two-thirds of both the workforce and GDP,[175] while the industrial sector accounts for a fifth of GDP and a similar proportion of employment. France is the third-biggest manufacturing country in Europe, behind Germany and Italy, and ranks eighth in the world by share of global manufacturing output, at 1.9 percent.[176] Less than 2 percent of GDP is generated by the primary sector, namely agriculture;[177] however, France’s agricultural sector is among the largest in value and leads the EU in terms of overall production.[178]

In 2018, France was the fifth-largest trading nation in the world and the second-largest in Europe, with the value of exports representing over a fifth of GDP.[179] Its membership in the Eurozone and the broader European Single Market facilitates access to capital, goods, services, and skilled labour.[180] Despite protectionist policies over certain industries, particularly in agriculture, France has generally played a leading role in fostering free trade and commercial integration in Europe to enhance its economy.[181][182] In 2019, it ranked first in Europe and 13th in the world in foreign direct investment, with European countries and the United States being leading sources.[183] According to the Bank of France, the leading recipients of FDI were manufacturing, real estate, finance and insurance.[184] The Paris region has the highest concentration of multinational firms in Europe.[184]

Under the doctrine of Dirigisme, the government historically played a major role in the economy; policies such as indicative planning and nationalisation are credited for contributing to three decades of unprecedented postwar economic growth known as Trente Glorieuses. At its peak in 1982, the public sector accounted for one-fifth of industrial employment and over four-fifths of the credit market. Beginning in the late 20th century, France loosened regulations and state involvement in the economy, with most leading companies now being privately owned; state ownership now dominates only transportation, defence and broadcasting.[185] Policies aimed at promoting economic dynamism and privatisation have improved France’s economic standing globally: it is among the world’s 10 most innovative countries in the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index,[186] and the 15th most competitive, according to the 2019 Global Competitiveness Report (up two places from 2018).[187]

According to the IMF, France ranked 30th in GDP per capita, with roughly $45,000 per inhabitant. It placed 23rd on the Human Development Index, indicating very high human development. Public corruption is among the lowest in the world, with France consistently ranking among the 30 least corrupt countries since the Corruption Perceptions Index began in 2012; it placed 22nd in 2021, up one place from the previous year.[188][189] France is Europe’s second-largest spender in research and development, at over 2 percent of GDP; globally, it ranks 12th.[190]

Financial services, banking, and insurance are important part of the economy. AXA is the world’s second-largest insurance company by total nonbanking assets in 2020.[191][192] As of 2011, the three largest financial institutions cooperatively owned by their customers were French: Crédit Agricole, Groupe Caisse D’Epargne, and Groupe Caisse D’Epargne.[193] According to a 2020 report by S&P Global Market Intelligenc, France’s leading banks, BNP Paribas and Crédit Agricole, are among the world’s 10 largest bank by assets, with Société Générale and Groupe BPCE ranking 17th and 19th globally, respectively.[194]

The Paris stock exchange (French: La Bourse de Paris) is one of the oldest in the world, created by Louis XV in 1724.[195] In 2000, it merged with counterparts in Amsterdam and Brussels to form Euronext,[196] which in 2007 merged with the New York stock exchange to form NYSE Euronext, the world’s largest stock exchange.[196] Euronext Paris, the French branch of NYSE Euronext, is Europe’s second-largest stock exchange market, behind the London Stock Exchange.

Agriculture

France has historically been one of the world’s major agricultural centres and remains a «global agricultural powerhouse».[197][198] Nicknamed «the granary of the old continent»,[199] over half its total land area is farmland, of which 45 percent is devoted to permanent field crops such as cereals. The country’s diverse climate, extensive arable land, modern farming technology, and EU subsidies have made it Europe’s leading agricultural producer and exporter;[200] it accounts for one-fifth of the EU’s agricultural production, including over one-third of its oilseeds, cereals, and wine.[201] As of 2017, France ranked first in Europe in beef and cereals; second in dairy and aquaculture; and third in poultry, fruits, vegetables, and manufactured chocolate products.[202] France has the EU’s largest cattle herd, at 18-19 million.[203]

France is the world’s sixth-biggest exporter of agricultural products, generating a trade surplus of over €7.4 billion.[202] Its primary agricultural exports are wheat, poultry, dairy, beef, pork, and internationally recognised brands, particularly beverages.[203][204] France is the fifth largest grower of wheat, after China, India, Russia, and the United States, all of which are significantly larger.[203] It is the world’s top exporter of natural spring water, flax, malt, and potatoes.[202] In 2020, France exported over €61 billion in agricultural products, compared to €37 billion in 2000.[205][206]

France was an early centre of viviculture, dating back to at least the sixth century BCE. It is the world’s second-largest producer of wine, with many varieties enjoying global renown, such as Champagne and Bordeaux;[202] domestic consumption is also high, particularly of Rosé. France produces rum primarily from overseas territories such as Martinique, Guadeloupe and La Réunion.

Relative to other developed countries, agriculture is an important sector of France’s economy: 3.8% of the active population is employed in agriculture, whereas the total agri-food industry made up 4.2% of the French GDP in 2005.[201] France remains the largest recipient of EU agricultural subsidies, receiving an annual average of €8 billion from 2007 to 2019.[207][208]

Tourism

The Eiffel Tower is the world’s most-visited paid monument, an icon of both Paris and France

With 89 million international tourist arrivals in 2018,[209] France is the world’s top tourist destination, ahead of Spain (83 million) and the United States (80 million). However, it ranks third in tourism-derived income due to the shorter duration of visits.[210] The most popular tourist sites include (annual visitors): Eiffel Tower (6.2 million), Château de Versailles (2.8 million), Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (2 million), Pont du Gard (1.5 million), Arc de Triomphe (1.2 million), Mont Saint-Michel (1 million), Sainte-Chapelle (683,000), Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg (549,000), Puy de Dôme (500,000), Musée Picasso (441,000), and Carcassonne (362,000).[211]

France, especially Paris, has some of the world’s largest and most renowned museums, including the Louvre, which is the most visited art museum in the world (5.7 million), the Musée d’Orsay (2.1 million), mostly devoted to Impressionism, the Musée de l’Orangerie (1.02 million), which is home to eight large Water Lily murals by Claude Monet, as well as the Centre Georges Pompidou (1.2 million), dedicated to contemporary art. Disneyland Paris is Europe’s most popular theme park, with 15 million combined visitors to the resort’s Disneyland Park and Walt Disney Studios Park in 2009.[212]

With more than 10 million tourists a year, the French Riviera (French: Côte d’Azur), in Southeast France, is the second leading tourist destination in the country, after the Paris region.[213] It benefits from 300 days of sunshine per year, 115 kilometres (71 mi) of coastline and beaches, 18 golf courses, 14 ski resorts and 3,000 restaurants.[214]: 31 Each year the Côte d’Azur hosts 50% of the world’s superyacht fleet.[214]: 66

With 6 million tourists a year, the castles of the Loire Valley (French: châteaux) and the Loire Valley itself are the third leading tourist destination in France;[215][216] this World Heritage Site is noteworthy for its architectural heritage, in its historic towns but in particular its castles, such as the Châteaux d’Amboise, de Chambord, d’Ussé, de Villandry, Chenonceau and Montsoreau. The Château de Chantilly, Versailles and Vaux-le-Vicomte, all three located near Paris, are also visitor attractions.

France has 37 sites inscribed in UNESCO’s World Heritage List and features cities of high cultural interest, beaches and seaside resorts, ski resorts, as well as rural regions that many enjoy for their beauty and tranquillity (green tourism). Small and picturesque French villages are promoted through the association Les Plus Beaux Villages de France (literally «The Most Beautiful Villages of France»). The «Remarkable Gardens» label is a list of the over 200 gardens classified by the Ministry of Culture. This label is intended to protect and promote remarkable gardens and parks. France attracts many religious pilgrims on their way to St. James, or to Lourdes, a town in the Hautes-Pyrénées that hosts several million visitors a year.

Energy

France is the world’s tenth-largest producer of electricity.[217] Électricité de France (EDF), which is majority-owned by the French government, is the country’s main producer and distributor of electricity, and one of the world’s largest electric utility companies, ranking third in revenue globally.[218] In 2018, EDF produced around one-fifth of the European Union’s electricity, primarily from nuclear power.[219] As of 2021, France was the biggest energy exporter in Europe, mostly to the U.K. and Italy,[220] and the largest net exporter of electricity in the world.[220]