|

Freddie Mercury |

|

|---|---|

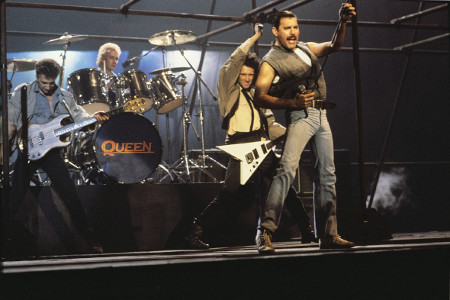

Mercury performing with Queen in New Haven, Connecticut, 1977 |

|

| Born |

Farrokh Bulsara 5 September 1946 Stone Town, Zanzibar |

| Died | 24 November 1991 (aged 45)

Kensington, London, England |

| Cause of death | Bronchopneumonia as a complication of AIDS |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1969–1991 |

| Partners |

|

| Musical career | |

| Genres | Rock |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels |

|

| Formerly of |

|

| Signature | |

|

Freddie Mercury (born Farrokh Bulsara; 5 September 1946 – 24 November 1991)[2] was a British singer and songwriter, who achieved worldwide fame as the lead vocalist of the rock band Queen. Regarded as one of the greatest singers in the history of rock music, he was known for his flamboyant stage persona and four-octave vocal range. Mercury defied the conventions of a rock frontman with his theatrical style, influencing the artistic direction of Queen.

Born in 1946 in Zanzibar to Parsi-Indian parents, Mercury attended English-style boarding schools in India from the age of eight and returned to Zanzibar after secondary school. In 1964, his family fled the Zanzibar Revolution, moving to Middlesex, England. Having studied and written music for years, he formed Queen in 1970 with guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor. Mercury wrote numerous hits for Queen, including «Killer Queen», «Bohemian Rhapsody», «Somebody to Love», «We Are the Champions», «Don’t Stop Me Now» and «Crazy Little Thing Called Love». His charismatic stage performances often saw him interact with the audience, as displayed at the 1985 Live Aid concert. He also led a solo career and was a producer and guest musician for other artists.

Mercury was diagnosed with AIDS in 1987. He continued to record with Queen, and posthumously featured on their final album, Made in Heaven (1995). He announced his diagnosis the day before his death, from complications from the disease, in 1991 at the age of 45. In 1992, a concert in tribute to him was held at Wembley Stadium, in benefit of AIDS awareness. His career with Queen was dramatised in the 2018 biopic Bohemian Rhapsody.

As a member of Queen, Mercury was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2001, the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2003, and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2004. In 1990, he and the other Queen members were awarded the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to British Music, and one year after his death, Mercury was awarded it individually. In 2005, Queen were awarded an Ivor Novello Award for Outstanding Song Collection from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers, and Authors. In 2002, Mercury was voted number 58 in the BBC’s poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Early life

The house in Zanzibar where Mercury lived in his early years

Mercury was born Farrokh Bulsara in Stone Town in the British protectorate of Zanzibar (now part of Tanzania) on 5 September 1946.[3][4] His parents, Bomi (1908–2003) and Jer Bulsara (1922–2016),[a][5] were from the Parsi community of western India. The Bulsaras had origins in the city of Bulsar (now Valsad) in Gujarat.[b][3] He had a younger sister, Kashmira (b. 1952).[6][7][8]

The family had moved to Zanzibar so that Bomi could continue his job as a cashier at the British Colonial Office. As Parsis, the Bulsaras practised Zoroastrianism.[9] Mercury was born with four extra incisors, to which he attributed his enhanced vocal range.[10][11] As Zanzibar was a British protectorate until 1963, Mercury was born a British subject, and on 2 June 1969 was registered a citizen of the United Kingdom and colonies after the family had emigrated to England.[12]

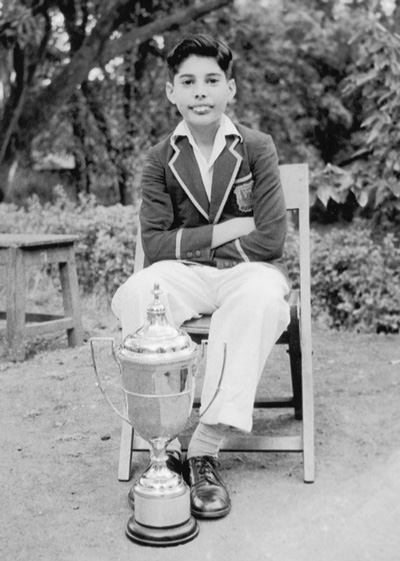

Mercury spent most of his childhood in India where he began taking piano lessons at the age of seven while living with relatives.[13] In 1954, at the age of eight, Mercury was sent to study at St. Peter’s School, a British-style boarding school for boys, in Panchgani near Bombay.[14] At the age of 12, he formed a school band, the Hectics, and covered rock and roll artists such as Cliff Richard and Little Richard.[15][16] One of Mercury’s former bandmates from the Hectics has said «the only music he listened to, and played, was Western pop music».[17] A friend recalls that he had «an uncanny ability to listen to the radio and replay what he heard on piano».[18] It was also at St. Peter’s where he began to call himself «Freddie». In February 1963, he moved back to Zanzibar where he joined his parents at their flat.[19]

In the spring of 1964, Mercury and his family fled to England from Zanzibar to escape the violence of the revolution against the Sultan of Zanzibar and his mainly Arab government,[20] in which thousands of ethnic Arabs and Indians were killed.[21] They moved to 19 Hamilton Close, Feltham, Middlesex, a town 13 miles (21 km) west of central London. The Bulsaras briefly relocated to 122 Hamilton Road, before settling into a small house at 22 Gladstone Avenue in late October.[22] After first studying art at Isleworth Polytechnic in West London, Mercury studied graphic art and design at Ealing Art College, graduating with a diploma in 1969.[2] He later used these skills to design heraldic arms for his band Queen.[23]

Following graduation, Mercury joined a series of bands and sold second-hand Edwardian clothes and scarves in Kensington Market in London with Roger Taylor. Taylor recalls, «Back then, I didn’t really know him as a singer—he was just my mate. My crazy mate! If there was fun to be had, Freddie and I were usually involved.»[24] He also held a job as a baggage handler at Heathrow Airport.[25] Other friends from the time remember him as a quiet and shy young man with a great interest in music.[26] In 1969, he joined Liverpool-based band Ibex, later renamed Wreckage, which played «very Hendrix-style, heavy blues».[27] He briefly lived in a flat above the Dovedale Towers, a pub on Penny Lane in Liverpool’s Mossley Hill district.[28][29] When this band failed to take off, he joined an Oxford-based band, Sour Milk Sea, but by early 1970 this group had broken up as well.[30]

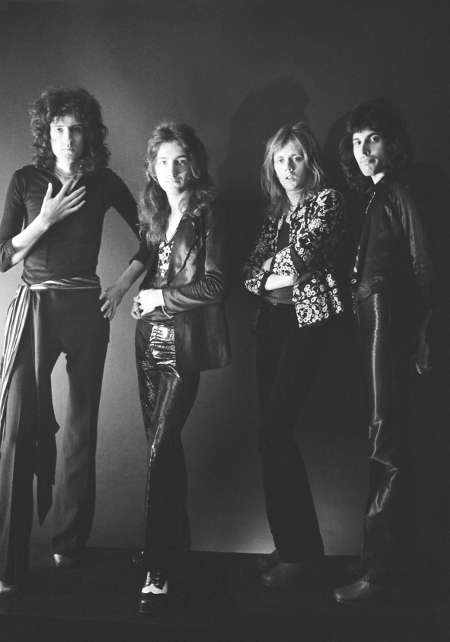

In April 1970, Mercury teamed up with guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor, to become lead singer of their band Smile.[2] They were joined by bassist John Deacon in 1971. Despite the reservations of the other members and Trident Studios, the band’s initial management, Mercury chose the name «Queen» for the new band. He later said, «It’s very regal obviously, and it sounds splendid. It’s a strong name, very universal and immediate. I was certainly aware of the gay connotations, but that was just one facet of it.»[31] At about the same time, he legally changed his surname, Bulsara, to Mercury.[32] It was inspired by the line «Mother Mercury, look what they’ve done to me» from his song «My Fairy King».[33]

Shortly before the release of Queen’s self-titled first album, Mercury designed the band’s logo, known as the «Queen crest».[23] The logo combines the zodiac signs of the four band members: two lions for Deacon and Taylor (sign Leo), a crab for May (Cancer), and two fairies for Mercury (Virgo).[23] The lions embrace a stylised letter Q, the crab rests atop the letter with flames rising directly above it, and the fairies are each sheltering below a lion.[23] A crown is shown inside the Q, and the whole logo is over-shadowed by an enormous phoenix. The Queen crest bears a passing resemblance to the Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, particularly with the lion supporters.[23]

Artistry

Vocals

Although Mercury’s speaking voice naturally fell in the baritone range, he delivered most songs in the tenor range.[34] His known vocal range extended from bass low F (F2) to soprano high F (F6).[35] He could belt up to tenor high F (F5).[35] Biographer David Bret described his voice as «escalating within a few bars from a deep, throaty rock-growl to tender, vibrant tenor, then on to a high-pitched, perfect coloratura, pure and crystalline in the upper reaches».[36] Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballé, with whom Mercury recorded an album, expressed her opinion that «the difference between Freddie and almost all the other rock stars was that he was selling the voice».[37] She adds:

His technique was astonishing. No problem of tempo, he sang with an incisive sense of rhythm, his vocal placement was very good and he was able to glide effortlessly from a register to another. He also had a great musicality. His phrasing was subtle, delicate and sweet or energetic and slamming. He was able to find the right colouring or expressive nuance for each word.[35]

Mercury singing on stage in November 1977

The Who lead singer Roger Daltrey described Mercury as «the best virtuoso rock ‘n’ roll singer of all time. He could sing anything in any style. He could change his style from line to line and, God, that’s an art. And he was brilliant at it.»[38] Discussing what type of person he wanted to play the lead role in his musical Jesus Christ Superstar, Andrew Lloyd Webber said: «He has to be of enormous charisma, but he also has to be a genuine, genuine rock tenor. That’s what it is. Really think Freddie Mercury, I mean that’s the kind of range we’re talking about.»[39]

A research team undertook a study in 2016 to understand the appeal behind Mercury’s voice.[40] Led by Professor Christian Herbst, the team identified his notably faster vibrato and use of subharmonics as unique characteristics of Mercury’s voice, particularly in comparison to opera singers.[41] The research team studied vocal samples from 23 commercially available Queen recordings, his solo work, and a series of interviews of the late artist. They also used an endoscopic video camera to study a rock singer brought in to imitate Mercury’s singing voice.[41][42]

Songwriting

Mercury wrote 10 of the 17 songs on Queen’s Greatest Hits album: «Bohemian Rhapsody», «Seven Seas of Rhye», «Killer Queen», «Somebody to Love», «Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy», «We Are the Champions», «Bicycle Race», «Don’t Stop Me Now», «Crazy Little Thing Called Love», and «Play the Game».[43] In 2003 Mercury was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame with the rest of Queen, and in 2005 all four band members were awarded an Ivor Novello Award for Outstanding Song Collection from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers, and Authors.[44][45]

The most notable aspect of his songwriting involved the wide range of genres that he used, which included, among other styles, rockabilly, progressive rock, heavy metal, gospel, and disco. As he explained in a 1986 interview, «I hate doing the same thing again and again and again. I like to see what’s happening now in music, film and theatre and incorporate all of those things.»[46] Compared to many popular songwriters, Mercury also tended to write musically complex material. For example, «Bohemian Rhapsody» is non-cyclical in structure and comprises dozens of chords.[47][48] He also wrote six songs from Queen II which deal with multiple key changes and complex material. «Crazy Little Thing Called Love», on the other hand, contains only a few chords. Although Mercury often wrote very intricate harmonies, he claimed that he could barely read music.[49] He composed most of his songs on the piano and used a wide variety of key signatures.[47]

Live performer

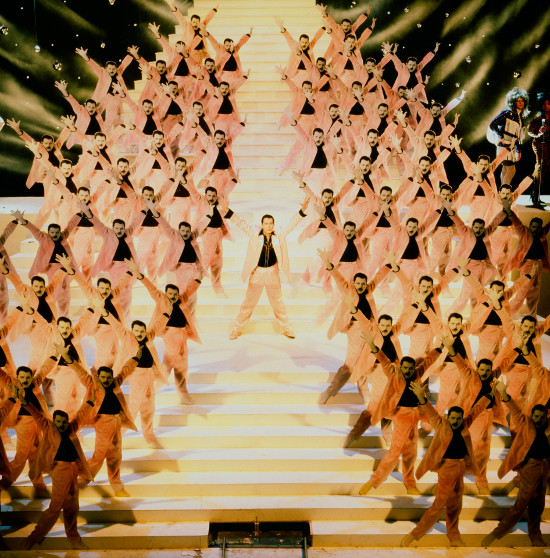

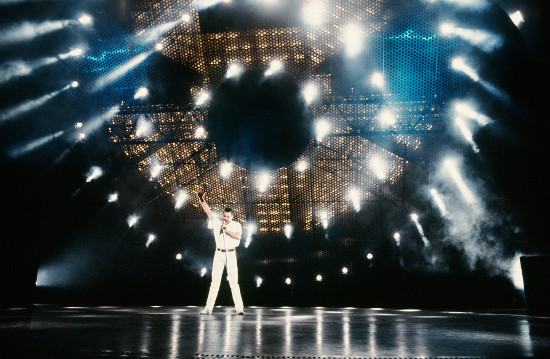

Mercury performing live in September 1984

Mercury was noted for his live performances, which were often delivered to stadium audiences around the world. He displayed a highly theatrical style that often evoked a great deal of participation from the crowd.[50] A writer for The Spectator described him as «a performer out to tease, shock and ultimately charm his audience with various extravagant versions of himself.»[51] David Bowie, who performed at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert and recorded the song «Under Pressure» with Queen, praised Mercury’s performance style, saying: «Of all the more theatrical rock performers, Freddie took it further than the rest … he took it over the edge. And of course, I always admired a man who wears tights. I only saw him in concert once and as they say, he was definitely a man who could hold an audience in the palm of his hand.»[52] Queen guitarist Brian May wrote that Mercury could make «the last person at the back of the furthest stand in a stadium feel that he was connected».[53] Mercury’s main prop on stage was a broken microphone stand; after accidentally snapping it off the heavy base during an early performance, he realised it could be used in endless ways.[54]

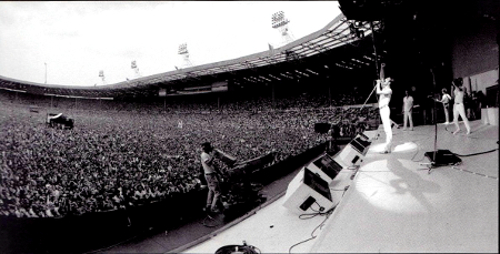

One of Mercury’s most notable performances with Queen took place at Live Aid in 1985.[2] Queen’s performance at the event has since been voted by a group of music executives as the greatest live performance in the history of rock music. The results were aired on a television program called «The World’s Greatest Gigs».[55][56] Mercury’s powerful, sustained note during the a cappella section came to be known as «The Note Heard Round the World».[57][58] In reviewing Live Aid in 2005, one critic wrote, «Those who compile lists of Great Rock Frontmen and award the top spots to Mick Jagger, Robert Plant, etc. all are guilty of a terrible oversight. Freddie, as evidenced by his Dionysian Live Aid performance, was easily the most godlike of them all.»[59] Photographer Denis O’Regan, who captured a definitive pose of Mercury on stage—arched back, knee bent and facing toward the sky—during his final tour with Queen in 1986, commented «Freddie was a once-in-a-lifetime showman».[60] Queen roadie Peter Hince states, «It wasn’t just about his voice but the way he commanded the stage. For him it was all about interacting with the audience and knowing how to get them on his side. And he gave everything in every show.»[50]

Throughout his career, Mercury performed an estimated 700 concerts in countries around the world with Queen. A notable aspect of Queen concerts was the large scale involved.[46] He once explained, «We’re the Cecil B. DeMille of rock and roll, always wanting to do things bigger and better.»[46] The band was the first ever to play in South American stadiums, breaking worldwide records for concert attendance in the Morumbi Stadium in São Paulo in 1981.[61] In 1986, Queen also played behind the Iron Curtain when they performed to a crowd of 80,000 in Budapest, in what was one of the biggest rock concerts ever held in Eastern Europe.[62] Mercury’s final live performance with Queen took place on 9 August 1986 at Knebworth Park in England and drew an attendance estimated as high as 200,000.[63] A week prior to Knebworth, May recalled Mercury saying «I’m not going to be doing this forever. This is probably the last time.»[63] With the British national anthem «God Save the Queen» playing at the end of the concert, Mercury’s final act on stage saw him draped in a robe, holding a golden crown aloft, bidding farewell to the crowd.[64][65]

Instrumentalist

Mercury playing rhythm guitar during a Queen concert in Frankfurt, West Germany, 1984

As a young boy in India, Mercury received formal piano training up to the age of nine. Later on, while living in London, he learned guitar. Much of the music he liked was guitar-oriented: his favourite artists at the time were the Who, the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, and Led Zeppelin. He was often self-deprecating about his skills on both instruments. However, Brian May states Mercury «had a wonderful touch on the piano. He could play what came from inside him like nobody else – incredible rhythm, incredible passion and feeling.»[66] Keyboardist Rick Wakeman praised Mercury’s playing style, saying he «discovered [the piano] for himself» and successfully composed a number of Queen songs on the instrument.[67] From the early 1980s Mercury began extensively using guest keyboardists. Most notably, he enlisted Fred Mandel (a Canadian musician who also worked for Pink Floyd, Elton John, and Supertramp) for his first solo project. From 1982 Mercury collaborated with Morgan Fisher (who performed with Queen in concert during the Hot Space leg),[68] and from 1985 onward Mercury collaborated with Mike Moran (in the studio) and Spike Edney (in concert).[69]

Mercury played the piano in many of Queen’s most popular songs, including «Killer Queen», «Bohemian Rhapsody», «Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy», «We Are the Champions», «Somebody to Love», and «Don’t Stop Me Now». He used concert grand pianos (such as a Bechstein) and, occasionally, other keyboard instruments such as the harpsichord. From 1980 onward, he also made frequent use of synthesisers in the studio. Brian May claims that Mercury used the piano less over time because he wanted to walk around on stage and entertain the audience.[70][71] Although he wrote many lines for the guitar, Mercury possessed only rudimentary skills on the instrument. Songs like «Ogre Battle» and «Crazy Little Thing Called Love» were composed on the guitar; the latter featured Mercury playing rhythm guitar on stage and in the studio.[72]

Solo career

As well as his work with Queen, Mercury put out two solo albums and several singles. Although his solo work was not as commercially successful as most Queen albums, the two off-Queen albums and several of the singles debuted in the top 10 of the UK Music Charts. His first solo effort goes back to 1972 under the pseudonym Larry Lurex, when Trident Studios’ house engineer Robin Geoffrey Cable was working in a musical project, at the time when Queen were recording their debut album; Cable enlisted Mercury to perform lead vocals on the songs «I Can Hear Music» and «Goin’ Back», both were released together as a single in 1973.[1] Eleven years later, Mercury contributed to the soundtrack for the restoration of the 1927 Fritz Lang film Metropolis. The song «Love Kills» was written for the film by Giorgio Moroder in collaboration with Mercury, and produced by Moroder and Mack; in 1984 it debuted at the number 10 position in the UK Singles Chart.[73]

I won’t be touring on my own or splitting up with Queen. Without the others I would be nothing. The press always makes out that I’m the wild one and they’re all quiet, but it’s not true. I’ve got some wild stories about Brian May you wouldn’t believe.

—Mercury on his solo career, January 1985.[74]

Mercury’s two full albums outside the band were Mr. Bad Guy (1985) and Barcelona (1988).[2] His first album, Mr. Bad Guy, debuted in the top ten of the UK Album Charts.[73] In 1993, a remix of «Living on My Own», a single from the album, posthumously reached number one on the UK Singles Charts. The song also garnered Mercury a posthumous Ivor Novello Award from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors.[75] AllMusic critic Eduardo Rivadavia describes Mr. Bad Guy as «outstanding from start to finish» and expressed his view that Mercury «did a commendable job of stretching into uncharted territory».[76] In particular, the album is heavily synthesiser-driven; that is not characteristic of previous Queen albums.

His second album, Barcelona, recorded with Spanish soprano vocalist Montserrat Caballé, combines elements of popular music and opera. Many critics were uncertain what to make of the album; one referred to it as «the most bizarre CD of the year».[77] The album was a commercial success,[78] and the album’s title track debuted at No. 8 in the UK and was also a hit in Spain.[79] The title track received massive airplay as the official anthem of the 1992 Summer Olympics (held in Barcelona one year after Mercury’s death). Caballé sang it live at the opening of the Olympics with Mercury’s part played on a screen, and again before the start of the 1999 UEFA Champions League Final between Manchester United and Bayern Munich in Barcelona.[80]

In addition to the two solo albums, Mercury released several singles, including his own version of the hit «The Great Pretender» by the Platters, which debuted at No. 5 in the UK in 1987.[73] In September 2006 a compilation album featuring Mercury’s solo work was released in the UK in honour of what would have been his 60th birthday. The album debuted in the UK top 10.[81] In 2012, Freddie Mercury: The Great Pretender, a documentary film directed by Rhys Thomas on Mercury’s attempts to forge a solo career, premiered on BBC One.[82]

In 1981–1983 Mercury recorded several tracks with Michael Jackson, including a demo of «State of Shock», «Victory», and «There Must Be More to Life Than This».[83][84] None of these collaborations were officially released at the time, although bootleg recordings exist. Jackson went on to record the single «State of Shock» with Mick Jagger for the Jacksons’ album Victory.[85] Mercury included the solo version of «There Must Be More To Life Than This» on his Mr. Bad Guy album.[86] «There Must Be More to Life Than This» was eventually reworked by Queen and released on their compilation album Queen Forever in 2014.[87] In addition to working with Michael Jackson, Mercury and Roger Taylor sang on the title track for Billy Squier’s 1982 studio release, Emotions in Motion and later contributed to two tracks on Squier’s 1986 release, Enough Is Enough, providing vocals on «Love is the Hero» and musical arrangements on «Lady With a Tenor Sax».[88] In 2020, Mercury’s music video for «Love Me Like There’s No Tomorrow» was nominated for Best Animation at the Berlin Music Video Awards. Woodlock studio is behind the animation.[89]

Personal life

Relationships

12 Stafford Terrace in Kensington, London, one of Mercury’s former homes

In the early 1970s, Mercury had a long-term relationship with Mary Austin, whom he met through guitarist Brian May. Austin, born in Fulham, London, met Mercury in 1969 when she was 19 and he was 24 years old, a year before Queen had formed.[90] He lived with Austin for several years in West Kensington, London. By the mid-1970s, he had begun an affair with David Minns, an American record executive at Elektra Records. In December 1976, Mercury told Austin of his sexuality, which ended their romantic relationship.[69][91] Mercury moved out of the flat they shared, and bought Austin a place of her own nearby his new address of 12 Stafford Terrace, Kensington.[92]

Mercury and Austin remained friends through the years; Mercury often referred to her as his only true friend. In a 1985 interview, he said of Austin: «All my lovers asked me why they couldn’t replace Mary, but it’s simply impossible. The only friend I’ve got is Mary, and I don’t want anybody else. To me, she was my common-law wife. To me, it was a marriage. We believe in each other, that’s enough for me.»[93] Mercury’s final home, Garden Lodge, a 28-room Georgian mansion in Kensington set in a quarter-acre manicured garden surrounded by a high brick wall, was picked out by Austin.[94] Austin married the painting artist Piers Cameron; they have two children. Mercury was the godfather of her older son, Richard.[70] In his will, Mercury left his London home to Austin having told her, «You would have been my wife, and it would have been yours anyway.»[95]

During the early-to-mid-1980s, he was reportedly involved with Barbara Valentin, an Austrian actress, who is featured in the video for «It’s a Hard Life».[91][96] In another article, he said Valentin was «just a friend»; Mercury was dating German restaurateur Winfried «Winnie» Kirchberger during this time.[97] Mercury lived at Kirchberger’s apartment[98] and thanked him «for board and lodging» in the liner notes of his 1985 album Mr. Bad Guy.[99] He wore a silver wedding band given to him by Kirchberger.[100] A close friend described him as Mercury’s «great love» in Germany.[101]

By 1985, he began another long-term relationship with Irish-born hairdresser Jim Hutton (1949–2010), whom he referred to as his husband.[102] Mercury described their relationship as one built on solace and understanding, and said that he «honestly couldn’t ask for better».[103] Hutton, who tested HIV-positive in 1990, lived with Mercury for the last seven years of his life, nursed him during his illness, and was present at his bedside when he died. Mercury wore a gold wedding band, given to him by Hutton in 1986, until the end of his life. He was cremated with it on.[100] Hutton later relocated from London to the bungalow he and Mercury had built for themselves in Ireland.[100]

Friendship with Kenny Everett

Radio disc jockey Kenny Everett met Mercury in 1974, when he invited the singer onto his Capital London breakfast show.[104] As two of Britain’s most flamboyant, outrageous and popular entertainers, they shared much in common and became close friends.[104] In 1975, Mercury visited Everett, bringing with him an advance copy of the single «Bohemian Rhapsody».[94] Despite doubting that any station would play the six-minute track, Everett placed the song on the turntable, and, after hearing it, exclaimed: «Forget it, it’s going to be number one for centuries».[94] Although Capital Radio had not officially accepted the song, Everett talked incessantly about a record he possessed but could not play. He then frequently proceeded to play the track with the excuse: «Oops, my finger must’ve slipped.»[94] On one occasion, Everett aired the song fourteen times over a single weekend.[105] Capital’s switchboard was overwhelmed with callers inquiring when the song would be released.[104][106]

During the 1970s, Everett became advisor and mentor to Mercury and Mercury served as Everett’s confidant.[104] Throughout the early-to-mid-1980s, they continued to explore their homosexuality and use drugs. Although they were never lovers, they did experience London nightlife together.[104] By 1985, they had fallen out, and their friendship was further strained when Everett was outed in the autobiography of his ex-wife Lee Everett Alkin.[104] In 1989, with their health failing, Mercury and Everett were reconciled.[104]

Sexual orientation

While some commentators claimed Mercury hid his sexual orientation from the public,[20][37][107] others claimed he was «openly gay».[108][109] In December 1974, when asked directly, «So how about being bent?» by the New Musical Express, Mercury replied, «You’re a crafty cow. Let’s put it this way: there were times when I was young and green. It’s a thing schoolboys go through. I’ve had my share of schoolboy pranks. I’m not going to elaborate further.»[110] Homosexual acts between adult males over the age of 21 had been decriminalised in the United Kingdom in 1967, seven years earlier. During public events in the 1980s, Mercury often kept a distance from his partner, Jim Hutton.[111]

Mercury’s flamboyant stage performances sometimes led journalists to allude to his sexuality. Dave Dickson, reviewing Queen’s performance at Wembley Arena in 1984 for Kerrang!, noted Mercury’s «camp» addresses to the audience and even described him as a «posing, pouting, posturing tart».[112] In 1992, John Marshall of Gay Times opined: «[Mercury] was a ‘scene-queen,’ not afraid to publicly express his gayness, but unwilling to analyse or justify his ‘lifestyle’ … It was as if Freddie Mercury was saying to the world, ‘I am what I am. So what?’ And that in itself for some was a statement.»[113] In an article for AfterElton, Robert Urban said: «Mercury did not ally himself to ‘political outness,’ or to LGBT causes.»[113]

Some believe Mercury was bisexual; for example, regarding the creation of Celebrate Bisexuality Day, Wendy Curry said: «We were sitting around at one of the annual bi conventions, venting and someone – I think it was Gigi – said we should have a party. We all loved the great bisexual, Freddie Mercury. His birthday was in September, so why not Sept? We wanted a weekend day to ensure the most people would do something. Gigi’s birthday was September 23rd. It fell on a weekend day, so, poof! We had a day.»[114][115] The Advocate said in May 2018, «Closeted throughout his life, Mercury, who was bisexual, engaged in affairs with men but referred to a woman he loved in his youth, Mary Austin, as ‘the love of his life,’ according to the biography Somebody to Love: The Life, Death, and Legacy of Freddie Mercury.»[116] Additionally, according to an obituary Mercury was a «self-confessed bisexual».[117][118] The 2018 biopic of Mercury, Bohemian Rhapsody, received criticism for its portrayal of Mercury’s sexuality, which was described as «sterilized» and «confused», and was even accused of being «dangerous».[119][120][121]

Personality

Although he cultivated a flamboyant stage personality, Mercury was shy and retiring when not performing, particularly around people he did not know well,[18][37] and granted very few interviews. He once said of himself: «When I’m performing I’m an extrovert, yet inside I’m a completely different man.»[122] On this contrast to «his larger-than-life stage persona», BBC music broadcaster Bob Harris adds he was «lovely, bright, sensitive, and quite vulnerable.»[123] While on stage, Mercury basked in the love from his audience. Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain’s suicide note mentions how he admired and envied the way Mercury «seemed to love, relish in the love and adoration from the crowd».[124][125]

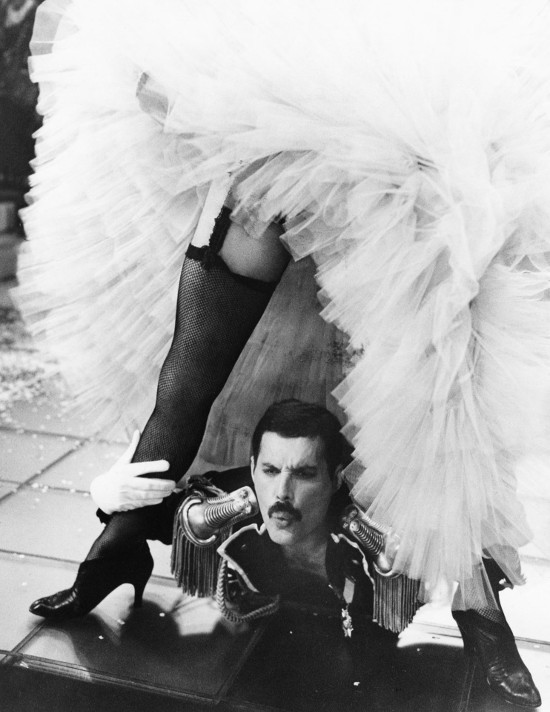

A flamboyant personality on stage, Mercury, pictured wearing a Harlequin outfit in 1977, adopted glam rock aesthetics in the 1970s

Mercury never discussed his ethnic or religious background with journalists. The closest he came to doing so was in response to a question about his outlandish persona, he said, «that’s something inbred, it’s a part of me. I will always walk around like a Persian popinjay»,[126] an oblique reference to his Indian Parsi background. Feeling a connection to Britain prior to arriving in England, the young Bulsara was heavily influenced by British fashion and music trends while growing up.[126] According to his longtime assistant Peter Freestone, «if Freddie had his way, he would have been born aged 18 in Feltham.»[126] Harris states, «One of the things about Freddie was that he was very civilised and quite ‘English’. I’d go over to his flat near Shepherd’s Bush in the afternoon, and he’d get out the fine china and the sugar lumps and we’d have a cup of tea.»[123] His flamboyant dress sense and the emergence of glam rock in the UK in the early 1970s saw Mercury wear outfits designed by Zandra Rhodes.[127]

When asked by Melody Maker in 1981 if rock stars should use their power to try to shape the world for the better, Mercury responded, «Leave that to the politicians. Certain people can do that kind of thing, but very few. John Lennon was one. Because of his status, he could do that kind of preaching and affect people’s thoughts. But to do this you have to have a certain amount of intellect and magic together, and the John Lennons are few and far between. People with mere talent, like me, have not got the ability or power.»[128] Mercury dedicated a song to the former member of The Beatles. The song, «Life Is Real (Song for Lennon)», is included in the 1982 album Hot Space.[129] Mercury did occasionally express his concerns about the state of the world in his lyrics. His most notable «message» songs are «Under Pressure», «Is This the World We Created…?» (a song which Mercury and May performed at Live Aid, and also featured in Greenpeace – The Album), «There Must Be More to Life Than This», «The Miracle» (a song May called «one of Freddie’s most beautiful creations») and «Innuendo».[130][131]

Mercury cared for at least ten cats throughout his life, including: Tom, Jerry, Oscar, Tiffany, Dorothy, Delilah, Goliath, Miko, Romeo, and Lily. He was against the inbreeding of cats for specific features and all except for Tiffany and Lily, both given as gifts, were adopted from the Blue Cross. Mercury «placed as much importance on these beloved animals as on any human life», and showed his adoration by having the artist Ann Ortman paint portraits of each of them. Mercury wrote a song for Delilah, «his favourite cat of all», which appeared on the Queen album Innuendo.[132] Mercury dedicated his liner notes in his 1985 solo album Mr. Bad Guy to Jerry and his other cats. It reads, «This album is dedicated to my cat Jerry—also Tom, Oscar, and Tiffany and all the cat lovers across the universe—screw everybody else!»[133]

In 1987, Mercury celebrated his 41st birthday at the Pikes Hotel, Ibiza, Spain, several months after discovering that he had contracted HIV.[94] Mercury sought much comfort at the retreat and was a close friend of the owner, Anthony Pike, who described Mercury as «the most beautiful person I’ve ever met in my life. So entertaining and generous.»[134] According to biographer Lesley-Ann Jones, Mercury «felt very much at home there. He played some tennis, lounged by the pool, and ventured out to the odd gay club or bar at night.»[135] The birthday party, held on 5 September 1987, has been described as «the most incredible example of excess the Mediterranean island had ever seen», and was attended by some 700 people.[136] A cake in the shape of Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Família was provided for the party. The original cake collapsed and was replaced with a two-metre-long sponge cake decorated with the notes from Mercury’s song «Barcelona».[134] The bill, which included 232 broken glasses, was presented to Queen’s manager, Jim Beach.[137] Before his death, Mercury had told Beach, «You can do what you want with my music, but don’t make me boring.»[138]

Illness and death

Mercury exhibited HIV/AIDS symptoms as early as 1982. Authors Matt Richards and Mark Langthorne have stated in their biographical book about Mercury, Somebody to Love: The Life, Death, and Legacy of Freddie Mercury, that Mercury secretly visited a doctor in New York City to get a white lesion on his tongue checked (which might have been hairy leukoplakia, one of the first signs of an infection) a few weeks before Queen’s final American appearance with Mercury on Saturday Night Live on 25 September 1982.[139] They also stated that he had associated with someone who was recently infected with HIV on the same day of their final US appearance, when he began to exhibit more symptoms.[139]

Mountain Studios in Montreux, Switzerland, Queen’s recording studio from 1978 to 1995. Mercury recorded his final vocals here in May 1991. In December 2013, the studio was opened free as the «Queen Studio Experience», with fans asked for a donation to the Mercury Phoenix Trust charity.[140]

In October 1986, the British press reported that Mercury had his blood tested for HIV/AIDS at a Harley Street clinic. According to his partner, Jim Hutton, Mercury was diagnosed with AIDS in late April 1987.[141] Around that time, Mercury claimed in an interview to have tested negative for HIV.[37]

The British press pursued the rumours over the next few years, fuelled by Mercury’s increasingly gaunt appearance, Queen’s absence from touring, and reports from his former lovers to tabloid journals. By 1990, rumours about Mercury’s health were rife.[142] At the 1990 Brit Awards held at the Dominion Theatre, London, on 18 February, Mercury made his final appearance on stage, when he joined the rest of Queen to collect the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to British Music.[143][144]

Mercury and his inner circle of colleagues and friends continually denied the stories. It has been suggested that Mercury could have helped AIDS awareness by speaking earlier about his illness.[52][145] Mercury kept his condition private to protect those closest to him; May later confirmed that Mercury had informed the band of his illness much earlier.[146][147] Filmed in May 1991, the music video for «These Are the Days of Our Lives» features a very thin Mercury in his final scenes in front of the camera.[148] Director of the video Rudi Dolezal comments, «AIDS was never a topic. We never discussed it. He didn’t want to talk about it. Most of the people didn’t even 100 percent know if he had it, apart from the band and a few people in the inner circle. He always said, ‘I don’t want to put any burden on other people by telling them my tragedy.‘«[149] The rest of the band were ready to record when Mercury felt able to come into the studio, for an hour or two at a time. May said of Mercury: «He just kept saying. ‘Write me more. Write me stuff. I want to just sing this and do it and when I am gone you can finish it off.’ He had no fear, really.»[140] Justin Shirley-Smith, the assistant engineer for those last sessions, said: «This is hard to explain to people, but it wasn’t sad, it was very happy. He [Freddie] was one of the funniest people I ever encountered. I was laughing most of the time, with him. Freddie was saying [of his illness] ‘I’m not going to think about it, I’m going to do this.‘«[140]

After the conclusion of his work with Queen in June 1991, Mercury retired to his home in Kensington, West London. His former partner, Mary Austin, was a particular comfort in his final years, and in the last few weeks made regular visits to look after him.[150] Near the end of his life, Mercury began to lose his sight, and declined so that he was unable to leave his bed.[150] Mercury chose to hasten his death by refusing medication and took only painkillers.[150] On 22 November 1991, Mercury called Queen’s manager Jim Beach to his Kensington home to prepare a public statement, which was released the following day:[146]

Following the enormous conjecture in the press over the last two weeks, I wish to confirm that I have been tested HIV positive and have AIDS. I felt it correct to keep this information private to date to protect the privacy of those around me. However, the time has come now for my friends and fans around the world to know the truth and I hope that everyone will join with me, my doctors and all those worldwide in the fight against this terrible disease. My privacy has always been very special to me and I am famous for my lack of interviews. Please understand this policy will continue.

Death

On the evening of 24 November 1991, about 24 hours after issuing the statement, Mercury died at the age of 45 at his home in Kensington.[151] The cause of death was bronchial pneumonia resulting from AIDS.[152] His close friend Dave Clark of the Dave Clark Five was at the bedside vigil when Mercury died. Austin phoned Mercury’s parents and sister to break the news, which reached newspaper and television crews in the early hours of 25 November.[153]

The outer walls of Mercury’s final home, Garden Lodge, Logan Place, west London, became a shrine to the late singer

Mercury’s funeral service was conducted on 27 November 1991 by a Zoroastrian priest at West London Crematorium, where he is commemorated by a plinth under his birth name. In attendance at Mercury’s service were his family and 35 of his close friends, including Elton John and the members of Queen.[154][155] His coffin was carried into the chapel to the sounds of «Take My Hand, Precious Lord»/»You’ve Got a Friend» by Aretha Franklin.[156] In accordance with Mercury’s wishes, Mary Austin took possession of his cremated remains and buried them in an undisclosed location.[71] The whereabouts of his ashes are believed to be known only to Austin, who has said that she will never reveal them.[157]

Mercury spent and donated to charity much of his wealth during his lifetime, with his estate valued around £8 million at the time of his death. He bequeathed his home, Garden Lodge, and the adjoining Mews, as well as a 50% of all privately owned shares, to Mary Austin. His sister, Kashmira Cooke, received 25%, as did his parents, Bomi and Jer Bulsara, which Cooke acquired upon their deaths. He willed £500,000 to Joe Fannelli; £500,000 to Jim Hutton; £500,000 to Peter Freestone; and £100,000 to Terry Giddings.[158] Mercury, who never drove a car because he had no licence, was often chauffeured around London in his Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow from 1979 until his death. The car was passed to his sister Kashmira who made it available for display at public events, including the West End premiere of the musical We Will Rock You in 2002, before it was auctioned off at the NEC in Birmingham in 2013 for £74,600.[159][160]

Following his death, the outer walls of Garden Lodge in Logan Place became a shrine to Mercury, with mourners paying tribute by covering the walls in graffiti messages.[161] Three years later Time Out magazine reported that «the wall outside the house has become London’s biggest rock ‘n’ roll shrine».[161] Fans continued to visit to pay their respects with letters appearing on the walls[162] until 2017, when Austin had the wall cleared.[163] Hutton was involved in a 2000 biography of Mercury, Freddie Mercury, the Untold Story, and also gave an interview for The Times in September 2006 for what would have been Mercury’s 60th birthday.[141]

Legacy

Continued popularity

The charisma and power in his performance style has over the years led to many artists quoting him as one of their biggest inspirations today. The diverse scope of artists that love Mercury is huge.

—Amy Weller, Gigwise[164]

Regarded as one of the greatest lead singers in the history of rock music,[165][166] he was known for his flamboyant stage persona and four-octave vocal range.[167][168][169] Mercury defied the conventions of a rock frontman, with his highly theatrical style influencing the artistic direction of Queen.[170]

The extent to which Mercury’s death may have enhanced Queen’s popularity is not clear. In the United States, where Queen’s popularity had lagged in the 1980s, sales of Queen albums went up dramatically in 1992, the year following his death.[171] In 1992, one American critic noted, «What cynics call the ‘dead star’ factor had come into play—Queen is in the middle of a major resurgence.»[172] The movie Wayne’s World, which featured «Bohemian Rhapsody», also came out in 1992.[173] According to the Recording Industry Association of America, Queen had sold 34.5 million albums in the United States by 2004, about half of which had been sold since Mercury’s death in 1991.[174]

Estimates of Queen’s total worldwide record sales to date have been set as high as 300 million.[175] In the United Kingdom, Queen have now spent more collective weeks on the UK Album Charts than any other musical act (including the Beatles),[176] and Queen’s Greatest Hits is the best-selling album of all time in the United Kingdom.[177] Two of Mercury’s songs, «We Are the Champions» and «Bohemian Rhapsody», have also each been voted as the greatest song of all time in major polls by Sony Ericsson[178] and Guinness World Records.[179] Both songs have been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame; «Bohemian Rhapsody» in 2004 and «We Are the Champions» in 2009.[180] In October 2007 the video for «Bohemian Rhapsody» was voted the greatest of all time by readers of Q magazine.[181]

Since his death, Queen were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2001, and all four band members were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2003.[182][183] Their Rock Hall of Fame citation reads, «in the golden era of glam rock and gorgeously hyper-produced theatrical extravaganzas that defined one branch of ’70s rock, no group came close in either concept or execution to Queen.»[184] The band were among the inaugural inductees into the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2004. Mercury was individually posthumously awarded the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to British Music in 1992.[185] They received the Ivor Novello Award for Outstanding Song Collection from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers, and Authors in 2005, and in 2018 they were presented the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.[45][186]

Posthumous Queen album

In November 1995, Mercury appeared posthumously on Queen’s final studio album Made in Heaven.[2][187] The album featured Mercury’s previously unreleased final recordings from 1991, as well as outtakes from previous years and reworked versions of solo works by the other members.[188] The album cover features the Freddie Mercury statue that overlooks Lake Geneva superimposed with Mercury’s Duck House lake cabin that he had rented. This is where he had written and recorded his last songs at Mountain Studios.[188] The sleeve of the album contains the words, «Dedicated to the immortal spirit of Freddie Mercury.»[188]

Featuring tracks such as «Too Much Love Will Kill You» and «Heaven for Everyone», the album also contains the song «Mother Love», the last vocal recording Mercury made before his death, which he completed using a drum machine, over which May, Taylor, and Deacon later added the instrumental track.[189] After completing the penultimate verse, Mercury had told the band he «wasn’t feeling that great» and stated, «I will finish it when I come back next time». He never made it back into the studio, so May later recorded the final verse of the song.[140]

Tributes

A statue in Montreux, Switzerland, by sculptor Irena Sedlecká, was erected as a tribute to Mercury.[190] It stands almost 10 feet (3.0 metres) high overlooking Lake Geneva and was unveiled on 25 November 1996 by Mercury’s father and Montserrat Caballé, with bandmates Brian May and Roger Taylor also in attendance.[191] Beginning in 2003 fans from around the world have gathered in Switzerland annually to pay tribute to the singer as part of the «Freddie Mercury Montreux Memorial Day» on the first weekend of September.[192]

In 1997 the three remaining members of Queen released «No-One but You (Only the Good Die Young)», a song dedicated to Mercury and all those that die too soon.[193] In 1999 a Royal Mail stamp with an image of Mercury on stage was issued in his honour as part of the UK postal service’s Millennium Stamp series.[194][195] In 2009 a star commemorating Mercury was unveiled in Feltham, west London where his family moved upon arriving in England in 1964. The star in memory of Mercury’s achievements was unveiled on Feltham High Street by his mother Jer Bulsara and Queen bandmate May.[196]

A statue of Mercury stood over the entrance to the Dominion Theatre in London’s West End from May 2002 to May 2014 for Queen and Ben Elton’s musical We Will Rock You.[197] A tribute to Queen was on display at the Fremont Street Experience in downtown Las Vegas throughout 2009 on its video canopy.[198] In December 2009 a large model of Mercury wearing tartan was put on display in Edinburgh as publicity for the run of We Will Rock You.[199] Sculptures of Mercury often feature him wearing a military jacket with his fist in the air. In 2018, GQ magazine called Mercury’s yellow military jacket from his 1986 concerts his best known look,[200] while CNN called it «an iconic moment in fashion.»[201]

For Mercury’s 65th birthday in 2011, Google dedicated its Google Doodle to him. It included an animation set to his song, «Don’t Stop Me Now».[202] Referring to «the late, great Freddie Mercury» in their 2012 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction speech, Guns N’ Roses quoted Mercury’s lyrics from «We Are the Champions»; «I’ve taken my bows, my curtain calls, you’ve brought me fame and fortune and everything that goes with it, and I thank you all.»[203][204]

Tribute was paid to Queen and Mercury at the closing ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. The band’s performance of «We Will Rock You» with Jessie J was opened with a video of Mercury’s «call and response» routine from 1986’s Wembley Stadium performance, with the 2012 crowd at the Olympic Stadium responding appropriately.[205][206] The frog genus Mercurana, discovered in 2013 in Kerala, India, was named as a tribute because Mercury’s «vibrant music inspires the authors». The site of the discovery is very near to where Mercury spent most of his childhood.[207] In 2013, a newly discovered species of damselfly from Brazil was named Heteragrion freddiemercuryi, honouring the «superb and gifted musician and songwriter whose wonderful voice and talent still entertain millions» — one of four similar damselflies named after the Queen bandmates, in tribute to Queen’s 40th anniversary.[208]

On 1 September 2016, an English Heritage blue plaque was unveiled at Mercury’s home in 22 Gladstone Avenue in Feltham, west London by his sister, Kashmira Cooke, and Brian May.[209] Attending the ceremony, Karen Bradley, the UK Secretary of State for Culture, called Mercury «one of Britain’s most influential musicians», and added he «is a global icon whose music touched the lives of millions of people around the world».[210] On 24 February 2020 a street in Feltham was renamed Freddie Mercury Close during a ceremony attended by his sister Kashmira.[211] On 5 September 2016, the 70th anniversary of Mercury’s birth, asteroid 17473 Freddiemercury was named after him.[212] Issuing the certificate of designation to the «charismatic singer», Joel Parker of the Southwest Research Institute added: «Freddie Mercury sang, ‘I’m a shooting star leaping through the sky’ — and now that is even more true than ever before.»[212] In an April 2019 interview, British rock concert promoter Harvey Goldsmith referred to Mercury as «one of our most treasured talents».[213]

In August 2019, Mercury was one of the honorees inducted in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco’s Castro neighbourhood noting LGBTQ people who have «made significant contributions in their fields».[214][215][216] Freddie Mercury Alley is a 107-yard-long (98 m) alley next to the British embassy in the Ujazdów district in Warsaw, Poland, which is dedicated to Mercury, and was unveiled on 22 November 2019.[217] Until the Freddie Mercury Close in Feltham was dedicated, Warsaw was the only city in Europe with a street dedicated to the singer.[218][219] In January 2020, Queen became the first band to join Queen Elizabeth II on a British coin. Issued by the Royal Mint, the commemorative £5 coin features the instruments of all four band members, including Mercury’s Bechstein grand piano and his mic and stand.[220] In April 2022, a life-size statue of Mercury was unveiled in South Korea’s resort island of Jeju.[221]

Mercury has featured in international advertising to represent the UK. In 2001, a parody of Mercury, along with prints of other British music icons consisting of The Beatles, Elton John, Spice Girls, and The Rolling Stones, appeared in the Eurostar national advertising campaign in France for the Paris to London route.[222] In September 2017 the airline Norwegian painted the tail fin of two of its aircraft with a portrait of Mercury to mark what would have been his 71st birthday. Mercury is one of the company’s six «British tail fin heroes», alongside England’s 1966 FIFA World Cup winning captain Bobby Moore, children’s author Roald Dahl, novelist Jane Austen, pioneering pilot Amy Johnson, and aviation entrepreneur Sir Freddie Laker.[223][224]

Importance in AIDS history

«Good evening Wembley and the world. We are here tonight to celebrate the life, and work, and dreams, of one Freddie Mercury. We’re gonna give him the biggest send off in history!»

—Brian May at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert.[225]

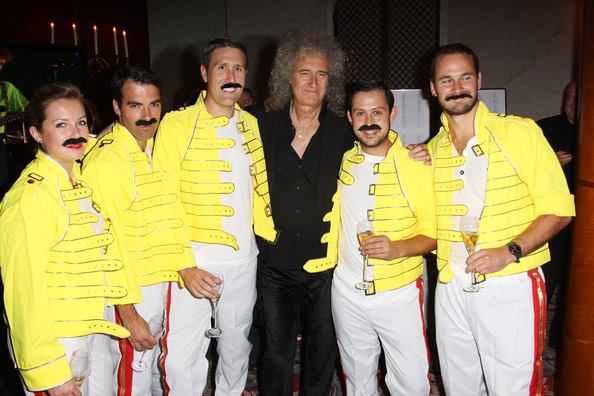

As the first major rock star to die of AIDS-related complications, Mercury’s death represented an important event in the history of the disease.[226] In April 1992, the remaining members of Queen founded The Mercury Phoenix Trust and organised The Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert for AIDS Awareness, to celebrate the life and legacy of Mercury and raise money for AIDS research, which took place on 20 April 1992.[227] The Mercury Phoenix Trust has since raised millions of pounds for various AIDS charities. The tribute concert, which took place at London’s Wembley Stadium for an audience of 72,000, featured a wide variety of guests including Robert Plant (of Led Zeppelin), Roger Daltrey (of the Who), Extreme, Elton John, Metallica, David Bowie, Annie Lennox, Tony Iommi (of Black Sabbath), Guns N’ Roses, Elizabeth Taylor, George Michael, Def Leppard, Seal and Liza Minnelli, with U2 also appearing via satellite. Elizabeth Taylor spoke of Mercury as «an extraordinary rock star who rushed across our cultural landscape like a comet shooting across the sky».[228] The concert was broadcast live to 76 countries and had an estimated viewing audience of 1 billion people.[229] The Freddie For A Day fundraiser on behalf of the Mercury Phoenix Trust takes place every year in London, with supporters of the charity including Monty Python comedian Eric Idle, and Mel B of the Spice Girls.[230]

The documentary, Freddie Mercury: The Final Act, aired on BBC Two in 2021 and The CW in the US in April 2022. It covered Mercury’s last days, how his bandmates and friends put together the Tribute Concert at Wembley, and interviewed medical professionals, people who tested HIV positive, and others who knew someone who died of AIDS.[231][232] At the 50th International Emmy Awards in 2022 it won the International Emmy Award for Best Arts Programming.[233]

Appearances in lists of influential individuals

Several popularity polls conducted over the past decade indicate that Mercury’s reputation may have been enhanced since his death. For instance, in a 2002 vote to determine who the UK public considers the greatest British people in history, Mercury was ranked 58 in the list of the 100 Greatest Britons, broadcast by the BBC.[234] He was further listed at the 52nd spot in a 2007 Japanese national survey of the 100 most influential heroes.[235] Although he had been criticised by gay activists for hiding his HIV status, author Paul Russell included Mercury in his book The Gay 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Gay Men and Lesbians, Past and Present.[236] In 2008, Rolling Stone ranked Mercury 18 on its list of the Top 100 Singers Of All Time.[168] Mercury was voted the greatest male singer in MTV’s 22 Greatest Voices in Music.[108] In 2011 a Rolling Stone readers’ pick placed Mercury in second place of the magazine’s Best Lead Singers of All Time.[124] In 2015, Billboard magazine placed him second on their list of the 25 Best Rock Frontmen (and Women) of All Time.[237] In 2016, LA Weekly ranked him first on the list of 20 greatest singers of all time, in any genre.[238]

Portrayal on stage

On 24 November 1997, a monodrama about Freddie Mercury’s life, titled Mercury: The Afterlife and Times of a Rock God, opened in New York City.[239] It presented Mercury in the hereafter: examining his life, seeking redemption and searching for his true self.[240] The play was written and directed by Charles Messina and the part of Mercury was played by Khalid Gonçalves (né Paul Gonçalves) and then later, Amir Darvish.[241] Billy Squier opened one of the shows with an acoustic performance of a song he had written about Mercury titled «I Have Watched You Fly».[242]

In 2016 a musical titled Royal Vauxhall premiered at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in Vauxhall, London. Written by Desmond O’Connor, the musical told the alleged tales of the nights that Mercury, Kenny Everett and Princess Diana spent out at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in London in the 1980s.[243] Following several successful runs in London, the musical was taken to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in August 2016 starring Tom Giles as Mercury.[243]

Portrayal in film and television

Mural promoting the release of Bohemian Rhapsody on the side of Mercury’s former art college in West London in October 2018

The 2018 biographical film Bohemian Rhapsody was, at its release, the highest-grossing musical biographical film of all time.[244][245] Mercury was portrayed by Rami Malek, who received the Academy Award, BAFTA Award, Golden Globe Award and Screen Actors Guild Award for Best Actor, for his performance.[246][247] While the film received mixed reviews and contained historical inaccuracies, it won the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture – Drama.[248][249][250]

Mercury appeared as a supporting character in the BBC television drama Best Possible Taste: The Kenny Everett Story, first broadcast in October 2012. He was portrayed by actor James Floyd.[251] He was played by actor John Blunt in The Freddie Mercury Story: Who Wants to Live Forever, first broadcast in the UK on Channel 5 in November 2016. Although the programme was criticised for focusing on Mercury’s love life and sexuality, Blunt’s performance and likeness to the singer did receive praise.[252]

In 2018, David Avery portrayed Mercury in the Urban Myths comedy series in an episode focusing on the antics backstage at Live Aid, and Kayvan Novak portrayed Mercury in an episode titled «The Sex Pistols vs. Bill Grundy».[253][254][255] He was also portrayed by Eric McCormack (as the character Will Truman) on Will & Grace in the October 2018 episode titled «Tex and the City».[256]

Discography

Notes

- ^ The Bulsara family gets its name from Bulsar, now Valsad, a city and district that is now in the Indian state of Gujarat. In the 17th century, Bulsar was one of the five centres of the Zoroastrian religion (the other four were also in what is today Gujarat) and consequently «Bulsara» is a relatively common name amongst Parsi Zoroastrians.

- ^ On Mercury’s birth certificate, his parents identified as «Nationality: British Indian» and «Race: Parsi».[3] The Parsis are an ethnic group of Persian origin and have lived on the Indian subcontinent for more than a thousand years.

References

- ^ a b Runtagh, Jordan (23 November 2016). «Freddie Mercury: 10 Things You Didn’t Know Queen Singer Did». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f «Freddie Mercury, British singer and songwriter». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Linda B (5 October 2000), Certificate of Birth, Chorley: Mr Mercury, archived from the original (JPEG) on 28 February 2008

- ^ «Freddie Mercury (real name Farrokh Bulsara) Biography». Inout Star. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ^ May, Brian (18 November 2016). «Freddie’s Mum – R.I.P.» brianmay.com. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Simpson, George (15 June 2022). «Freddie Mercury’s sister shuts down myth on Queen singer’s death». Daily Express.

- ^ Whitfield, David (3 April 2019). «Freddie Mercury’s sister Kashmira on the success of ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ – and what happened when the Queen legend used to visit her in Nottingham». Nottingham Post. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Canning, Tom (12 August 2011). «Why Freddie Mercury will always be the champion to his Notts relatives». Nottingham Post. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Sky, Rick (1992), The Show Must Go On, London: Fontana, pp. 8–9, ISBN 978-0-00-637843-3

- ^ Coyle, Jake (29 October 2018). «Review: ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ won’t rock you, but Malek will». Yahoo!. Associated Press.

- ^ «‘Bohemian Rhapsody’: Sinking one’s teeth into a role». CBS News. Retrieved 3 March 2019

- ^ «Registrations of British Nationality. Certificate Number: R1/117889 . Name: Frederick Bulsara also known as Freddie Mercury». National Archives.gov.uk. Retrieved 6 October 2019

- ^ Queen Online – History: Freddie Mercury, Archived on 8 August 2010.

- ^ Jones 2011.

- ^ Hodkinson, Mark (2004), Queen: The Early Years, London: Omnibus Press, pp. 2, 61, ISBN 978-1-84449-012-7

- ^ Bhatia, Shekhar (16 October 2011). «Freddie Mercury’s family tell of singer’s pride in his Asian heritage». Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Alikhan, Anvar (5 September 2016). «‘Freddie Mercury was a prodigy’: Rock star’s Panchgani school bandmates remember ‘Bucky’«. Scroll.in. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ a b O’Donnell, Lisa (7 July 2005), «Freddie Mercury, WSSU professor were boyhood friends in India, Zanzibar», RelishNow!, archived from the original on 18 February 2008, retrieved 24 September 2009

- ^ Jones, Lesley-Ann (2012). Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury. Simon and Schuster. p. 327. ISBN 978-1-4516-6397-6.

- ^ a b Januszczak, Waldemar (17 November 1996), «Star of India», The Sunday Times, London, archived from the original on 16 March 2015, retrieved 1 September 2008

- ^ Plekhanov, Sergey (2004), A Reformer on the Throne: Sultan Qaboos Bin Said Al Said, Trident Press Ltd, p. 91, ISBN 978-1-900724-70-8

- ^ @UkNatArchives (19 June 2019). «Farrokh Bulsara fled to England from Zanzibar in 1964 as a refugee to escape the violence of the revolution for independence. He’s more widely known as #FreddieMercury, lead singer of the band #Queen. This is his registration of British citizenship from 1969 #RefugeeWeek» (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c d e Garlak. «10 The best Rock/Metal Bands Logos». Tooft Design. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ «Roger Taylor «I remember»«. Reader’s Digest. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ «Freddie Mercury fans hit Heathrow to celebrate Queen star’s stint as a baggage handler». The Times. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Davis, Andy (1996), «Queen Before Queen», Record Collector, vol. 3, no. 199

- ^ Tremlett, George (1976). The Queen Story. Futura Publications. p. 38. ISBN 0860074129.

- ^ Hodkinson, Mark (1995), Queen The Early Years, Omnibus Press, p. 117, ISBN 978-0-7119-6012-1

- ^ «The pub that hosted John Lennon and Freddie Mercury needs your band…» Jade’s Music Blog. Liverpool Echo. Musicblog.merseyblogs.co.uk. 8 August 2008. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Skala, Martin (2006), Concertography Freddie Mercury live Early days, Plzen, Czech Republic: queenconcerts.com

- ^ Highleyman, Liz (9 September 2005), «Who was Freddie Mercury?», Seattle Gay News, vol. 33, no. 36, archived from the original on 11 October 2007

- ^ Sutcliffe, Phil; Hince, Peter; Mack, Reinhold (2009), Queen: The Ultimate Illustrated History of the Crown Kings of Rock, London: Voyageur Press, p. 22, ISBN 978-0-7603-3719-6[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dilara Onen (27 October 2020). «The real story of why Freddie Mercury decided to change his original name, Farrokh Bulsara». Metalhead Zone. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021.

- ^ Evans, David; Peter Freestone (2001), Freddie Mercury: an intimate memoir by the man who knew him best, London: Omnibus, pp. 108–9, ISBN 978-0-7119-8674-9

- ^ a b c Soto-Morettini, D. (2006), Popular Singing: A Practical Guide To: Pop, Jazz, Blues, Rock, Country and Gospel, A & C Black, ISBN 978-0713672664

- ^ Bret 1996, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d Cain, Matthew (2006), Freddie Mercury: A Kind of Magic, London: British Film Institute, 9:00/Roger Taylor, archived from the original on 21 September 2021.

- ^ O’Donnell, Jim (2013). Queen Magic: Freddie Mercury Tribute and Brian May Interview. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1491235393

- ^ Love, Brian (18 January 2012). «Andrew Lloyd Webber: ‘Jesus actor must have Freddie Mercury range’«. Digital Spy. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ «Why Freddie Mercury’s Voice Was So Great, As Explained By Science». NPR.org. NPR News «All Things Considered». 25 April 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ a b Herbst, Christian T.; Hertegard, Stellan; Zangger-Borch, Daniel; Lindestad, Per-Åke (15 April 2016). «Freddie Mercury—acoustic analysis of speaking fundamental frequency, vibrato, and subharmonics». Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology. 42 (1): 29–38. doi:10.3109/14015439.2016.1156737. PMID 27079680. S2CID 11434921.

- ^ «Scientists explain Freddie Mercury’s incredible singing voice». Foxnews.com. 19 April 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ «Queen – Greatest Hits, Vols. 1». AllMusic. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ «2003 Award and Induction Ceremony: Queen». Songwritershalloffame.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b «The 50th Ivor Novello Awards». theivors.com. The Ivors. 26 May 2005. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Wenner, Jann (2001), «Queen», Hall of Fame Inductees, Cleveland: Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

- ^ a b Queen (1992), «Bohemian Rhapsody», Queen: Greatest Hits: Off the Record, Eastbourne/Hastings: Barnes Music Engraving, ISBN 978-0-86359-950-7

- ^ Aledort, And (29 November 2003), Guitar Tacet for Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, MIT

- ^ Coleman, Ray, ed. (2 May 1981), «The Man Who Would Be Queen», Melody Maker (interview), archived from the original on 20 October 2007, retrieved 24 September 2009

- ^ a b «What Queen lead singer Freddie Mercury Was Really Like: An Insider’s Story». Louder Sound. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Blaikie, Thomas (7 December 1996), «Camping at High Altitude», The Spectator, archived from the original on 13 November 2007

- ^ a b Ressner, Jeffry (9 January 1992), «Queen singer is rock’s first major AIDS casualty», Rolling Stone, vol. 621, archived from the original on 12 March 2007

- ^ May, Brian (4 September 2011). «Happy birthday, Freddie Mercury». Googleblog.blogspot.com. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ Lenig, Stuart (2010). The Twisted Tale of Glam Rock. Santa Barbara CA: Praeger. p. 81. ISBN 978-0313379864.

- ^ Minchin, Ryan (2005), The World’s Greatest Gigs, London: Initial Film & Television, archived from the original on 21 September 2021.

- ^ Queen win greatest live gig poll, London: BBC News, 9 November 2005, retrieved 4 January 2010

- ^ McKee, Briony (13 July 2015). «30 fun facts for the 30th birthday of Live Aid». Digital Spy. Hearst Corporation. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Holly (6 November 2018). «33 years later, Queen’s Live Aid performance is still pure magic». CNN. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Harris, John (14 January 2005), «The Sins of St Freddie», Guardian on Friday, London

- ^ Simpson, Dave (16 November 2022). «Freddie Mercury in his definitive pose – Denis O’Regan’s best photograph». The Guardian. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ Bret 1996, p. 91.

- ^ «Queen Plays For 80,000 Rock Fans In Budapest». Billboard. 16 August 1986. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ a b Blake 2016.

- ^ Grech, Herman (20 November 2011). «Mercury’s magic lives forever». Times of Malta. No. 8 February 2015.

- ^ Jones, Tim (July 1999), «How Great Thou Art, King Freddie», Record Collector, archived from the original on 20 October 2009

- ^ Inglis, Ian (2013). Popular Music And Television In Britain. Ashgate Publishing. p. 51.

- ^ «Perspectives: Freddie Mercury Saved My Life with Alfie Boe, ITV, review: ‘an interesting reflection on raw talent versus technical virtuosity’«. The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Mr.Scully. «QUEEN CONCERTS – Complete Queen live concertography». www.queenconcerts.com. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b Jones 2011, p. 3, Ch. 7, Mary

- ^ a b Longfellow, Matthew (21 March 2006), Classic Albums: Queen: The Making of «A Night at the Opera, Aldershot: Eagle Rock Entertainment.

- ^ a b O’Connor, Roisin (24 November 2016). «Freddie Mercury 25th anniversary: 5 things you may not know about the Queen legend». The Independent. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ «Lights! Action! Sound! It’s That Crazy Little Thing Called Queen». Queenonline.com. 1980. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Rees & Crampton 1999, p. 809.

- ^ «Freddie Mercury: The Man, The Star … In His Own Words». Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Rees & Crampton 1999, p. 811.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo, «Mr. Bad Guy (Overview)», AllMusic, Ann Arbor

- ^ Bradley, J. (20 July 1992), «Mercury soars in opera CD: Bizarre album may be cult classic», The Denver Post, Denver: MNG

- ^ Larkin, Colin (1998) The encyclopedia of popular music: Louvin, Charlie – Paul, Clarence, Volume 5. Macmillan. p. 3633. ISBN 9780333741344

- ^ Rees & Crampton 1999, p. 810.

- ^ «World-renowned Spanish opera singer Montserrat Caballé who performed ‘Barcelona’ with Freddie Mercury, dies aged 85». London Evening Standard. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums. London: Guinness World Records Limited

- ^ «‘The Great Pretender’ Was Also the Real Deal». PopMatters. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ «Freddie Mercury – Collaborations: Michael Jackson». Ultimatequeen.co.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ «Freddie Mercury: 10 Things You Didn’t Know Queen Singer Did». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Campbell, Lisa D. (January 1993). Michael Jackson: the king of pop. p. 90. ISBN 9780828319577. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ «There Must Be More To Life Than This». Ultimatequeen.co.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ «Queen Forever – Queen | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic». AllMusic. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Unger, Adam. «QueenVault.com – Freddie +». Queenvaultom. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Berlin Music Video Awards (7 May 2021). «Nominees 2020». www.berlinmva.com.

- ^ «Freddie Mercury and Mary Austin: Their love story in pictures». Vogue. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ a b Teckman, Kate (2004), Freddie’s Loves, London: North One Television *part 2* on YouTube

- ^ Jones, Lesley-Ann (2012). Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury. Simon and Schuster. p. 162.

- ^ Jones, Lesley-Ann (2012). Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury. Simon & Schuster. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4516-6397-6.

- ^ a b c d e Jackson, Laura (2011). Freddie Mercury: The biography. Little, Brown Book Group. pp. 187–190. ISBN 978-0-7481-2907-2.

- ^ Austin, Mary; Freddie Mercury (12 November 2011). «The Mysterious Mr Mercury». BBC Radio 4 (Interview). Interviewed by Midge Ure. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ «The Star – AIDS Kills The King of Rock». Queen archives. 25 November 1991. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Raab, Klaus (17 May 2010). «The Love of Sebastianseck». Suddetsche Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Freestone, Peter (7 January 2010). Freddie Mercury: An Intimate Memoir by the Man who Knew Him Best. Omnibus Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0857121271.

- ^ «Mr Bad Guy». QueenVault. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Hutton, Jim (7 July 1995). Mercury and Me. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. ISBN 0747521344.

- ^ Bauszus, Jan (24 November 2011). «Zum 20. Todestag von Freddie Mercury: Freddie war keine Hete, er war schwul». FOCUS Online. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Sweeney, Ken (4 January 2010). «Partner of Queen star Freddie buried». Irish Independent. Dublin. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Brooks, Greg; Lupton, Simon (5 September 2019). Freddie Mercury: A Life, In His Own Words. Mercury Songs Ltd. p. 88. ASIN B07X35NLG7.

- ^ a b c d e f g «When Freddie Mercury Met Kenny Everett» (1 June 2002). Channel 4

- ^ Collins, Jeff (2007). Rock Legends at Rockfield. University of Wales Press. p. 76.

- ^ «Kenny Everett – The best possible way to remember a true pioneer», The Independent, 30 September 2012, retrieved 19 January 2015

- ^ Landesman, Cosmo (10 September 2006), «Freddie, a Very Private Rock Star», The Times, London, retrieved 2 May 2010

- ^ a b Fitzpatrick, Liam (13 November 2006), «Farrokh Bulsara», Time Asia, 60 Years of Asian Heroes, Hong Kong, vol. 168, no. 21, archived from the original on 28 December 2008

- ^ Zanzibar angry over Mercury bash, London: BBC News, 1 September 2006, retrieved 4 January 2010

- ^ Sommerlad, Joe (22 January 2019). «Bohemian Rhapsody: Why the Oscar-nominated Queen biopic has suffered a backlash». The Independent. London, England: Independent Print Ltd. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ Hutton, Jim (22 October 1994), «Freddie and Jim, A Love Story», Weekend Magazine, The Guardian, archived from the original on 12 October 2007

Hutton, Jim; Waspshott, Tim (1994), Mercury and Me, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-0-7475-1922-5 - ^ «Kerrang! – UK – Queen, Wembley Arena London». Queen Cuttings. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ a b Leung, Helen Hok-Sze (2009). Undercurrents: Queer Culture and Postcolonial Hong Kong. HBC Press. p. 88. ISBN 9780774858298.

- ^ Oboza, Michael C. (2013). «Our Fence» (PDF). binetusa.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ «A Brief History of the Bisexual Movement». BiNet USA. 30 June 1990. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Gilchrist, Tracy E. (15 May 2018). «Blink and You’ll Miss Freddie Mercury’s Queerness in Bohemian Rhapsody Teaser Trailer». The Advocate. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ «1991: Giant of rock dies». BBC. 24 November 1991. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ «Queen Interviews – Freddie Mercury – 11-25-1991 – The Star – AIDS Kills The King of Rock – Queen Archives: Freddie Mercury, Brian May, Roger Taylor, John Deacon, Interviews, Articles, Reviews». www.queenarchives.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Henderson, Taylor (24 October 2018). «How Bohemian Rhapsody Sterilized Freddie Mercury’s Bisexuality». Pride. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Dry, Jude (2 November 2018). «‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ Doesn’t Straightwash, but It’s Confused About Freddie Mercury’s Sexuality». Indiewire. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Kumar, Naveen (3 November 2018). «Bohemian Rhapsody’s Queer Representation Is Downright Dangerous». them. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Myers, Paul (25 November 1991), «Queen star dies after Aids statement», The Guardian, London, retrieved 2 May 2010

- ^ a b Yates, Henry (23 February 2018). «Bob Harris on Marc Bolan, David Bowie, Queen, Robert Plant and more…» Louder Sound. Future plc. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ a b «Readers Pick the Best Lead Singers of All Time. 2. Freddie Mercury». Rolling Stone. 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ «Kurt Cobain’s Suicide Note». kurtcobainssuicidenote. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Chapman, Ian (2012). Global Glam and Popular Music: Style and Spectacle from the 1970s to the 2000s. Abingdon, England: Routledge. pp. 86, 87.

- ^ Breward, Christopher (2004). The London Look: Fashion from Street to Catwalk. Yale University Press. p. 137.

- ^ «Mercury interview for Melody Maker. queenarchives.com (5 February 1981). Retrieved 28 February 2019

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. «Hot Space review». AllMusic. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Prato, Greg. «Innuendo review». AllMusic. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ «Queen — Days of Our Lives (Episode 2)». BBC. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Freestone, Peter (2001). Freddie Mercury: An Intimate Memoir by the Man who Knew Him Best. Omnibus Press. p. 234. ISBN 0711986746.

- ^ Tenreyro, Tatiana (1 November 2018). «Freddie Mercury’s Cats In Real Life Were Just As Spoiled As ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ Shows». Bustle. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ a b Husband, Stuart (4 August 2002). «The Beach: Hedonism – Last of the International; Playboys; Pike’s is a notorious Ibiza hotel where anything goes». The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Jones 2011, p. 212

- ^ «Just months after finding out he had AIDS he threw the biggest and wildest birthday party for 700 people». The People. 26 May 1996.[dead link]

- ^ Jackson, Laura (1997), Mercury: The King of Queen, London: Smith Gryphon, ISBN 978-1-85685-132-9

- ^ Sullivan, Caroline (27 September 2012). «Freddie Mercury: the great enigma». The Guardian. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ a b Anderson-Minshall, Diane (23 November 2016). «Freddie Mercury’s Life Is the Story of HIV, Bisexuality, and Queer Identity». The Advocate. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d «Inside the studio where Freddie Mercury sang his last song». The Telegraph. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ a b Teeman, Tim (7 September 2006), «I Couldn’t Bear to See Freddie Wasting Away», The Times, London, retrieved 2 May 2010

- ^ Bret 1996, p. 138.

- ^ «The Highs and Lows of the Brit Awards». BBC. 2 December 1999. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ «Queen, Freddie Mercury, Roger Taylor, Brian May, BRITS 1990». Brts.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Sky, Rick (1992). The Show Must Go On. London, England: Fontana. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-00-637843-3.

- ^ a b Bret 1996, p. 179.

- ^ «Heir Apparent With Freddie Mercury Dead And Queen Disbanded, Brian May Carries On The Tradition». The Sacramento Bee. 4 February 1993. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Sherwin, Adam (30 May 2011). «Final Freddie Mercury performance discovered». The Independent. London. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ «Freddie Mercury’s Final Bow: Director Rudi Dolezal Recalls the Queen Legend’s Poignant Last Video». People. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ a b c «Mary Austin Shares Her Memories» – March, 17th 2000. OK!. Retrieved 27 September 2014

- ^ «1991: Giant of rock dies». BBC News. 24 November 1991. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Freddie Mercury, London: Biography Channel, 2007, archived from the original on 13 October 2007

- ^ «Singer Freddie Mercury dies, aged 45». Ceefax. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ «Elton’s Sad Farewell». Mr-mercury.co.uk. 28 November 1991. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ «Freddie, I’ll Love You Always». Mr-mercury.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Bret, David (2014). Freddie Mercury: An Intimate Biography. Lulu. p. 198. ISBN 9781291811087.

- ^ Simmonds, Jeremy (2008). The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars: Heroin, Handguns, and Ham Sandwiches. Chicago Review Press. p. 282. ISBN 9781556527548.

- ^ Last will and testament of Frederick Mercury otherwise Freddie Mercury

- ^ «Flash! Freddie Mercury’s Rolls-Royce goes for more than SIX times the guide price». London Evening Standard. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ «Freddie’s Roller on eBay». London Evening Standard. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b Womack, Kenneth; Davis, Todd F. (2012). ‘Reading the Beatles: Cultural Studies, Literary Criticism, and the Fab Four. SUNY Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780791481967.

- ^ Humphreys, Rob (2008). Rough Guide to London. Rough Guides. p. 338.

- ^ Matthews, Alex (19 November 2017). «Freddie Mercury shrine at his £20m mansion taken down». Daily Mirror.

- ^ Weller, Amy (5 September 2013). «If it wasn’t for Freddie Mercury… 13 artists inspired by the Queen icon». Gigwise. Retrieved 13 March 2018.