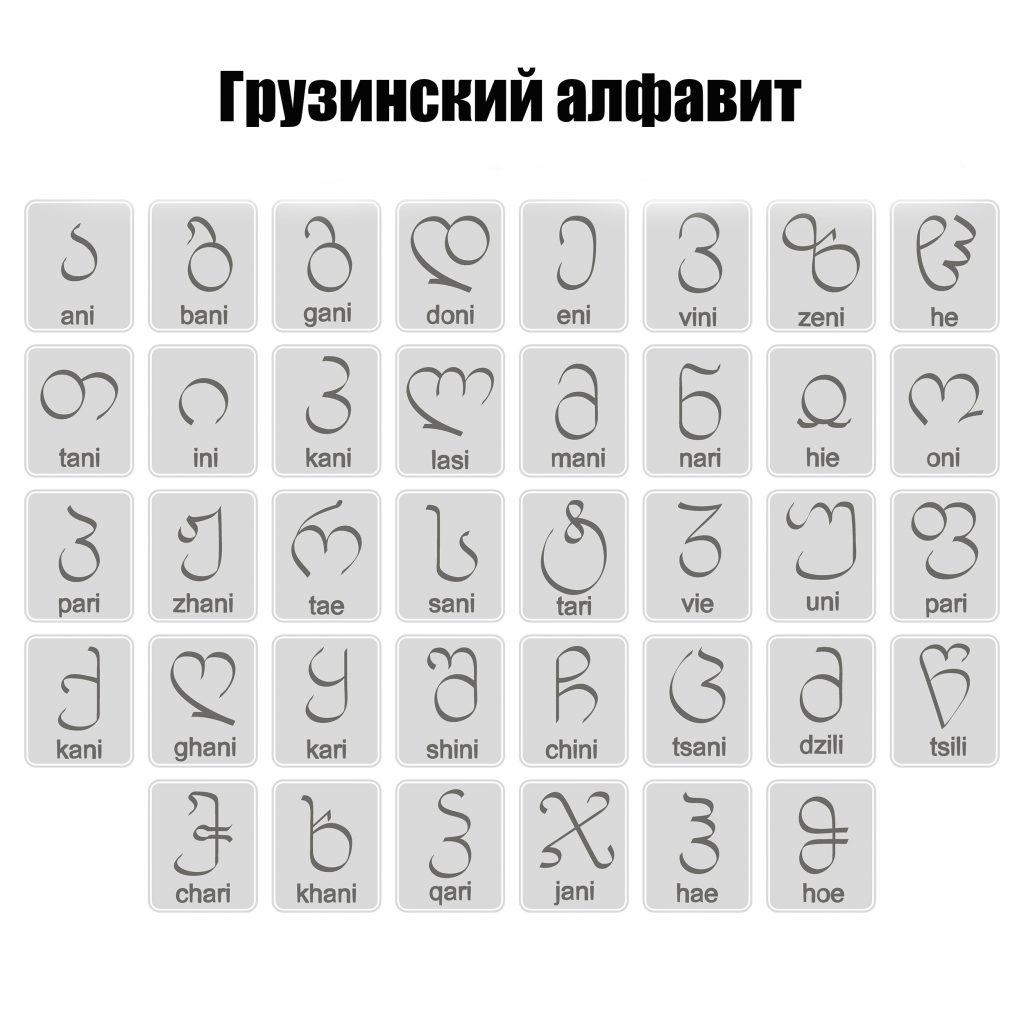

Грузинский алфавит с произношением

Есть несколько грузинских алфавитов (и, соответственно, письменностей), которые отличаются между собой внешним видом и несколькими буквами:

- ასომთავრული (асомтавру́ли) – самый старый алфавит, ныне не используется;

- ნუსხური (нусху́ри) или ხუცური (хуцу́ри) – церковный алфавит;

- მხედრული (мхедру́ли) – современный грузинский алфавит, используемый как в быту, так и на официальном уровне;

- მთავრული (мтавру́ли) – тот же мхедрули, но с более высокими и широкими формами букв. Часто используется для заголовков и выделения важной информации.

Итак, в современном грузинском алфавите 33 буквы. Каждая из них обозначает строго один звук и наоборот. Некоторые буквы, как и в русском языке, пишутся не так, как выглядят в печатном виде.

Также в грузинском алфавите не существует понятий заглавная или строчная буква. Каждая из них имеет свою фиксированную высоту и ширину на письме, независимо от положения в предложении.

| # | Аудио | Печатная (мхедрули) |

Русский аналог | Наименование | МФА (IPA) | Письменная | Оф. транслит. | Неоф. транслит. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ა | а | ანი (а́ни) | ɑ |  |

a | a | |

| 2 | ბ | б | ბანი (ба́ни) | b |  |

b | b | |

| 3 | გ | г | განი (га́ни) | ɡ |  |

g | g | |

| 4 | დ | д | დონი (до́ни) | d |  |

d | d | |

| 5 | ე | э/е | ენი (э́ни) | ɛ |  |

e | e | |

| 6 | ვ | в | ვინი (ви́ни) | v |  |

v | v | |

| 7 | ზ | з | ზენი (зэ́ни) | z |  |

z | z | |

| 8 | თ |

т

лёгкое, на выдохе |

თანი (та́ни) | tʰ |  |

t | T, t | |

| 9 | ი | и | ინი (и́ни) | i |  |

i | i | |

| 10 | კ |

к

резкое, без выдоха |

კანი (ка́ни) | kʼ |  |

kʼ | k | |

| 11 | ლ | л | ლასი (ла́си) | l |  |

l | l | |

| 12 | მ | м | მანი (ма́ни) | m |  |

m | m | |

| 13 | ნ | н | ნარი (на́ри) | n |  |

n | n | |

| 14 | ო | о | ონი (о́ни) | ɔ |  |

o | o | |

| 15 | პ |

п

резкое, без выдоха |

პარი (па́ри) | pʼ |  |

pʼ | p | |

| 16 | ჟ |

ж

мягкое |

ჟანი (жа́ни) | ʒ |  |

zh | J, zh, j | |

| 17 | რ | р | რაე (ра́э) | r |  |

r | r | |

| 18 | ს | с | სანი (са́ни) | s |  |

s | s | |

| 19 | ტ |

т

резкое, без выдоха |

ტარი (та́ри) | tʼ |  |

tʼ | t | |

| 20 | უ | у | უნი (у́ни) | u |  |

u | u | |

| 21 | ფ |

п

лёгкое, на выдохе |

ფარი (па́ри) | pʰ |  |

p | p, f | |

| 22 | ქ |

к

лёгкое, на выдохе |

ქანი (ка́ни) | kʰ |  |

k | q, k | |

| 23 | ღ | г/х | ღანი (га́ни) | ʁ |  |

gh | g, gh, R | |

| 24 | ყ |

к/х

глубокое, без выдоха |

ყარი (ка́ри) | χʼ |  |

qʼ | y | |

| 25 | შ |

ш

мягкое |

შინი (ши́ни) | ʃ |  |

sh | sh, S | |

| 26 | ჩ |

ч

лёгкое, на выдохе |

ჩინი (чи́ни) | t͡ʃʰ |  |

ch | ch, C | |

| 27 | ც |

ц

лёгкое, на выдохе |

ცანი (ца́ни) | t͡sʰ |  |

ts | c, ts | |

| 28 | ძ |

дз

совмещённое |

ძილი (дзи́ли) | d͡z |  |

dz | dz, Z | |

| 29 | წ |

ц

резкое, без выдоха |

წილი (ци́ли) | t͡sʼ |  |

tsʼ | w, c, ts | |

| 30 | ჭ |

ч

резкое, без выдоха |

ჭარი (ча́ри) | t͡ʃʼ |  |

chʼ | W, ch, tch | |

| 31 | ხ |

х

глубокое |

ხანი (ха́ни) | χ |  |

kh | x, kh | |

| 32 | ჯ |

дж

совмещённое |

ჯანი (джа́ни) | d͡ʒ |  |

j | j | |

| 33 | ჰ |

х

лёгкое, на выдохе |

ჰაე (ха́э) | h |  |

h | h |

Далее пояснения для некоторых столбцов:

- Наименование – имя буквы в грузинском алфавите (как в старославянском было «аз, буки, веди, глаголь…», – т.е. первый звук соответствует самой букве). Некоторые «переводят» такие имена на русский язык без “и” на конце, что неправильно;

- МФА (IPA) – звук буквы по Международному Фонетическому Алфавиту (International Phonetic Alphabet). Русские аналоги, являются лишь адаптацией. Самым правильным вариантом было бы изучать звуки по этой колонке и аудиозаписям;

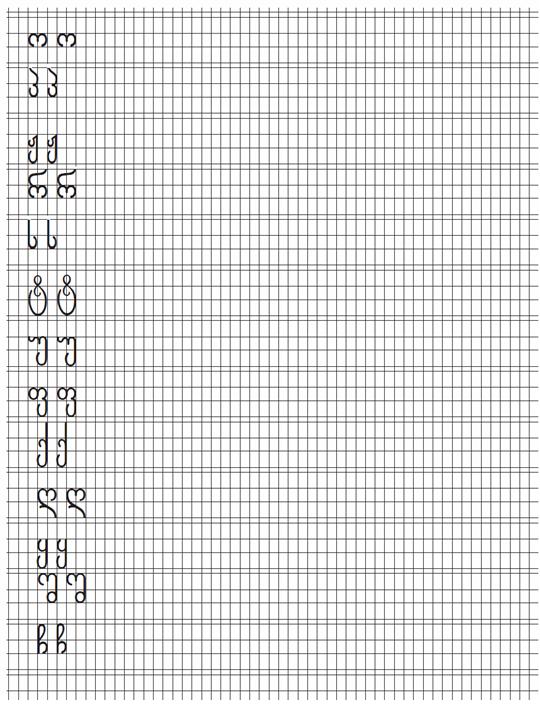

- Письменная – варианты письменного представления буквы;

- Официальная транслитерация – написание буквы на английской раскладке клавиатуры, принятое грузинской национальной системой романизации и конвенцией BGN/PCGN;

- Неофициальная транслитерация – написание буквы на английской раскладке клавиатуры, используемое в народе (в социальных сетях, на форумах, в чатах и т.д.), потому что «так сложилось». Это может быть по причине внешнего или звукового сходства, но не полного соответствия или по другим причинам.

Также есть несколько букв, которые когда-то присутствовали в грузинском алфавите, но сейчас исключены из него и поэтому не рассматриваются в данном курсе: ჱ, ჲ, ჳ, ჴ, ჵ.

Весь алфавит в ряд в письменном виде:

Среднюю часть строки, подобно русской “а”, при письме занимают:

- ა, თ, ი, ო.

Среднюю и верхнюю части строки, подобно русской “б”, при письме занимают:

- ბ, ზ, მ, ნ, პ, რ, ს, შ, ჩ, ძ, წ, ხ, ჰ.

Среднюю и нижнюю части строки, подобно русской “р”, при письме занимают:

- გ, დ, ე, ვ, კ, ლ, ჟ, ტ, უ, ფ, ღ, ყ, ც.

Все три части строки при письме занимают:

- ქ, ჭ, ჯ.

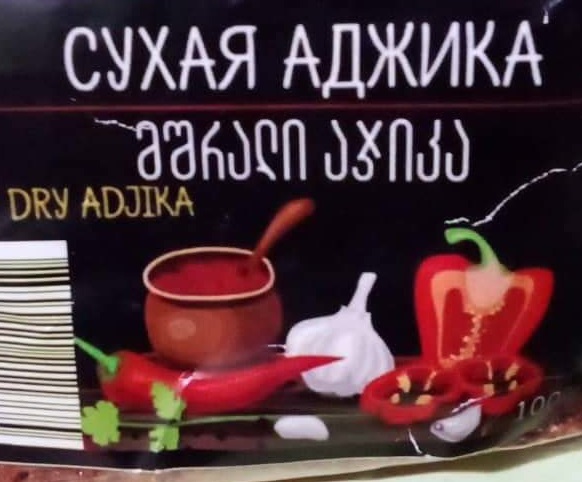

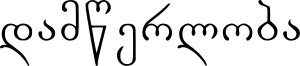

Примеры использования мтаврули

Во всех уроках данного курса примеры на грузинском языке написаны с использованием алфавита мхедрули. Он является основным и используется практически в любой ситуации. Но если нужно написать информацию заглавными буквами или выделить её жирным, то вместо всего этого используется другой алфавит, который называется мтаврули. В нём те же самые буквы, но с немного более упрощёнными формами и одинаковой высотой (они занимают все три части строки):

Источники фотографий:

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Street_sign_in_Georgian_and_Latin_alphabets.jpg

- https://sputnik-georgia.com/20190909/batumshi-avtomobili-xididan-gadavarda-246448792.html

- https://ge.kavkazplus.com/news.php?id=19666

- https://goo.gl/maps/s3TUwLM8crWsHs4TA

- https://www.interpressnews.ge/ka/article/416138-rustavshi-cignis-magazia-libra-gakurdes

Произношение звуков

Закрепим произношение всех звуков в грузинском языке.

16 из 33 звуков произносятся почти так же, как их русские аналоги:

| ა | ბ | გ | დ | ვ | ზ | ი | ლ | მ | ნ | ო | რ | ს | უ | ჩ | ც |

| а | б | г | д | в | з | и | л | м | н | о | р | с | у | ч | ц |

Далее другие звуки:

- ე – это что-то между “э” и “е” (как в словах “рейтинг”, “отель”, “уже” и “бренд”);

- შ – это мягкое “ш” (примерно как в слове “мышьи”);

- ჟ – мягкое “ж” (примерно как в слове “побережье”);

- ღ – между “г” и “х”. Похожий звук используется в южнорусских говорах. Иногда его можно услышать в обычной русской речи в слове “господи”;

- ძ – это совмещенное “дз” (примерно как в слове “дзэн”);

- ჯ – совмещенное “дж” (примерно как в словах “джаз” и “джинсы”).

Согласные, которые похожи по звучанию и поэтому «переводятся» на русский язык одной и той же буквой:

- ფ и პ можно передать буквой “п”, но разница в том, что ფ произносится легко и на выдохе, напоминая букву “ф” (примерно как в слове “храп”), а პ произносится резче и без выдоха (подходящего аналога нет);

- თ и ტ передаются буквой “т”, но разница между ними примерно такая же: თ – лёгкий звук на выдохе (примерно как в слове “рот”), тогда как ტ – наоборот, резкий и без выдоха (подходящего аналога нет);

- ჩ и ჭ передаются буквой “ч”, разница та же: ჩ – лёгкий на выдохе (примерно как в слове “чайка”), ჭ – резкий при отсутствии выдоха (подходящего аналога нет);

- ც и წ передаются буквой “ц”, разница та же: ც – лёгкий на выдохе (примерно как в слове “цапля”), წ – резкий при отсутствии выдоха (подходящего аналога нет);

- ჰ и ხ передаются буквой “х”, но ჰ произносится легко и на выдохе (примерно как в слове “стих”), а ხ – задней частью языка, то есть практически горлом (подходящего аналога нет);

- И, наконец, целые три буквы (ქ, კ и ყ) можно передать русской “к”, но разница в следующем:

- ქ – самый глухой звук из этих трёх, произносится легко и на выдохе (примерно как в слове “срок”);

- კ – это резкое “к” без выдоха (подходящего аналога нет);

- ყ – гортанное (т.е. глубокое) “к”. Данный звук произносится тоже без выдоха, но тем местом, что используется при полоскании горла, т.е. самой дальней частью языка (подходящего аналога нет).

Если вы будете путать эти звуки, то в большинстве случаев вас все равно поймут, но иногда из-за таких ошибок может полностью поменяться смысл слова и, соответственно, предложения:

კარი – дверь

ქარი – ветер

პაპა / ბაბუა – дед

ფაფა – каша

ტარო – початок

თარო – полка

არაკი – басня

არაყი – водка

ცურავს – плавает

წურავს – выжимает

გორები – горы

ღორები – свиньи

პირი – рот

ფირი – киноплёнка

ჩირი – сухофрукты

ჭირი – мор (чума)

ცელი – коса (для покоса)

წელი – год / поясница

კუდი – хвост

ქუდი – шапка

Также имейте в виду, что существует несколько ругательств, которые созвучны с повседневными бытовыми словами. Они будут рассмотрены в отдельном уроке, посвящённом ругательствам.

Задания

- Выучите грузинский алфавит по столбцу «Наименование».

- Проверьте, насколько понятно вы пишете: гугл переводчик поддерживает рукописный ввод, то есть вы можете нарисовать букву, а переводчик должен будет её распознать.

- Если вы ещё не установили себе грузинскую клавиатуру, то обязательно это сделайте, иначе искать переводы слов будет очень сложно.

- Если вы ещё не пробовали написать/напечатать свои имя и фамилию на грузинском – попробуйте.

Грузинский алфавит или азбука — это форма письменности используемая в Грузии. Помимо грузинского языка, ее используют мегрельский, сванский и лазский. Грузинский алфавит содержит 33 буквы, читается слева направо и не имеет прописных (заглавных) букв. Мтаврули — это грузинское способ написания текста без выносных элементов, он представляет собой аналог прописных букв в кириллице, латинице. Учатся правильно писать в тетрадях со специальной разлиновкой, представляющей собой вытянутый прямоугольник, квадрат, и слова вытянутый прямоугольник.

В грузинском алфавите 33 звука, то-есть каждая буква создает свой звук: 5 гласных и 28 согласных. Некоторые буквы встречаются только в грузинском алфавите и тяжело даются иностранцам. Помимо этого некоторые слова содержащие большое количество согласных следующих друг за другом вызывают сложности.Так например в современном грузинском языке есть слово из 8 согласных подряд «გვფრცქვნის» (пристыженный), звучит как гвпртсквнис. А есть и более сложное устаревшее слово из 11 согласных: «ვეფხვთმბრდღვნელი» (убийца тигров), звучащее как вефхвтмбрдгвнели.

Многие буквы грузинского алфавита при первом взгляде могут показаться очень похожими и совершенно непонятными. Нужно постараться найти закономерности и разбить буквы на похожие по написанию буквы, так будет проще. Вы конечно все равно будете путаться некоторое время, перепутав букву и написав хвостик или кружочек не в том месте. Не расстраивайтесь, а обратите больше внимания на эту букву.

Грузинский алфавит с русской транскрипцией

| Буква | Русская транскрипция | Буква | Русская транскрипция | Буква | Русская транскрипция |

| ა | а | მ | м | ღ | гэ |

| ბ | б | ნ | н | ყ | кʼ |

| გ | г | ო | о | შ | ш |

| დ | д | პ | п | ჩ | ч |

| ე | е | ჟ | ж | ც | тс |

| ვ | в | რ | р | ძ | дз |

| ზ | з | ს | с | წ | ц |

| თ | тэ | ტ | т | ჭ | чʼ |

| ი | и | უ | у | ხ | х |

| კ | кэ | ფ | пэ | ჯ | дж |

| ლ | л | ქ | к | ჰ | хʼ |

В современном грузинском алфавите 33 буквы, каждой из которых соответствует определенный звук.

Письмо мхедрули (мхедрули-хели, саэро, гражданское), которое используется сегодня, сформировалось в XI веке. До этого с ранних веков использовалось древнегрузинское письмо мргловани (асомтаврули); с IX века — письмо нусхури (нусха-хуцури, хуцури,церковное).

Если вы решили изучать грузинский язык, то вам не обойтись без умения читать и писать, иначе вы не сможете пользоваться учебниками и самоучителями. К тому же, грузинский алфавит вошел в пятерку самых красивых алфавитов мира!

Для того, чтобы освоить грузинские буквы, сохраните у себя и распечатайте эту пропись.

Грузинский алфавит

| Буквы | Название | Латинская транслитерация | Транскрипция | Примеры |

ა |

ан | A a | А а | анекдот :: anegdot’i :: ანეგდოტი |

ბ |

бан | B b | Б б | бежать :: rbena :: (mirbis, morbis) რბენა |

გ |

ган | G g | Г г | вагон :: vagoni :: ვაგონი |

დ |

дон | D d | Д д | день :: dghe :: დღე |

ე |

эн | E e | Э э | врач :: ekimi :: ექიმი |

ვ |

вин | V v | В в | кто :: vis :: ვის |

ზ |

зен | Z z | З з | зима :: zamtari :: ზამთარი |

თ |

т’ан | T’ t’ | Т’ т’ | голова :: tavi :: თავი |

ი |

ин | I i | И и | идея :: idea :: იდეა |

კ |

кан | K k | К к | класс :: k’lasi :: კლასი |

ლ |

лас | L l | Л л | лимон :: limoni :: ლიმონი |

მ |

ман | M m | М м | много :: mravali :: მრავალი |

ნ |

нар | N n | Н н | нежный :: nazi :: ნაზი |

ო |

он | O o | О о | однажды :: odesghats :: ოდესღაც |

პ |

пар | P p | П п | проблема :: p’roblema :: პრობლემა |

ჟ |

жан | Zh zh | Ж ж | журнал :: zhurnali :: ჟურნალი |

რ |

раэ | R r | Р р | ряд :: rigi :: რიგი |

ს |

сан | S s | С с | свет :: sinatle :: სინათლე |

ტ |

тар | T t | Т т | тело :: t’ani :: ტანი |

უ |

ун | U u | У у | холостяк :: utsolo :: უცოლო |

ფ |

п’ар | P’ p’ | П’ п’ | яростный :: pitsch’i :: ფიცხი |

ქ |

к’ан | K’ k’ | К’ к’ | бумага :: kaghaldi :: ქაღალდი |

ღ |

ған | Gh gh | Ғ ғ | ночь :: ghame :: ღამე |

ყ |

қар | Q’ q’ | Қ қ | ребенок :: q’mats’vili :: ყმაწვილი |

შ |

шин | Sh sh | Ш ш | эффект :: shedegi :: შედეგი |

ჩ |

чин | Ch ch | Ч ч | чай :: chai :: ჩაი |

ც |

цан | Ts ts | Ц ц | цифра :: tsipri :: ციფრი |

ძ |

дзил | Dz dz | Дз дз | довольно :: dzalian :: ძალიან |

წ |

ц’ил | Ts’ ts’ | Ц’ ц’ | уходить :: ts’asvla :: წასვლა |

ჭ |

ч’ар | Ch’ ch’ | Ч’ ч’ | сомнение :: ekhvi :: ეჭვი |

ხ |

хан | Kh kh | Х х | шутка :: ch’umroba :: ხუმრობა |

ჯ |

джан | J j | Дж дж | еще :: jer :: ჯერ |

ჰ |

х’аэ | H h | Х’ х’ | воздух :: haeri :: ჰაერი |

Выучите грузинский алфавит всего за 10 дней!!!

Если вам понравился данный материал, нажмите на кнопку любимой соц. сети, чтобы о нем узнали другие люди. Спасибо!

Гамаржоба!

Видели ли вы когда-нибудь надписи на грузинском языке? Полагаем, что видели. А поняли ли вы хоть что-нибудь? Если нет, то эта методичка для вас.

Вы когда-нибудь хотели понимать грузинский алфавит. Ведь его же возможно выучить, в конце концов. Ну, как?

Ладно, есть пути.

PictureCredit

Когда электронный переводчик не готов помочь

Зачем нам в 21 веке знать алфавиты редких языков? Копируешь текст- вставляешь в переводчик – получаешь какой-никакой перевод.

Дело усложняется, если алфавит у языка не кириллица, не латиница и даже не греческий, а, например, грузинский.

Ладно, есть такие приложения, которые позволяют наводить камеру или выделить текст на фото, и они переводят.

Но готовы ли вы скачивать и настраивать эти приложения в момент, когда вывеска (внезапно) на грузинском всплывает неожиданно перед глазами.

Или можно написать сообщение другу-грузину и отвлечь его от дел с просьбой перевести.

Или запостить фото на форум и ждать ответа.

Также есть способ: найти в поиске ВЕСЬ грузинский алфавит и, выискивая каждую букву, пытаться сложить их в слово. Или в настройках добавить грузинский в качестве ещё одного языка для телефона. Только вот беда: грузинская азбука выглядит для неподготовленного картвело-читателя как набор сплошных З, б, m, крючков, и пойди разберись, какой конкретно крючок или какая из троечек написана на вывеске.

Эти буквы вообще похожи на облака и баранов, горы и виноградные лозы, изгибы рек и даже цифры…

На случай вроде этого есть данная статья.

В ней мы решили классифицировать по форме, образу и подобию. Не слишком вдаваясь в личные ассоциации (где ო – это Макдональдс, დ – лев или цветок, ზ – процент), сколько в чистую геометрию и сходство грузинских букв с хорошо знакомыми носителям кириллицы буквами, цифрами и символами.

И эту статью лучше не терять. Сохраните ссылку, сделайте скриншот, а лучше распечатайте и носите с собой. Последним образом вы защите себя от отсутствия вай-фая, разряженной батарейки, отключения электричества или потери/порчи смартфона.

Итак, сначала посмотрим на сам алфавит в собственном порядке и на то, как буквы называются.

ა ბ გ დ ე ვ ზ თ ი კ ლ მ ნ ო პ ჟ რ ს ტ უ ფ ქ ღ ყ შ ჩ ც ძ წ ჭ ხ ჯ ჰ

Графонимика грузинского алфавита звучит как считалочка:

Ани · Бани · Гани ·

Дони · Эни · Вини ·

Зени · Тхани · Ини ·

Кани · Ласи ·Мани · Нари ·

Они · Пари · Жани ·

Раэ · Сани · Тари ·

Уни · Пхари · Кхани ·

Гхани · Кари · Шини ·

Чини · Цани · Дзили · Цили ·

Чари · Хани · Джани ·

Хаэ!

И да, хорошая новость: заглавных букв нет.

Теперь внимательно посмотрите на одну из букв, которую хотите прочесть и решите, на какую знакомую вам букву или цифру она похожа, есть ли замкнутая окружность или крючок, напоминает ли дугу, скобу или сердце. А теперь просто ищите её в соответствующей выборке.

З – образные

ვ -вини, звук в

კ – кани, звук к

პ – пари, звук п

ფ – пхари, звук твёрдый п

ც – цани, звук ц

ჰ – хаэ, звук х

(Двойки, тройки и колы – все приятели мои. Не знаю, как двойки и колы, но после данной выборки все грузинские «тройки» действительно ваши приятели. Приятно познакомиться!)

m-образные

ლ -ласи, звук л

ო – они, звук о

რ – раэ, звук р

ღ – гхани, звук фрикативный г.

У – образные

ჟ – жани, звук ж

უ – уни, звук у

ყ – кари, твёрдый звук к

ჭ – чари, звук ч

Б/Д – образные

ბ – бани, звук б

გ – гани, звук г

მ – мани, звук м

ნ – нари, звук н

შ – шини, звук ш

ძ – дзили, звук дз

ჭ – чари, звук ч

ჩ – чини, другой звук ч

ხ – хани, твердый звук Х

Сердцеобразные

წ – цили, звук ц

Цифрообразные (нули, восьмёрки, тройки)

Для похожих на тройку, см. З-образные

ზ – зени, звук з

ტ – тари, звук т

Дугообразные

ი – ини, звук и

ე – эни, звук э

Х-образные

ჯ – джан, звук дж

ჩ – чини, другой звук ч

რ – раэ, звук р

Безобразные

Таких нет.

Давайте рассмотрим что есть.

Есть замкнутые окружности

ბ – бани, звук б

გ – гани, звук г

დ – дони, звук д

ზ – зени, звук з

თ – тхани, звук т

მ – мани, звук м

ნ – нари, звук н

შ – шини, звук ш

ზ – зени, звук з

Есть крючки

ა – ани, звук а

ე – эни, звук э

ს – сани, звук с

ქ – кхани, звук кх

ჯ – джан, звук дж

Неужели, это всё?

Да, мы прошли все 33 грузинских буквы, некоторые аж два раза, но повторение – мать учения.

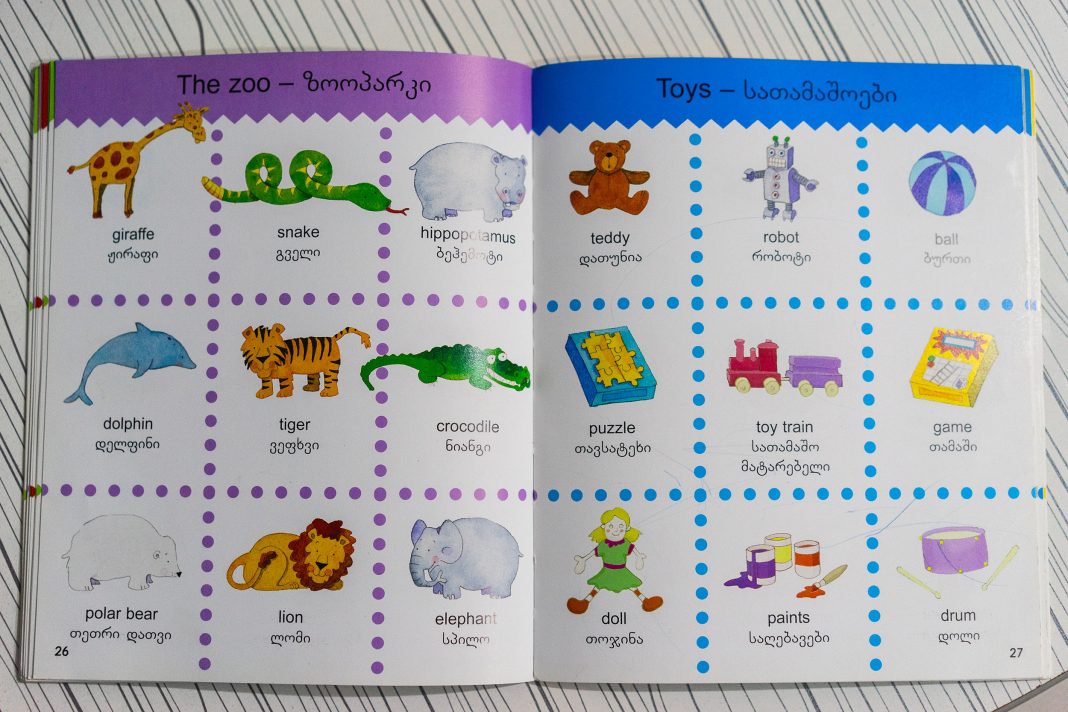

Возьмём несколько слов для демонстрации:

საქართველო – Сакартвело. Самоназвание Грузии.

თბილისი – Тбилиси. Буква ი [и] в грузинском очень распространена в конце слов.

ბათუმი – Батуми

Мой знакомый Илико говорил: «если будешь в конце каждого слова говорить “и” тебя примут за грузина, пусть даже за деревенского».

ლიმონათი – лимонади (т.е. лимонад, Илико же говорил)

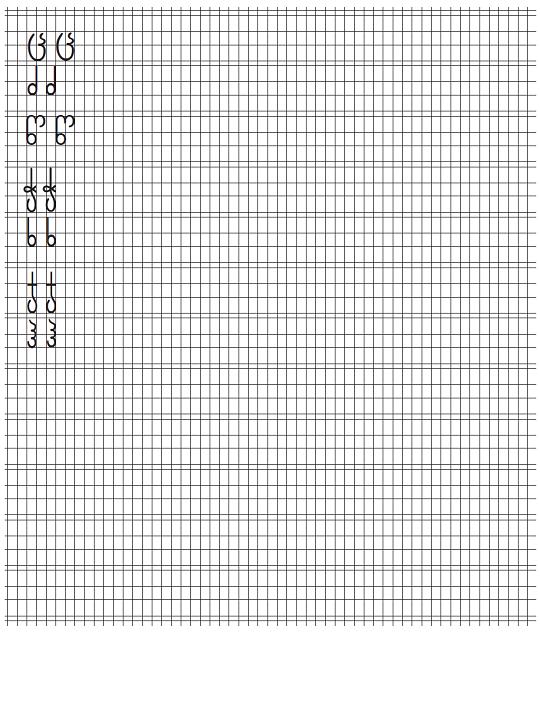

აჯიკა – аджика (дж – одна буква)

Мшрали аджика

Буквы р, л немного отличаются от обычных печатных. По сути, это те же m-образные, но лишние дуги справа убраны. Бывает и такое. Ну, и дж всего с одним крючком.

ხმელი სუნელი – хмели-сунели

საწებელი – сацебели

ხაჭაპური – хачапури

ჩახოხბილი – чахохбили

ხარჩო – харчо

ჯონჯოლი – джонджоли (цветы кустарника клекачки колхидской, из которых маринованных делают салат)

ღვინო – вино (по-грузински произносится ГХвино, с фрикативным Г в начале)

ბორჯომი – Борджоми (по-русски Боржоми или Боржом)

მზიური – «Мзиури»

მელაძე – Меладзе (дз – одна буква)

გვერდწითელი – Гвердцители ( д ц – отдельные буквы)

პავლიაშვილი – Павлиашвили

გამარჯობა – Гамарджоба (здравствуйте)

Важно понять, что мы ознакомились лишь с графической частью грузинского алфавита. А впереди фонетика. Ведь нужно же разобраться, чем отличаются звуки Ц, К, Т,Ч, каждому из которых, как вы заметили, соответствуют две-три буквы.

И, конечно же, лексика, грамматика и практика с носителями.

Зато теперь вы уже сами прочтёте надписи на этикетках с напитками, указатели на дорогах Грузии, титры к грузинским фильмам и даже тексты знаменитых протяжных песен.

И пусть на вашей горной дороге к знаниям солнце светит прямо в глаз, а попутный ветер дует в спину!

Что ж, дорогие генацвале, приглашаем теперь уже продолжить освоение грузинского языка с Language Heroes!

Фото автора

Содержание статьи

- 1 Как по-грузински здравствуйте и почему грузины не говорят привет

- 2 Говорим спасибо по-грузински

- 3 Особенности грузинского алфавита и языка

- 4 Грузинский алфавит с русской транскрипцией и переводом

- 5 Русско-грузинский словарь

- 5.1 Цифры

- 5.2 Дни недели

- 5.3 Да и нет

- 5.4 Люди, родственники и кто такой по грузински биджо

- 6 Русско-грузинский разговорник

- 6.1 Выражение чувств и комплименты на грузинском языке

- 6.1.1 Комплименты

- 6.1.2 Антикомплименты

- 6.1.3 Обращение

- 6.1.4 Фразы и слова подходящие для выражения своих чувств

- 6.2 Знакомство и встреча

- 6.3 В магазине и ресторане

- 6.4 Напитки и еда:

- 6.5 Цвета и предметы гардероба

- 6.6 Месторасположение

- 6.1 Выражение чувств и комплименты на грузинском языке

Многочисленные туристы, посещающие Грузию отмечают, что часть населения в крупных городах говорит на русском и английском. Однако стоит отъехать немного в сторону от Тбилиси и Батуми, как возникает необходимость в маломальском знании грузинского языка. Знание элементарных фраз вежливости, таких как здравствуйте по-грузински и слов благодарности, не будет лишним. Если же вы планируете задержаться в Грузии на пару-тройку месяцев, то вам наверняка будет интересен алфавит и различные нюансы этого удивительного по своей красоте языка. А также русско-грузинский словарь, в котором собраны фразы, необходимые для обычного общения и выяснения информации

Как по-грузински здравствуйте и почему грузины не говорят привет

Любая встреча начинается с взаимного приветствия и пожелания здоровья. Здравствуйте по-грузински звучит просто – гамарджобат (გამარჯობათ) А вот переводится дословно не как пожелание здравия, а пожелание победы. Если нужно сказать обычное здравствуй на грузинском, то говорим (გამარჯობა). В ответ говорят гагимарджос (გაგიმარჯოს).

Общепринятое приветствие в русском языке «Привет» практически не используется в обыденной жизни, но мы вам обязательно скажем, что привет по-грузински будет салами (სალამი). Слово «салами» часто встречается в литературе, преимущественно написанной в годы советской власти, но не в обычной жизни.

Многие для приветствия используют русское слово привет, но произносят его на грузинский манер «привэт». Ниже представлен грузинский алфавит, вы можете заметить, что в нем отсутствует буква «е», поэтому вместо нее всегда говорится «э» (ე). Если вы хотите передать привет кому-либо, то нужно сказать мокитхва гадаэци (მოკითხვა გადაეცი). Дословный перевод с грузинского – передай, что я спрашивал о нем.

Говорим спасибо по-грузински

Конечно же, мы не могли пропустить самые главные слова во всех языках – слова благодарности, которые в Грузии принято употреблять постоянно. Простое спасибо по грузински, звучит как мадлоба (მადლობა), можно сказать гмадлобт (გმადლობთ) что будет означать благодарю.

Для выражения переполняющих вас чувств благодарности можно использовать следующие фразы: большое спасибо по-грузински произноситься как – диди мадлоба (დიდი მადლობა); огромное спасибо (უღრმესი მადლობა) говорим угрмэси мадлоба. При этом фраза огромное спасибо дословно переводится как «глубочайшее спасибо».

Особенности грузинского алфавита и языка

Современный алфавит, в отличие от древнего, состоит из 33 букв. По инициативе Ильи Чавчавадзе из алфавита изъяли 3 буквы, которые практически не использовались к тому времени. В итоге в грузинском алфавите остались 5 гласных и 28 согласных букв. Если вы знаете грузинский алфавит, то прочитать любую надпись для вас не составит труда.

Огромный плюс грузинского языка – все буквы читаются и пишутся одинаково, при этом каждая буква означает всего один звук. Буквы в словах никогда не объединяются для создания каких-либо дополнительных звуков. Впрочем, учитывая количество согласных в языке, трудность может возникнуть при чтении четырех согласных подряд, что встречается не так уж и редко.

Помимо простоты написания и чтения, в грузинском языке есть еще несколько особенностей, которые делают его изучение легким и простым. Так у грузинских слов нет рода. Да и зачем он нужен? Учить грузинский язык не сложно, ведь зеленый всегда будет мцванэ (მწვანე).

К примеру, зеленый слон, зеленое дерево, зеленая трава, к чему нужны эти окончания, указывающие на род, ведь можно просто написать мцванэ спило (зеленый слон), мцванэ хэ (зеленое дерево), мцванэ балахи (зеленая трава). Согласитесь, это значительно облегчает изучение языка.

Еще один плюс грузинского письма, в нем нет заглавных букв. Все слова, в том числе, имена собственные, имена и фамилии, а также первое слово в предложении всегда пишется с маленькой буквы. А если учесть, что все грузинские слова пишутся, так же как и слышатся, то вы поймете что выучить язык не так уж трудно. Нужно лишь прислушиваться к речи грузин и проявить немного усердия.

Постараться придется если вы решите освоить письмо, ведь все буквы грузинского очень изящные и не имеют острых углов (скругленные). В школе с большим вниманием относятся к каллиграфии и умению красиво писать, поэтому большая часть людей пишет очень красиво. Из плюсов письма, в грузинском практически нет соединения букв, то есть каждая буква пишется отдельно.

Здесь же стоить отметить наличие нескольких диалектов, которые делятся на три группы. При этом последняя группа грузинских диалектов используется за пределами Грузии.

К первой группе диалектов относят: картлийский, кахетинский (Восточная Грузия), хевсурский, тушинский, пшавский, мохевийский и гудамакарский.

Ко второй группе диалектов причисляют: аджарский (Западная Грузия), имеретинский, рачинский, лечхумский, гурийский и месхетино-джавахский (Юго-Восточная Грузия).

Третья группа диалектов, на которой говорят за пределами страны: ферейданский, ингилойский, имерхевский (кларджетский).

Не пытайтесь выучить грузинские слова так, как их произносят в регионах. Изучайте литературный язык, используя русско-грузинский переводчик. Дело в том, что жители из разных уголков Грузии, порой сами не понимают друг друга, настолько сильно отличаются диалекты в грузинском языке.

Грузинский алфавит с русской транскрипцией и переводом

Ниже представляем вам грузинский алфавит с переводом на русский, который поможет вам как минимум прочитать вывески на грузинском и названия продуктов в магазине, как максимум осилить «Витязя в тигровой шкуре» на языке оригинала. Большое количество слов на грузинском звучит сходно с русским. Например: магазиа (მაღაზია) – магазин, аптиаки (აფთიაქი) – аптека, мандарини (მანდარინი) – мандарины, комбосто (კომბოსტო)– капуста.

ა — а

ბ — б

გ — г

დ — д

ე — э

ვ — в

ზ — з

თ — т (глухая Т произносится мягко с придыханием, как в слове кит)

ი — и

კ — к (звонкая К, как в слове школа)

ლ — л

მ — м

ნ — н

ო — о

პ — п (твердая, звонкая П, как в слове пост)

ჟ — ж

რ — р

ს — с

ტ — т (твердая звонкая Т, как в слове трус)

უ — у

ფ — п (глухая П, с придыханием, как в слове крап)

ქ — к (глухая К, с придыханием, как в слове прок)

ღ — г (звучит как гэканье, звук между Г и Х)

ყ — х (гортанный звук Х)

შ — ш

ჩ — ч

ც — ц (глухая Ц, с придыханием, как в слове цыпа)

ძ — дз (звонкий звук, образованный двумя буквами ДЗ)

წ — ц (твердая звонкая Ц, как в слове ТЭЦ)

ჭ — тч (мягкий звук из двух букв ТЧ)

ხ — х

ჯ — дж

ჰ — х (глухая, легкая и воздушная буква, произносится как еле слышное Х с придыханием)

Глядя на грузинский алфавит можно увидеть, что он содержит несколько букв, аналогов которых нет в русском языке. Можно сказать, что в грузинском языке есть по две буквы Т, К и П. Только не говорите об этом грузиноговорящим людям, так как они скажут что კ и ქ это разные буквы (и это действительно так)!

Русско-грузинский словарь

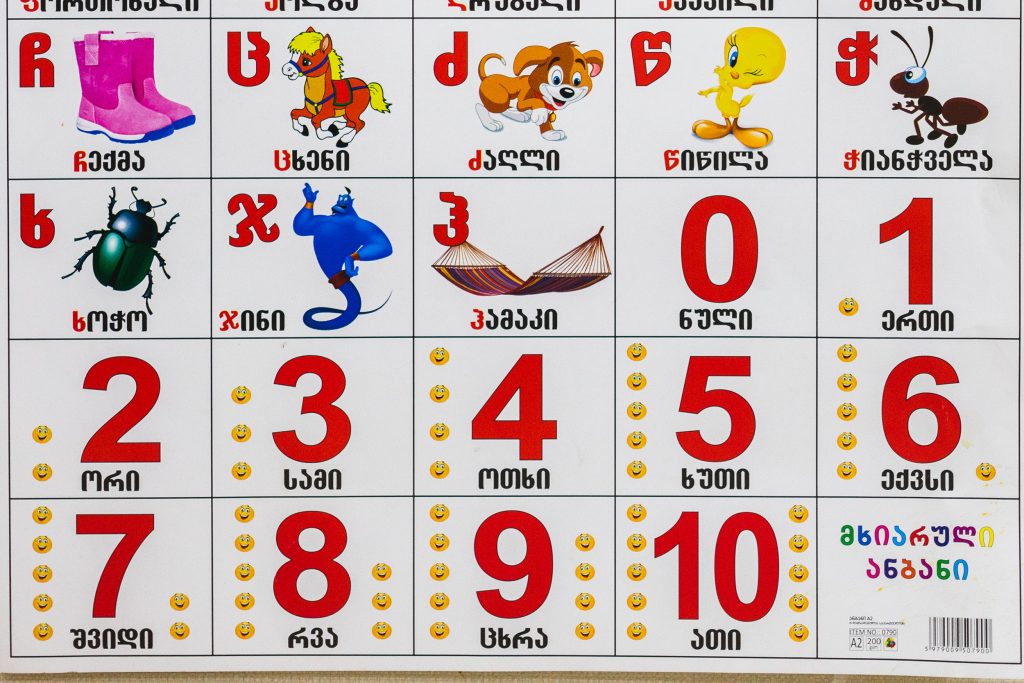

Цифры

Для того чтобы выучить числа в русском языке, достаточно запомнить первые десять цифр, в грузинском языке принята двадцатеричная система (также как у племен Майя) и поэтому вам нужно выучить первые 20 чисел.

Ответим на вопрос, зачем нужно знать числа на грузинском языке. Не секрет, туристам часто называют завышенные цены на рынке, да и просто в магазинах. Поэтому можно смело походить по базару, послушать, какие цены называют продавцы местному населению, а затем сделать выводы о реальной стоимости продуктов.

Так как русско-грузинский словарь не всегда находится под рукой, то запомните следующие цифры, которые образуют числа в грузинском языке.

1 эрти (ერთი)

2 ори (ორი)

3 сами (სამი)

4 отхи (ოთხი)

5 хути (ხუთი)

6 эквси (ექვსი)

7 швиди (შვიდი)

8 рва (რვა)

9 цхра(ცხრა)

10 ати (ათი)

11 тертмети (თერთმეტი)

12 тормети (თორმეტი)

13 цамети (ცამეტი)

14 тотхмэти (თოთხმეტი)

15 тхутмэти (თხუთმეტი)

16 тэквсмэти (თექვსმეტი)

17 тчвидмети (ჩვიდმეტი)

18 тврамэти (თვრამეტი)

19 цхрамэти (ცხრამეტი)

20 оци (ოცი)

Чтобы сказать 21, используем 20+1 получаем оцдаэрти (ოცდაერთი), 26 – (это 20+6) оцдаэквси (ოცდაექვსი), 30 (20+10) оцдаати (ოცდაათი).

40 ормоци (ორმოცი) (в переводе дважды по 20)

50 ормоцдаати (ორმოცდაათი)(40 и 10)

60 самоци (სამოცი) (в переводе трижды по 20)

70 самоцдаати (სამოცდაათი) (60+10)

80 отхмоци (ოთხმოცი) (в переводе четырежды по 20)

90 отхмоцдаати (ოთხმოცდაათი) (80+10)

100 – аси (ასი)

200 ораси (ორასი) (дословно с грузинского два по сто, «ори» это два, а «аси» это сто)

300 самаси (სამასი) (три по сто)

400 отхаси (ოთხასი) (четыре по сто)

500 хутаси (ხუთასი) (пять по сто)

600 эквсаси (ექვსასი) (шесть по сто)

700 швидаси (შვიდასი) семь по сто)

800 рвааси (რვაასი) (восемь по сто)

900 цхрааси (ცხრაასი) (девять по сто)

1000 атаси (ათასი) (десять по сто).

Дни недели

Самым главным днем недели для грузин является – суббота. Ведь это чудесный день, для шумного застолья в кругу семьи и друзей. Возможно, поэтому дни недели на грузинском языке отсчитываются именно от субботы и называются весьма своеобразно – какой по счету день после субботы.

Так слово ორშაბათი образовано из двух слов ори (два) и шабати (суббота), что означает второй день от субботы, аналогично за понедельником следует вторник სამშაბათი то есть третий день после субботы. Исключение составляют лишь пятница и воскресенье. Обратите внимание, слово კვირა квира переводится не только как воскресенье, но и как неделя (временной промежуток).

Понедельник ორშაბათი (оршабати)

Вторник სამშაბათი (самшабати)

Среда ოთხშაბათი (отхшабати)

Четверг ხუთშაბათი (хутшабати)

Пятница პარასკევი (параскэви)

Суббота შაბათი (шабати)

Воскресенье კვირა (квира)

Да и нет

Если вы согласны с тем, что грузинский язык не так уж сложен, то предлагаем выучить часто используемые фразы и слова. К слову, согласиться на грузинском можно несколькими способами, а именно можно сказать:

Диах (დიახ) – литературное и уважительное да.

Ки (კი) – обычное да, используемое чаще всего.

Хо – (ჰო) неформальное да, используется в общении между близкими людьми.

Отказ выражается одним словом — ара (ударение на первую А) (არა) – нет.

Люди, родственники и кто такой по грузински биджо

Прежде чем предоставить вам сборник из самых часто используемых грузинских слов и фраз, дадим перевод нескольких слов, обозначающих родственников на грузинском языке. Из нашего небольшого списка вы узнаете как на грузинском мама и другие близкие родственники.

Мама – дэда (დედა), ласково дэдико (დედიკო) мамочка.

Папа – мама (მამა), ласково мамико (მამიკო) папочка.

Бабушка – бэбиа (ბებია), можно бэбо (ბებო)бабуля.

Дедушка – бабуа (ბაბუა), можно бабу (ბაბუ) дедуля.

Брат – дзма (ძმა), ласково дзамико (ძამიკო) братишка.

Сестра – да (და), ласково даико (დაიკო) сестричка.

Муж – кмари (ქმარი)

Жена –цоли (ცოლი)

Что неизменно удивляет иностранцев, так это обращение старших родственников к детям. Итак, если ребенок зовет мать, то он зовет ее дэда. Мать отвечая ребенку, обращается также, а именно: мама спрашивает ребенка хочет ли он воды, дэдико цхали гинда (დედიკო წყალი გინდა?) Дословно переводится так: мамочка воды хочешь?

Аналогично обращение бабушек и дедушек к внукам. Бэбо згвазэ гинда? (ბებო ზღვაზე გინდა?) Бабуленька на море хочешь? Так обратится бабушка к внуку или внучке. Даже любой дедушка на улице, обратится за помощью к молодому человеку со словами: бабу дамэхмарэ (ბაბუ დამეხმარე).

Здесь же укажем как будет друг по грузински – произносится мэгобари, пишется მეგობარი. Однако учтите следующий нюанс, если по-русски вы обращаетесь к другу: друг помоги! То в грузинском нужно изменить окончание и сказать мэгобаро дамэхмарэ! (მეგობარო დამეხმარე). Отметим, что при обращении, всегда окончание меняется на «о».

В грузинском языке часто встречается слово биджо хотя в русско-грузинском словаре этого слова не найти. На самом деле это слово «бичи» (мальчик), которое произносится как обращение или окрик «бичо!». Но при этом слово трансформировалась в уличное сленговое обращение «биджо».

Также поражает туристов то, что в семье грузин есть четкое понятие с какой стороны ты родня, с маминой или с отцовской. Сказать тетя по-грузински можно так: дейда, мамида, бицола. При этом учтите, что дейда (დეიდა) это сестра мамы, мамида (მამიდა)– сестра папы, а бицола (ბიცოლა) жена дяди (дяди с любой стороны, что с маминой, что с папиной). И только дядя со всех сторон это просто – бидзиа (ბიძია).

Если вы хотите окликнуть или позвать девушку (что-то типа тетенька), то обратиться к ней нужно дейда (დეიდა).

И еще несколько часто упоминающихся при разговоре родственников:

Невестка – рдзали (რძალი)

Зять – сидзэ (სიძე).

Свекровь – дэдамтили (დედამთილი)

Свекр – мамамтили (მამამთილი)

Теща – сидэдрэ (სიდედრი)

Тесть – симамрэ (სიმამრი).

Мальчик – бичи (ბიჭი)

Девочка – гого (გოგო)

Парень – ахалгазрда бичи (ახალგაზრდა ბიჭი)

Девушка — калишвили (ქალიშვილი)

Мужчина – каци (კაცი)

Женщина — кали (ქალი)

Ниже представлен русско-грузинский разговорник, в котором собрано более 100 самых распространенных слов и выражений на грузинском языке.

Русско-грузинский разговорник

Далее вы найдете небольшой переводчик с грузинского на русский который мы разделили на две части. В первой части собраны часто употребляемые слова, которые трудно перевести одним словом. Во второй части русские слова, значение которых в Грузии изменено. В третьей, самой большой, самые популярные и чаще всего используемые слова.

В словарь включены слова, которые можно часто услышать на улице, но трудно найти в словарике.

Барака (ბარაქა) — достаток, материальное процветание, разные формы материальных благ. Обычно этого желают во время тостов, если коротко, то достатка во всем.

Биржа (ბირჟა)- не имеет ничего общего с другими биржами и представляет собой мистическое место в районе или городе где собираются парни, мужчины или пожилые люди для общения и обсуждения последних новостей и проблем.

Гэнацвале (გენაცვალე)- человек, которого ты одновременно любишь, уважаешь и обнимаешь.

Дзвэли бичи (ძველი ბიჭი)– дословный перевод «старый мальчик». Это молодой представитель мужского пола, который редко работает, часто тусит на бирже, живет по неписаному кодексу и уверен в своей крутости на 100%.

Джандаба (ჯანდაბა) – ругательство, восклицание и выражение недовольства, что-то типа черт побери. Можно послать туда человека (ориентировочно он попадет во что-то среднее между преисподней, адом и еще сотней самых жутких мест).

Джигари (ჯიგარი) – восхищение и похвала. Обычно оценка свойств человека мужского пола, произносимая от полноты чувств, после выполнения какого-либо стоящего поступка.

Мэтичара (მეტიჩარა) – обычно девчонка показушница, которая кривляется, а ее кокетство переходит дозволенные границы. Может быть обращено к ребенку с улыбкой и ко взрослой девшуке с пренебрежением.

Супра гавшалот (სუფრა გავშალოთ)– накроем стол и ай-да пир горой. В точном переводе звучит как «раскроем стол».

Харахура (ხარახურა) — хлам, который складируется в: гараже, кладовке, на заднем дворе или балконе. Хлам не пригоден для дела, но почему-то хранится долгие годы в одном из вышеуказанных мест.

Хатабала (ხათაბალა)– процесс, действие или дело у которого не видно ни конца ни края. Используется в негативном смысле, дело, которое требует сил, от того, что кто-то тянет кота за хвост.

Пэхэбзэ мкидия (ფეხებზე მკიდია) – точный перевод «висит на ногах» часто используемое выражение, для показа наплевательского отношения к чему-либо или кому-либо (аналог мне по барабану).

Цутисопэли (წუთისოფელი) – дословно «минутная деревня» означает быстротечности жизни. Часто произносится с сожалением, когда сказать уже нечего.

Чичилаки (ჩიჩილაკი) – грузинская елка, которая представляет собой палку со стружками, которые спускаются с макушки.

Шени чириме (შენი ჭირიმე)– дословно «возьму твою болезнь, боль или страдание на себя». Употребляется от избытка чувств со смыслом ой мой хороший, моя милая.

Шемогевле (შემოგევლე) — аналогичное по смыслу шени чириме.

Шемомечама (შემომეჭამა) – случайно съел, другими словами съел, сам не замечая как.

Слова, которые имеют данное значение только на территории Грузии:

Роллинг — обычная водолазка или свитер с горлышком.

Чусты — домашние тапочки.

Шпильки – прищепки для белья.

Бамбанерка – прямоугольная коробка конфет.

Паста – обычная ручка, которой пишут в школе.

Метлах – напольная плитка, кафель – настенная плитка, оба слова являются взаимозаменяемыми.

Если вы внимательно читали статью, то вы знаете, что в грузинском языке нет рода, поэтому красивый и красивая будут звучать одинаково.

Исходя из этого, предлагаем небольшую подборку комплиментов, которые можно сказать женщине и мужчине:

Выражение чувств и комплименты на грузинском языке

Комплименты

Красивая ლამაზი (ламази)

Умная ჭკვიანი (чквиани)

Хорошая კარგი (карги)

Милая ნაზი (нази)

Антикомплименты

Некрасивый უშნო (ушно)

Глупый სულელი (сулэли)

Плохой ცუდი (цуди)

Злой ბოროტი (бороти)

Обращение

Мой дорогой ჩემო ძვირფასო (чэмо дзвирпасо)

Мой красавчик ჩემო ლამაზო (чэмо ламазо)

Моя хорошая ჩემო კარგო (чемо карго)

Душа моя ჩემო სულო (чэми суло)

Мое золотце ჩემო ოქრო (чэмо окро)

Жизнь моя ჩემო სიცოცხლე (чэмо сицоцхле)

Радость моя ჩემო სიხარულო (чэмо сихаруло)

Фразы и слова подходящие для выражения своих чувств

Любовь სიყვარული (сихварули)

Я тебя люблю მე შენ მიყვარხარ (мэ шэн михвархар)

Очень сильно люблю უზომოდ მიყვარხარ (узомод михвархар)

Соскучился მომენატრე (момэнатрэ)

Ты мне снишься მესიზმრები (мэсизмрэби)

Целую გკოცნი (гкоцни)

Поцелуй меня მაკოცე (макоцэ)

Иди ко мне, я тебя поцелую მოდი ჩემთან გაკოცებ (моди чэмтан, гакоцеб)

Ты мне очень нравишься — შენ მე ძალიან მომწონხარ (шэн мэ дзалиан момцонхар)

Никогда тебя не брошу არასდროს მიგატოვებ (арасдрос мигатовэб)

Я всегда буду с тобой სულ შენთან ვიქნები (сул шэнтан викнэби)

Ты — моя жизнь შენ ჩემი ცხოვრება ხარ (шэн чэми цховрэба хар)

Ты — смысл моей жизни შენ ჩემი ცხოვრების აზრი ხარ (шэн чэми цховрэбис азри хар)

Почему ты не звонишь? რატომ არ მირეკავ? (ратом ар мирэкав?)

Буду ждать დაგელოდები (дагэлодэби)

Мне очень грустно без тебя ძალიან მოწყენილი ვარ უშენოდ (дзалиан моцхэнили вар ушэнод)

Приезжай скорее მალე ჩამოდი (малэ чамоди)

Не пиши ნუ მწერ (ну мцер)

Забудь меня დამივიწყე (дамивицхэ)

Не звони мне больше აღარ დამირეკო (агар дамирэко)

Теперь вы знаете, как сделать комплимент на грузинском мужчине и женщине.

Знакомство и встреча

Здравствуй გამარჯობა (гамарджоба)

Здравствуйте გამარჯობათ (гамарджобат)

Ответ на здравствуй გაგიმარჯოს (гагимарджос)

До встречи, до свидания ნახვამდის (нахвамдис)

Пока კარგად (каргад)

Доброе утро დილა მშვიდობისა (дила мшвидобиса)

Добрый день დღე მშვიდობისა (дгэ мшвидобиса)

Добрый вечер საღამო მშვიდობისა (сагамо мшвидобиса)

Спокойной ночи ძილი ნებისა (дзили нэбиса)

Спасибо мадлоба (მადლობა)

Большое спасибо დიდი მადლობა (диди мадлоба)

Благодарю გმადლობთ (гмадлобт)

Пожалуйста, не за что არაფრის (араприс)

Как ты? როგორ ხარ? (рогор хар?)

Как дела? Как вы? როგორ ხართ? (рогор харт?)

Хорошо. Как у вас? კარგად. თქვენ? (Каргад. Тквэн?)

Спасибо, хорошо გმადლობთ, კარგად (гмадлобт, каргад)

Плохо ცუდად (цудад)

Извините უკაცრავად (укацравад)

Простите ბოდიში (бодиши)

Как тебя зовут? რა გქვია? (ра гквиа?)

Меня зовут … მე მქვია… (мэ мквиа …)

Я не говорю по-грузински არ ვლაპარაკობ ქართულად (ар влапаракоб картулад)

Я не знаю грузинский მე არ ვიცი ქართული (мэ ар вици картули)

В магазине и ресторане

Сколько стоит? რა ღირს? (ра гирс?)

Что это такое? ეს რა არის? (эс ра арис?)

У вас есть… თქვენ გაქვთ… (тквэн гаквт…)

Хочу მინდა (минда)

Не хочу არ მინდა (ар минда)

Нельзя არ შეიძლება (ар шэидзлэба)

Чуть-чуть ცოტა (цота)

Много ბევრი (бэври)

Все ყველა (хвэла)

Сколько? რამდენი? (рамдени?)

Принесите счет ანგარიში მოიტანეთ (ангариши моитанэт)

Напитки и еда:

Вода წყალი (цхали)

Сок წვენი (цвэни)

Кофе ყავა (хава)

Чай ჩაი (чаи)

Вино ღვინო (гвино)

Фрукты ხილი (хили)

Орехи თხილი (тхили)

Орехи грецкие ნიგოზი (нигози)

Мороженое ნაყინი (нахини)

Мед თაფლი (тапли)

Соль მარილი (марили)

Перец პილპილი (пилпили)

Хлеб პური (пури)

Мясо ხორცი (хорци)

Сыр ყველი (хвэли)

Шашлык მწვადი (мцвади)

Зелень მწვანილი (мцванили)

Завтрак საუზმე (саузмэ)

Обед სადილი (садили)

Ужин ვახშამი (вахшами)

Цвета и предметы гардероба

Черный შავი (шави)

Белый თეთრი (тэтри)

Синий ლურჯი (лурджи)

Красный წითელი (цитэли)

Желтый ყვითელი (хвитэли)

Зеленый მწვანე (мцванэ)

Розовый ვარდისფერი (вардиспэри)

Оранжевый ნარინჯისფერი (наринджиспэри)

Платье კაბა (каба)

Юбка ქვედატანი (квэдатани)

Брюки შარვალი (шарвали)

Носки წინდები (циндеби)

Месторасположение

Левый მარცხენა (марцхэна)

Правый მარჯვენა (марджвэна)

Прямо პირდაპირ (пирдапир)

Вверх ზემოთ (зэмот)

Вниз ქვემოთ (квэмот)

Далеко შორს (шорс)

Близко ახლოს (ахлос)

Карта რუკა (ударение на у) (рука)

Где…? სად არის? (сад арис…?)

Который час? რომელი საათია? (ромэли саатиа?)

Какой адрес? რა მისამართია? (ра мисамартиа?)

Где находится гостиница? სად არის სასტუმრო? (сад арис састумро?)

Железнодорожный вокзал რკინიგზის ვაგზალი (ркинигзис вагзали)

Аэропорт აეროპორტი (аэропорти)

Порт პორტი (порти)

Такси ტაქსი (такси)

Автобус ავტობუსი (автобуси)

Площадь მოედანი (моэдани)

Если вам хочется больше, то по ссылке вы найдете самый удобный и полный русско-грузинский переводчик онлайн:

http://www.nplg.gov.ge/gwdict/index.php?a=index&d=9

Искренне надеемся, что статья ответила на все интересующие вас вопросы и теперь вы можете понимать, что говорят грузины, а также смело вступать в беседу с ними. Мы постарались охватить различные темы для бесед, которые могут возникнуть у туристов в Грузии. Научили вас не только литературной речи, но и познакомили с часто употребляющимися сленговыми выражениями. Если у вас все же остались вопросы, задавайте их в комментариях. Мы постараемся ответить всем.

Полезная информация про Грузию:

Лучшие экскурсии из Тбилиси с конкретными рекомендациями гидов

Где искать и покупать дешёвые авиабилеты

Топ 15 — самые интересные достопримечательности Грузии

Лари — знакомимся с валютой Грузии

Сациви и оджахури — знакомимся с грузинской кухней

Более 15 лет я путешествую по миру. Ежегодно в поездках нахожусь от 3 до 6 месяцев. За эти годы я накопил огромный опыт и научился не переплачивать за туристические услуги.

Вот несколько ссылок, которые помогут вам сэкономить в путешествии по Грузии:

- Найти недорогие авиабилеты: aviasales.ru

- Подобрать отель: booking.com

- Купить экскурсии: georgia4travel.ru

- Арендовать авто: myrentacar.com

- Трансфер из аэропорта и между городами: findlocaltrip.com

- Страховка туриста: cherehapa.ru

| Georgian | |

|---|---|

damts’erloba «script» in Mkhedruli |

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

AD 430[1] – present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages |

|

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Uncertain, alphabetical order modelled on Greek

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Geor (240), Georgian (Mkhedruli and Mtavruli) – Georgian (Mkhedruli) Geok, 241 – Khutsuri (Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Georgian |

|

Unicode range |

|

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

| Living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage |

|

|

|

| Country | Georgia |

| Reference | 01205 |

| Region |

|

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2016 (11 session) |

The Georgian scripts are the three writing systems used to write the Georgian language: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli. Although the systems differ in appearance, their letters share the same names and alphabetical order and are written horizontally from left to right. Of the three scripts, Mkhedruli, once the civilian royal script of the Kingdom of Georgia and mostly used for the royal charters, is now the standard script for modern Georgian and its related Kartvelian languages, whereas Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are used only by the Georgian Orthodox Church, in ceremonial religious texts and iconography.[2]

Georgian scripts are unique in their appearance and their exact origin has never been established; however, in strictly structural terms, their alphabetical order largely corresponds to the Greek alphabet, with the exception of letters denoting uniquely Georgian sounds, which are grouped at the end.[3][4] Originally consisting of 38 letters,[5] Georgian is presently written in a 33-letter alphabet, as five letters are obsolete. The number of Georgian letters used in other Kartvelian languages varies. Mingrelian uses 36: thirty-three that are current Georgian letters, one obsolete Georgian letter, and two additional letters specific to Mingrelian and Svan. Laz uses the same 33 current Georgian letters as Mingrelian plus that same obsolete letter and a letter borrowed from Greek for a total of 35. The fourth Kartvelian language, Svan, is not commonly written, but when it is, it uses Georgian letters as utilized in Mingrelian, with an additional obsolete Georgian letter and sometimes supplemented by diacritics for its many vowels.[2][6]

The «living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet» was granted the national status of intangible cultural heritage in Georgia in 2015[7] and inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016.[8]

The three Georgian scripts: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri, and Mkhedruli.

Origins[edit]

The origin of the Georgian script is poorly known, and no full agreement exists among Georgian and foreign scholars as to its date of creation, who designed the script, and the main influences on that process.

The first attested version of the script is Asomtavruli, which dates back to the 5th century; the other scripts were formed in the following centuries. Most scholars link the creation of the Georgian script to the process of Christianization of Iberia (not to be confused with the Iberian Peninsula), a core Georgian kingdom of Kartli.[9] The alphabet was therefore most probably created between the conversion of Iberia under King Mirian III (326 or 337) and the Bir el Qutt inscriptions of 430,[9] contemporaneously with the Armenian alphabet.[10] It was first used for translation of the Bible and other Christian literature into Georgian, by monks in Georgia and Palestine.[4] Professor Levan Chilashvili’s dating of fragmented Asomtavruli inscriptions, discovered by him at the ruined town of Nekresi, in Georgia’s easternmost province of Kakheti, in the 1980s, to the 1st or 2nd century has not been accepted.[11]

A Georgian tradition first attested in the medieval chronicle Lives of the Kings of Kartli (ca. 800),[4] assigns a much earlier, pre-Christian origin to the Georgian alphabet, and names King Pharnavaz I (3rd century BC) as its inventor. This account is now considered legendary, and is rejected by scholarly consensus, as no archaeological confirmation has been found.[4][12][13] Rapp considers the tradition to be an attempt by the Georgian Church to rebut the earlier tradition that the alphabet was invented by the Armenian scholar Mesrop Mashtots, and is a Georgian application of an Iranian model in which primordial kings are credited with the creation of basic social institutions.[14] Georgian linguist Tamaz Gamkrelidze offers an alternative interpretation of the tradition, in the pre-Christian use of foreign scripts (alloglottography in the Aramaic alphabet) to write down Georgian texts.[15]

Another point of contention among scholars is the role played by Armenian clerics in that process. According to medieval Armenian sources and a number of scholars, Mesrop Mashtots, generally acknowledged as the creator of the Armenian alphabet, also created the Georgian and Caucasian Albanian alphabets. This tradition originates in the works of Koryun, a fifth-century historian and biographer of Mashtots,[16] and has been quoted by Donald Rayfield and James R. Russell,[17][18] but has been rejected by Georgian scholarship and some Western scholars who judge the passage in Koryun unreliable or even a later interpolation.[4] In his study on the history of the invention of the Armenian alphabet and the life of Mashtots, the Armenian linguist Hrachia Acharian strongly defended Koryun as a reliable source and rejected criticisms of his accounts on the invention of the Georgian script by Mashtots.[19] Acharian dated the invention to 408, four years after Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet (he dated the latter event to 404).[20] Some Western scholars quote Koryun’s claims without taking a stance on its validity[21][22] or concede that Armenian clerics, if not Mashtots himself, must have played a role in the creation of the Georgian script.[4][13][23]

Another controversy regards the main influences at play in the Georgian alphabet, as scholars have debated whether it was inspired more by the Greek alphabet, or by Semitic alphabets such as Aramaic.[15] Recent historiography focuses on greater similarities with the Greek alphabet than in the other Caucasian writing systems, most notably the order and numeric value of letters.[3][4] Some scholars have also suggested certain pre-Christian Georgian cultural symbols or clan markers as a possible inspiration for particular letters.[24]

Asomtavruli[edit]

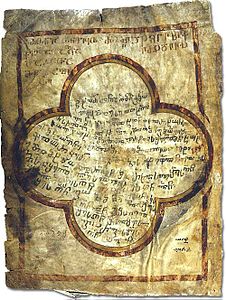

Asomtavruli (Georgian: ასომთავრული; Georgian pronunciation: [ɑsɔmtʰɑvɾuli]) is the oldest Georgian script. The name Asomtavruli means «capital letters», from aso (ასო) «letter» and mtavari (მთავარი) «principal/head». It is also known as Mrgvlovani (Georgian: მრგვლოვანი) «rounded», from mrgvali (მრგვალი) «round», so named because of its round letter shapes. Despite its name, this «capital» script is unicameral.[25]

The oldest Asomtavruli inscriptions found so far date from the 5th century[26] and are Bir el Qutt[27] and the Bolnisi inscriptions.[28]

From the 9th century, Nuskhuri script started becoming dominant, and the role of Asomtavruli was reduced. However, epigraphic monuments of the 10th to 18th centuries continued to be written in Asomtavruli script. Asomtavruli in this later period became more decorative. In the majority of 9th-century Georgian manuscripts which were written in Nuskhuri script, Asomtavruli was used for titles and the first letters of chapters.[29] However, some manuscripts written completely in Asomtavruli can be found until the 11th century.[30]

Form of Asomtavruli letters[edit]

In early Asomtavruli, the letters are of equal height. Georgian historian and philologist Pavle Ingorokva believes that the direction of Asomtavruli, like that of Greek, was initially boustrophedon, though the direction of the earliest surviving texts is from left to the right.[31]

In most Asomtavruli letters, straight lines are horizontal or vertical and meet at right angles. The only letter with acute angles is Ⴟ (ჯ jani). There have been various attempts to explain this exception. Georgian linguist and art historian Helen Machavariani believes jani derives from a monogram of Christ, composed of the Ⴈ (ი ini) and Ⴕ (ქ kani).[32] According to Georgian scholar Ramaz Pataridze, the cross-like shape of letter jani indicates the end of the alphabet, and has the same function as the similarly shaped Phoenician letter taw (), Greek chi (Χ), and Latin X,[33] though these letters do not have that function in Phoenician, Greek, or Latin.

From the 7th century, the forms of some letters began to change. The equal height of the letters was abandoned, with letters acquiring ascenders and descenders.[34][35]

| Ⴀ ani |

Ⴁ bani |

Ⴂ gani |

Ⴃ doni |

Ⴄ eni |

Ⴅ vini |

Ⴆ zeni |

Ⴡ he |

Ⴇ tani |

Ⴈ ini |

Ⴉ kʼani |

Ⴊ lasi |

Ⴋ mani |

Ⴌ nari |

Ⴢ hie |

Ⴍ oni |

Ⴎ pʼari |

Ⴏ zhani |

Ⴐ rae |

| Ⴑ sani |

Ⴒ tʼari |

Ⴣ vie |

ႭჃ Ⴓ uni |

Ⴔ pari |

Ⴕ kani |

Ⴖ ghani |

Ⴗ qʼari |

Ⴘ shini |

Ⴙ chini |

Ⴚ tsani |

Ⴛ dzili |

Ⴜ ts’ili |

Ⴝ ch’ari |

Ⴞ khani |

Ⴤ qari |

Ⴟ jani |

Ⴠ hae |

Ⴥ hoe |

Asomtavruli illumination[edit]

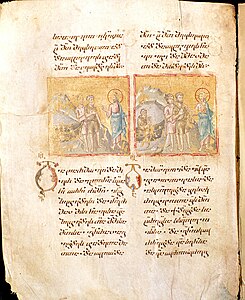

In Nuskhuri manuscripts, Asomtavruli are used for titles and illuminated capitals. The latter were used at the beginnings of paragraphs which started new sections of text. In the early stages of the development of Nuskhuri texts, Asomtavruli letters were not elaborate and were distinguished principally by size and sometimes by being written in cinnabar ink. Later, from the 10th century, the letters were illuminated. The style of Asomtavruli capitals can be used to identify the era of a text. For example, in the Georgian manuscripts of the Byzantine era, when the styles of the Byzantine Empire influenced Kingdom of Georgia, capitals were illuminated with images of birds and other animals.[36]

Decorative Asomtavruli capital letters, მ (m) and თ (t), 12–13th century.

From the 11th-century «limb-flowery», «limb-arrowy» and «limb-spotty» decorative forms of Asomtavruli are developed. The first two are found in 11th- and 12th-century monuments, whereas the third one is used until the 18th century.[37][38]

Importance was attached also to the colour of the ink itself.[39]

Asomtavruli letter დ (doni) is often written with decoration effects of fish and birds.[40]

The «Curly» decorative form of Asomtavruli is also used where the letters are wattled or intermingled on each other, or the smaller letters are written inside other letters. It was mostly used for the headlines of the manuscripts or the books, although there are complete inscriptions which were written in the Asomtavruli «Curly» form only.[41]

The title of Gospel of Matthew in Asomtavruli «Curly» decorative form.

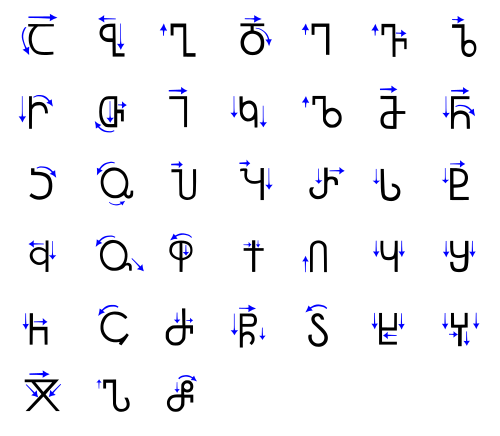

Handwriting of Asomtavruli[edit]

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Asomtavruli letter:[42]

Nuskhuri[edit]

Nuskhuri (Georgian: ნუსხური; Georgian pronunciation: [nusχuɾi]) is the second Georgian script. The name nuskhuri comes from nuskha (ნუსხა), meaning «inventory» or «schedule». Nuskhuri was soon augmented with Asomtavruli illuminated capitals in religious manuscripts. The combination is called Khutsuri (Georgian: ხუცური, «clerical», from khutsesi (ხუცესი «cleric»), and it was principally used in hagiography.[43]

Nuskhuri first appeared in the 9th century as a graphic variant of Asomtavruli.[9] The oldest inscription is found in the Ateni Sioni Church and dates to 835 AD.[44] The oldest surviving Nuskhuri manuscripts date to 864 AD.[45] Nuskhuri becomes dominant over Asomtavruli from the 10th century.[43]

Form of Nuskhuri letters[edit]

Nuskhuri letters vary in height, with ascenders and descenders, and are slanted to the right. Letters have an angular shape, with a noticeable tendency to simplify the shapes they had in Asomtavruli. This enabled faster writing of manuscripts.[46]

→

→

Asomtavruli letters ო (oni) and ჳ (vie). A ligature of these letters produced a new letter in Nuskhuri, უ uni.

| ⴀ ani |

ⴁ bani |

ⴂ gani |

ⴃ doni |

ⴄ eni |

ⴅ vini |

ⴆ zeni |

ⴡ he |

ⴇ tani |

ⴈ ini |

ⴉ kʼani |

ⴊ lasi |

ⴋ mani |

ⴌ nari |

ⴢ hie |

ⴍ oni |

ⴎ pʼari |

ⴏ zhani |

ⴐ rae |

| ⴑ sani |

ⴒ tʼari |

ⴣ vie |

ⴍⴣ ⴓ uni |

ⴔ pari |

ⴕ kani |

ⴖ ghani |

ⴗ qʼari |

ⴘ shini |

ⴙ chini |

ⴚ tsani |

ⴛ dzili |

ⴜ tsʼili |

ⴝ chʼari |

ⴞ khani |

ⴤ qari |

ⴟ jani |

ⴠ hae |

ⴥ hoe |

- Note: Without proper font support, you may see question marks, boxes or other symbols instead of Nuskhuri letters.

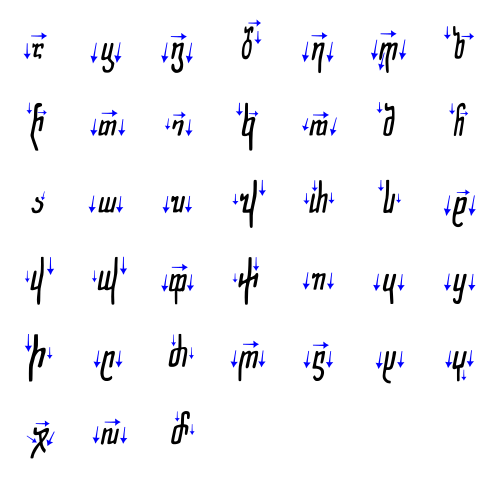

Handwriting of Nuskhuri[edit]

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Nuskhuri letter:[47]

Use of Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri today[edit]

Asomtavruli is used intensively in iconography, murals, and exterior design, especially in stone engravings.[48] Georgian linguist Akaki Shanidze made an attempt in the 1950s to introduce Asomtavruli into the Mkhedruli script as capital letters to begin sentences, as in the Latin script, but it did not catch on.[49] Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are officially used by the Georgian Orthodox Church alongside Mkhedruli. Patriarch Ilia II of Georgia called on people to use all three Georgian scripts.[50]

Mkhedruli[edit]

Mkhedruli (Georgian: მხედრული; Georgian pronunciation: [mχɛdɾuli]) is the third and current Georgian script. Mkhedruli, literally meaning «cavalry» or «military», derives from mkhedari (მხედარი) meaning «horseman», «knight», «warrior»[51] and «cavalier».[52]

Mkhedruli is bicameral, with capital letters that are called Mkhedruli Mtavruli (მხედრული მთავრული) or simply Mtavruli (მთავრული; Georgian pronunciation: [mtʰɑvɾuli]). Nowadays, Mkhedruli Mtavruli is only used in all-caps text in titles or to emphasize a word, though in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was occasionally used, as in Latin and Cyrillic scripts, to capitalize proper nouns or the first word of a sentence. Contemporary Georgian script does not recognize capital letters and their usage has become decorative.[53]

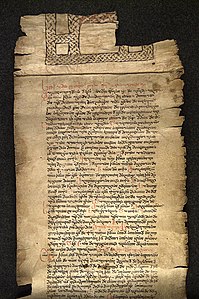

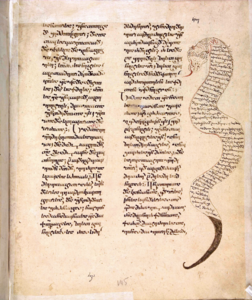

Mkhedruli first appears in the 10th century. The oldest Mkhedruli inscription is found in Ateni Sioni Church dating back to 982 AD. The second oldest Mkhedruli-written text is found in the 11th-century royal charters of King Bagrat IV of Georgia. Mkhedruli was mostly used then in the Kingdom of Georgia for the royal charters, historical documents, manuscripts and inscriptions.[54] Mkhedruli was used for non-religious purposes only and represented the «civil», «royal» and «secular» script.[55][56]

Mkhedruli became more and more dominant over the two other scripts, though Khutsuri (Nuskhuri with Asomtavruli) was used until the 19th century. Mkhedruli became the universal writing Georgian system outside of the Church in the 19th century with the establishment and development of printed Georgian fonts.[57]

Form of Mkhedruli letters[edit]

Mkhedruli inscriptions of the 10th and 11th centuries are characterized in rounding of angular shapes of Nuskhuri letters and making the complete outlines in all of its letters. Mkhedruli letters are written in the four-linear system, similar to Nuskhuri.

Mkhedruli becomes more round and free in writing. It breaks the strict frame of the previous two alphabets, Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri. Mkhedruli letters begin to get coupled and more free calligraphy develops.[58]

Example of one of the oldest Mkhedruli-written texts found in the royal charter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia, 11th century.

«Gurgen : King : of Kings : great-grandfather : of mine : Bagrat Curopalates»

Modern Georgian alphabet[edit]

The modern Georgian alphabet consists of 33 letters:

| ა ani |

ბ bani |

გ gani |

დ doni |

ე eni |

ვ vini |

ზ zeni |

თ tani |

ი ini |

კ k’ani |

ლ lasi |

| მ mani |

ნ nari |

ო oni |

პ p’ari |

ჟ zhani |

რ rae |

ს sani |

ტ t’ari |

უ uni |

ფ pari |

ქ kani |

| ღ ghani |

ყ q’ari |

შ shini |

ჩ chini |

ც tsani |

ძ dzili |

წ ts’ili |

ჭ ch’ari |

ხ khani |

ჯ jani |

ჰ hae |

Letters removed from the Georgian alphabet[edit]

The Society for the Spreading of Literacy among Georgians, founded by Prince Ilia Chavchavadze in 1879, discarded five letters from the Georgian alphabet that had become redundant:[25]

| ჱ he |

ჲ hie |

ჳ vie |

ჴ qari |

ჵ hoe |

- ჱ (he) /eɪ/, Svan /eː/, sometimes called «ei«[59] or «e-merve» («eighth e«),[60] was equivalent to ეჲ ey, as in ქრისტჱ ~ ქრისტეჲ kristʼey ‘Christ’.

- ჲ (hie) /je/, also called yota,[60] appeared instead of ი (ini) after a vowel, but came to have the same pronunciation as ი (ini) and was replaced by it. Thus, ქრისტჱ ~ ქრისტეჲ kristʼey «Christ» is now written ქრისტე kristʼe.

- ჳ (vie) /uɪ/, Svan /w/[60] came to be pronounced the same as ვი vi and was replaced by that sequence, as in სხჳსი > სხვისი skhvisi «others'».

- ჴ (qari, hari) /q⁽ʰ⁾/[60] came to be pronounced the same as ხ (khani), and was replaced by it. e.g. ჴელმწიფე qelmtsʼipe became ხელმწიფე khelmtsʼipe «sovereign».

- ჵ (hoe) /oː/[60] was used for the interjection hoi! and is now spelled ჰოი. Also used in Bats for the /ʕ/ or /ɦ/ sound.

All but ჵ (hoe) continue to be used in the Svan alphabet; ჲ (hie) is used in the Mingrelian and Laz alphabets as well, for the y-sound /j/. Several others were used for Abkhaz and Ossetian in the short time they were written in Mkhedruli script.

Letters added to other alphabets[edit]

Mkhedruli has been adapted to languages besides Georgian. Some of these alphabets retained letters obsolete in Georgian, while others required additional letters:

| ჶ fi |

ჷ shva |

ჸ elifi |

ჹ turned gani |

ჺ aini |

ჼ modifier letter nar |

ჽ aen |

ჾ hard sign |

ჿ labial sign |

- ჶ (fi «phi») is used in Laz and Svan, and formerly in Ossetian and Abkhazian.[2] It derives from the Greek letter Φ (phi).

- ჷ (shva «schwa»), also called yn, is used for the schwa sound in Svan and Mingrelian, and formerly in Ossetian and Abkhazian.[2]

- ჸ (elifi «alif») is used in for the glottal stop in Svan and Mingrelian.[2] It is a reversed ⟨ყ⟩ (q’ari).

- ჹ (turned gani) was once used for [ɢ] in evangelical literature in Dagestanian languages.[2]

- ჼ (modifier nar) is used in Bats. It nasalizes the preceding vowel.[61]

- ჺ (aini «ain») is occasionally used for [ʕ] in Bats.[2] It derives from the Arabic letter ⟨ع⟩ (ʿayn)

- ჽ (aen) was used in the Ossetian language when it was written in the Georgian script. It was pronounced [ə].[62]

- ჾ (hard sign) was used in Abkhaz for velarization of the preceding consonant.[63]

- ჿ (labial sign) was used in Abkhaz for labialization of the preceding consonant.[63]

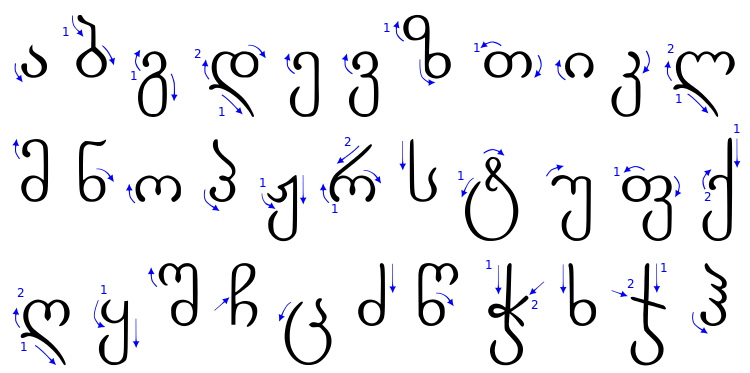

Handwriting of Mkhedruli[edit]

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Mkhedruli letter:[64][65][66]

ზ, ო, and ხ (zeni, oni, khani) are almost always written without the small tick at the end, while the handwritten form of ჯ (jani) often uses a vertical line, (sometimes with a taller ascender, or with a diagonal cross bar); even when it is written at a diagonal, the cross-bar is generally shorter than in print.

- Only four letters are x-height, with neither ascenders nor descenders: ა, თ, ი, ო.

- Thirteen have ascenders, like b or d in English: ბ, ზ, მ, ნ, პ, რ, ს, შ, ჩ, ძ, წ, ხ, ჰ

- An equal number have descenders, like p or q in English: გ, დ, ე, ვ, კ, ლ, ჟ, ტ, უ, ფ, ღ, ყ, ც

- Three letters have both ascenders and descenders, like þ in Old English: ქ, ჭ, and (in handwriting) ჯ. წ has both ascender and descender in print, and sometimes in handwriting.

Variation[edit]

There is individual and stylistic variation in many of the letters. For example, the top circle of ზ (zeni) and the top stroke of რ (rae) may go in the other direction than shown in the chart (that is, counter-clockwise starting at 3 o’clock, and upwards – see the external-link section for videos of people writing).

Other common variants:

- გ (gani) may be written like ვ (vini) with a closed loop at the bottom.

- დ (doni) is frequently written with a simple loop at top,

.

- კ, ც, and ძ (k’ani, tsani, dzili) are generally written with straight, vertical lines at the top, so that for example ც (tsani) resembles a U with a dimple in the right side.

- ლ (lasi) is frequently written with a single arc,

. Even when all three are written, they’re generally not all the same size, as they are in print, but rather riding on one wide arc like two dimples in it.

- Rarely, ო (oni) is written as a right angle,

.

- რ (rae) is frequently written with one arc,

, like a Latin ⟨h⟩.

- ტ (t’ari) often has a small circle with a tail hanging into the bowl, rather than two small circles as in print, or as an O with a straight vertical line intersecting the top. It may also be rotated a bit clockwise, with the small circles further to the right and not as close to the top.

- წ (ts’ili) is generally written with a round bowl at the bottom,

. Another variation features a triangular bowl.

- ჭ (ch’ari) may be written without the hook at the top, and often with a completely straight vertical line.

- ჱ (he) may be written without the loop, like a conflation of ს and ჰ.

- ჯ (jani) is sometimes written so that it looks like a hooked version of the Latin «X»

Similar letters[edit]

Several letters are similar and may be confused at first, especially in handwriting.

- For ვ (vini) and კ (k’ani), the critical difference is whether the top is a full arc or a (more-or-less) vertical line.

- For ვ (vini) and გ (gani), it is whether the bottom is an open curve or closed (a loop). The same is true of უ (uni) and შ (shini); in handwriting, the tops may look the same. Similarly ს (sani) and ხ (khani).

- For კ (k’ani) and პ (p’ari), the crucial difference is whether the letter is written below or above x-height, and whether it’s written top-down or bottom-up.

- ძ (dzili) is written with a vertical top.

Ligatures, abbreviations and calligraphy[edit]

Asomtavruli is often highly stylized and writers readily formed ligatures, intertwined letters, and placed letters within letters or other such monograms.[67]

A ligature of the Asomtavruli initials of King Vakhtang I of Iberia, Ⴂ Ⴌ (გნ, GN)

A ligature of the Asomtavruli letters Ⴃ Ⴀ (და, da) «and»

Nuskhuri, like Asomtavruli, is also often highly stylized. Writers readily formed ligatures and abbreviations for nomina sacra, including diacritics called karagma, which resemble titla. Because writing materials such as vellum were scarce and therefore precious, abbreviating was a practical measure widespread in manuscripts and hagiography by the 11th century.[68]

A Nuskhuri abbreviation of რომელი (romeli) «which»

A Nuskhuri abbreviation of იესუ ქრისტე (iesu kriste) «Jesus Christ»

Mkhedruli, in the 11th to 17th centuries also came to employ digraphs to the point that they were obligatory, requiring adherence to a complex system.[69]

A Mkhedruli ligature of და (da) «and»

Typefaces[edit]

Georgian scripts come in only a single typeface, though word processors can apply automatic («fake»)[70] oblique and bold formatting to Georgian text. Traditionally, Asomtavruli was used for chapter or section titles, where Latin script might use bold or italic type.

Punctuation[edit]

In Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri punctuation, various combinations of dots were used as word dividers and to separate phrases, clauses, and paragraphs. In monumental inscriptions and manuscripts of 5th to 10th centuries, these were written as dashes, like −, = and =−. In the 10th century, clusters of one (·), two (:), three (჻) and six (჻჻) dots (later sometimes small circles) were introduced by Ephrem Mtsire to indicate increasing breaks in the text. One dot indicated a «minor stop» (presumably a simple word break), two dots marked or separated «special words», three dots for a «bigger stop» (such as the appositive name and title «the sovereign Alexander», below, or the title of the Gospel of Matthew, above), and six dots were to indicate the end of the sentence. Starting in the 11th century, marks resembling the apostrophe and comma came into use. An apostrophe was used to mark an interrogative word, and a comma appeared at the end of an interrogative sentence. From the 12th century on, these were replaced with the semicolon (the Greek question mark). In the 18th century, Patriarch Anton I of Georgia reformed the system again, with commas, single dots, and double dots used to mark «complete», «incomplete», and «final» sentences, respectively.[71] For the most part, Georgian today uses the punctuation as in international usage of the Latin script.[72]

Summary[edit]

This table lists the three scripts in parallel columns, including the letters that are now obsolete in all alphabets (shown with a blue background), obsolete in Georgian but still used in other alphabets (green background), or additional letters in languages other than Georgian (pink background). The «national» transliteration is the system used by the Georgian government, whereas «Laz» is the Latin Laz alphabet used in Turkey. The table also shows the traditional numeric values of the letters.[73]

| Letters | Unicode (mkhedruli) |

Name | IPA | Transcriptions | Numeric value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asomtavruli | nuskhuri | mkhedruli | mtavruli | National | ISO 9984 | BGN | Laz | ||||

| Ⴀ | ⴀ | ა | Ა | U+10D0 | ani | /ɑ/, Svan /a, æ/ | A a | A a | A a | A a | 1 |

| Ⴁ | ⴁ | ბ | Ბ | U+10D1 | bani | /b/ | B b | B b | B b | B b | 2 |

| Ⴂ | ⴂ | გ | Გ | U+10D2 | gani | /ɡ/ | G g | G g | G g | G g | 3 |

| Ⴃ | ⴃ | დ | Დ | U+10D3 | doni | /d/ | D d | D d | D d | D d | 4 |

| Ⴄ | ⴄ | ე | Ე | U+10D4 | eni | /ɛ/ | E e | E e | E e | E e | 5 |

| Ⴅ | ⴅ | ვ | Ვ | U+10D5 | vini | /v/ | V v | V v | V v | V v | 6 |

| Ⴆ | ⴆ | ზ | Ზ | U+10D6 | zeni | /z/ | Z z | Z z | Z z | Z z | 7 |

| Ⴡ | ⴡ | ჱ | Ჱ | U+10F1 | he | /eɪ/, Svan /eː/ | — | Ē ē | Ey ey | — | 8 |

| Ⴇ | ⴇ | თ | Თ | U+10D7 | tani | /t⁽ʰ⁾/ | T t | Tʼ tʼ | Tʼ tʼ | T t | 9 |

| Ⴈ | ⴈ | ი | Ი | U+10D8 | ini | /i/ | I i | I i | I i | I i | 10 |

| Ⴉ | ⴉ | კ | Კ | U+10D9 | kʼani | /kʼ/ | Kʼ kʼ | K k | K k | Ǩ ǩ | 20 |

| Ⴊ | ⴊ | ლ | Ლ | U+10DA | lasi | /l/ | L l | L l | L l | L l | 30 |

| Ⴋ | ⴋ | მ | Მ | U+10DB | mani | /m/ | M m | M m | M m | M m | 40 |

| Ⴌ | ⴌ | ნ | Ნ | U+10DC | nari | /n/ | N n | N n | N n | N n | 50 |

| Ⴢ | ⴢ | ჲ | Ჲ | U+10F2 | hie | /je/, Mingrelian, Laz, & Svan /j/ | — | Y y | J j | Y y | 60 |

| Ⴍ | ⴍ | ო | Ო | U+10DD | oni | /ɔ/, Svan /ɔ, œ/ | O o | O o | O o | O o | 70 |

| Ⴎ | ⴎ | პ | Პ | U+10DE | pʼari | /pʼ/ | Pʼ pʼ | P p | P p | P̌ p̌ | 80 |

| Ⴏ | ⴏ | ჟ | Ჟ | U+10DF | zhani | /ʒ/ | Zh zh | Ž ž | Zh zh | J j | 90 |

| Ⴐ | ⴐ | რ | Რ | U+10E0 | rae | /r/ | R r | R r | R r | R r | 100 |

| Ⴑ | ⴑ | ს | Ს | U+10E1 | sani | /s/ | S s | S s | S s | S s | 200 |

| Ⴒ | ⴒ | ტ | Ტ | U+10E2 | tʼari | /tʼ/ | Tʼ tʼ | T t | T t | Ť t̆ | 300 |

| Ⴣ | ⴣ | ჳ | Ჳ | U+10F3 | vie | /uɪ/, Svan /w/ | — | W w | — | — | 400[74] |

| Ⴓ | ⴓ | უ | Უ | U+10E3 | uni | /u/, Svan /u, y/ | U u | U u | U u | U u | 400[74] |

| Ⴧ | ⴧ | ჷ | Ჷ | U+10F7 | yn, schva | Mingrelian & Svan /ə/ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴔ | ⴔ | ფ | Ფ | U+10E4 | pari | /p⁽ʰ⁾/ | P p | Pʼ pʼ | Pʼ pʼ | P p | 500 |

| Ⴕ | ⴕ | ქ | Ქ | U+10E5 | kani | /k⁽ʰ⁾/ | K k | Kʼ kʼ | Kʼ kʼ | K k | 600 |

| Ⴖ | ⴖ | ღ | Ღ | U+10E6 | ghani | /ɣ/ | Gh gh | Ḡ ḡ | Gh gh | Ğ ğ | 700 |

| Ⴗ | ⴗ | ყ | Ყ | U+10E7 | qʼari | /qʼ/ | Qʼ qʼ | Q q | Q q | Q q | 800 |

| — | — | ჸ | Ჸ | U+10F8 | elif | Mingrelian & Svan /ʔ/ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴘ | ⴘ | შ | Შ | U+10E8 | shini | /ʃ/ | Sh sh | Š š | Sh sh | Ş ş | 900 |

| Ⴙ | ⴙ | ჩ | Ჩ | U+10E9 | chini | /tʃ⁽ʰ⁾/ | Ch ch | Čʼ čʼ | Chʼ chʼ | Ç ç | 1000 |

| Ⴚ | ⴚ | ც | Ც | U+10EA | tsani | /ts⁽ʰ⁾/ | Ts ts | Cʼ cʼ | Tsʼ tsʼ | Ʒ ʒ | 2000 |

| Ⴛ | ⴛ | ძ | Ძ | U+10EB | dzili | /dz/ | Dz dz | J j | Dz dz | Ž ž | 3000 |

| Ⴜ | ⴜ | წ | Წ | U+10EC | tsʼili | /tsʼ/ | Tsʼ tsʼ | C c | Ts ts | Ǯ ǯ | 4000 |

| Ⴝ | ⴝ | ჭ | Ჭ | U+10ED | chʼari | /tʃʼ/ | Chʼ chʼ | Č č | Ch ch | Ç̌ ç̌ | 5000 |

| Ⴞ | ⴞ | ხ | Ხ | U+10EE | khani | /χ/ | Kh kh | X x | Kh kh | X x | 6000 |

| Ⴤ | ⴤ | ჴ | Ჴ | U+10F4 | qari, hari | /q⁽ʰ⁾/ | — | H̱ ẖ | qʼ | — | 7000 |

| Ⴟ | ⴟ | ჯ | Ჯ | U+10EF | jani | /dʒ/ | J j | J̌ ǰ | J j | C c | 8000 |

| Ⴠ | ⴠ | ჰ | Ჰ | U+10F0 | hae | /h/ | H h | H h | H h | H h | 9000 |

| Ⴥ | ⴥ | ჵ | Ჵ | U+10F5 | hoe | /oː/, Bats /ʕ, ɦ/ | — | Ō ō | — | — | 10000 |

| — | — | ჶ | Ჶ | U+10F6 | fi | Laz /f/ | — | F f | — | F f | — |

| — | — | ჹ | Ჹ | U+10F9 | turned gani | Dagestanian languages /ɢ/ in evangelical literature[2] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჺ | Ჺ | U+10FA | aini | Bats /ʕ/[2] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჼ | — | U+10FC | modifier nar | Bats /◌̃/ nasalization of preceding vowel[61] | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴭ | ⴭ | ჽ | Ჽ | U+10FD | aen[63] | Ossetian /ə/[62] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჾ | Ჾ | U+10FE | hard sign[63] | Abkhaz velarization of preceding consonant[63] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჿ | Ჿ | U+10FF | labial sign[63] | Abkhaz labialization of preceding consonant[63] | — | — | — | — | — |

Use for other non-Kartvelian languages[edit]

Ossetian text written in Mkhedruli script, from a book on Ossetian folklore published in South Ossetia in 1940. The non-Georgian letters ჶ [f] and ჷ [ə] can be seen.

Old Avar crosses with Avar inscriptions in Asomtavruli script.

- Ossetian language until the 1940s.[75]

- Abkhaz language until the 1940s.[76]

- Ingush language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[77]

- Chechen language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[78]

- Avar language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[79][80]

- Turkish language and Azerbaijani language. A Turkish Gospel, dictionary, poems, medical book dating from the 18th century.[81]

- Persian language. The 18th-century Persian translation of the Arabic Gospel is kept at the National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi.

- Armenian language. In the Armenian community in Tbilisi, the Georgian script was occasionally used for writing Armenian in the 18th and 19th centuries, and some samples of this kind of texts are kept at the Georgian National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi.[82]

- Russian language. In the collections of the National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi there are also a few short poems in the Russian language written in Georgian script dating from the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

- Azerbaijani language. Used by Azeris in Georgia.[83]

- Other Northeast Caucasian languages. The Georgian script was used for writing North Caucasian and Dagestani languages in connection with Georgian missionary activities in the areas starting in the 18th century.[84]

Computing[edit]

The Georgian letter ⟨ღ⟩ (ghani) is often used as a love or heart symbol online.

The Georgian letter ⟨ლ⟩ (lasi) is sometimes used as a hand or fist in emoticons ( ex: ლ(╹◡╹ლ) ).

Unicode[edit]