|

Hayao Miyazaki |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

宮崎 駿 |

|||

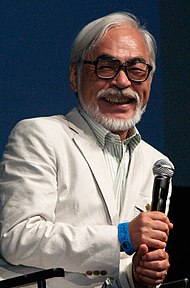

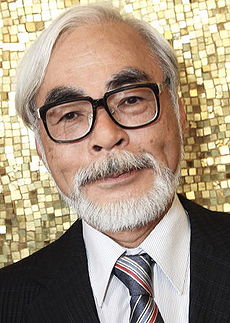

Miyazaki in 2012 |

|||

| Born | January 5, 1941 (age 82)

Tokyo City, Empire of Japan |

||

| Other names |

|

||

| Alma mater | Gakushuin University | ||

| Occupations |

|

||

| Years active | 1963–present | ||

| Employers |

|

||

| Spouse |

Akemi Ōta (m. 1965) |

||

| Children |

|

||

| Parents |

|

||

| Relatives | Daisuke Tsutsumi (nephew-in-law) | ||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 宮崎 駿 | ||

| Kana | みやざき はやお | ||

|

Hayao Miyazaki (宮崎 駿, Miyazaki Hayao, [mijaꜜzaki hajao]; born January 5, 1941) is a Japanese animator, director, producer, screenwriter, author, and manga artist. A co-founder of Studio Ghibli, he has attained international acclaim as a masterful storyteller and creator of Japanese animated feature films, and is widely regarded as one of the most accomplished filmmakers in the history of animation.

Born in Tokyo City in the Empire of Japan, Miyazaki expressed interest in manga and animation from an early age, and he joined Toei Animation in 1963. During his early years at Toei Animation he worked as an in-between artist and later collaborated with director Isao Takahata. Notable films to which Miyazaki contributed at Toei include Doggie March and Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon. He provided key animation to other films at Toei, such as Puss in Boots and Animal Treasure Island, before moving to A-Pro in 1971, where he co-directed Lupin the Third Part I alongside Takahata. After moving to Zuiyō Eizō (later known as Nippon Animation) in 1973, Miyazaki worked as an animator on World Masterpiece Theater, and directed the television series Future Boy Conan (1978). He joined Tokyo Movie Shinsha in 1979 to direct his first feature film The Castle of Cagliostro as well as the television series Sherlock Hound. In the same period, he also began writing and illustrating the manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1982–1994), and he also directed the 1984 film adaptation produced by Topcraft.

Miyazaki co-founded Studio Ghibli in 1985. He directed numerous films with Ghibli, including Castle in the Sky (1986), My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), and Porco Rosso (1992). The films were met with critical and commercial success in Japan. Miyazaki’s film Princess Mononoke was the first animated film ever to win the Japan Academy Prize for Picture of the Year, and briefly became the highest-grossing film in Japan following its release in 1997;[a] its distribution to the Western world greatly increased Ghibli’s popularity and influence outside Japan. His 2001 film Spirited Away became the highest-grossing film in Japanese history,[b] winning the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, and is frequently ranked among the greatest films of the 2000s. Miyazaki’s later films—Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), Ponyo (2008), and The Wind Rises (2013)—also enjoyed critical and commercial success. Following the release of The Wind Rises, Miyazaki announced his retirement from feature films, though he returned in 2016 to work on the upcoming feature film How Do You Live? (2023).

Miyazaki’s works are characterized by the recurrence of themes such as humanity’s relationship with nature and technology, the wholesomeness of natural and traditional patterns of living, the importance of art and craftsmanship, and the difficulty of maintaining a pacifist ethic in a violent world. The protagonists of his films are often strong girls or young women, and several of his films present morally ambiguous antagonists with redeeming qualities. Miyazaki’s works have been highly praised and awarded; he was named a Person of Cultural Merit for outstanding cultural contributions in November 2012, and received the Academy Honorary Award for his impact on animation and cinema in November 2014. Miyazaki has frequently been cited as an inspiration for numerous animators, directors, and writers.

Early life[edit]

Hayao Miyazaki was born on January 5, 1941, in Tokyo City, Empire of Japan, the second of four sons.[1][2][c] His father, Katsuji Miyazaki (born 1915),[3] was the director of Miyazaki Airplane, his brother’s company,[4] which manufactured rudders for fighter planes during World War II.[5] The business allowed his family to remain affluent during Miyazaki’s early life.[6][d] Miyazaki’s father enjoyed purchasing paintings and demonstrating them to guests, but otherwise had little known artistic understanding.[2] He said that he was in the Imperial Japanese Army around 1940; after declaring to his commanding officer that he wished not to fight because of his wife and young child, he was discharged after a lecture about disloyalty.[8] According to Miyazaki, his father often told him about his exploits, claiming that he continued to attend nightclubs after turning 70.[9] Katsuji Miyazaki died on March 18, 1993.[10] After his death, Miyazaki felt that he had often looked at his father negatively and that he had never said anything «lofty or inspiring».[9] He regretted not having a serious discussion with his father, and felt that he had inherited his «anarchistic feelings and his lack of concern about embracing contradictions».[9]

Several characters from Miyazaki’s films were inspired by his mother Yoshiko.[11][e]

Miyazaki has noted that some of his earliest memories are of «bombed-out cities».[12] In 1944, when he was three years old, Miyazaki’s family evacuated to Utsunomiya.[5] After the bombing of Utsunomiya in July 1945, he and his family evacuated to Kanuma.[6] The bombing left a lasting impression on Miyazaki, then aged four.[6] As a child, Miyazaki suffered from digestive problems, and was told that he would not live beyond 20, making him feel like an outcast.[11][13] From 1947 to 1955, Miyazaki’s mother Yoshiko suffered from spinal tuberculosis; she spent the first few years in hospital before being nursed from home.[5] Yoshiko was frugal,[2] and described as a strict, intellectual woman who regularly questioned «socially accepted norms».[4] She was closest with Miyazaki, and had a strong influence on him and his later work.[2][e] Yoshiko Miyazaki died in July 1983 at the age of 72.[17][18]

Miyazaki began school in 1947, at an elementary school in Utsunomiya, completing the first through third grades. After his family moved back to Suginami-ku, Miyazaki completed the fourth grade at Ōmiya Elementary School, and fifth grade at Eifuku Elementary School, which was newly established after splitting off from Ōmiya Elementary. After graduating from Eifuku as part of the first graduating class,[19] he attended Ōmiya Junior High School.[20] He aspired to become a manga artist,[21] but discovered he could not draw people; instead, he only drew planes, tanks, and battleships for several years.[21] Miyazaki was influenced by several manga artists, such as Tetsuji Fukushima, Soji Yamakawa [ja] and Osamu Tezuka. Miyazaki destroyed much of his early work, believing it was «bad form» to copy Tezuka’s style as it was hindering his own development as an artist.[22][23][24] Around this time, Miyazaki would often see movies with his father, who was an avid moviegoer; memorable films for Miyazaki include Meshi (1951) and Tasogare Sakaba (1955).[25]

After graduating from Ōmiya Junior High, Miyazaki attended Toyotama High School.[25] During his third and final year, Miyazaki’s interest in animation was sparked by Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958),[26] Japan’s first feature-length animated film in color;[25] he had sneaked out to watch the film instead of studying for his entrance exams.[2] Miyazaki later recounted that he fell in love with the film’s heroine, Bai-Niang, and that the film moved him to tears and left a profound impression;[f] he wrote that he was «moved to the depths of [his] soul» and that the «pure, earnest world of the film» affirmed a side of him that «yearned desperately to affirm the world rather than negate it».[28] After graduating from Toyotama, Miyazaki attended Gakushuin University in the department of political economy, majoring in Japanese Industrial Theory.[25] He joined the «Children’s Literature Research Club», the «closest thing back then to a comics club»;[29] he was sometimes the sole member of the club.[25] In his free time, Miyazaki would visit his art teacher from middle school and sketch in his studio, where the two would drink and «talk about politics, life, all sorts of things».[30] Around this time, he also drew manga; he never completed any stories, but accumulated thousands of pages of the beginnings of stories. He also frequently approached manga publishers to rent their stories. In 1960, Miyazaki was a bystander during the Anpo protests, having developed an interest after seeing photographs in Asahi Graph; by that point, he was too late to participate in the demonstrations.[25] Miyazaki graduated from Gakushuin in 1963 with degrees in political science and economics.[29]

Career[edit]

Early career[edit]

Miyazaki first worked with Isao Takahata in 1964, spawning a lifelong collaboration and friendship.[31][32][33]

In 1963, Miyazaki was employed at Toei Animation;[31] this was the last year the company hired regularly.[34] After gaining employment, he began renting a four-and-a-half tatami (7.4 m2; 80 sq ft) apartment in Nerima, Tokyo; the rent was ¥6,000. His salary at Toei was ¥19,500.[34][g] Miyazaki worked as an in-between artist on the theatrical feature anime Doggie March and the television anime Wolf Boy Ken (both 1963). He also worked on Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon (1964).[35] He was a leader in a labor dispute soon after his arrival, and became chief secretary of Toei’s labor union in 1964.[31] Miyazaki later worked as chief animator, concept artist, and scene designer on The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun (1968). Throughout the film’s production, Miyazaki worked closely with his mentor, Yasuo Ōtsuka, whose approach to animation profoundly influenced Miyazaki’s work.[36] Directed by Isao Takahata, with whom Miyazaki would continue to collaborate for the remainder of his career, the film was highly praised, and deemed a pivotal work in the evolution of animation.[37][38][39] Miyazaki moved to a residence in Ōizumigakuenchō in April 1969, after the birth of his second son.[40]

Under the pseudonym Akitsu Saburō (秋津 三朗), Miyazaki wrote and illustrated the manga People of the Desert, published in 26 installments between September 1969 and March 1970 in Boys and Girls Newspaper (少年少女新聞, Shōnen shōjo shinbun).[40] He was influenced by illustrated stories such as Fukushima’s Evil Lord of the Desert (沙漠の魔王, Sabaku no maō).[41] Miyazaki also provided key animation for The Wonderful World of Puss ‘n Boots (1969), directed by Kimio Yabuki.[42] He created a 12-chapter manga series as a promotional tie-in for the film; the series ran in the Sunday edition of Tokyo Shimbun from January to March 1969.[43][44] Miyazaki later proposed scenes in the screenplay for Flying Phantom Ship (1969), in which military tanks would cause mass hysteria in downtown Tokyo, and was hired to storyboard and animate the scenes.[45] In 1970, Miyazaki moved residence to Tokorozawa.[40] In 1971, he developed structure, characters and designs for Hiroshi Ikeda’s adaptation of Animal Treasure Island; he created the 13-part manga adaptation, printed in Tokyo Shimbun from January to March 1971.[43][44][46] Miyazaki also provided key animation for Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.[47]

Miyazaki left Toei Animation in August 1971, and was hired at A-Pro,[48] where he directed, or co-directed with Takahata, 23 episodes of Lupin the Third Part I, often using the pseudonym Teruki Tsutomu (照樹 務).[47] The two also began pre-production on a series based on Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking books, designing extensive storyboards; the series was canceled after Miyazaki and Takahata were unable to meet with Lindgren, and permission was refused to complete the project.[48][49] In 1972 and 1973, Miyazaki wrote, designed and animated two Panda! Go, Panda! shorts, directed by Takahata.[50] After moving from A-Pro to Zuiyō Eizō in June 1973,[51] Miyazaki and Takahata worked on World Masterpiece Theater, which featured their animation series Heidi, Girl of the Alps, an adaptation of Johanna Spyri’s Heidi. Zuiyō Eizō continued as Nippon Animation in July 1975.[51] Miyazaki also directed the television series Future Boy Conan (1978), an adaptation of Alexander Key’s The Incredible Tide.[52]

Breakthrough films[edit]

Miyazaki left Nippon Animation in 1979, during the production of Anne of Green Gables;[53] he provided scene design and organization on the first fifteen episodes.[54] He moved to Telecom Animation Film, a subsidiary of TMS Entertainment, to direct his first feature anime film, The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), a Lupin III film.[55] In his role at Telecom, Miyazaki helped train the second wave of employees.[52] Miyazaki directed six episodes of Sherlock Hound in 1981, until issues with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s estate led to a suspension in production; Miyazaki was busy with other projects by the time the issues were resolved, and the remaining episodes were directed by Kyosuke Mikuriya. They were broadcast from November 1984 to May 1985.[56] Miyazaki also wrote the graphic novel The Journey of Shuna, inspired by the Tibetan folk tale «Prince who became a dog». The novel was published by Tokuma Shoten in June 1983,[57] dramatised for radio broadcast in 1987,[58] and published in English as Shuna’s Journey in 2022.[59] Hayao Miyazaki’s Daydream Data Notes was also irregularly published from November 1984 to October 1994 in Model Graphix;[60] selections of the stories received radio broadcast in 1995.[58]

After the release of The Castle of Cagliostro, Miyazaki began working on his ideas for an animated film adaptation of Richard Corben’s comic book Rowlf and pitched the idea to Yutaka Fujioka at TMS. In November 1980, a proposal was drawn up to acquire the film rights.[61][62] Around that time, Miyazaki was also approached for a series of magazine articles by the editorial staff of Animage. During subsequent conversations, he showed his sketchbooks and discussed basic outlines for envisioned animation projects with editors Toshio Suzuki and Osamu Kameyama, who saw the potential for collaboration on their development into animation. Two projects were proposed: Warring States Demon Castle (戦国魔城, Sengoku ma-jō), to be set in the Sengoku period; and the adaptation of Corben’s Rowlf. Both were rejected, as the company was unwilling to fund anime projects not based on existing manga, and the rights for the adaptation of Rowlf could not be secured.[63][64] An agreement was reached that Miyazaki could start developing his sketches and ideas into a manga for the magazine with the proviso that it would never be made into a film.[65][66] The manga—titled Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind—ran from February 1982 to March 1994. The story, as re-printed in the tankōbon volumes, spans seven volumes for a combined total of 1060 pages.[67] Miyazaki drew the episodes primarily in pencil, and it was printed monochrome in sepia-toned ink.[68][69][66] Miyazaki resigned from Telecom Animation Film in November 1982.[70]

Miyazaki opened his own personal studio in 1984, named Nibariki.[71]

Following the success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the founder of Tokuma Shoten, encouraged Miyazaki to work on a film adaptation.[72] Miyazaki initially refused, but agreed on the condition that he could direct.[73] Miyazaki’s imagination was sparked by the mercury poisoning of Minamata Bay and how nature responded and thrived in a poisoned environment, using it to create the film’s polluted world. Miyazaki and Takahata chose the minor studio Topcraft to animate the film, as they believed its artistic talent could transpose the sophisticated atmosphere of the manga to the film.[72] Pre-production began on May 31, 1983; Miyazaki encountered difficulties in creating the screenplay, with only sixteen chapters of the manga to work with.[74] Takahata enlisted experimental and minimalist musician Joe Hisaishi to compose the film’s score.[75] Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was released on March 11, 1984. It grossed ¥1.48 billion at the box office, and made an additional ¥742 million in distribution income.[76] It is often seen as Miyazaki’s pivotal work, cementing his reputation as an animator.[77][h] It was lauded for its positive portrayal of women, particularly that of main character Nausicaä.[79][80][i] Several critics have labeled Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind as possessing anti-war and feminist themes; Miyazaki argues otherwise, stating that he only wishes to entertain.[82][j] The successful cooperation on the creation of the manga and the film laid the foundation for other collaborative projects.[83] In April 1984, Miyazaki opened his own office in Suginami Ward, naming it Nibariki.[71]

Studio Ghibli[edit]

Early films (1985–1996)[edit]

In June 1985, Miyazaki, Takahata, Tokuma and Suzuki founded the animation production company Studio Ghibli, with funding from Tokuma Shoten. Studio Ghibli’s first film, Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), employed the same production crew of Nausicaä. Miyazaki’s designs for the film’s setting were inspired by Greek architecture and «European urbanistic templates».[84] Some of the architecture in the film was also inspired by a Welsh mining town; Miyazaki witnessed the mining strike upon his first visit to Wales in 1984, and admired the miners’ dedication to their work and community.[85] Laputa was released on August 2, 1986. It was the highest-grossing animation film of the year in Japan.[84] Miyazaki’s following film, My Neighbor Totoro, was released alongside Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies in April 1988 to ensure Studio Ghibli’s financial status. The simultaneous production was chaotic for the artists, as they switched between projects.[86][k] My Neighbor Totoro features the theme of the relationship between the environment and humanity—a contrast to Nausicaä, which emphasises technology’s negative effect on nature.[87] While the film received critical acclaim, it was commercially unsuccessful at the box office. However, merchandising was successful, and the film was labelled as a cult classic.[88][89]

In 1987, Studio Ghibli acquired the rights to create a film adaptation of Eiko Kadono’s novel Kiki’s Delivery Service. Miyazaki’s work on My Neighbor Totoro prevented him from directing the adaptation; Sunao Katabuchi was chosen as director, and Nobuyuki Isshiki was hired as script writer. Miyazaki’s dissatisfaction of Isshiki’s first draft led him to make changes to the project, ultimately taking the role of director. Kadono was unhappy with the differences between the book and the screenplay. Miyazaki and Suzuki visited Kadono and invited her to the studio; she allowed the project to continue.[90] The film was originally intended to be a 60-minute special, but expanded into a feature film after Miyazaki completed the storyboards and screenplay.[91] Kiki’s Delivery Service premiered on July 29, 1989. It earned ¥2.15 billion at the box office,[92] and was the highest-grossing film in Japan in 1989.[93]

From March to May 1989, Miyazaki’s manga Hikōtei Jidai was published in the magazine Model Graphix.[94] Miyazaki began production on a 45-minute in-flight film for Japan Airlines based on the manga; Suzuki ultimately extended the film into the feature-length film, titled Porco Rosso, as expectations grew. Due to the end of production on Takahata’s Only Yesterday (1991), Miyazaki initially managed the production of Porco Rosso independently.[95] The outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars in 1991 affected Miyazaki, prompting a more sombre tone for the film;[96] Miyazaki would later refer to the film as «foolish», as its mature tones were unsuitable for children.[97] The film featured anti-war themes, which Miyazaki would later revisit.[98][l] The airline remained a major investor in the film, resulting in its initial premiere as an in-flight film, prior to its theatrical release on July 18, 1992.[96] The film was critically and commercially successful,[m] remaining the highest-grossing animated film in Japan for several years.[95][n]

Studio Ghibli set up its headquarters in Koganei, Tokyo in August 1992.[100] In November 1992, two television spots directed by Miyazaki were broadcast by Nippon Television Network (NTV): Sora Iro no Tane, a 90-second spot loosely based on the illustrated story Sora Iro no Tane by Rieko Nakagawa and Yuriko Omura, and commissioned to celebrate NTV’s fortieth anniversary;[101] and Nandarou, aired as one 15-second and four 5-second spots, centered on an undefinable creature which ultimately became NTV’s mascot.[102] Miyazaki designed the storyboards and wrote the screenplay for Whisper of the Heart (1995), directed by Yoshifumi Kondō.[103][o]

Global emergence (1997–2008)[edit]

Miyazaki began work on the initial storyboards for Princess Mononoke in August 1994,[104] based on preliminary thoughts and sketches from the late 1970s.[105] While experiencing writer’s block during production, Miyazaki accepted a request for the creation of On Your Mark, a music video for the song of the same name by Chage and Aska.[106] In the production of the video, Miyazaki experimented with computer animation to supplement traditional animation, a technique he would soon revisit for Princess Mononoke.[107] On Your Mark premiered as a short before Whisper of the Heart.[108] Despite the video’s popularity, Suzuki said that it was not given «100 percent» focus.[109]

Miyazaki used 3D rendering in Princess Mononoke (1997) to create writhing «demon flesh» and composite them onto the hand-drawn characters. Approximately five minutes of the film uses similar techniques.[110]

In May 1995, Miyazaki took a group of artists and animators to the ancient forests of Yakushima and the mountains of Shirakami-Sanchi, taking photographs and making sketches.[111] The landscapes in the film were inspired by Yakushima.[112] In Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki revisited the ecological and political themes of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.[113][p] Miyazaki supervised the 144,000 cels in the film, about 80,000 of which were key animation.[114][115] Princess Mononoke was produced with an estimated budget of ¥2.35 billion (approximately US$23.5 million),[116] making it the most expensive film by Studio Ghibli at the time.[117] Approximately fifteen minutes of the film uses computer animation: about five minutes uses techniques such as 3D rendering, digital composition, and texture mapping; the remaining ten minutes uses ink and paint. While the original intention was to digitally paint 5,000 of the film’s frames, time constraints doubled this.[110]

Upon its premiere on July 12, 1997, Princess Mononoke was critically acclaimed, becoming the first animated film to win the Japan Academy Prize for Picture of the Year.[118][119] The film was also commercially successful, earning a domestic total of ¥14 billion (US$148 million),[117] and becoming the highest-grossing film in Japan for several months.[120][a] Miramax Films purchased the film’s distributions rights for North America;[85] it was the first Studio Ghibli production to receive a substantial theatrical distribution in the United States. While it was largely unsuccessful at the box office, grossing about US$3 million,[121] it was seen as the introduction of Studio Ghibli to global markets.[122][q] Miyazaki claimed that Princess Mononoke would be his final film.[122]

Tokuma Shoten merged with Studio Ghibli in June 1997.[100] Miyazaki’s next film was conceived while on vacation at a mountain cabin with his family and five young girls who were family friends. Miyazaki realised that he had not created a film for 10-year-old girls, and set out to do so. He read shōjō manga magazines like Nakayoshi and Ribon for inspiration, but felt they only offered subjects on «crushes and romance», which is not what the girls «held dear in their hearts». He decided to produce the film about a female heroine whom they could look up to.[123] Production of the film, titled Spirited Away, commenced in 2000 on a budget of ¥1.9 billion (US$15 million). As with Princess Mononoke, the staff experimented with computer animation, but kept the technology at a level to enhance the story, not to «steal the show».[124] Spirited Away deals with symbols of human greed,[125][r] and a liminal journey through the realm of spirits.[126][s] The film was released on July 20, 2001; it received critical acclaim, and is considered among the greatest films of the 2000s.[127] It won the Japan Academy Prize for Picture of the Year,[128] and the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.[129] The film was also commercially successful, earning ¥30.4 billion (US$289.1 million) at the box office.[130] It became the highest-grossing film in Japan,[131] a record it maintained for almost 20 years.[132][b] Following the death of Tokuma in September 2000, Miyazaki served as the head of his funeral committee.[133]

In September 2001, Studio Ghibli announced the production of Howl’s Moving Castle, based on the novel by Diana Wynne Jones.[134] Mamoru Hosoda of Toei Animation was originally selected to direct the film,[135] but disagreements between Hosoda and Studio Ghibli executives led to the project’s abandonment.[134] After six months, Studio Ghibli resurrected the project. Miyazaki was inspired to direct the film upon reading Jones’ novel, and was struck by the image of a castle moving around the countryside; the novel does not explain how the castle moved, which led to Miyazaki’s designs.[2] He travelled to Colmar and Riquewihr in Alsace, France, to study the architecture and the surroundings for the film’s setting.[136] Additional inspiration came from the concepts of future technology in Albert Robida’s work,[137] as well as the «illusion art» of 19th century Europe.[138][t] The film was produced digitally, but the characters and backgrounds were drawn by hand prior to being digitized.[139] It was released on November 20, 2004, and received widespread critical acclaim. The film received the Osella Award for Technical Excellence at the 61st Venice International Film Festival,[134] and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.[140] In Japan, the film grossed a record $14.5 million in its first week of release.[2] It remains among the highest-grossing films in Japan, with a worldwide gross of over ¥19.3 billion.[141] Miyazaki received the honorary Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award at the 62nd Venice International Film Festival in 2005.[134]

In March 2005, Studio Ghibli split from Tokuma Shoten.[142] In the 1980s, Miyazaki contacted Ursula K. Le Guin expressing interest in producing an adaptation of her Earthsea novels; unaware of Miyazaki’s work, Le Guin declined. Upon watching My Neighbor Totoro several years later, Le Guin expressed approval to the concept of the adaptation. She met with Suzuki in August 2005, who wanted Miyazaki’s son Goro to direct the film, as Miyazaki had wished to retire. Disappointed that Miyazaki was not directing, but under the impression that he would supervise his son’s work, Le Guin approved of the film’s production.[143] Miyazaki later publicly opposed and criticized Gorō’s appointment as director.[144] Upon Miyazaki’s viewing of the film, he wrote a message for his son: «It was made honestly, so it was good».[145]

Miyazaki designed the covers for several manga novels in 2006, including A Trip to Tynemouth; he also worked as editor, and created a short manga for the book.[146] Miyazaki’s next film, Ponyo, began production in May 2006.[147] It was initially inspired by «The Little Mermaid» by Hans Christian Andersen, though began to take its own form as production continued.[148] Miyazaki aimed for the film to celebrate the innocence and cheerfulness of a child’s universe. He intended for it to only use traditional animation,[147] and was intimately involved with the artwork. He preferred to draw the sea and waves himself, as he enjoyed experimenting.[149] Ponyo features 170,000 frames—a record for Miyazaki.[150] The film’s seaside village was inspired by Tomonoura, a town in Setonaikai National Park, where Miyazaki stayed in 2005.[151] The main character, Sōsuke, is based on Gorō.[152] Following its release on July 19, 2008, Ponyo was critically acclaimed, receiving Animation of the Year at the 32nd Japan Academy Prize.[153] The film was also a commercial success, earning ¥10 billion (US$93.2 million) in its first month[152] and ¥15.5 billion by the end of 2008, placing it among the highest-grossing films in Japan.[154]

Later films (2009–present)[edit]

In early 2009, Miyazaki began writing a manga called Kaze Tachinu (風立ちぬ, The Wind Rises), telling the story of Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter designer Jiro Horikoshi. The manga was first published in two issues of the Model Graphix magazine, published on February 25 and March 25, 2009.[155] Miyazaki later co-wrote the screenplay for Arrietty (2010) and From Up on Poppy Hill (2011), directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi and Gorō Miyazaki respectively.[156] Miyazaki wanted his next film to be a sequel to Ponyo, but Suzuki convinced him to instead adapt Kaze Tachinu to film.[157] In November 2012, Studio Ghibli announced the production of The Wind Rises, based on Kaze Tachinu, to be released alongside Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya.[158]

Miyazaki was inspired to create The Wind Rises after reading a quote from Horikoshi: «All I wanted to do was to make something beautiful».[159] Several scenes in The Wind Rises were inspired by Tatsuo Hori’s novel The Wind Has Risen (風立ちぬ), in which Hori wrote about his life experiences with his fiancée before she died from tuberculosis. The female lead character’s name, Naoko Satomi, was borrowed from Hori’s novel Naoko (菜穂子).[160] The Wind Rises continues to reflect Miyazaki’s pacifist stance,[159] continuing the themes of his earlier works, despite stating that condemning war was not the intention of the film.[161][u] The film premiered on July 20, 2013,[159] and received critical acclaim; it was named Animation of the Year at the 37th Japan Academy Prize,[162] and was nominated for Best Animated Feature at the 86th Academy Awards.[163] It was also commercially successful, grossing ¥11.6 billion (US$110 million) at the Japanese box office, becoming the highest-grossing film in Japan in 2013.[164]

In September 2013, Miyazaki announced that he was retiring from the production of feature films due to his age, but wished to continue working on the displays at the Studio Ghibli Museum.[165][166] Miyazaki was awarded the Academy Honorary Award at the Governors Awards in November 2014.[167] He developed Boro the Caterpillar, a computer-animated short film which was first discussed during pre-production for Princess Mononoke.[168] It was screened exclusively at the Studio Ghibli Museum in July 2017.[169] He is also working on an untitled samurai manga.[170] In August 2016, Miyazaki proposed a new feature-length film, Kimi-tachi wa Dō Ikiru ka (tentatively titled How Do You Live? in English), on which he began animation work without receiving official approval.[169] In December 2020, Suzuki stated that the film’s animation was «half finished» and added that he does not expect the film to release for another three years.[171] In December 2022, Studio Ghibli announced the film would open in Japanese theaters on July 14, 2023.[172]

In January 2019, it was reported that Vincent Maraval, a frequent collaborator of Miyazaki, tweeted a hint that Miyazaki may have plans for another film in the works.[173] In February 2019, a four-part documentary was broadcast on the NHK network titled 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki, documenting production of his films in his private studio.[174] In 2019, Miyazaki approved a musical adaptation of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, as it was performed by a kabuki troupe.[175]

Views[edit]

«If you don’t spend time watching real people, you can’t do this, because you’ve never seen it. Some people spend their lives interested only in themselves. Almost all Japanese animation is produced with hardly any basis taken from observing real people… It’s produced by humans who can’t stand looking at other humans. And that’s why the industry is full of otaku!»

Hayao Miyazaki, television interview, January 2014[176]

Miyazaki has often criticized the current state of the anime industry, stating that animators are unrealistic when creating people. He has stated that modern anime is «produced by humans who can’t stand looking at other humans … that’s why the industry is full of otaku!».[176] He has also frequently criticized otaku, including «fanatics» of guns and fighter aircraft, declaring it a «fetish» and refusing to identify himself as such.[177][178]

In 2013, several Studio Ghibli staff members, including Miyazaki, criticized Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s policies, and the proposed Constitutional amendment that would allow Abe to revise the clause which outlaws war as a means to settle international disputes.[v] Miyazaki felt that Abe wished to «leave his name in history as a great man who revised the Constitution and its interpretation», describing it as «despicable».[180][w] Miyazaki has expressed his disapproval of Abe’s denial of Japan’s military aggression, stating that Japan «should clearly say that [they] inflicted enormous damage on China and express deep remorse over it».[180] He also felt that the country’s government should give a «proper apology» to Korean comfort women who serviced the Japanese army during World War II, suggesting that the Senkaku Islands should be «split in half» or controlled by both Japan and China.[98] After the release of The Wind Rises in 2013, some online critics labeled Miyazaki a «traitor» and «anti-Japanese», describing the film as overly «left-wing».[98] Miyazaki recognized leftist values in his films, citing his influence by and appreciation of communism as defined by Karl Marx, though he criticized the Soviet Union’s experiments with socialism.[182]

Miyazaki refused to attend the 75th Academy Awards in Hollywood, Los Angeles in 2003, in protest of the United States’ involvement in the Iraq War, later stating that he «didn’t want to visit a country that was bombing Iraq».[183] He did not publicly express this opinion at the request of his producer until 2009, when he lifted his boycott and attended San Diego Comic Con International as a favor to his friend John Lasseter.[183] Miyazaki also expressed his opinion about the terrorist attack at the offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, criticizing the magazine’s decision to publish the content cited as the catalyst for the incident.[184][x] In November 2016, Miyazaki stated that he believed «many of the people who voted for Brexit and Trump» were affected by the increase in unemployment due to companies «building cars in Mexico because of low wages and [selling] them in the US». He did not think that Donald Trump would be elected president, calling it «a terrible thing», and said that Trump’s political opponent Hillary Clinton was «terrible as well».[185]

Themes[edit]

Miyazaki’s works are characterized by the recurrence of themes such as environmentalism, pacifism, feminism, love and family.[186] His narratives are also notable for not pitting a hero against an unsympathetic antagonist.[187][188][189][y]

Miyazaki’s films often emphasize environmentalism and the Earth’s fragility.[191] Margaret Talbot stated that Miyazaki dislikes modern technology, and believes much of modern culture is «thin and shallow and fake»; he anticipates a time with «no more high-rises».[192][z] Miyazaki felt frustrated growing up in the Shōwa period from 1955 to 1965 because «nature — the mountains and rivers — was being destroyed in the name of economic progress».[193] Peter Schellhase of The Imaginative Conservative identified that several antagonists of Miyazaki’s films «attempt to dominate nature in pursuit of political domination, and are ultimately destructive to both nature and human civilization».[186][aa] Miyazaki is critical of exploitation under both communism and capitalism, as well as globalization and its effects on modern life, believing that «a company is common property of the people that work there».[194] Ram Prakash Dwivedi identified values of Mahatma Gandhi in the films of Miyazaki.[195]

Several of Miyazaki’s films feature anti-war themes. Daisuke Akimoto of Animation Studies categorized Porco Rosso as «anti-war propaganda»;[l] he felt that the main character, Porco, transforms into a pig partly due to his extreme distaste of militarism.[99][ab] Akimoto also argues that The Wind Rises reflects Miyazaki’s «antiwar pacifism», despite the latter stating that the film does not attempt to «denounce» war.[196] Schellhase also identifies Princess Mononoke as a pacifist film due to the protagonist, Ashitaka; instead of joining the campaign of revenge against humankind, as his ethnic history would lead him to do, Ashitaka strives for peace.[186] David Loy and Linda Goodhew argue that both Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke do not depict traditional evil, but the Buddhist roots of evil: greed, ill will, and delusion; according to Buddhism, the roots of evil must transform into «generosity, loving-kindness and wisdom» in order to overcome suffering, and both Nausicaä and Ashitaka accomplish this.[197] When characters in Miyazaki’s films are forced to engage in violence, it is shown as being a difficult task; in Howl’s Moving Castle, Howl is forced to fight an inescapable battle in defense of those he loves, and it almost destroys him, though he is ultimately saved by Sophie’s love and bravery.[186]

Suzuki described Miyazaki as a feminist in reference to his attitude to female workers.[198][ac] Miyazaki has described his female characters as «brave, self-sufficient girls that don’t think twice about fighting for what they believe in with all their heart», stating that they may «need a friend, or a supporter, but never a saviour» and that «any woman is just as capable of being a hero as any man».[199] Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was lauded for its positive portrayal of women, particularly the protagonist Nausicaä.[79][i] Schellhase noted that the female characters in Miyazaki’s films are not objectified or sexualized, and possess complex and individual characteristics absent from Hollywood productions.[186][ad] Schellhase also identified a «coming of age» element for the heroines in Miyazaki’s films, as they each discover «individual personality and strengths».[186][ae] Gabrielle Bellot of The Atlantic wrote that, in his films, Miyazaki «shows a keen understanding of the complexities of what it might mean to be a woman». In particular, Bellot cites Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, praising the film’s challenging of gender expectations, and the strong and independent nature of Nausicaä. Bellot also noted that Princess Mononoke‘s San represents the «conflict between selfhood and expression».[200]

Miyazaki is concerned with the sense of wonder in young people, seeking to maintain themes of love and family in his films.[186][af] Michael Toscano of Curator found that Miyazaki «fears Japanese children are dimmed by a culture of overconsumption, overprotection, utilitarian education, careerism, techno-industrialism, and a secularism that is swallowing Japan’s native animism».[201] Schellhase wrote that several of Miyazaki’s works feature themes of love and romance, but felt that emphasis is placed on «the way lonely and vulnerable individuals are integrated into relationships of mutual reliance and responsibility, which generally benefit everyone around them».[186] He also found that many of the protagonists in Miyazaki’s films present an idealized image of families, whereas others are dysfunctional.[186][ag] He felt that the non-biological family in Howl’s Moving Castle (consisting of Howl, Sophie, Markl, the Witch of the Waste, and Heen) gives a message of hope: that those cast out by society can «find a healthy place to belong».[186]

Creation process and influences[edit]

Miyazaki forgoes traditional screenplays in his productions, instead developing the film’s narrative as he designs the storyboards. «We never know where the story will go but we just keep working on the film as it develops,» he said.[202] In each of his films, Miyazaki has employed traditional animation methods, drawing each frame by hand; computer-generated imagery has been employed in several of his later films, beginning with Princess Mononoke, to «enrich the visual look»,[203] though he ensures that each film can «retain the right ratio between working by hand and computer … and still be able to call my films 2D».[204] He oversees every frame of his films.[205]

Miyazaki has cited several Japanese artists as his influences, including Sanpei Shirato,[21] Osamu Tezuka, Soji Yamakawa,[23] and Isao Takahata.[206] A number of Western authors have also influenced his works, including Frédéric Back,[202] Lewis Carroll,[204] Roald Dahl,[207] Jean Giraud,[208][ah] Paul Grimault,[202] Ursula K. Le Guin,[210] and Yuri Norstein, as well as animation studio Aardman Animations (specifically the works of Nick Park).[211][ai] Specific works that have influenced Miyazaki include Animal Farm (1945),[204] The Snow Queen (1957),[202] and The King and the Mockingbird (1980);[204] The Snow Queen is said to be the true catalyst for Miyazaki’s filmography, influencing his training and work.[213] When animating young children, Miyazaki often takes inspiration from his friends’ children, as well as memories of his own childhood.[214]

Personal life[edit]

Miyazaki married fellow animator Akemi Ōta in October 1965;[34] the two had met while colleagues at Toei Animation.[2][215] The couple have two sons: Goro, born in January 1967, and Keisuke, born in April 1969.[40] Miyazaki felt that becoming a father changed him, as he tried to produce work that would please his children.[216] Miyazaki initially fulfilled a promise to his wife that they would both continue to work after Goro’s birth, dropping him off at preschool for the day; however, upon seeing Goro’s exhaustion walking home one day, Miyazaki decided that they could not continue, and his wife stayed at home to raise their children.[215] Miyazaki’s dedication to his work harmed his relationship with his children, as he was often absent. Goro watched his father’s works in an attempt to «understand» him, since the two rarely talked.[217] Miyazaki said that he «tried to be a good father, but in the end I wasn’t a very good parent».[215] During the production of Tales from Earthsea in 2006, Goro said that his father «gets zero marks as a father but full marks as a director of animated films».[217][aj]

Goro worked at a landscape design firm before beginning to work at the Ghibli Museum;[2][215] he designed the garden on its rooftop and eventually became its curator.[2][216] Keisuke studied forestry at Shinshu University and works as a wood artist;[2][215][218] he designed a woodcut print that appears in Whisper of the Heart.[218] Miyazaki’s niece, Mei Okuyama, who was the inspiration behind the character Mei in My Neighbor Totoro, is married to animation artist Daisuke Tsutsumi.[219]

Legacy[edit]

Miyazaki was described as the «godfather of animation in Japan» by BBC’s Tessa Wong in 2016, citing his craftsmanship and humanity, the themes of his films, and his inspiration to younger artists.[220] Courtney Lanning of Arkansas Democrat-Gazette named him one of the world’s greatest animators, comparing him to Osamu Tezuka and Walt Disney.[221] Swapnil Dhruv Bose of Far Out Magazine wrote that Miyazaki’s work «has shaped not only the future of animation but also filmmaking in general», and that it helped «generation after generation of young viewers to observe the magic that exists in the mundane».[222] Richard James Havis of South China Morning Post called him a «genius … who sets exacting standards for himself, his peers and studio staff».[223] Paste‘s Toussaint Egan described Miyazaki as «one of anime’s great auteurs», whose «stories of such singular thematic vision and unmistakable aesthetic» captured viewers otherwise unfamiliar with anime.[224] Miyazaki became the subject of an exhibit at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles in 2021, featuring over 400 objects from his films.[225]

Miyazaki has frequently been cited as an inspiration to numerous animators, directors and writers around the world, including Wes Anderson,[226] James Cameron,[227] Dean DeBlois,[228] Guillermo del Toro,[229] Pete Docter,[230] Mamoru Hosoda,[231] Bong Joon-Ho,[232] Glen Keane,[233] Travis Knight,[234] John Lasseter,[235] Nick Park,[236] Henry Selick,[237] Makoto Shinkai,[238] and Steven Spielberg.[239] Keane said Miyazaki is a «huge influence» on Walt Disney Animation Studios and has been «part of our heritage» ever since The Rescuers Down Under (1990).[233] The Disney Renaissance era was also prompted by competition with the development of Miyazaki’s films.[240] Artists from Pixar and Aardman Studios signed a tribute stating, «You’re our inspiration, Miyazaki-san!»[236] He has also been cited as inspiration for video game designers including Shigeru Miyamoto[241] and Hironobu Sakaguchi,[242] as well as the television series Avatar: The Last Airbender,[243] and the video game Ori and the Blind Forest (2015).[244]

Selected filmography[edit]

- The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)

- Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

- Castle in the Sky (1986)

- My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

- Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

- Porco Rosso (1992)

- Princess Mononoke (1997)

- Spirited Away (2001)

- Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)

- Ponyo (2008)

- The Wind Rises (2013)

- How Do You Live? (2023)

Awards and nominations[edit]

Miyazaki won the Ōfuji Noburō Award at the Mainichi Film Awards for The Castle of Cagliostro (1979),[245] Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986),[246] and My Neighbor Totoro (1988),[245] and the Mainichi Film Award for Best Animation Film for Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989),[247] Porco Rosso (1992),[245] Princess Mononoke (1997),[247] Spirited Away[248] and Whale Hunt (both 2001).[245] Spirited Away was also awarded the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature,[128] while Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and The Wind Rises (2013) received nominations.[140][163] He was named a Person of Cultural Merit by the Japanese government in November 2012, for outstanding cultural contributions.[249] His other accolades include eight Tokyo Anime Awards,[250][251] eight Kinema Junpo Awards,[246][247][252][253] six Japan Academy Awards,[119][124][153][162][246][247] five Annie Awards,[247][254][255] and three awards from the Anime Grand Prix[246][247] and the Venice Film Festival.[134][256]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Princess Mononoke was eclipsed as the highest-grossing film in Japan by Titanic, released several months later.[120]

- ^ a b Spirited Away was eclipsed as the highest-grossing film in Japan by Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train in December 2020.[132]

- ^ Miyazaki’s brothers are Arata (born July 1939), Yutaka (born January 1944), and Shirou.[3] Influenced by their father, Miyazaki’s brothers went into business; Miyazaki’s son Goro believes this gave him a «strong motivation to succeed at animation».[2]

- ^ Miyazaki admitted later in life that he felt guilty over his family’s profiting from the war and their subsequent affluent lifestyle.[7]

- ^ a b Miyazaki based the character Captain Dola from Laputa: Castle in the Sky on his mother, noting that «My mom had four boys, but none of us dared oppose her».[14] Other characters inspired by Miyazaki’s mother include: Yasuko from My Neighbor Totoro, who watches over her children while suffering from illness; Sophie from Howl’s Moving Castle, who is a strong-minded and kind woman;[15] and Toki from Ponyo.[11][16]

- ^ McCarthy (1999) states: «He realized the folly of trying to succeed as manga writer by echoing what was fashionable, and decided to follow his true feelings in his work even if that might seem foolish.»[27]

- ^ During his three-month training period at Toei Animation, his salary was ¥18,000.[34]

- ^ Cavallaro (2006) states: «Nausicaä constitutes an unprecedented accomplishment in the world of Japanese animation — and one to which any contemporary Miyazaki aficionado ought to remain grateful given that it is precisely on the strength of its performance that Studio Ghibli was founded.»[78]

- ^ a b Napier (1998) states: «Nausicaä … possesses elements of the self-sacrificing sexlessness of [Mai, the Psychic Girl‘s] Mai, but combines them with an active and resolute personality to create a remarkably powerful and yet fundamentally feminine heroine.»[81]

- ^ Quoting Miyazaki, McCarthy (1999) states: «I don’t make movies with the intention of presenting any messages to humanity. My main aim in a movie is to make the audience come away from it happy.»[82]

- ^ Producer Toshio Suzuki stated: «The process of making these films at the same time in a single studio was sheer chaos. The studio’s philosophy of not sacrificing quality was to be strictly maintained, so the task at hand seemed almost impossible. At the same time, nobody in the studio wanted to pass up the chance to make both of these films.»[86]

- ^ a b Akimoto (2014) states: «Porco Rosso (1992) can be categorized as ‘anti-war propaganda’ … the film conveys the important memory of war, especially the interwar era and the post-Cold War world.»[99]

- ^ Miyazaki was surprised by the success of Porco Rosso, as he considered it «too idiosyncratic for a toddlers-to-old-folks general audience».[95]

- ^ Porco Rosso was succeeded as the highest-grossing animated film in Japan by Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke in 1997.[95]

- ^ Cavallaro (2006) states: «[Kondō’s] association with Miyazaki and Takahata dated back to their days together at A-Pro … He would also have been Miyazaki’s most likely successor had he not tragically passed away in 1998 at the age of 47, victim of an aneurysm.»[103]

- ^ McCarthy (1999) states: «From the Utopian idealism of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Miyazaki’s vision has developed to encompass the mature and kindly humanism of Princess Mononoke.»[113]

- ^ Tasker (2011) states: «Princess Mononoke marked a turning point in Miyazaki’s career not merely because it broke Japanese box office records, but also because it, arguably, marked the emergence (through a distribution deal with Disney) into the global animation markets.»[122]

- ^ Regarding a letter written by Studio Ghibli which paraphrases Miyazaki, Gold (2016) states: «Chihiro’s parents turning into pigs symbolizes how some humans become greedy … There were people that ‘turned into pigs’ during Japan’s bubble economy of the 1980s, and these people still haven’t realized they’ve become pigs.»[125]

- ^ Protagonist Chihiro stands outside societal boundaries in the supernatural setting. The use of the word kamikakushi (literally «hidden by gods») within the Japanese title reinforces this symbol. Reider (2005) states: «Kamikakushi is a verdict of ‘social death’ in this world, and coming back to this world from Kamikakushi meant ‘social resurrection’.»[126]

- ^ Quoting producer Toshio Suzuki, Cavallaro (2015) states: «[Miyazaki] is said to feel instinctively drawn back to the sorts of artists who ‘drew «illusion art» in Europe back then… They drew many pictures imagining what the 20th century would look like. They were illusions and were never realized at all.’ What Miyazaki recognizes in these images is their unique capacity to evoke ‘a world in which science exists as well as magic, since they are illusion’.»[138]

- ^ Foundas (2013) states: «The Wind Rises continues the strong pacifist themes of [Miyazaki’s] earlier Nausicaä and Princess Mononoke, marveling at man’s appetite for destruction and the speed with which new technologies become weaponized.»[161]

- ^ Abe’s party proposed the amendment to Article 96 of the Constitution of Japan, a clause that stipulates procedures needed for revisions. Ultimately, this would allow Abe to revise Article 9 of the Constitution, which outlaws war as a means to settle international disputes.[179]

- ^ Miyazaki stated: «It goes without saying that I am against constitutional reform… I’m taken aback by the lack of knowledge among government and political party leaders on historical facts. People who don’t think enough shouldn’t meddle with the constitution.»[181]

- ^ Miyazaki stated: «I think it’s a mistake to caricature the figures venerated by another culture. You shouldn’t do it… Instead of doing something like that, you should make caricatures of your own country’s politicians.»[184]

- ^ Regarding Spirited Away, Miyazaki (2002) states: «the heroine [is] thrown into a place where the good and bad dwell together. […] She manages not because she has destroyed the ‘evil’, but because she has acquired the ability to survive.»[190]

- ^ In Cappello (2005), Talbot states: «[Miyazaki’s] said, not entirely jokingly, that he looks forward to the time when Tokyo is submerged by the ocean and the NTV tower becomes an island, when the human population plummets and there are no more high-rises.»[192]

- ^ Schellhase (2014) states: «Most of the few true villains in Mr. Miyazaki’s films are exploiters: the Tolmeckians in Nausicaä who want to revive an incredibly destructive giant warrior; the shadowy Prince Muska in Laputa: Castle in the Sky, who hopes to harness the power of a flying city for world domination; or Madam Suliman in Howl’s Moving Castle, a sorceress who attempts to bring all the magicians in the land under her control and turn them into monsters of war.»[186]

- ^ Akimoto (2014) states: «Porco became a pig because he hates the following three factors: man (egoism), the state (nationalism) and war (militarism).»[99]

- ^ In The Birth of Studio Ghibli (2005), Suzuki states: «Miyazaki is a feminist, actually. He also has this conviction that to be successful, companies have to make it possible for their female employees to succeed too. You can see this attitude in Princess Mononoke: all the characters working the bellows in the iron works are women. Then there’s Porco Rosso: Porco’s plane is rebuilt entirely by women.»[198]

- ^ Schellhase (2014) states: «Miyazaki’s female characters are not objectified or overly sexualized. They are as complex and independent as his male characters, or even more so. Male and female characters alike are unique individuals, with specific quirks and even inconsistencies, like real people. They are also recognizably masculine and feminine, yet are not compelled to exist within to narrowly-defined gender roles. Sexuality is not as important as personality and relationships. If this is feminism, Hollywood needs much, much more of it.»[186]

- ^ Schellhase (2014) states: «Princess Nausicäa, already a leader, successfully overcomes an extreme political and ecological crisis to save her people and become queen. Kiki’s tale is distinctly framed as a rite of passage in which the young ‘witch in training’ establishes herself in an unfamiliar town, experiencing the joys and trials of human interdependence. In Spirited Away, Chihiro must work hard and overcome difficulties to redeem her bestial parents. Howl‘s heroine Sophie is already an ‘old soul,’ but a jealous witch’s curse sends her on an unexpected journey in which she and Howl both learn to shoulder the burden of love and responsibility. Umi, the heroine of Poppy Hill, is also very mature and responsible at the beginning of the film, but in the course of the story she grows in self-understanding and is able to deal with grief over the loss of her father.»[186]

- ^ Schellhase (2014) states: «Miyazaki is especially concerned about the way Japan’s young people have lost their sense of wonder from living in a completely disenchanted, materialistic world.»[186]

- ^ Schellhase (2014) states: «Many of [Miyazaki’s] young protagonists lack one or both parents. Some parents are bad role models, like Chihiro’s materialistic glutton parents, or Sophie’s shallow fashion-plate mother. Some families are just dysfunctional, like the sky pirates in Laputa, sons hanging on Dola’s matriarchal apron-strings while Dad spends all his time secluded in the engine room. But there are also realistic, stable families with diligent and committed fathers and wise, caring mothers, as in Totoro, Ponyo, and Poppy Hill.»[186]

- ^ Miyazaki and Giraud (also known as Moebius) influenced each other’s works, and became friends as a result of their mutual admiration.[208] Monnaie de Paris held an exhibition of their work titled Miyazaki et Moebius: Deux Artistes Dont Les Dessins Prennent Vie (Two Artists’s Drawings Taking on a Life of Their Own) from December 2004 to April 2005; both artists attended the opening of the exhibition.[209]

- ^ An exhibit based upon Aardman Animations’s works ran at the Ghibli Museum from 2006 to 2007.[211] Aardman Animations founders Peter Lord and David Sproxton visited the exhibition in May 2006, where they also met Miyazaki.[212]

- ^ Original text: «私にとって、宮崎駿は、父としては0点でも、アニメーション映画監督としては満点なのです。»

References[edit]

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 435.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Talbot 2005.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 11.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c McCarthy 1999, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Miyazaki 1988.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Miyazaki 1996, p. 209.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Han 2020.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 239.

- ^ Arakawa 2019, 14:00.

- ^ Bayle 2017.

- ^ Arakawa 2019, 23:28.

- ^ Arakawa 2019, 29:51.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 40.

- ^ Arakawa 2019, 21:82.

- ^ Miyazaki 2009, p. 431.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c McCarthy 1999, p. 27.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 193.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Comic Box 1982, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e f Miyazaki 1996, p. 436.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 15.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Miyazaki 2009, p. 70.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 200.

- ^ a b c McCarthy 1999, p. 30.

- ^ Batkin 2017, p. 141.

- ^ Mahmood 2018.

- ^ a b c d Miyazaki 1996, p. 437.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 217.

- ^ LaMarre 2009, pp. 56ff.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Anime News Network 2001.

- ^ Drazen 2002, pp. 254ff.

- ^ a b c d Miyazaki 1996, p. 438.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 194.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 219.

- ^ a b Comic Box 1982, p. 111.

- ^ a b Animage 1983.

- ^ Lenburg 2012, p. 22.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 27, 219.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 220.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 39.

- ^ Takahata, Miyazaki & Kotabe 2014.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 221.

- ^ a b Miyazaki 1996, p. 440.

- ^ a b Miyazaki 1996, p. 441.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 40.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 223.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 50.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 225.

- ^ Miyazaki 1983, p. 147.

- ^ a b Kanō 2006, p. 324.

- ^ Mateo 2022.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 163.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 249.

- ^ Kanō 2006, pp. 37ff, 323.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 146.

- ^ Miyazaki 2007, p. 146.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Saitani 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Ryan.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 94.

- ^ Miyazaki 2007, p. 94.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 442.

- ^ a b Miyazaki 1996, p. 443.

- ^ a b Cavallaro 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Hiranuma.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 75.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, pp. 77.

- ^ Kanō 2006, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Osmond 1998, pp. 57–81.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 48.

- ^ a b Moss 2014.

- ^ Nakamura & Matsuo 2002, p. 73.

- ^ Napier 1998, p. 101.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 89.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 45.

- ^ a b Cavallaro 2006, p. 58.

- ^ a b Brooks 2005.

- ^ a b Cavallaro 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 194.

- ^ Camp & Davis 2007, p. 227.

- ^ Macdonald 2014.

- ^ Miyazaki 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Gaulène 2011.

- ^ Hairston 1998.

- ^ Lamar 2010.

- ^ a b c d Cavallaro 2006, p. 96.

- ^ a b Havis 2016.

- ^ Sunada 2013, 46:12.

- ^ a b c Blum 2013.

- ^ a b c Akimoto 2014.

- ^ a b Matsutani 2008.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 104.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 105.

- ^ a b Cavallaro 2006, p. 114.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 185.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 182.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, pp. 211.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 112.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, pp. 214.

- ^ a b Cavallaro 2006, p. 127.

- ^ McCarthy 1999, p. 186.

- ^ Ashcraft 2013.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1999, p. 203.

- ^ Toyama.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 126.

- ^ Karrfalt 1997.

- ^ a b Cavallaro 2006, p. 120.

- ^ CBS News 2014, p. 15.

- ^ a b Cavallaro 2006, p. 32.

- ^ a b Ebert 1999.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 121.

- ^ a b c Tasker 2011, p. 292.

- ^ Toyama 2001.

- ^ a b Howe 2003a.

- ^ a b Gold 2016.

- ^ a b Reider 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Dietz 2010.

- ^ a b Howe 2003b.

- ^ Howe 2003c.

- ^ Sudo 2014.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 135.

- ^ a b Brzeski 2020.

- ^ Miyazaki 1996, p. 446.

- ^ a b c d e Cavallaro 2006, p. 157.

- ^ Schilling 2002.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 167.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 168.

- ^ a b Cavallaro 2015, p. 145.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 165.

- ^ a b Wellham 2016.

- ^ Osaki 2013.

- ^ Macdonald 2005.

- ^ Le Guin 2006.

- ^ Collin 2013.

- ^ G. Miyazaki 2006b.

- ^ Miyazaki 2009, pp. 398–401.

- ^ a b Miyazaki 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Castro 2012.

- ^ Ghibli World 2007.

- ^ Sacks 2009.

- ^ Yomiuri Shimbun 2008.

- ^ a b Ball 2008.

- ^ a b Loo 2009.

- ^ Landreth 2009.

- ^ Animekon 2009.

- ^ Cavallaro 2014, p. 183.

- ^ Loo 2014.

- ^ Armitage 2012.

- ^ a b c Keegan 2013.

- ^ Newtype 2011, p. 93.

- ^ a b Foundas 2013.

- ^ a b Green 2014.

- ^ a b Loveridge 2014.

- ^ Ma 2014.

- ^ Loo 2013a.

- ^ Akagawa 2013.

- ^ CBS News 2014, p. 24.

- ^ The Birth of Studio Ghibli 2005, 24:47.

- ^ a b Loo 2017.

- ^ Loo 2013b.

- ^ Hazra 2021.

- ^ Hodgkins 2022.

- ^ Screen Rant 2019.

- ^ Lattanzio 2020.

- ^ Radulovic 2020.

- ^ a b Baseel 2014a.

- ^ Baseel 2014b.

- ^ Sunada 2013, 1:08:30.

- ^ Fujii 2013.

- ^ a b Yoshida 2015.

- ^ McCurry 2013.

- ^ Seguret 2014.

- ^ a b Pham 2009.

- ^ a b Hawkes 2015.

- ^ MBS TV 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Schellhase 2014.

- ^ Loy & Goodhew 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Reinders 2016, p. 181.

- ^ Romano 2013.

- ^ Miyazaki 2002, p. 15.

- ^ McDougall 2018.

- ^ a b Cappello 2005.

- ^ Schilling 2008.

- ^ Ghibli World 2008.

- ^ Dwivedi 2017.

- ^ Akimoto 2013.

- ^ Loy & Goodhew 2004.

- ^ a b The Birth of Studio Ghibli 2005, 22:05.

- ^ Denham 2016.

- ^ Bellot 2016.

- ^ Toscano 2014.

- ^ a b c d Mes 2002.

- ^ Ebert 2002.

- ^ a b c d Andrews 2005.

- ^ Calvario 2016.

- ^ Schley 2019.

- ^ Poland 1999.

- ^ a b Cotillon 2005.

- ^ Montmayeur 2005.

- ^ Cavallaro 2014, p. 55.

- ^ a b The Japan Times 2006.

- ^ Animage 2006.

- ^ Ghibli Museum Library 2007.

- ^ Japanorama 2002.

- ^ a b c d e Miyazaki 1996, p. 204.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 20.

- ^ a b G. Miyazaki 2006a.

- ^ a b Lenburg 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Loo 2011.

- ^ Wong 2016.

- ^ Lanning 2021.

- ^ Bose 2021.

- ^ Havis 2020.

- ^ Egan 2017.

- ^ Del Barco 2021.

- ^ Ongley & Wheeler 2018.

- ^ Ito 2009.

- ^ Phipps 2019.

- ^ Chitwood 2013.

- ^ Accomando 2009.

- ^ Brady 2018.

- ^ Raup 2017.

- ^ a b Lee 2010.

- ^ Lambie 2016.

- ^ Brzeski 2014.

- ^ a b Kelts 2007, p. 49.

- ^ Leader 2009.

- ^ Manry 2011.

- ^ Komatsu 2018.

- ^ Pallant 2011, p. 90.

- ^ Nintendo 2002.

- ^ Rogers 2006.

- ^ Hamessley & London 2010.

- ^ Nakamura 2014.

- ^ a b c d Animations 2008.

- ^ a b c d Cavallaro 2006, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d e f Cavallaro 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Mainichi Shimbun 2001.

- ^ Komatsu 2012.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, p. 185.

- ^ Schilling 2009.

- ^ Kinema Junpo Movie Database.

- ^ Komatsu 2017.

- ^ The Japan Times 2014.

- ^ International Animated Film Association 1998.

- ^ Transilvania International Film Festival.

Sources[edit]

- Accomando, Beth (May 29, 2009). «Interview with Up Director Peter Docter». KPBS Public Media. San Diego State University. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Akagawa, Roy (September 6, 2013). «Excerpts of Hayao Miyazakis news conference announcing his retirement». Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Akimoto, Daisuke (September 2, 2013). «Miyazaki’s new animated film and its antiwar pacifism: The Wind Rises (Kaze Tachinu)». Ritsumeikan Journal of Asia Pacific Studies. 32: 165–167.

- Akimoto, Daisuke (October 1, 2014). Ratelle, Amy (ed.). «A Pig, the State, and War: Porco Rosso (Kurenai no Buta)». Animation Studies. Society for Animation Studies. 9. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- Andrews, Nigel (September 20, 2005). «Japan’s visionary of innocence and apocalypse». Financial Times. The Nikkei. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- «ナウシカの道 連載 1 宮崎駿・マンガの系譜» [The Road to Nausicaä, episode 1, Hayao Miyazaki’s Manga Genealogy]. Animage (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten (61): 172–173. June 10, 1983.

- «宮崎駿Xピーター・ロードXデイビッド・スプロスクトンat三鷹の森ジブリ美術館». Animage (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten (338): 13. August 2006.

- «毎日映画コンクール» [Everyday Movie Competition] (in Japanese). Animations. 2008. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- «Miyazaki Starts New Manga, Kaze Tachinu». Animekon. February 12, 2009. Archived from the original on May 14, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- «Animage Top-100 Anime Listing». Anime News Network. January 16, 2001. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- Arakawa, Kaku (director) (March 30, 2019). «Drawing What’s Real». 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki. Episode 2 (in Japanese). Japan: NHK.

- Armitage, Hugh (November 21, 2012). «Studio Ghibli unveils two films ‘The Wind Rises’, ‘Princess Kaguya’«. Digital Spy. Hearst Communications. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Ashcraft, Brian (September 10, 2013). «Visit the Real Princess Mononoke Forest». Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- Ball, Ryan (August 25, 2008). «Miyazaki’s Ponyo Hits B.O. Milestone». Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- Baseel, Casey (January 30, 2014). «Ghibli’s Hayao Miyazaki says the anime industry’s problem is that it’s full of anime fans». RocketNews24. Socio Corporation. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Baseel, Casey (December 12, 2014). «Hayao Miyazaki reveals the kind of otaku he hates the most». RocketNews24. Socio Corporation. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- Batkin, Jane (2017). Identity in Animation: A Journey Into Self, Difference, Culture and the Body. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-53325-2.

- Bayle, Alfred (October 4, 2017). «Hayao Miyazaki modeled character in ‘Laputa: Castle in the Sky’ after his mom». Philippine Daily Inquirer. Inquirer Group of Companies. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- Bellot, Gabrielle (October 19, 2016). «Hayao Miyazaki and the Art of Being a Woman». The Atlantic. Atlantic Media. Archived from the original on November 28, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- The Birth of Studio Ghibli. Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. 2005.

- Blum, Jeremy (August 13, 2013). «Animation legend Hayao Miyazaki under attack in Japan for anti-war film». South China Morning Post. Alibaba Group. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- Bose, Swapnil Dhruv (January 5, 2021). «Hayao Miyazaki: The life and lasting influence of the Studio Ghibli auteur-animator». Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- Brady, Tara (October 30, 2018). «Mamoru Hosoda’s poignant and strange inversion of It’s a Wonderful Life». The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- Brooks, Xan (September 15, 2005). «A god among animators». The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 2, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- Brzeski, Patrick (October 24, 2014). «John Lasseter Pays Emotional Tribute to Hayao Miyazaki at Tokyo Film Festival». The Hollywood Reporter. Eldridge Industries. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Brzeski, Patrick (December 28, 2020). «‘Demon Slayer’ Overtakes ‘Spirited Away’ to Become Japan’s Biggest Box Office Hit Ever». The Hollywood Reporter. PMRC. Archived from the original on December 28, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- Calvario, Liz (August 3, 2016). «Studio Ghibli: The Techniques & Unimaginable Work That Goes Into Each Animation Revealed». IndieWire. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Cappello, Daniel (January 10, 2005). «The Animated Life». The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on May 24, 2006. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- Castro, Adam-Troy (December 14, 2012). «Legendary animator Miyazaki reveals Ponyo’s inspirations». Sci Fi Wire. Syfy. Archived from the original on June 11, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Cavallaro, Dani (January 24, 2006). The Animé Art of Hayao Miyazaki. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2369-9.

- Cavallaro, Dani (November 28, 2014). The Late Works of Hayao Miyazaki: A Critical Study 2004–2013. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-9518-4.

- Cavallaro, Dani (March 2, 2015). Hayao Miyazaki’s World Picture. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-9647-1.

- «Oscars honors animator Hayao Miyazaki». CBS News. CBS. November 8, 2014. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- 特集宮崎駿 「風の谷のナウシカ」1 [Special Edition Hayao Miyazaki Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind]. Comic Box (in Japanese). Fusion Products (3): 77–137. 1982.

- Camp, Brian; Davis, Julie (2007). Anime Classics Zettai!: 100 Most-See Japanese Animation Masterpieces. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-933330-22-8.

- Chitwood, Adam (July 12, 2013). «Guillermo del Toro Talks His Favorite Kaiju Movies, Hayao Miyazaki, Why He’s Not Likely to Direct a Film in an Established Franchise, and More». Collider. Complex. Archived from the original on May 7, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Collin, Robbie (August 2, 2013). «Studio Ghibli: Japan’s dream factory». The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Cotillon, Laurent (January 2005). «A talk between Hayao Miyazaki and Moebius». Ciné Live. Cyber Press Publishing (86). Archived from the original on June 16, 2017.

- Del Barco, Mandalit (October 2, 2021). «You can now enter Hayao Miyazaki’s enchanting animated world at the Academy Museum». NPR. Archived from the original on October 2, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- Denham, Jess (June 7, 2016). «Studio Ghibli hires male directors because they have a ‘more idealistic’ approach to fantasy than women». The Independent. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- Dietz, Jason (January 3, 2010). «Critics Pick the Best Movies of the Decade». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Drazen, Patrick (January 1, 2002). Anime Explosion!. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-61172-013-6.

- Dwivedi, Ram (June 29, 2017). «A Discourse on Modern Civilization: The Cinema of Miyazaki and Gandhi» (PDF). International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention. 6 (6): 63–68.

- Ebert, Roger (October 24, 1999). «Director Miyazaki draws American attention». Chicago Sun-Times. Sun-Times Media Group. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- Ebert, Roger (September 12, 2002). «Hayao Miyazaki interview». RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Egan, Toussaint (June 25, 2017). «Hayao Miyazaki’s Legacy Is Far Greater Than His Films». Paste. Paste Media Group. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- Foundas, Scott (August 29, 2013). «‘The Wind Rises’ Review: Hayao Miyazaki’s Haunting Epic». Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Fujii, Moeko (July 26, 2013). «Japanese Anime Legend Miyazaki Denounces Push to Change the ‘Peace Constitution’«. The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- Gaulène, Mathieu (April 4, 2011). «Studio Ghibli, A New Force in Animation». INA Global. National Audiovisual Institute. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- Ghibli Museum Library (2007). «映画『雪の女王』新訳版公式サイト — イントロダクション» [Official website for the new translation of the ovie «Snow Queen»] (in Japanese). Tokuma Memorial Cultural Foundation for Animation. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- «Executive Producer & Former President of Studio Ghibli Suzuki Toshio Reveals the Story Behind Ponyo». Ghibli World. 2007. Archived from the original on March 5, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- «A Neppu Interview with Miyazaki Hayao». Ghibli World. November 30, 2008. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- Gold, Corey (July 14, 2016). «Studio Ghibli letter sheds new light on Spirited Away mysteries». RocketNews24. Socio Corporation. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Green, Scott (March 11, 2014). ««The Wind Rises» Takes Animation Prize at Japan Academy Awards». Crunchyroll. Ellation. Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Hamessley, London; London, Matt (July 8, 2010). «Interview: Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko, Creators of the Original Televised Avatar: The Last Airbender». Tor Books. Macmillan Publishers. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Hairston, Marc (November 1998). «Kiki’s Delivery Service». University of Texas at Dallas. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- Han, Karen (May 20, 2020). «Watch the 4-hour documentary that unravels Hayao Miyazaki’s obsessions». Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- Havis, Richard James (August 6, 2016). «Flashback: Porco Rosso – genius animator Hayao Miyazaki’s most personal film». South China Morning Post. Alibaba Group. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- Havis, Richard James (October 6, 2020). «Hayao Miyazaki’s movies: why are they so special?». South China Morning Post. Alibaba Group. Archived from the original on October 6, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- Hawkes, Rebecca (February 17, 2015). «Hayao Miyazaki: Charlie Hedbo Mohammed cartoons were ‘a mistake’«. The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- Hazra, Adriana (March 8, 2021). «Ghibli Producer: Hayao Miyazaki’s ‘How Do You Live?’ Film’s Animation Is Half Finished». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- Hiranuma, G.B. «Anime and Academia: Interview with Marc Hairston on pedagogy and Nausicaa». University of Texas at Dallas. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- Hodgkins, Crystalyn (December 13, 2022). «Hayao Miyazaki’s How Do You Live? Film Opens in Japan on July 14, 2023». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- Howe, Michael (April 14, 2003). «The Making of Hayao Miyazaki’s «Spirited Away» – Part 1″. Jim Hill Media. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Howe, Michael (April 15, 2003). «The Making of Hayao Miyazaki’s «Spirited Away» – Part 2″. Jim Hill Media. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Howe, Michael (April 20, 2003). «The Making of Hayao Miyazaki’s «Spirited Away» – Part 5″. Jim Hill Media. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- «26th Annual Annie». Annie Award. International Animated Film Association. 1998. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- Ito, Norihiro (December 25, 2009). «新作「アバター」宮崎アニメにオマージュ J・キャメロン監督 (New Film Avatar Homage to Miyazaki’s Animated Film: J. Cameron)». Sankei Shimbun (in Japanese). Fuji Media Holdings. Archived from the original on December 28, 2009. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- «Aardman exhibits, new Miyazaki anime on view». The Japan Times. Nifco. November 24, 2006. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- «Miyazaki wins Annie Award for ‘Kaze Tachinu’ screenplay». The Japan Times. Nifco. February 2, 2014. Archived from the original on September 17, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- «Youth». Japanorama. Series 1. Episode 2. June 16, 2002. BBC Choice.

- Kanō, Seiji (2006). 宮崎駿全書 [The Complete Miyazaki Hayao] (in Japanese) (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Film Art Inc. pp. 34–73, 323. ISBN 978-4-8459-0687-1.