Определение иррациональных чисел

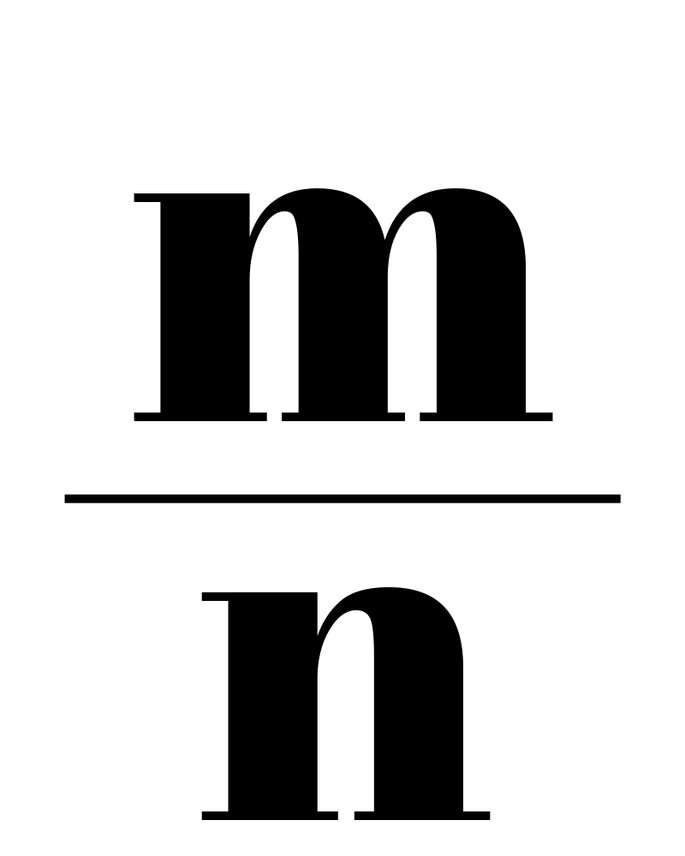

Иррациональное число — это действительное число, которое невозможно выразить в форме деления двух целых чисел, то есть в рациональной дроби:

Оно может быть выражено в форме бесконечной непериодической десятичной дроби.

Бесконечная периодическая десятичная дробь — это такая дробь, десятичные знаки которой повторяются в виде группы цифр или одного и того же числа.

Примеры иррациональных чисел:

- π = 3,1415926…

- √2 = 1,41421356…

- e = 2,71828182…

- √8 = 2.828427…

- -√11= -3.31662…

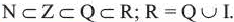

Множество иррациональных чисел договорились обозначать латинской буквой I.

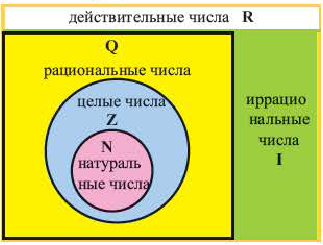

Действительныеили вещественные числа — это все рациональные и иррациональные числа: положительные, отрицательные и нуль.

Если натуральное число n не является точным квадратом, т. е. n ≠ k2, где k ∈ Q, то √n — иррациональное число.

Получай лайфхаки, статьи, видео и чек-листы по обучению на почту

Реши домашку по математике на 5.

Подробные решения помогут разобраться в самой сложной теме.

Свойства иррациональных чисел

Какие числа являются иррациональными мы уже поняли, но это еще не все. Есть еще важная тема для изучения: их основные свойства.

Свойства иррациональных чисел:

- результат суммы иррационального числа и рационального равен иррациональному числу;

- результат умножения иррационального числа на любое рациональное число (≠ 0) равен иррациональному числу;

- результат вычитания двух иррациональных чисел равен иррациональному числу или рациональному;

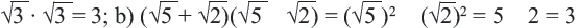

- результат суммы или произведения двух иррациональных чисел равен рациональному или иррациональному, например: √2 * √8 = √16 = 4).

Онлайн-подготовка к ОГЭ по математике — отличный способ снять стресс и закрепить знания перед экзаменом.

Определение рациональных чисел

А теперь наоборот: рассмотрим противоположное заданной теме определение.

Рациональное число — это такое число, которое можно представить в виде положительной или отрицательной обыкновенной дроби или нуля. Если число можно получить делением двух целых чисел — это число точно рациональное.

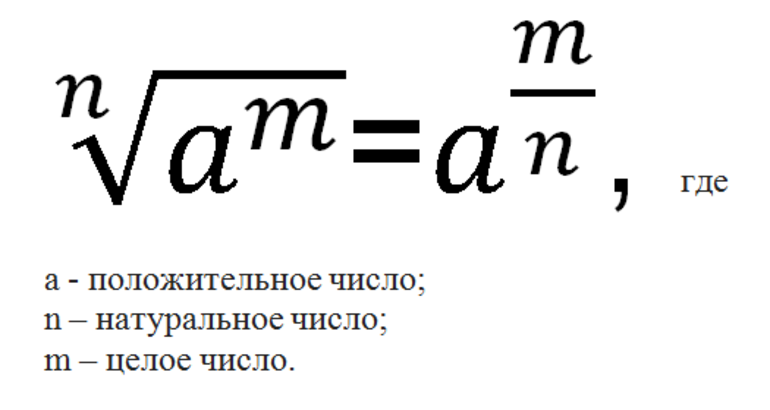

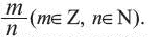

Рациональные числа — это те, которые можно представить в виде:

где числитель m — целое число, а знаменатель n — натуральное число.

Рациональные числа – это все натуральные, целые числа, обыкновенные дроби, бесконечные периодические дроби и конечные десятичные дроби.

Множество рациональных чисел принято обозначать латинской буквой Q.

Примеры рациональных чисел:

- десятичная дробь 1,15 — это 115/100;

- десятичная дробь 0,2 — это 1/5;

- целое число 0 — это 0/1;

- целое число 6 — это 6/1;

- целое число 1 — это 1/1;

- бесконечная периодическая дробь 0,33333… — это 1/3;

- смешанное число

это 25/10;

- отрицательная десятичная дробь -3,16 — это -316/100.

У рациональных чисел есть определенные законы и ряд свойств — рассмотрим каждый их них. Пусть а, b и c — любые рациональные числа.

Основные свойства действий с рациональными числами

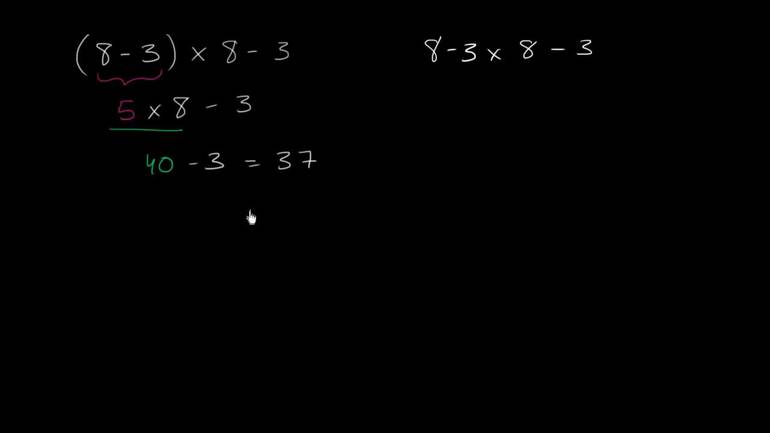

- Переместительное свойство сложения: a + b = b + a.

- Сочетательное свойство сложения: (a + b) +c = a + (b + c).

- Сложение рационального числа и нейтрального элемента (нуля) не изменяет это число: a + 0 = a.

- У каждого рационального числа есть противоположное число, а их сумма всегда равна нулю: a + (-a) = 0.

- Переместительное свойство умножения: ab = ba.

- Сочетательное свойство умножения: (a * b) * c = a * (b * c).

- Произведение рационального числа и едины не изменяет это число: a * 1 = a.

- У каждого отличного от нуля рационального числа есть обратное число. Их произведение равно единице: a * a−1 = 1.

- Распределительное свойство умножения относительно сложения: a * (b + c) = a * b + a * c.

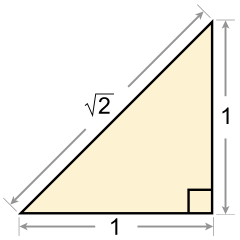

The number √2 is irrational.

In mathematics, the irrational numbers (from in- prefix assimilated to ir- (negative prefix, privative) + rational) are all the real numbers that are not rational numbers. That is, irrational numbers cannot be expressed as the ratio of two integers. When the ratio of lengths of two line segments is an irrational number, the line segments are also described as being incommensurable, meaning that they share no «measure» in common, that is, there is no length («the measure»), no matter how short, that could be used to express the lengths of both of the two given segments as integer multiples of itself.

Among irrational numbers are the ratio π of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, Euler’s number e, the golden ratio φ, and the square root of two.[1] In fact, all square roots of natural numbers, other than of perfect squares, are irrational.[2]

Like all real numbers, irrational numbers can be expressed in positional notation, notably as a decimal number. In the case of irrational numbers, the decimal expansion does not terminate, nor end with a repeating sequence. For example, the decimal representation of π starts with 3.14159, but no finite number of digits can represent π exactly, nor does it repeat. Conversely, a decimal expansion that terminates or repeats must be a rational number. These are provable properties of rational numbers and positional number systems, and are not used as definitions in mathematics.

Irrational numbers can also be expressed as non-terminating continued fractions and many other ways.

As a consequence of Cantor’s proof that the real numbers are uncountable and the rationals countable, it follows that almost all real numbers are irrational.[3]

History[edit]

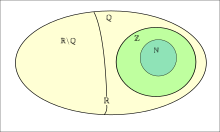

Set of real numbers (R), which include the rationals (Q), which include the integers (Z), which include the natural numbers (N). The real numbers also include the irrationals (RQ).

Ancient Greece[edit]

The first proof of the existence of irrational numbers is usually attributed to a Pythagorean (possibly Hippasus of Metapontum),[4] who probably discovered them while identifying sides of the pentagram.[5]

The then-current Pythagorean method would have claimed that there must be some sufficiently small, indivisible unit that could fit evenly into one of these lengths as well as the other. Hippasus, in the 5th century BC, however, was able to deduce that there was in fact no common unit of measure, and that the assertion of such an existence was in fact a contradiction. He did this by demonstrating that if the hypotenuse of an isosceles right triangle was indeed commensurable with a leg, then one of those lengths measured in that unit of measure must be both odd and even, which is impossible. His reasoning is as follows:

- Start with an isosceles right triangle with side lengths of integers a, b, and c. The ratio of the hypotenuse to a leg is represented by c:b.

- Assume a, b, and c are in the smallest possible terms (i.e. they have no common factors).

- By the Pythagorean theorem: c2 = a2+b2 = b2+b2 = 2b2. (Since the triangle is isosceles, a = b).

- Since c2 = 2b2, c2 is divisible by 2, and therefore even.

- Since c2 is even, c must be even.

- Since c is even, dividing c by 2 yields an integer. Let y be this integer (c = 2y).

- Squaring both sides of c = 2y yields c2 = (2y)2, or c2 = 4y2.

- Substituting 4y2 for c2 in the first equation (c2 = 2b2) gives us 4y2= 2b2.

- Dividing by 2 yields 2y2 = b2.

- Since y is an integer, and 2y2 = b2, b2 is divisible by 2, and therefore even.

- Since b2 is even, b must be even.

- We have just shown that both b and c must be even. Hence they have a common factor of 2. However this contradicts the assumption that they have no common factors. This contradiction proves that c and b cannot both be integers, and thus the existence of a number that cannot be expressed as a ratio of two integers.[6]

Greek mathematicians termed this ratio of incommensurable magnitudes alogos, or inexpressible. Hippasus, however, was not lauded for his efforts: according to one legend, he made his discovery while out at sea, and was subsequently thrown overboard by his fellow Pythagoreans «… for having produced an element in the universe which denied the… doctrine that all phenomena in the universe can be reduced to whole numbers and their ratios.»[7] Another legend states that Hippasus was merely exiled for this revelation. Whatever the consequence to Hippasus himself, his discovery posed a very serious problem to Pythagorean mathematics, since it shattered the assumption that number and geometry were inseparable–a foundation of their theory.

The discovery of incommensurable ratios was indicative of another problem facing the Greeks: the relation of the discrete to the continuous. This was brought into light by Zeno of Elea, who questioned the conception that quantities are discrete and composed of a finite number of units of a given size. Past Greek conceptions dictated that they necessarily must be, for «whole numbers represent discrete objects, and a commensurable ratio represents a relation between two collections of discrete objects»,[8] but Zeno found that in fact «[quantities] in general are not discrete collections of units; this is why ratios of incommensurable [quantities] appear… .[Q]uantities are, in other words, continuous».[8] What this means is that, contrary to the popular conception of the time, there cannot be an indivisible, smallest unit of measure for any quantity. That in fact, these divisions of quantity must necessarily be infinite. For example, consider a line segment: this segment can be split in half, that half split in half, the half of the half in half, and so on. This process can continue infinitely, for there is always another half to be split. The more times the segment is halved, the closer the unit of measure comes to zero, but it never reaches exactly zero. This is just what Zeno sought to prove. He sought to prove this by formulating four paradoxes, which demonstrated the contradictions inherent in the mathematical thought of the time. While Zeno’s paradoxes accurately demonstrated the deficiencies of current mathematical conceptions, they were not regarded as proof of the alternative. In the minds of the Greeks, disproving the validity of one view did not necessarily prove the validity of another, and therefore further investigation had to occur.

The next step was taken by Eudoxus of Cnidus, who formalized a new theory of proportion that took into account commensurable as well as incommensurable quantities. Central to his idea was the distinction between magnitude and number. A magnitude «…was not a number but stood for entities such as line segments, angles, areas, volumes, and time which could vary, as we would say, continuously. Magnitudes were opposed to numbers, which jumped from one value to another, as from 4 to 5».[9] Numbers are composed of some smallest, indivisible unit, whereas magnitudes are infinitely reducible. Because no quantitative values were assigned to magnitudes, Eudoxus was then able to account for both commensurable and incommensurable ratios by defining a ratio in terms of its magnitude, and proportion as an equality between two ratios. By taking quantitative values (numbers) out of the equation, he avoided the trap of having to express an irrational number as a number. «Eudoxus’ theory enabled the Greek mathematicians to make tremendous progress in geometry by supplying the necessary logical foundation for incommensurable ratios».[10] This incommensurability is dealt with in Euclid’s Elements, Book X, Proposition 9. It was not until Eudoxus developed a theory of proportion that took into account irrational as well as rational ratios that a strong mathematical foundation of irrational numbers was created.[11]

As a result of the distinction between number and magnitude, geometry became the only method that could take into account incommensurable ratios. Because previous numerical foundations were still incompatible with the concept of incommensurability, Greek focus shifted away from those numerical conceptions such as algebra and focused almost exclusively on geometry. In fact, in many cases algebraic conceptions were reformulated into geometric terms. This may account for why we still conceive of x2 and x3 as x squared and x cubed instead of x to the second power and x to the third power. Also crucial to Zeno’s work with incommensurable magnitudes was the fundamental focus on deductive reasoning that resulted from the foundational shattering of earlier Greek mathematics. The realization that some basic conception within the existing theory was at odds with reality necessitated a complete and thorough investigation of the axioms and assumptions that underlie that theory. Out of this necessity, Eudoxus developed his method of exhaustion, a kind of reductio ad absurdum that «…established the deductive organization on the basis of explicit axioms…» as well as «…reinforced the earlier decision to rely on deductive reasoning for proof».[12] This method of exhaustion is the first step in the creation of calculus.

Theodorus of Cyrene proved the irrationality of the surds of whole numbers up to 17, but stopped there probably because the algebra he used could not be applied to the square root of 17.[13]

India[edit]

Geometrical and mathematical problems involving irrational numbers such as square roots were addressed very early during the Vedic period in India. There are references to such calculations in the Samhitas, Brahmanas, and the Shulba Sutras (800 BC or earlier). (See Bag, Indian Journal of History of Science, 25(1-4), 1990).

It is suggested that the concept of irrationality was implicitly accepted by Indian mathematicians since the 7th century BC, when Manava (c. 750 – 690 BC) believed that the square roots of numbers such as 2 and 61 could not be exactly determined.[14] Historian Carl Benjamin Boyer, however, writes that «such claims are not well substantiated and unlikely to be true».[15]

It is also suggested that Aryabhata (5th century AD), in calculating a value of pi to 5 significant figures, used the word āsanna (approaching), to mean that not only is this an approximation but that the value is incommensurable (or irrational).

Later, in their treatises, Indian mathematicians wrote on the arithmetic of surds including addition, subtraction, multiplication, rationalization, as well as separation and extraction of square roots.[16]

Mathematicians like Brahmagupta (in 628 AD) and Bhāskara I (in 629 AD) made contributions in this area as did other mathematicians who followed. In the 12th century Bhāskara II evaluated some of these formulas and critiqued them, identifying their limitations.

During the 14th to 16th centuries, Madhava of Sangamagrama and the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics discovered the infinite series for several irrational numbers such as π and certain irrational values of trigonometric functions. Jyeṣṭhadeva provided proofs for these infinite series in the Yuktibhāṣā.[17]

Middle Ages[edit]

In the Middle ages, the development of algebra by Muslim mathematicians allowed irrational numbers to be treated as algebraic objects.[18] Middle Eastern mathematicians also merged the concepts of «number» and «magnitude» into a more general idea of real numbers, criticized Euclid’s idea of ratios, developed the theory of composite ratios, and extended the concept of number to ratios of continuous magnitude.[19] In his commentary on Book 10 of the Elements, the Persian mathematician Al-Mahani (d. 874/884) examined and classified quadratic irrationals and cubic irrationals. He provided definitions for rational and irrational magnitudes, which he treated as irrational numbers. He dealt with them freely but explains them in geometric terms as follows:[19]

«It will be a rational (magnitude) when we, for instance, say 10, 12, 3%, 6%, etc., because its value is pronounced and expressed quantitatively. What is not rational is irrational and it is impossible to pronounce and represent its value quantitatively. For example: the roots of numbers such as 10, 15, 20 which are not squares, the sides of numbers which are not cubes etc.«

In contrast to Euclid’s concept of magnitudes as lines, Al-Mahani considered integers and fractions as rational magnitudes, and square roots and cube roots as irrational magnitudes. He also introduced an arithmetical approach to the concept of irrationality, as he attributes the following to irrational magnitudes:[19]

«their sums or differences, or results of their addition to a rational magnitude, or results of subtracting a magnitude of this kind from an irrational one, or of a rational magnitude from it.»

The Egyptian mathematician Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam (c. 850 – 930) was the first to accept irrational numbers as solutions to quadratic equations or as coefficients in an equation, often in the form of square roots, cube roots and fourth roots.[20] In the 10th century, the Iraqi mathematician Al-Hashimi provided general proofs (rather than geometric demonstrations) for irrational numbers, as he considered multiplication, division, and other arithmetical functions.[19] Iranian mathematician, Abū Ja’far al-Khāzin (900–971) provides a definition of rational and irrational magnitudes, stating that if a definite quantity is:[19]

«contained in a certain given magnitude once or many times, then this (given) magnitude corresponds to a rational number. . . . Each time when this (latter) magnitude comprises a half, or a third, or a quarter of the given magnitude (of the unit), or, compared with (the unit), comprises three, five, or three fifths, it is a rational magnitude. And, in general, each magnitude that corresponds to this magnitude (i.e. to the unit), as one number to another, is rational. If, however, a magnitude cannot be represented as a multiple, a part (1/n), or parts (m/n) of a given magnitude, it is irrational, i.e. it cannot be expressed other than by means of roots.»

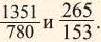

Many of these concepts were eventually accepted by European mathematicians sometime after the Latin translations of the 12th century. Al-Hassār, a Moroccan mathematician from Fez specializing in Islamic inheritance jurisprudence during the 12th century, first mentions the use of a fractional bar, where numerators and denominators are separated by a horizontal bar. In his discussion he writes, «…, for example, if you are told to write three-fifths and a third of a fifth, write thus,

Modern period[edit]

The 17th century saw imaginary numbers become a powerful tool in the hands of Abraham de Moivre, and especially of Leonhard Euler. The completion of the theory of complex numbers in the 19th century entailed the differentiation of irrationals into algebraic and transcendental numbers, the proof of the existence of transcendental numbers, and the resurgence of the scientific study of the theory of irrationals, largely ignored since Euclid. The year 1872 saw the publication of the theories of Karl Weierstrass (by his pupil Ernst Kossak), Eduard Heine (Crelle’s Journal, 74), Georg Cantor (Annalen, 5), and Richard Dedekind. Méray had taken in 1869 the same point of departure as Heine, but the theory is generally referred to the year 1872. Weierstrass’s method has been completely set forth by Salvatore Pincherle in 1880,[23] and Dedekind’s has received additional prominence through the author’s later work (1888) and the endorsement by Paul Tannery (1894). Weierstrass, Cantor, and Heine base their theories on infinite series, while Dedekind founds his on the idea of a cut (Schnitt) in the system of all rational numbers, separating them into two groups having certain characteristic properties. The subject has received later contributions at the hands of Weierstrass, Leopold Kronecker (Crelle, 101), and Charles Méray.

Continued fractions, closely related to irrational numbers (and due to Cataldi, 1613), received attention at the hands of Euler, and at the opening of the 19th century were brought into prominence through the writings of Joseph-Louis Lagrange. Dirichlet also added to the general theory, as have numerous contributors to the applications of the subject.

Johann Heinrich Lambert proved (1761) that π cannot be rational, and that en is irrational if n is rational (unless n = 0).[24] While Lambert’s proof is often called incomplete, modern assessments support it as satisfactory, and in fact for its time it is unusually rigorous. Adrien-Marie Legendre (1794), after introducing the Bessel–Clifford function, provided a proof to show that π2 is irrational, whence it follows immediately that π is irrational also. The existence of transcendental numbers was first established by Liouville (1844, 1851). Later, Georg Cantor (1873) proved their existence by a different method, which showed that every interval in the reals contains transcendental numbers. Charles Hermite (1873) first proved e transcendental, and Ferdinand von Lindemann (1882), starting from Hermite’s conclusions, showed the same for π. Lindemann’s proof was much simplified by Weierstrass (1885), still further by David Hilbert (1893), and was finally made elementary by Adolf Hurwitz[citation needed] and Paul Gordan.[25]

Examples[edit]

Square roots[edit]

The square root of 2 was likely the first number proved irrational.[26] The golden ratio is another famous quadratic irrational number. The square roots of all natural numbers that are not perfect squares are irrational and a proof may be found in quadratic irrationals.

General roots[edit]

The proof above[clarification needed] for the square root of two can be generalized using the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. This asserts that every integer has a unique factorization into primes. Using it we can show that if a rational number is not an integer then no integral power of it can be an integer, as in lowest terms there must be a prime in the denominator that does not divide into the numerator whatever power each is raised to. Therefore, if an integer is not an exact kth power of another integer, then that first integer’s kth root is irrational.

Logarithms[edit]

Perhaps the numbers most easy to prove irrational are certain logarithms. Here is a proof by contradiction that log2 3 is irrational (log2 3 ≈ 1.58 > 0).

Assume log2 3 is rational. For some positive integers m and n, we have

It follows that

The number 2 raised to any positive integer power must be even (because it is divisible by 2) and the number 3 raised to any positive integer power must be odd (since none of its prime factors will be 2). Clearly, an integer cannot be both odd and even at the same time: we have a contradiction. The only assumption we made was that log2 3 is rational (and so expressible as a quotient of integers m/n with n ≠ 0). The contradiction means that this assumption must be false, i.e. log2 3 is irrational, and can never be expressed as a quotient of integers m/n with n ≠ 0.

Cases such as log10 2 can be treated similarly.

Types[edit]

- number theoretic distinction : transcendental/algebraic

- normal/ abnormal (non-normal)

Transcendental/algebraic[edit]

Almost all irrational numbers are transcendental and all real transcendental numbers are irrational (there are also complex transcendental numbers): the article on transcendental numbers lists several examples. So e r and π r are irrational for all nonzero rational r, and, e.g., eπ is irrational, too.

Irrational numbers can also be found within the countable set of real algebraic numbers (essentially defined as the real roots of polynomials with integer coefficients), i.e., as real solutions of polynomial equations

where the coefficients

Because the algebraic numbers form a subfield of the real numbers, many irrational real numbers can be constructed by combining transcendental and algebraic numbers. For example, 3π + 2, π + √2 and e√3 are irrational (and even transcendental).

Decimal expansions[edit]

The decimal expansion of an irrational number never repeats or terminates (the latter being equivalent to repeating zeroes), unlike any rational number. The same is true for binary, octal or hexadecimal expansions, and in general for expansions in every positional notation with natural bases.

To show this, suppose we divide integers n by m (where m is nonzero). When long division is applied to the division of n by m, there can never be a remainder greater than or equal to m. If 0 appears as a remainder, the decimal expansion terminates. If 0 never occurs, then the algorithm can run at most m − 1 steps without using any remainder more than once. After that, a remainder must recur, and then the decimal expansion repeats.

Conversely, suppose we are faced with a repeating decimal, we can prove that it is a fraction of two integers. For example, consider:

Here the repetend is 162 and the length of the repetend is 3. First, we multiply by an appropriate power of 10 to move the decimal point to the right so that it is just in front of a repetend. In this example we would multiply by 10 to obtain:

Now we multiply this equation by 10r where r is the length of the repetend. This has the effect of moving the decimal point to be in front of the «next» repetend. In our example, multiply by 103:

The result of the two multiplications gives two different expressions with exactly the same «decimal portion», that is, the tail end of 10,000A matches the tail end of 10A exactly. Here, both 10,000A and 10A have .162162162… after the decimal point.

Therefore, when we subtract the 10A equation from the 10,000A equation, the tail end of 10A cancels out the tail end of 10,000A leaving us with:

Then

is a ratio of integers and therefore a rational number.

Irrational powers[edit]

Dov Jarden gave a simple non-constructive proof that there exist two irrational numbers a and b, such that ab is rational:[27]

Consider √2√2; if this is rational, then take a = b = √2. Otherwise, take a to be the irrational number √2√2 and b = √2. Then ab = (√2√2)√2 = √2√2·√2 = √22 = 2, which is rational.

Although the above argument does not decide between the two cases, the Gelfond–Schneider theorem shows that √2√2 is transcendental, hence irrational. This theorem states that if a and b are both algebraic numbers, and a is not equal to 0 or 1, and b is not a rational number, then any value of ab is a transcendental number (there can be more than one value if complex number exponentiation is used).

An example that provides a simple constructive proof is[28]

The base of the left side is irrational and the right side is rational, so one must prove that the exponent on the left side,

which we can assume, for the sake of establishing a contradiction, equals a ratio m/n of positive integers. Then

A stronger result is the following:[29] Every rational number in the interval

Open questions[edit]

It is not known if

It is not known if

In constructive mathematics[edit]

In constructive mathematics, excluded middle is not valid, so it is not true that every real number is rational or irrational. Thus, the notion of an irrational number bifurcates into multiple distinct notions. One could take the traditional definition of an irrational number as a real number that is not rational.[31] However, there is a second definition of an irrational number used in constructive mathematics, that a real number

Set of all irrationals[edit]

Since the reals form an uncountable

set, of which the rationals are a countable subset, the complementary set of

irrationals is uncountable.

Under the usual (Euclidean) distance function

the induced metric is not complete. Being a G-delta set—i.e., a countable intersection of open subsets—in a complete metric space, the space of irrationals is completely metrizable: that is, there is a metric on the irrationals inducing the same topology as the restriction of the Euclidean metric, but with respect to which the irrationals are complete. One can see this without knowing the aforementioned fact about G-delta sets: the continued fraction expansion of an irrational number defines a homeomorphism from the space of irrationals to the space of all sequences of positive integers, which is easily seen to be completely metrizable.

Furthermore, the set of all irrationals is a disconnected metrizable space. In fact, the irrationals equipped with the subspace topology have a basis of clopen sets so the space is zero-dimensional.

See also[edit]

- Brjuno number

- Computable number

- Diophantine approximation

- Proof that e is irrational

- Proof that π is irrational

- Square root of 3

- Square root of 5

- Trigonometric number

Complex

|

|

References[edit]

- ^ The 15 Most Famous Transcendental Numbers. by Clifford A. Pickover. URL retrieved 24 October 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Terence (2011-07-01). «95.42 Irrational square roots of natural numbers — a geometrical approach». The Mathematical Gazette. 95 (533): 327–330. doi:10.1017/S0025557200003193. ISSN 0025-5572. S2CID 123995083.

- ^ Cantor, Georg (1955) [1915]. Philip Jourdain (ed.). Contributions to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-60045-1.

- ^ Kurt Von Fritz (1945). «The Discovery of Incommensurability by Hippasus of Metapontum». The Annals of Mathematics.

- ^ James R. Choike (1980). «The Pentagram and the Discovery of an Irrational Number». The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal..

- ^ Kline, M. (1990). Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times, Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press (original work published 1972), p. 33.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 32.

- ^ a b Kline 1990, p. 34.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 48.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 49.

- ^ Charles H. Edwards (1982). The historical development of the calculus. Springer.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 50.

- ^ Robert L. McCabe (1976). «Theodorus’ Irrationality Proofs». Mathematics Magazine..

- ^ T. K. Puttaswamy, «The Accomplishments of Ancient Indian Mathematicians», pp. 411–2, in Selin, Helaine; D’Ambrosio, Ubiratan, eds. (2000). Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-0260-2..

- ^ Boyer (1991). «China and India». A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). p. 208. ISBN 0471093742. OCLC 414892.

It has been claimed also that the first recognition of incommensurables appears in India during the Sulbasutra period, but such claims are not well substantiated. The case for early Hindu awareness of incommensurable magnitudes is rendered most unlikely by the lack of evidence that Indian mathematicians of that period had come to grips with fundamental concepts.

- ^ Datta, Bibhutibhusan; Singh, Awadhesh Narayan (1993). «Surds in Hindu mathematics» (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 28 (3): 253–264. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ Katz, V. J. (1995), «Ideas of Calculus in Islam and India», Mathematics Magazine (Mathematical Association of America) 68 (3): 163–74.

- ^ O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (1999). «Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance?». MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews..

- ^ a b c d e Matvievskaya, Galina (1987). «The theory of quadratic irrationals in medieval Oriental mathematics». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 500 (1): 253–277. Bibcode:1987NYASA.500..253M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37206.x. S2CID 121416910. See in particular pp. 254 & 259–260.

- ^ Jacques Sesiano, «Islamic mathematics», p. 148, in Selin, Helaine; D’Ambrosio, Ubiratan (2000). Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-0260-2..

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1928). A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol.1). La Salle, Illinois: The Open Court Publishing Company. pg. 269.

- ^ (Cajori 1928, pg.89)

- ^ Salvatore Pincherle (1880). «Saggio di una introduzione alla teoria delle funzioni analitiche secondo i principii del prof. C. Weierstrass». Giornale di Matematiche: 178–254, 317–320.

- ^ Lambert, J. H. (1761). «Mémoire sur quelques propriétés remarquables des quantités transcendentes, circulaires et logarithmiques» (PDF). Mémoires de l’Académie royale des sciences de Berlin (in French): 265–322. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-28.

- ^ Gordan, Paul (1893). «Transcendenz von e und π». Mathematische Annalen. Teubner. 43 (2–3): 222–224. doi:10.1007/bf01443647. S2CID 123203471.

- ^ Fowler, David H. (2001), «The story of the discovery of incommensurability, revisited», Neusis (10): 45–61, MR 1891736

- ^ George, Alexander; Velleman, Daniel J. (2002). Philosophies of mathematics (PDF). Blackwell. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-631-19544-0.

- ^ Lord, Nick, «Maths bite: irrational powers of irrational numbers can be rational», Mathematical Gazette 92, November 2008, p. 534.

- ^ a b Marshall, Ash J., and Tan, Yiren, «A rational number of the form aa with a irrational», Mathematical Gazette 96, March 2012, pp. 106-109.

- ^ Albert, John. «Some unsolved problems in number theory» (PDF). Department of Mathematics, University of Oklahoma. (Senior Mathematics Seminar, Spring 2008 course)

- ^ Mark Bridger (2007). Real Analysis: A Constructive Approach through Interval Arithmetic. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-470-45144-8.

- ^ Errett Bishop; Douglas Bridges (1985). Constructive Analysis. Springer. ISBN 0-387-15066-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Adrien-Marie Legendre, Éléments de Géometrie, Note IV, (1802), Paris

- Rolf Wallisser, «On Lambert’s proof of the irrationality of π», in Algebraic Number Theory and Diophantine Analysis, Franz Halter-Koch and Robert F. Tichy, (2000), Walter de Gruyer

External links[edit]

- Zeno’s Paradoxes and Incommensurability Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, 2008

The number √2 is irrational.

In mathematics, the irrational numbers (from in- prefix assimilated to ir- (negative prefix, privative) + rational) are all the real numbers that are not rational numbers. That is, irrational numbers cannot be expressed as the ratio of two integers. When the ratio of lengths of two line segments is an irrational number, the line segments are also described as being incommensurable, meaning that they share no «measure» in common, that is, there is no length («the measure»), no matter how short, that could be used to express the lengths of both of the two given segments as integer multiples of itself.

Among irrational numbers are the ratio π of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, Euler’s number e, the golden ratio φ, and the square root of two.[1] In fact, all square roots of natural numbers, other than of perfect squares, are irrational.[2]

Like all real numbers, irrational numbers can be expressed in positional notation, notably as a decimal number. In the case of irrational numbers, the decimal expansion does not terminate, nor end with a repeating sequence. For example, the decimal representation of π starts with 3.14159, but no finite number of digits can represent π exactly, nor does it repeat. Conversely, a decimal expansion that terminates or repeats must be a rational number. These are provable properties of rational numbers and positional number systems, and are not used as definitions in mathematics.

Irrational numbers can also be expressed as non-terminating continued fractions and many other ways.

As a consequence of Cantor’s proof that the real numbers are uncountable and the rationals countable, it follows that almost all real numbers are irrational.[3]

History[edit]

Set of real numbers (R), which include the rationals (Q), which include the integers (Z), which include the natural numbers (N). The real numbers also include the irrationals (RQ).

Ancient Greece[edit]

The first proof of the existence of irrational numbers is usually attributed to a Pythagorean (possibly Hippasus of Metapontum),[4] who probably discovered them while identifying sides of the pentagram.[5]

The then-current Pythagorean method would have claimed that there must be some sufficiently small, indivisible unit that could fit evenly into one of these lengths as well as the other. Hippasus, in the 5th century BC, however, was able to deduce that there was in fact no common unit of measure, and that the assertion of such an existence was in fact a contradiction. He did this by demonstrating that if the hypotenuse of an isosceles right triangle was indeed commensurable with a leg, then one of those lengths measured in that unit of measure must be both odd and even, which is impossible. His reasoning is as follows:

- Start with an isosceles right triangle with side lengths of integers a, b, and c. The ratio of the hypotenuse to a leg is represented by c:b.

- Assume a, b, and c are in the smallest possible terms (i.e. they have no common factors).

- By the Pythagorean theorem: c2 = a2+b2 = b2+b2 = 2b2. (Since the triangle is isosceles, a = b).

- Since c2 = 2b2, c2 is divisible by 2, and therefore even.

- Since c2 is even, c must be even.

- Since c is even, dividing c by 2 yields an integer. Let y be this integer (c = 2y).

- Squaring both sides of c = 2y yields c2 = (2y)2, or c2 = 4y2.

- Substituting 4y2 for c2 in the first equation (c2 = 2b2) gives us 4y2= 2b2.

- Dividing by 2 yields 2y2 = b2.

- Since y is an integer, and 2y2 = b2, b2 is divisible by 2, and therefore even.

- Since b2 is even, b must be even.

- We have just shown that both b and c must be even. Hence they have a common factor of 2. However this contradicts the assumption that they have no common factors. This contradiction proves that c and b cannot both be integers, and thus the existence of a number that cannot be expressed as a ratio of two integers.[6]

Greek mathematicians termed this ratio of incommensurable magnitudes alogos, or inexpressible. Hippasus, however, was not lauded for his efforts: according to one legend, he made his discovery while out at sea, and was subsequently thrown overboard by his fellow Pythagoreans «… for having produced an element in the universe which denied the… doctrine that all phenomena in the universe can be reduced to whole numbers and their ratios.»[7] Another legend states that Hippasus was merely exiled for this revelation. Whatever the consequence to Hippasus himself, his discovery posed a very serious problem to Pythagorean mathematics, since it shattered the assumption that number and geometry were inseparable–a foundation of their theory.

The discovery of incommensurable ratios was indicative of another problem facing the Greeks: the relation of the discrete to the continuous. This was brought into light by Zeno of Elea, who questioned the conception that quantities are discrete and composed of a finite number of units of a given size. Past Greek conceptions dictated that they necessarily must be, for «whole numbers represent discrete objects, and a commensurable ratio represents a relation between two collections of discrete objects»,[8] but Zeno found that in fact «[quantities] in general are not discrete collections of units; this is why ratios of incommensurable [quantities] appear… .[Q]uantities are, in other words, continuous».[8] What this means is that, contrary to the popular conception of the time, there cannot be an indivisible, smallest unit of measure for any quantity. That in fact, these divisions of quantity must necessarily be infinite. For example, consider a line segment: this segment can be split in half, that half split in half, the half of the half in half, and so on. This process can continue infinitely, for there is always another half to be split. The more times the segment is halved, the closer the unit of measure comes to zero, but it never reaches exactly zero. This is just what Zeno sought to prove. He sought to prove this by formulating four paradoxes, which demonstrated the contradictions inherent in the mathematical thought of the time. While Zeno’s paradoxes accurately demonstrated the deficiencies of current mathematical conceptions, they were not regarded as proof of the alternative. In the minds of the Greeks, disproving the validity of one view did not necessarily prove the validity of another, and therefore further investigation had to occur.

The next step was taken by Eudoxus of Cnidus, who formalized a new theory of proportion that took into account commensurable as well as incommensurable quantities. Central to his idea was the distinction between magnitude and number. A magnitude «…was not a number but stood for entities such as line segments, angles, areas, volumes, and time which could vary, as we would say, continuously. Magnitudes were opposed to numbers, which jumped from one value to another, as from 4 to 5».[9] Numbers are composed of some smallest, indivisible unit, whereas magnitudes are infinitely reducible. Because no quantitative values were assigned to magnitudes, Eudoxus was then able to account for both commensurable and incommensurable ratios by defining a ratio in terms of its magnitude, and proportion as an equality between two ratios. By taking quantitative values (numbers) out of the equation, he avoided the trap of having to express an irrational number as a number. «Eudoxus’ theory enabled the Greek mathematicians to make tremendous progress in geometry by supplying the necessary logical foundation for incommensurable ratios».[10] This incommensurability is dealt with in Euclid’s Elements, Book X, Proposition 9. It was not until Eudoxus developed a theory of proportion that took into account irrational as well as rational ratios that a strong mathematical foundation of irrational numbers was created.[11]

As a result of the distinction between number and magnitude, geometry became the only method that could take into account incommensurable ratios. Because previous numerical foundations were still incompatible with the concept of incommensurability, Greek focus shifted away from those numerical conceptions such as algebra and focused almost exclusively on geometry. In fact, in many cases algebraic conceptions were reformulated into geometric terms. This may account for why we still conceive of x2 and x3 as x squared and x cubed instead of x to the second power and x to the third power. Also crucial to Zeno’s work with incommensurable magnitudes was the fundamental focus on deductive reasoning that resulted from the foundational shattering of earlier Greek mathematics. The realization that some basic conception within the existing theory was at odds with reality necessitated a complete and thorough investigation of the axioms and assumptions that underlie that theory. Out of this necessity, Eudoxus developed his method of exhaustion, a kind of reductio ad absurdum that «…established the deductive organization on the basis of explicit axioms…» as well as «…reinforced the earlier decision to rely on deductive reasoning for proof».[12] This method of exhaustion is the first step in the creation of calculus.

Theodorus of Cyrene proved the irrationality of the surds of whole numbers up to 17, but stopped there probably because the algebra he used could not be applied to the square root of 17.[13]

India[edit]

Geometrical and mathematical problems involving irrational numbers such as square roots were addressed very early during the Vedic period in India. There are references to such calculations in the Samhitas, Brahmanas, and the Shulba Sutras (800 BC or earlier). (See Bag, Indian Journal of History of Science, 25(1-4), 1990).

It is suggested that the concept of irrationality was implicitly accepted by Indian mathematicians since the 7th century BC, when Manava (c. 750 – 690 BC) believed that the square roots of numbers such as 2 and 61 could not be exactly determined.[14] Historian Carl Benjamin Boyer, however, writes that «such claims are not well substantiated and unlikely to be true».[15]

It is also suggested that Aryabhata (5th century AD), in calculating a value of pi to 5 significant figures, used the word āsanna (approaching), to mean that not only is this an approximation but that the value is incommensurable (or irrational).

Later, in their treatises, Indian mathematicians wrote on the arithmetic of surds including addition, subtraction, multiplication, rationalization, as well as separation and extraction of square roots.[16]

Mathematicians like Brahmagupta (in 628 AD) and Bhāskara I (in 629 AD) made contributions in this area as did other mathematicians who followed. In the 12th century Bhāskara II evaluated some of these formulas and critiqued them, identifying their limitations.

During the 14th to 16th centuries, Madhava of Sangamagrama and the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics discovered the infinite series for several irrational numbers such as π and certain irrational values of trigonometric functions. Jyeṣṭhadeva provided proofs for these infinite series in the Yuktibhāṣā.[17]

Middle Ages[edit]

In the Middle ages, the development of algebra by Muslim mathematicians allowed irrational numbers to be treated as algebraic objects.[18] Middle Eastern mathematicians also merged the concepts of «number» and «magnitude» into a more general idea of real numbers, criticized Euclid’s idea of ratios, developed the theory of composite ratios, and extended the concept of number to ratios of continuous magnitude.[19] In his commentary on Book 10 of the Elements, the Persian mathematician Al-Mahani (d. 874/884) examined and classified quadratic irrationals and cubic irrationals. He provided definitions for rational and irrational magnitudes, which he treated as irrational numbers. He dealt with them freely but explains them in geometric terms as follows:[19]

«It will be a rational (magnitude) when we, for instance, say 10, 12, 3%, 6%, etc., because its value is pronounced and expressed quantitatively. What is not rational is irrational and it is impossible to pronounce and represent its value quantitatively. For example: the roots of numbers such as 10, 15, 20 which are not squares, the sides of numbers which are not cubes etc.«

In contrast to Euclid’s concept of magnitudes as lines, Al-Mahani considered integers and fractions as rational magnitudes, and square roots and cube roots as irrational magnitudes. He also introduced an arithmetical approach to the concept of irrationality, as he attributes the following to irrational magnitudes:[19]

«their sums or differences, or results of their addition to a rational magnitude, or results of subtracting a magnitude of this kind from an irrational one, or of a rational magnitude from it.»

The Egyptian mathematician Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam (c. 850 – 930) was the first to accept irrational numbers as solutions to quadratic equations or as coefficients in an equation, often in the form of square roots, cube roots and fourth roots.[20] In the 10th century, the Iraqi mathematician Al-Hashimi provided general proofs (rather than geometric demonstrations) for irrational numbers, as he considered multiplication, division, and other arithmetical functions.[19] Iranian mathematician, Abū Ja’far al-Khāzin (900–971) provides a definition of rational and irrational magnitudes, stating that if a definite quantity is:[19]

«contained in a certain given magnitude once or many times, then this (given) magnitude corresponds to a rational number. . . . Each time when this (latter) magnitude comprises a half, or a third, or a quarter of the given magnitude (of the unit), or, compared with (the unit), comprises three, five, or three fifths, it is a rational magnitude. And, in general, each magnitude that corresponds to this magnitude (i.e. to the unit), as one number to another, is rational. If, however, a magnitude cannot be represented as a multiple, a part (1/n), or parts (m/n) of a given magnitude, it is irrational, i.e. it cannot be expressed other than by means of roots.»

Many of these concepts were eventually accepted by European mathematicians sometime after the Latin translations of the 12th century. Al-Hassār, a Moroccan mathematician from Fez specializing in Islamic inheritance jurisprudence during the 12th century, first mentions the use of a fractional bar, where numerators and denominators are separated by a horizontal bar. In his discussion he writes, «…, for example, if you are told to write three-fifths and a third of a fifth, write thus,

Modern period[edit]

The 17th century saw imaginary numbers become a powerful tool in the hands of Abraham de Moivre, and especially of Leonhard Euler. The completion of the theory of complex numbers in the 19th century entailed the differentiation of irrationals into algebraic and transcendental numbers, the proof of the existence of transcendental numbers, and the resurgence of the scientific study of the theory of irrationals, largely ignored since Euclid. The year 1872 saw the publication of the theories of Karl Weierstrass (by his pupil Ernst Kossak), Eduard Heine (Crelle’s Journal, 74), Georg Cantor (Annalen, 5), and Richard Dedekind. Méray had taken in 1869 the same point of departure as Heine, but the theory is generally referred to the year 1872. Weierstrass’s method has been completely set forth by Salvatore Pincherle in 1880,[23] and Dedekind’s has received additional prominence through the author’s later work (1888) and the endorsement by Paul Tannery (1894). Weierstrass, Cantor, and Heine base their theories on infinite series, while Dedekind founds his on the idea of a cut (Schnitt) in the system of all rational numbers, separating them into two groups having certain characteristic properties. The subject has received later contributions at the hands of Weierstrass, Leopold Kronecker (Crelle, 101), and Charles Méray.

Continued fractions, closely related to irrational numbers (and due to Cataldi, 1613), received attention at the hands of Euler, and at the opening of the 19th century were brought into prominence through the writings of Joseph-Louis Lagrange. Dirichlet also added to the general theory, as have numerous contributors to the applications of the subject.

Johann Heinrich Lambert proved (1761) that π cannot be rational, and that en is irrational if n is rational (unless n = 0).[24] While Lambert’s proof is often called incomplete, modern assessments support it as satisfactory, and in fact for its time it is unusually rigorous. Adrien-Marie Legendre (1794), after introducing the Bessel–Clifford function, provided a proof to show that π2 is irrational, whence it follows immediately that π is irrational also. The existence of transcendental numbers was first established by Liouville (1844, 1851). Later, Georg Cantor (1873) proved their existence by a different method, which showed that every interval in the reals contains transcendental numbers. Charles Hermite (1873) first proved e transcendental, and Ferdinand von Lindemann (1882), starting from Hermite’s conclusions, showed the same for π. Lindemann’s proof was much simplified by Weierstrass (1885), still further by David Hilbert (1893), and was finally made elementary by Adolf Hurwitz[citation needed] and Paul Gordan.[25]

Examples[edit]

Square roots[edit]

The square root of 2 was likely the first number proved irrational.[26] The golden ratio is another famous quadratic irrational number. The square roots of all natural numbers that are not perfect squares are irrational and a proof may be found in quadratic irrationals.

General roots[edit]

The proof above[clarification needed] for the square root of two can be generalized using the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. This asserts that every integer has a unique factorization into primes. Using it we can show that if a rational number is not an integer then no integral power of it can be an integer, as in lowest terms there must be a prime in the denominator that does not divide into the numerator whatever power each is raised to. Therefore, if an integer is not an exact kth power of another integer, then that first integer’s kth root is irrational.

Logarithms[edit]

Perhaps the numbers most easy to prove irrational are certain logarithms. Here is a proof by contradiction that log2 3 is irrational (log2 3 ≈ 1.58 > 0).

Assume log2 3 is rational. For some positive integers m and n, we have

It follows that

The number 2 raised to any positive integer power must be even (because it is divisible by 2) and the number 3 raised to any positive integer power must be odd (since none of its prime factors will be 2). Clearly, an integer cannot be both odd and even at the same time: we have a contradiction. The only assumption we made was that log2 3 is rational (and so expressible as a quotient of integers m/n with n ≠ 0). The contradiction means that this assumption must be false, i.e. log2 3 is irrational, and can never be expressed as a quotient of integers m/n with n ≠ 0.

Cases such as log10 2 can be treated similarly.

Types[edit]

- number theoretic distinction : transcendental/algebraic

- normal/ abnormal (non-normal)

Transcendental/algebraic[edit]

Almost all irrational numbers are transcendental and all real transcendental numbers are irrational (there are also complex transcendental numbers): the article on transcendental numbers lists several examples. So e r and π r are irrational for all nonzero rational r, and, e.g., eπ is irrational, too.

Irrational numbers can also be found within the countable set of real algebraic numbers (essentially defined as the real roots of polynomials with integer coefficients), i.e., as real solutions of polynomial equations

where the coefficients

Because the algebraic numbers form a subfield of the real numbers, many irrational real numbers can be constructed by combining transcendental and algebraic numbers. For example, 3π + 2, π + √2 and e√3 are irrational (and even transcendental).

Decimal expansions[edit]

The decimal expansion of an irrational number never repeats or terminates (the latter being equivalent to repeating zeroes), unlike any rational number. The same is true for binary, octal or hexadecimal expansions, and in general for expansions in every positional notation with natural bases.

To show this, suppose we divide integers n by m (where m is nonzero). When long division is applied to the division of n by m, there can never be a remainder greater than or equal to m. If 0 appears as a remainder, the decimal expansion terminates. If 0 never occurs, then the algorithm can run at most m − 1 steps without using any remainder more than once. After that, a remainder must recur, and then the decimal expansion repeats.

Conversely, suppose we are faced with a repeating decimal, we can prove that it is a fraction of two integers. For example, consider:

Here the repetend is 162 and the length of the repetend is 3. First, we multiply by an appropriate power of 10 to move the decimal point to the right so that it is just in front of a repetend. In this example we would multiply by 10 to obtain:

Now we multiply this equation by 10r where r is the length of the repetend. This has the effect of moving the decimal point to be in front of the «next» repetend. In our example, multiply by 103:

The result of the two multiplications gives two different expressions with exactly the same «decimal portion», that is, the tail end of 10,000A matches the tail end of 10A exactly. Here, both 10,000A and 10A have .162162162… after the decimal point.

Therefore, when we subtract the 10A equation from the 10,000A equation, the tail end of 10A cancels out the tail end of 10,000A leaving us with:

Then

is a ratio of integers and therefore a rational number.

Irrational powers[edit]

Dov Jarden gave a simple non-constructive proof that there exist two irrational numbers a and b, such that ab is rational:[27]

Consider √2√2; if this is rational, then take a = b = √2. Otherwise, take a to be the irrational number √2√2 and b = √2. Then ab = (√2√2)√2 = √2√2·√2 = √22 = 2, which is rational.

Although the above argument does not decide between the two cases, the Gelfond–Schneider theorem shows that √2√2 is transcendental, hence irrational. This theorem states that if a and b are both algebraic numbers, and a is not equal to 0 or 1, and b is not a rational number, then any value of ab is a transcendental number (there can be more than one value if complex number exponentiation is used).

An example that provides a simple constructive proof is[28]

The base of the left side is irrational and the right side is rational, so one must prove that the exponent on the left side,

which we can assume, for the sake of establishing a contradiction, equals a ratio m/n of positive integers. Then

A stronger result is the following:[29] Every rational number in the interval

Open questions[edit]

It is not known if

It is not known if

In constructive mathematics[edit]

In constructive mathematics, excluded middle is not valid, so it is not true that every real number is rational or irrational. Thus, the notion of an irrational number bifurcates into multiple distinct notions. One could take the traditional definition of an irrational number as a real number that is not rational.[31] However, there is a second definition of an irrational number used in constructive mathematics, that a real number

Set of all irrationals[edit]

Since the reals form an uncountable

set, of which the rationals are a countable subset, the complementary set of

irrationals is uncountable.

Under the usual (Euclidean) distance function

the induced metric is not complete. Being a G-delta set—i.e., a countable intersection of open subsets—in a complete metric space, the space of irrationals is completely metrizable: that is, there is a metric on the irrationals inducing the same topology as the restriction of the Euclidean metric, but with respect to which the irrationals are complete. One can see this without knowing the aforementioned fact about G-delta sets: the continued fraction expansion of an irrational number defines a homeomorphism from the space of irrationals to the space of all sequences of positive integers, which is easily seen to be completely metrizable.

Furthermore, the set of all irrationals is a disconnected metrizable space. In fact, the irrationals equipped with the subspace topology have a basis of clopen sets so the space is zero-dimensional.

See also[edit]

- Brjuno number

- Computable number

- Diophantine approximation

- Proof that e is irrational

- Proof that π is irrational

- Square root of 3

- Square root of 5

- Trigonometric number

Complex

|

|

References[edit]

- ^ The 15 Most Famous Transcendental Numbers. by Clifford A. Pickover. URL retrieved 24 October 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Terence (2011-07-01). «95.42 Irrational square roots of natural numbers — a geometrical approach». The Mathematical Gazette. 95 (533): 327–330. doi:10.1017/S0025557200003193. ISSN 0025-5572. S2CID 123995083.

- ^ Cantor, Georg (1955) [1915]. Philip Jourdain (ed.). Contributions to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-60045-1.

- ^ Kurt Von Fritz (1945). «The Discovery of Incommensurability by Hippasus of Metapontum». The Annals of Mathematics.

- ^ James R. Choike (1980). «The Pentagram and the Discovery of an Irrational Number». The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal..

- ^ Kline, M. (1990). Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times, Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press (original work published 1972), p. 33.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 32.

- ^ a b Kline 1990, p. 34.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 48.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 49.

- ^ Charles H. Edwards (1982). The historical development of the calculus. Springer.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 50.

- ^ Robert L. McCabe (1976). «Theodorus’ Irrationality Proofs». Mathematics Magazine..

- ^ T. K. Puttaswamy, «The Accomplishments of Ancient Indian Mathematicians», pp. 411–2, in Selin, Helaine; D’Ambrosio, Ubiratan, eds. (2000). Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-0260-2..

- ^ Boyer (1991). «China and India». A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). p. 208. ISBN 0471093742. OCLC 414892.

It has been claimed also that the first recognition of incommensurables appears in India during the Sulbasutra period, but such claims are not well substantiated. The case for early Hindu awareness of incommensurable magnitudes is rendered most unlikely by the lack of evidence that Indian mathematicians of that period had come to grips with fundamental concepts.

- ^ Datta, Bibhutibhusan; Singh, Awadhesh Narayan (1993). «Surds in Hindu mathematics» (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 28 (3): 253–264. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ Katz, V. J. (1995), «Ideas of Calculus in Islam and India», Mathematics Magazine (Mathematical Association of America) 68 (3): 163–74.

- ^ O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (1999). «Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance?». MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews..

- ^ a b c d e Matvievskaya, Galina (1987). «The theory of quadratic irrationals in medieval Oriental mathematics». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 500 (1): 253–277. Bibcode:1987NYASA.500..253M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37206.x. S2CID 121416910. See in particular pp. 254 & 259–260.

- ^ Jacques Sesiano, «Islamic mathematics», p. 148, in Selin, Helaine; D’Ambrosio, Ubiratan (2000). Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-0260-2..

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1928). A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol.1). La Salle, Illinois: The Open Court Publishing Company. pg. 269.

- ^ (Cajori 1928, pg.89)

- ^ Salvatore Pincherle (1880). «Saggio di una introduzione alla teoria delle funzioni analitiche secondo i principii del prof. C. Weierstrass». Giornale di Matematiche: 178–254, 317–320.

- ^ Lambert, J. H. (1761). «Mémoire sur quelques propriétés remarquables des quantités transcendentes, circulaires et logarithmiques» (PDF). Mémoires de l’Académie royale des sciences de Berlin (in French): 265–322. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-28.

- ^ Gordan, Paul (1893). «Transcendenz von e und π». Mathematische Annalen. Teubner. 43 (2–3): 222–224. doi:10.1007/bf01443647. S2CID 123203471.

- ^ Fowler, David H. (2001), «The story of the discovery of incommensurability, revisited», Neusis (10): 45–61, MR 1891736

- ^ George, Alexander; Velleman, Daniel J. (2002). Philosophies of mathematics (PDF). Blackwell. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-631-19544-0.

- ^ Lord, Nick, «Maths bite: irrational powers of irrational numbers can be rational», Mathematical Gazette 92, November 2008, p. 534.

- ^ a b Marshall, Ash J., and Tan, Yiren, «A rational number of the form aa with a irrational», Mathematical Gazette 96, March 2012, pp. 106-109.

- ^ Albert, John. «Some unsolved problems in number theory» (PDF). Department of Mathematics, University of Oklahoma. (Senior Mathematics Seminar, Spring 2008 course)

- ^ Mark Bridger (2007). Real Analysis: A Constructive Approach through Interval Arithmetic. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-470-45144-8.

- ^ Errett Bishop; Douglas Bridges (1985). Constructive Analysis. Springer. ISBN 0-387-15066-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Adrien-Marie Legendre, Éléments de Géometrie, Note IV, (1802), Paris

- Rolf Wallisser, «On Lambert’s proof of the irrationality of π», in Algebraic Number Theory and Diophantine Analysis, Franz Halter-Koch and Robert F. Tichy, (2000), Walter de Gruyer

External links[edit]

- Zeno’s Paradoxes and Incommensurability Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, 2008

Слово «рациональный» (по-латински ratio — разум ) переводится как «разумный». Соответственно, слово «иррациональный» означает «неразумный».

Иррациональным числом называют действительное число, которое не является рациональным (его нельзя записать обыкновенной дробью). Иррациональное число — только бесконечная непериодическая дробь.

Если натуральное число (n) не является точным квадратом, т. е. n≠k2, где k∈ℚ, то n является иррациональным числом.

Пример:

5=2,23606798…11=3,31662479…

Число π≈ (3,141592…) также является иррациональным. Это доказал в (1766) году немецкий математик И. Ламберт. Интересно, что для этого числа была взята буква греческого алфавита «пи», так как с этой буквы начинается греческое слово периферия — окружность.

Итак,

1. в результате всякого арифметического действия над рациональными числами (помимо деления на (0)) получаем рациональное число.

2. Любое арифметическое действие над иррациональными числами может привести в итоге к рациональному или к иррациональному числу.

3. Если в арифметическом действии принимают участие рациональное и иррациональное числа, то в итоге будет иррациональное число (исключение — умножение и деление на (0)).

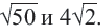

4. Т. к. в результате действий по извлечению корней (квадратного и кубического) из неотрицательного числа получается иррациональное число, определились, что иррациональным выражением считают любое алгебраическое выражение, где есть действие по извлечению квадратного и кубического корня из переменной.

Иррациональные числа: определение, примеры

Иррациональные числа известны людям с глубокой древности. Еще за несколько веков до нашей эры индийский математик Манава выяснил, что квадратные корни некоторых чисел (например, 2) невозможно выразить явно.

Данная статья является своего рода вводным уроком в тему «Иррациональные числа». Приведем определение и примеры иррациональных чисел с пояснением, а также выясним, как определить, является ли данное число иррациональным.

Иррациональные числа. Определение

Само название «иррациональные числа» как бы подсказывает нам определение. Иррациональное число — это действительное число, которое не является рациональным. Другими словами, такое число нельзя представить в виде дроби mn, где m — целое, а n — натуральное число.

Иррациональные числа — это такие числа, которые в десятичной форме записи представляют собой бесконечные непериодические десятичные дроби.

Для обозначения множества иррациональных чисел используется символ

Преподаватель математики и информатики. Кафедра бизнес-информатики Российского университета транспорта

Содержание:

Иррациональные числа

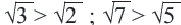

Практическая работа 1. Великий греческий математик, физик, астроном и изобретатель Архимед хотел найти рациональное число, квадрат которого равен 3. С этой целью он выбрал числа

Классификация чисел

Любое рациональное число можно записать в виде дроби

Каждую конечную десятичную дробь можно записать в виде бесконечной десятичной периодической дроби с цифрой 0 в периоде. Но есть такие числа, которые невозможно представить в виде десятичной периодической дроби. Бесконечная десятичная непериодическая дробь выражает число, которое не является рациональным. Такие числа называются иррациональными числами. Иррациональное число невозможно представить в виде

a) 0,1010010001… (количество нулей после каждой единицы увеличивается на один);

b) 0,123456789101112… (в дробной части записана последовательность натуральных чисел);

c)

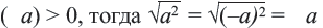

Если

Практическая работа.

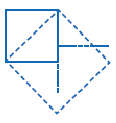

1) Начертите квадрат со стороной равной единичному отрезку и проведите диагональ данного квадрата. На диагонали квадрата постройте новый квадрат. Убедитесь, что площадь полученного квадрата в два раза больше площади единичного квадрата. Покажите, что сторона полученного квадрата равна соответственно

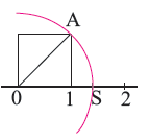

2) Повторите работу по алгоритму, представленному ниже. На координатной оси постройте квадрат, сторона которого равна единичному отрезку. Начертите окружность с центром в точке нуль, радиусом равным диагонали квадрата и отметьте точку пересечения с числовой осью. Объясните связь между соответствующим данной точке числом и длиной диагонали квадрата.

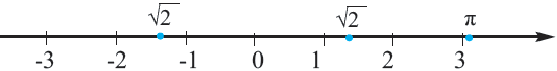

Числовая ось, рациональные, иррациональные числа

Каждой точке на числовой оси соответствует единственное число (рациональное или иррациональное) и каждому числу, на числовой оси соответствует единственная точка. Опираясь на это числа можно сравнивать. Число, соответствующее точке, которая расположена правее, больше числа, соответствующему точке, расположенной левее.

Практическая работа.

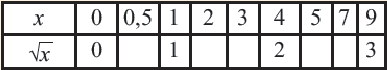

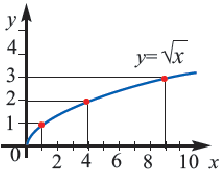

1) При помощи калькулятора вычислите значения

2) На координатной плоскости отметьте точки из таблицы, с соответствующими координатами, и соедините их плавной линией.

3) Может ли

4) Как изменяются соответствующие значения

Функция y=√x и её график

Функция

В таблице, которую вы заполнили, показаны некоторые значения аргументов

График функции

Приближенное значение квадратного корня

Практическая работа.

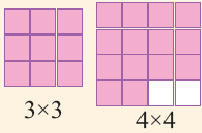

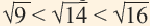

Какова наибольшая длина стороны квадрата, составленного из 14 одинаковых единичных квадратов? Как вы нашли результат? Между какими последовательными натуральными числами, являющимися точными квадратами, расположено число 14?

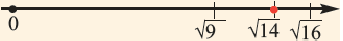

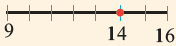

Приближённое значение квадратного корня можно найти при помощи калькулятора, но существуют и другие методы. Вычислить приближённое значение квадратного корня можно при помощи числовой оси и чисел, являющихся точными квадратами. Например, найдём при помощи данного метода,

Число 14 расположено между числами 9 и 16. Квадратные корни этих чисел соответственно равны 3 и 4. Целая часть квадратного корня из 14 равна 3. Найдём приближённое значение дробной части:

На числовой прямой от 14 до 9-ти 5 единиц, от 9-ти до 16 — 7 единиц.

Дробная часть числа

Полученное приближённое значение

Значение, найденное при помощи калькулятора

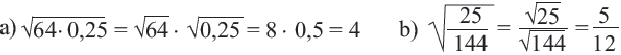

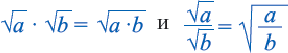

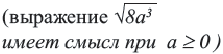

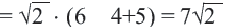

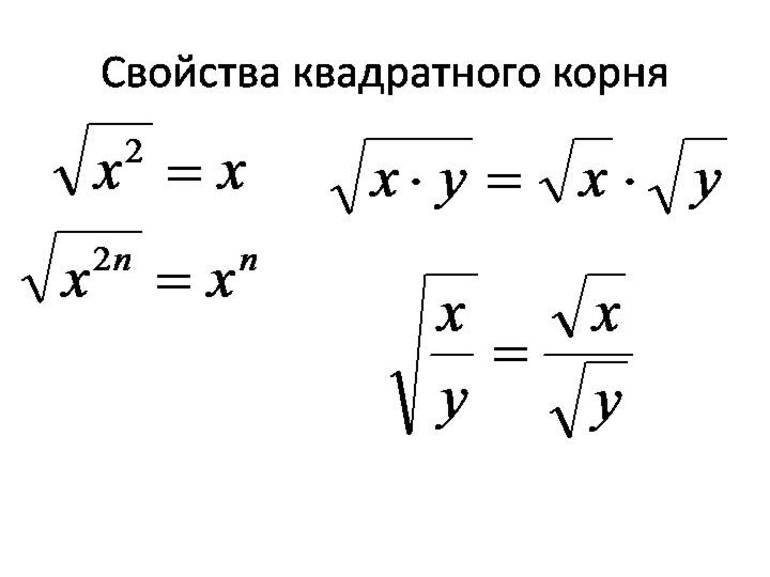

Квадратный корень из произведения и частного

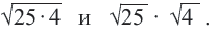

Исследование: Найдите значение выражений

Верно ли равенство?

Проверьте, что соответствующее равенство верно для любых двух неотрицательных чисел.

Квадратный корень из произведения и частного

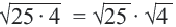

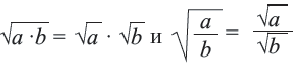

При

Корень из произведения неотрицательных множителей равен произведению корней из этих же множителей. Это свойство верно и для более двух множителей

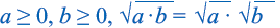

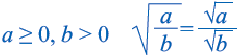

Аналогичным образом можно показать, что при

Корень из дроби, числитель которой неотрицателен, а знаменатель положителен, равен корню из числителя, деленному на корень из знаменателя.

Пример:

Пример:

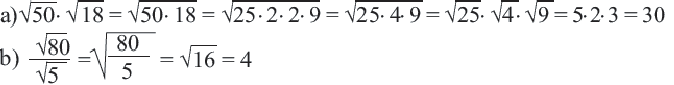

Квадратный корень степени

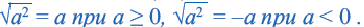

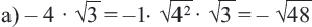

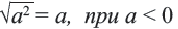

Из того, что арифметический квадратный корень не может принимать отрицательных значений, следует что равенство

Действительно, при ,

Таким образом,

Приняв во внимание, что абсолютное значение числа всегда положительное или равно нулю) и объединив два равенства, приведённых выше получим следующее

Для извлечения корня чётной степени подкоренное выражение надо записать в виде квадрата идентичного выражения, а затем применить тождество

Пример:

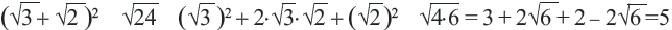

Преобразование выражений, содержащих квадратные корни

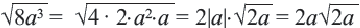

Вынесение множителя из-под знака корни

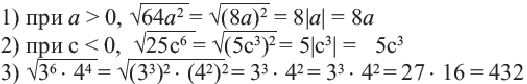

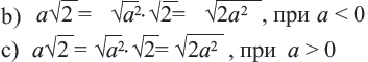

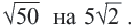

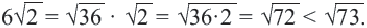

Пример 1. Сравним числа

При решении мы заменили

- Заказать решение задач по высшей математике

Пример 2.

Внесение множителя под знак корня

Пример 3. Сравним числа

Заменим число 6 на

Пример 4.

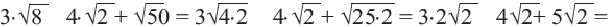

Сложение и вычитание корней, имеющих одинаковое подкоренное выражение вида

Пример:

Чему равна длина двух досок, если длина одной доски равна

Пример:

Пример:

Пример:

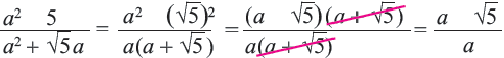

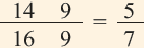

Сократите дробь.

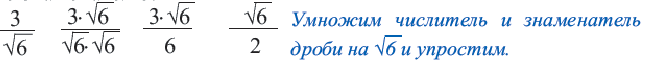

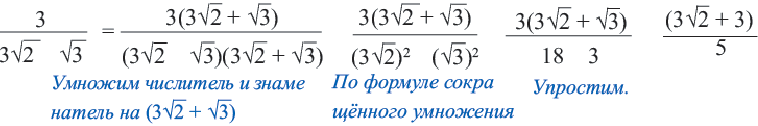

Освобождение знаменателя от иррациональности

Сумма, разность, произведение (кроме умножения на «0» ) и отношение рационального и иррационального чисел является иррациональным числом. А вот сумма, разность, произведение и отношение двух иррациональных чисел может быть рациональным числом.

Пример:

а) При

Пример:

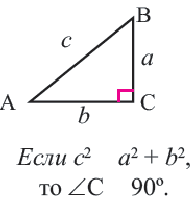

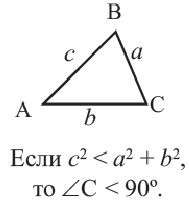

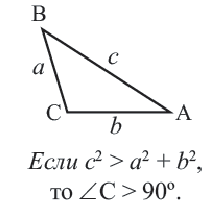

Определение вида треугольника по длинам его сторон

Пусть

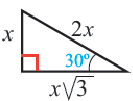

Особые прямоугольные треугольники

Теорема 1. В равнобедренном прямоугольном треугольнике гипотенузы больше любого из катетов в

Отношение сторон: 1 : 1 :

Теорема 2. В прямоугольном треугольнике с острым углом

Отношение сторон: 1 :

- Действительные числа

- Решение уравнений высших степеней

- Системы неравенств

- Квадратные неравенства

- Уравнения и неравенства содержащие знак модуля

- Уравнение

- Метод математической индукции

- Система координат в пространстве

История открытия

Одни учёные считают, что иррациональные числа были открыты Пифагором. Другие полагают, что существование таких величин было выявлено пифагорейцами в V веке до нашей эры. Третьи выдвигают версию, что открытие принадлежит древним учёным Азии.

Несмотря на то что возникновение нового типа чисел связывают с именем Пифагора, сам великий учёный этих величин не признавал. Математик основывал свои труды на рациональности значений, а потому их иные виды были неприменимы к его теориям. Из-за огромного авторитета учёного иррациональные значения стали использоваться в науке только после его смерти.

Аристотель доказал иррациональность квадратного корня из 2. Теодор из Кирены привёл подобные доказательства в отношении корня из 3, 5 и так далее. Есть версия, что даже термины для соответствующей теории ввёл этот математик. Его ученик Теэтет на основании указанных данных создал общее учение об иррациональности. Полная теория иррациональных количественных значений Эвклид изложил в пятой книге «Начал».

Понятие и характеристика

Огромным прорывом в математической науке стали числа, которые называются иррациональными. Какие-либо ограничения, связанные с целыми величинами или обыкновенными дробями, были сняты. Люди получили возможность открывать и даже изобретать новые количественные значения.

Иррациональным считается вещественное число, не являющееся рациональным. Оно не может быть представлено в виде арифметической дроби n/m, где числитель и знаменатель являются целыми величинами, а n не равно 0. Также подобные значения невозможно точно выразить целой величиной. Это значит, что иррациональные числа всегда выглядят, как бесконечные непериодические десятичные дроби. Для их обозначения применяют радикалы или специальные буквы, например, е, π. Множество чисел обозначается заглавной буквой в полужирном начертании без заливки.

В геометрии оно представляется в качестве отрезка, длина которого несоизмерима с единичной. Об этой несоизмеримости упоминали и древние математики. Они установили, что диагональ квадрата не имеет общей меры с его стороной, что равносильно иррациональности корня из 2.

Не всякая величина из множества значений, не относящихся к рациональным, так известна, как число π. В школьной программе его часто определяют, как 3,14, но истинный показатель π значительно ближе к 3. Следует отметить, что даже известная длинная десятичная дробь является лишь приближённым вариантом, поскольку указанное число нельзя точно установить. Дробь, которую используют для этого, бесконечна, а цифры в ней распределяются без какой-либо закономерности.

Самыми известными примерами таких иррациональных чисел являются:

- γ — постоянная Эйлера — Маскерони;

- ζ(3) — постоянная Апери;

- φ — золотое сечение;

- α, δ — постоянные Фейгенбаума;

- e — число;

- π — число Пи;

- ψ — сверхзолотое сечение.

Математиками составлены специальные таблицы величин, не являющихся рациональными. Но так как множество бесконечно, определить тип значения по данным таблицам довольно сложно.

Зачастую понять, что число иррационально, можно по его соответствию одному из перечисленных признаков:

- квадратный корень для любого натурального n, которое не является точным квадратом;

- e в степени x для любого рационального x, не равного 0;

- ln x для любого положительного рационального x, который не равен 1;

- π и π в степени n для любого целого n, не равного 0.

Но в ряде случаев установить иррациональность значения возможно только посредством доказательства. К примеру, школьникам часто дают задание доказать, что число log3 4 не относится к рациональным.

Отличительные качества

Значения, которые нельзя выразить дробью, существенно отличаются от других чисел. К их уникальным свойствам относятся следующие:

- Запись бесконечными десятичными дробями, не имеющими групп повторяющихся цифр.

- Результат сложения двух положительных иррациональных величин может быть рациональным, но сумма рационального и иррационального чисел будет иррациональной.

- Определение дедекиндовых сечений в множестве рациональных величин, не имеющих в нижнем классе наибольшего значения, а в верхнем — наименьшего.

- Любое вещественное или комплексное число, которое не является алгебраическим.

- Каждое значение относится или к алгебраическим, или к трансцендентным.

- Множество этих величин относится ко второй категории. Оно бесконечно и несчётно, расположено на прямой плотно. Между каждой парой составляющих его чисел всегда присутствует иррациональное значение.

Виды преобразования выражений

Иррациональные выражения содержат операцию извлечения корня. Это особые записи, состоящие из радикалов и знаков алгебраических действий.

Во время преобразования таких выражений нельзя допускать сужения области допустимых значений. С ними разрешается проводить любые из основных тождественных преобразований:

- раскрытие скобок;

- группировка подобных множителей и слагаемых;

- перестановка множителей и слагаемых;

- замена разности суммой.

В основе подобного упрощения выражений лежат действия, общие для всех количественных значений. Поэтому в процессе преобразования этих записей необходимо сохранять установленный порядок выполнения действий.

Замена исходной записи

Подкоренное выражение можно заменить тождественно равным, то есть математической записью, значение которой будет равно исходному. Следует учитывать, что равенство должно соблюдаться при любых допустимых значениях переменных, которые входят в состав обоих выражений.

Это утверждение основывается на единственности корня из числа. Иными словами, нет значения, которое, отличаясь от исходной величины, сохраняло бы равенство с нею.

Использование свойств корней

Для упрощения сложных выражений часто применяются свойства корней, к примеру, перемножение их степеней. Делать это необходимо в соответствии со специальными формулами.