Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | ита̀ло-америка́нец | ита̀ло-америка́нцы |

| Р. | ита̀ло-америка́нца | ита̀ло-америка́нцев |

| Д. | ита̀ло-америка́нцу | ита̀ло-америка́нцам |

| В. | ита̀ло-америка́нца | ита̀ло-америка́нцев |

| Тв. | ита̀ло-америка́нцем | ита̀ло-америка́нцами |

| Пр. | ита̀ло-америка́нце | ита̀ло-америка́нцах |

ита̀ло-америка́нец

Существительное, одушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 5*a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -итал-; интерфикс: -о-; корень: -америк-; интерфикс: -ан-; суффикс: -ец.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [ɪˌtaɫə ɐmʲɪrʲɪˈkanʲɪt͡s]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- то же, что италоамериканец ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

Библиография[править]

- Новые слова и значения. Словарь-справочник по материалам прессы и литературы 80-х годов / Под ред. Е. А. Левашова. — СПб. : Дмитрий Буланин, 1997.

Слово «итало-американец»

Слово состоит из 16 букв, начинается на гласную, заканчивается на согласную, первая буква — «и», вторая буква — «т», третья буква — «а», четвёртая буква — «л», пятая буква — «о», шестая буква — «-», седьмая буква — «а», восьмая буква — «м», девятая буква — «е», 10-я буква — «р», 11-я буква — «и», 12-я буква — «к», 13-я буква — «а», 14-я буква — «н», 15-я буква — «е», последняя буква — «ц».

- Написание слова наоборот

- Написание слова в транслите

- Написание слова шрифтом Брайля

- Передача слова на азбуке Морзе

- Произношение слова на дактильной азбуке

- Остальные слова из 16 букв

Невероятные приключения итальянцев в России (комедия, реж. Эльдар Рязанов, 1973 г.)

Движение вверх (2017) | Фильм в HD

когда не читаешь гайды и не шаришь за роль итало-американца

Mafia 2 #1 — Чесный итало-американец.

ITALO DISCO SUPER HITS 80s Итальянские хиты 80х Без Перерыва

![Видео [18+] ✪ Mafia 2 [ИГРОФИЛЬМ] Все катсцены+Урезанный Геймплей [PC, 1080p] (автор: Gaming Cinema)](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/HlS8daFErcE/mqdefault.jpg)

[18+] ✪ Mafia 2 [ИГРОФИЛЬМ] Все катсцены+Урезанный Геймплей [PC, 1080p]

Написание слова «итало-американец» наоборот

Как это слово пишется в обратной последовательности.

ценакирема-олати 😀

Написание слова «итало-американец» в транслите

Как это слово пишется в транслитерации.

в армянской🇦🇲 իտալո-ամերիկանեց

в грузинской🇬🇪 ითალო-ამერიკანეც

в еврейской🇮🇱 יטאלו-אמאריכאנאצ

в латинской🇬🇧 italo-amerikanets

Как это слово пишется в пьюникоде — Punycode, ACE-последовательность IDN

xn—-7sbbaybpesfnqf6aw1f

Как это слово пишется в английской Qwerty-раскладке клавиатуры.

bnfkj-fvthbrfytw

Написание слова «итало-американец» шрифтом Брайля

Как это слово пишется рельефно-точечным тактильным шрифтом.

⠊⠞⠁⠇⠕⠤⠁⠍⠑⠗⠊⠅⠁⠝⠑⠉

Передача слова «итало-американец» на азбуке Морзе

Как это слово передаётся на морзянке.

⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ – – – – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – – – ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ – – ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅

Произношение слова «итало-американец» на дактильной азбуке

Как это слово произносится на ручной азбуке глухонемых (но не на языке жестов).

Передача слова «итало-американец» семафорной азбукой

Как это слово передаётся флажковой сигнализацией.

Остальные слова из 16 букв

Какие ещё слова состоят из такого же количества букв.

- абажуродержатель

- аббревиироваться

- абдоминопластика

- аберрировавшийся

- аберрометрически

- аберроскопически

- абиогенетический

- аблактировавшись

- аболиционистский

- абордировавшийся

- абортировавшийся

- абразивоструйное

- абразивоструйщик

- абрютировавшийся

- абсолютизировать

- абсолютизируемый

- абсолютизирующий

- абсолютировавший

- абсолютироваться

- абсолютирующийся

- абсорбировавшись

- абстрагировавший

- абстрагированный

- абстрагироваться

×

Здравствуйте!

У вас есть вопрос или вам нужна помощь?

Спасибо, ваш вопрос принят.

Ответ на него появится на сайте в ближайшее время.

Народный словарь великого и могучего живого великорусского языка.

Онлайн-словарь слов и выражений русского языка. Ассоциации к словам, синонимы слов, сочетаемость фраз. Морфологический разбор: склонение существительных и прилагательных, а также спряжение глаголов. Морфемный разбор по составу словоформ.

По всем вопросам просьба обращаться в письмошную.

Что Такое итало-американец- Значение Слова итало-американец

Русский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | ита̀ло-америка́нец | ита̀ло-америка́нцы |

| Р. | ита̀ло-америка́нца | ита̀ло-америка́нцев |

| Д. | ита̀ло-америка́нцу | ита̀ло-америка́нцам |

| В. | ита̀ло-америка́нца | ита̀ло-америка́нцев |

| Тв. | ита̀ло-америка́нцем | ита̀ло-америка́нцами |

| Пр. | ита̀ло-америка́нце | ита̀ло-америка́нцах |

ита̀ло-америка́нец

Существительное, одушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 5*a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -итал-; интерфикс: -о-; корень: -америк-; интерфикс: -ан-; суффикс: -ец.

Произношение

- МФА: [ɪˌtaɫə ɐmʲɪrʲɪˈkanʲɪt͡s]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- то же, что италоамериканец ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

Гиперонимы

Гипонимы

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

Библиография

- Новые слова и значения. Словарь-справочник по материалам прессы и литературы 80-х годов / Под ред. Е. А. Левашова. — СПб. : Дмитрий Буланин, 1997.

Орфографический словарь русского языка (онлайн)

Как пишется слово «итало-американский» ?

Правописание слова «итало-американский»

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

ита́ло-америка́нский

Рядом по алфавиту:

исщипа́ть(ся) , -иплю́(сь), -и́плет(ся), -и́плют(ся) и -и́пет(ся), -и́пят(ся), также -а́ю(сь), -а́ет(ся) (к щипа́ть)

исщи́пывание , -я

исщи́пывать(ся) , -аю(сь), -ает(ся)

и та́к , (уже́) (и без того)

и так да́лее , (и т. д.)

и та́к и ся́к

и та́к и э́так

ИТ , [итэ́] и [айти́], нескл., мн. (сокр.: информационные технологии)

итабири́т , -а

ита́к , вводн. сл.; но (сочетание союза с наречием) и та́к

итако́новый

итали́йский

итали́йцы , -ев, ед. -и́ец, -и́йца, тв. -и́йцем

ита́лики , -ов, ед. -ик, -а

ита́ло-австри́йский

ита́ло-америка́нский

ита́ло-герма́нский

ита́ло-гре́ческий

ита́ло-росси́йский

ита́ло-туре́цкий

ита́ло-швейца́рский

италорома́нский

италоязы́чный

италья́нистый

италья́нка , -и, р. мн. -нок

италья́ночка , -и, р. мн. -чек

италья́нский , (к Ита́лия и италья́нцы)

италья́нско-ру́сский

италья́нцы , -ев, ед. -нец, -нца, тв. -нцем

италья́нщина , -ы

италья́шка , -и, р. мн. -шек, м. (сниж.)

This article is about Italians and their descendants in America. For the 1974 Martin Scorsese documentary film, see Italianamerican.

|

Italoamericani |

|---|

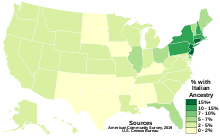

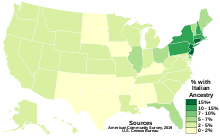

Americans with Italian ancestry by state according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey in 2019 |

| Total population |

| 17,767,630 (4.8%) alone or in combination

5,953,262 (1.8%) Italian alone 12,183,692 (1980)[7] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Northeastern United States (parts of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut and Rhode Island); Illinois (especially Chicago); also, parts of Baltimore–Washington, Ohio, St. Louis, Kansas City, Milwaukee, Detroit; parts of California (such as Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego), Florida (particularly the southern part of the state) and the Atlantic coast, Louisiana (especially New Orleans), with growing populations in Denver, Las Vegas, Phoenix and Albuquerque |

| Languages |

Italian American pidgin[8][9] |

| Religion |

| Predominantly Catholicism with small minorities practicing Protestantism and Judaism |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Italian Argentines, Italian Brazilians, Italian Chileans, Italian Venezuelans, Italian Uruguayans, Italian Peruvians, Italian Canadians, Italian Mexicans, Italian Australians, Italian South Africans, Italian Britons, Italian New Zealanders, Sicilian Americans, Corsican Americans, Corsican-Puerto Ricans, Maltese Americans, and other Italians |

Italian Americans (Italian: italoamericani or italo-americani, pronounced [ˌitaloameriˈkaːni]) are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, with significant communities also residing in many other major U.S. metropolitan areas.[10]

Between 1820 and 2004 approximately 5.5 million Italians migrated from Italy to the United States, in several distinct waves, with the greatest number arriving in the 20th century from Southern Italy. Initially, many Italian immigrants (usually single men), so-called «birds of passage», sent remittance back to their families in Italy and, eventually, returned to Italy; however, many other immigrants eventually stayed in the United States, creating the large Italian American communities that exist today.[11]

In 1870, prior to the large wave of Italian immigrants to the United States, there were fewer than 25,000 Italian immigrants in America, many of them Northern Italian refugees from the wars that accompanied the Risorgimento—the struggle for Italian reunification and independence from foreign rule which ended in 1870.[12]

Immigration began to increase during the 1870s, when more than twice as many Italians immigrated than during the five previous decades combined.[13][14] The 1870s were followed by the greatest surge of immigration, which occurred between 1880 and 1914 and brought more than 4 million Italians to the United States,[13][14] the largest number coming from the Southern Italian regions of Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily, which were still mainly rural and agricultural and where much of the populace had been impoverished by centuries of foreign rule and the heavy tax burdens levied after unification of Italy in 1861.[15][16][17] This period of large-scale immigration ended abruptly with the onset of World War I in 1914 and, except for one year (1922), never fully resumed, though many Italians managed to immigrate despite new quota-based immigration restrictions. Italian immigration was limited by several laws Congress passed in the 1920s, such as the Immigration Act of 1924, which was specifically intended to reduce immigration from Italy and other Southern European countries, as well as immigration from Eastern European countries, by restricting annual immigration per country to a number proportionate to each nationality’s existing share of the U.S. population in 1920, as determined by the National Origins Formula (which calculated Italy to be the fifth-largest national origin of the U.S., to be allotted 3.87% of annual quota immigrant spots).[18][19][20][21][22][23]

Following Italian unification, the Kingdom of Italy initially encouraged emigration to relieve economic pressures in Southern Italy.[17] After the American Civil War, which resulted in over a half million killed or wounded, immigrant workers were recruited from Italy and elsewhere to fill the labor shortage caused by the war. In the United States, most Italians began their new lives as manual laborers in eastern cities, mining camps and farms.[24] Italians settled mainly in the Northeastern U.S. and other industrial cities in the Midwest where working-class jobs were available. The descendants of the Italian immigrants steadily rose from a lower economic class in the first and second generation to a level comparable to the national average by 1970. The Italian community has often been characterized by strong ties to family, the Catholic Church, fraternal organizations, and political parties.[25]

History[edit]

Age of Discovery and early settlement[edit]

Christopher Columbus (Italian: Cristoforo Colombo) leads an expedition to the New World, 1492. His voyages are celebrated as the discovery of the Americas from a European perspective, and they opened a new era in the history of humankind and sustained contact between the two worlds.

Italian[27] navigators and explorers played a key role in the exploration and settlement of the Americas by Europeans. Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus (Italian: Cristoforo Colombo [kriˈstɔːforo koˈlombo]) completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean for the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, opening the way for the widespread European exploration and colonization of the Americas.

Another Italian, John Cabot (Italian: Giovanni Caboto [dʒoˈvanni kaˈbɔːto]), together with his son Sebastian, explored the eastern seaboard of North America for Henry VII in the early 16th century. In 1524 the Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano was the first European to map the Atlantic coast of today’s United States, and to enter New York Bay.[28]

Verrazzano’s voyage of 1524. The Italian explorer was the first documented European to enter New York Harbor and the Hudson River.

A number of Italian navigators and explorers in the employ of Spain and France were involved in exploring and mapping their territories, and in establishing settlements; but this did not lead to the permanent presence of Italians in America. In 1539 Marco da Nizza explored the territory that later became the states of Arizona and New Mexico.

The first Italian to be registered as residing in the area corresponding to the current U.S. was Pietro Cesare Alberti,[29] a Venetian seaman who, in 1635, settled in what would eventually become New York City.

A small wave of Protestants, known as Waldensians, who were of French and northern Italian heritage (specifically Piedmontese), occurred during the 17th century. The first Waldensians began arriving around 1640, with the majority coming between 1654 and 1663.[30] They spread out across what was then called New Netherland, and what would become New York, New Jersey and the Lower Delaware River regions. The total American Waldensian population that immigrated to New Netherland is currently unknown; however, a 1671 Dutch record indicates that, in 1656 alone, the Duchy of Savoy near Turin, Italy, had exiled 300 Waldensians due to their Protestant faith.

Henri de Tonti (Enrico de Tonti), together with the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, explored the Great Lakes region. De Tonti founded the first European settlement in Illinois in 1679, and in Arkansas in 1683. With LaSalle, he co-founded New Orleans, and was governor of the Louisiana Territory for the next 20 years. His brother Alphonse de Tonty (Alfonso de Tonti), with French explorer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, was the co-founder of Detroit in 1701, and was its acting colonial governor for 12 years.

Spain and France were Catholic countries and sent many missionaries to convert the native American population. Included among these missionaries were numerous Italians. In 1519–25, Alessandro Geraldini was the first Catholic bishop in the Americas, at Santo Domingo. Father François-Joseph Bressani (Francesco Giuseppe Bressani) labored among the Algonquin and Huron peoples in the early 17th century. The southwest and California were explored and mapped by Italian Jesuit priest Eusebio Kino (Chino) in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. His statue, commissioned by the state of Arizona, is displayed in the United States Capitol Visitor Center.

The Taliaferro family (originally Tagliaferro), believed to have roots in Venice, was one of the First Families to settle Virginia. The Wythe House, a historic Georgian home built in Williamsburg, Virginia in 1754, was designed by architect Richard Taliaferro for his son-in-law, American Founding Father George Wythe, who married Richard’s daughter Elizabeth Taliaferro. The elder Taliaferro designed much of Colonial Williamsburg including the Governor’s Palace, the Capitol of the Colony of Virginia, and the President’s House at the College of William & Mary.[31]

Francesco Maria de Reggio, an Italian nobleman of the House of Este who served under the French as François Marie, Chevalier de Reggio, came to Louisiana in 1747 where King Louis XV appointed him Captain General of French Louisiana, until 1763.[32] Scion of the De Reggios, a Louisiana Creole first family of St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, Francesco Maria’s granddaughter Hélène Judith de Reggio would give birth to famed Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard.[33]

A colonial merchant, Francis Ferrari of Genoa, was naturalized as a citizen of Rhode Island in 1752.[34] He died in 1753 and in his will speaks of Genoa, his ownership of three ships, cargo of wine and his wife Mary,[35] who went on to own one of the oldest coffee houses in America, the Merchant Coffee House of New York on Wall Street at Water St. Her Merchant Coffee House moved across Wall Street in 1772, retaining the same name and patronage.[36]

Today, the descendants of the Alberti-Burtis, Taliaferro, Fonda, Reggio and other early families are found all across the United States.[37]

War of Independence, late eighteenth and early nineteenth century[edit]

This period saw a small stream of new arrivals from Italy. Some brought skills in agriculture and the making of glass, silk and wine, while others brought skills as musicians.

In 1773–1785, Filippo Mazzei, a physician and promoter of liberty, was a close friend and confidant of Thomas Jefferson. He published a pamphlet containing the phrase: «All men are by nature equally free and independent»,[38] which Jefferson incorporated essentially intact into the Declaration of Independence.

Italian Americans served in the American Revolutionary War both as soldiers and officers. Francesco Vigo aided the colonial forces of George Rogers Clark during the American Revolutionary War by being one of the foremost financiers of the Revolution in the frontier Northwest. Later, he was a co-founder of Vincennes University in Indiana.

After American independence numerous political refugees arrived, most notably: Giuseppe Avezzana, Alessandro Gavazzi, Silvio Pellico, Federico Confalonieri, and Eleuterio Felice Foresti. Giuseppe Garibaldi resided in the United States in 1850–51. At the invitation of Thomas Jefferson, Carlo Bellini became the first professor of modern languages at the College of William & Mary, in the years 1779–1803.[39][40]

In 1801, Philip Trajetta (Filippo Traetta) established the nation’s first conservatory of music in Boston, where, in the first half of the century, organist Charles Nolcini and conductor Louis Ostinelli were also active.[41] In 1805 Thomas Jefferson recruited a group of musicians from Sicily to form a military band, later to become the nucleus of the U.S. Marine Band. The musicians included the young Venerando Pulizzi, who became the first Italian director of the band, and served in this capacity from 1816 to 1827.[42] Francesco Maria Scala, an Italian-born naturalized American citizen, was one of the most important and influential directors of the U.S. Marine Band, from 1855 to 1871, and was credited with the instrumental organization the band still maintains. Joseph Lucchesi, the third Italian leader of the U.S. Marine Band, served from 1844 to 1846.[43] The first opera house in the country opened in 1833 in New York through the efforts of Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart’s former librettist, who had immigrated to America and had become the first professor of Italian at Columbia College in 1825.

During this period Italian explorers continued to be active in the West. In 1789–91 Alessandro Malaspina mapped much of the west coast of the Americas, from Cape Horn to the Gulf of Alaska. In 1822–23 the headwater region of the Mississippi was explored by Giacomo Beltrami in the territory that was later to become Minnesota, which named a county in his honor.

Joseph Rosati was named the first Catholic bishop of St. Louis in 1824. In 1830–64 Samuel Mazzuchelli, a missionary and expert in Indian languages, ministered to European colonists and Native Americans in Wisconsin and Iowa for 34 years and, after his death, was declared Venerable by the Catholic Church. Father Charles Constantine Pise, a Jesuit, served as Chaplain of the Senate from 1832 to 1833,[44][45] the only Catholic priest ever chosen to serve in this capacity.

In 1833, Lorenzo Da Ponte, formerly Mozart’s librettist, and a naturalized U.S. citizen, founded the first opera house in the United States, the Italian Opera House in New York City, which was the predecessor of the New York Academy of Music and of the New York Metropolitan Opera.

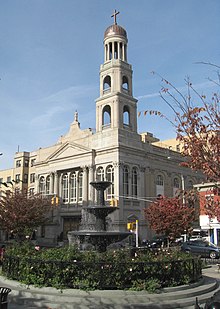

Missionaries of the Jesuit and Franciscan orders were active in many parts of America. Italian Jesuits founded numerous missions, schools and two colleges in the west. Giovanni Nobili founded the Santa Clara College (now Santa Clara University) in 1851. The St. Ignatius Academy (now University of San Francisco) was established by Anthony Maraschi in 1855. The Italian Jesuits also laid the foundation for the wine-making industry that would later flourish in California. In the east, the Italian Franciscans founded hospitals, orphanages, schools, and the St. Bonaventure College (now St. Bonaventure University), established by Panfilo da Magliano in 1858.

In 1837, John Phinizy (Finizzi) became the mayor of Augusta, Georgia. Samuel Wilds Trotti of South Carolina was the first Italian American to serve in the U.S. Congress (a partial term, from December 17, 1842, to March 3, 1843).[46]

In 1849, Francesco, de Casale began publishing the Italian American newspaper L’Eco d’Italia in New York, the first of many to eventually follow. In 1848 Francis Ramacciotti, piano string inventor and manufacturer, immigrated to the U.S. from Tuscany.

Civil War and late 19th century[edit]

Approximately 7,000 Italian Americans served in the American Civil War. The great majority of Italian Americans, for both demographic and ideological reasons, served in the Union Army (including generals Edward Ferrero and Francis B. Spinola), though some Americans of Italian descent from the Southern states fought in the Confederate Army, such as General William B. Taliaferro (of English-American and Anglo-Italian descent) and P. G. T. Beauregard.[33] The Garibaldi Guard recruited volunteers for the Union Army from Italy and other European countries to form the 39th New York Infantry.[47] Six Italian Americans received the Medal of Honor during the war, among whom was Colonel Luigi Palma di Cesnola, who later became the first Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Arts in New York (1879-1904).

Beginning in 1863, Italian immigrants were one of the principal groups, along with the Irish, that built the Transcontinental Railroad west from Omaha, Nebraska.[48]

In 1866 Constantino Brumidi completed the frescoed interior of the United States Capitol dome in Washington, and spent the rest of his life executing still other artworks to beautify the Capitol.

The first Columbus Day celebration was organized by Italian Americans in San Francisco in 1869.[49]

An immigrant, Antonio Meucci, brought with him a concept for the telephone. He is credited by many researchers with being the first to demonstrate the principle of the telephone in a patent caveat he submitted to the U.S. Patent Office in 1871; however, considerable controversy existed relative to the priority of invention, with Alexander Graham Bell also being accorded this distinction. (In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution on Meucci (H.R. 269) declaring that «his work in the invention of the telephone should be acknowledged.»)[50]

During this period, Italian Americans established a number of institutions of higher learning. Las Vegas College (now Regis University) was established by a group of exiled Italian Jesuits in 1877 in Las Vegas, New Mexico. The Jesuit Giuseppe Cataldo, founded Gonzaga College (now Gonzaga University) in Spokane, Washington in 1887. In 1886, Rabbi Sabato Morais, a Jewish Italian immigrant, was one of the founders and first president of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York. Also during this period, there was a growing presence of Italian Americans in higher education. Vincenzo Botta was a distinguished professor of Italian at New York University from 1856 to 1894,[51] and Gaetano Lanza was a professor of mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for over 40 years, beginning in 1871.[52]

Italian Americans continued their involvement in politics. Anthony Ghio became the mayor of Texarkana, Texas in 1880. Francis B. Spinola, the first Italian American to serve a full term in Congress, was elected in 1887 from New York.

The great Italian diaspora (1880–1914)[edit]

The «Bambinos» of Little Italy — Syracuse, New York in 1899

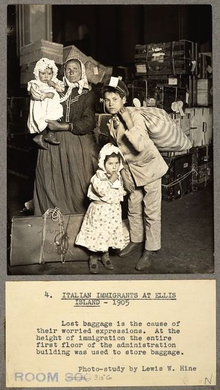

Italian immigrants entering the United States via Ellis Island in 1905

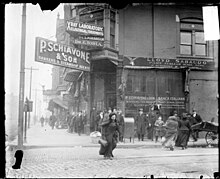

Little Italy in Chicago, 1909

From 1880 to 1914, 13 million Italians migrated out of Italy, making Italy the scene of one of the largest voluntary emigration in recorded world history.[53] During this period of mass migration, 4 million Italians arrived in the United States, 3 million of them between 1900 and 1914. Most planned to stay a few years, then take their earnings and return home. The immigrants often faced great challenges. Unskilled immigrants found employment primarily in low-wage manual-labor jobs and, if unable to find jobs on their own, turned to the padrone system whereby Italian middlemen (padroni) found jobs for groups of men and controlled their wages, transportation, and living conditions for a fee.[54][55]

According to historian Alfred T. Banfield:

- Criticized by many as slave traders who preyed upon poor, bewildered peasants, the ‘padroni’ often served as travel agents, with fees reimbursed from paychecks, as landlords who rented out shacks and boxcars, and as storekeepers who extended exorbitant credit to their Italian laborer clientele. Despite such abuse, not all ‘padroni’ were dastardly and most Italian immigrants reached out to their ‘padroni’ for economic salvation, considering them either as godsends or necessary evils. The Italians whom the ‘padroni’ brought to Maine generally had no intention of settling there, and most were sojourners who either returned to Italy or moved on to another job somewhere else. Nevertheless, thousands of Italians did settle in Maine, creating «Little Italies» in Portland, Millinocket, Rumford, and other towns where the ‘padroni’ remained as strong shaping forces in the new communities.[56]

In terms of the push-pull model of immigration,[57] America provided the pull factor by the prospect of jobs that unskilled uneducated Italian peasant farmers could do. Peasant farmers accustomed to hard work in the Mezzogiorno, for example, took jobs building railroads and constructing buildings, while others took factory jobs that required little or no skill.[58]

The push factor came from Italian unification in 1861, which caused economic conditions to considerably worsen for many. Major factors that contributed to the large exodus from both northern and southern Italy after unification included political and social unrest, the government’s allocation of much more of its resources to the industrialization of the North than to that of the South, an inequitable tax burden on the South, tariffs on the products of the South, soil exhaustion and erosion, and military conscription lasting seven years.[17] The poor economic situation following unification became untenable for many sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and small business and land owners. Multitudes chose to emigrate rather than face the prospect of a deepening poverty. A large number of these were attracted to the U.S., which at the time was actively recruiting workers from Italy and elsewhere to fill the labor shortage that existed in the years following the Civil War. Often the father and older sons would go first, leaving the mother and the rest of the family behind until the male members could afford their passage.

Many sought housing in the older sections of the large Northeastern cities where they settled, that became known as «Little Italies», frequently in overcrowded substandard tenements which were often dimly lit with poor heating and ventilation. Tuberculosis and other communicable diseases were a constant health threat for the immigrant families that were compelled by economic circumstances to live in these dwellings. Other immigrant families lived in single-family abodes, which was more typical in areas outside of the enclaves of the large Northeastern cities, and other parts of the country as well.

An estimated 49 per cent of Italians who migrated to the Americas between 1905 (when return migration statistics began) and 1920 did not remain in the United States.[59] These so-called «birds of passage», intended to stay in the United States for only a limited time, followed by a return to Italy with enough in savings to re-establish themselves there.[60] While many did return to Italy, others chose to stay, or were prevented from returning by the outbreak of World War I.

The Italian male immigrants in the Little Italies were most often employed in manual labor and were heavily involved in public works, such as the construction of roads, railroad tracks, sewers, subways, bridges and the first skyscrapers in the northeastern cities. As early as 1890, it was estimated that around 90 percent of New York City’s and 99% of Chicago’s public works employees were Italians.[61] The women most frequently worked as seamstresses in the garment industry or in their homes. Many established small businesses in the Little Italies to satisfy the day-to-day needs of fellow immigrants.

A New York Times article from 1895 provides a glimpse into the status of Italian immigration at the turn of the century. The article states:

- Of the half million Italians that are in the United States, about 100,000 live in the city, and including those who live in Brooklyn, Jersey City, and the other suburbs the total number in the vicinity is estimated at about 160,000. After learning our ways they become good, industrious citizens.[62]

The New York Times in May 1896 sent its reporters to characterize the Little Italy/Mulberry neighborhood:

- They are laborers; toilers in all grades of manual work; they are artisans, they are junkmen, and here, too, dwell the rag pickers….There is a monster colony of Italians who might be termed the commercial or shop keeping community of the Latins. Here are all sorts of stores, pensions, groceries, fruit emporiums, tailors, shoemakers, wine merchants, importers, musical instrument makers….There are notaries, lawyers, doctors, apothecaries, undertakers…. There are more bankers among the Italians than among any other foreigners except the Germans in the city.[63]

The masses of Italian immigrants that entered the United States (1890-1900) posed a change in the labor market, prompting Fr. Michael J. Henry to write a letter in October 1900 to the Bishop John J. Clency of Sligo, Ireland; warning:[64]

- [that unskilled young Irishmen] would have to enter into competition with their pick-axe and shovel against other nationalities — Italians, Poles etc. to eke out bare existence. The Italians are more economic, can live on poor fare and consequently can afford to work for less wages than the ordinary Irishman

The Brooklyn Eagle in a 1900 article addressed the same reality:[64]

- The day of the Irish hod-carrier has long been past … But it is the Italian now that does the work. Then came the Italian carpenter and finally the mason and the bricklayer

In spite of the economic hardship of the immigrants, civil and social life flourished in the Italian American neighborhoods of the large Northeastern cities. Italian theater, band concerts, choral recitals, puppet shows, mutual-aid societies, and social clubs were available to the immigrants.[65] An important event, the «festa», became for many an important connection to the traditions of their ancestral villages in Italy. The festa involved an elaborate procession through the streets in honor of a patron saint or the Virgin Mary in which a large statue was carried by a team of men, with musicians marching behind. Followed by food, fireworks and general merriment, the festa became an important occasion that helped give the immigrants a sense of unity and common identity.

An American teacher who had studied in Italy, Sarah Wool Moore was so concerned with grifters luring immigrants into rooming houses or employment contracts in which the bosses got kickbacks that she pressed for the founding of the Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants (often called the Society for Italian Immigrants). The Society published lists of approved living quarters and employers. Later, the organization began establishing schools in work camps to help adult immigrants learn English.[66][67] Wool and the Society began organizing schools in the labor camps which employed Italian workers on various dam and quarry projects in Pennsylvania and New York. The schools focused on teaching phrases that workers needed in their everyday tasks.[68] Because of the Society’s success in helping immigrants, they received a commendation from the Commissioner of Emigration for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1907.[69]

The destinations of many of the Italian immigrants were not only the large cities of the East Coast, but also more remote regions of the country, such as Florida and California. They were drawn there by opportunities in agriculture, fishing, mining, railroad construction, lumbering and other activities underway at the time. Oftentimes, the immigrants contracted to work in these areas of the country as a condition for payment of their passage. It was not uncommon, especially in the South, for the immigrants to be subjected to economic exploitation, hostility and sometimes even violence.[70] The Italian laborers who went to these areas were in many cases later joined by wives and children, which resulted in the establishment of permanent Italian American settlements in diverse parts of the country. A number of towns, such as Roseto, Pennsylvania,[71] Tontitown, Arkansas,[72] and Valdese, North Carolina[73] were founded by Italian immigrants during this era.

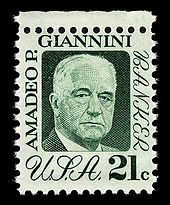

A number of major business ventures were founded by Italian Americans. Amadeo Giannini originated the concept of branch banking to serve the Italian American community in San Francisco. He founded the Bank of Italy, which later became the Bank of America. His bank also provided financing to the film industry developing on the West Coast at the time, including that for Walt Disney’s Snow White, the first full-length animated motion picture to be made in the U.S. Other companies founded by Italian Americans – such as Ghirardelli Chocolate Company, Progresso, Planters Peanuts, Contadina, Chef Boyardee, Italian Swiss Colony wines and Jacuzzi – became nationally known brand names in time. An Italian immigrant, Italo Marciony (Marcioni), is credited with inventing the earliest version of an ice cream cone in 1898. Another Italian immigrant, Giuseppe Bellanca, brought with him in 1912 an advanced aircraft design, which he began producing. It was Charles Lindbergh’s first choice for his flight across the Atlantic, but other factors ruled this out; however, one of Bellanca’s planes, piloted by Cesare Sabelli and George Pond, made one of the first non-stop trans-Atlantic flights in 1934.[74] A number of Italian immigrant families, including Grucci, Zambelli and Vitale, brought with them expertise in fireworks displays, and their pre-eminence in this field has continued to the present day.

Following in the footsteps of Constantino Brumidi, other Italians and their descendants helped create Washington’s impressive monuments. An Italian immigrant, Attilio Piccirilli, and his five brothers carved the Lincoln Memorial, which they began in 1911 and completed in 1922. Italian construction workers helped build Washington’s Union Station, considered one of the most beautiful in the country, which was begun in 1905 and completed in 1908. The six statues that decorate the station’s facade were sculpted by Andrew Bernasconi between 1909 and 1911. Two Italian American master stone carvers, Roger Morigi and Vincent Palumbo, spent decades creating the sculptural works that embellish Washington National Cathedral.[75]

Italian conductors contributed to the early success of the Metropolitan Opera of New York (founded in 1880), but it was the arrival of impresario Giulio Gatti-Casazza in 1908, who brought with him conductor Arturo Toscanini, that made the Met an internationally known musical organization. Many Italian operatic singers and conductors were invited to perform for American audiences, most notably, tenor Enrico Caruso. The premiere of the opera La Fanciulla del West on December 10, 1910, with conductor Toscanini and tenor Caruso, and with the composer Giacomo Puccini in attendance, was a major international success as well as an historic event for the entire Italian American community.[76] Francesco Fanciulli (1853-1915) succeeded John Philip Sousa as the director of United States Marine Band, serving in this capacity from 1892 to 1897.[77]

Italian Americans became involved in entertainment and sports. Rudolph Valentino was one of the first great film icons. Dixieland jazz music had a number of important Italian American innovators, the most famous being Nick LaRocca of New Orleans, whose quintet made the first jazz recording in 1917. The first Italian American professional baseball player, Ping Bodie (Francesco Pizzoli), began playing for the Chicago White Sox in 1912. Ralph DePalma won the Indianapolis 500 in 1915.

Italian Americans became increasingly involved in politics, government and the labor movement. Andrew Longino was elected Governor of Mississippi in 1900. Charles Bonaparte was Secretary of the Navy and later Attorney General in the Theodore Roosevelt administration, and founded the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[78][79] Joe Petrosino was a New York City Police Department (NYPD) officer who was a pioneer in the fight against organized crime. Crime fighting techniques that Petrosino pioneered are still practiced by law enforcement agencies. Salvatore A. Cotillo was the first Italian-American to serve in both houses of the New York State Legislature and the first who served as Justice of the New York State Supreme Court. Fiorello La Guardia was elected from New York in 1916 to serve in the US Congress. Numerous Italian Americans were at the forefront in fighting for worker’s rights in industries such as the mining, textiles and garment industries, the most notable among these being Arturo Giovannitti, Carlo Tresca and Joseph Ettor.

World War I and interwar period[edit]

The United States entered World War I in 1917. The Italian American community wholeheartedly supported the war effort and its young men, both American-born and Italian-born, enlisted in large numbers in the American Army.[80] It was estimated that, during the two years of the war (1917–18), Italian-American servicemen made up approximately 12% of the total American forces, a disproportionately high percentage of the total.[81] An Italian-born American infantryman, Michael Valente, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his service. Another 103 Italian Americans (83 Italian born) were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest decoration.[82] Italian Americans also accounted for more than 10% of war casualties World War I, despite making up less than 4% of the U.S. population.[83]

The war, together with the restrictive Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and Immigration Act of 1924, heavily curtailed Italian immigration. Total annual immigration was capped at 357,000 in 1921, lowered to 150,000 in 1924, and quotas were allotted on a national basis in proportion to a nationality’s existing share of the population. The National Origins Formula, which sought to preserve the existing demographic makeup of the United States and generally favored Northwestern European immigration, computed Italians to be the fifth-largest national origin of the U.S. population in 1920, to be assigned 3.87% of annual quota immigrant spots.[18][19] Despite implementation of the quota, the inflow of Italian immigrants remained between 6 or 7% of all immigrants.[84][85][86] And when the restrictive quota system was abolished by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, Italians had already grown to be the second-largest immigrant group in America, with 5,067,717 immigrants from Italy admitted between 1820 and 1966—constituting 12% of all immigrants to the United States—more than from Great Britain (4,711,711) and from Ireland (4,706,854).[13]

Historical advertisement of an Italian American restaurant, between circa 1930 and 1945

In the interwar period, jobs as policemen, firemen and civil servants became increasingly available to Italian Americans; while others found employment as plumbers, electricians, mechanics and carpenters. Women found jobs as civil servants, secretaries, dressmakers, and clerks. With better paying jobs they moved to more affluent neighborhoods outside of the Italian enclaves. The Great Depression (1929–1939) had a major impact on the Italian American community, and temporarily reversed some of the earlier gains made. Many unemployed men and some women found jobs on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal work programs, such as the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corp.

By 1920, numerous Little Italies had stabilized and grown considerably more prosperous as workers were able to obtain higher-paying jobs, often in skilled trades. In the 1920s and 1930s Italian Americans contributed significantly to American life and culture, politics, music, film, the arts, sports, the labor movement and business.

In politics, Al Smith (Anglicized form of the Italian surname Ferraro) became the first governor of New York of Italian ancestry—although the media characterized him as an Irish Catholic. He was the first Catholic to receive a major party presidential nomination, as Democratic candidate for president in 1928. He lost Protestant strongholds in the South, but energized the Democratic vote in immigrant centers across the entire North. Angelo Rossi was mayor of San Francisco in 1931–1944. In 1933–34 Ferdinand Pecora led a Senate investigation of the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which exposed major financial abuses, and spurred Congress to rein in the banking industry.[87] Liberal leader Fiorello La Guardia served as Republican and Fusion mayor of New York City in 1934–1945. On the far left Vito Marcantonio was first elected to Congress in 1934 from New York.[88] Robert Maestri was mayor of New Orleans in 1936–1946.

The Metropolitan Opera continued to flourish under the leadership of Giulio Gatti-Casazza, whose tenure continued until 1935. Rosa Ponselle and Dusolina Giannini, daughters of Italian immigrants, performed regularly at the Metropolitan Opera and became internationally known. Arturo Toscanini returned in the United States as the main conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (1926–1936) and introduced many Americans to classical music through his NBC Symphony Orchestra radio broadcasts (1937–54). Ruggiero Ricci, a child prodigy born of Italian immigrant parents, gave his first public performance in 1928 at the age of 10, and had a long international career as a concert violinist.

Popular singers of the period included Russ Columbo, who established a new singing style that influenced Frank Sinatra and other singers that followed. On Broadway, Harry Warren (Salvatore Guaragna) wrote the music for 42nd Street, and received three Academy Awards for his compositions. Other Italian American musicians and performers, such as Jimmy Durante, who later achieved fame in movies and television, were active in vaudeville. Guy Lombardo formed a popular dance band, which played annually on New Year’s Eve in New York City’s Times Square.

The film industry of this era included Frank Capra, who received three Academy Awards for directing and Frank Borzage, who received two Academy Awards for directing. Italian American cartoonists were responsible for some of the most popular animated characters: Donald Duck was created by Al Taliaferro, Woody Woodpecker was a creation of Walter Lantz (Lanza), Casper the Friendly Ghost was co-created by Joseph Oriolo, and Tom and Jerry was co-created by Joseph Barbera. The voice of Snow White was provided by Adriana Caselotti, a 21-year-old soprano.

In public art, Luigi Del Bianco was the chief stone carver at Mount Rushmore from 1933 to 1940.[89] Simon Rodia, an immigrant construction worker, built the Watts Towers over a period of 33 years, from 1921 to 1954.

In sports, Gene Sarazen (Eugenio Saraceni) won both the Professional Golf Association and U.S. Open Tournaments in 1922. Pete DePaolo won the Indianapolis 500 in 1925. Tony Lazzeri and Frank Crosetti started playing for the New York Yankees in 1926. Tony Canzoneri won the lightweight boxing championship in 1930. Lou Little (Luigi Piccolo) began coaching the Columbia University football team in 1930. Joe DiMaggio, who was destined to become one of the most famous players in baseball history, began playing for the New York Yankees in 1936. Hank Luisetti was a three time All-American basketball player at Stanford University from 1936 to 1940. Louis Zamperini, the American distance runner, competed in the 1936 Olympics, and later became the subject of the bestselling book Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand, published in 2010, and a 2014 movie of the same title.

Italian Americans continued their significant involvement in the labor movement during this period. Well known labor organizers included Carlo Tresca, Luigi Antonini, James Petrillo, and Angela Bambace.

Italian American businessmen specialized in growing and selling fresh fruits and vegetables, which were cultivated on small tracts of land in the suburban parts of many cities.[90][91] They cultivated the land and raised produce, which was trucked into the nearby cities and often sold directly to the consumer through farmer’s markets. In California, the DiGiorgio Corporation was founded, which grew to become a national supplier of fresh produce in the United States. Italian Americans in California were leading growers of grapes, and producers of wine. Many well known wine brands, such as Mondavi, Carlo Rossi, Petri, Sebastiani, and Gallo emerged from these early enterprises. Italian American companies were major importers of Italian wines, processed foods, textiles, marble and manufactured goods.[92]

World War II[edit]

Italian-American veterans of all wars memorial, Southbridge, Massachusetts

As a member of the Axis powers, Fascist Italy declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, four days after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. As a consequence, Executive Order 9066 called for the compulsory relocation of more than 10,000 Italian-Americans and restricted the movements of more than 600,000 Italian-Americans nationwide.[96] They were targeted despite a lack of evidence that Italians were conducting spy or sabotage operations in the United States.[97][98][99][100]

While some Italian Americans had been briefly captivated by the rise of Mussolini in the 1920s, they were no moreso than many non-Italians in America and Britain, where Mussolini’s Fascist experiment enjoyed positive coverage among mainstream figures and the Western press until the late 1930s, when Fascist Italy moved into wartime Axis alliance with Germany and Japan. Compared to the Japanese and even the Germans, Italians lacked Old World nationalist loyalties; even among those who might have held favorable views of Mussolini’s leadership in Italy, Italian Americans did not demonstrate any desire to transfer Fascist ideology to America.[83]

Anti-fascist Italian expatriates in the United States founded the Mazzini Society in Northampton, Massachusetts in September 1939 to work toward ending Fascist rule in Italy. These political refugees from Mussolini’s regime disagreed among themselves whether to ally with Communists and anarchists or to exclude them. The Mazzini Society joined with other anti-Fascist Italian expatriates in the Americas at a conference in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1942. They unsuccessfully promoted one of their members, Carlo Sforza, to become the post-Fascist leader of a republican Italy. The Mazzini Society dispersed after the fall of Mussolini as most of its members returned to Italy.[101][102]

Between 750,000 and 1.5 million people of Italian descent are thought to have served in the U.S. armed forces during the war, about 10% of the total, and 14 Italian Americans received the Medal of Honor for their service.[103][104] Among these was Sgt. John Basilone, one of the most decorated and famous servicemen in World War II, who was later featured in the HBO series The Pacific. Army Ranger Colonel Henry Mucci led one of the most successful rescue missions in U.S. history, that freed 511 survivors of the Bataan Death March from a Japanese prison camp in the Philippines, in 1945. In the air, Capt. Don Gentile became one of the war’s leading aces, with 25 German planes destroyed. Film director, producer and writer Frank Capra made a series of wartime documentaries known as Why We Fight, for which he received the U.S. Distinguished Service Medal in 1945, and the Order of the British Empire Medal in 1962.

Biagio (Max) Corvo, an agent of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.), drew up plans for the invasion of Sicily, and organized operations behind enemy lines in the Mediterranean region during World War II. He led the Italian Secret Intelligence branch of the O.S.S., which was able to smuggle hundreds of agents behind enemy lines, supply Italian partisan fighters, and maintain a liaison between Allied field commands and Italy’s first post-Fascist Government. Corvo was awarded the Legion of Merit for his efforts during the war.[105]

The work of Enrico Fermi was crucial in developing the atom bomb. Fermi, a Nobel Prize laureate nuclear physicist, who immigrated to the United States from Italy in 1938, led a research team at the University of Chicago that achieved the world’s first sustained nuclear chain reaction, which clearly demonstrated the feasibility of an atom bomb. Fermi later became a key member of the team at Los Alamos Laboratory that developed the first atom bomb. He was subsequently joined at Los Alamos by Emilio Segrè, one of his colleagues from Italy, who was also destined to receive the Nobel Prize in physics.

Three United States World War II destroyers were named after Italian Americans: USS Basilone (DD-824) was named for Sgt. John Basilone; USS Damato (DD-871) was named for Corporal Anthony P. Damato, who was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for his valor during World War II; and USS Gherardi (DD-637) was named for Rear Admiral Bancroft Gherardi, who served during the Mexican–American War and the American Civil War.

World War II ended the mass unemployment and relief programs that characterized the 1930s, opening up new employment opportunities for large numbers of Italian Americans, who significantly contributed to the nation’s war effort. Much of the Italian American population was concentrated in urban areas where the new war materiel plants were located. Many Italian American women took war jobs, such as Rose Bonavita, who was recognized by President Roosevelt with a personal letter commending her for her performance as an aircraft riveter. She, together with a number of other women workers, provided the basis of the name, «Rosie the Riveter», which came to symbolize the millions of American women workers in the war industries.[106] Chef Boyardee, the company founded by Ettore Boiardi, was one of the largest suppliers of rations for U.S. and allied forces during World War II. For his contribution to the war effort, Boiardi was awarded a gold star order of excellence from the United States War Department.

Wartime violation of Italian-American civil liberties[edit]

From the onset of the (second world) war, and particularly following Pearl Harbor attack, Italian Americans were increasingly placed under suspicion. Groups such as The Los Angeles Council of California Women’s Clubs petitioned General DeWitt to place all enemy aliens in concentration camps immediately, and the Young Democratic Club of Los Angeles went a step further, demanding the removal of American-born Italians and Germans—U.S. citizens—from the Pacific Coast.[107] These calls along with substantial political pressure from congress resulted in President Franklin D. Roosevelt issuing Executive Order No. 9066, as well as the Department of Justice classifying unnaturalised Italian Americans as «enemy aliens» under the Alien and Sedition Act. Thousands of Italians were arrested, and hundreds of Italians were interned in military camps, some for up to 2 years.[108] As many as 600,000 others were required to carry identity cards identifying them as «resident alien». Thousands more on the West Coast were required to move inland, often losing their homes and businesses in the process. A number of Italian-language newspapers were forced to close.[109] Two books, Una Storia Segreta by Lawrence Di Stasi and Uncivil Liberties by Stephen Fox; and a movie, Prisoners Among Us, document these World War II developments.

On November 7, 2000, Bill Clinton signed the Wartime Violation of Italian American Civil Liberties Act.[107][110] This act ordered a comprehensive review by the Attorney General of the United States of the treatment of Italian Americans during the Second World War. The findings concluded that:

- The freedom of more than 600,000 Italian-born immigrants in the United States and their families was restricted during World War II by Government measures that branded them ‘enemy aliens’ and included carrying identification cards, travel restrictions, and seizure of personal property.

- During World War II more than 10,000 Italian Americans living on the West Coast were forced to leave their homes and prohibited from entering coastal zones. More than 50,000 were subjected to curfews.

- During World War II thousands of Italian-American immigrants were arrested, and hundreds were interned in military camps.

- Hundreds of thousands of Italian Americans performed exemplary service and thousands sacrificed their lives in defense of the United States.

- At the time, Italians were the largest foreign-born group in the United States, and today are the fifth largest immigrant group in the United States, numbering approximately 15 million.

- The impact of the wartime experience was devastating to Italian-American communities in the United States, and its effects are still being felt.

- A deliberate policy kept these measures from the public during the war. Even 50 years later much information is still classified, the full story remains unknown to the public, and it has never been acknowledged in any official capacity by the United States Government.

In 2010, California officially issued an apology to the Italian Americans whose civil liberties had been violated.[111]

Post-World War II period[edit]

Italians continued to immigrate to the United States, and an estimated 600,000 arrived in the decades following the war. Many of the new arrivals had professional training, or were skilled in various trades. After the end of World War II, a small number of Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians also emigrated to the United States during the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, leaving their homelands, which were lost by Italy and annexed by Yugoslavia after the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947.[113] Notable Istrian-Dalmatian exiles who emigrated to the United States are Mario Andretti and Lidia Bastianich.[114][115]

The post-war period was a time of great social change for Italian Americans. Many aspired to a college education, which became possible for returning veterans through the GI Bill. With better job opportunities and better educated, Italian Americans entered mainstream American life in great numbers. The Italian enclaves were sometimes abandoned by members of the younger generation who chose to live in other urban areas and in the suburbs. Many married outside of their ethnic group, most frequently with other ethnic Catholics, but increasingly also with those of diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds.[116][117] According to Dr. Richard D. Alba, director of the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the State University of New York at Albany, 8 percent of Americans of Italian descent born before 1920 had mixed ancestry, but 70 percent of them born after 1970 were the children of intermarriage. In 1985 among Americans of Italian descent under the age of 30, 72 percent of men and 64 percent of women married someone with no Italian background.[118]

Italian Americans took advantage of the new opportunities that generally became available to all in the post-war decades. They made many significant contributions to American life and culture.

Joe DiMaggio, considered one of the greatest baseball players of all time, in 1951

Numerous Italian Americans became involved in politics at the local, state and national levels in the post-war decades. Those that became U.S. senators included: John Pastore of Rhode Island, who was the first Italian American elected to the Senate in 1950; Pete Domenici, who was elected to the U.S. Senate from New Mexico in 1972, and served six terms; Patrick Leahy, who was elected to the U.S. Senate from Vermont in 1974, and has served continuously since then; and Alfonse D’Amato, who served as U.S. Senator from New York from 1981 to 1999. Anthony Celebrezze served for five two-year terms as mayor of Cleveland, from 1953 to 1962 and, in 1962, President John Kennedy appointed him as United States Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (now the Department of Health and Human Services). Benjamin Civiletti served as the United States Attorney General during the last year and a half of the Carter administration, from 1979 to 1981. Frank Carlucci served as the United States Secretary of Defense, from 1987 to 1989 in the administration of President Ronald Reagan.

Scores of Italian Americans became well known singers in the post-war period, including: Frank Sinatra, Mario Lanza, Perry Como, Dean Martin, Tony Bennett, Frankie Laine, Bobby Darin, Julius La Rosa, Connie Francis, and Madonna. Italian Americans who hosted popular musical/variety TV shows in the post-war decades included: Perry Como (1949 to 1967), piano virtuoso Liberace (1952–1956), Jimmy Durante (1954–1956), Frank Sinatra (1957–1958) and Dean Martin (1965–1974). Broadway, musical stars included: Rose Marie, Carol Lawrence, Anna Maria Alberghetti, Sergio Franchi, Patti LuPone, Ezio Pinza, and Liza Minnelli.

In music composition, Henry Mancini and Bill Conti received numerous Academy Awards for their songs and film scores. Classical and operatic composers John Corigliano, Norman Dello Joio, David Del Tredici, Paul Creston, Dominick Argento, Gian Carlo Menotti, and Donald Martino were honored with Pulitzer Prizes and Grammy Awards.

Numerous Italian Americans became well known in movies, both as actors and directors, and many were Academy Award recipients. Movie directors included: Frank Capra, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Cimino, Vincente Minnelli, Martin Scorsese, and Brian De Palma.

Italian Americans were active in professional sports as players, coaches and commissioners. Well-known professional baseball coaches in the post-war decades included: Yogi Berra, Billy Martin, Tony La Russa, Tommy Lasorda, and Joe Torre. In professional football, Vince Lombardi set the standard of excellence for all coaches to follow. A. Bartlett Giamatti became president of the National Baseball League in 1986, and Commissioner of Baseball in 1989. Paul Tagliabue was Commissioner of the National Football League from 1989 to 2006.

In college football, Joe Paterno became one of the most successful coaches ever. Seven Italian American players won the Heisman Trophy: Angelo Bertelli of Notre Dame, Alan Ameche of Wisconsin, Gary Beban of UCLA, Joe Bellino of Navy, John Cappelletti of Penn State, Gino Torretta, and Vinny Testaverde of Miami.

In college basketball, a number of Italian Americans became well known coaches in the post-war decades, including: John Calipari, Lou Carnesecca, Rollie Massimino, Rick Pitino, Jim Valvano, Dick Vitale, Tom Izzo, Mike Fratello, Ben Carnevale, and Geno Auriemma.

Italian Americans became nationally known in other diverse sports. Rocky Marciano was the undefeated heavyweight boxing champion from 1952 to 1956; Ken Venturi won both the British and U.S. Open golf championships in 1956; Donna Caponi won the U.S. Women’s Open golf championships in 1969 and 1970; Linda Frattianne was the woman’s U.S. figure skating champion four years in a row, from 1975 to 1978, and world champion in 1976 and 1978; Willie Mosconi was a 15-time World Billiard champion; Eddie Arcaro was a 5-time Kentucky Derby winner; Mario Andretti was a 3-time national race car champion; Mary Lou Retton won the all-around gold medal in Olympic woman’s gymnastics; Matt Biondi won a total of 8 gold medals in Olympic swimming; and Brian Boitano won a gold medal in Olympic men’s singles figure skating.

Italian Americans founded many successful enterprises, both small and large, in the post-war decades, including: Barnes & Noble, Tropicana Products, Zamboni, Transamerica, Subway, Mr. Coffee, and Conair Corporation. Other enterprises founded by Italian Americans were Fairleigh Dickinson University, the Eternal Word Television Network and the Syracuse Nationals basketball team – later to become the Philadelphia 76ers. Robert Panara was a co-founder of the National Technical Institute for the Deaf and founder of the National Theater of the Deaf. Recognized as a pioneer in deaf culture studies in the United States, he was honored with a commemorative U.S. stamp in 2017.

Eight Italian Americans became Nobel Prize laureates in the post-war decades: Mario Capecchi, Renato Dulbecco, Riccardo Giacconi, Salvatore Luria, Franco Modigliani, Rita Levi Montalcini, Emilio G. Segrè, and Carolyn Bertozzi.

Italian Americans continued to serve with distinction in the military, with four Medal of Honor recipients in the Korean War and eleven in the Vietnam War,[119] including Vincent Capodanno, a Catholic chaplain.

At the close of the 20th century, 31 men and women of Italian descent were serving in the U.S. House and Senate and 82 of the 1,000 largest U.S. cities had mayors of Italian descent, and 166 college and university presidents were of Italian descent.[120] Two Italian Americans, Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito, were serving as U.S. Supreme Court justices. Over two dozen Italian Americans were serving in the Catholic Church as bishops. Four—Joseph Bernardin, Justin Rigali, Anthony Bevilacqua, and Daniel DiNardo—had been elevated to Cardinals. Italian Americans had served with distinction in all of America’s wars, and over thirty had been awarded the Medal of Honor. A number of Italian Americans were serving as top-ranking generals in the military, including Anthony Zinni, Raymond Odierno, Carl Vuono, and Peter Pace, the latter three having also been appointed Chief of Staff of their respective services. Over two dozen of Italian descent had been elected as state governors including, most recently, Paul Cellucci of Massachusetts, John Baldacci of Maine, Janet Napolitano of Arizona, and Donald Carcieri of Rhode Island.

Influence on American culture and society[edit]

Italian Americans have influenced the American culture and society in a variety of ways, such as: foods,[121][122] coffees and desserts; wine production (in California and elsewhere in the U.S.); popular music, starting in the 1940s and 1950s, and continuing into the present;[123] operatic, classical and instrumental music;[124] jazz;[125] fashion and design;[126] cinema, literature, Italianate architecture, in homes, churches, and public buildings; Montessori schools; Christmas crèches; fireworks displays;[127] sports (e.g. bocce and beach tennis).

The historical figure of Christopher Columbus is commemorated on Columbus Day and is reflected in numerous monuments, city names, names of institutions, and the poetic name, «Columbia», for the United States itself. Italian American identification with the Genoese explorer whose fame lay in his grand voyages departing Europe across the Atlantic Ocean to make discoveries in the New World—playing an important role in American history and identity, but of negligible significance to the history of Italy—typifies Italian Americans’ limited sense of nationalism and generally loose attachment to Italy itself as a foreign country, in contrast to e.g. the preoccupations of Irish Americans with the political situation in Ireland throughout the 20th century, or American Jews’ deep personal investment in the fate of Israel.[83]

Politics[edit]

Al Smith, governor of New York in the 1920s. His father, Alfred Emanuele Ferraro, was of Italian and German descent.

Mario Cuomo, first New York governor to identify with the Italian community

In the 1930s, Italian Americans voted heavily Democratic.[128]

Carmine DeSapio in the late 1940s became the first to break the Irish Catholic hold on Tammany Hall since the 1870s. By 1951 more than twice as many Italian American legislators as in 1936 served in the six states with the most Italian Americans.[129] Since 1968, voters have split about evenly between the Democratic (37%) and the Republican (36%) parties.[130] The U.S. Congress includes Italian Americans who are leaders in both the Republican and Democratic parties. In 2007, Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) became the first woman and Italian American Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. Former Republican New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani was a candidate for the U.S. presidency in the 2008 election, as was Colorado Congressman Tom Tancredo. Rick Santorum won many primaries in his candidacy for the 2012 Republican presidential nomination. In the 2016 election, Santorum and New Jersey governor Chris Christie ran for the Republican nomination, as did Ted Cruz and George Pataki, who both have a smaller amount of Italian ancestry. Mike Pompeo, American politician, diplomat, businessman, and attorney, served as the 70th United States secretary of state from 2018 to 2021.

Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman on a major party ticket, running for Vice President as a Democrat in 1984. Two justices of the Supreme Court have been Italian Americans, Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito. Both were appointed by Republican presidents, Scalia by Ronald Reagan and Alito by George W. Bush.

The Italian American Congressional Delegation currently includes 30 members of Congress who are of Italian descent. They are joined by more than 150 associate members, who are not Italian American but have large Italian American constituencies. Since its founding in 1975, the National Italian American Foundation (NIAF) has worked closely with the bicameral and bipartisan Italian American Congressional Delegation, which is led by co-chairs Rep. Bill Pascrell of New Jersey and Rep. Pat Tiberi of Ohio.

The NIAF hosts a variety of public policy programs, contributing to public discourse on timely policy issues facing the nation and the world. These events are held on Capitol Hill and other locations under the auspices of NIAF’s Frank J. Guarini Public Policy Forum and its sister program, the NIAF Public Policy Lecture Series. NIAF’s 2009 public policy programs on Capitol Hill featured prominent Italians and Italian Americans as keynote speakers, including Leon Panetta, Director of the CIA, and Franco Frattini, Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Republic of Italy.

By the 1890s Italian Americans in New York City were mobilizing as a political force. They helped elect Fiorello La Guardia (a Republican) as mayor in 1933, and helped reelect him in 1937 and 1941. They rallied for Vincent R. Impellitteri (a Democrat) in 1950, and Rudolph W. Giuliani (a Republican) in 1989 (when he lost), and in 1993 and 1997 (when he won). All three Italian Americans aggressively fought to reduce crime in the city; each was known for his good relations with the city’s powerful labor unions.[131] La Guardia and Giuliani have had the reputation among specialists on urban politics as two of the best mayors in American history.[132][133] Democrat Bill de Blasio, the third mayor of Italian ancestry, served as the 109th mayor of New York City for two terms, from 2014 to 2021. Mario Cuomo (Democratic) served as the 52nd Governor of New York for three terms, from 1983 to 1995. His son Andrew Cuomo was the 56th Governor of New York and previously served as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development from 1997 to 2001 and as the Attorney General of New York from 2007 to 2010.

However, in contrast to other ethnic groups, Italian Americans demonstrate a marked lack of ethnocentrism and long history of political individualism, eschewing ethnic bloc voting, preferring to vote based on individual candidates and issues, embracing maverick political candidates over ethnic loyalties. Popular New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in fact underperformed among his own demographic; in 1941, La Guardia even lost the Italian vote to his Irish opponent William O’Dwyer. In 1965, when New York Democrats backed Mario Procaccino, an Italian-born candidate for city comptroller, Procaccino lost the Italian vote and only won his election due to support in Jewish voter precincts. In the 1973 New York City mayoral election, the son of Italian immigrants Mario Biaggi failed to unite Italian voters as an ethnic bloc the way his Jewish opponent Abraham Beame could do to win the Democratic primary.[83]

In the 1962 Massachusetts gubernatorial election, incumbent Italian American Governor John Volpe lost his re-election campaign by a razor-thin 0.2%—a final margin that could be more than sufficiently explained by Volpe polling only 51% among the state’s significant population of Italian Americans, roughly half of whom voted for old-line Anglo-Saxon Protestant Endicott Peabody over a fellow ethnic.[83]

The pragmatic maverick streak of Italian American voters, reacting to individual candidates and circumstances, emerged clearly amid the urban race riots of the 1960s. Black Republican Edward Brooke won more than 40% of the Italian vote running for the U.S. Senate from Massachusetts. And a majority of Italian voters living in mostly white rural Upstate New York backed black Democratic nominee Basil A. Paterson for Lieutenant Governor of New York in 1970—but not Italian voters who lived in racially diverse metro New York City. In urban environments, race relations deteriorated severely over Italian American support for law and order policies against urban riots and crime. In the 1968 presidential election, independent George Wallace won 21% of the Italian vote in Newark, New Jersey, 29% of the Italian vote in Cleveland, Ohio, and more than 10% of the Italian American vote nationwide—compared to 8% among non-Southern Whites as a whole—presaging the rightward shift of Italian Americans away from the Democratic Party, first as Reagan Democrats, then ultimately realigning with the Republican Party.[83]

Economy[edit]

Italian Americans have played a prominent role in the economy of the United States, and have founded companies of great national importance, such as Bank of America (by Amadeo Giannini in 1904), Qualcomm, Subway, Home Depot and Airbnb among many others. Italian Americans have also made important contributions to the growth of the U.S. economy through their business expertise. Italian Americans have served as CEO’s of numerous major corporations, such as the Ford Motor Company and Chrysler Corporation by Lee Iacocca, IBM Corporation by Samuel Palmisano, Lucent Technologies by Patricia Russo, The New York Stock Exchange by Richard Grasso, Honeywell Incorporated by Michael Bonsignore and Intel by Paul Otellini. Economist Franco Modigliani was awarded the Nobel prize in Economics «for his pioneering analyses of saving and of financial markets.»[134] Economist Eugene Fama was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2013 for his contribution to the empirical analysis of portfolio theory, asset pricing, and the efficient-market hypothesis.

Social and economic conditions of Italian Americans[edit]

About two thirds of America’s Italian immigrants arrived during 1900–1914. Many were of agrarian backgrounds, with little formal education and industrial skills, who became manual laborers heavily concentrated in the cities. Others came with traditional Italian skills as: tailors; barbers; bricklayers; stonemasons; stone cutters; marble, tile and terrazzo workers; fishermen; musicians; singers; shoe makers; shoe repairers; cooks; bakers; carpenters; grape growers; wine makers; silk makers; dressmakers; and seamstresses. Others came to provide for the needs of the immigrant communities, notably doctors, dentists, midwives, lawyers, teachers, morticians, priests, nuns, and brothers. Many of the skilled workers found work in their speciality, first in the Italian enclaves and eventually in the broader society. Traditional skills were often passed down from father to son, and from mother to daughter.

By the second-generation approximately 70% of the men had blue collar jobs, and the proportion was down to approximately 50% in the third generation, according to surveys in 1963.[24] By 1987, the level of Italian-American income exceeded the national average, and since the 1950s it grew faster than any other ethnic group except the Jews.[135] By 1990, according to the U.S. census, more than 65% of Italian Americans were employed as managerial, professional, or white-collar workers. In 1999, the median annual income of Italian-American families was $61,300, while the median annual income of all American families was $50,000.[136]

A University of Chicago study[137] of fifteen ethnic groups showed that Italian Americans were among those groups having the lowest percentages of divorce, unemployment, people on welfare and those incarcerated. On the other hand, they were among those groups with the highest percentages of two-parent families, elderly family members still living at home, and families who eat together on a regular basis.

Science[edit]

Italian Americans have been responsible for major breakthroughs in virtually all fields of science, including engineering, medicine and physics. Physicist and Nobel-prize laureate Enrico Fermi was the creator of the world’s first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and among the leading scientist involved in the Manhattan Project during WW2. One of the main Fermi’s collaborators, Franco Rasetti, was awarded the Charles Doolittle Walcott Medal by the National Academy of Sciences for his contributions to Cambrian paleontology. Federico Faggin developed the first micro-chip and micro-processor. Robert Gallo led research that identified a cancer-causing virus. Anthony Fauci in 2008 was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his work on the AIDS relief program PEPFAR.[138] Astrophysicist Riccardo Giacconi was awarded the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to the discovery of cosmic X-ray sources. Virologist Renato Dulbecco won the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on oncoviruses. Pharmacologist Louis Ignarro was co-recipient of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for demonstrating the signaling properties of nitric oxide. Microbiologist Salvador Luria won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1969 for his contribution to major discoveries on the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses. Physicist William Daniel Phillips in 1997 won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to laser cooling. Physicist Emilio Segrè discovered the elements technetium and astatine, and the antiproton, a subatomic antiparticle, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1959. Nine Italian Americans, including a woman, have gone into space as astronauts: Wally Schirra, Dominic Antonelli, Charles Camarda, Mike Massimino, Richard Mastracchio, Ronald Parise, Mario Runco, Albert Sacco and Nicole Marie Passonno Stott. Rocco Petrone was the third director of the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, from 1973 to 1974.

Women[edit]

A fourteen year old Italian girl working at a paper-box factory (1913)

Italian women who arrived during the period of mass immigration had to adapt to new and unfamiliar social and economic conditions. Mothers, who had the task of raising the children and providing for the welfare of the family, commonly demonstrated great courage and resourcefulness in meeting these obligations, often under adverse living conditions. Their cultural traditions, which placed the highest priority on the family, remained strong as Italian immigrant women adapted to these new circumstances.

To assist the immigrants in the Little Italies, who were overwhelmingly Catholic, Pope Leo XIII dispatched a contingent of priests, nuns and brothers of the Missionaries of St. Charles Borromeo and other orders. Among these was Sister Francesca Cabrini, who founded dozens of schools, hospitals and orphanages. She was canonized as the first American saint in 1946.