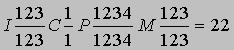

Зубная

формула —

записанное в виде специальных обозначений

краткое описание зубной

системы млекопитающих

и иных гетеродонтных четвероногих.

При

записи зубной формулы используют

сокращенные названия типов зубов

гетеродонтной зубной системы: I

(лат. dentes

incisivi) —

резцы;

C

(лат. d.

canini) —

клыки;

P

(лат. d.

premolares) —

предкоренные, или малые коренные, или

премоляры;

M

(лат. d.

molares) —

коренные, или большие коренные, или

моляры.

За сокращенным названием типа зубов

следует указание количества пар зубов

данной группы: в числителе —

верхней и в знаменателе —

нижней челюсти.

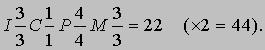

Образец

записи зубной формулы (на примере

человека):

Эта

запись означает: две пары резцов (I), одна

пара клыков (C), две пары малых коренных

(P) и три пары больших коренных зубов

(M).

Помимо

этих основных типов зубов, у представителей

некоторых групп млекопитающих выделяют

характерные только для них типы. Таковы

промежуточные

(лат. d.

intercalares,

in)

зубы землеройковых,

соответствующие, предположительно,

слабо дифференцированным резцам,

премолярам и, вероятно, клыкам, и большие

предкоренные

(лат. d.

praemolares prominantes,

PmP)

зубы рукокрылых,

располагающиеся между премолярами и

молярами.[1]

Зубная

формула широко применяется в систематике

позвоночных

при составлении характеристик групп

самого разного ранга

от отрядов

до подсемейств

и даже родов,

поскольку позволяет компактно изложить

основные характеристики зубной системы.

В

практической стоматологии

такие обозначения применяются редко,

и зубы челюстей человека просто нумеруются

от резцов к большим коренным (от 1 до 8).

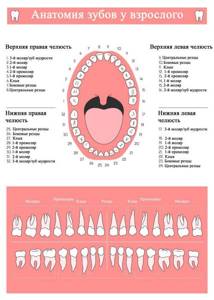

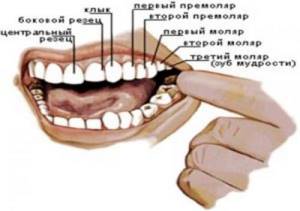

Все

зубы разделяются на 4 сектора (против

часовой стрелки):

-

Зубы

верхней челюсти справа (соответственно

центральный резец — 11, второй резец —

12, клык — 13, первый премоляр — 14,

второй премоляр — 15, первый моляр —

16, второй моляр — 17, третий моляр или

зуб мудрости −18). -

Зубы

верхней челюсти слева (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26,

27, 28 по аналогии с правой стороной). -

Зубы

нижней челюсти слева (31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37,

38). -

Зубы

нижней челюсти справа (41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46,

47, 48).

Для

детских зубов используется аналогичная

нумерация от 51 до 85, либо они указываются

латинскими цифрами.

Примеры

зубных формул постоянных зубов некоторых

млекопитающих

|

Вид |

Латинское |

Отряд |

Семейство |

Зубная |

|

Коала |

Phascolarctos |

Двурезцовые |

Коалы |

|

|

Кутора |

Neomys |

Насекомоядные |

Землеройковые |

|

|

Ушан |

Plecotus |

Рукокрылые |

Кожановые |

|

|

Заяц-беляк |

Lepus |

Зайцеобразные |

Зайцевые |

|

|

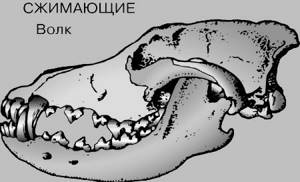

Волк |

Canis |

Хищные |

Собачьи |

|

|

Кошка |

Felis |

Хищные |

Кошачьи |

|

|

Лошадь |

Equus |

Непарнокопытные |

Лошадиные |

|

|

Кабан |

Sus |

Парнокопытные |

Свиные |

|

|

Лось |

Alces |

Парнокопытные |

Оленьи |

|

|

Крупный |

Bos |

Парнокопытные |

Полорогие |

|

|

Мышь |

Mus |

Грызуны |

Мышиные |

|

|

Слон |

Elephas |

Хоботные |

Слоновые |

|

собаки: 1, 2, 3 — резцы,

4 — клыки,

5 — премоляры,

6 — моляры

Резцы

(лат. Dentes

incisivi) — зубы,

функция которых заключается в откусывании

пищи.

Резцы

относительно острые и расположены в

передней части челюсти.

У человека

в верхней и нижней челюсти имеются по

два центральных и два боковых резца, из

которых два центральных верхней челюсти

более крупные. Вместе с клыками

резцы образуют передние зубы. У разных

видов млекопитающих

резцы в течение эволюции

претерпели различные преобразования.

У слонов,

например, верхние резцы образуют бивни.

У грызунов

и зайцеобразных

резцы имеют особое значение и являются

одним из главных отличительных признаков

этих отрядов. У жвачных

в верхней челюсти нет резцов, а

противоположенным препятствием для

резцов нижней челюсти служит нёбо.

Клыки —

конусовидные зубы,

которые служат для разрывания и удержания

пищи.

У

человека

и других млекопитающих

клыки располагаются между резцами

и коренными

зубами.

Кроме

участия в пищеварительной

системе, клыки также используются

животными для обороны.

У

ядовитых змей

клыки полые внутри и используются для

выделения яда

из ядовитых желёз.

Премоляр, зуб коренной малый —

(лат.

premolar, dentes premolares) — один из

двух зубов, расположенных в зубном ряду

взрослых людей с обеих сторон челюстей

за клыками перед большими коренными

зубами.

Моля́ры, больше известные как

коренны́е зу́бы — зубы, служащие

в основном для первичной механической

обработки пищи.

Зубы,

присутствующие у подавляющего большинства

млекопитающих, представляют собой

твердые структуры, которые развиваются

из особых соединительнотканных

(мезодермальных) клеток — одонтобластов

и состоят в основном из фосфата кальция

(апатита), т.е. по химическому составу

очень похожи на кости. Однако фосфат

кальция кристаллизуется и сочетается

с другими веществами по-разному, так

что в результате образуются различные

зубные ткани — дентин, эмаль и цемент. В

основном зуб состоит из дентина. (Бивни

слона и соответственно слоновая кость

— сплошной дентин; небольшое количество

эмали, покрывающее сначала конец бивня,

быстро стирается.) Полость в центре зуба

содержит питающую его «пульпу» из

мягкой соединительной ткани, кровесных

сосудов и нервов. Обычно выступающая

наружу поверхность зуба хотя бы частично

покрыта тонким, но исключительно твердым

слоем эмали (самое твердое вещество в

организме), которая образуется особыми

клетками — амелобластами (адамантобластами).

Зубы ленивцев и броненосцев ее лишены,

на зубах морской выдры (калана) и пятнистой

гиены, которым приходится регулярно

разгрызать твердые раковины моллюсков

или кости, ее слой, наоборот, очень

толстый. Зуб крепится в ячейке на челюсти

с помощью цемента, который по твердости

занимает промежуточное положение между

эмалью и дентином. Он может также

присутствовать внутри самого зуба и на

его жевательной поверхности, например

у лошадей. Зубы млекопитающих обычно

делятся на четыре группы в соответствии

со своими фунциями и местоположением:

резцы, клыки, премоляры (малые коренные,

ложнокоренные, или предкоренные) и

моляры (коренные). Резцы находятся в

передней части рта (на межчелюстных

костях верхней челюсти и, как и все зубы

нижней челюсти, на зубных костях). У них

режущие края и простые конические корни.

Они служат в основном для удерживания

пищи и откусывания ее частей. Клыки (у

кого они есть) представляют собой обычно

длинные заостренные на конце стержни.

Их, как правило, четыре (по 2 верхних и

нижних), и расположены они позади резцов:

верхние — в передней части верхнечелюстных

костей. Клыки используются в основном

для нанесения проникающих ран при

нападении и защите, удерживания и

переноса пищи. Премоляры находятся

между клыками и молярами. У некоторых

примитивных млекопитающих их по четыре

с каждой стороны верхней и нижней челюсти

(всего 16), но большинство групп в ходе

эволюции утратили часть ложнокоренных

зубов, и у человека, например, их всего

8. Моляры, расположенные в задней части

челюстей, вместе с премолярами объединяются

в группу щечных зубов. Ее элементы могут

различаться по размерам и форме в

зависимости от характера питания вида,

но обычно обладают широкой, ребристой

или бугорчатой жевательной поверхностью

для раздавливания и перемалывания пищи.

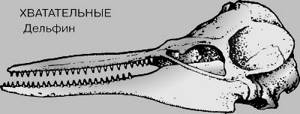

У рыбоядных млекопитающих, например

зубатых китов, все зубы почти одинаковые,

приближающиеся по форме к простому

конусу. Они используются только для

ловли и удержания добычи, которая либо

заглатывается целиком, либо предварительно

разрывается на куски, но не пережевывается.

Некоторые млекопитающие, в частности

ленивцы, зубатые киты и утконос, развивают

всего одну смену зубов на протяжении

всей жизни (у утконоса она присутствует

только на стадии эмбриона) и называются

монофиодонтными. Однако большинство

зверей — дифиодонтные, т.е. у них две

смены зубов — первая, временная, называемая

молочной, и постоянная, свойственная

взрослым животным. У них резцы, клыки и

премоляры раз в жизни полностью

замещаются, а моляры вырастают без

молочных предшественников, т.е. по сути

дела являются поздно развивающейся

частью первой смены зубов. Сумчатые

занимают промежуточное положение между

монофиодонтами и дифиодонтами, поскольку

сохраняют все молочные зубы, кроме

сменяющегося четвертого премоляра. (У

многих из них ему соответствует третий

щечный зуб, поскольку один премоляр

утрачен в ходе эволюции.) Поскольку у

разных видов млекопитающих зубы

гомологичны, т.е. одинаковы по эволюционному

происхождению (за редкими исключениями,

например, у речных дельфинов зубов

больше сотни), каждый из них занимает

строго определенное положение относительно

других и может быть обозначен порядковым

номером. В результате характерный для

вида зубной набор нетрудно записать в

виде формулы. Поскольку млекопитающие

— двусторонне-симметричные животные,

такую формулу составляют только для

одной стороны верхней и нижней челюстей,

помня, что для подсчета общего числа

зубов необходимо умножить соответствующие

цифры на два. Развернутая формула (I —

резцы, C — клыки, P — премоляры и M — моляры,

верхняя и нижняя челюсти — числитель и

знаменатель дроби) для примитивного

набора из шести резцов, двух клыков,

восьми ложнокоренных и шести коренных

зубов выглядит следующим образом:

(*2

= 44, полное число зубов).

Однако

обычно используется сокращенная формула,

где указано лишь общее число зубов

каждого типа. Для вышеприведенного

примитивного зубного набора она выглядит

так:

div=»» pagespeed_url_hash=»3521456244″>

Для

домашней коровы, у которой нет верхних

резцов и клыков, запись принимает

следующую форму:

div=»» pagespeed_url_hash=»3451387543″>

а

у человека выглядит так:

div=»» pagespeed_url_hash=»3495707974″>

Поскольку

все типы зубов расположены в неизменном

порядке — I, C, P, M, — зубные формулы часто

еще более упрощают, опуская эти буквы.

Тогда для человека получаем:

div=»» pagespeed_url_hash=»3086021326″>

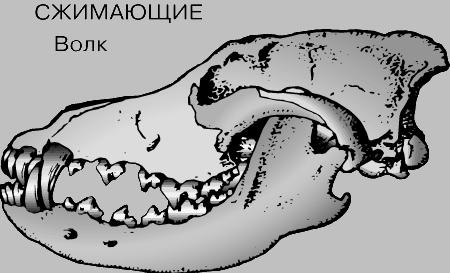

Некоторые

зубы, выполняющие особые функции в ходе

эволюции, могут претерпевать очень

сильные изменения. Например, в отряде

хищных (Carnivora), т.е. у кошек, собак и т.п.,

четвертый верхний премоляр (обозначаемый

P4) и первый нижний моляр (M1) крупнее всех

прочих щечных зубов и снабжены острыми,

как лезвия, режущими кромками. Эти зубы,

называемые хищническими, расположены

друг напротив друга и действуют наподобие

ножниц, разрезая мясо на куски, которые

животному удобнее проглотить. Система

P4/M1 — отличительный признак отряда

Carnivora, хотя ее функцию могут выполнять

и другие зубы. Например, молочный набор

Carnivora не содержит моляров, и в качестве

хищнических используются только

премоляры (dP3/dP4), а у некоторых представителей

вымершего отряда Creodonta для этой же цели

служили две пары коренных зубов —

M1+2/M2+3.

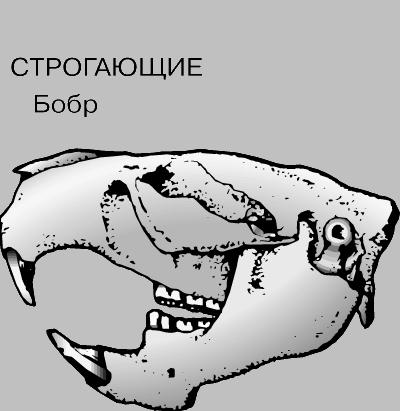

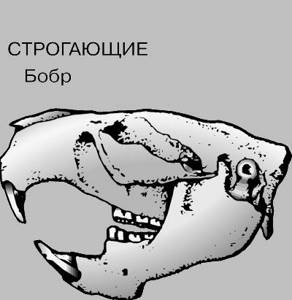

ТИПЫ

ЗУБОВ. ХВАТАТЕЛЬНЫЕ

ТИПЫ

ЗУБОВ. РУБЯЩИЕ

ТИПЫ

ЗУБОВ. СТРОГАЮЩИЕ

ТИПЫ

ЗУБОВ. СЖИМАЮЩИЕ

ТИПЫ

ЗУБОВ. ДРОБЯЩИЕ

ТИПЫ

ЗУБОВ. ПЕРЕТИРАЮЩИЕ

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

-

2 слайд

ЗУБНАЯ ФОРМУЛА

Зубная формула — записанное в виде специальных обозначений краткое описание зубной системы

млекопитающих и иных гетеродонтных четвероногих.

При записи зубной формулы используют сокращенные названия типов зубов гетеродонтной зубной системы:

I (с латинского языка — dentes incisivi) — резцы;

C (с латинского языка – dentes canini) —клыки;

P (с латинского языка — premolares) — предкоренные, или малые коренные, или премоляры;

M (с латинского языка — molares) — коренные, или большие коренные, или моляры.

За сокращенным названием типа зубов следует указание количества пар зубов данной группы: в числителе — верхней и в знаменателе — нижней челюсти. -

3 слайд

ЗУБНАЯ ФОРМУЛА ЧЕЛОВЕКА

-

4 слайд

КОАЛА (отряд Сумчатые)

ЗУБНАЯ ФОРМУЛА -

5 слайд

СЛОН (отряд Хоботные)

-

6 слайд

МЫШЬ (отряд Грызуны)

-

7 слайд

КОРОВА (отряд Парнокопытные)

Крупный рогатый скот -

8 слайд

ЛОСЬ (отряд Парнокопытные)

-

9 слайд

КАБАН (отряд Парнокопытные)

-

10 слайд

ЛОШАДЬ (отряд Непарнокопытные)

-

11 слайд

КОШКА (отряд Хищные)

-

12 слайд

ВОЛК (отряд Хищные)

-

13 слайд

ЗАЯЦ-БЕЛЯК (отряд Зайцеобразные)

-

14 слайд

КУТОРА (отряд Насекомоядные)

-

15 слайд

УШАН (отряд Рукокрылые)

-

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age.[1] That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology (that is, the relationship between the shape and form of the tooth in question and its inferred function) of the teeth of an animal.[2]

Animals whose teeth are all of the same type, such as most non-mammalian vertebrates, are said to have homodont dentition, whereas those whose teeth differ morphologically are said to have heterodont dentition. The dentition of animals with two successions of teeth (deciduous, permanent) is referred to as diphyodont, while the dentition of animals with only one set of teeth throughout life is monophyodont. The dentition of animals in which the teeth are continuously discarded and replaced throughout life is termed polyphyodont.[2] The dentition of animals in which the teeth are set in sockets in the jawbones is termed thecodont.

Overview[edit]

The evolutionary origin of the vertebrate dentition remains contentious. Current theories suggest either an «outside-in» or «inside-out» evolutionary origin to teeth, with the dentition arising from odontodes on the skin surface moving into the mouth, or vice versa.[3] Despite this debate, it is accepted that vertebrate teeth are homologous to the dermal denticles found on the skin of basal Gnathostomes (i.e. Chondrichtyans).[4] Since the origin of teeth some 450 mya, the vertebrate dentition has diversified within the reptiles, amphibians, and fish: however most of these groups continue to possess a long row of pointed or sharp-sided, undifferentiated teeth (homodont) that are completely replaceable. The mammalian pattern is significantly different. The teeth in the upper and lower jaws in mammals have evolved a close-fitting relationship such that they operate together as a unit. «They ‘occlude’, that is, the chewing surfaces of the teeth are so constructed that the upper and lower teeth are able to fit precisely together, cutting, crushing, grinding or tearing the food caught between.»[5]

All mammals except the monotremes, the xenarthrans, the pangolins, and the cetaceans[citation needed] have up to four distinct types of teeth, with a maximum number for each. These are the incisor (cutting), the canine, the premolar, and the molar (grinding). The incisors occupy the front of the tooth row in both upper and lower jaws. They are normally flat, chisel-shaped teeth that meet in an edge-to-edge bite. Their function is cutting, slicing, or gnawing food into manageable pieces that fit into the mouth for further chewing. The canines are immediately behind the incisors. In many mammals, the canines are pointed, tusk-shaped teeth, projecting beyond the level of the other teeth. In carnivores, they are primarily offensive weapons for bringing down prey. In other mammals such as some primates, they are used to split open hard-surfaced food. In humans, the canine teeth are the main components in occlusal function and articulation. The mandibular teeth function against the maxillary teeth in a particular movement that is harmonious to the shape of the occluding surfaces. This creates the incising and grinding functions. The teeth must mesh together the way gears mesh in a transmission. If the interdigitation of the opposing cusps and incisal edges are not directed properly the teeth will wear abnormally (attrition), break away irregular crystalline enamel structures from the surface (abrasion), or fracture larger pieces (abfraction). This is a three-dimensional movement of the mandible in relation to the maxilla. There are three points of guidance: the two posterior points provided by the temporomandibular joints and the anterior component provided by the incisors and canines. The incisors mostly control the vertical opening of the chewing cycle when the muscles of mastication move the jaw forwards and backwards (protrusion/retrusion). The canines come into function guiding the vertical movement when the chewing is side to side (lateral). The canines alone can cause the other teeth to separate at the extreme end of the cycle (cuspid guided function) or all the posterior teeth can continue to stay in contact (group function). The entire range of this movement is the envelope of mastacatory function. The initial movement inside this envelope is directed by the shape of the teeth in contact and the Glenoid Fossa/Condyle shape. The outer extremities of this envelope are limited by muscles, ligaments and the articular disc of the TMJ. Without the guidance of anterior incisors and canines, this envelope of function can be destructive to the remaining teeth resulting in periodontal trauma from occlusion seen as wear, fracture or tooth loosening and loss. The premolars and molars are at the back of the mouth. Depending on the particular mammal and its diet, these two kinds of teeth prepare pieces of food to be swallowed by grinding, shearing, or crushing. The specialised teeth—incisors, canines, premolars, and molars—are found in the same order in every mammal.[6] In many mammals, the infants have a set of teeth that fall out and are replaced by adult teeth. These are called deciduous teeth, primary teeth, baby teeth or milk teeth.[7][8] Animals that have two sets of teeth, one followed by the other, are said to be diphyodont. Normally the dental formula for milk teeth is the same as for adult teeth except that the molars are missing.

Dental formula[edit]

Because every mammal’s teeth are specialised for different functions, many mammal groups have lost the teeth that are not needed in their adaptation. Tooth form has also undergone evolutionary modification as a result of natural selection for specialised feeding or other adaptations. Over time, different mammal groups have evolved distinct dental features, both in the number and type of teeth and in the shape and size of the chewing surface.[9]

The number of teeth of each type is written as a dental formula for one side of the mouth, or quadrant, with the upper and lower teeth shown on separate rows. The number of teeth in a mouth is twice that listed, as there are two sides. In each set, incisors (I) are indicated first, canines (C) second, premolars (P) third, and finally molars (M), giving I:C:P:M.[9][10] So for example, the formula 2.1.2.3 for upper teeth indicates 2 incisors, 1 canine, 2 premolars, and 3 molars on one side of the upper mouth. The deciduous dental formula is notated in lowercase lettering preceded by the letter d: for example: di:dc:dp.[10]

An animal’s dentition for either deciduous or permanent teeth can thus be expressed as a dental formula, written in the form of a fraction, which can be written as I.C.P.MI.C.P.M, or I.C.P.M / I.C.P.M.[10][11] For example, the following formulae show the deciduous and usual permanent dentition of all catarrhine primates, including humans:

- Deciduous:

[7] This can also be written as di2.dc1.dm2di2.dc1.dm2. Superscript and subscript denote upper and lower jaw, i.e. do not indicate mathematical operations; the numbers are the count of the teeth of each type. The dashes (-) in the formula are likewise not mathematical operators, but spacers, meaning «to»: for instance the human formula is 2.1.2.2-32.1.2.2-3 meaning that people may have 2 or 3 molars on each side of each jaw. ‘d’ denotes deciduous teeth (i.e. milk or baby teeth); lower case also indicates temporary teeth. Another annotation is 2.1.0.22.1.0.2, if the fact that it pertains to deciduous teeth is clearly stated, per examples found in some texts such as The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution[10]

- Permanent:

[7] This can also be written as 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. When the upper and lower dental formulae are the same, some texts write the formula without a fraction (in this case, 2.1.2.3), on the implicit assumption that the reader will realise it must apply to both upper and lower quadrants. This is seen, for example, throughout The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution.

The greatest number of teeth in any known placental land mammal[specify] was 48, with a formula of 3.1.5.33.1.5.3.[9] However, no living placental mammal has this number. In extant placental mammals, the maximum dental formula is 3.1.4.33.1.4.3 for pigs. Mammalian tooth counts are usually identical in the upper and lower jaws, but not always. For example, the aye-aye has a formula of 1.0.1.31.0.0.3, demonstrating the need for both upper and lower quadrant counts.[10]

Tooth naming discrepancies[edit]

Teeth are numbered starting at 1 in each group. Thus the human teeth are I1, I2, C1, P3, P4, M1, M2, and M3.[12] (See next paragraph for premolar naming etymology.) In humans, the third molar is known as the wisdom tooth, whether or not it has erupted.[13]

Regarding premolars, there is disagreement regarding whether the third type of deciduous tooth is a premolar (the general consensus among mammalogists) or a molar (commonly held among human anatomists).[8] There is thus some discrepancy between nomenclature in zoology and in dentistry. This is because the terms of human dentistry, which have generally prevailed over time, have not included mammalian dental evolutionary theory. There were originally four premolars in each quadrant of early mammalian jaws. However, all living primates have lost at least the first premolar. «Hence most of the prosimians and platyrrhines have three premolars. Some genera have also lost more than one. A second premolar has been lost in all catarrhines. The remaining permanent premolars are then properly identified as P2, P3 and P4 or P3 and P4; however, traditional dentistry refers to them as P1 and P2».[7]

Dental eruption sequence[edit]

The order in which teeth emerge through the gums is known as the dental eruption sequence. Rapidly developing anthropoid primates such as macaques, chimpanzees, and australopithecines have an eruption sequence of M1 I1 I2 M2 P3 P4 C M3, whereas anatomically modern humans have the sequence M1 I1 I2 C P3 P4 M2 M3. The later that tooth emergence begins, the earlier the anterior teeth (I1–P4) appear in the sequence.[12]

Dental formulae examples[edit]

| Species | Dental formula | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Non placental | Non-placental mammals such as marsupials (e.g., opossums) can have more teeth than placentals. | |

| Bilby | 5.1.3.43.1.3.4[15] | |

| Kangaroo | 3.1.2.41.0.2.4[16] | |

| Musky rat-kangaroo | 3.1.1.42.0.1.4[17] | |

| Rest of Potoroidae | 3.1.1.41.0.1.4[17] | The marsupial family Potoroidae includes the bettongs, potoroos, and two of the rat-kangaroos. All are rabbit-sized, brown, jumping marsupials and resemble a large rodent or a very small wallaby. |

| Tasmanian devil | 4.1.2.43.1.2.4 [18] | |

| Opossum | 5.1.3.44.1.3.4 [19] | |

| Placental | Some examples of dental formulae for placental mammals. | |

| Apes | 2.1.2.32.1.2.3 | All apes (excluding 20–23% of humans) and Old World monkeys share this formula, sometimes known as the cercopithecoid dental formula.[13] |

| Armadillo | 0.0.7.10.0.7.1[20] | |

| Aye-aye | 1.0.1.31.0.0.3[21] | A prosimian. The aye-aye’s deciduous dental formula (dI:dC:dM) is 2.1.22.1.2.[10] |

| Badger | 3.1.3.13.1.3.2[22] | |

| Big brown bat | 2.1.1.33.1.2.3[19] | |

| Red bat, hoary bat, Seminole bat, Mexican free-tailed bat | 1.1.2.33.1.2.3[19] | |

| Camel | 1.1.3.33.1.2.3[23] | |

| Cat (deciduous) | 3.1.3.03.1.2.0[24] | |

| Cat (permanent) | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[11] | The last upper premolar and first lower molar of the cat, since it is a carnivore, are called carnassials and are used to slice meat and skin. |

| Cow | 0.0.3.33.1.3.3[25] | The cow has no upper incisors or canines, the rostral portion of the upper jaw forming a dental pad. The lower canine is incisiform, giving the appearance of a 4th incisor. |

| Dog (deciduous) | 3.1.3.03.1.3.0[24] | |

| Dog (permanent) | 3.1.4.23.1.4.3[22] | |

| Eared Seal | 3.1.4.1-32.1.4.1[26] | |

| Eulemur | 3.1.3.33.1.3.3 | Prosimian genus to which the large Malagasy or ‘true’ lemurs belong.[27] Ruffed lemurs (genus Varecia),[28] dwarf lemurs (genus Mirza),[29] and mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus) also have this dental formula, but the mouse lemurs have a dental comb.[30] |

| Euoticus | 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 | Prosimian genus to which the needle-clawed bushbabies (or galagos) belong. Specialised morphology for gummivory includes procumbent dental comb and caniniform upper anterior premolars.[27] |

| Fox (red) | 3.1.4.23.1.4.3[22] | |

| Guinea pig | 1.0.1.31.0.1.3[31] | |

| Hedgehog | 3.1.3.32.1.2.3[22] | |

| Horse (deciduous) | 3.0.3.03.0.3.0[32][33] | |

| Horse (permanent) | 3.0-1.3-4.33.0-1.3.3 | Permanent dentition varies from 36 to 42, depending on the presence or absence of canines and the number of premolars.[34] The first premolar (wolf tooth) may be absent or rudimentary,[32][33] and is mostly present only in the upper (maxillary) jaw.[33] The canines are small and spade-shaped, and usually present only in males.[34] Canines appear in 20–25% of females and are usually smaller than in males.[33][35] |

| Human (deciduous teeth) | 2.1.2.02.1.2.0 | |

| Human (permanent teeth) | 2.1.2.2-32.1.2.2-3 | Wisdom teeth are congenitally absent in 20–23% of the human population; the proportion of agenesis of wisdom teeth varies considerably among human populations, ranging from a near 0% incidence rate among Aboriginal Tasmanians to near 100% among Indigenous Mexicans.[36] |

| Indri | See comment | A prosimian. Dental formula disputed. Either 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 or 2.1.2.31.1.2.3. Proponents of both formulae agree there are 30 teeth and that there are only four teeth in the dental comb.[37] |

| Lepilemur | 0.1.3.32.1.3.3 | A prosimian. The upper incisors are lost in the adult, but are present in the deciduous dentition.[38] |

| Lion | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[39] | |

| Mole | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[22] | |

| Mouse | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | Plains pocket mouse (Perognathus flavescens) have dental formula of 1.0.1.31.0.1.3.[40] |

| New World monkeys | See comment | All New World monkeys have a dentition formula of 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 or 2.1.3.22.1.3.2.[13] |

| Pantodonta | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[41] | Extinct suborder of early eutherians. |

| Pig (deciduous) | 3.1.4.03.1.4.0[24] | |

| Pig (permanent) | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[22] | |

| Rabbit | 2.0.3.31.0.2.3[11] | |

| Raccoon | 3.1.4.23.1.4.2 | |

| Rat | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | |

| Sheep (deciduous) | 0.0.3.04.0.3.0[24] | |

| Sheep (permanent) | 0.0.3.33.1.3.3[19] | |

| Shrew | 3.1.3.33.1.3.3[22] | |

| Sifakas | See comment | Prosimians. Dental formula disputed. Either 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 or 2.1.2.31.1.2.3. Possess dental comb comprising four teeth.[42] |

| Slender loris Slow loris |

2.1.3.32.1.3.3 | Prosimians. Lower incisors and canines form a dental comb; upper anterior dentition is peg-like and short.[43][44] |

| Squirrel | 1.0.2.31.0.1.3[22] | |

| Tarsiers | 2.1.3.31.1.3.3 | Prosimians.[45] |

| Tiger | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[46] | |

| Vole (field) | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | |

| Weasel | 3.1.3.13.1.3.2[22] |

Dentition use in archaeology[edit]

Dentition, or the study of teeth, is an important area of study for archaeologists, especially those specializing in the study of older remains.[47][48][49] Dentition affords many advantages over studying the rest of the skeleton itself (osteometry). The structure and arrangement of teeth is constant and, although it is inherited, does not undergo extensive change during environmental change, dietary specializations, or alterations in use patterns. The rest of the skeleton is much more likely to exhibit change because of adaptation. Teeth also preserve better than bone, and so the sample of teeth available to archaeologists is much more extensive and therefore more representative.

Dentition is particularly useful in tracking ancient populations’ movements, because there are differences in the shapes of incisors, the number of grooves on molars, presence/absence of wisdom teeth, and extra cusps on particular teeth. These differences can not only be associated with different populations across space, but also change over time so that the study of the characteristics of teeth could say which population one is dealing with, and at what point in that population’s history they are.

Dinosaurs[edit]

A dinosaur’s dentition included all the teeth in its jawbones, which consist of the dentary, maxillary, and in some cases the premaxillary bones. The maxilla is the main bone of the upper jaw. The premaxilla is a smaller bone forming the anterior of the animal’s upper jaw. The dentary is the main bone that forms the lower jaw (mandible). The predentary is a smaller bone that forms the anterior end of the lower jaw in ornithischian dinosaurs; it is always edentulous and supported a horny beak.

Unlike modern lizards, dinosaur teeth grew individually in the sockets of the jawbones, which are known as the alveoli. This thecodont dentition is also present in crocodilians and mammals, but is not found among the non-archosaur reptiles, which instead have acrodont or pleurodont dentition.[50] Teeth that were lost were replaced by teeth below the roots in each tooth socket. Occlusion refers to the closing of the dinosaur’s mouth, where the teeth from the upper and lower parts of the jaw meet. If the occlusion causes teeth from the maxillary or premaxillary bones to cover the teeth of the dentary and predentary, the dinosaur is said to have an overbite, the most common condition in this group. The opposite condition is considered to be an underbite, which is rare in theropod dinosaurs.

The majority of dinosaurs had teeth that were similarly shaped throughout their jaws but varied in size. Dinosaur tooth shapes included cylindrical, peg-like, teardrop-shaped, leaf-like, diamond-shaped and blade-like. A dinosaur that has a variety of tooth shapes is said to have heterodont dentition. An example of this are dinosaurs of the group Heterodontosauridae and the enigmatic early dinosaur, Eoraptor. While most dinosaurs had a single row of teeth on each side of their jaws, others had dental batteries where teeth in the cheek region were fused together to form compound teeth. Individually these teeth were not suitable for grinding food, but when joined together with other teeth they would form a large surface area for the mechanical digestion of tough plant materials. This type of dental strategy is observed in ornithopod and ceratopsian dinosaurs as well as the duck-billed hadrosaurs, which had more than one hundred teeth in each dental battery. The teeth of carnivorous dinosaurs, called ziphodont, were typically blade-like or cone-shaped, curved, with serrated edges. This dentition was adapted for grasping and cutting through flesh. In some cases, as observed in the railroad-spike-sized teeth of Tyrannosaurus rex, the teeth were designed to puncture and crush bone. Some dinosaurs had procumbent teeth, which projected forward in the mouth.[51]

See also[edit]

- Deciduous teeth

- Dental notation

- Dentistry

- Dentition analysis

- Odontometrics

- Permanent teeth

- Phalangeal formula

- Teething

- Tooth eruption

Dentition discussions in other articles[edit]

Some articles have helpful discussions on dentition, which will be listed as identified.

- Lemur

Citations[edit]

- ^ Angus Stevenson, ed. (2007), «Dentition definition», Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, vol. 1: A–M (6th ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 646, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- ^ a b Martin (1983), p. 103

- ^ Fraser, G. J.; et al. (2010). «The odontode explosion: The origin of tooth-like structures in vertebrates». BioEssays. 32 (9): 808–817. doi:10.1002/bies.200900151. PMC 3034446. PMID 20730948.

- ^ Martin et al. (2016) Sox2+ progenitors in sharks link taste development with the evolution of regenerative teeth from denticles, PNAS

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 130–131

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 132–135

- ^ a b c d Swindler (2002), p. 11

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 135

- ^ a b c Weiss & Mann (1985), p. 134

- ^ a b c d e f Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 139

- ^ a b c Martin (1983), p. 102

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 139. See section on dental eruption sequence, where numbering used is per this text.

- ^ a b c Marvin Harris (1988), Culture, People, Nature: An Introduction to General Anthropology (5th ed.), New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-06-042697-2

- ^ Unless otherwise stated, the formulae can be assumed to be for adult, or permanent dentition.

- ^ Johnson, Ken A. (n.d.). ««Fauna of Australia»» (PDF). Fauna of Australia Volume 1b — Mammalia. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

Fauna of Australia Volume 1b — Mammalia

- ^ «Kangaroo». www.1902encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b Andrew W. Claridge; John H. Seebeck; Randy Rose (2007), Bettongs, Potoroos and the Musky Rat-kangaroo, Csiro Publishing, ISBN 978-0-643-09341-6

- ^ University Of Edinburgh Natural History Collection, archived from the original on 2012-03-01

- ^ a b c d Dental formulae of mammal skulls of North America, Wildwood Tracking, archived from the original on 2011-04-14

- ^ Freeman, Patricia W.; Genoways, Hugh H. (December 1998), «Recent northern records of the Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypodidae) in Nebraska», The Southwestern Naturalist, 43 (4): 491–504, JSTOR 30054089, archived from the original on 2011-06-11

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), pp. 134, 139

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l «The Skulls». Chunnie’s British Mammal Skulls. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Bravo, P. Walter (2016-08-27). «Camelidae». veteriankey.com. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

The dental formula for both Bactrian and dromedary camels is incisors (I) 1/3, canines (C) 1/1, premolars (P) 3/2, molars (M) 3/3.

- ^ a b c d «Dental formulae». www.provet.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Using Dentition to Age Cattle». fsis.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ Myers, Phil (2000). ««Otariidae»«. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

The dental formula is 3/2, 1/1, 4/4, 1-3/1 = 34-38.

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 177

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 550

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 340

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 335

- ^ Noonan, Denise. «The Guinea Pig (Cavia porcellus)» (PDF). ANZCCART. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-04.

- ^ a b Pence (2002), p. 7

- ^ a b c d Cirelli

- ^ a b Ultimate Ungulates

- ^ Regarding horse dentition, Pence (2002, p. 7) gives erroneous upper and lower figures of 40 to 44 for the dental range. It is not possible to arrive at this range from the figures she provides. The figures from Cirelli and Ultimate Ungulates are more reliable, although there is a self-evident error for Cirelli’s calculation of the upper female range of 40, which is not possible from the figures he provides. One can only arrive at an upper figure of 38 without canines, which for females Cirelli shows as 0/0. It appears canines do sometimes appear in females, hence the sentence in Ultimate Ungulates that canines are «usually present only in males». However, Pence’s and Cirelli’s references are clearly otherwise useful, hence the inclusion, but with the caveat of this footnote.

- ^ Rozkovcová, E.; Marková, M.; Dolejší, J. (1999). «Studies on agenesis of third molars amongst populations of different origin». Sborník Lékařský. 100 (2): 71–84. PMID 11220165.

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 267

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 300

- ^ «Dental Formula». www.geocities.ws. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Plains Pocket Mouse (Perognathus flavescens)». www.nsrl.ttu.edu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Rose, Kenneth David (2006). «Cimolesta». The Beginning of the Age of Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 94–118. ISBN 978-0-8018-8472-6.

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 438

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 309

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 371

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 520

- ^ Emily, Peter P.; Eisner, Edward R. (2021-06-16). Zoo and Wild Animal Dentistry. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 319. ISBN 978-1119545811.

- ^ Towle, Ian; Irish, Joel D.; Groote, Isabelle De (2017). «Behavioral inferences from the high levels of dental chipping in Homo naledi» (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 164 (1): 184–192. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23250. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 28542710.

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 130–135

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005). The utility of dental formulae in species identification is indicated throughout this dictionary. Dental formulae are noted for many species, both extant and extinct, and where unknown (in some extinct species) this is noted.

- ^ «Palaeos Vertebrates > Bones > Teeth: Tooth Implantation». Palaeos: Life through Deep Time. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Martin, A. J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. 560 pp. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.

General references[edit]

- Adovasio, J. M.; Pedler, David (2005), «The peopling of North America», in Pauketat, Timothy R.; Loren, Diana DiPaolo (eds.), North American Archaeology, Blackwell Publishing, pp. 35–36, ISBN 978-0-631-23184-4

- Cirelli, Al, Equine Dentition (PDF), Nevada: University of Nevada, retrieved 7 June 2010

- Mai, Larry L.; Young Owl, Marcus; Kersting, M. Patricia (2005), The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution, Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66486-8

- Martin, E. A. (1983), Macmillan Dictionary of Life Sciences (2nd revised ed.), London: Macmillan Press, ISBN 978-0-333-34867-3

- Pence, Patricia (2002), Equine Dentistry: A Practical Guide, Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, ISBN 978-0-683-30403-9

- Swindler, Daris R. (2002), Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates (PDF), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65289-6

- Ultimate Ungulates, Family Equidae: Horses, asses, and zebras, Ultimate Unqulate.com, retrieved 7 June 2010

- Weiss, M. L.; Mann, A. E. (1985), Human Biology and Behaviour: An Anthropological Perspective (4th ed.), Boston: Little Brown, ISBN 978-0-673-39013-4

Further reading[edit]

- Daris R. Swindler (2002), «Chapter 1: Introduction (pp. 1–11) and Chapter 2: Dental anatomy (pp. 12–20).» (PDF), Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65289-6 See also preview pages in Google books

- Feldhamer, George A.; Lee C. Drickhamer; Stephen H. Vessey; Joseph F. Merritt; Carey Krajewski (2007), «4: Evolution and Dental Characteristics», Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 48–67, ISBN 978-0-8018-8695-9, retrieved 7 June 2010 (link provided to title page to give reader choice of scrolling straight to relevant chapter or perusing other material).

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dentition.

- Colorado State’s Dental Anatomy Page

- For image of skulls and more information on dental formula of mammals.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age.[1] That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology (that is, the relationship between the shape and form of the tooth in question and its inferred function) of the teeth of an animal.[2]

Animals whose teeth are all of the same type, such as most non-mammalian vertebrates, are said to have homodont dentition, whereas those whose teeth differ morphologically are said to have heterodont dentition. The dentition of animals with two successions of teeth (deciduous, permanent) is referred to as diphyodont, while the dentition of animals with only one set of teeth throughout life is monophyodont. The dentition of animals in which the teeth are continuously discarded and replaced throughout life is termed polyphyodont.[2] The dentition of animals in which the teeth are set in sockets in the jawbones is termed thecodont.

Overview[edit]

The evolutionary origin of the vertebrate dentition remains contentious. Current theories suggest either an «outside-in» or «inside-out» evolutionary origin to teeth, with the dentition arising from odontodes on the skin surface moving into the mouth, or vice versa.[3] Despite this debate, it is accepted that vertebrate teeth are homologous to the dermal denticles found on the skin of basal Gnathostomes (i.e. Chondrichtyans).[4] Since the origin of teeth some 450 mya, the vertebrate dentition has diversified within the reptiles, amphibians, and fish: however most of these groups continue to possess a long row of pointed or sharp-sided, undifferentiated teeth (homodont) that are completely replaceable. The mammalian pattern is significantly different. The teeth in the upper and lower jaws in mammals have evolved a close-fitting relationship such that they operate together as a unit. «They ‘occlude’, that is, the chewing surfaces of the teeth are so constructed that the upper and lower teeth are able to fit precisely together, cutting, crushing, grinding or tearing the food caught between.»[5]

All mammals except the monotremes, the xenarthrans, the pangolins, and the cetaceans[citation needed] have up to four distinct types of teeth, with a maximum number for each. These are the incisor (cutting), the canine, the premolar, and the molar (grinding). The incisors occupy the front of the tooth row in both upper and lower jaws. They are normally flat, chisel-shaped teeth that meet in an edge-to-edge bite. Their function is cutting, slicing, or gnawing food into manageable pieces that fit into the mouth for further chewing. The canines are immediately behind the incisors. In many mammals, the canines are pointed, tusk-shaped teeth, projecting beyond the level of the other teeth. In carnivores, they are primarily offensive weapons for bringing down prey. In other mammals such as some primates, they are used to split open hard-surfaced food. In humans, the canine teeth are the main components in occlusal function and articulation. The mandibular teeth function against the maxillary teeth in a particular movement that is harmonious to the shape of the occluding surfaces. This creates the incising and grinding functions. The teeth must mesh together the way gears mesh in a transmission. If the interdigitation of the opposing cusps and incisal edges are not directed properly the teeth will wear abnormally (attrition), break away irregular crystalline enamel structures from the surface (abrasion), or fracture larger pieces (abfraction). This is a three-dimensional movement of the mandible in relation to the maxilla. There are three points of guidance: the two posterior points provided by the temporomandibular joints and the anterior component provided by the incisors and canines. The incisors mostly control the vertical opening of the chewing cycle when the muscles of mastication move the jaw forwards and backwards (protrusion/retrusion). The canines come into function guiding the vertical movement when the chewing is side to side (lateral). The canines alone can cause the other teeth to separate at the extreme end of the cycle (cuspid guided function) or all the posterior teeth can continue to stay in contact (group function). The entire range of this movement is the envelope of mastacatory function. The initial movement inside this envelope is directed by the shape of the teeth in contact and the Glenoid Fossa/Condyle shape. The outer extremities of this envelope are limited by muscles, ligaments and the articular disc of the TMJ. Without the guidance of anterior incisors and canines, this envelope of function can be destructive to the remaining teeth resulting in periodontal trauma from occlusion seen as wear, fracture or tooth loosening and loss. The premolars and molars are at the back of the mouth. Depending on the particular mammal and its diet, these two kinds of teeth prepare pieces of food to be swallowed by grinding, shearing, or crushing. The specialised teeth—incisors, canines, premolars, and molars—are found in the same order in every mammal.[6] In many mammals, the infants have a set of teeth that fall out and are replaced by adult teeth. These are called deciduous teeth, primary teeth, baby teeth or milk teeth.[7][8] Animals that have two sets of teeth, one followed by the other, are said to be diphyodont. Normally the dental formula for milk teeth is the same as for adult teeth except that the molars are missing.

Dental formula[edit]

Because every mammal’s teeth are specialised for different functions, many mammal groups have lost the teeth that are not needed in their adaptation. Tooth form has also undergone evolutionary modification as a result of natural selection for specialised feeding or other adaptations. Over time, different mammal groups have evolved distinct dental features, both in the number and type of teeth and in the shape and size of the chewing surface.[9]

The number of teeth of each type is written as a dental formula for one side of the mouth, or quadrant, with the upper and lower teeth shown on separate rows. The number of teeth in a mouth is twice that listed, as there are two sides. In each set, incisors (I) are indicated first, canines (C) second, premolars (P) third, and finally molars (M), giving I:C:P:M.[9][10] So for example, the formula 2.1.2.3 for upper teeth indicates 2 incisors, 1 canine, 2 premolars, and 3 molars on one side of the upper mouth. The deciduous dental formula is notated in lowercase lettering preceded by the letter d: for example: di:dc:dp.[10]

An animal’s dentition for either deciduous or permanent teeth can thus be expressed as a dental formula, written in the form of a fraction, which can be written as I.C.P.MI.C.P.M, or I.C.P.M / I.C.P.M.[10][11] For example, the following formulae show the deciduous and usual permanent dentition of all catarrhine primates, including humans:

- Deciduous:

[7] This can also be written as di2.dc1.dm2di2.dc1.dm2. Superscript and subscript denote upper and lower jaw, i.e. do not indicate mathematical operations; the numbers are the count of the teeth of each type. The dashes (-) in the formula are likewise not mathematical operators, but spacers, meaning «to»: for instance the human formula is 2.1.2.2-32.1.2.2-3 meaning that people may have 2 or 3 molars on each side of each jaw. ‘d’ denotes deciduous teeth (i.e. milk or baby teeth); lower case also indicates temporary teeth. Another annotation is 2.1.0.22.1.0.2, if the fact that it pertains to deciduous teeth is clearly stated, per examples found in some texts such as The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution[10]

- Permanent:

[7] This can also be written as 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. When the upper and lower dental formulae are the same, some texts write the formula without a fraction (in this case, 2.1.2.3), on the implicit assumption that the reader will realise it must apply to both upper and lower quadrants. This is seen, for example, throughout The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution.

The greatest number of teeth in any known placental land mammal[specify] was 48, with a formula of 3.1.5.33.1.5.3.[9] However, no living placental mammal has this number. In extant placental mammals, the maximum dental formula is 3.1.4.33.1.4.3 for pigs. Mammalian tooth counts are usually identical in the upper and lower jaws, but not always. For example, the aye-aye has a formula of 1.0.1.31.0.0.3, demonstrating the need for both upper and lower quadrant counts.[10]

Tooth naming discrepancies[edit]

Teeth are numbered starting at 1 in each group. Thus the human teeth are I1, I2, C1, P3, P4, M1, M2, and M3.[12] (See next paragraph for premolar naming etymology.) In humans, the third molar is known as the wisdom tooth, whether or not it has erupted.[13]

Regarding premolars, there is disagreement regarding whether the third type of deciduous tooth is a premolar (the general consensus among mammalogists) or a molar (commonly held among human anatomists).[8] There is thus some discrepancy between nomenclature in zoology and in dentistry. This is because the terms of human dentistry, which have generally prevailed over time, have not included mammalian dental evolutionary theory. There were originally four premolars in each quadrant of early mammalian jaws. However, all living primates have lost at least the first premolar. «Hence most of the prosimians and platyrrhines have three premolars. Some genera have also lost more than one. A second premolar has been lost in all catarrhines. The remaining permanent premolars are then properly identified as P2, P3 and P4 or P3 and P4; however, traditional dentistry refers to them as P1 and P2».[7]

Dental eruption sequence[edit]

The order in which teeth emerge through the gums is known as the dental eruption sequence. Rapidly developing anthropoid primates such as macaques, chimpanzees, and australopithecines have an eruption sequence of M1 I1 I2 M2 P3 P4 C M3, whereas anatomically modern humans have the sequence M1 I1 I2 C P3 P4 M2 M3. The later that tooth emergence begins, the earlier the anterior teeth (I1–P4) appear in the sequence.[12]

Dental formulae examples[edit]

| Species | Dental formula | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Non placental | Non-placental mammals such as marsupials (e.g., opossums) can have more teeth than placentals. | |

| Bilby | 5.1.3.43.1.3.4[15] | |

| Kangaroo | 3.1.2.41.0.2.4[16] | |

| Musky rat-kangaroo | 3.1.1.42.0.1.4[17] | |

| Rest of Potoroidae | 3.1.1.41.0.1.4[17] | The marsupial family Potoroidae includes the bettongs, potoroos, and two of the rat-kangaroos. All are rabbit-sized, brown, jumping marsupials and resemble a large rodent or a very small wallaby. |

| Tasmanian devil | 4.1.2.43.1.2.4 [18] | |

| Opossum | 5.1.3.44.1.3.4 [19] | |

| Placental | Some examples of dental formulae for placental mammals. | |

| Apes | 2.1.2.32.1.2.3 | All apes (excluding 20–23% of humans) and Old World monkeys share this formula, sometimes known as the cercopithecoid dental formula.[13] |

| Armadillo | 0.0.7.10.0.7.1[20] | |

| Aye-aye | 1.0.1.31.0.0.3[21] | A prosimian. The aye-aye’s deciduous dental formula (dI:dC:dM) is 2.1.22.1.2.[10] |

| Badger | 3.1.3.13.1.3.2[22] | |

| Big brown bat | 2.1.1.33.1.2.3[19] | |

| Red bat, hoary bat, Seminole bat, Mexican free-tailed bat | 1.1.2.33.1.2.3[19] | |

| Camel | 1.1.3.33.1.2.3[23] | |

| Cat (deciduous) | 3.1.3.03.1.2.0[24] | |

| Cat (permanent) | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[11] | The last upper premolar and first lower molar of the cat, since it is a carnivore, are called carnassials and are used to slice meat and skin. |

| Cow | 0.0.3.33.1.3.3[25] | The cow has no upper incisors or canines, the rostral portion of the upper jaw forming a dental pad. The lower canine is incisiform, giving the appearance of a 4th incisor. |

| Dog (deciduous) | 3.1.3.03.1.3.0[24] | |

| Dog (permanent) | 3.1.4.23.1.4.3[22] | |

| Eared Seal | 3.1.4.1-32.1.4.1[26] | |

| Eulemur | 3.1.3.33.1.3.3 | Prosimian genus to which the large Malagasy or ‘true’ lemurs belong.[27] Ruffed lemurs (genus Varecia),[28] dwarf lemurs (genus Mirza),[29] and mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus) also have this dental formula, but the mouse lemurs have a dental comb.[30] |

| Euoticus | 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 | Prosimian genus to which the needle-clawed bushbabies (or galagos) belong. Specialised morphology for gummivory includes procumbent dental comb and caniniform upper anterior premolars.[27] |

| Fox (red) | 3.1.4.23.1.4.3[22] | |

| Guinea pig | 1.0.1.31.0.1.3[31] | |

| Hedgehog | 3.1.3.32.1.2.3[22] | |

| Horse (deciduous) | 3.0.3.03.0.3.0[32][33] | |

| Horse (permanent) | 3.0-1.3-4.33.0-1.3.3 | Permanent dentition varies from 36 to 42, depending on the presence or absence of canines and the number of premolars.[34] The first premolar (wolf tooth) may be absent or rudimentary,[32][33] and is mostly present only in the upper (maxillary) jaw.[33] The canines are small and spade-shaped, and usually present only in males.[34] Canines appear in 20–25% of females and are usually smaller than in males.[33][35] |

| Human (deciduous teeth) | 2.1.2.02.1.2.0 | |

| Human (permanent teeth) | 2.1.2.2-32.1.2.2-3 | Wisdom teeth are congenitally absent in 20–23% of the human population; the proportion of agenesis of wisdom teeth varies considerably among human populations, ranging from a near 0% incidence rate among Aboriginal Tasmanians to near 100% among Indigenous Mexicans.[36] |

| Indri | See comment | A prosimian. Dental formula disputed. Either 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 or 2.1.2.31.1.2.3. Proponents of both formulae agree there are 30 teeth and that there are only four teeth in the dental comb.[37] |

| Lepilemur | 0.1.3.32.1.3.3 | A prosimian. The upper incisors are lost in the adult, but are present in the deciduous dentition.[38] |

| Lion | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[39] | |

| Mole | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[22] | |

| Mouse | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | Plains pocket mouse (Perognathus flavescens) have dental formula of 1.0.1.31.0.1.3.[40] |

| New World monkeys | See comment | All New World monkeys have a dentition formula of 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 or 2.1.3.22.1.3.2.[13] |

| Pantodonta | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[41] | Extinct suborder of early eutherians. |

| Pig (deciduous) | 3.1.4.03.1.4.0[24] | |

| Pig (permanent) | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[22] | |

| Rabbit | 2.0.3.31.0.2.3[11] | |

| Raccoon | 3.1.4.23.1.4.2 | |

| Rat | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | |

| Sheep (deciduous) | 0.0.3.04.0.3.0[24] | |

| Sheep (permanent) | 0.0.3.33.1.3.3[19] | |

| Shrew | 3.1.3.33.1.3.3[22] | |

| Sifakas | See comment | Prosimians. Dental formula disputed. Either 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 or 2.1.2.31.1.2.3. Possess dental comb comprising four teeth.[42] |

| Slender loris Slow loris |

2.1.3.32.1.3.3 | Prosimians. Lower incisors and canines form a dental comb; upper anterior dentition is peg-like and short.[43][44] |

| Squirrel | 1.0.2.31.0.1.3[22] | |

| Tarsiers | 2.1.3.31.1.3.3 | Prosimians.[45] |

| Tiger | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[46] | |

| Vole (field) | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | |

| Weasel | 3.1.3.13.1.3.2[22] |

Dentition use in archaeology[edit]

Dentition, or the study of teeth, is an important area of study for archaeologists, especially those specializing in the study of older remains.[47][48][49] Dentition affords many advantages over studying the rest of the skeleton itself (osteometry). The structure and arrangement of teeth is constant and, although it is inherited, does not undergo extensive change during environmental change, dietary specializations, or alterations in use patterns. The rest of the skeleton is much more likely to exhibit change because of adaptation. Teeth also preserve better than bone, and so the sample of teeth available to archaeologists is much more extensive and therefore more representative.

Dentition is particularly useful in tracking ancient populations’ movements, because there are differences in the shapes of incisors, the number of grooves on molars, presence/absence of wisdom teeth, and extra cusps on particular teeth. These differences can not only be associated with different populations across space, but also change over time so that the study of the characteristics of teeth could say which population one is dealing with, and at what point in that population’s history they are.

Dinosaurs[edit]

A dinosaur’s dentition included all the teeth in its jawbones, which consist of the dentary, maxillary, and in some cases the premaxillary bones. The maxilla is the main bone of the upper jaw. The premaxilla is a smaller bone forming the anterior of the animal’s upper jaw. The dentary is the main bone that forms the lower jaw (mandible). The predentary is a smaller bone that forms the anterior end of the lower jaw in ornithischian dinosaurs; it is always edentulous and supported a horny beak.

Unlike modern lizards, dinosaur teeth grew individually in the sockets of the jawbones, which are known as the alveoli. This thecodont dentition is also present in crocodilians and mammals, but is not found among the non-archosaur reptiles, which instead have acrodont or pleurodont dentition.[50] Teeth that were lost were replaced by teeth below the roots in each tooth socket. Occlusion refers to the closing of the dinosaur’s mouth, where the teeth from the upper and lower parts of the jaw meet. If the occlusion causes teeth from the maxillary or premaxillary bones to cover the teeth of the dentary and predentary, the dinosaur is said to have an overbite, the most common condition in this group. The opposite condition is considered to be an underbite, which is rare in theropod dinosaurs.

The majority of dinosaurs had teeth that were similarly shaped throughout their jaws but varied in size. Dinosaur tooth shapes included cylindrical, peg-like, teardrop-shaped, leaf-like, diamond-shaped and blade-like. A dinosaur that has a variety of tooth shapes is said to have heterodont dentition. An example of this are dinosaurs of the group Heterodontosauridae and the enigmatic early dinosaur, Eoraptor. While most dinosaurs had a single row of teeth on each side of their jaws, others had dental batteries where teeth in the cheek region were fused together to form compound teeth. Individually these teeth were not suitable for grinding food, but when joined together with other teeth they would form a large surface area for the mechanical digestion of tough plant materials. This type of dental strategy is observed in ornithopod and ceratopsian dinosaurs as well as the duck-billed hadrosaurs, which had more than one hundred teeth in each dental battery. The teeth of carnivorous dinosaurs, called ziphodont, were typically blade-like or cone-shaped, curved, with serrated edges. This dentition was adapted for grasping and cutting through flesh. In some cases, as observed in the railroad-spike-sized teeth of Tyrannosaurus rex, the teeth were designed to puncture and crush bone. Some dinosaurs had procumbent teeth, which projected forward in the mouth.[51]

See also[edit]

- Deciduous teeth

- Dental notation

- Dentistry

- Dentition analysis

- Odontometrics

- Permanent teeth

- Phalangeal formula

- Teething

- Tooth eruption

Dentition discussions in other articles[edit]

Some articles have helpful discussions on dentition, which will be listed as identified.

- Lemur

Citations[edit]

- ^ Angus Stevenson, ed. (2007), «Dentition definition», Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, vol. 1: A–M (6th ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 646, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- ^ a b Martin (1983), p. 103

- ^ Fraser, G. J.; et al. (2010). «The odontode explosion: The origin of tooth-like structures in vertebrates». BioEssays. 32 (9): 808–817. doi:10.1002/bies.200900151. PMC 3034446. PMID 20730948.

- ^ Martin et al. (2016) Sox2+ progenitors in sharks link taste development with the evolution of regenerative teeth from denticles, PNAS

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 130–131

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 132–135

- ^ a b c d Swindler (2002), p. 11

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 135

- ^ a b c Weiss & Mann (1985), p. 134

- ^ a b c d e f Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 139

- ^ a b c Martin (1983), p. 102

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 139. See section on dental eruption sequence, where numbering used is per this text.

- ^ a b c Marvin Harris (1988), Culture, People, Nature: An Introduction to General Anthropology (5th ed.), New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-06-042697-2

- ^ Unless otherwise stated, the formulae can be assumed to be for adult, or permanent dentition.

- ^ Johnson, Ken A. (n.d.). ««Fauna of Australia»» (PDF). Fauna of Australia Volume 1b — Mammalia. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

Fauna of Australia Volume 1b — Mammalia

- ^ «Kangaroo». www.1902encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b Andrew W. Claridge; John H. Seebeck; Randy Rose (2007), Bettongs, Potoroos and the Musky Rat-kangaroo, Csiro Publishing, ISBN 978-0-643-09341-6

- ^ University Of Edinburgh Natural History Collection, archived from the original on 2012-03-01

- ^ a b c d Dental formulae of mammal skulls of North America, Wildwood Tracking, archived from the original on 2011-04-14

- ^ Freeman, Patricia W.; Genoways, Hugh H. (December 1998), «Recent northern records of the Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypodidae) in Nebraska», The Southwestern Naturalist, 43 (4): 491–504, JSTOR 30054089, archived from the original on 2011-06-11

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), pp. 134, 139

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l «The Skulls». Chunnie’s British Mammal Skulls. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Bravo, P. Walter (2016-08-27). «Camelidae». veteriankey.com. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

The dental formula for both Bactrian and dromedary camels is incisors (I) 1/3, canines (C) 1/1, premolars (P) 3/2, molars (M) 3/3.

- ^ a b c d «Dental formulae». www.provet.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Using Dentition to Age Cattle». fsis.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ Myers, Phil (2000). ««Otariidae»«. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

The dental formula is 3/2, 1/1, 4/4, 1-3/1 = 34-38.

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 177

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 550

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 340

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 335

- ^ Noonan, Denise. «The Guinea Pig (Cavia porcellus)» (PDF). ANZCCART. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-04.

- ^ a b Pence (2002), p. 7

- ^ a b c d Cirelli

- ^ a b Ultimate Ungulates

- ^ Regarding horse dentition, Pence (2002, p. 7) gives erroneous upper and lower figures of 40 to 44 for the dental range. It is not possible to arrive at this range from the figures she provides. The figures from Cirelli and Ultimate Ungulates are more reliable, although there is a self-evident error for Cirelli’s calculation of the upper female range of 40, which is not possible from the figures he provides. One can only arrive at an upper figure of 38 without canines, which for females Cirelli shows as 0/0. It appears canines do sometimes appear in females, hence the sentence in Ultimate Ungulates that canines are «usually present only in males». However, Pence’s and Cirelli’s references are clearly otherwise useful, hence the inclusion, but with the caveat of this footnote.

- ^ Rozkovcová, E.; Marková, M.; Dolejší, J. (1999). «Studies on agenesis of third molars amongst populations of different origin». Sborník Lékařský. 100 (2): 71–84. PMID 11220165.

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 267

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 300

- ^ «Dental Formula». www.geocities.ws. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Plains Pocket Mouse (Perognathus flavescens)». www.nsrl.ttu.edu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Rose, Kenneth David (2006). «Cimolesta». The Beginning of the Age of Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 94–118. ISBN 978-0-8018-8472-6.

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 438

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 309

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 371

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 520

- ^ Emily, Peter P.; Eisner, Edward R. (2021-06-16). Zoo and Wild Animal Dentistry. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 319. ISBN 978-1119545811.

- ^ Towle, Ian; Irish, Joel D.; Groote, Isabelle De (2017). «Behavioral inferences from the high levels of dental chipping in Homo naledi» (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 164 (1): 184–192. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23250. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 28542710.

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 130–135

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005). The utility of dental formulae in species identification is indicated throughout this dictionary. Dental formulae are noted for many species, both extant and extinct, and where unknown (in some extinct species) this is noted.

- ^ «Palaeos Vertebrates > Bones > Teeth: Tooth Implantation». Palaeos: Life through Deep Time. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Martin, A. J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. 560 pp. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.

General references[edit]

- Adovasio, J. M.; Pedler, David (2005), «The peopling of North America», in Pauketat, Timothy R.; Loren, Diana DiPaolo (eds.), North American Archaeology, Blackwell Publishing, pp. 35–36, ISBN 978-0-631-23184-4

- Cirelli, Al, Equine Dentition (PDF), Nevada: University of Nevada, retrieved 7 June 2010

- Mai, Larry L.; Young Owl, Marcus; Kersting, M. Patricia (2005), The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution, Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66486-8

- Martin, E. A. (1983), Macmillan Dictionary of Life Sciences (2nd revised ed.), London: Macmillan Press, ISBN 978-0-333-34867-3

- Pence, Patricia (2002), Equine Dentistry: A Practical Guide, Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, ISBN 978-0-683-30403-9

- Swindler, Daris R. (2002), Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates (PDF), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65289-6

- Ultimate Ungulates, Family Equidae: Horses, asses, and zebras, Ultimate Unqulate.com, retrieved 7 June 2010

- Weiss, M. L.; Mann, A. E. (1985), Human Biology and Behaviour: An Anthropological Perspective (4th ed.), Boston: Little Brown, ISBN 978-0-673-39013-4

Further reading[edit]

- Daris R. Swindler (2002), «Chapter 1: Introduction (pp. 1–11) and Chapter 2: Dental anatomy (pp. 12–20).» (PDF), Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65289-6 See also preview pages in Google books

- Feldhamer, George A.; Lee C. Drickhamer; Stephen H. Vessey; Joseph F. Merritt; Carey Krajewski (2007), «4: Evolution and Dental Characteristics», Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 48–67, ISBN 978-0-8018-8695-9, retrieved 7 June 2010 (link provided to title page to give reader choice of scrolling straight to relevant chapter or perusing other material).

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dentition.

- Colorado State’s Dental Anatomy Page

- For image of skulls and more information on dental formula of mammals.

1.

2.

У всех позвоночных животных зубы состоят из

дентина, ткани, сходной по структуре с костной.

Внутри зуба как правило расположена полость,

заполненная живой тканью — пульпой, пронизанной

нервами и кровеносными сосудами. Снаружи зуб

(тоже как правило) покрыт твердой эмалью.

1-бурозубка;

2-лисица;

3-лошадь;

4-заяц

3. ЗУБЫ У МЛЕКОПИТАЮЩИХ ДИФФЕРЕНЦИРОВАНЫ!

• Число зубов и распределение их по группам

служат хорошим систематическим признаком.

Зубную систему изображают в виде зубной

формулы, в которой группы зубов обозначают

начальными буквами их латинских

наименований: резцы — I (incisivi), клыки — C

(canini), предкоренные — Рm (praemolares) и

истинно коренные — М (molares). Формулу

пишут в виде дробей: в числителе — число

зубов в верхней челюсти, в знаменателе — в

нижней. Для сокращения указывают число

зубов в одной половине челюсти

4.

Зубы собаки:

1, 2, 3 — резцы,

4 — клыки,

5 — премоляры,

6 — моляры

5. ПОЧЕМУ ДИФФЕРЕНЦИРОВКА ЗУБОВ БОЛЕЕ ВЫРАЖЕНА У ХИЩНИКОВ?!

Ф-ции зубов ( на примере зубов хищников):

1.долотообразные резцы –

соскабливание мяса

2. клыки –

удержание и умерщвление добычи

3. коренные –

острые, имеют несколько вершин с режущей поверхностью

При смыкании челюстей верхние и нижние коренные зубы не

совпадают , образуя ножницы.

• На рисунке найдите особый зуб-ХИЩНЫЙ =ПЛОТОЯДНЫЙ (

крупный,имеет 3 острые вершины, это последний предкоренной в

верхней челюсти и первый коренной в нижней челюсти)

6. Зубные формулы млекопитающих

Вид

Отряд

Семейство

Коала

Двурезцовые

сумчатые

Коалы

Кутора

Насекомоядные

Землеройковые

Ушан

Рукокрылые

Кожановые

Зубная формула

7. Зубные формулы млекопитающих

Вид

Отряд

Семейство

Заяц-беляк

Зайцеобразные

Зайцевые

Волк

Хищные

Собачьи

Кошка

Хищные

Кошачьи

Зубная формула

8. Зубные формулы млекопитающих

Вид

Отряд

Семейство

Лошадь

Непарнокопытные

Лошадиные

Кабан

Парнокопытные

Свиные

Лось

Парнокопытные

Оленьи

Зубная формула

9. Такое строение зубов является приспособлением для питания твердой пищей.?!

Зубная система грызунов очень специализирована.

Клыков нет, вместо них пространство – диастема.

Резцы сильно увеличены,острые ,не имеют корней.

Растут всю жизнь.

Наружная поверхность резцов покрыта эмалью, на

внутренней стороне эмаль отсутствует.При употреблении

твердой пищи стирается мягкая внутренняя поверхность

зубов.

• При постоянном росте резцов происходит

самозатачивание зубов.

• I 1/1 Pm 2(1) /1 M 3/3 * 2= 20

• Поясните такую особенность строения зубной системы?!

10. Какими зубами жвачные копытные срезают траву?!

• У жвачных копытных ( олени, лоси, косули, коровы )

клыки, как правило, отсутствуют, есть диастема.

• Резцы только на нижней челюсти.

• I 0/4 Pm3/3 M3/3 * 2 = 32

• У насекомоядных зубы дифференцированы слабо:

• все зубы сходны по строению

• I 3/3 C 1/1 Pm 4/4 M 3/3 * 2 = 44

• Какая зубная система будет более прогрессивной?!

более примитивной?!

11. Кому принадлежат зубы? 1.найти хозяина;2.рассказать, чем он питается;3. местообитание животного

12.

Зубы гомодонтные

(все зубы

одинаковы по

форме и функции),

у большинства

дельфинов

небольших

размеров, иногда

крупные и

массивные. Верхние

входят в

промежутки между

нижними.

Амазонский дельфин

13.

Пятнистый олень

Ягуар

14. ЗУБОВ У ПЕРВОЗВЕРЕЙ НЕТ! Свидетельством чего может быть этот факт?

15. Бивни слона – это зубы? Если да, то какие? Клыков нет+резцы( бивни) 1 пара на верхней челюсти+по 2 пары премоляров+1 пара

моляров с широкой жевательной

поверхностью

Одновременно работают как жернова 4 зуба до истирания.Слон

меняет зубы 6 раз.

16. ВЫВОД!

• ЧЕРЕП МЛЕКОПИТАЮЩЕГО С ЕГО ЗУБАМИ –

«ПАСПОРТ» ЗВЕРЯ!

ПО ЧЕРЕПУ И ЗУБАМ МОЖНО СКАЗАТЬ, КАКОЙ

ОБРАЗ ЖИЗНИ ВЕДЕТ ЖИВОТНОЕ И ЧЕМ

ПИТАЕТСЯ!!!

Предложите, как улучшить StudyLib

(Для жалоб на нарушения авторских прав, используйте

другую форму

)

Ваш е-мэйл

Заполните, если хотите получить ответ

Оцените наш проект

1

2

3

4

5

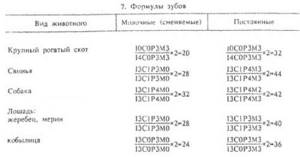

Количество зубов у животных. Зубы животных (часть 3)

Позади резцовых зубов у свиней, собак, жеребца, мерина расположены клыки — dentes canini — зубы конической формы для захвата и удержания корма. Клыков нет у крупного и мелкого рогатого скота и большинства кобылиц. Сзади клыков находятся коренные зубы. Первые 3-4 коренных зуба называют предмелющими — премолярами — dentes premolares. За ними расположены мелющие зубы — моляры — dentes molares. Между резцовыми зубами и премолярами расположен межальвеолярный беззубый край нижней челюсти, покрытый десной — gingiva. Беззубый край значителен по длине у крупного и мелкого рогатого скота и лошадей. У жеребца и мерина беззубый край расположен от клыка до премоляра. Первый нижний премоляр у свиней отделен от второго значительным межзубым пространством (диастемой). Расположение и количество зубов в аркадах принято показывать цифрами в формулах одной половины ротовой полости: верхняя аркада — в числителе, нижняя — в знаменателе. Первыми показывают количество резцов, затем клыков, премоляров и моляров. Перед цифрами ставят первую букву названия зубов по международной номенклатуре. Для краткости эти буквы часто не пишут. В таблице 7 показаны формулы молочных и постоянных зубов основных видов домашних животных.

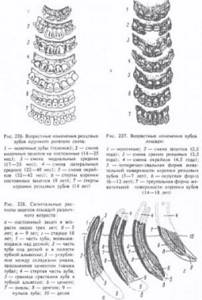

Моляры домашних животных и первый премоляр у свиней и собак не имеют молочных предшественников, поэтому количество молочных коренных зубов меньше, чем постоянных.Возрастные изменения зубов проявляются в сроках прорезывания (появления) молочных зубов в ротовой полости, затем при росте и смене их на постоянные зубы, росте и стирании постоянных зубов.Молочные зубы — резцы, клыки, премоляры имеют коронку, покрытую эмалью молочно-беловатого цвета, гладкую, с блеском. Корни короткие (рис. 226, 227, 228).

При стирании зубов изменяется форма трущейся (смыкательной, жевательной) поверхности зубов, их наклон в аркадах, что используют при определении возраста животных.В таблицах 8 и 9 указаны сроки смены зубов. У животных разных пород они отличаются: у скороспелых пород зубы сменяются раньше, чем у позднеспелых. На росте и смене зубов отражается состояние обмена веществ в организме животных. У незрелорождающихся животных, таких, как щенки, котята, прорезывание молочных зубов происходит через несколько недель после рождения. У зрелорождающихся (телят, ягнят, жеребят) молочные зубы прорезываются перед рождением или в первую неделю после рождения.

Зубы номера. Как считают зубы стоматологи: схема расположения и принципы нумерации

Каждая зубная единица имеет собственные функции, в зависимости от строения и расположения на челюсти. Так, резцы предназначены для откусывания кусочков пищи, клыки помогают удерживать твердую пищу и «отрывать» неподатливые кусочки, премоляры нужны для первичной обработки, а плотные «толстенькие» моляры предназначены для тщательного жевания и перетирания еды. Порядок зубов во рту, соответственно, будет таким: на каждой челюсти четыре резца, два клыка, четыре премоляра (по два с каждой стороны) и шесть моляров (по три с каждой стороны).

Номера зубов в стоматологии присваиваются в соответствии с их расположением на челюсти и функциями. Так как резцы с молярами располагаются симметрично справа и слева, отсчет начинают от середины ряда, то есть от центральных резцов и дальше вправо и влево. Если разделить этот ряд на две половины и начать отсчет на одной из них, мы получаем: два резца (зубы под номерами 1 и 2), клык (3-й номер), два премоляра (4-й и 5-й), три моляра (6-й, 7-й и 8-й, причем последний – это зуб мудрости). Именно такие названия и номера зубов повсеместно приняты в стоматологии.

Если у вас возникла проблема, похожая на описанную в данной статье, обязательно обратитесь к нашим специалистам. Не ставьте диагноз самостоятельно!

Почему стоит позвонить нам сейчас: