Оксид железа (III)

Оксид железа (III) – это твердое, нерастворимое в воде вещество красно-коричневого цвета.

Способы получения

Оксид железа (III) можно получить различными методами:

1. Окисление оксида железа (II) кислородом.

4FeO + O2 → 2Fe2O3

2. Разложение гидроксида железа (III) при нагревании:

2Fe(OH)3 → Fe2O3 + 3H2O

Химические свойства

Оксид железа (III) – амфотерный.

1. При взаимодействии оксида железа (III) с кислотными оксидами и кислотами образуются соли.

Например, оксид железа (III) взаимодействует с азотной кислотой:

Fe2O3 + 6HNO3 → 2Fe(NO3)3 + 3H2O

2. Оксид железа (III) взаимодействует с щелочами и основными оксидами. Реакция протекает в расплаве, при этом образуется соответствующая соль (феррит).

Например, оксид железа (III) взаимодействует с гидроксидом натрия:

Fe2O3 + 2NaOH → 2NaFeO2 + H2O

3. Оксид железа (III) не взаимодействует с водой.

4. Оксид железа (III) окисляется сильными окислителями до соединений железа (VI).

Например, хлорат калия в щелочной среде окисляет оксид железа (III) до феррата:

Fe2O3 + KClO3 + 4KOH → 2K2FeO4 + KCl + 2H2O

Нитраты и нитриты в щелочной среде также окисляют оксид железа (III):

Fe2O3 + 3KNO3 + 4KOH → 2K2FeO4 + 3KNO2 + 2H2O

5. Оксид железа (III) проявляет окислительные свойства. Но есть интересный нюанс — при восстановлении оксида железа (III), как правило, образуется смесь продуктов: это может быть оксид железа (II), просто вещество железо, или железная окалина Fe3O4. Но в реакции мы записываем при этом только один продукт. А вот какой именно это будет продукт, зависит от условий реакции. Как правило, в экзаменах по химии нам даются указания на возможный продукт (цвет образовавшегося вещества или дальнейшие характерные реакции).

Например, оксид железа (III) реагирует с угарным газом при нагревании. При этом возможно восстановление как до простого железа, так и до оксида железа (II) или железной окалины:

Fe2O3 + 3СO → 2Fe + 3CO2

Fe2O3 + СO → 2FeO + CO2

3Fe2O3 + СO → 2Fe3O4 + CO2

При восстановлении оксида железа (III) водородом также возможно образование различных продуктов, например, простого железа:

Fe2O3 + 3Н2 → 2Fe + 3H2O

Железом можно восстановить оксид железа только до оксида железа (II):

Fe2O3 + Fe → 3FeO

Оксид железа (III) реагирует с более активными металлами.

Например, с алюминием (алюмотермия):

Fe2O3 + 2Al → 2Fe + Al2O3

Оксид железа (III) реагирует также с некоторыми другими сильными восстановителями.

Например, с гидридом натрия:

Fe2O3 + 3NaH → 3NaOH + 2Fe

6. Оксид железа (III) – твердый, нелетучий и амфотерный. А следовательно, он вытесняет более летучие оксиды (как правило, углекислый газ) из солей при сплавлении.

Например, из карбоната натрия:

Fe2O3 + Na2CO3 → 2NaFeO2 + CO2

1

H

1,008

1s1

2,2

Бесцветный газ

t°пл=-259°C

t°кип=-253°C

2

He

4,0026

1s2

Бесцветный газ

t°кип=-269°C

3

Li

6,941

2s1

0,99

Мягкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=180°C

t°кип=1317°C

4

Be

9,0122

2s2

1,57

Светло-серый металл

t°пл=1278°C

t°кип=2970°C

5

B

10,811

2s2 2p1

2,04

Темно-коричневое аморфное вещество

t°пл=2300°C

t°кип=2550°C

6

C

12,011

2s2 2p2

2,55

Прозрачный (алмаз) / черный (графит) минерал

t°пл=3550°C

t°кип=4830°C

7

N

14,007

2s2 2p3

3,04

Бесцветный газ

t°пл=-210°C

t°кип=-196°C

8

O

15,999

2s2 2p4

3,44

Бесцветный газ

t°пл=-218°C

t°кип=-183°C

9

F

18,998

2s2 2p5

4,0

Бледно-желтый газ

t°пл=-220°C

t°кип=-188°C

10

Ne

20,180

2s2 2p6

Бесцветный газ

t°пл=-249°C

t°кип=-246°C

11

Na

22,990

3s1

0,93

Мягкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=98°C

t°кип=892°C

12

Mg

24,305

3s2

1,31

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=649°C

t°кип=1107°C

13

Al

26,982

3s2 3p1

1,61

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=660°C

t°кип=2467°C

14

Si

28,086

3s2 3p2

1,9

Коричневый порошок / минерал

t°пл=1410°C

t°кип=2355°C

15

P

30,974

3s2 3p3

2,2

Белый минерал / красный порошок

t°пл=44°C

t°кип=280°C

16

S

32,065

3s2 3p4

2,58

Светло-желтый порошок

t°пл=113°C

t°кип=445°C

17

Cl

35,453

3s2 3p5

3,16

Желтовато-зеленый газ

t°пл=-101°C

t°кип=-35°C

18

Ar

39,948

3s2 3p6

Бесцветный газ

t°пл=-189°C

t°кип=-186°C

19

K

39,098

4s1

0,82

Мягкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=64°C

t°кип=774°C

20

Ca

40,078

4s2

1,0

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=839°C

t°кип=1487°C

21

Sc

44,956

3d1 4s2

1,36

Серебристый металл с желтым отливом

t°пл=1539°C

t°кип=2832°C

22

Ti

47,867

3d2 4s2

1,54

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1660°C

t°кип=3260°C

23

V

50,942

3d3 4s2

1,63

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1890°C

t°кип=3380°C

24

Cr

51,996

3d5 4s1

1,66

Голубовато-белый металл

t°пл=1857°C

t°кип=2482°C

25

Mn

54,938

3d5 4s2

1,55

Хрупкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1244°C

t°кип=2097°C

26

Fe

55,845

3d6 4s2

1,83

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1535°C

t°кип=2750°C

27

Co

58,933

3d7 4s2

1,88

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1495°C

t°кип=2870°C

28

Ni

58,693

3d8 4s2

1,91

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1453°C

t°кип=2732°C

29

Cu

63,546

3d10 4s1

1,9

Золотисто-розовый металл

t°пл=1084°C

t°кип=2595°C

30

Zn

65,409

3d10 4s2

1,65

Голубовато-белый металл

t°пл=420°C

t°кип=907°C

31

Ga

69,723

4s2 4p1

1,81

Белый металл с голубоватым оттенком

t°пл=30°C

t°кип=2403°C

32

Ge

72,64

4s2 4p2

2,0

Светло-серый полуметалл

t°пл=937°C

t°кип=2830°C

33

As

74,922

4s2 4p3

2,18

Зеленоватый полуметалл

t°субл=613°C

(сублимация)

34

Se

78,96

4s2 4p4

2,55

Хрупкий черный минерал

t°пл=217°C

t°кип=685°C

35

Br

79,904

4s2 4p5

2,96

Красно-бурая едкая жидкость

t°пл=-7°C

t°кип=59°C

36

Kr

83,798

4s2 4p6

3,0

Бесцветный газ

t°пл=-157°C

t°кип=-152°C

37

Rb

85,468

5s1

0,82

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=39°C

t°кип=688°C

38

Sr

87,62

5s2

0,95

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=769°C

t°кип=1384°C

39

Y

88,906

4d1 5s2

1,22

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1523°C

t°кип=3337°C

40

Zr

91,224

4d2 5s2

1,33

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1852°C

t°кип=4377°C

41

Nb

92,906

4d4 5s1

1,6

Блестящий серебристый металл

t°пл=2468°C

t°кип=4927°C

42

Mo

95,94

4d5 5s1

2,16

Блестящий серебристый металл

t°пл=2617°C

t°кип=5560°C

43

Tc

98,906

4d6 5s1

1,9

Синтетический радиоактивный металл

t°пл=2172°C

t°кип=5030°C

44

Ru

101,07

4d7 5s1

2,2

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=2310°C

t°кип=3900°C

45

Rh

102,91

4d8 5s1

2,28

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1966°C

t°кип=3727°C

46

Pd

106,42

4d10

2,2

Мягкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1552°C

t°кип=3140°C

47

Ag

107,87

4d10 5s1

1,93

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=962°C

t°кип=2212°C

48

Cd

112,41

4d10 5s2

1,69

Серебристо-серый металл

t°пл=321°C

t°кип=765°C

49

In

114,82

5s2 5p1

1,78

Мягкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=156°C

t°кип=2080°C

50

Sn

118,71

5s2 5p2

1,96

Мягкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=232°C

t°кип=2270°C

51

Sb

121,76

5s2 5p3

2,05

Серебристо-белый полуметалл

t°пл=631°C

t°кип=1750°C

52

Te

127,60

5s2 5p4

2,1

Серебристый блестящий полуметалл

t°пл=450°C

t°кип=990°C

53

I

126,90

5s2 5p5

2,66

Черно-серые кристаллы

t°пл=114°C

t°кип=184°C

54

Xe

131,29

5s2 5p6

2,6

Бесцветный газ

t°пл=-112°C

t°кип=-107°C

55

Cs

132,91

6s1

0,79

Мягкий серебристо-желтый металл

t°пл=28°C

t°кип=690°C

56

Ba

137,33

6s2

0,89

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=725°C

t°кип=1640°C

57

La

138,91

5d1 6s2

1,1

Серебристый металл

t°пл=920°C

t°кип=3454°C

58

Ce

140,12

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=798°C

t°кип=3257°C

59

Pr

140,91

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=931°C

t°кип=3212°C

60

Nd

144,24

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1010°C

t°кип=3127°C

61

Pm

146,92

f-элемент

Светло-серый радиоактивный металл

t°пл=1080°C

t°кип=2730°C

62

Sm

150,36

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1072°C

t°кип=1778°C

63

Eu

151,96

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=822°C

t°кип=1597°C

64

Gd

157,25

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1311°C

t°кип=3233°C

65

Tb

158,93

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1360°C

t°кип=3041°C

66

Dy

162,50

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1409°C

t°кип=2335°C

67

Ho

164,93

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1470°C

t°кип=2720°C

68

Er

167,26

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1522°C

t°кип=2510°C

69

Tm

168,93

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1545°C

t°кип=1727°C

70

Yb

173,04

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=824°C

t°кип=1193°C

71

Lu

174,96

f-элемент

Серебристый металл

t°пл=1656°C

t°кип=3315°C

72

Hf

178,49

5d2 6s2

Серебристый металл

t°пл=2150°C

t°кип=5400°C

73

Ta

180,95

5d3 6s2

Серый металл

t°пл=2996°C

t°кип=5425°C

74

W

183,84

5d4 6s2

2,36

Серый металл

t°пл=3407°C

t°кип=5927°C

75

Re

186,21

5d5 6s2

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=3180°C

t°кип=5873°C

76

Os

190,23

5d6 6s2

Серебристый металл с голубоватым оттенком

t°пл=3045°C

t°кип=5027°C

77

Ir

192,22

5d7 6s2

Серебристый металл

t°пл=2410°C

t°кип=4130°C

78

Pt

195,08

5d9 6s1

2,28

Мягкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1772°C

t°кип=3827°C

79

Au

196,97

5d10 6s1

2,54

Мягкий блестящий желтый металл

t°пл=1064°C

t°кип=2940°C

80

Hg

200,59

5d10 6s2

2,0

Жидкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=-39°C

t°кип=357°C

81

Tl

204,38

6s2 6p1

Серебристый металл

t°пл=304°C

t°кип=1457°C

82

Pb

207,2

6s2 6p2

2,33

Серый металл с синеватым оттенком

t°пл=328°C

t°кип=1740°C

83

Bi

208,98

6s2 6p3

Блестящий серебристый металл

t°пл=271°C

t°кип=1560°C

84

Po

208,98

6s2 6p4

Мягкий серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=254°C

t°кип=962°C

85

At

209,98

6s2 6p5

2,2

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

t°пл=302°C

t°кип=337°C

86

Rn

222,02

6s2 6p6

2,2

Радиоактивный газ

t°пл=-71°C

t°кип=-62°C

87

Fr

223,02

7s1

0,7

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

t°пл=27°C

t°кип=677°C

88

Ra

226,03

7s2

0,9

Серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл

t°пл=700°C

t°кип=1140°C

89

Ac

227,03

6d1 7s2

1,1

Серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл

t°пл=1047°C

t°кип=3197°C

90

Th

232,04

f-элемент

Серый мягкий металл

91

Pa

231,04

f-элемент

Серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл

92

U

238,03

f-элемент

1,38

Серебристо-белый металл

t°пл=1132°C

t°кип=3818°C

93

Np

237,05

f-элемент

Серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл

94

Pu

244,06

f-элемент

Серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл

95

Am

243,06

f-элемент

Серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл

96

Cm

247,07

f-элемент

Серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл

97

Bk

247,07

f-элемент

Серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл

98

Cf

251,08

f-элемент

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

99

Es

252,08

f-элемент

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

100

Fm

257,10

f-элемент

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

101

Md

258,10

f-элемент

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

102

No

259,10

f-элемент

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

103

Lr

266

f-элемент

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

104

Rf

267

6d2 7s2

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

105

Db

268

6d3 7s2

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

106

Sg

269

6d4 7s2

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

107

Bh

270

6d5 7s2

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

108

Hs

277

6d6 7s2

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

109

Mt

278

6d7 7s2

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

110

Ds

281

6d9 7s1

Нестабильный элемент, отсутствует в природе

Металлы

Неметаллы

Щелочные

Щелоч-зем

Благородные

Галогены

Халькогены

Полуметаллы

s-элементы

p-элементы

d-элементы

f-элементы

Наведите курсор на ячейку элемента, чтобы получить его краткое описание.

Чтобы получить подробное описание элемента, кликните по его названию.

Оксид железа (III) – неорганическое вещество, имеет химическую формулу Fe2O3.

Краткая характеристика оксида железа (III)

Модификации оксида железа (III)

Физические свойства оксида железа (III)

Получение оксида железа (III)

Химические свойства оксида железа (III)

Химические реакции оксида железа (III)

Применение и использование оксида железа (III)

Краткая характеристика оксида железа (III):

Оксид железа (III) – неорганическое вещество красно-коричневого цвета.

Оксид железа (III) содержит три атома кислорода и два атома железа.

Химическая формула оксида железа (III) Fe2O3.

В воде не растворяется. С водой не реагирует.

Термически устойчив.

Оксид железа (III) – амфотерный оксид с большим преобладанием основных свойств. Как амфотерный оксид проявляет в зависимости от условий либо основные, либо кислотные свойства.

Модификации оксида железа (III):

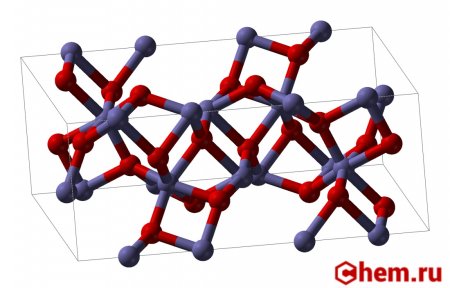

Известны следующие кристаллические модификации железа: α-Fe2O3, γ-Fe2O3.

Физические свойства оксида железа (III)*:

| Наименование параметра: | Значение: |

| Химическая формула | Fe2O3 |

| Синонимы и названия иностранном языке | iron(III) oxide (англ.)

гематит (рус.) красный железняк (рус.) |

| Тип вещества | неорганическое |

| Внешний вид | красно-коричневые тригональные кристаллы |

| Цвет | красно-коричневый |

| Вкус | —** |

| Запах | — |

| Агрегатное состояние (при 20 °C и атмосферном давлении 1 атм.) | твердое вещество |

| Плотность (состояние вещества – твердое вещество, при 20 °C), кг/м3 | 5242 |

| Плотность (состояние вещества – твердое вещество, при 20 °C), г/см3 | 5,242 |

| Температура кипения, °C | 1987 |

| Температура плавления, °C | 1566 |

| Молярная масса, г/моль | 159,69 |

Примечание:

* оксид железа α-форма.

** — нет данных.

Получение оксида железа (III):

В природе встречается в виде минералов гематита (красный железняк), лимонита и маггемита.

Оксид железа (III) получают в результате следующих химических реакций:

- 1. окисления железа:

4Fe + 3O2 → 2Fe2O3.

- 2. термического разложения полигидрата оксида железа (III):

Fe2O3•nH2O → Fe2O3 + nH2O (t = 500-700 oC).

- 3. термического разложения метагидроксида железа:

2FeO(OH) → Fe2O3 + H2O (t = 500-700 oC).

- 4. термического разложения гидроксида железа (III):

2Fe(OH)3 → Fe2O3 + 3H2O (t°).

- 5. термического разложения сульфата железа (III):

Fe2(SO4)3 → Fe2O3 + 3SO3 (t = 500-700 oC).

Химические свойства оксида железа (III). Химические реакции оксида железа (III):

Оксид железа (III) относится к амфотерным оксидам, но с большим преобладанием основных свойств.

Химические свойства оксида железа (III) аналогичны свойствам амфотерных оксидов других металлов. Поэтому для него характерны следующие химические реакции:

1. реакция оксида железа (III) с алюминием:

2Al + Fe2O3 → 2Fe + Al2О (t°).

В результате реакции образуется оксид алюминия и железо.

2. реакция оксида железа (III) с углеродом:

Fe2O3 + 3С → 2Fe + 3CО (t°).

В результате реакции образуется железо и оксид углерода.

3. реакция оксида железа (III) с водородом:

Fe2O3 + H2 → 2FeO + H2О (t°),

Fe2O3 + 3H2 → 2Fe + 3H2О (t = 1050-1100 °C),

3Fe2O3 + H2 → 2Fe3O4 + H2О (t = 400 °C).

В результате реакции в первом случае образуется оксид железа (II) и вода, во втором – железо и вода, в третьем – оксид железа (II, III) и вода.

4. реакция оксида железа (III) с железом:

Fe2O3 + Fe → 3FeО (t = 900 °C).

В результате реакции образуется оксид железа (II).

5. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом натрия:

5Na2О + Fe2O3 → 2Na5FeО4 (t = 450-500 °C).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррат натрия.

6. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом магния:

MgО + Fe2O3 → MgFe2О4 (t°).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррит магния.

7. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом меди (II):

CuО + Fe2O3 → CuFe2О4 (t°).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррит меди.

8. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом титана:

TiО + Fe2O3 → TiFe2О4 (t°).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррит титана.

9. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом марганца:

MnО + Fe2O3 → MnFe2О4 (t°).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррит марганца.

10. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом никеля:

NiО + Fe2O3 → NiFe2О4 (t°).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррит никеля.

11. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом кадмия:

CdО + Fe2O3 → CdFe2О4 (t°).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррит кадмия.

12. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом цинка:

ZnО + Fe2O3 → ZnFe2О4 (t = 450-500 °C),

ZnО + Fe2O3 → Fe2ZnО4 (t = 450-500 °C).

В результате реакции образуется оксид железа-цинка.

13. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом кальция:

CaО + Fe2O3 → CaFe2О4 (t = 900-1000 °C)

В результате реакции образуется оксид кальция-железа.

14. реакция оксида железа (III) с оксидом углерода:

Fe2O3 + 3СО → 2Fe + 3СО2 (t = 700 °C),

Fe2O3 + СО → 2FeО + СО2 (t = 500-600 °C),

3Fe2O3 + СО → 2Fe3О4 + СО2 (t = 400 °C),

В результате реакции в первом случае образуется железо и углекислый газ, во втором – оксид железа (II) и углекислый газ, в третьем – оксид железа (II, III) и углекислый газ.

15. реакция оксида железа (III) с гидроксидом натрия:

Fe2O3 + 2NaOH → 2NaFeO2 + H2О (t = 600 oC, p).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррит натрия и вода. Реакция протекает при избыточном давлении.

16. реакция оксида железа (III) с карбонатом натрия:

Fe2O3 + Na2СO3 → 2NaFeO2 + СО2 (t = 800-900 oC).

В результате реакции образуется соль – феррит натрия и оксид углерода.

17. реакция оксида железа (III) с плавиковой кислотой:

Fe2O3 + 6HF → 2FeF3 + 3H2O.

В результате химической реакции получается соль – фторид железа и вода.

18. реакция оксида железа (III) с азотной кислотой:

Fe2O3 + 6HNO3 → 2Fe(NO3)3 + 3H2O.

В результате химической реакции получается соль – нитрат железа и вода. Азотная кислота – разбавленный раствор.

Аналогично проходят реакции оксида железа и с другими кислотами.

19. реакция оксида железа (III) с бромистым водородом (бромоводородом):

Fe2O3 + 6HBr → 2FeBr3 + 3H2O.

В результате химической реакции получается соль – бромид железа и вода.

20. реакция оксида железа (III) с йодоводородом:

Fe2O3 + 6HI → 2FeI3 + 3H2O.

В результате химической реакции получается соль – йодид железа и вода.

21. реакция оксида железа (III) с хлоридом железа:

Fe2O3 + FeСl3 → 3FeOCl3 (t = 350 oC).

В результате химической реакции получается оксид хлорида-железа.

22. реакция термического разложения оксида железа (III):

6Fe2O3 → 4Fe3O4 + O2 (t = 1200-1390 oC).

В результате химической реакции получается оксид железа (II, III) и кислород.

Применение и использование оксида железа:

Оксид железа используется в металлургии для выплавки чугуна, как катализатор в химической и нефтехимической промышленности, как пищевая добавка (E172), как компонент керамики, красок и пр. целей.

Примечание: © Фото //www.pexels.com, //pixabay.com

оксид железа реагирует кислота 1 2 3 4 5 вода

уравнение реакций соединения масса взаимодействие оксида железа

реакции с оксидом железа

Коэффициент востребованности

14 303

| Оксид железа (III) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Систематическое наименование |

Оксид железа (III) |

| Традиционные названия | окись железа, колькотар, крокус, железный сурик |

| Хим. формула | Fe2O3 |

| Рац. формула | Fe2O3 |

| Состояние | твёрдое |

| Молярная масса | 159,69 г/моль |

| Плотность | 5,242 г/см³ |

| Температура | |

| • плавления | 1566 °C |

| • кипения | 1987 °C |

| Давление пара | 0 ± 1 мм рт.ст. |

| Рег. номер CAS | 1309-37-1 |

| PubChem | 518696 |

| Рег. номер EINECS | 215-168-2 |

| SMILES |

[Fe+3].[Fe+3].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2] |

| InChI |

1S/2Fe.3O JEIPFZHSYJVQDO-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

| Кодекс Алиментариус | E172(ii) |

| RTECS | NO7400000 |

| ChEBI | 50819 |

| ChemSpider | 14147 |

| Приведены данные для стандартных условий (25 °C, 100 кПа), если не указано иное. |

Оксид железа (III) — сложное неорганическое вещество, соединение железа и кислорода с химической формулой Fe2O3.

Свойства

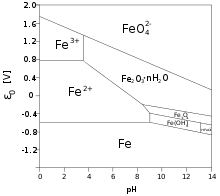

Оксид железа (III) — амфотерный оксид с большим преобладанием осно́вных свойств. Красно-коричневого цвета. Термически устойчив до температур выше температуры испарения (1987 °C). Образуется при сгорании железа на воздухе. Не реагирует с водой. Медленно реагирует с кислотами и щелочами. Восстанавливается монооксидом углерода, расплавленным железом. Сплавляется с оксидами других металлов и образует двойные оксиды — шпинели.

В природе встречается как широко распространённый минерал гематит, примеси которого обусловливают красноватую окраску латерита, краснозёмов, а также поверхности Марса; другая кристаллическая модификация встречается как минерал маггемит.

Получение

Термическое разложение соединений солей железа (III) на воздухе:

-

- Fe2(SO4)3 → Fe2O3 + 3SO3

- 4Fe(NO3)3 ⋅ 9H2O → 2Fe2O3 + 12NO2 + 3O2 + 36H2O

Обезвоживание метагидроксида железа прокаливанием:

-

- 2FeO(OH) → Fe2O3 + H2O

В природе — оксидные руды железа гематит Fe2O3 и лимонит Fe2O3·nH2O

Химические свойства

1. Взаимодействие с разбавленной соляной кислотой:

Fe2O3 + 6HCl ⟶ 2FeCl3 + 3H2O

2. Взаимодействие с карбонатом натрия:

Fe2O3 + Na2CO3 ⟶ 2NaFeO2 + CO2

3. Взаимодействие с гидроксидом натрия при сплавлении:

Fe2O3 + 2NaOH ⟶ 2NaFeO2 + H2O

4. Восстановление до железа водородом:

Fe2O3 + 3H2 →1000∘C 2Fe + 3H2O

Физические свойства

В ромбоэдральной альфа-фазе оксид железа является антиферромагнетиком ниже температуры 260 К; от этой температуры и до 960 K α-Fe2O3 — слабый ферромагнетик. Кубическая метастабильная гамма-фаза γ-Fe2O3 (в природе встречается как минерал маггемит) является ферримагнетиком.

Применение

Применяется при выплавке чугуна в доменном процессе, катализатор в производстве аммиака, компонент керамики, цветных цементов и минеральных красок, при термитной сварке стальных конструкций, как носитель аналоговой и цифровой информации (напр. звука и изображения) на магнитных лентах (ферримагнитный γ-Fe2O3), как полирующее средство (красный крокус) для стали и стекла.

В пищевой промышленности используется в качестве пищевого красителя (E172).

В ракетомоделировании применяется для получения катализированного карамельного топлива, которое имеет скорость горения на 80 % выше, чем обычное топливо.

Является основным компонентом железного сурика (колькотара).

В нефтехимической промышленности используется в качестве основного компонента катализатора дегидрирования при синтезе диеновых мономеров.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a red-colored oxide of iron. For other uses, see Red Iron.

Fe O |

|

|

|

|

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Iron(III) oxide |

|

| Other names

ferric oxide, haematite, ferric iron, red iron oxide, rouge, maghemite, colcothar, iron sesquioxide, rust, ochre |

|

| Identifiers | |

|

CAS Number |

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.790 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E172(ii) (colours) |

|

Gmelin Reference |

11092 |

| KEGG |

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

InChI

|

|

|

SMILES

|

|

| Properties | |

|

Chemical formula |

Fe2O3 |

| Molar mass | 159.687 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Red-brown solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 5.25 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 1,539 °C (2,802 °F; 1,812 K)[1] decomposes 105 °C (221 °F; 378 K) β-dihydrate, decomposes 150 °C (302 °F; 423 K) β-monohydrate, decomposes 50 °C (122 °F; 323 K) α-dihydrate, decomposes 92 °C (198 °F; 365 K) α-monohydrate, decomposes[3] |

|

Solubility in water |

Insoluble |

| Solubility | Soluble in diluted acids,[1] barely soluble in sugar solution[2] Trihydrate slightly soluble in aq. tartaric acid, citric acid, CH3COOH[3] |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

+3586.0×10−6 cm3/mol |

|

Refractive index (nD) |

n1 = 2.91, n2 = 3.19 (α, hematite)[4] |

| Structure | |

|

Crystal structure |

Rhombohedral, hR30 (α-form)[5] Cubic bixbyite, cI80 (β-form) Cubic spinel (γ-form) Orthorhombic (ε-form)[6] |

|

Space group |

R3c, No. 161 (α-form)[5] Ia3, No. 206 (β-form) Pna21, No. 33 (ε-form)[6] |

|

Point group |

3m (α-form)[5] 2/m 3 (β-form) mm2 (ε-form)[6] |

|

Coordination geometry |

Octahedral (Fe3+, α-form, β-form)[5] |

| Thermochemistry[7] | |

|

Heat capacity (C) |

103.9 J/mol·K[7] |

|

Std molar |

87.4 J/mol·K[7] |

|

Std enthalpy of |

−824.2 kJ/mol[7] |

|

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) |

−742.2 kJ/mol[7] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

[8] [8]

|

|

Signal word |

Warning |

|

Hazard statements |

H315, H319, H335[8] |

|

Precautionary statements |

P261, P305+P351+P338[8] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

[10] 0 0 0 |

|

Threshold limit value (TLV) |

5 mg/m3[1] (TWA) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

|

LD50 (median dose) |

10 g/kg (rats, oral)[10] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 10 mg/m3[9] |

|

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 5 mg/m3[9] |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

2500 mg/m3[9] |

| Related compounds | |

|

Other anions |

Iron(III) fluoride |

|

Other cations |

Manganese(III) oxide Cobalt(III) oxide |

|

Related iron oxides |

Iron(II) oxide Iron(II,III) oxide |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Iron(III) oxide in a vial

Iron(III) oxide or ferric oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula Fe2O3. It is one of the three main oxides of iron, the other two being iron(II) oxide (FeO), which is rare; and iron(II,III) oxide (Fe3O4), which also occurs naturally as the mineral magnetite. As the mineral known as hematite, Fe2O3 is the main source of iron for the steel industry. Fe2O3 is readily attacked by acids. Iron(III) oxide is often called rust, and to some extent this label is useful, because rust shares several properties and has a similar composition; however, in chemistry, rust is considered an ill-defined material, described as Hydrous ferric oxide.[11]

Structure[edit]

Fe2O3 can be obtained in various polymorphs. In the main one, α, iron adopts octahedral coordination geometry. That is, each Fe center is bound to six oxygen ligands. In the γ polymorph, some of the Fe sit on tetrahedral sites, with four oxygen ligands.

Alpha phase[edit]

α-Fe2O3 has the rhombohedral, corundum (α-Al2O3) structure and is the most common form. It occurs naturally as the mineral hematite which is mined as the main ore of iron. It is antiferromagnetic below ~260 K (Morin transition temperature), and exhibits weak ferromagnetism between 260 K and the Néel temperature, 950 K.[12] It is easy to prepare using both thermal decomposition and precipitation in the liquid phase. Its magnetic properties are dependent on many factors, e.g. pressure, particle size, and magnetic field intensity.

Gamma phase[edit]

γ-Fe2O3 has a cubic structure. It is metastable and converted from the alpha phase at high temperatures. It occurs naturally as the mineral maghemite. It is ferromagnetic and finds application in recording tapes,[13] although ultrafine particles smaller than 10 nanometers are superparamagnetic. It can be prepared by thermal dehydratation of gamma iron(III) oxide-hydroxide. Another method involves the careful oxidation of iron(II,III) oxide (Fe3O4).[13] The ultrafine particles can be prepared by thermal decomposition of iron(III) oxalate.

Other solid phases[edit]

Several other phases have been identified or claimed. The β-phase is cubic body-centered (space group Ia3), metastable, and at temperatures above 500 °C (930 °F) converts to alpha phase. It can be prepared by reduction of hematite by carbon,[clarification needed] pyrolysis of iron(III) chloride solution, or thermal decomposition of iron(III) sulfate.[14]

The epsilon (ε) phase is rhombic, and shows properties intermediate between alpha and gamma, and may have useful magnetic properties applicable for purposes such as high density recording media for big data storage.[15] Preparation of the pure epsilon phase has proven very challenging. Material with a high proportion of epsilon phase can be prepared by thermal transformation of the gamma phase. The epsilon phase is also metastable, transforming to the alpha phase at between 500 and 750 °C (930 and 1,380 °F). It can also be prepared by oxidation of iron in an electric arc or by sol-gel precipitation from iron(III) nitrate.[citation needed] Research has revealed epsilon iron(III) oxide in ancient Chinese Jian ceramic glazes, which may provide insight into ways to produce that form in the lab.[16][non-primary source needed]

Additionally, at high pressure an amorphous form is claimed.[6][non-primary source needed]

Liquid phase[edit]

Molten Fe2O3 is expected to have a coordination number of close to 5 oxygen atoms about each iron atom, based on measurements of slightly oxygen deficient supercooled liquid iron oxide droplets, where supercooling circumvents the need for the high oxygen pressures required above the melting point to maintain stoichiometry.[17]

Hydrated iron(III) oxides[edit]

Several hydrates of Iron(III) oxide exist.

When alkali is added to solutions of soluble Fe(III) salts, a red-brown gelatinous precipitate forms. This is not Fe(OH)3, but Fe2O3·H2O (also written as Fe(O)OH).

Several forms of the hydrated oxide of Fe(III) exist as well. The red lepidocrocite (γ-Fe(O)OH) occurs on the outside of rusticles, and the orange goethite (α-Fe(O)OH) occurs internally in rusticles.

When Fe2O3·H2O is heated, it loses its water of hydration. Further heating at 1670 K converts Fe2O3 to black Fe3O4 (FeIIFeIII2O4), which is known as the mineral magnetite.

Fe(O)OH is soluble in acids, giving [Fe(H2O)6]3+. In concentrated aqueous alkali, Fe2O3 gives [Fe(OH)6]3−.[13]

Reactions[edit]

The most important reaction is its carbothermal reduction, which gives iron used in steel-making:

- Fe2O3 + 3 CO → 2 Fe + 3 CO2

Another redox reaction is the extremely exothermic thermite reaction with aluminium.[18]

- 2 Al + Fe2O3 → 2 Fe + Al2O3

This process is used to weld thick metals such as rails of train tracks by using a ceramic container to funnel the molten iron in between two sections of rail. Thermite is also used in weapons and making small-scale cast-iron sculptures and tools.

Partial reduction with hydrogen at about 400 °C produces magnetite, a black magnetic material that contains both Fe(III) and Fe(II):[19]

- 3 Fe2O3 + H2 → 2 Fe3O4 + H2O

Iron(III) oxide is insoluble in water but dissolves readily in strong acid, e.g. hydrochloric and sulfuric acids. It also dissolves well in solutions of chelating agents such as EDTA and oxalic acid.

Heating iron(III) oxides with other metal oxides or carbonates yields materials known as ferrates (ferrate (III)):[19]

- ZnO + Fe2O3 → Zn(FeO2)2

Preparation[edit]

Iron(III) oxide is a product of the oxidation of iron. It can be prepared in the laboratory by electrolyzing a solution of sodium bicarbonate, an inert electrolyte, with an iron anode:

- 4 Fe + 3 O2 + 2 H2O → 4 FeO(OH)

The resulting hydrated iron(III) oxide, written here as FeO(OH), dehydrates around 200 °C.[19][20]

- 2 FeO(OH) → Fe2O3 + H2O

Uses[edit]

Iron industry[edit]

The overwhelming application of iron(III) oxide is as the feedstock of the steel and iron industries, e.g. the production of iron, steel, and many alloys.[20]

Polishing[edit]

A very fine powder of ferric oxide is known as «jeweler’s rouge», «red rouge», or simply rouge. It is used to put the final polish on metallic jewelry and lenses, and historically as a cosmetic. Rouge cuts more slowly than some modern polishes, such as cerium(IV) oxide, but is still used in optics fabrication and by jewelers for the superior finish it can produce. When polishing gold, the rouge slightly stains the gold, which contributes to the appearance of the finished piece. Rouge is sold as a powder, paste, laced on polishing cloths, or solid bar (with a wax or grease binder). Other polishing compounds are also often called «rouge», even when they do not contain iron oxide. Jewelers remove the residual rouge on jewelry by use of ultrasonic cleaning. Products sold as «stropping compound» are often applied to a leather strop to assist in getting a razor edge on knives, straight razors, or any other edged tool.

Pigment[edit]

Two different colors at different hydrate phase (α: red, β: yellow) of iron(III) oxide hydrate;[3] they are useful as pigments.

Iron(III) oxide is also used as a pigment, under names «Pigment Brown 6», «Pigment Brown 7», and «Pigment Red 101».[21] Some of them, e.g. Pigment Red 101 and Pigment Brown 6, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in cosmetics. Iron oxides are used as pigments in dental composites alongside titanium oxides.[22]

Hematite is the characteristic component of the Swedish paint color Falu red.

Magnetic recording[edit]

Iron(III) oxide was the most common magnetic particle used in all types of magnetic storage and recording media, including magnetic disks (for data storage) and magnetic tape (used in audio and video recording as well as data storage). Its use in computer disks was superseded by cobalt alloy, enabling thinner magnetic films with higher storage density.[23]

Photocatalysis[edit]

α-Fe2O3 has been studied as a photoanode for solar water oxidation.[24] However, its efficacy is limited by a short diffusion length (2–4 nm) of photo-excited charge carriers[25] and subsequent fast recombination, requiring a large overpotential to drive the reaction.[26] Research has been focused on improving the water oxidation performance of Fe2O3 using nanostructuring,[24] surface functionalization,[27] or by employing alternate crystal phases such as β-Fe2O3.[28]

Medicine[edit]

Calamine lotion, used to treat mild itchiness, is chiefly composed of a combination of zinc oxide, acting as astringent, and about 0.5% iron(III) oxide, the product’s active ingredient, acting as antipruritic. The red color of iron(III) oxide is also mainly responsible for the lotion’s pink color.

See also[edit]

- Chalcanthum

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Haynes, p. 4.69

- ^ «A dictionary of chemical solubilities, inorganic». archive.org. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ a b c Comey, Arthur Messinger; Hahn, Dorothy A. (February 1921). A Dictionary of Chemical Solubilities: Inorganic (2nd ed.). New York: The MacMillan Company. p. 433.

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.141

- ^ a b c d Ling, Yichuan; Wheeler, Damon A.; Zhang, Jin Zhong; Li, Yat (2013). Zhai, Tianyou; Yao, Jiannian (eds.). One-Dimensional Nanostructures: Principles and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-118-07191-5.

- ^ a b c d Vujtek, Milan; Zboril, Radek; Kubinek, Roman; Mashlan, Miroslav. «Ultrafine Particles of Iron(III) Oxides by View of AFM – Novel Route for Study of Polymorphism in Nano-world» (PDF). Univerzity Palackého. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Haynes, p. 5.12

- ^ a b c Sigma-Aldrich Co., Iron(III) oxide. Retrieved on 2014-07-12.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. «#0344». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b «SDS of Iron(III) oxide» (PDF). KJLC. England: Kurt J Lesker Company Ltd. 5 January 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ PubChem. «Iron oxide (Fe2O3), hydrate». pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Greedan, J. E. (1994). «Magnetic oxides». In King, R. Bruce (ed.). Encyclopedia of Inorganic chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-93620-6.

- ^ a b c Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2008). «Chapter 22: d-block metal chemistry: the first row elements». Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Pearson. p. 716. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ «Mechanism of Oxidation & Thermal Decomposition of Iron Sulphides» (PDF).

- ^ Tokoro, Hiroko; Namai, Asuka; Ohkoshi, Shin-Ichi (2021). «Advances in magnetic films of epsilon-iron oxide toward next-generation high-density recording media». Dalton Transactions. Royal Society of Chemistry. 50 (2): 452–459. doi:10.1039/D0DT03460F. PMID 33393552. S2CID 230482821. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Dejoie, Catherine; Sciau, Philippe; Li, Weidong; Noé, Laure; Mehta, Apurva; Chen, Kai; Luo, Hongjie; Kunz, Martin; Tamura, Nobumichi; Liu, Zhi (2015). «Learning from the past: Rare ε-Fe2O3 in the ancient black-glazed Jian (Tenmoku) wares». Scientific Reports. 4: 4941. doi:10.1038/srep04941. PMC 4018809. PMID 24820819.

- ^ Shi, Caijuan; Alderman, Oliver; Tamalonis, Anthony; Weber, Richard; You, Jinglin; Benmore, Chris (2020). «Redox-structure dependence of molten iron oxides». Communications Materials. 1 (1): 80. Bibcode:2020CoMat…1…80S. doi:10.1038/s43246-020-00080-4.

- ^ Adlam; Price (1945). Higher School Certificate Inorganic Chemistry. Leslie Slater Price.

- ^ a b c Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 1661.

- ^ a b Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Element (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-3365-9.

- ^ Paint and Surface Coatings: Theory and Practice. William Andrew Inc. 1999. ISBN 978-1-884207-73-0.

- ^ Banerjee, Avijit (2011). Pickard’s Manual of Operative Dentistry. United States: Oxford University Press Inc., New York. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-957915-0.

- ^ Piramanayagam, S. N. (2007). «Perpendicular recording media for hard disk drives». Journal of Applied Physics. 102 (1): 011301–011301–22. Bibcode:2007JAP…102a1301P. doi:10.1063/1.2750414.

- ^ a b Kay, A., Cesar, I. and Grätzel, M. (2006). «New Benchmark for Water Photooxidation by Nanostructured α-Fe2O3 Films». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (49): 15714–15721. doi:10.1021/ja064380l. PMID 17147381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kennedy, J.H. and Frese, K.W. (1978). «Photooxidation of Water at α-Fe2O3 Electrodes». Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 125 (5): 709. doi:10.1149/1.2131532.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Le Formal, F. (2014). «Back Electron–Hole Recombination in Hematite Photoanodes for Water Splitting». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 136 (6): 2564–2574. doi:10.1021/ja412058x. PMID 24437340.

- ^ Zhong, D.K. and Gamelin, D.R. (2010). «Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation by Cobalt Catalyst («Co−Pi»)/α-Fe2O3 Composite Photoanodes: Oxygen Evolution and Resolution of a Kinetic Bottleneck». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (12): 4202–4207. doi:10.1021/ja908730h. PMID 20201513.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Emery, J.D. (2014). «Atomic Layer Deposition of Metastable β-Fe2O3 via Isomorphic Epitaxy for Photoassisted Water Oxidation». ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 6 (24): 21894–21900. doi:10.1021/am507065y. OSTI 1355777. PMID 25490778.

External links[edit]

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about a red-colored oxide of iron. For other uses, see Red Iron.

Fe O |

|

|

|

|

|

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Iron(III) oxide |

|

| Other names

ferric oxide, haematite, ferric iron, red iron oxide, rouge, maghemite, colcothar, iron sesquioxide, rust, ochre |

|

| Identifiers | |

|

CAS Number |

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.790 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E172(ii) (colours) |

|

Gmelin Reference |

11092 |

| KEGG |

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

InChI

|

|

|

SMILES

|

|

| Properties | |

|

Chemical formula |

Fe2O3 |

| Molar mass | 159.687 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Red-brown solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 5.25 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 1,539 °C (2,802 °F; 1,812 K)[1] decomposes 105 °C (221 °F; 378 K) β-dihydrate, decomposes 150 °C (302 °F; 423 K) β-monohydrate, decomposes 50 °C (122 °F; 323 K) α-dihydrate, decomposes 92 °C (198 °F; 365 K) α-monohydrate, decomposes[3] |

|

Solubility in water |

Insoluble |

| Solubility | Soluble in diluted acids,[1] barely soluble in sugar solution[2] Trihydrate slightly soluble in aq. tartaric acid, citric acid, CH3COOH[3] |

|

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

+3586.0×10−6 cm3/mol |

|

Refractive index (nD) |

n1 = 2.91, n2 = 3.19 (α, hematite)[4] |

| Structure | |

|

Crystal structure |

Rhombohedral, hR30 (α-form)[5] Cubic bixbyite, cI80 (β-form) Cubic spinel (γ-form) Orthorhombic (ε-form)[6] |

|

Space group |

R3c, No. 161 (α-form)[5] Ia3, No. 206 (β-form) Pna21, No. 33 (ε-form)[6] |

|

Point group |

3m (α-form)[5] 2/m 3 (β-form) mm2 (ε-form)[6] |

|

Coordination geometry |

Octahedral (Fe3+, α-form, β-form)[5] |

| Thermochemistry[7] | |

|

Heat capacity (C) |

103.9 J/mol·K[7] |

|

Std molar |

87.4 J/mol·K[7] |

|

Std enthalpy of |

−824.2 kJ/mol[7] |

|

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) |

−742.2 kJ/mol[7] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

[8] [8]

|

|

Signal word |

Warning |

|

Hazard statements |

H315, H319, H335[8] |

|

Precautionary statements |

P261, P305+P351+P338[8] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

[10] 0 0 0 |

|

Threshold limit value (TLV) |

5 mg/m3[1] (TWA) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

|

LD50 (median dose) |

10 g/kg (rats, oral)[10] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

|

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 10 mg/m3[9] |

|

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 5 mg/m3[9] |

|

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

2500 mg/m3[9] |

| Related compounds | |

|

Other anions |

Iron(III) fluoride |

|

Other cations |

Manganese(III) oxide Cobalt(III) oxide |

|

Related iron oxides |

Iron(II) oxide Iron(II,III) oxide |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Iron(III) oxide in a vial

Iron(III) oxide or ferric oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula Fe2O3. It is one of the three main oxides of iron, the other two being iron(II) oxide (FeO), which is rare; and iron(II,III) oxide (Fe3O4), which also occurs naturally as the mineral magnetite. As the mineral known as hematite, Fe2O3 is the main source of iron for the steel industry. Fe2O3 is readily attacked by acids. Iron(III) oxide is often called rust, and to some extent this label is useful, because rust shares several properties and has a similar composition; however, in chemistry, rust is considered an ill-defined material, described as Hydrous ferric oxide.[11]

Structure[edit]

Fe2O3 can be obtained in various polymorphs. In the main one, α, iron adopts octahedral coordination geometry. That is, each Fe center is bound to six oxygen ligands. In the γ polymorph, some of the Fe sit on tetrahedral sites, with four oxygen ligands.

Alpha phase[edit]

α-Fe2O3 has the rhombohedral, corundum (α-Al2O3) structure and is the most common form. It occurs naturally as the mineral hematite which is mined as the main ore of iron. It is antiferromagnetic below ~260 K (Morin transition temperature), and exhibits weak ferromagnetism between 260 K and the Néel temperature, 950 K.[12] It is easy to prepare using both thermal decomposition and precipitation in the liquid phase. Its magnetic properties are dependent on many factors, e.g. pressure, particle size, and magnetic field intensity.

Gamma phase[edit]

γ-Fe2O3 has a cubic structure. It is metastable and converted from the alpha phase at high temperatures. It occurs naturally as the mineral maghemite. It is ferromagnetic and finds application in recording tapes,[13] although ultrafine particles smaller than 10 nanometers are superparamagnetic. It can be prepared by thermal dehydratation of gamma iron(III) oxide-hydroxide. Another method involves the careful oxidation of iron(II,III) oxide (Fe3O4).[13] The ultrafine particles can be prepared by thermal decomposition of iron(III) oxalate.

Other solid phases[edit]

Several other phases have been identified or claimed. The β-phase is cubic body-centered (space group Ia3), metastable, and at temperatures above 500 °C (930 °F) converts to alpha phase. It can be prepared by reduction of hematite by carbon,[clarification needed] pyrolysis of iron(III) chloride solution, or thermal decomposition of iron(III) sulfate.[14]

The epsilon (ε) phase is rhombic, and shows properties intermediate between alpha and gamma, and may have useful magnetic properties applicable for purposes such as high density recording media for big data storage.[15] Preparation of the pure epsilon phase has proven very challenging. Material with a high proportion of epsilon phase can be prepared by thermal transformation of the gamma phase. The epsilon phase is also metastable, transforming to the alpha phase at between 500 and 750 °C (930 and 1,380 °F). It can also be prepared by oxidation of iron in an electric arc or by sol-gel precipitation from iron(III) nitrate.[citation needed] Research has revealed epsilon iron(III) oxide in ancient Chinese Jian ceramic glazes, which may provide insight into ways to produce that form in the lab.[16][non-primary source needed]

Additionally, at high pressure an amorphous form is claimed.[6][non-primary source needed]

Liquid phase[edit]

Molten Fe2O3 is expected to have a coordination number of close to 5 oxygen atoms about each iron atom, based on measurements of slightly oxygen deficient supercooled liquid iron oxide droplets, where supercooling circumvents the need for the high oxygen pressures required above the melting point to maintain stoichiometry.[17]

Hydrated iron(III) oxides[edit]

Several hydrates of Iron(III) oxide exist.

When alkali is added to solutions of soluble Fe(III) salts, a red-brown gelatinous precipitate forms. This is not Fe(OH)3, but Fe2O3·H2O (also written as Fe(O)OH).

Several forms of the hydrated oxide of Fe(III) exist as well. The red lepidocrocite (γ-Fe(O)OH) occurs on the outside of rusticles, and the orange goethite (α-Fe(O)OH) occurs internally in rusticles.

When Fe2O3·H2O is heated, it loses its water of hydration. Further heating at 1670 K converts Fe2O3 to black Fe3O4 (FeIIFeIII2O4), which is known as the mineral magnetite.

Fe(O)OH is soluble in acids, giving [Fe(H2O)6]3+. In concentrated aqueous alkali, Fe2O3 gives [Fe(OH)6]3−.[13]

Reactions[edit]

The most important reaction is its carbothermal reduction, which gives iron used in steel-making:

- Fe2O3 + 3 CO → 2 Fe + 3 CO2

Another redox reaction is the extremely exothermic thermite reaction with aluminium.[18]

- 2 Al + Fe2O3 → 2 Fe + Al2O3

This process is used to weld thick metals such as rails of train tracks by using a ceramic container to funnel the molten iron in between two sections of rail. Thermite is also used in weapons and making small-scale cast-iron sculptures and tools.

Partial reduction with hydrogen at about 400 °C produces magnetite, a black magnetic material that contains both Fe(III) and Fe(II):[19]

- 3 Fe2O3 + H2 → 2 Fe3O4 + H2O

Iron(III) oxide is insoluble in water but dissolves readily in strong acid, e.g. hydrochloric and sulfuric acids. It also dissolves well in solutions of chelating agents such as EDTA and oxalic acid.

Heating iron(III) oxides with other metal oxides or carbonates yields materials known as ferrates (ferrate (III)):[19]

- ZnO + Fe2O3 → Zn(FeO2)2

Preparation[edit]

Iron(III) oxide is a product of the oxidation of iron. It can be prepared in the laboratory by electrolyzing a solution of sodium bicarbonate, an inert electrolyte, with an iron anode:

- 4 Fe + 3 O2 + 2 H2O → 4 FeO(OH)

The resulting hydrated iron(III) oxide, written here as FeO(OH), dehydrates around 200 °C.[19][20]

- 2 FeO(OH) → Fe2O3 + H2O

Uses[edit]

Iron industry[edit]

The overwhelming application of iron(III) oxide is as the feedstock of the steel and iron industries, e.g. the production of iron, steel, and many alloys.[20]

Polishing[edit]

A very fine powder of ferric oxide is known as «jeweler’s rouge», «red rouge», or simply rouge. It is used to put the final polish on metallic jewelry and lenses, and historically as a cosmetic. Rouge cuts more slowly than some modern polishes, such as cerium(IV) oxide, but is still used in optics fabrication and by jewelers for the superior finish it can produce. When polishing gold, the rouge slightly stains the gold, which contributes to the appearance of the finished piece. Rouge is sold as a powder, paste, laced on polishing cloths, or solid bar (with a wax or grease binder). Other polishing compounds are also often called «rouge», even when they do not contain iron oxide. Jewelers remove the residual rouge on jewelry by use of ultrasonic cleaning. Products sold as «stropping compound» are often applied to a leather strop to assist in getting a razor edge on knives, straight razors, or any other edged tool.

Pigment[edit]

Two different colors at different hydrate phase (α: red, β: yellow) of iron(III) oxide hydrate;[3] they are useful as pigments.

Iron(III) oxide is also used as a pigment, under names «Pigment Brown 6», «Pigment Brown 7», and «Pigment Red 101».[21] Some of them, e.g. Pigment Red 101 and Pigment Brown 6, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in cosmetics. Iron oxides are used as pigments in dental composites alongside titanium oxides.[22]

Hematite is the characteristic component of the Swedish paint color Falu red.

Magnetic recording[edit]

Iron(III) oxide was the most common magnetic particle used in all types of magnetic storage and recording media, including magnetic disks (for data storage) and magnetic tape (used in audio and video recording as well as data storage). Its use in computer disks was superseded by cobalt alloy, enabling thinner magnetic films with higher storage density.[23]

Photocatalysis[edit]

α-Fe2O3 has been studied as a photoanode for solar water oxidation.[24] However, its efficacy is limited by a short diffusion length (2–4 nm) of photo-excited charge carriers[25] and subsequent fast recombination, requiring a large overpotential to drive the reaction.[26] Research has been focused on improving the water oxidation performance of Fe2O3 using nanostructuring,[24] surface functionalization,[27] or by employing alternate crystal phases such as β-Fe2O3.[28]

Medicine[edit]

Calamine lotion, used to treat mild itchiness, is chiefly composed of a combination of zinc oxide, acting as astringent, and about 0.5% iron(III) oxide, the product’s active ingredient, acting as antipruritic. The red color of iron(III) oxide is also mainly responsible for the lotion’s pink color.

See also[edit]

- Chalcanthum

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Haynes, p. 4.69

- ^ «A dictionary of chemical solubilities, inorganic». archive.org. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ a b c Comey, Arthur Messinger; Hahn, Dorothy A. (February 1921). A Dictionary of Chemical Solubilities: Inorganic (2nd ed.). New York: The MacMillan Company. p. 433.

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.141

- ^ a b c d Ling, Yichuan; Wheeler, Damon A.; Zhang, Jin Zhong; Li, Yat (2013). Zhai, Tianyou; Yao, Jiannian (eds.). One-Dimensional Nanostructures: Principles and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-118-07191-5.

- ^ a b c d Vujtek, Milan; Zboril, Radek; Kubinek, Roman; Mashlan, Miroslav. «Ultrafine Particles of Iron(III) Oxides by View of AFM – Novel Route for Study of Polymorphism in Nano-world» (PDF). Univerzity Palackého. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Haynes, p. 5.12

- ^ a b c Sigma-Aldrich Co., Iron(III) oxide. Retrieved on 2014-07-12.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. «#0344». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b «SDS of Iron(III) oxide» (PDF). KJLC. England: Kurt J Lesker Company Ltd. 5 January 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ PubChem. «Iron oxide (Fe2O3), hydrate». pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Greedan, J. E. (1994). «Magnetic oxides». In King, R. Bruce (ed.). Encyclopedia of Inorganic chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-93620-6.

- ^ a b c Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2008). «Chapter 22: d-block metal chemistry: the first row elements». Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Pearson. p. 716. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ «Mechanism of Oxidation & Thermal Decomposition of Iron Sulphides» (PDF).

- ^ Tokoro, Hiroko; Namai, Asuka; Ohkoshi, Shin-Ichi (2021). «Advances in magnetic films of epsilon-iron oxide toward next-generation high-density recording media». Dalton Transactions. Royal Society of Chemistry. 50 (2): 452–459. doi:10.1039/D0DT03460F. PMID 33393552. S2CID 230482821. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Dejoie, Catherine; Sciau, Philippe; Li, Weidong; Noé, Laure; Mehta, Apurva; Chen, Kai; Luo, Hongjie; Kunz, Martin; Tamura, Nobumichi; Liu, Zhi (2015). «Learning from the past: Rare ε-Fe2O3 in the ancient black-glazed Jian (Tenmoku) wares». Scientific Reports. 4: 4941. doi:10.1038/srep04941. PMC 4018809. PMID 24820819.

- ^ Shi, Caijuan; Alderman, Oliver; Tamalonis, Anthony; Weber, Richard; You, Jinglin; Benmore, Chris (2020). «Redox-structure dependence of molten iron oxides». Communications Materials. 1 (1): 80. Bibcode:2020CoMat…1…80S. doi:10.1038/s43246-020-00080-4.

- ^ Adlam; Price (1945). Higher School Certificate Inorganic Chemistry. Leslie Slater Price.

- ^ a b c Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 1661.

- ^ a b Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Element (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-3365-9.

- ^ Paint and Surface Coatings: Theory and Practice. William Andrew Inc. 1999. ISBN 978-1-884207-73-0.

- ^ Banerjee, Avijit (2011). Pickard’s Manual of Operative Dentistry. United States: Oxford University Press Inc., New York. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-957915-0.

- ^ Piramanayagam, S. N. (2007). «Perpendicular recording media for hard disk drives». Journal of Applied Physics. 102 (1): 011301–011301–22. Bibcode:2007JAP…102a1301P. doi:10.1063/1.2750414.

- ^ a b Kay, A., Cesar, I. and Grätzel, M. (2006). «New Benchmark for Water Photooxidation by Nanostructured α-Fe2O3 Films». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (49): 15714–15721. doi:10.1021/ja064380l. PMID 17147381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kennedy, J.H. and Frese, K.W. (1978). «Photooxidation of Water at α-Fe2O3 Electrodes». Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 125 (5): 709. doi:10.1149/1.2131532.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Le Formal, F. (2014). «Back Electron–Hole Recombination in Hematite Photoanodes for Water Splitting». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 136 (6): 2564–2574. doi:10.1021/ja412058x. PMID 24437340.

- ^ Zhong, D.K. and Gamelin, D.R. (2010). «Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation by Cobalt Catalyst («Co−Pi»)/α-Fe2O3 Composite Photoanodes: Oxygen Evolution and Resolution of a Kinetic Bottleneck». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (12): 4202–4207. doi:10.1021/ja908730h. PMID 20201513.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Emery, J.D. (2014). «Atomic Layer Deposition of Metastable β-Fe2O3 via Isomorphic Epitaxy for Photoassisted Water Oxidation». ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 6 (24): 21894–21900. doi:10.1021/am507065y. OSTI 1355777. PMID 25490778.

External links[edit]

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

Справочник содержит названия веществ и описания химических формул (в т.ч. структурные формулы и скелетные формулы).

Введите часть названия или формулу для поиска:

Общее число найденных записей: 1.

Показано записей: 1.

Оксид железа(III)

Брутто-формула:

Fe2O3

CAS# 1309-37-1

Названия

Русский:

- Оксид железа(III) [Wiki]

- железный сурик

- колькотар

- крокус

- окись железа

English:

- 100ED

- Ariabel Sienna 300406

- Auvicorb BL

- Bayer 4125

- Bayer S 11

- Bayferrox 110

- Bayferrox 111

- Bayferrox 120M

- Bayferrox 130

- Bayferrox 180

- Bayferrox 910

- Bayferrox BF 110

- Bayferrox Red 110

- Bayferrox Red 110M

- Bayferrox Red 180M

- Bayferrox120NM

- Bayferrox140

- Bayferrox225

- Bengara EP 40

- Bengara N 58

- Blood stone

- C 7051

- C.I. 77491

- C.I. Pigment Red 101

- C888-1045F

- CWD 8801

- E172(ii)

- EINECS:215-168-2

- Iron oxide red

- Iron(III) oxide [Wiki]

- diferric oxygen(2-)

- ferricoxide

- iron(3+) oxide

- oxo(oxoferriooxy)iron(IUPAC)

Варианты формулы:

$L(1.4)O^2-/0Fe^3+O^2-/0Fe^3+O^2-

Реакции, в которых участвует Оксид железа(III)

-

4FeS2 + 11O2 «800^oC»—> 2Fe2O3 + 8SO2

-

Fe2O3 + 6HF «T»-> 2FeF3 + 3H2O

-

Fe2(SO4)3 «500-700^oC»—> Fe2O3 + 3SO3″|^»

-

2Fe(OH)3 «350-400^oC»—> Fe2O3 + 3H2O

-

{M}2O3 + 6H{X} = 2{M}{X}3 + 3H2O

, где M =

Fe Al Cr La Sc Y; X =

F Cl Br I (NO3)