Загрузить PDF

Загрузить PDF

У вас есть идея для пьесы, возможно даже блестящая. Вы хотите развернуть ее в комичный или драматический сюжет, но как? Драматургия — это дар, который либо есть у вас, либо его у вас нет. Однако ниже вы можете познакомиться с методами, которых должно быть достаточно, чтобы начать писать.

-

1

Сформулируйте свою концепцию. В вашей истории должен быть центр — либо это плохой парень, которого надо спасти, либо плохой парень, которого надо победить. Как только у вас есть основная идея, можете разрабатывать другие элементы.

-

2

Создайте логическую серию событий. Начните с абзаца, описывающего, что происходит. Определите главное действующее лицо, опишите, что он (или она) должен сделать, создайте несколько препятствий и способов преодолеть их, придумайте развязку.

- Не волнуйтесь, если на данном этапе вы идете по шаблону. Рассмотрите такую последовательность: мужчина встречает женщину; они влюбляются; они изо всех сил пытаются преодолеть силы против них; мужчина умирает благородно. Это «Кинг Конг» или «Ромео и Джульетта»? Ответ в обоих случаях: да. То, как вы обрабатываете детали, ваше дело.

-

3

Выберите структуру. В этом месте все, что вы должны сделать, это открыть себя для возможностей и посмотреть, куда они вас приведут. Это может быть один акт на двадцать минут или двухчасовая эпопея.

-

4

Сделайте первый набросок. Вам пока не нужны имена персонажей, но вы должны дать персонажам что-то сказать. Пусть диалог течет на основе того, что мотивирует персонажи.

- У Эдварда Олби в “Кто боится Вирджинии Вульф?” Марта, исполнительница главной роли, возвращается домой с вечеринки, осматривает дом и говорит “Иисус Х. Христос!” Это было довольно необычной первой строкой в 1962 г., но привлекло интерес аудитории.

-

5

Станьте безжалостным редактором. Даже самым блестящим писателям нужно редактирование, и это часто — зверский процесс вырезания слов или даже целых речей, изменение последовательности событий, вывод персонажей, которые не работают. Вам нужна храбрость, чтобы распознать и сохранить только лучшие части вашей пьесы.

-

6

Просите обратную связь. Не просто найти кого-то, кто даст объективное и честное мнение, но это может быть очень полезным. Попытайтесь определить, где можно найти таких людей онлайн или там, где вы живете. Совершенно необходим взгляд еще одной пары глаз.

-

7

Посмотрите еще раз. С обратной связью, которую вы имеете в виду, перечитайте пьесу. Посмотрите пристально и внесите изменения, чтобы улучшить состоятельность, характеристики и удалить все ошибки.

-

8

Начните продавать. Отправляете ли вы рукопись агенту, издателю, или пытаетесь предложить местному театру ее поставить, маркетинг зависит от вас. Верьте в ценность пьесы и не сдавайтесь.

Реклама

Советы

- Действие большинства пьес происходит в определенное время с указанием места, так что избегайте противоречий. Персонаж в 1930-х гг. мог сделать телефонный звонок или отправить телеграмму, но не мог смотреть телевизор.

- Проверьте источники в конце этой статьи для надлежащего форматирования сценария и следуйте установленным правилам.

- Удостоверьтесь, что вы сохраняете динамику действия, не забывайте, что она должна следовать из вашего текста! Иногда хорошая динамика еще важнее, чем удачное начало!

- Прочитайте сценарий вслух на малочисленную аудиторию. Пьесы основываются на словах, и ее сила или слабость быстро становятся очевидными, при прочтении.

- Не кладите пьесу под сукно, пусть все знают, что вы — писатель!

Реклама

Предупреждения

- Театральный мир полон идей, но пусть ваша обработка истории будет оригинальной. Кража чьей-либо истории не только нравственно несостоятельна, но вас почти наверняка поймают.

- Защитите свою работу. Убедитесь, что титульный лист пьесы включает ваше имя и год написания пьесы, а далее — символ авторского права: ©.

- Отказ значительно перевешивает принятие, но не расстраивайтесь. Если вашу пьесу настойчиво игнорируют, напишите другую.

Реклама

Об этой статье

Эту страницу просматривали 22 451 раз.

Была ли эта статья полезной?

Как правильно оформить сценарий – правила с примерами

Продюсер по одному взгляду на сценарий может сказать, кто его прислал — новичок или опытный автор. Все дело в оформлении. Из этой статьи вы узнаете, как правильно оформить сценарий по форме и содержанию.

Редактор, автор блога Band

Русская и американская запись киносценариев — какую выбрать?

Существуют два вида записи киносценариев — русская и американская, она же голливудская. И так как вторая общепризнана на мировом уровне, хорошим тоном считается оформлять сценарии именно так.

Требования к оформлению сценария

Подписаться на полезные материалы, бесплатные лекции и скидки

Правила оформления сценариев фильмов делятся на два типа: по форме и содержанию. Главное, что вам нужно знать: требования разметки крайне строгие. Размер шрифта, отступ от левого и правого края, прописные или строчные буквы — каждый блок подчиняется своим правилам. Обратите внимание: это не рекомендации, а именно правила, которые необходимо строго соблюдать.

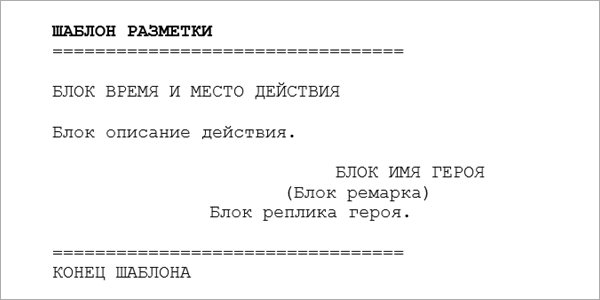

Образец оформления сценария. Здесь и далее во всех примерах приводятся отрывки из пособия Ольги Смирновой «Формат разметки сценария».

Базовые правила разметки:

Первая страница — титульная, после нее сразу идет текст сценария. Оформляется по строгим правилам: никаких замечаний, пролога, синопсиса, благодарностей, напутствий членам съемочной группы. Фрагменты биографии автора тоже стоит опустить.

Сценарии пишутся только в настоящем времени: думает, видит, говорит, кричит. Никаких «он подумал» или «увидел».

Повествование в сценарии должно быть обезличенное, от третьего лица. Никаких «я подошел и протянул руку для приветствия». Только «Он стоит, едет, смотрит, идет, говорит, садится в кресло, пьет кофе» и т.п.

Все страницы нумеруются в правом верхнем углу, за исключением титульного листа, его нумеровать не нужно.

Правила форматирования:

Классический сценарный шрифт: Courier New.

Кегль (размер шрифта): 12.

Выравнивание (всегда, если не указано иначе в конкретном разделе): по левому краю.

Поля: верхний отступ – 2,5 см, нижний – 1,25 см (может быть больше, но не меньше), левый – 3,75 см, правый– 2,5 см. У разных блоков сценария отличается оформление, дальше расскажем об особенностях разметки каждого.

Как правильно оформить титульный лист

Корректное оформление первой страницы сразу покажет ваш профессиональный подход к делу. Что нужно указать на титульном листе:

Название сценария. Пишется заглавными буквами, отступ сверху — 14 строк, слева — 3,25 см, справа – 3,25 см.

Имя автора. Пишется строчными буквами по обычным правилам. Нужно отбить его от названия пустой строкой. Отступы по краям аналогичные.

Указание авторства: источник экранизации или оригинальный сценарий. Оформляется так же, как имя автора, отбивается пустой строкой.

Контактную информацию. Отступ слева – 8,25 см, сам текст нужно выровнять по левому краю. Здесь укажите свои данные или агента.

Даже если очень захочется дополнить текст рисунками и иллюстрациями, сдержите этот порыв. Титульный лист — не обложка книги.

Пример оформления титульного листа сценария «Мама не горюй».

Блоки, из которых состоит сценарий

Текст сценария, как конструктор, собирается из стандартных разделов. Каждый из них пишется и оформляется строго по своим правилам.

«Время и место действия»

С этого блока начинается каждая сцена. Состоит из трех частей: вид места, название и время суток. Таким образом вы сразу обозначаете, где будет происходить сцена. Вид места указывается сокращением «НАТ.» или «ИНТ.» — натура (съемки на природе) или интерьер. Запомните: между частями не ставятся ни точки, ни запятые, только пробелы.

Отступ от левого края — 3,75 см (1,5 дюйма), от правого края 2,5 см (1 дюйм).

Текст набирается заглавными буквами (капслоком).

Пример правильного и неправильного отступа.

«Описание действия»

Следующий блок после «Времени и места действия», пропускать его нельзя. Оформляется аналогично, но набирается по обычным правилам текста, строчными буквами. Выделяются заглавными только персонажи, появившиеся в сцене впервые. Следующий текст делается с отбивкой пустой строкой, чтобы его было легче читать.

Пример правильного оформления «Описания действия».

Совет: не стесняйтесь подробно описывать действие. Здесь вы можете развернуться как сценарист. Не нужно просто писать «герои целуются», «герои дерутся», «герои ссорятся». Лучше расскажите, как они тяжело дышат, улыбаются, ходят по комнате, роняют или разбивают от волнения предметы. Создавайте картинку при помощи слов. Но увлекаться деталями и становиться многословными тоже не стоит: старайтесь делать куски описаний короткими, но емкими.

«Имя героя»

Появляется перед речью персонажа после описания действия. С его помощью вы показываете, кто автор прямой речи. Если в литературных формах допустимо опускать имя персонажа в диалоги, то здесь строго подписывается каждая реплика.

Правила оформления: отступ от левого края всегда 10,5 см (4,2 дюйма), от правого — 2,5 см (1 дюйм). Не выравнивается по центру, а делается с отступом.

Пример правильных и неправильных отступов блока «Имя героя».

После «Имени героя» обычно идет реплика:

Как выглядит реплика героя.

Может быть и такая структура: «Имя героя», после «Ремарка» и, наконец, «Реплика».

Пример реплики героя с ремаркой.

При таком оформлении блоки друг от друга не отбиваются пустой строкой.

«Реплика героя»

Диалоги в сценариях оформляются не как в книгах или статьях, а отдельными репликами.

Правила разметки: отступ от левого края всегда 7,5 см (3 дюйма), от правого — 6,25 см (2,5 дюйма).

Пишется строчными буквами, по всем базовым правилам русского языка. Реплики разных героев обозначаются «Именем героя» и отбиваются пустой строкой.

Пример двух «Реплик героя». Здесь хорошо видно, как оформлять диалоги.

«Ремарка»

Правила разметки: отступ от левого края всегда 9,25 см (3,7 дюйма), от правого — 6,25 см (2,5 дюйма). Так она дополнительно выделяется в тексте и обращает на себя внимание.

Пишется в скобках, набирается строчными буквами, на новой строчке. В ремарке можно указать интонацию, описать, что делает персонаж во время речи.

Пример использования ремарок.

«Титр»

Всегда выравнивается по левому краю, но оформляться может по-разному. Например, идти следом после двоеточия или отдельной строкой с отбивкой и выравниванием по центру.

Пример трех корректных вариантов оформления «Титра».

Профессиональные сокращения

ИНТ — расшифровывается «интерьер», означает съемку сцены в помещении или павильоне (раньше использовалось сокращение ПАВ, сейчас редко).

НАТ — расшифровывается «натура», означает съемку сцены на природе или улице, в любой локация под открытым небом.

КРП — так обозначают крупный план.

ЗТМ — затемнение, которым обычно заканчивается сценарий (а начинается ИЗ ЗТМ — из затемнения).

ВПЗ — вне поле зрения, ремарка, когда герой говорит и находится на месте действия, но его не видно в кадре.

ПАН — панорама, когда камера двигается по полукругу.

Что еще почитать по этой теме:

Где посмотреть примеры оформления сценария

Пользуясь базами русских сценариев и переводов зарубежных, будьте аккуратны. Многие из них интересно почитать с точки зрения содержания, но брать как пример разметки их нельзя.

Советы опытных сценаристов

Каждый делает свою работу. Не надо думать за оператора и писать «камера наехала», «камера отъехала», постоянно выделять крупный и средний план. Оставьте эту работу специалистам.

Неважно, как зовут уборщицу. Вам не нужно придумывать имена всем родственникам и проходным персонажам фильма. Смело пишите роли в сюжете — УБОРЩИЦА, СОСЕД, КОЛЛЕГА, БАБУШКА У ПОДЪЕЗДА. Именно так, прописными буквами.

«Же не манж па си жур». Если в сценарии есть иностранные реплики, не нужно переводить их самостоятельно или с помощью гугл-переводчика. Пишите этот текст, как и основной, по-русски (не транслитерацией, а обычным русским языком). По правилам иностранная речь выделяется ремаркой «говорит по-немецки».

Насколько важно следовать всем этим правилам?

Конечно, важна не только форма сценария, но и его содержание. Если вы где-то ошибетесь с разметкой, выровняете текст по центру, забудете сделать пустую строку, гениальный текст это не испортит.

Но если вы новичок, лучше оформить сценарий по всем правилам. Особенно, если вы планируете подавать его на конкурсы: в их условиях прописываются все условия участия, в том числе требования к оформлению.

Мечтаете стать писателем?

Учитесь у лучших современных авторов – Гузель Яхина, Галина Юзефович, Алексей Иванов, Линор Горалик и других.

В школе БЭНД более 20 программ для авторов с разными запросами и разным уровнем опыта: нужны оригинальные посты для блога и нативный сторителлинг? Хотите написать серию рассказов и опубликовать их в толстом журнале? Всегда мечтали о крупной форме – романе или детской книге? BAND поможет найти свой уникальный авторский голос и выйти на писательскую орбиту.

Театр начинается с вешалки, а театральная постановка – со сценария. Пытаться поставить спектакль или снять фильм без сценария – все равно, что пытаться пересечь океан без всякой навигации.

Сценарий в его общем виде может понадобиться и тем, кому приходится выступать на публике. Возможно, вам уже приходилось испытывать неловкость, произнося речь перед аудиторией. Если это так, причиной этому могут быть неумение пользоваться приемами риторики или неправильно подготовленный сценарий выступления. Для решения первой проблемы рекомендуем пройти нашу онлайн-программу «Современная риторика», где вы научитесь хорошо говорить, правильно вести себя на сцене, пользоваться ораторскими приемами и многому другому, что позволит вам успешно выступать перед любой аудиторией.

Ну а начало решению второй проблемы положит наша статья. Что такое сценарное мастерство, почему сценарий так важен и как освоить основы сценарного мастерства, мы и расскажем далее.

Что такое сценарий и почему он так важен?

Сценарий – это руководство для продюсеров, режиссера, актеров, съемочной группы. Сценарий является общей почвой, с которой все в фильме будут работать от начала до конца производства.

Он рассказывает полную историю, содержит все действия и диалоги для каждого персонажа, а также описывает персонажей визуально, чтобы кинематографисты могли воплотить их стиль, внешний вид или атмосферу в реальность. Поскольку сценарий является своего рода чертежом фильма или телешоу, он отражает и стоимость проекта.

Создание фильма требует тщательного планирования бюджета. Например, если сценарий содержит спецэффекты и сцены в разных локациях, то бюджет должен быть значительно выше, чем в фильме, в основном ориентированном на диалог.

Итак, откуда же берется сценарий? Обычно он создается одним из следующих способов:

- Стандартный сценарий подается продюсерам или студии, и если они заинтересованы, то разрабатывается и пишется с их участием. Иногда к известному сценаристу обращаются с просьбой написать сценарий.

- Специальный сценарий пишется писателем заранее в надежде, что он будет выбран и в конечном итоге куплен продюсером или студией.

- Адаптированный сценарий производится из чего-то, что уже существует в другой форме, такой как книга, пьеса, телешоу, предыдущий фильм или даже реальная история. Существует так много бесчисленных примеров адаптированных сценариев, но, вероятно, наиболее распространенными являются самые продаваемые книги. Если художественная книга становится бестселлером, это почти гарантия, что она будет адаптирована для фильма.

Хотя может показаться, что адаптированные сценарии писателю легче готовить, так как история уже есть, тут есть свой набор проблем.

Чрезвычайно страстные поклонники оригинального материала могут быть очень жесткими к сценаристу (поклонникам комиксов и научной фантастики, как известно, трудно угодить).

К тому же, материал должен быть написан в формате сценария, который очень отличается от того, как пишутся книги. В самых общих чертах, сценарий – это документ на 90-120 страницах, написанный шрифтом Courier 12pt. Интересно, почему используется шрифт Courier? Это вопрос времени. Одна отформатированная страница сценария в шрифте Courier равна примерно одной минуте экранного времени. Вот почему среднее количество страниц в сценарии должно составлять от 90 до 120 страниц.

Секреты сценарного мастерства от успешных сценаристов

Для создания стоящего фильма, спектакля, шоу и любого вида представления человеку требуется особое сценарное мастерство, так же как для исполнения ролей необходимо актерское мастерство. К слову, у нас есть соответствующий курс, где начинающие актеры узнают о существующих театральных системах и освоят искусство перевоплощения и переживания. Ну а сейчас мы поделимся секретами сценарного мастерства известных деятелей этой сферы.

Персонажи никогда не говорят то, чего они хотят на самом деле

Все дело в подтексте. Эрнест Хемингуэй лучше всего выразился, ставшей теперь знаменитой, цитатой: «Если писатель достаточно хорошо знает то, о чем пишет, он может опустить известные ему подробности. Величавость движения айсберга обусловлена тем, что над водой видна только одна девятая его часть».

Представьте, было бы крайне скучно, если бы мистер Оранжевый в первом акте «Бешеных псов» прямо сказал мистеру Белому: «Послушайте, я полицейский. Спасибо, что спасли мне жизнь, и мне очень жаль, но, пожалуйста, не позволяйте им убить меня». Вместо этого его диалоги никогда не показывают, чего он хочет, но сценарист дает зрителям ключи на протяжении всего фильма.

Когда персонажи раскрывают свои секреты, нет места для открытия, таким образом, ничто не удерживает внимание аудитории.

Это один из самых больших секретов написания сценария. Навык необходимо освоить и постоянно оттачивать, и если вы сумеете выполнить то, что советует Хемингуэй, вы заметно продвинетесь к тому, чтобы стать хорошим сценаристом.

Спросите себя: «Так ли необходимо персонажу передавать эту информацию?»

Дэвид Мэмет (киносценарист, лауреат Пулитцеровской премии 1984 года за пьесу «Гленгарри Глен Росс»), задающий этот вопрос, считает, что если ответ «нет», то лучше вырезать эту информацию. «Потому что вы не ставите аудиторию в такое же положение с главным героем – я пытаюсь принять это как абсолютный принцип. Я имею в виду, если я пишу не для публики, если я пишу не для того, чтобы им было легче, тогда для кого, черт возьми, я это делаю? И вы следуйте этим принципам: сокращайте, создавайте кульминацию, оставляйте экспозицию и всегда продвигайтесь к единственной цели главного героя. Это очень строгие правила, но именно они, по моему мнению и опыту, облегчают задачу аудитории».

Помните: действие говорит громче слов

«Если вы притворитесь, что персонажи не могут говорить, и напишете немое кино, вы напишите большую драму», – Дэвид Мэмет обучал этому свой писательский персонал.

Хороший диалог часто является результатом того, что сценарист не пишет ни одного диалога. Это может звучать как оксюморон, но это правда. Гораздо больше мы узнаем о персонажах через их действия и реакции.

Посмотрите, как много мы узнаем о характере Антона Чигура в его вступительной сцене в фильме «Старикам тут не место». Он безжалостный убийца, и мы узнаем это через его действия и реакции. Красота этого заключается в том, что когда герой что-то говорит — зритель его слушает, и это имеет значение.

Используя меньше диалога и фокусируясь на действиях и реакциях, сценарист усиливает существующий диалог.

Конфликт – это все

Лучший диалог исходит от двух или более персонажей в одной сцене, которые преследуют разные цели. Все очень просто. Если это присутствует почти в каждой сцене вашего сценария, диалог выскочит из страницы, и аудитория будет следить за героями, ожидая, кто победит в споре.

Конфликт – это все. Если есть конфликт, есть и история.

Аарон Соркин – американский сценарист и лауреат премий BAFTA, «Золотой глобус», «Оскар» и «Эмми» – однажды сказал: «Каждый раз, когда вы видите двух людей в комнате, несогласных друг с другом хоть в чём-то, пусть даже если речь идёт о времени дня, – это сцена, которая должна быть записана. Вот что я ищу».

Вспомогательные персонажи являются поддерживающими

Слишком часто сценаристы допускают ошибку, давая строки диалога персонажам, которые их не заслуживают.

Дэвид Мэмет однажды мудро заявил: «Без сомнения, одна из самых больших ошибок, которую я вижу у любителей, – это персонажи, которые говорят только потому что они находятся в сцене. Если персонажи говорят только потому что это написано в сценарии, сцена будет невыносимо скучной».

Каждая линия диалога в фильме должна иметь значение и продвигать историю и персонажей вперед. Пустые слова второстепенных героев отнимают у остального диалога время и ценность. Вспомогательные персонажи существуют, чтобы поддержать главных героев и историю. Если то, что они говорят, не относится к истории, это следует сократить.

Забудьте о том, что диалоги должны звучать реально

Отличный диалог в фильмах звучит не так, как мы разговариваем в жизни. Это усиленная реальность, предназначенная для передачи эмоции момента в двух-трех словах.

Внимательно послушайте популярные строки в известных фильмах.

В реальном мире мы так не разговариваем. Мы заикаемся. Мы произносим такие слова, как «эмм», «как», «ну» и т.д. Мы идем по касательной. Мы начинаем рассказ, возвращаемся назад, когда упускаем детали, начинаем снова. Если бы сценаристы писали диалоги так, как люди действительно разговаривают в реальной жизни, никто не мог бы слушать это в кинотеатре. Мы ходим на хорошие фильмы, чтобы послушать развлекательную кинематографическую поэзию.

Поэтому избегайте часто даваемых советов изучать реальные разговоры и подражать им. Да, вы хотите избежать деревянного диалога. Да, вы хотите, чтобы персонажи прерывали друг друга и говорили фрагментами, как мы часто делаем в реальной жизни. Но если вы прислушаетесь к тому, как мы действительно говорим, и сравните это с некоторыми из лучших кинематографических диалогов, вы быстро поймете, что персонажи фильма говорят в гиперреалистичном формате, приправленном развлекательной, привлекательной и иногда поэтической вспышкой. Они разговаривают с ритмом и темпом рассказа.

Мастер диалога Квентин Тарантино сказал об этом лучше всего: «Я думаю, что в моем диалоге есть немного того, что вы бы назвали музыкой или поэзией, и повторение определенных слов помогает придать ему ритм. Это просто происходит, и я просто иду с ним, ища ритм сцены».

Сценарного мастерства, как у Тарантино, Мэмета, Хемингуэя, Соркина, Филда, Коэнса и других, достичь сложно. Вам понадобится немало времени, чтобы приблизиться к тому, что они сделали в своих фильмах, пьесах и историях. Но даже выполнив небольшой процент того, что они применяют в своих работах, вы будете впереди большинства сценаристов.

Просмотрите свои написанные сценарии. Держите эти шесть секретов от мастеров в уме и подумайте, можете ли вы выйти на новый уровень со сценарием, который действительно продуман до мелочей и имеет значение.

И напоследок: если вы хотите основательнее изучить сценарное мастерство, курсы от 4Brain окажут вам в этом хорошую помощь. Например, пройдя наш курс «Скорочтение: как научиться быстро читать» вы быстрее и эффективнее осилите следующие интересные книги по сценарному мастерству:

- Сид Филд «Киносценарий: основы написания».

- Майкл Хейг «Голливудский стандарт. Как написать сценарий для кино и ТВ, который купят».

- Джон Труби «Анатомия истории. 22 шага к созданию успешного сценария».

- Александр Митта «Кино между адом и раем».

- Дэвид Троттьер «Библия сценариста».

Желаем вам успехов!

Download Article

Download Article

You have an idea for a play script — perhaps a very good idea. You want to expand it into a comedic or dramatic storyline, but how? Although you may want to dive right into the writing, your play will be much stronger if you spend the time planning out your storyline, before you start your first draft. Once you’ve brainstormed your narrative and outlined your structure, writing your play will seem a much less daunting task.

-

1

Decide what kind of story you want to tell. Though every story is different, most plays fall into categories that help the audience understand how to interpret the relationships and events they see. Think about the characters you want to write, then consider how you want their stories to unfold.[1]

Do they:- Have to solve a mystery? Sometimes you can even have other people write the script for you .

- Go through a series of difficult events in order to achieve personal growth?

- Come of age by transitioning from childlike innocence to worldly experience?

- Go on a journey, like Odysseus’s perilous journey in The Odyssey?[2]

- Bring order to chaos?

- Overcome a series of obstacles to achieve a goal?

-

2

Brainstorm the basic parts of your narrative arc. The narrative arc is the progression of the play through beginning, middle, and end. The technical terms for these three parts are exposition, rising action, and resolution, and they always come in that order. Regardless of how long your play is or how many acts you have, a good play will develop all three pieces of this puzzle. Taken notes on how you want to flesh each one out before sitting down to write your play.

Advertisement

-

3

Decide what needs to be included in the exposition. Exposition opens a play by providing basic information needed to follow the story: When and where does this story take place? Who is the main character? Who are the secondary characters, including the antagonist (person who presents the main character with his or her central conflict), if you have one? What is the central conflict these characters will face? What is the mood of this play (comedy, romantic drama, tragedy)?

-

4

Transition the exposition into rising action. In the rising action, events unfold in a way that makes circumstances more difficult for the characters. The central conflict comes into focus as events raise the audience’s tension higher and higher. This conflict may be with another character (antagonist), with an external condition (war, poverty, separation from a loved one), or with oneself (having to overcome one’s own insecurities, for example). The rising action culminates in the story’s climax: the moment of highest tension, when the conflict comes to a head.[3]

-

5

Decide how your conflict will resolve itself. The resolution releases the tension from the climactic conflict to end the narrative arc. You might have a happy ending, where the main character gets what he/she wants; a tragic ending where the audience learns something from the main character’s failure; or a denouement, in which all questions are answered.

-

6

Understand the difference between plot and story. The narrative of your play is made up of the plot and the story — two discrete elements that must be developed together to create a play that holds your audience’s attention. E.M. Forster defined story as what happens in the play — the chronological unfolding of events. The plot, on the other hand, can be thought of as the logic that links the events that unfold through the plot and make them emotionally powerful.[4]

An example of the difference is:- Story: The protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him. Then the protagonist lost his job.

- Plot: The protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him. Heartbroken, he had an emotional breakdown at work that resulted in his firing.

- You must develop a story that’s compelling and moves the action of the play along quickly enough to keep the audience’s attention. At the same time, you must show how the actions are all causally linked through your plot development. This is how you make the audience care about the events that are transpiring on stage.

-

7

Develop your story. You can’t deepen the emotional resonance of the plot until you have a good story in place. Brainstorm the basic elements of story before fleshing them out with your actual writing by answering the following questions:[5]

- Where does your story take place?

- Who is your protagonist (main character), and who are the important secondary characters?

- What is the central conflict these characters will have to deal with?

- What is the “inciting incident” that sets off the main action of the play and leads up to that central conflict?[6]

- What happens to your characters as they deal with this conflict?

- How is the conflict resolved at the end of the story? How does this impact the characters?

-

8

Deepen your story with plot development. Remember that the plot develops the relationship between all the elements of story that were listed in the previous step. As you think about plot, you should try to answer the following questions: [7]

- What are the relationships between the characters?

- How do the characters interact with the central conflict? Which ones are most impacted by it, and how does it affect them?

- How can you structure the story (events) to bring the necessary characters into contact with the central conflict?

- What is the logical, casual progression that leads each event to the next one, building in a continuous flow toward the story’s climactic moment and resolution?

Advertisement

-

1

Begin with a one-act play if you are new to playwriting. Before writing the play, you should have a sense of how you want to structure it. The one-act play runs straight through without any intermissions, and is a good starting point for people new to playwriting. Examples of one-act plays include «The Bond,» by Robert Frost and Amy Lowell, and «Gettysburg,» by Percy MacKaye.[8]

[9]

Although the one-act play has the simplest structure, remember that all stories need a narrative arc with exposition, rising tension, and resolution.- Because one-act plays lack intermissions, they call for simpler sets and costume changes. Keep your technical needs simple.

-

2

Don’t limit the length of your one-act play. The one-act structure has nothing to do with the duration of the performance. These plays can vary widely in length, with some productions as short as 10 minutes and others over an hour long.

- Flash dramas are very short one-act plays that can run from a few seconds up to about 10 minutes long. They’re great for school and community theater performances, as well as competitions specifically for flash theater. See Anna Stillaman’s «A Time of Green» for an example of a flash drama.

-

3

Allow for more complex sets with a two-act play. The two-act play is the most common structure in contemporary theater. Though there’s no rule for how long each act should last, in general, acts run about half an hour in length, giving the audience a break with an intermission between them. The intermission gives the audience time to use the restroom or just relax, think about what’s happened, and discuss the conflict presented in the first act. However, it also lets your crew make heavy changes to set, costume, and makeup. Intermissions usually last about 15 minutes, so keep your crew’s duties reasonable for that amount of time.[10]

- For examples of two-act plays, see Peter Weiss’ «Hölderlin» or Harold Pinter’s «The Homecoming.»

-

4

Adjust the plot to fit the two-act structure.[11]

The two-act structure changes more than just the amount of time your crew has to make technical adjustments. Because the audience has a break in the middle of the play, you can’t treat the story as one flowing narrative. You must structure your story around the intermission to leave the audience tense and wondering at the end of the first act. When they come back from intermission, they should immediately be drawn back into the rising tension of the story.- The “inciting incident” should occur about half-way through the first act, after the background exposition.

- Follow the inciting incident with multiple scenes that raise the audience’s tension — whether dramatic, tragic, or comedic. These scenes should build toward a point of conflict that will end the first act.

- End the first act just after the highest point of tension in the story to that point. The audience will be left wanting more at intermission, and they’ll come back eager for the second act.

- Begin the second act at a lower point of tension than where you left off with the first act. You want to ease the audience back into the story and its conflict.

- Present multiple second-act scenes that raise the stakes in the conflict toward the story’s climax, or the highest point of tension and conflict, just before the end of the play.

- Relax the audience into the ending with falling action and resolution. Though not all plays need a happy ending, the audience should feel as though the tension you’ve built throughout the play has been released.

-

5

Pace longer, more complex plots with a three-act structure. If you’re new to playwriting, you may want to start with a one- or two-act play because a full-length, three-act play might keep your audience in its seats for two hours![12]

It takes a lot of experience and skill to put together a production that can captivate an audience for that long, so you might want to set your sights lower at first. However, if the story you want to tell is complex enough, a three-act play might be your best bet. Just like the 2-act play, it allows for major changes to set, costumes, etc. during the intermissions between acts. Each act of the play should achieve its own storytelling goal:[13]

- Act 1 is the exposition: take your time introducing the characters and background information. Make the audience care about the main character (protagonist) and his or her situation to ensure a strong emotional reaction when things start going wrong. The first act should also introduce the problem that will develop throughout the rest of the play.

- Act 2 is the complication: the stakes become higher for the protagonist as the problem becomes harder to navigate. One good way to raise the stakes in the second act is to reveal an important piece of background information close to the act’s climax.[14]

This revelation should instill doubt in the protagonist’s mind before he or she finds the strength to push through the conflict toward resolution. Act 2 should end despondently, with the protagonist’s plans in shambles. - Act 3 is the resolution: the protagonist overcomes the obstacles of the second act and finds a way to reach the play’s conclusion. Note that not all plays have happy endings; the hero may die as part of the resolution, but the audience should learn something from it.[15]

- Examples of three-act plays include Honore de Balzac’s «Mercadet» and John Galsworthy’s «Pigeon: A Fantasy in Three Acts.»

Advertisement

-

1

Outline your acts and scenes. In the first two sections of this article, you brainstormed your basic ideas about narrative arc, story and plot development, and play structure. Now, before sitting down to write the play, you should place all these ideas into a neat outline. For each act, lay out what happens in each scene.

- When are important characters introduced?

- How many different scenes do you have, and what specifically happens in each scene?

- Make sure each scene’s events build toward the next scene to achieve plot development.

- When might you need set changes? Costume changes? Take these kinds of technical elements into consideration when outlining how your story will unfold.

-

2

Flesh out your outline by writing your play. Once you have your outline, you can write your actual play. Just get your basic dialogue on the page at first, without worrying about how natural the dialogue sounds or how the actors will move about the stage and give their performances. In the first draft, you simply want to “get black on white,” as Guy de Maupassant said.

-

3

Work on creating natural dialogue. You want to give your actors a solid script, so they can deliver the lines in a way that seems human, real, and emotionally powerful. Record yourself reading the lines from your first draft aloud, then listen to the recording. Make note of points where you sound robotic or overly grand. Remember that even in literary plays, your characters still have to sound like normal people. They shouldn’t sound like they’re delivery fancy speeches when they’re complaining about their jobs over a dinner table.

-

4

Allow conversations to take tangents. When you’re talking with your friends, you rarely stick to a single subject with focused concentration. While in a play, the conversation must steer the characters toward the next conflict, you should allow small diversions to make it feel realistic. For example, in a discussion of why the protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him, there might be a sequence of two or three lines where the speakers argue about how long they’d been dating in the first place.

-

5

Include interruptions in your dialogue. Even when we’re not being rude, people interrupt each other in conversation all the time — even if just to voice support with an “I get it, man” or a “No, you’re completely right.” People also interrupt themselves by changing track within their own sentences: “I just — I mean, I really don’t mind driving over there on a Saturday, it’s just that — listen, I’ve just been working really hard lately.”

- Don’t be afraid to use sentence fragments, either. Although we’re trained never to use fragments in writing, we use them all the time when we’re speaking: “I hate dogs. All of them.”

-

6

Add stage directions.[16]

Stage directions let the actors understand your vision of what’s unfolding onstage. Use italics or brackets to set your stage directions apart from the spoken dialogue. While the actors will use their own creative license to bring your words to life, some specific directions you give might include:- Conversation cues: [long, awkward silence]

- Physical actions: [Silas stands up and paces nervously]; [Margaret chews her nails]

- Emotional states: [Anxiously], [Enthusiastically], [Picks up the dirty shirt as though disgusted by it]

-

7

Rewrite your draft as many times as needed. You’re not going to nail your play on the first draft. Even experienced writers need to write several drafts of a play before they’re satisfied with the final product. Don’t rush yourself! With each pass, add more detail that will help bring your production to life.

- Even as you’re adding detail, remember that the delete key can be your best friend. As Donald Murray says, you must “cut what is bad, to reveal what is good.” Remove all dialogue and events that don’t add to the emotional resonance of the play.

- The novelist Leonard Elmore’s advice applies to plays as well: “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”[17]

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

How do you format a script?

Melessa Sargent is the President of Scriptwriters Network, a non-profit organization that brings in entertainment professionals to teach the art and business of script writing for TV, features and new media. The Network serves its members by providing educational programming, developing access and opportunity through alliances with industry professionals, and furthering the cause and quality of writing in the entertainment industry. Under Melessa’s leadership, SWN has won numbers awards including the Los Angeles Award from 2014 through 2021, and the Innovation & Excellence award in 2020.

Scriptwriter

Expert Answer

Support wikiHow by

unlocking this expert answer.Using a writing software can be really helpful if you’ve never formatted a script before. You can also go online and look at examples of other scripts to get an idea of what the formatting should look like.

-

Question

Can anyone write a script or do you need formal training?

Melessa Sargent is the President of Scriptwriters Network, a non-profit organization that brings in entertainment professionals to teach the art and business of script writing for TV, features and new media. The Network serves its members by providing educational programming, developing access and opportunity through alliances with industry professionals, and furthering the cause and quality of writing in the entertainment industry. Under Melessa’s leadership, SWN has won numbers awards including the Los Angeles Award from 2014 through 2021, and the Innovation & Excellence award in 2020.

Scriptwriter

Expert Answer

Support wikiHow by

unlocking this expert answer.Yes, anyone can write a script! If you put your mind to it and really commit to doing it, you definitely can. You don’t necessarily have to go to school or have formal training first, although a lot of people do.

-

Question

How do I build a relationship in a play in a short time?

Make it as though the characters have just met. Something as simple as having something in common triggers their connection. Intense, stressful, life-or-death situations typically hasten connection, so you might think in that direction. Then simply let yourself script-writing skills do the work, making sure that there are not too many obstacles for them to overcome to make their relationship strong.

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Video

-

Read the script out loud to a small audience. Plays are based on words, and that power or the lack of it quickly becomes obvious when spoken.

-

Most plays are set in specific times and places, so be consistent. A character in the 1930s could make a telephone call or send a telegraph, but couldn’t watch television.

-

Write a lot of drafts, even if you are satisfied with the first one you write.

Show More Tips

Advertisement

-

Protect your work. Make sure the play’s title page includes your name and the year you wrote the play, preceded by the copyright symbol: ©.

-

Rejection vastly outweighs acceptance, but don’t be discouraged. If you get worn out with one play being ignored, write another.

-

The theatrical world is full of ideas, but take care your treatment of a story is original. Stealing someone else’s story is not only morally bankrupt, and you’ll almost certainly be caught.

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

If you’re writing a play script, start by brainstorming a story. Then write an exposition, or beginning, some rising action, or conflict, and a resolution. Write dialogue that’s natural by reading, recording, and listening to what you’ve written to be sure it sounds authentic. Include interruptions and go off on tangents, since that’s what happens in real life! Remember to add stage directions, using italics or brackets to set them apart from dialogue, so the actors have a sense for the actions you expect to see on stage. For more tips on writing a play script, including how to structure 1-, 2-, and 3-act plays, scroll down!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 624,007 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

Alex Solhdoost

May 28, 2017

«I always thought that writing a play is super difficult. One night I was super-bored, and I love reading plays so…» more

Did this article help you?

Download Article

Download Article

You have an idea for a play script — perhaps a very good idea. You want to expand it into a comedic or dramatic storyline, but how? Although you may want to dive right into the writing, your play will be much stronger if you spend the time planning out your storyline, before you start your first draft. Once you’ve brainstormed your narrative and outlined your structure, writing your play will seem a much less daunting task.

-

1

Decide what kind of story you want to tell. Though every story is different, most plays fall into categories that help the audience understand how to interpret the relationships and events they see. Think about the characters you want to write, then consider how you want their stories to unfold.[1]

Do they:- Have to solve a mystery? Sometimes you can even have other people write the script for you .

- Go through a series of difficult events in order to achieve personal growth?

- Come of age by transitioning from childlike innocence to worldly experience?

- Go on a journey, like Odysseus’s perilous journey in The Odyssey?[2]

- Bring order to chaos?

- Overcome a series of obstacles to achieve a goal?

-

2

Brainstorm the basic parts of your narrative arc. The narrative arc is the progression of the play through beginning, middle, and end. The technical terms for these three parts are exposition, rising action, and resolution, and they always come in that order. Regardless of how long your play is or how many acts you have, a good play will develop all three pieces of this puzzle. Taken notes on how you want to flesh each one out before sitting down to write your play.

Advertisement

-

3

Decide what needs to be included in the exposition. Exposition opens a play by providing basic information needed to follow the story: When and where does this story take place? Who is the main character? Who are the secondary characters, including the antagonist (person who presents the main character with his or her central conflict), if you have one? What is the central conflict these characters will face? What is the mood of this play (comedy, romantic drama, tragedy)?

-

4

Transition the exposition into rising action. In the rising action, events unfold in a way that makes circumstances more difficult for the characters. The central conflict comes into focus as events raise the audience’s tension higher and higher. This conflict may be with another character (antagonist), with an external condition (war, poverty, separation from a loved one), or with oneself (having to overcome one’s own insecurities, for example). The rising action culminates in the story’s climax: the moment of highest tension, when the conflict comes to a head.[3]

-

5

Decide how your conflict will resolve itself. The resolution releases the tension from the climactic conflict to end the narrative arc. You might have a happy ending, where the main character gets what he/she wants; a tragic ending where the audience learns something from the main character’s failure; or a denouement, in which all questions are answered.

-

6

Understand the difference between plot and story. The narrative of your play is made up of the plot and the story — two discrete elements that must be developed together to create a play that holds your audience’s attention. E.M. Forster defined story as what happens in the play — the chronological unfolding of events. The plot, on the other hand, can be thought of as the logic that links the events that unfold through the plot and make them emotionally powerful.[4]

An example of the difference is:- Story: The protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him. Then the protagonist lost his job.

- Plot: The protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him. Heartbroken, he had an emotional breakdown at work that resulted in his firing.

- You must develop a story that’s compelling and moves the action of the play along quickly enough to keep the audience’s attention. At the same time, you must show how the actions are all causally linked through your plot development. This is how you make the audience care about the events that are transpiring on stage.

-

7

Develop your story. You can’t deepen the emotional resonance of the plot until you have a good story in place. Brainstorm the basic elements of story before fleshing them out with your actual writing by answering the following questions:[5]

- Where does your story take place?

- Who is your protagonist (main character), and who are the important secondary characters?

- What is the central conflict these characters will have to deal with?

- What is the “inciting incident” that sets off the main action of the play and leads up to that central conflict?[6]

- What happens to your characters as they deal with this conflict?

- How is the conflict resolved at the end of the story? How does this impact the characters?

-

8

Deepen your story with plot development. Remember that the plot develops the relationship between all the elements of story that were listed in the previous step. As you think about plot, you should try to answer the following questions: [7]

- What are the relationships between the characters?

- How do the characters interact with the central conflict? Which ones are most impacted by it, and how does it affect them?

- How can you structure the story (events) to bring the necessary characters into contact with the central conflict?

- What is the logical, casual progression that leads each event to the next one, building in a continuous flow toward the story’s climactic moment and resolution?

Advertisement

-

1

Begin with a one-act play if you are new to playwriting. Before writing the play, you should have a sense of how you want to structure it. The one-act play runs straight through without any intermissions, and is a good starting point for people new to playwriting. Examples of one-act plays include «The Bond,» by Robert Frost and Amy Lowell, and «Gettysburg,» by Percy MacKaye.[8]

[9]

Although the one-act play has the simplest structure, remember that all stories need a narrative arc with exposition, rising tension, and resolution.- Because one-act plays lack intermissions, they call for simpler sets and costume changes. Keep your technical needs simple.

-

2

Don’t limit the length of your one-act play. The one-act structure has nothing to do with the duration of the performance. These plays can vary widely in length, with some productions as short as 10 minutes and others over an hour long.

- Flash dramas are very short one-act plays that can run from a few seconds up to about 10 minutes long. They’re great for school and community theater performances, as well as competitions specifically for flash theater. See Anna Stillaman’s «A Time of Green» for an example of a flash drama.

-

3

Allow for more complex sets with a two-act play. The two-act play is the most common structure in contemporary theater. Though there’s no rule for how long each act should last, in general, acts run about half an hour in length, giving the audience a break with an intermission between them. The intermission gives the audience time to use the restroom or just relax, think about what’s happened, and discuss the conflict presented in the first act. However, it also lets your crew make heavy changes to set, costume, and makeup. Intermissions usually last about 15 minutes, so keep your crew’s duties reasonable for that amount of time.[10]

- For examples of two-act plays, see Peter Weiss’ «Hölderlin» or Harold Pinter’s «The Homecoming.»

-

4

Adjust the plot to fit the two-act structure.[11]

The two-act structure changes more than just the amount of time your crew has to make technical adjustments. Because the audience has a break in the middle of the play, you can’t treat the story as one flowing narrative. You must structure your story around the intermission to leave the audience tense and wondering at the end of the first act. When they come back from intermission, they should immediately be drawn back into the rising tension of the story.- The “inciting incident” should occur about half-way through the first act, after the background exposition.

- Follow the inciting incident with multiple scenes that raise the audience’s tension — whether dramatic, tragic, or comedic. These scenes should build toward a point of conflict that will end the first act.

- End the first act just after the highest point of tension in the story to that point. The audience will be left wanting more at intermission, and they’ll come back eager for the second act.

- Begin the second act at a lower point of tension than where you left off with the first act. You want to ease the audience back into the story and its conflict.

- Present multiple second-act scenes that raise the stakes in the conflict toward the story’s climax, or the highest point of tension and conflict, just before the end of the play.

- Relax the audience into the ending with falling action and resolution. Though not all plays need a happy ending, the audience should feel as though the tension you’ve built throughout the play has been released.

-

5

Pace longer, more complex plots with a three-act structure. If you’re new to playwriting, you may want to start with a one- or two-act play because a full-length, three-act play might keep your audience in its seats for two hours![12]

It takes a lot of experience and skill to put together a production that can captivate an audience for that long, so you might want to set your sights lower at first. However, if the story you want to tell is complex enough, a three-act play might be your best bet. Just like the 2-act play, it allows for major changes to set, costumes, etc. during the intermissions between acts. Each act of the play should achieve its own storytelling goal:[13]

- Act 1 is the exposition: take your time introducing the characters and background information. Make the audience care about the main character (protagonist) and his or her situation to ensure a strong emotional reaction when things start going wrong. The first act should also introduce the problem that will develop throughout the rest of the play.

- Act 2 is the complication: the stakes become higher for the protagonist as the problem becomes harder to navigate. One good way to raise the stakes in the second act is to reveal an important piece of background information close to the act’s climax.[14]

This revelation should instill doubt in the protagonist’s mind before he or she finds the strength to push through the conflict toward resolution. Act 2 should end despondently, with the protagonist’s plans in shambles. - Act 3 is the resolution: the protagonist overcomes the obstacles of the second act and finds a way to reach the play’s conclusion. Note that not all plays have happy endings; the hero may die as part of the resolution, but the audience should learn something from it.[15]

- Examples of three-act plays include Honore de Balzac’s «Mercadet» and John Galsworthy’s «Pigeon: A Fantasy in Three Acts.»

Advertisement

-

1

Outline your acts and scenes. In the first two sections of this article, you brainstormed your basic ideas about narrative arc, story and plot development, and play structure. Now, before sitting down to write the play, you should place all these ideas into a neat outline. For each act, lay out what happens in each scene.

- When are important characters introduced?

- How many different scenes do you have, and what specifically happens in each scene?

- Make sure each scene’s events build toward the next scene to achieve plot development.

- When might you need set changes? Costume changes? Take these kinds of technical elements into consideration when outlining how your story will unfold.

-

2

Flesh out your outline by writing your play. Once you have your outline, you can write your actual play. Just get your basic dialogue on the page at first, without worrying about how natural the dialogue sounds or how the actors will move about the stage and give their performances. In the first draft, you simply want to “get black on white,” as Guy de Maupassant said.

-

3

Work on creating natural dialogue. You want to give your actors a solid script, so they can deliver the lines in a way that seems human, real, and emotionally powerful. Record yourself reading the lines from your first draft aloud, then listen to the recording. Make note of points where you sound robotic or overly grand. Remember that even in literary plays, your characters still have to sound like normal people. They shouldn’t sound like they’re delivery fancy speeches when they’re complaining about their jobs over a dinner table.

-

4

Allow conversations to take tangents. When you’re talking with your friends, you rarely stick to a single subject with focused concentration. While in a play, the conversation must steer the characters toward the next conflict, you should allow small diversions to make it feel realistic. For example, in a discussion of why the protagonist’s girlfriend broke up with him, there might be a sequence of two or three lines where the speakers argue about how long they’d been dating in the first place.

-

5

Include interruptions in your dialogue. Even when we’re not being rude, people interrupt each other in conversation all the time — even if just to voice support with an “I get it, man” or a “No, you’re completely right.” People also interrupt themselves by changing track within their own sentences: “I just — I mean, I really don’t mind driving over there on a Saturday, it’s just that — listen, I’ve just been working really hard lately.”

- Don’t be afraid to use sentence fragments, either. Although we’re trained never to use fragments in writing, we use them all the time when we’re speaking: “I hate dogs. All of them.”

-

6

Add stage directions.[16]

Stage directions let the actors understand your vision of what’s unfolding onstage. Use italics or brackets to set your stage directions apart from the spoken dialogue. While the actors will use their own creative license to bring your words to life, some specific directions you give might include:- Conversation cues: [long, awkward silence]

- Physical actions: [Silas stands up and paces nervously]; [Margaret chews her nails]

- Emotional states: [Anxiously], [Enthusiastically], [Picks up the dirty shirt as though disgusted by it]

-

7

Rewrite your draft as many times as needed. You’re not going to nail your play on the first draft. Even experienced writers need to write several drafts of a play before they’re satisfied with the final product. Don’t rush yourself! With each pass, add more detail that will help bring your production to life.

- Even as you’re adding detail, remember that the delete key can be your best friend. As Donald Murray says, you must “cut what is bad, to reveal what is good.” Remove all dialogue and events that don’t add to the emotional resonance of the play.

- The novelist Leonard Elmore’s advice applies to plays as well: “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”[17]

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

How do you format a script?

Melessa Sargent is the President of Scriptwriters Network, a non-profit organization that brings in entertainment professionals to teach the art and business of script writing for TV, features and new media. The Network serves its members by providing educational programming, developing access and opportunity through alliances with industry professionals, and furthering the cause and quality of writing in the entertainment industry. Under Melessa’s leadership, SWN has won numbers awards including the Los Angeles Award from 2014 through 2021, and the Innovation & Excellence award in 2020.

Scriptwriter

Expert Answer

Support wikiHow by

unlocking this expert answer.Using a writing software can be really helpful if you’ve never formatted a script before. You can also go online and look at examples of other scripts to get an idea of what the formatting should look like.

-

Question

Can anyone write a script or do you need formal training?

Melessa Sargent is the President of Scriptwriters Network, a non-profit organization that brings in entertainment professionals to teach the art and business of script writing for TV, features and new media. The Network serves its members by providing educational programming, developing access and opportunity through alliances with industry professionals, and furthering the cause and quality of writing in the entertainment industry. Under Melessa’s leadership, SWN has won numbers awards including the Los Angeles Award from 2014 through 2021, and the Innovation & Excellence award in 2020.

Scriptwriter

Expert Answer

Support wikiHow by

unlocking this expert answer.Yes, anyone can write a script! If you put your mind to it and really commit to doing it, you definitely can. You don’t necessarily have to go to school or have formal training first, although a lot of people do.

-

Question

How do I build a relationship in a play in a short time?

Make it as though the characters have just met. Something as simple as having something in common triggers their connection. Intense, stressful, life-or-death situations typically hasten connection, so you might think in that direction. Then simply let yourself script-writing skills do the work, making sure that there are not too many obstacles for them to overcome to make their relationship strong.

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Video

-

Read the script out loud to a small audience. Plays are based on words, and that power or the lack of it quickly becomes obvious when spoken.

-

Most plays are set in specific times and places, so be consistent. A character in the 1930s could make a telephone call or send a telegraph, but couldn’t watch television.

-

Write a lot of drafts, even if you are satisfied with the first one you write.

Show More Tips

Advertisement

-

Protect your work. Make sure the play’s title page includes your name and the year you wrote the play, preceded by the copyright symbol: ©.

-

Rejection vastly outweighs acceptance, but don’t be discouraged. If you get worn out with one play being ignored, write another.

-

The theatrical world is full of ideas, but take care your treatment of a story is original. Stealing someone else’s story is not only morally bankrupt, and you’ll almost certainly be caught.

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

If you’re writing a play script, start by brainstorming a story. Then write an exposition, or beginning, some rising action, or conflict, and a resolution. Write dialogue that’s natural by reading, recording, and listening to what you’ve written to be sure it sounds authentic. Include interruptions and go off on tangents, since that’s what happens in real life! Remember to add stage directions, using italics or brackets to set them apart from dialogue, so the actors have a sense for the actions you expect to see on stage. For more tips on writing a play script, including how to structure 1-, 2-, and 3-act plays, scroll down!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 624,007 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

Alex Solhdoost

May 28, 2017

«I always thought that writing a play is super difficult. One night I was super-bored, and I love reading plays so…» more

Did this article help you?

Как написать сценарий

Мы уже говорили о том, что такое сценарий фильма. Теперь мы постараемся сами научиться писать сценарии по литературным произведениям — например, по рассказам В. Драгунского.

Мы написали небольшую инструкцию — не стóит запоминать всё, что здесь написано. Этот текст полезно иметь перед глазами, как справочник или словарь, и проверять по нему свой рабочий вариант сценария.

Давайте посмотрим на фрагмент настоящего киносценария, написанного по рассказу писателя О’Генри «Персики».

Для удобства мы выделили цветом разные элементы, из которых состоит сценарий.

ИНТ. ПОЛИЦЕЙСКИЙ УЧАСТОК УТРО

На столе лежит несколько свежих заявлений, авторучка и зажигалка, рядом стоит кружка с горячим кофе.

ДЕЖУРНЫЙ (45 лет), откинувшись на стуле, внимательно читает какую-то статью в газете. Он полноват,

у него кудрявые волосы. В участок заходит МАЛЫШ МАК-ГАРИ (20 лет) и решительно подходит к Дежурному.

МАЛЫШ МАК-ГАРИ

Капитан здесь?

ДЕЖУРНЫЙ

(Громко)

Сэр, к вам пришли!

Откуда-то из темноты за спиной Дежурного появляется КАПИТАН (60 лет) — высокий мужчина в тёмных брюках

и белой рубашке, на поясе висит полицейский значок и кобура с пистолетом. Костяшки на правой руке,

в которой он держит папку с делом, украшают свежие ссадины.

КАПИТАН

(Пожимает руку Малышу)

Здорóво, Мак-Гари! Я думал, ты в свадебном

путешествии.

МАЛЫШ МАК-ГАРИ

Вчера вернулись. Скажите-ка, капитан, вы бы

хотели накрыть заведение Денвера Дика?

КАПИТАН

Поздно! Денвера накрыли два месяца назад.

Капитан хлопает по плечу Дежурного, который пытается сделать глоток кофе.

МАЛЫШ МАК-ГАРИ

Верно. Два месяца назад его выкурили с Сорок

Третьей. Но теперь он неплохо обосновался на вашем участке.

И дела у него идут лучше прежнего.

Итак, сценарий всегда состоит из сцен. Сцены в кино очень похожи на эпизоды в литературе, а с эпизодами в «Денискиных раcсказах» Драгунского мы уже научились работать. Чтобы нам было проще, мы будем считать, что у нас в сценарии будет столько же сцен, сколько эпизодов в произведении, по которому мы пишем сценарий. Поэтому первым делом, когда мы начинаем писать сценарий, например, по рассказу Драгунского, нам нужно выделить в этом рассказе эпизоды — это и будут наши сцены.

Каждая сцена в сценарии состоит из нескольких блоков. Сначала это может показаться сложным, но на самом деле блоки помогают сразу увидеть, как устроена сцена. Поэтому читать сценарий всегда проще, чем рассказ или повесть. Давайте посмотрим, какие блоки есть в нашем сценарии и зачем они нужны.

1. Время и место действия

В нашем примере этот блок выделен жёлтым цветом и выглядит так: ИНТ. ПОЛИЦЕЙСКИЙ УЧАСТОК УТРО

Этот блок называется «Время и место действия». С него всегда начинается любая сцена. Нужен он для того, чтобы показать, где и когда происходит действие в этой сцене.

Мы начинаем этот блок со слова «ИНТ.» или «НАТ.» Так в кино говорят, когда действие происходит в помещении (интерьер, ИНТ) или на улице (натура, НАТ).

На самом деле всё очень просто — если сцена происходит на открытом воздухе, то надо написать НАТ., а в любом другом случае — в комнате, в классе, в машине, в цирке — ИНТ.

Дальше мы указываем место действия — в нашем примере это полицейский участок. Другие примеры мест действия — «тихая улица», «комната», «арена цирка». Если для фильма важно, где именно происходит действие, то так и надо писать — «комната Дениски», «арена цирка на Цветном бульваре».

И, наконец, время действия — это всегда только одно из четырёх слов — УТРО, ДЕНЬ, ВЕЧЕР или НОЧЬ.В каждой сцене есть только один такой блок — в самом начале.

2. Описание действия

В нашем сценарии эти блоки выделены голубым цветом. Цель такого блока — помочь режиссёру фильма и съёмочной группе точно представить себе, что делают герои в сцене, как они выглядят, обратить внимание на важные детали, предметы. В этом блоке мы как бы рисуем картинку словами.

Если в сцене появляется герой, которого раньше не было в фильме, то его имя в первый раз пишется ЗАГЛАВНЫМИ БУКВАМИ и в скобках указывается его возраст — например, КАПИТАН (60 лет). Если автору сценария это важно, он может включить описание внешности героя, его одежды, особых признаков (например морщины, веснушки). Обратите внимание — в нашем сценарии такие описания есть. Они нужны для того, чтобы выбрать на эту роль подходящих актёров. Если мы уже знакомы с героем, то его имя пишется как обычно — Капитан, и его внешность описывать уже не нужно.

Вот как правильно написать этот блок:

- В сцене должен быть хотя бы один блок «Описание действия» — сразу после первого блока «Время и место действия».

Их может быть и больше — такие блоки появляются почти каждый раз, когда герои что-то делают, а не просто разговаривают. Или когда в сцене появляется или исчезает герой. Обратите внимание — в нашем фрагменте сценария таких блоков три. - Когда мы пишем блок «Описание действия», мы используем только настоящее время глаголов. «Ручка лежит на столе», «Дениска подходит к плите и открывает кастрюлю», а не «Ручка лежала на столе», «Дениска подошёл к плите и открыл кастрюлю». Почему так делается, очень просто понять, если вспомнить наш текст «Что такое сценарий» — мы можем описывать только то, что зрители увидят глазами, всё должно происходить здесь и сейчас.

- Ещё раз — мы пишем только о том, что можно увидеть глазами. «Дениска думает о том, что сказал Мишка» — так мы не можем написать в сценарии, нам нужно сначала придумать, как показать это зрителям, чтобы они поняли, о чём именно думает Дениска. Если мы просто покажем, как Дениска задумался, как зрители поймут, что он думает именно о том, что говорил Мишка?

- Обо всех героях мы говорим только в третьем лице, как будто мы смотрим на них со стороны (Мишка думает, Дениска идёт в школу, папа возмущается, капитан появляется). Писать «я», «ты», «мы» и так далее в этом блоке нельзя — режиссёр и съёмочная группа должны всегда чётко понимать, о каком герое идёт речь. Мы как бы представляем себе, что наши глаза — это камера, которая снимает фильм.

3. Диалоги

Диалоги нужны для описания того, что и как именно герои говорят. Они состоят из трёх элементов —

- ИМЯ ГЕРОЯ (в нашем примере такие элементы обозначены оранжевым цветом) — дает нам понять, кто говорит. В диалоге имя всегда записывается заглавными буквами. Имя героя должно быть таким же, как в блоке «Описание действия».

- Ремарка (в нашем примере ремарки обозначены зелёным цветом) — необязательный элемент. Пишется в скобках. Нужна только тогда, когда важно уточнить, как именно герой говорит, к кому он обращается, или если герой что-то делает одновременно с разговором, какое-то простое действие. Если герой должен сделать что-то посложнее, нам понадобится блок «Описание действия», после которого можно будет продолжить писать диалог. Обратите внимание — в нашем фрагменте сценария есть две ремарки.

- Реплика (в нашем примере реплики обозначены синим цветом) — то, что говорит герой.

Герои всегда говорят по очереди, и это записывается именно так, как в нашем фрагменте сценария:

ИМЯ ГЕРОЯ

(Ремарка, если есть)

Реплика

Иногда герои при разговоре перебивают друг друга — и тогда реплика одного героя может закончиться внезапно. Например:

ДЕНИСКА

Видеть не могу манную ка…

МАМА

(Громко)

Посмотри, на кого ты стал похож! Вылитый Кощей! Ешь. Ты должен поправиться.

Написание сценария — это творческая работа. Даже когда сценарий основан на литературном произведении, автор сценария совсем не обязан точно повторять то, что там написано. В сценариях фильмов по произведениям Драгунского, например, часто объединяются сцены из разных рассказов, меняется порядок событий, сами герои и то, что они говорят. Что-то выбрасывается, а что-то, наоборот, добавляется. Даже в тех сценариях, которые написал сам Драгунский! Главное, о чём думает автор сценария — это то, какой у него получится фильм, как он будет выглядеть на экране.

Последнее изменение: Среда, 12 Август 2020, 00:18