tags: windows — malware

Путь от проекта на Си и ассемблера, к шеллкоду

Оригинал

От hasherezade для @vxunderground

Отдельное спасибо Duchy за проверку материала

Содержание

-

Введение

-

Предыдущие работы и мотивация

-

Шеллкод — основные принципы

-

Базонезависимый код

-

Вызов API без таблицы импорта

-

Подведение итогов заголовочный файл

-

Написание и компиляция ассемблерного кода

-

Компиляция Си проекта — шаг за шагом

-

Путь от Си проекта к шеллкоду

-

Основная идея

-

Подготовка Си проекта

-

Рефакторинг ассемблерного кода

-

Расширенный пример — сервер

-

Сборка

-

Запуск

-

Тестирование

-

Вывод

Введение

Авторы малвари (как и разработчики эксплоитов) часто используют в своей работе куски самостоятельного, базонезависимого кода, называемые шеллкод. Такой код можно легко внедрять в любые подходящие места в памяти и сразу же исполнять — без необходимости во внешних загрузчиках. Хотя шеллкоды дают много преимуществ исследователям (и авторам малвари), создавать их очень нудно. Шеллкоды должны подчиняться большому количеству правил, в отличие от того, что сгенерировал компилятор. Поэтому, обычно люди пишут их на языке ассемблера, чтобы контролировать конечный результат.

Создание шеллкодов на языке ассемблера — это самый правильный путь, но и в то же время скучный и на нем легко ошибиться. Поэтому разные исследователи придумывают идеи упрощения данного процесса, заручившись поддержкой компилятора Си, вместо ручного создания. В этой статье я поделюсь своим опытом и методами, для создания шеллкодов.

Чтобы статья была полезна начинающим, я подробно расскажу об известных техниках создания шеллкодов. В первой части, я покажу общие принципы, которым должен следовать шеллкод и причины этого. Затем, я покажу примеры таких шеллкодов.

С продемонстрированной техникой, мы сможем избежать самостоятельного написания ассемблерного кода и в то же время сможем с уверенностью редактировать сгенерированный. Мы избавим процесс от рутины, но не потеряем при этом преимуществ.

Предыдущие работы и мотивация

Идея создания шеллкодов из Си кода не нова.

В книге 2012 года “The Rootkit Arsenal — Second Edition”, автор Bill Blunden, рассказывает о своем способе создания шеллкодов из Си кода (Глава 10: Building Shellcode in C). Похожий метод был описан Matt Graeber (Mattifestation) в статье “Writing Optimized Windows Shellcode in C”. В обоих случаях, шеллкоды создавались непосредственно из Си кода и идея заключалась в изменении настроек компилятора, для создания PE файла, из которого можно вытащить конкретный кусок кода.

В этих способах мне не хватает преимуществ, который имеет шеллкод, написанный вручную. Используя эти способы, мы получаем лишь готовый код и не имеем контроля над сгенерированным ассемблерным кодом, а также лишаемся возможности его менять.

Я искала метод, который берет лучшее из обоих миров: позволяет избежать утомительное написание ассемблерного кода и использует автоматическую генерацию.

Шеллкод — основные принципы

В случае с PE форматом, мы просто пишем код и не заботимся о том, как он будет загружен: загрузчик Windows сделает все за нас. Но это не так, при написании шеллкода. Мы не можем надеяться на PE формат и загрузчик:

- Отсутствуют секции

- Отсутствует таблица импорта/перемещений

У нас есть только сам код…

Обзор самых важных отличий между PE и шеллкодом:

| Особенность | PE файл | Шеллкод |

| Загрузка | с помощью загрузчика Windows; запуск EXE создает новый процесс | Можно настроить; должен находится в существующем процессе (через внедрение кода + внедрение в поток), или расположен в существующем PE (в случае вируса) |

| Структура | Секции с правами доступа, которые содержат код, данные, ресурсы, … | Находится полностью в памяти (права могут быть на чтение, запись, исполнение) |

| Адрес по которому загружается | Определяется таблицей перемещений, устанавливается загрузчиком Windows | Можно настроить, базонезависим |

| Доступ к API (таблица импорта) | Определяется таблицей импорта, устанавливается загрузчиком Windows | Можно настроить: получить импорты из PEB; без таблицы импорта (или с ее упрощенной версией) |

Базонезависимый код

В PE файлах есть таблица перемещений, которая используется загрузчиком Windows, для изменения всех адресов, относительно базового адреса, по которому файл был загружен в память. Это происходит автоматически во время выполнения.

Для шеллкода у нас нет такой фичи, поэтому нам надо писать код, не требующий корректировки адресов. Такой код называется базонезависимым.

Предположим, что одним из шагов создания шеллкода будет создание PE, чья кодовая секция будет полностью базонезависима. Для этого нам запрещено использовать любой адрес, который ссылается на данные из других секций. Если надо использовать строки или другие структуры, мы должны их прописать прямо в коде.

Вызов API без таблицы импорта

В PE файле, все вызовы API, в коде, прописаны в таблице импорта. Таблица импорта создается компоновщиком (linker, программа, собирающая объектные файлы в один исполняемый — прим.пер.). Далее, она заполняется загрузчиком, во время выполнения. Все происходит, как обычно.

В шеллкоде, мы не можем обращаться к таблице импорта, поэтому надо заботиться о вызовах функций самим.

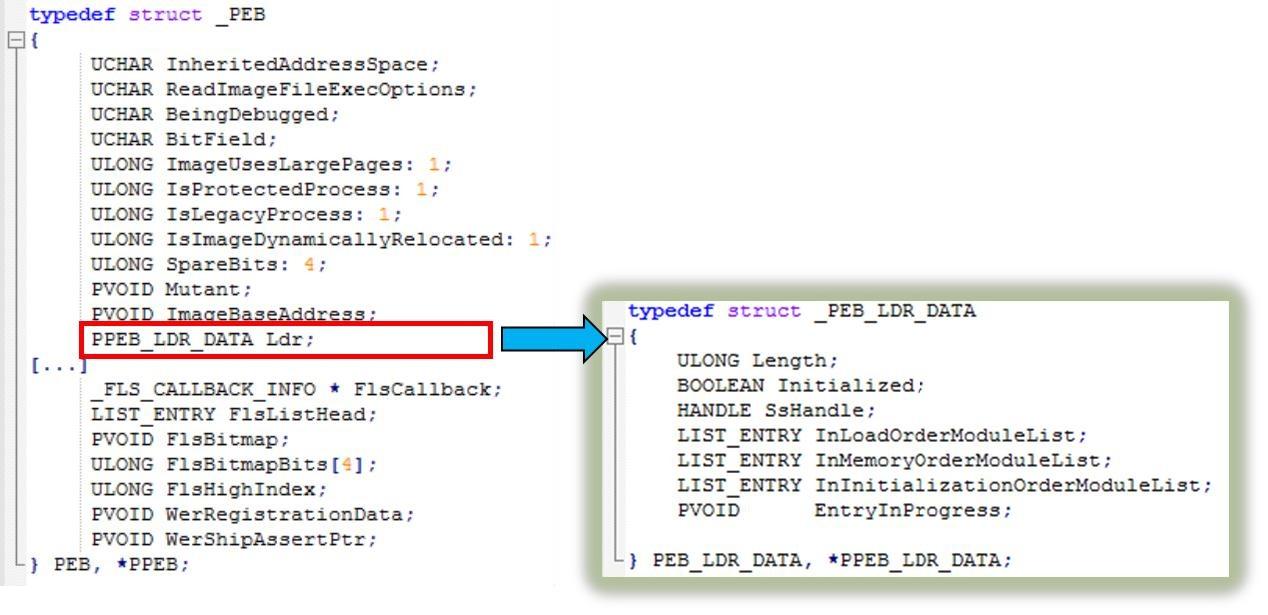

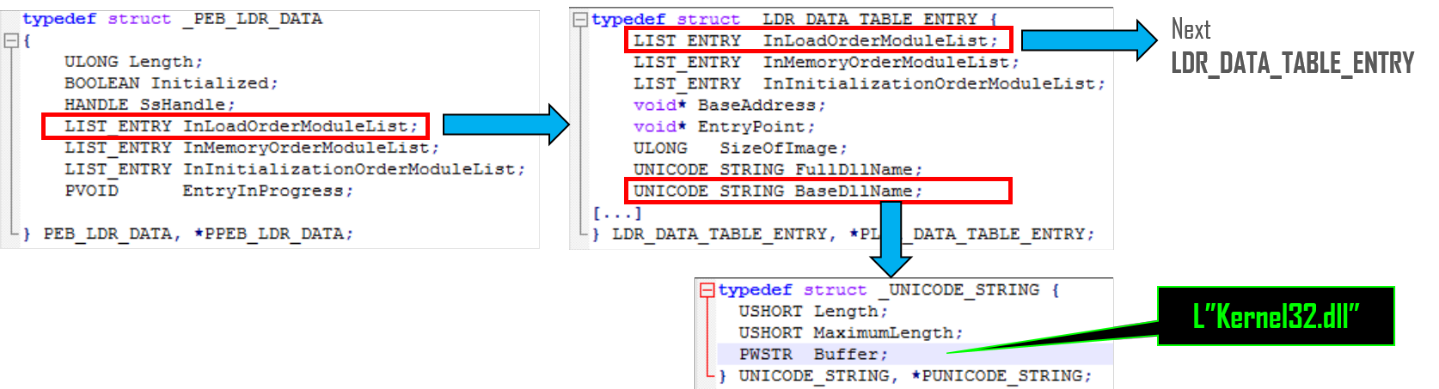

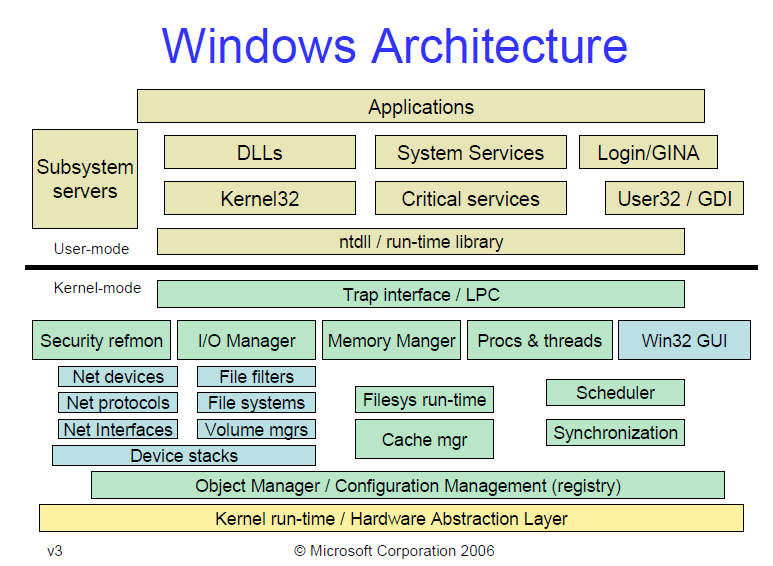

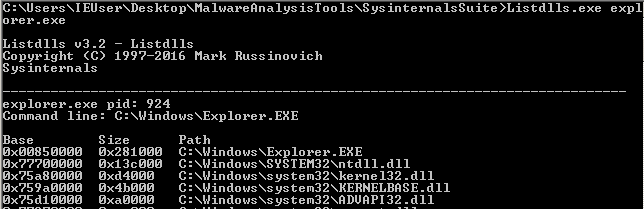

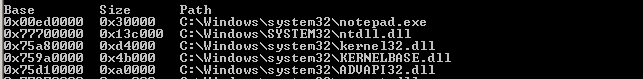

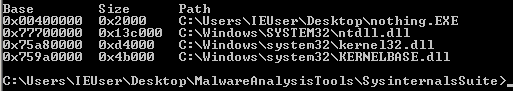

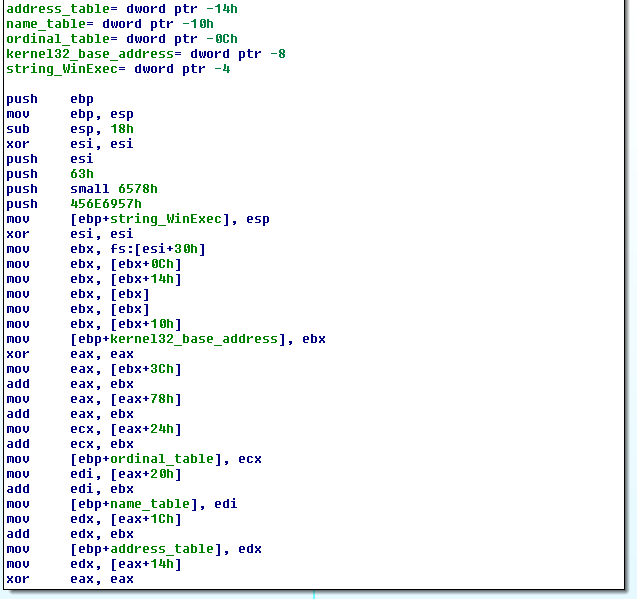

Чтобы получить доступ к API (имеется в виду Windows API — прим.пер.) из шеллкода, мы воспользуемся PEB (Process Environment Block — одна из системных структур, которая создается в ходе работы процесса). Как только шеллкод попадает внутрь процесса, мы получаем PEB и используем ее для поиска DLL, загруженных в адресное пространство этого процесса. Мы получаем доступ к Ntdll.dll или Kernel32.dll для доступа к остальным импортам. Ntdll.dll загружается в каждый процесс, в самом начале его создания. Kernel32.dll загружается в большинство процессов, на этапе инициализации — поэтому предположим, что она есть в интересующем нас процессе. Как только мы получим любую из DLL, мы используем их для загрузки других.

Общий алгоритм получения импортов, для шеллкода:

- Получить адрес PEB

- Через PEB->Ldr->InMemoryOrderModuleList, найти:

- kernel32.dll (в большинство процессов загружен по умолчанию)

- или ntdll.dll (если мы хотим использовать более низкоуровневую альтернативу)

- Проходимся по таблице экспорта kernel32.dll (или ntdll), для поиска адресов:

- kernel32.LoadLibraryA (а по сути: ntdll.LdrLoadDLL)

- kernel32.GetProcAddress (а по сути: ntdll.LdrGetProcedureAddress)

- Используем LoadLibraryA (или LdrLoadDll) для загрузки необходимых DLL

- Используем GetProcAddress (или LdrGetProcedureAddress) для получения нужных функций

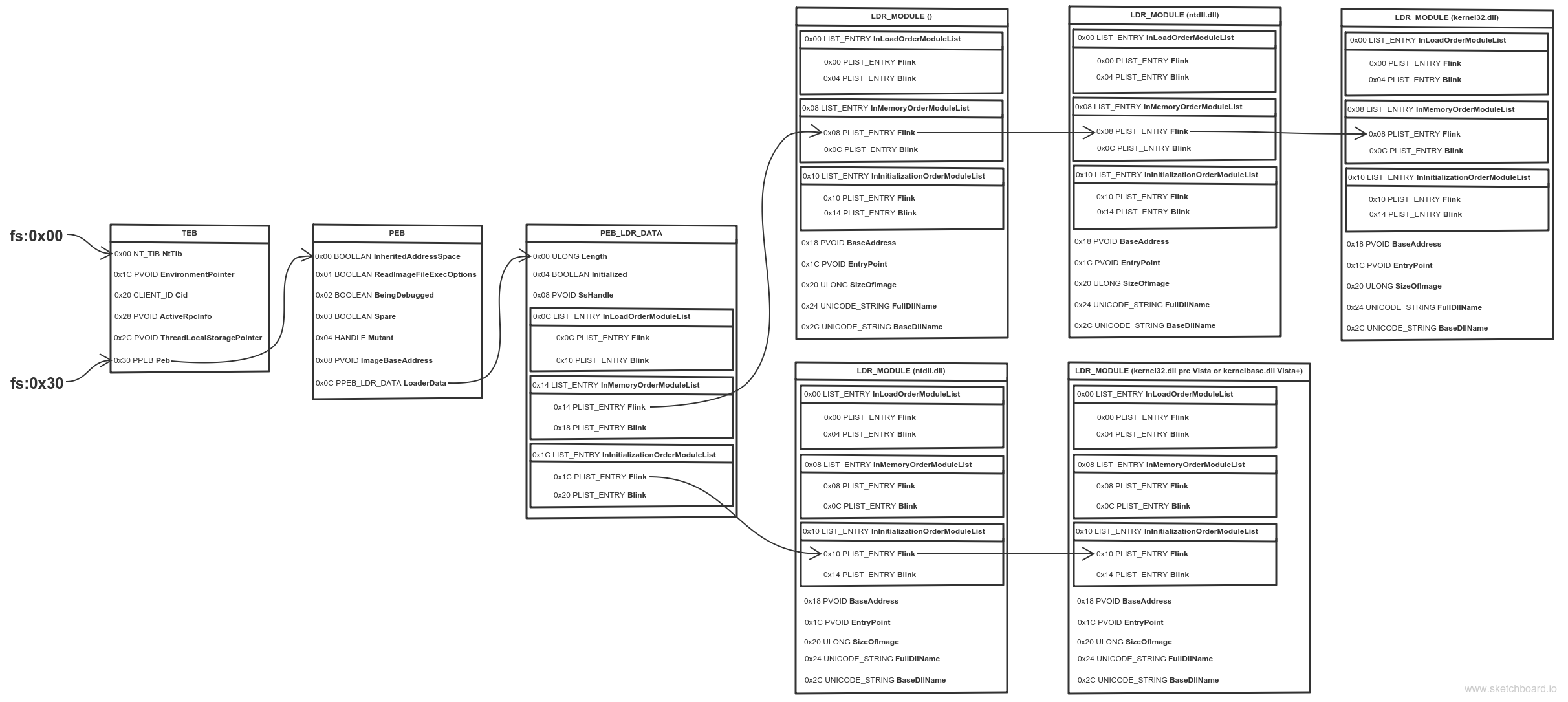

Получение PEB

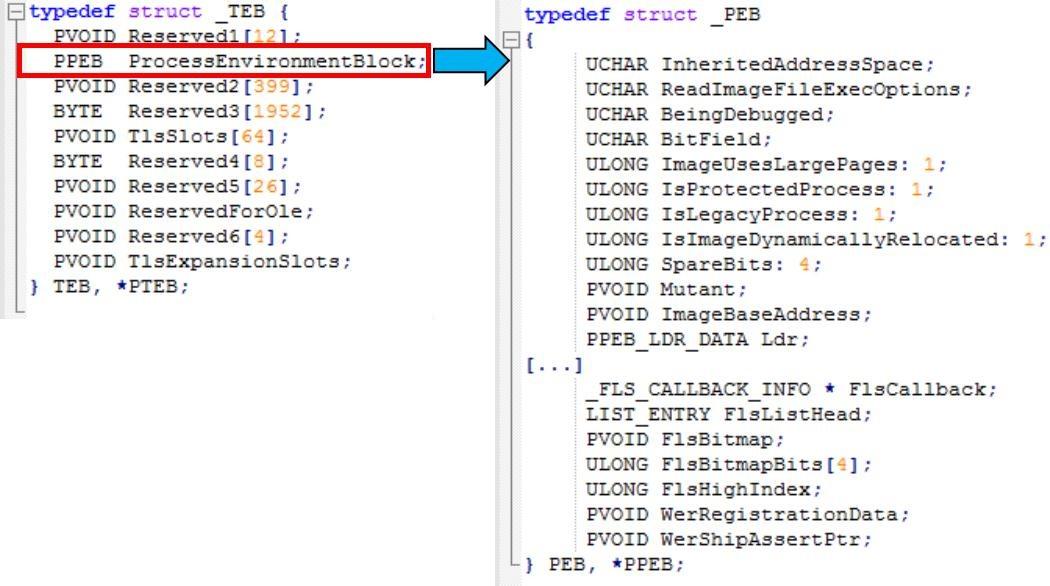

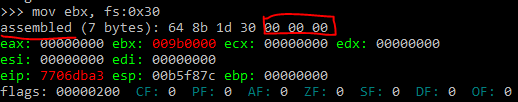

К счастью, PEB можно получить кодом на чистом языке ассемблера. Указатель на PEB — это поле в другой структуре: TEB (Thread Environment Block).

В 32 битной системе, указатель на TEB находится в сегментном регистре FS (GS в 64 битном).

| разрядность процесса | 32 бита | 64 бита |

| указатель на TEB | регистр FS | регистр GS |

| отступ до PEB в TEB | 0x30 | 0x60 |

Чтобы получить PEB в ассемблерном коде, нам надо лишь получить поле по определенному отступу, относительно сегментного регистра, указывающего на TEB. Пример на Си:

PPEB peb = NULL;

#if defined(_WIN64)

peb = (PPEB)__readgsqword(0x60);

#else

peb = (PPEB)__readfsdword(0x30);

#endif

Ищем DLL в PEB

Одно из полей PEB — это связный список всех DLL, загруженных в память процесса:

Мы проходимся по списку, пока не найдем нужную DLL

Нам нужна DLL, которая поможет найти другие API для импорта. Мы можем это сделать с помощью Kernel32.dll (или Ntdll.dll, но с Kernel32 удобнее).

Весь процесс получения DLL по имени:

#include <Windows.h>

#ifndef __NTDLL_H__

#ifndef TO_LOWERCASE

#define TO_LOWERCASE(out, c1) (out = (c1 <= 'Z' && c1 >= 'A') ? c1 = (c1 - 'A') + 'a': c1)

#endif

typedef struct _UNICODE_STRING

{

USHORT Length;

USHORT MaximumLength;

PWSTR Buffer;

} UNICODE_STRING, * PUNICODE_STRING;

typedef struct _PEB_LDR_DATA

{

ULONG Length;

BOOLEAN Initialized;

HANDLE SsHandle;

LIST_ENTRY InLoadOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

PVOID EntryInProgress;

} PEB_LDR_DATA, * PPEB_LDR_DATA;

// здесь мы не хотим использовать импортируемые функции из сторонних библиотек

typedef struct _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY

{

LIST_ENTRY InLoadOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

void* BaseAddress;

void* EntryPoint;

ULONG SizeOfImage;

UNICODE_STRING FullDllName;

UNICODE_STRING BaseDllName;

ULONG Flags;

SHORT LoadCount;

SHORT TlsIndex;

HANDLE SectionHandle;

ULONG CheckSum;

ULONG TimeDateStamp;

} LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY, * PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY;

typedef struct _PEB

{

BOOLEAN InheritedAddressSpace;

BOOLEAN ReadImageFileExecOptions;

BOOLEAN BeingDebugged;

BOOLEAN SpareBool;

HANDLE Mutant;

PVOID ImageBaseAddress;

PPEB_LDR_DATA Ldr;

// [...] это фрагмент, остальные элементы располагаются тут

} PEB, * PPEB;

#endif //__NTDLL_H__

inline LPVOID get_module_by_name(WCHAR* module_name)

{

PPEB peb = NULL;

#if defined(_WIN64)

peb = (PPEB)__readgsqword(0x60);

#else

peb = (PPEB)__readfsdword(0x30);

#endif

PPEB_LDR_DATA ldr = peb->Ldr;

LIST_ENTRY list = ldr->InLoadOrderModuleList;

PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY Flink = *((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY*)(&list));

PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY curr_module = Flink;

while (curr_module != NULL && curr_module->BaseAddress != NULL) {

if (curr_module->BaseDllName.Buffer == NULL) continue;

WCHAR* curr_name = curr_module->BaseDllName.Buffer;

size_t i = 0;

for (i = 0; module_name[i] != 0 && curr_name[i] != 0; i++) {

WCHAR c1, c2;

TO_LOWERCASE(c1, module_name[i]);

TO_LOWERCASE(c2, curr_name[i]);

if (c1 != c2) break;

}

if (module_name[i] == 0 && curr_name[i] == 0) {

//найден

return curr_module->BaseAddress;

}

// не найден, пробуем следующий:

curr_module = (PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)curr_module->InLoadOrderModuleList.Flink;

}

return NULL;

}

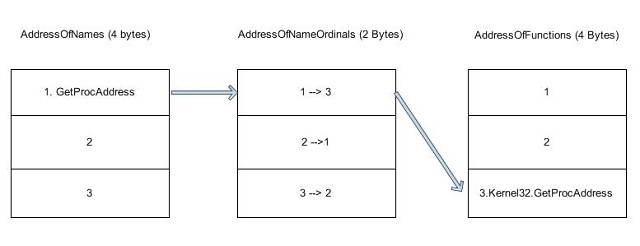

Поиск по экспортам

После получения адреса Kernel32.dll, нам все еще требуется получить адреса функций: LoadLibraryA и GetProcAddress. Мы сделаем это при помощи поиска по таблице экспорта.

Для начала нам надо ее получить из Data Directory в найденной DLL. Затем мы проходим по всем именам экспортированных функций, пока не найдем нужное имя. Мы достаем RVA (relative virtual address — относительный виртуальный адрес — прим.пер.), относящийся к этому имени, и добавляем к базовому адресу, для получения абсолютного адреса (VA).

Функция поиска по экспортам:

inline LPVOID get_func_by_name(LPVOID module, char* func_name)

{

IMAGE_DOS_HEADER* idh = (IMAGE_DOS_HEADER*)module;

if (idh->e_magic != IMAGE_DOS_SIGNATURE) {

return NULL;

}

IMAGE_NT_HEADERS* nt_headers = (IMAGE_NT_HEADERS*)((BYTE*)module + idh->e_lfanew);

IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY* exportsDir = &(nt_headers->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT]);

if (exportsDir->VirtualAddress == NULL) {

return NULL;

}

DWORD expAddr = exportsDir->VirtualAddress;

IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY* exp = (IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY*)(expAddr + (ULONG_PTR)module);

SIZE_T namesCount = exp->NumberOfNames;

DWORD funcsListRVA = exp->AddressOfFunctions;

DWORD funcNamesListRVA = exp->AddressOfNames;

DWORD namesOrdsListRVA = exp->AddressOfNameOrdinals;

// цикл по именам:

for (SIZE_T i = 0; i < namesCount; i++) {

DWORD* nameRVA = (DWORD*)(funcNamesListRVA + (BYTE*)module + i * sizeof(DWORD));

WORD* nameIndex = (WORD*)(namesOrdsListRVA + (BYTE*)module + i * sizeof(WORD));

DWORD* funcRVA = (DWORD*)(funcsListRVA + (BYTE*)module + (*nameIndex) * sizeof(DWORD));

LPSTR curr_name = (LPSTR)(*nameRVA + (BYTE*)module);

size_t k = 0;

for (k = 0; func_name[k] != 0 && curr_name[k] != 0; k++) {

if (func_name[k] != curr_name[k])

break;

}

if (func_name[k] == 0 && curr_name[k] == 0) {

// найден

return (BYTE*)module + (*funcRVA);

}

}

return NULL;

}

Подведение итогов заголовочный файл

Мы соберем весь код выше в заголовочный файл peb_lookup.h (доступен здесь), который можно включить в проект.

#pragma once

#include < Windows.h >

#ifndef __NTDLL_H__

#ifndef TO_LOWERCASE

#define TO_LOWERCASE(out, c1) (out = (c1 <= 'Z' && c1 >= 'A') ? c1 = (c1 - 'A') + 'a' : c1)

#endif

typedef struct _UNICODE_STRING {

USHORT Length;

USHORT MaximumLength;

PWSTR Buffer;

} UNICODE_STRING, *PUNICODE_STRING;

typedef struct _PEB_LDR_DATA {

ULONG Length;

BOOLEAN Initialized;

HANDLE SsHandle;

LIST_ENTRY InLoadOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

PVOID EntryInProgress;

} PEB_LDR_DATA, *PPEB_LDR_DATA;

// мы не хотим использовать функции из сторонних библиотек

typedef struct _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY {

LIST_ENTRY InLoadOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InMemoryOrderModuleList;

LIST_ENTRY InInitializationOrderModuleList;

void* BaseAddress;

void* EntryPoint;

ULONG SizeOfImage;

UNICODE_STRING FullDllName;

UNICODE_STRING BaseDllName;

ULONG Flags;

SHORT LoadCount;

SHORT TlsIndex;

HANDLE SectionHandle;

ULONG CheckSum;

ULONG TimeDateStamp;

} LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY, *PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY;

typedef struct _PEB {

BOOLEAN InheritedAddressSpace;

BOOLEAN ReadImageFileExecOptions;

BOOLEAN BeingDebugged;

BOOLEAN SpareBool;

HANDLE Mutant;

PVOID ImageBaseAddress;

PPEB_LDR_DATA Ldr;

// [...] это фрагмент, остальные элементы располагаются здесь

} PEB, *PPEB;

#endif //__NTDLL_H__

inline LPVOID

get_module_by_name(WCHAR* module_name)

{

PPEB peb = NULL;

#if defined(_WIN64)

peb = (PPEB)__readgsqword(0x60);

#else

peb = (PPEB)__readfsdword(0x30);

#endif

PPEB_LDR_DATA ldr = peb->Ldr;

LIST_ENTRY list = ldr->InLoadOrderModuleList;

PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY Flink = *((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY*)(&list));

PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY curr_module = Flink;

while (curr_module != NULL && curr_module->BaseAddress != NULL) {

if (curr_module->BaseDllName.Buffer == NULL)

continue;

WCHAR* curr_name = curr_module->BaseDllName.Buffer;

size_t i = 0;

for (i = 0; module_name[i] != 0 && curr_name[i] != 0; i++) {

WCHAR c1, c2;

TO_LOWERCASE(c1, module_name[i]);

TO_LOWERCASE(c2, curr_name[i]);

if (c1 != c2)

break;

}

if (module_name[i] == 0 && curr_name[i] == 0) {

//найден

return curr_module->BaseAddress;

}

// не найден, ищем дальше:

curr_module = (PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)curr_module->InLoadOrderModuleList.Flink;

}

return NULL;

}

inline LPVOID get_func_by_name(LPVOID module, char* func_name)

{

IMAGE_DOS_HEADER* idh = (IMAGE_DOS_HEADER*)module;

if (idh->e_magic != IMAGE_DOS_SIGNATURE) {

return NULL;

}

IMAGE_NT_HEADERS* nt_headers = (IMAGE_NT_HEADERS*)((BYTE*)module + idh->e_lfanew);

IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY* exportsDir = &(nt_headers->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT]);

if (exportsDir->VirtualAddress == NULL) {

return NULL;

}

DWORD expAddr = exportsDir->VirtualAddress;

IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY* exp = (IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY*)(expAddr + (ULONG_PTR)module);

SIZE_T namesCount = exp->NumberOfNames;

DWORD funcsListRVA = exp->AddressOfFunctions;

DWORD funcNamesListRVA = exp->AddressOfNames;

DWORD namesOrdsListRVA = exp->AddressOfNameOrdinals

//цикл по именам:

for (SIZE_T i = 0; i < namesCount; i++)

{

DWORD* nameRVA = (DWORD*)(funcNamesListRVA + (BYTE*)module + i * sizeof(DWORD));

WORD* nameIndex = (WORD*)(namesOrdsListRVA + (BYTE*)module + i * sizeof(WORD));

DWORD* funcRVA = (DWORD*)(funcsListRVA + (BYTE*)module + (*nameIndex) * sizeof(DWORD));

LPSTR curr_name = (LPSTR)(*nameRVA + (BYTE*)module);

size_t k = 0;

for (k = 0; func_name[k] != 0 && curr_name[k] != 0; k++) {

if (func_name[k] != curr_name[k])

break;

}

if (func_name[k] == 0 && curr_name[k] == 0) {

//найден

return (BYTE*)module + (*funcRVA);

}

}

return NULL;

}

Написание и компиляция ассемблерного кода

Как было сказано ранее, обычно шеллкоды пишут на языке ассемблера.

Когда мы пишем ассемблерный код, мы должны выбрать ассемблер, для компиляции. Выбор определяет разницу в используемом синтаксисе.

Самый популярный ассемблер для Windows — MASM, который является частью Visual Studio и представлен в двух версиях: 32 битной (ml.exe) и 64 битной (ml64.exe). Результат генерируемый MASM — это объектный файл, который можно скомпоновать в PE. Предположим, что у нас есть простой код, написанный на 32 битном MASM, показывающий MessageBox:

.386

.model flat

extern _MessageBoxA@16:near

extern _ExitProcess@4:near

.data

msg_title db "Demo!", 0

msg_content db "Hello World!", 0

.code

main proc

push 0

push 0

push offset msg_title

push offset msg_content

push 0

call _MessageBoxA@16

push 0

call _ExitProcess@4

main endp

end

Компилировать будем командой:

Теперь скомпануем стандартным компоновщиком Visual Studio:

link demo32.obj /subsystem:console /defaultlib:kernel32.lib /defaultlib:user32.lib /entry:main /out:demo32_masm.exe

Иногда можно компоновать и компилировать одновременно:

MASM — это стандартный ассемблер для Windows. Хотя, самый популярный выбор для создания шеллкодов: YASM (преемник NASM). Он бесплатен и подходит для всех платформ. На нем можно создать PE файл, как и на MASM. Синтаксис YASM немного отличается. Перепишем пример на 32 битный YASM:

bits 32

extern _MessageBoxA@16:proc

extern _ExitProcess@4:proc

msg_title db "Demo!", 0

msg_content db "Hello World!", 0

global main

main:

push 0

push 0

push msg_title

push msg_content

push 0

call _MessageBoxA@16

push 0

call _ExitProcess@4

Компилируем:

yasm -f win32 demo32.asm -o demo32.obj

Как и для MASM кода, используем компоновщик Visual Studio (или любой другой на выбор):

link demo32.obj /defaultlib:user32.lib /defaultlib:kernel32.lib /subsystem:windows /entry:main /out:demo32_yasm.exe

В отличие от MASM, YASM можно использовать для компиляции кода в бинарник, а не в объектный файл. Тем самым мы получаем готовый буфер с шеллкодом. Пример компиляции в бинарник:

Помните, что ни один из вышеприведенных примеров не может быть скомпилирован в шеллкод, потому что у них существуют внешние зависимости, что противоречит принципам написания шеллкодов. Но примеры можно изменить, удалив зависимости.

Метод в статье использует MASM. Причина такого решения проста: если мы генерируем ассемблерный код из Си файла, с помощью компилятора Visual Studio, то он будет иметь MASM синтаксис. YASM же не позволит напрямую получить шеллкод, придется вручную вырезать его из PE. Как мы увидим, хотя это может показаться незначительным неудобством, у него есть свои плюсы, такие как упрощение тестирования.

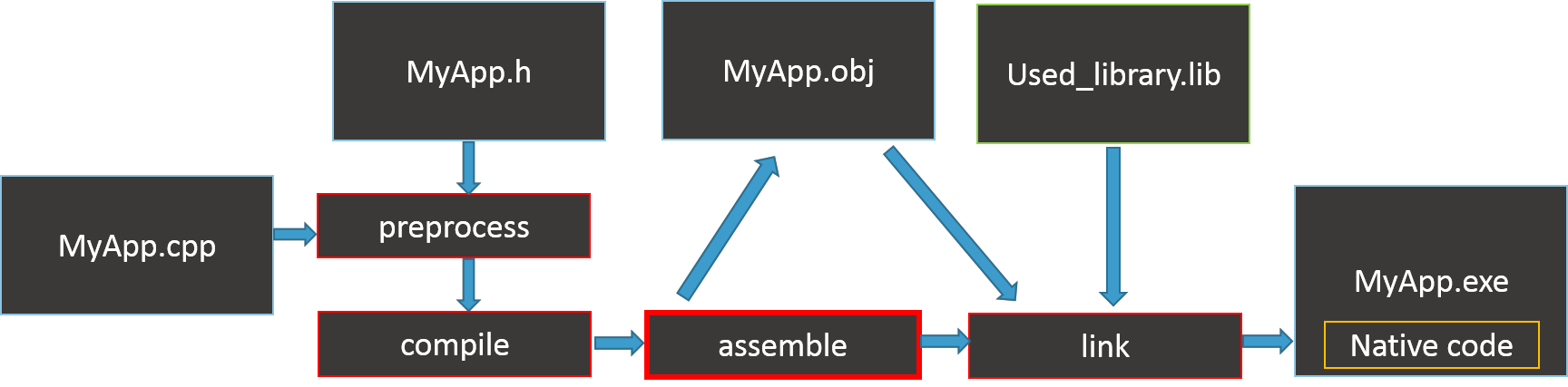

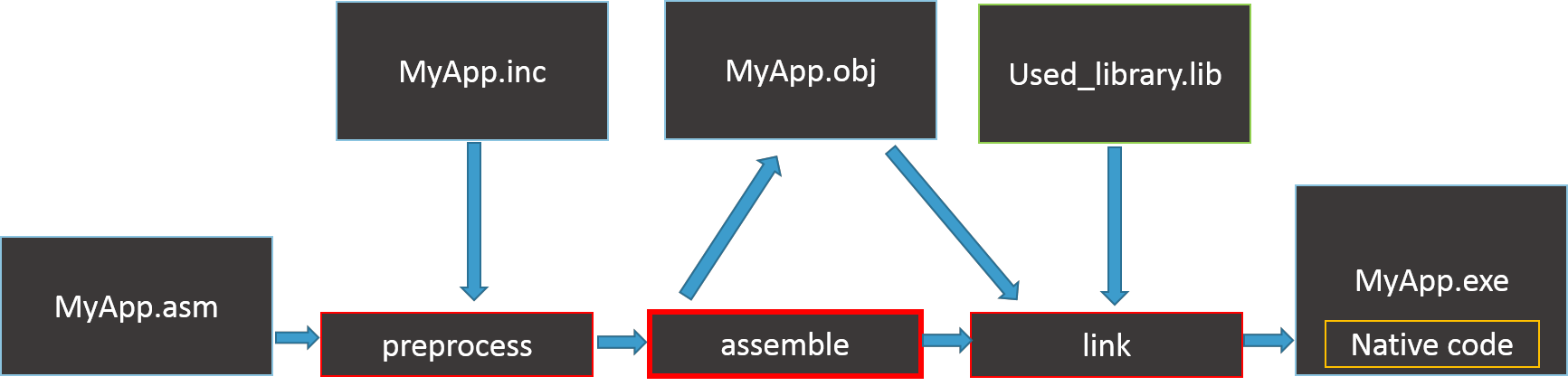

Компиляция Си проекта — шаг за шагом

Сегодня, программисты компилируют код, используя IDE (например Visual Studio), которая скрывает детали этого процесса. Мы просто пишем код, компилируем, компонуем и всё. По умолчанию, в конце получаем PE файл: формат исполняемого файла Windows.

Иногда полезно разделить процесс на шаги, для большего контроля.

Давайте вспомним как на концептуальном уровне выглядит компиляция С/С++ кода:

Теперь сравним с процессом создания программы из ассемблерного кода:

Как мы видим, компиляция кода из высокоуровневого языка отличается только в начале. Также, при компиляции Си кода, на одном из шагов генерируется ассемблерный код. Это довольно интересно, так как вместо написания вручную, мы можем написать код на Си и попросить компилятор дать нам ассемблерный код. Затем, нам останется только модифицировать его для соблюдения принципов шеллкодирования. Подробнее об этом в следующих главах.

У нас есть следующий код:

#include <Windows.h>

int main()

{

const char msg_title[] = "Demo!";

const char msg_content[] = "Hello World!";

MessageBoxA(0, msg_title, msg_content, MB_OK);

ExitProcess(0);

}

Давайте вызовем компилятор и компоновщик Visual Studio из командной строки, а не из IDE. Мы можем это сделать выбрав “VS Native Tools Command Prompt”. Затем перейти в директорию с нашим кодом.

Разрядность бинарника (32 или 64 бит) будет выбрана по умолчанию, в зависимости от версии выбранной командной строки.

Для компиляции используется cl.exe. Использование ключа /c компилирует код, но не компонует: в результате получается объектный файл (*.obj)

Затем, мы можем скомпоновать объектный файл при помощи стандартного компоновщика Visual Studio: link.exe. Иногда необходимо указать дополнительные библиотеки, с которыми должна компоноваться программа, или точку входа (если используется нестандартное имя). Пример компоновки:

link demo.obj /defaultlib:user32.lib /out:demo_cpp.exe

Несмотря на то что каждый шаг независим от предыдущего, вы можете использовать альтернативный компоновщик, вместо стандартного, например, для обфускации. Хороший пример — crinkler — упаковщик исполняемых файлов, в виде компоновщика, но это уже совсем другая история…

Если вы добавите ключ /FA, в дополнение к *.obj файлу, вы получите ассемблерный MASM код.

Далее вы можете скомпилировать сгенерированный файл в объектный, используя MASM:

Разделение этого процесса на шаги дает нам возможность манипулировать ассемблерным кодом и настраивать его под свои нужды, нежели писать все с нуля.

Путь от Си проекта к шеллкоду

Основная идея

Продемонстрированный метод создания шеллкодов имеет преимущества, так как мы можем скомпилировать Си код в ассемблерный. Он состоит из нескольких шагов:

- Подготовка Си проекта

- Рефакторинг проекта, для загрузки всех импортов, поиском по PEB (избавление от зависимости от таблицы импорта)

- Использование Си компилятора, для генерации ассемблерного кода:

cl /c /FA /GS- <file_name>.cpp

- Рефакторинг ассемблерного кода, для получения валидного шеллкода (избавление от оставшихся зависимостей, встроенные строки, переменные, …)

- Компиляция MASM:

- Компонование в валидный PE файл, проверка, запускается ли он корректно

- Дамп кодовой секции (например при помощи PE-bear) — это и есть наш шеллкод

Ассемблерный код, сгенерированный Си компилятором, не является 100% гарантированно правильным MASM кодом, потому что он в основном носит информационный характер. Поэтому иногда требуется ручное вмешательство.

Подготовка Си проекта

Когда мы подготавливаем Си проект, для получения шеллкода, мы должны следовать некоторым правилам: не использовать импорты напрямую (всегда получать их динамически, через PEB), не использовать статические библиотеки, использовать только локальные переменные (никаких глобальных или статических, иначе они будут хранится в разных секциях и нарушат базонезависимый код), использовать строки на стеке (или позже прописать их прямо в ассемблерном коде).

Для демонстрации идеи, мы будем использовать простой пример отображения MessageBox:

#include <Windows.h>

int main()

{

MessageBoxW(0, L"Hello World!", L"Demo!", MB_OK);

ExitProcess(0);

}

Подготовка импортов

Первым шагом нам надо получить доступ к вызову функций динамически. В проекте у нас два импорта: MessageBoxA из user32.dll и ExitProcess из kernel32.dll.

Обычно, если мы хотим импортировать их динамически, не включая в таблицу импорта, мы переписываем код вот так:

#include <Windows.h>

int main()

{

LPVOID u32_dll = LoadLibraryA("user32.dll");

int(WINAPI * _MessageBoxW)(

_In_opt_ HWND hWnd,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR lpText,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR lpCaption,

_In_ UINT uType)

= (int(WINAPI*)(_In_opt_ HWND,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR,

_In_ UINT))GetProcAddress((HMODULE)u32_dll, "MessageBoxW");

if (_MessageBoxW == NULL)

return 4;

_MessageBoxW(0, L"Hello World!", L"Demo!", MB_OK);

return 0;

}

Это хороший первый шаг, но недостаточный: у нас по-прежнему две зависимости: LoadLibraryA и GetProcAddress. Мы должны получить их поиском по PEB, поэтому задействуем наш peb_lookup.h, который был создан в предыдущей части. Финальный результат (popup.cpp):

#include <Windows.h>

#include "peb_lookup.h"

int main()

{

LPVOID base = get_module_by_name((const LPWSTR)L"kernel32.dll");

if (!base) {

return 1;

}

LPVOID load_lib = get_func_by_name((HMODULE)base, (LPSTR) "LoadLibraryA");

if (!load_lib) {

return 2;

}

LPVOID get_proc = get_func_by_name((HMODULE)base, (LPSTR) "GetProcAddress");

if (!get_proc) {

return 3;

}

HMODULE(WINAPI * _LoadLibraryA)

(LPCSTR lpLibFileName) = (HMODULE(WINAPI*)(LPCSTR))load_lib;

FARPROC(WINAPI * _GetProcAddress)

(HMODULE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName)

= (FARPROC(WINAPI*)(HMODULE, LPCSTR))get_proc;

LPVOID u32_dll = _LoadLibraryA("user32.dll");

int(WINAPI * _MessageBoxW)(

_In_opt_ HWND hWnd,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR lpText,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR lpCaption,

_In_ UINT uType)

= (int(WINAPI*)(_In_opt_ HWND,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR,

_In_ UINT))_GetProcAddress((HMODULE)u32_dll, "MessageBoxW");

if (_MessageBoxW == NULL)

return 4;

_MessageBoxW(0, L"Hello World!", L"Demo!", MB_OK);

return 0;

}

Остерегайтесь jmp таблиц

Если в коде используется оператор switch, он может быть скомпилирован в jmp таблицу. Это результат автоматической оптимизации компилятора. В нормальном исполняемом файле — это дает преимущества. Но при написании шеллкода, надо остерегаться такой оптимизации, потому что она ломает базонезависимый код: jmp таблица — это структура, которая требует перемещения.

Пример jmp таблицы в ассемблерном коде:

$LN14@switch_sta:

DD $LN8@switch_sta

DD $LN6@switch_sta

DD $LN10@switch_sta

DD $LN4@switch_sta

DD $LN2@switch_sta

$LN13@switch_sta:

DB 0

DB 1

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 2

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 4

DB 3

Решение, будет ли таблица сгенерирована или нет, для switch, принимается компилятором. Для нескольких условий (меньше 4) она обычно не генерируется. Но если условий много, то мы должны переписать код: разбить на несколько функций или заменить на if-else.

Пример:

Этот большой switch, будет причиной генерации jmp таблицы:

bool switch_state(char* buf, char* resp)

{

switch (resp[0]) {

case 0:

if (buf[0] != '9')

break;

resp[0] = 'Y';

return true;

case 'Y':

if (buf[0] != '3')

break;

resp[0] = 'E';

return true;

case 'E':

if (buf[0] != '5')

break;

resp[0] = 'S';

return true;

case 'S':

if (buf[0] != '8')

break;

resp[0] = 'D';

return true;

case 'D':

if (buf[0] != '4')

break;

resp[0] = 'O';

return true;

case 'O':

if (buf[0] != '7')

break;

resp[0] = 'N';

return true;

case 'N':

if (buf[0] != '!')

break;

resp[0] = 'E';

return true;

}

return false;

}

мы можем избежать этого, разбив switch на несколько сегментов:

bool switch_state(char* buf, char* resp)

{

{

switch (resp[0]) {

case 0:

if (buf[0] != '9')

break;

resp[0] = 'Y';

return true;

case 'Y':

if (buf[0] != '3')

break;

resp[0] = 'E';

return true;

case 'E':

if (buf[0] != '5')

break;

resp[0] = 'S';

20 return true;

}

}

{

switch (resp[0]) {

case 'S':

if (buf[0] != '8')

break;

resp[0] = 'D';

return true;

case 'D':

if (buf[0] != '4')

break;

resp[0] = 'O';

return true;

case 'O':

if (buf[0] != '7')

break;

resp[0] = 'N';

return true;

}

}

{

switch (resp[0]) {

case 'N':

if (buf[0] != '!')

break;

resp[0] = 'E';

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

можно переписать на if-else:

bool switch_state(char* buf, char* resp)

{

if (resp[0] == 0 && buf[0] == '9') {

resp[0] = 'Y';

}

else if (resp[0] == 'Y' && buf[0] == '3') {

resp[0] = 'E';

}

else if (resp[0] == 'E' && buf[0] == '5') {

resp[0] = 'S';

}

else if (resp[0] == 'S' && buf[0] == '8') {

resp[0] = 'D';

}

else if (resp[0] == 'D' && buf[0] == '4') {

resp[0] = 'O';

}

else if (resp[0] == 'O' && buf[0] == '7') {

resp[0] = 'N';

}

else if (resp[0] == 'N' && buf[0] == '!') {

resp[0] = 'E';

}

return false;

}

Устранение неявных зависимостей

Надо быть аккуратным, чтобы не добавить неявные зависимости в наш проект. Например, если мы инициализируем переменную:

struct sockaddr_in sock_config = { 0 };

Такая инициализация делает неявный вызов memset, из внешней библиотеки. В ассемблерном коде мы увидим зависимость, обозначенную ключевым словом EXTRN:

Для удаление такой зависимости, мы должны инициализировать структуру по-другому: своей функцией или функциями, которые гарантированно будут включены в код (например SecureZeroMemory):

struct sockaddr_in sock_config;

SecureZeroMemory(&sock_config, sizeof(sock_config));

Подготовка строк опционально

На этом этапе мы можем изменить текущий способ хранения строк на хранение в стеке, как было описано в статье Nick Harbour. Пример:

char load_lib_name[] = {'L','o','a','d','L','i','b','r','a','r','y','A',0};

LPVOID load_lib = get_func_by_name((HMODULE)base, (LPSTR)load_lib_name);

После компиляции в ассемблерный код, строки выглядят так:

; Line 10

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp], 76 ; 0000004cH

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+1], 111 ; 0000006fH

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+2], 97 ; 00000061H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+3], 100 ; 00000064H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+4], 76 ; 0000004cH

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+5], 105 ; 00000069H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+6], 98 ; 00000062H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+7], 114 ; 00000072H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+8], 97 ; 00000061H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+9], 114 ; 00000072H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+10], 121 ; 00000079H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+11], 65 ; 00000041H

mov BYTE PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp+12], 0

; Line 11

lea eax, DWORD PTR _load_lib_name$[ebp]

Это альтернативный способ хранения строк. Мы можем выбрать любой подходящий способ. Если мы выбрали хранение на стеке, код будет выглядеть так:

#include <Windows.h>

#include "peb_lookup.h"

int main()

{

wchar_t kernel32_dll_name[] = { 'k', 'e', 'r', 'n', 'e', 'l', '3', '2', '.', 'd', 'l', 'l', 0 };

LPVOID base = get_module_by_name((const LPWSTR)kernel32_dll_name);

if (!base) {

return 1;

}

char load_lib_name[] = { 'L', 'o', 'a', 'd', 'L', 'i', 'b', 'r', 'a', 'r', 'y', 'A', 0 };

LPVOID load_lib = get_func_by_name((HMODULE)base, (LPSTR)load_lib_name);

if (!load_lib) {

return 2;

}

char get_proc_name[] = { 'G', 'e', 't', 'P', 'r', 'o', 'c', 'A', 'd', 'd', 'r', 'e', 's', 's', 0 };

LPVOID get_proc = get_func_by_name((HMODULE)base, (LPSTR)get_proc_name);

if (!get_proc) {

return 3;

}

HMODULE(WINAPI * _LoadLibraryA)

(LPCSTR lpLibFileName) = (HMODULE(WINAPI*)(LPCSTR))load_lib;

FARPROC(WINAPI * _GetProcAddress)

(HMODULE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName)

= (FARPROC(WINAPI*)(HMODULE, LPCSTR))get_proc;

char user32_dll_name[] = { 'u', 's', 'e', 'r', '3', '2', '.', 'd', 'l', 'l', 0 };

LPVOID u32_dll = _LoadLibraryA(user32_dll_name);

char message_box_name[] = { 'M', 'e', 's', 's', 'a', 'g', 'e', 'B', 'o', 'x', 'W', 0 };

int(WINAPI * _MessageBoxW)(

_In_opt_ HWND hWnd,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR lpText,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR lpCaption,

_In_ UINT uType)

= (int(WINAPI*)(_In_opt_ HWND,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR,

_In_opt_ LPCWSTR,

_In_ UINT))_GetProcAddress((HMODULE)u32_dll, message_box_name);

if (_MessageBoxW == NULL)

return 4;

wchar_t msg_content[] = { 'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', ' ', 'W', 'o', 'r', 'l', 'd', '!', 0 };

wchar_t msg_title[] = { 'D', 'e', 'm', 'o', '!', 0 };

_MessageBoxW(0, msg_title, msg_content, MB_OK);

return 0;

}

Использование строк на стеке имеет свои плюсы и минусы. Плюс в том, что мы можем написать для этого код на Си и не надо его потом менять в ассемблерном виде позже. Но, встраивание строк в ассемблерный код может быть автоматизировано (например этой небольшой программкой), поэтому это не является большим неудобством (это также облегчает дальнейшую обфускацию строк).

В этой статье я решила показать другой способ: мы не меняем строки в Си коде, а вместо этого обрабатываем ассемблерный код. Тем не менее, для справки, представлен метод, использующий строки на стеке. (Конечно, можно использовать оба метода вместе: переписать строки так, чтобы они хранились на стеке и встроить оставшиеся).

Компиляция в ассемблерный код

Теперь мы готовый скомпилировать проект в ассемблерный код. Данный шаг одинаков для 32 и 64 битной версий — единственное отличие в том, что нам надо выбрать правильную командную строку (Visual Studio Native Tools Command Prompt):

Не забудьте сохранить peb_lookup.h в той же папке, что и demo.cpp — таким образом он подключиться автоматически.

Флаг /FA очень важен. Он ответственен за генерацию ассемблерного кода.

##### Отключение проверки cookie

Флаг /GS- отключает проверку stack cookie. Если мы забудем его прописать, то наш код будет содержать следующие внешние зависимости:

EXTRN __GSHandlerCheck:PROC

EXTRN __security_check_cookie:PROC

EXTRN __security_cookie:QWORD

И будет ссылаться на них:

sub rsp, 664 ; 00000298H

mov rax, QWORD PTR __security_cookie

xor rax, rsp

...

mov rcx, QWORD PTR __$ArrayPad$[rsp]

xor rcx, rsp

call __security_check_cookie

add rsp, 664 ; 00000298H

pop rdi

pop rsi

ret 0

Мы можем удалить их вручную, как показано ниже, но рекомендуется просто отключить флаг на стадии компиляции.

Присваиваем security cookie — 0:

sub rsp, 664 ; 00000298H

mov rax, 0; QWORD PTR __security_cookie

xor rax, rsp

И удаляем строку с проверкой:

mov rcx, QWORD PTR __$ArrayPad$[rsp]

xor rcx, rsp

;call __security_check_cookie

add rsp, 664 ; 00000298H

pop rdi

pop rsi

ret 0

Рефакторинг ассемблерного кода

Описанный метод может использоваться для создания 32 и 64 битных шеллкодов. Однако, между ними есть некоторые тонкие различия, и шаги могут различаться. Поэтому мы их опишем отдельно:

Большинство шагов описанных здесь, могут быть автоматизированы, с помощью masm_shc. Я все же рекомендую пройтись по всему процессу руками, хотя бы раз, для лучшего понимания.

32 бита

Чтобы начать, нам необходим 32 битный ассемблерный код, сгенерированный командой cl /c /FA /GS- demo.cpp, выполненной в 32 битной версии Visual Studio Native Tools Command Prompt.

0. Редактируем ассемблерный код

Для начала попробуем как есть и проверим, сможем ли мы получить на выходе EXE. Мы скомпилируем код 32 битным MASM:

Так как мы используем регистр FS, ассемблер выдаст ошибку:

Error A2108: use of register assumed to ERROR

Чтобы она не появлялась, надо добавить следующую строку в самом верху нашего файла (сразу после заголовка):

После этого, файл должен компилироваться без ошибок.

Запустите получившийся файл и убедитесь, что все нормально работает. На этом этапе мы должны получить работающий EXE. Если мы загрузим его в PE viewer (или PE-bear), мы увидим, что несмотря на удаление всех зависимостей в Си коде, некоторые все равно остались. В PE по-прежнему есть таблица импорта. Это из-за стандартных библиотек, которые были скомпонованы по умолчанию. Нам надо от них избавиться.

- Избавление от оставшихся внешних зависимостей

На этом шаге мы избавляемся от оставшихся импортов, которые появились из-за автоматического включения статических библиотек.

Закомментируйте следующие строки:

INCLUDELIB LIBCMT

INCLUDELIB OLDNAMES

Вы также можете закомментировать строку:

На предыдущем шаге, объектный файл был скомпонован со статической библиотекой LibCMT, с точкой входа: _mainCRTStartup. После удаления этой зависимости, компоновщик не найдет входную точку. Мы должны явно указать ее:

ml /c <file_name>.asm

link <file_name>.obj /entry:main

или в одну строку (после компиляции используется компоновщик по умолчанию):

ml /c <file_name>.asm /link /entry:main

Проверьте, все ли работает правильно. Откройте получившийся PE файл в PE-bear. Вы увидите, что теперь таблица импорта отсутствует. Кода также стало меньше. Входной точкой является наша функция main

- Создание базонезависимого кода: обработка строк

Этот шаг можно пропустить, если все строки располагаются на стеке, как было описано здесь.

Мы не можем, в базонезависимом шеллкоде, хранить данные в разных секциях. Мы можем использовать только секцию .text (для всего). До этого, строки находились в секции .data. Поэтому нам надо отредактировать ассемблерный код, чтобы они находились в нем.

Пример встраивания (inlining — прим.пер.) строк:

- мы копируем строку из секции data, и вставляем до момента добавления на стек. Мы кладем ее на стек вызовом функции, которая находится после строки:

call after_kernel32_str

DB 'k', 00H, 'e', 00H, 'r', 00H, 'n', 00H, 'e', 00H, 'l', 00H

DB '3', 00H, '2', 00H, '.', 00H, 'd', 00H, 'l', 00H, 'l', 00H, 00H

DB 00H

ORG $+2

after_kernel32_str:

;push OFFSET $SG89718

Если в нашем проекте много строк, становится очень сложно встроить их все вручную, но можно сделать это автоматически с помощью masm_shc.

После встраивания всех строк, компилируем заново:

ml /c <file_name>.asm /link /entry:main

Иногда встраивание строк делает дистанцию между инструкциями слишком большим и не дает возможность сделать короткий jmp. Мы можем легко исправить это заменой коротких jmp на длинные. Пример:

- До:

jmp SHORT $LN1@main

- После:

jmp $LN1@main

Также можно скопировать инструкции, на которые указывает jmp.

Пример — вместо jmp на конец функции, для завершения ветвления, мы можем завершиться по другому:

;jmp SHORT $LN1@main

; Line 183

mov esp, ebp

pop ebp

ret 0

Проверьте получившийся файл. Если он не запускает, то вы допустили ошибки, при встраивании строк.

Не забывайте, что сейчас все строки находятся в секции .text. Поэтому, если вы работаете со встроенными строками (изменяете, декодируете), вы должны для начала выставить права на запись для .text (изменить флаг в заголовке секции), иначе вы получите ошибку. После того как шеллкод будет извлечен из EXE, он все равно будет загружен в RWX память (память с правами на чтение, запись, исполнение), так что с точки зрения шеллкода, никакой разницы нет. Подробнее об этом в дальнейших примерах.

- Извлечение и тестирование шеллкода

- Откройте финальную версию приложения в PE-bear. Заметьте, что сейчас у EXE нет таблицы импорта и таблицы перемещений.

- Сделайте дамп секции .text с помощью PE-bear

- Проверьте шеллкод, запустив runshc32.exe из пакета masm_shc

- Если все хорошо, шеллкод будет работать также как и EXE

64 бита

Для начала нам потребуется 64 битный ассемблерный код, полученный командой cl /c /FA /GS- demo.cpp, запущенной из 64 битной версии Visual Studio Native Tools Command Prompt.

Выравнивание стека

В случае с 64 битным кодом, нам надо убедиться, что стек выровнен на 16 байт. Выравнивание необходимо для XMM инструкций в коде. Если его не соблюдать, приложение завершится с ошибкой, как только будет попытка использования XMM регистра. Больше деталей вы найдете в статье @mattifestation, в главе “Ensuring Proper Stack Alignment in 64-bit Shellcode”.

Код, для выравнивания стека от @mattifestation:

_TEXT SEGMENT

; AlignRSP - это простая функция, которая проверяет, что стек выровнен на 16 байт

; перед вызовом входной точки нагрузки. Это важно, так как 64 битные функции

; в Windows, требуют 16 байтного выравнивания. Когда выполняется amd64

; шеллкод, вы не можете быть уверены в правильном выравнивании. Например,

; если ваш шеллкод работает в условиях 8 байтного выравнивания, любой вызов Win32 функции скорее всего

; даст сбой, при обращении к любой ассемблерной инструкции, использующей XMM регистры (которые требуют 16 байтного выравнивания)

AlignRSP PROC

push rsi ; Сохраняем RSI, так как мы его меняем

mov rsi, rsp ; Сохраняем RSP, чтобы позже восстановить

and rsp, 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0h ; Выравниваем RSP на 16 байт

sub rsp, 020h ; Выделяем память для ExecutePayload

call main ; Вызываем входную точку нагрузки

mov rsp, rsi ; Восстанавливаем оригинальное значение RSP

pop rsi ; восстанавливаем RSI

ret ; возвращаемся

AlignRSP ENDP

_TEXT ENDS

Из него мы будем вызывать нашу функцию main.

Мы должны добавить этот код перед первым _TEXT SEGMENT в файле. Он станет нашей входной точкой:

ml64 <file.asm> /link /entry:AlignRSP

- Очищаем ассемблерный код

Для начала используем его как есть и проверим, дает ли он правильный вывод. Мы попробуем скомпилировать код ассемблером MASM 64 бит (из 64 битной версии Visual Studio Native Tools Command Prompt):

В этот раз мы получили несколько ошибок. Это потому что сгенерированный код не полностью совместим с MASM и необходимо вручную внести правки. Мы получим похожий список ошибок:

shellcode_task_step1.asm(75) : error A2006:undefined symbol : FLAT

shellcode_task_step1.asm(86) : error A2006:undefined symbol : FLAT

shellcode_task_step1.asm(98) : error A2006:undefined symbol : FLAT

shellcode_task_step1.asm(116) : error A2006:undefined symbol : FLAT

shellcode_task_step1.asm(120) : error A2006:undefined symbol : FLAT

shellcode_task_step1.asm(132) : error A2006:undefined symbol : FLAT

shellcode_task_step1.asm(133) : error A2006:undefined symbol : FLAT

shellcode_task_step1.asm(375) : error A2027:operand must be a memory expression

shellcode_task_step1.asm(30) : error A2006:undefined symbol : $LN16

shellcode_task_step1.asm(31) : error A2006:undefined symbol : $LN16

shellcode_task_step1.asm(36) : error A2006:undefined symbol : $LN13

shellcode_task_step1.asm(37) : error A2006:undefined symbol : $LN13

shellcode_task_step1.asm(41) : error A2006:undefined symbol : $LN7

shellcode_task_step1.asm(42) : error A2006:undefined symbol : $LN7

- Нам надо вручную удалить слово FLAT из файла. Просто замените FLAT: на пустоту.

- Нам надо удалить сегменты pdata и xdata

- Нам надо пофиксить ссылку на gs регистр на gs:[96]

с:

на:

mov rax, QWORD PTR gs:[96]

Теперь файл будет компилироваться без ошибок. Запустите получившийся файл и проверьте его в PE-bear.

- Удаление оставшихся внешних зависимостей

На этом шаге нам надо избавиться от оставшихся импортов, которые появились вследствие автоматического включения статических библиотек.

Как и в 32 битной версии, мы должны закомментировать включения:

INCLUDELIB LIBCMT

INCLUDELIB OLDNAMES

Если какие-то функции были автоматически добавлены из этих библиотек, то от них надо избавиться, как уже было описано в аналогичной части о 32 битной версии.

Компилируем, указываем точку входа:

ml64 /c <file_name>.asm /link /entry:<entry_function>

- Создание базонезависимого кода: обработка строк

Этот шаг можно пропустить, если все строки находятся на стеке, как описано тут.

Аналогично для 32 битной версии, нам надо удалить все ссылки на секции, кроме .text. В нашем случае это означает встраивание строк. Оно может быть таким же, как и в 32 битной версии, но теперь аргументы функции расположены в регистрах, а не на стеке. Поэтому вам надо положить их смещения в подходящий регистр, инструкцией pop.

Пример встраивания строк в 64 битной версии:

call after_msgbox_str

DB 'MessageBoxW', 00H

after_msgbox_str:

pop rdx

;lea rdx, OFFSET $SG90389

mov rcx, QWORD PTR u32_dll$[rsp]

call QWORD PTR _GetProcAddress$[rsp]

- Извлечение и тестирование шеллкода — аналогично 32 битной версии:

- Откройте финальную версию приложения в PE-bear. Заметьте, что сейчас у EXE нет таблицы импорта и таблицы перемещений.

- Сделайте дамп секции .text с помощью PE-bear

- Проверьте шеллкод, запустив runshc64.exe из пакета masm_shc

- Если все хорошо, шеллкод будет работать также как и EXE

Расширенный пример — сервер

До этого у нас был небольшой код, показывающий MessageBox. Но что на счет чего-то более функционального? Будет ли все работать также?

В этой главе мы посмотрим на другой пример — маленький локальный сервер. Он является частью кода из White Rabbit crackme. Эта часть кода открывает по очереди сокеты на 3 портах, в которые предполагается “стучаться”.

Это Си код (knock.cpp), который можно скомпилировать в ассемблерный:

#include <Windows.h>

#include "peb_lookup.h"

#define LOCALHOST_ROT13 ">?D;=;=;>"

typedef struct {

HMODULE(WINAPI* _LoadLibraryA)

(LPCSTR lpLibFileName);

FARPROC(WINAPI* _GetProcAddress)

(HMODULE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName);

} t_mini_iat;

typedef struct {

int(PASCAL FAR* _WSAStartup)(_In_ WORD wVersionRequired, _Out_ LPWSADATA lpWSAData);

SOCKET(PASCAL FAR* _socket)

(_In_ int af, _In_ int type, _In_ int protocol);

unsigned long(PASCAL FAR* _inet_addr)(_In_z_ const char FAR* cp);

int(PASCAL FAR* _bind)(_In_ SOCKET s,

_In_reads_bytes_(namelen) const struct sockaddr FAR* addr, _In_ int namelen);

int(PASCAL FAR* _listen)(_In_ SOCKET s, _In_ int backlog);

SOCKET(PASCAL FAR* _accept)

(_In_ SOCKET s, _Out_writes_bytes_opt_(*addrlen) struct sockaddr FAR* addr, _Inout_opt_ int FAR* addrlen);

int(PASCAL FAR* _recv)(_In_ SOCKET s, _Out_writes_bytes_to_(len, return ) __out_data_source(NETWORK) char FAR* buf, _In_ int len, _In_ int flags);

int(PASCAL FAR* _send)(_In_ SOCKET s, _In_reads_bytes_(len) const char FAR* buf, _In_ int len, _In_ int flags);

int(PASCAL FAR* _closesocket)(IN SOCKET s);

u_short(PASCAL FAR* _htons)(_In_ u_short hostshort);

int(PASCAL FAR* _WSACleanup)(void);

} t_socket_iat;

bool init_iat(t_mini_iat& iat)

{

LPVOID base = get_module_by_name((const LPWSTR)L"kernel32.dll");

if (!base) {

return false;

}

LPVOID load_lib = get_func_by_name((HMODULE)base, (LPSTR) "LoadLibraryA");

if (!load_lib) {

return false;

}

LPVOID get_proc = get_func_by_name((HMODULE)base, (LPSTR) "GetProcAddress");

if (!get_proc) {

return false;

}

iat._LoadLibraryA = (HMODULE(WINAPI*)(LPCSTR))load_lib;

iat._GetProcAddress = (FARPROC(WINAPI*)(HMODULE, LPCSTR))get_proc;

return true;

}

bool init_socket_iat(t_mini_iat& iat, t_socket_iat& sIAT)

{

LPVOID WS232_dll = iat._LoadLibraryA("WS2_32.dll");

sIAT._WSAStartup = (int(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_ WORD, _Out_ LPWSADATA))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "WSAStartup");

sIAT._socket = (SOCKET(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_ int af, _In_ int type, _In_ int protocol))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "socket");

sIAT._inet_addr = (unsigned long(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_z_ const char FAR* cp))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "inet_addr");

sIAT._bind = (int(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_ SOCKET s, _In_reads_bytes_(namelen) const struct sockaddr FAR* addr, _In_ int namelen))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "bind");

sIAT._listen = (int(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_ SOCKET s, _In_ int backlog))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "listen");

sIAT._accept = (SOCKET(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_ SOCKET s, _Out_writes_bytes_opt_(*addrlen) struct sockaddr FAR * addr, _Inout_opt_ int FAR* addrlen))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "accept");

;

sIAT._recv = (int(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_ SOCKET s, _Out_writes_bytes_to_(len, return ) __out_data_source(NETWORK) char FAR* buf, _In_ int len, _In_ int flags))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "recv");

;

sIAT._send = (int(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_ SOCKET s, _In_reads_bytes_(len) const char FAR* buf, _In_ int len, _In_ int flags))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "send");

sIAT._closesocket = (int(PASCAL FAR*)(IN SOCKET s))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "closesocket");

sIAT._htons = (u_short(PASCAL FAR*)(_In_ u_short hostshort))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "htons");

sIAT._WSACleanup = (int(PASCAL FAR*)(void))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)WS232_dll, "WSACleanup");

return true;

}

///--- bool

switch_state(char* buf, char* resp)

{

switch (resp[0]) {

case 0:

if (buf[0] != '9')

break;

resp[0] = 'Y';

return true;

case 'Y':

if (buf[0] != '3')

break;

resp[0] = 'E';

32 return true;

case 'E':

if (buf[0] != '5')

break;

resp[0] = 'S';

return true;

default:

resp[0] = 0;

break;

}

return false;

}

inline char* rot13(char* str, size_t str_size, bool decode)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < str_size; i++) {

if (decode) {

str[i] -= 13;

}

else {

str[i] += 13;

}

}

return str;

}

bool listen_for_connect(t_mini_iat& iat, int port, char resp[4])

{

t_socket_iat sIAT;

if (!init_socket_iat(iat, sIAT)) {

return false;

}

const size_t buf_size = 4;

char buf[buf_size];

LPVOID u32_dll = iat._LoadLibraryA("user32.dll");

int(WINAPI * _MessageBoxW)(_In_opt_ HWND hWnd, _In_opt_ LPCWSTR lpText, _In_opt_ LPCWSTR lpCaption, _In_ UINT uType) = (int(WINAPI*)(_In_opt_ HWND, _In_opt_ LPCWSTR, _In_opt_ LPCWSTR, _In_ UINT))iat._GetProcAddress((HMODULE)u32_dll, "MessageBoxW");

bool got_resp = false;

WSADATA wsaData;

SecureZeroMemory(&wsaData, sizeof(wsaData));

/// code:

if (sIAT._WSAStartup(MAKEWORD(2, 2), &wsaData) != 0) {

return false;

}

struct sockaddr_in sock_config;

SecureZeroMemory(&sock_config, sizeof(sock_config));

SOCKET listen_socket = 0;

if ((listen_socket = sIAT._socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP)) == INVALID_SOCKET) {

_MessageBoxW(NULL, L"Creating the socket failed", L"Stage 2", MB_ICONEXCLAMATION);

sIAT._WSACleanup();

return false;

}

33 char* host_str = rot13(LOCALHOST_ROT13, _countof(LOCALHOST_ROT13) - 1, true);

sock_config.sin_addr.s_addr = sIAT._inet_addr(host_str);

sock_config.sin_family = AF_INET;

sock_config.sin_port = sIAT._htons(port);

rot13(host_str, _countof(LOCALHOST_ROT13) - 1, false);

//encode it back

bool is_ok = true;

if (sIAT._bind(listen_socket, (SOCKADDR*)&sock_config, sizeof(sock_config)) == SOCKET_ERROR) {

is_ok = false;

_MessageBoxW(NULL, L"Binding the socket failed", L"Stage 2", MB_ICONEXCLAMATION);

}

if (sIAT._listen(listen_socket, SOMAXCONN) == SOCKET_ERROR) {

is_ok = false;

_MessageBoxW(NULL, L"Listening the socket failed", L"Stage 2", MB_ICONEXCLAMATION);

}

SOCKET conn_sock = SOCKET_ERROR;

while (is_ok && (conn_sock = sIAT._accept(listen_socket, 0, 0)) != SOCKET_ERROR) {

if (sIAT._recv(conn_sock, buf, buf_size, 0) > 0) {

got_resp = true;

if (switch_state(buf, resp)) {

sIAT._send(conn_sock, resp, buf_size, 0);

sIAT._closesocket(conn_sock);

break;

}

}

sIAT._closesocket(conn_sock);

}

sIAT._closesocket(listen_socket);

sIAT._WSACleanup();

return got_resp;

}

int main()

{

t_mini_iat iat;

if (!init_iat(iat)) {

return 1;

}

char resp[4];

SecureZeroMemory(resp, sizeof(resp));

listen_for_connect(iat, 1337, resp);

listen_for_connect(iat, 1338, resp);

listen_for_connect(iat, 1339, resp);

return 0;

}

В этом примере я использовала некоторые структуры, которые будут работать как псевдо-таблица импорта нашего шеллкода. Это очень удобный способ инкапсулировать функции — мы можем переиспользовать этот код в других проектах.

Мы также видим, что одна строка закодирована алгоритмом ROT13 и декодируется перед использованием. После встраивания этой строки, мы должны выставить секции .text права на запись, так как она будет меняться. После использования, мы ее кодируем заново, для дальнейшего переиспользования.

Заметьте, что я не использую функцию strlen, вместо этого используется макрос _countof, который считает количество элементов массива. Так как strlen не учитывает 0 в конце, эквивалентом будет выражение: _countof(str) -1:

rot13(LOCALHOST_ROT13, _countof(LOCALHOST_ROT13) - 1, true);

Сборка

Проект можно собрать так:

cl /c /FA /GS- main.cpp

masm_shc.exe main.asm main1.asm

ml main1.asm /link /entry:main

Запуск

Сделайте дамп .text секции в PE-bear. Сохраните как: serv32.bin или serv64.bin соответственно.

В зависимости от разрядности, запустите с помощью runshc32.exe или runshc64.exe (доступны здесь).

Пример:

Тестирование

Проверьте в Process Explorer (из пакета SySinternals — прим.пер.) открытые порты.

Для демонстрации, можно использовать следующий Python (Python 2.7) скрипт knock_test.py:

import socket

import sys

import argparse

def main():

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Send to the Crackme")

parser.add_argument('--port', dest="port", default="1337", help="Port to connect")

parser.add_argument('--buf', dest="buf", default="0", help="Buffer to send")

args = parser.parse_args()

my_port = int(args.port, 10)

print '[+] Connecting to port: ' + hex(my_port)

key = args.buf

try:

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(('127.0.0.1', my_port))

s.send(key)

result = s.recv(512)

if result is not None:

print "[+] Response: " + result

s.close()

except socket.error:

print "Could not connect to the socket. Is the crackme running?"

if __name__ == "__main__":

sys.exit(main())

Мы будем отправлять ожидаемые числа, которые будут менять внутренние состояния. Корректные запросы/ответы:

C:UserstesterDesktop>C:Python27python.exe ping.py --buf 9 --port 1337 [+] Connecting to port: 0x539 [+] Response: Y C:UserstesterDesktop>C:Python27python.exe ping.py --buf 3 --port 1338 [+] Connecting to port: 0x53a [+] Response: E C:UserstesterDesktop>C:Python27python.exe ping.py --buf 5 --port 1339 [+] Connecting to port: 0x53b [+] Response: S

После последнего ответа, шеллкод должен завершиться.

В случае некорректного запроса отправленного на корректный порт, ответ будет пустой:

C:UserstesterDesktop>C:Python27python.exe ping.py --buf 9 --port 1338 [+] Connecting to port: 0x53a [+] Response:

Вывод

Так как мы компилировали Си код в ассемблерный, мы вольны дальше его изменять. Это самая интересная часть.

В отличие от высокоуровневых языков, автоматическая обработка ассемблерного кода довольно тривиальна и дает много преимуществ при обфускации. Обрабатывая ассемблерный файл построчно, мы можем добавить мусора или некорректные ветвления. Мы можем заменить некоторые инструкции их эквивалентами ( полиморфизм). Можно добавить анти-дебаггинг техники. Существует очень много возможностей, но тема обфускации очень обширна и выходит за рамки этой статьи.

Моею целью было показать, что создание шеллкода, с помощью ассемблера, не такая трудоемкая задача. Нам не надо тратить часы на написание кода построчно. Достаточно использовать возможности MSVC. Хотя код генерируемый Си компилятором требует пост обработки, в реальности, этот подход проще и поддается автоматизации.

Вверх

Приветствую всех читателей этой статьи и посетителей <Codeby.net> 🖐

Хочу рассказать о шелл-кодах и особенностях их написания вручную. Вам понадобятся знания ассемблера на базовом уровне. Рассмотрим как пишут шелл-коды без инструментов, которые могут их автоматически создать. Вредоносные шелл-коды писать не будем! Будем писать псевдо шелл-коды для простоты и понимания. Если эта статья и её формат вам понравиться, тогда расскажу о вредоносных шелл-кодах

Написание шелл-кода будет показано для архитектуры x86. Алгоритм не сильно отличается для архитектуры x64. Для практики я рекомендую вам установить Linux в VirtualBox или VMware. Так же можно экспортировать готовый образ виртуальной машины.

План:

Теория: Что такое шелл-код и системные вызовы

Практика: Сравниваем программу на ассемблере и языке Си. Делаем hello world в виде шелл-кода

Что такое шелл-код и системные вызовы

Шелл-код — это двоичный исполняемый код, который выполняет определенную задачу. Например: Передать управление

Ссылка скрыта от гостей

(/bin/sh ) или даже выключить компьютер. Шелл-код пишут на языке ассемблер с помощью опкодов (Например: x90 означает команду:nop ).

Программы взаимодействуют с операционной системой через функции. Функции расположены в библиотеках. Функция printf(), exit() в библиотеке libc. Помимо функций существуют системные вызовы. Системные вызовы находятся в ядре операционной системы. Взаимодействие с операционной системой происходит через системные вызовы. Функции используют системные вызовы.

Системные вызовы не зависят от версии какой-либо из библиотеки. Из-за универсальности системные вызовы используют в шелл-кодах.

У системных вызовов есть кода. Например, функция printf() использует системный вызов write() с кодом 4.

Машины с архитектурой x86: Системные вызовы определены в файле /usr/include/i386-linux-gnu/asm/unistd_32.h

Машины с архитектурой x64: Системные вызовы определены в файле /usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/asm/unistd_64.h

Ссылка скрыта от гостей

с объяснениями.

Проверим существование системных вызовов на практике

Напишем программу на языке Си, печатающую строку BUG.

Код:

C:

#include <stdio.h>

void main(void) { printf("BUG"); }

Компиляция: gcc printf_prog.c -o printf_prog

Проверим наличие системных вызовов с помощью команды: strace ./printf_prog

Вывод strace

C:

execve("./printf_prog", ["./printf_prog"], 0xbffff330 /* 48 vars */) = 0

brk(NULL) = 0x405000

access("/etc/ld.so.nohwcap", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

mmap2(NULL, 8192, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xb7fcf000

access("/etc/ld.so.preload", R_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/etc/ld.so.cache", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

fstat64(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=92992, ...}) = 0

mmap2(NULL, 92992, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, 3, 0) = 0xb7fb8000

close(3) = 0

access("/etc/ld.so.nohwcap", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

read(3, "177ELF11133313002541004"..., 512) = 512

fstat64(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0755, st_size=1947056, ...}) = 0

mmap2(NULL, 1955712, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0) = 0xb7dda000

mprotect(0xb7df3000, 1830912, PROT_NONE) = 0

mmap2(0xb7df3000, 1368064, PROT_READ|PROT_EXEC, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0x19000) = 0xb7df3000

mmap2(0xb7f41000, 458752, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0x167000) = 0xb7f41000

mmap2(0xb7fb2000, 12288, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_DENYWRITE, 3, 0x1d7000) = 0xb7fb2000

mmap2(0xb7fb5000, 10112, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_FIXED|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xb7fb5000

close(3) = 0

set_thread_area({entry_number=-1, base_addr=0xb7fd00c0, limit=0x0fffff, seg_32bit=1, contents=0, read_exec_only=0, limit_in_pages=1, seg_not_present=0, useable=1}) = 0 (entry_number=6)

mprotect(0xb7fb2000, 8192, PROT_READ) = 0

mprotect(0x403000, 4096, PROT_READ) = 0

mprotect(0xb7ffe000, 4096, PROT_READ) = 0

munmap(0xb7fb8000, 92992) = 0

fstat64(1, {st_mode=S_IFCHR|0600, st_rdev=makedev(0x88, 0), ...}) = 0

brk(NULL) = 0x405000

brk(0x426000) = 0x426000

brk(0x427000) = 0x427000

write(1, "BUG", 3BUG) = 3

exit_group(3) = ?

+++ exited with 3 +++

В конце strace мы можем видеть системный вызов write(1, "BUG", 3BUG). Количество кода для шелл-кода слишком много, если использовать функции. Старайтесь писать небольшие шелл-коды. Так они будут меньше обнаруживаться и вероятность их срабатывания будет больше.

Сравниваем программу на ассемблере и языке Си

Шелл-код можно написать, как программу на языке Си, скомпилировать, при необходимости отредактировать и перевести в байтовое представление. Такой способ подходит, если мы пишем сложный шелл-код.

Шелл-код можно написать на языке ассемблер. Этот способ я хочу рассмотреть более подробно. Для сравнения мы напишем 2 программы, печатающие сроку Hello world!. Первая будет написана на языке Си, а вторая на ассемблере.

Код на языке Си:

C:

#include <stdio.h>

void main(void) { printf("Hello, world!"); }

Компиляция: gcc hello_world_c.c -o hello_world_c

Код на ассемблере:

C-подобный:

global _start

section .text

_start:

mov eax, 4 ; номер системного вызова (sys_write)

mov ebx, 1 ; файловый дескриптор (stdout)

mov ecx, hello_world ; сообщение hello_world

mov edx, len_hello ; длина строки hello_world

int 0x80 ; вызов системного прерывания

mov eax, 1 ; номер системного вызова (sys_exit)

xor ebx, ebx ; Обнуляем регистр ebx, чтобы первый аргумент системного вызова sys_exit был равен 0

int 0x80 ; вызов системного прерывания

hello_world: db "Hello, world!", 10 ; 10 - количество выделенных байт для строки

len_hello: equ $ - hello_world ; вычиляем длину строки. $ указывает на строку hello_world

Получаем объектный файл с помощью nasm: nasm -f elf32 hello_world.asm -o hello_world.o

Объединяем объектный файл в один исполняемый: ld -m elf_i386 hello_world.o -o hello_world

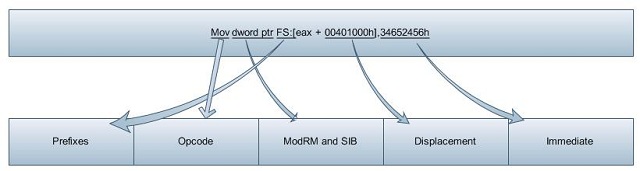

В ассемблерном коде присутствует инструкция int 0x80. Это системное прерывание. Когда процессор получает прерывание 0x80, он выполняет запрашиваемый системный вызов в режиме ядра, при этом получая нужный обработчик из Interrupt Descriptor Table (таблицы описателей прерываний). Номер системного вызова задаётся в регистре EAX. Аргументы функции должны содержаться в регистрах EBX, ECX, EDX, ESI, EDI и EBP. Если функция требует более шести аргументов, то необходимо поместить их в структуру и сохранить указатель на первый элемент этой структуры в регистр EBX.

Посмотрим на ассемблерный код получившихся файлов с помощью objdump.

Функция main в программе на языке Си:

C-подобный:

1199: 8d 4c 24 04 lea ecx,[esp+0x4]

119d: 83 e4 f0 and esp,0xfffffff0

11a0: ff 71 fc push DWORD PTR [ecx-0x4]

11a3: 55 push ebp

11a4: 89 e5 mov ebp,esp

11a6: 53 push ebx

11a7: 51 push ecx

11a8: e8 24 00 00 00 call 11d1 <__x86.get_pc_thunk.ax>

11ad: 05 53 2e 00 00 add eax,0x2e53

11b2: 83 ec 0c sub esp,0xc

11b5: 8d 90 08 e0 ff ff lea edx,[eax-0x1ff8]

11bb: 52 push edx

11bc: 89 c3 mov ebx,eax

11be: e8 6d fe ff ff call 1030 <printf@plt>

11c3: 83 c4 10 add esp,0x10

11c6: 90 nop

11c7: 8d 65 f8 lea esp,[ebp-0x8]

11ca: 59 pop ecx

11cb: 5b pop ebx

11cc: 5d pop ebp

11cd: 8d 61 fc lea esp,[ecx-0x4]

11d0: c3 retАссемблер:

C-подобный:

08049000 <_start>:

8049000: b8 04 00 00 00 mov eax,0x4

8049005: bb 01 00 00 00 mov ebx,0x1

804900a: b9 1f 90 04 08 mov ecx,0x804901f

804900f: ba 0e 00 00 00 mov edx,0xe

8049014: cd 80 int 0x80

8049016: b8 01 00 00 00 mov eax,0x1

804901b: 31 db xor ebx,ebx

804901d: cd 80 int 0x80

0804901f <hello_world>:

804901f: 48 dec eax

8049020: 65 6c gs ins BYTE PTR es:[edi],dx

8049022: 6c ins BYTE PTR es:[edi],dx

8049023: 6f outs dx,DWORD PTR ds:[esi]

8049024: 2c 20 sub al,0x20

8049026: 77 6f ja 8049097 <hello_world+0x78>

8049028: 72 6c jb 8049096 <hello_world+0x77>

804902a: 64 21 0a and DWORD PTR fs:[edx],ecxКажется, что больше кода в ассемблерном листинге, но это не так. В листинге языка Си я показал только функцию main, а она там не одна! В листинге ассемблера я показал программу целиком!

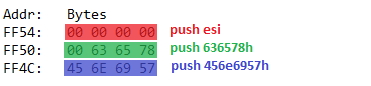

Делаем hello world в виде шелл-кода

Взгляните на листинг программы, написанной на ассемблере. Сначала идут адреса, затем байты, а далее инструкции (8049000: b8 04 00 00 00 mov eax, 0x4). Запишем опкоды инструкций в виде шелл-кода.

Вручную всё делать очень не удобно. Bash нам в помощь: objdump -d ./hello_world|grep '[0-9a-f]:'|grep -v 'file'|cut -f2 -d:|cut -f1-6 -d' '|tr -s ' '|tr 't' ' '|sed 's/ $//g'|sed 's/ /\x/g'|paste -d '' -s |sed 's/^/"/'|sed 's/$/"/g' (вместо ./hello_world можно подставить любую другую программу ).

Опкоды ( представлены в читаемом виде )

C:

"xb8x04x00x00x00"

"xbbx01x00x00x00"

"xb9x1fx90x04x08"

"xbax0ex00x00x00"

"xcdx80xb8x01x00"

"x00x00x31xdbxcd"

"x80x48x65x6cx6c"

"x6fx2cx20x77x6f"

"x72x6cx64x21x0a"

Но работать этот шелл-код не будет, так как в нём присутствуют байты x00 и строка hello_world указана по адресу ( "xb9x1f"x90x04x08" — это инструкция mov ecx, 0x8040901f ), а в программе адрес может быть разный из-за механизма защиты

Ссылка скрыта от гостей

. В шелл-коде точных адресов быть не должно. Решим проблему постепенно, начав заменять данные, расположенные по точному адресу, а затем уберём байты x00.

Убираем точные адреса

Строка, которую нам нужно напечатать — Hello, world! Представим её в виде байтов. Утилита xxd нам поможет: echo "Hello, World!" | xxd -pu

Байтовое представление строки Hello, world!: 48656c6c6f2c20576f726c64210a. Для удобства разделим по 4 всю последовательность байтов: 48656c6c 6f2c2057 6f726c64 210a. Байтов в конце недостаточно. Во всех отделённых нами наборов байтов, их по 4, а в последнем всего лишь 2. Добавим любые байты кроме x00, так как потом добавленные нами байты обрежутся программой. Я выберу байты x90. Нам нужно расположить байты в порядке: little-enidan ( в обратном порядке ). Получится такая последовательность байт: 90900a21 646c726f 57202c6f 6c6c6548. Это просто байты строки.

Теперь превратим их в инструкции на ассемблере. Тут нам поможет фреймворк

Ссылка скрыта от гостей

с утилитой rasm2.

Получаем опкоды инструкций

Bash:

rasm2 -a x86 -b 32 "push 0x90900a21"

rasm2 -a x86 -b 32 "push 0x646c726f"

rasm2 -a x86 -b 32 "push 0x57202c6f"

rasm2 -a x86 -b 32 "push 0x6c6c6548"

rasm2 -a x86 -b 32 "mov ecx, esp"Флаг -a x86 -b 32 обозначают вывод для архитектуры x86.

Чтобы передать байты в стек нужна инструкция push. Регистр [/COLOR]esp[COLOR=rgb(97, 189, 109)] указывает на вершину стека. Переместим на значение вершине стека в регистр ecx.

Команда PUSH размещает значение в стеке, т.е. помещает значение в ячейку памяти, на которую указывает регистр ESP, после этого значение регистра ESP увеличивается на 4.

Как будет выглядить код на ассемблере

C-подобный:

push 90900a21

push 646c726f

push 57202c6f

push 6c6c6548

mov ecx, esp

В итоге получаем: 68210a9090 686f726c64 686f2c2057 6848656c6c 89e1. Заменим точный адрес в нашем шелл-коде на новые инструкции.

C:

"xb8x04x00x00x00"

"xbbx01x00x00x00"

"x68x21x0ax90x90"

"x68x6fx72x6cx64"

"x68x6fx2cx20x57"

"x68x48x65x6cx6c"

"x89xe1"

"xbax0ex00x00x00"

"xcdx80xb8x01x00"

"x00x00x31xdbxcd"

"x80x48x65x6cx6c"

"x6fx2cx20x77x6f"

"x72x6cx64x21x0a"Замена нулевых байтов

Для удобства мы представим эти инструкции в виде ассемблерных команд. Нам поможет утилита ndisasm. Первым делом запишем наши байты в файл, а затем применим утилиту ndisasm.

Bash:

echo -ne 'xb8x04x00x00x00xbbx01x00x00x00x68x21x0ax90x90x68x6fx72x6cx64x68x6fx2cx20x57x68x48x65x6cx6cx89xe1xbax0ex00x00x00xcdx80xb8x01x00x00x00x31xdbxcdx80x48x65x6cx6cx6fx2cx20x77x6fx72x6cx64x21x0a' > test

ndisasm -b32 testВывод утилиты ndisasm

C-подобный:

00000000 B804000000 mov eax,0x4

00000005 BB01000000 mov ebx,0x1

0000000A 68210A9090 push dword 0x90900a21

0000000F 686F726C64 push dword 0x646c726f

00000014 686F2C2057 push dword 0x57202c6f

00000019 6848656C6C push dword 0x6c6c6548

0000001E 89E1 mov ecx,esp

00000020 BA0E000000 mov edx,0xe

00000025 CD80 int 0x80

00000027 B801000000 mov eax,0x1

0000002C 31DB xor ebx,ebx

0000002E CD80 int 0x80

00000030 48 dec eax

00000031 656C gs insb

00000033 6C insb

00000034 6F outsd

00000035 2C20 sub al,0x20

00000037 776F ja 0xa8

00000039 726C jc 0xa7

0000003B 64210A and [fs:edx],ecxИнструкции, содержащие нулевые байты

C-подобный:

00000000 B804000000 mov eax,0x4

00000005 BB01000000 mov ebx,0x1

00000020 BA0E000000 mov edx,0xe

00000027 B801000000 mov eax,0x1

Нам нужно заменить инструкции с нулевыми байтами на другие. Нулевые байты образуются из-за того, что инструкция mov — двухбайтовая, а оставшиеся 2 байта из 4 компилятору нужно заменить нулями. Предлагаю заменить эти инструкции mov на сочетание двухбайтовых инструкций xor и mov.

Ассемблерные инструкции и их опкоды

C-подобный:

xor eax, eax ; x31xc0

mov al, 4 ; xb0x04

xor ebx, ebx ; x31xdb

mov bl, 1 ; xb3x01

xor edx, edx ; x31xd2

mov dl, 14 ; xb2x0e

xor eax, eax ; x31xc0

mov al, 1 ; xb0x01Итоговый вариант Hello, World! в виде шелл-кода

C-подобный:

"x31xc0xb0x04"

"x31xdbxb3x01"

"x68x21x0ax90x90"

"x68x6fx72x6cx64"

"x68x6fx2cx20x57"

"x68x48x65x6cx6c"

"x89xe1"

"x31xd2xb2x0e"

"xcdx80"

"x31xc0xb0x01"

"x31xdbxcd"

"x80x48x65x6cx6c"

"x6fx2cx20x77x6f"

"x72x6cx64x21x0a"Оформим весь этот набор байтов в виде программы на языке Си.

Код программы

C:

unsigned char hello_world[]=

// Заменённые инструкции

//"xb8x04x00x00x00" mov eax,0x4

"x31xc0xb0x04"

//"xbbx01x00x00x00" mov ebx,0x1

"x31xdbxb3x01"

"x68x21x0ax90x90"

"x68x6fx72x6cx64"

"x68x6fx2cx20x57"

"x68x48x65x6cx6c"

"x89xe1"

//"xbax0ex00x00x00" mov edx,0xe

"x31xd2xb2x0e"

"xcdx80"

//"xbax01x00x00x00" mov eax,0x1

"x31xc0xb0x01"

"x31xdbxcd"

"x80x48x65x6cx6c"

"x6fx2cx20x77x6f"

"x72x6cx64x21x0a";

void main() {

int (*ret)() = (int(*)())hello_world;

ret();

}Ссылка скрыта от гостей

Компилируем: gcc hello_world_test.c -o hello_world_test -z execstack

Проверяем работоспособность: ./hello_world_test

Довольно долго это всё делать, если вы не хотите делать шелл-код для атаки на определённую компанию.

Существует замечательный инструменты Msfvenom и подобные ему. Msfvenom позволяет делать шелл-код по шаблону и даже закодировать его. Про этот инструмент и про сам metasploit на Codeby.net написано много информации. Про энкодеры информации в интернете тоже достаточно. Например:

Ссылка скрыта от гостей

.

Хочу порекомендовать сайты:

Ссылка скрыта от гостей

и

Ссылка скрыта от гостей

. На этих сайтах вы сможете найти множество шелл-кодов.

Желаю вам удачи и здоровья. Не болейте и 🧠прокачивайте мозги🧠.

- Download source code — 85.57 KB

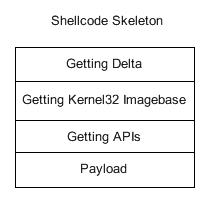

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: The Basics

- What’s Shellcode?

- The Types of Shellcode

- Part 2: Writing Shellcode

- Shellcode Skeleton

- The Tools

- Getting the Delta

- Getting the Kernel32 imagebase

- Getting the APIs

- Null-Free byte Shellcode

- Alphanumeric Shellcode

- Egg-hunting Shellcode

- Part 2: The Payload

- Socket Programming

- Bind Shell Payload

- Reverse Shell Payload

- Download & Execute Payload

- Put All Together

- Part 4: Implement your Shellcode into Metasploit

- Conclusion

- References

- Appendix I – Important Structures

1. Introduction

The secret behind any good exploit is the reliable shellcode. The shellcode is the most important element in your exploit. Working with the automated tools to generate a shellcode will not help you too much in bypassing the obstacles that you will face with every exploit. You should know how to create your own shellcode and that’s what this article will teach you.

In this article, I’m going to teach you how to write a reliable shellcode on win32, how to bypass the obstacles that you will face in writing a win32 shellcode and how to implement your shellcode into Metasploit.

2. Part 1: The Basics

2.1 What’s Shellcode?

Shellcode is simply a portable native code. This code has the ability to run at any place in memory. And this code is used from inside an Exploit to connect back to the attacker or do what the attacker needs to do.

2.2 The Types of Shellcode

Shellcode is classified by the limitations that you are facing while writing a shellcode for a specific vulnerability and it’s classified into 3 types:

Byte-Free Shellcode

In this type of shellcode, you are forced to write a shellcode without any null byte. You will be forced on that while exploiting a vulnerability in a string manipulation code inside a function. when this function uses strcpy() or sprintf() improperly … searching for the null byte in the string (as strings are null terminated) without checking on the maximum accepted size of this string … this will make this application vulnerable to the Buffer Overflow vulnerability.

In this type of vulnerabilities, if your shellcode contains a NULL byte, this byte will be interpreted as a string terminator, with the result that the program accepts the shellcode in front of the NULL byte and discards the rest. So you will have to avoid any null-byte inside your shellcode. But you will have the ability to use just one null byte … the last byte.

Alphanumeric Shellcode

In strings, it’s not common to see strange characters or Latin characters inside … in this case, some IDSs (Intrusion detection systems) detect these strings as malicious specially when they include suspicious sequence of opcodes inside … and they could detect the presence of shellcode. Not only that, but also … some applications filter the input string and accept only the normal characters and numbers (“a-z”, ”A-Z” and “0-9”). In this case, you need to write your shellcode in characters … you are forced to use only these characters and only accept bytes from 0x30 to 0x39 and from 0x40 to 0x5A and from 0x60 to 0x7A.

Egg-hunting Shellcode

In some vulnerabilities, you may have a very small buffer to put your shellcode into. Like off-by-one vulnerability, you are restricted to a specific size and you can’t send a shellcode bigger than that.

So, you could use 2 buffers to put your shellcode into, one is for your real shellcode and the second is for attacking and searching for the 1st buffer.

3. Part 2: Writing Shellcode

3.1 Shellcode Skeleton

Any shellcode consists of 4 parts: Getting the delta, get the kernel32 imagebase, getting your APIs and the payload.

Here we will talk about getting the delta, the kernel32 imagebase and getting the APIs and in the next part of this article, we will talk about the payload.

3.2 The Tools

- Masm: It is the Microsoft Macro Assembler. It’s a great assembler in windows and very powerful.

- Easy Code Masm: It’s an IDE for MASM. It’s a great visualizer and has the best code completion in assembly.

- OllyDbg: That’s your debugger and you can use it as an assembler for you.

- Data Ripper: It’s a plugin in OllyDbg which takes any instructions you select and converts them into an array of

chars suitable for C. It will help you when you need to take your shellcode into an Exploit.

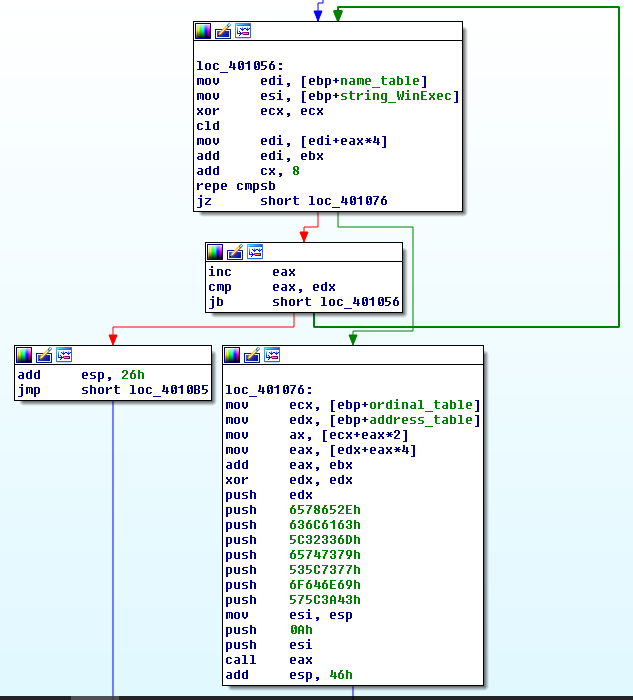

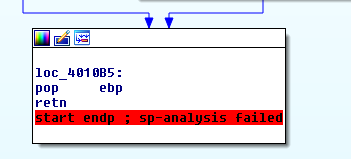

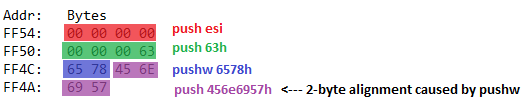

3.3 Getting the Delta

The first thing you should do in your shellcode is to know where you are in the memory (the delta). This is important because you will need to get the variables in your shellcode. You can’t get the variables in your shellcode without having the absolute address of them in the memory.