By

Last updated:

January 28, 2022

Poets and non-poets, unite!

Whether you have a poet’s soul or you haven’t written a poem since grade school, exploring the world of French poetry can be an excellent way to improve your French skills.

But today you won’t just be observing—you are going to become an active participant in this exciting world!

Using French to create something of your own is a surefire way to strengthen your language skills.

We are about to show you how to write your very own poem in French—four different types, in fact, with options suitable for beginners through advanced learners.

Jazz up your French learning routine today and boost your level by challenging yourself to write one poem this week.

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Why French Learners Should Write Poems in Français

Poetry is a great tool for language learners for a variety of reasons.

The first, of course, is French pronunciation. Given that poems are written with a very distinct style and rhythm, reading your own creations aloud can be a great way to get used to pronouncing the unfamiliar words and to learn the appropriate diction of the language.

But learning poetry can also be an exercise in cultural exploration. Think about what it would be like to have no grasp of Shakespeare’s sonnets, for example. While of course sonnets aren’t used all that often in the daily life of a native English speaker, having a familiarity with these famous verses can help both native anglophones and learners of English to get acclimated with the history of this language. It is much the same in French.

Finally, poems give you an outlet to use new words and grammatical structures that you have learned elsewhere. Reading or hearing new vocabulary and structures is the first step, but using them yourself (writing or speaking) will really solidify them into your knowledge.

Like in English, poetry in French exists in a variety of different styles. Each of these styles has something to offer to a French learner, be it an understanding of the rhythm of French, a new way to express yourself or an experiment in rhyming.

4 Types of Poems for All Levels of French Learners

1. Calligrammes

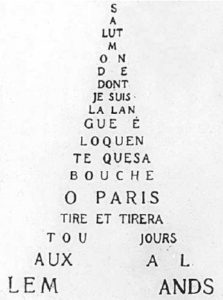

Calligrammes are very visual poems invented by poet Guillaume Apollinaire in the early 20th century. The poems are arranged in such a way as to have the words display the subject of the poem, like in this poem in the shape of a woman wearing a wide-brimmed hat, or this short poem, which is arranged in the shape of the Eiffel Tower:

« Salut monde dont je suis la langue éloquente que sa bouche Ô Paris tire et tirera toujours aux Allemands »

(Hello, world, of which I am the eloquent tongue that its mouth, Oh Paris, sticks out and shall always stick out at the Germans)

Try it yourself: Calligrammes are fun poems for any level of French learner to attempt. Because their actual rhythm is not imposed, you are free to use whatever words you have at your disposal to construct your own very visual poems.

2. Short Poems in Alexandrins

Short rhyming poems written in alexandrins are a great way to test your French rhyming skills. The alexandrin is the French answer to iambic pentameter: It is a rhythmic style of verse wherein each line of poetry has 12 syllables, divided in the middle to make six and six. Often, but not always, alexandrins will rhyme.

Victor Hugo offers some excellent examples of alexandrins in his work. His “Demain, dès l’aube,” (Tomorrow, at dawn) which appears in “Contemplations,” is made up of verses in alexandrins that are arranged in rimes croisées, or crossed rhymes.

What results is a poem of three stanzas, each of which is made up of four lines with the rhyme pattern ABAB:

Demain, dès l’aube, à l’heure // où blanchit la campagne,

Je partirai. Vois-tu, // je sais que tu m’attends.

J’irai par la forêt, // j’irai par la montagne.

Je ne puis demeurer // loin de toi plus longtemps.

Tomorrow at dawn, at the hour when the countryside grows white,

I shall leave. Do you see, I know that you are waiting for me.

I shall go by the forest; I shall go by the mountains.

I cannot remain far from you any longer.

The slashes show the break in the line, known as the césure. As you can see, it often appears at a place that is logical to the meaning of the sentence, as well as to its syllabic constraints.

Try it yourself: This sort of poem is great for a beginner, as its constraints force you to seek out new words. Try writing a poem in alexandrin verse by first picking a theme.

For example, you could choose to write about your backyard. Brainstorm words belonging to the champ lexical (lexical group of words) associated with your backyard: nouns like gazon (lawn) or arbre (tree), but also adjectives like verdoyant (verdent) or lumineux (luminous).

Use a thesaurus to help, if you need to. Here are two of the top French thesauruses:

- Larousse has an online version.

- Le Petit Robert is a must-have tool for any French learner.

Once you have come up with a list of words, you can begin to write your verses, paying close attention to the rhyming pattern and syllables as you write:

- This French rhyming dictionary will surely be helpful.

- This French guide to counting syllables (particularly those pesky sometimes silent “e” endings), will be a great aid too.

3. French Sonnet

A step up from the simple rhyming alexandrin is the sonnet, which uses not only alexandrins but a very specific rhyme scheme.

Several different types of sonnets exist throughout the world, but the types most often used in France are two versions of the model invented by Petrarch, which called for stanzas written in alexandrins in the following rhyme scheme: ABBA ABBA CDE CDE.

Two French poets, Marot and Pelletier, adapted this version, creating versions that called either for ABBA ABBA CCD EED or ABBA ABBA CCD EDE rhyme schemes, respectively. While Pelletier’s version is known as the “French” sonnet and Marot’s the “Italian,” both were quite common in the works of the Renaissance poets in France.

Near the end of his life, Renaissance poet Pierre de Ronsard dictated six sonnets for the “Sonnets pour Hélène,” three of which were in the Marot form and the other three of which were in the Pelletier form. This sonnet, “Quand vous serez bien vieille,” (When you are quite old) is of the Marot form.

Here is the first stanza:

Quand vous serez bien vieille, au soir, à la chandelle,

Assise auprès du feu, dévidant et filant,

Direz, chantant mes vers, en vous émerveillant :

Ronsard me célébrait du temps que j’étais belle.

When you are quite old, and sit in the evening by candlelight

Near the fire, rambling and burning out,

You will say, singing my verses and marveling at them:

Ronsard celebrated me back when I was beautiful.

Another interesting constraint that Ronsard imposed upon himself in these sonnets is the alternation of masculine and feminine rhymes. A masculine rhyme is one where the final syllable is not a silent “e.” You can see the masculine rhymes in bold above.

Try it yourself: Because this form has more constraints than a simple poem in alexandrin, it is great for intermediate learners of French. Many sonnets are love poems, so you may wish to look into your heart for inspiration.

The resources that you already discovered for your short alexandrin poems will be just as helpful now that you have graduated to sonnets.

4. Poèmes en prose

All languages have a style of free-form poem, and that of French, the poème en prose (prose poem), is attempted by many and mastered by few.

One excellent example of a prose poet is Charles Baudelaire, who wrote several different poems as he wandered Paris, compiling them into a book he called “Le Spleen de Paris.” One such poem is “Anywhere out of the world,” (title in English), a poem that explores the wanderlust of the poet via an imagined conversation between the narrator himself and his own soul.

The poem is laid out as though a prose work, complete with dialogue in quotes and prose punctuation and line breaks. Here is how it starts:

Cette vie est un hôpital où chaque malade est possédé du désir de changer de lit. Celui-ci voudrait souffrir en face du poêle, et celui-là croit qu’il guérirait à côté de la fenêtre.

Il me semble que je serais toujours bien là où je ne suis pas, et cette question de déménagement en est une que je discute sans cesse avec mon âme.

« Dis-moi, mon âme, pauvre âme refroidie, que penserais-tu d’habiter Lisbonne ? Il doit y faire chaud, et tu t’y ragaillardirais comme un lézard. Cette ville est au bord de l’eau ; on dit qu’elle est bâtie en marbre, et que le peuple y a une telle haine du végétal, qu’il arrache tous les arbres. Voilà un paysage selon ton goût ; un paysage fait avec la lumière et le minéral, et le liquide pour les réfléchir ! »

Mon âme ne répond pas.

This life is a hospital, where each patient is possessed with a desire to change beds. This one wants to suffer next to the stove, and that one thinks he’d heal better near the window.

It seems to me that I would always be better where I’m not, and this question of displacement is one that I discuss without end with my soul.

“Tell me, my soul, poor, cold soul, what would you think about living in Lisbon? It must be warm there, and you would perk up like a lizard. This city is on the edge of the water; they say it’s built of marble, and that the people there hate plants so very much that they rip up all the trees. That’s a landscape that would be to your liking, a landscape made of light and mineral, and liquid to reflect them!”

My soul does not answer me.

Try it yourself: While it’s easy to see why some believe that prose poetry is the easiest of all four, it can actually be the most difficult, at least to do well. Picking a theme and finding the images that will best illustrate it is a long process and requires extensive vocabulary and mastery of verb tenses.

However, with all of the work you have under your belt, there’s no reason not to give prose poems—or any poem on this list, for that matter—a go.

We’d love to see what you create if you want to share it with us!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

By

Last updated:

January 28, 2022

Poets and non-poets, unite!

Whether you have a poet’s soul or you haven’t written a poem since grade school, exploring the world of French poetry can be an excellent way to improve your French skills.

But today you won’t just be observing—you are going to become an active participant in this exciting world!

Using French to create something of your own is a surefire way to strengthen your language skills.

We are about to show you how to write your very own poem in French—four different types, in fact, with options suitable for beginners through advanced learners.

Jazz up your French learning routine today and boost your level by challenging yourself to write one poem this week.

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Why French Learners Should Write Poems in Français

Poetry is a great tool for language learners for a variety of reasons.

The first, of course, is French pronunciation. Given that poems are written with a very distinct style and rhythm, reading your own creations aloud can be a great way to get used to pronouncing the unfamiliar words and to learn the appropriate diction of the language.

But learning poetry can also be an exercise in cultural exploration. Think about what it would be like to have no grasp of Shakespeare’s sonnets, for example. While of course sonnets aren’t used all that often in the daily life of a native English speaker, having a familiarity with these famous verses can help both native anglophones and learners of English to get acclimated with the history of this language. It is much the same in French.

Finally, poems give you an outlet to use new words and grammatical structures that you have learned elsewhere. Reading or hearing new vocabulary and structures is the first step, but using them yourself (writing or speaking) will really solidify them into your knowledge.

Like in English, poetry in French exists in a variety of different styles. Each of these styles has something to offer to a French learner, be it an understanding of the rhythm of French, a new way to express yourself or an experiment in rhyming.

4 Types of Poems for All Levels of French Learners

1. Calligrammes

Calligrammes are very visual poems invented by poet Guillaume Apollinaire in the early 20th century. The poems are arranged in such a way as to have the words display the subject of the poem, like in this poem in the shape of a woman wearing a wide-brimmed hat, or this short poem, which is arranged in the shape of the Eiffel Tower:

« Salut monde dont je suis la langue éloquente que sa bouche Ô Paris tire et tirera toujours aux Allemands »

(Hello, world, of which I am the eloquent tongue that its mouth, Oh Paris, sticks out and shall always stick out at the Germans)

Try it yourself: Calligrammes are fun poems for any level of French learner to attempt. Because their actual rhythm is not imposed, you are free to use whatever words you have at your disposal to construct your own very visual poems.

2. Short Poems in Alexandrins

Short rhyming poems written in alexandrins are a great way to test your French rhyming skills. The alexandrin is the French answer to iambic pentameter: It is a rhythmic style of verse wherein each line of poetry has 12 syllables, divided in the middle to make six and six. Often, but not always, alexandrins will rhyme.

Victor Hugo offers some excellent examples of alexandrins in his work. His “Demain, dès l’aube,” (Tomorrow, at dawn) which appears in “Contemplations,” is made up of verses in alexandrins that are arranged in rimes croisées, or crossed rhymes.

What results is a poem of three stanzas, each of which is made up of four lines with the rhyme pattern ABAB:

Demain, dès l’aube, à l’heure // où blanchit la campagne,

Je partirai. Vois-tu, // je sais que tu m’attends.

J’irai par la forêt, // j’irai par la montagne.

Je ne puis demeurer // loin de toi plus longtemps.

Tomorrow at dawn, at the hour when the countryside grows white,

I shall leave. Do you see, I know that you are waiting for me.

I shall go by the forest; I shall go by the mountains.

I cannot remain far from you any longer.

The slashes show the break in the line, known as the césure. As you can see, it often appears at a place that is logical to the meaning of the sentence, as well as to its syllabic constraints.

Try it yourself: This sort of poem is great for a beginner, as its constraints force you to seek out new words. Try writing a poem in alexandrin verse by first picking a theme.

For example, you could choose to write about your backyard. Brainstorm words belonging to the champ lexical (lexical group of words) associated with your backyard: nouns like gazon (lawn) or arbre (tree), but also adjectives like verdoyant (verdent) or lumineux (luminous).

Use a thesaurus to help, if you need to. Here are two of the top French thesauruses:

- Larousse has an online version.

- Le Petit Robert is a must-have tool for any French learner.

Once you have come up with a list of words, you can begin to write your verses, paying close attention to the rhyming pattern and syllables as you write:

- This French rhyming dictionary will surely be helpful.

- This French guide to counting syllables (particularly those pesky sometimes silent “e” endings), will be a great aid too.

3. French Sonnet

A step up from the simple rhyming alexandrin is the sonnet, which uses not only alexandrins but a very specific rhyme scheme.

Several different types of sonnets exist throughout the world, but the types most often used in France are two versions of the model invented by Petrarch, which called for stanzas written in alexandrins in the following rhyme scheme: ABBA ABBA CDE CDE.

Two French poets, Marot and Pelletier, adapted this version, creating versions that called either for ABBA ABBA CCD EED or ABBA ABBA CCD EDE rhyme schemes, respectively. While Pelletier’s version is known as the “French” sonnet and Marot’s the “Italian,” both were quite common in the works of the Renaissance poets in France.

Near the end of his life, Renaissance poet Pierre de Ronsard dictated six sonnets for the “Sonnets pour Hélène,” three of which were in the Marot form and the other three of which were in the Pelletier form. This sonnet, “Quand vous serez bien vieille,” (When you are quite old) is of the Marot form.

Here is the first stanza:

Quand vous serez bien vieille, au soir, à la chandelle,

Assise auprès du feu, dévidant et filant,

Direz, chantant mes vers, en vous émerveillant :

Ronsard me célébrait du temps que j’étais belle.

When you are quite old, and sit in the evening by candlelight

Near the fire, rambling and burning out,

You will say, singing my verses and marveling at them:

Ronsard celebrated me back when I was beautiful.

Another interesting constraint that Ronsard imposed upon himself in these sonnets is the alternation of masculine and feminine rhymes. A masculine rhyme is one where the final syllable is not a silent “e.” You can see the masculine rhymes in bold above.

Try it yourself: Because this form has more constraints than a simple poem in alexandrin, it is great for intermediate learners of French. Many sonnets are love poems, so you may wish to look into your heart for inspiration.

The resources that you already discovered for your short alexandrin poems will be just as helpful now that you have graduated to sonnets.

4. Poèmes en prose

All languages have a style of free-form poem, and that of French, the poème en prose (prose poem), is attempted by many and mastered by few.

One excellent example of a prose poet is Charles Baudelaire, who wrote several different poems as he wandered Paris, compiling them into a book he called “Le Spleen de Paris.” One such poem is “Anywhere out of the world,” (title in English), a poem that explores the wanderlust of the poet via an imagined conversation between the narrator himself and his own soul.

The poem is laid out as though a prose work, complete with dialogue in quotes and prose punctuation and line breaks. Here is how it starts:

Cette vie est un hôpital où chaque malade est possédé du désir de changer de lit. Celui-ci voudrait souffrir en face du poêle, et celui-là croit qu’il guérirait à côté de la fenêtre.

Il me semble que je serais toujours bien là où je ne suis pas, et cette question de déménagement en est une que je discute sans cesse avec mon âme.

« Dis-moi, mon âme, pauvre âme refroidie, que penserais-tu d’habiter Lisbonne ? Il doit y faire chaud, et tu t’y ragaillardirais comme un lézard. Cette ville est au bord de l’eau ; on dit qu’elle est bâtie en marbre, et que le peuple y a une telle haine du végétal, qu’il arrache tous les arbres. Voilà un paysage selon ton goût ; un paysage fait avec la lumière et le minéral, et le liquide pour les réfléchir ! »

Mon âme ne répond pas.

This life is a hospital, where each patient is possessed with a desire to change beds. This one wants to suffer next to the stove, and that one thinks he’d heal better near the window.

It seems to me that I would always be better where I’m not, and this question of displacement is one that I discuss without end with my soul.

“Tell me, my soul, poor, cold soul, what would you think about living in Lisbon? It must be warm there, and you would perk up like a lizard. This city is on the edge of the water; they say it’s built of marble, and that the people there hate plants so very much that they rip up all the trees. That’s a landscape that would be to your liking, a landscape made of light and mineral, and liquid to reflect them!”

My soul does not answer me.

Try it yourself: While it’s easy to see why some believe that prose poetry is the easiest of all four, it can actually be the most difficult, at least to do well. Picking a theme and finding the images that will best illustrate it is a long process and requires extensive vocabulary and mastery of verb tenses.

However, with all of the work you have under your belt, there’s no reason not to give prose poems—or any poem on this list, for that matter—a go.

We’d love to see what you create if you want to share it with us!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

На чтение 8 мин. Опубликовано 30.10.2013

Научиться читать правильно всегда помогает транскрипция, и у нас есть статья, как научиться читать с транскрипцией, но, если вы с ней плохо справляетесь, то мы представляем вам стихотворения на французском языке с адаптированным переводом и возможностью прочесть русскими буквами. Вам будут представлены детские озорные стишки и красивая поэзия о любви, известные басни на французском языке и стихотворения на военную тематику.

Научиться читать правильно всегда помогает транскрипция. У нас есть статья, о том, как научиться читать с транскрипцией, но, если вы с ней плохо справляетесь, то мы представляем вам стихотворения на французском языке с адаптированным переводом и возможностью прочесть русскими буквами. Вам будут представлены детские озорные стишки и красивая поэзия о любви, известные басни на французском языке и стихотворения на военную тематику.

Содержание

- Стишки детские: «Souris, souris»

- Басня «Ворона и лисица»: «Le Corbeau et le Renard» Jean de la Fontaine

- Стихотворение о войне: «Sur une barricade» Victor Hugo

- Стихотворение о любви: «Pour toi, mon amour» J.Prevert

Стишки детские: «Souris, souris»

Souris (сури), souris (сури), où te caches-tu (у тё кашь тю) ? — Мышка-мышка, где ты прячешься?

Souris (сури), souris (сури), au museau pointu (о мюзо пуэнтю). — Мышка-мышка, остренькая мордочка.

Voici (вуаси) le chat (лё ша) Moustache (мусташь), — Вот кот усатый

Il ne faut pas (иль нё фо па) qu’il sache (киль сашь), — Ему это знать не нужно

Jolie (жоли) Souricette (сурисет) — Милая мышка

Où est ta (у э та) cachette (кашет)? — Где твоя норка?

Souris, souris, où te sauves-tu ?(Сури, Сури, у тё сове-тю) — Мышка-мышка, где ты спасаешься?

Souris( мышка), souris (мышка), dans l’arbre (дан лярб) moussu (мусю). — Мышка-мышка, во мху под деревом.

Voici (вуаси) venir(вёнир) Panache(панаш) — Вот придет Панаш (Плюмаж)

Il ne faut pas (иль нё фо па) qu’il sache (киль сашь) — Не нужно, чтобы он знал

Jolie (жоли) Souricette (сурисет) — Милая мышка

Où sont (у сон) tes noisettes ? (те нуазет). — Где твои орешки?

Souris (сури), souris (сури), où dormiras-tu (у дормира тю) ? — Мышка-мышка, где ты спишь?

Souris (сури), souris (сури), qui trotte (ки трот) menu (мёню).- Мышка-мышка которая быстро семенит

Il faut (иль фо) que tu t’en ailles(кё тю тан най) — Нужно, чтобы ты ушла

Dans ton (дан тон) petit nid (пёти ни) de paille (дё пай) — В свое маленькое соломенное гнездышко

Jolie (жоли) Souricette (сурсийет) — Милая мышка

C’est ta (сэ та) maisonnette(мэзонэт). — Это твой домик.

Басня «Ворона и лисица»: «Le Corbeau et le Renard» Jean de la Fontaine

Перевод к известной басне не предоставляется, так как в русском языке есть равносильный, всем известный аналог И. Крылова.

Maître (мэтр) Corbeau (Корбо) sur un arbre (сюран арбрё) perché (пэрше),

Tenait (тёнэ) en son bec (ан сон бэк) un fromage (эн фромаж).

Maître (Мэтр) Renard (Рёнар), par l’odeur (пар одёр) alléché (алеше),

Lui tint (люи тэн) à peu près (а пё прэ) ce langage (сё лангаж):

«Eh bonjour, (Э, борнжур) Monsieur (мёсьё) du Corbeau (дю корбо).

Que vous êtes joli! (кё вузэт жоли) que vous (кё ву) me semblez beau (мё самбле бо)!

Sans mentir (сан мантир), si votre ramage (си вотр рамаж)

Se rapporte(сё раппорт) à votre plumage (а вотрё плюмаж),

Vous êtes (везэт) le phénix (лё феникс) des hôtes (де от) de ces bois (дё сё буа).»

A ces mots(а се мо), le corbeau (лё корбо) ne se sent pas (нё сё сан па) de joie (дё жуа);

Et pour montrer (э пур монтрэ) sa belle voix (са бэль вуа),

Il ouvre (иль увр) un large bec (эн ларж бэк), laisse tomber (лэс томбэ) sa proie(са пруа).

Le renard (лё ренад) s’en saisit (сан сэзи), et dit (ди): «Mon bon (мон бон) monsieur (мёсьё),

Apprenez (апрёнэ) que tout (кё ту) flatteur (флаттёр)

Vit aux( вито) dépens de (депан дё) celui qui (сёлюи ки) l’écoute (лекут).

Cette leçon (сэт лёсон) vaut bien(во бьен) un fromage (эн фромаж) sans doute (сан дут).»

Le corbeau (лё корбо), honteux (онтё) et confus( э конфю),

Jura (жюра), mais un peu tard( мэнанпё тар), qu’on ne l’y ( кон нё ли) prendrait plus (прандрэ плю).

Стихотворение о войне: «Sur une barricade» Victor Hugo

Sur une (сюрюнё) barricade (баррикад), au milieu( о мильё) des pavés (де павэ)

За баррикадой в центре мостовой,

Souillés (суйе) d’un sang (дэн сан) coupable (купаблё) et d’un sang (э дан сан) pur lavés (пюр лавэ),

Обрызганной преступной кровью.

Un enfant (эннанфан) de douze ans (дё дузан) est pris (э при) avec des hommes (авэк дезом).

Захвачен мальчуган 12 лет с людской толпой

— Es-tu de (э тю дё) ceux-là, (сё ла) toi (туа)? — L’enfant (ланфан) dit (ди) : Nous en sommes (нузан сом).

— Ты с ними? — Да, мы вместе!

— C’est bon (сэ бон), — dit l’officier (ди лёфисье) , On va (он ва) te fusiller (тё фюзийе).

— Отлично, — молвил офицер, — Тебя мы тоже расстреляем!

Attends ton tour(атан тон тур). — L’enfant voit (ланфан ву) des éclairs (дезэклер) briller (брийе),

— Дождись своей очереди. — Мальчишка видел яркие вспышки

Et tous (э ту) ses compagnons (сэ компаньон) tomber sous (томбэ су) la muraille (ля мюрай).

И своих сотоварищей падающих у стены.

Il dit (иль ди) à l’officier (а лёфисье) : Permettez-vous (пэрметэ ву) que j’aille (кё жай)

И он сказал : «Позвольте мне сходить домой»

Rapporter (раппортэ) cette montre (сэт монтрё) à ma mère (а ма мэрё) chez nous (ше ну) ?

Отнести эти часы моей маме

— Tu veux (тю вё) t’enfuir (тан фюир) ? — Je vais (жё вэ) revenir (рёвенир). — Ces voyous (сэ вуайон)

— Хочешь сбежать? – Нет, я вернусь. – Ну, посмотрим!

Ont peur(он пёр) ! où loges-tu (у ложь тю)? — Là, près (ля, прэ) de la fontaine (дё ля фонтэн).

Испугался! Где ты живешь? – Там, у фонтана, и я вернусь, господин офицер!

Et je vais (э жё вэ) revenir (рёвёнир), monsieur le capitaine(мёсьё лё капитэн).

И я вернусь, господин офицер!

— Va-t’en, (ватан) drôle (дроль) ! — L’enfant s’en va (лянфан сан ва). — Piège grossier (пьеж гросье) !

Иди, забавный мальчуган. Ребенок ушел! Велика задача!

Et les soldats(э ле сольда) riaient (рийе) avec leur (авек лёр officier(офисье),

И солдаты засмеялись вместе с офицером.

Et les mourants (э ле муран) mêlaient (меле) à ce rire leur râle (а сё рирё лёр раль) ;

Картина смешивала мертвых с раскатистым их смехом.

Mais le rire (м элё рирё) cessa (сэса), car soudain (кар судэн) l’enfant pâle (лянфан паль),

Но смех резко прекратился, когда бледный мальчишка

Brusquement (брюскёман) reparu(рёпарю) , fier comme(фьер ком) Viala(вьяля),

Вдруг появился гордный как Вьяла( фр. Народный герой)

Vint s’adosser (вэн садоссэ) au mur (о мюр) et leur dit( э лёрдит) : Me voilà(Мё вуаля).

Вернулся, встав к стене и сказал: «А вот и я!»

La mort (ля мор) stupide(стюпид) eut honte (ю онт) et l’officier fit grâce ( э лёфисье фи грас).

Смерть была глупа, и офицер смилостивился

Стихотворение о любви: «Pour toi, mon amour» J.Prevert

Je suis allé (жё сюизалле) au marché (о маршэ) aux oiseaux (озуазо)

Я пошел на рынок за птицами

Et j’ai (э жэ) acheté (ашётэ) des oiseaux (деуазо)

И купил птиц

Pour toi (пур туа)

Для тебя

Mon amour(монамур)

Любовь моя

Je suis allé (жё сюизалле) au marché (о маршэ) aux fleurs (о флёр)

Я пошел на рынок за цветами

Et j’ai (э жэ) acheté (ашётэ) des fleurs (де флёр)

И купил цветов

Pour toi (пур туа)

Для тебя

Mon amour (мон амур)

Любовь моя

Je suis allé (жё сюизалле) au marché (о марше) a la ferraille (а ля ферай)

Я пошел на рынок железа

Et j’ai (э жэ) acheté (ашётэ) des chaînes (ле шэн)

И купил цепи

De lourdes chaînes (дё лурд шэн)

Тяжелые цепи

Pour toi (пур туа)

Для тебя

Mon amour (монамур)

Любовь моя

Et je suis allé (жё сьизлле) au marché (о маршэ) aux esclaves (озеклав)

Я пошел на рынок рабов

Et je t’ai (э жё тэ) cherchée (шершэ)

Я искал тебя

Mais je ne t’ai pas (мэ жё нё тэ па) trouvée (трувэ)

Но не нашел тебя

Mon amour (монамур)

Любовь моя.

Следует обратить внимание, что интонация в поэзии может изменять свое привычное положение. Иногда некоторое буквы могут читаться, которые согласно правилам чтения не читаются. Но во французском художественном, то есть страрокнижном языке – это норма. Например, многочисленные «е» которые могут читаться либо в каждом слове для мелодичности, либо в конце строф.

Читайте больше, учите стихотворения, знакомьтесь с мировыми известными авторами из Франции, расширяйте кругозор! Надеемся наши уроки вам очень помогут.

На чтение 7 мин Просмотров 13.4к.

Содержание

- La terre est bleue — Земля синеет (автор Paul Eluard)

- La Vie — Жизнь (автор Jules Verne)

- Les Poissons noirs — Чёрные рыбы (автор Louis Aragon)

- J’entre dans ton amour — Вхожу в тебя я (автор Georges Rodenbach)

- Première soirée — Первый вечер (автор Arthur Rimbaud)

Чтобы процесс изучения иностранного языка не был слишком скучным и однообразным, сегодня мы хотим познакомить Вас с поэзией. Вы увидите, как нежно, лирично и чувственно французские поэты раскрывают тему любви.

La terre est bleue — Земля синеет (автор Paul Eluard)

| На французском | На русском |

| La terre est bleue comme une orange

Jamais une erreur les mots ne mentent pas Ils ne vous donnent plus à chanter Au tour des baisers de s’entendre Les fous et les amours Elle sa bouche d’alliance Tous les secrets tous les sourires Et quels vêtements d’indulgence À la croire toute nue. |

Земля синеет словно апельсин

У слов нет больше права на ошибку Они вам впредь не позволяют петь Движеньем губ по телу — языком Безумцев и любовников Она… в её устах соитье Всех таинств всех улыбок В одеждах отпущения грехов Нагая откровенность. |

| Les guêpes fleurissent vert

L’aube se passe autour du cou Un collier de fenêtres Des ailes couvrent les feuilles Tu as toutes les joies solaires Tout le soleil sur la terre Sur les chemins de ta beauté. |

Бликуют осы зеленью

Рассвет себе затягивает шею Ошейником из окон Падший лист покрыт крылами Одарен сполна ты счастьем солнца Всем надземным солнцем Над всеми красоты твоей путями. |

La Vie — Жизнь (автор Jules Verne)

| На французском | На русском |

| Le passé n’est pas, mais il peut se peindre,

Et dans un vivant souvenir se voir ; L’avenir n’est pas, mais il peut se feindre Sous les traits brillants d’un crédule espoir ! Le présent seul est, mais soudain s’élance Semblable à l’éclair, au sein du néant ; Ainsi l’existence est exactement Un espoir, un point, une souvenance ! |

Прошлое мертво, но его нам живо

Память возвратит в красках прежних дней; Будущего нет, но надежды диво Блёсткой нам сулит счастье вместе с ней! Миг нам сущий дан, но и он в сознанье Искрой промелькнёт в вечное нигде; Жизнь проходит вся в этой череде: Упованье, миг и воспоминанье! |

Les Poissons noirs — Чёрные рыбы (автор Louis Aragon)

| На французском | На русском |

| La quille de bois dans l’eau blanche et bleue

Se balance à peine Elle enfonce un peu Du poids du pêcheur couché sur la barge Dans l’eau bleue et blanche il traîne un pied nu Et tout l’or brisé d’un ciel inconnu Fait au bateau brun des soleils en marge Filets filets blonds filets filets gris Dans l’eau toute bleue où le jour est pris Les lourds poissons noirs rêvent du grand large. |

В воде сияет неба синева,

В волне челнок колышется едва, И кренится под весом рыбака – Касается он волн ногой босой, Рябит вода, свет солнца золотой Дойдя к слоям придонного песка Рисует струек, струек светотень, Там, в голубой воде, где затаился день, У чёрных рыб в глазах – застывшая тоска. |

J’entre dans ton amour — Вхожу в тебя я (автор Georges Rodenbach)

| На французском | На русском |

| J’entre dans ton amour comme dans une église

Où flotte un voile bleu de silence et d’encens Je ne sais si mes yeux se trompent, mais je sens Des visions de ciel où mon coeur s’angélise. |

Вхожу в тебя я, как в ворота храма

Там голубая пелена и фимиам. Взгляд тщетно тянется к зеркальным небесам… но сердце видит через амальгаму. |

| Est-ce bien toi que j’aime ou bien est-ce l’amour ?

Est-ce la cathédrale ou plutôt la madone ? Qu’importe ! Si mon coeur remué s’abandonne Et vibre avec la cloche au sommet de la tour ! |

Тебя ли я люблю. И разве страсти

Должны и могут в храме обитать? Боготворить тебя? Ты мне не мать! И в чьей теперь находимся мы власти? |

| Qu’importent les autels et qu’importent les vierges,

Si je sens là, parmi la paix du soir tombé, Un peu de toi qui chante aux orgues du jubé, Quelque chose de moi qui brûle dans les cierges. |

Так к чёрту, к чёрту алтари и девы

Свеча сгорает в легкой тишине. Он знает…в той зеркальной вышине… Что я тебе Адам, а ты мне – Ева! |

Première soirée — Первый вечер (автор Arthur Rimbaud)

| На французском | На русском |

| — Elle était fort déshabillée

Et de grands arbres indiscrets Aux vitres jetaient leur feuillée Malinement, tout près, tout près. |

— Она была полураздета,

и шаловливо дерева глазели сквозь окно на это, дыша листвой едва-едва. |

| Assise sur ma grande chaise,

Mi-nue, elle joignait les mains. Sur le plancher frissonnaient d’aise Ses petits pieds si fins, si fins. |

На стул присев, полунагая

рукой она прикрыла грудь а ножки, негу предвкушая дрожали у нее чуть-чуть. |

| — Je regardai, couleur de cire

Un petit rayon buissonnier Papillonner dans son sourire Et sur son sein, — mouche au rosier. |

— А я бледнел от гнева, глядя,

как тонкий луч по ней пополз, как заскользил, с улыбкой гладя ей груди — мошка среди роз. |

| — Je baisai ses fines chevilles.

Elle eut un doux rire brutal Qui s’égrenait en claires trilles, Un joli rire de cristal. |

— Я ей поцеловал колени.

Хрустален был ее смешок, звучащий и как птичье пенье, и как весенний ручеек. |

| Les petits pieds sous la chemise

Se sauvèrent :»Veux-tu finir!» — La première audace permise, Le rire feignait de punir ! |

«Пусти!» — Прикрыв сорочкой ножки

она уселась без помех, но, что сердилась понарошку, сказал ее лукавый смех. |

| — Pauvrets palpitants sous ma lèvre

Je baisai doucement ses yeux: — Elle jeta sa tête mièvre En arrière : » Oh ! c’est encor mieux !… |

— Ее поцеловал я в глазки

и дрожь ресничек ощутил. — И, томно принимая ласки, она шепнула: «Как ты мил! |

| Monsieur, j’ai deux mots à te dire… »

— Je lui jetai le reste au sein Dans un baiser, qui la fit rire D’un bon rire qui voulait bien… |

Я пару слов сказать хотела…»

— Но с губ ее, когда сосок я ей поцеловал несмело, слетел желания смешок… |

| — Elle était fort déshabillée

Et de grands arbres indiscrets Aux vitres jetaient leur feuillée Malinement, tout près, tout près. |

— Она была полураздета,

и шаловливо дерева глазели сквозь окно на это, дыша листвой едва-едва. |

Источник: https://akyla.net/stihi-na-francuzskom/paul-eluard/317-paul-luard/12003-la-terre-est-bleue-zemlya-sineet

Источник: https://akyla.net/stihi-na-francuzskom/raznye-stihi-francuzskih-pisatelej/48-raznye-stihi-francuzskih-pisatelej/12002-la-vie-zhizn

Источник: https://akyla.net/stihi-na-francuzskom/louis-aragon/327-louis-aragon/12001-les-poissons-noirs-chjornye-ryby

Источник: https://akyla.net/stihi-na-francuzskom/raznye-stihi-francuzskih-pisatelej/48-raznye-stihi-francuzskih-pisatelej/12000-j-entre-dans-ton-amour-vkhozhu-v-tebya-ya

Источник: https://akyla.net/stihi-na-francuzskom/arthur-rimbaud/318-arthur-rimbaud/11997-premi-re-soir-e-pervyj-vecher-tri-potseluya

Стихи на французском языке с переводом и аудио

Представляем подборку стихотворений на французском языке, озвученных и переведённых на русский.

Arthur RIMBAUD «Le Cœur Volé»

Charles-Marie Leconte de Lisle «Midi»

Paul VERLAINE «Colloque Sentimental»

Paul VERLAINE «Promenade sentimentale»

Paul Verlaine «Crépuscule du soir mystique»

Alphonse De Lamartine «Invocation»

Charles Baudelaire «La géante»

Charles Baudelaire «Le balcon»

Charles Baudelaire «L’albatros»

Charles Baudelaire «L’homme et la mer»

Курсы английского языка по уровням

Beginner

Экспресс-курс

«I LOVE ENGLISH»

Elementary

Космический квест

«БЫСТРЫЙ СТАРТ»

Intermediate

Обычная жизнь

КЕВИНА БРАУНА

В разработке

Advanced

Продвинутый курс

«ПРОРЫВ»