Время на прочтение

2 мин

Количество просмотров 37K

Народ, это моя первая статья, так что задолбите меня критикой, дабы повысить качество следующих статей.

Вступление

Ну, начнем как и везде с определений, берите тетрадь и ручку сейчас начнется нудятина. Чтобы мы cмогли написать свой сервер, нужно для начала понимать как он вообще работает, ловите определение:

Сервер – это программное обеспечение, которое ожидает запросов клиентов и обслуживает или обрабатывает их соответственно.

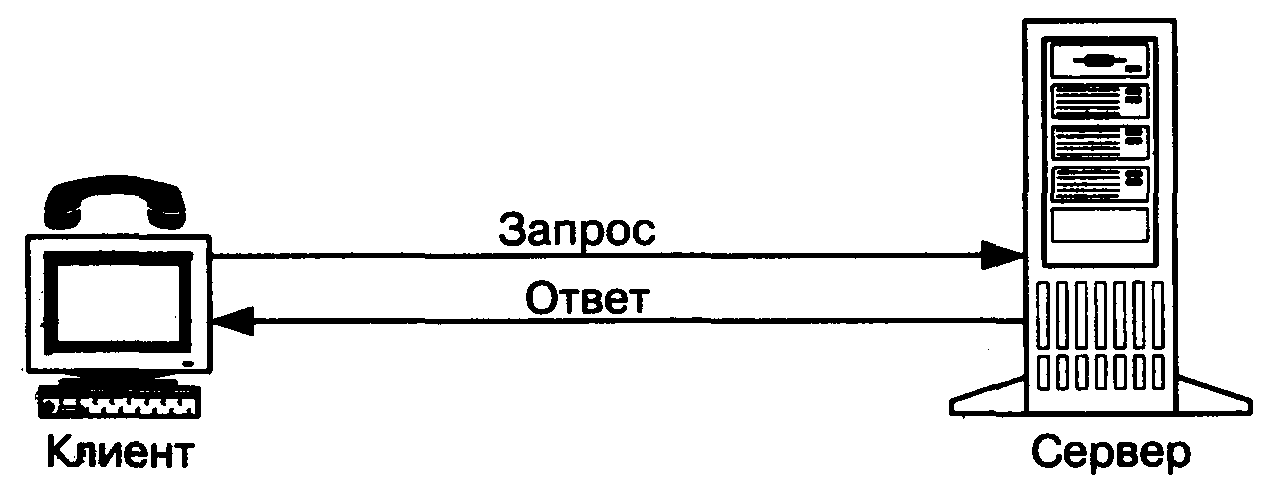

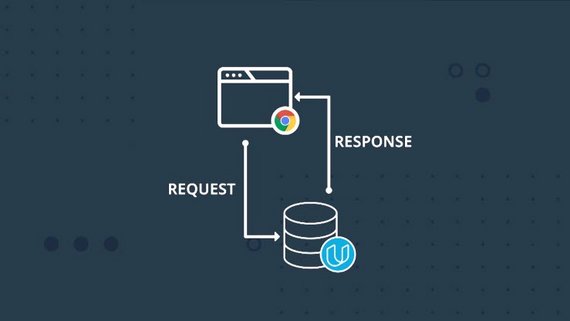

Если объяснять это своими словами, представьте фургон с хот-догами(сервер), проголодавшись, вы(клиент) подходите и говорите повару, что вы хотите заказать(запрос), после чего повар обрабатывает, что вы ему сказали и начинает готовить, в конечном итоге вы получаете свой хот-дог(результат) и сытый радуетесь жизни. Для наглядности посмотри схему.

Околопрактика

Для написания сервера мы будем использовать Python и модуль Socket.

Socket позволяет нам общаться с сервером с помощью сокетов. Весь код я постараюсь пояснять, дабы ты мой дорогой читатель все понял. В конце статьи будет готовый код.

Создайте два файла в одной директории:

-

socket_server.py

-

socket_client.py

Практика

Пишем код для серверной части, так что открывайте файл socket_server.py.

Начнем с импорта модуля и создания TCP-сокета:

import socketДалее весь код будет с комментариями:

s.bind(('localhost', 3030)) # Привязываем серверный сокет к localhost и 3030 порту.

s.listen(1) # Начинаем прослушивать входящие соединения

conn, addr = s.accept() # Метод который принимает входящее соединение.Добавим вечный цикл, который будет считывать данные с клиентской части, и отправлять их обратно.

while True: # Создаем вечный цикл.

data = conn.recv(1024) # Получаем данные из сокета.

if not data:

break

conn.sendall(data) # Отправляем данные в сокет.

print(data.decode('utf-8')) # Выводим информацию на печать.

conn.close()Переходим к клиентской части, весь код теперь пишем в файле socket_client.py.

Начало у клиентской части такое-же как и у серверной.

import socket

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)Далее подключимся к нашему серверу и отправим сообщение «Hello. Habr!».

s.connect(('localhost', 3030)) # Подключаемся к нашему серверу.

s.sendall('Hello, Habr!'.encode('utf-8')) # Отправляем фразу.

data = s.recv(1024) #Получаем данные из сокета.

s.close()Результат:

Заключение

Вот мы с вами и написали свой первый сервер, рад был стараться для вас, ниже будет готовый код.

socket_server.py:

import socket

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.bind(('localhost', 3030)) # Привязываем серверный сокет к localhost и 3030 порту.

s.listen(1) # Начинаем прослушивать входящие соединения.

conn, addr = s.accept() # Метод который принимает входящее соединение.

while True:

data = conn.recv(1024) # Получаем данные из сокета.

if not data:

break

conn.sendall(data) # Отправляем данные в сокет.

print(data.decode('utf-8'))

conn.close()socket_client.py:

import socket

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect(('localhost', 3030)) # Подключаемся к нашему серверу.

s.sendall('Hello, Habr!'.encode('utf-8')) # Отправляем фразу.

data = s.recv(1024) #Получаем данные из сокета.

s.close()Оглавление

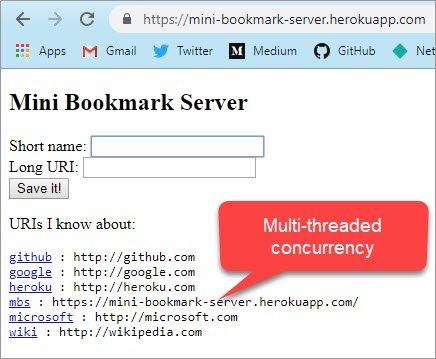

- Что определяет хорошего разработчика ПО?

- Что же такое веб-сервер?

- Как общаться с клиентами по сети

- Простейший TCP сервер

- Простейший TCP клиент

- Заключение

- Cсылки по теме

Лирическое отступление: что определяет хорошего разработчика?

Разработка ПО — это инженерная дисциплина. Если вы хотите стать действительно профессиональным разработчиком, то необходимо в себе развивать качества инженера, а именно: системный подход к решению задач и аналитический склад ума. Для вас должно перестать существовать слово магия. Вы должны точно знать как и почему работают системы, с которыми вы взаимодействуете (между прочим, полезное качество, которое находит применение и за пределами IT).

К сожалениею (или к счастью, ибо благоприятно складывается на уровне доходов тех, кто осознал), существует огромное множество людей, которые пишут код без должного понимания важности этих принципов. Да, такие горе-программисты могут создавать работающие до поры до времени системы, собирая их из найденных в Интернете кусочков кода, даже не удосужившись прочитать, как они реализованы. Но как только возникает первая нестандартная проблема, решение которой не удается найти на StackOverflow, вышеупомянутые персонажи превращаются в беспомощных жертв кажущейся простоты современной разработки ПО.

Для того, чтобы не оказаться одним из таких бедолаг, необходимо постоянно инвестировать свое время в получение фундаментальных знаний из области Computer Science. В частности, для прикладных разработчиков в большинстве случаев таким фундаментом является операционная система, в которой выполняются созданные ими программы.

Веб-фреймворки и контейнеры приложений рождаются и умирают, а инструменты, которыми они пользуются, и принципы, на которых они основаны, остаются неизменными уже десятки лет. Это означает, что вложение времени в изучение базовых понятий и принципов намного выгоднее в долгосрочной перспективе. Сегодня мы рассмотрим одну из основных для веб-разработчика концепций — сокеты. А в качестве прикладного аспекта, мы разберемся, что же такое на самом деле веб-сервер и начнем писать свой.

Что такое веб-сервер?

Начнем с того, что четко ответим на вопрос, что же такое веб-сервер?

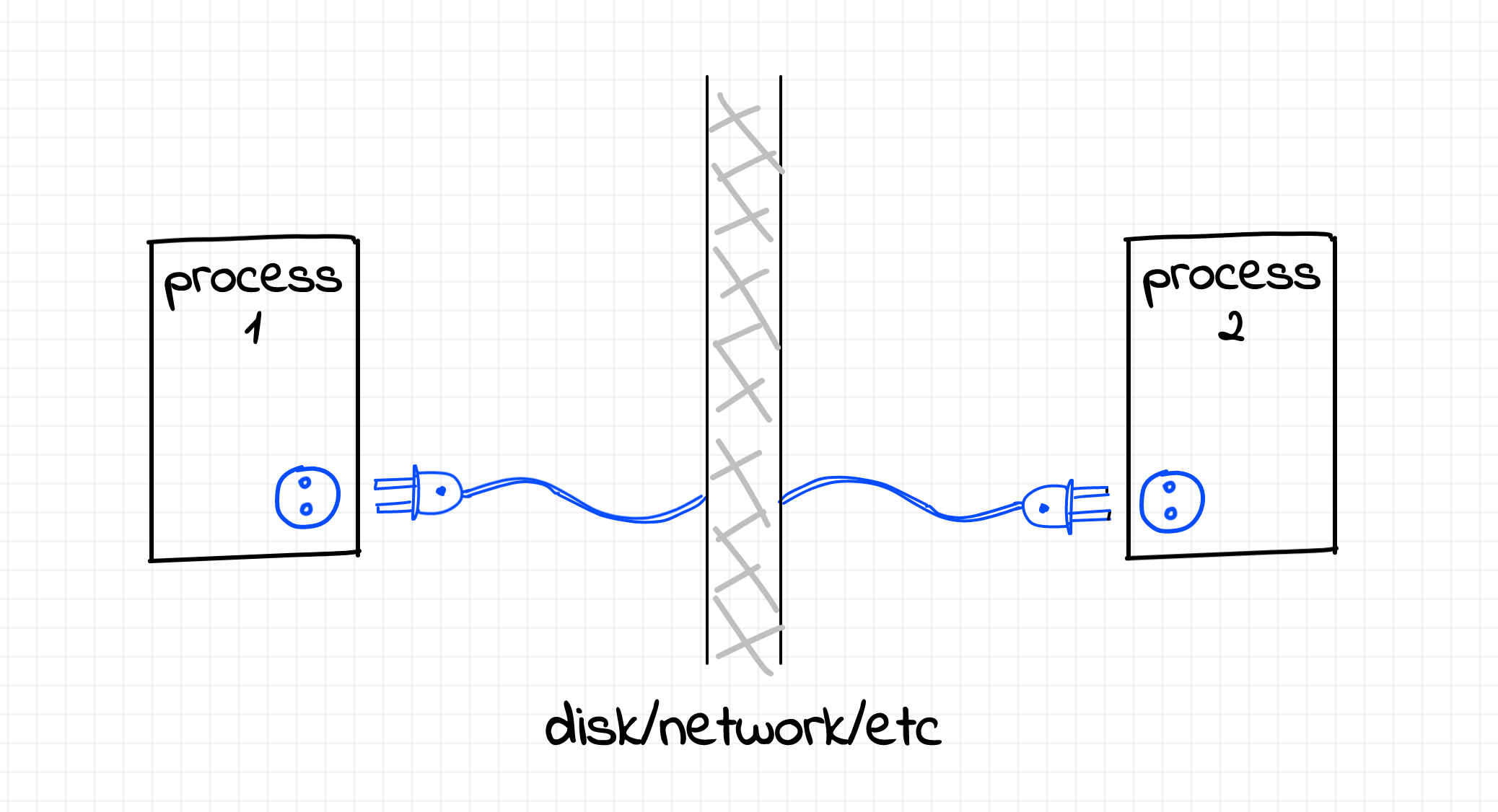

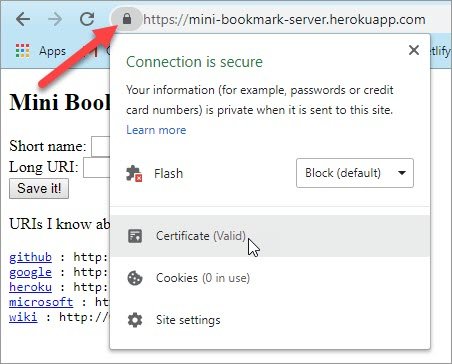

В первую очередь — это сервер. А сервер — это процесс (да, это не железка), обслуживающий клиентов. Сервер — фактически обычная программа, запущенная в операционной системе. Веб-сервер, как и большинство программ, получает данные на вход, преобразовывает их в соответствии с бизнес-требованиями и осуществляет вывод данных. Данные на вход и выход передаются по сети с использованием протокола HTTP. Входные данные — это запросы клиентов (в основном веб-браузеров и мобильных приложений). Выходные данные — это зачастую HTML-код подготовленных веб-страниц.

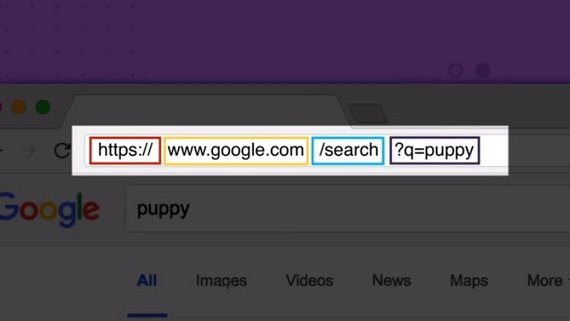

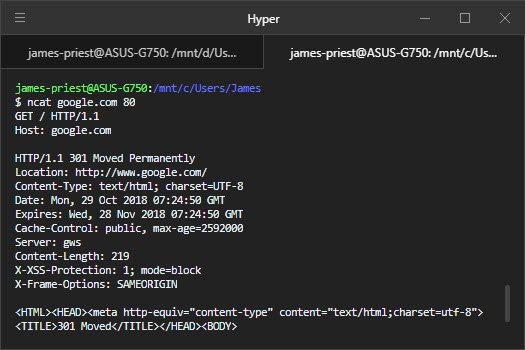

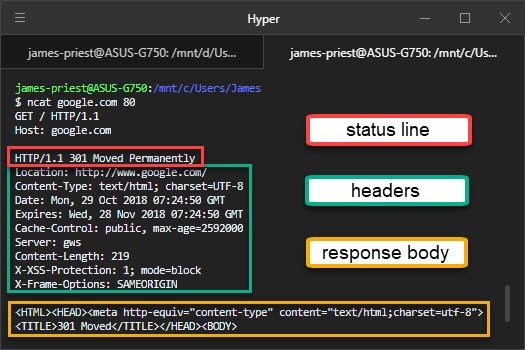

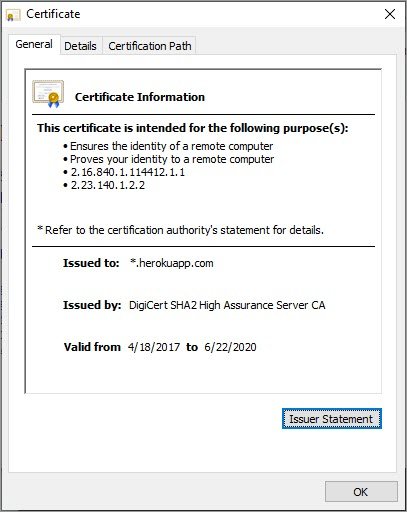

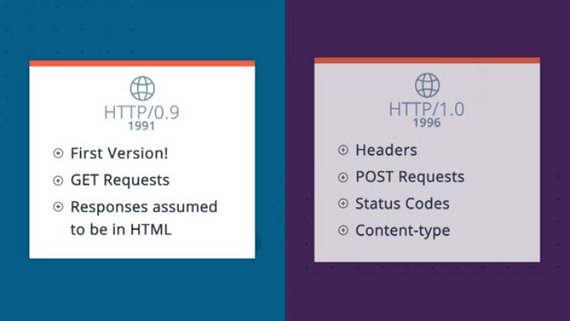

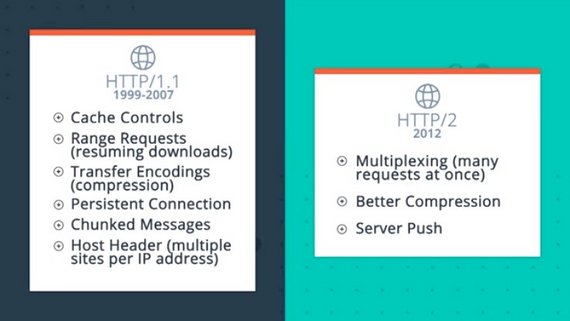

На данном этапе логичными будут следующие вопросы: что такое HTTP и как передавать данные по сети? HTTP — это простой текстовый (т.е. данные могут быть прочитаны человеком) протокол передачи информации в сети Интернет. Протокол — это не страшное слово, а всего лишь набор соглашений между двумя и более сторонами о правилах и формате передачи данных. Его рассмотрение мы вынесем в отдельную тему, а далее попробуем понять, как можно осуществлять передачу данных по сети.

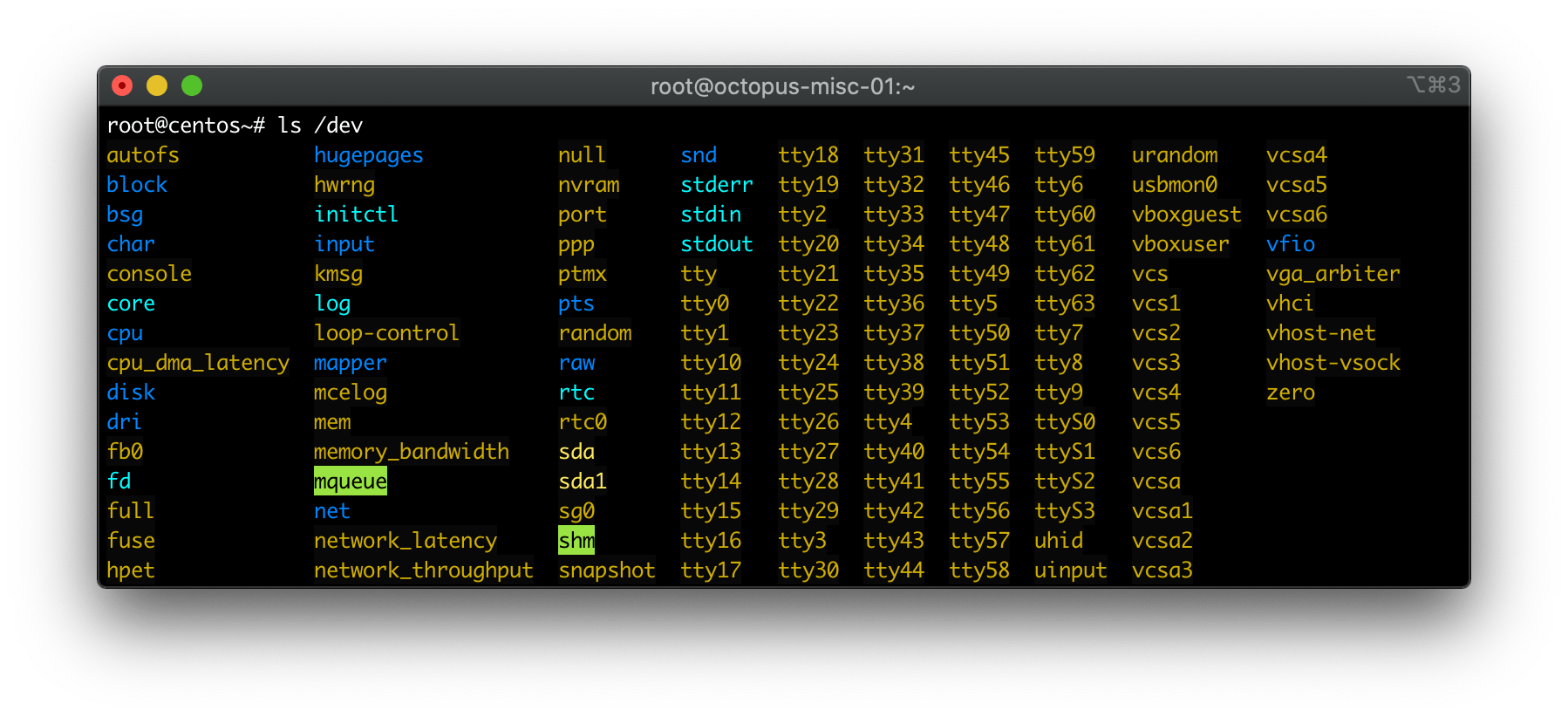

Как компьютеры взаимодействуют по сети

В Unix-подобных системах принят очень удобный подход для работы с различными устройствами ввода/вывода — рассматривать их как файлы. Реальные файлы на диске, мышки, принтеры, модемы и т.п. являются файлами. Т.е. их можно открыть, прочитать данные, записать данные и закрыть.

При открытии файла операционной системой создается т.н. файловый дескриптор. Это некоторый целочисленный идентификатор, однозначно определяющий файл в текущем процессе. Для того, чтобы прочитать или записать данные в файл, необходимо в соответсвующую функцию (например, read() или write()) передать этот дескриптор, чтобы четко указать, с каким файлом мы собираемся взаимодействовать.

int fd = open("/path/to/my/file", ...);

char buffer[1024];

read(fd, buffer, 1024);

write(fd, "some data", 10);

close(fd);

Очевидно, что т.к. общение компьютеров по сети — это также про ввод/вывод, то и оно должно быть организовано как работа с файлами. Для этого используется специальный тип файлов, т.н. сокеты.

Сокет — это некоторая абстракция операционной системы, представляющая собой интерфейс обмена данными между процессами. В частности и по сети. Сокет можно открыть, можно записать в него данные и прочитать данные из него.

Т.к. видов межпроцессных взаимодействий с помощью сокетов множество, то и сокеты могут иметь различные конфигурации: сокет характеризуется семейством протоколов (IPv4 или IPv6 для сетевого и UNIX для локального взаимодействия), типом передачи данных (потоковая или датаграммная) и протоколом (TCP, UDP и т.п.).

Далее будет рассматриваться исключительно клиент-серверное взаимодействие по сети с использованием сокетов и стека протоколов TCP/IP.

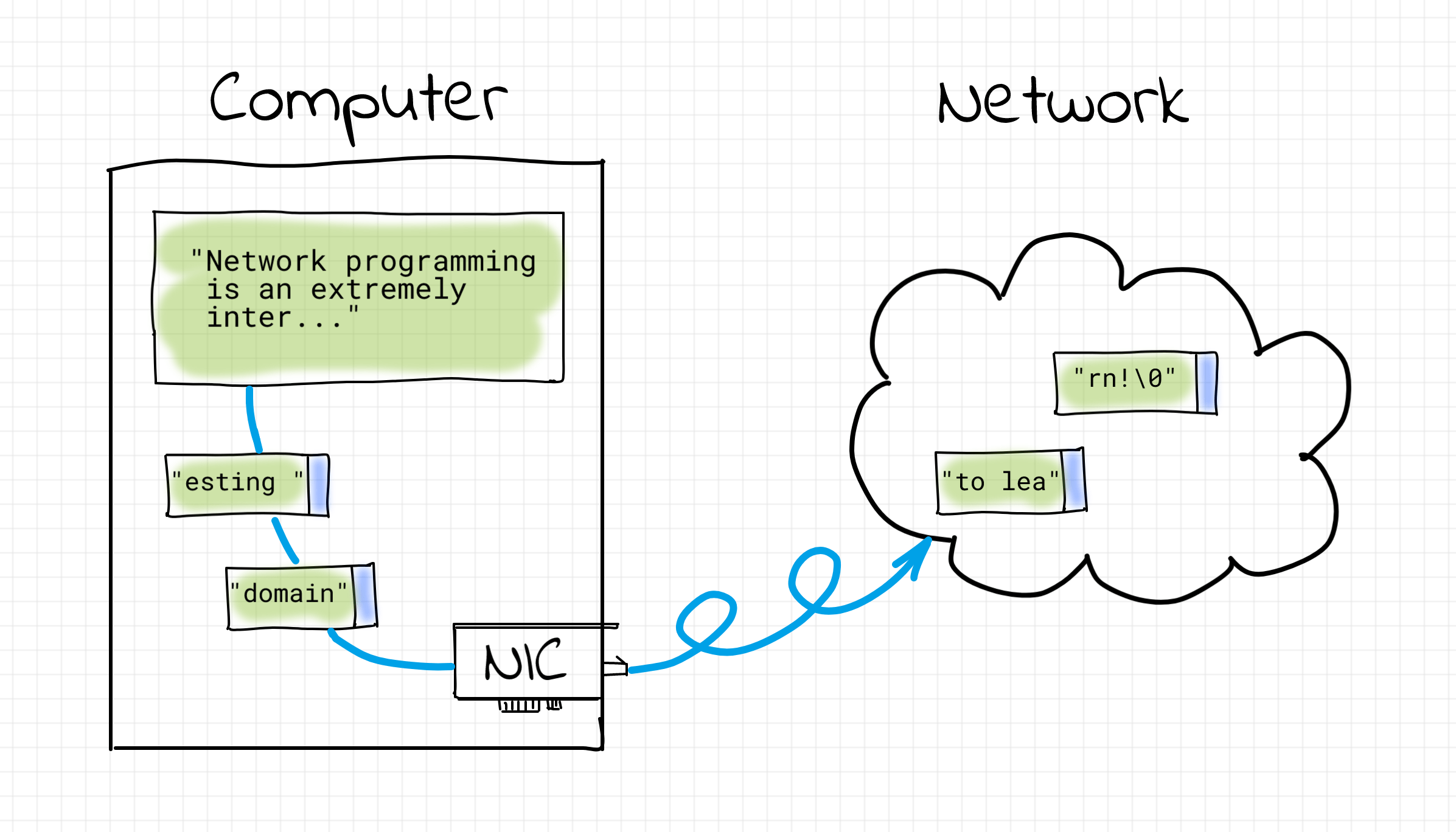

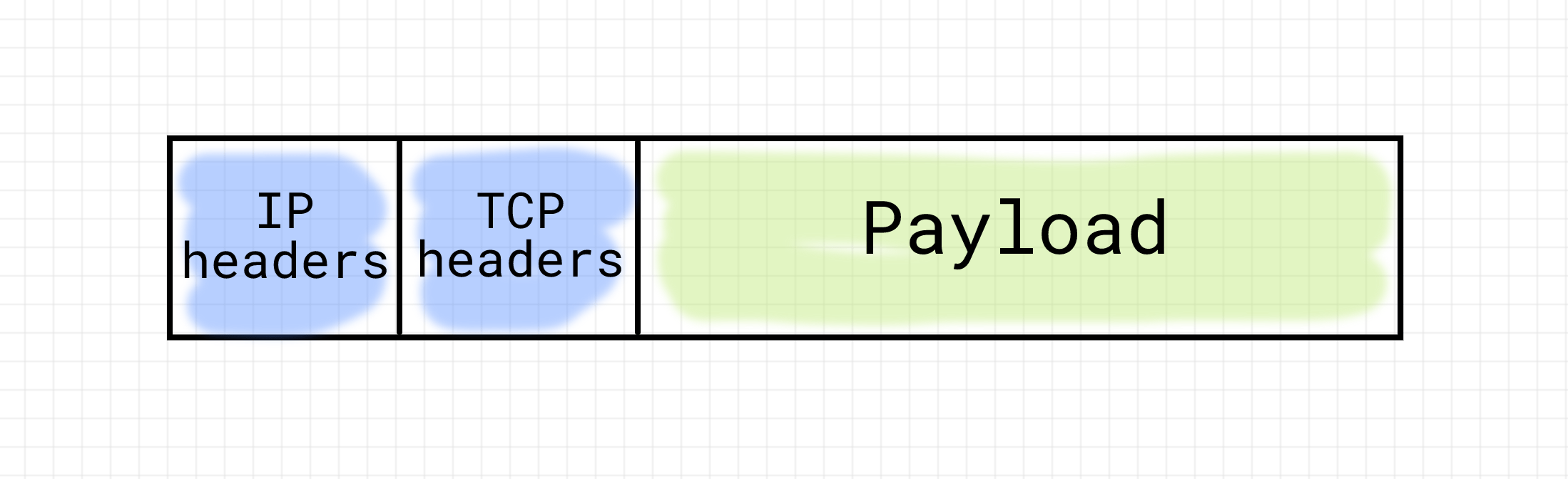

Предположим, что наша прикладная программа хочет передать строку «Hello World» по сети, и соответствующий сокет уже открыт. Программа осуществляет запись этой строки в сокет с использованием функции write() или send(). Как эти данные будут переданы по сети?

Т.к. в общем случае размер передаваемых программой данных не ограничен, а за один раз сетевой адаптер (NIC) может передать фиксировнный объем информации, данные необходимо разбить на фрагменты, не превышающие этот объем. Такие фрагменты называются пакетами. Каждому пакету добавляется некоторая служебная информация, в частности содержащая адреса получателя и отправителя, и они начинают свой путь по сети.

Адрес компьютера в сети — это т.н. IP-адрес. IP (Internet Protocol) — протокол, который позволил объединить множество разнородных сетей по всеми миру в одну общую сеть, которая называется Интернет. И произошло это благодаря тому, что каждому компьютеру в сети был назначен собственный адрес.

В силу особенности маршрутизации пакетов в сети, различные пакеты одной и той же логической порции данных могут следовать от отправителя к получателю разными маршрутами. Разные маршруты могут иметь различную сетевую задержку, следовательно, пакеты могут быть доставлены получателю не в том порядке, в котором они были отправлены. Более того, содержимое пакетов может быть повреждено в процессе передачи.

Вообще говоря, требование получать пакеты в том же порядке, в котором они были отправлены, не всегда является обязательным (например, при передаче потокового видео). Но, когда мы загружаем веб-страницу в браузере, мы ожидаем, что буквы на ней будут расположены ровно в том же порядке, в котором их нам отправил веб-сервер. Именно поэтому HTTP протокол работает поверх надеждного протокола передачи данных TCP, который будет рассмотрен ниже.

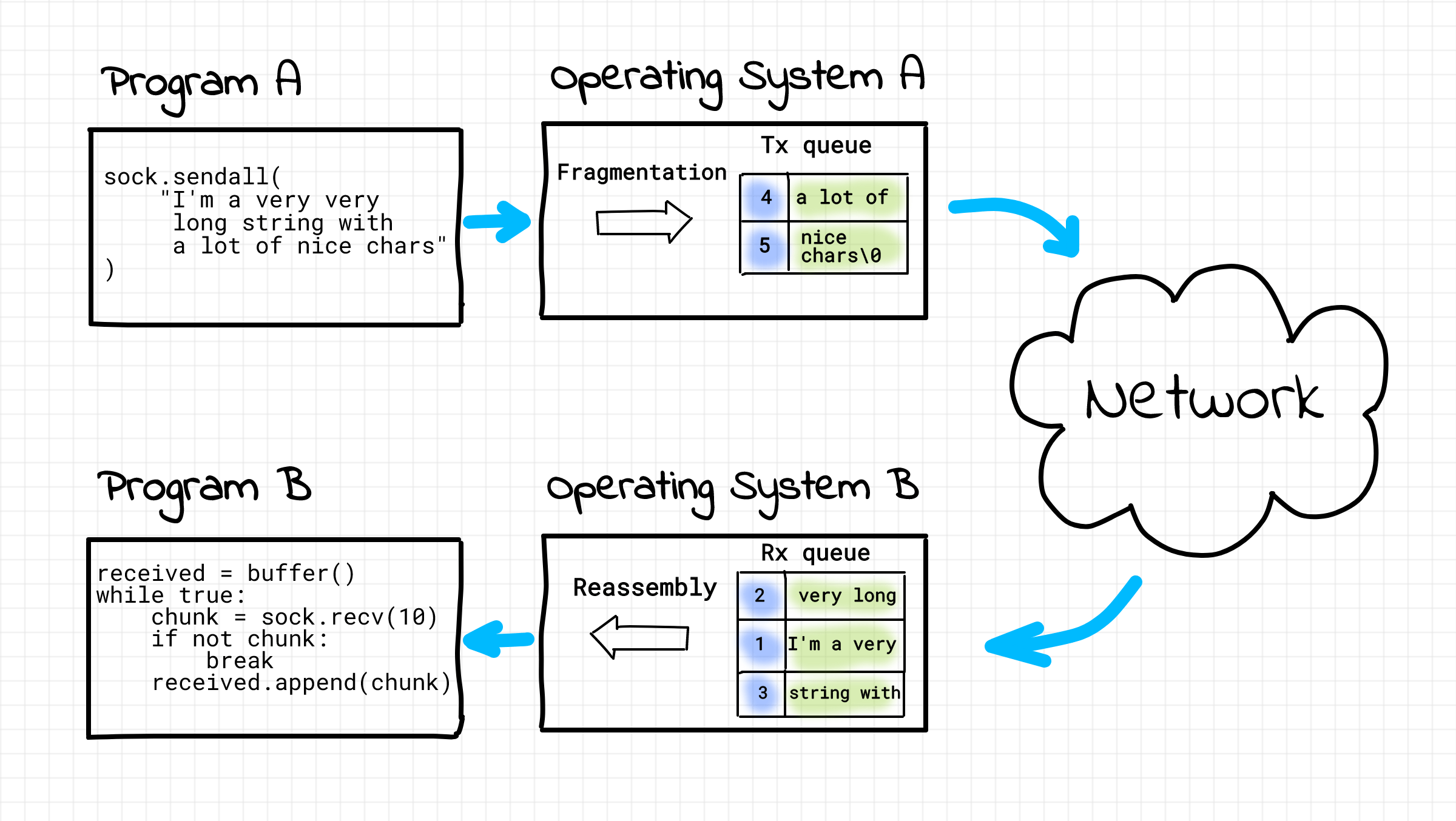

Чтобы организовать доставку пакетов в порядке их передачи, необходимо добавить в служебную информацию каждого пакета его номер в цепочке пакетов и на принимающей стороне делать сборку пакетов не в порядке их поступления, а в порядке, определенном этими номерами. Чтобы избежать доставки поврежденных пакетов, необходимо в каждый пакет добавить контрольную сумму и пакеты с неправильной контрольной суммой отбрасывать, ожидая, что они будут отправлены повторно.

Этим занимается специальный протокол потоковой передачи данных — TCP.

TCP — (Transmission Control Protocol — протокол управления передачей) — один из основных протоколов передачи данных в Интернете. Используется для надежной передачи данных с подтверждением доставки и сохранением порядка пакетов.

В силу того, что передачей данных по сети по протоколу TCP на одном и том же компьютере может заниматься одновременно несколько программ, для каждого из таких сеансов передачи данных необходимо поддерживать свою последовательность пакетов. Для этого TCP вводит понятие соединения. Соединение — это просто логическое соглашение между принимающей и передающей сторонами о начальных и текущих значениях номеров пакетов и состоянии передачи. Соединение необходимо установить (обменявшись несколькими служебными пакетами), поддерживать (периодически передавать данные, чтобы не наступил таймаут), а затем закрыть (снова обменявшись несколькими служебными пакетами).

Итак, IP определяет адрес компьютера в сети. Но, в силу наличия TCP соединений, пакеты могут принадлежать различным соединениям на одной и той же машине. Для того, чтобы различать соединения, вводится понятие TCP-порт. Это всего лишь пара чисел (одно для отправителя, а другое для получателя) в служебной информации пакета, определяющая, в рамках какого соединения должен рассматриваться пакет. Т.е. адрес соединения на этой машине.

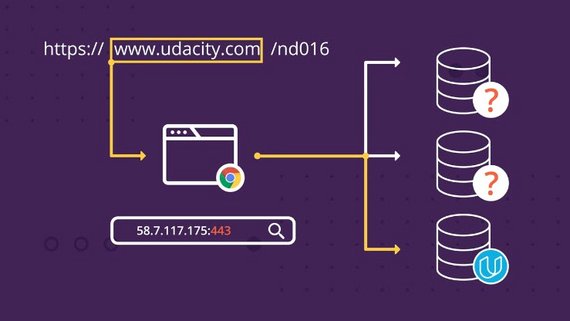

Простейший TCP сервер

Теперь перейдем к практике. Попробуем создать свой собственный TCP-сервер. Для этого нам понадобится модуль socket из стандартной библиотеки Python.

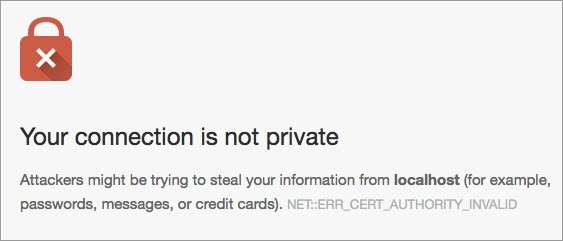

Основная проблема при работе с сокетами у новичков связана с наличием обязательного магического ритуала подготовки сокетов к работе. Но имея за плечами теоретические знания, изложенные выше, кажущаяся магия превращается в осмысленные действия. Также необходимо отметить, что в случае с TCP работа с сокетами на сервере и на клиенте различается. Сервер занимается ожиданием подключений клиентов. Т.е. его IP адрес и TCP порт известны потенциальным клиентам заранее. Клиент может подключиться к серверу, т.е. выступает активной стороной. Сервер же ничего не знает об адресе клиента до момента подключения и не может выступать инициатором соединения. После того, как сервер принимает входящее соединения клиента, на стороне сервера создается еще один сокет, который является симметричным сокету клиента.

Итак, создаем серверный сокет:

# python3

import socket

serv_sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, # задамем семейство протоколов 'Интернет' (INET)

socket.SOCK_STREAM, # задаем тип передачи данных 'потоковый' (TCP)

proto=0) # выбираем протокол 'по умолчанию' для TCP, т.е. IP

print(type(serv_sock)) # <class 'socket.socket'>

А где же обещанные int fd = open("/path/to/my/socket")? Дело в том, что системный вызов open() не позволяет передать все необходимые для инициализации сокета параметры, поэтому для сокетов был введен специальный одноименный системный вызов socket(). Python же является объектно-ориентированным языком, в нем вместо функций принято использовать классы и их методы. Код модуля socket является ОО-оберткой вокрут набора системных вызовов для работе с сокетами. Его можно представить себе, как:

class socket: # Да, да, имя класса с маленькой буквы :(

def __init__(self, sock_familty, sock_type, proto):

self._fd = system_socket(sock_family, sock_type, proto)

def write(self, data):

# на самом деле вместо write используется send, но об этом ниже

system_write(self._fd, data)

def fileno(self):

return self._fd

Т.е. доступ к целочисленному файловому дескриптору можно получить с помощью:

print(serv_sock.fileno()) # 3 или другой int

Так мы работаем с серверным сокетом, а в общем случае на серверной машине может быть несколько сетевых адаптеров, нам необходимо привязать созданный сокет к одному из них:

serv_sock.bind(('127.0.0.1', 53210)) # чтобы привязать сразу ко всем, можно использовать ''

Вызов bind() заставляет нас указать не только IP адрес, но и порт, на котором сервер будет ожидать (слушать) подключения клиентов.

Далее необходимо явно перевести сокет в состояние ожидания подключения, сообщив об этом операционной системе:

backlog = 10 # Размер очереди входящих подключений, т.н. backlog

serv_sock.listen(backlog)

После этого вызова операционная система готова принимать подключения от клиентов на этом сокете, хотя наш сервер (т.е. программа) — еще нет. Что же это означает и что такое backlog?

Как мы уже выяснили, взаимодействие по сети происходит с помощью отправки пакетов, а TCP требует установления соединения, т.е. обмена между клиентом и сервером несколькими служебными пакетами, не содержащими реальных бизнес-данных. Каждое TCP соединение обладает состоянием. Упростив, их можно представить себе так:

СОЕДИНЕНИЕ УСТАНАВЛИВАЕТСЯ -> УСТАНОВЛЕНО -> СОЕДИНЕНИЕ ЗАКРЫВАЕТСЯ

Таким образом, параметр backlog определяет размер очереди для установленных, но еще не обработанных программой соединений. Пока количество подключенных клиентов меньше, чем этот параметр, операционная система будет автоматически принимать входящие соединения на серверный сокет и помещать их в очередь. Как только количество установленных соединений в очереди достигнет значения backlog, новые соединения приниматься не будут. В зависимости от реализации (GNU Linux/BSD), OC может явно отклонять новые подключения или просто их игнорировать, давая возможность им дождаться освобождения места в очереди.

Теперь необходимо получить соединение из этой очереди:

client_sock, client_addr = serv_sock.accept()

В отличие от неблокирующего вызова listen(), который сразу после перевода сокета в слушающее состояние, возвращает управление нашему коду, вызов accept() является блокирующим. Это означает, что он не возвращает управление нашему коду до тех пор, пока в очереди установленных соединений не появится хотя бы одно подключение.

На этом этапе на стороне сервера мы имеем два сокета. Первый, serv_sock, находится в состоянии LISTEN, т.е. принимает входящие соединения. Второй, client_sock, находится в состоянии ESTABLISHED, т.е. готов к приему и передаче данных. Более того, client_sock на стороне сервера и клиенсткий сокет в программе клиента являются одинаковыми и равноправными участниками сетевого взаимодействия, т.н. peer’ы. Они оба могут как принимать и отправлять данные, так и закрыть соединение с помощью вызова close(). При этом они никак не влияют на состояние слушающего сокета.

Пример чтения и записи данных в клиентский сокет:

while True:

data = client_sock.recv(1024)

if not data:

break

client_sock.sendall(data)

И опять же справедливый вопрос — где обещанные read() и write()? На самом деле с сокетом можно работать и с помощью этих двух функций, но в общем случае сигнатуры read() и write() не позволяют передать все возможные параметры чтения/записи. Так, например, вызов send() с нулевыми флагами равносилен вызову write().

Немного коснемся вопроса адресации. Каждый TCP сокет определяется двумя парами чисел: (локальный IP адрес, локальный порт) и (удаленный IP адрес, удаленный порт). Рассмотрим, какие адреса на данный момент у наших сокетов:

serv_sock:

laddr (ip=<server_ip>, port=53210)

raddr (ip=0.0.0.0, port=*) # т.е. любой

client_sock:

laddr (ip=<client_ip>, port=51573) # случайный порт, назначенный системой

raddr (ip=<server_ip>, port=53210) # адрес слушающего сокета на сервере

Полный код сервера выглядит так:

# python3

import socket

serv_sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM, proto=0)

serv_sock.bind(('', 53210))

serv_sock.listen(10)

while True:

# Бесконечно обрабатываем входящие подключения

client_sock, client_addr = serv_sock.accept()

print('Connected by', client_addr)

while True:

# Пока клиент не отключился, читаем передаваемые

# им данные и отправляем их обратно

data = client_sock.recv(1024)

if not data:

# Клиент отключился

break

client_sock.sendall(data)

client_sock.close()

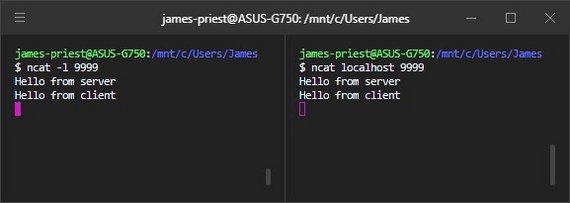

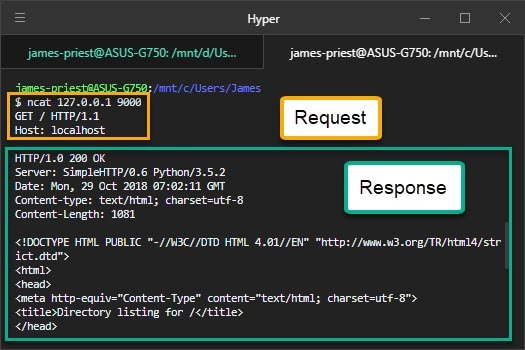

Подключиться к этому серверу можно с использованием консольной утилиты telnet, предназначенной для текстового обмена информацией поверх протокола TCP:

telnet 127.0.0.1 53210

> Trying 192.168.0.1...

> Connected to 192.168.0.1.

> Escape character is '^]'.

> Hello

> Hello

Простейший TCP клиент

На клиентской стороне работа с сокетами выглядит намного проще. Здесь сокет будет только один и его задача только лишь подключиться к заранее известному IP-адресу и порту сервера, сделав вызов connect().

# python3

import socket

client_sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

client_sock.connect(('127.0.0.1', 53210))

client_sock.sendall(b'Hello, world')

data = client_sock.recv(1024)

client_sock.close()

print('Received', repr(data))

Заключение

Запоминать что-то без понимания, как это работает — злое зло не самый разумный подход для разработчика. Работа с сокетами тому отличный пример. На первый взгляд может показаться, что уложить в голове последовательность приготовления клиентских и серверных сокетов к работе практически не возможно. Это происходит из-за того, что не сразу понятен смысл производимых манипуляций. Однако, понимая, как осуществляется сетевое взаимодействие, API сокетов сразу становится прозрачным и легко оседает в подкорке. А с точки зрения полезности полученных знаний, я считаю. что понимание принципов сетевого взаимодействия жизненно важно для разработки и отладки действительно сложных веб-проектов.

Другие статьи из серии:

- Пишем свой веб-сервер на Python: процессы, потоки и асинхронный I/O

- Пишем свой веб-сервер на Python: протокол HTTP

- Пишем свой веб-сервер на Python: стандарт WSGI

- Пишем свой веб-сервер на Python: фреймворк Flask

Ссылки по теме

Справочная информация:

- Сокеты

- Веб-сервер

- Протокол

- Файловый дескриптор

- Межпроцессное взаимодействие

- Пакет

- IP

- TCP

- Порт

- Модуль

socket

Литература

- Beej’s Guide to Network Programming — отличные основы

- UNIX Network Programming — продвинутый уровень

Мой вебинар на данную тему можно посмотреть на сайте GeekBrains.Ru.

Содержание

- Предисловие

- Простой сервер

- Конфигурируемый сервер

- Передача файлов и параметров

- Передеча параметров в GET запросе

- Передача параметров в POST запросе

- Сохраняем переданный файл

- WSGI

- Заставляем Python выполнить код на PHP

- ИТОГИ

Предисловие

Когда-то давно, читая вопросы ребят, работающих с Django пришел к мысли о том, что большинство вопросов вызваны непониманием механизма общения браузера и сервера. Поэтому я решил написать статью, в которой попытаюсь пролить свет и объяснить как все происходит. В данной статье будет частично рассмотрен протокол http.

Простой сервер

Для того, чтобы понять как все происходит, я создам свой собственный веб-сервер, на котором и буду объяснять процесс общения.

Итак, приступим.

Создаем сервер:

#!-*-coding: utf8-*- ''' Простой веб-сервер ''' import socket import select HOST = '' # Символическое имя. По умолчанию localhost PORT = 8080 # Указываем непривилированный порт if __name__ == "__main__": with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock: print('Socket created') # Связываем сокет с локальным хостом и портом sock.bind((HOST, PORT)) print('Привязка сокета') # Слушаем сокет sock.listen(10) print('Слушаем сокет') inputs = [sock] outputs = [sock] num = 0 # Теперь можем общаться с клиентами while True: # Ждем подключения клиентов reads, writes, excepts = select.select(inputs, outputs, inputs) for conn in reads: _conn, client_addr = conn.accept() with _conn as client_conn: ip_addr, client_port = client_addr print(f'Подключение с {ip_addr}:{client_port}') data = client_conn.recv(1024) print(data) answermsg = ( 'HTTP/1.1 200 OKnn' '<html>' ' <head>' ' <title>Test done!!!</title>' ' </head>' ' <body>' ' <b>' f' <i>ok {num}</i>' ' </b>' ' </body>' '</html>' ) client_conn.send(bytes(answermsg, 'utf-8')) num += 1

Как вы видите, я использую модуль socket. Поэтому настоятельно рекомендую вам ознакомиться с этим модулем, так как здесь я буду объяснять лишь используемые мною свойства и методы модуля. В коде мы указываем, что сервер будет работать на localhost и 8080м порте (веб). Теперь, если мы запустим наш сервер и в браузере введем адрес localhost, то в консоли (или командной строке в Windows) увидим запрос, посланный браузером серверу. Здесь вы можете прочитать про заголовки запроса и ответа в http . Я в данной статье буду использовать лишь некоторые заголовки. А здесь список Content-Type/MIME type.

Запускаем наш скрипт (сервер)

После запуска скрипта в консоли увидим сообщения о том, что сервер запустился.

Теперь осталось открывать браузер и перейти на localhost. Как только мы напечатаем в адресной строке и нажмем «Ввод», то браузер инициализирует соединение и передаст некоторую информацию. Что это за информация мы увидим чуть позже. В консоль мы выведем всю информацию, которую передаст нам браузер.

Теперь давайте разберемся, что же это за информация и как ее обрабатывать. В консоли мы видим, что к серверу подключились с ip-адреса 127.0.0.1:39494. А вот ниже уже идут строки данных, полученные от браузера. Разбираемся что это за информация. Согласно спецификации http , первой строкой в запросе идет так называемая стартовая строка и формат ее такой:

где:

- Метод — тип запроса, одно слово заглавными буквами. Список методов для версии 1.1 представлен в спецификации.

- URI определяет путь к запрашиваемому документу.

- Версия — пара разделённых точкой цифр. Например: 1.0.

Все 3 параметра разделены между собой одним пробелом.

Далее идет блок заголовков. Спецификация http регламентирует обязательно одну пустую строку после всех заголовков и перед началом тела самого сообщения.

Все заголовки разделяются на четыре основных группы:

- General Headers («Основные заголовки») — могут включаться в любое сообщение клиента и сервера

- Request Headers («Заголовки запроса») — используются только в запросах клиента;

- Response Headers («Заголовки ответа») — только для ответов от сервера;

- Entity Headers («Заголовки сущности») — сопровождают каждую сущность сообщения.

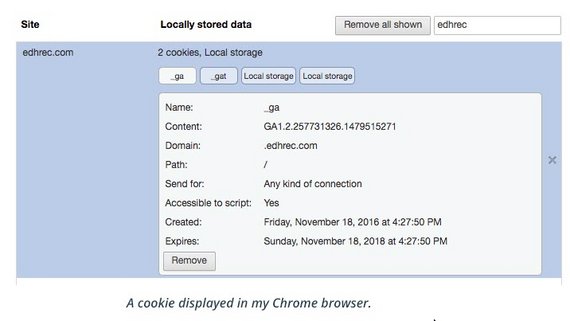

В стартовой строке мы видим, что браузер сообщает о методе GET (имена всех методов пишутся ПРОПИСНЫМИ БУКВАМИ). Обратился браузер к ресурсу по адресу / и версия HTTP = 1.1. Далее смотрим на общие заголовки. Название заголовка и его значение разделены символами «: «. Первым заголовком идет Host. Так как мы обращались к localhost, то здесь мы и видим наш адрес. Если когда-то ранее браузер уже обращался к ресурсу localhost (возможно запускали тестовый веб-сервер, на котором разрабатывали сайт) и сервер передал браузеру куки, то браузер передаст серверу уже имеющиеся куки, что мы и видим на скрине выше по наличию заголовка Cookie. Благодаря этому имеют место быть атаки на куки у пользователей. Так как в запросе мы больше ничего не передаем, то тело запроса осталось пустым. Чуть позже я покажу что будет, если передать нашему серверу файл или какие-то другие данные из формы в html странице.

После того, как сервер получил и обработал запрос от браузера, сервер должен отправить браузеру ответ. Ответ так же начинается со стартовой строки.

Стартовая строка ответа сервера имеет следующий формат:

HTTP/Версия КодСостояния Пояснение

где:

- Версия — пара разделённых точкой цифр, как в запросе;

- Код состояния (англ. Status Code) — три цифры. По коду состояния определяется дальнейшее содержимое сообщения и поведение клиента;

- Пояснение (англ. Reason Phrase) — текстовое короткое пояснение к коду ответа для пользователя. Никак не влияет на сообщение и является необязательным.

Я воспользуюсь таким соглашением. Например, стартовая строка ответа сервера на предыдущий запрос может выглядеть так:

После стартовой строки должны идти заголовки ответа. Но сейчас никаких заголовков я передавать не буду. Я лишь ограничусь только стартовой строкой, в которой указываю версию, код ответа (200) и пояснение (ОК). После этого я делаю одну пустую строку (она обязательна), иначе не будет работать. Ну а дальше уже я передаю простенькую html страницу (переменная answermsg). Если сделали все правильно, то вы увидите в браузере слово ok, выделенное жирным шрифтом и курсивом.

Но сейчас сервер получился не очень гибким. А точнее даже вообще не гибким. Если я захочу изменить страницу, то мне придется лезть в код и менять его. Поэтому сейчас я переделаю свой сервер так, чтобы я мог использовать конфигурационные файлы, в которых смогу указать пути, указать файлы и, может быть, что-нибудь еще.

Конфигурируемый сервер

Сейчас я покажу простой пример того, как можно сделать наш сервер конфигурируемым. Для этого я воспользуюсь модулем configparser. Для этого я создам простенький файл конфигурации:

Файл конфигаруции: conf/localhost.conf

[localhost]

Directory: ./sites

Первой строкой здесь будет являться хост, запрос для которого мы должны обработать. А во второй строке я указываю директорию, в которой лежит файл index.html.

Теперь код сервера выглядит так:

''' Конфигурируемый веб-сервер ''' import socket import select import configparser from pathlib import Path HOST = '' # Символическое имя. По умолчанию localhost PORT = 8080 # Указываем непривилированный порт if __name__ == '__main__': with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock: print('Socket created') # Связываем сокет с локальным хостом и портом sock.bind((HOST, PORT)) print('Привязка сокета') # Слушаем сокет sock.listen(10) print('Слушаем сокет') inputs = [sock] outputs = [sock] base_dir = Path(__file__).parent root_dir = base_dir.parent config = configparser.ConfigParser() config.read( root_dir.absolute() / Path('conf') / Path('localhost.conf') ) # Теперь можем общаться с клиентами while True: # Ждем подключения клиентов reads, writes, excepts = select.select(inputs, outputs, inputs) for conn in reads: _conn, client_addr = conn.accept() with _conn as client_conn: ip_addr, client_port = client_addr print(f'Подключение с {ip_addr}:{client_port}') data = client_conn.recv(1024) data = data.decode('utf-8') print(data) answer = '' data_list = data.split('rn') header_line, *other_lines = data_list headers = {} headers['method'], headers['uri'], headers['version'] = ( header_line.split() ) version = headers['version'] for header in other_lines: if header and ':' in header: header_name, header_value = map( lambda x: x.strip(), header.split(':', maxsplit=1) ) headers[header_name] = header_value if 'Host' in headers.keys(): host = headers['Host'] directory = Path(config.get( host.split(':')[0], 'Directory' )) status_code = 404 message = 'Not Found' answer_body = '' if headers['uri'] in ['/', '/index', '/index.html']: path = Path('index.html') else: path = Path().joinpath( *headers['uri'].split('/')[1:] ) file_path = base_dir / directory / path if file_path.exists(): status_code = 200 message = 'OK' answer_body = file_path.read_text() answer_headers = ( f'{version} {status_code} {message}nnn' ) answer = answer_headers + answer_body client_conn.send(bytes(answer, 'utf-8'))

Здесь я на всякий случай проверяю наличие заголовка Host в запросе. Если такой есть, то читаю к какому хосту направлен запрос. Далее я смотрю по какому uri идет обращение. Если uri обращен к главной странице сайта, то как правило uri будет равен «/», либо будет содержать ключевое слово /index[.html|.php]. Если обращение идет к главной странице сайта, то стоит проверить существование файла index[.html|.php] в корневой директории сайта. Если такой сайт есть, тогда надо отдать страницу. Если обращение идет к какой-то конкретной странице, тогда, если файл страницы существует, отдаем эту страницу. Если файлов страниц не существует, мы должны выдать ошибку с кодом 404 и пояснением «Not Found». Такой статус у меня сделан по-умолчанию.

В папку sites я положил два файла:

Теперь, если запустить сервер и сделать запрос к localhost, то увидим в браузере страницу с содержанием из файла index.html.

Если сделать запрос к localhost/test, то увидим страницу с содержанием из файла test.

Передача файлов и параметров

Теперь у нас есть сервер, который мы можем конфигурировать. В примере выше я не стал рассматривать вариант с несколькими конфигурационными файлами, как это сделано, например, в Apache2. Но здесь не сложно изменить код. Такой сервер уже можно назвать рабочим, но данный сервер пока еще не умеет работать с переданными в запросе параметрами.

Передеча параметров в GET запросе

Чтобы добавить параметры к GET запросу, нужно в конце URL-адреса поставить знак «?» и после него начинать задавать их по следующему правилу:

имя_параметра1=значение_параметра1&имя_параметра2=значение_параметра2&...

Разделителем между параметрами служит знак «&».

Если запустим текущий вариант сервера и обратиться по адресу localhost/test?te=15, то получим ошибку 404, так как файла с названием «test?te=15» не существует. Необходимо отделить название файла и параметры.

Я мог бы указать в коде и другой код ответа, но я придерживаюсь соглашения, чтобы любой браузер правильно понимал ответ.

Пара слов о шаблоне для кода 404. Как видно из примера, шаблон страницы ответа тоже нужно создавать.

Теперь у меня получился вот такой код:

#!-*-coding: utf8-*- ''' Конфигурируемый веб-сервер с параметрами ''' import socket import select import configparser from pathlib import Path HOST = '' # Символическое имя. По умолчанию localhost PORT = 8080 # Указываем непривилированный порт if __name__ == '__main__': with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock: print('Socket created') # Связываем сокет с локальным хостом и портом sock.bind((HOST, PORT)) print('Привязка сокета') # Слушаем сокет sock.listen(10) print('Слушаем сокет') inputs = [sock] outputs = [sock] base_dir = Path(__file__).parent root_dir = base_dir.parent config = configparser.ConfigParser() config.read( root_dir.absolute() / Path('conf') / Path('localhost.conf') ) # Теперь можем общаться с клиентами while True: # Ждем подключения клиентов reads, writes, excepts = select.select(inputs, outputs, inputs) for conn in reads: _conn, client_addr = conn.accept() with _conn as client_conn: ip_addr, client_port = client_addr print(f'Подключение с {ip_addr}:{client_port}') data = client_conn.recv(1024) data = data.decode('utf-8') print(data) answer = '' data_list = data.split('rn') header_line, *other_lines = data_list headers = {} headers['method'], headers['uri'], headers['version'] = ( header_line.split() ) version = headers['version'] for header in other_lines: if header and ':' in header: header_name, header_value = map( lambda x: x.strip(), header.split(':', maxsplit=1) ) headers[header_name] = header_value if 'Host' in headers.keys(): host = headers['Host'] directory = Path(config.get( host.split(':')[0], 'Directory' )) status_code = 404 message = 'Not Found' answer_body = '' if '?' in headers['uri']: uri_file, uri_params = headers['uri'].split('?') else: uri_file, uri_params = headers['uri'], '' if uri_file in ['/', '/index', '/index.html']: path = Path('index.html') else: path = Path().joinpath(*uri_file.split('/')[1:]) file_path = base_dir / directory / path if file_path.exists(): status_code = 200 message = 'OK' answer_body = file_path.read_text().format( data=uri_params.replace('&', 'n') ) answer_headers = ( f'{version} {status_code} {message}n{headers}nn' ) answer = answer_headers + answer_body client_conn.send(bytes(answer, 'utf-8'))

В папке sites у меня лежит файл test, в который я вставил вот такой код:

<html> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <title>Тестовая страница</title> </head> <body> {data} </body> </html>

Поэтому в коде сервера я указал answer_body.format(data=uri_params.replace("&", "n")).

Таким образом я лишь просто вывожу переданные параметры.

Теперь, если запустить сервер и обратиться по адресу localhost/test с передачей различных параметров в запросе, эти параметры с их значениями будут выведены на странице в браузере.

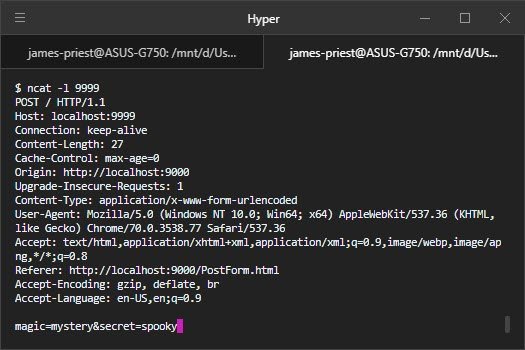

Передача параметров в POST запросе

Теперь осталось разобраться с тем, как происходит передача параметров в POST-запросе. Для этого в sites/index.html я создам форму, которая будет передавать POST-запрос к странице /test:

<html> <head> <meta charset="utf8"> <title>New page</title> </head> <body> <b> <i>Это новая страница сайта</i> </b> <p>Заполните форму ниже</p> <form method="post" action="test"> <input name="fullname"> <input name="email" type="email"> <button type="submit">Отправить</button> </form> </body> </html>

Сохраняем переданный файл

И вот здесь-то после нажатия на кнопку «Отправить» сервер у меня завершил процесс с ошибкой. Как оказалось, все дело в том, что параметры POST запроса передаются не в стартовой строке запроса, как в GET, а в теле сообщения запроса. Поэтому нужно переписать код так, чтобы обрабатывать текст сообщений запроса:

#!-*-coding: utf8-*- ''' Конфигурируемый веб-сервер с сохранением файлов ''' import socket import select import configparser from pathlib import Path HOST = '' # Символическое имя. По умолчанию localhost PORT = 8080 # Указываем непривилированный порт if __name__ == '__main__': with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock: print('Socket created') # Связываем сокет с локальным хостом и портом sock.bind((HOST, PORT)) print('Привязка сокета') # Слушаем сокет sock.listen(10) print('Слушаем сокет') inputs = [sock] outputs = [sock] base_dir = Path(__file__).parent root_dir = base_dir.parent config = configparser.ConfigParser() config.read( root_dir.absolute() / Path('conf') / Path('localhost.conf') ) # Теперь можем общаться с клиентами while True: # Ждем подключения клиентов reads, writes, excepts = select.select(inputs, outputs, inputs) for conn in reads: _conn, client_addr = conn.accept() with _conn as client_conn: ip_addr, client_port = client_addr print(f'Подключение с {ip_addr}:{client_port}') data = client_conn.recv(1024) data = data.decode('utf-8') print(data) answer = '' data_list = data.split('rn') header_line, *other_lines = data_list headers = {} headers['method'], headers['uri'], headers['version'] = ( header_line.split() ) version = headers['version'] msg_body = '' for header in other_lines: if header: if ':' in header: header_name, header_value = map( lambda x: x.strip(), header.split(':', maxsplit=1) ) headers[header_name] = header_value if ( header_name == 'Content-Type' and 'boundary=' in header_value ): boundary = ( header_value.split('boundary=')[1] ) boundary_data = data.split(boundary)[1:] for body_data in boundary_data: if 'filename' in body_data: data_file = ( body_data.split('rnrn')[1] ) filename = Path('test.txt') data_file_path = ( base_dir / Path('upload') / filename ) data_file_path.parent.mkdir( parents=True, exist_ok=True ) data_file_path.write_bytes( data_file ) else: msg_body += header + 'rn' if 'Host' in headers.keys(): host = headers['Host'] directory = Path(config.get(host, 'Directory')) status_code = 404 message = 'Not Found' answer_body = '' if '?' in headers['uri']: uri_file, uri_params = headers['uri'].split('?') else: uri_file, uri_params = headers['uri'], msg_body if uri_file in ['/', '/index', '/index.html']: path = Path('index.html') else: path = Path().joinpath(*uri_file.split('/')[1:]) file_path = base_dir / directory / path if file_path.exists(): status_code = 200 message = 'OK' answer_body = file_path.read_text().format( data=uri_params.replace('&', 'n') ) answer_headers = ( f'{version} {status_code} {message}n{headers}nn' ) answer = answer_headers + answer_body client_conn.send(bytes(answer, 'utf-8'))

Обратите внимание, что названия передаваемых параметров есть ни что иное, как значение атрибута name тега <input>. Если не указать значение атрибута name, то в запрос данное поле не будет передано. Поэтому считайте, что этот атрибут обязательный, хотя на самом деле в html атрибуты не являются обязательными.

Теперь все в порядке. Процесс не завершается с ошибкой после нажатия на кнопку «Отправить» на клиенте. Вместо этого браузер переходит на страницу test и показывает параметры, которые мы передали в запросе POST.

Но теперь я хочу передать на сервер файл. Первое, что приходит на ум — это использовать поле типа file в форме:

<html> <head> <meta charset="utf8"> <title>New page</title> </head> <body> <b> <i>Это новая страница сайта</i> </b> <p>Заполните форму ниже</p> <form method="post" action="test"> <input name="fullname"> <input name="email" type="email"> <input name="myfile" type="file"> <button type="submit">Отправить</button> </form> </body> </html>

Теперь на странице test мы увидим название файла. НО… Это ведь не сам файл, а лишь его наименование. Как сделать так, чтобы передать содержимое указанного файла??? Ответ на этот вопрос здесь. Перепишем код страницы:

<html> <head> <meta charset="utf8"> <title>New page</title> </head> <body> <b> <i>Это новая страница сайта</i> </b> <p>Заполните форму ниже</p> <form method="post" action="test" enctype="multipart/form-data"> <input name="fullname"> <input name="email" type="email"> <input name="myfile" type="file"> <button type="submit">Отправить</button> </form> </body> </html>

Теперь вроде все в порядке. Но после запуска первое с чем я сталкиваюсь — это с размером передаваемого файла. В коде циклически читается 1024 байт, но файл, который я передаю, занимает порядка 10 кБ. В коде не происходит склейки новой порции данных со старыми при чтении данных. Исправляю:

#!-*-coding: utf8-*- ''' Конфигурируемый веб-сервер с post-запросом ''' import socket import select import configparser from pathlib import Path HOST = '' # Символическое имя. По умолчанию localhost PORT = 8080 # Указываем непривилированный порт if __name__ == "__main__": with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock: print('Socket created') # Связываем сокет с локальным хостом и портом sock.bind((HOST, PORT)) print('Привязка сокета') # Слушаем сокет sock.listen(10) print('Слушаем сокет') inputs = [sock] outputs = [sock] base_dir = Path(__file__).parent root_dir = base_dir.parent config = configparser.ConfigParser() config.read( root_dir.absolute() / Path('conf') / Path('localhost.conf') ) # Теперь можем общаться с клиентами while True: # Ждем подключения клиентов reads, writes, excepts = select.select(inputs, outputs, inputs) for conn in reads: _conn, client_addr = conn.accept() with _conn as client_conn: ip_addr, client_port = client_addr print(f'Подключение с {ip_addr}:{client_port}') data = client_conn.recv(1024) data = data.decode('utf-8') print(data) answer = '' data_list = data.split("rn") header_line, *other_lines = data_list headers = {} headers["method"], headers["uri"], headers["version"] = ( header_line.split() ) version = headers['version'] msg_body = "" for header in other_lines: if header: if ":" in header: header_name, header_value = map( lambda x: x.strip(), header.split(':', maxsplit=1) ) headers[header_name] = header_value else: msg_body += header + "rn" if "Host" in headers.keys(): host = headers["Host"] directory = Path(config.get(host, "Directory")) status_code = 404 message = "Not Found" answer_body = "" if "?" in headers["uri"]: uri_file, uri_params = headers["uri"].split("?") else: uri_file, uri_params = headers["uri"], msg_body if uri_file in ["/", "/index", "/index.html"]: path = Path('index.html') else: path = Path().joinpath(*uri_file.split("/")[1:]) file_path = base_dir / directory / path if file_path.exists(): status_code = 200 message = "OK" answer_body = file_path.read_text().format( data=uri_params.replace('&', 'n') ) answer_headers = ( f"{version} {status_code} {message}n{headers}nn" ) answer = answer_headers + answer_body client_conn.send(bytes(answer, 'utf-8'))

Теперь можно увидеть, что после добавления атрибута enctype=»multipart/form-data» содержимое запроса изменилось и можно увидеть передаваемые байты файла с его названием.

Теперь в заголовке Content-Type помимо типа еще есть параметр boundary, который переводится как «граница». Эта граница между параметрами в теле сообщений. С помощью значения этого параметра я буду разделять передаваемые параметры и их значения. Я не стал усложнять код, поэтому у меня получился вот такой результат:

#!-*-coding: utf8-*- ''' Конфигурируемый веб-сервер с post-запросом ''' import socket import select import configparser from pathlib import Path HOST = '' # Символическое имя. По умолчанию localhost PORT = 8080 # Указываем непривилированный порт if __name__ == "__main__": with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock: print('Socket created') # Связываем сокет с локальным хостом и портом sock.bind((HOST, PORT)) print('Привязка сокета') # Слушаем сокет sock.listen(10) print('Слушаем сокет') inputs = [sock] outputs = [sock] base_dir = Path(__file__).parent root_dir = base_dir.parent config = configparser.ConfigParser() config.read( root_dir.absolute() / Path('conf') / Path('localhost.conf') ) # Теперь можем общаться с клиентами while True: # Ждем подключения клиентов reads, writes, excepts = select.select(inputs, outputs, inputs) for conn in reads: _conn, client_addr = conn.accept() with _conn as client_conn: ip_addr, client_port = client_addr print(f'Подключение с {ip_addr}:{client_port}') data = client_conn.recv(1024) data = data.decode('utf-8') print(data) answer = '' data_list = data.split("rn") header_line, *other_lines = data_list headers = {} headers["method"], headers["uri"], headers["version"] = ( header_line.split() ) version = headers['version'] msg_body = "" for header in other_lines: if header: if ":" in header: header_name, header_value = map( lambda x: x.strip(), header.split(':', maxsplit=1) ) headers[header_name] = header_value else: msg_body += header + "rn" if "Host" in headers.keys(): host = headers["Host"] directory = Path(config.get(host, "Directory")) status_code = 404 message = "Not Found" answer_body = "" if "?" in headers["uri"]: uri_file, uri_params = headers["uri"].split("?") else: uri_file, uri_params = headers["uri"], msg_body if uri_file in ["/", "/index", "/index.html"]: path = Path('index.html') else: path = Path().joinpath(*uri_file.split("/")[1:]) file_path = base_dir / directory / path if file_path.exists(): status_code = 200 message = "OK" answer_body = file_path.read_text().format( data=uri_params.replace('&', 'n') ) answer_headers = ( f"{version} {status_code} {message}n{headers}nn" ) answer = answer_headers + answer_body client_conn.send(bytes(answer, 'utf-8'))

После запуска сервера и передачи текстового файла в папке со скриптом сервера у меня появился файл test.txt с содержимым передаваемого файла. Думаю теперь многим станет ясно, что очень важно правильно прочитать и обработать входящие данные от браузера.

Я не буду здесь рассматривать способ скачивания файлов с сервера и его методы докачки. Об этом можно прочитать тут.

WSGI

Но сервер еще до сих пор не является гибким и если нужно что-то добавить на сайт, то скорее всего придется переделывать код самого сервера. Чтобы избежать этого существует стандарт WSGI.

WSGI — стандарт обмена данными между веб-сервером (backend) и веб-приложением (frontend). Под это определение попадают многие вещи, тот же самый CGI. Так что поясню.

- Во-первых, WSGI — Python-специфичный стандарт, его описывают PEP 333 и PEP 3333.

- Во-вторых, он уже принят (статус Final).

По стандарту, WSGI-приложение должно удовлетворять следующим требованиям:

- должно быть вызываемым (callable) объектом (обычно это функция или метод)

- принимать два параметра:

- словарь переменных окружения (environ)[2]

- обработчик запроса (start_response)[3]

- вызывать обработчик запроса с кодом HTTP-ответа и HTTP-заголовками

- возвращать итерируемый объект с телом ответа

Значит сейчас я создам простенькое приложение, которое будет удовлетворять всем выше изложенным требованиям. У меня оно выглядит так:

def start_response(status_message, list_of_headers): print(status_message) print(list_of_headers) def simplest_wsgi_app(environ, start_response): start_response('200 OK', [('Content-Type', 'text/plain')]) yield 'Hello, world!'

В данном случае я создал функцию-приложение с названием simplest_wsgi_app и обработчик запроса start_response. Как видно из кода я ничего не обрабатываю в обработчике запроса, так как это лишь тестовый пример, чтобы показать как работает WSGI. Теперь это приложение нужно импортировать в сервер и при запросе от клиента выполнить данное приложение.

У меня получился вот такой код сервера с WSGI:

#!-*-coding: utf8-*- ''' Простой веб-сервер с wsgi ''' import socket import select from wsgi.application import simplest_wsgi_app, start_response HOST = '' # Символическое имя. По умолчанию localhost PORT = 8080 # Указываем непривилированный порт if __name__ == "__main__": with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock: print('Socket created') # Связываем сокет с локальным хостом и портом sock.bind((HOST, PORT)) print('Привязка сокета') # Слушаем сокет sock.listen(10) print('Слушаем сокет') # Теперь можем общаться с клиентами while True: # Ждем подключения клиентов conn, addr = sock.accept() print('Подключение с ' + addr[0] + ':' + str(addr[1])) ready, _, _ = select.select([conn], [], [], 1) if ready: data = conn.recv(1024) print(data) while True: ready, _, _ = select.select([conn], [], [], 2) if ready: data += conn.recv(1024) else: break print(data) data_list = data.split("rn") headers = {} headers["method"], headers["uri"], headers["version"] = ( data_list[0].split() ) version = headers["version"] msg_body = "" for header in data_list[1:]: if header != "": if ": " in header: header_name, header_value = header.split(": ") headers[header_name] = header_value if ( header_name == "Content-Type" and "boundary=" in header_value ): boundary = header_value.split("boundary=")[1] boundary_data = data.split(boundary)[1:] for body_data in boundary_data: if "filename" in body_data: data_file = ( body_data.split("rnrn")[1] ) filename = "test.txt" with open(filename, "wb") as in_file: in_file.write(data_file) else: msg_body += header + "rn" if "Host" in headers.keys(): status_code = 404 message = "Not Found" answer_body = "" env = {"host": "localhost"} for ans in simplest_wsgi_app(env, start_response): answer_body += ans answer_headers = ( f"{version} {status_code} {message}n{headers}nn" ) answer = answer_headers + answer_body conn.send(answer) conn.close() else: conn.close()

Я вызываю созданное приложение и полученное значение сохраняю в тело ответа сервера. Полученный ответ ниже отдается браузеру.

Заставляем Python выполнить код на PHP

А для тех, кто все же хочет на своем сервере запускать скрипты php отвечу, что да, такое возможно. Решение взято отсюда.

У меня получился вот такой код:

#!-*-coding: utf8-*- ''' Простой веб-сервер с запуском php-кода ''' import socket import select import configparser import os from pathlib import Path HOST = '' # Символическое имя. По умолчанию localhost PORT = 8080 # Указываем непривилированный порт if __name__ == "__main__": with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as sock: print('Socket created') # Связываем сокет с локальным хостом и портом sock.bind((HOST, PORT)) print('Привязка сокета') # Слушаем сокет sock.listen(10) print('Слушаем сокет') inputs = [sock] outputs = [sock] base_dir = Path(__file__).parent root_dir = base_dir.parent config = configparser.ConfigParser() config.read( root_dir.absolute() / Path('conf') / Path('localhost.conf') ) # Теперь можем общаться с клиентами while True: # Ждем подключения клиентов conn, addr = sock.accept() print('Подключение с ' + addr[0] + ':' + str(addr[1])) ready, _, _ = select.select([conn], [], [], 1) if ready: data = conn.recv(1024) print(data) while True: ready, _, _ = select.select([conn], [], [], 2) if ready: data += conn.recv(1024) else: break print(data) data_list = data.split("rn") headers = {} headers["method"], headers["uri"], headers["version"] = ( data_list[0].split() ) version = headers['version'] msg_body = "" for header in data_list[1:]: if header != "": if ": " in header: header_name, header_value = header.split(": ") headers[header_name] = header_value if ( header_name == "Content-Type" and "boundary=" in header_value ): boundary = header_value.split("boundary=")[1] boundary_data = data.split(boundary)[1:] for body_data in boundary_data: if "filename" in body_data: data_file = ( body_data.split("rnrn")[1] ) filename = "test.txt" with open(filename, "wb") as in_file: in_file.write(data_file) else: msg_body += header + "rn" if "Host" in headers.keys(): host = headers["Host"] directory = Path(config.get( host, "Directory" )) status_code = 404 message = "Not Found" answer_body = "" if "?" in headers["uri"]: uri_file, uri_params = headers["uri"].split("?") else: uri_file, uri_params = headers["uri"], msg_body if uri_file in ["/", "/index", "/index.html"]: path = Path('index.html') else: path = os.path.join(*uri_file.split("/")[1:]) file_path = base_dir / directory / path if file_path.exists(): status_code = 200 message = "OK" if not file_path.endswith(".php"): answer_body = file_path.read_text().format( data=uri_params.replace("&", "n") ) else: answer_body = os.popen(f'php {file_path}').read() answer_headers = ( f"{version} {status_code} {message}n{headers}nn" ) answer = answer_headers + answer_body conn.send(answer) conn.close() else: conn.close()

Если сейчас обратиться по адресу localhost/test.php, то будет выполнен скрипт test.php. У меня test.php выведет информацию о php:

ИТОГИ

Теперь я надеюсь всем стало ясно следующее:

- Когда мы в браузере печатаем адрес ресурса, тогда веб-браузер, будучи программой, соединяется с сервером и передает ему некоторые сведения: стартовую строку, заголовки и тело сообщения. Эту всю информацию веб сервер парсит, анализирует и выдает клиенту результат обработки запроса.

- Передача параметров для GET и POST запросов отличается.

- Передача файлов от клиента на сервер и от сервера на клиент тоже имеет свои нюансы. Можно организовывать «докачку» файла.

- Можно создавать на питоне свое собственное приложение и это приложение будет вызываться при каждом обращении к веб-серверу. Эту возможность нам дает стандарт WSGI. Есть еще и CGI.

- В свою очередь браузер должен правильно составить тело сообщения, стартовую строку и блок заголовков. Но в данной статье процесс работы браузера я не рассматривал.

- При формировании ответа мы можем использовать шаблоны страниц, заменяя в них определенные теги. Именно так сделано в Django. Подстановочные теги в ходе обработки заменяются на необходимую информацию.

- Страницы для ответов с любым кодом состояния, будь то 404 или 500, необходимо создавать. Именно благодаря этому в Django мы можем создавать свою страницу, указывая серверу, какой шаблон использовать для ответа.

Ссылка на проект

Table of Contents

Python remains one of the best programming languages to learn in 2022, with applications in back-end web development, machine learning, scientific modelling, system operations, and several enterprise-specific software. It is generally considered one of the more approachable programming languages, with dynamically typed, English-like syntax and many libraries.

That accessibility extends to creating a Python web server, which you can do in only a few lines of code. Like our other Python tutorials, you’ll find that some of the most fundamental operations are carried out in a matter of minutes.

We’ll show you how to create your own Python web server for local testing. The whole process takes only a few minutes and a few lines of code.

But first, let’s go over what a web server is.

What is a Web Server? [Definition]

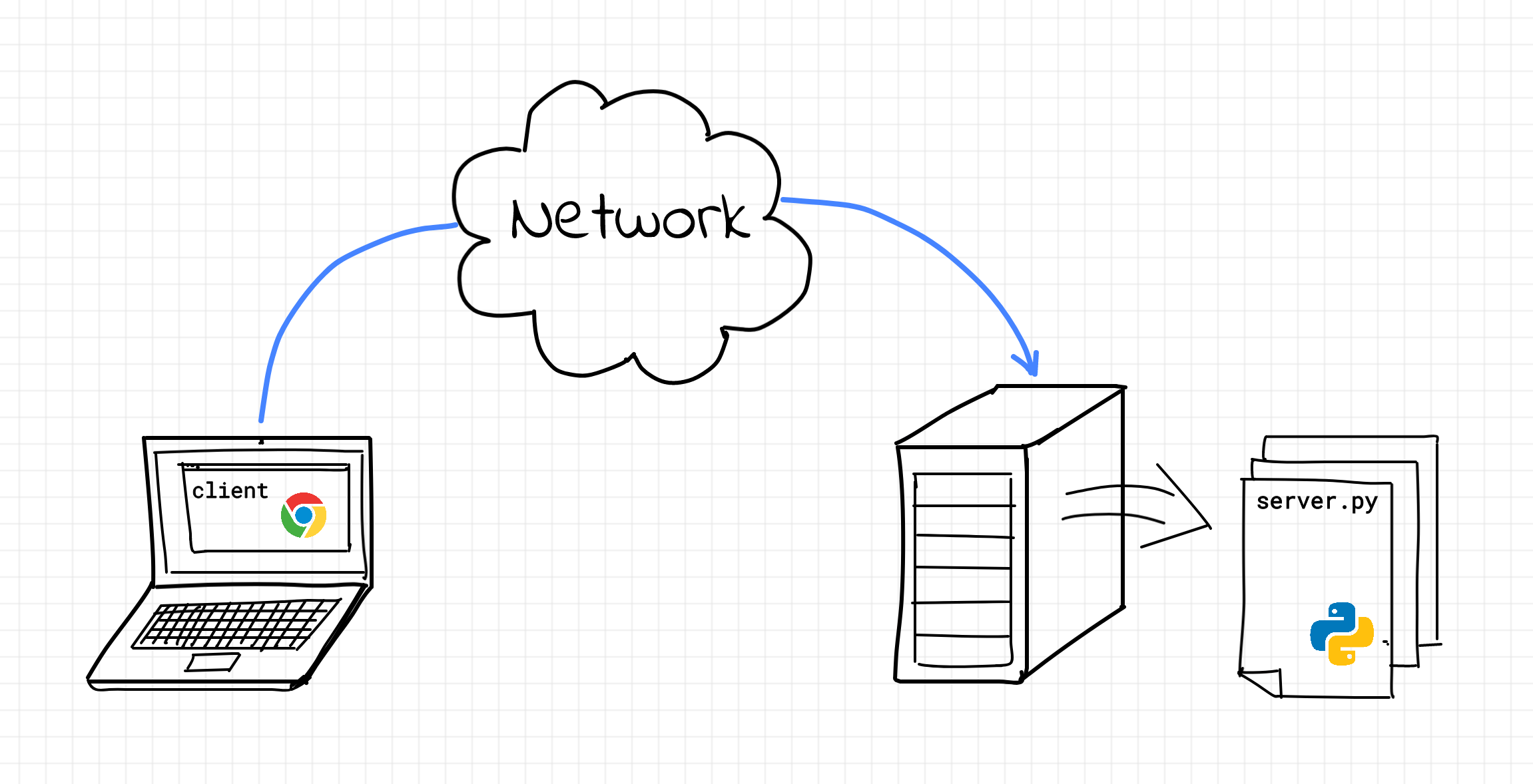

In the infrastructure of the internet, the server is one part of the client-server model. When a client browser visits a web page, it makes an HTTP request to the server containing the files needed to operate a website. The server listens to the client’s request, processes it, and responds with the required files to present the web page. This content could be HTML (the text and media you see on a website) and JSON (applications).

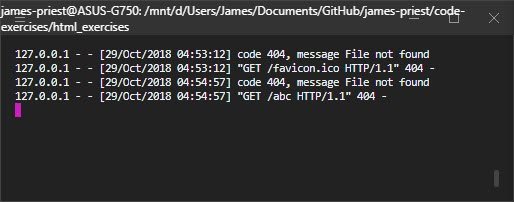

You might have encountered a few server error codes in your time browsing the internet — “file not found” or 404 being a more popular one. In these cases, the server has trouble accessing certain files. With a 404 error, the particular file is missing.

There are more nuances to web servers, including classification into static and dynamic web servers. For example, static web servers only return files as they are, with no extra processing. Dynamic web servers introduce databases and application servers, which you can proceed to once you’ve got the hang of static servers.

Having said all that, we should get into how you create a web server. We’ll assume you’re running the latest version of Python. There are resources for you to learn how to run a python script, among other useful lessons.

How Do You Create a Simple Python Web Server?

Launching a Python web server is quick and straightforward, and it’ll only take a few minutes for you to get up and to run. All it takes is one line of code to get the simplest of local servers running on your computer.

By local testing, your system becomes the server to the client that is your browser, and the files are stored locally on your system. The module you’ll be using to create a web server is Python’s http server. There is one caveat to this: it can only be used as a static file server. You’ll need a Python web framework, like Django, to run dynamic web servers.

Let’s get to the code, which looks like this follows:

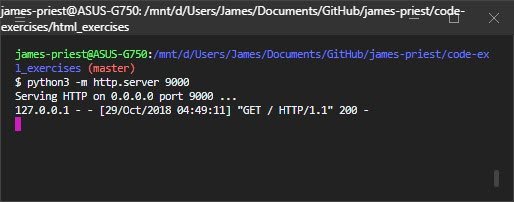

python -m http.server

Type this into the terminal or command prompt, depending on your system, and you should see a “server started” message and a “server stopped” when you close the server.

And there you have it — your first Python webserver! Admittedly, it’s a simple one, doing nothing more than opening up a web server on your system’s default port of 8000. The port can also be changed by specifying the port number at the end of the line, like this:

python -m http.server 8080

A simple web server like the one you’ve just created is all well and good. It’s far more interesting and educational, however, to create a custom web server. After all, the best way to learn python is through a hands-on approach — code, debug, fix, rinse and repeat.

Recommend Python Course

Complete Python Bootcamp From Zero to Hero in Python

Creating a Custom Web Server Using Python

A custom web server allows you to do more than a built-in web server. The code you’re about to see will teach you a lot about some important functions and processes. Don’t be put off by the length of the code — there are only a handful of key concepts at play here. You don’t have to manually type all of this out to test it yourself — but note the significance of those concepts.

from http.server import HTTPServer, BaseHTTPRequestHandler #Python’s built-in library

import time

hostName = "localhost"

serverPort = 8080 #You can choose any available port; by default, it is 8000

Class MyServer(BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

def do_GET(self): //the do_GET method is inherited from BaseHTTPRequestHandler

self.send_response(200)

self.send_header("Content-type", "text/html")

self.end_headers()

self.wfile.write(bytes("<html><head><title>https://testserver.com</title></head>", "utf-8"))

self.wfile.write(bytes("<p>Request: %s</p>" % self.path, "utf-8"))

self.wfile.write(bytes("<body>", "utf-8"))

self.wfile.write(bytes("<p>This is an example web server.</p>", "utf-8"))

self.wfile.write(bytes("</body></html>", "utf-8"))

if __name__ == "__main__":

webServer = HTTPServer((hostName, serverPort), MyServer)

print("Server started http://%s:%s" % (hostName, serverPort)) #Server starts

try:

webServer.serve_forever()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

pass

webServer.server_close() #Executes when you hit a keyboard interrupt, closing the server

print("Server stopped.")

Before we jump into the critical parts, let’s quickly go over a few things. If you’ve done your HTML homework, then you’ll see some familiar terms in the code. The class MyServer writes to the output stream (wfile) that’s sent as a response to the client using “self.wfile.write()”. What we’re doing here is writing an elementary HTML page on the fly.

We’ll address some of the more important executions going on here, namely:

- The module http.server

- The classes HTTPServer and BaseHTTPRequestHandler, derived from the library http.server

- The do_GET method

The HTTP server is a standard module in the Python library that has the classes used in client-server communication. Those two classes are HTTPServer and BaseHTTPRequestHandler. The latter accesses the server through the former. HTTPServer stores the server address as instance variables, while BaseHTTPRequestHandler calls methods to handle the requests.

To sum up, the code starts at the main function. Next, the class MyServer is called, and the BaseHTTPRequestHandler calls the do_GET() method to meet requests. When you interrupt the program, the server closes.

If you did this correctly, you should see messages like this:

Why would you want to use a custom web server? It lets you use more methods, like do_HEAD() and do_POST(), offering additional functionality. In any case, you can see that creating a custom web server is also fairly straightforward.

Conclusion

It doesn’t take much to get your web server going using Python. It’s the fundamental idea that you should absorb. Creating your server is a small but significant step forward on your path to creating full-stack applications.

Try the code yourself, and perhaps even search for Python projects incorporating server implementation. There are many projects available that make use of this concept, so it’s good to know how to implement it in a larger context.

If you’re looking for more such lessons, head over to our Python tutorials page, there’s a lot of information on everything from the best resources to lessons that focus on a specific concept.

And if you’re looking to build your own website, we found some great discounts on NameCheap for domain names and web hosting.

People are also reading:

- Best Python Books

- Best Python Compilers

- Best Python Interpreters

- Best way to learn python

- Python Conditional Statements

- What is PyCharm?

- Python for Data Science

- Python vs PHP

- Python vs Java

Table of Contents

Python remains one of the best programming languages to learn in 2022, with applications in back-end web development, machine learning, scientific modelling, system operations, and several enterprise-specific software. It is generally considered one of the more approachable programming languages, with dynamically typed, English-like syntax and many libraries.

That accessibility extends to creating a Python web server, which you can do in only a few lines of code. Like our other Python tutorials, you’ll find that some of the most fundamental operations are carried out in a matter of minutes.

We’ll show you how to create your own Python web server for local testing. The whole process takes only a few minutes and a few lines of code.

But first, let’s go over what a web server is.

What is a Web Server? [Definition]

In the infrastructure of the internet, the server is one part of the client-server model. When a client browser visits a web page, it makes an HTTP request to the server containing the files needed to operate a website. The server listens to the client’s request, processes it, and responds with the required files to present the web page. This content could be HTML (the text and media you see on a website) and JSON (applications).

You might have encountered a few server error codes in your time browsing the internet — “file not found” or 404 being a more popular one. In these cases, the server has trouble accessing certain files. With a 404 error, the particular file is missing.

There are more nuances to web servers, including classification into static and dynamic web servers. For example, static web servers only return files as they are, with no extra processing. Dynamic web servers introduce databases and application servers, which you can proceed to once you’ve got the hang of static servers.

Having said all that, we should get into how you create a web server. We’ll assume you’re running the latest version of Python. There are resources for you to learn how to run a python script, among other useful lessons.

How Do You Create a Simple Python Web Server?

Launching a Python web server is quick and straightforward, and it’ll only take a few minutes for you to get up and to run. All it takes is one line of code to get the simplest of local servers running on your computer.

By local testing, your system becomes the server to the client that is your browser, and the files are stored locally on your system. The module you’ll be using to create a web server is Python’s http server. There is one caveat to this: it can only be used as a static file server. You’ll need a Python web framework, like Django, to run dynamic web servers.

Let’s get to the code, which looks like this follows:

python -m http.server

Type this into the terminal or command prompt, depending on your system, and you should see a “server started” message and a “server stopped” when you close the server.

And there you have it — your first Python webserver! Admittedly, it’s a simple one, doing nothing more than opening up a web server on your system’s default port of 8000. The port can also be changed by specifying the port number at the end of the line, like this:

python -m http.server 8080

A simple web server like the one you’ve just created is all well and good. It’s far more interesting and educational, however, to create a custom web server. After all, the best way to learn python is through a hands-on approach — code, debug, fix, rinse and repeat.

Recommend Python Course

Complete Python Bootcamp From Zero to Hero in Python

Creating a Custom Web Server Using Python

A custom web server allows you to do more than a built-in web server. The code you’re about to see will teach you a lot about some important functions and processes. Don’t be put off by the length of the code — there are only a handful of key concepts at play here. You don’t have to manually type all of this out to test it yourself — but note the significance of those concepts.

from http.server import HTTPServer, BaseHTTPRequestHandler #Python’s built-in library

import time

hostName = "localhost"

serverPort = 8080 #You can choose any available port; by default, it is 8000

Class MyServer(BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

def do_GET(self): //the do_GET method is inherited from BaseHTTPRequestHandler

self.send_response(200)

self.send_header("Content-type", "text/html")

self.end_headers()

self.wfile.write(bytes("<html><head><title>https://testserver.com</title></head>", "utf-8"))

self.wfile.write(bytes("<p>Request: %s</p>" % self.path, "utf-8"))

self.wfile.write(bytes("<body>", "utf-8"))

self.wfile.write(bytes("<p>This is an example web server.</p>", "utf-8"))

self.wfile.write(bytes("</body></html>", "utf-8"))

if __name__ == "__main__":

webServer = HTTPServer((hostName, serverPort), MyServer)

print("Server started http://%s:%s" % (hostName, serverPort)) #Server starts

try:

webServer.serve_forever()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

pass

webServer.server_close() #Executes when you hit a keyboard interrupt, closing the server

print("Server stopped.")

Before we jump into the critical parts, let’s quickly go over a few things. If you’ve done your HTML homework, then you’ll see some familiar terms in the code. The class MyServer writes to the output stream (wfile) that’s sent as a response to the client using “self.wfile.write()”. What we’re doing here is writing an elementary HTML page on the fly.

We’ll address some of the more important executions going on here, namely:

- The module http.server

- The classes HTTPServer and BaseHTTPRequestHandler, derived from the library http.server

- The do_GET method

The HTTP server is a standard module in the Python library that has the classes used in client-server communication. Those two classes are HTTPServer and BaseHTTPRequestHandler. The latter accesses the server through the former. HTTPServer stores the server address as instance variables, while BaseHTTPRequestHandler calls methods to handle the requests.

To sum up, the code starts at the main function. Next, the class MyServer is called, and the BaseHTTPRequestHandler calls the do_GET() method to meet requests. When you interrupt the program, the server closes.

If you did this correctly, you should see messages like this:

Why would you want to use a custom web server? It lets you use more methods, like do_HEAD() and do_POST(), offering additional functionality. In any case, you can see that creating a custom web server is also fairly straightforward.

Conclusion

It doesn’t take much to get your web server going using Python. It’s the fundamental idea that you should absorb. Creating your server is a small but significant step forward on your path to creating full-stack applications.

Try the code yourself, and perhaps even search for Python projects incorporating server implementation. There are many projects available that make use of this concept, so it’s good to know how to implement it in a larger context.

If you’re looking for more such lessons, head over to our Python tutorials page, there’s a lot of information on everything from the best resources to lessons that focus on a specific concept.

And if you’re looking to build your own website, we found some great discounts on NameCheap for domain names and web hosting.

People are also reading:

- Best Python Books

- Best Python Compilers

- Best Python Interpreters

- Best way to learn python

- Python Conditional Statements

- What is PyCharm?

- Python for Data Science

- Python vs PHP

- Python vs Java

Человек — это звучит гордо, а выглядит отвратительно (Куклы).

Черт возьми, вы взаимодействуете с одним прямо сейчас!

Независимо от того, какой вы разработчик программного обеспечения, в какой-то момент вашей карьеры вам придется взаимодействовать с веб-серверами. Может быть, вы создаете сервер API для бэкэнда. Или, может быть, вы просто настраиваете веб-сервер для своего сайта.

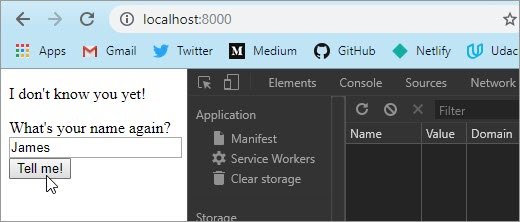

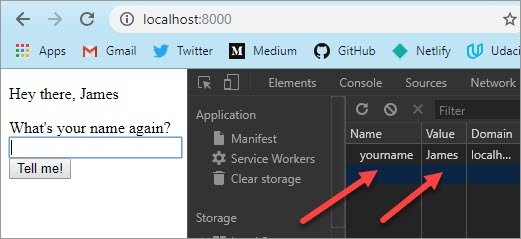

В этой статье мы расскажем, как создать самый простой http веб-сервер на Python.

Но поскольку мы хотим убедиться, что вы понимаете, что мы создаем, мы сначала дадим обзор о том, что такое веб-серверы и как они работают.

Если вы уже знаете, как работают веб-серверы, вы можете сразу перейти к этому разделу.

- Что такое HTTP-сервер?

- Адрес сокета TCP

- Создайте простой файл HTTP

- Создать HTTP веб-сервер

Что такое HTTP-сервер?

Веб-сервер HTTP — это не что иное, как процесс, который выполняется на вашем компьютере и выполняет ровно две вещи:

1- Прослушивает входящие HTTP-запросы на определенный адрес сокета TCP (IP-адрес и номер порта, о которых мы расскажем позже)

2- Обрабатывает этот запрос и отправляет ответ обратно пользователю.

Но что на самом деле происходит под капотом?

На самом деле много чего происходит, и мы могли бы посвятить целую статью, чтобы объяснить магию, как это произошло.

Но для простоты мы отвлечемся от некоторых деталей и расскажем об этом на очень высоком уровне.

На высоком уровне, когда вы набираете www.yandex.ru в своем браузере, ваш браузер создаст сетевое сообщение, называемое HTTP-запросом.

Этот запрос будет распространяться на компьютер yandex, на котором работает веб-сервер. Этот веб-сервер перехватит ваш запрос и обработает его, отвечая HTML-кодом домашней страницы yandex.

Наконец, ваш браузер отображает этот HTML на экране, и это то, что вы видите на своем экране.

Каждое взаимодействие с домашней страницей yandex после этого (например, когда вы нажимаете на ссылку) инициирует новый запрос и ответ точно так же, как первый.

Повторим еще раз: на машине, которая получает запрос http, работает программный процесс, называемый веб-сервером. Этот веб-сервер отвечает за перехват этих запросов и их обработку соответствующим образом.

Хорошо, теперь, когда вы знаете, что такое веб-сервер и какова его функция, вам может быть интересно, как запрос в первую очередь достигает машины yandex?

Хороший вопрос!

Позвольте нам объяснить, как, но опять же … на высоком уровне.

Адрес сокета TCP

Любое http-сообщение (будь то запрос или ответ) должно знать, как добраться до места назначения.

Чтобы достичь места назначения, каждое http-сообщение содержит адрес, называемый адресом TCP назначения.

И каждый TCP-адрес состоит из IP-адреса и номера порта.

Мы знаем, что все эти аббревиатуры (TCP, IP и т. д.) могут быть ошеломляющими, если ваши сетевые знания не сильны.

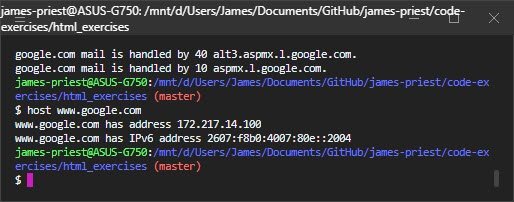

Так где же этот адрес, когда все, что вы сделали, и набрали www.yandex.ru в вашем браузере?

Ну, это доменное имя преобразуется в IP-адрес через большую распределенную базу данных, называемую DNS.

Хотите проверить, что это за IP-адрес?

Легко! Зайдите в свой терминал и сделайте следующее:

$ host yandex.ru Yandex.ru has address 77.88.55.66 Yandex.ru has address 5.255.255.70 Yandex.ru has address 77.88.55.70 Yandex.ru has address 5.255.255.60 Yandex.ru has IPv6 address 2a02:6b8:a::a Yandex.ru mail is handled by 10 mx.Yandex.ru.

Как видите, как DNS переведет yandex.ru на любой из указанных выше адресов.

Один только IP-адрес позволит HTTP-сообщению поступить на нужный компьютер, но вам все равно нужен номер порта, чтобы HTTP-запрос поступил именно на веб-сервер.

Другими словами, веб-сервер — это обычное сетевое приложение, которое прослушивает определенный порт.

И HTTP-запрос ДОЛЖЕН быть адресован этому порту.

Так где же номер порта при вводе www.yandex.ru ?

По умолчанию номер порта равен 80 для http и 443 для https, поэтому даже если вы не указали номер порта явно, он все еще там.

И если веб-сервер прослушивает номер порта не по умолчанию (ни 80, ни 443), вы должны явно указать номер порта следующим образом:

www.yandex.ru:445

К настоящему времени у вас должна быть вся необходимая информация для создания http-сервера на Python.

Так что без дальнейших церемоний, давайте начнем.

Создайте простой файл HTML

Вот что мы хотим сделать.

Мы хотим создать простой http-сервер, который обслуживает статическую HTML-страницу.

Давайте создадим нашу HTML-страницу.

<html>

<head>

<title>Python-это потрясающе!</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>yandex</h1>

<p>Поздравляю! Сервер HTTP работает!</p>

</body>

</html>

Теперь сохраните этот файл как index.html.

Теперь, для обслуживания веб-страницы, следующим шагом является создание веб-сервера, который будет обслуживать эту HTML-страницу.

Создать HTTP веб-сервер

Чтобы создать веб-сервер в Python 3, вам нужно импортировать два модуля: http.server и socketserver

Обратите внимание, что в Python 2 был модуль с именем SimpleHTTPServer. Этот модуль был объединен с http.server в Python 3

Давайте посмотрим на код для создания http-сервера

import http.server

import socketserver

PORT = 8080

Handler = http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandler

with socketserver.TCPServer(("", PORT), Handler) as httpd:

print("serving at port", PORT)

httpd.serve_forever()

Просто так у нас есть функциональный http-сервер.

Теперь давайте разберем этот код построчно.

Во-первых, как мы упоминали ранее, веб-сервер — это процесс, который прослушивает входящие запросы на определенный TCP-адрес.

И, как вы уже знаете, TCP-адрес идентифицируется по IP-адресу и номеру порта.

Во-вторых, веб-сервер также должен знать, как обрабатывать входящие запросы.

Эти входящие запросы обрабатываются специальными обработчиками. Вы можете думать о веб-сервере как о диспетчере, поступает запрос, http-сервер проверяет запрос и отправляет его назначенному обработчику.

Конечно, эти обработчики могут делать все что угодно.

Но что вы думаете, какой самый основной обработчик?

Ну, это будет обработчик, который просто обслуживает статический файл.

Другими словами, когда мы заходим на yandex.ru, веб-сервер на другом конце отправляет обратно статический HTML-файл.

Это на самом деле то, что мы пытаемся сделать.

И это, и есть то, что является http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandler : простой обработчик HTTP-запросов, который обслуживает файлы из текущего каталога и любых его подкаталогов.

Класс socketserver.TCPServer

Теперь поговорим о классе socketserver.TCPServer.

Экземпляр TCPServer описывает сервер, который использует протокол TCP для отправки и получения сообщений (http — это протокол прикладного уровня поверх TCP).

Чтобы создать экземпляр TCP-сервера, нам нужны две вещи:

- TCP-адрес (IP-адрес и номер порта)

- Обработчик

socketserver.TCPServer(("", PORT), Handler)

Как видите, TCP-адрес передается в виде кортежа (IP-адрес, номер порта)

Передача пустой строки в качестве IP-адреса означает, что сервер будет прослушивать любой сетевой интерфейс (все доступные IP-адреса).

А поскольку PORT хранит значение 8080, сервер будет прослушивать входящие запросы на этот порт.

Для обработчика мы передаем простой обработчик, о котором мы говорили ранее.

Handler = http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandler

Ну, а как насчет serve_forever?

serve_forever — это метод в экземпляре TCPServer, который запускает сервер и начинает прослушивать и отвечать на входящие запросы.

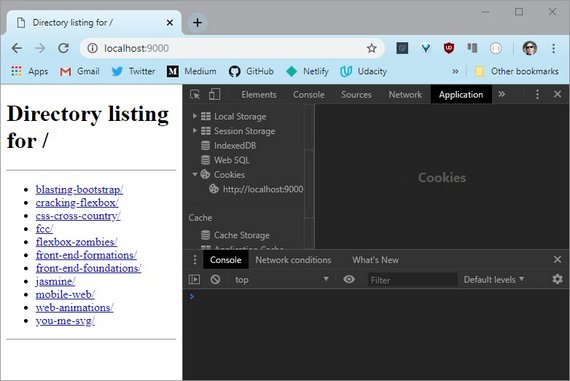

Круто, давайте сохраним этот файл как server.py в том же каталоге, что и index.html, потому что по умолчанию SimpleHTTPRequestHandler будет искать файл с именем index.html в текущем каталоге.

В этом каталоге запустите веб-сервер:

$ python server.py serving at port 8080

Благодаря этому теперь у вас есть HTTP-сервер, который прослушивает любой интерфейс на порте 8080 и ожидает входящие HTTP-запросы.

Пришло время для забавных вещей!

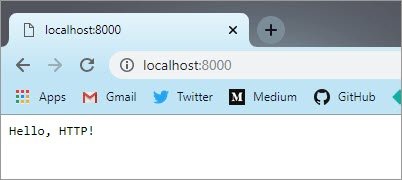

Откройте браузер и введите localhost:8080 в адресной строке.

Потрясающие! Похоже, все работает нормально.

Но что такое localhost ?

localhost — это имя хоста, которое означает этот компьютер. Он используется для доступа к сетевым службам, работающим на хосте, через петлевой сетевой интерфейс.

А поскольку веб-сервер прослушивает любой интерфейс, он также прослушивает интерфейс обратной связи.

Вы хотите знать, какой IP-адрес соответствует localhost?

Введите следующее:

$ host localhost localhost has address 127.0.0.1 localhost has IPv6 address ::1 Host localhost not found: 3(NXDOMAIN)

Фактически вы можете полностью заменить localhost на 127.0.0.1 в вашем браузере, и вы все равно получите тот же результат.

Одно последнее слово

На самом деле вы можете запустить веб-сервер с python, даже не создавая никаких скриптов.

Просто зайдите в свой терминал и сделайте следующее (но убедитесь, что вы на Python 3)

python -m http.server 8080

По умолчанию этот сервер будет прослушивать все интерфейсы и порт 8080.

Если вы хотите прослушать определенный интерфейс, сделайте следующее:

python -m http.server 8080 --bind 127.0.0.1

Также начиная с Python 3.7, вы можете использовать флаг –directory для обслуживания файлов из каталога, который не обязательно является текущим каталогом.