Загрузить PDF

Загрузить PDF

Писать от третьего лица просто, надо лишь немного попрактиковаться. Его использование в академических, то есть учебных или научных текстах означает отказ от местоимений «я» или «вы», как правило, с целью достижения более объективного и формального стиля. В художественной литературе третье лицо может принять форму различных точек зрения — точки зрения всезнающего автора, ограниченного повествования от третьего лица (одного или нескольких фокальных персонажей) или объективного повествования от третьего лица. Выбирайте сами, с какой из них вы будете вести свой рассказ.

-

1

Используйте третье лицо для любых академических текстов. Описывая результаты исследований и научные доказательства, пишите от третьего лица. Так ваш текст будет более объективным. В академических или профессиональных целях эта объективность важна, чтобы написанное вами производило впечатление непредвзятости и, следовательно, заслуживало большего доверия.[1]

- Третье лицо позволяет сосредоточиться на фактах и доказательствах, а не на личных мнениях.[2]

- Третье лицо позволяет сосредоточиться на фактах и доказательствах, а не на личных мнениях.[2]

-

2

Используйте правильные местоимения. В третьем лице о людях говорится «со стороны». Используйте существительные, имена собственные или местоимения третьего лица.

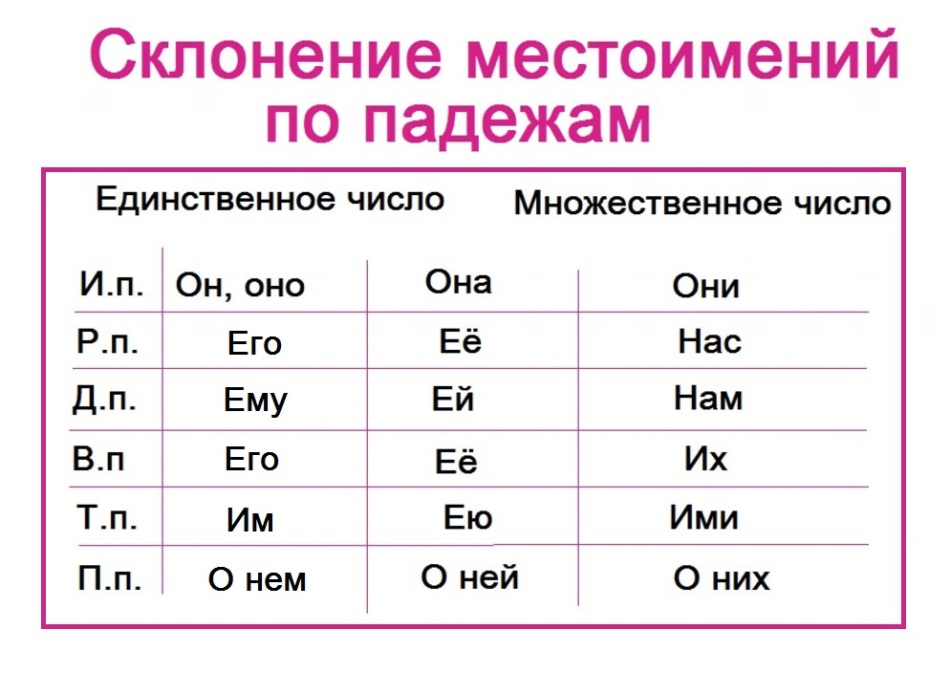

- К местоимениям третьего лица относятся: он, она, оно, они и их формы во всех падежах — его, ее, их, ему, ей, им, ими и так далее.

- Имена людей также подходят для изложения от третьего лица.

- Пример: «Орлов полагает иначе. Согласно его исследованиям, более ранние заявления по данной теме неверны».

-

3

Избегайте местоимений первого лица. Первое лицо предполагает личную точку зрения автора, а значит, такое изложение выглядит субъективным и основанным на мнении, а не на фактах. В академическом эссе следует избегать первого лица (если заданием не предусмотрено иное — скажем, изложить ваше мнение или результаты вашей работы).[3]

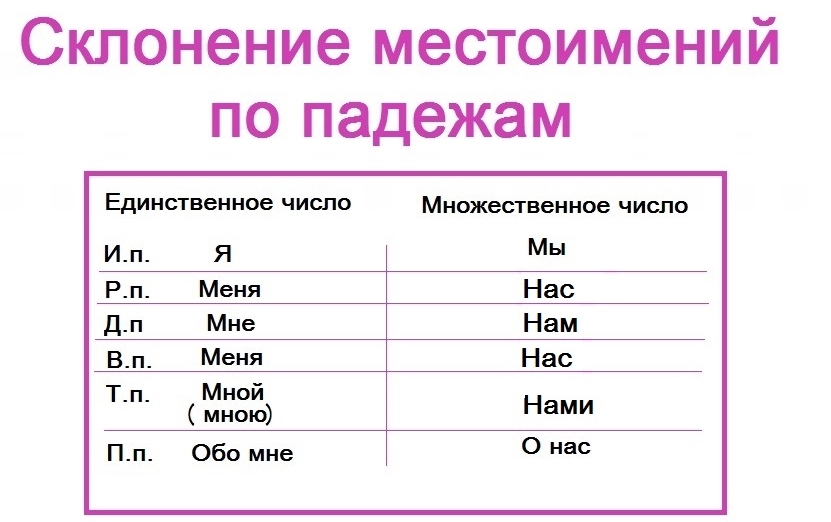

- К местоимениям первого лица относятся: я, мы, их формы во всех падежах — меня, мне, нас, нами, притяжательные местоимения — мой (моя, мои), наш (наша, наши).[4]

- Проблема первого лица заключается в том, что оно придает научной речи личный и субъективный характер. Иными словами, читателя будет сложно убедить, что взгляды и идеи изложены беспристрастно и не затронуты личными чувствами и воззрениям автора. Когда люди используют первое лицо в академических работах, они часто пишут «я думаю», «я считаю» или «на мой взгляд».

- Неправильно: «Хотя Орлов это утверждает, я считаю его аргументы ошибочными».

- Правильно: «Хотя Орлов это утверждает, другие с ним не согласны».

- К местоимениям первого лица относятся: я, мы, их формы во всех падежах — меня, мне, нас, нами, притяжательные местоимения — мой (моя, мои), наш (наша, наши).[4]

-

4

Избегайте местоимений второго лица. Посредством их вы обращаетесь непосредственно к читателю, как будто знаете его лично, и стиль вашего письма становится слишком фамильярным. Второе лицо никогда не следует использовать в научных работах.[5]

- Местоимения второго лица: ты, вы, их формы во всех падежах — тебя, тебе, тобой, вас, вам, вами, притяжательные местоимения — твой (твоя, твои), ваш (ваша, ваши).[6]

- Главная проблема второго лица — ему часто присуща обвинительная интонация. Отсюда вытекает риск возложить излишнюю ответственность на плечи именно того человека, что читает вашу работу в настоящий момент.

- Неправильно: «Если в наши дни вы по-прежнему не согласны, вы, должно быть, не знаете фактов».

- Правильно: «Тот, кто в наши дни по-прежнему не согласен, должно быть, не знает фактов».

- Местоимения второго лица: ты, вы, их формы во всех падежах — тебя, тебе, тобой, вас, вам, вами, притяжательные местоимения — твой (твоя, твои), ваш (ваша, ваши).[6]

-

5

Говорите о субъекте общими словами. Иногда автору нужно сделать отсылку к субъекту, не называя его конкретно. Другими словами, ему требуется упомянуть человека в общем, а не какое-то уже известное лицо. В этом случае обычно и возникает искушение написать «вы». Однако в данном случае уместно будет воспользоваться существительным, носящим обобщенный характер, или местоимением — неопределенным, определительным или отрицательным.

- К существительным общего характера, часто используемым при научном письме в третьем лице, относятся: автор, читатель, студент, преподаватель, человек, мужчина, женщина, ребенок, люди, исследователи, ученые, эксперты, представители.

- Пример: «Несмотря на множество возражений, исследователи продолжают отстаивать свою позицию».

- К местоимениям, которые могут использоваться с той же целью, относятся: кое-кто, кто-то, некоторые (неопределенные); все, каждый, любой (определительные); никто (отрицательное).

- Неправильно: «Вы можете согласиться, не зная фактов».

- Правильно: «Кто-то может согласиться, не зная фактов».[7]

-

6

Избегайте избыточной конструкции «он или она». Иногда современные авторы пишут «он или она» вместо «он», хотя субъект изначально упомянут в мужском роде.

- Такое использование местоимений продиктовано политкорректностью и является нормой, к примеру, в английском языке, но в русском обычно лишь делает фразу избыточной. После существительного «ученый», «врач», «ребенок», «человек» можно и нужно писать «он».

- Неправильно: «Свидетель хотел дать анонимные показания. Он или она боялся пострадать, если его или ее имя станет известно».

- Правильно: «Свидетель хотел дать анонимные показания. Он боялся пострадать, если его имя станет известно».

Реклама

-

1

Перемещайте фокус от одного персонажа к другому. Когда вы пишете художественный текст с точки зрения всезнающего автора, повествование перескакивает от одного персонажа к другому, а не следует за мыслями, действиями и словами одного героя. Автор знает все о каждом из них и о мире, в котором они живут. Он сам решает, какие мысли, чувства или поступки открыть читателю, а какие скрыть от него.[8]

- Допустим, в произведении четыре главных действующих лица: Уильям, Боб, Эрика и Саманта. В разные моменты повествования писателю следует изобразить действия и мысли каждого из них, причем он может делать это в пределах одной главы или абзаца.

- Пример: «Уильям подумал, что Эрика солгала, но ему хотелось верить, что у нее была на то веская причина. Саманта тоже была уверена, что Эрика лжет, к тому же ее мучила ревность, так как Тони посмел подумать хорошо о другой девушке».

- Авторам всеведущих повествований следует избегать резких скачков — не стоит менять взгляды персонажа в пределах одной главы. Это не нарушает канонов жанра, но является признаком повествовательной рыхлости.

-

2

Раскрывайте любую информацию, какую пожелаете. С точки зрения всезнающего автора рассказ не ограничен переживаниями и внутренним миром единственного персонажа. Наряду с мыслями и чувствами, писатель может открывать читателю прошлое или будущее героев непосредственно по ходу повествования. Кроме того, он может высказывать собственное мнение, оценивать события с позиции морали, описывать города, природу или животных отдельно от сцен с участием персонажей.[9]

- В определенном смысле автор, пишущий с этой точки зрения, является кем-то вроде «бога» в своем произведении. Писатель может наблюдать за действиями любого персонажа в любой момент, причем, в отличие от наблюдателя-человека, он не только видит внешние проявления, но и способен заглянуть во внутренний мир.

- Знайте, когда следует скрыть информацию от читателя. Хотя автор может рассказать обо всем, о чем он пожелает, произведению может пойти на пользу доля недосказанности, когда некоторые вещи открываются постепенно. Например, если один из героев окутан аурой загадочности, разумно будет не допускать читателя до его чувств, пока не раскроются его истинные мотивы.

-

3

Избегайте использования местоимений первого и второго лица. Местоимения первого лица — «я», «мы» и их формы — могут появляться только в диалогах. То же самое относится ко второму лицу — «ты» и «вы».

- Не используйте первое и второе лицо в повествовательной и описательной части текста.

- Правильно: «Боб сказал Эрике: „По-моему, это довольно страшно. А ты как думаешь?”»

- Неправильно: «Я подумал, что это довольно страшно, и Эрика с Бобом согласились. А вы как думаете?»

Реклама

-

1

Выберите героя, с точки зрения которого вы поведете рассказ. При ограниченном повествовании от третьего лица автор имеет полный доступ к действиям, мыслям, чувствам и взглядам единственного персонажа. Он может писать непосредственно с позиции мыслей и реакций этого персонажа или же отступить в сторону для более объективного рассказа.[10]

- Мысли и чувства остальных персонажей остаются неизвестными для рассказчика на протяжении всего текста. Выбрав ограниченное повествование, он уже не может свободно переключаться между разными действующими лицами.

- Когда повествование ведется от первого лица, рассказчик выступает в роли главного героя, в то время как в повествовании от третьего лица все с точностью до наоборот — здесь автор отдаляется от того, что пишет. В этом случае рассказчик может раскрыть какие-то детали, каких не раскрыл бы, если бы повествование велось от первого лица.

-

2

Описывайте поступки и мысли персонажа «со стороны». Хотя писатель и фокусируется на одном персонаже, он должен рассматривать его отдельно от себя: личности рассказчика и героя не сливаются! Даже если автор неотступно следует за его мыслями, чувствами и внутренними монологами, вести повествование нужно от третьего лица.[11]

- Иными словами, местоимения первого лица («я», «меня», «мой», «мы», «наш» и так далее) могут использоваться только в диалогах. Рассказчик видит мысли и чувства главного героя, но герой не превращается в рассказчика.

- Правильно: «Тиффани чувствовала себя ужасно после ссоры со своим парнем».

- Правильно: «Тиффани подумала: „Я чувствую себя ужасно после нашей с ним ссоры”».

- Неправильно: «Я чувствовала себя ужасно после ссоры с моим парнем».

-

3

Показывайте действия и слова других персонажей, а не их мысли и чувства. Автору известны только мысли и чувства главного героя, с позиции которого ведется рассказ. Однако он может описывать других персонажей так, как их видит герой. Рассказчик может все то, что может его персонаж; он только не может знать, что творится в голове у других действующих лиц.[12]

- Писатель может строить догадки или предположения в отношении мыслей других персонажей, но только с точки зрения главного героя.

- Правильно: «Тиффани чувствовала себя ужасно, но, видя выражение лица Карла, она понимала, что и ему не лучше — а то и хуже».

- Неправильно: «Тиффани чувствовала себя ужасно. Однако она не знала, что Карлу было еще хуже».

-

4

Не раскрывайте информацию, которой не владеет герой. Хотя рассказчик может сделать отступление и описать место действия или других персонажей, он не должен говорить ни о чем, чего не видит или не знает герой. Не перескакивайте от одного персонажа к другому в пределах одной сцены. Действия других персонажей могут стать известными, только если они происходят в присутствии героя (или он узнает о них от кого-то еще).

- Правильно: «Из окна Тиффани видела, как Карл подошел к дому и позвонил в дверь».

- Неправильно: «Как только Тиффани вышла из комнаты, Карл вздохнул с облегчением».

Реклама

-

1

Переключайтесь с одного персонажа на другой. Ограниченное повествование от лица нескольких персонажей, называемых фокальными, означает, что автор ведет рассказ с точки зрения нескольких героев поочередно. Используйте видение и мысли каждого из них, чтобы раскрыть важную информацию и помочь развитию сюжета.[13]

- Ограничьте количество фокальных персонажей. Вам не следует писать с точки зрения множества действующих лиц, чтобы не запутать читателя и не перегрузить произведение. Уникальное видение каждого фокального персонажа должно играть определенную роль в повествовании. Спросите себя, каков вклад каждого из них в развитие сюжета.

- Например, в романтической истории с двумя главными героями — Кевином и Фелицией — автор может дать читателю возможность понять, что творится на душе у них обоих, описывая события попеременно с двух точек зрения.

- Одному персонажу можно уделить больше внимания, чем другому, но каждый фокальный персонаж должен получить его долю в тот или иной момент развития истории.

-

2

Концентрируйтесь на мыслях и видении одного персонажа за раз. Хотя в произведении в целом используется прием множественного видения, в каждый его момент писателю следует смотреть на происходящее глазами только одного героя.

- Несколько точек зрения не должны сталкиваться в одном эпизоде. Когда заканчивается описание с позиции одного персонажа, может вступать другой, однако их точки зрения не должны смешиваться в пределах одной сцены или главы.[14]

- Неправильно: «Кевин был влюблен в Фелицию с самой первой их встречи. Фелиция же, со своей стороны, не до конца доверяла Кевину».

- Несколько точек зрения не должны сталкиваться в одном эпизоде. Когда заканчивается описание с позиции одного персонажа, может вступать другой, однако их точки зрения не должны смешиваться в пределах одной сцены или главы.[14]

-

3

Старайтесь делать плавные переходы. Хотя писатель и может переключаться с одного персонажа на другой и обратно, не следует делать этого произвольно, иначе рассказ станет запутанным.[15]

- В романе удачным моментом для переключения с персонажа на персонаж будет начало новой главы или сцены внутри главы.

- В начале сцены или главы, желательно в первом предложении, писателю следует обозначить, с чьей точки зрения он поведет рассказ, иначе читателю придется теряться в догадках.[16]

- Правильно: «Фелиции очень не хотелось этого признавать, но розы, которые Кевин оставил на пороге, были приятным сюрпризом».

- Неправильно: «Розы, оставленные на пороге, оказались приятным сюрпризом».

-

4

Различайте, кому что известно. Читатель получает информацию, известную разным персонажам, но каждый персонаж имеет доступ к разной информации. Проще говоря, одни герой может не знать того, что знает другой.

- Например, если Кевин поговорил о чувствах Фелиции к нему с ее лучшей подругой, сама Фелиция никак не может знать, о чем они беседовали, если только не присутствовала при разговоре, либо Кевин или подруга не рассказали ей о нем.

Реклама

-

1

Описывайте действия разных персонажей. Ведя объективное повествование от третьего лица, автор может описать слова и действия любого персонажа истории в любой момент и в любом месте.[17]

- Здесь автору необязательно сосредоточиваться на единственном главном герое. Он может переключаться между разными персонажами по ходу рассказа так часто, как ему нужно.

- Однако первого лица («я») и второго лица («ты») нужно все так же избегать. Их место — только в диалогах.

-

2

Не пытайтесь проникнуть в мысли персонажа. В отличие от точки зрения всезнающего автора, где рассказчику доступны мысли каждого, при объективном повествовании он не может заглянуть ни в чью голову.[18]

- Представьте, что вы — это невидимый свидетель, наблюдающий за поступками и диалогами персонажей. Вы не всеведущи, поэтому вам неизвестны их чувства и мотивы. Вы лишь можете описать их действия со стороны.

- Правильно: «После урока Грэхем в спешке покинул класс и помчался к себе».

- Неправильно: «Грэхем выбежал из класса и помчался к себе. Лекция настолько его взбесила, что он чувствовал себя готовым наброситься на первого встречного».

-

3

Показывайте, а не рассказывайте. Хотя при объективном повествовании от третьего лица писатель не может поведать о мыслях и внутреннем мире персонажей, он, тем не менее, может делать наблюдения, позволяющие предположить, что думал или испытывал герой. Описывайте происходящее. К примеру, не сообщайте читателю, что персонаж был в гневе, а опишите его жесты, выражение лица, тон голоса, чтобы читатель увидел этот гнев.[19]

- Правильно: «Когда вокруг никого не осталось, Изабелла расплакалась».

- Неправильно: «Изабелла была слишком гордой, чтобы плакать в присутствии других, но она чувствовала, что сердце ее разбито, и потому расплакалась, как только осталась одна».

-

4

Не вставляйте в рассказ собственные умозаключения. При объективном повествовании от третьего лица автор выступает в роли репортера, а не комментатора.[20]

- Позвольте читателю самому делать выводы. Описывайте действия персонажей, но не анализируйте их и не объясняйте, что они значат и как их следует оценивать.

- Правильно: «Прежде чем сесть, Иоланда трижды оглянулась через плечо».

- Неправильно: «Это могло показаться странным, но Иоланда трижды оглянулась через плечо, прежде чем сесть. Такая навязчивая привычка свидетельствовала о параноидальном мышлении».

Реклама

Об этой статье

Эту страницу просматривали 299 840 раз.

Была ли эта статья полезной?

Download Article

Download Article

Writing in third person can be a simple task, with a little practice. For academic purposes, third person writing means that the writer must avoid using subjective pronouns like “I” or “you.” For creative writing purposes, there are differences between third person omniscient, limited, objective, and episodically limited points of view. Choose which one fits your writing project.

-

1

Use third person for all academic writing. For formal writing, such as research and argumentative papers, use the third person. Third person makes writing more objective and less personal. For academic and professional writing, this sense of objectivity allows the writer to seem less biased and, therefore, more credible.[1]

- Third person helps the writing stay focused on facts and evidence instead of personal opinion.

-

2

Use the correct pronouns. Third person refers to people “on the outside.” Either write about someone by name or use third person pronouns.

- Third person pronouns include: he, she, it; his, her, its; him, her, it; himself, herself, itself; they; them; their; themselves.

- Names of other people are also considered appropriate for third person use.

- Example: “Smith believes differently. According to his research, earlier claims on the subject are incorrect.”

Advertisement

-

3

Avoid first person pronouns. First person refers to a point of view in which the writer says things from his or her personal perspective. This point of view makes things too personal and opinionated. Avoid first person in an academic essay.[2]

- First person pronouns include: I, me, my, mine, myself, we, us, our, ours, ourselves.[3]

- The problem with first person is that, academically speaking, it sounds too personalized and too subjective. In other words, it may be difficult to convince the reader that the views and ideas being expressed are unbiased and untainted by personal feelings. Many times, when using first person in academic writing, people use phrases like «I think,» «I believe,» or «in my opinion.»

- Incorrect example: “Even though Smith thinks this way, I think his argument is incorrect.”

- Correct example: “Even though Smith thinks this way, others in the field disagree.”

- First person pronouns include: I, me, my, mine, myself, we, us, our, ours, ourselves.[3]

-

4

Avoid second person pronouns. Second person refers to point of view that directly addresses the reader. This point of view shows too much familiarity with the reader, by speaking to them directly, as if the writer personally knows his or her reading audience. Second person should never be used in academic writing.

- Second person pronouns include: you, your, yours, yourself.[4]

- One main problem with second person is that it can sound accusatory. It runs to risk of placing too much responsibility on the shoulders of the reader specifically and presently reading the work.

- Incorrect example: “If you still disagree nowadays, then you must be ignorant of the facts.”

- Correct example: “Someone who still disagrees nowadays must be ignorant of the facts.”

- Second person pronouns include: you, your, yours, yourself.[4]

-

5

Refer to the subject in general terms. Sometimes, a writer will need to refer to someone in indefinite terms. In other words, they may need to generally address or speak about a person. This is usually when the temptation to slip into the second person “you” comes into play. An indefinite third person pronoun or noun is appropriate here.

- Indefinite third person nouns common to academic writing include: the writer, the reader, individuals, students, a student, an instructor, people, a person, a woman, a man, a child, researchers, scientists, writers, experts.

- Example: “In spite of the challenges involved, researchers still persist in their claims.”

- Indefinite third person pronouns include: one, anyone, everyone, someone, no one, another, any, each, either, everybody, neither, nobody, other, anybody, somebody, everything, someone.

- Incorrect example: «You might be tempted to agree without all the facts.»

- Correct example: “One might be tempted to agree without all the facts.”

-

6

Watch out for singular and plural pronoun use. One mistake that writers often make when writing in third person is accidentally conjugating a plural pronoun as singular.

- This is usually done in an attempt to avoid the gender-specific “he” and “she” pronouns. The mistake here would be to use the “they” pronoun with singular conjugation.[5]

- Incorrect example: “The witness wanted to offer anonymous testimony. They was afraid of getting hurt if their name was spread.”

- Correct example: “The witness wanted to offer anonymous testimony. They were afraid of getting hurt if their name was spread.”

- This is usually done in an attempt to avoid the gender-specific “he” and “she” pronouns. The mistake here would be to use the “they” pronoun with singular conjugation.[5]

Advertisement

-

1

Shift your focus from character to character. When using third person omniscient perspective, the narrative jumps around from person to person instead of following the thoughts, actions, and words of a single character. The narrator knows everything about each character and the world. The narrator can reveal or withhold any thoughts, feelings, or actions.

- For instance, a story may include four major characters: William, Bob, Erika, and Samantha. At various points throughout the story, the thoughts and actions of each character should be portrayed. These thoughts can occur within the same chapter or block of narration.

- Writers of omniscient narratives should be conscious of “head-hopping” — that is, shifting character perspectives within a scene. While this does not technically break the rules of Third Person Omniscience, it is widely considered a hallmark of narrative laziness.

- This is a good voice to use if you want to remove yourself from the work so the readers don’t confuse the narrator for you.[6]

-

2

Reveal any information you want. With third person omniscient view, the narration is not limited the inner thoughts and feelings of any character. Along with inner thoughts and feelings, third person omniscient point of view also permits the writer to reveal parts of the future or past within the story. The narrator can also hold an opinion, give a moral perspective, or discuss animals or nature scenes where the characters are not present.[7]

- In a sense, the writer of a third person omniscient story is somewhat like the “god” of that story. The writer can observe the external actions of any character at any time, but unlike a limited human observer, the writer can also peek into the inner workings of that character at will, as well.

- Know when to hold back. Even though a writer can reveal any information he or she chooses to reveal, it may be more beneficial to reveal some things gradually. For instance, if one character is supposed to have a mysterious aura, it would be wise to limit access to that character’s inner feelings for a while before revealing his or her true motives.

-

3

Avoid use of the first person and second person pronouns. Active dialog should be the only time that first person pronouns like “I” and “we” should appear. The same goes for second person pronouns like “you.”

- Do not use first person and second person points of view in the narrative or descriptive portions of the text.

- Correct example: Bob said to Erika, “I think this is creepy. What do you think?”

- Incorrect example: I thought this was creepy, and Bob and Erika thought so, too. What do you think?

Advertisement

-

1

Pick a single character to follow. When writing in third person limited perspective, a writer has complete access to the actions, thoughts, feelings, and belief of a single character. The writer can write as if the character is thinking and reacting, or the writer can step back and be more objective.[8]

- The thoughts and feelings of other characters remain an unknown for the writer throughout the duration of the text. There should be no switching back and forth between characters for this specific type of narrative viewpoint.

- Unlike first person, where the narrator and protagonist are the same, third person limited puts a critical sliver of distance between protagonist and narrator. The writer has the choice to describe one main character’s nasty habit — something they wouldn’t readily reveal if the narration were left entirely to them.

-

2

Refer to the character’s actions and thoughts from the outside. Even though the focus remains on one character, the writer still needs to treat that character as a separate entity. If the narrator follows the character’s thoughts, feelings, and internal dialogue, this still needs to be in third person.[9]

- In other words, do not use first person pronouns like “I,” “me,” “my,” “we,” or “our” outside of dialog. The main character’s thoughts and feelings are transparent to the writer, but that character should not double as a narrator.

- Correct example: “Tiffany felt awful after the argument with her boyfriend.”

- Correct example: “Tiffany thought, “I feel awful after that argument with my boyfriend.”

- Incorrect example: “I felt awful after the argument with my boyfriend.”

-

3

Focus on other characters’ actions and words, not their thoughts or feelings. The writer is as limited to just the protagonist’s thoughts and feelings with this point of view. However, with this point of view, other characters can be described without the protagonist noticing it. The narrator can anything the protagonist can; she just can’t get into the other character’s head.[10]

- Note that the writer can offer insight or guesses regarding the thoughts of other characters, but those guesses must be presented through the perspective of the main character.

- Correct example: “Tiffany felt awful, but judging by the expression on Carl’s face, she imagined that he felt just as bad if not worse.”

- Incorrect example: “Tiffany felt awful. What she didn’t know was that Carl felt even worse.”

-

4

Do not reveal any information your main character would not know. Although the narrator can step back and describe the setting or other characters, it has to be anything the viewpoint character can see. Do not bounce around from one character to one character within one scene. The external actions of other characters can only be known when the main character is present to view those actions.

- Correct example: “Tiffany watched from the window as Carl walked up to her house and rang the doorbell.”

- Incorrect example: “As soon as Tiffany left the room, Carl let out a sigh of relief.”

Advertisement

-

1

Jump from character to character. With episodically limited third person, also referred to as third person multiple vision, the writer may have a handful of main characters whose thoughts and perspectives take turns in the limelight. Use each perspective to reveal important information and move the story forward.[11]

- Limit the amount of pov characters you include. You don’t want to have too many characters that confuse your reader or serve no purpose. Each pov character should have a specific purpose for having a unique point of view. Ask yourself what each pov character contributes to the story.

- For instance, in a romance story following two main characters, Kevin and Felicia, the writer may opt to explain the inner workings of both characters at different moments in the story.

- One character may receive more attention than any other, but all main characters being followed should receive attention at some point in the story.

-

2

Only focus on one character’s thoughts and perspective at a time. Even though multiple perspectives are included in the overall story, the writer should focus on each character one at a time.

- Multiple perspectives should not appear within the same narrative space. When one character’s perspective ends, another character’s can begin. The two perspectives should not be intermixed within the same space.

- Incorrect example: “Kevin felt completely enamored of Felicia from the moment he met her. Felicia, on the other hand, had difficulty trusting Kevin.”

-

3

Aim for smooth transitions. Even though the writer can switch back and forth between different character perspectives, doing so arbitrarily can cause the narrative to become confusing for the narrative.[12]

- In a novel-length work, a good time to switch perspective is at the start of a new chapter or at a chapter break.

- The writer should also identify the character whose perspective is being followed at the start of the section, preferably in the first sentence. Otherwise, the reader may waste too much energy guessing.

- Correct example: “Felicia hated to admit it, but the roses Kevin left on her doorstep were a pleasant surprise.”

- Incorrect example: “The roses left on the doorstep seemed like a nice touch.”

-

4

Understand who knows what. Even though the reader may have access to information viewed from the perspective of multiple characters, those characters do not have the same sort of access. Some characters have no way of knowing what other characters know.

- For instance, if Kevin had a talk with Felicia’s best friend about Felicia’s feelings for him, Felicia herself would have no way of knowing what was said unless she witnessed the conversation or heard about it from either Kevin or her friend.

Advertisement

-

1

Follow the actions of many characters. When using third person objective, the writer can describe the actions and words of any character at any time and place within the story.

- There does not need to be a single main character to focus on. The writer can switch between characters, following different characters throughout the course of the narrative, as often as needed.

- Stay away from first person terms like “I” and second person terms like “you” in the narrative, though. Only use first and second person within dialog.

-

2

Do not attempt to get into directly into a character’s head. Unlike omniscient pov where the narrator looks into everyone’s head, objective pov doesn’t look into anyone’s head.

- Imagine that you are an invisible bystander observing the actions and dialog of the characters in your story. You are not omniscient, so you do not have access to any character’s inner thoughts and feelings. You only have access to each character’s actions.

- Correct example: “After class, Graham hurriedly left the room and rushed back to his dorm room.”

- Incorrect example: “After class, Graham raced from the room and rushed back to his dorm room. The lecture had made him so angry that he felt as though he might snap at the next person he met.”

-

3

Show but don’t tell. Even though a third person objective writer cannot share a character’s inner thoughts, the writer can make external observations that suggest what those internal thoughts might be. Describe what is going on. Instead of telling the reader that a character is angry, describe his facial expression, body language, and tone of voice to show that he is mad.

- Correct example: “When no one else was watching her, Isabelle began to cry.”

- Incorrect example: “Isabelle was too prideful to cry in front of other people, but she felt completely broken-hearted and began crying once she was alone.”

-

4

Avoid inserting your own thoughts. The writer’s purpose when using third person objective is to act as a reporter, not a commentator.

- Let the reader draw his or her own conclusions. Present the actions of the character without analyzing them or explaining how those actions should be viewed.

- Correct example: “Yolanda looked over her shoulder three times before sitting down.”

- Incorrect example: “It might seem like a strange action, but Yolanda looked over her shoulder three times before sitting down. This compulsive habit is an indication of her paranoid state of mind.”

Advertisement

Examples of Third Person POV

Add New Question

-

Question

How do you know when to write in first or third person?

Alicia Cook is a Professional Writer based in Newark, New Jersey. With over 12 years of experience, Alicia specializes in poetry and uses her platform to advocate for families affected by addiction and to fight for breaking the stigma against addiction and mental illness. She holds a BA in English and Journalism from Georgian Court University and an MBA from Saint Peter’s University. Alicia is a bestselling poet with Andrews McMeel Publishing and her work has been featured in numerous media outlets including the NY Post, CNN, USA Today, the HuffPost, the LA Times, American Songwriter Magazine, and Bustle. She was named by Teen Vogue as one of the 10 social media poets to know and her poetry mixtape, “Stuff I’ve Been Feeling Lately” was a finalist in the 2016 Goodreads Choice Awards.

Professional Writer

Expert Answer

Support wikiHow by

unlocking this expert answer.You might write in third person if you want to further remove yourself from the work so people reading don’t confuse the main character for you. It’s a way to create boundaries, and it also allows you to create different voices and characters.

-

Question

Can I move from third person to first person in different sections?

Teachers don’t encourage such a format, but as long as it’s done well stylistically, editors are interested in any exceptional story.

-

Question

Can I write a narration of my life journey in the 3rd person?

Sure, just use your name instead of »I» or «me».

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To write in third person, refer to people or characters by name or use third person pronouns like he, she, it; his, her, its; him, her, it; himself, herself, itself; they; them; their; and themselves. Avoid first and second person pronouns completely. For academic writing, focus on a general viewpoint rather than a specific person’s to keep things in third person. In other types of writing, you can write in third person by shifting your focus from character to character or by focusing on a single character. To learn more from our Literary Studies Ph.D., like the differences between third person omniscient and third person limited writing, keep reading the article!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 1,038,402 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

«Like a breath of fresh air to see this. Was always intended to be my platform to describe an incredibly negative…» more

Did this article help you?

Download Article

Download Article

Writing in third person can be a simple task, with a little practice. For academic purposes, third person writing means that the writer must avoid using subjective pronouns like “I” or “you.” For creative writing purposes, there are differences between third person omniscient, limited, objective, and episodically limited points of view. Choose which one fits your writing project.

-

1

Use third person for all academic writing. For formal writing, such as research and argumentative papers, use the third person. Third person makes writing more objective and less personal. For academic and professional writing, this sense of objectivity allows the writer to seem less biased and, therefore, more credible.[1]

- Third person helps the writing stay focused on facts and evidence instead of personal opinion.

-

2

Use the correct pronouns. Third person refers to people “on the outside.” Either write about someone by name or use third person pronouns.

- Third person pronouns include: he, she, it; his, her, its; him, her, it; himself, herself, itself; they; them; their; themselves.

- Names of other people are also considered appropriate for third person use.

- Example: “Smith believes differently. According to his research, earlier claims on the subject are incorrect.”

Advertisement

-

3

Avoid first person pronouns. First person refers to a point of view in which the writer says things from his or her personal perspective. This point of view makes things too personal and opinionated. Avoid first person in an academic essay.[2]

- First person pronouns include: I, me, my, mine, myself, we, us, our, ours, ourselves.[3]

- The problem with first person is that, academically speaking, it sounds too personalized and too subjective. In other words, it may be difficult to convince the reader that the views and ideas being expressed are unbiased and untainted by personal feelings. Many times, when using first person in academic writing, people use phrases like «I think,» «I believe,» or «in my opinion.»

- Incorrect example: “Even though Smith thinks this way, I think his argument is incorrect.”

- Correct example: “Even though Smith thinks this way, others in the field disagree.”

- First person pronouns include: I, me, my, mine, myself, we, us, our, ours, ourselves.[3]

-

4

Avoid second person pronouns. Second person refers to point of view that directly addresses the reader. This point of view shows too much familiarity with the reader, by speaking to them directly, as if the writer personally knows his or her reading audience. Second person should never be used in academic writing.

- Second person pronouns include: you, your, yours, yourself.[4]

- One main problem with second person is that it can sound accusatory. It runs to risk of placing too much responsibility on the shoulders of the reader specifically and presently reading the work.

- Incorrect example: “If you still disagree nowadays, then you must be ignorant of the facts.”

- Correct example: “Someone who still disagrees nowadays must be ignorant of the facts.”

- Second person pronouns include: you, your, yours, yourself.[4]

-

5

Refer to the subject in general terms. Sometimes, a writer will need to refer to someone in indefinite terms. In other words, they may need to generally address or speak about a person. This is usually when the temptation to slip into the second person “you” comes into play. An indefinite third person pronoun or noun is appropriate here.

- Indefinite third person nouns common to academic writing include: the writer, the reader, individuals, students, a student, an instructor, people, a person, a woman, a man, a child, researchers, scientists, writers, experts.

- Example: “In spite of the challenges involved, researchers still persist in their claims.”

- Indefinite third person pronouns include: one, anyone, everyone, someone, no one, another, any, each, either, everybody, neither, nobody, other, anybody, somebody, everything, someone.

- Incorrect example: «You might be tempted to agree without all the facts.»

- Correct example: “One might be tempted to agree without all the facts.”

-

6

Watch out for singular and plural pronoun use. One mistake that writers often make when writing in third person is accidentally conjugating a plural pronoun as singular.

- This is usually done in an attempt to avoid the gender-specific “he” and “she” pronouns. The mistake here would be to use the “they” pronoun with singular conjugation.[5]

- Incorrect example: “The witness wanted to offer anonymous testimony. They was afraid of getting hurt if their name was spread.”

- Correct example: “The witness wanted to offer anonymous testimony. They were afraid of getting hurt if their name was spread.”

- This is usually done in an attempt to avoid the gender-specific “he” and “she” pronouns. The mistake here would be to use the “they” pronoun with singular conjugation.[5]

Advertisement

-

1

Shift your focus from character to character. When using third person omniscient perspective, the narrative jumps around from person to person instead of following the thoughts, actions, and words of a single character. The narrator knows everything about each character and the world. The narrator can reveal or withhold any thoughts, feelings, or actions.

- For instance, a story may include four major characters: William, Bob, Erika, and Samantha. At various points throughout the story, the thoughts and actions of each character should be portrayed. These thoughts can occur within the same chapter or block of narration.

- Writers of omniscient narratives should be conscious of “head-hopping” — that is, shifting character perspectives within a scene. While this does not technically break the rules of Third Person Omniscience, it is widely considered a hallmark of narrative laziness.

- This is a good voice to use if you want to remove yourself from the work so the readers don’t confuse the narrator for you.[6]

-

2

Reveal any information you want. With third person omniscient view, the narration is not limited the inner thoughts and feelings of any character. Along with inner thoughts and feelings, third person omniscient point of view also permits the writer to reveal parts of the future or past within the story. The narrator can also hold an opinion, give a moral perspective, or discuss animals or nature scenes where the characters are not present.[7]

- In a sense, the writer of a third person omniscient story is somewhat like the “god” of that story. The writer can observe the external actions of any character at any time, but unlike a limited human observer, the writer can also peek into the inner workings of that character at will, as well.

- Know when to hold back. Even though a writer can reveal any information he or she chooses to reveal, it may be more beneficial to reveal some things gradually. For instance, if one character is supposed to have a mysterious aura, it would be wise to limit access to that character’s inner feelings for a while before revealing his or her true motives.

-

3

Avoid use of the first person and second person pronouns. Active dialog should be the only time that first person pronouns like “I” and “we” should appear. The same goes for second person pronouns like “you.”

- Do not use first person and second person points of view in the narrative or descriptive portions of the text.

- Correct example: Bob said to Erika, “I think this is creepy. What do you think?”

- Incorrect example: I thought this was creepy, and Bob and Erika thought so, too. What do you think?

Advertisement

-

1

Pick a single character to follow. When writing in third person limited perspective, a writer has complete access to the actions, thoughts, feelings, and belief of a single character. The writer can write as if the character is thinking and reacting, or the writer can step back and be more objective.[8]

- The thoughts and feelings of other characters remain an unknown for the writer throughout the duration of the text. There should be no switching back and forth between characters for this specific type of narrative viewpoint.

- Unlike first person, where the narrator and protagonist are the same, third person limited puts a critical sliver of distance between protagonist and narrator. The writer has the choice to describe one main character’s nasty habit — something they wouldn’t readily reveal if the narration were left entirely to them.

-

2

Refer to the character’s actions and thoughts from the outside. Even though the focus remains on one character, the writer still needs to treat that character as a separate entity. If the narrator follows the character’s thoughts, feelings, and internal dialogue, this still needs to be in third person.[9]

- In other words, do not use first person pronouns like “I,” “me,” “my,” “we,” or “our” outside of dialog. The main character’s thoughts and feelings are transparent to the writer, but that character should not double as a narrator.

- Correct example: “Tiffany felt awful after the argument with her boyfriend.”

- Correct example: “Tiffany thought, “I feel awful after that argument with my boyfriend.”

- Incorrect example: “I felt awful after the argument with my boyfriend.”

-

3

Focus on other characters’ actions and words, not their thoughts or feelings. The writer is as limited to just the protagonist’s thoughts and feelings with this point of view. However, with this point of view, other characters can be described without the protagonist noticing it. The narrator can anything the protagonist can; she just can’t get into the other character’s head.[10]

- Note that the writer can offer insight or guesses regarding the thoughts of other characters, but those guesses must be presented through the perspective of the main character.

- Correct example: “Tiffany felt awful, but judging by the expression on Carl’s face, she imagined that he felt just as bad if not worse.”

- Incorrect example: “Tiffany felt awful. What she didn’t know was that Carl felt even worse.”

-

4

Do not reveal any information your main character would not know. Although the narrator can step back and describe the setting or other characters, it has to be anything the viewpoint character can see. Do not bounce around from one character to one character within one scene. The external actions of other characters can only be known when the main character is present to view those actions.

- Correct example: “Tiffany watched from the window as Carl walked up to her house and rang the doorbell.”

- Incorrect example: “As soon as Tiffany left the room, Carl let out a sigh of relief.”

Advertisement

-

1

Jump from character to character. With episodically limited third person, also referred to as third person multiple vision, the writer may have a handful of main characters whose thoughts and perspectives take turns in the limelight. Use each perspective to reveal important information and move the story forward.[11]

- Limit the amount of pov characters you include. You don’t want to have too many characters that confuse your reader or serve no purpose. Each pov character should have a specific purpose for having a unique point of view. Ask yourself what each pov character contributes to the story.

- For instance, in a romance story following two main characters, Kevin and Felicia, the writer may opt to explain the inner workings of both characters at different moments in the story.

- One character may receive more attention than any other, but all main characters being followed should receive attention at some point in the story.

-

2

Only focus on one character’s thoughts and perspective at a time. Even though multiple perspectives are included in the overall story, the writer should focus on each character one at a time.

- Multiple perspectives should not appear within the same narrative space. When one character’s perspective ends, another character’s can begin. The two perspectives should not be intermixed within the same space.

- Incorrect example: “Kevin felt completely enamored of Felicia from the moment he met her. Felicia, on the other hand, had difficulty trusting Kevin.”

-

3

Aim for smooth transitions. Even though the writer can switch back and forth between different character perspectives, doing so arbitrarily can cause the narrative to become confusing for the narrative.[12]

- In a novel-length work, a good time to switch perspective is at the start of a new chapter or at a chapter break.

- The writer should also identify the character whose perspective is being followed at the start of the section, preferably in the first sentence. Otherwise, the reader may waste too much energy guessing.

- Correct example: “Felicia hated to admit it, but the roses Kevin left on her doorstep were a pleasant surprise.”

- Incorrect example: “The roses left on the doorstep seemed like a nice touch.”

-

4

Understand who knows what. Even though the reader may have access to information viewed from the perspective of multiple characters, those characters do not have the same sort of access. Some characters have no way of knowing what other characters know.

- For instance, if Kevin had a talk with Felicia’s best friend about Felicia’s feelings for him, Felicia herself would have no way of knowing what was said unless she witnessed the conversation or heard about it from either Kevin or her friend.

Advertisement

-

1

Follow the actions of many characters. When using third person objective, the writer can describe the actions and words of any character at any time and place within the story.

- There does not need to be a single main character to focus on. The writer can switch between characters, following different characters throughout the course of the narrative, as often as needed.

- Stay away from first person terms like “I” and second person terms like “you” in the narrative, though. Only use first and second person within dialog.

-

2

Do not attempt to get into directly into a character’s head. Unlike omniscient pov where the narrator looks into everyone’s head, objective pov doesn’t look into anyone’s head.

- Imagine that you are an invisible bystander observing the actions and dialog of the characters in your story. You are not omniscient, so you do not have access to any character’s inner thoughts and feelings. You only have access to each character’s actions.

- Correct example: “After class, Graham hurriedly left the room and rushed back to his dorm room.”

- Incorrect example: “After class, Graham raced from the room and rushed back to his dorm room. The lecture had made him so angry that he felt as though he might snap at the next person he met.”

-

3

Show but don’t tell. Even though a third person objective writer cannot share a character’s inner thoughts, the writer can make external observations that suggest what those internal thoughts might be. Describe what is going on. Instead of telling the reader that a character is angry, describe his facial expression, body language, and tone of voice to show that he is mad.

- Correct example: “When no one else was watching her, Isabelle began to cry.”

- Incorrect example: “Isabelle was too prideful to cry in front of other people, but she felt completely broken-hearted and began crying once she was alone.”

-

4

Avoid inserting your own thoughts. The writer’s purpose when using third person objective is to act as a reporter, not a commentator.

- Let the reader draw his or her own conclusions. Present the actions of the character without analyzing them or explaining how those actions should be viewed.

- Correct example: “Yolanda looked over her shoulder three times before sitting down.”

- Incorrect example: “It might seem like a strange action, but Yolanda looked over her shoulder three times before sitting down. This compulsive habit is an indication of her paranoid state of mind.”

Advertisement

Examples of Third Person POV

Add New Question

-

Question

How do you know when to write in first or third person?

Alicia Cook is a Professional Writer based in Newark, New Jersey. With over 12 years of experience, Alicia specializes in poetry and uses her platform to advocate for families affected by addiction and to fight for breaking the stigma against addiction and mental illness. She holds a BA in English and Journalism from Georgian Court University and an MBA from Saint Peter’s University. Alicia is a bestselling poet with Andrews McMeel Publishing and her work has been featured in numerous media outlets including the NY Post, CNN, USA Today, the HuffPost, the LA Times, American Songwriter Magazine, and Bustle. She was named by Teen Vogue as one of the 10 social media poets to know and her poetry mixtape, “Stuff I’ve Been Feeling Lately” was a finalist in the 2016 Goodreads Choice Awards.

Professional Writer

Expert Answer

Support wikiHow by

unlocking this expert answer.You might write in third person if you want to further remove yourself from the work so people reading don’t confuse the main character for you. It’s a way to create boundaries, and it also allows you to create different voices and characters.

-

Question

Can I move from third person to first person in different sections?

Teachers don’t encourage such a format, but as long as it’s done well stylistically, editors are interested in any exceptional story.

-

Question

Can I write a narration of my life journey in the 3rd person?

Sure, just use your name instead of »I» or «me».

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

To write in third person, refer to people or characters by name or use third person pronouns like he, she, it; his, her, its; him, her, it; himself, herself, itself; they; them; their; and themselves. Avoid first and second person pronouns completely. For academic writing, focus on a general viewpoint rather than a specific person’s to keep things in third person. In other types of writing, you can write in third person by shifting your focus from character to character or by focusing on a single character. To learn more from our Literary Studies Ph.D., like the differences between third person omniscient and third person limited writing, keep reading the article!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 1,038,402 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

«Like a breath of fresh air to see this. Was always intended to be my platform to describe an incredibly negative…» more

Did this article help you?

Простое объяснение правил русского языка. Что значит писать от первого и от третьего лица?

Содержание

- Что значит писать от первого лица?

- Что значит писать от третьего лица?

- Видео: Что значит писать от первого, третьего лица: объяснение, примеры

Рассказ от первого лица — это повествование, которое излагается персонажем или повествователем, являющимся главным участником сюжетного действия.

Что значит писать от первого лица?

Рассказ от первого лица — это рассказ от «Я» или от «Мы». Например:

- Я полетел на Марс.

- Я любил эту женщину.

- Я спустился на дно Марианской впадины.

- Мы исследовали потухший вулкан.

Если вы пишете рассказ от первого лица, используйте в нем местоимения в различных падежах.

Каким может быть рассказ с предложениями, которые вы прочитали выше?

- Постскриптум о любви.

Я любил эту женщину. Я знал, что никогда я и она не будем вместе. Она была красивой и веселой, а я был обычным и невзрачным парнем. Я издалека наблюдал, как она веселится с подругами и как за ней ухаживают красивые мужчины. Я видел, когда она влюбилась в одного из них и вскоре вышла за него замуж. Я радовался, когда у нее родился малыш, и веселая она катала его в коляске. Теперь срок моей любви истек и я рад, что я любил эту женщину. Любовь не может быть несчастной, и я благодарю за нее эту женщину.

- Как мы исследовали потухший вулкан.

На вершине потухшего вулкана мы обнаружили кратер, который порос деревьями и травой. Поскольку глубина кратера была большой, а стены практически отвесными, нами было принято решение спускаться на его дно с помощью альпинистского снаряжения. Спустившись на самое дно, мы обнаружили небольшой водопад и пещеру. Исследовать пещеру мы решили в следующий раз. Красота дикой природы, необычных цветов и деревьев поразила наше воображение.

Что значит писать от третьего лица?

Рассказ от третьего лица — это рассказ от «он», «она», «оно» или «они». Например:

- Он полетел на Марс.

- Она исследовала потухший вулкан.

- Оно прилетело сегодня с Марса.

- Они спустились на дно Марианской впадины.

При написании сочинения от третьего лица, склоняйте местоимения «Он», «Она», «Оно» и «Они» по падежам.

Каким может быть рассказ с предложениями, которые вы прочитали выше?

- Путешествие на Марс.

Сегодня на сверхмощной ракете Иван Иванов полетел на Марс. На космическое путешествие уйдет 2 года. Он совершит посадку на поверхность красной планеты. На Марсе он проведет 2 земных дня, возьмет пробы грунта и вернется на Землю. Также он оставит на красной планете капсулу, в которой будет послание для инопланетян.

- Исследование Марианской впадины.

Самая глубокая точка мирового океана находится на дне Марианской впадины. В 1960 году американский военный Дон Уолш и океанограф Жак Пикар спустились в батискафе на дно впадины. Они установили, что в грунте есть живые бактерии, а на дне живут некоторые рыбы, ранее неизвестные ученым.

Читайте больше статей о русском языке на нашем сайте:

- Как пишется НЕ с причастиями

- НЕВЫПОЛНЕНИЕ или НЕ ВЫПОЛНЕНИЕ, как пишется слитно или раздельно?

- ПОСЕРЕДИНЕ или ПО СЕРЕДИНЕ — как писать?

- НЕМНОГО или НЕ МНОГО — как пишется?

- НЕПРАВДА: как пишется слитно или раздельно?

- Как определить род, число и падеж прилагательного?

- Предметы, названия которых всегда во множественном числе.

- «Все-таки» как правильно пишется?

- Как правильно пишется слово «акклиматизация»?

Видео: Что значит писать от первого, третьего лица: объяснение, примеры

Вспомним уроки языка: личные местоимения

Первое лицо: я, мы

В таком виде повествования рассказчик становится непосредственно персонажем своей истории.

Управляющий сказал мне: «Держу вас только из уважения к вашему почтенному батюшке, а то бы вы у меня давно полетели». Я ему ответил: «Вы слишком льстите мне, ваше превосходительство, полагая, что я умею летать». И потом я слышал, как он сказал: «Уберите этого господина, он портит мне нервы»…

А. Чехов, «Моя жизнь. Рассказ провинциала»

Второе лицо: ты, вы

Открываешь глаза. Солнечный лучик пробирается сквозь приоткрытую занавеску – и зайчик запрыгивает на стену напротив окна. Какое-то время следишь за ним, а потом угол одеяла весело летит на сторону, и ты бежишь на кухню. Мама уже колдует у плиты, а шумный чайник сообщает, что вот-вот будет готов ароматный чай. За это время наскоро чистишь зубы, ополаскиваешь лицо холодной водой, проводишь мокрыми руками по непослушным вихрям. Готов к новому дню.

Как давно такое было. Три месяца назад…

Светлана Локтыш, «Доброе утро, солнышко»

Третье лицо: ты, вы

Рассказчик здесь передает историю, но персонажем ее не является. Иначе говоря, это когда кто-то, или сам автор, рассказывает о событиях, будто наблюдая за ними со стороны.

Которая беднота, может, и получила дворцы, а Иван Савичу дворца, между прочим, не досталось. Рылом не вышел. И жил Иван Савич в прежней своей квартирке, на Большой Пушкарской улице.

А уж и квартирка же, граждане! Одно заглавие, что квартира – в каждом углу притулившись фигура. Бабка Анисья– раз, бабка Фекла – два, Пашка Огурчик – три… Тьфу, ей-богу, считать грустно!В этакой квартирке да при такой профессии, как у Ивана Савича – маляр и живописец – нипочем невозможно было жить.

Давеча случай был: бабка Анисья подолом все контуры на вывеске смахнула. Вот до чего тесно. От этого, может, Иван Савич и из бедности никогда не вылезал…». Зощенко «Матрёнища».

У каждого вида повествования есть свои преимущества и недостатки. Рассмотрим их.

От первого лица

Вести повествование от 1-го лица в рассказе или новелле просто: произведение небольшое, текста немного. Гораздо сложнее выдержать такой формат в более крупных текстах – повестях, романах. Есть риск, что читателя замучают бесконечные «я» (реже – «мы»). Поэтому с текст придется вычистить от многочисленных повторов этих местоимений.

Преимущества повествования от 1-го лица:

- читатель чувствует связь с человеком, который будто разговаривает с ним;

- повествование воспринимается как свидетельство очевидца и может выглядеть более правдоподобным;

- начинающий писатель часто чувствует себя уверенней;

- легче показать эволюцию героя;

- позволяет четко обозначить личное отношение персонажа к описываемым событиям.

Недостатки повествования от 1-го лица:

- часто неопытный автор ассоциирует себя со своим персонажем. Важно помнить: он – не вы. Он может быть вовсе на вас не похож, например, маньяком, дезертиром, а рассказ будет идти именно от его имени;

- у рассказчика ограничено поле зрения. Читатель может слышать и видеть только то, что видит и слышит рассказчик;

- автору сложнее описать, как выглядит сам рассказчик;

- рассказчик не может переместиться туда, где оказаться не в состоянии, и читатель не узнает о некоторых событиях, свидетелем которых рассказчик не был;

- читатель не узнает, как выглядит персонаж, который, например, ударил рассказчика по голове так, что тот потерял сознание. Разве что автор придумает ход, как рассказчик мог об этом узнать. Например, был свидетель, или сестра описала человека, который приходил и спрашивал о нём;

- когда речь зайдет о чувствах или поступках героя, бесконечные «я» могут быть восприняты как жалобы или хвастовство;

- автору придется раскрывать внутренний мир других персонажей только через их поступки, взгляды и слова.

От третьего лица

Повествование от 3-го лица похоже на повествование от 1-го – только нет множественных «я». Однако здесь важно соблюдать правило: в каждой сцене надо излагать мысли только одного персонажа.

Например, если в комнате главный герой и два персонажа, то мы следим за мыслями только главного героя. Потом героя оставляем в комнате, а два персонажа выходят на улицу, идут вместе по проспекту и обсуждают недавний разговор: здесь мы следим за мыслями персонажа, который кажется нам наиболее важным. Если проигнорировать это правило, то повествование получится запутанным и тяжелым.

Преимущества повествования от 3-го лица:

- придает произведению кинематографичность, возникает ощущение «движения камеры»;

- можно перемещать фокус от одного персонажа к другому, смешивать небольшие авторские наблюдения с описанием мыслей и чувств персонажей и их точек зрения;

- автор знает все, что происходит в головах его героев и персонажей, а значит, читатель получает более объемную, объективную картинку;

- написание от третьего лица дает больше простора для творчества и возможность развития нескольких сюжетных линий сразу. Третье лицо – наиболее «маневренное».

Недостатки повествования от 3-го лица:

- по сравнению с первым лицом, сложнее отразить эмоциональную глубину персонажа;

- с возрастанием числа персонажей возрастает риск того, что читателю будет трудно за ними следить. Поэтому автору важно создать четкие образы персонажей и их целей;

- автор должен осторожно «прыгать» от точки зрения одного персонажа к точке зрения другого в рамках одной сцены или главы, иначе читатель перестанет понимать, в чьей голове он сейчас находится.

Странное второе лицо…

Существует также повествование и от 2-го лица: когда сам читатель и есть наблюдатель. Такой стиль изложения материала используют редко: он тяжеловесен, скучен и быстро надоедает читателю.

Однако второе лицо может быть включено в повествование эпизодически. Также второе лицо с успехом используется в стихах:

Ты помнишь, плыли в вышине

И вдруг погасли две звезды.

Но лишь теперь понятно мне,

Что это были я и ты…Леонид Дербенев

Независимо от того, какое лицо избрано для повествования, можно не зацикливаться на недостатках, лучше максимально использовать преимущества. А какая форма ближе, станет понятнее с опытом. Также стоит учитывать требования жанра, например:

- в детективах чаще повествование идет от 1-го лица;

- в любовных романах – от 3-го лица.

Перестройте отрывки, представленные ниже, так, чтобы повествование зазвучало сначала от 3-го лица, а затем – от 2-го лица. (Ответы можно записать в комментариях).

- Макс смотрел на нее и не знал, что ответить. Согласиться – значит, признать свою вину. Все отрицать – будет похоже на оправдания. Он молча развернулся и пошел прочь: если Дана не верит, нет смысла продолжать с ней общение.

2. Я, братцы мои, не люблю баб, которые в шляпках. Ежели баба в шляпке, ежели чулочки на ней фильдекосовые, или мопсик у ней на руках, или зуб золотой, то такая аристократка мне и не баба вовсе, а гладкое место.

А в свое время я, конечно, увлекался одной аристократкой. Гулял с ней, и в театр водил. В театре-то все и вышло. В театре она и развернула свою идеологию во всем объеме.

А встретился я с ней во дворе дома. На собрании. Гляжу, стоит этакая фря. Чулочки на ней, зуб золоченый.

– Откуда, – говорю, – ты, гражданка? Из какого номера?

– Я, – говорит, – из седьмого.

– Пожалуйста, – говорю, – живите.

М. Зощенко «Аристократка»

Урок окончен. Легких вам перьев, дорогие авторы!

Если материал был интересен и полезен, помни, что таковым он может быть и для других людей. 🙂

Понравилась публикация?

Поделись ею с друзьями!