From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Anubis | |

|---|---|

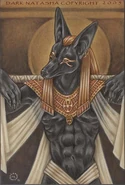

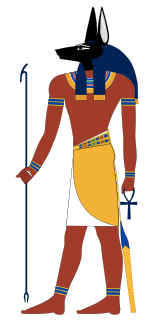

The Egyptian god Anubis (a modern rendition inspired by New Kingdom tomb paintings) |

|

| Name in hieroglyphs | |

| Major cult center | Lycopolis, Cynopolis |

| Symbol | Mummy gauze, fetish, jackal, flail |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Nepthys and Set, Osiris (Middle and New kingdom), or Ra (Old kingdom). |

| Siblings | Wepwawet |

| Consort | Anput, Nephthys[1] |

| Offspring | Kebechet |

| Greek equivalent | Hades or Hermes |

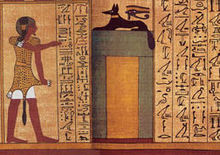

Anubis as a jackal perched atop a tomb, symbolizing his protection of the necropolis

Anubis (;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἄνουβις), also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian (Coptic: ⲁⲛⲟⲩⲡ, romanized: Anoup) is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumed different roles in various contexts. Depicted as a protector of graves as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2890 BC), Anubis was also an embalmer. By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) he was replaced by Osiris in his role as lord of the underworld. One of his prominent roles was as a god who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the «Weighing of the Heart», in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. Anubis is one of the most frequently depicted and mentioned gods in the Egyptian pantheon, however, no relevant myth involved him.[3]

Anubis was depicted in black, a color that symbolized regeneration, life, the soil of the Nile River, and the discoloration of the corpse after embalming. Anubis is associated with his brother Wepwawet, another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog’s head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.[4] Anubis’ female counterpart is Anput. His daughter is the serpent goddess Kebechet.

Name

«Anubis» is a Greek rendering of this god’s Egyptian name.[5][6] Before the Greeks arrived in Egypt, around the 7th century BC, the god was known as Anpu or Inpu. The root of the name in ancient Egyptian language means «a royal child.» Inpu has a root to «inp», which means «to decay.» The god was also known as «First of the Westerners,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «He Who is Upon his Sacred Mountain,» «Ruler of the Nine Bows,» «The Dog who Swallows Millions,» «Master of Secrets,» «He Who is in the Place of Embalming,» and «Foremost of the Divine Booth.»[7] The positions that he had were also reflected in the titles he held such as «He Who Is upon His Mountain,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «Foremost of the Westerners,» and «He Who Is in the Place of Embalming.»[8]

In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – c. 2181 BC), the standard way of writing his name in hieroglyphs was composed of the sound signs inpw followed by a jackal[a] over a ḥtp sign:[10]

A new form with the jackal on a tall stand appeared in the late Old Kingdom and became common thereafter:[10]

Anubis’ name jnpw was possibly pronounced [a.ˈna.pʰa(w)], based on Coptic Anoup and the Akkadian transcription 𒀀𒈾𒉺⟨a-na-pa⟩ in the name <ri-a-na-pa> «Reanapa» that appears in Amarna letter EA 315.[11][12] However, this transcription may also be interpreted as rˁ-nfr, a name similar to that of Prince Ranefer of the Fourth Dynasty.

History

In Egypt’s Early Dynastic period (c. 3100 – c. 2686 BC), Anubis was portrayed in full animal form, with a «jackal» head and body.[13] A jackal god, probably Anubis, is depicted in stone inscriptions from the reigns of Hor-Aha, Djer, and other pharaohs of the First Dynasty.[14] Since Predynastic Egypt, when the dead were buried in shallow graves, jackals had been strongly associated with cemeteries because they were scavengers which uncovered human bodies and ate their flesh.[15] In the spirit of «fighting like with like,» a jackal was chosen to protect the dead, because «a common problem (and cause of concern) must have been the digging up of bodies, shortly after burial, by jackals and other wild dogs which lived on the margins of the cultivation.»[16]

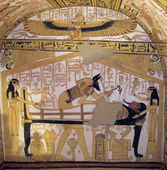

Anubis attending the mummy of the deceased.

Anubis receiving offerings, hieroglyph name in third column from left, 14th century BC; painted limestone; from Saqqara (Egypt)

In the Old Kingdom, Anubis was the most important god of the dead. He was replaced in that role by Osiris during the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BC).[17] In the Roman era, which started in 30 BC, tomb paintings depict him holding the hand of deceased persons to guide them to Osiris.[18]

The parentage of Anubis varied between myths, times and sources. In early mythology, he was portrayed as a son of Ra.[19] In the Coffin Texts, which were written in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), Anubis is the son of either the cow goddess Hesat or the cat-headed Bastet.[20] Another tradition depicted him as the son of Ra and Nephthys.[19] The Greek Plutarch (c. 40–120 AD) reported a tradition that Anubis was the illegitimate son of Nephthys and Osiris, but that he was adopted by Osiris’s wife Isis:[21]

For when Isis found out that Osiris loved her sister and had relations with her in mistaking her sister for herself, and when she saw a proof of it in the form of a garland of clover that he had left to Nephthys – she was looking for a baby, because Nephthys abandoned it at once after it had been born for fear of Seth; and when Isis found the baby helped by the dogs which with great difficulties lead her there, she raised him and he became her guard and ally by the name of Anubis.

George Hart sees this story as an «attempt to incorporate the independent deity Anubis into the Osirian pantheon.»[20] An Egyptian papyrus from the Roman period (30–380 AD) simply called Anubis the «son of Isis.»[20] In Nubia, Anubis was seen as the husband of his mother Nephthys.[1]

In the Ptolemaic period (350–30 BC), when Egypt became a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by Greek pharaohs, Anubis was merged with the Greek god Hermes, becoming Hermanubis.[23][24] The two gods were considered similar because they both guided souls to the afterlife.[25] The center of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name means «city of dogs.» In Book XI of The Golden Ass by Apuleius, there is evidence that the worship of this god was continued in Rome through at least the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egyptian animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was mockingly called «Barker» by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens and Cerberus and Hades in the underworld.[26] In his dialogues, Plato often has Socrates utter oaths «by the dog» (Greek: kai me ton kuna), «by the dog of Egypt», and «by the dog, the god of the Egyptians», both for emphasis and to appeal to Anubis as an arbiter of truth in the underworld.[27]

Roles

Embalmer

As jmy-wt (Imiut or the Imiut fetish) «He who is in the place of embalming», Anubis was associated with mummification. He was also called ḫnty zḥ-nṯr «He who presides over the god’s booth», in which «booth» could refer either to the place where embalming was carried out or the pharaoh’s burial chamber.[28][29]

In the Osiris myth, Anubis helped Isis to embalm Osiris.[17] Indeed, when the Osiris myth emerged, it was said that after Osiris had been killed by Set, Osiris’s organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers; during the rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a wolf-mask-wearing priest supporting the upright mummy.

Protector of tombs

Anubis was a protector of graves and cemeteries. Several epithets attached to his name in Egyptian texts and inscriptions referred to that role. Khenty-Amentiu, which means «foremost of the westerners» and was also the name of a different canine funerary god, alluded to his protecting function because the dead were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile.[30] He took other names in connection with his funerary role, such as tpy-ḏw.f (Tepy-djuef) «He who is upon his mountain» (i.e. keeping guard over tombs from above) and nb-t3-ḏsr (Neb-ta-djeser) «Lord of the sacred land», which designates him as a god of the desert necropolis.[28][29]

The Jumilhac papyrus recounts another tale where Anubis protected the body of Osiris from Set. Set attempted to attack the body of Osiris by transforming himself into a leopard. Anubis stopped and subdued Set, however, and he branded Set’s skin with a hot iron rod. Anubis then flayed Set and wore his skin as a warning against evil-doers who would desecrate the tombs of the dead.[31] Priests who attended to the dead wore leopard skin in order to commemorate Anubis’ victory over Set. The legend of Anubis branding the hide of Set in leopard form was used to explain how the leopard got its spots.[32]

Most ancient tombs had prayers to Anubis carved on them.[33]

Guide of souls

By the late pharaonic era (664–332 BC), Anubis was often depicted as guiding individuals across the threshold from the world of the living to the afterlife.[34] Though a similar role was sometimes performed by the cow-headed Hathor, Anubis was more commonly chosen to fulfill that function.[35] Greek writers from the Roman period of Egyptian history designated that role as that of «psychopomp», a Greek term meaning «guide of souls» that they used to refer to their own god Hermes, who also played that role in Greek religion.[25] Funerary art from that period represents Anubis guiding either men or women dressed in Greek clothes into the presence of Osiris, who by then had long replaced Anubis as ruler of the underworld.[36]

Weigher of hearts

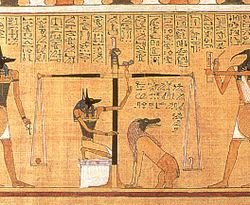

The «weighing of the heart,» from the book of the dead of Hunefer. Anubis is portrayed as both guiding the deceased forward and manipulating the scales, under the scrutiny of the ibis-headed Thoth.

One of the roles of Anubis was as the «Guardian of the Scales.»[37] The critical scene depicting the weighing of the heart, in the Book of the Dead, shows Anubis performing a measurement that determined whether the person was worthy of entering the realm of the dead (the underworld, known as Duat). By weighing the heart of a deceased person against Ma’at (or «truth»), who was often represented as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. Souls heavier than a feather would be devoured by Ammit, and souls lighter than a feather would ascend to a heavenly existence.[38][39]

Portrayal in art

Anubis was one of the most frequently represented deities in ancient Egyptian art.[3] He is depicted in royal tombs as early as the First Dynasty.[7] The god is typically treating a king’s corpse, providing sovereign to mummification rituals and funerals, or standing with fellow gods at the Weighing of the Heart of the Soul in the Hall of Two Truths.[8] One of his most popular representations is of him, with the body of a man and the head of a jackal with pointed ears, standing or kneeling, holding a gold scale while a heart of the soul is being weighed against Ma’at’s white truth feather.[7]

In the early dynastic period, he was depicted in animal form, as a black canine.[40] Anubis’s distinctive black color did not represent the animal, rather it had several symbolic meanings.[41] It represented «the discolouration of the corpse after its treatment with natron and the smearing of the wrappings with a resinous substance during mummification.»[41] Being the color of the fertile silt of the River Nile, to Egyptians, black also symbolized fertility and the possibility of rebirth in the afterlife.[42] In the Middle Kingdom, Anubis was often portrayed as a man with the head of a jackal.[43] An extremely rare depiction of him in fully human form was found in a chapel of Ramesses II in Abydos.[41][6]

Anubis is often depicted wearing a ribbon and holding a nḫ3ḫ3 «flail» in the crook of his arm.[43] Another of Anubis’s attributes was the jmy-wt or imiut fetish, named for his role in embalming.[44] In funerary contexts, Anubis is shown either attending to a deceased person’s mummy or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the enemies of Egypt.[45]

-

Porable shrine of Anubis, exposition in Paris, from the Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62)

-

Isis, left, and Nephthys stand by as Anubis embalms the deceased, 13th century BC

-

The king with Anubis, from the tomb of Horemheb; 1323-1295 BC; tempera on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Anubis amulet; 664–30 BC; faience; height: 4.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Recumbent Anubis; 664–30 BC; limestone, originally painted black; height: 38.1 cm, length: 64 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Statuette of Anubis; 332–30 BC; plastered and painted wood; 42.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Worship

Although he does not appear in many myths, he was extremely popular with Egyptians and those of other cultures.[7] The Greeks linked him to their god Hermes, the god who guided the dead to the afterlife. The pairing was later known as Hermanubis. Anubis was heavily worshipped because, despite modern beliefs, he gave the people hope. People marveled in the guarantee that their body would be respected at death, their soul would be protected and justly judged.[7]

Anubis had male priests who sported wood masks with the god’s likeness when performing rituals.[7][8] His cult center was at Cynopolis in Upper Egypt but memorials were built everywhere and he was universally revered in every part of the nation.[7]

In popular culture

In popular and media culture, Anubis is often falsely portrayed as the sinister god of the dead. He gained popularity during the 20th and 21st centuries through books, video games, and movies where artists would give him evil powers and a dangerous army. Despite his nefarious reputation, his image is still the most recognizable of the Egyptian gods and replicas of his statues and paintings remain popular.

See also

- Abatur, Mandaean uthra who weighs the souls of the dead to determine their fate

- Animal mummy#Miscellaneous animals

- Anput

- Anubias

- Bhairava

- Hades

Notes

- ^ The wild canine species in Egypt, long thought to have been a geographical variant of the golden jackal in older texts, was reclassified in 2015 as a separate species known as the African wolf, which was found to be more closely related to wolves and coyotes than to the jackal.[9] Nevertheless, ancient Greek texts about Anubis constantly refer to the deity as having a dog’s head, not a jackal or wolf’s, and there is still uncertainty as to what canid represents Anubis. Therefore the Name and History section uses the names the original sources used but in quotation marks.

References

- ^ a b Lévai, Jessica (2007). Aspects of the Goddess Nephthys, Especially During the Graeco-Roman Period in Egypt. UMI.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 56

- ^ a b Johnston 2004, p. 579.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Coulter & Turner 2000, p. 58.

- ^ a b «Gods and Religion in Ancient Egypt – Anubis». Archived from the original on 27 December 2002. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Anubis». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c «Anubis». Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Johnson, Warren E.; o’Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015). «Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species». Current Biology. 25 (#16): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- ^ a b Leprohon 1990, p. 164, citing Fischer 1968, p. 84 and Lapp 1986, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Conder 1894, p. 85.

- ^ «CDLI-Archival View». cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 (burials in shallow graves in Predynastic Egypt); Freeman 1997, p. 91 (rest of the information).

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 («fighting like with like» and «by jackals and other wild dogs»).

- ^ a b Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 166–67.

- ^ a b Hart 1986, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Campbell, Price (2018). Ancient Egypt — Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ Peacock 2000, pp. 437–38 (Hellenistic kingdom).

- ^ «Hermanubis | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon». Babylon.com. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b Riggs 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Hoerber 1963, p. 269 (for Cerberus and Hades).

- ^ E.g., Gorgias, 482b (Blackwood, Crossett & Long 1962, p. 318), or The Republic, 399e, 567e, 592a (Hoerber 1963, p. 268).

- ^ a b Hart 1986, pp. 23–24; Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

- ^ a b Vischak, Deborah (27 October 2014). Community and Identity in Ancient Egypt: The Old Kingdom Cemetery at Qubbet el-Hawa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107027602.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 23.

- ^ Armour 2001.

- ^ Zandee 1960, p. 255.

- ^ «The Gods of Ancient Egypt – Anubis». touregypt.net. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Kinsley 1989, p. 178; Riggs 2005, p. 166 («The motif of Anubis, or less frequently Hathor, leading the deceased to the afterlife was well-established in Egyptian art and thought by the end of the pharaonic era.»).

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127 and 166.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127–28 and 166–67.

- ^ Faulkner, Andrews & Wasserman 2008, p. 155.

- ^ «Museum Explorer / Death in Ancient Egypt – Weighing the heart». British Museum. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ «Gods of Ancient Egypt: Anubis». Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 22; Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ a b «Ancient Egypt: the Mythology – Anubis». Egyptianmyths.net. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 281.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

Bibliography

- Armour, Robert A. (2001), Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press

- Blackwood, Russell; Crossett, John; Long, Herbert (1962), «Gorgias 482b», The Classical Journal, 57 (7): 318–19, JSTOR 3295283.

- Conder, Claude Reignier (trans.) (1894) [1893], The Tell Amarna Tablets (Second ed.), London: Published for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund by A.P. Watt, ISBN 978-1-4147-0156-1.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Jefferson (NC) and London: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-0317-2.

- Faulkner, Raymond O.; Andrews, Carol; Wasserman, James (2008), The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day, Chronicle Books, ISBN 978-0-8118-6489-3.

- Fischer, Henry George (1968), Dendera in the Third Millennium B. C., Down to the Theban Domination of Upper Egypt, London: J.J. Augustin.

- Freeman, Charles (1997), The Legacy of Ancient Egypt, New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-816-03656-1.

- Gryglewski, Ryszard W. (2002), «Medical and Religious Aspects of Mummification in Ancient Egypt» (PDF), Organon, 31 (31): 128–48, PMID 15017968, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Hart, George (1986), A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 978-0-415-34495-1.

- Hoerber, Robert G. (1963), «The Socratic Oath ‘By the Dog’«, The Classical Journal, 58 (6): 268–69, JSTOR 3293989.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles (general ed.) (2004), Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- Kinsley, David (1989), The Goddesses’ Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West, Albany (NY): State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-835-5. (paperback).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lapp, Günther (1986), Die Opferformel des Alten Reiches: unter Berücksichtigung einiger späterer Formen [The offering formula of the Old Kingdom: considering a few later forms], Mainz am Rhein: Zabern, ISBN 978-3805308724.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (1990), «The Offering Formula in the First Intermediate Period», The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 76: 163–64, doi:10.1177/030751339007600115, JSTOR 3822017, S2CID 192258122.

- Peacock, David (2000), «The Roman Period», in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Riggs, Christina (2005), The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003), The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt, London: Routledge

- Zandee, Jan (1960), Death as an Enemy: According to Ancient Egyptian Conceptions, Brill Archive, GGKEY:A7N6PJCAF5Q

Further reading

- Duquesne, Terence (2005). The Jackal Divinities of Egypt I. Darengo Publications. ISBN 978-1-871266-24-5.

- El-Sadeek, Wafaa; Abdel Razek, Sabah (2007). Anubis, Upwawet, and Other Deities: Personal Worship and Official Religion in Ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-437-231-5.

- Grenier, J.-C. (1977). Anubis alexandrin et romain (in French). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04917-8.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anubis.

Look up Anubis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Anubis | |

|---|---|

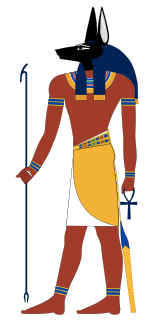

The Egyptian god Anubis (a modern rendition inspired by New Kingdom tomb paintings) |

|

| Name in hieroglyphs | |

| Major cult center | Lycopolis, Cynopolis |

| Symbol | Mummy gauze, fetish, jackal, flail |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Nepthys and Set, Osiris (Middle and New kingdom), or Ra (Old kingdom). |

| Siblings | Wepwawet |

| Consort | Anput, Nephthys[1] |

| Offspring | Kebechet |

| Greek equivalent | Hades or Hermes |

Anubis as a jackal perched atop a tomb, symbolizing his protection of the necropolis

Anubis (;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἄνουβις), also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian (Coptic: ⲁⲛⲟⲩⲡ, romanized: Anoup) is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumed different roles in various contexts. Depicted as a protector of graves as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2890 BC), Anubis was also an embalmer. By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) he was replaced by Osiris in his role as lord of the underworld. One of his prominent roles was as a god who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the «Weighing of the Heart», in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. Anubis is one of the most frequently depicted and mentioned gods in the Egyptian pantheon, however, no relevant myth involved him.[3]

Anubis was depicted in black, a color that symbolized regeneration, life, the soil of the Nile River, and the discoloration of the corpse after embalming. Anubis is associated with his brother Wepwawet, another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog’s head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.[4] Anubis’ female counterpart is Anput. His daughter is the serpent goddess Kebechet.

Name

«Anubis» is a Greek rendering of this god’s Egyptian name.[5][6] Before the Greeks arrived in Egypt, around the 7th century BC, the god was known as Anpu or Inpu. The root of the name in ancient Egyptian language means «a royal child.» Inpu has a root to «inp», which means «to decay.» The god was also known as «First of the Westerners,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «He Who is Upon his Sacred Mountain,» «Ruler of the Nine Bows,» «The Dog who Swallows Millions,» «Master of Secrets,» «He Who is in the Place of Embalming,» and «Foremost of the Divine Booth.»[7] The positions that he had were also reflected in the titles he held such as «He Who Is upon His Mountain,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «Foremost of the Westerners,» and «He Who Is in the Place of Embalming.»[8]

In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – c. 2181 BC), the standard way of writing his name in hieroglyphs was composed of the sound signs inpw followed by a jackal[a] over a ḥtp sign:[10]

A new form with the jackal on a tall stand appeared in the late Old Kingdom and became common thereafter:[10]

Anubis’ name jnpw was possibly pronounced [a.ˈna.pʰa(w)], based on Coptic Anoup and the Akkadian transcription 𒀀𒈾𒉺⟨a-na-pa⟩ in the name <ri-a-na-pa> «Reanapa» that appears in Amarna letter EA 315.[11][12] However, this transcription may also be interpreted as rˁ-nfr, a name similar to that of Prince Ranefer of the Fourth Dynasty.

History

In Egypt’s Early Dynastic period (c. 3100 – c. 2686 BC), Anubis was portrayed in full animal form, with a «jackal» head and body.[13] A jackal god, probably Anubis, is depicted in stone inscriptions from the reigns of Hor-Aha, Djer, and other pharaohs of the First Dynasty.[14] Since Predynastic Egypt, when the dead were buried in shallow graves, jackals had been strongly associated with cemeteries because they were scavengers which uncovered human bodies and ate their flesh.[15] In the spirit of «fighting like with like,» a jackal was chosen to protect the dead, because «a common problem (and cause of concern) must have been the digging up of bodies, shortly after burial, by jackals and other wild dogs which lived on the margins of the cultivation.»[16]

Anubis attending the mummy of the deceased.

Anubis receiving offerings, hieroglyph name in third column from left, 14th century BC; painted limestone; from Saqqara (Egypt)

In the Old Kingdom, Anubis was the most important god of the dead. He was replaced in that role by Osiris during the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BC).[17] In the Roman era, which started in 30 BC, tomb paintings depict him holding the hand of deceased persons to guide them to Osiris.[18]

The parentage of Anubis varied between myths, times and sources. In early mythology, he was portrayed as a son of Ra.[19] In the Coffin Texts, which were written in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), Anubis is the son of either the cow goddess Hesat or the cat-headed Bastet.[20] Another tradition depicted him as the son of Ra and Nephthys.[19] The Greek Plutarch (c. 40–120 AD) reported a tradition that Anubis was the illegitimate son of Nephthys and Osiris, but that he was adopted by Osiris’s wife Isis:[21]

For when Isis found out that Osiris loved her sister and had relations with her in mistaking her sister for herself, and when she saw a proof of it in the form of a garland of clover that he had left to Nephthys – she was looking for a baby, because Nephthys abandoned it at once after it had been born for fear of Seth; and when Isis found the baby helped by the dogs which with great difficulties lead her there, she raised him and he became her guard and ally by the name of Anubis.

George Hart sees this story as an «attempt to incorporate the independent deity Anubis into the Osirian pantheon.»[20] An Egyptian papyrus from the Roman period (30–380 AD) simply called Anubis the «son of Isis.»[20] In Nubia, Anubis was seen as the husband of his mother Nephthys.[1]

In the Ptolemaic period (350–30 BC), when Egypt became a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by Greek pharaohs, Anubis was merged with the Greek god Hermes, becoming Hermanubis.[23][24] The two gods were considered similar because they both guided souls to the afterlife.[25] The center of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name means «city of dogs.» In Book XI of The Golden Ass by Apuleius, there is evidence that the worship of this god was continued in Rome through at least the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egyptian animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was mockingly called «Barker» by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens and Cerberus and Hades in the underworld.[26] In his dialogues, Plato often has Socrates utter oaths «by the dog» (Greek: kai me ton kuna), «by the dog of Egypt», and «by the dog, the god of the Egyptians», both for emphasis and to appeal to Anubis as an arbiter of truth in the underworld.[27]

Roles

Embalmer

As jmy-wt (Imiut or the Imiut fetish) «He who is in the place of embalming», Anubis was associated with mummification. He was also called ḫnty zḥ-nṯr «He who presides over the god’s booth», in which «booth» could refer either to the place where embalming was carried out or the pharaoh’s burial chamber.[28][29]

In the Osiris myth, Anubis helped Isis to embalm Osiris.[17] Indeed, when the Osiris myth emerged, it was said that after Osiris had been killed by Set, Osiris’s organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers; during the rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a wolf-mask-wearing priest supporting the upright mummy.

Protector of tombs

Anubis was a protector of graves and cemeteries. Several epithets attached to his name in Egyptian texts and inscriptions referred to that role. Khenty-Amentiu, which means «foremost of the westerners» and was also the name of a different canine funerary god, alluded to his protecting function because the dead were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile.[30] He took other names in connection with his funerary role, such as tpy-ḏw.f (Tepy-djuef) «He who is upon his mountain» (i.e. keeping guard over tombs from above) and nb-t3-ḏsr (Neb-ta-djeser) «Lord of the sacred land», which designates him as a god of the desert necropolis.[28][29]

The Jumilhac papyrus recounts another tale where Anubis protected the body of Osiris from Set. Set attempted to attack the body of Osiris by transforming himself into a leopard. Anubis stopped and subdued Set, however, and he branded Set’s skin with a hot iron rod. Anubis then flayed Set and wore his skin as a warning against evil-doers who would desecrate the tombs of the dead.[31] Priests who attended to the dead wore leopard skin in order to commemorate Anubis’ victory over Set. The legend of Anubis branding the hide of Set in leopard form was used to explain how the leopard got its spots.[32]

Most ancient tombs had prayers to Anubis carved on them.[33]

Guide of souls

By the late pharaonic era (664–332 BC), Anubis was often depicted as guiding individuals across the threshold from the world of the living to the afterlife.[34] Though a similar role was sometimes performed by the cow-headed Hathor, Anubis was more commonly chosen to fulfill that function.[35] Greek writers from the Roman period of Egyptian history designated that role as that of «psychopomp», a Greek term meaning «guide of souls» that they used to refer to their own god Hermes, who also played that role in Greek religion.[25] Funerary art from that period represents Anubis guiding either men or women dressed in Greek clothes into the presence of Osiris, who by then had long replaced Anubis as ruler of the underworld.[36]

Weigher of hearts

The «weighing of the heart,» from the book of the dead of Hunefer. Anubis is portrayed as both guiding the deceased forward and manipulating the scales, under the scrutiny of the ibis-headed Thoth.

One of the roles of Anubis was as the «Guardian of the Scales.»[37] The critical scene depicting the weighing of the heart, in the Book of the Dead, shows Anubis performing a measurement that determined whether the person was worthy of entering the realm of the dead (the underworld, known as Duat). By weighing the heart of a deceased person against Ma’at (or «truth»), who was often represented as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. Souls heavier than a feather would be devoured by Ammit, and souls lighter than a feather would ascend to a heavenly existence.[38][39]

Portrayal in art

Anubis was one of the most frequently represented deities in ancient Egyptian art.[3] He is depicted in royal tombs as early as the First Dynasty.[7] The god is typically treating a king’s corpse, providing sovereign to mummification rituals and funerals, or standing with fellow gods at the Weighing of the Heart of the Soul in the Hall of Two Truths.[8] One of his most popular representations is of him, with the body of a man and the head of a jackal with pointed ears, standing or kneeling, holding a gold scale while a heart of the soul is being weighed against Ma’at’s white truth feather.[7]

In the early dynastic period, he was depicted in animal form, as a black canine.[40] Anubis’s distinctive black color did not represent the animal, rather it had several symbolic meanings.[41] It represented «the discolouration of the corpse after its treatment with natron and the smearing of the wrappings with a resinous substance during mummification.»[41] Being the color of the fertile silt of the River Nile, to Egyptians, black also symbolized fertility and the possibility of rebirth in the afterlife.[42] In the Middle Kingdom, Anubis was often portrayed as a man with the head of a jackal.[43] An extremely rare depiction of him in fully human form was found in a chapel of Ramesses II in Abydos.[41][6]

Anubis is often depicted wearing a ribbon and holding a nḫ3ḫ3 «flail» in the crook of his arm.[43] Another of Anubis’s attributes was the jmy-wt or imiut fetish, named for his role in embalming.[44] In funerary contexts, Anubis is shown either attending to a deceased person’s mummy or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the enemies of Egypt.[45]

-

Porable shrine of Anubis, exposition in Paris, from the Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62)

-

Isis, left, and Nephthys stand by as Anubis embalms the deceased, 13th century BC

-

The king with Anubis, from the tomb of Horemheb; 1323-1295 BC; tempera on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Anubis amulet; 664–30 BC; faience; height: 4.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Recumbent Anubis; 664–30 BC; limestone, originally painted black; height: 38.1 cm, length: 64 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Statuette of Anubis; 332–30 BC; plastered and painted wood; 42.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Worship

Although he does not appear in many myths, he was extremely popular with Egyptians and those of other cultures.[7] The Greeks linked him to their god Hermes, the god who guided the dead to the afterlife. The pairing was later known as Hermanubis. Anubis was heavily worshipped because, despite modern beliefs, he gave the people hope. People marveled in the guarantee that their body would be respected at death, their soul would be protected and justly judged.[7]

Anubis had male priests who sported wood masks with the god’s likeness when performing rituals.[7][8] His cult center was at Cynopolis in Upper Egypt but memorials were built everywhere and he was universally revered in every part of the nation.[7]

In popular culture

In popular and media culture, Anubis is often falsely portrayed as the sinister god of the dead. He gained popularity during the 20th and 21st centuries through books, video games, and movies where artists would give him evil powers and a dangerous army. Despite his nefarious reputation, his image is still the most recognizable of the Egyptian gods and replicas of his statues and paintings remain popular.

See also

- Abatur, Mandaean uthra who weighs the souls of the dead to determine their fate

- Animal mummy#Miscellaneous animals

- Anput

- Anubias

- Bhairava

- Hades

Notes

- ^ The wild canine species in Egypt, long thought to have been a geographical variant of the golden jackal in older texts, was reclassified in 2015 as a separate species known as the African wolf, which was found to be more closely related to wolves and coyotes than to the jackal.[9] Nevertheless, ancient Greek texts about Anubis constantly refer to the deity as having a dog’s head, not a jackal or wolf’s, and there is still uncertainty as to what canid represents Anubis. Therefore the Name and History section uses the names the original sources used but in quotation marks.

References

- ^ a b Lévai, Jessica (2007). Aspects of the Goddess Nephthys, Especially During the Graeco-Roman Period in Egypt. UMI.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 56

- ^ a b Johnston 2004, p. 579.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Coulter & Turner 2000, p. 58.

- ^ a b «Gods and Religion in Ancient Egypt – Anubis». Archived from the original on 27 December 2002. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Anubis». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c «Anubis». Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Johnson, Warren E.; o’Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015). «Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species». Current Biology. 25 (#16): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- ^ a b Leprohon 1990, p. 164, citing Fischer 1968, p. 84 and Lapp 1986, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Conder 1894, p. 85.

- ^ «CDLI-Archival View». cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 (burials in shallow graves in Predynastic Egypt); Freeman 1997, p. 91 (rest of the information).

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 («fighting like with like» and «by jackals and other wild dogs»).

- ^ a b Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 166–67.

- ^ a b Hart 1986, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Campbell, Price (2018). Ancient Egypt — Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ Peacock 2000, pp. 437–38 (Hellenistic kingdom).

- ^ «Hermanubis | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon». Babylon.com. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b Riggs 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Hoerber 1963, p. 269 (for Cerberus and Hades).

- ^ E.g., Gorgias, 482b (Blackwood, Crossett & Long 1962, p. 318), or The Republic, 399e, 567e, 592a (Hoerber 1963, p. 268).

- ^ a b Hart 1986, pp. 23–24; Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

- ^ a b Vischak, Deborah (27 October 2014). Community and Identity in Ancient Egypt: The Old Kingdom Cemetery at Qubbet el-Hawa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107027602.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 23.

- ^ Armour 2001.

- ^ Zandee 1960, p. 255.

- ^ «The Gods of Ancient Egypt – Anubis». touregypt.net. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Kinsley 1989, p. 178; Riggs 2005, p. 166 («The motif of Anubis, or less frequently Hathor, leading the deceased to the afterlife was well-established in Egyptian art and thought by the end of the pharaonic era.»).

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127 and 166.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127–28 and 166–67.

- ^ Faulkner, Andrews & Wasserman 2008, p. 155.

- ^ «Museum Explorer / Death in Ancient Egypt – Weighing the heart». British Museum. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ «Gods of Ancient Egypt: Anubis». Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 22; Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ a b «Ancient Egypt: the Mythology – Anubis». Egyptianmyths.net. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 281.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

Bibliography

- Armour, Robert A. (2001), Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press

- Blackwood, Russell; Crossett, John; Long, Herbert (1962), «Gorgias 482b», The Classical Journal, 57 (7): 318–19, JSTOR 3295283.

- Conder, Claude Reignier (trans.) (1894) [1893], The Tell Amarna Tablets (Second ed.), London: Published for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund by A.P. Watt, ISBN 978-1-4147-0156-1.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Jefferson (NC) and London: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-0317-2.

- Faulkner, Raymond O.; Andrews, Carol; Wasserman, James (2008), The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day, Chronicle Books, ISBN 978-0-8118-6489-3.

- Fischer, Henry George (1968), Dendera in the Third Millennium B. C., Down to the Theban Domination of Upper Egypt, London: J.J. Augustin.

- Freeman, Charles (1997), The Legacy of Ancient Egypt, New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-816-03656-1.

- Gryglewski, Ryszard W. (2002), «Medical and Religious Aspects of Mummification in Ancient Egypt» (PDF), Organon, 31 (31): 128–48, PMID 15017968, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Hart, George (1986), A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 978-0-415-34495-1.

- Hoerber, Robert G. (1963), «The Socratic Oath ‘By the Dog’«, The Classical Journal, 58 (6): 268–69, JSTOR 3293989.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles (general ed.) (2004), Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- Kinsley, David (1989), The Goddesses’ Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West, Albany (NY): State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-835-5. (paperback).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lapp, Günther (1986), Die Opferformel des Alten Reiches: unter Berücksichtigung einiger späterer Formen [The offering formula of the Old Kingdom: considering a few later forms], Mainz am Rhein: Zabern, ISBN 978-3805308724.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (1990), «The Offering Formula in the First Intermediate Period», The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 76: 163–64, doi:10.1177/030751339007600115, JSTOR 3822017, S2CID 192258122.

- Peacock, David (2000), «The Roman Period», in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Riggs, Christina (2005), The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003), The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt, London: Routledge

- Zandee, Jan (1960), Death as an Enemy: According to Ancient Egyptian Conceptions, Brill Archive, GGKEY:A7N6PJCAF5Q

Further reading

- Duquesne, Terence (2005). The Jackal Divinities of Egypt I. Darengo Publications. ISBN 978-1-871266-24-5.

- El-Sadeek, Wafaa; Abdel Razek, Sabah (2007). Anubis, Upwawet, and Other Deities: Personal Worship and Official Religion in Ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-437-231-5.

- Grenier, J.-C. (1977). Anubis alexandrin et romain (in French). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04917-8.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anubis.

Look up Anubis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

|

|

| Анубис (Инпу) | |

|---|---|

Анубис бог с головой шакала |

|

| Мифология: | Древний Египет |

| Имя на других языках: | греч. Ἄνουβις лат. Anubis |

| Занятие: | проводник умерших в загробном царстве, оберегатель кладбищ и мумий |

| Отец: | Осирис |

| Мать: | Нефтида |

| Супруга: | Инпут |

| Связанные персонажи: | Гор, Осирис, Исида |

| Иллюстрации на Викискладе? |

Ану́бис (греч.), Инпу (др. егип.) — божество Древнего Египта с головой шакала и телом человека, проводник умерших в загробный мир. В Старом царстве являлся покровителем некрополей и кладбищ, один из судей царства мертвых, хранитель ядов и лекарств. В древнеегипетской мифологии сын Осириса.[1][2][3][4][5] Центром культа Анубиса являлась столица XVII верхнеегипетского нома г. Кинополь. Изображался в образе шакала или дикой собаки Саб; иногда в виде человека с головой шакала или собаки[6]. В Цикле Осириса помогал Исиде в поисках частей Осириса. Священные животные — шакал[7], собака.

Содержание

- 1 История

- 2 Место в пантеоне

- 3 Анубис в Цикле Осириса

- 4 Анубис в античной литературе

- 5 Связанные божества

- 6 Примечания

- 7 Ссылки

История

В период анимизма Анубис представлялся в образе волка[8]. С определённого периода развития религии Древнего Египта Анубиса стали изображать в виде человека с головой собаки, при этом функции божества изменились. Столица XVII египетского нома Кинополь на протяжении всей истории Древнего Египта был центром культа Анубиса[7]. Египтологи отмечают быстрое и повсеместное распространение данного культа в ранний период. В период Древнего царства Анубис был правителем загробного мира и носил эпитет Хентиаменти. К тому же, до появления культа Осириса он являлся главным божеством Запада. Согласно некоторым источникам «Хентиаментиу» является названием местоположения храма, в котором поклонялись этому божеству[8].

Анубис в образе собаки. Статуэтка из гробницы Тутанхамона

Одним из вариантов перевода данного эпитета является «Первый из жителей Запада». С расцветом культа Осириса эпитет правителя Дуата и некоторые функции Анубиса переходят непосредственно к богу Осирису (в Старом Царстве он олицетворял умершего фараона)[7]. Сам же Анубис становится проводником умерших по Аменти (др.-егип. «Запад») — область Дуата, через которую душа попадала на Суд Осириса.

В одном из текстов Книги Мёртвых, приведённых в Папирусе Ани, даётся подробное описание представлений египтян о загробном мире. Данный текст, предположительно был написан во времена XVIII династии. В одной из глав данного текста приводится описание Суда Осириса, на котором Анубис взвешивал сердце на Весах истины. На левой чаше весов помещалось сердце умершего, на правое — перо богини Маат, которое символизировало истину.

Место в пантеоне

Анубис с мумией. Роспись на стене гробницы Сеннеджема

В период анимизма Анубис представлялся в образе шакала[8]. С определённого периода развития религии Древнего Египта Анубиса стали изображать в виде человека с головой собаки, при этом функции божества изменились. Столица XVII египетского нома Кинополь на протяжении всей истории Древнего Египта был центром культа Анубиса[7]. Египтологи отмечают быстрое и повсеместное распространение данного культа в ранний период. В период Древнего царства Анубис был правителем загробного мира и носил эпитет Хентиаменти. К тому же, до появления культа Осириса он являлся главным божеством Запада. Согласно некоторым источникам «Хентиаментиу» является названием местоположения храма, в котором поклонялись этому божеству[8]. Анубис в образе собаки. Статуэтка из гробницы Тутанхамона

Одним из вариантов перевода данного эпитета является «Первый из жителей Запада». С расцветом культа Осириса эпитет правителя Дуата и некоторые функции Анубиса переходят непосредственно к богу Осирису (в Старом Царстве он олицетворял умершего фараона)[7]. Сам же Анубис становится проводником умерших по Аменти (др.-егип. «Запад») — область Дуата, через которую душа попадала на Суд Осириса.

В одном из текстов Книги Мёртвых, приведённых в Папирусе Ани, даётся подробное описание представлений египтян о загробном мире. Данный текст, предположительно был написан во времена XVIII династии. В одной из глав данного текста приводится описание Суда Осириса, на котором Анубис взвешивал сердце на Весах истины. На левой чаше весов помещалось сердце умершего, на правое — перо богини Маат, которое символизировало истину.

Анубис в Цикле Осириса

Статуэтка Анубиса.

В Цикле Осириса Анубис был сыном Осириса и Нефтиды. Жена Сета Нефтида влюбилась в Осириса и, приняв облик Исиды, совратила его. В результате соития был рожден бог Анубис. Испугавшись возмездия Сета за измену, Нефтида бросила младенца в камышовых зарослях, где его потом нашла богиня Исида. После бог Анубис стал помогать Исиде в поисках частей Осириса и принял участие в бальзамировании воссозданного тела Осириса.

Анубис в античной литературе

В произведении Плутарха «Исида и Осирис» приводится трактовка, в которой Анубис есть сын Сета и Нефтиды, который был найден и воспитан Исидой [9]. Страбон упоминает, что это — египетское божество, почитаемое в XVII (Кинополисском) верхнеегипетском номе[10]. Согласно Вергилию, Анубис был изображен на щите Энея[11]. Ювенал упоминает о почитании божества в Риме[12].

Греки отождествляли Анубиса с Гермесом.[1][2][3][4]

Связанные божества

- Инпут (др.-егип.) — в египетской мифологии богиня Дуата (место пребывания умерших). Изображалась в виде женщины с головой собаки. В XVII (Кинополисском) верхнеегипетском номе, носящем её имя, считалась женой Анубиса. Иногда почиталась как женская форма Анубиса[8].

Суд Анубиса: взвешивание души.

- Упуаут (др.-егип. «Открывающий пути»), Офоис (греч.) — в египетской мифологии бог в образе волка, проводник умершего в Дуат.

- Исдес (также произносится как Астенну, Астен, Истен или Астес) — один из покровителей загробного мира (Дуат, Западной пустыни) в египетской мифологии, близкий в этом плане к Анубису. Исдес изображался в виде крупного чёрного пса, подобно тому, как Анубис изображался в виде шакала. В Поздний период отождествлялся с Анубисом[7].

Примечания

- ↑ 1 2 «Мифы народов мира»[1]

- ↑ 1 2 «Древнеегипетский словарь-справочник»[2]

- ↑ 1 2 «Словарь духов и богов германо-скандинавской, египетской, греческой, ирландской, японской мифологии, мифологий индейцев майя и ацтеков.»[3]

- ↑ 1 2 «Краткий словарь мифологии и древностей». М.Корш. Санкт-Петербург, издание А. С. Суворина, 1894.[4]

- ↑ «Словарь иностранных слов русского языка»[5]

- ↑ Мифы народов мира / Ред. С. А. Токарев. — М.: Советская энциклопедия, 1991. — Т. 1, с. 89.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Иван Рак. Мифы Древнего Египта.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Макс Мюллер. Египетская Мифология.

- ↑ Плутарх. Об Исиде и Осирисе 14; 44, см. Любкер Ф. Реальный словарь классических древностей. М., 2001. В 3 т. Т.1. С.127.

- ↑ Страбон. География XVII 1, 40 (стр.812)

- ↑ Вергилий. Энеида VIII 698

- ↑ См. Ювенал. Сатиры VI 534

Ссылки

- Анубис // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона: В 86 томах (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- Статья об Анубисе

- В. Д. Гладкий «Древний Мир» Том 2

- Анубисы

- Символы Египта

| |

||

|---|---|---|

| Мифология | Аб • Аменти • Андросфинкс • Анх • Атет • Ба • Бенбен • Бенну • Грифоны • Джед • Дуат • Ка • Криосфинкс • Нумерология • Огдоада • Пантеизм • Политеизм • Поля Иалу • Сах • Священный скарабей • Сектет • Сфинкс • Уаджет • Уас • Урей • Фиванская триада • Хат • Хиеракосфинкс • Ху • Четыре сына Хора • Эманация • Эннеада • Язычество |  |

| Боги | Абеш-ими-дуат • Аби • Айхи • Акен • Акер • Ам-хех • Амон • Амонемипет • Амсет • Анеджти • Анубис • Апис • Атон • Атум • Аха • Аш • Ба-Пеф • Баби • Банебджедет • Бата • Бес • Бухис • Венег • Геб • Германубис • Гор • Гор-ахти • Дуамутеф • Имиут • Имхотеп • Ипет-хемет • Квебехсенуф • Кебу • Кук • Маахес • Мандулис • Меримутеф • Мехен • Мин • Мневис • Монту • Немти • Непри • Нефертум • Нехебкау • Нун • Онурис • Осирис • Петбе • Птах • Ра • Рем • Себек • Серапис • Сет • Сокар • Сопду • Татенен • Текем • Тот • Туту • Уадж-вер • Упуаут • Ха • Хапи • Хапи • Хека • Хемен • Хентиаменти • Хепри • Херишеф • Хех • Хнум • Хнум-Ра • Хонсу • Ченти-чети • Шаи • Шед • Шезму • Шу • Ях | |

| Богини | Амаунет • Аментет • Анат • Анит • Анукет • Астарта • Бат • Баст • Иабет • Инпут • Исида • Иунит • Иусат • Кадеш • Кебхут • Маат • Мафдет • Менхит • Меритсегер • Мерт • Месхенет • Мехурт • Мут • Нейт • Нефтида • Нехбет • Нут • Око Ра • Пахт • Рат-тауи • Рененутет • Сатис • Селкет • Сехмет • Сешат • Сиа • Сопдет • Та-Бичет • Таурт • Тененет • Тефнут • Уаджит • Унут • Уретхекау • Усрет • Хатмехит • Хатхор • Хаухет • Хедетет • Хекат • Хемсут • Хенсит • Царица Небесная | |

| Демоны | Амат • Апоп • Шезму | |

| Тексты | Амдуат • Книга врат • Книги дыхания • Книга загробного мира • Книга земли • Книга мёртвых • Книга Небесной Коровы • Книга пещер • Литания Ра • Тексты пирамид • Тексты Саркофагов | |

| Верования | Атонизм • Философия • Канопа • Отверзение уст • Погребальные обряды • Проклятие фараонов • Ушебти • Формула подношения • Храмы | |

Категории:

- Древнеегипетские боги

- Боги смерти и загробного мира

- Киноцефалы

- Африка в древнегреческой мифологии

- Боги по алфавиту

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

Игры ⚽ Нужен реферат?

Синонимы:

бог, покровитель

- Уаджет

- Эннеада

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «Анубис» в других словарях:

-

Анубис — (Anubis, Ανουβις). Египетское божество, сын Осириса и Изиды. Его изображали в виде человека с головой шакала (или собаки). Анубиса сопоставляют с греческим Гермесом. (Источник: «Краткий словарь мифологии и древностей». М.Корш. Санкт Петербург,… … Энциклопедия мифологии

-

Анубис — извлекает сердце умершего, чтобы взвесить его на суде Осириса. Роспись гробницы. XIII в. до н. э. Анубис извлекает сердце умершего, чтобы взвесить его на суде Осириса. Роспись гробницы. XIII в. до н. э. Анубис () в мифах древних египтян… … Энциклопедический словарь «Всемирная история»

-

Анубис — Анубис. Деталь погребальной пелены. Сер. 2 в. Музей изобразительных искусств имени А.С. Пушкина. АНУБИС, в египетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых. Почитался в облике шакала. Анубис, завершающий мумификацию покойника . Древнеегипетская… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

АНУБИС — (древн. егип.). Древнеегипетское божество, сын Озириса, почитавшееся охранителем границ Египта и изображавшееся обыкновенно с собачьей головой. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910. АНУБИС бог египетской… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

АНУБИС — АНУБИС, в египетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых. Почитался в облике шакала … Современная энциклопедия

-

АНУБИС — в древнеегипетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых, а также некрополей, погребальных обрядов и бальзамирования. Изображался в облике волка, шакала или человека с головой шакала … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

анубис — сущ., кол во синонимов: 2 • бог (375) • покровитель (40) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

Анубис — в древнеегипетской мифологии бог покровитель мёртвых, а также некрополей, погребальных обрядов и бальзамирования. Изображался в облике волка, шакала или человека с головой шакала. * * * АНУБИС АНУБИС, в древнеегипетской мифологии бог покровитель … Энциклопедический словарь

-

АНУБИС — древнеегипетский бог загробного мира. В ранний период развития египетской религии это шакалообразное божество, пожирающее умерших. Позже Анубис сохранил лишь отдельные черты, выдававшие его животное происхождение. Будучи богом некрополя Сиута… … Энциклопедия Кольера

-

АНУБИС (обезьяна) — АНУБИС (зеленый павиан; Papio anubis), вид обезьян рода павианов (см. ПАВИАНЫ). Немного крупнее гамадрила (см. ГАМАДРИЛ): масса его тела 25–30 кг, длина тела около 80 см, хвоста 50–60 см. Самки меньше самцов. Туловище анубисов более удлиненное,… … Энциклопедический словарь

18+

© Академик, 2000-2023

-

Обратная связь:

Техподдержка,

Реклама на сайте

- 👣 Путешествия

Экспорт словарей на сайты, сделанные на PHP,

Joomla,

Drupal,

WordPress, MODx.

- Пометить текст и поделиться

- Искать во всех словарях

- Искать в переводах

- Искать в Интернете

Поделиться ссылкой на выделенное

| This article needs more links. Please improve this article by adding links that are relevant to the context within the existing article. (June 2018) |

For the Stargate SG-1 character, see Anubis (Stargate)

Anubis (Ancient Greek: Ἄνουβις) is the Greek name for a jackal-headed god associated with mummification and the afterlife in Egyptian mythology. In the ancient Egyptian language, Anubis is known as Inpu, (variously spelled Anupu, Ienpw etc.). The oldest known mention of Anubis is in the Old Kingdom pyramid texts, where he is associated with the burial of the Pharaoh. At this time, Anubis was the most important god of the Dead but he was replaced during the Middle Kingdom by Osiris.

He takes names in connection with his funerary role, such as He who is upon his mountain, which underscores his importance as a protector of the deceased and their tombs, and the title He who is in the place of embalming, associating him with the process of mummification. Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumes different roles in various contexts, and no public procession in Egypt would be conducted without an Anubis to march at the head.

Anubis’ wife is a goddess called Anput, his female aspect, and their daughter is the goddess Kebechet.

Portrayal

Anubis was associated with the mummification and protection of the dead for their journey into the afterlife. He was usually portrayed as a half human, half jackal, or in full jackal form wearing a ribbon and holding a flail in the crook of its arm. The jackal was strongly associated with cemeteries in ancient Egypt, since it was a scavenger which threatened to uncover human bodies and eat their flesh. The distinctive black color of Anubis «did not have to do with the jackal [per se] but with the color of rotting flesh and with the black soil of the Nile valley, symbolizing rebirth.»[7]

Anubis is depicted in funerary contexts where he is shown attending to the mummies of the deceased or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. In fact, during embalming, the «head embalmer» wore an Anubis costume. The critical weighing of the heart scene in Book of the Dead also show Anubis performing the measurement that determined the worthiness of the deceased to enter the realm of the dead (the underworld). New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the foes of Egypt.

Embalmer

Following the merging of the Ennead and Ogdoad belief systems, as a result of the identification of Atum with Ra, and their compatibility, Anubis became a lesser god in the underworld, giving way to the more popular Osiris during the Middle Kingdom. However, Anubis is the «Keeper of Divine Justice», and was given by the gods the role of sovereignty of souls. Deciding the weight of «truth» by weighing the Heart against Ma’at, who was often depicted as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. In this manner, he was a Lord of the Underworld, only usurped by Osiris.

Anubis is a son of Ra in early myths, but later he became known as son of Osiris and Nephthys, and in this role he helped Isis mummify his dead father. Indeed, when the Myth of Osiris and Isis emerged, it was said that when Osiris had died, Osiris’ organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers: during the funerary rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a priest wearing the jackal mask supporting the upright mummy. Anubis’ half-brother is Horus the Younger, son of Osiris and Isis.

Perceptions outside Egypt

In later times, during the Ptolemaic period, Anubis was merged with the Greek god [[[Hermes]], becoming Hermanubis. The centre of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name simply means «city of dogs». In Book XI of «The Golden Ass» by Apuleius, we find evidence that the worship of this god was maintained in Rome at least up to the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egypt’s animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was known to be mockingly called «Barker» by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens, and Cerberus in Hades. In his dialogues (e.g. Republic 399e, 592a), Plato has Socrates utter, «by the dog» (kai me ton kuna), «by the dog of Egypt»,»by the dog, the god of the Egyptians» (Gorgias, 482b), for emphasis.

Gallery

| This article needs more links. Please improve this article by adding links that are relevant to the context within the existing article. (June 2018) |

For the Stargate SG-1 character, see Anubis (Stargate)

Anubis (Ancient Greek: Ἄνουβις) is the Greek name for a jackal-headed god associated with mummification and the afterlife in Egyptian mythology. In the ancient Egyptian language, Anubis is known as Inpu, (variously spelled Anupu, Ienpw etc.). The oldest known mention of Anubis is in the Old Kingdom pyramid texts, where he is associated with the burial of the Pharaoh. At this time, Anubis was the most important god of the Dead but he was replaced during the Middle Kingdom by Osiris.

He takes names in connection with his funerary role, such as He who is upon his mountain, which underscores his importance as a protector of the deceased and their tombs, and the title He who is in the place of embalming, associating him with the process of mummification. Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumes different roles in various contexts, and no public procession in Egypt would be conducted without an Anubis to march at the head.

Anubis’ wife is a goddess called Anput, his female aspect, and their daughter is the goddess Kebechet.

Portrayal

Anubis was associated with the mummification and protection of the dead for their journey into the afterlife. He was usually portrayed as a half human, half jackal, or in full jackal form wearing a ribbon and holding a flail in the crook of its arm. The jackal was strongly associated with cemeteries in ancient Egypt, since it was a scavenger which threatened to uncover human bodies and eat their flesh. The distinctive black color of Anubis «did not have to do with the jackal [per se] but with the color of rotting flesh and with the black soil of the Nile valley, symbolizing rebirth.»[7]

Anubis is depicted in funerary contexts where he is shown attending to the mummies of the deceased or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. In fact, during embalming, the «head embalmer» wore an Anubis costume. The critical weighing of the heart scene in Book of the Dead also show Anubis performing the measurement that determined the worthiness of the deceased to enter the realm of the dead (the underworld). New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the foes of Egypt.

Embalmer

Following the merging of the Ennead and Ogdoad belief systems, as a result of the identification of Atum with Ra, and their compatibility, Anubis became a lesser god in the underworld, giving way to the more popular Osiris during the Middle Kingdom. However, Anubis is the «Keeper of Divine Justice», and was given by the gods the role of sovereignty of souls. Deciding the weight of «truth» by weighing the Heart against Ma’at, who was often depicted as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. In this manner, he was a Lord of the Underworld, only usurped by Osiris.

Anubis is a son of Ra in early myths, but later he became known as son of Osiris and Nephthys, and in this role he helped Isis mummify his dead father. Indeed, when the Myth of Osiris and Isis emerged, it was said that when Osiris had died, Osiris’ organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers: during the funerary rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a priest wearing the jackal mask supporting the upright mummy. Anubis’ half-brother is Horus the Younger, son of Osiris and Isis.

Perceptions outside Egypt

In later times, during the Ptolemaic period, Anubis was merged with the Greek god [[[Hermes]], becoming Hermanubis. The centre of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name simply means «city of dogs». In Book XI of «The Golden Ass» by Apuleius, we find evidence that the worship of this god was maintained in Rome at least up to the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egypt’s animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was known to be mockingly called «Barker» by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens, and Cerberus in Hades. In his dialogues (e.g. Republic 399e, 592a), Plato has Socrates utter, «by the dog» (kai me ton kuna), «by the dog of Egypt»,»by the dog, the god of the Egyptians» (Gorgias, 482b), for emphasis.

Gallery

Анибус (др.-греч. Ἄνουβις, егип. jnpw Инпу) — древнеегипетский бог погребальных ритуалов и мумификации (бальзамирования)[1], «страж весов» на суде Осириса в царстве мёртвых[2], знаток целебных трав[3].

Изображение

В период анимизма Анубис представлялся в образе североафриканского волка, который до 2015 года классифицировался как подвид шакала[4][5]. С определённого периода развития религии Древнего Египта Анубиса стали изображать в виде человека с головой дикой собаки Саб (егип. sb «судья») или человека с головой шакала, североафриканского волка или собаки[6][3][7]. Апулей упоминает о двух ликах Анубиса «один чёрный, как ночь, другой — золотой, как день»[2].

Анубиса изображали в некрополе Фив на печати в виде лежащего на девяти луках шакала[1][6].

О небесном характере Анубиса Плутарх писал[2]:

Под Анубисом они понимают горизонтальный круг, отделяющий невидимую часть мира, называемую ими Нефтидой, от видимой, которой они дали имя Исиды. И поскольку этот круг равно соприкасается с границами тьмы и света, его можно считать общим для них. Из этого обстоятельства и возникает сходство, которое они вообразили между Анубисом и Собакой, животным, которое одинаково бдительно и днём, и ночью.

Мифология

Осирис под опекой Анубиса и Гора. Фрагмент росписи гробницы Хоремхеба.

Жена Сета по имени Нефтида полюбила Осириса и, приняв облик его супруги Исиды, зачала от него сына. Опасаясь гнева мужа, Нефтида бросила младенца в камышовых зарослях, где его с помощью собак[3] нашла Исида и вырастила[8]. После Анубис вместе с Исидой ищет тело Осириса, охраняет его от врагов, в некоторых версиях мифа — погребает его, присутствует на суде Осириса[1].

Осуждённого Сета, обернувшегося в пантеру, боги решили сжечь, а Анубис снял шкуру с Сета и надел на себя. Затем он отправился в святилище Осириса и калёным железом выжег на шкуре свой знак. В память об этой легенде жрецы Анубиса-Имнута набрасывали шкуру леопарда на правое плечо[3].

Жрецы Гелиополя считали женой Анубиса богиню Инпут[3], которая иногда почиталась женской формой Анубиса[4]. Его братом был Бата, что отразилось в «Сказке о двух братьях». Дочерью Анубиса была Кебхут[1][3][6].

В глубокой древности Анубис был космическим богом и олицетворял какую-либо фазу ночного мрака, отчего запад — обиталище мёртвых — был его царством[2]. Деревом Анубиса считался тамариск[9].

В поздний период с Анубисом стали отождествлять чёрного пса (одного из богов Дуата) Исдеса., кто в Легенде об Осирисе помогал искать Сета[3]. Греки отождествляли Анубиса с Гермесом (как проводник мёртвых в Загробный мир)[7][6][10], иногда с Кроном[3].

Функции

Анубис возлагает руки на мумию. Роспись на стене гробницы Сеннеджема (TT1)

Первоначально (согласно «Текстам пирамид») Анубис был единственным судьёй мёртвых в Дуате, но эта высокая должность с конца Древнего царства (конец 3-го тысячелетия до н. э.) узурпировалась Осирисом (считавшимся умершим фараоном), перенявшим и титулы Анубиса «владыка запада» (Хентиаменти), «владыка тех, кто на западе». Анубис в этот же период связывается с мумификацией умерших и погребальными обрядами[2][3][6]. Именно Анубис наблюдал за установкой стрелки на коромысле весов и решал, уравновесило ли сердце покойного перо Маат или нет. Бог мудрости Тот принимал решение без возражений, как и советы богов, на которых Гор основывал своё обращение Осирису. В «Книге мёртвых» часто изображено, как Анубис подводит усопшего к весам, на других изображениях весы показаны с навершием в виде головы шакала[2].

Анубис подготавливал тело покойного к бальзамированию и превращению его в мумию. Затем он возлагал на неё руки и превращал покойника в ах («просветлённого», «блаженного»). Анубис расставлял в погребальной камере детей Гора и давал каждому канопу с внутренностями покойника для их охраны[1][6]. Анубис заботился о телах умерших и вёл их души по каменистой пустыне запада к месту, где находился рай Осириса. В этой работе ему помогал бог-волк Упуату («тот, кто открывает дороги»)[2].

Культ

Столица XVII египетского нома Каса (греч. Кинополь «город собаки»)[7] на протяжении всей истории Древнего Египта был центром культа Анубиса[3]. Египтологи отмечают быстрое и повсеместное распространение данного культа в ранний период. Согласно некоторым источникам «Хентиаментиу» является названием местоположения храма, в котором поклонялись этому божеству[4].

Анубис в античной литературе

В произведении Плутарха «Исида и Осирис» приводится трактовка, в которой Анубис приходился сыном Сета и Нефтиды, который был найден и воспитан Исидой[11]. Также он сравнивает Анубиса с Гекатой — божеством, общим для небес и преисподней; считает, что Анубис обозначает время. Плутарх считал, что одно имя Анубиса выражает отношение к высшему, а второе Германубис (др.-греч. Ἑρμανοῦβις) — к низшему миру[2]. Германубис в античной мифологии сочетал в себе внешность Гермеса (древнегреческая мифология) и Анубиса (древнеегипетская мифология)[12][13], был сыном Осириса и Нефтиды и разделял обязанности Анубиса (проводник душ)[14].

Страбон упоминает, что Анубис — египетское божество, почитаемое в XVII (Кинополисском) верхнеегипетском номе[15]. Согласно Вергилию, Анубис изображён на щите Энея[16]. Ювенал упоминает о почитании божества в Риме[17].

См. также

- Список египетских богов

- Megasoma anubis

- Кинокефалы

Примечания

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Анубис. — Словарь египетской мифологии. — М.: Центрполиграф, 2008. — 256 с. — (Загадки древнего Египта).

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Эрнест Альфред Уоллис Бадж. Древний Египет. Духи, идолы, боги = From Fetish to God in Ancient Egypt / Переводчик: Игоревский Л. А.. — М.: Центрполиграф, 2009. — С. 204—206. — 480 с. — (Загадки древнего Египта).

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Иван Рак. Мифы и легенды Древнего Египта. — Стрекоза, 2013. — С. 101, 254, 257.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Макс Мюллер. Египетская Мифология.

- ↑ Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Niemann, Jonas; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Vieira, Filipe G.; Carøe, Christian; de Montero, Marc Manuel; Kuderna, Lukas; Serres, Aitor; González-Basallote, Víctor Manuel; Liu, Yan-Hu; Wang, Guo-Dong; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Mirarab, Siavash; Fernandes, Carlos; Gaubert, Philippe; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Budd, Jane; Rueness, Eli Knispel; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Petersen, Bent; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Bachmann, Lutz; Wiig, Øystein; Hansen, Anders J.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2018). “Interspecific gene flow shaped the evolution of the genus Canis”. Current Biology. 28 (21): 3441—3449.e5. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.041. PMC 6224481. PMID 30344120.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Рубинштейн Р. И. Анубис / Ред. С. А. Токарев. — Советская энциклопедия. — М.: Мифы народов мира, 1991.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Анубис // Энциклопедия мифологии. // Гладкий В. Д. (укр.) (рус. «Древнеегипетский словарь-справочник»

- ↑ Freeman, 1997, p. 91.

- ↑ Тураев Б.А. Рассказ египтянина Синухета и образцы египетских документальных автобиографий. / Под. общ. ред. проф. Тураева Б.А.. — М.: Поставщик двора его величества Т-во скоропечатни Левенсон А.А., 1915. — С. 4. — (Культурно-исторические памятники Древнего Востока).

- ↑ М. Корш. Краткий словарь мифологии и древностей. — СПб.: издание А. С. Суворина, 1894.

- ↑ Плутарх. Об Исиде и Осирисе 14; 44, см. Любкер Ф. Реальный словарь классических древностей. М., 2001. В 3 т. Т. 1. С. 127.

- ↑ Peacock, 2000, pp. 437–38 (Hellenistic kingdom).

- ↑ Hermanubis | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon. Babylon.com. Дата обращения: 15 июня 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2016 года.

- ↑ Riggs, 2005, p. 166.

- ↑ Страбон. География XVII 1, 40 (стр. 812)

- ↑ Вергилий. Энеида VIII 698

- ↑ См. Ювенал. Сатиры VI 534

Литература

- на русском языке

- Анубис // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- на других языках

- Freeman, Charles (1997), The Legacy of Ancient Egypt, New York: Facts on File, ISBN 0-816-03656-X

- Peacock, D. (2000), The Roman Period, in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-815034-2, <https://books.google.com/?id=092jP1lBhtoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Oxford+History+of+Ancient+Egypt&cd=1#v=onepage&q>

- Riggs, C. (2005), The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-927665-3, <http://www.questia.com/read/120480192/the-beautiful-burial-in-roman-egypt-art-identity>

Эта страница в последний раз была отредактирована 25 февраля 2023 в 21:12.

Как только страница обновилась в Википедии она обновляется в Вики 2.

Обычно почти сразу, изредка в течении часа.

Древнеегипетский бог погребальных обрядов

| Анубис | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Бог смерти, мумификации, бальзамирования, загробной жизни, кладбищ, гробниц, подземный мир | |||||

египетский бог Анубис (современная интерпретация, вдохновленная картинами гробниц Нового царства) египетский бог Анубис (современная интерпретация, вдохновленная картинами гробниц Нового царства) |

|||||

| Имя в иероглифах |

|

||||

| Главный культовый центр | Ликополис, Цинополис | ||||

| Символ | марлевые мумии, фетиш, шакал, цеп | ||||

| Личная информация | |||||

| Родители | Нептис и Сет, Осирис (Среднее и Новое царство) или Ра (Старое царство). | ||||

| Братья и сестры | Вепуавет | ||||

| Консорт | Анпут | ||||

| Потомство | Кебечет | ||||

| греческий эквивалент | Аид или Гермес |

Анубис или Инпу, Анпу в Древнем Египте (; Древнегреческий : Ἄνουβις, египетский : inpw, коптский : ⲁⲛⲟⲩⲡ Anoup) — греческое имя бога смерть, мумификация, бальзамирование, загробная жизнь, кладбища, гробницы, и Подземный мир в древнеегипетской религии, обычно изображаемый как псовый или человек с собачьей головой. Археологи идентифицировали священное животное Анубиса как египетского псового, африканского золотого волка. Африканского волка раньше называли «африканским золотым шакалом », пока генетический анализ 2015 года не обновил таксономию и общее название вида. В результате Анубиса часто называют имеющим голову «шакала», но теперь этот «шакал» более правильно называть «волком».

Подобно многим древнеегипетским божествам, Анубис играл разные роли в разных контекстах. Изображенный в качестве защитника могил еще в Первой династии (ок. 3100 — ок. 2890 до н.э.), Анубис также был бальзамировщиком. В Среднем царстве (ок. 2055 — 1650 гг. До н.э.) его заменил Осирис в своей роли повелителя подземного мира. Одна из его выдающихся ролей была в роли бога , который проводил души в загробную жизнь. Он присутствовал на весах во время «Взвешивания сердца», в котором определялось, будет ли душе позволено войти в царство мертвых. Несмотря на то, что Анубис был одним из самых древних и «одним из наиболее часто изображаемых и упоминаемых богов» в египетском пантеоне, он почти не играл никакой роли в египетских мифах.

Анубис был изображен в черном цвете, цвет, который символизировал возрождение, жизнь, почву реки Нил и изменение цвета трупа после бальзамирования. Анубис связан со своим братом Wepwawet, другим египетским богом, изображенным с головой собаки или в форме собаки, но с серым или белым мехом. Историки предполагают, что в конечном итоге эти две фигуры были объединены. Женский аналог Анубиса — Анпут. Его дочь — богиня змей Кебечет.

Содержание

- 1 Имя

- 2 История

- 3 Роли

- 3.1 Защитник гробниц

- 3.2 Бальзамировщик

- 3.3 Путеводитель душ

- 3.4 Взвешивание сердца

- 4 Изображение в искусстве

- 5 Галерея

- 6 Поклонение

- 7 В популярной культуре

- 8 См. Также

- 9 Ссылки

- 10 Библиография

- 11 Дополнительная литература

- 12 Внешние ссылки

Имя