БЦЖ

БЦЖ — это вакцина от туберкулёза, которой прививают более 80% новорождённых в тех странах, где она включена в прививочный календарь. БЦЖ не гарантирует 100%-ной защиты от заболевания, но эффективно предотвращает развитие его смертельно опасной формы — туберкулёзного менингита.

СОДЕРЖАНИЕ

Как проводится вакцинация БЦЖ: по календарю и индивидуально

Противопоказания к проведению вакцинации

Осложнения после прививки

Вакцинация от туберкулёза: за и против

БЦЖ: что это за вакцина

БЦЖ — это вакцина на основе Mycobacterium bovis (бычьей туберкулёзной палочки), вида микобактерий из группы Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

Mycobacterium bovis обычно вызывает туберкулёз у крупного рогатого скота, но может быть опасной и для человека. Например, если он выпьет непастеризованного молока от больной коровы.

БЦЖ — транслитерация французской аббревиатуры BCG, образованной от словосочетания «bacillus Calmette — Guérin». То есть расшифровка названия «БЦЖ» — «бацилла Кальметта — Герена».

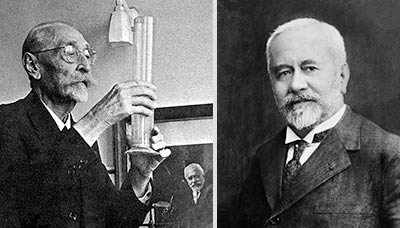

Альбер Кальметт и Камиль Герен — французские учёные, которым удалось культивировать в лаборатории ослабленный живой штамм бычьей туберкулёзной палочки. При этом он утратил вирулентность, то есть способность вызывать болезнь у человека.

Камиль Герен (слева) и Альбер Кальметт (справа) — учёные, создатели противотуберкулёзной вакцины БЦЖ.

Источник фото Альбера Кальметта — Kaufmann & Fabry

Исследования продолжались 12 лет, и в 1921 году была создана противотуберкулёзная вакцина БЦЖ. Спустя всего 4 года, в 1925-м, вакцина была доставлена в Москву. В Советском Союзе прививку от туберкулёза новорождённым начали делать с 1928 года, а с 1950-го вакцинация БЦЖ стала обязательной.

От чего новорождённым делают прививку БЦЖ

Вакциной БЦЖ прививают детей практически во всех странах мира, чтобы защитить их от туберкулёза, особенно от его внелёгочных форм, в том числе туберкулёзного менингита.

Туберкулёзный менингит (поражение мозговых оболочек) — наиболее тяжёлая форма туберкулёза. Без вакцинации БЦЖ, как правило, приводит к смерти ребёнка.

Эффективность прививки БЦЖ подтверждают данные о заболеваемости туберкулёзным менингитом. Так, за полвека количество зарегистрированных случаев болезни у детей сократилось в 175 раз.

Как проводится вакцинация БЦЖ: по календарю и индивидуально

Как правило, детей прививают БЦЖ в соответствии с прививочным календарём. Но если у ребёнка есть временные противопоказания к прививке, то сроки вакцинации устанавливаются индивидуально.

В каком возрасте делают прививку БЦЖ по календарю прививок

Детей прививают вакциной БЦЖ уже в роддоме, на 3–7-й день жизни, если нет противопоказаний.

Противопоказанием к вакцинации БЦЖ в первые дни жизни может стать, например, малый вес новорождённого — меньше 2,5 кг.

Чтобы поддержать иммунитет, ревакцинацию БЦЖ проводят в 7 и 14 лет при отрицательном результате пробы Манту.

В каком возрасте делают прививку БЦЖ индивидуально

В случае если противопоказания к вакцинации были сняты уже после выписки из роддома, младенца могут привить в поликлинике.

Ребёнку младше 2 месяцев вакцинацию БЦЖ проводят без дополнительных исследований.

Если же ребёнку уже исполнилось 2 месяца, сначала делают пробу Манту. Это нужно, чтобы удостовериться, что он не был инфицирован микобактериями туберкулёза. При отрицательном результате кожной пробы делают прививку.

При проведении пробы Манту пациенту вводят туберкулёзный аллерген и проверяют кожную реакцию в месте укола

В дальнейшем проводят ревакцинацию при отрицательном результате пробы Манту по стандартной схеме — в 7 и 14 лет.

Особенности вакцинации

Прививку делают в плечо. На месте введения вакцины примерно через 1,5–3 месяца образуется небольшой гнойничок (пустула), покрытый корочкой. Через 4–6 месяцев после прививки эта корочка отпадает, а на коже остаётся небольшой рубец.

Примерно через 1,5–3 месяца на месте введения вакцины образуется пустула

Такая реакция на прививку подтверждает, что организм «заметил» введённые микобактерии и сформировал иммунный ответ. А значит, при реальной встрече с возбудителем туберкулёза иммунной системе будет легче распознать инфекцию и бороться с ней.

Через некоторое время после вакцинации на месте укола остаётся небольшой рубец

Противопоказания к проведению вакцинации

При некоторых заболеваниях и состояниях новорождённого нельзя вакцинировать БЦЖ.

Противопоказания к вакцинации:

- Недоношенность: ребёнок родился с весом менее 2,5 кг.

- Внутриутробная гипотрофия (нарушение питания, из-за которого новорождённый весит меньше нормы) III–IV степени.

При этом, когда вес новорождённого достигнет 2,5 кг, его можно привить вакциной БЦЖ-М. Она отличается от обычной БЦЖ тем, что содержит вдвое меньше микобактерий.

- Острые состояния (внутриутробная инфекция, гнойно-септические заболевания, гемолитическая болезнь новорождённых среднетяжёлой и тяжёлой формы, тяжёлые поражения нервной системы с выраженной неврологической симптоматикой, генерализованные кожные поражения и другие заболевания).

- Врождённые (первичные) иммунодефицитные состояния, злокачественные новообразования. Если ребёнку назначили лечение иммунодепрессантами или лучевую терапию, сделать прививку можно будет через полгода после окончания терапии.

- Генерализованная БЦЖ-инфекция (осложнение вакцинации БЦЖ), выявленная у других детей в семье.

- Неопределённый ВИЧ-статус детей, рождённых ВИЧ-инфицированными матерями, которые не получали лечения. ВИЧ-статус таких детей определяется, когда ребёнку исполнится 1,5 года. До этого момента вакцинация не проводится.

Осложнения после прививки

Чаще всего прививка БЦЖ переносится хорошо и не вызывает осложнений. Однако в некоторых случаях может развиться нежелательная реакция на БЦЖ.

Возможные осложнения после вакцинации или ревакцинации БЦЖ:

- Местные реакции: подкожные инфильтраты (болезненная припухлость в месте укола из-за попадания крови и лимфы в ткани), холодные абсцессы (нагноение на небольшом участке тела без боли и повышения температуры), язвы, келоиды (блестящие гладкие рубцы).

- Лимфадениты: могут воспаляться лимфатические узлы, расположенные в подмышечной области, над или под ключицами.

- Персистирующая (длительная) и диссеминированная (широко распространившаяся) БЦЖ-инфекция. К примеру, БЦЖ-остит — воспаление костей из-за того, что введённые при вакцинации микобактерии с током крови попали в костную ткань. Такие побочные реакции развиваются крайне редко.

Если после прививки БЦЖ родители замечают изменения в состоянии ребёнка или он жалуется, например, на боли в костях, стоит как можно скорее обратиться к врачу. Важно своевременно начать лечение поствакцинального осложнения, чтобы ребёнок полностью выздоровел.

Вакцинация от туберкулёза: за и против

Полная средняя эффективность вакцинации БЦЖ — 50%. Это значит, что прививка не может защитить от заражения туберкулёзом на 100%, но во многих случаях позволяет предотвратить инфицирование или облегчить протекание болезни: в среднем привитые дети болеют туберкулёзом в 15 раз реже, чем непривитые, и значительно легче.

Важно помнить, что в России заболеваемость туберкулёзом, в том числе его формами, которые плохо поддаются лечению антибиотиками, очень высока. А значит, вакцинация новорождённых от туберкулёза — жизненно важная мера.

В то же время решение о вакцинации БЦЖ принимает врач, оценивая состояние ребёнка при рождении и семейную историю болезней. Это позволяет избежать развития тяжёлых поствакцинальных осложнений.

Частые вопросы

Вакцинация БЦЖ проводится, чтобы защитить ребёнка от туберкулёза, в особенности от его внелёгочных форм, в том числе смертельно опасного туберкулёзного менингита.

Если у новорождённого нет противопоказаний к вакцинации, прививку БЦЖ делают уже в роддоме — на 3–7-й день жизни. А в 7 и 14 лет проводят ревакцинацию.

Если противопоказания к вакцинации сняли после выписки из роддома, решение о сроках вакцинации принимается индивидуально. В случае когда ребёнку уже исполнилось 2 месяца, а прививку БЦЖ ещё не сделали, перед вакцинацией сначала проводят пробу Манту. Это нужно, чтобы убедиться, что ребёнок не успел инфицироваться туберкулёзом.

Детям, у которых нет противопоказаний к вакцинации, прививку БЦЖ делают на 3–7-й день жизни, затем проводят ревакцинацию в 7 и 14 лет.

Прививку БЦЖ делают на границе верхней и средней трети наружной поверхности левого плеча.

Прививку от туберкулёза впервые делают новорождённым: если противопоказаний к вакцинации нет — на 3–7-й день жизни, если есть противопоказания — сроки устанавливают индивидуально. В случае когда ребёнку уже исполнилось 2 месяца, а прививку БЦЖ ещё не сделали, перед вакцинацией сначала проводят пробу Манту. Это важно, чтобы убедиться, что ребёнок не успел инфицироваться туберкулёзом. В 7 и 14 лет проводят ревакцинацию.

Информацию проверил

врач-эксперт

Информацию проверил врач-эксперт

Роман Иванов

Врач-дерматовенеролог

Оцените статью:

Полезная статья? Поделитесь в социальных сетях:

ВАЖНО

Информация из данного раздела не может служить достаточным основанием для постановки диагноза или назначения лечения. Решение об этом должен принимать врач на основании всех имеющихся у него данных.

Вам может быть интересно

Вам телеграм.

Telegram-канал,

которому, на наш взгляд,

можно доверять

Вакцина туберкулезная (БЦЖ) (лиофилизат для приготовления суспензии для внутрикожного введения, 0.05 мг/доза), инструкция по медицинскому применению РУ № Р N001969/01

Дата последнего изменения: 26.07.2018

Особые отметки:

Содержание

- Действующее вещество

- ATX

- Нозологическая классификация (МКБ-10)

- Фармакологическая группа

- Лекарственная форма

- Состав

- Описание лекарственной формы

- Фармакокинетика

- Фармакодинамика

- Показания

- Противопоказания

- Применение при беременности и кормлении грудью

- Способ применения и дозы

- Побочные действия

- Взаимодействие

- Передозировка

- Меры предосторожности

- Особые указания

- Форма выпуска

- Условия отпуска из аптек

- Условия хранения

- Срок годности

- Отзывы

Действующее вещество

ATX

Фармакологическая группа

Лекарственная форма

Лиофилизат для приготовления

суспензии для внутрикожного введения

Состав

Одна доза содержит:

Действующее вещество:

Лиофилизат Mycobacterium bovis BCG 0,05 мг

Вспомогательные вещества:

Натрия глутамата моногидрат не

более 0,3 мг

Раствор натрия хлорида 0,9% для

инъекций до 0,1 мл

Препарат не содержит консервантов

и антибиотиков. Выпускается в комплекте с растворителем — натрия хлорид

растворитель для приготовления лекарственных форм для инъекций 0,9%.

Описание лекарственной формы

Лиофилизат. Однородная пористая

масса, порошкообразная или в виде тонкой ажурной таблетки (колечка) белого или

светло-желтого цвета. Гигроскопична.

Фармакокинетика

Вакцина БЦЖ — иммунобиологический

препарат, исследования фармакокинетики не проводились.

Фармакодинамика

Вакцина представляет собой

культуру микобактерий вакцинного штамма Mycobacterium bovis, субштамм BCG-1 (Russia), лиофилизированную в 1,5%

растворе стабилизатора — натрия глутамата моногидрата.

Живые микобактерии вакцинного

штамма БЦЖ-1, размножаясь в организме привитого, приводят к развитию длительного

иммунитета к туберкулезу.

В норме у вакцинированных на месте

внутрикожного введения вакцины БЦЖ через 4–6 недель последовательно развивается местная

специфическая реакция в виде инфильтрата, папулы, пустулы, язвы размером 5–10

мм в диаметре. Реакция подвергается обратному развитию в течение 2–3 мес.,

иногда и в более длительные сроки. У ревакцинированных местная реакция

развивается через 1–2 недели. У 90–95% вакцинированных на месте прививки

формируется поверхностный рубчик размером до 10 мм.

Показания

Активная специфическая

профилактика туберкулеза у детей на территориях с показателями заболеваемости

туберкулезом, превышающими 80 на 100 тыс. населения, а также при наличии в

окружении новорожденного больных туберкулезом.

Противопоказания

Вакцинация

1. Недоношенность — масса тела при

рождении менее 2500 г.

2. Внутриутробная гипотрофия III–IV степени.

3. Острые заболевания. Вакцинация

откладывается до окончания острых проявлений заболевания и обострения

хронических заболеваний (внутриутробная инфекция, гнойно-септические

заболевания, гемолитическая болезнь новорожденных среднетяжелой и тяжелой

формы, тяжелые поражения нервной системы с выраженной неврологической

симптоматикой, генерализованные кожные поражения и т.п.).

4. Иммунодефицитное состояние

(первичное), злокачественные новообразования.

При назначении иммунодепрессантов

и лучевой терапии прививку проводят не ранее, чем через 6 мес после

окончания лечения.

5. Генерализованная инфекция БЦЖ,

выявленная у других детей в семье.

6. Детям, рожденным матерями,

необследованными на ВИЧ во время беременности и родов, а также детям, рожденным

ВИЧ-инфицированными матерями, не получавшими трехэтапную химиопрофилактику

передачи ВИЧ от матери к ребенку, вакцинация не проводится до установления

ВИЧ-статуса ребенка в возрасте 18 месяцев.

Вакцинация против туберкулеза

детей, рожденных от матерей с ВИЧ-инфекцией и получавших трехэтапную

химиопрофилактику передачи ВИЧ от матери к ребенку (во время беременности,

родов и в период новорожденности), проводится в родильном доме вакциной

туберкулезной для щадящей первичной иммунизации (БЦЖ-М).

Дети, имеющие противопоказания к

иммунизации вакциной БЦЖ, прививаются вакциной БЦЖ-М с соблюдением инструкции к

этой вакцине.

Ревакцинация

1. Острые инфекционные и

неинфекционные заболевания, обострение хронических заболеваний, в том числе

аллергических. Прививку проводят через 1 мес. после выздоровления или

наступления ремиссии.

2. Иммунодефицитные состояния,

злокачественные заболевания крови и новообразования.

При назначении иммунодепрессантов

и лучевой терапии прививку проводят не ранее, чем через 6 мес. после

окончания лечения.

3. ВИЧ-инфекция, обнаружение

нуклеиновых кислот ВИЧ молекулярными методами.

4. Больные туберкулезом, лица,

перенесшие туберкулез и инфицированные микобактериями.

5. Положительная и сомнительная

реакция на пробу Манту с 2 ТЕ ППД-Л.

6. Осложнения на предыдущее введение

вакцины БЦЖ.

При контакте с инфекционными

больными в семье, детском учреждении и т.д. прививки проводят по окончании

срока карантина или максимального срока инкубационного периода для данного

заболевания.

Лица, временно освобожденные от

прививок, должны быть взяты под наблюдение и учет, и привиты после полного выздоровления

или снятия противопоказаний. В случае необходимости проводят соответствующие

клинико-лабораторные обследования.

Применение при беременности и кормлении грудью

Не применимо. Препарат

используется для вакцинации детей.

Способ применения и дозы

Вакцину БЦЖ применяют внутрикожно

в дозе 0,05 мг в 0,1 мл прилагаемого растворителя (раствор натрия

хлорида 0,9% для инъекций).

Вакцинацию осуществляют здоровым

новорожденным детям на 3–7 день жизни (как правило, в день выписки из

родильного дома).

Дети,

не привитые в период новорожденности, получают после выздоровления вакцину БЦЖ-М. Детям в возрасте 2 мес. и

старше предварительно проводят пробу Манту с 2 ТЕ очищенного туберкулина в

стандартном разведении и вакцинируют только туберкулин-отрицательных.

Ревакцинации подлежат дети в

возрасте 7 лет, имеющие отрицательную реакцию на пробу Манту с 2 ТЕ ППД-Л.

Реакция Манту считается отрицательной при полном отсутствии инфильтрата,

гиперемии или при наличии уколочной реакции (1 мм). Инфицированные микобактериями

туберкулеза дети, имеющие отрицательную реакцию на пробу Манту, ревакцинации не

подлежат. Интервал между постановкой пробы Манту и ревакцинацией должен быть не

менее 3 дней и не более 2 недель.

Прививки должен проводить

специально обученный и имеющий сертификат медицинский персонал родильных домов

(отделений), отделений выхаживания недоношенных, детских поликлиник или

фельдшерско-акушерских пунктов. Вакцинацию новорожденных проводят в утренние

часы в специально отведенной комнате после осмотра детей педиатром. В

поликлиниках отбор детей на вакцинацию предварительно проводит врач (фельдшер)

с обязательной термометрией в день прививки, учетом медицинских

противопоказаний и данных анамнеза. При необходимости проводят консультацию с

врачами-специалистами, исследование крови и мочи. При проведении ревакцинации в

школе должны соблюдаться все вышеперечисленные требования. Во избежание

контаминации живыми микобактериями БЦЖ недопустимо совмещение в один день

прививки против туберкулеза с другими парентеральными манипуляциями.

Факт выполнения вакцинации

(ревакцинации) регистрируют в установленных учетных формах с указанием даты

прививки, названия вакцины, предприятия- производителя, номера серии, и срока

годности препарата.

Для вакцинации (ревакцинации)

применяют одноразовые стерильные туберкулиновые шприцы вместимостью 1 мл с

тонкими короткими иглами с коротким срезом. Для внесения в ампулу с вакциной

растворителя используют одноразовый стерильный шприц вместимостью 2 мл с

длинной иглой. Запрещается применять шприцы и иглы с истекшим сроком годности и

инсулиновые шприцы, у которых отсутствует градуировка в мл. Запрещается

проводить прививку безигольным инъектором. После каждой инъекции шприц с иглой

и ватные тампоны замачивают в аттестованном дезинфицирующем растворе (следуя

режимам дезинфекции, указанным в инструкции по применению), а затем

централизованно уничтожают. Запрещается применение для других целей

инструментов, предназначенных для проведения прививок против туберкулеза.

Вакцину хранят в холодильнике

(под замком) в кабинете для прививок. Лица, не имеющие отношения к вакцинации

БЦЖ, в помещение, где проводятся прививки (родильный дом) и в прививочный

кабинет (поликлиника), в день прививок не допускаются. В день вакцинации

(ревакцинации) БЦЖ в прививочном кабинете (комнате) запрещается проводить

другие профилактические прививки.

Ампулы с вакциной перед вскрытием

тщательно просматривают.

Препарат не подлежит применению

при:

—

отсутствии

маркировки на ампуле или неправильном ее заполнении;

—

истекшем

сроке годности;

—

наличии

трещин и насечек на ампуле;

—

изменении

физических свойств препарата (изменение цвета, сморщенная таблетка и т.д.).

Вакцину растворяют

непосредственно перед употреблением стерильным раствором натрия хлорида 0,9%

для инъекций, приложенным к вакцине. Растворитель должен быть прозрачным,

бесцветным и не иметь посторонних включений.

Вакцина

герметизирована под вакуумом: Шейку

и головку ампулы обтирают спиртом. Сначала надпиливают и осторожно, с помощью

пинцета, отламывают место запайки. Затем надпиливают и отламывают шейку

ампулы, завернув надпиленный конец в стерильную марлевую салфетку.

Вакцина

герметизирована под инертным газом: Шейку и головку ампулы обтирают спиртом. Отламывают

шейку ампулы по кольцу или точке надлома, завернув головку в стерильную марлевую

салфетку.

Для получения дозы 0,05 мг

БЦЖ в 0,1 мл в ампулу, содержащую 20 доз вакцины, переносят стерильным

шприцем 2 мл раствора натрия хлорида 0,9% для инъекций, а в ампулу,

содержащую 10 доз вакцины — 1 мл раствора натрия хлорида 0,9% для

инъекций. Вакцина должна раствориться в течение 1 мин. Допускается наличие

хлопьев, которые должны разбиваться при 2–4-кратном перемешивании с помощью

шприца (не допускается попадание воздуха в шприц). Растворенная вакцина должна

иметь вид грубодисперсной суспензии белого с сероватым или желтоватым оттенком

цвета. При наличии в разведенном препарате крупных хлопьев, которые не

разбиваются при 2–4-кратном перемешивании с помощью шприца, или осадка эту

ампулу с вакциной уничтожают, не используя.

Разведенную вакцину необходимо

предохранять от действия солнечного и дневного света (например, цилиндром из

черной бумаги). Разведенная вакцина пригодна к применению не более 1 часа после

разведения при хранении в асептических условиях, при температуре от 2 до

8 °С. Обязательно ведение протокола с указанием времени разведения

препарата и уничтожения ампулы с вакциной.

Для одной прививки в

туберкулиновый шприц набирают 0,2 мл (2 дозы) разведенной вакцины, затем

выпускают через иглу в стерильный ватный тампон примерно 0,1 мл вакцины

для того, чтобы вытеснить воздух и подвести поршень шприца под нужную

градуировку — 0,1 мл. Перед каждым набором вакцину следует аккуратно

перемешивать 2–3 раза с помощью шприца. Одним шприцем вакцина может быть

введена только одному ребенку.

Вакцину БЦЖ вводят строго внутрикожно на границе верхней и средней

трети наружной поверхности левого плеча после предварительной обработки кожи

70 ° спиртом. Иглу вводят срезом вверх в поверхностный слой натянутой

кожи. Сначала

вводят незначительное количество вакцины, чтобы убедиться, что игла вошла точно

внутрикожно, а затем всю дозу препарата (всего 0,1 мл). При правильной

технике введения должна образоваться папула беловатого цвета диаметром 7–9 мм,

исчезающая обычно в течение 15–20 мин.

Побочные действия

После вакцинации и ревакцинации

осложнения отмечаются редко и обычно носят местный характер (лимфадениты,

диаметром более 1 см, — регионарные, чаще подмышечные, иногда над- или

подключичные, реже — подкожные инфильтраты, холодные абсцессы, язвы, келоиды).

Крайне редко встречаются персистирующая и диссеминированная БЦЖ-инфекция без

летального исхода (волчанка, оститы и др.), пост-БЦЖ синдром аллергического

характера, который возникает вскоре после прививки (узловатая эритема,

кольцевидная гранулема, сыпи и др.), чрезвычайно редко — генерализованное

поражение БЦЖ при врожденном иммунодефиците. Осложнения выявляются в различные

сроки после прививки — от нескольких недель до года и более.

Взаимодействие

Другие профилактические прививки

могут быть проведены с интервалом не менее 1 мес. до и после вакцинации

(ревакцинации) БЦЖ (за исключением вакцины против гепатита В, которую вводят в

соответствии с Национальным календарем профилактических прививок в РФ).

Передозировка

Случаи передозировки не

установлены.

Меры предосторожности

Введение препарата под

кожу недопустимо, так как при этом образуется холодный абсцесс.

Запрещается наложение повязки и

обработка йодом и другими дезинфицирующими растворами места введения вакцины

во время развития местной прививочной реакции: инфильтрата, папулы,

пустулы, язвы; место реакции следует предохранять от механического

раздражения, особенно во время водных процедур, о чем следует

обязательно предупредить родителей ребенка.

Более полная информация о

проведении вакцинопрофилактики туберкулеза представлена в Приказе Минздрава

России № 109 «О совершенствовании противотуберкулезных мероприятий в Российской

Федерации» от 21 марта 2003 г.

Особые указания

Неиспользованную вакцину уничтожают

кипячением в течение 30 мин, автоклавированием при 126 °С 30 мин или

погружением вскрытых ампул в дезинфицирующий раствор в концентрации,

эффективной в отношении микобактерий туберкулеза. Концентрацию раствора и время

экспозиции определяют в соответствии с инструкцией по применению

дезинфицирующего средства.

Влияние на способность управлять

транспортными средствами, механизмами

Не применимо. Препарат

используется для вакцинации детей.

Форма выпуска

В ампулах, содержащих 0,5 мг

(10 доз) или 1,0 мг препарата (20 доз), в комплекте с растворителем —

раствором натрия хлорида 0,9% для инъекций — по 1 или 2 мл в ампуле,

соответственно.

В одной пачке картонной

содержится 5 ампул вакцины БЦЖ (герметизация под вакуумом/герметизация под

инертным газом) и 5 ампул раствора натрия хлорида 0,9% для инъекций (5

комплектов).

В одной пачке картонной

содержится 5 ампул вакцины БЦЖ (герметизация под инертным газом) и 5 ампул

раствора натрия хлорида 0,9% для инъекций в контурных ячейковых упаковках (пять

комплектов).

В пачку вкладывают инструкцию по

медицинскому применению.

Для ампул ШПВ-6 в пачку

дополнительно вкладывают скарификатор ампульный.

Условия отпуска из аптек

Для лечебно-профилактических

учреждений.

Условия хранения

Условия хранения

Хранить по СП 3.3.2.3332-16 при

температуре от 2 до 8 °С.

Хранить в недоступном для детей месте.

Условия транспортирования

Транспортировать по СП

3.3.2.3332-16 при температуре от 2 до 8 °С.

Срок годности

2 года.

Не применять по истечении срока

годности.

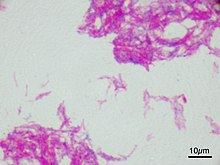

Microscopic image of the Calmette–Guérin bacillus, Ziehl–Neelsen stain, magnification: 1,000nn |

|

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| Vaccine type | Attenuated |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | BCG Vaccine, BCG Vaccine AJV |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration |

Percutaneous, intravesical, intradermal |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII |

|

| KEGG |

|

Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine is a vaccine primarily used against tuberculosis (TB).[8] It is named after its inventors Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin.[9][10] In countries where tuberculosis or leprosy is common, one dose is recommended in healthy babies as soon after birth as possible.[8] In areas where tuberculosis is not common, only children at high risk are typically immunized, while suspected cases of tuberculosis are individually tested for and treated.[8] Adults who do not have tuberculosis and have not been previously immunized, but are frequently exposed, may be immunized, as well.[8] BCG also has some effectiveness against Buruli ulcer infection and other nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.[8] Additionally, it is sometimes used as part of the treatment of bladder cancer.[11][12]

Rates of protection against tuberculosis infection vary widely and protection lasts up to 20 years.[8] Among children, it prevents about 20% from getting infected and among those who do get infected, it protects half from developing disease.[13] The vaccine is given by injection into the skin.[8] No evidence shows that additional doses are beneficial.[8]

Serious side effects are rare. Often, redness, swelling, and mild pain occur at the site of injection.[8] A small ulcer may also form with some scarring after healing.[8] Side effects are more common and potentially more severe in those with immunosuppression.[8] It is not safe for use during pregnancy.[8] The vaccine was originally developed from Mycobacterium bovis, which is commonly found in cattle.[8] While it has been weakened, it is still live.[8]

The BCG vaccine was first used medically in 1921.[8] It is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines.[14][15] As of 2004, the vaccine is given to about 100 million children per year globally.[16]

Medical uses[edit]

Tuberculosis[edit]

The main use of BCG is for vaccination against tuberculosis. BCG vaccine can be administered after birth intradermally.[6] BCG vaccination can cause a false positive Mantoux test, although a very high-grade reading is usually due to active disease.[citation needed]

The most controversial aspect of BCG is the variable efficacy found in different clinical trials, which appears to depend on geography. Trials conducted in the UK have consistently shown a protective effect of 60 to 80%, but those conducted elsewhere have shown no protective effect, and efficacy appears to fall the closer one gets to the equator.[17][18]

A 1994 systematic review found that BCG reduces the risk of getting tuberculosis by about 50%.[17] Differences in effectiveness depend on region, due to factors such as genetic differences in the populations, changes in environment, exposure to other bacterial infections, and conditions in the laboratory where the vaccine is grown, including genetic differences between the strains being cultured and the choice of growth medium.[19][18]

A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2014 demonstrated that the BCG vaccine reduced infections by 19–27% and reduced progression to active tuberculosis by 71%.[13] The studies included in this review were limited to those that used interferon gamma release assay.

The duration of protection of BCG is not clearly known. In those studies showing a protective effect, the data are inconsistent. The MRC study showed protection waned to 59% after 15 years and to zero after 20 years; however, a study looking at Native Americans immunized in the 1930s found evidence of protection even 60 years after immunization, with only a slight waning in efficacy.[20]

BCG seems to have its greatest effect in preventing miliary tuberculosis or tuberculosis meningitis, so it is still extensively used even in countries where efficacy against pulmonary tuberculosis is negligible.[21]

The 100th anniversary of BCG was in 2021. It remains the only vaccine licensed against tuberculosis, which is an ongoing pandemic. Tuberculosis elimination is a goal of the World Health Organization (WHO), although the development of new vaccines with greater efficacy against adult pulmonary tuberculosis may be needed to make substantial progress.[22]

Efficacy[edit]

A number of possible reasons for the variable efficacy of BCG in different countries have been proposed. None has been proven, some have been disproved, and none can explain the lack of efficacy in both low tuberculosis-burden countries (US) and high tuberculosis-burden countries (India). The reasons for variable efficacy have been discussed at length in a WHO document on BCG.[23]

- Genetic variation in BCG strains: Genetic variation in the BCG strains used may explain the variable efficacy reported in different trials.[24]

- Genetic variation in populations: Differences in genetic make-up of different populations may explain the difference in efficacy. The Birmingham BCG trial was published in 1988. The trial, based in Birmingham, United Kingdom, examined children born to families who originated from the Indian subcontinent (where vaccine efficacy had previously been shown to be zero). The trial showed a 64% protective effect, which is very similar to the figure derived from other UK trials, thus arguing against the genetic variation hypothesis.[25]

- Interference by nontuberculous mycobacteria: Exposure to environmental mycobacteria (especially Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium intracellulare) results in a nonspecific immune response against mycobacteria. Administering BCG to someone who already has a nonspecific immune response against mycobacteria does not augment the response already there. BCG will, therefore, appear not to be efficacious because that person already has a level of immunity and BCG is not adding to that immunity. This effect is called masking because the effect of BCG is masked by environmental mycobacteria. Clinical evidence for this effect was found in a series of studies performed in parallel in adolescent school children in the UK and Malawi.[26] In this study, the UK school children had a low baseline cellular immunity to mycobacteria which was increased by BCG; in contrast, the Malawi school children had a high baseline cellular immunity to mycobacteria and this was not significantly increased by BCG. Whether this natural immune response is protective is not known.[27] An alternative explanation is suggested by mouse studies; immunity against mycobacteria stops BCG from replicating and so stops it from producing an immune response. This is called the block hypothesis.[28]

- Interference by concurrent parasitic infection: In another hypothesis, simultaneous infection with parasites changes the immune response to BCG, making it less effective. As Th1 response is required for an effective immune response to tuberculous infection, concurrent infection with various parasites produces a simultaneous Th2 response, which blunts the effect of BCG.[29]

Mycobacteria[edit]

BCG has protective effects against some nontuberculosis mycobacteria.

- Leprosy: BCG has a protective effect against leprosy in the range of 20 to 80%.[8]

- Buruli ulcer: BCG may protect against or delay the onset of Buruli ulcer.[8][30]

Cancer[edit]

BCG has been one of the most successful immunotherapies.[31] BCG vaccine has been the «standard of care for patients with bladder cancer (NMIBC)» since 1977.[31][32] By 2014 there were more than eight different considered biosimilar agents or strains used for the treatment of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer.[31]

[32]

- A number of cancer vaccines use BCG as an additive to provide an initial stimulation of the person’s immune systems.[citation needed]

- BCG is used in the treatment of superficial forms of bladder cancer. Since the late 1970s, evidence has become available that instillation of BCG into the bladder is an effective form of immunotherapy in this disease.[33] While the mechanism is unclear, it appears a local immune reaction is mounted against the tumor. Immunotherapy with BCG prevents recurrence in up to 67% of cases of superficial bladder cancer.[citation needed]

- BCG has been evaluated in a number of studies as a therapy for colorectal cancer.[34] The US biotech company Vaccinogen is evaluating BCG as an adjuvant to autologous tumour cells used as a cancer vaccine in stage II colon cancer.[citation needed]

Method of administration[edit]

An apparatus (4–5 cm length, with 9 short needles) used for BCG vaccination in Japan, shown with ampules of BCG and saline

A tuberculin skin test is usually carried out before administering BCG. A reactive tuberculin skin test is a contraindication to BCG due to the risk of severe local inflammation and scarring; it does not indicate any immunity. BCG is also contraindicated in certain people who have IL-12 receptor pathway defects.[citation needed]

BCG is given as a single intradermal injection at the insertion of the deltoid. If BCG is accidentally given subcutaneously, then a local abscess may form (a «BCG-oma») that can sometimes ulcerate, and may require treatment with antibiotics immediately, otherwise without treatment it could spread the infection, causing severe damage to vital organs. An abscess is not always associated with incorrect administration, and it is one of the more common complications that can occur with the vaccination. Numerous medical studies on treatment of these abscesses with antibiotics have been done with varying results, but the consensus is once pus is aspirated and analysed, provided no unusual bacilli are present, the abscess will generally heal on its own in a matter of weeks.[35]

The characteristic raised scar that BCG immunization leaves is often used as proof of prior immunization. This scar must be distinguished from that of smallpox vaccination, which it may resemble.[citation needed]

When given for bladder cancer, the vaccine is not injected through the skin, but is instilled into the bladder through the urethra using a soft catheter.[36]

Adverse effects[edit]

BCG immunization generally causes some pain and scarring at the site of injection. The main adverse effects are keloids—large, raised scars. The insertion to the deltoid muscle is most frequently used because the local complication rate is smallest when that site is used. Nonetheless, the buttock is an alternative site of administration because it provides better cosmetic outcomes.[citation needed]

BCG vaccine should be given intradermally. If given subcutaneously, it may induce local infection and spread to the regional lymph nodes, causing either suppurative (production of pus) and nonsuppurative lymphadenitis. Conservative management is usually adequate for nonsuppurative lymphadenitis. If suppuration occurs, it may need needle aspiration. For nonresolving suppuration, surgical excision may be required. Evidence for the treatment of these complications is scarce.[37]

Uncommonly, breast and gluteal abscesses can occur due to haematogenous (carried by the blood) and lymphangiomatous spread. Regional bone infection (BCG osteomyelitis or osteitis) and disseminated BCG infection are rare complications of BCG vaccination, but potentially life-threatening. Systemic antituberculous therapy may be helpful in severe complications.[38]

When BCG is used for bladder cancer, around 2.9% of treated patients discontinue immunotherapy due to a genitourinary or systemic BCG-related infection,[39] however while symptomatic bladder BCG infection is frequent, the involvement of other organs is very uncommon.[40] When systemic involvement occurs, liver and lungs are the first organs to be affected (1 week [median] after the last BCG instillation).[41]

If BCG is accidentally given to an immunocompromised patient (e.g., an infant with severe combined immune deficiency), it can cause disseminated or life-threatening infection. The documented incidence of this happening is less than one per million immunizations given.[42] In 2007, the WHO stopped recommending BCG for infants with HIV, even if the risk of exposure to tuberculosis is high,[43] because of the risk of disseminated BCG infection (which is roughly 400 per 100,000 in that higher risk context).[44][45]

Usage[edit]

The age of the person and the frequency with which BCG is given has always varied from country to country. The WHO currently recommends childhood BCG for all countries with a high incidence of tuberculosis and/or high leprosy burden.[8] This is a partial list of historic and current BCG practice around the globe. A complete atlas of past and present practice has been generated.[46]

Americas[edit]

- Brazil introduced universal BCG immunization in 1967–1968, and the practice continues until now. According to Brazilian law, BCG is given again to professionals of the health sector and to people close to patients with tuberculosis or leprosy.[citation needed]

- Canadian Indigenous communities currently receive the BCG vaccine,[47] and in the province of Quebec the vaccine was offered to children until the mid-70s.[48]

- Most countries in Central and South America have universal BCG immunizations.[49]

- The United States has never used mass immunization of BCG due to the rarity of tuberculosis in the US, relying instead on the detection and treatment of latent tuberculosis.[citation needed]

Europe[edit]

| Country | Mandatory now | Mandatory in the past | Years vaccine was mandatory |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952–1990 | |||

| N/A | |||

| 1950–present | |||

| 1951–present | |||

| 1948–present | |||

| 1953–2010 | |||

| 1946–1986 | |||

| ?–present | |||

| 1941–2006 | |||

| 1950–2007 | |||

| 1961–1998 (East Germany began 1951) | |||

| ?–2016 | |||

| 1953–present | |||

| 1950s–2015 | |||

| N/A | |||

| 1940s–present | |||

| ?–present | |||

| ?–present | |||

| tba | ?-1979? | ||

| 1950–present | |||

| 1947–1995, voluntary 1995–2009 | |||

| 1955–present | |||

| ?–2016 | |||

| 1928–present | |||

| 1962–present | |||

| ?–present | |||

| 1953–2012 | |||

| 1947–2005 | |||

| 1965–1981 | |||

| 1940–1975 | |||

| 1960s–1987 | |||

| 1952–present | |||

| ?–present | |||

| 1953–2005 |

Asia[edit]

- China: Introduced in 1930s. Increasingly widespread after 1949. Majority inoculated by 1979.[74]

- South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Malaysia. In these countries, BCG was given at birth and again at age 12. In Malaysia and Singapore from 2001, this policy was changed to once only at birth. South Korea stopped re-vaccination in 2008.

- Hong Kong: BCG is given to all newborns.[75]

- Japan: In Japan, BCG was introduced in 1951, given typically at age 6. From 2005 it is administered between five and eight months after birth, and no later than a child’s first birthday. BCG was administered no later than the fourth birthday until 2005, and no later than six months from birth from 2005 to 2012; the schedule was changed in 2012 due to reports of osteitis side effects from vaccinations at 3–4 months. Some municipalities recommend an earlier immunization schedule.[76]

- Thailand: In Thailand, the BCG vaccine is given routinely at birth.[77]

- India and Pakistan: India and Pakistan introduced BCG mass immunization in 1948, the first countries outside Europe to do so.[78] In 2015, millions of infants were denied BCG vaccine in Pakistan for the first time due to shortage globally.[79]

- Mongolia: All newborns are vaccinated with BCG. Previously, the vaccine was also given at ages 8 and 15, although this is no longer common practice.[80]

- Philippines: BCG vaccine started in the Philippines in 1979 with the Expanded Program on Immunization.

- Sri Lanka: In Sri Lanka, The National Policy of Sri Lanka is to give BCG vaccination to all newborn babies immediately after birth. BCG vaccination is carried out under the Expanded Programme of Immunisation (EPI).[81]

Middle East[edit]

- Israel: BCG was given to all newborns between 1955 and 1982.[82]

- Iran: Iran’s vaccination policy implemented in 1984. Vaccination with the Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) is among the most important tuberculosis control strategies in Iran [2]. According to Iranian neonatal vaccination policy, BCG has been given as a single dose at children aged <6 years, shortly after birth or at first contact with the health services.[83][84]

Africa[edit]

- South Africa: In South Africa, the BCG Vaccine is given routinely at birth, to all newborns, except those with clinically symptomatic AIDS. The vaccination site in the right shoulder.[85]

- Morocco: In Morocco, the BCG was introduced in 1949. The current policy is BCG vaccination at birth, to all newborns.[86]

- Kenya: In Kenya, the BCG Vaccine is given routinely at birth to all newborns.[87]

South Pacific[edit]

- Australia: BCG vaccination was used between 1950s and mid 1980. BCG is not part of routine vaccination since mid 1980.[88]

- New Zealand: BCG Immunisation was first introduced for 13 yr olds in 1948. Vaccination was phased out 1963–1990.[46]

Manufacture[edit]

BCG is prepared from a strain of the attenuated (virulence-reduced) live bovine tuberculosis bacillus, Mycobacterium bovis, that has lost its ability to cause disease in humans. Because the living bacilli evolve to make the best use of available nutrients, they become less well-adapted to human blood and can no longer induce disease when introduced into a human host. Still, they are similar enough to their wild ancestors to provide some degree of immunity against human tuberculosis. The BCG vaccine can be anywhere from 0 to 80% effective in preventing tuberculosis for a duration of 15 years; however, its protective effect appears to vary according to geography and the lab in which the vaccine strain was grown.[19]

A number of different companies make BCG, sometimes using different genetic strains of the bacterium. This may result in different product characteristics. OncoTICE, used for bladder instillation for bladder cancer, was developed by Organon Laboratories (since acquired by Schering-Plough, and in turn acquired by Merck & Co.). A similar application is the product of Onko BCG[89] of the Polish company Biomed-Lublin, which owns the Brazilian substrain M. bovis BCG Moreau which is less reactogenic than vaccines including other BCG strains. Pacis BCG, made from the Montréal (Institut Armand-Frappier) strain,[90] was first marketed by Urocor in about 2002. Urocor was since acquired by Dianon Systems. Evans Vaccines (a subsidiary of PowderJect Pharmaceuticals). Statens Serum Institut in Denmark markets BCG vaccine prepared using Danish strain 1331.[91] Japan BCG Laboratory markets its vaccine, based on the Tokyo 172 substrain of Pasteur BCG, in 50 countries worldwide.

According to a UNICEF report published in December 2015, on BCG vaccine supply security, global demand increased in 2015 from 123 to 152.2 million doses. To improve security and to [diversify] sources of affordable and flexible supply,» UNICEF awarded seven new manufacturers contracts to produce BCG. Along with supply availability from existing manufacturers, and a «new WHO prequalified vaccine» the total supply will be «sufficient to meet both suppressed 2015 demand carried over to 2016, as well as total forecast demand through 2016–2018.»[92]

Supply shortage[edit]

In 2011, the Sanofi Pasteur plant flooded, causing problems with mold.[93] The facility, located in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, produced BCG vaccine products made with substrain Connaught such as a tuberculosis vaccine and ImmuCYST, a BCG immunotherapeutic and bladder cancer drug.[94] By April 2012 the FDA had found dozens of documented problems with sterility at the plant including mold, nesting birds and rusted electrical conduits.[93] The resulting closure of the plant for over two years caused shortages of bladder cancer and tuberculosis vaccines.[95] On 29 October 2014 Health Canada gave the permission for Sanofi to resume production of BCG.[96] A 2018 analysis of the global supply concluded that the supplies are adequate to meet forecast BCG vaccine demand, but that risks of shortages remain, mainly due to dependence of 75 percent of WHO pre-qualified supply on just two suppliers.[97]

Preparation[edit]

A weakened strain of bovine tuberculosis bacillus, Mycobacterium bovis is specially subcultured in a culture medium, usually Middlebrook 7H9.[98]

Dried[edit]

Some BCG vaccines are freeze dried and become fine powder. Sometimes the powder is sealed with vacuum in a glass ampoule. Such a glass ampoule has to be opened slowly to prevent the airflow from blowing out the powder. Then the powder has to be diluted with saline water before injecting.[99]

History[edit]

French poster promoting the BCG vaccine

The history of BCG is tied to that of smallpox. By 1865 Jean Antoine Villemin had demonstrated that rabbits could be infected with tuberculosis from humans;[100] by 1868 he had found that rabbits could be infected with tuberculosis from cows, and that rabbits could be infected with tuberculosis from other rabbits.[101] Thus, he concluded that tuberculosis was transmitted via some unidentified microorganism (or «virus», as he called it).[102][103] In 1882 Robert Koch regarded human and bovine tuberculosis as identical.[104] But in 1895, Theobald Smith presented differences between human and bovine tuberculosis, which he reported to Koch.[105][106] By 1901 Koch distinguished Mycobacterium bovis from Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[107] Following the success of vaccination in preventing smallpox, established during the 18th century, scientists thought to find a corollary in tuberculosis by drawing a parallel between bovine tuberculosis and cowpox: it was hypothesized that infection with bovine tuberculosis might protect against infection with human tuberculosis. In the late 19th century, clinical trials using M. bovis were conducted in Italy with disastrous results, because M. bovis was found to be just as virulent as M. tuberculosis.[citation needed]

Albert Calmette, a French physician and bacteriologist, and his assistant and later colleague, Camille Guérin, a veterinarian, were working at the Institut Pasteur de Lille (Lille, France) in 1908. Their work included subculturing virulent strains of the tuberculosis bacillus and testing different culture media. They noted a glycerin-bile-potato mixture grew bacilli that seemed less virulent, and changed the course of their research to see if repeated subculturing would produce a strain that was attenuated enough to be considered for use as a vaccine. The BCG strain was isolated after subculturing 239 times during 13 years from virulent strain on glycerine potato medium. The research continued throughout World War I until 1919, when the now avirulent bacilli were unable to cause tuberculosis disease in research animals. Calmette and Guerin transferred to the Paris Pasteur Institute in 1919. The BCG vaccine was first used in humans in 1921.[108]

Public acceptance was slow, and the Lübeck disaster, in particular, did much to harm it. Between 1929 and 1933 in Lübeck, 251 infants were vaccinated in the first 10 days of life; 173 developed tuberculosis and 72 died. It was subsequently discovered that the BCG administered there had been contaminated with a virulent strain that was being stored in the same incubator, which led to legal action against the manufacturers of the vaccine.[109]

Dr. R. G. Ferguson, working at the Fort Qu’Appelle Sanatorium in Saskatchewan, was among the pioneers in developing the practice of vaccination against tuberculosis. In Canada, more than 600 children from residential schools were used as involuntary participants in BCG vaccine trials between 1933 and 1945.[110] In 1928, BCG was adopted by the Health Committee of the League of Nations (predecessor to the World Health Organization (WHO)). Because of opposition, however, it only became widely used after World War II. From 1945 to 1948, relief organizations (International Tuberculosis Campaign or Joint Enterprises) vaccinated over eight million babies in eastern Europe and prevented the predicted typical increase of tuberculosis after a major war.[citation needed]

BCG is very efficacious against tuberculous meningitis in the pediatric age group, but its efficacy against pulmonary tuberculosis appears to be variable. As of 2006, only a few countries do not use BCG for routine vaccination. Two countries that have never used it routinely are the United States and the Netherlands (in both countries, it is felt that having a reliable Mantoux test and therefore being able to accurately detect active disease is more beneficial to society than vaccinating against a condition that is now relatively rare there).[111][112]

Other names include «Vaccin Bilié de Calmette et Guérin vaccine» and «Bacille de Calmette et Guérin vaccine».[citation needed]

Research[edit]

Tentative evidence exists for a beneficial non-specific effect of BCG vaccination on overall mortality in low income countries, or for its reducing other health problems including sepsis and respiratory infections when given early,[113] with greater benefit the earlier it is used.[114]

In rhesus macaques, BCG shows improved rates of protection when given intravenously.[115][116] Some risks must be evaluated before it can be translated to humans.[117]

Type 1 diabetes[edit]

As of 2017, BCG vaccine is in the early stages of being studied in type 1 diabetes (T1D).[118][119]

COVID-19[edit]

Use of the BCG vaccine may provide protection against COVID‑19.[120][121] However, epidemiologic observations in this respect are ambiguous.[122] The WHO does not recommend its use for prevention as of 12 January 2021.[123]

As of January 2021, twenty BCG trials are in various clinical stages.[124] As of October 2022, the results are extremely mixed. A 15-month trial involving people thrice-vaccinated over the two years before the pandemic shows positive results in preventing infection in BCG-naive people with type 1 diabetes.[125] On the other hand, a 5-month trial shows that re-vaccinating with BCG does not help prevent infection in healthcare workers. Both were double-blind randomized controlled trials.[126]

References[edit]

- ^ «Summary for ARTG Entry:53569 BCG VACCINE Mycobacterium bovis (Mycobacterium bovis (Bacillus Calmette and Guerin (BCG) strain) (BCG) strain) 1.5mg powder for injection multidose vial with diluent vial». Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

- ^ «Regulatory Decision Summary — Verity-BCG». Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ «Verity-BCG Product information». Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ «BCG Vaccine AJV — Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)». (emc). Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ «BCG Vaccine- bacillus Calmette–Guerin substrain TICE live antigen injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution». DailyMed. 3 September 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ a b «FREEZE — DRIED GLUTAMATE BCG VACCINE (JAPAN) FOR INTRADERMAL USE» (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T (November 2007). «Historical review of BCG vaccine in Japan». Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 60 (6): 331–336. PMID 18032829.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s World Health Organization (February 2018). «BCG vaccines: WHO position paper – February 2018». Weekly Epidemiological Record. 93 (8): 73–96. hdl:10665/260307. PMID 29474026.

- ^ Hawgood BJ (August 2007). «Albert Calmette (1863-1933) and Camille Guérin (1872-1961): the C and G of BCG vaccine». Journal of Medical Biography. 15 (3): 139–146. doi:10.1258/j.jmb.2007.06-15. PMID 17641786. S2CID 41880560.

- ^ Luca S, Mihaescu T (March 2013). «History of BCG Vaccine». Maedica. 8 (1): 53–58. PMC 3749764. PMID 24023600.

- ^ Fuge O, Vasdev N, Allchorne P, Green JS (May 2015). «Immunotherapy for bladder cancer». Research and Reports in Urology. 7: 65–79. doi:10.2147/RRU.S63447. PMC 4427258. PMID 26000263.

- ^ Houghton BB, Chalasani V, Hayne D, Grimison P, Brown CS, Patel MI, et al. (May 2013). «Intravesical chemotherapy plus bacille Calmette-Guérin in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis». BJU International. 111 (6): 977–983. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11390.x. PMID 23253618. S2CID 24961108.

- ^ a b Roy A, Eisenhut M, Harris RJ, Rodrigues LC, Sridhar S, Habermann S, et al. (August 2014). «Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis». BMJ. 349: g4643. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4643. PMC 4122754. PMID 25097193.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ «BCG Vaccine: WHO position paper» (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 4 (79): 25–40. 23 January 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2015.

- ^ a b Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, Wilson ME, Burdick E, Fineberg HV, Mosteller F (March 1994). «Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature». JAMA. 271 (9): 698–702. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03510330076038. PMID 8309034.

- ^ a b Fine PE (November 1995). «Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity». Lancet. 346 (8986): 1339–1345. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92348-9. PMID 7475776. S2CID 44737409.

- ^ a b Venkataswamy MM, Goldberg MF, Baena A, Chan J, Jacobs WR, Porcelli SA (February 2012). «In vitro culture medium influences the vaccine efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG». Vaccine. 30 (6): 1038–1049. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.044. PMC 3269512. PMID 22189700.

- ^ Aronson NE, Santosham M, Comstock GW, Howard RS, Moulton LH, Rhoades ER, Harrison LH (May 2004). «Long-term efficacy of BCG vaccine in American Indians and Alaska Natives: A 60-year follow-up study». JAMA. 291 (17): 2086–2091. doi:10.1001/jama.291.17.2086. PMID 15126436.

- ^ Rodrigues LC, Diwan VK, Wheeler JG (December 1993). «Protective effect of BCG against tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis». International Journal of Epidemiology. 22 (6): 1154–1158. doi:10.1093/ije/22.6.1154. PMID 8144299.

- ^ Kupz A. «Tuberculosis kills as many people each year as COVID-19. It’s time we found a better vaccine». The Conversation.

- ^ Fine PE, Carneiro IA, Milstein JB, Clements CJ (1999). «Chapter 8: Reasons for variable efficacy» (PDF). Issues relating to the use of BCG in immunization programmes: a discussion document (Report). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/66120. WHO/V&B/99.23.

- ^ Brosch R, Gordon SV, Garnier T, Eiglmeier K, Frigui W, Valenti P, et al. (March 2007). «Genome plasticity of BCG and impact on vaccine efficacy». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (13): 5596–5601. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.5596B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700869104. PMC 1838518. PMID 17372194.

- ^ Packe GE, Innes JA (March 1988). «Protective effect of BCG vaccination in infant Asians: a case-control study». Archives of Disease in Childhood. 63 (3): 277–281. doi:10.1136/adc.63.3.277. PMC 1778792. PMID 3258499.

- ^ Black GF, Weir RE, Floyd S, Bliss L, Warndorff DK, Crampin AC, et al. (April 2002). «BCG-induced increase in interferon-gamma response to mycobacterial antigens and efficacy of BCG vaccination in Malawi and the UK: two randomised controlled studies». Lancet. 359 (9315): 1393–1401. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08353-8. PMID 11978337. S2CID 24334622.

- ^ Palmer CE, Long MW (October 1966). «Effects of infection with atypical mycobacteria on BCG vaccination and tuberculosis». The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 94 (4): 553–568. doi:10.1164/arrd.1966.94.4.553 (inactive 31 December 2022). PMID 5924215.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2022 (link) - ^ Brandt L, Feino Cunha J, Weinreich Olsen A, Chilima B, Hirsch P, Appelberg R, Andersen P (February 2002). «Failure of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine: some species of environmental mycobacteria block multiplication of BCG and induction of protective immunity to tuberculosis». Infection and Immunity. 70 (2): 672–678. doi:10.1128/IAI.70.2.672-678.2002. PMC 127715. PMID 11796598.

- ^ Rook GA, Dheda K, Zumla A (March 2005). «Do successful tuberculosis vaccines need to be immunoregulatory rather than merely Th1-boosting?» (PDF). Vaccine. 23 (17–18): 2115–2120. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.069. PMID 15755581. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2017.

- ^ Tanghe A, Content J, Van Vooren JP, Portaels F, Huygen K (September 2001). «Protective efficacy of a DNA vaccine encoding antigen 85A from Mycobacterium bovis BCG against Buruli ulcer». Infection and Immunity. 69 (9): 5403–5411. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.9.5403-5411.2001. PMC 98650. PMID 11500410.

- ^ a b c Rentsch CA, Birkhäuser FD, Biot C, Gsponer JR, Bisiaux A, Wetterauer C, et al. (October 2014). «Bacillus Calmette-Guérin strain differences have an impact on clinical outcome in bladder cancer immunotherapy». European Urology. 66 (4): 677–688. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.061. PMID 24674149.

- ^ a b Brandau S, Suttmann H (July 2007). «Thirty years of BCG immunotherapy for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a success story with room for improvement». Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 61 (6): 299–305. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2007.05.004. PMID 17604943.

- ^ Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, Montie JE, Scardino P, Grossman HB, et al. (October 1991). «A randomized trial of intravesical doxorubicin and immunotherapy with bacille Calmette-Guérin for transitional-cell carcinoma of the bladder». The New England Journal of Medicine. 325 (17): 1205–1209. doi:10.1056/NEJM199110243251703. PMID 1922207.

- ^ Mosolits S, Nilsson B, Mellstedt H (June 2005). «Towards therapeutic vaccines for colorectal carcinoma: a review of clinical trials». Expert Review of Vaccines. 4 (3): 329–350. doi:10.1586/14760584.4.3.329. PMID 16026248. S2CID 35749038.

- ^ «BestBets: Is medical therapy effective in the treatment of BCG abscesses?». bestbets.org. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ «Intravesical Therapy for Bladder Cancer». www.cancer.org. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Cuello-García CA, Pérez-Gaxiola G, Jiménez Gutiérrez C (January 2013). «Treating BCG-induced disease in children». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (1): CD008300. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008300.pub2. PMC 6532703. PMID 23440826.

- ^ Govindarajan KK, Chai FY (April 2011). «BCG Adenitis-Need for Increased Awareness». The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences. 18 (2): 66–69. PMC 3216207. PMID 22135589. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences Archived 26 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nummi A, Järvinen R, Sairanen J, Huotari K (4 May 2019). «A retrospective study on tolerability and complications of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) instillations for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer». Scandinavian Journal of Urology. 53 (2–3): 116–122. doi:10.1080/21681805.2019.1609080. PMID 31074322. S2CID 149444603.

- ^ Liu Y, Lu J, Huang Y, Ma L (10 March 2019). «Clinical Spectrum of Complications Induced by Intravesical Immunotherapy of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin for Bladder Cancer». Journal of Oncology. 2019: 6230409. doi:10.1155/2019/6230409. PMC 6431507. PMID 30984262.

- ^ Cabas P, Rizzo M, Giuffrè M, Antonello RM, Trombetta C, Luzzati R, et al. (February 2021). «BCG infection (BCGitis) following intravesical instillation for bladder cancer and time interval between treatment and presentation: A systematic review». Urologic Oncology. 39 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.11.037. PMID 33308969. S2CID 229179250.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (April 1996). «The role of BCG vaccine in the prevention and control of tuberculosis in the United States. A joint statement by the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices» (PDF). MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 45 (RR-4): 1–18. PMID 8602127.

- ^ World Health Organization (May 2007). «Revised BCG vaccination guidelines for infants at risk for HIV infection». Weekly Epidemiological Record. 82 (21): 193–196. hdl:10665/240940. PMID 17526121.

- ^ Trunz BB, Fine P, Dye C (April 2006). «Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness». Lancet. 367 (9517): 1173–1180. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68507-3. PMID 16616560. S2CID 40371125.

- ^ Mak TK, Hesseling AC, Hussey GD, Cotton MF (September 2008). «Making BCG vaccination programmes safer in the HIV era». Lancet. 372 (9641): 786–787. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61318-5. PMID 18774406. S2CID 6702107.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai «Database of Global BCG Vaccination Policies and Practices». The BCG World Atlas. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ «Bacille Calmette–Guerin (BCG) Information for Health Professionals». toronto.ca. January 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Rousseau MC, Conus F, Kâ K, El-Zein M, Parent MÉ, Menzies D (August 2017). «Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination patterns in the province of Québec, Canada, 1956-1974». Vaccine. 35 (36): 4777–4784. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.064. PMID 28705514.

- ^ «Ficha metodológica». Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ «Prevention». sciensano.be.

- ^ «Задължителни и препоръчителни имунизации» [Mandatory and recommended immunizations]. mh.government.bg. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ «Kopie – cem05_14.p65» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Rieckmann A, Villumsen M, Sørup S, Haugaard LK, Ravn H, Roth A, et al. (April 2017). «Vaccinations against smallpox and tuberculosis are associated with better long-term survival: a Danish case-cohort study 1971-2010». International Journal of Epidemiology. 46 (2): 695–705. doi:10.1093/ije/dyw120. PMC 5837789. PMID 27380797. S2CID 3792173.

- ^ «THL». BCG- eli tuberkuloosirokote. THL. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Loi n° 50-7 du 5 janvier 1950

- ^ décret n° 2007-1111 du 17 juillet 2007

- ^ «relatif à l’obligation de vaccination par le BCG des professionnels listés aux articles L» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ BCG World Atlas. «A Database of Global BCG Vaccination Policies and Practices». Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Gabriele F, Katragkou A, Roilides E (October 2014). «BCG vaccination policy in Greece: time for another review?». The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 18 (10): 1258. doi:10.5588/ijtld.14.0282. PMID 25216844.

- ^ «Διακοπή της εφαρμογής καθολικού αντιφυματικού εμβολιασμού (εμβόλιο BCG) στα παιδιά της Α΄ Δημοτικού 2016». Υπουργείο Υγείας.

- ^ «A tuberkulózis és a tuberkulózis elleni védőoltás (BCG)» [Tuberculosis and tuberculosis vaccination]. ÁNTSZ. 17 July 2015.

- ^ «Integrált Jogvédelmi Szolgálat» (PDF). Integrált Jogvédelmi Szolgálat (in Hungarian). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ O’Sullivan K. «Coronavirus: More «striking» evidence BCG vaccine might protect against Covid-19″. The Irish Times. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ «Tuberkulosevaksinasjon – veileder for helsepersonell» [Tuberculosis vaccination — guide for healthcare professionals]. FHI.no (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

- ^ «Portugal data» (PDF). venice.cineca.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ «Vaccinări cu obligativitate generală» [Vaccinations with general obligation]. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ «Vacunas disponibles | Vacunas / Asociación Española de Vacunología» [Vaccines available; Vaccines / Spanish Association of Vaccination].

- ^ «Tuberkulos (TB) – om vaccination – Folkhälsomyndigheten» [Tuberculosis (TB) — on vaccination — Public Health Agency]. folkhalsomyndigheten.se.

- ^ Zwerling A, Behr MA, Verma A, Brewer TF, Menzies D, Pai M (March 2011). «The BCG World Atlas: a database of global BCG vaccination policies and practices». PLOS Medicine. 8 (3): e1001012. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001012. PMC 3062527. PMID 21445325.

- ^ «ІПС ЛІГА:ЗАКОН — система пошуку, аналізу та моніторингу нормативно-правової бази». ips.ligazakon.net. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Styblo K, Meijer J (March 1976). «Impact of BCG vaccination programmes in children and young adults on the tuberculosis problem». Tubercle. 57 (1): 17–43. doi:10.1016/0041-3879(76)90015-5. PMID 1085050.

- ^ «School «TB jabs» to be scrapped». BBC News Online. 6 July 2005. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ «BCG tuberculosis (TB) vaccine overview». NHS.uk. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ Chen ZR, Wei XH, Zhu ZY (June 1982). «BCG in China». Chinese Medical Journal. 95 (6): 437–442. PMID 6813052.

- ^ «Child health – Immunisation». Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ «結核とBCGワクチンに関するQ&A|厚生労働省» [Q & A about tuberculosis and BCG vaccine, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare]. mhlw.go.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ «Thai Pediatrics». Thai Pediatrics. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015.

- ^ Mahler HT, Mohamed Ali P (1955). «Review of mass B.C.G. project in India». Ind J Tuberculosis. 2 (3): 108–16. Archived from the original on 13 February 2007.

- ^ Chaudhry A (24 February 2015). «Millions of infants denied anti-TB vaccination». Dawn. Pakistan. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Rauniyar SK, Munkhbat E, Ueda P, Yoneoka D, Shibuya K, Nomura S (September 2020). «Timeliness of routine vaccination among children and determinants associated with age-appropriate vaccination in Mongolia». Heliyon. 6 (9): e04898. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04898. PMC 7505765. PMID 32995607.

- ^ «Role of BC Vaccination». The National Programme for tuberculosis Control & Chest Diseases. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013.

- ^ Hamiel U, Kozer E, Youngster I (June 2020). «SARS-CoV-2 Rates in BCG-Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Young Adults». JAMA. 323 (22): 2340–2341. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8189. PMC 7221856. PMID 32401274.

- ^ Sadeghi-Shanbestari M, Ansarin K, Maljaei SH, Rafeey M, Pezeshki Z, Kousha A, et al. (December 2009). «Immunologic aspects of patients with disseminated bacille Calmette-Guerin disease in north-west of Iran». Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 35 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/1824-7288-35-42. PMC 2806263. PMID 20030825.

- ^ «Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG)», SpringerReference, Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2011, doi:10.1007/springerreference_91899, retrieved 1 July 2022

- ^ «BCG» (PDF). South African National Department of Health. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013.

- ^ «Évolution du calendrier vaccinal au Maroc». 29 May 2006.

- ^ «BCG Vaccine – Its Evolution and Importance». Centre for Health Solutions — Kenya. 12 January 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ «BCG vaccine for TB». Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ «Onko BCG 100 Biomed Lublin». biomedlublin.com. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ «Pharmaceutical Information – PACIS». RxMed. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ «BCG Vaccine Danish Strain 1331 – Statens Serum Institut». Ssi.dk. 19 September 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ «Bacillus Calmette–Guérin Vaccine Supply & Demand Outlook» (PDF), UNICEF Supply Division, p. 5, December 2015, archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2016, retrieved 29 January 2016

- ^ a b «April 2012 Inspectional Observations (form 483)», U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Vaccines, Blood & Biologics, 12 April 2012, archived from the original on 6 February 2016, retrieved 29 January 2016

- ^ «Sanofi Pasteur Product Monograph – Immucyst» (PDF). Sanofi Pasteur Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Palmer E (10 September 2014). «UPDATED: Merck again shipping BCG cancer treatment but Sanofi still is not». FiercePharma.

- ^ Palmer E (31 March 2015), «Sanofi Canada vax plant again producing ImmuCyst bladder cancer drug», FiercePharma, archived from the original on 5 February 2016, retrieved 29 January 2016

- ^ Cernuschi T, Malvolti S, Nickels E, Friede M (January 2018). «Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine: A global assessment of demand and supply balance». Vaccine. 36 (4): 498–506. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.010. PMC 5777639. PMID 29254839.

- ^ Atlas RM, Snyder JW (2006). Handbook of media for clinical microbiology. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-3795-6.

- ^ Ungar J, Muggleton PW, Dudley JA, Griffiths MI (October 1962). «Preparation and properties of a freeze-dried B.C.G. vaccine of increased stability». British Medical Journal. 2 (5312): 1086–1089. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5312.1086. PMC 1926490. PMID 13995378.

- ^ Villemin JA (1865). «Cause et nature de la tuberculose» [Cause and nature of tuberculosis]. Bulletin de l’Académie Impériale de Médecine (in French). 31: 211–216.

- ^ Villemin JA (1868). Études sur la Tuberculose [Studies of Tuberculosis] (in French). Paris, France: J.-B. Baillière et fils. pp. 528–597. (§ «Seizième Étude: La tuberculose est inoculable» (Sixteenth study: Tuberculosis can be transmitted by inoculation))

- ^ (Villemin, 1868), pp. 598–631. From p. 598: «La tuberculose est inoculable, voilà maintenant un fait incontestable. Désormais cette affection devra se placer parmi les maladies virulentes, … « (Tuberculosis [can be transmitted by] inoculation; that’s now an incontestable fact. Henceforth this malady should be placed among the virulent maladies [i.e., those diseases that are transmitted via microorganisms], … ) From p. 602: «Les virus, comme les parasites, se multiplient eux-même, nous ne leur fournissons que les moyens de vivre et de se reproduire, jamais nous les créons.» (Viruses, like parasites, multiply themselves; we merely furnish them with the means of living and reproducing; we never create them.)

- ^ Villemin JA (1868a). De la virulence et de la spécificité de la tuberculose [On the virulence [i.e., infectious nature] and specificity of tuberculosis] (in French). Paris, France: Victor Masson et fils.

- ^ Koch R (10 April 1882). «Die Aetologie der Tuberculose» [The etiology of tuberculosis]. Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift (in German). 19 (15): 221–230. From p. 230: «Die Perlsucht ist identisch mit der Tuberculose des Menschen und also eine auf diesen übertragbare Krankheit.» (Pearl disease [i.e., bovine tuberculosis] is identical with the tuberculosis of humans and thus [is] a disease that can be transmitted to them.)

- ^ Smith T (1895). «Investigations of diseases of domesticated animals». Annual Report of the Bureau of Animal Industry. U.S. Department of Agriculture. 12/13: 119–185. See § «Two varieties of the tubercle bacillus from mammals.» pp. 149-161.

- Smith T (1896). «Two varieties of the tubercle bacillus from mammals». Transactions of the Association of American Physicians. 11: 75–95.

- ^ Palmer MV, Waters WR (May 2011). «Bovine tuberculosis and the establishment of an eradication program in the United States: role of veterinarians». Veterinary Medicine International. 2011 (1): 816345. doi:10.4061/2011/816345. PMC 3103864. PMID 21647341. S2CID 18020962. From p. 2: «In 1895, Smith visited Koch in Europe and described his findings.»

- ^ Koch R (27 July 1901). «An address on the combatting of tuberculosis in the light of experience that has been gained in the successful combatting of other infectious diseases». The Lancet. 158 (4065): 187–191. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)85122-9. From p. 189: «Considering all these facts, I feel justified in maintaining that human tuberculosis differs from bovine and cannot be transmitted to cattle.»

- ^ Fine PE, Carneiro IA, Milstein JB, Clements CJ (1999). Issues relating to the use of BCG in immunization programs. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO).

- ^ Rosenthal SR (1957). BCG vaccination against tuberculosis. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

- ^ Blackburn M (24 July 2013). «First Nation infants subject to «human experimental work» for TB vaccine in 1930s-40s». APTN News. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ «Fact Sheets: BCG Vaccine». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 October 2011. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Vaccination of young children against tuberculosis (PDF). The Hague:Health Council of the Netherlands. 2011. ISBN 978-90-5549-844-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Aaby P, Roth A, Ravn H, Napirna BM, Rodrigues A, Lisse IM, et al. (July 2011). «Randomized trial of BCG vaccination at birth to low-birth-weight children: beneficial nonspecific effects in the neonatal period?». The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 (2): 245–252. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir240. PMID 21673035.

- ^ Biering-Sørensen S, Aaby P, Napirna BM, Roth A, Ravn H, Rodrigues A, et al. (March 2012). «Small randomized trial among low-birth-weight children receiving bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination at first health center contact». The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 31 (3): 306–308. doi:10.1097/inf.0b013e3182458289. PMID 22189537. S2CID 1240058.

- ^ Darrah PA, Zeppa JJ, Maiello P, Hackney JA, Wadsworth MH, Hughes TK, et al. (January 2020). «Prevention of tuberculosis in macaques after intravenous BCG immunization». Nature. 577 (7788): 95–102. Bibcode:2020Natur.577…95D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1817-8. PMC 7015856. PMID 31894150.

- ^ Behar SM, Sassetti C (January 2020). «Tuberculosis vaccine finds an improved route». Nature. 577 (7788): 31–32. Bibcode:2020Natur.577…31B. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03597-y. PMID 31894152. S2CID 209528484.

- ^ «The trick that could inject new life into an old tuberculosis vaccine». Nature. 577 (7789): 145. January 2020. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..145.. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00003-w. PMID 31911698. S2CID 210044794.

- ^ Kühtreiber WM, Tran L, Kim T, Dybala M, Nguyen B, Plager S, et al. (2018). «Long-term reduction in hyperglycemia in advanced type 1 diabetes: the value of induced aerobic glycolysis with BCG vaccinations». NPJ Vaccines. 3: 23. doi:10.1038/s41541-018-0062-8. PMC 6013479. PMID 29951281.

- ^ Kowalewicz-Kulbat M, Locht C (July 2017). «BCG and protection against inflammatory and auto-immune diseases». Expert Review of Vaccines. 16 (7): 699–708. doi:10.1080/14760584.2017.1333906. PMID 28532186. S2CID 4723444.

- ^ Gong W, Mao Y, Li Y, Qi Y (July 2022). «BCG Vaccination: A potential tool against COVID-19 and COVID-19-like Black Swan incidents». International Immunopharmacology. 108 (108): 108870. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108870. PMC 9113676. PMID 35597119.

- ^ Faustman DL, Lee A, Hostetter ER, Aristarkhova A, Ng NC, Shpilsky GF, et al. (September 2022). «Multiple BCG vaccinations for the prevention of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases in type 1 diabetes». Cell Reports. Medicine. 3 (9): 100728. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100728. PMC 9376308. PMID 36027906.