|

Ludwig van Beethoven |

|

|---|---|

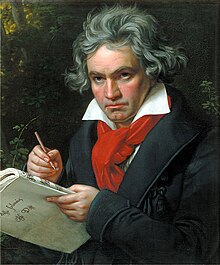

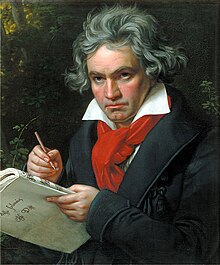

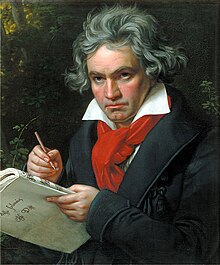

Portrait by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820 |

|

| Born |

Bonn |

| Baptised | 17 December 1770 |

| Died | 26 March 1827 (aged 56)

Vienna |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | List of compositions |

| Parent(s) | Johann van Beethoven Maria Magdalena Keverich |

| Signature | |

Ludwig van Beethoven[n 1] (baptised 17 December 1770 – 26 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical music repertoire and span the transition from the Classical period to the Romantic era in classical music. His career has conventionally been divided into early, middle, and late periods. His early period, during which he forged his craft, is typically considered to have lasted until 1802. From 1802 to around 1812, his middle period showed an individual development from the styles of Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and is sometimes characterized as heroic. During this time, he began to grow increasingly deaf. In his late period, from 1812 to 1827, he extended his innovations in musical form and expression.

Beethoven was born in Bonn. His musical talent was obvious at an early age. He was initially harshly and intensively taught by his father Johann van Beethoven. Beethoven was later taught by the composer and conductor Christian Gottlob Neefe, under whose tutelage he published his first work, a set of keyboard variations, in 1783. He found relief from a dysfunctional home life with the family of Helene von Breuning, whose children he loved, befriended, and taught piano. At age 21, he moved to Vienna, which subsequently became his base, and studied composition with Haydn. Beethoven then gained a reputation as a virtuoso pianist, and he was soon patronized by Karl Alois, Prince Lichnowsky for compositions, which resulted in his three Opus 1 piano trios (the earliest works to which he accorded an opus number) in 1795.

His first major orchestral work, the First Symphony, premiered in 1800, and his first set of string quartets was published in 1801. Despite his hearing deteriorating during this period, he continued to conduct, premiering his Third and Fifth Symphonies in 1804 and 1808, respectively. His Violin Concerto appeared in 1806. His last piano concerto (No. 5, Op. 73, known as the Emperor), dedicated to his frequent patron Archduke Rudolf of Austria, was premiered in 1811, without Beethoven as soloist. He was almost completely deaf by 1814, and he then gave up performing and appearing in public. He described his problems with health and his unfulfilled personal life in two letters, his Heiligenstadt Testament (1802) to his brothers and his unsent love letter to an unknown «Immortal Beloved» (1812).

After 1810, increasingly less socially involved, Beethoven composed many of his most admired works, including later symphonies, mature chamber music and the late piano sonatas. His only opera, Fidelio, first performed in 1805, was revised to its final version in 1814. He composed Missa solemnis between 1819 and 1823 and his final Symphony, No. 9, one of the first examples of a choral symphony, between 1822 and 1824. Written in his last years, his late string quartets, including the Grosse Fuge, of 1825–1826 are among his final achievements. After some months of bedridden illness, he died in 1827. Beethoven’s works remain mainstays of the classical music repertoire.

Life and career

Family and early life

Beethoven’s birthplace at Bonngasse 20, Bonn, now the Beethoven House museum

Beethoven was the grandson of Ludwig van Beethoven,[n 2] a musician from the town of Mechelen in the Austrian Duchy of Brabant (in what is now the Flemish region of Belgium) who had moved to Bonn at the age of 21.[2][3] Ludwig was employed as a bass singer at the court of Clemens August, Archbishop-Elector of Cologne, eventually rising to become, in 1761, Kapellmeister (music director) and hence a pre-eminent musician in Bonn. The portrait he commissioned of himself towards the end of his life remained displayed in his grandson’s rooms as a talisman of his musical heritage.[4] Ludwig had two sons, the younger of which (Johann) worked as a tenor in the same musical establishment and gave keyboard and violin lessons to supplement his income.[2]

Johann married Maria Magdalena Keverich in 1767; she was the daughter of Heinrich Keverich (1701–1751), who had been the head chef at the court of Johann IX Philipp von Walderdorff, Archbishop of Trier.[5] Beethoven was born of this marriage in Bonn, at what is now the Beethoven House Museum, Bonnstrasse 20.[6] There is no authentic record of the date of his birth; but the registry of his baptism, in the Catholic Parish of St. Remigius on 17 December 1770, survives, and the custom in the region at the time was to carry out baptism within 24 hours of birth. There is a consensus (with which Beethoven himself agreed) that his birth date was 16 December, but no documentary proof of this.[7]

Of the seven children born to Johann van Beethoven, only Ludwig, the second-born, and two younger brothers survived infancy. Kaspar Anton Karl (generally known as Karl) was born on 8 April 1774, and Nikolaus Johann (generally known as Johann), the youngest, was born on 2 October 1776.[8]

Beethoven’s first music teacher was his father. He later had other local teachers: the court organist Gilles van den Eeden (d. 1782), Tobias Friedrich Pfeiffer (a family friend, who provided keyboard tuition), Franz Rovantini (a relative, who instructed him in playing the violin and viola),[2] and court concertmaster Franz Anton Ries for the violin.[9] His tuition began in his fifth year. The regime was harsh and intensive, often reducing him to tears. With the involvement of the insomniac Pfeiffer, there were irregular late-night sessions, with the young Beethoven being dragged from his bed to the keyboard.[10] His musical talent was obvious at a young age. Johann, aware of Leopold Mozart’s successes in this area (with his son Wolfgang and daughter Nannerl), attempted to promote his son as a child prodigy, claiming that Beethoven was six (he was seven) on the posters for his first public performance in March 1778.[11]

1780–1792: Bonn

Christian Gottlob Neefe. Engraving after Johann Georg Rosenberg, c. 1798

In 1780 or 1781, Beethoven began his studies with his most important teacher in Bonn, Christian Gottlob Neefe.[12] Neefe taught him composition; in March 1783 Beethoven’s first published work appeared, a set of keyboard variations (WoO 63).[8][n 3] Beethoven soon began working with Neefe as assistant organist, at first unpaid (1782), and then as a paid employee (1784) of the court chapel.[14] His first three piano sonatas, WoO 47, sometimes known as Kurfürst (Elector) for their dedication to Elector Maximilian Friedrich, were published in 1783.[15] In the same year, the first printed reference to Beethoven appeared in the Magazin der Musik – «Louis van Beethoven [sic] … a boy of 11 years and most promising talent. He plays the piano very skilfully and with power, reads at sight very well … the chief piece he plays is Das wohltemperierte Klavier of Sebastian Bach, which Herr Neefe puts into his hands».[2] Maximilian Friedrich’s successor as Elector of Bonn was Maximilian Franz. He gave some support to Beethoven, appointing him Court Organist and paying towards his visit to Vienna of 1792.[5][16]

He was introduced in these years to several people who became important in his life. He often visited the cultivated von Breuning family, at whose home he taught piano to some of the children, and where the widowed Frau von Breuning offered him a motherly friendship. Here he also met Franz Wegeler, a young medical student, who became a lifelong friend (and was to marry one of the von Breuning daughters). The von Breuning family environment offered an alternative to his home life, which was increasingly dominated by his father’s decline. Another frequenter of the von Breunings was Count Ferdinand von Waldstein, who became a friend and financial supporter during Beethoven’s Bonn period.[17][18][19] Waldstein was to commission in 1791 Beethoven’s first work for the stage, the ballet Musik zu einem Ritterballett (WoO 1).[20]

In the period 1785–90 there is virtually no record of Beethoven’s activity as a composer. This may be attributed to the lukewarm response his initial publications had attracted, and also to ongoing problems in the Beethoven family.[21] His mother died in 1787, shortly after Beethoven’s first visit to Vienna, where he stayed for about two weeks and almost certainly met Mozart.[17] In 1789 Beethoven’s father was forcibly retired from the service of the Court (as a consequence of his alcoholism) and it was ordered that half of his father’s pension be paid directly to Ludwig for support of the family.[22] He contributed further to the family’s income by teaching (to which Wegeler said he had «an extraordinary aversion»[23]) and by playing viola in the court orchestra. This familiarized him with a variety of operas, including works by Mozart, Gluck and Paisiello.[24] Here he also befriended Anton Reicha, a composer, flautist and violinist of about his own age who was a nephew of the court orchestra’s conductor, Josef Reicha.[25]

From 1790 to 1792, Beethoven composed several works (none were published at the time) showing a growing range and maturity. Musicologists have identified a theme similar to those of his Third Symphony in a set of variations written in 1791.[26] It was perhaps on Neefe’s recommendation that Beethoven received his first commissions; the Literary Society in Bonn commissioned a cantata to mark the occasion of the death in 1790 of Joseph II (WoO 87), and a further cantata, to celebrate the subsequent accession of Leopold II as Holy Roman Emperor (WoO 88), may have been commissioned by the Elector.[27] These two Emperor Cantatas were never performed at the time and they remained lost until the 1880s when they were described by Johannes Brahms as «Beethoven through and through» and as such prophetic of the style which would mark his music as distinct from the classical tradition.[28]

Beethoven was probably first introduced to Joseph Haydn in late 1790 when the latter was travelling to London and stopped in Bonn around Christmas time.[29] A year and a half later, they met in Bonn on Haydn’s return trip from London to Vienna in July 1792, when Beethoven played in the orchestra at the Redoute in Godesberg. Arrangements were likely made at that time for Beethoven to study with the older master.[30] Waldstein wrote to him before his departure: «You are going to Vienna in fulfilment of your long-frustrated wishes … With the help of assiduous labour you shall receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands.»[17]

1792–1802: Vienna – the early years

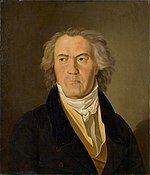

Portrait of Beethoven as a young man, c. 1800, by Carl Traugott Riedel (1769–1832)

Beethoven left Bonn for Vienna in November 1792, amid rumours of war spilling out of France; he learned shortly after his arrival that his father had died.[31][32] Over the next few years, Beethoven responded to the widespread feeling that he was a successor to the recently deceased Mozart by studying that master’s work and writing works with a distinctly Mozartian flavour.[33]

He did not immediately set out to establish himself as a composer, but rather devoted himself to study and performance. Working under Haydn’s direction,[34] he sought to master counterpoint. He also studied violin under Ignaz Schuppanzigh.[35] Early in this period, he also began receiving occasional instruction from Antonio Salieri, primarily in Italian vocal composition style; this relationship persisted until at least 1802, and possibly as late as 1809.[36]

With Haydn’s departure for England in 1794, Beethoven was expected by the Elector to return home to Bonn. He chose instead to remain in Vienna, continuing his instruction in counterpoint with Johann Albrechtsberger and other teachers. In any case, by this time it must have seemed clear to his employer that Bonn would fall to the French, as it did in October 1794, effectively leaving Beethoven without a stipend or the necessity to return.[37] However, several Viennese noblemen had already recognised his ability and offered him financial support, among them Prince Joseph Franz Lobkowitz, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, and Baron Gottfried van Swieten.[38]

Assisted by his connections with Haydn and Waldstein, Beethoven began to develop a reputation as a performer and improviser in the salons of the Viennese nobility.[39] His friend Nikolaus Simrock began publishing his compositions, starting with a set of keyboard variations on a theme of Dittersdorf (WoO 66).[40] By 1793, he had established a reputation in Vienna as a piano virtuoso, but he apparently withheld works from publication so that their eventual appearance would have greater impact.[38]

In 1795 Beethoven made his public debut in Vienna over three days,[41] beginning with a performance of one of his own piano concertos on 29 March at the Burgtheater[n 4] and ending with a Mozart concerto on 31 March, probably the D minor concerto for which he had written a cadenza soon after his arrival in Vienna. By this year he had two piano concertos available for performance, one in B-flat major he had begun composing before moving to Vienna and had worked on for over a decade, and one in C major composed for the most part during 1795.[46] Viewing the latter as the more substantive work, he chose to designate it as his first piano concerto, publishing it in March 1801 as Opus 15, before publishing the former as Opus 19 the following December. He wrote new cadenzas for both works in 1809.[47]

Shortly after his public debut he arranged for the publication of the first of his compositions to which he assigned an opus number, the three piano trios, Opus 1. These works were dedicated to his patron Prince Lichnowsky,[42] and were a financial success; Beethoven’s profits were nearly sufficient to cover his living expenses for a year.[48] In 1799 Beethoven participated in (and won) a notorious piano ‘duel’ at the home of Baron Raimund Wetzlar (a former patron of Mozart) against the virtuoso Joseph Wölfl; and in the following year he similarly triumphed against Daniel Steibelt at the salon of Count Moritz von Fries.[49] Beethoven’s eighth piano sonata the Pathétique (Op. 13), published in 1799 is described by the musicologist Barry Cooper as «surpass[ing] any of his previous compositions, in strength of character, depth of emotion, level of originality, and ingenuity of motivic and tonal manipulation».[50]

Beethoven composed his first six string quartets (Op. 18) between 1798 and 1800 (commissioned by, and dedicated to, Prince Lobkowitz). They were published in 1801. He also completed his Septet (Op. 20) in 1799, which was one of his most popular works during his lifetime. With premieres of his First and Second Symphonies in 1800 and 1803, he became regarded as one of the most important of a generation of young composers following Haydn and Mozart. But his melodies, musical development, use of modulation and texture, and characterisation of emotion all set him apart from his influences, and heightened the impact some of his early works made when they were first published.[51] For the premiere of his First Symphony, he hired the Burgtheater on 2 April 1800, and staged an extensive programme, including works by Haydn and Mozart, as well as his Septet, the Symphony, and one of his piano concertos (the latter three works all then unpublished). The concert, which the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung described as «the most interesting concert in a long time», was not without difficulties; among the criticisms was that «the players did not bother to pay any attention to the soloist».[52] By the end of 1800, Beethoven and his music were already much in demand from patrons and publishers.[53]

Josephine Brunsvik, pencil miniature (unknown artist), before 1804

In May 1799, he taught piano to the daughters of Hungarian Countess Anna Brunsvik. During this time, he fell in love with the younger daughter Josephine. Amongst his other students, from 1801 to 1805, he tutored Ferdinand Ries, who went on to become a composer and later wrote about their encounters. The young Carl Czerny, who later became a renowned music teacher himself, studied with Beethoven from 1801 to 1803. In late 1801, he met a young countess, Julie Guicciardi, through the Brunsvik family; he mentions his love for Julie in a November 1801 letter to a friend, but class difference prevented any consideration of pursuing this. He dedicated his 1802 Sonata Op. 27 No. 2, now commonly known as the Moonlight Sonata, to her.[54]

In the spring of 1801 he completed The Creatures of Prometheus, a ballet. The work received numerous performances in 1801 and 1802, and he rushed to publish a piano arrangement to capitalise on its early popularity.[55] In the spring of 1802 he completed the Second Symphony, intended for performance at a concert that was cancelled. The symphony received its premiere instead at a subscription concert in April 1803 at the Theater an der Wien, where he had been appointed composer in residence. In addition to the Second Symphony, the concert also featured the First Symphony, the Third Piano Concerto, and the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives. Reviews were mixed, but the concert was a financial success; he was able to charge three times the cost of a typical concert ticket.[56]

His business dealings with publishers also began to improve in 1802 when his brother Kaspar, who had previously assisted him casually, began to assume a larger role in the management of his affairs. In addition to negotiating higher prices for recently composed works, Kaspar also began selling some of his earlier unpublished compositions and encouraged him (against Beethoven’s preference) to also make arrangements and transcriptions of his more popular works for other instrument combinations. Beethoven acceded to these requests, as he could not prevent publishers from hiring others to do similar arrangements of his works.[57]

1802–1812: The ‘heroic’ period

Deafness

Beethoven told the English pianist Charles Neate (in 1815) that he dated his hearing loss from a fit in 1798 induced by a quarrel with a singer.[58] During its gradual decline, his hearing was further impeded by a severe form of tinnitus.[59] As early as 1801, he wrote to Wegeler and another friend Karl Amenda, describing his symptoms and the difficulties they caused in both professional and social settings (although it is likely some of his close friends were already aware of the problems).[60] The cause was probably otosclerosis, perhaps accompanied by degeneration of the auditory nerve.[61][n 5]

On the advice of his doctor, Beethoven moved to the small Austrian town of Heiligenstadt, just outside Vienna, from April to October 1802 in an attempt to come to terms with his condition. There he wrote the document now known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, a letter to his brothers which records his thoughts of suicide due to his growing deafness and records his resolution to continue living for and through his art. The letter was never sent and was discovered in his papers after his death.[64] The letters to Wegeler and Amenda were not so despairing; in them Beethoven commented also on his ongoing professional and financial success at this period, and his determination, as he expressed it to Wegeler, to «seize Fate by the throat; it shall certainly not crush me completely».[61] In 1806, Beethoven noted on one of his musical sketches: «Let your deafness no longer be a secret – even in art.»[65]

Beethoven’s hearing loss did not prevent him from composing music, but it made playing at concerts—an important source of income at this phase of his life—increasingly difficult. (It also contributed substantially to his social withdrawal.)[61] Czerny remarked however that Beethoven could still hear speech and music normally until 1812.[66] Beethoven never became totally deaf; in his final years he was still able to distinguish low tones and sudden loud sounds.[67]

The heroic style

Titlepage of ms. of the Eroica Symphony, with Napoleon’s name scored through by Beethoven

Beethoven’s return to Vienna from Heiligenstadt was marked by a change in musical style, and is now often designated as the start of his middle or «heroic» period, characterised by many original works composed on a grand scale.[68] According to Carl Czerny, Beethoven said: «I am not satisfied with the work I have done so far. From now on I intend to take a new way.»[69] An early major work employing this new style was the Third Symphony in E-flat, Op. 55, known as the Eroica, written in 1803–04. The idea of creating a symphony based on the career of Napoleon may have been suggested to Beethoven by General Bernadotte in 1798.[70] Beethoven, sympathetic to the ideal of the heroic revolutionary leader, originally gave the symphony the title «Bonaparte», but disillusioned by Napoleon declaring himself Emperor in 1804, he scratched Napoleon’s name from the manuscript’s title page, and the symphony was published in 1806 with its present title and the subtitle «to celebrate the memory of a great man».[71] The Eroica was longer and larger in scope than any previous symphony. When it premiered in early 1805 it received a mixed reception. Some listeners objected to its length or misunderstood its structure, while others viewed it as a masterpiece.[72]

Other middle period works extend in the same dramatic manner the musical language Beethoven had inherited. The Rasumovsky string quartets, and the Waldstein and Appassionata piano sonatas share the heroic spirit of the Third Symphony.[71] Other works of this period include the Fourth through Eighth Symphonies, the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, the opera Fidelio, and the Violin Concerto.[73] Beethoven was hailed in 1810 by the writer and composer E. T. A. Hoffmann, in an influential review in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, as the greatest of (what he considered) the three Romantic composers (that is, ahead of Haydn and Mozart); in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony his music, wrote Hoffmann, «sets in motion terror, fear, horror, pain, and awakens the infinite yearning that is the essence of romanticism».[74]

During this time Beethoven’s income came from publishing his works, from performances of them, and from his patrons, for whom he gave private performances and copies of works they commissioned for an exclusive period before their publication. Some of his early patrons, including Prince Lobkowitz and Prince Lichnowsky, gave him annual stipends in addition to commissioning works and purchasing published works.[75] Perhaps his most important aristocratic patron was Archduke Rudolf of Austria, the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II, who in 1803 or 1804 began to study piano and composition with him. They became friends, and their meetings continued until 1824.[76] Beethoven dedicated 14 compositions to Rudolf, including some of his major works such as the Archduke Trio Op. 97 (1811) and Missa solemnis Op. 123 (1823).

His position at the Theater an der Wien was terminated when the theatre changed management in early 1804, and he was forced to move temporarily to the suburbs of Vienna with his friend Stephan von Breuning. This slowed work on Leonore (his original title for his opera), his largest work to date, for a time. It was delayed again by the Austrian censor and finally premiered, under its present title of Fidelio, in November 1805 to houses that were nearly empty because of the French occupation of the city. In addition to being a financial failure, this version of Fidelio was also a critical failure, and Beethoven began revising it.[77]

Despite this failure, Beethoven continued to attract recognition. In 1807 the musician and publisher Muzio Clementi secured the rights for publishing his works in England, and Haydn’s former patron Prince Esterházy commissioned a mass (the Mass in C, Op. 86) for his wife’s name-day. But he could not count on such recognition alone. A colossal benefit concert which he organized in December 1808, and was widely advertised, included the premieres of the Fifth and Sixth (Pastoral) symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto, extracts from the Mass in C, the scena and aria Ah! perfido Op. 65 and the Choral Fantasy op. 80. There was a large audience (including Czerny and the young Ignaz Moscheles), but it was under-rehearsed, involved many stops and starts, and during the Fantasia Beethoven was noted shouting at the musicians «badly played, wrong, again!» The financial outcome is unknown.[78]

In the autumn of 1808, after having been rejected for a position at the Royal Theatre, Beethoven had received an offer from Napoleon’s brother Jérôme Bonaparte, then king of Westphalia, for a well-paid position as Kapellmeister at the court in Cassel. To persuade him to stay in Vienna, Archduke Rudolf, Prince Kinsky and Prince Lobkowitz, after receiving representations from Beethoven’s friends, pledged to pay him a pension of 4000 florins a year.[79] In the event, Archduke Rudolf paid his share of the pension on the agreed date.[80] Kinsky, immediately called to military duty, did not contribute and died in November 1812 after falling from his horse.[81][82] The Austrian currency destabilized and Lobkowitz went bankrupt in 1811 so that to benefit from the agreement Beethoven eventually had recourse to the law, which in 1815 brought him some recompense.[83]

The imminence of war reaching Vienna itself was felt in early 1809. In April, Beethoven completed writing his Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73,[81] which the musicologist Alfred Einstein has described as «the apotheosis of the military concept» in Beethoven’s music.[84] Archduke Rudolf left the capital with the Imperial family in early May, prompting Beethoven’s piano sonata Les Adieux (Sonata No. 26, Op. 81a), actually entitled by Beethoven in German Das Lebewohl (The Farewell), of which the final movement, Das Wiedersehen (The Return), is dated in the manuscript with the date of Rudolf’s homecoming of 30 January 1810.[85] During the French bombardment of Vienna in May, Beethoven took refuge in the cellar of the house of his brother Kaspar.[86] The subsequent occupation of Vienna and the disruptions to cultural life and to Beethoven’s publishers, together with Beethoven’s poor health at the end of 1809, explain his significantly reduced output during this period,[87] although other notable works of the year include his String Quartet No. 10 in E flat major, Op. 74 (known as The Harp) and the Piano Sonata No. 24 in F sharp major op. 78, dedicated to Josephine’s sister Therese Brunsvik.[88]

Goethe

At the end of 1809 Beethoven was commissioned to write incidental music for Goethe’s play Egmont. The result (an overture, and nine additional entractes and vocal pieces, Op. 84), which appeared in 1810, fitted well with Beethoven’s heroic style and he became interested in Goethe, setting three of his poems as songs (Op. 83) and learning about the poet from a mutual acquaintance, Bettina Brentano (who also wrote to Goethe at this time about Beethoven). Other works of this period in a similar vein were the F minor String Quartet Op. 95, to which Beethoven gave the subtitle Quartetto serioso, and the Op. 97 Piano Trio in B flat major known, from its dedication to his patron Rudolph as the Archduke Trio.[89]

In the spring of 1811, Beethoven became seriously ill, having headaches and high fever. His doctor Johann Malfatti recommended him to take a cure at the spa of Teplitz (now Teplice in the Czech Republic), where he wrote two more overtures and sets of incidental music for dramas, this time by August von Kotzebue – King Stephen Op. 117 and The Ruins of Athens Op. 113. Advised again to visit Teplitz in 1812 he met there with Goethe, who wrote: «His talent amazed me; unfortunately he is an utterly untamed personality, who is not altogether wrong in holding the world to be detestable, but surely does not make it any more enjoyable … by his attitude.» Beethoven wrote to his publishers Breitkopf and Härtel that «Goethe delights far too much in the court atmosphere, far more than is becoming in a poet.»[89] But following their meeting he began a setting for choir and orchestra of Goethe’s Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt (Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage) (Op. 112), completed in 1815. After this was published in 1822 with a dedication to the poet, Beethoven wrote to him: «The admiration, the love and esteem which already in my youth I cherished for the one and only immortal Goethe have persisted.»[90]

The Immortal Beloved

While he was at Teplitz in 1812 he wrote a ten-page love letter to his «Immortal Beloved», which he never sent to its addressee.[91] The identity of the intended recipient was long a subject of debate, although the musicologist Maynard Solomon has convincingly demonstrated that the intended recipient must have been Antonie Brentano; other candidates have included Julie Guicciardi, Therese Malfatti and Josephine Brunsvik.[92][n 6]

All of these had been regarded by Beethoven as possible soulmates during his first decade in Vienna. Guicciardi, although she flirted with Beethoven, never had any serious interest in him and married Wenzel Robert von Gallenberg in November 1803. (Beethoven insisted to his later secretary and biographer, Anton Schindler, that Gucciardi had «sought me out, crying, but I scorned her».)[94] Josephine had, since Beethoven’s initial infatuation with her, married the elderly Count Joseph Deym, who died in 1804. Beethoven began to visit her and commenced a passionate correspondence. Initially, he accepted that Josephine could not love him, but he continued to address himself to her even after she had moved to Budapest, finally demonstrating that he had got the message in his last letter to her of 1807: «I thank you for wishing still to appear as if I were not altogether banished from your memory».[95] Malfatti was the niece of Beethoven’s doctor, and he had proposed to her in 1810. He was 40, she was 19 – the proposal was rejected.[96] She is now remembered as the recipient of the piano bagatelle Für Elise.[97][n 7]

Antonie (Toni) Brentano (née von Birkenstock), ten years younger than Beethoven, was the wife of Franz Brentano, the half-brother of Bettina Brentano, who provided Beethoven’s introduction to the family. It would seem that Antonie and Beethoven had an affair during 1811–1812. Antonie left Vienna with her husband in late 1812 and never met with (or apparently corresponded with) Beethoven again, although in her later years she wrote and spoke fondly of him.[99] Some speculate that Beethoven was the father of Antonie’s son Karl Josef, though the two never met.[100]

After 1812 there are no reports of any romantic liaisons of Beethoven; it is, however, clear from his correspondence of the period and, later, from the conversation books, that he would occasionally meet with prostitutes.[101]

1813–1822: Acclaim

Family problems

Karl van Beethoven, c. 1820: miniature portrait by unknown artist

In early 1813 Beethoven apparently went through a difficult emotional period, and his compositional output dropped. His personal appearance degraded—it had generally been neat—as did his manners in public, notably when dining.[102]

Family issues may have played a part in this. Beethoven had visited his brother Johann at the end of October 1812. He wished to end Johann’s cohabitation with Therese Obermayer, a woman who already had an illegitimate child. He was unable to convince Johann to end the relationship and appealed to the local civic and religious authorities, but Johann and Therese married on 8 November.[103]

The illness and eventual death of his brother Kaspar from tuberculosis became an increasing concern. Kaspar had been ill for some time; in 1813 Beethoven lent him 1500 florins, to procure the repayment of which he was ultimately led to complex legal measures.[104] After Kaspar died on 15 November 1815, Beethoven immediately became embroiled in a protracted legal dispute with Kaspar’s wife Johanna over custody of their son Karl, then nine years old. Beethoven had successfully applied to Kaspar to have himself named the sole guardian of the boy. A late codicil to Kaspar’s will gave him and Johanna joint guardianship.[105] While Beethoven was successful at having his nephew removed from her custody in January 1816, and had him removed to a private school[106] in 1818 he was again preoccupied with the legal processes around Karl. While giving evidence to the court for the nobility, the Landrechte, Beethoven was unable to prove that he was of noble birth and as a consequence, on 18 December 1818 the case was transferred to the civil magistrate of Vienna, where he lost sole guardianship.[106][n 8] He only regained custody after intensive legal struggles in 1820.[107] During the years that followed, Beethoven frequently interfered in his nephew’s life in what Karl perceived as an overbearing manner.[108]

Post-war Vienna

Beethoven was finally motivated to begin significant composition again in June 1813, when news arrived of the French defeat at the Battle of Vitoria by a coalition led by the Duke of Wellington. The inventor Mälzel persuaded him to write a work commemorating the event for his mechanical instrument the Panharmonicon. This Beethoven also transcribed for orchestra as Wellington’s Victory (Op. 91, also known as the Battle Symphony).[n 9] It was first performed on 8 December, along with his Seventh Symphony, Op. 92, at a charity concert for victims of the war, a concert whose success led to its repeat on 12 December. The orchestra included several leading and rising musicians who happened to be in Vienna at the time, including Giacomo Meyerbeer and Domenico Dragonetti.[110] The work received repeat performances at concerts staged by Beethoven in January and February 1814.[111] These concerts brought Beethoven more profit than any others in his career, and enabled him to buy the bank shares that were eventually to be the most valuable assets in his estate at his death.[112]

Beethoven’s renewed popularity led to demands for a revival of Fidelio, which, in its third revised version, was also well received at its July opening in Vienna, and was frequently staged there during the following years.[113] Beethoven’s publishers, Artaria, commissioned the 20-year old Moscheles to prepare a piano score of the opera, which he inscribed «Finished, with God’s help!» – to which Beethoven added «O Man, help thyself.»[n 10][114] That summer Beethoven composed a piano sonata for the first time in five years, his Sonata in E minor, Opus 90.[115] He was also one of many composers who produced music in a patriotic vein to entertain the many heads of state and diplomats who came to the Congress of Vienna that began in November 1814, with the cantata Der glorreiche Augenblick (The Glorious Moment) (Op. 136) and similar choral works which, in the words of Maynard Solomon «broadened Beethoven’s popularity, [but] did little to enhance his reputation as a serious composer».[116]

In April and May 1814, playing in his Archduke Trio, Beethoven made his last public appearances as a soloist. The composer Louis Spohr noted: «the piano was badly out of tune, which Beethoven minded little, since he did not hear it … there was scarcely anything left of the virtuosity of the artist … I was deeply saddened.»[117] From 1814 onwards Beethoven used for conversation ear-trumpets designed by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (a number of these are on display at the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn).[118]

His 1815 compositions include an expressive second setting of the poem An die Hoffnung (Op. 94) in 1815. Compared to its first setting in 1805 (a gift for Josephine Brunsvik), it was «far more dramatic … The entire spirit is that of an operatic scena.»[119] But his energy seemed to be dropping: apart from these works, he wrote the two cello sonatas Op. 102 nos. 1 and 2, and a few minor pieces, and began but abandoned a sixth piano concerto.[120]

Pause

Between 1815 and 1819 Beethoven’s output dropped again to a level unique in his mature life.[121] He attributed part of this to a lengthy illness (he called it an inflammatory fever) that he had for more than a year, starting in October 1816.[122] His biographer Maynard Solomon suggests it is also doubtless a consequence of the ongoing legal problems concerning his nephew Karl,[123] and of Beethoven finding himself increasingly at odds with current musical trends. Unsympathetic to developments in German romanticism that featured the supernatural (as in operas by Spohr, Heinrich Marschner and Carl Maria von Weber), he also «resisted the impending Romantic fragmentation of the … cyclic forms of the Classical era into small forms and lyric mood pieces» and turned towards study of Bach, Handel and Palestrina.[124] An old connection was renewed in 1817 when Maelzel sought, and obtained, Beethoven’s endorsement for his newly developed metronome.[125] During these years the few major works he completed include the 1818 Hammerklavier Sonata (Sonata No. 29 in B flat major, Op. 106) and his settings of poems by Alois Jeitteles, An die ferne Geliebte Op. 98 (1816), which introduced the song cycle into classical repertoire.[126] In 1818 he began musical sketches that were eventually to form part of his final Ninth Symphony.[127]

By early 1818 Beethoven’s health had improved, and his nephew Karl, now aged 11, moved in with him in January (although within a year Karl’s mother had won him back in the courts).[128] By now Beethoven’s hearing had again seriously deteriorated, necessitating Beethoven and his interlocutors writing in notebooks to carry out conversations. These ‘conversation books’ are a rich written resource for his life from this period onwards. They contain discussions about music, business, and personal life; they are also a valuable source for his contacts and for investigations into how he intended his music should be performed, and of his opinions of the art of music.[129] [n 11] His household management had also improved somewhat with the help of Nannette Streicher. A proprietor of the Stein piano workshop and a personal friend, Streicher had assisted in Beethoven’s care during his illness; she continued to provide some support, and in her he finally found a skilled cook.[135][136] A testimonial to the esteem in which Beethoven was held in England was the presentation to him in this year by Thomas Broadwood, the proprietor of the company, of a Broadwood piano, for which Beethoven expressed thanks. He was not well enough, however, to carry out a visit to London that year which had been proposed by the Philharmonic Society.[137][n 12]

Resurgence

Despite the time occupied by his ongoing legal struggles over Karl, which involved continuing extensive correspondence and lobbying,[139] two events sparked off Beethoven’s major composition projects in 1819. The first was the announcement of Archduke Rudolf’s promotion to Cardinal-Archbishop as Archbishop of Olomouc (now in the Czech Republic), which triggered the Missa solemnis Op. 123, intended to be ready for his installation in Olomouc in March 1820. The other was the invitation by the publisher Antonio Diabelli to fifty Viennese composers, including Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Czerny and the 8-year old Franz Liszt, to compose a variation each on a theme which he provided. Beethoven was spurred to outdo the competition and by mid-1819 had already completed 20 variations of what were to become the 33 Diabelli Variations op. 120. Neither of these works was to be completed for a few years.[140][141] A significant tribute of 1819, however, was Archduke Rudolf’s set of forty piano variations on a theme written for him by Beethoven (WoO 200) and dedicated to the master.[142] Beethoven’s portrait by Ferdinand Schimon [de] of this year, which was one of the most familiar images of him for the next century, was described by Schindler as, despite its artistic weaknesses, «in the rendering of that particular look, the majestic forehead … the firmly shut mouth and the chin shaped like a shell, … truer to nature than any other picture».[143]

Beethoven’s determination over the following years to write the Mass for Rudolf was not motivated by any devout Catholicism. Although he had been born a Catholic, the form of religion as practised at the court in Bonn where he grew up was, in the words of Maynard Solomon, «a compromise ideology that permitted a relatively peaceful coexistence between the Church and rationalism».[144] Beethoven’s Tagebuch (a diary he kept on an occasional basis between 1812 and 1818) shows his interest in a variety of religious philosophies, including those of India, Egypt and the Orient and the writings of the Rig-Veda.[145] In a letter to Rudolf of July 1821, Beethoven shows his belief in a personal God: «God … sees into my innermost heart and knows that as a man I perform most conscientiously and on all occasions the duties which Humanity, God, and Nature enjoin upon me.» On one of the sketches for the Missa solemnis he wrote «Plea for inner and outer peace».[146]

Beethoven’s status was confirmed by the series of Concerts sprituels given in Vienna by the choirmaster Franz Xaver Gebauer in the 1819/1820 and 1820/1821 seasons, during which all eight of his symphonies to date, plus the oratorio Christus and the Mass in C, were performed. Beethoven was typically underwhelmed: when in an April 1820 conversation book a friend mentioned Gebauer, Beethoven wrote in reply «Geh! Bauer» (Begone, peasant!)[147]

written between 1821 and 1822, during Beethoven’s late period

It was in 1819 that Beethoven was first approached by the publisher Moritz Schlesinger who won the suspicious composer round, whilst visiting him at Mödling, by procuring for him a plate of roast veal.[148] One consequence of this was that Schlesinger was to secure Beethoven’s three last piano sonatas and his final quartets; part of the attraction to Beethoven was that Schlesinger had publishing facilities in Germany and France, and connections in England, which could overcome problems of copyright piracy.[149] The first of the three sonatas, for which Beethoven contracted with Schlesinger in 1820 at 30 ducats per sonata (further delaying completion of the Mass), was sent to the publisher at the end of that year (the Sonata in E major, Op. 109, dedicated to Maximiliane, Antonie Brentano’s daughter).[150]

The start of 1821 saw Beethoven once again in poor health, having rheumatism and jaundice. Despite this he continued work on the remaining piano sonatas he had promised to Schlesinger (the Sonata in A flat major Op. 110 was published in December), and on the Mass.[151] In early 1822 Beethoven sought a reconciliation with his brother Johann, whose marriage in 1812 had met with his disapproval, and Johann now became a regular visitor (as witnessed by the conversation books of the period) and began to assist him in his business affairs, including him lending him money against ownership of some of his compositions. He also sought some reconciliation with the mother of his nephew, including supporting her income, although this did not meet with the approval of the contrary Karl.[152] Two commissions at the end of 1822 improved Beethoven’s financial prospects. In November the Philharmonic Society of London offered a commission for a symphony, which he accepted with delight, as an appropriate home for the Ninth Symphony on which he was working.[153] Also in November Prince Nikolai Galitzin of Saint Petersburg offered to pay Beethoven’s asking price for three string quartets. Beethoven set the price at the high level of 50 ducats per quartet in a letter dictated to his nephew Karl, who was then living with him.[154]

During 1822, Anton Schindler, who in 1840 became one of Beethoven’s earliest and most influential (but not always reliable) biographers, began to work as the composer’s unpaid secretary. He was later to claim that he had been a member of Beethoven’s circle since 1814, but there is no evidence for this. Cooper suggests that «Beethoven greatly appreciated his assistance, but did not think much of him as a man».[155]

1823–1827: The final years

The year 1823 saw the completion of three notable works, all of which had occupied Beethoven for some years, namely the Missa solemnis, the Ninth Symphony and the Diabelli Variations.[156]

Beethoven at last presented the manuscript of the completed Missa to Rudolph on 19 March (more than a year after the archduke’s enthronement as archbishop). He was not however in a hurry to get it published or performed as he had formed a notion that he could profitably sell manuscripts of the work to various courts in Germany and Europe at 50 ducats each. One of the few who took up this offer was Louis XVIII of France, who also sent Beethoven a heavy gold medallion.[157] The Symphony and the variations took up most of the rest of Beethoven’s working year. Diabelli hoped to publish both works, but the potential prize of the Mass excited many other publishers to lobby Beethoven for it, including Schlesinger and Carl Friedrich Peters. (In the end, it was obtained by Schotts).[158]

Beethoven had become critical of the Viennese reception of his works. He told the visiting Johann Friedrich Rochlitz in 1822:

You will hear nothing of me here … Fidelio? They cannot give it, nor do they want to listen to it. The symphonies? They have no time for them. My concertos? Everyone grinds out only the stuff he himself has made. The solo pieces? They went out of fashion long ago, and here fashion is everything. At the most, Schuppanzigh occasionally digs up a quartet.[159]

He, therefore, enquired about premiering the Missa and the Ninth Symphony in Berlin. When his Viennese admirers learnt of this, they pleaded with him to arrange local performances. Beethoven was won over, and the symphony was first performed, along with sections of the Missa solemnis, on 7 May 1824, to great acclaim at the Kärntnertortheater.[160][n 13] Beethoven stood by the conductor Michael Umlauf during the concert beating time (although Umlauf had warned the singers and orchestra to ignore him), and because of his deafness was not even aware of the applause which followed until he was turned to witness it.[162] The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung gushed, «inexhaustible genius had shown us a new world», and Carl Czerny wrote that the Symphony «breathes such a fresh, lively, indeed youthful spirit … so much power, innovation, and beauty as ever [came] from the head of this original man, although he certainly sometimes led the old wigs to shake their heads». The concert did not net Beethoven much money, as the expenses of mounting it were very high.[163] A second concert on 24 May, in which the producer guaranteed him a minimum fee, was poorly attended; nephew Karl noted that «many people [had] already gone into the country». It was Beethoven’s last public concert.[164] Beethoven accused Schindler of either cheating him or mismanaging the ticket receipts; this led to the replacement of Schindler as Beethoven’s secretary by Karl Holz, the second violinist in the Schuppanzigh Quartet, although by 1826 Beethoven and Schindler were reconciled.[165]

Beethoven then turned to writing the string quartets for Galitzin, despite failing health. The first of these, the quartet in E♭ major, Op. 127 was premiered by the Schuppanzigh Quartet in March 1825. While writing the next, the quartet in A minor, Op. 132, in April 1825, he was struck by a sudden illness. Recuperating in Baden, he included in the quartet its slow movement to which he gave the title «Holy song of thanks (Heiliger Dankgesang) to the Divinity, from a convalescent, in the Lydian mode».[161] The next quartet to be completed was the Thirteenth, op. 130, in B♭ major. In six movements, the last, contrapuntal movement proved to be very difficult for both the performers and the audience at its premiere in March 1826 (again by the Schuppanzigh Quartet). Beethoven was persuaded by the publisher Artaria, for an additional fee, to write a new finale, and to issue the last movement as a separate work (the Grosse Fugue, Op. 133).[166] Beethoven’s favourite was the last of this series, the quartet in C♯ minor Op. 131, which he rated as his most perfect single work.[167]

Beethoven’s relations with his nephew Karl had continued to be stormy; Beethoven’s letters to him were demanding and reproachful. In August, Karl, who had been seeing his mother again against Beethoven’s wishes, attempted suicide by shooting himself in the head. He survived and after discharge from hospital went to recuperate in the village of Gneixendorf with Beethoven and his uncle Johann. Whilst in Gneixendorf, Beethoven completed a further quartet (Op. 135 in F major) which he sent to Schlesinger. Under the introductory slow chords in the last movement, Beethoven wrote in the manuscript «Muss es sein?» (Must it be?); the response, over the faster main theme of the movement, is «Es muss sein!» (It must be!). The whole movement is headed Der schwer gefasste Entschluss (The difficult decision).[168] Following this in November Beethoven completed his final composition, the replacement finale for the op. 130 quartet.[161] Beethoven at this time was already ill and depressed;[161] he began to quarrel with Johann, insisting that Johann made Karl his heir, in preference to Johann’s wife.[169]

Death

On his return journey to Vienna from Gneixendorf in December 1826, illness struck Beethoven again. He was attended until his death by Dr. Andreas Wawruch, who throughout December noticed symptoms including fever, jaundice and dropsy, with swollen limbs, coughing and breathing difficulties. Several operations were carried out to tap off the excess fluid from Beethoven’s abdomen.[161][170]

Karl stayed by Beethoven’s bedside during December, but left after the beginning of January to join the army at Iglau and did not see his uncle again, although he wrote to him shortly afterwards: «My dear father … I am living in contentment and regret only that I am separated from you.» Immediately following Karl’s departure, Beethoven wrote a will making his nephew his sole heir.[171] Later in January, Beethoven was attended by Dr. Malfatti, whose treatment (recognizing the seriousness of his patient’s condition) was largely centred on alcohol. As the news spread of the severity of Beethoven’s condition, many old friends came to visit, including Diabelli, Schuppanzigh, Lichnowsky, Schindler, the composer Johann Nepomuk Hummel and his pupil Ferdinand Hiller. Many tributes and gifts were also sent, including £100 from the Philharmonic Society in London and a case of expensive wine from Schotts.[161][172] During this period, Beethoven was almost completely bedridden despite occasional efforts to rouse himself. On 24 March, he said to Schindler and the others present «Plaudite, amici, comoedia finita est» («Applaud, friends, the comedy is over»). Later that day, when the wine from Schott arrived, he whispered, «Pity – too late.»[173]

Beethoven’s funeral procession: watercolour by F. X. Stoeber

Beethoven died on 26 March 1827 at the age of 56; only his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner and a «Frau van Beethoven» (possibly his old enemy Johanna van Beethoven) were present. According to Hüttenbrenner, at about 5 pm there was a flash of lightning and a clap of thunder: «Beethoven opened his eyes, lifted his right hand and looked up for several seconds with his fist clenched … not another breath, not a heartbeat more.»[174] Many visitors came to the death-bed; some locks of the dead man’s hair were retained by Hüttenbrenner and Hiller, amongst others.[175][176] An autopsy revealed Beethoven had significant liver damage, which may have been due to his heavy alcohol consumption,[177] and also considerable dilation of the auditory and other related nerves.[178][179][n 14]

Beethoven’s funeral procession in Vienna on 29 March 1827 was attended by an estimated 10,000 people.[184] Franz Schubert and the violinist Joseph Mayseder were among the torchbearers. A funeral oration by the poet Franz Grillparzer was read by the actor Heinrich Anschütz.[185] Beethoven was buried in the Währing cemetery, north-west of Vienna, after a requiem mass at the church of the Holy Trinity (Dreifaltigkeitskirche) in Alserstrasse. Beethoven’s remains were exhumed for study in 1863, and moved in 1888 to Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof where they were reinterred in a grave adjacent to that of Schubert.[177][186]

Music

The three periods

The historian William Drabkin notes that as early as 1818 a writer had proposed a three-period division of Beethoven’s works and that such a division (albeit often adopting different dates or works to denote changes in period) eventually became a convention adopted by all of Beethoven’s biographers, starting with Schindler, F.-J. Fétis and Wilhelm von Lenz. Later writers sought to identify sub-periods within this generally accepted structure. Its drawbacks include that it generally omits a fourth period, that is, the early years in Bonn, whose works are less often considered; and that it ignores the differential development of Beethoven’s composing styles over the years for different categories of work. The piano sonatas, for example, were written throughout Beethoven’s life in a progression that can be interpreted as continuous development; the symphonies do not all demonstrate linear progress; of all of the types of composition, perhaps the quartets, which seem to group themselves in three periods (Op. 18 in 1801–1802, Opp. 59, 74 and 95 in 1806–1814, and the quartets, today known as ‘late’, from 1824 onwards) fit this categorization most neatly. Drabkin concludes that «now that we have lived with them so long … as long as there are programme notes, essays written to accompany recordings, and all-Beethoven recitals, it is hard to imagine us ever giving up the notion of discrete stylistic periods.»[187][188]

Bonn 1782–1792

Some forty compositions, including ten very early works written by Beethoven up to 1785, survive from the years that Beethoven lived in Bonn. It has been suggested that Beethoven largely abandoned composition between 1785 and 1790, possibly as a result of negative critical reaction to his first published works. A 1784 review in Johann Nikolaus Forkel’s influential Musikalischer Almanack compared Beethoven’s efforts to those of rank beginners.[189] The three early piano quartets of 1785 (WoO 36), closely modelled on violin sonatas of Mozart, show his dependency on the music of the period. Beethoven himself was not to give any of the Bonn works an opus number, save for those which he reworked for use later in his career, for example, some of the songs in his Op. 52 collection (1805) and the Wind Octet reworked in Vienna in 1793 to become his String Quintet, Op. 4.[190][191] Charles Rosen points out that Bonn was something of a backwater compared to Vienna; Beethoven was unlikely to be acquainted with the mature works of Haydn or Mozart, and Rosen opines that his early style was closer to that of Hummel or Muzio Clementi.[192] Kernan suggests that at this stage Beethoven was not especially notable for his works in sonata style, but more for his vocal music; his move to Vienna in 1792 set him on the path to develop the music in the genres he became known for.[190]

The first period

The conventional first period begins after Beethoven’s arrival in Vienna in 1792. In the first few years he seems to have composed less than he did at Bonn, and his Piano Trios, op.1 were not published until 1795. From this point onward, he had mastered the ‘Viennese style’ (best known today from Haydn and Mozart) and was making the style his own. His works from 1795 to 1800 are larger in scale than was the norm (writing sonatas in four movements, not three, for instance); typically he uses a scherzo rather than a minuet and trio; and his music often includes dramatic, even sometimes over-the-top, uses of extreme dynamics and tempi and chromatic harmony. It was this that led Haydn to believe the third trio of Op.1 was too difficult for an audience to appreciate.[193]

He also explored new directions and gradually expanded the scope and ambition of his work. Some important pieces from the early period are the first and second symphonies, the set of six string quartets Opus 18, the first two piano concertos, and the first dozen or so piano sonatas, including the famous Pathétique sonata, Op. 13.

The middle period

His middle period began shortly after the personal crisis brought on by his recognition of encroaching deafness. It includes large-scale works that express heroism and struggle. Middle-period works include six symphonies (Nos. 3–8), the last two piano concertos, the Triple Concerto and violin concerto, five string quartets (Nos. 7–11), several piano sonatas (including the Waldstein and Appassionata sonatas), the Kreutzer violin sonata and his only opera, Fidelio.

This period is sometimes associated with a heroic manner of composing,[194] but the use of the term «heroic» has become increasingly controversial in Beethoven scholarship. The term is more frequently used as an alternative name for the middle period.[195] The appropriateness of the term heroic to describe the whole middle period has been questioned as well: while some works, like the Third and Fifth Symphonies, are easy to describe as heroic, many others, like his Symphony No. 6, Pastoral or his Piano Sonata No. 24, are not.[196]

The late period

Beethoven’s late period began in the decade 1810-1819.[197] He began a renewed study of older music, including works by Palestrina, Johann Sebastian Bach, and George Frideric Handel, whom Beethoven considered «the greatest composer who ever lived».[198] Beethoven’s late works incorporated polyphony and Baroque-era devices.[199] For example, the overture The Consecration of the House (1822) included a fugue influenced by Handel’s music.[200] A new style emerged, as he returned to the keyboard to compose his first piano sonatas in almost a decade; the works of the late period include the last five piano sonatas and the Diabelli Variations, the last two sonatas for cello and piano, the late string quartets (including the massive Große Fuge), and two works for very large forces: the Missa solemnis and the Ninth Symphony.[201][202] Works from this period are characterised by their intellectual depth, their formal innovations, and their intense, highly personal expression. The String Quartet, Op. 131 has seven linked movements, and the Ninth Symphony adds choral forces to the orchestra in the last movement.[203]

Beethoven’s pianos

Beethoven’s earlier preferred pianos included those of Johann Andreas Stein; he may have been given a Stein piano by Count Waldstein.[204] From 1786 onwards there is evidence of Beethoven’s cooperation with Johann Andreas Streicher, who had married Stein’s daughter Nannette. Streicher left Stein’s business to set up his own firm in 1803, and Beethoven continued to admire his products, writing to him in 1817 of his «special preference» for his pianos.[204] Amongst the other pianos Beethoven possessed was an Érard piano given to him by the manufacturer in 1803.[205] The Érard piano, with its exceptional resonance, may have influenced Beethoven’s piano style – shortly after receiving it he began writing his Waldstein Sonata[206] – but despite initial enthusiasm he seems to have abandoned it before 1810, when he wrote that it was «simply not of any use any more»; in 1824 he gave it to his brother Johann.[206][n 15] In 1818 Beethoven received, also as gift, a grand piano by John Broadwood & Sons. Although Beethoven was proud to receive it, he seems to have been dissatisfied by its tone (a dissatisfaction which was perhaps also a consequence of his increasing deafness), and sought to get it remodelled to make it louder.[208][n 16] In 1825 Beethoven commissioned a piano from Conrad Graf, which was equipped with quadruple strings and a special resonator to make it audible to him, but which failed in this task.[210][n 17]

Legacy

Museums

There is a museum—the Beethoven House, the place of his birth—in central Bonn. The same city has hosted a musical festival, the Beethovenfest, since 1845. The festival was initially irregular but has been organised annually since 2007.

The Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, in the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Library, in the campus of San Jose State University, California, serves as a museum, research center, and host of lectures and performances devoted solely to Beethoven’s life and works.[212]

Sculptures

The Beethoven Monument in Bonn was unveiled in August 1845, in honour of the 75th anniversary of his birth. It was the first statue of a composer created in Germany, and the music festival that accompanied the unveiling was the impetus for the very hasty construction of the original Beethovenhalle in Bonn (it was designed and built within less than a month, on the urging of Franz Liszt). Vienna honoured Beethoven with a statue in 1880.[213]

Space

The third-largest crater on Mercury is named in his honour,[214] as is the main-belt asteroid 1815 Beethoven.[215]

Beethoven’s music features twice on the Voyager Golden Record, a phonograph record containing a broad sample of the images, common sounds, languages, and music of Earth, sent into outer space with the two Voyager probes.[216]

References

Notes

- ^ LUUD-vig van BAY-toh-vən; German: [ˈluːtvɪç fan ˈbeːtˌhoːfn̩] (

listen)

- ^ The prefix van to the surname Beethoven reflects the Flemish origins of the family name.[1]

- ^ Most of Beethoven’s early works and those to which he did not give an opus number were listed by Georg Kinsky and Hans Halm as «WoO», works without opus number. Kinsky and Halm also listed 18 doubtful works in their appendix («WoO Anhang»). In addition, some minor works not listed with opus numbers or in the WoO list have Hess catalogue numbers.[13]

- ^ It is uncertain whether this was the First (Op. 15) or Second (Op. 19 which was in fact written earlier than Op. 15). Documentary evidence is lacking, and both concertos were still in manuscript (neither was completed or published for several years).[42] Some authorities favour Op. 15,[43][44] but Oxford Music Online suggests it was probably Op. 19.[45]

- ^ The cause of Beethoven’s deafness has also variously been attributed to, amongst other possibilities, lead poisoning from Beethoven’s preferred wines.[62] Another possibility is that it was caused by complications from a case of murine typhus from 1796.[63]

- ^ Solomon sets out his case in detail in his biography of Beethoven.[93]

- ^ The manuscript (now lost) was found in Therese Malfatti’s papers after her death by Beethoven’s early biographer Ludwig Nohl. It has been suggested that Nohl misread the title, which may have been Für Therese.[98]

- ^ Their ruling stated: «It … appears from the statement of Ludwig van Beethoven … is unable to prove nobility: hence the matter of guardianship is transferred to the Magistrate».[106]

- ^ The work is not a true symphony, but a programmatic piece including French and British soldiers’ songs, a battle scene with artillery effects and a fugal treatment of «God Save the King».[109]

- ^ «Fine mit Gottes Hülfe» – «O, Mensch, hilf dir selber.»

- ^ It was suggested by Beethoven’s biographer Alexander Wheelock Thayer that, of 400 conversation books, 264 were destroyed (and others were altered) after his death by his secretary Schindler, who wished only an idealised biography to survive.[130] The music historian Theodore Albrecht has, however, demonstrated that Thayer’s allegations were over the top. «[It is now] abundantly clear that Schindler never possessed as many as c. 400 conversation books, and that he never destroyed roughly five-eighths of that number.»[131] Schindler did however insert a number of fraudulent entries that bolstered his own profile and his prejudices.[132][133] Presently 136 books covering the period 1819–1827 are preserved at the Staatsbibliothek Berlin, with another two at the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn.[134]

- ^ The Broadwood piano is now in the collection of the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest.[138]

- ^ The first full performance of the Missa solemnis had already been given in St. Petersburg by Galitzin, who had been a subscriber for the manuscript ‘preview’ that Beethoven had arranged.[161]

- ^ There is dispute about the actual cause of his death: alcoholic cirrhosis, syphilis, infectious hepatitis, lead poisoning, sarcoidosis and Whipple’s disease have all been proposed.[180] Surviving locks of his hair have been subjected to additional analysis, as have skull fragments removed during an 1863 exhumation.[181] Some of these analyses have led to controversial assertions that he was accidentally poisoned by excessive doses of lead-based treatments administered under instruction from his doctor.[182][183]

- ^ The piano is now in the Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum in Linz.[207]

- ^ The piano is now in the Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, to which it was donated by Franz Liszt; it was restored to playing condition in 1991.[209]

- ^ Now in the Beethoven-Haus, Bonn.[211]

Citations

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 1.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 407.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 12–17.

- ^ a b Thayer 1967a, p. 50.

- ^ «Beethoven-Haus History». Beethoven-Haus Bonn. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 53.

- ^ a b Stanley 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Swafford 2014, p. 74.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 22, 32.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 57–8.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 210.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 65–70.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 69.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 2.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 55.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 121–122.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 95.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 51.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 95–98.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 96.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 35–41.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 107–111.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 41.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 3.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 47, 54.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 149.

- ^ Ronge 2013.

- ^ a b Cooper 2008, p. 53.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 59.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 46.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Cooper 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 221.

- ^ Swafford 2014, p. 174-175.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, §3.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Steinberg, Michael (1998). The Concerto: A Listener’s Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 52–59. ISBN 0195103300.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 79.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 58.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 97.

- ^ Steblin 2009.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 98–103.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 112–127.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 112–115.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 160.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 5.

- ^ Stevens 2013, pp. 2854–2858.

- ^ Caeyers, Jan (8 September 2020). Beethoven: A Life. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-520-34354-2.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 169–172.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 162.

- ^ Ealy 1994, p. 262.

- ^ «‘Deaf’ genius Beethoven was able to hear his final symphony after all». The Guardian. 1 February 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Tyson 1969, p. 138–141.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 131.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 4.

- ^ a b Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 6.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 148.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 14 and 15.

- ^ Cassedy 2010, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Lockwood 2005, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 445–448.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 457.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 195.

- ^ a b Cooper 1996, p. 48.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 194.

- ^ Einstein 1958, p. 248.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 464.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 465.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 467–473.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 475.

- ^ a b Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 7.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 47.

- ^ Brandenburg 1996, p. 582.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 107.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 223–231.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 197–199.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 196.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 20.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 502.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 231–239.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (25 February 2017). «Did Beethoven’s Love for a Married Aristocrat and a Doomed Son Colour His Darkest Work?». The Guardian. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 284, 339–340.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 282.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 302–303.

- ^ a b c Solomon 1998, p. 303.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 316–321.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 220.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 559–565.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 575–576.

- ^ Scherer 2004, p. 112.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 288, 348.

- ^ Conway 2012, p. 129.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 292.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 287.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 577–578.

- ^ Ealy 1994, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Lockwood 2005, p. 278.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 296.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 254.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 297.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 295.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 684–686.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 675–677.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 322.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 41.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 164–167.

- ^ Clive 2001, p. 239.

- ^ Albrecht 2009, p. 181.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 52.

- ^ Nettl 1994, p. 103.

- ^ Hammelmann 1965, p. 187.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 260.

- ^ Morrisroe, Patricia (6 November 2020). «The Woman Who Built Beethoven’s Pianos». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 696–698.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 43.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, p. 790.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 8.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 741, 745.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, p. 742.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 54.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 342.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 770–771, (editor’s translation).

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 734–735.

- ^ Conway 2012, pp. 185–187.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 776–777, 781–782.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 362–363.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 833–834.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 815–816.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 52, 309–310.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, p. 879.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 812–829.

- ^ Conway 2012, p. 186.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, p. 801.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, §10.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 351.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 317.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 318.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 310.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 974–975.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 213.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, p. 977.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, p. 1014.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 1017–1024.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 377.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 378–379.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 380–381.

- ^ Thayer 1967b, p. 1050–1051.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Conway 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b Cooper 2008, pp. 318, 349.

- ^ SaccentiSmildeSaris 2011.

- ^ SaccentiSmildeSaris 2012.

- ^ Mai 2006.

- ^ Meredith 2005, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Eisinger 2008.

- ^ Lorenz 2007.

- ^ Taruskin 2010, p. 687.

- ^ «Franz Grillparzer, Rede zu Beethovens Begräbnis am 29. März 1827, Abschrift», Beethoven House, Bonn (in German)

- ^ Thayer 1967b, pp. 1053–1056.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 198–200.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 11.

- ^ Solomon 1972, p. 169.

- ^ a b Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, 12.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 227, 230.

- ^ Rosen 1972, pp. 379–380.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001, § 13.

- ^ Solomon 1990, p. 124.

- ^ Steinberg, Michael P. (2006). Listening to reason: culture, subjectivity, and nineteenth-century music. Princeton University Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-691-12616-6. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Burnham, Scott G.; Steinberg, Michael P. (2000). Beethoven and his world. Princeton University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-691-07073-5. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Brendel 1991, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Cooper 1970, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Brendel 1991, p. 62.

- ^ Cooper 1970, pp. 347–348.

- ^ Cooper 1970, p. 10.

- ^ Brendel 1991, pp. 60–63.

- ^ Kerman, Tyson & Burnham 2001.

- ^ a b Newman 1970, p. 486.

- ^ Skowroneck 2002, p. 523.

- ^ a b Skowroneck 2002, p. 530-531.

- ^ Skowroneck 2002, p. 522.

- ^ Newman 1970, p. 489-490.

- ^ Winston 1993.

- ^ Newman 1970, p. 491.

- ^ «Beethoven’s Last Grand Piano». Beethoven House, Bonn. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ «Beethoven Centre». San Jose State University. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Comini 2008, p. 316.

- ^ Spudis, P. D.; Prosser, J. G. (1984). «Geologic map of the Michelangelo quadrangle of Mercury». U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series. Map I-1659, scale 1:5,000,000. United States Geological Survey: 1659. Bibcode:1984USGS…IM.1659S. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «1815 Beethoven (1932 CE1)». Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Golden Record Music List». NASA. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

Sources

- Albrecht, Theodore (2009). «Anton Schindler as destroyer and forger of Beethoven’s conversation books: A case for decriminalization» (PDF). In Blažeković, Zdravko (ed.). Music’s Intellectual History. New York: RILM. pp. 169–181. ISBN 978-1-932765-05-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Brandenburg, Sieghard, ed. (1996). Ludwig van Beethoven: Briefwechsel. Gesamtausgabe. Munich: Henle. ISBN 978-3-87328-061-8.

- Brendel, Alfred (1991). Music Sounded Out. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-37452-331-2.

- Cassedy, Steven (January 2010). «Beethoven the Romantic: How E. T. A. Hoffmann Got It Right». Journal of the History of Ideas. 71 (1): 1–34. doi:10.1353/jhi.0.0071. JSTOR 20621921. S2CID 170552244.

- Clive, H.P. (2001). Beethoven and His World: A Biographical Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816672-6.

- Comini, Allesandra (2008). The Changing Image of Beethoven: A Study in Mythmaking. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-661-1.

- Conway, David (2012). Jewry in Music: Entry to the Profession from the Enlightenment to Richard Wagner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01538-8.

- Cooper, Barry, ed. (1996). The Beethoven Compendium: A Guide to Beethoven’s Life and Music (revised ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50-027871-0.

- Cooper, Barry (2008). Beethoven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531331-4.

- Cooper, Martin (1970). Beethoven, The Last Decade 1817–1827. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315310-6.

- Ealy, George Thomas (Spring 1994). «Of Ear Trumpets and a Resonance Plate: Early Hearing Aids and Beethoven’s Hearing Perception». 19th-Century Music. 17 (3): 262–273. doi:10.1525/ncm.1994.17.3.02a00050. JSTOR 746569.

- Einstein, Alfred (1958). Essays on Music. London: Faber and Faber. OCLC 713913183.

- Eisinger, Josef (2008). «The lead in Beethoven’s hair». Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry. 90 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/02772240701630588. S2CID 95824344.

- Hammelmann, Han (March 1965). «Beethoven’s Conversation Books». The Musical Times. 106 (1465): 187–189. doi:10.2307/948240. JSTOR 948240.

- Kerman, Joseph; Tyson, Alan; Burnham, Scott G. (2001). «Ludwig van Beethoven». Oxford Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40026.

- Lockwood, Lewis (2005). Beethoven: The Music and the Life. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32638-3.

- Lorenz, Michael (Winter 2007). «Commentary on Wawruch’s Report: Biographies of Andreas Wawruch and Johann Seibert, Schindler’s Responses to Wawruch’s Report, and Beethoven’s Medical Condition and Alcohol Consumption». Beethoven Journal. 22 (2): 92–100.

- Mai, F. M. M. (2006). «Beethoven’s terminal illness and death». Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 36 (3): 258–263. PMID 17214130.

- Meredith, William Rhea (2005). «The History of Beethoven’s Skull Fragments». Beethoven Journal. 20 (1–2): 3–46. OCLC 64392567.

- Morris, Edmund (2010). Beethoven: The Universal Composer. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-075975-9.

- Nettl, Paul (1994). Beethoven Encyclopedia. Secaucus, New Jersey: Carel Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7351-0113-5.

- Newman, William S. (1970). «Beethoven’s Pianos versus His Piano Ideals». Journal of the American Musicological Society. 23 (3): 484–504. doi:10.2307/830617. JSTOR 830617.

- Ronge, Julia (2013). «Beethoven’s Studies with Joseph Haydn (With a Postscript on the Length of Beethoven’s Bonn Employment)». Beethoven Journal. 28 (1): 4–25.

- Rosen, Charles (1972). The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. London: Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-10234-1.

- Saccenti, Edoardo; Smilde, Age K; Saris, Wim H M (2011). «Beethoven’s deafness and his three styles». The BMJ. 343: d7589. doi:10.1136/bmj.d7589. PMID 22187391. S2CID 206894214.

- Saccenti, Edoardo; Smilde, Age K; Saris, Wim H M (2012). «Beethoven’s deafness and his three styles». The BMJ. 344: e512. doi:10.1136/bmj.e512.

- Scherer, E. M. (2004). Quarter Notes and Bank Notes: the Economics of Music Composition in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-6911-1621-1.