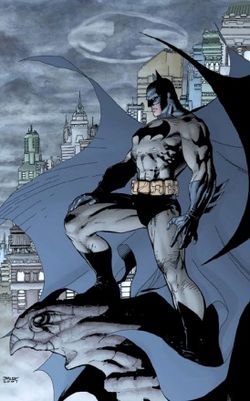

I’m mad about comics and movies based on fantastic stories about superheroes, mutants and other fictional extraordinary characters with super-powers. My favorite one is Batman. This character is a member of DC and he could be found in a plenty of cartoons, comics and video games.

Batman is a nickname of a rich orphan Bruce Wayne who lost his parents when he was a kid — they were gunned down within sight of a small boy (Bruce). This moment changed a lot in his life. He inherited big money, family business and lived in a big house with a family butler, Albert. But Bruce didn’t become an ordinary man, but a billionaire industrialist and a well-known playboy with secrets. He decided to be the greatest weapon against crime and save lives of ordinary people.

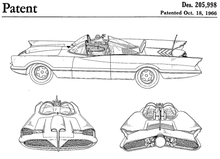

Unlike most of Marvel and DC superheroes Batman has no such unusual skills and super-powers as super-strength, super-speed, flight, invulnerability, x-ray vision, self-healing, etc. Although, he is the most featured superhero of all, because he’s a brilliant detective, a talented jack-of-all-trades, who’s mastered fighting aircrafts. Batman has created his own Batarangs, Batmobile and Utility Belt filled with different types of weapon. He’s always five steps ahead of his foes. Batman is the main protector of Gotham City, dressed like a bat.

I suppose that all Batman movies have become a part of classical cinematography. My favorite one is The Dark Knight with Christian Bale. Now I’m waiting with impatience for a new movie Batman vs. Superman with Ben Affleck.

In my opinion, Batman is the obvious proof you don’t need any super-powers to protect somebody and become somebody’s personal hero. He shows people, that the world is our oyster and everybody could change it.

Я без ума от комиксов, фантастических фильмов о супергероях, мутантах и прочих вымышленных необычных персонажей, наделенных супер-способностями. Мой самый любимый из них — Бэтмен. Этого героя, персонажа вселенной DC, можно увидеть во множестве мультфильмов, комиксов и видеоигр.

Бэтмен — прозвище богатого сироты Брюса Уэйна, потерявшего родителей, будучи еще ребенком — их застрелили на глазах у маленького мальчика (Брюса). Это изменило многое в его жизни. Он получил в наследство много денег, семейный бизнес и жил в большом доме с дворецким, Альбертом. Но Брюс стал не обыкновенным человеком, а магнатом-миллиардером и известным плейбоем со своими секретами. Он решил стать величайшим борцом с преступностью и спасать жизни обычных людей.

В отличие от большинства супергероев вселенных Marvel и DC, у Бэтмена нет таких необычных навыков и супер-способностей как суперсила, суперскорость, левитация, неуязвимость, регенерация и т.д. Однако Бэтмен имеет наиболее мощное техническое оснащение по сравнению с другими героями, так как он — потрясающий детектив, мастер на все руки, изобретающий летательные аппараты. Он создал Бэтаранги, Бэтмобиль и пояс, оснащенный разнообразными орудиями. Он всегда на пять шагов опережает своих врагов. Бэтмен — главный защитник города Готэм в костюме летучей мыши.

Мне кажется, что все фильмы про Бэтмена уже стали классикой мирового кинематографа. Мой любимый — Темный рыцарь с Кристианом Бейлом. Сейчас я с нетерпением жду новый фильм Бэтмен против Супермена с Беном Аффлеком.

По-моему, Бэтмен — очевидное доказательство того, что не нужно иметь каких либо суперспособностей для того чтобы защитить кого-то и стать для кого-то личным героем . Он показывает людям, что все находится в их руках, и каждый может изменить мир.

Мой любимый киногерой это Бэтмен. Бэтмен не обладает супер силой, как другие супер герои. Но он очень умный, знает много языков и у него хорошее здоровье. Его родители были убиты преступниками когда он был маленьким. С тех пор он решил бороться с плохими парнями. Никто не знает его в лицо, так как он носит маску и черную форму «летучей мыши». Форма изготовлена из латекса. Он использует различные автомобили, оружие, которые помогают ему в его борьбе с преступниками. Обычно он действует ночью один или со своими друзьями. Мне нравится Бэтмен за его силу, ум и чувство справедливости.

Мой любимый киногерой это Бэтмен. Бэтмен не обладает супер силой, как другие супер герои. Но он очень умный, знает много языков и у него хорошее здоровье. Его родители были убиты преступниками когда он был маленьким. С тех пор он решил бороться с плохими парнями. Никто не знает его в лицо, так как он носит маску и черную форму «летучей мыши». Форма изготовлена из латекса. Он использует различные автомобили, оружие, которые помогают ему в его борьбе с преступниками. Обычно он действует ночью один или со своими друзьями. Мне нравится Бэтмен за его силу, ум и чувство справедливости.

Определить язык Клингонский Клингонский (pIqaD) азербайджанский албанский английский арабский армянский африкаанс баскский белорусский бенгальский болгарский боснийский валлийский венгерский вьетнамский галисийский греческий грузинский гуджарати датский зулу иврит игбо идиш индонезийский ирландский исландский испанский итальянский йоруба казахский каннада каталанский китайский китайский традиционный корейский креольский (Гаити) кхмерский лаосский латынь латышский литовский македонский малагасийский малайский малайялам мальтийский маори маратхи монгольский немецкий непали нидерландский норвежский панджаби персидский польский португальский румынский русский себуанский сербский сесото словацкий словенский суахили суданский тагальский тайский тамильский телугу турецкий узбекский украинский урду финский французский хауса хинди хмонг хорватский чева чешский шведский эсперанто эстонский яванский японский

Клингонский Клингонский (pIqaD) азербайджанский албанский английский арабский армянский африкаанс баскский белорусский бенгальский болгарский боснийский валлийский венгерский вьетнамский галисийский греческий грузинский гуджарати датский зулу иврит игбо идиш индонезийский ирландский исландский испанский итальянский йоруба казахский каннада каталанский китайский китайский традиционный корейский креольский (Гаити) кхмерский лаосский латынь латышский литовский македонский малагасийский малайский малайялам мальтийский маори маратхи монгольский немецкий непали нидерландский норвежский панджаби персидский польский португальский румынский русский себуанский сербский сесото словацкий словенский суахили суданский тагальский тайский тамильский телугу турецкий узбекский украинский урду финский французский хауса хинди хмонг хорватский чева чешский шведский эсперанто эстонский яванский японский

Источник:

Цель:

Результаты (английский

) 1:

My favorite action hero is Batman. Batman does not possess Super strength as other Super Heroes. But he»s very smart, knows many languages and have good health. His parents were killed by criminals when he was a kid. Since then, he decided to fight the bad guys. Nobody knows him in the face, because he wears a mask and black bat «form. The form is made of LaTeX. He uses a variety of vehicles, weapons, which help him in his fight with criminals. It usually operates at night alone or with your friends. I like Batman for his strength, intelligence and sense of Justice.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (английский

) 2:

My favorite movie character is Batman. Batman does not have super strength, the other super heroes. But he is very smart, knows many languages, and he has a good health. His parents were killed by criminals when he was little. Since then, he decided to fight the bad guys. No one knows his face as he wears a mask and black uniforms «bat.» Form made of latex. He uses a variety of vehicles and weapons to help him in his fight with the criminals. He usually works at night alone or with your friends. Like Batman for his strength, intellect and sense of justice.

transcription, транскрипция: [ ʹbæt|mən

]

n (pl -men -ʹbætmən) воен.

денщик, вестовой, ординарец

Англо-Русско-Английский словарь общей лексики, сборник из лучших словарей.

English-Russian-English dictionary of general lexis, the collection of the best dictionaries.

2012

→

English-Russian-English vocabularies

→

English-Russian-English dictionary of general lexis, the collection of the best dictionaries

Еще значения слова и перевод BATMAN с английского на русский язык в англо-русских словарях.

Что такое и перевод BATMAN с русского на английский язык в русско-английских словарях.

More meanings of this word and English-Russian, Russian-English translations for BATMAN in dictionaries.

- BATMAN — servitor de oficero; soldate de ordonantie

English interlingue dictionary

- BATMAN — noun Etymology: French bât packsaddle Date: 1755 an orderly of a British military officer

Толковый словарь английского языка — Merriam Webster

- BATMAN — I. ˈbatmən noun (-s) Etymology: Turkish: any of various old Persian or Turkish units of weight: as …

Webster»s New International English Dictionary

- BATMAN

Английский словарь Webster

- BATMAN — (n.) A weight used in the East, varying according to the locality; in Turkey, the greater batman is about 157 …

Английский словарь Webster

- BATMAN — (n.) A weight used in the East, varying according to the locality; in Turkey, the greater batman is …

- BATMAN — (n.) A man who has charge of a bathorse and his load.

Webster»s Revised Unabridged English Dictionary

- BATMAN — /bat»meuhn/ , n. , pl. batmen . (in the British army) a soldier assigned to an officer as a servant. …

Random House Webster»s Unabridged English Dictionary

- BATMAN — n. soldier serving as a personal servant to an officer

Толковый словарь английского языка — Редакция bed

- BATMAN — noun Etymology: French bât packsaddle Date: 1755: an orderly of a British military officer

Merriam-Webster»s Collegiate English vocabulary

- BATMAN — noun a man who has charge of a bathorse and his load. 2. batman ·noun a weight used in the …

Webster English vocab - BATMAN — (or batwoman) ■ noun (plural batmen or batwomen) dated (in the British armed forces) an officer»s personal …

Concise Oxford English vocab - BATMAN — n (1755): an orderly of a British military officer

Merriam-Webster English vocab - BATMAN — town, southeastern Turkey, in the centre of the nation»s oil-producing region. It is located about 5 miles (8 km) west …

Britannica English vocabulary - BATMAN — Batman cartoon character BrE AmE ˈbæt mæn

- BATMAN — batman «army servant» BrE AmE ˈbæt mən ▷ batmen ˈbæt mən -men

Longman Pronunciation English Dictionary

- BATMAN — / ˈbætmən; NAmE / noun (pl. -men / -mən; NAmE /) (BrE) the personal servant of an …

Oxford Advanced Learner»s English Dictionary

- BATMAN — bat ‧ man /ˈbætmən/ BrE AmE noun (plural batmen /-mən/) an officer’s personal servant in the British army

- BATMAN — Bat ‧ man /ˈbætmæn/ BrE AmE trademark a popular character in cartoon strip s , films, and television programmes, …

Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English

- BATMAN — n. (pl. -men) Mil. an attendant serving an officer.

Английский основной разговорный словарь

- BATMAN — n. (pl. -men) Mil. an attendant serving an officer. [ OF bat, bast f. med.L bastum pack-saddle + MAN ]

Concise Oxford English Dictionary

- BATMAN — n. (pl. -men) Mil. an attendant serving an officer. Etymology: OF bat, bast f. med.L bastum pack-saddle + MAN

Oxford English vocab - BATMAN — (batmen) In the British armed forces, an officer’s batman is his personal servant. N-COUNT: usu sing , oft …

Collins COBUILD Advanced Learner»s English Dictionary

- BATMAN — (batmen) In the British armed forces, an officer’s ~ is his personal servant. N-COUNT: usu sing, oft poss N

Collins COBUILD — Толковый словарь английского языка для изучающих язык

- BATMAN — noun EXAMPLES FROM CORPUS ▪ Despite years of being taken care of by a batman he knew exactly what was …

Longman DOCE5 Extras English vocabulary

- BATMAN — [C] -men — the personal servant of an officer esp. in the British armed forcesOfficers also have batmen …

Cambridge English vocab - BATMAN — Synonyms and related words: Ganymede, Hebe, airline hostess, airline stewardess, attendant, bellboy, bellhop, bellman, bootblack, boots, cabin boy, caddie, …

Moby Thesaurus English vocabulary

- BATMAN — Taken from the first modern Batman movie (Keaton, Nicholson), the word comes from an early scene where Batman, on a …

Slang English vocab - BATMAN

Большой Англо-Русский словарь

- BATMAN — сущ.; воен. вестовой, денщик, ординарец Syn: valet (военное) денщик, вестовой, ординарец batman воен. денщик, вестовой, ординарец

Новый большой Англо-Русский словарь

- BATMAN — n. Pronunciation: » bat-m ə n Function: noun Etymology: French bât packsaddle Date: 1755: an orderly of a British …

Merriam Webster Collegiate English Dictionary

- BATMAN — a character in US comics , on television and in films who wears a costume like a bat (= a …

Oxford Guide to British and American Culture English vocabulary

- BATMAN — Бэтмен

Американский Англо-Русский словарь

- BATMAN — ординарец

Англо-Русский словарь Tiger

- BATMAN — (n) вестовой; денщик; ординарец

English-Russian Lingvistica»98 dictionary

- BATMAN — n (pl -men [-{ʹbæt}mən]) воен. денщик, вестовой, ординарец

Новый большой Англо-Русский словарь — Апресян, Медникова

- BATMAN — n (pl -men -ʹbætmən) воен. денщик, вестовой, ординарец

Большой новый Англо-Русский словарь

Композитор

Нелсон Риддл

Монтаж

Гарри В. Герштад

Оператор

Ховард Шварц

Сценаристы

Боб Кейн ,

Лоренцо Семпл мл. ,

Эдмонд Хэмилтон ,

еще

Художники

Серж Кризман ,

Джек Мартин Смит

,

Пэт Барто ,

еще

Знаете ли вы, что

- Сесар Ромеро, исполняющий роль Джокера, отказался сбривать свои усы, а потому их пришлось прятать за слоем макияжа.

- Съемки фильма начались до того, как Ли Меривезер утвердили на роль, а потому Женщина-кошка не присутствует в первой сцене на подводной лодке Пингвина.

- Джули Ньюмар, которая исполняла роль Женщины-кошки в сериале, не появилась в фильме, так как не знала о предстоящих съемках, а потому подписала контракт на другой проект. Когда ее проинформировали о съемках полнометражного фильма, то ее обязательства помешали ей поучаствовать в нем.

- Изначально данный фильм должен был стать пилотом к сериалу «Бэтмен» (1966–1968), но вместо этого вышел между первым и вторым сезонами.

- Во время финальной схватки один из каскадеров, исполняющих роль приспешника злодеев, нырнул в воду и ударился головой о металлический пруд на дне пруда. Он потерял сознание и был немедленно отправлен в больницу.

Больше фактов (+2)

Ошибки в фильме

- Когда Загадочник, Пингвин и Женщина-кошка обезвоживают своих пиратских прислужников, то слышно, как Загадочник смеется, хотя его рот не двигается.

- В сцене в Бэтпещере Бэтмен говорит Робину: «Как ты и сказал, яхта не может просто исчезнуть». Хотя на пресс-конференции ранее он сам произнес эти слова.

- Когда Робин передает Бэтмену акулий репеллент, то расстояние между ними меняется между планами.

- Когда Брюса Уэйна и мисс Китку похищают, то на ней надето розовое платье. Позже, когда ему разрешают ее увидеть, то на ней надето уже белое платье.

- Когда Бэтмен и Робин прибывают в доки, то там виден знак «Моби Дик». Позже они возвращаются к Бэтмобилю, и знака уже нет.

- Во время битвы на подводной лодке каждый из приспешников злодеев, а также сам Джокер, оказываются сбиты в воду. Однако затем они появляются снова абсолютно сухими.

- Когда Бэтмен и Робин едут к докам, чтобы добраться до Бэтлодки, то оставляют свою машину носом к воде. Позже она возвращаются к Бэтмобилю, и тот уже развернут в сторону суши.

-

1

batman

воен.денщи́к, вестово́й, ордина́рец

Англо-русский словарь Мюллера > batman

-

2

batman

Англо-русский синонимический словарь > batman

-

3

batman

Большой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > batman

-

4

Batman

[ˊbætmǝn]

Бэтмен, Человек—Летучая Мышь, персонаж комиксов, телепередач и мультфильмов, в которых он сражается против преступников и защищает простых людей, обычно вместе со своим помощником Робином. Одет в длинный чёрный плащ, лицо закрыто чёрной маской, передвигается со страшной скоростью на «Бэтмобиле» [Batmobile], оборудованном разными хитрыми приспособлениями. Фраза ‘Good thinking, Batman’, которую произносит Робин, когда Бэтмену приходит в голову очередная блестящая идея, часто употребляется американцамиСША. Лингвострановедческий англо-русский словарь > Batman

-

5

batman

[ˈbætmən]

batman воен. денщик, вестовой, ординарец

English-Russian short dictionary > batman

-

6

batman

[ʹbæt|mən]

(pl -men [-{ʹbæt}mən]

денщик, вестовой, ординарец

НБАРС > batman

-

7

Batman

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > Batman

-

8

batman

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > batman

-

9

batman

[`bætmən]

вестовой, денщик, ординарец

Англо-русский большой универсальный переводческий словарь > batman

-

10

Batman

Англо-русский географический словарь > Batman

-

11

Batman

Бэтмен («человек-летучая мышь»)

English-Russian dictionary of regional studies > Batman

-

12

batman

noun mil.

денщик, вестовой, ординарец

Syn:

valet

* * *

(n) вестовой; денщик; ординарец

* * *

вестовой, денщик, ординарец

* * *

[bat·man || ‘bætmən]

денщик, вестовой, ординарец* * *

Новый англо-русский словарь > batman

-

13

batman

Англо-русский морской словарь > batman

-

14

Batman

Батман Город на востоке Турции. 147 тыс. жителей (1990). Нефтеперерабатывающий завод.

Англо-русский словарь географических названий > Batman

-

15

batman

English-Russian military dictionary > batman

-

16

batman

English-Russian dictionary of technical terms > batman

-

17

batman

[‘bætmən]

;

мн.

batmen;

воен.

;

уст.

вестовой, денщик, ординарец

Syn:

Англо-русский современный словарь > batman

-

18

batman

English-Russian smart dictionary > batman

-

19

batman

n воен. денщик, вестовой, ординарец

English-Russian base dictionary > batman

-

20

John Batman Festival

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > John Batman Festival

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

См. также в других словарях:

-

Batman — (engl. für „Fledermausmann“) ist ein Comic Held, der von Bob Kane geschaffen und von Bill Finger vor dem Erscheinen weiterentwickelt wurde. Finger veränderte das ursprünglich steife Cape in ein wallendes und konzipierte Batman als zweite… … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

BATMAN — Pour les articles homonymes, voir Batman (homonymie). Bruce Wayne Personnage de Batman … Wikipédia en Français

-

Batman (MD) — Batman (Megadrive) Pour les articles homonymes, voir Batman (homonymie). Batman … Wikipédia en Français

-

Batman 3 — est un projet de film d action et fantastique qui sera réalisé par Christopher Nolan, est basé sur le célèbre personnage de fiction DC Comics, Batman. Sa sortie est prévue pour 2012. C est la suite de Batman Begins, sorti en 2005 et de The Dark… … Wikipédia en Français

-

Batman 3 — may refer to:* Batman Forever , the second sequel to the 1989 film Batman * Batman 3 , the proposed second sequel to the 2005 film Batman Begins … Wikipedia

-

Batman 2 — may refer to:* Batman Returns , the 1992 sequel to the 1989 film Batman * The Dark Knight , the 2008 sequel to the 2005 film Batman Begins … Wikipedia

-

Batman — Bat man (b[a^]t m[a^]n), n. [Turk. ba[.t]man.] A weight used in the East, varying according to the locality; in Turkey, the greater batman is about 157 pounds, the lesser only a fourth of this; at Aleppo and Smyrna, the batman is 17 pounds.… … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

-

Batman — Batman, también conocido como el Hombre Murciélago es un personaje ficticio y superhéroe creado por el escritor Bill Finger y el artista Bob Kane (aunque solo Kane recibe crédito oficial) para una de las historietas del número 27 del comic book… … Enciclopedia Universal

-

batman — batmán s. m., pl. batmáni Trimis de siveco, 10.08.2004. Sursa: Dicţionar ortografic BATMÁN s.m. (Sport) Jucător din ofensiva unei echipe de crichet. [< engl. batsman]. Trimis de LauraGellner, 13.09.2007. Sursa: DN BATMÁN s. m. Jucător din… … Dicționar Român

-

Batman — Bat man (b[add] man or b[a^]t man), n.; pl. {Batmen} (b[a^]t men). [F. b[^a]t packsaddle + E. man. Cf. {Bathorse}.] A man who has charge of a bathorse and his load. Macaulay. [1913 Webster] || … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

-

Batman — Batman, türkisches u. persisches Gewicht. In der Türkei ist ein großes B. = 20,4 Zollpfd., ein kleines B. = 1/4 des großen. In Constantinopel 1 B. persische Seide = 73/4 Zollpfd., in Persien 1 B. = 11,56 Zollpfd … Pierer’s Universal-Lexikon

| Batman | |

|---|---|

Cover of the DC Comics Absolute Edition of Batman: Hush (2011) |

|

| Publication information | |

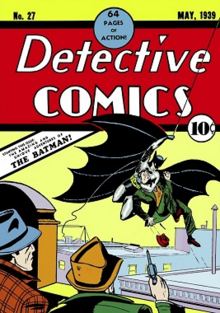

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| First appearance | Detective Comics #27 (cover-dated May 1939; published March 30, 1939)[1] |

| Created by |

|

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Bruce Wayne |

| Place of origin | Gotham City |

| Team affiliations |

|

| Partnerships |

|

| Notable aliases |

|

| Abilities |

|

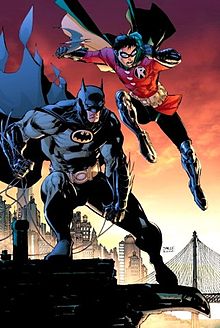

The Batman[a] is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, and debuted in the 27th issue of the comic book Detective Comics on March 30, 1939. In the DC Universe continuity, Batman is the alias of Bruce Wayne, a wealthy American playboy, philanthropist, and industrialist who resides in Gotham City. Batman’s origin story features him swearing vengeance against criminals after witnessing the murder of his parents Thomas and Martha as a child, a vendetta tempered with the ideal of justice. He trains himself physically and intellectually, crafts a bat-inspired persona, and monitors the Gotham streets at night. Kane, Finger, and other creators accompanied Batman with supporting characters, including his sidekicks Robin and Batgirl; allies Alfred Pennyworth, James Gordon, and Catwoman; and foes such as the Penguin, the Riddler, Two-Face, and his archenemy, the Joker.

Kane conceived Batman in early 1939 to capitalize on the popularity of DC’s Superman; although Kane frequently claimed sole creation credit, Finger substantially developed the concept from a generic superhero into something more bat-like. The character received his own spin-off publication, Batman, in 1940. Batman was originally introduced as a ruthless vigilante who frequently killed or maimed criminals, but evolved into a character with a stringent moral code and strong sense of justice. Unlike most superheroes, Batman does not possess any superpowers, instead relying on his intellect, fighting skills, and wealth. The 1960s Batman television series used a camp aesthetic, which continued to be associated with the character for years after the show ended. Various creators worked to return the character to his darker roots in the 1970s and 1980s, culminating with the 1986 miniseries The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller.

DC has featured Batman in many comic books, including comics published under its imprints such as Vertigo and Black Label. The longest-running Batman comic, Detective Comics, is the longest-running comic book in the United States. Batman is frequently depicted alongside other DC superheroes, such as Superman and Wonder Woman, as a member of organizations such as the Justice League and the Outsiders. In addition to Bruce Wayne, other characters have taken on the Batman persona on different occasions, such as Jean-Paul Valley / Azrael in the 1993–1994 «Knightfall» story arc; Dick Grayson, the first Robin, from 2009 to 2011; and Jace Fox, son of Wayne’s ally Lucius, as of 2021.[4] DC has also published comics featuring alternate versions of Batman, including the incarnation seen in The Dark Knight Returns and its successors, the incarnation from the Flashpoint (2011) event, and numerous interpretations from Elseworlds stories.

One of the most iconic characters in popular culture, Batman has been listed among the greatest comic book superheroes and fictional characters ever created. He is one of the most commercially successful superheroes, and his likeness has been licensed and featured in various media and merchandise sold around the world; this includes toy lines such as Lego Batman and video games like the Batman: Arkham series. Batman has been adapted in live-action and animated incarnations, including the 1960s Batman television series played by Adam West and in film by Michael Keaton in Batman (1989), Batman Returns (1992), and The Flash (2023), Val Kilmer in Batman Forever (1995), George Clooney in Batman and Robin (1997), Christian Bale in The Dark Knight trilogy (2005–2012), Ben Affleck in the DC Extended Universe (2016–present), and Robert Pattinson in The Batman (2022). Kevin Conroy, Diedrich Bader, Jensen Ackles and Will Arnett, among others, have provided the character’s voice.

Publication history

Creation

In early 1939, the success of Superman in Action Comics prompted editors at National Comics Publications (the future DC Comics) to request more superheroes for its titles. In response, Bob Kane created «the Bat-Man».[6] Collaborator Bill Finger recalled that «Kane had an idea for a character called ‘Batman,’ and he’d like me to see the drawings. I went over to Kane’s, and he had drawn a character who looked very much like Superman with kind of …reddish tights, I believe, with boots …no gloves, no gauntlets …with a small domino mask, swinging on a rope. He had two stiff wings that were sticking out, looking like bat wings. And under it was a big sign …BATMAN».[7] The bat-wing-like cape was suggested by Bob Kane, inspired as a child by Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch of an ornithopter flying device.[8]

Finger suggested giving the character a cowl instead of a simple domino mask, a cape instead of wings, and gloves; he also recommended removing the red sections from the original costume.[9][10][11][12] Finger said he devised the name Bruce Wayne for the character’s secret identity: «Bruce Wayne’s first name came from Robert the Bruce, the Scottish patriot. Wayne, being a playboy, was a man of gentry. I searched for a name that would suggest colonialism. I tried Adams, Hancock …then I thought of Mad Anthony Wayne.»[13] He later said his suggestions were influenced by Lee Falk’s popular The Phantom, a syndicated newspaper comic-strip character with which Kane was also familiar.[14]

Kane and Finger drew upon contemporary 1930s popular culture for inspiration regarding much of the Bat-Man’s look, personality, methods, and weaponry. Details find predecessors in pulp fiction, comic strips, newspaper headlines, and autobiographical details referring to Kane himself.[15] As an aristocratic hero with a double identity, Batman had predecessors in the Scarlet Pimpernel (created by Baroness Emmuska Orczy, 1903) and Zorro (created by Johnston McCulley, 1919). Like them, Batman performed his heroic deeds in secret, averted suspicion by playing aloof in public, and marked his work with a signature symbol. Kane noted the influence of the films The Mark of Zorro (1920) and The Bat Whispers (1930) in the creation of the character’s iconography. Finger, drawing inspiration from pulp heroes like Doc Savage, The Shadow, Dick Tracy, and Sherlock Holmes, made the character a master sleuth.[16][17]

In his 1989 autobiography, Kane detailed Finger’s contributions to Batman’s creation:

One day I called Bill and said, ‘I have a new character called the Bat-Man and I’ve made some crude, elementary sketches I’d like you to look at.’ He came over and I showed him the drawings. At the time, I only had a small domino mask, like the one Robin later wore, on Batman’s face. Bill said, ‘Why not make him look more like a bat and put a hood on him, and take the eyeballs out and just put slits for eyes to make him look more mysterious?’ At this point, the Bat-Man wore a red union suit; the wings, trunks, and mask were black. I thought that red and black would be a good combination. Bill said that the costume was too bright: ‘Color it dark grey to make it look more ominous.’ The cape looked like two stiff bat wings attached to his arms. As Bill and I talked, we realized that these wings would get cumbersome when Bat-Man was in action and changed them into a cape, scalloped to look like bat wings when he was fighting or swinging down on a rope. Also, he didn’t have any gloves on, and we added them so that he wouldn’t leave fingerprints.[14]

Golden Age

Subsequent creation credit

Kane signed away ownership in the character in exchange for, among other compensation, a mandatory byline on all Batman comics. This byline did not originally say «Batman created by Bob Kane»; his name was simply written on the title page of each story. The name disappeared from the comic book in the mid-1960s, replaced by credits for each story’s actual writer and artists. In the late 1970s, when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster began receiving a «created by» credit on the Superman titles, along with William Moulton Marston being given the byline for creating Wonder Woman, Batman stories began saying «Created by Bob Kane» in addition to the other credits.

Finger did not receive the same recognition. While he had received credit for other DC work since the 1940s, he began, in the 1960s, to receive limited acknowledgment for his Batman writing; in the letters page of Batman #169 (February 1965) for example, editor Julius Schwartz names him as the creator of the Riddler, one of Batman’s recurring villains. However, Finger’s contract left him only with his writing page rate and no byline. Kane wrote, «Bill was disheartened by the lack of major accomplishments in his career. He felt that he had not used his creative potential to its fullest and that success had passed him by.»[13] At the time of Finger’s death in 1974, DC had not officially credited Finger as Batman co-creator.

Jerry Robinson, who also worked with Finger and Kane on the strip at this time, has criticized Kane for failing to share the credit. He recalled Finger resenting his position, stating in a 2005 interview with The Comics Journal:

Bob made him more insecure, because while he slaved working on Batman, he wasn’t sharing in any of the glory or the money that Bob began to make, which is why …[he was] going to leave [Kane’s employ]. …[Kane] should have credited Bill as co-creator, because I know; I was there. …That was one thing I would never forgive Bob for, was not to take care of Bill or recognize his vital role in the creation of Batman. As with Siegel and Shuster, it should have been the same, the same co-creator credit in the strip, writer, and artist.[18]

Although Kane initially rebutted Finger’s claims at having created the character, writing in a 1965 open letter to fans that «it seemed to me that Bill Finger has given out the impression that he and not myself created the »Batman, t’ [sic] as well as Robin and all the other leading villains and characters. This statement is fraudulent and entirely untrue.» Kane himself also commented on Finger’s lack of credit. «The trouble with being a ‘ghost’ writer or artist is that you must remain rather anonymously without ‘credit’. However, if one wants the ‘credit’, then one has to cease being a ‘ghost’ or follower and become a leader or innovator.»[19]

In 1989, Kane revisited Finger’s situation, recalling in an interview:

In those days it was like, one artist and he had his name over it [the comic strip] — the policy of DC in the comic books was, if you can’t write it, obtain other writers, but their names would never appear on the comic book in the finished version. So Bill never asked me for it [the byline] and I never volunteered — I guess my ego at that time. And I felt badly, really, when he [Finger] died.[20]

In September 2015, DC Entertainment revealed that Finger would be receiving credit for his role in Batman’s creation on the 2016 superhero film Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice and the second season of Gotham after a deal was worked out between the Finger family and DC.[2] Finger received credit as a creator of Batman for the first time in a comic in October 2015 with Batman and Robin Eternal #3 and Batman: Arkham Knight Genesis #3. The updated acknowledgment for the character appeared as «Batman created by Bob Kane with Bill Finger».[3]

Early years

The first Batman story, «The Case of the Chemical Syndicate», was published in Detective Comics #27 (cover dated May 1939). Finger said, «Batman was originally written in the style of the pulps»,[21] and this influence was evident with Batman showing little remorse over killing or maiming criminals. Batman proved a hit character, and he received his own solo title in 1940 while continuing to star in Detective Comics. By that time, Detective Comics was the top-selling and most influential publisher in the industry; Batman and the company’s other major hero, Superman, were the cornerstones of the company’s success.[22] The two characters were featured side by side as the stars of World’s Finest Comics, which was originally titled World’s Best Comics when it debuted in fall 1940. Creators including Jerry Robinson and Dick Sprang also worked on the strips during this period.

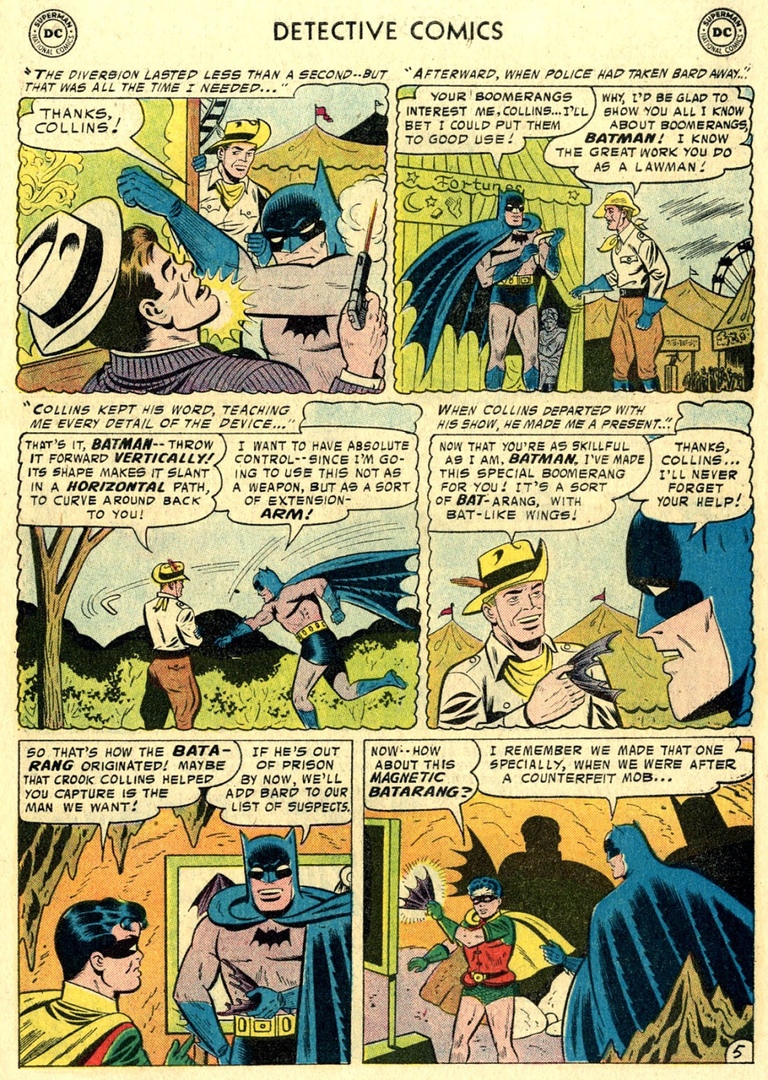

Over the course of the first few Batman strips elements were added to the character and the artistic depiction of Batman evolved. Kane noted that within six issues he drew the character’s jawline more pronounced, and lengthened the ears on the costume. «About a year later he was almost the full figure, my mature Batman», Kane said.[23] Batman’s characteristic utility belt was introduced in Detective Comics #29 (July 1939), followed by the boomerang-like batarang and the first bat-themed vehicle, the Batplane, in #31 (September 1939). The character’s origin was revealed in #33 (November 1939), unfolding in a two-page story that establishes the brooding persona of Batman, a character driven by the death of his parents. Written by Finger, it depicts a young Bruce Wayne witnessing his parents’ murder at the hands of a mugger. Days later, at their grave, the child vows that «by the spirits of my parents [I will] avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals».[24][25][26]

The early, pulp-inflected portrayal of Batman started to soften in Detective Comics #38 (April 1940) with the introduction of Robin, Batman’s junior counterpart.[27] Robin was introduced, based on Finger’s suggestion, because Batman needed a «Watson» with whom Batman could talk.[28] Sales nearly doubled, despite Kane’s preference for a solo Batman, and it sparked a proliferation of «kid sidekicks».[29] The first issue of the solo spin-off series Batman was notable not only for introducing two of his most persistent enemies, the Joker and Catwoman, but for a pre-Robin inventory story, originally meant for Detective Comics #38, in which Batman shoots some monstrous giants to death.[30][31] That story prompted editor Whitney Ellsworth to decree that the character could no longer kill or use a gun.[32]

By 1942, the writers and artists behind the Batman comics had established most of the basic elements of the Batman mythos.[33] In the years following World War II, DC Comics «adopted a postwar editorial direction that increasingly de-emphasized social commentary in favor of lighthearted juvenile fantasy». The impact of this editorial approach was evident in Batman comics of the postwar period; removed from the «bleak and menacing world» of the strips of the early 1940s, Batman was instead portrayed as a respectable citizen and paternal figure that inhabited a «bright and colorful» environment.[34]

Silver and Bronze Ages

1950s and early 1960s

Batman was one of the few superhero characters to be continuously published as interest in the genre waned during the 1950s. In the story «The Mightiest Team in the World» in Superman #76 (June 1952), Batman teams up with Superman for the first time and the pair discover each other’s secret identity.[35] Following the success of this story, World’s Finest Comics was revamped so it featured stories starring both heroes together, instead of the separate Batman and Superman features that had been running before.[36] The team-up of the characters was «a financial success in an era when those were few and far between»;[37] this series of stories ran until the book’s cancellation in 1986.

Batman comics were among those criticized when the comic book industry came under scrutiny with the publication of psychologist Fredric Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent in 1954. Wertham’s thesis was that children imitated crimes committed in comic books, and that these works corrupted the morals of the youth. Wertham criticized Batman comics for their supposed homosexual overtones and argued that Batman and Robin were portrayed as lovers.[38] Wertham’s criticisms raised a public outcry during the 1950s, eventually leading to the establishment of the Comics Code Authority, a code that is no longer in use by the comic book industry. The tendency towards a «sunnier Batman» in the postwar years intensified after the introduction of the Comics Code.[39] Scholars have suggested that the characters of Batwoman (in 1956) and the pre-Barbara Gordon Bat-Girl (in 1961) were introduced in part to refute the allegation that Batman and Robin were gay, and the stories took on a campier, lighter feel.[40]

In the late 1950s, Batman stories gradually became more science fiction-oriented, an attempt at mimicking the success of other DC characters that had dabbled in the genre.[41] New characters such as Batwoman, the original Bat-Girl, Ace the Bat-Hound, and Bat-Mite were introduced. Batman’s adventures often involved odd transformations or bizarre space aliens. In 1960, Batman debuted as a member of the Justice League of America in The Brave and the Bold #28 (February 1960), and went on to appear in several Justice League comic book series starting later that same year.

«New Look» Batman and camp

By 1964, sales of Batman titles had fallen drastically. Bob Kane noted that, as a result, DC was «planning to kill Batman off altogether».[42] In response to this, editor Julius Schwartz was assigned to the Batman titles. He presided over drastic changes, beginning with 1964’s Detective Comics #327 (May 1964), which was cover-billed as the «New Look». Schwartz introduced changes designed to make Batman more contemporary, and to return him to more detective-oriented stories. He brought in artist Carmine Infantino to help overhaul the character. The Batmobile was redesigned, and Batman’s costume was modified to incorporate a yellow ellipse behind the bat-insignia. The space aliens, time travel, and characters of the 1950s such as Batwoman, Ace the Bat-Hound, and Bat-Mite were retired. Bruce Wayne’s butler Alfred was killed off (though his death was quickly reversed) while a new female relative for the Wayne family, Aunt Harriet Cooper, came to live with Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson.[43]

The debut of the Batman television series in 1966 had a profound influence on the character. The success of the series increased sales throughout the comic book industry, and Batman reached a circulation of close to 900,000 copies.[44] Elements such as the character of Batgirl and the show’s campy nature were introduced into the comics; the series also initiated the return of Alfred. Although both the comics and TV show were successful for a time, the camp approach eventually wore thin and the show was canceled in 1968. In the aftermath, the Batman comics themselves lost popularity once again. As Julius Schwartz noted, «When the television show was a success, I was asked to be campy, and of course when the show faded, so did the comic books.»[45]

Starting in 1969, writer Dennis O’Neil and artist Neal Adams made a deliberate effort to distance Batman from the campy portrayal of the 1960s TV series and to return the character to his roots as a «grim avenger of the night».[46] O’Neil said his idea was «simply to take it back to where it started. I went to the DC library and read some of the early stories. I tried to get a sense of what Kane and Finger were after.»[47]

O’Neil and Adams first collaborated on the story «The Secret of the Waiting Graves» in Detective Comics #395 (January 1970). Few stories were true collaborations between O’Neil, Adams, Schwartz, and inker Dick Giordano, and in actuality these men were mixed and matched with various other creators during the 1970s; nevertheless the influence of their work was «tremendous».[48] Giordano said: «We went back to a grimmer, darker Batman, and I think that’s why these stories did so well …»[49] While the work of O’Neil and Adams was popular with fans, the acclaim did little to improve declining sales; the same held true with a similarly acclaimed run by writer Steve Englehart and penciler Marshall Rogers in Detective Comics #471–476 (August 1977 – April 1978), which went on to influence the 1989 movie Batman and be adapted for Batman: The Animated Series, which debuted in 1992.[50] Regardless, circulation continued to drop through the 1970s and 1980s, hitting an all-time low in 1985.[51]

Modern Age

The Dark Knight Returns

Frank Miller’s limited series The Dark Knight Returns (February – June 1986) returned the character to his darker roots, both in atmosphere and tone. The comic book, which tells the story of a 55-year-old Batman coming out of retirement in a possible future, reinvigorated interest in the character. The Dark Knight Returns was a financial success and has since become one of the medium’s most noted touchstones.[52] The series also sparked a major resurgence in the character’s popularity.[53]

That year Dennis O’Neil took over as editor of the Batman titles and set the template for the portrayal of Batman following DC’s status quo-altering 12-issue miniseries Crisis on Infinite Earths. O’Neil operated under the assumption that he was hired to revamp the character and as a result tried to instill a different tone in the books than had gone before.[54] One outcome of this new approach was the «Year One» storyline in Batman #404–407 (February – May 1987), in which Frank Miller and artist David Mazzucchelli redefined the character’s origins. Writer Alan Moore and artist Brian Bolland continued this dark trend with 1988’s 48-page one-shot issue Batman: The Killing Joke, in which the Joker, attempting to drive Commissioner Gordon insane, cripples Gordon’s daughter Barbara, and then kidnaps and tortures the commissioner, physically and psychologically.

The Batman comics garnered major attention in 1988 when DC Comics created a 900 number for readers to call to vote on whether Jason Todd, the second Robin, lived or died. Voters decided in favor of Jason’s death by a narrow margin of 28 votes (see Batman: A Death in the Family).[55]

Knightfall

The 1993 «Knightfall» story arc introduced a new villain, Bane, who critically injures Batman after pushing him to the limits of his endurance. Jean-Paul Valley, known as Azrael, is called upon to wear the Batsuit during Bruce Wayne’s convalescence. Writers Doug Moench, Chuck Dixon, and Alan Grant worked on the Batman titles during «Knightfall», and would also contribute to other Batman crossovers throughout the 1990s. 1998’s «Cataclysm» storyline served as the precursor to 1999’s «No Man’s Land», a year-long storyline that ran through all the Batman-related titles dealing with the effects of an earthquake-ravaged Gotham City. At the conclusion of «No Man’s Land», O’Neil stepped down as editor and was replaced by Bob Schreck.[56]

Another writer who rose to prominence on the Batman comic series, was Jeph Loeb. Along with longtime collaborator Tim Sale, they wrote two miniseries (The Long Halloween and Dark Victory) that pit an early-in-his-career version of Batman against his entire rogues gallery (including Two-Face, whose origin was re-envisioned by Loeb) while dealing with various mysteries involving serial killers Holiday and the Hangman. In 2003, Loeb teamed with artist Jim Lee to work on another mystery arc: «Batman: Hush» for the main Batman book. The 12–issue story line has Batman and Catwoman teaming up against Batman’s entire rogues gallery, including an apparently resurrected Jason Todd, while seeking to find the identity of the mysterious supervillain Hush.[57] While the character of Hush failed to catch on with readers, the arc was a sales success for DC. The series became #1 on the Diamond Comic Distributors sales chart for the first time since Batman #500 (October 1993) and Todd’s appearance laid the groundwork for writer Judd Winick’s subsequent run as writer on Batman, with another multi-issue arc, «Under the Hood», which ran from Batman #637–650 (April 2005 – April 2006).

21st century

All Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder

In 2005, DC launched All Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder, a stand-alone comic book miniseries set outside the main DC Universe continuity. Written by Frank Miller and drawn by Jim Lee, the series was a commercial success for DC Comics,[58][59] although it was widely panned by critics for its writing and strong depictions of violence.[60][61]

Starting in 2006, Grant Morrison and Paul Dini were the regular writers of Batman and Detective Comics, with Morrison reincorporating controversial elements of Batman lore. Most notably of these elements were the science fiction-themed storylines of the 1950s Batman comics, which Morrison revised as hallucinations Batman experienced under the influence of various mind-bending gases and extensive sensory deprivation training. Morrison’s run climaxed with «Batman R.I.P.», which brought Batman up against the villainous «Black Glove» organization, which sought to drive Batman into madness. «Batman R.I.P.» segued into Final Crisis (also written by Morrison), which saw the apparent death of Batman at the hands of Darkseid. In the 2009 miniseries Batman: Battle for the Cowl, Wayne’s former protégé Dick Grayson becomes the new Batman, and Wayne’s son Damian becomes the new Robin.[62][63] In June 2009, Judd Winick returned to writing Batman, while Grant Morrison was given their own series, titled Batman and Robin.[64]

In 2010, the storyline Batman: The Return of Bruce Wayne saw Bruce travel through history, eventually returning to the present day. Although he reclaimed the mantle of Batman, he also allowed Grayson to continue being Batman as well. Bruce decided to take his crime-fighting cause globally, which is the central focus of Batman Incorporated. DC Comics would later announce that Grayson would be the main character in Batman, Detective Comics, and Batman and Robin, while Wayne would be the main character in Batman Incorporated. Also, Bruce appeared in another ongoing series, Batman: The Dark Knight.

The New 52

In September 2011, DC Comics’ entire line of superhero comic books, including its Batman franchise, were cancelled and relaunched with new #1 issues as part of The New 52 reboot. Bruce Wayne is the only character to be identified as Batman and is featured in Batman, Detective Comics, Batman and Robin, and Batman: The Dark Knight. Dick Grayson returns to the mantle of Nightwing and appears in his own ongoing series. While many characters have their histories significantly altered to attract new readers, Batman’s history remains mostly intact. Batman Incorporated was relaunched in 2012–2013 to complete the «Leviathan» storyline.

With the beginning of The New 52, Scott Snyder was the writer of the Batman title. His first major story arc was «Night of the Owls», where Batman confronts the Court of Owls, a secret society that has controlled Gotham for centuries. The second story arc was «Death of the Family», where the Joker returns to Gotham and simultaneously attacks each member of the Batman family. The third story arc was «Batman: Zero Year», which redefined Batman’s origin in The New 52. It followed Batman vol. 2 #0, published in June 2012, which explored the character’s early years. The final storyline before the Convergence (2015) storyline was «Endgame», depicting the supposed final battle between Batman and the Joker when he unleashes the deadly Endgame virus onto Gotham City. The storyline ends with Batman and the Joker’s supposed deaths.

Starting with Batman vol. 2 #41, Commissioner James Gordon takes over Bruce’s mantle as a new, state-sanctioned, robotic-Batman, debuting in the Free Comic Book Day special comic Divergence. However, Bruce Wayne is soon revealed to be alive, albeit now with almost total amnesia of his life as Batman and only remembering his life as Bruce Wayne through what he has learned from Alfred. Bruce Wayne finds happiness and proposes to his girlfriend, Julie Madison, but Mr. Bloom heavily injures Jim Gordon and takes control of Gotham City and threatens to destroy the city by energizing a particle reactor to create a «strange star» to swallow the city. Bruce Wayne discovers the truth that he was Batman and after talking to a stranger who smiles a lot (it is heavily implied that this is the amnesic Joker) he forces Alfred to implant his memories as Batman, but at the cost of his memories as the reborn Bruce Wayne. He returns and helps Jim Gordon defeat Mr. Bloom and shut down the reactor. Gordon gets his job back as the commissioner, and the government Batman project is shut down.[65]

In 2015, DC Comics released The Dark Knight III: The Master Race, the sequel to Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and The Dark Knight Strikes Again.[66]

DC Rebirth and Infinite Frontier

In June 2016, the DC Rebirth event relaunched DC Comics’ entire line of comic book titles. Batman was rebooted as starting with a one-shot issue entitled Batman: Rebirth #1 (August 2016). The series then began shipping twice-monthly as a third volume, starting with Batman vol. 3 #1 (August 2016). The third volume of Batman was written by Tom King, and artwork was provided by David Finch and Mikel Janín. The Batman series introduced two vigilantes, Gotham and Gotham Girl. Detective Comics resumed its original numbering system starting with June 2016’s #934, and the New 52 series was labeled as volume 2, with issues numbering from #1-52.[67] Similarly with the Batman title, the New 52 issues were labeled as volume 2 and encompassed issues #1-52. Writer James Tynion IV and artists Eddy Barrows and Alvaro Martinez worked on Detective Comics #934, and the series initially featured a team consisting of Tim Drake, Stephanie Brown, Cassandra Cain, and Clayface, led by Batman and Batwoman.

DC Comics ended the DC Rebirth branding in December 2017, opting to include everything under a larger DC Universe banner and naming. The continuity established by DC Rebirth continues across DC’s comic book titles, including volume 1 of Detective Comics and volume 3 of Batman.[68][69]

After the conclusion of Batman vol. 3 #85[70] a new creative team consisting of James Tynion IV with art by Tony S. Daniel and Danny Miki replaced Tom King, David Finch and Mikel Janín. Following Tynion’s departure from DC Comics, Joshua Williamson, who previously wrote the backup story in issue #106, briefly became the new head writer in December 2021 starting with issue #118.[71] Chip Zdarsky then became the head writer with artist Jorge Jimenez returning after having previously illustrated parts of Tynion’s run. Their run begun with issue #125, which was released on July 5, 2022 and starts with «Failsafe», a six-issue story arc.[72]

Characterization

Bruce Wayne

DC Comics concept art of Bruce Wayne by Mikel Janín

Batman’s secret identity is Bruce Wayne, a wealthy American industrialist. As a child, Bruce witnessed the murder of his parents, Dr. Thomas Wayne and Martha Wayne, which ultimately led him to craft the Batman persona and seek justice against criminals. He resides on the outskirts of Gotham City in his personal residence, Wayne Manor. Wayne averts suspicion by acting the part of a superficial playboy idly living off his family’s fortune and the profits of Wayne Enterprises, his inherited conglomerate.[73][74] He supports philanthropic causes through his nonprofit Wayne Foundation, which in part addresses social issues encouraging crime as well as assisting victims of it, but is more widely known as a celebrity socialite.[75] In public, he frequently appears in the company of high-status women, which encourages tabloid gossip while feigning near-drunkenness with consuming large quantities of disguised ginger ale since Wayne is actually a strict teetotaler to maintain his physical and mental prowess.[76] Although Bruce Wayne leads an active romantic life, his vigilante activities as Batman account for most of his time.[77]

Various modern stories have portrayed the extravagant, playboy image of Bruce Wayne as a facade.[78] This is in contrast to the Post-Crisis Superman, whose Clark Kent persona is the true identity, while the Superman persona is the facade.[79][80] In Batman Unmasked, a television documentary about the psychology of the character, behavioral scientist Benjamin Karney notes that Batman’s personality is driven by Bruce Wayne’s inherent humanity; that «Batman, for all its benefits and for all of the time Bruce Wayne devotes to it, is ultimately a tool for Bruce Wayne’s efforts to make the world better». Bruce Wayne’s principles include the desire to prevent future harm and a vow not to kill. Bruce Wayne believes that our actions define us, we fail for a reason and anything is possible.[81]

Writers of Batman and Superman stories have often compared and contrasted the two. Interpretations vary depending on the writer, the story, and the timing. Grant Morrison[82] notes that both heroes «believe in the same kind of things» despite the day/night contrast their heroic roles display. Morrison notes an equally stark contrast in their real identities. Bruce Wayne and Clark Kent belong to different social classes: «Bruce has a butler, Clark has a boss.» T. James Musler’s book Unleashing the Superhero in Us All explores the extent to which Bruce Wayne’s vast personal wealth is important in his life story, and the crucial role it plays in his efforts as Batman.[83]

Will Brooker notes in his book Batman Unmasked that «the confirmation of the Batman’s identity lies with the young audience …he doesn’t have to be Bruce Wayne; he just needs the suit and gadgets, the abilities, and most importantly the morality, the humanity. There’s just a sense about him: ‘they trust him …and they’re never wrong.»[84]

Personality

Batman’s primary character traits can be summarized as «wealth; physical prowess; deductive abilities and obsession».[85] The details and tone of Batman comic books have varied over the years with different creative teams. Dennis O’Neil noted that character consistency was not a major concern during early editorial regimes: «Julie Schwartz did a Batman in Batman and Detective and Murray Boltinoff did a Batman in the Brave and the Bold and apart from the costume they bore very little resemblance to each other. Julie and Murray did not want to coordinate their efforts, nor were they asked to do so. Continuity was not important in those days.»[86]

The driving force behind Bruce Wayne’s character is his parents’ murder and their absence. Bob Kane and Bill Finger discussed Batman’s background and decided that «there’s nothing more traumatic than having your parents murdered before your eyes».[87] Despite his trauma, he sets his mind on studying to become a scientist[88][89] and to train his body into physical perfection[88][89] to fight crime in Gotham City as Batman, an inspired idea from Wayne’s insight into the criminal mind.[88][89] He also speaks over 40 different languages.[90]

Another of Batman’s characterizations is that of a vigilante; in order to stop evil that started with the death of his parents, he must sometimes break the law himself. Although manifested differently by being re-told by different artists, it is nevertheless that the details and the prime components of Batman’s origin have never varied at all in the comic books, the «reiteration of the basic origin events holds together otherwise divergent expressions».[91] The origin is the source of the character’s traits and attributes, which play out in many of the character’s adventures.[85]

Batman is often treated as a vigilante by other characters in his stories. Frank Miller views the character as «a dionysian figure, a force for anarchy that imposes an individual order».[92] Dressed as a bat, Batman deliberately cultivates a frightening persona in order to aid him in crime-fighting,[93] a fear that originates from the criminals’ own guilty conscience.[94] Miller is often credited with reintroducing anti-heroic traits into Batman’s characterization,[95] such as his brooding personality, willingness to use violence and torture, and increasingly alienated behavior. Batman, shortly a year after his debut and the introduction of Robin, was changed in 1940 after DC editor Whitney Ellsworth felt the character would be tainted by his lethal methods and DC established their own ethical code, subsequently he was retconned to have a stringent moral code,[32][96] which has stayed with the character of Batman ever since. Miller’s Batman was closer to the original pre-Robin version, who was willing to kill criminals if necessary.[97]

Others

On several occasions former Robin Dick Grayson has served as Batman; most notably in 2009 while Wayne was believed dead, and served as a second Batman even after Wayne returned in 2010.[57] As part of DC’s 2011 continuity relaunch, Grayson returned to being Nightwing following the Flashpoint crossover event.

In an interview with IGN, Morrison detailed that having Dick Grayson as Batman and Damian Wayne as Robin represented a «reverse» of the normal dynamic between Batman and Robin, with, «a more light-hearted and spontaneous Batman and a scowling, badass Robin». Morrison explained their intentions for the new characterization of Batman: «Dick Grayson is kind of this consummate superhero. The guy has been Batman’s partner since he was a kid, he’s led the Teen Titans, and he’s trained with everybody in the DC Universe. So he’s a very different kind of Batman. He’s a lot easier; He’s a lot looser and more relaxed.»[62]

Over the years, there have been numerous others to assume the name of Batman, or to officially take over for Bruce during his leaves of absence. Jean-Paul Valley, also known as Azrael, assumed the cowl after the events of the Knightfall saga.[57] Jim Gordon donned a mecha-suit after the events of Batman: Endgame, and served as Batman in 2015 and 2016. In 2021, as part of the Fear State crossover event, Lucius Fox’s son Jace Fox succeeds Bruce as Batman in a 2021 storyline, depicted in the series I Am Batman, after Batman was declared dead.

Additionally, members of the group Batman Incorporated, Bruce Wayne’s experiment at franchising his brand of vigilantism, have at times stood in as the official Batman in cities around the world.[57] Various others have also taken up the role of Batman in stories set in alternative universes and possible futures, including, among them, various former proteges of Bruce Wayne.

Supporting characters

Batman’s interactions with both villains and cohorts have, over time, developed a strong supporting cast of characters.[85]

Enemies

Batman faces a variety of foes ranging from common criminals to outlandish supervillains. Many of them mirror aspects of the Batman’s character and development, often having tragic origin stories that lead them to a life of crime.[98] These foes are commonly referred to as Batman’s rogues gallery. Batman’s «most implacable foe» is the Joker, a homicidal maniac with a clown-like appearance. The Joker is considered by critics to be his perfect adversary, since he is the antithesis of Batman in personality and appearance; the Joker has a maniacal demeanor with a colorful appearance, while Batman has a serious and resolute demeanor with a dark appearance. As a «personification of the irrational», the Joker represents «everything Batman [opposes]».[33] Other long-time recurring foes that are part of Batman’s rogues gallery include Catwoman (a cat burglar anti-heroine who is an occasional ally and romantic interest), the Penguin, Ra’s al Ghul, Two-Face, the Riddler, the Scarecrow, Mr. Freeze, Poison Ivy, Harley Quinn, Bane, Clayface, and Killer Croc, among others. Many of Batman’s adversaries are often psychiatric patients at Arkham Asylum.

Allies

- Alfred

Batman’s butler, Alfred Pennyworth, first appeared in Batman #16 (1943). He serves as Bruce Wayne’s loyal father figure and is one of the few persons to know his secret identity. Alfred raised Bruce after his parents’ death and knows him on a very personal level. He is sometimes portrayed as a sidekick to Batman and the only other resident of Wayne Manor aside from Bruce. The character «[lends] a homely touch to Batman’s environs and [is] ever ready to provide a steadying and reassuring hand» to the hero and his sidekick.[98]

- «Batman family»

The informal name «Batman family» is used for a group of characters closely allied with Batman, generally masked vigilantes who either have been trained by Batman or operate in Gotham City with his tacit approval. They include: Barbara Gordon, Commissioner Gordon’s daughter, who has fought crime under the vigilante identity of Batgirl and, during a period in which she was reliant on a wheelchair due to a gunshot wound inflicted by the Joker, the computer hacker the Oracle; Helena Bertinelli, the sole surviving member of a mob family turned vigilante, who has worked with Batman on occasion, primarily as the Huntress and as Batgirl for a brief stint; Cassandra Cain, the daughter of professional assassins David Cain, and Lady Shiva, who succeeded Bertinelli as Batgirl.

- Civilians

Lucius Fox, a technology specialist and Bruce Wayne’s business manager who is well aware of his employer’s clandestine vigilante activities; Dr. Leslie Thompkins, a family friend who like Alfred became a surrogate parental figure to Bruce Wayne after the deaths of his parents, and is also aware of his secret identity; Vicki Vale, an investigative journalist who often reports on Batman’s activities for the Gotham Gazette; Ace the Bat-Hound, Batman’s canine partner who was mainly active in the 1950s and 1960s;[99] and Bat-Mite, an extra-dimensional imp mostly active in the 1960s who idolizes Batman.[99]

- GCPD

As Batman’s ally in the Gotham City police, Commissioner James «Jim» Gordon debuted along with Batman in Detective Comics #27 and has been a consistent presence ever since. As a crime-fighting everyman, he shares Batman’s goals while offering, much as the character of Dr. Watson does in Sherlock Holmes stories, a normal person’s perspective on the work of Batman’s extraordinary genius.

- Justice League

Batman is at times a member of superhero teams such as the Justice League of America and the Outsiders. Batman has often been paired in adventures with his Justice League teammate Superman, notably as the co-stars of World’s Finest Comics and Superman/Batman series. In Pre-Crisis continuity, the two are depicted as close friends; however, in current continuity, they are still close friends but an uneasy relationship, with an emphasis on their differing views on crime-fighting and justice. In Superman/Batman #3 (December 2003), Superman observes, «Sometimes, I admit, I think of Bruce as a man in a costume. Then, with some gadget from his utility belt, he reminds me that he has an extraordinarily inventive mind. And how lucky I am to be able to call on him.»[100]

- Robin

Robin, Batman’s vigilante partner, has been a widely recognized supporting character for many years.[101] Bill Finger stated that he wanted to include Robin because «Batman didn’t have anyone to talk to, and it got a little tiresome always having him thinking.»[102] The first Robin, Dick Grayson, was introduced in 1940. In the 1970s he finally grew up, went off to college and became the hero Nightwing. A second Robin, Jason Todd, appeared in the 1980s. In the stories he was eventually badly beaten and then killed in an explosion set by the Joker, but was later revived. He used the Joker’s old persona, the Red Hood, and became an antihero vigilante with no qualms about using firearms or deadly force. Carrie Kelley, the first female Robin to appear in Batman stories, was the final Robin in the continuity of Frank Miller’s graphic novels The Dark Knight Returns and The Dark Knight Strikes Again, fighting alongside an aging Batman in stories set out of the mainstream continuity.

The third Robin in the mainstream comics is Tim Drake, who first appeared in 1989. He went on to star in his own comic series, and currently goes by the Red Robin, a variation on the traditional Robin persona. In the first decade of the new millennium, Stephanie Brown served as the fourth in-universe Robin between stints as her self-made vigilante identity the Spoiler, and later as Batgirl.[103] After Brown’s apparent death, Drake resumed the role of Robin for a time. The role eventually passed to Damian Wayne, the 10-year-old son of Bruce Wayne and Talia al Ghul, in the late 2000s.[104] Damian’s tenure as du jour Robin ended when the character was killed off in the pages of Batman Incorporated in 2013.[105] Batman’s next young sidekick is Harper Row, a streetwise young woman who avoids the name Robin but followed the ornithological theme nonetheless; she debuted the codename and identity of the Bluebird in 2014. Unlike the Robins, the Bluebird is willing and permitted to use a gun, albeit non-lethal; her weapon of choice is a modified rifle that fires taser rounds.[106] In 2015, a new series began titled We Are…Robin, focused on a group of teenagers using the Robin persona to fight crime in Gotham City. The most prominent of these, Duke Thomas, later becomes Batman’s crimefighting partner as The Signal.

Relationships

Family tree

Helena Wayne is the biological daughter of Bruce Wayne and Selina Kyle of an alternate universe established in the early 1960s (Multiverse) where the Golden Age stories took place. Damian Wayne is the biological son of Bruce Wayne and Talia al Ghul,[62][107][108] and thus the grandson of Ra’s al Ghul. Terry McGinnis and his brother Matt are the biological sons of Bruce Wayne and Mary McGinnis in the DC animated universe, and Terry has taken over the role as Batman when Bruce has become too old to do so.

Romantic interests

Writers have varied in the approach over the years to the «playboy» aspect of Bruce Wayne’s persona. Some writers show his playboy reputation as a manufactured illusion to support his mission as Batman, while others have depicted Bruce Wayne as genuinely enjoying the benefits of being «Gotham’s most eligible bachelor». Bruce Wayne has been portrayed as being romantically linked with many women throughout his various incarnations. The most significant relationships occurred with Selina Kyle, who is also Catwoman[109] and Talia al Ghul, as both women gave birth to his biological offsprings, Helena Wayne and Damian Wayne, respectively.

Batman’s first romantic interest was Julie Madison in Detective Comics #31 (September 1939); however, their romance was short-lived. Some of Batman’s romantic interests have been women with a respected status in society, such as Julie Madison, Vicki Vale, and Silver St. Cloud. Batman has also been romantically involved with allies, such as Kathy Kane (Batwoman), Sasha Bordeaux, and Wonder Woman, and with villains, such as Selina Kyle (Catwoman), Jezebel Jet, Pamela Isley (Poison Ivy), and Talia al Ghul.

- Catwoman

While most of Batman’s romantic relationships tend to be short in duration, Catwoman has been his most enduring romance throughout the years.[110] The attraction between Batman and Catwoman, whose real name is Selina Kyle, is present in nearly every version and medium in which the characters appear, including a love story between their two secret identities as early as in the 1966 film Batman. Although Catwoman is typically portrayed as a villain, Batman and Catwoman have worked together in achieving common goals and are usually depicted as having a romantic connection.

In an early 1980s storyline, Selina Kyle and Bruce Wayne develop a relationship, in which the closing panel of the final story shows her referring to Batman as «Bruce». However, a change in the editorial team brought a swift end to that storyline and, apparently, all that transpired during the story arc. Out of costume, Bruce and Selina develop a romantic relationship during The Long Halloween. The story shows Selina saving Bruce from Poison Ivy. However, the relationship ends when Bruce rejects her advances twice; once as Bruce and once as Batman. In Batman: Dark Victory, he stands her up on two holidays, causing her to leave him for good and to leave Gotham City for a while. When the two meet at an opera many years later, during the events of the 12-issue story arc called «Hush», Bruce comments that the two no longer have a relationship as Bruce and Selina. However, «Hush» sees Batman and Catwoman allied against the entire rogues gallery and rekindling their romantic relationship. In «Hush», Batman reveals his true identity to Catwoman.

The Earth-Two Batman, a character from a parallel world, partners with and marries the reformed Earth-Two Selina Kyle, as shown in Superman Family #211. They have a daughter named Helena Wayne, who becomes the Huntress. Along with Dick Grayson, the Earth-Two Robin, the Huntress takes the role as Gotham’s protector once Bruce Wayne retires to become police commissioner, a position he occupies until he is killed during one final adventure as Batman.

Batman and Catwoman are shown having a sexual encounter on the roof of a building in Catwoman vol. 4 #1 (2011); the same issue implies that the two have an ongoing sexual relationship.[111] Following the 2016 DC Rebirth continuity reboot, the two once again have a sexual encounter on top of a building in Batman vol. 3 #14 (2017).[112]

Following the 2016 DC Rebirth continuity reboot, Batman and Catwoman work together in the third volume of Batman. The two also have a romantic relationship, in which they are shown having a sexual encounter on a rooftop and sleeping together.[112][113][114] Bruce proposes to Selina in Batman vol. 3 #24 (2017),[115] and in issue #32, Selina asks Bruce to propose to her again. When he does so, she says, «Yes.»[114]

Batman vol. 3 Annual #2 (January 2018) centers on a romantic storyline between Batman and Catwoman. Towards the end, the story is flash-forwarded to the future, in which Bruce Wayne and Selina Kyle are a married couple in their golden years. Bruce receives a terminal medical diagnosis, and Selina cares for him until his death.[114]

Abilities

Skills and training

Batman has no inherent superhuman powers; he relies on «his own scientific knowledge, detective skills, and athletic prowess».[27] Batman’s inexhaustible wealth gives him access to advanced technologies, and as a proficient scientist, he is able to use and modify these technologies to his advantage. In the stories, Batman is regarded as one of the world’s greatest detectives, if not the world’s greatest crime solver.[116] Batman has been repeatedly described as having a genius-level intellect, being one of the greatest martial artists in the DC Universe, and having peak human physical and mental conditioning.[117] As a polymath, his knowledge and expertise in countless disciplines is nearly unparalleled by any other character in the DC Universe. He has shown prowess in assorted fields such as mathematics, biology, physics, chemistry, and several levels of engineering. [118] He has traveled the world acquiring the skills needed to aid him in his endeavors as Batman. In the Superman: Doomed story arc, Superman considers Batman to be one of the most brilliant minds on the planet.[119]

Batman has trained extensively in various different fighting styles, making him one of the best hand-to-hand fighters in the DC Universe. He has fully utilized his photographic memory to master a total of 127 different forms of martial arts including, but not limited to, Aikido, boxing, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, Capoeira, Eskrima, fencing, Gatka, Hapkido, Jeet Kune Do, Judo, Kalaripayattu, Karate, Kenjutsu, Kenpo, kickboxing, Kobudo, Krav Maga, Kyudo, Muay Thai, Ninjutsu, Pankration, Sambo, Savate, Silat, Taekwondo, wrestling, numerous different styles of Wushu (Kung Fu) (such as Baguazhang, Chin Na, Hung Ga, Shaolinquan, Tai Chi, Wing Chun), and Yaw-Yan.[120] In terms of his physical condition, Batman is in peak, Olympic-athlete-level condition, easily-able to run-across rooftops in a Parkour-esque fashion. Superman describes Batman as «the most dangerous man on Earth», able to defeat an entire team of superpowered extra-terrestrials by himself in order to rescue his imprisoned teammates in Grant Morrison’s first storyline in JLA.

Batman is strongly disciplined, and he has the ability to function under great physical pain and resist most forms of telepathy and mind control. He is a master of disguise, multilingual, and an expert in espionage, often gathering information under the identity of a notorious gangster named Matches Malone. Batman is highly skilled in stealth movement and escapology, which allows him to appear and disappear at will and to break free of nearly inescapable deathtraps with little to no harm.

Batman is an expert in interrogation techniques and his intimidating and frightening appearance alone is often all that is needed in getting information from suspects. Despite having the potential to harm his enemies, Batman’s most defining characteristic is his strong commitment to justice and his reluctance to take a life. This unyielding moral rectitude has earned him the respect of several heroes in the DC Universe, most notably that of Superman and Wonder Woman.

Among physical and other crime fighting related training, he is also proficient at other types of skills. Some of these include being a licensed pilot (in order to operate the Batplane), as well as being able to operate other types of machinery. In some publications, he underwent some magician training.

Technology

Batman utilizes a vast arsenal of specialized, high-tech vehicles and gadgets in his war against crime, the designs of which usually share a bat motif. Batman historian Les Daniels credits Gardner Fox with creating the concept of Batman’s arsenal with the introduction of the utility belt in Detective Comics #29 (July 1939) and the first bat-themed weapons the batarang and the «Batgyro» in Detective Comics #31 and 32 (Sept. and October 1939).[23]

- Personal armor

Batman’s batsuit aids in his combat against enemies, having the properties of both Kevlar and Nomex. It protects him from gunfire and other significant impacts, and incorporates the imagery of a bat in order to frighten criminals.[121]

The details of the Batman costume change repeatedly through various decades, stories, media and artists’ interpretations, but the most distinctive elements remain consistent: a scallop-hem cape; a cowl covering most of the face; a pair of bat-like ears; a stylized bat emblem on the chest; and the ever-present utility belt. His gloves typically feature three scallops that protrude from long, gauntlet-like cuffs, although in his earliest appearances he wore short, plain gloves without the scallops.[122] The overall look of the character, particularly the length of the cowl’s ears and of the cape, varies greatly depending on the artist. Dennis O’Neil said, «We now say that Batman has two hundred suits hanging in the Batcave so they don’t have to look the same …Everybody loves to draw Batman, and everybody wants to put their own spin on it.»[123]

Finger and Kane originally conceptualized Batman as having a black cape and cowl and grey suit, but conventions in coloring called for black to be highlighted with blue.[121] Hence, the costume’s colors have appeared in the comics as dark blue and grey;[121] as well as black and grey. In the Tim Burton’s Batman and Batman Returns films, Batman has been depicted as completely black with a bat in the middle surrounded by a yellow background. Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Trilogy depicted Batman wearing high-tech gear painted completely black with a black bat in the middle. Ben Affleck’s Batman in the DC Extended Universe films wears a suit grey in color with a black cowl, cape, and bat symbol.

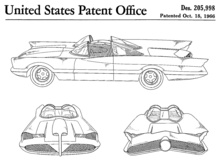

- Batmobile

Batman’s primary vehicle is the Batmobile, which is usually depicted as an imposing black car, often with tailfins that suggest a bat’s wings.

Batman also has an aircraft called the Batplane (later called the «Batwing»), along with various other means of transportation.

In proper practice, the «bat» prefix (as in Batmobile or batarang) is rarely used by Batman himself when referring to his equipment, particularly after some portrayals (primarily the 1960s Batman live-action television show and the Super Friends animated series) stretched the practice to campy proportions. For example, the 1960s television show depicted a Batboat, Bat-Sub, and Batcycle, among other bat-themed vehicles. The 1960s television series Batman has an arsenal that includes such «bat-» names as the Bat-computer, Bat-scanner, bat-radar, bat-cuffs, bat-pontoons, bat-drinking water dispenser, bat-camera with polarized bat-filter, bat-shark repellent bat-spray, and Bat-rope. The storyline «A Death in the Family» suggests that given Batman’s grim nature, he is unlikely to have adopted the «bat» prefix on his own. In The Dark Knight Returns, Batman tells Carrie Kelley that the original Robin came up with the name «Batmobile» when he was young, since that is what a kid would call Batman’s vehicle.