Всего найдено: 9

Добрый день и спасибо за вашу замечательную работу! Мы знаем, что официальная лексика используется в официальных документах, а в живой устной и письменной речи рекомендуется разговорная норма. Тем не менее, русская служба Би-Би-Си не так давно объявила, что будет в своих текстах придерживаться официальных, а не разговорных, вариантов названий бывших республик СССР (http://www.bbc.com/russian/features-42708107) — «Белоруссия становится Беларусью, Киргизия — Кыргызстаном, Туркмения — Туркменистаном, Молдавия — Молдовой и так далее». Допустимо ли такое решение? Могут ли СМИ свободно выбирать официальную или разговорную норму, или их текстам однозначно предписана разговорная норма и использование официальной будет стилистической ошибкой? Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Официальные названия государств могут свободно использоваться в СМИ, как в новостных, так и публицистических текстах. Выбор варианта в этом случае остается за автором текста и редакторами.

Приветствую! У нас тут в Википедии развернулась жаркая инструкция относительно того, как правильно пишется слово Хэллоуин — через э или через е. Единственным аргументом в пользу е оказалась ваша разъяснительная публикация относительно этого слова. Причем мои оппоненты абсолютно игнорируют множественные примеры употребления из жизни (а в 2016 мы уже можем говорить о том, что в реальной жизни слово Хэллоуин звучит достаточно часто, особенно в преддверии праздника (мне 26 лет и я живу даже не в столице)). В наших городах на всех вывесках везде значится слово Хэллоуин. И только в Википедии, упорно ссылаясь на авторитетное мнение грамоты.ру используют вариант Хеллоуин. Я призываю вас ознакомиться с жаркой дискуссией со всеми аргументами по проблеме написания данного слова и выразить свое, возможно, обновленное мнение по этому поводу. Отдельно хочется заметить, что уважаемые редакции, такие как Би-би-си, используют в своей речи именно Хэллоуин (http://www.bbc.com/russian/blog-jana-litvinova-37801171) да и вообще примеров — тьма. Идея написать вам с целью разъяснения всех точек над и уже давно витает. Зачем же отступать от общепринятого термина? Кто-то говорит, что он не устоялся — я же вторю, что в 2016 уже есть устоявшаяся норма. и это Хэллоуин. Имея такие слова в языке как «хех», «хер», «Хельсинки» и т.д. мы неизбежно будем произносить все новые слова именно через е. люди это интуитивно понимают и пишут через э. Ветка дискуссии на Википедии (не пугайтесь страшной ссылки, это кириллица в заголовках шалит) https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%92%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%BF%D0%B5%D0%B4%D0%B8%D1%8F:%D0%9A_%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B8%D0%BC%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%8E/16_%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D1%8F%D0%B1%D1%80%D1%8F_2016#.D0.A5.D0.B5.D0.BB.D0.BB.D0.BE.D1.83.D0.B8.D0.BD_.E2.86.92_.D0.A5.D1.8D.D0.BB.D0.BB.D0.BE.D1.83.D0.B8.D0.BD

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мы пишем подавляющее большинство новых иноязычных слов с буквой Е при произносимом твердом предшествующем согласном (от Интернета до бутерброда). При этом написание буквы Э в иноязычных словах жестко регламентируется правилами (ряд односложных слов, не более того). Так что Хеллоуин — отнюдь не исключение из правила. Скорее, это написание следует и правилам, и традициям письма.

Добрый день! Русский вариант английской аббревиатуры ВВС — «Би-би-си». А как быть с русским названием банка UBS? «Ю Би Эс»? или «Ю-би-эс»? Необходимо написать название русскими буквами.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Официально зарегистрированное название: «Ю Би Эс Банк», без дефисов.

Уважаемая Редакция!

Русская служба Би-Би-Си пишет сегодня, 04-ДЕК-2012: «…в свое время (будущий) ребенок (принца Уильяма и герцогини Кембриджской) станет монархом, в независимости от своего пола». Внутреннее чувство мне подсказывает, что правильно следует написать так: «…вне зависимости от своего пола»? — но вот никакого правила для этой конструкции я подобрать не могу. Быть может, в данном случае нужно руководствоваться здравым смыслом? А Вы как думаете?

Заранее спасибо,

Д-р С.О. Балякин

sbalyakin@yahoo.com

Orange County, CA, USA

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вы правы. Верно: вне зависимости от своего пола. Предлог пишется именно так: вне зависимости от (чего-либо) (см. словарную фиксацию). Но: в независимости – сочетание предлога в и существительного независимость, например: каталонцы видят много плюсов в независимости от Испании.

Статья на сайте Русской службы Би-Би-Си называется «Оператор МТС оспорит аннуляцию лицензии в Узбекистане» (http://www.bbc.co.uk/russian/rolling_news/2012/08/120813_rn_mts_license_uzbekistan.shtml). Вопрос: следует ли использовать в данной статье слово «аннулирование» вместо слова «аннуляция»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Можно использовать оба слова, это синонимы, обозначающие процесс по глаголу «аннулировать».

Скажите, пожалуйста, по традиционным нормам правильно писать «Би-Би-Си» («Си-Эн-Эн») или «Би-би-си» («Си-эн-эн»)? Т.е. после дефисов буквы прописные или нет? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Би-би-си, Си-эн-эн.

Добрый день. Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильно: Би-би-си или Би-Би-Си. На сколько я знаю, по правилам первый вариант верный, но часто вижу, что употребляется второй.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильное написание: Би-би-си.

Подскажите, пожалуйста, в каких случаях нужны кавычки:

программа Planet Earth

компания БиБиСи

компания REN-TV (российская)

компания BBC

Корпорация DNK (общее название)

Можно ли где-нибудь посмотреть соответствующие правила?

Большое спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Определенного правила нет, однако в большинстве случае названия, написанные латиницей, в русском тексте не заключаются в кавычки. Правильно: _компания «Би-би-си»_, остальное предпочтительно писать без кавычек.

BBC

БиБиСи

Би-Би-Си

би-би-си

Би.Би.Си.

би.би.си.Какие из этих вариантов написания являются:

а) допустимыми

б) недопустимыми

в) желательными

— например, в текстах газетных статей или художественных произведений?

Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вариант _Би-би-си_, зафиксированный в «Русском орфографическом словаре РАН».

This article is about the British Broadcasting Corporation. For the limited company operating between 1922 and 1926 also abbreviated BBC, see British Broadcasting Company. For other uses, see BBC (disambiguation).

Logo used since 20 October 2021 |

|

| Type | Statutory corporation with a royal charter |

|---|---|

| Industry | Mass media |

| Predecessor | British Broadcasting Company |

| Founded | 18 October 1922; 100 years ago (as British Broadcasting Company) 1 January 1927; 96 years ago (as British Broadcasting Corporation) |

| Founder | HM Government |

| Headquarters | Broadcasting House London, England, UK |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Services |

|

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Owner | Public |

|

Number of employees |

|

| Divisions | BBC Television BBC Studios BBC Sport BBC Radio BBC News BBC Online BBC Sounds BBC Weather BBC Music BBC English Regions BBC Scotland BBC Cymru Wales BBC Northern Ireland BBC North |

| Website | www.bbc.com |

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is the national broadcaster of the United Kingdom, based at Broadcasting House in London, England. It is the world’s oldest national broadcaster, and the largest broadcaster in the world by number of employees, employing over 22,000 staff in total, of whom approximately 19,000 are in public-sector broadcasting.[1][2][3][4][5]

The BBC is established under a royal charter[6] and operates under its agreement with the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport.[7] Its work is funded principally by an annual television licence fee[8] which is charged to all British households, companies, and organisations using any type of equipment to receive or record live television broadcasts or watch using iPlayer.[9] The fee is set by the British Government, agreed by Parliament,[10] and is used to fund the BBC’s radio, TV, and online services covering the nations and regions of the UK. Since 1 April 2014, it has also funded the BBC World Service (launched in 1932 as the BBC Empire Service), which broadcasts in 28 languages and provides comprehensive TV, radio, and online services in Arabic and Persian.

Around a quarter of the BBC’s revenue comes from its commercial subsidiary BBC Studios (formerly BBC Worldwide), which sells BBC programmes and services internationally and also distributes the BBC’s international 24-hour English-language news services BBC World News, and from BBC.com, provided by BBC Global News Ltd. In 2009, the company was awarded the Queen’s Award for Enterprise in recognition of its international achievements.[11]

From its inception, through the Second World War (where its broadcasts helped to unite the nation), to the popularisation of television in the post-WW2 era and the internet in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the BBC has played a prominent role in British life and culture.[12] It is colloquially known as the Beeb, Auntie, or a combination of both (Auntie Beeb).[13][14]

History

The birth of British broadcasting, 1920 to 1922

Britain’s first live public broadcast was made from the factory of Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company in Chelmsford in June 1920. It was sponsored by the Daily Mail‘s Lord Northcliffe and featured the famous Australian soprano Dame Nellie Melba. The Melba broadcast caught the people’s imagination and marked a turning point in the British public’s attitude to radio.[15] However, this public enthusiasm was not shared in official circles where such broadcasts were held to interfere with important military and civil communications. By late 1920, pressure from these quarters and uneasiness among the staff of the licensing authority, the General Post Office (GPO), was sufficient to lead to a ban on further Chelmsford broadcasts.[16]

But by 1922, the GPO had received nearly 100 broadcast licence requests[17] and moved to rescind its ban in the wake of a petition by 63 wireless societies with over 3,000 members.[18] Anxious to avoid the same chaotic expansion experienced in the United States, the GPO proposed that it would issue a single broadcasting licence to a company jointly owned by a consortium of leading wireless receiver manufacturers, to be known as the British Broadcasting Company Ltd, which was formed on 18 October 1922.[19] John Reith, a Scottish Calvinist, was appointed its general manager in December 1922 a few weeks after the company made its first official broadcast.[20] L. Stanton Jefferies was its first director of music.[21] The company was to be financed by a royalty on the sale of BBC wireless receiving sets from approved domestic manufacturers.[22] To this day, the BBC aims to follow the Reithian directive to «inform, educate and entertain».[23]

From private company towards public service corporation, 1923 to 1926

The financial arrangements soon proved inadequate. Set sales were disappointing as amateurs made their own receivers and listeners bought rival unlicensed sets.[24] By mid-1923, discussions between the GPO and the BBC had become deadlocked and the Postmaster General commissioned a review of broadcasting by the Sykes Committee.[25] The Committee recommended a short term reorganisation of licence fees with improved enforcement in order to address the BBC’s immediate financial distress, and an increased share of the licence revenue split between it and the GPO. This was to be followed by a simple 10 shillings licence fee to fund broadcasts.[25] The BBC’s broadcasting monopoly was made explicit for the duration of its current broadcast licence, as was the prohibition on advertising. To avoid competition with newspapers, Fleet Street persuaded the government to ban news bulletins before 7 pm and the BBC was required to source all news from external wire services.[25]

Mid-1925 found the future of broadcasting under further consideration, this time by the Crawford committee. By now, the BBC, under Reith’s leadership, had forged a consensus favouring a continuation of the unified (monopoly) broadcasting service, but more money was still required to finance rapid expansion. Wireless manufacturers were anxious to exit the loss-making consortium with Reith keen that the BBC be seen as a public service rather than a commercial enterprise. The recommendations of the Crawford Committee were published in March the following year and were still under consideration by the GPO when the 1926 general strike broke out in May. The strike temporarily interrupted newspaper production, and with restrictions on news bulletins waived, the BBC suddenly became the primary source of news for the duration of the crisis.[26]

The crisis placed the BBC in a delicate position. On the one hand Reith was acutely aware that the government might exercise its right to commandeer the BBC at any time as a mouthpiece of the government if the BBC were to step out of line, but on the other he was anxious to maintain public trust by appearing to be acting independently. The government was divided on how to handle the BBC, but ended up trusting Reith, whose opposition to the strike mirrored the PM’s own. Although Winston Churchill in particular wanted to commandeer the BBC to use it «to the best possible advantage», Reith wrote that Stanley Baldwin’s government wanted to be able to say «that they did not commandeer [the BBC], but they know that they can trust us not to be really impartial».[27] Thus the BBC was granted sufficient leeway to pursue the government’s objectives largely in a manner of its own choosing. The resulting coverage of both striker and government viewpoints impressed millions of listeners who were unaware that the PM had broadcast to the nation from Reith’s home, using one of Reith’s sound bites inserted at the last moment, or that the BBC had banned broadcasts from the Labour Party and delayed a peace appeal by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Supporters of the strike nicknamed the BBC the BFC for British Falsehood Company. Reith personally announced the end of the strike which he marked by reciting from Blake’s «Jerusalem» signifying that England had been saved.[28]

While the BBC tends to characterise its coverage of the general strike by emphasising the positive impression created by its balanced coverage of the views of government and strikers, Jean Seaton, Professor of Media History and the Official BBC Historian, has characterised the episode as the invention of «modern propaganda in its British form».[26] Reith argued that trust gained by ‘authentic impartial news’ could then be used. Impartial news was not necessarily an end in itself.[29]

The BBC did well out of the crisis, which cemented a national audience for its broadcasting, and it was followed by the Government’s acceptance of the recommendation made by the Crawford Committee (1925–26) that the British Broadcasting Company be replaced by a non-commercial, Crown-chartered organisation: the British Broadcasting Corporation.

1927 to 1939

The Radio Times masthead from 25 December 1931, including the BBC motto «Nation shall speak peace unto Nation»

The British Broadcasting Corporation came into existence on 1 January 1927, and Reith – newly knighted – was appointed its first Director General. To represent its purpose and (stated) values, the new corporation adopted the coat of arms, including the motto «Nation shall speak peace unto Nation».[32]

British radio audiences had little choice apart from the upscale programming of the BBC. Reith, an intensely moralistic executive, was in full charge. His goal was to broadcast «All that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement…. The preservation of a high moral tone is obviously of paramount importance.»[33] Reith succeeded in building a high wall against an American-style free-for-all in radio in which the goal was to attract the largest audiences and thereby secure the greatest advertising revenue. There was no paid advertising on the BBC; all the revenue came from a tax on receiving sets. Highbrow audiences, however, greatly enjoyed it.[34] At a time when American, Australian and Canadian stations were drawing huge audiences cheering for their local teams with the broadcast of baseball, rugby and hockey, the BBC emphasised service for a national rather than a regional audience. Boat races were well covered along with tennis and horse racing, but the BBC was reluctant to spend its severely limited air time on long football or cricket games, regardless of their popularity.[35]

The BBC’s radio studio in Birmingham, from the BBC Hand Book 1928, which described it as «Europe’s largest studio».

John Reith and the BBC, with support from the Crown, determined the universal needs of the people of Britain and broadcast content according to these perceived standards.[36] Reith effectively censored anything that he felt would be harmful, directly or indirectly.[37] While recounting his time with the BBC in 1935, Raymond Postgate claims that BBC broadcasters were made to submit a draft of their potential broadcast for approval. It was expected that they tailored their content to accommodate the modest, church-going elderly or a member of the Clergy.[38] Until 1928, entertainers broadcasting on the BBC, both singers and «talkers» were expected to avoid biblical quotations, Clerical impersonations and references, references to drink or Prohibition in America, vulgar and doubtful matter and political allusions.[37] The BBC excluded popular foreign music and musicians from its broadcasts, while promoting British alternatives.[39] On 5 March 1928, Stanley Baldwin, the Prime Minister, maintained the censorship of editorial opinions on public policy, but allowed the BBC to address matters of religious, political or industrial controversy.[40] The resulting political «talk series», designed to inform England on political issues, were criticised by members of parliament, including Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George and Sir Austen Chamberlain. Those who opposed these chats claimed that they silence the opinions of those in Parliament who are not nominated by Party Leaders or Party Whips, thus stifling independent, non-official views.[40] In October 1932, the policemen of the Metropolitan Police Federation marched in protest at a proposed pay cut. Fearing dissent within the police force and public support for the movement, the BBC censored its coverage of the events, only broadcasting official statements from the government.[40]

Throughout the 1930s, political broadcasts had been closely monitored by the BBC.[41] In 1935, the BBC censored the broadcasts of Oswald Mosley and Harry Pollitt.[40] Mosley was a leader of the British Union of Fascists, and Pollitt a leader of the Communist Party of Great Britain. They had been contracted to provide a series of five broadcasts on their parties’ politics. The BBC, in conjunction with The Foreign Office of Britain, first suspended this series and ultimately cancelled it without the notice of the public.[41][40] Less radical politicians faced similar censorship. In 1938, Winston Churchill proposed a series of talks regarding British domestic and foreign politics and affairs but was similarly censored.[41] The censorship of political discourse by the BBC was a precursor to the total shutdown of political debate that manifested over the BBC’s wartime airwaves.[41] The Foreign Office maintained that the public should not be aware of their role in the censorship.[40] From 1935 to 1939, the BBC also attempted to unite the British Empire’s radio waves, sending staff to Egypt, Palestine, Newfoundland, Jamaica, India, Canada and South Africa.[42] Reith personally visited South Africa, lobbying for state-run radio programmes which was accepted by South African Parliament in 1936.[42] A similar programme was adopted in Canada. Through collaboration with these state-run broadcasting centres, Reith left a legacy of cultural influence across the empire of Great Britain with his departure from the corporation in 1938.[42]

Experimental television broadcasts were started in 1929, using an electromechanical 30-line system developed by John Logie Baird.[43] Limited regular broadcasts using this system began in 1934, and an expanded service (now named the BBC Television Service) started from Alexandra Palace in November 1936, alternating between an improved Baird mechanical 240-line system and the all-electronic 405-line Marconi-EMI system which had been developed by an EMI research team led by Sir Isaac Shoenberg.[44] The superiority of the electronic system saw the mechanical system dropped early the following year, with the Marconi-EMI system the first fully electronic television system in the world to be used in regular broadcasting.[45]

BBC versus other media

The success of broadcasting provoked animosities between the BBC and well-established media such as theatres, concert halls and the recording industry. By 1929, the BBC complained that the agents of many comedians refused to sign contracts for broadcasting, because they feared it harmed the artist «by making his material stale» and that it «reduces the value of the artist as a visible music-hall performer». On the other hand, the BBC was «keenly interested» in a cooperation with the recording companies who «in recent years … have not been slow to make records of singers, orchestras, dance bands, etc. who have already proved their power to achieve popularity by wireless.» Radio plays were so popular that the BBC had received 6,000 manuscripts by 1929, most of them written for stage and of little value for broadcasting: «Day in and day out, manuscripts come in, and nearly all go out again through the post, with a note saying ‘We regret, etc.'»[46] In the 1930s music broadcasts also enjoyed great popularity, for example the friendly and wide-ranging organ broadcasts at St George’s Hall, London by Reginald Foort, who held the official role of BBC Staff Theatre Organist from 1936 to 1938.[47]

Second World War

Television broadcasting was suspended from 1 September 1939 to 7 June 1946, during the Second World War, and it was left to BBC Radio broadcasters such as Reginald Foort to keep the nation’s spirits up. The BBC moved most of its radio operations out of London, initially to Bristol, and then to Bedford. Concerts were broadcast from the Bedford Corn Exchange; the Trinity Chapel in St Paul’s Church, Bedford was the studio for the daily service from 1941 to 1945, and, in the darkest days of the war in 1941, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York came to St Paul’s to broadcast to the UK and the world on the National Day of Prayer. BBC employees during the war included George Orwell who spent two years with the broadcaster.[48]

During his role as prime minister during the war, Winston Churchill delivered 33 major wartime speeches by radio, all of which were carried by the BBC within the UK.[49] On 18 June 1940, French general Charles de Gaulle, in exile in London as the leader of the Free French, made a speech, broadcast by the BBC, urging the French people not to capitulate to the Nazis.[50] In October 1940, Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret made their first radio broadcast for the BBC’s Children’s Hour, addressing other children who had been evacuated from cities.[51]

In 1938, John Reith and the British government, specifically the Ministry of Information which had been set up for WWII, designed a censorship apparatus for the inevitability of war.[52] Due to the BBC’s advancements in shortwave radio technology, the corporation could broadcast across the world during the Second World War.[53] Within Europe, the BBC European Service would gather intelligence and information regarding the current events of the war in English.[52][54] Regional BBC workers, based on their regional geo-political climate, would then further censor the material their broadcasts would cover. Nothing was to be added outside the preordained news items.[52][54] For example, the BBC Polish Service was heavily censored due to fears of jeopardising relations with the Soviet Union. Controversial topics, i.e. the contested Polish and Soviet border, the deportation of Polish citizens, the arrests of Polish Home Army members and the Katyn massacre, were not included in Polish broadcasts.[55] American radio broadcasts were broadcast across Europe on BBC channels. This material also passed through the BBC’s censorship office, which surveilled and edited American coverage of British affairs.[53] By 1940, across all BBC broadcasts, music by composers from enemy nations was censored. In total, 99 German, 38 Austrian and 38 Italian composers were censored. The BBC argued that like the Italian or German languages, listeners would be irritated by the inclusion of enemy composers.[56] Any potential broadcasters said to have pacifist, communist or fascist ideologies were not allowed on the BBC’s airwaves.[57] In 1937, a MI5 security officer was given a permanent office within the organisation. This officer would examine the files of potential political subversives and mark the files of those deemed a security risk to the organisation, blacklisting them. This was often done on spurious grounds; even so, the practice would continue and expand during the years of the Cold War.[58][59]

Later 20th century

There was a widely reported urban myth that, upon resumption of the BBC television service after the war, announcer Leslie Mitchell started by saying, «As I was saying before we were so rudely interrupted …» In fact, the first person to appear when transmission resumed was Jasmine Bligh and the words said were «Good afternoon, everybody. How are you? Do you remember me, Jasmine Bligh … ?»[61] The European Broadcasting Union was formed on 12 February 1950, in Torquay with the BBC among the 23 founding broadcasting organisations.[62]

Competition to the BBC was introduced in 1955, with the commercial and independently operated television network of ITV. However, the BBC monopoly on radio services would persist until 8 October 1973 when under the control of the newly renamed Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA), the UK’s first Independent local radio station, LBC came on-air in the London area. As a result of the Pilkington Committee report of 1962, in which the BBC was praised for the quality and range of its output, and ITV was very heavily criticised for not providing enough quality programming,[63] the decision was taken to award the BBC a second television channel, BBC2, in 1964, renaming the existing service BBC1. BBC2 used the higher resolution 625-line standard which had been standardised across Europe. BBC2 was broadcast in colour from 1 July 1967 and was joined by BBC1 and ITV on 15 November 1969. The 405-line VHF transmissions of BBC1 (and ITV) were continued for compatibility with older television receivers until 1985.

Starting in 1964, a series of pirate radio stations (starting with Radio Caroline) came on the air and forced the British government finally to regulate radio services to permit nationally based advertising-financed services. In response, the BBC reorganised and renamed their radio channels. On 30 September 1967, the Light Programme was split into Radio 1 offering continuous «Popular» music and Radio 2 more «Easy Listening».[64] The «Third» programme became Radio 3 offering classical music and cultural programming. The Home Service became Radio 4 offering news, and non-musical content such as quiz shows, readings, dramas and plays. As well as the four national channels, a series of local BBC radio stations were established in 1967, including Radio London.[65] In 1969, the BBC Enterprises department was formed to exploit BBC brands and programmes for commercial spin-off products. In 1979, it became a wholly owned limited company, BBC Enterprises Ltd.[66]

In 1974, the BBC’s teletext service, Ceefax, was introduced, created initially to provide subtitling, but developed into a news and information service. In 1978, BBC staff went on strike just before the Christmas, thus blocking out the transmission of both channels and amalgamating all four radio stations into one.[67][68] Since the deregulation of the UK television and radio market in the 1980s, the BBC has faced increased competition from the commercial sector (and from the advertiser-funded public service broadcaster Channel 4), especially on satellite television, cable television, and digital television services. In the late 1980s, the BBC began a process of divestment by spinning off and selling parts of its organisation. In 1988, it sold off the Hulton Press Library, a photographic archive which had been acquired from the Picture Post magazine by the BBC in 1957. The archive was sold to Brian Deutsch and is now owned by Getty Images.[69] In 1987, BBC decided to centralize its operations by the management team with the radio and television divisions joining forces together for the first time, the activities of the news and currents departments and coordinated jointly under the new directorate.[70] During the 1990s, this process continued with the separation of certain operational arms of the corporation into autonomous but wholly owned subsidiaries, with the aim of generating additional revenue for programme-making. BBC Enterprises was reorganised and relaunched in 1995, as BBC Worldwide Ltd.[66] In 1998, BBC studios, outside broadcasts, post production, design, costumes and wigs were spun off into BBC Resources Ltd.[71]

The BBC Research Department has played a major part in the development of broadcasting and recording techniques. The BBC was also responsible for the development of the NICAM stereo standard. In recent decades, a number of additional channels and radio stations have been launched: Radio 5 was launched in 1990, as a sports and educational station, but was replaced in 1994, with Radio 5 Live to become a live radio station, following the success of the Radio 4 service to cover the 1991 Gulf War. The new station would be a news and sport station. In 1997, BBC News 24, a rolling news channel, launched on digital television services, and the following year, BBC Choice was launched as the third general entertainment channel from the BBC. The BBC also purchased The Parliamentary Channel, which was renamed BBC Parliament. In 1999, BBC Knowledge launched as a multimedia channel, with services available on the newly launched BBC Text digital teletext service, and on BBC Online. The channel had an educational aim, which was modified later on in its life to offer documentaries.

2000 to 2011

In 2002, several television and radio channels were reorganised. BBC Knowledge was replaced by BBC Four and became the BBC’s arts and documentaries channel. CBBC, which had been a programming strand as Children’s BBC since 1985, was split into CBBC and CBeebies, for younger children, with both new services getting a digital channel: the CBBC Channel and CBeebies Channel.[72] In addition to the television channels, new digital radio stations were created: 1Xtra, 6 Music and BBC7. BBC 1Xtra was a sister station to Radio 1 and specialised in modern black music, BBC 6 Music specialised in alternative music genres and BBC7 specialised in archive, speech and children’s programming.[73]

The following few years resulted in repositioning of some channels to conform to a larger brand: in 2003, BBC Choice was replaced by BBC Three, with programming for younger adults and shocking real-life documentaries, BBC News 24 became the BBC News Channel in 2008, and BBC Radio 7 became BBC Radio 4 Extra in 2011, with new programmes to supplement those broadcast on Radio 4. In 2008, another channel was launched, BBC Alba, a Scottish Gaelic service.

During this decade, the corporation began to sell off a number of its operational divisions to private owners; BBC Broadcast was spun off as a separate company in 2002,[74] and in 2005, it was sold off to Australian-based Macquarie Capital Alliance Group and Macquarie Bank Limited and rebranded Red Bee Media.[75] The BBC’s IT, telephony and broadcast technology were brought together as BBC Technology Ltd in 2001,[74] and the division was later sold to the German company Siemens IT Solutions and Services (SIS).[76] SIS was subsequently acquired from Siemens by the French company Atos.[77] Further divestments included BBC Books (sold to Random House in 2006);[78] BBC Outside Broadcasts Ltd (sold in 2008 to Satellite Information Services);[79] Costumes and Wigs (stock sold in 2008 to Angels The Costumiers);[80] and BBC Magazines (sold to Immediate Media Company in 2011).[81] After the sales of OBs and costumes, the remainder of BBC Resources was reorganised as BBC Studios and Post Production, which continues today as a wholly owned subsidiary of the BBC.

The 2004 Hutton Inquiry and the subsequent report raised questions about the BBC’s journalistic standards and its impartiality. This led to resignations of senior management members at the time including the then Director General, Greg Dyke. In January 2007, the BBC released minutes of the board meeting which led to Greg Dyke’s resignation.[82]

Unlike the other departments of the BBC, the BBC World Service was funded by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office, more commonly known as the Foreign Office or the FCO, is the British government department responsible for promoting the interests of the United Kingdom abroad.

A strike in 2005 by more than 11,000 BBC workers, over a proposal to cut 4,000 jobs, and to privatise parts of the BBC, disrupted much of the BBC’s regular programming.[83][84]

In 2006, BBC HD launched as an experimental service and became official in December 2007. The channel broadcast HD simulcasts of programmes on BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three and BBC Four as well as repeats of some older programmes in HD. In 2010, an HD simulcast of BBC One launched: BBC One HD. The channel uses HD versions of BBC One’s schedule and uses upscaled versions of programmes not currently produced in HD. The BBC HD channel closed in March 2013 and was replaced by BBC Two HD in the same month.

On 18 October 2007, BBC Director General Mark Thompson announced a controversial plan to make major cuts and reduce the size of the BBC as an organisation. The plans included a reduction in posts of 2,500; including 1,800 redundancies, consolidating news operations, reducing programming output by 10% and selling off the flagship Television Centre building in London.[85] These plans were fiercely opposed by unions, who threatened a series of strikes; however, the BBC stated that the cuts were essential to move the organisation forward and concentrate on increasing the quality of programming.

On 20 October 2010, the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne announced that the television licence fee would be frozen at its current level until the end of the current charter in 2016. The same announcement revealed that the BBC would take on the full cost of running the BBC World Service and the BBC Monitoring service from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and partially finance the Welsh broadcaster S4C.[86]

2011 to present

Further cuts were announced on 6 October 2011, so the BBC could reach a total reduction in their budget of 20%, following the licence fee freeze in October 2010, which included cutting staff by 2,000 and sending a further 1,000 to the MediaCityUK development in Salford, with BBC Three moving online only in 2016, the sharing of more programmes between stations and channels, sharing of radio news bulletins, more repeats in schedules, including the whole of BBC Two daytime and for some original programming to be reduced. BBC HD was closed on 26 March 2013, and replaced with an HD simulcast of BBC Two; however, flagship programmes, other channels and full funding for CBBC and CBeebies would be retained.[87][88][89] Numerous BBC facilities have been sold off, including New Broadcasting House on Oxford Road in Manchester. Many major departments have been relocated to Broadcasting House in central London and MediaCityUK in Salford, particularly since the closure of BBC Television Centre in March 2013.[90] On 16 February 2016, the BBC Three television service was discontinued and replaced by a digital outlet under the same name, targeting its young adult audience with web series and other content.[91][92]

Under the new royal charter instituted in 2017, the corporation must publish an annual report to Ofcom, outlining its plans and public service obligations for the next year. In its 2017–18 report, released July 2017, the BBC announced plans to «re-invent» its output to better compete against commercial streaming services such as Netflix. These plans included increasing the diversity of its content on television and radio, a major increase in investments towards digital children’s content, and plans to make larger investments in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland to «rise to the challenge of better reflecting and representing a changing UK».[93][94] Since 2017, the BBC has also funded the Local Democracy Reporting Service, with up to 165 journalists employed by independent news organisations to report on local democracy issues on a pooled basis.[95]

In 2016, the BBC Director General Tony Hall announced a savings target of £800 million per year by 2021, which is about 23% of annual licence fee revenue. Having to take on the £700 million cost for free TV licences for the over-75 pensioners, and rapid inflation in drama and sport coverage costs, was given as the reason. Duplication of management and content spending would be reduced, and there would be a review of BBC News.[96][97] In 2020, the BBC announced a BBC News savings target of £80 million per year by 2022, involving about 520 staff reductions. The BBC’s director of news and current affairs Fran Unsworth said there would be further moves toward digital broadcasting, in part to attract back a youth audience, and more pooling of reporters to stop separate teams covering the same news.[98][99] In 2020, the BBC reported a £119 million deficit because of delays to cost reduction plans, and the forthcoming ending of the remaining £253 million funding towards pensioner licence fees would increase financial pressures.[100]

In January 2021, it was reported that former banker Richard Sharp would succeed David Clementi, as chairman, when he stepped down in February.[101]

In 2023, BBC’s offices in New Delhi were searched by officials from the Income Tax Department. The move comes after BBC released a documentary on Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The documentary investigated Modi’s role in the 2002 Gujarat riots, which resulted in more than 1,000 casualties. The Indian Government banned viewing of the documentary in India and restricted clips of the documentary on social media.[102]

Governance and corporate structure

The BBC is a statutory corporation, independent from direct government intervention, with its activities being overseen from April 2017 by the BBC Board and regulated by Ofcom.[103][104] The chairman is Richard Sharp.[105]

Charter

The BBC operates under a royal charter.[6] The current charter came into effect on 1 January 2017 and runs until 31 December 2027.[106] The 2017 charter abolished the BBC Trust and replaced it with external regulation by Ofcom, with governance by the BBC Board.[106]

Under the royal charter, the BBC must obtain a licence from the home secretary.[107] This licence is accompanied by an agreement which sets the terms and conditions under which the BBC is allowed to broadcast.[107]

BBC Board

The BBC Board was formed in April 2017. It replaced the previous governing body, the BBC Trust, which in itself had replaced the Board of Governors in 2007. The Board sets the strategy for the corporation, assesses the performance of the BBC Executive Board in delivering the BBC’s services, and appoints the director-general. Regulation of the BBC is now the responsibility of Ofcom. The board consists of the following members.[108][109]

| Name | Position | Term of office | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard Sharp | Chairman | 16 February 2021 | 15 February 2025 |

| Tim Davie, CBE | Director-General | 1 September 2020 | — |

| Sir Nicholas Serota, CH | Senior Independent Director | 3 April 2017 | 2 April 2024 |

| Shumeet Banerji | Non-executive Director | 1 January 2022 | 31 December 2025 |

| Sir Damon Buffini | Non-executive Director | 1 January 2022 | 31 December 2025 |

| Shirley Garrood | Non-executive Director | 3 July 2019 | 2 July 2023 |

| Ian Hargreaves, CBE | Non-executive Director | 2 April 2020 | 2 April 2023 |

| Sir Robbie Gibb | Member for England | 7 May 2021 | 6 May 2024 |

| Muriel Gray | Member for Scotland | 3 January 2022 | 2 January 2026 |

| Dame Elan Closs Stephens | Member for Wales | 20 July 2017 | 19 July 2020 |

| 20 January 2021 | 20 July 2023 | ||

| To be appointed by the Northern Ireland Executive | Member for Northern Ireland | — | — |

| Charlotte Moore | Chief Content Officer | 1 September 2020 | 2 September 2022 |

| Leigh Tavaziva | Chief Operating Officer | February 2021 | — |

| Jonathan Munro | Acting Director, News and Current Affairs | January 2022 | — |

Executive committee

The executive committee is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the broadcaster. Consisting of senior managers of the BBC, the committee meets once per month and is responsible for operational management and delivery of services within a framework set by the board, and is chaired by the director-general, currently Tim Davie, who is chief executive and (from 1994) editor-in-chief.[110]

| Name | Position |

|---|---|

| Tim Davie | Director-general (chair of the executive committee) |

| Kerris Bright | Chief Customer Officer |

| Tom Fussell | CEO, BBC Studios |

| Leigh Tavaziva | Chief Operating Officer |

| Rhodri Talfan Davies | Director of Nations & Regions |

| Charlotte Moore | Chief Content Officer |

| Gautam Rangarajan | Group Director of Strategy and Performance |

| June Sarpong | Director, creative diversity |

| Jonathan Munro | Interim Director of News & Current Affairs |

Operational divisions

The corporation has the following in-house divisions covering the BBC’s output and operations:[111][112]

- Content, headed by Charlotte Moore is in charge of the corporation’s television channels including the commissioning of programming.

- Nations and Regions, headed by Rhodri Talfan Davies is responsible for the corporation’s divisions in Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales, the English Regions.

Commercial divisions

The BBC also operates a number of wholly owned commercial divisions:

- BBC Studios is the former in-house television production; Entertainment, Music & Events, Factual and Scripted (drama and comedy). Following a merger with BBC Worldwide in April 2018, it also operates international channels and sells programmes and merchandise in the UK and abroad to gain additional income that is returned to BBC programmes. It is kept separate from the corporation due to its commercial nature.

- BBC World News department is in charge of the production and distribution of its commercial global television channel. It works closely with the BBC News group, but is not governed by it, and shares the corporation’s facilities and staff. It also works with BBC Studios, the channel’s distributor.

- BBC Studioworks is also separate and officially owns and operates some of the BBC’s studio facilities, such as the BBC Elstree Centre, leasing them out to productions from within and outside of the corporation.[113]

MI5 vetting policy

From as early as the 1930s until the 1990s, MI5, the British domestic intelligence service, engaged in vetting of applicants for BBC positions, a policy designed to keep out persons deemed subversive.[114][115] In 1933, BBC executive Colonel Alan Dawnay began to meet the head of MI5, Sir Vernon Kell, to informally trade information; from 1935, a formal arrangement was made wherein job applicants would be secretly vetted by MI5 for their political views (without their knowledge).[114] The BBC took up a policy of denying any suggestion of such a relationship by the press (the existence of MI5 itself was not officially acknowledged until the Security Service Act 1989).[114]

This relationship garnered wider public attention after an article by David Leigh and Paul Lashmar appeared in The Observer in August 1985, revealing that MI5 had been vetting appointments, running operations out of Room 105 in Broadcasting House.[114][116] At the time of the exposé, the operation was being run by Ronnie Stonham. A memo from 1984 revealed that blacklisted organisations included the far-left Communist Party of Great Britain, the Socialist Workers Party, the Workers Revolutionary Party and the Militant Tendency, as well as the far-right National Front and the British National Party. An association with one of these groups could result in a denial of a job application.[114]

In October 1985, the BBC announced that it would stop the vetting process, except for a few people in top roles, as well as those in charge of Wartime Broadcasting Service emergency broadcasting (in event of a nuclear war) and staff in the BBC World Service.[114] In 1990, following the Security Service Act 1989, vetting was further restricted to only those responsible for wartime broadcasting and those with access to secret government information.[114] Michael Hodder, who succeeded Stonham, had the MI5 vetting files sent to the BBC Information and Archives in Reading, Berkshire.[114]

Finances

The BBC has the second largest budget of any UK-based broadcaster with an operating expenditure of £4.722 billion in 2013/14[117] compared with £6.471 billion for British Sky Broadcasting in 2013/14[118] and £1.843 billion for ITV in the calendar year 2013.[119][needs update]

Revenue

The principal means of funding the BBC is through the television licence, costing £154.50 per year per household since April 2019.[120] Such a licence is required to legally receive broadcast television across the UK, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. No licence is required to own a television used for other means, or for sound only radio sets (though a separate licence for these was also required for non-TV households until 1971). The cost of a television licence is set by the government and enforced by the criminal law. A discount is available for households with only black-and-white television sets. A 50% discount is also offered to people who are registered blind or severely visually impaired,[121] and the licence is completely free for any household containing anyone aged 75 or over. However, from August 2020, the licence fee will only be waived if over 75 and receiving pension credit.[122]

The BBC pursues its licence fee collection and enforcement under the trading name «TV Licensing». The revenue is collected privately by Capita, an outside agency, and is paid into the central government Consolidated Fund, a process defined in the Communications Act 2003. Funds are then allocated by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and the Treasury and approved by Parliament via legislation. Additional revenues are paid by the Department for Work and Pensions to compensate for subsidised licences for eligible over-75-year-olds.

The licence fee is classified as a tax,[123] and its evasion is a criminal offence. Since 1991, collection and enforcement of the licence fee has been the responsibility of the BBC in its role as TV Licensing Authority.[124] The BBC carries out surveillance (mostly using subcontractors) on properties (under the auspices of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000) and may conduct searches of a property using a search warrant.[125] According to TV Licensing, 216,900 people in the UK were caught watching TV without a licence in 2018/19.[126] Licence fee evasion makes up around one-tenth of all cases prosecuted in magistrates’ courts, representing 0.3% of court time.[127]

Income from commercial enterprises and from overseas sales of its catalogue of programmes has substantially increased over recent years,[128] with BBC Worldwide contributing some £243 million to the BBC’s core public service business.[129]

According to the BBC’s 2018/19 Annual Report, its total income was £4.889 billion a decrease from £5.062 billion in 2017/18 – partly owing to a 3.7% phased reduction in government funding for free over-75s TV licences,[129] which can be broken down as follows:

- £3.690 billion in licence fees collected from householders;

- £1.199 billion from the BBC’s commercial businesses and government grants some of which will cease in 2020

The licence fee has, however, attracted criticism. It has been argued that in an age of multi-stream, multi-channel availability, an obligation to pay a licence fee is no longer appropriate. The BBC’s use of private sector company Capita Group to send letters to premises not paying the licence fee has been criticised, especially as there have been cases where such letters have been sent to premises which are up to date with their payments, or do not require a TV licence.[130]

The BBC uses advertising campaigns to inform customers of the requirement to pay the licence fee. Past campaigns have been criticised by Conservative MP Boris Johnson and former MP Ann Widdecombe for having a threatening nature and language used to scare evaders into paying.[131][132] Audio clips and television broadcasts are used to inform listeners of the BBC’s comprehensive database.[133] There are a number of pressure groups campaigning on the issue of the licence fee.[134]

The majority of the BBC’s commercial output comes from its commercial arm BBC Worldwide who sell programmes abroad and exploit key brands for merchandise. Of their 2012/13 sales, 27% were centred on the five key «superbrands» of Doctor Who, Top Gear, Strictly Come Dancing (known as Dancing with the Stars internationally), the BBC’s archive of natural history programming (collected under the umbrella of BBC Earth) and the (now sold) travel guide brand Lonely Planet.[135]

Headquarters and regional offices

Broadcasting House in Portland Place, central London, is the official headquarters of the BBC. It is home to six of the ten BBC national radio networks, BBC Radio 1, BBC Radio 1xtra, BBC Asian Network, BBC Radio 3, BBC Radio 4, and BBC Radio 4 Extra. It is also the home of BBC News, which relocated to the building from BBC Television Centre in 2013. On the front of the building are statues of Prospero and Ariel, characters from William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, sculpted by Eric Gill. Renovation of Broadcasting House began in 2002, and was completed in 2012.[136]

Until it closed at the end of March 2013, BBC Television was based at BBC Television Centre, a purpose built television facility opened in 1960 located in White City, four miles (6 km) west of central London.[137] This facility was host to a number of famous guests and programmes through the years, and its name and image is familiar with many British citizens. Nearby, the BBC White City complex contains numerous programme offices, housed in Centre House, the Media Centre and Broadcast Centre. It is in this area around Shepherd’s Bush that the majority of BBC employees worked.

As part of a major reorganisation of BBC property, the entire BBC News operation relocated from the News Centre at BBC Television Centre to the refurbished Broadcasting House to create what is being described as «one of the world’s largest live broadcast centres».[138] The BBC News Channel and BBC World News relocated to the premises in early 2013.[139] Broadcasting House is now also home to most of the BBC’s national radio stations, and the BBC World Service. The major part of this plan involved the demolition of the two post-war extensions to the building and construction of an extension[140] designed by Sir Richard MacCormac of MJP Architects. This move concentrated the BBC’s London operations, allowing them to sell Television Centre.[141]

In addition to the scheme above, the BBC is in the process of making and producing more programmes outside London, involving production centres such as Belfast, Cardiff, Glasgow, Newcastle and, most notably, in Greater Manchester as part of the «BBC North Project» scheme where several major departments, including BBC North West, BBC Manchester, BBC Sport, BBC Children’s, CBeebies, Radio 5 Live, BBC Radio 5 Live Sports Extra, BBC Breakfast, BBC Learning and the BBC Philharmonic have all moved from their previous locations in either London or New Broadcasting House, Manchester to the new 200-acre (80ha) MediaCityUK production facilities in Salford, that form part of the large BBC North Group division and will therefore become the biggest staffing operation outside London.[142][143]

As well as the two main sites in London (Broadcasting House and White City), there are seven other important BBC production centres in the UK, mainly specialising in different productions. Cardiff is home to BBC Cymru Wales, which specialises in drama production. Open since 2012, and containing 7 new studios, Roath Lock[144] is notable as the home of productions such as Doctor Who and Casualty. Broadcasting House Belfast, home to BBC Northern Ireland, specialises in original drama and comedy, and has taken part in many co-productions with independent companies and notably with RTÉ in the Republic of Ireland. BBC Scotland, based in Pacific Quay, Glasgow is a large producer of programmes for the network, including several quiz shows. In England, the larger regions also produce some programming.

Previously, the largest hub of BBC programming from the regions is BBC North West. At present they produce all religious and ethical programmes on the BBC, as well as other programmes such as A Question of Sport. However, this is to be merged and expanded under the BBC North project, which involved the region moving from New Broadcasting House, Manchester, to MediaCityUK. BBC Midlands, based at The Mailbox in Birmingham, also produces drama and contains the headquarters for the English regions and the BBC’s daytime output. Other production centres include Broadcasting House Bristol, home of BBC West and famously the BBC Natural History Unit and to a lesser extent, Quarry Hill in Leeds, home of BBC Yorkshire. There are also many smaller local and regional studios throughout the UK, operating the BBC regional television services and the BBC Local Radio stations.

The BBC also operates several news gathering centres in various locations around the world, which provide news coverage of that region to the national and international news operations.

Technology (Atos service)

In 2004, the BBC contracted out its former BBC Technology division to the German engineering and electronics company Siemens IT Solutions and Services (SIS), outsourcing its IT, telephony and broadcast technology systems.[76] When Atos Origin acquired the SIS division from Siemens in December 2010 for €850 million (£720m),[145] the BBC support contract also passed to Atos, and in July 2011, the BBC announced to staff that its technology support would become an Atos service.[77] Siemens staff working on the BBC contract were transferred to Atos; the BBC’s Information Technology systems are now managed by Atos.[146] In 2011, the BBC’s chief financial officer Zarin Patel stated to the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee that, following criticism of the BBC’s management of major IT projects with Siemens (such as the Digital Media Initiative), the BBC partnership with Atos would be instrumental in achieving cost savings of around £64 million as part of the BBC’s «Delivering Quality First» programme.[147] In 2012, the BBC’s then-Chief Technology Officer John Linwood, expressed confidence in service improvements to the BBC’s technology provision brought about by Atos. He also stated that supplier accountability had been strengthened following some high-profile technology failures which had taken place during the partnership with Siemens.[148]

Services

Television

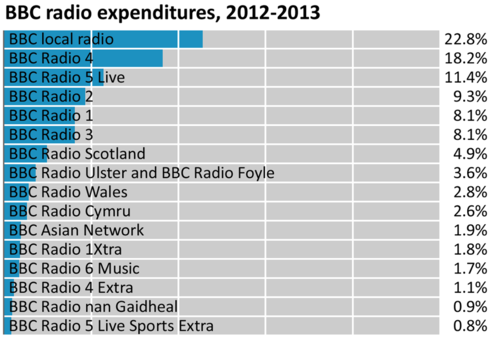

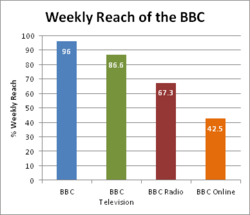

Weekly reach of the BBC’s domestic services from 2011 to 2012[149][150] Reach is the number of people who use the service at any point for more than 15 minutes in a week.[150]

The BBC operates several television channels nationally and internationally. BBC One and BBC Two are the flagship television channels. Others include the youth channel BBC Three, which originally ceased broadcasting as a linear television channel in February 2016 and returned to television in February 2022,[151] cultural and documentary channel BBC Four, news channels BBC News and the BBC World News, parliamentary channel BBC Parliament, and two children’s channels, CBBC and CBeebies. Digital television is now entrenched in the UK, with analogue transmission completely phased out as of December 2012.[152]

Weekly reach of the BBC’s domestic television channels 2011–12[153]

BBC One is a regionalised TV service which provides opt-outs throughout the day for local news and other local programming. These variations are more pronounced in the BBC «Nations», i.e. Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, where the presentation is mostly carried out locally on BBC One and Two, and where programme schedules can vary greatly from that of the network. BBC Two variations exist in the Nations; however, English regions today rarely have the option to opt out as regional programming now only exists on BBC One. In 2019, the Scottish variation of BBC Two ceased operation and was replaced with the networked version in favour of the BBC Scotland channel. BBC Two was also the first channel to be transmitted on 625 lines in 1964, then carry a small-scale regular colour service from 1967. BBC One would follow in November 1969.

A new Scottish Gaelic television channel, BBC Alba, was launched in September 2008. It is also the first multi-genre channel to come entirely from Scotland with almost all of its programmes made in Scotland. The service was initially only available via satellite but since June 2011 has been available to viewers in Scotland on Freeview and cable television.[154]

The BBC currently operates HD simulcasts of all its nationwide channels with the exception of BBC Parliament. Until 26 March 2013, a separate channel called BBC HD was available, in place of BBC Two HD. It launched on 15 May 2006, following a 12-month trial of the broadcasts. It became a proper channel in 2007, and screened HD programmes as simulcasts of the main network, or as repeats. The corporation has been producing programmes in the format for many years, and stated that it hoped to produce 100% of new programmes in HDTV by 2010.[155] On 3 November 2010, a high-definition simulcast of BBC One was launched, entitled BBC One HD, and BBC Two HD launched on 26 March 2013, replacing BBC HD. Scotland’s new television channel, BBC Scotland, launched in February 2019.[156]

In the Republic of Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland, the BBC channels are available in a number of ways. In these countries digital and cable operators carry a range of BBC channels. These include BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Four and BBC World News, although viewers in the Republic of Ireland may receive BBC services via overspill from transmitters in Northern Ireland or Wales, or via «deflectors»—transmitters in the Republic which rebroadcast broadcasts from the UK,[157] received off-air, or from digital satellite.

Since 1975, the BBC has also provided its TV programmes to the British Forces Broadcasting Service (BFBS), allowing members of UK military serving abroad to watch them on four dedicated TV channels. From 27 March 2013, BFBS will carry versions of BBC One and BBC Two, which will include children’s programming from CBBC, as well as carrying programming from BBC Three on a new channel called BFBS Extra.

Since 2008, all the BBC channels are available to watch online through the BBC iPlayer service. This online streaming ability came about following experiments with live streaming, involving streaming certain channels in the UK.[158] In February 2014, Director-General Tony Hall announced that the corporation needed to save £100 million. In March 2014, the BBC confirmed plans for BBC Three to become an internet-only channel.[159]

BBC Genome Project

In December 2012, the BBC completed a digitisation exercise, scanning the listings of all BBC programmes from an entire run of about 4,500 copies of the Radio Times magazine from the first, 1923, issue to 2009 (later listings already being held electronically), the «BBC Genome project», with a view to creating an online database of its programme output.[160] An earlier ten months of listings are to be obtained from other sources.[160] They identified around five million programmes, involving 8.5 million actors, presenters, writers and technical staff.[160] The Genome project was opened to public access on 15 October 2014, with corrections to OCR errors and changes to advertised schedules being crowdsourced.[161]

Radio

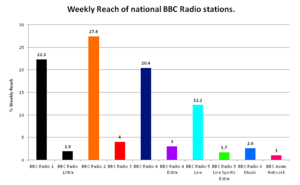

Weekly reach of the BBC’s national radio stations, on both analogue and digital. (2012)[150]

The BBC has ten radio stations serving the whole of the UK, a further seven stations in the «national regions» (Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland), and 39 other local stations serving defined areas of England. Of the ten national stations, five are major stations and are available on FM and/or AM as well as on DAB and online. These are BBC Radio 1, offering new music and popular styles and being notable for its chart show; BBC Radio 2, playing Adult contemporary, country and soul music amongst many other genres; BBC Radio 3, presenting classical and jazz music together with some spoken-word programming of a cultural nature in the evenings; BBC Radio 4, focusing on current affairs, factual and other speech-based programming, including drama and comedy; and BBC Radio 5 Live, broadcasting 24-hour news, sport and talk programmes.

Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman being interviewed on BBC Radio in October 1954

In addition to these five stations, the BBC runs a further five stations that broadcast on DAB and online only. These stations supplement and expand on the big five stations, and were launched in 2002. BBC Radio 1Xtra sisters Radio 1, and broadcasts new black music and urban tracks. BBC Radio 5 Live Sports Extra sisters 5 Live and offers extra sport analysis, including broadcasting sports that previously were not covered. BBC Radio 6 Music offers alternative music genres and is notable as a platform for new artists.

BBC Radio 7, later renamed BBC Radio 4 Extra, provided archive drama, comedy and children’s programming. Following the change to Radio 4 Extra, the service has dropped a defined children’s strand in favour of family-friendly drama and comedy. In addition, new programmes to complement Radio 4 programmes were introduced such as Ambridge Extra, and Desert Island Discs revisited. The final station is the BBC Asian Network, providing music, talk and news to this section of the community. This station evolved out of Local radio stations serving certain areas, and as such this station is available on Medium Wave frequency in some areas of the Midlands.

As well as the national stations, the BBC also provides 40 BBC Local Radio stations in England and the Channel Islands, each named for and covering a particular city and its surrounding area (e.g. BBC Radio Bristol), county or region (e.g. BBC Three Counties Radio), or geographical area (e.g. BBC Radio Solent covering the central south coast). A further six stations broadcast in what the BBC terms «the national regions»: Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. These are BBC Radio Wales (in English), BBC Radio Cymru (in Welsh), BBC Radio Scotland (in English), BBC Radio nan Gaidheal (in Scottish Gaelic), BBC Radio Ulster, and BBC Radio Foyle, the latter being an opt-out station from Radio Ulster for the north-west of Northern Ireland.

The BBC’s UK national channels are also broadcast in the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man (although these Crown Dependencies are outside the UK), and in the former there are two local stations – BBC Guernsey and BBC Radio Jersey. There is no BBC local radio station, however, in the Isle of Man, partly because the island has long been served by the popular independent commercial station, Manx Radio, which predates the existence of BBC Local Radio. BBC services in the dependencies are financed from television licence fees which are set at the same level as those payable in the UK, although collected locally. This is the subject of some controversy in the Isle of Man since, as well as having no BBC Local Radio service, the island also lacks a local television news service analogous to that provided by BBC Channel Islands.[162]

For a worldwide audience, the BBC World Service provides news, current affairs and information in 28 languages, including English, around the world and is available in over 150 capital cities. It is broadcast worldwide on shortwave radio, DAB and online and has an estimated weekly audience of 192 million, and its websites have an audience of 38 million people per week.[163] Since 2005, it is also available on DAB in the UK, a step not taken before, due to the way it is funded. The service is funded by a Parliamentary Grant-in-Aid, administered by the Foreign Office; however, following the Government’s spending review in 2011, this funding will cease, and it will be funded for the first time through the Licence fee.[164][165] In recent years, some services of the World Service have been reduced: the Thai service ended in 2006,[166] as did the Eastern European languages. Resources were diverted instead into the new BBC Arabic Television.[167]

Historically, the BBC was the only legal radio broadcaster based in the UK mainland until 1967, when University Radio York (URY), then under the name Radio York, was launched as the first, and now oldest, legal independent radio station in the country. However, the BBC did not enjoy a complete monopoly before this, as several Continental stations, such as Radio Luxembourg, had broadcast programmes in English to Britain since the 1930s and the Isle of Man-based Manx Radio began in 1964. Today, despite the advent of commercial radio, BBC radio stations remain among the most listened-to in the country. Radio 2 has the largest audience share (up to 16.8% in 2011–12) and Radios 1 and 4 ranked second and third in terms of weekly reach.[168]

BBC programming is also available to other services and in other countries. Since 1943, the BBC has provided radio programming to the British Forces Broadcasting Service, which broadcasts in countries where British troops are stationed. BBC Radio 1 is also carried in Canada on Sirius XM Radio (online streaming only).

The BBC is a patron of The Radio Academy.[169]

News

The new newsroom in Broadcasting House, central London, officially opened by the Queen in 2013

BBC News is the largest broadcast news gathering operation in the world,[170] providing services to BBC domestic radio as well as television networks such as the BBC News, BBC Parliament and BBC World News. In addition to this, news stories are available on the BBC Red Button service and BBC News Online. In addition to this, the BBC has been developing new ways to access BBC News and as a result, has launched the service on BBC Mobile, making it accessible to mobile phones and PDAs, as well as developing alerts by email, on digital television, and on computers through a desktop alert.

Ratings figures suggest that during major incidents such as the 7 July 2005 London bombings or royal events, the UK audience overwhelmingly turns to the BBC’s coverage as opposed to its commercial rivals.[171]

On 7 July 2005, the day that there were a series of coordinated bomb blasts on London’s public transport system, the BBC Online website recorded an all time bandwidth peak of 11 Gb/s at 12.00 on 7 July. BBC News received some 1 billion total hits on the day of the event (including all images, text, and HTML), serving some 5.5 terabytes of data. At peak times during the day, there were 40,000-page requests per second for the BBC News website. The previous day’s announcement of the 2012 Olympics being awarded to London caused a peak of around 5 Gbit/s. The previous all-time high at BBC Online was caused by the announcement of the Michael Jackson verdict, which used 7.2 Gbit/s.[172]

Internet

The BBC’s online presence includes a comprehensive news website and archive. The BBC’s first official online service was the BBC Networking Club, which was launched on 11 May 1994. The service was subsequently relaunched as BBC Online in 1997, before being renamed BBCi, then bbc.co.uk, before it was rebranded back as BBC Online. The website is funded by the Licence fee, but uses GeoIP technology, allowing advertisements to be carried on the site when viewed outside of the UK.[173] The BBC claims the site to be «Europe’s most popular content-based site»[174] and states that 13.2 million people in the UK visit the site’s more than two million pages each day.[175]

The centre of the website is the Homepage, which features a modular layout. Users can choose which modules, and which information, is displayed on their homepage, allowing the user to customise it. This system was first launched in December 2007, becoming permanent in February 2008, and has undergone a few aesthetical changes since then.[176] The home page then has links to other micro-sites, such as BBC News Online, Sport, Weather, TV, and Radio. As part of the site, every programme on BBC Television or Radio is given its own page, with bigger programmes getting their own micro-site, and as a result it is often common for viewers and listeners to be told website addresses (URLs) for the programme website.

2008 advertisement for BBC iPlayer at Old Street, London

Another large part of the site also allows users to watch and listen to most Television and Radio output live and for seven days after broadcast using the BBC iPlayer platform, which launched on 27 July 2007, and initially used peer-to-peer and DRM technology to deliver both radio and TV content of the last seven days for offline use for up to 30 days, since then video is now streamed directly. Also, through participation in the Creative Archive Licence group, bbc.co.uk allowed legal downloads of selected archive material via the internet.[177]

The BBC has often included learning as part of its online service, running services such as BBC Jam, Learning Zone Class Clips and also runs services such as BBC WebWise and First Click which are designed to teach people how to use the internet. BBC Jam was a free online service, delivered through broadband and narrowband connections, providing high-quality interactive resources designed to stimulate learning at home and at school. Initial content was made available in January 2006; however, BBC Jam was suspended on 20 March 2007 due to allegations made to the European Commission that it was damaging the interests of the commercial sector of the industry.[178]

In recent years, some major on-line companies and politicians have complained that BBC Online receives too much funding from the television licence, meaning that other websites are unable to compete with the vast amount of advertising-free on-line content available on BBC Online.[179] Some have proposed that the amount of licence fee money spent on BBC Online should be reduced—either being replaced with funding from advertisements or subscriptions, or a reduction in the amount of content available on the site.[180] In response to this the BBC carried out an investigation, and has now set in motion a plan to change the way it provides its online services. BBC Online will now attempt to fill in gaps in the market, and will guide users to other websites for currently existing market provision. (For example, instead of providing local events information and timetables, users will be guided to outside websites already providing that information.)

Part of this plan included the BBC closing some of its websites, and rediverting money to redevelop other parts.[181][182]

On 26 February 2010, The Times claimed that Mark Thompson, Director General of the BBC, proposed that the BBC’s web output should be cut by 50%, with online staff numbers and budgets reduced by 25% in a bid to scale back BBC operations and allow commercial rivals more room.[183] On 2 March 2010, the BBC reported that it would cut its website spending by 25% and close BBC 6 Music and Asian Network, as part of Mark Thompson’s plans to make «a smaller, fitter BBC for the digital age».[184][185]

Interactive television

BBC Red Button is the brand name for the BBC’s interactive digital television services, which are available through Freeview (digital terrestrial), as well as Freesat, Sky (satellite), and Virgin Media (cable). Unlike Ceefax, the service’s analogue counterpart, BBC Red Button is able to display full-colour graphics, photographs, and video, as well as programmes and can be accessed from any BBC channel. The service carries News, Weather and Sport 24 hours a day, but also provides extra features related to programmes specific at that time. Examples include viewers to play along at home to gameshows, to give, voice and vote on opinions to issues, as used alongside programmes such as Question Time. At some points in the year, when multiple sporting events occur, some coverage of less mainstream sports or games are frequently placed on the Red Button for viewers to watch. Frequently, other features are added unrelated to programmes being broadcast at that time, such as the broadcast of the Doctor Who animated episode Dreamland in November 2009.[186]

Music

The BBC employs 5 staff orchestras, a professional choir, and supports two amateur choruses, based in BBC venues across the UK;[187] the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the BBC Singers and BBC Symphony Chorus based in London, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra in Glasgow, the BBC Philharmonic in Salford, the BBC Concert Orchestra based in Watford, and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and BBC National Chorus of Wales in Cardiff. It also buys a selected number of broadcasts from the Ulster Orchestra in Belfast and the BBC Big Band.

The BBC Proms have been produced by the BBC every year since 1927,[188] stepping in to fund the popular classical music festival when music publishers Chappell and Co withdrew their support. In 1930, the newly formed BBC Symphony Orchestra gave all 49 Proms, and have performed at every Last Night of the Proms since then. Nowadays, the BBC’s orchestras and choirs are the backbone of the Proms,[189] giving around 40%–50% of all performances each season.

Many famous musicians of every genre have played at the BBC, such as The Beatles (Live at the BBC is one of their many albums). The BBC is also responsible for the broadcast of Glastonbury Festival, Reading Festival and United Kingdom coverage of the Eurovision Song Contest, a show with which the broadcaster has been associated for over 60 years.[190] The BBC also operates the division of BBC Audiobooks sometimes found in association with Chivers Audiobooks.

Other

The BBC operates other ventures in addition to their broadcasting arm. In addition to broadcasting output on television and radio, some programmes are also displayed on the BBC Big Screens located in several central-city locations. The BBC and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office also jointly run BBC Monitoring, which monitors radio, television, the press and the internet worldwide. The BBC also developed several computers throughout the 1980s, most notably the BBC Micro, which ran alongside the corporation’s educational aims and programming.

In 1951, in conjunction with Oxford University Press the BBC published The BBC Hymn Book which was intended to be used by radio listeners to follow hymns being broadcast. The book was published both with and without music, the music edition being entitled The BBC Hymn Book with Music.[191] The book contained 542 popular hymns.

Ceefax

The BBC provided the world’s first teletext service called Ceefax (near-homophonous with «See Facts») on 23 September 1974 until 23 October 2012 on the BBC 1 analogue channel then later on BBC 2. It showed informational pages, such as News, Sport, and the Weather. From New Year’s Eve in 1974, ITV’s Oracle tried to compete with Ceefax. Oracle closed on New Year’s Eve, 1992. During its lifetime, Ceefax attracted millions of viewers, right up to 2012, prior to the digital switchover in the United Kingdom. Since then, the BBC’s Red Button Service has provided a digital information system that replaced Ceefax.[192]

BritBox

In 2016, the BBC, in partnership with fellow UK Broadcasters ITV and Channel 4 (who later withdrew from the project), set up ‘project kangaroo’ to develop an international online streaming service to rival services such as Netflix and Hulu.[193][194] During the development stages ‘Britflix’ was touted as a potential name. However, the service eventually launched as BritBox in March 2017. The online platform shows a catalogue of classic BBC and ITV shows, as well as making a number of programmes available shortly after their UK broadcast. As of 2021, BritBox is available in the UK, the US, Canada, Australia, and, more recently, South Africa, with the potential availability for new markets in the future.[193][195][196][197][198]

Commercial activities

BBC Studios (formerly BBC Worldwide) is the wholly owned commercial subsidiary of the BBC, responsible for the commercial exploitation of BBC programmes and other properties, including a number of television stations throughout the world. It was formed following the restructuring of its predecessor, BBC Enterprises, in 1995.