|

Sandro Botticelli |

|

|---|---|

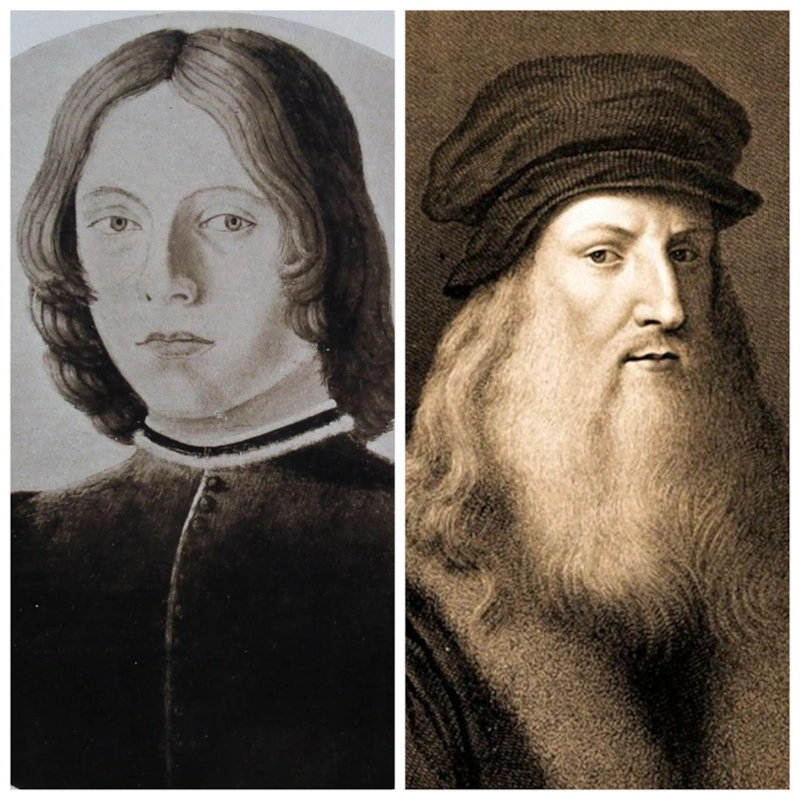

Probable self-portrait of Botticelli, in his Adoration of the Magi (1475). |

|

| Born |

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi c. 1445[1] Florence, Republic of Florence (now Italy) |

| Died | May 17, 1510 (aged 64–65)[2][3]

Florence, Republic of Florence |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Filippo Lippi |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Primavera The Birth of Venus The Adoration of the Magi Other works |

| Movement | Italian Renaissance |

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi (c. 1445[1] – May 17, 1510), known as Sandro Botticelli (, Italian: [ˈsandro bottiˈtʃɛlli]), was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. Botticelli’s posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century, when he was rediscovered by the Pre-Raphaelites who stimulated a reappraisal of his work. Since then, his paintings have been seen to represent the linear grace of late Italian Gothic and some Early Renaissance painting, even though they date from the latter half of the Italian Renaissance period.

In addition to the mythological subjects for which he is best known today, Botticelli painted a wide range of religious subjects (including dozens of renditions of the Madonna and Child, many in the round tondo shape) and also some portraits. His best-known works are The Birth of Venus and Primavera, both in the Uffizi in Florence, which holds many of Botticelli’s works.[5] Botticelli lived all his life in the same neighbourhood of Florence; his only significant times elsewhere were the months he spent painting in Pisa in 1474 and the Sistine Chapel in Rome in 1481–82.[6]

Only one of Botticelli’s paintings, the Mystic Nativity (National Gallery, London) is inscribed with a date (1501), but others can be dated with varying degrees of certainty on the basis of archival records, so the development of his style can be traced with some confidence. He was an independent master for all the 1470s, which saw his reputation soar. The 1480s were his most successful decade, the one in which his large mythological paintings were completed along with many of his most famous Madonnas. By the 1490s his style became more personal and to some extent mannered. His last works show him moving in a direction opposite to that of Leonardo da Vinci (seven years his junior) and the new generation of painters creating the High Renaissance style, and instead returning to a style that many have described as more Gothic or «archaic.»

Early life[edit]

Via Borgo Ognissanti in 2008, with the eponymous church halfway down on the right. Like the street, it has had a Baroque makeover since Botticelli’s time.

Botticelli was born in the city of Florence in a house in the street still called Borgo Ognissanti. He lived in the same area all his life and was buried in his neighbourhood church called Ognissanti («All Saints»). Sandro was one of several children to the tanner Mariano di Vanni d’Amedeo Filipepi and mother Smeralda Filipepi, and the youngest of his four to survive into adulthood.[7][5] The date of his birth is not known, but his father’s tax returns in following years give his age as two in 1447 and thirteen in 1458, meaning he must have been born between 1444 and 1446.[8]

In 1460 Botticelli’s father ceased his business as a tanner and became a gold-beater with his other son, Antonio. This profession would have brought the family into contact with a range of artists.[9] Giorgio Vasari, in his Life of Botticelli, reported that Botticelli was initially trained as a goldsmith.[10]

The Ognissanti neighbourhood was «a modest one, inhabited by weavers and other workmen,»[11] but there were some rich families, most notably the Rucellai, a wealthy clan of bankers and wool-merchants. The family’s head, Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, commissioned the famous Palazzo Rucellai, a landmark in Italian Renaissance architecture, from Leon Battista Alberti, between 1446 and 1451, Botticelli’s earliest years. By 1458, Botticelli’s family was renting their house from the Rucellai, which was just one of many dealings that involved the two families.[11]

In 1464, his father bought a house in the nearby Via Nuova (now called Via della Porcellana) in which Sandro lived from 1470 (if not earlier) until his death in 1510.[12] Botticelli both lived and worked in the house (a rather unusual practice) despite his brothers Giovanni and Simone also being resident there.[13] The family’s most notable neighbours were the Vespucci, including Amerigo Vespucci, after whom the Americas were named. The Vespucci were Medici allies and eventually regular patrons of Botticelli.[12]

The nickname Botticelli, meaning «little barrel», derives from the nickname of Sandro’s brother, Giovanni, who was called Botticello apparently because of his round stature. A document of 1470 refers to Sandro as «Sandro Mariano Botticelli», meaning that he had fully adopted the name.[8]

Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, c. 1470–1475, Louvre

Career before Rome[edit]

From around 1461 or 1462 Botticelli was apprenticed to Fra Filippo Lippi, one of the leading Florentine painters and a favorite of the Medici.[14] It was from Lippi that Botticelli learned how to create intimate compositions with beautiful, melancholic figures drawn with clear contours and only slight contrasts of light and shadow. In the late 1450s, Botticelli entered into Filippo Lippi’s workshop, and Lippi’s style is seen in many of Botticelli’s paintings, especially his earliest works.[5] For much of this period Lippi was based in Prato, a few miles west of Florence, frescoing the apse of what is now Prato Cathedral. Botticelli probably left Lippi’s workshop by April 1467, when the latter went to work in Spoleto.[15] There has been much speculation as to whether Botticelli spent a shorter period of time in another workshop, such as that of the Pollaiuolo brothers or Andrea del Verrocchio. However, although both artists had a strong impact on the young Botticelli’s development, the young artist’s presence in their workshops cannot be definitively proven.[16]

Lippi died in 1469. Botticelli must have had his own workshop by then, and in June of that year he was commissioned a panel of Fortitude (Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi) to accompany a set of all Seven Virtues commissioned one year earlier from Piero del Pollaiuolo.[17] Botticelli’s panel adopts the format and composition of Piero’s but features a more elegant and naturally posed figure and includes an array of «fanciful enrichments so as to show up Piero’s poverty of ornamental invention.»[18]

In 1472 Botticelli took on his first apprentice, the young Filippino Lippi, son of his master.[19] Botticelli and Filippino’s works from these years, including many Madonna and Child paintings, are often difficult to distinguish from one another. The two also routinely collaborated, as in the panels from a dismantled pair of cassoni, now divided between the Louvre, the National Gallery of Canada, the Musée Condé in Chantilly and the Galleria Pallavicini in Rome.[20]

Key early paintings[edit]

Botticelli’s earliest surviving altarpiece is a large sacra conversazione of about 1470–72, now in the Uffizi. The painting shows Botticelli’s early mastery of composition, with eight figures arranged with an «easy naturalness in a closed architectural setting».[21]

Another work from this period is the Saint Sebastian in Berlin, painted in 1474 for a pier in Santa Maria Maggiore, Florence.[22] This work was painted soon after the Pollaiuolo brothers’ much larger altarpiece of the same saint (London, National Gallery). Though Botticelli’s saint is very similar in pose to that by the Pollaiuolo, he is also calmer and more poised. The almost nude body is very carefully drawn and anatomically precise, reflecting the young artist’s close study of the human body. The delicate winter landscape, referring to the saint’s feast-day in January, is inspired by contemporary Early Netherlandish painting, widely-appreciated in Florentine circles.[23]

At the start of 1474 Botticelli was asked by the authorities in Pisa to join the work frescoing the Camposanto, a large prestigious project mostly being done by Benozzo Gozzoli, who spent nearly twenty years on it. Various payments up to September are recorded, but no work survives, and it seems that whatever Botticelli started was not finished. Nevertheless, that Botticelli was approached from outside Florence demonstrates a growing reputation.[24]

The Adoration of the Magi for Santa Maria Novella (c. 1475–76, now in the Uffizi, and the first of 8 Adorations),[25] was singled out for praise by Vasari, and was in a much-visited church, so spreading his reputation. It can be thought of as marking the climax of Botticelli’s early style. Despite being commissioned by a money-changer, or perhaps money-lender, not otherwise known as an ally of the Medici, it contains the portraits of Cosimo de Medici, his sons Piero and Giovanni (all these by now dead), and his grandsons Lorenzo and Giuliano. There are also portraits of the donor and, in the view of most, Botticelli himself, standing at the front on the right. The painting was celebrated for the variety of the angles from which the faces are painted, and of their expressions.[26]

A large fresco for the customs house of Florence, that is now lost, depicted the execution by hanging of the leaders of the Pazzi conspiracy of 1478 against the Medici. It was a Florentine custom to humiliate traitors in this way, by the so-called «pittura infamante«.[27] This was Botticelli’s first major fresco commission (apart from the abortive Pisa excursion), and may have led to his summons to Rome. The figure of Francesco Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa was removed in 1479, after protests from the Pope, and the rest were destroyed after the expulsion of the Medici and return of the Pazzi family in 1494.[28] Another lost work was a tondo of the Madonna ordered by a Florentine banker in Rome to present to Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga; this perhaps spread awareness of his work to Rome. A fresco in the Palazzo Vecchio, headquarters of the Florentine state, was lost in the next century when Vasari remodelled the building.[29]

In 1480 the Vespucci family commissioned a fresco figure of Saint Augustine for the Ognissanti, their parish church, and Botticelli’s. Someone else, probably the order running the church,[30] commissioned Domenico Ghirlandaio to do a facing Saint Jerome; both saints were shown writing in their studies, which are crowded with objects. As in other cases, such direct competition «was always an inducement to Botticelli to put out all his powers», and the fresco, now his earliest to survive, is regarded as his finest by Ronald Lightbown.[31] The open book above the saint contains one of the practical jokes for which Vasari says he was known. Most of the «text» is scribbles, but one line reads: «Where is Brother Martino? He went out. And where did he go? He is outside Porta al Prato», probably dialogue overheard from the Umiliati, the order who ran the church. Lightbown suggests that this shows Botticelli thought «the example of Jerome and Augustine likely to be thrown away on the Umiliati as he knew them».[32]

-

-

Madonna with Lilies and Eight Angels, c. 1478

Sistine Chapel[edit]

In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV summoned Botticelli and other prominent Florentine and Umbrian artists to fresco the walls of the newly completed Sistine Chapel. This large project was to be the main decoration of the chapel. Botticelli painted a series of portraits of popes.[33] These works were called Temptation of Moses, Temptation of Christ, and Conturbation of the Laws of Moses.[5] Most of the frescos remain but are greatly overshadowed and disrupted by Michelangelo’s work of the next century, as some of the earlier frescos were destroyed to make room for his paintings.[34] The Florentine contribution is thought to be part of a peace deal between Lorenzo Medici and the papacy. After Sixtus was implicated in the Pazzi conspiracy hostilities had escalated into excommunication for Lorenzo and other Florentine officials and a small «Pazzi War».[35]

The iconographic scheme was a pair of cycles, facing each other on the sides of the chapel, of the Life of Christ and the Life of Moses, together suggesting the supremacy of the Papacy. Botticelli’s contribution included three of the original fourteen large scenes: the Temptations of Christ, Youth of Moses and Punishment of the Sons of Corah (or various other titles),[36] as well as several of the imagined portraits of popes in the level above, and paintings of unknown subjects in the lunettes above, where Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling now is. He may have also done a fourth scene on the end wall opposite the altar, now destroyed.[37] Each painter brought a team of assistants from his workshop, as the space to be covered was considerable; each of the main panels is some 3.5 by 5.7 metres, and the work was done in a few months.[38]

Vasari implies that Botticelli was given overall artistic charge of the project, but modern art historians think it more likely that Pietro Perugino, the first artist to be employed, was given this role, if anyone was.[39] The subjects and many details to be stressed in their execution were no doubt handed to the artists by the Vatican authorities. The schemes present a complex and coherent programme asserting Papal supremacy, and are more unified in this than in their artistic style, although the artists follow a consistent scale and broad compositional layout, with crowds of figures in the foreground and mainly landscape in the top half of the scene. Allowing for the painted pilasters that separate each scene, the level of the horizon matches between scenes, and Moses wears the same yellow and green clothes in his scenes.[40]

Botticelli differs from his colleagues in imposing a more insistent triptych-like composition, dividing each of his scenes into a main central group with two flanking groups at the sides, showing different incidents.[41] In each the principal figure of Christ or Moses appears several times, seven in the case of the Youth of Moses.[42] The thirty invented portraits of the earliest popes seem to have been mainly Botticelli’s responsibility, at least as far as producing the cartoons went. Of those surviving, most scholars agree that ten were designed by Botticelli, and five probably at least partly by him, although all have been damaged and restored.[43]

The Punishment of the Sons of Corah contains what was for Botticelli an unusually close, if not exact, copy of a classical work. This is the rendering in the centre of the north side of the Arch of Constantine in Rome, which he repeated in about 1500 in The Story of Lucretia.[44] If he was apparently not spending his spare time in Rome drawing antiquities, as many artists of his day were very keen to do, he does seem to have painted there an Adoration of the Magi, now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington.[45] In 1482 he returned to Florence, and apart from his lost frescos for the Medici villa at Spedaletto a year or so later, no further trips away from home are recorded. He had perhaps been away from July 1481 to, at the latest, May 1482.[46]

Mythological subjects of the 1480s[edit]

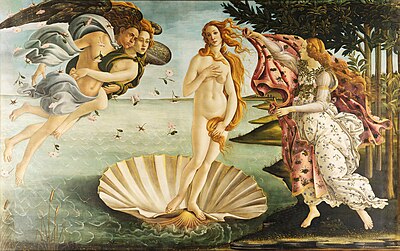

The masterpieces Primavera (c. 1482) and The Birth of Venus (c. 1485) are not a pair, but are inevitably discussed together; both are in the Uffizi. They are among the most famous paintings in the world, and icons of the Italian Renaissance. As depictions of subjects from classical mythology on a very large scale they were virtually unprecedented in Western art since classical antiquity. Together with the smaller and less celebrated Venus and Mars and Pallas and the Centaur, they have been endlessly analysed by art historians, with the main themes being: the emulation of ancient painters and the context of wedding celebrations, the influence of Renaissance Neo-Platonism, and the identity of the commissioners and possible models for the figures.[47]

Though all carry differing degrees of complexity in their meanings, they also have an immediate visual appeal that accounts for their enormous popularity. All show dominant and beautiful female figures in an idyllic world of feeling, with a sexual element. Continuing scholarly attention mainly focuses on the poetry and philosophy of contemporary Renaissance humanists. The works do not illustrate particular texts; rather, each relies upon several texts for its significance. Their beauty was characterized by Vasari as exemplifying «grace» and by John Ruskin as possessing linear rhythm. The pictures feature Botticelli’s linear style at its most effective, emphasized by the soft continual contours and pastel colours.[48]

The Primavera and the Birth were both seen by Vasari in the mid-16th century at the Villa di Castello, owned from 1477 by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, and until the publication in 1975 of a Medici inventory of 1499,[49] it was assumed that both works were painted specifically for the villa. Recent scholarship suggests otherwise: the Primavera, also known as the Allegory of Spring, was painted for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco’s townhouse in Florence, and The Birth of Venus was commissioned by someone else for a different site.[5][50]

Botticelli painted only a small number of mythological subjects, but these are now probably his best known works. A much smaller panel than those discussed before is his Venus and Mars in the National Gallery, London. This was of a size and shape to suggest that it was a spalliera, a painting made to fitted into either furniture, or more likely in this case, wood panelling. The wasps buzzing around Mars’ head suggest that it may have been painted for a member of his neighbours the Vespucci family, whose name means «little wasps» in Italian, and who featured wasps in their coat of arms. Mars lies asleep, presumably after lovemaking, while Venus watches as infant satyrs play with his military gear, and one tries to rouse him by blowing a conch shell in his ear. The painting was no doubt given to celebrate a marriage, and decorate the bedchamber.[51]

Three of these four large mythologies feature Venus, a central figure in Renaissance Neoplatonism, which gave divine love as important a place in its philosophy as did Christianity. The fourth, Pallas and the Centaur is clearly connected with the Medici by the symbol on Pallas’ dress. The Pallas and the Centaur was another painting that was painted for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici.[5] The two figures are roughly life-size, and a number of specific personal, political or philosophic interpretations have been proposed to expand on the basic meaning of the submission of passion to reason.[52]

A series of panels in the form of an spalliera or cassone were commissioned from Botticelli by Antonio Pucci in 1483 on the occasion of the marriage of his son Giannozzo with Lucrezia Bini. The subject was the story of’ Nastagio degli Onesti from the eighth novel of the fifth day of Boccaccio’s Decameron, in four panels. The coats of arms of the Medici and the bride and groom’s families appear in the third panel.[53]

Religious paintings after Rome[edit]

Botticelli returned from Rome in 1482 with a reputation considerably enhanced by his work there. As with his secular paintings, many religious commissions are larger and no doubt more expensive than before.[54] Altogether more datable works by Botticelli come from the 1480s than any other decade,[55] and most of these are religious. By the mid-1480s, many leading Florentine artists had left the city, some never to return. The rising star Leonardo da Vinci, who scoffed at Botticelli’s landscapes,[56] left in 1481 for Milan, the Pollaiolo brothers in 1484 for Rome, and Andrea Verrochio in 1485 for Venice.[57]

The remaining leaders of Florentine painting, Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Filippino Lippi, worked on a major fresco cycle with Perugino, for Lorenzo the Magnificent’s villa at Spedalletto near Volterra.[57] Botticelli painted many Madonnas, covered in a section below, and altarpieces and frescos in Florentine churches. In 1491 he served on a committee to decide upon a façade for the Cathedral of Florence, receiving the next year three payments for a design for a scheme, eventually abortive, to put mosaics on some interior roof vaults in the cathedral.[58]

The Bardi Altarpiece, 1484–85, 185 x 180 cm

Bardi Altarpiece[edit]

The first major church commission after Rome was the Bardi Altarpiece, finished and framed by February 1485,[59] and now in Berlin. The frame was by no less a figure than Giuliano da Sangallo, who was just becoming Lorenzo il Magnifico’s favourite architect. An enthroned Madonna and (rather large) Child sit on an elaborately-carved raised stone bench in a garden, with plants and flowers behind them closing off all but small patches of sky, to give a version of the hortus conclusus or closed garden, a very traditional setting for the Virgin Mary. Saints John the Baptist and an unusually elderly John the Evangelist stand in the foreground. Small and inconspicuous banderoles or ribbons carrying biblical verses elucidate the rather complex theological meaning of the work, for which Botticelli must have had a clerical advisor, but do not intrude on a simpler appreciation of the painting and its lovingly detailed rendering, which Vasari praised.[60] It is somewhat typical of Botticelli’s relaxed approach to strict perspective that the top ledge of the bench is seen from above, but the vases with lilies on it from below.[61]

The donor, from the leading Bardi family, had returned to Florence from over twenty years as a banker and wool merchant in London, where he was known as «John de Barde»,[62] and aspects of the painting may reflect north European and even English art and popular devotional trends.[63] There may have been other panels in the altarpiece, which are now missing.[64]

San Barnaba Altarpiece, c. 1487, Uffizi, 268 x 280 cm

San Barnaba Altarpiece[edit]

A larger and more crowded altarpiece is the San Barnaba Altarpiece of about 1487, now in the Uffizi, where elements of Botticelli’s emotional late style begin to appear. Here the setting is a palatial heavenly interior in the latest style, showing Botticelli taking a new degree of interest in architecture, possibly influenced by Sangallo. The Virgin and Child are raised high on a throne, at the same level as four angels carrying the Instruments of the Passion. Six saints stand in line below the throne. Several figures have rather large heads, and the infant Jesus is again very large. While the faces of the Virgin, child and angels have the linear beauty of his tondos, the saints are given varied and intense expressions. Four small and rather simple predella panels survive; there were probably originally seven.[65]

Other works[edit]

With the phase of painting large secular works probably over by the late 1480s, Botticelli painted several altarpieces, and this appears to have been a peak period for his workshop’s production of Madonnas. Botticelli’s largest altarpiece, the San Marco Altarpiece (378 x 258 cm, Uffizi), is the only one to remain with its full predella, of five panels. In the air above four saints, the Coronation of the Virgin is taking place in a heavenly zone of gold and bright colours that recall his earlier works, with encircling angels dancing and throwing flowers.[66]

In contrast, the Cestello Annunciation (1489–90, Uffizi) forms a natural grouping with other late paintings, especially two of the Lamentation of Christ that share its sombre background colouring, and the rather exaggerated expressiveness of the bending poses of the figures. It does have an unusually detailed landscape, still in dark colours, seen through the window, which seems to draw on north European models, perhaps from prints.[5][67]

Of the two Lamentations, one is in an unusual vertical format, because, like his 1474 Saint Sebastian, it was painted for the side of a pillar in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Florence; it is now in Milan. The other, horizontal, one was painted for a chapel on the corner of Botticelli’s street; it is now in Munich. In both the crowded, intertwined figures around the dead Christ take up nearly all the picture space, with only bare rock behind. The Virgin has swooned, and the other figures form a scrum to support her and Christ.[68] The Munich painting has three less involved saints with attributes (somewhat oddly including Saint Peter, usually regarded as in Jerusalem on the day, but not present at this scene), and gives the figures (except Christ) flat halos shown in perspective, which from now on Botticelli often uses. Both probably date from 1490 to 1495.[69]

Early records mentioned, without describing it, an altarpiece by Botticelli for the Convertite, an institution for ex-prostitutes, and various surviving unprovenanced works were proposed as candidates. It is now generally accepted that a painting in the Courtauld Gallery in London is the Pala delle Convertite, dating to about 1491–93. Its subject, unusual for an altarpiece, is the Holy Trinity, with Christ on the cross, supported from behind by God the Father. Angels surround the Trinity, which is flanked by two saints, with Tobias and the Angel on a far smaller scale right in the foreground. This was probably a votive addition, perhaps requested by the original donor. The four predella scenes, showing the life of Mary Magdalen, then taken as a reformed prostitute herself, are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[70]

After about 1493 or 1495 Botticelli seems to have painted no more large religious paintings, though production of Madonnas probably continued. The smaller narrative religious scenes of the last years are covered below.

-

San Marco Altarpiece, c. 1490-93, 378 x 258 cm, Uffizi

-

-

Madonnas, and tondos[edit]

Paintings of the Madonna and Child, that is, the Virgin Mary and infant Jesus, were enormously popular in 15th-century Italy in a range of sizes and formats, from large altarpieces of the sacra conversazione type to small paintings for the home. They also often hung in offices, public buildings, shops and clerical institutions. These smaller paintings were a steady source of income for painters at all levels of quality, and many were probably produced for stock, without a specific commission.[71]

Botticelli painted Madonnas from the start of his career until at least the 1490s. He was one of the first painters to use the round tondo format, with the painted area typically some 115 to 145 cm across (about four to five feet). This format was more associated with paintings for palaces than churches, though they were large enough to be hung in churches, and some were later donated to them.[72] Several Madonnas use this format, usually with a seated Virgin shown down to the knees, and though rectangular pictures of the Madonna outnumber them, Madonnas in tondo form are especially associated with Botticelli. He used the tondo format for other subjects, such as an early Adoration of the Magi in London,[73] and was apparently more likely to paint a tondo Madonna himself, usually leaving rectangular ones to his workshop.[71]

Botticelli’s Virgins are always beautiful, in the same idealized way as his mythological figures, and often richly dressed in contemporary style. Although Savonarola’s main strictures were against secular art, he also complained of the paintings in Florentine churches that «You have made the Virgin appear dressed as a whore»,[55] which may have had an effect on Botticelli’s style. They are often accompanied by equally beautiful angels, or an infant Saint John the Baptist (the patron saint of Florence). Some feature flowers, and none the detailed landscape backgrounds that other artists were developing. Many exist in several versions of varying quality, often with the elements other than the Virgin and Child different. Many of these were produced by Botticelli or, especially, his workshop, and others apparently by unconnected artists. When interest in Botticelli revived in the 19th century, it was initially largely in his Madonnas, which then began to be forged on a considerable scale.[74]

In the Magnificat Madonna in the Uffizi (118 cm or 46.5 inches across, c. 1483), Mary is writing down the Magnificat, a speech from the Gospel of Luke (1:46–55) where it is spoken by Mary upon the occasion of her Visitation to her cousin Elizabeth, some months before the birth of Jesus. She holds the baby Jesus, and is surrounded by wingless angels impossible to distinguish from fashionably-dressed Florentine youths.[75]

Botticelli’s Madonna and Child with Angels Carrying Candlesticks (1485/1490) was destroyed during World War II. It was stored in the Friedrichshain flak tower in Berlin for safe keeping, but in May 1945, the tower was set on fire and most of the objects inside were destroyed. Also lost were Botticelli’s Madonna and Child with Infant Saint John and an Annunciation.[76]

Portraits[edit]

Botticelli painted a number of portraits, although not nearly as many as have been attributed to him. There are a number of idealized portrait-like paintings of women which probably do not represent a specific person (several closely resemble the Venus in his Venus and Mars).[77] Traditional gossip links these to the famous beauty Simonetta Vespucci, who died aged twenty-two in 1476, but this seems unlikely.[78] These figures represent a secular link to his Madonnas.

With one or two exceptions his small independent panel portraits show the sitter no further down the torso than about the bottom of the rib-cage. Women are normally in profile, full or just a little turned, whereas men are normally a «three-quarters» pose, but never quite seen completely frontally. Even when the head is facing more or less straight ahead, the lighting is used to create a difference between the sides of the face. Backgrounds may be plain, or show an open window, usually with nothing but sky visible through it. A few have developed landscape backgrounds. These characteristics were typical of Florentine portraits at the beginning of his career, but old-fashioned by his last years.[79]

Many portraits exist in several versions, probably most mainly by the workshop; there is often uncertainty in their attribution.[80] Often the background changes between versions while the figure remains the same. His male portraits have also often held dubious identifications, most often of various Medicis, for longer than the real evidence supports.[81] Lightbown attributes him only with about eight portraits of individuals, all but three from before about 1475.[82]

Botticelli often slightly exaggerates aspects of the features to increase the likeness.[83] He also painted portraits in other works, as when he inserted a self-portrait and the Medici into his early Adoration of the Magi.[84] Several figures in the Sistine Chapel frescos appear to be portraits, but the subjects are unknown, although fanciful guesses have been made.[85] Large allegorical frescos from a villa show members of the Tornabuoni family together with gods and personifications; probably not all of these survive but ones with portraits of a young man with the Seven Liberal Arts and a young woman with Venus and the Three Graces are now in the Louvre.[86]

Dante, printing and manuscripts[edit]

Botticelli had a lifelong interest in the great Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, which produced works in several media.[89] He is attributed with an imagined portrait.[90] According to Vasari, he «wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante», which is also referred to dismissively in another story in the Life,[91] but no such text has survived.

Botticelli’s attempt to design the illustrations for a printed book was unprecedented for a leading painter, and though it seems to have been something of a flop, this was a role for artists that had an important future.[92] Vasari wrote disapprovingly of the first printed Dante in 1481 with engravings by the goldsmith Baccio Baldini, engraved from drawings by Botticelli: «being of a sophistical turn of mind, he there wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante and illustrated the Inferno which he printed, spending much time over it, and this abstention from work led to serious disorders in his living.»[93] Vasari, who lived when printmaking had become far more important than in Botticelli’s day, never takes it seriously, perhaps because his own paintings did not sell well in reproduction.

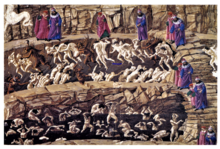

One of the few fully coloured pages of the Divine Comedy Illustrated by Botticelli, illustrating canto XVIII in the eighth circle of Hell. Dante and Virgil descending through the ten chasms of the circle via a ridge.

The Divine Comedy consists of 100 cantos and the printed text left space for one engraving for each canto. However, only 19 illustrations were engraved, and most copies of the book have only the first two or three. The first two, and sometimes three, are usually printed on the book page, while the later ones are printed on separate sheets that are pasted into place. This suggests that the production of the engravings lagged behind the printing, and the later illustrations were pasted into the stock of printed and bound books, and perhaps sold to those who had already bought the book. Unfortunately Baldini was neither very experienced nor talented as an engraver, and was unable to express the delicacy of Botticelli’s style in his plates.[94] Two religious engravings are also generally accepted to be after designs by Botticelli.[95]

Botticelli later began a luxury manuscript illustrated Dante on parchment, most of which was taken only as far as the underdrawings, and only a few pages are fully illuminated. This manuscript has 93 surviving pages (32 x 47 cm), now divided between the Vatican Library (8 sheets) and Berlin (83), and represents the bulk of Botticelli’s surviving drawings.[96]

Once again, the project was never completed, even at the drawing stage, but some of the early cantos appear to have been at least drawn but are now missing. The pages that survive have always been greatly admired, and much discussed, as the project raises many questions. The general consensus is that most of the drawings are late; the main scribe can be identified as Niccolò Mangona, who worked in Florence between 1482 and 1503, whose work presumably preceded that of Dante. Botticelli then appears to have worked on the drawings over a long period, as stylistic development can be seen, and matched to his paintings. Although other patrons have been proposed (inevitably including Medicis, in particular the younger Lorenzo, or il Magnifico), some scholars think that Botticelli made the manuscript for himself.[97]

There are hints that Botticelli may have worked on illustrations for printed pamphlets by Savonarola, almost all destroyed after his fall.[98]

-

Purgatory X (10)

-

Purgatorio XVII

-

Purgatorio XXXI

-

Paradise, Canto XXX

-

Inferno, Canto XXXI

The Medici[edit]

Botticelli became associated by historians with the Florentine School under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici, a movement historians would later characterize as a «golden age».[99] The Medici family were effective rulers of Florence, which was nominally a republic, throughout Botticelli’s lifetime up to 1494, when the main branch were expelled. Lorenzo il Magnifico became the head of the family in 1469, just around the time Botticelli started his own workshop. He was a great patron of both the visual and literary arts, and encouraged and financed the humanist and Neoplatonist circle from which much of the character of Botticelli’s mythological painting seems to come. In general Lorenzo does not seem to have commissioned much from Botticelli, preferring Pollaiuolo and others,[100] although views on this differ.[101] A Botticello who was probably Sandro’s brother Giovanni was close to Lorenzo.[102]

Although the patrons of many works not for churches remain unclear, Botticelli seems to have been used more by Lorenzo il Magnifico’s two young cousins, his younger brother Giuliano,[103] and other families allied to the Medici. Tommaso Soderini, a close ally of Lorenzo, obtained the commission for the figure of Fortitude of 1470 which is Botticelli’s earliest securely dated painting, completing a series of the Seven Virtues left unfinished by Piero del Pollaiuolo. Possibly they had been introduced by a Vespucci who had tutored Soderini’s son. Antonio Pucci, another Medici ally, probably commissioned the London Adoration of the Magi, also around 1470.[104]

Giuliano de’ Medici was assassinated in the Pazzi conspiracy of 1478 (Lorenzo narrowly escaped, saved by his bank manager), and a portrait said to be Giuliano which survives in several versions may be posthumous, or with at least one version from not long before his death.[105] He is also a focus for theories that figures in the mythological paintings represent specific individuals from Florentine high society, usually paired with Simonetta Vespucci, who John Ruskin persuaded himself had posed nude for Botticelli.[106]

Last years[edit]

According to Vasari, Botticelli became a follower of the deeply moralistic Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola, who preached in Florence from 1490 until his execution in 1498:[107]

Botticelli was a follower of Savonarola’s, and this was why he gave up painting and then fell into considerable distress as he had no other source of income. None the less, he remained an obstinate member of the sect, becoming one of the piagnoni, the snivellers, as they were called then, and abandoning his work; so finally, as an old man, he found himself so poor that if Lorenzo de’ Medici … and then his friends and … [others] had not come to his assistance, he would have almost died of hunger.[107]

The extent of Savonarola’s influence on Botticelli remains uncertain; his brother Simone was more clearly a follower.[108] The story, sometimes seen, that he had destroyed his own paintings on secular subjects in the 1497 bonfire of the vanities is not told by Vasari. Vasari’s assertion that Botticelli produced nothing after coming under the influence of Savonarola is not accepted by modern art historians. The Mystical Nativity, Botticelli’s only painting to carry an actual date, if one cryptically expressed, comes from late 1500,[109] eighteen months after Savonarola died, and the development of his style can be traced through a number of late works, as discussed below.

In late 1502, some four years after Savonarola’s death, Isabella d’Este wanted a painting done in Florence. Her agent Francesco Malatesta wrote to inform her that her first choice, Perugino, was away, Filippino Lippi had a full schedule for six months, but Botticelli was free to start at once, and ready to oblige. She preferred to wait for Perugino’s return.[95] This again casts serious doubt on Vasari’s assertion, but equally he does not seem to have been in great demand.[110]

Many datings of works have a range up to 1505, though he did live a further five years.[111] But Botticelli apparently produced little work after 1501, or perhaps earlier, and his production had already reduced after about 1495. This may be partly because of the time he devoted to the drawings for the manuscript Dante.[55] In 1504 he was a member of the committee appointed to decide where Michelangelo’s David would be placed.[112]

Botticelli returned to subjects from antiquity in the 1490s, with a few smaller works on subjects from ancient history containing more figures and showing different scenes from each story, including moments of dramatic action. These are the Calumny of Apelles (c. 1494–95), a recreation of a lost allegory by the ancient Greek painter Apelles, which he may have intended for his personal use,[113] and the pair of The Story of Virginia and The Story of Lucretia, which are probably from around 1500.[114]

The Mystical Nativity, a relatively small and very personal painting, perhaps for his own use, appears to be dated to the end of 1500.[115] It takes to an extreme the abandonment of consistent scale among the figures that had been a feature of Botticelli’s religious paintings for some years, with the Holy Family much larger than the other figures, even those well in front of them in the picture space.[116] This may be seen as a partial reversion to Gothic conventions. The iconography of the familiar subject of the Nativity is unique, with features including devils hiding in the rock below the scene, and must be highly personal.[117]

Another painting, known as the Mystic Crucifixion (now Fogg Art Museum), clearly relates to the state, and fate, of Florence, shown in the background behind Christ on the Cross, beside which an angel whips a marzocco, the heraldic lion that is a symbol of the city. This can be connected more directly to the convulsions of the expulsion of the Medici, Savonarola’s brief supremacy, and the French invasion. Unfortunately it is very damaged, such that it may not be by Botticelli, while it is certainly in his style.[118]

His later work, especially as seen in the four panels with Scenes from the Life of Saint Zenobius, witnessed a diminution of scale, expressively distorted figures, and a non-naturalistic use of colour reminiscent of the work of Fra Angelico nearly a century earlier. Botticelli has been compared to the Venetian painter Carlo Crivelli, some ten years older, whose later work also veers away from the imminent High Renaissance style, instead choosing to «move into a distinctly Gothic idiom».[119] Other scholars have seen premonitions of Mannerism in the simplified expressionist depiction of emotions in his works of the last years.[120]

Ernst Steinmann (d. 1934) detected in the later Madonnas a «deepening of insight and expression in the rendering of Mary’s physiognomy», which he attributed to Savonarola’s influence (also pushing back the dating of some of these Madonnas.)[121] More recent scholars are reluctant to assign direct influence, though there is certainly a replacement of elegance and sweetness with forceful austerity in the last period.

Botticelli continued to pay his dues to the Compagnia di San Luca (a confraternity rather than the artist’s guild) until at least October 1505;[122] the tentative date ranges assigned to his late paintings run no further than this. By then he was aged sixty or more, in this period definitely into old age. Vasari, who lived in Florence from around 1527, says that Botticelli died «ill and decrepit, at the age of seventy-eight», after a period when he was «unable to stand upright and moving around with the help of crutches».[123] He died in May 1510, but is now thought to have been something under seventy at the time. He was buried with his family outside the Ognissanti Church in a spot the church has now built over.[124] This had been his parish church since he was baptized there, and contained his Saint Augustine in His Study.[125]

Other media[edit]

Vasari mentions that Botticelli produced very fine drawings, which were sought out by artists after his death.[126] Apart from the Dante illustrations, only a small number of these survive, none of which can be connected with surviving paintings, or at least not their final compositions, although they appear to be preparatory drawings rather than independent works. Some may be connected with the work in other media that we know Botticelli did. Three vestments survive with embroidered designs by him, and he developed a new technique for decorating banners for religious and secular processions, apparently in some kind of appliqué technique (called commesso).[127]

Workshop[edit]

In 1472 the records of the painter’s guild record that Botticelli had only Filippino Lippi as an assistant, though another source records a twenty-eight-year old, who had trained with Neri di Bicci. By 1480 there were three, none of them subsequently of note. Other names occur in the record, but only Lippi became a well-known master.[128] A considerable number of works, especially Madonnas, are attributed to Botticelli’s workshop, or the master and his workshop, generally meaning that Botticelli did the underdrawing, while the assistants did the rest, or drawings by him were copied by the workshop.[129]

Botticelli’s linear style was relatively easy to imitate, making different contributions within one work hard to identify,[130] though the quality of the master’s drawing makes works entirely by others mostly identifiable. The attribution of many works remains debated, especially in terms of distinguishing the share of work between master and workshop. Lightbown believed that «the division between Botticelli’s autograph works and the paintings from his workshop and circle is a fairly sharp one», and that in only one major work on panel «do we find important parts executed by assistants»;[131] but others might disagree.

The National Gallery have an Adoration of the Kings of about 1470, which they describe as begun by Filippino Lippi but finished by Botticelli, noting how unusual it was for a master to take over a work begun by a pupil.[132]

Personal life[edit]

Finances[edit]

According to Vasari’s perhaps unreliable account, Botticelli «earned a great deal of money, but wasted it all through carelessness and lack of management».[123] He continued to live in the family house all his life, also having his studio there. On his father’s death in 1482 it was inherited by his brother Giovanni, who had a large family. By the end of his life it was owned by his nephews. From the 1490s he had a modest country villa and farm at Bellosguardo (now swallowed up by the city), which was leased with his brother Simone.[133]

Sexuality[edit]

Botticelli never married, and apparently expressed a strong dislike of the idea of marriage. An anecdote records that his patron Tommaso Soderini, who died in 1485, suggested he marry, to which Botticelli replied that a few days before he had dreamed that he had married, woke up «struck with grief», and for the rest of the night walked the streets to avoid the dream resuming if he slept again. The story concludes cryptically that Soderini understood «that he was not fit ground for planting vines».[134]

There has been over a century of speculation that Botticelli may have been homosexual. Many writers observed homo-eroticism in his portraits. The American art historian Bernard Berenson, for example, detected what he believed to be latent homosexuality.[135] In 1938, Jacques Mesnil discovered a summary of a charge in the Florentine Archives for November 16, 1502, which read simply «Botticelli keeps a boy», an accusation of sodomy (homosexuality). No prosecution was brought. The painter would then have been about fifty-eight. Mesnil dismissed it as a customary slander by which partisans and adversaries of Savonarola abused each other. Opinion remains divided on whether this is evidence of bisexuality or homosexuality.[136] Many have backed Mesnil.[137] Art historian Scott Nethersole has suggested that a quarter of Florentine men were the subject of similar accusations, which «seems to have been a standard way of getting at people»[138] but others have cautioned against hasty dismissal of the charge.[139] Mesnil nevertheless concluded «woman was not the only object of his love».[140]

The Renaissance art historian, James Saslow, has noted that: «His [Botticelli’s] homo-erotic sensibility surfaces mainly in religious works where he imbued such nude young saints as Sebastian with the same androgynous grace and implicit physicality as Donatello’s David».[141]

He might have had a close relationship with Simonetta Vespucci (1453–1476), who has been claimed, especially by John Ruskin, to be portrayed in several of his works and to have served as the inspiration for many of the female figures in the artist’s paintings. It is possible that he was at least platonically in love with Simonetta, given his request to have himself buried at the foot of her tomb in the Ognissanti – the church of the Vespucci – in Florence, although this was also Botticelli’s church, where he had been baptized. When he died in 1510, his remains were placed as he requested.[142][143]

Later reputation[edit]

Portrait, probably imagined, of Botticelli from Vasari’s Life

After his death, Botticelli’s reputation was eclipsed longer and more thoroughly than that of any other major European artist.[citation needed] His paintings remained in the churches and villas for which they had been created,[144] and his frescos in the Sistine Chapel were upstaged by those of Michelangelo.[145]

There are a few mentions of paintings and their location in sources from the decades after his death. Vasari’s Life is relatively short and, especially in the first edition of 1550, rather disapproving. According to the Ettlingers «he is clearly ill at ease with Sandro and did not know how to fit him into his evolutionary scheme of the history of art running from Cimabue to Michelangelo».[146] Nonetheless, this is the main source of information about his life, even though Vasari twice mixes him up with Francesco Botticini, another Florentine painter of the day. Vasari saw Botticelli as a firm partisan of the anti-Medici faction influenced by Savonarola, while Vasari himself relied heavily on the patronage of the returned Medicis of his own day. Vasari also saw him as an artist who had abandoned his talent in his last years, which offended his high idea of the artistic vocation. He devotes a good part of his text to rather alarming anecdotes of practical jokes by Botticelli.[147] Vasari was born the year after Botticelli’s death, but would have known many Florentines with memories of him.

In 1621 a picture-buying agent of Ferdinando Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua bought him a painting said to be a Botticelli out of historical interest «as from the hand of an artist by whom Your Highness has nothing, and who was the master of Leonardo da Vinci».[148] That mistake is perhaps understandable, as although Leonardo was only some six years younger than Botticelli, his style could seem to a Baroque judge to be a generation more advanced.

The Birth of Venus was displayed in the Uffizi from 1815, but is little mentioned in travellers’ accounts of the gallery over the next two decades. The Berlin gallery bought the Bardi Altarpiece in 1829, but the National Gallery, London only bought a Madonna (now regarded as by his workshop) in 1855.[145]

The English collector William Young Ottley bought Botticelli’s The Mystical Nativity in Italy, bringing it to London in 1799. But when he tried to sell it in 1811, no buyer could be found.[145] After Ottley’s death, its next purchaser, William Fuller Maitland of Stansted, allowed it to be exhibited in a major art exhibition held in Manchester in 1857, the Art Treasures Exhibition,[149] where among many other art works it was viewed by more than a million people. His only large painting with a mythological subject ever to be sold on the open market is the Venus and Mars, bought at Christie’s by the National Gallery for a rather modest £1,050 in 1874.[150] The rare 21st-century auction results include in 2013 the Rockefeller Madonna, sold at Christie’s for US$10.4 million, and in 2021 the Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel, sold at Sotheby’s for US$92.2 million.[151]

The first nineteenth-century art historian to be enthusiastic about Botticelli’s Sistine frescoes was Alexis-François Rio; Anna Brownell Jameson and Charles Eastlake were alerted to Botticelli as well, and works by his hand began to appear in German collections. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood incorporated elements of his work into their own.[152]

Walter Pater created a literary picture of Botticelli, who was then taken up by the Aesthetic movement. The first monograph on the artist was published in 1893, the same year as Aby Warburg’s seminal dissertation on the mythologies; then, between 1900 and 1920 more books were written on Botticelli than on any other painter.[153] Herbert Horne’s monograph in English from 1908 is still recognised as of exceptional quality and thoroughness,[154] «one of the most stupendous achievements in Renaissance studies».[155]

Botticelli appears as a character, sometimes a main one, in numerous fictional depictions of 15th-century Florence in various media. He was portrayed by Sebastian de Souza in the second season of the TV series Medici: Masters of Florence.[156]

The main belt asteroid 29361 Botticelli discovered on 9 February 1996, is named after him.[157]

-

The Virgin Adoring the Sleeping Christ Child, 1490

-

-

The Outcast (Despair), c. 1496

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Ettlingers, 7. Other sources give 1446, 1447 or 1444–45.

- ^ «Sandro Botticelli — Biography and Legacy». theartstory.org.

- ^ Edelstein, Bruce (December 21, 2020). «Botticelli in the Florence of Lorenzo the Magnificent». sothebys.com. Sotheby’s.

- ^ Ettlingers, 134; Legouix, 118

- ^ a b c d e f g National Gallery of Art (2003). Italian paintings of the fifteenth century. Miklós. Boskovits. Washington: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 0-89468-305-5. OCLC 52687917.

- ^ Ettlingers, 199; Lightbown, 53 on the Pisa work, which does not survive

- ^ Lightbown, 17–19

- ^ a b Ettlingers, 7

- ^ Lightbown, 19

- ^ He was still in school in February 1458 (Lightbown, 19). According to Vasari, 147, he was an able pupil, but easily grew restless, and was initially apprenticed as a goldsmith.

- ^ a b Lightbown, 18

- ^ a b Lightbown, 18–19

- ^ Ettlingers, 12

- ^ Lightbown, 20–26

- ^ Lightbown, 22, 25

- ^ Lightbown, 26; but see Hartt, 324, saying «Botticelli was active in the shop of Verrocchio».

- ^ Lightbown, 52; they were the Sei della Mercanzia, a tribunal of six judges, chosen by the main Guilds of Florence.

- ^ Lightbown, 46 (quoted); Ettlingers, 19–22

- ^ Dempsey, Hartt, 324; Legouix, 8

- ^ Nelson, Jonathan Katz (2009). ««Botticelli» or «Filippino»? How to Define Authorship in a Renaissance Workshop». Sandro Botticelli and Herbert Horne: New Research: 137–167.

- ^ Lightbown, 50

- ^ Lightbown, 50–51

- ^ Lightbown, 51–52; Ettlingers, 22–23

- ^ Lightbown, 52

- ^ Hartt, 324

- ^ Lightbown, 65–69; Vasari, 150–152; Hartt, 324–325

- ^ Ettlingers, 10

- ^ Hartt, 325–326; Ettlingers, 10; Dempsey

- ^ Lightbown, 70

- ^ Lightbown, 77

- ^ Lightbown, 73–78, 74 quoted

- ^ Lightbown, 77 (different translation to same effect)

- ^ National Gallery of Art (2003). Italian paintings of the fifteenth century. Miklós. Boskovits. Washington: National Gallery of Art. p. 145. ISBN 0-89468-305-5. OCLC 52687917.

- ^ Shearman, 38–42, 47; Lightbown, 90–92; Hartt, 326

- ^ Shearman, 47; Hartt, 326; Martines, Chapter 10 for the hostilities.

- ^ Shearman, 70–75; Hartt, 326–327

- ^ Shearman, 47

- ^ Hartt, 327; Shearman, 47

- ^ Hartt, 326–327; Lightbown, 92–94, thinks no one was, but that Botticelli set the style for the figures of the popes.

- ^ Lightbown, 90–92, 97–99, 105–106; Hartt, 327; Shearman, 47, 50–75

- ^ Hartt, 327

- ^ Lightbown, 99–105

- ^ Lightbown, 96–97

- ^ Lightbown, 106–108; Ettlingers, 202

- ^ Lightbown, 111–113

- ^ Lightbown, 90, 94

- ^ Covered at length in: Lightbown, Ch. 7 & 8; Wind, Ch. V, VII and VIII; Ettlingers, Ch. 3; Dempsey; Hartt, 329–334

- ^ R. W. Lightbown (1978). Sandro Botticelli: Life and work. University of California Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-520-03372-8. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

During the colouring Botticelli strengthened many of the contours by means of a pointed instrument, probably to give them the bold clarity so characteristic of his linear style.

- ^ «Web Gallery of Art, searchable fine arts image database». www.wga.hu. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Lightbown, 122–123; 152–153; Smith, Webster, «On the Original Location of the Primavera», The Art Bulletin, vol. 57, no. 1, 1975, pp. 31–40. JSTOR Archived April 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lightbown, 164–168; Dempsey; Ettlingers, 138–141, with a later date.

- ^ Lightbown, 148–152; Legouix, 113

- ^ «Scenes from The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti — The Collection — Museo Nacional del Prado». www.museodelprado.es. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Lightbown, 180

- ^ a b c Dempsey

- ^ Hartt, 329. According to Leonardo, Botticelli anticipated the method of some 18th century watercolourists by claiming that a landscape could be begun by throwing a sponge loaded with paint at the panel.

- ^ a b Ettlingers, 11

- ^ Lightbown, 211–213

- ^ Lightbown, 182

- ^ Lightbown, 180–185; Ettlingers, 72–74

- ^ Legouix, 38

- ^ Lightbown, 180; Ettlingers, 73

- ^ Lightbown, 184

- ^ Ettlingers, 73

- ^ Lightbown, 187–190; Legouix, 31, 42

- ^ Lightbown, 198–200; Legouix, 42–44

- ^ Lightbown, 194–198; Legouix, 103

- ^ Lightbown, 207–209; Legouix, 107, 109

- ^ Lightbown dates the Munich picture to 1490–92, and the Milan one to c. 1495

- ^ Lightbown, 202–207

- ^ a b Lightbown, 82

- ^ Lightbown, 47

- ^ Lightbown, 47–50

- ^ Ettlingers, 80; Lightbown, 82, 185–186

- ^ Ettlingers, 81–84

- ^ “Madonna and Child with Angels Carrying Candlesticks ; image

- ^ Campbell, 6

- ^ Ettlingers, 164

- ^ Ettlingers, 171; Lightbown, 54–57

- ^ Ettlingers, 156

- ^ Ettlingers, 156, 163–164, 168–172

- ^ Lightbown, 54. This appears to exclude the idealized females, and certainly the portraits included in larger works.

- ^ Campbell, 12

- ^ «The Adoration of the Magi by Botticelli». Virtual Uffizi Gallery. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ Ettlingers, 156–164

- ^ Campbell, 56, 136–136

- ^ The evidence for this identification is in fact slender to non-existent. Ettlingers, 168; Legouix, 64

- ^ Davies, 98-99

- ^ Lightbown, 16–17, 86–87

- ^ Dante’s features were well-known, from his death mask and several earlier paintings. Botticelli’s aquiline version influenced many later depictions.

- ^ Vasari, 152, 154

- ^ Landau, 35, 38

- ^ Vasari, 152, a different translation

- ^ Lightbown, 89; Landau, 108; Dempsey

- ^ a b Lightbown, 302

- ^ Lightbown, 280; some are drawn on both sides of the sheet.

- ^ Dempsey; Lightbown, 280–282, 290

- ^ Landau, 95

- ^ Classics, Delphi; Russell, Peter (April 7, 2017). The History of Art in 50 Paintings. ISBN 9781786565082. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Hartt, 323

- ^ Lightbown, 11, 58; Dempsey

- ^ Lightbown, 58

- ^ Lightbown, 58–59

- ^ Lightbown, 42–50; Dempsey

- ^ Lightbown, 58–65, believes it is Giuliano, and the Washington version probably pre-dates his death; the Ettlingers, 168, are sceptical it is Giuliano at all. The various museums with versions still support the identification.

- ^ Ettlingers, 164; Clark, 372 note for p. 92 quote.

- ^ a b Vasari, 152

- ^ Hartt, 335–336; Davies, 105–106; Ettlingers, 13–14

- ^ Ettlingers, 14; Vasari, 152

- ^ Ettlingers, 14; Legouix, 18

- ^ Legouix, 18; Dempsey

- ^ Legouix, 18; Ettlingers, 203

- ^ Lightbown, 230–237; Legouix, 114;

- ^ Lightbown, 260–269; Legouix, 82–83

- ^ Davies, 103–106

- ^ Lightbown, 221–223

- ^ Lightbown, 248–253; Dempsey; Ettlingers, 96–103

- ^ Lightbown, 242–247; Ettlingers, 103–105. Lightbown connects it more specifically to Savonarola than the Ettlingers.

- ^ Legouix, 11–12; Dempsey

- ^ Hartt, 334, 337

- ^ Steinmann, Ernst, Botticelli, 26–28

- ^ Lightbown, 303–304

- ^ a b Vasari, 154

- ^ Lightbown, 305; Ettlingers, 15

- ^ Lightbown, 17

- ^ Vasari, 155

- ^ Lightbown, 213, 296–298: Ettlingers, 175–178, who are more ready to connect studies to surviving paintings.

- ^ Legouix, 8; Lightbown, 311, 314

- ^ Lightbown, 314

- ^ Ettlingers, 79

- ^ Lightbown, 312

- ^ National Gallery page Archived June 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine; see Davies, 97 for a slightly different view, and Lightbown, 311 for a very different one.

- ^ Ettlingers, 12–14

- ^ Lightbown, 44

- ^ Hudson

- ^ Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and Civilization, Harvard University, 2003

- ^ Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence, Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-19-506975-4; Lightbown, 302

- ^ Scott Nethersole (Courtauld Institute), quoted in Hudson

- ^ Andre Chastel, Art et humanisme a Florence au temps de Laurent le Magnifique, Presses Universitaires de France, 1959

- ^ Jacques Mesnil, Botticelli, Paris, 1938

- ^ James Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in art and society, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1986, 88

- ^ Harness, Brenda. «The Face That Launched A Thousand Prints». Fine Art Touch. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ^ Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2007). Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America. Random House. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-4000-6281-2. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ Primavera and The Birth of Venus remained in the Grand Ducal Medici villa of Castello until 1815. (Levey 1960:292

- ^ a b c Ettlingers, 204

- ^ Ettlingers, 203

- ^ Lightbown, 16–17; Vasari, 147–155

- ^ Lightbown, 14

- ^ Davies, 106

- ^ Reitlinger, 99, 127

- ^ Gleadell, Colin (January 28, 2021). «Botticelli Portrait Goes for $92 M., Becoming Second-Most Expensive Old Masters Work Ever Auctioned». ARTnews.com. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Pre-Raphaelite Art in the Victoria & Albert Museum, Suzanne Fagence Cooper, p.95-96 ISBN 1-85177-394-0

- ^ Dempsey; Lightbown, 328–329, with a list marking which «are of a certain importance»; Michael Levey, «Botticelli and Nineteenth-Century England» Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 23.3/4 (July 1960:291–306); Ettlingers, 205

- ^ Lightbown, 328; Dempsey, Legouix, 127

- ^ Ettlingers, 205 quoted, 208

- ^ Clarke, Stewart (August 10, 2017). «Daniel Sharman and Bradley James Join Netflix’s ‘Medici’ (EXCLUSIVE)». Variety. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ «29361 Botticelli (1996 CY)». JPL Small-Body Database Browser. Jet Propulsion Laboratories. April 9, 2012. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

References[edit]

- Campbell, Lorne, Renaissance Portraits, European Portrait-Painting in the 14th, 15th and 16th Centuries, 1990, Yale, ISBN 0-300-04675-8

- Davies, Martin, Catalogue of the Earlier Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, 1961, reprinted 1986, ISBN 0-901791-29-6

- Dempsey, Charles, «Botticelli, Sandro», Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 15 May 2017. subscription required Archived January 22, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- «Ettlingers»: Leopold Ettlinger with Helen S. Ettlinger, Botticelli, 1976, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 0-500-20153-6

- Hartt, Frederick, History of Italian Renaissance Art, (2nd ed.) 1987, Thames & Hudson (U.S. Harry N. Abrams), ISBN 0-500-23510-4

- Hudson, Mark, «Before Bowie, there was Botticelli» Archived September 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Telegraph, 14 February 2016

- Landau, David, in Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter. The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- Legouix, Susan, Botticelli, 2004 (rev’d ed.), Chaucer Press, ISBN 1-904449-21-2

- Lightbown, Ronald, Sandro Botticelli: Life and Work, 1989, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-09206-4

- Martines, Lauro, April Blood: Florence and the Plot Against the Medici, 2003, Johnathan Cape, ISBN 0-224-06167-4

- Reitlinger, Gerald; The Economics of Taste, Vol I: The Rise and Fall of Picture Prices 1760–1960, 1961, Barrie and Rockliffe, London

- Shearman, John, in Pietrangeli, Carlo, et al., The Sistine Chapel: The Art, the History, and the Restoration, 1986, Harmony Books/Nippon Television, ISBN 0-517-56274-X

- Vasari, selected and edited by George Bull, Artists of the Renaissance, Penguin 1965 (page nos. from BCA ed., 1979). Vasari Life on-line Archived April 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (in a different translation)

- Wind, Edgar, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance, 1967 ed., Peregrine Books

Further reading[edit]

- Zollner, Frank, Sandro Botticelli, Prestel, 2015 (2nd edn), with complete illustrations

External links[edit]

- «Botticelli». Panopticon Virtual Art Gallery. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007.

- World of Dante Botticelli’s Dante illustrations and interactive version in the Chart of Hell

- sandrobotticelli.net, 200 works by Sandro Botticelli

- Botticelli Reimagined at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- Colvin, Sidney (1911). «Botticelli, Sandro» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). pp. 306–309.

- Italian Paintings: Florentine School, a Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) collection catalog (see pages: 159–167).

- Carl Brandon Strehlke, «Predella Panels from the High Altarpiece of Sant’Elisabetta delle Convertite, Florence by Sandro Botticelli (cat. 44—47)»[permanent dead link] in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works[permanent dead link], a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication.

|

Sandro Botticelli |

|

|---|---|

Probable self-portrait of Botticelli, in his Adoration of the Magi (1475). |

|

| Born |

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi c. 1445[1] Florence, Republic of Florence (now Italy) |

| Died | May 17, 1510 (aged 64–65)[2][3]

Florence, Republic of Florence |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Filippo Lippi |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Primavera The Birth of Venus The Adoration of the Magi Other works |

| Movement | Italian Renaissance |

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi (c. 1445[1] – May 17, 1510), known as Sandro Botticelli (, Italian: [ˈsandro bottiˈtʃɛlli]), was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. Botticelli’s posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century, when he was rediscovered by the Pre-Raphaelites who stimulated a reappraisal of his work. Since then, his paintings have been seen to represent the linear grace of late Italian Gothic and some Early Renaissance painting, even though they date from the latter half of the Italian Renaissance period.

In addition to the mythological subjects for which he is best known today, Botticelli painted a wide range of religious subjects (including dozens of renditions of the Madonna and Child, many in the round tondo shape) and also some portraits. His best-known works are The Birth of Venus and Primavera, both in the Uffizi in Florence, which holds many of Botticelli’s works.[5] Botticelli lived all his life in the same neighbourhood of Florence; his only significant times elsewhere were the months he spent painting in Pisa in 1474 and the Sistine Chapel in Rome in 1481–82.[6]

Only one of Botticelli’s paintings, the Mystic Nativity (National Gallery, London) is inscribed with a date (1501), but others can be dated with varying degrees of certainty on the basis of archival records, so the development of his style can be traced with some confidence. He was an independent master for all the 1470s, which saw his reputation soar. The 1480s were his most successful decade, the one in which his large mythological paintings were completed along with many of his most famous Madonnas. By the 1490s his style became more personal and to some extent mannered. His last works show him moving in a direction opposite to that of Leonardo da Vinci (seven years his junior) and the new generation of painters creating the High Renaissance style, and instead returning to a style that many have described as more Gothic or «archaic.»

Early life[edit]

Via Borgo Ognissanti in 2008, with the eponymous church halfway down on the right. Like the street, it has had a Baroque makeover since Botticelli’s time.

Botticelli was born in the city of Florence in a house in the street still called Borgo Ognissanti. He lived in the same area all his life and was buried in his neighbourhood church called Ognissanti («All Saints»). Sandro was one of several children to the tanner Mariano di Vanni d’Amedeo Filipepi and mother Smeralda Filipepi, and the youngest of his four to survive into adulthood.[7][5] The date of his birth is not known, but his father’s tax returns in following years give his age as two in 1447 and thirteen in 1458, meaning he must have been born between 1444 and 1446.[8]

In 1460 Botticelli’s father ceased his business as a tanner and became a gold-beater with his other son, Antonio. This profession would have brought the family into contact with a range of artists.[9] Giorgio Vasari, in his Life of Botticelli, reported that Botticelli was initially trained as a goldsmith.[10]

The Ognissanti neighbourhood was «a modest one, inhabited by weavers and other workmen,»[11] but there were some rich families, most notably the Rucellai, a wealthy clan of bankers and wool-merchants. The family’s head, Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, commissioned the famous Palazzo Rucellai, a landmark in Italian Renaissance architecture, from Leon Battista Alberti, between 1446 and 1451, Botticelli’s earliest years. By 1458, Botticelli’s family was renting their house from the Rucellai, which was just one of many dealings that involved the two families.[11]

In 1464, his father bought a house in the nearby Via Nuova (now called Via della Porcellana) in which Sandro lived from 1470 (if not earlier) until his death in 1510.[12] Botticelli both lived and worked in the house (a rather unusual practice) despite his brothers Giovanni and Simone also being resident there.[13] The family’s most notable neighbours were the Vespucci, including Amerigo Vespucci, after whom the Americas were named. The Vespucci were Medici allies and eventually regular patrons of Botticelli.[12]

The nickname Botticelli, meaning «little barrel», derives from the nickname of Sandro’s brother, Giovanni, who was called Botticello apparently because of his round stature. A document of 1470 refers to Sandro as «Sandro Mariano Botticelli», meaning that he had fully adopted the name.[8]

Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, c. 1470–1475, Louvre

Career before Rome[edit]

From around 1461 or 1462 Botticelli was apprenticed to Fra Filippo Lippi, one of the leading Florentine painters and a favorite of the Medici.[14] It was from Lippi that Botticelli learned how to create intimate compositions with beautiful, melancholic figures drawn with clear contours and only slight contrasts of light and shadow. In the late 1450s, Botticelli entered into Filippo Lippi’s workshop, and Lippi’s style is seen in many of Botticelli’s paintings, especially his earliest works.[5] For much of this period Lippi was based in Prato, a few miles west of Florence, frescoing the apse of what is now Prato Cathedral. Botticelli probably left Lippi’s workshop by April 1467, when the latter went to work in Spoleto.[15] There has been much speculation as to whether Botticelli spent a shorter period of time in another workshop, such as that of the Pollaiuolo brothers or Andrea del Verrocchio. However, although both artists had a strong impact on the young Botticelli’s development, the young artist’s presence in their workshops cannot be definitively proven.[16]

Lippi died in 1469. Botticelli must have had his own workshop by then, and in June of that year he was commissioned a panel of Fortitude (Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi) to accompany a set of all Seven Virtues commissioned one year earlier from Piero del Pollaiuolo.[17] Botticelli’s panel adopts the format and composition of Piero’s but features a more elegant and naturally posed figure and includes an array of «fanciful enrichments so as to show up Piero’s poverty of ornamental invention.»[18]

In 1472 Botticelli took on his first apprentice, the young Filippino Lippi, son of his master.[19] Botticelli and Filippino’s works from these years, including many Madonna and Child paintings, are often difficult to distinguish from one another. The two also routinely collaborated, as in the panels from a dismantled pair of cassoni, now divided between the Louvre, the National Gallery of Canada, the Musée Condé in Chantilly and the Galleria Pallavicini in Rome.[20]

Key early paintings[edit]

Botticelli’s earliest surviving altarpiece is a large sacra conversazione of about 1470–72, now in the Uffizi. The painting shows Botticelli’s early mastery of composition, with eight figures arranged with an «easy naturalness in a closed architectural setting».[21]

Another work from this period is the Saint Sebastian in Berlin, painted in 1474 for a pier in Santa Maria Maggiore, Florence.[22] This work was painted soon after the Pollaiuolo brothers’ much larger altarpiece of the same saint (London, National Gallery). Though Botticelli’s saint is very similar in pose to that by the Pollaiuolo, he is also calmer and more poised. The almost nude body is very carefully drawn and anatomically precise, reflecting the young artist’s close study of the human body. The delicate winter landscape, referring to the saint’s feast-day in January, is inspired by contemporary Early Netherlandish painting, widely-appreciated in Florentine circles.[23]

At the start of 1474 Botticelli was asked by the authorities in Pisa to join the work frescoing the Camposanto, a large prestigious project mostly being done by Benozzo Gozzoli, who spent nearly twenty years on it. Various payments up to September are recorded, but no work survives, and it seems that whatever Botticelli started was not finished. Nevertheless, that Botticelli was approached from outside Florence demonstrates a growing reputation.[24]

The Adoration of the Magi for Santa Maria Novella (c. 1475–76, now in the Uffizi, and the first of 8 Adorations),[25] was singled out for praise by Vasari, and was in a much-visited church, so spreading his reputation. It can be thought of as marking the climax of Botticelli’s early style. Despite being commissioned by a money-changer, or perhaps money-lender, not otherwise known as an ally of the Medici, it contains the portraits of Cosimo de Medici, his sons Piero and Giovanni (all these by now dead), and his grandsons Lorenzo and Giuliano. There are also portraits of the donor and, in the view of most, Botticelli himself, standing at the front on the right. The painting was celebrated for the variety of the angles from which the faces are painted, and of their expressions.[26]

A large fresco for the customs house of Florence, that is now lost, depicted the execution by hanging of the leaders of the Pazzi conspiracy of 1478 against the Medici. It was a Florentine custom to humiliate traitors in this way, by the so-called «pittura infamante«.[27] This was Botticelli’s first major fresco commission (apart from the abortive Pisa excursion), and may have led to his summons to Rome. The figure of Francesco Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa was removed in 1479, after protests from the Pope, and the rest were destroyed after the expulsion of the Medici and return of the Pazzi family in 1494.[28] Another lost work was a tondo of the Madonna ordered by a Florentine banker in Rome to present to Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga; this perhaps spread awareness of his work to Rome. A fresco in the Palazzo Vecchio, headquarters of the Florentine state, was lost in the next century when Vasari remodelled the building.[29]

In 1480 the Vespucci family commissioned a fresco figure of Saint Augustine for the Ognissanti, their parish church, and Botticelli’s. Someone else, probably the order running the church,[30] commissioned Domenico Ghirlandaio to do a facing Saint Jerome; both saints were shown writing in their studies, which are crowded with objects. As in other cases, such direct competition «was always an inducement to Botticelli to put out all his powers», and the fresco, now his earliest to survive, is regarded as his finest by Ronald Lightbown.[31] The open book above the saint contains one of the practical jokes for which Vasari says he was known. Most of the «text» is scribbles, but one line reads: «Where is Brother Martino? He went out. And where did he go? He is outside Porta al Prato», probably dialogue overheard from the Umiliati, the order who ran the church. Lightbown suggests that this shows Botticelli thought «the example of Jerome and Augustine likely to be thrown away on the Umiliati as he knew them».[32]

-

-

Madonna with Lilies and Eight Angels, c. 1478

Sistine Chapel[edit]

In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV summoned Botticelli and other prominent Florentine and Umbrian artists to fresco the walls of the newly completed Sistine Chapel. This large project was to be the main decoration of the chapel. Botticelli painted a series of portraits of popes.[33] These works were called Temptation of Moses, Temptation of Christ, and Conturbation of the Laws of Moses.[5] Most of the frescos remain but are greatly overshadowed and disrupted by Michelangelo’s work of the next century, as some of the earlier frescos were destroyed to make room for his paintings.[34] The Florentine contribution is thought to be part of a peace deal between Lorenzo Medici and the papacy. After Sixtus was implicated in the Pazzi conspiracy hostilities had escalated into excommunication for Lorenzo and other Florentine officials and a small «Pazzi War».[35]