|

Brigitte Bardot |

|

|---|---|

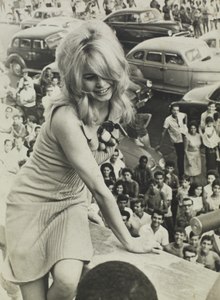

Bardot in a publicity photo for A Very Private Affair (1962) |

|

| Born |

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot 28 September 1934 (age 88) Paris, France |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1952–present |

| Works |

|

| Spouses |

Roger Vadim (m. 1952; div. 1957) Jacques Charrier (m. 1959; div. 1962) Gunter Sachs (m. 1966; div. 1969) Bernard d’Ormale (m. 1992) |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Mijanou Bardot (sister) |

| Signature | |

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot ( brizh-EET bar-DOH; French: [bʁiʒit baʁdo] (listen); born 28 September 1934), often referred to by her initials B.B.,[1][2] is a French, former actress, singer and model. Famous for portraying sexually emancipated characters with hedonistic lifestyles, she was one of the best known sex symbols of the 1950s and 1960s. Although she withdrew from the entertainment industry in 1973, she remains a major popular culture icon.[3]

Born and raised in Paris, Bardot was an aspiring ballerina in her early life. She started her acting career in 1952. She achieved international recognition in 1957 for her role in And God Created Woman (1956), and also caught the attention of French intellectuals. She was the subject of Simone de Beauvoir’s 1959 essay The Lolita Syndrome, which described her as a «locomotive of women’s history» and built upon existentialist themes to declare her the first and most liberated woman of post-war France. She won a 1961 David di Donatello Best Foreign Actress Award for her work in The Truth. Bardot later starred in Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le Mépris (1963). For her role in Louis Malle’s film Viva Maria! (1965) she was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress.

Bardot retired from the entertainment industry in 1973. She had acted in 47 films, performed in several musicals, and recorded more than 60 songs. She was awarded the Legion of Honour in 1985. After retiring, she became an animal rights activist and created the Fondation Brigitte Bardot. Bardot is known for her strong personality, outspokenness, and speeches on animal defence; she has been fined twice for public insults. She has also been a controversial political figure, having been fined five times for inciting racial hatred when she criticised immigration and Islam in France.[4] She is married to Bernard d’Ormale, a former adviser to Jean-Marie Le Pen, a French far-right politician. Bardot is a member of the Global 500 Roll of Honour of the United Nations Environment Programme and has received awards from UNESCO and PETA. Los Angeles Times Magazine ranked her second on the «50 Most Beautiful Women In Film».

Early life[edit]

Bardot was born on 28 September 1934 in the 15th arrondissement of Paris, to Louis Bardot (1896–1975) and Anne-Marie Mucel (1912–1978).[5] Bardot’s father, originated from Ligny-en-Barrois, was an engineer and the proprietor of several industrial factories in Paris.[6][7] Her mother was the daughter of an insurance company director.[8] She grew up in a conservative Catholic family, as had her father.[9][10] She suffered from amblyopia as a child, which resulted in decreased vision of her left eye.[11] She has one younger sister, Mijanou Bardot.[12]

Bardot’s childhood was prosperous; she lived in her family’s seven-bedroom apartment in the luxurious 16th arrondissement.[10][13] However, she recalled feeling resentful in her early years.[14] Her father demanded that she follow strict behavioural standards, including good table manners, and wear appropriate clothes.[15] Her mother was extremely selective in choosing companions for her, and as a result, Bardot had very few childhood friends.[16] Bardot cited a personal traumatic incident when she and her sister broke her parents’ favourite vase while they were playing in the house; her father whipped the sisters 20 times and henceforth treated them like «strangers», demanding them to address their parents by the pronoun «vous», which is a formal style of address, used when speaking to unfamiliar or higher-status persons outside the immediate family.[17] The incident decisively led to Bardot resenting her parents, and to her future rebellious lifestyle.[18]

During World War II, when Paris was occupied by Nazi Germany, Bardot spent more time at home due to increasingly strict civilian surveillance.[13] She became engrossed in dancing to records, which her mother saw as a potential for a ballet career.[13] Bardot was admitted at the age of seven to the private school Cours Hattemer.[19] She went to school three days a week, which gave her ample time to take dance lessons at a local studio, under her mother’s arrangements.[16] In 1949, Bardot was accepted at the Conservatoire de Paris. For three years she attended ballet classes held by Russian choreographer Boris Knyazev.[20] She also studied at the Institut de la Tour, a private Catholic high school near her home.[21]

Hélène Gordon-Lazareff, the then-director of the magazines Elle and Le Jardin des Modes, hired Bardot in 1949 as a «junior» fashion model.[22] On 8 March 1950, Bardot (aged 15 at the time) appeared on the cover of Elle, which brought her an acting offer for the film Les Lauriers sont coupés from director Marc Allégret.[23] Her parents opposed her becoming an actress, but her grandfather was supportive, saying that «If this little girl is to become a whore, cinema will not be the cause.»[A] At the audition, Bardot met Roger Vadim, who later notified her that she did not get the role.[25] They subsequently fell in love.[26] Her parents fiercely opposed their relationship; her father announced to her one evening that she would continue her education in England and that he had bought her a train ticket, the journey to take place the following day.[27] Bardot reacted by putting her head into an oven with open fire; her parents stopped her and ultimately accepted the relationship, on condition that she marry Vadim at the age of 18.[28]

Career[edit]

Beginnings: 1952–1955[edit]

Bardot appeared on the cover of Elle again in 1952, which landed her a movie offer for the comedy Crazy for Love (1952), starring Bourvil and directed by Jean Boyer.[29] She was paid 200,000 francs (5558.69 US dollars) for the small role portraying a cousin of the main character.[29] Bardot had her second film role in Manina, the Girl in the Bikini (1953),[B] directed by Willy Rozier.[30] She also had roles in the films The Long Teeth and His Father’s Portrait (both 1953).

Bardot had a small role in a Hollywood-financed film being shot in Paris, Act of Love (1953), starring Kirk Douglas. She received media attention when she attended the Cannes Film Festival in April 1953.[31]

Bardot had a leading role in an Italian melodrama, Concert of Intrigue (1954) and in a French adventure film, Caroline and the Rebels (1954). She had a good part as a flirtatious student in School for Love (1955), opposite Jean Marais, for director Marc Allégret.

Bardot played her first sizeable English-language role in Doctor at Sea (1955), as the love interest for Dirk Bogarde. The film was the third-most-popular movie at the British box-office that year.[32]

She had a small role in The Grand Maneuver (1955) for director René Clair, supporting Gérard Philipe and Michelle Morgan. The part was bigger in The Light Across the Street (1956) for director Georges Lacombe. She had another in the Hollywood film, Helen of Troy, playing Helen’s handmaiden.

For the Italian movie Mio figlio Nerone (1956) Bardot was asked by the director to appear as a blonde. Rather than wear a wig to hide her naturally brunette hair she decided to dye her hair. She was so pleased with the results that she decided to retain the hair colour.[33]

Rise to stardom: 1956–1962[edit]

Bardot then appeared in four movies that made her a star. First up was a musical, Naughty Girl (1956), where Bardot played a troublesome school girl. Directed by Michel Boisrond, it was co-written by Roger Vadim and was a big hit, the 12th most popular film of the year in France.[34] It was followed by a comedy, Plucking the Daisy (1956), written by Vadim with the director Marc Allégret, and another success in France. So too was the comedy The Bride Is Much Too Beautiful (1956) with Louis Jourdan.

Finally there was the melodrama And God Created Woman (1956), Vadim’s debut as director, with Bardot starring opposite Jean-Louis Trintignant and Curt Jurgens. The film, about an immoral teenager in a respectable small-town setting, was a huge success, not just in France but also around the world – it was among the ten most popular films in Britain in 1957.[35] It turned Bardot into an international star.[31] From at least 1956,[36] she was being hailed as the «sex kitten».[37][38][39] The film scandalized the United States and theatre managers were arrested for screening it.[40]

During her early career, professional photographer Sam Lévin’s photos contributed to the image of Bardot’s sensuality. One showed Bardot from behind, dressed in a white corset. British photographer Cornel Lucas made images of Bardot in the 1950s and 1960s that have become representative of her public persona.

Bardot followed And God Created Woman with La Parisienne (1957), a comedy co-starring Charles Boyer for director Boisrond. She was reunited with Vadim in another melodrama The Night Heaven Fell (1958) and played a criminal who seduced Jean Gabin in In Case of Adversity (1958). The latter was the 13th most seen movie of the year in France.[41] In 1958, Bardot became the highest-paid French actress.[42]

The Female (1959) for director Julien Duvivier was popular, but Babette Goes to War (1959), a comedy set in World War II, was a huge hit, the fourth biggest movie of the year in France.[43] Also widely seen was Come Dance with Me (1959) from Boisrond.

Her next film was the courtroom drama The Truth (1960), from Henri-Georges Clouzot. It was a highly publicised production, which resulted in Bardot having an affair and attempting suicide. The film was Bardot’s biggest commercial success in France, the third biggest hit of the year, and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film.[44] Bardot was awarded a David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Actress for her role in the film.[45]

She made a comedy with Vadim, Please, Not Now! (1961), and had a role in the all-star anthology, Famous Love Affairs (1962).

Bardot starred alongside Marcello Mastroianni in a film inspired by her life in A Very Private Affair (Vie privée, 1962), directed by Louis Malle. More popular in France was Love on a Pillow (1962), another for Vadim.

International films and singing career: 1962–1968[edit]

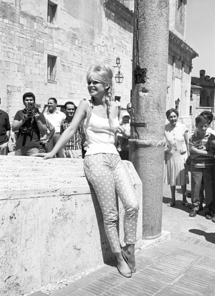

Bardot visiting Brazil, 1964

In the mid-1960s, Bardot made films that seemed to be more aimed at the international market. She starred in Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le Mépris (1963), produced by Joseph E. Levine and starring Jack Palance. The following year she co-starred with Anthony Perkins in the comedy Une ravissante idiote (1964).

Dear Brigitte (1965), Bardot’s first Hollywood film, was a comedy starring James Stewart as an academic whose son develops a crush on Bardot. Bardot’s appearance was relatively brief and the film was not a big hit.

More successful was the Western buddy comedy Viva Maria! (1965) for director Louis Malle, appearing opposite Jeanne Moreau. It was a big hit in France and worldwide, although it did not break through in the US as much as it had been hoped.[46]

After a cameo in Godard’s Masculin Féminin (1966), she had her first outright flop for some years, Two Weeks in September (1968), a French–English co-production. She had a small role in the all-star Spirits of the Dead (1968), acting opposite Alain Delon, then tried a Hollywood film again: Shalako (1968), a Western starring Sean Connery, which was a box-office disappointment.[47]

She participated in several musical shows and recorded many popular songs in the 1960s and 1970s, mostly in collaboration with Serge Gainsbourg, Bob Zagury and Sacha Distel, including «Harley Davidson»; «Je Me Donne À Qui Me Plaît»; «Bubble gum»; «Contact»; «Je Reviendrai Toujours Vers Toi»; «L’Appareil À Sous»; «La Madrague»; «On Déménage»; «Sidonie»; «Tu Veux, Ou Tu Veux Pas?»; «Le Soleil De Ma Vie» (a cover of Stevie Wonder’s «You Are the Sunshine of My Life»); and «Je t’aime… moi non-plus». Bardot pleaded with Gainsbourg not to release this duet and he complied with her wish; the following year, he rerecorded a version with British-born model and actress Jane Birkin that became a massive hit all over Europe. The version with Bardot was issued in 1986 and became a download hit in 2006 when Universal Music made its back catalogue available to purchase online, with this version of the song ranking as the third most popular download.[48]

Final films: 1969–1973[edit]

From 1969 to 1978, Bardot was the official face of Marianne (who had previously been anonymous) to represent the liberty of France.[49]

Les Femmes (1969) was a flop, although the screwball comedy The Bear and the Doll (1970) performed better. Her last few films were mostly comedies: Les Novices (1970), Boulevard du Rhum (1971) (with Lino Ventura). The Legend of Frenchie King (1971) was more popular, helped by Bardot co-starring with Claudia Cardinale.

She made one more with Vadim, Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman (1973), playing the title role. Vadim said the film marked «Underneath what people call ‘the Bardot myth’ was something interesting, even though she was never considered the most professional actress in the world. For years, since she has been growing older, and the Bardot myth has become just a souvenir… I was curious in her as a woman and I had to get to the end of something with her, to get out of her and express many things I felt were in her. Brigitte always gave the impression of sexual freedom – she is a completely open and free person, without any aggression. So I gave her the part of a man – that amused me».[50]

«If Don Juan is not my last movie it will be my next to last», said Bardot during filming.[51] She kept her word and only made one more film, The Edifying and Joyous Story of Colinot (1973).

In 1973, Bardot announced she was retiring from acting as «a way to get out elegantly».[52]

Animal rights activism[edit]

After appearing in more than 40 motion pictures and recording several music albums, Bardot used her fame to promote animal rights.

In 1986, she established the Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the Welfare and Protection of Animals.[53] She became a vegetarian[54] and raised three million francs (959169.7 US dollars) to fund the foundation by auctioning off jewellery and personal belongings.[53]

She once had a neighbour’s donkey castrated while looking after it, on the grounds of its «sexual harassment» of her own donkey and mare, for which she was taken to court by the donkey’s owner in 1989.[55][56] Bardot wrote a 1999 letter to Chinese President Jiang Zemin, published in French magazine VSD, in which she accused the Chinese of «torturing bears and killing the world’s last tigers and rhinos to make aphrodisiacs».

She has donated more than $140,000 over two years for a mass sterilization and adoption program for Bucharest’s stray dogs, estimated to number 300,000.[57]

Bardot is a strong animal rights activist and a major opponent of the consumption of horse meat. In support of animal protection, she condemned seal hunting in Canada during a visit to that country with Paul Watson of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society.[58] In August 2010, Bardot addressed a letter to the Queen of Denmark, Margarethe II, appealing for the sovereign to halt the killing of dolphins in the Faroe Islands. In the letter, Bardot describes the activity as a «macabre spectacle» that «is a shame for Denmark and the Faroe Islands … This is not a hunt but a mass slaughter … an outmoded tradition that has no acceptable justification in today’s world».[59]

On 22 April 2011, French culture minister Frédéric Mitterrand officially included bullfighting in the country’s cultural heritage. Bardot wrote him a highly critical letter of protest.[60] On 25 May 2011, the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society renamed its fast interceptor vessel, MV Gojira, as MV Brigitte Bardot in appreciation of her support.[61]

From 2013 onwards, the Brigitte Bardot Foundation in collaboration with Kagyupa International Monlam Trust of India has operated an annual veterinary care camp. She has committed to the cause of animal welfare in Bodhgaya year after year.[62]

On 23 July 2015, Bardot condemned Australian politician Greg Hunt’s plan to eradicate 2 million cats to save endangered species such as the Warru and night parrot.[63]

Personal life[edit]

Marriages and relationships[edit]

Throughout her life, Bardot had seventeen relationships with men and was married four times.[64] Bardot was leaving for another relationship when «the present was getting lukewarm»; she said, «I have always looked for passion. That’s why I was often unfaithful. And when the passion was coming to an end, I was packing my suitcase».[65]

On 20 December 1952, aged 18, Bardot married director Roger Vadim.[66] In 1956, she had become romantically involved with Jean-Louis Trintignant, who was her co-star in And God Created Woman. Trintignant at the time was married to actress Stéphane Audran. Bardot and Vadim divorced in 1957; they had no children together, but remained in touch, and even collaborated on later projects. The stated reason for the divorce was Bardot’s affairs with two other men.[67][31] Bardot and Trintignant lived together for about two years, spanning the period before and after Bardot’s divorce from Vadim, but they never married. Their relationship was complicated by Trintignant’s frequent absence due to military service and Bardot’s affair with musician Gilbert Bécaud.[67]

After her separation from Vadim, Bardot acquired a historic property dating from the 16th century, called Le Castelet, in Cannes. The fourteen-bedroom villa, surrounded by lush gardens, olive trees, and vineyards, consisted of several buildings.[68]

In 1958, she bought a second property called La Madrague, located in Saint-Tropez.[68] In early 1958, her break-up with Trintignant was followed in quick order by a reported nervous breakdown in Italy, according to newspaper reports. A suicide attempt with sleeping pills two days earlier was also noted but was denied by her public relations manager.[69] She recovered within weeks and began a relationship with actor Jacques Charrier. She became pregnant well before they were married on 18 June 1959. Bardot’s only child, her son Nicolas-Jacques Charrier, was born on 11 January 1960.[67] Bardot had an affair with Glenn Ford in the early 1960s.[70] After she and Charrier divorced in 1962, Nicolas was raised in the Charrier family and had little contact with his biological mother until his adulthood.[67] Sami Frey was mentioned as the reason for her divorce from Charrier. Bardot was enamoured of Frey, but he quickly left her.[71]

From 1963 to 1965, she lived with musician Bob Zagury.[72]

Bardot’s third marriage was to German millionaire playboy Gunter Sachs, lasting from 14 July 1966 to 7 October 1969, though they had separated the previous year.[67][31][73] As she was on the set of Shalako, she had rejected Sean Connery’s advances; she said, «It didn’t last long because I wasn’t a James Bond girl! I have never succumbed to his charm!»[74] In 1968, she began dating Patrick Gilles, who co-starred with her in The Bear and the Doll (1970); but she ended their relationship in spring 1971.[72]

Over the next few years, Bardot dated in succession bartender/ski instructor Christian Kalt, club owner Luigi Rizzi, singer Serge Gainsbourg, writer John Gilmore, actor Warren Beatty, and Laurent Vergez, her co-star in Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman.[72][75]

In 1974, Bardot appeared in a nude photo shoot in Playboy magazine, which celebrated her 40th birthday. In 1975, she entered a relationship with artist Miroslav Brozek and posed for some of his sculptures. Brozek was also an actor; his stage name is Jean Blaise [fr].[76] The couple lived together at La Madrague. They separated in December 1979.[77]

From 1980 to 1985, Bardot had a live-in relationship with French TV producer Allain Bougrain-Dubourg [fr].[77] On 28 September 1983, her 49th birthday, Bardot took an overdose of sleeping pills or tranquilizers with red wine. She had to be rushed to the hospital, where her life was saved after a stomach pump was used to evacuate the pills from her body.[77] Bardot was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1984. She refused to undergo chemotherapy treatment and decided only to do radiation therapy. She recovered in 1986.[78][79]

Bardot’s fourth and current husband is Bernard d’Ormale; they have been married since 16 August 1992.[80] In 2018, in an interview accorded to Le Journal du Dimanche, she denied rumors of relationships with Johnny Hallyday, Jimi Hendrix, and Mick Jagger.[71]

Politics and legal issues[edit]

Bardot expressed support for President Charles de Gaulle in the 1960s.[67][81]

In her 1999 book Le Carré de Pluton (Pluto’s Square), Bardot criticizes the procedure used in the ritual slaughter of sheep during the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha. Additionally, in a section in the book entitled «Open Letter to My Lost France», she writes that «my country, France, my homeland, my land is again invaded by an overpopulation of foreigners, especially Muslims». For this comment, a French court fined her 30,000 francs (7096.2 US dollars) in June 2000. She had been fined in 1997 for the original publication of this open letter in Le Figaro and again in 1998 for making similar remarks.[82][83][84]

In her 2003 book, Un cri dans le silence (A Scream in the Silence), she contrasted her close gay friends with homosexuals who «jiggle their bottoms, put their little fingers in the air and with their little castrato voices moan about what those ghastly heteros put them through,» and said some contemporary homosexuals behave like «fairground freaks».[85] In her own defence, Bardot wrote in a letter to a French gay magazine: «Apart from my husband — who maybe will cross over one day as well — I am entirely surrounded by homos. For years, they have been my support, my friends, my adopted children, my confidants.»[86][87]

In her book, she addressed issues such as racial mixing, immigration, the role of women in politics and the religion of Islam. The book also contained a section attacking what she called the mixing of genes and praised previous generations who, she said, had given their lives to push out invaders.[88] On 10 June 2004, Bardot was convicted for a fourth time by a French court for inciting racial hatred and fined €5,000 (5913.5 US dollars).[89] Bardot denied the racial hatred charge and apologized in court, saying: «I never knowingly wanted to hurt anybody. It is not in my character.»[90] In 2008, Bardot was convicted of inciting racial/religious hatred in regard to a letter she wrote, a copy of which she sent to Nicolas Sarkozy when he was Interior Minister of France. The letter stated her objections to Muslims in France ritually slaughtering sheep by slitting their throats without anesthetizing them first. She also said, in reference to Muslims, that she was «fed up with being under the thumb of this population which is destroying us, destroying our country and imposing its habits». The trial concluded on 3 June 2008, with a conviction and fine of €15,000 (17740.5 US dollars). The prosecutor stated she was tired of charging Bardot with offences related to racial hatred.[87]

During the 2008 United States presidential election, Bardot branded Republican Party vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin as «stupid» and a «disgrace to women». She criticized the former Alaskan governor for her stance on global warming and gun control. She was further offended by Palin’s support for Arctic oil exploration and by her lack of consideration in protecting polar bears.[91]

On 13 August 2010, Bardot criticised American filmmaker Kyle Newman for his plan to produce a biographical film about her. She told him, «Wait until I’m dead before you make a movie about my life!» otherwise «sparks will fly».[92]

In 2014, Bardot wrote an open letter demanding the ban in France of shechita, describing it as «ritual sacrifice». In response, the European Jewish Congress released a statement saying “Bardot has once again shown her clear insensitivity for minority groups with the substance and style of her letter…She may well be concerned for the welfare of animals but her longstanding support for the far-Right and for discrimination against minorities in France shows a constant disdain for human rights instead.”[93]

In 2015, Bardot threatened to sue a Saint-Tropez boutique selling items featuring her face.[94] In 2018, Bardot expressed support for the yellow vests movement.[95]

On 19 March 2019, Bardot issued an open letter to Réunion prefect Amaury de Saint-Quentin [fr] in which she accused inhabitants of the Indian Ocean island of animal cruelty and referred to them as «autochthonous who have kept the genes of savages». In her letter relating to animal abuse and sent through her foundation, she mentioned the «beheadings of goats and billy goats» during festivals, and associated these practices with «reminiscences of cannibalism from past centuries». The public prosecutor filed a lawsuit the following day.[96]

In June 2021, eighty-six-year-old Bardot was fined €5,000 (5913.5 US dollars) by the Arras court for public insults against the hunters and their national president Willy Schraen [fr]. Initially, she had published a post at the end of 2019 on her foundation’s website, calling hunters «sub-men» and «drunkards» and carriers of «genes of cruel barbarism inherited from our primitive ancestors». Schraen was also insulted. At the time of the hearing, she had not removed the comments from the website.[97] Following her letter sent to the prefect of Réunion in 2019, she was convicted on 4 November 2021 by a French court for public insults and fined €20,000 (23654 US dollars), the largest of her fines to date.[98]

Bardot’s husband Bernard d’Ormale is a former adviser to Jean-Marie Le Pen, former leader of the far-right party National Front (now National Rally), the main far-right party in France, known for its nationalist beliefs.[31][81] Bardot expressed support for Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Front (National Rally), calling her «the Joan of Arc of the 21st century».[99] She endorsed Le Pen in the 2012 and 2017 French presidential elections.[100][101]

Legacy[edit]

Brigitte Bardot statue in Búzios, Brazil

The Guardian named Bardot «one of the most iconic faces, models, and actors of the 1950s and 1960s». She has been called a «style icon» and a «muse for Dior, Balmain, and Pierre Cardin».[102]

In fashion, the Bardot neckline (a wide-open neck that exposes both shoulders) is named after her. Bardot popularized this style which is especially used for knitted sweaters or jumpers although it is also used for other tops and dresses. Bardot popularized the bikini in her early films such as Manina (1952) (released in France as Manina, la fille sans voiles). The following year she was also photographed in a bikini on every beach in the south of France during the Cannes Film Festival.[103] She gained additional attention when she filmed …And God Created Woman (1956) with Jean-Louis Trintignant (released in France as Et Dieu Créa La Femme). In it Bardot portrays an immoral teenager cavorting in a bikini who seduces men in a respectable small-town setting. The film was an international success.[31] Bardot’s image was linked to the shoemaker Repetto, who created a pair of ballerinas for her in 1956.[104] The bikini was in the 1950s relatively well accepted in France but was still considered risqué in the United States. As late as 1959, Anne Cole, one of the United States’ largest swimsuit designers, said, «It’s nothing more than a G-string. It’s at the razor’s edge of decency.»[105]

She also brought into fashion the choucroute («Sauerkraut») hairstyle (a sort of beehive hair style) and gingham clothes after wearing a checkered pink dress, designed by Jacques Esterel, at her wedding to Charrier.[106] She was the subject of an Andy Warhol painting.

Isabella Biedenharn of Elle wrote that Bardot «has inspired thousands (millions?) of women to tease their hair or try out winged eyeliner over the past few decades». A well-known evocative pose describes an iconic modelling portrait shot around 1960 where Bardot is dressed only in a pair of black pantyhose, cross-legged over her front and cross-armed over her breasts.[107] This pose has been emulated numerous times by models and celebrities such as Lindsay Lohan,[108] Elle Macpherson,[109] Gisele Bündchen,[110] and Rihanna.[111] In the late 1960s, Bardot’s silhouette was used as a model for designing and modelling the statue’s bust of Marianne, a symbol of the French Republic.[42]

In addition to popularizing the bikini swimming suit, Bardot has been credited with popularizing the city of St. Tropez and the town of Armação dos Búzios in Brazil, which she visited in 1964 with her boyfriend at the time, Brazilian musician Bob Zagury. The place where she stayed in Búzios is today a small hotel, Pousada do Sol, and also a French restaurant, Cigalon.[112] The town hosts a Bardot statue by Christina Motta.[113]

Bardot was idolized by the young John Lennon and Paul McCartney.[114][115] They made plans to shoot a film featuring The Beatles and Bardot, similar to A Hard Day’s Night, but the plans were never fulfilled.[31] Lennon’s first wife Cynthia Powell lightened her hair colour to more closely resemble Bardot, while George Harrison made comparisons between Bardot and his first wife Pattie Boyd, as Cynthia wrote later in A Twist of Lennon. Lennon and Bardot met in person once, in 1968 at the May Fair Hotel, introduced by Beatles press agent Derek Taylor; a nervous Lennon took LSD before arriving, and neither star impressed the other. Lennon recalled in a memoir: «I was on acid, and she was on her way out.»[116] According to the liner notes of his first (self-titled) album, musician Bob Dylan dedicated the first song he ever wrote to Bardot. He also mentioned her by name in «I Shall Be Free», which appeared on his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. The first-ever official exhibition spotlighting Bardot’s influence and legacy opened in Boulogne-Billancourt on 29 September 2009 – a day after her 75th birthday.[117] The Australian pop group Bardot was named after her.

Women who emulated and were inspired by Bardot include Claudia Schiffer, Emmanuelle Béart, Elke Sommer, Kate Moss, Faith Hill, Isabelle Adjani, Diane Kruger, Lara Stone, Kylie Minogue, Amy Winehouse, Georgia May Jagger, Zahia Dehar, Scarlett Johansson, Louise Bourgoin, and Paris Hilton. Bardot said: «None have my personality.» Laetitia Casta embodied Bardot in the 2010 French drama film Gainsbourg: A Heroic Life by Joann Sfar.[118]

In 2011, Los Angeles Times Magazine‘s list of «50 Most Beautiful Women In Film» ranked her number two.[119]

Bardot inspired Nicole Kidman to promote the 2013 campaign shoot of the British brand Jimmy Choo.[120]

In 2015, Bardot was ranked number six in «The Top Ten Most Beautiful Women Of All Time», according to a survey carried out by Amway’s beauty company in the UK which involved 2,000 women.[121]

In 2020, Vogue named Bardot number one of «The most beautiful French actresses of all time».[122] In a retrospective retracing women throughout the history of cinema, she was listed among «the most accomplished, talented and beautiful actresses of all time» by Glamour.[123]

The French drama television series Bardot is scheduled to be broadcast on France 2 in 2023. It stars Julia de Nunez and is about Bardot’s career from her first casting at age 15 and until the filming of La Vérité ten years later.[124]

Filmography[edit]

Discography[edit]

Studio albums[edit]

| Year | Original title | Translation | Songwriters(s) | Label | Main tracks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Et dieu… créa la femme (music from Roger Vadim’s motion picture) |

And God Created Woman | Paul Misraki | Versailles | |

| 1963 | Brigitte | Brigitte Bardot Sings | Serge Gainsbourg Claude Bolling Jean-Max Rivière Fernand Bonifay Spencer Williams Gérard Bourgeois |

Philips | L’appareil à sous Invitango Les amis de la musique La Madrague El Cuchipe |

| 1964 | B.B. | André Popp Jean-Michel Rivat Jean-Max Rivière Fernand Bonifay Gérard Bourgeois |

Moi je joue Une histoire de plage Maria Ninguém Je danse donc je suis Ciel de lit |

||

| 1968 | Bonnie and Clyde (with Serge Gainsbourg) |

Serge Gainsbourg Alain Goraguer Spencer Williams Jean-Max Rivière |

Fontana | Bonnie And Clyde Bubble Gum Comic Strip |

|

| Show | Serge Gainsbourg Francis Lai Jean-Max Rivière |

AZ | Harley Davidson Ay Que Viva La Sangria Contact |

Other notable singles[edit]

| Year | Original Title | Translation | Songwriters(s) | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Sidonie (music from Louis Malle’s the motion picture Vie Privée) |

Fiorenzo Capri Charles Cros Jean-Max Rivière |

Barclay | |

| 1965 | Viva Maria! (music from Louis Malle’s eponymous motion picture) (with Jeanne Moreau) |

Jean-Claude Carrière Georges Delerue |

Philips | |

| 1966 | Le soleil | The Sun | Jean-Max Rivière Gérard Bourgeois |

AZ |

| 1969 | La fille de paille | The Straw Girl | Franck Gérald Gérard Lenorman |

Philips |

| 1970 | Tu veux ou tu veux pas (Nem Vem Que Nao Tem) |

Do You Want Or Not | Pierre Cour Carlos Imperial |

Barclay |

| Nue au soleil | Naked Under The Sun | Jean Fredenucci Jean Schmidtt |

||

| 1972 | Tu es venu mon amour / Vous Ma Lady (with Laurent Vergez) |

You Came My Love / You My Lady | Hugues Aufray Eddy Marnay Eddie Barclay |

|

| Boulevard du rhum (with Guy Marchand) (music from Robert Enrico’s motion picture) |

Boulevard Of Rhum | François De Roubaix Jean-Paul-Egide Martini |

||

| 1973 | Soleil de ma vie (with Sacha Distel) |

Sun Of My Life | Stevie Wonder Jean Broussolle |

Pathé |

| 1982 | Toutes les bêtes sont à aimer | All Animals Must Be Loved | Jean-Max Rivière | Polydor |

| 1986 | Je t’aime… moi non plus (with Serge Gainsbourg) (released and shelved in 1968) |

I Love You… Me Neither | Serge Gainsbourg | Philips |

Books[edit]

Bardot has also written five books:

- Noonoah: Le petit phoque blanc (Grasset, 1978)

- Initiales B.B. (autobiography, Grasset & Fasquelle, 1996)

- Le Carré de Pluton (Grasset & Fasquelle, 1999)

- Un Cri Dans Le Silence (Editions Du Rocher, 2003)

- Pourquoi? (Editions Du Rocher, 2006)

Accolades[edit]

Awards and nominations[edit]

- 12th Victoires du cinéma français (French cinema victories) (1957): Best Actress, win, as Juliette Hardy in And God Created Woman.[125]

- 11th Bambi Awards (1958): Best Actress, nomination, as Juliette Hardy in And God Created Woman.[126]

- 14th Victoires du cinéma français (1959): Best Actress, win, as Yvette Maudet in In Case of Adversity.[127]

- Brussels European Awards (1960): Best Actress, win, as Dominique Marceau in The Truth.[128]

- 5th David di Donatello Awards (1961): Best Foreign Actress, win, as Dominique Marceau in The Truth.[45]

- 12th Étoiles de cristal (Crystal stars) by the French Cinema Academy (1966): Best Actress, win, as Marie Fitzgerald O’Malley in Viva Maria!.[129]

- 18th Bambi Awards (1967): Bambi Award of Popularity, win.[130]

- 20th BAFTA Awards (1967): BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress, nomination, as Marie Fitzgerald O’Malley in Viva Maria!.[131]

Honours[edit]

- 1980: Medal of the City of Trieste.[132]

- 1985: Legion of Honour.[C][134] Medal of the City of Lille.[132]

- 1989: Peace Prize in humanitarian merit.[132]

- 1992: Induction into the United Nations Environment Programme’s Global 500 Roll of Honour.[135] Creation in Hollywood of the Brigitte Bardot International Award as part of the Genesis Awards.[136]

- 1994: Medal of the City of Paris.[137]

- 1995: Medal of the City of Saint-Tropez.[138]

- 1996: Medal of the City of La Baule.[132]

- 1997: Greece’s UNESCO Ecology Award. Medal of the City of Athens.[132]

- 1999: Asteroid 17062 Bardot was named after her.[139]

- 2001: PETA Humanitarian Award.[104]

- 2008: Spanish Altarriba foundation Award.[140]

- 2017: A statue of 700 kilograms (1,500 lb) and 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) high was erected in her honour in central Saint-Tropez.[141]

- 2019: GAIA Lifetime Achievement Award from the Belgian association for the defence of animal rights.[142]

- 2021: Her effigy in Saint-Tropez was dressed in 1400 gold leaves of 23.75 carats each.[143]

See also[edit]

- List of animal rights advocates

Notes[edit]

- ^ Original quote: «Si cette petite doit devenir putain ou pas, ce ne sera pas le cinéma qui en sera la cause.»[24]

- ^ While this is Bardot’s second role, the film was released after The Long Teeth (1952).[30]

- ^ Although she was awarded, Bardot refused to go for the medal (Catherine Deneuve and Claudia Cardinale did the same).[133]

References[edit]

- ^ «And Bardot Became BB». Institut français du Royaume-Uni. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Probst 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Cherry 2016, p. 134; Vincendeau 1992, p. 73–76.

- ^ «Brigitte Bardot at 80: still outrageous, outspoken and controversial». The Guardian. 20 September 2014.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 15.

- ^ «Brigitte Bardot: ‘J’en ai les larmes aux yeux’«. Le Républicain Lorrain (in French). 23 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- ^ Singer 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Bigot 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Bigot 2014, p. 11.

- ^ a b Poirier, Agnès (20 September 2014). «Brigitte Bardot at 80: still outrageous, outspoken and controversial». The Observer. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Lelièvre 2012, p. 18.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Singer 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 45; Singer 2006, p. 10–14.

- ^ Singer 2006, p. 10–12.

- ^ a b Singer 2006, p. 10–11.

- ^ Singer 2006, p. 11–12.

- ^ Singer 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Singer 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Caron 2009, p. 62.

- ^ Pigozzi, Caroline. «Bardot s’en va toujours en guerre… pour les animaux». Paris Match. No. January 2018. pp. 76–83.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 67.

- ^ Singer 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 68–69.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 69.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 70.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Bardot 1996, p. 73; Singer 2006, p. 22.

- ^ a b Bardot 1996, p. 81.

- ^ a b Bardot 1996, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robinson, Jeffrey (1994). Bardot — Two Lives (First British ed.). London: Simon & Schuster. ASIN: B000KK1LBM.

- ^ «‘The Dam Busters’.» Times [London, England] 29 December 1955: 12. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 11 July 2012.

- ^ Servat. Page 76.

- ^ Box office figures in France for 1956 at Box Office Story

- ^ Most Popular Film of the Year. The Times (London, England), Thursday, 12 December 1957; pg. 3; Issue 54022.

- ^ «Mam’selle Kitten New box-office beauty». Australian Women’s Weekly. 5 December 1956. p. 32. Retrieved 5 March 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ «Brigitte Bardot: her life and times so far – in pictures». The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ «Brigitte Bardot: Rare and Classic Photos of the Original ‘Sex Kitten’«. time.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ The earliest use cited in the OED Online (accessed 26 November 2011) is in the Daily Sketch, 2 June 1958.

- ^ Poirier, Agnès (22 September 2009). «Happy birthday, Brigitte Bardot». The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ «Box office information for Love is My Profession». Box office story.

- ^ a b Bricard, Manon (12 October 2020). «La naissance d’un sex symbol» [The birth of a sex symbol]. L’Internaute (in French). Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «1959 French box office». Box Office Story. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ Box office information for film at Box Office Story

- ^ a b Roberts, Paul G (2015). «Brigitte Bardot». Style icons Vol 3 − Bombshells. Sydney: Fashion Industry Broadcast. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-6277-6189-5.

- ^ Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 281.

- ^ «ABC’s 5 Years of Film Production Profits & Losses», Variety, 31 May 1973 p. 3.

- ^ «Bardot revived as download star». BBC News. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Anne-Marie Sohn (teacher at the ÉNS-Lyon), Marianne ou l’histoire de l’idée républicaine aux XIXe et XXe siècles à la lumière de ses représentations (résumé of Maurice Agulhon’s three books, Marianne au combat, Marianne au pouvoir and Les métamorphoses de Marianne) (in French)

- ^ Wilson, Timothy (7 April 1973). «ROGER VADIM». The Guardian. London (UK). p. 9.

- ^ Morgan, Gwen (4 March 1973). «Brigitte Bardot: No longer a sex symbol». Chicago Tribune. p. d3.

- ^ «Brigitte Bardot Gives Up Films at Age of 39». The Modesto Bee. Modesto, California. UPI. 7 June 1973. p. A-8. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ a b

«Brigitte Bardot foundation for the welfare and protection of animals». fondationbrigittebardot.fr. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2010. - ^ Follain, John (9 April 2006) Brigitte Bardot profile, The Times Online: Life & Style. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ^ «Photoicon Online Features: Andy Martin: Brigitte Bardot». Photoicon.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ «Mr Pop History». Mr Pop History. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ «Bardot ‘saves’ Bucharest’s dogs». BBC News. 2 March 2001. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ «Hardline warrior in war to save the whale». The New Zealand Herald. 11 January 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Brigitte Bardot pleads to Denmark in dolphin ‘slaughter’, AFP, 19 August 2010.

- ^ Victoria Ward, Devorah Lauter (4 January 2013). «Brigitte Bardot’s sick elephants add to circus over French wealth tax protests», telegraph.co.uk; accessed 4 August 2015.

- ^ «Sea Shepherd Conservation Society». Seashepherd.org. 25 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ Bardot commits to animal welfare in Bodhgaya Archived 19 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, phayul.com; accessed 4 August 2015.

- ^ «Bardot condemns Australia’s plan to cull 2 million feral cats». ABC News. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Némard, Perrine (19 November 2020). «Brigitte …» [Brigitte Bardot talks about her many conquests: ‘I was the one who chose’]. Paris Match (in French). Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021 – via Orange S.A.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Arlin, Marc (1 February 2018). «Brigitte …» [Brigitte Bardot: unfaithful, she reveals the reason for her multiple adulteries]. Télé-Loisirs (in French). Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Neuhoff, Éric (12 August 2013). «Brigitte Bardot et Roger Vadim – Le loup et la biche». Le Figaro (in French). p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e f Bardot 1996

- ^ a b R.P. (7 July 2020). «La sublime villa cannoise de Brigitte Bardot est à vendre (photos)» [Brigitte Bardot’s sublime Cannes villa is for sale [photos]]. Paris Match (in French). Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «Brigitte Bardot in Italy After Breakdown». The Los Angeles Times. 9 February 1958. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ «A Ford Fiesta».

- ^ a b «Brigitte …» [Brigitte Bardot: She settles her accounts!]. France Dimanche (in French). 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c Singer, B. (2006). Brigitte Bardot: A Biography. McFarland, Incorporated Publishers. ISBN 9780786484263. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ «Gunter Sachs». The Daily Telegraph. London. 9 May 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Tizio, Alexandra (1 November 2020). «Flashback …» [Flashback: when Brigitte Bardot refused the advances of Sean Connery]. Gala (in French). Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Malossi, G. (1996). Latin Lover: The Passionate South. Charta. ISBN 9788881580491. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Brigitte Bardot and sculptor Miroslav Brozek at La Madrague in St.-Tropez. June 1975, Getty Images

- ^ a b c Carlson, Peter (24 October 1983). «Swept Away by Her Sadness». People. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ «Les célébrités touchées par le cancer du sein» [Celebrities affected by breast cancer]. Gala (in French). n.d. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Madelmond, Marine (17 January 2018). «Brigitte …» [Brigitte Bardot: why she refused chemotherapy during her breast cancer?]. Gala (in French). Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Goodman, Mark (30 November 1992). «A Bardot Mystery». People. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b Riding, Alan (30 March 1994). «Drinking champagne with: Brigitte Bardot; And God Created An Animal Lover». The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ «Bardot fined for racist remarks». BBC News. London. 16 June 2000. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ «Bardot racism conviction upheld». BBC News. London. 11 May 2001. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ «Bardot anti-Muslim comments draw fire». BBC News. London. 14 May 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ Webster, Paul; Hearst, David (5 May 2003). «Anti-gay, anti-Islam Bardot to be sued». The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ Usborne, David (24 March 2006). «Brigitte a Political Animal». The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- ^ a b «Bardot fine for stoking race hate». BBC News. London, UK. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ «Bardot fined for ‘race hate’ book». BBC News. 10 June 2004. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ Larent, Shermy (12 May 2003). «Brigitte Bardot unleashes colourful diatribe against Muslims and modern France». Indybay. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ «Bardot denies ‘race hate’ charge». BBC News. 7 May 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ «Brigitte Bardot calls Sarah Palin a ‘disgrace to women'» The Telegraph, 8 October 2008.

- ^ «Brigitte Bardot: ‘Wait Until I’M Dead Before You Make Biopic’«. Showbiz Spy. 14 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ «EJC outraged at Brigitte Bardot’s demand for French government to ban Shechita». Official Site of the European Jewish Congress. 9 September 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Samuel, Henry (9 June 2015). «Brigitte Bardot declares war on commercial ‘abuse’ of her image». The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Fourny, Marc (3 December 2018). «Brigitte Bardot demande » une prime de Noël » pour les Gilets jaunes». Le Point (in French). Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ «La justice …» [Justice being seized after offensive remarks by Brigitte Bardot against Reunionese]. Le Monde (in French). AFP; Reuters. 20 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Mesureur, Claire (29 June 2021). «Brigitte …» [Brigitte Bardot convicted for public insult against Willy Schraen, the president of the hunters]. France Bleu (in French). Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «France …» [France: Brigitte Bardot is fined 20,000 euros for insulting the Reunionese]. RTBF (in French). Belgium. 4 November 2021. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Chazan, David (22 August 2014). «Brigitte Bardot calls Marine Le Pen ‘modern Joan of Arc». The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ Willsher, Kim (13 September 2012). «Brigitte Bardot: celebrity crushed me». The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Zoltany, Monika (7 May 2017). «Brigitte Bardot Supports Underdog Marine Le Pen in French Presidential Election, Says Macron Has Cold Eyes». Inquisitr. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ «Brigitte Bardot: the style icon − in pictures». The Guardian. 1 December 2016. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ «Bikinis: a brief history». Telegraph. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ a b «Brigitte Bardot». Grazia (in French). n.d. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Johnson, William Oscar (7 February 1989). «In The Swim». Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ «Style Icon: Brigitte Bardot». Femminastyle.com. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Biedenharn, Isabella (4 November 2014). «The 20 Best Legs Throughout History». Elle. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

Note: slide 18

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Sweeney, Kathleen (2008). Maiden USA: Girl Icons Come of Age. Atlanta: Peter Lang. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-820-48197-5.

- ^ «Ces stars qui ont posé pour Playboy» [These stars who posed for Playboy]. Gala (in French). Paris. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «Gisele Bündchen topless joue les Brigitte Bardot…» [Gisele Bündchen topless plays Brigitte Bardot…]. Puremédias (in French). Levallois-Perret. 28 April 2011. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «Rihanna on GQ magazine». GQ. UK. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021 – via Fashion Has It.

- ^ «TOemBUZIOS.com». toembuzios.com (in Portuguese). TOemBUZIOS.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ «BúziosOnline.com». BúziosOnline.com. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Miles, Barry (1998). Many Years From Now. Vintage–Random House. ISBN 978-0-7493-8658-0. pg. 69.

- ^ Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Little, Brown and Company (New York). ISBN 978-1-84513-160-9. pg. 171.

- ^ Lennon, John (1986). Skywriting by Word of Mouth. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-015656-5. pg. 24.

- ^ Brigitte Bardot at 75: the exhibition Archived 26 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, connexionfrance.com, September 2009; accessed 4 August 2015.

- ^ Bigot 2014, p. 26–27.

- ^ Spencer, Kathleen (2011). «L.A Times Magazine Names Their 50 Most Beautiful Women In Film». Momtastic. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Milligan, Lauren (28 October 2013). «Nicole Kidman Talks Becoming Bardot». Vogue. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ «The Top Ten Most Beautiful Women Of ALL Time». Heart. 6 January 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Garrigues, Manon (4 June 2020). «The most beautiful French actresses of all time». Vogue. Translated by Stephanie Green. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Smith, Josh (4 August 2020). «From Marilyn to Margot: the most accomplished, talented and beautiful actresses of all time». Glamour. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «Bardot : découvrez la première photo de Julia de Nunez en Brigitte Bardot et le casting cinq étoiles de la série de France 2». AlloCiné. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Choulant 2019, p. 65.

- ^ Lee, Sophie (28 September 2020). «The 10 Chicest Moments in Brigitte Bardot’s Career». L’Officiel. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Choulant 2019, p. 93.

- ^ Choulant 2019, p. 103.

- ^ Choulant 2019, p. 156.

- ^ «Bambi Awards 1967» (PDF). Elke Sommer Online (in German). n.d. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «BAFTA: Film in 1967». British Academy of Film and Television Arts. n.d. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e «Media and Art Advisory Board». Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. n.d. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «Légion d’Honneur: quelles célébrités l’ont refusée?» [Legion of Honor: which celebrities have refused it?]. La Dépêche du Midi (in French). 10 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ C. Trott, William (11 April 1985). «Brigitte Bardot accepts the French Legion of Honor medal». United Press International.

- ^ Töpfer, Klaus (n.d.). «1992 Global 500 Laureates». UNEP − The Global 500 Roll of Honour for Environmental Achievement. Yumpu. p. 63.

- ^ Robinson, Jeffrey (2014). Bardot, deux vies (in French). Translated by Jean-paul Mourlon. New York: L’Archipel. p. 252. ISBN 978-2-809-81562-7.

- ^ Bigot 2014, p. 303.

- ^ Bigot 2014, p. 255.

- ^ «Discovered at Anderson Mesa on 1999-04-10 by Loneos. (17062) Bardot − 1999 GR8». Minor Planet Center. n.d. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «La Fundación Altarriba …» 20 minutos (in Spanish). 3 May 2008. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ «Saint-Tropez …» [Saint-Tropez: A statue of Brigitte Bardot installed in front of the gendarmerie]. 20 minutes (in French). AFP. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021. [The bronze is inspired by a watercolor by the Italian master of erotic cartoon comic, Milo Manara.]

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «Brigitte…» [Brigitte Bardot awarded by GAIA]. DPG Media (in French). 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Peté, Rodolphe (27 June 2021). «Désormais …» [Now covered with thousands of gold leaves, the statue of Brigitte Bardot unveiled in Saint-Tropez]. Nice-Matin (in French). Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Other sources

- Bardot, Brigitte (1996). Initiales B.B. : Mémoires (in French). Éditions Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246526018.

- Bigot, Yves (2014). Brigitte Bardot. La femme la plus belle et la plus scandaleuse au monde (in French). Don Quichotte. ISBN 978-2-359490145.

- Caron, Leslie (2009). Thank Heaven. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670021345.

- Cherry, Elizabeth (2016). Culture and Activism: Animal Rights in France and the United States. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317156154.

- Choulant, Dominique (2019). Brigitte Bardot pour toujours [Brigitte Bardot forever] (in French). Paris: Éditions Lanore. ISBN 978-2-8515-7903-4.

- Lelièvre, Marie-Dominique (2012). Brigitte Bardot – Plein la vue (in French). Groupe Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-124624-9.

- Probst, Ernst (2012). Das Sexsymbol der 1950-er Jahre (in German). GRIN Publishing. ISBN 978-3-656186212.

- Singer, Barnett (2006). Brigitte Bardot : A Biography. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0786425150.

- Vincendeau, Ginette (March 1992). «The old and the new: Brigitte Bardot in 1950s France». Paragraph. Edinburgh University Press. 15 (1): 73–96. doi:10.3366/para.1992.0004. JSTOR 43151735.

Literature[edit]

- Brigitte Tast, Hans-Jürgen Tast (Hrsg.) Brigitte Bardot. Filme 1953–1961. Anfänge des Mythos B.B. (Hildesheim 1982) ISBN 3-88842-109-8.

- Servat, Henry-Jean (2016). Brigitte Bardot – My Life in Fashion (Hardback). Paris: Flammation S.A. ISBN 978-2—08-0202697.

External links[edit]

- Official website (in English)

- Fondation Brigitte Bardot (in French)

- Brigitte Bardot at IMDb

- Brigitte Bardot at the TCM Movie Database

- Brigitte Bardot at AllMovie

|

Brigitte Bardot |

|

|---|---|

Bardot in a publicity photo for A Very Private Affair (1962) |

|

| Born |

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot 28 September 1934 (age 88) Paris, France |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1952–present |

| Works |

|

| Spouses |

Roger Vadim (m. 1952; div. 1957) Jacques Charrier (m. 1959; div. 1962) Gunter Sachs (m. 1966; div. 1969) Bernard d’Ormale (m. 1992) |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Mijanou Bardot (sister) |

| Signature | |

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot ( brizh-EET bar-DOH; French: [bʁiʒit baʁdo] (listen); born 28 September 1934), often referred to by her initials B.B.,[1][2] is a French, former actress, singer and model. Famous for portraying sexually emancipated characters with hedonistic lifestyles, she was one of the best known sex symbols of the 1950s and 1960s. Although she withdrew from the entertainment industry in 1973, she remains a major popular culture icon.[3]

Born and raised in Paris, Bardot was an aspiring ballerina in her early life. She started her acting career in 1952. She achieved international recognition in 1957 for her role in And God Created Woman (1956), and also caught the attention of French intellectuals. She was the subject of Simone de Beauvoir’s 1959 essay The Lolita Syndrome, which described her as a «locomotive of women’s history» and built upon existentialist themes to declare her the first and most liberated woman of post-war France. She won a 1961 David di Donatello Best Foreign Actress Award for her work in The Truth. Bardot later starred in Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le Mépris (1963). For her role in Louis Malle’s film Viva Maria! (1965) she was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress.

Bardot retired from the entertainment industry in 1973. She had acted in 47 films, performed in several musicals, and recorded more than 60 songs. She was awarded the Legion of Honour in 1985. After retiring, she became an animal rights activist and created the Fondation Brigitte Bardot. Bardot is known for her strong personality, outspokenness, and speeches on animal defence; she has been fined twice for public insults. She has also been a controversial political figure, having been fined five times for inciting racial hatred when she criticised immigration and Islam in France.[4] She is married to Bernard d’Ormale, a former adviser to Jean-Marie Le Pen, a French far-right politician. Bardot is a member of the Global 500 Roll of Honour of the United Nations Environment Programme and has received awards from UNESCO and PETA. Los Angeles Times Magazine ranked her second on the «50 Most Beautiful Women In Film».

Early life[edit]

Bardot was born on 28 September 1934 in the 15th arrondissement of Paris, to Louis Bardot (1896–1975) and Anne-Marie Mucel (1912–1978).[5] Bardot’s father, originated from Ligny-en-Barrois, was an engineer and the proprietor of several industrial factories in Paris.[6][7] Her mother was the daughter of an insurance company director.[8] She grew up in a conservative Catholic family, as had her father.[9][10] She suffered from amblyopia as a child, which resulted in decreased vision of her left eye.[11] She has one younger sister, Mijanou Bardot.[12]

Bardot’s childhood was prosperous; she lived in her family’s seven-bedroom apartment in the luxurious 16th arrondissement.[10][13] However, she recalled feeling resentful in her early years.[14] Her father demanded that she follow strict behavioural standards, including good table manners, and wear appropriate clothes.[15] Her mother was extremely selective in choosing companions for her, and as a result, Bardot had very few childhood friends.[16] Bardot cited a personal traumatic incident when she and her sister broke her parents’ favourite vase while they were playing in the house; her father whipped the sisters 20 times and henceforth treated them like «strangers», demanding them to address their parents by the pronoun «vous», which is a formal style of address, used when speaking to unfamiliar or higher-status persons outside the immediate family.[17] The incident decisively led to Bardot resenting her parents, and to her future rebellious lifestyle.[18]

During World War II, when Paris was occupied by Nazi Germany, Bardot spent more time at home due to increasingly strict civilian surveillance.[13] She became engrossed in dancing to records, which her mother saw as a potential for a ballet career.[13] Bardot was admitted at the age of seven to the private school Cours Hattemer.[19] She went to school three days a week, which gave her ample time to take dance lessons at a local studio, under her mother’s arrangements.[16] In 1949, Bardot was accepted at the Conservatoire de Paris. For three years she attended ballet classes held by Russian choreographer Boris Knyazev.[20] She also studied at the Institut de la Tour, a private Catholic high school near her home.[21]

Hélène Gordon-Lazareff, the then-director of the magazines Elle and Le Jardin des Modes, hired Bardot in 1949 as a «junior» fashion model.[22] On 8 March 1950, Bardot (aged 15 at the time) appeared on the cover of Elle, which brought her an acting offer for the film Les Lauriers sont coupés from director Marc Allégret.[23] Her parents opposed her becoming an actress, but her grandfather was supportive, saying that «If this little girl is to become a whore, cinema will not be the cause.»[A] At the audition, Bardot met Roger Vadim, who later notified her that she did not get the role.[25] They subsequently fell in love.[26] Her parents fiercely opposed their relationship; her father announced to her one evening that she would continue her education in England and that he had bought her a train ticket, the journey to take place the following day.[27] Bardot reacted by putting her head into an oven with open fire; her parents stopped her and ultimately accepted the relationship, on condition that she marry Vadim at the age of 18.[28]

Career[edit]

Beginnings: 1952–1955[edit]

Bardot appeared on the cover of Elle again in 1952, which landed her a movie offer for the comedy Crazy for Love (1952), starring Bourvil and directed by Jean Boyer.[29] She was paid 200,000 francs (5558.69 US dollars) for the small role portraying a cousin of the main character.[29] Bardot had her second film role in Manina, the Girl in the Bikini (1953),[B] directed by Willy Rozier.[30] She also had roles in the films The Long Teeth and His Father’s Portrait (both 1953).

Bardot had a small role in a Hollywood-financed film being shot in Paris, Act of Love (1953), starring Kirk Douglas. She received media attention when she attended the Cannes Film Festival in April 1953.[31]

Bardot had a leading role in an Italian melodrama, Concert of Intrigue (1954) and in a French adventure film, Caroline and the Rebels (1954). She had a good part as a flirtatious student in School for Love (1955), opposite Jean Marais, for director Marc Allégret.

Bardot played her first sizeable English-language role in Doctor at Sea (1955), as the love interest for Dirk Bogarde. The film was the third-most-popular movie at the British box-office that year.[32]

She had a small role in The Grand Maneuver (1955) for director René Clair, supporting Gérard Philipe and Michelle Morgan. The part was bigger in The Light Across the Street (1956) for director Georges Lacombe. She had another in the Hollywood film, Helen of Troy, playing Helen’s handmaiden.

For the Italian movie Mio figlio Nerone (1956) Bardot was asked by the director to appear as a blonde. Rather than wear a wig to hide her naturally brunette hair she decided to dye her hair. She was so pleased with the results that she decided to retain the hair colour.[33]

Rise to stardom: 1956–1962[edit]

Bardot then appeared in four movies that made her a star. First up was a musical, Naughty Girl (1956), where Bardot played a troublesome school girl. Directed by Michel Boisrond, it was co-written by Roger Vadim and was a big hit, the 12th most popular film of the year in France.[34] It was followed by a comedy, Plucking the Daisy (1956), written by Vadim with the director Marc Allégret, and another success in France. So too was the comedy The Bride Is Much Too Beautiful (1956) with Louis Jourdan.

Finally there was the melodrama And God Created Woman (1956), Vadim’s debut as director, with Bardot starring opposite Jean-Louis Trintignant and Curt Jurgens. The film, about an immoral teenager in a respectable small-town setting, was a huge success, not just in France but also around the world – it was among the ten most popular films in Britain in 1957.[35] It turned Bardot into an international star.[31] From at least 1956,[36] she was being hailed as the «sex kitten».[37][38][39] The film scandalized the United States and theatre managers were arrested for screening it.[40]

During her early career, professional photographer Sam Lévin’s photos contributed to the image of Bardot’s sensuality. One showed Bardot from behind, dressed in a white corset. British photographer Cornel Lucas made images of Bardot in the 1950s and 1960s that have become representative of her public persona.

Bardot followed And God Created Woman with La Parisienne (1957), a comedy co-starring Charles Boyer for director Boisrond. She was reunited with Vadim in another melodrama The Night Heaven Fell (1958) and played a criminal who seduced Jean Gabin in In Case of Adversity (1958). The latter was the 13th most seen movie of the year in France.[41] In 1958, Bardot became the highest-paid French actress.[42]

The Female (1959) for director Julien Duvivier was popular, but Babette Goes to War (1959), a comedy set in World War II, was a huge hit, the fourth biggest movie of the year in France.[43] Also widely seen was Come Dance with Me (1959) from Boisrond.

Her next film was the courtroom drama The Truth (1960), from Henri-Georges Clouzot. It was a highly publicised production, which resulted in Bardot having an affair and attempting suicide. The film was Bardot’s biggest commercial success in France, the third biggest hit of the year, and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film.[44] Bardot was awarded a David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Actress for her role in the film.[45]

She made a comedy with Vadim, Please, Not Now! (1961), and had a role in the all-star anthology, Famous Love Affairs (1962).

Bardot starred alongside Marcello Mastroianni in a film inspired by her life in A Very Private Affair (Vie privée, 1962), directed by Louis Malle. More popular in France was Love on a Pillow (1962), another for Vadim.

International films and singing career: 1962–1968[edit]

Bardot visiting Brazil, 1964

In the mid-1960s, Bardot made films that seemed to be more aimed at the international market. She starred in Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le Mépris (1963), produced by Joseph E. Levine and starring Jack Palance. The following year she co-starred with Anthony Perkins in the comedy Une ravissante idiote (1964).

Dear Brigitte (1965), Bardot’s first Hollywood film, was a comedy starring James Stewart as an academic whose son develops a crush on Bardot. Bardot’s appearance was relatively brief and the film was not a big hit.

More successful was the Western buddy comedy Viva Maria! (1965) for director Louis Malle, appearing opposite Jeanne Moreau. It was a big hit in France and worldwide, although it did not break through in the US as much as it had been hoped.[46]

After a cameo in Godard’s Masculin Féminin (1966), she had her first outright flop for some years, Two Weeks in September (1968), a French–English co-production. She had a small role in the all-star Spirits of the Dead (1968), acting opposite Alain Delon, then tried a Hollywood film again: Shalako (1968), a Western starring Sean Connery, which was a box-office disappointment.[47]

She participated in several musical shows and recorded many popular songs in the 1960s and 1970s, mostly in collaboration with Serge Gainsbourg, Bob Zagury and Sacha Distel, including «Harley Davidson»; «Je Me Donne À Qui Me Plaît»; «Bubble gum»; «Contact»; «Je Reviendrai Toujours Vers Toi»; «L’Appareil À Sous»; «La Madrague»; «On Déménage»; «Sidonie»; «Tu Veux, Ou Tu Veux Pas?»; «Le Soleil De Ma Vie» (a cover of Stevie Wonder’s «You Are the Sunshine of My Life»); and «Je t’aime… moi non-plus». Bardot pleaded with Gainsbourg not to release this duet and he complied with her wish; the following year, he rerecorded a version with British-born model and actress Jane Birkin that became a massive hit all over Europe. The version with Bardot was issued in 1986 and became a download hit in 2006 when Universal Music made its back catalogue available to purchase online, with this version of the song ranking as the third most popular download.[48]

Final films: 1969–1973[edit]

From 1969 to 1978, Bardot was the official face of Marianne (who had previously been anonymous) to represent the liberty of France.[49]

Les Femmes (1969) was a flop, although the screwball comedy The Bear and the Doll (1970) performed better. Her last few films were mostly comedies: Les Novices (1970), Boulevard du Rhum (1971) (with Lino Ventura). The Legend of Frenchie King (1971) was more popular, helped by Bardot co-starring with Claudia Cardinale.

She made one more with Vadim, Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman (1973), playing the title role. Vadim said the film marked «Underneath what people call ‘the Bardot myth’ was something interesting, even though she was never considered the most professional actress in the world. For years, since she has been growing older, and the Bardot myth has become just a souvenir… I was curious in her as a woman and I had to get to the end of something with her, to get out of her and express many things I felt were in her. Brigitte always gave the impression of sexual freedom – she is a completely open and free person, without any aggression. So I gave her the part of a man – that amused me».[50]

«If Don Juan is not my last movie it will be my next to last», said Bardot during filming.[51] She kept her word and only made one more film, The Edifying and Joyous Story of Colinot (1973).

In 1973, Bardot announced she was retiring from acting as «a way to get out elegantly».[52]

Animal rights activism[edit]

After appearing in more than 40 motion pictures and recording several music albums, Bardot used her fame to promote animal rights.

In 1986, she established the Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the Welfare and Protection of Animals.[53] She became a vegetarian[54] and raised three million francs (959169.7 US dollars) to fund the foundation by auctioning off jewellery and personal belongings.[53]

She once had a neighbour’s donkey castrated while looking after it, on the grounds of its «sexual harassment» of her own donkey and mare, for which she was taken to court by the donkey’s owner in 1989.[55][56] Bardot wrote a 1999 letter to Chinese President Jiang Zemin, published in French magazine VSD, in which she accused the Chinese of «torturing bears and killing the world’s last tigers and rhinos to make aphrodisiacs».

She has donated more than $140,000 over two years for a mass sterilization and adoption program for Bucharest’s stray dogs, estimated to number 300,000.[57]

Bardot is a strong animal rights activist and a major opponent of the consumption of horse meat. In support of animal protection, she condemned seal hunting in Canada during a visit to that country with Paul Watson of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society.[58] In August 2010, Bardot addressed a letter to the Queen of Denmark, Margarethe II, appealing for the sovereign to halt the killing of dolphins in the Faroe Islands. In the letter, Bardot describes the activity as a «macabre spectacle» that «is a shame for Denmark and the Faroe Islands … This is not a hunt but a mass slaughter … an outmoded tradition that has no acceptable justification in today’s world».[59]

On 22 April 2011, French culture minister Frédéric Mitterrand officially included bullfighting in the country’s cultural heritage. Bardot wrote him a highly critical letter of protest.[60] On 25 May 2011, the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society renamed its fast interceptor vessel, MV Gojira, as MV Brigitte Bardot in appreciation of her support.[61]

From 2013 onwards, the Brigitte Bardot Foundation in collaboration with Kagyupa International Monlam Trust of India has operated an annual veterinary care camp. She has committed to the cause of animal welfare in Bodhgaya year after year.[62]

On 23 July 2015, Bardot condemned Australian politician Greg Hunt’s plan to eradicate 2 million cats to save endangered species such as the Warru and night parrot.[63]

Personal life[edit]

Marriages and relationships[edit]

Throughout her life, Bardot had seventeen relationships with men and was married four times.[64] Bardot was leaving for another relationship when «the present was getting lukewarm»; she said, «I have always looked for passion. That’s why I was often unfaithful. And when the passion was coming to an end, I was packing my suitcase».[65]

On 20 December 1952, aged 18, Bardot married director Roger Vadim.[66] In 1956, she had become romantically involved with Jean-Louis Trintignant, who was her co-star in And God Created Woman. Trintignant at the time was married to actress Stéphane Audran. Bardot and Vadim divorced in 1957; they had no children together, but remained in touch, and even collaborated on later projects. The stated reason for the divorce was Bardot’s affairs with two other men.[67][31] Bardot and Trintignant lived together for about two years, spanning the period before and after Bardot’s divorce from Vadim, but they never married. Their relationship was complicated by Trintignant’s frequent absence due to military service and Bardot’s affair with musician Gilbert Bécaud.[67]

After her separation from Vadim, Bardot acquired a historic property dating from the 16th century, called Le Castelet, in Cannes. The fourteen-bedroom villa, surrounded by lush gardens, olive trees, and vineyards, consisted of several buildings.[68]

In 1958, she bought a second property called La Madrague, located in Saint-Tropez.[68] In early 1958, her break-up with Trintignant was followed in quick order by a reported nervous breakdown in Italy, according to newspaper reports. A suicide attempt with sleeping pills two days earlier was also noted but was denied by her public relations manager.[69] She recovered within weeks and began a relationship with actor Jacques Charrier. She became pregnant well before they were married on 18 June 1959. Bardot’s only child, her son Nicolas-Jacques Charrier, was born on 11 January 1960.[67] Bardot had an affair with Glenn Ford in the early 1960s.[70] After she and Charrier divorced in 1962, Nicolas was raised in the Charrier family and had little contact with his biological mother until his adulthood.[67] Sami Frey was mentioned as the reason for her divorce from Charrier. Bardot was enamoured of Frey, but he quickly left her.[71]

From 1963 to 1965, she lived with musician Bob Zagury.[72]

Bardot’s third marriage was to German millionaire playboy Gunter Sachs, lasting from 14 July 1966 to 7 October 1969, though they had separated the previous year.[67][31][73] As she was on the set of Shalako, she had rejected Sean Connery’s advances; she said, «It didn’t last long because I wasn’t a James Bond girl! I have never succumbed to his charm!»[74] In 1968, she began dating Patrick Gilles, who co-starred with her in The Bear and the Doll (1970); but she ended their relationship in spring 1971.[72]

Over the next few years, Bardot dated in succession bartender/ski instructor Christian Kalt, club owner Luigi Rizzi, singer Serge Gainsbourg, writer John Gilmore, actor Warren Beatty, and Laurent Vergez, her co-star in Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman.[72][75]

In 1974, Bardot appeared in a nude photo shoot in Playboy magazine, which celebrated her 40th birthday. In 1975, she entered a relationship with artist Miroslav Brozek and posed for some of his sculptures. Brozek was also an actor; his stage name is Jean Blaise [fr].[76] The couple lived together at La Madrague. They separated in December 1979.[77]