| Brucellosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | undulant fever, undulating fever, Mediterranean fever, Malta fever, Cyprus fever, rock fever (Micrococcus melitensis)[1] |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | fever, chills, loss of appetite, sweats, weakness, fatigue, Joint, muscle and back pain, Headache.[2] |

| Complications | central nervous system infections, inflammation and infection of the spleen and liver, inflammation and infection of the testicles (epididymo-orchitis), Arthritis, Inflammation of the inner lining of the heart chambers (endocarditis).[2] |

| Diagnostic method | x-rays, computerized tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cerebrospinal fluid culture, echocardiography.[3] |

| Prevention | avoid unpasteurized dairy foods, cook meat thoroughly, wear gloves, take safety precautions in high-risk workplaces, vaccinate domestic animals.[2] |

| Treatment | antibiotics |

| Medication | tetracyclines, rifampicin, aminoglycosides |

Brucellosis[4][5] is a highly contagious zoonosis caused by ingestion of unpasteurized milk or undercooked meat from infected animals, or close contact with their secretions.[6] It is also known as undulant fever, Malta fever, and Mediterranean fever.[7]

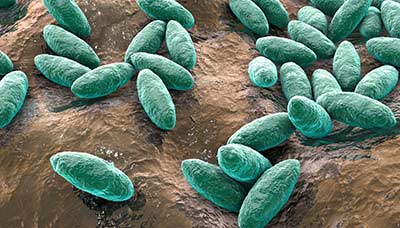

The bacteria causing this disease, Brucella, are small, Gram-negative, nonmotile, nonspore-forming, rod-shaped (coccobacilli) bacteria. They function as facultative intracellular parasites, causing chronic disease, which usually persists for life. Four species infect humans: B. abortus, B. canis, B. melitensis, and B. suis. B. abortus is less virulent than B. melitensis and is primarily a disease of cattle. B. canis affects dogs. B. melitensis is the most virulent and invasive species; it usually infects goats and occasionally sheep. B. suis is of intermediate virulence and chiefly infects pigs. Symptoms include profuse sweating and joint and muscle pain. Brucellosis has been recognized in animals and humans since the early 20th century.[8][9]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

A graph of the cases of brucellosis in humans in the United States from the years 1993–2010 surveyed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System[10]

The symptoms are like those associated with many other febrile diseases, but with emphasis on muscular pain and night sweats. The duration of the disease can vary from a few weeks to many months or even years.

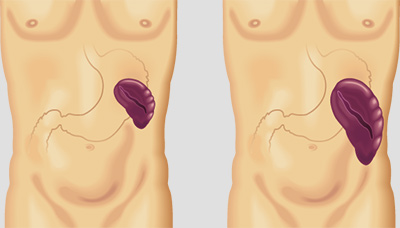

In the first stage of the disease, bacteremia occurs and leads to the classic triad of undulant fevers, sweating (often with characteristic foul, moldy smell sometimes likened to wet hay), and migratory arthralgia and myalgia (joint and muscle pain).[citation needed] Blood tests characteristically reveal a low number of white blood cells and red blood cells, show some elevation of liver enzymes such as aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, and demonstrate positive Bengal rose and Huddleston reactions. Gastrointestinal symptoms occur in 70% of cases and include nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, unintentional weight loss, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, an enlarged liver, liver inflammation, liver abscess, and an enlarged spleen.[citation needed]

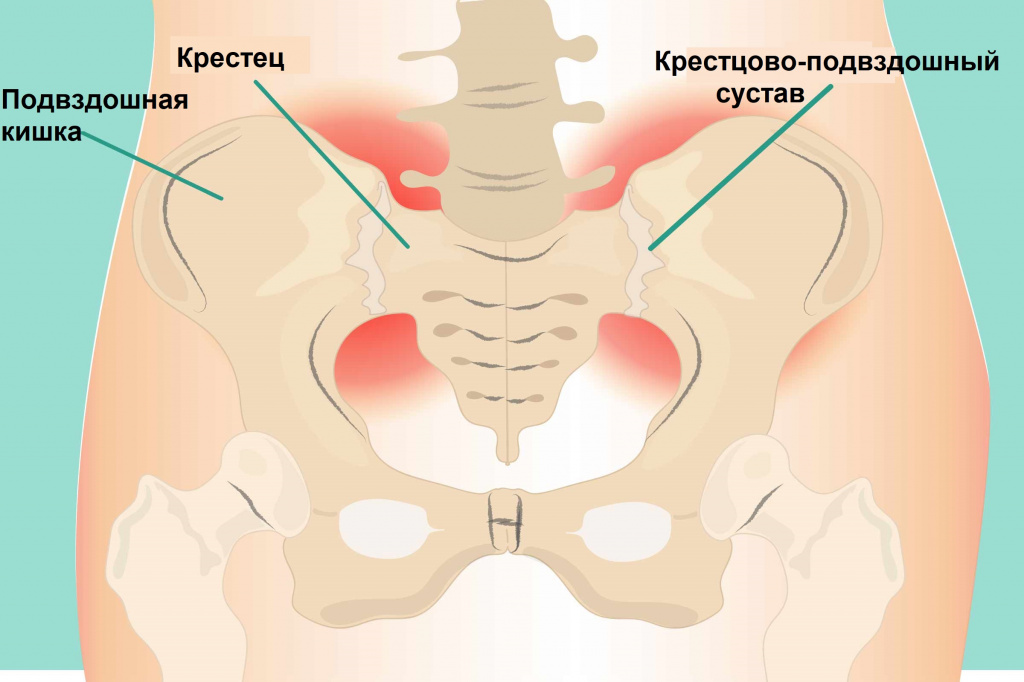

This complex is, at least in Portugal, Israel, Syria, and Jordan, known as Malta fever. During episodes of Malta fever, melitococcemia (presence of brucellae in the blood) can usually be demonstrated by means of blood culture in tryptose medium or Albini medium. If untreated, the disease can give origin to focalizations[clarification needed] or become chronic. The focalizations of brucellosis occur usually in bones and joints, and osteomyelitis or spondylodiscitis of the lumbar spine accompanied by sacroiliitis is very characteristic of this disease. Orchitis is also common in men.

The consequences of Brucella infection are highly variable and may include arthritis, spondylitis, thrombocytopenia, meningitis, uveitis, optic neuritis, endocarditis, and various neurological disorders collectively known as neurobrucellosis.

Cause[edit]

Brucellosis in humans is usually associated with consumption of unpasteurized milk and soft cheeses made from the milk of infected animals—primarily goats, infected with B. melitensis and with occupational exposure of laboratory workers, veterinarians, and slaughterhouse workers.[11] Some vaccines used in livestock, most notably B. abortus strain 19, also cause disease in humans if accidentally injected. Brucellosis induces inconstant fevers, miscarriage, sweating, weakness, anemia, headaches, depression, and muscular and bodily pain. The other strains, B. suis and B. canis, cause infection in pigs and dogs, respectively.[citation needed]

Overall findings support that brucellosis poses an occupational risk to goat farmers with specific areas of concern including weak awareness of disease transmission to humans and lack of knowledge on specific safe farm practices such as quarantine practices.[12]

Diagnosis[edit]

Brucella Coombs Gel Test. Seropositivity detected to GN177

The diagnosis of brucellosis relies on:[citation needed]

- Demonstration of the agent: blood cultures in tryptose broth, bone marrow cultures: The growth of brucellae is extremely slow (they can take up to two months to grow) and the culture poses a risk to laboratory personnel due to high infectivity of brucellae.

- Demonstration of antibodies against the agent either with the classic Huddleson, Wright, and/or Bengal Rose reactions, either with ELISA or the 2-mercaptoethanol assay for IgM antibodies associated with chronic disease

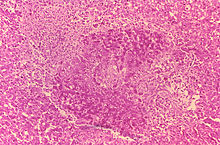

- Histologic evidence of granulomatous hepatitis on hepatic biopsy

- Radiologic alterations in infected vertebrae: the Pedro Pons sign (preferential erosion of the anterosuperior corner of lumbar vertebrae) and marked osteophytosis are suspicious of brucellic spondylitis.

Definite diagnosis of brucellosis requires the isolation of the organism from the blood, body fluids, or tissues, but serological methods may be the only tests available in many settings. Positive blood culture yield ranges between 40 and 70% and is less commonly positive for B. abortus than B. melitensis or B. suis. Identification of specific antibodies against bacterial lipopolysaccharide and other antigens can be detected by the standard agglutination test (SAT), rose Bengal, 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), antihuman globulin (Coombs’) and indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). SAT is the most commonly used serology in endemic areas.[13][14] An agglutination titre greater than 1:160 is considered significant in nonendemic areas and greater than 1:320 in endemic areas.[citation needed]

Due to the similarity of the O polysaccharide of Brucella to that of various other Gram-negative bacteria (e.g. Francisella tularensis, Escherichia coli, Salmonella urbana, Yersinia enterocolitica, Vibrio cholerae, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia), the appearance of cross-reactions of class M immunoglobulins may occur. The inability to diagnose B. canis by SAT due to lack of cross-reaction is another drawback. False-negative SAT may be caused by the presence of blocking antibodies (the prozone phenomenon) in the α2-globulin (IgA) and in the α-globulin (IgG) fractions.[citation needed]

Dipstick assays are new and promising, based on the binding of Brucella IgM antibodies, and are simple, accurate, and rapid. ELISA typically uses cytoplasmic proteins as antigens. It measures IgM, IgG, and IgA with better sensitivity and specificity than the SAT in most recent comparative studies.[15] The commercial Brucellacapt test, a single-step immunocapture assay for the detection of total anti-Brucella antibodies, is an increasingly used adjunctive test when resources permit. PCR is fast and should be specific. Many varieties of PCR have been developed (e.g. nested PCR, realtime PCR, and PCR-ELISA) and found to have superior specificity and sensitivity in detecting both primary infection and relapse after treatment.[16] Unfortunately, these are not standardized for routine use, and some centres have reported persistent PCR positivity after clinically successful treatment, fuelling the controversy about the existence of prolonged chronic brucellosis.[citation needed]

Other laboratory findings include normal peripheral white cell count, and occasional leucopenia with relative lymphocytosis. The serum biochemical profiles are commonly normal.[17]

Prevention[edit]

Surveillance using serological tests, as well as tests on milk such as the milk ring test, can be used for screening and play an important role in campaigns to eliminate the disease. Also, individual animal testing both for trade and for disease-control purposes is practiced. In endemic areas, vaccination is often used to reduce the incidence of infection. An animal vaccine is available that uses modified live bacteria. The World Organisation for Animal Health Manual of Diagnostic Test and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals provides detailed guidance on the production of vaccines. As the disease is closer to being eliminated, a test and eradication program is required to eliminate it.[citation needed]

The main way of preventing brucellosis is by using fastidious hygiene in producing raw milk products, or by pasteurizing all milk that is to be ingested by human beings, either in its unaltered form or as a derivative, such as cheese.[citation needed]

Treatment[edit]

Antibiotics such as tetracyclines, rifampicin, and the aminoglycosides streptomycin and gentamicin are effective against Brucella bacteria. However, the use of more than one antibiotic is needed for several weeks, because the bacteria incubate within cells.[citation needed]

The gold standard treatment for adults is daily intramuscular injections of streptomycin 1 g for 14 days and oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 45 days (concurrently). Gentamicin 5 mg/kg by intramuscular injection once daily for 7 days is an acceptable substitute when streptomycin is not available or contraindicated.[18] Another widely used regimen is doxycycline plus rifampicin twice daily for at least 6 weeks. This regimen has the advantage of oral administration. A triple therapy of doxycycline, with rifampicin and co-trimoxazole, has been used successfully to treat neurobrucellosis.[19] Doxycycline plus streptomycin regimen (for 2 to 3 weeks) is more effective than doxycycline plus rifampicin regimen (for 6 weeks).[20]

Doxycycline is able to cross the blood–brain barrier, but requires the addition of two other drugs to prevent relapse. Ciprofloxacin and co-trimoxazole therapy is associated with an unacceptably high rate of relapse. In brucellic endocarditis, surgery is required for an optimal outcome. Even with optimal antibrucellic therapy, relapses still occur in 5 to 10% of patients with Malta fever.[citation needed]

Prognosis[edit]

The mortality of the disease in 1909, as recorded in the British Army and Navy stationed in Malta, was 2%. The most frequent cause of death was endocarditis. Recent advances in antibiotics and surgery have been successful in preventing death due to endocarditis. Prevention of human brucellosis can be achieved by eradication of the disease in animals by vaccination and other veterinary control methods such as testing herds/flocks and slaughtering animals when infection is present. Currently, no effective vaccine is available for humans. Boiling milk before consumption, or before using it to produce other dairy products, is protective against transmission via ingestion. Changing traditional food habits of eating raw meat, liver, or bone marrow is necessary, but difficult to implement.[citation needed] Patients who have had brucellosis should probably be excluded indefinitely from donating blood or organs. Exposure of diagnostic laboratory personnel to Brucella organisms remains a problem in both endemic settings and when brucellosis is unknowingly imported by a patient.[21] After appropriate risk assessment, staff with significant exposure should be offered postexposure prophylaxis and followed up serologically for 6 months.[22]

Epidemiology[edit]

Argentina[edit]

According to a study published in 2002, an estimated 10–13% of farm animals are infected with Brucella species.[23] Annual losses from the disease were calculated at around $60 million. Since 1932, government agencies have undertaken efforts to contain the disease. Currently, all cattle of ages 3–8 months must receive the Brucella abortus strain 19 vaccine.[24]

Australia[edit]

Australia is free of cattle brucellosis, although it occurred in the past. Brucellosis of sheep or goats has never been reported. Brucellosis of pigs does occur. Feral pigs are the typical source of human infections.[25][26]

Canada[edit]

On 19 September 1985, the Canadian government declared its cattle population brucellosis-free. Brucellosis ring testing of milk and cream, and testing of cattle to be slaughtered ended on 1 April 1999. Monitoring continues through testing at auction markets, through standard disease-reporting procedures, and through testing of cattle being qualified for export to countries other than the United States.[27]

China[edit]

An outbreak infecting humans took place in Lanzhou in 2020 after the Lanzhou Biopharmaceutical Plant, which was involved in vaccine production, accidentally pumped out the bacteria into the atmosphere in exhaust air due to use of expired disinfectant. The outbreak affected over 6,000 people.[28][29]

Europe[edit]

Disease incidence map of B. melitensis infections in animals in Europe during the first half of 2006

never reported

not reported in this period

confirmed clinical disease

confirmed infection

no information

Malta[edit]

Until the early 20th century, the disease was endemic in Malta to the point of it being referred to as «Maltese fever». Since 2005, due to a strict regimen of certification of milk animals and widespread use of pasteurization, the illness has been eradicated from Malta.[30]

Republic of Ireland[edit]

Ireland was declared free of brucellosis on 1 July 2009. The disease had troubled the country’s farmers and veterinarians for several decades.[31][32] The Irish government submitted an application to the European Commission, which verified that Ireland had been liberated.[32] Brendan Smith, Ireland’s then Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, said the elimination of brucellosis was «a landmark in the history of disease eradication in Ireland».[31][32] Ireland’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine intends to reduce its brucellosis eradication programme now that eradication has been confirmed.[31][32]

UK[edit]

Mainland Britain has been free of brucellosis since 1979, although there have been episodic re-introductions since.[33] The last outbreak of brucellosis in Great Britain was in cattle in Cornwall in 2004.[33][34] Northern Ireland was declared officially brucellosis-free in 2015.[33]

New Zealand[edit]

Brucellosis in New Zealand is limited to sheep (B. ovis). The country is free of all other species of Brucella.[35]

United States[edit]

Dairy herds in the U.S. are tested at least once a year to be certified brucellosis-free[36] with the Brucella milk ring test.[37] Cows confirmed to be infected are often killed. In the United States, veterinarians are required[citation needed] to vaccinate all young stock, to further reduce the chance of zoonotic transmission. This vaccination is usually referred to as a «calfhood» vaccination. Most cattle receive a tattoo in one of their ears, serving as proof of their vaccination status. This tattoo also includes the last digit of the year they were born.[38]

The first state–federal cooperative efforts towards eradication of brucellosis caused by B. abortus in the U.S. began in 1934.[citation needed]

Brucellosis was originally imported to North America with non-native domestic cattle (Bos taurus), which transmitted the disease to wild bison (Bison bison) and elk (Cervus canadensis). No records exist of brucellosis in ungulates native to America until the early 19th century.[39]

History[edit]

David Bruce (centre), with members of the Mediterranean Fever Commission (Brucellosis)

Brucellosis first came to the attention of British medical officers in the 1850s in Malta during the Crimean War, and was referred to as Malta Fever. Jeffery Allen Marston (1831–1911) described his own case of the disease in 1861. The causal relationship between organism and disease was first established in 1887 by David Bruce.[40][41] Bruce considered the agent spherical and classified it as a coccus.[citation needed]

In 1897, Danish veterinarian Bernhard Bang isolated a bacillus as the agent of heightened spontaneous abortion in cows, and the name «Bang’s disease» was assigned to this condition. Bang considered the organism rod-shaped and classified it as a bacillus. So at the time, no one knew that this bacillus had anything to do with the causative agent in Malta fever.[42]

Maltese scientist and archaeologist Themistocles Zammit identified unpasteurized goat milk as the major etiologic factor of undulant fever in June 1905.[43]

In the late 1910s, American bacteriologist Alice C. Evans was studying the Bang bacillus and gradually realized that it was virtually indistinguishable from the Bruce coccus.[44] The short-rod versus oblong-round morphologic borderline explained the leveling of the erstwhile bacillus/coccus distinction (that is, these «two» pathogens were not a coccus versus a bacillus but rather were one coccobacillus).[44] The Bang bacillus was already known to be enzootic in American dairy cattle, which showed itself in the regularity with which herds experienced contagious abortion.[44] Having made the discovery that the bacteria were certainly nearly identical and perhaps totally so, Evans then wondered why Malta fever was not widely diagnosed or reported in the United States.[44] She began to wonder whether many cases of vaguely defined febrile illnesses were in fact caused by the drinking of raw (unpasteurized) milk.[44] During the 1920s, this hypothesis was vindicated. Such illnesses ranged from undiagnosed and untreated gastrointestinal upset to misdiagnosed[44] febrile and painful versions, some even fatal. This advance in bacteriological science sparked extensive changes in the American dairy industry to improve food safety. The changes included making pasteurization standard and greatly tightening the standards of cleanliness in milkhouses on dairy farms. The expense prompted delay and skepticism in the industry,[44] but the new hygiene rules eventually became the norm. Although these measures have sometimes struck people as overdone in the decades since, being unhygienic at milking time or in the milkhouse, or drinking raw milk, are not a safe alternative.[citation needed]

In the decades after Evans’s work, this genus, which received the name Brucella in honor of Bruce, was found to contain several species with varying virulence. The name «brucellosis» gradually replaced the 19th-century names Mediterranean fever and Malta fever.[45]

Neurobrucellosis, a neurological involvement in brucellosis, was first described in 1879. In the late 19th century, its symptoms were described in more detail by M. Louis Hughes, a Surgeon-Captain of the Royal Army Medical Corps stationed in Malta who isolated brucella organisms from a patient with meningo-encephalitis.[46] In 1989, neurologists in Saudi Arabia made significant contributions to the medical literature involving neurobrucellosis.[47][48]

These obsolete names have previously been applied to brucellosis:[45][49]

- Crimean fever

- Cyprus fever

- Gibraltar fever

- Goat fever

- Italian fever

- Neapolitan fever

Biological warfare[edit]

Brucella species were weaponized by several advanced countries by the mid-20th century. In 1954, B. suis became the first agent weaponized by the United States at its Pine Bluff Arsenal near Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Brucella species survive well in aerosols and resist drying. Brucella and all other remaining biological weapons in the U.S. arsenal were destroyed in 1971–72 when the American offensive biological warfare program was discontinued by order of President Richard Nixon.[50]

The experimental American bacteriological warfare program focused on three agents of the Brucella group:[citation needed]

- Porcine brucellosis (agent US)

- Bovine brucellosis (agent AA)

- Caprine brucellosis (agent AM)

Agent US was in advanced development by the end of World War II. When the United States Air Force (USAF) wanted a biological warfare capability, the Chemical Corps offered Agent US in the M114 bomblet, based on the four-pound bursting bomblet developed for spreading anthrax during World War II. Though the capability was developed, operational testing indicated the weapon was less than desirable, and the USAF designed it as an interim capability until it could eventually be replaced by a more effective biological weapon.[citation needed]

The main drawback of using the M114 with Agent US was that it acted mainly as an incapacitating agent, whereas the USAF administration wanted weapons that were deadly. The stability of M114 in storage was too low to allow for storing it at forward air bases, and the logistical requirements to neutralize a target were far higher than was originally planned. Ultimately, this would have required too much logistical support to be practical in the field.[citation needed]

Agents US and AA had a median infective dose of 500 organisms/person, and for Agent AM it was 300 organisms/person. The incubation time was believed to be about 2 weeks, with a duration of infection of several months. The lethality estimate was, based on epidemiological information, 1 to 2

per cent. Agent AM was believed to be a somewhat more virulent disease, with a fatality rate of 3 per cent being expected.[citation needed]

Other animals[edit]

Species infecting domestic livestock are B. abortus (cattle, bison, and elk), B. canis (dogs), B. melitensis (goats and sheep), B. ovis (sheep), and B. suis (caribou and pigs). Brucella species have also been isolated from several marine mammal species (cetaceans and pinnipeds).[citation needed]

Cattle[edit]

B. abortus is the principal cause of brucellosis in cattle. The bacteria are shed from an infected animal at or around the time of calving or abortion. Once exposed, the likelihood of an animal becoming infected is variable, depending on age, pregnancy status, and other intrinsic factors of the animal, as well as the number of bacteria to which the animal was exposed.[51] The most common clinical signs of cattle infected with B. abortus are high incidences of abortions, arthritic joints, and retained placenta.[citation needed]

The two main causes for spontaneous abortion in animals are erythritol, which can promote infections in the fetus and placenta,[clarification needed] and the lack of anti-Brucella activity in the amniotic fluid. Males can also harbor the bacteria in their reproductive tracts, namely seminal vesicles, ampullae, testicles, and epididymises.[citation needed]

Dogs[edit]

The causative agent of brucellosis in dogs, B. canis, is transmitted to other dogs through breeding and contact with aborted fetuses. Brucellosis can occur in humans who come in contact with infected aborted tissue or semen. The bacteria in dogs normally infect the genitals and lymphatic system, but can also spread to the eyes, kidneys, and intervertebral discs. Brucellosis in the intervertebral disc is one possible cause of discospondylitis. Symptoms of brucellosis in dogs include abortion in female dogs and scrotal inflammation and orchitis in males. Fever is uncommon. Infection of the eye can cause uveitis, and infection of the intervertebral disc can cause pain or weakness. Blood testing of the dogs prior to breeding can prevent the spread of this disease. It is treated with antibiotics, as with humans, but it is difficult to cure.[52]

Aquatic wildlife[edit]

Brucellosis in cetaceans is caused by the bacterium B. ceti. First discovered in the aborted fetus of a bottlenose dolphin, the structure of B. ceti is similar to Brucella in land animals. B. ceti is commonly detected in two suborders of cetaceans, the Mysticeti and Odontoceti. The Mysticeti include four families of baleen whales, filter-feeders, and the Odontoceti include two families of toothed cetaceans ranging from dolphins to sperm whales. B. ceti is believed to transfer from animal to animal through sexual intercourse, maternal feeding, aborted fetuses, placental issues, from mother to fetus, or through fish reservoirs. Brucellosis is a reproductive disease, so has an extreme negative impact on the population dynamics of a species. This becomes a greater issue when the already low population numbers of cetaceans are taken into consideration. B. ceti has been identified in four of the 14 cetacean families, but the antibodies have been detected in seven of the families. This indicates that B. ceti is common amongst cetacean families and populations. Only a small percentage of exposed individuals become ill or die. However, particular species apparently are more likely to become infected by B. ceti. The harbor porpoise, striped dolphin, white-sided dolphin, bottlenose dolphin, and common dolphin have the highest frequency of infection amongst odontocetes. In the mysticetes families, the northern minke whale is by far the most infected species. Dolphins and porpoises are more likely to be infected than cetaceans such as whales. With regard to sex and age biases, the infections do not seem influenced by the age or sex of an individual. Although fatal to cetaceans, B. ceti has a low infection rate for humans.[53]

Terrestrial wildlife[edit]

The disease in its various strains can infect multiple wildlife species, including elk (Cervus canadensis), bison (Bison bison), African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), European wild boar (Sus scrofa), caribou (Rangifer tarandus), moose (Alces alces), and marine mammals (see section on aquatic wildlife above).[54][55] While some regions use vaccines to prevent the spread of brucellosis between infected and uninfected wildlife populations, no suitable brucellosis vaccine for terrestrial wildlife has been developed.[56] This gap in medicinal knowledge creates more pressure for management practices that reduce spread of the disease.[56]

Wild bison and elk in the greater Yellowstone area are the last remaining reservoir of B. abortus in the US. The recent transmission of brucellosis from elk back to cattle in Idaho and Wyoming illustrates how the area, as the last remaining reservoir in the United States, may adversely affect the livestock industry. Eliminating brucellosis from this area is a challenge, as many viewpoints exist on how to manage diseased wildlife. However, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department has recently begun to protect scavengers (particularly coyotes and red fox) on elk feedgrounds, because they act as sustainable, no-cost, biological control agents by removing infected elk fetuses quickly.[57]

The National Elk Refuge in Jackson, Wyoming asserts that the intensity of the winter feeding program affects the spread of brucellosis more than the population size of elk and bison.[54] Since concentrating animals around food plots accelerates spread of the disease, management strategies to reduce herd density and increase dispersion could limit its spread.[54]

Effects on hunters[edit]

Hunters may be at additional risk for exposure to brucellosis due to increased contact with susceptible wildlife, including predators that may have fed on infected prey. Hunting dogs can also be at risk of infection.[58] Exposure can occur through contact with open wounds or by directly inhaling the bacteria while cleaning game.[59] In some cases, consumption of undercooked game can result in exposure to the disease.[59] Hunters can limit exposure while cleaning game through the use of precautionary barriers, including gloves and masks, and by washing tools rigorously after use.[56][60] By ensuring that game is cooked thoroughly, hunters can protect themselves and others from ingesting the disease.[59] Hunters should refer to local game officials and health departments to determine the risk of brucellosis exposure in their immediate area and to learn more about actions to reduce or avoid exposure.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- Brucella suis

References[edit]

- ^ Wyatt HV (2014). «How did Sir David Bruce forget Zammit and his goats ?» (PDF). Journal of Maltese History. Malta: Department of History, University of Malta. 4 (1): 41. ISSN 2077-4338. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-21. Journal archive

- ^ a b c «Brucellosis». mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ «Brucellosis». mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ «Brucellosis». American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

- ^ «Maltese Fever». wrongdiagnosis.com. February 25, 2009.

- ^ «Diagnosis and Management of Acute Brucellosis in Primary Care» (PDF). Brucella Subgroup of the Northern Ireland Regional Zoonoses Group. August 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-13.

- ^ Di Pierdomenico A, Borgia SM, Richardson D, Baqi M (July 2011). «Brucellosis in a returned traveller». CMAJ. 183 (10): E690-2. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091752. PMC 3134761. PMID 21398234.

- ^ Park. K., Park’s textbook of preventive and social medicine, 23 editions. Page 290-91

- ^ Roy, Rabindra (2013), «Chapter-23 Biostatistics», Mahajan and Gupta Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd, pp. 434–449, retrieved 2022-11-13

- ^ «Brucellosis: Resources: Surveillance». CDC. 2018-10-09.

- ^ Wyatt HV (October 2005). «How Themistocles Zammit found Malta Fever (brucellosis) to be transmitted by the milk of goats». Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. The Royal Society of Medicine Press. 98 (10): 451–4. doi:10.1177/014107680509801009. OCLC 680110952. PMC 1240100. PMID 16199812.

- ^ Peck ME, Jenpanich C, Amonsin A, Bunpapong N, Chanachai K, Somrongthong R, et al. (January 2019). «Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Associated with Brucellosis among Small-Scale Goat Farmers in Thailand». Journal of Agromedicine. 24 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2018.1538916. PMID 30350754. S2CID 53034163.

- ^ Franco MP, Mulder M, Gilman RH, Smits HL (December 2007). «Human brucellosis». The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 7 (12): 775–86. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70286-4. PMID 18045560.

- ^ Al Dahouk S, Nöckler K (July 2011). «Implications of laboratory diagnosis on brucellosis therapy». Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 9 (7): 833–45. doi:10.1586/eri.11.55. PMID 21810055. S2CID 5068325.

- ^ Mantur B, Parande A, Amarnath S, Patil G, Walvekar R, Desai A, et al. (August 2010). «ELISA versus conventional methods of diagnosing endemic brucellosis». The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 83 (2): 314–8. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0790. PMC 2911177. PMID 20682874.

- ^ Yu WL, Nielsen K (August 2010). «Review of detection of Brucella spp. by polymerase chain reaction». Croatian Medical Journal. 51 (4): 306–13. doi:10.3325/cmj.2010.51.306. PMC 2931435. PMID 20718083.

- ^ Vrioni G, Pappas G, Priavali E, Gartzonika C, Levidiotou S (June 2008). «An eternal microbe: Brucella DNA load persists for years after clinical cure». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 46 (12): e131-6. doi:10.1086/588482. PMID 18462106.

- ^ Hasanjani Roushan MR, Mohraz M, Hajiahmadi M, Ramzani A, Valayati AA (April 2006). «Efficacy of gentamicin plus doxycycline versus streptomycin plus doxycycline in the treatment of brucellosis in humans». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 42 (8): 1075–80. doi:10.1086/501359. PMID 16575723.

- ^ McLean DR, Russell N, Khan MY (October 1992). «Neurobrucellosis: clinical and therapeutic features». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 15 (4): 582–90. doi:10.1093/clind/15.4.582. PMID 1420670.

- ^ Yousefi-Nooraie R, Mortaz-Hejri S, Mehrani M, Sadeghipour P (October 2012). «Antibiotics for treating human brucellosis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD007179. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007179.pub2. PMC 6532606. PMID 23076931.

- ^ Yagupsky P, Baron EJ (August 2005). «Laboratory exposures to brucellae and implications for bioterrorism». Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (8): 1180–5. doi:10.3201/eid1108.041197. PMC 3320509. PMID 16102304.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (January 2008). «Laboratory-acquired brucellosis—Indiana and Minnesota, 2006». MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (2): 39–42. PMID 18199967.

- ^ Samartino LE (December 2002). «Brucellosis in Argentina». Veterinary Microbiology. 90 (1–4): 71–80. doi:10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00247-x. PMID 12414136.

- ^ «SENASA – Direcci n Nacional de Sanidad Animal». viejaweb.senasa.gov.ar. Archived from the original on 2016-02-16. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ^ «Queensland Health: Brucellosis». State of Queensland (Queensland Health). 2010-11-24. Archived from the original on 2011-04-22. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^

Lehane, Robert (1996) Beating the Odds in a Big Country: The eradication of bovine brucellosis and tuberculosis in Australia, CSIRO Publishing, ISBN 0-643-05814-1 - ^ «Reportable Diseases». Accredited Veterinarian’s Manual. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ China reports outbreak of brucellosis disease ‘way larger’ than originally thought 18 September 2020 www.news.com.au, accessed 18 September 2020

- ^ «兰州药厂泄漏事件布病患者:肿痛无药可吃,有人已转成慢性病_绿政公署_澎湃新闻-The Paper». www.thepaper.cn. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Naudi JR (2005). Brucellosis, The Malta Experience. Malta: Publishers Enterprises group (PEG) Ltd. ISBN 978-99909-0-425-3.

- ^ a b c «Ireland free of brucellosis». RTÉ. 2009-07-01. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ a b c d «Ireland declared free of brucellosis». The Irish Times. 2009-07-01. Archived from the original on 2021-04-03. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

Michael F Sexton, president of Veterinary Ireland, which represents vets in practice, said: «Many vets and farmers in particular suffered significantly with brucellosis in past decades and it is greatly welcomed by the veterinary profession that this debilitating disease is no longer the hazard that it once was.»

- ^ a b c Monitoring brucellosis in Great Britain 3 September 2020 veterinary-practice.com, accessed 18 September 2020

- ^ Guidance Brucellosis: how to spot and report the disease 18 October 2018 www.gov.uk, accessed 18 September 2020

- ^ «MAF Biosecurity New Zealand: Brucellosis». Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ Brucellosis Eradication APHIS 91–45–013. United States Department of Agriculture. October 2003. p. 14.

- ^ Hamilton AV, Hardy AV (March 1950). «The brucella ring test; its potential value in the control of brucellosis». American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health. 40 (3): 321–3. doi:10.2105/AJPH.40.3.321. PMC 1528431. PMID 15405523.

- ^ Vermont Beef Producers. «How important is calfhood vaccination?» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-09.

- ^ Meagher M, Meyer ME (September 1994). «On the Origin of Brucellosis in Bison of Yellowstone National Park: A Review» (PDF). Conservation Biology. 8 (3): 645–653. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1994.08030645.x. JSTOR 2386505. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-08. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- ^ Wilkinson L (1993). «Brucellosis». In Kiple KF (ed.). The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Brucellosis named after Major-General Sir David Bruce at Who Named It?

- ^ Evans, Alice (1963). Dr. Alice C. Evans Memoir.

- ^ Wyatt HV (2015). «The Strange Case of Temi Zammit’s missing experiments» (PDF). Journal of Maltese History. Malta: Department of History, University of Malta. 4 (2): 54–56. ISSN 2077-4338. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-21. Journal archive

- ^ a b c d e f g de Kruif P (1932). «Ch. 5 Evans: death in milk». Men Against Death. New York: Harcourt, Brace. OCLC 11210642.

- ^ a b Wyatt HV (31 July 2004). «Give A Disease A Bad Name». British Medical Journal. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. 329 (7460): 272–278. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7460.272. ISSN 0959-535X. JSTOR 25468794. OCLC 198096808. PMC 498028.

- ^ Madkour, M. Monir (2014). Brucellosis. Elsevier Science. p. 160. ISBN 9781483193595.

- ^ Malhotra R (2004). «Saudi Arabia». Practical Neurology. 4 (3): 184–185. doi:10.1111/j.1474-7766.2004.03-225.x.

- ^ Al-Sous MW, Bohlega S, Al-Kawi MZ, Alwatban J, McLean DR (March 2004). «Neurobrucellosis: clinical and neuroimaging correlation». AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 25 (3): 395–401. PMC 8158553. PMID 15037461.

- ^ «Medicine: Goat Fever». Time. 1928-12-10. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ Woods, Jon B. (April 2005). USAMRIID’s Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook (PDF) (6th ed.). Fort Detrick, Maryland: U.S. Army Medical Institute of Infectious Diseases. p. 53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-09.

- ^ Radostits, O.M., C.C. Gay, D.C. Blood, and K.W. Hinchcliff. (2000). Veterinary Medicine, A textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses. Harcourt Publishers Limited, London, pp. 867–882. ISBN 0702027774.

- ^ Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-4679-4.

- ^ Guzmán-Verri C, González-Barrientos R, Hernández-Mora G, Morales JA, Baquero-Calvo E, Chaves-Olarte E, Moreno E (2012). «Brucella ceti and brucellosis in cetaceans». Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2: 3. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00003. PMC 3417395. PMID 22919595.

- ^ a b c «Brucellosis». www.fws.gov. U.S. Fish &Wildlife Service. 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ^ Godfroid J (August 2002). «Brucellosis in wildlife» (PDF). Revue Scientifique et Technique. 21 (2): 277–86. doi:10.20506/rst.21.2.1333. PMID 11974615. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-06. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ^ a b c Godfroid J, Garin-Bastuji B, Saegerman C, Blasco JM (April 2013). «Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife» (PDF). Revue Scientifique et Technique. 32 (1): 27–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1020.9652. doi:10.20506/rst.32.1.2180. PMID 23837363. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-06. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ^ Cross PC, Maichak EJ, Brennan A, Scurlock BM, Henningsen J, Luikart G (April 2013). «An ecological perspective on Brucella abortus in the western United States» (PDF). Revue Scientifique et Technique. 32 (1): 79–87. doi:10.20506/rst.32.1.2184. PMID 23837367.

- ^ CDC — Hunters Risks — Animals That Can Put Hunters at Risk

- ^ a b c «CDC – Home – Brucellosis». www.cdc.gov. Center for Disease Control. 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ^ «Zoonoses – Brucellosis». www.who.int/en/. World Health Organization. 2016. Archived from the original on March 9, 2005. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

Further reading[edit]

- Fact sheet on Brucellosis from World Organisation for Animal Health

- Brucella genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

- Prevention about Brucellosis from Centers for Disease Control

- Capasso L (August 2002). «Bacteria in two-millennia-old cheese, and related epizoonoses in Roman populations». The Journal of Infection. 45 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1053/jinf.2002.0996. PMID 12217720. – re high rate of brucellosis in humans in ancient Pompeii

- Brucellosis, factsheet from European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

| Brucellosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | undulant fever, undulating fever, Mediterranean fever, Malta fever, Cyprus fever, rock fever (Micrococcus melitensis)[1] |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | fever, chills, loss of appetite, sweats, weakness, fatigue, Joint, muscle and back pain, Headache.[2] |

| Complications | central nervous system infections, inflammation and infection of the spleen and liver, inflammation and infection of the testicles (epididymo-orchitis), Arthritis, Inflammation of the inner lining of the heart chambers (endocarditis).[2] |

| Diagnostic method | x-rays, computerized tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cerebrospinal fluid culture, echocardiography.[3] |

| Prevention | avoid unpasteurized dairy foods, cook meat thoroughly, wear gloves, take safety precautions in high-risk workplaces, vaccinate domestic animals.[2] |

| Treatment | antibiotics |

| Medication | tetracyclines, rifampicin, aminoglycosides |

Brucellosis[4][5] is a highly contagious zoonosis caused by ingestion of unpasteurized milk or undercooked meat from infected animals, or close contact with their secretions.[6] It is also known as undulant fever, Malta fever, and Mediterranean fever.[7]

The bacteria causing this disease, Brucella, are small, Gram-negative, nonmotile, nonspore-forming, rod-shaped (coccobacilli) bacteria. They function as facultative intracellular parasites, causing chronic disease, which usually persists for life. Four species infect humans: B. abortus, B. canis, B. melitensis, and B. suis. B. abortus is less virulent than B. melitensis and is primarily a disease of cattle. B. canis affects dogs. B. melitensis is the most virulent and invasive species; it usually infects goats and occasionally sheep. B. suis is of intermediate virulence and chiefly infects pigs. Symptoms include profuse sweating and joint and muscle pain. Brucellosis has been recognized in animals and humans since the early 20th century.[8][9]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

A graph of the cases of brucellosis in humans in the United States from the years 1993–2010 surveyed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System[10]

The symptoms are like those associated with many other febrile diseases, but with emphasis on muscular pain and night sweats. The duration of the disease can vary from a few weeks to many months or even years.

In the first stage of the disease, bacteremia occurs and leads to the classic triad of undulant fevers, sweating (often with characteristic foul, moldy smell sometimes likened to wet hay), and migratory arthralgia and myalgia (joint and muscle pain).[citation needed] Blood tests characteristically reveal a low number of white blood cells and red blood cells, show some elevation of liver enzymes such as aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, and demonstrate positive Bengal rose and Huddleston reactions. Gastrointestinal symptoms occur in 70% of cases and include nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, unintentional weight loss, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, an enlarged liver, liver inflammation, liver abscess, and an enlarged spleen.[citation needed]

This complex is, at least in Portugal, Israel, Syria, and Jordan, known as Malta fever. During episodes of Malta fever, melitococcemia (presence of brucellae in the blood) can usually be demonstrated by means of blood culture in tryptose medium or Albini medium. If untreated, the disease can give origin to focalizations[clarification needed] or become chronic. The focalizations of brucellosis occur usually in bones and joints, and osteomyelitis or spondylodiscitis of the lumbar spine accompanied by sacroiliitis is very characteristic of this disease. Orchitis is also common in men.

The consequences of Brucella infection are highly variable and may include arthritis, spondylitis, thrombocytopenia, meningitis, uveitis, optic neuritis, endocarditis, and various neurological disorders collectively known as neurobrucellosis.

Cause[edit]

Brucellosis in humans is usually associated with consumption of unpasteurized milk and soft cheeses made from the milk of infected animals—primarily goats, infected with B. melitensis and with occupational exposure of laboratory workers, veterinarians, and slaughterhouse workers.[11] Some vaccines used in livestock, most notably B. abortus strain 19, also cause disease in humans if accidentally injected. Brucellosis induces inconstant fevers, miscarriage, sweating, weakness, anemia, headaches, depression, and muscular and bodily pain. The other strains, B. suis and B. canis, cause infection in pigs and dogs, respectively.[citation needed]

Overall findings support that brucellosis poses an occupational risk to goat farmers with specific areas of concern including weak awareness of disease transmission to humans and lack of knowledge on specific safe farm practices such as quarantine practices.[12]

Diagnosis[edit]

Brucella Coombs Gel Test. Seropositivity detected to GN177

The diagnosis of brucellosis relies on:[citation needed]

- Demonstration of the agent: blood cultures in tryptose broth, bone marrow cultures: The growth of brucellae is extremely slow (they can take up to two months to grow) and the culture poses a risk to laboratory personnel due to high infectivity of brucellae.

- Demonstration of antibodies against the agent either with the classic Huddleson, Wright, and/or Bengal Rose reactions, either with ELISA or the 2-mercaptoethanol assay for IgM antibodies associated with chronic disease

- Histologic evidence of granulomatous hepatitis on hepatic biopsy

- Radiologic alterations in infected vertebrae: the Pedro Pons sign (preferential erosion of the anterosuperior corner of lumbar vertebrae) and marked osteophytosis are suspicious of brucellic spondylitis.

Definite diagnosis of brucellosis requires the isolation of the organism from the blood, body fluids, or tissues, but serological methods may be the only tests available in many settings. Positive blood culture yield ranges between 40 and 70% and is less commonly positive for B. abortus than B. melitensis or B. suis. Identification of specific antibodies against bacterial lipopolysaccharide and other antigens can be detected by the standard agglutination test (SAT), rose Bengal, 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), antihuman globulin (Coombs’) and indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). SAT is the most commonly used serology in endemic areas.[13][14] An agglutination titre greater than 1:160 is considered significant in nonendemic areas and greater than 1:320 in endemic areas.[citation needed]

Due to the similarity of the O polysaccharide of Brucella to that of various other Gram-negative bacteria (e.g. Francisella tularensis, Escherichia coli, Salmonella urbana, Yersinia enterocolitica, Vibrio cholerae, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia), the appearance of cross-reactions of class M immunoglobulins may occur. The inability to diagnose B. canis by SAT due to lack of cross-reaction is another drawback. False-negative SAT may be caused by the presence of blocking antibodies (the prozone phenomenon) in the α2-globulin (IgA) and in the α-globulin (IgG) fractions.[citation needed]

Dipstick assays are new and promising, based on the binding of Brucella IgM antibodies, and are simple, accurate, and rapid. ELISA typically uses cytoplasmic proteins as antigens. It measures IgM, IgG, and IgA with better sensitivity and specificity than the SAT in most recent comparative studies.[15] The commercial Brucellacapt test, a single-step immunocapture assay for the detection of total anti-Brucella antibodies, is an increasingly used adjunctive test when resources permit. PCR is fast and should be specific. Many varieties of PCR have been developed (e.g. nested PCR, realtime PCR, and PCR-ELISA) and found to have superior specificity and sensitivity in detecting both primary infection and relapse after treatment.[16] Unfortunately, these are not standardized for routine use, and some centres have reported persistent PCR positivity after clinically successful treatment, fuelling the controversy about the existence of prolonged chronic brucellosis.[citation needed]

Other laboratory findings include normal peripheral white cell count, and occasional leucopenia with relative lymphocytosis. The serum biochemical profiles are commonly normal.[17]

Prevention[edit]

Surveillance using serological tests, as well as tests on milk such as the milk ring test, can be used for screening and play an important role in campaigns to eliminate the disease. Also, individual animal testing both for trade and for disease-control purposes is practiced. In endemic areas, vaccination is often used to reduce the incidence of infection. An animal vaccine is available that uses modified live bacteria. The World Organisation for Animal Health Manual of Diagnostic Test and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals provides detailed guidance on the production of vaccines. As the disease is closer to being eliminated, a test and eradication program is required to eliminate it.[citation needed]

The main way of preventing brucellosis is by using fastidious hygiene in producing raw milk products, or by pasteurizing all milk that is to be ingested by human beings, either in its unaltered form or as a derivative, such as cheese.[citation needed]

Treatment[edit]

Antibiotics such as tetracyclines, rifampicin, and the aminoglycosides streptomycin and gentamicin are effective against Brucella bacteria. However, the use of more than one antibiotic is needed for several weeks, because the bacteria incubate within cells.[citation needed]

The gold standard treatment for adults is daily intramuscular injections of streptomycin 1 g for 14 days and oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 45 days (concurrently). Gentamicin 5 mg/kg by intramuscular injection once daily for 7 days is an acceptable substitute when streptomycin is not available or contraindicated.[18] Another widely used regimen is doxycycline plus rifampicin twice daily for at least 6 weeks. This regimen has the advantage of oral administration. A triple therapy of doxycycline, with rifampicin and co-trimoxazole, has been used successfully to treat neurobrucellosis.[19] Doxycycline plus streptomycin regimen (for 2 to 3 weeks) is more effective than doxycycline plus rifampicin regimen (for 6 weeks).[20]

Doxycycline is able to cross the blood–brain barrier, but requires the addition of two other drugs to prevent relapse. Ciprofloxacin and co-trimoxazole therapy is associated with an unacceptably high rate of relapse. In brucellic endocarditis, surgery is required for an optimal outcome. Even with optimal antibrucellic therapy, relapses still occur in 5 to 10% of patients with Malta fever.[citation needed]

Prognosis[edit]

The mortality of the disease in 1909, as recorded in the British Army and Navy stationed in Malta, was 2%. The most frequent cause of death was endocarditis. Recent advances in antibiotics and surgery have been successful in preventing death due to endocarditis. Prevention of human brucellosis can be achieved by eradication of the disease in animals by vaccination and other veterinary control methods such as testing herds/flocks and slaughtering animals when infection is present. Currently, no effective vaccine is available for humans. Boiling milk before consumption, or before using it to produce other dairy products, is protective against transmission via ingestion. Changing traditional food habits of eating raw meat, liver, or bone marrow is necessary, but difficult to implement.[citation needed] Patients who have had brucellosis should probably be excluded indefinitely from donating blood or organs. Exposure of diagnostic laboratory personnel to Brucella organisms remains a problem in both endemic settings and when brucellosis is unknowingly imported by a patient.[21] After appropriate risk assessment, staff with significant exposure should be offered postexposure prophylaxis and followed up serologically for 6 months.[22]

Epidemiology[edit]

Argentina[edit]

According to a study published in 2002, an estimated 10–13% of farm animals are infected with Brucella species.[23] Annual losses from the disease were calculated at around $60 million. Since 1932, government agencies have undertaken efforts to contain the disease. Currently, all cattle of ages 3–8 months must receive the Brucella abortus strain 19 vaccine.[24]

Australia[edit]

Australia is free of cattle brucellosis, although it occurred in the past. Brucellosis of sheep or goats has never been reported. Brucellosis of pigs does occur. Feral pigs are the typical source of human infections.[25][26]

Canada[edit]

On 19 September 1985, the Canadian government declared its cattle population brucellosis-free. Brucellosis ring testing of milk and cream, and testing of cattle to be slaughtered ended on 1 April 1999. Monitoring continues through testing at auction markets, through standard disease-reporting procedures, and through testing of cattle being qualified for export to countries other than the United States.[27]

China[edit]

An outbreak infecting humans took place in Lanzhou in 2020 after the Lanzhou Biopharmaceutical Plant, which was involved in vaccine production, accidentally pumped out the bacteria into the atmosphere in exhaust air due to use of expired disinfectant. The outbreak affected over 6,000 people.[28][29]

Europe[edit]

Disease incidence map of B. melitensis infections in animals in Europe during the first half of 2006

never reported

not reported in this period

confirmed clinical disease

confirmed infection

no information

Malta[edit]

Until the early 20th century, the disease was endemic in Malta to the point of it being referred to as «Maltese fever». Since 2005, due to a strict regimen of certification of milk animals and widespread use of pasteurization, the illness has been eradicated from Malta.[30]

Republic of Ireland[edit]

Ireland was declared free of brucellosis on 1 July 2009. The disease had troubled the country’s farmers and veterinarians for several decades.[31][32] The Irish government submitted an application to the European Commission, which verified that Ireland had been liberated.[32] Brendan Smith, Ireland’s then Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, said the elimination of brucellosis was «a landmark in the history of disease eradication in Ireland».[31][32] Ireland’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine intends to reduce its brucellosis eradication programme now that eradication has been confirmed.[31][32]

UK[edit]

Mainland Britain has been free of brucellosis since 1979, although there have been episodic re-introductions since.[33] The last outbreak of brucellosis in Great Britain was in cattle in Cornwall in 2004.[33][34] Northern Ireland was declared officially brucellosis-free in 2015.[33]

New Zealand[edit]

Brucellosis in New Zealand is limited to sheep (B. ovis). The country is free of all other species of Brucella.[35]

United States[edit]

Dairy herds in the U.S. are tested at least once a year to be certified brucellosis-free[36] with the Brucella milk ring test.[37] Cows confirmed to be infected are often killed. In the United States, veterinarians are required[citation needed] to vaccinate all young stock, to further reduce the chance of zoonotic transmission. This vaccination is usually referred to as a «calfhood» vaccination. Most cattle receive a tattoo in one of their ears, serving as proof of their vaccination status. This tattoo also includes the last digit of the year they were born.[38]

The first state–federal cooperative efforts towards eradication of brucellosis caused by B. abortus in the U.S. began in 1934.[citation needed]

Brucellosis was originally imported to North America with non-native domestic cattle (Bos taurus), which transmitted the disease to wild bison (Bison bison) and elk (Cervus canadensis). No records exist of brucellosis in ungulates native to America until the early 19th century.[39]

History[edit]

David Bruce (centre), with members of the Mediterranean Fever Commission (Brucellosis)

Brucellosis first came to the attention of British medical officers in the 1850s in Malta during the Crimean War, and was referred to as Malta Fever. Jeffery Allen Marston (1831–1911) described his own case of the disease in 1861. The causal relationship between organism and disease was first established in 1887 by David Bruce.[40][41] Bruce considered the agent spherical and classified it as a coccus.[citation needed]

In 1897, Danish veterinarian Bernhard Bang isolated a bacillus as the agent of heightened spontaneous abortion in cows, and the name «Bang’s disease» was assigned to this condition. Bang considered the organism rod-shaped and classified it as a bacillus. So at the time, no one knew that this bacillus had anything to do with the causative agent in Malta fever.[42]

Maltese scientist and archaeologist Themistocles Zammit identified unpasteurized goat milk as the major etiologic factor of undulant fever in June 1905.[43]

In the late 1910s, American bacteriologist Alice C. Evans was studying the Bang bacillus and gradually realized that it was virtually indistinguishable from the Bruce coccus.[44] The short-rod versus oblong-round morphologic borderline explained the leveling of the erstwhile bacillus/coccus distinction (that is, these «two» pathogens were not a coccus versus a bacillus but rather were one coccobacillus).[44] The Bang bacillus was already known to be enzootic in American dairy cattle, which showed itself in the regularity with which herds experienced contagious abortion.[44] Having made the discovery that the bacteria were certainly nearly identical and perhaps totally so, Evans then wondered why Malta fever was not widely diagnosed or reported in the United States.[44] She began to wonder whether many cases of vaguely defined febrile illnesses were in fact caused by the drinking of raw (unpasteurized) milk.[44] During the 1920s, this hypothesis was vindicated. Such illnesses ranged from undiagnosed and untreated gastrointestinal upset to misdiagnosed[44] febrile and painful versions, some even fatal. This advance in bacteriological science sparked extensive changes in the American dairy industry to improve food safety. The changes included making pasteurization standard and greatly tightening the standards of cleanliness in milkhouses on dairy farms. The expense prompted delay and skepticism in the industry,[44] but the new hygiene rules eventually became the norm. Although these measures have sometimes struck people as overdone in the decades since, being unhygienic at milking time or in the milkhouse, or drinking raw milk, are not a safe alternative.[citation needed]

In the decades after Evans’s work, this genus, which received the name Brucella in honor of Bruce, was found to contain several species with varying virulence. The name «brucellosis» gradually replaced the 19th-century names Mediterranean fever and Malta fever.[45]

Neurobrucellosis, a neurological involvement in brucellosis, was first described in 1879. In the late 19th century, its symptoms were described in more detail by M. Louis Hughes, a Surgeon-Captain of the Royal Army Medical Corps stationed in Malta who isolated brucella organisms from a patient with meningo-encephalitis.[46] In 1989, neurologists in Saudi Arabia made significant contributions to the medical literature involving neurobrucellosis.[47][48]

These obsolete names have previously been applied to brucellosis:[45][49]

- Crimean fever

- Cyprus fever

- Gibraltar fever

- Goat fever

- Italian fever

- Neapolitan fever

Biological warfare[edit]

Brucella species were weaponized by several advanced countries by the mid-20th century. In 1954, B. suis became the first agent weaponized by the United States at its Pine Bluff Arsenal near Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Brucella species survive well in aerosols and resist drying. Brucella and all other remaining biological weapons in the U.S. arsenal were destroyed in 1971–72 when the American offensive biological warfare program was discontinued by order of President Richard Nixon.[50]

The experimental American bacteriological warfare program focused on three agents of the Brucella group:[citation needed]

- Porcine brucellosis (agent US)

- Bovine brucellosis (agent AA)

- Caprine brucellosis (agent AM)

Agent US was in advanced development by the end of World War II. When the United States Air Force (USAF) wanted a biological warfare capability, the Chemical Corps offered Agent US in the M114 bomblet, based on the four-pound bursting bomblet developed for spreading anthrax during World War II. Though the capability was developed, operational testing indicated the weapon was less than desirable, and the USAF designed it as an interim capability until it could eventually be replaced by a more effective biological weapon.[citation needed]

The main drawback of using the M114 with Agent US was that it acted mainly as an incapacitating agent, whereas the USAF administration wanted weapons that were deadly. The stability of M114 in storage was too low to allow for storing it at forward air bases, and the logistical requirements to neutralize a target were far higher than was originally planned. Ultimately, this would have required too much logistical support to be practical in the field.[citation needed]

Agents US and AA had a median infective dose of 500 organisms/person, and for Agent AM it was 300 organisms/person. The incubation time was believed to be about 2 weeks, with a duration of infection of several months. The lethality estimate was, based on epidemiological information, 1 to 2

per cent. Agent AM was believed to be a somewhat more virulent disease, with a fatality rate of 3 per cent being expected.[citation needed]

Other animals[edit]

Species infecting domestic livestock are B. abortus (cattle, bison, and elk), B. canis (dogs), B. melitensis (goats and sheep), B. ovis (sheep), and B. suis (caribou and pigs). Brucella species have also been isolated from several marine mammal species (cetaceans and pinnipeds).[citation needed]

Cattle[edit]

B. abortus is the principal cause of brucellosis in cattle. The bacteria are shed from an infected animal at or around the time of calving or abortion. Once exposed, the likelihood of an animal becoming infected is variable, depending on age, pregnancy status, and other intrinsic factors of the animal, as well as the number of bacteria to which the animal was exposed.[51] The most common clinical signs of cattle infected with B. abortus are high incidences of abortions, arthritic joints, and retained placenta.[citation needed]

The two main causes for spontaneous abortion in animals are erythritol, which can promote infections in the fetus and placenta,[clarification needed] and the lack of anti-Brucella activity in the amniotic fluid. Males can also harbor the bacteria in their reproductive tracts, namely seminal vesicles, ampullae, testicles, and epididymises.[citation needed]

Dogs[edit]

The causative agent of brucellosis in dogs, B. canis, is transmitted to other dogs through breeding and contact with aborted fetuses. Brucellosis can occur in humans who come in contact with infected aborted tissue or semen. The bacteria in dogs normally infect the genitals and lymphatic system, but can also spread to the eyes, kidneys, and intervertebral discs. Brucellosis in the intervertebral disc is one possible cause of discospondylitis. Symptoms of brucellosis in dogs include abortion in female dogs and scrotal inflammation and orchitis in males. Fever is uncommon. Infection of the eye can cause uveitis, and infection of the intervertebral disc can cause pain or weakness. Blood testing of the dogs prior to breeding can prevent the spread of this disease. It is treated with antibiotics, as with humans, but it is difficult to cure.[52]

Aquatic wildlife[edit]

Brucellosis in cetaceans is caused by the bacterium B. ceti. First discovered in the aborted fetus of a bottlenose dolphin, the structure of B. ceti is similar to Brucella in land animals. B. ceti is commonly detected in two suborders of cetaceans, the Mysticeti and Odontoceti. The Mysticeti include four families of baleen whales, filter-feeders, and the Odontoceti include two families of toothed cetaceans ranging from dolphins to sperm whales. B. ceti is believed to transfer from animal to animal through sexual intercourse, maternal feeding, aborted fetuses, placental issues, from mother to fetus, or through fish reservoirs. Brucellosis is a reproductive disease, so has an extreme negative impact on the population dynamics of a species. This becomes a greater issue when the already low population numbers of cetaceans are taken into consideration. B. ceti has been identified in four of the 14 cetacean families, but the antibodies have been detected in seven of the families. This indicates that B. ceti is common amongst cetacean families and populations. Only a small percentage of exposed individuals become ill or die. However, particular species apparently are more likely to become infected by B. ceti. The harbor porpoise, striped dolphin, white-sided dolphin, bottlenose dolphin, and common dolphin have the highest frequency of infection amongst odontocetes. In the mysticetes families, the northern minke whale is by far the most infected species. Dolphins and porpoises are more likely to be infected than cetaceans such as whales. With regard to sex and age biases, the infections do not seem influenced by the age or sex of an individual. Although fatal to cetaceans, B. ceti has a low infection rate for humans.[53]

Terrestrial wildlife[edit]

The disease in its various strains can infect multiple wildlife species, including elk (Cervus canadensis), bison (Bison bison), African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), European wild boar (Sus scrofa), caribou (Rangifer tarandus), moose (Alces alces), and marine mammals (see section on aquatic wildlife above).[54][55] While some regions use vaccines to prevent the spread of brucellosis between infected and uninfected wildlife populations, no suitable brucellosis vaccine for terrestrial wildlife has been developed.[56] This gap in medicinal knowledge creates more pressure for management practices that reduce spread of the disease.[56]

Wild bison and elk in the greater Yellowstone area are the last remaining reservoir of B. abortus in the US. The recent transmission of brucellosis from elk back to cattle in Idaho and Wyoming illustrates how the area, as the last remaining reservoir in the United States, may adversely affect the livestock industry. Eliminating brucellosis from this area is a challenge, as many viewpoints exist on how to manage diseased wildlife. However, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department has recently begun to protect scavengers (particularly coyotes and red fox) on elk feedgrounds, because they act as sustainable, no-cost, biological control agents by removing infected elk fetuses quickly.[57]

The National Elk Refuge in Jackson, Wyoming asserts that the intensity of the winter feeding program affects the spread of brucellosis more than the population size of elk and bison.[54] Since concentrating animals around food plots accelerates spread of the disease, management strategies to reduce herd density and increase dispersion could limit its spread.[54]

Effects on hunters[edit]

Hunters may be at additional risk for exposure to brucellosis due to increased contact with susceptible wildlife, including predators that may have fed on infected prey. Hunting dogs can also be at risk of infection.[58] Exposure can occur through contact with open wounds or by directly inhaling the bacteria while cleaning game.[59] In some cases, consumption of undercooked game can result in exposure to the disease.[59] Hunters can limit exposure while cleaning game through the use of precautionary barriers, including gloves and masks, and by washing tools rigorously after use.[56][60] By ensuring that game is cooked thoroughly, hunters can protect themselves and others from ingesting the disease.[59] Hunters should refer to local game officials and health departments to determine the risk of brucellosis exposure in their immediate area and to learn more about actions to reduce or avoid exposure.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- Brucella suis

References[edit]

- ^ Wyatt HV (2014). «How did Sir David Bruce forget Zammit and his goats ?» (PDF). Journal of Maltese History. Malta: Department of History, University of Malta. 4 (1): 41. ISSN 2077-4338. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-21. Journal archive

- ^ a b c «Brucellosis». mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ «Brucellosis». mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ «Brucellosis». American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

- ^ «Maltese Fever». wrongdiagnosis.com. February 25, 2009.

- ^ «Diagnosis and Management of Acute Brucellosis in Primary Care» (PDF). Brucella Subgroup of the Northern Ireland Regional Zoonoses Group. August 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-13.

- ^ Di Pierdomenico A, Borgia SM, Richardson D, Baqi M (July 2011). «Brucellosis in a returned traveller». CMAJ. 183 (10): E690-2. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091752. PMC 3134761. PMID 21398234.

- ^ Park. K., Park’s textbook of preventive and social medicine, 23 editions. Page 290-91

- ^ Roy, Rabindra (2013), «Chapter-23 Biostatistics», Mahajan and Gupta Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd, pp. 434–449, retrieved 2022-11-13

- ^ «Brucellosis: Resources: Surveillance». CDC. 2018-10-09.

- ^ Wyatt HV (October 2005). «How Themistocles Zammit found Malta Fever (brucellosis) to be transmitted by the milk of goats». Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. The Royal Society of Medicine Press. 98 (10): 451–4. doi:10.1177/014107680509801009. OCLC 680110952. PMC 1240100. PMID 16199812.

- ^ Peck ME, Jenpanich C, Amonsin A, Bunpapong N, Chanachai K, Somrongthong R, et al. (January 2019). «Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Associated with Brucellosis among Small-Scale Goat Farmers in Thailand». Journal of Agromedicine. 24 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2018.1538916. PMID 30350754. S2CID 53034163.

- ^ Franco MP, Mulder M, Gilman RH, Smits HL (December 2007). «Human brucellosis». The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 7 (12): 775–86. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70286-4. PMID 18045560.

- ^ Al Dahouk S, Nöckler K (July 2011). «Implications of laboratory diagnosis on brucellosis therapy». Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 9 (7): 833–45. doi:10.1586/eri.11.55. PMID 21810055. S2CID 5068325.

- ^ Mantur B, Parande A, Amarnath S, Patil G, Walvekar R, Desai A, et al. (August 2010). «ELISA versus conventional methods of diagnosing endemic brucellosis». The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 83 (2): 314–8. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0790. PMC 2911177. PMID 20682874.

- ^ Yu WL, Nielsen K (August 2010). «Review of detection of Brucella spp. by polymerase chain reaction». Croatian Medical Journal. 51 (4): 306–13. doi:10.3325/cmj.2010.51.306. PMC 2931435. PMID 20718083.

- ^ Vrioni G, Pappas G, Priavali E, Gartzonika C, Levidiotou S (June 2008). «An eternal microbe: Brucella DNA load persists for years after clinical cure». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 46 (12): e131-6. doi:10.1086/588482. PMID 18462106.

- ^ Hasanjani Roushan MR, Mohraz M, Hajiahmadi M, Ramzani A, Valayati AA (April 2006). «Efficacy of gentamicin plus doxycycline versus streptomycin plus doxycycline in the treatment of brucellosis in humans». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 42 (8): 1075–80. doi:10.1086/501359. PMID 16575723.

- ^ McLean DR, Russell N, Khan MY (October 1992). «Neurobrucellosis: clinical and therapeutic features». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 15 (4): 582–90. doi:10.1093/clind/15.4.582. PMID 1420670.

- ^ Yousefi-Nooraie R, Mortaz-Hejri S, Mehrani M, Sadeghipour P (October 2012). «Antibiotics for treating human brucellosis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD007179. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007179.pub2. PMC 6532606. PMID 23076931.

- ^ Yagupsky P, Baron EJ (August 2005). «Laboratory exposures to brucellae and implications for bioterrorism». Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (8): 1180–5. doi:10.3201/eid1108.041197. PMC 3320509. PMID 16102304.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (January 2008). «Laboratory-acquired brucellosis—Indiana and Minnesota, 2006». MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (2): 39–42. PMID 18199967.

- ^ Samartino LE (December 2002). «Brucellosis in Argentina». Veterinary Microbiology. 90 (1–4): 71–80. doi:10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00247-x. PMID 12414136.

- ^ «SENASA – Direcci n Nacional de Sanidad Animal». viejaweb.senasa.gov.ar. Archived from the original on 2016-02-16. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ^ «Queensland Health: Brucellosis». State of Queensland (Queensland Health). 2010-11-24. Archived from the original on 2011-04-22. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^

Lehane, Robert (1996) Beating the Odds in a Big Country: The eradication of bovine brucellosis and tuberculosis in Australia, CSIRO Publishing, ISBN 0-643-05814-1 - ^ «Reportable Diseases». Accredited Veterinarian’s Manual. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ China reports outbreak of brucellosis disease ‘way larger’ than originally thought 18 September 2020 www.news.com.au, accessed 18 September 2020

- ^ «兰州药厂泄漏事件布病患者:肿痛无药可吃,有人已转成慢性病_绿政公署_澎湃新闻-The Paper». www.thepaper.cn. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ Naudi JR (2005). Brucellosis, The Malta Experience. Malta: Publishers Enterprises group (PEG) Ltd. ISBN 978-99909-0-425-3.

- ^ a b c «Ireland free of brucellosis». RTÉ. 2009-07-01. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ^ a b c d «Ireland declared free of brucellosis». The Irish Times. 2009-07-01. Archived from the original on 2021-04-03. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

Michael F Sexton, president of Veterinary Ireland, which represents vets in practice, said: «Many vets and farmers in particular suffered significantly with brucellosis in past decades and it is greatly welcomed by the veterinary profession that this debilitating disease is no longer the hazard that it once was.»

- ^ a b c Monitoring brucellosis in Great Britain 3 September 2020 veterinary-practice.com, accessed 18 September 2020

- ^ Guidance Brucellosis: how to spot and report the disease 18 October 2018 www.gov.uk, accessed 18 September 2020

- ^ «MAF Biosecurity New Zealand: Brucellosis». Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ Brucellosis Eradication APHIS 91–45–013. United States Department of Agriculture. October 2003. p. 14.

- ^ Hamilton AV, Hardy AV (March 1950). «The brucella ring test; its potential value in the control of brucellosis». American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health. 40 (3): 321–3. doi:10.2105/AJPH.40.3.321. PMC 1528431. PMID 15405523.

- ^ Vermont Beef Producers. «How important is calfhood vaccination?» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-09.

- ^ Meagher M, Meyer ME (September 1994). «On the Origin of Brucellosis in Bison of Yellowstone National Park: A Review» (PDF). Conservation Biology. 8 (3): 645–653. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1994.08030645.x. JSTOR 2386505. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-08. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- ^ Wilkinson L (1993). «Brucellosis». In Kiple KF (ed.). The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Brucellosis named after Major-General Sir David Bruce at Who Named It?

- ^ Evans, Alice (1963). Dr. Alice C. Evans Memoir.

- ^ Wyatt HV (2015). «The Strange Case of Temi Zammit’s missing experiments» (PDF). Journal of Maltese History. Malta: Department of History, University of Malta. 4 (2): 54–56. ISSN 2077-4338. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-21. Journal archive

- ^ a b c d e f g de Kruif P (1932). «Ch. 5 Evans: death in milk». Men Against Death. New York: Harcourt, Brace. OCLC 11210642.

- ^ a b Wyatt HV (31 July 2004). «Give A Disease A Bad Name». British Medical Journal. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. 329 (7460): 272–278. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7460.272. ISSN 0959-535X. JSTOR 25468794. OCLC 198096808. PMC 498028.

- ^ Madkour, M. Monir (2014). Brucellosis. Elsevier Science. p. 160. ISBN 9781483193595.

- ^ Malhotra R (2004). «Saudi Arabia». Practical Neurology. 4 (3): 184–185. doi:10.1111/j.1474-7766.2004.03-225.x.

- ^ Al-Sous MW, Bohlega S, Al-Kawi MZ, Alwatban J, McLean DR (March 2004). «Neurobrucellosis: clinical and neuroimaging correlation». AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 25 (3): 395–401. PMC 8158553. PMID 15037461.

- ^ «Medicine: Goat Fever». Time. 1928-12-10. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ Woods, Jon B. (April 2005). USAMRIID’s Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook (PDF) (6th ed.). Fort Detrick, Maryland: U.S. Army Medical Institute of Infectious Diseases. p. 53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-09.

- ^ Radostits, O.M., C.C. Gay, D.C. Blood, and K.W. Hinchcliff. (2000). Veterinary Medicine, A textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses. Harcourt Publishers Limited, London, pp. 867–882. ISBN 0702027774.

- ^ Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-4679-4.

- ^ Guzmán-Verri C, González-Barrientos R, Hernández-Mora G, Morales JA, Baquero-Calvo E, Chaves-Olarte E, Moreno E (2012). «Brucella ceti and brucellosis in cetaceans». Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2: 3. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00003. PMC 3417395. PMID 22919595.

- ^ a b c «Brucellosis». www.fws.gov. U.S. Fish &Wildlife Service. 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ^ Godfroid J (August 2002). «Brucellosis in wildlife» (PDF). Revue Scientifique et Technique. 21 (2): 277–86. doi:10.20506/rst.21.2.1333. PMID 11974615. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-06. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- ^ a b c Godfroid J, Garin-Bastuji B, Saegerman C, Blasco JM (April 2013). «Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife» (PDF). Revue Scientifique et Technique. 32 (1): 27–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1020.9652. doi:10.20506/rst.32.1.2180. PMID 23837363. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-06. Retrieved 2016-10-07.