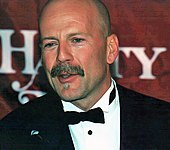

Walter Bruce Willis (born March 19, 1955) is a retired American actor. He achieved fame with a leading role on the comedy-drama series Moonlighting (1985–1989) and appeared in over a hundred films, gaining recognition as an action hero after his portrayal of John McClane in the Die Hard franchise (1988–2013) and other roles.[1][2]

|

Bruce Willis |

|

|---|---|

Willis at the 2018 San Diego Comic-Con |

|

| Born |

Walter Bruce Willis March 19, 1955 (age 67) Idar-Oberstein, West Germany |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1980–2022 |

| Works |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5, including Rumer |

| Awards | Full list |

Willis’s other credits include The Last Boy Scout (1991), Death Becomes Her (1992), Pulp Fiction (1994), 12 Monkeys (1995), The Fifth Element (1997), Armageddon (1998), The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Sin City (2005), Red (2010), Moonrise Kingdom (2012), Looper (2012) and Red 2 (2013). In the later years of his career, Willis starred in many low-budget direct-to-video films, which were poorly received. In March 2022, Willis’s family announced that he was retiring after being diagnosed with aphasia, which damages language comprehension. In February 2023, he was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia.

As a singer, Willis released his debut album, The Return of Bruno, in 1987, followed by two more albums in 1989 and 2001. He made his Broadway debut in the stage adaptation of Misery in 2015. Willis has received various accolades throughout his career, including a Golden Globe Award, two Primetime Emmy Awards, and two People’s Choice Awards. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2006. Films featuring Willis have grossed between US$2.64 billion and US$3.05 billion at North American box offices, making him in 2010 the eighth-highest-grossing leading actor.

Early life

Walter Bruce Willis[3] was born in Idar-Oberstein, West Germany, on March 19, 1955.[4][5] His mother, Marlene,[6] was German, from Kassel.[4] His father, David Willis, was an American soldier. Willis has a younger sister, Florence, and two younger brothers, Robert (deceased) and David.[7] After being discharged from the military in 1957, his father relocated the family to his hometown of Carneys Point, New Jersey.[8] Willis has described his background as a «long line of blue-collar people».[8] His mother worked in a bank and his father was a welder, master mechanic, and factory worker.[3]

Willis, who spoke with a stutter,[8] attended Penns Grove High School, where his schoolmates nicknamed him «Buck-Buck».[3][9][10] He joined the drama club, found that acting on stage reduced his stutter, and was eventually elected student council president.[3]

After graduating from high school in 1973, Willis worked as a security guard at the Salem Nuclear Power Plant[11][12] and transported crew members at the DuPont Chambers Works factory in Deepwater, New Jersey.[12] After working as a private investigator (a role he would later play in the comedy-drama series Moonlighting and the action-comedy film The Last Boy Scout), he turned to acting. He enrolled in the Drama Program at Montclair State University,[13] where he was cast in a production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. He left school in 1977 and moved to New York City, where he supported himself in the early 1980s as a bartender at the Manhattan art bar Kamikaze[14][15] while living in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood.[16]

Career

1980s: Die Hard and rise to fame

Willis was cast as David Addison Jr. in the television series Moonlighting (1985–1989), competing against 3,000 other actors for the position.[17] His starring role in Moonlighting, opposite Cybill Shepherd, helped to establish him as a comedic actor. During the show’s five seasons, he won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series and a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor — Television Series Musical or Comedy.[8] During the height of the show’s success, beverage maker Seagram hired Willis as the pitchman for their Golden Wine Cooler products.[18] The advertising campaign paid Willis US$5–7 million over two years. Willis chose not to renew his contract when he decided to stop drinking alcohol in 1988.[19]

Willis had his first lead role in a feature film in the 1987 Blake Edwards film Blind Date, with Kim Basinger and John Larroquette.[8] Edwards cast him again to play the real-life cowboy actor Tom Mix in Sunset (1988). However, it was his unexpected turn in the film Die Hard (1988) as John McClane that catapulted him to movie star and action hero status.[8] He performed most of his own stunts in the film,[20] and the film grossed $138,708,852 worldwide.[21] Following his success with Die Hard, Willis had a leading role in the drama In Country as Vietnam veteran Emmett Smith and also provided the voice for a talking baby in Look Who’s Talking (1989) and the sequel Look Who’s Talking Too (1990).[citation needed]

In the late 1980s, Willis enjoyed moderate success as a recording artist, recording an album of pop-blues, The Return of Bruno, which included the hit single «Respect Yourself» featuring the Pointer Sisters.[22] The LP was promoted by a Spinal Tap–like rockumentary parody featuring scenes of Willis performing at famous events including Woodstock. He released a version of the Drifters song «Under the Boardwalk» as a second single; it reached No. 2 on the UK Singles Chart, but was less successful in the US. Willis returned to the recording studio several times.[23]

1990s: Die Hard sequels, Pulp Fiction and dramatic roles

Having acquired major personal success and pop culture influence playing John McClane in Die Hard, Willis reprised his role in the sequels Die Hard 2 (1990) and Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995).[8] These first three installments in the Die Hard series grossed over US$700 million internationally and propelled Willis to the first rank of Hollywood action stars.[citation needed]

In the early 1990s, Willis’s career suffered a moderate slump, as he starred in flops such as The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) and Hudson Hawk (1991), although he did find box office success with The Last Boy Scout. He gained more success with Striking Distance (1993) but flopped again with Color of Night (1994): it was savaged by critics but did well in the home video market and became one of the Top 20 most-rented films in the United States in 1995.[24] Maxim also ranked his sex scene in the film as the best in film history.[25]

In 1994, Willis also had a leading role in one part of Quentin Tarantino’s acclaimed Pulp Fiction;[8] the film’s success gave a boost to his career, and he starred alongside his Look Who’s Talking co-star John Travolta.[26] In 1996, he was the executive producer and star of the cartoon Bruno the Kid which featured a CGI representation of himself.[27] That same year, he starred in Mike Judge’s animated film Beavis and Butt-head Do America with his then-wife Demi Moore. In the movie, he plays a drunken criminal named «Muddy Grimes», who mistakenly sends Judge’s titular characters to kill his wife, Dallas (voiced by Moore). He then played the lead roles in 12 Monkeys (1995) and The Fifth Element (1997). However, by the end of the 1990s his career had fallen into another slump with critically panned films like The Jackal (which despite negative reviews was a box office hit), Mercury Rising, and Breakfast of Champions, as well as the implosion of the production of Broadway Brawler, a debacle salvaged only by the success of the Michael Bay-directed Armageddon, which Willis had agreed to star in as compensation for the failed production, and which turned out to be the highest-grossing film of 1998 worldwide.[28][29] The same year his voice and likeness were featured in the PlayStation video game Apocalypse.[30] In 1999, Willis played the starring role in M. Night Shyamalan’s film The Sixth Sense, which was both a commercial and critical success.[8]

2000s

Willis after a ceremony where he was named Hasty Pudding Theatrical’s Man of the Year in 2002

In 2000, Willis won an Emmy[31] for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series for his work on Friends (in which he played the father of Ross Geller’s much-younger girlfriend).[32] He was also nominated for a 2001 American Comedy Award (in the Funniest Male Guest Appearance in a TV Series category) for his work on Friends. Also in 2000, Willis played Jimmy «The Tulip» Tudeski in The Whole Nine Yards alongside Matthew Perry. Willis was originally cast as Terry Benedict in Ocean’s Eleven (2001) but dropped out to work on recording an album.[33] In the sequel, Ocean’s Twelve (2004), he makes a cameo appearance as himself. In 2005, he appeared in the film adaptation of Sin City. In 2006, he lent his voice as RJ the Raccoon in Over the Hedge. In 2007, he appeared in the Planet Terror half of the double feature Grindhouse as the villain, a mutant soldier. This marked Willis’s second collaboration with the director Robert Rodriguez, following Sin City.

Willis appeared on the Late Show with David Letterman several times throughout his career. He filled in for an ill David Letterman on his show on February 26, 2003, when he was supposed to be a guest.[34] On many of his appearances on the show, Willis staged elaborate jokes, such as wearing a day-glo orange suit in honor of the Central Park gates, having one side of his face made up with simulated birdshot wounds after the Harry Whittington shooting, or trying to break a record (a parody of David Blaine) of staying underwater for only twenty seconds.

On April 12, 2007, he appeared again, this time wearing a Sanjaya Malakar wig.[35] On his June 25, 2007, appearance, he wore a mini-wind turbine on his head to accompany a joke about his own fictional documentary titled An Unappealing Hunch (a wordplay on An Inconvenient Truth).[36] Willis also appeared in Japanese Subaru Legacy television commercials.[37] Tying in with this, Subaru did a limited run of Legacys, badged «Subaru Legacy Touring Bruce», in honor of Willis.

Willis has appeared in five films with Samuel L. Jackson (National Lampoon’s Loaded Weapon 1, Pulp Fiction, Die Hard with a Vengeance, Unbreakable, and Glass) and both actors were slated to work together in Black Water Transit, before dropping out. Willis also worked with his eldest daughter, Rumer, in the 2005 film Hostage. In 2007, he appeared in the thriller Perfect Stranger, opposite Halle Berry, the crime/drama film Alpha Dog, opposite Sharon Stone, and reprised his role as John McClane in Live Free or Die Hard. Subsequently, he appeared in the films What Just Happened and Surrogates, based on the comic book of the same name.[38]

Willis was slated to play U.S. Army general William R. Peers in director Oliver Stone’s Pinkville, a drama about the investigation of the 1968 My Lai massacre.[39] However, due to the 2007 Writers Guild of America strike, the film was canceled. Willis appeared on the 2008 Blues Traveler album North Hollywood Shootout, giving a spoken word performance over an instrumental blues rock jam on the track «Free Willis (Ruminations from Behind Uncle Bob’s Machine Shop)». In early 2009, he appeared in an advertising campaign to publicize the insurance company Norwich Union’s change of name to Aviva.[40]

2010s

Willis starred with Tracy Morgan in the comedy Cop Out, directed by Kevin Smith, about two police detectives investigating the theft of a baseball card.[41] The film was released in February 2010. Willis appeared in the music video for the song «Stylo» by Gorillaz.[42] Also in 2010, he appeared in a cameo with former Planet Hollywood co-owners and ’80s action stars Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger in the film The Expendables. Willis played the role of CIA agent «Mr. Church». This was the first time these three notable action movie actors appeared on screen together. Although the scene featuring the three was short, it was one of the most highly anticipated scenes in the film. The trio filmed their scene in an empty church on October 24, 2009.[43] Willis next starred in RED, an adaptation of the comic book mini-series of the same name, in which he portrayed Frank Moses. The film was released on October 15, 2010.[44]

Willis starred alongside Bill Murray, Edward Norton, and Frances McDormand in Moonrise Kingdom (2012). Filming took place in Rhode Island under the direction of Wes Anderson, in 2011.[45] Willis returned, in an expanded role, in The Expendables 2 (2012).[46] He appeared alongside Joseph Gordon-Levitt in the sci-fi action film Looper (2012), as the older version of Gordon-Levitt’s character, Joe.

Willis teamed up with 50 Cent in a film directed by David Barrett called Fire with Fire, starring opposite Josh Duhamel and Rosario Dawson, about a fireman who must save the love of his life.[47] Willis also joined Vince Vaughn and Catherine Zeta-Jones in Lay the Favorite, directed by Stephen Frears, about a Las Vegas cocktail waitress who becomes an elite professional gambler.[48] The two films were distributed by Lionsgate Entertainment.

Willis reprised his most famous role, John McClane, for a fifth time, starring in A Good Day to Die Hard, which was released on February 14, 2013.[49] In an interview, Willis said, «I have a warm spot in my heart for Die Hard….. it’s just the sheer novelty of being able to play the same character over 25 years and still be asked back is fun. It’s much more challenging to have to do a film again and try to compete with myself, which is what I do in Die Hard. I try to improve my work every time.»[50]

On October 12, 2013, Willis hosted Saturday Night Live with Katy Perry as a musical guest.[51] In 2015, Willis made his Broadway debut in William Goldman’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel Misery opposite Laurie Metcalf at the Broadhurst Theatre. His performance was generally panned by critics, who called it «vacant» and «inert».[52] Willis was the subject of a roast by Comedy Central in a program broadcast on July 29, 2018.[53]

Films featuring Willis have grossed between US$2.64 billion and US$3.05 billion at the North American box offices, making him in 2010 the eighth highest-grossing actor in a leading role and 12th-highest including supporting roles.[54][55] He is a two-time Emmy Award winner, a Golden Globe Award winner, and has been nominated for a Saturn Award four times.

2020s: Critical decline, health problems and retirement

In the final years of his career, Willis starred in many low-budget independent thrillers and science fiction films.[56] He worked primarily with the production companies Emmett/Furla Oasis, headed by Randall Emmett, and 308 Entertainment Inc, headed by Corey Large. Emmett/Furla Oasis produced 20 films starring Willis.[57] Described by Chris Nashawaty of Esquire as «a profitable safe harbor» for older actors, similar to The Expendables, most of the films were released direct-to-video and were widely panned.[56] Willis would often earn US$2 million for two days’ work, with an average of 15 minutes’ screentime per film.[58] He nonetheless featured heavily in the films’ promotional materials, earning them the derogatory nickname «geezer teasers».[59][60]

Those working on the films later said Willis appeared confused, did not understand why he was there and had to be fed lines through an earpiece.[57] Days before Willis was scheduled to arrive on set for Out of Death (2021), the screenwriter was instructed to reduce his role and abbreviate his dialogue, and the director, Mike Burns, was told to complete all of Willis’s scenes in a single day of filming.[57] The Golden Raspberry Awards, an annual award for the year’s worst films and performances, created a dedicated category, the Worst Bruce Willis Performance in a 2021 Movie, for his roles in eight films released that year.[61]

On March 30, 2022, Willis’s family announced that he was retiring because he had been diagnosed with aphasia, a disorder typically caused by damage to the area of the brain that controls language expression and comprehension.[62] The Golden Raspberry Awards retracted its Willis category, saying it was inappropriate to award a Golden Raspberry to someone whose performance was affected by a medical condition.[63] At the time of his retirement, Willis had completed eleven films awaiting release.[62][64][65] On February 16, 2023, Willis’s family announced that he had been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia.[66] In a statement, the family said that Willis’s condition had «progressed» and that «challenges with communication are just one symptom of the disease».[67]

Business activities

Willis owns houses in Los Angeles and Penns Grove, New Jersey. He also rents apartments at Trump Tower[68] and in Riverside South, Manhattan.[69]

In 2000, Willis and his business partner Arnold Rifkin started a motion picture production company called Cheyenne Enterprises. He left the company to be run solely by Rifkin in 2007 after Live Free or Die Hard.[70] He also owns several small businesses in Hailey, Idaho, including The Mint Bar and The Liberty Theater and was one of the first promoters of Planet Hollywood, with actors Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone.[71] Willis and the other actors were paid for their appearances and endorsements through an employee stock ownership plan.[72]

In 2009, Willis signed a contract to become the international face of Belvedere SA’s Sobieski Vodka in exchange for 3.3 percent ownership in the company.[73]

Personal life

Willis’s acting role models are Gary Cooper, Robert De Niro, Steve McQueen, and John Wayne.[74] He is left-handed.[75] He resides in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles with his family.[76]

Relationships and children

At the premiere for the film Stakeout, Willis met actress Demi Moore. They married on November 21, 1987, and had three daughters, including Rumer, who was born in August 1988.[77][78][79][80] Willis and Moore announced their separation on June 24, 1998.[81] They filed for divorce on October 18, 2000,[82] and the divorce was finalized later that day.[83][84] Regarding the divorce, Willis stated, «I felt I had failed as a father and a husband by not being able to make it work.» He credited actor Will Smith for helping him cope with the situation.[18] He has maintained a close friendship with both Moore and her subsequent husband, actor Ashton Kutcher, and attended their wedding.[85]

Willis was engaged to actress Brooke Burns until they broke up in 2004 after ten months together.[17] He married model Emma Heming in Turks and Caicos on March 21, 2009;[86] guests included his three daughters, as well as Moore and Kutcher. The ceremony was not legally binding, so the couple wed again in a civil ceremony in Beverly Hills six days later. The couple has two daughters, one born in 2012[87] and another born in 2014.[88]

Religious views

Willis was a Lutheran,[89] but no longer practices. In a July 1998 interview with George magazine, he stated: «Organized religions in general, in my opinion, are dying forms. They were all very important when we didn’t know why the sun moved, why weather changed, why hurricanes occurred, or volcanoes happened. Modern religion is the end trail of modern mythology. But there are people who interpret the Bible literally. Literally! I choose not to believe that’s the way. And that’s what makes America cool, you know?»[90]

Political views

In 1988, Willis and then-wife Demi Moore campaigned for Democratic Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis’s Presidential bid. Four years later, he supported President George H. W. Bush for reelection and was an outspoken critic of Bill Clinton. However, in 1996, he declined to endorse Clinton’s Republican opponent Bob Dole, because Dole had criticized Demi Moore for her role in the film Striptease.[91] Willis was an invited speaker at the 2000 Republican National Convention,[92] and supported George W. Bush that year.[18]

In 2006, Willis said that the United States should intervene more in Colombia in order to end drug trafficking.[93] In several interviews Willis has said that he supports large salaries for teachers and police officers, and said he is disappointed in the United States foster care system as well as treatment of Native Americans.[91][94] Willis also stated that he is a supporter of gun rights, stating, «Everyone has a right to bear arms. If you take guns away from legal gun owners, then the only people who have guns are the bad guys.»[95]

In February 2006, Willis was in Manhattan to promote his film 16 Blocks with reporters. One reporter attempted to ask Willis about his opinion on the Bush administration, but was interrupted by Willis in mid-sentence when he said: «I’m sick of answering this fucking question. I’m a Republican only as far as I want a smaller government, I want less government intrusion. I want them to stop shitting on my money and your money and tax dollars that we give 50 percent of every year. I want them to be fiscally responsible and I want these goddamn lobbyists out of Washington. Do that and I’ll say I’m a Republican. I hate the government, OK? I’m apolitical. Write that down. I’m not a Republican.»[96] Willis did not make any contributions or public endorsements in the 2008 presidential campaign. In several June 2007 interviews, he declared that he maintains some Republican ideologies.[18]

Willis’s name was in an advertisement in the Los Angeles Times on August 17, 2006, that condemned Hamas and Hezbollah and supported Israel in the 2006 Israel-Lebanon war.[97]

In 2012, Willis stated that he had a negative opinion of Mitt Romney.[98]

Military interests

Throughout his film career, Willis has depicted several military characters in films such as In Country, The Siege, Hart’s War, Tears of the Sun, Grindhouse, and G.I. Joe: Retaliation. Growing up in a military family, Willis has donated Girl Scout cookies to the United States armed forces. In 2002, Willis’s then 8-year-old daughter, Tallulah, suggested that he purchase Girl Scout cookies to send to troops. Willis purchased 12,000 boxes of cookies, and they were distributed to sailors aboard USS John F. Kennedy and other troops stationed throughout the Middle East at the time.[99]

In 2003, Willis visited Iraq as part of the USO tour, singing to the troops with his band, The Accelerators.[100] Willis considered joining the military to help fight the second Iraq War, but was deterred by his age.[101] It was believed he offered US$1 million to any noncombatant who turned in terrorist leaders Osama bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, or Abu Musab al-Zarqawi; in the June 2007 issue of Vanity Fair, however, he clarified that the statement was made hypothetically and not meant to be taken literally. Willis has also criticized the media for its coverage of the war, complaining that the press was more likely to focus on the negative aspects of the war:

I went to Iraq because what I saw when I was over there was soldiers—young kids for the most part—helping people in Iraq; helping getting the power turned back on, helping get hospitals open, helping get the water turned back on and you don’t hear any of that on the news. You hear, «X number of people were killed today,» which I think does a huge disservice. It’s like spitting on these young men and women who are over there fighting to help this country.[102]

In popular culture

In 1996, Roger Director, a writer and producer from Moonlighting, wrote a roman à clef on Willis titled A Place to Fall.[103] Cybill Shepherd wrote in her 2000 autobiography, Cybill Disobedience, that Willis became angry at Director when he read the book and discovered the character had been written as a «neurotic, petulant actor».

A Lego version of himself appeared in the 2019 film The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part, with Willis providing the voice.[104]

Filmography

Discography

Solo albums

- 1987: The Return of Bruno (Motown, OCLC 15508727)

- 1989: If It Don’t Kill You, It Just Makes You Stronger (Motown/Pgd, OCLC 21322754)

- 2001: Classic Bruce Willis: The Universal Masters Collection (Polygram Int’l, OCLC 71124889)

Compilations/guest appearances

- 1986: Moonlighting soundtrack; track «Good Lovin’ »

- 1991: Hudson Hawk soundtrack; tracks «Swinging on a Star» and «Side by Side», both duets with Danny Aiello

- 2000: The Whole Nine Yards soundtrack; tracks «Tenth Avenue Tango»

- 2003: Rugrats Go Wild soundtrack; «Big Bad Cat» with Chrissie Hynde and «Lust for Life»

- 2008: North Hollywood Shootout, Blues Traveler; track «Free Willis (Ruminations from Behind Uncle Bob’s Machine Shop)»

Awards and honors

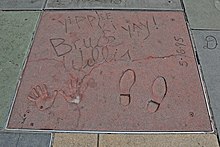

Willis’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

Willis has won a variety of awards and has received various honors throughout his career in television and film.

- 1987: Golden Apple Awards honored with the Sour Apple.[105]

- 1994: Maxim magazine ranked his sex scene in Color of Night the No. 1 sex scene in film history[25]

- 2000: American Cinematheque Gala Tribute honored Willis with the American Cinematheque Award for an extraordinary artist in the entertainment industry who is fully engaged in his or her work and is committed to making a significant contribution to the art of the motion pictures.

- 2002: The Hasty Pudding Man of the Year award from Harvard’s Hasty Pudding Theatricals – given to performers who give a lasting and impressive contribution to the world of entertainment[106]

- 2002: Appointed as national spokesman for Children in Foster Care by President George W. Bush;[107] Willis wrote online: «I saw Foster Care as a way for me to serve my country in a system by which shining a little bit of light could benefit a great deal by helping kids who were literally wards of the government.»[108]

- 2005: Golden Camera Award for Best International Actor by the Manaki Brothers Film Festival.[109]

- 2006: Honored by French government for his contributions to the film industry; appointed an Officer of the French Order of Arts and Letters in a ceremony in Paris; the French Prime Minister stated, «This is France’s way of paying tribute to an actor who epitomizes the strength of American cinema, the power of the emotions that he invites us to share on the world’s screens and the sturdy personalities of his legendary characters.»[110]

- 2006: Honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on October 16; located at 6915 Hollywood Boulevard and it was the 2,321st star awarded in its history; at the reception, he stated, «I used to come down here and look at these stars and I could never quite figure out what you were supposed to do to get one…time has passed and now here I am doing this, and I’m still excited. I’m still excited to be an actor.»[111]

- 2011: Inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame[112]

- 2013: Promoted to the dignity of Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters on February 11 by French Minister of Culture Aurélie Filippetti[113]

References

- ^ «12 Most Unlikely Action Movie Stars». Rolling Stone. July 30, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ Thomas, David (May 4, 2008). «Ford and Willis voted best action heroes». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d «Bruce Willis». Biography.com. FYI / A&E Networks). Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b «Surprise German visit from Willis». BBC. August 8, 2005. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

His mother Marlene was born in the nearby town of Kassel.

- ^ «Monitor». Entertainment Weekly. No. 1251. March 22, 2013. p. 25.

- ^ Archerd, Army (December 11, 2003). «Inside Move: Flu KOs Smart Set yule bash». Variety.com. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ «Robert Willis». Variety. July 1, 2001. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stated on Inside the Actors Studio, 2001

- ^ Petersen, Melody (May 9, 1997). «Bruce Willis Drops Project, Leaving Town More Troubled». The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis: The Uncut Interview» (PDF). Reader’s Digest. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis». The Daily Show. June 26, 2007. Comedy Central.

- ^ a b Segal, David (March 10, 2005). «Bruce Willis’s Tragic Mask». The Washington Post. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Bruce Willis Answers the Web’s Most Searched Questions. Wired. March 1, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Curley, Mallory (2010). A Cookie Mueller Encyclopedia. Randy Press. p. 260.

- ^ Longsdorf, Amy (February 24, 1996). «Spotlight on Linda Fiorentino & John Dahl: Director, Actress Make an ‘Unforgettable’ Team». The Morning Call. Allentown, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

[Linda] Fiorentino supported herself by working at the Kamikaze nightclub, where her fellow bartender was Bruce Willis. ‘He was a good partner,’ she says approvingly.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (July 1, 1990). «Bruce Willis Looks for the Man Within the Icon». The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ a b «Yahoo! Movies». Bruce Willis Biography. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c d «How Bruce Willis Keeps His Cool». Time. June 21, 2007. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Grobel, Lawrence (November 1988). «Playboy Interview: Bruce Willis». Playboy. pp. 59–79.

- ^ «Bruce Willis: Biography». People. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Die Hard». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Top 100 Songs of 1987». The Eighties Club. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Giles, Jeff. «25 Years Ago: Bruce Willis Tries His Hand at Singing With ‘The Return of Bruno’«. Diffuser.fm. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Billboard vol 108 No. 1 (1/6/1996) p.54.

- ^ a b «Top Sex Scenes of All-Time». Extra (American TV program). December 6, 2000. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ D’Aless, Anthony; ro (May 14, 2021). «Bruce Willis & John Travolta To Reteam For First Time Since ‘Pulp Fiction’ In ‘Paradise City’; Praya Lundberg Also Stars». Deadline. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ «Bruce Willis Biography (1955–)». Filmreference. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Brennan, Judy (March 13, 1997). «The Fight Over ‘Broadway Brawler’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ «1998 Worldwide Grosses». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Walk, Gary Eng (December 4, 1998). ««Apocalypse» Now». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Bruce Willis Emmy Award Winner. Emmys.com. Retrieved on June 8, 2012.

- ^ «The 52nd Annual Emmy Awards». Los Angeles Times. September 11, 2000. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Rohan, Virginia (June 28, 2004). «Let’s Make a Deal». The Record. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Susman, Gary (February 28, 2003). «The Eyes Have It». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «The Week’s Best Celeb Quotes». People. August 17, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis Wears Mini-Wind Turbine on His Head». Star Pulse. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: «1991 Subaru Legacy Ad». YouTube. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Tatiana Siegel (November 18, 2007). «Films halted due to strike». Variety. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Mayberry, Carly (November 13, 2007). «The Vine: Pitt targeted for ‘Pinkville’«. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 18, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Dunkley, Jamie (April 29, 2009). «Aviva lambasted for rebranding costs». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis Circling Several New Movies». Empire. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis takes aim at Gorillaz in Stylo video». Billboard. Retrieved March 2, 2009.

- ^ Stallone Shot a Scene with Arnold and Bruce Archived October 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine News in Film

- ^ «Red Begins Principal Photography». /Film. January 18, 2010. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ «Film starring Bruce Willis to be shot in RI». The Boston Globe. Providence, R.I. Associated Press. March 24, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

Steven Feinberg, executive director for the Rhode Island Film and Television Office, says on-site work on the film, ‘Moonrise Kingdom,’ is scheduled to begin this spring. Feinberg says the film will be shot in several locations in Rhode Island.

- ^ Jason Barr (August 29, 2010). «Sylvester Stallone Wants Bruce Willis to Play a «Super Villain» in THE EXPENDABLES Sequel». Collider. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012.

- ^ Anderton, Ethan (May 5, 2011). «Bruce Willis and 50 Cent Teaming Up Again to Fight ‘Fire with Fire’«. Firstshowing.net. Variety. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

Now Variety reports that for some reason, the two will team-up again for an indie drama called Fire with Fire.

- ^ Bettinger, Brendan (May 5, 2011). «Vince Vaughn Joins Rebecca Hall, Bruce Willis, and Catherine Zeta-Jones in LAY THE FAVORITE». Collider.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

Vince Vaughn will join Rebecca Hall, Bruce Willis, and Catherine Zeta-Jones in the gambling drama Lay the Favorite.

- ^ «Die Hard 5 Given a Name and a 2013 Release Date». Yahoo! News. October 12, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ «Bruce Willis: Women Should Be In Charge Of Everything». UKScreen. February 13, 2013. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ «SNL Promo: Bruce Willis and Katy Perry». NBC. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ «Bruce Willis in Misery on Broadway – what the critics said»,The Guardian, November 16, 2015

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Comedy Central (April 10, 2018). «Coming This Summer: The Roast of Bruce Willis». YouTube. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ «People Index». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ «All Time Top 100 Stars at the Box Office». The Numbers. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ a b Nashawaty, Nashawaty (August 21, 2020). «Why Does Bruce Willis Keep Making Films He Clearly Hates?». Esquire. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c «Concerns about Bruce Willis’s declining cognitive state swirled around sets in recent years». Los Angeles Times. March 31, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (December 30, 2020). «The Bruce Willis Journey From In Demand to On Demand». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ «What Happened to Bruce Willis?». Collider. July 29, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ Donohoo, Timothy (May 5, 2022). «What Are ‘Geezer Teasers’ — and Why Does Bruce Willis Have So Many?». CBR.com. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Fuster, Jeremy; Rossi, Rosemary (February 7, 2022). «Razzie Awards: Bruce Willis Bags His Own Category for 8 Bad Performances in One Year». The Wrap. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Shoard, Catherine (March 30, 2022). «Bruce Willis to retire from acting due to aphasia diagnosis». The Guardian.

- ^ Haring, Bruce (March 31, 2022). «Razzie Awards Retract Bruce Willis Worst Performance Category After His Aphasia Reveal». Deadline. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Kusiak, Lindsay (May 22, 2022). «YouTube Chief Product Officer Neal Mohan». ScreenRant. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ Kois, Dan (September 7, 2022). «How We Should Remember Bruce Willis». Slate. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ Rosenbloom, Alli (February 16, 2023). «Bruce Willis’ family shares an update on his health and new diagnosis». CNN. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Sandee; LaMotte, Kristen (February 17, 2023). «Bruce Willis has a progressive brain condition you may not have heard of». CNN. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ Ambinder, Marc (November 18, 2016). «How Donald Trump will retrofit Midtown Manhattan as a presidential getaway». The Washington Post. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^ Abelson, Max (November 5, 2007). «Bruce Willis Pays $4.26 M. for Trump Enemy’s Condo». The New York Observer. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (November 12, 2002). «Willis held ‘Hostage’«. Variety. Retrieved May 10, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Martinson, Jane; Vikram Dodd (August 18, 1999). «Planet Hollywood crashes to earth». The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «Stars like Bruce Willis, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone endorse Planet Hollywood». The Economic Times. Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. September 11, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Baubeau, Amelie and David Kesmodel (December 23, 2009). «Bruce Willis Sees Spirits in Equity Deal With Belvedere». The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ «Bruce Willis Biography». biography.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ^ Hennen, Emily (December 31, 2013). «59 Famous People Who Are Left-Handed». BuzzFeed. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ David, Mark (March 7, 2019). «Bruce Willis and Emma Heming Buy Brand New Brentwood Mansion». Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ «Baby Girl Is a Rumer». Gainesville Sun. August 18, 1988.

- ^ «Demi Moore Has Her Baby». The Philadelphia Inquirer. July 22, 1991. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018.

- ^ «It’s Another Girl for Demi, Bruce». The Vindicator. Youngstown, Ohio. February 5, 1994.

- ^ «Willis, Moore Welcome Daughter Tallulah Belle». Deseret News. Salt Lake City, Utah. February 6, 1994. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

Actors Bruce Willis and Demi Moore have a new daughter, Tallulah Belle, born Thursday [February 3, 1994]

- ^ Gliatto, Tom (July 13, 1998). «Dreams Die Hard». People. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- ^ «That’s a Wrap». People. November 6, 2000. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ «Demi and Bruce get a divorce in secret». Free Online Library. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Davis, Simon (October 26, 2000). «Moore and Willis are divorced». Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2020 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Oldenburg, Ann (September 27, 2006). «Changing of the ‘Guardian‘«. USA Today. Retrieved September 30, 2006.

- ^ «Bruce Willis Married to Super Model Emma heming». Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Leonard, Elizabeth (April 2, 2012). «Bruce Willis and Emma Heming welcome a Daughter». People. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ «Bruce Willis’ Wife Emma Heming-Willis Gives Birth, Couple Welcomes Second Girl, Baby Evelyn Penn». Us Weekly. May 7, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ «Famous Lutherans». Hope-elca.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Tom, Dunkel (July 1998). «Bruce Willis Kicks Asteroid». George. HFM U.S. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Vincent, Mal (March 3, 2006). «Playing the bad boy is a natural for Bruce Willis». HamptonRoads.com. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «Bush and Cheney head toward Philadelphia as party vanguard makes preparations». CNN. July 28, 2000. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Walls, Jeannette (March 14, 2006). «Bruce Willis blasts Colombian drug trade». Today.com. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ West, Kevin (June 24, 2007). «A Big Ride of a Life». USA Weekend. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Roach, Mary (February 13, 2000). «Being Bruce Willis». USA Weekend. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «Willis Is Mad As Hell…» MSN Movies. February 24, 2006. Archived from the original on April 25, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «Nicole Kidman and 84 Others Stand United Against Terrorism.» Hollywood Grind. August 18, 2006. Archived September 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mcdevitt, Caitlin (May 22, 2012). «Bruce Willis trash-talks Mitt Romney». Politico. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Leah N. (May 29, 2002). «Bruce Willis Moonlights as Off-Screen Hero with Cookie Donation». USS John F. Kennedy Public Affairs. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Neal, Rome (September 26, 2003). «Bruce Willis Sings for the Troops». CBS News. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «Hollywood’s right reluctant to join Iraq debate». CNN. March 7, 2003. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «Willis Fights for Iraqi Troops». Hollywood.com. March 9, 2005. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Gates, Anita (March 24, 1996). «Moonlighting». The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Coulston, John Connor (January 26, 2019). «‘The Lego Movie 2’ Features Secret Cameo From an A-List Action Star». PopCulture.com. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ «Golden Apple Awards (1987)». IMDb. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (February 12, 2002). «For Bruce Willis, Award Is a Drag». People. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ «President, Mrs. Bush & Bruce Willis Announce Adoption Initiative». whitehouse.gov. July 23, 2002. Archived from the original on July 25, 2002. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «Make a difference». BruceWillis.com. 2005. Archived from the original on February 3, 2005. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ «Golden Camera, Germany (2005)». IMDb. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- ^ «Internet Movie Database«. Willis Receives French Honor. January 12, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «Willis Gets Hollywood Walk of Fame Star». The Washington Post. Associated Press. October 17, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ «New Jersey Hall of Fame – 2011 Inductees». New Jersey Hall of Fame. April 9, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ «Hoge Franse Onderscheiding Voor Bruce Willis – Achterklap – Video» (in Dutch). Zie.nl. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

External links

- Bruce Willis at IMDb

- Bruce Willis at the Internet Broadway Database

- Bruce Willis at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Bruce Willis at Rotten Tomatoes

- Bruce Willis at the TCM Movie Database

- Bruce Willis interview with KVUE in 1988 about Die Hard from Texas Archive of the Moving Image

|

Bruce Willis |

|

|---|---|

Willis at the 2018 San Diego Comic-Con |

|

| Born |

Walter Bruce Willis March 19, 1955 (age 67) Idar-Oberstein, West Germany |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1980–2022 |

| Works |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5, including Rumer |

| Awards | Full list |

Walter Bruce Willis (born March 19, 1955) is a retired American actor. He achieved fame with a leading role on the comedy-drama series Moonlighting (1985–1989) and appeared in over a hundred films, gaining recognition as an action hero after his portrayal of John McClane in the Die Hard franchise (1988–2013) and other roles.[1][2]

Willis’s other credits include The Last Boy Scout (1991), Death Becomes Her (1992), Pulp Fiction (1994), 12 Monkeys (1995), The Fifth Element (1997), Armageddon (1998), The Sixth Sense (1999), Unbreakable (2000), Sin City (2005), Red (2010), Moonrise Kingdom (2012), Looper (2012) and Red 2 (2013). In the later years of his career, Willis starred in many low-budget direct-to-video films, which were poorly received. In March 2022, Willis’s family announced that he was retiring after being diagnosed with aphasia, which damages language comprehension. In February 2023, he was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia.

As a singer, Willis released his debut album, The Return of Bruno, in 1987, followed by two more albums in 1989 and 2001. He made his Broadway debut in the stage adaptation of Misery in 2015. Willis has received various accolades throughout his career, including a Golden Globe Award, two Primetime Emmy Awards, and two People’s Choice Awards. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2006. Films featuring Willis have grossed between US$2.64 billion and US$3.05 billion at North American box offices, making him in 2010 the eighth-highest-grossing leading actor.

Early life

Walter Bruce Willis[3] was born in Idar-Oberstein, West Germany, on March 19, 1955.[4][5] His mother, Marlene,[6] was German, from Kassel.[4] His father, David Willis, was an American soldier. Willis has a younger sister, Florence, and two younger brothers, Robert (deceased) and David.[7] After being discharged from the military in 1957, his father relocated the family to his hometown of Carneys Point, New Jersey.[8] Willis has described his background as a «long line of blue-collar people».[8] His mother worked in a bank and his father was a welder, master mechanic, and factory worker.[3]

Willis, who spoke with a stutter,[8] attended Penns Grove High School, where his schoolmates nicknamed him «Buck-Buck».[3][9][10] He joined the drama club, found that acting on stage reduced his stutter, and was eventually elected student council president.[3]

After graduating from high school in 1973, Willis worked as a security guard at the Salem Nuclear Power Plant[11][12] and transported crew members at the DuPont Chambers Works factory in Deepwater, New Jersey.[12] After working as a private investigator (a role he would later play in the comedy-drama series Moonlighting and the action-comedy film The Last Boy Scout), he turned to acting. He enrolled in the Drama Program at Montclair State University,[13] where he was cast in a production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. He left school in 1977 and moved to New York City, where he supported himself in the early 1980s as a bartender at the Manhattan art bar Kamikaze[14][15] while living in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood.[16]

Career

1980s: Die Hard and rise to fame

Willis was cast as David Addison Jr. in the television series Moonlighting (1985–1989), competing against 3,000 other actors for the position.[17] His starring role in Moonlighting, opposite Cybill Shepherd, helped to establish him as a comedic actor. During the show’s five seasons, he won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series and a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor — Television Series Musical or Comedy.[8] During the height of the show’s success, beverage maker Seagram hired Willis as the pitchman for their Golden Wine Cooler products.[18] The advertising campaign paid Willis US$5–7 million over two years. Willis chose not to renew his contract when he decided to stop drinking alcohol in 1988.[19]

Willis had his first lead role in a feature film in the 1987 Blake Edwards film Blind Date, with Kim Basinger and John Larroquette.[8] Edwards cast him again to play the real-life cowboy actor Tom Mix in Sunset (1988). However, it was his unexpected turn in the film Die Hard (1988) as John McClane that catapulted him to movie star and action hero status.[8] He performed most of his own stunts in the film,[20] and the film grossed $138,708,852 worldwide.[21] Following his success with Die Hard, Willis had a leading role in the drama In Country as Vietnam veteran Emmett Smith and also provided the voice for a talking baby in Look Who’s Talking (1989) and the sequel Look Who’s Talking Too (1990).[citation needed]

In the late 1980s, Willis enjoyed moderate success as a recording artist, recording an album of pop-blues, The Return of Bruno, which included the hit single «Respect Yourself» featuring the Pointer Sisters.[22] The LP was promoted by a Spinal Tap–like rockumentary parody featuring scenes of Willis performing at famous events including Woodstock. He released a version of the Drifters song «Under the Boardwalk» as a second single; it reached No. 2 on the UK Singles Chart, but was less successful in the US. Willis returned to the recording studio several times.[23]

1990s: Die Hard sequels, Pulp Fiction and dramatic roles

Having acquired major personal success and pop culture influence playing John McClane in Die Hard, Willis reprised his role in the sequels Die Hard 2 (1990) and Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995).[8] These first three installments in the Die Hard series grossed over US$700 million internationally and propelled Willis to the first rank of Hollywood action stars.[citation needed]

In the early 1990s, Willis’s career suffered a moderate slump, as he starred in flops such as The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) and Hudson Hawk (1991), although he did find box office success with The Last Boy Scout. He gained more success with Striking Distance (1993) but flopped again with Color of Night (1994): it was savaged by critics but did well in the home video market and became one of the Top 20 most-rented films in the United States in 1995.[24] Maxim also ranked his sex scene in the film as the best in film history.[25]

In 1994, Willis also had a leading role in one part of Quentin Tarantino’s acclaimed Pulp Fiction;[8] the film’s success gave a boost to his career, and he starred alongside his Look Who’s Talking co-star John Travolta.[26] In 1996, he was the executive producer and star of the cartoon Bruno the Kid which featured a CGI representation of himself.[27] That same year, he starred in Mike Judge’s animated film Beavis and Butt-head Do America with his then-wife Demi Moore. In the movie, he plays a drunken criminal named «Muddy Grimes», who mistakenly sends Judge’s titular characters to kill his wife, Dallas (voiced by Moore). He then played the lead roles in 12 Monkeys (1995) and The Fifth Element (1997). However, by the end of the 1990s his career had fallen into another slump with critically panned films like The Jackal (which despite negative reviews was a box office hit), Mercury Rising, and Breakfast of Champions, as well as the implosion of the production of Broadway Brawler, a debacle salvaged only by the success of the Michael Bay-directed Armageddon, which Willis had agreed to star in as compensation for the failed production, and which turned out to be the highest-grossing film of 1998 worldwide.[28][29] The same year his voice and likeness were featured in the PlayStation video game Apocalypse.[30] In 1999, Willis played the starring role in M. Night Shyamalan’s film The Sixth Sense, which was both a commercial and critical success.[8]

2000s

Willis after a ceremony where he was named Hasty Pudding Theatrical’s Man of the Year in 2002

In 2000, Willis won an Emmy[31] for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series for his work on Friends (in which he played the father of Ross Geller’s much-younger girlfriend).[32] He was also nominated for a 2001 American Comedy Award (in the Funniest Male Guest Appearance in a TV Series category) for his work on Friends. Also in 2000, Willis played Jimmy «The Tulip» Tudeski in The Whole Nine Yards alongside Matthew Perry. Willis was originally cast as Terry Benedict in Ocean’s Eleven (2001) but dropped out to work on recording an album.[33] In the sequel, Ocean’s Twelve (2004), he makes a cameo appearance as himself. In 2005, he appeared in the film adaptation of Sin City. In 2006, he lent his voice as RJ the Raccoon in Over the Hedge. In 2007, he appeared in the Planet Terror half of the double feature Grindhouse as the villain, a mutant soldier. This marked Willis’s second collaboration with the director Robert Rodriguez, following Sin City.

Willis appeared on the Late Show with David Letterman several times throughout his career. He filled in for an ill David Letterman on his show on February 26, 2003, when he was supposed to be a guest.[34] On many of his appearances on the show, Willis staged elaborate jokes, such as wearing a day-glo orange suit in honor of the Central Park gates, having one side of his face made up with simulated birdshot wounds after the Harry Whittington shooting, or trying to break a record (a parody of David Blaine) of staying underwater for only twenty seconds.

On April 12, 2007, he appeared again, this time wearing a Sanjaya Malakar wig.[35] On his June 25, 2007, appearance, he wore a mini-wind turbine on his head to accompany a joke about his own fictional documentary titled An Unappealing Hunch (a wordplay on An Inconvenient Truth).[36] Willis also appeared in Japanese Subaru Legacy television commercials.[37] Tying in with this, Subaru did a limited run of Legacys, badged «Subaru Legacy Touring Bruce», in honor of Willis.

Willis has appeared in five films with Samuel L. Jackson (National Lampoon’s Loaded Weapon 1, Pulp Fiction, Die Hard with a Vengeance, Unbreakable, and Glass) and both actors were slated to work together in Black Water Transit, before dropping out. Willis also worked with his eldest daughter, Rumer, in the 2005 film Hostage. In 2007, he appeared in the thriller Perfect Stranger, opposite Halle Berry, the crime/drama film Alpha Dog, opposite Sharon Stone, and reprised his role as John McClane in Live Free or Die Hard. Subsequently, he appeared in the films What Just Happened and Surrogates, based on the comic book of the same name.[38]

Willis was slated to play U.S. Army general William R. Peers in director Oliver Stone’s Pinkville, a drama about the investigation of the 1968 My Lai massacre.[39] However, due to the 2007 Writers Guild of America strike, the film was canceled. Willis appeared on the 2008 Blues Traveler album North Hollywood Shootout, giving a spoken word performance over an instrumental blues rock jam on the track «Free Willis (Ruminations from Behind Uncle Bob’s Machine Shop)». In early 2009, he appeared in an advertising campaign to publicize the insurance company Norwich Union’s change of name to Aviva.[40]

2010s

Willis starred with Tracy Morgan in the comedy Cop Out, directed by Kevin Smith, about two police detectives investigating the theft of a baseball card.[41] The film was released in February 2010. Willis appeared in the music video for the song «Stylo» by Gorillaz.[42] Also in 2010, he appeared in a cameo with former Planet Hollywood co-owners and ’80s action stars Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger in the film The Expendables. Willis played the role of CIA agent «Mr. Church». This was the first time these three notable action movie actors appeared on screen together. Although the scene featuring the three was short, it was one of the most highly anticipated scenes in the film. The trio filmed their scene in an empty church on October 24, 2009.[43] Willis next starred in RED, an adaptation of the comic book mini-series of the same name, in which he portrayed Frank Moses. The film was released on October 15, 2010.[44]

Willis starred alongside Bill Murray, Edward Norton, and Frances McDormand in Moonrise Kingdom (2012). Filming took place in Rhode Island under the direction of Wes Anderson, in 2011.[45] Willis returned, in an expanded role, in The Expendables 2 (2012).[46] He appeared alongside Joseph Gordon-Levitt in the sci-fi action film Looper (2012), as the older version of Gordon-Levitt’s character, Joe.

Willis teamed up with 50 Cent in a film directed by David Barrett called Fire with Fire, starring opposite Josh Duhamel and Rosario Dawson, about a fireman who must save the love of his life.[47] Willis also joined Vince Vaughn and Catherine Zeta-Jones in Lay the Favorite, directed by Stephen Frears, about a Las Vegas cocktail waitress who becomes an elite professional gambler.[48] The two films were distributed by Lionsgate Entertainment.

Willis reprised his most famous role, John McClane, for a fifth time, starring in A Good Day to Die Hard, which was released on February 14, 2013.[49] In an interview, Willis said, «I have a warm spot in my heart for Die Hard….. it’s just the sheer novelty of being able to play the same character over 25 years and still be asked back is fun. It’s much more challenging to have to do a film again and try to compete with myself, which is what I do in Die Hard. I try to improve my work every time.»[50]

On October 12, 2013, Willis hosted Saturday Night Live with Katy Perry as a musical guest.[51] In 2015, Willis made his Broadway debut in William Goldman’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel Misery opposite Laurie Metcalf at the Broadhurst Theatre. His performance was generally panned by critics, who called it «vacant» and «inert».[52] Willis was the subject of a roast by Comedy Central in a program broadcast on July 29, 2018.[53]

Films featuring Willis have grossed between US$2.64 billion and US$3.05 billion at the North American box offices, making him in 2010 the eighth highest-grossing actor in a leading role and 12th-highest including supporting roles.[54][55] He is a two-time Emmy Award winner, a Golden Globe Award winner, and has been nominated for a Saturn Award four times.

2020s: Critical decline, health problems and retirement

In the final years of his career, Willis starred in many low-budget independent thrillers and science fiction films.[56] He worked primarily with the production companies Emmett/Furla Oasis, headed by Randall Emmett, and 308 Entertainment Inc, headed by Corey Large. Emmett/Furla Oasis produced 20 films starring Willis.[57] Described by Chris Nashawaty of Esquire as «a profitable safe harbor» for older actors, similar to The Expendables, most of the films were released direct-to-video and were widely panned.[56] Willis would often earn US$2 million for two days’ work, with an average of 15 minutes’ screentime per film.[58] He nonetheless featured heavily in the films’ promotional materials, earning them the derogatory nickname «geezer teasers».[59][60]

Those working on the films later said Willis appeared confused, did not understand why he was there and had to be fed lines through an earpiece.[57] Days before Willis was scheduled to arrive on set for Out of Death (2021), the screenwriter was instructed to reduce his role and abbreviate his dialogue, and the director, Mike Burns, was told to complete all of Willis’s scenes in a single day of filming.[57] The Golden Raspberry Awards, an annual award for the year’s worst films and performances, created a dedicated category, the Worst Bruce Willis Performance in a 2021 Movie, for his roles in eight films released that year.[61]

On March 30, 2022, Willis’s family announced that he was retiring because he had been diagnosed with aphasia, a disorder typically caused by damage to the area of the brain that controls language expression and comprehension.[62] The Golden Raspberry Awards retracted its Willis category, saying it was inappropriate to award a Golden Raspberry to someone whose performance was affected by a medical condition.[63] At the time of his retirement, Willis had completed eleven films awaiting release.[62][64][65] On February 16, 2023, Willis’s family announced that he had been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia.[66] In a statement, the family said that Willis’s condition had «progressed» and that «challenges with communication are just one symptom of the disease».[67]

Business activities

Willis owns houses in Los Angeles and Penns Grove, New Jersey. He also rents apartments at Trump Tower[68] and in Riverside South, Manhattan.[69]

In 2000, Willis and his business partner Arnold Rifkin started a motion picture production company called Cheyenne Enterprises. He left the company to be run solely by Rifkin in 2007 after Live Free or Die Hard.[70] He also owns several small businesses in Hailey, Idaho, including The Mint Bar and The Liberty Theater and was one of the first promoters of Planet Hollywood, with actors Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone.[71] Willis and the other actors were paid for their appearances and endorsements through an employee stock ownership plan.[72]

In 2009, Willis signed a contract to become the international face of Belvedere SA’s Sobieski Vodka in exchange for 3.3 percent ownership in the company.[73]

Personal life

Willis’s acting role models are Gary Cooper, Robert De Niro, Steve McQueen, and John Wayne.[74] He is left-handed.[75] He resides in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles with his family.[76]

Relationships and children

At the premiere for the film Stakeout, Willis met actress Demi Moore. They married on November 21, 1987, and had three daughters, including Rumer, who was born in August 1988.[77][78][79][80] Willis and Moore announced their separation on June 24, 1998.[81] They filed for divorce on October 18, 2000,[82] and the divorce was finalized later that day.[83][84] Regarding the divorce, Willis stated, «I felt I had failed as a father and a husband by not being able to make it work.» He credited actor Will Smith for helping him cope with the situation.[18] He has maintained a close friendship with both Moore and her subsequent husband, actor Ashton Kutcher, and attended their wedding.[85]

Willis was engaged to actress Brooke Burns until they broke up in 2004 after ten months together.[17] He married model Emma Heming in Turks and Caicos on March 21, 2009;[86] guests included his three daughters, as well as Moore and Kutcher. The ceremony was not legally binding, so the couple wed again in a civil ceremony in Beverly Hills six days later. The couple has two daughters, one born in 2012[87] and another born in 2014.[88]

Religious views

Willis was a Lutheran,[89] but no longer practices. In a July 1998 interview with George magazine, he stated: «Organized religions in general, in my opinion, are dying forms. They were all very important when we didn’t know why the sun moved, why weather changed, why hurricanes occurred, or volcanoes happened. Modern religion is the end trail of modern mythology. But there are people who interpret the Bible literally. Literally! I choose not to believe that’s the way. And that’s what makes America cool, you know?»[90]

Political views

In 1988, Willis and then-wife Demi Moore campaigned for Democratic Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis’s Presidential bid. Four years later, he supported President George H. W. Bush for reelection and was an outspoken critic of Bill Clinton. However, in 1996, he declined to endorse Clinton’s Republican opponent Bob Dole, because Dole had criticized Demi Moore for her role in the film Striptease.[91] Willis was an invited speaker at the 2000 Republican National Convention,[92] and supported George W. Bush that year.[18]

In 2006, Willis said that the United States should intervene more in Colombia in order to end drug trafficking.[93] In several interviews Willis has said that he supports large salaries for teachers and police officers, and said he is disappointed in the United States foster care system as well as treatment of Native Americans.[91][94] Willis also stated that he is a supporter of gun rights, stating, «Everyone has a right to bear arms. If you take guns away from legal gun owners, then the only people who have guns are the bad guys.»[95]

In February 2006, Willis was in Manhattan to promote his film 16 Blocks with reporters. One reporter attempted to ask Willis about his opinion on the Bush administration, but was interrupted by Willis in mid-sentence when he said: «I’m sick of answering this fucking question. I’m a Republican only as far as I want a smaller government, I want less government intrusion. I want them to stop shitting on my money and your money and tax dollars that we give 50 percent of every year. I want them to be fiscally responsible and I want these goddamn lobbyists out of Washington. Do that and I’ll say I’m a Republican. I hate the government, OK? I’m apolitical. Write that down. I’m not a Republican.»[96] Willis did not make any contributions or public endorsements in the 2008 presidential campaign. In several June 2007 interviews, he declared that he maintains some Republican ideologies.[18]

Willis’s name was in an advertisement in the Los Angeles Times on August 17, 2006, that condemned Hamas and Hezbollah and supported Israel in the 2006 Israel-Lebanon war.[97]

In 2012, Willis stated that he had a negative opinion of Mitt Romney.[98]

Military interests

Throughout his film career, Willis has depicted several military characters in films such as In Country, The Siege, Hart’s War, Tears of the Sun, Grindhouse, and G.I. Joe: Retaliation. Growing up in a military family, Willis has donated Girl Scout cookies to the United States armed forces. In 2002, Willis’s then 8-year-old daughter, Tallulah, suggested that he purchase Girl Scout cookies to send to troops. Willis purchased 12,000 boxes of cookies, and they were distributed to sailors aboard USS John F. Kennedy and other troops stationed throughout the Middle East at the time.[99]

In 2003, Willis visited Iraq as part of the USO tour, singing to the troops with his band, The Accelerators.[100] Willis considered joining the military to help fight the second Iraq War, but was deterred by his age.[101] It was believed he offered US$1 million to any noncombatant who turned in terrorist leaders Osama bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, or Abu Musab al-Zarqawi; in the June 2007 issue of Vanity Fair, however, he clarified that the statement was made hypothetically and not meant to be taken literally. Willis has also criticized the media for its coverage of the war, complaining that the press was more likely to focus on the negative aspects of the war:

I went to Iraq because what I saw when I was over there was soldiers—young kids for the most part—helping people in Iraq; helping getting the power turned back on, helping get hospitals open, helping get the water turned back on and you don’t hear any of that on the news. You hear, «X number of people were killed today,» which I think does a huge disservice. It’s like spitting on these young men and women who are over there fighting to help this country.[102]

In popular culture

In 1996, Roger Director, a writer and producer from Moonlighting, wrote a roman à clef on Willis titled A Place to Fall.[103] Cybill Shepherd wrote in her 2000 autobiography, Cybill Disobedience, that Willis became angry at Director when he read the book and discovered the character had been written as a «neurotic, petulant actor».

A Lego version of himself appeared in the 2019 film The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part, with Willis providing the voice.[104]

Filmography

Discography

Solo albums

- 1987: The Return of Bruno (Motown, OCLC 15508727)

- 1989: If It Don’t Kill You, It Just Makes You Stronger (Motown/Pgd, OCLC 21322754)

- 2001: Classic Bruce Willis: The Universal Masters Collection (Polygram Int’l, OCLC 71124889)

Compilations/guest appearances

- 1986: Moonlighting soundtrack; track «Good Lovin’ »

- 1991: Hudson Hawk soundtrack; tracks «Swinging on a Star» and «Side by Side», both duets with Danny Aiello

- 2000: The Whole Nine Yards soundtrack; tracks «Tenth Avenue Tango»

- 2003: Rugrats Go Wild soundtrack; «Big Bad Cat» with Chrissie Hynde and «Lust for Life»

- 2008: North Hollywood Shootout, Blues Traveler; track «Free Willis (Ruminations from Behind Uncle Bob’s Machine Shop)»

Awards and honors

Willis’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

Willis has won a variety of awards and has received various honors throughout his career in television and film.

- 1987: Golden Apple Awards honored with the Sour Apple.[105]

- 1994: Maxim magazine ranked his sex scene in Color of Night the No. 1 sex scene in film history[25]

- 2000: American Cinematheque Gala Tribute honored Willis with the American Cinematheque Award for an extraordinary artist in the entertainment industry who is fully engaged in his or her work and is committed to making a significant contribution to the art of the motion pictures.

- 2002: The Hasty Pudding Man of the Year award from Harvard’s Hasty Pudding Theatricals – given to performers who give a lasting and impressive contribution to the world of entertainment[106]

- 2002: Appointed as national spokesman for Children in Foster Care by President George W. Bush;[107] Willis wrote online: «I saw Foster Care as a way for me to serve my country in a system by which shining a little bit of light could benefit a great deal by helping kids who were literally wards of the government.»[108]

- 2005: Golden Camera Award for Best International Actor by the Manaki Brothers Film Festival.[109]

- 2006: Honored by French government for his contributions to the film industry; appointed an Officer of the French Order of Arts and Letters in a ceremony in Paris; the French Prime Minister stated, «This is France’s way of paying tribute to an actor who epitomizes the strength of American cinema, the power of the emotions that he invites us to share on the world’s screens and the sturdy personalities of his legendary characters.»[110]

- 2006: Honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on October 16; located at 6915 Hollywood Boulevard and it was the 2,321st star awarded in its history; at the reception, he stated, «I used to come down here and look at these stars and I could never quite figure out what you were supposed to do to get one…time has passed and now here I am doing this, and I’m still excited. I’m still excited to be an actor.»[111]

- 2011: Inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame[112]

- 2013: Promoted to the dignity of Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters on February 11 by French Minister of Culture Aurélie Filippetti[113]

References

- ^ «12 Most Unlikely Action Movie Stars». Rolling Stone. July 30, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ Thomas, David (May 4, 2008). «Ford and Willis voted best action heroes». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d «Bruce Willis». Biography.com. FYI / A&E Networks). Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ a b «Surprise German visit from Willis». BBC. August 8, 2005. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

His mother Marlene was born in the nearby town of Kassel.

- ^ «Monitor». Entertainment Weekly. No. 1251. March 22, 2013. p. 25.

- ^ Archerd, Army (December 11, 2003). «Inside Move: Flu KOs Smart Set yule bash». Variety.com. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ «Robert Willis». Variety. July 1, 2001. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stated on Inside the Actors Studio, 2001

- ^ Petersen, Melody (May 9, 1997). «Bruce Willis Drops Project, Leaving Town More Troubled». The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis: The Uncut Interview» (PDF). Reader’s Digest. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis». The Daily Show. June 26, 2007. Comedy Central.

- ^ a b Segal, David (March 10, 2005). «Bruce Willis’s Tragic Mask». The Washington Post. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Bruce Willis Answers the Web’s Most Searched Questions. Wired. March 1, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Curley, Mallory (2010). A Cookie Mueller Encyclopedia. Randy Press. p. 260.

- ^ Longsdorf, Amy (February 24, 1996). «Spotlight on Linda Fiorentino & John Dahl: Director, Actress Make an ‘Unforgettable’ Team». The Morning Call. Allentown, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

[Linda] Fiorentino supported herself by working at the Kamikaze nightclub, where her fellow bartender was Bruce Willis. ‘He was a good partner,’ she says approvingly.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (July 1, 1990). «Bruce Willis Looks for the Man Within the Icon». The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ a b «Yahoo! Movies». Bruce Willis Biography. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c d «How Bruce Willis Keeps His Cool». Time. June 21, 2007. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Grobel, Lawrence (November 1988). «Playboy Interview: Bruce Willis». Playboy. pp. 59–79.

- ^ «Bruce Willis: Biography». People. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Die Hard». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Top 100 Songs of 1987». The Eighties Club. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Giles, Jeff. «25 Years Ago: Bruce Willis Tries His Hand at Singing With ‘The Return of Bruno’«. Diffuser.fm. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Billboard vol 108 No. 1 (1/6/1996) p.54.

- ^ a b «Top Sex Scenes of All-Time». Extra (American TV program). December 6, 2000. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ D’Aless, Anthony; ro (May 14, 2021). «Bruce Willis & John Travolta To Reteam For First Time Since ‘Pulp Fiction’ In ‘Paradise City’; Praya Lundberg Also Stars». Deadline. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ «Bruce Willis Biography (1955–)». Filmreference. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Brennan, Judy (March 13, 1997). «The Fight Over ‘Broadway Brawler’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ «1998 Worldwide Grosses». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Walk, Gary Eng (December 4, 1998). ««Apocalypse» Now». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Bruce Willis Emmy Award Winner. Emmys.com. Retrieved on June 8, 2012.

- ^ «The 52nd Annual Emmy Awards». Los Angeles Times. September 11, 2000. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Rohan, Virginia (June 28, 2004). «Let’s Make a Deal». The Record. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Susman, Gary (February 28, 2003). «The Eyes Have It». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «The Week’s Best Celeb Quotes». People. August 17, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis Wears Mini-Wind Turbine on His Head». Star Pulse. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: «1991 Subaru Legacy Ad». YouTube. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Fleming, Michael; Tatiana Siegel (November 18, 2007). «Films halted due to strike». Variety. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Mayberry, Carly (November 13, 2007). «The Vine: Pitt targeted for ‘Pinkville’«. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 18, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Dunkley, Jamie (April 29, 2009). «Aviva lambasted for rebranding costs». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis Circling Several New Movies». Empire. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ «Bruce Willis takes aim at Gorillaz in Stylo video». Billboard. Retrieved March 2, 2009.

- ^ Stallone Shot a Scene with Arnold and Bruce Archived October 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine News in Film

- ^ «Red Begins Principal Photography». /Film. January 18, 2010. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ «Film starring Bruce Willis to be shot in RI». The Boston Globe. Providence, R.I. Associated Press. March 24, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

Steven Feinberg, executive director for the Rhode Island Film and Television Office, says on-site work on the film, ‘Moonrise Kingdom,’ is scheduled to begin this spring. Feinberg says the film will be shot in several locations in Rhode Island.

- ^ Jason Barr (August 29, 2010). «Sylvester Stallone Wants Bruce Willis to Play a «Super Villain» in THE EXPENDABLES Sequel». Collider. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012.

- ^ Anderton, Ethan (May 5, 2011). «Bruce Willis and 50 Cent Teaming Up Again to Fight ‘Fire with Fire’«. Firstshowing.net. Variety. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

Now Variety reports that for some reason, the two will team-up again for an indie drama called Fire with Fire.

- ^ Bettinger, Brendan (May 5, 2011). «Vince Vaughn Joins Rebecca Hall, Bruce Willis, and Catherine Zeta-Jones in LAY THE FAVORITE». Collider.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

Vince Vaughn will join Rebecca Hall, Bruce Willis, and Catherine Zeta-Jones in the gambling drama Lay the Favorite.

- ^ «Die Hard 5 Given a Name and a 2013 Release Date». Yahoo! News. October 12, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ «Bruce Willis: Women Should Be In Charge Of Everything». UKScreen. February 13, 2013. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ «SNL Promo: Bruce Willis and Katy Perry». NBC. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ «Bruce Willis in Misery on Broadway – what the critics said»,The Guardian, November 16, 2015

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Comedy Central (April 10, 2018). «Coming This Summer: The Roast of Bruce Willis». YouTube. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ «People Index». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ «All Time Top 100 Stars at the Box Office». The Numbers. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ a b Nashawaty, Nashawaty (August 21, 2020). «Why Does Bruce Willis Keep Making Films He Clearly Hates?». Esquire. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c «Concerns about Bruce Willis’s declining cognitive state swirled around sets in recent years». Los Angeles Times. March 31, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (December 30, 2020). «The Bruce Willis Journey From In Demand to On Demand». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ «What Happened to Bruce Willis?». Collider. July 29, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ Donohoo, Timothy (May 5, 2022). «What Are ‘Geezer Teasers’ — and Why Does Bruce Willis Have So Many?». CBR.com. Retrieved October 19, 2022.