Бесплатный переводчик онлайн с испанского на русский

Хотите перевести с испанского на русский сообщения в чатах, письма бизнес-партнерам и в службы поддержки,

официальные документы, домашнее задание, имена, рецепты, песни, какие угодно сайты? PROMT.One мгновенно переведет с испанского на русский и обратно.

Точный переводчик

С помощью PROMT.One наслаждайтесь точным переводом, а для слов и фраз смотрите транскрипцию, произношение и варианты переводов с примерами употребления в разных контекстах.

Бесплатный онлайн-переводчик PROMT.One — достойная альтернатива Google Translate и другим сервисам, предоставляющим машинный перевод нового поколения.

Переводите в браузере на персональных компьютерах, ноутбуках, на мобильных устройствах или установите мобильное приложение Переводчик PROMT.One для iOS и Android.

Нужно больше языков?

PROMT.One также бесплатно переводит онлайн с испанского на

английский, арабский, итальянский, казахский, китайский, корейский, немецкий, португальский, турецкий, украинский, финский, французский, японский.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Перевод «Буэнос-Айрес» на испанский

Предложения

По менталитету я аргентинец и потому хочу вернуться в Буэнос-Айрес.

Mi mentalidad es argentina y mi deseo es estar en Buenos Aires.

Они возвращались в Буэнос-Айрес из отпуска и врезались в грузовик.

Volvían a su casa en Buenos Aires y chocaron con un camión.

С этого времени оно образует границу с провинцией Буэнос-Айрес.

Con ello, ha traspasado las fronteras de la provincia de Buenos Aires.

Буэнос-Айрес сочетает в себе увядшее европейское величие с латинской страстью.

Buenos Aires combina la grandeza europea desvanecida con la pasión latina.

Принимать решение о федеральной интервенции в провинцию или в город Буэнос-Айрес.

Disponer la intervención federal de una provincia o a la ciudad de Buenos Aires.

Я вернулся в Буэнос-Айрес в октябре и подписал все бумаги.

Volví a Buenos Aires en octubre y firmé todos los papeles.

Буэнос-Айрес знаменит также своими рынками антиквариата и ремесла.

Buenos Aires también es conocida por sus mercados de antigüedades.

Мы тогда в первый раз приехали вместе в Буэнос-Айрес.

Aquella era la primera vez que íbamos juntos a Buenos Aires.

Буэнос-Айрес станет одним из исследуемых городов по проекту.

Buenos Aires será una de las ciudades estudiadas en el proyecto.

Следующим этапом кампании стало наступление союзников на Буэнос-Айрес.

La etapa siguiente de la campaña aliada era el ataque a Buenos Aires.

Он любил играть на фортепиано с детства и намеревался поехать в Буэнос-Айрес.

Le gustaba tocar el piano y tuvo desde chico el propósito de viajar a Buenos Aires.

Москва и Буэнос-Айрес станут ближе для туристов и российских и аргентинских бизнесменов.

Moscú y Buenos Aires estarán más cerca para los turistas y los empresarios rusos y argentinos.

Она прибыла в Буэнос-Айрес, когда ей было всего пятнадцать лет.

Ella llegó a Buenos Aires hace quince años, cuando aún tenía dieciséis.

В последний раз мы слышали о войне, когда покинули Буэнос-Айрес.

Lo último que oímos de la guerra fue cuando dejamos Buenos Aires.

Поэтому попасть в Буэнос-Айрес на поезде невозможно.

Por lo tanto, llegar a Buenos Aires en tren es imposible.

Кортасар отправляется в Буэнос-Айрес для презентации книги.

Cortázar viaja a Buenos Aires para presentar el libro.

Это лишь небольшая часть путешествия по Буэнос-Айрес.

Esta es sólo una pequeña parte del viaje de Buenos Aires.

Один из самых интенсивных опытов в Буэнос-Айрес это пойти на футбольный матч.

Una de las experiencias más intensas en Buenos Aires es ir a un partido de fútbol.

Буэнос-Айрес является домом для ключевых литературных деятелей.

Buenos Aires es el hogar de figuras literarias fundamentales.

Буэнос-Айрес также будет вашим классом, когда вы увидите богатые европейские влияния города.

Buenos Aires también será su aula mientras presenciará las ricas influencias europeas de la ciudad.

Предложения, которые содержат Буэнос-Айрес

Результатов: 2098. Точных совпадений: 2098. Затраченное время: 102 мс

буэнос-айрес

-

1

Буэнос-Айрес

Буэ́нос-А́йрес

Buenos-Ajreso.

* * *

Buenos Aires

* * *

n

Diccionario universal ruso-español > Буэнос-Айрес

-

2

налоговая контора провинции Буэнос-Айрес

Diccionario universal ruso-español > налоговая контора провинции Буэнос-Айрес

-

3

прилагательное от Буэнос-Айрес

Diccionario universal ruso-español > прилагательное от Буэнос-Айрес

См. также в других словарях:

-

Буэнос-Айрес — столица Аргентины. В 1536 г. исп. конкистадор Педро де Мендоса заложил на юж. берегу залива Ла Плата город, который включил собственно поселение, ставшее опорным пунктом для движения в глубь материка, и гавань, открывавшую морской путь из колонии … Географическая энциклопедия

-

Буэнос-Айрес — (Buenos Aires) столица Аргентины, административно составляет Федеральный столичный округ. Город расположен на западном (правом) берегу… … Города мира

-

Буэнос-Айрес — Буэнос Айрес. Авенида 9 июля. БУЭНОС АЙРЕС, столица (официально с 1880) Аргентины. Около 3 млн. жителей. Порт в эстуарии река Ла Плата (один из крупнейших портов Латинской Америки); международный аэропорт. Метрополитен. Автомобиле и судостроение … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

Буэнос-Айрес — (Buenos Aires), столица Аргентины. Буэнос Айрес современный город с многоэтажными зданиями, в том числе небоскрёбами, но некоторые улицы и общая застройка сохраняют черты архитектуры колониального периода с главной площадью, открытой в… … Художественная энциклопедия

-

буэнос-айрес — город добрых ветров Словарь русских синонимов. буэнос айрес сущ., кол во синонимов: 3 • город (2765) • … Словарь синонимов

-

БУЭНОС-АЙРЕС — столица Аргентины. В официальных границах федеральный столичный округ. 2,96 млн. жителей (1991), с пригородами 11,8 млн. жителей. Крупнейший транспортный узел и морской порт страны (грузооборот 20 млн. т в год). Международный аэропорт Эсейса.… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

БУЭНОС-АЙРЕС — (Buenos Aires) провинция в Аргентине. 307,8 тыс. км². Население 12,2 млн. человек (1986). Адм. ц. Ла Плата … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Буэнос-Айрес — I (Buenos Aires), провинция в Аргентине. 307,6 тыс. км2. Население 13,3 млн. человек (1995). Административный центр Ла Плата. II столица Аргентины. В официальных границах Федеральный столичный округ. 2,96 млн. жителей (1991), с пригородами… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Буэнос-Айрес — (т. е., хороший воздух, собственно Ciudad de NuestraSenora de Bnenos Ayres) главный гор. Аргентинской республики,резиденция правительства и конгресса конфедерации, дипломатическогокорпуса, большинства консульств и аргентинского архиепископа,… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

Буэнос-Айрес — Это слово имеет Буэнос Айрес (значения) Город, столица Аргентины Буэнос Айрес Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires … Википедия

-

Буэнос-айрес — Это слово имеет и другие значения, см. Буэнос Айрес (значения) Столица Буэнос Айрес Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires Флаг Герб … Википедия

|

Buenos Aires |

|

|---|---|

|

Capital city and autonomous city |

|

| Autonomous City of Buenos Aires Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires |

|

|

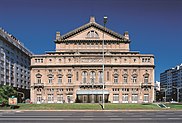

Panorama of the Puerto Madero Obelisk on July 9 Avenue Casa Rosada and the Plaza de Mayo Buenos Aires Metropolitan Cathedral Caminito in La Boca National Congress Teatro Colón |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms Brandmark |

|

| Nicknames:

The Queen of El Plata (La reina del Plata)[1][2] |

|

|

Buenos Aires Location in Argentina Buenos Aires Buenos Aires (South America) |

|

| Coordinates: 34°36′12″S 58°22′54″W / 34.60333°S 58.38167°WCoordinates: 34°36′12″S 58°22′54″W / 34.60333°S 58.38167°W | |

| Country | Argentina |

| Established | 2 February 1536 (by Pedro de Mendoza) 11 June 1580 (by Juan de Garay) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Autonomous city |

| • Body | City Legislature |

| • Mayor | Horacio Rodríguez Larreta (PRO) |

| • National Deputies | 25 |

| • National Senators |

|

| Area | |

| • Capital city and autonomous city | 203 km2 (78 sq mi) |

| • Land | 203 km2 (78.5 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,758 km2 (1,837 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 25 m (82 ft) |

| Population

(2022 census)[4] |

|

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 15,372/km2 (39,810/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,120,612 |

| • Metro | 15,624,000 |

| Demonyms | porteño (m), porteña (f) |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (ART) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−2 (ARST) |

| Area code | 011 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.882 Very High (1st)[5] |

| Website | www.buenosaires.gob.ar |

Buenos Aires ( or ;[6] Spanish pronunciation: [ˈbwenos ˈajɾes] (listen)),[7] officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (Spanish: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South America’s southeastern coast. «Buenos Aires» can be translated as «fair winds» or «good airs», but the former was the meaning intended by the founders in the 16th century, by the use of the original name «Real de Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Ayre», named after the Madonna of Bonaria in Sardinia, Italy. Buenos Aires is classified as an alpha global city, according to the Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC) 2020 ranking.[8]

The city of Buenos Aires is neither part of Buenos Aires Province nor the Province’s capital; rather, it is an autonomous district. In 1880, after decades of political infighting, Buenos Aires was federalized and removed from Buenos Aires Province.[9] The city limits were enlarged to include the towns of Belgrano and Flores; both are now neighborhoods of the city. The 1994 constitutional amendment granted the city autonomy, hence its formal name of Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. Its citizens first elected a Chief of Government in 1996; previously, the Mayor was directly appointed by the President of Argentina.

The Greater Buenos Aires conurbation, which also includes several Buenos Aires Province districts, constitutes the fourth-most populous metropolitan area in the Americas, with a population of around 15.6 million.[10] It is also the second largest city south of the Tropic of Capricorn. The quality of life in Buenos Aires was ranked 91st in the world in 2018, being one of the best in Latin America.[11][12] In 2012, it was the most visited city in South America, and the second-most visited city of Latin America.[13]

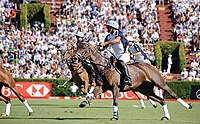

It is known for its preserved eclectic European architecture[14] and rich cultural life.[15] It is a multicultural city that is home to multiple ethnic and religious groups, contributing to its culture as well as to the dialect spoken in the city and in some other parts of the country. This is because since the 19th century, the city, and the country in general, has been a major recipient of millions of immigrants from all over the world, making it a melting pot where several ethnic groups live together. Thus, Buenos Aires is considered one of the most diverse cities of the Americas.[16] Buenos Aires held the 1st FIBA World Championship in 1950 and 11th FIBA World Championship in 1990, the 1st Pan American Games in 1951, was the site of two venues in the 1978 FIFA World Cup and one in the 1982 FIVB Men’s World Championship. Most recently, Buenos Aires had a venue in the 2001 FIFA World Youth Championship and in the 2002 FIVB Volleyball Men’s World Championship, hosted the 125th IOC Session in 2013, the 2018 Summer Youth Olympics[17] and the 2018 G20 summit.[18]

Etymology[edit]

Our Lady of Buen Aire in front of the National Migration Department

It is recorded under the Aragonese’s archives that Catalan missionaries and Jesuits arriving in Cagliari (Sardinia) under the Crown of Aragon, after its capture from the Pisans in 1324 established their headquarters on top of a hill that overlooked the city.[19] The hill was known to them as Bonaira (or Bonaria in Sardinian language), as it was free of the foul smell prevalent in the old city (the castle area), which is adjacent to swampland. During the Cagliari’s siege, the Catalans built a sanctuary to the Virgin Mary on top of the hill. In 1335, King Alfonso the Gentle donated the church to the Mercedarians, who built an abbey that stands to this day. In the years after that, a story circulated, claiming that a statue of the Virgin Mary was retrieved from the sea after it miraculously helped to calm a storm in the Mediterranean Sea. The statue was placed in the abbey. Spanish sailors, especially Andalusians, venerated this image and frequently invoked the «Fair Winds» to aid them in their navigation and prevent shipwrecks. A sanctuary to the Virgin of Buen Ayre would be later erected in Seville.[19]

In the first foundation of Buenos Aires, Spanish sailors arrived thankfully in the Río de la Plata by the blessings of the «Santa Maria de los Buenos Aires», the «Holy Virgin Mary of the Good Winds» who was said to have given them the good winds to reach the coast of what is today the modern city of Buenos Aires.[20] Pedro de Mendoza called the city «Holy Mary of the Fair Winds», a name suggested by the chaplain of Mendoza’s expedition – a devotee of the Virgin of Buen Ayre – after the Madonna of Bonaria from Sardinia[21] (which is still to this day the patroness of the Mediterranean island[22]). Mendoza’s settlement soon came under attack by indigenous people, and was abandoned in 1541.[20]

For many years, the name was attributed to a Sancho del Campo, who is said to have exclaimed: How fair are the winds of this land!, as he arrived. But in 1882, after conducting extensive research in Spanish archives, Argentine merchant Eduardo Madero ultimately concluded that the name was indeed closely linked with the devotion of the sailors to Our Lady of Buen Ayre.[23] A second (and permanent) settlement was established in 1580 by Juan de Garay, who sailed down the Paraná River from Asunción (now the capital of Paraguay). Garay preserved the name originally chosen by Mendoza, calling the city Ciudad de la Santísima Trinidad y Puerto de Santa María del Buen Aire («City of the Most Holy Trinity and Port of Saint Mary of the Fair Winds»). The short form that eventually became the city’s name, «Buenos Aires», became commonly used during the 17th century.[24]

The usual abbreviation for Buenos Aires in Spanish is Bs.As.[25] It is common as well to refer to it as «B.A.» or «BA».[26] When referring specifically to the autonomous city, it is very common to colloquially call it «Capital» in Spanish. Since the autonomy obtained in 1994, it has been called «CABA» (per Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Autonomous City of Buenos Aires).

History[edit]

Colonial times[edit]

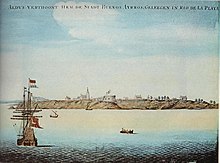

Aldus verthoont hem de stadt Buenos Ayrros geleegen in Rio de la Plata, painting by a Dutch sailor who anchored at the port around 1628.

In 1516, navigator and explorer Juan Díaz de Solís, navigating in the name of Spain, was the first European to reach the Río de la Plata. His expedition was cut short when he was killed during an attack by the native Charrúa tribe in what is now Uruguay. The city of Buenos Aires was first established as Ciudad de Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Ayre[2] (literally «City of Our Lady Saint Mary of the Fair Winds») after Our Lady of Bonaria (Patroness Saint of Sardinia) on 2 February 1536 by a Spanish expedition led by Pedro de Mendoza. The settlement founded by Mendoza was located in what is today the San Telmo district of Buenos Aires, south of the city center.

More attacks by the indigenous people forced the settlers away, and in 1542, the site was thusly abandoned.[27][28] A second (and permanent) settlement was established on 11 June 1580 by Juan de Garay, who arrived by sailing down the Paraná River from Asunción (now the capital of Paraguay). He dubbed the settlement «Santísima Trinidad» and its port became «Puerto de Santa María de los Buenos Aires.»[24]

From its earliest days, Buenos Aires depended primarily on trade. During most of the 17th century, Spanish ships were menaced by pirates, so they developed a complex system where ships with military protection were dispatched to Central America in a convoy from Seville (the only port allowed to trade with the colonies) to Lima, Peru, and from it to the inner cities of the viceroyalty. Because of this, products took a very long time to arrive in Buenos Aires, and the taxes generated by the transport made them prohibitive. This scheme frustrated the traders of Buenos Aires, and a thriving informal yet accepted by the authorities contraband industry developed inside the colonies and with the Portuguese. This also instilled a deep resentment among porteños towards the Spanish authorities.[2]

Sensing these feelings, Charles III of Spain progressively eased the trade restrictions before finally declaring Buenos Aires an open port in the late 18th century. The capture of Portobelo in Panama by British forces also fueled the need to foster commerce via the Atlantic route, to the detriment of Lima-based trade. One of his rulings was to split a region from the Viceroyalty of Perú and create instead the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, with Buenos Aires as the capital. However, Charles’s placating actions did not have the desired effect, and the porteños, some of them versed in the ideology of the French Revolution, instead became even more convinced of the need for independence from Spain.

War of Independence[edit]

During the British invasions of the Río de la Plata, British forces attacked Buenos Aires twice. In 1806 the British successfully invaded Buenos Aires, but an army from Montevideo led by Santiago de Liniers defeated them. In the brief period of British rule, the viceroy Rafael Sobremonte managed to escape to Córdoba and designated this city as capital. Buenos Aires became the capital again after its recapture by Argentine forces, but Sobremonte could not resume his duties as viceroy. Santiago de Liniers, chosen as new viceroy, prepared the city against a possible new British attack and repelled a second invasion by Britain in 1807. The militarization generated in society changed the balance of power favorably for the criollos (in contrast to peninsulars), as well as the development of the Peninsular War in Spain.

An attempt by the peninsular merchant Martín de Álzaga to remove Liniers and replace him with a Junta was defeated by the criollo armies. However, by 1810 it would be those same armies who would support a new revolutionary attempt, successfully removing the new viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros. This is known as the May Revolution, which is now celebrated as a national holiday. This event started the Argentine War of Independence, and many armies left Buenos Aires to fight the diverse strongholds of royalist resistance, with varying levels of success. The government was held first by two Juntas of many members, then by two triumvirates, and finally by a unipersonal office, the Supreme Director. Formal independence from Spain was declared in 1816, at the Congress of Tucumán. Buenos Aires managed to endure the whole Spanish American wars of independence without falling again under royalist rule.

Historically, Buenos Aires has been Argentina’s main venue of liberal, free-trading, and foreign ideas. In contrast, many of the provinces, especially those to the city’s northwest, advocated a more nationalistic and Catholic approach to political and social issues. In fact, much of the internal tension in Argentina’s history, starting with the centralist-federalist conflicts of the 19th century, can be traced back to these contrasting views. In the months immediately following said «May Revolution», Buenos Aires sent a number of military envoys to the provinces with the intention of obtaining their approval. Instead, the enterprise fueled tensions between the capital and the provinces; many of these missions ended in violent clashes.

In the 19th century the city was blockaded twice by naval forces: by the French from 1838 to 1840, and later by an Anglo-French expedition from 1845 to 1848. Both blockades failed to bring the Argentine government to the negotiating table, and the foreign powers eventually desisted from their demands.

19th and 20th century[edit]

During most of the 19th century, the political status of the city remained a sensitive subject. It was already the capital of Buenos Aires Province, and between 1853 and 1860 it was the capital of the seceded State of Buenos Aires. The issue was fought out more than once on the battlefield, until the matter was finally settled in 1880 when the city was federalized and became the seat of government, with its mayor appointed by the president. The Casa Rosada became the seat of the president.[24]

Health conditions in poor areas were appalling, with high rates of tuberculosis. Contemporaneous public health physicians and politicians typically blamed both the poor themselves and their ramshackle tenement houses (conventillos) for the spread of the dreaded disease. People ignored public-health campaigns to limit the spread of contagious diseases, such as the prohibition of spitting on the streets, the strict guidelines to care for infants and young children, and quarantines that separated families from ill loved ones.[29]

In addition to the wealth generated by customs duties and Argentine foreign trade in general, as well as the existence of fertile pampas, railroad development in the second half of the 19th century increased the economic power of Buenos Aires as raw materials flowed into its factories. A leading destination for immigrants from Europe, particularly Italy and Spain, from 1880 to 1930, Buenos Aires became a multicultural city that ranked itself alongside the major European capitals. During this time, the Colón Theater became one of the world’s top opera venues, and the city became the regional capital of radio, television, cinema, and theater. The city’s main avenues were built during those years, and the dawn of the 20th century saw the construction of South America’s tallest buildings and its first underground system. A second construction boom, from 1945 to 1980, reshaped downtown and much of the city.

Buenos Aires also attracted migrants from Argentina’s provinces and neighboring countries. Shanty towns (villas miseria) started growing around the city’s industrial areas during the 1930s, leading to pervasive social problems and social contrasts with the largely upwardly-mobile Buenos Aires population. These laborers became the political base of Peronism, which emerged in Buenos Aires during the pivotal demonstration of 17 October 1945, at the Plaza de Mayo.[30] Industrial workers of the Greater Buenos Aires industrial belt have been Peronism’s main support base ever since, and Plaza de Mayo became the site for demonstrations and many of the country’s political events; on 16 June 1955, however, a splinter faction of the Navy bombed the Plaza de Mayo area, killing 364 civilians (see Bombing of Plaza de Mayo). This was the only time the city was attacked from the air, and the event was followed by a military uprising which deposed President Perón, three months later (see Revolución Libertadora).

In the 1970s the city suffered from the fighting between left-wing revolutionary movements (Montoneros, ERP and F.A.R.) and the right-wing paramilitary group Triple A, supported by Isabel Perón, who became president of Argentina in 1974 after Juan Perón’s death.

The March 1976 coup, led by General Jorge Videla, only escalated this conflict; the «Dirty War» resulted in 30,000 desaparecidos (people kidnapped and killed by the military during the years of the junta).[31] The silent marches of their mothers (Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo) are a well-known image of Argentines’ suffering during those times. The dictatorship’s appointed mayor, Osvaldo Cacciatore, also drew up plans for a network of freeways intended to relieve the city’s acute traffic gridlock. The plan, however, called for a seemingly indiscriminate razing of residential areas and, though only three of the eight planned were put up at the time, they were mostly obtrusive raised freeways that continue to blight a number of formerly comfortable neighborhoods to this day.

The city was visited by Pope John Paul II twice, firstly in 1982 and again in 1987; on these occasions gathered some of the largest crowds in the city’s history. The return of democracy in 1983 coincided with a cultural revival, and the 1990s saw an economic revival, particularly in the construction and financial sectors.

On 17 March 1992, a bomb exploded in the Israeli Embassy, killing 29 and injuring 242. Another explosion, on 18 July 1994, destroyed a building housing several Jewish organizations, killing 85 and injuring many more, these incidents marked the beginning of Middle Eastern terrorism to South America. Following a 1993 agreement, the Argentine Constitution was amended to give Buenos Aires autonomy and rescinding, among other things, the president’s right to appoint the city’s mayor (as had been the case since 1880). On 30 June 1996, voters in Buenos Aires chose their first elected mayor, Jefe de Gobierno.

21st century[edit]

In 1996, following the 1994 reform of the Argentine Constitution, the city held its first mayoral elections under the new statutes, with the mayor’s title formally changed to «Head of Government». The winner was Fernando de la Rúa, who would later become President of Argentina from 1999 to 2001.

De la Rúa’s successor, Aníbal Ibarra, won two popular elections, but was impeached (and ultimately deposed on 6 March 2006) as a result of the fire at the República Cromagnon nightclub. In the meantime, Jorge Telerman, who had been the acting mayor, was invested with the office. In the 2007 elections, Mauricio Macri of the Republican Proposal (PRO) party won the second-round of voting over Daniel Filmus of the Frente para la Victoria (FPV) party, taking office on 9 December 2007. In 2011, the elections went to a second round with 60.96 percent of the vote for PRO, compared to 39.04 percent for FPV, thus ensuring Macri’s reelection as mayor of the city with María Eugenia Vidal as deputy mayor.[32]

PRO is established in the most affluent area of the city and in those over fifty years of age.[33]

The 2015 elections were the first to use an electronic voting system in the city, similar to the one used in Salta Province.[34] In these elections held on 5 July 2015, Macri stepped down as mayor and pursue his presidential bid and Horacio Rodríguez Larreta took his place as the mayoral candidate for PRO. In the first round of voting, FPV’s Mariano Recalde obtained 21.78% of the vote, while Martín Lousteau of the ECO party obtained 25.59% and Larreta obtained 45.55%, meaning that the elections went to a second round since PRO was unable to secure the majority required for victory.[35] The second round was held on 19 July 2015 and Larreta obtained 51.6% of the vote, followed closely by Lousteau with 48.4%, thus, PRO won the elections for a third term with Larreta as mayor and Diego Santilli as deputy. In these elections, PRO was stronger in wealthier northern Buenos Aires, while ECO was stronger in the southern, poorer neighborhoods of the city.[36][37]

Geography[edit]

The city of Buenos Aires lies in the pampa region, with the exception of some areas such as the Buenos Aires Ecological Reserve, the Boca Juniors (football club)’s «sports city», Jorge Newbery Airport, the Puerto Madero neighborhood and the main port itself; these were all built on reclaimed land along the coasts of the Rio de la Plata (the world’s widest river).[38][39][40]

The region was formerly crossed by different streams and lagoons, some of which were refilled and others tubed. Among the most important streams are the Maldonado, Vega, Medrano, Cildañez, and White. In 1908, as floods were damaging the city’s infrastructure, many streams were channeled and rectified; furthermore, starting in 1919, most streams were enclosed. Most notably, the Maldonado was tubed in 1954; it currently runs below Juan B. Justo Avenue.

Parks[edit]

Buenos Aires has over 250 parks and green spaces, the largest concentration of which are on the city’s eastern side in the neighborhoods of Puerto Madero, Recoleta, Palermo, and Belgrano. Some of the most important are:

- Parque Tres de Febrero was designed by urbanist Jordán Czeslaw Wysocki and architect Julio Dormal. The park was inaugurated on 11 November 1875. The subsequent dramatic economic growth of Buenos Aires helped to lead to its transfer to the municipal domain in 1888, whereby French Argentine urbanist Carlos Thays was commissioned to expand and further beautify the park, between 1892 and 1912. Thays designed the Zoological Gardens, the Botanical Gardens, the adjoining Plaza Italia and the Rose Garden.

- Botanical Gardens, designed by French architect and landscape designer Carlos Thays, the garden was inaugurated on 7 September 1898. Thays and his family lived in an English style mansion, located within the gardens, between 1892 and 1898, when he served as director of parks and walks in the city. The mansion, built in 1881, is currently the main building of the complex.

- Buenos Aires Japanese Gardens Is the largest of its type in the world, outside Japan. Completed in 1967, the gardens were inaugurated on the occasion of a State visit to Argentina by Crown Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko of Japan.

- Plaza de Mayo Since being the scene of May Revolution of 1810 that led to Argentinian independence, the plaza has been a hub of political life in Argentina.

- Plaza San Martín is a park located in the city’s neighborhood of Retiro. Situated at the northern end of pedestrianized Florida Street, the park is bounded by Libertador Ave. (N), Maipú St. (W), Santa Fe Avenue (S), and Leandro Alem Av. (E).

Climate[edit]

Under the Köppen climate classification, Buenos Aires has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) with four distinct seasons.[41][42] As a result of maritime influences from the adjoining Atlantic Ocean,[43] the climate is temperate with extreme temperatures being rare.[44] Because the city is located in an area where the Pampero and Sudestada winds pass by,[45] the weather is variable due to these contrasting air masses.[46]

Heavy rain and thunderstorm in Plaza San Martin. Thunderstorms are usual during the summer.

Summers are hot and humid.[44] The warmest month is January, with a daily average of 24.9 °C (76.8 °F).[47] Heat waves are common during summers.[48] However, most heat waves are of short duration (less than a week) and are followed by the passage of the cold, dry Pampero wind which brings violent and intense thunderstorms followed by cooler temperatures.[46][49] The highest temperature ever recorded was 43.3 °C (110 °F) on 29 January 1957.[50] In January 2022, a heatwave caused power grid failure in parts of Buenos Aires metropolitan area affecting more than 700,000 households.[51]

Winters are cool with mild temperatures during the day and chilly nights.[44] Highs during the season average 16.6 °C (61.9 °F) while lows average 8.3 °C (46.9 °F).[52] Relative humidity averages in the upper 70s%, which means the city is noted for moderate-to-heavy fogs during autumn and winter.[53] July is the coolest month, with an average temperature of 11.0 °C (51.8 °F).[47] Cold spells originating from Antarctica occur almost every year, and can persist for several days.[52] Occasionally, warm air masses from the north bring warmer temperatures.[54] The lowest temperature ever recorded in central Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires Central Observatory) was −5.4 °C (22 °F) on 9 July 1918.[50] Snow is very rare in the city: the last snowfall occurred on 9 July 2007 when, during the coldest winter in Argentina in almost 30 years, severe snowfalls and blizzards hit the country. It was the first major snowfall in the city in 89 years.[55][56]

Spring and autumn are characterized by changeable weather conditions.[57] Cold air from the south can bring cooler temperatures while hot humid air from the north brings hot temperatures.[46]

The city receives 1,257.6 mm (50 in) of precipitation per year.[47] Because of its geomorphology along with an inadequate drainage network, the city is highly vulnerable to flooding during periods of heavy rainfall.[58][59][60][61]

| Climate data for Buenos Aires Central Observatory, located in Agronomía (1991–2020, extremes 1906-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 43.3 (109.9) |

38.0 (100.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

31.6 (88.9) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.3 (95.5) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.8 (98.2) |

40.5 (104.9) |

43.3 (109.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.1 (86.2) |

28.9 (84.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.9 (76.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 20.2 (68.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−4 (25) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−4 (25) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−2 (28) |

1.6 (34.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 134.4 (5.29) |

129.3 (5.09) |

120.0 (4.72) |

130.3 (5.13) |

93.5 (3.68) |

61.5 (2.42) |

74.4 (2.93) |

70.3 (2.77) |

80.6 (3.17) |

122.9 (4.84) |

117.6 (4.63) |

122.8 (4.83) |

1,257.6 (49.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 9.0 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 99.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64.7 | 69.7 | 72.6 | 76.3 | 77.5 | 78.7 | 77.4 | 73.2 | 70.1 | 69.1 | 66.7 | 63.6 | 71.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 279.0 | 240.8 | 229.0 | 220.0 | 173.6 | 132.0 | 142.6 | 173.6 | 189.0 | 227.0 | 252.0 | 266.6 | 2,525.2 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 12 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 7 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional[47][62] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990),[63][note 1] Weather Atlas (UV)[64] |

Government and politics[edit]

Government structure[edit]

Since the adoption of the city’s Constitution in 1996, Buenos Aires has counted with a democratically elected executive; Article 61 of the Constitution of the states that «Suffrage is free, equal, secret, universal, compulsory and non-accumulative. Resident aliens enjoy this same right, with its corresponding obligations, on equal terms with Argentine citizens registered in the district, under the terms established by law.»[65] The executive power is vested on the Chief of Government (Spanish: Jefe de Gobierno), who is elected alongside a Deputy Chief of Government. In analogous fashion to the Vice President of Argentina, the Deputy Chief of Government presides over the city’s legislative body, the City Legislature.

The Chief of Government and the Legislature are both elected for four-year terms; half of the Legislature’s members are renewed every two years. Elections use the D’Hondt method of proportional representation. The judicial branch comprises the Supreme Court of Justice (Tribunal Superior de Justicia), the Council of Magistracy (Consejo de la Magistratura), the Public Ministry, and other city courts.

Legally, the city has less autonomy than the Provinces. In June 1996, shortly before the city’s first Executive elections were held, the Argentine National Congress issued the National Law 24.588 (known as Ley Cafiero, after the Senator who advanced the project) by which the authority over the 25,000-strong Argentine Federal Police and the responsibility over the federal institutions residing at the city (e.g., National Supreme Court of Justice buildings) would not be transferred from the National Government to the Autonomous City Government until a new consensus could be reached at the National Congress. Furthermore, it declared that the Port of Buenos Aires, along with some other places, would remain under constituted federal authorities.[66] As of 2011, the deployment of the Metropolitan Police of Buenos Aires is ongoing.[67]

Beginning in 2007, the city has embarked on a new decentralization scheme, creating new Communes (comunas) which are to be managed by elected committees of seven members each. Buenos Aires is represented in the Argentine Senate by three senators (as of 2017, Federico Pinedo, Marta Varela and Pino Solanas).[68] The people of Buenos Aires also elect 25 national deputies to the Argentine Chamber of Deputies.

Law enforcement[edit]

The Guardia Urbana de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires Urban Guard) was a specialized civilian force of the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina, that used to deal with different urban conflicts with the objective of developing actions of prevention, dissuasion and mediation, promoting effective behaviors that guarantee the security and the integrity of public order and social coexistence. The unit continuously assisted the personnel of the Argentine Federal Police, especially in emergency situations, events of massive concurrence, and protection of tourist establishments. Urban Guard officials did not carry any weapons in the performing of their duties. Their basic tools were a HT radio transmitter and a whistle. As of March 2008, the Guardia Urbana was removed.

The Buenos Aires Metropolitan Police was the police force under the authority of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. The force was created in 2010 and was composed of 1,850 officers. In 2016, the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Police and part of the Argentine Federal Police were merged to create the new Buenos Aires City Police force. The Buenos Aires City Police force began operations on 1 January 2017. Security in the city is now the responsibility of the Buenos Aires City Police.[69] The police is headed by the Chief of Police who is appointed by the head of the executive branch of the city of Buenos Aires. Geographically, the force is divided into 56 stations throughout the city. All police station employees are civilians. The Buenos Aires City Police force is composed of over 25,000 officers.

Demographics[edit]

The population in 1825 was over 81,000 people.[70]

Census data[edit]

Historical population| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 5,166,140 | — |

| 1960 | 6,761,837 | +30.9% |

| 1970 | 8,416,170 | +24.5% |

| 1980 | 9,919,781 | +17.9% |

| 1990 | 11,147,566 | +12.4% |

| 2000 | 12,503,871 | +12.2% |

| 2010 | 14,245,871 | +13.9% |

| 2019 | 15,057,273 | +5.7% |

| for Buenos Aires Agglomeration:[71] |

In the census of 2010 there were 2,891,082 people residing in the city.[72] The population of Greater Buenos Aires was 13,147,638 according to 2010 census data.[73] The population density in Buenos Aires proper was 13,680 inhabitants per square kilometer (34,800 per mi2), but only about 2,400 per km2 (6,100 per mi2) in the suburbs.[74]

Buenos Aires’ population has hovered around 3 million since 1947, due to low birth rates and a slow migration to the suburbs. However, the surrounding districts have expanded over fivefold (to around 10 million) since then.[72]

The 2001 census showed a relatively aged population: with 17% under the age of fifteen and 22% over sixty, the people of Buenos Aires have an age structure similar to those in most European cities. They are older than Argentines as a whole (of whom 28% were under 15, and 14% over 60).[75]

Two-thirds of the city’s residents live in apartment buildings and 30% in single-family homes; 4% live in sub-standard housing.[76] Measured in terms of income, the city’s poverty rate was 8.4% in 2007 and, including the metro area, 20.6%.[77] Other studies estimate that 4 million people in the metropolitan Buenos Aires area live in poverty.[78]

The city’s resident labor force of 1.2 million in 2001 was mostly employed in the services sector, particularly social services (25%), commerce and tourism (20%) and business and financial services (17%); despite the city’s role as Argentina’s capital, public administration employed only 6%. Manufacturing still employed 10%.[76]

Districts[edit]

The city is divided into barrios (neighborhoods) for administrative purposes, a division originally based on Catholic parroquias (parishes).[79] A common expression is that of the Cien barrios porteños («One hundred porteño neighborhoods»), referring to a composition made popular in the 1940s by tango singer Alberto Castillo; however, Buenos Aires only consists of 48 official barrios. There are several subdivisions of these districts, some with a long history and others that are the product of a real estate invention. A notable example is Palermo – the city’s largest district – which has been subdivided into various barrios, including Palermo Soho, Palermo Hollywood, Las Cañitas and Palermo viejo, among others. A newer scheme has divided the city into 15 comunas (communes).[80]

Population origin[edit]

The majority of porteños have European origins, mostly from the Andalusian, Galician, Asturian, and Basque regions of Spain. As well as the Italian regions of Calabria, Liguria, Piedmont, Lombardy, Sicily and Campania. [81][82] Unrestricted waves of European immigrants to Argentina starting in the mid-19th century significantly increased the country’s population, even causing the number of porteños to triple between 1887 and 1915 from 500,000 to 1.5 million.[83]

The Immigrants’ Hotel, constructed in 1906, received and assisted the thousands of immigrants arriving to the city. The hotel is now a National Museum.

Other significant European origins include French, Portuguese, German, Irish, Norwegian, Polish, Swedish, Greek, Czech, Albanian, Croatian, Slovenian, Dutch, Russian, Serbian, English, Scottish, Slovak, Hungarian and Bulgarian. In the 1980s and 1990s, there was a small wave of immigration from Romania and Ukraine.[84] There is a minority of criollo citizens, dating back to the Spanish colonial days. The Criollo and Spanish-Indigenous (mestizo) population in the city has increased mostly as a result of immigration from the inner northern provinces and from other countries such as neighboring Bolivia, Paraguay, Chile and Peru, since the second half of the 20th century.[citation needed]

The Jewish community in Greater Buenos Aires numbers around 250,000 and is the largest in the country. The city is also eighth largest in the world in terms of Jewish population.[85] Most are of Northern, Western, Central, and Eastern European Ashkenazi origin, primarily Swedish, Dutch, Polish, German, and Russian Jews, with a significant Sephardic minority, mostly made up of Syrian Jews and Lebanese Jews.[86] Important Lebanese, Georgian, Syrian and Armenian communities have had a significant presence in commerce and civic life since the beginning of the 20th century.

Most East Asian immigration in Buenos Aires comes from China. Chinese immigration is the fourth largest in Argentina, with the vast majority of them living in Buenos Aires and its metropolitan area.[87] In the 1980s, most of them were from Taiwan, but since the 1990s the majority of Chinese immigrants come from the Mainland Chinese province of Fukien (Fujian).[87] The mainland Chinese who came from Fukien mainly installed supermarkets throughout the city and the suburbs; these supermarkets are so common that, in average, there is one every two and a half blocks and are simply referred to as el chino («the Chinese»).[87][88] Japanese immigrants are mostly from the Okinawa Prefecture. They started the dry cleaning business in Argentina, an activity that is considered idiosyncratic to the Japanese immigrants in Buenos Aires.[89] Korean Immigration occurred after the division of Korea; they mainly settled in Flores and Once.[90]

In the 2010 census [INDEC], 2.1% of the population or 61,876 persons declared to be Indigenous or first-generation descendants of Indigenous people in Buenos Aires (not including the 24 adjacent Partidos that make up Greater Buenos Aires).[91] Amongst the 61,876 persons who are of indigenous origin, 15.9% are Quechua people, 15.9% are Guaraní, 15.5% are Aymara and 11% are Mapuche.[91] Within the 24 adjacent Partidos, 186,640 persons or 1.9% of the total population declared themselves to be Indigenous.[91] Amongst the 186,640 persons who are of indigenous origin, 21.2% are Guaraní, 19% are Toba, 11.3% are Mapuche, 10.5% are Quechua and 7.6% are Diaguita.[91]

In the city, 15,764 people identified themselves as Afro-Argentine in the 2010 Census.[92]

Urban problems[edit]

Villa 31, a villa miseria in Buenos Aires

Villas miseria are a type of slum whose size ranges from small groups of precarious houses to large communities with thousands of residents.[93] In rural areas, the houses in the villas miseria might be made of mud and wood. Villas miseria are found around and inside the large cities of Buenos Aires, Rosario, Córdoba and Mendoza, among others.

Buenos Aires has below 2 m2 (22 sq ft) of green space per person, which is 90% less than New York, 85% less than Madrid and 80% less than Paris. The World Health Organization (WHO), in its concern for public health, produced a document stating that every city should have a minimum of 9 m2 (97 sq ft) of green space per person; an optimal amount of space per person would range from 10 to 15 m2 (161 sq ft).[94][95]

Language[edit]

Buenos Aires’ dialect of Spanish, which is known as Rioplatense Spanish, is distinguished by its use of voseo, yeísmo, and aspiration of s in various contexts. It is heavily influenced by the dialects of Spanish spoken in Andalusia and Murcia, and shares its features with that of other cities like Rosario and Montevideo, Uruguay. In the early 20th century, Argentina absorbed millions of immigrants, many of them Italians, who spoke mostly in their local dialects (mainly Neapolitan, Sicilian and Genoese). Their adoption of Spanish was gradual, creating a pidgin of Italian dialects and Spanish that was called cocoliche. Its usage declined around the 1950s. A phonetic study conducted by the Laboratory for Sensory Investigations of CONICET and the University of Toronto showed that the prosody of porteño is closer to the Neapolitan language of Italy than to any other spoken language.[96] Many Spanish immigrants were from Galicia, and Spaniards are still generically referred to in Argentina as gallegos (Galicians). Galician language, cuisine and culture had a major presence in the city for most of the 20th century. In recent years, descendants of Galician immigrants have led a mini-boom in Celtic music (which also highlighted the Welsh traditions of Patagonia). Yiddish was commonly heard in Buenos Aires, especially in the Balvanera garment district and in Villa Crespo until the 1960s. Most of the newer immigrants learn Spanish quickly and assimilate into city life.

The Lunfardo argot originated within the prison population, and in time spread to all porteños. Lunfardo uses words from Italian dialects, from Brazilian Portuguese, from African and Caribbean languages and even from English. Lunfardo employs humorous tricks such as inverting the syllables within a word (vesre). Today, Lunfardo is mostly heard in tango lyrics;[97] the slang of the younger generations has been evolving away from it. Buenos Aires was also the first city to host a Mundo Lingo event on 7 July 2011, which have been after replicated in up to 15 cities in 13 countries.[98]

Religion[edit]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Buenos Aires was the second-largest Catholic city in the world after Paris.[99][100] Christianity is still the most prevalently practiced religion in Buenos Aires (~71.4%),[101] a 2019 CONICET survey on religious beliefs and attitudes found that the inhabitants of the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area (Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires, AMBA) were 56.4% Catholic, 26.2% non-religious and 15% Evangelical; making it the region of the country with the highest proportion of irreligious people.[101] A previous CONICET survey from 2008 had found that 69.1% were Catholic, 18% «indifferent», 9.1% Evangelical, 1.4% Jehovah’s Witnesses or Mormons and 2.3% adherents to other religions.[102] The comparison between both surveys reveals that the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area is the region in which the decline of Catholicism was most pronounced during the last decade.[101]

Buenos Aires is also home to the largest Jewish community in Latin America and the second largest in the Western Hemisphere after the United States.[103][104] The Jewish community of Buenos Aires has historically been characterized by its high level of assimilation, organization and influence in the cultural history of the city.[105]

Buenos Aires is the seat of a Roman Catholic metropolitan archbishop (the Catholic primate of Argentina), currently Archbishop Mario Poli. His predecessor, Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, was elected to the Papacy as Pope Francis on 13 March 2013. There are Protestant, Orthodox, Eastern Catholic, Buddhist and various other religious minorities as well.[106]

Education[edit]

Primary education comprises grades 1–7. Most primary schools in the city still adhere to the traditional seven-year primary school, but kids can do grades 1–6 if their high school lasts 6 years, such as ORT Argentina. Secondary education in Argentina is called Polimodal (having multiple modes) since it allows the student to choose their orientation. Polimodal is usually 3 years of schooling, although some schools have a fourth year. Before entering the first year of polimodal, students choose an orientation from the following five specializations. Some high schools depend on the University of Buenos Aires, and these require an admission course when students are taking the last year of high school. These high schools are ILSE, CNBA, Escuela Superior de Comercio Carlos Pellegrini and Escuela de Educación Técnica Profesional en Producción Agropecuaria y Agroalimentaria (School of Professional Technique Education in Agricultural and Agrifood Production). The last two do have a specific orientation. In December 2006 the Chamber of Deputies of the Argentine Congress passed a new National Education Law restoring the old system of primary followed by secondary education, making secondary education obligatory and a right, and increasing the length of compulsory education to 13 years. The government vowed to put the law in effect gradually, starting in 2007.[107]

There are many public universities in Argentina, as well as a number of private universities. The University of Buenos Aires, one of the top learning institutions in South America, has produced five Nobel Prize winners and provides taxpayer-funded education for students from all around the globe.[108][109][110] Buenos Aires is a major center for psychoanalysis, particularly the Lacanian school. Buenos Aires is home to several private universities of different quality, such as: Universidad Argentina de la Empresa, Buenos Aires Institute of Technology, CEMA University, Favaloro University, Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina, University of Belgrano, University of Palermo, University of Salvador, Universidad Abierta Interamericana, Universidad Argentina John F. Kennedy, Universidad de Ciencias Empresariales y Sociales, Universidad del Museo Social Argentino, Universidad Austral, Universidad CAECE and Torcuato di Tella University.

Economy[edit]

Puerto Madero, in the Buenos Aires Central Business District, currently represents the largest urban renewal project in the city of Buenos Aires. Having undergone an impressive revival in merely a decade, it is one of the most successful recent waterfront renewal projects in the world.[111]

Buenos Aires is the financial, industrial, and commercial hub of Argentina. The economy in the city proper alone, measured by Gross Geographic Product (adjusted for purchasing power), totaled US$102.7 billion (US$34,200 per capita) in 2020[112] and amounts to nearly a quarter of Argentina’s as a whole.[113] Metro Buenos Aires, according to one well-quoted study, constitutes the 13th largest economy among the world’s cities in 2005.[114] The Buenos Aires Human Development Index (0.889 in 2019) is likewise high by international standards.[115]

The city’s services sector is diversified and well-developed by international standards, and accounts for 76 percent of its economy (compared to 59% for all of Argentina’s).[116] Advertising, in particular, plays a prominent role in the export of services at home and abroad. However, the financial and real estate services sector is the largest and contributes to 31 percent of the city’s economy. Finance (about a third of this) in Buenos Aires is especially important to Argentina’s banking system, accounting for nearly half the nation’s bank deposits and lending.[116] Nearly 300 hotels and another 300 hostels and bed & breakfasts are licensed for tourism, and nearly half the rooms available were in four-star establishments or higher.[117]

Manufacturing is, nevertheless, still prominent in the city’s economy (16 percent) and, concentrated mainly in the southern part of the city. It benefits as much from high local purchasing power and a large local supply of skilled labor as it does from its relationship to massive agriculture and industry just outside the city limits. Construction activity in Buenos Aires has historically been among the most accurate indicators of national economic fortunes, and since 2006 around 3 million square meters (32×106 sq ft) of construction has been authorized annually.[116] Meat, dairy, grain, tobacco, wool and leather products are processed or manufactured in the Buenos Aires metro area. Other leading industries are automobile manufacturing, oil refining, metalworking, machine-building, and the production of textiles, chemicals, clothing and beverages.

The city’s budget, per Mayor Macri’s 2011 proposal, included US$6 billion in revenues and US$6.3 billion in expenditures. The city relies on local income and capital gains taxes for 61 percent of its revenues, while federal revenue sharing contributes 11 percent, property taxes, 9 percent, and vehicle taxes, 6 percent. Other revenues include user fees, fines, and gambling duties. The city devotes 26 percent of its budget to education, 22 percent for health, 17 percent for public services and infrastructure, 16 percent for social welfare and culture, 12 percent in administrative costs and 4 percent for law enforcement. Buenos Aires maintains low debt levels and its service requires less than 3 percent of the budget.[118]

Tourism[edit]

Buenos Aires Bus, the city’s tour bus service. The official estimate is that the bus carries between 700 and 800 passengers per day.[119]

According to the World Travel & Tourism Council,[120] tourism has been growing in the Argentine capital since 2002. In a survey by the travel and tourism publication Travel + Leisure Magazine in 2008, visitors voted Buenos Aires the second most desirable city to visit after Florence, Italy.[121] In 2008, an estimated 2.5 million visitors visited the city.[122] Buenos Aires is an international hub of highly active and diverse nightlife with bars, dance bars and nightclubs staying open well past midnight.[123][124][125][126][127]

Visitors have many options for travel such as going to a tango show, an estancia in the Province of Buenos Aires, or enjoying the traditional asado. New tourist circuits have recently evolved, devoted to Argentines such as Carlos Gardel, Eva Perón or Jorge Luis Borges. Before 2011, due to the Argentine peso’s favorable exchange rate, its shopping centers such as Alto Palermo, Paseo Alcorta, Patio Bullrich, Abasto de Buenos Aires and Galerías Pacífico were frequently visited by tourists. Nowadays, the exchange rate has hampered tourism and shopping in particular. In fact, notable consumer brands such as Burberry and Louis Vuitton have abandoned the country due to the exchange rate and import restrictions. The city also plays host to musical festivals, some of the largest of which are Quilmes Rock, Creamfields BA, Ultra Music Festival (Buenos Aires), and the Buenos Aires Jazz Festival.

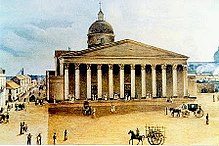

The most popular tourist sites are found in the historic core of the city, specifically, in the Montserrat and San Telmo neighborhoods. Buenos Aires was conceived around the Plaza de Mayo, the colony’s administrative center. To the east of the square is the Casa Rosada, the official seat of the executive branch of the government of Argentina. To the north, the Catedral Metropolitana which has stood in the same location since colonial times, and the Banco de la Nación Argentina building, a parcel of land originally owned by Juan de Garay. Other important colonial institutions were Cabildo, to the west, which was renovated during the construction of Avenida de Mayo and Julio A. Roca. To the south is the Congreso de la Nación (National Congress), which currently houses the Academia Nacional de la Historia (National Academy of History). Lastly, to the northwest, is City Hall.

Buenos Aires has become a recipient of LGBT tourism,[128][129] due to the existence of some gay-friendly sites and the legalization of same-sex marriage on 15 July 2010, making it the first country in Latin America, the second in the Americas, and the tenth in the world to do so. Its Gender Identity Law, passed in 2012, made Argentina the «only country that allows people to change their gender identities without facing barriers such as hormone therapy, surgery or psychiatric diagnosis that labels them as having an abnormality». In 2015, the World Health Organization cited Argentina as an exemplary country for providing transgender rights. Despite these legal advances, however, homophobia continues to be a hotly contested social issue in the city and the country.[130]

Buenos Aires has various types of accommodation ranging from luxurious five star hotels in the city center to budget hotels located in suburban neighborhoods. Nonetheless, the city’s transportation system allows easy and inexpensive access to the city. There were, as of February 2008, 23 five-star, 61 four-star, 59 three-star and 87 two or one-star hotels, as well as 25 boutique hotels and 39 apart-hotels; another 298 hostels, bed & breakfasts, vacation rentals and other non-hotel establishments were registered in the city. In all, nearly 27,000 rooms were available for tourism in Buenos Aires, of which about 12,000 belonged to four-star, five-star, or boutique hotels. Establishments of a higher category typically enjoy the city’s highest occupation rates.[131] The majority of the hotels are located in the central part of the city, in close proximity to most main tourist attractions.

Transportation[edit]

According to data released by Moovit in July 2017, the average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Buenos Aires, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 79 min. 23% of public transit riders, ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 14 min, while 20 percent of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 8.9 km, while 21% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[132]

Roads[edit]

Buenos Aires is based on a rectangular grid pattern, save for natural barriers or the relatively rare developments explicitly designed otherwise (most notably, the Parque Chas neighborhood). The rectangular grid provides for 110-meter (361 ft)-long square blocks named manzanas . Pedestrian zones in the central business district such as Florida Street are partially car-free and always bustling, access provided by bus and the Underground (subte) Line C. Buenos Aires, for the most part, is a very walkable city and the majority of residents in Buenos Aires use public transport.

Two diagonal avenues alleviate traffic and provide better access to Plaza de Mayo and the city center in general; most avenues running into and out of it are one-way and feature six or more lanes, with computer-controlled green waves to speed up traffic outside of peak times. The city’s principal avenues include the 140-meter (459 ft)-wide July 9 Avenue, the over 35-kilometer (22 mi)-long Rivadavia Avenue,[133] and Corrientes Avenue, the main thoroughfare of culture and entertainment.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the construction of the General Paz Avenue beltway that surrounds the city along its border with Buenos Aires Province, and the freeways leading to the new international airport and to the northern suburbs, heralded a new era for Buenos Aires traffic. Encouraged by pro-automaker policies that were pursued towards the end of the Perón (1955) and Frondizi administrations (1958–62) in particular, auto sales nationally grew from an average of 30,000 during the 1920–57 era to around 250,000 in the 1970s and over 600,000 in 2008.[134] Today, over 1.8 million vehicles (nearly one-fifth of Argentina’s total) are registered in Buenos Aires.[135]

Toll motorways opened in the late 1970s by mayor Osvaldo Cacciatore, now used by over a million vehicles daily, provide convenient access to the city center.[136] Cacciatore likewise had financial district streets (roughly 1 square kilometer (0.39 sq mi) in area) closed to private cars during daytime. Most major avenues are, however, gridlocked at peak hours. Following the economic mini-boom of the 1990s, record numbers started commuting by car and congestion increased, as did the time-honored Argentine custom of taking weekends off in the countryside.

Airports[edit]

The Ministro Pistarini International Airport, commonly known as Ezeiza Airport, is located in the suburb of Ezeiza, in Buenos Aires Province, approximately 22 km south of the city. This airport handles most international air traffic to and from Argentina as well as some domestic flights.

The Aeroparque Jorge Newbery airport, located in the Palermo district of the city next to the riverbank, is only within the city limits and serves primarily domestic traffic within Argentina and some regional flights to neighboring South American countries.

Other minor airports near the city are El Palomar Airport, which is located 18 km west of the city and handles some scheduled domestic flights to a number of destinations in Argentina, and the smaller San Fernando Airport which serves only general aviation.

Urban rail[edit]

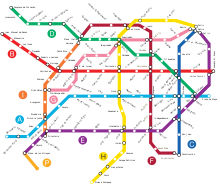

The Buenos Aires Underground (locally known as subte, from «subterráneo» meaning underground or subway), is a high-yield[clarification needed] system providing access to various parts of the city. Opened in 1913, it is the oldest underground system in the Southern Hemisphere and oldest in the Spanish-speaking world. The system has six underground lines and one overground line, named by letters (A to E, and H) and there are 100 stations, and 58.8 km (37 mi) of route, including the Premetro line.[137] An expansion program is underway to extend existing lines into the outer neighborhoods and add a new north–south line. Route length is expected to reach 89 km (55 mi) by 2011.

Line A is the oldest one (service opened to public in 1913) and stations kept the «belle-époque» decoration, while the original rolling stock from 1913, affectionately known as Las Brujas were retired from the line in 2013. Daily ridership on weekdays is 1.7 million and on the increase.[138][139] Fares remain relatively cheap, although the city government raised fares by over 125% in January 2012. A single journey, with unlimited interchanges between lines, costs AR$42, which is roughly US$0.23 as of January 2023.[140]

The most recent expansions to the network were the addition of numerous stations to the network in 2013: San José de Flores and San Pedrito to Line A, Echeverría and Juan Manuel de Rosas to Line B and Hospitales to Line H. Current works include the completion of Line H northwards and addition of three new stations to Line E in the city center.[141][142] The construction of Line F is due to commence in 2015,[143] while two other lines are planned for construction in the future.

The Buenos Aires commuter rail system has seven lines: Belgrano Norte; Belgrano Sur; Roca; San Martín; Sarmiento; Mitre; and Urquiza. The Buenos Aires commuter network system is very extensive: every day more than 1.3 million people commute to the Argentine capital. These suburban trains operate between 4 am and 1 am. The Buenos Aires commuter rail network also connects the city with long-distance rail services to Rosario and Córdoba, among other metropolitan areas. The city center is home to four principal terminals for both long-distance and local passenger services: Constitucion, Retiro, Federico Lacroze and Once. In addition, Buenos Aires station serves as a minor terminus.

Commuter rail in the city is mostly operated by the state-owned Trenes Argentinos, though the Urquiza Line and Belgrano Norte Line are operated by private companies Metrovías and Ferrovías respectively.[144][145][146] All services had been operated by Ferrocarriles Argentinos until the company’s privatization in 1993, and were then operated by a series of private companies until the lines were put back under state control following a series of high-profile accidents.[147][148]

Since 2013, there has been a series of large investments on the network, with all lines (with the exception of the Urquiza Line) receiving new rolling stock, along with widespread infrastructure improvements, track replacement, electrification work, refurbishments of stations and building entirely new stations.[149][150][151] Similarly, almost all level crossings have been replaced by underpasses and overpasses in the city, with plans to replace all of them in the near future.[152] One of the most major projects under way is the electrification of the remaining segments of the Roca Line – the most widely used in the network – and also moving the entire section of the Sarmiento Line which runs through the heart of the city’s underground to allow for better frequencies on the line and reduce congestion above ground.[153][154]

There are also three other major projects on the table. The first would elevate a large segment of the San Martín Line which runs through the city center and electrify the line, while the second would see the electrification and extension of the Belgrano Sur Line to Constitucion station in the city center.[155][156] If these two projects are completed, then the Belgrano Norte Line would be the only diesel line to run through the city. The third and most ambitious is to build a series of tunnels between three of the city’s railway terminals with a large underground central station underneath the Obelisk, connecting all the commuter railway lines in a network dubbed the Red de Expresos Regionales.[157]

Buenos Aires had an extensive street railway (tram) system with over 857 km (533 mi) of track, which was dismantled during the 1960s after the advent of bus transportation, but surface rail transport has made a small comeback in some parts of the city. The PreMetro or Line E2 is a 7.4 km (4.6 mi) light rail line that connects with Underground Line E at Plaza de los Virreyes station and runs to General Savio and Centro Cívico. It is operated by Metrovías. The official inauguration took place on 27 August 1987. A 2-meter (7 ft)-long modern tramway, the Tranvía del Este, opened in 2007 in the Puerto Madero district, using two tramcars on temporary loan. However, plans to extend the line and acquire a fleet of trams did not come to fruition, and declining patronage led to the line’s closure in October 2012.[158] A heritage streetcar maintained by tram fans operates on weekends, near the Primera Junta line A Underground station in the neighborhood of Caballito.

Cycling[edit]

In December 2010, the city government launched a bicycle sharing program with bicycles free for hire by users upon registration. Located in mostly central areas, there are 31 rental stations throughout the city providing over 850 bicycles to be picked up and dropped off at any station within an hour.[159] As of 2013, the city has constructed 110 km (68.35 mi) of protected bicycle lanes and has plans to construct another 100 km (62.14 mi).[160] In 2015, the stations were automated and the service became 24 hours through use of a smart card or mobile phone application.

Buses[edit]

Federico Lacroze Transfer Center of the Metrobus

There are over 150 city bus lines called Colectivos, each one managed by an individual company. These compete with each other and attract exceptionally high use with virtually no public financial support.[161] Their frequency makes them equal to the underground systems of other cities, but buses cover a far wider area than the underground system. Colectivos in Buenos Aires do not have a fixed timetable, but run from four to several per hour, depending on the bus line and time of the day. With inexpensive tickets and extensive routes, usually no further than four blocks from commuters’ residences, the colectivo is the most popular mode of transport around the city.[161]

Buenos Aires has recently opened a bus rapid transit system, the Metrobus. The system uses modular median stations that serve both directions of travel, which enable pre-paid, multiple-door, level boarding. The first line, opened on 31 May 2011, runs across the Juan B. Justo Ave has 21 stations.[162] The system now has 4 lines with 113 stations on its 43.5 km (27.0 mi) network, while numerous other lines are under construction and planned.[163]

Port[edit]

The port of Buenos Aires is one of the busiest in South America, as navigable rivers by way of the Rio de la Plata connect the port to northeastern Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay. As a result, it serves as the distribution hub for said vast area of the South American continent. The Port of Buenos Aires handles over 11,000,000 metric tons (11,000,000 long tons; 12,000,000 short tons) annually,[164] and Dock Sud, just south of the city proper, handles another 17,000,000 metric tons (17,000,000 long tons; 19,000,000 short tons) .[165] Tax collection related to the port has caused many political problems in the past, including a conflict in 2008 that led to protests and a strike in the agricultural sector after the government raised export tariffs.[166]

Ferries[edit]

Buenos Aires is also served by a ferry system operated by the company Buquebus that connects the port of Buenos Aires with the main cities of Uruguay, (Colonia del Sacramento, Montevideo and Punta del Este). More than 2.2 million people per year travel between Argentina and Uruguay with Buquebus. One of these ships is a catamaran, which can reach a top speed of about 80 km/h (50 mph).[167]

Taxis[edit]

A fleet of 40,000 black-and-yellow taxis ply the streets at all hours. Some taxi drivers may try to take advantage of tourists.[168], but radio-link companies provide reliable and safe service; many such companies provide incentives for frequent users. Low-fare limo services, known as remises, are also popular.[169][170] though currently giving way to ridesharing companies like Uber or Cabify, whose legal status has been the cause of much dispute with the city government[171][172]

Culture[edit]

As Buenos Aires is strongly influenced by European culture, the city is sometimes referred to as the «Paris of South America».[2][173] With its scores of theaters and productions, the city has the busiest live theater industry in Latin America.[174] In fact, every weekend, there are about 300 active theaters with plays, a number that places the city as 1st worldwide, more than either London, New York or Paris, cultural Meccas in themselves. The number of cultural festivals with more than 10 sites and 5 years of existence also places the city as 2nd worldwide, after Edinburgh.[175] The Centro Cultural Kirchner (Kirchner Cultural Center), located in Buenos Aires, is the largest cultural center of Latin America,[176][177] and the third worldwide.[178]

Buenos Aires is the home of the Teatro Colón, an internationally rated opera house.[179] There are several symphony orchestras and choral societies. The city has numerous museums related to arts and crafts, history, fine arts, modern arts, decorative arts, popular arts, sacred art, theater and popular music, as well as the preserved homes of noted art collectors, writers, composers and artists. The city is home to hundreds of bookstores, public libraries and cultural associations (it is sometimes called «the city of books»), as well as the largest concentration of active theaters in Latin America. It has a zoo and botanical garden, a large number of landscaped parks and squares, as well as churches and places of worship of many denominations, many of which are architecturally noteworthy.[179]

The city has been a member of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network after it was named «City of Design» in 2005.[180]

Porteño identity[edit]

The identity of porteños has a rich and complex history, and has been the subject of much analysis and scrutiny.[181] The great European immigration wave of the early 20th century was integral to «the growing primacy of Buenos Aires and the accompanying urban identity», and established the division between urban and rural Argentina more deeply.[182] Immigrants «brought new traditions and cultural markers to the city,» which were «then reimagined in the porteño context, with new layers of meanings because of the new location.»[183] The heads of state’s attempt to populate the country and reframe the national identity resulted in the concentration of immigrants in the city and its suburbs, who generated a culture that is a «product of their conflicts of integration, their difficulties to live and their communication puzzles.»[184] In response to the immigration wave, during the 1920s and 1930s a nationalist trend within the Argentine intellectual elite glorified the gaucho figure as an exemplary archetype of Argentine culture; its synthesis with the European traditions conformed the new urban identity of Buenos Aires.[185] The complexity of Buenos Aires’ integration and identity formation issues increased when immigrants realized that their European culture could help them gain a greater social status.[186] As the rural population moved to the industrialized city from the 1930s onwards, they reaffirmed their European roots,[187] adopting endogamy and founding private schools, newspapers in foreign languages, and associations that promoted adherence to their countries of origin.[186]

Porteños are generally characterized as night owls, cultured, talkative, uninhibited, sensitive, nostalgic, observant and arrogant.[15][181] Argentines outside Buenos Aires often stereotype its inhabitants as egotist people, a feature that people from the Americas and westerners in general commonly attribute to the entire Argentine population and use as the subject of numerous jokes.[188] Writing for BBC Mundo Cristina Pérez felt that «the idea of the [Argentines’] vastly developed ego finds strong evidence in lunfardo dictionaries,» in words such as «engrupido» (meaning «vain» or «conceited») and «compadrito» (meaning both «brave» and «braggart»), the latter being an archetypal figure of tango.[189] Paradoxically, porteños are also described as highly self-critical, something that has been called «the other side of the ego coin.»[189] Writers consider the existence of these behaviors the consequence of the European immigration and prosperity that the city experienced during the early 20th century, which generated a feeling of superiority in parts of the population.[188]

Art[edit]

Buenos Aires has a thriving arts culture,[190] with «a huge inventory of museums, ranging from obscure to world-class.»[191] The barrios of Palermo and Recoleta are the city’s traditional bastions in the diffusion of art, although in recent years there has been a tendency of appearance of exhibition venues in other districts such as Puerto Madero or La Boca; renowned venues include MALBA, the National Museum of Fine Arts, Fundación Proa, Faena Arts Center, and the Usina del Arte.[192] Other popular institutions are the Buenos Aires Museum of Modern Art, the Quinquela Martín Museum, the Evita Museum, the Fernández Blanco Museum, the José Hernández Museum, and the Palais de Glace, among others.[193] A traditional event that occurs once a year is La Noche de los Museos («Night of the Museums»), when the city’s museums, universities, and artistic spaces open their doors for free until early morning; it usually takes place in November.[194][195]

The first major artistic movements in Argentina coincided with the first signs of political liberty in the country, such as the 1913 sanction of the secret ballot and universal male suffrage, the first president to be popularly elected (1916), and the cultural revolution that involved the University Reform of 1918. In this context, in which there continued to be influence from the Paris School (Modigliani, Chagall, Soutine, Klee), three main groups arose.

Buenos Aires has been the birthplace of several artists and movements of national and international relevance, and has become a central motif in Argentine artistic production, especially since the 20th century.[196]