| Genghis Khan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

Genghis Khan as portrayed in a 14th-century Yuan era album; now located in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. The original version was in black and white; produced by the Mongol painter Ho-li-hosun in 1278 under the commission of Kublai Khan. |

||||||

| Great Khan of the Mongol Empire | ||||||

| Reign | Spring 1206 – 25 August, 1227 | |||||

| Coronation | Spring 1206 in a Kurultai at the Onon River, in modern-day Mongolia | |||||

| Successor | Tolui (as regent) Ögedei Khan |

|||||

| Born | Temüjin c. 1162[2] Khentii Mountains, Khamag Mongol |

|||||

| Died | August 25, 1227[3] Xingqing, Western Xia |

|||||

| Burial |

Unknown |

|||||

| Spouse |

|

|||||

| Issue |

|

|||||

|

||||||

| House | Borjigin | |||||

| Dynasty | Genghisid | |||||

| Father | Yesügei | |||||

| Mother | Hoelun | |||||

| Religion | Tengrism |

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; c. 1162 — 25 August 1227), also known as Chinggis Khan,[a] was the founder and first khagan of the Mongol Empire, which later became the largest contiguous land empire in history. Having spent the majority of his life uniting the Mongol tribes, he launched a series of military campaigns which conquered large parts of China and Central Asia.

Born between 1155 and 1167 and given the name of Temüjin, he was the oldest child of Yesugei, a Mongol chieftain of the Borjigin clan, and his wife Hoelun of the Olkhonuds. Yesugei died when Temüjin was eight, and his family was abandoned by their tribe in the Mongol steppe. Temüjin gradually built up a small following and allied with Jamukha and Toghrul, two other Mongol chieftains, in campaigns against other tribes. Due to the erratic nature of the sources, this period of Temüjin’s life is uncertain; he may have spent time as a servant of the Jin dynasty. The alliances with Jamukha and Toghrul failed completely in the early 13th century, but Temüjin was able to defeat both and claim sole rulership of the Mongol tribes. He formally adopted the name Genghis Khan at a kurultai in 1206.

With the tribes fully united under his command, Genghis Khan expanded eastwards. He vassalised the Western Xia state by 1211 and then invaded the Jin dynasty in northern China, forcing the Jin emperor to abandon the northern half of his kingdom in 1214. Mongol forces annexed the Qara Khitai khanate in 1218, allowing Genghis Khan to lead an invasion of the neighbouring Khwarazmian Empire the following year. The invading Mongols toppled the Khwarazmian state and devastated the regions of Transoxania and Khorasan, while an expedition penetrated as far as Georgia and the Kievan Rus’. Genghis Khan died in 1227 while besieging the rebellious Western Xia; his third son and heir Ögedei succeeded to the throne two years later.

The Mongol campaigns started by Genghis Khan saw widespread destruction and millions of deaths in the areas they conquered. The Mongol army he built was renowned for its flexibility, discipline, and organisation, while his empire established upon meritocratic principles. Genghis Khan also codified the Mongol legal system, promoted religious tolerance, and encouraged pan-Eurasian trade through the Pax Mongolica. He is revered and honored in modern Mongolia as a symbol of national identity and a central figure of Mongolian culture.

Name and titles

Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan is an honorary title meaning «universal ruler» that represents an aggrandization of the pre-existing title of Khan that is used to denote a clan chief in Mongolian. The appellation of «Genghis» to the term is thought to derive from the Turkic word «tengiz«, meaning sea, making the honorary title literally «oceanic ruler», but understood more broadly as a metaphor for the universality or totality of Temüjin’s rule from a Mongol perspective.[8][9]

There is no standardised system of transliterating original Mongolian names into English; many different systems continue to be in use today, resulting in modern spellings that often differ considerably from the original pronunciation.[10] Ultimately, the honorific most commonly spelt Genghis derives from the autochthonous Mongolian ᠴᠢᠩᠭᠢᠰ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ (Mongolian pronunciation: [t͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋ]), most closely represented in English by the spelling Čhinggis. From this origin derived the Chinese 成吉思汗; Chéngjísī Hán and the Persian: چنگیز خان; Čəngīz H̱ān. As Arabic lacks a similar sound to «Č», writers using the language transliterated the name to Şıñğıs xan or Cənġīz H̱ān.[11] In modern English, common spellings include Chinggis, Chingis, Jinghis, and Jengiz, in addition to the dominant Genghis.[12][13]

Temujin

According to The Secret History of the Mongols, Genghis Khan’s birth name Temüjin ᠲᠡᠮᠦᠵᠢᠨ (Chinese: 鐵木真; Mongolian pronunciation: [tʰemut͡ʃiŋ]) came from the Tatar chief Temüjin-üge whom his father had just captured. His birth name is most commonly spelt Temüjin in English, although Temuchin is also sometimes used.

The name Temüjin is also equated with the Turco-Mongol temürči(n), «blacksmith», and there existed a tradition that viewed Genghis Khan as a smith, according to Paul Pelliot, which, though unfounded, was well established by the middle of the 13th century.[12][14]

Temple and posthumous names

When Genghis’ grandson Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty in 1271, he bestowed the temple name Taizu (太祖, meaning «Supreme Progenitor») and the posthumous name Shengwu huangdi (Chinese: 聖武皇帝, meaning «Holy-Martial Emperor») upon his grandfather. Külüg Khan later expanded this title into Fatian Qiyun Shengwu Huangdi (法天啟運聖武皇帝, meaning «Interpreter of the Heavenly Law, Initiator of the Good Fortune, Holy-Martial Emperor»).[6][15]

Sources

Historians have found it difficult to fully compile and understand early sources describing the life of Genghis Khan, on account of their great geographic and linguistic dispersion.[16] All accounts of his adolescence and rise to power under the name Temüjin derive from two Mongolian sources—The Secret History of the Mongols, and the Altan Debter («Golden Book»). The latter, now lost, served as inspiration for two Chinese chronicles—the 14th-century Yuán Shǐ (元史; lit. ‘History of the Yuan’) and the Shengwu qinzheng lu (聖武親征錄; lit. ‘Campaigns of Genghis Khan’).[17] The poorly edited Yuán Shǐ provides a large amount of extra detail on individual campaigns and biographies; the Shengwu is more disciplined in terms of chronology but does not criticise Genghis Khan and occasionally deteriorates in quality.[18]

The Secret History survived through translation into Chinese script in the 14th and 15th centuries.[19] The reliability of the Secret History as a historical source has been disputed: while the sinologist Arthur Waley saw it as near-useless from a historical standpoint and valued it only as a literary work, recent historians have increasingly used it to explore Genghis Khan’s early life.[20][21] Although it is clear that the chronology of the work is suspect and that some passages were removed or modified for better narration, the Secret History is valued more highly because the author is often critical of Genghis Khan. In addition to presenting him as indecisive and cynophobic, the Secret History also recounts events such as the murder of his half-brother Behter and the abduction of his wife Börte.[22]

Multiple chronicles in Persian have also survived, which display a mix of positive and negative attitudes towards Genghis Khan and the Mongols. Both the Tabaqat-i Nasiri of Minhaj-i Siraj Juzjani and the Tarikh-i Jahangushay of Ata-Malik Juvayni were completed in 1260.[23] Juzjani was an eyewitness to the brutality of the Mongol conquests, and the hostility of his chronicle reflects his experiences.[24] His contemporary Juvayni, who had travelled twice to Mongolia and attained a high position in the Ilkhanate administration, was more sympathetic; his account is the most reliable for Genghis Khan’s western campaigns.[25][26] The most important Persian source was the Jami’ al-tawarikh, compiled by Rashid al-Din on the order of Ilkhan Ghazan in the early 14th century. al-Din was allowed privileged access to both confidential Mongol sources such as the Altan Debter and to experts on the Mongol oral tradition, including Kublai Khan’s ambassador Bolad Chingsang and Ghazan himself. As he was writing an official chronicle, he omitted inconvenient or taboo details.[27][28][29]

There are many other contemporary histories which include more information on the Mongols, although their neutrality and reliability are often suspect. Additional Chinese sources include the Jin Shi and the Song shi, chronicles of the two major Chinese dynasties conquered by the Mongols. Persian sources include Ibn al-Athir’s Al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh, and a biography of Jalal al-Din by his companion al-Nasawi. There are also several Christian chronicles, including the Georgian Chronicles, the Nikon Chronicle, a 16th-century compilation of previous texts, and works by Europeans such as Carpini.[30][31]

Birth and early life

The year of Temüjin’s birth is disputed, as historians favour different dates: 1155, 1162 or 1167. Some traditions place his birth in the Year of the Pig, which was either 1155 or 1167.[32] While a dating to 1155 is supported by the writings of both Rashid al-Din and the Chinese diplomat Zhao Hong, other major sources such as the Yuán Shǐ and the Shengwu favour the year 1162.[33][b] The 1167 dating, favoured by Paul Pelliot, is derived from a minor source—a text of the Yuan artist Yang Weizhen—but is far more compatible with the events of Genghis Khan’s life. For example, an 1155 placement implies that he did not have children until after the age of thirty and continued actively campaigning into his seventh decade.[33][34] Nevertheless, Pelliot was not certain of the accuracy of his theory, which remains controversial; the historian Paul Ratchnevsky notes that Temüjin himself may not have known the truth.[35][36] The location of Temüjin’s birth is similarly debated: the Secret History records his birthplace as Delüün Boldog on the Onon River, but this has been placed at either Dadal in Khentii Province or in southern Agin-Buryat Okrug, Russia.[37]

Temüjin was born into the Borjigin clan to Yesügei, a chieftain descended from the revered warlord Bodonchar Munkhag, and his principal wife Hoelun, originally of the Olkhonud clan, whom Yesügei had abducted from her Merkit bridegroom Chiledu.[38][39] The origin of his birth-name is contested: the earliest traditions hold that his father had just returned from a successful expedition against the Tatars with a captive named Temüchin-uge, after whom he named the newborn in celebration of his victory, while later traditions highlight the root temür (meaning iron), also present in the names of two of his siblings, and connect to theories that Temüjin means «blacksmith».[40][41][42] Several legends surround Temüjin’s birth. The most prominent is that of a blood clot he clutched in his hand as he was born, an Asian folklorish motif which indicated the child would be a warrior.[43][44] Others claimed that Hoelun was impregnated by a ray of light which announced the child’s destiny, a legend which echoed that of the mythical ancestor Alan Gua.[42] Yesügei and Hoelun had three younger sons after Temüjin: Qasar, Hachiun, and Temüge, as well as one daughter, Temülen. Temüjin also had two half-brothers, Behter and Belgutei, from Yesügei’s second wife Sochigel, whose identity is uncertain. The siblings grew up at Yesugei’s main camp on the banks of the Onon, where they learned how to ride a horse and shoot a bow.[45]

A 16th century depiction of Börte and Genghis Khan in later life

When Temüjin was eight years old, Yesügei decided to betroth him to a suitable girl; he took his heir to the pastures of the prestigious Onggirat tribe, which Hoelun had been born into, and arranged a marriage between Temüjin and Börte, the daughter of an Onggirat chieftain named Dei Sechen. As the betrothal meant Yesügei would gain a powerful ally, and as Börte commanded a high bride price, Dei Sechen held the stronger negotiating position, and demanded that Temüjin remain in his household to work off his future bride’s dowry.[46][47] While riding homewards alone, having accepted this condition, Yesügei requested a meal from a band of Tatars he encountered, relying on the steppe tradition of hospitality to strangers. However, the Tatars recognised their old enemy, and slipped poison into his food. Yesügei gradually sickened but managed to return home; close to death, he requested a trusted retainer called Münglig to retrieve Temüjin from the Onggirat. He died soon after.[48][49]

Adolescence

Yesügei’s death shattered the unity of his people. As Temüjin was only around ten, and Behter around two years older, neither was considered old enough to rule. Led by the widows of Ambaghai, a previous Mongol khan, a Tayichiud faction excluded Hoelun from the ancestor worship ceremonies which followed a ruler’s death and soon abandoned the camp. The Secret History relates that the entire Borjigin clan followed, despite Hoelun’s attempts to shame them into staying with her family.[50][51][52] Rashid al-Din and the Shengwu qinzheng lu however imply that Yesügei’s brothers stood by the widow. It is possible that Hoelun may have refused to join in levirate marriage with one, or that the author of the Secret History dramatised the situation.[53][54] All the sources agree that most of Yesügei’s people renounced his family in favour of the Tayichiuds and that Hoelun’s family were reduced to a much harsher life.[43][55] Taking up a traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle, they collected roots and nuts, hunted for small animals, and caught fish.[51]

Tensions developed as the children grew older. Both Temüjin and Behter had claims to be their father’s heir: although Temüjin was the child of Yesügei’s chief wife, Behter was at least two years his senior. There was even the possiblity that, as permitted under levirate law, Behter could marry Hoelun upon attaining his majority and become Temüjin’s stepfather.[56] As the friction, excarbated by regular disputes over the division of hunting spoils, intensified, Temüjin and his younger brother Qasar ambushed and killed Behter. This taboo act was omitted from the official chronicles but not from the Secret History, which recounts that Hoelun angrily reprimanded her sons. Behter’s younger full-brother Belgutei did not seek vengeance, and became one of Temüjin’s highest-ranking followers alongside Qasar.[57][58] Around this time, Temüjin developed a close friendship with Jamukha, another boy of aristocratic descent; the Secret History notes that they exchanged knucklebones and arrows as gifts and swore the anda pact—the traditional oath of Mongol blood brothers–at the age of eleven.[59][60][61]

As the family lacked allies, Temüjin was likely taken prisoner on multiple occasions.[62][63] The Secret History relates one such occasion when he was captured by the Tayichiuds who had abandoned him after his father’s death. Escaping during a Tayichiud feast, he hid first in the River Onon and then in the tent of Sorkan-Shira, a man who had seen him in the river and not raised the alarm; Sorkan-Shira sheltered Temüjin for three days at great personal risk before allowing him to escape.[64][65] Temüjin was assisted on another occasion by an adolescent named Bo’orchu who aided him in retrieving stolen horses. Soon afterwards, Bo’orchu joined Temüjin’s camp as his first nökor, (personal companion; pl. nökod).[66] These incidents are indicative of the emphasis the author of Secret History put on personal charisma.[67]

Rise to power

Early campaigns

Accompanied by Belgutei, Temüjin returned to Dei Sechen to marry Börte when he became an adult at fifteen. The Onggirat chieftain, delighted to see the son-in-law he feared had been lost, immediately consented to the marriage, and accompanied the newlyweds back to Temüjin’s camp; his wife Čotan presented Hoelun with a black sable cloak, a sign of great wealth.[66][68] Seeking a patron, he then chose to approach Toghrul, khan of the Kerait tribe, who had fought alongside Yesügei and sworn the anda pact with him. Toghrul ruled hundreds of miles and commanded up to 20,000 warriors, but he was suspicious of the loyalty of his chief followers and, after being presented with the sable cloak, he welcomed Temüjin into his protection. The two grew close, and Temüjin began to build a following, as nökod such as Jelme entered into his service.[69][70][71]

Soon afterwards, seeking revenge for Yesügei’s abduction of Hoelun, around 300 Merkits raided Temüjin’s camp. While Temüjin and his brothers were able to hide on Burkhan Khaldun, Börte and Sochigel were abducted. In accordance with levirate law, Börte was given to Chilger, younger brother of Chiledu.[72][73] Temüjin appealed for aid from Toghrul and his childhood anda Jamukha, who had risen to become chief of the Jadaran tribe. Both chiefs were willing to field armies of 20,000 warriors, and with Jamukha in command, the campaign was soon won. A now-pregnant Börte was recovered successfully and soon gave birth to a son, Jochi; although Temüjin raised him as his own, questions over his true paternity followed Jochi throughout his life.[74][75] This is narrated in the Secret History and contrasts with Rashid al-Din’s account, which protects the family’s reputation by removing any hint of illegitimacy.[72][76]

Temüjin and Jamukha camped together for a year and a half, during which, according to the Secret History, they reforged their anda pact, even sleeping together under one blanket. Traditionally seen as a bond solely of friendship, as presented in the source, Ratchnevsky has questioned if Temüjin was actually serving as Jamukha’s nökor, in return for the assistance with the Merkits.[77] Tensions arose and the two leaders parted, ostensibly on account of a cryptic remark made by Jamukha on the subject of camping; scholarly analysis has focused on the active role of Börte in this separation, and whether her ambitions may have outweighed Temüjin’s own. In any case, the major trial rulers remained with Jamukha, but forty-one named leaders joined Temüjin along with many commoners: these included Subutai and others of the Uriankhai, the Barulas, the Olkhonuds, and many more.[78][79]

Temüjin was soon acclaimed by his close followers as khan of the Mongols.[55][80] Toghrul was pleased at his vassal’s elevation but Jamukha was resentful. Tensions escalated into open hostility, and in around 1187 the two leaders clashed in battle at Dalan Baljut: the two forces were evenly matched but Temüjin suffered a clear defeat. Later chroniclers including Rashid al-Din instead state that he was victorious but their accounts contradict themselves and each other.[81]

Modern historians consider it very likely that Temüjin spent a large portion of the decade following the clash at Dalan Baljut as a servant of the Chinese Jin dynasty. Zhao Hong, a 1221 ambassador from the Song dynasty, recorded that the future Genghis Khan spent several years as a slave of the Jin. Traditionally seen as an expression of Chinese arrogance, the statement is now thought to be based in fact, especially as no other source convincingly explains Temüjin’s activities between Dalan Baljut and c. 1195. Taking refuge across the border was a common practice both for disaffected steppe leaders and disgraced Chinese officials. Temüjin’s reemergence c. 1195 having retained significant power indicates that he probably profited in the service of the Jin. As he would later go on to overthrow that state, such an episode, detrimental to Mongol prestige, was omittted from all their sources. Zhao Hong was bound by no such taboos.[82][59][83]

Defeating rivals

The Serven Khallga inscription, which commemorates the 1196 campaign against the Tatars.

The sources do not agree on the events of Temüjin’s return to the steppe. In early summer 1196, he participated in a joint campaign with the Jin against the Tatars, who had begun to exert their power; as a reward, the Jin awarded him the honorific cha-ut kuri. At around the same time, he assisted Toghrul with reclaiming the lordship of the Kereit, which had been taken by a family member with the support of the powerful Naiman tribe.[84][85] Toghrul was given the title of Ong Khan by the Jin, traditionally as a reward for his support during the Tatar campaign. In fact, Toghrul may not have participated in the warfare, and the title was only thus given as a pacificatory gesture. At all events, the actions of 1196 fundamentally changed Temüjin’s position in the steppe—he was now Toghrul’s equal ally, rather than his junior vassal.[84][86]

Jamukha behaved poorly following his victory at Dalan Baljut, allegedly beheading enemy leaders and humiliating their corpses, or boiling seventy prisoners alive. As a consequence, a number of disaffected followers, including Yesügei’s nökor Münglig and his sons, defected to Temüjin.[87][83] Temüjin was able to subdue the disobedient Jurkin tribe, who had previously offended him at a feast and had refused to participate in the Tatar campaign: after eliminating their leaders, he had Belgutei symbolically break a leading Jurkin’s back in a staged wrestling match in retribution. This latter incident, which contravened Mongol customs of justice, was only noted by the author of the Secret History, who openly disapproved. These events occurred c. 1197.[88]

During the following years, Temüjin and Toghrul campaigned separately and together against the Merkits, the Naimans, and the Tatars. In around 1201, a collection of dissatisfied tribes including the Onggirat, the Tayichiud, and the Tatars, swore to break the domination of the Borjigin-Kereit alliance, electing Jamukha as gurkhan and their leader. After some initial successes, this loose confederation was routed at Yedi Qunan, and Jamukha was forced to beg for Toghrul’s clemency.[89][90] Desiring complete supremacy in eastern Mongolia, Temüjin defeated first the Tayichiud and then, in 1202, the Tatars; after both campaigns, he executed the clan leaders and took the remaining warriors into his service. These included Sorkan-Shira, who had come to his aid previously, and a young warrior named Jebe, who, by killing Temüjin’s horse and refusing to hide that fact, had displayed military skill and personal courage.[91][92][93]

The absorption of the Tatars left three military powers in the steppe: the Naimans in the west, the Mongols in the east, and the Kereit in between.[94] Seeking to cement his position, Temüjin proposed that his son Jochi marry one of Toghrul’s daughters. Led by Toghrul’s son Senggum, the Kereit elite believed the proposal to be an attempt to gain control over their tribe, while the doubts over Jochi’s parentage would have offended them further. In addition, Jamukha drew attention to the threat Temüjin posed to the traditional steppe aristocracy. Yielding eventually to these demands, Toghrul attempted to lure his vassal into an ambush, but his plans were overheard by two herdsmen. Temüjin was able to gather some of his forces, but was soundly defeated at the Qalaqaljid Sands.[55][95][96]

Temüjin retreated southeast to Baljuna, an unidentified lake or river, where he waited for his scattered forces to regroup: Bo’orchu had lost his horse and was forced to flee on foot, while Temüjin’s badly wounded son Ögedei had been transported and tended to by Borokhula, a leading warrior. He called in every possible ally, including the Onggirat and Muslim merchants who provided his camp with sheep. According to many sources but not the Secret History, he also swore an oath of loyalty to his faithful followers; this oath, later known as the Baljuna Covenant, gave those present exclusivity and great prestige, although its historicity has been questioned.[80][97][98] A ruse de guerre involving Qasar allowed the Mongols to catch the Kereit unawares at the Jej’er Heights, but though the ensuing battle still lasted three days, it ended in a decisive victory for Temüjin. Toghrul and Senggum were both forced to flee, and while the latter escaped to Tibet, Toghrul was killed by a Naiman who did not recognise him. Temüjin sealed his victory by absorbing the Kereit elite into his own tribe: he took the princess Ibaqa to be his own wife, and gave her sister Sorghaghtani and niece Doquz to his youngest son Tolui.[99][55][100]

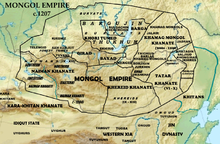

The tribal polities united by Temüjin to found the Mongol Empire

The ranks of the Naimans had been swelled by the arrival of Jamukha and others defeated by the Mongols, and they soon prepared for war. Temüjin was informed of these events by Alaqush, the sympathetic ruler of the Ongud tribe. In the Battle of Chakirmaut, which occurred in May 1204 in the Altai Mountains, the Naimans were decisively defeated: their leader Tayang Khan was killed, and his son Kuchlug was forced to flee west.[101][102] The Merkits would be decimated later that year, while Jamukha, who had abandoned the Naimans at Chakirmaut, was betrayed to Temüjin by companions who were executed for their lack of loyalty. According to the Secret History, Jamukha convinced his childhood anda to execute him honourably; other accounts state that he was killed by dismemberment.[80][103][104]

Main Mongol military campaigns, 1206–1227

Genghis Khan proclaimed Khagan of all Mongols. Illustration from a 15th-century Jami’ al-tawarikh manuscript.

The next year, in 1206, Temüjin was formally proclaimed Genghis Khan, marking the official start of the Mongol Empire. By this point, Temüjin had managed to unite or subdue the Merkits, Naimans, Mongols, Keraites, Tatars, Uyghurs, and other disparate smaller tribes under his rule, transforming previously warring tribes into a single political and military force. The union became known as the Mongols. At a Kurultai, a council of Mongol chiefs, Temüjin was acknowledged as Khan of the consolidated tribes and took the new title «Genghis Khan». According to The Secret History of the Mongols, the chieftains of the conquered tribes pledged to Genghis Khan by proclaiming:

«We will make you Khan; you shall ride at our head, against our foes. We will throw ourselves like lightning on your enemies. We will bring you their finest women and girls, their rich tents like palaces.»[105][106]

Western Xia, 1207–1209

The same year as Temüjin was proclaimed Khan, Emperor Huanzong of Western Xia was deposed by Li Anquan, leaving the territory in a weakened state. In 1207, Genghis Khan led another raid into Western Xia, invading the Ordos region and sacking Wuhai, the main garrison along the Yellow River, before withdrawing in 1208. Genghis then began preparing for a full-scale invasion.[107] By invading Western Xia, Genghis sought to gain a tribute-paying vassal and control of the caravan routes along the Silk Road.[108]

Mongol invasion of Western Xia in 1209

In 1209, Genghis Khan launched a campaign to conquer Western Xia. Li Anquan requested aid from the Jin dynasty, but the new Jin emperor, Wanyan Yongji, refused to send help, stating that it was to the Jin’s advantage for the Mongols and Western Xia to fight each other.[109] Genghis captured several cities along the Yellow River, including Wulahai, and reached the fortress Kiemen which guarded the only pass through the Helan Mountains to the capital, Yinchuan.[109] The fortress proved too difficult to capture, but after a two-month stand-off the Mongols feinted a retreat, lured the garrison out and destroying it.[109] With the path now open, Genghis advanced to the capital, which held a garrison of about 150,000 soldiers, nearly twice the size and the Mongol army.[110] The Mongols arrived in May, but were not equipped or experienced enough to take the city, and by October were still unsuccessful.[111] Genghis attempted to flood the capital by diverting the river, but the plan failed.[111] Despite this setback, the Mongols still posed a threat to Western Xia, and with the state’s crops destroyed and no relief coming from the Jin, Li Anquan agreed to submit to Mongol rule by giving a daughter, Chaka, in marriage to Genghis and paying a tribute of camels, falcons, and textiles.[112]

Jin dynasty, 1211–1215

In 1211, after the conquest of Western Xia, Genghis Khan planned to conquer the Jin dynasty. The Jin army made several early tactical mistakes, including not attacking the Mongols early on when it had overwhelming numerical superiority, and instead initially fortifying behind the Great Wall. At the subsequent Battle of Yehuling, the Jin emissary Shimo Ming’an defected and divulged intelligence to the Mongols that allowed them to outmaneuver the Jin army, resulting in hundreds of thousands of Jin casualties. In 1215, Genghis besieged the Jin capital of Zhongdu (modern-day Beijing) and the inhabitants resorted to firing gold and silver cannon shot on the Mongols with their muzzle-loading cannons when their supply of metal for ammunition ran out.[113][114][115] The city was ultimately captured and sacked, forcing Emperor Xuanzong of Jin to move his capital south to Kaifeng, abandoning the northern half of his empire. Under Genghis’s successor Ögedei Khan, Kaifeng fell to the Mongols in 1233. The Jin dynasty collapsed a year later in 1234.

Qara Khitai, 1218

After his defeat by Genghis Khan, Kuchlug, the former Khan of the Naimans, fled west and usurped the khanate of Qara Khitai. Since the Mongol army was exhausted after ten years of continuous campaigning against the Western Xia and Jin dynasty, Genghis Khan sent just two tumen (20,000 soldiers) under his general Jebe, known as «the Arrow», to pursue Kuchlug. With such a small force, the invading Mongols were forced to change strategies and resort to inciting internal revolt among Kuchlug’s supporters to weaken the Qara Khitai. Kuchlug’s army was eventually defeated west of Kashgar, and Kuchlug fled again, but was soon hunted down and executed. By 1218, as a result of the defeat of Qara Khitai, the Mongol Empire extended its control as far west as Lake Balkhash and the borders of Khwarezmia, a Muslim state that reached the Caspian Sea to the west and Persian Gulf to the south.[116]

Khwarazmian Empire, 1219–1221

In the early 13th century, the Khwarazmian dynasty was governed by Shah Muhammad II of Khwarezm. Genghis Khan saw the potential advantage in Khwarazmia as a commercial trading partner using the Silk Road, and he initially sent a 500-man caravan to establish official trade ties with the empire. Genghis Khan, his family and commanders invested in the caravan, loading it with gold, silver, silk, various kinds of textiles and fabrics and pelts to trade with the Muslim traders in the Khwarazmian lands.[117] However, Inalchuq, the governor of the Khwarazmian city of Otrar, attacked the caravan, claiming that the caravan contained spies. Later, when Genghis Khan sent a group of three ambassadors (two Mongols and a Muslim) to complain to the Shah, Muhammad II had all the men shaved and the Muslim beheaded. Outraged, Genghis Khan began planning one of his largest invasion campaigns and gathered around 100,000 soldiers (10 tumens), his most capable generals and some of his sons. He left a commander and number of troops in China, designated his family members as his successors and headed for Khwarazmia.

When war was declared, Genghis Khan maneuvered his forces over the treacherous Altai Mountains. The crossing was made even more difficult by being achieved in the middle of winter when there was over 5 feet of snow. The march has been compared to Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps, and had similarly devastating effects. Despite suffering losses and exhaustion, the Mongols were able to surprise the Khwarezm leadership and permanently steal the initiative. Once over the mountains, Genghis Khan dispatched a detachment of 20,000-30,000 men led by his son Jochi and elite general Jebe to raid into the fertile Fergana Valley in the eastern part of the Khwarezmian Empire. The Shah, unsure if this Mongol army was a diversion or their main force, dispatched his elite cavalry reserve to intervene. However, Jebe and Jochi were able to keep their army in good shape, plundering the valley while avoiding defeat by the much superior force.[118]

Meanwhile, another Mongol force under Chagatai and Ogedei descended on Otrar and immediately laid siege to it. Genghis kept his main force further back near the mountain ranges and stayed out of contact. Frank McLynn argues that this disposition can only be explained as Genghis laying a trap for the Shah, enticing him to march his army up from Samarkand to attack the besiegers of Otrar so that Genghis could encircle. However, the Shah avoided the trap, and Genghis had to change his plans.[119] The siege ultimately lasted for five months without results, until a traitor within the walls opened the gates, allowing th Mongols to storm the city and slaughter the majority of the garrison.[120] The citadel held out for another month and was only taken after heavy Mongol casualties. Genghis Khan proceeded to kill many of the inhabitants, enslave the rest and execute the governor Inalchuq.[121][122]

Next, Genghis Khan besieged the city of Bukhara, which was not heavily fortified, with just a moat and a single wall. The city leaders opened the gates to the Mongols, though a unit of Turkish defenders held the city’s citadel for another twelve days. The survivors from the citadel were executed, artisans and craftsmen were sent back to Mongolia, while young men who had not fought were drafted into the Mongolian army and the rest of the population was sent into slavery.[123] After the surrender of Bukhara, Genghis Khan also took the unprecedented step of personally entering the city, after which he had the city’s aristocrats and elites brought to the mosque, where, through interpreters, he lectured them on their misdeeds, saying: «If you had not committed great sins, God would not have sent a punishment like me upon you.»[124]

With the capture of Bukhara, the way was clear for the Mongols to advance on the capital of Samarkand, which possessed significantly better fortifications and a larger garrison compared to Bukhara. To overcome the city, the Mongols engaged in intensive psychological warfare, including the use of captured Khwarazmian prisoners as body shields. After several days only a few remaining soldiers, loyal supporters of the Shah, held out in the citadel. After the fortress fell, Genghis executed every soldier that had taken arms against him.

According to the Persian historian Ata-Malik Juvayni, the people of Samarkand were then ordered to evacuate and assemble in a plain outside the city, where they were killed and pyramids of severed heads raised as a symbol of victory.[125] Similarly, Juvayni wrote that in the city Termez, to the south of Samarkand, «all the people, both men and women, were driven out onto the plain, and divided in accordance with their usual custom, then they were all slain».[125] Juvayni’s account of mass killings at these sites is not corroborated by modern archaeology. Instead of killing local populations, the Mongols tended to enslave the conquered and either send them to Mongolia to act as menial labor or retain them for use in the war effort. The effect was still mass depopulation.[124] The account of a «pyramid of severed heads» happened not at Samarkand, but at Nishapur, where Genghis Khan’s son-in-law Toquchar was killed by an arrow shot from the city walls after the residents revolted. The Khan then allowed his widowed daughter, who was pregnant at the time, to decide the fate of the city, and she decreed that the entire population be killed. She also supposedly ordered that every dog, cat and any other animals in the city by slaughtered, «so that no living thing would survive the murder of her husband».[124] The sentence was duly carried out by the Khan’s youngest son Tolui.[126] According to widely circulated but unverified stories, the severed heads were then erected in separate piles for the men, women and children.[124]

Near to the end of the battle for Samarkand, the Shah fled to a small island in the Caspian Sea rather than surrender to the Mongols, but died the same year, leaving his son, Jalal al-Din Mangburni to resist the invaders. Genghis Khan subsequently ordered two of his generals, Subutai and Jebe, to destroy the remnants of the Khwarazmian Empire, giving them 20,000 men and two years to do this.

At this point, the wealthy trading city of Urgench remained in the hands of Khwarazmian forces. The assault on Urgench proved to be the most difficult battle of the Mongol invasion and the city fell only after the defenders put up a stout defense, fighting block for block. Mongolian casualties were higher than normal, due to the difficulty of adapting Mongolian tactics to ubran fighting.

As usual, the artisans were sent back to Mongolia, young women and children were given to the Mongol soldiers as slaves, and the rest of the population was massacred. The Persian scholar Juvayni states that 50,000 Mongol soldiers were given the task of executing twenty-four Urgench citizens each, which would mean that 1.2 million people were killed. These numbers are considered logistically implausible by modern scholars, but the sacking of Urgench was no doubt a bloody affair.[124]

Georgia, Crimea, Kievan Rus and Volga Bulgaria, 1220–1225

Significant conquests and movements of Genghis Khan and his generals

Gold dinar of Genghis Khan, struck at the Ghazna (Ghazni) mint, dated 1221/2

After the defeat of the Khwarazmian Empire in 1220, Genghis Khan gathered his forces in Persia and Armenia to return to the Mongolian steppes. Under the suggestion of Subutai, the Mongol army was split into two forces. Genghis Khan led the main army on a raid through Afghanistan and northern India towards Mongolia, while another 20,000 (two tumen) contingent marched through the Caucasus and into Russia under generals Jebe and Subutai. They pushed deep into Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Mongols defeated the kingdom of Georgia, sacked the Genoese trade-fortress of Caffa in Crimea and overwintered near the Black Sea. Heading home, Subutai’s forces attacked the allied forces of the Cuman–Kipchaks and the poorly coordinated 80,000 Kievan Rus’ troops led by Mstislav the Bold of Halych and Mstislav III of Kiev who went out to stop the Mongols’ actions in the area. Subutai sent emissaries to the Slavic princes calling for a separate peace, but the emissaries were executed. At the Battle of Kalka River in 1223, Subutai’s forces defeated the larger Kievan force. They may have been defeated by the neighbouring Volga Bulgars at the Battle of Samara Bend. There is no historical record except a short account by the Arab historian Ibn al-Athir, writing in Mosul some 1,800 kilometres (1,100 miles) away from the event.[127] Various historical secondary sources – Morgan, Chambers, Grousset – state that the Mongols actually defeated the Bulgars, Chambers even going so far as to say that the Bulgars had made up stories to tell the (recently crushed) Russians that they had beaten the Mongols and driven them from their territory.[127] The Russian princes then sued for peace. Subutai agreed but was in no mood to pardon the princes. Not only had the Rus put up strong resistance, but also Jebe – with whom Subutai had campaigned for years – had been killed just prior to the Battle of Kalka River.[128] As was customary in Mongol society for nobility, the Russian princes were given a bloodless death. Subutai had a large wooden platform constructed on which he ate his meals along with his other generals. Six Russian princes, including Mstislav III of Kiev, were put under this platform and crushed to death.

The Mongols learned from captives of the abundant green pastures beyond the Bulgar territory, allowing for the planning for conquest of Hungary and Europe. Genghis Khan recalled Subutai back to Mongolia soon afterwards. The famous cavalry expedition led by Subutai and Jebe, in which they encircled the entire Caspian Sea defeating all armies in their path, remains unparalleled to this day, and word of the Mongol triumphs began to trickle to other nations, particularly in Europe. These two campaigns are generally regarded as reconnaissance campaigns that tried to get the feel of the political and cultural elements of the regions. In 1225 both divisions returned to Mongolia. These invasions added Transoxiana and Persia to an already formidable empire while destroying any resistance along the way. Later under Genghis Khan’s grandson Batu and the Golden Horde, the Mongols returned to conquer Volga Bulgaria and Kievan Rus’ in 1237, concluding the campaign in 1240.

Western Xia and Jin dynasty, 1226–1227

The vassal emperor of the Tanguts (Western Xia) had earlier refused to take part in the Mongol war against the Khwarezmid Empire. Western Xia and the defeated Jin dynasty formed a coalition to resist the Mongols, counting on the campaign against the Khwarazmians to preclude the Mongols from responding effectively.

In 1226, immediately after returning from the west, Genghis Khan began a retaliatory attack on the Tanguts. His armies quickly took Heisui, Ganzhou, and Suzhou (not the Suzhou in Jiangsu province), and in the autumn he took Xiliang-fu. One of the Tangut generals challenged the Mongols to a battle near Helan Mountains but was defeated. In November, Genghis laid siege to the Tangut city Lingzhou and crossed the Yellow River, defeating the Tangut relief army. According to legend, it was here that Genghis Khan reportedly saw a line of five stars arranged in the sky and interpreted it as an omen of his victory.

In 1227, Genghis Khan’s army attacked and destroyed the Tangut capital of Ning Hia and continued to advance, seizing Lintiao-fu, Xining province, Xindu-fu, and Deshun province in quick succession in the spring. At Deshun, the Tangut general Ma Jianlong put up a fierce resistance for several days and personally led charges against the invaders outside the city gate. Ma Jianlong later died from wounds received from arrows in battle. Genghis Khan, after conquering Deshun, went to Liupanshan (Qingshui County, Gansu Province) to escape the severe summer. The new Tangut emperor quickly surrendered to the Mongols, and the rest of the Tanguts officially surrendered soon after. Not happy with their betrayal and resistance, Genghis Khan ordered the entire imperial family to be executed, effectively ending the Tangut royal lineage.

Death and succession

Mongol Empire in 1227 at Genghis Khan’s death

According to the official History of Yuan commissioned during China’s Ming dynasty, Genghis Khan died during his final campaign against the Western Xia, falling ill on 18 August 1227 and passing away on 25 August 1227.[3][129] The exact cause of his death remains a mystery, and is variously attributed to illness, being killed in action or from wounds sustained in hunting or battle.[130][131][132] According to The Secret History of the Mongols, Genghis Khan fell from his horse while hunting and died because of the injury. The Galician–Volhynian Chronicle alleges he was killed by the Western Xia in battle, while Marco Polo wrote that he died after the infection of an arrow wound he received during his final campaign.[133] Later Mongol chronicles connect Genghis’s death with a Western Xia princess taken as war booty. One chronicle from the early 17th century even relates the legend that the princess hid a small dagger and stabbed or castrated him.[134] All of these legends were invented well after Genghis Khan’s death, however.[129] In contrast, a 2021 study found that the he likely died from bubonic plague, after investigating reports of the clinical signs exhibited by both the Khan and his army, which in turn matched the symptoms associated with the strain of plague present in Western Xia at that time.[135]

Genghis Khan (center) at the coronation of his son Ögedei, Rashid al-Din, early 14th century

Years before his death, Genghis Khan asked to be buried without markings, according to the customs of his tribe.[136] After he died, his body was returned to Mongolia and presumably to his birthplace in Khentii Aimag, where many assume he is buried somewhere close to the Onon River and the Burkhan Khaldun mountain (part of the Khentii mountain range). According to legend, the funeral escort killed anyone and anything across their path to conceal where he was finally buried. The Genghis Khan Mausoleum, constructed many years after his death, is his memorial, but not his burial site.

Before Genghis Khan died, he assigned Ögedei Khan as his successor. Genghis Khan left behind an army of more than 129,000 men; 28,000 were given to his various brothers and his sons. Tolui, his youngest son, inherited more than 100,000 men. This force contained the bulk of the elite Mongolian cavalry. By tradition, the youngest son inherits his father’s property. Jochi, Chagatai, Ögedei Khan, and Kulan’s son Gelejian received armies of 4,000 men each. His mother and the descendants of his three brothers received 3,000 men each. The title of Great Khan passed to Ögedei, the third son of Genghis Khan, making him the second Great Khan (Khagan) of the Mongol Empire. Genghis Khan’s eldest son, Jochi, died in 1226, during his father’s lifetime. Chagatai, Genghis Khan’s second son was meanwhile passed over, according to The Secret History of the Mongols, over a row just before the invasion of the Khwarezmid Empire in which Chagatai declared before his father and brothers that he would never accept Jochi as Genghis Khan’s successor due to questions about his elder brother’s parentage. In response to this tension and possibly for other reasons, Ögedei was appointed as successor.[137]

Later, his grandsons split his empire into khanates.[138] His descendants extended the Mongol Empire across most of Eurasia by conquering or creating vassal states in all of modern-day China, Korea, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and substantial portions of Eastern Europe and Southwest Asia. Many of these invasions repeated the earlier large-scale slaughters of local populations.

Organizational philosophy

Political, economic and social governance

The Mongol Empire was governed by a civilian and military code, called the Yassa, created by Genghis Khan. The Mongol Empire did not emphasize the importance of ethnicity and race in the administrative realm, instead adopting an approach grounded in meritocracy.[139] The Mongol Empire was one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse empires in history, as befitted its size. Many of the empire’s nomadic inhabitants considered themselves Mongols in military and civilian life, including the Mongol people, Turkic peoples, and others. There were Khans of various non-Mongolian ethnicities such as Muhammad Khan.

There were tax exemptions for religious figures and, to some extent, teachers and doctors. The Mongol Empire practiced religious tolerance because Mongol tradition had long held that religion was a personal concept, and not subject to law or interference.[140] Genghis Khan was a Tengrist, but was religiously tolerant and interested in learning philosophical and moral lessons from other religions. He consulted Buddhist monks (including the Zen monk Haiyun), Muslims, Christian missionaries, and the Daoist monk Qiu Chuji.[141] Sometime before the rise of Genghis Khan, Ong Khan, his mentor and eventual rival, had converted to Nestorian Christianity. Various Mongol tribes were Shamanist, Buddhist or Christian. Religious tolerance was thus a well established concept on the Asian steppe.

Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongol Empire, is said to have attempted to create a civil state under the Great Yassa that would have established legal equality for all individuals, including women.[142] However, there is no clear evidence of this. Women did play a relatively important role in the Mongol Empire and in the family, such as Töregene Khatun who briefly held power while the next leader was being chosen. The alleged policy of encouraging trade and communication is referred to as the Pax Mongolica. Genghis Khan also recognized the need for administrators to govern cities and states conquered by him, and so invited a Khitan prince, Chu’Tsai, who had experience governing cities and worked for the Jin dynasty before being captured by the Mongol army. Chu’Tsai went on to administer parts of the empire and become a confidant to successive Mongol Khans.[citation needed]

Mongol military tactics

Mural of siege warfare, Genghis Khan Exhibit in San Jose, California, US

Reenactment of Mongol battle

Genghis Khan put absolute trust in his generals, such as Muqali, Jebe, and Subutai, and regarded them as close advisors, often extending them the same privileges and trust normally reserved for close family members. He allowed them to make decisions on their own when they embarked on campaigns far from the Mongol Empire capital Karakorum. Muqali, a trusted lieutenant, was given command of the Mongol forces against the Jin dynasty while Genghis Khan was fighting in Central Asia, and Subutai and Jebe were allowed to pursue the Great Raid into the Caucasus and Kievan Rus’, an idea they had presented to the Khagan on their own initiative. While granting his generals a great deal of autonomy in making command decisions, Genghis Khan also expected unwavering loyalty from them.

The Mongol military was also successful in siege warfare, cutting off resources for cities and towns by diverting certain rivers, taking enemy prisoners and driving them in front of the army, and adopting new ideas, techniques and tools from the people they conquered, particularly in employing Muslim and Chinese siege engines and engineers to aid the Mongol cavalry in capturing cities. Another standard tactic of the Mongol military was the commonly practiced feigned retreat to break enemy formations and to lure small enemy groups away from the larger group and defended position for ambush and counterattack.

Another important aspect of the military organization of Genghis Khan was the communications and supply route or Yam, adapted from previous Chinese models. Genghis Khan dedicated special attention to this in order to speed up the gathering of military intelligence and official communications. To this end, Yam waystations were established all over the empire.[143]

Impact

Positive

Genghis Khan on the reverse of a Kazakh 100 tenge collectible coin.

Genghis Khan is credited with bringing the Silk Road under one cohesive political environment. This allowed increased communication and trade between the West, Middle East and Asia, thus expanding the horizons of all three cultural areas. Some historians have noted that Genghis Khan instituted certain levels of meritocracy in his rule, was tolerant of religions and explained his policies clearly to all his soldiers.[144] Genghis Khan had a notably positive reputation among some western European authors in the Middle Ages, who knew little concrete information about his empire in Asia.[145] The Italian explorer Marco Polo said that Genghis Khan «was a man of great worth, and of great ability, and valor»,[146][147] while philosopher and inventor Roger Bacon applauded the scientific and philosophical vigor of Genghis Khan’s empire,[148] and the famed writer Geoffrey Chaucer wrote concerning Cambinskan:[149]

The noble king was called Genghis Khan,

Who in his time was of so great renown,

That there was nowhere in no region,

So excellent a lord in all things

Portrait on a hillside in Ulaanbaatar, 2006

In Mongolia, Genghis Khan has meanwhile been revered for centuries by Mongols and many Turkic peoples because of his association with tribal statehood, political and military organization, and victories in war. As the principal unifying figure in Mongolian history, he remains a larger-than-life figure in Mongolian culture. He is credited with introducing the Mongolian script and creating the first written Mongolian code of law, in the form of the Yassa.

During the communist period in Mongolia, Genghis was often described by the government as a reactionary figure, and positive statements about him were avoided.[150] In 1962, the erection of a monument at his birthplace and a conference held in commemoration of his 800th birthday led to criticism from the Soviet Union and the dismissal of secretary Tömör-Ochir of the ruling Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party Central Committee.

In the early 1990s, the memory of Genghis Khan underwent a powerful revival, partly in reaction to its suppression during the Mongolian People’s Republic period. Genghis Khan became a symbol of national identity for many younger Mongolians, who maintain that the historical records written by non-Mongolians are unfairly biased against Genghis Khan and that his butchery is exaggerated, while his positive role is underrated.[151]

Mixed

There are conflicting views of Genghis Khan in China, which suffered a drastic decline in population.[152] The population of north China decreased from 50 million in the 1195 census to 8.5 million in the Mongol census of 1235–36; however, many were victims of plague. In Hebei province alone, 9 out of 10 were killed by the Black Death when Toghon Temür was enthroned in 1333.[153][dubious – discuss][better source needed] Northern China was also struck by floods and famine long after the war in northern China was over in 1234 and not killed by Mongols.[154][failed verification] The Black Death also contributed. By 1351, two out of three people in China had died of the plague, helping to spur armed rebellion,[155][failed verification] most notably in the form of the Red Turban Rebellions. However according to Richard von Glahn, a historian of Chinese economics, China’s population only fell by 15% to 33% from 1340 to 1370 and there is «a conspicuous lack of evidence for pandemic disease on the scale of the Black Death in China at this time.»[156] An unknown number of people also migrated to Southern China in this period,[157] including under the preceding Southern Song dynasty.[158]

The Mongols also spared many cities from massacre and sacking if they surrendered,[159] including Kaifeng,[160] Yangzhou,[161] and Hangzhou.[162] Ethnic Han and Khitan soldiers defected en masse to Genghis Khan against the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty.[163] Equally, while Genghis never conquered all of China, his grandson Kublai Khan, by completing that conquest and establishing the Yuan dynasty, is often credited with re-uniting China, and there is a great deal of Chinese artwork and literature praising Genghis as a military leader and political genius. The Yuan dynasty left an indelible imprint on Chinese political and social structures and a cultural legacy that outshone the preceding Jin dynasty.[164]

Negative

The conquests and leadership of Genghis Khan included widespread devastation and mass murder.[165][166][167][168] The targets of campaigns that refused to surrender would often be subject to reprisals in the form of enslavement and wholesale slaughter.[169] The second campaign against Western Xia, the final military action led by Genghis Khan, and during which he died, involved an intentional and systematic destruction of Western Xia cities and culture.[169] According to John Man, because of this policy of total obliteration, Western Xia is little known to anyone other than experts in the field because so little record is left of that society. He states that «There is a case to be made that this was the first ever recorded example of attempted genocide. It was certainly very successful ethnocide.»[167] In the conquest of Khwarezmia under Genghis Khan, the Mongols razed the cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, Herāt, Ṭūs, and Neyshābūr and killed the respective urban populations.[170] His invasions are considered the beginning of a 200-year period known in Iran and other Islamic societies as the «Mongol catastrophe.»[168] Ibn al-Athir, Ata-Malik Juvaini, Seraj al-Din Jozjani, and Rashid al-Din Fazl-Allah Hamedani, Iranian historians from the time of Mongol occupation, describe the Mongol invasions as a catastrophe never before seen.[168] A number of present-day Iranian historians, including Zabih Allah Safa, have likewise viewed the period initiated by Genghis Khan as a uniquely catastrophic era.[168] Steven R. Ward writes that the Mongol violence and depredations in the Iranian Plateau «killed up to three-fourths of the population… possibly 10 to 15 million people. Some historians have estimated that Iran’s population did not again reach its pre-Mongol levels until the mid-20th century.»[171]

Although the famous Mughal emperors were proud descendants of Genghis Khan and particularly Timur, they clearly distanced themselves from the Mongol atrocities committed against the Khwarizim Shahs, Turks, Persians, the citizens of Baghdad and Damascus, Nishapur, Bukhara and historical figures such as Attar of Nishapur and many other notable Muslims.[citation needed] However, Mughal Emperors directly patronized the legacies of Genghis Khan and Timur; together their names were synonymous with the names of other distinguished personalities particularly among the Muslim populations of South Asia.[172]

Cultural depictions

16th century Ottoman miniature of Genghis Khan

Medieval

Unlike most emperors, Genghis Khan never allowed his image to be portrayed in paintings or sculptures.[173]

The earliest known images of Genghis Khan were produced half a century after his death, including the famous National Palace Museum portrait in Taiwan.[174][175] The portrait portrays Genghis Khan wearing white robes, a leather warming cap and his hair tied in braids, much like a similar depiction of Kublai Khan.[176] This portrait is often considered to represent the closest resemblance to what Genghis Khan actually looked like, though it, like all others renderings, suffers from the same limitation of being, at best, a facial composite.[177] Like many of the earliest images of Genghis Khan, the Chinese-style portrait presents him in a manner more akin to a Mandarin sage than a Mongol warrior.[178] Other portrayals of Genghis Khan from other cultures likewise characterized him according to their particular image of him: in Persia he was portrayed as a Turkic sultan and in Europe he was pictured as an ugly barbarian with a fierce face and cruel eyes.[179] According to sinologist Herbert Allen Giles, a Mongol painter known as Ho-li-hosun (also known as Khorisun or Qooriqosun) was commissioned by Kublai Khan in 1278 to paint the National Palace Museum portrait.[180] The story goes that Kublai Khan ordered Khorisun, along with the other entrusted remaining followers of Genghis Khan, to ensure the portrait reflected the Genghis Khan’s true image.[181]

The only individuals to have recorded Genghis Khan’s physical appearance during his lifetime were the Persian chronicler Minhaj al-Siraj Juzjani and Chinese diplomat Zhao Hong.[182] Minhaj al-Siraj described Genghis Khan as «a man of tall stature, of vigorous build, robust in body, the hair of his face scanty and turned white, with cats’ eyes, possessed of dedicated energy, discernment, genius, and understanding, awe-striking…».[183] The chronicler had also previously commented on Genghis Khan’s height, powerful build, with cat’s eyes and lack of grey hair, based on the evidence of eyes witnesses in 1220, which saw Genghis Khan fighting in the Khorasan (modern day northwest Persia).[184][185] According to Paul Ratchnevsky, the Song dynasty envoy Zhao Hong who visited the Mongols in 1221,[186] described Genghis Khan as «of tall and majestic stature, his brow is broad and his beard is long».[184]

Other descriptions of Genghis Khan come from 14th century texts. The Persian historian Rashid-al-Din in Jami’ al-tawarikh, written in the beginning of the 14th century, stated that most Borjigin ancestors of Genghis Khan were «tall, long-bearded, red-haired, and bluish green-eyed,» features which Genghis Khan himself had. The factual nature of this statement is considered controversial.[177] In the Georgian Chronicles, in a passage written in the 14th century, Genghis Khan is similarly described as a large, good-looking man, with red hair.[187] However, according to John Andrew Boyle, Rashid al-Din’s text of red hair referred to ruddy skin complexion, and that Genghis Khan was of ruddy complexion like most of his children except for Kublai Khan who was swarthy. He translated the text as “It chanced that he was born 2 months before Möge, and when Chingiz-Khan’s eye fell upon him he said: “all our children are of a ruddy complexion, but this child is swarthy like his maternal uncles. Tell Sorqoqtani Beki to give him to a good nurse to be reared”.[188]

In modern culture

In Mongolia today, Genghis Khan’s name and likeness appear on products, streets, buildings, and other places. His face can be found on everyday commodities, from liquor bottles to candy, and on the largest denominations of 500, 1,000, 5,000, 10,000, and 20,000 Mongolian tögrög (₮). Mongolia’s main international airport in Ulaanbaatar is named Chinggis Khaan International Airport, and there is a 40m-high equestrian statue of Genghis Khan east of the Mongolian capital. There has been talk about regulating the use of his name and image to avoid trivialization.[189] Genghis Khan’s birthday, on the first day of winter (according to the Mongolian lunar calendar), is a national holiday.[190]

There have been numerous works of literature, films and other adaptation works based on the Mongolian ruler and his legacy.

- Literature

- «The Squire’s Tale», one of The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, is set at the court of Genghis Khan.

- Genghis Khan[191] by Vasily Yan, 1939—the first installment of an epic trilogy about the Mongol conquests and winner of a USSR state prize in 1942

- The End of Genghis, a poem by F. L. Lucas, in which the dying Khan, attended by his Khitan counsellor Yelü Chucai, looks back on his life.[192]

- The Conqueror series of novels by Conn Iggulden

- White cloud of Genghis Khan by Chingiz Aitmatov[193]

- The Private Life of Genghis Khan by Douglas Adams and Graham Chapman

- Films

- Genghis Khan, a 1950 Philippine film directed by Manuel Conde.

- The Conqueror, released in 1956 and starring John Wayne as Temüjin and Susan Hayward as Börte.

- Changez Khan, a 1957 Indian Hindi-language film directed by Kedar Kapoor, starring Sheikh Mukhtar as the emperor along with Bina Rai and Prem Nath in the lead roles.[194]

- Genghis Khan, a 1965 film starring Omar Sharif.

- Genghis Khan: To the Ends of the Earth and Sea, also known as The Descendant of Gray Wolf, a Japanese-Mongolian film released in 2007.

- Mongol, a 2007 film directed by Sergei Bodrov, starring Tadanobu Asano. (Academy Award nominee for Best Foreign Language Film).

- No Right to Die – Chinggis Khaan, a Mongolian film released in 2008.

- Genghis Khan, a Chinese film released in 2018.

- Television series

- Genghis Khan, a 1987 Hong Kong television series produced by TVB, starring Alex Man.

- Genghis Khan, a 1987 Hong Kong television series produced by ATV, starring Tony Liu.

- Genghis Khan, a 2004 Chinese-Mongolian co-produced television series, starring Batdorj-in Baasanjab, who is a descendant of Genghis Khan’s second son Chagatai.

- Video games

- Temüjin (video game), a 1997 computer game.

- Aoki Ōkami to Shiroki Mejika, Genghis Khan-themed Japanese game series.

References

Notes

- ^ According to History of Yuan, Genghis Khan was buried at Qinian valley (起輦谷).[4] The concrete location of the valley is never mentioned in any documents, many assume that it is somewhere close to the Onon River and the Burkhan Khaldun mountain, Khentii Province, Mongolia.

- ^ See #Name and titles.

- ^ The Mongolian People’s Republic chose to commemorate the 800th anniversary of Temüjin’s birth in 1962.[32]

Citations

- ^ Biran 2012, p. 165?.

- ^ Terbish, L. (1992). «The birth date of Chinghis Khaan as determined through Mongolian astrology». ‘Nomads of Central Asia and the Silk Roads’ international seminar. Unesco.

- ^ a b You, Wenpeng; Galassi, Francesco M.; Varotto, Elena; Henneberg, Maciej (2021). «Genghis Khan’s death (AD 1227): An unsolvable riddle or simply a pandemic disease?». International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 104: 347–348. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.089. ISSN 1201-9712. PMID 33444749. S2CID 231610775.

- ^ a b c «Volume 1 Annals 1: Taizu». History of Yuan (in Chinese).

壽六十六,葬起輦谷。至元三年冬十月,追諡聖武皇帝。至大二年冬十一月庚辰,加諡法天啟運聖武皇帝,廟號太祖。

- ^ Fiaschetti 2014, p. 82.

- ^ a b Porter 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Zhao, George (2008). Marriage as Political Strategy and Cultural Expression: Mongolian Royal Marriages from World Empire to Yuan Dynasty. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-4331-0275-2.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark (16 September 2019). «Definition:Genghis Khan». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ ЧИНГИСХА́Н Archived June 20, 2022, at the Wayback Machine — Big Russian Encyclopedia, 2010

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. x–xi.

- ^ Pelliot 1959, p. 281.

- ^ a b Bawden 2022, § «Introduction».

- ^ Morgan 1990.

- ^ Denis Sinor (1997). Studies in Medieval Inner Asia. p. 248.

- ^ Fiaschetti 2014, pp. 77–82.

- ^ Morgan 1986, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, p. xii.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017, p. xiv.

- ^ Hung 1951, p. 481.

- ^ Waley 2002, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Morgan 1986, p. 11.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. xiv–xv.

- ^ Morgan 1986, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017, p. xvi.

- ^ Morgan 1986, p. 18.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. xv–xvi.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, p. xv.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 117.

- ^ Morgan 1986, pp. 18–21.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017, pp. xiv–xvi.

- ^ Wright 2017.

- ^ a b Morgan 1986, p. 55.

- ^ a b Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Pelliot 1959, pp. 284–287.

- ^ Pelliot 1959, p. 287.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 19.

- ^ Atwood 2004, p. 97.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 14–15.

- ^ May 2018, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Pelliot 1959, pp. 289–291.

- ^ Man 2004, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 17.

- ^ a b Brose 2014, § «The Young Temüjin».

- ^ Pelliot 1959, p. 288.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 15–19.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009, p. 100.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 21–22.

- ^ de Hartog 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 22.

- ^ a b May 2018, p. 25.

- ^ de Rachewiltz 2015, § 71–73.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 22–3.

- ^ Atwood 2004, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b c d Atwood 2004, p. 98.

- ^ May 2018, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 23–4.

- ^ de Rachewiltz 2015, §76–78.

- ^ a b Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009, p. 101.

- ^ Man 2004, p. 74.

- ^ de Rachewiltz 2015, §116.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 25–6.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009, p. 100–101.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 26–7.

- ^ May 2018, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b May 2018, p. 28.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 27.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 31.

- ^ de Hartog 1999, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 32–33.

- ^ May 2018, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Brose 2014, § «Emergence of Chinggis Khan».

- ^ May 2018, p. 30.

- ^ Bawden 2022, § «Early struggles».

- ^ May 2018, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 37–38.

- ^ May 2018, p. 31.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 38–41.

- ^ a b c Brose 2014, § «Building the Mongol Confederation».

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b May 2018, p. 32.

- ^ a b Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Pelliot 1959, pp. 291–295.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017, p. 56.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 61–62.

- ^ May 2018, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 63–67.

- ^ de Hartog 1999, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009, p. 102.

- ^ May 2018, p. 36.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 67–70.

- ^ May 2018, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 70–73.

- ^ Man 2004, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Lane 2004, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Hyslop, Stephen Garrison; Daniels, Patricia; Society (U.S.), National Geographic (2011). Great Empires: An Illustrated Atlas. National Geographic Books. pp. 174, 179. ISBN 978-1-4262-0829-4.

- ^ Cummins, Joseph (2011). History’s Greatest Wars: The Epic Conflicts that Shaped the Modern World. Fair Winds Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-61058-055-7.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Kohn 2007, p. 205.

- ^ a b c Man 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Weatheford 2004, p. 85.

- ^ a b May 2012, p. 1211.

- ^ Man 2004, p. 133.

- ^ Ivar Lissner (1957). The living past (4 ed.). Putnam’s. p. 193. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Wolter J. Fabrycky; Paul E. Torgersen (1966). Operations economy: industrial applications of operations research (2 ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-13-637967-6. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Wolter J. Fabrycky; P. M. Ghare; Paul E. Torgersen (1972). Industrial operations research (illustrated ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-13-464263-5. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Stephen Pow: The Last Campaign and Death of Jebe Noyan. In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. 27, Nr. 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Enkhbold, Enerelt (2 October 2019). «The role of the ortoq in the Mongol Empire in forming business partnerships». Central Asian Survey. 38 (4): 531–547. doi:10.1080/02634937.2019.1652799. S2CID 203044817 – via Taylor and Francis+NEJM.

- ^ Frank McLynn, Genghis Khan (2015).

- ^ Frank Mclynn, Genghis Khan (2015)

- ^ Juvayni, pp. 83–84

- ^ John Man (2007). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. Macmillan. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-312-36624-7.

- ^ Juvayni, p. 85

- ^ Morgan 1986, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d e Weatherford 2005, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Modelski, George (29 September 2007). «Central Asian world cities?». University of Washington. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- ^ The Truth About Nishapur Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine How Stuff Works. Retrieved April 27, 2021

- ^ a b John Chambers, The Devil’s Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe, Atheneum, 1979. p. 31

- ^ Stephen Pow: The Last Campaign and Death of Jebe Noyan. In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. 27, Nr. 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2017, S. 31–51 (englisch).

- ^ a b Choi, Charles Q. (3 February 2021). «The story you heard about Genghis Khan’s death is probably all wrong». Live Science.

- ^ Emmons, James B. (2012). «Genghis Khan». In Li, Xiaobing (ed.). China at War: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-59884-415-3. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ Hart-Davis, Adam (2007). History: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Present Day. London: Dorling Kindersley. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4053-1809-9.

- ^ Man 2007, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Lange, Brenda (2003). Genghis Khan. New York City: Infobase Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7910-7222-6.

- ^ Heissig, Walther (1964). Die Mongolen. Ein Volk sucht seine Geschichte. Düsseldorf. p. 124.

- ^ Wenpeng You; Francesco M. Galassi; Elena Varotto; Maciej Henneberg (2021). «Genghis Khan’s death (AD 1227): An unsolvable riddle or simply a pandemic disease?». International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 104: 247–348. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.089. PMID 33444749. S2CID 231610775.

- ^ Man 2007, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991, p. 126.

- ^ Saunders, John Joseph (2001) [1972]. History of the Mongol Conquests. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1766-7.

- ^ Weatherford 2004, p. [page needed].

- ^ Amy Chua (2007). Day of Empire: How hyperpowers rise to global dominance, and why they fall. New York: Random House. p. 95.

- ^ Eskildsen, Stephen (2004). The Teachings and Practices of the Early Quanzhen Taoist Masters. SUNY Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7914-6045-0.

- ^ Pocha, Jehangir S. (10 May 2005). «Mongolia sees Genghis Khan’s good side». International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ Weatherford 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Clive Foss (2007). The Tyrants. London: Quercus. p. 57.

- ^ Weatherford 2005, p. 239.

- ^ Polo, Marco (1905). The Adventures of Marco Polo. D. Appleton and Company. p. 21.

- ^ Brooks, Noah (2008). The Story of Marco Polo. Cosimo, Inc. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-60520-280-8.

- ^ Weatherford 2005, p. xxiv.

- ^ Chaucer, Geoffrey. «The Squieres Tale». In Skeat, Walter William (ed.). The Canterbury Tales (in Middle English). Retrieved 13 June 2021.

This noble king was cleped Cambinskan,/Which in his tyme was of so greet renoun/That ther nas no-wher in no regioun/So excellent a lord in alle thing;

- ^ Christopher Kaplonski: The case of the disappearing Chinggis Khaan Archived July 31, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Griffiths, Daniel (11 January 2007). «Asia-Pacific | Post-communist Mongolia’s struggle». BBC News. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ William Bonner, Addison Wiggin (2006). Empire of debt: the rise of an epic financial crisis Archived November 2, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0-471-73902-2

- ^ Chua, Amy (2009). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance—and Why They Fall. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-307-47245-8.

- ^ «Yuan Dynasty: Ancient China Dynasties, paragraph 3». Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Brook, Timothy (1999). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-22154-3.

- ^ von Glahn 2016, p. 440.

- ^ Graziella Caselli, Gillaume Wunsch, Jacques Vallin (2005). «Demography: Analysis and Synthesis, Four Volume Set: A Treatise in Population«. Academic Press. p. 34. ISBN 0-12-765660-X

- ^ Waterson 2013, p. 88.

- ^ Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan Ricardo; Hanagan, Michael P.; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise (2015). Global Connections: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Vol. 1 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-521-19189-0.

- ^ Waterson 2013, p. 92.

- ^ Waterson 2013, p. 230.

- ^ Balfour, Alan H.; Zheng, Shiling (2002). Balfour, Alan H. (ed.). Shanghai (illustrated ed.). Wiley-Academy. p. 25. ISBN 0-471-87733-6.

- ^ Waterson 2013, p. 84.

- ^ Abbott 2014, p. 54.

- ^ Jonassohn & Björnson 1999, p. 276.

- ^ Jacobs 1999, pp. 247–248.

- ^ a b Man 2007, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b c d Edelat, Abbas (2010). «Trauma Hypothesis: The enduring legacy of the Mongol Catastrophe on the Political, Social and Scientific History of Iran» (PDF). Bukhara. 13 (77–78): 277–263 – via Imperial College London.

- ^ a b «Mongol empire | Facts, History, & Map». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ «Iran – The Mongol invasion». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Ward, Steven R. (2009). Immortal: a military history of Iran and its armed forces. Georgetown University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-58901-258-5.

- ^ Abbott 2014, p. 507.

- ^ Weatherford 2005, p. 24:»Unlike any other conqueror in history, Genghis Khan never allowed anyone to paint his portrait, sculpt his image, or engrave his name or likeness on a coin, and the only descriptions of him from contemporaries are intriguing rather than informative. In the words of a modern Mongolian folk song about Genghis Khan, «we imagined your appearance but our minds went blank.»

- ^ «Portraits of Emperors T’ai-tsu (Chinggis Khan), Shih-tsu (Khubilai Khan), and Wen-tsung (Tegtemur)». National Palace Museum. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Shambaugh Elliott, Jeanette; Shambaugh, David (2015). The Odyssey of China’s Imperial Art Treasures. University of Washington Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-295-99755-1.

- ^ «Portraits of Emperors Taizu (Genghis Khan), Shizu (Kublai Khan), and Wenzong (Tegtemur)». National Palace Museum. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b Lkhagvasuren, Gavaachimed; Shin, Heejin; Lee, Si Eun; Tumen, Dashtseveg; Kim, Jae-Hyun; Kim, Kyung-Yong; Kim, Kijeong; Park, Ae Ja; Lee, Ho Woon; Kim, Mi Jin; Choi, Jaesung (14 September 2016). «Molecular Genealogy of a Mongol Queen’s Family and Her Possible Kinship with Genghis Khan». PLoS ONE. 11 (9): e0161622. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1161622L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161622. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5023095. PMID 27627454.

- ^ Weatherford 2005, pp. 24–25, 197.

- ^ Weatherford 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Allen Giles, Herbert (1918). An Introduction to the History of Chinese Pictorial Art. London, England: London, B. Quaritch.

- ^ Currie, Lorenzo (2013). Through the Eyes of the Pack. Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-4931-4517-1.

- ^ Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- ^ Weatherford 2005, p. 6.

- ^ a b Mote, Frederick W. (2003). Imperial China 900–1800. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- ^ Peers, Chris (2015). Genghis Khan and the Mongol War Machine. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78340-056-0.

- ^ Allsen, Thomas (2001). «The Circulation of Military Technology in the Mongolian Empire». In Di Cosmo, Nicola (ed.). Warfare in Inner Asian History (500–1800). Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 268. ISBN 978-90-04-39178-9.

- ^ Brosset, Marie-Félicité. Histoire de la Georgie. Saint Petersburg, Russia: Imperial Academy of Sciences. p. 488.

- ^ Andrew Boyle, John (1971). The Successors of Genghis Khan. New York: Robert Bedrosian. p. 241.

- ^ «Business | Genghis Khan may get protection». BBC News. 6 October 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ «Mongolia to celebrate the birthday of Great Chinggis Khaan». InfoMongolia.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.