From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

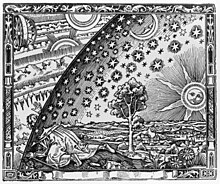

Figure of the heavenly bodies — an illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric system by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho, 1568 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris), depicting Earth as the centre of the Universe.

The center of the Universe is a concept that lacks a coherent definition in modern astronomy; according to standard cosmological theories on the shape of the universe, it has no center.

Historically, different people have suggested various locations as the center of the Universe. Many mythological cosmologies included an axis mundi, the central axis of a flat Earth that connects the Earth, heavens, and other realms together. In the 4th century BC Greece, philosophers developed the geocentric model, based on astronomical observation; this model proposed that the center of the Universe lies at the center of a spherical, stationary Earth, around which the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars rotate. With the development of the heliocentric model by Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century, the Sun was believed to be the center of the Universe, with the planets (including Earth) and stars orbiting it.

In the early-20th century, the discovery of other galaxies and the development of the Big Bang theory led to the development of cosmological models of a homogeneous, isotropic Universe, which lacks a central point and is expanding at all points.

Outside astronomy[edit]

In religion or mythology, the axis mundi (also cosmic axis, world axis, world pillar, columna cerului, center of the world) is a point described as the center of the world, the connection between it and Heaven, or both.

Mount Hermon in Lebanon was regarded in some cultures as the axis mundi.

Mount Hermon was regarded as the axis mundi in Canaanite tradition, from where the sons of God are introduced descending in 1 Enoch (1En6:6).[1] The ancient Greeks regarded several sites as places of earth’s omphalos (navel) stone, notably the oracle at Delphi, while still maintaining a belief in a cosmic world tree and in Mount Olympus as the abode of the gods. Judaism has the Temple Mount and Mount Sinai, Christianity has the Mount of Olives and Calvary, Islam has Mecca, said to be the place on earth that was created first, and the Temple Mount (Dome of the Rock). In Shinto, the Ise Shrine is the omphalos. In addition to the Kun Lun Mountains, where it is believed the peach tree of immortality is located, the Chinese folk religion recognizes four other specific mountains as pillars of the world.

A 1581 map depicting Jerusalem as the center of the world.

Sacred places constitute world centers (omphalos) with the altar or place of prayer as the axis. Altars, incense sticks, candles and torches form the axis by sending a column of smoke, and prayer, toward heaven. The architecture of sacred places often reflects this role. «Every temple or palace—and by extension, every sacred city or royal residence—is a Sacred Mountain, thus becoming a Centre.»[2] The stupa of Hinduism, and later Buddhism, reflects Mount Meru. Cathedrals are laid out in the form of a cross, with the vertical bar representing the union of Earth and heaven as the horizontal bars represent union of people to one another, with the altar at the intersection. Pagoda structures in Asian temples take the form of a stairway linking Earth and heaven. A steeple in a church or a minaret in a mosque also serve as connections of Earth and heaven. Structures such as the maypole, derived from the Saxons’ Irminsul, and the totem pole among indigenous peoples of the Americas also represent world axes. The calumet, or sacred pipe, represents a column of smoke (the soul) rising form a world center.[3] A mandala creates a world center within the boundaries of its two-dimensional space analogous to that created in three-dimensional space by a shrine.[4]

In medieval times some Christians thought of Jerusalem as the center of the world (Latin: umbilicus mundi, Greek: Omphalos), and was so represented in the so-called T and O maps. Byzantine hymns speak of the Cross being «planted in the center of the earth.»

Center of a flat Earth[edit]

The Flat Earth model is a belief that the Earth’s shape is a plane or disk covered by a firmament containing heavenly bodies. Most pre-scientific cultures have had conceptions of a Flat Earth, including Greece until the classical period, the Bronze Age and Iron Age civilizations of the Near East until the Hellenistic period, India until the Gupta period (early centuries AD) and China until the 17th century.[citation needed] It was also typically held in the aboriginal cultures of the Americas, and a flat Earth domed by the firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl is common in pre-scientific societies.[5]

«Center» is well-defined in a Flat Earth model. A flat Earth would have a definite geographic center. There would also be a unique point at the exact center of a spherical firmament (or a firmament that was a half-sphere).

Earth as the center of the Universe[edit]

The Flat Earth model gave way to an understanding of a Spherical Earth. Aristotle (384–322 BC) provided observational arguments supporting the idea of a spherical Earth, namely that different stars are visible in different locations, travelers going south see southern constellations rise higher above the horizon, and the shadow of Earth on the Moon during a lunar eclipse is round, and spheres cast circular shadows while discs generally do not.

This understanding was accompanied by models of the Universe that depicted the Sun, Moon, stars, and naked eye planets circling the spherical Earth, including the noteworthy models of Aristotle (see Aristotelian physics) and Ptolemy.[6] This geocentric model was the dominant model from the 4th century BC until the 17th century AD.

Sun as center of the Universe[edit]

The heliocentric model from Nicolaus Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism,[7][note 1] is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a relatively stationary Sun at the center of the Solar System. The word comes from the Greek (ἥλιος helios «sun» and κέντρον kentron «center»).

The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the 3rd century BC by Aristarchus of Samos,[8][9][note 2] but had received no support from most other ancient astronomers.

Nicolaus Copernicus’ major theory of a heliocentric model was published in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), in 1543, the year of his death, though he had formulated the theory several decades earlier. Copernicus’ ideas were not immediately accepted, but they did begin a paradigm shift away from the Ptolemaic geocentric model to a heliocentric model. The Copernican revolution, as this paradigm shift would come to be called, would last until Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

Johannes Kepler published his first two laws about planetary motion in 1609, having found them by analyzing the astronomical observations of Tycho Brahe.[10] Kepler’s third law was published in 1619.[10] The first law was «The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.»

On 7 January 1610 Galileo used his telescope, with optics superior to what had been available[citation needed] before. He described «three fixed stars, totally invisible[11] by their smallness», all close to Jupiter, and lying on a straight line through it.[12] Observations on subsequent nights showed that the positions of these «stars» relative to Jupiter were changing in a way that would have been inexplicable if they had really been fixed stars. On 10 January Galileo noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. Within a few days he concluded that they were orbiting Jupiter:[13] Galileo stated that he had reached this conclusion on 11 January.[12] He had discovered three of Jupiter’s four largest satellites (moons). He discovered the fourth on 13 January.

Modern illustration of the cosmic neighborhood centered on the Sun.

His observations of the satellites of Jupiter created a revolution in astronomy: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotelian Cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth.[12][14] Many astronomers and philosophers initially refused to believe that Galileo could have discovered such a thing; by showing that, like Earth, other planets could also have moons of their own that followed prescribed paths, and hence that orbital mechanics didn’t apply only to the Earth, planets, and Sun, what Galileo had essentially done was to show that other planets might be «like Earth».[12]

Newton made clear his heliocentric view of the Solar System – developed in a somewhat modern way, because already in the mid-1680s he recognised the «deviation of the Sun» from the centre of gravity of the solar system.[15] For Newton, it was not precisely the centre of the Sun or any other body that could be considered at rest, but rather «the common centre of gravity of the Earth, the Sun and all the Planets is to be esteem’d the Centre of the World», and this centre of gravity «either is at rest or moves uniformly forward in a right line» (Newton adopted the «at rest» alternative in view of common consent that the centre, wherever it was, was at rest).[16]

Milky Way’s Galactic Center as center of the Universe[edit]

Before the 1920s, it was generally believed that there were no galaxies other than the Milky Way (see for example The Great Debate). Thus, to astronomers of previous centuries, there was no distinction between a hypothetical center of the galaxy and a hypothetical center of the universe.

In 1750 Thomas Wright, in his work An original theory or new hypothesis of the Universe, correctly speculated that the Milky Way might be a body of a huge number of stars held together by gravitational forces rotating about a Galactic Center, akin to the Solar System but on a much larger scale. The resulting disk of stars can be seen as a band on the sky from the Earth’s perspective inside the disk.[17] In a treatise in 1755, Immanuel Kant elaborated on Wright’s idea about the structure of the Milky Way. In 1785, William Herschel proposed such a model based on observation and measurement,[18] leading to scientific acceptance of galactocentrism, a form of heliocentrism with the Sun at the center of the Milky Way.

The 19th century astronomer Johann Heinrich von Mädler proposed the Central Sun Hypothesis, according to which the stars of the universe revolved around a point in the Pleiades.

The nonexistence of a center of the Universe[edit]

In 1917, Heber Doust Curtis observed a nova within what then was called the «Andromeda Nebula». Searching the photographic record, 11 more novae were discovered. Curtis noticed that novas in Andromeda were drastically fainter than novas in the Milky Way. Based on this, Curtis was able to estimate that Andromeda was 500,000 light-years away. As a result, Curtis became a proponent of the so-called «island Universes» hypothesis, which held that objects previously believed to be spiral nebulae within the Milky Way were actually independent galaxies.[19]

In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis took place, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the dimensions of the Universe. To support his claim that the Great Andromeda Nebula (M31) was an external galaxy, Curtis also noted the appearance of dark lanes resembling the dust clouds in this galaxy, as well as the significant Doppler shift. In 1922 Ernst Öpik presented an elegant and simple astrophysical method to estimate the distance of M31. His result put the Andromeda Nebula far outside this galaxy at a distance of about 450,000 parsec, which is about 1,500,000 ly.[20] Edwin Hubble settled the debate about whether other galaxies exist in 1925 when he identified extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos of M31. These were made using the 2.5 metre (100 in) Hooker telescope, and they enabled the distance of Great Andromeda Nebula to be determined. His measurement demonstrated conclusively that this feature was not a cluster of stars and gas within this galaxy, but an entirely separate galaxy located a significant distance from the Milky Way. This proved the existence of other galaxies.[21]

Expanding Universe[edit]

Hubble also demonstrated that the redshift of other galaxies is approximately proportional to their distance from Earth (Hubble’s law). This raised the appearance of this galaxy being in the center of an expanding Universe, however, Hubble rejected the findings philosophically:

…if we see the nebulae all receding from our position in space, then every other observer, no matter where he may be located, will see the nebulae all receding from his position. However, the assumption is adopted. There must be no favoured location in the Universe, no centre, no boundary; all must see the Universe alike. And, in order to ensure this situation, the cosmologist postulates spatial isotropy and spatial homogeneity, which is his way of stating that the Universe must be pretty much alike everywhere and in all directions.»[22]

The redshift observations of Hubble, in which galaxies appear to be moving away from us at a rate proportional to their distance from us, are now understood to be a result of the metric expansion of space. This is the increase of the distance between two distant parts of the Universe with time, and is an intrinsic expansion whereby the scale of space itself changes. As Hubble theorized, all observers anywhere in the Universe will observe a similar effect.

Copernican and cosmological principles[edit]

The Copernican principle, named after Nicolaus Copernicus, states that the Earth is not in a central, specially favored position.[23] Hermann Bondi named the principle after Copernicus in the mid-20th century, although the principle itself dates back to the 16th-17th century paradigm shift away from the geocentric Ptolemaic system.

The cosmological principle is an extension of the Copernican principle which states that the Universe is homogeneous (the same observational evidence is available to observers at different locations in the Universe) and isotropic (the same observational evidence is available by looking in any direction in the Universe). A homogeneous, isotropic Universe does not have a center.[24]

See also[edit]

- Center of the universe (disambiguation)

- Cosmic microwave background

- Earth’s inner core

- Galactic Center

- Geographical centre of Earth

- Great Attractor

- Illustris project

- List of places referred to as the Center of the Universe

- Multiverse

- Religious cosmology

- Sun – the center of the Solar System

- Three-torus model of the universe

Notes[edit]

- ^ Copernican heliocenterism held that the Sun itself was the center of the entire Universe. As it is modernly understood, Heliocenterism refers to the much narrower concept that the Sun is the center of the Solar System, not the center of the entire Universe.

- ^ The work of Aristarchus’s in which he proposed his heliocentric system has not survived. We only know of it now from a brief passage in Archimedes’s The Sand Reckoner.

References[edit]

- ^ Kelley Coblentz Bautch (25 September 2003). A Study of the Geography of 1 Enoch 17-19: «no One Has Seen what I Have Seen». BRILL. pp. 62–. ISBN 9789004131033. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Willard Trask). ‘Archetypes and Repetition’ in The Myth of the Eternal Return. Princeton, 1971. p.12

- ^ Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols. Editions Robert Lafont S. A. et Editions Jupiter: Paris, 1982. Penguin Books: London, 1996. pp.148-149

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). ‘Symbolism of the Centre’ in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. p.52-54

- ^ «Their cosmography as far as we know anything about it was practically of one type up til the time of the white man’s arrival upon the scene. That of the Borneo Dayaks may furnish us with some idea of it. ‘They consider the Earth to be a flat surface, whilst the heavens are a dome, a kind of glass shade which covers the Earth and comes in contact with it at the horizon.'»

Lucien Levy-Bruhl, Primitive Mentality (repr. Boston: Beacon, 1966) 353;

«The usual primitive conception of the world’s form … [is] flat and round below and surmounted above by a solid firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl.» H. B. Alexander, The Mythology of All Races 10: North American (repr. New York: Cooper Square, 1964) 249. - ^ Lawson, Russell M. (2004). Science in the ancient world: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1851095346.

- ^ Teaching about Evolution and the Nature of Science (National Academy of Sciences, 1998), p.27; also, Don O’ Leary, Roman Catholicism and Modern Science: A History (Continuum Books, 2006), p.5.

- ^ Dreyer, J.L.E. (1906). History of the planetary systems from Thales to Kepler. Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–48.

- ^ Linton, C.M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein: A History of Mathematical Astronomy. E-Libro. Cambridge University Press. p. 38,205. ISBN 9781139453790.

- ^ a b Holton, Gerald James; Brush, Stephen G. (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure: From Copernicus to Einstein and Beyond (3rd paperback ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-8135-2908-0. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ i.e., invisible to the naked eye.

- ^ a b c d Drake, Stillman (1978). Galileo at Work: His Scientific Biography. University of Chicago Press. pp. 146, 152, 157–163. ISBN 9780226162263.

- ^ In Sidereus Nuncius,1892, 3:81 (in Latin)

- ^ Linton, C.M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein: A History of Mathematical Astronomy. E-Libro. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9781139453790.

- ^ See Curtis Wilson, «The Newtonian achievement in astronomy», pages 233–274 in R Taton & C Wilson (eds) (1989) The General History of Astronomy, Volume, 2A’, at page 233.

- ^ Text quotations are from 1729 translation of Newton’s Principia, Book 3 (1729 vol.2) at pages 232–233.

- ^ Evans, J. C. (1995). «Our Galaxy». Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Herschel, William (1 January 1785). «XII. On the construction of the heavens». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 75: 213–266. doi:10.1098/rstl.1785.0012. S2CID 186213203.

- ^

Curtis, H. D. (1988). «Novae in Spiral Nebulae and the Island Universe Theory». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 100: 6. Bibcode:1988PASP..100….6C. doi:10.1086/132128. - ^

Öpik, E. (1922). «An estimate of the distance of the Andromeda Nebula». Astrophysical Journal. 55: 406–410. Bibcode:1922ApJ….55..406O. doi:10.1086/142680. - ^

Hubble, E. P. (1929). «A spiral nebula as a stellar system, Messier 31». Astrophysical Journal. 69: 103–158. Bibcode:1929ApJ….69..103H. doi:10.1086/143167. - ^

Hubble, E. P. (1937). The observational approach to cosmology. Oxford University Press. - ^ H. Bondi (1952). Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 13.

- ^ Livio, Mario (2001). The Accelerating Universe: Infinite Expansion, the Cosmological Constant, and the Beauty of the Cosmos. John Wiley and Sons. p. 53. ISBN 9780471437147. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Figure of the heavenly bodies — an illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric system by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho, 1568 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris), depicting Earth as the centre of the Universe.

The center of the Universe is a concept that lacks a coherent definition in modern astronomy; according to standard cosmological theories on the shape of the universe, it has no center.

Historically, different people have suggested various locations as the center of the Universe. Many mythological cosmologies included an axis mundi, the central axis of a flat Earth that connects the Earth, heavens, and other realms together. In the 4th century BC Greece, philosophers developed the geocentric model, based on astronomical observation; this model proposed that the center of the Universe lies at the center of a spherical, stationary Earth, around which the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars rotate. With the development of the heliocentric model by Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century, the Sun was believed to be the center of the Universe, with the planets (including Earth) and stars orbiting it.

In the early-20th century, the discovery of other galaxies and the development of the Big Bang theory led to the development of cosmological models of a homogeneous, isotropic Universe, which lacks a central point and is expanding at all points.

Outside astronomy[edit]

In religion or mythology, the axis mundi (also cosmic axis, world axis, world pillar, columna cerului, center of the world) is a point described as the center of the world, the connection between it and Heaven, or both.

Mount Hermon in Lebanon was regarded in some cultures as the axis mundi.

Mount Hermon was regarded as the axis mundi in Canaanite tradition, from where the sons of God are introduced descending in 1 Enoch (1En6:6).[1] The ancient Greeks regarded several sites as places of earth’s omphalos (navel) stone, notably the oracle at Delphi, while still maintaining a belief in a cosmic world tree and in Mount Olympus as the abode of the gods. Judaism has the Temple Mount and Mount Sinai, Christianity has the Mount of Olives and Calvary, Islam has Mecca, said to be the place on earth that was created first, and the Temple Mount (Dome of the Rock). In Shinto, the Ise Shrine is the omphalos. In addition to the Kun Lun Mountains, where it is believed the peach tree of immortality is located, the Chinese folk religion recognizes four other specific mountains as pillars of the world.

A 1581 map depicting Jerusalem as the center of the world.

Sacred places constitute world centers (omphalos) with the altar or place of prayer as the axis. Altars, incense sticks, candles and torches form the axis by sending a column of smoke, and prayer, toward heaven. The architecture of sacred places often reflects this role. «Every temple or palace—and by extension, every sacred city or royal residence—is a Sacred Mountain, thus becoming a Centre.»[2] The stupa of Hinduism, and later Buddhism, reflects Mount Meru. Cathedrals are laid out in the form of a cross, with the vertical bar representing the union of Earth and heaven as the horizontal bars represent union of people to one another, with the altar at the intersection. Pagoda structures in Asian temples take the form of a stairway linking Earth and heaven. A steeple in a church or a minaret in a mosque also serve as connections of Earth and heaven. Structures such as the maypole, derived from the Saxons’ Irminsul, and the totem pole among indigenous peoples of the Americas also represent world axes. The calumet, or sacred pipe, represents a column of smoke (the soul) rising form a world center.[3] A mandala creates a world center within the boundaries of its two-dimensional space analogous to that created in three-dimensional space by a shrine.[4]

In medieval times some Christians thought of Jerusalem as the center of the world (Latin: umbilicus mundi, Greek: Omphalos), and was so represented in the so-called T and O maps. Byzantine hymns speak of the Cross being «planted in the center of the earth.»

Center of a flat Earth[edit]

The Flat Earth model is a belief that the Earth’s shape is a plane or disk covered by a firmament containing heavenly bodies. Most pre-scientific cultures have had conceptions of a Flat Earth, including Greece until the classical period, the Bronze Age and Iron Age civilizations of the Near East until the Hellenistic period, India until the Gupta period (early centuries AD) and China until the 17th century.[citation needed] It was also typically held in the aboriginal cultures of the Americas, and a flat Earth domed by the firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl is common in pre-scientific societies.[5]

«Center» is well-defined in a Flat Earth model. A flat Earth would have a definite geographic center. There would also be a unique point at the exact center of a spherical firmament (or a firmament that was a half-sphere).

Earth as the center of the Universe[edit]

The Flat Earth model gave way to an understanding of a Spherical Earth. Aristotle (384–322 BC) provided observational arguments supporting the idea of a spherical Earth, namely that different stars are visible in different locations, travelers going south see southern constellations rise higher above the horizon, and the shadow of Earth on the Moon during a lunar eclipse is round, and spheres cast circular shadows while discs generally do not.

This understanding was accompanied by models of the Universe that depicted the Sun, Moon, stars, and naked eye planets circling the spherical Earth, including the noteworthy models of Aristotle (see Aristotelian physics) and Ptolemy.[6] This geocentric model was the dominant model from the 4th century BC until the 17th century AD.

Sun as center of the Universe[edit]

The heliocentric model from Nicolaus Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism,[7][note 1] is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a relatively stationary Sun at the center of the Solar System. The word comes from the Greek (ἥλιος helios «sun» and κέντρον kentron «center»).

The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the 3rd century BC by Aristarchus of Samos,[8][9][note 2] but had received no support from most other ancient astronomers.

Nicolaus Copernicus’ major theory of a heliocentric model was published in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), in 1543, the year of his death, though he had formulated the theory several decades earlier. Copernicus’ ideas were not immediately accepted, but they did begin a paradigm shift away from the Ptolemaic geocentric model to a heliocentric model. The Copernican revolution, as this paradigm shift would come to be called, would last until Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

Johannes Kepler published his first two laws about planetary motion in 1609, having found them by analyzing the astronomical observations of Tycho Brahe.[10] Kepler’s third law was published in 1619.[10] The first law was «The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.»

On 7 January 1610 Galileo used his telescope, with optics superior to what had been available[citation needed] before. He described «three fixed stars, totally invisible[11] by their smallness», all close to Jupiter, and lying on a straight line through it.[12] Observations on subsequent nights showed that the positions of these «stars» relative to Jupiter were changing in a way that would have been inexplicable if they had really been fixed stars. On 10 January Galileo noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. Within a few days he concluded that they were orbiting Jupiter:[13] Galileo stated that he had reached this conclusion on 11 January.[12] He had discovered three of Jupiter’s four largest satellites (moons). He discovered the fourth on 13 January.

Modern illustration of the cosmic neighborhood centered on the Sun.

His observations of the satellites of Jupiter created a revolution in astronomy: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotelian Cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth.[12][14] Many astronomers and philosophers initially refused to believe that Galileo could have discovered such a thing; by showing that, like Earth, other planets could also have moons of their own that followed prescribed paths, and hence that orbital mechanics didn’t apply only to the Earth, planets, and Sun, what Galileo had essentially done was to show that other planets might be «like Earth».[12]

Newton made clear his heliocentric view of the Solar System – developed in a somewhat modern way, because already in the mid-1680s he recognised the «deviation of the Sun» from the centre of gravity of the solar system.[15] For Newton, it was not precisely the centre of the Sun or any other body that could be considered at rest, but rather «the common centre of gravity of the Earth, the Sun and all the Planets is to be esteem’d the Centre of the World», and this centre of gravity «either is at rest or moves uniformly forward in a right line» (Newton adopted the «at rest» alternative in view of common consent that the centre, wherever it was, was at rest).[16]

Milky Way’s Galactic Center as center of the Universe[edit]

Before the 1920s, it was generally believed that there were no galaxies other than the Milky Way (see for example The Great Debate). Thus, to astronomers of previous centuries, there was no distinction between a hypothetical center of the galaxy and a hypothetical center of the universe.

In 1750 Thomas Wright, in his work An original theory or new hypothesis of the Universe, correctly speculated that the Milky Way might be a body of a huge number of stars held together by gravitational forces rotating about a Galactic Center, akin to the Solar System but on a much larger scale. The resulting disk of stars can be seen as a band on the sky from the Earth’s perspective inside the disk.[17] In a treatise in 1755, Immanuel Kant elaborated on Wright’s idea about the structure of the Milky Way. In 1785, William Herschel proposed such a model based on observation and measurement,[18] leading to scientific acceptance of galactocentrism, a form of heliocentrism with the Sun at the center of the Milky Way.

The 19th century astronomer Johann Heinrich von Mädler proposed the Central Sun Hypothesis, according to which the stars of the universe revolved around a point in the Pleiades.

The nonexistence of a center of the Universe[edit]

In 1917, Heber Doust Curtis observed a nova within what then was called the «Andromeda Nebula». Searching the photographic record, 11 more novae were discovered. Curtis noticed that novas in Andromeda were drastically fainter than novas in the Milky Way. Based on this, Curtis was able to estimate that Andromeda was 500,000 light-years away. As a result, Curtis became a proponent of the so-called «island Universes» hypothesis, which held that objects previously believed to be spiral nebulae within the Milky Way were actually independent galaxies.[19]

In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis took place, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the dimensions of the Universe. To support his claim that the Great Andromeda Nebula (M31) was an external galaxy, Curtis also noted the appearance of dark lanes resembling the dust clouds in this galaxy, as well as the significant Doppler shift. In 1922 Ernst Öpik presented an elegant and simple astrophysical method to estimate the distance of M31. His result put the Andromeda Nebula far outside this galaxy at a distance of about 450,000 parsec, which is about 1,500,000 ly.[20] Edwin Hubble settled the debate about whether other galaxies exist in 1925 when he identified extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos of M31. These were made using the 2.5 metre (100 in) Hooker telescope, and they enabled the distance of Great Andromeda Nebula to be determined. His measurement demonstrated conclusively that this feature was not a cluster of stars and gas within this galaxy, but an entirely separate galaxy located a significant distance from the Milky Way. This proved the existence of other galaxies.[21]

Expanding Universe[edit]

Hubble also demonstrated that the redshift of other galaxies is approximately proportional to their distance from Earth (Hubble’s law). This raised the appearance of this galaxy being in the center of an expanding Universe, however, Hubble rejected the findings philosophically:

…if we see the nebulae all receding from our position in space, then every other observer, no matter where he may be located, will see the nebulae all receding from his position. However, the assumption is adopted. There must be no favoured location in the Universe, no centre, no boundary; all must see the Universe alike. And, in order to ensure this situation, the cosmologist postulates spatial isotropy and spatial homogeneity, which is his way of stating that the Universe must be pretty much alike everywhere and in all directions.»[22]

The redshift observations of Hubble, in which galaxies appear to be moving away from us at a rate proportional to their distance from us, are now understood to be a result of the metric expansion of space. This is the increase of the distance between two distant parts of the Universe with time, and is an intrinsic expansion whereby the scale of space itself changes. As Hubble theorized, all observers anywhere in the Universe will observe a similar effect.

Copernican and cosmological principles[edit]

The Copernican principle, named after Nicolaus Copernicus, states that the Earth is not in a central, specially favored position.[23] Hermann Bondi named the principle after Copernicus in the mid-20th century, although the principle itself dates back to the 16th-17th century paradigm shift away from the geocentric Ptolemaic system.

The cosmological principle is an extension of the Copernican principle which states that the Universe is homogeneous (the same observational evidence is available to observers at different locations in the Universe) and isotropic (the same observational evidence is available by looking in any direction in the Universe). A homogeneous, isotropic Universe does not have a center.[24]

See also[edit]

- Center of the universe (disambiguation)

- Cosmic microwave background

- Earth’s inner core

- Galactic Center

- Geographical centre of Earth

- Great Attractor

- Illustris project

- List of places referred to as the Center of the Universe

- Multiverse

- Religious cosmology

- Sun – the center of the Solar System

- Three-torus model of the universe

Notes[edit]

- ^ Copernican heliocenterism held that the Sun itself was the center of the entire Universe. As it is modernly understood, Heliocenterism refers to the much narrower concept that the Sun is the center of the Solar System, not the center of the entire Universe.

- ^ The work of Aristarchus’s in which he proposed his heliocentric system has not survived. We only know of it now from a brief passage in Archimedes’s The Sand Reckoner.

References[edit]

- ^ Kelley Coblentz Bautch (25 September 2003). A Study of the Geography of 1 Enoch 17-19: «no One Has Seen what I Have Seen». BRILL. pp. 62–. ISBN 9789004131033. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Willard Trask). ‘Archetypes and Repetition’ in The Myth of the Eternal Return. Princeton, 1971. p.12

- ^ Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols. Editions Robert Lafont S. A. et Editions Jupiter: Paris, 1982. Penguin Books: London, 1996. pp.148-149

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). ‘Symbolism of the Centre’ in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. p.52-54

- ^ «Their cosmography as far as we know anything about it was practically of one type up til the time of the white man’s arrival upon the scene. That of the Borneo Dayaks may furnish us with some idea of it. ‘They consider the Earth to be a flat surface, whilst the heavens are a dome, a kind of glass shade which covers the Earth and comes in contact with it at the horizon.'»

Lucien Levy-Bruhl, Primitive Mentality (repr. Boston: Beacon, 1966) 353;

«The usual primitive conception of the world’s form … [is] flat and round below and surmounted above by a solid firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl.» H. B. Alexander, The Mythology of All Races 10: North American (repr. New York: Cooper Square, 1964) 249. - ^ Lawson, Russell M. (2004). Science in the ancient world: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1851095346.

- ^ Teaching about Evolution and the Nature of Science (National Academy of Sciences, 1998), p.27; also, Don O’ Leary, Roman Catholicism and Modern Science: A History (Continuum Books, 2006), p.5.

- ^ Dreyer, J.L.E. (1906). History of the planetary systems from Thales to Kepler. Cambridge University Press. pp. 135–48.

- ^ Linton, C.M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein: A History of Mathematical Astronomy. E-Libro. Cambridge University Press. p. 38,205. ISBN 9781139453790.

- ^ a b Holton, Gerald James; Brush, Stephen G. (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure: From Copernicus to Einstein and Beyond (3rd paperback ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-8135-2908-0. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ i.e., invisible to the naked eye.

- ^ a b c d Drake, Stillman (1978). Galileo at Work: His Scientific Biography. University of Chicago Press. pp. 146, 152, 157–163. ISBN 9780226162263.

- ^ In Sidereus Nuncius,1892, 3:81 (in Latin)

- ^ Linton, C.M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein: A History of Mathematical Astronomy. E-Libro. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9781139453790.

- ^ See Curtis Wilson, «The Newtonian achievement in astronomy», pages 233–274 in R Taton & C Wilson (eds) (1989) The General History of Astronomy, Volume, 2A’, at page 233.

- ^ Text quotations are from 1729 translation of Newton’s Principia, Book 3 (1729 vol.2) at pages 232–233.

- ^ Evans, J. C. (1995). «Our Galaxy». Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Herschel, William (1 January 1785). «XII. On the construction of the heavens». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 75: 213–266. doi:10.1098/rstl.1785.0012. S2CID 186213203.

- ^

Curtis, H. D. (1988). «Novae in Spiral Nebulae and the Island Universe Theory». Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 100: 6. Bibcode:1988PASP..100….6C. doi:10.1086/132128. - ^

Öpik, E. (1922). «An estimate of the distance of the Andromeda Nebula». Astrophysical Journal. 55: 406–410. Bibcode:1922ApJ….55..406O. doi:10.1086/142680. - ^

Hubble, E. P. (1929). «A spiral nebula as a stellar system, Messier 31». Astrophysical Journal. 69: 103–158. Bibcode:1929ApJ….69..103H. doi:10.1086/143167. - ^

Hubble, E. P. (1937). The observational approach to cosmology. Oxford University Press. - ^ H. Bondi (1952). Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 13.

- ^ Livio, Mario (2001). The Accelerating Universe: Infinite Expansion, the Cosmological Constant, and the Beauty of the Cosmos. John Wiley and Sons. p. 53. ISBN 9780471437147. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

Всего найдено: 16

Добрый день! Проконсультируйте, пожалуйста. Есть вымышленная вселенная, в которой живут Ваятели — магические пришельцы, обладающие энергией Ваяния — создание практически любых материальных объектов из этой энергии (то есть Ваятели и Ваяние — пишутся с прописной, потому что это слова в непривычном значении). Так вот, как написать их деятельность, они ваяют или Ваяют? Другими словами, сохраняется ли прописная буква у глагола, как у существительного или прилагательного, в этом случае?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Род пришельцев нужно писать со строчной буквы аналогично названиям народностей (ср.: эвенки, коми, буряты), так же нужно писать и глагол. Непривычное значение не является основанием для написания слова с заглавной буквы. При этом существительное от глагола ваять может записываться со строчной, но возможно написание и с заглавной, если ему приписывается особо высокий смысл.

Здравствуйте, подскажите, пожалуйста, в сочетаниях типа «вселенная Marvel», «вселенная «Звездных войн»» и т.д. слово «вселенная» лучше писать с большой или с маленькой буквы? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В приведенных Вами контекстах (то есть не в терминологическом значении ‘космос со всеми космическими объектами как единое целое’) слово вселенная лучше писать со строчной буквы. Такое написание подчеркнет смысловой сдвиг – употребление слова в нарицательном значении «весь мир художественного произведения или автора». По нашим наблюдениям, в подобном значении преобладает именно написание со строчной буквы.

Подскажите, нужна ли запятая перед как: Расскажем как создавалась наша вселенная, отметим успехи….

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятая ставится.

Здравствуйте. скажите, пожалуйста, с какой буквы пишется слово Вселенная. Благодарю!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вселенная пишется с большой буквы как астрономический термин (в знач. «космос, мироздание»): строение Вселенной, тайны Вселенной. В знач. ‘вся земля, все страны’ это слово пишется с маленькой буквы.

Когда следует писать слово «вселенная» с маленькой буквы, а когда с большой буквы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вселенная пишется с большой буквы как астрономический термин (в знач. «космос, мироздание»): строение Вселенной, тайны Вселенной. В знач. ‘вся земля, все страны’ это слово пишется с маленькой буквы.

Здравствуйте, уважаемые грамотеи! Помогите, пожалуйста. Названия конкурсов красоты принято писать: «Мисс ВселеннАЯ«, «Мисс РоссИЯ», «Миссис планетА», но «Мисс мирА». Верно ли это и как объяснить, почему в первых трёх вариантах второе слово не склоняется, а в последнем окончание меняется? Заранее благодарю.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Названия этих титулов, как правило, являются дословными и однотипными переводами с английского языка, этим обусловлено несклонение. Мисс мира выпадает из общего списка — это название, вероятно, появилось раньше и успело подвергнуться грамматическому освоению в русском языке.

Помогите, пожалуйста, рассавит знаки препинания в предложении:

Ты бываешь такая разная-

То капризная, то прекрасная,

То хозяюшка офигенная,

То красавица — Мисс Вселенная.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вместо тире в первой строчке нужно поставить двоеточие.

Здравствуйте! Могу ли я узнать, откуда произошло удивительное выражение «свет сошелся клином». Спасибо.

Сергей Пригоров

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Это оборот собственно русский. Слово свет употребляется здесь в значении ‘земля со всем существующим не ней, мир, вселенная‘, а клин – ‘маленький участок земли малоземельного крестьянина’. Первоначальный смысл оборота свет не клином сошелся такой: «земля широка, просторна, представляет большие возможности для какой-либо деятельности». А широко известная песенная строка на тебе сошелся клином белый свет – утверждение огромной значимости любимого человека для лирического героя (все мысли замыкаются на любимом человеке, подобно тому как весь мир сходится на маленьком клочке земли).

Бывшая «мисс Вселенная! — нужны кавычки?

обращаться на Вы — с прописной и без кавычек?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

1. Кавычки нужны. 2. Написано верно.

Уважаемые сотрудники «Справочного бюро»!

Согласно каким правилам разграничивалось написание букв «и» и «i» в словах до отмены последней?

С уважением,

Вл.Марченко

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Буква i («и десятеричное») употреблялась перед гласными и перед Й (в том числе в словах иностранного происхождения: _патрiархъ_). Она писалась также в слове _мiръ_ в значении ‘вселенная‘ (в отличие от _миръ_ ‘покой, тишина’) и в производных от него: _мiрской, мiровой_. Исключения составляли слова, образованные путем слияния двух слов, из которых первое оканчивалось на И: это И сохранялось и в том случае, когда второе слово начиналось с гласной: _пятиалтынный, ниоткуда_. Только слова с приставкой _при_ писались по общему правилу: перед гласной _и_ менялось на _i_, например: _прiобщить, прiуныть_.

Здравствуйте! Скажите пожалуйста, «то есть» нужно с обоих сторо выделять запятыми? Например, в предложении «Это мир, то есть, вселенная» и подобных.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запяатя ставится только перед _то есть_: _Этот мир, то есть Вселенная_.

Для чего нужны словори

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

См. в разделе «Словари» — статья «Вселенная в алфавите».

Для чего нужен словарь? Как он устроен? Какая информация есть в словаре?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

См. статью «Вселенная в алфавите» в левой колонке в http://slovari.gramota.ru/ [разделе «Словари»].

Напишите пожалуйстаантонимы следующих слов:

вселенная, сваха, смазка, великан, матрица (в штамповке), стужа, грубость, живот.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Пожалуйста, воспользуйтесь окном «Проверка слова».

Добрый день! — очень прошу подсказать — в каких случаях по правилам дореволюционной орфографии — в словах писалась десятеричная i? — заранее благодарю.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Десятеричное i писалось перед гласными и Й, например: _сiять, позднiй_, а также в слове _мiръ_ (вселенная). Перед согласной писалось всегда и.

На букву Ц Со слова «центр»

Фраза «центр вселенной»

Фраза состоит из двух слов и 14 букв без пробелов.

- Ассоциации к фразе

- Каким бывает

- Синонимы к фразе

- Написание фразы наоборот

- Написание фразы в транслите

- Написание фразы шрифтом Брайля

- Передача фразы на азбуке Морзе

- Произношение фразы на дактильной азбуке

- Остальные фразы со слова «центр»

- Остальные фразы из 2 слов

Путешествие на край Вселенной

ЧТО НАХОДИТСЯ В ЦЕНТРЕ ВСЕЛЕННОЙ?

ЧТО-ТО СТРАННОЕ ПРОИСХОДИТ В ЦЕНТРЕ ВСЕЛЕННОЙ…

Маша Горбань — В центре моей вселенной

Где находится центр Вселенной

женщина — центр Вселенной

Ассоциации к фразе «центр вселенной»

Какие слова мужского и женского рода, а также фразы ассоциируются с этой фразой.

Мужские слова

+ центр −

Ваша ассоциация добавлена!

Каким бывает центр вселенной

Какие слова в именительном падеже характеризуют эту фразу.

+ неподвижный −

+ абсолютный −

+ единственный −

+ подлинный −

+ политический −

Ваш вариант добавлен!

Синонимы к фразе «центр вселенной»

Какие близкие по смыслу слова и фразы, а также похожие выражения существуют. Как можно написать по-другому или сказать другими словами.

Фразы

- + альфа и омега −

- + бесконечная вселенная −

- + быть в центре внимания −

- + венец творения −

- + вершина эволюции −

- + вселенная существует −

- + вселенская катастрофа −

- + высокий разум −

- + высшее существо −

- + древние философы −

- + женская суть −

- + законченный эгоист −

- + избалованный ребёнок −

- + маленькая вселенная −

- + маленький мирок −

- + мало значит −

- + материальная вселенная −

- + небесная сфера −

- + независимая женщина −

- + неотъемлемая частица −

- + новая вселенная −

- + приходить к мысли −

- + пространство и время −

- + пуп земли −

Ваш синоним добавлен!

Написание фразы «центр вселенной» наоборот

Как эта фраза пишется в обратной последовательности.

йоннелесв ртнец 😀

Написание фразы «центр вселенной» в транслите

Как эта фраза пишется в транслитерации.

в армянской🇦🇲 ցենտր վսելեննոյ

в грузинской🇬🇪 ცენთრ ვსელენნოი

в еврейской🇮🇱 צאנטר בסאלאננוי

в латинской🇬🇧 tsentr vselennoy

Как эта фраза пишется в пьюникоде — Punycode, ACE-последовательность IDN

xn--e1aqjhr xn--b1agaqinaiv

Как эта фраза пишется в английской Qwerty-раскладке клавиатуры.

wtynhdctktyyjq

Написание фразы «центр вселенной» шрифтом Брайля

Как эта фраза пишется рельефно-точечным тактильным шрифтом.

⠉⠑⠝⠞⠗⠀⠺⠎⠑⠇⠑⠝⠝⠕⠯

Передача фразы «центр вселенной» на азбуке Морзе

Как эта фраза передаётся на морзянке.

– ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ – – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ – – – ⋅ – – –

Произношение фразы «центр вселенной» на дактильной азбуке

Как эта фраза произносится на ручной азбуке глухонемых (но не на языке жестов).

Передача фразы «центр вселенной» семафорной азбукой

Как эта фраза передаётся флажковой сигнализацией.

Остальные фразы со слова «центр»

Какие ещё фразы начинаются с этого слова.

- центр абсорбции

- центр активности

- центр американского английского

- центр аномальных явлений

- центр аппетита

- центр арены

- центр армии

- центр астрономических данных в страсбурге

- центр бассейна

- центр беженцев

- центр безопасности

- центр безопасности коммуникаций

- центр берлина

- центр борьбы

- центр боя

- центр брока

- центр бури

- центр бытия

- центр величины

- центр вены

- центр взрыва

- центр власти

- центр влияния

- центр внимания

Ваша фраза добавлена!

Остальные фразы из 2 слов

Какие ещё фразы состоят из такого же количества слов.

- а вдобавок

- а вдруг

- а ведь

- а вот

- а если

- а ещё

- а именно

- а капелла

- а каторга

- а ну-ка

- а приятно

- а также

- а там

- а то

- аа говорит

- аа отвечает

- аа рассказывает

- ааронов жезл

- аароново благословение

- аароново согласие

- аб ово

- абажур лампы

- абазинская аристократия

- абазинская литература

Комментарии

22:33

Что значит фраза «центр вселенной»? Как это понять?..

Ответить

20:52

×

Здравствуйте!

У вас есть вопрос или вам нужна помощь?

Спасибо, ваш вопрос принят.

Ответ на него появится на сайте в ближайшее время.

А Б В Г Д Е Ё Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Ъ Ы Ь Э Ю Я

Транслит Пьюникод Шрифт Брайля Азбука Морзе Дактильная азбука Семафорная азбука

Палиндромы Сантана

Народный словарь великого и могучего живого великорусского языка.

Онлайн-словарь слов и выражений русского языка. Ассоциации к словам, синонимы слов, сочетаемость фраз. Морфологический разбор: склонение существительных и прилагательных, а также спряжение глаголов. Морфемный разбор по составу словоформ.

По всем вопросам просьба обращаться в письмошную.

Выбираем вариант: Спустя много лет вселенная свела нас вместе.

ПОЯСНЕНИЕ

ВСЕЛЕННАЯ, 1. [Как термин ― с прописной буквы] Вся система мироздания, весь мир. Строение Вселенной. Тайны Вселенной. Во всей вселенной ни звука (о полной тишине вокруг). 2. Вся земля, все страны. Объехать всю вселенную. Кричать на всю вселенную.

Итак, с прописной буквы пишется астрономический термин. В переносном значении ― это весь окружающий мир. Обычно пишется со строчной буквы, даже если речь идет о высшей силе. В то же время орфография позволяет использовать прописную букву в словах особой важности, но здесь это будет авторским вариантом.

Примеры:

Он поцеловал её, поцеловал с таким жаром, что вся вселенная показалась ей в огне горящею! [Н. М. Карамзин. Бедная Лиза (1792)]

Это была очень неловкая секунда, очень. Но вселенная пришла мне на помощь. Я услышал зуммер. [Виктор Пелевин. Бэтман Аполло (2013)]

Центр Вселенной, это не гипотетическая точка, это не вымышленная координата, а действительно существующая точка и координата, но, какие дефиниции покажут центр Вселенной, как этим воспользоваться и вычислить невидимый, неуловимый и противоречивый центр Вселенной, поговорим далее…

Содержание

- 1 Структура Вселенной

- 2 Звёзды вокруг нас

- 3 Заблуждения и ничего лишнего относительно центра Вселенной

- 4 С помощью чего определить центр Вселенной?

- 5 Как определить центр Вселенной?

- 6 Что нам это дарует, центр Вселенной

Структура Вселенной[править]

Структура Вселенной по своему виду схожа со структурой нейронной сети. Структуру Вселенной составляют суперкластеры, а суперкластеры состоят из скопления кластеров. Суперкластер достигает размера в 500 квадратных Мпк, а один кластер имеет размер в 120 квадратных Мпк (мегапарсек). Один кластер заключает в себе группу из сотен галактик, а галактика состоит из множества звёздных систем и газопылевых облаков. Галактика может иметь средний размер 50 квадратных кпк (килопарсек), а звёздная система имеет средний размер 0,5 пк (парсек). Получается, что звёздная система меньше суперкластера в миллиард раз, а суперкластер меньше Вселенной в тысячи раз.

Рассматривая такие огромные величины, и такое огромное количество суперкластеров, кластеров, галактик и звездных систем, астрономам очень трудно сказать о количестве звёзд во Вселенной, а о количестве планет и вовсе астрономы сказать затрудняются.

Звёзды вокруг нас[править]

Звездная область с солнечной системой во Млечном Пути.

Мы видим звезды, но видим лишь часть звездного неба, прямо говоря; видим только две третьи звезд от всего небосвода. Это неудобство доставляет не только планета Земля, точней говоря, поверхность планеты, а так же и наша галактика – Млечный Путь. Чтобы в полном размере охватить все окружающие нас звезды, нужно смотреть за пределами планеты и галактики. Так же мы видим плоское изображение, звезды, словно на киноэкране, но сегодня доступно рассмотреть и трехмерную картину окружающих нас светил в собственном суперкластере и соседних суперкластерах. И, получается, что область в которой находится Солнечная Система в миллион раз меньше суперкластера, как и в миллион раз больше в суперкластере звёзд чем в области из рукава Ориона, который в галактике Млечный Путь.

Звездная карта с планеты Земля.

Мы видим вокруг себя так много светил, что они затмевают нам одну треть обзора Вселенной. Почему, именно светил, а потому, что на одном квадратном сантиметре звёздного неба, мы видим десятки тысяч ярких точек излучающих свет, и свет излучают не только звезды, а ещё и галактики, которые по своей светимости превосходят гигантские звезды. Но самыми яркими объектами во вселенной являются Квазары, что является конечной стадией существования галактики, когда черная дыра уничтожает свою галактику, излучая энергию из переработанной окружающей звездной массы.

Сколько мы видим светил?

Вопрос совершенно простой, и ответ на этот вопрос не затруднителен. В суперкластере Ланиакея 100 тысяч галактик, в галактике Млечный Путь 400 миллионов звёзд, и если посчитать среднее количиство звёзд в суперкластере Ланиакея, то их число 2·1016 звёзд. И это намного больше чем звёзд в каталогах и звёзд которые классифицировали. И примерно столько звёзд в соседнем суперкластере Персея-Рыб. Следовательно, мы даже не можем отметить все эти звёзды, не говоря о том, чтобы их все классифицировать. Но, это только количество звёзд в двух суперкластерах, а их рядом не менее десятка, и сотни суперкластеров немного поодаль. Получается, что 1% звёзд мы только видим, и столь малую долю процента от видимых звёзд только отметили и классифицировали. Ведь, если на одну звезду уйдёт времени одна секунда для поиска и классификации, то, чтобы все звёзды в округе найти и классифицировать уйдёт времени 19 миллионов лет, но, это невозможно, человечество живёт только всего несколько десятков тысяч лет.

Если, посредством красного смещения, высчитать отдалённость объекта от наблюдателя, и использовать остальные две известные долготу и высоту на небосводе, можно преобразовать плоскую картину звездного неба, привычную для всех с древних времён, в реальную, трехмерную, картину Вселенной. Что совершенно изменит наше видение окружающих светил во Вселенной.

Заблуждения и ничего лишнего относительно центра Вселенной[править]

С помощью чего определить центр Вселенной?[править]

Как определить центр Вселенной?[править]

Что нам это дарует, центр Вселенной[править]

Эта статья нуждается в доработке. Прямо сейчас Вы можете отредактировать её — дополнить, исправить замеченные ошибки, добавить ссылки.

(Этой пометке соответствует строчка {{Черновик}} в теле статьи. Все статьи с такой пометкой отнесены к категории Викизнание:Черновики.)

—Kot Da Vinchi (обсуждение)

Вселенная > Центр Вселенной

Где искать центр Вселенной? В период существования геоцентрической системы все было намного проще. Люди просто были убеждены, что в центре Вселенной находится Земля, а остальные объекты вращаются вокруг нас. Затем возникла гелиоцентрическая система, которая в центр Солнечной системы поставила звезду.

Но ведь наша система – это лишь часть галактики, которая входит в скопление, считающееся частью большей конструкции. Наше понимание Вселенной сильно расширилось и выходит, что чем больше мы знаем и понимаем, тем сложнее нам разобраться с вопросом о вселенском центре.

Предполагаемая карта Вселенной

Теория с Большим Взрывом дает спутанные объяснения, так как базируется на идее, что центра вообще нет. Обычно нас тянет приравнять событие, положившее начало всей жизни, к обычному взрыву, а значит, отыскать источник. Тогда, что является центром Вселенной?

Художественная концепция логарифмического масштаба в наблюдаемой Вселенной.

Это сложный вопрос. Например, если вы запускаете фейерверк, то можно его сфотографировать. Дальние осколки будут отмечать границы, а направление каждого укажет на точку, в которой все произошло.

Если бы это срабатывало в случае со Вселенной, то начальная точка должна быть намного теплее (чем дальше от центра, тем ниже температура). Ученые пытались следовать этой дорожкой и направляли детекторы в разные стороны. Но результат один – Вселенная однородна. Пока нет области, которая явно бы выделялась по температурным показателям.

Конечно, звезды горячее окружающего пространства. Но если всматриваться в галактики, то видим, что в общем наблюдается ровная картинка. В таком случае, центра просто не существует. Чтобы это проанализировать, ученые используют пример с надувным шариком. Мы знаем, что Вселенная расширяется. Тогда, нанеся на шарик точки (галактики), при надувании можем проследить, как они отодвигаются.

Вселенная выглядит примерно одинаковой во всех направлениях, но далекие галактики кажутся моложе и менее развиты, чем приближенные.

Но важно концентрироваться на поверхности. Не поддавайтесь искушению перенести расширение на весь шарик (внутреннее наполнение – сфера), иначе вы примете середину за центр. Итак, точки на поверхности расширяются и раздвигается, но ни одна не будет центральной.

Некоторые полагают, что если Большой Взрыв воспринимается в качестве стартовой точки, создавшей расширяющуюся Вселенную, то это место и должно быть центром. Однако суть в том, что у нашего пространства вообще может и не быть центра. То есть, это не обязательное условие. Например, область Большого Взрыва способна быть бесконечностью. Если же центр и существует, то он может находиться в любом месте и недоступен для нашего наблюдения.

Здесь главное не запутаться в понятиях. Нет места, которое стало началом расширения Вселенной. Но существует время, когда наша Вселенная начала расширяться. Именно это «время» и будет точкой Большого Взрыва. Поэтому чем дальше смотрим, тем глубже в прошлое оглядываемся, а Вселенная при этом сохраняет однородность.