ВНИМАНИЕ! ОБЯЗАТЕЛЬНО ДЛЯ ПРОЧТЕНИЯ ВСЕМ ПОЛЬЗОВАТЕЛЯМ!

| This is a direct translation of the original English article! Прямой перевод текста с Англовики! [личность • способность • битвы • интересные факты • истории] Подробное описание внешности персонажей — собственность русской вики! Информация о прототипах персонажей имеется в свободном доступе на просторах интернета! |

Статья • История • Галерея

Содержание

Внешность • Личность • Способность • Навыки • Из прошлого • Битвы • Отношения • Цитаты • Этимология • Прототип • Интересные факты

Примечания

| “ | Не жалей себя. Если начнёшь барахтаться в жалости к самому себе, жизнь станет бесконечным кошмаром. | ” |

Осаму Дазай (太宰治 Dazai Osamu?) — второй главный персонаж манги и аниме-адаптации. Является одним из старших сотрудников Вооружённого Детективного Агентства и напарником Куникиды Доппо. Ранее входил в состав Исполнительного комитета Портовой Мафии и являлся напарником Чуи Накахары. Обладает способностью «Неполноценный Человек».

Внешность

Дазай — молодой мужчина с частично волнистыми, короткими, темно-каштановыми волосами и узкими темно-карими глазами. Его челка обрамляет его лицо, в то время, как некоторые пряди собраны в середине его лица. Он достаточно высокий и стройный. Носит бинты по всему телу из-за ранений, полученных в бою, а также это результат попыток Дазая к суициду.

Осаму Дазай. 15 лет

Осаму Дазай. 16 лет

Осаму Дазай. Портовая Мафия

Осаму Дазай. Детективное Агенство

Осаму Дазай. Мёрсо

Дазай Осаму. Последствия Каннибализма

Осаму Дазай. Мёртвое Яблоко

Осаму Дазай. Пёс. Wan!

Осаму Дазай. Портовая Мафия. Wan!

Осаму Дазай. Детективное Агенство. Wan!

Осаму Дазай. Старшеклассник. Wan!

Осаму Дазай. Учитель. Wan!

Осаму Дазай. BEAST

Личность

Обладает весьма задиристым и весёлым характером, при этом самодостаточен, периодически принимает попытки суицида. Дазай весьма загадочная личность, его истинные мотивы никогда не раскроются, если он сам не раскроет их. Всё время предпринимает попытки покончить с собой, чем доставляет неудобства коллегам. Очень любит подшучивать над Куникидой Доппо, говоря ему сначала важные слова, дабы он записал их в свой блокнот, а потом, когда тот выполняет сказанное, Осаму говорит, что все что он сказал — ложь, в результате чего Куникида недолюбливает Дазая и часто дает ему хорошую взбучку. Несмотря на это, Дазай показал невероятно острый ум, благодаря которому он быстро сумел догадаться, кем является Ацуши, от чего сразу становится понятно, он что настоящий детектив, который не упускает ни единой зацепки. Он хранит полное спокойствие в сражениях даже тогда, когда ситуация предпринимает неслыханные обороты.

Способность

Неполноценный Человек (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku?) — способность, позволяющая Дазаю посредством прямого физического контакта нейтрализовать способности другого эспера. Не действует на расстоянии, что является минусом. Так же он может аннулировать способность будучи связанным, если оппонент коснётся его участка кожи. Со слов Ранпо способность Дазая считается очень могущественной, а среди стран Европы не найдётся человека с похожими силами.

| Неполноценный Человек (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku?) | ||

|

Дебют в манге: | Глава 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Дебют в аниме: | Эпизод 1 | |

| Способность: | Нейтрализация Способностей |

Навыки

Из прошлого

Битвы

Отношения

Цитаты

| “ | Человек боится смерти, но в то же время его к ней влечёт. Она не перестаёт быть продуктом потребления как в реальном мире, так и в художественном. Это одно из событий в нашей жизни, от которого не сбежать. Поэтому я так стремлюсь к ней. | ” |

| “ | Хорошая книга хуже не станет, сколько ни читай. | ” |

| “ | Люди и правда безобразно глупы. Но что в этом плохого? | ” |

Этимология

Прототип

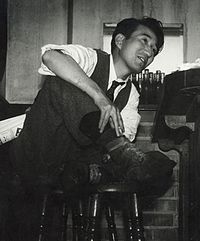

Осаму Дазай (19 июня 1909 — 13 июня 1948) — один из самых известных японских прозаиков начала XX века. Настоящее имя — Сюдзи Цусима. В 1933 году в газете «То-окуниппо» появился рассказ «Поезд», получивший первую премию на проводимом этой газетой конкурсе.

Писатель совершил несколько попыток суицида, и единственной его целью было написать историю своей жизни и умереть. Для этой книги он даже заранее выбрал название — «На закате дней». В целом, Дазай Осаму, наверное, один из самых неординарных японских писателей. Одну из попыток суицида он совершил, бросившись с официанткой в море (его спасли, её — нет), впоследствии этот случай он не раз обыгрывал в своих рассказах. Всего за свою жизнь Дазай совершил четыре попытки суицида, последняя из которых была удачной.

В реальной жизни Акутагава Рюноскэ был кумиром Дазая, и после смерти первого второй слёзно просил вручить ему премию имени этого писателя. Есть даже версия, что попытку суицида посредством передозировки Дазай совершил под влиянием самоубийства Рюуноске Акутагавы, поскольку эта весть его сильно потрясла. Также стоит упомянуть, что Дазай был захоронен рядом с могилой Мори Огая, одного из его любимейших писателей.

«Исповедь „неполноценного“ человека» — одно из самых известных произведений Осаму Дазая. Эта повесть об Обе Ёдзу, человеке, неспособном раскрыться другим людям и вынужденном играть роль беззаботного шутника. Произведение очень автобиографично: тут и суицид, и общение с коммунистами, и наркомания, и психиатрия, даже слабые лёгкие!

Интересные факты

- Он, наряду с несколькими другими персонажами, появлялся в мобильных играх «Небесная Любовь», «Kimito Lead Puzzle 18» и «Yumeiro Cast», правда на ограниченное время.

- Во второй главе манги Куникида называет его «Автоматом по порче бинтов».

- Его постоянные попытки совершить двойной суицид с красивой женщиной могут быть отсылкой на попытку самоубийства его прототипа с Шимеко Танабе и Хацуё Ояма. Попытка самоубийства с его возлюбленной Томи Ямазаки была успешной.

- Не исключается факт того, что это так же может быть отсылкой к неоднократным попыткам самоубийства в истории протагониста «Исповеди Неполноценного Человека», что считается отражением бурной жизни Осаму Дазая.

- В реальной жизни его часто группировали вместе с Сакагучи Анго и Одой Сакуноске как «Бурайху» или «Декадентскую школу».

- В аниме и ранобе нас часто отсылают к этому факту, так как эти трое часто встречались в определённом баре, что можно заметить в «Дазай Осаму и Тёмная Эра» и на календаре.

- Он был самым молодым руководителем в истории Портовой Мафии.

- Во время разговора Дазай обычно называет себя полу нейтральной фразой «Watashi», а не более мужской как, например, «Boku».

- Дазай очень плохо водит машину, это демонстрируется в новелле «Вступительный экзамен Дазая Осаму».

- Напиток, который мы часто видим перед Дазаем, когда он находится в кафе — обычный чёрный чай.

- До его прихода в Мафию Дазая приглашали вступить в организацию «Овцы» («Агнцы»).

- Согласно официальному руководству по аниме (Bungo Stray Dogs Official Guidebook Kaikaroku):

- В последнее время он не делает ничего.

- У него сбит режим сна и спит он не много

- Он чувствует, что он должен придумать новый способ побесить Чую, если их вновь заставят сотрудничать.

- Он считает, что все подвластно ему.

- Его идеальный тип — любой человек, что согласен на двойной суицид с ним.

- Его девиз — «Соверши чистое, веселое и энергическое самоубийство.

- По его словам, не было случая, когда он считал, что умирал больше всего.

Примечания

|

Навигация

| ПОЛЬЗОВАТЕЛИ СПОСОБНОСТЕЙ | ||

|---|---|---|

| ВООРУЖЁННОЕ ДЕТЕКТИВНОЕ АГЕНСТВО |

СОСТАВ | Акико Йосано • Ацуши Накаджима • Джуничиро Танизаки • Доппо Куникида • Кенджи Миядзава • Кёка Изуми • Осаму Дазай • Юкичи Фукудзава |

| БЫВШИЕ | Катай Таяма | |

| ПОРТОВАЯ МАФИЯ | СОСТАВ | Коё Озаки • Кюсаку Юмено • Мичизу Тачихара • Мотоджиро Каджи • Огай Мори • Рьюро Хироцу • Рюноске Акутагава • Чуя Накахара • Эйс † |

| БЫВШИЕ | Сакуноске Ода † | |

| ЗНАМЯ | Альбатросс † • Пиано Мэн † | |

| ГИЛЬДИЯ | НОВАЯ ГИЛЬДИЯ | Фрэнсис Фицджеральд • Луиза Олкотт |

| СТАРАЯ ГИЛЬДИЯ | Джон Стейнбек | |

| БЫВШИЕ | Герман Мелвилл • Говард Лавкрафт • Люси Монтгомери • Маргарет Митчелл • Марк Твен • Натаниэль Готорн • Эдгар По | |

| КРЫСЫ МЁРТВОГО ДОМА | Александр Пушкин • Иван Гончаров • Муситаро Огури • Натаниэль Готорн • Фёдор Достоевский | |

| СМЕРТЬ НЕБОЖИТЕЛЕЙ | Брэм Стокер • Николай Гоголь • Камуи • Сигма • Фёдор Достоевский | |

| ИЩЕЙКИ | СОСТАВ | Очи Фукучи • Сайгику Дзёно • Теруко Оокура • Тэтте Суэхиро |

| БЫВШИЕ | Мичизу Тачихара | |

| ОРДЕН ЧАСОВОЙ БАШНИ | Агата Кристи | |

| ОВЦЫ | Чуя Накахара | |

| ТРАНСЦЕНДЕНТЫ | Артур Рембо † • Виктор Гюго • Иоганн Вольфганг Гёте • Поль Верлен • Уильям Шекспир | |

| МИМИК | Андре Жид † | |

| СЕМЬ ПРЕДАТЕЛЕЙ | Жюль Габриэль Верн † | |

| СПЕЦИАЛЬНЫЙ ОТДЕЛ | Анго Сакагучи • Мизуки Цудзимура • Сантока Танеда | |

| ОСТАЛЬНЫЕ | Герберт Джордж Уэллс • Мать Кёки † • Нацухико Кёгоку • Неизвестный † • Немо • Солдат † • Сосэки Нацумэ • Тацухико Шибусава † • Юкито Аяцудзи |

| ДЕТЕКТИВНОЕ АГЕНСТВО | ||

|---|---|---|

| ЛИДЕР | Юкичи Фукудзава | |

| ОСОБЫЙ ДЕТЕКТИВ | Ранпо Эдогава | |

| ДЕТЕКТИВЫ | Доппо Куникида • Осаму Дазай • Кенджи Миядзава | |

| НОВИЧКИ | Ацуши Накаджима • Кёка Изуми | |

| ВРАЧ | Акико Йосано | |

| ТЕХНИК | Джуничиро Танизаки | |

| ПЕРСОНАЛ | СЕКРЕТАРЬ | Кирако Харуно |

| СОТРУДНИК | Наоми Танизаки | |

| ИНФОРМАТОР | Катай Таяма |

| ПОРТОВАЯ МАФИЯ | ||

|---|---|---|

| ЛИДЕР | Огай Мори | |

| СПОСОБНОСТЬ | Элис | |

| ИСПОЛНИТЕЛЬНЫЙ КОМИТЕТ |

Эйс † • Полковник • Чуя Накахара • Коё Озаки • Поль Верлен | |

| ЗНАМЯ | Альбатросс † • Док † • Айс Мэн † • Липпманн † • Пиано Мэн † | |

| ПАРТИЗАНСКИЙ ОТРЯД | Рюноске Акутагава • Ичиё Хигучи | |

| ЧЁРНЫЕ ЯЩЕРИЦЫ | ЛИДЕР | Рьюро Хироцу |

| ЛЕЙТЕНАНТЫ | Гин Акутагава • Мичизу Тачихара | |

| ЧЛЕНЫ ОРГАНИЗАЦИИ | Артур Рембо † • Карма † • Сакуноске Ода † • Кюсаку Юмено Мотоджиро Каджи |

|

| ОСТАЛЬНЫЕ | Казума Утагава † • Курэхито Умеки † • Мироку Исигэ † Сёкити Саэгуса † |

|

| БЫВШИЕ | ЛИДЕР | Предыдущий Босс |

| РУКОВОДИТЕЛЬ | Осаму Дазай | |

| ОСТАЛЬНЫЕ | Кёка Изуми • Анго Сакагучи |

|

Osamu Dazai |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 太宰 治 | |||

Dazai in 1948 |

|||

| Born |

Shūji Tsushima June 19, 1909 Kanagi, Aomori, Empire of Japan |

||

| Died | June 13, 1948 (aged 38)

Tokyo, Allied-occupied Japan |

||

| Cause of death | Double suicide with Tomie Yamazaki by drowning | ||

| Occupation(s) | Novelist, Short story writer | ||

| Notable work |

|

||

| Movement | I-Novel, Buraiha | ||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 太宰 治 | ||

| Hiragana | だざい おさむ | ||

|

Shūji Tsushima (津島 修治, Tsushima Shūji, 19 June 1909 — 13 June 1948), known by his pen name Osamu Dazai (太宰 治, Dazai Osamu), was a Japanese novelist and author.[1] A number of his most popular works, such as The Setting Sun (Shayō) and No Longer Human (Ningen Shikkaku), are considered modern-day classics.[2]

His influences include Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Murasaki Shikibu and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. While Dazai continues to be widely celebrated in Japan, he remains relatively unknown elsewhere, with only a handful of his works available in English. His last book, No Longer Human, is his most popular work outside of Japan.

Early life[edit]

Tsushima in a 1924 high school yearbook photo

Shūji Tsushima was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner[3] and politician[1] in Kanagi, a remote corner of Japan at the northern tip of Tōhoku in Aomori Prefecture. He was the tenth of eleven children by his parents. At the time of his birth, the huge, newly-completed Tsushima mansion, where he would spend his early years, was home to some thirty family members.[4] The Tsushima family was of obscure peasant origins, with Dazai’s great-grandfather building up the family’s wealth as a moneylender, and his son increasing it further. They quickly rose in power and, after some time, became highly respected across the region.[5]

Dazai’s father, Gen’emon, a younger son of the Matsuki family, which due to «its exceedingly ‘feudal’ tradition» had no use for sons other than the eldest son and heir, was adopted into the Tsushima family to marry the eldest daughter, Tane; he became involved in politics due to his position as one of the four wealthiest landowners in the prefecture, and was offered membership into the House of Peers.[5] This made Dazai’s father absent during much of his early childhood, and with his mother, Tane, being ill,[6] Tsushima was brought up mostly by the family’s servants and his aunt Kiye.[7]

Education and literary beginnings[edit]

In 1916, Tsushima began his education at Kanagi Elementary.[8] On March 4, 1923, Tsushima’s father Gen’emon died from lung cancer,[9] and then a month later in April Tsushima attended Hirosaki High School,[10] followed by entering Hirosaki University’s literature department in 1927.[8] He developed an interest in Edo culture and began studying gidayū, a form of chanted narration used in the puppet theaters.[11] Around 1928, Tsushima edited a series of student publications and contributed some of his own works. He also published a magazine called Saibō bungei (Cell Literature) with his friends, and subsequently became a staff member of the college’s newspaper.[12]

Tsushima’s success in writing was brought to a halt when his idol, the writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, committed suicide in 1927 at 35 years old. Tsushima started to neglect his studies, and spent the majority of his allowance on clothes, alcohol, and prostitutes. He also dabbled with Marxism, which at the time was heavily suppressed by the government. On the night of December 10, 1929, Tsushima committed his first suicide attempt, but survived and was able to graduate the following year. In 1930, Tsushima enrolled in the French Literature Department of Tokyo Imperial University and promptly stopped studying again. In October, he ran away with a geisha named Hatsuyo Oyama [ja] and was formally disowned by his family.

Dazai (right) and Oyama Hatsuyo (second from left)

Nine days after being expelled from Tokyo Imperial University, Tsushima attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in Kamakura with another woman, 19-year-old bar hostess Shimeko Tanabe [ja]. Tanabe died, but Tsushima lived, rescued by a fishing boat and was charged as an accomplice in Tanabe’s death. Shocked by the events, Tsushima’s family intervened to drop a police investigation. His allowance was reinstated, and he was released of any charges. In December, Tsushima recovered at Ikarigaseki and married Hatsuyo there.

Soon after, Tsushima was arrested for his involvement with the banned Japanese Communist Party and, upon learning this, his elder brother Bunji promptly cut off his allowance again. Tsushima went into hiding, but Bunji, despite their estrangement, managed to get word to him that charges would be dropped and the allowance reinstated yet again if Tsushima solemnly promised to graduate and swear off any involvement with the party. Tsushima accepted.

Leftist movement[edit]

In 1929, when its principal’s misappropriation of public funds was discovered at Hirosaki High School, the students, under the leadership of Ueda Shigehiko (Ishigami Genichiro), leader of the Social Science Study Group, staged a five-day allied strike, which resulted in the principal’s resignation and no disciplinary action against the students. Tsushima hardly participated in the strike, but in imitation of the proletarian literature in vogue at the time, he summarized the incident in a novel called Student Group and read it to Ueda. The Tsushima family was wary of Dazai’s leftist activities. On January 16 of the following year, the Special High Police arrested Ueda and nine other students of the Hiroko Institute of Social Studies, who were working as terminal activists for Seigen Tanaka’s armed Communist Party.

In college, Dazai met activist Eizo Kudo, and made a monthly financial contribution of ¥10 to the Communist Party. The reason why he was expelled from his family after his marriage with Hatsuyo Oyama was to prevent the accumulation of illegal activities on Bunji, who was a politician. After his marriage, Dazai was ordered to hide his sympathies and moved repeatedly. In July 1932, Bunji tracked him down, and had him turn himself in at the Aomori Police Station. In December, Dazai signed and sealed a pledge at the Aomori Prosecutor’s Office to completely withdraw from leftist activities.[13][14]

Early literary career[edit]

Tsushima kept his promise and settled down a bit. He managed to obtain the assistance of established writer Masuji Ibuse, whose connections helped him get his works published and establish his reputation. The next few years were productive for Tsushima. He wrote at a feverish pace and used the pen name «Osamu Dazai» for the first time in a short story called «Ressha» («列車», «Train») in 1933: His first experiment with the first-person autobiographical style that later became his trademark.[15]

However, in 1935 it started to become clear to Dazai that he would not graduate. He failed to obtain a job at a Tokyo newspaper as well. He finished The Final Years (Bannen), which was intended to be his farewell to the world, and tried to hang himself March 19, 1935, failing yet again. Less than three weeks later, Tsushima developed acute appendicitis and was hospitalized. In the hospital, he became addicted to Pavinal, a morphine-based painkiller. After fighting the addiction for a year, in October 1936 he was taken to a mental institution,[16] locked in a room and forced to quit cold turkey.

The treatment lasted over a month. During this time Tsushima’s wife Hatsuyo committed adultery with his best friend Zenshirō Kodate.[citation needed] This eventually came to light, and Tsushima attempted to commit double suicide with his wife. They both took sleeping pills, but neither died. Soon after, Dazai divorced Hatsuyo. He quickly remarried, this time to a middle school teacher named Michiko Ishihara (石原美知子). Their first daughter, Sonoko (園子), was born in June 1941.

Dazai and Ishihara Michiko at their wedding

In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of subtle novels and short stories that are autobiographical in nature. His first story, Gyofukuki (魚服記, «Transformation», 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include Dōke no hana (道化の花, «Flowers of Buffoonery», 1935), Gyakkō (逆行, «Losing Ground», 1935), Kyōgen no kami (狂言の神, «The God of Farce», 1936), an epistolary novel called Kyokō no Haru (虚構の春, False Spring, 1936) and those published in his 1936 collection Bannen (Declining Years or The Final Years), which describe his sense of personal isolation and his debauchery.

Wartime years[edit]

Japan entered the Pacific War in December, but Tsushima was excused from the draft because of his chronic chest problems, as he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The censors became more reluctant to accept Dazai’s offbeat work, but he managed to publish quite a bit regardless, remaining one of very few authors who managed to get this kind of material accepted in this period. A number of the stories which Dazai published during World War II were retellings of stories by Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693). His wartime works included Udaijin Sanetomo (右大臣実朝, «Minister of the Right Sanetomo», 1943), Tsugaru (1944), Pandora no hako (パンドラの匣, Pandora’s Box, 1945–46), and Otogizōshi (お伽草紙, Fairy Tales, 1945) in which he retold a number of old Japanese fairy tales with «vividness and wit.»[This quote needs a citation]

Dazai’s house was burned down twice in the American bombing of Tokyo, but his family escaped unscathed, with a son, Masaki (正樹), born in 1944. His third child, daughter Satoko (里子), who later became a famous writer under the pseudonym Yūko Tsushima (津島佑子), was born in May 1947.

Postwar career[edit]

In the immediate postwar period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity. He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in Viyon no Tsuma (ヴィヨンの妻, «Villon’s Wife», 1947), depicting the wife of a poet who had abandoned her and her continuing will to live through hardships.

In 1946, Osamu Dazai released a controversial literary piece titled Kuno no Nenkan (Almanac of Pain), a political memoir of Dazai himself. It describes the immediate aftermath of losing the second World War, and encapsulates how Japanese people felt following the country’s defeat. Dazai reaffirms his loyalty to the Japanese Emperor of the time, Emperor Hirohito and his son Akihito. Dazai was a known communist throughout his career, and also expresses his beliefs through this Almanac of Pain.

Alongside this Dazai also wrote Jugonenkan (For Fifteen Years), another autobiographical piece. This, alongside Almanac of Pain, may serve as a prelude to a consideration of Dazai’s postwar fiction.[17]

In July 1947, Dazai’s best-known work, Shayo (The Setting Sun, translated 1956) depicting the decline of the Japanese nobility after the war, was published, propelling the already popular writer into celebrityhood. This work was based on the diary of Shizuko Ōta (太田静子), an admirer of Dazai’s works who first met him in 1941. She bore him a daughter, Haruko, (治子) in 1947.

A heavy drinker, Dazai became an alcoholic[18] and his health deteriorated rapidly. At this time he met Tomie Yamazaki (山崎富栄), a beautician and war widow who had lost her husband after just ten days of marriage. Dazai effectively abandoned his wife and children and moved in with Tomie.

Dazai began writing his novel No Longer Human (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku, 1948) at the hot-spring resort Atami. He moved to Ōmiya with Tomie and stayed there until mid-May, finishing his novel. A quasi-autobiography, it depicts a young, self-destructive man seeing himself as disqualified from the human race.[19] The book is considered one of the classics of Japanese literature and has been translated into several foreign languages.

Dazai and Tomie’s bodies discovered in 1948

In the spring of 1948, Dazai worked on a novelette scheduled to be serialized in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, titled Guddo bai (the Japanese pronunciation of the English word «Goodbye») but it was never finished.

Death[edit]

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal, near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until six days later, on June 19, which would have been his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, in Mitaka, Tokyo.

At the time, there was a lot of speculation about the incident, with theories of forced suicide by Tomie. Keikichi Nakahata, a kimono merchant who frequented the young Tsushima family, was shown the scene of the water ingress by a detective from the Mitaka police station. He also speculates that «Dazai was asked to die, and he simply agreed, but just before his death, he suddenly felt an obsession with life».[20]

Major works[edit]

| Year | Japanese Title | English Title | Translator(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1928 | Mugen naraku | «Bottomless Hell» | ||

| Aware ga | «The Pitiable Mosquitoes» | Referenced in «Leaves.» | ||

| 1930 | Jinushi ichidai | “A Landlord’s Life” | incomplete | |

| 1933 | 列車

Ressha |

«The Train» | McCarthy | Wins prize from Tōō Nippō newspaper.[21] In The Final Years. |

| 魚服記

Gyofukuki |

«Metamorphosis» or «Transformation»; also translated as «Undine» | O’Brien | In The Final Years. | |

| 思い出

Omoide |

«Memories» or «Recollections» | Dunlop; Lyons; O’Brien | First published in Kaihyō;[22] In The Final Years. | |

| 1934 | Yonosuke no kien | «Big Talk from Yonosuke» | Partially ghost-written piece published under Ibuse Masuji’s name.[21] | |

| 葉

Ha |

«Leaves»[1] | Gangloff | In The Final Years. | |

| 猿面冠者Sarumenkanja | «Monkey-Faced Youth» | In The Final Years. | ||

| 彼は昔の彼ならず

Kare wa mukashi no kare narazu |

«He Is Not the Man He Used to Be» | In The Final Years. | ||

| ロマネスコRomanesuku | «Romanesque» | Published in the first and only issue of Aoi Hana.[23] In The Final Years. | ||

| 1935 | 逆行

Gyakkō |

«Losing Ground» | First appeared in literary magazine Bungei.[24] Was submitted for the first Akutagawa Prize, but did not win. The story was judged by Yasunari Kawabata to be unworthy due to the author’s moral character, a pronouncement that prompted an angry reply from Dazai.[25] In The Final Years. | |

| 道化の華 Dōke no Hana |

«The Flowers of Buffoonery» | In The Final Years. | ||

| Dasu gemaine | «Das Gemeine» | O’Brien | ||

| Kawabata Yasunari e | «To Yasunari Kawabata» | |||

| 猿ヶ島

Sarugashima |

«Monkey Island» | O’Brien | In The Final Years. | |

| 玩具

Gangu |

«Toys» | O’Brien | In The Final Years. | |

| 陰火

Inka |

«Inka» (Will-o’-the-Wisp) | In The Final Years. | ||

| 1936 | 虚構の春 Kyokō no Haru |

«False Spring» | ||

| 晩年 Bannen |

The Final Years | First collection of short stories. | ||

| 1937 | 二十世紀旗手 Nijusseiki Kishu |

«A Standard-bearer of the Twentieth Century» | ||

| HUMAN LOST | «HUMAN LOST» | |||

| 1938 | 満願

Mangan |

«Fulfilment of a Vow» or «A Promise Fulfilled»[2] | Brudnoy & Kazuko; McCarthy | First appeared in the September 1938 issue of Bungakukai. In Schoolgirl. |

| 姥捨

Ubasute |

«Putting Granny Out to Die» | O’Brien | First appeared in the October 1938 issue of Shinchō. In Schoolgirl. | |

| Hino tori | «The Firebird» | |||

| 1939 | I can speak | «I Can Speak»[3] | Brudnoy & Kazuko; McCarthy | In Schoolgirl. |

| 富嶽百景 Fugaku Hyakkei |

«One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji» | McCarthy | First appeared in Bungakukai, February & March 1939. In Schoolgirl. | |

| 黄金風景

Ōgon fūkei |

«Golden Landscape» or «Seascape with Figures in Gold» | Dunlop; McCarthy | First appeared in Kokumin Shinbun, March 2–3 1939. In Schoolgirl. | |

| 女生徒 Joseito |

Schoolgirl | Powell | Novella which first appeared in the April 1939 issue of Bungakukai; also the title of a collection of stories in which it appears. Winner of the Kitamura Tokoku Award[26] | |

| 懶惰の歌留多 | «Slothful Utaruta» | First appeared in the April 1939 issue of Bungei. In Schoolgirl. | ||

| Oshare doji | «The Stylish Child» | |||

| 1940 | 女の決闘 Onna no Kettō |

«Women’s Duel» | ||

| Zokutenshi | «Worldly Angel» | |||

| Anitachi | «My Older Brothers» | McCarthy; O’Brien | ||

| Haru no tozoku | «A Burglar in Spring» | |||

| Zenzō o omou | «Thinking of Zenzō» | McCarthy | ||

| Kojiki gakusei | «Beggar Student» | |||

| 駈込み訴へ Kakekomi Uttae |

«Heed My Plea» | O’Brien | ||

| 走れメロス Hashire Merosu |

«Run, Melos!» | McCarthy; O’Brien | ||

| 1941 | Tokyo hakkei | «Eight Views of Tokyo» | Lyons; McCarthy; O’Brien | |

| 新ハムレット Shin-Hamuretto |

«New Hamlet» | |||

| Fukusō ni tsuite | «On the Question of Apparel» | O’Brien | ||

| 1942 | Hanabi | «Fireworks» | Censored by the authorities, but published after the war as «Before the Dawn» (Hinode mae).[27] | |

| 正義と微笑 Seigi to Bisho |

«Righteousness and Smiles» | |||

| Kikyorai | «Going Home» | Lyons | ||

| 1943 | Hibari no koe | «Voice of the Lark» | Marshall | Published after the war in 1945 as «Pandora’s Box» (パンドラの匣 Pandora no Hako).[27] |

| Kokyō | «Homecoming» | O’Brien | ||

| 右大臣実朝 Udaijin Sanetomo |

«Sanetomo, Minister of the Right» | |||

| 1944 | Kajitsu | «Happy Day» | Filmed as Four Marriages Yottsu no kekkon). | |

| 津軽 Tsugaru |

Tsugaru | Marshall; Westerhoven | ||

| Hin no iji | «A Poor Man’s Got His Pride» | O’Brien | ||

| Saruzuka | «The Monkey’s Mound» | O’Brien | ||

| 1945 | 新釈諸国噺 Shinshaku Shokoku Banashi |

New Tales of the Provinces | ||

| 惜別 Sekibetsu |

Regretful Parting | |||

| お伽草紙 Otogizōshi |

Fairy Tales | Collection of short stories | ||

| Kobutori | «Taking the Wen Away» | O’Brien | ||

| 1946 | 冬の花火 Fuyu no Hanabi |

Fireworks in Winter | Play | |

| Niwa | «The Garden» | McCarthy | ||

| 苦悩の年鑑 Kuno no Nenkan |

Almanac of Pain | Lyons | Autobiography | |

| 十五年間 Jugonenkan |

For Fifteen Years | Autobiography | ||

| Haru no kareha | «Dry Leaves in Spring» | Broadcast as a radio play on NHK the following year.[28] | ||

| Shin’yu kokan | «The Courtesy Call» | |||

| Kahei | «Currency» | O’Brien | ||

| 1947 | Tokatonton | «The Sound of Hammering» | O’Brien | |

| ヴィヨンの妻

Viyon No Tsuma |

«Villon’s Wife» | McCarthy | ||

| Osan | «Osan» | O’Brien | ||

| 斜陽 Shayō |

The Setting Sun | Keene | ||

| 1948 | 如是我聞 Nyoze gamon |

«Thus Have I Heard» | Essay responding to Shiga Naoya’s criticism of his work[28] | |

| 桜桃 Ōtō |

«Cherries» | McCarthy | ||

| 人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku |

No Longer Human | Gibeau; Keene | (2018 English Translation/Variation: A Shameful Life) | |

| グッド・バイ Guddo-bai |

Good-Bye | Marshall | incomplete | |

| Katei no kofuku | «The Happiness of the Home» | |||

| 19?? | Chikukendan | «Canis familiaris» | McCarthy | |

| 地球図

Chikyūzu |

«Chikyūzu» | Before 1937. In The Final Years. | ||

| Chiyojo | «Chiyojo» | Dunlop | ||

| Kachikachiyama | «Crackling Mountain» | O’Brien | ||

| Hakumei | «Early Light» | McCarthy | ||

| Sange | «Fallen Flowers»[4] | Swann | ||

| Chichi | «The Father»[5] | Brudnoy & Kazuko | ||

| Mesu ni tsuite | «Female» | McCarthy | ||

| Bidanshi to tabako | «Handsome Devils and

Cigarettes» |

McCarthy | ||

| Bishōjo | «A Little Beauty» | McCarthy | ||

| めくら草紙

Mekura no sōshi |

«Mekura no sōshi» | «The Blind Book.» Title is intended as a parody of Makura no sōshi (The Pillow Book).[29] Before 1937. In The Final Years. | ||

| Merii kurisumasu | «Merry Christmas» | McCarthy | ||

| Asa | «Morning»[6] | Brudnoy & Yumi | ||

| Haha | «Mother»[7] | Brudnoy & Yumi | ||

| Zakyō ni arazu | «No Kidding» | McCarthy | ||

| «Shame»[8] | Dunlop | |||

| Yuki no yo no hanashi | «A Snowy Night’s Tale» | Swann | ||

| 雀こ

Suzumeko |

«Suzumeko» | Before 1937. In The Final Years. | ||

| Oya to iu niji | «Two Little Words» | McCarthy | ||

| Matsu | «Waiting»[9] | Brudnoy & Kazuko; Turvill |

- Omoide

- «Omoide» is an autobiography where Tsushima created a character named Osamu to use instead of himself to enact his own memories. Furthermore, Tsushima also conveys his perspective and analysis of these situations.[30]

- The Flowers of Buffoonery

- «The Flowers of Buffoonery» relates the story of Oba Yozo and his time recovering in the hospital from an attempted suicide. Although his friends attempt to cheer him up, their words are fake, and Oba sits in the hospital simply reflecting on his life.[31]

- One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji

- «One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji» shares Tsushima’s experience staying at Misaka. He meets with a man named Ibuse Masuji, a previous mentor, who has arranged an o-miai for Dazai. Dazai meets the woman, Ishihara Michiko, who he later decides to marry.[32]

- The Setting Sun

- The Setting Sun focuses on a small, formerly rich, family: a widowed mother, a divorced daughter, and a drug-addicted son who has just returned from the army and the war in the South Pacific. After WWII the family has to vacate their Tokyo home and move to the countryside, in Izu, Shizuoka, as the daughter’s uncle can no longer support them financially [33]

- No Longer Human

- No Longer Human focuses on the main character, Oba Yozo. Oba explains his life from a point in his childhood to somewhere in adulthood. Unable to properly understand how to interact and understand people he resorts to tomfoolery to make friends and hide his misinterpretations of social cues. His façade doesn’t fool everyone and doesn’t solve every problem. Due to the influence of a classmate named Horiki, he falls into a world of drinking and smoking. He relies on Horiki during his time in college to assist with social situations. With his life spiraling downwards after failing in college, Oba continues his story and conveys his feelings about the people close to him and society in general.[34]

- Good-Bye

- An editor tries to avoid women with whom he had past sexual relations. Using the help of a female friend he does his best to avoid their advances and hide the unladylike qualities of his friend.[35]

Selected bibliography of English translations[edit]

- The Setting Sun (斜陽 Shayō), translated by Donald Keene. Norfolk, Connecticut, James Laughlin, 1956. (Japanese publication: 1947).

- No Longer Human (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku), translated by Donald Keene. Norfolk, Connecticut, New Directions Publishers, 1958.

- Dazai Osamu, Selected Stories and Sketches, translated by James O’Brien. Ithaca, New York, China-Japan Program, Cornell University, 1983?

- Return to Tsugaru: Travels of a Purple Tramp (津軽), translated by James Westerhoven. New York, Kodansha International Ltd., 1985.

- Run, Melos! and Other Stories. Trans. Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1988. Tokyo: Kodansha English Library, 1988.

- Crackling Mountain and Other Stories, translated by James O’Brien. Rutland, Vermont, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1989.

- Self Portraits: Tales from the Life of Japan’s Great Decadent Romantic, translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo, New York, Kodansha International, Ltd., 1991.

- Blue Bamboo: Tales of Fantasy and Romance, translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo and New York, Kodansha International, 1993.

- Schoolgirl (女生徒 Joseito), translated by Allison Markin Powell. New York: One Peace Books, 2011.

- Otogizōshi: The Fairy Tale Book of Dazai Osamu (お伽草紙 Otogizōshi), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Fukuoka, Kurodahan Press, 2011.

- Blue Bamboo: Tales by Dazai Osamu (竹青 Chikusei), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Fukuoka, Kurodahan Press, 2012.

- A Shameful Life: (Ningen Shikkaku) (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku), translated by Mark Gibeau. Berkeley, Stone Bridge Press, 2018.

- «Wish Fulfilled» (満願), translated by Reiko Seri and Doc Kane. Kobe, Japan, 2019.

In popular culture[edit]

Dazai’s literary work No Longer Human has received quite a few adaptations: a graphic novel written by the horror manga artist Junji Ito, a film directed by Genjiro Arato, the first four episodes of the anime series Aoi Bungaku, and a variety of mangas one of which was serialized in Shinchosha’s Comic Bunch magazine. It is also the name of an ability in the anime Bungo Stray Dogs and Bungo and Alchemist, used by a character named after Dazai himself.

The book is also the central work in one of the volumes of the Japanese light novel series Book Girl, Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime,[36] although other works of his are also mentioned. Dazai’s works are also discussed in the Book Girl manga and anime series. Dazai is often quoted by the male protagonist, Kotaro Azumi, in the anime series Tsuki ga Kirei, as well as by Ken Kaneki in Tokyo Ghoul.

See also[edit]

- Dazai Osamu Prize

- List of Japanese writers

- Osamu Dazai Memorial Museum

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Dazai Osamu | Japanese author | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ «Many of Japan’s most interesting creative writers cite ‘No Longer Human’ by Osamu Dazai as their favourite book or one that had a huge influence on them». Red Circle Authors. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 8, 21. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- ^ O’Brien, James A. (1975). Dazai Osamu. Boston: Twayne Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 0805726640.

- ^ a b Lyons, pp. 21–22.

- ^ O’Brien 1975.

- ^ Lyons, pp. 21, 53, 57–58.

- ^ a b O’Brien 1975, p. 12.

- ^ 野原, 一夫 (1998). 太宰治生涯と文学 (in Japanese). p. 36. ISBN 4480033971. OCLC 676259180.

- ^ Lyons.

- ^ Lyons, p. 26.

- ^ Lyons, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Inose, Naoki; 猪瀬直樹 (2001). Pikaresuku : Dazai Osamu den = Picaresque. 猪瀬直樹 (Shohan ed.). Tōkyō: Shōgakkan. ISBN 4-09-394166-1. OCLC 47158889.

- ^ Nohara, Kazuo; 野原一夫 (1998). Dazai Osamu, shōgai to bungaku. Tōkyō: Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 4-480-03397-1. OCLC 41370809.

- ^ Lyons, p. 34.

- ^ Lyons, p. 39.

- ^ Wolfe, Alan Stephen (2014-07-14). Suicidal Narrative in Modern Japan: The Case of Dazai Osamu. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6100-2.

- ^ Sakanishi, Shio. «Publishing Trend.» Japan Quarterly 2.3 (1955): 384. «Dazai, a Bohemian and an alcoholic»

- ^ «The Disqualified Life of Osamu Dazai» by Eugene Thacker, Japan Times, 26 Mar. 2016.

- ^ 山内祥史 (1998). 太宰治に出会った日 : 珠玉のエッセイ集. Yumani Shobō. OCLC 680437760.

- ^ a b Lyons, p. 391.

- ^ Classe, Olive, ed. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, Vol. I. London & Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 347. ISBN 1884964362.

- ^ Lyons, p. 36.

- ^ Magill, Frank N., ed. (1997). Cyclopedia of World Authors, Vol. 2 (Revised 3rd ed.). Pasadena, California: Salem Press. p. 514. ISBN 0893564362.

- ^ Starrs, Roy (2021-10-01). Japanese Cultural Nationalism: At Home and in the Asia-Pacific. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-21395-1.

- ^ Lyons, p. 392.

- ^ a b Lyons, p. 393.

- ^ a b Lyons, p. 395.

- ^ James O’Brien (1983-06-01). O. Dazai Selected Stories And Sketches.

- ^ Lyons, pp. 79–83.

- ^ O’Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. pp. 55–58.

- ^ O’Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. pp. 74–76.

- ^ Dazai, Osamu; Keene, Donald (2002). The setting sun. Boston: Tuttle. ISBN 4805306726. OCLC 971573193.

- ^ Dazai, Osamu; Keene, Donald (1958). No longer human. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0811204812. OCLC 708305173.

- ^ O’Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. p. 147. OCLC 56775972.

- ^ «Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime». Contemporary Japanese Literature. 19 February 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Sources[edit]

- O’Brien, James A., ed. Akutagawa and Dazai: Instances of Literary Adaptation. Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Ueda, Makoto. Modern Japanese Writers and the Nature of Literature. Stanford University Press, 1976.

- «Nation and Region in the Work of Dazai Osamu,» in Roy Starrs Japanese Cultural Nationalism: At Home and in the Asia Pacific. London: Global Oriental. 2004. ISBN 1-901903-11-7.

External links[edit]

- e-texts of Osamu’s works at Aozora bunko

- Osamu’s short story «Waiting» at the Wayback Machine (archived December 11, 2007)

- Osamu Dazai’s grave

- Synopsis of Japanese Short Stories (Otogi Zoshi) at JLPP (Japanese Literature Publishing Project) (in English)

- Osamu Dazai at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Works by Osamu Dazai at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

|

Osamu Dazai |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 太宰 治 | |||

Dazai in 1948 |

|||

| Born |

Shūji Tsushima June 19, 1909 Kanagi, Aomori, Empire of Japan |

||

| Died | June 13, 1948 (aged 38)

Tokyo, Allied-occupied Japan |

||

| Cause of death | Double suicide with Tomie Yamazaki by drowning | ||

| Occupation(s) | Novelist, Short story writer | ||

| Notable work |

|

||

| Movement | I-Novel, Buraiha | ||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 太宰 治 | ||

| Hiragana | だざい おさむ | ||

|

Shūji Tsushima (津島 修治, Tsushima Shūji, 19 June 1909 — 13 June 1948), known by his pen name Osamu Dazai (太宰 治, Dazai Osamu), was a Japanese novelist and author.[1] A number of his most popular works, such as The Setting Sun (Shayō) and No Longer Human (Ningen Shikkaku), are considered modern-day classics.[2]

His influences include Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Murasaki Shikibu and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. While Dazai continues to be widely celebrated in Japan, he remains relatively unknown elsewhere, with only a handful of his works available in English. His last book, No Longer Human, is his most popular work outside of Japan.

Early life[edit]

Tsushima in a 1924 high school yearbook photo

Shūji Tsushima was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner[3] and politician[1] in Kanagi, a remote corner of Japan at the northern tip of Tōhoku in Aomori Prefecture. He was the tenth of eleven children by his parents. At the time of his birth, the huge, newly-completed Tsushima mansion, where he would spend his early years, was home to some thirty family members.[4] The Tsushima family was of obscure peasant origins, with Dazai’s great-grandfather building up the family’s wealth as a moneylender, and his son increasing it further. They quickly rose in power and, after some time, became highly respected across the region.[5]

Dazai’s father, Gen’emon, a younger son of the Matsuki family, which due to «its exceedingly ‘feudal’ tradition» had no use for sons other than the eldest son and heir, was adopted into the Tsushima family to marry the eldest daughter, Tane; he became involved in politics due to his position as one of the four wealthiest landowners in the prefecture, and was offered membership into the House of Peers.[5] This made Dazai’s father absent during much of his early childhood, and with his mother, Tane, being ill,[6] Tsushima was brought up mostly by the family’s servants and his aunt Kiye.[7]

Education and literary beginnings[edit]

In 1916, Tsushima began his education at Kanagi Elementary.[8] On March 4, 1923, Tsushima’s father Gen’emon died from lung cancer,[9] and then a month later in April Tsushima attended Hirosaki High School,[10] followed by entering Hirosaki University’s literature department in 1927.[8] He developed an interest in Edo culture and began studying gidayū, a form of chanted narration used in the puppet theaters.[11] Around 1928, Tsushima edited a series of student publications and contributed some of his own works. He also published a magazine called Saibō bungei (Cell Literature) with his friends, and subsequently became a staff member of the college’s newspaper.[12]

Tsushima’s success in writing was brought to a halt when his idol, the writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, committed suicide in 1927 at 35 years old. Tsushima started to neglect his studies, and spent the majority of his allowance on clothes, alcohol, and prostitutes. He also dabbled with Marxism, which at the time was heavily suppressed by the government. On the night of December 10, 1929, Tsushima committed his first suicide attempt, but survived and was able to graduate the following year. In 1930, Tsushima enrolled in the French Literature Department of Tokyo Imperial University and promptly stopped studying again. In October, he ran away with a geisha named Hatsuyo Oyama [ja] and was formally disowned by his family.

Dazai (right) and Oyama Hatsuyo (second from left)

Nine days after being expelled from Tokyo Imperial University, Tsushima attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in Kamakura with another woman, 19-year-old bar hostess Shimeko Tanabe [ja]. Tanabe died, but Tsushima lived, rescued by a fishing boat and was charged as an accomplice in Tanabe’s death. Shocked by the events, Tsushima’s family intervened to drop a police investigation. His allowance was reinstated, and he was released of any charges. In December, Tsushima recovered at Ikarigaseki and married Hatsuyo there.

Soon after, Tsushima was arrested for his involvement with the banned Japanese Communist Party and, upon learning this, his elder brother Bunji promptly cut off his allowance again. Tsushima went into hiding, but Bunji, despite their estrangement, managed to get word to him that charges would be dropped and the allowance reinstated yet again if Tsushima solemnly promised to graduate and swear off any involvement with the party. Tsushima accepted.

Leftist movement[edit]

In 1929, when its principal’s misappropriation of public funds was discovered at Hirosaki High School, the students, under the leadership of Ueda Shigehiko (Ishigami Genichiro), leader of the Social Science Study Group, staged a five-day allied strike, which resulted in the principal’s resignation and no disciplinary action against the students. Tsushima hardly participated in the strike, but in imitation of the proletarian literature in vogue at the time, he summarized the incident in a novel called Student Group and read it to Ueda. The Tsushima family was wary of Dazai’s leftist activities. On January 16 of the following year, the Special High Police arrested Ueda and nine other students of the Hiroko Institute of Social Studies, who were working as terminal activists for Seigen Tanaka’s armed Communist Party.

In college, Dazai met activist Eizo Kudo, and made a monthly financial contribution of ¥10 to the Communist Party. The reason why he was expelled from his family after his marriage with Hatsuyo Oyama was to prevent the accumulation of illegal activities on Bunji, who was a politician. After his marriage, Dazai was ordered to hide his sympathies and moved repeatedly. In July 1932, Bunji tracked him down, and had him turn himself in at the Aomori Police Station. In December, Dazai signed and sealed a pledge at the Aomori Prosecutor’s Office to completely withdraw from leftist activities.[13][14]

Early literary career[edit]

Tsushima kept his promise and settled down a bit. He managed to obtain the assistance of established writer Masuji Ibuse, whose connections helped him get his works published and establish his reputation. The next few years were productive for Tsushima. He wrote at a feverish pace and used the pen name «Osamu Dazai» for the first time in a short story called «Ressha» («列車», «Train») in 1933: His first experiment with the first-person autobiographical style that later became his trademark.[15]

However, in 1935 it started to become clear to Dazai that he would not graduate. He failed to obtain a job at a Tokyo newspaper as well. He finished The Final Years (Bannen), which was intended to be his farewell to the world, and tried to hang himself March 19, 1935, failing yet again. Less than three weeks later, Tsushima developed acute appendicitis and was hospitalized. In the hospital, he became addicted to Pavinal, a morphine-based painkiller. After fighting the addiction for a year, in October 1936 he was taken to a mental institution,[16] locked in a room and forced to quit cold turkey.

The treatment lasted over a month. During this time Tsushima’s wife Hatsuyo committed adultery with his best friend Zenshirō Kodate.[citation needed] This eventually came to light, and Tsushima attempted to commit double suicide with his wife. They both took sleeping pills, but neither died. Soon after, Dazai divorced Hatsuyo. He quickly remarried, this time to a middle school teacher named Michiko Ishihara (石原美知子). Their first daughter, Sonoko (園子), was born in June 1941.

Dazai and Ishihara Michiko at their wedding

In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of subtle novels and short stories that are autobiographical in nature. His first story, Gyofukuki (魚服記, «Transformation», 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include Dōke no hana (道化の花, «Flowers of Buffoonery», 1935), Gyakkō (逆行, «Losing Ground», 1935), Kyōgen no kami (狂言の神, «The God of Farce», 1936), an epistolary novel called Kyokō no Haru (虚構の春, False Spring, 1936) and those published in his 1936 collection Bannen (Declining Years or The Final Years), which describe his sense of personal isolation and his debauchery.

Wartime years[edit]

Japan entered the Pacific War in December, but Tsushima was excused from the draft because of his chronic chest problems, as he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The censors became more reluctant to accept Dazai’s offbeat work, but he managed to publish quite a bit regardless, remaining one of very few authors who managed to get this kind of material accepted in this period. A number of the stories which Dazai published during World War II were retellings of stories by Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693). His wartime works included Udaijin Sanetomo (右大臣実朝, «Minister of the Right Sanetomo», 1943), Tsugaru (1944), Pandora no hako (パンドラの匣, Pandora’s Box, 1945–46), and Otogizōshi (お伽草紙, Fairy Tales, 1945) in which he retold a number of old Japanese fairy tales with «vividness and wit.»[This quote needs a citation]

Dazai’s house was burned down twice in the American bombing of Tokyo, but his family escaped unscathed, with a son, Masaki (正樹), born in 1944. His third child, daughter Satoko (里子), who later became a famous writer under the pseudonym Yūko Tsushima (津島佑子), was born in May 1947.

Postwar career[edit]

In the immediate postwar period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity. He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in Viyon no Tsuma (ヴィヨンの妻, «Villon’s Wife», 1947), depicting the wife of a poet who had abandoned her and her continuing will to live through hardships.

In 1946, Osamu Dazai released a controversial literary piece titled Kuno no Nenkan (Almanac of Pain), a political memoir of Dazai himself. It describes the immediate aftermath of losing the second World War, and encapsulates how Japanese people felt following the country’s defeat. Dazai reaffirms his loyalty to the Japanese Emperor of the time, Emperor Hirohito and his son Akihito. Dazai was a known communist throughout his career, and also expresses his beliefs through this Almanac of Pain.

Alongside this Dazai also wrote Jugonenkan (For Fifteen Years), another autobiographical piece. This, alongside Almanac of Pain, may serve as a prelude to a consideration of Dazai’s postwar fiction.[17]

In July 1947, Dazai’s best-known work, Shayo (The Setting Sun, translated 1956) depicting the decline of the Japanese nobility after the war, was published, propelling the already popular writer into celebrityhood. This work was based on the diary of Shizuko Ōta (太田静子), an admirer of Dazai’s works who first met him in 1941. She bore him a daughter, Haruko, (治子) in 1947.

A heavy drinker, Dazai became an alcoholic[18] and his health deteriorated rapidly. At this time he met Tomie Yamazaki (山崎富栄), a beautician and war widow who had lost her husband after just ten days of marriage. Dazai effectively abandoned his wife and children and moved in with Tomie.

Dazai began writing his novel No Longer Human (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku, 1948) at the hot-spring resort Atami. He moved to Ōmiya with Tomie and stayed there until mid-May, finishing his novel. A quasi-autobiography, it depicts a young, self-destructive man seeing himself as disqualified from the human race.[19] The book is considered one of the classics of Japanese literature and has been translated into several foreign languages.

Dazai and Tomie’s bodies discovered in 1948

In the spring of 1948, Dazai worked on a novelette scheduled to be serialized in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, titled Guddo bai (the Japanese pronunciation of the English word «Goodbye») but it was never finished.

Death[edit]

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal, near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until six days later, on June 19, which would have been his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, in Mitaka, Tokyo.

At the time, there was a lot of speculation about the incident, with theories of forced suicide by Tomie. Keikichi Nakahata, a kimono merchant who frequented the young Tsushima family, was shown the scene of the water ingress by a detective from the Mitaka police station. He also speculates that «Dazai was asked to die, and he simply agreed, but just before his death, he suddenly felt an obsession with life».[20]

Major works[edit]

| Year | Japanese Title | English Title | Translator(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1928 | Mugen naraku | «Bottomless Hell» | ||

| Aware ga | «The Pitiable Mosquitoes» | Referenced in «Leaves.» | ||

| 1930 | Jinushi ichidai | “A Landlord’s Life” | incomplete | |

| 1933 | 列車

Ressha |

«The Train» | McCarthy | Wins prize from Tōō Nippō newspaper.[21] In The Final Years. |

| 魚服記

Gyofukuki |

«Metamorphosis» or «Transformation»; also translated as «Undine» | O’Brien | In The Final Years. | |

| 思い出

Omoide |

«Memories» or «Recollections» | Dunlop; Lyons; O’Brien | First published in Kaihyō;[22] In The Final Years. | |

| 1934 | Yonosuke no kien | «Big Talk from Yonosuke» | Partially ghost-written piece published under Ibuse Masuji’s name.[21] | |

| 葉

Ha |

«Leaves»[1] | Gangloff | In The Final Years. | |

| 猿面冠者Sarumenkanja | «Monkey-Faced Youth» | In The Final Years. | ||

| 彼は昔の彼ならず

Kare wa mukashi no kare narazu |

«He Is Not the Man He Used to Be» | In The Final Years. | ||

| ロマネスコRomanesuku | «Romanesque» | Published in the first and only issue of Aoi Hana.[23] In The Final Years. | ||

| 1935 | 逆行

Gyakkō |

«Losing Ground» | First appeared in literary magazine Bungei.[24] Was submitted for the first Akutagawa Prize, but did not win. The story was judged by Yasunari Kawabata to be unworthy due to the author’s moral character, a pronouncement that prompted an angry reply from Dazai.[25] In The Final Years. | |

| 道化の華 Dōke no Hana |

«The Flowers of Buffoonery» | In The Final Years. | ||

| Dasu gemaine | «Das Gemeine» | O’Brien | ||

| Kawabata Yasunari e | «To Yasunari Kawabata» | |||

| 猿ヶ島

Sarugashima |

«Monkey Island» | O’Brien | In The Final Years. | |

| 玩具

Gangu |

«Toys» | O’Brien | In The Final Years. | |

| 陰火

Inka |

«Inka» (Will-o’-the-Wisp) | In The Final Years. | ||

| 1936 | 虚構の春 Kyokō no Haru |

«False Spring» | ||

| 晩年 Bannen |

The Final Years | First collection of short stories. | ||

| 1937 | 二十世紀旗手 Nijusseiki Kishu |

«A Standard-bearer of the Twentieth Century» | ||

| HUMAN LOST | «HUMAN LOST» | |||

| 1938 | 満願

Mangan |

«Fulfilment of a Vow» or «A Promise Fulfilled»[2] | Brudnoy & Kazuko; McCarthy | First appeared in the September 1938 issue of Bungakukai. In Schoolgirl. |

| 姥捨

Ubasute |

«Putting Granny Out to Die» | O’Brien | First appeared in the October 1938 issue of Shinchō. In Schoolgirl. | |

| Hino tori | «The Firebird» | |||

| 1939 | I can speak | «I Can Speak»[3] | Brudnoy & Kazuko; McCarthy | In Schoolgirl. |

| 富嶽百景 Fugaku Hyakkei |

«One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji» | McCarthy | First appeared in Bungakukai, February & March 1939. In Schoolgirl. | |

| 黄金風景

Ōgon fūkei |

«Golden Landscape» or «Seascape with Figures in Gold» | Dunlop; McCarthy | First appeared in Kokumin Shinbun, March 2–3 1939. In Schoolgirl. | |

| 女生徒 Joseito |

Schoolgirl | Powell | Novella which first appeared in the April 1939 issue of Bungakukai; also the title of a collection of stories in which it appears. Winner of the Kitamura Tokoku Award[26] | |

| 懶惰の歌留多 | «Slothful Utaruta» | First appeared in the April 1939 issue of Bungei. In Schoolgirl. | ||

| Oshare doji | «The Stylish Child» | |||

| 1940 | 女の決闘 Onna no Kettō |

«Women’s Duel» | ||

| Zokutenshi | «Worldly Angel» | |||

| Anitachi | «My Older Brothers» | McCarthy; O’Brien | ||

| Haru no tozoku | «A Burglar in Spring» | |||

| Zenzō o omou | «Thinking of Zenzō» | McCarthy | ||

| Kojiki gakusei | «Beggar Student» | |||

| 駈込み訴へ Kakekomi Uttae |

«Heed My Plea» | O’Brien | ||

| 走れメロス Hashire Merosu |

«Run, Melos!» | McCarthy; O’Brien | ||

| 1941 | Tokyo hakkei | «Eight Views of Tokyo» | Lyons; McCarthy; O’Brien | |

| 新ハムレット Shin-Hamuretto |

«New Hamlet» | |||

| Fukusō ni tsuite | «On the Question of Apparel» | O’Brien | ||

| 1942 | Hanabi | «Fireworks» | Censored by the authorities, but published after the war as «Before the Dawn» (Hinode mae).[27] | |

| 正義と微笑 Seigi to Bisho |

«Righteousness and Smiles» | |||

| Kikyorai | «Going Home» | Lyons | ||

| 1943 | Hibari no koe | «Voice of the Lark» | Marshall | Published after the war in 1945 as «Pandora’s Box» (パンドラの匣 Pandora no Hako).[27] |

| Kokyō | «Homecoming» | O’Brien | ||

| 右大臣実朝 Udaijin Sanetomo |

«Sanetomo, Minister of the Right» | |||

| 1944 | Kajitsu | «Happy Day» | Filmed as Four Marriages Yottsu no kekkon). | |

| 津軽 Tsugaru |

Tsugaru | Marshall; Westerhoven | ||

| Hin no iji | «A Poor Man’s Got His Pride» | O’Brien | ||

| Saruzuka | «The Monkey’s Mound» | O’Brien | ||

| 1945 | 新釈諸国噺 Shinshaku Shokoku Banashi |

New Tales of the Provinces | ||

| 惜別 Sekibetsu |

Regretful Parting | |||

| お伽草紙 Otogizōshi |

Fairy Tales | Collection of short stories | ||

| Kobutori | «Taking the Wen Away» | O’Brien | ||

| 1946 | 冬の花火 Fuyu no Hanabi |

Fireworks in Winter | Play | |

| Niwa | «The Garden» | McCarthy | ||

| 苦悩の年鑑 Kuno no Nenkan |

Almanac of Pain | Lyons | Autobiography | |

| 十五年間 Jugonenkan |

For Fifteen Years | Autobiography | ||

| Haru no kareha | «Dry Leaves in Spring» | Broadcast as a radio play on NHK the following year.[28] | ||

| Shin’yu kokan | «The Courtesy Call» | |||

| Kahei | «Currency» | O’Brien | ||

| 1947 | Tokatonton | «The Sound of Hammering» | O’Brien | |

| ヴィヨンの妻

Viyon No Tsuma |

«Villon’s Wife» | McCarthy | ||

| Osan | «Osan» | O’Brien | ||

| 斜陽 Shayō |

The Setting Sun | Keene | ||

| 1948 | 如是我聞 Nyoze gamon |

«Thus Have I Heard» | Essay responding to Shiga Naoya’s criticism of his work[28] | |

| 桜桃 Ōtō |

«Cherries» | McCarthy | ||

| 人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku |

No Longer Human | Gibeau; Keene | (2018 English Translation/Variation: A Shameful Life) | |

| グッド・バイ Guddo-bai |

Good-Bye | Marshall | incomplete | |

| Katei no kofuku | «The Happiness of the Home» | |||

| 19?? | Chikukendan | «Canis familiaris» | McCarthy | |

| 地球図

Chikyūzu |

«Chikyūzu» | Before 1937. In The Final Years. | ||

| Chiyojo | «Chiyojo» | Dunlop | ||

| Kachikachiyama | «Crackling Mountain» | O’Brien | ||

| Hakumei | «Early Light» | McCarthy | ||

| Sange | «Fallen Flowers»[4] | Swann | ||

| Chichi | «The Father»[5] | Brudnoy & Kazuko | ||

| Mesu ni tsuite | «Female» | McCarthy | ||

| Bidanshi to tabako | «Handsome Devils and

Cigarettes» |

McCarthy | ||

| Bishōjo | «A Little Beauty» | McCarthy | ||

| めくら草紙

Mekura no sōshi |

«Mekura no sōshi» | «The Blind Book.» Title is intended as a parody of Makura no sōshi (The Pillow Book).[29] Before 1937. In The Final Years. | ||

| Merii kurisumasu | «Merry Christmas» | McCarthy | ||

| Asa | «Morning»[6] | Brudnoy & Yumi | ||

| Haha | «Mother»[7] | Brudnoy & Yumi | ||

| Zakyō ni arazu | «No Kidding» | McCarthy | ||

| «Shame»[8] | Dunlop | |||

| Yuki no yo no hanashi | «A Snowy Night’s Tale» | Swann | ||

| 雀こ

Suzumeko |

«Suzumeko» | Before 1937. In The Final Years. | ||

| Oya to iu niji | «Two Little Words» | McCarthy | ||

| Matsu | «Waiting»[9] | Brudnoy & Kazuko; Turvill |

- Omoide

- «Omoide» is an autobiography where Tsushima created a character named Osamu to use instead of himself to enact his own memories. Furthermore, Tsushima also conveys his perspective and analysis of these situations.[30]

- The Flowers of Buffoonery

- «The Flowers of Buffoonery» relates the story of Oba Yozo and his time recovering in the hospital from an attempted suicide. Although his friends attempt to cheer him up, their words are fake, and Oba sits in the hospital simply reflecting on his life.[31]

- One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji

- «One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji» shares Tsushima’s experience staying at Misaka. He meets with a man named Ibuse Masuji, a previous mentor, who has arranged an o-miai for Dazai. Dazai meets the woman, Ishihara Michiko, who he later decides to marry.[32]

- The Setting Sun

- The Setting Sun focuses on a small, formerly rich, family: a widowed mother, a divorced daughter, and a drug-addicted son who has just returned from the army and the war in the South Pacific. After WWII the family has to vacate their Tokyo home and move to the countryside, in Izu, Shizuoka, as the daughter’s uncle can no longer support them financially [33]

- No Longer Human

- No Longer Human focuses on the main character, Oba Yozo. Oba explains his life from a point in his childhood to somewhere in adulthood. Unable to properly understand how to interact and understand people he resorts to tomfoolery to make friends and hide his misinterpretations of social cues. His façade doesn’t fool everyone and doesn’t solve every problem. Due to the influence of a classmate named Horiki, he falls into a world of drinking and smoking. He relies on Horiki during his time in college to assist with social situations. With his life spiraling downwards after failing in college, Oba continues his story and conveys his feelings about the people close to him and society in general.[34]

- Good-Bye

- An editor tries to avoid women with whom he had past sexual relations. Using the help of a female friend he does his best to avoid their advances and hide the unladylike qualities of his friend.[35]

Selected bibliography of English translations[edit]

- The Setting Sun (斜陽 Shayō), translated by Donald Keene. Norfolk, Connecticut, James Laughlin, 1956. (Japanese publication: 1947).

- No Longer Human (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku), translated by Donald Keene. Norfolk, Connecticut, New Directions Publishers, 1958.

- Dazai Osamu, Selected Stories and Sketches, translated by James O’Brien. Ithaca, New York, China-Japan Program, Cornell University, 1983?

- Return to Tsugaru: Travels of a Purple Tramp (津軽), translated by James Westerhoven. New York, Kodansha International Ltd., 1985.

- Run, Melos! and Other Stories. Trans. Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1988. Tokyo: Kodansha English Library, 1988.

- Crackling Mountain and Other Stories, translated by James O’Brien. Rutland, Vermont, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1989.

- Self Portraits: Tales from the Life of Japan’s Great Decadent Romantic, translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo, New York, Kodansha International, Ltd., 1991.

- Blue Bamboo: Tales of Fantasy and Romance, translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo and New York, Kodansha International, 1993.

- Schoolgirl (女生徒 Joseito), translated by Allison Markin Powell. New York: One Peace Books, 2011.

- Otogizōshi: The Fairy Tale Book of Dazai Osamu (お伽草紙 Otogizōshi), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Fukuoka, Kurodahan Press, 2011.

- Blue Bamboo: Tales by Dazai Osamu (竹青 Chikusei), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Fukuoka, Kurodahan Press, 2012.

- A Shameful Life: (Ningen Shikkaku) (人間失格 Ningen Shikkaku), translated by Mark Gibeau. Berkeley, Stone Bridge Press, 2018.

- «Wish Fulfilled» (満願), translated by Reiko Seri and Doc Kane. Kobe, Japan, 2019.

In popular culture[edit]

Dazai’s literary work No Longer Human has received quite a few adaptations: a graphic novel written by the horror manga artist Junji Ito, a film directed by Genjiro Arato, the first four episodes of the anime series Aoi Bungaku, and a variety of mangas one of which was serialized in Shinchosha’s Comic Bunch magazine. It is also the name of an ability in the anime Bungo Stray Dogs and Bungo and Alchemist, used by a character named after Dazai himself.

The book is also the central work in one of the volumes of the Japanese light novel series Book Girl, Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime,[36] although other works of his are also mentioned. Dazai’s works are also discussed in the Book Girl manga and anime series. Dazai is often quoted by the male protagonist, Kotaro Azumi, in the anime series Tsuki ga Kirei, as well as by Ken Kaneki in Tokyo Ghoul.

See also[edit]

- Dazai Osamu Prize

- List of Japanese writers

- Osamu Dazai Memorial Museum

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Dazai Osamu | Japanese author | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ «Many of Japan’s most interesting creative writers cite ‘No Longer Human’ by Osamu Dazai as their favourite book or one that had a huge influence on them». Red Circle Authors. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Lyons, Phyllis I; Dazai, Osamu (1985). The saga of Dazai Osamu: a critical study with translations. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 8, 21. ISBN 0804711976. OCLC 11210872.

- ^ O’Brien, James A. (1975). Dazai Osamu. Boston: Twayne Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 0805726640.

- ^ a b Lyons, pp. 21–22.

- ^ O’Brien 1975.

- ^ Lyons, pp. 21, 53, 57–58.

- ^ a b O’Brien 1975, p. 12.

- ^ 野原, 一夫 (1998). 太宰治生涯と文学 (in Japanese). p. 36. ISBN 4480033971. OCLC 676259180.

- ^ Lyons.

- ^ Lyons, p. 26.

- ^ Lyons, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Inose, Naoki; 猪瀬直樹 (2001). Pikaresuku : Dazai Osamu den = Picaresque. 猪瀬直樹 (Shohan ed.). Tōkyō: Shōgakkan. ISBN 4-09-394166-1. OCLC 47158889.

- ^ Nohara, Kazuo; 野原一夫 (1998). Dazai Osamu, shōgai to bungaku. Tōkyō: Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 4-480-03397-1. OCLC 41370809.

- ^ Lyons, p. 34.

- ^ Lyons, p. 39.

- ^ Wolfe, Alan Stephen (2014-07-14). Suicidal Narrative in Modern Japan: The Case of Dazai Osamu. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6100-2.

- ^ Sakanishi, Shio. «Publishing Trend.» Japan Quarterly 2.3 (1955): 384. «Dazai, a Bohemian and an alcoholic»

- ^ «The Disqualified Life of Osamu Dazai» by Eugene Thacker, Japan Times, 26 Mar. 2016.

- ^ 山内祥史 (1998). 太宰治に出会った日 : 珠玉のエッセイ集. Yumani Shobō. OCLC 680437760.

- ^ a b Lyons, p. 391.

- ^ Classe, Olive, ed. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, Vol. I. London & Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 347. ISBN 1884964362.

- ^ Lyons, p. 36.

- ^ Magill, Frank N., ed. (1997). Cyclopedia of World Authors, Vol. 2 (Revised 3rd ed.). Pasadena, California: Salem Press. p. 514. ISBN 0893564362.

- ^ Starrs, Roy (2021-10-01). Japanese Cultural Nationalism: At Home and in the Asia-Pacific. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-21395-1.

- ^ Lyons, p. 392.

- ^ a b Lyons, p. 393.

- ^ a b Lyons, p. 395.

- ^ James O’Brien (1983-06-01). O. Dazai Selected Stories And Sketches.

- ^ Lyons, pp. 79–83.

- ^ O’Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. pp. 55–58.

- ^ O’Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. pp. 74–76.

- ^ Dazai, Osamu; Keene, Donald (2002). The setting sun. Boston: Tuttle. ISBN 4805306726. OCLC 971573193.

- ^ Dazai, Osamu; Keene, Donald (1958). No longer human. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0811204812. OCLC 708305173.

- ^ O’Brien, James; G.K. Hall & Company (1999). Dazai Osamu. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. p. 147. OCLC 56775972.

- ^ «Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime». Contemporary Japanese Literature. 19 February 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Sources[edit]

- O’Brien, James A., ed. Akutagawa and Dazai: Instances of Literary Adaptation. Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Ueda, Makoto. Modern Japanese Writers and the Nature of Literature. Stanford University Press, 1976.

- «Nation and Region in the Work of Dazai Osamu,» in Roy Starrs Japanese Cultural Nationalism: At Home and in the Asia Pacific. London: Global Oriental. 2004. ISBN 1-901903-11-7.

External links[edit]

- e-texts of Osamu’s works at Aozora bunko

- Osamu’s short story «Waiting» at the Wayback Machine (archived December 11, 2007)

- Osamu Dazai’s grave

- Synopsis of Japanese Short Stories (Otogi Zoshi) at JLPP (Japanese Literature Publishing Project) (in English)

- Osamu Dazai at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Works by Osamu Dazai at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Имя и Фамилия

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Имя и Фамилия Вашего персонажа

:arrow_down: :arrow_down: :arrow_down:

:heavy_check_mark: На русском :heavy_check_mark:

Дазай Осаму

:heavy_check_mark: На японском — кандзи :heavy_check_mark:

太宰治

:heavy_check_mark: На японском — романдзи :heavy_check_mark:

Dazai Osamu

:heavy_check_mark: На английском :heavy_check_mark:

Osamu Dazai

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Прозвища

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Урод Самоубийца, Демонический вундеркинд из портовой мафии, Бессердечный пёс

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Статус

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Жив

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Возраст

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: 17 лет

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Пол

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Мужской

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: День Рождения

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: 19 июня

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Рост

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: 181 см

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Вес

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: 67 кг

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Группа Крови и Резус-Фактор

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Группа крови Вашего персонажа

:arrow_down: :arrow_down: :arrow_down:

:heavy_check_mark: Четвертая — АВ (IV) :heavy_check_mark:

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Лояльность

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Зло

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Семья//Друзья

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Семья: Неизвестно

:arrow_right_hook: Друзья: Одасаку Сакуноскэ; Анго Сакагучи

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Что любит?

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Самоубийства, алкоголь, крабов, MSG

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Что не любит?

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Собак, Чую Накахару

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Каноничность

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Канон

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Профессия

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Член исполнительного комитета портовой Мафии

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Организация

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Портовая Мафия

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Напарники//Ученики//Наставники

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Есть ли у Вашего персонажа напарник//ученики//наставник?

:arrow_down: :arrow_down: :arrow_down:

Напарник: Чуя Накахара

Ученики: Рюноске Акутагава, Кимико Йокота (по сюжету ролевой)

Наставник: Мори Огай

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Название Способности

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Исповедь неполноценного человека(人間失格)

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Описание Способности

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Исповедь неполноценного человека (人間失格, Ningen Shikkaku) Эта способность позволяет Осаму, посредством физического контакта, нейтрализовать способности другого человека. Его способность опирается только на контакт с кожей, так что она не сработает на расстоянии, что является слабостью его способности.

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:black_small_square: Характер

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Обладает весьма задиристым и высокомерным характером, при этом самодостаточная, которая периодически принимает попытки суицида.

Дазай весьма загадочная личность, его истинные мотивы никогда не раскроются, если он сам не раскроет их.

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Внешность

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Дазай имеет слегка волнистые, короткие темно-каштановые волосы и узкие темно-карие глаза.Чёлка обрамляет его лицо, а некоторые ее пряди собраны в центре лба. Он довольно высокий и стройный телосложением.

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

┃ :black_small_square: Биография

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

:arrow_right_hook: Прошлое

До вступление в Детективное агентство Дазай был одним из пяти великих боссов мафии. За всю историю мафии он был самым молодым, кто удостоился чести быть им, из-за чего стал живой легендой. В последующие годы он в основном занимался руководством, принося мафии около половины её общей прибыли, из-за чего действующий босс — Мори Огай сказал: «Дайте ему ещё 4-5 лет, и я не удивлюсь, если он убьёт меня и займёт это место». Помимо руководства Дазай прославился ещё и своими пытками, как-то упоминая, что «не было ни одного заключённого, кто выдержал бы мой допрос». Помимо всего этого он применял жестокие методы обучения для Акутагавы Рюноске, и частно надругался над ним.

Толчком к тому, чтобы покинуть мафию стал его старый друг — Ода Сакуноске, исполнитель низшего ранга, который был убит во время конфликта Портовой мафии организацией «Имитаторы», которую подстроил Мори Огай, чтобы получить правительственную лицензию на существование Портовой мафии как официальной организации. Обезумевший от осознания того, что всё это время Одой управлял Огай, чтобы тот совершил атаку на вражеского командира, Дазай особенно близко принимает к сердцу его последние слова: «Стань тем, кто спасает людей! Обе стороны равноценны, так стань хорошим человеком. Спасай слабых, защищай сирот. Для тебя нет большой разницы между злом и справедливостью… но так будет правильно» — после этого Ода умирает, а Дазай решает уйти из мафии

По словам Акутагавы, он неожиданно прервал одну из миссий и дезертировал. Позже Дазай выследил человека по имени Танеда — капитана сверхъестественного подразделения японского министерства и попросил найти место, где он мог бы помогать людям. Танеда в ответ спросил не хочет ли Дазай вступить в Детективное агентство, но при условии, что исчезнет на два года, чтобы очистить своё прошлое. Неизвестно что он делал всё это время, лишь упоминается, что перед вступлением в агентство он По словам Акутагавы, он неожиданно прервал одну из миссий и дезертировал. Позже Дазай выследил человека по имени Танеда — капитана сверхъестественного подразделения японского министерства и попросил найти место, где он мог бы помогать людям. Танеда в ответ спросил не хочет ли Дазай вступить в Детективное агентство, но при условии, что исчезнет на два года, чтобы очистить своё прошлое. Неизвестно что он делал всё это время, лишь упоминается, что перед вступлением в агентство он был безработным и являлся частым посетителем баров, где без причины напивался.

•⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝•

| | | | | | | |

| | | | |

| |

|

✓

|

|

This Article Contains Spoilers — |

|

|

This article’s content is marked as Mature The page contains mature content that may include coarse language, sexual references, and/or graphic violent images which may be disturbing to some. Mature pages are recommended for those who are 18 years of age and older. If you are 18 years or older or are comfortable with graphic material, you are free to view this page. Otherwise, you should close this page and view another page. |