|

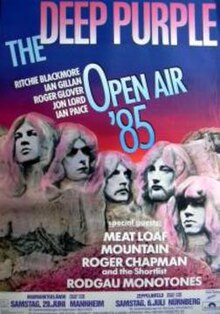

Deep Purple |

|

|---|---|

Deep Purple Mark II in 1970. Left to right: Jon Lord, Roger Glover, Ian Paice, Ian Gillan & Ritchie Blackmore. |

|

| Background information | |

| Also known as | Roundabout (1967) |

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres |

|

| Years active |

|

| Labels |

|

| Spinoffs |

|

| Members |

|

| Past members |

|

| Website | deep-purple.com |

Deep Purple are an English rock band formed in London in 1968.[1] They are considered to be among the pioneers of heavy metal and modern hard rock,[2][3] but their musical approach has changed over the years.[4] Originally formed as a psychedelic rock and progressive rock band, they shifted to a heavier sound with their 1970 album Deep Purple in Rock.[5] Deep Purple, together with Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, have been referred to as the «unholy trinity of British hard rock and heavy metal in the early to mid-seventies».[6] They were listed in the 1975 Guinness Book of World Records as «the globe’s loudest band» for a 1972 concert at London’s Rainbow Theatre[7][8] and have sold over 100 million albums worldwide.[9][10][11]

Deep Purple have had several line-up changes and an eight-year hiatus (1976–1984). The first four line-ups, which constituted the band’s original 1968–1976 run, are officially indicated as Mark I (1968–1969), Mark II (1969–1973), Mark III (1973–1975) and Mark IV (1975–1976).[12][13] Mark I comprised the founding members of Deep Purple, Ritchie Blackmore (guitar), Rod Evans (vocals), Jon Lord (keyboards), Ian Paice (drums) and Nick Simper (bass), while Mark II was the most commercially successful line-up, with Ian Gillan (vocals) and Roger Glover (bass) replacing Evans and Simper. Mark III saw David Coverdale (vocals) and Glenn Hughes (bass and vocals) replace Gillan and Glover, while Mark IV featured Tommy Bolin (guitar) replacing Blackmore. Mark II was revived from 1984–1989 and again from 1992–1993, with Joe Lynn Turner (vocals) replacing Gillan in the intervening 1989–1992 period. Mark II definitively ended in 1993, when Blackmore left Deep Purple for the second and final time. He was replaced temporarily by Joe Satriani (guitar) and then permanently by Steve Morse (guitar). In 2002 Don Airey (keyboards) replaced Lord, which saw Deep Purple settle into its longest running line-up, unchanged for the next twenty years, until Morse announced his departure from the band in 2022. His place was taken by Simon McBride (guitar). Ian Paice, Roger Glover, Ian Gillan, Don Airey and Simon McBride comprise the current line-up of Deep Purple.

Deep Purple were ranked number 22 on VH1’s Greatest Artists of Hard Rock programme,[14] and a poll on radio station Planet Rock ranked them 5th among the «most influential bands ever».[15] The band received the Legend Award at the 2008 World Music Awards. Deep Purple (specifically Blackmore, Lord, Paice, Gillan, Glover, Coverdale, Evans, and Hughes) were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2016.

History[edit]

Beginnings (1967–1968)[edit]

In 1967, former Searchers drummer Chris Curtis contacted London businessman Tony Edwards, in the hope he would manage a new group he was putting together, to be called Roundabout. Curtis’ vision was a «supergroup» where the band members would get on and off, like a musical roundabout. Impressed with the plan, Edwards agreed to finance the venture with his two business partners John Coletta and Ron Hire, who comprised Hire-Edwards-Coletta Enterprises (HEC).[16]

The first recruit to the band was classically trained Hammond organ player Jon Lord, Curtis’s flatmate, who had most notably played with the Artwoods (led by Art Wood, brother of future Faces and Rolling Stones guitarist Ronnie Wood, and including Keef Hartley).[17] Lord was then performing in a backing band for the vocal group The Flower Pot Men (formerly known as the Ivy League), along with bassist Nick Simper and drummer Carlo Little. (Simper had previously been in Johnny Kidd and the Pirates, and survived the 1966 car crash that killed Kidd.) Lord alerted the two that he had been recruited for the Roundabout project, after which Simper and Little suggested guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, whom Lord had never met.[18] Simper had known Blackmore since the early 1960s when his first band, the Renegades, debuted around the same time as one of Blackmore’s early bands, the Dominators.[19]

HEC persuaded Blackmore to travel in from Hamburg to audition for the new group. He was making a name for himself as a studio session guitarist, and had also been a member of the Outlaws, Screaming Lord Sutch, and Neil Christian, the latter artist prompting Blackmore’s move to Germany. Curtis’s erratic behaviour and lifestyle, fuelled by his use of LSD, caused him to display a sudden lack of interest in the project he had started, forcing HEC to dismiss him from Roundabout. However, HEC was now intrigued with the possibilities Lord and Blackmore brought and persuaded Ritchie to return from Hamburg a second time. Lord and Blackmore began the recruitment of additional members, retaining Tony Edwards as their manager.[20] Lord convinced Nick Simper to join on bass, but Blackmore insisted they leave Carlo Little behind in favour of drummer Bobby Woodman.[18] Woodman was the former drummer for Vince Taylor’s Play-Boys (for whom he had played under the name Bobbie Clarke). The band, still calling themselves Roundabout, started rehearsing and writing in Cadogan Gardens in South Kensington.

In March 1968, Lord, Blackmore, Simper and Woodman moved into Deeves Hall, a country house in South Mimms, Hertfordshire.[21][22] The band would live, write and rehearse at the house; it was fully kitted out with the latest Marshall amplification[23] and, at Lord’s request, a Hammond C3 organ.[16] According to Simper, «dozens» of singers were auditioned (including Rod Stewart and Woodman’s friend Dave Curtiss)[16] until the group heard Rod Evans of club band the Maze, and thought his voice fitted their style well. Tagging along with Evans was his band’s drummer Ian Paice. Blackmore had seen an 18-year-old Paice on tour with the Maze in Germany in 1966, and had been impressed by his drumming. The band hastily arranged an audition for Paice, given that Woodman was vocally unhappy with the direction of the band’s music.[18] Both Paice and Evans won their respective jobs, and the line-up was complete.[24]

During a brief tour of Denmark and Sweden in April, in which they were still billed as Roundabout, Blackmore suggested a new name: «Deep Purple», named after his grandmother’s favourite song.[20][23] The group had resolved to choose a name after everyone had posted one on a board in rehearsal. Second to Deep Purple was «Concrete God», which the band thought was too harsh to take on.[25][26]

Mark I (1968–1969): Shades of Deep Purple, The Book of Taliesyn and Deep Purple[edit]

In May 1968, the band moved into Pye Studios in London’s Marble Arch to record their debut album, Shades of Deep Purple, which was released in America in July by Tetragrammaton Records, and in Britain in September by EMI Records.[27] Vanilla Fudge was a notable influence on the band, Lord and Blackmore even claiming that, when the group started, they wanted to be a «Vanilla Fudge clone».[28] The group had success in North America with a cover of Joe South’s «Hush», and by September 1968, the song had reached number 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the US and number 2 in the Canadian RPM chart, pushing the Shades LP up to No. 24 on Billboard‘s pop albums chart.[29][30] The following month, Deep Purple were booked to support Cream on the US leg of their Goodbye tour.[29]

The band’s second album, The Book of Taliesyn, was quickly recorded, then released in North America in October 1968 to coincide with the tour. The album included Neil Diamond’s «Kentucky Woman», which cracked the Top 40 in both the US (No. 38 on the Billboard chart) and Canada (No. 21 on the RPM chart),[31][32] though sales for the album were not as strong (No. 54 in US, No. 48 in Canada).[33][34] The Book of Taliesyn would not be released in the band’s home country until the following year and, like its predecessor, it failed to have much impact in the UK Albums Chart.

Early in 1969, the band released the non-album single «Emmaretta», named after Emmaretta Marks, then a cast member of the musical Hair, whom Evans was trying to seduce.[35] By March of that year, the band had completed recording for their third album, Deep Purple. The album included the track «April», which featured strings and woodwind, showcasing Lord’s classical antecedents such as Bach and Rimsky-Korsakov. This would be the last recording by Deep Purple Mark I.

Deep Purple’s North American record label, Tetragrammaton, delayed production of the Deep Purple album until after the band’s 1969 American tour ended. This, as well as lackluster promotion by the nearly broke label, caused the album to sell poorly, finishing well out of the Billboard Top 100. Soon after Deep Purple was finally released in late June 1969, Tetragrammaton went out of business, leaving the band with no money and an uncertain future (Tetragrammaton’s assets were eventually assumed by Warner Bros. Records, who would release Deep Purple’s records in the US throughout the 1970s).

During the 1969 American tour, Lord and Blackmore met with Paice to discuss their desire to progress the heavy rock side of the band further. Having decided that Evans and Simper would not fit well with the style they envisioned, both were replaced that summer.[36] Paice stated, «A change had to come. If they hadn’t left, the band would have totally disintegrated.» Both Simper and Blackmore noted that Rod Evans already had one foot out of the door. Simper said that Evans had met a girl in Hollywood and had eyes on being an actor, while Blackmore explained, «Rod just wanted to go to America and live in America.»[37] Evans and Simper would go on to co-form the bands Captain Beyond and Warhorse respectively.

Mark II (1969–1973): Concerto for Group and Orchestra, In Rock, Fireball, Machine Head, Made in Japan and Who Do We Think We Are[edit]

In search of a replacement vocalist, Blackmore set his own sights on 19-year-old singer Terry Reid. Though he found the offer «flattering», Reid was still bound by an exclusive recording contract with his producer Mickie Most and more interested in his solo career.[38] Blackmore had no other choice but to look elsewhere. The band sought out singer Ian Gillan from Episode Six, a band that had released several singles in the UK without achieving any great commercial success. Six’s drummer Mick Underwood – an old comrade of Blackmore’s from his days in the Outlaws – introduced the band to Gillan and bassist Roger Glover. According to Nick Simper, «Gillan would join only with Roger Glover.»[39] This effectively killed Episode Six, which gave Underwood a persistent feeling of guilt that lasted nearly a decade, until Gillan recruited him for his new post-Purple band in the late 1970s. According to Blackmore, Deep Purple was only interested in Gillan and not Glover, but Glover was retained on the advice of Ian Paice.[37]

«He turned up for the session…he was their [Episode Six’s] bass player. We weren’t originally going to take him until Paicey said, ‘he’s a good bass player, let’s keep him.’ So I said okay.»

— Ritchie Blackmore on the hiring of Roger Glover.[37]

This created Deep Purple Mark II, whose first release was a Roger Greenaway-Roger Cook tune titled «Hallelujah».[40] At the time of its recording, Nick Simper still thought he was in the band and had called John Coletta to inquire about the recording dates for the song. He then found that the song had already been recorded with Glover on bass. The remaining original members of Deep Purple then instructed management to inform Simper that he had been officially replaced.[41] Despite television appearances to promote the «Hallelujah» single in the UK, the song flopped.[40] Blackmore had told the British weekly music newspaper Record Mirror that the band «need to have a commercial record in Britain», and described the song as «an in-between sort of thing»—a compromise between the type of material the band would normally record, and openly commercial material.[40]

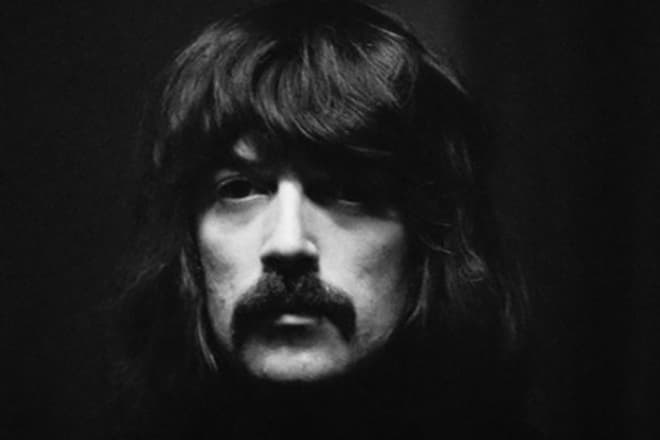

Ritchie Blackmore in Hannover, Germany, 1970

In September 1969, the band gained some much-needed publicity in the UK with the Concerto for Group and Orchestra, a three-movement epic composed by Lord as a solo project and performed by the band at the Royal Albert Hall in London with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Malcolm Arnold.[29] Alongside Days of Future Passed by the Moody Blues and Five Bridges by the Nice, it was one of the first collaborations between a rock band and an orchestra. This live album became their first release with any kind of chart success in the UK.[42] Gillan and Blackmore were less than happy at the band being tagged as «a group who played with orchestras», both feeling that the Concerto was a distraction that would get in the way of developing their desired hard-rocking style. Lord acknowledged that while the band members were not keen on the project going in, at the end of the performance «you could have put the five smiles together and spanned the Thames.» Lord would also write the Gemini Suite, another orchestra/group collaboration in the same vein, for the band in late 1970, although the band’s recording of the piece wouldn’t be released until 1993. In 1975, Blackmore stated that he thought the Concerto for Group and Orchestra wasn’t bad but the Gemini Suite was horrible and very disjointed.[43] Roger Glover later claimed Jon Lord had appeared to be the leader of the band in the early years.[44]

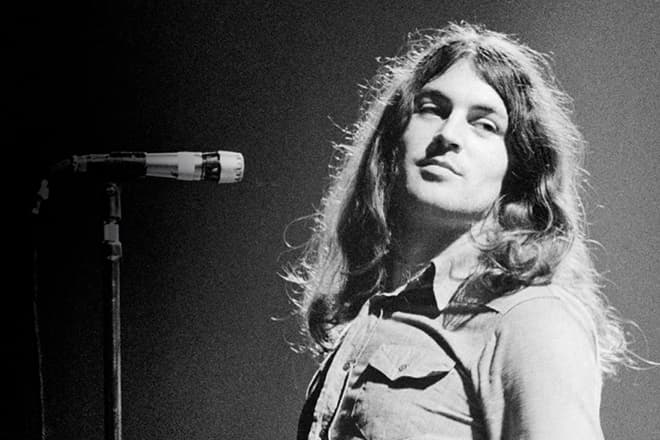

Mark II live in Germany 1970.

Shortly after the orchestral release, Mark II began a hectic touring and recording schedule that was to see little respite for the next four years. The second album, and first studio album, of the Mark II era, released in 1970, was In Rock (a name supported by the album’s Mount Rushmore-inspired cover), which contained the then-concert staples «Speed King», «Into The Fire» and «Child in Time». The non-album single «Black Night», released around the same time, finally put Deep Purple into the UK Top Ten.[45] The interplay between Blackmore’s guitar and Lord’s distorted organ, coupled with Gillan’s powerful, wide-ranging vocals and the rhythm section of Glover and Paice, now started to take on a unique identity that separated the band from its earlier albums.[5] Along with Zeppelin’s Led Zeppelin II and Sabbath’s Paranoid, In Rock codified the budding heavy metal genre.[2]

Mark II in 1971. Left to right: Lord, Glover, Gillan, Blackmore, Paice.

On the album’s development, Blackmore stated: «I got fed up with playing with classical orchestras, and thought, ‘well, this is my turn.’ Jon was into more classical. I said, ‘well you’ve done that, I’ll do rock, and whatever turns out best we’ll carry on with.'»[46] In Rock performed well, especially in the UK where it reached No. 4, while the «Black Night» single reached No. 2 on the UK Singles Chart, and the band performed the song live on the BBC’s Top of the Pops.[47][48] In addition to increasing sales in the UK, the band were making a name for themselves as a live act, particularly with regard to the sheer volume of their shows and the improvisational skills of Blackmore and Lord. Said Lord, «We took from jazz, we took from old fashioned rock and roll, we took from the classics. Ritchie and myself…used to swap musical jokes and attacks. He would play something, and I’d have to see if I could match it. That provided a sense of humour, a sense of tension to the band, a sense of, ‘what the hell’s going to happen next?’ The audience didn’t know, and nine times out of ten, neither did we!»[16]

A second Mark II studio album, the creatively progressive Fireball, was issued in the summer of 1971, reaching number 1 on the UK Albums Chart.[48] The title track «Fireball» was released as a single, as was «Strange Kind of Woman», not from the album but recorded during the same sessions (although it replaced «Demon’s Eye» on the US version of the album).[49] «Strange Kind of Woman» became their second UK Top 10 single, reaching No. 8.[48]

Within weeks of Fireball‘s release, the band were already performing songs planned for the next album. One song (which later became «Highway Star») was performed at the first show of the Fireball tour, having been written on the bus to a show in Portsmouth, in answer to a journalist’s question: «How do you go about writing songs?» On 24 October 1971 during the US leg of the Fireball tour, the band was set to play the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago when Ian Gillan contracted hepatitis, forcing the band to play without him, with bassist Glover singing the set. After this, the rest of the US dates were canceled and the band flew home.[50]

In early December 1971, the band travelled to Switzerland to record Machine Head. The album was due to be recorded at the Montreux Casino using the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio, but a fire during a Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention concert, caused by a man firing a flare gun into the ceiling, burned down the Casino. This incident famously inspired the song «Smoke on the Water». The album was later recorded in a corridor at the nearby empty Grand Hôtel de Territet, with the exception of the music track to «Smoke on the Water». That was recorded at a vacant theatre called The Pavillon before the band was asked to leave.[51][52][53] On recording «Smoke on the Water», Blackmore stated to BBC Radio 2: “We did the whole thing in about four takes because we had to. The police were banging on the door. We knew it was the police, but we had such a good sound in this hall. We were waking up all the neighbours for about five miles in Montreux, because it was echo-ing through the mountains. I was just getting the last part of the riff down, we’d just finished it, when the police burst in and said ‘you’ve got to stop’. We had the track down.»[54]

Continuing to progress the musical direction of the previous two albums, Machine Head was released in late March 1972 and became one of the band’s most famous releases. It was the band’s second No. 1 album in the UK while re-establishing them in North America, hitting No. 7 in the US and No. 1 in Canada.[48] It included tracks that became live classics, such as «Highway Star», «Space Truckin'», «Lazy» and «Smoke on the Water», the last of which remains Deep Purple’s most famous song.[45][55] They continued to tour and record at a rate that would be rare thirty years on; when Machine Head was recorded, the group had only been together three-and-a-half years, yet it was their sixth studio album and seventh album overall.

In January 1972 the band returned to tour the US once again, then headed over to play Europe before resuming US dates in March. While in America Blackmore contracted hepatitis, and the band attempted one show in Flint, Michigan, without a guitarist before attempting to acquire the services of Al Kooper, who rehearsed with the band before bowing out, suggesting Spirit guitarist Randy California instead. California played one show with the group, in Quebec City, Quebec on 6 April, but the rest of this tour was cancelled as well.[56]

The band returned to the US in late May 1972 to undertake their third North America tour (of four total that year). A Japan tour in August of that year led to a double live album, Made in Japan. Originally intended as a Japan-only release, its worldwide release became an instant hit, reaching platinum status in five countries, including the US. It remains one of rock music’s most popular and highest selling live albums.[57]

Mark II continued to work and released the album Who Do We Think We Are in 1973. Spawning the hit single «Woman from Tokyo», the album hit No. 4 in the UK charts and No. 15 in the US chart, while achieving gold record status faster than any Deep Purple album released up to that time.[58][59] But internal tensions and exhaustion were more noticeable than ever. Following the successes of Machine Head and Made in Japan, the addition of Who Do We Think We Are made Deep Purple the top-selling artists of 1973 in the US.[60][61]

Gillan admitted in a 1984 interview that the band was pushed by management to complete the Who Do We Think We Are album on time and go on tour, although they badly needed a break.[62] The bad feelings, including tensions with Blackmore, culminated in Gillan quitting the band after their second tour of Japan in the summer of 1973, followed by the dismissal of Glover, at Blackmore’s insistence.[63][64][65] In interviews later, Lord called the end of Mark II while the band was at its peak «the biggest shame in rock and roll; God knows what we would have done over the next three or four years. We were writing so well.»[66]

Mark III (1973–1975): Burn and Stormbringer[edit]

The band hired Midlands bassist/vocalist Glenn Hughes, formerly of Trapeze. According to Paice, Glover told him and Lord a few months before his official termination that he wanted to leave the band, so they had started to drop in on Trapeze shows. After acquiring Hughes, they debated continuing as a four-piece, with Hughes as bassist and lead vocalist.[67][68] According to Hughes, he was told the band was bringing in Paul Rodgers of Free as a co-lead vocalist, but by that time Rodgers had just started Bad Company.[69] «They did ask», Rodgers recalled, «and I spoke to all of them at length about the possibility. Purple had toured Australia with Free’s final lineup. I didn’t do it because I was very much into the idea of forming Bad Company.»[70] Instead, auditions were held for lead vocal replacements. They settled on David Coverdale, an unknown singer from Saltburn in north-east England, primarily because Blackmore liked his masculine, blues-tinged voice.[68]

Collage of Mark III in 1975, with Hughes (left), Coverdale (top), Lord (middle), Paice (bottom), Blackmore (right).

Deep Purple Mark III’s first album, Burn, released in February 1974, was highly successful, reaching No. 3 in the UK and No. 9 in the US, and was followed by another world tour.[48] The title track, which opens the album and would open most concerts during the Mark III and IV eras, was a conscious effort by the band to embrace the progressive rock movement, which was popularised at the time by bands such as Yes, King Crimson, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Genesis and Gentle Giant.

Mark III embarked on a spring tour that included shows at Madison Square Garden, New York, on 13 March, and Nassau Coliseum four days later.[71] The band co-headlined (with Emerson, Lake & Palmer) the California Jam festival at Ontario Motor Speedway in Ontario, southern California, on 6 April 1974. Attracting over 250,000 fans, the festival also included 1970s rock giants Black Sabbath, Eagles and Earth, Wind & Fire.[72] Portions of the show were telecast on ABC Television in the US, exposing the band to a wider audience. During the show Blackmore, accidentally, blew up the stage, when his intention to set fire to his amplifiers, for visual effect, didn’t go according to plan, although he was still pleased with the result.[73] A month later, the band’s 22 May performance at the Gaumont State Cinema in Kilburn, London, was recorded and later released in 1982 as Live in London.

Hughes and Coverdale brought vocal harmonies and elements of funk and blues, respectively, to the band’s music, a sound that was even more apparent on the late 1974 release Stormbringer.[68] Along with the title track, the Stormbringer album had a number of songs that received much radio play, such as «Lady Double Dealer», «The Gypsy» and «Soldier of Fortune», and the album reached No. 6 in the UK and No. 20 on the US Billboard chart.[48] Blackmore publicly disliked most of the album, however, particularly it’s funk and soul elements, derisively calling it «shoeshine music».[74][75][76] A new live album, Made in Europe, culled from three shows on the Stormbringer tour, was assembled during the summer of 1975, but wouldn’t see release until late 1976. Blackmore left the band on 21 June 1975 to form his own band with Ronnie James Dio of Elf, called Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow, shortened to Rainbow after the first album.[77]

Mark IV (1975–1976): Come Taste the Band[edit]

Deep Purple Mark IV in 1976. Standing left to right: David Coverdale, Ian Paice; seated left to right: Glenn Hughes, Tommy Bolin, Jon Lord

Following Blackmore’s departure, the group considered disbanding but decided to continue and find another guitarist. Clem Clempson (Colosseum, Humble Pie), Zal Cleminson (The Sensational Alex Harvey Band), Mick Ronson (The Spiders From Mars) and Rory Gallagher were considered, and the final choice was American Tommy Bolin.[78] There are at least two versions of the Bolin recruitment story: Coverdale claims to have been the one who suggested auditioning Bolin.[79] «He walked in, thin as a rake, his hair coloured green, yellow and blue with feathers in it. Slinking along beside him was this stunning Hawaiian girl in a crochet dress with nothing on underneath. He plugged into four Marshall 100-watt stacks and…the job was his.» But in an interview published by Melody Maker in June 1975, Bolin claimed that he came to the audition following a recommendation from Blackmore.[80] Bolin had been a member of many late-1960s bands – Denny & The Triumphs, American Standard, and Zephyr, which released three albums from 1969 to 1972. Before he joined Deep Purple, Bolin’s best-known recordings had been made as a session musician on Billy Cobham’s 1973 jazz fusion album Spectrum, and as lead guitarist on two post-Joe Walsh James Gang albums: Bang (1973) and Miami (1974). He had also played with Dr. John, Albert King, the Good Rats, Moxy and Alphonse Mouzon, and was busy working on his first solo album, Teaser, when he accepted the invitation to join Deep Purple.[81]

The resulting album from Deep Purple Mark IV, Come Taste the Band, was released in October 1975, one month before Bolin’s Teaser album. Despite mixed reviews and middling sales (#19 in the UK and #43 in the US), the collection revitalised the band once again, bringing a new, extreme funk edge to their hard rock sound.[82] Bolin’s influence was crucial, and with encouragement from Hughes and Coverdale, the guitarist developed much of the album’s material. Despite Bolin’s talents, his personal problems with hard drugs began to surface. During the Come Taste the Band tour many fans openly booed Bolin’s inability to play solos like Ritchie Blackmore, not realising that Bolin was physically hampered by his addiction. At this same time, as he admitted in interviews years later, Hughes was suffering from cocaine addiction.[83]

The last show on the tour was on 15 March 1976 at the Liverpool Empire Theatre.[84] The break-up was finally made public in July 1976, with then-manager Rob Cooksey issuing a statement: «the band will not record or perform together as Deep Purple again».[85] Bolin went on to record his second solo album, Private Eyes. On 4 December 1976, after a show in Miami supporting Jeff Beck, Bolin was found unconscious by his girlfriend and bandmates. Unable to wake him, she hurriedly called paramedics, but it was too late. The official cause of death was multiple-drug intoxication. Bolin was 25 years old.[81]

Band split (1976–1984)[edit]

After the break-up, most of the members of Deep Purple went on to have considerable success in a number of other bands, including Rainbow (1975–1984, Ritchie Blackmore and, from 1979, Roger Glover), Whitesnake (1978–present, David Coverdale, Jon Lord until 1984 and Ian Paice from 1979–1982) and Gillan (1978–1982, Ian Gillan). Ian Gillan also joined Black Sabbath from the end of 1982 to the beginning of 1984 (Glenn Hughes would also join Sabbath for a short time later in the 1980s). The now-defunct Deep Purple began to gain a type of mystical status, with fan-driven reissues and newly assembled live and compilation albums being released throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s.[86] This fueled a number of promoter-led attempts to get the band to reform, especially with the revival of the hard rock market in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In 1980, a touring version of the band surfaced with Rod Evans, who had left Captain Beyond at the end of 1973, as the only member who had ever been in Deep Purple, eventually ending in successful legal action from the legitimate Deep Purple camp over unauthorised use of the name. Evans was ordered to pay damages of US$672,000 for using the band name without permission.[87]

Mark II reunion (1984–1989): Perfect Strangers and The House of Blue Light[edit]

Mark II at the Cow Palace, San Francisco, 1985. Pictured left to right: Glover, Gillan, Paice, Blackmore (not pictured: Lord).

In April 1984, eight years after the demise of Deep Purple, a full-scale (and legal) reunion took place with the «classic» Mark II line-up of 1969–1973: Jon Lord, Ian Paice, Ritchie Blackmore, Ian Gillan and Roger Glover.[88][89] The reformed band signed a worldwide deal with PolyGram, with Mercury Records releasing their albums in the US, and Polydor Records in the UK and other countries. The album Perfect Strangers was recorded in Vermont and released in October 1984. The album was commercially successful, reaching number 5 in the UK Albums Chart and number 12 on the Billboard 200 in the US.[48][90] The album included the singles and concert staples «Knockin’ At Your Back Door» and «Perfect Strangers».[91] Perfect Strangers became the second Deep Purple album to go platinum in the US, following Machine Head (Made in Japan would also finally hit platinum status in the US in 1986, the same year Machine Head increased to double platinum).[92]

The reunion tour followed, starting in Australia and winding its way across the world to North America, then into Europe by the following summer. Financially, the tour was also a tremendous success. In the US, the 1985 tour out-grossed every other artist except Bruce Springsteen.[93] The UK homecoming saw the band perform a concert at Knebworth on 22 June 1985 (with main support from the Scorpions; also on the bill were UFO and Meat Loaf), where the weather was bad (torrential rain and 6 inches (15 cm) of mud) in front of 80,000 fans.[94] The gig was called the «Return of the Knebworth Fayre».[95]

Mark II followed Perfect Strangers with The House of Blue Light in 1987, which was supported by another world tour (interrupted after Blackmore broke a finger on stage while trying to catch his guitar after throwing it in the air). A new live album Nobody’s Perfect, which was culled from several shows on this tour, was released in 1988. In the UK a new Mark II version of «Hush» was also released in 1988 to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of Deep Purple.

Mark V (1989–1992): Slaves and Masters[edit]

Deep Purple in 1991. Back: Jon Lord; front left to right: Joe Lynn Turner, Ritchie Blackmore, Ian Paice, Roger Glover.

Gillan was fired in 1989; his relations with Blackmore had again soured, and their musical differences had diverged too far. Originally, the band intended to recruit Survivor frontman Jimi Jamison as Gillan’s replacement. After two weeks of sessions with the band, however, Jamison announced he could not join Deep Purple owing to complications with Scotti Brothers Records, his record label.[96][97] Eventually, after auditioning several high-profile candidates, including Brian Howe (White Spirit, Ted Nugent, Bad Company), Doug Pinnick (King’s X), Australians Jimmy Barnes (Cold Chisel) and John Farnham (Little River Band), Terry Brock (Strangeways, Giant) and Norman «Kal» Swan (Tytan, Lion, Bad Moon Rising),[98] the band agreed on Joe Lynn Turner, who had previously been a member of Rainbow with Blackmore and Glover. This Mark V line-up recorded just one album, Slaves and Masters (1990), and undertook a world tour for most of 1991. The album achieved modest success, reaching number 45 in the UK and number 87 in the US Billboard chart,[90] with some fans and critics feeling the music was closer in style to Rainbow than to Deep Purple.

Second Mark II reunion (1992–1993) and Mark VI (1993–1994): The Battle Rages On…[edit]

With the tour complete, the band set to work on another album, the early sessions of which saw Turner being forced out. 1993 would be Deep Purple’s twenty-fifth anniversary year, with Lord, Paice and Glover (and the record company) wanting Gillan back for another Mark II reunion to celebrate this milestone. Although Blackmore preferred Turner to remain in the group, he eventually, grudgingly, relented, after requesting and eventually receiving 250,000 dollars in his bank account[99] and Mark II completed the aptly-titled The Battle Rages On… in 1993. Despite going ahead with another reunion, Blackmore still disagreed with the decision, which led to a new level of tension between himself and the rest of the band, particularly Gillan. Of particular contention was that Gillan reworked much of the existing material which had been written with Turner for the new album. Blackmore felt Gillan’s rewrites made the songs less melodic than they had been in their original versions.[100] The band began a European tour, which was documented on the live album Come Hell or High Water, released in 1994. A live home video of the same name was also released, covering a show in Birmingham, England, with an album of the complete show being released in 2006 as Live at the NEC, but this latter release was quickly withdrawn after Gillan publicly complained, feeling it represented a bad time in the group’s history:[101] «It was one of the lowest points of my life – all of our lives, actually».[101] Ritchie Blackmore left Deep Purple for the second and final time, after a show in Helsinki, Finland on 17 November 1993.[101] Joe Satriani was drafted to complete the Japanese dates in December and stayed on for a European summer tour in 1994. He was asked to join permanently, but his commitments to his contract with Epic Records prevented this. The band unanimously chose Dixie Dregs/Kansas guitarist Steve Morse to become Satriani’s successor on August 23, 1994.[102]

«Musically, it was very satisfying. The setlist was straight out of classic rock heaven. And the band were just great. Their timing was just fantastic.»

— Guitarist Joe Satriani on his brief period with Deep Purple.[103]

Mark VII (1994–2002): Purpendicular and Abandon[edit]

Morse’s arrival revitalised the band creatively, and in 1996 a new album titled Purpendicular was released, showing a wide variety of musical styles. Though in the post-grunge mid ’90s it was no surprise that it never made chart success on the Billboard 200 in the U.S.[90] This Mark VII line-up then released a new live album Live at The Olympia ’96 in 1997. With a revamped set list to tour, Deep Purple enjoyed successful tours throughout the rest of the 1990s, releasing the harder-sounding Abandon in 1998, and touring with renewed enthusiasm.

Deep Purple in 1995. Left to right: Steve Morse, Roger Glover, Jon Lord, Ian Gillan, Ian Paice.

In 1999, Lord, with the help of a Dutch fan, who was also a musicologist and composer, Marco de Goeij, painstakingly recreated the Concerto for Group and Orchestra, the original score having been lost. It was once again performed at the Royal Albert Hall in September 1999, this time with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paul Mann.[104] The concert also included songs from each member’s solo careers, as well as a short Deep Purple set, and the occasion was commemorated on the 2000 album In Concert with The London Symphony Orchestra.[104] 2001 saw the release of the box set The Soundboard Series, containing concerts from the 2001 Australian Tour plus two from Tokyo, Japan.[105] Much of the next few years was spent on the road touring. The group continued forward until 2002 when founding member Lord (who, along with Paice, was the only member to be in all incarnations of the band) announced his amicable retirement from the band to pursue personal projects (especially orchestral work). Lord left his Hammond organ to his replacement, rock keyboard veteran Don Airey, who had helped Deep Purple out when Lord’s knee was injured in 2001. Airey had previously worked with Glover as a member of Rainbow from 1979-1982.

Mark VIII (2002–2022): Bananas, Rapture of the Deep, Now What?!, Infinite, Whoosh! and Turning to Crime[edit]

In 2003, the new Mark VIII line-up released Bananas, their first studio album in five years, and began touring in support. EMI Records refused a contract extension with Deep Purple, possibly because of lower than expected sales. Actually In Concert with The London Symphony Orchestra sold more than Bananas.[106]

The band played at the Live 8 concert in Park Place (Barrie, Ontario) in July 2005, and in October released their next album, Rapture of the Deep, which was followed by the Rapture of the Deep tour. Both Bananas and Rapture of the Deep were produced by Michael Bradford.[107] In 2009 Ian Gillan said, «Record sales have been steadily declining, but people are prepared to pay a lot for concert tickets.»[108] In addition, Gillan stated: «I don’t think happiness comes with money.»[108]

Deep Purple did concert tours in 48 countries in 2011.[109] The Songs That Built Rock Tour used a 38-piece orchestra, and included a performance at the O2 Arena in London.[110] Until May 2011, the band members had disagreed about whether to make a new studio album, because it would not really make money any more. Roger Glover stated that Deep Purple should make a new studio album «even if it costs us money.»[111] In early 2011, David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes told VH1 they would like to reunite Mark III for the right opportunity, such as a benefit concert.[112] The current band’s chief sound engineer on nine years of tours, Moray McMillin, died in September 2011, aged 57.[113] After a lot of songwriting sessions in Europe,[114] Deep Purple decided to record through the summer of 2012, and the band announced they would release their new studio album in 2013.[109] Steve Morse announced to French magazine Rock Hard that the new studio album would be produced by Bob Ezrin.[115]

Glover and Morse in 2013 in Spain

On 16 July 2012 the band’s co-founding member and former organ player, Jon Lord, died in London, aged 71.[116][117] In December 2012 Roger Glover stated that the band had completed work on 14 songs for a new studio album, with 11 or 12 tracks set to appear on the final album to be released in 2013.[118][119] On 26 February 2013 the title of the band’s nineteenth studio album was announced as Now What?!, which was recorded and mixed in Nashville, Tennessee, and released on 26 April 2013.[120] The album contains the track “Vincent Price”, named after the horror actor who had worked with both Gillan and Glover earlier in their careers.[121] The band’s performance at Waken Open Air later 2013, and in Tokyo in 2014, were released in 2015 as the live albums and DVDs From the Setting Sun… and …to the Rising Sun.

Deep Purple live at Wacken Open Air in 2013. Left to right: Ian Paice, Roger Glover, Steve Morse, Don Airey, Ian Gillan.

On 25 November 2016, Deep Purple announced Infinite as the title of their twentieth studio album,[114] which was released on 7 April 2017.[122] In support for the album, Deep Purple embarked on 13 May 2017 in Bucharest, Romania on The Long Goodbye Tour. At the time of the tour’s announcement in December 2016, Paice told the Heavyworlds website it «may be the last big tour», adding that the band «don’t know». He described the tour as being long in duration and said: «We haven’t made any hard, fast plans, but it becomes obvious that you cannot tour the same way you did when you were 21. It becomes more and more difficult. People have other things in their lives, which take time. But never say never.»[123] On 3 February 2017, Deep Purple released a video version of «Time for Bedlam», the first track taken from the new album and the first new Deep Purple track for almost four years.[124]

On 29 February 2020, a new track, «Throw My Bones» was released online, with a new album Whoosh! planned for release in June.[125][126] The release of the full-length album would later be postponed to 7 August 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[127] A review in NME said the album sounded nothing like contemporary music of 2020, but suggested that «maybe that’s a good thing».[128] Gillan confirmed in an interview on 4 August 2020 that he and the other members of Deep Purple have no immediate plans to retire.[129]

On October 6, 2021, the band had announced the title of their covers album, Turning to Crime which was released on 26 November 2021.[130][131]

Mark IX (2022–present)[edit]

The current lineup of Deep Purple live in Germany, July 2022. Left to right: Roger Glover, Ian Paice, Ian Gillan, Don Airey, Simon McBride.

In March 2022, Morse announced that he had to take a hiatus from the band after his wife was diagnosed with cancer. The band, who had recently returned to live performances, continued touring with Simon McBride, formerly of Sweet Savage, standing in for Morse who at that point officially remained in the band.[132] On 23 July 2022, it was announced that Morse would be leaving permanently in order to focus on caring for his wife as she battles cancer.[133] Later that September, McBride was made an official member of the band.[134]

Glover, Gillan and McBride performing in 2022

In June 2022, Gillan announced that the band plans to work on their twenty-third studio album after the conclusion of the Whoosh! tour: «Deep Purple has got a writing session booked in March 2023, which I believe is to get started on thinking about our next record.»[135]

Legacy[edit]

«In 1971, there were only three bands that mattered, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and Deep Purple.»

— Def Leppard vocalist Joe Elliot.[3]

Deep Purple are cited as one of the pioneers of hard rock and heavy metal, along with Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath.[2][136] The BBC states they “made up the ‘unholy trinity’ of British hard rock and heavy metal during the genre’s 1970s golden age.”[54] The group have influenced a number of rock and metal bands including Metallica,[137] Judas Priest,[138] Queen,[139] Aerosmith,[140] Van Halen,[141] Alice in Chains,[142] Pantera,[143] Bon Jovi,[144] Europe,[145] Rush,[146] Motörhead,[147] and many new wave of British heavy metal bands such as Iron Maiden,[148] and Def Leppard.[149] Iron Maiden’s bassist and primary songwriter, Steve Harris, states that his band’s «heaviness» was inspired by «Black Sabbath and Deep Purple with a bit of Zeppelin thrown in.»[150] Van Halen founder Eddie Van Halen named “Burn” one of his favourite ever guitar riffs.[54] Queen guitarist Brian May referred to Ritchie Blackmore as «a trail blazer and technically incredible — unpredictable in every possible way…you never knew what you were gonna see when you went to see Purple».[151] Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich states, «When I was nine years old it was all about Deep Purple. My all time favourite [album] is still Made in Japan«.[152] The band’s 1974 album Stormbringer was the first record owned by Till Lindemann, vocalist of German Neue Deutsche Härte band Rammstein.[153]

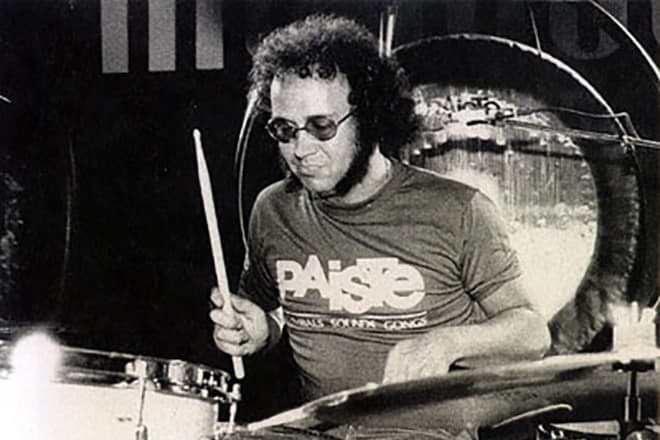

Ian Paice (pictured in 2017). Ranked number 21 in Rolling Stone’s 100 Greatest Drummers list, his magazine entry states, «without Deep Purple’s only continuous member, there would be no heavy metal drumming.»[154]

While firmly placed in the hard rock and heavy metal categories, Deep Purple’s music frequently incorporated elements of progressive rock and blues rock, prompting Canadian journalist Martin Popoff to once call the band «a reference point of a genre in metal without categorisation.»[155]

In 2000, Deep Purple were ranked number 22 on VH1’s «100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock» programme.[156] At the 2008 World Music Awards, the band received the Legend Award.[157] In 2011, they received the Innovator Award at the 2011 Classic Rock Awards in London.[158] A Rolling Stone readers’ poll in 2012 ranked Made in Japan the sixth best live album of all time.[57] As part of the 40th anniversary celebrations of Machine Head (1972), Re-Machined: A Tribute to Deep Purple’s Machine Head was released in 2012.[159] This tribute album included Iron Maiden, Metallica, Steve Vai, Carlos Santana, The Flaming Lips, Black Label Society, Papa Roach vocalist Jacoby Shaddix, Chickenfoot (former Van Halen members Sammy Hagar and Michael Anthony, guitarist Joe Satriani and Chad Smith of Red Hot Chili Peppers) and the supergroup Kings of Chaos (Def Leppard vocalist Joe Elliott, Steve Stevens, and former Guns N’ Roses members Duff McKagan and Matt Sorum).[159]

In 2007, Deep Purple were one of the featured artists in the fourth episode of the BBC/VH1 series Seven Ages of Rock – an episode focusing on heavy metal.[160] In May 2019 the group received the Ivor Novello Award for International Achievement from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers, and Authors.[161]

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame[edit]

Before October 2012, Deep Purple had never been nominated for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (though they have been eligible since 1993), but were nominated for induction in 2012 and 2013.[162][163] Despite ranking second in the public’s vote on the Rock Hall fans’ ballot, which had over half a million votes, they were not inducted by the Rock Hall committee.[164] Kiss bassist Gene Simmons and Rush bassist Geddy Lee commented that Deep Purple should obviously be among the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees.[165][166] There have been criticisms in the past over Deep Purple not having been inducted. Toto guitarist Steve Lukather commented, «they put Patti Smith in there but not Deep Purple? What’s the first song every kid learns how to play? [«Smoke on the Water»] … And they’re not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? … the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has lost its cool because of the glaring omissions.»[167] Guns N’ Roses and Velvet Revolver guitarist Slash expressed his surprise and disagreement regarding the non-induction of Deep Purple: «The list of people who haven’t even been nominated is mind-boggling … [the] big one for me is Deep Purple. How could you not induct Deep Purple?».[168][169] Metallica band members James Hetfield, Lars Ulrich and Kirk Hammett have also lobbied for the band’s induction.[170][171] In an interview with Rolling Stone in April 2014, Ulrich pleaded: «I’m not going to get into the politics or all that stuff, but I got two words to say: ‘Deep Purple’. That’s all I have to say: Deep Purple. Seriously, people, Deep Purple. Two simple words in the English language … ‘Deep Purple’! Did I say that already?»[172] In 2015, Chris Jericho, professional wrestler and vocalist of rock band Fozzy, stated: «that Deep Purple are not in it [Hall of Fame]. It’s bullshit. Obviously there’s some politics against them from getting in there.»[173]

«With almost no exceptions, every hard rock band in the last 40 years, including mine, traces its lineage directly back to Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple. Where I grew up, and in the rest of the world outside of North America, all were equal in status, stature and influence. So in my heart – and I know I speak for many of my fellow musicians and millions of Purple fans when I confess that – I am somewhat bewildered that they are so late in getting in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.»

—Excerpt from Lars Ulrich’s speech, inducting Deep Purple into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.[174]

In response to these, a Hall of Fame chief executive said, «The definition of ‘rock and roll’ means different things to different people, but as broad as the classifications may be, they all share a common love of the music.»[165] Roger Glover remained ambivalent about induction and got an inside word from the Hall, «One of the jurors said, ‘You know, Deep Purple, they’re just one-hit wonders.’ How can you deal with that kind of Philistinism, you know?».[175] Ian Gillan also commented, «I’ve fought all my life against being institutionalised and I think you have to actively search these things out, in other words mingle with the right people, and we don’t get invited to those kind of things.»[176] On 16 October 2013 Deep Purple were again announced as nominees for inclusion to the Hall, and once again they were not inducted.[175][177]

In April 2015, Deep Purple topped the list in a Rolling Stone readers poll of acts that should be inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2016.[178] In October 2015, the band were nominated for induction for the third time.[179] In December 2015, the band were announced as 2016 inductees into the Hall of Fame, with the Hall stating: «Deep Purple’s non-inclusion in the Hall is a gaping hole which must now be filled», adding that along with fellow inductees Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, the band make up «the Holy Trinity of hard rock and metal bands.»[180] The band was officially inducted on 8 April 2016. The Hall of Fame announced that the following members were included as inductees: Ian Paice, Jon Lord, Ritchie Blackmore, Roger Glover, Ian Gillan, Rod Evans, David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes. Excluded from induction were Nick Simper, Tommy Bolin, Joe Lynn Turner, Joe Satriani, Steve Morse and Don Airey.[181]

Prior to the induction ceremony, Ian Gillan announced that he was barring Hughes, Coverdale, Evans and Blackmore from playing with them onstage, as these members are not in the current «living, breathing» version of the band.[182] Of the seven living inducted members, five showed up. Blackmore didn’t attend; a posting on his Facebook page claimed he was honoured by the induction and had considered attending, until he received correspondence from Bruce Payne, manager from the current touring version of Deep Purple saying, «No!»[183] In interviews at the Rock Hall, however, Gillan insisted he personally invited Blackmore to attend. In an interview later on, Gillan mentioned he invited Blackmore to play «Smoke on the Water» at the ceremony, but Blackmore believes he did not receive that invitation. Evans, who had disappeared from the music scene more than three decades prior, also didn’t appear. Since Lord had died in 2012, his wife Vickie accepted his award on his behalf. The current members of the band played «Highway Star» for the opening performance. After a brief interlude playing the Booker T. & the M.G.’s song «Green Onions» while photos of the late Jon Lord flashed on the screen behind them, the current Deep Purple members played two more songs: «Hush» and their signature tune «Smoke on the Water». Although barred from playing with Deep Purple, both David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes (as well as Roger Glover) joined fellow inductees Cheap Trick and an all-star cast to perform a cover of the Fats Domino song «Ain’t That a Shame».[184]

Band members[edit]

Current members[edit]

- Ian Paice – drums (1968–1976, 1984–present)

- Roger Glover – bass (1969–1973, 1984–present)

- Ian Gillan – vocals, harmonica, percussion (1969–1973, 1984–1989, 1992–present)

- Don Airey – keyboards (2002–present)

- Simon McBride – guitar (2022–present)

Former members[edit]

- Jon Lord – keyboards, string arrangements, backing vocals (1968–1976, 1984–2002; died 2012)

- Ritchie Blackmore – guitars (1968–1975, 1984–1993)

- Nick Simper – bass, backing vocals (1968–1969)

- Rod Evans – lead vocals (1968–1969)

- Glenn Hughes – bass, backing and lead vocals (1973–1976)

- David Coverdale – lead and backing vocals (1973–1976)

- Tommy Bolin – guitars, backing vocals (1975–1976; died 1976)

- Joe Lynn Turner – lead vocals (1989–1992)

- Joe Satriani – guitars (1993–1994)

- Steve Morse – guitars (1994–2022)

Touring musicians[edit]

- Christopher Cross – guitar (substitute for Blackmore at one show in 1970)[185]

- Randy California – guitar (substitute for Blackmore at one show in 1972; died 1997)

- Candice Night – backing vocals (1993)[186]

- Nick Fyffe – bass (substitute for Glover at some shows in 2011)

- Jordan Rudess – keyboards (substitute for Airey at one show in 2020)

Concert tours[edit]

Deep Purple are considered to be one of the hardest touring bands in the world.[187][188] They have toured the world since 1968 (with the exception of their 1976–1984 split). In 2007, the band received a special award for selling more than 150,000 tickets in France, with 40 dates in the country in 2007 alone.[189] Also in 2007, Deep Purple’s Rapture of the Deep tour was voted number 6 concert tour of the year (in all music genres) by Planet Rock listeners.[190] The Rolling Stones’ A Bigger Bang tour was voted number 5 and beat Purple’s tour by only 1%. Deep Purple released a new live compilation DVD box, Around the World Live, in May 2008. In February 2008, the band made their first-ever appearance at the State Kremlin Palace in Moscow, Russia[191] at the personal request of Dmitry Medvedev who at the time was a chairman of the state owned Gazprom company, which sponsored the concert,[192] and who was considered a shoo-in for the seat of the Presidency of Russia. Prior to that, Deep Purple has toured Russia several times starting as early as 1996 but has not been considered to have played such a significant venue previously. The band was part of the entertainment for the FIS Nordic World Ski Championships 2009 in Liberec, the Czech Republic.[193]

- Deep Purple Debut Tour, 1968 in Scandinavian countries

- Shades of Deep Purple Tour, 1968

- The Book of Taliesyn Tour, 1968–1969

- Deep Purple European Tour, (pre-tour for In Rock) 1969–1970

- In Rock World Tour, 1970–1971

- Fireball World Tour, 1971–1972

- Machine Head World Tour, 1972–1973

- Deep Purple European Tour, (pre-tour for Burn) 1973–1974

- Burn World Tour, 1974

- Stormbringer World Tour, 1974–1975

- Come Taste The Band World Tour, 1975–1976

- Perfect Strangers Tour, World Tour, aka Reunion Tour 1984–1985

- The House of Blue Light World Tour, 1987–1988

- Slaves and Masters World Tour, 1991

- Deep Purple 25 Years Anniversary World Tour, aka The Battle Rages on Tour, 1993

- Deep Purple and Joe Satriani Tour, 1993–1994

- Deep Purple Secret Mexican Tour (short warm-up tour with Steve Morse), 1994

- Deep Purple Secret USA Tour, 1994–1995

- Deep Purple Asian & African Tour, 1995

- Purpendicular World Tour, 1996–1997

- A Band on World Tour, 1998–1999

- Concerto World Tour, 2000–2001

- Deep Purple World Tour, 2001–2003

- Bananas World Tour, 2003–2005

- Rapture of the Deep tour, 2006–2011

- The Songs That Built Rock Tour, 2011–2012

- Now What? World Tour, 2013–2015

- World Tour 2016, 2016

- The Long Goodbye Tour, 2017–2019[194]

- Whoosh! Tour, 2022[126]

Discography[edit]

Studio albums[edit]

- Shades of Deep Purple (1968)

- The Book of Taliesyn (1968)

- Deep Purple (1969)

- Deep Purple in Rock (1970)

- Fireball (1971)

- Machine Head (1972)

- Who Do We Think We Are (1973)

- Burn (1974)

- Stormbringer (1974)

- Come Taste the Band (1975)

- Perfect Strangers (1984)

- The House of Blue Light (1987)

- Slaves and Masters (1990)

- The Battle Rages On… (1993)

- Purpendicular (1996)

- Abandon (1998)

- Bananas (2003)

- Rapture of the Deep (2005)

- Now What?! (2013)

- Infinite (2017)

- Whoosh! (2020)

- Turning to Crime (2021)[195]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Shades of Deep Purple album sleeve notes pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Wasler, Robert (1993). Running with the Devil: power, gender, and madness in heavy metal music. Wesleyan University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780819562609.

- ^ a b Michael Campbell & James Brody (2008). Rock and Roll: An Introducction. p. 213. ISBN 978-0534642952.

- ^ Jeb Wright (2009). «The Naked Truth: An Exclusive Interview with Deep Purple’s Ian Gillan». Classic Rock Revisited. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009.

- ^ a b Charlton, Katherine (2003). Rock Music Styles: A History. p. 241. McGraw Hill.

- ^ McIver, Joel (2006). «Black Sabbath: Sabbath Bloody Sabbath». Chapter 12, p. 1.

- ^ McWhirter, Ross (1975). Guinness Book of World Records (14 ed.). Sterling Pub. Co. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-8069-0012-4.

- ^ Jason Ankeny. «Deep Purple». Allmusic. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ «Jon Lord, keyboard player with seminal hard rock act Deep Purple, dies». CNN. Retrieved 25 July 2012

- ^ «Deep Purple keyboard player Jon Lord dies aged 71». The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 July 2012

- ^ «Deep Purple’s Jon Lord dies at 71» . MSNBC. Retrieved 25 July 2012

- ^ «Deep Purple reviews». Ram.org.

- ^ «Deep Purple Mark I & Mark II». Rock.co.za.

- ^ «VH1 Counts Down the ‘100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock’ In Five-Hour, Five-Night Special». Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ «Planet Rock: Most Influential Band Ever – The Results». Planet Rock. Retrieved 25 February 2013

- ^ a b c d Thompson, Dave (2004). Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story. ISBN 9781550226188. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. The Artwoods Allmusic. Retrieved 12 December 2011

- ^ a b c Robinson, Simon (July 1983). «Nick Simper Interview from «Darker than Blue», July 1983″. Darker than Blue. Nick Simper official website. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2004). «Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story» p.5. ECW Press

- ^ a b Thompson, Dave. Chris Curtis Biography Allmusic. Retrieved 12 December 2011

- ^ Dafydd Rees, Luke Crampton (1999). «Rock stars encyclopedia» p.279. DK Publishing.

- ^ Frame, Pete (2000). «Pete Frame’s Rocking Around Britain» p.54. Music Sales Group, 2000

- ^ a b Jerry Bloom (2006). Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore. Omnibus Press 2008. ISBN 9781846097577.

Blackmore has stated; «It was a song my grandmother used to play on the piano.»

- ^ Welch, Chris. «The Story of Deep Purple.» In Deep Purple: HM Photo Book, copyright 1983, Omnibus Press.

- ^ Rock Formations: Categorical Answers to How Band Names Were Formed p.53. Cidermill Books. Retrieved 29 April 2011

- ^ Tyler, Kieron On The Roundabout With Deep Purple Retrieved 29 April 2011

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2004). «Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story» pp.41–42. ECW Press. Retrieved 19 February 2012

- ^ «Ritchie Blackmore, Interviews». Thehighwaystar.com. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Miles, Barry (2009) The British Invasion: The Music, the Times, the Era p.264. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2009

- ^ The RPM 100: Deep Purple Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 12 November 2011

- ^ «The Book of Taliesyn Billboard Singles». AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ «Top Singles – Volume 10, No. 16, December 16, 1968». Library and Archives Canada. 16 December 1968. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ «The Book of Taliesyn Billboard Albums». AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ «Top Albums/CDs – Volume 11, No. 2, March 10, 1969». Library and Archives Canada. 10 March 1969. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2004). «Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story» p.324. ECW Press

- ^ Joel Whitburn (2007). «The Billboard Albums: Includes Every Album That Made the Billboard 200 Chart». p.227. Record Research Inc., 2007

- ^ a b c Steve Rosen Interview with Ritchie Blackmore, 1974 Retrieved from YouTube «Ritchie Blackmore, Guitar God|Part 1/5» on 14 January 2014.

- ^ «Interview: Singer and guitarist Terry Reid». The Independent. 7 March 2007. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ Anasontzis, George. «Rockpages.gr interview with Nick Simper». Rockpages. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Bloom, Jerry (2008). «Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore» p.128. Omnibus Press, 2008

- ^ «Simper recalls pain of Purple sacking». Louder Sound.com. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ «Deep Purple The Official Charts Company». Official Charts Company. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ Steven Rosen (1975). «Ritchie Blackmore Interview: Deep Purple, Rainbow and Dio». Guitar International. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011.

- ^ «A Highway Star: Deep Purple’s Roger Glover Interviewed». The Quietus. 20 January 2011.

- ^ a b Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums. London: Guinness World Records Limited

- ^ Steve Rosen Interview with Ritchie Blackmore, 1974 Retrieved from YouTube «Ritchie Blackmore, Guitar God|Part 2/5» on 14 January 2014.

- ^ Jerry Bloom (2007). «Black Knight». p. 139. Music Sales Group.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Deep Purple: UK Charts». Official Charts Company. Retrieved 27 February 2015

- ^ Deep Purple: Fireball, AllMusic. Retrieved 12 November 2011

- ^ «Frequently Asked Questions». Thehighwaystar.com. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ «Deep Purple revient sur le lieu où est né «Smoke on the Water»«. Tribune deGeneve. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ «How Deep Purple created their best hit ‘Smoke on the Water’«. The Independent. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Deep Purple release ‘Machine Head’ BBC. Retrieved 19 October 2011

- ^ a b c «Six solid reasons Deep Purple are the ultimate rock band». BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Billboard – Machine Head, AllMusic. Retrieved 12 November 2011

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ a b «Readers’ Poll: The 10 Best Live Albums of All Time» Archived 27 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 22 November 2012

- ^ «The Official Charts Company – Who Do We Think We Are». The Official Charts Company. 5 May 2013.

- ^ «Who Do We Think We Are on Billboard«. Billboard. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ «Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story». p.154.

- ^ «RIAA Gold & Platinum database». Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Deep Purple: The Interview. Interview picture disc, 1984, Mercury Records.

- ^ Peter Buckley (2003). The Rough Guide to Rock p.279. Rough Guides. Retrieved 1 March 2012

- ^ Mike Clifford, Pete Frame (1992). The Harmony Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock, p.41. Harmony Books. Retrieved 1 March 2012

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2008). Joel Whitburn’s Top Pop Singles 1955–2006, p.227. Record Research

- ^ «Deep Purple People». Rock Family Trees. BBC 2. 8 July 1995. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ^ Liner notes for the 30th anniversary edition of Burn.

- ^ a b c «Van der Lee, Matthijs. Burn review at». Sputnikmusic.com. 15 October 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ «The Glenn Hughes Interview». Vintage Rock.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ Ling, Dave (March 2000). «My classic career». Classic Rock #12. p. 90.

- ^ Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story. p.158.

- ^ «Deep Purple’s Glenn Hughes digs into his past». Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Deep Purple: Heavy Metal Pioneers 1991 documentary|websource=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9_-SziEOBxM

- ^ «History» track on the «Deep Purple: History and Hits» DVD.

- ^ Mike Jefferson (1 April 2009). «Deep Purple – Stormbringer». Coffeerooms on Music. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ Steven Rosen (1975). «Ritchie Blackmore Interview». Guitar International. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011.

- ^ Dafydd Rees, Luke Crampton (1991). Rock Movers & Shakers, Volume 1991, Part 2. p.419. ABC-CLIO, 1991

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2004). Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story, pp.179–180.

- ^ liner notes in the Deep Purple 4-CD boxed set:

- ^ Deep Purple Appreciation Society (28 June 1975). «1975 Tommy Bolin interview». Deep-purple.net. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ a b Nick Talevski (2006). Knocking on Heaven’s Door: Rock Obituaries p.42-43. Omnibus Press, 2006

- ^ Moffitt, Greg. «BBC — Music — Review of Deep Purple — Come Taste the Band: 35th Anniversary Edition».

- ^ «Gettin’ Tighter: The Story Of Deep Purple Mk. IV». YouTube. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2008) Black Knight: Ritchie Blackmore p.198. Omnibus Press. Retrieved 23 October 2011

- ^ Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story p. 191. Retrieved 23 October 2011

- ^ «Deep Purple #4 June 1975-March 1976». Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Hartmut Kreckel (1998). «Rod Evans: The Dark Side of the Music Industry». Captain Beyond website. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012.

- ^ Billboard (18 May 1985). Deep Purple: ‘Surprise Of The Year’ Billboard. p.41. Retrieved 2 March 2012

- ^ Pete Prown, Harvey P. Newquist (1997). Legends of rock guitar: the essential reference of rock’s greatest guitarists p.65. Hal Leonard Corporation. Retrieved 2 March 2012

- ^ a b c «Billboard album listings for Deep Purple». AllMusic.com.

- ^ Deep Purple: Perfect Strangers, AllMusic. Retrieved 2 March 2012

- ^ «Deep Purple & A Momentous Mark II Reunion». udiscovermusic.com. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ «Jon Lord Interview at www.thehighwaystar.com». Thehighwaystar.com. 12 February 1968. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ «Knebworth House – Rock Concerts». KnebworthHouse.com. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ «Deep Purple – Knebworth 1985». DeepPurple.net. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ «Interview: Jimi Jamison». aor.nu. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ «25 Years of Deep Purple The Battle Rages On…:Interview with Jon Lord». pictured within.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Dave Thompson (2004). Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story. p. 259.

- ^ George Anasontzis. «Ian Gillan Interview». Rockpages.gr. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Gillan, Ian; Cohen, David (1993). «Chapter 14». Child in Time: The Life Story of the Singer from Deep Purple. Smith Gryphon Limited. ISBN 1-85685-048-X.

- ^ a b c Deep Purple live album withdrawn BBC News. Retrieved 2 March 2012

- ^ Daniel Bukszpan, Ronnie James Dio (2003).The Encyclopedia of Heavy Metal p.56. Barnes & Noble Publishing. Retrieved 1 March 2012

- ^ Shrivastava, Rahul. «Joe Satriani Interview». BBC. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- ^ a b Buckley, Peter (2003). The rough guide to rock. p.280. Rough Guides. Retrieved 23 October 2011

- ^ «Soundboard Series: Australian Tour 2001». AllMusic. Retrieved 4 November 2012

- ^ Garry Sharpe-Young (10 November 2005). «Roger Glover interview». Rockdetector. Archived from the original on 9 February 2006.

- ^ deep purple michael bradford. Billboard. 15 June 2002. p. 12. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b Mark Anstead (12 March 2009). «Deep Purple’s Ian Gillan talks money». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ a b «Deep Purple To Release New Studio Album Next Year». Blabbermouth.net. 22 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ «Gig Of The Week: Deep Purple». Classic Rock Magazine. Retrieved 7 February 2014

- ^ Matt Wardlaw (3 June 2011). «Deep Purple’s Roger Glover Says Band Disagrees on the Importance of Recording New Albums». Contactmusic.com.

- ^ «Glenn Hughes Up For Deep Purple Mk. III Reunion». Blabbermouth.net. 2 May 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Lee Baldock (22 September 2011). «Moray McMillin loses battle with cancer». LSI Online. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ a b «Deep Purple: New Album Title Revealed – Feb. 26, 2013». Blabbermouth.net. Roadrunner Records. 26 February 2013. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Mathieu Pinard (13 April 2012). «Album producer chosen?». Darker Than Blue.

- ^ «Jon Lord, founder of Deep Purple, dies aged 71». BBC News. Retrieved 16 July 2012

- ^ Deep Purple Keyboardist Jon Lord Dead at 71 Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 16 July 2012

- ^ «Deep Purple: Quality Toulouse Footage Available – Dec. 7, 2012»[permanent dead link]. Blabbermouth.net. Retrieved 24 December 2012

- ^ «Deep Purple Confirm New Album». Ultimate Guitar.

- ^ «DEEP PURPLE Completes Recording New Album». Blabbermouth. Retrieved 10 December 2017

- ^ «Ian Gillan: ‘New Song Vincent Price Is Just A Bit Of Fun’«. Contactmusic.com. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ «Deep Purple Unveils ‘InFinite’ Album Artwork, Releases ‘Time For Bedlam’ Single». Blabbermouth.net. 14 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Ian Paice: Deep Purple Hasn’t Decided Yet If ‘Long Goodbye’ Will Be Band’s Last Big Tour — Blabbermouth.net. 20 January 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ «DEEP PURPLE Unveils ‘InFinite’ Album Artwork, Releases ‘Time For Bedlam’ Single». Blabbermouth. Retrieved 10 December 2017

- ^ «Deep Purple Announce New Album ‘Whoosh!’«. Ultimate Classic Rock. 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ a b «Deep Purple announce new album Whoosh! and European tour». Louder Sound. 29 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ «Deep Purple push back release of new album Whoosh!». Louder Sound. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ Cooper, Leonie (6 August 2020). «Deep Purple – ‘Whoosh!’ review: rockers’ 21st record is stupidly fun and outrageously silly». NME. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ «DEEP PURPLE Has No Plans To Retire: ‘We’ve Got A Bit To Go Yet,’ Says IAN GILLAN». Blabbermouth. 4 August 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Irwin, Corey (6 October 2021). «Deep Purple Announce ‘Turning to Crime’ Covers Album». Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ Henne, Bruce. «Deep Purple Stream New Album ‘Turning To Crime’«. antiMusic. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ «Deep Purple’s Steve Morse Announces Hiatus From the Band Following Wife’s Cancer Diagnosis | Music News @». Ultimate-guitar.com. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ «Steve Morse Officially Quits Deep Purple To Care For Ailing Wife». Blabbermouth.net. 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ «Deep Purple Officially Welcomes Guitarist Simon McBride As Permanent Member». Blabbermouth.net. 16 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ «Deep Purple — To Start Writing Next Album In 2023». Metal Storm. 29 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ Eduardo Rivadavia. «Deep Purple: Machine Head» Allmusic. Retrieved 6 March 2013

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Metallica AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Judas Priest AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Queen Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Aerosmith AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Van Halen AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Alice in Chains AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Birchmeier, Jason. Pantera AllMusic. Retrieved 26 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Bon Jovi AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ «Europe – Interview with Joey Tempest». metal-rules.com. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. Rush AllMusic. Retrieved 26 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Motorhead AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Iron Maiden AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Def Leppard AllMusic. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ «IRON MAIDEN Bassist Talks About His Technique And Influences». Archive.today. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Liz (19 January 2014). «Brian May ‘My Planet Rocks’ Interview». Planet Rock. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Mick Wall (2010). «Metallica: Enter Night: The Biography». Hachette UK. Retrieved 17 November 2013

- ^ «Sex, schnapps, and German repression: meet Lindemann, the most politically incorrect men in rock». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ «100 Greatest Drummers of All Time. #21. Ian Paice». Rolling Stone. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (1 November 2005). The Collector’s Guide to Heavy Metal: Volume 2: The Eighties. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Collector’s Guide Publishing. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1894959315.

- ^ VH1: ‘100 Greatest Hard Rock Artists’: 1–50 Rock on the Net. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ «World Music Awards: Legends». WorldMusicAwards.com. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ «CR Awards: The Winners». Classic Rock Magazine. Retrieved 17 June 2012

- ^ a b «Re-Machined Deep Purple Tribute». Eagle Rock Entertainment. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ «Seven Ages of Rock». BBC. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ «The Bittersweet Symphony dispute is over». BBC. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ «Rush, Deep Purple, Public Enemy Nominated for Rock Hall of Fame». Billboard. Retrieved 11 October 2012

- ^ Andy Greene (4 October 2012). «Rush, Public Enemy, Deep Purple Nominated for Rock and Roll Hall of Fame» Archived 2 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 October 2012

- ^ «Rush, Randy Newman, Donna Summer among 2013 Rock Hall inductees». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 December 2012

- ^ a b Martin Kielty (4 October 2012). «Rush, Deep Purple finally nominated for Rock and Roll Hall of Fame». Classic Rock.

- ^ «Geddy Lee on Rush’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction: ‘We’ll Show Up Smiling». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 11 December 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ «Toto told Jann Wenner to ‘stick it up his‘» Future Rock Legends. Retrieved 22 February 2012

- ^ Jane Stevenson (23 March 2012). «Slash plays to Canadian Crowd». Toronto Sun. Retrieved 27 April 2012

- ^ «Slash on Closing the Book on Guns ‘N’ Roses at the Hall of Fame» Archived 24 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 27 April 2012

- ^ «Metallica Want to Avoid «Drama of a Van Halen» at Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction» Archived 24 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 28 February 2012

- ^ «Metallica Guitarist: ‘Deep Purple Definitely Belongs in the Rock and Roll Hall of Game’«. Blabbermouth.net. 17 October 2012.

- ^ Grow, Kory (9 April 2014). «Metallica’s Lars Ulrich on the Rock Hall – ‘Two Words: Deep Purple’«. rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ «Chris Jericho huge Hall of Fame rant 2015». YouTube. 19 October 2015. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016.

- ^ Grow, Kory (9 April 2016). «Read Lars Ulrich’s Passionate Deep Purple Rock Hall Induction». rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ a b Sean Michaels (4 September 2014). «Roger Glover: Deep Purple ‘ambivalent’ over Hall of Fame call-up». The Guardian.

- ^ «Deep Purple – Ian Gillan: ‘I Don’t Expect Heavy Rock’s Finest To Get Knighthoods’«. Contactmusic.com. 19 May 2013.

- ^ «Nirvana, Kiss, Hall and Oates Nominated for Rock and Roll Hall of Fame». Archived 18 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine Rolling Stone. 16 October 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Green, Andy (29 April 2015). «Readers Poll: 10 Acts That Should Enter the Hall of Fame in 2016». rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ «Vote for the 2016 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductees». Rolling Stone. 8 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ «NWA, Deep Purple and Chicago enter Hall of Fame». BBC. 17 December 2015.

- ^ Reed, Ryan (21 December 2015). «Deep Purple Singer: Rock Hall Band Member Exclusions Are ‘Very Silly’«. rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ «Ian Gillan Comments on Deep Purple’s Decision to Perform With Current Lineup at Rock Hall Induction». Ultimateclassicriock.com. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Greene, Andy (16 February 2016). «Deep Purple Guitarist Ritchie Blackmore Won’t Attend Hall of Fame Ceremony». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ «Deep Purple Rocks Hall of Fame With Hits-Filled Set» Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 19 October 2016

- ^ By Cross’s account, he was recommended by a local promoter as a last-minute replacement when Blackmore fell ill before a scheduled performance in San Antonio, Texas during the band’s first tour of the United States. The group played the Deep Purple songs Cross felt able to perform, along with blues standards. Cross, Christopher (18 October 2013). «Christopher Cross». Songfacts (Interview). Interviewed by Greg Prato. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Gary Hill, Rick Damigella and Larry Toering (28 January 2011). «Interview with Candice Night of Blackmore’s Night from 2010». Music Street Journal.

He asked me to join him on tour in 1993, Purple’s last tour as the famous Mark 2 line up, and requested I sing back up vocals on his Difficult to Cure solo

- ^ «The Highway Star — Fall tour of Germany». Thehighwaystar.com. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ «The Highway Star — Pisco Sour under Peruvian skies». Thehighwaystar.com. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ «Deep Purple, 2007 Tour Reviews». Deep-purple.net.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ «Deep Purple — Live At Gazprom’s 15th Anniversary», YouTube, archived from the original on 28 October 2021, retrieved 23 June 2021

- ^ Gillan, Ian (17 February 2008). «Deep Purple perform for Russia’s future president». The Times. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ FIS Newsflash 215. 21 January 2009.

- ^ «Deep Purple Announces ‘The Long Goodbye Tour’«. Blabbermouth.net. 2 December 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ «DEEP PURPLE Officially Announces ‘Turning To Crime’ Album, Shares ‘7 And 7 Is’ Single». BLABBERMOUTH.NET. 6 October 2021.

References[edit]