This article is about the computer animation studio. For other uses, see Pixar (disambiguation).

Logo used since 1995 |

|

Headquarters in Emeryville, California |

|

| Type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Animation |

| Predecessor | The Graphics Group (1979–1986) Disney Circle 7 Animation (2005-2006) |

| Founded | February 3, 1986; 37 years ago in Richmond, California |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | 1200 Park Avenue,

Emeryville, California , U.S. |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products | Computer animations |

| Brands |

|

| Owner | Lucasfilm (1979-1986) Steve Jobs (1986–2006) The Walt Disney Company (2006–present) |

|

Number of employees |

1,233 (2020) |

| Parent | Walt Disney Studios (Disney Entertainment) (2006–present) |

| Website | pixar.com |

| Footnotes / references [1][2][3] |

Pixar Animation Studios () is an American computer animation studio known for its critically and commercially successful computer animated feature films. It is based in Emeryville, California, United States. Since 2006, Pixar has been a subsidiary of Walt Disney Studios, a division of Disney Entertainment, which owned by The Walt Disney Company.

Pixar started in 1979 as part of the Lucasfilm computer division, known as the Graphics Group, before its spin-off as a corporation in 1986, with funding from Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, who became its majority shareholder.[2] Disney purchased Pixar in January 2006 at a valuation of $7.4+ billion by converting each share of Pixar stock to 2.3 shares of Disney stock.[4][5] Pixar is best known for its feature films, technologically powered by RenderMan, the company’s own implementation of the industry-standard RenderMan Interface Specification image-rendering API. The studio’s mascot is Luxo Jr., a desk lamp from the studio’s 1986 short film of the same name.

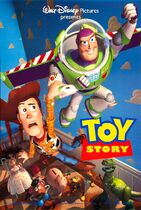

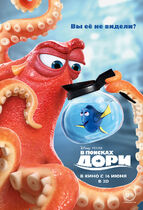

Pixar has produced 26 feature films, starting with Toy Story (1995), which is the first fully computer-animated feature film; its most recent film was Lightyear (2022). The studio has also produced many short films. As of July 2019, its feature films have earned approximately $14 billion at the worldwide box office,[6] with an average worldwide gross of $680 million per film.[7] Toy Story 3 (2010), Finding Dory (2016), Incredibles 2 (2018), and Toy Story 4 (2019) are all among the 50 highest-grossing films of all time, with Incredibles 2 being the fourth-highest-grossing animated film of all time, with a gross of $1.2 billion; the other three also grossed over $1 billion. Moreover, 15 of Pixar’s films are in the 50 highest-grossing animated films of all time.

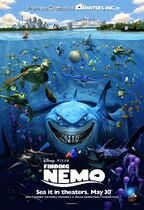

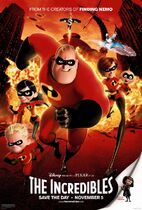

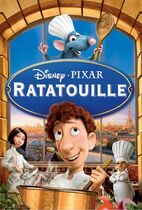

Pixar has earned 23 Academy Awards, 10 Golden Globe Awards, and 11 Grammy Awards, along with numerous other awards and acknowledgments. Its films are frequently nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, since its inauguration in 2001, with eleven winners being Finding Nemo (2003), The Incredibles (2004), Ratatouille (2007), WALL-E (2008), Up (2009), Toy Story 3 (2010), Brave (2012), Inside Out (2015), Coco (2017), Toy Story 4 (2019), and Soul (2020); the five nominated without winning are Monsters, Inc. (2001), Cars (2006), Incredibles 2 (2018), Onward (2020), and Luca (2021). Up and Toy Story 3 were also nominated for the more competitive and inclusive Academy Award for Best Picture.

On February 10, 2009, Pixar executives John Lasseter, Brad Bird, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton, and Lee Unkrich were presented with the Golden Lion award for Lifetime Achievement by the Venice Film Festival. The physical award was ceremoniously handed to Lucasfilm’s founder, George Lucas.

History

Early history

Pixar got its start in 1974, when New York Institute of Technology’s (NYIT) founder, Alexander Schure, who was also the owner of a traditional animation studio, established the Computer Graphics Lab (CGL) and recruited computer scientists who shared his ambitions about creating the world’s first computer-animated film. Edwin Catmull and Malcolm Blanchard were the first to be hired and were soon joined by Alvy Ray Smith and David DiFrancesco some months later, which were the four original members of the Computer Graphics Lab, located in a converted two-story garage acquired from the former Vanderbilt-Whitney estate.[8][9] Schure kept pouring money into the computer graphics lab, an estimated $15 million, giving the group everything they desired and driving NYIT into serious financial troubles.[10] Eventually, the group realized they needed to work in a real film studio in order to reach their goal. Francis Ford Coppola then invited Smith to his house for a three-day media conference, where Coppola and George Lucas shared their visions for the future of digital moviemaking.[11]

When Lucas approached them and offered them a job at his studio, six employees moved to Lucasfilm. During the following months, they gradually resigned from CGL, found temporary jobs for about a year to avoid making Schure suspicious, and joined the Graphics Group at Lucasfilm.[12][13]

The Graphics Group, which was one-third of the Computer Division of Lucasfilm, was launched in 1979 with the hiring of Catmull from NYIT,[14] where he was in charge of the Computer Graphics Lab. He was then reunited with Smith, who also made the journey from NYIT to Lucasfilm, and was made the director of the Graphics Group. At NYIT, the researchers pioneered many of the CG foundation techniques—in particular, the invention of the alpha channel by Catmull and Smith.[15] Over the next several years, the CGL would produce a few frames of an experimental film called The Works. After moving to Lucasfilm, the team worked on creating the precursor to RenderMan, called REYES (for «renders everything you ever saw») and developed several critical technologies for CG—including particle effects and various animation tools.[16]

John Lasseter was hired to the Lucasfilm team for a week in late 1983 with the title «interface designer»; he animated the short film The Adventures of André & Wally B.[17] In the next few years, a designer suggested naming a new digital compositing computer the «Picture Maker». Smith suggested that the laser-based device have a catchier name, and came up with «Pixer», which after a meeting was changed to «Pixar».[18]

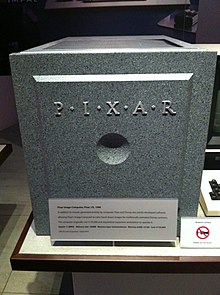

In 1982, the Pixar team began working on special-effects film sequences with Industrial Light & Magic. After years of research, and key milestones such as the Genesis Effect in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and the Stained Glass Knight in Young Sherlock Holmes,[14] the group, which then numbered 40 individuals, was spun out as a corporation in February 1986 by Catmull and Smith. Among the 38 remaining employees, there were also Malcolm Blanchard, David DiFrancesco, Ralph Guggenheim, and Bill Reeves, who had been part of the team since the days of NYIT. Tom Duff, also an NYIT member, would later join Pixar after its formation.[2] With Lucas’s 1983 divorce, which coincided with the sudden dropoff in revenues from Star Wars licenses following the release of Return of the Jedi, they knew he would most likely sell the whole Graphics Group. Worried that the employees would be lost to them if that happened, which would prevent the creation of the first computer-animated movie, they concluded that the best way to keep the team together was to turn the group into an independent company. But Moore’s Law also suggested that sufficient computing power for the first film was still some years away, and they needed to focus on a proper product until then. Eventually, they decided they should be a hardware company in the meantime, with their Pixar Image Computer as the core product, a system primarily sold to governmental, scientific, and medical markets.[2][10][19] They also used SGI computers.[20]

In 1983, Nolan Bushnell founded a new computer-guided animation studio called Kadabrascope as a subsidiary of his Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatres company (PTT), which was founded in 1977. Only one major project was made out of the new studio, an animated Christmas special for NBC starring Chuck E. Cheese and other PTT mascots; known as «Chuck E. Cheese: The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t». The animation movement would be made using tweening instead of traditional cel animation. After the video game crash of 1983, Bushnell started selling some subsidiaries of PTT to keep the business afloat. Sente Technologies (another division, was founded to have games distributed in PTT stores) was sold to Bally Games and Kadabrascope was sold to Lucasfilm. The Kadabrascope assets were combined with the Computer Division of Lucasfilm.[21] Coincidentally, one of Steve Jobs’s first jobs was under Bushnell in 1973 as a technician at his other company Atari, which Bushnell sold to Warner Communications in 1976 to focus on PTT.[22] PTT would later go bankrupt in 1984 and be acquired by ShowBiz Pizza Place.[23]

Independent company (1986–1999)

In 1986, the newly independent Pixar was headed by President Edwin Catmull and Executive Vice President Alvy Ray Smith. Lucas’s search for investors led to an offer from Steve Jobs, which Lucas initially found too low. He eventually accepted after determining it impossible to find other investors. At that point, Smith and Catmull had been declined 45 times, and 35 venture capitalists and ten large corporations had declined.[24] Jobs, who had been edged out of Apple in 1985,[2] was now founder and CEO of the new computer company NeXT. On February 3, 1986, he paid $5 million of his own money to George Lucas for technology rights and invested $5 million cash as capital into the company, joining the board of directors as chairman.[2][25]

In 1985, while still at Lucasfilm, they had made a deal with the Japanese publisher Shogakukan to make a computer-animated movie called Monkey, based on the Monkey King. The project continued sometime after they became a separate company in 1986, but it became clear that the technology was not sufficiently advanced. The computers were not powerful enough and the budget would be too high. So they focused on the computer hardware business for years until a computer-animated feature became feasible according to Moore’s law.[26][27]

At the time, Walt Disney Studios was interested and eventually bought and used the Pixar Image Computer and custom software written by Pixar as part of its Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) project, to migrate the laborious ink and paint part of the 2D animation process to a more automated method. The company’s first feature film to be released using this new animation method was The Rescuers Down Under (1990).[28][29]

In a bid to drive sales of the system and increase the company’s capital, Jobs suggested releasing the product to the mainstream market. Pixar employee John Lasseter, who had long been working on not-for-profit short demonstration animations, such as Luxo Jr. (1986) to show off the device’s capabilities, premiered his creations to great fanfare at SIGGRAPH, the computer graphics industry’s largest convention.[30]

However, the Image Computer had inadequate sales[30] which threatened to end the company as financial losses grew. Jobs increased investment in exchange for an increased stake, reducing the proportion of management and employee ownership until eventually, his total investment of $50 million gave him control of the entire company. In 1989, Lasseter’s growing animation department, originally composed of just four people (Lasseter, Bill Reeves, Eben Ostby, and Sam Leffler), was turned into a division that produced computer-animated commercials for outside companies.[1][31][32] In April 1990, Pixar sold its hardware division, including all proprietary hardware technology and imaging software, to Vicom Systems, and transferred 18 of Pixar’s approximately 100 employees. That year, Pixar moved from San Rafael to Richmond, California.[33] Pixar released some of its software tools on the open market for Macintosh and Windows systems. RenderMan is one of the leading 3D packages of the early 1990s, and Typestry is a special-purpose 3D text renderer that competed with RayDream.[citation needed]

During this period, Pixar continued its successful relationship with Walt Disney Feature Animation, a studio whose corporate parent would ultimately become its most important partner. As 1991 began, however, the layoff of 30 employees in the company’s computer hardware department—including the company’s president, Chuck Kolstad,[34] reduced the total number of employees to just 42, approximately its original number.[35] Pixar made a historic $26 million deal with Disney to produce three computer-animated feature films, the first of which was Toy Story, the product of the technological limitations that challenged CGI.[36] By then the software programmers, who were doing RenderMan and IceMan, and Lasseter’s animation department, which made television commercials (and four Luxo Jr. shorts for Sesame Street the same year), were all that remained of Pixar.[37]

Even with income from these projects, the company continued to lose money and Steve Jobs, as chairman of the board and now the full owner, often considered selling it. Even as late as 1994, Jobs contemplated selling Pixar to other companies such as Hallmark Cards, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, and Oracle CEO and co-founder Larry Ellison.[38] Only after learning from New York critics that Toy Story would probably be a hit—and confirming that Disney would distribute it for the 1995 Christmas season—did he decide to give Pixar another chance.[39][40] For the first time, he also took an active leadership role in the company and made himself CEO.[citation needed] Toy Story grossed more than $373 million worldwide[41] and, when Pixar held its initial public offering on November 29, 1995, it exceeded Netscape’s as the biggest IPO of the year. In its first half-hour of trading, Pixar stock shot from $22 to $45, delaying trading because of unmatched buy orders. Shares climbed to US$49 and closed the day at $39.[42]

The television commercials, which the company had continued to make during the production of Toy Story, came to an end on July 9, 1996, when Pixar announced they would shut down its televion-commercial unit, which counted 18 employees, to focus on longer projects and interactive entertainment.[43][44]

During the 1990s and 2000s, Pixar gradually developed the «Pixar Braintrust», the studio’s primary creative development process, in which all of its directors, writers, and lead storyboard artists regularly examine each other’s projects and give very candid «notes», the industry term for constructive criticism.[45] The Braintrust operates under a philosophy of a «filmmaker-driven studio», in which creatives help each other move their films forward through a process somewhat like peer review, as opposed to the traditional Hollywood approach of an «executive-driven studio» in which directors are micromanaged through «mandatory notes» from development executives outranking the producers.[46][47] According to Catmull, it evolved out of the working relationship between Lasseter, Stanton, Docter, Unkrich, and Joe Ranft on Toy Story.[45]

As a result of the success of Toy Story, Pixar built a new studio at the Emeryville campus which was designed by PWP Landscape Architecture and opened in November 2000.[citation needed]

Collaboration with Disney (1999–2006)

Pixar and Disney had disagreements over the production of Toy Story 2. Originally intended as a direct-to-video release (and thus not part of Pixar’s three-picture deal), the film was eventually upgraded to a theatrical release during production. Pixar demanded that the film then be counted toward the three-picture agreement, but Disney refused.[48] Though profitable for both, Pixar later complained that the arrangement was not equitable. Pixar was responsible for creation and production, while Disney handled marketing and distribution. Profits and production costs were split equally, but Disney exclusively owned all story, character, and sequel rights and also collected a 10- to 15-percent distribution fee. The lack of these rights was perhaps the most onerous aspect for Pixar and precipitated a contentious relationship.[citation needed]

The two companies attempted to reach a new agreement for ten months and failed on January 26, 2001, July 26, 2002, April 22, 2003, January 16, 2004, July 22, 2004, and January 14, 2005. The new deal would be only for distribution, as Pixar intended to control production and own the resulting story, character, and sequel rights while Disney would own the right of first refusal to distribute any sequels. Pixar also wanted to finance its own films and collect 100 percent profit, paying Disney only the 10- to 15-percent distribution fee.[49] More importantly, as part of any distribution agreement with Disney, Pixar demanded control over films already in production under the old agreement, including The Incredibles (2004) and Cars (2006). Disney considered these conditions unacceptable, but Pixar would not concede.[49]

Disagreements between Steve Jobs and Disney chairman and CEO Michael Eisner made the negotiations more difficult than they otherwise might have been. They broke down completely in mid-2004, with Disney forming Circle Seven Animation and Jobs declaring that Pixar was actively seeking partners other than Disney.[50] Even with this announcement and several talks with Warner Bros., Sony Pictures, and 20th Century Fox, Pixar did not enter negotiations with other distributors,[51] although a Warner Bros. spokesperson told CNN, «We would love to be in business with Pixar. They are a great company.»[49] After a lengthy hiatus, negotiations between the two companies resumed following the departure of Eisner from Disney in September 2005. In preparation for potential fallout between Pixar and Disney, Jobs announced in late 2004 that Pixar would no longer release movies at the Disney-dictated November time frame, but during the more lucrative early summer months. This would also allow Pixar to release DVDs for its major releases during the Christmas shopping season. An added benefit of delaying Cars from November 4, 2005, to June 9, 2006, was to extend the time frame remaining on the Pixar-Disney contract, to see how things would play out between the two companies.[51]

Pending the Disney acquisition of Pixar, the two companies created a distribution deal for the intended 2007 release of Ratatouille, to ensure that if the acquisition failed, this one film would be released through Disney’s distribution channels. In contrast to the earlier Pixar deal, Ratatouille was meant to remain a Pixar property and Disney would have received only a distribution fee. The completion of Disney’s Pixar acquisition, however, nullified this distribution arrangement.[52]

Walt Disney Studios subsidiary (2006–present)

On January 24, 2006, Disney ultimately agreed to buy Pixar for approximately $7.4 billion in an all-stock deal.[53] Following Pixar shareholder approval, the acquisition was completed on May 5, 2006. The transaction catapulted Jobs, who owned 49.65% of total share interest in Pixar, to Disney’s largest individual shareholder with 7%, valued at $3.9 billion, and a new seat on its board of directors.[5][54] Jobs’s new Disney holdings exceeded holdings belonging to ex-CEO Michael Eisner, the previous top shareholder, who still held 1.7%; and Disney Director Emeritus Roy E. Disney, who held almost 1% of the corporation’s shares. Pixar shareholders received 2.3 shares of Disney common stock for each share of Pixar common stock redeemed.[citation needed]

As part of the deal, John Lasseter, by then Executive Vice President, became Chief Creative Officer (reporting directly to president and CEO Robert Iger and consulting with Disney Director Roy E. Disney) of both Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios (including its division DisneyToon Studios), as well as the Principal Creative Adviser at Walt Disney Imagineering, which designs and builds the company’s theme parks.[54] Catmull retained his position as President of Pixar, while also becoming President of Walt Disney Animation Studios, reporting to Iger and Dick Cook, chairman of the Walt Disney Studios. Jobs’s position as Pixar’s chairman and chief executive officer was abolished, and instead, he took a place on the Disney board of directors.[55]

After the deal closed in May 2006, Lasseter revealed that Iger had realized Disney needed to buy Pixar while watching a parade at the opening of Hong Kong Disneyland in September 2005.[56] Iger noticed that of all the Disney characters in the parade, not one was a character that Disney had created within the last ten years since all the newer ones had been created by Pixar.[56] Upon returning to Burbank, Iger commissioned a financial analysis that confirmed that Disney had actually lost money on animation for the past decade, then presented that information to the board of directors at his first board meeting after being promoted from COO to CEO, and the board, in turn, authorized him to explore the possibility of a deal with Pixar.[57] Lasseter and Catmull were wary when the topic of Disney buying Pixar first came up, but Jobs asked them to give Iger a chance (based on his own experience negotiating with Iger in summer 2005 for the rights to ABC shows for the fifth-generation iPod Classic),[58] and in turn, Iger convinced them of the sincerity of his epiphany that Disney really needed to re-focus on animation.[56]

Lasseter and Catmull’s oversight of both the Disney Feature Animation and Pixar studios did not mean that the two studios were merging, however. In fact, additional conditions were laid out as part of the deal to ensure that Pixar remained a separate entity, a concern that analysts had expressed about the Disney deal.[59][page needed] Some of those conditions were that Pixar HR policies would remain intact, including the lack of employment contracts. Also, the Pixar name was guaranteed to continue, and the studio would remain in its current Emeryville, California, location with the «Pixar» sign. Finally, branding of films made post-merger would be «Disney•Pixar» (beginning with Cars).[60]

Jim Morris, producer of WALL-E (2008), became general manager of Pixar. In this new position, Morris took charge of the day-to-day running of the studio facilities and products.[61]

After a few years, Lasseter and Catmull were able to successfully transfer the basic principles of the Pixar Braintrust to Disney Animation, although meetings of the Disney Story Trust are reportedly «more polite» than those of the Pixar Braintrust.[62] Catmull later explained that after the merger, to maintain the studios’ separate identities and cultures (notwithstanding the fact of common ownership and common senior management), he and Lasseter «drew a hard line» that each studio was solely responsible for its own projects and would not be allowed to borrow personnel from or lend tasks out to the other.[63][64] That rule ensures that each studio maintains «local ownership» of projects and can be proud of its own work.[63][64] Thus, for example, when Pixar had issues with Ratatouille and Disney Animation had issues with Bolt (2008), «nobody bailed them out» and each studio was required «to solve the problem on its own» even when they knew there were personnel at the other studio who theoretically could have helped.[63][64]

Expansion (2010–2018)

On April 20, 2010, Pixar opened Pixar Canada in the downtown area of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.[65] The roughly 2,000 square meters studio produced seven short films based on Toy Story and Cars characters. In October 2013, the studio was closed down to refocus Pixar’s efforts at its main headquarters.[66]

In November 2014, Morris was promoted to president of Pixar, while his counterpart at Disney Animation, general manager Andrew Millstein, was also promoted to president of that studio.[67] Both continued to report to Catmull, who retained the title of president of both Disney Animation and Pixar.[67]

On November 21, 2017, Lasseter announced that he was taking a six-month leave of absence after acknowledging what he called «missteps» in his behavior with employees in a memo to staff. According to The Hollywood Reporter and The Washington Post, Lasseter had a history of alleged sexual misconduct towards employees.[68][69][70] On June 8, 2018, it was announced that Lasseter would leave Disney Animation and Pixar at the end of the year, but would take on a consulting role until then.[71] Pete Docter was announced as Lasseter’s replacement as chief creative officer of Pixar on June 19, 2018.[72]

Studio resurgence (2018–present)

On October 23, 2018, it was announced that Catmull would be retiring. He stayed in an adviser role until July 2019.[73] On January 18, 2019, it was announced that Lee Unkrich would be leaving Pixar after 25 years.[74]

Campus

The Steve Jobs Building at the Pixar campus in Emeryville

The atrium of the Pixar campus

When Steve Jobs, chief executive officer of Apple Inc. and Pixar, and John Lasseter, then-executive vice president of Pixar, decided to move their studios from a leased space in Point Richmond, California, to larger quarters of their own, they chose a 20-acre site in Emeryville, California,[75] formerly occupied by Del Monte Foods, Inc. The first of several buildings, the high-tech structure designed by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson[76] has special foundations and electricity generators to ensure continued film production, even through major earthquakes. The character of the building is intended to abstractly recall Emeryville’s industrial past. The two-story steel-and-masonry building is a collaborative space with many pathways.[77]

The digital revolution in filmmaking was driven by applied mathematics, including computational physics and geometry.[78] In 2008, this led Pixar senior scientist Tony DeRose to offer to host the second Julia Robinson Mathematics Festival at the Emeryville campus.[79]

Feature films and shorts

Traditions

Some of Pixar’s first animators were former cel animators including John Lasseter, and others came from computer animation or were fresh college graduates.[80] A large number of animators that make up its animation department had been hired around the releases of A Bug’s Life (1998), Monsters, Inc. (2001), and Finding Nemo (2003). The success of Toy Story (1995) made Pixar the first major computer-animation studio to successfully produce theatrical feature films. The majority of the animation industry was (and still is) located in Los Angeles, and Pixar is located 350 miles (560 km) north in the San Francisco Bay Area. Traditional hand-drawn animation was still the dominant medium for feature animated films.[citation needed]

With the scarcity of Los Angeles-based animators willing to move their families so far north to give up traditional animation and try computer animation, Pixar’s new hires at this time either came directly from college or had worked outside feature animation. For those who had traditional animation skills, the Pixar animation software Marionette was designed so that traditional animators would require a minimum amount of training before becoming productive.[80]

In an interview with PBS talk show host Tavis Smiley,[81] Lasseter said that Pixar’s films follow the same theme of self-improvement as the company itself has: with the help of friends or family, a character ventures out into the real world and learns to appreciate his friends and family. At the core, Lasseter said, «it’s gotta be about the growth of the main character and how he changes.»[81]

Actor John Ratzenberger, who had previously starred in the television series Cheers, has voiced a character in every Pixar feature film from Toy Story through Onward (2020). At this point, he does not have a role in future Pixar films; however, a non-speaking background character in Soul bears his likeness. Pixar paid tribute to Ratzenberger in the end credits of Cars (2006) by parodying scenes from three of its earlier films (Toy Story, Monsters, Inc., and A Bug’s Life), replacing all of the characters with motor vehicle versions of them and giving each film an automotive-based title. After the third scene, Mack (his character in Cars) realizes that the same actor has been voicing characters in every film.

Due to the traditions that have occurred within the films and shorts such as anthropomorphic creatures and objects, and easter egg crossovers between films and shorts that have been spotted by Pixar fans, a blog post titled The Pixar Theory was published in 2013 by Jon Negroni, and popularized by the YouTube channel Super Carlin Brothers,[82] proposing that all of the characters within the Pixar universe were related, surrounding Boo from Monsters Inc. and the Witch from Brave (2012).[83][84][85]

Additionally, Pixar is known for their films having expensive budgets, ranging from $150–200 million. Some of their films include Ratatouille (2007), Toy Story 3 (2010), Toy Story 4 (2019), Incredibles 2 (2018), Soul (2020), The Good Dinosaur (2015), Onward (2020), Turning Red (2022), and Lightyear (2022).

Sequels and prequels

As of September 2022, six Pixar films have received or will receive sequels or prequels. These films are Toy Story, Cars, Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, and Inside Out.

Toy Story 2 was originally commissioned by Disney as a 60-minute direct-to-video film. Expressing doubts about the strength of the material, John Lasseter convinced the Pixar team to start from scratch and make the sequel their third full-length feature film.

Following the release of Toy Story 2 in 1999, Pixar and Disney had a gentlemen’s agreement that Disney would not make any sequels without Pixar’s involvement though retaining a right to do so. After the two companies were unable to agree on a new deal, Disney announced in 2004 they would plan to move forward on sequels with or without Pixar and put Toy Story 3 into pre-production at Disney’s then-new CGI division Circle Seven Animation. However, when Lasseter was placed in charge of all Disney and Pixar animation following Disney’s acquisition of Pixar in 2006, he put all sequels on hold and Toy Story 3 was canceled. In May 2006, it was announced that Toy Story 3 was back in pre-production with a new plot and under Pixar’s control. The film was released on June 18, 2010, as Pixar’s eleventh feature film.

Shortly after announcing the resurrection of Toy Story 3, Lasseter fueled speculation on further sequels by saying, «If we have a great story, we’ll do a sequel.»[86] Cars 2, Pixar’s first non-Toy Story sequel, was officially announced in April 2008 and released on June 24, 2011, as their twelfth. Monsters University, a prequel to Monsters, Inc. (2001), was announced in April 2010 and initially set for release in November 2012;[87] the release date was pushed to June 21, 2013, due to Pixar’s past success with summer releases, according to a Disney executive.[88]

In June 2011, Tom Hanks, who voiced Woody in the Toy Story series, implied that Toy Story 4 was «in the works», although it had not yet been confirmed by the studio.[89][90] In April 2013, Finding Dory, a sequel to Finding Nemo, was announced for a June 17, 2016 release.[91] In March 2014, Incredibles 2 and Cars 3 were announced as films in development.[92] In November 2014, Toy Story 4 was confirmed to be in development with Lasseter serving as director.[93] However, in July 2017, Lasseter announced that he had stepped down, leaving Josh Cooley as sole director.[94] Released in June 2019, Toy Story 4 ranks among the 40 top-grossing films in American cinema.[95]

After Toy Story 4, Pixar chief Pete Docter said that the studio would take a break from sequels and focus on original projects. However, in a later interview, Docter said the studio would have to return to making sequels at some point as they are more «financially secure and help keep the studio running.»[96] On September 9, 2022, during the D23 Expo, Docter and Amy Poehler (voice of Joy) confirmed that Inside Out 2 is in the works, scheduled to release on June 14, 2024.[97]

Adaptation to television

Toy Story is the first Pixar film to be adapted for television as Buzz Lightyear of Star Command film and TV series on the UPN television network, now The CW. Cars became the second with the help of Cars Toons, a series of 3-to-5-minute short films running between regular Disney Channel show intervals and featuring Mater from Cars.[98] Between 2013 and 2014, Pixar released its first two television specials, Toy Story of Terror![99] and Toy Story That Time Forgot. Monsters at Work, a television series spin-off of Monsters, Inc., premiered in July 2021, on Disney+.[100][101]

On December 10, 2020, it was announced that three series would be released on Disney+. The first is Dug Days (featuring Dug from Up) where Dug explores suburbia. Dug Days premiered on September 1, 2021.[102] Next, a Cars show, titled Cars on the Road, was announced to come to Disney+ on September 8, 2022[103] following Mater and Lightning McQueen as they go on a road trip.[102][104] Lastly, an original show entitled Win or Lose would be released on Disney+ in Fall 2023. The series will follow a middle school softball team the week leading up to the big championship game where each episode will be from a different perspective.[102]

2D animation and live-action

The Pixar filmography to date has been computer-animated features, but so far, WALL-E (2008) has been the only Pixar film not to be completely animated as it featured a small amount of live-action footage including Hello, Dolly! while Day & Night (2010), Kitbull (2019), Burrow (2020), and Twenty Something (2021) are the only four shorts to feature 2D animation. 1906, the live-action film by Brad Bird based on a screenplay and novel by James Dalessandro about the 1906 earthquake, was in development but has since been abandoned by Bird and Pixar. Bird has stated that he was «interested in moving into the live-action realm with some projects» while «staying at Pixar [because] it’s a very comfortable environment for me to work in». In June 2018, Bird mentioned the possibility of adapting the novel as a TV series, and the earthquake sequence as a live-action feature film.[105]

The Toy Story Toons short Hawaiian Vacation (2011) also includes the fish and shark as live-action.

Jim Morris, president of Pixar, produced Disney’s John Carter (2012) which Andrew Stanton co-wrote and directed.[106]

Pixar’s creative heads were consulted to fine tune the script for the 2011 live-action film The Muppets.[107] Similarly, Pixar assisted in the story development of Disney’s The Jungle Book (2016) as well as providing suggestions for the film’s end credits sequence.[108] Both Pixar and Mark Andrews were given a «Special Thanks» credit in the film’s credits.[109] Additionally, many Pixar animators, both former and current, were recruited for a traditional hand-drawn animated sequence for the 2018 film Mary Poppins Returns.[110]

Pixar representatives have also assisted in the English localization of several Studio Ghibli films, mainly those from Hayao Miyazaki.[111]

In 2019, Pixar developed a live-action hidden camera reality show, titled Pixar in Real Life, for Disney+.[112]

Upcoming films

Six upcoming films have been announced: Elemental, directed by Peter Sohn, to be released on June 16, 2023,[113][114] Elio, directed by Adrian Molina, to be released on March 1, 2024,[115] Inside Out 2, directed by Kelsey Mann, to be released June 14, 2024,[116][117] and three untitled films on June 13, 2025, March 6, 2026, and June 19, 2026.[118]

Co-op Program

The Pixar Co-op Program, a part of the Pixar University professional development program, allows their animators to use Pixar resources to produce independent films.[119][120] The first 3D project accepted to the program was Borrowed Time (2016); all previously accepted films were live-action.[121]

Franchises

This does not include the Cars spinoffs produced by DisneyToon Studios.

| Titles | Films | Short films | TV series | Release Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toy Story | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1995–present |

| Monsters, Inc. | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2001–present |

| Finding Nemo | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2003–present |

| The Incredibles | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2004–present |

| Cars | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2006–present |

| Inside Out | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2015–present |

Exhibitions

Since December 2005, Pixar has held a variety of exhibitions celebrating the art and artists of the organization and its contribution to the world of animation.[122]

Pixar: 20 Years of Animation

Upon its 20th anniversary, in 2006, Pixar celebrated with the release of its seventh feature film Cars, and held two exhibitions from April to June 2006 at Science Centre Singapore in Jurong East, Singapore and the London Science Museum in London.[123] It was their first time holding an exhibition in Singapore.[citation needed]

The exhibition highlights consist of work-in-progress sketches from various Pixar productions, clay sculptures of their characters and an autostereoscopic short showcasing a 3D version of the exhibition pieces which is projected through four projectors. Another highlight is the Zoetrope, where visitors of the exhibition are shown figurines of Toy Story characters «animated» in real-life through the zoetrope.[123]

Pixar: 25 Years of Animation

Pixar celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2011 with the release of its twelfth feature film Cars 2, and held an exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California from July 2010 until January 2011.[124] The exhibition tour debuted in Hong Kong and was held at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum in Sha Tin from March 27 to July 11, 2011.[125][126] In 2013, the exhibition was held in the EXPO in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. For 6 months from July 6, 2012, until January 6, 2013, the city of Bonn (Germany) hosted the public showing,[127]

On November 16, 2013, the exhibition moved to the Art Ludique museum in Paris, France with a scheduled run until March 2, 2014.[128] The exhibition moved to three Spanish cities later in 2014 and 2015: Madrid (held in CaixaForum from March 21 until June 22),[129] Barcelona (held also in Caixaforum from February until May) and Zaragoza.[130]

Pixar: 25 Years of Animation includes all of the artwork from Pixar: 20 Years of Animation, plus art from Ratatouille, WALL-E, Up and Toy Story 3.[citation needed]

The Science Behind Pixar

The Science Behind Pixar is a travelling exhibition that first opened on June 28, 2015, at the Museum of Science in Boston, Massachusetts. It was developed by the Museum of Science in collaboration with Pixar. The exhibit features forty interactive elements that explain the production pipeline at Pixar. They are divided into eight sections, each demonstrating a step in the filmmaking process: Modeling, Rigging, Surfaces, Sets & Cameras, Animation, Simulation, Lighting, and Rendering. Before visitors enter the exhibit, they watch a short video at an introductory theater showing Mr. Ray from Finding Nemo and Roz from Monsters, Inc..[citation needed]

The exhibition closed on January 10, 2016, and was moved to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where it ran from March 12 to September 5. Afterwards, it moved to the California Science Center in Los Angeles, California and was open from October 15, 2016, to April 9, 2017. It made another stop at the Science Museum of Minnesota in St. Paul, Minnesota from May 27 through September 4, 2017.[131]

The exhibition opened in Edmonton, Alberta on July 1, 2017, at the TELUS World of Science – Edmonton (TWOSE).[citation needed]

Pixar: The Design of Story

Pixar: The Design of Story was an exhibition held at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City from October 8, 2015, to September 11, 2016.[132][133] The museum also hosted a presentation and conversation with John Lasseter on November 12, 2015, entitled «Design By Hand: Pixar’s John Lasseter».[132]

Pixar: 30 Years of Animation

Pixar celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2016 with the release of its seventeenth feature film Finding Dory, and put together another milestone exhibition. The exhibition first opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, Japan from March 5, 2016, to May 29, 2016. It subsequently moved to the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum National Museum of History, Dongdaemun Design Plaza where it ended on March 5, 2018, at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum.[134]

Legacy

Pixar has a strong legacy with its reach on many different generations. Its emotional depth combined with its playfulness integrated in a cutting-edge technology has left it with a lasting legacy among children and adult viewers. With Pixar’s success, many have considered it an integral part of what it means to be a child, which may contribute to its popularity in an often separate adult audience. From the 1990s to the present, Pixar movies have become a central force in animation.[135] Discover Magazine wrote:

The message hidden inside Pixar’s magnificent films is this: humanity does not have a monopoly on personhood. In whatever form non- or super-human intelligence takes, it will need brave souls on both sides to defend what is right. If we can live up to this burden, humanity and the world we live in will be better for it.[135]

See also

- The Walt Disney Company

- Disney’s Nine Old Men

- 12 basic principles of animation

- Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life

- Modern animation in the United States: Disney

- Animation studios owned by The Walt Disney Company

- Walt Disney Animation Studios

- Disneytoon Studios

- Blue Sky Studios

- 20th Century Animation

- List of animation studios

- List of Disney theatrical animated feature films

References

- ^ a b «COMPANY FAQS». Pixar. Archived from the original on July 2, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e f Smith, Alvy Ray. «Pixar Founding Documents». Alvy Ray Smith Homepage. Archived from the original on April 27, 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Alvy Ray. «Proof of Pixar Cofounders» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ^ «Walt Disney Company, Form 8-K, Current Report, Filing Date Jan 26, 2006» (PDF). secdatabase.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ a b «Walt Disney Company, Form 8-K, Current Report, Filing Date May 8, 2006». secdatabase.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ «Pixar». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ When added to foreign grosses Pixar Movies at the Box Office Box Office Mojo

- ^ «Brief History of the New York Institute of Technology Computer Graphics Lab». Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ «Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries». Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ a b «The Story Behind Pixar – with Alvy Ray Smith». mixergy.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ Sito, Tom (2013). Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation. p. 137. ISBN 9780262019095. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ «CGI Story: The Development of Computer Generated Imaging». lowendmac.com. June 8, 2014. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ «ID 797 – History of Computer Graphics and Animation». Ohio State University. Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Hormby, Thomas (January 22, 2007). «The Pixar Story: Fallon Forbes, Dick Shoup, Alex Schure, George Lucas and Disney». Low End Mac. Archived from the original on August 14, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ Smith, Alvy Ray (August 15, 1995). «Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing» (PDF). Princeton University—Department of Computer Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ^ «Everything You Ever Saw | Computer Graphics World». www.cgw.com. 32. February 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ «What will Pixar’s John Lasseter do at Disney – May. 17, 2006». archive.fortune.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Brian Jay (2016). George Lucas: A Life. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 289–90. ISBN 978-0316257442.

- ^ «Alvy Pixar Myth 3». alvyray.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ «Pixar Selects Silicon Graphics Octane2 Workstations». HPCwire. July 28, 2000. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ Coll, Steve (October 1, 1984). «When The Magic Goes». Inc. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ «An exclusive interview with Daniel Kottke». India Today. September 13, 2011. Archived from the original on May 6, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ Oates, Sarah (July 15, 1985). «Chuck E. Cheese Gets New Lease on Life». Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ Kieron Johnson (April 28, 2017). «Pixar’s Co-Founders Heard ‘No’ 45 Times Before Steve Jobs Said ‘Yes’«. Entrepreneur.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Paik 2015, p. 52.

- ^ Smith, Alvy Ray (April 17, 2013). «How Pixar Used Moore’s Law to Predict the Future». Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ Price, David A. (November 22, 2008). «Pixar’s film that never was: «Monkey»«. The Pixar Touch. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

- ^ «First fully digital feature film». Guinness World Records. Guinness World Records Limited. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (December 16, 2020). «‘The Rescuers Down Under’: The Untold Story of How the Sequel Changed Disney Forever». Collider. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ a b «Pixar Animation Studios». Ohio State University. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ Paik, Karen (November 3, 2015). To Infinity and Beyond!: The Story of Pixar Animation Studios. Chronicle Books. p. 58. ISBN 9781452147659. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ «Toy Stories and Other Tales». University of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ «Pixar Animation Studios—Company History». Fundinguniverse.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ «History of Computer Graphics: 1990–99». Hem.passagen.se. Archived from the original on April 18, 2005. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Fisher, Lawrence M. (April 2, 1991). «Hard Times For Innovator in Graphics». The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ «The Illusion and Emotion Behind ‘Toy Story 4’ – Newsweek». Newsweek. July 5, 2019. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Calonius, Erik (March 31, 2011). Ten Steps Ahead: What Smart Business People Know That You Don’t. Headline. p. 68. ISBN 9780755362363. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Price, David A. (2008). The Pixar Touch: The making of a Company (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 137. ISBN 9780307265753.

- ^ Schlender, Brent (September 18, 1995). «Steve Jobs’ Amazing Movie Adventure Disney Is Betting on Computerdom’s Ex-Boy Wonder to Deliver This Year’s Animated Christmas Blockbuster. Can He Do for Hollywood What He Did for Silicon Valley?». CNNMoney. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Nevius, C.W. (August 23, 2005). «Pixar tells story behind ‘Toy Story’«. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ «Toy Story» Archived August 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ <Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson, page 291>

«Company FAQ’s». Pixar. Retrieved March 29, 2015. - ^ THE MEDIA BUSINESS;Pixar Plans End To Commercials

- ^ `Toy Story’ Maker Did Well In 2nd Quarter — SFGATE

- ^ a b Catmull, Ed (March 12, 2014). «Inside The Pixar Braintrust». Fast Company. Mansueto Ventures, LLC. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- ^ Wloszczyna, Susan (October 31, 2012). «‘Wreck-It Ralph’ is a Disney animation game-changer». USA Today. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Pond, Steve (February 21, 2014). «Why Disney Fired John Lasseter—And How He Came Back to Heal the Studio». The Wrap. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ Hartl, John (July 31, 2000). «Sequels to ‘Toy Story,’ ‘Tail,’ ‘Dragonheart’ go straight to video». The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c «Pixar dumps Disney». CNNMoney. January 29, 2004. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- ^ «Pixar Says ‘So Long’ to Disney». Wired. January 29, 2004. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Grover, Ronald (December 9, 2004). «Steve Jobs’s Sharp Turn with Cars». Business Week. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ «Pixar Perfectionists Cook Up ‘Ratatouille’ As Latest Animated Concoction». Star Pulse. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (January 24, 2006). «Disney buys Pixar». CNN. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Holson, Laura M. (January 25, 2006). «Disney Agrees to Acquire Pixar in a $7.4 Billion Deal». The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (January 24, 2006). «Disney buys Pixar». CNN. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c Schlender, Brent (May 17, 2006). «Pixar’s magic man». CNN. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Issacson, Walter (2013). Steve Jobs (1st paperback ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 439. ISBN 9781451648546.

- ^ Issacson, Walter (2013). Steve Jobs (1st paperback ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 438. ISBN 9781451648546.

- ^ «Agreement and Plan of Merger by and among The Walt Disney Company, Lux Acquisition Corp. and Pixar». Securities and Exchange Commission. January 24, 2006. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Bunk, Matthew (January 21, 2006). «Sale unlikely to change Pixar culture». Inside Bay Area. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ Graser, Marc (September 10, 2008). «Morris and Millstein named manager of Disney studios». Variety. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (December 4, 2013). «Pixar vs. Disney Animation: John Lasseter’s Tricky Tug-of-War». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c Bell, Chris (April 5, 2014). «Pixar’s Ed Catmull: interview». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c Zahed, Ramin (April 2, 2012). «An Interview with Disney/Pixar President Dr. Ed Catmull». Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

- ^ «Pixar Canada sets up home base in Vancouver, looks to expand». The Vancouver Sun. Canada. Archived from the original on April 22, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ «Pixar Canada shuts its doors in Vancouver». The Province. October 8, 2013. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Graser, Marc (November 18, 2014). «Walt Disney Animation, Pixar Promote Andrew Millstein, Jim Morris to President». Variety. Penske Business Media. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ Masters, Kim (November 21, 2017). «John Lasseter’s Pattern of Alleged Misconduct Detailed by Disney/Pixar Insiders». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 21, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (November 21, 2017). «Disney animation guru John Lasseter takes leave after sexual misconduct allegations». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ Masters, Kim (April 25, 2018). «He Who Must Not Be Named»: Can John Lasseter Ever Return to Disney?». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (June 8, 2018). «Pixar Co-Founder to Leave Disney After ‘Missteps’«. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 9, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Kit, Borys (June 19, 2018). «Pete Docter, Jennifer Lee to Lead Pixar, Disney Animation». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ Kit, Borys (October 23, 2018). «Pixar Co-Founder Ed Catmull to Retire». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Kit, Borys (January 18, 2019). «‘Toy Story 3,’ ‘Coco’ Director Lee Unkrich Leaving Pixar After 25 Years (Exclusive)». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ Pimentel, Benjamin (August 28, 2000). «Lucasfilm Unit Looking at Move To Richmond / Pixar shifting to Emeryville». San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015.

- ^ «Bohlin Cywinski Jackson | Pixar Animation Studios». Bohlin Cywinski Jackson. Archived from the original on August 30, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ «Pixar Animation Studios, The Steve Jobs Building». Auerbach Consultants.

- ^ OpenEdition: Hollywood and the Digital Revolution Archived May 11, 2018, at the Wayback Machine by Alejandro Pardo [in French]

- ^ Julia Robinson Mathematics Festival 2008 Archived May 11, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Mathematical Sciences Research Institute

- ^ a b Hormby, Thomas (January 22, 2007). «The Pixar Story: Fallon Forbes, Dick Shoup, Alex Schure, George Lucas and Disney». Low End Mac. Archived from the original on August 14, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ a b Smiley, Tavis (January 24, 2007). «Tavis Smiley». PBS. Archived from the original on November 24, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ «JonNegroni : The Pixar Theory Debate, Featuring SuperCarlinBros». June 27, 2016. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Dunn, Gaby (July 12, 2013). ««Pixar Theory» connects all your favorite movies in 1 universe». The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Whitney, Erin (July 12, 2013). «The (Mind-Blowing) Pixar Theory: Are All the Films Connected?». Moviefone. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ McFarland, Kevin (July 12, 2013). «Read This: A grand unified theory connects all Pixar films in one timeline». The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ Douglas, Edwards (June 3, 2006). «Pixar Mastermind John Lasseter». comingsoon.net. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2007.

- ^ «Disney announce Monsters Inc sequel». BBC News. April 23, 2010. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ «Monsters University Pushed to 2013». movieweb.com. April 4, 2011. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ «Tom Hanks reveals Toy Story 4». Digital Spy. June 27, 2011. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- ^ Access Hollywood June 27, 2011

- ^ Keegan, Rebecca (September 18, 2013). «‘The Good Dinosaur’ moved to 2015, leaving Pixar with no 2014 film». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ^ Vejvoda, Jim (March 18, 2014). «Disney Officially Announces The Incredibles 2 and Cars 3 Are in the Works». IGN. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (November 6, 2014). «John Lasseter to Direct Fourth ‘Toy Story’ Film». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Khatchatourian, Maane (July 14, 2017). «‘Toy Story 4’: Josh Cooley Becomes Sole Director as John Lasseter Steps Down». Variety. Archived from the original on July 15, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ «U.S. Box Office: ‘Toy Story 4’ Among 40 Top-Grossing Movies Ever». Forbes. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ «Pixar’s Pete Docter Reminds Us Sequels Help Keep the Lights on». January 6, 2021.

- ^ Grobar, Matt (September 10, 2022). «‘Inside Out’ Sequel Plans Confirmed By Pixar At D23″. Deadline. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ^ «Cars Toons Coming in October To Disney Channel». AnimationWorldNetwork. September 26, 2008. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ Cheney, Alexandra (October 13, 2013). «Watch A Clip from Pixar’s First TV Special ‘Toy Story OF TERROR!’«. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Littleton, Cynthia (November 9, 2017). «New ‘Star Wars’ Trilogy in Works With Rian Johnson, TV Series Also Coming to Disney Streaming Service». Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (April 9, 2019). «‘Monsters, Inc.’ Voice Cast to Return for Disney+ Series (Exclusive)». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c «Three New Pixar Series Coming to Disney+, Including the Very Adorable ‘Up’ Spin-Off ‘Dug Days’«. /Film. December 11, 2020. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ Behzadi, Sofia (August 1, 2022). «‘Cars On The Road’ Pixar Series Gets Premiere Date On Disney+, First-Look Trailer». Deadline. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ Del Rosario, Alexandra (November 12, 2021). «Disney+’s ‘Cars’ Series Gets Title, ‘Tiana’ Enlists Stella Meghie As Writer/Director; First-Look Images Released». Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ Adam Chitwood (June 18, 2018). «Brad Bird Says ‘1906’ May Get Made as an «Amalgam» of a TV and Film Project». Collider. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin (February 16, 2012). «‘John Carter’ Producer Jim Morris Confirms Sequel ‘John Carter: The Gods Of Mars’ Already In The Works». The Playlist. Indiewire.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ Kit, Borys (October 14, 2010). «Disney Picks Pixar Brains for Muppets Movie». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Drew. «9 Things Disney Fans Need to Know About The Jungle Book, According to Jon Favreau». Disney Insider. The Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ «The Jungle Book: Press Kit» (PDF). wdsmediafile.com. The Walt Disney Studios. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ «Mary Poppins Returns – Press Kit» (PDF). wdsmediafile.com. Walt Disney Studios. Retrieved November 29, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ TURAN, KENNETH (September 20, 2002). «Under the Spell of ‘Spirited Away’«. Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ Palmer, Roger (August 27, 2019). «‘Pixar in Real Life’ Coming Soon To Disney+». What’s On Disney Plus. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Pixar (May 16, 2022). «[Elemental announcement]». Instagram. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ «Disney Dates a Ton of Pics into 2023 & Juggles Fox Releases with Ridley Scott’s ‘The Last Duel’ to Open Christmas 2020, ‘The King’s Man’ Next Fall – Update». November 16, 2019. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Grobar, Erik Pedersen,Matt; Pedersen, Erik; Grobar, Matt (September 10, 2022). «‘Elio’: Pixar Sets New Pic About 11-Year-Old Boy Beamed Into Space; America Ferrera Stars & ‘Coco’s Adrian Molina Directs». Deadline. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Couch, Aaron (September 10, 2022). «‘Inside Out’ Sequel, Alien Movie ‘Elio’ Set at Pixar». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ Kit, Borys (September 10, 2021). «Disney’s Live-Action ‘The Little Mermaid’ to Open on Memorial Day Weekend in 2023». The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ Trenholm, Richard (January 20, 2023). «Disney Adds A Ton of ‘Untitled Disney’ Movies, Including One This Year».

- ^ Hill, Libby (October 17, 2016). «Two Pixar animators explore the depths of grief and guilt in ‘Borrowed Time’«. LA Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Desowitz, Bill (October 24, 2016). «‘Borrowed Time’: How Two Pixar Animators Made a Daring, Off-Brand Western Short». Indiewire. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Failes, Ian (July 29, 2016). «How Andrew Coats and Lou Hamou-Lhadj Made The Independent Short ‘Borrowed Time’ Inside Pixar». Cartoon Brew. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ «Pixar: 20 Years of Animation». Pixar. Archived from the original on January 8, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Eng Eng, Wang (April 1, 2010). «Pixar animation comes to life at Science Centre exhibition». MediaCorp Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ «Pixar: 25 Years of Animation». Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ «Pixar: 25 Years of Animation». Leisure and Cultural Services Department. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ «Pixar brings fascinating animation world to Hong Kong Archived August 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Xinhua, March 27, 2011

- ^ GmbH, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. «Pixar – Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland – Bonn». www.bundeskunsthalle.de. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ «Exposition Pixar» (in French). Art Ludique. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ «Pixar: 25 años de animación». Obra Social «la Caixa». Archived from the original on January 24, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ ««Pixar. 25 years of animation» Exhibition in Spain». motionpic.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ «The Science Behind Pixar at pixar.com». Archived from the original on July 8, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ a b «Pixar: The Design of Story». Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. October 8, 2015. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ «Cooper Hewitt to Host Pixar Exhibition». The New York Times. July 26, 2015. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ «Pixar: 30 Years Of Animation». Pixar Animation Studios. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ a b «The Hidden Message in Pixar’s Films». Discover Magazine. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

External links

- Official website

- Pixar’s channel on YouTube

- Pixar Animation Studios at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- List of the 40 founding employees of Pixar

This article is about the computer animation studio. For other uses, see Pixar (disambiguation).

Logo used since 1995 |

|

Headquarters in Emeryville, California |

|

| Type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Animation |

| Predecessor | The Graphics Group (1979–1986) Disney Circle 7 Animation (2005-2006) |

| Founded | February 3, 1986; 37 years ago in Richmond, California |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | 1200 Park Avenue,

Emeryville, California , U.S. |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products | Computer animations |

| Brands |

|

| Owner | Lucasfilm (1979-1986) Steve Jobs (1986–2006) The Walt Disney Company (2006–present) |

|

Number of employees |

1,233 (2020) |

| Parent | Walt Disney Studios (Disney Entertainment) (2006–present) |

| Website | pixar.com |

| Footnotes / references [1][2][3] |

Pixar Animation Studios () is an American computer animation studio known for its critically and commercially successful computer animated feature films. It is based in Emeryville, California, United States. Since 2006, Pixar has been a subsidiary of Walt Disney Studios, a division of Disney Entertainment, which owned by The Walt Disney Company.

Pixar started in 1979 as part of the Lucasfilm computer division, known as the Graphics Group, before its spin-off as a corporation in 1986, with funding from Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, who became its majority shareholder.[2] Disney purchased Pixar in January 2006 at a valuation of $7.4+ billion by converting each share of Pixar stock to 2.3 shares of Disney stock.[4][5] Pixar is best known for its feature films, technologically powered by RenderMan, the company’s own implementation of the industry-standard RenderMan Interface Specification image-rendering API. The studio’s mascot is Luxo Jr., a desk lamp from the studio’s 1986 short film of the same name.

Pixar has produced 26 feature films, starting with Toy Story (1995), which is the first fully computer-animated feature film; its most recent film was Lightyear (2022). The studio has also produced many short films. As of July 2019, its feature films have earned approximately $14 billion at the worldwide box office,[6] with an average worldwide gross of $680 million per film.[7] Toy Story 3 (2010), Finding Dory (2016), Incredibles 2 (2018), and Toy Story 4 (2019) are all among the 50 highest-grossing films of all time, with Incredibles 2 being the fourth-highest-grossing animated film of all time, with a gross of $1.2 billion; the other three also grossed over $1 billion. Moreover, 15 of Pixar’s films are in the 50 highest-grossing animated films of all time.

Pixar has earned 23 Academy Awards, 10 Golden Globe Awards, and 11 Grammy Awards, along with numerous other awards and acknowledgments. Its films are frequently nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, since its inauguration in 2001, with eleven winners being Finding Nemo (2003), The Incredibles (2004), Ratatouille (2007), WALL-E (2008), Up (2009), Toy Story 3 (2010), Brave (2012), Inside Out (2015), Coco (2017), Toy Story 4 (2019), and Soul (2020); the five nominated without winning are Monsters, Inc. (2001), Cars (2006), Incredibles 2 (2018), Onward (2020), and Luca (2021). Up and Toy Story 3 were also nominated for the more competitive and inclusive Academy Award for Best Picture.

On February 10, 2009, Pixar executives John Lasseter, Brad Bird, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton, and Lee Unkrich were presented with the Golden Lion award for Lifetime Achievement by the Venice Film Festival. The physical award was ceremoniously handed to Lucasfilm’s founder, George Lucas.

History

Early history

Pixar got its start in 1974, when New York Institute of Technology’s (NYIT) founder, Alexander Schure, who was also the owner of a traditional animation studio, established the Computer Graphics Lab (CGL) and recruited computer scientists who shared his ambitions about creating the world’s first computer-animated film. Edwin Catmull and Malcolm Blanchard were the first to be hired and were soon joined by Alvy Ray Smith and David DiFrancesco some months later, which were the four original members of the Computer Graphics Lab, located in a converted two-story garage acquired from the former Vanderbilt-Whitney estate.[8][9] Schure kept pouring money into the computer graphics lab, an estimated $15 million, giving the group everything they desired and driving NYIT into serious financial troubles.[10] Eventually, the group realized they needed to work in a real film studio in order to reach their goal. Francis Ford Coppola then invited Smith to his house for a three-day media conference, where Coppola and George Lucas shared their visions for the future of digital moviemaking.[11]

When Lucas approached them and offered them a job at his studio, six employees moved to Lucasfilm. During the following months, they gradually resigned from CGL, found temporary jobs for about a year to avoid making Schure suspicious, and joined the Graphics Group at Lucasfilm.[12][13]

The Graphics Group, which was one-third of the Computer Division of Lucasfilm, was launched in 1979 with the hiring of Catmull from NYIT,[14] where he was in charge of the Computer Graphics Lab. He was then reunited with Smith, who also made the journey from NYIT to Lucasfilm, and was made the director of the Graphics Group. At NYIT, the researchers pioneered many of the CG foundation techniques—in particular, the invention of the alpha channel by Catmull and Smith.[15] Over the next several years, the CGL would produce a few frames of an experimental film called The Works. After moving to Lucasfilm, the team worked on creating the precursor to RenderMan, called REYES (for «renders everything you ever saw») and developed several critical technologies for CG—including particle effects and various animation tools.[16]

John Lasseter was hired to the Lucasfilm team for a week in late 1983 with the title «interface designer»; he animated the short film The Adventures of André & Wally B.[17] In the next few years, a designer suggested naming a new digital compositing computer the «Picture Maker». Smith suggested that the laser-based device have a catchier name, and came up with «Pixer», which after a meeting was changed to «Pixar».[18]

In 1982, the Pixar team began working on special-effects film sequences with Industrial Light & Magic. After years of research, and key milestones such as the Genesis Effect in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and the Stained Glass Knight in Young Sherlock Holmes,[14] the group, which then numbered 40 individuals, was spun out as a corporation in February 1986 by Catmull and Smith. Among the 38 remaining employees, there were also Malcolm Blanchard, David DiFrancesco, Ralph Guggenheim, and Bill Reeves, who had been part of the team since the days of NYIT. Tom Duff, also an NYIT member, would later join Pixar after its formation.[2] With Lucas’s 1983 divorce, which coincided with the sudden dropoff in revenues from Star Wars licenses following the release of Return of the Jedi, they knew he would most likely sell the whole Graphics Group. Worried that the employees would be lost to them if that happened, which would prevent the creation of the first computer-animated movie, they concluded that the best way to keep the team together was to turn the group into an independent company. But Moore’s Law also suggested that sufficient computing power for the first film was still some years away, and they needed to focus on a proper product until then. Eventually, they decided they should be a hardware company in the meantime, with their Pixar Image Computer as the core product, a system primarily sold to governmental, scientific, and medical markets.[2][10][19] They also used SGI computers.[20]

In 1983, Nolan Bushnell founded a new computer-guided animation studio called Kadabrascope as a subsidiary of his Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatres company (PTT), which was founded in 1977. Only one major project was made out of the new studio, an animated Christmas special for NBC starring Chuck E. Cheese and other PTT mascots; known as «Chuck E. Cheese: The Christmas That Almost Wasn’t». The animation movement would be made using tweening instead of traditional cel animation. After the video game crash of 1983, Bushnell started selling some subsidiaries of PTT to keep the business afloat. Sente Technologies (another division, was founded to have games distributed in PTT stores) was sold to Bally Games and Kadabrascope was sold to Lucasfilm. The Kadabrascope assets were combined with the Computer Division of Lucasfilm.[21] Coincidentally, one of Steve Jobs’s first jobs was under Bushnell in 1973 as a technician at his other company Atari, which Bushnell sold to Warner Communications in 1976 to focus on PTT.[22] PTT would later go bankrupt in 1984 and be acquired by ShowBiz Pizza Place.[23]

Independent company (1986–1999)

In 1986, the newly independent Pixar was headed by President Edwin Catmull and Executive Vice President Alvy Ray Smith. Lucas’s search for investors led to an offer from Steve Jobs, which Lucas initially found too low. He eventually accepted after determining it impossible to find other investors. At that point, Smith and Catmull had been declined 45 times, and 35 venture capitalists and ten large corporations had declined.[24] Jobs, who had been edged out of Apple in 1985,[2] was now founder and CEO of the new computer company NeXT. On February 3, 1986, he paid $5 million of his own money to George Lucas for technology rights and invested $5 million cash as capital into the company, joining the board of directors as chairman.[2][25]

In 1985, while still at Lucasfilm, they had made a deal with the Japanese publisher Shogakukan to make a computer-animated movie called Monkey, based on the Monkey King. The project continued sometime after they became a separate company in 1986, but it became clear that the technology was not sufficiently advanced. The computers were not powerful enough and the budget would be too high. So they focused on the computer hardware business for years until a computer-animated feature became feasible according to Moore’s law.[26][27]

At the time, Walt Disney Studios was interested and eventually bought and used the Pixar Image Computer and custom software written by Pixar as part of its Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) project, to migrate the laborious ink and paint part of the 2D animation process to a more automated method. The company’s first feature film to be released using this new animation method was The Rescuers Down Under (1990).[28][29]

In a bid to drive sales of the system and increase the company’s capital, Jobs suggested releasing the product to the mainstream market. Pixar employee John Lasseter, who had long been working on not-for-profit short demonstration animations, such as Luxo Jr. (1986) to show off the device’s capabilities, premiered his creations to great fanfare at SIGGRAPH, the computer graphics industry’s largest convention.[30]

However, the Image Computer had inadequate sales[30] which threatened to end the company as financial losses grew. Jobs increased investment in exchange for an increased stake, reducing the proportion of management and employee ownership until eventually, his total investment of $50 million gave him control of the entire company. In 1989, Lasseter’s growing animation department, originally composed of just four people (Lasseter, Bill Reeves, Eben Ostby, and Sam Leffler), was turned into a division that produced computer-animated commercials for outside companies.[1][31][32] In April 1990, Pixar sold its hardware division, including all proprietary hardware technology and imaging software, to Vicom Systems, and transferred 18 of Pixar’s approximately 100 employees. That year, Pixar moved from San Rafael to Richmond, California.[33] Pixar released some of its software tools on the open market for Macintosh and Windows systems. RenderMan is one of the leading 3D packages of the early 1990s, and Typestry is a special-purpose 3D text renderer that competed with RayDream.[citation needed]

During this period, Pixar continued its successful relationship with Walt Disney Feature Animation, a studio whose corporate parent would ultimately become its most important partner. As 1991 began, however, the layoff of 30 employees in the company’s computer hardware department—including the company’s president, Chuck Kolstad,[34] reduced the total number of employees to just 42, approximately its original number.[35] Pixar made a historic $26 million deal with Disney to produce three computer-animated feature films, the first of which was Toy Story, the product of the technological limitations that challenged CGI.[36] By then the software programmers, who were doing RenderMan and IceMan, and Lasseter’s animation department, which made television commercials (and four Luxo Jr. shorts for Sesame Street the same year), were all that remained of Pixar.[37]

Even with income from these projects, the company continued to lose money and Steve Jobs, as chairman of the board and now the full owner, often considered selling it. Even as late as 1994, Jobs contemplated selling Pixar to other companies such as Hallmark Cards, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, and Oracle CEO and co-founder Larry Ellison.[38] Only after learning from New York critics that Toy Story would probably be a hit—and confirming that Disney would distribute it for the 1995 Christmas season—did he decide to give Pixar another chance.[39][40] For the first time, he also took an active leadership role in the company and made himself CEO.[citation needed] Toy Story grossed more than $373 million worldwide[41] and, when Pixar held its initial public offering on November 29, 1995, it exceeded Netscape’s as the biggest IPO of the year. In its first half-hour of trading, Pixar stock shot from $22 to $45, delaying trading because of unmatched buy orders. Shares climbed to US$49 and closed the day at $39.[42]