From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Donatello |

|

|---|---|

Donatello, in a 15th-century portrait by an unknown artist[1] |

|

| Born |

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi c. 1386 Republic of Florence |

| Died | 13 December 1466 (aged 79–80)

Republic of Florence |

| Nationality | Florentine |

| Education | Lorenzo Ghiberti |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Notable work | Saint George, David, Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi (c. 1386 – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello ([2] Italian: [donaˈtɛllo]), was an Italian[a] sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used this to develop a complete Renaissance style in sculpture. He spent time in other cities, and while there he worked on commissions and taught others; his periods in Rome, Padua, and Siena introduced to other parts of Italy his techniques, developed in the course of a long and productive career. Financed by Cosimo de’ Medici, Donatello’s David was the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity.

He worked with stone, bronze, wood, clay, stucco, and wax, and had several assistants, with four perhaps being a typical number. Although his best-known works mostly were statues in the round, he developed a new, very shallow, type of bas-relief for small works, and a good deal of his output was larger architectural reliefs.

Early life[edit]

Donatello was the son of Niccolò di Betto Bardi, who was a member of the Florentine Arte della Lana. He was born in Florence, probably in the year 1386. Donatello was educated in the house of the Martelli family.[4] He apparently received his early artistic training in a goldsmith’s workshop,[citation needed] and then worked briefly in the studio of Lorenzo Ghiberti.[5]

In Pistoia in 1401, Donatello met the older Filippo Brunelleschi. They likely went to Rome together around 1403, staying until the next year, to study the architectural ruins. Brunelleschi informally tutored Donatello in goldsmithing and sculpture.[6] Brunelleschi’s buildings and Donatello’s sculptures are both considered supreme expressions of the spirit of this era in architecture and sculpture, and they exercised a potent influence upon the artists of the age.

Work in Florence[edit]

In Florence, Donatello assisted Lorenzo Ghiberti with the statues of prophets for the north door of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, for which he received payment in November 1406 and early 1408. In 1409–1411 he executed the colossal seated figure of Saint John the Evangelist, which occupied a niche of the old cathedral façade until 1588, and now is placed in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo. This work marks a decisive step forward from late Gothic Mannerism in the search for naturalism and the rendering of human feelings.[7] The face, the shoulders, and the bust are still idealized, while the hands and the fold of cloth over the legs are more realistic.

In 1411–1413, Donatello worked on a statue of St. Mark for the guild church of Orsanmichele. In 1417 he completed the Saint George for the Confraternity of the Cuirass-makers. From 1423 is the Saint Louis of Toulouse for the Orsanmichele, now in the Museum of the Basilica di Santa Croce. Donatello also sculpted the classical frame for this work, which remains, while the statue was moved in 1460 and replaced by the Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Verrocchio.

Between 1415 and 1426, Donatello created five statues for the campanile of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, also known as the Duomo. These works are the Beardless Prophet; Bearded Prophet (both from 1415); the Sacrifice of Isaac (1421); Habbakuk (1423–25); and Jeremiah (1423–26); which follow the classical models for orators and are characterized by strong portrait details. In 1425, he executed the notable Crucifix for Santa Croce; this work portrays Christ in a moment of agony, eyes, and mouth partially opened, the body contracted in an ungraceful posture.

Pazzi Madonna (1425-1430), marble bas-relief in stiacciato, Bode Museum, Berlin

From 1425 to 1427, Donatello collaborated with Michelozzo on the funerary monument of the Antipope John XXIII for the Battistero in Florence. Donatello made the recumbent bronze figure of the deceased, under a shell. In 1427, he completed in Pisa a marble relief for the funerary monument of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci at the church of Sant’Angelo a Nilo in Naples. In the same period, he executed the relief of The Feast of Herod (c. 1427) and the statues of Faith and Hope for the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Siena. The Feast of Herod is mostly in stiacciato (a very low bas-relief), with the foreground figures done in bas-relief, and is considered one of the first examples of one-point perspective in sculpture.[citation needed]

During the period 1425-1430 the Pazzi Madonna was created. It is a rectangular marble bas-relief sculpture, also in stiacciato. Its original owner is not known, but the work is thought to have been commissioned for private devotion by a resident of Florence.[8] It is in the collection of the Bode Museum in Berlin, Germany. It was copied frequently and admired for the tender nature of the depiction of the Virgin Mary and her smiling infant child.

Donatello also restored antique sculptures for the Palazzo Medici.[9]

Bronze David[edit]

Donatello’s bronze David, now in the Bargello museum, is his most famous work, and the first known free-standing nude statue produced since antiquity. Conceived fully in the round, independent of any architectural surroundings, and largely representing an allegory of the civic virtues triumphing over brutality and irrationality, it is arguably the first major work of Renaissance sculpture. It was commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici for the courtyard of his Palazzo Medici, but its date remains the subject of debate. It is most often dated to the 1440s, but dates as late as the 1460s have support from some scholars. It is not to be confused with his stone David, with clothes, of about 1408–09.

Some have perceived the David as having homoerotic qualities and have argued that this reflected the artist’s own orientation.[10] The historian Paul Strathern makes the claim that Donatello made no secret of his homosexuality, and that his behaviour was tolerated by his friends.[11] The main evidence comes from anecdotes by Angelo Poliziano in his «Detti piacevoli«, where he writes about Donatello surrounding himself with «handsome assistants» and chasing in search of one that had fled his workshop.[12] This may not be surprising in the context of attitudes prevailing in the 15th- and 16th-century Florentine Republic. However, little detail is known with certainty about his private life, and no mention of his sexuality has been found in the Florentine archives (in terms of denunciations)[13] albeit which during this period are incomplete.[14]

Rome, Prato, and Venice[edit]

When Cosimo was exiled from Florence, Donatello went to Rome, remaining until 1433. The two works that testify to his presence in this city, the Tomb of Giovanni Crivelli at Santa Maria in Aracoeli, and the Ciborium at St. Peter’s Basilica, bear a strong stamp of classical influence.

Donatello’s return to Florence almost coincided with Cosimo’s. In May 1434, he signed a contract for the marble pulpit on the facade of Prato cathedral, the last project executed in collaboration with Michelozzo. This work, a passionate, pagan, rhythmically conceived bacchanalian dance of half-nude putti, was the forerunner of the great Cantoria, or singing tribune, at the Duomo in Florence on which Donatello worked intermittently from 1433 to 1440 and was inspired by ancient sarcophagi and Byzantine ivory chests. In 1435, he executed the Annunciation for the Cavalcanti altar in Santa Croce, inspired by 14th-century iconography, and in 1437–1443, he worked in the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo in Florence, on two doors and lunettes portraying saints, as well as eight stucco tondos. From 1438 is the wooden statue of St. John the Baptist for Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice.

In Padua[edit]

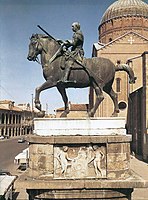

In 1443, Donatello was called to Padua by the heirs of the famous condottiere Erasmo da Narni (better known as the Gattamelata, or «Honey-Cat»), who had died that year. Completed in 1450 and placed on the left side of the square facing the Basilica of St. Anthony, his Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata was the first example of such a monument since ancient times. (Other equestrian statues, from the 14th century, had not been executed in bronze and had been placed over tombs rather than erected independently, in a public place.) This work became the prototype for other equestrian monuments executed in Italy and Europe in the following centuries.

For the Basilica of St. Anthony, Donatello created, most famouslywhy?, the bronze Crucifix of 1444–47 and additional statues for the choir, including a Madonna with Child and six saints, constituting a Holy Conversation, which is no longer visible since the renovation by Camillo Boito in 1895. The Madonna with Child portrays the Child being displayed to the faithful by Mary who is whether standing nor sitting on the throne that is flanked by two sphinxes, an allegorical figure of knowledge. On the throne’s back is a relief of Adam and Eve. During this period—1446–50—Donatello also executed four importantwhy? reliefs with scenes from the life of St. Anthony for the high altar. He remained in Padua until 1453, when he returned to Florence.

Gallery[edit]

-

Donatello’s David head and shoulders front right

-

-

-

-

Il Cristo di Sant’Angelo di Legnaia

Works[edit]

| Title | Form | Material | Year | Original location | Current location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crucifix | Statue | Wood, polychromed | 1407–1408 | Florence, Santa Croce | Florence, Santa Croce, Cappella Bardi di Vernio |

| Prophet | Statue | Marble | 1410, before | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Porta della Mandorla | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| David (with the head of Goliath) | Statue (originally with sling) | Marble | 1408–1409 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, planned for butress, Palazzo Vecchio (1416) | Florence, Museo nazionale del Bargello |

| John Evangelist | Statue in niche, sitting | Marble | 1408–1415 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, façade | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| Joshua | Statue (5.5 mts high) | Terracotta, whitened | 1410, before | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, north tribune | disintegrated |

| Saint Mark | Statue in niche | Marble | 1411–1413 | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florenz, Orsanmichele museum |

| St. Louis of Toulouse | Statue in niche | Bronze, gilded (ormolu) | 1411–1415 | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florence, Santa Croce (since the 1450s) |

| Prophets | Statues in niche (two of four) | Marble | 1415 and 1418–1420 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| St. George (with Saint George Freeing the Princess) | Statue and niche with predella in relief | Marble | 1416, circa | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello (with niche) |

| Marzocco | Statue | Sandstone | 1418–1420 | Florence, Santa Maria Novella, papal apartment | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Pazzi Madonna | Relief, low | Marble | 1420, circa | uncertain | Berlin, Bode Museum, Skulpturensammlung |

| San Rossore Reliquary | Bust | Bronze, gilded | 1422–1427 | Florence, Ognissanti | Pisa, Museo nazionale di San Matteo |

| Jeremiah | Statue in niche (third of four) | Marble | 1423, circa | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| Zuccone (Prophet Habakkuk) | Statue in niche (last of four) | Marble | 1423–1425 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| The Feast of Herod | Relief | Bronze | 1423–1427 | Siena, Baptistry of San Giovanni, Baptismal font | Siena, Baptistry |

| Madonna of the Clouds | Relief | Bronze | 1425-1435 | Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | |

| Tomb of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci | Tomb monument with Statues, reliefs, partly gilded and polychrome | Marble | 1426–1428 | Naples, Sant’Angelo a Nilo | Neapel, Sant’Angelo a Nilo |

| Dovizia (on the Colonna dell’Abbondanza) | Statue on column | Marble (with a working bell) | 1431 | Florence, Piazza della Repubblica | deteriorated and destroyed in a fall in 1721 (replaced with a version by Giovanni Battista Foggini that was replaced by a copy) |

| David (with head of Goliath) | Statue | Bronze, partly gilded | 1430s–1450s (?) | Florence, Casa Vecchia de’ Medici | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Pulpit, Cantoria | Pulpit with high reliefs | Marble, mosaic, bronze | 1433–1438 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| Pulpit, external | Reliefs | Marble | 1434–1438 | Prato, cathedral | Prato, Cathedral Museum |

| Old Sacristy (doors, lunettes, tondi and frieze) | Reliefs, low | Bronze (doors), polychromed stucco | 1434–1443 | Florence, San Lorenzo | Florence, San Lorenzo |

| Cavalcanti Annunciation | Relief, high, in an aedicula | Pietra serena (Macigno) and terracotta, whitened and gilded | 1435, circa | Florence, Santa Croce | Florence, Santa Croce |

| John the Baptist | Statue | Wood, painted partially gilded | 1438 | Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari | Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari |

| Amor-Attys (Notname) | Statue | Bronze | 1440, circa | Florence | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Penitent Magdalene | Statue | Wood and stucco pigmented and gilded | 1440–1442 (?) | Florence | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| Madonna and Child | Relief, low | Terracotta, pigmented | 1445 (1455) | unknown | Paris, Louvre |

| Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata | Statue, equestrian monument | Bronze | 1445–1450 | Padua, Piazza Sant’Antonio | Padua, Piazza Sant’Antonio |

| High altar with Madonna with Child, six statues of Saints and four episodes of the life of St. Anthony | Statues (seven) and 21 reliefs | Bronze (and one stone relief) | 1446, after | Padua, Basilica di Sant’Antonio | Padua, Basilica di Sant’Antonio (reconstruction) |

| Judith and Holofernes | Statue group | Bronze | 1453–1457 | Florence, Palazzo Medici, garden | Florence, Palazzo Vecchio |

| John the Baptist | Statue | Bronze | 1455, circa | Siena, Cathedral | Siena, Cathedral |

| Virgin and Child with Four Angels or Chellini Madonna | Relief, low, tondo | Bronze, gilded | 1456, before | Florence | London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

| Pulpits, one with scenes of the Passion, one with post-Passion scenes | Reliefs | Bronze | 1460, after | Florence, San Lorenzo | Florence, San Lorenzo |

2020 discovery[edit]

In 2020 art historian Gianluca Amato, as part of his research on wooden crucifixes crafted between the late thirteenth and the first half of the sixteenth century for his doctoral thesis at the University of Naples Federico II, discovered that the crucifix of the church of Sant’Angelo a Legnaia was sculpted by Donatello.

This discovery has been evaluated historically, considering that the work belonged to the Compagnia di Sant’Agostino that was based in the oratory adjacent to the mother church of Sant’Angelo a Legnaia. Silvia Bensì performed restoration work on the crucifix.[15][16][17][18]

In popular culture[edit]

Donatello is portrayed by Ben Starr in the 2016 television series Medici: Masters of Florence.[19]

The fictional crimefighter Donatello, one of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, is named after him.

Donatello is portrayed by Rhett McLaughlin in the 2014 Epic Rap Battles of History video Artists versus Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, in which he appears working on Gattamelata and is mocked for being less famous than other Renaissance artists. [20]

The Donatello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) built by the Italian Space Agency, was one of three MPLMs operated by NASA to transfer supplies and equipment to and from the International Space Station. The others were named Leonardo and Raffaello.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Though an Italian nation state had yet to be established, the Latin equivalent of the term Italian (italus) had been in use for natives of the region since antiquity.[3]

References[edit]

- ^ Unknown master, Italian (active late 15th century). «CINQ MAÎTRES DE LA RENAISSANCE FLORENTINE» [Five masters of the Florentine renaissance]. Le Louvre. (Note: historic attribution of this picture to Paolo Uccello is no longer accepted.)

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Letters 9.23.

- ^ Rubin, Patricia Lee (January 1995). Giorgio Vasari: Art and History. p. 350. ISBN 9780300049091.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (2003). The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance. New York: William Morrow. pp. xi. ISBN 9780061743559.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (2003). The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance. New York: William Morrow. pp. 26, 30, 34. ISBN 9780061743559.

- ^ Horst W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1963, p. ?page needed.

- ^ (in German) Wirtz, Rolf C., Donatello, Könemann, Colonia 1998. ISBN 3-8290-4546-8

- ^ Hesson, Robert (28 July 2019). «Collections and restoration of antiquities – Ancient Monuments». Northern Architecture. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ H. W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1957, II, 77–86; Laurie Schneider, «Donatello’s Bronze David,» The Art Bulletin, 55 (1973) 213–216.

- ^ Paul Strathern, The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, London, 2003

- ^ Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence[page needed]

- ^ Joachim Poeschke, Donatello and His World. Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance, Volume 1, Harry N Abrams, New York 1993, p. ?

- ^ Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and Civilization, Harvard Press, 2003, p. 264.

- ^ Mugnaini, Olga (6 March 2020). «‘Quel crocifisso ligneo è di Donatello’, la sensazionale scoperta a Firenze». La Nazione (in Italian). Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ «Studioso scopre Crocifisso inedito di Donatello». Adnkronos. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Salzano, Marco Pipolo & Guido. «E». QAeditoria.it – QA turismo cultura & arte. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ «Crocifisso di Donatello nella chiesa di Legnaia, la storia». Isolotto Legnaia Firenze (in Italian). 6 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ «Medici: Masters of Florence». Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ ERB. «Artists vs TMNT. Epic Rap Battles of History». YouTube. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Donatello». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 406–408.

Further reading[edit]

- Avery, Charles, Donatello: An Introduction, New York, 1994.

- Avery, Charles, Donatello. Catalogo completo delle opere, Firenze 1991.

- Avery, Charles and McHam, Sarah Blake, «Donatello». Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- Bennett, Bonnie A. and Wilkins, David G., Donatello, Oxford 1984.

- Coonin, A. Victor, Donatello and the Dawn of Renaissance Art, Reaktion Books, London, 2019.

- Greenhalgh, Michael, Donatello and His Sources, Holmes & Meier Pub., 1982.

- Hartt, Frederick and Wilkins, David G., History of Italian Renaissance Art (7th ed.), Pearson, 2010.

- Janson, Horst W., The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Leach, Patricia Ann, Images of Political Triumph: Donatello’s Iconography of Heroes, Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Olson, Roberta J.M., Italian Renaissance Sculpture, 1992, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 978-0500202531

- Randolph, Adrian W.B., Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence. Yale University Press, 2002.

- Vasari, Giorgio, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Firenze 1568, edizione a cura di R. Bettarini e P. Barocchi, Firenze, 1971.

- Wilson, Carolyn C., Renaissance Small Bronze Sculpture and Associated Decorative Arts, 1983, National Gallery of Art (Washington), ISBN 0894680676

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Donatello.

- Donatello: Biography, style, and artworks

- Donatello: Art in Tuscany

- Donatello at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Donatello: Photograph Gallery

- Donatello, by David Lindsay, 27th Earl of Crawford, from Project Gutenberg

- The Chellini Madonna Sculpture. Victoria and Albert Museum

донателло

-

1

Донателло

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Донателло

См. также в других словарях:

-

Донателло — (Donatello; собственно Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди, Donato di Niccolo di Betto Bardi) (около 1386 1466), итальянский скульптор эпохи Раннего Возрождения. Представитель флорентийской школы. Одним из первых скульпторов Италии… … Художественная энциклопедия

-

Донателло — Донателло. Памятник кондотьеру Гаттамелате в Падуе. ДОНАТЕЛЛО (Donatello) (настоящее имя Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди) (около 1386 1466), итальянский скульптор флорентийской школы Раннего Возрождения. Осмысливая опыт античного искусства,… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

Донателло — (Donatello, собственно Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди, D.di Betto Bardi) один из самых замечательных итальянск. скульпторовэпохи возрождения, род. во Флоренции, или близ нее, между 1382 и 1387гг., учился в мастерской живописца и скульптора… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

Донателло — (Donatello), настоящее имя Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди (Donato di Niccoló di Betto Bardi) (около 1386 1466), итальянский скульптор флорентийской школы, один из основоположников искусства Раннего Возрождения. Развивал демократические… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Донателло — (Donatello), наст. имя мастера Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди (Donate di Niccolo di Betto Bardi) 1383/1386, Флоренция 1466, Флоренция. Итальянский скульптор, один из выдающихся мастеров итальянского Раннего Возрождения. Первые упоминания о… … Европейское искусство: Живопись. Скульптура. Графика: Энциклопедия

-

Донателло — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Донателло (значения). Донателло Donatello … Википедия

-

Донателло — (Donatello; собственно Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди, Donate di Niccolo di Betto Bardi) (около 1386, Флоренция, 13.12.1466, там же), итальянский скульптор. Один из основоположников скульптуры Возрождения в Италии. В 1404 07 работал в… … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

ДОНАТЕЛЛО — (Donatello) (ок. 1386 1466), флорентийский скульптор; его полное имя Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди (Donato di Niccol di Betto Bardi). Вместе с архитектором Брунеллески и живописцем Мазаччо Донателло считается одним из основоположников… … Энциклопедия Кольера

-

ДОНАТЕЛЛО — Ап. Иоанн Богослов. 1408 1415 гг. (Музей кафедрального собора, Флоренция) Ап. Иоанн Богослов. 1408 1415 гг. (Музей кафедрального собора, Флоренция) [полное имя Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди; итал. Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi] (ок. 1386,… … Православная энциклопедия

-

Донателло — (собств. Донато ди Никколо ди Бетто Барди) (ок 1386 1466) ит. скульптор, представитель Раннего Возрождения. Родился во Флоренции в семье чесальщика шерсти. Между 1404 и 1407 г. работал помощником в мастерской Гиберти, в 1406 г. получил первый… … Средневековый мир в терминах, именах и названиях

-

Донателло (значения) — Донателло итальянский скульптор эпохи Возрождения. Донателло персонаж комиксов, мультсериалов и фильмов серии «Черепашки ниндзя». С … Википедия

Раньше ждал, если мистер Кейн так хотел.

Приписывается Донателло. Куплено во Флоренции.

Снято. Следующая.

I can remember when they’d wait all day if Mr. Kane said so.

Better get going.

Take a picture of that.

— Не торопитесь.

Мистер Катхарт, джентльмен в вашем кабинете хочет купить Донателло.

— Он также хочет и пьедестал.

— No hurry.

Mr Cathcart, a gentleman in your office wishes to purchase the Donatello.

— He wants the pedestal too.

— Спокойной ночи.

Одно из самых прекрасных произведений Донателло.

— Сколько это стоит?

— Good night.

This is one of Donatello’s finest pieces.

— How much is it?

— «Заверните это»?

Донателло?

— Да, сэр.

— «Wrap it up»?

The Donatello?

— Yes, sir.

Эй, Марио! Раз так, то зайди.

Донателла! Постыдилась бы.

Ты плохая девочка. Быстро в угол!

Ah, Mario, yes, come here, come here.

Donatella, aren’t you ashamed of spying?

You’re a bad girl, go immediately to the corner!

Добро пожаловать в Белый Дом.

Меня зовут Донателла Мосс.

Я работаю здесь, в Западном крыле, ассистентом заместителя главы администрации Джошуа Лаймана

Welcome to the White House.

My name is Donatella Moss.

I work here as an assistant to Deputy Chief of Staff Joshua Lyman.

Два жирных пуэрториканца.

Майк Донателли…

Мы прозвали его «Кирпич».

You’re 2 fat Puerto Ricans.

Hey. Bobby: Mike Donatelli.

Aaah! Bobby:

Джозефина была сестрой Хавьера, и его единственной наследницей.

За день она превратилась из гадкого утенка в Донателлу Версаче.

Безусловно, смерть была ей к лицу.

Josephina was Javier’s sister and heir apparent to the Javier industry.

In a day she had gone from ugly duckling to Donatella Versace.

Death definitely became her.

Позвоню тебе через час.

Донателла Мосс. Главный представитель Индонезии будет сегодня.

Тоби и я хотим поговорить с ним наедине пару минут.

I’ll call in an hour.

a senior Indonesian deputy is coming tonight.

Toby and I wanna talk to him alone.

— Тоска, блин!

Донателла Версаче.

— Красиво.

Fucking depressing.

Now, this is a Donatella Versace.

Nice.

Ведь дети — наша опора, или же убийцы.

Антонио Донато, Джозеф Пистелла, Майкл Донателли, Роберт Бартеллемео.

— Ты так напряжена.

But she’ll understand. I mean, children are a blessing… or they try and kill ya, one of the two.

«Anthony Donato, Joseph Pistella, Olivia: Michael Donatelli, Robert Bartellemeo.»

Officer: Wow, you look tense.

Которая заметна в этом творении, Ваше Высочество.

Давид, скульптура Донателло.

Господь, который спас меня от когтей льва и медведя, спасёт и от этой мерзости.

Which is distinctly true of this creation, Your Highness.

David, as sculpted by Donatello.

The Lord who saved me from the claws of the lion and the bear will save me from this abomination.

Вы приехали увидеть меня, мистер Голт.

Насчет Донателло, не так ли?

Вообще-то, я интересуюсь произведениями современных мастеров.

You came to see me, Mr Galt.

About the Donatello, wasn’t it?

Actually, I’m interested in a piece of modern art.

— И 13, 14.

— Иди кушай фрукты, Донателла.

Аккуратно. Не запачкай скатерть.

And 13, 14..

Go eat some fruit, Donatella.

Alcira, come on, you have to change the tablecloth.

Сейчас мы свяжемся с медицинским центом Святого Иосифа, чтобы узнать новости.

Здравствуйте, меня зовут доктор Донателла Брекенридж.

Это птичий грипп или, как мы его называем, «H5N1».

We go live now to St. Joseph’s Medical Center for an update. Hello, my name is

Donatella Breckinridge, M.D. I graduated first in my class from Harvard Medical School, so I know what I’m talking about.

This is the avian flu, or we call «H5N1.»

Бам! Тебя хакнули!

И это сделал Донателло.

Помнишь?

You’ve been hacked!

By Donatello. Remember me?

Turtle.

Рафаэль,

Микеланджело и Донателло.

Ваши фанаты хотят на вас посмотреть!

Raphael,

Michelangelo and Donatello.

The fans want to see you!

Это сигналы радиомаяка.

Он у Донателло!

Иди, Рафаэль.

It’s some kind of tracker.

It’s Donatello!

Go, Raphael.

Херня, Птаха!

Каким боком Донателло вдруг оказался лучшим из черепашек Ниндзя?

— Во, я за Мака!

Bollocks, Bird.

No way is Donatello the best Ninja Turtle.

Aye, I’m with Mac.

— Ясен пень, ты за Мака.

Донателло самый умный, и лучше всех дерется. Так что…

Да чем он там дерется?

Course you are.

Donatello is the smart one and he’s got the fighting skills.

So…?

Делов-то!

Да Донателло против Рафаэля…

Нет, нет, нет, нет, нет…

Duh!

If Raphael fought Donatello…

No, no, no, no, no.

Слушайте.

Как думаете, вам бы понравилось шоу с участием Донателло, Рафаэля,

Микеланджело и Леонардо?

Listen.

Do you think that you would enjoy a show featuring Donatello, Raphael,

Michelangelo and Leonardo?

— Нет, не убивали.

Леонардо, Микеланджело, Донателло и Рафаэль никогда бы не сделали ничего подобного.

Они жили по кодексу!

No, they didn’t.

Leonardo, Michelangelo, Donatello and Raphael would never have done any of them things.

They lived by a code!

Вале-де-Ногейраш:

Милан: Сильвио Берлускони (голос — Донателло Брида)

Париж: Николя Саркози (голос — Жан-Пьер Рем)

January 21st 1975, Vale de Nogueiras

July 13th 2011, Milan

May 6th 2012, Paris

Можно мне их послушать 30 секунд?

(Донателла Ретторе песня «Amore stella»)

Потяни.

Can I listen to it for 30 seconds?

(Donatella Rettore singing «Amore stella»)

Pull it.

Он спасает всех не дожидаясь подсказки!

Дружище Донателло изобретает неустанно,

А Рафаэль — это турбодвигатель команды!

♪ does anything it takes to get his ninjas through ♪

♪ Donatello is the fellow has a way with machines ♪

♪ Raphael’s got the most attitude on the team ♪

Эм, ребят, не думаю, что этот лазерный генератор от Крэнга и Шреддера.

С чего ты взял, Донателло?

Ну, потому что на этикетке написано «Сделано в Тайвани.»

Uh, guys. I don’t think this laser generator came from Krang and Shredder.

How can you tell, Donatello?

Well, because this label says «Made in Taiwan.»

Нам надо на 6 канал, отключить эту взрывчатку.

Донателло, когда ты сможешь починить машину?

Ну, минут через 15.

We’ve got to get over to Channel 6 and disable that explosive.

Donatello, how much longer will it take you to fix the van?

Oh, about 15 minutes.

Сейчас это не важно, Микеланджело.

Сделал, Донателло?

Нет.

We can’t worry about that now, Michelangelo.

LEONARDO: Got it running yet, Donatello?

DONATELLO: No.

Теплее.

— Донателла.

Нет, там нет «эн».

— (Stephen) Closer.

— Donatella.

— Forget the N.

Показать еще

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi (c. 1386 – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello ([2] Italian: [donaˈtɛllo]), was an Italian[a] sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used this to develop a complete Renaissance style in sculpture. He spent time in other cities, and while there he worked on commissions and taught others; his periods in Rome, Padua, and Siena introduced to other parts of Italy his techniques, developed in the course of a long and productive career. Financed by Cosimo de’ Medici, Donatello’s David was the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity.

He worked with stone, bronze, wood, clay, stucco, and wax, and had several assistants, with four perhaps being a typical number. Although his best-known works mostly were statues in the round, he developed a new, very shallow, type of bas-relief for small works, and a good deal of his output was larger architectural reliefs.

Early life

Donatello was the son of Niccolò di Betto Bardi, who was a member of the Florentine Arte della Lana. He was born in Florence, probably in the year 1386. Donatello was educated in the house of the Martelli family.[4] He apparently received his early artistic training in a goldsmith’s workshop,[citation needed] and then worked briefly in the studio of Lorenzo Ghiberti.[5]

In Pistoia in 1401, Donatello met the older Filippo Brunelleschi. They likely went to Rome together around 1403, staying until the next year, to study the architectural ruins. Brunelleschi informally tutored Donatello in goldsmithing and sculpture.[6] Brunelleschi’s buildings and Donatello’s sculptures are both considered supreme expressions of the spirit of this era in architecture and sculpture, and they exercised a potent influence upon the artists of the age.

Work in Florence

In Florence, Donatello assisted Lorenzo Ghiberti with the statues of prophets for the north door of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, for which he received payment in November 1406 and early 1408. In 1409–1411 he executed the colossal seated figure of Saint John the Evangelist, which occupied a niche of the old cathedral façade until 1588, and now is placed in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo. This work marks a decisive step forward from late Gothic Mannerism in the search for naturalism and the rendering of human feelings.[7] The face, the shoulders, and the bust are still idealized, while the hands and the fold of cloth over the legs are more realistic.

In 1411–1413, Donatello worked on a statue of St. Mark for the guild church of Orsanmichele. In 1417 he completed the Saint George for the Confraternity of the Cuirass-makers. From 1423 is the Saint Louis of Toulouse for the Orsanmichele, now in the Museum of the Basilica di Santa Croce. Donatello also sculpted the classical frame for this work, which remains, while the statue was moved in 1460 and replaced by the Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Verrocchio.

Between 1415 and 1426, Donatello created five statues for the campanile of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, also known as the Duomo. These works are the Beardless Prophet; Bearded Prophet (both from 1415); the Sacrifice of Isaac (1421); Habbakuk (1423–25); and Jeremiah (1423–26); which follow the classical models for orators and are characterized by strong portrait details. In 1425, he executed the notable Crucifix for Santa Croce; this work portrays Christ in a moment of agony, eyes, and mouth partially opened, the body contracted in an ungraceful posture.

Pazzi Madonna (1425-1430), marble bas-relief in stiacciato, Bode Museum, Berlin

From 1425 to 1427, Donatello collaborated with Michelozzo on the funerary monument of the Antipope John XXIII for the Battistero in Florence. Donatello made the recumbent bronze figure of the deceased, under a shell. In 1427, he completed in Pisa a marble relief for the funerary monument of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci at the church of Sant’Angelo a Nilo in Naples. In the same period, he executed the relief of The Feast of Herod (c. 1427) and the statues of Faith and Hope for the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Siena. The Feast of Herod is mostly in stiacciato (a very low bas-relief), with the foreground figures done in bas-relief, and is considered one of the first examples of one-point perspective in sculpture.[citation needed]

During the period 1425-1430 the Pazzi Madonna was created. It is a rectangular marble bas-relief sculpture, also in stiacciato. Its original owner is not known, but the work is thought to have been commissioned for private devotion by a resident of Florence.[8] It is in the collection of the Bode Museum in Berlin, Germany. It was copied frequently and admired for the tender nature of the depiction of the Virgin Mary and her smiling infant child.

Donatello also restored antique sculptures for the Palazzo Medici.[9]

Bronze David

Donatello’s bronze David, now in the Bargello museum, is his most famous work, and the first known free-standing nude statue produced since antiquity. Conceived fully in the round, independent of any architectural surroundings, and largely representing an allegory of the civic virtues triumphing over brutality and irrationality, it is arguably the first major work of Renaissance sculpture. It was commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici for the courtyard of his Palazzo Medici, but its date remains the subject of debate. It is most often dated to the 1440s, but dates as late as the 1460s have support from some scholars. It is not to be confused with his stone David, with clothes, of about 1408–09.

Some have perceived the David as having homoerotic qualities and have argued that this reflected the artist’s own orientation.[10] The historian Paul Strathern makes the claim that Donatello made no secret of his homosexuality, and that his behaviour was tolerated by his friends.[11] The main evidence comes from anecdotes by Angelo Poliziano in his «Detti piacevoli«, where he writes about Donatello surrounding himself with «handsome assistants» and chasing in search of one that had fled his workshop.[12] This may not be surprising in the context of attitudes prevailing in the 15th- and 16th-century Florentine Republic. However, little detail is known with certainty about his private life, and no mention of his sexuality has been found in the Florentine archives (in terms of denunciations)[13] albeit which during this period are incomplete.[14]

Rome, Prato, and Venice

When Cosimo was exiled from Florence, Donatello went to Rome, remaining until 1433. The two works that testify to his presence in this city, the Tomb of Giovanni Crivelli at Santa Maria in Aracoeli, and the Ciborium at St. Peter’s Basilica, bear a strong stamp of classical influence.

Donatello’s return to Florence almost coincided with Cosimo’s. In May 1434, he signed a contract for the marble pulpit on the facade of Prato cathedral, the last project executed in collaboration with Michelozzo. This work, a passionate, pagan, rhythmically conceived bacchanalian dance of half-nude putti, was the forerunner of the great Cantoria, or singing tribune, at the Duomo in Florence on which Donatello worked intermittently from 1433 to 1440 and was inspired by ancient sarcophagi and Byzantine ivory chests. In 1435, he executed the Annunciation for the Cavalcanti altar in Santa Croce, inspired by 14th-century iconography, and in 1437–1443, he worked in the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo in Florence, on two doors and lunettes portraying saints, as well as eight stucco tondos. From 1438 is the wooden statue of St. John the Baptist for Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice.

In Padua

In 1443, Donatello was called to Padua by the heirs of the famous condottiere Erasmo da Narni (better known as the Gattamelata, or «Honey-Cat»), who had died that year. Completed in 1450 and placed on the left side of the square facing the Basilica of St. Anthony, his Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata was the first example of such a monument since ancient times. (Other equestrian statues, from the 14th century, had not been executed in bronze and had been placed over tombs rather than erected independently, in a public place.) This work became the prototype for other equestrian monuments executed in Italy and Europe in the following centuries.

For the Basilica of St. Anthony, Donatello created, most famouslywhy?, the bronze Crucifix of 1444–47 and additional statues for the choir, including a Madonna with Child and six saints, constituting a Holy Conversation, which is no longer visible since the renovation by Camillo Boito in 1895. The Madonna with Child portrays the Child being displayed to the faithful by Mary who is whether standing nor sitting on the throne that is flanked by two sphinxes, an allegorical figure of knowledge. On the throne’s back is a relief of Adam and Eve. During this period—1446–50—Donatello also executed four importantwhy? reliefs with scenes from the life of St. Anthony for the high altar. He remained in Padua until 1453, when he returned to Florence.

Gallery

-

Donatello’s David head and shoulders front right

-

-

-

-

Il Cristo di Sant’Angelo di Legnaia

Works

| Title | Form | Material | Year | Original location | Current location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crucifix | Statue | Wood, polychromed | 1407–1408 | Florence, Santa Croce | Florence, Santa Croce, Cappella Bardi di Vernio |

| Prophet | Statue | Marble | 1410, before | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Porta della Mandorla | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| David (with the head of Goliath) | Statue (originally with sling) | Marble | 1408–1409 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, planned for butress, Palazzo Vecchio (1416) | Florence, Museo nazionale del Bargello |

| John Evangelist | Statue in niche, sitting | Marble | 1408–1415 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, façade | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| Joshua | Statue (5.5 mts high) | Terracotta, whitened | 1410, before | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, north tribune | disintegrated |

| Saint Mark | Statue in niche | Marble | 1411–1413 | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florenz, Orsanmichele museum |

| St. Louis of Toulouse | Statue in niche | Bronze, gilded (ormolu) | 1411–1415 | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florence, Santa Croce (since the 1450s) |

| Prophets | Statues in niche (two of four) | Marble | 1415 and 1418–1420 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| St. George (with Saint George Freeing the Princess) | Statue and niche with predella in relief | Marble | 1416, circa | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello (with niche) |

| Marzocco | Statue | Sandstone | 1418–1420 | Florence, Santa Maria Novella, papal apartment | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Pazzi Madonna | Relief, low | Marble | 1420, circa | uncertain | Berlin, Bode Museum, Skulpturensammlung |

| San Rossore Reliquary | Bust | Bronze, gilded | 1422–1427 | Florence, Ognissanti | Pisa, Museo nazionale di San Matteo |

| Jeremiah | Statue in niche (third of four) | Marble | 1423, circa | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| Zuccone (Prophet Habakkuk) | Statue in niche (last of four) | Marble | 1423–1425 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| The Feast of Herod | Relief | Bronze | 1423–1427 | Siena, Baptistry of San Giovanni, Baptismal font | Siena, Baptistry |

| Madonna of the Clouds | Relief | Bronze | 1425-1435 | Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | |

| Tomb of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci | Tomb monument with Statues, reliefs, partly gilded and polychrome | Marble | 1426–1428 | Naples, Sant’Angelo a Nilo | Neapel, Sant’Angelo a Nilo |

| Dovizia (on the Colonna dell’Abbondanza) | Statue on column | Marble (with a working bell) | 1431 | Florence, Piazza della Repubblica | deteriorated and destroyed in a fall in 1721 (replaced with a version by Giovanni Battista Foggini that was replaced by a copy) |

| David (with head of Goliath) | Statue | Bronze, partly gilded | 1430s–1450s (?) | Florence, Casa Vecchia de’ Medici | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Pulpit, Cantoria | Pulpit with high reliefs | Marble, mosaic, bronze | 1433–1438 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| Pulpit, external | Reliefs | Marble | 1434–1438 | Prato, cathedral | Prato, Cathedral Museum |

| Old Sacristy (doors, lunettes, tondi and frieze) | Reliefs, low | Bronze (doors), polychromed stucco | 1434–1443 | Florence, San Lorenzo | Florence, San Lorenzo |

| Cavalcanti Annunciation | Relief, high, in an aedicula | Pietra serena (Macigno) and terracotta, whitened and gilded | 1435, circa | Florence, Santa Croce | Florence, Santa Croce |

| John the Baptist | Statue | Wood, painted partially gilded | 1438 | Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari | Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari |

| Amor-Attys (Notname) | Statue | Bronze | 1440, circa | Florence | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Penitent Magdalene | Statue | Wood and stucco pigmented and gilded | 1440–1442 (?) | Florence | Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo |

| Madonna and Child | Relief, low | Terracotta, pigmented | 1445 (1455) | unknown | Paris, Louvre |

| Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata | Statue, equestrian monument | Bronze | 1445–1450 | Padua, Piazza Sant’Antonio | Padua, Piazza Sant’Antonio |

| High altar with Madonna with Child, six statues of Saints and four episodes of the life of St. Anthony | Statues (seven) and 21 reliefs | Bronze (and one stone relief) | 1446, after | Padua, Basilica di Sant’Antonio | Padua, Basilica di Sant’Antonio (reconstruction) |

| Judith and Holofernes | Statue group | Bronze | 1453–1457 | Florence, Palazzo Medici, garden | Florence, Palazzo Vecchio |

| John the Baptist | Statue | Bronze | 1455, circa | Siena, Cathedral | Siena, Cathedral |

| Virgin and Child with Four Angels or Chellini Madonna | Relief, low, tondo | Bronze, gilded | 1456, before | Florence | London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

| Pulpits, one with scenes of the Passion, one with post-Passion scenes | Reliefs | Bronze | 1460, after | Florence, San Lorenzo | Florence, San Lorenzo |

2020 discovery

In 2020 art historian Gianluca Amato, as part of his research on wooden crucifixes crafted between the late thirteenth and the first half of the sixteenth century for his doctoral thesis at the University of Naples Federico II, discovered that the crucifix of the church of Sant’Angelo a Legnaia was sculpted by Donatello.

This discovery has been evaluated historically, considering that the work belonged to the Compagnia di Sant’Agostino that was based in the oratory adjacent to the mother church of Sant’Angelo a Legnaia. Silvia Bensì performed restoration work on the crucifix.[15][16][17][18]

In popular culture

Donatello is portrayed by Ben Starr in the 2016 television series Medici: Masters of Florence.[19]

The fictional crimefighter Donatello, one of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, is named after him.

Donatello is portrayed by Rhett McLaughlin in the 2014 Epic Rap Battles of History video Artists versus Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, in which he appears working on Gattamelata and is mocked for being less famous than other Renaissance artists. [20]

The Donatello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) built by the Italian Space Agency, was one of three MPLMs operated by NASA to transfer supplies and equipment to and from the International Space Station. The others were named Leonardo and Raffaello.

Notes

- ^ Though an Italian nation state had yet to be established, the Latin equivalent of the term Italian (italus) had been in use for natives of the region since antiquity.[3]

References

- ^ Unknown master, Italian (active late 15th century). «CINQ MAÎTRES DE LA RENAISSANCE FLORENTINE» [Five masters of the Florentine renaissance]. Le Louvre. (Note: historic attribution of this picture to Paolo Uccello is no longer accepted.)

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Letters 9.23.

- ^ Rubin, Patricia Lee (January 1995). Giorgio Vasari: Art and History. p. 350. ISBN 9780300049091.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (2003). The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance. New York: William Morrow. pp. xi. ISBN 9780061743559.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert (2003). The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance. New York: William Morrow. pp. 26, 30, 34. ISBN 9780061743559.

- ^ Horst W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1963, p. ?page needed.

- ^ (in German) Wirtz, Rolf C., Donatello, Könemann, Colonia 1998. ISBN 3-8290-4546-8

- ^ Hesson, Robert (28 July 2019). «Collections and restoration of antiquities – Ancient Monuments». Northern Architecture. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ H. W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1957, II, 77–86; Laurie Schneider, «Donatello’s Bronze David,» The Art Bulletin, 55 (1973) 213–216.

- ^ Paul Strathern, The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, London, 2003

- ^ Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence[page needed]

- ^ Joachim Poeschke, Donatello and His World. Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance, Volume 1, Harry N Abrams, New York 1993, p. ?

- ^ Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and Civilization, Harvard Press, 2003, p. 264.

- ^ Mugnaini, Olga (6 March 2020). «‘Quel crocifisso ligneo è di Donatello’, la sensazionale scoperta a Firenze». La Nazione (in Italian). Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ «Studioso scopre Crocifisso inedito di Donatello». Adnkronos. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Salzano, Marco Pipolo & Guido. «E». QAeditoria.it – QA turismo cultura & arte. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ «Crocifisso di Donatello nella chiesa di Legnaia, la storia». Isolotto Legnaia Firenze (in Italian). 6 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ «Medici: Masters of Florence». Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ ERB. «Artists vs TMNT. Epic Rap Battles of History». YouTube. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Donatello». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 406–408.

Further reading

- Avery, Charles, Donatello: An Introduction, New York, 1994.

- Avery, Charles, Donatello. Catalogo completo delle opere, Firenze 1991.

- Avery, Charles and McHam, Sarah Blake, «Donatello». Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- Bennett, Bonnie A. and Wilkins, David G., Donatello, Oxford 1984.

- Coonin, A. Victor, Donatello and the Dawn of Renaissance Art, Reaktion Books, London, 2019.

- Greenhalgh, Michael, Donatello and His Sources, Holmes & Meier Pub., 1982.

- Hartt, Frederick and Wilkins, David G., History of Italian Renaissance Art (7th ed.), Pearson, 2010.

- Janson, Horst W., The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Leach, Patricia Ann, Images of Political Triumph: Donatello’s Iconography of Heroes, Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Olson, Roberta J.M., Italian Renaissance Sculpture, 1992, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 978-0500202531

- Randolph, Adrian W.B., Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence. Yale University Press, 2002.

- Vasari, Giorgio, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Firenze 1568, edizione a cura di R. Bettarini e P. Barocchi, Firenze, 1971.

- Wilson, Carolyn C., Renaissance Small Bronze Sculpture and Associated Decorative Arts, 1983, National Gallery of Art (Washington), ISBN 0894680676

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Donatello.

- Donatello: Biography, style, and artworks

- Donatello: Art in Tuscany

- Donatello at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Donatello: Photograph Gallery

- Donatello, by David Lindsay, 27th Earl of Crawford, from Project Gutenberg

- The Chellini Madonna Sculpture. Victoria and Albert Museum

This page was last edited on 18 February 2023, at 17:49

Донателло перевод на английский

73 параллельный перевод

Приписывается Донателло. Куплено во Флоренции.

Better get going.

Одно из самых прекрасных произведений Донателло.

This is one of Donatello’s finest pieces.

Мистер Катхарт, джентльмен в вашем кабинете хочет купить Донателло.

Mr Cathcart, a gentleman in your office wishes to purchase the Donatello.

Насчет Донателло, не так ли?

About the Donatello, wasn’t it?

С чего ты взял, Донателло?

How can you tell, Donatello?

Донателло, когда ты сможешь починить машину?

Donatello, how much longer will it take you to fix the van?

Сделал, Донателло?

LEONARDO : Got it running yet, Donatello?

Я только что имела беседу с Донателлой…

Actually, I was just talking to Donatella.

Свяжитесь с Донателлой.

Call Donatella.

Я… Вот я и решил разбить Донателло.

I TH—I THOUGHT IT WAS TIME TO BREAK DONATELLO OPEN.

Его зовут Донателло.

His name is Donatello.

Думаю, я тоже позвоню Донателло.

I think I’m going to call Donatello.

Донателло мой.

Donatello is all mine!

Как минимум, ты моложе остальных, потому что бедному Донателло, должно быть, всегда звонят одни старушки.

At the very least, you must be his youngest customer, old ladies must call him all the time.

Донателло не настоящее его имя.

Donatello isn’t really his name.

Кардинал видел Давида мастера Донателло и дивился, откуда в нем столько чувственности.

The cardinal has seen Donatello’s David and marvelled at the source of its eros.

Руди Донателло.

Rudy Donatello.

Приятно познакомиться, мистер Донателло.

Nice to meet you, Mr. Donatello.

— Руди Донателло.

— Rudy Donatello.

Мистер Донателло?

Mr. Donatello?

Э… Звонит тот парень, Мистер Донателло.

Uh, that guy, Mr. Donatello, is on the phone.

У нее нет родных и она подписала экстренное разрешение на временную опеку мистеру Донателло.

There are no known relatives… and she’s signed emergency orders granting Mr. Donatello temporary custody.

Мистер Донателло нашел местную школу, в которой есть специальная программа обучения.

Mr. Donatello found a local school that has a special education program.

А миссис Донателло существует?

And is there a Mrs. Donatello?

Мистер Донателло имеет в виду, что не женат в настоящее время.

What Mr. Donatello means is that he is not currently married.

Я вижу, что мистер Донателло живет вместе с вами.

I see here that Mr. Donatello lives with you.

— Помните мистера Донателло?

— You remember Mr. Donatello?

— Мистер Донателло…

— Mr. Donatello —

— Мистер Донателло..

— Mr. Donatello —

Мистер Донателло, если я услышу еще хотя бы единое слово от вас этим утром я обвиню вас в неуважении суда и брошу за решетку.

Mr. Donatello, if I so much as hear one more word out of your mouth this morning… I will find you in contempt of court and have you tossed back into jail.

Через какое время после вашей встречи мистер Донателло с ребенком переехали к вам?

And how long after you met did Mr. Donatello and the child move in?

Итак, по вашему мнению, изменения, которые вы видите, произошли благодаря мистеру Донателло и мистеру Флейгеру?

So, in your estimation, the change you’ve seen is in part due… to Mr. Donatello and Mr. Fleiger?

Мистер Донателло и мистер Флейгер… самые сочувствующие и любящие родители из тех, кого я встречала.

Mr. Donatello and Mr. Fleiger… are as compassionate and loving parents as I’ve ever seen.

Выражал ли он желание жить со мной и мистером Донателло?

And did he express his desire to live with Mr. Donatello and myself?

Расскажите о ваших отношениях с мистером Донателло.

Can you tell us about your relationship with Mr. Donatello?

У меня никогда не было отношений с мистером Донателло.

I never had a relationship with Mr. Donatello.

Мистер Донателло.

Mr. Donatello.

Все понятно, мистер Донателло.

That’s very clear, Mr. Donatello.

— Мистер Донателло.

— Mr. Donatello.

— Мистер Донателло.

— Mr. Donatello —

Мистер Донателло.

Mr. Donatello —

Бесспорно, мистер Донателло и мистер Флейгер оказали большое положительное влияние на жизнь Марко.

It’s very clear that Mr. Donatello and Mr. Fleiger… have had a powerful and positive effect on Marco’s life.

Очевидно, что мистер Донателло и мистер Флейгер любят ребенка.

While Mr. Donatello and Mr. Fleger obviously love the child.

— Это Руди Донателло?

— Is this Rudy Donatello?

— Алло, это Руди Донателло.

— Hello. Uh, this is Rudy Donatello.

Мисс Дилеон также просит судебный запрет от имени своего сына против мистера Флейгера и мистера Донателло.

Miss Deleon has also filed a restraining order on behalf of her son… against Mr. Fleiger and Mr. Donatello.

А вот и Донателло.

Here’s Donatella!

Давид, скульптура Донателло.

David, as sculpted by Donatello.

Вчера я воспользовалась услугами Донателло.

I’plucked up courage, I did it, yesterday I contracted Donatello’s services.

Дружище Донателло изобретает неустанно,

♪ Donatello is the fellow has a way with machines ♪

- перевод на «донателло» турецкий

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Перевод «Донателло» на английский

Помимо создания скульптур живых людей, Донателло получал комиссионные за скульптуры святых и мертвых вождей.

In addition to producing sculptures of living people, Donatello would receive commissions for sculptures of saints and dead leaders.

Донателло в своих скульптурах пытался изобразить достоинство человеческого тела с реалистичными и часто драматическими подробностями.

In his sculptures, Donatello tried to portray the dignity of the human body in realistic and often dramatic detail.

Одно из самых прекрасных произведений Донателло.

Думаю, я тоже позвоню Донателло.

Донателло считается основоположник индивидуализированного скульптурного портрета.

Donatello is considered the founder of the individualized sculptural portrait.

Марка разработки Донателло и примечательный алтарный шатёр.

Mark of development Donatello and a remarkable altar tent.

Донателло продолжил свою работу, получая комиссионные от богатых меценатов.

Donatello continued his work taking on commissions from wealthy patrons of the arts.

Он испытал также существенное влияние скульптур Донателло.

He was greatly influenced also by the work of the sculptor Donatello.

Донателло — парень, разбирающийся в механизмах.

Donatello is the fellow, has a way with machines.

Одежда полностью скрывает тело фигуры, но Донателло успешно передал впечатление гармоничной органической структуры тела под драпировкой.

The garments completely hide the body of the figure, but Donatello successfully conveyed the impression of harmonious organic structure beneath the drapery.

Над алтарём висит распятие, созданное Донателло.

On the high altar there is a wooden crucifix attributed to Donatello.

Своей работой итальянский скульптор Донателло повторил традиционное для античных времен изображение человека.

With his work, the Italian sculptor Donatello repeated the image of a man traditional for ancient times.

Гармоничное спокойствие делает Давида самым классическим из произведений Донателло.

Its harmonious calm makes it the most classical of Donatello’s works.

Работа флорентинца Донателло выделяется среди них особым характером построения перспективы и создания рельефности.

The work of Florentine Donatello is distinguished among them by the special nature of building perspectives and creating relief.

Скульптура, созданная и установленная Донателло в Падуе, принципиально отличалась от предшествующих образцов.

The sculpture, created by Donatello and located in Padua, was fundamentally different from the previous models.

Влияние скульптуры Донателло заметно на фигуре святого Николая.

The influence of Donatello’s sculpture is visible in the figure of Saint Nicholas.

В молодости испытал влияние флорентийской школы, в частности Донателло.

In his youth has been influenced by the Florentine school, including Donatello.

Почти все элементы гробницы приписывались различными историками искусства как Микелоццо, так и Донателло.

Nearly every element of the tomb monument has been attributed to both Donatello and Michelozzo by different art historians.

Я не писала гневных писем Донателло или Уолдо.

I have never written a letter to Donatello or Waldo.

Гиберти завершил еще один набор бронзовых дверей для баптистерия с помощью гиганта эпохи Возрождения Донателло.

Ghiberti went on to complete another set of bronze doors for the baptistery with the help of Renaissance giant Donatello.

Результатов: 799. Точных совпадений: 441. Затраченное время: 112 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200