|

Dubai دبي |

|

|---|---|

|

Metropolis |

|

|

From top, left to right: Dubai’s skyline, Dubai Marina, The World Islands, Palm Jumeirah, dune bashing in Dubai, Museum of the Future, Burj Al Arab |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms Wordmark |

|

|

Dubai Location within the United Arab Emirates Dubai Dubai (Asia) |

|

| Coordinates: 25°15′47″N 55°17′50″E / 25.26306°N 55.29722°ECoordinates: 25°15′47″N 55°17′50″E / 25.26306°N 55.29722°E | |

| Country | |

| Emirate | Dubai |

| Founded by | Obeid bin Said & Maktoum bin Butti Al Maktoum |

| Subdivisions |

Towns & villages

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Absolute monarchy |

| • Director General of Dubai Municipality | Dawoud Al Hajri |

| Area

[2][3][4] |

|

| • Total | 1,610 km2 (620 sq mi) |

| Population

(2021)[5] |

|

| • Total | 3,515,813 |

| • Density | 2,200/km2 (5,700/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Dubaian |

| Time zone | UTC+04:00 (UAE Standard Time) |

| Nominal GDP | 2021 estimate |

| Total | US$ 177.01 billion[6] |

| Website | Official website |

Dubai (, doo-BY; Arabic: دبي, romanized: Dubayy, IPA: [dʊˈbajj], Gulf Arabic pronunciation: [dəˈbaj]) is the most populous city in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the capital of the Emirate of Dubai, the most populated of the 7 emirates of the United Arab Emirates.[7][8][9] Established in the 18th century as a small fishing village, the city grew rapidly in the early 21st century with a focus on tourism and luxury,[10] having the second most five-star hotels in the world,[11] and the tallest building in the world, the Burj Khalifa, which is 828 metres (2,717 ft) tall.[12]

In the eastern Arabian Peninsula on the coast of the Persian Gulf,[13] it is also a major global transport hub for passengers and cargo.[14] Oil revenue helped accelerate the development of the city, which was already a major mercantile hub. A centre for regional and international trade since the early 20th century, Dubai’s economy relies on revenues from trade, tourism, aviation, real estate, and financial services.[15][16][17][18] Oil production contributed less than 1 percent of the emirate’s GDP in 2018.[19] The city has a population of around 3.49 million (as of 2021).[20]

Etymology[edit]

Many theories have been proposed as to the origin of the word «Dubai». One theory suggests the word used to be the souq in Ba.[21] An Arabic proverb says «Daba Dubai» (Arabic: دبا دبي), meaning «They came with a lot of money.»[22] According to Fedel Handhal, a scholar on the UAE’s history and culture, the word Dubai may have come from the word daba (Arabic: دبا) (a past tense derivative of yadub (Arabic: يدب), which means «to creep»), referring to the slow flow of Dubai Creek inland. The poet and scholar Ahmad Mohammad Obaid traces it to the same word, but to its alternative meaning of «baby locust» (Arabic: جراد) due to the abundance of locusts in the area before settlement.[23]

History[edit]

Bronze and iron alloy dagger, Saruq Al Hadid archaeological site (1100 BC)

The history of human settlement in the area now defined by the United Arab Emirates is rich and complex, and points to extensive trading links between the civilisations of the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia, but also as far afield as the Levant.[24] Archaeological finds in the emirate of Dubai, particularly at Al-Ashoosh, Al Sufouh and the notably rich trove from Saruq Al Hadid[25] show settlement through the Ubaid and Hafit periods, the Umm Al Nar and Wadi Suq periods and the three Iron Ages in the UAE. The area was known to the Sumerians as Magan, and was a source for metallic goods, notably copper and bronze.[26]

The area was covered with sand about 5,000 years ago as the coast retreated inland, becoming part of the city’s present coastline.[27] Pre-Islamic ceramics have been found from the 3rd and 4th centuries.[28] Prior to the introduction of Islam to the area, the people in this region worshiped Bajir (or Bajar).[28] After the spread of Islam in the region, the Umayyad Caliph of the eastern Islamic world invaded south-east Arabia and drove out the Sassanians. Excavations by the Dubai Museum in the region of Al-Jumayra (Jumeirah) found several artefacts from the Umayyad period.[29]

An early mention of Dubai is in 1095 in the Book of Geography by the Andalusian-Arab geographer Abu Abdullah al-Bakri.[citation needed] The Venetian pearl merchant Gasparo Balbi visited the area in 1580 and mentioned Dubai (Dibei) for its pearling industry.[29]

Establishment of modern Dubai[edit]

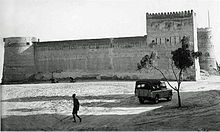

Al Fahidi fort in the 1950s

Dubai is thought to have been established as a fishing village in the early 18th century[30] and was, by 1822, a town of some 700–800 members of the Bani Yas tribe and subject to the rule of Sheikh Tahnun bin Shakhbut of Abu Dhabi.[31] In 1822, a British naval surveyor noted that Dubai was at that time populated with a thousand people living in an oval-shaped town surrounded by a mud wall, scattered with goats and camels. The main footpath out of the village led to a reedy creek while another trailed off into the desert which merged into caravan routes.[32]: 17

In 1833, following tribal feuding, members of the Al Bu Falasah tribe seceded from Abu Dhabi and established themselves in Dubai. The exodus from Abu Dhabi was led by Obeid bin Saeed and Maktoum bin Butti, who became joint leaders of Dubai until Ubaid died in 1836, leaving Maktum to establish the Maktoum dynasty.[30]

Dubai signed the General Maritime Treaty of 1820 with the British government along with other Trucial States, following the British campaign in 1819 against the Ras Al Khaimah. This led to the 1853 Perpetual Maritime Truce. Dubai also – like its neighbours on the Trucial Coast – entered into an exclusivity agreement in which the United Kingdom took responsibility for the emirate’s security in 1892.

In 1841, a smallpox epidemic broke out in the Bur Dubai locality, forcing residents to relocate east to Deira.[33] In 1896, fire broke out in Dubai, a disastrous occurrence in a town where many family homes were still constructed from barasti – palm fronds. The conflagration consumed half the houses of Bur Dubai, while the district of Deira was said to have been totally destroyed. The following year, more fires broke out. A female slave was caught in the act of starting one such blaze and was subsequently put to death.[34]

In 1901, Maktoum bin Hasher Al Maktoum established Dubai as a free port with no taxation on imports or exports and also gave merchants parcels of land and guarantees of protection and tolerance. These policies saw a movement of merchants not only directly from Lingeh,[35] but also those who had settled in Ras Al Khaimah and Sharjah (which had historical links with Lingeh through the Al Qawasim tribe) to Dubai. An indicator of the growing importance of the port of Dubai can be gained from the movements of the steamer of the Bombay and Persia Steam Navigation Company, which from 1899 to 1901 paid five visits annually to Dubai. In 1902 the company’s vessels made 21 visits to Dubai and from 1904 on,[36] the steamers called fortnightly – in 1906, trading 70,000 tonnes of cargo.[37] The frequency of these vessels only helped to accelerate Dubai’s role as an emerging port and trading hub of preference. Lorimer notes the transfer from Lingeh «bids fair to become complete and permanent»,[35] and also that the town had by 1906 supplanted Lingeh as the chief entrepôt of the Trucial States.[38]

The «great storm» of 1908 struck the pearling boats of Dubai and the coastal emirates towards the end of the pearling season that year, resulting in the loss of a dozen boats and over 100 men. The disaster was a major setback for Dubai, with many families losing their breadwinner and merchants facing financial ruin. These losses came at a time when the tribes of the interior were also experiencing poverty. In a letter to the Sultan of Muscat in 1911, Butti laments, «Misery and poverty are raging among them, with the result that they are struggling, looting and killing among themselves.»[39]

In 1910, in the Hyacinth incident the town was bombarded by the HMS Hyacinth, with 37 people killed.

Pre-oil Dubai[edit]

Dubai’s geographical proximity to Iran made it an important trade location. The town of Dubai was an important port of call for foreign tradesmen, chiefly those from Iran, many of whom eventually settled in the town. By the beginning of the 20th century, it was an important port.[40] At that time, Dubai consisted of the town of Dubai and the nearby village of Jumeirah, a collection of some 45 areesh (palm leaf) huts.[38] By the 1920s many Iranians settled in Dubai permanently, moving across the Persian Gulf. By then, amenities in the town grew and a modern quarter was established, Al Bastakiya.[32]: 21–23

Dubai was known for its pearl exports until the 1930s; the pearl trade was damaged irreparably by the 1929 Great Depression and the innovation of cultured pearls. With the collapse of the pearling industry, Dubai fell into a deep depression and many residents lived in poverty or migrated to other parts of the Persian Gulf.[27]

In 1937 an oil exploration contract was signed which guaranteed royalty rights for Dubai and concessionary payments to Sheikh Saeed bin Maktoum. However, due to World War II, oil would not be struck until 1966.[32]: 36–37

In the early days since its inception, Dubai was constantly at odds with Abu Dhabi. In 1947, a border dispute between Dubai and Abu Dhabi on the northern sector of their mutual border escalated into war.[41] Arbitration by the British government resulted in a cessation of hostilities.[42]

The Al Ras district in Deira and Dubai Creek in the mid 1960s

Despite a lack of oil, Dubai’s ruler from 1958, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, used revenue from trading activities to build infrastructure. Private companies were established to build and operate infrastructure, including electricity, telephone services and both the ports and airport operators.[43] An airport of sorts (a runway built on salt flats) was established in Dubai in the 1950s and, in 1959, the emirate’s first hotel, the Airlines Hotel, was constructed. This was followed by the Ambassador and Carlton Hotels in 1968.[44]

Sheikh Rashid commissioned John Harris from Halcrow, a British architecture firm, to create the city’s first master plan in 1959. Harris imagined a Dubai that would rise from the historic centre on Dubai Creek, with an extensive road system, organised zones, and a town centre, all of which could feasibly be built with the limited financial resources at the time.[45]

1959 saw the establishment of Dubai’s first telephone company, 51% owned by IAL (International Aeradio Ltd) and 49% by Sheikh Rashid and local businessmen and in 1961 both the electricity company and telephone company had rolled out operational networks.[46] The water company (Sheikh Rashid was chairman and majority shareholder) constructed a pipeline from wells at Awir and a series of storage tanks and, by 1968, Dubai had a reliable supply of piped water.[46]

On 7 April 1961, the Dubai-based MV Dara, a five thousand ton British flagged vessel that plied the route between Basra (Iraq), Kuwait and Bombay (India), was caught in unusually high winds off Dubai. Early the next morning in heavy seas off Umm al-Quwain, an explosion tore out the second class cabins and started fires. The captain gave the order to abandon ship but two lifeboats capsized and a second explosion occurred. A flotilla of small boats from Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman and Umm al-Quwain picked up survivors, but 238 of the 819 persons on board were lost in the disaster.[47]

The construction of Dubai’s first airport was started on the Northern edge of the town in 1959 and the terminal building opened for business in September 1960. The airport was initially serviced by Gulf Aviation (flying Dakotas, Herons and Viscounts) but Iran Air commenced services to Shiraz in 1961.[46]

In 1962 the British Political Agent noted that «Many new houses and blocks of offices and flats are being built… the Ruler is determined, against advice [from the British authorities] to press on with the construction of a jet airport… More and more European and Arab firms are opening up and the future looks bright.»[44]

In 1962, with expenditure on infrastructure projects already approaching levels some thought imprudent, Sheikh Rashid approached his brother in law, the Ruler of Qatar, for a loan to build the first bridge crossing Dubai’s creek. This crossing was finished in May 1963 and was paid for by a toll levied on the crossing from the Dubai side of the creek to the Deira side.[43]

BOAC was originally reluctant to start regular flights between Bombay and Dubai, fearing a lack of demand for seats. However, by the time the asphalt runway of Dubai Airport was constructed in 1965, opening Dubai to both regional and long haul traffic, a number of foreign airlines were competing for landing rights.[43] In 1970 a new airport terminal building was constructed which included Dubai’s first duty-free shops.[48]

Throughout the 1960s Dubai was the centre of a lively gold trade, with 1968 imports of gold at some £56 million. This gold was, in the vast majority, re-exported – mainly to customers who took delivery in international waters off India. The import of gold to India had been banned and so the trade was characterised as smuggling, although Dubai’s merchants were quick to point out that they were making legal deliveries of gold and that it was up to the customer where they took it.[49]

In 1966, more gold was shipped from London to Dubai than almost anywhere else in the world (only France and Switzerland took more), at 4 million ounces. Dubai also took delivery of over $15 million-worth of watches and over 5 million ounces of silver. The 1967 price of gold was $35 an ounce but its market price in India was $68 an ounce – a healthy markup. Estimates at the time put the volume of gold imports from Dubai to India at around 75% of the total market.[50]

Oil era[edit]

After years of exploration following large finds in neighbouring Abu Dhabi, oil was eventually discovered in territorial waters off Dubai in 1966, albeit in far smaller quantities. The first field was named «Fateh» or «good fortune». This led to an acceleration of Sheikh Rashid’s infrastructure development plans and a construction boom that brought a massive influx of foreign workers, mainly Asians and Middle easterners. Between 1968 and 1975 the city’s population grew by over 300%.[51]

As part of the infrastructure for pumping and transporting oil from the Fateh field, located offshore of the Jebel Ali area of Dubai, two 500,000 gallon storage tanks were built, known locally as 2Kazzans2,[52] by welding them together on the beach and then digging them out and floating them to drop onto the seabed at the Fateh field. These were constructed by the Chicago Bridge and Iron Company, which gave the beach its local name (Chicago Beach), which was transferred to the Chicago Beach Hotel, which was demolished and replaced by the Jumeirah Beach Hotel in the late 1990s. The Kazzans were an innovative oil storage solution which meant supertankers could moor offshore even in bad weather and avoided the need to pipe oil onshore from Fateh, which is some 60 miles out to sea.[53]

Dubai had already embarked on a period of infrastructural development and expansion. Oil revenue, flowing from 1969 onwards supported a period of growth with Sheikh Rashid embarking on a policy of building infrastructure and a diversified trading economy before the emirate’s limited reserves were depleted. Oil accounted for 24% of GDP in 1990, but had reduced to 7% of GDP by 2004.[14]

Critically, one of the first major projects Sheikh Rashid embarked upon when oil revenue started to flow was the construction of Port Rashid, a deep water free port constructed by British company Halcrow. Originally intended to be a four-berth port, it was extended to sixteen berths as construction was ongoing. The project was an outstanding success, with shipping queuing to access the new facilities. The port was inaugurated on 5 October 1972, although its berths were each pressed into use as soon as they had been built. Port Rashid was to be further expanded in 1975 to add a further 35 berths before the larger port of Jebel Ali was constructed.[14]

Port Rashid was the first of a swath of projects designed to create a modern trading infrastructure, including roads, bridges, schools and hospitals.[54]

Reaching the UAE’s Act of Union[edit]

Dubai and the other «Trucial States» had long been a British protectorate where the British government took care of foreign policy and defence, as well as arbitrating between the rulers of the Eastern Gulf, the result of a treaty signed in 1892 named the «Exclusive Agreement». This was to change with PM Harold Wilson’s announcement, on 16 January 1968, that all British troops were to be withdrawn from «East of Aden». The decision was to pitch the coastal emirates, together with Qatar and Bahrain, into fevered negotiations to fill the political vacuum that the British withdrawal would leave behind.[55]

The principle of union was first agreed upon between the ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, and Sheikh Rashid of Dubai on 18 February 1968 meeting in an encampment at Argoub Al Sedirah, near Al Semeih, a desert stop between the two emirates.[56] The two agreed to work towards bringing the other emirates, including Qatar and Bahrain, into the union. Over the next two years, negotiations and meetings of the rulers followed -often stormy- as a form of union was thrashed out. The nine-state union was never to recover from the October 1969 meeting where British intervention against aggressive activities by two of the Emirates resulted in a walk-out by them, Bahrain and Qatar. They dropped out of talks, leaving six of the seven «trucial» emirates to agree on union on 18 July 1971.[57]

On 2 December 1971, Dubai, together with Abu Dhabi, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm al-Quwain and Fujairah joined in the Act of Union to form the United Arab Emirates. The seventh emirate, Ras Al Khaimah, joined the UAE on 10 February 1972, following Iran’s annexation of the RAK-claimed Tunbs islands.[58]

In 1973, Dubai joined the other emirates to adopt a uniform currency: the UAE dirham.[40] In that same year, the prior monetary union with Qatar was dissolved and the UAE Dirham was introduced throughout the Emirates.[59]

Modern Dubai[edit]

Dubai Palm Jumeirah and Marina in 2011

During the 1970s, Dubai continued to grow from revenues generated from oil and trade, even as the city saw an influx of immigrants fleeing the Lebanese civil war.[60] Border disputes between the emirates continued even after the formation of the UAE; it was only in 1979 that a formal compromise was reached that ended disagreements.[61] The Jebel Ali port, a deep-water port that allowed larger ships to dock, was established in 1979. The port was not initially a success, so Sheikh Mohammed established the JAFZA (Jebel Ali Free Zone) around the port in 1985 to provide foreign companies unrestricted import of labour and export capital.[62] Dubai airport and the aviation industry also continued to grow.

The Gulf War in early 1991 had a negative financial effect on the city, as depositors withdrew their money and traders withdrew their trade, but subsequently, the city recovered in a changing political climate and thrived. Later in the 1990s, many foreign trading communities—first from Kuwait, during the Gulf War, and later from Bahrain, during the Shia unrest—moved their businesses to Dubai.[63] Dubai provided refuelling bases to allied forces at the Jebel Ali Free Zone during the Gulf War, and again during the 2003 Invasion of Iraq. Large increases in oil prices after the Gulf War encouraged Dubai to continue to focus on free trade and tourism.[64]

Geography[edit]

This time-lapse video shows the rate of Dubai’s growth at one frame per year from 2000 through 2011. In the false-colour satellite images making up the video, bare desert is tan, plant-covered land is red, water is black and urban areas are silver.

Dune bashing in one of the deserts of Dubai

Dubai is situated on the Persian Gulf coast of the United Arab Emirates and is roughly at sea level (16 m or 52 ft above). The emirate of Dubai shares borders with Abu Dhabi in the south, Sharjah in the northeast, and the Sultanate of Oman in the southeast. Hatta, a minor exclave of the emirate, is surrounded on three sides by Oman and by the emirates of Ajman (in the west) and Ras Al Khaimah (in the north). The Persian Gulf borders the western coast of the emirate. Dubai is positioned at 25°16′11″N 55°18′34″E / 25.2697°N 55.3095°E and covers an area of 1,588 sq mi (4,110 km2), which represents a significant expansion beyond its initial 1,500 sq mi (3,900 km2) designation due to land reclamation from the sea.[citation needed]

Dubai lies directly within the Arabian Desert. However, the topography of Dubai is significantly different from that of the southern portion of the UAE in that much of Dubai’s landscape is highlighted by sandy desert patterns, while gravel deserts dominate much of the southern region of the country.[65] The sand consists mostly of crushed shell and coral and is fine, clean and white. East of the city, the salt-crusted coastal plains, known as sabkha, give way to a north–south running line of dunes. Farther east, the dunes grow larger and are tinged red with iron oxide.[51]

The flat sandy desert gives way to the Western Hajar Mountains, which run alongside Dubai’s border with Oman at Hatta. The Western Hajar chain has an arid, jagged and shattered landscape, whose mountains rise to about 1,300 metres (4,265 feet) in some places. Dubai has no natural river bodies or oases; however, Dubai does have a natural inlet, Dubai Creek, which has been dredged to make it deep enough for large vessels to pass through. Dubai also has multiple gorges and waterholes, which dot the base of the Western Al Hajar mountains. A vast sea of sand dunes covers much of southern Dubai and eventually leads into the desert known as The Empty Quarter. Seismically, Dubai is in a very stable zone—the nearest seismic fault line, the Zagros Fault, is 200 kilometres (124 miles) from the UAE and is unlikely to have any seismic impact on Dubai.[66] Experts also predict that the possibility of a tsunami in the region is minimal because the Persian Gulf waters are not deep enough to trigger a tsunami.[66]

The sandy desert surrounding the city supports wild grasses and occasional date palms. Desert hyacinths grow in the sabkha plains east of the city, while acacia and ghaf trees grow in the flat plains within the proximity of the Western Al Hajar mountains. Several indigenous trees such as the date palm and neem as well as imported trees such as the eucalyptus grow in Dubai’s natural parks. The macqueen’s bustard, striped hyena, caracal, desert fox, falcon and Arabian oryx are common in Dubai’s desert. Dubai is on the migration path between Europe, Asia and Africa, and more than 320 migratory bird species pass through the emirate in spring and autumn. The waters of Dubai are home to more than 300 species of fish, including the hammour. The typical marine life off the Dubai coast includes tropical fish, jellyfish, coral, dugong, dolphins, whales and sharks. Various types of turtles can also be found in the area including the hawksbill turtle and green turtle, which are listed as endangered species.[67][68]

Dubai Creek runs northeast–southwest through the city. The eastern section of the city forms the locality of Deira and is flanked by the emirate of Sharjah in the east and the town of Al Aweer in the south. The Dubai International Airport is located south of Deira, while the Palm Deira is located north of Deira in the Persian Gulf. Much of Dubai’s real-estate boom is concentrated to the west of Dubai Creek, on the Jumeirah coastal belt. Port Rashid, Jebel Ali, Burj Al Arab, the Palm Jumeirah and theme-based free-zone clusters such as Business Bay are all located in this section.[69] Dubai is notable for sculpted artificial island complexes including the Palm Islands and The World archipelago.

Climate[edit]

Dubai has a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh). Summers in Dubai are extremely hot, prolonged, windy, and humid, with an average high around 40 °C (104 °F) and overnight lows around 30 °C (86 °F) in the hottest month, August. Most days are sunny throughout the year. Winters are comparatively cool, though mild to warm, with an average high of 24 °C (75 °F) and overnight lows of 14 °C (57 °F) in January, the coolest month. Precipitation, however, has been increasing in the last few decades, with accumulated rain reaching 110.7 mm (4.36 in) per year.[70] Dubai summers are also known for the very high humidity level, which can make it very uncomfortable for many with exceptionally high dew points in summer. Heat index values can reach over 60 °C (140 °F) at the height of summer.[71] The highest recorded temperature in Dubai is 48.8 °C (119.8 °F).

| Climate data for Dubai (1977–2015 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.8 (89.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

41.3 (106.3) |

43.5 (110.3) |

47.0 (116.6) |

47.9 (118.2) |

49.0 (120.2) |

48.8 (119.8) |

45.1 (113.2) |

42.4 (108.3) |

38.0 (100.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

49.0 (120.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.9 (75.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.9 (84.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.7 (99.9) |

39.8 (103.6) |

40.9 (105.6) |

41.3 (106.3) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.4 (95.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

31.4 (88.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

35.5 (95.9) |

35.9 (96.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

28.1 (82.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.3 (81.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.4 (86.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

22.6 (72.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18.8 (0.74) |

25.0 (0.98) |

22.1 (0.87) |

7.2 (0.28) |

0.4 (0.02) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (0.03) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.1 (0.04) |

2.7 (0.11) |

16.2 (0.64) |

94.3 (3.71) |

| Average precipitation days | 5.5 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 25.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 251 | 241 | 270 | 306 | 350 | 345 | 332 | 326 | 309 | 307 | 279 | 254 | 3,570 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.1 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 10.2 | 11.3 | 11.5 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 9.9 | 9.3 | 8.2 | 9.8 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| Source 1: Dubai Meteorological Office[72] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: UAE National Center of Meteorology[73] |

Government[edit]

Dubai has been ruled by the Al Maktoum family since 1833; the emirate is a constitutional monarchy. Dubai citizens participate in the electoral college to vote representatives to the Federal National Council of the UAE. The ruler, His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, is also the vice-president and Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates and member of the Supreme Council of the Union (SCU). Dubai appoints 8 members in two-term periods to the Federal National Council (FNC) of the UAE, the supreme federal legislative body.[74]

The Dubai Municipality (DM) was established by the then ruler of Dubai, Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, in 1954 for purposes of city planning, citizen services and upkeep of local facilities.[75] It has since then evolved into an autonomous subnational authority, collectively known as the Government of Dubai which is responsible for both the city of Dubai and the greater emirate.[76] The Government of Dubai has over 58 governmental departments responsible for security, economic policy, education, transportations, immigration, and is only one of the three emirates to have a separate judicial system independent from the federal judiciary of the UAE.[77] The Ruler of Dubai is the head of government and emir (head of state) and laws, decrees, and court judgements are issued in his name, however, since 2003, executive authority of managing and overseeing Dubai Governmental agencies has been delegated to the Dubai Executive Council, led by Crown Prince of Dubai Hamdan bin Mohammed Al Maktoum. Although no legislative assembly exists, the traditional open majlis (council) where citizens and representatives of the Ruler meet are often used for feedback on certain domestic issues.[78][79]

Law enforcement[edit]

The Dubai Police Force, founded in 1956 in the locality of Naif, has law enforcement jurisdiction over the emirate. The force is under direct command of Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum.[80]

Dubai and Ras al Khaimah are the only emirates that do not conform to the federal judicial system of the United Arab Emirates.[81] The emirate’s judicial courts comprise the Court of First Instance, the Court of Appeal, and the Court of Cassation. The Court of First Instance consists of the Civil Court, which hears all civil claims; the Criminal Court, which hears claims originating from police complaints; and Sharia Court, which is responsible for matters between Muslims. Non-Muslims do not appear before the Sharia Court. The Court of Cassation is the supreme court of the emirate and hears disputes on matters of law only.[82]

Alcohol laws[edit]

Alcohol sale and consumption, though legal, is regulated. Adult non-Muslims are allowed to consume alcohol in licensed venues, typically within hotels, or at home with the possession of an alcohol licence. Places other than hotels, clubs, and specially designated areas are typically not permitted to sell alcohol.[83] As in other parts of the world, drinking and driving is illegal, with 21 being the legal drinking age in the Emirate of Dubai.[84]

Human rights[edit]

Latifa, daughter of Dubai’s ruler, escaped Dubai in February 2018 but was captured in the Indian Ocean.[85]

Companies in Dubai have in the past been criticised for human rights violations against labourers.[86][87][88] Some of the 250,000 foreign labourers in the city have been alleged to live in conditions described by Human Rights Watch as «less than humane».[89][90][91][92] The mistreatment of foreign workers was a subject of the difficult-to-make documentary, Slaves in Dubai (2009).[93] The Dubai government has denied labour injustices and stated that the watchdog’s (Human Rights Watch) accusations were «misguided». The filmmaker explained in interviews how it was necessary to go undercover to avoid discovery by the authorities, who impose high fines on reporters attempting to document human rights abuses, including the conditions of construction workers.

Towards the end of March 2006, the government had announced steps to allow construction unions. UAE labour minister Ali al-Kaabi said: «Labourers will be allowed to form unions.»[94] As of 2020, the federal public prosecution has clarified that «it is an offense when at least three public employees collectively leave work or one of the duties to achieve an unlawful purpose. Each employee will be punished with not less than 6 months in prison and not more than a year, as the imprisonment will be for leaving the job or duties that affect the health or the security of the people, or affect other public services of public benefit.» Any act of spreading discord among employees will be punishable by imprisonment, and in all cases, foreigners will be deported.[95]

Homosexual acts are illegal under UAE law.[96] Freedom of speech in Dubai is limited, with both residents and citizens facing severe sanctions from the government for speaking out against the royal family or local laws and culture.[97] Some of the labourers lured by the higher pay available in Dubai are victims of human trafficking or forced labour while some women are even forced into the growing sex trade in Dubai, a centre of human trafficking and prostitution.[98]

Defamation on social media is a punishable offence in Dubai with fines up to half a million dirhams and jail term for up to 2 years. In January 2020, three Sri Lankan ex-pats were fined AED 500,000 each for posting defamatory Islamaphobic Facebook posts.[99]

On 3 September 2020, The Guardian reported that hundreds of thousands of migrant workers lost their jobs and were left stranded in Dubai, due to oil price crash and COVID-19. Many were trapped in desperate situations in crowded labour camps with no salary or any other financial source. Those migrant workers had to rely on food donations while they waited for work and to get paid.[100]

Crime[edit]

Dubai has one of the world’s lowest violent crime rates,[101] and in 2019 was ranked the seventh-safest city in the world.[102][103][104] The Security Industry Regulatory Agency classified the crimes into six categories.[105] These crimes include theft, forced robbery, domestic burglary, fraud, sexual assault and abuse, and criminal damages.[105]

As per Gulf News, Dubai Police stated that the crime in Dubai was reduced by fifteen percent during 2017. However, the cases of drugs operation increased by eight per cent. Major-General Abdullah Khalifa Al Merri, Commander-in-Chief of Dubai Police, hailed the force which solved 86 per cent of criminal cases.[106]

The statistics also indicated that murder crimes dropped from 0.5 in 2016 to 0.3 in 2017 for every 100,000 population, while violent and aggressive crimes in the past 5 years went from 2.2 crimes per 100,000 and dropped to 1.2 by the end of 2017, pointed out Al Mansouri.[101] General crimes have decreased since 2013, registering around 0.2 by the end of 2017. Robberies went from 3.8 in 2013 to 2.1 by the end of last year, while kidnapping cases also dropped from 0.2 in 2013 to 0.1 in 2017.

Vehicle thefts in 2013 were 3.8 per 100,000 population and fell to 1.7 in 2017. According to the US Bureau of Diplomatic Security, petty theft, pickpocketing, scams, and sexual harassment still occur although they are usually not violent and weapons are not involved.[107]

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1822[108] | 1,200 | — |

| 1900[109] | 10,000 | +733.3% |

| 1930[110] | 20,000 | +100.0% |

| 1940[108] | 38,000 | +90.0% |

| 1960[111] | 40,000 | +5.3% |

| 1968[112] | 58,971 | +47.4% |

| 1975[113] | 183,000 | +210.3% |

| 1985[114] | 370,800 | +102.6% |

| 1995[114] | 674,000 | +81.8% |

| 2005 | 1,204,000 | +78.6% |

| 2010[115] | 1,905,476 | +58.3% |

| 2015[116] | 2,446,675 | +28.4% |

| 2019[117] | 3,355,900 | +37.2% |

| c-census; e-estimate |

Ethnicity and languages[edit]

As of September 2019, the population is 3,331,420 – an annual increase of 177,020 people which represents a growth rate of 5.64%.[118] The region covers 1,287.5 square kilometres (497.1 sq mi). The population density is 408.18/km2 – more than eight times that of the entire country. Dubai is the second most expensive city in the region and 20th most expensive city in the world.[119]

As of 2013, only about 15% of the population of the emirate was made up of UAE nationals,[120] with the rest comprising expatriates, many of whom either have been in the country for generations or were born in the UAE.[121][122] Approximately 85% of the expatriate population (and 71% of the emirate’s total population) was Asian, chiefly Indian (51%) and Pakistani (16%); other significant Asian groups include Bangladeshis (9%) and Filipinos (3%).[123] A quarter of the population (local and foreign) reportedly traces their origins to Iran.[124] In addition, 16% of the population (or 288,000 persons) living in collective labour accommodation were not identified by ethnicity or nationality, but were thought to be primarily Asian.[125] 461,000 Westerners live in the United Arab Emirates, making up 5.1% of its total population.[126][127] There are over 100,000 British expatriates in Dubai, by far the largest group of Western expatriates in the city.[128] The median age in the emirate was about 27 years. In 2014, there were estimated to be 15.54 births and 1.99 deaths per 1,000 people.[129] There are other Arab nationals, including GCC nationals.[citation needed]

Arabic is the national and official language of the United Arab Emirates. The Gulf dialect of Arabic is spoken natively by the Emirati people.[130] English is used as a second language. Other major languages spoken in Dubai due to immigration are Malayalam, Hindi-Urdu (or Hindustani), Gujarati, Persian, Sindhi, Tamil, Punjabi, Pashto, Bengali, Balochi, Tulu,[131] Kannada, Sinhala, Marathi, Telugu, Tagalog and Chinese, in addition to many other languages.[132]

Religion[edit]

Article 7 of the UAE’s Provisional Constitution declares Islam the official state religion of the UAE. The government subsidises almost 95% of mosques and employs all Imams; approximately 5% of mosques are entirely private, and several large mosques have large private endowments.[133] All mosques in Dubai are managed by the Islamic Affairs and Charitable Activities Department also known as «Awqaf» under the Government of Dubai and all Imams are appointed by the Government.[134] The Constitution of the United Arab Emirates provides for freedom of religion. Expats held to be preaching religious hatred or promoting religious extremism are usually jailed and deported.[135]

Dubai has large Christian, Hindu, Sikh, Baháʼí, Buddhist and other religious communities residing in the city, as well as a small but growing Jewish community.[136] In 2014, more than 56% of Dubai residents were Muslims, while 25% of the Dubai residents were Christians and 16% were Hindus. While around 2% of the Dubai residents were adherent of other religions.[137]

The Churches Complex in Jebel Ali Village is an area for a number of churches and temples of different religious denominations, especially Christian denominations.[138]

Non-Muslim groups can own their own houses of worship, where they can practice their religion freely, by requesting a land grant and permission to build a compound. Groups that do not have their own buildings are allowed to use the facilities of other religious organisations or worship in private homes.[139] Non-Muslim religious groups are also permitted to advertise group functions openly and distribute various religious literature. Catholics are served pastorally by the Apostolic Vicariate of Southern Arabia. British preacher Reverend Andrew Thompson claimed that the United Arab Emirates is one of the most tolerant places in the world towards Christians and that it is easier to be a Christian in the UAE than in the UK.[140]

On 5 April 2020, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints announced the building of one of their temples in Dubai. As part of the announcement, church President Russell M. Nelson said that “The plan for a temple in Dubai comes in response to their gracious invitation, which we gratefully acknowledge.”[141]

Economy[edit]

One of the world’s fastest growing economies,[142] Dubai’s gross domestic product is projected at over US$177 billion in 2021, with a growth rate of 6.1% in 2014.[143] Although a number of core elements of Dubai’s trading infrastructure were built on the back of the oil industry,[144] revenues from oil and natural gas account for less than 5% of the emirate’s revenues.[15] It is estimated that Dubai produces 50,000 to 70,000 barrels (7,900 to 11,100 m3) of oil a day[145] and substantial quantities of gas from offshore fields. The emirate’s share in the UAE’s total gas revenues is about 2%. Dubai’s oil reserves have diminished significantly and are expected to be exhausted in 20 years.[146] Real estate and construction (22.6%),[17] trade (16%), entrepôt (15%) and financial services (11%) are the largest contributors to Dubai’s economy.[147]

Dubai’s non-oil foreign trade stood at $362 billion in 2014. Of the overall trade volumes, imports had the biggest share with a value of $230 billion while exports and re-exports to the emirate stood at $31 billion and $101 billion respectively.[148]

By 2014, China had emerged as Dubai’s largest international trading partner, with a total of $47.7 billion in trade flows, up 29% from 2013. India was second among Dubai’s key trading partners with a trade of $29.7 billion, followed by the United States at $22.62 billion. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was Dubai’s fourth trading partner globally and first in the GCC and Arab world with a total trade value of $14.2 billion. Trade with Germany in 2014 totalled $12.3 billion, Switzerland and Japan both at $11.72 billion and UK trade totalled $10.9 billion.[148]

Historically, Dubai and its twin across Dubai Creek, Deira (independent of Dubai City at that time), were important ports of call for Western manufacturers. Most of the new city’s banking and financial centres were headquartered in the port area. Dubai maintained its importance as a trade route through the 1970s and 1980s. Dubai has a free trade in gold and, until the 1990s, was the hub of a «brisk smuggling trade»[40] of gold ingots to India, where gold import was restricted. Dubai’s Jebel Ali port, constructed in the 1970s, has the largest man-made harbour in the world and was ranked seventh globally for the volume of container traffic it supports.[149] Dubai is also a hub for service industries such as information technology and finance, with industry-specific free zones throughout the city.[150] Dubai Internet City, combined with Dubai Media City as part of TECOM (Dubai Technology, Electronic Commerce and Media Free Zone Authority), is one such enclave, whose members include IT firms such as Hewlett Packard Enterprise, HP Inc., Halliburton, Google, EMC Corporation, Oracle Corporation, Microsoft, Dell and IBM, and media organisations such as MBC, CNN, BBC, Reuters, Sky News and AP.[151] Various programmes, resources and value-added services support the growth of startups in Dubai and help them connect to new business opportunities.[152]

The Dubai Financial Market (DFM) was established in March 2000 as a secondary market for trading securities and bonds, both local and foreign. As of the fourth quarter 2006, its trading volume stood at about 400 billion shares, worth $95 billion in total. The DFM had a market capitalisation of about $87 billion.[125] The other Dubai-based stock exchange is NASDAQ Dubai, which is the international stock exchange in the Middle East. It enables a range of companies, including UAE and regional small and medium-sized enterprises, to trade on an exchange with an international brand name, with access by both regional and international investors.[153]

DMCC (Dubai Multi Commodities Centre) was established in 2002. It’s the world’s fastest-growing free zone and been nominated as «Global Free Zone of the Year 2016» by The Financial Times Magazine.

Dubai is also known as the City of Gold because a major part of the economy is based on gold trades, with Dubai’s total gold trading volumes in H1 2011 reaching 580 tonnes, with an average price of US$1,455 per troy ounce.[154]

A City Mayors survey ranked Dubai 44th among the world’s best financial cities in 2007,[155] while another report by City Mayors indicated that Dubai was the world’s 27th richest city in 2012, in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP).[156] Dubai is also an international financial centre (IFC) and has been ranked 37th within the top 50 global financial cities as surveyed by the MasterCard Worldwide Centres of Commerce Index (2007),[157] and 1st within the Middle East. Since it opened in September 2004, the Dubai IFC has attracted, as a regional hub, leading international firms and set-up the NASDAQ Dubai which lists equity, derivatives, structured products, Islamic bonds (sukuk) and other bonds. The Dubai IFC model is an independent risk-based regulator with a legislative system consistent with English common law.[158]

In 2012, the Global City Competitiveness Index by the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked Dubai at No. 40 with a total score of 55.9. According to its 2013 research report on the future competitiveness of cities, in 2025, Dubai will have moved up to 23rd place overall in the Index.[159] Indians, followed by Britons and Pakistanis are the top foreign investors in Dubai realty.[160]

Dubai has launched several major projects to support its economy and develop different sectors. These include Dubai Fashion 2020,[161] and Dubai Design District,[162] expected to become a home to leading local and international designers. The AED 4 billion first phase of the project was completed in 2015.[163]

In September 2019, Dubai’s ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum ordered to establish the Higher Committee for Real Estate Planning to study and evaluate future real estate construction projects, in ordered to achieve a balance between supply and demand,[164] which is seen as a move to curb the pace of construction projects following property prices fall.[165]

Since the economy of Dubai relies majorly on real estate, transportation and tourism, it was highly exposed to the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. In April 2020, the American business and financial services company, Moody’s Corporation reported that the coronavirus outbreak is likely to pose acute “negative growth and fiscal implications” in Dubai.[166] It was reported that in order to bolster its finances and overcome the impact of coronavirus on its economy, Dubai was in talks to raise billions of dollars of debt privately, where it was seeking loans of 1 billion dirhams ($272 million) to 2 billion dirhams from each lender.[167] On 6 May, Dubai’s businessman from the hospitality sector, Khalaf Al Habtoor stated that the coronavirus pandemic left the economy and his companies “bleeding”. The owner of seven hotels in the country, including the Waldorf Astoria on the man-made island Palm Jumeirah, Habtoor stated that Dubai’s economy cannot afford to wait for the vaccine, before resuming the major activities.[168] In June 2020, the Moody’s Investors Service cut down its ratings for eight of the biggest banks based in the UAE from stable to negative.[169] In effect, the benchmark stock index of Dubai dropped the most among all the Gulf nations, where the DFM General Index lost as much as 1.3 per cent.[170]

In July 2020, a report released by an NGO, Swissaid, denounced the gold trade between Dubai and Switzerland. The documents revealed that Dubai firms, including Kaloti Jewellery International Group and Trust One Financial Services (T1FS), have been obtaining gold from poor African countries like Sudan. Between 2012 and 2018, 95 per cent of gold from Sudan ended up in the UAE. The gold imported from Sudan by Kaloti was from the mines controlled by militias responsible for war crimes and human rights violations in the country. World’s largest refinery in Switzerland, Valcambi, was denounced by Swissaid for importing extensive gold from these Dubai firms. In 2018 and 2019, Valcambi received 83 tonnes of gold from the two companies.[171][172] In a letter on 11 October 2021, the Switzerland State Secretariat for Economic Affairs asked the country’s gold refineries to keep a strict check on the imports from the Emirates to ensure no involvement of illicit African bullion. Switzerland accounted for high volume of imports from the UAE, which were to be 10% of the total Swiss gold imports in 2021. The refineries were required to identify the country of origin of all gold that came from the UAE.[173]

Real estate and property[edit]

Dubai Creek, which separates Deira from Bur Dubai, played a vital role in the economic development of the city.

The government’s decision to diversify from a trade-based, oil-reliant economy to one that is service- and tourism-oriented made property more valuable, resulting in the property appreciation from 2004 to 2006. A longer-term assessment of Dubai’s property market, however, showed depreciation; some properties lost as much as 64% of their value from 2001 to November 2008.[174] The large-scale real estate development projects have led to the construction of some of the tallest skyscrapers and largest projects in the world such as the Emirates Towers, the Burj Khalifa, the Palm Islands and the most expensive hotel, the Burj Al Arab.[175] Dubai’s property market experienced a major downturn in 2008[176] and 2009 as a result of the slowing economic climate.[87] By early 2009, the situation had worsened with the Great Recession taking a heavy toll on property values, construction and employment.[177] This has had a major impact on property investors in the region, some of whom were unable to release funds from investments made in property developments.[178] As of February 2009, Dubai’s foreign debt was estimated at $80 billion, although this is a tiny fraction of the sovereign debt worldwide.[179]

In Dubai, many of the property owners are residents or genuine investors. However, the 2020 Data from the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS) exposed that a number of real estate owners in the city were either facing international sanctions or were involved in criminal activities. Some others were public officials, with a minimal possibility of purchasing it with their known incomes. The report, “Dubai Uncovered” mentioned names of 100 Russian oligarchs, public officials and Europeans involved in money laundering. Benefiting from Dubai’s lack of real estate regulations, a number of corrupt people owned a house away from home, laundered their illicit money, and even invested to store their wealth. Names of some of such questionable figures included Daniel Kinahan, Alexander Borodai, Roman Lyabikhov, Tibor Bokor, Ruslan Baisarov, Miroslav Výboh and others.[180]

Tourism and retail[edit]

Tourism is an important part of the Dubai government’s strategy to maintain the flow of foreign cash into the emirate. Dubai’s lure for tourists is based mainly on shopping,[181][182] but also on its possession of other ancient and modern attractions.[183] As of 2018, Dubai is the fourth most-visited city in the world based on the number of international visitors and the fastest growing, increasing by a 10.7% rate.[184] The city hosted 14.9 million overnight visitors in 2016, and is expected to reach 20 million tourists by 2020.[185]

A great tourist attraction in Dubai is the Burj Khalifa, currently the tallest building on Earth. Although, Jeddah Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia is aiming to be taller.

Dubai has been called the «shopping capital of the Middle East».[186] Dubai alone has more than 70 shopping centres, including the world’s second largest shopping centre, Dubai Mall. Dubai is also known for the historical souk districts located on either side of its creek. Traditionally, dhows from East Asia, China, Sri Lanka, and India would discharge their cargo and the goods would be bargained over in the souks adjacent to the docks. Dubai Creek played a vital role in sustaining the life of the community in the city and was the resource which originally drove the economic boom in Dubai.[187] As of September 2013, Dubai creek has been proposed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[188] Many boutiques and jewellery stores are also found in the city. Dubai is also referred to as «the City of Gold» as the Gold Souk in Deira houses nearly 250 gold retail shops.[189]

Dubai Creek Park in Dubai Creek also plays a vital role in Dubai tourism as it showcase some of the most famous tourist attractions in Dubai such as Dolphinarium, Cable Car, Camel Ride, Horse Carriage and Exotic Birds Shows.[190]

Dubai has a wide range of parks like Safa park, Mushrif park, Hamriya park, etc. Each park is uniquely distinct from the other. Mushrif park showcases different houses around the world. A visitor can check out the architectural features of the outside as well as the inside of each house.

Some of the most popular beaches in Dubai are Umm Suqeim Beach, Al Mamzar Beach Park, JBR Open Beach, Kite Beach, Black Palace Beach and Royal Island Beach Club. Mastercard’s Global Destination Cities Index 2019 found that tourists spend more in Dubai than in any other country. In 2018, the country topped the list for the fourth year in a row with a total spend of $30.82 billion. The average spend per day was found to be $553.[191]

In October 2019, Dubai loosened its liquor laws for the first time, under which it allowed tourists to purchase alcohol from state-controlled stores. Previously, alcohol was accessible only for locals with special licences. The crucial policy shift came as the United Arab Emirates witnessed a severe economic crisis that led to a drop in alcohol sales by volume.[192]

In 2021, the UAE was amongst 20 most dangerous places for the LGBTQ tourists to visit.[193] Even in 2022, there were cases where a number of LGBTQ tourists who travelled to Dubai faced issues and were deported. In March 2022, a Thai model Rachaya Noppakaroon visited Dubai for her performance at the Expo 2020, but was sent back because she identified as a woman, but her passport stated her gender as male.[194] In another case, a French influencer on TikTok and Snapchat, Ibrahim Godin was sent back from Dubai, because the authorities assumed her male friend travelling with him as his boyfriend. Ibrahim filed a complaint for “public defamation because of sexual orientation” and investigation was opened by Vesoul prosecution. He said, “Dubai is not all pretty, all rosy as we see on social networks.”[195][196]

Expo 2020[edit]

On 2 November 2011, four cities had their bids for Expo 2020[10] already lodged, with Dubai making a last-minute entry. The delegation from the Bureau International des Expositions, which visited Dubai in February 2013 to examine the Emirate’s readiness for the largest exposition, was impressed by the infrastructure and the level of national support. In May 2013, Dubai Expo 2020 Master Plan was revealed.[197] Dubai then won the right to host Expo 2020 on 27 November 2013.[198]

The main site of Dubai Expo 2020 was planned to be a 438-hectare area (1,083 acres), part of the new Dubai Trade Centre Jebel Ali urban development, located midway between Dubai and Abu Dhabi.[199] Moreover, the Expo 2020 also created various social enlistment projects and monetary boons to the city targeting the year 2020, such as initiating the world’s largest solar power project.[200]

The Dubai Expo 2020 was scheduled to take place from 20 October 2020 until 10 April 2021 for 173 days where there would be 192 country pavilions featuring narratives from every part of the globe, have different thematic districts that would promote learning the wildlife in the forest exhibit too many other experiences.[201]

Due to the impact of COVID-19 the organisers of Expo 2020 postponed the Expo by one year to begin in 2021 (the new dates are 1 October 2021 – 31 March 2022).[202][203]

Dubai has targets to build an inclusive, barrier-free and disabled-friendly city, which opened as Expo City Dubai. The city has already brought in changes by introducing wheelchair friendly taxis, pavements with slopes and tactile indicators on the floor for the visually impaired at all the metro stations.[204]

Architecture[edit]

Skyline of Downtown Dubai from a helicopter in 2015

Dubai has a rich collection of buildings and structures of various architectural styles. Many modern interpretations of Islamic architecture can be found here, due to a boom in construction and architectural innovation in the Arab World in general, and in Dubai in particular, supported not only by top Arab or international architectural and engineering design firms such as Al Hashemi and Aedas, but also by top firms of New York and Chicago.[205] As a result of this boom, modern Islamic – and world – architecture has literally been taken to new levels in skyscraper building design and technology. Dubai now has more completed or topped-out skyscrapers higher than 2⁄3 km (2,200 ft), 1⁄3 km (1,100 ft), or 1⁄4 km (820 ft) than any other city. A culmination point was reached in 2010 with the completion of the Burj Khalifa (Khalifa Tower), now by far the world’s tallest building at 829.8 m (2,722 ft). The Burj Khalifa’s design is derived from the patterning systems embodied in Islamic architecture, with the triple-lobed footprint of the building based on an abstracted version of the desert flower hymenocallis which is native to the Dubai region.[206]

The completion of the Khalifa Tower, following the construction boom that began in the 1980s, accelerated in the 1990s, and took on a rapid pace of construction during the decade of the 2000s, leaves Dubai with the world’s tallest skyline as of 4 January 2010.[207][208] At the top, Burj Khalifa, the world’s second highest observatory deck after the Shanghai Tower with an outdoor terrace is one of Dubai’s most popular tourist attractions, with over 1.87 million visitors in 2013.[209]

The Creek Tower had been planned in the 2010s to keep Dubai atop the list of tallest buildings.[210] However, construction was placed on indefinite hold during the coronavirus pandemic and no date has been announced for the project to continue.[211]

Burj Al Arab[edit]

The Burj Al Arab (Arabic: برج العرب, Tower of the Arabs), a luxury hotel, is frequently described as «the world’s only 7-star», though its management has never made that claim but has claimed to be a “five-star deluxe property.” The term «7-star hotel» was coined by a British journalist to describe their initial experience of the hotel.[212] A Jumeirah Group spokesperson is quoted as saying: «There’s not a lot we can do to stop it. We’re not encouraging the use of the term. We’ve never used it in our advertising.»[212] The hotel opened in December 1999.

Burj Khalifa[edit]

Dubai Police Agusta A-109K-2 in flight near Burj Khalifa

Burj Khalifa, known as the Burj Dubai before its inauguration, is a 828 metres (2,717 ft) high[213] skyscraper in Dubai, and the tallest building in the world. The tower was inspired by the structure of the desert flower Hymenocallis. It was constructed by more than 30 contracting companies around the world with workers of a hundred nationalities. It is an architectural icon, named after Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan.[214] The building opened on 4 January 2010.[215]

Palm Jumeirah[edit]

The Palm Jumeirah is an artificial archipelago, created using land reclamation by Nakheel, a company owned by the Dubai government, and designed and developed by Helman Hurley Charvat Peacock/Architects, Inc. It is one of three planned islands called the Palm Islands which extend into the Persian Gulf. The Palm Jumeirah is the smallest and the original of three Palm Islands, and it is located on the Jumeirah coastal area of Dubai. It was built between 2001 and 2006.[216]

The World Islands[edit]

The World Islands is an archipelago of small artificial islands constructed in the shape of a world map, located in the waters of the Persian Gulf, 4.0 kilometres (2.5 mi) off the coast of Dubai, United Arab Emirates.[217] The World islands are composed mainly of sand dredged from Dubai’s shallow coastal waters, and are one of several artificial island developments in Dubai.

Dubai Miracle Garden[edit]

On 14 February 2013, the Dubai Miracle Garden, a 72,000-metre (236,000-foot) flower garden, opened in Dubailand. It is the world’s largest flower garden. The garden displays more than 50 million flowers with more than 70 species of flowering plants.[218] The garden uses retreated waste water from city’s municipality and utilises drip irrigation method for watering the plants. During the summer seasons from late May to September when the climate can get extremely hot with an average high of about 40 °C (104 °F), the garden stays closed.[219][220]

Dubai Marina[edit]

Dubai Marina (Arabic: مرسى دبي) is a district in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. It is an artificial canal city, built along a 3-kilometre (2 mi) stretch of Persian Gulf shoreline. As of 2018, it has a population of 55,052.[221]

Address Beach Resort and Address Beach Residences[edit]

The structure is a set of two towers connected at the bottom and with a sky bridge at the top which connects the 63rd through to the 77th levels. The sky bridge houses luxury apartments on the world’s highest occupiable sky bridge floor, at 294.36 metres.[citation needed] Known as Jumeirah Gate, it opened in December 2020 and is situated along the beach. The towers have the world’s highest infinity pool in a building, on the roof, at a height of 293.906 metres.[222]

Transportation[edit]

Dubai Metro is the first kind of rail transportation in the UAE, and is the Arabian Peninsula’s first urban train network.[223]

Abras and dhows are traditional modes of waterway transport.

Transport in Dubai is controlled by the Roads and Transport Authority (RTA), an agency of the government of Dubai, formed by royal decree in 2005.[226] The public transport network has in the past faced congestion and reliability issues which a large investment programme has addressed, including over AED 70 billion of improvements planned for completion by 2020, when the population of the city is projected to exceed 3.5 million.[227] In 2009, according to Dubai Municipality statistics, there were an estimated 1,021,880 cars in Dubai.[228] In January 2010, the number of Dubai residents who use public transport stood at 6%.[229]

Road[edit]

Five main routes – E 11 (Sheikh Zayed Road), E 311 (Sheikh Mohammed Bin Zayed Road), E 44 (Dubai-Hatta Highway), E 77 (Dubai-Al Habab Road) and E 66 (Oud Metha Road, Dubai-Al Ain Road, or Tahnoun Bin Mohammad Al Nahyan Road)[230] – run through Dubai, connecting the city to other towns and emirates. Additionally, several important intra-city routes, such as D 89 (Al Maktoum Road/Airport Road), D 85 (Baniyas Road), D 75 (Sheikh Rashid Road), D 73 (Al Dhiyafa Road now named as 2 December street), D 94 (Jumeirah Road) and D 92 (Al Khaleej/Al Wasl Road) connect the various localities in the city. The eastern and western sections of the city are connected by Al Maktoum Bridge, Al Garhoud Bridge, Al Shindagha Tunnel, Business Bay Crossing and Floating Bridge.[231]

The Public Bus Transport system in Dubai is run by the RTA. The bus system services 140 routes and transported over 109 million people in 2008. By the end of 2010, there will be 2,100 buses in service across the city.[232] In 2006, the Transport authority announced the construction of 500 air-conditioned (A/C) Passenger Bus Shelters, and planned for 1,000 more across the emirates in a move to encourage the use of public buses.[233]

All taxi services are licensed by the RTA. Dubai licensed taxis are easily identifiable by their cream bodywork colour and varied roof colours identifying the operator. Dubai Taxi Corporation, a division of the RTA, is the largest operator and has taxis with red roofs. There are five private operators: Metro Taxis (orange roofs); Network Taxis (yellow roofs); Cars Taxis (blue roofs); Arabia Taxis (green roofs); and City Taxis (purple roof). In addition, there is a Ladies and Families taxi service (pink roofs) with female drivers, which caters exclusively for women and children. There are more than 3000 taxis operating within the emirate making an average of 192,000 trips every day, carrying about 385,000 persons. In 2009 taxi trips exceeded 70 million trips serving around 140.45 million passengers.[234][235][236]

Air[edit]

Dubai International Airport (IATA: DXB), the hub for Emirates, serves the city of Dubai and other emirates in the country. The airport is the third-busiest airport in the world by passenger traffic and the world’s busiest airport by international passenger traffic.[237] In addition to being an important passenger traffic hub, the airport is the sixth-busiest cargo airport in world, handling 2.37 million tons of cargo in 2014.[238] Emirates is the national airline of Dubai. As of 2018, it operated internationally serving over 150 destinations in over 70 countries across six continents.[239]

The development of Al Maktoum International Airport (IATA: DWC) was announced in 2004. The first phase of the airport, featuring one A380 capable runway, 64 remote stands, one cargo terminal with an annual capacity for 250,000 tonnes of cargo, and a passenger terminal building designed to accommodate five million passengers per year, has been opened.[240] When completed, Dubai World Central-Al Maktoum International will be the largest airport in the world with five runways, four terminal buildings and capacity for 160 million passengers and 12 million tons of cargo.[241]

Metro rail[edit]

Dubai Metro consists of two lines (Red line and Green line) which run through the financial and residential areas of the city. It was opened in September 2009.[242] UK-based international service company Serco is responsible for operating the metro.

The Red Line as of 2020, which has 29 stations (4 underground, 24 elevated and 1 at ground level) running from Rashidiya Station to UAE Xchange Station in Jebel Ali, is the major backbone line. The Green Line, running from the Etisalat Station to the Creek Station, has 20 stations (8 underground, 12 elevated). An extension to the Red Line connecting the EXPO 2020 site opened on June 1, 2021. A Blue and a Purple Line have also been planned. The Dubai Metro is the first urban train network in the Arabian Peninsula.[223] The trains are fully automated and driverless.[243]

Palm Jumeirah Monorail[edit]

A monorail line connecting the Palm Jumeirah to the mainland opened on 30 April 2009.[244] It is the first monorail in the Middle East.[245] An extension to connect to the Red Line of the Dubai Metro is planned.[246]

Tram[edit]

A tramway located in Al Sufouh, will run for 14.5 km (9.0 mi) along Al Sufouh Road from Dubai Marina to the Burj Al Arab and the Mall of the Emirates with two interchanges with Dubai Metro’s Red Line. The first section, a 10.6 km (6.6 mi) long tram line which serves 11 stations, was opened in 2014.[247]

High-speed rail[edit]

Dubai has announced it will complete a link of the UAE high-speed rail system which is planned to link with the whole GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council, also known as Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf) and then possibly Europe.[citation needed] The High-Speed Rail will serve passengers and cargo.[248]

Waterways[edit]

There are two major commercial ports in Dubai, Port Rashid and Port Jebel Ali. Port Jebel Ali is the world’s largest man-made harbour, the biggest port in the Middle East,[249] and the 7th-busiest port in the world.[149] One of the more traditional methods of getting across Bur Dubai to Deira is by abras, small boats that ferry passengers across the Dubai Creek, between abra stations in Bastakiya and Baniyas Road.[250] The Marine Transport Agency has also implemented the Dubai Water Bus System. Water bus is a fully air conditioned boat service across selected destinations across the creek. One can also avail oneself of the tourist water bus facility in Dubai. Latest addition to the water transport system is the Water Taxi.[251]

Dubai is increasingly activating its logistics and ports in order to participate in trade between Europe and China or Africa in addition to oil transport. For this purpose, ports such as Port of Jebel Ali or Mina Rashid are rapidly expanded and investments are made in their technology. The country is historically and currently, part of the Maritime Silk Road that runs from the Chinese coast to the south via the southern tip of India to Mombasa, from there through the Red Sea via the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean, there to the Upper Adriatic region to the northern Italian hub of Trieste with its rail connections to Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the North Sea.[252][253][254]

Culture[edit]

The UAE culture mainly revolves around traditional Arab culture. The influence of Arab and Islamic culture on its architecture, music, attire, cuisine, and lifestyle is very prominent as well. Five times every day, Muslims are called to prayer from the minarets of mosques that are scattered around the country. Since 2006, the weekend has been Friday and Saturday, as a compromise between Friday’s holiness to Muslims and the Western weekend of Saturday and Sunday.[255] Prior to 2006, the weekend was Thursday-Friday.

Because of the touristic approach of many Dubaites in the entrepreneurial sector and the high standard of living, Dubai’s culture has gradually evolved towards one of luxury, opulence, and lavishness with a high regard for leisure-related extravagance.[256][257][258] Annual entertainment events such as the Dubai Shopping Festival[259] (DSF) and Dubai Summer Surprises (DSS) attract over 4 million visitors from across the region and generate revenues in excess of $2.7 billion.[260][261]

Meydan Beach Club, Jumeirah

Dubai is known for its nightlife. Clubs and bars are found mostly in hotels because of liquor laws. The New York Times described Dubai as «the kind of city where you might run into Michael Jordan at the Buddha Bar or stumble across Naomi Campbell celebrating her birthday with a multiday bash».[262]

The city’s cultural imprint as a small, ethnically homogeneous pearling community was changed with the arrival of other ethnic groups and nationals—first by the Iranians in the early 1900s, and later by Indians and Pakistanis in the 1960s. In 2005, 84% of the population of metropolitan Dubai was foreign-born, about half of them from India.[123]

Major holidays in Dubai include Eid al Fitr, which marks the end of Ramadan, and National Day (2 December), which marks the formation of the United Arab Emirates.[263]

The International Festivals and Events Association (IFEA), the world’s leading events trade association, has crowned Dubai as IFEA World Festival and Event City, 2012 in the cities category with a population of more than one million.[264][265] Large shopping malls in the city, such as Deira City Centre, Mirdiff City Centre, BurJuman, Mall of the Emirates, Dubai Mall (the world’s largest), Dubai Marina Mall, Dubai Hills Mall, Dragon Mart (Dubai), Dubai Festival City Mall and Ibn Battuta Mall as well as traditional Dubai Gold Souk, Al Souk Al Kabir (known as Meena Bazaar) and other souks attract shoppers from the region.[266]

Cuisine[edit]

Arabic cuisine is very popular and is available everywhere in the city, from the small shawarma diners in Deira and Al Karama to the restaurants in Dubai’s hotels. Fast food, South Asian, and Chinese cuisines are also very popular and are widely available. The sale and consumption of pork is regulated and is sold only to non-Muslims, in designated areas of supermarkets and airports.[267] Similarly, the sale of alcoholic beverages is regulated. A liquor permit is required to purchase alcohol; however, alcohol is available in bars and restaurants within hotels.[268] Shisha and qahwa boutiques are also popular in Dubai. Biryani is also a popular cuisine across Dubai with being the most popular among Indians and Pakistanis present in Dubai.[269]

The inaugural Dubai Food Festival was held between 21 February to 15 March 2014.[270] According to Vision magazine, the event was aimed at enhancing and celebrating Dubai’s position as the gastronomic capital of the region. The festival was designed to showcase the variety of flavours and cuisines on offer in Dubai featuring the cuisines of over 200 nationalities at the festival.[271] The next food festival was held between 23 February 2017 to 11 March 2017.[272]

Entertainment[edit]

Dubai Opera opened its door on 31 August 2016 in Downtown Dubai with a performance by Plácido Domingo. The venue is a 2000-seat, multifunctional performing arts centre able to host not only theatrical shows, concerts and operas, but also weddings, gala dinners, banquets and conferences.

Arabic movies are popular in Dubai and the UAE. Since 2004, the city has hosted the annual Dubai International Film Festival which serves as a showcase for Arab and Middle Eastern film making talent.[273] The Dubai Desert Rock Festival was also another major festival consisting of heavy metal and rock artists but is no longer held in Dubai.

One of the lesser-known sides of Dubai is the importance of its young contemporary art gallery scene. Since 2008, the leading contemporary art galleries such as Carbon 12 Dubai,[274] Green Art, gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, and The Third Line have brought the city onto the international art map. Art Dubai, the growing and reputable art fair of the region is as well a major contributor of the contemporary art scene’s development.[275] The Theatre of Digital Art Dubai (ToDA) opened in 2020 and presents immersive digital art, including contemporary work.[276]

Media[edit]

Many international news agencies such as Reuters, APTN, Bloomberg L.P. and Middle East Broadcasting Center (MBC) operate in Dubai Media City and Dubai Internet City. Additionally, several local network television channels such as Dubai One (formerly Channel 33), and Dubai TV (EDTV) provide programming in English and Arabic respectively. Dubai is also the headquarters for several print media outlets. Dar Al Khaleej, Al Bayan and Al Ittihad are the city’s largest circulating Arabic language newspapers,[277] while Gulf News, Khaleej Times, Khaleej Mag and 7days are the largest circulating English newspapers.[278]

Etisalat, the government-owned telecommunications provider, held a virtual monopoly over telecommunication services in Dubai prior to the establishment of other, smaller telecommunications companies such as Emirates Integrated Telecommunications Company (EITC—better known as Du) in 2006. Internet was introduced into the UAE (and therefore Dubai) in 1995. The network has an Internet bandwidth of 7.5 Gbit/s with capacity of 49 STM1 links.[279] Dubai houses two of four Domain Name System (DNS) data centres in the country (DXBNIC1, DXBNIC2).[280] Censorship is common in Dubai and used by the government to control content that it believes violates the cultural and political sensitivities of Emirates.[281] Homosexuality, drugs, and the theory of evolution are generally considered taboo.[268][282]

Internet content is regulated in Dubai. Etisalat uses a proxy server to filter Internet content that the government deems to be inconsistent with the values of the country, such as sites that provide information on how to bypass the proxy; sites pertaining to dating, gay and lesbian networks, and pornography; and previously, sites originating from Israel.[283] Emirates Media and Internet (a division of Etisalat) notes that as of 2002, 76% of Internet users are male. About 60% of Internet users were Asian, while 25% of users were Arab. Dubai enacted an Electronic Transactions and Commerce Law in 2002 which deals with digital signatures and electronic registers. It prohibits Internet Service Providers (ISPs) from disclosing information gathered in providing services.[284] The penal code contains official provisions that prohibit digital access to pornography; however, it does not address cyber crime or data protection.[285]

Sports[edit]

Football and cricket are the most popular sports in Dubai. Headquarters of International Cricket Council is in Dubai. Three football teams (Al Wasl FC, Shabab Al-Ahli Dubai FC and Al Nasr SC) represent Dubai in UAE Pro-League.[268] Al-Wasl have the second-most championships in the UAE League, after Al Ain. Dubai also hosts both the annual Dubai Tennis Championships and The Legends Rock Dubai tennis tournaments, as well as the Dubai Desert Classic golf tournament and the DP World Tour Championship, all of which attract sports stars from around the world. The Dubai World Cup, a thoroughbred horse race, is held annually at the Meydan Racecourse. The city’s top basketball team has traditionally been Shabab Al Ahli Basket. Dubai also hosts the traditional rugby union tournament Dubai Sevens, part of the Sevens World Series Event pictures of Rugby 7 Dubai 2015. In 2009, Dubai hosted the 2009 Rugby World Cup Sevens. Auto racing is also a big sport in Dubai, the Dubai Autodrome is home to many auto racing events throughout the year. It also features a state-of-the-art indoor and outdoor Kartdrome, popular among racing enthusiasts and recreational riders. The Indian Premier League cricket competition was held in UAE in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dress code[edit]

The Emirati attire is typical of several countries in the Arabian Peninsula. Women usually wear the «abaya», a long black robe with a hijab (the head-scarf which covers the neck and part of the head-all of the hair and ears). Some women may add a niqab which cover the mouth and nose and only leaves the eyes exposed. Men wear the «kandurah» also referred to as «dishdasha» or even «thawb» (long white robe) and the headscarf (ghotrah). The UAE traditional ghutrah is white and is held in place by an accessory called «egal», which resembles a black cord. The younger Emiratis prefer to wear red and white ghutrah and tie it around their head like a turban.[286]

The above dress code is never compulsory and many people wear western or other eastern clothing without any problems, but prohibitions on wearing «indecent clothing» or revealing too much skin are aspects of the UAE to which Dubai’s visitors are expected to conform, and are encoded in Dubai’s criminal law.[287] The UAE has enforced decency regulations in most public places, aside from waterparks, beaches, clubs, and bars.[288]

Education[edit]