Сегодня каждый из нас не представляет жизнь без компьютера. Компьютер — это устройство, которое может работать с разными видами данных (текстовыми, графическими, звуковыми). Чтобы эти данные компьютер мог сохранить, обработать, передать, они должны быть представлены в цифровом виде. Данные в компьютере хранятся, обрабатываются, передаются в двоичном коде.

Двоичный код — это строка символов, состоящих из (0) и (1).

Как и каждый язык (формальный или естественный), двоичный код имеет свой алфавит и мощность алфавита.

Алфавит, который состоит из двух символов, называется двоичным алфавитом.

Мощность алфавита — это количество символов, которые в него входят.

Запись информации с помощью двоичного алфавита называют двоичным кодированием.

Почему именно (0) и (1)? Потому что в технике проще всего реализовать такие наборы цифр: если есть сигнал, то это (1), если нет — это (0).

Двоичная система кодирования появилась не с созданием компьютера, ещё задолго до этого математик Г. В. Лейбниц использовал двоичные числа.

Рис. (1). Портрет Г. В. Лейбница

В своей бинарной (двоичной) арифметике Лейбниц видел прообраз творения. Ему представлялось, что единица представляет божественное начало, а нуль — небытие, и что Высшее Существо создаёт все сущее из небытия точно таким же образом, как единица и нуль в его системе выражают все числа.

Существуют ряд устройств, работающих по принципу двоичного кодирования. Например, обычный выключатель, где свет горит/не горит.

Всем известная азбука Морзе тоже состоит из двух знаков: точки и тире.

Рис. (2). Алфавит азбуки Морзе

Память компьютера можно представить в виде листочка в клетку, и в каждой клетке хранится либо (1), либо (0).

Рис. (3). Представление битов памяти

Что же происходит, когда мы нажимаем на клавиатуре цифру, например (5)?

Каждая клавиша имеет свой порядковый номер (по кодировочной таблице), и именно он переводится в двоичный код.

Рис. (4). Схема двоичного кодирования

Как узнать, сколько бит (клеточек) в памяти компьютера необходимо для кодирования различных знаков?

Как кодируются числа при помощи двоичного кодирования?

Пусть нам нужно закодировать две цифры — (0) и (1). Для кодирования этих цифр нужно (2) ячейки памяти, в одну напишем (0), а в другую — (1).

А если цифр больше? Сколько битов нужно для кодирования каждой цифры? Рассмотрим, как закодировать (4) цифры.

Если будем использовать однозначные числа, то хватит только для кодирования (2) цифр, а нам нужно больше. Попробуем сделать коды двузначными:

(0) — (00),

(1) — (01),

(2) — (10),

(3) — (11).

Цепочка из двух символов достаточна для кодирования (4) знаков, а если нужно закодировать (8) знаков? Попробуем увеличить длину цепочки:

(0) — (000),

(1) — (001),

(2) — (010),

(3) — (011),

(4) — (100),

(5) — (101),

(6) — (110),

(7) — (111).

Получается, если цифр будет (16), то длина цепочки будет (4)?

Длина цепочки знаков в двоичном коде называется разрядностью двоичного кода.

Рассмотри таблицу.

| Разрядность двоичного кода |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

|

Количество цифр (комбинаций), которые можно закодировать |

(2) |

(4) |

(8) |

(16) |

(32) |

(64) |

(128) |

(256) |

(512) |

(1024) |

Проанализировав таблицу, можно увидеть зависимость между разрядностью и количеством цифр.

Чтобы получить коды для (2) цифр, нужно взять цепочку из (1) знака, чтобы получить (4) цифры, нужно взять цепочку из (2) знаков, чтобы получить (8) цифр, нужно взять цепочку из (3) знаков и т. д.

(2 = 2);

(4 = 2·2);

(8 = 2·2·2);

(16 = 2·2·2·2);

(32 = 2·2·2·2·2).

Из математики ты знаешь, что степень показывает количество множителей числа на само себя.

Если обозначить количество цифр (комбинаций) через (N), а степень — через (i), получим формулу:

N=2i

.

Задача (1). Определи, сколько нужно знаков для кодирования (11) цифр?

Решение: посмотри в таблицу.

Число (8<11<16), значит, цепочка из (3) символов нам не подходит, а вот цепочки из (4) символов нам достаточно.

Проверим:

(0) — (0000), (1) — (0001), (2) — (0010), (3) — (0011), (4) — (0100), (5) — (0101), (6) — (0110), (7) — (0111), (8) — (1000), (9) — (1001), (10) — (1010), (11) — (1011).

Задача (2). Определи, сколько можно составить различных последовательностей, если длина цепочки (6) символов?

Решение: для решения воспользуемся таблицей.

Если длина цепочки (разрядность двоичного кода) равна (6), следовательно, можно закодировать (64) различные последовательности.

Источники:

Цитата с сайта https://www.livelib.ru/quote/1343718-chto-takoe-matematika-kurant-r-robbins-g (Дата обращения: 14.11.2021.)

Рис. 1. Портрет Г. В.Лейбница By Christoph Bernhard Francke — Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum Braunschweig, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57268659 (Дата обращения: 14.11.2021.)

Рис. 2. Алфавит азбуки Морзе. © ЯКласс.

Рис. 3. Представление битов памяти. © ЯКласс.

Рис. 4. Схема двоичного кодирования. © ЯКласс.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the binary form of computer software, see Machine code.

The word ‘Wikipedia’ represented in ASCII binary code, made up of 9 bytes (72 bits).

A binary code represents text, computer processor instructions, or any other data using a two-symbol system. The two-symbol system used is often «0» and «1» from the binary number system. The binary code assigns a pattern of binary digits, also known as bits, to each character, instruction, etc. For example, a binary string of eight bits (which is also called a byte) can represent any of 256 possible values and can, therefore, represent a wide variety of different items.

In computing and telecommunications, binary codes are used for various methods of encoding data, such as character strings, into bit strings. Those methods may use fixed-width or variable-width strings. In a fixed-width binary code, each letter, digit, or other character is represented by a bit string of the same length; that bit string, interpreted as a binary number, is usually displayed in code tables in octal, decimal or hexadecimal notation. There are many character sets and many character encodings for them.

A bit string, interpreted as a binary number, can be translated into a decimal number. For example, the lower case a, if represented by the bit string 01100001 (as it is in the standard ASCII code), can also be represented as the decimal number «97».

History of binary codes[edit]

The modern binary number system, the basis for binary code, was invented by Gottfried Leibniz in 1689 and appears in his article Explication de l’Arithmétique Binaire. The full title is translated into English as the «Explanation of the binary arithmetic», which uses only the characters 1 and 0, with some remarks on its usefulness, and on the light it throws on the ancient Chinese figures of Fu Xi.[1] Leibniz’s system uses 0 and 1, like the modern binary numeral system. Leibniz encountered the I Ching through French Jesuit Joachim Bouvet and noted with fascination how its hexagrams correspond to the binary numbers from 0 to 111111, and concluded that this mapping was evidence of major Chinese accomplishments in the sort of philosophical visual binary mathematics he admired.[2][3] Leibniz saw the hexagrams as an affirmation of the universality of his own religious belief.[3]

Binary numerals were central to Leibniz’s theology. He believed that binary numbers were symbolic of the Christian idea of creatio ex nihilo or creation out of nothing.[4] Leibniz was trying to find a system that converts logic verbal statements into a pure mathematical one[citation needed]. After his ideas were ignored, he came across a classic Chinese text called I Ching or ‘Book of Changes’, which used 64 hexagrams of six-bit visual binary code. The book had confirmed his theory that life could be simplified or reduced down to a series of straightforward propositions. He created a system consisting of rows of zeros and ones. During this time period, Leibniz had not yet found a use for this system.[5]

Binary systems predating Leibniz also existed in the ancient world. The aforementioned I Ching that Leibniz encountered dates from the 9th century BC in China.[6] The binary system of the I Ching, a text for divination, is based on the duality of yin and yang.[7] Slit drums with binary tones are used to encode messages across Africa and Asia.[7] The Indian scholar Pingala (around 5th–2nd centuries BC) developed a binary system for describing prosody in his Chandashutram.[8][9]

The residents of the island of Mangareva in French Polynesia were using a hybrid binary-decimal system before 1450.[10] In the 11th century, scholar and philosopher Shao Yong developed a method for arranging the hexagrams which corresponds, albeit unintentionally, to the sequence 0 to 63, as represented in binary, with yin as 0, yang as 1 and the least significant bit on top. The ordering is also the lexicographical order on sextuples of elements chosen from a two-element set.[11]

In 1605 Francis Bacon discussed a system whereby letters of the alphabet could be reduced to sequences of binary digits, which could then be encoded as scarcely visible variations in the font in any random text.[12] Importantly for the general theory of binary encoding, he added that this method could be used with any objects at all: «provided those objects be capable of a twofold difference only; as by Bells, by Trumpets, by Lights and Torches, by the report of Muskets, and any instruments of like nature».[12]

George Boole published a paper in 1847 called ‘The Mathematical Analysis of Logic’ that describes an algebraic system of logic, now known as Boolean algebra. Boole’s system was based on binary, a yes-no, on-off approach that consisted of the three most basic operations: AND, OR, and NOT.[13] This system was not put into use until a graduate student from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Claude Shannon, noticed that the Boolean algebra he learned was similar to an electric circuit. In 1937, Shannon wrote his master’s thesis, A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits, which implemented his findings. Shannon’s thesis became a starting point for the use of the binary code in practical applications such as computers, electric circuits, and more.[14]

Other forms of binary code[edit]

The bit string is not the only type of binary code: in fact, a binary system in general, is any system that allows only two choices such as a switch in an electronic system or a simple true or false test.

Braille[edit]

Braille is a type of binary code that is widely used by the blind to read and write by touch, named for its creator, Louis Braille. This system consists of grids of six dots each, three per column, in which each dot has two states: raised or not raised. The different combinations of raised and flattened dots are capable of representing all letters, numbers, and punctuation signs.

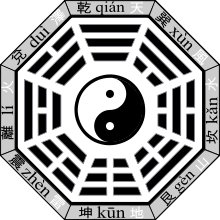

Bagua [edit]

The bagua are diagrams used in feng shui, Taoist cosmology and I Ching studies. The ba gua consists of 8 trigrams; bā meaning 8 and guà meaning divination figure. The same word is used for the 64 guà (hexagrams). Each figure combines three lines (yáo) that are either broken (yin) or unbroken (yang). The relationships between the trigrams are represented in two arrangements, the primordial, «Earlier Heaven» or «Fuxi» bagua, and the manifested, «Later Heaven,»or «King Wen» bagua.[15] (See also, the King Wen sequence of the 64 hexagrams).

Ifá, Ilm Al-Raml and Geomancy[edit]

The Ifá/Ifé system of divination in African religions, such as of Yoruba, Igbo, and Ewe, consists of an elaborate traditional ceremony producing 256 oracles made up by 16 symbols with 256 = 16 x 16. An initiated priest, or Babalawo, who had memorized oracles, would request sacrifice from consulting clients and make prayers. Then, divination nuts or a pair of chains are used to produce random binary numbers,[16] which are drawn with sandy material on an «Opun» figured wooden tray representing the totality of fate.

Through the spread of Islamic culture, Ifé/Ifá was assimilated as the «Science of Sand» (ilm al-raml), which then spread further and became «Science of Reading the Signs on the Ground» (Geomancy) in Europe.

This was thought to be another possible route from which computer science was inspired,[17] as Geomancy arrived at Europe at an earlier stage (about 12th Century, described by Hugh of Santalla) than I Ching (17th Century, described by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz).

Coding systems[edit]

ASCII code[edit]

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII), uses a 7-bit binary code to represent text and other characters within computers, communications equipment, and other devices. Each letter or symbol is assigned a number from 0 to 127. For example, lowercase «a» is represented by 1100001 as a bit string (which is «97» in decimal).

Binary-coded decimal[edit]

Binary-coded decimal (BCD) is a binary encoded representation of integer values that uses a 4-bit nibble to encode decimal digits. Four binary bits can encode up to 16 distinct values; but, in BCD-encoded numbers, only ten values in each nibble are legal, and encode the decimal digits zero, through nine. The remaining six values are illegal and may cause either a machine exception or unspecified behavior, depending on the computer implementation of BCD arithmetic.

BCD arithmetic is sometimes preferred to floating-point numeric formats in commercial and financial applications where the complex rounding behaviors of floating-point numbers is inappropriate.[18]

Early uses of binary codes[edit]

- 1875: Émile Baudot «Addition of binary strings in his ciphering system,» which, eventually, led to the ASCII of today.

- 1884: The Linotype machine where the matrices are sorted to their corresponding channels after use by a binary-coded slide rail.

- 1932: C. E. Wynn-Williams «Scale of Two» counter[19]

- 1937: Alan Turing electro-mechanical binary multiplier

- 1937: George Stibitz «excess three» code in the Complex Computer[19]

- 1937: Atanasoff–Berry Computer[19]

- 1938: Konrad Zuse Z1

Current uses of binary[edit]

Most modern computers use binary encoding for instructions and data. CDs, DVDs, and Blu-ray Discs represent sound and video digitally in binary form. Telephone calls are carried digitally on long-distance and mobile phone networks using pulse-code modulation, and on voice over IP networks.

Weight of binary codes[edit]

The weight of a binary code, as defined in the table of constant-weight codes,[20] is the Hamming weight of the binary words coding for the represented words or sequences.

See also[edit]

- Binary number

- List of binary codes

- Binary file

- Unicode

- Gray code

References[edit]

- ^ Leibniz G., Explication de l’Arithmétique Binaire, Die Mathematische Schriften, ed. C. Gerhardt, Berlin 1879, vol.7, p.223; Engl. transl.[1]

- ^ Aiton, Eric J. (1985). Leibniz: A Biography. Taylor & Francis. pp. 245–8. ISBN 978-0-85274-470-3.

- ^ a b J.E.H. Smith (2008). Leibniz: What Kind of Rationalist?: What Kind of Rationalist?. Springer. p. 415. ISBN 978-1-4020-8668-7.

- ^ Yuen-Ting Lai (1998). Leibniz, Mysticism and Religion. Springer. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-7923-5223-5.

- ^ «Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646 — 1716)». www.kerryr.net.

- ^ Edward Hacker; Steve Moore; Lorraine Patsco (2002). I Ching: An Annotated Bibliography. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-415-93969-0.

- ^ a b Jonathan Shectman (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 18th Century. Greenwood Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-313-32015-6.

- ^ Sanchez, Julio; Canton, Maria P. (2007). Microcontroller programming: the microchip PIC. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8493-7189-9.

- ^ W. S. Anglin and J. Lambek, The Heritage of Thales, Springer, 1995, ISBN 0-387-94544-X

- ^ Bender, Andrea; Beller, Sieghard (16 December 2013). «Mangarevan invention of binary steps for easier calculation». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (4): 1322–1327. doi:10.1073/pnas.1309160110. PMC 3910603. PMID 24344278.

- ^ Ryan, James A. (January 1996). «Leibniz’ Binary System and Shao Yong’s «Yijing»«. Philosophy East and West. 46 (1): 59–90. doi:10.2307/1399337. JSTOR 1399337.

- ^ a b Bacon, Francis (1605). «The Advancement of Learning». London. pp. Chapter 1.

- ^ «What’s So Logical About Boolean Algebra?». www.kerryr.net.

- ^ «Claude Shannon (1916 — 2001)». www.kerryr.net.

- ^ Wilhelm, Richard (1950). The I Ching or Book of Changes. trans. by Cary F. Baynes, foreword by C. G. Jung, preface to 3rd ed. by Hellmut Wilhelm (1967). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 266, 269. ISBN 978-0-691-09750-3.

- ^ Olupona, Jacob K. (2014). African Religions: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-19-979058-6. OCLC 839396781.

- ^ Eglash, Ron (June 2007). «The fractals at the heart of African designs». www.ted.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-27. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ^ Cowlishaw, Mike F. (2015) [1981,2008]. «General Decimal Arithmetic». IBM. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ^ a b c Glaser 1971

- ^ Table of Constant Weight Binary Codes

External links[edit]

- Sir Francis Bacon’s BiLiteral Cypher system, predates binary number system.

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Error-Correcting Code». MathWorld.

- Table of general binary codes. An updated version of the tables of bounds for small general binary codes given in M.R. Best; A.E. Brouwer; F.J. MacWilliams; A.M. Odlyzko; N.J.A. Sloane (1978), «Bounds for Binary Codes of Length Less than 25», IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, 24: 81–93, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.391.9930, doi:10.1109/tit.1978.1055827.

- Table of Nonlinear Binary Codes. Maintained by Simon Litsyn, E. M. Rains, and N. J. A. Sloane. Updated until 1999.

- Glaser, Anton (1971). «Chapter VII Applications to Computers». History of Binary and other Nondecimal Numeration. Tomash. ISBN 978-0-938228-00-4. cites some pre-ENIAC milestones.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the binary form of computer software, see Machine code.

The word ‘Wikipedia’ represented in ASCII binary code, made up of 9 bytes (72 bits).

A binary code represents text, computer processor instructions, or any other data using a two-symbol system. The two-symbol system used is often «0» and «1» from the binary number system. The binary code assigns a pattern of binary digits, also known as bits, to each character, instruction, etc. For example, a binary string of eight bits (which is also called a byte) can represent any of 256 possible values and can, therefore, represent a wide variety of different items.

In computing and telecommunications, binary codes are used for various methods of encoding data, such as character strings, into bit strings. Those methods may use fixed-width or variable-width strings. In a fixed-width binary code, each letter, digit, or other character is represented by a bit string of the same length; that bit string, interpreted as a binary number, is usually displayed in code tables in octal, decimal or hexadecimal notation. There are many character sets and many character encodings for them.

A bit string, interpreted as a binary number, can be translated into a decimal number. For example, the lower case a, if represented by the bit string 01100001 (as it is in the standard ASCII code), can also be represented as the decimal number «97».

History of binary codes[edit]

The modern binary number system, the basis for binary code, was invented by Gottfried Leibniz in 1689 and appears in his article Explication de l’Arithmétique Binaire. The full title is translated into English as the «Explanation of the binary arithmetic», which uses only the characters 1 and 0, with some remarks on its usefulness, and on the light it throws on the ancient Chinese figures of Fu Xi.[1] Leibniz’s system uses 0 and 1, like the modern binary numeral system. Leibniz encountered the I Ching through French Jesuit Joachim Bouvet and noted with fascination how its hexagrams correspond to the binary numbers from 0 to 111111, and concluded that this mapping was evidence of major Chinese accomplishments in the sort of philosophical visual binary mathematics he admired.[2][3] Leibniz saw the hexagrams as an affirmation of the universality of his own religious belief.[3]

Binary numerals were central to Leibniz’s theology. He believed that binary numbers were symbolic of the Christian idea of creatio ex nihilo or creation out of nothing.[4] Leibniz was trying to find a system that converts logic verbal statements into a pure mathematical one[citation needed]. After his ideas were ignored, he came across a classic Chinese text called I Ching or ‘Book of Changes’, which used 64 hexagrams of six-bit visual binary code. The book had confirmed his theory that life could be simplified or reduced down to a series of straightforward propositions. He created a system consisting of rows of zeros and ones. During this time period, Leibniz had not yet found a use for this system.[5]

Binary systems predating Leibniz also existed in the ancient world. The aforementioned I Ching that Leibniz encountered dates from the 9th century BC in China.[6] The binary system of the I Ching, a text for divination, is based on the duality of yin and yang.[7] Slit drums with binary tones are used to encode messages across Africa and Asia.[7] The Indian scholar Pingala (around 5th–2nd centuries BC) developed a binary system for describing prosody in his Chandashutram.[8][9]

The residents of the island of Mangareva in French Polynesia were using a hybrid binary-decimal system before 1450.[10] In the 11th century, scholar and philosopher Shao Yong developed a method for arranging the hexagrams which corresponds, albeit unintentionally, to the sequence 0 to 63, as represented in binary, with yin as 0, yang as 1 and the least significant bit on top. The ordering is also the lexicographical order on sextuples of elements chosen from a two-element set.[11]

In 1605 Francis Bacon discussed a system whereby letters of the alphabet could be reduced to sequences of binary digits, which could then be encoded as scarcely visible variations in the font in any random text.[12] Importantly for the general theory of binary encoding, he added that this method could be used with any objects at all: «provided those objects be capable of a twofold difference only; as by Bells, by Trumpets, by Lights and Torches, by the report of Muskets, and any instruments of like nature».[12]

George Boole published a paper in 1847 called ‘The Mathematical Analysis of Logic’ that describes an algebraic system of logic, now known as Boolean algebra. Boole’s system was based on binary, a yes-no, on-off approach that consisted of the three most basic operations: AND, OR, and NOT.[13] This system was not put into use until a graduate student from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Claude Shannon, noticed that the Boolean algebra he learned was similar to an electric circuit. In 1937, Shannon wrote his master’s thesis, A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits, which implemented his findings. Shannon’s thesis became a starting point for the use of the binary code in practical applications such as computers, electric circuits, and more.[14]

Other forms of binary code[edit]

The bit string is not the only type of binary code: in fact, a binary system in general, is any system that allows only two choices such as a switch in an electronic system or a simple true or false test.

Braille[edit]

Braille is a type of binary code that is widely used by the blind to read and write by touch, named for its creator, Louis Braille. This system consists of grids of six dots each, three per column, in which each dot has two states: raised or not raised. The different combinations of raised and flattened dots are capable of representing all letters, numbers, and punctuation signs.

Bagua [edit]

The bagua are diagrams used in feng shui, Taoist cosmology and I Ching studies. The ba gua consists of 8 trigrams; bā meaning 8 and guà meaning divination figure. The same word is used for the 64 guà (hexagrams). Each figure combines three lines (yáo) that are either broken (yin) or unbroken (yang). The relationships between the trigrams are represented in two arrangements, the primordial, «Earlier Heaven» or «Fuxi» bagua, and the manifested, «Later Heaven,»or «King Wen» bagua.[15] (See also, the King Wen sequence of the 64 hexagrams).

Ifá, Ilm Al-Raml and Geomancy[edit]

The Ifá/Ifé system of divination in African religions, such as of Yoruba, Igbo, and Ewe, consists of an elaborate traditional ceremony producing 256 oracles made up by 16 symbols with 256 = 16 x 16. An initiated priest, or Babalawo, who had memorized oracles, would request sacrifice from consulting clients and make prayers. Then, divination nuts or a pair of chains are used to produce random binary numbers,[16] which are drawn with sandy material on an «Opun» figured wooden tray representing the totality of fate.

Through the spread of Islamic culture, Ifé/Ifá was assimilated as the «Science of Sand» (ilm al-raml), which then spread further and became «Science of Reading the Signs on the Ground» (Geomancy) in Europe.

This was thought to be another possible route from which computer science was inspired,[17] as Geomancy arrived at Europe at an earlier stage (about 12th Century, described by Hugh of Santalla) than I Ching (17th Century, described by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz).

Coding systems[edit]

ASCII code[edit]

The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII), uses a 7-bit binary code to represent text and other characters within computers, communications equipment, and other devices. Each letter or symbol is assigned a number from 0 to 127. For example, lowercase «a» is represented by 1100001 as a bit string (which is «97» in decimal).

Binary-coded decimal[edit]

Binary-coded decimal (BCD) is a binary encoded representation of integer values that uses a 4-bit nibble to encode decimal digits. Four binary bits can encode up to 16 distinct values; but, in BCD-encoded numbers, only ten values in each nibble are legal, and encode the decimal digits zero, through nine. The remaining six values are illegal and may cause either a machine exception or unspecified behavior, depending on the computer implementation of BCD arithmetic.

BCD arithmetic is sometimes preferred to floating-point numeric formats in commercial and financial applications where the complex rounding behaviors of floating-point numbers is inappropriate.[18]

Early uses of binary codes[edit]

- 1875: Émile Baudot «Addition of binary strings in his ciphering system,» which, eventually, led to the ASCII of today.

- 1884: The Linotype machine where the matrices are sorted to their corresponding channels after use by a binary-coded slide rail.

- 1932: C. E. Wynn-Williams «Scale of Two» counter[19]

- 1937: Alan Turing electro-mechanical binary multiplier

- 1937: George Stibitz «excess three» code in the Complex Computer[19]

- 1937: Atanasoff–Berry Computer[19]

- 1938: Konrad Zuse Z1

Current uses of binary[edit]

Most modern computers use binary encoding for instructions and data. CDs, DVDs, and Blu-ray Discs represent sound and video digitally in binary form. Telephone calls are carried digitally on long-distance and mobile phone networks using pulse-code modulation, and on voice over IP networks.

Weight of binary codes[edit]

The weight of a binary code, as defined in the table of constant-weight codes,[20] is the Hamming weight of the binary words coding for the represented words or sequences.

See also[edit]

- Binary number

- List of binary codes

- Binary file

- Unicode

- Gray code

References[edit]

- ^ Leibniz G., Explication de l’Arithmétique Binaire, Die Mathematische Schriften, ed. C. Gerhardt, Berlin 1879, vol.7, p.223; Engl. transl.[1]

- ^ Aiton, Eric J. (1985). Leibniz: A Biography. Taylor & Francis. pp. 245–8. ISBN 978-0-85274-470-3.

- ^ a b J.E.H. Smith (2008). Leibniz: What Kind of Rationalist?: What Kind of Rationalist?. Springer. p. 415. ISBN 978-1-4020-8668-7.

- ^ Yuen-Ting Lai (1998). Leibniz, Mysticism and Religion. Springer. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-7923-5223-5.

- ^ «Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646 — 1716)». www.kerryr.net.

- ^ Edward Hacker; Steve Moore; Lorraine Patsco (2002). I Ching: An Annotated Bibliography. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-415-93969-0.

- ^ a b Jonathan Shectman (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 18th Century. Greenwood Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-313-32015-6.

- ^ Sanchez, Julio; Canton, Maria P. (2007). Microcontroller programming: the microchip PIC. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8493-7189-9.

- ^ W. S. Anglin and J. Lambek, The Heritage of Thales, Springer, 1995, ISBN 0-387-94544-X

- ^ Bender, Andrea; Beller, Sieghard (16 December 2013). «Mangarevan invention of binary steps for easier calculation». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (4): 1322–1327. doi:10.1073/pnas.1309160110. PMC 3910603. PMID 24344278.

- ^ Ryan, James A. (January 1996). «Leibniz’ Binary System and Shao Yong’s «Yijing»«. Philosophy East and West. 46 (1): 59–90. doi:10.2307/1399337. JSTOR 1399337.

- ^ a b Bacon, Francis (1605). «The Advancement of Learning». London. pp. Chapter 1.

- ^ «What’s So Logical About Boolean Algebra?». www.kerryr.net.

- ^ «Claude Shannon (1916 — 2001)». www.kerryr.net.

- ^ Wilhelm, Richard (1950). The I Ching or Book of Changes. trans. by Cary F. Baynes, foreword by C. G. Jung, preface to 3rd ed. by Hellmut Wilhelm (1967). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 266, 269. ISBN 978-0-691-09750-3.

- ^ Olupona, Jacob K. (2014). African Religions: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-19-979058-6. OCLC 839396781.

- ^ Eglash, Ron (June 2007). «The fractals at the heart of African designs». www.ted.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-27. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ^ Cowlishaw, Mike F. (2015) [1981,2008]. «General Decimal Arithmetic». IBM. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ^ a b c Glaser 1971

- ^ Table of Constant Weight Binary Codes

External links[edit]

- Sir Francis Bacon’s BiLiteral Cypher system, predates binary number system.

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Error-Correcting Code». MathWorld.

- Table of general binary codes. An updated version of the tables of bounds for small general binary codes given in M.R. Best; A.E. Brouwer; F.J. MacWilliams; A.M. Odlyzko; N.J.A. Sloane (1978), «Bounds for Binary Codes of Length Less than 25», IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, 24: 81–93, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.391.9930, doi:10.1109/tit.1978.1055827.

- Table of Nonlinear Binary Codes. Maintained by Simon Litsyn, E. M. Rains, and N. J. A. Sloane. Updated until 1999.

- Glaser, Anton (1971). «Chapter VII Applications to Computers». History of Binary and other Nondecimal Numeration. Tomash. ISBN 978-0-938228-00-4. cites some pre-ENIAC milestones.

Перевод текста в двоичный код

На чтение 3 мин Опубликовано 02.03.2021

Обновлено 23.10.2022

Всем привет, сегодня поговорим про то, как осуществляется перевод текста в двоичный код. Благодаря этому вы узнаете, как в памяти компьютере записываются различные знаки и символы. Также на этой странице вы сможете осуществить перевод ваших слов в язык юникода.

Содержание статьи

- Конвертер для перевода в Unicode

- Основные определения

- ASCII

- Unicode

- Заключение

Конвертер для перевода в Unicode

Получить текст в Юникод

Введите ваш текст

Конвертация

Основные определения

В начале изучим основы, чтобы в дальнейшем всё было понятно. Здесь не будет ничего сложного, чтобы полностью разобраться в теме, надо знать всего два определения и иметь представление о том, как работать с числами в двоичной системе счисления. Итак, приступим.

Код (в информатике) – это взаимно однозначное отображение символов одного алфавита (цифр) с помощью другого, который удобен для хранения, отображения и передачи данных.

На первый взгляд понятие может показаться непонятным, однако, оно совсем простое. Так, например, буквы русского алфавита мы можем представить с помощью десятичных, двоичных или любых других чисел в различных системах исчисления. Также буквы или слова можно закодировать любыми знаками. Однако тут есть одно условие – должны существовать правила, чтобы переводить значения назад. Исходя из этого положения возникает другое:

Кодирование(в информатике) – это процесс преобразования информации в код.

Для отображения текста разработчиками были придуманы так называемые кодировки – таблицы, где символам одного алфавита сопоставляются определенные числовые или текстовые значения. На данный момент относительно широкую популярность имеют две из них – ASCII и Unicode (Юникод). Ниже предложена информация, для ознакомления.

ASCII

Таблица была разработана в Соединенных Штатах Америки в одна тысяча девятьсот шестьдесят третьем году. Изначально предназначалась для использования в телетайпах. Эти устройства представляли собой печатные машинки, с помощью которых передавались сообщения по электрическому каналу. Физическая модель канала была простейшей – если по нему шел ток, то это трактовали как 1, если тока не было, то 0.

Такой системой пользовались высокопоставленные политические деятели. Например, так передавались слова между руководствами двух сверхдержав – США и СССР. Изначально в этой кодировке использовалось 7 бит информации (можно было переводить 128 символов), однако потом их значение увеличили до 256 (8 бит – 1 байт). Небольшая табличка значений двоичных величин, которые помогут с переводом в АСКИ, представлена ниже.

Unicode

Более современная кодировка. Данный стандарт был предложен в Соединенных штатах в 1991 году. Стоит отметить, что его разработала некоммерческая фирма, которая называлась «Консорциум Юникода». Популярность свою стандарт получил из-за его большого символьного охвата – на данный момент с помощью него можно отобразить почти все знаки и буквы, которые используются на планете. Начиная от символов Римской нотации и заканчивая китайскими иероглифами. Символ в этой кодировке использует 1-4 байта машинной памяти. Числовые значения для перевода различных знаков в двузначный формат можно посмотреть здесь.

Заключение

Вот и все, теперь вы знаете про перевод текста в двоичный код в информатике, а также имеете представление о двух самых популярных кодировках, которые используются на данный момент. При возникновении вопросов можете написать их в комментариях.

Python программист. Увлекаюсь с детства компьютерами и созданием сайтов. Закончил НГТУ (Новосибирский Государственный Технический Университет ) по специальности «Инфокоммуникационные технологии и системы связи».

Онлайн конвертер для перевода текста в бинарный код и наоборот. Поможет выполнить кодирование двоичным кодом записав буквы, цифры и символы в бинарный код. Произведёт декодирование двоичного кода в слова, буквы, цифры и символы. Кодирование слов двоичным кодом. Зашифровка и расшифровка производится по стандартам кодировки таблиц ASCII или UTF-8 (Юникод) (UTF-16).

Будьте внимательны, если переводить символы в двоичную систему с помощью онлайн конвертеров, то первый нулевой ведущий бит может быть отброшен, что может сбить с толку. Наш конвертер избавлен от данного недостатка.

×

Пожалуйста напишите с чем связна такая низкая оценка:

×

Для установки калькулятора на iPhone — просто добавьте страницу

«На главный экран»

Для установки калькулятора на Android — просто добавьте страницу

«На главный экран»

Если у вас в школе была информатика, не исключено, что там было упражнение на перевод обычных чисел в двоичную систему и обратно. Маловероятно, что кто-то вам объяснял практический смысл этой процедуры и откуда вообще берётся двоичное счисление. Давайте закроем этот разрыв.

Эта статья не имеет практической ценности — читайте её просто ради интереса к окружающему миру. Если нужны практические статьи, заходите в наш раздел «Где-то баг», там каждая статья — это практически применимый проект.

Отличный план

Чтобы объяснить всё это, нам понадобится несколько тезисов:

- Система записи числа — это шифр.

- Мы привыкли шифровать десятью знаками.

- Но система записи чисел может быть любой. Это условность.

- Двоичная система — это тоже нормальная система.

- Всё тлен и суета.

Система записи — это шифр

Если у нас есть девять коров, мы можем записать их как 🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄 или как 9 × 🐄.

Почему 9 означает «девять»? И почему вообще есть такое слово? Почему такое количество мы называем этим словом? Вопрос философский, и короткий ответ — нам нужно одинаково называть числа, чтобы друг друга понимать. Слово «девять», цифра 9, а также остальные слова — это шифр, который мы выучили в школе, чтобы друг с другом общаться.

Допустим, к нашему стаду прибиваются еще 🐄🐄🐄. Теперь у нас 🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄 — двенадцать коров, 12. Почему мы знаем, что 12 — это «двенадцать»? Потому что мы договорились так шифровать числа.

Нам очень легко расшифровывать записи типа 12, 1920, 100 500 и т. д. — мы к ним привыкли, мы учили это в школе. Но это шифр. 12 × 🐄 — это не то же самое, что 🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄🐄. Это некая абстракция, которой мы пользуемся, чтобы упростить себе счёт.

Мы привыкли шифровать десятью знаками

У нас есть знаки 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 и 9 — всего десять знаков. Этим числом знаков мы шифруем количество единиц, десятков, сотен, тысяч и так далее.

Мы договорились, что нам важен порядок записи числа. Мы знаем, что самый правый знак в записи означает число единиц, следующий знак (влево) означает число десятков, потом сотен и далее.

Например, перед нами число 19 547. Мы знаем, что в нём есть:

1 × 10 000

9 × 1000

5 × 100

4 × 10

7 × 1

Если приглядеться, то каждый следующий разряд числа показывает следующую степень десятки:

1 × 104

9 × 103

5 × 102

4 × 101

7 × 100

Нам удобно считать степенями десятки, потому что у нас по десять пальцев и мы с раннего детства научились считать до десяти.

Система записи — это условность

Представим бредовую ситуацию: у нас не 10 пальцев, а 6. И в школе нас учили считать не десятками, а шестёрками. И вместо привычных цифр мы бы использовали знаки ØABCDE. Ø — это по-нашему ноль, A — 1, B — 2, E — 5.

Вот как выглядели бы привычные нам цифры в этой бредовой системе счисления:

| 0 — Ø 1 — A 2 — B 3 — C 4 — D 5 — E |

6 — AØ 7 — AA 8 — AB 9 — AC 10 — AD 11 — AE |

12 — BØ 13 — BA 14 — BB 15 — BC 16 — BD 17 — BE |

18 — CØ 19 — CA 20 — CB 21 — CC 22 — CD 23 — CE |

24 — DØ 25 — DA 26 — DB 27 — DC 28 — DD 29 — DE |

30 — EØ 31 — EA 32 — EB 33 — EC 34 — ED 35 — EE |

36 — AØØ 37 — AØA 38 — AØB 39 — AØC 40 — AØD 41 — AØE |

В этой системе мы считаем степенями шестёрки. Число ABADØ можно было бы перевести в привычную нам десятичную запись вот так:

A × 64 = 1 × 1296 = 1296

B × 63 = 2 × 216 = 432

A × 62 = 1 × 36 = 36

D × 61 = 4 × 6 = 24

Ø × 60 = 0 × 1 = 0

1296 + 432 + 36 + 24 + 0 = 1788. В нашей десятичной системе это 1788, а у людей из параллельной вселенной это ABADØ, и это равноценно.

Выглядит бредово, но попробуйте вообразить, что у нас в сумме всего шесть пальцев. Каждый столбик — как раз шесть чисел. Очень легко считать в уме. Если бы нас с детства учили считать шестёрками, мы бы спокойно выучили этот способ и без проблем всё считали. А счёт десятками вызывал бы у нас искреннее недоумение: «Что за бред, считать числом AD? Гораздо удобнее считать от Ø до E!»

То, как мы шифруем и записываем числа, — это следствие многовековой традиции и физиологии. Вселенной, космосу, природе и стадам коров глубоко безразлично, что мы считаем степенями десятки. Природа не укладывается в эту нашу систему счёта.

Например, свет распространяется в вакууме со скоростью 299 792 458 метров в секунду. Ему плевать, что нам для ровного счёта хотелось бы, чтобы он летел со скоростью 300 тысяч километров в секунду. А ускорение свободного падения тела возле поверхности Земли — 9,81 м/с2. Так и хочется спросить: «Тело, а ты не могло бы иметь ускорение 10 м/с2?» — но телу плевать на наши системы счисления.

Двоичная система (тоже нормальная)

Внутри компьютера работают транзисторы. У них нет знаков 0, 1, 2, 3… 9. Транзисторы могут быть только включёнными и выключенными — обозначим их 💡 и ⚫.

Мы можем научить компьютер шифровать наши числа этими транзисторами так же, как шестипалые люди шифровали наши числа буквами. Только у нас будет не 6 букв, а всего две: 💡 и ⚫. И выходит, что в каждом разряде будет стоять не число десяток в разной степени, не число шестёрок в разной степени, а число… двоек в разной степени. И так как у нас всего два знака, то получается, что мы можем обозначить либо наличие двойки в какой-то степени, либо отсутствие:

| 0 — ⚫ 1 — 💡 2 — 💡⚫ 4 — 💡⚫⚫ |

8 — 💡⚫⚫⚫ 9 — 💡⚫⚫💡 10 — 💡⚫💡⚫ 11 — 💡⚫💡💡 12 — 💡💡⚫⚫ 13 — 💡💡⚫💡 14 — 💡💡💡⚫ 15 — 💡💡💡💡 |

16 — 💡⚫⚫⚫⚫ 17 — 💡⚫⚫⚫💡 18 — 💡⚫⚫💡⚫ 19 — 💡⚫⚫💡💡 20 — 💡⚫💡⚫⚫ 21 — 💡⚫💡⚫💡 21 — 💡⚫💡💡⚫ 23 — 💡⚫💡💡💡 24 — 💡💡⚫⚫⚫ 25 — 💡💡⚫⚫💡 26 — 💡💡⚫💡⚫ 27 — 💡💡⚫💡💡 28 — 💡💡💡⚫⚫ 29 — 💡💡💡⚫💡 30 — 💡💡💡💡⚫ 31 — 💡💡💡💡💡 |

32 — 💡⚫⚫⚫⚫⚫ 33 — 💡⚫⚫⚫⚫💡 34 — 💡⚫⚫⚫💡⚫ 35 — 💡⚫⚫⚫💡💡 36 — 💡⚫⚫💡⚫⚫ 37 — 💡⚫⚫💡⚫💡 38 — 💡⚫⚫💡💡⚫ 39 — 💡⚫⚫💡💡💡 40 — 💡⚫💡⚫⚫⚫ 41 — 💡⚫💡⚫⚫💡 42 — 💡⚫💡⚫💡⚫ 43 — 💡⚫💡⚫💡💡 44 — 💡⚫💡💡⚫⚫ 45 — 💡⚫💡💡⚫💡 46 — 💡⚫💡💡💡⚫ 47 — 💡⚫💡💡💡💡 48 — 💡💡⚫⚫⚫⚫ 49 — 💡💡⚫⚫⚫💡 50 — 💡💡⚫⚫💡⚫ 51 — 💡💡⚫⚫💡💡 52 — 💡💡⚫💡⚫⚫ 53 — 💡💡⚫💡⚫💡 54 — 💡💡⚫💡💡⚫ 55 — 💡💡⚫💡💡💡 56 — 💡💡💡⚫⚫⚫ 57 — 💡💡💡⚫⚫💡 58 — 💡💡💡⚫💡⚫ 59 — 💡💡💡⚫💡💡 60 — 💡💡💡💡⚫⚫ 61 — 💡💡💡💡⚫💡 62 — 💡💡💡💡💡⚫ 63 — 💡💡💡💡💡💡 |

Если перед нами число 💡 ⚫💡⚫⚫ 💡💡⚫⚫, мы можем разложить его на разряды, как в предыдущих примерах:

💡 = 1 × 28 = 256

⚫ = 0 × 27 = 0

💡 = 1 × 26 = 64

⚫ = 0 × 25 = 0

⚫ = 0 × 24 = 0

💡 = 1 × 23 = 8

💡 = 1 × 22 = 4

⚫ = 0 × 21 = 0

⚫ = 0 × 20 = 0

256 + 0 + 64 + 0 + 0 + 8 + 4 + 0 + 0 = 332

Получается, что десятипалые люди могут записать это число с помощью цифр 332, а компьютер с транзисторами — последовательностью транзисторов 💡⚫💡⚫⚫ 💡💡⚫⚫.

Если теперь заменить включённые транзисторы на единицы, а выключенные на нули, получится запись 1 0100 1100. Это и есть наша двоичная запись того же самого числа.

Почему говорят, что компьютер состоит из единиц и нулей (и всё тлен)

Инженеры научились шифровать привычные для нас числа в последовательность включённых и выключенных транзисторов.

Дальше эти транзисторы научились соединять таким образом, чтобы они умели складывать зашифрованные числа. Например, если сложить 💡⚫⚫ и ⚫⚫💡, получится 💡⚫💡. Мы писали об этом подробнее в статье о сложении через транзисторы.

Дальше эти суммы научились получать супербыстро. Потом научились получать разницу. Потом умножать. Потом делить. Потом всё это тоже научились делать супербыстро. Потом научились шифровать не только числа, но и буквы. Научились их хранить и считывать. Научились шифровать цвета и координаты. Научились хранить картинки. Последовательности картинок. Видео. Инструкции для компьютера. Программы. Операционные системы. Игры. Нейросети. Дипфейки.

И всё это основано на том, что компьютер умеет быстро-быстро складывать числа, зашифрованные как последовательности включённых и выключенных транзисторов.

При этом компьютер не понимает, что он делает. Он просто гоняет ток по транзисторам. Транзисторы не понимают, что они делают. По ним просто бежит ток. Лишь люди придают всему этому смысл.

Когда человека не станет, скорость света будет по-прежнему 299 792 458 метров в секунду. Но уже не будет тех, кто примется считать метры и секунды. Такие дела.

First invented by Gottfried Leibniz in the 17th century, the binary number system became widely used once computers required a way to represent numbers using mechanical switches.

What Is Binary Code?

Binary is a base-2 number system representing numbers using a pattern of ones and zeroes.

Early computer systems had mechanical switches that turned on to represent 1, and turned off to represent 0. By using switches in series, computers could represent numbers using binary code. Modern computers still use binary code in the form of digital ones and zeroes inside the CPU and RAM.

A digital one or zero is simply an electrical signal that’s either turned on or turned off inside of a hardware device like a CPU, which can hold and calculate many millions of binary numbers.

Binary numbers consist of a series of eight «bits,» which are known as a «byte.» A bit is a single one or zero that makes up the 8 bit binary number. Using ASCII codes, binary numbers can also be translated into text characters for storing information in computer memory.

geralt/pixabay

How Binary Numbers Work

Converting a binary number into a decimal number is very simple when you consider that computers use a base 2 binary system. The placement of each binary digit determines its decimal value. For an 8-bit binary number, the values are calculated as follows:

- Bit 1: 2 to the power of 0 = 1

- Bit 2: 2 to the power of 1 = 2

- Bit 3: 2 to the power of 2 = 4

- Bit 4: 2 to the power of 3 = 8

- Bit 5: 2 to the power of 4 = 16

- Bit 6: 2 to the power of 5 = 32

- Bit 7: 2 to the power of 6 = 64

- Bit 8: 2 to the power of 7 = 128

By adding together individual values where the bit has a one, you can represent any decimal number from 0 to 255. Much larger numbers can be represented by adding more bits to the system.

When computers had 16-bit operating systems, the largest individual number the CPU could calculate was 65,535. 32-bit operating systems could work with individual decimal numbers as large as 2,147,483,647. Modern computer systems with 64-bit architecture have the ability to work with decimal numbers that are impressively large, up to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807!

Representing Information With ASCII

Now that you understand how a computer can use the binary number system to work with decimal numbers, you may wonder how computers use it to store text information.

This is accomplished thanks to something called ASCII code.

The ASCII table consists of 128 text or special characters that each have an associated decimal value. All ASCII-capable applications (like word processors) can read or store text information to and from computer memory.

Some examples of binary numbers converted to ASCII text include:

- 11011 = 27, which is the ESC key in ASCII

- 110000 = 48, which is 0 in ASCII

- 1000001 = 65, which is A in ASCII

- 1111111 = 127, which is the DEL key in ASCII

While base 2 binary code is used by computers for text information, other forms of binary math are used for other data types. For example, base64 is used for transferring and storing media like images or video.

Binary Code and Storing Information

All of the documents you write, web pages you view, and even the video games you play are all made possible thanks to the binary number system.

Binary code allows computers to manipulate and store all types of information to and from computer memory. Everything computerized, even the computers inside your car or your mobile phone, make use of the binary number system for everything you use it for.

Thanks for letting us know!

Get the Latest Tech News Delivered Every Day

Subscribe